Spiritual Science as a Foundation for Social Forms

GA 199

3 September 1920, Dornach

Lecture XII

In our spiritual-scientific endeavors, it is important to acquaint ourselves gradually from the most diverse points of view with what we are supposed to understand. One can say that, particularly in regard to spiritual-scientific subjects, the world expects an uncomplicated, facile approach towards conviction; however, this is not easily provided. For as far as spiritual-scientific facts are concerned, it is actually necessary to attain our conviction in a gradually evolving manner. To begin with, this conviction is still weak. One becomes acquainted with the same things from ever changing new viewpoints; thus, conviction increasingly gains in strength. This is the one premise from which I should like to start today. The other will relate to various matters that I have discussed here for weeks; it will relate to what has been said concerning the differentiation of humanity throughout the civilized world.84 See Lecture VII of this volume. Let me indicate briefly a few of the most salient facts that are of some importance to our considerations in the next three days.

I have pointed out in what sense the Orient is the source of humanity's essential spiritual life. I then indicated that in the central areas, in Greece, Middle Europe and the Roman Empire—what must be discussed covers vast periods of time—there primarily exists the predisposition for developing the legal, political concepts. The West is notably predisposed to contribute economic concepts to the totality of human civilization. It has already been mentioned that when we look across to the Orient, we find that the life of its civilization is basically decadent today. In order to evaluate properly what the Orient really signifies for the whole of human civilization, we have to turn back to more ancient periods of time. Among the historically accessible documents which are proof of the Orient's essential nature, the Vedas, the Vedanta philosophy, stand out above all; they and others are in turn evidence, however, of what was present in the Orient in still more ancient epochs. They indicate how a cultural life was born out of a primeval, wholly spiritual disposition of Oriental humanity. Subsequently, for the Orient too, ensued the times of obscuration of this spiritual life. Yet, a person who is able to contemplate in the right way what is happening in the Orient at present—although it is a mere caricature of what was formerly there—even today will still note the aftereffect of the ancient spiritual life in the decadent phenomena.

During a somewhat later period, the essentially legalistic, political thinking developed throughout the central regions of the earth. It evolved in ancient Greece and Rome, later on in the regions spread over Europe from the Middle Ages onward. The Orient originally possessed no actual political thinking, particularly not what we today define as juridical thinking. This is not in contradiction to the existence of codes of law such as Hammurabi's and others. For if you study the contents of these codes, you recognize from the whole tone and attitude that you are dealing with something quite different from the mode of thinking defined in the Occident as juridical. It is only in recent times that an actually economic form of thinking has developed in the West. As I have already explained, even science as it is practiced now is assuming those forms that really belong to the economic life.

As far as the Oriental spiritual life is concerned, it is interesting to observe how everything that the Occident has possessed up to now is basically also a legacy of the Oriental spiritual life, although in metamorphosed forms. Some time ago, I pointed out here how considerably this spiritual life of the Orient has been transformed in Europe. We are confronted by the fact that the capacities that held sway in the Orient have yielded up a perception of the immortal human soul, but in such a manner that this immortality was intrinsically bound up with prenatal existence before birth. The soul perception of the Oriental mind had a view, above all else, of preexistent life, of the soul's life between birth and death preceding this earthly existence. Everything else followed in consequence of this in a manner of speaking. From this view resulted the mighty relationships, only dimly glimpsed by the Westerner to this day, that one might call the karmic relationships, which subsequently left a reflection, albeit only a faint one, in the Greek concept of destiny. What is it, really, that passed over, that flowed across into the Occidental version of those concepts, even those with which an attempt was made to understand the Mystery of Golgotha? It was something that was strongly tinged by legalistic thinking. There is a radical contrast between contemplating the path of the soul in the sense of the Oriental world conception as descending from a spiritual world into the physical realm, noting how the karmic relationships are viewed there from wide perspectives, and considering the juridical idea of holding court over the soul that, in the Occident, has invaded these Oriental concepts. We need only recall Michelangelo's magnificent painting in the Vatican, in the Sistine Chapel, where the World Judge, like a cosmic magistrate, adjudicates upon good and evil men. This is the Oriental world view translated into Occidental legalism; this is in no way the original Eastern world conception. This legalistic thinking lies entirely outside Oriental perception. Indeed, the more advanced the concept of the spirit became in Central Europe, the more it culminated in the Roman legalistic element.

Hence, in the central regions, we are dealing primarily with the element predisposed for the juridical and political thinking. Civilization is, however, not only differentiated over the earth in this manner but in yet another way. If we study the accomplishments of the East, if we consider the special nuance of Oriental soul life, in particular where it is at its greatest, we find that this soul life is most eminently atavistic and instinctive, notwithstanding the fact that its fruits are primarily cultural; and all of mankind has continued to sustain itself on them. This spiritual life emerges out of unconscious imaginations that are, however, already muted by a certain ray of consciousness. Nevertheless, it contains much that is unconscious and instinctive.

The spiritual life produced by humanity up until now is indeed brought forth in a way that points to the highest spheres of which the human soul can partake, but the lofty heights of these spheres were reached in a sort of instinctive flight. It does not suffice to retrace the concepts or images produced by the Orient. Rather, it is necessary to focus on the singular kind of spiritual and soul life, by means of which, especially in its flowering time, the Oriental arrived at these conceptions. To be sure, we only gain an idea of this distinctive soul quality that I have already characterized by relating it with the life of the metabolism, if we want to have a feeling for the whole original soul structure contained in the Vedas and other texts. We simply must not overlook the fact that the Orient has reached its decadence today; for example, we should in no way confuse the mystic, nebulous manner which, despite his greatness, distinguishes Rabindranath Tagore,85 See Note #54 from the true essence of Oriental soul life. For, although Rabindranath Tagore possesses what has been handed down to this day of the ancient Eastern soul life, he permeates it with all manner of modern, Western European affectations and is, above all, an affected individual.

Spiritual science must indeed lay hold of these matters, step by step, and in such a way that we do not merely accept some rigidly set up concepts, but really envision the unique soul nuance involved here. Thus, we find in the Orient an instinctive cultural life, permeated through and through with the trend for the legalistic and political soul life developing in the central regions. There, we come to the development of the half instinctive, the half conscious. It is most interesting to examine how a purely juridical thinking is produced from the souls of people, say, like Fichte, Goethe, Schelling or Hegel. It is purely juridical, but it is partly instinctive, partly a fully conscious thinking; something that is, for example, the special charm of Hegel's mode of thinking. A completely conscious element only appears in the Western soul, where consciousness develops out of the instincts themselves. The conscious element is still instinctive in the Western soul, but instinctively the conscious emerges in Western economic thinking. Here, for the first time, mankind is called upon to attain to a conscious penetration of even public, social affairs.

Now we come across something quite strange. One might actually recommend that those to whom it matters for one reason or another should now try to understand the configuration of civilized humanity's thinking by becoming acquainted with the attempts of the English thinkers to arrive at a mode of social thinking, say, the attempts of Spencer, Bentham, particularly Huxley, and so on. These thinkers are indeed all rooted in the same atmosphere of thought in which Darwin was rooted; they all really think as Darwin thought, except that they try, as does Huxley, to develop a social view out of their scientific way of thinking. A strange feeling pervades us when we delve into the attempts by Huxley86 Thomas Huxley: 1825–1895. to achieve a social thinking, for instance, about the state, about the legal aspects of human relationships. It gives one a strange feeling. Let us suppose the following: Someone wishes to acquire a sense, a feeling for what I have here in mind, and to that end reads Hegel's book on natural rights,87 Friedrich Hegel: Grundlinien einer Philosophie des Rechts, 1821. on political sciences, Fichte's philosophy of rights,88 Johann Gottlieb Fichte: Grundlage des Naturrechts, 1796. or something else by a minor Middle European mind; afterwards, he reads, possibly, Huxley's attempts to advance from scientific to political thinking. He would experience something like the following. He would say to himself, "I read Hegel and Fichte; the concepts here are fully developed, they have strong contours and are precisely drawn. Now I read Huxley or Spencer, and I find the concepts primitive; it as though one had just begun to contemplate these questions. Confronted by such things, it does not do to say, “Well, the one was perfect, the other imperfect.” This does not suffice at all when one confronts realities.

Let me present to you a parallel taken from an entirely different realm. It can happen that one lectures on some spiritual-scientific subject, say, the former embodiment of the earth, the Moon embodiment. A variety of facts are set forth. Someone reads or listens to this lecture who is clairvoyant in a quite atavistic manner. It could be an individual who is outwardly illogical, who in practical life is unable to put five words together in logical sequence, who is inept in everything and therefore of no use in ordinary life. Such a person listens to what is being related about the configuration of some Moon era. Now, this same person who is quite dull and blundering in outer life and unable to count up to five properly, yet who is atavistically clairvoyant, can take in what he has heard, enlarge upon it, develop it further and discover additional facts not mentioned earlier. The things that such a person then adds can be infused with extraordinarily penetrating logic, a logic that arouses admiration, while, in everyday life, this person is clumsy and illogical. This is entirely possible, for if someone is atavistically clairvoyant, it is not his ego that joins his images together in a logical manner, although he can discover the images by himself. The images are joined by various spiritual beings dwelling within him. We become acquainted with their logic, not his.

