The Human Soul in Relation to World Evolution

GA 212

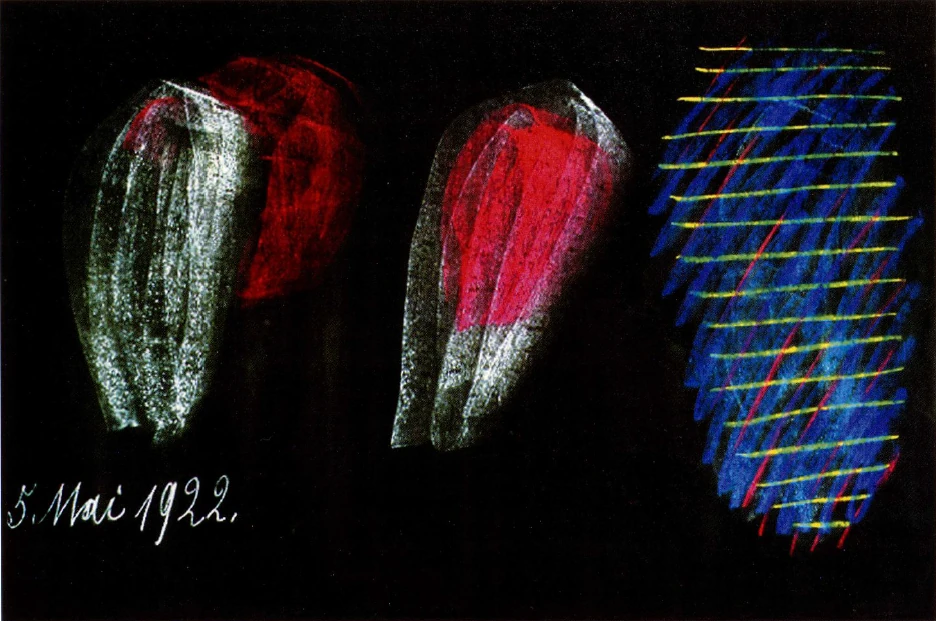

5 May 1922, Dornach

3. The True Nature of Memory II

In order to extend our considerations and link on to what was said last week, let us bring to mind some of the things already known to us. When we consider man as he lives between birth and death we see his life divided into sections which can be studied from various aspects. Attention has often been drawn to the alternating states of waking and sleeping and we know that dreaming is a state between these two. Thus, we have three states of consciousness in ordinary life—waking, dreaming and sleeping. Human nature itself can be divided correspondingly. When we trace the content of ordinary consciousness we experience thinking—i.e., forming mental pictures. I have often pointed out that only in this state, or to the extent that we are in this state, are we really awake. Anyone who observes himself without prejudice will acknowledge that feeling presents a much duller state of consciousness than thinking. Feelings surge through the soul and, unlike mental pictures, we cannot relate them so definitely either to something in the external world or to something remembered. And we are conscious, or at least could become conscious, that as soon as we are awake, feelings come and go very much the way dreams come and go in the intermediate state between waking and sleeping. Anyone who has a sense for comparing different states of consciousness must say to himself: Dreams have a pictorial quality; feelings are more like indefinite forces surging within us. But apart from their content, dreams come and go just as feelings come and go. Furthermore, dreams emerge from a general darkness and dullness of consciousness just as feelings emerge and again submerge within a general inner existence.

When we consider the will we find that what takes place within us when we have a will impulse remains as unknown to us as that which we sleep through. The only aspect that is clear in a will impulse is the thought that initiated it. What next comes into consciousness is the movement of our limbs or the event taking place in the external world through our will. But what takes place in the legs when walking or in the arms when we lift them remains as unconscious as that which takes place between falling asleep and waking. So we can say that while we are awake we experience all three conditions of waking, dreaming and sleeping.

However, we shall only arrive at a comprehensive knowledge of man if we use discernment when comparing what is given us, on the one hand, as sleeping, dreaming and waking; and, on the other, as willing, feeling and thinking. Let us consider sleeping man, on the one hand, and, on the other, man engaged in an act of will. The characteristic feature of sleeping man is that the very factor that makes us human—the experience of the I or ego—is absent. This situation is usually described by saying that the I, between falling asleep and waking up, is outside of what is present before us as physical man.

Let us now compare dreaming man with man experiencing feelings. By means of ordinary self-observation you will immediately recognize that dream pictures come before the soul in a, so to speak, neutral fashion. When we dream, either on waking or before falling asleep, we cannot really say that the pictures come before the soul like a tapestry, rather do they surge and weave within the soul. Thus, what then takes place in the soul differs from what occurs when fully awake. When awake we know that we take hold of the pictures which we then have; we grasp them in our inner being. They are not so nebulous and indefinite as dreams.

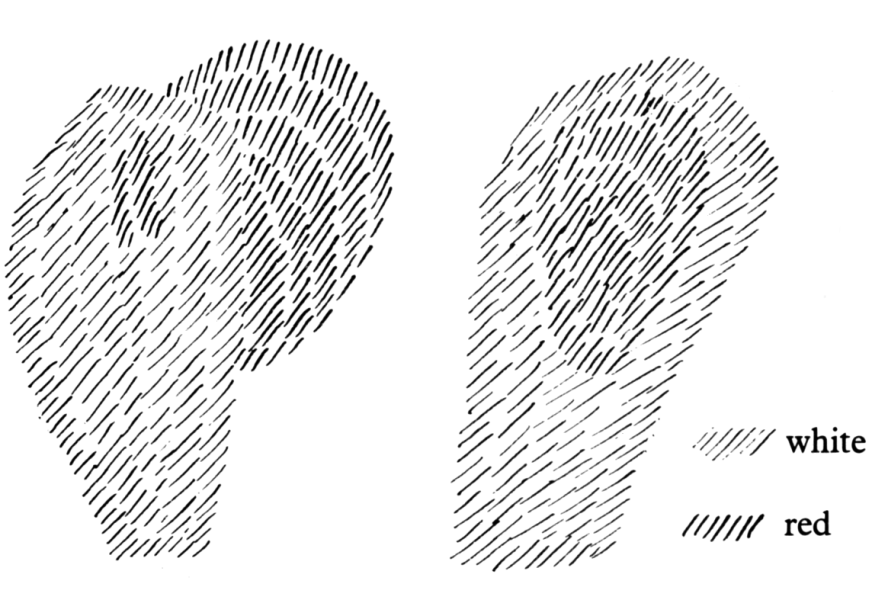

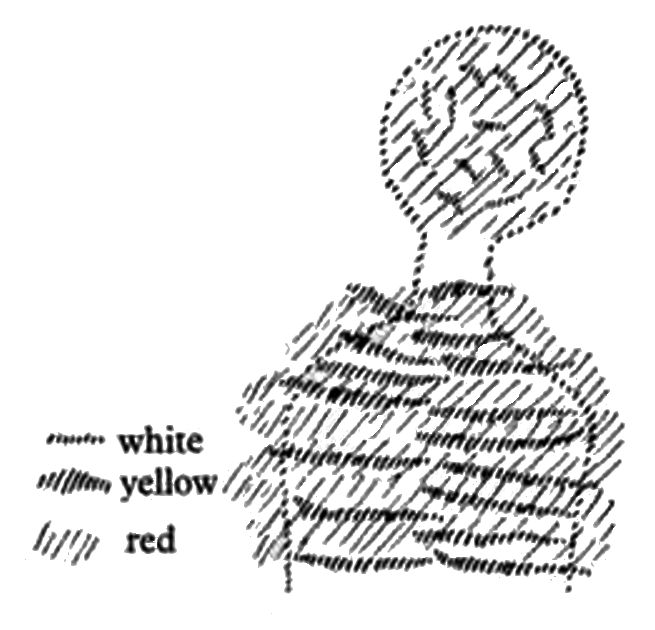

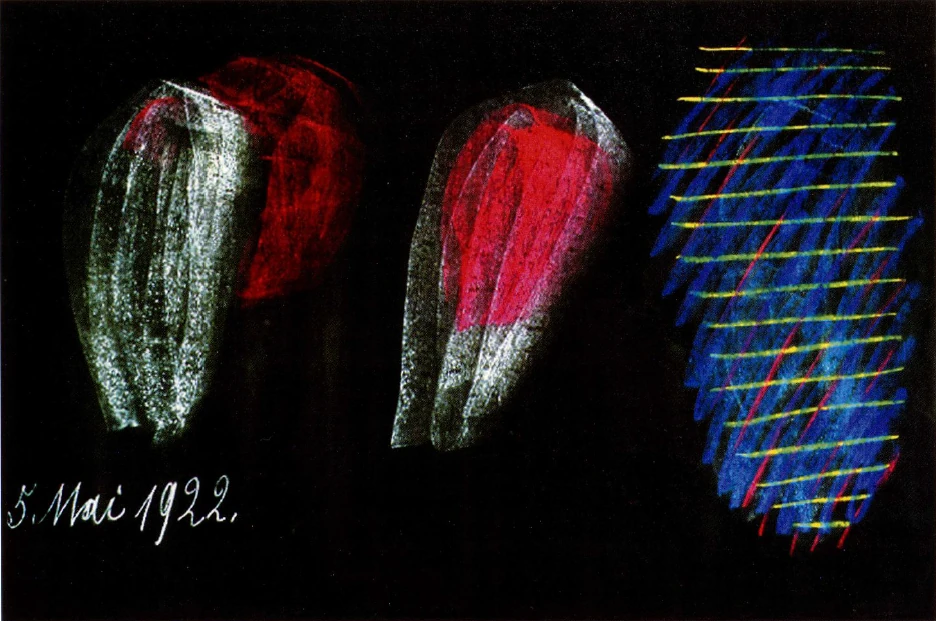

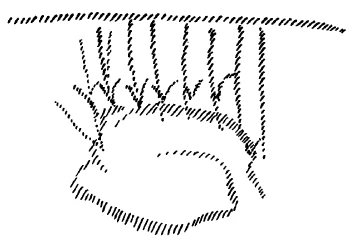

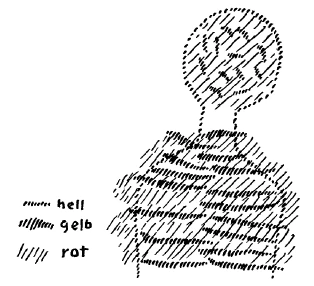

Let me illustrate what has just been described (left hand drawing). Let us imagine man schematically (white lines) and draw what we imagine to be weaving dreams (red lines). One must imagine the red part as a tissue of dreams experienced by the soul which continually withdraws and again approaches the soul.

The moment he wakes up man does not experience such a tissue of weaving pictures. He now has the pictures of whatever he is experiencing firmly within him (right hand drawing). The weaving pictures which were formerly outside are now within him; he lays hold of them with his body and because he does so they are no longer undefined weaving pictures but something which he controls inwardly.

When man is fully awake then what weaves and hovers as dreams become thoughts within him. He is then in control of what now lives in his soul as mental pictures. In this relationship you can see that the soul is taking hold of something which from outside draws into man. What has just been described is in fact the entry of what we call the astral body into man's inner being. To ordinary consciousness it is that which before entry weaves and hovers as dreams. The astral body is, therefore, within us when after waking we begin to think. We then form mental pictures and we know that we do so, for these mental pictures are under our control. As long as they are dreams they hover outside. You need only imagine a kind of cloud that hovers near you in which dreams are weaving. You then draw in this cloud, you now control it from within. Because it is no longer outside you cease to dream. Just as you grasp objects with your hands so do you grasp dreams with your inner being; which means that you have drawn in the astral body.

