Cosmogony, Freedom, Altruism

GA 191

11 October 1919, Dornach

II. A Different Way of Thinking is Needed to Rescue European Civilization

The hour is so late, that I shall make this lecture a short one, and leave over till tomorrow the main substance of what I have to say in these three lectures. Tomorrow the Eurythmies are put earlier, so that it will be possible to have a longer lecture.

I pointed out yesterday that in order to master the conditions of our present declining civilisation, one needs to differentiate,—so to differentiate between the various groups of peoples massed together over the face of the earth, that one's attention is actually directed to what is living and working in each of the separate groups, in particular among the Anglo-American peoples, among the peoples of what is properly Europe, and among the peoples of the East. And we have seen that the aptitude for founding a cosmogony suited to the new age is to be found pre-eminently among the Anglo- American peoples,—the faculty for developing the idea of freedom, amongst the peoples of Europe, whilst that for developing the impulse of altruism, the religious impulse with all that it connotes by way of human brotherhood, is to be found amongst the population of the East. There is no other way in which a new civilisation can be founded than by making it possible hereafter for man, all the world over, to work together in real co-operation. But, my dear friends, in order that this may be possible, in order that any such real co-operation may be possible, several things are necessary. It Is necessary to recognise, dispassionately and as a matter of fact, how much our present civilisation lacks, and how strong the forces of decline in this present civilisation are. When one considers the forces present in our civilisation, one cannot say: “It is altogether bad;” that is not the way to look at it; in the first place, it would be an unhistoric point of view; in the second place, it could lead to nothing positive. The impulses that reside in our civilisation were, in some age, and in some place, justified. But everything that in the historic course of mankind's evolution leads to ruin, leads to ruin for the very reason that something which has a rightful title in one age and one place has been passed on to another age and another place, and because men, from various Ahrimanic and Luciferic motives, cling to whatever they have grown accustomed to, and are not ready to join in with that actual forward movement which the whole cosmic order requires.

Our age prides itself on being a scientific one. And, at bottom, it is from this, its scientific character, that the great social errors and perversions of the age proceed. That is why it is so imperative that the light should shine in upon our whole life of thought and action, inasmuch as the activities of modern times are entirely dependent on the modern system of thought. We noticed yesterday, in the general survey into which we were led, how the collective civilisation of the earth was made up of a scientific civilisation, a political civilisation tending towards freedom, and of an altruistic economic civilisation that really is derived from the altruistic religious element.

People nowadays,—as I said before, yesterday,—when they consider the forces actually at work in our social structure, remain on the surface of things; they are not willing to penetrate deeper. The lectures in our class-rooms teach what professes to pass for economic wisdom, drawn from the natural science methods of the present day; but what lives in men, and what stirs the minds and the being of men,—that is regarded as a sort of unappetising stew. No attention is paid to what are really its true features.

Let us turn first to the civilisation of Europe. What is the pre-eminent trait of this European civilisation? If one follows up this trait of European civilisation, one finds that one has to go a long way back in order to understand it. One has to form a clear idea of how, out of the ancient primal impulses of the original Celtic population, which still really lies at the base of our European life and being, there gradually grew up, by admixture with the various later strata of peoples, our present European population, with all its religious, political, economic and scientific tendencies. In Europe, in contradistinction to America on the West and Asia on the East,—in Europe a certain intellectual strain was always predominant. Romanism—all that I Indicated yesterday as the specifically Roman element—could never have so got the upper hand, unless intellectualism had been a radical feature of European civilisation. Now there are two things peculiar to intellectualism. In the first place, it never can rouse Itself to make a clean sweep of the religious impulses within it. Religious impulses always acquire an abstract character under the influence of intellectualism. Nor can intellectualism ever really find the energy for grappling with questions of practical economics. The experiments now being carried out in Russia will hereafter show how incapable European intellectualism is of introducing order into the world of economics, of industry. What Leninism is shaping is nothing hut unadulterated intellectualism. It is all reasoned out; an order of society built up by thought alone. And they are attempting the experiment of propping up this brain spun communal system upon the actual conditions prevailing amongst men. Time will show—and very terribly—how impossible it is to prop up a piece of intellectual reasoning upon a human social edifice.

But these things are what people to-day refuse as yet to recognise in all their full force. There is unquestionably among the population of Europe this alarming trait, this sleepiness, this inability to throw the whole man into the stream so needed to permeate the social life of Europe. But the thing that above all others must be recognised is the source from which our European civilisation is fed,—whence this European civilisation is, at bottom, derived. Of itself, of its own proper nature, European civilisation has only produced a form of culture that is intellectual, a thought-culture. Prosaicness and aridity of thought dominate our science and our social institutions.

For many, many years, we have suffered from this intellectualism in the parliaments of Europe. If people could but feel how the parliaments of Europe have been pervaded by the intellectualist, utilitarian attitude, by this element that can never soar above the ground, that lacks the energy for any religious impulse, that lacks the energy for any sort of economic impulse! As for our religious life, just think how we came by it. The whole history of the introduction and spread of this religious life in Europe goes to show that Europe, within herself, had no religious impulses. Just think, how flat and dull the world was, how interminably flat and dull—prosaic to the excess at the time of the expansion of the Roman Empire. Yet that was only the beginning of it. Just conceive what Europe would have become if Roman civilisation in all its flat prosaicness had gone on without the impulse that came over from the Asiatic East, and which was religious, Christian,—what it would have been without the Christian impulse, which sprang from the p lap of the East, which could only spring from the lap of the East, never from that of Europe. The religious impulse was taken over as a wave of culture, of civilisation, from the East. The first and the only thing Europe did was to cram this religious impulse, that came over from the East, with the concepts of Roman law, thread this Eastern impulse through and through with bald, abstract, intellectualist, legal forms.

But this religious impulse from the East was, at bottom, alien to the life of Europe, and remained alien to it. It never completely amalgamated with the being of Europe. And Protestantism acted in a most remarkable way as what I might call a test-tube, in which they separated out. It is just like watching two substances separating out from one another in a test-tube, to watch how European civilisation reacted with respect to its religious element. In the seventh, in the sixth, seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth centuries a kind of experiment was being made to combine religious feeling and sentiment with scientific and economic thought into one homogeneous substance; and then, actually, just as two substances react in a test-tube and separate out, so these two separated out,—the cold intellectualist thought and the religious impulse fell apart and deposited Protestantism, Lutheranism. Science on the one side, one truth; on the other side the rival truth, Faith. And the two shall mix no further. If anyone tries to saturate the substance of Faith with the substance of Thought, or to warm the substance of Thought with the substance of Faith, the experiment is regarded as downright sacrilege. And then, as the climax of all that was cold and dreary, came the Konigsberg-Kant-school with its Critique of Pure Reason alongside its Critique of Applied Reason—Ethics alongside Science,—making a most terrible gulf between what in man's nature must be felt and lived as a single whole. These are the conditions under which European civilisation still exists. And these are the conditions under which European civilisation will be brought ever nearer and nearer to its downfall. It was as an alien element from the East that Europe adopted the religious impulse, and it has never combined organically with the rest of her spiritual and physical life. So much with regard to the spiritual life of Europe.

You see, my dear friends, the progress of modern civilisation has had Its praises sung long enough. They have gone on singing its praises until millions of human beings in this civilised world have been done to death, and three times as many maimed for life. It has been blessed in unctuous phrases from the pulpits of the churches, till untold blood has been shed. Every lecturer's desk has sounded the praises of this progress, until this progress has ended in its own annihilation. There can be no cure before we look these things straight in the face. And to-day, people of the Lenin type and others come and beat their brains over socialist systems and economic systems, and fancy that with these concepts which have long since proved inadequate to direct European civilisation, they can now, without any new concepts, without any revolution of thought, effect a reform in our economic system, in our system of society.

