Ancient Myths, Their Meaning and Connection with Evolution

GA 180

11 January 1918, Dornach

Lecture V

It is our aim in these lectures to speak of important questions of mankind's evolution, and you have already seen that all sorts of preparatory facts drawn from distant sources are necessary to our purpose. In order that we may have a foundation as broad as possible, I shall remind you today of various things that have been said from one or another standpoint during my present stay here, but which are essential for a right understanding of the two coming lectures.

I have pointed out to you that in that evolutionary course of mankind which can be regarded as first interesting us after the great Atlantean catastrophe, significant changes took place in humanity. I have already some months ago indicated how changes in humanity as a whole differ from changes taking place in a single individual. The individual as the years go on becomes older. In a certain respect one can say that for humanity as such, the reverse is the case. A man is first child, then grows up and attains the age known to us as the average age of life. In so doing the man's physical forces undergo manifold changes and transformations. Now we have already described in what sense I a reverse path is to be attributed to mankind. During the 2,160 years that followed the great Atlantean catastrophe mankind can be said to have been capable of development in a way quite different from what was possible later. This is that ancient time which followed immediately upon the great flooding of the earth—called in geology the Ice Age, in religious tradition, the Flood—from which there actually proceeded a kind of glacial state.

We know that at our present time we are capable of development up to a certain age independently of our own action; we are capable of development through our nature, our physical forces. We have stated that in the first epoch after the great Atlantean catastrophe man remained capable of development for a much longer time. He remained so into the fifth decade of his life, and he always knew that the process of growing older was connected with a transformation of the soul and spirit nature. If today we wish to have a development of the soul and spirit nature after our twenties, we must seek for this development by our power of will. We become physically different in our twenties and in this becoming different physically there lives at the same time something that determines our progress of soul and spirit. Then the physical ceases to let us be dependent on it; then, so to speak, our physical nature hands over nothing more, and through our own willpower we must make any further advance. This is how it seems, externally considered—we shall see immediately how matters stand inwardly.

There was in fact a great difference in the first 2,160 years after the great Atlantean catastrophe. Then indeed man was still dependent on his physical element far into old age, but he had also the joy of this dependence. He had the joy of not only progressing during his growth, and increasing, but of experiencing, even in the decline of life-forces, the fruit of these declining life-forces as a kind of blooming of soul qualities, which man can feel no longer. Yes, external physical cosmic conditions of human existence alter in relatively not such a very long time.

Then again came a time in which man no more remained capable of development to such a great age, into the fifties. In the second epoch after the great Atlantean catastrophe, which again lasted for approximately 2,160 years, and which we call the Old Persian, man remained still capable of development up to the end of his forties. Then in the next epoch, the Egypto-Chaldean, he could develop up to the time of his forty-second year. We are now living—since the 15th Century—in the period where man carries his development only into his twenties. This is all something of which external history tells us nothing, which moreover is not believed by external historical science, but with which infinitely many secrets of mankind's evolution are connected. So that one can say: Mankind as a whole drew in, became younger and younger—if we call this change in development a becoming-younger! And we have seen what consequence must be drawn from it. This consequence was not so pressing in the Greco-Latin age; a man then remained capable of development up to his thirty-fifth year through his natural forces. It becomes more and more pressing, and from our time onward quite specially significant. For as regards humanity as a whole we are living, so to say, in the twenty-seventh year, are entering the twenty-sixth and so on. So that men are condemned to carry right through life the development they acquired in early youth through natural forces, if they do nothing of their own freewill to take their further development in hand. And the future of mankind will consist in their receding more and more, receding further, so that I, if no spiritual impulse grips mankind, times can come in which only the views and opinions of youth prevail.

This becoming younger of humanity is shown in external symptoms—and one who regards historical development with more sharpened senses can see it—it is shown by the fact that in Greece, let us say, a man had still to be of a definite age before he could take any part in public affairs. Today we see the claim made by great circles of mankind to reduce this age as much as possible, since people think that they already know in the twenties everything that is to be attained. More and more demands will be made in this direction, and unless an insight arises to paralyse them there will be demands that not only in the beginning of his twenties a man is clever enough to take part in any kind of parliamentary business in the world, but the nineteen-year-olds and eighteen-year-olds will believe that they contain in themselves all that a man can compass.

This kind of growing younger is at the same time a challenge to mankind to draw for themselves from the spirit what is no longer given by nature. I called your attention last time to the immense incision in the evolutionary history of mankind which lies in the 15th Century. This is again something of which external history gives no tidings, for external history, as I have often said, is a fable convenue. There must come an entirely new knowledge of the being of man. For only when an entirely new knowledge of man's being is reached, will the impulse really be found which mankind needs if it is to take in hand of its own freewill what nature no longer provides. We dare not believe that, the future of humanity will come through with the thoughts and ideas which the modern age has brought and of which it is so proud. One cannot do enough to make oneself clear how necessary it is to seek for fresh and different impulses for the evolution of humanity. It is of course a triviality to say, as I have often remarked, that our time is a transition age—for in reality each age is a transition. But it is a different thing to know what is changing in a definite age. Every age is assuredly an age of transition, but in each age one should also look about and see what is passing over.

I will link this to a fact—I could take a hundred others—but I will link on to a definite fact and let it serve as an example—one could draw on hundreds from every part of Europe. In the first half of the 19th Century, in 1828 in Vienna, a number of lectures were held by Friedrich Schlegel, one of the two brothers Schlegel, who have deserved so well of Central European culture. Friedrich Schlegel sought in these lectures to show from a lofty historical standpoint what the development of the time required, and how these requirements should be studied if the right direction were to be given to the evolution of the 19th Century and the coming age.

Friedrich Schlegel was influenced at that time by two main historical impressions. On the one hand he looked back at the 18th Century, how it had gradually evolved to atheism, materialism, irreligion. He saw how what had gone on in people's minds during the course of the 18th Century then exploded in the French Revolution. (We wish to make no criticism, merely to bring forward a fact, to consider a human outlook.) Friedrich Schlegel saw a great onesidedness in the French Revolution. To be sure, one might find it today reactionary if such a man as Friedrich Schlegel sees a great onesidedness in the French Revolution, but one would also have to look on such a verdict from other aspects. On the whole it is fairly simple to say to oneself that this or the other was gained for mankind through the French Revolution. It is no doubt very simple; but it is a question whether someone who speaks enthusiastically in this way of the French Revolution is really altogether sincere in his inmost heart. One questions it! There is a crucial test of this sincerity which simply consists in this: one should consider how one would look at such a Movement if it broke out round one at the present day? What would one say to it then? One should really put oneself this question when judging these matters. Only then does one have a kind of crucial test of one's own sincerity, for on the whole it is not so very difficult to be enthusiastic over something that went on so and so many decades ago. The question is whether one could also be enthusiastic if one were directly sharing in it at the present day.

Friedrich Schlegel, as I have said, looked on the Revolution as an explosion of the so-called Enlightenment, the atheistic Enlightenment of the 18th Century. And side by side with this event to which he turned his attention he set another: the appearance of that man who took the place of the Revolution, who contributed so enormously to the later shaping of Europe—Napoleon. Friedrich Schlegel from the lofty standpoint from which he viewed world-history, pointed out that when such a personality enters with such a force into world-evolution he must really be considered from a different standpoint from the one that is generally taken. He makes a very fine observation where he speaks of Napoleon. He says: ‘One should not forget that Napoleon had seven years in which to grow familiar with what he later looked on as his task; for twice seven years the tumult lasted that he carried through Europe, and then for seven years more the life-time lasted that was granted him after his fall. Four times seven years is the career of this man.’ In a very fine way this is pointed out by Friedrich Schlegel.

I have indicated on various occasions what a role is played by this inner law in the case of men who are really representative in the historical evolution of humanity. I have pointed out to you how remarkable it is that Raphael always makes an important painting after a definite number of years. I have pointed out how a flaring-up of Goethe's poetic power always takes place in seven-year periods, whereas between these periods there is a dying down. And one could bring forward many, many such examples. Friedrich Schlegel did not look on Napoleon exactly as an impulse of blessing for European humanity!

Now in these lectures Friedrich Schlegel showed what, in his view, the salvation of Europe demanded after the confusion brought by the Revolution and the Napoleonic age. And he finds that the deeper reason of the disorder lies in the fact that men cannot lift themselves to a more all-embracing standpoint in their world conception, which indeed can only come from an understanding of the spiritual world. Hence, thinks Friedrich Schlegel, instead of a common human world-conception, we have everywhere party-standpoints in which everyone looks on his point of view as something absolute, something which must bring salvation to all. According to Friedrich Schlegel the only salvation of mankind would be for each man to be aware that he takes a certain standpoint and others take others, and an agreement must come about through life itself. No one stand point should gain a footing as the absolute. Now Friedrich Schlegel considers that true Christianity is the one and only thing that can show man how to realize the tolerance that he means—a tolerance not inclining to indifference, but to strong and active life. And therefore he draws the conclusion (I must emphasize it is in 1828) from what he has put before his audience: the whole life of Europe, above all, however, the life of science and life of the State, must be Christianized. And he sees the great evil to be that science has become unchristian, States have become unchristian, and that nowhere has what is meant by the actual Christ-Impulse penetrated in modern times into scientific thought or the life of the State. Now he demands that the Christ-Impulse should once more permeate the scientific and State-life.

