Karma of Untruthfulness II

GA 173b

1 January 1917, Dornach

Lecture XIV

What was said yesterday about so-called poisonous substances indicated strongly how all the impulses of life are graded in relation to one another. For instance, some substance is said to be poisonous, and yet the higher nature of the human being is intimately related to this poison; indeed, the higher nature of man cannot exist without the effects of poisons. We are touching here on a most important area of knowledge, one with many ramifications and without which it is impossible to understand a good many secrets of life and existence.

Looking at the human physical body, we have to admit that if it were not filled with those higher components of existence, the etheric body, the astral body and the ego, it could not be the physical body as we know it. The moment man steps through the portal of death, leaving behind his physical body—that is, the moment the higher components withdraw from the physical body—it begins to obey laws other than those which governed it while those components were present there. The physical body disintegrates; after death it obeys the physical and chemical forces and laws of the earth.

The physical body of man as we know it cannot be constructed in accordance with earthly laws, for it is these very laws which destroy it. The body can only be what it is because there work within it those parts of man that are not of the earth: his higher components of soul and spirit. There is nothing in the whole realm of physical and chemical laws which could justify the presence of such a thing as the human physical body on the earth.

Measured by the physical laws of the earth, the human body is an impossible creation. It is prevented from disintegrating by the higher components of man's being. It follows, therefore, that the moment these higher components—the ego, the astral body and the etheric body—desert the human body, it becomes a corpse.

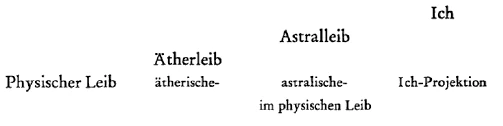

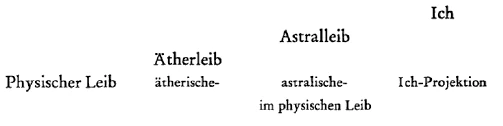

You know from many earlier lectures that the diagram of the human being we have often given is quite correct as such, but that in reality it is not as simple as some would like. To begin with, we divide the human being into physical body, etheric body, astral body and ego. I have pointed out on other occasions that this in itself implies a further complication. The physical body, of course, is what it is—the physical body. But the etheric body, as such, is something super-sensible, invisible, something that cannot be perceived by the senses. It lives in the human being as something that cannot be perceived by the senses. But it has, in a sense, its physical counterpart because it imprints itself on the physical body. The physical body contains not only the physical body itself, but also an imprint of the etheric body. The etheric body projects itself onto the physical body; so we can speak of an etheric projection onto the physical body.

It is the same in the case of the astral body. We can speak of the astral projection onto the physical body. You know some of the details already. You know that the ego projection onto the physical body may be sought in certain features of the blood circulation, where the ego projects itself onto the blood. In a similar way the other higher components project themselves onto the physical body. So the physical body in its physical aspect is in itself a complicated system, for it is fourfold. And just as the most important aspect cannot exist in the physical body if the ego and the astral body are not in it—for it then becomes a corpse—so is it also in the case of these projections, for they are all present in the physical substance. Without the ego there can be no human blood, without the astral body there can be no human nervous system as a whole. These things exist in us as a counterpart of man's higher components.

When the ego has been, shall we say, ‘lifted out’ of the physical body, when it has passed through the portal of death, the physical body has no real life any longer, but becomes a corpse. In a similar way, under certain conditions, these projections cannot live in a proper way either.

| Ego |

|||

| Astral Body |

|||

| Etheric Body |

|||

| Physical Body |

etheric |

astral |

ego |

| projections onto the physical body | |||

For instance the ego projection—that is, a certain quality of the blood—cannot be present in a proper way in the human organism if the ego is not properly fostered. To turn the physical body into a corpse it is, of course, necessary for the ego to depart entirely from the physical body. But the blood can go a quarter of the way towards becoming a corpse if you prevent it from being permeated with what ought to live in the ego, so that it can work in the right manner of soul and spirit on the blood. You will gather from this that is possible to bring disorder into man's soul in such a way that the right influences cannot be brought to bear on the blood nature, the blood substance. That is then the point when the blood can change into a poisonous substance—not entirely, for in that case the person would die, but in part. The human physical body is abandoned to destruction if the ego departs from it, and in a similar way the blood is brought into a state of ill health—even if this is not necessarily noticeable—if the ego is not fostered and interwoven with the right care.

So when is the ego not fostered and interwoven with the right care? This is the case under certain quite definite circumstances. Let us look for the moment at the post-Atlantean period. We see that as human evolution proceeds, certain definite capacities, certain definite impulses are developed in each succeeding cultural epoch. It is impossible to imagine people living in the ancient Indian period having a condition of soul development similar to ours. From epoch to epoch, as human beings pass through succeeding incarnations on earth, different impulses are needed for the human soul.

Let me draw you a diagram. Imagine this to be the main, the actual physical body, the one that has to be filled with all the higher components of human nature in order to be a physical body at all.

Of all these higher components, I shall deal solely with the ego, though I could deal with all three. The shading here indicates that the physical body is permeated by the ego. So, in a certain way, the other projections also have to be permeated. Here let me indicate the projection of the etheric body, which is for the most part anchored in the human being's glandular system; for this, too, has to be permeated and interwoven. Thirdly, let me indicate what is anchored chiefly in the nervous system. This, again, in a certain way, must be interwoven with the workings of the ego. And the ego body itself—this, too, has to be interwoven in the proper way.

As I said just now, as man passes through succeeding periods of evolution he has to step into different developmental impulses with each period. He has to absorb whatever the contemporary age requires him to take in. In the first post-Atlantean period, ancient India, impulses of soul and spirit had to be absorbed which enabled the etheric body to be developed; in the next period, ancient Persia, the astral body was developed; in the period of Egypt and Chaldea it was the turn of the sentient soul; in the Greco-Latin period, the intellectual or mind soul; and today, the consciousness soul.

Whether the human being absorbs in the right way whatever is suitable for the age in which he is living will depend on whether he has properly entered into all these bodily principles—just as the physical body is permeated by the higher components of his being—so that they absorb what the age requires. Suppose an individual during the fifth post-Atlantean period were to resist absorbing anything of what ought to be absorbed during this period; suppose he were to reject everything which could cultivate his soul in the manner required by the fifth post-Atlantean period. What would be the consequence?

His bodily nature cannot revert to an earlier state if he belongs to that part of mankind which is called upon at present to absorb the impulses of the fifth post-Atlantean period. Not everyone is called upon at the same time, but at present all the white races are called upon to absorb the culture of the fifth post-Atlantean period. Now suppose an individual were to resist this. A certain member of his bodily nature—above all, the blood—would remain void of all that could be taken in, were he not to put up this resistance. This member of his bodily nature would then lack what ought to permeate its substance and its forces. This substance and the forces living in it—though not to a degree comparable to bodily death brought about by the departure of the ego—would then become sick in its life forces, which become degraded so that man bears them as a poison within him. Thus to remain behind in evolution means that man impregnates his being with a kind of formative phantom which is poisonous. On the other hand, if he were to absorb what his cultural impulses require him to absorb, the state of his soul would be such that he could dissolve this poisonous phantom he bears within him. By failing to do so, he allows this phantom to coagulate and become a part of his body.

