Karma of Untruthfulness I

GA 173a

18 December 1916, Dornach

Lecture VII

Let me begin by repeating yet again my urgent request that you do not take notes during these lectures. It is mystifying that my wish in this respect seems to meet with absolutely no compliance. Yet I must make this request particularly with regard to these lectures. Firstly, the current situation gives no opportunity for someone who is seriously concerned with human evolution to give properly rounded-off lectures; at best only isolated remarks are possible. Secondly, we all know what misunderstandings came about at the beginning of this painful time because parts of my lectures were taken down and disseminated in every direction, in some cases with the praiseworthy intention of saying: Look, the things he says aren't as bad as all that—but in others with the less praiseworthy aim of raising people's hackles so that they might build up all sorts of resentments.

Isolated sentences quoted out of context, especially when taken from a series of lectures, can never mean anything and can be interpreted in all manner of ways. I am concerned solely with the quest for the truth, in this case particularly because a number of our friends have requested discussions of this sort and have a real desire for them. I am not concerned that it might be possible to report here or there that what I have to say is really not so bad after all. What I am concerned with is the truth. Surely all those of us who take spiritual science seriously, and who are concerned with the findings of spiritual science with regard to human evolution in our time, should be concerned with the truth.

I shall continue today to give you some more of the viewpoints which furnish a basis on which to form a judgement fitting for today—that is, not for the next few days or weeks, or even for the next year, but for the present time in the wider sense. Let us remember above all that spiritual science is a serious matter and that to understand it in the proper way we must take it more seriously than anything else. If, on the other hand—as is so frequently the case when there is a society which serves as an instrument for the endeavours of spiritual science—if spiritual science is approached with all sorts of prejudices and premature feelings which lead to a state of furious zeal over all manner of things, then this proves a lack of readiness for spiritual science. Yet it is perfectly possible to understand today that spiritual science alone is suitable for the development of that earnestness which is so needed in these tragic times.

Each individual must set aside his preferences for one direction or another and endeavour to accept things without any prejudice. It is impossible to say certain things without making one person or another feel uncomfortable. There are plenty of people today who regard it as a sin even to hint at certain facts, because they imagine that the mere mention of some fact or other is tantamount to taking sides—which is, of course, not the case at all. Some facts must be looked calmly and squarely in the face because only then can a valid judgement be reached. Of course, perhaps a person does not want to reach such a judgement, but he could reach it if he wanted to stand on the foundation of spiritual science.

I shall now present you with a number of preparatory remarks in order to bring forward, at the end of today's discussion, some points which may awaken an understanding for the manner in which certain—shall we say—occult knowledge is forcing its way into the present-day spiritual development of mankind. Actually, this knowledge is forcing its way to the surface of its own accord as a result of the process of human evolution, so that it is not necessary to make any extra effort to place it within the development of mankind. I shall take my departure from certain details, which I beg you will simply accept as the groundwork, so that later the main emphasis can be placed on what I shall put forward as the outcome of these considerations.

At the beginning of these discussions I said: If, as a good European, one makes every effort to go thoroughly through all the events and facts that have been taking place over decades and have also come to be known recently, if one makes the effort to go thoroughly into them without prejudice, and if one then examines the judgements made on the periphery as a matter of course—and I mean as a matter of course—by people who have rightly borne famous names during the period leading up to today's painful events, then one cannot but reach a certain conclusion. This conclusion is that certain judgements are such that, whatever one might say or assert, the answer is always the same: Never mind, the German will be burnt-after the old pattern: ‘Never mind, the Jew will be burnt.’ Many, many judgements contain nothing but a certain aversion—whether justified or not is open to question—against anything in the world that might be called German. I am weighing my words carefully.

This aversion has recently intensified into a burning hatred which has no inclination whatsoever to scrutinize anything carefully, nor to accept anything that has been carefully scrutinized, but which finds its total justification simply in hating. Yet advantage is not necessarily taken of this justification. If someone says: I hate—and if he really wants to do so and announces that he intends to do so, then why not? Everyone has the right to hate as much as he likes; no objection can be made to it. But very many people are most concerned not to admit to their feelings of hatred in such a situation. They try to lull themselves into forgetting about them by saying all sorts of things which are supposed to wipe away the hatred and put in its place a supposedly objective and just judgement. But this puts everything into a false light. If someone admits honestly: I hate this or that person—then you can talk with him, or perhaps not, depending on the intensity of his hatred. Truthfulness, absolute truthfulness towards oneself and the world in all things is necessary, and if we fail to comprehend that truthfulness is necessary in all things, then we shall be unable to make what spiritual science ought to be for mankind into the most intimate impulse of our own heart and of our own soul. We then say: Certainly, we want a part of spiritual science, that part which is not concerned with our sympathies or antipathies, that part which is useful for us; but we shall reject those parts which do not suit us. It is possible to take this stance, but it is not a standpoint that is beneficial today for human evolution. What I have to say is based on certain remarks, but truly without anger!

It is a well-known fact that very many people see a connection between today's events and the foundation of the German Reich which lies in the centre of Europe. It is not my task to speak about the politics of the German Reich or about any other politics, and I shall not do so. I simply want to give you certain isolated facts as a foundation. It is possible to form an opinion about the events which led to the foundation of this German Reich. It is also possible to form the opinion—whether justified or not—that it is a calamity for mankind that Germans exist at all. Even this is open to discussion. Why not, if someone is open and honest enough to admit that he holds these views? But this is not our concern at the moment.

Let us look at the fact that this German nation led to the founding of the German Reich during the final third of the nineteenth century. There are people who challenge the founding of the German Reich from quite another point of view. They consider that the founding of this empire was not good for human evolution. But people who share the standpoint of the western empires have no right to form a judgement of this kind. For let us not forget that these very nations of the West are exceedingly attached to the concept of empire, the concept of the state, and that their way of thinking with regard to nationality is very much linked to the various ideas about the state. Therefore, those who unite patriotism with the idea of the state, as do the western nations, have no right to question the idea of an empire at all. If they did they would be quite illogical, for they would be stating that another nation has no right to do what their own nation has done. In a discussion you have to take up a standpoint which provides a basis for discussion and also makes it possible to remain logical. It would be easy to have a discussion with Bakunin about whether a German Reich in Central Europe is something beneficial. But the basis for such a discussion would differ greatly if it were held, not with statesmen but with almost any member of a western nation, because they are so immersed in the idea of the state. So there must be one presupposition, namely, that the idea of empire as such is not rejected out of hand, otherwise there is no basis for discussion. But one's presuppositions must be known if one wants to arrive at valid judgements.

