From Symptom to Reality in Modern History

GA 185

25 October 1918, Dornach

Lecture IV

Before turning to other matters I must speak of certain wider conceptions that follow from our consideration of the recent development of human history. We attempted to examine this development from the stand-point of a symptomatology; we tried to show that what are usually called historical facts are not the essential elements in history, but that they are symbols of the true reality that lies behind them. This true reality, at least in the sphere of the historical evolution of mankind, is thus detached from what can be perceived in the phenomenal world, i.e. the so-called historical facts. If we do not regard the so-called historical facts as the true reality but seek in them manifestations of something that lies behind them then we discover of course a super-sensible element.

In studying history it is not easy to show the true nature of the super-sensible because people believe, when they discover certain thoughts or ideas in history, or when they record historical events, that they are already in touch with the super-sensible. We must be quite clear that whatever the phenomenal world presents to the senses, to the intellect or emotions cannot in any way be regarded as super-sensible. Therefore everything that is normally depicted as history belongs to the sensible world. Of course when we study the symptomatology of history we shall not regard the symptoms as having equal value; the study itself will show that, in order to arrive at the super-sensible reality behind the events, a particular Symptom is of capital importance, whilst other symptoms are perhaps of no importance.

I have already mentioned many of the more or less important symptoms manifested since mankind entered the epoch of the Consciousness Soul. I should now like to try to describe to you, step by step, a few characteristics of the super-sensible present in the background. Some I have already described. For of course a fundamental feature pulsing in the super-sensible is the entrance of mankind into the civilization of the Consciousness Soul, that is to say, the acquisition of the organs necessary for the development of the Consciousness Soul. That is the essential. But we have recently seen that the other pole, the complement to this inner elaboration of the Consciousness Soul, must be the aspiration to a revelation from the spiritual world. Men must realize that henceforth they will be unable to progress spiritually unless they open themselves to the new revelation of the super-sensible world.

Let us now consider these two poles of evolution. To a certain extent they have come to the fore in the centuries since 1413 when mankind entered the epoch of the Consciousness Soul. These two impulses will continue to develop, will assume a wide diversity of forms in the different epochs up to the third millennium and will be responsible for the manifold vicissitudes that befall mankind. Individuals will gradually become aware of this. In considering these two impulses in particular, we learn that fundamental changes have occurred since the fifteenth century. Today we are in a position to draw attention to these important developments. In the eighteenth century, and even in the early nineteenth century it would not have been possible to show the operation of these two impulses purely from the observation of external phenomena. They had not yet been operative for a sufficient length of time to show their full effect. Now such is their dynamic power that it is perceptible in external phenomena.

Let us now consider an essential fact which has an important bearing today. Whilst early indications were apparent only to those who were more or less acquainted with the true state of affairs—I am referring to the Russian Revolution in its last phase, namely from October 1917 to the peace negotiations of Brest-Litovsk—this extraordinarily interesting development which can easily be followed, since it lasted only a few months, is of immense importance to those who seriously wish to understand the historical symptoms, for this development is of course a historical symptom. In the final analysis the origin of the Russian Revolution is to be found in the deeper impulses of contemporary evolution. In this revolution it is a question of new ideas. For when we speak of real evolution in mankind we are concerned only with new ideas. Everything else—as we have already indicated, and we will recur to this later—is subject to a certain extent to the symptoms of death. It is a question of making new ideas effective. As you will have gathered from the many discussions which I have had upon this subject over recent decades—these new ideas must be able to capture the broad masses of peasantry in Eastern Europe. Of course we are dealing here with a passivity of soul, but a soul that, as you know, is receptive especially to new and modern ideas, for the simple reason that it bears within it the seed of the Spirit Self. Whereas, on the whole, the rest of the world's population bears within it the impulse to develop the Consciousness Soul, the broad mass of the Russian population, together with a few satellites, bears within it the seed from which the Spirit Self will be developed in the course of the sixth postAtlantean epoch. This necessitates, of course, very special circumstances. But this has an important bearing on what we are about to study next.

Now this idea—partly correct, partly false or wholly mistaken—this modern idea of something entirely new which was destined to capture the broad mass of the population could only come from those who had had the opportunity to be educated, namely from the ruling classes.

After the fall of Czarism the centre of the state was at first occupied by an element that was closely connected with a totally sterile class, the upper middle class—called in the West, heavy industry, etcetera. This could only be an interlude which we need not discuss, for this class is destitute of ideas and, as a class, is of course quite incapable of developing ideas. (When speaking of these matters I never indulge in personalities.)

Now at first those elements which were of middle class origin, together with a sprinkling of working class elements, formed the party of the left. They formed the leading wing of the so-called Social Revolutionaries and were gradually joined by the Mensheviks. They were men who—purely in terms of their numbers—could easily have played a leading part in determining the future course of the Russian Revolution. As you know events took a different course. The radical wing of the Russian Social Democratic party, the Bolsheviks, took over the helm. When they (the Bolsheviks) came to power, the Social Revolutionaries, the Mensheviks and their followers in the West were quite sure that the whole charade would not last more than a week before everything collapsed. Well, the Bolsheviks have now been in power more than a week and you can rest assured of this: if many prophets are bad prophets, then those who today base their predictions of historical events upon the outmoded world conceptions of certain middle classes are certainly the worst! What is the cause of this situation? This problem of the October Revolution, throughout the months following its outbreak and until today, is, in the terminology of physics, not a problem of pressure, but of suction. It is important that we can infer from the historical situation that we are dealing here not with a problem of pressure, but of suction. What do we understand by a problem of suction? As you know, when we create a vacuum by sucking out the air in the glass jar of an air pump and then remove the stopper, the air rushes in with a hissing sound. The air rushes in, not of its own volition, but because a vacuum has been created.

This was the situation of those elements which to some extent stood midway between the peasantry and the Bolsheviks, between the Social Revolutionaries, the Mensheviks, and the radical revolutionary groups of the extreme left, i.e. the Petrograd Soviet. What had happened was that the Mensheviks, though they had an overwhelming majority in the Provisional Government were totally destitute of ideas. They had not a word to say about the future of mankind. No doubt they cherished touching ethical sentiments and other romantic ideals, but, as I have often pointed out, ethical good intentions do not provide the impulses which can further the development of mankind. Thus a vacuum was created, an ideological vacuum, and the radical left wing rushed in. It is impossible to believe that, by their very nature, the most radical socialist elements who were alien to Russian tradition and culture were destined to take over in Russia. They could never have done so if the Social Revolutionaries and the various groups associated with them had had any ideas of how to give a lead. But you will ask: what ideas ought they to have had? A fruitful answer can only be found today by those who are no longer afraid to face this fact: for this section of the population the only fertile ideas are those which spring from spiritual experience. Nothing else avails.

It is true that these people have become more or less radical and will now deny their middle class origin, many at least will deny it, but there is no mistaking their origin. But the essential point is that this section of the population which created a vacuum, who were bereft of ideas, simply could not be induced to develop anything in the nature of positive ideas.

And this applies, of course, not only to Russia. But the Russian Revolution in its final phase—provisionally the final phase—demonstrates this fact with particular clarity to those who are prepared to study the matter. We see how, day after day, these people (i.e. the Mensheviks and their supporters) who have created a vacuum are gradually forced back and how others rush in to fill the vacuum, i.e. to replace them. But today this phenomenon is world-wide. The fact is that the section of the population which today stands politically between the right and the left has steadily refused to make the slightest effort to develop a positive Weltanschauung. In our epoch of the Consciousness Soul a creative Weltanschauung must of necessity be one which also promotes social cohesion.

It was this which from the very beginning permeated our Anthroposophical movement. It was not intended in any way to be a sectarian movement, but endeavoured to come to terms with the impulse of our time, with everything that is essential and important for mankind today. This was increasingly our goal. It is this which is most difficult to bring to men's understanding today for the simple reason that the belief persists (not in all, but in the majority) that what they are looking for in Anthroposophy, as they understand it, is a little moral uplift, something necessary for one's private and personal edification, something which insulates one from the serious matters which are settled in Parliament, in the Federal Councils, in this or that Corporation, or even round the beer table. What we must realize is that the whole of life must be impregnated with ideas which can be derived only from spiritual science.

Whilst this section of the population, i.e. the bourgeoisie, was indifferent to spiritual ideas, the proletariat showed and still shows today a lively interest in them. But as a consequence of the historical evolution of modern times the horizon of the proletariat is limited purely to the sensible world. It is prisoner of materialistic impulses and seeks to steer the evolution of mankind into utilitarian channels. The bourgeoisie knows only empty rhetoric, what it is pleased to call its Weltanschauung is simply verbiage, because it has no roots in contemporary life and is a survival from earlier times. The proletariat, on the other hand, because it is motivated by a totally new economic impulse lives therefore in realities, but only in realities of a sensible nature.

This provides us with an important criterion. In the course of the last few centuries the life of mankind has undergone a fundamental change; we have entered the machine age. The life of the middle class and the upper middle class has scarcely felt the impact of the machine age. For the new and powerful influences which have affected the life of the bourgeoisie in recent centuries belong to the pre-machine age ... for example, the introduction of coffee as the favourite beverage for cafe gossip. Equally the new banking practices, etcetera, introduced by the bourgeoisie are wholly unsuited to the new impulses of today. They are simply a hotchpotch of the ancient usages formerly practised in commercial life.

