The Sense-Organs and Aesthetic Experience

GA 170

Published in The Golden Blade, 1975. Topics include: Enlivening the Sense Processes and Ensouling the Life Processes; Aesthetic Enjoyment and Aesthetic Creativity; and Logic and the Sense for Reality.

15 August 1916, Dornach

Translator Unknown

We have been concerned with getting to know the human being as he is related to the world through the realm of his senses and the organs of his life-processes, and we have attempted to consider some of the consequences of the fact which underlies such knowledge. Above all, we have cured ourselves of the trivial attitude which is taken by many people who like to regard themselves as spiritually minded, when they think they should despise everything that is called material or sense-perceptible. For we have seen that here in the physical world man has been given in his lower organs and his lower activities a reaction of higher activities and higher connections. The sense of touch and the Life-sense, as they are now, we have had to regard as very much tied to the physical, earthly world. The same applies to the Ego-sense, the Thought-sense and the Speech-sense.

It is different with the senses which serve the bodily organism only in an internal way; the sense of Movement, the sense of Balance, the sense of Smell, the sense of Taste, to a certain extent even the sense of Sight. We have had to accustom ourselves to regard these senses as a shadowy reflection of something which becomes great and significant in the spiritual world, when we have gone through death.

We have emphasised that through the sense of Movement we move in the spiritual world among the beings of the several Hierarchies, according to the attraction or repulsion they exercise upon us, expressed in the form of the spiritual sympathies and antipathies we experience after death. The sense of Balance does not only keep us in physical balance, as it does with the physical body here, but in a moral balance towards the beings and influences found in the spiritual world. It is similar with the other senses; the senses of Taste, Smell and Sight. And just where the hidden spiritual plays into the physical world, we cannot look to the higher senses for explanations, but have to turn to those realms of the senses which are regarded as lower. At the present day it is impossible to speak about many significant things of this kind, because today prejudices are so great. Many things that are in a higher spiritual sense interesting and important have only to be said, and at once they are misunderstood and in all sorts of ways attacked. For the time being I have therefore to abstain from pointing out many interesting processes in the realms of the senses which are responsible for important facts of life.

In this respect the situation in ancient times was more favourable, though knowledge could not be disseminated as it can be today. Aristotle could speak much more freely about certain truths than is now possible, for such truths are at once taken in too personal a way and awaken personal likes and dislikes. You will find in the works of Aristotle, for example, truths which concern the human being very deeply but could not be outlined today before a considerable gathering of people. They are truths of the kind indicated recently when I said: the Greeks knew more about the connection between the soul and spirit on the one hand and the physical bodily nature on the other, without becoming materialistic. In the writings of Aristotle you can find, for example, very beautiful descriptions of the outer forms of courageous men, of cowards, of hot-tempered people, of sleepyheads. In a way that has a certain justification he describes what sort of hair, what sort of complexion, what kind of wrinkles brave or cowardly men have, what sort of bodily proportions the sleepyheads have, and so on. Even these things would cause some difficulties if they were set forth today, and other things even more. Nowadays, when human beings have become so personal and really want to let personal feelings cloud their perception of the truth, one has to speak more in generalities if one has, under some circumstances, to describe the truth.

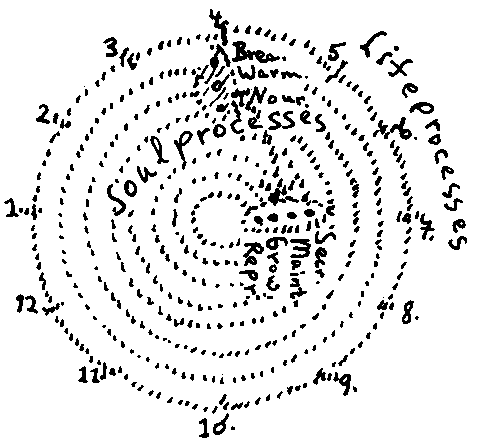

From a certain point of view, every human quality and activity can be comprehended, if we ask the right questions about what has been recently described here. For instance, we have said: the realms of the senses, as they exist in the human being today, are in a way separate and stationary regions, as the constellations of the Zodiac are stationary regions out in cosmic space as compared with the orbiting planets, which make their journeys and alter their positions relatively quickly. In the same way, the regions of the senses have definite boundaries, while the life-processes work through the whole organism, circling through the regions of the senses and permeating them with the effects of their work.

Now we have also said that during the Old Moon period our present sense-organs were still organs of life, still worked as life-organs, and that our present life-organs were then more in the realm of the soul. Think of what has often been emphasised: that there is an atavism in human life, a kind of return to the habits and peculiarities of what was once natural; a falling back, in this case into the Old Moon period. In other words, there can be an atavistic return to the dreamlike, imaginative way of looking at things that was characteristic of Old Moon. Such an atavistic falling back into Moon-visions must today be regarded as pathological.

Please take this accurately: it is not the visions themselves which are pathological, for if this were so, and if all that man experienced during the Old Moon time, when he lived only in such visions, had to be regarded as pathological—then one would have to say that humanity was ill during the Old Moon period; that during the Old Moon period man was in fact out of his mind. That, of course, would be complete nonsense. What is pathological is not the visions themselves, but that they occur in the present earthly organisation of the human being in such a way that they cannot be endured; that they are used by this earthly organisation in a way that is inappropriate for them as Moon visions. For if someone has a Moon vision, this is suited only to lead to a feeling, an activity, a deed which would have been appropriate on the Old Moon. But if someone has a Moon vision here during the Earth period and does things as they are done with an earthly organism, that is pathological. A man acts in that way only because his earthly organism cannot cope with the vision, is in a sense impregnated by it.

Take the crudest example: someone is led to have a vision. Instead of remaining calm before it, and contemplating it inwardly, he applies it in some way to the physical world—although it should be applied only to the spiritual world—and acts accordingly with his body. He begins to act wildly, because the vision penetrates and stirs his body in a way it should not do. There you have the crudest example. The vision should remain within the region to which it naturally belongs. It does not do so if today, as an atavistic vision, it is not tolerated by the physical body. If the physical body is too weak to prevail against the vision, a state of helplessness sets in. If the physical body is strong enough to prevail, it weakens the vision. Then it no longer has the character of pretending to be the same as a thing or process in the sense-world; that is the illusion imposed by a vision on someone made ill by it. If the physical organism is so strong that it can fight the tendency of an atavistic vision to lie about itself, then the person concerned will be strong enough to relate himself to the world in the same way as during the Old Moon period, and yet to adapt this behaviour to his present organism.

What does this mean? It means that the person will to some extent inwardly alter his Zodiac, with its twelve sense-regions. He will alter it in such a way that in his Zodiac, with its twelve sense-regions, more life-processes than sense-processes will occur. Or, to put it better, the effect is to transform the sense-process in the sense-region into a life-process and so to raise it out of its present lifeless condition into life. Thus a man sees, but at the same time something is living in his seeing; he hears and at the same time something is living inwardly in his hearing; instead of living only in the stomach or on the tongue, it lives now in the eye and in the ear. The sense-processes are brought into movement. Their life is stimulated. This is quite acceptable. Then something is incorporated in these sense-organs which today is possessed only to this degree by the life-organs. The life-organs are imbued with a strong activity of sympathy and antipathy. Think how much the whole of life depends upon sympathy and antipathy! One thing is taken, another rejected. These powers of sympathy and antipathy, normally developed by the life-organs, are now poured into the sense-organs. The eye not only sees the colour red; it feels sympathy or antipathy for the colour. Permeation by life streams hack into the sense organs, so we can say that the sense-organs become in a certain way life-regions once more.

The life-processes, too, then have to be altered. They acquire more activity of soul than they normally possess for life on earth. It happens in this way: three life-processes, breathing, warming and nutrition, are brought together and imbued with heightened activity of soul. In ordinary breathing we breathe crude material air; with the ordinary development of warmth it is just warmth, and so on. Now a kind of symbiosis occurs; when these life-processes form a unity, when they are imbued with activity of soul, they form a unity. They are not separate as in the present organism, but set up a kind of association. An inward community is formed by the processes of breathing, warming and nutrition; not coarse nutrition, but a process of nutrition which takes place without it being necessary to eat, and it does not occur alone, as eating does, but in conjunction with the other processes.

Similarly, the other four life-processes are united. Secretion, sustenance, growth and reproduction are united and also form a process embracing activity of soul. Then the two parties can themselves unite: not that all the life-processes then work together, but that, having entered into separate unities of three and four processes, they work together in that form.

This leads to the emergence of soul-powers which have the character of thinking, feeling and willing; again three. But they are different; not thinking, feeling and willing as they normally are on earth, but somewhat different. They are nearer to life-processes, but not as separate as life-processes are on earth. A very intimate and delicate process occurs in a man when he is able to endure something like a thinking back into the Old Moon, not to the extent of having visions, and yet a form of comprehension arises which has a certain similarity to them. The sense-regions become life-regions; the life-processes become soul-processes. A man cannot stay always in that condition, or he would be unfitted for the earth. He is fitted for the earth through his senses and his life-organs being normally such as we have described. But in some cases a man can shape himself in this other way, and then, if his development tends more towards the will, it leads to aesthetic creativity; or, if it tends more towards comprehension, towards perception, it leads to aesthetic experience. Real aesthetic life in human beings consists in this, that the sense-organs are brought to life, and the life-processes filled with soul.