This is why we cannot simply say that one view is on a higher, the other on a lower level; in every case we have to go into the specific character of the matter. This is true here too. The views of Fichte, Hegel and other less illustrious minds are half instinctive, only partly fully conscious ones. What arises, on the other hand, in the West as primitive economic thinking is indeed fully conscious. The concepts such as those thought out by Huxley, Spencer and others are impertinently conscious, but conceived in a primitive way. What had appeared in former times in instinctive or half instinctive form emerges here consciously but in quite an elementary way. I shall illustrate this by means of a concrete example.

Huxley tells himself that if we observe nature—he naturally looks at it from the Darwinian standpoint—we find the struggle for survival. Every creature fights ruthlessly for self-preservation, and the whole animal kingdom's struggle is waged so that the naturally strong survive by annihilating the weak. This theory has penetrated into Huxley's flesh and blood. This, however, cannot be continued on into humanity. Freedom such as we must seek in human social life is nonexistent in nature, for there can be no freedom—thinks Huxley—in a realm where every creature must either assert itself ruthlessly or perish. There can be no equality where the fittest must always eliminate the less fit. Now Huxley turns from the natural realm to the social sphere and is compelled to conclude that, indeed, this is true, but in the social realm goodness should prevail, freedom should reign. Something should come to pass that as yet cannot be found in nature.

It is again the great chasm that I have characterized from so many points of view. Once, Huxley very aptly calls man “the splendid rebel,” who, in order to establish a human kingdom, rebels against all that prevails in nature. Something therefore ensues here that is not yet found in nature. Now again, Huxley actually thinks along scientific lines. He is compelled to search for natural forces in man that constitute the social life and rebel against nature herself. He looks in man for something concrete that serves as the basis for the human social community. The other forces of the kingdoms of nature cannot establish this social community; in nature, the struggle for survival holds sway, and there is nothing that could hold humanity together in a social structure. Nonetheless, as far as Huxley is concerned, there is nothing but this natural cohesion. Hence, this “splendid rebel” must in turn have natural forces which, although they are forces of nature, rebel against the natural forces in general. Now, Huxley finds two natural forces that are at the same time the basic forces of the social life. The first one is actually worked out wrongly, for it is not yet capable of establishing a social life, only family egoism. It is what Huxley calls the family attraction, something that is active within blood relationships. The second force he lists that could form a sort of natural foundation for the social life is something that he calls “the human instinct for mimicry,” the human talent for imitation.

Now, there is something that appears in the human being in the sense referred to by Huxley, namely, the faculty of imitation. It means that one person follows what the other does. This is the reason the individual pursues not merely his own directions, but society as a whole, the social life, runs along the same lines, as it were, because one person imitates the other. This is as far as Huxley goes. It is very interesting, because you know that in describing the human being we list the following: The element of imitation from the first to the seventh year; from the seventh to the fourteenth year, the element of authority; the one of independent judgment from the fourteenth to the twenty-first year. All three, of course, participate in the social development. Huxley, however, stops short at the first; he is only laboring to emerge from the primitive level. He has taken hold of nothing but the force that is active in the human being only until his seventh year. We are confronted with nothing less than the fact that if the social community as envisioned by Huxley were actually to exist, it would have to consist entirely of children; human beings would have to remain children perpetually. Thus, in envisioning the social life, Western society has, in fact, only advanced to the stage applicable to children. The social science striven for in full consciousness has progressed no further than this That is most interesting.

Here, you can detect the primitive aspect in connection with a particular element. The West works its way out of the scientific-economic thinking and attains something in a conscious manner that has been reached in the central regions in a half conscious, half instinctive way on a higher level. We can actually follow up these things in detail and they can thus become most interesting. All matters brought to light by spiritual science can invariably be followed up by means of details. It only requires a sufficiently large number of people to develop enough diligence to pursue all details of spiritual-scientific matters.

Is it not actually rubbed into us in this instance that something else must be present that cooperates in the social development of existence? For, certainly, social structures cannot be established in which only forces of imitation hold sway. Otherwise, they could only contain children; human beings would have to remain children forever, if the social life would originate only through mutual imitation. In order to arrive at something that can throw light on the primitive attempts, and can also bring together East, Middle and West, we must proceed from initiation science. This means that we have to link the train of thought that we tried to connect with the above to what initiation science can offer to humanity, so that mankind may be capable of developing a social life truly structured in conformity with the Spirit.

People fail to observe how the environment of the human being is pervaded with quite clearly differentiated forces. Modern science has reached the point where it states that we are surrounded by air, for we inhale and exhale it; but there is something that is even more obvious in our life than “the air around us,” something that people fail to notice. Take the following simple fact that no one today takes into consideration, yet is something that could be understood by anybody. An animal kingdom is spread out around our human kingdom. This animal kingdom includes creatures of every imaginable form. Let us picture to ourselves this whole manifold animal kingdom around us. In the case of a table, everybody knows that there are forces present that gave this table its shape. In regard to the animal kingdom surrounding us, we ought, naturally, to assume the same, namely, that just as air is present, so, in the environment, the forces are contained that bestow form upon the creatures of the animal kingdom. We all dwell within the same realm. The dog, the horse, the oxen and donkey do not move about in a different world from the one which we also inhabit. And the forces that bestow the donkey shape on the donkey affect us human beings too; yet—forgive me for speaking so bluntly—we do not acquire the form of a donkey. There are also elephants in our environment, but we do not assume the shape of elephants. Yet all the forces fashioning these shapes surround us everywhere. Why is it that we do not take on the forms of, say, a donkey or an elephant? We possess other forces that counteract them. We would indeed acquire these shapes if we did not have these other opposing forces. It is a fact that if we as human beings confront a donkey, our etheric body constantly has the tendency to assume the shape of a donkey. We restrain our etheric body from doing so only because we have a physical body possessing a solid form. Again, if we face an elephant, our etheric body endeavors to assume the elephant shape and is prevented from doing so only because of the physical body's solid shape. Whether it be elephant, stag-beetle or dirt-beetle, the etheric body tries to assume the shapes of any and all creatures. Potentially, all the forms are present in our etheric body, and we comprehend these forms only when we retrace them inwardly, as it were. Our physical body merely prevents us from turning into all these shapes. Therefore, we can say that we carry the entire animal kingdom within our etheric body. We are human only in our physical body. In our etheric body, we bear with us the whole animal kingdom.

Again, there flows all around us the same complex of forces that creates the plant forms. Just as our etheric body is predisposed to assume all animal shapes, our astral body is inclined to reproduce all the plant forms. Here it is already more pleasant to make comparisons, for, while the etheric body is imbued with the tendency to become a donkey when it sees one, the astral body wishes merely to become the thistle on which the donkey feeds. But this astral body is definately ensouled with the tendency to accommodate itself to those forces that find their external expression in the plant forms. Thus we may say that the astral body reacts to the complex of forces that shapes the plant kingdom.

The mineral kingdom is again a force complex that develops the various shapes of this specific realm. This acts within our ego. It is quite evident in the case of the ego, for you only think in terms of the mineral realm. After all, it has been reiterated time and again that the intellect can only grasp the inanimate. Hence, what is contained in the human ego understands the lifeless. Consequently, our ego dwells in the complex of forces that creates the mineral kingdom. The physical body, as such, lives in none of these realms; it has, as you know, a realm of its own. In my Occult Science, an Outline, the mineral, plant and animal kingdoms are dealt with separately; this signifies that the physical body possesses a domain of its own. The animal kingdom, on the other hand, is actually found in the etheric body; as far as this viewpoint is concerned, the plant kingdom is found in the astral body, and the mineral kingdom in the ego. From my various books, however, you are familiar with something else. You know that during earthly life these various bodies are worked upon. I have described how the ego, the astral body, the etheric body and even the physical body are worked on. I initially outlined it there, I might say, from the human, the humanistic intention. Now let us try to depict it from another point of view.

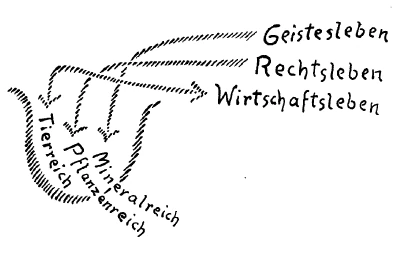

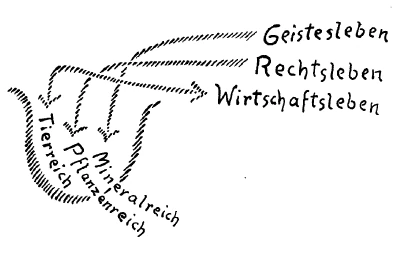

Take the mineral concepts that the human being acquires. He experiences the external world, after all, by experiencing it in mineral concepts and forms. Only enlightened minds like Goethe work their way up to the pictorial forms, to the morphology of plants, to metamorphosis. Here, the shapes are transformed. The ordinary view, still prevailing today, on the other hand, only dwells in the solid, mineral forms. If, now, the ego works on these forms and develops them, what is the result? Then, the result is the conscious cultural life, one of the domains of the threefold social organism. The ego creates the cultural life while working inwardly upon itself. All cultural life is, in fact, inner formative development of the ego. What the ego acquires from the mineral realm and in turn transforms into art, religion, science, and so forth, that is the cultural sphere, the transformed mineral kingdom, the spiritual realm.