We must ask: What precisely is it that we now have within us? We can perhaps find a point of reference by looking at certain dreams which are not just pictures but begin also to become indefinite feelings. Just think how often dreams can be quite unpleasant. Many dreams are connected with anxiety. You wake up feeling anxious. In this undefined state of anxiety—less often it may be a state of joy—you have the first glimmer of something which as it further develops becomes fully present as you wake up. What is it that glimmers forth when a dream causes, for example, anxiety?

Such dreams are interwoven with feelings; anxiety is a feeling. The feeling is undefined because the dream is still partly outside the organism; yet it is far enough within to intermingle with feeling. It interweaves with what already lives in the soul as feeling. Only when the astral body has entered completely do you have definite feelings. These are conditioned by the physical organization and can now be penetrated by mental pictures present in the astral body.

When we consider certain nightmares and anxiety dreams in the right light we draw near to what actually takes place when the astral body enters man's physical body. You will always find that it is some disorder in the breathing which causes the state of anxiety of some dreams. From this you can see clearly that the astral body draws in and again draws out through the breath. It is really possible to observe these things if only the observation is thorough enough and free from prejudice. Something can be seen here that enables us to recognize that what weaves in dreams is in fact the astral body and that it draws into our organism by taking hold of the breath as we wake up.

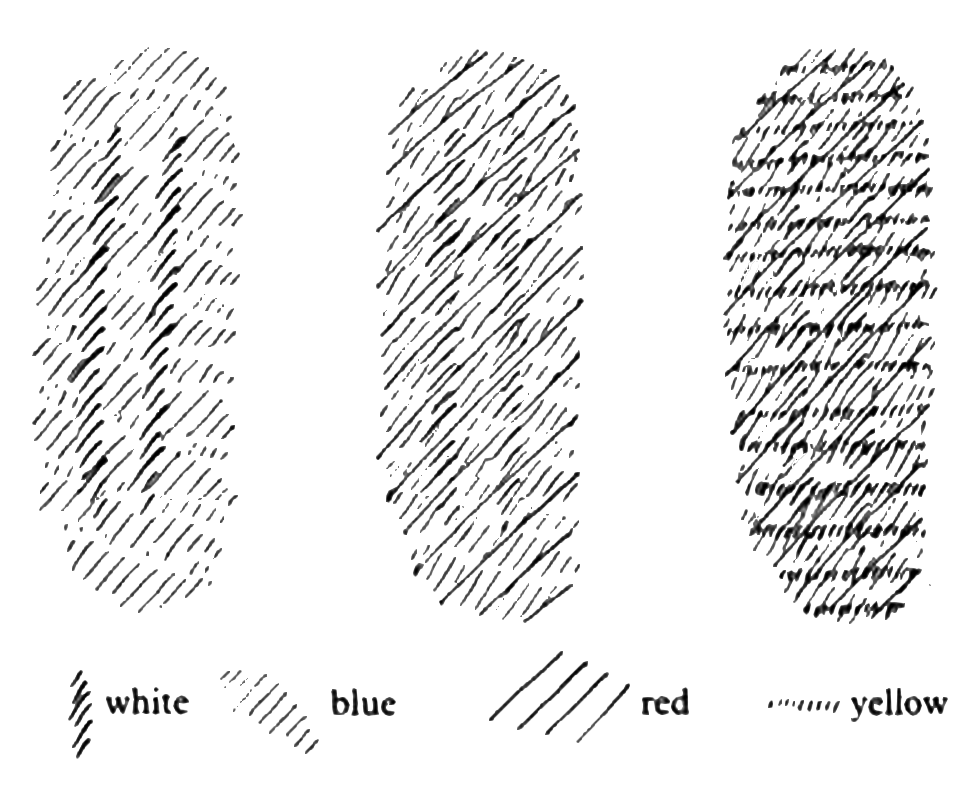

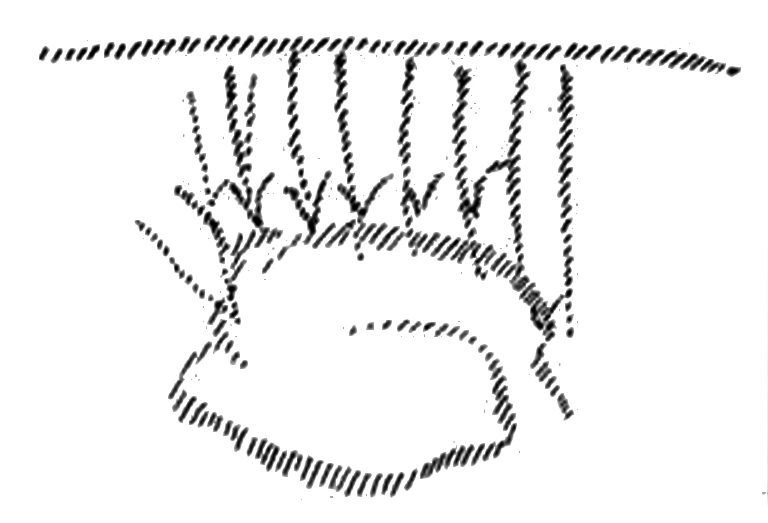

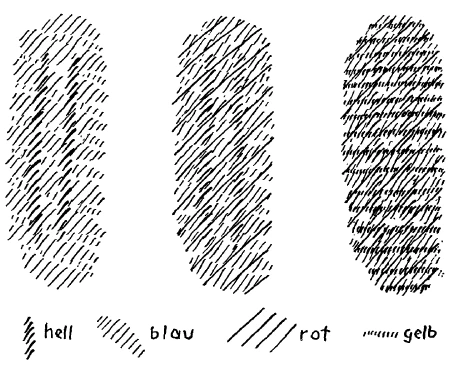

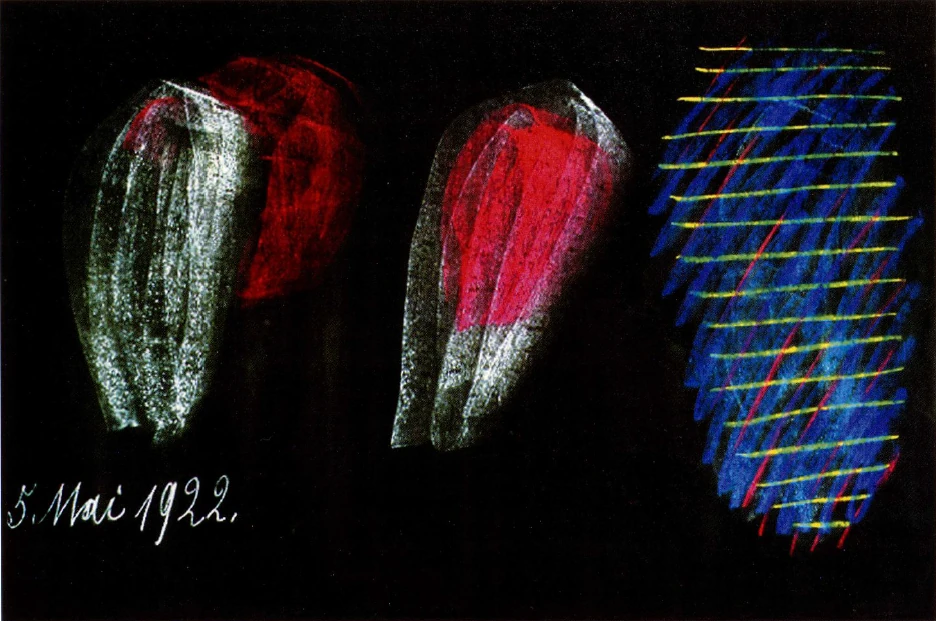

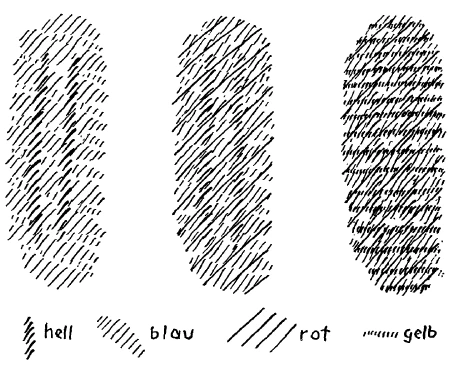

This leads to the recognition of something else that is not normally taken into account but is of great significance. The human being is usually regarded as if he were simply a physical organism, a body built up of solid matter. That is just not true. The least part of the human body is solid, less than ten percent. For the rest it is a water organism, an organism of liquid, so that in reality we must think of this organism built up in such a way that one tenth is solid (see drawing, white lines) and the solid saturated with water (blue lines). You only represent the human organism truly when you see it as a column of liquid in which the solid is deposited.

However, there is more to it. We must also picture the human organism as an organism of air. The air is outside, we breathe it in; a part of the outside air is now within us and we breathe it out again. So we are also an air organism. Let us draw that, too (red lines). It is just this air organism which is taken hold of by the astral body as we wake up. We breathe in the air, it goes through transformations the effect of which pours through the whole organism. The oxygen takes up the carbon and transforms it into carbonic acid. Thus, an air process continually takes place within us.

As we wake up the air process is permeated by the astral body. The movement of the astral body follows the same path as the air through the organism. The air process consists solely of air when we sleep; when we are awake then the movements of the astral body, as it were, swim along within what lives in us as air processes. But now depict to yourselves the following: the astral body draws into that which I have schematically drawn in red and carries out its movements, in fact, carries out its general activity, within the air organism. This all takes place within the watery organism, which is represented in the blue lines. When we are awake, these air processes are in reality processes of the astral body and they continually push against the watery organism. Man's etheric body is within the watery organism both night and day. So you have simultaneously a reciprocal effect between the etheric body and the astral body, as well as between their physical counterparts which are the air processes and the water processes. Thus, you can visualize these processes running their course within man between his breathing and the movements of all the bodily fluids. Yet that is again merely a copy of what takes place between the astral and etheric bodies.

The whole organism consisting of solid, fluid and air is also permeated with warmth (see drawing, yellow lines, page 38). The whole organism has its own warmth—i.e., its own warmth ether. On the gaseous waves moves astrality and in the warmth flowing through the body moves the actual I or ego of man.

So you have the physical body as such, then the fluid body, which is also physical but differentiated from the solid physical body. The fluid physical body has an intimate connection with the etheric body. Then the gaseous organism which has an intimate connection with the astral body, and finally all the warmth processes—that is, the warmth ether in man, which has an intimate connection with the human I. Thus, one can say that in the various physical constituents of man we have a picture of the whole man. The solid part, so to speak, exists by itself; the fluid within the organism cannot exist by itself. Within the head we have very little solid and what there is swims in the cerebral fluid. Within this fluid is the etheric part of the head.

