Historical Necessity and Freewill

GA 179

17 December 1917, Dornach

7. The Inadequacy of Natural Science for the Knowledge of the Life of the Soul. The Experiences of Man's Spirit-Soul with the Hierarchies

In the lectures given during this week there lies much which can lead us to understand the nature of man in its connection with the historical evolution of humanity in such a way as to enable us to gradually form a conception of necessity and free will. Such questions can be less easily decided by means of definitions and combinations of words than by bringing together the relevant truths from the spiritual world. In our age humanity must accustom itself more and more to acquire a different form of understanding for reality from the one so prevalent today, which, after all, holds to very secondary and nebulous concepts bound up with the definitions of words. If we consider what certain persons who think themselves especially clever write and say, we have the feeling that they speak in concepts and ideas which are only apparently clear; in reality however, they are as lacking in clarity as if someone were to speak of a certain object which is made, for example, out of a gourd, so that the gourd is transformed into a flask and used as such. We can then speak about this object as if we were speaking of a gourd, for it is a gourd in reality; but we can also speak of it as if it were a flask, for it is used as a flask. Indeed, the things of which we speak are first determined by the connections we are dealing with; as soon as we no longer rely upon words when we are speaking, but upon a certain perception, then everyone will know whether we mean a flask or a gourd. But then we may not confine ourselves to a description or a definition of the object. For as long as we confine ourselves to a description or definition of this object it can just as well be a gourd as a flask. In a similar way, that which is spoken of today by many philologists—persons who consider themselves very clever—may be the human soul, but it may also be the human body—it may be gourd or it may be flask. I include in this remark a great deal of what is taken seriously at the present time (partly to the detriment of humanity). For this reason it is necessary that a striving should proceed from anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, for which clear, precise thinking is above all a necessity, a striving to perceive the world not in the way in which it is customary today (not by confusing the gourd and the flask) but to see everywhere what is real, be it outer physical reality, or spiritual reality.

We cannot in any case arrive at a real concept of what comes into consideration for the human being when we hold only to definitions and the like; we can do so only when we bear in mind the relationships of life in their reality. And just where such important concepts as freedom (free will) and necessity in social and moral life are concerned, we attain clarity only when we place side by side such spiritual facts as those brought out in these lectures, and always strive to balance one against the other in order to reach a judgment as to reality.

Bear in mind that over and over again—even in public lectures and also here—I have brought out with a certain intensity, from the most varied points of view, the fact that we can only rightly grasp what we call concepts when we bring them into relation with our bodily organism, in such a way that the basis of concepts in the body is not seen in something growing and flourishing, but just the opposite—something dying, something in partial decay in the body. I have expressed this in public lectures by saying that the human being really dies continually in his nervous system. The nerve-process is such that it must limit itself to the nervous system. For if it were to spread itself over the rest of the organism, if in the rest of the organism the same thing were to go on that goes on in the nerves, this would signify the death of man at every moment. We may say that concepts arise where the organism destroys itself. We die continuously in our nervous system. For this reason spiritual science is placed under the necessity of pursuing other processes besides the ascending processes which natural science of today considers authentic. These ascending processes are the processes of growth; they reach their summit within the unconscious. Only when the organism begins to develop the processes of decline does the activity of the soul appear which we designate as conceptual or indeed as perceptive activity of the senses. This process of destruction, this slow process of death, must exist if anything at all is to be conceived. I have shown that the free actions of human beings rest upon just this fact, that the human being is in a position to seek the impulses for his actions out of pure thoughts. These pure thoughts have [the] most influence upon the processes of disintegration in the human organism. What happens in reality when man enacts a free deed? Let us realize what happens in the case of an ordinary person when he performs an act out of moral fantasy—you know now what I mean by this—out of moral fantasy, this means out of a thinking which is not ruled by sense-impulses, sense-desires and passions—what really takes place here in man? The following takes place: He gives himself up to pure thoughts; these form his impulses. They cannot impel him through what they are; the impulses must come from man himself. Thoughts are mere mirror-pictures, they belong to Maya. Mirror-pictures cannot compel. Man must compel himself under the influence of clear concepts.

Upon what do clear concepts work? They work most strongly upon the process of disintegration in the human organism; they bring this about. So we may say that on the one side the process of disintegration arises out of the organism, and on the other, the pure deed-thought (Tat-Gedanke) comes to meet this disintegrating process out of the spiritual world. I mean by this the thought that lies at the basis of deed. Free actions arise by uniting these two through the interaction of the process of disintegration and willed thinking.

I have said that the process of disintegration is not caused by pure thinking; it is there in any case, in fact it is always there. If man does not oppose these processes of disintegration with something coming out of pure thinking, then the disintegrating process is not transformed into an up-building process, then a part that is slowly dying remains within the human being. If you think this through, you will see that the possibility exists that just through the failure to perform free actions man fails to arrest a death process within him. Herein lies one of the subtlest thoughts which man must accept. He who understands this thought can no longer have any doubt in life about the existence of human freedom. An action that is performed in freedom does not occur through something that is caused within the organism but occurs where the cause ceases, in other words, out of a process of disintegration. There must be something in the organism where the causes cease; only then can the pure thought, as motive of the action, set in. But such disintegrating processes are always there, they only remain unused to a certain extent when man does not perform free deeds.

But this also shows the characteristics of an age that will have nothing to do with an understanding of the idea of freedom in its widest extent. The age running from the second half of the 19th century to the present has set itself the particular task of dimming down more and more the idea of freedom in all spheres of life, as far as knowledge is concerned, and of excluding it entirely from practical life. People did not wish to understand freedom, they would not have freedom. Philosophers have made every effort to prove that everything arises out of human nature through a certain necessity. Certainly, a necessity underlies man's nature; but this necessity ceases as disintegrating processes begin, as the sequence of causes comes to an end. When freedom has set in at the point where the necessity in the organism ceases, one cannot say that man's actions arise out of an inner necessity, for they arise only when this necessity ceases. The whole mistake consists in the fact that people have been unwilling to understand not only the up-building forces in the organism, but also the disintegrating processes. However, in order to understand what really underlies man's nature it will be necessary to develop a greater capacity to do this than in our age. Yesterday we saw how necessary it is to be able to look with the eye of the soul upon what we call the human Ego. But just in our times human beings are not very gifted in comprehending this reality of the Ego. I will give an illustration.

I have often referred to the remarkable scientific achievement of Theodor Ziehen “Die physiologische Psychologie”—“Physiological Psychology.” On page 205 the Ego is also spoken of; but Ziehen is never in a position even to indicate the real Ego, he merely speaks of the Ego-concept. We know that this is only a mirror-picture of the real Ego. But it is particularly interesting to hear how a distinguished thinker of today—but one who believes that he can exhaust everything with natural scientific ideas—speaks about the Ego. Ziehen says:

It will perhaps occur to you that the Ego-concept which is expressed in the small word “I,” is a very complex threefold entity containing thousands and thousands of partial concepts. But I beg you to ponder this, the word is indeed short, but its conceptual content must be complex, as shown by the fact that each one of you would be at a loss if he were asked to render in thoughts the content of his so-called Ego-concept.

And now Ziehen attempts to say something about the thought-content of the Ego-concept. Let us now see what the distinguished scholar has to say concerning what we must really think when we think about our Ego.

You will immediately think of your body, [you notice that he says—you will think of your body] of your relationships to the outer world, [connection with the outer world] your family and personal relationships, [in other words you will soon begin to think of your bank account and to count your money!] of your name and title.

Now the distinguished scholar emphatically points out that we must also think of our name and of our title if we are to grasp or to encompass our Ego in the form of concept.

..... Your principal inclinations, predominating ideas and finally your past, and thus prove to yourself how extremely complex this Ego-concept is. Indeed, the reflective human being reduces this complexity of the Ego-concept to a relative simplicity by placing his own Ego as the subject of his feelings, thoughts and movements, against the outer objects and other Egos. Of course, this contrast and this sharpening of the Ego-concept has also its deeper scientific and philosophical basis, but considered purely psychologically this simple Ego is only a theoretical fiction.

Thus “this simple Ego” is only a “theoretical fiction” that means a mere fantasy-concept, which constructs itself when we put together our name, title, or let us assume our rank and other such things also, which make us important! By means of such points we can see the whole weakness of the present way of thinking. And this weakness must be held in mind the more firmly because of the fact that what proves itself to be a decided weakness for the knowledge of the life of the soul is a strength for the knowledge of outer natural scientific facts. What is inadequate for a knowledge of the life of the soul, just this is adequate for penetrating the obvious facts in their immediate outer necessity.

We must not deceive ourselves in regard to the fact that it is one of the characteristics of our times, that people who may be great in one field are exponents of the greatest nonsense in another. Only when we hold this fact clearly in mind—which is so well adapted to throw sand in the eyes of humanity—can we in any way follow with active thought what is required in order to raise again that power which man needs in order to acquire concepts that can penetrate fruitfully and healingly into life. For only those concepts can take firm hold of life as it is today, which are drawn out of the depths of true reality—where we are not afraid to enter deeply into true reality. But it is just this that many people shun today.

At present people are very often inclined to reform the spiritual reality, without first having perceived the true reality out of which they should draw their impulses.

