From Symptom to Reality in Modern History

GA 185

19 October 1918, Dornach

Lecture II

Yesterday I attempted to sketch in broad outline the symptoms of the recent historical evolution of mankind and finally included in this complex of symptoms—at first not pursuing this in greater detail, for we shall have time for that later on, but confining ourselves more to the general characteristics—the strange figure of James I, King of England, at the beginning of the seventeenth century. This enigmatic figure appeared on the stage of history midway between the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch and the nineteenth century, a century that was important and decisive. It is not my task today—we can discuss this later—to speak of the many mysteries associated with the personality of James I. I must, however, draw your attention to the strange part, strange in a symptomatic manner, which James I plays in contemporary history. He was a man who was a bundle of contradictions and yesterday I attempted to show two contradictory aspects of his character. One can point to his virtues or his defects, according to one's point of view.

James's whole environment, the framework of the political and social conditions which developed out of the conditions I have described to you—his reign which saw the emergence of the idea of the state born of the national impulse and witnessed the rise of the parliamentary system of government or at least of a democratic system tending towards liberal ideas—this world was wholly alien to him, it was a world in which he was never really at home. If we look a little more closely at what characterizes the entire post-Atlantean epoch from the point of view of the birth of the Consciousness Soul, we shall have a clearer understanding of James I. We then see him as a personality who exhibits that radical contradiction that we so easily associate with personalities of the era of the Consciousness Soul. In the epoch of the Consciousness Soul the personality lost the value it owed in former times to the instinctive life, because it had not yet fully developed self-awareness. In earlier epochs the personality expressed itself with elemental force—and I hope I shall not be misunderstood if I say this—with brute force, with an animal force that was nonetheless endowed with soul and human attributes. The personality expressed itself instinctively, it had not yet emerged from the group soul. And now it had to break free, to become self-sufficient and stand on its own feet. Consequently the personality was faced with a strange and paradoxical situation. On the one hand, everything that had formerly existed for the purposes of personal satisfaction was sloughed off, the instincts were blunted and henceforth the soul had gradually to become the seat of the personality. In brief, the soul had to take full command.

That a contradiction exists is evident from what I said yesterday. Whereas in earlier times, when the personality had not developed self-consciousness, men had been creative and had assimilated the creative forces of their culture, these creative energies were now exhausted and the soul had become sterile. And yet the soul occupies the central place in man's being; for the essence of the personal element is that the self-sufficient soul becomes the focal point of man's being. Consequently great personalities of antiquity such as Augustus, Julius Caesar, Pericles—and I could mention many others—will never be seen again. The dynamic, elemental energy of the personality declines and there emerges what is later called the democratic outlook which, with its egalitarian doctrine, standardizes the personality. And it is precisely in this egalitarian process that the personality seeks to manifest itself—truly a radical contradiction!

Now everyone's station in life is determined by his Karma. It was the karmic destiny of James I to occupy the throne. In the epoch of the Persian Kings, of the Mongol Khans and even in the century when the Pope crowned the Magyar Istwan I1Stephen I (992–1038) King of Hungary, patron saint of Hungary. He brought Hungary into the orbit of Western Culture. The ‘sacred crown’ is now in America. with the sacred crown of St. Stephen, the personality counted for something in a position of authority, he regarded himself as the natural heir to his position. In the position he occupied, even in his position as Sovereign, James I resembled a man dressed in an ill-fitting garment. One could say that in relation to the duties and responsibilities that devolved upon him he was, in every respect, like a man dressed in a garment that ill became him. As a child he had been brought up as a Calvinist; later he was converted to Anglicanism, but fundamentally he was indifferent to both confessions. In his heart of hearts he felt all this to be a masquerade which was foreign to him. He was called upon to rule as sovereign in the coming age of parliamentary liberalism which had already been in existence for some time. In conversation with others he was intelligent and shrewd, but nobody really understood what he wanted because all the others wanted something different. He came of an old Catholic family, the Stuarts. But when he ascended the throne of England the Catholics were the first to realize that they had nothing to hope for from him. In 1605 a group of Catholics drew up plans to blow up the Houses of Parliament when the King and his chief ministers were present. They planted twenty barrels of gunpowder in the cellar beneath the parliamentary building. This was the famous Gunpowder Plot. The conspiracy failed because a Catholic fellow-conspirator betrayed the plot, otherwise James I would have been blown up together with his parliament. James I was a misfit because he was a personality, and the personality has something singular, something unusual in its make-up. It is characterized by a certain detachment, a certain self-sufficiency.

But in the era of the personality everyone wishes to be a personality and that is the inherent contradiction of this epoch. We must always bear this in mind. It is not that one rejects the idea of king or pope; it is not a question of suppressing these offices, but simply that if a king or a pope already exists, everyone would like to be pope, everyone would like to be king. Thus papacy, royalty and democracy would be realized at the same time. All these things come to mind when we consider the symptom typified by this strange personality, James I. He was in every respect a man of the new age and was involved in this age with all the contradictions latent in the personality. As I mentioned yesterday those who characterized him from the one angle were mistaken, and those who characterized from the other angle were equally mistaken; and the picture of him which we derive from his writings is also misleading. For even what he himself wrote does not give us any clear insight into his soul. Thus, if we do not consider him from an esoteric point of view he remains a great enigma on the threshold of the seventeenth century, occupying a position which, from a certain point of view, revealed in the most radical fashion the dawn of the impulse of modern times.

I spoke yesterday of the developments in Western Europe and of the difference between the French and English character. This differentiation began to show itself in the fifteenth century, and this turning point was signalized by the appearance of Joan of Arc in 1429. And we saw how, in England, the emancipation of the personality was associated with the aspiration to extend the principle of the personality to the whole world, how in France the emancipation of the personality—in both countries originating in the national idea—was associated with the aspiration to lay hold of the inner life as far as possible and to make it autonomous. This was the situation in which James I found himself at the beginning of the seventeenth century, a personality who typified all the contradictions inherent in the personal element. In characterizing symptoms one must never seek to be over scrupulously explicit, one must always leave room for something unexplained, otherwise one makes no headway. And this is why I prefer not to provide you with a neatly finished portrait of James I, but to leave something to the imagination, something to reflect upon.

A radical difference between the English and French make-up became increasingly evident. Out of the chaos of the Thirty Years' War there developed in France an increasing emphasis upon what may be called the idea of the state. If one wishes to study the consolidation of the state idea one need only take the example, though the example is somewhat unusual, of the French national state and its rise to power and splendour under Louis XIV and its subsequent decline. We see how within this national state the first shoots then develop into that widespread emancipation of the personality which is the legacy of the French Revolution.

The French Revolution brought to the fore three impulses of human life which are fully justified—the desire for fraternity, liberty and equality. But I have already indicated on another occasionT1In the lecture of 18th October, 1916 in Inner Entwicklungsimpulse der Menschheit (Bibl. Nr. 171). how, within the framework of the French Revolution, this triad, fraternity, liberty and equality, conflicted with the genuine evolution of mankind. When dealing with the evolution of mankind one cannot speak of fraternity, liberty and equality without relating them in some way to the tripartite division of man. In relation to the community life at the physical level mankind must gradually develop fraternity in the epoch of the Consciousness Soul. It would be the greatest misfortune and a sign of regression in evolution if, at the close of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch, the epoch of the Consciousness Soul, mankind had not developed fraternity at least to a large extent. But we can only fully understand fraternity if we think of it in connection with community life, the physical bond between man and man. Only at the level of the psychic life is it possible to speak of liberty. It would be a mistake to imagine that liberty can be realized in the external, corporeal life of the community; liberty, however, can be realized between individuals at the psychic level. One must not envisage man as a hybrid unity and then speak of fraternity, liberty and equality. We must realize that man is divided into body, soul and spirit, that men only attain to liberty when they seek to become inwardly free, free in their soul life, and can only be equal in relation to the spirit. That which lays hold of us spiritually is the same for all. Men strive for the spirit because the fifth post-Atlantean epoch, the era of the Consciousness Soul, strives for the Spirit Self. And in this aspiration to the spirit all men are equal, just as in death all men are equal, as the popular adage says. But if one does not apportion fraternity, liberty and equality rightly amongst these three different vehicles of man, but simply assigns them indiscriminately, saying: man shall live fraternally on earth, he shall be free and equal—then only confusion results.

