Oswald Spengler, Prophet of World Chaos

GA 198

2 July 1920, Dornach

I. Spengler's Decline of the West

One who looks around a little in Germany today, and not at externals but with the eye of the soul; one who sees not only what offers itself to the casual visitor, who seldom learns the true conditions during his visit; one who does not cling to the fact that a few chimneys are smoking again and the trains are running on time; one who can to some degree see into the spiritual situation; such a person sees a picture which is symptomatic not only for this territory but for the whole decay of our world-culture in the present cycle. I would like today to point out to you, in an introductory way, a psycho-spiritual symptom which is far more significant than many sleeping souls even in Germany allow themselves to dream.

In old Germany decay and decline rule today, and the external things which I have mentioned cannot deceive us about this. But this is not what I want to point to now, for in the course of world-history we often see decay set in and then out of the decay there again spring upward impulses. But if we judge externally, basing our opinion on mere custom and routine and saying that here again everything will be just as it has been before, then we do not see certain deeper-lying symptoms. One such symptom (but only one of many), a psycho-spiritual symptom which I want to bring before you, is the remarkable impression made by Oswald Spengler's book The Decline of the West, which is already symptomatic in having been able to appear in our time. It is a thick book and widely read, a book which has made an extraordinarily deep impression on the younger generation in Germany today. And the remarkable thing is that the author expressly states that he conceived the basic idea of this book, not during the war or after the war, but already some years before the catastrophe of 1914.

As I have said, this book makes a particularly strong impression on the younger generation. And if you try to sense the imponderables of life, the things which are between the lines, then you will be particularly struck by such a thing. In Stuttgart I recently had to give a lecture to the students of the technical college, and I went to this lecture entirely under the impression made by Oswald Spengler's Decline of the West. It is a thick book. Thick books are very costly now in Germany, yet it is much read. You will realize their costliness when I tell you that a pamphlet which cost five cents in 1914 now costs thirty-five cents. Of course, books have not risen in the same proportion as beer, which now costs ten times as much as in 1914. Books must always be handled more modestly, even under the present impossible economic conditions. Still the price increase on books shows what has happened to the economic system in the last few years.

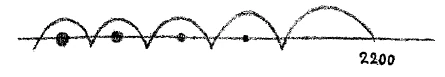

The contents of this book may be easily characterized. It demonstrates how the culture of the Occident has now reached a point which, at a certain period, was also reached by the declining cultures of the old Orient, of Greece, and of Rome. Spengler calculates in a strictly historical way that the complete collapse of the culture of the Occident must be accomplished by the year 2200. In my public lecture in Stuttgart I treated Spengler's book very seriously, and I also combatted it strenuously. But today the contents of such a thing are not so important. More important than the contents or the psycho-spiritual qualities of a book is whether the author (no matter what view of life he may adopt) has spiritual qualities, whether he is a personality who may be taken earnestly, or even highly esteemed, in a spiritual way. The author of this book is, beyond any doubt, such a personality. He has completely mastered ten or fifteen sciences. He has a penetrating judgment on the whole historical process, as far as history reaches. And he also has something which men of today almost never have, a sound eye for the phenomena of decline in the civilizations of the present day. There is a fundamental difference between Spengler and those who do not grasp the nature of the impulses of decline and who try all kinds of arrangements for extracting from the decayed ideas some appearance of upward motion. Were it not heart-rending it might be humorous to see how people with traditional ideas all riddled with decay meet today in conferences and believe that out of decay they can create progress by means of programs. Such a man as Oswald Spengler, who really knows something, does not yield to such a deception. He calculates like a precise mathematician the rapidity of our decline and comes out with the prediction (which is more than a vague prophecy) that by the year 2200 this Occidental culture will have fallen into complete barbarism.

This combination of universal outward decline, especially in the psycho-spiritual field, with the revelation by a serious thinker that such decline is necessary in accordance with the laws of history—this combination is something remarkable, and it is this which has made such a strong impression on the younger generation. We have today not only signs of decay, we have theories which describe this decay as necessary in a demonstrable scientific way. In other words, we have not only decay but a theory of decay, and a very formidable theory too. One may well ask where we shall find the forces, the inner will-forces, to spur men to work upward again, if our best people, after surveying ten or fifteen sciences, have reached the point of saying that this decay is not only present but can be proved like a phenomenon in physics. This means that the time has begun when belief in decay is not represented by the worst people. We must stress again and again how really serious the times are, and what a mistake it is to sleep away this seriousness of the times.

If one grasps the entire urgency of the situation, one is driven to the question: How can we orient thinking so that pessimism toward western civilization will not appear to be natural and obvious while faith in a new ascent seems a delusion? We must ask if there is anything that can still lead us out of this pessimism. Just the way in which Spengler comes to his results is extremely interesting for the spiritual-scientist. Spengler does not consider the single cultures to be as sharply demarcated as we do when, for example, within the post-Atlantean time we distinguish the Indian, Persian, Egypto-Chaldean, Greco-Latin, and present-day cultures. He is not familiar with spiritual science, but in a certain way, he too considers such cultures. He looks at them with the eye of the scientific researcher. He examines them with the methods which in the last three or four centuries have grown up in occidental civilization and been adopted by all who are not prejudiced by narrow traditional faith, Catholic, Protestant, Monadistic, etc. Oswald Spengler is a man who is completely permeated by materialistic modern science. And he observes the rise and fall of cultures—oriental, Indian, Persian, Greek, Roman, modern occidental—as he would observe an organism which goes through a certain infancy, a time of maturity, and a time of aging, and then, when it has grown old, dies. Thus Spengler regards the single cultures; they go through their childhood, their maturity, and their old age, and then they die. And the death-day of our present Occidental civilization is to be the year 2200.

Only the first volume of the book is now available. One who lets this first volume work upon him finds a strict theoretical vindication and proof of the decline, and nowhere a spark of light pointing to a rise, nothing which gives any hint of a rise. And one cannot say that this is an erroneous method of thought for a scientist. For if you consider the life of today and do not yield to the delusion that fruit for the future can grow out of bodiless programs, then you see that an upward movement nowhere appears in what the majority of men recognize in the outer world. If you regard rising and declining cultures as organisms, and then look at our culture, our entire Occidental civilization, as an organism, then you can only say that the Occident is perishing, declining into barbarism. You find no indication where an upward movement could appear, where another center of the world could form itself.

The Decline of the West is a book with spiritual qualities, based on keen observation, and written out of a real permeation with modern science. Only our habitual frivolity can ignore such things.

When a phenomenon like this appears, there springs up in the world-observer that historical concern of which I have so often spoken and which I can briefly characterize in the following words: One who today makes himself really acquainted with the inner nature of what is working in social, political, and spiritual life, one who sees how all that is so working strives toward decline—such a person, if he knows spiritual science as it is here meant, must say that there can only be a recovery if what we call the wisdom of initiation flows into human evolution. For if this wisdom of initiation were entirely ignored by men, if it were suppressed, if it could play no role in the further development of mankind—what would be the necessary consequence? You see, if we look at the old Indian culture, it is like an organism in having infancy, maturity, aging, decay, and death; then it continues itself. Then we have the Persian, Egyptian, Chaldean, Greco-Latin, and our own time, but always we have something which Oswald Spengler did not take into account. He has been reproached for this by several of his opponents. For a good deal has already been written against Spengler's book, most of it cleverer than Benedetto Croce's extraordinarily simple article. Croce, who has always written cleverly apart from this, suddenly became a simpleton with Spengler's book. But it has been pointed out to Spengler that the cultures do not always have only infancy, maturity, aging, and death, they continue themselves and will do so in this case also; when our culture dies in the year 2200, it will continue itself again. The singular thing here is that Spengler is a good observer and therefore he finds no moment of continuation and cannot speak of a seed somewhere in our culture, but only of the signs of decay which are evident to him as a scientific observer. And those who speak of cultures continuing themselves have not known how to say anything particularly clever about this book. One very young man has brought forward a rather confused mysticism in which he speaks of world-rhythm; but that creates nothing which can transform a documented pessimism into optimism. And so it follows from Spengler's book that the decline will come, but no upward movement can follow.

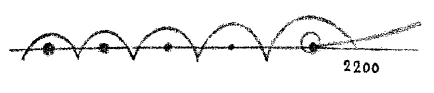

What Spengler does is to observe scientifically the infancy of the organism which is a culture or civilization, its maturity, decline, aging, death. He observes these in the different epochs in the only way in which, fundamentally, one can observe scientifically. But one who can look a little deeper into things knows that in the old Indian life, apart from the external civilization, there lived the initiation-wisdom of primeval times. And this initiation-wisdom of primeval times, which was still mighty in India, inserted a new seed into the Persian culture. The Persian mysteries were already weaker, but they could still insert the seed into the Egypto-Chaldean time. The seed could also be carried over into the Greco-Latin period. And then the stream of culture continued itself as it were by the law of inertia into our own time. And there it dries up.