Who today does not go about reforming everything in the world—or at least, believing he can reform it? What do people not draw up from the soul out of sheer nothingness! But at a time such as this only those things can be fruitful which are drawn up from the depths of spiritual reality itself. For this the Will must be active.

The vanity that wishes to take up every possible idea of reform on the basis of emptiness of soul is just as harmful for the development of our present time as materialism itself. At the conclusion of a previous lecture I called your attention to how the true Ego of man, the Ego which indeed belongs to the will-nature and which for this reason is immersed in sleep for the ordinary consciousness, must be fructified through the fact that already through public instruction man is led to a concrete grasp of the great interests of the times, by realizing what

(Gap in the text)

struction man is led to a concrete grasp of the great interests of the times, by realizing what spiritual forces and activities enter into our events and have an influence upon them. This cannot be accomplished with generalized, nebulous speeches about the spirit, but with knowledge of the concrete spiritual events, as we have described them in these lectures, where we have indicated, according to dates, how here and there certain of these powers and forces from the spiritual world have intervened here in the physical.

This brought about what I was able to describe to you as the joint work of the so-called dead and of the so-called living in the whole development of humanity. For the reality of our life of feeling and of will is in the realm where the dead also are. We can say that the reality of our Ego and of our astral body is in the same realm where the dead can also be found. The same thing is meant in both cases. This, however, indicates a common realm in which we are embedded, in which the dead and the living work together upon the tapestry which we may call the social, moral, and historical life of man in its totality; the periods of existence which are lived through between death and a new birth also belong to this realm. We have indicated in these lectures how between death and a new birth the so-called departed one has the animal kingdom as his lowest kingdom, just as the mineral kingdom is our lowest kingdom. We have also pointed out in a certain way, how the departed one has to work within the being of the animal kingdom, and has to build up out of the laws of the animalic the organization that again forms the basis for his next incarnation. We have shown how as second kingdom the departed one experiences all those connections which have their karmic foundation here in the physical world and which, correspondingly transformed, continue within the spiritual world. A second kingdom thus arises for the departed one, which is woven together of all the karmic connections that he has established at any time in an earthly incarnation. Through this, however, everything that the human being has developed between death and a new birth gradually spreads itself out, one might say, quite concretely over the whole of humanity.

The third kingdom through which the human being then passes can be conceived as the kingdom of the Angels. In a certain sense we have already pointed out the role of the Angels during the life between death and a new birth. They carry as it were the thoughts from one human soul to another and back again; they are the messengers of the common life of thought. Fundamentally speaking, the Angels are those Beings among the higher Hierarchies of whom the departed one has the clearest living experience—he has a clear living experience of the relationships with animals and human beings, established through his karma; but among the Beings of the higher Hierarchies he has the clearest conception of those belonging to the Hierarchy of the Angels, who are really the bearers of thoughts, indeed of the soul-content from one being to another, and who also help the dead to transform the animal world. When we speak of the concerns of the dead as personal concerns, we might say that the Beings of the Hierarchy of the Angels must strive above all to look after the personal concerns of the dead. The more universal affairs of the dead that are not personal are looked after more by the Beings of the Kingdom of the Archangeloi and Archai.

If you recall the lectures in which I have spoken about the life between death and a new birth, you will remember that part of the life of the so-called dead consists in spreading out his being over the world and in drawing it together again within himself I have already described and substantiated this more deeply. The life of the dead takes its course in such a way that a kind of alternation takes place between day and night, but so that active life arises from within the departed. He knows that this active life which thus arises is only the reappearance of what he has experienced in that other state which alternates with this one, when his being is spread out over the world and is united with the outer world. Thus when we come into contact with one who is dead we meet alternating conditions, a condition, for instance, where his being is spread out over the world, where he grows, as it were, with his own being into the real existence of his surroundings, into the events of his surroundings. The time when he knows least of all is when his own being that is in a kind of sleeping state grows into the spiritual world around him. When this again rises up within him it constitutes a kind of waking state and he is aware of everything, for his life takes its course within Time and not in space. Just as with our waking day-consciousness we have outside in space that which we take up in our consciousness, and then again withdraw from it in sleep—so from a certain moment onward the departed one takes over into the next period of time the experiences which he has passed through in a former one; these then fill his consciousness. It is a life entirely within Time. And we must become familiar with this.

Through this rhythmic life within Time, the departed enters into a very definite relationship with the Beings of the hierarchy of the Archangeloi and of the Archai. He has not as clear a conception of these Archangeloi and Archai Beings as of the Angels, of man, and of the animal; above all he always has this conception that these Beings, the Archai and Archangeloi, work together with him in this awaking and falling asleep, awaking and falling asleep, in this rhythm which takes place within the course of time. The departed one, when he is able to do so, must always bring to consciousness what he experienced unknowingly in the preceding period of time; then he always has the consciousness that a Being of the Hierarchy of the Archai has awakened him; he is always conscious that he works together with the Archai and Archangeloi in all that concerns this rhythmic life.

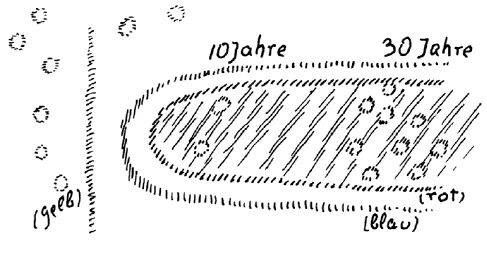

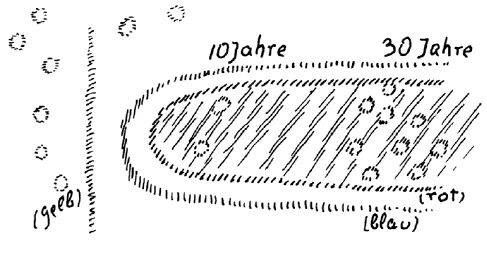

Let us firmly grasp the fact that just as in a waking state we realize that we perceive the outer world of which we know nothing during sleep, just as we realize that this outer world sinks into darkness when we fall asleep, so in the soul of the so-called dead lives this consciousness—Archai, Archangeloi, these are the Beings with whom I am united in a common work in order that I may pass through this life of falling asleep and awaking, falling asleep and awaking, and so forth. We might say that the departed one associates with the Archangeloi and Archai just as in waking consciousness we associate with the plant and mineral world of our physical surroundings. Man cannot however look back upon this interplay of forces in which he is interwoven between death and a new birth. Why not? We may indeed say, why not, but just this looking back is something which man must learn; yet it is difficult for him to learn this owing to the materialistic mentality of today. I would like to show you in a diagram why man does not look back upon this.

Let us suppose that you are facing the world with all your organs of perception and understanding. This will give you a conceptual and perceptive content of a varied kind. I will designate the consciousness of a single moment by drawing different rings or small circles. These indicate what exists in the consciousness during the space of a moment. You know that a memory-process takes place when you look back over events—but in a different manner than modern psychologists imagine this. The time into which you can look back, to which your memory extends, is indicated by this line; it really indicates the space which here reaches a blind alley. This would be the point in your third, fourth or fifth year that is as far back as you can remember in life. Thus all the thoughts which arise when you look back upon your past experiences lie within this space of time. Let us suppose that you think of something in your thirtieth year for instance, and while you are thinking of this you remember something that you experienced ten years ago. If you picture very vividly what is actually taking place in the soul you will be able to form the following thought. You will say, if I look back to the point of time in my childhood which is as far back as I can remember, this constitutes a “sack” in the soul, which has its limits; its blunt end is the point which lies as far back in my childhood as I am able to remember. This is a sort of “sack” in the soul; it is the space of time which we can grasp in memory. Imagine such a “soul-sack” into which you can look while you are looking back in memory; these are the extreme limits of the sack which correspond in reality to the limit between the etheric body and the physical. This boundary must exist, otherwise ... well, to picture it roughly, the events that call forth memory would then always fall through at this point. You would be able to remember nothing, the soul would be a sack without a bottom, everything would fall through it. Thus, a boundary must be there. An actual “soul-sack” must be there. But at the same time this “soul-sack” prevents you from perceiving what you have lived through outside it. You yourself are non-transparent in the life of your soul because you have memories; you are non-transparent because you have the faculty of memory.

You see therefore—that which causes us to have a proper consciousness for the physical plane is at the same time the cause of our being unable to look with our ordinary consciousness into the region that lies behind memory. For it does really lie behind memory. But we can make the effort to gradually transform our memories to some extent. However we must do this carefully. We can begin by trying to keep before us in meditation with more and more accuracy something which we can remember, until we feel that it is not merely something which we take hold of in memory, but something which really remains there. One who develops an intensive, active life of the spirit will gradually have the feeling that memory is not something that comes and goes, comes and goes—but that memory contains something permanent. Indeed, work in this direction can only lead to the conviction that what rises within memory is of a lasting nature and really remains present as Akashic Record, for it does not disappear. What we remember remains in the world, it is there in reality. But we do not progress any further with this method; for merely to remember accurately our personal experiences, and the knowledge that memory remains—this method is in a higher sense too egotistical to lead farther than just to this conviction. On the contrary, if you were to develop beyond a certain point just this capacity of looking upon the permanency of your own experiences, you would obstruct all the more your outlook into the free world of spirit. Instead of the sack of memories, your own life stands there all the more compactly and prevents you from looking through.