On the other hand the proletariat of today is the caste or class which is dominated by a modern impulse in the external life and to a certain extent is the creation of modern impulses themselves. Since the invention of the spinning jenny and the mechanical loom in the eighteenth century, the entire political economy of mankind has been transformed, and these inventions have been largely responsible for the birth of the modern proletariat. The proletariat is a creation of the modern epoch, that is the point to bear in mind. The bourgeois is not a creation of modern times. For the class or group which existed in earlier times and which could be compared with the proletariat of today did not belong to the third estate; it still formed part of the old patriarchal order. And the patriarchal order is totally different from the social order of the machine age. In this new order the proletarian is surrounded by a completely mechanized environment wholly divorced from living nature. He is entirely engaged in practical activities, but he thirsts for a Weltanschauung and he has endeavoured to model his conception of the universe on the pattern of a vast machine. For men see the universe as a reflection of their own environment. Now I have already pointed out there is an affinity between the theologian and the soldier. They see the universe as a battleground, the scene of the clash between the forces of good and evil, etcetera and leave it at that. Equally there is a close affinity between the jurist and the civil servant; they and the metaphysician see in the universe the realization of abstract ideas. Small wonder then that the proletarian sees the universe as a vast machine in which he is simply a cog. That is why he wishes to model the social order on the pattern of a vast machine.

But there was and still is a vast difference between, for example, the modern proletarian and the modern bourgeois—we can ignore the class which is already in decline. The modern bourgeois has not the slightest interest in deeper ideological questions, whereas the proletarian is passionately interested in them. It is true the modern bourgeois holds frequent meetings for an exchange of views, but for the most part they are so much hot air; the proletarian on the other hand discusses his daily life and working conditions and the daily output of mass production. When one passes from a middle class reunion to a proletarian meeting one has the following impression—In the former they spend time in discussing what a fine thing it would be if men lived in peace, if all were pacifists for example, or other fine sentiments of alike nature. But all this is merely verbal dialectic seasoned with a pinch of sentimentality. The bourgeoisie is not imbued with a desire to open a window on the universe, to realize their objectives from out of the mysteries of the Cosmos. When you attend a proletarian meeting you are immediately aware that the workers are talking of realities, even if they are the realities of the physical plane. They have the history of the working class at their finger-tips, from the invention of the mechanical loom and the spinning jenny until the present day. Every man has had dinned into him the history of those early beginnings and their subsequent development, and how the proletariat has become what it is today. How this situation arose is familiar ground to every worker who is actively involved in this development and who is not completely stupid, and there are few amongst this section of the population who haven't a good head on their shoulders.

One could give many typical instances of the obtuseness of the present bourgeoisie with regard to ideological questions. One need only recall how these people react when a poet presents on the stage figures from the super-sensible world (those who are not poets dare not take this risk for fear of being labelled visionaries). The spectators half accept these figures because there is no need to believe in them, because they are totally unreal—they are merely poetic inventions! This situation has arisen in the course of the development of the epoch of the Consciousness Soul. If we consider this situation spatially, we see the growth of a section of the population which, unless it takes heed, is increasingly in danger of ending completely in empty talk. But one can also consider this same situation in relation to time, and in this respect I have repeatedly called attention from widely different angles to certain important moments in time.

The epoch of the Consciousness Soul began approximately in 1413. In the forties of the nineteenth century, about 1840 or 1845, the first fifth of this era had already run its course. The forties were an important period. For the powers impelling world evolution foresaw a kind of crisis for this period. Externally this crisis arose because these years in particular were the hey-day of the so called liberal ideas. In the forties it seemed as if the impulse of the Consciousness Soul in the form of liberalism might breach the walls of reactionary conservatism in Europe. Two things concurred in these years. The proletariat was still the prisoner of its historical origins, it lacked self-assurance, confidence in itself. Only in the sixties was it ready to play a conscious part in historical evolution; before this one cannot speak of proletarian consciousness in the modern sense of the term. The social question of course existed before the sixties, but the middle class was totally unaware of it. At the end of the sixties an Austrian minister1The Austrian Minister was Dr. Giskra (1820–79). of repute made the famous remark: ‘The social question ends at Bodenbach!’ Bodenbach, as you perhaps know, lies on the frontier between Saxony and Austria. Such was the famous dictum of a bourgeois minister!

In the forties therefore the proletarian consciousness did not yet exist. In the main, the bearer of the political life at that time was the bourgeoisie. Now the ideas which could have become a political force in the 1840's were exceedingly abstract. You are all familiar (at least to a certain extent I hope) with what are called the revolutionary ideas—in reality they were liberal ideas—which swept over Europe in the forties and unleashed the storm of 1848. As you know, the bearer of these ideas was the middle class. But all these ideas which were prevalent at the time and which were struggling to find a place in the historical evolution of mankind were totally abstract, sometimes merely empty words! But there was no harm in that, for in the epoch of the Consciousness Soul one had to go through the abstractive phase and apprehend the leading ideas of mankind first of all in this abstract form.

Now you know from your own experience and that of others that the human being does not learn to read or write overnight. In order to develop certain potentialities mankind also needs time to prepare the ground. And mankind was given until the end of the seventies to develop new ideas. Let us look at this a little more closely. Starting from the year 1845, add thirty-three years and we arrive at the year 1878. Up to this year, approximately, mankind was given the opportunity of becoming acclimatized to the reality of the ideas of the forties. The decades between the forties and the seventies are most important for an understanding of modern evolution, for it was in the forties that what are called liberal ideas, albeit in an abstract form, began to take root and mankind was given until the end of the seventies to apprehend those ideas and relate them to the realities of the time.

But the bearer of these ideas, the bourgeoisie, missed their opportunity. The evolution of the nineteenth century is fraught with tragedy. For those who listened to the speeches of the outstanding personalities of the bourgeoisie in the forties (and there were many such throughout thc whole civilized world) announcing their programme for a radical change in every sphere, the forties and fifties seemed to herald the dawn of a new age. But, owing to the characteristics of the middle class which I have already described, hopes were dashed. By the end of the seventies the bourgeoisie had failed to grasp the import of liberal ideas. From the forties to the seventies the middle class had been asleep and we cannot afford to ignore the consequence. The tide of events is subject to a pattern of ebb and flow and mankind can only look forward to a favourable development in the future if we are prepared to face frankly what occurred in the immediate past. We can only wake up in the epoch of the Consciousness Soul if we are aware that we have hitherto been asleep! If we are unaware when and how long we have been asleep, we shall not awake up, but continue to sleep on.

When the Archangel Michael took over his task as Time Spirit at the end of the seventies the bourgeoisie had not understood the political impact of liberal ideas. The powers which in this epoch intervened in the life of mankind began by obscuring the nature of these ideas. And if you take the trouble, you can follow this very clearly. How different was the configuration of the political life at the end of the nineteenth century from that envisaged in the forties! One cannot imagine a greater contrast than the ideas of 1840–1848 (which were certainly abstract, yet lucid despite their abstract nature), and the ‘lofty human ideals’, as they were called, in the different countries in the nineteenth century and even up to our own time, when they ended in catastrophe.

The temporal complement therefore to the spatial picture is this: in the most productive and fertile years for the bourgeoisie, from the forties to the end of the seventies, they had been asleep. Afterwards it was too late, for nothing could then be achieved by following the path along which the liberal ideal might have been realised in this period. Afterwards only through conscious experience of spiritual realities could anything be achieved. There we see the connection between historical events.

In the period between the forties and the seventies the ideas of liberalism, though abstract, were such that they tended to promote tolerance between men. And assuming for the moment that these ideas were realized, then we should see the beginning, only the first steps it is true, but nonetheless a beginning of a tolerant attitude towards others, a respect for their ideas and sentiments which is so conspicuously lacking today. And so in social life a far more radical, a far more powerful idea, an idea which has its source in the spirit, must lay hold of men. I propose first of all, purely from the point of view of future history, to indicate this idea and will then substantiate it in greater detail.

Only a genuine concern of each man for his neighbour can bring salvation to mankind in the future—I mean to his community life. The characteristic feature of the epoch of the Consciousness Soul is man's isolation. That he is inwardly isolated from his neighbour is the consequence of individuality, of the development of personality. But this separative tendency must have a reciprocal pole and this counterpole must consist in the cultivation of an active concern of every man for his neighbour.