One must feel this, and those who belong to our spiritual science could have felt it for twenty years. For one of my first remarks at the time of founding our movement was that, if you want a comparison for what the cultural life of mankind brings forth externally, you may compare it with the trunk, leaves, blossoms, and so forth, of a tree. But what we want to insert into this continuous stream can only be compared with the pith of the tree; it must be compared with the activating growth-forces of the pith. I wanted thereby to point out that through spiritual science we must seek again what has died out with the old atavistic primeval wisdom.

The consciousness of being thus placed into the world should be gained by all those who count themselves a part of the anthroposophical movement. But I have made another remark, especially here in recent years but also in other places. I have said that, if you take all that can be drawn out of modern science and form therefrom a method of contemplation which you then apply to social or, better still, to historical life, you will be able to grasp thereby only phenomena of degeneration. If you examine history with the methods of observation taught by science, you will see only what is declining, if you apply this method to social life, you will create only the phenomena of degeneration.

What I have thus said over the course of years could really find no better illustration than Spengler's book. A genuinely scientific thinker appears, writes history, and discovers through this writing of history that the civilization of the Occident will die in the year 2200. He really could not have discovered anything else. For in the first place, with the scientific method of contemplation you can find or create only phenomena of degeneration; while in the second place the whole Occident in its spiritual, political, and social life is saturated with scientific impulses, hence is in the midst of a period of decline. The important thing is that what formerly drew one culture out of another has now dried up, and in the third millennium no new civilization will spring out of our collapsing Occidental civilization.

You may bring up ever so many social questions, or questions on women's suffrage, and so forth, and you may hold ever so many meetings; but if you form your programs out of the traditions of the past, you will be making something which is only seemingly creative and to which the ideas of Oswald Spengler are thoroughly applicable. The concern of which I have spoken must be spoken of because it is now necessary that a wholly new initiation-wisdom should begin out of the human will and human freedom. If we resign ourselves to the outer world and to what is mere tradition, we shall perish in the Occident, fall into barbarism; while we can move upward again only out of the will, out of the creative spirit. The initiation-wisdom which must begin in our time must, like the old initiation wisdom (which only gradually succumbed to egoism, selfishness, and prejudice), proceed from objectivity, impartiality, and selflessness. From this base it must permeate everything.

We can see this as a necessity. We must grasp it as a necessity if we look deeper into the present unhappy trend of Occidental civilization. But then you also notice something else; you notice that when a justified appeal is made it is distorted into a caricature. And it is especially necessary that we should see through this. Now in our time no appeal is more justifiable than that for democracy; yet this is distorted into a caricature as long as democracy is not recognized as a necessary impulse only for the life of politics and rights and the state, from which the economic life and the cultural life must be dissociated. It is distorted into a caricature when today, instead of objectivity, impartiality, and selflessness, we find personal whims and self-interest made into cultural factors. Everything is being drawn into the political field. But if this happens, then gradually objectivity and impartiality will disappear; for the cultural life cannot thrive if it takes its directions from the political life. It is always entangled in prejudice thereby. And selflessness cannot thrive if the economic life creeps into the political life, because then self-interest is necessarily introduced. If the associative life, which can produce selflessness in the economic field, is spoiled, then everything will tend to leave men to wander in prejudice and self-interest. And the result of this will be to reject what must be based on objectivity and selflessness—the science of initiation. In external life everything possible is done today to reject this science of initiation, although it alone can lead us beyond the year 2200.

This is the great anxiety as regards our culture, which can come over you if you look with a clear eye at the events of the present. On this basis, I regard Spengler's book as only a symptom, but can anyone possibly say today: “Ah yes, but Spengler is wrong. Cultures have risen and fallen; ours will fall, but another will arise out of it.”? No, there can be no such refutation of Spengler's views. It is falsely reasoned, because trust in an upward movement cannot today be based on a faith that out of the Occidental culture another will develop. No, if we rely on such a faith nothing will develop. There is simply nothing in the world at present which can be the seed to carry us over the beginning of the third millennium. Just because we are living in the fifth post-Atlantean epoch, we must first create a seed.

You cannot say to people—Believe in the Gods, believe in this, believe in that, and then all will be well. You must confess that those who speak of, and even demonstrate, the phenomena of degeneration are right with regard to what lives in the outer world. But we, every individual human being must take care that they shall not remain right. For the upward movement does not come out of anything objective, it comes out of the subjective will. Each person must will, each person must will to take up the spirit anew, and from the newly received spirit of the declining civilization each person must himself give a new thrust; otherwise it will perish. You cannot appeal today to any objective law, you can appeal only to the human will, to the good-will of men. Here in Switzerland, where things have unrolled themselves differently, there is little to be seen of the real course of events (although it is also present here); but if you step over the border into Middle Europe you are immediately struck, in all that you observe with the eye of the soul, by what I have just described to you. There comes before your soul the sharp and painful contrast between the need for adopting initiation-wisdom into our spiritual, legal, and economic life and the perverted instincts which reject everything which comes from this quarter. One who feels this contrast must search hard for the right way to describe it, and one who does not choose words haphazardly often has trouble in finding the right expression for it. In Stuttgart I spoke on Spengler's book and I used this expression, “perverted instincts of the present.” I have used it again today because I find it is the only adequate one. As I left the stand that day I was accosted by one of those who best understand the word “perverted” in a technical sense, a physician. He was shocked that I had used just this word, but out of curious reasons. It is no longer commonly supposed that one who speaks on a foundation of facts, out of reality, chooses his words with pain; rather is it supposed that everyone forms his words as they are usually formed out of the superficial consciousness of the times. I had a talk with this physician, told him this and that, and then he said he was glad that I had not meant this word “perverted” in any elegant literary sense. I could only reply that this was certainly not the case, because I was not in the habit of meaning things in an elegant literary way. The point is that the man in the street today never assumes that there is such a thing as a creation out of the spirit; he simply believes, if you say something like “perverted instincts,” that you are speaking on the same basis as the last litterateur. That tone dominates our minds today; our minds educate themselves by it. Just in such an episode you can see the contrast between what is so necessary to mankind today—a real deepening, which must even go back as far as the basis of initiation-wisdom—and that which, through the caricature of democracy, comes before us today as spiritual life. People are much too lazy to draw something up from the hidden forces of consciousness within themselves; they prefer to dabble at tea-parties, in beer-gardens, at political meetings, or in parliaments. It is the easiest thing in the world now to say witty things, for we live in a dying culture where wit comes easily to people. But the wit that we need, the wit of initiation-wisdom, we must fetch up from the will; and we will not find it unless the power of this initiation-wisdom flows into our souls. Hence, we cannot say that we have refuted such a book as Spengler's. Naturally, we can describe it. It is born out of the scientific spirit. But the same is true of what others bring to birth out of the scientific spirit. Thus he is right if there does not enter into the wills of men that which will make him wrong. We can no longer have the comfort of proving that his demonstration of decline is wrong; we must, through the force of our wills, make wrong what seems to be right.

You see, this must be said in sentences which seem paradoxical. But we live in a time when the old prejudices must be demolished and when it must be recognized that we can never create a new world out of the old prejudices. Is it not understandable that people should encounter spiritual science and say they do not understand it? It is the most understandable thing in the world. For what they understand is what they have learned, and what they have learned, is decay or leading to decay. It is a question, not of assimilating something which can easily be understood out of the phenomena of decline, but of assimilating something to understand which one must first enhance his powers. Such is the nature of initiation-wisdom. But how can we expect that those who now aspire to be the teachers or leaders of the people should discern that what gives man a capacity for judgment must first be fetched out of the subconscious depths of soul-life and is not sitting up there in the head all ready-made. What really sits up there in the head is the destructive element.

Such is the nature of the things which you encounter wherever the consequences have already been drawn, where you have only to look at this seeming success. It is comprehensible that in the decline of occidental civilization our consciousness cannot easily enter into this field. Hence, we stand today entirely under the influence of this contrast which has been described to you; on the one side the need for a new impulse to enter into our civilization, and on the other side a rejection of this impulse. Things simply cannot improve if a sufficiently large number of people do not grasp the need for this impulse from initiation-wisdom. If you lay weight on temporary improvement you will not notice the great lines of decline, you will delude yourself about it, and you will march just so much more surely toward decline because you fail to grasp the only means there is to kindle a new spirit out of the will of men. But this spirit must lay hold of everything. Above all, this spirit must not linger over any theoretical philosophical problems. It would be a terrible delusion if a great number of people—perhaps just those who were somewhat pleased by the new initiation-wisdom and derived therefrom a somewhat voluptuous soul-feeling—should believe it would suffice to pursue this initiation-wisdom as something which was merely comfortable and good for the soul. For just through this the remainder of our real external life would more and more fall into barbarism, and the little bit of mysticism that could be pursued by those whose souls had an inclination in that direction would right soon vanish in the face of universal barbarism. Everywhere, and in an earnest way, initiation-wisdom must penetrate into the various branches of science and teaching, and above all into practical life, especially practical will. Fundamentally everything is lost time today that is not willed out of the impulses of initiation-wisdom. For all strength which we apply to other kinds of willing retards matters. Instead of wasting our time and strength in this way, we should apply whatever time and strength we have to bringing the impulse of initiation-wisdom into the different branches of life and knowledge.