Friedrich Schlegel was of course speaking of the science, the political life of his time, 1828. But for certain reasons which will shortly be clearer to us than they are now, one could look at modern science and modern political life as he regarded them in 1828. Try for once to inquire of the sciences which count for the most in public life: physics, chemistry, biology, national-economy, political science too, try to inquire of them whether the Christian impulse is seriously anywhere within them! People do not acknowledge it, but all the sciences are actually atheistic. And the various churches try to get along well with them, as they do not feel strong enough really to permeate science with the principle of Christianity! Hence the cheap and comfortable theory that the religious life makes different demands from those of official science, that science must keep to what can be observed, the religious life to the feelings. Both are to be nicely separate, the one direction is to have no say in the other. One can live together in this way, my dear friends, one can indeed! But it gives rise to the sort of conditions that now exist.

Now what Friedrich Schlegel brought forward at that time was imbued with a deep inner warmth, and his great personal impulse was to serve his age, to demand that religion should not merely be made a Sunday School affair but should be carried into the whole of life, above all the life of science and State. And one can see from the way he spoke at that time in Vienna that he had a hope, a great hope, that out of the disorder produced by the Revolution and Napoleon, a Europe would come forth which would be Christianized in its life of State and Science. The final lecture treated especially of the prevailing spirit of the age and the general revival. And as motto for the lecture, which is truly delivered with great power, he put the Bible text: ‘I come quickly and make all things new.’ And he headed it with this motto because he believed that in the men of the 19th Century, to whom he could speak at that time as young men, there lay the power to receive that which can make all things new.

Anyone who reads through these lectures of Friedrich Schlegel's leaves them with mixed feelings. On the one hand, one says: From what lofty standpoints, from what lucid conceptions men have spoken formerly of science and political life! How one must have longed for such words to kindle a fire in countless souls. And had they kindled this fire what would Europe have become in the course of the 19th Century! I repeat: it is with mixed feelings that one leaves off reading. For in the first place: that is not what came about; what came about are these catastrophic events which now stand so terribly before us. And these catastrophes were preceded by a preparation in which one could have seen exactly that such events had to come. They were preceded by the age of materialistic science—which had become stronger than it was in Friedrich Schlegel's time—preceded by the age of materialistic statesmanship over the whole of Europe. And only with sorrowful feelings can one now behold such a motto: ‘For lo, I come quickly and make all things new.’ Somewhere there must be a mistake. Friedrich Schlegel most certainly spoke from utterly honest conviction. And he was in no slight degree a keen observer of his time; he could judge of the conditions—but yet there must have been something not quite in accord.

For, my dear friends, what did Friedrich Schlegel understand by the Christianizing of Europe? One can admit that he had a feeling for the greatness, the significance of the Christ-Impulse. And hence he also had the feeling that the Christ-Impulse must be grasped in a new way in a new age, that one cannot stop short at the way in which earlier centuries had grasped it. That he knows; a feeling of that is present in him. But, nevertheless, with this feeling he finds support in the already existing Christianity, Christianity as it had developed historically up to his time. He believed that a movement could proceed from Rome of which it could be said ‘I come quickly and make all things new’. He was in fact one of those men of the 19th Century who turned from Protestantism to Catholicism because they believed they could trace more strength in the Catholic life than in the Protestant. But he was a free spirit enough not to become a Catholic zealot.

There is, however, something which Friedrich Schlegel has not said to himself. What he has not told himself is that one of the deepest and most significant truths of Christianity lies in the words: ‘I am with you always even unto the end of the Earth-time.’ Revelation has not ceased; it returns periodically. And whereas Friedrich Schlegel built upon what was already there, he should have seen, have felt, that a real Christianizing of science and the life of the State can only enter if fresh knowledge is drawn out of the spiritual world. This he did not see; he knew nothing of it. And this, my dear friends, shows us, by one of the most significant examples of the 19th Century, that again and again even in the most enlightened minds the illusion crops up that one can link on to something already existing. It is thought that one need not draw something new from the well of rejuvenescence. With these illusions people can no doubt say things and carry out things that are great and brilliant, but it leads to nothing. For Friedrich Schlegel's hope was for a Europe of the 19th Century with its science and political life permeated by Christianity. It must come quickly, he thought, a general renewal of the world, a general re-establishing of the Christ-Impulse. And what came? A materialistic trend in the science of the second half of the 19th Century, compared with which the materialism known by Friedrich Schlegel in 1828 was child's play. And then also came a materializing of political life (one must know history, real history, not the fable convenue which is taught in schools and universities) of which likewise in 1828 he could see nothing around him. Thus he prophesied a Christianizing of Europe and was so bad a prophet that a materializing of Europe came about!

Men live willingly in illusions. And this is connected with the great problem that is now occupying us, the problem that will become clear to us in the coming days: men have forgotten how really to become old, and we must learn again to become old. We must learn in a new way how to become old, and we can only do so through spiritual deepening. But, as I said, this can only become clear in the course of our study. Our time is in general disinclined for it, still disinclined, and it must cease to be disinclined and grow inclined for it.

In any case, my dear friends, the customary thought and feeling of today are not aiming at familiarizing themselves with a certain ease and facility with what, for instance, forms the spiritual challenge of the anthroposophical Spiritual Science. One can see that by various examples: I will bring forward one that lies to hand.

I had a letter the day before yesterday from a man of learning. He writes to me that he has just read a lecture of mine on the task of Spiritual Science,1See: ‘The Mission of Spiritual Science and of its Building at Dornach.’ which I gave two years ago, and that he now sees that this Spiritual Science has, after all, something very fruitful for him. There is a thoroughly warm tone in this letter, a thoroughly amiable, kindly tone. One sees that the man is gripped by what he has read in this lecture on the task of Spiritual Science. He is a trained Natural Scientist, standing in the difficult life of today, and he has seen from this lecture that Spiritual Science is not stupid and not unpractical, but can give an impulse to the time. But now let us look at the reverse side of the matter. The same man five years ago sought to attach himself to this Spiritual Science, to join a group where Spiritual Science was studied, begged moreover at that time to have various conversations with me, and these he had. He took part in group meetings five years ago, and five years ago he so reacted that the whole matter became repugnant to him, and he turned away from it so strongly that in the meantime he has become an enthusiastic panegyrist of Herr Freimark, whom you know from his various writings. Now the same man excuses himself by saying that it would perhaps have been better, instead of doing what he did, to have read something of mine, some books of mine, and made himself acquainted with the subject. But he had not done that, he had judged by what others had imparted to him, and then he had got such a forbidding picture of Spiritual Science that he found it was not at all suited to his own path of development. Now after five years he has read a lecture and has found that this is not the case.

I quote this example—and it could be multiplied—of the way in which people stand to what desires in the only possible way—not in the way of Friedrich Schlegel—a Christianizing of all science—a Christianizing of all public life. I quote it as an example of the habits of thought of today, especially of the science of our time. It is therefore no proof that a man has found something antipathetic to him, if he approaches the Anthroposophical Movement, has various talks, takes part in group meetings, grumbles vigorously about the members of these meetings and what they say to him, concludes that he must now abuse Anthroposophy as a whole, and afterwards becomes an enthusiastic panegyrist of Freimark, who has written the vilest articles on Spiritual Science. After five years the same person decides that he will really read something! So it is no proof at all, if so and so many people today are abusive or agree with the abuse, that deep down they might not have a natural tendency to attach themselves to anthroposophical Spiritual Science. If they have as much good will as the man in question, they need five years, many need ten, many fifteen, many fifty, many so long that they can no longer experience it in this incarnation. You see how little people's behaviour is any kind of proof that they are not seeking what is to be found in anthroposophical Spiritual Science.

I bring this example forward because it points to the profoundly important fact I have often mentioned—namely the lack of stability in going into a matter, the holding fast to old traditional prejudices, which people will not let go! And that again is connected with other things. One only needs to transpose oneself in feeling into those ancient times of which I have spoken to you earlier and today. Think of a young man after the Atlantean catastrophe in his connection with other people. He was, let us say—twenty, twenty-five years old; near him he saw someone of forty, fifty, sixty years. He said to himself: What happiness someday to be as old as that, for as one lives one goes on gaining more and more. There was a perfectly obvious, immense veneration for one who had grown old; a looking up to the aged, linked with the consciousness that they had something else to say about life than the young men. Merely to know this theoretically is of no consequence, what matters is to have it in one's whole feeling, and to grow up under this impression. It is of infinite consequence to grow up in such a way as not merely to look back at one's youth and say: Ah, how fine it was when I was a child! This beauty of life will certainly never be taken from men by any kind of spiritual reflection. But it is a one-sided reflection which was supplemented in ancient times by the other: How beautiful it is to become old! For in the same degree as one became weaker in body, one grew into strength of soul, one grew into union with the wisdom of the world. This was at one time an accepted part of training and education.