I think I have here, once before, spoken of the beautiful concepts that our learned professors arrive at when they are dealing with these subjects. But it is so beautiful that I must really come back to it once more. There is a well-known political economist called Brentano, Lujo Brentano. Not long ago an article appeared by him, entitled: “The Business Director (Der Unternehmer).” In it Brentano tries to construct the concept of the Business Director the Capitalist Director. He enumerates the various distinctive marks of the capitalist director. The third of these distinctive marks, as given by Lujo Brentano, is this: That he expends the means of production at his private venture, at his own risk, in the service of mankind. Mark of the capitalist director! Then that excellent Brentano goes on to examine the function of the Worker, of the ordinary Labourer, in social life; and now, see what he says: That the labour-power, the physical labour-power of the labourer is the labourer's means of production; he expends it at his own venture and risk in the service of the community. Therefore, the labourer is a Business Director (Untemahmer); there is absolutely no difference between a labourer and a business director; they are both one and the same thing! You see, what they nowadays call scientific thought has by now got into such a muddle that when people are constructing concepts, they are no longer able to distinguish between two opposite poles. It is not quite so obvious here, perhaps, as in another case of a Professor of Philosophy at Berne, one of whose specialities was that he wrote such an awful lot of books, and had to write them so awfully fast, that he had not time to consider exactly what it was he was writing. However, he lectured on philosophy at the Berne University. And in one of the books by this Professor of Philosophy at Berne, this statement occurs:—A civilisation can only be evolved in the temperate zone; for at the North Pole it cannot be evolved, there it would be frozen up; nor could it be evolved at the South Pole, for there the opposite would occur, it would be burnt up! That is actually the fact. A regular Professor of Philosophy did once write in a book that it is cold at the North Pole and hot at the South Pole, because he was writing so fast that he had no time to consider what he was writing.

Well, that excellent Brentano's blunders in political economy are not quite so readily perceived; but at bottom they proceed from just the same surface view of things, from which so much in Europe has proceeded. People take for granted what already exists, and starting from this, proceed to build up their whole system of concepts just on what exists already. That is what they learn from natural science, from the natural science methods. This is how the science institutes do it; and in our day,—the age when people set no store by authority and take nothing on faith, (of course not!)—that is what they obediently copy. For nowadays, if a man is an Authority, that is sufficient reason for what he says being true,—not a reason for turning to his truth because one sees it to be true, but because he is an Authority. And people regard economic facts, too, in this way. They regard economic facts as being all exactly on a par with one another. Whereas, as a matter of fact, they are made up of mixed elements, each of which requires individual consideration.

The current of religious impulse had come from the East into European civilisation; and for the economic structure of Europe something again different was needed. The approach of the Fifth post-Atlantean age was also the time for the irruption of those events which set their stamp upon the whole civilisation of the new age and gave to it its special physiognomy. The discovery of America, the finding of a sea-route round the Cape of Good Hope to India, to the East-Indies,—this set its stamp on the civilisation of the new age. It is impossible to study the whole economic evolution of Europe by Itself alone. It is absurd to believe that from the study of existing economic facts one can thereby arrive at the economic laws that sway the common life of Europe. In order to arrive at these laws, one must bear constantly in mind that Europe was able to shift any amount off on to America. The whole social structure of Europe has only grown up owing to the fact that there was an unfailing supply of virgin soil in America, and that everything flung off from Europe passed Westwards into this virgin soil. Just as she had drawn her religions impulse from the East, so she sent forth an economic impulse towards the West. And the whole system of industrial economy peculiar to Europe was conditioned by this Westward outflowing, just as her spiritual life was developed under the inflow of the religious impulse from the East. European life, the whole course of the rise of European civilisation, has gone on through the centuries until now, under the Influence of these two currents. Here, in the middle, was European civilisation; here from the East came the religious impulse pouring in; here, in a westward stream, the economic impulse, pouring out.—Inflow of the religious impulse from the East, outflow of the economic impulse towards the West. Now this, you see, towards the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries reached a sold, of crisis. There came a gradual stoppage. Things no longer went on the same as they had been going for four centuries. And to-day we are still lining in this stoppage and are affected by it. The religious impulse came in as an alien and brought forth our spiritual life. And our economic life came about under a process of being continually drawn off and weakened. If America had not been there, and if our industrial economy had been obliged to grow up solely according to its own principles,—had it not been able continually to fling off what it could not assimilate,—then it could never have developed at all in Europe. Now there is a stoppage; and accordingly, an outlet must be found within. It Is from within that the way must be found to lead off into the right channel what no longer can go on externally in space. It must be done by bringing about the threefold social order. What has been mixed together in inorganic confusion must be combined into an actual organism. There is not one reason, there is every conceivable reason for the adoption of the threefold social order,—scientific reasons, economic reasons, historic reasons. And only he can fully appreciate the claims of the threefold social order, who is in a position to survey all these various grounds on which it rests.

The current of religious impulse had come from the East into European civilisation; and for the economic structure of Europe something again different was needed. The approach of the Fifth post-Atlantean age was also the time for the irruption of those events which set their stamp upon the whole civilisation of the new age and gave to it its special physiognomy. The discovery of America, the finding of a sea-route round the Cape of Good Hope to India, to the East-Indies,—this set its stamp on the civilisation of the new age. It is impossible to study the whole economic evolution of Europe by Itself alone. It is absurd to believe that from the study of existing economic facts one can thereby arrive at the economic laws that sway the common life of Europe. In order to arrive at these laws, one must bear constantly in mind that Europe was able to shift any amount off on to America. The whole social structure of Europe has only grown up owing to the fact that there was an unfailing supply of virgin soil in America, and that everything flung off from Europe passed Westwards into this virgin soil. Just as she had drawn her religions impulse from the East, so she sent forth an economic impulse towards the West. And the whole system of industrial economy peculiar to Europe was conditioned by this Westward outflowing, just as her spiritual life was developed under the inflow of the religious impulse from the East. European life, the whole course of the rise of European civilisation, has gone on through the centuries until now, under the Influence of these two currents. Here, in the middle, was European civilisation; here from the East came the religious impulse pouring in; here, in a westward stream, the economic impulse, pouring out.—Inflow of the religious impulse from the East, outflow of the economic impulse towards the West. Now this, you see, towards the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries reached a sold, of crisis. There came a gradual stoppage. Things no longer went on the same as they had been going for four centuries. And to-day we are still lining in this stoppage and are affected by it. The religious impulse came in as an alien and brought forth our spiritual life. And our economic life came about under a process of being continually drawn off and weakened. If America had not been there, and if our industrial economy had been obliged to grow up solely according to its own principles,—had it not been able continually to fling off what it could not assimilate,—then it could never have developed at all in Europe. Now there is a stoppage; and accordingly, an outlet must be found within. It Is from within that the way must be found to lead off into the right channel what no longer can go on externally in space. It must be done by bringing about the threefold social order. What has been mixed together in inorganic confusion must be combined into an actual organism. There is not one reason, there is every conceivable reason for the adoption of the threefold social order,—scientific reasons, economic reasons, historic reasons. And only he can fully appreciate the claims of the threefold social order, who is in a position to survey all these various grounds on which it rests.

That is a thing that one would so like to tell the people of the present day; for people of the present day suffer under a poverty of concepts that has grown positively alarming. This poverty of concepts is really such that anyone who has got any feeling for ideas finds to-day that quite a small number of ideas dominate our spiritual life, and they meet him at every turn. If anyone is hunting for ideas, this is what he finds; he takes up a work on Physics; it contains a certain limited number of ideas. Next, he studies, say, a work on Geology; there he finds fresh facts, but precisely the same ideas. Then he studies a biological work; there he finds fresh facts, but the same ideas. He reads a book on Psychology, dealing with the life of the soul. There he finds more facts, which really only consist of words, for they only know the soul really as a collection of words. When they talk of the will, there is a word there; but of the actual will itself they know nothing. When they talk of Thought they know nothing of real thinking; for people still only think in words. Nor do they know anything of feeling. The whole field of Psychology is to-day just a game of words, in which words are shaken up together in every conceivable kind of way. Just as the bits in a kaleidoscope combine into all sorts of different patterns, so it is with our concepts. They are jumbled up together into various sciences; but the total number of ideas is quite a small one, and keeps meeting one again and again. These ideas are forcibly fitted on to the facts. And people have no desire to find the concepts that fit the facts, to examine into the ideas that fit the facts. People simply do not notice things.