If something is rolling along with the ancient impulses, no one will stop it in its rolling; and we should have an eye to how many younger people (especially in the conquered countries) are still filled with old catch-words, old chauvinism. These young people do not come into consideration. But those young people do come into consideration on whom rests the whole pain of the decline. And there are such. They are the ones whose wills can be broken by such theories as those of Spengler's book. Therefore, in Stuttgart I called this book of Oswald Spengler's a clever but fearful book, which contains the most fearful dangers, for it is so clever that it actually conjures up a sort of fog in front of people, especially young people.

The refutations must come out of an entirely different tone than that to which we are accustomed in such things, and it will never be a faith in this or that which will save us. People recommend one happily nowadays to such a faith, saying that if we only have faith in the good forces of men the new culture will come like a new youth. No, today it cannot be a question of faith, today it is a question of will; and spiritual science speaks to the will. Hence it is not understood by anyone who tries to grasp it through faith or as a theory. Only he understands it who knows how it appeals to the will, to the will in the deepest recesses of the heart when a man is alone with himself, and to the will when a man stands in the battle of daily life and in such battle, must assert himself as a man. Only when such a will is striven for can spiritual science be understood. I have said to you that for anyone who reads my Occult Science as he would read a novel, passively giving himself to it, it is really only a thicket of words—and so are my other books. Only one who knows that in every moment of reading he must, out of the depths of his own soul, and through his most intimate willing, create something for which the books should be only a stimulus—only such a one can regard these books as musical scores out of which he can gain the experience in his own soul of the true piece of music.

We need this active experiencing within our own souls.

Neunter Vortrag

Wer heute in Deutschland sich ein wenig umsieht und nicht auf Äußerlichkeiten geht, sondern mit dem Auge der Seele sieht, wer also nicht allein ins Auge faßt, was sich etwa dem Besucher darbietet, der ja in der Regel die Verhältnisse während seines Besuches gar nicht kennenlernt, wer nicht dabei stehenbleibt, daß wiederum einige Schornsteine rauchen, daß die Eisenbahnzüge zur rechten Zeit an ihrem Bestimmungsorte ankommen, sondern wer etwas in die geistige Verfassung hineinzuschauen vermag, dem bietet sich heute ein Bild, das symptomatisch ist nicht für dieses Territorium allein — denn das könnte vielleicht noch von der einen oder von der anderen Seite weniger bedenklich beleuchtet werden -, sondern für den ganzen Verfall unserer Weltkultur im gegenwärtigen Zyklus der Menschheit. Ich möchte heute gerade auf ein geistig-seelisches Symptom Sie einleitend hinweisen, das bedeutsamer ist, als viele schlafende Seelen auch in Deutschland sich träumen lassen.

Innerhalb des alten Deutschland herrscht ja heute Verfall, Niedergang, und die äußerlichen Dinge, die ich natürlich nur zum Teil aufgezählt habe, können nicht über diesen Niedergang täuschen. Aber das alles ist in geistig-seelischer Beziehung nicht das, worauf ich jetzt hinweisen möchte, denn Verfall sehen wir vielfach im Laufe der Weltgeschichte auftreten, und aus dem Verfall sehen wir dann wiederum die Aufgangsimpulse herausquellen. Aber wer zunächst äußerlich urteilt, wer von dem, was oftmals erfahren worden ist, aus einem Gewohnheitsurteil heraus sich sagt: Nun, das wird schon auch hier in derselben Weise wiederum so sein wie früher -, der sieht doch nicht auf gewisse tieferliegende Symptome. Ein solches Symptom, aber eben nur eines von vielen, ein geistig-seelisches, das ich hervorheben möchte, ist der merkwürdige Eindruck, den ein Buch hervorgerufen hat, ich meine das Buch «Der Untergang des Abendlandes» von Oswald Spengler, welches schon dadurch symptomatisch ist, daß es in unserer Zeit hat entstehen können. Es ist ein dickes Buch und es ist ein vielgelesenes Buch, ein namentlich unter der jungen Generation des heutigen deutschen Territoriums außerordentlich eindrucksvolles Buch. Und das Merkwürdige ist: der Verfasser erzählt ausdrücklich, daß er die Grundidee dieses Buches nicht etwa gefaßt habe während des Krieges oder nach dem Kriege, sondern daß er diese Grundidee schon einige Jahre vor der Katastrophe vom Jahre 1914 gefaßt hat.

Das Buch macht einen sehr bedeutsamen Eindruck gerade auf die junge Generation. Und wenn man in seinen Empfindungen versucht, aus dem heraus zu sprechen, was da vorhanden ist, so tritt einem, ich möchte sagen, unter den Imponderabilien des Lebens, so zwischen den Zeilen des Lebens dies ganz besonders stark entgegen. Ich hatte einen Vortrag zu halten vor den Stuttgarter Studenten der Technischen Hochschule, und ich ging eigentlich zu diesem Vortrage durchaus unter dem Eindrucke des Buches von Oswald Spengler «Der Untergang des Abendlandes». Es ist ein sehr dickes Buch. Dicke Bücher sind jetzt in Deutschland teuer; dennoch wird es viel gelesen. Daß sie teuer sind, das kann ich Ihnen daran veranschaulichen, daß ein Reclam-Heftchen, das 1914 noch zwanzig Pfennig gekostet hat, jetzt eine Mark und fünfundvierzig Pfennig kostet. Bücher sind ja nicht in demselben Verhältnisse gestiegen wie Bier, das wohl das Zehnfache des Preises von 1914 kostet, Fett sogar das Dreißigfache. Bücher müssen sich immer in bescheidenen Grenzen halten, selbst wenn solch unhaltbare wirtschaftliche Verhältnisse zugrunde liegen. Aber immerhin zeigt auch der Preisaufschlag der Bücher, was in den wirtschaftlichen Untergründen der letzten Jahre sich vollzogen hat.

Das Buch von Oswald Spengler habe ich bei einem meiner öffentlichen Vorträge in Stuttgart sehr ernst genommen, aber auch sehr ernst bekämpft. Dieses Buch ist im Grunde genommen seinem Inhalte nach bald charakterisiert. Es stellt dar, wie die Kultur des Abendlandes heute an einem Punkte angekommen ist, an welchem die untergegangenen Kulturen, wenn man sie nacheinander studiert, im alten Morgenlande, in Griechenland und Rom, auch einmal in einem gewissen Zeitabschnitte angekommen waren; und Spengler rechnet aus, daß dieses völlige Untergehen der gesamten abendländischen Kultur nach strenger historischer Rechnung mit dem Jahre 2200 vollendet sein müsse. Aber heute kommt es nicht nur auf den Inhalt einer solchen Sache an, sondern ebenso stark wie auf den Inhalt auf die geistig-seelischen Qualitäten eines Buches. Heute kommt es darauf an, ob der Verfasser, gleichgültig welcher Weltanschauungstendenz er angehört, geistige Qualitäten hat, ob er eine geistig ernst zu nehmende und vielleicht sogar geistig hoch einzuschätzende Persönlichkeit ist. Das ist ohne Zweifel der Verfasser des Buches, denn der Mann beherrscht, man darf sagen vielleicht zehn bis fünfzehn gegenwärtige Wissenschaften vollstänständig. Der Mann hat ein eindringliches Urteil über das, was im historischen Werden, so weit die Geschichte reicht, sich ereignet hat, und er hat auch, was ja die jetzigen Menschen eigentlich fast gar nicht haben, einen gesunden Blick für die Niedergangserscheinungen der gegenwärtigen Zivilisationen. Es ist im Grunde genommen ein großer Unterschied zwischen einem Spengler und all denjenigen Leuten, die heute gar nicht fühlen, was Niedergangsimpulse sind und alle möglichen Veranstaltungen treffen, um aus den Niedergangsurteilen heraus, was ja unmöglich ist, irgendeine Aufgangserscheinung abzuleiten. Wäre es nicht zum Herzschmerzbekommen, so wäre es eigentlich humoristisch, wie sehr die Menschen heute mit den altgewohnten, aber eben von Niedergangsimpulsen durchzogenen Ideen sich versammeln und glauben, aus dem Niedergange heraus durch allerlei Programme Aufgangserscheinungen schaffen zu können. Solch einem Wahnaberglauben gibt sich aber ein Mensch, der nun wirklich etwas weiß, wie Oswald Spengler, eben nicht hin, sondern er rechnet gewissermaßen — ich möchte sagen als strenger Mathematiker — die Geschwindigkeit der Niedergangserscheinungen aus, und mit einem Urteil, das wahrhaftig mehr als eine vage Prophetie ist, kommt er dazu, abzuleiten, wie bis zum Jahre 2200 diese abendländische Kultur in die vollständige Barbarei verfallen sein müsse.