In the breathing process the following takes place: As we breathe in, the breath pushes inwards up through the spinal fluid towards the brain. In our waking state the astral also moves along this thrusting movement towards the etheric part of the head. We have then, on the one hand, an interaction of the movement of the cerebral fluid with the movement of the breath, and, on the other, an interaction of the etheric part of the head—of which what takes place in the cerebral fluid is only an image—with the breathing process, which is again only an image of the astrality in man. We also have a continuous interplay of warmth; the movement of the blood mediates the warmth. On the waves of this sea of warmth our I also moves.

To become clear about these interactions within man's bodily nature it is essential that we represent them vividly to ourselves. Only the solid organism can be observed by itself. The fluid organism does not have the possibility of moving

in waves the way water moves in the external world. The play of movement in the fluid organism is an image of what takes place in the etheric body. Again, what takes place in the delicate processes of breathing is an image of what takes place in man's astral body. Keeping this in mind let us once more look at the cerebral fluid: within it certain movements take place copying movements of the etheric body. Man acquires the etheric body when he descends from spiritual worlds into the physical world. Within the spiritual world he does not yet possess it. But as man takes hold of his physical body he also takes possession of his etheric body; he, as it were, draws out the ether from the cosmos. He can unite with the physical body, which he receives through heredity, only when he has drawn the ether from the cosmos. So that all that lives in the etheric body of man we bring with us when we take hold of the physical body.

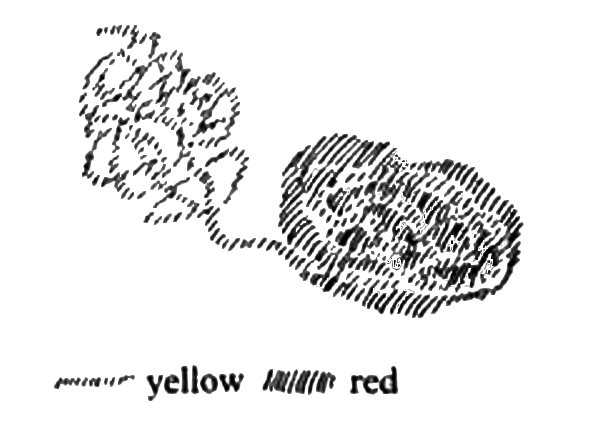

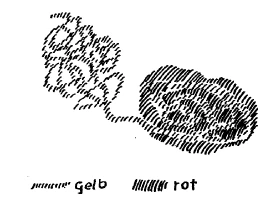

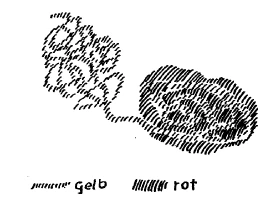

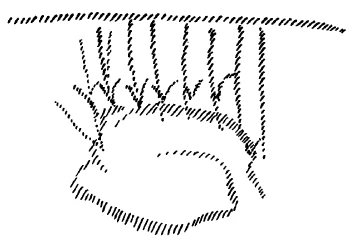

The human embryo develops within the maternal body. Let us consider the fluid within the embryo. In general physiology only the solid components, or what appear to be solid components, are examined, not the fluid. Were this to be investigated it would be found that the cerebral fluid, in particular, contains an image of all that which was present already in the ether body, as the ether was drawn together, and which then slips into physical man.

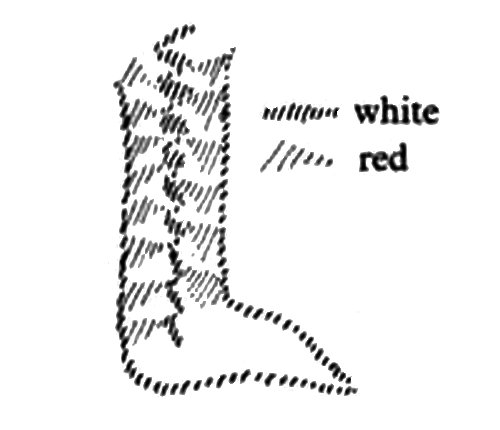

If this is the physical body (see drawing) in which the physical human embryo develops—I do not draw the solid, only the fluid embryo (red lines)—then what as astral and `I' is present descends from the spiritual world; what has been drawn together from the ether slips in (yellow lines). In fact, as he dives down into his physical body the fluid part of the organism absorbs what man brings with him. Therefore, if the movements within the cerebral fluid of the child were to be investigated they would be found to be like a photograph of what the human being had been before he united with the physical body. You see, it is very significant to realize that a photograph is to be found in the cerebral fluid, that is to say in the movements of the cerebral fluid, of what has taken place before conception.

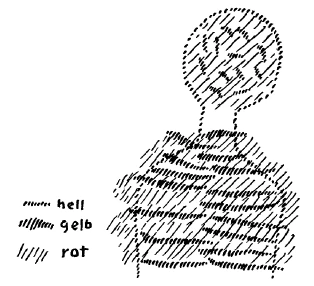

It is fairly easy to understand that a kind of photograph of what existed before conception is to be found in the cerebral fluid. But let us now consider the process of breathing. Breathing appears to be an out and out physical process because of the way our lungs function. Air is drawn in and, under the influence of the external world, the breathing takes place even when we are asleep—that is, even when the eternal part of our being is not united with the temporal part. Our breathing is not affected by whether we are awake or asleep. When we sleep the wave movements of the breath go through the organism; when we are awake they, in addition, carry the astral body. In other words, they are able to carry the astral body but it is not incumbent on them to do so, for when we are asleep they do not.

What follows from this? It follows that the reason the cerebral fluid can carry on by itself is because it is isolated within man's inner being. It constitutes a kind of continuation of what existed before. On the other hand, nothing of what existed before can be continued in this intimate way within our breath. When we consider the human head, we find within the cerebral fluid, that is, within the physical body itself, the actual continuation of pre-natal spiritual man; whereas when we consider the organization of the chest and the process of breathing we find a different situation. The physical breath takes place by itself (see drawing, yellow lines); the spiritual is less strongly connected with the physical process (red lines). Therefore, one must say that in the head, spiritual man, the man of soul and spirit, is closely connected with physical man; they have become a unity. In the chest that is not the case—there the two are more apart; the physical organism is more by itself and so, too, the soul-spiritual.

Let us now compare this with the state of dreaming. When we dream the I and astral body are outside, they are separated from the sleeping body. However, for the chest man, that is to some extent always the case. The chest man—that is, the man of breath and heart, in short, rhythmic man—is the organism for feeling. Feelings run their course like dreams because the soul-spiritual is not so firmly connected with the physical organism, is not so completely within physical man. So you see, if one wants to consider the whole man one must take into account these different interactions of what pertains to the soul and what pertains to the body.

In our materialistic age the human being is considered only in the most external way. This is evident from the way modern science looks upon man as if he were nothing but a solid organism within which the soul is somehow active. On this basis it is impossible to visualize how, for example, an impulse of will, experienced purely within the soul, can lead to the lifting of the arms or legs. In fact, from the point of view of what we experience as the soul's part in an act of will, the human organism, as conceived by modern anatomy and physiology, is like a piece of wood, as alien to the soul as a piece of wood. What in physiology today is described as human legs is like a description of two pieces of wood. They are related to the soul as if they were wooden legs. As little as the soul could have any relationship with two pieces of wood lying about, just as little could it have any relationship with legs as described by modern physiology. However, human legs are penetrated by liquid. Here we already come upon something in which it is easier to understand that the spiritual can be active within it. Yet, it is still difficult.

Once we come to the gaseous, the airy element, then we are in a physical material so fine that it is much easier to visualize the soul element to be within it, and easier still when we come to warmth. Just think how close a connection can come about between the warmth of the physical organism and the soul. You may at some time have had a terrible fright and grown quite hot. There you have an inner experience of the connection between the soul and the warmth in the physical organism. In fact, when we examine the solid, fluid, gaseous and warmth components of the whole organism, we gradually arrive at the soul.

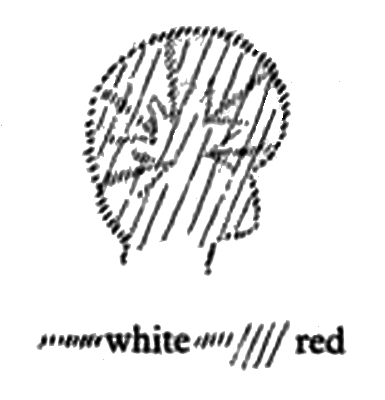

It can be said that the 'I' takes hold of the inner warmth; the astral body of the gaseous; the ether body of the fluid and only the solid remains untouched; in the solid nothing enters. Picture to yourselves the way the human organism functions: You have the human brain (see drawing, page 46) that has fluid in it and also solid parts into which, as I said, the soul does not enter. The solid parts are, in reality, salt deposits; whatever solid we have within us is always salt-like deposit. Our bones consist solely of such deposits. In the brain very fine deposits continually occur and again dissolve. There is always a tendency in our brain to bone formation. The brain has a tendency to become quite bony. But it does not become bony because everything is in movement and is continually dissolved. When we examine the organism, especially the brain, we first find within it a condition of warmth, and within the warmth the air which is the bearer of the astral body and is continually playing into the cerebral fluid while being breathed in and out. We then have the cerebral fluid in which the ether body lives. Then we come to the solid into which the soul cannot enter because it consists of deposited salt. Because of this salt formation, which is less than ten percent of the total organism, we have within us something into which the soul cannot enter.

As human beings we have an organism; within this organism there are warmth, gaseous and fluid elements, all of which the soul can penetrate. But there is something which the soul cannot penetrate. This is comparable to having objects on which light falls but cannot penetrate and is therefore thrown back. Let us say we have a mirror; light cannot go through it and is therefore reflected. Similarly, the soul cannot penetrate the solid salt organism and is, therefore, continually reflected.

If this were not the case, there would be no consciousness at all. Your consciousness consists of soul experiences reflected from the salt organism. You are not aware of the soul life as it is absorbed by the warmth, gaseous and fluid organism; you experience it only because the soul life within the warmth, gaseous and fluid, is reflected everywhere by salt, just as sunbeams are reflected by a mirror. The outcome of this reflection is our mental pictures.

When someone deposits too much salt—salt always takes on forms—then he produces a lot of mental pictures; he becomes rich in thoughts. If too little salt is secreted the thoughts have vague outlines, like reflections from a faulty mirror. Or, said differently, when too much salt is secreted thoughts predominate and become very precise, and he who has them becomes pedantic. He is convinced of the rightness of his thoughts because they arise from so much solid, he becomes materialistic. When too little salt is secreted, or perhaps too much in the rest of the organism but too little in the head, then the thoughts become indefinite and the person becomes fanciful or perhaps he becomes a mystic. Our soul life is dependent on the material processes taking place within us.

It may be necessary, when someone is too prone to fanciful ideas, to administer some remedy that will enable him to deposit more salt or else give better form to the salt he does deposit. He will then escape from his fantasies. However, one should not make too great an effort to cure a human being by physical means of his fantasies or pedantry; not much can be done anyway. To do something different is more important and can be of great value—someone who knows how to observe human beings in regard to both soul and body will notice if there is too much sediment, whether in the head, or in the organs of the rhythmic or metabolic systems. He will notice it because the whole thought configuration becomes different. The manner in which a person alters his thoughts can contribute significantly to a diagnosis. But such delicate reactions are not often noticed. For example, someone may suddenly make mistakes repeatedly when speaking. He does not normally do so, but suddenly he makes mistakes again and again. It may last a few days and then cease. He has suffered a slight ailment, and the mistakes in speaking are merely a symptom. Such instances can often be described quite exactly.