This is the source of all the sicknesses of civilization, the cultural decadence, all the emptiness of soul, the states of hypochondria, the eccentricities, the dissatisfactions, the crankinesses and so on, and also of all those instincts which attack culture, which are aggressive and antagonistic towards cultural impulses. Either the individual accepts the culture of his age, and fits in with it, or he develops the corresponding poison which deposits itself within him and can only be dissolved if he does accept the culture. But if the poison is allowed to become deposited, it leads to the development of instincts which are opposed to the culture of the age. The working of a poison is also always an aggressive instinct. In the languages of Central Europe this can be felt quite clearly: many dialects do not say that a person is angry but that he is poisonous. This expresses a deep sense for something that is indeed the case. Someone who is irrascible is described in Austria, for instance, as ‘gachgiftig’ which means that he is quick to grow poisonous, quick to anger. Human beings acquire poison, sometimes in a very concentrated form, if they refuse to accept what could dissolve such poison. Nowadays, untold people refuse to accept spiritual life in the form fitting for today, which we have been endeavouring to describe for such a long time, more recently even in public.

In such people, the lotus flower here [on the forehead] reveals very clearly what occurs in these cases, for the effects reach right into the realm of warmth, and such people leap up like flames against anything in the world around them which happens to reveal something that could bring healing to our times. Certainly, Mephistopheles—that is, the devil—is abroad amongst us; but the development of even a small beginning—tiny flames stirring—starts when we refuse to accept something that is fitting for our time, so that we do not dissolve the poison but make it into a partial corpse and allow it to coagulate in our organism as a phantom of formative forces.

If you think this through properly, you will discover the cause of many dissatisfactions in life. For those who bear such a poisonous phantom within them are unhappy indeed. We would call these people nervous, or neurasthenic; but it can also make them cruel, quarrelsome, monists, materialists, for these characteristics are the result, more often than we might think, of physiological causes brought about by the poison being deposited in the human organism instead of being assimilated.

You will see from all this that there belongs to the overall balance of the world in which we are embedded a kind of unstable equilibrium between what is good and right on the one hand, and its opposite, the effects of poisons, on the other. If it is to be possible for what is good and right to come about, then it must also be possible to err from what is right, for poisons to have their effect.

If we now apply this to the wider situation, we see that it must be possible today for people to attain to some degree of spiritual life, to develop within themselves impulses for a free, inner spiritual life. To make it possible for the individual to attain to a life of the spirit, the opposite must also exist, namely a corresponding possibility to err along the path of grey or black magic. Without the one, the other is not possible. Just as you, as a human being, cannot maintain yourself without the firm foundation of the earth beneath your feet, so it is not possible for the illumination of spiritual life to be pursued without the resistance which must be permitted to exist and which is inevitable for the higher realms of life.

We have already mentioned the highly contradictory and yet no less important fact that the question: To whom do we owe the Mystery of Golgotha? could elicit the reply: To Judas. For it could be argued that if Judas had not betrayed Christ Jesus, the Mystery of Golgotha would not have taken place, so therefore we ought to be grateful to Judas, since Christianity—that is, the Mystery of Golgotha—stems from him. However, to be grateful to Judas and perhaps recognize him as the founder of Christianity is going too far! Wherever we strive to enter higher realms we have to reckon with living, not dead truth, and the living truth bears within it its own counter-image, just as in physical existence life bears death within it.

This is something I wanted to place in your soul today, for on this basis much can be understood. There has to exist the possibility for what is spiritual, but also for the deposition of the poison which is its polar opposite. And if it can be deposited then it can also be used—it can be utilized in every realm.

Many questions could be asked about this, but today we shall deal with only one: How can we find our way through the maze? Is there not a very great danger that anything we approach in the world might contain the polar opposite, namely the poison, or at least that somebody or other might seek to make something poisonous out of it? Of course there is always this possibility. Everything that is potentially very good can also be perverted and become the opposite. This must be the case in order that human evolution can take its course in freedom in accordance with the present cultural age. Indeed, the very best evolutionary impulses in our age are those most likely to be turned into their opposite.

This is valid for social life as well as for the human organism. In lectures given here last year, we saw that in the present age, to start with only germinally, the capacity is beginning to develop which will enable us to create a life of Imaginations—to develop thoughts which rise up freely—though so far this possibility is denied by materialists. However, it lies in the very nature of our present age that a life of Imagination must develop little by little. What is the counter-image of a life of Imagination? The counter-image of Imaginative life is fabrication, the creation of fabrications about reality and a corresponding thoughtlessness in alleging this or that. I have often described it in these lectures as an inattentiveness to truth, to what is actual and real. The most wonderful thing with which mankind is presented in the fifth post-Atlantean period is the gradual ascent from mere one-sided intellectual life into Imaginative life, which is the first step into the spiritual world. This can err and become untruthfulness, the fabrication of untruths in relation to reality. I am not, of course, referring to poetry, which is entirely justified, but to fabrication with regard to what is real.

Another element which must come into being during the present age—we have discussed this here, too—is a form of thinking that is particularly conscientious and aware of its responsibility. When you see what anthroposophical spiritual science has to offer, you cannot but admit that, to understand what is said, sharply delineated thoughts are needed, thoughts which are imbued with the will to pursue reality in an objective way. Clear thinking is certainly necessary if our teachings—if I may call them that—are to be understood. Above all, what is needed are not fleeting thoughts, but a certain quietness of thought. We must work towards achieving this kind of thinking. We must strive unremittingly to force ourselves to think thoughts with clear contours and not wallow in sympathies and antipathies when alleging something to ourselves and others. We must seek for the foundation, the basis, of what we maintain—otherwise we shall never penetrate in the right way into the realm of spiritual science. We must demand this of ourselves. We shall fulfil our task if we demand this of ourselves. If we are asked what we can do in these difficult times, our answer must be based on what I have just said. We must be fully aware of the fact that at the present time every human being who longs for the evolution of the earth to proceed in a healthy way must seek conscientiously and honestly for objectivity of thinking, in the manner described. This is the task of the human soul today.

It is just because this is so that the corresponding poison can develop, which is a state of being utterly devoid of clarity of thought, devoid of thought that unites with reality and fabricates nothing, but seeks to depict solely what is. During the course of the nineteenth century the yearning for objectivity deserted us increasingly. And the absence of conscience in what we have been describing here as the truth has reached a certain climax in the twentieth century in comparison to all that went before. The effect is at its worst when people entirely fail to notice it; yet, in this very aspect, it is characteristic of our time.