Es ist dieses Zusammentreffen des äußerlich, namentlich auf geistig-seelischem Gebiete überall auftretenden Niederganges mit der Auffassung eines ernst zu nehmenden Theoretikers, daß dieser Niedergang ein notwendiger sei, ein solcher, der sich mit einer gewissen natürlichhistorischen Gesetzmäßigkeit vollzieht, es ist dieses Zusammentreffen das Merkwürdige an diesem Buche und es ist dieses Zusammentreffen dasjenige, was eigentlich auf die junge Generation einen besonderen Eindruck macht. Man hat heute nicht-nur Niedergangserscheinungen, man hat auch schon Theorien, welche diesen Niedergang als notwendig bezeichnen, ihn als streng wissenschaftlich erweislich darstellen. Man hat mit anderen Worten nicht nur den Niedergang, man hat eine Theorie des Niederganges, und zwar eine sehr ernst zu nehmende Theorie. Und man möchte fragen: Woher sollen die Kräfte kommen, jene innerlichen Willenskräfte, welche die Menschen anspornen, aus sich heraus zu einem Aufstieg zu kommen, wenn die Besten aus ihren Theorien heraus, aus einem umfassenden Überblicke über zehn bis fünfzehn Wissenschaften der Gegenwart heraus dahin kommen, mit alledem, was diese Wissenschaften enthüllen wollen über den Gang der Natur und der Menschheit, zu sagen: Dieser Niedergang ist nicht nur da, dieser Niedergang läßt sich beweisen wie irgendein physikalischer Vorgang! — Das heißt, es beginnt bereits die Zeit, wo der Glaube an den Niedergang nicht von den Schlechtesten vertreten wird. Man muß immer wieder und wiederum betonen, wie ernst eigentlich die Zeit ist, und wie fehlerhaft es ist, diesen Ernst der Zeit zu verschlafen, zu verträumen.

Man kann nicht anders, wenn man sich den ganzen Ernst dieser Lage vor Augen führt, als sich doch die Frage aufzuwerfen: Wie muß eigentlich unser Denken orientiert werden, damit der Pessimismus gegenüber der abendländischen Zivilisation nicht als etwas Selbstverständliches erscheine und der Glaube an den Aufstieg als ein Aberglaube sich offenbare? Man muß fragen: Gibt es etwas, das aus diesem Pessimismus noch herausführen kann? Gerade die Art und Weise, wie Spengler zu seinen Resultaten kommt, ist für den Geisteswissenschafter im höchsten Grade interessant. Spengler betrachtet die einzelnen Kulturen nicht so scharf abgegrenzt, wie wir es zum Beispiel für die nachatlantische Zeit tun, indem wir unterscheiden: urindische, urpersische, chaldäisch-ägyptische, griechisch-lateinische und neuzeitliche Kulturen. Es steht ihm eben Geisteswissenschaft nicht zur Verfügung; aber er betrachtet doch in einer gewissen Weise auch solche Kulturen. Und er betrachtet sie mit dem Blicke des Naturforschers. Er betrachtet sie mit denjenigen Methoden, welche im Laufe der letzten drei bis vier Jahrhunderte in der abendländischen Zivilisation heraufgezogen sind und welche im weitesten Umkreise diejenigen Geister ergriffen haben, die nicht am altherkömmlichen traditionellen, katholischen, evangelischen, mosaischen und so weiter Glaubensbekenntnis in Engigkeit befangen bleiben. Oswald Spengler ist sozusagen ein Mensch, der ganz und gar durchsetzt ist mit der materialistischen modernen Naturforschung. Und nun betrachtet er in seiner Art das Auf- und Absteigen der Kulturen - orientalische, indische, persische, griechische, römische Kultur, Kultur des jetzigen Abendlandes — wie bei einem Organismus, der eine gewisse Kindheit durchmacht, ein gewisses Reifezeitalter erlebt, dann ein Altern durchmacht, und nachdem er gealtert ist, stirbt. So betrachtet Spengler die einzelnen Kulturen: sie machen ihre Kindheit durch, ein Reifezeitalter, eine Zeit des Alterns und sterben dann ab. Und der Todestag unserer abendländischen gegenwärtigen Zivilisation wäre eben das Jahr 2200.

Das Buch ist zunächst nur im ersten Bande vorliegend. Wer nun diesen ersten Band auf sich wirken läßt, findet eine streng theoretische Rechtfertigung des Niederganges, den streng theoretischen Beweis des Niederganges, aber nirgends irgendeinen Lichtfunken, der hinwiese auf irgendeinen Aufgang, nirgends etwas, was auf irgendeinen Aufstieg hindeutete. Und man kann nicht einmal sagen, daß für den naturwissenschaftlichen Betrachter dies eine unrichtige Denk weise sei. Denn betrachtet man das heutige Leben — obwohl alle möglichen Fragen auftauchen, die Fragen, über die Nietzsche sich schon lustig gemacht hat -, und gibt man sich nicht dem Wahne hin, daß aus wesenlosen Programmen Zukunftsfrüchte reifen können, dann sieht man auch zunächst in dem, was die Mehrzahl der Menschen in der Außenwelt anerkennt, nirgends einen Aufstieg erscheinen. Betrachtet man also die aufsteigende und niedergehende Kultur wie Organismen und betrachtet man dann auch unsere Kultur als einen Organismus, unsere ganze abendländische Zivilisation, dann kann man nicht anders, als sagen: Das Abendland geht zugrunde, geht in die Barbarei hinein. Nichts vermag zu entscheiden, wo irgendein neuer Aufstieg, irgendein anderes Zentrum der Welt sich wiederum erzeigen werde.

Es ist das Spenglersche Buch ein Buch mit geistigen Qualitäten, aus scharfer Beobachtung herrührend und aus einem wirklichen Durchdrungensein mit der heutigen Wissenschaftlichkeit heraus geschrieben, und nur der gewöhnliche Lebensleichtsinn kann über solche Dinge oberflächlich hinwegsehen. Wenn solch eine Erscheinung kommt, dann tritt eben jene historische Sorge auf in dem Weltenbetrachter, von welcher ich hier des öfteren gesprochen habe und welche ich mit den folgenden Worten kurz zusammenfassend charakterisieren kann. Wer heute sich wirklich bekanntmacht mit dem inneren Wesen dessen, was im sozialen, im politischen, im geistigen Leben wirkt, wer da sieht, wie alles das, was wirkt, nach dem Niedergang hinstrebt, der muß sich sagen, wenn er nun Geisteswissenschaft kennt, wie sie hier gemeint ist: Eine Heilung kann es nur geben, wenn dasjenige, was man die Weisheit der Initiation nennt, in die Menschheitsentwickelung hineinfließt. — Denn denken wir uns einmal diese Weisheit der Initiation fort, denken wir einmal, das, was wir hier in gutem Sinne geistige Anschauung nennen, würde von der Menschheit vollständig außer acht gelassen, würde verbannt, würde keine Rolle spielen im weiteren Fortgange der Menschheitsentwickelung, — was würde die notwendige Folge sein müssen? Sehen Sie, wenn wir hinschauen auf die alte indische Kultur, so hat sie wie ein Organismus einen Kindheitszustand, Reife, Altern, Verfall, Tod; dann setzt sie sich fort. Aber das, was sie fortsetzt, lebt ja nicht in Wirklichkeit mehr. Wir haben dann die persische, die chaldäischägyptische, die griechisch-lateinische, unsere Zeit; aber immer haben wir etwas, was Oswald Spengler nicht berücksichtigt hat, was er eigentlich als streng naturwissenschaftlicher Beobachter nicht berücksichtigen konnte. Es ist ihm das vorgeworfen worden von einigen seiner Gegner. Denn einiges ist auch schon gegen das Buch von Spengler geschrieben worden, sogar manches, was gescheiter ist als der außerordentlich einfältige Artikel, den Benedetto Croce geschrieben hat gegen das Spenglersche Buch. Croce, der sonst immer Gescheites geschrieben hat, ist an dem Spenglerschen Buche plötzlich zum Toren geworden. Es ist Spengler also vorgeworfen worden, daß ja die Kulturen immer nicht nur Kindheit, Reife, Verfall, Tod haben, sondern daß sie sich fortsetzen, und so werde es auch mit der unsrigen sein: wenn sie eines seligen Todes sterbe im Jahre 2200, so werde sie sich schon wiederum fortsetzen. — Es ist dabei nur das Eigentümliche zu beachten, daß Spengler eben ein guter naturwissenschaftlicher Beobachter ist und deshalb keine Fortsetzungsmomente findet, daß er daher nicht von einem Samen sprechen kann, der etwa in unserer Kultur drinnen ist, sondern nur von den Niedergangserscheinungen, die sich ihm, dem naturwissenschaftlichen Beobachter, darbieten. Und diejenigen, die davon sprechen, daß sich die Kulturen fortsetzen, haben auch nichts besonders Gescheites gerade über dieses Buch zu sagen gewußt. Ein ganz junger Mann hat eine etwas verschwommene Mystik vorgebracht, in der er von «Weltrhythmus» spricht; aber auch damit ist eben nur eine verschwommene Mystik geschaffen, nicht irgend etwas, was den bewiesenen Pessimismus in einen Optimismus verwandelt hätte. So geht eigentlich aus dem Spenglerschen Buche nur hervor, daß der Untergang kommen wird, nicht aber ein Aufstieg erfolgen könne.