For example, someone may for a few days secrete too much gastric acid. Now what occurs? This gastric acid dissolves certain substances in the stomach, which ought to pass on beyond the stomach. This means that the organism is deprived of these substances with the result that the person's inner mirror pictures lack the necessary sharpness. His thoughts become vague and he makes mistakes in speaking. You will have realized what must be done: One must provide a remedy that will ensure less acidity in the stomach, then the person's thoughts will again become ordered. His digestion is now in order and he ceases to make mistakes when speaking.

Or take the example of someone who absorbs gastric acid too intensely. This can occur if the spleen is abnormally active. When this happens the gastric acid is distributed throughout the body; the body, as it were, becomes all stomach. Such acid sediments are, in fact, the cause of many illnesses. A specific pricking pain may be felt or, if the head is affected, a feeling of dullness. When you look at such a person with insight it will often be found that the absorption of all the acidity has created in him a certain greediness. When someone is permeated with acidity his eyes may lose their friendly expression. If someone is suffering from too much acidity his eyes will reveal it. It is sometimes possible to restore his friendly expression by administering an acid that can be digested in the stomach because it is of a kind that has no tendency to spread throughout the organism.

The reason I am saying all this is to show you that the science of the spirit meant here does not simply contemplate the human soul in a nebulous way. It recognizes the soul as the ruler and builder of the body, active within it everywhere.

The human organism is described nowadays as if it were solid through and through; the solid alone is taken into account. It is impossible to arrive at any conception of how the soul actually exists within the body unless one also considers the fluid, gaseous and warmth elements of the organism. The soul does not live in the solid part of the organism; it does not enter the solid any more than light penetrates a mirror. Light is thrown back from the mirror, the soul retreats everywhere from the salt.

The peculiarity of the soul is that it is deflected from the bones (see drawing, red lines). We carry our bones within us empty of soul. The soul is not within them but is rayed back into the organism.

The bones in the skull are really ingeniously arranged. The soul rays out in all directions and is reflected into our inner being. We do exist within the skull bones but only as solid physical man. If we would make a comprehensive sketch of the head we would have to depict the soul as raying out within the head (see drawing, red lines). If nothing else happened, we would be in a dull unconscious condition. However, as the soul cannot enter the bones of the skull it is rayed back into our inner being (arrows, short red lines).

We experience the soul only when it is reflected into our inner being. So, you see how matters stand: The reality is that you have the soul within you rayed back from the mirror of the skull bones.

Spiritual science does not exclude what is material; on the contrary, recognition of how the soul controls matter makes it, at last, comprehensible. After all one does not come to know that someone is a baker by the fact that he makes certain movements, but from knowing that the movements he makes shape the rolls and croissants. Neither does one come to know the soul through abstract considerations but by knowing that a reflection of the soul's activity is to be found in the physical organism. It is a question of understanding the organism rightly and recognizing that it is an image of the soul. If we cannot make the effort to understand even man's physical nature we shall never learn to know the soul. We must have the goodwill to understand how human nature comes to expression through the physical. What is usually spoken of as soul, by those who will not approach the physical with spiritual insight, is something utterly unreal. It is as unreal as if you had a tasty meal before you and, instead of eating it, tried to eat its reflection in a mirror standing beside it. One can become knowledgeable about the soul only by observing her creative activity and not by persisting to regard it as a mere abstraction. And one should certainly not adopt the view that to be a conscientious spiritual scientist one must scorn the material. Rather should the material be understood spiritually; it will then reveal itself as spirit through and through. To do otherwise is to live in intellectual abstractions, and they obscure rather than enlighten.

Dritter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Wir müssen uns heute einiges vor Augen rücken, das uns von gewissen Seiten her schon bekannt ist, um die weiteren Betrachtungen anzustellen, die sich anschließen an das in der vorigen Woche Gesagte. Wenn wir den Menschen so, wie er einmal in der Welt zwischen Geburt und Tod steht, betrachten, so zerfällt uns sein Leben in Gliederungen, die von verschiedenen Gesichtspunkten aus betrachtet werden können. Wir haben ja oftmals unsere Aufmerksamkeit auf den Wechselzustand gelenkt zwischen Wachen und Schlafen. Wir wissen, daß ein Zwischenzustand zwischen Wachen und Schlafen der des Träumens ist. Das sind die drei Zustände, in denen das Bewußtsein des gewöhnlichen Lebens verläuft: Wachen, Träumen, Schlafen. Aber diese drei Zustände, sie finden sich auch sonst als Gliederungen der menschlichen Wesenheit vor. Wenn wir die Inhalte, die Erlebnisse dieses gewöhnlichen Bewußitseins verfolgen, so haben wir das Erlebnis des Denkens, des Vorstellunghabens, und ich habe oft gesagt: Wir sind eigentlich nur dann wirklich wach, wenn wir in diesem Zustand oder insofern wir in diesem Zustande des Vorstellunghabens sind. Jeder, der sich mit unbefangenem Sinn selbst beobachtet, wird erkennen können, daß das Fühlen einen viel dumpferen Bewußtseinszustand darstellt als das Denken. Die Gefühle, sie durchwogen unsere Seele, ohne daß wir in einer so bestimmten Weise sie beziehen können auf irgend etwas in der Außenwelt oder auf Erinnerungen, wie die Vorstellungen. Wir haben auch durchaus das Bewußtsein, oder können es wenigstens haben, daß in dem Augenblicke unseres Wachens diese Gefühle kommen und gehen, wirklich so ähnlich, wie in dem Zwischenzustande zwischen Wachen und Schlafen die Träume kommen und gehen. Und wer einen Sinn dafür hat, solche Dinge des Bewußtseins wirklich miteinander zu vergleichen, der wird sich eben sagen müssen: Die Träume sind Bilder; die Gefühle sind etwas wie unbestimmte, in uns wogende Kräfte. Aber in allem übrigen, wenn wir von diesem Inhaltlichen absehen, in allem übrigen kommen und gehen die Träume, wie die Gefühle kommen und gehen. Und aus einem, ich möchte sagen, allgemein Finsteren und Dumpfen des Bewußtseins heraus tauchen die Träume auf, wie aus einem allgemeinen Innenbefinden die Gefühle herauftauchen und wiederum sich hinuntersenken.

[ 2 ] Mit dem Wollen ist es so, daß dasjenige, was eigentlich in unserem Inneren vorgeht, wenn wir einen Willensimpuls haben, uns so unbekannt bleibt wie das, was wir verschlafen. Klar ist von dem, was beim Wollen vor sich geht, eben nur der Gedanke, der den Zweck einer Willenshandlung in sich hat. Es ist dann die Anschauung etwa unserer Bewegung oder desjenigen, was durch unser Wollen äußerlich geschieht, wieder vor unserer Seele, in unserem Bewußtsein. Aber das, was, sagen wir, im Bein oder im Arm vor sich geht, während wir das Bein heben, mit dem Bein ausschreiten wollen, oder während wir den Arm heben wollen, das ist etwas, was so unbewußt bleibt wie dasjenige, was sich abspielt zwischen Einschlafen und Aufwachen. So daß wir, auch während wir wachen, schon gleichzeitig in einem gewissen Sinne diese drei Zustände des Bewußtseins erleben: Wachen, Träumen, Schlafen.

[ 3 ] Nun kommen wir aber zu einer vollständigen Erkenntnis des Menschen nur, wenn wir dies, was uns damit gegeben ist, daß wir auf der einen Seite Schlafen, Träumen, Wachen, auf der anderen Seite Wollen, Fühlen, Denken betrachten, nun eben einer vernünftigen, wenn ich so sagen darf, Betrachtung unterziehen.

[ 4 ] ‚Nehmen wir einmal den schlafenden Menschen einerseits, den wollenden Menschen andererseits. Der schlafende Mensch, er ist dadurch charakterisiert, daß derjenige Inhalt des Bewußtseins, der sonst uns eigentlich zum Menschen macht, das Ich-Erlebnis, nicht da ist. Das Ich-Erlebnis also ist nicht da. Wir bezeichnen das gewöhnlich dadurch, daß wir sagen: Das Ich ist vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen außerhalb dessen, was als physischer Mensch vor uns ist.

[ 5 ] Nun aber betrachten wir den träumenden Menschen auf der einen Seite und den fühlenden Menschen auf der anderen Seite. Es wird Ihnen ohne weiteres bei einer gewöhnlichen Selbstbeobachtung klar sein, daß die Träume gewissermaßen als neutrale Bilder vor der Seele stehen, daß, indem Sie, sagen wir, beim Aufwachen oder vor dem Einschlafen träumen, diese Bilder wie ein Gewebe, man kann nicht gut sagen, vor, aber im Seelischen schweben und weben. Das unterscheidet sich, was da im Seelischen vorgeht, von demjenigen, was bei vollem Wachen da ist. Beim vollen Wachen wissen wir, daß wir die Bilder, die wir dann auch haben, gewissermaßen innerlich festhalten, daß wir sie mit unserem menschlichen Wesen ergreifen; sie schweben nicht so nebelhaft im Unbestimmten wie beim Träumen. Wir ergreifen sie mit unserem menschlichen Wesen.

[ 6 ] Ich will das, was ich jetzt eben ausgesprochen habe, einmal schematisch auf die Tafel zeichnen (Zeichnung links). Nehmen wir einfach schematisch den Menschen (hell), und zeichnen wir das, was wir uns vorstellen können als das Schema für die webenden Träume (rot), etwa in der folgenden Weise an den Menschen heran. Man möchte sagen, das, was ich da rot an die Tafel gezeichnet habe, das ist ein Gewebe, das die Seele erlebt, indem es ihr fortwährend entschlüpft, wiederum an sie herankommt.

[ 7 ] In dem Augenblicke des Aufwachens hat der Mensch ein solches Gewebe im seelischen Erleben nicht. Dagegen hat er dasjenige, was er so erlebt, jetzt innerlich. Ich will jetzt aufzeichnen (Zeichnung rechts), wie es nun beim Wachzustand ist. Er hat dieses Gewebe, das sonst gewissermaßen außerhalb ist, jetzt im Inneren, er faßt es mit seinem Leib, und dadurch ist es nicht ein unbestimmtes Gewebe, sondern es ist etwas, was der Mensch innerlich beherrscht.

[ 8 ] An diesem Verhältnis dessen, was als Traum verwebt und verschwebt, und dessen, was dann im Inneren des Menschen der Gedanke ist, wenn der Mensch völlig wach ist und von sich aus das, was jetzt als solche Bildgedanken in seinem Seelischen lebt, beherrscht, an dem können Sie, ich möchte sagen, bis zum seelischen Greifen wahrnehmen: da ist einfach etwas aus dem Äußeren in das Innere hineingezogen. Und wir schildern, indem wir so etwas darstellen, nichts anderes als den Einzug dessen, was zunächst für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein in den Träumen verwebt und verschwebt, was wir den astralischen Leib nennen, in das Innere des Menschen. So daß wir sagen können: Wenn wir nach dem Aufwachen anfangen zu denken, so ist der astralische Leib in unserem Inneren. Wir stellen dann vor. Aber wir wissen, wir haben diese Vorstellungen in unserer Gewalt. Solange sie Träume sind, verschweben sie da draußen. Sie brauchen sich nur vorzustellen eine Art Wolke, die in Ihrer Nähe ist und in der sich die Träume weben. Sie saugen gewissermaßen diese Wolke ein; Sie beherrschen sie von innen aus. Sie ist nicht mehr draußen. Sie träumen daher nicht mehr. Aber so, wie Sie irgendeinen Gegenstand mit den Händen ergreifen, so ergreifen Sie diesen Traum mit Ihrem Inneren. Und Sie haben Ihren astralischen Leib eingesogen, Sie haben ihn jetzt drinnen.

