Christ and the Evolution of Consciousness

GA 214

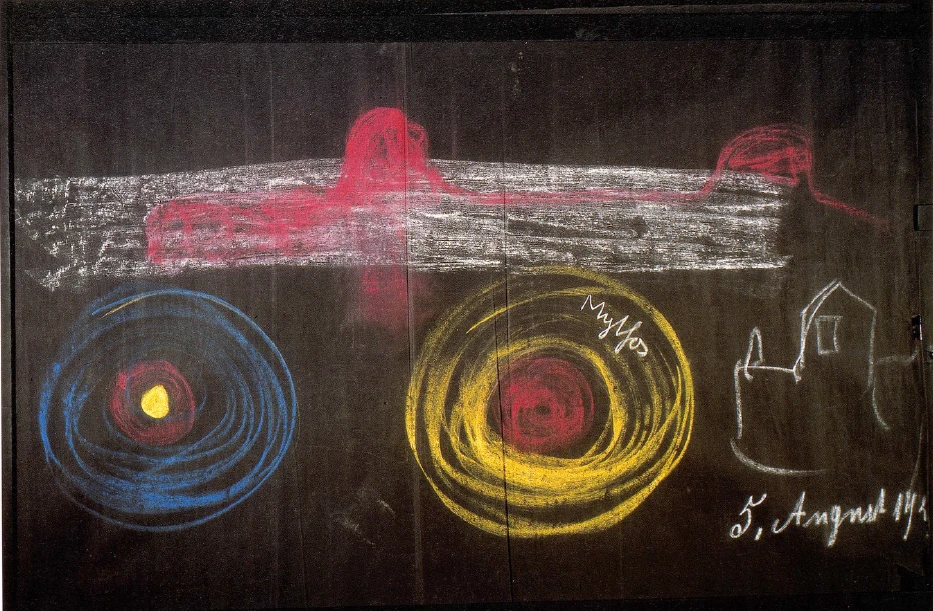

5 August 1922, Dornach

Translator Unknown

With his ordinary consciousness man knows only a fragment of all that is bound up with his existence. Looking out into the world with our ordinary consciousness we get pictures and images of the outer world through our senses. And when we proceed to think about what the senses have thus given us, when we form thoughts about what we have perceived, memory-pictures of these thoughts remain. Our life of soul is such that we perceive and live with the outer world and bear within us memory-pictures of what is past.

The process of memory, however, is not rightly understood by the ordinary consciousness of man. He thinks that he has known and perceived certain things in the outer world, that pictures have remained somewhere in the background of his being and that he can call them up again in his soul as memory-pictures. But the process is by no means so simple. Consider for a moment what goes on in man, step by step. You are certainly familiar with the ‘after-images’ that arise from what is perceived by the senses, by the eye, for example. As a rule we do not stop to think about them, but they are aptly described by Goethe in his Theory of Colours. He speaks of them as ‘vanishing after-images.’ We look intently at some object and then close the eyes. Different images or pictures linger for a while on the retina and then die away like an echo. In ordinary life we pay little heed to these images because we set up a more forceful activity than that of mere perception. We begin to think. If our thought-activity is weak when some object in the outer world is perceived, an after-image remains on the retina. But if we really think, we take the outer stimulus further inwards, as it were, and a thought-image lingers on as a kind of echo.

A thought-image is stronger and its ‘echoing’ more intense than that of an after-image produced by one of the senses, but it is really only a higher development of the same process. And yet these after-images of thought would also fade away, just as an after-image fades away from the eye, if they came into being merely as thought ¬pictures – which, however, they do not. Man has a head, but as well as this the rest of his organism, which is of quite a different nature. The head is pre-eminently an after-image of what happens before the human being descends from the spiritual to the physical world through birth, or rather, through conception. The head is much more physical than the rest of the organism. The rest of the organism is less developed, so far as the Physical is concerned, than the head. Let me put it thus: In the human head the Spiritual is present only as an image; in the rest of the organism the Spiritual works strongly as spirit. The head is intensely physical; it contains little of the spirit as being spirit. The physical substance of which the rest of the organism is composed is not a faithful after-image of what the human being was before his descent to birth. The Physical is more highly developed in the head of man, the Spiritual in the other parts of his organism.

Now our thoughts would fade away just as visual after-images fade away, if they were not taken over and worked upon by our spiritual organism. But the spiritual organism could not do much with these images if something else as well were not taking place. For something else is taking place while we are perceiving these images of which we then make the fleeting thoughts that really only reside in our head. Through the eye we receive the pictures which we then work up into thoughts. We receive these visual images from the physical and etheric universe. But at the same time, in addition to the pictures, we absorb into us the Spiritual from the remain¬ing universe. We do not only bear the spirit within us, but the spirit of the remaining universe is constantly pouring into us. We may therefore say that with the eye we perceive something or other in the physical and etheric universe and it remains within us as an image. But behind this an absolutely real spiritual process is working, although we are unconscious of it. In the act of memory, this is what happens: We look inwards and become aware of the spiritual process which worked in our inner being during the act of perception.

I will make this clearer by a concrete example. We look at some object in the outer world – a machine, perhaps. We then have the image of the machine. As Goethe described it, an after-image lingers for a short time and then ‘echoes’ away. The thought of the machine arises and this thought remains a little longer, although it too would ultimately fade away if something else were not taking place. The fact is that the machine sends something else into our spiritual organism – (nothing very beautiful when the object is a machine, far more beautiful if the object is a plant, for instance). And now – perhaps after the lapse of a month – we look inwards and a memory arises because, although we were entirely unconscious of it, something else passed into us together with the perception of the object which stimulated the thought. This thought has not been wandering around somewhere in the depths of our being. A spiritual process has been at work and later on we become aware of it. Memory is observation, later observation of the spiritual process which ran parallel with the act of physical perception.

In his onward-flowing stream of existence man is contained within the ocean of the spiritual world. During the period between death and a new birth his existence continues within this spiritual world. But there are times when with his head he comes forth from the spiritual world. In other words, with a part of his being he leaves the spiritual world like a fish that tosses itself above the water. This is earthly life. Then he plunges once more back into the ocean of spirit and later on again returns to an earthly life. Man never leaves this ocean of spiritual existence with the whole of his being but only with his head. The lower part of him remains always in the spiritual world, although in his ordinary conscious¬ness he has no knowledge of what is really going on. Spiritual insight, then, tells us the following: Between death and a new birth man lives in the spiritual world. At birth he peeps out with his head, as it were, into a physical existence, but the greater part of his being remains in the spiritual world, even between birth and death. And it is well that this is so, for otherwise we should have no memories. Memories are only possible because the spiritual world is working in us. An act of memory is a spiritual process appertaining to an objective and not merely to a subjective world.

In his ordinary consciousness man does not regard memory as being a real process, but here he is in error. It is as though he were looking at a castle on a mountain just in front of him and seeing it actually there, believes in its reality. Then he moves away a certain distance, sees the castle in greater perspective, and says to himself: Now I have nothing but a picture, there is no longer any reality. And so it is in ordinary life. In the stream of time we imagine that we get further and further away from reality. But the reality of the castle in space does not change because our picture of it changes, any more than does the reality of that which has given rise to our memory-picture. It remains, just as the castle remains. Our explanation of memory is erroneous because we cannot rightly estimate the perspective of time. Consciousness which flows with the stream of time is able to open up a vista of the past in perspective. The past does not disappear; it remains. But our pictures of it arise in the Perspective of time.

Man’s relation to the more spiritual processes in his being between birth and death has undergone a fundamental change in the course of earthly existence. If we were to regard man as a being consisting merely of physical body and etheric body, this would be only the part of him which remains lying there in bed when he is asleep at night. By day, the astral body and Ego come down into the physical and etheric bodies. The Ego of those men who lived before the Mystery of Golgotha – and in earlier incarnations we ourselves were they – began to fade in a certain sense as the time of the Mystery of Golgotha drew near. After the Mystery of Golgotha there was something different about the process of waking. The astral body always comes right down into the etheric body and in earlier times the Ego penetrated far down into the etheric body. In our modern age it is not so.

In our age the Ego only comes down into the head-region of the etheric body. In men of olden times the Ego came right down and penetrated into the lower parts of the etheric body as well. Today it only comes down into the head. The outcome of this is man’s faculty of intellectual thinking. If the Ego were at any moment to descend lower, instinctive pictures would arise within us. The Ego of modern man is quite definitely outside his physical body. Indeed his intellectual nature is due to the fact that the Ego no longer comes down into the whole of his etheric body. If such were the case he would have instinctive clairvoyance. But instead of this, modern man has a clear-cut vision of the outer world, albeit he perceives it only with his head. In ancient times man saw and perceived with his whole being – nowadays only with his head. And between birth and death the head is the most physical part of his being. That is why in the age of intellectualism man knows only what he perceives with his physical head and the thoughts he can unfold within his etheric head. Even the process of memory eludes his consciousness and, as I said, is interpreted falsely.