What results from the tendency of the astral body, residing in the subconscious depths of most human beings, to assume every plant form possible? When you transform this tendency indwelling the astral body, when it radiates up into consciousness in half instinctive, half conscious form, what comes about then? The domain of rights, of the state, comes about.

Now, if you comprehend what holds sway in the relationships between human beings, namely, what is now, within external life, transformed from man's experiences of animality in the ether body, then you arrive at the third domain of the threefold social organism. Were we to stop at the etheric body as it comes to us from birth, we would only have the tendency in this etheric body to turn now into a donkey, now into an oxen, now into a cow, now into a Butterfly. We would reproduce the entire animal kingdom. As human beings we do not merely do this, however, we also transform the ether body. We accomplish this within the social life by living together with others. When we face a donkey, our etheric body wishes to become a donkey. When we confront another human being, we certainly cannot say without uttering a real insult that now, too, we wish to turn into a donkey. This is not possible, at least not in ordinary life; here we must change in another way. I should like to say that, here, the transformation becomes visible; here, those forces come into play that are effective in the economic life. These are the forces that assert themselves when a human being confronts his fellowman in brotherliness. In this way, in the brotherly confrontation, those forces are active that represent the work on the etheric body; thus, through the work on this body, the third realm, the economic sphere, comes into being.

Animal Kingdom: Etheric Body Economic Realm

Plant Kingdom: Astral Body Realm of Rights, of State

Mineral Kingdom: Ego; Cultural, Spiritual Realm

Thus, just as man is connected on the one side with the animal kingdom through his etheric body, he is related on the other side in the external environment with the economic sphere of the social organism. We could say that if man is viewed inwardly, spiritually, from the physical body towards the etheric, we find the animal kingdom within man. Outwardly, in his surroundings, we find the economic life.

When we penetrate into the human being and search out what he represents by virtue of his astral body, we find the plant kingdom. Outwardly, in the social configuration, the life of rights corresponds to the plant kingdom. Again, penetrating the human being, we discover the mineral kingdom corresponding to the ego. Outside, in the environment, corresponding to the mineral kingdom, we have the cultural life. Thus, through his constitution, man is linked to the three kingdoms of nature. By working on his whole being, he becomes a social being.

You see that we can never arrive at a comprehension of the social life if we are not in a position to ascend to the etheric body, astral body and ego. For we do not understand man's relationship to the social order if we don't ascend like that. If one proceeds merely from natural science, one stops short at the “human instinct for mimicry,” the faculty of imitation; one cannot progress. In thoughts, one makes the whole world puerile, for it is the child that still retains most of the natural forces. If one wishes to advance further, one needs the insight into initiation science. We need the insight into the fact that the human being is bound up with his etheric body through the animal kingdom, with the astral body through the plant world, and with the ego through the mineral realm. We need to know that owing to his observation of the mineral world man attains to his cultural life; that due to the transformation of the deep instincts harbored by him and owing to his kinship with the surrounding plant world he attains to the life of rights, of the state. We realize that these deep instincts correspond to the sphere of rights and the state. This is why, at first, the life of the state contains so much of the instinctive element if it is not infused with the cultural element of jurisprudence. Finally, we have the economic sphere which basically represents the metamorphosis of those inner experiences gained in the etheric body.

Now, these experiences are not brought to the surface from within by the science of initiation, for Huxley is not motivated in any sense by initiation science to explore the connection between man and the economic life. He observes the exterior, the conditions economically present outside. The whole complex of relations between the economic sphere, the etheric body and the animal kingdom is unclear to him. He looks at what is outwardly present. Consequently, he can certainly not advance beyond the most primitive, elementary level, the faculty of imitation.

From this we realize that if people would wish to continue extracting social thinking from modern science, they would remain caught up in absurdities and something quite dreadful would have to ensue. Over the whole earth, a social life would have to arise that would bring about the most primitive conditions; it would lead humanity back to a puerile social life. Gradually, untruth and lying would become a matter of course simply because people could not do otherwise even if they wanted to. They would be thirty, forty, fifty or even older, yet they would have to behave like children, if, with their consciousness, they only wanted to comprehend what is derived from science. People would only be able to develop the instincts of imitation. Even today we frequently have the feeling that only these instincts of imitation are being developed. We watch the appearance, somewhere, of yet another reform movement of a radical nature. It really only contains the instincts of imitation derived from some university philistine. Much of what, today, looks most illustrious when given the polish derived from the customary falsehoods would appear very different in the light of initiation science. Modern comprehension of the world, however, is limited to what can be seen in the light of the concept of imitation unless one is willing to advance from ordinary, official science to the science of initiation, the science that draws its substance from the inner impulses of existence.

Thus I have tried to show you how the aspects that are lacking in the present, the very. aspects through which it becomes evident where the present age must remain stuck because of its inability to penetrate reality, can be fructified and illuminated by the science of initiation.

Zwolfter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Es handelt sich gegenüber den geisteswissenschaftlichen Bestrebungen darum, daß man dasjenige, was eingesehen werden soll, nach und nach von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten her kennenlernt. Man kann sagen, die Welt erwartet gerade von dem, was geisteswissenschaftlich ist, eine leichtgeschürzte Überzeugungsmöglichkeit. Allein, die ist nicht so ohne weiteres zu schaffen. Denn gegenüber den geisteswissenschaftlichen Tatsachen handelt es sich darum, daß man die Überzeugung eigentlich entwickelungsgemäß erhält. Sie beginnt mit einem gewissen Stadium, das noch schwach ist, und man lernt dann dieselben Dinge von immer neuen und neuen Gesichtspunkten kennen, und dadurch verstärkt sich immer mehr und mehr diese Überzeugung. Das ist das eine, von dem ich heute ausgehen möchte. Das andere möchte anknüpfen an verschiedenes, das ich seit Wochen hier zur Erörterung gebracht habe, anknüpfen an dasjenige, was gesagt worden ist über die Differenzierung der Menschheit über die zivilisierte Erde hin. Nur kurz lassen Sie mich einige der wesentlicheren Tatsachen andeuten, die für unsere Betrachtungen in diesen drei Tagen von einiger Wichtigkeit sind.

[ 2 ] Ich habe darauf hingewiesen, in welchem Sinne der Orient die Quelle des eigentlichen Geisteslebens der Menschheit ist. Ich habe dann darauf hingewiesen, daß in mittleren Gegenden, Griechenland, Mitteleuropa, das Römische Reich — es erstreckt sich ja das, was zu sagen ist, über weite Zeiträume -, vor allen Dingen die Anlage dafür vorhanden ist, die rechtlichen, die staatlichen Begriffe zur Ausbildung zu bringen, und daß der Westen vorzugsweise daraufhin veranlagt ist, die wirtschaftlichen Begriffe zu der Gesamtzivilisation der Menschheit beizusteuern. Wenn wir nach dem Orient hinüberschauen — auch das ist ja schon erwähnt worden -, so finden wir, daß heute sein zivilisatorisches Leben im wesentlichen in der Dekadenz ist, und wir müssen, um so recht einzusehen, was der Orient eigentlich für die Gesamtzivilisation der Menschheit ist, in ältere Zeiträume zurückgehen. Von den geschichtlich erlangbaren Dokumenten, die ein Beweis dafür sind, was der Orient ist, leuchten uns ja vor allen Dingen die Veden, die Vedantaphilosophie aus dem Orient entgegen und manches andere, was aber wiederum Zeugnis ist von dem, was in noch älteren Zeiten im Orient vorhanden war. Und diese Dinge weisen darauf hin, wie aus einer ursprünglichen, ganz geistigen Veranlagung der Menschheit des Orients ein Geistesleben geboren worden ist. Dann kamen für den Orient auch die Zeiten der Verdunklung dieses Geisteslebens. Wer aber das, was heute im Orient geschieht, selbst wenn es nur noch die Karikatur des Alten ist, in richtiger Weise ins Auge zu fassen versteht, der sieht auch heute in den dekadenten Dingen noch immer die Nachwirkung des alten Geisteslebens.

[ 3 ] In einer etwas späteren Zeit hat sich über die mittleren Gegenden der Erde hin, im alten Griechenland, im alten Rom, später in jenen Gebieten, die sich vom Mittelalter ab über Europa ausgebreitet haben, entwickelt, was das eigentliche rechtliche oder staatliche Denken ist. Der Orient hatte ursprünglich kein eigentliches staatliches, hatte vor allen Dingen nicht das, was wir ein juristisches Denken nennen. Dem widerspricht auch nicht, daß es etwa Gesetzbücher gibt wie die des Hammurabi und dergleichen. Denn wer den Inhalt dieser Gesetzbücher nimmt, der wird aus dem ganzen Ton und der ganzen Haltung erkennen, daß es sich da um etwas anderes handelt als um eine Denkweise, die wir innerhalb des Abendlandes als eine juristische bezeichnen. Und im Westen ist es erst die neueste Zeit, wo sich ein eigentliches wirtschaftliches Denken entwickelt. Selbst die Wissenschaft, wie sie da getrieben wird, nimmt, wie ich ja schon ausgeführt habe, die Formen an, die eigentlich in das Wirtschaftsleben hineingehören.