Now, my dear friends, let us look at still another truth which, to be sure, I have not expressed in the course of these weeks, but which in the course of years I have already mentioned here and there to our friends: We grow older. But only our physical body grows older. For from the spiritual aspect it is not true that we grow older. It is a maya, an external deception. It is certainly a reality in respect of physical life, but it is not true in respect of the full nature of man's life. Yet, we only have the right to say it is not true, if we know that this human being who lives here in the physical world between birth and death is something else than merely his physical body. He consists of the higher members, in the first place of what we have called the etheric body or the body of formative forces, and then the astral body, the ego—if we only speak of these four. But even if we stop short at the etheric body, at the invisible, super-sensible body of formative forces, we see that we bear it within us between birth and death, just as we carry about our physical body of flesh and blood and bones. We carry in us this etheric body of formative forces, but we see there is a difference: the physical body grows ever older, the etheric or body of formative forces is old when we are born; in fact, if we examine its true nature, it is old then and it becomes ever younger and younger. We can say, therefore, that the first spiritual member in us continually becomes more vigorous and younger, in contrast to the physical-corporeal that becomes weak and powerless. And it is true, literally true, that when our face begins to get wrinkled then our etheric body blooms and becomes chubby-cheeked. Yes but, the materialistic thinker could say this is completely contradicted by the fact that one does not perceive it! In ancient times it was perceived. It is only that modern times are such that people pay no attention to the matter and give it no value. In ancient times nature itself brought it in its course, in modern times it is almost an exception. But even so, there are such exceptions. I remember that I once spoke of a similar subject at the end of the eighties with Eduard von Hartmann, the philosopher of the ‘Unconscious’. We came to speak of two men who were both professors at the Berlin University. One was Zeller, a Schwabian, then seventy-two years old, who had just petitioned for his pensioning off, and who thus had the idea ‘I have got so old that I can no longer hold my lectures.’ He was old and fragile with his seventy-two years. And the other was Michelet; he was ninety-three years old. And Michelet had just been with Eduard von Hartmann and said ‘Well, I don't understand Zeller! When I was as old as Zeller I was just a young fellow, and now, only now, do I feel really fitted to say something to people ... As for me, I shall still lecture for many long years!’ But Michelet had something of what can be called a ‘having-grown-young-in-forces’. There is of course no inner necessity that he had grown so old; for instance, a tile from a roof might have killed him when he was fifty years old or earlier. I am not speaking of such things. But after he had grown so old, in his soul he had in fact not grown old, but precisely young. This Michelet, however, in his whole being, was no materialist. Even the Hegel followers have in many ways become materialistic, although they would not assent to that, but Michelet, although he spoke in difficult sentences, was inwardly gripped by the spirit. Only a few, however, can be so inwardly gripped by the spirit. But this is just what is sought for through anthroposophical spiritual science: to give something that can be something to all men, just as religion must be something to all men, that can speak to all men. But this is connected with our whole training and education.

Our whole educational system is constructed on entirely materialistic impulses—and this must be seen in much deeper connections than is generally indicated. People reckon only with man's physical body, never with his becoming-younger. No account is taken of one's growing younger as one grows older! At first glance it is not always immediately evident. But nevertheless, all that in course of time has become the subject of pedagogy and instruction is actually only able to lay hold of men in their youth, unless they happen to become professors or scientific writers. It is not very often that one finds that someone cares to take up in the same way in later life, when he no longer needs it, the material which is absorbed today during one's schooldays. I have known doctors who were leaders in their special subject, that is to say, who had so passed their student years and youth that they had been able to become intellectual leaders. But there was no question at all of their continuing the same methods of acquiring knowledge in later years. I once knew a very famous man—I will not mention his name, he was so renowned—who stood in the front rank in medical science. He made his assistant attend to the later editions of his books, because he himself no longer took part in science; that did not suit his later years.

This is connected however with something else. We are gradually developing a consciousness that what one can absorb through learning is really only of service for one's youth and that one gets beyond it later on. And this is so. One can still force oneself later to turn back to many things, but then one must really force oneself—it does not come naturally as a rule. And yet, unless a man is always taking in something new—not just by allowing it to enter him through the concert hall, the theatre, or, with all due respect, the newspaper or something of that kind—then he grows old in his soul. We must absorb in another way, we must really have the feeling in the soul that one experiences something new, one is being transformed, and that one reacts to what one takes in just as the child reacts. One cannot do this in an artificial way, it can only happen when something is there which one can approach in later life precisely as one approaches the ordinary educational subjects when one is a child.

But now, take our anthroposophical spiritual science. We need not puzzle our heads over what it will be like in later centuries; for them the right form will be found. But in any case, as it is now—to the dislike however, of many—there is no primary necessity to cease absorbing it. No matter how extremely aged one may have become at the present time, one can always find in it something new that grips the soul, that makes the soul young again. And many new things have already been found on spiritual scientific soil—even such new things as let one look into the most important problems of today. But above all the present needs an impulse which directly seizes upon men themselves. Only in that way can this present time come through the calamity into which it has entered, and which works so catastrophically. The impulses in question must approach men direct.

And now if one is not Friedrich Schlegel but a person having insight into what humanity really needs, one can nevertheless keep to several beautiful thoughts that Friedrich Schlegel had and at least rejoice in them. He has spoken of how things must not be treated as absolute from a definite standpoint. He has, in the first place, only seen the parties which always regard their own principle as the only one to make all mankind happy. But in our time much more is treated as absolute! Above all, it is not perceived that an impulse in life can be harmful by itself, but can be beneficial in co-operation with other impulses, because it then becomes something different. Think of three directions that take their course together—I shall make a sketch.

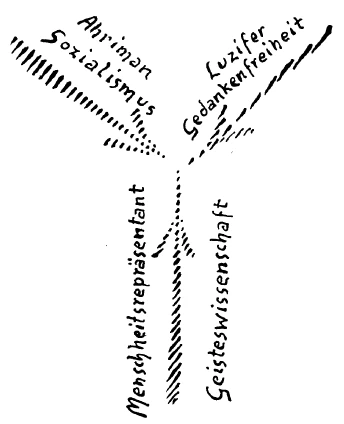

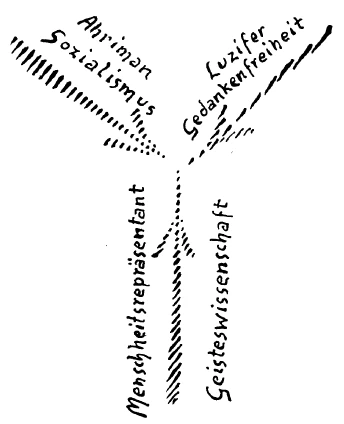

One direction is to symbolize for us the socialism to which modern mankind is striving—not just the current Lenin socialism. The second line is to symbolize what I have often characterized to you as freedom of thought, and the third direction is Spiritual Science. These three things belong to one another; they must work together in life.

If socialism, in the crude materialistic form in which it appears today, attempts to force itself upon mankind, it will bring the greatest unhappiness upon humanity. It is symbolized for us through the Ahriman at the foot of our Group, in all his forms. If the false freedom of thought, which wants to stop short at every thought and make it valid, seeks to force itself, then harm is again brought to mankind. This is symbolized in our Group through Lucifer. But you can exclude neither Ahriman nor Lucifer from the present day, they must only be balanced through Pneumatology, through Spiritual Science, which is represented by the Representative of mankind who stands in the centre of our Group. It must be repeatedly pointed out that Spiritual Science is not meant to be merely something for people who have cut themselves adrift from ordinary life through some circumstance or other and who want to be stimulated a little through all sorts of things connected with higher matters. Rather is Spiritual Science, anthroposophical Spiritual Science, intended to be something that is connected with the deepest needs of our age. For the nature of our age is such that its forces can only be discovered if one looks into the spiritual. It is connected with the worst evil of our time—that countless men today have no idea that in the social, the moral, the historical life, super-sensible forces are ruling; indeed, just as the air is all around us, so do super-sensible forces hold sway around us. The forces are there, and they demand that we shall receive them consciously, in order to direct them consciously, otherwise they can be led into false paths by the ignorant, or those who have no understanding. In any case the matter must not be made trivial. It must not be thought that one can point to these forces as one often prophesies the future from coffee grounds and so on! But nevertheless in a certain way and sometimes in a very close way the future and the shaping of the future are connected with what can only be recognized if one proceeds from principles of spiritual science.

People will need perhaps longer than five years to see that. But precisely because of these actual events—the signs of the time demand it—there must again and again be emphasized how it is the great demand of our age that people realize the fact that certain things which happen today can only be discovered and, above all, rightly judged, if one proceeds from the standpoint gained through anthroposophical Spiritual Science.

Zwölfter Vortrag

In diesen Betrachtungen wollen wir ja über wichtige Fragen der Menschheitsentwickelung sprechen, und Sie haben bereits gesehen, daß dazu mancherlei weither geholte Vorbereitungen notwendig sind. Heute will ich, damit wir eine möglichst breite Grundlage haben können, Sie an einzelnes erinnern, das im Laufe der Auseinandersetzungen während meines diesmaligen hiesigen Aufenthaltes von diesem oder jenem Gesichtspunkte aus gesagt worden ist, das uns aber notwendig ist, wenn wir morgen und übermorgen die Betrachtung in dem richtigen Lichte sehen wollen.

Ich habe Sie darauf hingewiesen, wie in jenem Entwickelungsgange der Menschheit, den man als den uns zunächst seit der großen atlantischen Katastrophe interessierenden betrachten kann, bedeutungsvolle Veränderungen mit der Menschheit vor sich gegangen sind. Ich habe vor Monaten schon darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie anders sich die Menschheit im allgemeinen verändert als der einzelne Mensch. Der einzelne Mensch wird, indem die Jahre vorrücken, älter. In einer gewissen Beziehung kann man sagen, bei der Menschheit als solcher ist das Entgegengesetzte der Fall. Der Mensch ist zuerst Kind, wächst dann heran und erreicht eben das Alter, das uns als das durchschnittliche Lebensalter bekannt ist. Dabei ist die Sache so, daß die physischen Kräfte des Menschen einer mannigfaltigen Veränderung und Verwandlung unterliegen. Nun haben wir schon charakterisiert, in welchem Sinne bei der Menschheit ein umgekehrter Gang stattfindet. Man kann sagen, daß die Menschheit in jener alten Zeit, die auf die große atlantische Katastrophe folgte - in der Geologie nennt man es die Eiszeit, in den religiösen Traditionen die Sintflut —, in jener Zeit also, die unmittelbar auf diese große Überflutung der Erde folgte, aus der wirklich eine Art Vereisung hervorging, in den nächsten 2160 Jahren in einer ganz andern Art entwickelungsfähig war als später.