In days of old, man saw the physical world and behind it a world of spirit. Objects in the physical world were less clear-cut, far more shadowy than they are to the sight of modern man. Behind the physical world, divine-spiritual beings of a lower and also of a higher order were perceived. To state that ancient descriptions of the Gods in Nature are nothing but the weavings of phantasy is just as childish as to say that a man merely imagines something he has actually seen in waking life. It was no mere phantasy on the part of man in olden days when he spoke of spiritual beings behind the world of sense. He actually saw these beings and against this background of the spiritual world, objects in the physical world were much less clearly defined. Thus the man of antiquity had a very different picture of the world. When he awoke from sleep his Ego penetrated more deeply into his etheric body and divine-spiritual beings were revealed to him.

He gazed into those spiritual worlds which had been the forerunners of his own world. The Gods revealed their destinies to him and he was able to say: ‘I know from whence I come, I know the divine world with which I am connected.’ This was because he had the starting-point of his perspective within him. He made his etheric body an organ to perceive the world of the Gods. Modern man cannot do so. He has no other starting-point for his perspective than in his head and the head is outside the most spiritual part of the etheric body. The etheric counterpart of the head is somewhat chaotic, not so highly organised as the other parts of the etheric body, and that is why modern man has a more defined vision of the physical world, although he no longer sees the Gods behind it. But the present epoch is one of preparation for what lies in the future. Man is gradually progressing to the stage where the centre of his perspective will be outside his physical being. Nowadays, when he is really only living in his head, he can have nothing but abstract thoughts about the world. It may seem rather extreme to say that man lives in his head, for the head can only make him aware of earthly, physical existence. But it is none the less a fact that as he ‘goes out of his head’ he will begin to know what he is as a human being. When he lived in his whole being he had knowledge of the destinies of the Gods. As he gradually passes out of himself he can have knowledge of his own destiny in the cosmos. He can look back into his own being. If men would only make more strenuous efforts in this direction, the head would not hinder them so much from seeing their own destinies. The obstacle in the way of this is that everyone is so intent upon living only in the head. It is simply an unwillingness to look beyond what the head produces that makes people loath to admit that the wisdom which Anthroposophy has to offer in regard to the being of man is something that can be understood by ordinary, healthy intelligence.

And so man is on the way to a knowledge of his own being, because he will gradually begin to focus his perspective from a point that lies, not inside, but outside himself. It is the destiny of man to pass out of his etheric body and so, finally, to attain to knowledge of himself as a human being. But obviously there is a certain danger here. It is possible for man to lose connection with his etheric body. This danger was mitigated by the Mystery of Golgotha. Whereas before the Mystery of Golgotha man was able to look out and see the destinies of the Gods, after that Event it became possible for him to see his own world-destiny. In the course of his evolution, man’s tendency is more and more to ‘go out of himself ‘ in the sense described above. But if, as he does so, he understands the words of Paul: “Not I but Christ in me” in their true meaning, his connection with the Christ will bring him back again into the realm of the human. His link with the Christ sets up a counter¬balance to the process which gradually takes him ‘out of himself.’ This experience must deepen and intensify. In the course of world-destiny the outer Gods passed into twilight, but just because of this it was possible for a God to work out His destiny on the Earth itself and thus be wholly united with mankind.

Think, then, of the man of olden times. He looked around him, perceived the Gods who arose before him in pictures, and he then embodied these pictures in his myths. Today, man’s vision of the Gods has faded. He sees only the physical world around him. But as a compensation he can now be united in his inner life with the destiny of a God, with the death and resurrection of a God. Looking out with their clairvoyant faculties in days of yore, men saw the destinies of Gods in fleeting pictures upon which they then based their myths. The difference in the myths is due to the fact that experience of the spiritual world varied according to men’s capabilities of beholding it. Perceived by this instinctive clairvoyance the world of the Gods was dim and shadowy – hence the diversity in the myths of the various peoples. It was a real world that was seen but it arose in a kind of dream-consciousness. The figures of the Gods were sometimes more and sometimes less distinct, but never distinct enough to guarantee absolute uniformity in the different myths.

And then it happened that a God worked out His destiny on the Earth itself. The destinies of the other Gods were more remote from man in his earthly life. He saw them in perspective and for that reason less distinctly. The Christ-Event is quite near to men—too near, indeed, to be seen aright. The old Gods arose before men’s vision in the perspective of distance and for this reason somewhat indistinctly. If it had been otherwise, the myths would have been all alike. The Mystery of Golgotha is too near to man, too intimately part of him. He must first find the perspective in which to behold the destiny of a God on Earth and therewith the Mystery of Golgotha.

Those who lived in the time when the Mystery of Golgotha took place could behold with spiritual vision and so understand the Christ. They could readily understand Him for they had seen the world of the Gods. So now they knew: Christ has gone forth from the world of the Gods. He has come to this Earth for His further destiny beginning with the Mystery of Golgotha. As a matter of fact they no longer saw the Mystery of Golgotha itself in clear outline but until this moment they could see the Christ Himself quite well. Therefore they had very much to say of the Christ as a God. They only began to discuss what had become of this God at the moment when he came down into a human being at the Baptism of John in Jordan. Hence in the earliest time of Christianity we have a strongly developed Christology but no ‘Jesuology’.

It was because the whole world of the Gods was no longer within man’s ken that Christology afterwards became transformed into mere Jesuology—which grew stronger and stronger until the nineteenth century, when Christ was no longer understood even with the intellect and modern Theology was very proud of understanding Jesus in the most human way and letting the Christ go altogether.

Precisely through spiritual knowledge the perspective must be found once more to recognise what is the most important of all—the Christ in Jesus. For otherwise we should no longer remain united with the human being at all. Increasingly we should only be looking at him from outside. But now, by recognising Christ in Jesus, through our union with the Christ we shall be able to partake once more with living sympathy in man and in humanity—precisely through our understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha.

Thus we may say: In going more and more out of himself, man is on the way by-and-by to transform all spiritual reality into mere abstract concepts and ideas. Mankind has already gone very far in this direction and such might be its impending fate already at this moment. Men would go farther and farther in their abstract, intellectual capacity and would develop within them a kind of faith whereby they would say to themselves: Yes, now we experience the Spiritual, but this Spiritual is a Fata Morgana. It has no weight. It consists of so many ideas.

Man must find the possibility once more to replenish these ideas with spiritual substance. This he will do inasmuch as he takes the Christ with him and experiences the Christ as he passes over into the intellectual life. Modern intelligence must grow together with the consciousness of Christ.

In olden times man spoke of the Fall into Sin. He spoke of this picture of the Fall as though with his own being he had belonged to a higher world and had fallen down into a lower, into a deeper world. Take it in a pictorial sense and it is quite true to the reality. We can in a very real sense speak of a Fall into Sin. But just as the man of olden times felt truly when he said to himself: ‘I am fallen from a spiritual height and have united myself with something lower’—so should man of modern time discover how his increasingly abstract thoughts are also bringing him into a kind of Fall. But this is another kind of Fall. It is a Fall that goes upwards. Man as it were falls upward, that is to say he ascends, but he ascends to his own detriment just as the man of olden times felt himself fall to his detriment. The man of old who still understood the Fall into Sin in the old sense could recognise in Christ Him Who had brought the human being into the right relation to this Sin, that is to say, into the possibility of a salvation. The man of old, when he developed the right consciousness, could recognise in Christ the Being Who had lifted him again out of the Fall. So should the man of modern time as he goes on into intellectualism see the Christ as the one who gives him weight so that he shall not spiritually fly away from the Earth or from the world in which he should be.

The man of old perceived the Christ Event paramountly in relation to the unfolding of the will which is, of course, connected with the Fall into Sin. So should the man of modern time learn to recognise the Christ in relation to thought—thought which must lose all reality if man were unable to give it weight. For only so will reality again be found in the life of thought.

Mankind indeed is going through an evolution. And as Paul might speak of the old Adam and of the new Adam, of the Christ, so too may the modern man in a certain sense. Only the modern man must realise it clearly. He must perceive that the man of old who still had the old consciousness within him, felt himself lifted up by the Christ. The man of the new age, on the other hand, should feel himself protected by the Christ from rushing forth into the spiritual emptiness of mere abstraction, mere intellectualism.

The modern man needs Christ to transform within him this sin of going out into the void, to make it good again. Thought becomes good by uniting itself once more with the true reality, that is, the spiritual reality. Therefore, for a man who can see through the secrets of the universe there is the fullest possibility to place the Christ into the very centre even of the most modern evolution of human consciousness.

And now go back to the image with which we began. I began by speaking of the faculty of memory in man. We human beings live on and on in the spiritual world. We only lift ourselves out of the spiritual world inasmuch as with our heads we peer forth into the physical. But we never emerge from the spiritual world altogether. We only emerge with our head. So much do we remain in the spiritual world that even our memory processes are constantly taking place within it. Our world of memories remains beneath, in the ocean of the spiritual world.