This awakening of an active concern for others must be developed ever more consciously in the epoch of the Consciousness Soul. Amongst the fundamental impulses indicated in my book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds. How is it achieved? you will find mentioned the impulse which, when applied to social life, aims at enhancing understanding for others. You will find frequent mention of ‘positiveness,’ the need to develop a positive attitude. The majority of men today will certainly have to foreswear their present ways if they wish to develop this positive attitude, for at the moment they have not the slightest notion what it means. When they perceive something in their neighbour which displeases them—I do not mean something to which they have given careful consideration, but something which from a superficial angle meets with their disapproval—they immediately begin to criticize, without attempting to put themselves in their neighbour's skin. It is highly anti-social from the point of view of the future evolution of mankind—this may perhaps seem paradoxical, but it is none the less true—to harbour these tendencies and to approach one's neighbour with undisguised sympathy or antipathy. On the other hand the finest and most important social attribute in the future will be the development of a scientific objective understanding of the shortcomings of others, when we are more interested in their shortcomings than in our concern to criticize them. For gradually in the course of the fifth, sixth and seventh cultural epochs the individual will have to devote himself increasingly and with loving care to the shortcomings of his neighbour. On the pediment of the famous temple of Apollo in Greece was inscribed this motto: ‘Know thyself’. Self knowledge in the highest sense could still be achieved at that time through introspection. But that is becoming progressively less possible. Today man has made little advance in self knowledge through introspection. Fundamentally men know so little of each other because they are concerned only with themselves, and because they pay so little attention to others, especially to what they call the shortcomings of others.

This can be confirmed by a purely scientific fact. Today when the scientist wants to discover the secrets of human, animal and plant life he does two things. I have often spoken of this and it is most important. First of all he carries out an experiment, following the same procedure for inorganic life as for organic life. But by experimentation he loses touch with living nature. He who is able to follow with true insight the results of experimentation knows that the experimental method is shot through with the forces of death. All that experimentation can offer, even the patient and painstaking work of Oskar Hertwig2Oskar Hertwig (1849–1922). Director of the Anatomical-biological Institute in Berlin (1888–1921). Author of works on biology, zoology. Rejected Darwin's theory of sexual selection. for example, is dead-sea fruit. It cannot explain how a living being is fertilized, nor how it is born. By this method one can only explain the inorganic. The art of experimentation can tell us nothing of the secrets of life. That is the one side.

Today however there is one field of investigation which operates with very inadequate means and is as yet in its very early stages, but which is calculated to give valuable information about human nature, namely, the study of pathological conditions in man. When we study the case history of a man who is not quite normal we feel that we can be at one with him, that with sympathetic understanding we can break through the barrier that separates us from him and so draw nearer to him. By experimentation we are detached from reality; by the study of what are called today pathological conditions—malformations as Goethe so aptly called themwe are brought back to reality. We must not be repelled by them, but must develop an understanding for them. We must say to ourselves: the tragic element in life—without ever wishing it for anybody—can sometimes be most instructive, it can throw a flood of light upon the deepest mysteries of life. We shall only understand the significance of the brain for the life of the soul through a more intensive study of the mentally disturbed. And this is the training ground for a sympathetic understanding of others. Life uses the crude instrument of sickness in order to awaken our interest in others. It is this concern for our neighbour which can promote the social progress of mankind in the immediate future, whereas the reverse of positiveness, a superficial attitude of sympathy or antipathy towards others makes for social regression. These things are all related to the mystery of the epoch of the Consciousness Soul.

In every epoch of history mankind develops some definite faculty and this faculty plays an important role in evolution. Recall my words at the end of the last lecture. I said: men must be prepared to recognize more and more in the events of external history creation and destruction, birth and death, birth through impregnation with a new spiritual revelation, death through everything that we create. For the fundamental characteristic of the epoch of the Consciousness Soul is that, on the physical plane, we can only create if we are aware that everything we create is destined to perish. Death is inherent in everything we create. On the physical plane the most important achievements of recent time are fraught with death. And the mistake we make is not that our creations are fraught with death, but that we refuse to recognize that they are vehicles of death.

After the first fifth of the epoch of the Consciousness Soul has elapsed, people still say today: man is born and dies. They avoid saying, for it seems absurd: to what end is man born if he is destined to die? Why bring a man into the world when we know that death is his lot. In that event birth is meaningless! Now people do not say this, because nature in her wisdom compels them to accept birth and death in the sphere of external nature. In the sphere of history, however, they have not yet reached the stage when they accept birth and death as the natural order of things. Everything created in the domain of history, they believe, is without exception good and is destined to subsist for ever. In the epoch of the Consciousness Soul we must develop a sense that the external events of history are subject to birth and death, and that, whatever we create, be it a child's toy or an empire, we create in the knowledge that it must one day perish. Failure to recognize the impermanence of things is irrational, just as it would be irrational to believe that one could bear a child which was entitled to live on earth for ever.

In the epoch of the Consciousness Soul we must become fully aware that the works of man are impermanent. In the Graeco-Latin epoch this was not necessary, for at that time the course of history followed the natural cycle of birth and death. Civilizations rose and fell as a natural process. In the epoch of the Consciousness Soul it is man who weaves birth and death into the web of his social life. And in this epoch man can acquire a sense for this because in the GraecoLatin epoch this seed had been implanted in him under quite specific circumstances.

For a man of the middle Graeco-Latin epoch the most important moment in his development was the early thirties. These years were to some extent the focal point of two forces which are active in every man. The forces which operate in the symptoms of birth are active throughout the whole period from birth to death; but their characteristic features are manifested at birth. Birth is only one significant symptom of the activity of these forces; and the other occasions when the same forces are active throughout the whole of physical life are less important. In the same way, the forces of death begin to act at the moment of birth and when man dies they are especially evident. These two polar forces, the forces of birth and the forces of death, always maintain a kind of balance. In the Graeco-Latin epoch they were most evenly balanced when man reached the early thirties. Up to this age he developed his sentient life and afterwards, through his own efforts, his intellect. Before the thirties his intellectual life could only be awakened through teaching and education. And therefore we speak of the Graeco-Latin epoch as the era of the Rational or Intellectual Soul because the sentient life up to the age of thirty and the intellectual life which developed later were united. But this no longer applies in the epoch of the Consciousness Soul. Today intellectual development ceases before middle life. The majority of people one meets today, especially amongst the middle classes, do not mature after the age of twenty-seven; thereafter they are content to plough the same furrow. You can easily see what I mean by looking around you. How few people today have radically changed in any way since the age of twenty-seven. They have aged physically, their hair has turned grey, they have become decrepit ... (perhaps that is going a little too far), but, on the whole, man reckons that he has reached maximum potentiality by the age of twenty-seven. Let us take the case of a member of the so-called intellectual class. If he has had a sound training up to the age of twenty-seven he wants to establish himself; if he has gained a qualification he wants to make use of it and advance his career potential. Would you expect a man of average intelligence today to become a second Faust, that is to say, to study not only one faculty, but four faculties in succession up to the age of fifty? I do not mean that he should of necessity go to the university, perhaps there are better possibilities than the four faculties. A man who is prepared to continue his studies, to expand his knowledge, a man who remains plastic and capable of transformation is a rarity today. This was far more common amongst the Greeks, at least amongst the intellectual section of the population, because development did not cease in the early thirties. The forces inherited at birth were still very active. They began to encounter the forces leading to death; a state of equilibrium was established at the midway stage of life. Today this situation has come to an end; the majority hopes to be ‘made’ men, as the saying goes, by the age of twenty-seven. Yet at the end of their thirties they could recapture something of their youthful idealism and go forward to wider fields if they really wished to do so! But I wonder how many there are today who are prepared to make the readjustment necessary for the future evolution of mankind: to develop a constant readiness to learn, to remain plastic and to be ever receptive to change. This will not be possible without that active sympathy for others of which I have already spoken. Our hearts must be filled with a tender concern for our neighbour, with sympathetic understanding for his peculiarities. And precisely because this compassion and understanding must take hold of mankind it is so rarely found today.

What I have just described throws light upon an important fact of man's inner psychic development. The thread linking birth and death is broken to some extent between the ages of twenty-six to twenty-seven and thirty-seven to thirty-eight. In this decade of man's evolution the forces of birth and death are not fully in harmony. The disposition of soul which man needs, and which he could still experience in the Graeco-Latin epoch because the forces of birth and death were still naturally conjoined, this disposition of soul he must develop in the epoch of the Consciousness Soul because he is able to observe birth and death in the external life of history. In brief, our observation of external life must be such that we can face the world around us fearlessly and courageously, saying to ourselves: we must consciously create and destroy in all domains of life. It is impossible to create forms of social life that last forever. He who works for social ends must have the courage constantly to build afresh, not to stagnate, because the works of man are impermanent and are doomed to perish, because new forms must replace the old.

Now in the fourth post-Atlantean epoch, the epoch of the Intellectual or Rational Soul, birth and death were active in man in characteristic fashion; as yet there was no need for him to be aware of them externally. Now, in the epoch of the Consciousness Soul he must perceive them externally; to this end he must again develop in himself something else, and this is very important.

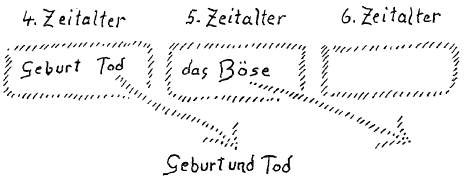

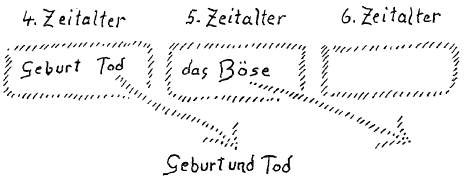

Let us look at man schematically in relation to the fourth, fifth and sixth cultural epochs.