Was Spengler tut, ist, daß er naturwissenschaftlich betrachtet: Kindheitsalter des Kultur- oder Zivilisationsorganismus, Reifezeit, Verfall, Altern, Tod in den verschiedenen Zeitaltern betrachtet er so, wie man auch naturwissenschaftlich im Grunde genommen einzig und allein betrachten kann. Aber wer etwas weiter auszuschauen vermag, der weiß, daß im alten indischen Leben außer dem Außerlichen der Zivilisation die Mysterienweisheit, die Initiationsweisheit der Urzeiten gelebt hat. Und diese Initiationsweisheit der Urzeiten, die in Indien noch mächtig war, sie hat wiederum den neuen Keim in die persische Kultur hineingetrieben. Die persischen Mysterien waren schon schwächer, aber sie konnten noch den Keim in die ägyptisch-chaldäische Zeit hineintreiben. Es konnte auch noch der Keim in die griechisch-lateinische Zeit hineingetrieben werden. Dann setzte sich gleichsam die Kulturströmung fort nach dem Gesetze der Trägheit bis in unsere Zeit herein, und da versiegt sie.

Das muß man fühlen! Diejenigen, die zu unserer Geisteswissenschaft gehören, die könnten das seit nahezu zwanzig Jahren fühlen. Denn eine der ersten Bemerkungen, die ich gleich bei der Begründung unserer geisteswissenschaftlichen Bewegung gemacht habe, ist diese: Wenn man dasjenige, was das Kulturleben der Menschheit äußerlich hervorbringt, was eben so weitertreibt, vergleichen will mit etwas, so kann man es vergleichen mit dem Stamm, den Blättern und Blüten und so weiter eines Baumes. Dasjenige aber, was wir hineinversetzen wollen in diese fortgehende Strömung, das läßt sich vergleichen mit dem Mark des Baumes, das muß verglichen werden mit den im Marke sich betätigenden Wachstumskräften. Ich wollte darauf aufmerksam machen, daß durch Geisteswissenschaft wiederum gesucht werden müsse, was, einst aus alter atavistischer Urweisheit überliefert, heute versiegt ist. Dieses Bewußtsein, so hineingestellt zu sein in die Welt, das ist es, was im Grunde genommen das Bewußtsein derjenigen ausmachen soll, die sich zur anthroposophischen Bewegung zählen. Aber noch eine andere Bemerkung habe ich gemacht, allerdings in den letzten Jahren besonders hier, sehr häufig aber auch an anderen Orten. Ich habe gesagt: Wenn man alles dasjenige, was man aus der heutigen Wissenschaft aufnehmen kann, nimmt und sich daraus eine Anschauungsweise bildet und diese Anschauungsweise anwendet zum Beispiel auf das soziale oder namentlich auch auf das geschichtliche Leben, so kann man dadurch nur die Niedergangserscheinungen fassen. Mit dem, was Naturwissenschaft uns lehrt als Betrachtungsweise, trifft man, wenn man Geschichte betrachtet, nur das, was in der Geschichte niedergeht, und wenn man es auf das soziale Leben anwendet, schafft man nur Niedergangserscheinungen.

Was ich da im Laufe der Jahre gesagt habe, hätte im Grunde keine bessere Illustration finden können als die jetzt durch das Spenglersche Buch gegebene. Ein echt naturwissenschaftlich Betrachtender tritt auf, schreibt Geschichte und entdeckt durch diese Geschichtsschreibung, daß die Zivilisation des Abendlandes im Jahre 2200 stirbt. Er konnte im Grunde genommen nichts anderes entdecken. Denn erstens kann man mit naturwissenschaftlicher Betrachtungsweise überhaupt nur Niedergangserscheinungen schaffen oder entdecken, zweitens aber ist das ganze Abendland mit Bezug auf sein geistiges, politisches und soziales Leben ganz durchtränkt mit naturwissenschaftlichen Impulsen und ist dadurch in einer Niedergangsepoche drinnen. Um was es sich handelt, das ist, daß das, was bisher eine Kultur aus der anderen hervorgetrieben hat, versiegt ist, und daß im 3. Jahrtausend aus unserer niedergehenden abendländischen Zivilisation keine neue Zivilisation hervorgetrieben wird.

Sie können noch so viele Nuancen sozialer Fragen aufwerfen, noch so viele Nuancen von Frauenfragen aufwerfen, noch so viele Versammlungen für diese oder jene Fragen halten, wenn Sie aus dem heraus, was aus Altem übertragen ist, Ihr Programm prägen, dann schaffen Sie etwas, was nur scheinbar ein Schaffen ist, und für das durchaus anwendbar sind die Ideen des Oswald Spengler.

Die Sorge, von der ich gesprochen habe, von ihr muß deshalb gesprochen werden, weil es notwendig ist, daß nun eine ganz neue Initiationsweise beginnt aus dem menschlichen Willen, aus der menschlichen Freiheit heraus; weil in der Tat, wenn wir uns bloß auf die Außenwelt und auf das Überkommene verlassen, wir untergehen im Abendlande, wir in die Barbarei verfallen und wir nur aufwärtskommen können aus dem Willen heraus, aus dem Schöpferischen des Geistes heraus. Eine neue Initiationsweisheit muß einsetzen. Diese Initiationsweisheit, die in unserer Epoche ihren Anfang nehmen muß, wird ebenso wie die alte Initiationsweisheit, die nur allmählich dem Egoismus, der Selbstsucht und dem Vorurteil verfallen ist, ausgehen müssen von Sachlichkeit und Vorurteilslosigkeit und von Selbstlosigkeit. Sie wird von da aus alles durchdringen müssen.

Dies kann man als eine Notwendigkeit einsehen. Man muß es als eine Notwendigkeit einsehen, wenn man tiefer hineinschaut in den heutigen unglückseligen Gang dieser abendländischen Zivilisation. Sieht man aber so hinein, so bemerkt man eben noch etwas anderes; man bemerkt, daß ein berechtigter Ruf in die Karikatur verzerrt wird. Und nun liegt die besondere Notwendigkeit vor, das Zur-Karikatur-Verzerrtwerden eines berechtigten Rufes gründlich einzusehen. Gewiß ist kein Ruf berechtigter in unserer Gegenwart als der nach Demokratie. Aber er wird zur Karikatur verzerrt, solange die Demokratie nicht erkannt wird als ein bloß für das rein politische, staatlichrechtliche Leben notwendiger Impuls, und solange nicht erkannt wird, daß davon abgegliedert werden muß das wirtschaftliche und das geistige Leben. Er wird zur Karikatur verzerrt, indem im Grunde genommen statt Sachlichkeit, das heißt Vorurteilslosigkeit und Selbstlosigkeit, heute Unsachlichkeit, nämlich persönliche Willkür sowohl über Wissenschaft wie im sozialen Leben, und Selbstsucht zu Kulturfaktoren gemacht werden. Alles wird in das Gebiet hineingezogen, das man gewöhnlich das politische nennt, in das Gebiet, in dem herrschen soll das Recht. Geschieht aber das, so verschwinden allmählich Sachlichkeit und Vorurteilslosigkeit, denn das geistige Leben kann nicht gedeihen, wenn es seine Richtung empfängt von dem politischen Leben. Es wird immer dadurch in das Vorurteil eingespannt. Und Selbstlosigkeit kann nicht gedeihen, wenn das wirtschaftliche Leben innerhalb des politischen steht, denn dann wird es notwendigerweise in die Selbstsucht hineingetrieben. Wird nun dasjenige, was Selbstlosigkeit auf wirtschaftlichem Gebiete erzeugen kann, das assoziative Leben, verdorben, so tendiert alles darauf hin, heute die Menschen in Vorurteilen und in Selbstsucht ihre Wege wandeln zu lassen. Und die Folge davon ist, daß sie gerade das abweisen, was Sachlichkeit und Selbstlosigkeit basieren muß: die Wissenschaft der Initiation. Im äußeren Leben ist heute alles dazu angetan, zurückzuweisen diese Wissenschaft der Initiation, die einzig und allein über das Jahr 2200 hinausführen kann.