Let me give you a few examples to show you what I mean. Let me place these examples before you sine ira—without sympathies or antipathies. Here is a man whom I know very well, someone who could be called a truly kind and nice person. He holds a position in public life and would certainly not allow himself to stray, even minutely, from the upright attitudes expected of those in public positions. Yet a short time ago this man found it possible to say something quite typical. At the end of an essay he wrote: ‘Finally we cannot avoid at least a brief discussion of ...’ [Gap in report]

It is understandable that such things should be said today, and I have quoted it precisely because the person who said it was such a serious man with truly upright attitudes. Yet when you look more closely, you discover that it is as utterly dishonest as anything can possibly be; for how can you say anything more dishonest than: ‘I shall join in singing “Now thank we all our God” and “A safe stronghold our God is still” ’ and so on, in a mood that makes these hymns into prayers, if you hold opinions such as those expressed by this man. Frankly, he is eulogizing untruthfulness. You may find such eulogies to untruthfulness wherever you look these days, yet they are given, I am bound to say, in good faith. They are the poison that corresponds to what must develop as a spiritual life of Imagination. The best among us, especially, are prone, more or less unconsciously, to harbouring the effects of this poison. Of course, once you realize that something of this kind pulsating through society is no different from a drop of poison administered to the human organism, then you are in a position to judge all these things correctly. And once you do realize it, you cannot but feel bound to strive for something in life which I have now described a number of times. You will feel bound to be alert to the facts, you will want your observation of life to be sound, for without this there is no way forward today. The karma that is being fulfilled at the moment, the karma about which I have spoken before, is not the karma of a single nation; it is the karma of the whole of European and American humanity in the nineteenth century; it is the karma of untruthfulness, the insidious poison of untruthfulness.

This untruthfulness may be experienced particularly strongly in movements of a more elevated variety. During the course of my life I have come across a great deal of untruthfulness, but I must say I have never met lies as grandiose as those promulgated among certain people who proclaim the principle: There is no religion higher than Truth. I could say that such intense mendacity is only found where there is at the same time a profound consciousness of striving for only the truth and nothing but the truth! The greatest watchfulness is needed when striving for the ultimate. For we must realize that, while in earlier cultural epochs the possibilities of erring were different, today the greatest danger is an aberration into untruthfulness brought about by a failure to take reality into account in a living way—a failure to take reality into account! The man I mentioned, who wrote such lies, would rather have his tongue cut out than consciously speak an untruth. Yet it is through such upright people that these things work, seeping into the social organism and turning into social poison. Obviously, since they must needs exist amongst us, they can also err in the opposite direction. Other human beings can take them into their awareness and use them for all kinds of mischief—to put it mildly.

Some of you might remember how strange it seemed to people when I first made some fairly radical statements about these things a few years ago, in a public lecture in Munich. I said at that time: During the course of human evolution, impulses for both good and evil develop on the physical plane. What causes these impulses to develop? They come into being when certain forces, which actually belong to the higher, spiritual world, are misused down here in the physical world. If thieves were to use their thieving instincts, and murderers their murderous instincts, and liars their lying instincts to develop higher forces, instead of enjoying them here on the physical plane, they would develop quite considerable higher forces. Their mistake is only that they develop their powers on the wrong plane. Evil, I said, is good that has been transposed down from another plane. Of course, if we know this it does not make a thief or a murderer or a liar any better. But we must understand these things, otherwise we cannot fathom what is going on, falling unconscious victim to these dangers.

It is not surprising that many people today simply do not realize that it is becoming mankind's task to be concerned with spiritual matters. Therefore they fail to take up this task, abandoning themselves instead to materialistic instincts. In doing so, they develop within themselves those poisons which ought to be dissolved by the spiritual element. What is the consequence? In those who deny the spirit, the poisons develop into forces which cause them to become veritable liars; whether conscious or unconscious is merely a question of degree. Yet these very forces could be used to achieve a reasonable comprehension of spiritual knowledge.

Consider how important it is for us to understand this and how, in understanding it, we can come to comprehend one of the central aspects of the karma of our time, if we add to it what I said yesterday: that a single instance cannot be detached from mankind as a whole, for mankind is a totality. As a counter-image of spiritual endeavour it is essential for a violent evil to exist. And one of man's tasks today is to recognize the true nature of this evil, in order to be able properly to recognize and oppose it when he comes upon it in life.

In speaking about these things we come to realize the relationship between the greater aspects of the karma of our time and something that is living in our time which is everywhere in the world bringing about very, very much that is terrible. Superficially, we see how falsehood throbs through the world in mighty waves which devour much more than one might think. For falsehood is monstrously vigorous. But as we have seen today, falsehood is nothing other than the corresponding counter-image for spiritual endeavour which ought to exist but does not. The divine, spiritual wisdom of the universe has given to the human being the possibility of spiritual endeavour. We have within us the poison which we can dissolve. Indeed, we must dissolve it, for otherwise it will become a kind of partial corpse within us.

Let me give you examples of such things from daily life. These will at the same time serve the pursuit of our aim to better understand certain things which meet us at every turn today and which are connected with life and with all the evil and suffering of the present time. For one of the things we are striving for in these talks, in so far as we have been permitted to give them, is an understanding of the painful events of today. I bring these things forward in order to show you in a structured way how these impulses work. The examples I give are intended to characterize the facts, not any particular person or persons.

Hanging around here in Switzerland is a man who many years ago was a lawyer in Berlin, a pettifogger who was forced to seek his fortune abroad because of all the mischief he had concocted. He has been hanging around abroad for years, and now that war has broken out has written a book, J'accuse, which has caused a furore throughout the countries of the periphery. This whole J'accuse affair can be said to be one of the saddest symptoms of our time, because it is so very characteristic. J'accuse is a fat book, and certain people who ought to know maintain that there is not a log cabin in distant Norway that does not house a copy. It is, in other words, one of the most widely disseminated books. In Berlin last spring I read an article about it written by quite a well-known person. He says J'accuse was recommended to him by someone whom he greatly admires. From the way he describes his friend, we gather who he must mean, namely, someone who counts for a good deal in Holland. Yet this person was quite unable to assess even the gutter-press style of the book. It is possible to be thought a great man and yet be incompetent to form a judgement in such matters.