Another method may be used in contrast to this; through it, the impressions in the Akashic Record become remarkably transparent, if I may use this expression. When we are once able to look through the stationary memories, we look with a sure eye into the spiritual world with which we are connected between death and a new birth. But to attain this we must not use merely the stationary memories of our own life; these become more and more compact, and we can see through them less and less. They must become transparent. And they become transparent if we make an ever stronger attempt to remember not so much what we have experienced from our own point of view, but more what has come to us from outside. Instead of remembering for instance what we have learned, we should remember the teacher, his manner of speech, what effect he had upon us and what he did with us. We should try to remember how the book arose out of which we learned this or that. We should remember above all what has worked upon us from the outer world. A beautiful and really wonderful beginning, indeed an introduction to such a memory, is Goethe's Wahrheit and Dichtung (his autobiography) where he shows how Time has formed him, how various forces have worked upon him. Because Goethe was able to achieve this in his life, and looked back on his life not from the standpoint of his own experiences, but from the standpoint of others and of the events of the times that worked upon him, he was able to have such deep insight into the spiritual world.

But this is at the same time the way that enables us to come into deeper touch with the time which has taken its course between our last death and our present birth.

Thus you see that today I am referring you, from another point of view, to the same thing to which I have already referred—to extend our interests beyond the personal, to turn our interests and attention not upon ourselves, but upon that that has formed us, that out of which we have arisen. It is an ideal to be able to look back upon time, upon a remote antiquity, and to investigate all the forces that have formed these “fine fellows”—the human beings.

Indeed, when we describe it thus, this offers few difficulties; it is no simple task, but it bears rich fruit because it requires great selflessness. It is just this method that awakens the forces which enable us to enter with our Ego the sphere which the dead have in common with the living. To know ourselves, is less important than to know our time; the task of public instruction in a not too distant future will be to know our time in its concrete reality, not as it now stands in history books ... but time such as it has evolved out of spiritual impulses.

Thus we are also led to extend out interest to a characteristic of our age and its rise from the universal world process. Why did Goethe strive so intense to know Greek art, to understand his age, through and through, to weigh it against earlier ages? Why did he make his Faust go back as far as the Greek age, as far as the age of Helen of Troy, and seek Chiron and the Sphinxes? Because he wished to know his own age and how it had worked upon him, as he could know it only by measuring it against an earlier age. But Goethe does not let his Faust sit still and decipher old state-records, but he leads him back along paths of the soul to the impulses by which he himself has been formed. Within him lies much of that which leads the human being on the one hand to a meeting with the dead, and on the other hand with the Spirits of Time, with the Archangels (this is now evident through the connection of the dead with the Archangels). Through the fact that man comes together with the dead, he also comes in touch with the Archangels and with the Spirits of Time.

Just the impulses that Goethe indicated in his Faust contain that through which the human being extends his interest to the Time Spirit, and that which is preeminently necessary for our times. It is indeed necessary for our times to look in a different way for instance upon Faust. Most of those who study Faust hardly find the real problems contained in it. A few are able to formulate these problems, but the answers are most curious.

Take for example the passage where Goethe really indicates to us that we should reflect. Do people always reflect at this point? Yet Goethe spares no effort to make it clearly understood that people should reflect upon certain things. For instance you know that Erichtho speaks about the site of the Classical Walpurgis-night; she withdraws and the air-traveler Homunculus appears with Faust and Mephistopheles. You will recall the first speeches of Homunculus, Mephistopheles and Faust. After Faust has touched the ground and called out. “Where is she?”—Homunculus says:—

It's more than we can tell

But to enquire would here be well.

Thou 'rt free to hasten, ere the day,

From flame to flame, and seek her so:

Who to the Mothers found his way,

Has nothing more to undergo.

Homunculus says:—

Who to the Mothers found his way,

Has nothing more to undergo.

How does he know that Faust has been with the Mothers? This is a question which necessarily arises; for if you will look back through the book you will find that there is nowhere any indication that Homunculus, a distinct and separate being from Faust, could have known that Faust had been with the Mothers. Now suddenly Homunculus pipes out that, “Who to the Mothers found his way, has nothing more to undergo.” You see, Goethe propounds riddles. With clear-cut necessity it ensues that Homunculus, if he is anything at all, is something within the sphere of consciousness of Faust himself, for he can know what is contained in the sphere of Faust's consciousness only if he himself belongs to this same sphere of consciousness.

Call to mind the various expositions we have given of Faust:—how Homunculus is really nothing else than what must be prepared as astral body, in order that Helen may appear. But for this reason he is in another state of consciousness; his consciousness is spread out over the astral body. When we know that Homunculus comes within the sphere of Faust's consciousness we can understand his knowledge. Goethe makes Homunculus come into existence because, through the creation of Homunculus, Faust's consciousness finds the possibility of transcending itself as it were, not merely of remaining within itself, but of being outside. He, too, is where Homunculus is to be found; Homunculus is a part of Faust's consciousness. Goethe as you see takes alchemy very seriously. There are many such riddles in Faust which are directly connected with the secrets of the spiritual world. We must allow Faust to work upon us so that we become aware of the depths of spiritual reality which are really contained in it. We can only understand a man like Goethe when we realize on the one hand, that he had studied what had formed him really as if he had viewed it from outside, as can be seen in his autobiography (Wahrheit and Dichtung)—and that on the other hand, he knew that this must lead back to distant perspectives, to distant connections with the dead. Faust enters the life of very ancient civilizations of humanity, the life of spiritual Beings lying far back in the past.

[But if one wants to see clearly what is necessary in a positive sense for the present, then one must also have an eye and a feeling for the negative in many respects, one must develop the right feeling for the negative. One must have an eye for everything that prevents the necessary coming together of living people in a common plan with the work of the dead. You can discover these obstacles everywhere today. You find them at every turn. You find them precisely where education — forgive me for using this ugly word — is spread today.1The section in brackets was not available in the original translation.

How can a person today feel truly intelligent, deeply intelligent, enlightened, when he can write something like this: “Swedenborg, whose dark and enigmatic personality even Goethe explored with reverent hesitation, communicated with angels beyond the earth. He said that these supernatural beings, armed with thoughts, even walk around dressed in robes. The struggle for knowledge and enlightenment is not foreign to them, for they have set up a printing press from which they sometimes send a few sheets to particularly fortunate people. The newspapers of the hereafter are then covered with Hebrew letters. A peculiar feature of the venerable biblical symbols is that every line, every edge, every curve conceals a mysterious spiritual value. Man only has to learn to read the angelic squiggles correctly in order to be initiated into the truth of the hereafter, into the reversed, eternally sunlit life, into the blissful festivity and exhilarating paradise of the hereafter. Swedenborg, who sometimes managed to die to earthly life while still alive and to make the transition to the afterlife before physical death, asked the angels many questions and reported on them. Centuries before him, Babylonians, Egyptians, and Jews practiced the same craft of exploration. Generations after him, even to this day, it is done by those beings on earth who are dissatisfied, who want to seek counsel from God about their future, who do not want to renounce the company of their dead, and who finally believe that the bridge built from their dream-filled beds to the realms of the incomprehensible is a solid, seraphic path, cemented and supported by spirits.

And so the person in question, who considers himself very clever, continues his reflections, indulging in cheap mockery of those who try to build a bridge to the hereafter; for this very clever man has read the book of another person who considers himself very clever and writes about it: “This beyond of the senses, inhabited by the soul, is what the weighty book by Max Dessoir wants to describe anew, after thousands of thinkers have already entered this path to the afterlife. This time, therefore, it is a philosopher who speaks, who has strived more for knowledge of human nature than for the separation of orphaned schools of thought, an art lover who has not shied away from interpreting the enigmatic moment of an artist's birth, a man who has occasionally searched the bones and nerves of human beings with a knife in his hand in order to find his way through the numerous earthly hiding places of the soul.”

Because Dessoir is so multifaceted in his protection against the rashness of fanatics and the coldness of arrogant rationalists, his judgment on matters of the hereafter, which he has been preparing for more than thirty years, deserves respect and attention even from those who cannot follow him on his path,” and so on.

I had to discuss this individual, Max Dessoir, in the second chapter of my book, “Von Seelenrätseln” (On the Riddles of the Soul), because this university professor had the audacity to discuss anthroposophy as such. I had to undertake the task of proving that the whole way Max Dessoir works is the most unscrupulous, superficial way imaginable. This man has the audacity to pass a disparaging judgment based almost exclusively on nonsensical quotations that he extracts from a few of my books and always quotes in such a way that they are distorted in the most absurd manner. One must state the facts in this way if one wants to see the scandal that is possible within what is today often called science. I have only seen Dessoir once in my life; it was in the early 1990s. At that time, he made a very clever remark to me. My “Philosophy of Freedom” had not yet been written. Max Dessoir said at the time—it was at a Goethe dinner in Weimar: “Yes, you do have one fault, you concern yourself with too many sciences.” That was the great mistake, trying not to be one-sided!