Das ist die große Kultursorge, die einen überkommen kann, wenn man einen unbefangenen, nicht schläfrigen oder träumerischen Blick hineinwirft in die Geschehnisse der Gegenwart. Denn ich betrachte auf diesem Boden das Spenglersche Buch auch nur als ein Symptom. Gibt es denn eine Möglichkeit, heute etwa zu sagen: Nun ja, der Spengler hat sich geirrt, Kulturen sind gekommen, sind untergegangen, unsere wird untergehen, es wird aus ihr wiederum eine neue entstehen? — Nein, solch eine Widerlegung einer Anschauung wie der Spenglerschen gibt es überhaupt nicht. Sie ist ganz falsch gedacht. Denn die Zuversicht auf einen Aufstieg kann heute nicht auf dem Glauben aufgebaut werden, daß sich aus den Kulturen des Abendlandes etwas schon herausentwickeln werde. Nein, gerade wenn man auf diesem Glauben aufbaut, wird sich nichts herausentwickeln. Denn es ist einfach im Objektiven zunächst nichts vorhanden, was wie ein Same dasteht über den Beginn des 3. Jahrtausends hinaus, sondern da wir in Wirklichkeit in der fünften nachatlantischen Kulturepoche leben, muß erst ein Same geschaffen werden. Man kann daher zu den Leuten nicht sagen: Glaubt an die Götter, glaubt an das, glaubt an jenes, es wird schon gut gehen! — Das ist heute keine Widerlegung, sondern man muß heute zu den Leuten sagen: Diejenigen, die von Niedergangserscheinungen sprechen und sie sogar beweisen, die haben gegenüber dem, was in der Außenwelt lebt, recht. Aber daß sie nicht recht behalten, dafür muß jeder einzelne sorgen. Denn der Aufstieg kommt nicht aus dem Objektiven, der Aufstieg kommt aus dem Subjektiven des Willens. Ein jeder muß wollen und muß den Geist neu aufnehmen, und muß aus dem neu aufgenommenen Geiste der untergehenden Zivilisation selber einen neuen Antrieb geben, sonst geht sie unter. - Man kann also heute nicht an ein objektives Gesetz appellieren, man kann einzig und allein an den guten Willen der Menschen appellieren. Hier [in der Schweiz] ist ja, weil selbstverständlich die Dinge sich anders abgespielt haben, kaum von dem wirklichen Gang der Ereignisse etwas zu merken, obwohl er auch hier vorhanden ist. Kommt man aber über die Grenze nach Deutschland, dann tritt in allem, was man erleben kann, wenn man mit geistig-seelischem Auge schaut, das auf, was ich Ihnen eben jetzt charakterisiert habe. Dann tritt einem der große, furchtbar schmerzliche Kontrast vor die Seele zwischen der Notwendigkeit, die Initiationsweisheit einzuverleiben dem geistigen, dem rechtlichen, dem wirtschaftlichen Leben, und zwischen den perversen Instinkten, alles, was von dieser Seite kommt, zurückzuweisen. Es ist so, daß man heute, wenn man diesen Kontrast empfindet, wirklich lange nachdenkt, wie man ihn charakterisieren soll; und wer nicht leichtsinnig nach den Worten greift, dem werden heute die Worte gar nicht besonders leicht.

Ich habe in Stuttgart über das Spenglersche Buch und im Zusammenhange damit über allerlei Erscheinungen der Gegenwart gesprochen und habe auch diesen Ausdruck im Sinne von «perversen Instinkten der Gegenwart» gebraucht; und ich muß sagen: Ich habe ihn heute wiederum gebraucht, weil ich ihn als den einzig angemessenen empfinde. Als ich damals vom Podium herabstieg, sprach mich einer von denjenigen Leuten an, die ja das Wort «pervers» in seiner terminologischen Bedeutung am besten verstehen, ein Arzt. Er war sehr betroffen, daß ich just dieses Wort gebrauchte. Aber die Betroffenheit ging, ich möchte sagen, aus sehr merkwürdigen Untergründen hervor. Man setzt im Grunde genommen heute gar nicht mehr voraus, daß jemand, der nur aus den Untergründen der Tatsachenwelt der Wirklichkeit heraus charakterisiert, mit Schmerz seine Worte wählt, sondern man setzt voraus, daß jeder die Worte so prägt, wie sie heute aus der Oberflächlichkeit des Zeitbewußtseins heraus geprägt werden. Und ich hatte dann ein Zwiegespräch mit jenem Arzte und sagte ihm dies und jenes, und er sagte dann dazu: Nun ja, dann bin ich froh, daß wenigstens der Ausdruck «pervers» nicht feuilletonistisch, belletristisch gemeint war! — Ich konnte nur sagen: Ganz gewiß ist das nicht der Fall, denn ich bin überhaupt nicht gewohnt, irgend etwas belletristisch oder feuilletonistisch zu meinen.

Es handelte sich also darum, daß in der gegenwärtigen Verständigung der heutigen Menschen zunächst gar nicht mehr vorausgesetzt wird, daß es so etwas wie ein Schöpfen-aus-dem-Geiste geben könne, und daß jeder einfach glaubt, wenn man so etwas sagt wie «perverse Instinkte», daß man aus denselben Untergründen heraus redet wie der letztbeste Belletrist oder Feuilletonist. Denn, was heute belletristisch oder feuilletonistisch geredet wird, das beherrscht im Grunde genommen heute die Gemüter, und die Gemüter bilden sich daran. Und die Schwere der Ausdrücke prägen aus der Sache heraus — das wird dem Menschen gar nicht mehr bewußt. Gerade an einer solchen Erscheinung tritt einem der Kontrast entgegen zwischen dem, was so notwendig ist der heutigen Menschheit: einer wirklichen Vertiefung, die aber zurückgehen muß bis in die Untergründe der Initiationsweisheit, und dem, was heute durch die Karikatur der Demokratie auch als geistiges Leben zum Vorschein kommt. Die Leute sind viel zu bequem, erst irgend etwas in sich heraufzuholen von verborgenen Bewußtseinskräften. Jeder feuilletonisiert und belletristisiert darauf los, sei es bei Kaffeeklatsch, sei es beim Dämmerschoppen, sei es in der politischen Versammlung, sei es in den Parlamenten. Das hängt mit dem zusammen, was ich öfters gesagt habe, daß heute der Wortlaut nichts ist, daß aber dasjenige, was als Kraft des Geistes im Wortlaut zu verspüren ist, die Hauptsache ist. Geistreiche Dinge auszusprechen, ist heute das leichteste von der Welt, denn wir leben eben in einer sterbenden Kultur, wo die Geistreichigkeit den Leuten nur so zufließt. Aber den Geist, den wir brauchen, den Geist der Initiationsweisheit, den müssen die Menschen aus dem Willen herausholen. Und den werden sie nicht finden, wenn die Kraft dieser Initiationsweisheit nicht über sie, das heißt, über ihre Seelen kommt. Daher kann man nicht sagen: Man widerlegt solche Bücher wie das Spenglersche. - Man kann ein solches Buch natürlich charakterisieren: es ist aus naturwissenschaftlichem Geiste heraus geboren. — Aber das, was die anderen aus naturwissenschaftlichem Geiste heraus gebären, ist ja schließlich dasselbe. Also Spengler hat recht — wenn nicht hineinfährt in die Willenssphäre der Menschen dasjenige, was erst dieses Recht zum Unrecht macht! Man hat heute nicht die Bequemlichkeit mehr, zu beweisen, daß der Beweis des Unterganges falsch ist, sondern man muß das, was richtig ist, durch die Kraft des Willens zum Unrichtigen machen.

Sie sehen, daß man scheinbar in ganz paradoxen Sätzen sprechen muß. Aber wir leben in dem Zeitalter, in dem die alten Vorurteile zertrümmert werden müssen, und in dem erkannt werden muß, daß wir aus den alten Vorurteilen heraus keine neue Welt schaffen können. Ist es nicht ganz selbstverständlich, daß die Leute an die Geisteswissenschaft herankommen und sich sagen: Das verstehen wir nicht? — Es ist so selbstverständlich wie irgend etwas. Denn, was sie verstehen, das haben sie gelernt, und was sie gelernt haben, ist Niedergang, das führt also in den Niedergang hinein. Es handelt sich also darum, nicht dasjenige aufzunehmen, was man ohne weiteres aus Niedergangserscheinungen heraus versteht, sondern das aufzunehmen, zu dessen Verständnis man sich erst heraufleben muß. Solcherart ist eben die Initiationsweisheit. Aber wie sollte man von denen, die heute Volkslehrer, Volksleiter oder dergleichen sein wollen, erwarten, daß sie einsehen, daß der Mensch das, was ihn heute urteilsfähig macht, erst heraufholen muß aus den unterbewußten Tiefen des Seelenlebens, daß das nicht schon da oben sitzt im Kopfe! Was aber in Wirklichkeit da oben sitzt im Kopfe, ist zerstörerisches Element.