Wir wissen, daß wir in unserer Gegenwart entwickelungsfähig sind bis zu einem gewissen Alter, frei ohne unser Zutun, durch unsere Natur, durch unsere physischen Kräfte entwickelungsfähig sind. In der ersten Zeit nach der großen atlantischen Katastrophe, haben wir gesagt, war der Mensch viel länger entwickelungsfähig. Er blieb entwickelungsfähig bis in die Fünfzigerjahre seines Lebens, so daß er immer wußte: in dieser Zeit, mit dem vorschreitenden Älterwerden ist verbunden auch eine Umwandlung des Seelisch-Geistigen. Wenn wir heute nach unseren Zwanzigerjahren eine Entwickelung des Seelisch-Geistigen haben wollen, dann müssen wir diese Entwickelung durch unsere Willenskraft suchen. Bis in die Zwanzigerjahre hinein werden wir physisch anders; und im Physisch-Anderswerden lebt zugleich etwas, das unser geistig-seelisches Weiterschreiten bestimmt. Dann hört das Physische auf, uns abhängig sein zu lassen von sich; dann gibt sozusagen unser Physisches nichts mehr her, und wir müssen uns eben durch unsere Willenskraft weiterbringen. So erscheint es zunächst äußerlich angesehen. Wir werden gleich nachher sehen, wie die Sache innerlich liegt.

Das war anders in den ersten 2160 Jahren ungefähr nach der großen atlantischen Katastrophe. Da blieb der Mensch von seinem Physischen zwar abhängig bis in sein hohes Alter hinein, aber er hatte auch die Freude dieser Abhängigkeit. Er hatte die Freude, nicht nur während des Wachsens und im Wachstumzunehmen weiterzuschreiten, sondern er hatte die Freude, auch bei abnehmenden Lebenskräften die Früchte dieser abnehmenden Lebenskräfte im Seelischen als eine Art Aufblühen des Seelischen zu erleben, was man jetzt nicht mehr kann. Ja, es ändern sich eben die äußeren, physisch-kosmischen Bedingungen des menschlichen Daseins in verhältnismäßig gar nicht so langer Zeit.

Dann wiederum kam die Zeit, in der der Mensch nicht mehr in ein so hohes Alter, bis in die Fünfzigerjahre hinauf entwickelungsfähig blieb. In dem zweiten Zeitraume nach der großen atlantischen Katastrophe, der wiederum ungefähr 2160 Jahre dauerte, den wir den urpersischen nennen, blieb der Mensch aber immer noch entwickelungsfähig bis in die Höhe der Vierzigerjahre hinauf. Dann, in dem nächsten Zeitraume, in dem ägyptisch-chaldäischen, blieb er entwickelungsfähig bis in die Zeit vom 35. bis 42. Jahre. In der griechisch-lateinischen Zeit blieb der Mensch entwickelungsfähig bis in die Zeit des 35. Jahres hinein. Jetzt leben wir in der Zeit seit dem 15. Jahrhundert, wo der Mensch seine Entwickelung nur bis in die Zwanzigerjahre hineinträgt.

Das alles ist etwas, wovon uns die äußere Geschichte nichts erzählt und was auch von der äußeren Geschichtswissenschaft nicht geglaubt wird, womit aber unendlich viele Geheimnisse der menschheitlichen Entwickelung zusammenhängen. So daß man sagen kann, die gesamte Menschheit rückte herein, wurde immer jünger und jünger — wenn wir dieses Verändern in der Entwickelung ein Jüngerwerden nennen. Und wir haben gesehen, welche Folgerung daraus gezogen werden muß. Diese Folgerung war noch nicht so brennend in der griechisch-lateinischen Zeit; da blieb der Mensch bis zu seinem fünfunddreißigsten Jahre naturgemäß entwickelungsfähig. Diese Folgerung wird immer brennender und brennender und von unserer Zeit ab ganz besonders bedeutungsvoll. Denn mit Bezug auf die ganze Menschheit leben wir sozusagen jetzt im siebenundzwanzigsten Jahre, gehen in das sechsundzwanzigste, und so weiter; so daß die Menschen darauf angewiesen sind, durch das ganze Leben hindurchzutragen dasjenige, was ihnen in ihrer frühen Jugend durch die naturgemäße Entwickelung wird, wenn sie nichts dazutun, aus freiem Willen heraus die Weiterentwickelung von sich selbst in die Hand zu nehmen. Und die Zukunft der Menschheit wird darinnen bestehen, daß sie immer mehr zurückgeht, immer weiter zurückgeht, so daß, wenn nicht ein spiritueller Impuls die Menschheit ergreift, Zeiten kommen könnten, in denen nur Jugendansichten herrschen.

In äußeren Symptomen prägt sich ja dieses Jüngerwerden der Menschheit dadurch aus — und derjenige, der mit einigem klügeren Sinnen die geschichtliche Entwickelung betrachtet, kann das auch äußerlich sehen -,'es prägt sich dadurch aus, daß, sagen wir, noch in Griechenland man ein bestimmtes Alter haben mußte, wenn man an den öffentlichen Angelegenheiten irgendwie teilnehmen sollte. Heute sehen wir die Forderung gestellt von großen Kreisen der Menschheit, dieses Alter so weit wie möglich hereinzurücken, weil die Menschen denken, daß sie schon alles, was der Mensch erreichen kann, in den Zwanzigerjahren wissen. Und es werden Forderungen kommen, immer weiter und weitergehend nach dieser Richtung, wenn nicht die Einsicht diese Forderungen paralysiert: nicht nur etwa den Menschen vom Beginn der Zwanzigerjahre ab so gescheit sein zu lassen, daß er an allein Parlamentarischen, irgendwie gearteten Parlamentarischen der Welt teilnehmen kann, sondern die Neunzehn-, Achtzehnjährigen werden glauben, daß sie alles dasjenige, was der Mensch umfassen kann, eben in sich tragen.

Diese Art des Jüngerwerdens der Menschen ist zugleich eine Aufforderung an die Menschheit, dasjenige, was die Natur dem Menschen nicht mehr gibt, aus dem Geistigen sich herzuholen. Ich habe Sie das letzte Mal darauf aufmerksam gemacht, welch ungeheurer Einschnitt in der Entwickelungsgeschichte der Menschheit im 15. Jahrhundert liegt, wiederum etwas, wovon die äußere Geschichte keine Kunde gibt, denn diese äußere Geschichte ist, wie ich schon oft gesagt habe, eine fable convenue. Kommen muß eine ganz neue Erkenntnis der menschlichen Wesenheit, denn nur, wenn eine ganz neue Erkenntnis der menschlichen Wesenheit kommt, läßt sich der Impuls, den die Menschheit braucht, um das aus freiem Willen in die Hand zu nehmen, was die Natur nicht mehr hergibt, dann wirklich finden. Wir dürfen nicht glauben, daß die Zukunft der Menschheit auskommen werde mit denjenigen Gedanken und Ideen, welche die neuere Zeit gebracht hat, und auf welche diese neuere Zeit so stolz ist. Man kann nicht genug tun, um sich klarzumachen, wie notwendig es ist, neue, neuartige Impulse für die Entwickelung der Menschheit zu suchen. Gewiß ist es eine Trivialität, wie ich oftmals gesagt habe, zu sagen, unsere Zeit sei ein Übergangszeitalter, denn das ist wirklich jede Zeit. Aber etwas anderes ist es, zu wissen, was übergeht in einer bestimmten Zeit. Gewiß ist. jede Zeit eine Übergangszeit; aber in jeder Zeit sollte man auch sich umsehen nach dem, was im Übergange begriffen ist.

Ich will anknüpfen an eine Tatsache. Ich könnte an hundert andere anknüpfen, aber ich will an eine bestimmte Tatsache anknüpfen, die nur als Beispiel dienen soll für vieles. Wie gesagt, aus allen Orten Europas, in hundertfacher Weise könnte man an ähnliche Dinge anknüpfen. Es war noch in der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, da hielt Friedrich Schlegel, der eine der beiden um die mitteleuropäische Kultur so hochverdienten Gebrüder Schlegel, eine Anzahl von Vorlesungen in Wien, 1828. In diesen Vorlesungen versuchte Friedrich Schlegel von einem hohen geschichtlichen Standpunkte aus den Menschen zu sagen, welche Bedürfnisse in der Zeitentwickelung liegen, wohin man die Augen richten solle, um das Rechte zu treffen für die Entwickelung des 19. Jahrhunderts und der kommenden Zeit.