Considered as a symptom, the French Revolution is extraordinarily interesting. It presents—in the form of slogans applied haphazardly and indiscriminately to the whole human being—that which must gradually be developed in the course of the epoch of the Consciousness Soul, from 1413 to the year 3573, with all the spiritual resources at man's disposal. The task of this epoch is to achieve fraternity on the physical plane, liberty on the psychic plane and equality on the spiritual plane. But without any understanding of this relationship, confusing everything indiscriminately, this quintessence of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch appears in the French Revolution in the form of slogans. The soul of this epoch is comprised in three words (fraternity, liberty and equality), but they are not understood. It is unable therefore at first to find social embodiment and this leads to untold confusion. It cannot find any external social embodiment, but significantly, is present as the ‘demanding soul,’ a soul in search of embodiment. All the inner soul life which must inform this fifth post-Atlantean epoch remains uncomprehended and cannot find any means of expression. And here we are confronted with a symptom of immense importance.

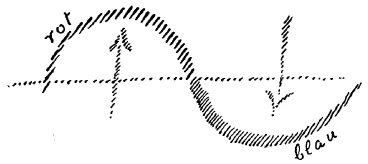

When that which is to be realized in the course of the coming epoch manifests itself almost violently at first, we are far removed from that state of equilibrium which man needs for his development, far removed from those forces which are innate in men through their connection with their own particular hierarchies. The beam of the balance dips sharply to one side. In the interplay between the Luciferic and Ahrimanic influences it dips sharply to the side of Lucifer as a result of the French Revolution. This provokes a reaction. I am here speaking more than figuratively, I am speaking imaginatively. You must not read too much into the words; above all you must not take them literally. In what appeared in the French Revolution we see, to some extent, the soul of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch without social embodiment, without corporeal existence. It is abstract, purely emotional, a soul in search of embodiment ... and this can only be realized in the course of millennia, or at least in the course of centuries. But because in the course of evolution the balance inclines to one side, it provokes a reaction and swings to the other pole. In the French Revolution everything is in a state of ferment, everything runs counter to the rhythm of human evolution. Because the balance inclines to the opposite pole a situation now arises where everything (no longer in a state of equilibrium, but alternating between the Luciferic and Ahrimanic poles) is once again fully in accordance with the human rhythm, with the impersonal claims of the personality. In Napoleon there appears subsequently a figure who is fashioned entirely in conformity with the rhythm of the personality, but with a tendency to the opposite pole. Seven years of sovereignty, fourteen years of imperial splendour and harassment of Europe, the years of his ascent to power, then seven years of decline, the first years of which he spent once again in disrupting the peace of Europe—all in accordance with a strict rhythm: seven years, then twice seven years and then again seven years, a rhythm of septennia.

I have been at great pains (and I have alluded to this on various occasions) to trace the soul of Napoleon. It is possible, as you know, to undertake these studies of the human soul in divers ways by means of spiritual scientific investigation. And you will recall no doubt how investigations were undertaken to discover the previous incarnations of Novalis.2Novalis (Friedrich von Hardenberg) (1772–1802). His unfinished novel Heinrich von Ofterdingen 1802 is an allegory of Novalis' spiritual life and was the representative novel of early Romanticism. I have been at great pains to follow the destiny of Napoleon's soul in its journey after his death. I have been unable to find it and do not think I shall ever be able to find it, for it is probably not to be found. And this no doubt accounts for the enigma of Napoleon's life that unfolds with clockwork precision in seven-year rhythms. We can best understand this soul if we regard it as the complete antithesis of a soul such as that of James I, or again as the antithesis of the abstraction of the French Revolution: the Revolution all soul without body, Napoleon all body without soul, but a body compounded of all the contradictions of the age. In this strange juxtaposition of the Revolution and Napoleon lies one of the greatest enigmas of contemporary evolution. One has the impression that a soul wanted to incarnate in the world, appeared without a body, clamoured for incarnation amongst the revolutionaries of the eighteenth century, but was unable to find a body ... and that only externally a body offered itself, a body which for its part could not find a soul, i.e. Napoleon. In these things there are more than merely ingenious allusions or characterizations, they harbour important impulses of historical development. They must of course be regarded as symptoms. Here, amongst ourselves, I use the terminology of spiritual science. But what I have just said could equally well be said anywhere if clothed in slightly different terminology.

When we attempt to pursue further the symptomatology of recent times we see the English character unfolding in successive stages in relative peace. Up to the end of the nineteenth century it developed fairly uniformly, it shaped the ideal of liberalism in relative peace. The development of the French character was more tempestuous, so much so that when we follow the thread of events in the history of France in the nineteenth century we never really know how a later event came to be associated with the previous event; they seem to follow each other without motivation so to speak. The major feature of the historical development of France in the nineteenth century is this absence of motivation. No reproach is implied here—I am speaking quite dispassionately. I merely wish to characterize.

We shall never be able to understand the whole symptom-complex of contemporary history if we do not perceive, as I mentioned yesterday, that in everything that takes place, both on the external plane or on the plane of the inner life, something else to be at work which I would like to characterize as follows. Even before the dawn of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch, the epoch of the Consciousness Soul, one already sensed its approach. Certain sensitives had a prophetic intimation of its advent and they felt its true character. They felt that the epoch was approaching when the personality was destined to emancipate itself, that in a certain respect it would be an unproductive era, an era without creative energy, that especially in the cultural field which fertilizes both the historical and the social life, it would be compelled to live on the legacy of the past.

This is the real motive behind the Crusades which preceded the epoch of the Consciousness Soul. Why did the people of Europe take up arms in order to recover the Holy Land and the City of Jerusalem with the Holy Sepulchre? Because they were neither able, nor willing, in the era of the Consciousness Soul, to search for a new mission, for an idea that was new and original; they endeavoured to recover the true form and substance of the ancient traditions. ‘To Jerusalem’ was the watchword—in order to rediscover the past and incorporate it in evolution in a form different from that of Rome. People sensed that the Crusades marked the dawn of the era of the Consciousness Soul with its characteristic sterility. And it was in connection with the Crusades that there was founded the Order of the TemplarsT2See note 3 to Lecture I. which was suppressed by Philip the Fair. With this Order the oriental mysteries were introduced into Europe and left their impress on European culture. It is true that Philip the Fair had the members of the Order executed as heretics and their wealth confiscatedT3Also discussed in Kosmische und menschliche Geschichte Vol III, Lecture VI; Vol IV, Lecture I. but the Templar impulses had penetrated into European life through various channels and continued to exercise an influence through the medium of numerous occult lodges which then began to work exoterically and so gradually built up opposition to Rome. On the one side stood Rome, alone at first; then she allied herself with the Jesuits. On the other side was ranged—closely connected with the Christian element and completely alien to Rome—everything that of necessity had to stand in opposition to Rome and which even Rome felt, and still feels, to be a powerful body of opposition. How is one to account for the fact that, in the face of what I described yesterday as the suggestive power of this universalist impulse which emanated from Rome, people in the West came to accept and adopt gnostic teachings, ideas, symbols and rites which were of oriental provenance? What was the deeper underlying impulse behind this phenomenon? If we look into this question we shall be able to discover the real motive behind it.

The Consciousness Soul was destined to emerge. As a bulwark against the Consciousness Soul Rome wished to preserve, and still preserves today, a culture based on suggestionism, a culture that is calculated to arrest man's progress towards the development of the Consciousness Soul and keep him at the level of the Rational or Intellectual Soul. This is the real battle which Rome wages against the tide of progress. Rome wishes to cling to an outlook which is valid for the Rational Soul at a time when mankind seeks to progress towards the development of the Consciousness Soul.

On the other hand, in progressing towards the Consciousness Soul mankind in effect finds itself in a most unhappy position which for the vast majority of people during the first centuries of the era of the Consciousness Soul and up to our own time was felt at first to be rather disturbing. The epoch of the Consciousness Soul demands that man should stand on his own feet, be self-sufficient and, as personality, emancipate himself. He must abandon the old supports. He can no longer allow himself to be persuaded into what he should believe; he must work out for himself his own religious faith. This was felt to be a dangerous precedent. When the epoch of the Consciousness Soul dawned it was instinctively felt that man was losing his former centre of gravity ... and must find a new one. But on the other hand if he remains passive, what are the possibilities before him? One possibility is simply to give him a free hand in his search for the Consciousness Soul, to set him free to develop in his own way. A second possibility is that, if left to himself, Rome then assumes great importance and may exercise considerable influence upon him, if it should succeed in curbing his efforts to develop the Consciousness Soul in order to keep him at the stage of the Rational Soul. And the consequence of that would be that man could attain neither to the Consciousness Soul nor to the Spirit Self and would therefore sacrifice his possibility of future development. This would be only one of the paths by which future evolution might be imperilled.