Das sind die Dinge, die einem überall da entgegentreten, wo schon die Konsequenzen gezogen sind des Niederganges, wo diese Konsequenzen des Niederganges schon an der Oberfläche liegen. Selbstverständlich, daß da, wo zunächst Scheinerfolge da sind, wo man nur nötig hat, auf diese Scheinerfolge zunächst hinzuschauen, daß da das, Bewußtsein von dem Niedergang der abendländischen Zivilisation ganz und gar nicht leicht auftreten kann, das ist ja begreiflich. Und so steht man heute durchaus gerade unter dem Eindrucke dieses Ihnen charakterisierten Kontrastes von der Notwendigkeit eines Einflusses der Initiationsweisheit in die ganze Zivilisation auf der einen Seite, und auf der anderen Seite von der Zurückweisung dieses Impulses. Es kann einfach nicht besser werden, wenn nicht in einer genügend großen Anzahl von Menschen das Bewußtsein auftritt von der Notwendigkeit dieses Einschlages von seiten der Initiationsweisheit. Gerade wenn man auf zeitweilige Besserung großen Wert legt, wird man die großen Linien des Niederganges nicht bemerken, wird sich darüber täuschen und wird um so mehr diesem Niedergange entgegengehen, indem man nicht das einzige Mittel ergreift, das es gibt: anzufachen einen neuen Geist aus dem Willen der Menschen heraus. Dieser Geist muß aber alles ergreifen. Dieser Geist darf vor allen Dingen nicht stehenbleiben bei irgendwelchen theoretischen Weltanschauungsfragen. Das wäre sogar eine sehr herbe Täuschung, wenn eine große Anzahl von Menschen, vielleicht gerade diejenigen, denen die neue Initiationsweisheit ein wenig gefällt und ein wenig innere seelische Wollust macht, wenn die glauben würden, es genüge, wenn man bloß als etwas seelisch-wohlbehagliches Gutes diese Initiationsweisheit treiben würde. Denn dadurch würde man es gerade erreichen, daß alles übrige äußerliche wirkliche Leben immer mehr und mehr in den Barbarismus hineingeht, und das bißchen Mystik, das auf diesem Wege erzielt werden könnte bei einer Anzahl von Menschen, die einen gewissen seelischen Hang zu unklarer Mystik haben, das würde gegenüber dem allgemeinen Barbarismus sehr, sehr bald verschwinden müssen. Überall hinein und vor allen Dingen in allem Ernste hinein in die einzelnen Zweige der Wissenschaft und des Unterrichtes muß dasjenige, was Initiationsweisheit ist, und vor allen Dingen auch in die wesentlichsten Gebiete des praktischen Lebens, insbesondere des praktischen Wollens. Im Grunde genommen ist alles verlorene Zeit, was heute nicht aus dem Impulse der Initiationsweisheit heraus gewollt wird. Denn alle Kraft, die man auf anderes Wollen verwendet, hält im Grunde genommen nur auf, weil man sich zufrieden gibt mit solchem Willenssurrogat. Statt Zeit und Kraft in dieser Weise zu verschwenden, sollte man alles, was man an Zeit und Kraft hat, anwenden, um den Impuls der Initiationsweisheit in die verschiedenen Zweige des Erkennens und Lebens hineinzutragen.

Was mit den Impulsen des Alten rollt - niemand wird es in seinem Rollen aufhalten, und man sollte schon ein wenig hinschauen, wie in der Jugend, zunächst der der besiegten Länder, noch fortwallt eine ganz undefinierbare Erfülltheit mit alten Schlagworten, alten Chauvinismen oder dergleichen. Diese Jugend kommt schon gar nicht in Betracht. Aber die Jugend kommt in Betracht, auf der heute der ganze Schmerz des Niederganges ruht. Und sie ist vorhanden. Sie ist es, deren Wollen zunächst gebrochen werden könnte durch solche Theorien wie die des Spenglerschen Buches. Daher nannte ich in Stuttgart dieses Oswald Spenglersche Buch ein geistvolles, aber furchtbares Buch, ein Buch, das die furchtbarsten Gefahren birgt, denn es ist so geistvoll, daß es in der Tat vor den Menschen einen Nebel hinzaubert, insbesondere vor die Jugend.

Die Widerlegungen müssen aus einem ganz anderen 'Ton heraus kommen als dem, an den man gewöhnt ist, wenn man von solchen Sachen spricht, und niemals kann es ein Glaube an das oder jenes sein, was retten könnte. Man verweist ja heute billigerweise die Menschen an einen solchen Glauben und sagt ihnen: Glaubt nur an die guten Kräfte der Menschen und so weiter, dann wird schon auch die neue Kultur wie mit einer neuen Jugend kommen. — Nein, heute kann es sich nicht um den Glauben handeln, heute handelt es sich um das Wollen, und zum Wollen spricht die Geisteswissenschaft. Daher versteht sie derjenige nicht, der sie bloß durch einen Glauben oder als eine Theorie aufnehmen will. Der nur versteht sie, der da weiß, wie sie an das Wollen appelliert, an das Wollen in der tiefsten Herzenskammer, wenn der Mensch still in Einsamkeit mit sich ist, und an das Wollen, wenn der Mensch im Lebenskampfe steht und im Lebenskampfe seinen Menschen zu stellen hat. Nicht ohne daß das Wollen angestrebt wird, kann die Geisteswissenschaft begriffen werden. Ich sagte Ihnen, wer meine «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß», liest, so wie man heute einen Roman liest oder ein anderes Buch, wer nur passiv sich hingeben will, für den ist diese «Geheimwissenschaft» ein Gestrüpp von Worten, sind es im Grunde genommen auch meine anderen Bücher. Nur demjenigen, der weiß, daß in jedem Augenblick, wo er sich der Lektüre hingibt, er aus seinen eigenen Seelentiefen heraus durch sein intimstes Wollen etwas schaffen muß, wozu die Bücher der anregende Impuls sein wollen, nur dem gelingt es, diese Bücher wie Partituren zu betrachten und das eigentliche Musikstück aus ihnen erst zu gewinnen im eigenen Erleben der Seele. Dieses eigene aktive Erleben der Seele aber brauchen wir.

Ninth Lecture

Anyone who looks around Germany today and does not focus on outward appearances, but sees with the eye of the soul, anyone who does not merely see what presents itself to the visitor, who as a rule is unfamiliar with the circumstances during his visit, anyone who does not dwell on the fact that a few chimneys are smoking, that the trains arrive at their destinations on time, but who is able to look into the spiritual condition, will see a picture that is symptomatic not only of this territory alone — for that could perhaps be viewed less seriously from one side or the other — but of the entire decline of our world culture in the present cycle of humanity. Today, I would like to begin by pointing out a spiritual symptom that is more significant than many sleeping souls, even in Germany, allow themselves to dream.

Within old Germany, decay and decline reign today, and the external things, which I have of course only listed in part, cannot hide this decline. But all this is not what I want to point out now in a spiritual-soul relationship, for we see decay occurring many times in the course of world history, and out of decay we then see the impulses of new growth springing forth. But those who judge primarily from outward appearances, who say, based on habitual judgment and on what has often been experienced, “Well, it will be the same here as it was in the past,” do not see certain deeper symptoms. One such symptom, but only one of many, a spiritual-soul symptom that I would like to highlight, is the strange impression made by a book, namely Oswald Spengler's “The Decline of the West,” which is symptomatic in itself because it was able to come into being in our time. It is a thick book and a widely read book, a book that has made an extraordinary impression, especially on the younger generation in Germany today. And the strange thing is that the author expressly states that he did not conceive the basic idea for this book during the war or after the war, but that he had already conceived this basic idea several years before the catastrophe of 1914.

The book makes a very significant impression on the younger generation in particular. And when one tries to express one's feelings about what is there, one is struck, I would say, by the imponderables of life, between the lines of life. I had to give a lecture to students at the Technical University in Stuttgart, and I went to this lecture very much under the impression of Oswald Spengler's book “The Decline of the West.” It is a very thick book. Thick books are expensive in Germany now, but they are still widely read. I can illustrate how expensive they are by the fact that a Reclam booklet that cost twenty pfennigs in 1914 now costs one mark and forty-five pfennigs. Books have not risen in price to the same extent as beer, which now costs ten times what it did in 1914, and fat even thirty times as much. Books must always remain within modest limits, even when such untenable economic conditions prevail. But the increase in book prices does at least reflect what has been happening in the economic background of recent years.

I took Oswald Spengler's book very seriously during one of my public lectures in Stuttgart, but I also fought against it very seriously. This book can basically be characterized by its content. It describes how Western culture has now reached a point where, if one studies them in succession, the cultures that have disappeared in the ancient East, in Greece and Rome, and even in a certain period of time; and Spengler calculates that, according to strict historical calculations, the complete demise of the entire Western culture must be complete by the year 2200. But today, it is not only the content of such a thing that matters, but just as much as the content, the spiritual and emotional qualities of a book. Today, it depends on whether the author, regardless of his worldview, has spiritual qualities, whether he is a spiritually serious and perhaps even highly esteemed personality. This is undoubtedly the case with the author of this book, for the man has mastered, one might say, ten to fifteen contemporary sciences completely. He has a penetrating judgment of what has happened in the course of history, as far back as history reaches, and he also has what people today hardly have at all: a healthy view of the signs of decline in contemporary civilizations. There is basically a big difference between a Spengler and all those people who today have no sense of what the impulses of decline are and who take all kinds of measures to derive some kind of sign of revival from the judgments of decline, which is of course impossible. If it weren't so heartbreaking, it would actually be humorous how much people today gather around old familiar ideas that are riddled with impulses of decline and believe that they can create signs of revival out of decline through all kinds of programs. But a person who really knows something, like Oswald Spengler, does not indulge in such delusional beliefs. Instead, he calculates, as a strict mathematician, the speed of the signs of decline, and with a judgment that is truly more than a vague prophecy, he concludes that by the year 2200, Western culture will have fallen into complete barbarism.