[ 9 ] Wir müssen uns allerdings genauer fragen: Was haben wir denn da drinnen? Wenn wir uns das einmal genauer ansehen, was wir da drinnen haben, so können wir vielleicht einen Anhaltspunkt dafür gewinnen, indem wir auf manche Träume, die nicht nur Bilder bleiben, sondern die schon beginnen, unbestimmte Gefühle zu werden, hinschauen. Bedenken Sie nur einmal, wie manche Träume recht unangenehm sind; sie sind einfach ein Bildergewebe. Manche Träume sind mit Angstzuständen verbunden. Sie wachen aus Angstzuständen auf. Sie sehen in diesen unbestimmten Angstzuständen, auch oftmals in unbestimmten Freudenzuständen, aber zumeist sind es eigentlich beängstigende Zustände, in denen sehen Sie schon, ich möchte sagen, das Aufglimmen von etwas, was, indem es sich weiter entwickelt, dann beim völligen Erwachen da ist. Was glimmt denn da auf, wenn der Traum Ihnen zum Beispiel Angst macht?

[ 10 ] Ja, der Traum verwebt sich mit dem Gefühl. Angst ist ein Gefühl. Der Traum ist noch halb draußen; dadurch ist das Gefühl unbestimmt. Aber er verwebt sich schon mit dem Gefühl. Dadurch tritt es auf, das Gefühl. Aber er verwebt sich mit dem, was sonst in der Seele lebt beim Fühlen. Und erst wenn Sie den Astralleib nun ganz herinnen haben, dann haben Sie diese bestimmten, in Ihrer physischen Organisation bedingten Gefühle da, die Ihnen jetzt die Vorstellungen des astralischen Leibes durchsetzen können.

[ 11 ] Wenn Sie gewisse Alp- und Angstträume richtig ins Auge fassen, so haben Sie es wiederum, ich möchte sagen, bis zum seelischen Greifen nahe, was da eigentlich bei diesem Einzug, wie wir es nennen, des astralischen Leibes in den physischen Menschen geschieht. Dasjenige nämlich, was die Beängstigung macht, die zuweilen den Traum begleitet, werden Sie immer entdecken als etwas, was nicht in der Ordnung ist in Ihrem Atmungsprozeß..

[ 12 ] Sie sehen daraus ganz deutlich, daß der astralische Leib durch das, was in der Atmung liegt, einzieht und auch wiederum auszieht. Es ist wirklich nicht so, daß man diese Dinge, wenn man das Leben nur unbefangen beobachten will, nicht beobachten könnte. Man stellt nur nicht gehörig solche Beobachtungen an. Aber es ist etwas da, was uns durchaus die Anleitung dazu gibt, zu erkennen, daß dasjenige, was in den Träumen webt und was in der Wirklichkeit der astralische Leib ist, in unseren Organismus hineingeht, indem es den Atmungsprozeß beim Erwachen ergreift.

[ 13 ] Das führt uns zu einer Betrachtung über den Menschen, die außerordentlich wichtig ist, die aber gewöhnlich nicht angestellt wird. Man sieht den Menschen gewöhnlich so an, als ob er eigentlich ganz und gar ein Organismus wäre, ein Körper wäre, der aus festen Bestandteilen aufgebaut ist. Das ist aber doch nicht wahr. Der menschliche Organismus besteht eigentlich zum geringsten Teile, kaum zu zehn Prozent, aus Festem. Im übrigen ist er ein Wasserorganismus, ein Flüssigkeitsorganismus. So daß wir in Wahrheit diesen Organismus uns so aufgebaut denken müssen, daß wir sagen: Da ist der Organismus, und in einer gewissen Beziehung ein Zehntel fest (siehe Zeichnung, hell); aber dieses Feste ist durchsetzt von dem wässerigen Elemente (blau). Und dann erst stellen Sie sich den menschlichen Organismus ordentlich vor, wenn Sie ihn eigentlich als Wassersäule vorstellen, die das Feste eingelagert hat.

[ 14 ] Aber das genügt noch nicht. Wir müssen den menschlichen Organismus auch als einen Luftorganismus vorstellen. Die Luft ist draußen; wir atmen sie ein. Da ist ein Teil der Luft, die da draußen ist, nun in unserem Inneren drinnen. Die atmen wir wieder aus. Wir sind zu gleicher Zeit ein Luftorganismus. Wollen wir auch das schematisch zeichnen (rot). Aber gerade dieser Luftorganismus ist es, der beim Aufwachen von dem astralischen Leib ergriffen wird. Wir atmen die Luft ein. Die Luft macht ferner einen Prozeß durch; ihre Wirkungen ergießen sich in den ganzen Organismus. Der Sauerstoff nimmt den Kohlenstoff auf, verwandelt sich in Kohlensäure. So ein Luftvorgang findet fortwährend in uns statt.

[ 15 ] Beim Wachen ist aber dieser Luftvorgang durchsetzt von dem astralischen Leib. Auf denselben Bahnen, die die Luft in unserem Organismus durchmacht, läuft die Bewegung des astralischen Leibes. Der Luftvorgang ist ein Luftvorgang ja nur, wenn wir schlafen; wenn wir wach sind, dann schwimmen gewissermaßen die Bewegungen dieses astralischen Leibes in demjenigen, was als Luftvorgang in uns lebt. Aber jetzt denken Sie sich einmal: indem der astralische Leib da einzieht in dasjenige, was ich in Rot schematisch aufgezeichnet habe, und innerhalb des Luftorganismus seine Bewegungen ausführt, dasjenige ausführt, was er überhaupt tut, geht das in dem blau schematisch Gezeichneten, in dem wäßrigen Organismus vor sich. Diese Luftvorgänge, die eigentlich beim Wachen die Vorgänge des astralischen Leibes sind, stoßen immer heran an den wäßrigen Organismus.

[ 16 ] Im wäßrigen Organismus ist aber nun Tag und Nacht der ätherische Leib des Menschen. Und da haben Sie zu gleicher Zeit eine Wechselwirkung des astralischen und des ätherischen Leibes, aber auch das physische Abbild davon: die Luftvorgänge und die Wasservorgänge im Menschen. Sie können sich also durchaus vorstellen, daß im Menschen zunächst diese physischen Prozesse vorhanden sind, die ablaufen zwischen seinem Atmen und den Bewegungen seiner Säfte, überhaupt alledem, was da flüssig im Organismus vor sich geht. Das aber ist wieder nur ein Abbild von dem, was zwischen astralischem und ätherischem Leib vor sich geht.

[ 17 ] Nun ist aber alles dasjenige, was nun da fester, flüssiger, gasförmiger Organismus ist, wiederum durchzogen von Wärme (Zeichnung S. 55, gelb). Der ganze Organismus hat seine eigene Wärme: WärmeÄther. Ich möchte sagen: Auf den Wellen des Luftigen im Menschen bewegt sich das Astralische, und auf demjenigen, was da als Wärme den Organismus durchspielt, da bewegt sich das eigentliche Ich.

[ 18 ] Jetzt haben Sie den physischen Leib als solchen; den flüssigen Leib, der auch physisch ist, aber der nun sich abgrenzt von dem festen physischen Leib, den flüssigen physischen Leib, der einen innigen Zusammenhang mit dem ätherischen Leib hat; den gasförmigen Organismus des Menschen, der einen inneren Zusammenhang hat mit dem astralischen Leib, und dasjenige, was Wärmevorgänge sind, was mit anderen Worten Wärme-Äther ist im Menschen, das einen innigen Zusammenhang hat mit dem menschlichen Ich. So daß wir im Physischen, ich möchte sagen, überall das Bild sehen des ganzen Menschen. Das Feste ist sozusagen etwas, was für sich besteht. Aber das Flüssige im Organismus, das kann nicht für sich bestehen. Wir haben sehr wenig in unserem Kopfe vom Festen. Dasjenige, was wir Festes haben, schwimmt im Gehirnwasser, also in Flüssigkeit. Sehen Sie auf dieses Flüssige innerhalb des menschlichen Kopfes, so haben Sie in diesem Flüssigen zunächst den Ätherteil des Kopfes.

[ 19 ] Das Atmen geht nun so vor sich: Sie atmen ein. Der Atem stößt nach innen, setzt sich fort durch das Rückenmarkswasser nach dem Gehirn. In dieser Stoßbewegung bewegt sich aber zu gleicher Zeit dasjenige, was das Astralische ist, nach dem Ätherischen des Kopfes herauf im Wachzustande. So daß wir auf der einen Seite ein Zusammenwirken der Bewegungen des Gehirnwassers mit den Atmungsbewegungen haben, auf der anderen Seite ein Zusammenwirken des Ätherteiles des Kopfes, von dem das, was im Gehirnwasser vor sich geht, nur ein Abbild ist, mit demjenigen, was Atmungsvorgänge sind, die wiederum nur ein Abbild sind desjenigen, was astralisch ist im Menschen. Und dann haben wir ein fortwährendes Spiel der Wärmezustände. Und das Blut in seiner Bewegung vermittelt diese Wärmezustände. Auf diesem Wogen des Wärmemeeres in uns bewegt sich zu gleicher Zeit unser Ich.

[ 20 ] Es handelt sich darum, daß wir uns dieses ganz lebendig vorstellen, daß wir uns darüber klar sind. Für sich können wir nur den festen Organismus betrachten. Sobald wir an den flüssigen Organismus herankommen, hat er gar nicht mehr die Möglichkeit, etwa bloß sich so zu bewegen, wie sich Wasserwellen draußen bewegen, sondern der bewegt sich so, daß sein Bewegungsspiel ein Abbild ist dessen, was im Ätherleib des Menschen vor sich geht. Wiederum dasjenige, was in den feineren Zuständen der Körperatmung vor sich geht, ist ein Abbild dessen, was astralisch im Menschen vor sich geht. Nun aber, wenn wir das ins Auge fassen, so müssen wir uns sagen: Sehen wir nur einmal auf das Gehirnwasser. Das hat in sich gewisse Bewegungen. Die sind ein Abbild des Ätherleibes. Aber den Ätherleib, den bekommt der Mensch, indem er aus den geistigen Welten in diese physische Welt heruntersteigt; innerhalb der geistigen Welten hat er ihn noch nicht. Aber indem der Mensch überhaupt seinen physischen Leib ergreift, hat er schon seinen Ätherleib. Er zieht gewissermaßen den Äther aus dem Kosmos heran. Und erst indem er den Äther herangezogen hat aus dem Kosmos, kann er sich mit dem Physischen, das ihm dann durch die Vererbung vermittelt wird, verbinden. So daß wir dasjenige, was innerlich im Ätherleib des Menschen lebt, schon mitbringen, indem wir unseren physischen Leib ergreifen.