Now quite recently the author—known, and yet unknown—of J'accuse has gone into print once more in L'Humanité with the following thoughts. As I have said, I am not concerned with the person himself, but want to characterize something that is typical of our time:

In the Reichstag in Berlin a social democrat gives a speech in which he unfolds his views about various happenings in the period leading up to the outbreak of war. It does not matter whether we agree with him or not; what I am concerned with is the form such things take. In his speech, this member of the Reichstag refers to a remark made by Sir Edward Grey on 30 July 1914 to the effect that if the Austrians would content themselves with marching as far as Belgrade, occupying the city and awaiting the outcome of a possible European congress on the relationship between Austria and Serbia, then it might still be possible to preserve peace. This remark by Sir Edward Grey is well-documented, for he made it to the German ambassador and also wrote it to the English ambassador in St Petersburg. The matter is so well-documented that there can be no doubt that Sir Edward Grey did make this remark. Nevertheless, by bringing it up again in the Reichstag, this member has aroused the anger of the author of J'accuse. So what does the author of J'accuse do? He writes an utterly slanderous article in L'Humanité in which he accuses the member of the Reichstag of mendaciousness, false citation, and so on. Yet the matter is very well-documented, and the member of the Reichstag did not say anything which is not vouched for in books, or in the letter sent by Sir Edward Grey to the English ambassador in St Petersburg. So how can the author of J'accuse make the claim of mendaciousness? He did it by saying: What the member of the Reichstag was saying cannot refer to a remark made by Sir Edward Grey on 30 July; it must refer to one made by Sasonov on 31 December. But Sasonov's remark, not Grey's, was as I shall now quote. In other words, the member of the Reichstag quoted Sasonov wrongly, for Sasonov's remark went as follows, and in addition he claims that Sasonov's remark was made by Sir Edward Grey.

The fact is that the member of the Reichstag refers to a remark by Grey. The author of J'accuse wants to counter him and says: What he is saying refers not to a remark by Grey but to one by Sasonov, which he misquotes; Sasonov said the following ...; in other words what he said in the Reichstag in Berlin is doubly false, for firstly the quotation is false, and secondly he claims that the remark was made in London, when in fact it was made in St Petersburg. Ergo, the member of the Reichstag is a liar.

The whole of J'accuse is of this calibre; all the argumentation is like this. You see how narrow, how confused and how unscrupulous must be the thinking of a person who is capable of writing such things. And what does he achieve? The countless people who read L'Humanité and what the author—known, and yet unknown—of J'accuse has to say, will, of course, not check the facts for themselves. They believe what they see before their eyes. So by this means he proves not only that the member of the Reichstag has lied, but also—and the author of J'accuse is indeed capable of allowing this to be seen as proof—that the Central Powers never replied to the proposals made by the periphery. The author of J'accuse states that the member of the Reichstag is saying that the Central Powers did react to the proposals made by the periphery. And yet, he says, look what Sasonov said, for it is Sasonov whom he is quoting! The Central Powers never replied, so you see how they managed the affair; they did not even reply to these important proposals.

Now what the member of the Reichstag said did indeed refer to a proposal made by Grey and telegraphed by him to his ambassador, who then passed it on to Sasonov. Sasonov turned Grey's whole proposal, which was not at all bad, upside down. The author of J'accuse demands that this proposal, turned into its opposite by Sasonov, should have been taken into account, even though Sasanov did not take it into account. However, it can be proved that Grey sent a telegram to his ambassador in St Petersburg and that this was presented to Sasonov, who took no account of it. At the same time Grey sent his proposal to Berlin and from Berlin it was sent on to Vienna. It can indeed be proved that negotiations were carried on between Vienna and Berlin in order to persuade Austria to make a halt in Belgrade and await European negotiations. This is documented in a letter telegraphed by the King of England to Prince Heinrich. In other words, the Central Powers did indeed consider Grey's proposals. But Sasonov did not consider them! Even so, the author of J'accuse concludes that the Central Powers did not reply and have thus made themselves guilty of these terrible events.

This whole matter is not insignificant, for in yesterday's lamentable document the same sentence may be seen. Here we have an extraordinary—let me say—kinship, family relationship, between a terrible document of world history and an individual who has been hanging around for years because his own homeland became too hot to hold him and who now writes all kinds of rubbish under the bombastic title J'accuse. By a German—rubbish that is protected by such further excesses as the latest achievement of L'Humanité.

It is not surprising if people then defend themselves in the way the German member of the Reichstag has done, having been accused by the author of J'accuse of being a slanderer, a hypocrite and a liar. He drew the following comparison: You send your maid on an errand to Mr Miller at Number 35, Long Lane. When she returns after having taken much longer than the expected two hours she says: I couldn't find Mr Miller. I went to No 85, Short Street. Mr Miller the carpenter doesn't live there, but Mrs Smith the washerwoman does. This, said the member of the Reichstag, is just about the level of connection between what the author of J'accuse says and what really happened.

The author of J'accuse is, of course, a particularly nasty example. It is this manner of treating reality which is today the obverse, the corresponding counter-image of spiritual endeavour, flowing as it does through the veins of society in place of what we should all be striving for: spiritual knowledge, spiritual knowledge with which to fill our being. We can find such things everywhere, in manifold variations. I have given you just one example—dishonesty, as it appears in an individual whom I know very well. Everywhere we shall see how such things appear as the counter-image of what is necessary in our time. Spiritual knowing is necessary for those who want to recognize anything worthwhile today; all other knowing lags behind what should be evolving. Therefore, if an attitude of mind disposed towards peace is to come about among the nations of Europe, feelings about these nations will have to develop which are imbued with the spirit, feelings which can come into being if nations are seen in the way they are shown in the lecture cycle about the folk spirits which I gave long before the war in Christiania. We must resolve to approach the spirit of a nation in this way. Only then can our human spirit become active in a manner which will enable us to form a valid judgement which encompasses a whole group, such as a nation. Just think how judgements could be formed about nations if sufficient spiritual preparation had been undertaken first of all! Yet all that we have seen going astray so drastically in one direction or another lives not only in the worst; it also lives in the best of us. In describing this it is not my intention to apportion blame. I am simply describing a lack which exists because there is no will to create the spiritual foundation on which judgements could be formed about the interrelationships of nations. Judgements are formed on the basis of sympathies and antipathies rather than true insights.

A typical example of this may be found in a famous novel written quite recently. A perfectly honest attempt is made in this context to describe a certain nation—in this case the German nation—through the various characters who represent it. Yet the way it is done is defective because a lack of spirituality prevents the author from achieving a judgement based on reality. There would be no reason for me to mention a genuine novel here, for in a true work of art such a question would not arise. But a novel that is tendentious in its descriptions can certainly be quoted in this connection. Let me clarify further what I mean: In a really good novel you will never hear the voice of the author himself, for the characters will express what is typical for their nation, their standing, their class and so on. Thus if John Smith or Adrian Swallowtail says something about the Germans, or the French, or the English, there is no cause to object. But this is not the case in the novel in question. Here, the author keeps stepping out in front of the curtain and giving his opinion, so that when he describes a person he gives his own opinion about the Germans, or whatever. You can see this straightaway in the description of a relative of the hero:

‘He was a fine talker, well, though a little heavily, built, and was of the type which passes in Germany for classic beauty; he had a large brow that expressed nothing, large regular features, and a curled beard—a Jupiter of the banks of the Rhine.’