This is a very important truth about human beings, for it enables us to understand many things. The stronger life of the sense-organs and the different life of the sense-realms must be sought in art and the experience of art. And it is the same with the processes of life; they are permeated with more activity of soul in the experience of art than in ordinary life. Because these things are not considered in their reality in our materialistic time, the significance of the alteration which goes on in a human being within the realm of art cannot be properly understood. Nowadays man is regarded more or less as a definite, finished being; but within certain limits he is variable. This is shown by a capacity for change such as the one we have now considered.

What we have gone into here embraces far-reaching truths. Take one example: it is those senses best fitted for the physical plane which have to be transformed most if they are to be led back halfway to the Old Moon condition. The Ego—sense, the Thought-sense, the immediate sense of Touch, because they are directly fitted for the earthly physical world, have to be completely transformed if they are to serve the human condition which results from this going back halfway to the Old Moon period.

For example, you cannot use in art the encounters we have in life with an Ego, or with the world of thought. At the most, in some arts which are not quite arts the same relationship to the Ego and to thought can be present as in ordinary earthly life. To paint the portrait of a man as an Ego, just as he stands there in immediate reality, is not a work of art. The artist has to do something with the Ego, go through a process with it, through which he raises this Ego out of the specialisation in which it lives today, at the present stage in the development of the earth; he has to give it a wide general significance, something typical. The artist does that as a matter of course.

In the same way the artist cannot express the world of thought, as it finds expression in the ordinary earthly world, in an artistic way immediately; for he would then produce not a poem or any work of art, but something of a didactic, instructive kind, which could never really be a work of art. The alterations made by the artist in what is actually present form a way back towards that reanimation of the senses I have described.

There is something else we must consider when we contemplate this transformation of the senses. The life-processes, I said, interpenetrate. Just as the planets cover one another, and have a significance in their mutual relationships, while the constellations remain stationary, so is it with the regions of the senses if they pass over into a planetary condition in human life, becoming mobile and living; then they achieve relationships to one another. Thus artistic perception is never so confined to the realm of a particular sense as ordinary earthly perception is. Particular senses enter into relationships with one another. Let us take the example of painting.

If we start from real Spiritual Science, the following result is reached. For ordinary observation through the senses, the senses of sight, warmth, taste and smell are separate senses. In painting, a remarkable symbiosis, a remarkable association of these senses comes about, not in the external sense-organs themselves, but in what lies behind them, as I have indicated.

A painter, or someone who appreciates a painting, does not merely look at its colours, the red or blue or violet; he really tastes the colours, not of course with the physical sense-organ—then he would have to lick it with his tongue. But in everything connected with the sphere of the tongue a process goes on which has a delicate similarity to the process of tasting. If you simply look at a green parrot in the way we grasp things through the senses, it is your eyes that see the green colour. But if you appreciate a painting, a delicate imaginative process comes about in the region behind your tongue which still belongs to the sense of taste, and this accompanies the process of seeing. Not what happens upon the tongue, but what follows, more delicate physiological processes—they accompany the process of seeing, so that the painter really tastes the colour in a deeper sense in his soul. And the shades of colour are smelt by him, not with the nose, but with all that goes on deeper in the organism, more in the soul, with every activity of smelling. These conjoined sense-activities occur when the realms of the senses pass over more into processes of life.

If we read a description which is intended to inform us about the appearance of something, or what is done with something, we let our speech-sense work, the word-sense through which we learn about this or that. If we listen to a poem, and listen in the same way as to something intended to convey information, we do not understand the poem. The poem is expressed in such a way that we perceive it through the speech-sense, but with the speech-sense alone we do not understand it. We have also to direct towards the poem the ensouled sense of balance and the ensouled sense of movement; but they must be truly ensouled. Here again united activities of the sense-organs arise, and the whole realm of the senses passes over into the realm of life. All this must be accompanied by life-processes which are ensouled, transformed in such a way that they participate in the life of the soul, and are not working only as ordinary life-processes belonging to the physical world.

If the listener to a piece of music develops the fourth life-process, secretion, so far that he begins to sweat, this goes too far; it does not belong to the aesthetic realm when secretion leads to physical excretion. It should be a process in the soul, not going as far as physical excretion; but it should be the same process that underlies physical excretion. Moreover, secretion should not appear alone. All four life-processes—secretion, sustenance, growth and reproduction—should work together, but all in the realm of soul. So do the life-processes become soul-processes.

On the one hand, Spiritual Science will have to lead earth-evolution towards the spiritual world; otherwise, as we have often seen, the downfall of mankind will come about in the future. On the other hand, Spiritual Science must renew the capacity to take hold of and comprehend the physical by means of the spirit. Materialism has brought not only an inability to find the spiritual, but also an inability to understand the physical. For the spirit lives in all physical things, and if one knows nothing of the spirit, one cannot understand the physical. Think of those who know nothing of the spirit; what do they know of this, that all the realms of the senses can be transformed in such a way that they become realms of life, and that the life-processes can be transformed in such a way that they appear as processes of the soul? What do present-day physiologists know about these delicate changes in the human being? Materialism has led gradually to the abandonment of everything concrete in favour of abstractions, and gradually these abstractions are abandoned, too. At the beginning of the nineteenth century people still spoke of vital forces. Naturally, nothing can be done with such an abstraction, for one understands something only by going into concrete detail. If one grasps the seven life-processes fully, one has the reality; and this is what matters—to get hold of the reality again. The only effect of renewing such abstractions as elan vital and other frightful abstractions, which have no meaning but are only admissions of ignorance, will be to lead mankind—although the opposite may be intended—into the crudest materialism, because it will be a mystical materialism. The need for the immediate future of mankind is for real knowledge, knowledge of the facts which can be drawn only from the spiritual world. We must make a real advance in the spiritual comprehension of the world.

Once more we have to think back to the good Aristotle, who was nearer to the old vision than modern man. I will remind you of only one thing about old Aristotle, a peculiar fact. A whole library has been written about catharsis, by which he wished to describe the underlying purpose of tragedy. Aristotle says: Tragedy is a connected account of occurrences in human life by which feelings of fear and compassion are aroused; but through the arousing of these feelings, and the course they take, the soul is led to purification, to catharsis. Much has been written about this in the age of materialism, because the organ for understanding Aristotle was lacking. The phrase has been understood only by those who saw that Aristotle in his own way (not, of course, the way of a modern materialist) means by catharsis a medical or half-medical term. Because the life-processes become soul-processes, the aesthetic experience of a tragedy carries right into the bodily organism those life-processes which normally accompany fear and compassion. Through tragedy these processes are purified and at the same time ensouled. In Aristotle's definition of catharsis the entire ensouling of the life-processes is embraced. If you read more of his Poetics you will feel in it something like a breath of this deeper understanding of the aesthetic activity of man, gained not through a modern way of knowledge, but from the old traditions of the Mysteries. In reading Aristotle's Poetics one is seized by immediate life much more than one can be in reading anything by present day writers on aesthetics, who only sniff round things and encompass them with dialectics, but never reach the things themselves.

Later on a significant high-point in comprehending aesthetic activity of man was reached in Schiller's Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man (1795). It was a time given more to abstractions. Today we have to add the spiritual to a thinking that remains in the realm of idealism. But if we look at this more abstract character of the time of Goethe and Schiller, we can see that the abstractions in Schiller's Aesthetic Letters embrace something of what has been said here. With Schiller it seems that the process has been carried down more into the material, but only because this material existence requires to be penetrated more deeply by the power of the spiritual, taken hold of intensively. What does Schiller say? He says: Man as he lives here on earth has two fundamental impulses, the impulse of reason and the impulse that comes from nature. Through a natural necessity the impulse of reason works logically. One is compelled to think in a particular way; there is no freedom in thinking. What is the use of speaking of freedom where this necessity of reason prevails? One is compelled to think that three times three is not ten, but nine. Logic signifies the absolute necessity of reason. So, says Schiller, when man accepts the pure necessity of reason, he submits to spiritual compulsion.

Schiller contrasts the necessity of reason with the needs of the senses, which live in everything present in instinct, in emotion. Here, too, man is not free, but follows natural necessity. Now Schiller looks for the condition midway between rational necessity and natural necessity. This middle condition, he finds, emerges when rational necessity bows before the feelings that lead us to love or not to love something; so that we no longer follow a rigid logical necessity when we think but allow our inner impulses to work in shaping our mental images, as in aesthetic creation. And then natural necessity, on its side, is transcended. Then it is no longer the needs of the senses which bring compulsion, for they are ensouled and spiritualised. A man no longer desires simply what his body desires, for sensuous enjoyment is spiritualised. Thus rational necessity and natural necessity come nearer to one another.