[ 4 ] Was das orientalische Geistesleben betrifft, so ist es ja interessant, zu beobachten, wie alles das, was das Abendland bisher gehabt hat, im Grunde genommen auch Erbe des orientalischen Geisteslebens ist, allerdings in Umwandlungen. Ich habe hier einmal aufmerksam darauf gemacht, wie sehr das orientalische Geistesleben sich umgewandelt hat innerhalb Europas. Da liegt ja doch die Tatsache vor, daß jene Fähigkeiten, die im Orient gewaltet haben, eine Anschauung der unsterblichen Menschenseele hervorgetrieben haben, aber so, daß diese Unsterblichkeit mit einer Ungeburtlichkeit eben wesentlich verbunden war. Das präexistente Leben, das Leben der Seele vor diesem irdischen Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod, das war vor allen Dingen das, was für den orientalischen Geist vor der Seele, vor der Anschauung der Seele lag. Das andere ergab sich gewissermaßen als eine Konsequenz. Und daraus ergaben sich dann jene großen Zusammenhänge, die vom Abendländer ja bis heute nur geahnt werden, die man die karmischen Zusammenhänge nennen kann, die dann einen Abglanz hinterlassen haben in der griechischen Schicksalsidee, aber nur einen schwachen Abglanz. Und was ist denn eigentlich übergegangen in das Abendland, selbst von denjenigen Begriffen, durch die man das Mysterium von Golgatha zu verstehen versucht hat, was ist denn übergegangen in diese abendländische Ausbildung? Etwas, was sehr stark gefärbt ist von juristischem Denken. Es ist etwas radikal verschiedenes, wenn man auf der einen Seite betrachtet den Weg der Seele im Sinne der orientalischen Weltanschauung, wie sie aus der geistigen Welt heruntersteigt in die physische Welt, wieder hinaufsteigt in die geistige Welt, wie man da nach großen Gesichtspunkten die Schicksalszusammenhänge ins Auge faßt, und das juristische Gerichthalten über die Seele, von dem diese orientalischen Vorstellungen im Abendlande durchdrungen worden sind. Man erinnere sich nur an das gewaltige Bild Michelangelos im Vatikan, in der Sixtinischen Kapelle, man erinnere sich daran, wie da der Weltenrichter wie der universelle Jurist über die Guten und über die Bösen urteilt. Das ist ins abendländische Juristische umgesetzte orientalische Weltanschauung, das ist in keiner Weise ursprüngliche orientalische Weltanschauung. Dieses juristische Denken liegt ganz außerhalb des orientalischen Anschauens. Und je weiter fortgeschritten gerade in Mitteleuropa die Anschauung vom Geistigen ist, um so mehr lief das Geistige in das Römisch- Juristische ein.

[ 5 ] Also in mittleren Gegenden haben wir es vor allem zu tun mit dem, was veranlagt ist für das Juristisch-Staatliche. Nun aber ist die Zivilisation doch nicht bloß in der Weise differenziert über die Erde hin, sondern auch noch in einer andern Weise. Wenn man eingeht auf das, was der Orient geleistet hat, wenn man die besondere Nuance des Seelenlebens des Orients gerade da, wo dieses Seelenleben am größten ist, ins Auge faßt, dann findet man, daß dieses orientalische Seelenleben, trotzdem es vorzugsweise Geistiges produziert, von dem, wie gesagt, die ganze Menschheit weiterzehrte, im eminentesten Sinne instinktiv, atavistisch instinktiv ist. Es kommt heraus aus unterbewußten Imaginationen, die allerdings schon von einem gewissen Strahl des Bewußtseins übertönt sind. Aber es ist viel Unbewußtes, viel Instinktives darinnen.

[ 6 ] So wird eigentlich das, was die Menschheit an geistigem Leben bisher hervorgebracht hat, so hervorgebracht, daß es hinaufweist in die höchsten Gebiete, deren die menschliche Seele teilhaftig werden kann; aber in einer Art instinktiven Höhenflugs wurden diese Gebiete erreicht. Es genügt nicht, wenn man den Begriffen oder den Bildern nachzeichnet, was der Orient ausgebildet hat, sondern man muß die besondere Art des Geistes- und Seelenlebens ins Auge fassen, durch die der Orientale gerade in seiner Blütezeit zu diesen Vorstellungen gekommen ist. Von dieser besonderen Seelenart, die ich hier auch schon charakterisiert habe, indem ich sie an das Stoffwechselleben anknüpfte, bekommt man allerdings nur eine Vorstellung, wenn man den ganzen ursprünglichen Seelenduktus von so etwas, wie die Veden und dergleichen sind, empfinden kann. Man darf eben durchaus nicht aus dem Auge verlieren, daß heute der Orient in seiner Dekadenz angekommen ist, und man dürfte zum Beispiel in keiner Weise jene mystisch-nebulose Art, die trotz seiner Größe Rabindranath Tagore auszeichnet, verwechseln mit dem, was wirklich das Wesen orientalischen Seelenlebens ist; denn Rabindranath Tagore hat allerdings dasjenige, was sich vom alten orientalischen Seelenleben bis heute herauf verpflanzt hat, aber er durchwebt es mit allen möglichen neueren westeuropäischen Koketterien und ist vor allen Dingen ein koketter Geist.

[ 7 ] Diese Dinge, die müssen nach und nach von der Geisteswissenschaft wirklich so erfaßt werden, daß man nicht bloß hingepfahlte Begriffe nimmt, sondern daß man die besondere Seelennuance, die dabei in Betracht kommt, wirklich ins Auge faßt. Also ein instinktives Geistesleben im Orient, durchwoben durch und durch von der Anschauung desjenigen, was sich als juristisch-staatliches Seelenleben entwickelt in den mittleren Gegenden. Da kommen wir dazu, daß sich das Halbinstinktive entwickelt, halbbewußt, halbinstinktiv. Es ist höchst interessant, wie, sagen wir, aus Fichtes, aus Goethes, aus Schellings, aus Hegels Seele heraus sich ein rein juristisches Denken ergibt. Es ist rein juristisch, aber es ist halb instinktiv und halb stark bewußt. Das ist zum Beispiel gerade bei Hegel das Reizvolle, dieses halb Instinktive und halb Vollbewußte. Und etwas ganz Bewußtes tritt erst auf im Westen, in der westlichen Seele, wo aus den Instinkten selber das Bewußtsein sich herausbildet — es ist das Bewußte noch instinktiv in der westlichen Seele, aber es kommt instinktiv das Bewußte heraus — in dem westlichen wirtschaftlichen Denken. So daß da zum ersten Male die Menschheit angewiesen ist, aus dem Bewußtsein heraus zu einer Durchdringung auch der öffentlichen sozialen Angelegenheiten zu kommen.

[ 8 ] Und da stellt sich denn etwas höchst Merkwürdiges heraus. Man könnte geradezu empfehlen, die Leute, denen es irgendwie darauf ankommt, sollten jetzt versuchen, die ganze Konfiguration des Denkens der zivilisierten Menschheit zu verstehen, sollten sich bekanntmachen mit den Versuchen, zu einer sozialen Denkweise zu kommen, bei den englischen Denkern, sagen wir Spencer, Bentham, namentlich Huxley und so weiter. Diese Denker wurzeln ja alle in derselben Denkatmosphäre, in der Darwin wurzelte, und sie denken alle eigentlich so, wie Darwin dachte, nur bemühen sie sich, zum Beispiel Huxley, aus ihrem naturwissenschaftlichen Denken ein soziales Denken herauszuentwikkeln. Man hat ja ein merkwürdiges Gefühl, wenn man sich so vertieft, sagen wir, in die Huxleyschen Versuche, zu einem sozialen Denken zu kommen, sagen wir über den Staat, über das rechtliche Zusammenleben der Menschen. Man hat ein eigentümliches Gefühl. Man nehme einmal folgendes an: Jemand wollte sich ein Gefühl von dem, was ich hier meine, verschaffen, und er würde zu diesem Zwecke, sagen wir, so etwas wie Hegels Buch über das Naturrecht oder die Staatswissenschaften oder Fichtes Rechtsphilosophie in die Hand nehmen oder irgend etwas anderes, auch von unbedeutenderen Geistern Mitteleuropas, und würde hinterher etwa Huxleys Versuche, aus dem naturwissenschaftlichen Denken in ein staatliches Denken hineinzukommen, lesen. Da würde man etwa folgendes erleben. Man würde sich sagen: Ja, jetzt lese ich Fichte, jetzt Hegel, das alles, das sind ausgebildete Begriffe, das sind Begriffe, die wirklich stark konturiert und intensiv gemalt sind. Und nun lese ich Huxley oder Spencer: das ist primitiv, das ist, wie wenn man eben anfangen würde, über diese Dinge nachzudenken. — Wenn man solchen Dingen gegenübersteht, kommt man nicht etwa damit aus, daß man sagt, das eine war vollkommen, das andere unvollkommen. Mit solchen Dingen kommt man überhaupt nicht aus, wenn man Realitäten gegenübersteht.