You will agree that this is not likely to lead to an objective judgement, even if it could be true in isolated cases. A German chamber orchestra is described as follows:

‘They played neither very accurately nor in good time, but they never went off the rails, and followed faithfully the marked changes of tone. They had that musical facility which is easily satisfied, that mediocre perfection which is so plentiful in the race which is said to be the most musical in the world.’

Now the hero's uncle is described:

‘He was a partner in a great commercial house which did business in Africa and the Far East. He was the exact type of one of those Germans of the new style, whose affectation it is scoffingly to repudiate the old idealism of the race, and, intoxicated by conquest, to maintain a cult of strength and success which shows that they are not accustomed to seeing them on their side. But it is as difficult at once to change the age-old nature of a people, the despised idealism springs up again in him at every turn in language, manners, and moral habits, and the quotations from Goethe to fit the smallest incidents of domestic life, and he was a singular compound of conscience and self-interest. There was in him a curious effort to reconcile the honest principles of the old German bourgeoisie with the cynicism of these new commercial condottieri—a compound which for ever gave out a repulsive flavour of hypocrisy, for ever striving to make of German strength, avarice, and self-interest the symbols of all right, justice and truth.’

Of the hero it is said:

‘... he lacked that easy Germanic idealism, which does not wish to see, and does not see, what would be displeasing to its sight, for fear of disturbing the very proper tranquility of its judgment and the pleasantness of its existence.’

Here is another example of the author peeping out through the curtains and giving his own opinion:

‘Especially since the German victories they had been striving to make a compromise, a revolting intrigue between their new power and their old principles. The old idealism had not been renounced. There should have been a new effort of freedom of which they were incapable. They were content with a forgery, with making it subservient to German interests. Like the serene and subtle Schwabian, Hegel, who had waited until after Leipzig and Waterloo to assimilate the cause of his philosophy with the Prussian State ...’

This gentleman has a strange view of the history of philosophy. Those of us with a real understanding of what went on know that the principles of Hegel's philosophy on the phenomenology of consciousness were written down in Jena in 1806 to the thundering of canon as Napoleon approached. Yet in the novel it is said with a certain ‘sense for the truth’ that Hegel waited for the Battle of Leipzig in order to adapt to the Prussian State.

‘... their interests having changed, their principles had changed, too. When they were defeated, they said that Germany's ideal was humanity. Now that they had defeated others, they said that Germany was the ideal of humanity.’

What a fine sentence!

‘When other countries were more powerful, they said, with Lessing, that “patriotism is a heroic weakness which it is well to be without,” and they called themselves “citizens of the world”. Now that they were in the ascendant, they could not enough despise the Utopias “à la Francaise”. Universal peace, fraternity, pacific progress, the rights of man, natural equality: they said that the strongest people had absolute rights against the others, and that the others, being weaker, had no rights against themselves.’

As you can see, once the war had started, these sentences could have formed the basis for many a leading article in the countries of the periphery. Yet they were written long before the war.

‘It was the living God and the Incarnate Idea, the progress of which is accomplished by war, violence, and oppression. Force had become holy now that it was on their side. Force had become the only idealism and the only intelligence.’

Now there is a sentence missing in my notes. You know it is not easy to bring things across the border just now, and I have the book in Berlin.

Let me quote a few more passages in which the author peeps through the curtains:

‘The Germans are very mildly induigent to physical imperfections: they cannot see them; they are even able to embellish them, by virtue of an easy imagination which finds unexpected qualities in the face of their desire to make them like the most illustrious examples of human beauty. Old Euler would not have needed much urging to make him declare that his granddaughter had the nose of the Ludovisi Juno.’

It should be added that this nose and face are described as being especially ugly.

About Schumann it is said:

‘But that was just it: his example made Christopher understand that the worst falsity in German art came into it not when the artists tried to express something which they had not felt, but rather when they tried to express the feelings which they did in fact feel—feelings which were false.’

Then we are reminded with a certain amount of pleasure of something said by Madame de Staël:

‘ “They have submitted doughtily. They find philosophic reasons for explaining the least philosophic theory in the world: respect for power and the chastening emotion of fear which changes that respect into admiration.” ’

The author of the novel adds that his hero ‘found that feeling’, namely that they have submitted doughtily, that they have respect and fear:

‘... everywhere in Germany, from the highest to the lowest—from the William Tell of Schiller, that limited little bourgeois with muscles like a porter, who, as the free Jew Borne says, “to reconcile honour and fear passes before the pillar of dear Herr Gessler, with his eyes down, so as to be able to say that he did not see the hat; did not disobey”—to the aged and respectable Professor Weisse, a man of seventy, and one of the most honoured men of learning in the town, who, when he saw a Herr Lieutenant coming, would make haste to give him the path, and would step down into the road. Christopher's blood boiled whenever he saw one of these small acts of daily servility. They hurt him as much as though he had demeaned himself. The arrogant manners of the officers whom he met in the street, their haughty insolence, made him speechless with anger. He never would make way for them. Whenever he passed them he returned their arrogant stare. More than once he was very near causing a scene. He seemed to be looking for trouble. However, he was the first to understand the futility of such bravado; but he had moments of aberration; the perpetual constraint which he imposed on himself, and the accumulation of force in him that had no outlet, made him furious. Then he was ready to go any length, and he had a feeling that if he stayed a year longer in the place he would be lost. He loathed the brutal militarism which he felt weighing down upon him, the sabres clanking on the pavement, the piles of arms, the guns placed outside the barracks, their muzzles gaping down on the town, ready to fire.’

All this is interesting for a number of reasons. You know that I am not mentioning these things for personal reasons or in order to characterize somebody. Once the novel had been written and had caused a considerable sensation there were, of course, individuals who praised it as the greatest work of art of all time. This always happens. The opinion expressed by an esteemed Austrian critic is rather nice—I mean ‘esteemed’ in inverted commas: ‘This novel is the most important event since 1871, which could bring France and Germany closer together again.’

You see how much truth lies hidden in these things! Yet we are dealing here with a man who is highly praised today, and I have no intention of raising even the slightest objection to his outward activities during wartime. However, what is said in this ‘world famous’ novel provides plenty of material for slogans and leading articles in the periphery. What I have read aloud to you today may indeed be admired—with all due respect to the hacks of the periphery—at any time in those leading articles. These things were written long before the war, as that Austrian critic said ‘to bring France and Germany closer together’, and may be found in Romain Rolland's novel John Christopher.

Here you have an example of somebody who excludes the spirit, who does not want the spirit, and therefore fails to see what is essential in the events and situations of the present time. What can someone who writes such things possibly really know about the German character? We have a right to speak in this way because the subjective judgements of the author are here dressed up in the guise of an inferior novel. It is my personal opinion that this novel is one of the worst. As you have seen from the opinion of the critic from Vienna, it is held to be one of the best. Internationally, too, the critics have hailed it as one of the best. If we did not hold the opinion—which is not all that unjustified nowadays—that anything the critics praise must of necessity be rubbish, we might even have a certain respect for something they tell us is the foremost and greatest achievement of our time. From the viewpoint of cultural history, however, this is a good example for us of how impossible it is for people today to draw near to the task set for mankind by the fifth post-Atlantean period. For this reason alone, karma will have to fulfil itself. It is our task, however, to think about these things impartially. Above all we should not accept or parrot without criticism what is said out there in the materialistic world, but should strive instead to form our own judgement about these things.