You should, of course, read this in Schiller's Aesthetic Letters themselves; they are among the most important philosophical works in the evolution of the world. In Schiller's exposition there lives what we have just heard here, though with him it takes the form of metaphysical abstraction. What Schiller calls the liberation of rational necessity from its rigidity, this is what happens when the senses are reanimated, when they are led back once more to the process of life. What Schiller calls the spiritualisation of natural need—he should really have called it “ensouling”—this happens where the life-processes work like soul-processes. Life-processes become more ensouled; sense-processes become more alive. That is the real procedure, though given a more abstract conceptual form, that can be traced in Schiller's Aesthetic Letters. Only thus could he express it at that time, when there was not yet enough spiritual strength in human thoughts to reach down into that realm where spirit lives in the way known to the seer. Here spirit and matter need not be contrasted, for it can be seen how spirit penetrates all matter everywhere, so that nowhere can one come upon matter without spirit. Thinking remains mere thinking because man is not able to make his thoughts strong enough, spiritual enough, to master matter, to penetrate into matter as it really is.

Schiller was not able to recognise that life-processes can work as soul-processes. He could not go so far as to see that the activity which finds material expression in nutrition, in the development of warmth and in breathing, can live enhanced in the soul, so that it ceases to be material. The material particles vanish away under the power of the concepts with which the material processes are comprehended. Nor was Schiller able to get beyond regarding logic as simply a dialectic of ideas; he could not reach the higher stage of development, attainable through initiation, where the spiritual is experienced as a process in its own right, so that it enters as a living force into what otherwise is merely cognition. Schiller in his Aesthetic Letters could not quite trust himself to reach the concrete facts. But through them pulses an adumbration of something that can be exactly grasped if one tries to lay hold of the living through the spiritual and the material through the living.

So we see in every field how evolution as a whole is pressing on towards knowledge of the spirit. When, at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, a philosophy was developed more or less out of concepts, longings were alive in it for a greater concreteness, though this could not yet be achieved. Because the power to achieve it was inadequate, the endeavour and the longing for greater concreteness fell into the crude materialism that has continued from the middle of the nineteenth century up to the present day. But it must be realised that spiritual understanding cannot reside only in a turning towards the spiritual, but must and can overcome the material and recognise the spirit in matter. As you will see, this has further consequences. You will see that man as an aesthetic being is raised above earthly evolution into another world. And this is important. Through his aesthetic attitude of mind or aesthetic creativity a man no longer acts in a way that is entirely appropriate for the earth, but raises the sphere of his being above the sphere of the earth. In this way through our study of aesthetics we approach some deep mysteries of existence.

In saying such things, one may touch the highest truths, and yet sound as if one were crazy. But life cannot be understood if one retreats faint heartedly before the real truths. Take a work of art, the Sistine Madonna, the Venus of Milo—if it is really a work of art, it does not entirely belong to the earth. It is raised above the events of earth; that is quite obvious. What sort of power, then, lives in it—in a Sistine Madonna, in a Venus of Milo? A power, which is also in man, but which is not entirely fitted for the earth. If everything in man were fitted only for the earth, he would be unable to live on any other level of existence as well. He would never go on to the Jupiter evolution. Not everything is fitted for the earth; and for occult vision not everything in man is in accord with his condition as a being of the earth. There are hidden forces which will one day give man the impetus to develop beyond earth-existence. But art itself can be understood only if we realise that its task is to point the way beyond the purely earthly, beyond adaptation to earthly conditions, to where the reality in the Venus of Milo can be found.

We can never acquire a true comprehension of the world unless we first recognise something which there will be increasing need to recognise as we go forward to meet the future and its demands.

It is often thought today that when anyone makes a logical statement that can be logically proved, the statement must be applicable to life. Logic alone, however, is not enough. People are always pleased when they can prove something logically; and we have seen arise in our midst, as you know, all kinds of world outlooks and philosophical systems, and no-one familiar with logic will doubt they can all be logically proved. But nothing is achieved for life by these logical proofs. The point is that our thinking must be brought into line with reality, not merely with logic. What is merely logical is not valid—only what is in keeping with reality.

Let me make this clear by an example. Imagine a tree-trunk lying there before you, and you set out to describe it. You can describe it quite correctly, and you can prove, beyond a doubt, that something real is lying there because you have described it in exact accordance with external reality. But in fact you have described an untruth; what you have described has no real existence. It is a tree-trunk from which the roots have been cut away, and the boughs and branches lopped off. But it could have come into existence only along with boughs and blossoms and roots, and it is nonsense to think of the mere trunk as a reality. By itself it is no reality; it must be taken together with its forces of growth, with all the inner forces which enabled it to come into being. We need to see with certainty that the tree-trunk as it rests there is a lie; we have a reality before us only when we look at a tree. Logically it is not necessary to regard a tree-trunk as a lie, but a sense for reality demands that only the whole tree be regarded as truth. A crystal is a truth, for it can exist independently—independently in a certain sense, for of course everything is relative. A rosebud is not a truth. A crystal is; but a rosebud is a lie if regarded only as a rosebud.

A lack of this sense for reality is responsible for many phenomena in the life of today. Crystallography and, at a stretch, mineralogy are still real sciences; not so geology. What geology describes is as much an abstraction as the tree-trunk. The so-called “earth's crust” includes everything that grows up out of it, and without that it is unthinkable. We must have philosophers who allow themselves to think abstractly only in so far as they know what they are doing. To think in accordance with reality, and not merely in accordance with logic—that is what we shall have to learn to do, more and more. It will change for us the whole aspect of evolution and history. Seen from the standpoint of reality, what is the Venus of Milo, for instance, or the Sistine Madonna? From the point of view of the earth such works of art are lies; they are no reality. Take them just as they are and you will never come to the truth of them. You have to be carried away from the earth if you are to see any fine work of art in its reality. You have to stand before it with a soul attuned quite differently from your state of mind when you are concerned with earthly things. The work of art that has here no reality will then transport you into the realm where it has reality—the elemental world. We can stand before the Venus of Milo in a way that accords with reality only if we have the power to wrest ourselves free from mere sense-perception.

I have no wish to pursue teleology in a futile sense. We will therefore not speak of the purpose of Art; that would be pedantic, philistine. But what comes out of Art, how it arises in life—these are questions that can be asked and answered. There is no time today for a complete answer, only for a brief indication. It will be helpful if we consider first the opposite question: What would happen if there were no Art in the world? All the forces which flow into Art, and the enjoyment of Art, would then be diverted into living out of harmony with reality. Eliminate Art from human evolution and you would have in its place as much untruth as previously there had been Art.

It is just here, in connection with Art, that we encounter a dangerous situation which is always present at the Threshold of the spiritual world. Listen to what comes from beyond the Threshold and you will hear that everything has two sides! If a man has a sense of reality, he will come through aesthetic comprehension to a higher truth; but if he lacks this sense of reality he can be led precisely by aesthetic comprehension of the world into untruth. There is always this forking of the road, and to grasp this is very important: it applies not only to occultism but to Art. To comprehend the world in accordance with reality will be an accompaniment of the spiritual life that Spiritual Science has to bring about. Materialism has brought about the exact opposite—a thinking that is not in accord with reality.

Contradictory as this may sound, it is so only for those who judge the world according to their own picture of it, and not in accordance with reality. We are living at a stage of evolution when the faculty for grasping even ordinary facts of the physical world is steadily diminishing, and this is a direct result of materialism. In this connection some interesting experiments have been made. They proceed from materialistic thinking; but, as in many other cases, the outcome of materialistic thinking can work to the benefit of the human faculties that are needed for developing a spiritual outlook. The following is one of the many experiments that have been made.

A complete scene was thought out in advance and agreed upon. Someone was to give a lecture, and during it he was to say something that would be felt as a direct insult by a certain man in the audience. This man was to spring from his seat, and a scuffle was to ensue. During the scuffle the insulted man was to thrust his hand into his pocket and draw out a revolver—and the scene was to go on developing from there.

Picture it for yourselves—a whole prearranged programme carried out in every detail! Thirty persons were invited to be the audience. They were no ordinary people: they were law students well advanced in their studies, or lawyers who had already graduated. These thirty witnessed the whole affair and were afterwards asked to describe what had occurred. Those who were in the secret had drawn up a protocol which showed that everything had taken place exactly as planned.

The thirty were no fools, but well-educated people whose task later on would be to go out into the world and investigate how scuffles and scrimmages and many other things come about. Of the thirty, twenty-six gave a completely false account of what they had seen, and only four were even approximately correct ... only four!

For years experiments like this have been made for the purpose of demonstrating how little weight can be attached to depositions given before a court of justice. The twenty-six were all present; they could all say: “I saw it with my own eyes.” People do not in the least realise how much is required in order to set forth correctly a series of events that has taken place before their very eyes.

The art of forming a true picture of something that takes place in our presence needs to be cultivated. If there is no feeling of responsibility towards a sense-perceptible fact, the moral responsibility which is necessary for grasping spiritual facts can never be attained. In our present world, with its stamp of materialism, what feeling is there for the seriousness of the fact that among thirty descriptions by eyewitnesses of an event, twenty-six were completely false, and four only could be rated as barely correct? If you pause to consider such a thing, you will see how tremendously important for ordinary life the fruits of a spiritual outlook can become.

Perhaps you will ask: Were things different in earlier times? Yes, in those times men had not developed the kind of thinking we have today. The Greeks were not possessed of the purely abstract thinking we have, and need to have, in order that we may find our place in the world in the right way for our time. But here were are concerned not with ways of thinking, but with truth.