In the fourth post-Atlantean epoch (the Graeco-Latin epoch) man was conscious of birth and death when he looked within himself. Today he must first perceive the forces of birth and death externally, in the events of history, in order to discover them within himself. That is why it is so vitally important that in the epoch of the Consciousness Soul man should have a clear understanding of forces of birth and death in their true sense, i.e. a knowledge of repeated lives on earth, in order to acquire an understanding for birth and death in the unfolding of history.

But just as man's consciousness of birth and death has passed from an inner experience to an external realization, so in the fifth post-Atlantean epoch he must develop within himself something which in the sixth post-Atlantean epoch beginning in the fourth millennium will once again be experienced externally, namely, evil. In the fifth post-Atlantean epoch evil is destined to develop in man; it will ray outwards in the sixth epoch and be experienced externally just as birth and death were experienced externally in the fifth epoch. Evil is destined to develop in man's inner being.

That is indeed an unpleasant truth! One can accept the fact that in the fourth post-Atlantean epoch man was familiar with birth and death as an inner experience and then perceived them in the cosmos as I pointed out in my lectures on the Immaculate Conception and the Resurrection, and the Mystery of Golgotha. Therefore mankind of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch is brought face to face with the phenomenon of the birth and death of Christ Jesus because birth and death were of vital importance in this epoch.

Today when Christ is destined to appear again in the etheric body, when a kind of Mystery of Golgotha is to be experienced anew, evil will have a significance akin to that of birth and death for the fourth post-Atlantean epoch! In the fourth epoch the Christ impulse was born out of the forces of death for the salvation of mankind. We can say that we owe the new impulse that permeated mankind to the event on Golgotha. Thus by a strange paradox mankind is led to a renewed experience of the Mystery of Golgotha in the fifth epoch through the forces of evil. Through the experience of evil it will be possible for the Christ to appear again, just as He appeared in the fourth post-Atlantean epoch through the experience of death.

In order to understand this—we have already given here and there a few indications of the Mystery of Evil—we must now say a few words about the relationship between the Mystery of Evil and the Mystery of Golgotha. This relationship will be the subject of our next lecture.

Vierter Vortrag

Bevor ich zu anderem übergehe, muß ich noch sprechen von gewissen umfassenderen Gedanken, die sich ergeben aus dem, was wir über die neuzeitliche menschliche Geschichtsentwickelung betrachtet haben. Wir haben versucht, diese neuzeitliche menschliche Geschichtsentwickelung ins Auge zu fassen vom Gesichtspunkte einer Symptomatologie, das heißt, wir haben entschieden den Versuch unternommen, dasjenige, was man gewöhnlich historische Tatsachen nennt, nicht als das zu betrachten, was das Wesentliche in der geschichtlichen Wirklichkeit ist, sondern diese historischen Tatsachen so hinzustellen, daß sie bildhafte Offenbarungen desjenigen darstellen, was eigentlich hinter ihnen als die wahre Wirklichkeit liegt. Diese wahre Wirklichkeit ist damit wenigstens auf dem Gebiete des geschichtlichen Werdens der Menschheit herausgehoben aus dem, was bloß äußerlich in der sinnenfälligen Welt wahrgenommen werden kann. Denn das, was äußerlich in der sinnenfälligen Welt wahrgenommen werden kann, das sind eben die sogenannten historischen Tatsachen. Und erkennt man die sogenannten historischen Tatsachen nicht als die wahre Wirklichkeit an, sondern sucht in ihnen als in Symptomen von der wahren Wirklichkeit Offenbarungen eines hinter ihnen Stehenden, dann kommt man ganz selbstverständlich zu einem übersinnlichen Elemente.

Es ist im ganzen gerade bei der Betrachtung der Geschichte vielleicht nicht so leicht, vom Übersinnlichen in seinem wahren Charakter zu sprechen, weil viele glauben, wenn sie irgendwelche Gedanken oder Ideen in der Geschichte finden, oder einfach wenn sie geschichtliche Ereignisse notifizieren, dann hätten sie schon etwas Übersinnliches. Wir müssen uns ganz klar sein darüber, daß wir zum Übersinnlichen überhaupt nicht rechnen können, was uns, sei es für die Sinne, sei es für den Verstand, sei es für das Empfindungsvermögen, innerhalb der sinnenfälligen Welt entgegentritt. Daher muß uns alles, was eigentlich im gewöhnlichen Sinne als Geschichte erzählt wird, zum Sinnenfälligen gehören. Man wird natürlich, wenn man so historisch Symptomatologie treibt, die Symptome nicht immer gleichwertig nehmen dürfen, sondern man wird aus der Betrachtung selbst erkennen, daß das eine Symptom von ganz besonderer Wichtigkeit ist, um hinter die Ereignisse auf die Wirklichkeit zu kommen; andere Symptome sind vielleicht ganz bedeutungslos, wenn man den Weg einschlagen will in die wahre übersinnliche Wirklichkeit.

Nun, ich möchte, nachdem ich Ihnen eine größere Anzahl von mehr oder weniger wichtigen Symptomen aus jenem Zeitraume aufgezählt habe, der seit dem Eintritt der Menschheit in die Bewußtseinsseelenkultur verflossen ist, jetzt versuchen, Ihnen nach und nach einiges zu charakterisieren von dem dahinterstehenden Übersinnlichen. Einiges haben wir ja schon charakterisiert. Denn natürlich, ein wesentlicher Grundzug, der im Übersinnlichen pulsiert, ist ja das Eintreten der Menschheit in die Bewußtseinsseelenkultur selbst, das heißt das Aneignen der Organe für die Entwickelung der Bewußtseinsseele. Das ist das Wesentliche. Aber wir haben schon neulich erkannt, daß gewissermaßen der andere Pol, die Ergänzung zu diesem innerlichen Erarbeiten der Bewußtseinsseele, sein muß die Hinneigung zu einer Offenbarung aus der geistig-übersinnlichen Welt heraus. Diese Gesinnung muß die Menschen durchdringen, daß sie fortan nicht werden weiterkommen können, ohne der neuen Art von Offenbarung der übersinnlichen Welt entgegenzugehen.

Diese zwei Pole der Menschheitsentwickelung müssen wir zunächst sehen. Sie sind bis zu einem gewissen Grade schon heraufgekommen in den Jahrhunderten seit 1413, seit die Menschheit in das Bewußtseinszeitalter eingetreten ist. Sie werden sich als zwei mächtige Impulse weiterentwickeln müssen, werden in den verschiedenen Epochen bis ins vierte Jahrtausend die verschiedensten Formen annehmen, werden über die Menschen die mannigfaltigsten Schicksale bringen. Das alles wird sich nach und nach für die einzelnen Menschenseelen eben enthüllen. Aber gerade mit dem Hinblick auf die beiden Impulse werden wir dann belehrt darüber, wie Wesentliches verlaufen ist seit diesem 15. Jahrhundert. Und wir können sagen: Man ist heute schon imstande, darauf aufmerksam zu machen, wie Wesentliches verlaufen ist. Sehen Sie, im 18. Jahrhundert zum Beispiel, auch im Beginne des 19. Jahrhunderts, wäre es noch nicht möglich gewesen, strikte aus äußeren Erscheinungen auf die Wirksamkeit der beiden genannten Impulse hinzudeuten. Sie waren noch nicht lange genug wirksam, um sich intensiv genug zu zeigen. Sie sind nun intensiv genug wirksam gewesen, um sich auch schon in den äußerlichen Erscheinungen zu zeigen.

Eine wesentliche Tatsache, die heute schon signifikant hervortritt, wollen wir zunächst einmal vor unsere Seele hinstellen. Man kann sagen: Wenn frühere Erscheinungen nur für den mehr oder weniger Eingeweihten das sichtbar machten, was ich jetzt meine - die russische Revolution in ihrer letzten Phase, namentlich vom Oktober 1917 bis zu den sogenannten Friedensverhandlungen von Brest-Litowsk, diese ungeheuer interessante Entwickelung, die ja übersichtlich ist, weil sie nur durch wenige Monate läuft, sie hat für denjenigen, der nun wirklich ernsthaftig aus den geschichtlichen Symptomen lernen will — denn auch diese Entwickelung ist selbstverständlich nur ein geschichtliches Symptom -, eine ungeheuer große Bedeutung. Alles das, was da geschehen ist, ist ja zuletzt zusammengeflossen aus den Impulsen, von denen wir als den tieferen Impulsen der neuzeitlichen Entwickelung gesprochen haben. Man kann sagen, es handelt sich gerade bei dieser Revolution um neue Ideen. Denn um neue Ideen kann es sich heute nur handeln, wo man von wirklicher Entwickelung der Menschheit spricht. Alles andere unterliegt, wie wir später noch hören werden und neulich schon andeuteten, gewissermaßen den 'Todessymptomen. Um das Wirksammachen neuer Ideen handelt es sich. Diese neuen Ideen — Sie werden das ja entnehmen können aus den mancherlei Ausführungen, die ich gerade über dieses Thema im Laufe von jetzt schon Jahrzehnten gemacht habe — müssen in die ganze breite Bevölkerung der osteuropäischen Bauernschaft einfließen können. Selbstverständlich hat man es da mit einem seelisch wesentlich passiven Elemente zu tun, aber mit einem Elemente, das aufnahmefähig ist gerade für Modernstes, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil, wie Sie ja wissen, in diesem Volkselemente der Keim liegt zur Entwickelung des Geistselbstes. Während die andere Bevölkerung der Erde im wesentlichen den Impuls zur Entwickelung der Bewußstseinsseele in sich trägt, trägt die breite Masse der russischen Bevölkerung, mit einigen Anhängseln noch, den Keim in sich für die Entwickelung des Geistselbstes im sechsten nachatlantischen Kulturzeitraum. Das bedingt natürlich ganz besondere Verhältnisse. Aber für dasjenige, was wir jetzt betrachten wollen, ist es weiter nichts als eben signifikant.