People today no longer think of the historical impulses out of which this empire in Central Europe arose. They do not consider, for instance, that the soil on which this empire has been founded was for many centuries a kind of reservoir, a kind of fountain-head for the rest of Europe. You see, something Roman, in the sense of a continuation of what used to be Roman, no longer exists today. What used to be Roman has, if I may say so, evaporated and has only entered into other folk elements in the form of isolated impulses. Take the soil of Italy. During the course of the Middle Ages all sorts of Germanic elements kept migrating to Italy. I might have an opportunity to define this more closely later on. In today's Italian population, even in their very blood, there flows a tremendous amount of what can be called Germanic. This was instilled into them by the Roman element, but not in any way which might make it possible today to call the people of present-day Italy a continuation of the old Roman people. It was always the case that from Central Europe, as from a reservoir of peoples, all sorts of tribes migrated to the periphery, to Spain, North Africa, Italy, France, Britain. And as the peoples rayed out in this way, something not of these peoples came to meet them: the Roman element. In the middle, as it were, was the reservoir:

A man such as Dante, about whom I spoke to you yesterday, is simply a characteristic expression of a general phenomenon. Who are today's French people? Not merely descendants of the Latin element. Franks, in other words former Germanic tribes, spread out over this land. Their make-up became mingled with folk elements no longer their own, elements containing Latin aspects, via Roman civic attitudes, mixed with ancient Celtic aspects; the result of all this being something in which many more Germanic impulses live than might be imagined. A great many Germanic impulses live in today's Italian population as well. If we wanted to, we could study the migration of the Lombards into northern Italy, a Germanic element which simply absorbed the Roman. Britain was originally inhabited by elements which were then pushed back into Wales and Brittany and even as far as Caledonia, but not before they had sent out messengers to draw the Jutes, Angles and Saxons over to the island so that they might deter the predatory Picts and Scots. Out of all this an element emerged in which the Germanic obviously predominates.

This spreading out took place in all directions. In Central Europe the reservoir remained behind. Connected with the fact that the centre had to develop differently is that jump—which I do not want to brag about as a jump forward—which is expressed in Grimm's law of sound shifts. This law need not be measured with the yardstick of sympathy or antipathy, for it is simply a fact. Anyone can imagine what led to it, but this need not be confused with sympathy or antipathy.

When the Roman Caesars were carrying out their campaigns against the Germanic tribes, those who were first conquered formed by far the greater part of the army, so the Romans fought the Germanic tribes with Germanic tribesmen. Even in later times the massed peoples of the periphery stood by what was to be found in the centre to the extent that it became necessary to form the empire which, in its final phase, was the Holy Roman Empire. You know the passage in Faust where the students are glad that they need not worry about the Holy Roman Empire. But, on the other hand, it also came about that the periphery made terrible war on the middle element, it was constantly rebelling against the middle element. One must also take into account that much of what is present in the consciousness of Central Europe is linked with the way the soil of this empire in Central Europe has constantly been chosen as the scene of battle for all the quarrelling nations. This was particularly the case in the seventeenth century, during the Thirty Years' War, in which Central Europe lost up to one third of its population through the fault of the surrounding peoples. Not only towns and villages but whole tracts of countryside were destroyed. The peoples of Central Europe were utterly flayed by those of the periphery. These are historical facts which must simply be looked at squarely.

Now it is not surprising that in Central Europe the inclination arose to want something other peoples had already achieved, namely an empire. But the population of this soil has far less of a relationship to the idea of empire than has that of western Europe, which clings particularly strongly to it, regardless of whether it is a republic or a monarchy. This is irrelevant. You have to look beyond the mere words and see how the individual, whether in a republic or some other form, stands in relation to the state he belongs to, whether his feeling for the way he belongs to it is of this kind or that. I said it is not surprising that the impulse arose in Central Europe to want an empire, a state which makes it possible, on the one side, to build up some protection against the centuries of attack from the West and, on the other, to put up a barrier against what comes from the East—which is something that is still necessary for Central Europe though not, of course, for the East. These things are, I believe, comprehensible.

The Central European population has a different relationship to what might be called the idea of a state; that is it differs from that of the Western European, especially the French, population. In Central Europe the idea of a state has not been living for centuries as it has, for instance, in France, and furthermore the idea of a state as it exists in France is not suitable for what has remained in Central Europe. On the other hand, in what has remained in Central Europe something developed around the turn of the eighteenth to the nineteenth century which is of such spiritual stature that it will even be admired in the West when one day the hatred will have abated somewhat. And this spiritual stature, which mankind will continue to savour for centuries to come, was achieved in Central Europe at a time when the West was making it utterly impossible for Central Europe to build a coherent state structure. Lessing, Goethe, Schiller, Herder and all the others who are connected with this stream did not become great within a coherent state structure. They became great despite the absence of a proper state structure. It is hardly possible to imagine how different it was for Goethe, who became great without any coherent state structure, compared with Corneille, or Racine, who can scarcely be imagined without the background of that state structure which was given its brilliance and eminence by Louis XIV, the king who said: ‘L'état, c'est moi!’ These things should be looked at together.

However, during the course of the nineteenth century impulses arose among the inhabitants of Central Europe which were at first entirely inward, impulses which gave birth to the inclination to want some form of state structure also. This inclination first came into being in an intensely idealistic way, and those who are familiar with the development of the nineteenth century know that the idea of a state which moved the inhabitants of Central Europe was at first anchored, above all, in the heads of all sorts of idealists, people who were more idealistic than practical, who were most unpractical with regard to the idea of a state, compared with the practical westerners.

So we follow the development of the endeavours to form a German Reich which could encompass the German peoples of Central Europe. We see, particularly in the year 1848, how the idea takes on certain forms which have a definite idealistic stamp. But because the nineteenth century was the age of materialism, anything of an idealistic stamp was not favoured with much luck. The blame for this bad luck lay not so much with the nation as with the materialism of the nineteenth century. So then it became necessary to achieve in a practical way what could not be achieved in an idealistic way; in other words it had to be achieved just as it had always been achieved during the course of European history. For how did states come into being? States came into being through wars, and through all the other things which also led to the German Reich between the years 1864 and 1870.

Those who experienced the days when the new German Reich was being founded know how pain-filled were the hearts of the ones who were still imbued with the ideas of 1848, when the aim was to found this Reich out of feelings and ideals. There were, in the sixties and seventies, those who favoured a ‘great German’ arrangement, while others favoured a ‘little German’ arrangement. Those who favoured a ‘greater’ Germany stood by the old idealistic principles and hoped to found the Reich on idealistic foundations and impulses. They did not want to make any conquests; they simply wanted to unite everything that was German, including Austria, in a common Reich or state. Anyone who imagines that these people desired to make even the smallest conquest has failed to grasp the degree of national idealism that lived in them. For a long period they were in bitter opposition to those who favoured a ‘little’ Germany, and who, under Bismarck, founded the present German Reich-that is, the German Reich under the leadership of Prussia. But in the end the ‘greater German’ party made their peace with the others because they came to understand that in Central Europe in the nineteenth century things had to go the way they did. They came to terms with this and realized that in the end Germany had to be founded in the same way as had been France and England. In this way those who favoured a ‘greater’ Germany gradually came to terms with something that went utterly against their ideals. These things have to be taken into consideration.

Consider further: Whatever opinion one might have about the events that took place between 1866 and 1870/71, whomsoever one might blame or not blame for the war of 1870, one must not forget that on the side of France efforts were made to prevent the foundation of the German Reich, that French politics were aimed at preventing the creation of a German Reich. Of course this can be denied, but things which are denied nevertheless remain true. When I speak of the French side, or the English side, I never mean the people themselves. I mean the cohesion of those who are at the helm at any given time, those who cause the external events to happen. People may think what they like about the Spanish succession, or about a French or a German party in favour of war. But there is no disputing the fact that there were people in France who made every effort to implement their judgement: namely, that the creation of an independent German Reich in Central Europe was not in keeping with the ‘gloire’ of the French state. This was one of the causes of the war of 1870/71. As a counter-stroke another impulse developed, about which once again one may think what one likes. This was the opinion that the German Reich might just as well be founded in the same manner as the French Empire, namely, by making war on a neighbour. These things must be looked at in cold blood.