What I have read aloud to you today was written many years ago, but now it provides marvellous slogans for the leading articles perpetrated by the journalists of the Entente. Its tenor is terribly anti-German, but that is not the point, for any point of view has its validity. It is, however, a strange distortion of the truth to praise a book as something new when it was in fact written years ago, even though the final volumes have only recently been published. Other strange things happen in this way, for instance in connection with quotations which keep appearing and are said to stem from Nietzsche or Treitschke and others. In the case of Treitschke you can search his works in vain for the passages, and in Nietzsche's case the passages have the opposite meaning to that claimed today by the journalists of the Entente.

I used to be acquainted with Nietzsche's publisher and discussed a number of matters with him. At that time the man who translated the whole of Nietzsche into French wrote to that publisher every few days from Paris. Nietzsche was a god to him. Today he abuses him mightily. You can have the strangest experiences in such connections. You will search the works of Treitschke and Nietzsche in vain for anything that could have been said in that book, for when they are quoted the texts are taken out of context, and furthermore they are also mutilated; the beginning of a sentence is quoted, the middle is torn out, and then the end is quoted. Only by doing this can they quote these writers.

But they can quote Romain Rolland unabridged. I have read to you only a few short passages from his novel. There is no need for you to judge it by these passages, though they could be augmented by countless others. You could, however, judge it on the basis of the ending, which shows that the whole novel is riddled with the attitudes revealed in the quoted passages. None of this is intended as a condemnation of the person himself. However, it is essential to illuminate clearly the poison seeping into our lives today.

Vierzehnter Vortrag

Wenn Sie sich besinnen auf dasjenige, was gestern gesagt worden ist mit Bezug auf die sogenannten Giftsubstanzen, werden Sie, ich möchte sagen, sich stark auf das Relative in allen Daseinsimpulsen hingewiesen fühlen. Sie werden bemerken, daß irgend etwas Substantielles als Gift bezeichnet werden kann, daß aber auf der andern Seite gerade die höhere menschliche Natur mit diesem Giftwesen innig verwandt ist, und daß eigentlich diese höhere menschliche Natur gar nicht möglich ist ohne Giftwirkungen. Man berührt damit allerdings ein für die Erkenntnis sehr bedeutungsvolles Gebiet, das viele Verzweigungen hat, und ohne dessen Kenntnis man manches Geheimnis des Lebens und Daseins überhaupt nicht einsehen kann.

Wenn wir den menschlichen physischen Leib betrachten, so müssen wir sagen: Wäre dieser physische Leib nicht ausgefüllt von den höheren Wesenheiten oder Wesensgliedern des Daseins, dem Ätherleib, astralischen Leib, Ich, könnte er nicht der physische Leib sein, der er ist. In dem Augenblicke, wo der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes geht, seinen physischen Leib verläßt, das heißt, wenn die höheren Glieder sich aus dem physischen Leibe zurückziehen, so folgt dieser ganz andern Gesetzen als während der Zeit, wo die höheren Glieder in ihm sind. Man sagt, er löst sich auf; das heißt, er folgt, wenn er stirbt, den physischen und chemischen Kräften und Gesetzen der Erde.

So wie der physische Leib des Menschen vor uns steht, kann er nicht gemäß den gewöhnlichen Erdengesetzen aufgebaut sein, denn die Erdengesetze zerstören ihn ja. Nur dadurch, daß das, was am Menschen nicht irdisch ist — seine höheren seelisch-geistigen Glieder -, in seinem Leibe wirksam ist, ist der Leib dasjenige, was er eben ist. Nichts im ganzen Bereich der physischen und chemischen Gesetze rechtfertigt das Vorhandensein eines solchen Leibes auf der Erde, wie es der Menschenleib ist.

Wir können daher sagen: Nach physisch-irdischen Gesetzen ist der Menschenleib ein unmögliches Wesen; er wird nur zusammengehalten durch seine höheren Wesensglieder. Hieraus ergibt sich als notwendige Ergänzung, daß, sobald die höheren Wesensglieder — das Ich, der astralische Leib, der Ätherleib - den menschlichen Leib verlassen, er Leichnam wird.

Nun wissen Sie ja aus mancherlei früheren Betrachtungen, daß das, was man so mit Recht als schematische Einteilung des Menschen gibt, nicht so einfach ist, wie es mancher gern haben würde. Wir gliedern den Menschen zunächst in physischen, ätherischen, astralischen Leib und Ich. Ich habe schon früher darauf hingewiesen, daß dies alles eine weitere Komplikation bedingt. Der physische Leib steht allerdings für sich, er ist eben physischer Leib. Aber der ätherische Leib als solcher, als ätherischer Leib, ist ein Übersinnliches, ein Unsichtbares, ein nicht sinnlich Wahrnehmbares. Als solches nicht sinnlich Wahrnehmbares ist er in der menschlichen Wesenheit. Aber er hat auch gewissermaßen sein physisches Korrelat, er drückt sich ab im physischen Leib. Wir haben im physischen Leib nicht nur den eigentlichen physischen Leib, sondern auch einen Abdruck des Ätherleibes. Der Ätherleib projiziert sich im physischen Leibe; wir können also von der ätherischen Projektion im physischen Leibe sprechen.

Das ist ebenso der Fali für den astralischen Leib: wir können von der astralischen Projektion im physischen Leibe sprechen. Sie wissen ja für einzelnes schon Bescheid. Sie wissen, daß Sie die Ich-Projektion im physischen Leibe in gewissen Eigentümlichkeiten der Blutzirkulation zu suchen haben, da projiziert sich das Ich ins Blut hinein. In ähnlicher Weise projizieren sich die andern Glieder in den physischen Leib hinein. Der physische Leib selber, insoferne er physisch ist, ist also ein kompliziertes Wesen, er ist für sich schon viergliedrig. Und so wie das Hauptsächliche im physischen Leibe nicht bestehen kann, wenn das Ich und der astralische Leib nicht darinnen sind, wie das dann zum Leichnam wird, so ist es auch in einer gewissen Beziehung mit diesen Projektionen, denn das sind ja alles substantielle Dinge: Ohne das Ich kann es kein Menschenblut geben, ohne den Astralleib kann es kein menschliches Gesamtnervensystem geben. Diese Dinge haben wir gewissermaßen als die Korrelate der höheren Gliedwesen des Menschen in uns.

Wie es nun überhaupt kein rechtes Leben, sondern nur ein Leichnamsein des physischen Leibes geben kann, wenn das Ich — sagen wir «herausgehoben» — durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen ist, so kann unter gewissen Bedingungen auch das, was diese Projektionen sind, nicht in rechter Weise leben.