Friedrich Schlegel stand dazumal unter zwei hauptsächlichsten geschichtlichen Eindrücken. Auf der einen Seite blickte er hin auf das 18. Jahrhundert, wie es sich entwickelt hat allmählich zum Atheismus, zum Materialismus, zur Irreligiosität. Und Friedrich Schlegel - wir wollen keine Kritik üben, sondern nur eine Tatsache vorführen, eine menschliche Anschauung in Betracht ziehen -, Friedrich Schlegel sah, wie dasjenige, was in den Köpfen sich im Laufe des 18. Jahrhunderts abgespielt hat, dann explodiert ist in der Französischen Revolution. Er sah in dieser Französischen Revolution eine große Einseitigkeit. Gewiß, man kann es heute reaktionär finden, wenn solch ein Mensch wie Friedrich Schlegel in der Französischen Revolution eine große Einseitigkeit sieht, aber solch ein Urteil müßte man doch auch noch unter andern Gesichtspunkten anschauen. Es ist im allgemeinen ziemlich einfach, sich zu sagen, das und jenes sei für die Menschheit errungen worden durch die Französische Revolution. Gewiß ist das recht einfach; aber es fragt sich, ob jeder, der mit Enthusiasmus in dieser Weise von der Französischen Revolution spricht, wirklich in seinem allerinnersten Herzen auch ganz aufrichtig ist. Es gibt, ich möchte sagen, eine Kreuzprobe auf diese Aufrichtigkeit, und diese Kreuzprobe besteht lediglich darinnen, daß man sich überlegen sollte: Wie würde man solch eine Bewegung, wenn sie um einen herum ausbräche in der Gegenwart, selber ansehen? Was würde man dann dazu sagen? Diese Frage sollte man sich eigentlich immer vorlegen, wenn man sich diese Sachen ansieht. Dann erst bekommt man eine Art von Kreuzprobe für seine eigene Aufrichtigkeit. Denn es ist im allgemeinen nicht gerade schwierig, begeistert zu sein über dasjenige, was vor so und so viel Jahrzehnten sich zugetragen hat. Es fragt sich, ob man auch begeistert sein könnte, wenn man unmittelbar in der Gegenwart daran beteiligt wäre.

Friedrich Schlegel, wie gesagt, betrachtete die Revolution als eine Explosion der sogenannten Aufklärung, der atheistischen Aufklärung des 18. Jahrhunderts. Und neben dieses Ereignis, auf das er seine Blicke richtet, stellte er hin ein anderes: das Auftreten desjenigen Menschen, der die Revolution abgelöst hat, der so ungeheuer viel beigetragen hat zu der späteren Gestaltung von Europa: Napoleon. Und Friedrich Schlegel - wie gesagt, er betrachtete die Weltgeschichte von einem hohen Gesichtspunkte aus -, Friedrich Schlegel macht aufmerksam bei dieser Gelegenheit, daß eine solche Persönlichkeit, wenn sie eintritt mit einer solchen Kraft in die Weltentwickelung, wirklich auch von einem andern Gesichtspunkte aus noch betrachtet werden muß als von dem, den man gewöhnlich anlegt. Friedrich Schlegel macht eine sehr schöne Bemerkung da, wo er über Napoleon spricht. Er sagt, man solle nicht vergessen: Sieben Jahre habe Napoleon Zeit gehabt, sich hineinzuleben in dasjenige, was er dann später als seine Aufgabe betrachtete; zweimal sieben Jahre dauerte der Tumult, den er durch Europa trug, und einmal sieben Jahre dauerte dann noch die Lebenszeit, die ihm nach seinem Sturze gegönnt war. Viermal sieben Jahre ist die Laufbahn dieses Menschen. Darauf macht Friedrich Schlegel in sehr schöner Weise aufmerksam.

Ich habe Sie bei den verschiedensten Gelegenheiten darauf hingewiesen, welche Rolle solche innere Gesetzmäßigkeit bei Menschen spielt, die wirklich repräsentativ sind in der Entwickelungsgeschichte der Menschheit. Ich habe Sie darauf hingewiesen, wie merkwürdig es ist, daß Raffael immer nach einer bestimmten Anzahl von Jahren eine bedeutende malerische Leistung macht; ich habe Sie darauf hingewiesen, wie bei Goethe in siebenjährigen Perioden immer ein Aufflackern der Dichterkraft stattfindet, während in der Zwischenzeit, zwischen den siebenjährigen Terminen, ein Abflauen stattfindet. Und so könnte man viele, viele Beispiele anführen für diese Dinge. Friedrich Schlegel betrachtete Napoleon auch nicht gerade als einen Segensimpuls für die europäische Menschheit.

Nun macht Friedrich Schlegel in diesen Vorträgen darauf aufmerksam, worinnen nach seiner Ansicht das Heil Europas bestehen müsse, nachdem die Verwirrung durch die Revolution, die Verwirrung durch das napoleonische Zeitalter gekommen ist. Und Friedrich Schlegel findet, daß der tiefere Grund zu der Verwirrung darinnen besteht, daß die Menschen nicht in der Lage sind, sich zu erheben mit ihrer Weltanschauung zu einem umfassenderen Standpunkte, der ja nur aus einem Einleben in die geistige Welt kommen kann. Dadurch, meint Friedrich Schlegel, ist das gekommen, was an die Stelle einer allgemein menschlichen Weltanschauung überall Parteigesichtspunkte stellt, Parteigesichtspunkte, die darinnen bestehen, daß jemand dasjenige, was sich ihm auf seinem Standpunkte des Lebens ergibt, als etwas Absolutes betrachtet, als dasjenige, was allen Heil bringen muß; während nach Anschauung Friedrich Schlegels das einzige Heil der Menschheit darinnen besteht, daß man sich dessen bewußt ist: man steht auf einem gewissen Standpunkt, und andere stehen auf einem andern Standpunkte, und es muß sich ein Ausgleich der Standpunkte durch das Leben finden. Nicht die Verabsolutierung eines Standpunktes darf Platz greifen.

Nun findet Friedrich Schlegel, daß das einzige, welches den Menschen anweisen kann, wirklich diese nicht zum Indifferentismus hinneigende, sondern zum kraftvollen Lebenswirken hinneigende Toleranz, die er meint, zu verwirklichen, einzig und allein das wahre Christentum ist. Deshalb zieht Friedrich Schlegel - 1828, ich muß das immer betonen — aus den Betrachtungen, die er vor seine Zuhörer hingestellt hat, den Schluß, daß alles Leben Europas, vor allem aber das Leben der Wissenschaft und das Leben der Staaten, durchchristet werden müsse. Und darinnen sieht er das große Unheil, daß die Wissenschaft unchristlich geworden ist, daß die Staaten unchristlich geworden sind, daß nirgends dasjenige, was den eigentlichen ChristusImpuls bedeutet, eingedrungen ist in der neueren Zeit in die wissenschaftlichen Betrachtungen und eingedrungen ist in das Leben der Staaten. Nun fordert er, daß wiederum der christliche Impuls in das Wissenschafts- und in das Staatsleben eindringe.

Friedrich Schlegel sprach natürlich über die Wissenschaftlichkeit und über das Staatsleben seiner Zeit, also des Jahres 1828. Aber man kann schon aus gewissen Gründen, die uns gleich nachher besser einleuchten werden als eben jetzt, auch die heutige Wissenschaft und das heutige Staatsleben so betrachten, wie Friedrich Schlegel sie 1828 betrachtet hat. Versuchen Sie heute einmal Anfragen zu stellen bei den Wissenschaften, die ja vorzugsweise heute im öffentlichen Leben Geltung haben, bei der Physik, der Chemie, der Biologie, der Nationalökonomie, auch bei der Staatswissenschaft, versuchen Sie bei ihnen anzufragen, ob irgendwo im Ernste der christliche Impuls drinnen ist. Man gesteht es nicht, aber in Wahrheit sind die Wissenschaften alle atheistisch; und die verschiedenen Kirchen versuchen, mit diesen atheistischen Wissenschaften ein gutes Auskommen zu haben, weil sie ja doch sich nicht stark genug fühlen, die Wissenschaft wirklich mit dem Prinzip des Christentums zu durchdringen. Daher die bequeme, billige Theorie, daß das religiöse Leben eben anderes erfordere als die äußere Wissenschaft, daß die äußere Wissenschaft sich halten müsse an das, was man beobachten kann, das religiöse Leben an das Gefühl. Beide sollen hübsch getrennt sein; die eine Richtung soll nicht in die andere hineinsprechen. Auf diese Weise kann man ja miteinander leben, das kann man schon, aber man führt solche Zustände herbei, wie es die gegenwärtigen sind.

Nun war, was Friedrich Schlegel dazumal vorgebracht hat, von tiefer, innerer Wärme durchdrungen, durchdrungen wirklich von dem großen Persönlichkeitsimpuls bei ihm, seiner Zeit zu dienen, aufzufordern, die Religion nicht bloß zu einer Sonntagsschule zu machen, sondern sie hineinzutragen in alles Leben, vor allem in das Wissenschafts- und in das Staatsleben. Und man kann sehen aus der Art und Weise, wie Friedrich Schlegel dazumal in Wien gesprochen hat, daß er Hoffnung hatte, große Hoffnung hatte darauf, daß aus dem Wirrwarr, den die Revolution und Napoleon angerichtet haben, ein Europa hervorgehen werde, welches durchchristet sein werde in seinem Wissenschafts- und in seinem Staatsleben. Die letzte von diesen Vorlesungen handelt insbesondere von dem herrschenden Zeitgeiste und von der allgemeinen Wiederherstellung. Als Motto setzte Friedrich Schlegel über diese Vorlesung, die wirklich getragen ist von großem Geiste, die Bibelworte: «Ich komme bald und mache alles neu», und er setzte dieses Motto darüber aus dem Grunde, weil er glaubte, es liege wirklich in den Menschen des 19. Jahrhunderts, es liege in den Menschen, die er dazumal als die jungen Menschen ansprechen konnte, die Kraft, zu empfangen dasjenige, was alles neu machen kann.