So this German Reich was founded in the manner with which you are familiar, though there is little inclination today to examine the historical facts minutely. However, most of you know them, at least in outline. So we can say: The German Reich was founded, while France and Germany were at war with one another, in such a way that the forces generated by this war were those that brought the German Reich into being.

Let us look at the moment when Paris was not yet under siege but when the German victories were already making the founding of the German Reich seem a possibility. There was cause to view the resistance to the founding of this German Reich as broken, and so in Central Europe the idea arose to set in motion the founding of the Reich favoured by the ‘little’ German party. We are looking approximately at November 1870. In doing this we come up against the fact that, out of all that took place in what later became Germany—that is, the German Reich—there arose the feeling that this way of founding the German Reich has done great damage to Europe, the feeling that the structure of this Reich is a structure of menace. To speak of ‘Germany’ is no more than a want of tact on the part of those who live in the periphery. There is no Germany today, any more than there is a Kaiser of Germany. There are individual German states and the one who has been chosen to represent these states before the rest of the world is expressly not called ‘Kaiser of Germany’ but ‘German Kaiser’, which is something quite different. This has come about out of certain characteristics of the nature of Central Europe. I might point out that when the new Romanian state was recently formed there was much discussion on whether the king should be entitled ‘King of the Romanians’ or ‘King of Romania’. Such things come to mean a great deal the moment one starts to look at realities and not only illusions. The title ‘King of Romania’ was chosen for quite specific historical reasons in place of the originally intended ‘Romanian King’ or ‘King of the Romanians.’

Now if we allow judgements which have been in the making for some time to work on us, judgements which have recently in some cases reached new peaks of folly—again, we are not discussing what is justified, for everything is, of course, always either justifiable or unjustifiable in its separate parts—if we summarize these judgements we find that there has come into a being a feeling that great damage has been done to Europe by the founding of the German Reich, a feeling that the structure of this Reich in Central Europe is, in a way, a structure of menace. In order to make this clear I should like to read to you a text which, in addition, contains a number of other things I am also concerned with at present. It has been said: Germany, or the Germans, feel themselves to be threatened in some way, and yet in fact it is Germany that poses a threat to the whole of Europe. A judgement has been expressed which is rather significant in connection with this. It was printed in the journal Matin dated 8 October 1905. Do not forget that when we are concerned with realities we need to know that behind the opinion of one person there always stand the judgements of countless others, and also that realities always proceed from realities. In Matin of 8 October 1905 we read:

‘If Herr von Bülow wants to complain that Germany is being isolated, he ought first to ask himself whether perhaps Germany has not isolated herself from the rest of Europe by her actions. The authors of the mistrust and the suspicious hatred which are squeezing the German Reich ever more tightly by the day are not called Delcassé, Lansdowne, Edward VII or Roosevelt, but Bismarck and Moltke, Wilhelm II and von Bülow. These are the ones who have created and developed this prickly, irritable and provoking Reich, bristling with weaponry, which has been casting challenging glances at Europe for the past quarter century and which Europe in the end cannot help looking at with envy. By making her ever more Prussian, they are the ones who are turning away the sympathy which she was guaranteed in earlier days by her active scientific ways and her sober modesty. They are the ones who are sending out sparks of barbaric menace or brutal passion in this time of weariness. Europe is afraid of the fire that never stops smouldering in Berlin; Europe is taking precautionary measures.’

So where do we stand with this judgement that the German Reich poses a threat for the whole of Europe?

Among those in the West who express opinions today there are unlikely to be any who do not see Germany as a threat for the whole of Europe, or who do not consider that the worst thing that could possibly have happened was to turn this people, who formerly shone through their sciences and their sober modesty—as is so aptly expressed here—into a threat for the whole of Europe. For that this is what it has become is repeated over and over again by countless voices and in rivers of printers' ink.

It is easy to say what is often said, namely that this Reich was not created out of a historical necessity but out of ‘Germanic arrogance’—a misuse, incidentally, of the word ‘Germanic’—and further that it is filled with people who never cease stressing that Germans lead the world, Germans are the saviours of the world, and so on. Countless times we have heard it said: The Germans have grown arrogant, they think they have been called to rule the world, they consider the Reich they have founded to be something urgently needed in modern times, and so on; the pride, the arrogance of the Germans has become utterly insufferable. Such are the judgements which one hears in ever-changing forms.

I have no intention of glossing over anything, but I now want to read to you a judgement which was made at the time the Reich was founded, a time I have already mentioned. I said: Let us return to November 1870. What I want to read to you might make some people jump up and down with impatience—pardon the flippant expression—and say: There you have it! This is the kind of idea people have about the importance of this German Reich! It had hardly come into being, indeed was still in the process of being founded, and already it was being presented as something beneficial, not only for Germans but for the whole of Europe, indeed for the whole world—even for the French themselves! To show you that I am not glossing over anything I shall read to you a judgement expressed in the year 1870:

‘No nation ever had so bad a neighbour as Germany has had in France for the last four hundred years; bad in all manner of ways; insolent, rapacious, insatiable, unappeasable, continually aggressive ... Germany, I do clearly believe, would be a foolish nation not to think of raising up some secure boundary-fence between herself and such a neighbour now that she has the chance. There is no law of nature that I know of, no Heaven's Act of Parliament, whereby France, alone of terrestrial beings, shall not restore any portion of her plundered goods when the owners they were wrenched from have an opportunity upon them ... The French complain dreadfully of threatened “loss of honour” ... But will it save the honour of France to refuse paying for the glass she has voluntarily broken in her neighbour's windows? For the present, I must say, France looks more and more delirious, miserable, blameable, pitiable, and even contemptible. She refuses to see the facts that are lying palpable before her face, and the penalties she has brought upon herself ... Ministers flying up in balloons ballasted with nothing but outrageous public lies, proclamations of victories that were creatures of the fancy; a Government subsisting altogether on mendacity, willing that horrid bloodshed should continue and increase rather than that they, beautiful Republican creatures, should cease to have the guidance of it: I know not when or where there was seen a nation so covering itself with dishonour ... The quantity of conscious mendacity that France, official and other, has perpetrated latterly, is something wonderful and fearful ... It is evidently their belief that new celestial wisdom is radiating out of France upon all the other overshadowed nations; that France is the new Mount Zion of the universe ... I believe Bismarck will get his Alsace and what he wants of Lorraine; and likewise that it will do him, and us, and all the world, and even France itself by and by, a great deal of good ... Bismarck seems to me to be striving with strong faculty, by patient, grand, and successful steps, towards an object beneficial to Germans and to all other men. That noble, patient, deep, pious, and solid Germany should be at length welded into a nation and become Queen of the Continent, instead of vapouring, vainglorious, gesticulating, quarrelsome, restless and oversensitive France, seems to me the hopefullest public fact that has occurred in my time ... The appearance of a strong German Reich brings about a new situation. If the military states of France and Russia were to join forces, they could crush a splintered Germany lying between them. But now their arbitrary actions are faced with a considerable restraint ...’

Now I am going to omit a phrase for a reason which you will understand in a moment:

‘What every English statesman has longed for has left the realm of ideas and become reality ...’