[ 9 ] Ich will Ihnen von einem ganz andern Gebiete her eine Parallele‘ sagen. Es kann einem vorkommen, daß man über irgend etwas aus der Geisteswissenschaft heraus vorträgt, sagen wir über die vorhergehende Verkörperung der Erde, über die Mondenverkörperung. Man gibt allerlei an. Irgend jemand liest das, oder hört zu, der in ganz atavistischer Weise hellsichtig ist. Das kann eine Persönlichkeit sein, die äußerlich unlogisch ist, die im gewöhnlichen praktischen Leben keine fünf Worte in logischer Weise aneinanderreihen kann, überall tapsig ist, so daß man sie zu dem oder jenem und zu allem andern auch noch dazu nicht gebrauchen kann im gewöhnlichen Leben. Nun hört solch eine Persönlichkeit das, was man eben über die Konfiguration irgendeiner Mondenzeit sagt, und die betreffende Persönlichkeit, die im äußeren Leben dumm und ungeschickt und so ist, daß sie kaum bis fünf ordentlich zählen kann, die aber atavistisch hellsichtig ist, die kann nun das aufnehmen, was sie da gehört hat, und sie kann es erweitern, kann weiteres ausbilden, und Dinge, die nicht gesagt worden sind, dazu finden. Aber die Dinge, die diese Persönlichkeit dann dazu findet, können von einer außerordentlich scharfsinnigen Logik durchzogen sein, von einer Logik, die bewunderungswürdig ist, während die Persönlichkeit im äußeren Leben tapsig und unlogisch ist, nicht fünf Worte logisch zusammenfügen kann. Das kann durchaus sein; denn wenn jemand atavistisch hellsehend ist, so fügt seine Bilder — und die Bilder kann er selber finden — in logischer Weise nicht sein Ich zusammen, sondern es fügen sie zusammen allerlei geistige Wesenheiten, die in ihm stecken. Deren Logik lernt man dann kennen, nicht seine Logik lernt man dann kennen.

[ 10 ] So darf man nicht so einfach sagen, das eine steht höher, das andere steht tiefer, sondern man muß überall auf den speziellen Charakter der Sache eingehen. Und so ist es auch hier. Fichtes oder Hegels oder minderer Geister juristische oder sonstige Anschauungen, die sind halb instinktiv, nur halb vollbewußt. Dasjenige, was aber da im Westen als primitives wirtschaftliches Denken auftritt, das ist nun allerdings ganz bewußt; impertinent bewußt sind solche Dinge wie diese, die von Huxley oder von Spencer oder dergleichen Leuten, aber in primitiver Weise ausgedacht werden; aber sie sind eben primitiv. Dasjenige, was früher in instinktiver Weise zutage getreten ist oder in halbinstinktiver Weise, das kommt da in bewußter Weise, aber so recht hübsch im Anfange zum Vorschein. Ich will Ihnen das an einem konkreten Beispiel verdeutlichen.

[ 11 ] Huxley sagt sich: Man betrachte die Natur — er betrachtet sie selbstverständlich im darwinistischen Sinne -, da ist Kampf ums Dasein. Jedes Wesen kämpft rücksichtslos für seine Selbsterhaltung, und das Ganze kämpft so, daß die in der Natur Stärksten übrigbleiben, indem sie die Schwächeren ausrotten. — Das ist ihm in Fleisch und Blut übergegangen, dem Huxley. Das aber kann sich doch nicht in die Menschheit herauf fortpflanzen. Freiheit, wie man sie im menschlich-sozialen Leben suchen soll, gibt es in der Natur nicht, denn Freiheit kann es nicht geben, meint Huxley, in einem Reiche, wo ein jedes Wesen entweder sich rücksichtslos selbst behaupten oder sterben muß. Gleichheit kann es nicht geben da, wo die Tüchtigsten immer die andern aus der Welt schaffen müssen. Nun sieht Huxley weg von diesem Naturreiche auf das soziale Reich, und nun ist er genötigt zu sagen: Ja, aber im sozialen Reich soll das Gute herrschen, soll Freiheit herrschen; da muß also etwas eintreten, was in der Natur noch nicht gefunden werden kann.

[ 12 ] Es ist wiederum die große Kluft, die ich schon von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten aus charakterisiert habe. Sehr schön nennt Huxley einmal den Menschen «the splendid rebel», den glänzenden Rebellen, der gerade, um ein menschliches Reich aufzurichten, Rebell ist gegenüber alledem, was in der Natur herrscht. Da tritt also etwas ein, was in der Natur noch nicht vorhanden ist. Aber nun denkt Huxley eigentlich wiederum naturwissenschaftlich. Da ist er genötigt, natürliche Kräfte im Menschen zu finden, welche das soziale Leben konstituieren, welche sich gegen die Natur selber auflehnen. Er will etwas Konkretes finden, was im Menschen ist und was die menschliche soziale Gemeinschaft begründet; denn die sonstigen natürlichen Kräfte der natürlichen Reiche können diese soziale Gemeinschaft nicht begründen, denn da ist Kampf ums Dasein, da ist nichts von alledem, was die Menschen in einem sozialen Zusammenhang eben zusammenhalten könnte. Und dennoch, fürHuxley gibt es ja wiederum nichts anderes als diesen natürlichen Zusammenhang. Also dieser «splendid rebel», der muß nun selber wiederum natürliche Kräfte haben, die eigentlich als Naturkräfte rebellieren gegen die allgemeinen Naturkräfte. Und da findet Huxley zwei Naturkräfte, die zugleich die Grundkräfte des sozialen Lebens sind. Die eine Naturkraft, die ist eigentlich per nefas aufgestellt, denn sie kann noch nicht eigentlich ein soziales Leben, sondern nur den Familienegoismus begründen. Es ist dasjenige, was Huxley die Familienanziehung nennt, also dasjenige, was innerhalb der Blutsverwandtschaft wirkt. Das andere aber, was er anführt, und was nun eine Art Grundlage bilden könnte, eine Naturgrundlage für das soziale Leben, das ist das, was er nennt «human instinct for mimicry», Nachahmungsbegabung des Menschen, Begabung für Nachahmung.

[ 13 ] Nun haben wir etwas, was im Menschen auftritt im Sinne von Huxley: Imitationskraft. Das heißt, der eine macht es dem andern nach, und deshalb geht nicht jeder bloß seine eigenen Wege, sondern es geht die ganze Gesellschaft, das soziale Leben gewissermaßen gleiche Wege, weil es einer dem andern nachmacht. Bis hierher kommt Huxley. Es ist interessant, denn Sie wissen, wir haben aufgestellt, wenn wir den Menschen verfolgen, vom ersten bis zum siebenten Jahre das Imitationselement, vom siebenten bis zum vierzehnten Jahre das Autoritätselement, und vom vierzehnten bis zum einundzwanzigsten Jahre das selbständige Urteilselement. Die wirken natürlich alle mit beim sozialen Gestalten. Aber Huxley bleibt beim ersten stehen; er arbeitet sich erst aus dem Primitiven heraus. Er hat nichts anderes als das, was im Menschen eigentlich nur bis zum siebenten Lebensjahre wirkt. Nichts Geringeres liegt eigentlich vor, als daß, wenn die soziale Gemeinschaft, wie sie Huxley sich denkt, wirklich bestehen würde, sie aus lauter Kindern bestehen müßte und die Menschen immer Kinder bleiben müßten. Also die soziale Gesellschaft dieses Westens ist eigentlich erst dazu gekommen, das soziale Leben so weit zu denken, wie es für Kinder gilt. Weiter ist sie noch nicht gekommen, die mit voller Bewußtheit angestrebte Sozialwissenschaft. Das ist außerordentlich interessant.

[ 14 ] Da sehen Sie das Primitive an einem besonderen Element. Da arbeitet aus dem naturwissenschaftlich-wirtschaftlichen Denken heraus dieser Westen und erlangt auf bewußte Weise etwas, was im mittleren Teile auf halbbewußte Weise oder auf halbinstinktive Weise auf einer höheren Stufe erlangt worden ist. Man kann diese Dinge geradezu im einzelnen verfolgen, und sie werden interessant, wenn man sie im einzelnen verfolgt. Alle Dinge, welche die Geisteswissenschaft zutage fördert, sie können immer durch Einzelheiten verfolgt werden. Es müßte nur bei einer genügend großen Anzahl von Menschen der genügende Fleiß entstehen, wirklich die Dinge der Geisteswissenschaft im einzelnen zu verfolgen.