Nun, nicht wahr, die Idee, die mehr oder weniger richtig, oder mehr oder weniger unrichtig, oder ganz unrichtig, aber als moderne Idee, als Idee von noch nicht Dagewesenem einfließen sollte in diese breite Masse der Bevölkerung, konnte nur kommen von denjenigen, die Gelegenheit haben im Leben, Ideen aufzunehmen, von führenden Klassen.

Nachdem der Zarismus gestürzt war, sah man zuerst aufkommen ein Element, das im wesentlichen zusammenhängt mit einer völlig unfruchtbaren Klasse, mit der Großbourgeoisie — weiter westlich nennt man sieSchwerindustrie und so weiter —, mit einer völlig unfruchtbaren Klasse. Das konnte nur eine Episode sein. Das war ja selbstverständlich, daß das nur eine Episode sein konnte. Von der braucht man eigentlich im Grunde wirklich nicht zu reden, denn dasjenige, was aus dieser Klasse hervorgeht, das hat ja selbstverständlich, möchte ich sagen, keine Ideen, es kann keine haben, als Klasse selbstverständlich. Ich rede nie, wenn ich von diesen Dingen spreche, von den einzelnen menschlichen Persönlichkeiten oder Individuen.

Nun waren, nach links stehend, zunächst diejenigen Elemente, die aufgestiegen waren aus dem Bürgertum, mehr oder weniger vermischt mit arbeitenden Elementen. Es war die führende Bevölkerung der sogenannten Sozialrevolutionäre, zu denen sich auch die Menschewiki nach und nach geschlagen haben. Es sind diejenigen Menschen, die im wesentlichen, rein äußerlich nach ihrer Zahl gerechnet, sehr leicht eine führende Rolle hätten spielen können innerhalb der weiteren Entwickelung der russischen Revolution. Sie wissen, es ist nicht so gekommen. Es sind die radikalen, nach links stehenden Elemente an die Führung gekommen. Und als sie an die Führung gekommen waren, da waren die Sozialrevolutionäre, die Menschewiki und ihre Gesinnungsgenossen im Westen, selbstverständlich davon überzeugt, daß die ganze Herrlichkeit nur acht Tage dauern werde, dann werde alles kaputt gehen. Nun, es dauert jetzt schon länger als acht Tage, und Sie können ganz sicher überzeugt sein, meine lieben Freunde: Wenn manche Propheten schlechte Propheten sind — diejenigen Menschen, die heute historische Vorgänge prophezeien aus den alten Weltanschauungen gewisser Mittelklassen heraus, sind ganz gewiß die schlechtesten Propheten! - Nun, was liegt da eigentlich zugrunde? Physikalisch gesprochen möchte ich sagen: Dieses Problem der russischen Revolution vom Oktober, durch die nächsten Monate hindurch und bis heute, ist kein Druckproblem, physikalisch gesprochen, sondern ein Saugproblem. Und das ist wichtig, daß man das wirklich den historischen Symptomen entnehmen kann, daß es sich nicht um ein Druckproblem, sondern um ein Saugproblem handelt. Was meint man mit einem Saugproblem? Sie wissen ja (es wird gezeichnet), wenn man hier den Rezipienten einer Luftpumpe hat, die Luft herausgesaugt und im Rezipienten einen luftleeren Raum geschaffen hat und öffnet den Stöpsel, so strömt pfeifend die Luft ein. Sie strömt ein, nicht weil die Luft dort hineinwill durch sich selber, sondern weil ein leerer Raum geschaffen ist. In diesen luftleeren Raum strömt die Luft ein. Sie pfeift hinein, wo ein luftleerer Raum ist.

So war es auch mit Bezug auf diejenigen Elemente, die gewissermaßen in der Mitte standen zwischen der Bauernschaft und den Sozialrevolutionären, den Menschewiki, und eben den weiter nach links stehenden, den radikalen Elementen, den Bolschewiki. Was ist denn eigentlich da geschehen? Nun, was geschehen ist, war das, daß die sozialrevolutionären Menschewiki absolut ideenlos waren. Sie waren in der überwiegenden Mehrzahl, aber sie waren absolut ideenlos; sie hatten gar nichts zu sagen, was geschehen soll mit der Menschheit gegen die Zukunft hin. Sie hatten zwar allerlei ethische und sonstige Sentimentalitäten im Kopfe, aber mit ethischen Sentimentalitäten, wie ich Ihnen öfter auseinandergesetzt habe, kann man nicht die wirklichen Impulse, welche die Menschheit weiter treiben können, finden. So ist ein luftleerer Raum, das heißt ideenleerer Raum entstanden, und da pfiff selbstverständlich dasjenige, was weiter nach links radikal steht, hinein. Man darf nicht glauben, daß es gewissermaßen durch ihr eigenes Wesen den radikalsten sozialistischen Elementen in Rußland, die wenig mit Rußland selbst zu tun haben, vorgezeichnet war, da besonders Fuß zu fassen. Sie hätten es nie gekonnt, wenn die Sozialrevolutionäre und andere mit ihnen Verbundene - es gibt ja die verschiedensten Gruppen — irgendwelche Ideen gehabt hätten, um Führende zu werden. Allerdings können Sie fragen: Welche Ideen hätten sie denn haben sollen? — Und da kann nur derjenige eine fruchtbringende Antwort heute finden, der nicht mehr erschrickt und auch nicht mehr feige wird, wenn man ihm sagt: Es gibt für diese Schichten keine anderen fruchtbaren Ideen als diejenigen, welche aus den geisteswissenschaftlichen Ergebnissen kommen. Es gibt keine andere Hilfe.

Aber das Wesentliche ist schließlich — gewiß, die Leute sind mehr oder weniger radikal geworden und werden es heute verleugnen, daß sie aus dem alten Bürgertum hervorgegangen sind, viele wenigstens, aber sie sind es doch -, das Wesentlichste ist, daß diejenige Schichte der Bevölkerung, aus welcher diese Leute, die den Raum luftleer, das heißt ideenleer gemacht haben, bis jetzt, im Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseelenentwickelung, eben absolut nicht dazu zu bringen war, irgendwelche Ideen zu haben. Dies ist nun natürlich nicht bloß in Rußland der Fall, sondern diese russische Revolution in einer letzten, vorläufig letzten Phase kann es eben nur für den, der die Sache studieren will, mit ganz besonderer Deutlichkeit zeigen: Sie sehen Tag für 'Tag, wie diese Leute, die den Raum luftleer machen, zurückgedrängt werden, und wie die anderen hineinpfeifen, das heißt, sich an ihre Stelle setzen. Aber diese Erscheinung, sie ist heute über die ganze Welt verbreitet. Sie ist durchaus über die ganze Welt heute verbreitet. Denn das ist das Wesentliche, daß diejenige Schichte der Bevölkerung, die gewissermaßen heute zwischen rechts und links steht, sich seit langer Zeit ablehnend verhalten hat, wenn es sich darum handelte, eine fruchtbare Weltanschauung irgendwie anzustreben. Eine fruchtbare Weltanschauung kann in unserem Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseelenentwickelung nicht anders sein als eine solche, die auch Impulse gibt für das Zusammenleben der Menschen.

Ja, das war es, was von allem Anfange an unsere geisteswissenschaftliche Bewegung durchpulste: nicht sollte sie nur irgendeine sektiererische Bewegung sein, sondern angestrebt wurde, daß sie wirklich mit dem Impulse unserer Zeit, mit all dem, was der Menschheit in unserer Zeit nach allen Richtungen hin wichtig und wesentlich ist, rechnet. Das wurde immer mehr angestrebt. Das ist allerdings dasjenige, was man heute am schwersten den Menschen zum Verständnis bringen kann, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil ja doch immer wieder und wiederum selbstverständlich nicht bei allen, sondern bei vielen — die Gesinnung durchschlägt, daß sie auch in dem, was sie Anthroposophie nennen, doch nichts anderes haben wollen als so ein bißchen bessere Sonntagnachmittagspredigt für dasjenige, was man so zu seiner privat-persönlichen Erbauung braucht, was man aber fernhält von all den ernsthaften Angelegenheiten, die man abmacht im Parlament, im Bundesrat oder in der oder jener Körperschaft, oder auch nur am Biertisch. Daß wirklich alles Leben durchdrungen werden muß mit Ideen, die nur aus dem Geisteswissenschaftlichen heraus geholt werden können, das ist es, was eben eingesehen werden muß.