You could ask, is this megalomania? Dear friends, I have just read to you a leading article which appeared in The Times in November 1870, but I omitted one word in the final sentence. The complete sentence reads:

‘But now their arbitrary actions are faced with a considerable restraint. The strong Central Power every English statesman has longed for has left the realm of ideas and become reality.’

As you see, it is necessary to look at things as they really are. Those who read The Times today should to some extent take into account the opinion of The Times of November 1870. They might even attain to an unusual view of that most ghastly phrase ever coined, that of ‘German militarism’, if they were to think a little about what was said from the English side at that time: that the appearance of a strong German Reich brings about a new situation. If the military states of France and Russia joined forces, they could crush a splintered Germany lying between them.

Times change, as you see. But people still believe they can make absolute judgements, and they are so happy in their absolute judgements. It is truly not enmity towards the English being and the English people if one passes a judgement which may seem wrong to many people from England, such as the one I passed yesterday about Sir Edward Grey. Those English who think it is enmity are, in fact, their own worst enemy. But I am not in the habit of passing judgement without any support from what can be regarded as a reliable source. You could say that whoever said what I said about Sir Edward Grey was no Englishman and cannot have known him. So now let me read to you a judgement about him by an Englishman who knew him well because he was a fellow minister. During the winter of 1912/13 this man said about Sir Edward Grey:

‘It is amusing for those of us who have known Grey since the beginning of his career to note how much he impresses his Continental colleagues. They seem to assume there is something in him which is, in fact, not there. He is one of the foremost sporting anglers of the kingdom and also quite a good tennis player. He does not, however, possess any political or diplomatic capacities, unless a certain wearisome tediousness in his manner of speaking and also an extraordinary tenacity, were to be seen as such. Earl Rosebery once said of him that the impression he gives of great concentration stems from the fact that there is never a thought in his head which might distract him from whatever paper he is studying. When recently a somewhat more lively diplomat expressed admiration for Grey's modest bearing, which never reveals what might be going on in his head, a rather pert secretary said: “A money box filled to the brim with gold sovereigns does not rattle when you shake it. Neither is there a sound if it contains not so much as a single penny. In the case of Winston Churchill, a few coppers rattle so loudly that it gets on your nerves. In the case of Grey there is not a sound. Only the one who holds the money box in his hand can tell whether it is full to the brim or completely empty!” Though impertinent, this is well put. I believe that Grey has the most decent character, though he does sometimes allow a rather unfortunate vanity to mislead him into getting involved with affairs which it would be better to leave alone in the interest of keeping his hands clean. He is always excused by the fact that on his own he is unable to comprehend or think anything through properly. On his own he is no kind of schemer, but the moment a skillful schemer takes possession of him he can appear as the most accomplished schemer. This is why political schemers have always been tempted to choose precisely him for their tool, and to this alone he owes his position.’

We must take note of these things so that we are not tempted to believe that the peace of Europe in July 1914 was in particularly good hands. By using a number of documents referred to in various books anything can be proved. What matters is whether these things were used in the right way in the handling of those forces which are important.

Another thing you must note is that historical processes grow out of one another, they gradually take shape. What led to the events of 1914 had been in preparation for a long time, a very long time. Much has been said about this preparation, for instance, that the countries of the Triple Entente did not have any agreement which was against Central Europe; that the only purpose of the Triple Entente was to cultivate peace in Europe. All sorts of facts have been paraded as ostensible proof for this supposition. I would have to tell you some very long stories if I wanted to prove fully what I have to say. This is not possible, but I want to give you a few points of reference. For instance, I should like to read you some passages from a speech made in France in October 1905, because in the future this will have a certain part to play in history. Such speeches are always one-sided, of course, but if one bears everything in mind—and here there are a number of important points to bear in mind—a judgement can be made. A number of important things may be taken from this speech by Jaurès from the year 1905. I am able to choose this example because I have recently spoken about Jaurès in quite another context. As you know, Jaurès was a democrat, indeed a social-democrat and, whatever else one might think of him, he was certainly a man who was seriously concerned not only with peace which would have been so necessary for Europe, or at least western Europe, but with calling together all those people in the world who seriously longed to keep peace. So in a way Jaurès had a right to speak as he did. In October 1905, shortly after the French democratic government had ditched Delcassé—pardon the flippant expression—when it had become apparent during a session of the chamber that he was capable of endangering peace in Europe in the near future, Jaurès commented as follows:

‘England has recognized Delcassé's dream and is quietly preparing to make use of it. The threat posed by German industry and German commerce, in all markets of the world, to English trade and English profits, is increasing daily.

It would by cynical, it would be scandalous, if England were to declare war on Germany merely in order to annihilate her military might, destroy her fleet and send her trade to the bottom of the ocean.

But if one day a conflict were to arise between France and Germany in which France brought forward legal reasons and the demand for the restoration of her national integrity, then behind these splendid pretexts the calculations of the English capitalists, who want to remove German competition by force, could creep in and use this as a means of achieving their aim.

So when difficulties arose in the Moroccan affair between France and Germany, and the latter, suspecting a coalition between France and England, made a brusque intervention in order to force the two to make declarations, it turned out that England—I have to say this I'm afraid—was all too inclined to fan the flames. It is a fact that, at the very moment when events were reaching a climax, England offered France an offensive-defensive pact in which she guaranteed us the fullest support and committed herself not only to sink the German fleet but also to occupy the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal and land one hundred thousand troops in Schleswig-Holstein. If this pact had been signed—and Monsieur Delcassé wanted to do so—this would have meant immediate war. This is the reason why we socialists demanded the resignation of Monsieur Delcassé, and by doing so we have rendered a service to France, Europe and mankind in general.’

Above all, Jaurès knew those things which many people do not know when they arrive at judgements—most essential and important things. He was even careless enough to express these essential and important things in such a way as to hint that he might say more in the future. It is well known to occultists that in the last third of the nineteenth century a member of a certain brotherhood made known to the world certain things which, in the opinion of the brotherhood, should not have been made public. One day soon after he had done this he disappeared; he had been murdered. Jaurès was not an occultist, but we may be excused for being curious as to whether the world will ever hear what led to his death on the eve of the war.

The things which Jaurès said go back to the session of the chamber during which Delcassé, the creature of Edward VII, as well as other creatures who worked behind the scenes, was ditched by the government, perhaps not so much because he wanted to smooth the way for war as for quite another reason.

We are in the year 1905. Russia is still engaged over in the East and it is, therefore, to be hoped that if the flames being fanned by Delcassé in the West really start to flare up the outcome will not be what it would be if Russia were no longer busy in the East. But Delcassé is not a person who takes things lying down. When those who did not want a war accused him of driving matters to the brink of war, he replied that England had let it be known to France that she was prepared to occupy the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal and attack Schleswig-Holstein with 100,000 troops and, if France so wished, this offer would be repeated in writing. This piece of news, which Delcassé presented to his ministerial colleagues who were about to turn him out was, of course, the upshot of negotiations he had been conducting behind their backs and in which King Edward VII had also been heavily involved.