Now so long as we are between birth and death and are not strong enough in our Ego to perceive all that is going on down there even with our memories—so long are we quite unaware of how it is with us as humanity in modern time. But when we die, then it becomes a very serious matter, this spiritual world from out of which we lift ourselves in physical existence, like a fish that gasps at air. Then we no longer look back on our life imagining that we perceive unreal memory-pictures, giving ourselves up to the illusion that the perspective of time kills the reality. For that is how man lives in relation to time when he gives himself up to his memory. He is like one who would consider what he perceives in the distance, in the perspective of space, as unreality, as a mere picture. He is like one who would say: ‘When I go far away from it, the castle there in the distance is so small, so tiny that it can have no reality, for surely no men could live in so tiny a castle. Therefore the castle can have no reality.’ Such, more or less, is the conclusion he draws in time. When he looks back in time he does not think his memory-pictures realities, for he leaves out of account the perspective of time. But this attitude ceases when all perspective ceases, that is to say when we are out of space and time. When we are dead it ceases. Then that which lives in the perspective of times emerges as a very strong reality.

Now it is possible that we had brought into our consciousness that which I call the consciousness of Christ. If we did so, then as we look back after our death we see that in life we united ourselves with reality, that we did not live in a mere abstract way. The perspective ceases and the reality is there. If in life we remained at the mere abstract experience, then too, of course, the reality is there. But we find that in earthly life we were building castles in the air. What we were building has no firmness in itself. With our intellectual knowledge and cognition we can indeed build, but our building is frail, it has no firmness. Therefore the modern man needs to be penetrated with the consciousness of Christ, to the end that by uniting himself with realities he may not build castles in the air but castles in the spirit. For earthly life, a castle in the air is something which in itself lies beneath the spirit. The castles in the air are always at their place, only for earthly life they are too thin and for the spiritual life too physically dense. Such human beings cannot free themselves from the dense physical, which in relation to the Spiritual, after all, has a far lesser reality. They remain earthbound. They get into no free relation to earthly life if in this life they build mere castles in the air through intellectualism.

So you see, precisely for intellectualism the Christ consciousness has a very real significance. And this significance is in the sense of a true doctrine of salvation—salvation from the building of castles in the air, salvation for our existence as it will be when we have passed through the gate of death.

For Anthroposophy these things are no articles of faith. They are clear knowledge which can be gained as clearly as mathematical knowledge can be gained by those who are able to manipulate the mathematical methods.

Fünfter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Der Mensch kennt, wenn er sich seines gewöhnlichen Bewußtseins bedient, nur einen Teil dessen, was mit seinem Dasein zusammenhängt. Wir erhalten, wenn wir uns in der Welt umschauen, durch unser gewöhnliches Bewußtsein die Bilder der Außenwelt, die wir durch unsere Sinne in uns erregen können. Und indem wir dann über das, was uns die Sinne geben, denken, indem wir uns Gedanken bilden, bleiben uns von diesen Gedanken Erinnerungsbilder. So daß also das Leben in der Seele so verläuft, daß der Mensch die Außenwelt anschaut, mit ihr lebt, aber, indem er mit der Außenwelt lebt, in sich auch trägt die Erinnerungsbilder an Vergangenes, das er erlebt hat.

[ 2 ] Nur wird von dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein das, was in der Erinnerung lebt, nicht richtig erkannt. Der Mensch stellt sich das ja ungefähr so vor: Er hat von der Außenwelt Erkenntnisse, Wahrnehmungen erhalten, die haben Bilder in ihm ergeben; diese Bilder bleiben irgendwo zurück, und er kann sie in seinem Seelenleben als Erinnerungsbilder wiederum heraufrufen. So ist aber die Sache nicht. Betrachten Sie einmal stufenweise, was sich eigentlich mit dem Menschen abspielt. Sie werden schon bemerkt haben, in welcher Weise dasjenige, um das man sich nicht besonders in Gedanken kümmert, sondern was man nur mit den Sinnen, zum Beispiel mit den Augen betrachtet, Nachbilder gibt. Goethe beschreibt solche Nachbilder, wie sie von den Augen gebildet werden, sehr gut in seiner Farbenlehre: als abklingende Bilder. Man sieht auf irgend etwas hin, schließt die Augen: veränderte Bilder klingen ab. Man beachtet im gewöhnlichen Leben diese abklingenden Bilder wenig, denn man setzt für das Wahrnehmen eine energischere Tätigkeit ein: man denkt nach. Wenn der Mensch eine schwache Gedankentätigkeit einsetzt, und die Außenwelt ihm ein Bild gibt im Auge, so klingt ein Nachbild nach. Wenn der Mensch aber jetzt nachdenkt, so nimmt er gewissermaßen die von außen kommende Tätigkeit weiter herein, und es klingt dann sein Gedankenbild nach. Das ist auch ein Nachklingen.

[ 3 ] Diese Gedankenbilder sind stärker, ihr Nachklingen ist auch ein intensiveres als das der bloßen Sinnesnachbilder; aber es ist im Grunde genommen eben doch nur eine höhere Stufe. Diese Gedankennachbilder würden aber dennoch verklingen, so wie die Sinnesnachbilder verklingen, wenn sie nur als Gedankenbilder erregt würden. Das ist aber gar nicht der Fall. Denn der Mensch hat ja nicht nur seinen Kopf, sondern auch seinen übrigen Organismus, der nun doch etwas ganz anderes als der Kopf ist. Der Kopf ist eigentlich vorzugsweise ein Nachbild dessen, was mit dem Menschen geschieht, bevor er aus der geistigen Welt in die physische Welt durch die Geburt oder Empfängnis heruntergestiegen ist. Er ist viel mehr physisch als der übrige Organismus. Der übrige Organismus ist weniger physisch entwickelt als der Kopf, und man könnte sagen: Das Geistige ist eigentlich im Kopfe nur wie ein Bild vorhanden, während es für den übrigen Organismus geistig stark ist. Sie haben einen stark physischen Kopf, plastisch ausgebildet; da ist wenig Geist darinnen im spirituellen Sinne. Und Sie haben einen Organismus, der ist physisch nicht stark ein Nachbild desjenigen, was der Mensch war vor der Geburt, vor dem Heruntersteigen, aber das Geistige ist im übrigen Organismus stärker. Beim Kopfe ist mehr das Physische, bei dem übrigen Organismus mehr das Geistige ausgebildet.

[ 4 ] Die Gedanken, die wir haben, die würden nun geradeso verklingen wie die Nachbilder der Augen, wenn sie nicht von unserem Geistorganismus übernommen und von ihm verarbeitet würden. Aber der Geist-Organismus könnte nicht viel mit diesen Bildern anfangen, wenn nicht noch etwas anderes stattfände. Während wir nämlich diese Bilder wahrnehmen, die wir dann zu diesen flüchtigen Gedanken machen, die eigentlich nur in unserem Kopfe sitzen, bekommen wir geradeso wie wir durch das Auge die Bilder bekommen, die wir dann zu Gedanken verarbeiten, außer dem Bilde noch — denn die Augenbilder erhalten wir ja von der physisch-ätherischen Welt - von der übrigen Welt das Geistige in uns hinein, so daß wir nicht nur in uns den Geist tragen, sondern daß fortwährend auch der übrige Geist der Welt in uns hineinkommt. Sie können also sagen: Mit dem Auge nehmen Sie aus der physisch-ätherischen Welt irgend etwas wahr, was in Ihnen als Bildwirkung ist; aber dahinter steht ein sehr realer geistiger Vorgang, der nur im Unbewußten bleibt. Der Mensch kann ihn mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nicht wahrnehmen. Das ist, durchaus parallel laufend der physischen Wahrnehmung, ein geistiger Vorgang. Und während Sie das Bild wahrnehmen, das kurze Zeit nachklingt im Auge, während Sie den Gedanken haben, den Sie ein bißchen behalten würden, aber der auch abklingen würde, geht da in Ihnen etwas Geistiges vor, und wenn Sie sich wieder erinnern, so wenden Sie einfach den Blick nach innen und schauen das an, was geistig im Inneren vorgegangen ist, während Sie wahrgenommen haben.