In a certain town in Central Europe, not long ago, there was a conference of Radical Socialists. These Radical Socialists were engaged in planning out a form of society suitable for adoption in Europe. The form of society as there planned by them was almost identical with what you can read in a collection of articles that appeared in the “Basler Vorwärts” of this week,—a series of articles in the Basel “Vorwärts,” putting forward in outline a scheme of society almost identical with what was thought out some time back in a Mid-European town. And what is the special feature of this scheme of society as planned out there? People think it very clever, of course. They think that it cannot be improved on.

But it is what it is, solely for the reason that it was drawn up by men who, as a matter of fact, had never really had anything to do with industrial and economic life, who had never acquired any practical acquaintance with the real sources and mainsprings of industrial and economic life. It was a scheme invented by men who have taken an active part in the political life of recent years. Well, you know what taking an active part in the political life of recent years means,—one was either elector or elected; one was elected either -in the first ballot, or in the second ballot. Say that one did not succeed in getting elected in the first ballot. Well, one had raised those huge sums of money, of course, subscriptions had been collected, and the huge sum raised, in order that one might have enough voters to get elected. The money was all spent; one had vented a terrible lot of abuse on the rival candidate the fellow was a fool, a knave and a cheat, If nothing worse. And came the second ballot. So far, no one had got an absolute majority, and now it was a question of electing one of those who had had proportional majorities. Now there was a change in the proceedings. Now, one-third of the election money was returned by one's opponent,—the same who was a fool, knave, cheat, etc. One accepted the returned money, and all of a sudden one's speeches took a different tone; there is nothing for it, one said, but to elect the man (the man who before was a knave, fool, cheat, etc),—he will have to be elected. After all, one had got back a third of the election money, and, inspired by this return of a third of the election money, one was gradually converted into his active supporter. For, after all, one of the two must be elected; the other man had no chance; all that could be done was to save a third of the election expenses.

So they had taken an active part in political life. So, too, no doubt, they had had a voice in the political administrations, but they had no notion, not the remotest, vaguest notion, of industrial and economic life. They simply took the political ideas they had acquired,—ideas that had, of course, become much corrupted, but still they were political ideas of a sort,—and they tried now to fit them on to industrial and economic life. And accordingly, if these ideas were put into effect, one would get an industrial and economic life organised on purely political lines. Industrial economic organisation has already become confounded with political organisation,—so impossible has it become for people to keep apart things that have become so welded, so wedged together. But the time has come when it is urgently necessary to carry into many, many places an insight into what really exists. And that is a thing for which people to-day show no zeal.

There is nothing to be expected from the influence of a civilisation which never contemplates external reality,—which wants to bind external reality to a couple of hard and fast concepts; nor need one hope with this little set of concepts to draw near to that true reality which is the business of anthroposophical science to discover. For it is this true reality that the spiritual science of Anthroposophy has to seek and find. Therefore, the spiritual science of Anthroposophy must not be taken after the pattern of what people were often pleased to call “religious persuasions.”

That, you see was what one suffered from so terribly in the course of the old Theosophic movement. What more was the old Theosophic movement than just that people wanted a sort of select religion? It consisted in no new impulse proceeding from the civilisation of Europe itself. It consisted merely in emotions, which were to be had out of the old religious element just as well. Only people had grown tired of these old religious concepts and ideas and feelings, and so had taken up something else. But the same atmosphere pervaded it as pervaded the old persuasion. They wanted to feel good, with an evangelical sort of goodness if they had been evangelicals, or with a catholic kind of goodness if they had been Catholics; but they did not at bottom want the thing really needed, namely, an actual new religious impulse along with other impulses, because the life of the European peoples has grown up habituated to an alien religious impulse, that of Asia. That is the point. And until those things are organically interwoven that were inorganically intermixed,—till then, European civilisation will not rise again. It cannot be taken too seriously; it must pervade everything that is going to live in science, in economic, in religion, in political life.

We will speak more of this, then, tomorrow. To-morrow the eurhythmic performance takes place here at 5 o'clock. Then, after the necessary interval, that is, I take It, about half past seven tomorrow, there will be the lecture.

Fünfter Vortrag

Es ist so spät geworden, daß ich diesen Vortrag heute kurz halten werde, und daß ich die Hauptsache, die ich zu sagen habe in diesen drei Vorträgen, für morgen lassen werde. Morgen wird ja die Eurythmie früher gelegt sein, und dann wird es möglich sein, dem Vortrag die entsprechende Länge zu geben.

Ich habe das letzte Mal darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie zur Beherrschung desjenigen, was in unserer gegenwärtigen niedergehenden Zivilisation liegt, nötig ist, über die verschiedenen Völkermassen der Erde hin so zu differenzieren, daß man das Augenmerk wirklich lenkt auf das, was in den einzelnen Völkermassen lebt, und zwar lebt in der anglo-amerikanischen Bevölkerung, in der eigentlich europäischen Bevölkerung und in der Bevölkerung des Ostens. Und wir haben gesehen, daß wir die Anlage, eine neuzeitliche Kosmogonie zu begründen, vor allen Dingen bei der anglo-amerikanischen Bevölkerung finden; die Fähigkeit, den Impuls der Freiheit auszubilden, bei der europäischen Bevölkerung; dann den Impuls des Altruismus auszubilden, den Impuls der Religiosität und desjenigen, was mit Bezug auf die menschliche Brüderlichkeit damit zusammenhängt, bei der Bevölkerung des Ostens. Es kann eine neue Zivilisation nicht anders begründet werden als dadurch, daß ein wirkliches Zusammenarbeiten der Menschen über die ganze Erde hin in der Zukunft möglich gemacht wird. Aber damit dieses möglich werde, damit ein wirkliches Zusammenarbeiten möglich werde, dazu ist verschiedenes nötig. Dazu ist nötig, daß tatsächlich unbefangen eingesehen werde, wieviel der gegenwärtigen Zivilisation fehlt, wieviel vom Niedergangsimpuls in dieser gegenwärtigen Zivilisation ist. Diejenigen Kräfte, die in unserer Zivilisation sind, man darf sie nicht etwa so betrachten, daß man sagt: Alles ist schlecht. - Das wäre erstens unhistorisch, zweitens würde es zu nichts Positivem führen. Diejenigen Impulse, die in unserer Zivilisation liegen, waren zu irgendeiner Zeit und an irgendeinem Orte voll berechtigt. Aber alles das, was im geschichtlichen Werden der Menschheit zum Niedergange führt, das führt aus dem Grunde zum Niedergange, weil das, was eben in der einen Zeit und an dem einen Orte berechtigt ist, sich hinsetzt in eine andere Zeit und an einen anderen Ort; und weil die Menschen aus gewissen ahrimanischen und luziferischen Antrieben heraus beharren bei dem, woran sie sich einmal gewöhnt haben und nicht an dem wirklichen, von der Kosmogonie geforderten Fortschritte der Menschheit teilnehmen wollen.

Unsere Zeit ist stolz auf ihre Wissenschaftlichkeit. Und doch gehen im Grunde aus dieser Wissenschaftlichkeit hervor auch die großen sozialen Irrtümer und Verkehrtheiten unserer Zeit. Daher muß schon einmal gründlich hineingeleuchtet werden in das Getriebe des Denkens und in das Getriebe des Handelns, insofern dieses Handeln der Gegenwart von dem Denken der Gegenwart ja ganz abhängig ist.

Wir haben gestern in dem Zusammenhange, den wir betrachten mußten, aufmerksam darauf gemacht, wie die Gesamtkultur der Erde sich zusammenfügt aus der wissenschaftlichen Kultur, aus der politisch-freiheitlichen Kultur und aus der altruistisch-ökonomischen Kultur, die eigentlich doch zurückgeht auf das altruistisch-religiöse Element. Wenn die Menschen heute — ich habe schon darauf hingewiesen — die Kräfte betrachten, die eigentlich in unserer sozialen Struktur wirken, so bleiben sie an der Oberfläche, sie wollen nicht in die Tiefe dringen. Auf unseren Lehrkanzeln lehren die Vortragenden über das, was ökonomische Weisheit sein soll, in einer Weise, die herausgeholt ist aus der gegenwärtigen naturwissenschaftlichen Methode. Allein es wird gewissermaßen wie ein ungenießbarer Brei das betrachtet, was in den Menschen lebt und die Menschengemüter und Menschenwesenheiten bewegt. Es wird nicht auf das eigentlich wahre Sachliche gesehen.