Wer diese Vorträge Friedrich Schlegels durchliest, der verläßt das Lesen mit gemischten Gefühlen. Auf der einen Seite sagt man sich: Von welch hohen Gesichtspunkten, von welch lichtvollen Anschauungen aus haben einmal Menschen über Wissenschaftlichkeit und Staatsleben gesprochen! Wie hätte man wünschen müssen, daß solche Worte gezündet hätten in zahlreichen Seelen. Und hätten sie gezündet, was wäre aus Europa im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts geworden. - Ich sage, mit gemischten Gefühlen verläßt man das Lesen. Denn erstens: Es ist ja nicht so geworden, es ist zu jenen katastrophalen Ereignissen gekommen, die jetzt in so furchtbarer Weise vor uns stehen, und es ist diesen katastrophalen Ereignissen vorangegangen jene Vorbereitung, in der man genau hat sehen können, daß diese katastrophalen Ereignisse kommen müssen; es ist ihnen vorangegangen das Zeitalter der materialistischen Wissenschaftlichkeit die noch stärker wurde, als sie zu Friedrich Schlegels Zeiten war -, vorangegangen das Zeitalter der materialistischen Staatskunst über ganz Europa. Und nur mit wehmütigen Gefühlen kann man auf ein solches Motto jetzt sehen: «Denn siehe, ich komme bald und mache alles neu.»

Es muß irgendwo ein Irrtum vorliegen. Friedrich Schlegel hat ganz gewiß aus ehrlichster Überzeugung heraus gesprochen, und er war in gar nicht geringem Maße ein scharfer Beobachter seiner Zeit. Er konnte schon die Verhältnisse beurteilen, aber etwas mußte doch nicht ganz stimmen. Ja, was versteht denn Friedrich Schlegel unter der Verchristung von Europa? Man kann sagen, ein Gefühl ist in ihm für die Größe, für die Bedeutung des Christus-Impulses. Und auch dafür ist ein Gefühl in ihm, daß der Christus-Impuls in einer neuen Zeit in einer neuen Weise ergriffen werden muß, daß man nicht stehenbleiben kann bei der Art und Weise, wie frühere Jahrhunderte den Christus-Impuls ergriffen haben. Das weiß er, davon ist ein Gefühl in ihm vorhanden. Aber er lehnt sich mit diesem Gefühl doch wieder an das schon bestehende Christentum an, das Christentum, wie es sich geschichtlich bis zu seiner Zeit entwickelt hat. Er glaubte, daß von Rom ausgehen kann eine Bewegung, von der man sagen kann: «Ich komme bald und mache alles neu. » Er ist ja auch unter denjenigen Menschen des 19. Jahrhunderts gewesen, die sich vom Protestantismus zum Katholizismus gewendet haben, weil sie glaubten, in dem katholischen Leben mehr Kraft zu verspüren als in dem protestantischen Leben. Aber er war freier Geist genug, um nicht katholischer Zelote zu werden.

Aber etwas hat sich Friedrich Schlegel nicht gesagt. Was er sich nicht gesagt hat, das ist dies, daß eine der tiefsten und bedeutungsvollsten Wahrheiten des Christentums jene ist, die in den Worten liegt: «Ich bin bei euch alle Tage bis ans Ende der Erdenzeit.» Die Offenbarung hat nicht aufgehört, sondern sie kommt periodenweise wieder. Und während Friedrich Schlegel auf dasjenige baute, was schon da war, hätte er sehen müssen, fühlen müssen, daß eine wirkliche Durchchristung von Wissenschaft und Staatsleben nur eintreten kann dann, wenn neuerdings aus der geistigen Welt Erkenntnisse herausgeholt werden. Das hat er nicht gesehen; davon weiß er nichts. Und das zeigt uns an einem der bedeutsamsten Beispiele des 19. Jahrhunderts, daß immer wieder und wiederum selbst bei erleuchtetsten Geistern die Illusion auftaucht, man könne an etwas Bestehendes jetzt noch anknüpfen, man brauche nicht aus dem Jungbrunnen eines Neuen heraus zu schöpfen, und daß sie unter diesen Illusionen zwar Großes, Geniales sprechen und leisten können, daß aber doch dieses Geniale zu nichts führt. Denn Friedrich Schlegels Hoffnung war ein nach Wissenschaft und Staatsleben durchchristetes Europa im 19. Jahrhundert. Bald müsse es kommen, meinte er, eine allgemeine Erneuerung der Welt, eine allgemeine Wiederherstellung des Christus-Impulses. Und was kam? Eine materialistische Richtung in der Wissenschaft in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, gegen welche dasjenige, was Friedrich Schlegel 1828 erlebt hatte, wahrhaftig an Materialismus ein Kinderspiel war. Und eine Vermaterialisierung des Staatslebens man muß nur die Geschichte kennen, die wirkliche Geschichte, nicht jene fable convenue, welche in den Schulen und Universitäten gelehrt wird —, eine Vermaterialisierung des Staatslebens, von der ebenfalls Friedrich Schlegel 1828 um sich herum noch nichts sehen konnte. Er hat also vorausgesagt eine Durchchristung Europas und war ein so schlechter Prophet, da eine Vermaterialisierung Europas gekommen ist.

Die Menschen leben eben gern in Illusionen. Und das hängt zusammen mit dem großen Problem, das uns jetzt beschäftigt, und das ich schon wiederholt genannt habe, das uns in diesen Tagen ganz klar werden wird, es hängt zusammen mit dem großen Problem: die Menschen haben verlernt, wirklich alt zu werden, und lernen müssen wir wiederum, alt zu werden. In einer neuen Weise müssen wir lernen, alt zu werden, und das können wir nur durch spirituelle Vertiefung. Aber wie gesagt, das kann uns nur im Laufe der Betrachtung ganz klar werden. Die Zeit ist im allgemeinen dem abgeneigt, noch abgeneigt, und sie muß zugeneigt werden, sie muß aus der Abneigung herauskommen.

Allerdings sind die Denk- und Empfindungsgewohnheiten der Zeit nicht darauf aus, sich mit einer gewissen Leichtigkeit, mit einer gewissen Fazilität in dasjenige hineinzuleben, was zum Beispiel die spirituelle Forderung der anthroposophisch orientierten Geisteswissenschaft ist. Man kann das an Beispielen sehr gut sehen. Ein naheliegendes Beispiel will ich anführen.

Vorgestern erst bekam ich einen Brief eines Mannes, der der Gelehrsamkeit angehört. Er schreibt mir, er habe jetzt einen Vortrag über die Aufgabe der Geisteswissenschaft gelesen, den ich vor zwei Jahren gehalten habe, und habe gesehen, nachdem er diesen Vortrag gelesen habe, daß diese Geisteswissenschaft doch etwas für ihn sehr Fruchtbares enthalte. Es ist ein recht warmer Ton in diesem Brief, ein recht liebenswürdiger, netter, lieber Ton. Man sieht, der Mann ist ergriffen von dem, was er in diesem Vortrage über die Aufgabe der Geisteswissenschaft gelesen hat. Er ist ein naturwissenschaftlich durchgebildeter Mensch, der im Leben, auch im schweren Leben der Gegenwart steht, der also einmal gesehen hat an diesem Vortrage, daß Geisteswissenschaft nichts Dummes und nichts Unpraktisches ist, sondern Impulse für die Zeit geben kann. Aber nun betrachten wir die Kehrseite der Sache: Derselbe Mann hat vor fünf Jahren den Anschluß gesucht an diese Geisteswissenschaft, suchte den Anschluß an einen Zweig, worin diese Geisteswissenschaft getrieben wurde, hatte dazumal auch gebeten, verschiedene Unterredungen mit mir zu haben, hatte sie auch, hatte teilgenommen an Zweigversammlungen vor fünf Jahren, und hat vor fünf Jahren so reagiert auf die Sache, daß sie ihm widerlich war, daß er sie abgelehnt hat, so stark abgelehnt, daß er in der Zwischenzeit ein enthusiastischer Lobredner des Herrn Freimark geworden ist, den Sie ja kennen aus seinen verschiedenen Schriften. Jetzt entschuldigt sich derselbe Mann damit, daß er sagt, es wäre vielleicht besser gewesen, statt dem, was er getan hat, dazumal schon etwas von mir zu lesen, irgendwelche Bücher zu lesen und sich mit der Sache bekanntzumachen; aber er habe das nicht getan, sondern er habe geurteilt nach dem, was ihm andere mitgeteilt haben, und da habe er ein so abschreckendes Bild bekommen von der Geisteswissenschaft, daß er sie recht wenig geeignet für seinen eigenen Entwickelungsweg gefunden hat. Jetzt, nach fünf Jahren, hat er einen Vortrag gelesen und hat gefunden, daß die Sache nicht so ist.

Ich führe dieses Beispiel nur an, man könnte wiederum dieses Beispiel vermannigfachen, für die Art und Weise, wie man sich zu der Sache stellt, die da will - nun nicht in der Friedrich Schlegelschen Weise, sondern in der einzig möglichen Weise - eine Durchchristung aller Wissenschaftlichkeit, eine Durchchristung alles öffentlichen Lebens. Ich führe das als ein Beispiel an für die Denkgewohnheiten der heutigen Zeit, insbesondere der Wissenschaften in unserer Zeit. Es ist also gar kein Beweis dafür, daß jemand, wenn er herankommt an die anthroposophische Bewegung — mehrere Unterredungen hat, an Zweigversammlungen teilnimmt, über die Mitglieder dieser Versammlungen und das, was sie ihm sagen, weidlich schimpft, daraus seine Schlüsse zieht, nun auch über die ganze Anthroposophie schimpfen zu müssen, nachher ein begeisterter Lobredner des Freimark wird, der die schmutzigsten Schriften geschrieben hat über die anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft -, daß dieser etwas ihm Antipathisches darin gefunden habe. Nach fünf Jahren entschließt sich nun dieselbe Persönlichkeit noch, einmal wirklich etwas zu lesen.