[ 5 ] Ich will es Ihnen noch durch etwas Anschauliches verdeutlichen. Nehmen wir an, Sie sehen irgend etwas in der Außenwelt, sagen wir zum Beispiel eine Maschine. Sie haben das Bild der Maschine. In dem Sinne, wie das Goethe beschrieben hat, gibt das ein Nachbild, das kurz erklingt, dann abklingt. Sie bekommen den Gedanken der Maschine, der sich länger hält, der aber auch abklingen würde. Aber die Maschine sendet außerdem in Ihren Geistesorganismus noch etwas hinein. Bei der Maschine ist das allerdings etwas sehr wenig Schönes, bei der Pflanze zum Beispiel ist es viel schöner. Die sendet etwas in Sie hinein. Und nun, nach meinetwillen einem Monat, blicken Sie in sich hinein. Die Erinnerung entsteht Ihnen durch das, was damals auch in Sie, ohne daß Sie es gewußt haben, gleichzeitig mit dem hineingegangen ist, was den Gedanken erregt hat. Nicht der Gedanke ist da unten herumgewandelt, sondern es ist ein unbewußter geistiger Vorgang gewesen. Der wird später beobachtet. Erinnerung ist Beobachtung, späteres Beobachten eines Geistvorganges, der parallel gegangen ist der physischen Wahrnehmung. — Sehen Sie, eigentlich leben wir Menschen so in der Welt: Da ist unser fortlaufender Strom des Daseins; wir sind in dem Meere der Geisteswelt drinnen. Und nun leben wir zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt in dieser geistigen Welt darinnen unser Dasein weiter. Nur gibt es Zeiten, da gehen wir aus der geistigen Welt heraus mit dem Kopf. Also wir bewegen uns fort, und zu gewissen Zeiten, wie ein Fisch, der über das Wasser hinausschnellt, kommen wir heraus. Das ist das Erdenleben. Dann tauchen wir wieder unter. Dann kommt wieder ein Erdenleben. Wir tauchen nämlich nicht mit unserem ganzen Geistwesen aus diesem Meere des geistigen Daseins auf, sondern nur mit dem Kopf. Da unten bleiben wir immer in der geistigen Welt drinnen. Nur wissen wir nicht mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein, was vorgeht. Also für die geistige Wahrnehmung ist es eigentlich so, daß wir sagen können: Der Mensch lebt zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt in der geistigen Welt. Dann guckt er herauf mit seinem Kopf in sein Physisches, aber mit dem Hauptteil bleibt er immer noch in der geistigen Welt, auch zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode. Und es ist gut für uns, daß wir dadrinnen schwimmen bleiben, denn wir hätten sonst keine Erinnerungen. Das, was uns die geistige Welt gibt, macht sie uns möglich. Das Erinnern ist schon ein geistiger Vorgang, der durchaus einer objektiven Welt angehört, nicht bloß etwa einer subjektiven. Das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein gibt sich dabei einem Irrtum hin. Es glaubt nicht, daß mit der Erinnerung ein realer Prozeß verknüpft ist. Aber das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein irrt sich, geradeso wie jemand, der einen Berg mit einem Schloß vor sich hat. Jetzt sieht er das ganz genau, jetzt glaubt er an die Wirklichkeit. Nun entfernt er sich. Die Sache wird immer perspektivischer, und er würde sagen, weil das immer perspektivischer wird: Jetzt habe ich nur ein Bild, keine Wirklichkeit mehr. So entfernen wir uns in der Zeit von der Wirklichkeit. Das Schloß, das ändert sich nicht .in bezug auf seine Wirklichkeit im Raume, wenn unser Bild sich ändert. Ebensowenig ändert sich in bezug auf seine Realität dasjenige, dem unser Erinnerungsbild entspricht. Das bleibt, wie unser Schloß bleibt. Wir irren uns nur, weil wir unsere zeitliche Perspektive nicht richtig einschätzen können. So sind viele Dinge, die sich auf den Menschen beziehen, einfach richtigzustellen. Was wir als ein in der Zeit verlaufendes Bewußtsein haben, das ist nämlich nichts anderes als ein perspektivischer Anblick der Vergangenheit. Vergangenheit vergeht nicht, sie bleibt. Unsere Bilder rücken nur in zeitliche Perspektive.

[ 6 ] Nun, aber gerade dieses Verhältnis zu dem in uns, was eigentlich auch zwischen Geburt und Tod geistigere Vorgänge sind, hat sich für die Menschen im Laufe des Erdenlebens ganz wesentlich geändert. Wenn wir den Menschen betrachten, so besteht er ja aus dem physischen und dem ätherischen Leibe. Aber das wäre von dem Menschen nur das, was in der Nacht, wenn er schläft, im Bette liegt. Bei Tag, da ist hineingesenkt in diesen physischen und ätherischen Leib noch der astralische Leib und das Ich. Das Ich derjenigen Menschen, die vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha gelebt haben - und wir waren ja selbst in früheren Inkarnationen diese Menschen -, dämmerte gegen das Mysterium von Golgatha hin ab. Da wachten die Menschen in einer anderen Weise auf, als diejenigen nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha. Der astralische Leib geht immer ganz in den Ätherleib hinein. Aber das Ich ging früher auch sehr weit in den Ätherleib hinein. Heute ist das nicht mehr der Fall. Heute geht das Ich nur in den Kopfteil des Ätherleibs hinein. So daß das Ich bei dem alten Menschen ganz untertauchte und daher auch in die unteren Partien des Ätherleibes kam. Heute geht es nicht dahinunter, sondern nur in den Kopf. Dadurch können wir intellektualistisch denken. In dem Augenblick, wo wir tiefer untertauchen würden, würden wir innerlich instinktive Bilder bekommen. Und das Ich ist eigentlich noch stark außerhalb des physischen Leibes bei dem Menschen der Gegenwart. So daß gerade sein intellektualistisches Wesen darauf beruht, daß er nun nicht mehr mit seinem Ich in seinen ganzen Ätherleib untertaucht. Würde das geschehen, so würde er instinktives Hellsehen haben. Da er aber nicht mehr in seinen ganzen Ätherleib untertaucht, sondern nur in den des Kopfes, so bekommt er nicht dieses instinktive Hellsehen, sondern ein klar bewußtes Sehen, ein klar bewußtes Wahrnehmen der Außenwelt, aber nur ein Kopfwahrnehmen der Außenwelt, so wie eben unser Wahrnehmen ist. Der alte Mensch hat mit seinem ganzen Menschen noch gesehen. Der neuere Mensch sieht nur mit dem Kopfe. Und der Kopf ist eben das am allermeisten physisch Geartete zwischen Geburt und Tod. Daher wird dem Menschen des intellektualistischen Zeitalters nur das gegeben, was er durch seinen physischen Kopf und dasjenige noch, was er durch den Ätherleib des Kopfes wahrnimmt: die Gedanken, die er sich machen kann. Schon der Vorgang des Erinnerns, der allerdings dann da unten vorgeht, entzieht sich dem Bewußtsein. Den deutet der moderne Mensch ganz falsch, wie ich ausgeführt habe. Dadurch sah der alte Mensch um sich herum nicht bloß die physische Außenwelt, sondern hinter ihr das geistige Wesen. Die physische Außenwelt wurde ihm gar nicht besonders klar, die hatte für ihn viel mehr Verschwommenes als für den neueren Menschen. Aber dafür sah er überall hinter den Dingen, die da sich in der physischen Welt ausbreiteten, göttlich-geistige Wesenheiten niederer Art, aber auch solche höherer Art. Es ist eine kindlich naive Vorstellung, wenn man glaubt, daß, wenn die alten Menschen ihre Götter in der Natur beschrieben haben, sie da etwas erdichtet hätten. Sie haben nichts erdichtet. Es wäre gerade so naiv, als wenn wir von irgend jemandem hören, er hat das und das im Wachen gesehen, und wir würden sagen: Das hat er bloß erdichtet. — Die Alten haben die Dinge nicht bloß erdichtet, sondern sie haben sie gesehen, verwoben in die sinnlichen Anschauungen, die deshalb auch viel undeutlicher waren, weil sie gewissermaßen auf dem Hintergrunde des Göttlich-Geistigen, das sich abspielte, gesehen wurden. Es war also ein ganz anderes Weltbild, das der alte Mensch hatte. Er tauchte eben beim Aufwachen tiefer in seinen Ätherleib ein und hatte dadurch ein anderes Weltbild. Er war in sich drinnen, und dadurch zeigten sich ihm die göttlich-geistigen Wesenheiten in ihren Schicksalen.