Bleiben wir zunächst einmal bei der Kultur Europas stehen. Was ist der hauptsächlichste Zug dieser Kultur Europas? Verfolgt man diesen Zug der Kultur Europas, so muß man eigentlich, wenn man ihn verstehen will, ziemlich weit zurückgehen. Man muß sich klar darüber sein, wie aus alten keltischen Urbevölkerungsimpulsen sich dadurch, daß verschiedene spätere Bevölkerungsschichten sich hineingeschoben haben in diese keltische Urbevölkerung, die eigentlich auf dem Grunde des europäischen Daseins noch immer vorhanden ist, wie dadurch diese europäische Bevölkerung mit allen ihren religiösen, politischen und ökonomischen und wissenschaftlichen Antrieben sich herausgebildet hat. In Europa herrschte im Grunde genommen immer, im Gegensatze zu dem amerikanischen Westen und zu dem asiatischen Osten, ein gewisser Intellektualismus. Es hätte gar nicht das so überhandnehmen können, was ich gestern als den eigentlichen Romanismus, als das romanische Element bezeichnet habe, wenn nicht in der europäischen Zivilisation der Grundzug des Intellektualismus wäre. Nun ist dem Intellektualismus zweierlei eigen: Erstens, er kann sich nicht aufraffen, rückhaltlos religiöse Impulse aus sich herauszutreiben. Die religiösen Impulse bekommen immer einen abstrakten Charakter unter dem Einflusse des Intellektualismus. Ebensowenig kann sich der Intellektualismus wirklich zu der Stoßkraft entwickeln, die ins Praktisch-Ökonomische hineingeht. Man wird an den Experimenten, die jetzt in Rußland gemacht werden, sehen, wie unmöglich es dem europäischen Intellektualismus ist, in das ökonomische Leben, in das wirtschaftliche Leben Ordnung hineinzubringen. Das, was der Leninismus ausbildet, ist ja reinster Intellektualismus. Das ist alles gedacht, da ist aus dem Denken heraus eine gesellschaftliche Ordnung konstruiert. Und es wird der Versuch gemacht, dieses aus dem Denken heraus gesponnene gesellschaftliche System aufzupfropfen auf die wirklichen Verhältnisse, die zwischen Menschen bestehen, und es wird sich mit der Zeit in einer fürchterlichen Weise zeigen, wie unmöglich es ist, das intellektualistisch Gedachte der menschlichen sozialen Struktur aufzupfropfen.

Diese Dinge wollen die heutigen Menschen noch nicht in aller Stärke einsehen. Es ist ja einmal in der europäischen Bevölkerung dieser furchtbare Zug der Schläfrigkeit, dieses Nichtmitkönnen des ganzen Menschen mit dem, was so nötig ist, daß es heute das soziale Leben Europas durchströmte. Das aber, was vor allen Dingen einzusehen ist, das ist: wovon eigentlich diese europäische Zivilisation genährt ist, woher diese europäische Zivilisation im Grunde stammt. Durch sich selber, durch ihre eigene Wesenheit hat diese europäische Zivilisation nur eine intellektualistische, eine Gedankenkultur hervorgebracht. Die Trockenheit und Nüchternheit des Denkens waltet in unserer Wissenschaft; die waltet auch in unseren sozialen Einrichtungen.

Wir haben ja durch viele, viele Jahrzente diesen Intellektualismus in den europäischen Parlamenten erlebt. Könnte man nur fühlen, wie durch alle diese europäischen Parlamente durchgegangen ist der intellektualistische Nützlichkeitsstandpunkt, das schwunglose Element, das keine Stoßkraft hat zu religiösen Impulsen, und das keine Stoßkraft hat zu irgendwelchen ökonomischen Impulsen! Bedenken Sie nur, wie wir unser religiöses Leben bekommen haben. Wir haben es so bekommen, daß man an der ganzen historischen Ausbreitung dieses religiösen Lebens sieht, daß Europa in sich selber keine religiösen Impulse hatte. Bedenken Sie, wie nüchtern, wie unendlich nüchtern die Welt war, als das Römische Reich sich ausgebreitet hatte, prosaisch nüchtern bis zum Exzeß. Und das war ja alles erst im Anfange. Denken Sie nur einmal, was Europa geworden wäre, wenn die romanische Kultur mit ihrer Prosanüchternheit die Fortsetzung gefunden hätte ohne den Impuls, der vom asiatischen Osten herüberkam und der ein religiöser Impuls war: ohne den christlichen Impuls. Was aus dem Schoße des Orients entsprungen ist, was nur aus dem Schoße des Orients, niemals aus europäischem Schoß entspringen konnte, der religiöse Impuls, ist als eine Kultur-, als eine Zivilisationswelle aus dem Osten herübergekommen. Europa hat ja nichts anderes getan, als zuerst römische Rechtsbegriffe hineingestopft in diesen religiösen Impuls, der vom Osten herübergekommen ist, hat durchzogen diesen östlichen Impuls mit nüchtern, abstrakt-intellektualistischen, juristischen Formen.

Dem europäischen Leben war im Grunde genommen der östliche religiöse Impuls etwas Fremdes; er ist ihm etwas Fremdes geblieben. Er hat sich niemals ganz amalgamiert mit dem europäischen Wesen. Und er ist, ich möchte sagen, im Protestantismus in einer merkwürdigen Weise wie in einem Reagenzglase ausgeschieden worden. Wie wenn man in einem Reagenzglase beobachtet, wie sich Substanzen voneinander trennen, so ist es geschehen mit der europäischen Zivilisation in bezug auf ihren religiösen Charakter. Es war im 6., 7., 8., 9., 10. Jahrhundert etwas wie ein Versuch, eine innere Einheit zu gestalten aus dem religiösen Fühlen und Empfinden und aus dem wissenschaftlichen und ökonomischen Denken. Aber dann traten, wirklich wie in einem Reagenzglas zwei Substanzen auseinandertreten, die beiden — das nüchterne Denken des Intellektualismus und der religiöse Impuls — auseinander, und endlich kam der Protestantismus, das Luthertum. Wissenschaft auf der einen Seite, eine Wahrheit; Glaube auf der anderen Seite, die andere Wahrheit. Die beiden sollen sich ja nicht weiter vermischen! Es wird geradezu als ein Sakrileg angesehen, wenn der Versuch unternommen wird, den Glaubensinhalt zu durchtränken mit dem Gedankeninhalt, den Gedankeninhalt zu erwärmen mit dem Glaubensinhalt. Und dann kam noch das Nüchternste, das Königsbergsche, der Kantianismus, der neben der Kritik der reinen Vernunft die Kritik der praktischen Vernunft, das Sittliche neben dem Wissenschaftlichen hinstellte, wodurch der furchtbarste Abgrund aufgerichtet ward zwischen demjenigen, was als einheitlich erfühlt und erlebt werden muß in der Menschennatur. Und unter diesen Verhältnissen lebt eigentlich die europäische Zivilisation noch immer. Unter diesen Verhältnissen wird auch die europäische Zivilisation immer mehr und mehr in ihren Niedergang hineinkommen. Wie etwas Fremdes aus dem Osten ist aufgenommen worden der religiöse Impuls, hat sich nicht organisch verbunden mit dem übrigen geistigen und physischen Leben Europas. Das ist mit Bezug auf das Geistesleben Europas zu sagen.

Sehen Sie, gelobhudelt wurde über den Fortschritt der neueren Zivilisation genug. Es ist so lange gelobhudelt worden, bis Millionen von Menschen innerhalb dieser Zivilisation totgeschlagen und dreimal soviel zu Krüppeln gemacht worden sind. So lange ist von allen Kirchenkanzeln die salbungsvolle Rede ertönt, bis unendliches Blut geflossen ist. So lange ist von allen Lehrkanzeln verkündet worden der gepriesene Fortschritt, bis dieser Fortschritt in seine Nullität hineingeführt hat. Nicht eher wird ein Heil kommen, bis man diesen Dingen unbefangen ins Antlitz schaut. Und heute kommen die Menschen Leninscher und anderer Prägung und denken nach über Sozialismus, über Ökonomismus, und es soll aus denjenigen Begriffen, die längst sich als unzulänglich erwiesen haben zur Führung der europäischen Zivilisation, ohne daß man zu neuen Begriffen, zu einem Umdenken kommt, unsere ökonomische Ordnung, unsere soziale Ordnung reformiert werden.