A third possibility is to proceed in a still more radical fashion. In order that man may not be caught between the striving for the Consciousness Soul and the limitations of consciousness imposed upon him by Rome, attempts were made to stifle his aspiration for the Consciousness Soul, to undermine this aspiration even more radically than Rome. This is achieved by emasculating the progressive impulses and substituting for their dynamism the dead hand of tradition which had been brought over from the East, though originally the Templars, who had been esoterically initiated, had had a different object in view. But after the leaders had been massacred, after the suppression of the Templar Order by Philip the Fair, something of this culture which had been brought over from the East survived, not amongst isolated individuals, but in the field of history. What the Templars had brought over gradually infiltrated into Europe through numerous channels (as I have already indicated), but to a large extent was divested of its spiritual substance. What the Templars transmitted was, in the main, the substance of the third post-Atlantean epoch ... Catholicism transmitted the substance of the fourth epoch. And that from which spiritual substance had been extracted like the juice from a lemon, that which was transmitted in the form of exoteric freemasonry in the York and Scottish Lodges and pervaded especially the false esotericism of the English speaking peoples—this squeezed out lemon which contained the secrets of the Egypto-Chaldaean epoch, the third post-Atlantean epoch, now served as a means of implanting desiccated impulses into the life of the Consciousness Soul.

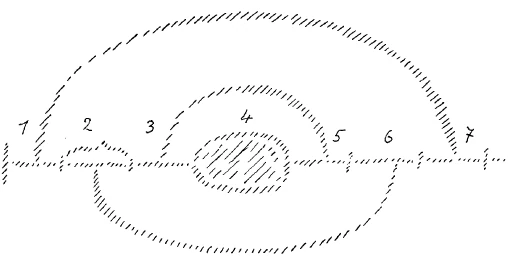

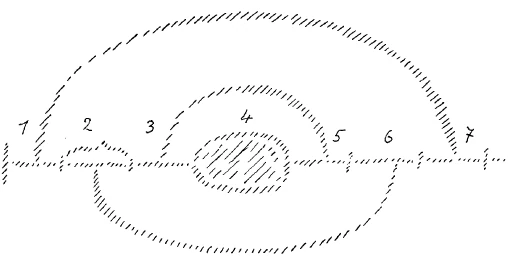

Thus there arises a situation which is a travesty of the future course of evolution. Recall for a moment what I said to you on a former occasionT4The Spiritual Guidance of Man and Humanity, Anthroposophic Press, 1970. when speaking of the seven epochs of evolution. We start from the Atlantean catastrophe; then follow the post-Atlantean epochs with their corresponding relationships. 1=7, 2=6, 3=5, 4. The fourth epoch constitutes the centre without any corresponding relationship. The characteristics of the third epoch are repeated at a higher level in the fifth epoch, those of the second epoch at a higher level in the sixth epoch and those of the old Indian epoch reappear in the seventh epoch. These overlapping correlations occur in history. Isolated individuals were conscious of this. For example, when Kepler attempted in the fifth post-Atlantean epoch to explain after his own fashion the harmony of the Cosmos by his three laws saying, ‘I offer you the golden vessels of the Egyptians ...’ etcetera—he was aware that in the man of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch there is a revival of the substance of the third epoch. In a certain sense, when one takes over the esotericism, the rites of the Egypto-Chaldaean epoch, one creates a semblance of what is destined to be realized in the present epoch. But what one takes over from the past can be used not only to suppress the autonomy of the Consciousness Soul by the power of suggestion, but also to blunt, even to paralyse its dynamic energy. And in this respect a large measure of success has been achieved; the incipient Consciousness Soul has been anaesthetized to a large extent.

Rome—I am now speaking figuratively—makes use of incense and induces a condition of semi-consciousness by evoking a dreamlike state. But the movement to which I am now referring lulls people to sleep (i.e. the Consciousness Soul) completely. Moreover as history bears witness, this condition penetrated also into contemporary evolution. Thus on the one hand we have what is created through the tempestuous emergence of fraternity, liberty and equality, whilst on the other hand the impulse already exists which prevents mankind in the course of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch from perceiving clearly how fraternity, liberty and equality are to lay hold of man; for they can only perceive this clearly when they are able to make use of the Consciousness Soul in order to arrive at true self-knowledge, i.e. when they awake in the Consciousness Soul. And when men awake in the Consciousness Soul they become aware of themselves in the Body, the soul and the spirit; and this is precisely what must be prevented. We have therefore two streams in contemporary history: on the one hand, since the impulse towards the Consciousness Soul already exists, there is the chaotic search for fraternity, liberty and equality. On the other hand we see the efforts on the part of widely differing Orders to suppress this awakening in the Consciousness Soul for their own ends. These two currents interact throughout the whole history of modern times.

Now as the new era bursts upon the eighteenth century and the early years of the nineteenth century, something new is being prepared. Up to the middle of the nineteenth century we see at first a powerful urge towards the emancipation of the personality because, when so many currents are active, the new development does not unfold gradually and smoothly, but ebbs and flows. And we see developing, on a basis of nationalism, and in response to the other impulses I have already mentioned in connection with the West of Europe, that which tends towards the emancipation of the personality, that which seeks to overcome nationality and to attain to the universal-human. But this impulse cannot really develop independently on account of the counter-impulse from those Orders which, especially in England, contaminate the whole of public life much more than people imagine. And so we see strange personalities appear, such as Richard Cobden and John Bright,3Richard Cobden (1804–54) and John Bright (1811–89), leaders of ‘Manchesterism’, the school of radical free trade principles. who were ardent advocates of the emancipation of the personality, of the triumph of the personality over nationalism the world over. They went so far as to touch upon something which could be of the greatest political significance if it should ever find its way into modern historical evolution! Differentiated according to the different countries, this principle of non-intervention in the affairs of others became the fundamental principle of English liberalism, and these two personalities of course defined it in terms of their own country. It was something of great significance, and scarcely had it been formulated before it was stifled by that other aspiration which stemmed from the impulse of the third post-Atlantean epoch. Thus up to the middle of the nineteenth century there emerged what is usually called liberalism, liberal opinion ... soon to be called free-thinking according to one's taste. I am referring to that outlook which, in the political sphere, expressed itself most clearly in the eighteenth century in the form of political enlightenment, in the nineteenth as the struggle for political liberalism4German liberalism. In 1848 the German liberals attempted to establish a constitutional state and the National Assembly offered the crown to Frederick William IV who refused to meet liberal demands. Later the movement split into moderates and radicals (the German Progressive Party). Finally the National Liberals supported Bismarck's anti-clericalism and imperialism. By the end of the century liberalism was a spent force. which gradually lost momentum and died out in the last third of the century.

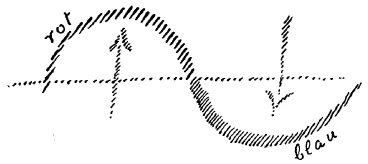

The liberal element which was still prevalent everywhere in the sixties gradually ceased to be a vital force in the life of the country and was replaced by something else. We now touch upon significant symptoms of recent history. For a time the impact of the Consciousness Soul was such that it threw up a wave of liberalism. But a flood tide is followed by an ebb tide (blue). And this ebb tide is the counter-thrust to liberalism (arrow pointing downwards). Let us look at this more closely. Liberalism was born of self-discipline; its representatives tried to free themselves from constraint. They cast off the fetters of narrow prejudice and conventional ideas; they cut their moorings, if I may use the nautical expression, and refused to allow their ship to be boarded. They were imbued with universal, human ideals, but socialism was active in the preparation of the new age and gradually attracted to itself these so-called liberal ideas which found so little support. By the middle of the nineteenth century there was no political future for liberal ideas, for their representatives in later years give more or less the impression of casualties of political thinking. The latter-day liberal parties were simply stragglers, for, after the middle of the nineteenth century, the effect of what emerged from the Orders and secret societies of the West began to make its influence increasingly felt, namely, the anaesthetization, the stifling of the Consciousness Soul. Under these circumstances spirit and soul are no longer active, and only the forces of the phenomenal or sensible world are operative. And so from the middle of the nineteenth century these forces manifested in the form of socialism of every kind, a socialism that was conscious of itself, of its power and importance.

But this socialism is only possible if imbued with spirit, not with pseudo-spirit, with the mask of spirit, with mere rationalism that can only apprehend the inorganic, i.e. dead forms. It was with this ‘dead’ knowledge that Lassalle5Friedrich Lassalle (1823–64), architect of the German labour movement. In his ‘Open letter’ 1863 he urged the proletariat to form an independent political party. Founder and president of the ‘General Association of German Workers’. first wrestled, but it was Marx and Engels who elaborated it. Thus, in socialism which endeavoured to translate theory into practice, and in practice was a total failure because it was too theoretical, there appeared one of the most important symptoms of the recent historical evolution of mankind. I now propose to examine a few characteristic features of this socialism.