Der Interesselosigkeit dieser Schichte der Bevölkerung stand und steht auch noch heute das rege Interesse des Proletariats entgegen. Dieses Proletariat hat natürlich, einfach durch die geschichtliche Entwickelung der neueren Zeit, nicht die Möglichkeit, über das bloß Sinnenfällige hinauszudringen. So kennt es nur sinnenfällige Impulse und will nur sinnenfällige Impulse in die Menschheitsentwickelung einführen. Aber während dasjenige, was die bürgerliche Bevölkerung, wenn wir so sagen dürfen, oftmals ihre Weltanschauung nennt, nur Worte, Phrasen oftmals sind — meistens sind, weil sie eigentlich nicht gehegt sind vom unmittelbaren Leben der Gegenwart, sondern weil sie heraufgebracht, überkommen sind aus älteren Zeiten, während die bürgerliche Bevölkerung in der Phrase lebt, lebt das Proletariat, weil es in einem wirklich neuen wirtschaftlichen Impuls drinnensteht, in Realitäten, aber nur in Realitäten sinnenfälliger Natur.

Hier haben wir einen bedeutsamen Angelpunkt. Sehen Sie, das Leben der Menschheit hat sich schon seit wenigen Jahrhunderten ganz wesentlich geändert. Seit wenigen Jahrhunderten sind wir innerhalb dieses Zeitalters der Bewußtseinsseele ins Maschinenzeitalter eingetreten. Die bürgerliche Bevölkerung und was über ihr ist wurde wenig berührt in ihren Lebensverhältnissen von diesem Eintritt ins Maschinenzeitalter. Denn was die bürgerliche Bevölkerung an besonders großen neuen Impulsen in der letzten Zeit aufgenommen hat, das liegt ja schon vor dem eigentlichen Maschinenzeitalter — Einführung des Kaffees und so weiter für den Kaffeeklatsch -, und dasjenige, was die bürgerliche Bevölkerung an neuen Bankusancen und dergleichen gebracht hat, das ist so wenig angemessen den neuzeitlichen Impulsen wie nur irgend denkbar. Es ist eigentlich nichts anderes als eine Komplikation der ururältesten Usancen, die man im kaufmännischen Leben gehabt hat.

Diejenige Kaste oder Klasse der Menschen dagegen, die wirklich von einem neuzeitlichen Impulse äußerlich im sinnenfälligen Leben unmittelbar ergriffen ist, die gewissermaßen durch die neuzeitlichen Impulse selber erst geschaffen ist, das ist das neuzeitliche Proletariat. Seit der Erfindung der Spinnmaschine und des mechanischen Webstuhls im 18. Jahrhundert ist die gesamte Volkswirtschaft der Menschheit umgewandelt, und es ist im wesentlichen erst durch diese Impulse des mechanischen Webstuhls und der Spinnmaschine das moderne Proletariat entstanden. Das ist also ein Geschöpf der neuen Zeit, und das ist das Wesentliche. Der Bürger ist kein Geschöpf der neuen Zeit, aber der Proletarier ist ein Geschöpf der neuen Zeit. Denn dasjenige, was früher vorhanden war und verglichen werden konnte mit dem Proletariat der neuen Zeit, es war nicht ein Proletariat, es war irgendein Mitglied der alten patriarchalischen Ordnung, und die ist grundverschieden von dem, was die Ordnung im Maschinenzeitalter ist. Aber damit war der Proletarier eben auch hineingestellt in dasjenige, was ganz von der lebendigen Natur herausgerissen ist: in das rein Mechanische. Er war ganz auf das sinnenfällige Tun gestellt, aber er durstete nach einer Weltanschauung, und er versuchte die ganze Welt sich so zu konstruieren, wie das konstruiert war, in dem er mit seinem Leib und mit seiner Seele drinnenstand. Denn die Menschen sehen schließlich im Weltengebäude dasjenige zuerst, in dem sie selber drinnenstehen. Nicht wahr, der Theologe und das Militär, sie gehören zusammen, wie ich Ihnen neulich angedeutet habe. Der Theologe und das Militär, sie sehen in vieler Beziehung im Weltengebäude Kampf, Kampf der guten und der bösen Mächte und so weiter, ohne weiter auf die Dinge einzugehen. Der Jurist und der Beamte — sie gehören wieder zusammen — und der Metaphysiker, sie sehen im Weltengebäude eine Realisierung abstrakter Ideen. Und kein Wunder, der moderne Proletarier sieht im Weltengebäude eine große Maschine, in die er selbst hineingestellt ist. Und so will er auch die soziale Ordnung gestalten als eine große Maschine.

Aber es war doch eben ein gewaltiger Unterschied und ist heute noch ein gewaltiger Unterschied zum Beispiel zwischen dem modernen Proletarier und dem modernen Bürger, dem modernen BourgeoisLeben. Von dem versinkenden Stande braucht man ja nicht zu reden. Es ist doch ein beträchtlicher Unterschied, daß der moderne Bourgeois eben gar kein Interesse an irgendwelchen tiefergehenden Weltanschauungsfragen hat, während der Proletarier ein brennendes Interesse für Weltanschauungsfragen hat. Nicht wahr, der moderne Bourgeois diskutiert allerdings in zahlreichen Versammlungen, diskutiert mit Worten zumeist. Der Proletarier diskutiert über dasjenige, in dem er lebendig drinnensteht, über dasjenige, was täglich die Maschinenkultur erzeugt. Man hat sogleich, wenn man heute aus einer bürgerlichen Versammlung in eine proletarische Versammlung geht, folgendes Gefühl: In der bürgerlichen Versammlung, da wird diskutiert, wie schön es wäre, wenn die Menschen Frieden hielten, wenn sie alle Pazifisten wären zum Beispiel, oder wie schön irgend etwas anderes wäre. Aber das alles ist Dialektik von Worten zumeist, allerdings mit etwas Sentimentalität durchspickt, aber nicht ergriffen von dem Impuls, wirklich ins Weltengebäude hineinzuschauen, dasjenige, was man will, aus den Geheimnissen des Weltengebäudes heraus zu realisieren. Gehen Sie dann in die proletarische Versammlung, so merken Sie: Die Leute reden von Wirklichkeiten, wenn das auch die Wirklichkeiten des physischen Planes sind. Die Leute kennen Geschichte, das heißt, ihre Geschichte; sie kennen genau die Geschichte, an den Fingern können sie es herzählen, von der Erfindung des mechanischen Webstuhles und der Spinnmaschine an. Das wird jedem eingebläut, was da angefangen hat, was sich da entwickelt hat, wie das Proletariat zu dem geworden ist, was es heute ist. Wie das geworden ist, das weiß jeder am Schnürchen, der nur einigermaßen nicht stumpfsinnig ist, sondern teilnimmt am Leben — und das sind ja nur wenige, es ist wenig Stumpfsinn eigentlich gerade in dieser Klasse von Bevölkerung.

Man könnte viele, viele charakteristische Momente aufzählen für die Stumpfheit gegenüber Weltanschauungsfragen bei der heutigen Mittelschichtsbevölkerung. Man braucht sich nur daran zu erinnern, wie sich die Leute verhalten, wenn einmal ein Dichter — derjenige, der nicht ein Dichter ist, darf es schon gar nicht tun, denn dann wird er ein Phantast genannt oder dergleichen —, wenn irgendein Dichter Gestalten aus der übersinnlichen Welt meinetwegen auf die Bühne bringt oder sonstwo hinbringt. Da lassen es sich die Leute so halb und halb gefallen, weil sie nicht daran zu glauben brauchen, weil sie kein Hauch der Wirklichkeit anweht, weil sie sich sagen können: Es ist bloß Dichtung! — Dieses ist so geworden im Lauf der Entwickelung des Bewußtseinsseelenzeitalters. So ist es, möchte ich sagen, die Sache räumlich betrachtet, daß sich herausgebildet hat eine Menschenklasse, die, wenn sie sich nicht besinnt, Gefahr läuft, immer mehr und mehr vollständig in die Phrase hineinzulaufen. Aber man kann dieselbe Sache auch zeitlich betrachten, und auf gewisse wichtige Zeitpunkte habe ich ja wiederholt hingewiesen von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten aus.

Sehen Sie, von diesem Zeitraum des Bewußtseinszeitalters, der 1413 approximativ begonnen hat, war in den vierziger Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts, ungefähr um das Jahr 1840 oder 45 herum, das erste Fünftel abgelaufen. Das war ein wichtiger Zeitpunkt, diese vierziger Jahre, denn in diesem Zeitpunkte war gewissermaßen vorgesehen durch die die Weltenentwickelung impulsierenden Mächte eine Art von bedeutsamer Krisis. Außen, im äußeren Leben, kam diese Krisis im wesentlichen dadurch zum Vorschein, daß die sogenannten liberalen Ideen der Neuzeit gerade in diesen Jahren ihre Blüte entwickelten. In den vierziger Jahren hatte es den Anschein, als ob auch in die äußere politische Welt der zivilisierten Menschheit der Impuls des Bewußtseinszeitalters in Form von politischen Anschauungen hineinstürmen könnte. Zwei Dinge fielen zusammen in diesen vierziger Jahren. Das Proletariat war noch nicht vollständig seiner historischen Grundlage entbunden, es existierte noch nicht mit vollem Selbstbewußtsein. Das Proletariat war erst in den sechziger Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts reif, bewußt einzutreten in die geschichtliche Entwickelung. Was vorher lag, ist nicht im modernen Sinne des Wortes proletarisches Bewußtsein. Die soziale Frage war natürlich früher da. Aber nicht einmal, daß die soziale Frage da ist, haben die Leute der Mittelschichte bemerkt. Ein österreichischer Minister, der eine große Berühmtheit erlangt hat, hat ja den berühmten Ausspruch noch Ende der sechziger Jahre getan: Die soziale Frage hört bei Bodenbach auf. -— Bodenbach liegt, wie Sie vielleicht wissen, an der Grenze zwischen Sachsen und Böhmen. Das ist ein berühmter Ausspruch eines bürgerlichen Ministers!