Ich habe, glaube ich, schon einmal auch hier gesagt, zu welchen schönen Begriffen unsere gelehrten Herren zum Beispiel auf diesem Gebiete kommen. Es ist zu schön, daher möchte ich diese Sache noch einmal hier besprechen. Da ist ein berühmter Nationalökonom, Lujo Brentano. Von ihm ist ein Artikel erschienen vor einiger Zeit, «Der Unternehmer». Brentano versucht den Begriff des kapitalistischen Unternehmers zu konstruieren. Er holt die Merkmale für den kapitalistischen Unternehmer zusammen. Das dritte Merkmal, das Lujo Brentano anführt, besteht darin, daß der Unternehmer die Produktionsmittel auf eigenes Risiko, auf eigene Gefahr im Dienste der Menschheit verwendet. Nun untersucht der gute Lujo Brentano die Funktion des gewöhnlichen Handarbeiters im sozialen Leben und sagt: Die körperliche Arbeitskraft des Handarbeiters, das ist sein Produktionsmittel; er verwendet es im Dienst der Gesellschaft auf eigenes Risiko und auf eigene Gefahr. Also ist der Arbeiter ein Unternehmer. Es ist gar kein Unterschied zwischen einem Unternehmer und einem Arbeiter, es ist beides eins und dasselbe! — Sehen Sie, so verworren ist das, was man heute wissenschaftliches Denken nennt, schon geworden, daß, wenn die Leute Begriffe bilden, sie nicht mehr unterscheiden können zwischen den zwei entgegengesetzten Polen.

Dabei ist es bei Brentano gar nicht so leicht bemerkbar, wie etwa bei einem Philosophieprofessor in Bern, der unter anderem die Eigenschaft hat, so furchtbar viele Bücher zu schreiben, und der so schnell schreiben mußte, daß er sich nicht genau überlegen konnte, was er schrieb. Aber er trug Philosophie an der Universität Bern vor. Und siehe da, in einem der Bücher dieses Philosophieprofessors aus Bern fand sich auch der Satz: Die Zivilisation kann sich nur entwickeln in der gemäßigten Zone, denn sie kann sich nicht entwickeln auf dem Nordpol — da würde sie erfrieren -, und sie kann sich auch nicht entwickeln auf dem Südpol, denn da ist es heiß, im Gegensatz zum Nordpol, da würde die Zivilisation verbrennen! — Es ist tatsächlich so, daß einmal ein regelrechter Philosophieprofessor in einem Buch schreibt, daß es auf dem Nordpol kalt und auf dem Südpol heiß ist, weil er so schnell schrieb, daß er es sich nicht gut überlegen konnte!

Die nationalökonomischen Fehler des guten Brentano sind im Grunde genommen aus derselben Oberflächenanschauung heraus geboren, wie vieles in Europa. Denn man betrachtet das, was da ist, eben als das Gegebene und knüpft seine Begriffsschemen an das an, was gerade da ist. Das lernt man von der naturwissenschaftlichen Methode, das treibt man an den naturwissenschaftlichen Anstalten, und das sprechen die Menschen heute in unserer Zeit - in der selbstverständlich nichts auf Autoritäten gegeben wird! — gläubig nach. Denn wenn man hört, daß irgendeiner heute eine Autorität ist, dann ist das ein Grund, anzunehmen, daß er die Wahrheit sagt! Nicht aus Einsicht nimmt man es an, zu seiner Wahrheit, sondern weil er eine Autorität ist. Und so betrachtet man auch die ökonomischen Tatsachen so, als ob sie nebeneinander die gleiche Bedeutung hätten, während sie in der Tat ineinandergeschobene Elemente sind, die gesondert betrachtet werden müssen.

Geradeso wie die europäische Zivilisation von Osten her die Strömung des religiösen Impulses gehabt hat, so war für die ökonomische Struktur Europas wieder etwas anderes notwendig. Als der fünfte nachatlantische Zeitraum, die Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts, herannahte, war auch die Zeit, wo jene Ereignisse eintraten, die der ganzen neuzeitlichen Zivilisation ihr Grundgepräge, ihre Physiognomie gaben: Entdeckung Amerikas, die Auffindung des Seeweges über das Kap der Guten Hoffnung nach Ostindien; das gab der neuzeitlichen Zivilisation das Gepräge. Und die ganze ökonomische Entwickelung Europas kann nicht aus sich selber studiert werden. Es ist ein Unsinn, zu glauben, daß man dadurch, daß man die ökonomischen Tatsachen studiert, auf die ökonomischen Gesetze kommt, die in der europäischen Gesellschaft walten. Man kommt auf diese Gesetze nur, wenn man fortdauernd berücksichtigt, daß von Europa Unzähliges abgeschoben werden konnte nach Amerika. Und die ganze soziale Struktur Tafel 4

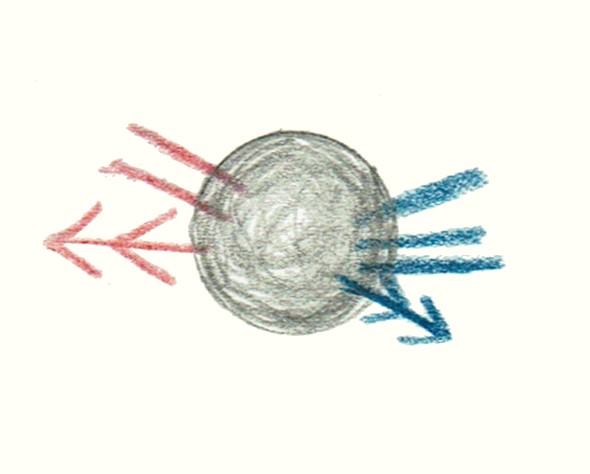

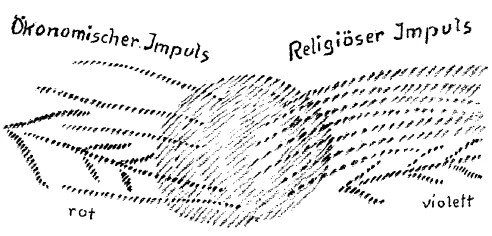

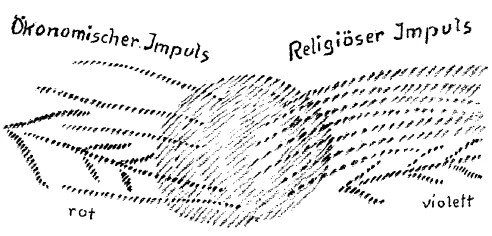

Europas ist nur entstanden dadurch, daß fortwährend in Amerika drüben Neuland war und in dieses Neuland abfloß das, was Europa nach dem Westen schickte. Wie es vom Osten bekommen hat den religiösen Impuls, so schickte es seinen ökonomischen Impuls nach dem Westen. Unter dem Regime dieser Strömung entwickelte sich seine eigene Ökonomie, wie sich sein Geistesleben unter dem Einströmen der religiösen Impulse vom Osten entwickelte. Das europäische Leben, der ganze Hergang im Zustandekommen der europäischen Zivilisation entwickelte sich in den bisherigen Jahrhunderten der neueren Zeit unter diesen zwei Strömungen. Da war die europäische Zivilisation in der Mitte, da kam vom Osten herüber wie ein Zufluß der religiöse Impuls (siehe Zeichnung violett), da strömte nach dem Westen hinüber wie ein Abfluß der ökonomische Impuls (rot). Einströmen des religiösen Impulses aus dem Osten, Abfließen des ökonomischen Impulses nach dem Westen, das war das, was im Hergang der europäischen Zivilisation lebte.