Among the other absurdities that Max Dessoir commits in his book is, for example, that he now refers to my Philosophy of Freedom as my “first work.” It was written about ten years after my actual first work; I had been a writer for ten years before Philosophy of Freedom. All this and much more is equally false in Dessoir's book. How many people will read the necessary, factual refutations in my book Von Seelenrätseln (On the Riddles of the Soul), which show what hot air Dessoir's scholarship is! But how much journalistic rabble of the sort found in Max Hochdorf in Zurich is gathering to trumpet Max Dessoir's nonsensical book Vom Jenseits der Seele (Beyond the Soul) in such a way that one says, “This beyond the senses, which is inhabited by the soul, is what Max Dessoir's weighty book wants to 'Vom Jenseits der Seele' (Beyond the Soul), after thousands of thinkers have already entered this path into the hereafter,” and so on.

It is necessary to focus on such things. It is well known that what is attempted on the basis of anthroposophically oriented spiritual science is distorted in the most unprecedented ways here and there, sometimes by people who know very well that the opposite of what they say is true. But these are mostly poor wretches who have been unable to satisfy their personal interests within society, who believed they could satisfy them, and whom one can pity, but about whom there is no need to talk further. And they themselves know best how it stands with the objective truth of what they say. But poison such as that spread by Max Dessoir must be taken more seriously, and I had to do my part to clarify, sentence by sentence, so to speak, the entire philosophical worthlessness of Dessoir's arguments. Until a healthy judgment prevails in the widest circles about such alleged science as that of Max Dessoir—and there are many such Max Dessoirs—and until a healthy judgment prevails about such followers of Max Dessoir, such as the author of this article, who of course cannot resist concluding his article with the words: “Because the path to the afterlife is so completely blocked” — of course, for the blocked mind of this Mr. Max Dessoir, the path to the afterlife is blocked! — ‘people have tried again and again over the millennia to break down the barriers.’ Dessoir calls these fighters for the desperately fixed yet intangible spirit realm ”magical idealists.” He lists them all, these faith healers, apostles of numbers, Egyptian magicians, Negro saints, anthroposophists, neo-Buddhists, Kabbalists, and Hasidim. He is a highly captivating chronicler of all those generations who have submitted to miracles and yet rebelled against them. A peculiar society forms when one lists all the men, wise and foolish, who wanted to gather around the pure spirit. Cagliostro and Kant, Hegel and even the modern sorcerer Svengali meet there as they wander aimlessly on their way to the afterlife.

It is, of course, impossible to prevent people from writing in this way, but in the widest circles a healthy judgment must prevail which prevents what comes into the public domain in this way from being accepted as authoritative. For it goes without saying that thought forms of this kind, spraying around in our social organism, prevent any possibility of beneficial progress for humanity. For oneself, when one has had to attack scientific rubbish such as that of Max Dessoir, one can wash one's hands and declare oneself satisfied. But this scientific rubbish flows and flows, and today there are far too many channels through which this rubbish can flow. Sometimes one has to nail down an example. In this case, it had to be done again, because you can imagine how many people's minds will once again be filled with a judgment about anthroposophy when a feature article such as the one that appeared on December 14, 1917, in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung is written by someone who is considered quite clever and who bases his views on someone else who is considered just as clever, namely Max Dessoir!

These things must be regarded as cultural-historical facts, and their cultural-historical significance must be taken into account. Certainly, there is unfortunately only a slight possibility today of bringing something like this chapter I have written, “Max Dessoir on Anthroposophy,” to the attention of the general public. For even in the Anthroposophical Society there is only a small circle that truly understands its task: the task of enlightening humanity about the way science is often practiced today, of enlightening it in the right and proper way. And what is practiced today as science is only a symptom of general thinking. For just as things are in science — of which Max Dessoir, with all his followers, is a glaring example — so they are in other fields. And if you ask the question: What deeper forces have led to today's catastrophe? — you will always remain on the surface if you do not go into these deeper reasons, into what lies in the contortion, in the deliberate contortion and in the deliberate superficiality, charlatanism, a charlatanism that seeks to maintain itself by attributing serious intellectuality precisely to charlatanism. This must be seen in its true form in a healthy sense. I cite the example of Max Dessoir only because it is so obvious. But it is an example of much that exists as negative in our time. If anyone in humanity wants to have a heart for the positive aspects of growing together with the spiritual world, then they must also have a heart for rejection, for strong, heartfelt rejection wherever possible, of the inauthentic, the superficial, the useless.

We are experiencing this very much in our own day, that often those who are portrayed in the worst light in public life are precisely the most decent people. There is no need to view these things with pessimism, but there is a need to seek forces within one's own soul that will produce and nurture a healthy judgment about these things in that soul.]

Siebenter Vortrag

Den Betrachtungen, die in diesen Wochen gehalten worden sind, lag verschiedenes zugrunde, das dazu führen kann, die menschliche Natur in ihrem Zusammenhang mit dem geschichtlichen Werden der Menschheit so zu verstehen, daß man sich allmählich eine Vorstellung bilden kann über Notwendigkeit und Freiheit. Weniger können solche Dinge entschieden werden durch Definitionen und Wortauseinandersetzungen als dadurch, daß man die entsprechenden Wahrheiten aus der geistigen Welt zusammenträgt. Die Menschheit wird sich in unserem Zeitalter immer mehr daran gewöhnen müssen, eine andere Art des Verständnisses der Wirklichkeit sich anzueignen, als es die heute so vielfach herrschende und übliche ist, die sich im Grunde genommen an sehr Sekundäres, an allerlei nebulose Vorstellungen in Anknüpfung an Wortdefinitionen und so weiter hält. Man hat heute, wenn man das vornimmt, was manche Leute schreiben oder sagen, die sich für ganz besonders gescheit halten, das Gefühl: sie reden in Begriffen und Vorstellungen, die nur scheinbar bestimmt, in Wirklichkeit aber so unbestimmt sind, wie wenn jemand über einen gewissen Gegenstand sprechen würde, der zum Beispiel aus einem Kürbis gemacht ist. Hat man einen Kürbis umgestaltet zu einer Flasche und benützt ihn als Flasche, so kann man über diesen Gegenstand so reden, als ob man über einen Kürbis redet, denn ein Kürbis ist es in Wirklichkeit; aber man kann auch wie über eine Flasche reden, denn eine Flasche ist er ja auch, er wird richtig benützt als Flasche. Nicht wahr, die Dinge, über die man spricht, bekommen erst ihre Valeurs in den Zusammenhängen, in denen man sich ergeht. Wenn man nicht in Anlehnung an Worte, sondern aus einer gewissen Anschauung heraus spricht, so wird jeder Mensch wissen, ob man eine Flasche meint oder einen Kürbis. Aber man darf sich dann nicht auf die Beschreibung des Gegenstandes oder die Definition des Gegenstandes beschränken. Denn solange man sich auf eine Beschreibung, auf eine Definition beschränkt, kann es ebensogut ein Kürbis oder eine Flasche sein. Und so kann heute dasjenige, worüber viele Philologen, Leute, die sich sehr gescheit dünken, reden, die Seele des Menschen sein, es kann aber auch der Leib des Menschen sein, es kann Kürbis und kann Flasche sein.

Ich meine mit dieser Bemerkung sehr vieles von dem, was in der Gegenwart sehr ernst genommen wird, zum Teil zum Unheil der Menschheit. Daher eben ist es notwendig, daß gerade von der anthroposophisch orientierten Geisteswissenschaft, zu der unter anderem auch klares, präzises Denken nötig ist, ausgehe ein Bestreben, nicht in einer solchen Weise, wie es heute üblich ist, die Welt anzuschauen, nicht den Kürbis mit der Flasche zu verwechseln, sondern überall auf das Reale zu sehen, sei es das äußere Physisch-Reale, sei es das Geistig-Reale.

Man kann ohnedies nicht zu einer wirklichen Vorstellung über dasjenige gelangen, was für den Menschen in Betracht kommt, wenn man sich an Definitionen und dergleichen hält, sondern nur dann, wenn man die Lebenszusammenhänge in ihrer Wirklichkeit ins Auge faßt. Und gar über solch wichtige Begriffe wie Freiheit und Notwendigkeit im sozialen, im sittlichen Leben, kann man nur Klarheit gewinnen, wenn man zusammenhält solche spirituellen Tatsachen, wie sie in diesen Betrachtungen vorgebracht worden sind, und gewissermaßen versucht, sie immer aneinander abzuwägen, um ein Urteil über die Wirklichkeit zu gewinnen.