[ 15 ] Ich möchte sagen: Wird man denn da nicht wie mit der Nase darauf gestoßen, daß ja nun auch noch etwas anderes da sein muß, was mitarbeitet an einer sozialen Gestaltung des Daseins? — Denn man kann doch nicht jetzt Sozietäten gründen, in denen nur diejenigen Kräfte walten, die Imitationskräfte sind; da würde man ja eigentlich nur Kinder drinnen haben können, und die Menschen müßten immerfort Kinder bleiben, wenn das Soziale nur dadurch entstünde, daß immer einer den andern nachahmt. Man muß, um nun wirklich zu etwas zu kommen, was auch wiederum Licht wirft auf das, was da primitiv versucht wird und was zusammenbringen kann Osten, Mitte und Westen, man muß von der Initiationswissenschaft ausgehen. Das heißt, wir müssen den Gedankengang, den wir jetzt versucht haben anzuknüpfen an das Vorliegende, den müssen wir jetzt anknüpfen an dasjenige, was die Initiationswissenschaft der Menschheit zu geben hat, damit diese Menschheit ein wirklich geistgemäß gestaltetes soziales Leben entwikkeln könne.

[ 16 ] Die Menschen beachten ja nicht, wie die Umgebung des Menschen durchsetzt ist mit ganz genau differenzierten Kräften. Nicht wahr, die heutige Wissenschaftlichkeit bringt es dahin, sich zu sagen: Luft, die ist um uns, denn wir atmen sie ein, wir atmen sie aus. — Aber dasjenige, was eigentlich im Grunde genommen fast noch klarer ist als das «Luft ist um uns» zu unserem Leben, das beachten dann die Menschen nicht. Nehmen Sie folgendes ganz Einfache, das heute sich keiner sagt, das aber eigentlich sich jeder sagen könnte. Um uns Menschen herum breitet sich ein Tierreich aus. Dieses Tierreich weist Wesen in den mannigfaltigsten Gestaltungen auf. Veranschaulichen wir uns einmal im Geiste das ganze um uns herum sich ausbreitende mannigfaltige Tierreich. Ja, wenn da ein Tisch steht, so setzt jeder voraus: da sind irgendwie Kräfte vorhanden, die diesem Tisch diese Gestalt gegeben haben. Wenn da sich das Tierreich ringsherum ausbreitet, so müßte natürlich auch jeder voraussetzen: da liegen in der Umgebung, geradeso wie die Luft da ist, diejenigen Kräfte, die den Wesen des Tierreiches diese Formen geben. Wir leben alle in demselben Reiche. Der Hund, das Pferd, der Ochs, der Esel, sie gehen ja nicht in einer andern Welt herum als in derjenigen, in der auch wir herumgehen. Und die Kräfte, die dem Esel die Eselsform geben, die wirken auch auf uns Menschen; wahrhaftig, sie wirken auch auf uns Menschen, und dennoch - verzeihen Sie, wenn man es radikal ausspricht — bekommen wir nicht die Eselsform. Es sind ja auch Elefanten in unserer Umgebung, und wir bekommen nicht die Elefantenform. Aber alle die Kräfte, die diese Formen bilden, die sind um uns herum. Warum bekommen wir denn nicht die Eselsform oder die Elefantenform? Weil wir andere Kräfte haben, die dem entgegenwirken. Wir würden die Esels- und die Elefantenform schon bekommen, wenn wir nicht andere Kräfte hätten, die dem entgegenwirken. Denn es ist schon so: wenn wir als Menschen einem Esel gegenüberstehen, da bekommt unser Ätherleib fortwährend die Tendenz, auch ein Esel zu werden. Er hat fortwährend das Bestreben, die Formen des Esels anzunehmen. Und nur dadurch, daß wir einen physischen Leib haben, der seine feste Form hat, dadurch verhindern wir unseren Ätherleib, die Eselsform anzunehmen. Und wiederum, wenn wir einem Elefanten gegenüberstehen, will unser Ätherleib die Elefantenform annehmen, und nur dadurch, daß unser physischer Leib seine feste Form hat, wird der Ätherleib verhindert, ein Elefant zu werden, und so ein Hirschkäfer oder Mistkäfer und alles will der Ätherleib werden. Die ganzen Formen sind der Anlage nach in unseren Ätherleibern, und nur dadurch können wir diese Formen verstehen, daß wir sie innerlich gewissermaßen nachzeichnen. Und unser physischer Leib verhindert uns nur, das alles zu werden. So daß wir sagen können: Das ganze Tierreich tragen wir in unserem Ätherleib eigentlich in uns. Mensch sind wir nur im physischen Leib. Das ganze Tierreich tragen wir in unserem Ätherleib in uns.

[ 17 ] Und wiederum sind wir umflossen von demselben Kräftegebiet, welches die Pflanzenformen bildet. Geradeso wie unser Ätherleib veranlagt ist, alle Tierformen anzunehmen, so ist unser Astralleib veranlagt, alle Pflanzenformen nachzubilden. Hier wird es schon angenehmer, Vergleiche zu machen, denn der Ätherleib ist von der Tendenz beseelt, wenn er einen Esel sieht, auch ein Esel zu werden; der Astralleib will bloß die Distel werden, die der Esel frißt. Aber dieser astralische Leib ist durchaus von der Tendenz durchseelt, sich auch denjenigen Kräften zu fügen, die ihren äußeren Ausdruck finden in den Pflanzenformen. So daß wir also sagen können, der Astralleib reagiert auf den Kräftekomplex, der die Pflanzenwelt bildet.

[ 18 ] Mineralreich: da ist wiederum ein Kräftekomplex, der die verschiedenen Formen des Mineralreiches bildet. Das wirkt in unserem Ich. Bei dem Ich, da haben Sie es nun ganz offenbar, denn Sie denken ja nur das Mineralreich. Bis zum Überdruß wird es ja immer gesagt, daß man nur das Tote begreifen kann mit dem Intellekt. Also das, was im Ich ist, versteht das Tote, So daß in diesem Kräftekomplex, der das Mineralreich formt, unser Ich lebt. Der physische Leib lebt als solcher eigentlich in keinem der Reiche, der hat ein Reich für sich, das wissen Sie ja. In meiner «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß» ist Mineralreich, Pflanzen- und Tierreich für sich aufgeführt, und das bedeutet, daß der physische Menschenleib ein Reich für sich hat. Aber das Tierreich ist eigentlich dem Ätherleib, das Pflanzenreich ist aus diesem Gesichtspunkte dem astralischen Leib, das Mineral dem Ich zugeteilt, Nun wissen Sie aber etwas anderes aus meinen verschiedenen Büchern. Sie wissen, daß während des Lebens gearbeitet wird an diesen verschiedenen Leibern. Ich habe es ja ausgeführt, wie gearbeitet wird an dem Ich, an dem Astralleib, an dem Ätherleib, sogar gearbeitet wird an dem physischen Leib. Ich habe das dort zunächst ausgeführt, ich möchte sagen, in menschlich humanistischer Absicht. Wollen wir es jetzt einmal von einem andern Gesichtspunkte ausführen.

[ 19 ] Nehmen Sie einmal die mineralischen Begriffe, die der Mensch aufnimmt. Die Außenwelt erlebt er ja so, daß er sie in mineralischen Begriffen, Formen erlebt. Nur erleuchtetere Geister wie Goethe arbeiten sich hinauf zu den Bildformen, zu der Morphologie der Pflanzen, zu der Metamorphose. Da verwandeln sich die Gestalten. Aber die gewöhnliche, heute noch bestehende Ansicht, die lebt ja nur in den festen mineralischen Formen. Aber wenn nun das Ich diese Formen ausarbeitet, wenn es sie heraufarbeitet, was wird denn dann? Ja, dann wird das geistige Leben, das bewußte Geistesleben, das eine Gebiet des dreigegliederten sozialen Organismus. Das geistige Leben ist dasjenige, was das Ich bildet, indem es sich selber innerlich bearbeitet. Alles geistige Leben ist ja innerlich bildende Bearbeitung des Ich. Was das Ich aus dem mineralischen Reich gewinnt und wiederum umbildet in Kunst, Religion, Wissenschaft und so weiter, das ist geistige Welt, das ist umgebildetes Mineralreich, geistiges Gebiet.

[ 20 ] Was entsteht nun dadurch, daß der Astralleib, der ja in unterbewußten Tiefen bei den meisten Menschen ist, eigentlich immer die Tendenz hat, alle möglichen Pflanzenformen zu werden? Wenn Sie das umbilden, was da im Astralleibe lebt, wenn das in halbinstinktiver, halbbewußter Form ins Bewußtsein heraufstrahlt, was entsteht dann? Dann entsteht das Rechts- oder Staatsgebiet.