Und das erreichte um die Wende des 19. zum 20. Jahrhundert eine gewisse Krisis. Das fing an zu stocken. Das fing an, nicht mehr so zu gehen, wie es durch vier Jahrhunderte gegangen war. Und unter dem Einflusse dieser Stockung stehen wir und leben wir heute. Wie etwas Fremdes hat sich der religiöse Impuls hereingeschoben und hat das geistige Leben bei uns erzeugt. Und unser ökonomisches Leben ist dadurch entstanden, daß es fortwährend Verdünnungen erlebte. Wäre nicht Amerika dagewesen und hätte unsere Ökonomie entstehen sollen aus ihren eigenen Gesetzen heraus, hätte sie nicht fortwährend aus sich ausspritzen können das, was sie nicht brauchen konnte, so hätte sie sich nicht entwickeln können in Europa. Das stockt jetzt. Daher muß ein innerer Ausweg gefunden werden. Von innen heraus muß die Möglichkeit gefunden werden, das in das richtige Fahrwasser zu bringen, was nicht mehr räumlich von außen geht.

Das soll durch die Dreigliederung geschehen. Das soll dadurch geschehen, daß das, was sich unorganisch ineinandergeschoben hat, nun wirklich organisch gegliedert wird. Für die Annahme der Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus liegt nicht ein Grund vor, sondern da liegen alle möglichen Gründe vor; da liegen wissenschaftliche, da liegen ökonomische Gründe, da liegen historische Gründe vor, und erst derjenige kann vollständig über die Berechtigung der Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus urteilen, der in der Lage ist, alle diese verschiedenen Begründungen zu überschauen.

Das möchte man so gern den Menschen der Gegenwart sagen; denn diese Menschen der Gegenwart leiden an einer Begriffsarmut, die eben nach und nach fürchterlich geworden ist. Diese Begriffsarmut ist wirklich so geworden, daß derjenige, der heute einen Sinn hat für Ideen, findet, daß eigentlich in unserem Geistesleben eine ganz kleine Summe Ideen nur herrscht, die man überall findet. Wer nach Ideen gräbt, dem geht es so: Er studiert ein physikalisches Werk; in dem Werk ist eine bestimmte Summe von Ideen. Dann studiert er meinetwillen ein geologisches Werk; er findet andere Tatsachen, aber er findet genau dieselben Ideen. Dann studiert er ein biologisches Werk, er findet andere 'Tatsachen, aber er findet dieselben Ideen. Er studiert ein psychologisches Buch, das über das Seelenleben handelt: er findet andere Tatsachen, die aber eigentlich nur in Worten bestehen, denn die Seele kennt man ja eigentlich nur als eine Summe von Worten. Spricht man vom Wollen, so ist ein Wort da; man weiß nichts vom wirklichen Wollen. Spricht man von Denken — man weiß nichts vom wirklichen Denken, denn die Leute denken nur noch in Worten. Man weiß auch nichts vom Fühlen. Das ganze psychologische Gebiet ist ja heute ein Spiel mit Worten, die man in der verschiedensten Weise durcheinanderkugelt: So wie im Kaleidoskop die Steine andere Gruppierungen erleiden, so ist es mit unseren Begriffen. Sie werden anders durcheinandergeschmissen in unseren verschiedenen Wissenschaften, aber es ist nur eine ganz geringe Summe von Ideen da, die einem immer wieder und wieder entgegentreten, die den Tatsachen übergestülpt werden. Und die Menschen drängen sich nicht dazu, für die Sache die entsprechenden Begriffe zu finden, für die Sache die entsprechenden Ideen zu erforschen! Man bemerkt die Dinge nur nicht.

Vor einiger Zeit hat in einer Stadt Mitteleuropas ein Kongreß radikaler Sozialisten stattgefunden. Diese radikalen Sozialisten beschäftigten sich damit, eine soziale Struktur auszudenken, wie sie Europa bekommen soll. Es ist ungefähr dieselbe soziale Struktur, wie Sie sie jetzt in einer Reihe von Artikeln im Basler «Vorwärts» lesen können. Was ist das Eigentümliche dieser sozialen Struktur? Die Leute finden sie sehr geistvoll, sie finden, daß sie gar nicht anders sein kann. Aber sie ist so geworden, wie sie geworden ist, nur aus dem Grunde, weil sie von Menschen gemacht worden ist, die eigentlich nie etwas Wirkliches mit dem Wirtschaftsleben zu tun gehabt haben, die niemals die wirklichen Quellen und Triebkräfte des Wirtschaftslebens kennengelernt haben. Sie ist von Menschen gemacht, die teilgenommen haben am politischen Leben der letzten Jahrzehnte. Wie hat man am politischen Leben der letzten Jahrzehnte teilgenommen? Nun, man war entweder Wähler oder Gewählter. Als Kandidat wurde man entweder gewählt in der elementaren Wahl oder in der Stichwahl. Man wurde, sagen wir, in der elementaren Wahl noch nicht gewählt; da hatte man aber seine riesigen Wahlgelder aufgebraucht. Man hatte Sammlungen gemacht, die Riesensumme war aufgebracht worden, damit man genügend Wähler gehabt hätte, um gewählt zu werden. Diese Summen waren ausgegeben. Man hatte fürchterlich losgezogen über seinen Parteigegner; der war ein Lump und ein Schurke und ein Betrüger, wenn nicht etwas noch Schlimmeres. Jetzt kam die Stichwahl. Bis jetzt hatte noch keine Partei eine Majorität gehabt, jetzt handelte es sich darum, irgendeinen zu wählen von denen, die die relative Majorität hatten. Da kam das andere Verfahren: Da ließ man sich ein Drittel von den ausgegebenen Wahlgeldern durch den Gegner, der bisher ein Schurke, ein Lump, ein Betrüger war, zurückzahlen! Man ließ es sich zurückzahlen, verwandelte sich plötzlich in einen Redner, der sagte: Es ist immerhin notwendig, daß der Mann gewählt wird! — Der früher ein Schurke, ein Lump, ein Betrüger wat, der mußte nunmehr gewählt werden. Nicht wahr, man hatte ja das Drittel der Wahlgelder zurückbekommen, und man verwandelte sich allmählich unter diesem Interesse, das Drittel der Wahlgelder wieder bekommen zu haben, in einen solchen, der nun für jenen eintrat. Denn einer von beiden mußte ja gewählt werden, der andere hatte keine Aussicht; es war höchstens noch das Drittel der Wahlgelder hereinzubekommen.

Also, nicht wahr, man hatte an diesem politischen Leben teilgenommen; man hatte teilgenommen daran, wie hineingeredet worden ist in die politische Verwaltung. Man hatte ja gelernt, wie man von Ämtern aus dirigiert und so weiter, kurz, man hatte die ganze politische Maschinerie kennengelernt, aber keinen blauen Dunst vom Wirtschaftsleben. Das, was man nun an politischen Begriffen bekommen hat — Begriffen, die ja natürlich sehr korrumpiert worden waren, aber immerhin, sie waren politische Begriffe -, das wollte man einfach über das Wirtschaftsleben drüberstülpen. Und so würde man, wenn man das ausführte, um was es sich da handelte, ein Wirtschaftsleben bekommen mit rein politischer Struktur. Man verwechselt heute schon die Struktur des Wirtschaftslebens mit der politischen Struktur, so wenig können die Leute noch auseinanderhalten, was sich allmählich ineinandergedrängt hat, ineinandergeschoben hat. Aber es wäre heute schon notwendig, daß an vielen, vielen Orten Einsicht verbreitet würde über dasjenige, was wirklich ist. Auf das wollen die Menschen heute nicht eingehen.

Nun soll man nur ja nicht glauben, daß man unter dem Einflusse der Zivilisation, welche die äußere Wirklichkeit nicht anschaut, sondern sie mit ein paar hingepfahlten Begriffen tyrannisiert, daß man mit einer solchen Summe von Begriffen sich nähern kann jener wahren Wirklichkeit, die durch anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft aufgesucht werden soll. Denn durch anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft soll eben die wahre Wirklichkeit aufgesucht werden. Daher muß anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft nicht nach dem Muster von dem genommen werden, was man früher oftmals religiöse Bekenntnisse genannt hat.