Bedenken Sie, daß ich schon in öffentlichen Vorträgen und auch hier wiederum in den verschiedensten Zusammenhängen mit einer gewissen Intensität immer wieder und wieder hervorgehoben habe, daß wir das, was wir Vorstellungen nennen, nur dann richtig begreifen können, wenn wir sie so in Beziehung bringen zu unserm leiblichen Organismus, daß wir den Vorstellungen im Leibe nicht etwas Wachsendes, Gedeihendes zugrunde liegend sehen, sondern gerade umgekehrt, etwas Absterbendes, etwas partiell im Leibe Absterbendes. Ich habe das so ausgesprochen in einem öffentlichen Vortrage, daß ich gesagt habe: Der Mensch stirbt eigentlich immer in sein Nervensystem hinein ab. Der Nervenprozeß ist ein solcher, daß er sich auf das Nervensystem beschränken muß. Denn würde er sich ausdehnen über den ganzen Organismus, würde dasselbe vorgehen im ganzen Organismus, was in den Nerven vorgeht, so würde dies den Tod des Menschen in jedem Augenblick bedeuten. Man kann sagen: Vorstellungen entstehen da, wo der Organismus sich selber abbaut, wir sterben in unser Nervensystem fortwährend hinein. - Dadurch ist Geisteswissenschaft in die Notwendigkeit versetzt, nicht nur diejenigen Prozesse zu verfolgen, welche die heutige Naturwissenschaft als die einzig maßgebenden betrachtet: die aufsteigenden Prozesse. Diese aufsteigenden Prozesse, sie sind Wachstumsprozesse, sie gipfeln noch im Unbewußten. Erst wenn der Organismus mit den absteigenden Prozessen beginnt, tritt im Organismus jene Tätigkeit der Seele auf, die man als Vorstellungs-, ja auch als sinnliche Wahrnehmungstätigkeit bezeichnen kann. Dieser Abbauprozeß, dieser Ersterbeprozeß, der muß da sein, wenn überhaupt vorgestellt werden soll.

Nun habe ich gezeigt, daß das freie Handeln des Menschen geradezu darauf beruht, daß der Mensch in die Lage kommt, aus reinen Gedanken heraus die Impulse für sein Handeln zu suchen. Diese reinen Gedanken werden am meisten von Einfluß sein auf die Abbauprozesse im menschlichen Organismus. Was geschieht denn eigentlich, wenn der Mensch so recht eine freie Handlung vollzieht? Machen wir uns das einmal klar, was da beim gewöhnlichen physischen Menschen geschieht, wenn der Mensch aus moralischer Phantasie heraus - Sie wissen jetzt, was ich damit meine -, aus moralischer Phantasie heraus, das heißt aus einem Denken, das von sinnlichen Impulsen, sinnlichen Trieben und Affekten nicht beherrscht ist, handelt, was geschieht da mit dem Menschen eigentlich? Dann geschieht das, daß er sich reinen Gedanken hingibt; die bilden seine Impulse. Sie können ihn nicht impulsieren durch sich selbst; er muß sich impulsieren, denn sie sind bloße Spiegelbilder, das haben wir ja betont. Sie gehören der Maja an. Spiegelbilder können nicht zwingen, der Mensch muß sich selber zwingen unter dem Einfluß der reinen Vorstellungen.

Worauf wirken reine Vorstellungen? Am stärksten wirken sie auf den Abbauprozeß im menschlichen Organismus. Auf der einen Seite kommt aus dem Organismus heraus der Abbauprozeß, und auf der andern Seite kommt aus dem geistigen Leben diesem Abbauprozeß entgegen der reine Tatgedanke. Ich meine damit den Gedanken, welcher der Tat zugrunde liegt. Durch die Vereinigung von beiden, durch das Aufeinanderwirken des Abbauprozesses und des Tatgedankens entsteht die freie Handlung.

Ich sagte, der Abbauprozeß wird nicht durch das reine Denken bewirkt; der ist sowieso da, er ist also eigentlich immer da. Wenn der Mensch diesem Abbauprozeß, gerade den bedeutsamsten Abbauprozessen in ihm, nichts aus dem reinen Denken heraus entgegenstellt, dann bleibt er Abbauprozeß, dann wird der Abbauprozeß nicht umgewandelt in einen Aufbauprozeß, dann bleibt ein ersterbender Teil im Menschen. Denken Sie das einmal durch, dann ersehen Sie daraus, daß die Möglichkeit besteht, daß der Mensch gerade durch Unterlassung von freien Handlungen einen Todesprozeß in sich nicht aufhebt. Darin liegt einer der subtilsten Gedanken, die der Mensch nötig hat, in sich aufzunehmen. Wer diesen Gedanken versteht, kann im Leben nicht mehr zweifeln an dem Vorhandensein der menschlichen Freiheit. Denn eine Handlung, die aus Freiheit geschieht, geschieht nicht durch etwas, was im Organismus verursacht wird, sondern wo die Ursachen aufhören, nämlich aus einem Abbauprozeß heraus. Dem Organismus muß etwas zugrunde liegen, wo die Ursachen aufhören, dann kann überhaupt erst die reine Vorstellung als Motiv des Handelns eingreifen. Aber solche Abbauprozesse sind immer da, sie bleiben nur gewissermaßen ungenützt, wenn der Mensch nicht freie Handlungen vollführt.

Was hier zugrunde liegt, bezeugt aber auch, wie es mit einem Zeitalter aussehen muß, welches sich nicht darauf einlassen will, die Idee der Freiheit im vollsten Umfange zu verstehen. Die zweite Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, das 20. Jahrhundert bis in unsere Zeit, diese Epoche hat es sich geradezu zur Aufgabe gesetzt, auf allen Gebieten des Lebens die Idee der Freiheit immer mehr und mehr für die Erkenntnis zu trüben, für das praktische Leben in Wirklichkeit auszuschalten. Freiheit wollte man nicht verstehen, Freiheit wollte man nicht haben. Die Philosophen haben sich bemüht, zu beweisen, daß alles mit einer gewissen Notwendigkeit aus der menschlichen Natur hervorgeht, Gewiß, der menschlichen Natur liegt eine Notwendigkeit zugrunde, aber diese Notwendigkeit hört auf, indem Abbauprozesse beginnen, in welchen der Zusammenhang der Ursachen sein Ende findet. Wenn Freiheit da eingegriffen hat, wo die Notwendigkeit im Organismus aufhört, dann kann man nicht sagen, daß die Handlungen der Menschen aus der inneren Notwendigkeit hervorgehen; sie gehen dann erst aus ihm hervor, wenn diese Notwendigkeit aufhört. Der ganze Fehler bestand darinnen, daß man sich nicht eingelassen hat darauf, im menschlichen Organismus nicht nur zu verstehen die aufbauenden Prozesse, sondern auch zu verstehen die abbauenden Prozesse. Es wäre aber allerdings nötig, daß man, um das zu erkennen, was eigentlich der menschlichen Natur zugrunde liegt, mehr Begabung entwickele, als die Gegenwart Neigung dazu hat. Wir haben gestern gesehen, daß es notwendig ist, dasjenige wirklich ins Seelenauge fassen zu können, was man als menschliches Ich bezeichnet. Aber es ist gerade in der Gegenwart wenig Talent vorhanden, diese Wirklichkeit des Ich irgendwie zu erfassen. Ich will Ihnen einen Beweis liefern.

Ich habe öfter die ausgezeichnete wissenschaftliche Leistung von Theodor Ziehen erwähnt: «Die physiologische Psychologie.» Da ist auf Seite 205 auch die Rede von dem Ich. Nur kommt Ziehen niemals in die Lage, auch nur hinzudeuten auf das wirkliche Ich, sondern er redet nur von der Ich-Vorstellung. Wir wissen, die ist jedoch nur ein Spiegelbild des wirklichen Ich. Aber interessant ist es gerade zu hören, wie ein ausgezeichneter Denker der Gegenwart, aber ein solcher, der da glaubt, mit naturwissenschaftlichen Vorstellungen alles erschöpfen zu können, über das Ich redet. Es sind Vorträge, die wiedergegeben werden, deshalb ist die Sache in Vortragsform vorgebracht. Ziehen sagt: «Es wird Ihnen vielleicht auffallen, daß die mit dem kurzen kleinen Wort Ich bezeichnete Ich-Vorstellung ein so komplexes dreigliedriges Gebilde sein soll, an welchem tausend und abertausend Teilvorstellungen beteiligt sein sollen. Aber ich bitte Sie zu erwägen: das Wort ist zwar kurz, aber daß sein Vorstellungsinhalt sehr komplex sein muß, geht schon daraus hervor, daß jeder von Ihnen in Verlegenheit geraten wird, wenn er den Denkinhalt seiner sogenannten Ich-Vorstellung angeben soll.»

Und jetzt geht Ziehen daran, etwas zu sagen über den Denkinhalt der Ich-Vorstellungen. Nun wollen wir einmal sehen, was der ausgezeichnete Gelehrte über dasjenige zu sagen weiß, woran man eigentlich denken soll, wenn man über sein Ich denkt: «Sie werden alsbald an Ihren Körper denken» - also an Ihren Körper denken! - «an Ihre Relationen zur Außenwelt, Ihre verwandtschaftlichen und Eigentumsbeziehungen» — also man wird bald daran gehen, an seine Börse zu denken und sein Geld abzuzählen! - «Ihre Namen und Titel .. .»

Nun, der ausgezeichnete Gelehrte weist ausdrücklich darauf hin, daß man auch an seinen Namen und an seinen Titel denken soll, wenn man sein Ich in der Vorstellung umfassen, umspannen soll.

«... Ihre Hauptneigungen und dominierenden Vorstellungen und endlich an Ihre Vergangenheit, und damit selbst den Beweis führen, wie äußerst zusammengesetzt diese Ich-Vorstellung ist. Freilich reduziert der reflektierende Mensch diese Kompliziertheit der Ich-Vorstellung wieder auf eine relative Einfachheit, indem er den äußeren Objekten und anderen Ichs sein eigenes Ich als das Subjekt seiner Empfindungen, Vorstellungen und Bewegungen gegenüberstellt. Gewiß hat auch diese Gegenüberstellung und diese Vereinfachung der Ich-Vorstellung ihre tiefe erkenntnistheoretische Begründung, aber, rein psychologisch betrachtet, ist dieses einfache Ich nur eine theoretische Fiktion.»