Aristotle tried, in his own way, to express an aesthetic understanding of life in much more concrete concepts. And in the earliest Greek times it was expressed, still more concretely, in Imaginations that came from the Mysteries. Instead of concepts, the men of those ancient times had pictures. They would say: Once upon a time lived Uranus. And in Uranus they saw all that man takes in through his head, through the forces which now work out through the senses into the external world. Uranus—all twelve senses—was wounded; drops of blood fell into Maya, into the ocean, and foam spurted up. Here we must think of the senses, when they were more living, sending down into the ocean of life something which rises up like foam from the pulsing of the blood through life-processes which have now become processes in the soul.

All this may be compared with the Greek Imagination of Aphrodite, Aphrogenea, the goddess of beauty rising from the foam that sprang from the blood-drops of the wounded Uranus. In the older form of the myth, where Aphrodite is a daughter of Uranus and the ocean, born from the foam that rises from the blood-drops of Uranus, we have an imaginative rendering of the aesthetic situation of mankind, and indeed a thought of great significance for human evolution at large.

We need to connect a further idea with this older form of the myth, where Aphrodite is the child not of Zeus and Dione, but of Uranus and the ocean. We need to add to it another Imagination which enters still more deeply into reality, reaching not merely into the elemental world but right down into physical reality. Beside the myth of Aphrodite, the myth of the origin of beauty among mankind, we must set the great truth of the entry into humanity of primal goodness, the Spirit showering down into Maya-Maria, even as the blood-drops of Uranus ran down into the ocean, which also is Maya. Then will appear in its beauty the dawn of the unending reign of the good and of knowledge of the good; the truly good, the spiritual. This is what Schiller had in mind when he wrote, referring especially to moral knowledge:

Nur durch das Morgentor des Schoenen

Dringst du in der Erkenntnis Land.*

* Only through the dawn of beauty canst thou penetrate into the land of knowledge.

You see how many tasks for Spiritual Science are mounting up. And they are not merely theoretical tasks; they are tasks of life.

Neunter Vortrag

Wir haben uns damit beschäftigt, den Menschen kennenzulernen, wie er drinnensteht in der Welt durch seine Sinnesbezirke, durch seine Lebensorgane, und wir haben versucht, einiges von den Folgen der Tatsache ins Auge zu fassen, die diesen Erkenntnissen zugrunde liegt. Wir haben uns vor allen Dingen gewissermaßen geheilt von der trivialen Auffassung, die namentlich manchen Geistig-gesinnt-sein-Wollenden eigen ist, daß alles das, was sie meinen, verachten zu sollen, mit dem Ausdruck «das Stoffliche», «das Sinnliche» belegt wird. Denn wir haben gesehen, daß dem Menschen hier in der physischen Welt gerade in seinen niederen Organen und in seinen niederen Tätigkeiten ein Abglanz gegeben ist von höheren Tätigkeiten und höheren Zusammenhängen. Den Tastsinn, den Lebenssinn, so wie sie jetzt sind, haben wir wohl ansehen müssen als sehr an die physische Erdenwelt gebunden; ebenso den Ichsinn, den Denksinn, den Sprachsinn. Aber dasjenige, was wir in der physischen Erdensphäre finden als die den leiblichen Organismus nur innerlich bedienenden Sinne: Bewegungssinn, Gleichgewichtssinn, Geruchssinn, Geschmackssinn, bis zu einem gewissen Grade auch Sehsinn — diese Sinne gerade haben wir uns bequemen müssen, als Abschattungen von etwas anzusehen, was zu Großem, Bedeutungsvollem wird in der geistigen Welt, wenn wir durch den Tod hindurchgegangen sind. Wir haben betont, daß wir durch den Bewegungssinn in der geistigen Welt uns bewegen zwischen den Wesen der verschiedenen Hierarchien, nach den Anziehungs- und Abstoßungskräften, die sie auf uns ausüben, und die sich in den geistigen Sympathien und Antipathien äußern, die dann nach dem Tode von uns erlebt werden. Der Gleichgewichtssinn erhält uns nicht nur im physischen Gleichgewicht, wie hier den physischen Leib, sondern in moralischem Gleichgewicht gegenüber den Wesen und Einwirkungen, die in der geistigen Welt sind. Und so die anderen Sinne: Geschmackssinn, Geruchssinn, Sehsinn. Und insofern gerade das verborgene Geistige hereinspielt in die physische Welt, können wir uns nicht an die höheren Sinne wenden, um Erklärungen dafür zu haben, sondern wir müssen uns an die sogenannten niederen Sinnesbezirke wenden. Allerdings ist es in der Gegenwart nicht möglich, über manche sehr bedeutsame Dinge nach dieser Richtung zu sprechen, weil ja heute die Vorurteile so groß sind, daß man gerade bedeutsame und in höherem geistigen Sinne interessante Dinge nur auszusprechen braucht, um mißverstanden und in allerlei Richtung angeschuldigt zu werden. Und so muß ich es denn auch vorläufig unterlassen, auf manche interessante Vorgänge der Sinnesgebiete mit wichtigen Tatsachen des Lebens hinzuweisen.

In dieser Beziehung waren ja in alten Zeiten günstigere Verhältnisse. Allerdings gab es auch nicht die Art der Verbreitungsmöglichkeit der Erkenntnisse wie heute. Aristoteles konnte über gewisse Wahrheiten viel unbefangener sprechen, als das heute möglich ist, wo diese Wahrheiten gleich in irgendeinem Sinne persönlich aufgefaßt werden und persönliche Sympathien oder Antipathien erwecken. Sie finden in Aristoteles®’ Werken zum Beispiel Wahrheiten, die den Menschen tief betreffen, und die man heute gar nicht gut entwickeln könnte vor einer großen Versammlung, Wahrheiten, auf die ich in den letzten Betrachtungen hindeutete, indem ich sagte: Die Griechen wußten noch mehr von dem Zusammenhange des Seelisch-Geistigen mit dem PhysischLeiblichen, ohne dadurch in Materialismus zu verfallen. In Aristoteles’ Schriften können Sie zum Beispiel sehr schöne Ausführungen finden, wie äußerlich gestaltet sind die tapferen Menschen, die feigen, die zornmütigen, die schlafsüchtigen Menschen. Da wird in einer gewissen richtigen Weise erzählt, was für Haare, was für eine Gesichtsfarbe, was für eine Art von Runzeln die Mutigen, die Feigen haben, wie die Schlafsüchtigen körperlich gestaltet sind und so weiter. Schon das darzustellen würde heute einigeSchwierigkeiten bereiten, andere Dinge noch mehr. Daher muß man heute, wo die Menschen so persönlich geworden sind und durch das Persönliche in vieler Beziehung über die Wahrheit sich direkt benebeln wollen, sich mehr in Allgemeinheiten verbreiten, wenn man unter gewissen Verhältnissen die Wahrheit darzustellen hat. |

Es ist jede menschliche Art und Betätigung von einer gewissen Richtung her zu verstehen, wenn man in der rechten Art und Weise die nötigen Fragen stellt an das, was wir in den letzten Betrachtungen vor unsere Seele hingestellt haben. Wir haben zum Beispiel gesagt: Die Sinnesbezirke, so wie sie heute im Menschen sind, sind gewissermaßen voneinander getrennte und ruhende Bezirke, wie die Tierkreisbilder draußen im Weltenraume ruhende Bezirke sind, im Gegensatz zu dem, was in den Planeten erscheint, die da kreisen, die da wandeln, die ihren Ort in verhältnismäßig rascher Weise ändern. So sind die Sinnesbezirke gewissermaßen fest abgegrenzt in ihren Regionen, während die Lebensprozesse durch den ganzen Organismus pulsen und die einzelnen Sinnesbezirke durchkreisen, das heißt durchkraften in ihrem Wirken.

Nun haben wir aber auch gesagt, daß während der alten Mondenzeit unsere heutigen Sinnesorgane noch Lebensorgane waren, daß sie noch gewirkt haben als Lebensorgane, und daß unsere heutigen Lebensorgane noch im wesentlichen mehr seelischer Art waren in der alten Mondenzeit. Nun denken Sie an das, was ja öfter betont worden ist: daß es einen Atavismus gibt im menschlichen Leben, eine Art Wiederum-Zurückkehren zu den Gewohnheiten, zu den Eigentümlichkeiten dessen, was früher einmal - in diesem Falle während der Mondenzeit — naturgemäß war; eine Art Zurückfallen. Wir wissen, daß es ein atavistisches Zurückfallen gibt in die Art der traumhaft-imaginativen Anschauungsweise der Mondenzeit. Dieses atavistische Zurückfallen in Mondenvisionen müssen wir heute als krankhaft bezeichnen.