I could quote many items which would verify this fact, which was published in Matin, and later also in other journals. But I only want to draw your attention to the fact that at least there was someone, even at the time, who looked at the matter more closely and found it suspicious. This was a personality who is possibly not at all liked by people, particularly in France. He was the clerical senator Gaudain de Villaine who, on 20 November 1906, when Clemenceau's ministry had already begun, asked what was the situation between France and England about which so much was being heard. Clemenceau answered that so far as the idea of revenge was concerned, he was indignant that a French senator could have set such a trap for him, obliging him either to disappoint the Orange Lodge or make a declaration of war, and he would therefore refuse to reply. So Clemenceau responded to the question from a senator as to whether anything existed in the way of a coalition between France and England, which could lead to a European war, by refusing to reply. For if he were to reply he would either have to disappoint the Orange Lodge with regard to the idea of revenge, or he would have to make a declaration of war. So you see: If Clemenceau had been open about the relationship at that time between France and England he would have had to make a declaration of war—not a declaration of peace but a declaration of war. He said this himself in 1906.

We must not forget that what works in every case in the world is what one person hears from another. Can you imagine that it was possible in Central Europe to believe in the ‘peaceful’ intentions of western Europe, while at the same time having to listen to not one, but to countless such facts? To judge such things a number of factors must be taken into account. One of these is the utter absurdity of speaking of Central European militarism in the context of Central Europe in its widest sense. For any such militarism is an obvious consequence of being sandwiched between two military states.

People with absolutely no sense of reality might ask: Were not all sorts of proposals made about disarmament? You need only look at these suggestions for disarmament! A particular goal can be achieved by quite a number of different routes. Of course some people—I do not say nations, I say people—in western Europe would have preferred to achieve what they wanted, and still want, without a war which would spill the blood of hundreds of thousands on all sides. They would have preferred to gloat gleefully and say: Look, we have created peace!

One of the means preferred by western European politicians of a certain calibre was the disarmament proposal, for this was simply a different means of achieving the goal. When it turned out that no headway was made with disarmament proposals, this particular route had to be abandoned as impassable. If it had been possible to fetter Central Europe by means of disarmament this would, of course, have been preferred. But this was only one of several possible methods.

One must not be misled by words or by illusions; one must be clear about what people want. So ever and again it is necessary to stand up for people with a healthy way of thinking, people who really want what they say they want, even if, under the influence of hate and all sorts of other feelings, they are identified as those who are to blame for something. One must stand up for them and be clear about how unfair it is to say: The English did this or that, the English are to blame for this or that. This is not a sensible judgement. But neither is it sensible if an English person feels hurt when facts such as the one just discussed are revealed. One must sit up and take notice when, on a basis of good sense, fingers are pointed to certain factors in the great complex of causes. Thus we find under the heading ‘The German Scene’ in the Daily News of 13 October 1905 a declaration that says the following about the British government of the time, which bears so much of the blame for what is still going on today. I must add that Sir Edward Grey's predecessor was not a nought. Lord Lansdowne knew much more about what was what. But from a certain point onwards, those who stood behind the scenes needed a nought, in order to be able to operate more easily:

‘And it is high time that Lord Lansdowne should explain and defend this chapter in the diplomacy for which he and his colleagues are constitutionally responsible. There has been a tendency of late to place Lord Lansdowne upon a pinnacle, but the country will have little reason to thank him if it be found that he has permitted this country to drift into entanglements directly involving a risk of European war ... The best of courts will sometimes harbour fleeting family feuds, but what have the people of Great Britain or the people of Germany to do with these things? ... The anti-German hotheads in this country and the anti-British hotheads in Germany alone stand in the way of such a consummation [of friendly and stable relations] and for their tempestuous fads vast populations may one day have to suffer dearly.’

You have to take into account the essential things in the right places. But never mind all the facts; good sense alone could prove that the two Central European states had not the least cause to bring about a war. How would the prospect of war have seemed to those who thought about it? France would have had to say that in the event of a European war, unless certain conditions came about, she would be likely to suffer a great deal. However, this was not believed in France because there was still such a strong faith in the France which had ruled Europe for centuries. In Italy the conditions are rather special. Perhaps if we have time we shall discuss them further in another connection. But Italy also, under certain conditions, could not imagine that any great advantages would come of a war which would throw everything in Europe into chaos. In Russia, too, conditions are rather special, as I have already told you in connection with Russia's relationship to the Slav peoples, the Slav race.

This gives me an opportunity, by the way, to quote you an example of the depths of Sir Edward Grey's thoughts. What did his colleague Rosebery say? That the impression he gave of great concentration stemmed from the fact that he never had a thought in his head to distract him? Well, once a thought was infiltrated into his meditating mind by those who worked by infiltrating thoughts into his mind, the upshot was that he suddenly said: The Russian race has a great future and is destined to accomplish great things. He had forgotten that it was the Slav peoples who had been meant and that there is no such thing as a Russian race. When speaking of realities it is absolutely necessary to distinguish between Russianism and the Slav peoples.

In Russia only those who represented Russianism could imagine any great outcome for a European war, namely, the realization, at least partially, of the testament of Peter the Great. Apart from that, a great deal of suffering was expected, but not that suffering on which the representatives of Russianism would have placed any value.

England was able to say to herself that she would lose and risk the least. Now that the sorrowful events of war have been going on for many months, if an assessment were to be made of who had suffered least, or indeed hardly at all—at least in regard to the opinion of world history—the answer would be: England. England will be able to continue waging war for a long time without suffering to any great degree.

But the so-called Central Powers would most certainly have had nothing to gain from a war and they had no desire for such a war. They always displayed two tendencies. On the one hand there was a certain carefree air which arose, not out of a knowledge of what was going on but out of a basic characteristic; for the Austrian character is fundamentally carefree. On the other hand emphasis was always placed on the statement that all they wanted was to keep what they already had, and that any other suggestion was nonsense. There is no question, for instance, that any part of Serbia was to be annexed, if those who attempted to do so had succeeded in localizing the war between Austria and Serbia.

If England had been led by a statesman who had not said as early as 23 July: If Austria makes war on Serbia, this could lead to a European war; if England had been led by one who had said: We shall do everything possible to make sure that the war is localized; then events would have taken quite a different turn. But this would have had to be someone who formed his judgements in a different way from Sir Edward Grey, who was hypnotized from the start by the thought: If Austria makes war on Serbia, there will be a European war. He never asked what Russia had to do with the whole matter of war between Austria and Serbia. This never occurred to him and the suspicion cannot be detected in anything he said. All he ever saw was the justification for Russia's influence in Serbia, a justification for an influence which had been prepared in a remarkable way and was borne on remarkable currents, as I have shown you.

Nothing that has taken place in this connection, including the 364 assassinations between the years 1883 and 1887, has anything whatever to do with any kind of judgement about the Serbian people. All they have done is to fight bravely, and in their present condition they are still doing so. To them alone is owed the only success achieved in recent weeks down there by the Entente. No one who understands these matters will judge against any people, let alone one who, right into its most tragic days, has shown that it is not only willing—to the extent of sacrificing its own blood—but also able to stand up for its true nature, always present and at the ready in grave times, if only it is allowed to be. But we must remember also that the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand was only the last great blow in a whole series of assassination attempts against Austrian government officials to have taken place within the space of a few months. This was in fact a particular campaign, which was even quite comprehensible and in keeping with certain people. You remember what I told you about the occult background of this individuality, Archduke Franz Ferdinand. You also remember that it is a fact, a paradoxical fact, that this couple, kindly disposed towards the Slavs in the highest sense, were slain by Slavs—or seemingly so. The deeper connections are made more approachable by a certain understanding of the heart. We see a human being, kindly disposed in the highest sense towards the Slavs, slain—together with his wife—by Slav bullets. At the last moment the Duchess espies from her carriage a young female standing quite near; smiles at her, seconds before the bullets strike, because she notices she is a Slav woman, and exclaims: ‘Look, a Slavka!’ Then the bullets strike. What a strange karma this reveals! Before the bullets strike her down, the Duchess exclaims in delight, because her eye has fallen on one of her beloved Slav people.