Also «dieses einfache Ich» ist nur eine «theoretische Fiktion», das heißt eine bloße Phantasievorstellung, die sich aufbaut, wenn man seinen Namen, seine Titel, vermutlich auch seine Orden und andere dergleichen Dinge zusammenstellt, die einem Gewicht geben! An solchen Punkten kann man die ganze Schwäche des heutigen Denkens erkennen. Und diese Schwäche muß um so mehr ins Auge gefaßt werden, weil ja dasjenige, was sich als entscheidende Schwäche für die Erkenntnis des seelischen Lebens erweist, eine Stärke ist für die Erkenntnis der äußeren naturwissenschaftlichen Tatsachen. Gerade was untauglich ist für die Erkenntnis des seelischen Lebens, ist sehr tauglich, um die äußere sinnenfällige Tatsache in ihrer unmittelbaren äußeren Notwendigkeit zu durchschauen.

Man muß sich nicht hinwegtäuschen darüber, daß es ein Charakteristikon unserer Zeit ist, daß Leute, die auf einem Gebiete groß sein können, auf dem andern Gebiete Vertreter des äußersten Unsinns sind. Nur wenn man diese Tatsache, die so sehr geeignet ist, der Menschheit Sand in die Augen zu streuen, scharf ins Auge faßt, dann kann man irgendwie mitdenken bei dem, was in Betracht kommt für die Wiederaufrichtung jener Kraft, die die Menschheit braucht, um solche Vorstellungen zu gewinnen, die fruchtbar und heilsam in das Leben eingreifen können. Denn in dieses Leben, wie es heute ist, werden nur Vorstellungen eingreifen, die tief aus der wahren Wirklichkeit heraus genommen sind, bei denen man sich nicht scheut, tief in die wahre Wirklichkeit hineinzugreifen. Davor aber scheuen sich gerade viele Menschen der Gegenwart.

Die Menschen der Gegenwart finden sich sehr häufig geneigt, ohne erst hineingeschaut zu haben in die wahre Wirklichkeit, aus der sie ihre Impulse schöpfen sollten, die geistige Wirklichkeit zu reformieren. Wer reformiert heute nicht alles Mögliche in der Welt, das heißt, glaubt zu reformieren. Was holt man nicht alles aus dem reinen Nichts der Seele heraus! Aber in einer Zeit, wie diese ist, können nur diejenigen Dinge fruchtbar sein, welche aus der Tiefe der geistigen Wirklichkeit heraus selbst geholt sind. Dazu muß Wille vorhanden sein.

Die Eitelkeit, die auf Grund des seelischen Nichts alle möglichen Reformgedanken fassen will, ist ebenso schädlich der Entwickelung in unserer heutigen Zeit wie der Materialismus selber. Ich habe gestern am Schluß darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie das wahre Ich des Menschen, dasjenige Ich, das allerdings der Willensnatur angehört, über das sich daher für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein Schlaf breitet, befruchtet werden muß dadurch, daß schon durch den öffentlichen Unterricht die Menschen hingeführt werden zum konkreten Begreifen der großen Zeitinteressen. Das kann man nicht anders machen in unserer Zeit, als indem man klarmacht, welche geistigen Kräfte und Wirksamkeiten hereingreifen in unser Geschehen. Nicht mit allgemeinen nebulosen Reden über den Geist ist es getan, sondern mit der Erkenntnis der konkreten geistigen Vorgänge, wie wir sie in diesen Betrachtungen geschildert haben, wo man per Jahrzahl darauf hinweist, wie da und dort diese gewissen Mächte und Kräfte aus der geistigen Welt hier in die physische hereingegriffen haben.

Dadurch aber kommt das zustande, was ich bezeichnen konnte im Gesamtwerden der Menschheit als das Zusammenarbeiten der sogenannten Toten mit den sogenannten Lebendigen. Denn im Wirklichen unseres Gefühls- und Willenslebens sind wir mit den Toten in einem Reich. Man kann ebensogut sagen, mit dem Wirklichen unseres Ich und unseres astralischen Leibes sind wir mit den Toten in einem Reich. Beides besagt dasselbe. Dadurch aber ist hingewiesen auf ein gemeinsames Gebiet, in das wir eingebettet sind, in dem die Toten und die Lebendigen zusammenarbeiten an demjenigen Gewebe, das man das soziale, das sittliche, das geschichtliche Menschenleben in seiner Ganzheit nennen kann, wozu auch diejenigen Lebensläufe gehören, die zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt zugebracht werden.

Wir haben darauf hingewiesen in diesen Betrachtungen, wie der sogenannte Tote zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt als unterstes Reich das tierische Reich hat, so wie wir das mineralische Reich als unterstes Reich haben. Wir haben auch in einer gewissen Weise darauf hingewiesen, wie der Tote zu arbeiten hat innerhalb des Wesens des tierischen Reiches, wie er aufzubauen hat aus den Gesetzen der Tierheit dasjenige, was wiederum der nächsten Inkarnation als Organisation zugrunde liegt. Wir haben darauf hingewiesen, wie als zweites Reich der Tote alle diejenigen Zusammenhänge erlebt, die hier in der physischen Welt karmisch begründet worden sind, und die sich in die geistige Welt hinein entsprechend verwandelt fortsetzen. Ein zweites Reich baut sich auf also für den Toten, das zusammengewoben ist aus all den karmischen Zusammenhängen, die er jemals in einer Inkarnation auf der Erde begründet hat. Dadurch dehnt sich aber allmählich alles, was der Mensch an Interesse entwickelt zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, man kann sagen, in Konkretheit über die ganze Menschheit aus.

Als drittes Reich, das der Mensch dann durchlebt, können wir auffassen das Reich der Angeloi. Und wir haben auch schon in einem gewissen Sinne darauf hingewiesen, welche Rolle die Angeloi spielen drüben in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Sie tragen gewissermaßen die Gedanken von der einen menschlichen Seele zur andern menschlichen Seele hin und bringen sie wieder zurück. Sie sind die Boten des gemeinschaftlichen Gedankenlebens. Die Angeloi sind im Grunde genommen von den Wesen der höheren Hierarchien diejenigen, über die der Tote das klarste Erleben hat; ein klares Erleben über die tierischen und ein klares Erleben über die menschlichen Zusammenhänge, das sein Karma begründet hat durch die Wesen der höheren Hierarchien. Die klarste Vorstellung hat er von jenen Wesen aus der Hierarchie der Angeloi, die eigentlich die Träger der Gedanken beziehungsweise überhaupt der Seeleninhalte von einem Wesen zu dem andern sind, die auch dem Toten helfen beim Bearbeiten der Tierheit. Man könnte sagen — wenn man von den Angelegenheiten der Toten als von persönlichen Angelegenheiten spricht -, die Wesen aus der Hierarchie der Angeloi haben sich vorzugsweise zu bestreben, die persönlichen Angelegenheiten der Toten zu besorgen. Allgemeinere Angelegenheiten der Toten, die nicht persönliche sind, werden mehr besorgt von den Wesen aus dem Reich der Archangeloi und der Archai.

Wenn Sie sich erinnern an den Vortragszyklus über «Inneres Wesen des Menschen und Leben zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt», dann werden Sie in Ihr Gedächtnis zurückrufen, daß es zum Leben des sogenannten Toten gehört, abwechselnd gewissermaßen sein Wesen auszudehnen über die Welt und es wieder zusammenzuziehen in sein Inneres. Ich habe das dort tiefer begründet und geschildert. Das Leben des Toten verläuft so, daß gewissermaßen eine Art Abwechselung stattfindet zwischen Tag und Nacht. Aber diese Art ist so, daß aus dem Innern auftaucht reges Leben. Man weiß: Was da auftaucht, dieses rege Leben, das ist nur das Wiederauftauchen dessen, was man in dem andern Zustande, mit dem dieser abwechselt, durchlebt hat, indem man sein Wesen ausgedehnt hat über die Welt, indem man zusammengewachsen ist mit der Außenwelt. Wenn man daher mit einem Toten zusammenkommt, trifft man abwechselnde Zustände: Solche Zustände, wo er sein Wesen über die Welt ausdehnt, wo er gewissermaßen mit seinem eigenen Wesen in die Wesenhaftigkeit seiner Umgebung, in die Vorgänge seiner Umgebung hineinwächst. Da weiß er am wenigsten, da ist für ihn eine Art von Schlafzustand vorhanden, wenn er mit seinem Wesen in die geistige Welt um ihn hineinwächst. Wenn das wieder auftaucht aus seinem Innern, dann ist für ihn eine Art Wachzustand vorhanden, dann weiß er alles das. Denn sein Leben verfließt in der Zeit, nicht im Raume. Wie wir als Besitzer des wachen Tagesbewußtseins draußen im Raume dasjenige haben, was wir hereinnehmen in unser Bewußtsein und dann wiederum uns von ihm zurückziehen im Schlafe, so ist es beim Toten so, daß er von einem gewissen Zeitraume, den er durchlebt hat, die Erlebnisse hereinnimmt in den nächsten Zeitraum und sie dann sein Bewußtsein ausfüllen. Vergangene Zeit füllt sein Bewußtsein aus, wie unser Wachbewußtsein der Raum ausfüllt. Es ist ein völliges Leben in der Zeit. Und damit muß man sich bekanntmachen.