[ 21 ] Und wenn Sie dasjenige, was nun umgekehrt wird innerhalb des äußerlichen Lebens an dem, was der Mensch im Ätherleib von der Tierheit erlebt, wenn Sie das auffassen, was da von Mensch zu Mensch ist, dann bekommen Sie das dritte Gebiet des dreigliedrigen sozialen Organismus. Würden wir nur beim Ätherleib stehenbleiben, so wie er uns vorliegt von unserer Geburt her, so würden wir in diesem Ätherleib nur die Tendenz haben, bald ein Esel, bald ein Ochs, bald eine Kuh, bald ein Schmetterling, bald das oder jenes zu sein, wir würden die ganze Tierwelt nachbilden. Nun bilden wir nicht bloß die Tierwelt nach, sondern wir arbeiten den Ätherleib um als Menschen. Das tun wir im sozialen Leben, indem wir zusammenleben. Wenn wir einem Esel gegenüberstehen, will der Ätherleib ein Esel werden, wenn man einem Menschen gegenübersteht, kann man durchaus nicht, ohne eine tiefe Beleidigung auszusprechen, sagen, daß man da auch ein Esel werden wollte. Nicht wahr, wenn man einem Menschen gegenübersteht, so geht das nicht, wenigstens im normalen Leben geht es nicht, da muß man was anderes werden. Ich möchte sagen, da sieht man die Umwandlung, und da wirken diejenigen Kräfte, die im wirtschaftlichen Leben spielen. Das sind die Kräfte, wenn der Mensch dem Menschen in Brüderlichkeit gegenübersteht. In dieser Art beim brüderlich Gegenüberstehen, da wirken diejenigen Kräfte, die nun Bearbeitung des Ätherleibes sind, so daß durch die Bearbeitung des Ätherleibes das dritte Gebiet, das Wirtschaftsgebiet entsteht.

Tierreich: Ätherleib Wirtschaftsgebiet

Pflanzenreich: Astralleib Rechts- oder Staatsgebiet

Mineralreich: Ich Geistiges Gebiet

[ 22 ] Und so wie der Mensch durch seinen ÄÄtherleib auf der einen Seite mit dem Tierleben zusammenhängt, so hängt er auf der andern Seite, in der äußeren Umgebung, zusammen mit dem Wirtschaftsgebiet des sozialen Organismus. Wir können sagen: Da ist der Mensch nach innen, das heißt geistig, nach innen gesehen; zunächst vom physischen Leib nach dem AÄtherleib gesehen, würden wir, wenn wir hineingehen in den Menschen, das Tierreich finden. Wenn wir hinausgehen, in der Umgebung, finden wir das Wirtschaftsleben.

[ 23 ] Wenn wir hineingehen in den Menschen und aufsuchen, was er durch seinen astralischen Leib ist, dann finden wir das Pflanzenreich. Draußen entspricht im sozialen Zusammenleben dem Pflanzenreich das Rechtsleben. Wenn wir hineingehen in den Menschen, finden wir dem Ich entsprechend das Mineralreich. Draußen in der Umgebung, dem Mineralreich entsprechend, das geistige Leben. So daß der Mensch in seiner Konstitution zusammenhängt mit den drei Naturreichen. Indem er an seinem ganzen Wesen arbeitet, wird er ein soziales Wesen.

[ 24 ] Sie sehen, man kann gar nicht zu einem Verständnis des Sozialen kommen, wenn man nicht in der Lage ist, zum ÄÄtherleib, Astralleib und Ich aufzusteigen, denn man bekommt keinen Zusammenhang des Menschen mit dem Sozialen, wenn man nicht aufsteigt. Wenn man von der bloßen Naturwissenschaft ausgeht, da bleibt man stehen bei «human instinct for mimicry», beim Imitationsvermögen; man kann nicht weiter, man macht in Gedanken die ganze Welt zu einer Kinderei, weil das Kind noch am meisten natürliche Kräfte in sich hat. Will man weiter aufsteigen, dann braucht man eben die Einsicht in die Initiationswissenschaft, daß der Mensch mit dem Ätherleib zusammenhängt durch das Tierische, mit dem Astralleib durch die Pflanze, mit dem Ich durch das Mineralische, und daß er durch das, was er der Beobachtung des Mineralischen zu verdanken hat, das geistige Leben erlangt, daß er durch Umwandeln desjenigen, was er an tiefen Instinkten trägt, an Verwandtschaft hat in der Umgebung des Pflanzenreiches, das Rechts- und Staatsleben erlangt, daß dieser tiefe Instinkt dem Rechts- und Staatsleben entspricht. Daher hat das Staatsleben zunächst, wenn es nicht mit geistiger Rechtswissenschaft durchflutet ist, so viel Instinktives. Dann haben wir das Wirtschaftsgebiet, das im Grunde genommen Umwandlung jener inneren Erlebnisse ist, welche im Ätherleib erlebt werden.

[ 25 ] Nun werden diese Erlebnisse nicht von innen heraus etwa durch die Initiationswissenschaft gehoben, denn Huxley kommt nicht durch die Initiationswissenschaft irgendwie dazu, den Zusammenhang des Menschen mit dem Wirtschaftsleben zu ergründen, sondern er beobachtet das Äußere, er beobachtet dasjenige, was wirtschaftlich draußen da ist. Der ganze Zusammenhang: Wirtschaftsgebiet, Ätherleib, Tierreich, ist ihm unklar. Er beobachtet das, was äußerlich ist. Da kann er allerdings nicht weiterkommen als bis zu dem, was das Primitivste, das Elementarste ist, die Imitationskraft.

[ 26 ] Wir sehen daraus, daß, wenn die Menschen fortfahren wollten, aus der Naturwissenschaft heraus ein soziales Denken zu gewinnen, sie steckenbleiben würden bei Absurditäten, und es würde etwas ganz Furchtbares entstehen müssen. Es müßte entstehen ein soziales Leben über die ganze Erde hin, das die allerprimitivsten Zustände brächte, das die Menschheit zurückführte auf ein kindisches Zusammenleben. Es würde nach und nach die Lüge Selbstverständlichkeit werden, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil die Menschen ja nicht anders könnten, wenn sie es auch wollten. Sie wären dreißig, vierzig, fünfzig Jahre alt, manche sogar noch älter, aber sie würden sich verhalten müssen, wenn sie mit dem Bewußtsein nur das erfassen wollten, was aus Naturwissenschaft folgt, wie die Kinder. Sie würden nur die Imitationsinstinkte entwickeln können. Man hat ja heute wirklich vielfach das Gefühl, daß nur die Imitationsinstinkte entwickelt werden. Da sehen wir, wie irgendwo wieder eine neue Reformbewegung radikaler Art auftritt. Sie hat aber nur die Imitationsinstinkte von irgendwelchem Universitätsphilister eigentlich in sich. Und so würde sich vieles von dem, was sich heute sehr illuster ausnimmt, wenn man es mit den gebräuchlichen verlogenen Worten beleuchtet, im Lichte der Imitationsanschauung ganz anders ausnehmen. Aber so viel versteht man eigentlich heute nur von der Welt, als im Lichte der Imitationsanschauung gesehen werden kann, wenn man nicht vorschreiten will von der gewöhnlichen offiziellen Wissenschaft zu der Wissenschaft der Initiation, zu der Wissenschaft, die aus den inneren Impulsen des Dasein heraus schöpft.

[ 27 ] So habe ich Ihnen zu zeigen versucht, wie das, was der Gegenwart fehlt, das, woran sich zeigt, wo die Gegenwart steckenbleiben muß, weil sie nicht eindringen kann in die Wirklichkeit, wie das befruchtet und beleuchtet werden muß von der Initiationswissenschaft.

Twelfth Lecture

[ 1 ] In contrast to the endeavors of the humanities, the aim is to gradually get to know what is to be understood from a wide variety of perspectives. It can be said that the world expects the humanities in particular to provide easily accessible means of conviction. However, this is not so easy to achieve. For in the case of spiritual scientific facts, conviction is something that develops gradually. It begins at a certain stage, when it is still weak, and then one learns the same things from ever new points of view, and in this way conviction grows stronger and stronger. That is the one thing I would like to start with today. The other thing I would like to tie in with various things I have been discussing here for weeks, tie in with what has been said about the differentiation of humanity across the civilized world. Let me just briefly mention some of the more essential facts that are of some importance for our considerations over these three days.

[ 2 ] I have pointed out in what sense the Orient is the source of the actual spiritual life of humanity. I then pointed out that in the middle regions, Greece, Central Europe, the Roman Empire — what needs to be said extends over long periods of time — the predisposition exists above all for developing legal and governmental concepts, and that the West is particularly inclined to contribute to contribute economic concepts to the overall civilization of humanity. When we look to the Orient — as has already been mentioned — we find that its civilized life today is essentially in decline, and in order to truly understand what the Orient actually means for the overall civilization of humanity, we must go back to earlier times. Among the historically available documents that prove what the Orient is, the Vedas, the Vedanta philosophy from the Orient, and many other things shine out above all, but these in turn bear witness to what existed in the Orient in even earlier times. And these things point to how a spiritual life was born out of an original, entirely spiritual disposition of the people of the Orient. Then came the times of darkness for this spiritual life in the Orient. But anyone who understands how to look at what is happening in the Orient today, even if it is only a caricature of the old, will still see the after-effects of the old spiritual life in the decadent things.