Modern socialism is characterized by three tenets or three interrelated tenets—the materialist conception of history, the theory of surplus value and the theory of the class struggle.6‘The materialist conception of history starts from the principle that production, and with production the exchange of its products, is the basis of every social order ... the ultimate causes of all social change and political revolutions are to be sought not in the minds of men ... but in changes in the mode of production and exchange’ (Marx: Anti-Dühring). ‘The mode of production of the material means of existence conditions the whole process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but it is their social existence which determines their consciousness’ (Marx: Preface to the Critique of Political Economy). ‘The division of labour implies from the outset the division of the conditions of labour, of tools and materials and thus the splitting up of accumulated capital among different owners, and thus, the division between capital and labour, and the different forms of property itself’ (Marx on the class war in The German Ideology). In the main these convictions are held by millions today. In order to have a clear understanding of these symptoms which will form the basis of our study tomorrow, let us first attempt to establish what we mean by the materialist conception of history.

The materialist conception of history believes that the course of evolution is determined by economic factors. Men must eat and drink, acquire the necessities of life from various sources. They must trade, exchange goods and produce what nature does not produce unaided without man's intervention. This constitutes the driving force of evolution. How is one to explain, for example, the appearance of men such as Lessing in the eighteenth century? Since the sixteenth century, and especially in the eighteenth century, the introduction of the mechanical loom and spinning-jenny has created a sharp division—and the first signs were already apparent—between the bourgeoisie and the rising proletariat. The proletariat hardly existed as yet, but it was already smouldering beneath the surface. In the course of recent economic development the bourgeoisie had gained in strength at the expense of the former estates. Through his mode of life which entailed the employment of labour, through his refusal to recognize the former estates, through his control over the production, distribution and manufacture of commodities, the bourgeois developed a certain way of thinking that was peculiar to his class and which was simply an ideological superstructure covering his methods of production, manufacture and distribution. And this determined his particular mode of thought. The peasant, by contrast, who is surrounded by nature and lives in communion with nature has a different outlook. But his way of thinking too is only an ideology. What matters is the way in which he produces and markets his merchandise. The middle classes have a different outlook from the peasant because they are crowded together in towns; they are urbanized, no longer bound to the soil, are indifferent to nature, and their relationship to nature is abstract and impersonal. The bourgeois becomes a rationalist and thinks of God in general and abstract terms. This is the consequence of his mercantile activity—an extreme view perhaps, hut nonetheless it contains a grain of truth. Because of the way in which goods have been manufactured and marketed since the sixteenth century, a way of thinking developed which was reflected in a particular way in Lessing. He represents the bourgeoisie at its apogee, whilst the proletariat lags behind in its development. In the same way Herder and Goethe are explained as the products of their environment, by their bourgeois mentality which is merely a superstructure. To the purely materialist outlook only the fruits of economic activities, the production, manufacture and marketing of goods, are real.

Such is the materialist conception of history. It accounts for Christianity by showing how, at the beginning of our era, the conditions of commercial exchange between East and West had changed, how the exploitation of slaves and the relationship between masters and slaves had been modified and how then an ideological superstructure—Christianity had been erected upon this play of economic interests. And because men were also under the necessity of producing what they ate and what they had to sell in order to provide for their sustenance in a different way from formerly, they developed in consequence a different way of thinking. And because a radical change occurred in the economic life at the beginning of our era, a radical change also occurred in the ideological superstructure which is characterized as Christianity. This is the first of those tenets which have found their way into the hearts of millions since the middle of the nineteenth century.

The entrenched bourgeoisie has no idea how firmly the materialist conception of history has taken hold of wide sections of the population. Of course the professors who expatiate on history, on the darker face of history, find a ready audience. But even amongst the professors a few have recently felt secretly drawn towards Marxism. But they have no following amongst the broad masses of the people. That is what we have come to in the epoch of the Consciousness Soul ... meanwhile the impulse of the Consciousness Soul continues to operate. People are beginning to wake up in so far as they are permitted to do so. On the one hand attempts are made to lull them to sleep; on the other hand, however, they would like to wake from their sleep. Since they are familiar only with the purely phenomenal world they have developed a materialist conception of history. Here is the origin of those strange symptoms.

Schiller, one of the noblest and most liberal of minds, was greatly admired and for years homage was paid to his memory. In 1859 monuments were erected everywhere to commemorate the centenary of his birth. In my youth there lived in Vienna a man called Heinrich Deinhardt who, in a beautiful book, tried to introduce people to the fundamental ideas which Schiller expressed in his Letters on the aesthetic education of man. The entire edition was pulped. The author had the misfortune to be caught, I believe, by a passing tram. He fell down in the street and broke his leg. Although he suffered only a minor fracture it refused to heal because he was badly undernourished. He never recovered from the accident. That is only a symptom of the treatment reserved in the nineteenth century for those who sought to interpret Schiller to the public, to awaken the consciousness of the time to the nobility of Schiller's ideas! Of course, you will say—others will say: do we not meet with noble aspirations in all spheres? Undoubtedly, and we will speak of them later, but for the most part they only lead into a blind alley.

Such is the first of the socialist tenets; the second is the theory of surplus value. It can be summarized roughly as follows: as a result of the new method of production, the man who is employed in the production and manufacture of goods must sell his labour-power as a commodity like other commodities. Thus two classes are created—the entrepreneurs and the workers. The entrepreneurs are the capitalists who control the means of production—factories, machinery, everything concerned with the means of production. The other class, the workers, have only their labour-power to sell. And because the capitalist who owns or controls the means of production can purchase on the open market the labour power of the worker, he is in a position to pay him a bare subsistence wage, to reduce to a minimum the remuneration for the commodity labour-power. But the commodity labour power, when put to use, creates a greater value than its own value. The difference between the value of labour and its product, i.e. the surplus value, goes into the pocket of the capitalist. Such is the Marxist theory of surplus value and it has the support of millions. And this situation has arisen simply through the particular economic structure of the social life in recent times. Ultimately this leads to the class struggle, to exploiters and exploited.

Fundamentally these are the tenets which, since the middle of the nineteenth century, have increasingly won over limited circles at first, then political groups and parties, and finally millions of men to the idea of a purely economic structure of society. One may easily conclude from an extension of the ideas sketched here that the individual ownership of the means of production therefore means the end of man's future evolution, that there must be common ownership and common administration of the means of production by the workers.—Expropriation of the means of production has become the ideal of the working class.

It is most important not to become the prisoner of fixed ideas which are unrelated to reality, ideas which are still held by many members of the bourgeoisie who have been asleep to recent developments. For many of the dyed-in-the wool representatives of the bourgeoisie who are oblivious of the developments of recent decades still imagine that there are communists and social democrats who believe in sharing, in joint ownership, etcetera. They would be astonished to learn that millions of people have a carefully elaborated and clear-cut idea of how this is to be realized and must be realized, namely, by eliminating surplus value and bringing the means of production under common ownership. Every socialist agitator of today, every socialist ‘stooge’ laughs at the bourgeois who talks to them of communist and social-democratic aims, for he realizes that the central issue is the socialization of the means of production, the collective administration of the means of production. For, in the workers' eyes the source of slavery lies in the ownership of the means of production by isolated individuals, because he who is without the means of production is defenceless against the industrial employer who controls them.

The social struggle of modern times, therefore, is fundamentally the struggle for the ownership of the means of production. This struggle is inevitable since ‘the history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggles’ (Marx in the Communist Manifesto). This is the third of the social-democratic tenets. The rise of the bourgeoisie was achieved at the expense of the feudal aristocracy. The rising proletariat in its turn will take over the control and administration of the means of production and finally eliminate the bourgeoisie, just as the bourgeoisie had eliminated the aristocracy. History is the history of class struggles; the progress of mankind is determined by the victory of one class over another.

These three ideals—first, that material impulses alone determine the progress of mankind and the rest is simply ideological superstructure; secondly that the real evil is surplus value which can only be overcome by the collective ownership and administration of the means of production; and thirdly that the bourgeoisie must be overthrown, in the same way as the bourgeoisie had overthrown the old feudal aristocracy, in order that the means of production may become common property ... these are the three socialist doctrines which have gradually spread throughout the civilized world. And a significant symptom of recent years is this: the surviving members of the aristocracy and of the bourgeoisie have opted out, have picked up at most a few cliches such as ‘sharing of goods’, ‘communism’—those cliches which are sometimes commented upon at length at the back of history books, though rarely is there a word about them in the text! People were oblivious of what had really happened; they were asleep whilst events took their course. And finally with great difficulty, under the compulsion of circumstances, under the influence of what has happened in the last four years (i.e. 1914–1918) a few people have begun to open their eyes. It is inconceivable how unaware people would have been but for the war, unaware that with every year thousands upon thousands were won over to the cause of socialism, never realizing that they were sitting on a volcano! It is disconcerting to have to admit that one is sitting on a volcano; people prefer to bury their heads in the sand. But that does not prevent the volcano from erupting and burying them alive.