[ 21 ] Nehmen Sie also an, im Leib des mütterlichen Organismus entsteht der Menschenkeim. Wir untersuchen dasjenige, was an diesem Menschenkeim das Flüssige ist. Man tut es nicht in der gewöhnlichen Physiologie. In der gewöhnlichen Physiologie untersucht man nur den Keim insofern, als er Festes enthält oder wenigstens sich so wie das Feste beobachten läßt. Das Flüssige wird gar nicht untersucht. Würde man aber das Flüssige untersuchen, dann würde man entdekken, wie in dem Flüssigen, namentlich im Gehirnwasser, ein Abbild dessen ist, was da hereingeschlüpft ist in den physischen Menschen und was zunächst schon im Ätherleib sich ausdrückte, als der Äther herangezogen worden ist.

[ 22 ] So können wir sagen: Wenn hier der physische Leib ist (siehe Zeichnung), der physische Menschenkeim sich bildet - ich zeichne jetzt das Feste gar nicht; was ich da zeichne, soll der flüssige Menschenkeim sein (rot) -, es kommt aus der geistigen Welt herunter dasjenige, was als Ich und Astralisches vorhanden ist. Was schon an Äther herangezogen ist (gelb), das schlüpft hier hinein. Indem einfach der Mensch untertaucht in den physischen Leib, wird im flüssigen Organismus aufgenommen das, was der Mensch von außen hereinbringt. Würden Sie also das Gehirnwasser des Kindes in seinen Bewegungen untersuchen, so müßten Sie sagen: Das ist eigentlich eine Photographie dessen, was der Mensch war, bevor er sich mit seinem physischen Leib verbunden hat. Sehen Sie, das ist sehr wichtig, daß man eigentlich sagen kann: Im Gehirnwasser, das heißt, in den Bewegungen des Gehirnwassers würde man eine Photographie von dem, was der Konzeption vorangegangen ist, finden.

[ 23 ] Nun, vom Gehirnwasser können Sie das gut begreifen, daß Sie da eine Art Photographie finden dessen, was vorangegangen ist. Aber bedenken Sie den Atmungsprozeß. Der Atmungsprozeß tritt uns als ein sehr physischer Prozeß dadurch entgegen, daß unsere Lunge in einer gewissen Beziehung organisiert ist, daß die Luft eingesogen wird, daß der Atmungsprozeß sich sogar abspielt unter dem Einfluß der Außenwelt, wenn wir schlafen, wenn also unser Ewiges gar nicht mit unserem Zeitlichen verbunden ist. Man möchte sagen, für den Atmungsprozeß ist es ja so: er verläuft sowohl, wenn wir schlafen, als auch wenn wir wachen. Wenn wir schlafen, nun, dann geht eben die Bewegungswelle des Atmungsprozesses durch unseren Organismus; wenn wir wachen, trägt diese Welle den astralischen Leib. Sie kann ihn also tragen; sie braucht ihn auch nicht zu tragen. Das tut sie beim Schlafen, da trägt sie ihn nicht.

[ 24 ] Was folgt daraus? Daraus folgt, daß das Gehirnwasser, weil das im Inneren abgeschlossen ist, sich fortsetzen kann, eine Art Fortsetzung sein kann dessen, was früher da war. Nicht so innig kann sich aber in dieser selben Art etwa in unserem Atmen irgend etwas fortsetzen von früher. Daher geschieht folgendes: Wenn wir den menschlichen Kopf betrachten und dann den menschlichen Brustorganismus, so finden wir, daß da drinnen im menschlichen Kopf, gewissermaßen sagen wir durch das Gehirnwasser, also im physischen Organismus, richtig die Fortsetzung des vorgeburtlichen geistigen Menschen drinnen ist. Beim Atmungsprozeß ist es nicht so. Da verläuft der physische Atmungsprozeß für sich (siehe Zeichnung, gelb), und das Geistige ist viel weniger stark mit dem physischen Prozeß verbunden (rot). Man möchte sagen: Im Kopf ist der geistige Mensch, der geistig-seelische Mensch mit dem physischen Menschen fest zusammen verbunden; sie sind eine Einheit geworden. Im Brustmenschen ist das nicht so, da sind sie mehr getrennt; da ist der physische Organismus mehr für sich und das Geistig-Seelische auch wiederum für sich.

[ 25 ] Aber jetzt vergleichen Sie das mit dem Traumzustande. Im Traumzustande ist es für den ganzen Menschen so, daß wiederum das Ich und der astralische Leib heraußen sind, daß sie getrennt sind. Aber ein wenig sind sie für den Brustmenschen immer getrennt. Der Brustmensch, das heißt Atmungs- und Herzmensch, der rhythmische Mensch, der ist aber der Organismus für das Fühlen. Weil also das Geistig-Seelische mit dem physischen Organismus in bezug auf den rhythmischen Menschen nicht so kompakt verbunden ist, nicht so da drinnen ist in dem physischen Menschen, deshalb verläuft das Fühlen so wie das Träumen. Sie sehen, will man den ganzen Menschen betrachten, so muß man diese verschiedenen Arten des Zusammenwirkens des Seelischen mit dem Leiblichen ins Auge fassen. Nun, wenn man die menschliche Wesenheit so grob betrachtet, wie das heute in unserem materialistischen Zeitalter geschieht - denn Sie können sich überall überzeugen, wo Sie die heutige Wissenschaft ins Auge fassen, daß man eigentlich so betrachtet, als ob der ganze Mensch eben ein fester Organismus wäre und da drinnen irgendwie das Seelische wirkte -, dann kann man nicht darauf kommen, wie dieses Seelische, das man erlebt, zum Beispiel der rein seelisch erlebte Willensakt, wie der ein Bein hebt oder einen Arm hebt. Ja, gegenüber dem, was man auf der einen Seite als Seelisches des Willensaktes erlebt, ist das, was man sich heute in der Anatomie, in der Physiologie unter menschlichem Organismus vorstellt, eigentlich wie ein Stück Holz, so fremd dem Seelischen wie ein Stück Holz. Was Sie heute beschrieben finden als Beine des Menschen in der Physiologie, ist wirklich wie zwei Holzstücke, wie Holzbeine. So verhalten sie sich zum Seelischen. Ebensowenig wie, wenn hier zwei Hölzer liegen, Sie eine Beziehung finden können zwischen diesen zwei Hölzern und einem Seelischen, ebensowenig kann man eine Beziehung finden zwischen dem, was einem die Physiologie heute beschreibt als menschliche Beine und dem Seelischen. Aber diese menschlichen Beine, die die Physiologie beschreibt, die sind durchzogen von dem Wässerigen. Da kommen wir schon zu etwas, von dem sich leichter begreifen läßt, daß da ein Geistiges hineinwirkt. Aber es geht noch schwer. Kommen wir aber zu dem Gasförmigen, zu dem Luftförmigen, so sind wir in dem Physischen in einer so dünnen Materie, daß wir uns nun da das Seelische leichter drinnen vorstellen können. Und erst wenn wir zu den Wärmezuständen kommen! Bedenken Sie nur, wie naheliegend Sie es haben, diese Wärmezustände des physischen Organismus mit dem Seelischen in Zusammenhang zu bringen. Denken Sie doch nur einmal, wie Sie eventuell da oder dort eine heillose Angst bekommen haben, und es wird Ihnen ganz warm; da haben Sie schon eine innere Anschauung von der Beziehung des Seelischen zu demjenigen, was nun im physischen Organismus als Wärmezustände auftritt. Kurz, wenn wir in einer vernünftigen Weise den ganzen menschlichen Organismus so erfassen, daß wir ihn in bezug auf sein Festes, Flüssiges, Gasförmiges, Wärmeartiges fassen, dann kommen wir nach und nach an das Seelische heran.

[ 26 ] Wir können sagen: Das Ich greift in den Wärmezustand ein, der astralische Leib in den gasförmigen Zustand, der Ätherleib in den flüssigen Zustand; nur das Feste bleibt unangetastet. Da geht es nicht herein. Denken Sie sich einmal das, wie es nun im menschlichen Organismus ist: Hier haben wir das Gehirn, aber das ist noch wässerig. Jetzt sind da darinnen feste Bestandteile. Da, sagte ich, geht das Seelische nicht herein. Zeichnen wir uns einmal irgendwie schematisch diese festen Bestandteile darinnen (siehe Zeichnung $. 60). In Wirklichkeit sind es Salzablagerungen. Das, was wir Festes in uns haben, sind ja immer salzartige Ablagerungen. Unsere Knochen sind nur Bestandteile solcher Ablagerungen. Aber in unserem Gehirn geschehen fortwährend ganz feine, sich immer wieder auflösende Ablagerungen. Ich möchte sagen: In unserem Gehirn ist immer die Tendenz vorhanden, sich einfach zu solchen Knochen zu bilden, das Gehirn ganz knöchern zu machen; es löst sich nur immer wieder auf, weil alles beweglich ist. So daß, wenn wir gerade das Gehirn betrachten, da haben wir also zunächst die Wärmezustände des Gehirns, da drinnen lebt die Luft, die fortwährend ein- und ausgeatmet wird, aber die ins Gehirnwasser heraufspielt; der astralische Leib lebt darinnen. Wir haben das Gehirnwasser; der ätherische Leib lebt darinnen. Jetzt bekommen wir das Feste. Da kann das Seelische nicht herein. Es kann nicht herein, indem wir in uns Salze ablagern. Indem wir dieses nicht ganze Zehntel unseres Organismus, diese Salzbildung da drinnen haben, haben wir in uns etwas, in das unser Seelisches nicht herein kann.

[ 27 ] Bedenken Sie: Da stehen Sie als Mensch. Da haben Sie Ihren Organismus. Da haben Sie in Ihrem Organismus die Wärme, das Gasförmige, das Flüssige: da kann Ihr Seelisches überall herein. Aber da ist etwas drinnen, in das Ihr Seelisches nicht herein kann. Das ist so, wie wenn Sie hier allerlei Gegenstände haben, die vom Lichte bestrahlt werden, die das Licht wieder zurückwerfen. Sie haben eine Spiegelfläche, da kann das Licht nicht durch, wird zurückgestrahlt. So haben Sie in sich Ihren festen Salzorganismus. Da kann das Seelische nicht herein, da wird das Seelische fortwährend zurückgestrahlt.

[ 28 ] Ja, wenn Sie das nicht hätten, so würden Sie zunächst überhaupt gar kein Bewußtsein haben können, denn das, was Sie nun in sich als Bewußtsein haben, das sind die von Ihrem Salzorganismus zurückgestrahlten Seelenerlebnisse. Diejenigen, die hineingehen in Ihr Ich, in Ihren gasförmigen Organismus, in Ihren flüssigen Organismus, die erleben Sie zunächst nicht. Erst weil überall das, was da in der Wärme, was in dem Gasförmigen, was in dem Flüssigen als Seelenleben vor sich geht, ebenso wie die Lichtstrahlen vom Spiegel zurückgeworfen werden, am Salz zurückgeworfen wird, erst dadurch erleben Sie das, was Seelisches ist. Dadurch haben Sie diese innerliche Spiegelung, die nun innen als Vorstellungen lebt.