It is this coincidence of the outward decline occurring everywhere, especially in the spiritual and intellectual realm, with the view of a serious theorist that this decline is necessary, that it is taking place with a certain natural historical regularity, it is this coincidence that is remarkable about this book, and it is this coincidence that actually makes a particular impression on the younger generation. Today, we not only have signs of decline, we also have theories that describe this decline as inevitable and present it as strictly scientifically provable. In other words, we not only have decline, we have a theory of decline, and a very serious one at that. And one wants to ask: Where are the forces supposed to come from, those inner forces of will that spur people on to rise up out of themselves, when the best minds, based on their theories and a comprehensive overview of ten to fifteen contemporary sciences, come to the conclusion, with all that these sciences seek to reveal about the course of nature and humanity, that This decline is not only happening, this decline can be proven like any physical process! — This means that the time is already beginning when belief in decline is not held by the worst people. We must emphasize again and again how serious the times actually are and how wrong it is to sleep through this seriousness, to dream it away.

When one considers the gravity of the situation, one cannot help but ask the question: How should we orient our thinking so that pessimism about Western civilization does not appear to be something self-evident and so that belief in progress does not reveal itself to be superstition? We must ask: Is there anything that can lead us out of this pessimism? The very way in which Spengler arrives at his conclusions is of the utmost interest to scholars of the humanities. Spengler does not view individual cultures as sharply delineated as we do, for example, in the post-Atlantic era, where we distinguish between Indo-European, Persian, Chaldean-Egyptian, Greek-Latin, and modern cultures. He does not have the humanities at his disposal, but he does consider such cultures in a certain way. And he views them with the eye of a natural scientist. He looks at them using the methods that have emerged in Western civilization over the last three to four centuries and which have, in the broadest sense, captured the minds of those who are not confined to the narrow confines of traditional Catholic, Protestant, Mosaic, and other creeds. Oswald Spengler is, so to speak, a man who is completely imbued with modern materialistic natural science. And now, in his own way, he looks at the rise and fall of cultures—Oriental, Indian, Persian, Greek, Roman, and the culture of the present-day West—as if they were organisms that go through a certain childhood, experience a certain age of maturity, then go through a period of aging, and after they have aged, they die. This is how Spengler views individual cultures: they go through childhood, an age of maturity, a period of aging, and then they die. And the day of death of our present Western civilization would be the year 2200.

Only the first volume of the book is currently available. Anyone who reads this first volume will find a strictly theoretical justification for decline, strict theoretical proof of decline, but nowhere is there any glimmer of light that points to any kind of rise, nowhere is there anything that points to any kind of ascent. And one cannot even say that this is an incorrect way of thinking for the scientific observer. For if one looks at life today—even though all kinds of questions arise, questions that Nietzsche already mocked—and does not succumb to the delusion that future fruits can ripen from insubstantial programs, then one sees nowhere, at first glance, any rise in what the majority of people in the outside world recognize. If we therefore consider rising and declining cultures as organisms, and if we then also consider our culture as an organism, our entire Western civilization, then we cannot help but say: The West is going under, it is sinking into barbarism. Nothing can decide where any new rise, any other center of the world will emerge.

Spengler's book is a book with intellectual qualities, written from keen observation and a real understanding of today's science, and only the usual frivolity of life can overlook such things superficially. When such a phenomenon occurs, the historical concern of which I have spoken frequently here arises in the observer of the world, and which I can characterize briefly with the following words. Anyone who today truly familiarizes themselves with the inner nature of what is at work in social, political, and spiritual life, anyone who sees how everything that is at work is striving toward decline, must say to themselves, if they are familiar with spiritual science as it is meant here: There can only be healing if what is called the wisdom of initiation flows into human evolution. For let us imagine that this wisdom of initiation were to be completely disregarded by humanity, that what we here call spiritual intuition in the positive sense were to be banished and play no part in the further course of human development — what would be the inevitable consequence? You see, if we look at ancient Indian culture, it has, like an organism, a state of childhood, maturity, aging, decay, and death; then it continues. But what continues does not really live anymore. Then we have the Persian, the Chaldean-Egyptian, the Greek-Latin, our own time; but we always have something that Oswald Spengler did not take into account, something that he, as a strictly scientific observer, could not take into account. He has been criticized for this by some of his opponents. For some things have already been written against Spengler's book, even some things that are more intelligent than the extraordinarily simple-minded article that Benedetto Croce wrote against Spengler's book. Croce, who otherwise always wrote intelligent things, suddenly became a fool when it came to Spengler's book. Spengler has been accused of claiming that cultures do not only experience childhood, maturity, decline, and death, but that they continue, and that this will also be the case with our culture: if it dies a blessed death in the year 2200, it will continue again. — The only thing to note here is that Spengler is a good observer of natural science and therefore cannot find any elements of continuity; he cannot therefore speak of a seed that is somehow present in our culture, but only of the signs of decline that are apparent to him, the observer of natural science. And those who speak of cultures continuing have not had anything particularly intelligent to say about this book. A very young man has put forward a somewhat vague mysticism in which he speaks of a “world rhythm”; but even that is just vague mysticism, not something that would have transformed the proven pessimism into optimism. Thus, Spengler's book actually only reveals that decline is coming, but not that an ascent is possible.

What Spengler does is to look at things from a scientific point of view: he looks at the childhood, maturity, decline, and death of the cultural or civilizational organism in the various ages in the same way that one can, in principle, only look at things scientifically. But anyone who is able to look a little further knows that in ancient Indian life, apart from the external aspects of civilization, the mystery wisdom, the initiation wisdom of primeval times, was alive. And this initiation wisdom of primeval times, which was still powerful in India, in turn drove the new seed into Persian culture. The Persian mysteries were already weaker, but they were still able to drive the seed into the Egyptian-Chaldean period. The seed was also driven into the Greek-Latin period. Then, as it were, the cultural current continued according to the law of inertia until our time, and there it dried up.

You have to feel this! Those who belong to our spiritual science have been able to feel this for almost twenty years. For one of the first remarks I made when founding our spiritual scientific movement was this: if one wants to compare what the cultural life of humanity produces outwardly, what it drives forward, with something else, one can compare it with the trunk, the leaves, and the flowers of a tree. But what we want to put into this ongoing stream can be compared to the marrow of the tree; it must be compared to the forces of growth at work in the marrow. I wanted to point out that spiritual science must once again seek what has been handed down from ancient atavistic wisdom but has now dried up. This awareness of being placed in the world is what should fundamentally constitute the consciousness of those who belong to the anthroposophical movement. But I have made another remark, especially here in recent years, but also very frequently in other places. I said: If you take everything that can be gleaned from modern science and form a worldview from it, and then apply this worldview to social life, or to historical life in particular, you will only be able to grasp the signs of decline. With the approach taught by natural science, when you look at history, you only encounter what is declining in history, and when you apply it to social life, you only create signs of decline.

What I have said over the years could not have found a better illustration than that now provided by Spengler's book. A genuine natural scientist appears, writes history, and discovers through this historiography that Western civilization will die in the year 2200. He could not have discovered anything else. Firstly, because a scientific approach can only create or discover signs of decline, and secondly, because the entire Western world is completely saturated with scientific influences in terms of its intellectual, political, and social life, and is therefore in a period of decline. What is at stake is that what has hitherto driven one culture out of another has dried up, and that in the third millennium, no new civilization will emerge from our declining Western civilization.

You can raise as many nuances of social issues as you like, raise as many nuances of women's issues as you like, hold as many meetings on this or that issue as you like, but if you shape your program from what has been handed down from the past, then you are creating something that is only seemingly a creation, and Oswald Spengler's ideas are entirely applicable to this.

The concern I have spoken of must be spoken of because it is necessary that a completely new form of initiation now begin out of the human will, out of human freedom; because in fact, if we rely solely on the external world and on what has been handed down to us, we will perish in the West, we will fall into barbarism, and we can only rise out of the will, from the creative power of the spirit. A new wisdom of initiation must begin. This wisdom of initiation, which must begin in our epoch, must, like the old wisdom of initiation, which only gradually fell prey to egoism, selfishness, and prejudice, proceed from objectivity, impartiality, and selflessness. From there it must permeate everything.