I have here described a further symptom of contemporary history. This socialist conviction belongs to the symptoms of our time. It is a fact and not merely some vague theory. It is efficacious. I do not attach any importance to the solid body of the Lassallean and Marxist theory, but I attach great importance to the fact that millions of men have chosen as their ideal to realize, as far as possible, what is advocated in the three tenets I have mentioned. This however is something which is radically opposed to the national element which, as I indicated earlier, was in some respect the founding father of modern history. Many things have developed out of this national element. Now the programme of the proletariat was first proclaimed in 1848 in the closing words of the Communist Manifesto, workers of the world unite’. There was scarcely a socialist meeting throughout the world that did not close with three cheers for international revolutionary socialism, republican social democracy. It was an international practice. And thus, alongside the internationalism of the Roman Church with its universalist idea there arose the Socialist International. That is a fact, and these countless numbers of socialists are a fact. It is important to bear this in mind.

In order to conclude tomorrow—at least provisionally—this symptomatology of recent times we must pay close attention to the path which will enable us to follow the symptoms until they reveal to us to some extent the point where we can penetrate to the underlying reality. In addition to this we must recognize the fact that others have also created insoluble problems—you must feel how things develop, how they come to a head and end as insoluble problems! We saw how, in the nineteenth century, the trend towards a more liberal form of parliamentary government developed relatively peacefully in England; in France amidst political ferment and turmoil, or rather without motivation. And the further we move eastwards, the more we find that the national element is something imported, something transmitted from outside ... and this gives rise to insoluble problems. And that too is a symptom! The naive imagine that there is a solution to everything. Now an insoluble problem of this nature (insoluble not to the abstract intellect, but insoluble in reality), was created 1870/71 between Western, Central and Eastern Europe—the problem of Alsace. The pundits of course know how to solve it—one state conquers the territory of its neighbour and the problem is solved. This has been tried by the one side or the other in the case of Alsace. Or if that solution is excluded, one can resort to the ballot box and the majority decides! That is simple enough. But those who are realists, who see more than one standpoint, who are aware that time is a real factor and that one cannot achieve in a short space of time what lies in the bosom of the future—in short, those who stand four square on the earth were aware that this was an insoluble problem. Read, for example, what was written, thought and said upon this problem in the seventies by those who attempted to throw light upon the future course of European evolution. They saw that what had happened in Alsace strangely anticipated later conditions in Europe, that the West would feel impelled to appeal to the East. At that time there were a few who were aware that the world would be confronted by the Slav problem because the West and Central Europe held different views upon the solution of this question. I only want to point out that this situation is an obvious Symptom like that of the Thirty Years' War which I mentioned yesterday in order to show you that in history it is impossible to demonstrate that subsequent effects are the consequence of antecedent causes. The Thirty Years' War shows that the situation at the beginning, and before the outbreak of the war in 1618 was identical with the situation at the end of the war. The consequences of the war were unrelated to the antecedent causes; there can be no question therefore of cause and effect here (i.e. in the case of the Thirty Years' War). We have a characteristic Symptom, and the same applies not only to the Alsatian problem, but also to many questions which have arisen in recent times. Problems are raised which do not lead to a solution, but to ever new conflicts and end in a blind alley. It is important to bear this in mind. These problems lead to such total deadlock that men cannot agree amongst themselves; opinions must differ because men inhabit different geographical regions in Europe. And it is a characteristic feature of the symptoms of recent history that men contrive to create situations that are incapable of solution.

We are now familiar with a whole series of features that are characteristic of the recent evolution of mankind—its sterility, the birth, in particular, of collective ideas which have no creative pretensions, such as the national impulse, for example. And in the midst of all this the continuous advance of the Consciousness Soul. We see everywhere problems that end in blind alleys, a characteristic feature of modern times. For what is discussed today, the measures undertaken by men today are to a large extent simply the revolving of the squirrel's cage. And a further characteristic is the attempt to damp down the consciousness, especially in relation to the Consciousness Soul which has to be developed. Nothing is more characteristic of our time than the lack of awareness amongst the educated section of the population of the real situation of the proletariat. They do not look beyond the external facade. Housewives complain that maidservants are unwilling to undertake certain duties; they seem unconcerned that not only factory workers, but also maidservants are saturated with Marxist theory. People are gradually beginning to talk of universal ideas of humanity in every shape and form. But if we show no concern for the individual and his welfare this is merely empty talk. For we must become aware of the important developments in evolution and we must take an active part in events.

I have felt compelled to draw your attention to this symptom of socialism, not in order to expound some particular social theory, but in order to present to you characteristic features of recent historical development.

We will continue our investigations tomorrow in order to round off this subject and to penetrate to the reality in isolated cases.

Zweiter Vortrag

Gestern habe ich versucht, Ihnen in großen Zügen ein Bild der Symptome der neueren geschichtlichen Entwickelung der Menschheit zu geben und habe zuletzt wie hineingestellt in diesen Komplex von Symptomen — den wir zunächst nicht schon so verfolgten, daß wir überall auf dasjenige etwa geschaut hätten, was er offenbart, das werden wir auch noch tun, sondern den wir mehr im allgemeinen charakterisiert haben — die merkwürdige Erscheinung Jakob I. von England. Er steht da zu Beginn des 17. Jahrhunderts als sogenannter Herrscher in England eigentlich wie eine Art Rätselgestalt, ungefähr um die Mitte desjenigen Zeitraumes, der verflossen ist vom Beginne des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraumes bis in das wichtige, Entscheidung bringende 19. Jahrhundert. Es wird hier noch nicht — das kann später geschehen — meine Aufgabe sein, über manches Geheimnis, das mit der Persönlichkeit Jakob I. verbunden ist, zu sprechen. Heute kann das noch nicht meine Aufgabe sein, aber ich muß schon heute darauf hinweisen, wie merkwürdig, wiederum symptomatisch merkwürdig dieser Jakob I. im Verlauf der neueren Geschichte drinnensteht. Man möchte sagen: Ein Mensch, der wirklich nach allen Seiten so widerspruchsvoll charakterisiert werden könnte, wie ich es gestern von zwei Seiten aus versucht habe. Man kann das Beste und man kann das Übelste, je nachdem man es färbt, über ihn sagen.

Man kann vor allen Dingen aber von diesem Jakob I. sagen, daß er auf dem Boden, auf dem er steht, und der sich herausentwickelt hat aus all den Verhältnissen, die ich Ihnen geschildert habe und auf dem sich besonders entwickelt ein Staatsgedanke, der aus dem Nationalimpuls herausgewachsen ist, auf dem sich das entwickelt, was wir charakterisiert haben als liberalisierenden, wenigstens dem Liberalisieren zuneigenden, zustrebenden Parlamentarismus, daß auf diesem Boden Jakob I. erscheint wie eine entwurzelte Pflanze, wie ein Wesen, das nicht so recht zusammenhängt mit diesem Boden. Schauen wir aber etwas tiefer auf dasjenige, was diesen ganzen fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum nach einer Seite hin charakterisiert, nach der Seite der Geburt der Bewußtseinsseele, dann wird es schon in einer gewissen Beziehung heller um diesen Jakob I. Dann sieht man, daß er die Persönlichkeit ist, welche jenen radikalen Widerspruch darlebt, der so leicht verbunden ist mit Persönlichkeiten aus der Zeit des Bewußtseinszeitalters. Nicht wahr, in dieser Zeit des Bewußtseinszeitalters, da verliert die Persönlichkeit denjenigen Wert, den sie früher kraft der Instinkte gerade dadurch gehabt hat, daß sie eigentlich als selbstbewußste Persönlichkeit nicht ausgebildet war. Die Persönlichkeit lebte sich dar in früheren Zeitaltern, man möchte sagen, mit elementarer Kraft, mit einer vermenschlichten, verseelten - man wird mich nicht mißverstehen, wenn ich das sage — tierischen Kraft. Instinktiv lebte sich die Persönlichkeit dar, noch nicht herausgeboren aus dem Gruppenseelentum, noch nicht ganz herausgeboren. Und jetzt sollte sie sich emanzipieren, sollte sich auf sich selbst stellen. Dadurch ergibt sich gerade für die Persönlichkeit ein ganz merkwürdiger Widerspruch. Auf der einen Seite wird alles das, was früher da war für das individuell-persönliche Ausleben, abgestreift, die Instinkte werden hinabgelähmt, und im Innern der Seele soll sich das Zentrum des Persönlichen allmählich gestalten. Die Seele soll vollinhaltliche Kraft gewinnen.