I described earlier the far-reaching connection existing between machinations in the Balkan countries and a number of well-prepared situations on the Apennine peninsula. And I now want to ask once again a question I have already put to you: Why was it written in a rather inferior Paris journal in January 1913 that it was necessary for the good of mankind for Archduke Franz Ferdinand to be killed? Why was it said twice in this so-called ‘Occult Almanac’ that he would be killed? It is necessary to look at all the facts at once. We will find that the alchemy of the bullets which were used for this assassination was exceedingly complicated and that, although they stemmed from a Serbian arsenal, they had been ‘anointed’ from quite another quarter—if I may put it symbolically.

These are things which expressed themselves in what could be seen, for instance, in Austria. Imagine Switzerland surrounded only by those who hate her. I doubt whether this would have a particularly reassuring influence, especially if the hatred were expressed in sayings such as those which have become current in Romania: Jos Austria perfida!—That is: Down with perfidious Austria!; or: Rather Russian than Austrian!—and so on. If this is how things stand, and if you consider all the things that were written in Italy quite a long time before the war against Austria broke out, then you will understand that the situation was far from reassuring. In this way an extensive campaign was organized which spread far and wide in the countries surrounding Austria. I am not defending any particular state, but merely mentioning facts.

Consider, for instance, also the following: At the Berlin Congress, Austria received, through the significant influence of Lord Salisbury, a mandate to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina. When England gave Austria the mandate to undertake this action in the Balkans during the seventies, it turned out that in Austria there was passionate opposition to the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina because the Germans in Austria said: We have enough Slavs already; we cannot possibly absorb any more Slavs. If the idea had arisen in Austria to seize some fragment of Serbia by an act of war it would have met with the sharpest opposition in the interests of Austria, which were well understood, for nothing would have been more stupid than to covet some fragment of Serbian territory. The only desire was to hold the empire together in order to counteract the campaign. This was perfectly honest, though it may have been careless. Seen objectively, it becomes perfectly obvious that the war would not have started as a consequence of the ultimatum of Austria to Serbia if Russia had not taken up the stance we all know about, despite knowing perfectly well that Austria was not bent on any form of conquest. In all this, however, we must remember the moods. The consequence of everything we have been discussing was that moods arose, not only in the periphery but also in Central Europe.

Now I want to give you a small example to show you how, despite everything, it is possible to form a judgement about these things if one really sets out in earnest to achieve a valid judgement. It is interesting to look at certain points at definite times, for only in this way can one recognize something. For example, we might ask: What must it have looked like in the soul of someone who felt responsible for Austria, let us say round about the time of the assassination of the heir to the throne—I mean immediately before and immediately after this?

In order to reach a valid judgement with regard to the mood amongst honest people in Austria, the best moment to choose would be that which immediately preceded the assassination, for people were not then influenced by what happened in the aftermath of the assassination. You see how cautious I am trying to be. I am not going to consider the nervous and anxious souls as they were immediately after the assassination. Instead, let us look at what lived in the soul of the honest Austrian under all the influences which, since Delcassé, had made themselves felt coming from western Europe and connecting up with eastern Europe, with Russia. Now, I can place before your souls such a judgement by reading to you a passage from an essay which was written just at the moment in question. Though it appeared after the assassination it was already in the process of being printed when it happened. So it was written by an Austrian in the weeks immediately preceding the assassination:

[Gap in the shorthand report.]

Here you have the judgement of a man whose thoughts are based on common sense, someone who saw all the factors at work in Europe just before the final event, the assassination, took place. Everyone knew that at the instigation of Russia the Balkan states would be forced to declare war on Austria. Therefore, the right thing to do in order to avoid war would have been to start just at this point with attempts to localize the situation, for externally the prospects looked quite good.

It is necessary when making judgements according to one's own feelings—for us, judgements are facts—to look at the facts themselves and use them as the foundation. Today I have only been able to give you a few isolated facts in order to explain what I mean. But I gave them to you expressly for the purpose of developing the facts; nothing more. Let us be clear about the purpose of introducing such facts: the purpose is to promote the truth. The truth, even if, paradoxically, it may be damaging, can never be as damaging as an untruth.

Those who understand the facts know what unending lies were fabricated, from the moment it became possible to lie, unhindered, as a result of the possibility of making oneself heard above the other side—that is, of drowning out the other side by means of the various methods which came to the fore in such a grievous way. But we are concerned with truth and with the admission of the truth. It is quite definitely not the truth to maintain that this war was provoked by Central Europe. Perhaps people cannot speak the truth because they do not know it. Obviously, when something like this war comes about, both parties are usually partly to blame, but in different ways. But I am not talking about blame, I am talking about the uselessness of judgements which have been made, which take no account of the actual truth of the matter. Of course, I do not expect that these judgements will cease to be made, for obviously I know what happens in the course of human evolution and that, especially in our time, there is no inclination to base judgements on valid foundations; for there is so much in our time that prevents judgements being based on valid foundations. But one really ought to state properly what one is talking about.

Those who are connected with certain sources of these grievous world events, which from sheer negligence of thought still tend to be called ‘war’, those who therefore feel connected with what is emanating in the periphery from certain centres, should admit quite openly: Yes, we want what certain centres in the periphery want, we want the people of Central Europe to be partly exterminated and partly condemned to serfdom.

Certain people in these centres, however, do not want the cultural life of Central Europe to perish. They talk of the wonderful science and culture and of the sober modesty which used to exist. In other words, they would be happy to lord it over these territories of culture and modesty by acting in the way the Romans behaved towards the Greeks. Obviously, Greek culture was higher; and the Romans did not destroy it. Similarly, no one in the Entente wants to destroy German culture. On the contrary, these people will be only too pleased if German culture continues to flourish vigorously, but they want a relationship similar to that of the Romans to the Greeks: that is, they want to make a kind of cultural helotry out of what exists in Central Europe. All right, then let them say so! Why deck it out with something so utterly ridiculous! For German militarism—which is not to be denied—has its true origin in French and Russian militarism. Without French and Russian militarism there would be no German militarism.

Let them say that what they want is to helotize Central Europe! Let them say they would be quite content if this could be the outcome! Let them admit that they hate the presence of such a people in the middle of Europe who want to do what all the other surrounding peoples are doing! If someone says: I hate everything German; I do not want the Germans to have what other peoples have—well and good. You can then talk with him about it, or not if he does not want to, but he is nevertheless telling the truth. But if he keeps repeating: I want to destroy German militarism, I don't want the Germans to oppress other peoples, I want the Germans to do this or that—as is said today and has been constantly repeated for years—then he is lying. Perhaps he does not know that he is lying—but he is lying, he really is lying. Objectively he is lying, even though perhaps subjectively he is not.