Es kann zum Beispiel die Ich-Projektion — also eine gewisse Beschaffenheit des Blutes - in einer nicht richtigen Weise im menschlichen Organismus vorhanden sein, wenn das Ich nicht richtig gepflegt wird. Um den physischen Leib zum Leichnam zu machen, dazu ist schon notwendig, daß wirklich, reell, möchte ich sagen, das Ich diesen physischen Leib verläßt. Aber Sie können das Blut gewissermaßen zum Viertelsleichnam machen, indem Sie es nicht durchsetzt sein lassen von dem, was ordnungsgemäß im Ich leben muß, damit das Seelisch-Geistige in der richtigen Weise auf das Blut wirkt. Daraus ersehen Sie, daß die Möglichkeit vorliegt, die Seele des Menschen so in Unordnung zu bringen, daß im Blutwesen, im Blutsubstantiellen nicht die richtigen Wirkungen sein können. Das ist der Moment, wo — wenn auch nicht ganz, sonst würde ja der Mensch daran sterben müssen, aber wenigstens zum Teil — das Blut in Giftsubstantialität übergehen kann. So wie der menschliche physische Leib gewissermaßen der Zerstörung anheimgegeben ist, wenn das Ich draußen ist, so wird das Blut der Ungesundheit, wenn man sie auch nicht so ohne weiteres bemerken kann, anheimgegeben, wenn das Ich nicht in der richtigen Weise gepflegt und durchsetzt wird.

Wann ist nun das Ich nicht in der richtigen Weise gepflegt und durchsetzt? Das ist unter ganz bestimmten Bedingungen der Fall. Wenn wir zunächst nur auf die nachatlantische Zeit sehen, so erfolgt die Evolution des Menschen so, daß in den aufeinanderfolgenden Kulturperioden der nachatlantischen Zeit bestimmte Fähigkeiten, bestimmte Impulse sich ausbilden. Sie können sich nicht denken, daß Menschen, die in bezug auf die seelische Entwickelung wie wir sind, in der urindischen Zeit gelebt hätten. Von Epoche zu Epoche, indem der Mensch durch die wiederholten Erdeninkarnationen hindurchgeht, sind andere Impulse für die menschliche Seele notwendig.

Ich will schematisch aufzeichnen, was da vorliegt. Denken Sie sich den hauptsächlichsten, den eigentlichen physischen Leib hier; das würde also derjenige sein, welcher von allen höheren Gliedern der menschlichen Natur ausgefüllt sein muß, damit er überhaupt dieser physische Leib ist.

Ich will von all diesen höheren Gliedern der menschlichen Natur nur das Ich berücksichtigen; ich könnte ebensogut alle drei berücksichtigen, will nur dadurch, daß ich schraffiere, andeuten, daß dieser physische Leib Ich-durchdrungen ist. So müssen die andern Projektionen auch in einer gewissen Weise durchdrungen sein. Ich will die Projektion des Ätherleibes, die ja im wesentlichen verankert ist im menschlichen Drüsensystem, so andeuten; das muß nun wiederum in einer gewissen Weise durchzogen und durchsetzt sein. Ich will als drittes andeuten, was hauptsächlich im Nervensystem verankert ist; das muß wiederum in einer bestimmten Weise von einer gewissen Auswirkung des Ich durchsetzt sein. Und der Ich-Leib selber muß nun auch in einer entsprechenden Weise durchsetzt sein.

Nun haben wir eben gesagt, daß der Mensch, indem er die aufeinanderfolgenden Evolutionsperioden durchläuft, in jeder Evolutionsperiode in andere Entwickelungsimpulse eintreten muß. Er muß gewissermaßen dasjenige annehmen, was seine Zeit von ihm verlangt. In der ersten nachatlantischen Zeit, in der urindischen Zeit, mußten die Menschen seelisch-geistige Impulse in sich aufnehmen, die möglich machten, daß dazumal besonders der Ätherleib seine Ausbildung erhielt, in der darauffolgenden Periode, der urpersischen Zeit, wurde der astralische Leib ausgebildet, in der ägyptisch-chaldäischen Zeit die Empfindungsseele, in der griechisch-lateinischen Zeit die Verstandesoder Gemütsseele, in unserer Zeit die Bewußtseinsseele. Nun hängt es davon, daß der Mensch in richtiger Weise das seinem jeweiligen Zeitalter Angemessene aufnimmt, ab, ob er in rechter Weise diese seine Leibesglieder so durchdringt, daß sie von dem, was das Zeitalter verlangt, so durchsetzt werden, wie auch der physische Leib von den höheren Gliedern durchsetzt ist. Nehmen Sie einmal an, ein Mensch würde sich ganz dagegen sträuben, in der fünften nachatlantischen Zeit irgend etwas aufzunehmen, was dieser fünften nachatlantischen Zeit notwendig ist, er wiese alles ab, was seine Seele so kultivieren würde, wie es die fünfte nachatlantische Zeit verlangt. Was würde die Folge sein?

Nun, sein Leibliches läßt sich ja nicht zurückschrauben, wenn es einem Teile der Menschheit angehört, der zunächst berufen ist, die Impulse der fünften nachatlantischen Zeit in sich aufzunehmen. Es sind ja nicht alle zugleich berufen; aber alle weißen Rassen sind jetzt dazu berufen, die Kultur der fünften nachatlantischen Zeit in sich aufzunehmen. Nehmen wir nun an, Menschen würden sich dagegen sträuben. Dann bliebe ein bestimmtes Glied ihrer Leiblichkeit, vor allem das Blut, ohne dasjenige, was hineinkommen würde, wenn sie sich nicht sträuben würden. Es fehlt dann diesem Gliede der Leiblichkeit das, was die entsprechende Substanz und ihre Kräfte in der rechten Weise durchsetzen würde. Dadurch aber werden diese Substanz und die ihr innewohnenden Kräfte, wenn auch nicht in so hohem Grade, wie wenn der Menschenleib Leichnam wird und das Ich heraustritt, in ihren Lebenskräften krank, herabgestimmt, und der Mensch trägt sie gewissermaßen als Gift in sich. Das Zurückbleiben hinter der Evolution bedeutet also, daß der Mensch sich gewissermaßen mit einem Formphantom, das giftig ist, imprägniert. Würde er aufnehmen, was seinen Kulturimpulsen entsprechend ist, so würde er durch diese Seelenart dieses Giftphantom, das er in sich trägt, auflösen. So aber läßt er es in den Leib hinein koagulieren.