Daß ein Widerspruch vorhanden ist, Sie sehen es vor allen Dingen an dem, was ich schon gestern sagte. Während man früher, in den Zeitaltern, in denen die Persönlichkeit noch nicht geboren war als selbstbewußte Persönlichkeit, der Kulturentwickelung ganz produktive Kräfte einverleibt hat, hört das jetzt auf. Die Seele wird steril. Und dennoch stellt sie sich in den Mittelpunkt des Menschen, denn darinnen besteht das Persönliche, daß die Seele sich auf sich selbst, in den Mittelpunkt der Persönlichkeit der Menschenwesenheit stellt. So daß solche überragenden Persönlichkeiten, wie sie dem Altertum eigen waren, Augustus, Julius Cäsar, Perikles — wir könnten alle möglichen nennen — nicht mehr möglich werden. Gerade das Elementare der Persönlichkeit verliert an Wert, und es taucht auf das, was sich später demokratische Gesinnung nennt, die die Persönlichkeit nivelliert, die alles gleichmacht. Aber gerade in diesem Gleichmachen will die Persönlichkeit erscheinen. Ein radikaler Widerspruch!

Jeder steht durch sein Karma auf irgendeinem Posten. Nun, Jakob I. stand gerade auf dem Posten des Herrschers. Gewiß, in der Zeit der Perserkönige, in der Zeit der Mongolenkhane, selbst noch in dem Zeitalter, in dem der Papst dem magyarischen Istwan, Stephan I., die heilige Stephanskrone aufsetzte, bedeutete die Persönlichkeit etwas in einer bestimmten Stellung drinnen, konnte sich auffassen als hineingehörig in diese Stellung. Jakob I. war in seiner Stellung, auch in seiner Herrscherstellung drinnen wie ein Mensch, der in einem Gewande drinnensteckt, von dem ihm aber auch gar nichts paßt. Man kann sagen, Jakob I. war in jeder Beziehung in all dem, worinnen er drinnensteckte, eben wie ein Mensch in einem Gewande, das ganz und gar nicht paßte. Er war als Kind calvinisch erzogen worden, war dann später zur anglikanischen Kirche übergegangen, allein im Grunde genommen war ihm der Calvinismus ebenso gleichgültig wie die anglikanische Kirche. Im Innern seiner Seele war das alles Gewand, das ihm nicht paßte. Er war berufen, im herannahenden Zeitalter des parlamentarischen Liberalismus, der sogar schon eine Zeitlang geherrscht hatte, als Herrscher zu regieren. Er war sehr klug, sehr gescheit, wenn er mit den Leuten sprach, aber niemand verstand eigentlich, was er wollte, denn alle anderen wollten etwas anderes. Er war aus einer urkatholischen Familie heraus, der Familie der Stuarts. Aber als er auf den Thron kam in England, da sahen die Katholiken am allermeisten, wie sie eigentlich nichts von ihm zu erwarten hatten. Daraus entsprang ja jener sonderbare Plan, der so merkwürdig in der Welt dasteht, 1605, nicht wahr, wo sich eine ganze Anzahl von Leuten, die aus dem Katholizismus herausgewachsen waren, zusammentaten, möglichst viel Pulver unter dem Londoner Parlament ansammelten, und in einem geeigneten Augenblicke sollten sämtliche Parlamentsmitglieder in die Luft gesprengt werden. Es war die bekannte Pulververschwörung. Die Sache ist nur dadurch verhindert worden, daß ein Katholik, der davon wußte, die Sache verraten hatte, sonst würde sich über diesem Jakob I. das Schicksal abgespielt haben, daß er mit seinem ganzen Parlamente eines Tages in die Luft geflogen wäre. In nichts paßte er hinein, denn er war eine Persönlichkeit, und die Persönlichkeit hat etwas Singuläres, etwas, was in der Isolierung gedacht, was auf sich selbst gestellt ist.

Aber im Zeitalter der Persönlichkeit will jeder eine Persönlichkeit sein. Das ist der radikale Widerspruch, der sich ergibt im Zeitalter der Persönlichkeit, das müssen wir nicht vergessen. Im Zeitalter der Persönlichkeit ist es nicht so, daß man zum Beispiel die Königs-Idee oder die Papst-Idee ablehnt. Es ist ja nicht darum zu tun, daß kein Papst oder kein König da sei. Nur möchte, wenn schon ein Papst oder ein König da ist, jeder ein Papst und jeder König sein, dann wären gleichzeitig Papsttum, Königtum und Demokratie erfüllt. Alle diese Dinge fallen einem bei, wenn man diese merkwürdige Persönlichkeit Jakob I. eben symptomatisch ins Auge faßt, denn er war durch und durch ein Mensch des neuen Zeitalters, aber damit auch mit allen Widersprüchen der Persönlichkeit in das neue Zeitalter hineingestellt. Und Unrecht hatten diejenigen, die ihn von der einen Seite charakterisierten, wie ich gestern mitteilte, und Unrecht hatten diejenigen, die ihn von der anderen Seite charakterisierten, und Unrecht hatten seine eigenen Bücher, die ihn charakterisierten, denn auch was er selber schrieb, führt uns durchaus nicht in irgendeiner direkten Weise in seine Seele hinein. So steht er, wenn man ihn nicht esoterisch betrachtet, wie ein großes Rätsel im Beginne des 17. Jahrhunderts gerade auf einem Posten, der von einer gewissen Seite her am allerradikalsten das Heraufkommen des neuzeitlichen Impulses zeigte.

Erinnern wir uns noch einmal an das gestern Gesagte: wie die Dinge eigentlich im Westen Europas zustande gekommen sind. Ich habe gesprochen von der Differenzierung des englischen, des französischen Wesens. Wir sehen diese Differenzierung seit dem 15. Jahrhundert. Der Wendepunkt kommt mit dem Auftreten der Jungfrau von Orleans, 1429. Wir sehen, wie die Dinge sich entwickeln. Wir sehen, wie in England die Emanzipation der Persönlichkeit Platz greift mit der Aspiration, die Persönlichkeit in die Welt hinauszutragen, wie in Frankreich die Emanzipation der Persönlichkeit Platz greift — auf beiden Böden aus der nationalen Idee heraus entspringend — mit der Aspiration, möglichst das Innere des Menschen zu ergreifen und es auf sich selbst zu stellen. Da drinnen steht zunächst, also im Beginne des 17. Jahrhunderts, eine Persönlichkeit, die wie der Repräsentant aller Widersprüche des Persönlichen dasteht, Jakob I. Wenn man Symptome charakterisiert, muß man niemals pedantisch fertig werden wollen, sondern immer einen unaufgelösten Rest lassen, sonst kommt man nicht weiter. So charakterisiere ich Ihnen Jakob I. keineswegs so, daß Sie ein schönes geschlossenes Bildchen haben, sondern so, daß Sie etwas daran zu denken, vielleicht auch zu rätseln haben.

Es ist immer mehr und mehr hervortretend ein radikaler Unterschied zwischen dem englischen Wesen und dem französischen Wesen. Gerade im französischen Wesen entwickelt sich aus den Wirren des Dreißigjährigen Krieges heraus auf nationalem Grunde dasjenige, was man nennen kann die Erstarkung des Staatsgedankens. Man kann, wenn man die Erstarkung des Staatsgedankens studieren will, dieses nur an dem Beispiele — aber das Beispiel ist ziemlich singulär — der Entstehung, des Hinaufkommens zu hohem Glanze und des Herabsteigens wiederum des französischen Nationalstaates tun, an Ludwig XIV. und so weiter. Wir sehen, wie dann im Schoße dieses Nationalstaates die Keime sich entwickeln zu jener weitergehenden Emanzipation der Persönlichkeit, die mit der Französischen Revolution gegeben ist.

Diese Französische Revolution, sie bringt herauf drei, man kann sagen, allerberechtigtste Impulse des menschlichen Lebens: das Brüderliche, das Freiheitliche, das Gleiche. Aber ich habe es schon einmal bei einer anderen Gelegenheit charakterisiert, wie widersprechend der eigentlichen Menschheitsentwickelung innerhalb der Französischen Revolution diese Dreiheit auftrat: Brüderlichkeit, Freiheit, Gleichheit. Man kann, wenn man mit der menschlichen Entwickelung rechnet, von diesen dreien, von Brüderlichkeit, Freiheit und Gleichheit, nicht sprechen, ohne daß man in irgendeiner Beziehung von den drei Gliedern der Menschennatur spricht. In bezug auf das leibliche Zusammenleben der Menschen muß die Menschheit allmählich gerade im Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele aufsteigen zu einem brüderlichen Element. Es würde einfach ein unsagbares Unglück und eine Zurückwerfung sein in der Entwickelung, wenn am Ende des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraumes, des Zeitalters der Bewußtseinsseele, nicht wenigstens bis zu einem hohen Grade unter den Menschen die Brüderlichkeit ausgebildet wäre. Aber die Brüderlichkeit kann man nur richtig verstehen, wenn man sie angewendet denkt auf das Zusammenleben von Menschenleib zu Menschenleib im physischen Sein. Steigt man aber herauf zum Seelischen, dann kann die Rede sein von der Freiheit. Man wird immer im Irrtum drinnen leben, wenn man glaubt, daß sich Freiheit irgendwie realisieren läßt im äußeren leiblichen Zusammenleben; aber von Seele zu Seele läßt sich Freiheit realisieren. Man darf nicht chaotisch den Menschen als eine Mischmasch-Einheit auffassen und dann von Brüderlichkeit, Freiheit und Gleichheit sprechen, sondern man muß wissen, daß der Mensch gegliedert ist in Leib, Seele und Geist, und muß wissen: Zur Freiheit kommen die Menschen nur, wenn sie in der Seele frei werden wollen. Und gleich sein können die Menschen nur in bezug auf den Geist. Der Geist, der uns spirituell ergreift, der ist für jeden derselbe. Er wird angestrebt dadurch, daß der fünfte Zeitraum, die Bewußtseinsseele, nach dem Geistselbst strebt. Und mit Bezug auf diesen Geist, nach dem da gestrebt wird, sind die Menschen gleich, geradeso wie, eigentlich zusammenhängend mit dieser Gleichheit des Geistes, das Volkssprichwort sagt: Im Tode sind alle Menschen gleich. - Aber wenn man nicht verteilt auf diese drei differenzierten Seelenglieder Brüderlichkeit, Freiheit und Gleichheit, sondern sie mischmaschartig durcheinanderwirft und einfach sagt: Der Mensch soll brüderlich leben auf der Erde, frei sein und gleich sein—, dann führt das nur zur Verwirrung.