What matters is to stand on the foundation of truth, even if this truth is perhaps harmful, even if it is embarrassing. It is necessary to admit these things and not anaesthetize oneself with empty phrases about German militarism for which one has a hatred to which one does not want to admit, even to oneself. One must admit that one wants to helotize the German people, yet cannot face up to wanting this. Perhaps an anaesthetic is needed; but it is not the truth! It is most important to stand on the foundation of truth. To have the courage to face the truth always leads one a little step further. But one must have the courage to stand by the truth.

It is a fact that every people, as a people, has a mission within the total evolution of mankind. Every people has a mission, and all these various missions together create a whole, namely, the evolution of mankind. But it is equally true that certain individuals, especially those who come to be familiar with the mission of mankind, have the arrogance to set in train certain things which are in the interest of a limited group, and for this they make use of what lies in human evolution.

Let us take the English people. If what is necessarily meant to come about in the fifth post-Atlantean period through the English people really does come about, then it will never be possible, through the very nature of this English people, for England to start a war. For the true being of the English people in their mission in world history is opposed to any kind of warlike impulse. The real nature of the English people makes them the least warlike nation possible. And yet for centuries there have never been ten consecutive years during which England has not been involved in war. We are living, after all, in the realm of maya. But despite this, truth is truth. In the nature of the English people lies the exclusion of any kind of war, just as for centuries it has been in the nature of the French people—not any longer; now it has to be artificially incited—to conduct war over and over again. It is not in the nature of the English people to wage war, and the reason for this is that the special configuration of the English folk spirit means that its purpose is to evolve what is to be incorporated into the consciousness soul of the fifth post-Atlantean period. This in turn is achieved through all those connections between people arising from logical and scientific thinking on the one hand, and on the other, from commercial and industrial thinking. And when Brooks Adams placed before the world the ideas I mentioned to you earlier, this was an advance thrust, coming from America, pointing towards what the English people must recognize as their mission in world history, based on their deeper nature which contains none of those warlike and imaginative characteristics such as those present, for instance, in the nature of the Russian people.

Now much will depend on whether this deeper nature of the English people will one day come to be understood in a deeper, spiritual scientific sense. In a more external way some individuals have understood it. The work of Herbert Spencer and John Stuart Mill shows that the most inspired spirits have fully understood it, though from their more materialistic standpoint and not, as yet, from a spiritual scientific standpoint. I can recommend that you read with some enthusiasm the political essays of Herbert Spencer and John Stuart Mill, for you can learn a very great deal from them. This spirit of peace which, among other things, makes possible in a special way a certain kind of political thinking, in the manner I have already described, has indeed overflowed to Europe from England. Someone who has entered into European life, from as many and varied points of view as I can really claim to have done, knows, for instance, that all the political sciences of Central Europe have certainly been influenced from the direction of England. And it is no coincidence that the founders of German socialism, Marx and Engels, founded this German socialism from England.

It happens very easily that the nature of Central Europe is misunderstood. The true nature of Central Europe is still almost always misunderstood in western Europe. How might it be otherwise? The culture of Central Europe was so permeated by the French element that one of the greatest, most important works of German literature, one which set the tone at the zenith of German culture, Lessing's Laokoon, had a peculiar destiny: Lessing considered seriously whether he should write it in German or French. Educated people in Central Europe in the eighteenth century wrote German badly and French well. This must not be forgotten. And in the nineteenth century Central Europe was in danger of becoming totally anglicized, of being fully taken over by Englishness. It is no wonder that the nature of Central Europe is so little known, since it is constantly being submerged from all sides, even spiritually and culturally. Think, for instance, of Goethe's theory of evolution in respect of animals and plants. This is truly a stage in advance of Darwin's materialism just as, in respect of Grimm's law, the German language is a stage ahead of Gothic-English. Yet in Germany herself materialistic Darwinism was favoured by fortune, and not her own German Goetheanism. So it is not surprising that the German spirit is poorly understood and that little effort is made to really understand it as it should be understood, if justice is to be done to it.

As I said, the political sciences, in particular, were strongly influenced by the English way of thinking. But what is urgently needed now is that the different peoples should come to a certain degree of self-knowledge. Without this self-knowledge, for which Herbert Spencer and John Stuart Mill are not adequate—but which must be based on spiritual science and on a sense for what spiritual science can give—without this, no healing can come.

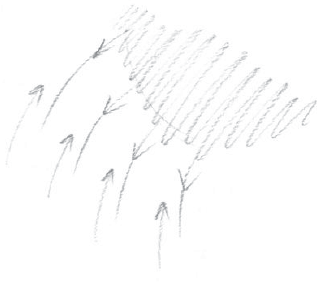

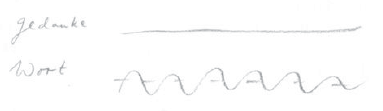

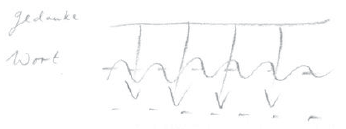

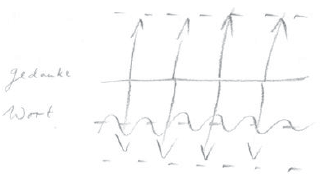

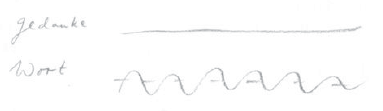

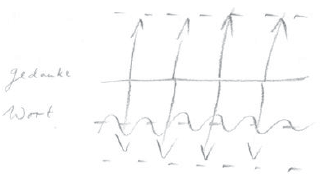

Just consider how difficult it is, for example, to grasp the following—whereby no arid theory is meant, but something at the basis of life: There exists in the soul a certain relationship between the thought and the word. This is a fact. Let us imagine that in the structure of the soul the word lies in this field, and the thought in this one:

The French people have the tendency to push the thought right down to the word; thus, when they speak, the thought is pushed right into what they are saying. That is why, especially in this field, there is so easily an intoxication with words, with phrases—and I mean phrases in the best sense:

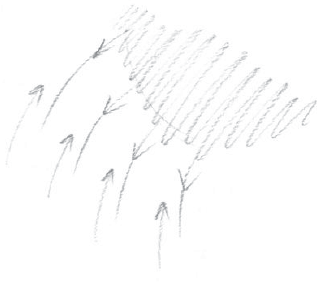

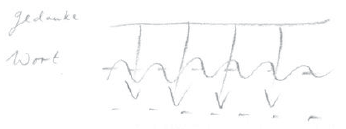

The English people press the thought down below the word, so that the thought mingles with the word and seeks reality beyond the word:

The German language has the peculiarity of not taking the thought as far as the word. Only because of this was it possible for philosophers such as Fichte, Schelling, Hegel—who it would be impossible to imagine anywhere else in the world—to do their work. The German language does not take the thought as far as the word, it retains the thought in the thought. Because of this, however, people will very easily misunderstand one another. For a true translation in this situation is impossible, it is always only a substitute. It is not possible to say what Hegel said, in English or French. It is impossible; such translations can only ever be a substitute. The fact that some understanding is possible comes about solely because certain basic Latin elements are common to more than one language, for it is the same whether you say ‘association’ in French, or ‘association’ in English; both go back to the Latin element. Such things build bridges. But every people has its own special mission and it is only possible to approach this through a longing to attain such an understanding.

The Slav people push the thought inwards so that it is here:

There, the word is quite far away from the thought. It floats, separately.