Das proletarische Bewußtsein war also in den vierziger Jahren noch nicht da. Träger der politischen Zivilisation der damaligen Zeit war im wesentlichen das Bürgertum, war im wesentlichen die Mittelschichte, von der ich eben gesprochen habe. Nun war das Eigentümliche der Ideen, die dazumal in den vierziger Jahren hätten politisch werden können, ihre ganz intensive Abstraktheit. Sie alle kennen ja, ich hoffe, wenigstens bis zu einem gewissen Grade, was alles an - man nennt es revolutionären Ideen, aber es war wirklich nur liberal —, was dazumal in den vierziger Jahren an liberalen Ideen in die Menschheit eingeströmt ist und sich 1848 entladen hat. Sie kennen das und wissen ja wohl auch, daß Träger dieser Ideen das Bürgertum war, das ich Ihnen eben charakterisiert habe. Aber alle diese Ideen, die dazumal lebten, die so eindringen wollten in die geschichtliche Entwickelung der Menschheit, waren restlos intensiv abstrakte Ideen. Sie waren die allerabstraktesten Ideen, manchmal bloße Worthülsen. Aber das schadete nichts, denn im Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele mußte man durch die Abstraktheit durch. Man mußte die leitenden Ideen der Menschheit einmal in dieser Abstraktheit fassen.

Nun, der einzelne Mensch lernt nicht an einem Tag schreiben, nicht an einem Tag lesen, das wissen Sie, nicht wahr, von sich und anderen. Die Menschheit braucht auch eine gewisse Zeit, wenn sie mit irgend etwas eine Entwickelung durchmachen soll, sie braucht immer eine gewisse Zeit. Es war — wir werden auf diese Dinge noch genauer eingehen — der Menschheit Zeit gelassen bis zum Ende der siebziger Jahre. Wenn Sie 1845 nehmen, 33 Jahre dazurechnen, dann bekommen Sie 1878; da erreichen sie ungefähr dasjenige Jahr, bis zu welchem der Menschheit Zeit gelassen war, sich hineinzufinden in die Realität der Ideen der vierziger Jahre. Das ist in der historischen Entwickelung der neuzeitlichen Menschheit etwas außerordentlich Wichtiges, daß man diese Jahrzehnte ins Auge zu fassen vermag, die da liegen zwischen den vierziger und den siebziger Jahren. Denn über diese Jahrzehnte muß sich der heutige Mensch völlig klarwerden. Er muß sich klarwerden darüber, daß in diesen Jahrzehnten, in den vierziger Jahren, begonnen hat, in abstrakter Form in die Menschenentwickelung einzufließen das, was man liberale Ideen nennt, und daß der Menschheit Zeit gelassen war bis zum Ende der siebziger Jahre, um diese Ideen zu begreifen, diese Ideen an die Wirklichkeiten anzuhängen.

Träger dieser Ideen war das Bourgeoistum. Aber das hat den Anschluß versäumt. Es liegt etwas ungeheuer Tragisches über der Entwickelung dieses 19, Jahrhunderts. Es ist wirklich für denjenigen, der in den vierziger Jahren manchen hervorragenden Menschen — über die ganze zivilisierte Welt waren solche ausgebreitet — aus dem Bürgerstande reden hörte über das, was der Menschheit gebracht werden sollte auf allen Gebieten, in diesen vierziger, noch Anfang der fünfziger Jahre manchmal etwas wie von einem kommenden Völkerfrühling. Aber aus den Eigenschaften heraus, die ich Ihnen charakterisiert habe für die Mittelschichte, wurde der Anschluß versäumt. Als die siebziger Jahre zu Ende gingen, hatte der Bürgerstand die liberalen Ideen nicht begriffen. Es wurde von dieser Klasse, von den vierziger bis in die siebziger Jahre, dieses Zeitalter verschlafen. Und die Folge davon ist etwas, auf das man schon hinschauen muß. Denn die Dinge müssen sich ja in auf- und absteigenden Wellen bewegen, und eine gedeihliche Entwickelung der Menschheit in die Zukunft kann nur stattfinden, wenn man rückhaltlos auf dasjenige sieht, was sich da in der Jüngsten Vergangenheit abgespielt hat. Man kann nur aufwachen im Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele, wenn man weiß, daß man vorher geschlafen hat. Wenn man nicht weiß, wann und wie lange und daß man geschlafen hat, so wird man eben nicht aufwachen, sondern wird weiterschlafen.

Als das Bürgertum beim Erscheinen des Erzengels Michael als Zeitgeist Ende der siebziger Jahre nicht begriffen hatte den Impuls der liberalen Ideen auf politischem Gebiete, da zeigte es sich, daß jene Mächte, die ich ja auch charakterisiert habe, die mit diesem Zeitraume in die Menschheit sich hineinmischten, zunächst Finsternis verbreiteten über diese Ideen. Und das können Sie wiederum sehr deutlich studieren, wenn Sie nur wirklich wollen. Wie anders haben sich die Menschen die Gestaltung des politischen Lebens in den vierziger Jahren gedacht, als es am Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts über die ganze zivilisierte Welt gekommen ist! Es gibt keinen größeren Gegensatz als die allerdings abstrakten, aber in ihrer Abstraktheit lichtvollen Ideen der Jahre von 1840 bis 1848, und das, was man im 19. Jahrhundert auf den verschiedensten Gebieten der Erde «hohe Menschheitsideale» genannt hat, was man hohe Menschheitsideale genannt hat noch bis in unsere Tage herein, bis alles in die Katastrophe hineingerutscht ist von diesen hohen Menschheitsidealen.

Also das ist es, was man als zeitliche Ergänzung zu dem Räumlichen hinzufügen muß, daß von den vierziger Jahren bis zu Ende der siebziger Jahre in den produktivsten und fruchtbarsten Zeiträumen für die bürgerliche Bevölkerung eine Art Schlafzustand vorhanden war. Nachher war es gewissermaßen zu spät. Denn nachher ist nichts mehr zu erreichen auf demjenigen Wege, auf dem das in dem genannten Zeitraume erreichbar gewesen wäre. Nachher ist nur durch völliges Erwachen im geisteswissenschaftlichen Erleben etwas zu erreichen. So hängen die Dinge historisch in der neueren Geschichte zusammen.

In diesem Zeitraume, von den vierziger bis in die siebziger Jahre, da waren die Ideen, wenn auch abstrakt, in einer ganz bestimmten Weise so geartet, daß sie hintendierten nach dem aktiven Geltenlassen des einen Menschen neben dem anderen. Und wäre - als Hypothese sei das angenommen - dasjenige, was in diesen Ideen lag, zur Verwirklichung gekommen, dann würde man schon sehen, daß der Anfang - es wäre ja auch nur der Anfang, aber es wäre eben damit ein Anfang da zu diesem toleranten, aktiven toleranten Geltenlassen des einen Menschen neben dem anderen, was der heutigen Zeit insbesondere mit Bezug auf die Ideen und Empfindungen ganz und gar fehlt. Und so muß gerade im sozialen Leben aus dem Spirituellen heraus eine viel tiefer greifende, eine viel intensivere Idee den Menschen eigen werden. Ich will zunächst, ich möchte sagen, rein äußerlich historisch, zukunftshistorisch diese Idee vor Sie hinstellen, um sie Ihnen dann weiter zu begründen.

Dasjenige, was der Menschheit einzig und allein Heil bringen kann gegen die Zukunft hin — ich meine der Menschheit, also dem sozialen Zusammenleben -, muß sein ein ehrliches Interesse des einen Menschen an dem anderen. Dasjenige, was dem Bewußtseinszeitalter besonders eigen ist, ist Absonderung des einen Menschen vom andern. Das bedingt ja die Individualität, das bedingt die Persönlichkeit, daß sich auch innerlich ein Mensch von dem andern absondert. Aber diese Absonderung muß einen Gegenpol haben, und dieser Gegenpol muß in dem Heranzüchten eines regen Interesses von Mensch zu Mensch bestehen.