[ 3 ] At a somewhat later time, what we call legal or state thinking developed in the middle regions of the earth, in ancient Greece, in ancient Rome, and later in those areas that spread across Europe from the Middle Ages onwards. The Orient originally had no real state and, above all, did not have what we call legal thinking. This is not contradicted by the existence of law books such as those of Hammurabi and the like. For anyone who takes the content of these law books, will recognize from the whole tone and attitude that this is something different from a way of thinking that we in the West call legal. And in the West, it is only in recent times that a real economic way of thinking has developed. Even science, as it is practiced there, takes on forms that actually belong to economic life, as I have already explained.

[ 4 ] As far as Oriental intellectual life is concerned, it is interesting to observe how everything that the West has had up to now is, in essence, also the legacy of Oriental intellectual life, albeit in a transformed form. I have drawn attention here to how much Oriental spiritual life has been transformed within Europe. The fact is that the abilities that prevailed in the Orient gave rise to a view of the immortal human soul, but in such a way that this immortality was essentially linked to infertility. The pre-existing life, the life of the soul before this earthly life between birth and death, was above all what lay before the Oriental spirit before the soul, before the perception of the soul. The other arose, as it were, as a consequence. And from this arose those great connections which Westerners have only guessed at until today, which can be called karmic connections, which then left a reflection in the Greek idea of fate, but only a faint reflection. And what has actually been transferred to the West, even from those concepts through which people have tried to understand the mystery of Golgotha? What has been transferred to this Western education? Something that is very strongly colored by legal thinking. It is something radically different when you consider, on the one hand, the path of the soul in the sense of the Eastern worldview, how it descends from the spiritual world into the physical world and ascends again into the spiritual world, how you view the connections of fate from a broad perspective, and, on the other hand, the legal judgment of the soul, which has permeated these Eastern ideas in the West. Just remember Michelangelo's powerful painting in the Vatican, in the Sistine Chapel, and how the judge of the world, like a universal jurist, judges the good and the evil. This is the Eastern worldview translated into Western law; it is in no way the original Eastern worldview. This legal thinking lies completely outside the Eastern view. And the more advanced the view of the spiritual is, especially in Central Europe, the more the spiritual has flowed into Roman law.

[ 5 ] So in middle regions we are primarily dealing with what is predisposed to the legal-state sphere. But civilization is not only differentiated in this way across the earth, but also in another way. If we consider what the Orient has achieved, if we consider the special nuances of the Oriental soul life precisely where this soul life is at its greatest, we find that this Oriental soul life, despite the fact that it produces primarily spiritual things, from which, as I have said, the whole of humanity has drawn sustenance, is in the most eminent sense instinctive, atavistically instinctive. It comes out of subconscious imaginations, which are, however, already drowned out by a certain ray of consciousness. But there is much that is unconscious, much that is instinctive in it.

[ 6 ] Thus, what humanity has produced in spiritual life so far has been produced in such a way that it points upward to the highest realms of which the human soul can become a part; but these realms have been reached in a kind of instinctive flight of fancy. It is not enough to trace the concepts or images that the Orient has developed; one must also consider the special nature of the spiritual and soul life through which the Oriental arrived at these ideas, especially during his heyday. However, one can only gain an idea of this special type of soul, which I have already characterized here by linking it to the metabolic life, if one can feel the whole original soul structure of something like the Vedas and the like. One must not lose sight of the fact that the Orient has now reached a state of decadence, and one should not, for example, confuse the mystical, nebulous nature that characterizes Rabindranath Tagore, despite his greatness, with what is really the essence of Oriental spiritual life; for Rabindranath Tagore has indeed taken what that has been transplanted from the ancient Oriental soul life to the present day, but he interweaves it with all kinds of newer Western European coquetries and is above all a coquettish spirit.

[ 7 ] These things must gradually be grasped by spiritual science in such a way that one does not merely take terms that have been nailed down, but really takes into account the particular soul nuance that comes into play. So there is an instinctive spiritual life in the Orient, interwoven through and through with the view of what develops as a legal-state soul life in the middle regions. This brings us to the development of the semi-instinctive, semi-conscious, semi-instinctive. It is highly interesting how, let us say, from the souls of Fichte, Goethe, Schelling, and Hegel, a purely legalistic way of thinking emerges. It is purely legalistic, but it is half instinctive and half strongly conscious. This is precisely what is so appealing about Hegel, for example, this half-instinctive and half-fully conscious aspect. And something entirely conscious only emerges in the West, in the Western soul, where consciousness develops out of the instincts themselves — consciousness is still instinctive in the Western soul, but the conscious emerges instinctively — in Western economic thinking. So that for the first time, humanity is required to move from consciousness to a penetration of public social affairs as well.

[ 8 ] And then something highly remarkable emerges. One could actually recommend that people who are somehow concerned with this should now try to understand the entire configuration of the thinking of civilized humanity, should familiarize themselves with the attempts to arrive at a social way of thinking made by English thinkers such as Spencer, Bentham, Huxley, and so on. These thinkers all have their roots in the same intellectual atmosphere as Darwin, and they all think in much the same way as Darwin did, except that they, Huxley for example, strive to develop a social way of thinking out of their scientific thinking. One has a strange feeling when one delves deeply into, say, Huxley's attempts to arrive at a social way of thinking, for example about the state or about the legal coexistence of human beings. One has a peculiar feeling. Let us assume the following: Someone wanted to gain a feeling for what I mean here, and to this end, let us say, something like Hegel's book on natural law or political science or Fichte's philosophy of law, or something else, even by lesser minds of Central Europe, and then read Huxley's attempts to move from scientific thinking to state thinking. One would experience something like the following. One would say to oneself: Yes, now I am reading Fichte, now Hegel, all of this is well-developed concepts, concepts that are really strongly contoured and intensely painted. And now I read Huxley or Spencer: this is primitive, it's like starting to think about these things for the first time. When you are confronted with such things, you cannot get away with saying that one was perfect and the other imperfect. You cannot get away with such things at all when you are confronted with realities.

[ 9 ] I want to give you a parallel from a completely different field. It can happen that you give a lecture on something from spiritual science, let's say on the previous embodiment of the Earth, on the embodiment of the moon. You give all kinds of information. Someone who is clairvoyant in a completely atavistic way reads this or listens to it. This may be a personality who is outwardly illogical, who cannot string five words together in a logical way in ordinary practical life, who is clumsy in everything, so that one cannot use them for this or that or anything else in ordinary life. Now such a personality hears what is said about the configuration of some lunar phase, and the personality in question, who is stupid and clumsy in outward life and can hardly count to five properly, but who is atavistically clairvoyant, can now take in what they have heard and expand on it, develop it further, and find things that have not been said. But the things that this personality then finds can be permeated by an extraordinarily astute logic, a logic that is admirable, while the personality in outer life is clumsy and illogical, unable to put five words together logically. That may well be the case; for when someone is atavistically clairvoyant, the images—and they can find these images themselves—are not put together logically by their ego, but by all kinds of spiritual beings that are within them. It is their logic that one then comes to know, not the logic of the person themselves.

[ 10 ] So one cannot simply say that one thing is higher and another lower, but one must always consider the special character of the matter. And so it is here. The legal or other views of Fichte or Hegel or lesser minds are half instinctive, only half fully conscious. But what appears in the West as primitive economic thinking is, of course, entirely conscious; things like these, which are thought up in a primitive way by Huxley or Spencer or the like, are impertinently conscious, but they are primitive. What previously came to light in an instinctive or semi-instinctive manner now comes to light in a conscious manner, but in a rather attractive way at first. Let me illustrate this with a concrete example.

[ 11 ] Huxley says to himself: Look at nature — he looks at it, of course, in the Darwinian sense — there is a struggle for existence. Every being fights ruthlessly for its own preservation, and the whole fights in such a way that the strongest in nature remain, exterminating the weaker. This has become second nature to Huxley. But this cannot be propagated in humanity. Freedom, as it should be sought in human social life, does not exist in nature, because freedom cannot exist, according to Huxley, in a realm where every creature must either ruthlessly assert itself or die. Equality cannot exist where the fittest must always eliminate the others from the world. Now Huxley looks away from this natural realm to the social realm, and now he is forced to say: Yes, but in the social realm, good must reign, freedom must reign; so something must come into play that cannot yet be found in nature.

[ 12 ] This is again the great divide that I have already characterized from various points of view. Huxley once beautifully called man “the splendid rebel,” who, precisely in order to establish a human realm, is a rebel against everything that prevails in nature. So something comes into play that does not yet exist in nature. But now Huxley is actually thinking in scientific terms again. He is compelled to find natural forces in humans that constitute social life, that rebel against nature itself. He wants to find something concrete that is in man and that constitutes human social community; for the other natural forces of the natural realm cannot constitute this social community, because there is a struggle for existence, there is nothing that could hold people together in a social context. And yet, for Huxley, there is nothing else but this natural connection. So this “splendid rebel” must in turn have natural forces that actually rebel as natural forces against the general forces of nature. And here Huxley finds two natural forces that are at the same time the fundamental forces of social life. One natural force is actually established per nefas, because it cannot yet actually establish social life, but only family egoism. It is what Huxley calls family attraction, i.e., that which acts within blood relations. The other force he cites, however, which could now form a kind of foundation, a natural foundation for social life, is what he calls the “human instinct for mimicry,” the human talent for imitation.