Sehen Sie, darunter hat man geradezu ungeheuerlich gelitten bei der alten theosophischen Bewegung. Was war diese alte theosophische Bewegung anderes, als daß man eine Art Extrareligion haben wollte! Die bestand nicht in einem neuen Impuls, der aus der Zivilisation Europas selber hervorgegangen wäre, sondern die bestand nur aus Gefühlen, die man im alten religiösen Element auch’ hatte. Nur waren einem diese alten religiösen Begriffe und Ideen und Empfindungen langweilig geworden, und so hatte man sich anderem zugewendet. Aber sie wurden von derselben Atmosphäre durchströmt, von denen die alten Bekenntnisse durchströmt waren. Man wollte geradeso fromm sein, wie man evangelisch fromm gewesen ist, wenn man evangelisch war, wie man katholisch fromm gewesen ist, wenn man Katholik war; aber man wollte im Grunde genommen nicht dasjenige, was man brauchte: Einen wirklichen neuen religiösen Impuls neben anderen Impulsen -, weil sich die europäische Bevölkerung hineingewöhnt hat in das Leben durch einen fremden, durch den asiatisch-religiösen Impuls. Das ist dasjenige, worauf es ankommt. Und ehe nicht organisch ineinanderverwoben werden diejenigen Dinge, die nur unorganisch ineinandergeschoben waren, ehedem gibt es keinen Aufstieg der europäischen Zivilisation. Das muß man durchaus ernst nehmen, und das muß durchdringen dasjenige, was zu leben hat in Wissenschaft, in Ökonomie, in Religiosität und im politischen Leben.

Fifth Lecture

It has become so late that I will keep this lecture short today and leave the main points I have to say in these three lectures for tomorrow. Tomorrow, eurythmy will be scheduled earlier, and then it will be possible to give the lecture the appropriate length.

Last time, I drew attention to how, in order to master what lies in our present declining civilization, it is necessary to differentiate between the various peoples of the earth in such a way that attention is really directed to what lives in the individual peoples, namely, what lives in the Anglo-American population, in the actual European population, and in the population of the East. And we have seen that we find the predisposition to establish a modern cosmogony above all in the Anglo-American population; the ability to develop the impulse of freedom in the European population; and then the impulse of altruism, the impulse of religiosity and of what is connected with it in terms of human brotherhood in the population of the East. A new civilization cannot be founded in any other way than by making real cooperation between people all over the world possible in the future. But for this to be possible, for real cooperation to be possible, various things are necessary. It is necessary to recognize, without prejudice, how much is lacking in the present civilization, how much of the impulse of decline is present in this present civilization. The forces that exist in our civilization should not be viewed in such a way that one says: Everything is bad. Firstly, that would be unhistorical; secondly, it would lead to nothing positive. The impulses that exist in our civilization were fully justified at some time and in some place. But everything that leads to decline in the historical development of humanity leads to decline for the reason that what is justified in one time and one place becomes established in another time and another place; and because human beings, out of certain Ahrimanic and Luciferic impulses, persist in what to which they have once become accustomed and do not want to participate in the real progress of humanity demanded by cosmogony.

Our age is proud of its scientific nature. And yet, fundamentally, it is this scientific nature that gives rise to the great social errors and perversions of our time. Therefore, we must first thoroughly examine the workings of thought and the workings of action, insofar as the actions of the present are entirely dependent on the thinking of the present.

Yesterday, in the context we had to consider, we drew attention to how the overall culture of the earth is composed of scientific culture, political-liberal culture, and altruistic-economic culture, which actually goes back to the altruistic-religious element. When people today — as I have already pointed out — consider the forces that are actually at work in our social structure, they remain on the surface; they do not want to penetrate to the depths. In our lecture halls, lecturers teach what economic wisdom is supposed to be in a way that is derived from the current scientific method. But what lives in human beings and moves human minds and human beings is regarded as a kind of indigestible mush. The true facts are not seen.

Let us first consider European culture. What is the main characteristic of this European culture? If we follow this characteristic of European culture, we must go back quite a long way in order to understand it. We must be clear about how, from the ancient impulses of the Celtic indigenous population, various later population groups pushed their way into this Celtic indigenous population, which is still present at the core of European existence, and how this European population with all its religious, political, economic, and scientific drives developed as a result. In Europe, in contrast to the American West and the Asian East, a certain intellectualism has always prevailed. What I referred to yesterday as true Romanism, as the Roman element, could never have gained such ascendancy if intellectualism had not been a fundamental feature of European civilization. Now, two things are characteristic of intellectualism: first, it cannot bring itself to drive religious impulses out of itself completely. Under the influence of intellectualism, religious impulses always take on an abstract character. Nor can intellectualism really develop into the driving force that enters into practical economic life. The experiments currently being conducted in Russia will show how impossible it is for European intellectualism to bring order to economic life. What Leninism is developing is pure intellectualism. Everything is thought out; a social order is constructed out of thought. And an attempt is being made to graft this social system, spun out of thought, onto the real conditions that exist between people, and in time it will become terribly clear how impossible it is to graft intellectualistic ideas onto the human social structure.

People today are not yet ready to fully comprehend these things. There is a terrible tendency toward sleepiness among the European population, an inability of the whole person to cope with what is so necessary, and this has permeated social life in Europe today. But what must be understood above all is what actually nourishes this European civilization, where this European civilization basically comes from. Through itself, through its own essence, this European civilization has produced only an intellectual, a thought culture. The dryness and sobriety of thinking reigns in our science; it also reigns in our social institutions.

We have experienced this intellectualism in European parliaments for many, many decades. If only one could feel how the intellectualistic utilitarian point of view has permeated all these European parliaments, the lifeless element that has no impetus for religious impulses and no impetus for any economic impulses! Just consider how we came to have our religious life. We came to it in such a way that the entire historical spread of this religious life shows that Europe had no religious impulses within itself. Consider how sober, how infinitely sober the world was when the Roman Empire spread, prosaically sober to excess. And that was only the beginning. Just think what Europe would have become if Roman culture, with its prosaic sobriety, had continued without the impulse that came from the Asian East, which was a religious impulse: without the Christian impulse. What sprang from the womb of the Orient, what could only spring from the womb of the Orient and never from the womb of Europe, the religious impulse, came over from the East as a wave of culture and civilization. Europe did nothing else but first cram Roman legal concepts into this religious impulse that came from the East, permeating this Eastern impulse with sober, abstract, intellectual, legal forms.

The Eastern religious impulse was basically something foreign to European life; it has remained something foreign to it. It has never completely amalgamated with the European essence. And I would say that in Protestantism it has been separated out in a strange way, as if in a test tube. Just as one observes substances separating from one another in a test tube, so it happened with European civilization in relation to its religious character. In the 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th centuries, there was something like an attempt to create an inner unity out of religious feeling and perception and out of scientific and economic thinking. But then, just as in a test tube, two substances separated, the two—the sober thinking of intellectualism and the religious impulse—and finally Protestantism, Lutheranism, emerged. Science on the one hand, one truth; faith on the other, the other truth. The two should not be mixed any further! It is considered downright sacrilegious to attempt to imbue the content of faith with the content of thought, or to warm the content of thought with the content of faith. And then came the most sobering of all, Kantianism, which, alongside its critique of pure reason, posited a critique of practical reason, morality alongside science, thereby creating a terrible chasm between what must be felt and experienced as unified in human nature. And it is under these conditions that European civilization still lives. It is under these conditions that European civilization will increasingly decline. The religious impulse was accepted as something foreign from the East and did not become organically connected with the rest of Europe's spiritual and physical life. This must be said with regard to the spiritual life of Europe.

You see, the progress of modern civilization has been praised enough. It has been praised until millions of people within this civilization have been beaten to death and three times as many have been crippled. The unctuous speeches have resounded from all the church pulpits until endless blood has been shed. The vaunted progress has been proclaimed from all the pulpits until this progress has led to its own nullity. Salvation will not come until we look impartially at these things. And today, people of Leninist and other persuasions are thinking about socialism and economism, and our economic and social order is to be reformed on the basis of concepts that have long since proved inadequate for guiding European civilization, without any new concepts or rethinking.