Es ist also gar kein Beweis, wenn so und so viele Leute heute das Schmählichste sagen oder dem Schmählichsten zustimmen, daß sie nicht die allertiefsten Anlagen haben könnten, der anthroposophischen Geisteswissenschaft sich anzuschließen. Sie brauchen, wenn sie so gutwillig sind wie der Betreffende, fünf Jahre; mancher braucht zehn, mancher fünfzehn, mancher fünfzig Jahre, mancher so lange, daß er es in dieser Inkarnation gar nicht mehr erleben kann. Sie sehen, wie wenig das Verhalten der Menschen irgendein Beweis dafür ist, daß die Menschen nicht suchen dasjenige, was in der anthroposophisch orientierten Geisteswissenschaft zu finden ist.

Ich führe dieses Beispiel an aus dem Grunde, weil es gerade auf das Wesentliche und Wichtige hinweist, das ich öfter erwähnt habe: auf den Mangel an Fazilität im Eingehen auf die Sache, in dem Stecken in althergebrachten Vorurteilen, deren man nicht sich entschlagen will. Und das wiederum hängt mit andern Dingen zusammen. Man braucht nur sich gefühlsmäßig in jene alten Zeiten zurückzuversetzen, von denen ich Ihnen früher und heute gesprochen habe. Denken Sie sich einen jungen Menschen nach der atlantischen Katastrophe in seinem sozialen Zusammenhange drinnen. Er war, sagen wir, zwanzig, fünfundzwanzig Jahre alt, er sah neben sich Vierzig-, Fünfzigjährige, Sechzigjährige. Er sagte sich: Welches Glück, einmal auch so alt sein zu können, denn es lebt sich einem so und so viel zu! - Es war eine ganz selbstverständliche, ungeheure Verehrung für das Altgewordene, ein Hinaufschauen zu dem Altgewordenen, verbunden mit dem Bewußtsein, daß das Altgewordene über das Leben etwas anderes zu sagen hat als das Jungdachsige. Das bloß theoretisch zu wissen, das macht es nicht aus, sondern das in seinem ganzen Gefühl zu haben und unter diesem Eindrucke heranzuwachsen, das macht es aus. Unendliches macht es aus, heranzuwachsen nicht nur so, daß man sich zurückerinnert an seine Jugend und sich sagt: Ach, wie schön war es, als ich Kind war! - Gewiß, diese Schönheit des Lebens wird niemals irgendeine geistige Betrachtung dem Menschen nehmen. Aber es ist eine einseitige Betrachtung, die ergänzt wurde in alten Zeiten durch die andere: Wie herrlich ist es, alt zu werden! - Denn man wächst hinein in demselben Maße, in dem man körperlich schwächer wird, in seelische Stärke; man wächst mit der Weisheit der Welt zusammen. Das war eine Formel, die der Mensch durch seine Erziehung einmal aufgenommen hat.

Nun betrachten wir zu diesem hinzu eine andere Wahrheit, die ich zwar im Laufe dieser Wochen nicht ausgesprochen habe, aber die ich im Laufe der Jahre da und dort auch schon unseren Freunden wiederholt mitgeteilt habe: Wir werden älter, aber nur unser physischer Leib wird älter. Denn vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus ist es nicht wahr, daß wir älter werden. Es ist eine Maja, es ist eine äußere Täuschung. Es ist zwar eine Wirklichkeit in bezug auf das physische Leben, aber es ist nicht wahr in bezug auf den ganzen Lebenszusammenhang des Menschen. Man hat freilich erst ein Recht zu sagen: Es ist nicht wahr -, wenn man weiß: Dieser Mensch, der da in der physischen Welt zwischen Geburt und Tod lebt, der ist noch etwas ganz anderes als sein physischer Leib; der besteht aus den höheren Gliedern; zunächst aus dem, was wir den Ätherleib oder Bildekräfteleib genannt haben, und dann dem astralischen Leib, dem Ich, wenn wir nur diese vier Teile bezeichnen.

Aber schon, wenn wir stehenbleiben beim Ätherleib, beim unsichtbaren, übersinnlichen Ätherleib oder Bildekräfteleib, schen wir: wir tragen ihn in uns zwischen Geburt und Tod gerade so, wie wir unsern physischen Leib aus Fleisch und Blut und Knochen an uns tragen; so tragen wir diesen Bildekräfteleib, diesen Ätherleib in uns, aber es ist ein Unterschied zwischen beiden. Der physische Leib wird immer älter. Der ätherische oder Bildekräfteleib, der ist alt, wenn wir geboren werden, er ist nämlich, wenn wir seiner wahren Natur nachforschen, da alt und er wird immer jünger und jünger. So daß wir sagen können, das erste Geistige in uns wird - im Gegensatze zu dem Physisch-Leiblichen, das schwach und unkräftig wird — immer kräftiger, immer jünger. Und wahr, wörtlich wahr ist es: Wenn wir anfangen, Runzeln im Gesicht zu kriegen, dann blüht unser Ätherleib auf und wird pausbackig.

Ja, aber dem widerspricht ja - könnte der materialistisch denkende Mensch sagen -, dem widerspricht es ganz und gar, daß man das nicht spürt! - In alten Zeiten wurde es gespürt. Die neueren Zeiten nur sind so, daß der Mensch die Sache nicht berücksichtigt, ihr keinen Wert beilegt. In alten Zeiten brachte es die Natur selber mit sich, in neueren Zeiten ist es fast eine Ausnahme. Aber solche Ausnahmen gibt es ja auch. Ich weiß, daß ich einmal ein ähnliches Thema mit Eduard von Hartmann, dem Philosophen des «Unbewußten », Ende der achtziger Jahre besprochen habe. Wir kamen auf zwei Menschen, die beide Professoren an der Berliner Universität waren, zu sprechen. Der eine war der damals zweiundsiebzig Jahre alte Zeller, ein Schwabe, der eben um seine Pensionierung nachgesucht hatte, und der also meinte: Ich bin so alt geworden, daß ich nicht mehr meine Vorlesungen halten kann -, der alt und gebrechlich war mit seinen zweiundsiebzig Jahren. Und der andere war Michelet; der war fast neunzig Jahre alt. Und Michelet, der war eben bei Eduard von Hartmann gewesen und sagte: Ja, ich verstehe den Zeller nicht! Wie ich so alt war wie der Zeller, da war ich überhaupt ein junger Dachs, und jetzt, jetzt fühle ich mich erst so recht befähigt, den Leuten was zu sagen. Ich, ich werde noch jahrelang, viele Jahre noch vortragen! Aber der Michelet hatte etwas von dem, was man nennen kann: ein Jung-kräftig-Gewordenes. Es ist ja selbstverständlich keine innere Notwendigkeit gewesen, daß er just so alt geworden ist; es hätte ihn ja ein Ziegelstein erschlagen können mit fünfzig Jahren oder noch früher, nicht wahr; von solchen Dingen rede ich nicht. Aber nachdem er so alt geworden ist, war er eben seiner Seele nach nicht alt geworden, sondern gerade jung geworden. Doch dieser Michelet war seinem ganzen Wesen nach eben gar kein Materialist. Auch die Hegelianer sind ja vielfach Materialisten geworden, wenn sie es auch nicht zugeben wollen, aber Michelet war, wenn er auch in schweren Sätzen sprach, vom Geiste innerlich ergriffen. Allerdings, so vom Geiste innerlich ergriffen werden können nur wenige. Aber das ist es ja gerade, was gesucht wird durch anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft: etwas zu geben, was allen Menschen etwas sein kann, so wahr wie Religion allen Menschen etwas sein muß, was zu allen Menschen sprechen kann. Das hängt aber zusammen mit unserem ganzen Erziehungswesen.

Unser ganzes Erziehungswesen ist aufgebaut - in viel tieferen Zusammenhängen muß man das sehen, als das irgendwie sonst angedeutet wird — auf ganz materialistischen Impulsen. Man rechnet nur mit dem physischen Leib des Menschen, niemals mit seinem Jüngerwerden. Mit dem Jüngerwerden beim Älterwerden rechnet man nicht. Es ist nicht auf den ersten Blick hin immer gleich durchschaubar, aber es ist doch so, daß alles das, was im Laufe der Zeit zum Gegenstand der Erziehungswissenschaft, zum Gegenstand des Unterrichts geworden ist, etwas ist, was eigentlich den Menschen, wenn er nicht just Professor wird oder ein wissenschaftlicher Schriftsteller, nur packen kann in seiner Jugend. Man macht nicht sehr oft die Erfahrung, daß jemand den Stoff, den man heute aufnimmt während seiner Schulzeit, in derselben Weise im späteren Alter, wenn er es nicht mehr nötig hat, noch aufnehmen möchte. Ich habe Mediziner kennengelernt, die Koryphäen in ihrem Fache waren, die also so ihre Studienzeit und ihre übrige Jugendzeit zugebracht hatten, daß sie Koryphäen haben werden können. Aber daß sie fortsetzten dieselbe Art und Weise des Sich-Aneignens des Wissensstoffes in späteren Jahren, davon war gar keine Rede. Einen ganz berühmten Mann ich will seinen Namen gar nicht aussprechen, so berühmt war er kannte ich, der also einen ersten Namen hat in der medizinischen Wissenschaft. Die spätere Auflage seiner Bücher hat er von seinem Assistenten besorgen lassen, weil er selber mit der Wissenschaft nicht mehr mitging; das paßte nicht mehr für sein späteres Alter.