[ 29 ] Wenn also ein Mensch zum Beispiel viel Salz absetzt — aber das Salz entsteht überall in Formen -, dann bekommt er viele solche Bilder, das heißt, er wird gedankenreich. Wenn er zuwenig Salz absondert, dann bekommen die Gedanken solche unbestimmte Konturen, wie von einem nicht ordentlichen Spiegel die Bilder die Konturen erhalten. Wir können das auch noch anders aussprechen: Wenn einer überflüssig viel Salz absondert, da überwiegen in ihm die Gedanken in seinem Inneren. Sie werden sehr bestimmt, aber er wird ein Pedant. Er glaubt, in seinen Gedanken, weil sie aus so viel Festen in ihm herrühren, etwas Reales zu haben. Er wird materialistisch. Wenn er zuwenig Salz absondert, oder sagen wir, wenn er zuviel Salz in seinen übrigen Organismus absondert und zuwenig in seinen Kopf, dann werden seine Gedanken unbestimmt; er wird ein Phantast oder vielleicht ein Mystiker. Es hängt schon zusammen mit materiellen Vorgängen in unserem Inneren, wie unser Seelenleben beschaffen ist.

[ 30 ] Es ist zum Beispiel manchmal notwendig, wenn einer zu phantastisch ist, daß man ihm Gelegenheit gibt durch irgendwelche Heilmittel, mehr Salz abzulagern oder das abgelagerte Salz besser zu gestalten. Dadurch wird er seiner Phantastik entrissen. Aber das Umgekehrte ist noch wichtiger; denn das sollte man eigentlich nicht sehr weit treiben, daß man die Menschen auf physischem Wege von Phantastik oder von Pedanterie heilt; es ist zunächst auch nicht viel zu machen. Aber das Umgekehrte hat einen großen Wert. Derjenige, der Menschenbeobachtung hat, für das Seelische ebenso wie für das Körperliche, der bemerkt genau, wenn zum Beispiel ein Mensch nach der einen oder nach der anderen Richtung, sagen wir im Kopfe oder in den Organen des rhythmischen Organismus oder in den Organen des Stoffwechselorganismus zuviel Ablagerungen hat. Er bemerkt dies daran, daß die ganze Gedankenkonfiguration anders wird, und die Art und Weise, wie der Mensch seine Gedanken verändert, kann zu der Diagnose außerordentlich viel beitragen. Nur beobachten die meisten Menschen solche feinen Vorgänge nicht.

[ 31 ] Es wird zum Beispiel sehr häufig nicht beobachtet, wie zusammenhängt, sagen wir, die Tatsache, daß nun plötzlich einmal ein Mensch sich immer wieder und wieder verspricht. Er hat es sonst nicht in seiner Gewohnheit, aber einmal fängt er an, sich immer wieder zu versprechen. Es dauert ein paar Tage, dann geht es vorüber. Es ist eine leise Erkrankung in ihm vor sich gegangen, und dieses Versprechen, das ist lediglich ein Symptom für die leichte Erkrankung. Zuweilen kann man solche Dinge sehr genau beschreiben.

[ 32 ] Nehmen wir zum Beispiel an, ein Mensch sondert einmal ein paar Tage, durch irgendwelche Vorgänge, zuviel Magensäure ab. Was geschieht? Diese Magensäure, die löst einmal schon im Magen gewisse Stoffe auf, die weitergehen sollten als in den Magen. Jetzt hat er das eben nicht in dem Organismus; jetzt hat er nicht die nötige Schärfe seiner inneren Spiegelbilder, jetzt werden seine Gedanken lose, er verspricht sich. Merken Sie den Hasen, der da läuft, und merken Sie, wie dieser Hase läuft, dann versuchen Sie eben, ihm irgendwo beizukommen, daß er weniger Magensäure hat, dann werden seine Gedanken wiederum ordentlich. Im Grunde genommen aber wird seine Verdauung ordentlich, und er hört auch wieder auf, sich zu versprechen.

[ 33 ] Oder aber, nehmen wir an, durch irgend etwas — es kann zum Beispiel durch Abnormitäten der Milztätigkeiten geschehen - sauge jemand seine Magensäure zu stark auf, er macht sich ganz zum Magen; er leitet die Magensäure überall hin. Solche Säureablagerungen, die sind eigentlich die Ursache für sehr viele Erkrankungen. Wenn es nicht bis zum Kopfe geht, dann entstehen sogar sehr eigentümliche prickelnde Schmerzen; wenn es bis zum Kopfe geht, entsteht Dumpfheit des Kopfes. Wenn Sie einen solchen Menschen dann anschauen, so sehen Sie oftmals, daß er in sich dieses ganze Aufsaugen des Säureartigen zu einer gewissen Gier macht; er wird ganz durchsäuert. Und wenn der Mensch durchsäuert wird, dann leidet zum Beispiel der freundliche Ausdruck seiner Augen darunter: Sie können es seinen Augen ansehen, wenn der Mensch durchsäuert ist, und Sie können unter Umständen, indem Sie ihm eine Säure beibringen, die er nun wirklich im Magen verarbeitet, weil sie nicht die Neigung hat, in den Organismus überzugehen, diesen Menschen wiederum freundlicher kriegen in seinem äußeren Ausdrucke.

[ 34 ] Ich sage das alles aus dem Grunde, um Ihnen zu zeigen, wie die Geisteswissenschaft, die hier gemeint ist, nicht ein unbestimmtes Seelisches bloß ins Auge faßt, sondern wie das Seelische, das nun wirklich der Herrscher des Leiblichen ist, das der Erbauer des Leiblichen ist, überall hereinwirkt ins Leibliche.

[ 35 ] Aber wenn man das, was heute beschrieben wird als menschlicher Organismus so, als wenn dieser Organismus eben durch und durch ein Festes wäre, wenn man das ins Auge faßt, wenn man nicht dazunimmt das Flüssige, das Gasförmige, das Wärmeartige des Organismus, was sich wenigstens dem Seelenleben nähert, so kommt man eben nicht zu einem Begreifen, wie dieses Seelische im Menschen lebt. Denn im festen menschlichen Organismus lebt eben das Seelische nicht. In den festen Organismus geht das Seelische so wenig hinein, wie das Licht durch den Spiegel durchgeht; daher wird es zurückreflektiert. Und so geht das Seelische gerade am Salz überall zurück.

[ 36 ] Wenn wir hier unseren Fuß haben und hier den Knochen, so hat eben gerade das Seelische das Eigentümliche, daß es sich am Knochen bricht (siehe Zeichnung, rot), daß wir unseren Knochen in uns so tragen, daß er leer ist vom Seelischen. Da ist es nicht drinnen; aber es strahlt wiederum in den Organismus zurück.

[ 37 ] Unsere Schädelknochen, die sind gar nicht so dumm angebracht an uns; denn das Seelische, das strahlt nach allen Seiten und wiederum nach dem Inneren zurück. Wir sind auch in unseren Schädelknochen, aber nur als physisch-feste Menschen drinnen. Aber unser Seelisches strahlt in uns hinein. So daß wir eigentlich, wenn wir vollständig unseren Kopf aufzeichnen, sagen müssen: Zunächst breitet sich da drinnen das Seelische aus (rot). Aber ich möchte sagen, das würde uns in einem dumpfen, unbewußten Zustande lassen. Aber nun, da kann es nicht hinein, wo die Schädelknochen sind, da wird es überall zurückgestrahlt, überall hinein in uns (Pfeile). Und erst wenn es da zurückgeht, dann haben wir es als Seelisches. So daß Sie wirklich in Ihrem Inneren Ihr Seelisches wie von allen Seiten an dem Spiegel der Schädelknochen zurückgeworfen haben. Das ist so. Geisteswissenschaft schließt nicht etwa das Materielle aus, sondern macht das Materielle erst recht verständlich, indem das Seelische so betrachtet wird, wie es das Materielle beherrscht. Nicht wahr, den Bäcker lernt man auch nicht dadurch kennen, daß er bloße Bewegungen ausführt, sondern die Bewegungen, die er ausführt, machen dann die Semmeln und die Gipferl. Die Seele lernen wir nicht dadurch kennen, daß wir sie nur in Abstraktionen betrachten, sondern was die Seele da macht, das tritt uns als Bild in unserem Organismus entgegen. Wir müssen gerade verstehen, diesen Organismus in der richtigen Weise als ein Bild des Seelischen zu betrachten. Wenn wir nicht den Willen haben, auf den Menschen einzugehen, auch wie er uns entgegentritt im Bilde des Physischen, wenn wir sozusagen zu bequem sind, den Menschen kennenzulernen als physischen Menschen, lernen wir auch das Seelische nicht kennen; denn das, was gewöhnlich so als Seelisches beschrieben wird von den Leuten, die das Physische nicht geistig auffassen wollen, das sind eigentlich Dinge, die ebenso real sind, wie wenn Sie eine leckere Speise hier haben und Sie stellen sich einen Spiegel her und dann essen Sie nicht die Speise, sondern das, was Ihnen der Spiegel zurückwirft. Sie werden nicht satt. So werden Sie auch nicht seelenkundig, wenn Sie die Seele nicht in ihrem Schöpferischen, Aktiven betrachten, in dem, was sie tut, sondern sie nur betrachten wollen als Bild. Man muß daher durchaus nicht auf dem Standpunkte stehen, daß man ein richtiger Geisteswissenschafter ist, wenn man das Materielle verachtet. Man muß das Materielle eben geistig fassen, dann wird es durch und durch Geist. Sonst lebt man in Abstraktionen, in Intellektualismen; die führen von dem Erkennen ab, nicht zu ihm hin.

Third Lecture

[ 1 ] Today we must remind ourselves of a few things that are already familiar to us from certain sources in order to continue our reflections on what was said last week. When we consider human beings as they exist in the world between birth and death, their lives can be divided into sections that can be viewed from different perspectives. We have often directed our attention to the transition between waking and sleeping. We know that there is an intermediate state between waking and sleeping, which is dreaming. These are the three states in which the consciousness of ordinary life proceeds: waking, dreaming, and sleeping. But these three states are also found elsewhere as divisions of human nature. If we follow the contents, the experiences of this ordinary consciousness, we have the experience of thinking, of having ideas, and I have often said: We are actually only really awake when we are in this state or insofar as we are in this state of having ideas. Anyone who observes themselves with an unbiased mind will be able to recognize that feeling represents a much duller state of consciousness than thinking. Feelings surge through our soul without our being able to relate them in any definite way to anything in the external world or to memories, as we can with ideas. We are also quite conscious, or at least we can be, that in the moments of our waking life these feelings come and go, really just as dreams come and go in the intermediate state between waking and sleeping. And anyone who has a sense for really comparing such things of consciousness with one another will have to say to himself: Dreams are images; feelings are something like indefinite forces surging within us. But in everything else, if we disregard this content, in everything else dreams come and go, just as feelings come and go. And out of what I would call a general darkness and dullness of consciousness, dreams emerge, just as feelings emerge from a general inner state and then sink back down again.