Nun bitte, fassen Sie streng ins Auge: Nicht die Visionen als solche sind krankhaft, denn sonst wäre ja alles, was der Mensch während der Mondenzeit erlebt hat, wo er nur in solchen Visionen lebte, als krankhaft zu bezeichnen, und man wäre genötigt zu sagen, der Mensch hat während der Mondenzeit einen Krankheitsprozeß, noch dazu einen seelischen Krankheitsprozeß durchgemacht, er war verrückt während der alten Mondenzeit. Das wäre natürlich ein vollständiger Unsinn, das kann man nicht sagen. Das Krankhafte liegt nicht in den Visionen als solchen, sondern es liegt darin, daß sie in der gegenwärtigen Erdenorganisation des Menschen so vorhanden sind, daß sie nicht ertragen werden, daß sie so angewendet werden von dieser Erdenorganisation, wie es ihnen als Mondenvisionen nicht angemessen ist. Denken Sie, wenn einer eine Mondenvision hat, so ist diese ja eigentlich nur geeignet, zu einem Gefühle, zu einer Tätigkeit, zu einer Handlung zu führen, wie es dem Monde entsprechend war. Wenn er aber eine Mondenvision hier während der Erdenzeit hat und er macht solche Dinge, wie man sie nur mit einem Erdenorganismus tut, so besteht darin das Krankhafte. Und das tut er nur, weil sein Erdenorganismus die Vision nicht erträgt, wenn sich der Erdenorganismus gewissermaßen imprägniert mit der Vision.

Nehmen Sie den gröbsten Fall: Jemand wird veranlaßt, eine Vision zu haben. Statt nun mit dieser Vision ruhig zu bleiben und sie innerlich anzuschauen, wendet er sie irgendwie, während sie nur auf die geistige Welt anzuwenden ist, auf die physische Welt an und verhält sich danach mit seinem Leib. Das heißt, er fängt an zu toben, weil die Vision seinen Leib durchdringt, durchkraftet, was sie nicht sollte. Da haben Sie den gröbsten Fall. Sie sollte stehenbleiben innerhalb der Region, in der die Vision lebt, und das tut sie nicht, wenn sie heute als atavistische Vision nicht ertragen wird von dem physischen Leib. Wenn der physische Leib zu schwach ist, um aufzukommen gegen die Vision, dann tritt Kraftlosigkeit ein. Wenn der physische Leib stark genug ist, um gegen sie aufzukommen, dann schwächt er die Vision ab. Sie hat dann nicht jenen Charakter, durch den sie einem vorlügt, sie wäre etwas gleich einem Dinge oder Vorgang in der Sinneswelt; denn das lügt ja die Vision demjenigen vor, der dadurch krankhaft wird. Wenn also der physische Organismus so stark ist, daß er die Neigung der atavistischen Vision, zu lügen, bekämpft, dann wird das Folgende eintreten: dann wird der Mensch stark genug sein, sich in einer ähnlichen Weise zur Welt zu verhalten, wie während der alten Mondenzeit, und doch dieses Verhalten dem heutigen Organismus anzupassen.

Was heißt denn das? Das heißt, der Mensch wird seinen Tierkreis mit den zwölf Sinnesbezirken innerlich etwas verändern. Er wird ihn so verändern, daß in diesem Tierkreis mit seinen zwölf Sinnesbezirken mehr Lebensprozesse als Sinnesprozesse sich abspielen, oder besser gesagt, Prozesse sich abspielen, die zwar den Sinnesprozeß anschlagen, aber ihn in dem Sinnesbezirk zum Lebensprozeß umgestalten, also den Sinnesprozeß aus dem Toten, das er heute hat, herausheben und ins Lebendige umsetzen, so daß der Mensch sieht, aber in dem Sehen zugleich drinnen etwas lebt; daß er hört und zugleich in dem Hören drinnen etwas lebt, wie es sonst nur im Magen lebt oder auf der Zunge, so im Auge und so im Ohr. Die Sinnesprozesse werden eben in Bewegung gebracht. Ihr Leben wird angeregt. Das kann ruhig geschehen. Dann wird diesen Sinnesorganen einverleibt etwas von dem, was sonst nur die Lebensorgane heute in demselben Grade haben. Die Lebensorgane haben eine starke innerliche Durchkraftung mit Sympathie - und Antipathie. Denken Sie, wie das ganze Leben abhängt von Sympathie und Antipathie! Das eine wird aufgenommen, das andere abgestoßen. Das, was die Lebensorgane sonst entfalten an sympathischen und antipathischen Kräften, das wird gleichsam den Sinnesorganen wieder eingeflößt. Das Auge sieht nicht nur das Rot, sondern es empfindet Sympathie oder Antipathie mit der Farbe. Das Durchdrungensein mit Leben strömt wieder zu den Sinnesorganen zurück. So daß wir also sagen können: Die Sinnesorgane werden wiederum Lebensbezirke in einer gewissen Weise.

Die Lebensprozesse müssen dann auch verändert werden. Und das geschieht so, daß die Lebensprozesse durchseelter werden als sie für das Erdenleben sind. Es geschieht so, daß die drei Lebensprozesse — Atmung, Wärmung, Ernährung — gewissermaßen zusammengefaßt und beseelt werden, seelischer auftreten. Bei der gewöhnlichen Atmung atmet man die derbe materielle Luft, bei der gewöhnlichen Wärmung die Wärme und so weiter. Nun aber findet eine Art Symbiose statt, das heißt die Lebensprozesse bilden dann eine Einheit, wenn sie durchseelt werden. Sie sind nicht getrennt wie im jetzigen Organismus, sondern sie bilden eine Art Verbindung miteinander, Eine innige Gemeinschaft schließen Atmung, Wärmung, Ernährung im Menschen - nicht die grobe Ernährung, sondern etwas, was Ernährungsprozeß ist; der Prozeß läuft ab, aber man braucht nicht zu essen dabei, aber er läuft auch nicht allein ab wie beim Essen, sondern mit den anderen Prozessen zusammen.

Ebenso werden die vier anderen Lebensprozesse vereinigt. Absonderung, Erhaltung, Wachstum, Reproduktion werden vereinigt und bilden wiederum mehr einen beseelten Prozeß, einen Lebensprozeß, der also mehr seelisch ist. Und dann können sich die zwei Partien selber wieder vereinigen, so daß nicht etwa alle Lebensprozesse zusammenwirken, sondern so zusammenwirken, daß sie sich in drei und vier gliedern, die drei mit den vieren zusammenwirken.

Dadurch entstehen — ähnlich, aber nicht ebenso, wie es jetzt auf der Erde ist — Seelenkräfte, die den Charakter von Denken, Fühlen und Wollen haben: auch drei. Die sind nun anders; nicht Denken, Fühlen und Wollen so wie auf der Erde, sondern etwas anders. Sie sind mehr Lebensprozesse, nicht solch abgesonderte Lebensprozesse wie die der Erde sind. Der Prozeß ist ein sehr intimer, feiner, der da in dem Menschen stattfindet, wo er dieses gleichsam Zurücksinken in den Mond verträgt, wo es nicht zu Visionen kommt, und dennoch eine ähnliche Art, eine leise ähnliche Art des Auffassens stattfindet, wo die Sinnesbezirke zu Lebensbezirken werden, die Lebensprozesse zu Seelenprozessen. Auch kann der Mensch nicht immer so bleiben, denn er würde dann für die Erde unbrauchbar sein. Der Erde ist er ja angepaßt dadurch, daß seine Sinne und auch seine Lebensorgane so sind, wie wir sie beschrieben haben. Aber in gewissen Fällen kann sich der Mensch doch so gestalten, und wenn er sich so gestaltet, dann tritt bei ihm, wenn die Gestaltung sich mehr auf das Wollen legt, ästhetisches Schaffen ein, wenn sich die Gestaltung mehr auf das Auffassen verlegt, auf das Wahrnehmen, ästhetisches Genießen. Das wirkliche ästhetische Verhalten des Menschen besteht darin, daß die Sinnesorgane in einer gewissen Weise verlebendigt werden, und die Lebensprozesse durchseelt werden. Dies ist eine sehr wichtige Wahrheit über den Menschen, denn sie bringt uns vieles zum Verständnis. Jenes stärkere Leben der Sinnesorgane und andersartige Leben der Sinnesgebiete, als das im gewöhnlichen der Fall ist, müssen wir in der Kunst und im Kunstgenuß suchen. Und ebenso ist es bei den Lebensvorgängen, die im Kunstgenuß durchseelter sind als im gewöhnlichen Leben. Weil man diese Dinge nicht der Wirklichkeit gemäß betrachtet in unserer materialistischen Zeit, kann das Bedeutungsvolle der ganzen Veränderung, die mit dem Menschen vorgeht, wenn er im Künstlerischen drinnensteht, auch nicht voll erfaßt werden. Heute betrachtet man ja den Menschen doch mehr oder weniger als ein grob abgeschlossenes Wesen. Aber innerhalb gewisser Grenzen ist doch der Mensch variabel. Und das zeigt eine solche Variabilität, wie wir sie jetzt eben betrachtet haben.

Wenn Sie so etwas wie das eben Ausgeführte haben, dann liegen darinnen eingeschlossen weite, weite Wahrheiten. Um eine solche Wahrheit nur zu erwähnen: Gerade diejenigen Sinne, welche am meisten für den physischen Plan eingerichtet sind, die müssen die größte Veränderung erfahren, wenn sie so gewissermaßen halb ins Mondendasein zurückgeleitet werden. Der Ichsinn, der Denksinn, der grobe Tastsinn, sie müssen, weil sie ja in ganz robustem Sinne für die physische Welt der Erde geeignet sind, sich ganz ändern, wenn sie derjenigen Konstitution des Menschen dienen sollen, welche diesen Weg halb in die Mondenzeit zurückmacht.