I believe I have already mentioned here what beautiful concepts our learned gentlemen have come up with in this area, for example. It is too beautiful, so I would like to discuss this matter again here. There is a famous economist, Lujo Brentano. Some time ago, he published an article entitled “The Entrepreneur.” Brentano attempts to construct the concept of the capitalist entrepreneur. He brings together the characteristics of the capitalist entrepreneur. The third characteristic that Lujo Brentano cites is that the entrepreneur uses the means of production at his own risk and peril in the service of humanity. Now, the good Lujo Brentano examines the function of the ordinary manual laborer in social life and says: The physical labor power of the manual laborer is his means of production; he uses it in the service of society at his own risk and peril. So the worker is an entrepreneur. There is no difference between an entrepreneur and a worker; they are one and the same! — You see, this is how confused what is called scientific thinking has become today, that when people form concepts, they can no longer distinguish between the two opposite poles.

This is not so easy to notice in Brentano as it is, for example, in a philosophy professor in Bern who, among other things, has the habit of writing an awful lot of books and who had to write so quickly that he could not think carefully about what he was writing. But he taught philosophy at the University of Bern. And lo and behold, in one of the books by this philosophy professor from Bern, the following sentence was found: Civilization can only develop in the temperate zone, because it cannot develop at the North Pole—it would freeze to death there—and it cannot develop at the South Pole either, because it is hot there, in contrast to the North Pole, where civilization would burn up! It is indeed true that a genuine professor of philosophy once wrote in a book that it is cold at the North Pole and hot at the South Pole because he wrote so quickly that he couldn't think it through properly!

The economic errors of the good Brentano are basically born out of the same superficial view as much else in Europe. For one regards what is there as the given and links one's conceptual schemes to what is there at the moment. This is what we learn from the scientific method, this is what we practice in scientific institutions, and this is what people today—in an age when, of course, no authority is accepted—repeat faithfully. For when we hear that someone is an authority today, that is a reason to assume that he is telling the truth! One does not accept it as truth out of insight, but because he is an authority. And so one also regards economic facts as if they had the same meaning side by side, whereas in fact they are interlocking elements that must be considered separately.

Just as European civilization received its religious impulse from the East, so something else was necessary for the economic structure of Europe. As the fifth post-Atlantic period, the middle of the 15th century, approached, it was also the time when those events occurred that gave modern civilization its basic character, its physiognomy: the discovery of America, the discovery of the sea route to the East Indies via the Cape of Good Hope; these events shaped modern civilization. And the entire economic development of Europe cannot be studied in isolation. It is nonsense to believe that by studying economic facts one can arrive at the economic laws that govern European society. These laws can only be discovered if one constantly bears in mind that Europe was able to export countless things to America. And the entire social structure Table 4

of Europe only came into being because there was always new land over in America, and what Europe sent to the West flowed into this new land. Just as it received its religious impulse from the East, it sent its economic impulse to the West. Under the influence of this current, its own economy developed, just as its spiritual life developed under the influence of the religious impulses from the East. European life, the entire process of the emergence of European civilization, developed in the centuries of modern times under these two currents. European civilization was in the middle, the religious impulse flowed in from the East (see drawing in purple), and the economic impulse flowed out to the West (red). The influx of the religious impulse from the East and the outflow of the economic impulse to the West was what lived in the course of European civilization.

And this reached a certain crisis at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century. Things began to stagnate. Things began to no longer function as they had for four centuries. And we stand and live today under the influence of this stagnation. The religious impulse has crept in like something foreign and has created spiritual life among us. And our economic life has come about as a result of undergoing constant dilution. If America had not been there and our economy had had to develop according to its own laws, if it had not been able to constantly expel what it did not need, it would not have been able to develop in Europe. That is now coming to a standstill. Therefore, an inner way out must be found. The possibility must be found from within to bring into the right channel that which can no longer be done spatially from outside.

This is to be achieved through the threefold social order. This is to be achieved by means of a genuine organic structuring of that which has become inorganically intertwined. There is not one reason for accepting the threefold social order, but many possible reasons: scientific reasons, economic reasons, historical reasons. Only those who are able to see all these different reasons can fully judge the validity of the threefold social order.

One would like to say this to the people of today, for they suffer from a poverty of concepts that has gradually become terrible. This poverty of concepts has become so great that anyone who has a sense for ideas today finds that only a very small number of ideas, which are found everywhere, actually prevail in our spiritual life. Those who search for ideas find themselves in the following situation: they study a work on physics; this work contains a certain number of ideas. Then, for my sake, they study a work on geology; they find different facts, but they find exactly the same ideas. Then they study a work on biology; they find different facts, but they find the same ideas. They study a psychological book about the life of the soul: they find other facts, but these actually consist only of words, because the soul is really only known as a sum of words. When we speak of wanting, there is a word; we know nothing of real wanting. When we speak of thinking, we know nothing of real thinking, because people only think in words anymore. We also know nothing of feeling. The whole field of psychology today is a game with words that are jumbled together in all sorts of ways: just as the stones in a kaleidoscope are rearranged into different groups, so it is with our concepts. They are jumbled together differently in our various sciences, but there is only a very small number of ideas that recur again and again, that are imposed on the facts. And people do not rush to find the appropriate concepts for the thing, to explore the appropriate ideas for the thing! They simply do not notice things.

Some time ago, a congress of radical socialists took place in a city in Central Europe. These radical socialists were concerned with devising a social structure for Europe. It is roughly the same social structure that you can now read about in a series of articles in the Basel newspaper Vorwärts. What is peculiar about this social structure? People find it very ingenious; they think it cannot be any other way. But it has become what it is solely because it was created by people who have never really had anything to do with economic life, who have never gotten to know the real sources and driving forces of economic life. It was created by people who participated in the political life of the last few decades. How did people participate in the political life of the last few decades? Well, you were either a voter or an elected representative. As a candidate, you were either elected in the primary election or in the runoff election. Let's say you weren't elected in the primary election, but you had already spent your huge campaign funds. You had collected donations, raised enormous sums of money, so that you would have enough voters to get elected. These sums had been spent. You had launched a terrible campaign against your opponent, who was a scoundrel and a crook, if not something even worse. Now came the runoff election. Until then, no party had had a majority, so now it was a matter of electing one of those who had a relative majority. Then came the other procedure: they had a third of the election funds spent by their opponent, who had previously been a scoundrel, a rogue, and a cheat, paid back! They had it paid back and suddenly turned into orators who said: After all, it is necessary that this man be elected! — The man who had previously been a scoundrel, a rogue, and a cheat now had to be elected. After all, they had got back a third of the election funds, and gradually, motivated by this interest in getting back a third of the election funds, they turned into people who now supported him. For one of the two had to be elected, the other had no chance; at most, there was still a third of the election funds to be gained.

So, you see, they had participated in this political life; they had participated in how political administration was talked about. They had learned how to direct things from official positions and so on; in short, they had become familiar with the entire political machinery, but they didn't have a clue about economic life. What one had now acquired in terms of political concepts—concepts that had, of course, been greatly corrupted, but at least they were political concepts—one simply wanted to impose on economic life. And so, if one carried out what was being proposed, one would end up with an economic life with a purely political structure. Today, people already confuse the structure of economic life with the political structure; they can no longer distinguish between what has gradually become intertwined and intertwined. But it would already be necessary today to spread understanding in many, many places about what is really going on. People today do not want to go into that.

Now, one should not believe that under the influence of civilization, which does not look at external reality but tyrannizes it with a few fixed concepts, that one can approach the true reality that is to be sought through anthroposophically oriented spiritual science with such a sum of concepts. For it is precisely through anthroposophically oriented spiritual science that true reality is to be sought. Therefore, anthroposophically oriented spiritual science must not be taken according to the pattern of what was often called religious confessions in the past.

You see, people suffered terribly from this in the old theosophical movement. What was this old theosophical movement other than a desire to have a kind of extra religion? It did not consist of a new impulse that had emerged from European civilization itself, but consisted only of feelings that were also present in the old religious element. It was just that these old religious concepts, ideas, and feelings had become boring, and so people turned to something else. But they were permeated by the same atmosphere that permeated the old creeds. People wanted to be just as devout as they had been Protestant if they were Protestant, or Catholic if they were Catholic; but basically they did not want what they needed: a real new religious impulse alongside other impulses – because the European population had become accustomed to life through a foreign, Asian religious impulse. That is what matters. And until those things that were previously only inorganically pushed together are organically interwoven, there will be no rise of European civilization. This must be taken very seriously, and it must permeate everything that has to live in science, in economics, in religiosity, and in political life.