Dieses, was ich jetzt meine als Hinzufügung eines regen Interesses von Mensch zu Mensch, das muß immer bewußter und bewußter im Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele an die Hand genommen werden. Alles Eigen-Interesse von Mensch zu Mensch muß immer mehr und mehr ins Bewußtsein heraufgehoben werden. Sie finden unter den, ich möchte sagen, elementarsten Impulsen, die angegeben werden in meinem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?», den Impuls verzeichnet, der, wenn er für das soziale Leben praktisch wird, gerade nach Erhöhung des Interesses für den Menschen hinzielt. Sie finden ja überall angegeben die sogenannte Positivität, die Entwickelung einer Gesinnung der Positivität. Die meisten Menschen der Gegenwart werden geradezu mit ihrer Seele umkehren müssen von ihren Wegen, wenn sie diese Positivität entwickeln wollen, denn die meisten Menschen der Gegenwart haben heute noch nicht einmal einen Begriff von dieser Positivität. Sie stehen von Mensch zu Mensch so, daß sie, wenn sie an dem anderen Menschen etwas bemerken, das ihnen nur nicht paßt — ich will gar nicht sagen, das sie tiefer betrachten, sondern das ihnen von obenher betrachtet, ganz äußerlich betrachtet, nicht paßt -, so fangen sie an abzuurteilen, aber ohne Interesse dafür zu entwickeln, abzuurteilen. Es ist im höchsten Grade antisozial — vielleicht klingt es paradox, aber richtig ist es doch - für die zukünftige Menschheitsentwickelung, solche Eigenschaften an sich zu haben, in unmittelbarer Sympathie und Antipathie an den anderen Menschen heranzugehen. Dagegen wird es die schönste, bedeutendste soziale Eigenschaft für die Zukunftsentwickelung sein, wenn man gerade ein naturwissenschaftliches, objektives Interesse für Fehler anderer Menschen entwickelt, wenn einen die Fehler anderer Menschen viel mehr interessieren, als daß man sie versucht zu kritisieren. Denn nach und nach, in diesen drei letzten Epochen, die noch folgen, der fünften, sechsten und siebenten Kulturepoche, da wird sich der eine Mensch ganz besonders immer mehr und mehr mit den Fehlern des andern Menschen liebevoll zu befassen haben. Im griechischen Zeitalter stand über dem berühmten Apollotempel das «Erkenne dich selbst». Das war dazumal im eminentesten Sinne noch zu erreichen, die Selbsterkenntnis, durch Hineinbrüten in die eigene Seele. Das wird immer unmöglicher und unmöglicher. Man lernt sich heute kaum noch irgendwie erheblich kennen durch das Hineinbrüten in sich selbst. Weil die Menschen nur in sich selbst hineinbrüten, deshalb kennen sie sich im Grunde genommen so wenig, und weil sie so wenig hinschauen auf andere Menschen, namentlich auf das, was sie Fehler der anderen Menschen nennen.

Eine rein naturwissenschaftliche Tatsache kann uns aufmerksam machen, ich möchte sagen, beweisend aufmerksam machen, daß diese Sache so ist. Sehen Sie, der Naturforscher tut heute zweierlei - ich habe das vielleicht schon erwähnt, aber es ist außerordentlich wichtig -, wenn er auf die Geheimnisse der menschlichen, der tierischen, der pflanzlichen Natur kommen will. Das erste ist, er experimentiert, so wie er in der unorganischen, in der leblosen Natur experimentiert, so auch in der organischen Natur. Nun, durch das Experiment entfernt man sich von der lebendigen Natur, und derjenige, der mit wahrem Erkenntnissinn verfolgen kann, was das Experiment der Welt gibt, der weiß, daß es den Tod allein gibt. Das Experiment gibt nur den Tod, und dasjenige, was einem die heutige Wissenschaft aus der Experimentierkunst, selbst aus einer so feinen Experimentierkunst bieten kann, wie sie zum Beispiel Oscar Hertwig entwickelt, das ist nur der Tod der Sache. Sie können durch das Experimentieren nicht erklären, wie irgendein Lebewesen empfangen und geboren wird, sondern Sie können nur den Tod erklären durch das Experimentieren, und so werden Sie nie etwas erfahren über die Geheimnisse des Lebens durch Experimentierkunst. Das ist die eine Seite.

Aber es gibt heute etwas, was allerdings mit sehr unzulänglichen Mitteln arbeitet, was erst ganz, ganz im Anfange ist, was aber geeignet ist, sehr große Aufschlüsse über die menschliche Natur zu geben: das ist die Betrachtung des pathologischen Menschen. Die Betrachtung eines nach irgendeiner Richtung hin nicht ganz, wie man im Philiströsen sagt, normalen Menschen, die bringt in uns das Gefühl hervor: Mit diesem Menschen kannst du eins werden, in diesen Menschen kannst du dich erkennend vertiefen; du kommst weiter, wenn du dich in ihn vertiefst. — Also durch das Experimentieren wird man von der Wirklichkeit weggetrieben; durch das Betrachten desjenigen, was man heute pathologisch nennt, was Goethe so schön die Mißbildungen nannte, wird man gerade hingebracht in die Wirklichkeit. Aber man muß sich einen Sinn aneignen für diese Betrachtung. Man darf nicht abgestoßen werden von solcher Betrachtung. Man muß wirklich sich sagen: Gerade das Tragische kann zuweilen, ohne daß man es je wünschen darf, unendlich aufklärend sein für die tiefsten Geheimnisse des Lebens. -— Was das Gehirn bedeutet für das Seelenleben, wird man nur dadurch erfahren, daß man immer mehr und mehr bekannt werden wird mit kranken Gehirnen. Das ist die Schule des Interesses für den anderen Menschen. Ich möchte sagen: Es kommt die Welt mit den groben Mitteln des Krankseins, um unser Interesse zu fesseln. Aber das Interesse am anderen Menschen ist es überhaupt, was die Menschheit sozial vorwärts bringen kann in der nächsten Zeit, während die Menschheit sozial zurückgebracht wird durch das Gegenteil der Positivität, durch das von obenherein Enthusiasmiert- oder Abgestoßensein von dem anderen Menschen. Diese Dinge hängen aber alle mit dem ganzen Geheimnis des Bewußtseinszeitalters zusammen.

In jedem solchen Zeitalter wird historisch innerhalb der Menschheit, ich möchte sagen, etwas ganz Bestimmtes entwickelt, und was da entwickelt wird, das spielt dann in der wahren geschichtlichen Entwickelung eine große Rolle. Erinnern Sie sich an die Worte, die ich am Ende der letzten Betrachtungsstunde hier ausgesprochen habe. Ich sagte: Die Menschen müssen sich entschließen, immer mehr und mehr auch in der äußeren geschichtlichen Wirklichkeit Geburt und Tod sehen zu können, — Geburt durch die Befruchtung mit der neuen geistigen Offenbarung, Tod durch alles dasjenige, was man schafft. Tod durch alles dasjenige, was man schafft! Denn das ist das Wesentliche im Bewußtseinszeitalter, daß man auf dem physischen Plane nicht anders schaffen kann als mit dem Bewußtsein: Was man schafft, geht zugrunde. Der Tod ist beigemischt demjenigen, was man schafft. Gerade die wichtigsten Dinge der neueren Zeit in bezug auf den physischen Plan sind todbringende Institutionen. Und der Fehler liegt nicht darinnen, daß man das Todbringende schafft, sondern daß man sich nicht zum Bewußstsein bringen will, daß es todbringend ist.

Heute noch, nach dem ersten Fünftel des Bewußtseinszeitalters, da sagen die Menschen, der Mensch wird geboren und stirbt; und nicht wahr, sie vermeiden es, weil sie es als unsinnig ansehen, zu sagen: Ja, wozu wird der Mensch geboren, wenn er nun doch stirbt? Es ist ja ganz unsinnig, wenn er geboren wird! Man braucht ihn ja nicht zu gebären, da man doch weiß, daß er stirbt! - Nun, das sagen die Menschen nicht, nicht wahr, weil sie auf diesem Gebiete der äußeren Natur unter dem Zwang der belehrenden Natur Geburt und Tod gelten lassen. Auf dem Gebiete des geschichtlichen Lebens sind die Menschen noch nicht so sehr weit, auch da Geburt und Tod gelten zu lassen, sondern da soll alles, was geboren ist, absolut gut sein und fortbestehen können in alle Ewigkeit. Der Sinn muß sich im Bewußtseinszeitalter ausbilden, daß im äußeren historischen Geschehen Geburt und Tod lebt, und daß, wenn man irgend etwas gebiert, sei es ein Kinderspielzeug oder sei es ein Weltreich, man es gebiert mit dem Bewußtsein, daß es auch einmal tot werden muß. Und wenn man es nicht mit dem Bewußtsein gebiert, daß es einmal tot werden muß, so macht man etwas Unsinniges; man macht dasselbe, als was man machen würde, wenn man glaubt, man würde einen kleinen Sprößling gebären können, der auf eine irdische Ewigkeit Anspruch hätte.

Dies muß aber in den Inhalt der menschlichen Seele hineinziehen im Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele. Im griechisch-lateinischen Zeitraum brauchte man das noch nicht in der Seele zu haben, denn da machte sich das geschichtliche Leben von selbst in Geburt und Tod. Es entstanden die Dinge und sie vergingen von selbst. Im Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele muß der Mensch es sein, der Geburt und Tod hineinwebt in sein soziales Leben. Das ist es, was hineinverwoben werden muß in das soziale Leben: Geburt und Tod. Und der Mensch kann in diesem Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele den Sinn dafür erwerben, Geburt und Tod ins soziale Wesen hineinzuweben, aus dem Grunde, weil unter ganz bestimmten Verhältnissen in der griechisch-lateinischen Kulturepoche dieses in seine menschliche Wesenheit hineinversetzt worden ist.