So wie wir im Leben dem Ich gegenüberstehen, wie wir im Leben der Gedankenwelt gegenüberstehen, können wir es zum Beispiel in der Kunst schon nicht brauchen. Höchstens in einigen Nebenkünsten kann ein gleiches Verhältnis zum Ich und zum Denken stattfinden wie in dem gewöhnlichen physischen Erdenleben. Einen Menschen seinem Ich nach unmittelbar, wie er in der Wirklichkeit drinnensteht, schildern, porträtieren, gibt keine Kunst. Der Künstler muß mit dem Ich etwas machen, einen Prozeß machen, wodurch er dieses Ich aus der Spezialisierung heraushebt, in der es heute im Erdenprozesse lebt, er muß ihm eine allgemeinste Bedeutung verleihen, etwas Typisches geben. Das tut der Künstler ganz von selber. Ebenso kann der Künstler nicht die Gedankenwelt unmittelbar so künstlerisch zum Ausdruck bringen, wie man sie für die gewöhnliche Erdenwelt zum Ausdruck bringt; denn sonst wird er keine Dichtung oder überhaupt kein Kunstprodukt hervorbringen, sondern höchstens ein lehrhaftes Produkt, irgend etwas Didaktisches, was niemals ein Künstlerisches im wahren Sinne des Wortes sein kann. Die Veränderungen, die da der Künstler vornimmt mit dem, was da ist, die sind ein gewisses Zurückführen zur Verlebendigung der Sinne in der Richtung, wie ich das hier angeführt habe.

Aber es kommt noch etwas dazu, was wir bedenken müssen, wenn diese Veränderung der Sinne ins Auge gefaßt wird. Die Lebensprozesse greifen ineinander, sagte ich. Wie die Planeten einer den andern bedecken und in ihrem gegenseitigen Verhältnis eine Bedeutung haben, während die Sternbilder ruhig bleiben, so werden die Sinnesbezirke, wenn sie gleichsam ins planetarische Menschenleben übergehen, beweglich, lebendig werden, sie werden zueinander Beziehungen erlangen, und daher kommt es, daß das künstlerische Wahrnehmen niemals so auf besondere Sinnesbezirke geht wie das gewöhnliche irdische Wahrnehmen. Es treten auch die einzelnen Sinne in gewisse Beziehungen zueinander. Nehmen wir irgendeinen Fall, zum Beispiel die Malerei.

Für eine von der wirklichen Geisteswissenschaft ausgehende Betrachtung stellt sich folgendes heraus: Für die gewöhnliche Sinnesbeobachtung hat man es zu tun für das Sehen und für den Wärmesinn, für den Geschmackssinn und für den Geruchssinn mit abgesonderten Sinnesbezirken. Da trennt man diese Bezirke. In der Malerei finder eine merkwürdige Symbiose, ein merkwürdiges Zusammengehen dieser Sinnesbezirke statt, nur nicht in den groben Organen, sondern in der Verbreiterung der Organe, wie ich es angedeutet habe in vorhergehenden Vorträgen.

Der Maler oder der die Malerei Genießende sieht nicht bloß den Inhalt der Farbe an, das Rot oder das Blau oder das Violett, sondern er schmeckt die Farbe in Wirklichkeit, nur nicht mit dem groben Organ, sonst müßte er mit der Zunge dran lecken; das tut er ja nicht. Aber mit alledem, was zusammenhängt mit der Sphäre der Zunge, geht etwas vor, was in feiner Weise ähnlich ist dem Geschmacksprozeß. Also wenn Sie einfach einen grünen Papagei anschauen durch den sinnlichen Auffassungsprozeß, so sehen Sie mit Ihren Augen die Grünheit der Farbe. Wenn Sie aber eine Malerei genießen, so geht ein feiner imaginativer Vorgang vor in dem, was hinter Ihrer Zunge liegt und noch zum Geschmackssinn der Zunge gehört, und nimmt teil an dem Sehprozeß. Es sind ähnlich feine Vorgänge wie sonst, wenn Sie schmekken und die Nahrungsmittel verspeisen. Nicht das, was auf der Zunge vorgeht, sondern was sich erst an die Zunge anschließt, feinere physiologische Prozesse, die gehen zugleich mit dem Sehprozeß vor sich, so daß der Maler die Farbe im tieferen seelischen Sinne wirklich schmeckt. Und die Nuancierung der Farbe, die riecht er, aber nicht mit der Nase, sondern mit dem, was bei jedem Riechen seelischer, tiefer in dem Organismus vorgeht. So finden solche Zusammenlagerungen der Sinnesbezirke statt, indem die Sinnesbezirke mehr in Lebensvorgänge, in Bezirke für Lebensvorgänge übergehen.

Wenn wir eine Beschreibung lesen, durch die wir nur unterrichtet werden sollen, wie etwas aussieht oder was mit etwas geschieht, da lassen wir unseren Sprachsinn wirken, den Wortsinn, durch dessen Vermittelung wir informiert werden über dies oder jenes. Wenn wir ein Gedicht anhören, und hören es ebenso an, wie wir etwas anhören, was uns bloß informieren soll, da verstehen wir das Gedicht nicht. Das Gedicht lebt sich zwar so aus, daß wir es durch den Sprachsinn wahrnehmen, aber wenn bloß der Sprachsinn auf das Gedicht gerichtet ist, da verstehen wir es nicht. Es muß außer dem Sprachsinn auf das Gedicht noch gerichtet sein der durchseelte Gleichgewichtssinn und der durchseelte Bewegungssinn; aber eben durchseelt. Da entstehen also wiederum Zusammenlagerungen, Zusammenwirkungen der Sinnesorgane, indem der ganze Sinnesbereich in den Lebensbereich übergeht. Und begleitet muß das alles werden von beseelten, in Seelisches verwandelten Lebensprozessen, die nur nicht so wirken wie die gewöhnlichen Lebensprozesse der physischen Welt.

Wenn einer beim Anhören eines Musikstückes den vierten Lebensprozeß so weit bringt, daß er schwitzt, so geht das zu weit; das gehört nicht mehr zum Ästhetischen, da ist die Absonderung bis zur physischen Absonderung getrieben. Aber erstens soll es nicht zur physischen Absonderung kommen, sondern der Prozeß als seelischer Prozeß verlaufen, aber genau derselbe Prozeß soll verlaufen, der der physischen Absonderung zugrunde liegt, und zweitens soll die Absonderung nicht für sich auftreten, sondern die vier zusammen - aber alle seelisch -: Absonderung, Wachstum, Erhaltung und Reproduktion. Also die Lebensprozesse werden seelischere Prozesse.

Auf der einen Seite wird die Geisteswissenschaft der Erdenentwikkelung die Hinlenkung zur geistigen Welt zu bringen haben, ohne die, wie wir aus Verschiedenem gesehen haben, die Menschheit in der Zukunft verderben wird. Aber auf der anderen Seite muß durch die Geisteswissenschaft auch wieder die Fähigkeit gebracht werden, das Physische mit dem Geistigen zu erfassen, es zu begreifen. Denn es hat ja der Materialismus nicht nur das gebracht, daß man zum Geistigen nicht recht hin kann, sondern er hat auch das gebracht, daß man das Physische nicht mehr verstehen kann. Denn in allem Physischen lebt der Geist, und wenn man vom Geist nichts weiß, kann man das Physische nicht verstehen. Denken Sie, diejenigen, die vom Geist nichts wissen, was wissen die davon, daß die ganzen Sinnesbezirke sich so verwandeln können, daß sie Lebensbezirke werden, daß die Lebensprozesse so sich verwandeln können, daß sie als seelische Prozesse auftreten? Was wissen die heutigen Physiologen von diesen feineren Vorgängen im Menschen? Der Materialismus hat allmählich dazu geführt, daß man von allem Konkreten abgekommen ist und zu Abstraktionen gekommen ist, und diese Abstraktionen, die läßt man nach und nach auch fallen. Im Anfang des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts sprach man noch von Vital- oder Lebenskraft. Natürlich kann man mit einem solchen Abstraktum nichts anfangen, denn erst dann begreift man die Sache, wenn man ins Konkrete hineingeht. Wenn man die sieben Lebensprozesse voll erfaßt, dann hat man die Wirklichkeit, und darum handelt es sich, daß man wieder das Wirkliche bekommt. Mit der Erneuerung von allerlei Abstraktionen wie «Elan vital» oder ähnlichen greulichen Abstraktionen, die nichts besagen, sondern nur Eingeständnisse des Unvermögens, zu erkennen, sind, wird man die Menschheit, trotzdem man vielleicht das Gegenteil will, nur immer mehr in den plumpesten Materialismus, weil sogar in einen mystischen Materialismus, hineinführen. Um das wirkliche Erkennen handelt es sich bei der nächsten Zukunftsentwickelung der Menschheit, um das Erkennen der Tatsachen, die sich nur aus der geistigen Welt heraus ergeben. Und vorrücken müssen wir wirklich in bezug auf die geistige Erfassung der Welt.