[ 2 ] With volition, what actually goes on inside us when we have an impulse of the will remains as unknown to us as what we sleep through. The only thing that is clear about what goes on in willing is the thought that has the purpose of a volitional act in itself. It is then the perception of, for example, our movement or of what happens externally through our willing that is again before our soul, in our consciousness. But what we say is going on in our leg or arm while we lift our leg, want to step forward with our leg, or want to lift our arm, is something that remains as unconscious as what happens between falling asleep and waking up. So that even while we are awake, we are already simultaneously experiencing these three states of consciousness in a certain sense: waking, dreaming, and sleeping.

[ 3 ] However, we can only come to a complete understanding of human beings if we subject what is given to us, namely that on the one hand we sleep, dream and wake, and on the other hand we want, feel and think, to what I would call a rational examination.

[ 4 ] Let us take, on the one hand, the sleeping human being and, on the other, the willing human being. The sleeping human being is characterized by the absence of that content of consciousness which otherwise actually makes us human, namely the experience of the I. The experience of the I is therefore absent. We usually describe this by saying that from the moment we fall asleep until we wake up, the ego is outside of what is physically present before us.

[ 5 ] Now, however, let us consider the dreaming human being on the one hand and the feeling human being on the other. It will be immediately clear to you from ordinary self-observation that dreams stand before the soul as neutral images, so to speak, that when you dream, say, upon waking or before falling asleep, these images float and weave like a web, not exactly before, but within the soul. What goes on in the soul differs from what is present when we are fully awake. When we are fully awake, we know that we hold the images we have internally, that we grasp them with our human being; they do not float as nebulously in the indefinite as they do in dreams. We grasp them with our human being.

[ 6 ] I will now sketch what I have just said on the board (drawing on the left). Let us simply take the human being schematically (light) and draw what we can imagine as the diagram for the weaving dreams (red), for example in the following way on the human being. One might say that what I have drawn in red on the board is a web that the soul experiences as it continually slips away from it and then returns to it.

[ 7 ] At the moment of waking up, the human being does not have such a web in their soul experience. Instead, what they experience is now within them. I will now sketch (drawing on the right) how this is in the waking state. They now have this fabric, which is otherwise outside them, within them; they grasp it with their body, and thus it is not an indefinite fabric, but something that human beings control internally.

[ 8 ] In this relationship between what is woven and floats away as a dream and what then becomes a thought within the human being when he is fully awake and controls what now lives as such image-thoughts in his soul, you can, I would say, perceive to the point of soulful grasping: there is simply something drawn from the outside into the inside. And when we describe something like this, we are describing nothing other than the entry into the inner being of what is initially woven and floats in dreams, what we call the astral body, which is invisible to ordinary consciousness. So we can say that when we begin to think after waking up, the astral body is within us. We then imagine things. But we know that we have control over these ideas. As long as they are dreams, they float around out there. Just imagine a kind of cloud near you in which dreams are woven. You suck this cloud in, as it were; you control it from within. It is no longer outside. Therefore, you no longer dream. But just as you grasp any object with your hands, you grasp this dream with your inner being. And you have sucked in your astral body; you now have it inside you.

[ 9 ] However, we must ask ourselves more precisely: What do we have in there? If we take a closer look at what we have in there, we may be able to gain some insight by looking at some dreams that are not just images but are already beginning to become vague feelings. Just think about how unpleasant some dreams are; they are simply a web of images. Some dreams are associated with anxiety. You wake up from states of anxiety. In these vague states of anxiety, often accompanied by vague feelings of joy, but mostly frightening states, you see, I would say, the glimmer of something that, as it develops further, is then there when you wake up completely. What glimmers there when the dream frightens you, for example?

[ 10 ] Yes, the dream interweaves with the feeling. Fear is a feeling. The dream is still half outside; this makes the feeling vague. But it is already interweaving with the feeling. This is what causes the feeling to arise. But it intertwines with what else lives in the soul when feeling. And only when you have the astral body completely inside you do you have these specific feelings, which are conditioned by your physical organization, and which can now enforce the ideas of the astral body upon you.

[ 11 ] If you look closely at certain nightmares and anxiety dreams, you will again have, I would say, almost a spiritual grasp of what actually happens during this entry, as we call it, of the astral body into the physical human being. For what causes the fear that sometimes accompanies dreams, you will always discover to be something that is not in order in your breathing process.

[ 12 ] You can see quite clearly from this that the astral body enters and also leaves through what lies in the breathing. It is really not the case that one cannot observe these things if one simply wants to observe life impartially. It is just that one does not make such observations properly. But there is something there that gives us the instruction to recognize that what weaves in dreams and what is the astral body in reality enters our organism by taking hold of the breathing process when we awaken.

[ 13 ] This leads us to a consideration of the human being that is extremely important but is not usually made. We usually view the human being as if he were actually a complete organism, a body made up of solid components. But that is not true. The human organism actually consists of very little solid matter, hardly ten percent. The rest is a water organism, a fluid organism. So in truth we must think of this organism as being constructed in such a way that we say: there is the organism, and in a certain sense one tenth of it is solid (see drawing, light color); but this solid is permeated by the watery element (blue). And only then can you imagine the human organism properly, if you actually imagine it as a column of water that has the solid embedded in it.

[ 14 ] But that is not enough. We must also imagine the human organism as an air organism. The air is outside; we breathe it in. Part of the air that is outside is now inside us. We breathe it out again. We are at the same time an air organism. Let us draw this schematically (in red). But it is precisely this air organism that is seized by the astral body when we wake up. We breathe in the air. The air also undergoes a process; its effects spread throughout the entire organism. The oxygen absorbs the carbon and is converted into carbon dioxide. Such an air process takes place continuously within us.

[ 15 ] When we are awake, however, this air process is permeated by the astral body. The movement of the astral body follows the same paths that the air takes in our organism. The air process is only an air process when we are asleep; when we are awake, the movements of this astral body swim, so to speak, in what lives within us as the air process. But now think about this: as the astral body enters into what I have schematically drawn in red and carries out its movements within the air organism, carrying out what it does in general, this takes place in what is schematically drawn in blue, in the watery organism. These air processes, which are actually the processes of the astral body when we are awake, always come into contact with the watery organism.

[ 16 ] But in the watery organism, the etheric body of the human being is present day and night. And there you have at the same time an interaction between the astral and etheric bodies, but also the physical image of this: the air processes and the water processes in the human being. So you can well imagine that these physical processes are initially present in the human being, taking place between his breathing and the movements of his juices, in fact in everything that is liquid in the organism. But this is again only a reflection of what is happening between the astral and etheric bodies.

[ 17 ] Now, however, everything that is a more solid, liquid, or gaseous organism is in turn permeated by warmth (drawing on p. 55, yellow).. The entire organism has its own warmth: warmth ether. I would like to say: the astral moves on the waves of the airy in the human being, and the actual I moves on that which flows through the organism as warmth.

[ 18 ] Now you have the physical body as such; the liquid body, which is also physical, but which is now separated from the solid physical body, the liquid physical body, which has an intimate connection with the etheric body; the gaseous organism of the human being, which has an inner connection with the astral body, and that which are heat processes, which in other words is heat ether in the human being, which has an intimate connection with the human I. So that in the physical, I would say, we see everywhere the image of the whole human being. The solid is, so to speak, something that exists in itself. But the liquid in the organism cannot exist in itself. We have very little of the solid in our heads. What we have that is solid floats in the cerebral fluid, that is, in liquid. If you look at this liquid inside the human head, you first have the etheric part of the head in this liquid.

[ 19 ] Breathing proceeds as follows: You breathe in. The breath pushes inward and continues through the spinal fluid to the brain. At the same time, however, the astral element moves upward toward the etheric element of the head in the waking state. So that on the one hand we have a interaction between the movements of the brain fluid and the respiratory movements, and on the other hand an interaction between the etheric part of the head, of which what goes on in the brain fluid is only a reflection, and what are respiratory processes, which in turn are only a reflection of what is astral in the human being. And then we have a continuous interplay of heat states. And the blood in its movement mediates these heat states. On this wave of the sea of heat within us, our ego moves at the same time.

[ 20 ] It is important that we imagine this very vividly, that we are clear about it. We can only observe the solid organism in itself. As soon as we approach the liquid organism, it no longer has the possibility of moving in the same way as water waves move outside, but moves in such a way that its movement is a reflection of what is happening in the etheric body of the human being. Again, what goes on in the finer states of bodily respiration is a reflection of what goes on in the astral body of the human being. But now, when we consider this, we must say to ourselves: Let us just look at the cerebral fluid. It has certain movements within itself. These are a reflection of the etheric body. But the etheric body is something that human beings acquire when they descend from the spiritual worlds into this physical world; they do not yet have it within the spiritual worlds. But by taking hold of their physical body, human beings already have their etheric body. They draw the ether out of the cosmos, so to speak. And only by drawing the ether from the cosmos can they connect with the physical, which is then conveyed to them through heredity. So that we already bring with us what lives inwardly in the etheric body of the human being when we take hold of our physical body.

[ 21 ] Suppose, then, that the human germ arises in the body of the maternal organism. We examine what is liquid in this human germ. This is not done in ordinary physiology. In ordinary physiology, the germ is only investigated insofar as it contains solid matter or at least can be observed as solid matter. The liquid is not examined at all. But if one were to examine the liquid, one would discover how in the liquid, namely in the cerebral fluid, there is an image of what has slipped into the physical human being and what was already expressed in the etheric body when the ether was drawn in.

[ 22 ] So we can say: When the physical body is here (see drawing), the physical human germ is formed—I am not drawing the solid part at all; what I am drawing is the liquid human germ (red)—and that which exists as the I and the astral descends from the spiritual world. That which has already been drawn in as ether (yellow) slips in here. Simply by the human being submerging itself in the physical body, what the human being brings in from outside is taken up into the liquid organism. If you were to examine the cerebral fluid of a child in its movements, you would have to say: This is actually a photograph of what the human being was before it connected with its physical body. You see, it is very important that one can actually say: In the cerebral fluid, that is, in the movements of the cerebral fluid, one would find a photograph of what preceded conception.

[ 23 ] Now, from the cerebral fluid you can easily understand that you find there a kind of photograph of what preceded it. But consider the breathing process. The breathing process appears to us as a very physical process because our lungs are organized in a certain way, because air is sucked in, because the breathing process even takes place under the influence of the outside world when we sleep, when our eternal self is not connected to our temporal self. One might say that the breathing process is like this: it takes place both when we sleep and when we are awake. When we sleep, the wave of movement of the breathing process passes through our organism; when we are awake, this wave carries the astral body. It can carry it, but it does not need to. It does so when we sleep, but it does not carry it then.

[ 24 ] What follows from this? It follows that the brain water, because it is enclosed within, can continue to exist, can be a kind of continuation of what was there before. But something from the past cannot continue in the same way in our breathing, for example. Therefore, the following happens: When we look at the human head and then at the human chest, we find that inside the human head, through the cerebral fluid, so to speak, that is, in the physical organism, there is indeed a continuation of the pre-birth spiritual human being. This is not the case with the breathing process. There, the physical breathing process takes place on its own (see drawing, yellow), and the spiritual is much less strongly connected to the physical process (red). One might say: in the head, the spiritual human being, the spiritual-soul human being, is firmly connected to the physical human being; they have become one. This is not the case in the chest human being, where they are more separated; there, the physical organism is more on its own and the spiritual-soul is also on its own.