[ 7 ] Der Mensch sah hinein in die Götterwelten, die seiner eigenen Welt vorangegangen waren. Die Götter zeigten dem Menschen ihr Schicksal, und er konnte, indem er in die Götterwelten hineinsah, die Schicksale der Götter wahrnehmen. Er konnte sagen: Ich weiß, woher ich komme, ich weiß, mit welcher Welt ich zusammenhänge. Das war deshalb, weil der Mensch den Ausgangspunkt seiner Perspektive in sich haben konnte. Er machte seinen Ätherleib zu einem Organ, um diese Götterwelt wahrnehmen zu können. Das kann der moderne Mensch nicht. Der kann seine Perspektive nur vom Kopf aus nehmen, und der ist außerhalb des geistigsten Teiles des Ätherleibes. Der Ätherleib des Kopfes ist etwas Chaotisches, ist nicht so durchorganisiert, wie es der Ätherleib des übrigen Organismus ist. Daher sieht der Mensch eben die physische Welt jetzt genauer als früher, aber er sieht nicht mehr die Götter dahinter. Aber dafür ist er im gegenwärtigen Zeitalter in einer gewissen Vorbereitung. Er ist auf dem Wege, ganz aus sich herauszugehen und seine Perspektive außerhalb zu nehmen. Das ist etwas, was dem Menschen beschert ist in der Zukunft. Jetzt ist er ja schon auf dem Wege dazu, denn wenn man sonst in nichts drinnen ist als in seinem Kopfe, so ist man eigentlich nur mehr mit den abstraktesten Gedanken in der Welt drinnen. Man ist in nichts Rechtem mehr drinnen, möchte man sagen; es ist das etwas extrem gesprochen, wenn man sagt: Man ist in nichts drinnen als in einem Menschenkopf. - Denn ein Menschenkopf gibt einem nur Bewußtsein von dem physisch-irdischen Dasein. In demselben Maße aber, in dem der Mensch herauswächst aus seinem Kopfe, wird er wiederum Kenntnis erlangen, jetzt aber von dem Menschen selber. Als der Mensch noch in sich war, hatte er von dem Schicksale der Götter Kenntnis erhalten. Indem der Mensch aus sich herausrückt, kann er von seinem eigenen Weltenschicksal Kenntnis erhalten. Er kann in sich hineinblicken. Und wenn sich die Menschen nur jetzt schon recht anstrengen würden, so würde der Kopf sie gar nicht so stark hindern, als man gewöhnlich glaubt, an diesem Hineinschauen in das eigene Menschenschicksal, in das Weltenschicksal des Menschen. Das Hindernis ist nur, daß sich die Menschen so darauf versteifen, in gar nichts anderem leben zu wollen als in ihrem Kopfe; und wie man sagt Kirchturmpolitik, so könnte man auch sagen Kopfmenschenkenntnis. Es ist ein nicht Hinausschauenwollen über das, was der Kopf erzeugt, wenn die Menschen sich gegenwärtig noch gar nicht dazu herbeilassen wollen, das, was nun Anthroposophie als Menschenweisheit bietet, als etwas, was man wissen kann über die Menschen, aus ihrem gesunden Menschenverstand einsehen zu wollen.

[ 8 ] So ist der Mensch auf dem Wege, den Menschen kennenzulernen, weil er seinen Ausgangspunkt allmählich von außerhalb des Menschen nimmt. So daß also das allgemeine Menschenschicksal ist, aus dem Ätherleib immer mehr und mehr herauszukommen und den Menschen kennenzulernen. Aber das ist natürlich etwas, was mit einer gewissen Gefahr verbunden ist. Man verliert allmählich - oder wenigstens ist die Möglichkeit vorhanden, den Zusammenhang zu verlieren mit seinem ätherischen Leibe. Es ist eben im Weltenschicksal der Menschheit dem abgeholfen worden durch das Mysterium von Golgatha. Während der Mensch vorher die Götterschicksale außen gesehen hat, ist er seither dazu veranlagt, sein eigenes Welten-Menschenschicksal zu sehen. Aber indem er immer mehr und mehr aus sich herausgeht und das Mysterium von Golgatha so verstanden wird, wie es Paulus haben wollte: «Nicht ich, sondern der Christus in mir», kommt der Mensch durch seine Verbindung mit dem Christus wieder in das Menschliche hinein. Also gerade durch das Christus-Erlebnis kann er dieses allmähliche Herausgehen ertragen. Aber dieses Christus-Erlebnis muß eben immer intensiver und intensiver werden. Deshalb, als im Verlaufe des Weltenschicksals die äußere Götterwelt immer mehr und mehr abdämmerte, dämmerte im Menschen die Möglichkeit auf, nun ein Götterschicksal zu haben, das sich auf der Erde selbst abgespielt hat, das also mit dem Menschen ganz verbunden ist.

[ 9 ] Es ist so, daß, wenn wir den alten Menschen vorstellen, er seine Götterwahrnehmungen um sich herum hatte. Er bildete sie sich aus den Bildern. Es war seine Mythologie, der Mythos. Diese Götterwahrnehmungen sind abgedämmert. Es ist gewissermaßen nur die physische Welt um den Menschen herum. Aber dafür hat er die Möglichkeit, jetzt sich in seinem Inneren zu verbinden mit einem Götterschicksal, mit dem Durchgehen des Gottes durch den Tod, mit der Auferstehung des Gottes. Nach außen hat der Mensch sein Geistesauge gelenkt in alten Zeiten, sah Götterschicksale, bildete sich daraus den Mythos, der in Bildern erlebt wird, in fluktuterenden Bildern, den Mythos, der vielgestaltig sein kann, weil er im Grunde genommen in der Geistwelt in der verschiedensten Weise lebt. Man möchte sagen, es war diese Götterwelt etwas, was mit einem gewissen Grad von Undeutlichkeit schon für den Erdenmenschen wahrnehmbar war, als er sie in seinem instinktiven Hellsehen wahrnahm. Daher bildeten die Menschen nach ihren verschiedenen Charakteren die Bilder von dieser Götterwelt verschieden aus. Die Mythen der verschiedenen Völker sind dadurch verschieden geworden. Der Mensch nahm eine wahre Welt war, aber diese wahre Welt mehr in Träumen, die jedoch von der Außenwelt kamen. Es waren Bilder von größerer oder geringerer Deutlichkeit, aber die Deutlichkeit war nicht groß genug, um für alle Menschen eindeutig zu sein.

[ 10 ] Nun kam ein Götterschicksal, das sich auf der Erde selber abspielte. Die anderen Götterschicksale waren dem Menschen ferner. Der Mensch sah sie in der Perspektive. Er sah sie daher nicht deutlich. Sie waren ihm in seinem Erdenleben ferner. Das Christus-Ereignis ist ihm seinem Erdenleben nach ganz nahe. Die Götter sah er undeutlich, weil er sie gewissermaßen in der Perspektive sah. Er überblickt das Mysterium von Golgatha noch nicht gehörig, weil ihm dieses zu nahe steht. Die Götter hat er in der Perspektive erblickt mit einigen perspektivischen Undeutlichkeiten, weil sie ihm ferne waren, zu ferne, um sie ganz deutlich zu sehen, sonst hätten alle Völker den gleichen Mythos gebildet. Das Mysterium von Golgatha ist dem Menschen zu nahe. Er ist mit ihm zu stark verbunden. Er muß erst noch Perspektive bekommen; dadurch, daß er immer weiter und weiter aus sich herausgeht, muß er Perspektive bekommen für das Götterschicksal auf der Erde, für das Mysterium von Golgatha.

[ 11 ] Das ist der Grund, warum diejenigen, die in der Zeit, als das Mysterium von Golgatha stattgefunden hat, lebten und noch schauen konnten — warum diese den Christus leicht verstehen. Sie konnten ihn leicht verstehen, weil sie ja die Götterwelt gesehen hatten und nun wußten: Der Christus ist aus dieser Götterwelt herausgegangen auf diese Erde für sein weiteres Schicksal, das mit dem Mysterium von Golgatha beginnt. Sie haben allerdings auch schon auf das Mysterium von Golgatha undeutlich hingesehen; aber den Christus konnten sie bis zum Mysterium von Golgatha gut sehen. Sie wußten daher von dem Christus als Gott sehr viel zu sagen. Sie fingen nur an zu diskutieren, was mit diesem Gotte geworden war, als er durch die Johannistaufe im Jordan in einen Menschen untergetaucht ist. Daher haben wir in den ersten Zeiten des Christentums eine sehr ausgeprägte Christologie und keine Jesulogie. Und weil überhaupt die Götterwelt aufhörte, ein Bekanntes zu sein, verwandelte sich zunächst die Christologie in eine bloße Jesulogie. Und die Jesulogie wurde immer stärker bis ins 19. Jahrhundert herauf, wo der Christus gar nicht einmal mehr mit dem Verstande begriffen wurde, sondern wo sich die moderne Theologie sehr viel darauf zugute tat, den Jesus möglichst menschlich zu verstehen und den Christus fahren zu lassen.

[ 12 ] Aber es muß wiederum gerade durch geistige Erkenntnis die Perspektive gefunden werden, um das Wichtige, den Christus in dem Jesus zu erkennen. Denn dadurch wird es erst möglich, statt daß man mit dem Menschen gar nicht mehr in Verbindung bleibt und nur von außen sich ihn anschaut, nun auf dem Umwege durch die Verbindung mit dem Christus den Menschen und die Menschheit selber wiederum mit Anteil zu sehen auf dem Umwege durch das Verständnis des Mysteriums von Golgatha.

[ 13 ] So daß wir sagen können: Die Menschheit ist auf dem Wege, im Herausgehen aus sich selber die geistige Realität nach und nach ganz in abstrakte Begriffe und Ideen zu verwandeln. In dieser Beziehung ist die Menschheit ja schon sehr weit gekommen, und es könnte ihr eigentlich folgendes bevorstehen: Die Menschen könnten im abstrakten, im intellektuellen Vermögen immer weiter und weiter kommen und eine Art von Bekenntnis in sich selber ausbilden, durch das sie sich sagen würden: Ja, wir erleben zwar Geistiges, aber dieses Geistige ist ja eine Fata Morgana, das hat kein Gewicht, das sind bloße Ideen. - Der Mensch muß wiederum die Möglichkeit finden, diese Ideen mit geistiger Substantialität auszufüllen. Das wird er dadurch, daß er den Christus miterlebt mit dem Übergang in das intellektuelle Leben. So daß zusammenwachsen muß der moderne Intellektualismus mit dem ChristusBewußtsein. Wir müssen als Menschen schon etwas gar nicht anerkennen wollen, wenn wir dieses Christus-Bewußtsein nicht gerade auf dem Wege des Intellektualismus finden können.