Da muß man zunächst auch wiederum zurückdenken an den guten Aristoteles, der der alten Anschauung noch nähergestanden hat als die heutigen Menschen. Nur an eines will ich Sie erinnern bei diesem alten Aristoteles, an eine eigentümliche Tatsache. Es ist eine ganze Bibliothek geschrieben worden über die Katharsis, durch die er darstellen wollte, was der Tragödie zugrunde liegt. Aristoteles sagt: Die Tragödie ist eine zusammenhängende Darstellung von Vorgängen des menschlichen Lebens, durch deren Verlauf die Affekte Furcht und Mitleid erregt werden; aber indem sie erregt werden, wird die Seele zu gleicher Zeit durch die Art des Ablaufes von Furcht und Mitleid zur Läuterung, zur Katharsis von diesen Affekten geführt. — Es ist viel darüber im Zeitalter des Materialismus geschrieben worden, weil man gar nicht das Organ hatte, Aristoteles zu verstehen. Erst diejenigen haben recht, die eingesehen haben, daß Aristoteles eigentlich in seiner Art — nicht im Sinne der heutigen Materialisten — einen medizinischen, halb medizinischen Ausdruck mit der Katharsis meint. Weil die Lebensprozesse seelische Prozesse werden, bedeuten für das ästhetische Empfangen der Eindrücke von der Tragödie die Vorgänge der Tragödie wirklich eine bis ins Leibliche hineingehende Erregung der Prozesse, die sonst als Lebensvorgänge Furcht und Mitleid begleiten. Und geläutert, das heißt zu gleicher Zeit durchseelt werden diese Lebensaffekte durch die Tragödie. Das ganze Seelische des Lebensprozesses liegt in dieser Definition des Aristoteles darinnen. Und wenn Sie mehr lesen in der «Poetik» des Aristoteles, dann werden Sie sehen, daß da - jetzt nicht aus unserer modernen Erkenntnisart heraus, sondern aus der alten Mysterientradition heraus — etwas wie ein Hauch von diesem tiefergehenden Verständnis des ästhetischen Menschen lebt. Beim Lesen der «Poetik» des Aristoteles wird man noch viel mehr ergriffen vom unmittelbaren Leben, als man heute ergriffen werden kann, wenn man irgendeine ästhetische Abhandlung der gewöhnlichen Asthetiker liest, die nur so an den Dingen herumschnüffeln und herumdialektisieren, aber nicht an die Dinge herankommen.

Dann ist wiederum ein bedeutender Höhepunkt in der Erfassung des ästhetischen Menschen bei Schiller in seinen «Briefen über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen». Es war damals eine mehr abstrakte Zeit. Das Geistig-Konkrete, das Spirituelle haben wir erst jetzt zu dem Idealistischen hinzuzufügen. Aber wenn wir auf dieses mehr Abstrakte der Goethe-Schiller-Zeit sehen, so sehen wir doch in den Abstraktionen, die sich in Schillers ästhetischen Briefen finden, etwas von dem, was hier gesagt worden ist, nur daß hier der Prozeß scheinbar mehr ins Materielle hinuntergetragen wird; aber nur, weil dieses Materielle noch mehr durch die Kraft des intensiv erfaßten Geistigen durchdrungen werden soll. Was sagt Schiller? Er sagt: Der Mensch, wie er hier lebt auf der Erde, hat zwei Grundtriebe, den Vernunfttrieb und den Naturtrieb. Der Vernunfttrieb wirkt durch Naturnotwendigkeit logisch. Man ist gezwungen, in einer gewissen Weise zu denken, man hat keine Freiheit zu denken; denn was hilft es einem, auf diesem Gebiete der Vernunftnotwendigkeit von Freiheit zu sprechen, wenn man doch gezwungen ist, nicht zu denken, daß drei mal drei zehn, sondern neun ist. Die Logik bedeutet eine strenge Vernunftnotwendigkeit. So daß Schiller sagt: Wenn der Mensch sich der reinen Vernunftnotwendigkeit fügt, dann steht er unter einem geistigen Zwang.

Der Vernunftnotwendigkeit stellt Schiller die sinnliche Notdurft entgegen, die in alledem, was in den Trieben, in den Emotionen ist, lebt. Da folgt der Mensch auch nicht seiner Freiheit, sondern der Naturnotwendigkeit. Nun sucht Schiller den mittleren Zustand zwischen der Vernunftnotwendigkeit und der Naturnotwendigkeit. Und diesen mittleren Zustand findet er darin, daß die Vernunftnotwendigkeit sich gewissermaßen herabneigt zu dem, was man liebt und nicht liebt, daß man nicht mehr einer starren logischen Notwendigkeit folgt, wenn man denkt, sondern dem inneren Triebe, die Vorstellungen zu fügen oder nicht zu fügen, wie es beim ästhetischen Gestalten der Fall ist. Aber dann geht auch die Naturnotwendigkeit herauf. Dann ist es nicht mehr die sinnliche Notdurft, der man wie unter einem Zwang folgt, sondern es wird die Notdurft verseeligt, vergeistigt. Der Mensch will nicht mehr bloß dasjenige, was sein Leib will,sondern es wird der sinnliche Genuß vergeistigt. Und so nähern sich Vernunftnotwendigkeit und Naturnotwendigkeit.

Sie müssen das natürlich in Schillers ästhetischen Briefen, die zu den bedeutendsten philosophischen Erzeugnissen in der Weltentwickelung gehören, selber nachlesen. In dem, was da Schiller auseinandersetzt, lebt schon das, was wir hier eben gehört haben, nur in metaphysischer Abstraktion. Was Schiller das Befreien der Vernunftnotwendigkeit von der Starrheit nennt, das lebt in dem Lebendigwerden der Sinnesbezirke, die wiederum bis zum Lebensvorgang zurückgeführt werden. Und das, was Schiller die Vergeistigung — besser sollte er sagen «Verseeligung» — der Naturnotdurft nennt, das lebt hier, indem die Lebensprozesse wie Seelenprozesse wirken. Die Lebensprozesse werden seelischer, die Sinnesprozesse werden lebendiger. Das ist der wahre Vorgang, der —- nur mehr in abstrakte Begriffe, in Begriffsgespinste gebracht - sich in Schillers ästhetischen Briefen findet, wie es eben in der damaligen Zeit noch sein mußte, wo man noch nicht spirituell stark genug war mit den Gedanken, um bis in das Gebiet hinunterzukommen, wo der Geist so lebt, wie es der Seher will: daß nicht gegenübergestellt wird Geist und Stoff, sondern erkannt wird, wie der Geist überall den Stoff durchzieht, daß man gar nirgends auf geistlose Stoffe stoßen kann. Die bloße Gedankenbetrachtung ist nur deshalb bloße Gedankenbetrachtung, weil der Mensch nicht imstande ist, seine Gedanken so stark, das heißt so dicht spirituell, so geistig zu machen, daß der Gedanke den Stoff bewältigt, also hineindringt in den wirklichen Stoff. Schiller ist noch nicht imstande, einzusehen, daß die Lebensprozesse wirklich als Seelenprozesse wirken können. Er ist noch nicht imstande, so weit zu gehen, daß er sieht, wie das, was im Materiellen als Ernährung, Wärmung, Atmung wirkt, sich gestalten, wie das seelisch sprühen und leben kann, und aufhört, das Materielle zu sein; so daß die materiellen Teilchen zerstieben unter der Macht des Begriffes, mit dem man die materiellen Prozesse erfaßt. Und ebensowenig ist Schiller schon imstande, so zum Logischen hinaufzuschauen, daß er es wirklich nicht bloß in begrifflicher Dialektik in sich wirken läßt, sondern daß er in jener Entwickelung, welche erreicht werden kann durch Initiation, das Geistige als den eigenen Prozeß erlebt, so daß es wirklich lebend hineinkommt in das, was sonst bloß Erkenntnis ist. Was in Schillers ästhetischen Briefen lebt, ist deshalb ein «Ich trau mich nicht recht heran an das Konkrete». Aber es pulsiert schon darinnen, was man genauer erfaßt, wenn man das Lebendige durch das Geistige und das Stoffliche durch das Lebendige zu erfassen versucht.

So sehen wir in allen Gebieten, wie die ganze Entwickelung hindrängt zu dem, was Geisteswissenschaft will. Als an der Wende des achtzehnten zum neunzehnten Jahrhundert eine mehr oder weniger begrifflich gestaltete Philosophie auftauchte, da lebten in dieser Philosophie die Sehnsuchten nach stärkerer Konkretheit, die aber noch nicht erreicht werden konnte. Und weil die Kraft zunächst ausging, verfiel man mit dem Streben, mit der Sehnsucht nach stärkerer Konkretheit, in den groben Materialismus in der Mitte des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts, in der zweiten Hälfte bis heute. Aber erfaßt werden muß dieses, daß der Spiritualismus nicht bloß darin bestehen kann, zum Geistigen hinzulenken, sondern das Stoffliche zu überwinden und den Geist im Stoffe zu erkennen. Das geschieht durch solche Erkenntnisse. Sie sehen daraus ganz andere Folgen. Sie sehen daraus, der ästhetische Mensch steht so in der Erdenentwickelung drinnen, daß er sich über diese Erdenentwickelung in einer gewissen Weise erhebt in eine andere Welt hinein. Und das ist wichtig. Der ästhetisch gesinnte oder ästhetisch handelnde Mensch tut nicht, was der Erde völlig angepaßt ist, sondern er erhebt in einer gewissen Weise seine Sphäre aus der Erdensphäre heraus. Und damit dringen wir mit dem Ästhetischen an manches tiefe Geheimnis des Daseins.