Wie tritt uns daher, symptomatisch betrachtet, die Französische Revolution entgegen? Gerade symptomatisch betrachtet ist die Französische Revolution außerordentlich interessant. Sie stellt dar, gewissermaßen in Schlagworten zusammengedrängt und mischmaschartig auf den ganzen Menschen undifferenziert angewendet, dasjenige, was mit allen Mitteln geistiger Menschheitsentwickelung im Laufe des Zeitalters der Bewußtseinsseele, von 1413, also 2160 Jahre mehr, bis zum Jahre 3573, allmählich entwickelt werden muß. Das ist die Aufgabe dieses Zeitraumes, daß für die Leiber die Brüderlichkeit, für die Seelen die Freiheit, für die Geister die Gleichheit erworben werden während dieses Zeitraumes. Aber ohne diese Einsicht, tumultuarisch alles durcheinanderwerfend, tritt dieses innerste Seelische des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraumes schlagwortartig in der Französischen Revolution auf. Es steht unverstanden da die Seele des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraumes in diesen drei Worten und kann daher zunächst keinen äußeren sozialen Leib gewinnen, führt im Grunde genommen zu Verwirrung über Verwirrung. Es kann keinen äußeren sozialen Leib gewinnen, steht aber da wie die fordernde Seele, außerordentlich bedeutsam. Man möchte sagen: Alles Innere, was dieser fünfte nachatlantische Zeitraum haben soll, steht unverstanden da und hat kein Äußeres. Aber gerade da tritt etwas symptomatisch ungeheuer Bedeutsames auf.

Sehen Sie, so etwas, wo das, was über den ganzen nächsten Zeitraum ausgedehnt werden soll, am Anfange fast tumultuarisch zutage tritt, so etwas entfernt sich sehr weit von der Gleichgewichtslage, in welcher sich die Menschheit entwickeln soll, von den Kräften, die den Menschen eingeboren sind dadurch, daß sie mit ihren ureigenen Hierarchien zusammenhängen. Der Waagebalken schlägt sehr stark einseitig aus. Luziferisch-ahrimanisch schlug durch die Französische Revolution der Waagebalken sehr stark nach der einen Seite aus, namentlich nach der luziferischen Seite. Das erzeugt einen Gegenschlag. Man spricht so, ich möchte sagen, schon mehr als bildlich, man spricht imaginativ, aber Sie müssen dabei die Worte nicht allzusehr pressen und müssen vor allen Dingen nicht die Sache wortwörtlich nehmen: In dem, was in der Französischen Revolution auftrat, ist gewissermaßen die Seele des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums ohne den sozialen Körper, ohne die Leiblichkeit. Es ist abstrakt, bloß seelenhaft, strebt nach Leiblichkeit; aber das soll erst geschehen im Verlauf von Jahrtausenden selbst, vielen Jahrhunderten wenigstens. Doch weil die Waagschale der Entwickelung so ausschlägt, ruft es einen Gegensatz hervor. Und was erscheint? Ein Extrem nach der anderen Seite. In der Französischen Revolution geht alles tumultuarisch zu, alles widerspricht dem Rhythmus der menschlichen Entwickelung. Indem es nach der anderen Seite ausschlägt, tritt etwas ein, wo alles nun wiederum ganz — und zwar jetzt nicht in der mittleren Gleichgewichtslage, sondern streng ahrimanisch-luziferisch - dem menschlichen Rhythmus entspricht, dem unpersönlichen Fordern der Persönlichkeit. In Napoleon stellt sich hinterher der Leib entgegen, der ganz nach dem Rhythmus der menschlichen Persönlichkeit, aber jetzt mit dem Ausschlag nach der anderen Seite, gebaut ist: sieben Jahre Vorbereitung - ich habe es schon einmal aufgezählt — für sein eigentliches Herrschertum, vierzehn Jahre Glanz, Beunruhigung von Europa, Aufstieg, sieben Jahre Abstieg, wovon er nur das erste Jahr dazu verwendet, Europa noch einmal zu beunruhigen, aber streng ablaufend im Rhythmus: einmal sieben plus zweimal sieben plus einmal sieben, streng im Rhythmus von sieben zu sieben Jahren ablaufend, viermal sieben Jahre im Rhythmus ablaufend.

Ich habe mir wirklich viel Mühe gegeben — manche wissen, wie ich da oder dort darüber eine Andeutung gegeben habe -, die Seele Napoleons zu finden. Sie wissen, solche Seelenstudien können in der mannigfaltigsten Weise mit den Mitteln der Geistesforschung gemacht werden. Sie erinnern sich, wie Novalis’ Seele in früheren Verkörperungen gesucht worden ist. Ich habe mir redlich Mühe gegeben, Napoleons Seele, zum Beispiel bei ihrer Weiterwanderung nach Napoleons Tod, irgendwie zu suchen - ich kann sie nicht finden, und ich glaube auch nicht, daß ich sie je finden werde, denn sie ist wohl nicht da. Und das wird wohl das Rätsel dieses Napoleon-Lebens sein, das abläuft wie eine Uhr, sogar nach dem siebenjährigen Rhythmus, das auch am besten verstanden werden kann, wenn man es als das volle Gegenteil eines solchen Lebens wie Jakobs I. betrachtet, oder auch als das Gegenteil der Abstraktion der Französischen Revolution: die Revolution ganz Seele ohne Leib, Napoleon ganz Leib ohne Seele, aber ein Leib, der wie zusammengebraut ist aus allen Widersprüchen des Zeitalters. Es verbirgt sich eines der größten Rätsel der neuzeitlichen Entwickelungssymptome, sagen wir, in dieser merkwürdigen Zusammenstellung Revolution und Napoleon. Es ist, als ob eine Seele sich verkörpern wollte auf der Welt und körperlos erschien, und unter den Revolutionären des 18. Jahrhunderts herumrumorte, aber keinen Körper finden konnte, und nur äußerlich ihr ein Körper sich genähert hätte, der wiederum keine Seele finden konnte: Napoleon. In solchen Dingen liegen mehr als etwa bloß geistreich sein sollende Anspielungen oder Charakterisierungen, in solchen Dingen liegen bedeutsame Impulse des historischen Werdens. Allerdings müssen die Dinge symptomatisch betrachtet werden. Hier unter Ihnen rede ich in den Formen der geisteswissenschaftlichen Forschung. Aber selbstverständlich, das, was ich jetzt zu Ihnen gesprochen habe, kann man, indem man die Worte ein bißchen anders wählt, überall sonst sagen.

Und dann, wenn wir versuchen die Symptomgeschichte der neueren Zeit weiter zu verfolgen, sehen wir, verhältnismäßig ruhig, wirklich wie Glieder aufeinander folgend, das englische Wesen sich fortentwikkeln. Im 19. Jahrhundert entwickelt sich das englische Wesen bis zum Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts ziemlich gleichmäßig, ich möchte sagen, in einer gewissen Ruhe das Ideal des Liberalismus geradezu ausprägend. Es entwickelt sich das französische Wesen etwas tumultuarischer, so daß man eigentlich, wenn man die Ereignisse der französischen Geschichte im 19. Jahrhundert verfolgt, nie recht weiß: wie kam eigentlich das Folgende dazu, sich an das Vorangehende anzureihen? — unmotiviert, möchte man sagen. Das ist der hauptsächlichste Grundzug der Entwickelungsgeschichte Frankreichs im 19. Jahrhundert: unmotiviert. Es ist kein Tadel — ich spreche ganz ohne Sympathie und Antipathie —, sondern nur eine Charakteristik.