[ 14 ] Sehen Sie, in alten Zeiten hat der Mensch gesprochen von dem Sündenfall. Er sprach von diesem Bilde des Sündenfalls in dem Sinne, als ob er seiner Wesenheit nach einer höheren Welt angehört hätte und in eine tiefere heruntergefallen wäre, was ja auch, wenn man es bildlich auffaßt, durchaus der Realität entspricht. Man kann durchaus im realen Sinne von einem Sündenfall sprechen. Geradeso wie aber der alte Mensch richtig gefühlt hat, wenn er sich sagte: Ich bin hinuntergestürzt aus einer geistigen Höhe und habe mich mit Tieferstehendem vereinigt -, so sollte der neuere Mensch finden, wie ihn die immer abstrakter werdenden Gedanken auch in eine Art von Fall bringen, aber in einen Fall, bei dem es hinaufgeht, wo der Mensch gewissermaßen nach oben fällt, also steigt, aber in demselben Sinne zu seinem Verderben steigt, wie der alte Mensch sich fallen gefühlt hat zu seinem Verderben. So wie der alte Mensch, der noch den Sündenfall im Sinne des Alten verstanden hat, in dem Christus denjenigen gesehen hat, der den Menschen in das rechte Verhältnis zu dieser Sünde gebracht hat, nämlich zu der Möglichkeit einer Erlösung -, also wie der alte Mensch, wenn er Bewußtsein entwickelt hat, in dem Christus denjenigen sah, der ihn aus dem Fall heraufgehoben hat, so sollte der neuere Mensch, der in den Intellektualismus hineingeht, in dem Christus denjenigen sehen, der ihm Gewicht gibt, daß er nicht geistig fortfliegt von der Erde beziehungsweise von der Welt, in der er drinnen sein soll.

[ 15 ] Hat der alte Mensch vorzugsweise das Christus-Ereignis im Sinne der Willensentwickelung angesehen, was ja zusammenhängt mit dem Sündenfall, so sollte der neuere Mensch lernen, den Christus anzusehen im Zusammenhange mit dem Gedanken, der aber die Realität verlieren muß, wenn der Mensch ihm nicht Gewicht zu geben vermag, so daß im Gedankenleben selber wiederum Realität zu finden ist.

[ 16 ] Man muß sich schon sagen: Die Menschheit macht eine Entwickelung durch. Und wie der Paulus sprechen durfte von dem alten Adam und von dem neuen Adam, von dem Christus, so darf das in gewissem Sinne der moderne Mensch auch; nur muß er sich klar sein darüber, daß der Mensch, der noch das alte Bewußtsein in sich hatte, sich durch den Christus aufgehoben fühlte, daß der neuere Mensch sich durch den Christus vor dem Hinausschnellen in das Wesenlose der bloßen Abstraktion, des bloßen Intellektualismus geschützt wissen soll. Der moderne Mensch braucht den Christus, um seine in die Weiten gehende Sünde zu dem zu machen in sich, was wiederum gut werden kann. Und der Gedanke wird dadurch gut, daß er sich wiederum mit der wirklichen Realität, mit der geistigen Realität verbinden kann. So gibt es gerade für denjenigen, der die Geheimnisse des Weltenalls durchschaut, durchaus die Möglichkeit, den Christus auch in die allermodernste Bewußtseinsentwickelung hineinzustellen.

[ 17 ] Und nun gehen Sie zu unserem früheren Bilde zurück, das ich angelehnt habe an die menschliche Erinnerungsfähigkeit. Da können wir sagen: Ja, wir leben fort als Menschenwesen in der geistigen Welt, erheben uns über die geistige Welt, indem wir mit unserem Kopf herausgucken in die physische Welt. Wir tauchen aber nicht ganz heraus, sondern nur mit unserem Kopf. Wir bleiben so in der geistigen Welt, daß selbst unsere Erinnerungen immer in ihr spielen. Unsere Erinnerungswelt bleibt unten im Meere der geistigen Welt. — Sehen Sie, solange wir zwischen Geburt und Tod stehen und nicht mächtig genug sind in unserem Ich, um all das zu sehen, was da unten selbst mit unseren Erinnerungen vor sich geht, so lange merken wir nichts davon, wie es eigentlich mit uns in der neueren Zeit als Menschheit steht. Wenn wir aber sterben, dann wird es mit dieser geistigen Welt, aus der wir uns wie ein luftschnappender Fisch heraus erheben im physischen Dasein, sehr ernst. Und da blicken wir nicht so zurück, daß wir glauben, wesenlose Erinnerungsbilder zu sehen, indem wir uns dem Irrtum hingeben, daß die Zeitperspektive auch die Realität tötet. Der Mensch gibt sich der Erinnerung für die Zeit so hin, wie einer, der das, was er in der Entfernung sieht, weil eine Raumperspektive da ist, nicht für Realität hält, sondern bloß für Bilder; der also sagen würde: Ja, wenn ich weit fortgehe, so ist das Schloß dort ja so klein, so furchtbar klein, daß es doch keine Realität haben kann, denn in einem so kleinen Schloß können doch nicht Menschen drinnen wohnen, also kann es auch keine Realität haben. — So ungefähr ist auch hier die Schlußfolgerung. Wenn der Mensch zurückblickt in der Zeit, da hält er die Erinnerungsbilder nicht für Realitäten, weil er die Zeitperspektive nicht berücksichtigt. Das aber hört auf, wenn alle Perspektive aufhört, wenn wir aus Raum und Zeit heraußen sind. Wenn wir gestorben sind, dann hört das auf. Da tritt das, was in der Zeitperspektive lebt, sehr stark als Realität auf.

[ 18 ] Es ist nun möglich, daß wir in unser Erleben das hineingebracht haben, was ich das Christus-Bewußtsein nenne. Dann blicken wir nach dem Tode zurück, und wir sehen, daß wir uns im Leben mit Realität verbunden haben, daß wir nicht bloß abstrakt gelebt haben. Die Perspektive hört auf, die Realität steht da. Sind wir aber beim bloßen abstrakten Erleben geblieben, dann steht freilich auch die Wirklichkeit da, aber wir haben im Erdenleben Luftschlösser gebaut. Wir haben etwas gebaut, was keine Festigkeit in sich hat. Mit dem intellektuellen Erkennen und Wissen kann man allerdings bauen, aber die Sache hat keine Festigkeit, ist brüchig.

[ 19 ] So daß der moderne Mensch die Durchsetzung mit dem ChristusBewußtsein braucht, damit er sich mit Realitäten verbindet, damit er nicht Luftschlösser baut, sondern Geistesschlösser. Für die Erde sind Luftschlösser etwas, wo das, was darunter liegt, zu wenig dicht ist. Für das geistige Leben sind Luftschlösser etwas, was unter dem Geist liegt. Luftschlösser liegen immer an ihrem Orte. Nur für das Erdendasein sind sie zu dünn, für das geistige Dasein sind sie zu dicht physisch. Die Menschen können dann nicht los von dem dicht Physischen, das dem Geistigen gegenüber aber eigentlich eine geringere Realität hat; sie bleiben erdengebunden, bekommen kein freies Verhältnis zum irdischen Dasein, wenn sie Luftschlösser gebaut haben durch den Intellektualismus.

[ 20 ] Sie sehen also, gerade für den Intellektualismus hat das ChristusBewußtsein eine sehr reale Bedeutung, eine Bedeutung im Sinne einer wirklichen Erlösungslehre - der Erlösung von dem Bauen von Luftschlössern - für unser Dasein, nachdem wir durch die Todespforte geschritten sind.

[ 21 ] Diese Dinge sind für Anthroposophie nicht Glaubensartikel, es sind Erkenntnisse, die nun ebenso gewonnen werden können, wie die mathematischen Erkenntnisse von demjenigen, der die mathematischen Methoden zu handhaben weiß.

Fifth Lecture

[ 1 ] When using their ordinary consciousness, human beings are aware of only a part of what is connected with their existence. When we look around us in the world, our ordinary consciousness provides us with images of the external world that we can perceive through our senses. And when we think about what our senses give us, when we form thoughts, these thoughts remain with us as images of memory. So life in the soul proceeds in such a way that man looks at the external world, lives with it, but while living with the external world, he also carries within himself the images of memory of past experiences.