Wenn man so etwas sagt, so wird es eigentlich etwas, was auf der einen Seite an die höchsten Wahrheiten rührt, nach der anderen Seite fast blödsinnig, verrückt, verdreht klingen kann. Aber man versteht das Leben nicht, wenn man sich feige zurückzieht vor den wirklichen Wahrheiten. Nehmen Sie irgendein Kunstwerk, die Sixtinische Madonna, die Venus von Milo — wenn es wirklich ein Kunstwerk ist, ganz von der Erde ist es nicht. Es ist herausgehoben aus den Geschehnissen der Erde; das ist ja ganz selbstverständlich. Ja, was lebt denn darinnen für eine Kraft? Was lebt in einer Sixtinischen Madonna, in einer Venus von Milo? Eine Kraft, die auch im Menschen ist, die nur nicht ganz der Erde angepaßt ist. Würde im Menschen alles nur der Erde angepaßt sein, so würde er auf keinem anderen Plane auch leben können. Er würde niemals zum Jupiter hinüberkommen, wenn im Menschen alles der Erde angepaßt wäre. Es ist nicht alles der Erde angepaßt, und für den okkult Blickenden stimmt im Menschen nicht alles zu dem, was Erdenmensch ist. Das sind geheimnisvolle Kräfte, die gerade einstmals dem Menschen den Schwung hinaus aus dem Erdendasein geben werden. Aber auch die Kunst als solche kann nur verstanden werden, wenn man sie in ihrer Aufgabe, über das bloß Irdische, über die bloße Erdenanpassung hinauszuweisen, erfaßt, wo das wirklich ist, was in der Venus von Milo ist.

Man kommt einer wirklichen Weltauffassung nicht nahe, wenn man nicht etwas ins Auge faßt, was ganz notwendig ins Auge gefaßt werden muß, je mehr der Mensch der Zukunft und ihren geistigen Anforderungen entgegengeht. Heute lebt man noch vielfach unter dem Vorurteile: Wenn irgend jemand etwas sagt, was logisch ist und logisch bewiesen werden kann, dann hat es auch die notwendige Bedeutung für das Leben. Aber Logizität, Logizismus allein genügen nicht. Und weil die Menschen immer zufrieden sind, wenn sie etwas irgendwie logisch beweisen können, so behaupten sie auch alle möglichen Weltanschauungen und philosophischen Systeme, die selbstverständlich logisch zu beweisen sind; kein Mensch, der mit Logik bekannt ist, zweifelt, daß sie logisch zu beweisen sind. Aber es ist nichts getan für das Leben mit den bloßen logischen Beweisen, sondern was gedacht wird, was innerlich ersonnen wird, muß nicht nur logisch erdacht, ersonnen sein, sondern wirklichkeitsgemäß. Was bloß logisch ist, gilt nicht; das Wirklichkeitsgemäße nur gilt. Ich werde es Ihnen nur an einem Beispiele klarmachen. Nehmen Sie an, ein Baumstamm liegt hier vor Ihnen, und Sie beschreiben den Baumstamm. Sie können etwas ganz ordentlich beschreiben und Sie können Jedem beweisen, daß da ein Wirkliches liegt, weil Sie der äußeren Wirklichkeit gemäß beschrieben haben. Sie haben aber doch eigentlich nur eine Lüge beschrieben. Denn das, was Sie da beschreiben, hat kein Dasein, weil es so nicht wirklich sein kann als Baumstamm, der da liegt; sondern von dem Baumstamm hat man die Wurzeln abgeschnitten, hat man die Äste, die Zweige abgeschnitten, und das Stück, das da liegt, das tritt nur ins Dasein so, daß Äste und Blüten und Wurzeln mit ins Dasein treten, und es ist Unsinn, den Stamm als ein Wirkliches zu denken. So wie er sich zeigt, ist er kein Wirkliches. Man muß ihn mit seinen Trieben, mit dem, was er innerlich enthält, damit er entstehen kann, zusammennehmen. Man muß überzeugt sein davon, daß das, was da vor einem liegt als Stamm, eine Lüge ist, weil man nur, wenn man einen Baum ansieht, eine Wahrheit vor sich hat. Logisch ist es nicht gefordert, daß man einen Baumstamm für eine Lüge ansieht, aber wirklichkeitsgemäß ist es gefordert, daß man einen Baumstamm für eine Lüge ansieht und nur einen ganzen Baum für eine Wahrheit. Ein Kristall ist eine Wahrheit, der kann bestehen für sich in einer gewissen Beziehung, allerdings immer nur in einer gewissen Beziehung, denn relativ ist wieder das alles. Aber eine Rosenknospe ist keine Wahrheit. Ein Kristall ist eine Wahrheit; aber eine Rosenknospe ist eine Lüge, wenn man sie nur als eine Rosenknospe ansieht.

Sehen Sie, weil man diese Begriffe des Wirklichkeitsgemäßen nicht hat, entstehen allerlei solche Dinge, wie sie heute entstehen. Kristallographie, auch noch zur Not Mineralogie sind wirklichkeitsgemäße Wissenschaften; Geologie nicht mehr, denn das, was der Geologe beschreibt, ist ebenso eine Abstraktion, wie der Baumstamm eine Abstraktion ist. Wenn er auch daliegt, so ist er doch eine Abstraktion, keine Wirklichkeit. Was geologisch die Erdkruste enthält, das enthält mit dasjenige, was aus ihr herauswächst und ist ohne das nicht denkbar. Und darauf kommt es an, daß Philosophen auftreten, die sich nicht gestatten, Abstraktionen anders zu denken, als indem sie sich der abstrahierenden Kraft bewußt sind, das heißt, indem sie wissen, sie machen bloß Abstraktionen. Wirklichkeitsgemäß denken, nicht bloß logisch denken, das ist etwas, was immer mehr und mehr kommen muß. Unter diesem wirklichkeitsgemäßen Denken aber ändert sich unsere gesamte Weltentwickelung. Denn was ist denn vom Standpunkte eines wirklichkeitsgemäßen Denkens die Venus von Milo, die Sixtinische Madonna oder anderes? Vom Erdenstandpunkte aus aufgefaßt eine Lüge, keine Wahrheit. Nimmt man sie so, wie sie sind, steht man nicht in der Wahrheit. Man muß entrückt werden. Nur der betrachtet ein wirkliches Kunstwerk richtig, der aus der Erdensphäre entrückt wird, weggenommen wird, der wirklich vor der Venus von Milo so steht, daß er anders seelisch konstituiert ist, als er den irdischen Dingen gegenüber konstituiert ist; denn dadurch wird er gerade durch das, was nicht hier wirklich ist, hineingestoßen in das Gebiet, wo es wirklich ist, in das Gebiet der elementarischen Welt, wo das wirklich ist, was in der Venus von Milo ist. Gerade dadurch steht man wirklichkeitsgemäß der Venus von Milo gegenüber, daß sie die Kraft besitzt, einen herauszureißen aus dem bloßen sinnlichen Anschauen.

Ich will nicht Teleologie treiben in schlechtem Sinne, das sei weit entfernt. Daher soll auch nichts gesagt werden über den Zweck der Kunst, denn das wäre außerdem Pedanterie, Philistrosität. Nicht über den Zweck der Kunst soll gesprochen werden. Aber was aus der Kunst wird, wodurch sie dasteht im Leben, das kann man sich beantworten. Es ist heute nicht mehr Zeit, das ganz zu beantworten, ich will nur mit ein paar Worten vorläufig darauf hindeuten. Man kann manches beantworten, wenn man sich die Gegenfrage stellt: Was würde denn geschehen, wenn nun gar keine Kunst in der Welt wäre? — Da würden alle die Kräfte, die sonst in die Kunst und in den Kunstgenuß hineingehen, verwendet werden, um unwirklichkeitsgemäß zu leben. Streichen Sie die Kunst aus der Menschheitsentwickelung, so haben Sie in der Menschheitsentwickelung ebensoviel Lüge, wie sonst Kunstentwikkelung da ist! Da haben Sie schon an der Kunst jenes eigentümliche gefährliche Verhältnis, das dort liegt, wo die Schwelle zur geistigen Welt vorhanden ist. Hinüberhören, wo immer die Dinge zwei Seiten haben! Wenn einer einen wirklichkeitsgemäßen Sinn hat, dann kommt er durch das Leben in ästhetischer Auffassung zu einer höheren Wahrheit. Wenn einer nicht wirklichkeitsgemäßen Sinn hat, so kann er gerade durch die ästhetische Auffassung der Welt in die Verlogenheit kommen. Die Dinge haben immer eine Gabelung; das ist sehr wichtig, diese Gabelung ins Auge zu fassen. Denn nicht nur dem Okkultismus gegenüber ist das der Fall, sondern schon sogar der Kunst gegenüber ist das der Fall. Wirklichkeitsgemäßes Auffassen der Welt, das wird als eine Begleiterscheinung eintreten des spirituellen Lebens, das die Geisteswissenschaft bringen soll. Denn der Materialismus hat gerade das unwirklichkeitsgemäße Auffassen gebracht.