Durch dieses rhythmische Zeitleben, das der Tote führt, kommt er nun in eine ganz bestimmte Beziehung zu den Wesen aus der Hierarchie der Archangeloi und der Archai. Von diesen Wesenheiten, von den Archangeloi und den Archai, hat er nicht eine so klare Vorstellung wie von den Angeloi und von den Menschen und von der Tierheit, aber er hat vor allen Dingen immer die Vorstellung, daß diese Wesenheiten, die Archai und Archangeloi, diejenigen sind, welche mit ihm zusammenarbeiten in diesem Aufwachen, Einschlafen, Aufwachen, Einschlafen in diesem Rhythmus, der sich im Laufe der Zeit abspielt. Der Tote hat wenn er dazu kommt, ein Bewußtsein von dem zu entwickeln, was er im vorhergehenden Zeitabschnitt erlebt, aber nicht gewußt hat -, er hat immer das Bewußtsein, daß ein Wesen aus der Hierarchie der Archai ihn aufgeweckt hat; er hat immer das Bewußtsein, daß er in bezug auf dieses rhythmische Leben zusammenarbeitet mit den Archai und Archangeloi.

Halten wir recht gut fest, geradeso wie wir hier im Aufwachen gewahr werden: uns wird bewußt die äußere Welt, von der wir während des Schlafens nicht wissen, wie wir hier gewahr werden: diese äußere Welt geht in die Finsternis hinunter, wenn wir einschlafen — so lebt in der Seele des sogenannten Toten das Bewußtsein: Archai, Archangeloi, mit ihnen arbeite ich zusammen, auf daß ich durchgehen kann durch dieses Leben des Einschlafens, Aufwachens, Einschlafens, Aufwachens und so weiter. Man möchte sagen, der Tote verkehrt mit Archangeloi und Archai so, wie wir hier im Wachbewußtsein mit der physischen Umgebung, der Pflanzen- und mineralischen Welt verkehren. Der Mensch kann nicht zurückschauen in dieses Zusammenspielen, in das er hineinverwoben ist zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Warum nicht? Nun, man meint: Warum nicht? — aber gerade dieses Zurückschauen ist etwas, was der Mensch wird lernen müssen, nur kann er es freilich aus den materialistischen Vorstellungen der Gegenwart heraus schwierig lernen. Ich möchte Ihnen graphisch darstellen, warum da der Mensch nicht zurücksieht (Siehe Zeichnung).

Nehmen Sie einmal an: Sie stehen mit Ihrem gesamten Sinnes- und Vorstellungsapparat der Welt gegenüber. Dadurch haben Sie Vorstellungen, Wahrnehmungsinhalte verschiedenster Art. Ich bezeichne das, was in einem Momente Bewußtsein ist, so, daß ich da verschiedene Ringe, kleine Kreise aufzeichne. Das ist in einem Momente im Bewußtsein. Jetzt wissen Sie, findet in anderer Art, als Psychologen heute meinen, aber es findet statt ein Erinnerungsprozeß, wenn Sie zurückschauen; und die Zeit, in die Sie zurückschauen können, indem Sie sich erinnern, die bezeichne ich mit dieser Linie, mit der aber eigentlich dieser Raum gemeint ist, der da blind ausläuft, hier wäre der Punkt im dritten, vierten oder fünften Jahre, bis zu dem man sich im Leben zurückerinnert. Da drinnen liegen also alle die Vorstellungen, die entstehen, wenn man sich an die Erlebnisse zurückerinnert, die man gehabt hat. Nehmen Sie an: Sie haben diese Vorstellungen, sagen wir mit dreiBig Jahren, so erinnern Sie sich, indem diese Vorstellungen vor Ihnen auftauchen, an etwas, das Sie vor zehn Jahren gehabt haben. Wenn Sie sich so recht lebhaft, bildhaft vorstellen, wie das eigentlich ist mit der Seele, so können Sie folgendes denken. Sie können sich sagen: Wenn wir so zurückschauen bis dahin, wo in der Kindheit dasjenige auftaucht, bis wohin wir uns erinnern, so ist das ein seelischer Sack, der ein Ende hat; er hat dort seinen Bogen, wo der Punkt liegt, bis zu dem wir uns in der Kindheit zurückerinnern. Das ist ein solcher Seelensack; das ist die Zeit, die überschaut wird. Stellen Sie sich solch einen seelischen Sack vor,in den Sie so zurück hineinblicken: hier ist die Grenze dieses Sackes, diese Grenze fällt in Wirklichkeit zusammen mit der Grenze zwischen Ätherleib und physischem Leib. Diese Grenze muß da sein, Sie können sich das sehr grob vorstellen: sonst würden nämlich die Vorgänge, welche die Erinnerung herbeiführen, immerfort da durchfallen. Sie würden sich an nichts erinnern können, die Seele wäre ein Sack, der keinen Boden hat, es würde alles durchfallen. Es muß also eine Grenze da sein, es muß ein wirklicher seelischer Sack vorliegen. Dieser seelische Sack aber hindert zu gleicher Zeit, auch dasjenige wahrzunehmen, was man so durchlebt hat, daß es außerhalb liegt. Sie sind sich selbst in Ihrem Seelenleben undurchsichtig, weil Sie Erinnerungen haben. Weil Sie das Vermögen der Erinnerung haben, sind Sie undurchsichtig.

Sie sehen, das, was macht, daß wir ein ordentliches Bewußtsein für den physischen Plan haben, ist zu gleicher Zeit der Grund, daß wir nicht hineinsehen mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein in dieses Gebiet, welches hinter der Erinnerung liegen müßte. Hinter der Erinnerung liegt es nämlich in Wirklichkeit. Man kann sich aber bemühen, die Erinnerung nach und nach etwas umzugestalten. Man muß nur vorsichtig dabei sein. Man kann damit beginnen, daß man versucht, dasjenige, an das man sich erinnert, immer genauer und genauer meditativ ins Auge zu fassen, bis man das Gefühl hat: Es ist nicht nur etwas, was man so in der Erinnerung ergreift, sondern etwas, was eigentlich da stehen bleibt. Ein Mensch, der ein intensives, reges Geistesleben entwickelt, bekommt schon allmählich dieses Gefühl, daß die Erinnerung nicht etwas ist, das kommt und geht, kommt und vergeht, sondern daß der Inhalt der Erinnerung etwas ist, was stehen bleibt. Nun allerdings, in dieser Weise arbeiten, kann nur dazu führen, die Überzeugung hervorzurufen, daß dasjenige, was in der Erinnerung sonst auftaucht, stehen bleibt, daß es wirklich als Akasha-Chronik vorhanden bleibt, daß es nicht weggeht. Dasjenige, was wir sonst in der Erinnerung überblicken: es steht da in der Welt, es ist in Wirklichkeit da. Aber weiter kommt man durch diese Methode eigentlich nicht, denn diese Methode, sich nur an seine persönlichen Erlebnisse zu erinnern, die gut hervorgerufen wird, die Erkenntnis, daß der Erinnerungsgehalt stehen bleibt — diese Methode ist in einem höheren Sinne zu egoistisch, um weiterzuführen als nur bis zu dieser Überzeugung. Im Gegenteil, wenn Sie über einen gewissen Punkt hin gerade diese Fähigkeit ausbilden würden, hinzuschauen auf das Stehenbleibende Ihrer eigenen Erlebnisse, so werden Sie sich erst recht den Ausblick in die freie Geisteswelt verbauen. Denn statt daß der Sack der Erinnerungen da ist, steht dann nur Ihr eigenes Leben um so kompakter da und läßt Sie nicht durchblicken.

Dagegen kann man eine andere Methode anwenden, die in ganz ausgezeichneter Weise, wenn ich den Ausdruck gebrauchen darf, die Einschreibungen der Akasha-Chronik durchsichtig macht. Und sieht man einmal durch die stehengebliebenen Erinnerungen, dann sieht man sicher hinein in die geistige Welt, mit der man verbunden war zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Aber dazu muß man nicht nur dasjenige, was als erinnerungsgemäß stehen bleibt aus dem eigenen Leben, benützen — das wird immer kompakter und kompakter, da sieht man dann erst recht nicht durch. Es muß das durchsichtig werden. Und durchsichtig wäre es, wenn man immer stärker und stärker den Versuch macht, nicht so sehr an das sich zu erinnern, was man von seinem Gesichtspunkte aus erlebt hat, sondern an das sich immer mehr zu erinnern, was von außen an einen herangetreten ist. Statt an das, was man gelernt hat, erinnert man sich an den Lehrer, an die Art, wie der Lehrer gesprochen, wie der Lehrer gewirkt hat, was der Lehrer mit einem gemacht hat. Man erinnert sich daran, wie das Buch entstanden ist, aus dem man dies oder jenes gelernt hat. Man erinnert sich vorzugsweise an dasjenige, was von der Außenwelt herein an einem gearbeitet hat.