[ 2 ] However, ordinary consciousness does not correctly recognize what lives in memory. Human beings imagine it something like this: they have received knowledge and perceptions from the external world, which have produced images in them; these images remain somewhere, and they can recall them in their soul life as memory images. But that is not how it is. Consider step by step what actually happens within a person. You will have already noticed how things that you do not pay particular attention to, but only observe with your senses, for example with your eyes, produce afterimages. Goethe describes such afterimages, as they are formed by the eyes, very well in his Theory of Colors: as fading images. You look at something, close your eyes, and altered images fade away. In everyday life, we pay little attention to these fading images because we use a more energetic activity for perception: we think. When a person engages in weak thought activity and the outside world presents an image to the eye, an afterimage lingers. But when a person thinks, they continue to take in the activity coming from outside, and their thought image lingers. This is also a lingering effect.p>

[ 3 ] These thought images are stronger, and their lingering effect is also more intense than that of mere sensory afterimages; but it is basically just a higher stage. However, these thought afterimages would still fade away, just as sensory afterimages fade away, if they were only aroused as thought images. But this is not the case at all. For human beings do not only have their heads, but also the rest of their organism, which is something quite different from the head. The head is actually primarily an afterimage of what happens to a person before they descend from the spiritual world into the physical world through birth or conception. It is much more physical than the rest of the organism. The rest of the organism is less physically developed than the head, and one could say: The spiritual is actually only present in the head as an image, while it is spiritually strong in the rest of the organism. You have a strongly physical head, plastically formed; there is little spirit in it in the spiritual sense. And you have an organism that is not physically a strong image of what the human being was before birth, before descending, but the spiritual is stronger in the rest of the organism. The physical is more developed in the head, the spiritual more in the rest of the organism.

[ 4 ] The thoughts we have would fade away just like the afterimages of the eyes if they were not taken over by our spiritual organism and processed by it. But the spiritual organism would not be able to do much with these images if something else did not take place. For while we perceive these images, which we then turn into fleeting thoughts that actually exist only in our head, we receive, just as we receive the images through the eye, which we then process into thoughts, except for the image itself — for we receive the images from the physical-etheric world — we also receive the spiritual from the rest of the world into ourselves, so that we not only carry the spirit within us, but that the rest of the spirit of the world also continually enters into us. So you can say: with your eyes you perceive something from the physical-etheric world that is in you as an image effect; but behind this there is a very real spiritual process that remains only in the unconscious. Human beings cannot perceive it with their ordinary consciousness. This is a spiritual process that runs completely parallel to physical perception. And while you perceive the image that lingers in your eye for a short time, while you have the thought that you would like to hold on to for a moment but that also fades away, something spiritual is going on within you, and when you remember it again, you simply turn your gaze inward and look at what has been going on spiritually within you while you were perceiving.

[ 5 ] I will illustrate this with something concrete. Let's assume you see something in the outside world, for example a machine. You have the image of the machine. In the sense described by Goethe, there is an afterimage that sounds briefly and then fades away. You get the thought of the machine, which lasts longer but would also fade away. But the machine also sends something else into your mental organism. In the case of the machine, however, this is something very unattractive; in the case of a plant, for example, it is much more beautiful. It sends something into you. And now, after a month, for example, you look inside yourself. The memory arises from what entered you at that moment, without your knowing it, at the same time as what aroused the thought. It is not the thought that has been wandering around down there, but rather an unconscious mental process. This is observed later. Memory is observation, the later observation of a mental process that has run parallel to physical perception. — You see, this is actually how we humans live in the world: there is our continuous stream of existence; we are inside the sea of the spiritual world. And now, between death and a new birth, we continue our existence in this spiritual world. Only there are times when we leave the spiritual world with our heads. So we move away, and at certain times, like a fish darting out of the water, we come out. That is earthly life. Then we dive back down again. Then another earthly life comes. For we do not emerge from this sea of spiritual existence with our entire spiritual being, but only with our head. Down there we always remain in the spiritual world. Only we do not know what is going on with our ordinary consciousness. So for spiritual perception, we can actually say that human beings live between death and new birth in the spiritual world. Then he looks up with his head into his physical body, but the main part of him remains in the spiritual world, even between birth and death. And it is good for us that we remain floating there, because otherwise we would have no memories. What the spiritual world gives us makes this possible. Remembering is already a spiritual process that belongs to an objective world, not just a subjective one. Ordinary consciousness is mistaken in this regard. It does not believe that memory is linked to a real process. But ordinary consciousness is mistaken, just like someone who sees a mountain with a castle in front of them. Now he sees it clearly, now he believes in reality. Now he moves away. The object becomes more and more distant, and he would say, because it becomes more and more distant: Now I only have an image, no longer reality. In this way we move away from reality in time. The castle does not change in relation to its reality in space when our image changes. Nor does that which corresponds to our memory image change in relation to its reality. It remains, just as our castle remains. We are only mistaken because we cannot correctly assess our temporal perspective. Many things that relate to human beings can be corrected in this way. What we have as consciousness passing through time is nothing more than a perspective view of the past. The past does not pass; it remains. Our images merely shift into a temporal perspective.

[ 6 ] Now, however, this relationship to what is actually also spiritual processes between birth and death has changed significantly for human beings in the course of their earthly life. When we look at human beings, we see that they consist of a physical and an etheric body. But that would be only what lies in bed at night when they are asleep. During the day, the astral body and the I are also immersed in these physical and etheric bodies. The I of those human beings who lived before the Mystery of Golgotha — and we ourselves were these human beings in earlier incarnations — began to fade toward the Mystery of Golgotha. Then human beings awoke in a different way than those who lived after the Mystery of Golgotha. The astral body always enters completely into the etheric body. But the ego also used to go very far into the etheric body. Today, this is no longer the case. Today, the ego only enters the head part of the etheric body. So that in the old human being, the ego was completely submerged and therefore also entered the lower parts of the etheric body. Today, it does not go down there, but only into the head. This enables us to think intellectually. The moment we submerged ourselves more deeply, we would receive instinctive images within ourselves. And the ego is actually still strongly outside the physical body in the human being of the present. So that his intellectual nature is based precisely on the fact that he no longer submerges himself with his ego into his entire etheric body. If that were to happen, they would have instinctive clairvoyance. But since they no longer submerge themselves in their entire etheric body, but only in that of the head, they do not obtain this instinctive clairvoyance, but rather a clearly conscious seeing, a clearly conscious perception of the external world, but only a perception of the external world with the head, just as our perception is. The old human being still saw with his whole human being. The newer human being sees only with the head. And the head is precisely the most physical thing between birth and death. Therefore, the human being of the intellectual age is given only what he perceives through his physical head and what he perceives through the etheric body of the head: the thoughts he can form. Even the process of remembering, which of course takes place down below, eludes consciousness. Modern man interprets this completely wrongly, as I have explained. As a result, ancient man saw not only the physical world around him, but also the spiritual essence behind it. The physical world was not particularly clear to him; it was much more blurred than it is for modern man. But instead, they saw everywhere behind the things that spread out in the physical world, divine-spiritual beings of a lower kind, but also of a higher kind. It is a childishly naive idea to believe that when ancient people described their gods in nature, they were inventing something. They did not invent anything. It would be just as naive as if we heard someone say they had seen this or that while awake, and we said, “They just made it up.” The ancients did not merely invent things, but they saw them, interwoven with sensory perceptions, which were therefore much more indistinct because they were seen, as it were, against the background of the divine-spiritual realm that was unfolding. The ancient human being therefore had a completely different worldview. When they woke up, they plunged deeper into their etheric body and thus had a different worldview. They were within themselves, and through this the divine-spiritual beings revealed themselves to them in their destinies.

[ 7 ] Human beings looked into the worlds of the gods that had preceded their own world. The gods showed humans their destiny, and by looking into the worlds of the gods, humans could perceive the destinies of the gods. They could say: I know where I come from, I know which world I am connected to. This was because humans could have the starting point of their perspective within themselves. They made their etheric body into an organ for perceiving this world of the gods. Modern humans cannot do this. They can only take their perspective from their heads, which are outside the most spiritual part of the etheric body. The etheric body of the head is chaotic and not as well organized as the etheric body of the rest of the organism. That is why humans now see the physical world more clearly than before, but they no longer see the gods behind it. But in the present age, they are in a state of preparation for this. They are on the way to stepping completely out of themselves and taking their perspective from outside. This is something that will be granted to human beings in the future. They are already on the way to this, because if you are inside nothing but your head, you are actually only inside the world with the most abstract thoughts. One is no longer inside anything real, one might say; it is somewhat extreme to say that one is inside nothing but a human head. For a human head only gives one consciousness of physical, earthly existence. But to the same extent that man grows out of his head, he will again gain knowledge, but now of man himself. When man was still within himself, he had gained knowledge of the fate of the gods. By stepping out of himself, man can gain knowledge of his own world destiny. He can look within himself. And if people would only make a real effort now, the head would not hinder them as much as is commonly believed from looking into their own human destiny, into the destiny of the world of man. The only obstacle is that people are so determined to live in nothing but their heads; and just as one speaks of parochialism, one could also speak of intellectualism. It is a refusal to look beyond what the head produces when people are not yet willing to accept what anthroposophy offers as human wisdom, as something that can be known about human beings through their common sense.