The strongest coincidence of thought with word, so that the thought disappears over against the word, is in French. The strongest independent life of the thought is in German. Therefore, a saying formulated by Hegel and the Hegelians: ‘The self-consciousness of thought’, is meaningful only in German. Something that is an abstraction for non-Germans is, for a German, the greatest experience it is possible to have, if he understands it in a living sense. The German language sets out to found a marriage between what is of itself spiritual and what is spiritual in the thought. Nowhere in the world, by no other people, can this be achieved except by the German people.

This has nothing to do with any kind of a Reich, but it will be endangered for centuries to come if people reject what is at present going through the world as the thought of peace. For then not only will a Reich in Central Europe be endangered but also the whole essence of what is German. That is why these times are heavily pregnant with destiny for those who understand these things. Let us at least hope that things will be judged differently this time, differently from the previous time when an impulse of destiny came into play, an impulse of destiny to which much thought should have been given—but was not—when Austria voluntarily declared her willingness to give to Italy what she needed to help her extricate herself from Irredentist ideas and the Grand Orient. But there was no thought in the periphery for what it meant at that time to think little of what Italy, or rather those three people, were doing. Let us hope that, whatever happens, the world will be more inclined this time to take these things seriously.

The German element has its particular task because of the special situation of German thought. If this independently living thought is not brought into play it will never be possible to accomplish the spiritual evolution which must be accomplished. Things must be seen as they really are. The English folk element makes it to a certain extent necessary to materialize what is spiritual. This is not something to be held against the English people; it is simply a fact. Within the English folk element things that are spiritual have to be made material to a certain degree. That is why there will be a greater understanding there for what comes from the folk element as opposed to the element of mankind as a whole, namely mediumistic and other atavistic activities. It is just there that ancient things have their source: the ancient Rosicrucians, the ancient Indians, and so on. This must always be revered there in a certain way, just as the language itself has remained behind at the Gothic stage, where ‘remained behind’ is not a moral judgement, nor one involving sympathy or antipathy, but simply an indication of a position in relation to others. It is a question of how things are arranged, not of getting left behind in evolution.

Let us take things as they are. Obviously every nation today can understand everything. Yet it is true to say that all really fruitful English spiritualism, in the best sense of the word, stems from Central Europe and has been imported. Its origin is in Central Europe, or else it is taken from elsewhere. Since intellectuality is so well-developed in England, this is where spirituality can be systemized, organized. A mind such as that of Jakob Böhme would be impossible, for instance, in France. But while Jakob Böhme was born entirely out of the spiritual thought of Central Europe, he gained a great following through Saint-Martin, the so-called philosophe inconnu, the unknown philosopher, the follower of Jakob Böhme.

Thus, these things have to work together, so there is no point in making judgements on the basis of national feelings. One has to take what is presented to mankind at face value. The moment one takes into account that karma is something serious, that one is connected to one's nation through karma in the way I described yesterday, the moment one sees these things from the point of view of karma and not of passions, one will find the proper attitude. I can imagine a time when even a people as passionate about national matters as the French will come to understand the fact of nationality as something karmic. I can even imagine that with their great talent for spirituality the English nation will come, through a certain science of the spirit, to recognize that there exist other nations who might be accorded some degree of equal status, something for which at present there is not the slightest understanding. This is not a reproach; least of all is it a reproach! But one never knows how often one keeps on saying things which one understands perfectly well oneself, while others think them curious beyond belief. That attitude is surpassed by that of the Americans. With them the total lack of awareness, that there might be others who intend to evolve in accordance with their own characteristics, is even more paradoxical; of course, only for those who do not share the same standpoint.

Because of the great talent possessed particularly by the English people for spirituality, a good deal could be expected to enter this people via the detour of spirituality, especially taking into account that in them there also lies the greatest talent for purely logical, that is, unspiritual thinking, as well as for systemizing everything. Nothing could be a better expression of this organizational talent than the writings of Herbert Spencer. In regard to everything scientific the English people have the greatest organizational talent. That is why they have such a flair for instituting systems for everything all over the world. Only those who prefer empty phrases can say that the Germans have a particular talent for organization. Such people leave unconsidered the fact that the talent for organization is most removed of all from the true nature of the German people.

It must not be forgotten that what has seemingly been achieved recently by Germans in certain directions, both territorially and culturally, has come about as a result of the way Germany is wedged between East and West. Because of this, during the course of the nineteenth century certain characteristics came to be developed more precisely in Germany than among those peoples to whom they really belong. This is eminently understandable. Self-knowledge has not penetrated to every corner yet, and since the Germans are so capable of assimilation and are able to take in and absorb so much in certain respects, the peoples of the West—not the East—have had an opportunity to discover, in certain respects, much about themselves through what the Germans have absorbed from them. Such characteristics, when seen in oneself, are always found to be excellent and obvious—naturally enough! But when they are met in another, one notices for the first time what they really are. You have no idea how much of what the West finds objectionable in Central Europe is no more than a reflection of what has been absorbed from there by Central Europe.

People have no idea what mystery lies hidden here. Looking at the matter objectively, it is most remarkable to discover how some members in particular of the French nation are quite incapable of seeing in themselves things which they find terribly objectionable in others who had absorbed them under French influence in the first place. Perhaps it is not all that nice if it comes to meet you as an imitation. But if mankind is to progress at all then, as I described it in my recent book Vom Menschenrätsel, it will be essential for this collaboration of Central European thought to take place. This is necessary and it cannot be eliminated; and it must not be brutally destroyed either.

Mankind is now faced with having to solve certain quite specific problems. This applies, above all, to something I have already spoken about, which is connected with today's much-admired technology—a consequence of natural science—which is also much admired by spiritual science. In the comparatively near future, this much-admired modern technology will reach a final stage where it will, in a certain way, cancel itself out. In contrast, something will come into being—I have mentioned it in passing here—which will enable people to make use of the delicate vibrations in their etheric bodies as a driving force with which to run machines. Machines will exist which are dependent on people and people will transfer their own vibrations to the machines. People alone will be capable of setting these machines in motion by means of certain vibrations stimulated by themselves. People who today see themselves as practitioners of science will, in the not too distant future, find themselves faced with a complete transformation of what they today call the practical application of science; for the human being is to be tuned in with his will to the objective sphere of feeling in the universe. This is one of the problems.

The second is, that people will, in a certain way, understand what we call the forces of coming-into-being and dying-away, the forces of birth and death. First of all they will have to make themselves morally ready for this. And to this will belong the gaining of insight into things about which nothing but nonsense is talked today. I have pointed this out before in connection with the questions people ask about how to improve the birthrate when it is declining. But they talk utter nonsense because they know nothing about the matter, and because the methods they suggest will certainly not achieve what they are talking about.

The third matter I want to mention is, that in the not too distant future a total reversal in the whole way people think about sickness and health will become apparent. Medicine will become filled with what can be understood spiritually when one learns to see illness as the consequence of spiritual causes.

I have already said it is not as yet fair to say to the spiritual scientist: Show us what you can do with regard to sickness and ill health! First his shackles must be removed! So long as the field is still totally occupied by materialistic medicine it is impossible to do anything, even in individual cases. In this field it is indeed necessary to be truly Christian—that is Pauline—and to know that sin comes from the law and not, conversely, the law from sin.