Das hängt aber damit zusammen: Wir bilden allmählich immer mehr und mehr ein Bewußtsein aus, daß dasjenige, was man lehrmäßig aufnehmen kann, eigentlich nur für die Jugendjahre etwas taugt, worüber man später hinaus ist. Und das ist es auch. Man kann sich ja später noch zwingen, zu manchem zurückzukehren, aber man muß sich dann schon zwingen; naturgemäß ist es gewöhnlich nicht. Und dennoch, ohne daß der Mensch immer Neues aufnimmt — und zwar nicht so aufnimmt, daß man sich herbeiläßt, aufzunehmen etwa durch den Konzertsaal, oder durch das Theater, oder, mit Respekt zu vermelden, durch die Zeitung oder sonstiges von der Art -, altert er in seiner Seele. Man muß aufnehmen in anderer Weise, so aufnehmen, daß man wirklich in der Seele das Gefühl hat: man erfährt Neues, man wandelt sich um, man verhält sich zu dem, was man aufnimmt, im Grunde genommen, wie sich das Kind verhalten hat. Das kann man nicht auf künstliche Weise, sondern das kann nur geschehen, wenn etwas da ist, zu dem man hinkommen kann in späterem Alter gerade so, wie man als Kind zu der gebräuchlichen Unterrichtswissenschaft kommt.

Aber nun nehmen Sie unsere anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft. Wie es in späteren Jahrhunderten mit ihr sein wird, darüber brauchen wir uns ja jetzt nicht die Köpfe zu zerbrechen. Sie wird schon für diese späteren Jahrhunderte auch die entsprechenden Formen finden, aber jetzt ist sie doch jedenfalls - allerdings noch zur Antipathie von manchem — so, daß man vorerst nicht aufzuhören braucht, sie aufzunehmen, wenn man noch so uralt geworden ist in der Gegenwart. Man kann immer in ihr Neues erfahren, das die Seele ergreift, das die Seele wieder jung macht. Und mancherlei Neues könnte schon auf geisteswissenschaftlichem Boden gefunden werden, auch solches Neue, welches Blicke hineintun ließe in wichtigste Probleme der Gegenwart. Vor allen Dingen aber braucht die Gegenwart einen Impuls, der den Menschen als solchen unmittelbar ergreift. Nur dadurch kann diese Gegenwart herauskommen aus den Kalamitäten, in die sie hineingekommen ist und die so katastrophal wirken.

Die Impulse, um die es sich handelt, müssen unmittelbar an den Menschen herankommen. Und wenn man nun nicht Friedrich Schlegel ist, sondern ein Einsichtiger ist in das, was wirklich der Menschheit not tut, dann kann man sich trotzdem an einzelne schöne Gedanken, die Friedrich Schlegel gehabt hat, halten und sich wenigstens an ihnen freuen. Er hat davon gesprochen, daß nicht von einem gewissen Standpunkte aus die Dinge verabsolutiert werden dürfen. Er hat zunächst nur die Parteien gesehen, die immer ihr eigenes Prinzip als das Alleinseligmachende für alle Menschen betrachten. Aber noch viel mehr wird in unserer Zeit verabsolutiert. Es wird vor allen Dingen nicht berücksichtigt, daß im Leben ein Impuls unheilvoll für sich sein kann, im Zusammenwirken aber mit andern Impulsen heilsam sein kann, weil er dann etwas anderes wird. Denken Sie sich einmal, wenn ich schematisch das aufzeichnen soll, drei Richtungen, die zusammenlaufen.

Die eine Richtung soll uns symbolisieren nicht gerade den landläufigen trivialen oder Leninschen, sondern den Sozialismus, welchem die moderne Menschheit zusteuert. Die zweite Linie soll uns symbolisieren dasjenige, was ich Ihnen oftmals charakterisiert habe als Gedankenfreiheit, und die dritte Richtung Geisteswissenschaft. Diese drei Dinge gehören zusammen. Im Leben müssen sie zusammenwirken.

Versuchte der Sozialismus, so wie er als grober materialistischer Sozialismus heute auftritt, in die Menschheit einzudringen, so würde er das größte Unglück über die Menschheit bringen. Er wird bei uns symbolisiert durch den Ahriman unten in unserer Gruppe, in allen seinen Formen. Versucht die falsche Gedankenfreiheit, die bei jedem Gedanken stehenbleiben will und ihn geltend machen will, einzudringen, wird wiederum Unheil über die Menschheit gebracht. Dieses wird symbolisiert durch Luzifer in unserer Gruppe. Aber ausschließen können Sie weder Ahriman noch Luzifer aus der Gegenwart; nur müssen sie ausgeglichen werden durch Pneumatologie, durch Geisteswissenschaft, die durch den Menschheitsrepräsentanten, der in der Mitte unserer Gruppe steht, repräsentiert wird.

Immer wieder und wiederum muß man darauf hinweisen, daß Geisteswissenschaft nicht bloß etwas sein soll für Menschen, die sich aus dem Lebenszusammenhange herausgerissen haben durch den einen oder den andern Umstand, und die sich ein bißchen anregen lassen wollen durch allerlei Dinge, die zusammenhängen mit höheren Angelegenheiten, sondern daß Geisteswissenschaft, anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft etwas sein soll, was mit den tiefsten Bedürfnissen unseres Zeitalters zusammenhängt. Denn dieses unser Zeitalter ist so, daß seine Kräfte nur überschaut werden können, wenn man ins Geistige hineinsieht. Das ist ja etwas, was mit den schlimmsten Übeln in unserer Zeit zusammenhängt, daß zahllose Menschen heute keine Ahnung davon haben, daß im sozialen, im sittlichen, im geschichtlichen Leben übersinnliche Kräfte walten, daß allerdings, ebenso wie die Luft, so übersinnliche Kräfte um uns herum walten. Die Kräfte sind da und sie fordern, daß wir sie wissend aufnehmen, um sie wissend zu dirigieren; sonst können sie von Unwissenden oder Unverständigen in falsche Bahnen gelenkt werden. Es darf allerdings die Sache nicht trivialisiert werden. Es darf nicht geglaubt werden, daß man auf diese Kräfte so hinweisen kann, wie man oftmals aus dem Kaffeesatz oder aus anderem die Zukunft vorhersagt. Aber mit der Zukunft, mit der Gestaltung der Zukunft hängt doch dasjenige zusammen in einer gewissen Weise, und manchmal in einer recht naheliegenden Weise, was nur dann erkannt werden kann, wenn man von geisteswissenschaftlichen Prinzipien ausgeht.

Um das einzusehen, werden vielleicht manche Leute noch länger als fünf Jahre brauchen. Aber es ist doch schon so - Sie wissen, solche Dinge sage ich nicht aus einer gewissen Albernheit heraus -, aber man wird einstmals den Beweis liefern können, daß in einem gewissen Sinn früher von mir klar vorausbestimmt worden ist zu einem gewissen Ziele, zu einem gewissen Zweck dasjenige, was jetzt als eine neue Kriegsfanfare von Wilsonscher Seite aus in die Welt geht. Und auch hier in diesem Saale sitzen einige Menschen, welche ganz genau wissen, daß der Inhalt dieser neuen Kriegsfanfare vorausgewußt worden ist und daß in einer richtigen Weise über den Inhalt dieser Kriegsfanfare gedacht worden ist. Es ist im allgemeinen schwierig, über diese Dinge so ganz unbefangen zu sprechen. Aber gerade diesen aktuellen Ereignissen gegenüber - die Zeichen der Zeit fordern es heute -, muß immer wieder und wiederum betont werden, wie es die große Forderung unserer Zeit ist, daß die Menschen aufmerksam darauf werden, daß eben gewisse Dinge, die heute geschehen, nur durchschaut werden können und vor allen Dingen richtig beurteilt werden können, wenn man von jenen Gesichtspunkten ausgeht, die doch nur durch anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft gewonnen werden können.

Twelfth Lecture

In these reflections, we want to talk about important questions concerning the development of humanity, and you have already seen that this requires a great deal of preparation. Today, in order to provide as broad a basis as possible, I would like to remind you of individual points that have been mentioned from various perspectives during the course of the discussions here during my current stay, but which are necessary if we are to see tomorrow and the day after tomorrow in the right light.

I have pointed out to you how, in that stage of human development which we may regard as the one that has been of interest to us since the great Atlantean catastrophe, significant changes have taken place within humanity. Months ago, I drew your attention to the difference between the way humanity in general changes and the way the individual human being changes. As the years pass, the individual human being grows older. In a certain sense, one can say that the opposite is true of humanity as such. Man is first a child, then grows up and reaches the age we know as the average lifespan. In the process, the physical powers of man undergo manifold changes and transformations. We have already characterized the sense in which a reverse process takes place in humanity. It can be said that in those ancient times that followed the great Atlantean catastrophe—in geology it is called the Ice Age, in religious traditions the Flood—in those times, immediately following this great flooding of the earth, which really resulted in a kind of glaciation, humanity was capable of developing in a completely different way than later, for the next 2,160 years.