[ 8 ] Thus, human beings are on the path to knowing themselves because they gradually take their starting point from outside themselves. So the general destiny of human beings is to emerge more and more from the etheric body and to get to know themselves. But this is, of course, something that involves a certain danger. One gradually loses—or at least there is the possibility of losing—the connection with one's etheric body. This has been remedied in the world destiny of humanity through the Mystery of Golgotha. Whereas previously human beings saw the destinies of the gods outside themselves, since then they have been predisposed to see their own world-human destiny. But by stepping more and more out of themselves and understanding the mystery of Golgotha as Paul wanted it to be understood: “Not I, but Christ in me,” human beings return to humanity through their connection with Christ. It is precisely through the Christ experience that they can endure this gradual stepping out. But this Christ experience must become more and more intense. Therefore, as the outer world of gods gradually faded in the course of world destiny, the possibility dawned in human beings of now having a divine destiny that took place on earth itself, that is, one that is completely connected with human beings.

[ 9 ] It is so that when we imagine the ancient human being, he had his perceptions of the gods around him. He formed them from images. This was his mythology, the myth. These perceptions of gods have faded. In a sense, there is now only the physical world around humans. But in return, humans now have the possibility of connecting within themselves with a divine destiny, with the passing of the gods through death, with the resurrection of the gods. In ancient times, humans directed their mind's eye outward, saw the destinies of gods, and formed myths from them, which are experienced in images, in fluctuating images, myths that can be multifaceted because they basically live in the spirit world in a wide variety of ways. One might say that this world of gods was something that was already perceptible to earthly human beings with a certain degree of vagueness when they perceived it in their instinctive clairvoyance. Therefore, human beings formed different images of this world of gods according to their different characters. This is why the myths of different peoples have become different. Man perceived a true world, but this true world was more in dreams, which, however, came from the outside world. These were images of greater or lesser clarity, but the clarity was not great enough to be unambiguous for all people.

[ 10 ] Then came a divine destiny that played out on Earth itself. The other divine destinies were more distant from humans. Humans saw them in perspective. They therefore did not see them clearly. They were more distant from them in their earthly life. The Christ event is very close to them in their earthly life. He saw the gods indistinctly because he saw them, as it were, in perspective. He does not yet properly understand the mystery of Golgotha because it is too close to him. He saw the gods in perspective with some perspectival ambiguities because they were distant from him, too distant to see them clearly; otherwise, all peoples would have formed the same myth. The mystery of Golgotha is too close to human beings. They are too strongly connected to it. They must first gain perspective; by going further and further out of themselves, they must gain perspective on the destiny of the gods on earth, on the mystery of Golgotha.

[ 11 ] That is why those who lived at the time when the mystery of Golgotha took place and were still able to see — why they easily understood Christ. They could easily understand him because they had seen the world of the gods and now knew: Christ had come out of this world of gods onto this earth for his further destiny, which begins with the mystery of Golgotha. They had, however, already glimpsed the mystery of Golgotha, albeit indistinctly; but they could see Christ clearly until the mystery of Golgotha. They therefore had a great deal to say about Christ as God. They only began to discuss what had become of this God when he was immersed in the Jordan by John the Baptist. That is why we have a very pronounced Christology and no Jesulogy in the early days of Christianity. And because the world of the gods ceased to be something familiar, Christology initially turned into mere Jesulogy. And Jesulogy grew stronger and stronger until the 19th century, when Christ was no longer even understood with the intellect, but when modern theology took great pride in understanding Jesus as human as possible and letting Christ go.

[ 12 ] But it is precisely through spiritual knowledge that the perspective must be found in order to recognize what is important, namely Christ in Jesus. For only then is it possible, instead of losing all connection with the human being and viewing him only from the outside, to see the human being and humanity itself again as having a share in the mystery of Golgotha through the connection with Christ.

[ 13 ] So we can say that humanity is on the way, in coming out of itself, to gradually transform spiritual reality entirely into abstract concepts and ideas. In this respect, humanity has already come very far, and the following could actually lie ahead for it: People could go further and further in their abstract, intellectual abilities and develop a kind of confession within themselves, through which they would say: Yes, we do experience the spiritual, but this spiritual is a mirage, it has no weight, it is mere ideas. - Man must again find the possibility of filling these ideas with spiritual substance.

They will do this by experiencing Christ with the transition into intellectual life. Thus, modern intellectualism must grow together with Christ consciousness. As human beings, we must not want to acknowledge something if we cannot find this Christ consciousness through intellectualism.[ 14 ] You see, in ancient times, people spoke of the Fall. They spoke of this image of the Fall in the sense that they felt they belonged by their very nature to a higher world and had fallen into a lower one, which, if taken figuratively, is entirely true. One can certainly speak of a Fall in a real sense. But just as the old man felt correctly when he said to himself: I have fallen down from a spiritual height and have united myself with something lower—so should the newer man find that his increasingly abstract thoughts also bring him into a kind of fall, but a fall in which he goes upward, where man falls upward, so to speak, that is, rises, but in the same sense rises to his ruin, just as the old human being felt himself falling to his ruin. Just as the old human being, who still understood the Fall in the old sense, saw in Christ the one who brought human beings into the right relationship to this sin, namely to the possibility of redemption, just as the old man, when he developed consciousness, saw in Christ the one who lifted him up from the Fall, so the newer man, who enters into intellectualism, should see in Christ the one who gives him weight so that he does not fly away spiritually from the earth or from the world in which he is supposed to be.

[ 15 ] If the old human being viewed the Christ event primarily in terms of the development of the will, which is connected with the Fall, then the newer human being should learn to view Christ in connection with the thought, which, however, must lose its reality if the human being is unable to give it weight, so that reality can be found again in the life of thought itself.

[ 16 ] One must say to oneself: Humanity is undergoing a development. And just as Paul was able to speak of the old Adam and the new Adam, of Christ, so too can modern man in a certain sense; only he must be clear about the fact that the human being who still had the old consciousness within himself felt himself to be redeemed by Christ, that the newer human being should feel himself protected by Christ from rushing headlong into the nothingness of mere abstraction, of mere intellectualism. Modern man needs Christ in order to transform his sin, which extends into the vastness, into something within himself that can become good again. And the thought becomes good through its ability to connect again with real reality, with spiritual reality. Thus, especially for those who see through the mysteries of the universe, there is certainly the possibility of placing Christ even in the most modern development of consciousness.

[ 17 ] And now go back to our earlier image, which I based on the human capacity for memory. There we can say: Yes, we live on as human beings in the spiritual world, rising above the spiritual world by looking out into the physical world with our heads. But we do not emerge completely, only with our heads. We remain in the spiritual world in such a way that even our memories always play out there. Our world of memory remains down in the sea of the spiritual world. — You see, as long as we stand between birth and death and are not powerful enough in our ego to see everything that is going on down there, even with our memories, we are unaware of how things actually stand with us in the newer era as humanity. But when we die, this spiritual world, from which we rise like a fish gasping for air in physical existence, becomes very serious. And we do not look back in such a way that we believe we see insubstantial images of memory, indulging in the error that the perspective of time also kills reality. Human beings surrender themselves to memory for time, just as someone who, because of spatial perspective, does not consider what he sees in the distance to be reality, but merely images; who would therefore say: Yes, when I go far away, the castle there is so small, so terribly small that it cannot be real, because people cannot live in such a small castle, so it cannot be real. — The conclusion here is roughly the same. When people look back in time, they do not consider the images of their memories to be real, because they do not take the perspective of time into account. But this ceases when all perspective ceases, when we are outside of space and time. When we die, this ceases. Then what lives in the perspective of time appears very strongly as reality.

[ 18 ] It is now possible that we have brought into our experience what I call Christ consciousness. Then we look back after death and see that we were connected with reality in life, that we did not live merely abstractly. Perspective ceases, reality stands there. But if we have remained at the level of mere abstract experience, then reality is still there, of course, but we have built castles in the air during our earthly life. We have built something that has no solidity in itself. With intellectual knowledge and understanding, one can build, but the thing has no solidity, it is fragile.

[ 19 ] So modern human beings need to be imbued with Christ consciousness in order to connect with reality, so that they do not build castles in the air, but castles of the spirit. For the earth, castles in the air are something where what lies beneath is not dense enough. For spiritual life, castles in the air are something that lies beneath the spirit. Castles in the air always remain in their place. They are too thin for earthly existence, but too dense physically for spiritual existence. People then cannot detach themselves from the dense physical world, which actually has less reality than the spiritual world; they remain bound to the earth and cannot develop a free relationship to earthly existence if they have built castles in the air through intellectualism.

[ 20 ] You see, therefore, that Christ consciousness has a very real significance for intellectualism in particular, a significance in the sense of a real doctrine of salvation — salvation from building castles in the air — for our existence after we have passed through the gates of death.