Nun wird man niemals hineinsehen können in dieses ganze Symptomgewebe der neueren Geschichte, wenn man nicht den Blick darauf wirft, wie eigentlich sich in all dem, was so mehr äußerlich — oder auch seelisch innerlich, aber doch in einem gewissen Sinne äußerlich, wie ich gestern erwähnt habe - sich abspielt, wiederum etwas anderes wirkt. Das möchte ich Ihnen so charakterisieren. Man empfindet schon in einer gewissen Weise, sogar bevor dieses fünfte nachatlantische Zeitalter beginnt, das Herannahen dieses Zeitalters der Bewußtseinsseele. Wie in einem Vorausahnen empfinden es gewisse Naturen. Und sie empfinden es eigentlich mit seinem Charakter, sie empfinden: Es kommt das Zeitalter, in dem die Persönlichkeit sich emanzipieren soll, das aber in einer gewissen Beziehung zunächst unproduktiv sein wird, nichts selbst wird hervorbringen können, das mit Bezug gerade auf die geistige Produktion, die ins soziale und geschichtliche Leben übergehen soll, vom Althergebrachten wird leben müssen.

Das ist ja der tiefere Impuls für die Kreuzzüge, die dem Zeitalter des Bewußtseinsmenschen vorangegangen sind. Warum streben die Leute hinüber nach dem Oriente? Warum streben sie hinüber nach dem heiligen Grabe? Weil sie nicht streben können und nicht streben wollen nach einer neuen Mission, nach einer neuen ursprünglichen speziellen Idee im Bewußtseinszeitalter. Sie streben danach, das Althergebrachte in seiner wahren Gestalt, in seiner wahren Substanz sogar, zu finden: Hin nach Jerusalem, um das Alte zu finden und es auf eine andere Weise in die Entwickelung hereinzustellen, als es Rom hereingestellt hat. - Mit den Kreuzzügen ahnt man, daß heraufkommt das Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele mit seiner Unproduktivität, die es zunächst entfaltet. Und im Zusammenhang mit den Kreuzzügen entsteht der Tempelherrenorden, von dem ich Ihnen gestern gesprochen habe, dem der König Philipp der Schöne den Garaus gemacht hat. Und mit dem Tempelherrenorden kommen nach Europa die Geheimnisse des orientalischen Wesens, und sie werden eingeimpft der europäischen Geisteskultur. Der König von Frankreich, Philipp - ich habe das im Laufe der Zeit ja von einer anderen Seite her charakterisiert —, konnte zwar die Tempelritter hinrichten lassen, konnte ihr Geld konfiszieren, aber die Impulse der Tempelritter waren durch zahlreiche Kanäle in das europäische Leben hineingeflossen und wirkten weiter fort, wirkten fort durch zahlreiche okkulte Logen, die dann wiederum ins Exoterische hinausgingen, und die im wesentlichen so charakterisiert werden können, daß man sagen kann, sie bildeten nach und nach die Opposition gegenüber Rom. Rom war auf der einen Seite, erst allein, dann mit dem Jesuitismus verbunden, und dann stellte sich auf die andere Seite alles dasjenige, was, mit dem christlichen Elemente tief zusammenhängend, Rom radikal fremd, in Opposition gegen Rom sich stellen mußte, und auch von Rom als eine Opposition empfunden wurde und empfunden wird.

Was war denn nun eigentlich der tiefere Impuls dieser Tatsache, daß man gegenüber dem, was von Rom ausströmte, gegenüber diesem suggestiven Universalimpuls, wie ich ihn gestern charakterisiert habe, orientalisch-gnostische Lehren und Anschauungen, Symbole und Kulte nahm, die man einimpfte dem europäischen Wesen? Betrachten wir einmal, was es ist, dann wird es uns auch auf den eigentlichen Impuls führen können.

Die Bewußtseinsseele sollte herankommen. Rom wollte bewahren gegenüber der Bewußtseinsseele - und bewahrt es bis heute — die suggestive Kultur, jene suggestive Kultur, welche geeignet ist, die Menschen zurückzuhalten vom Übergehen zum Bewußtseinsseelenzustand, welche geeignet sein soll, die Menschen auf dem Standpunkte der Verstandes- oder Gemütsseele zu halten. Das ist ja der eigentliche Kampf, den Rom gegen den Fortgang der Welt führt, daß es beharren will, dieses Rom, bei etwas, was für die Verstandes- oder Gemütsseele taugt, während die Menschheit in ihrer Entwickelung fortschreiten will zur Bewußtseinsseele.

Aber auf der anderen Seite bringt sich die Menschheit mit dem Fortschritt in die Bewußtseinsseele wahrhaftig in eine recht unbehagliche Lage, die für weitaus die meisten Menschen zunächst in den ersten Jahrhunderten des Bewußtseinszeitalters und bis heute unbequem empfunden wurde. Nicht wahr, der Mensch soll sich auf sich selbst stellen, der Mensch soll als Persönlichkeit sich emanzipieren. Das verlangt von ihm das Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele. Er muß heraus aus all den alten Stützen. Er kann sich nicht mehr bloß suggerieren lassen dasjenige, an was er glauben soll, er soll selbsttätig teilnehmen an der Erarbeitung dessen, was er glauben soll. Das empfand man, insbesondere als dieses Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele heraufstieg, als eine Gefahr für den Menschen. Instinktiv fühlte man: Der Mensch verliert seinen alten Schwerpunkt; er soll einen neuen suchen. — Aber auf der anderen Seite sagte man sich auch: Wenn man gar nichts tut, was sind dann die Möglichkeiten des Geschehens? — Die eine Möglichkeit besteht darinnen, daß man einfach den Menschen hinausfahren läßt auf das offene Meer des Suchens nach der Bewußtseinsseele, ihn gewissermaßen freigibt dem, was in den freien Impulsen des Fortschrittes liegt. Die andere Möglichkeit, wenn der Mensch so hinaussegelt, ist die, daß Rom dann eine große Bedeutung gewinnt, eine große Wirkung üben kann, wenn es ihm gelingt, abzudämpfen das Streben nach der Bewußtseinsseele, um den Menschen zu erhalten beim Stehen in der Verstandes- oder Gemütsseele. Dann würde das erreicht werden, daß der Mensch nicht aufsteigt zu der Bewußtseinsseele, daß der Mensch nicht zum Geistselbst kommt, daß der Mensch seine zukünftige Entwickelung verliert. Es wäre das nur eine von den Nuancen, durch welche die zukünftige Entwickelung verloren werden könnte.

Die dritte Möglichkeit ist die folgende: Man geht noch radikaler vor, man versucht sein Streben ganz abzutöten, damit der Mensch nicht in diese pendelnde Schwingung kommt zwischen dem Streben nach der Bewußtseinsseele und dem Streben, das ihm Rom auferlegt. Damit der Mensch nicht in diese pendelnden Schwingungen kommt, untergräbt man sein Streben vollständig, noch radikaler als Rom. Das tut man dann, wenn man die fortschreitenden Impulse eben gerade der Kraft des Fortschrittes entkleidet und das Alte wirken läßt. Vom Oriente hatte man es mitgebracht, allerdings ursprünglich bei den esoterisch eingeweihten Templern in einer anderen Absicht. Aber nachdem diesem Streben die Spitze abgebrochen war, nachdem der Tempelherrenorden zunächst so behandelt worden war, wie er eben von Philipp dem Schönen, dem König von Frankreich, behandelt worden ist, da war geblieben, was man so herübergebracht hatte aus Asien an Kultur. Aber es war ihm zunächst die Spitze abgebrochen, in der Historik, nicht bei einzelnen Persönlichkeiten, aber in der historischen Welt. Durch zahlreiche Kanäle, wie ich gesagt habe, war eingeträufelt das, was die Templer herübergebracht haben, aber der eigentliche spirituelle Gehalt war ihm vielfach genommen worden. Und was war es denn? Es war im wesentlichen der Inhalt der dritten nachatlantischen Zeit. Die Katholizität brachte den Inhalt der vierten. Und dasjenige, woraus der Geist ausgepreßt war wie der Saft aus einer Zitrone, was sich fortpflanzte als exoterisches Freimaurertum, als schottische oder Yorklogen oder wie immer, was namentlich ergriff der falsche Esoterismus der englischsprechenden Bevölkerung, das ist die ausgepreßte Zitrone, die daher, nachdem sie ausgepreßt ist, die Geheimnisse des dritten nachatlantischen, des ägyptisch-chaldäischen Zeitraumes enthält, und was nun angewendet wird, um Impulse hineinzusenden in das Leben der Bewußtseinsseele.