Ein sehr schöner, wunderbarer Anfang, ja eine Anleitung zu solcher Erinnerung ist Goethes Schrift «Dichtung und Wahrheit», wo er schildert, wie er, Goethe, aus der Zeit heraus geformt wird; wie die verschiedenen Kräfte an ihm arbeiten. Daß Goethe so etwas gemacht hat in seinem Leben, daß er in einer solchen Weise eine Art Rückschau gehalten hat, nicht von dem Gesichtspunkte der eigenen Erlebnisse, sondern von dem Gesichtspunkte der andern und der Zeitereignisse, die an ihm gearbeitet haben, dem verdankt er, daß er solche tiefen Einblicke hat tun können in die geistige Welt, wie er getan hat. Das aber ist auch zu gleicher Zeit der Weg, um in weiterem Umfange mit der Zeit in Berührung zu kommen, die zwischen dem letzten Tode und dieser unserer Geburt verflossen ist.

Also Sie sehen, von einem andern Gesichtspunkt aus weise ich Sie heute auf dasselbe hin, worauf ich Sie schon hingewiesen habe: Erweiterung der Interessen über das Persönliche hinaus, gerade Hinlenkung der Interessen und der Aufmerksamkeit auf dasjenige, was nicht wir sind, sondern was uns geformt hat, woraus wir entstanden sind. Ein Ideal ist es, hinzuschauen auf die Zeit und auf längere Vorzeit vor uns und all die Kräfte aufzusuchen, die diesen Kerl, der man geworden ist, aus sich heraus geformt haben.

Das allerdings bietet wenig Schwierigkeiten, wenn man es so schildert, aber es ist keine ganz leichte Aufgabe. Es ist auch eine Aufgabe, die, weil sie starke Selbstlosigkeit erfordert, großen Erfolg hat. Gerade diese Methode erweckt die Kräfte, mit seinem Ich in dieselbe Sphäre hineinzukommen, die die Toten mit den Lebendigen gemeinschaftlich haben. Weniger sich kennenzulernen, mehr seine Zeit kennenzulernen, das wird die Aufgabe eines öffentlichen Unterrichts in einer gar nicht zu fernen Zukunft sein, aber seine Zeit im Konkreten kennenzulernen, nicht so kennenzulernen, wie es jetzt in den Geschichtsbüchern steht; so, wie diese Zeit selbstverständlich sich entwickelt aus geistigen Impulsen heraus.

Also wieder werden wir auch auf diese Weise dazu geführt, die Interessen zu erweitern über eine Charakteristik unseres Zeitalters und seines Hervorgehens aus dem allgemeinen Weltengang. Warum hat denn Goethe so intensiv danach gestrebt, griechische Kunst kennenzulernen, seine Zeit durch und durch zu verstehen, sie abzumessen an der vorhergehenden Zeit? Warum läßt er seinen Faust bis in die griechische Zeit, bis in die Helena-Zeit zurückgehen, den Chiron aufsuchen, die Sphinxe aufsuchen? Weil er seine eigene Zeit, wie sie an ihm gearbeitet hat, so kennenlernen will, wie er sie nur kennenlernen kann, wenn er diese eigene Zeit an der früheren Zeit mißt. Aber Goethe läßt seinen Faust nicht sich hinsetzen und Pergamente entfalten, Urkunden der Staatsarchive entfalten, sondern er führt ihn zurück auf Seelenwegen in die Impulse, welche ihn selber geformt haben. Es steckt in ihm manches von dem, was den Menschen hinweist auf ein Zusammenkommen auf der einen Seite mit den Toten, auf der andern Seite - Sie können es jetzt sehen aus dem Zusammenhang der Toten und Archangeloi - mit den Zeitgeistern und den Erzengeln. Dadurch, daß der Mensch mit den Toten zusammenkommt, kommt er auch in Berührung mit den Erzengeln und den Zeitgeistern. Gerade in den Impulsen, auf die Goethe in seinem «Faust» hindeutet, liegt das, wodurch der Mensch seine Interessen erweitert über den Zeitgeist, liegt das, was im eminentesten Sinne unserer Zeit notwendig ist. Allerdings ist unserer Zeit notwendig, in anderer Art auf so etwas hinzuschauen, wie es zum Beispiel der «Faust» ist, als die Zeit bisher darauf hingeschaut hat. Die meisten derjenigen, die den «Faust» beurteilen, kommen kaum darauf, wo die Probleme liegen. Einige kommen darauf, die Fragen zu stellen. Die Antworten werden oft in der kuriosesten Weise gegeben.

Nehmen Sie ein Beispiel, wo Goethe nun wirklich darauf hinweist: Denkt nach! Wird da immer nachgedacht? Goethe macht aber alles, um Deutlichkeit dafür hervorzurufen, daß über gewisse Dinge nachzudenken ist. Zum Beispiel: Sie wissen, die Erichtho redet über dasjenige, was Schauplatz der klassischen Walpurgisnacht ist; sie entfernt sich, die Luftfahrer, Homunkulus mit Faust und Mephistopheles erscheinen. Sie erinnern sich an die ersten Reden des Homunkulus, des Mephisto, des Faust. Nachdem Faust den Boden berührt hat und die Frage aufgeworfen hat: Wo ist sie? — sagt Homunkulus:

Wüßten’s nicht zu sagen,

Doch hier wahrscheinlich zu erfragen.

In Eile magst du, eh’ es tagt,

Von Flamm’ zu Flamme spürend gehen:

Wer zu den Müttern sich gewagt,

Hat weiter nichts zu überstehen.

Homunkulus sagt: «Wer zu den Müttern sich gewagt, hat weiter nichts zu überstehen...» Woher weiß denn der, daß der Faust bei den Müttern war? Das ist eine Frage, die ganz notwendig sich ergibt, denn blättern Sie zurück, so werden Sie sehen, daß nirgends eine Andeutung darüber ist, daß Homunkulus erfahren haben könnte als ein Wesen außer dem Faust, daß der Faust bei den Müttern war. Jetzt auf einmal piepst der Homunkulus davon, daß «wer zu den Müttern sich gewagt, hat weiter nichts zu überstehen». Sie sehen, Goethe gibt schon Rätsel auf. Mit zwingender Notwendigkeit geht daraus hervor, daß Homunkulus, wenn er überhaupt irgend etwas ist, dieses innerhalb des Bewußtseinsbereiches des Faust selber ist; denn nur dann kann er dasjenige, was innerhalb des Bewußtseinsbereiches des Faust ist, wissen, wenn er zum Bewußtseinsbereiche des Faust selber gehört.

Erinnern Sie sich an manche Auseinandersetzungen, die wir über den «Faust» gegeben haben, daß Homunkulus eigentlich nichts anderes ist als dasjenige, was als astralischer Leib bereitet werden muß, damit die Helena erscheinen kann. Aber dadurch ist er in einem andern Bewußtsein, ist sein Bewußtsein erweitert über den Astralleib. Dann haben Sie eine Verständnismöglichkeit des Wissens des Homunkulus, wenn er in den Bewußtseinsbereich des Faust selber hineinkommt. Deshalb läßt Goethe den Homunkulus werden, weil durch das Werden des Homunkulus das Bewußtsein des Faust gewissermaßen die Möglichkeit findet, aus sich herauszugehen, nicht nur in sich zu sein, sondern draußen zu sein. Und er ist auch da, wo der Homunkulus ist; der Homunkulus ist im Bewußtsein des Faust darinnen.

Goethe nimmt in diesem Sinne Alchimie sehr ernst, wie Sie sehen. Solche Rätsel, die direkt mit Geheimnissen der geistigen Welt zusammenhängen, sind im «Faust» sehr viele. Man muß den «Faust» so auf sich wirken lassen, daß man gewahr wird, welche Tiefen geistiger Wirklichkeit eigentlich diesem «Faust» zugrunde liegen. Nur dadurch versteht man so jemanden wie Goethe, daß man sich klarmacht: Er hat auf der einen Seite getrachtet, das, was ihn gemacht hat, wirklich wie von außen anzusehen, wofür ein Beweis seine Darstellung in «Dichtung und Wahrheit» ist, und hat auf der andern Seite auch gewußt, das führt zurück sogar in weite perspektivische Zusammenhänge mit den Toten. Und Faust tritt in das Leben sehr weit zurückliegender Menschenentwickelung ein, tritt auch in das Leben weit zurückliegender geistiger Wesenheiten ein.

Aber, wenn man ganz durchschauen will, was nötig ist in positivem Sinne für die Gegenwart, dann muß man in vieler Beziehung auch einen Blick und ein Gefühl für das Negative haben, muß das richtige Fühlen entwickeln für das Negative. Man muß einen Blick haben für alles das, was verhindert das als notwendig bezeichnete Zusammenkommen der lebenden Menschen im gemeinsamen Plane mit dem Wirken der Toten. Überall können Sie heute die Hindernisse entdecken. Sie finden sie auf Schritt und Tritt. Sie finden sie gerade dort, wo Bildung — verzeihen Sie, daß ich dieses häßliche Wort gebrauche - heute verbreitet wird.