Daher kommen die Kulturkrankheiten, Kulturdekadenzen, alle die seelischen Leerheiten, Hypochondrien, Verschrobenheiten, Unbefriedigtheiten, Schrullenhaftigkeiten und so weiter, auch alle die Kultur attackierenden, aggressiven, gegen die Kultur sich auflehnenden Instinkte. Denn entweder nimmt man die Kultur eines Zeitalters an, paßt sich an, oder man entwickelt das entsprechende Gift, das sich absetzt und das sich nur auflösen würde durch die Annahme der Kultur. Dadurch aber, daß man dieses Gift absetzt, entwickelt man Instinkte gegen die betreffende Kultur. Giftwirkungen sind immer zugleich aggressive Instinkte. In der Volkssprache Mitteleuropas ist das deutlich durchgefühlt: viele Dialekte sagen nicht, ein Mensch sei zornig, sondern er sei giftig, was einem tiefen Empfinden der wirklichen Tatsache entspricht. Von einem Jähzornigen sagt man zum Beispiel in Österreich, er sei «gachgiftig», das heißt schnell giftig, er wird schnell zornig. Und daß dies wieder gradweise differenziert ist, können Sie am Schlangengift bemerken, das eben einen höheren Grad von Giftigkeit hat und das das Aggressive wohl in sich trägt. Aber in einem minderen Grade legt der Mensch solches Giftige, das sich sogar sehr konzentriert, in sich an, wenn er sich weigert, dasjenige anzunehmen, was das Gift auflösen würde. Gerade in unserem Zeitalter weigern sich zahlreiche Menschen, die unserem Zeitalter entsprechende Form des geistigen Lebens, die wir uns ja seit langem zu charakterisieren bemühen und die wir jetzt auch öffentlich charakterisiert haben, anzunehmen.

Nun ist es so, daß gerade diese Lotusblume hier [auf der Stirne] an solchen Menschen dasjenige, was da entsteht, sehr sichtbar macht; denn das geht bis zur Wärmewirkung, und solche Menschen züngeln gewissermaßen gegen die Verhältnisse der Außenwelt an, wenn diese etwas von dem zeigen, was für das Zeitalter heilsam wäre. Wir haben gewiß Mephistopheles, das heißt den Teufel, unter uns wandelnd; aber so ein kleiner Anfang, etwas Züngelndes zu entwickeln, geschieht schon dadurch, daß man sich weigert, dasjenige aufzunehmen, was der Kultur des Zeitalters angemessen ist, daß man also das Gift nicht auflöst, sondern es zum Partialleichnam macht, es gewissermaßen im Organismus zum Formphantom koagulieren läßt.

Sie werden, wenn Sie dies durchdenken, sich aufklären können über die Veranlassung mancherlei Unbefriedigtheiten im Leben. Denn solch ein Giftphantom in sich zu tragen, macht den Menschen unglücklich. In unserer Zeit nennt man ihn dann nervös oder neurasthenisch; es kann ihn aber auch grausam, zänkisch, monistisch, materialistisch machen, denn diese Eigenschaften hängen oft, viel mehr als man glaubt, mit diesem physiologischen Grunde zusammen, daß das Gift, statt aufgesogen zu werden, im menschlichen Organismus abgelagert wird.

Aus alldem ersehen Sie, daß zu dem Gesamtbestand, zu der Gesamtkonstitution der Welt, in die wir eingebettet sind, wirklich eine Art labilen Gleichgewichts gehört zwischen dem Guten, Richtigen, und seinem Gegenbilde, den Giftwirkungen. Damit auf der einen Seite das Gute, das Richtige entstehen kann, muß die Möglichkeit gegeben sein, daß vom Richtigen abgeirrt wird, daß die Giftwirkung entsteht.

Wenden wir das auf Umfänglicheres an, so werden Sie sich sagen: Es muß heute in der Welt die Möglichkeit geben, daß die Menschen zu einem gewissen spirituellen Leben kommen, daß sie Impulse für ein freies, inneres, spirituelles Leben in sich entwickeln. — Damit der einzelne zu dem spirituellen Leben kommen kann, muß das Gegenbild vorhanden sein: die entsprechende Möglichkeit, auf grau- oder schwarzmagische Weise davon abzuirren. Ohne das geht es nicht. Geradeso, wie Sie sich als Mensch nicht halten können, wenn Sie nicht unter sich die Erde haben, die Ihnen einen festen Boden gibt, so kann es dasjenige, was Verfolgen des lichten, spirituellen Lebens ist, nicht geben ohne den Widerstand, der zugelassen werden muß, und der für die höheren Gebiete des Lebens unausbleiblich ist.

Wir haben auf das ja ganz Widerspruchsvolle, aber deshalb nicht minder Bedeutsame hingewiesen, daß jemand auf die Frage: Wem verdanken wir das Mysterium von Golgatha? — antworten könnte: Dem Judas; denn hätte Judas den Christus Jesus nicht verraten, so hätte das Mysterium von Golgatha nicht stattgefunden, daher müßte man dem Judas dankbar sein, denn von ihm rührt eigentlich das Christentum, das heißt, das Mysterium von Golgatha her. — Aber das kann man eben doch wiederum nicht, dem Judas dankbar sein und ihn etwa als den Begründer des Christentums anerkennen! Überall, wo man sich in höhere Gebiete erhebt, muß man mit lebendiger, nicht mit toter Wahrheit rechnen, und die lebendige Wahrheit trägt ihr eigenes Gegenbild in sich, so wie im physischen Dasein das Leben den Tod in sich trägt.

Nehmen Sie das als etwas, das ich heute gerne in Ihre Seele senken möchte, weil sich daraus vieles begreifen läßt. Es muß die Möglichkeit bestehen, neben dem Spirituellen das polarisch entgegengesetzte Gift abzusetzen. Dann kann es aber, wenn es abgesetzt werden kann, auch benützt werden, und auf allen Gebieten kann es benützt werden.

An das Gesagte können sich viele Fragen angliedern. Aber wir wollen vorerst für heute nur diese Frage berühren: Wie kommt man da zurecht? Ist man nicht der großen Gefahr ausgesetzt, daß, wenn man an irgend etwas in der Welt herantritt, das Entgegengesetzte, das Giftmäßige darin enthalten ist, oder wenigstens, daß es irgend jemand zum Giftmäßigen ausbilden könnte? Diese Möglichkeit ist natürlich immer vorhanden. Alles das, was sehr gut sein kann in der Welt, kann in sein Gegenteil verkehrt werden. Aber das muß so sein, damit die Menschheitsentwickelung sich in Freiheit vollziehen kann gemäß unserem Kulturzeitalter. Und gerade die schönsten Entwickelungsimpulse unseres Zeitalters können am meisten Veranlassung geben, in ihr Gegenteil verkehrt zu werden.

Ebenso wie für den menschlichen Organismus gilt das für das soziale Leben. Aus früheren hier gehaltenen Vorträgen haben wir gesehen, daß in unserem Zeitalter sich zunächst im Keime die Anlage zu entwickeln beginnt, imaginatives Leben zu entfalten, frei aufsteigende Gedanken zu bilden, die allerdings die materialistisch gesinnten Menschen noch abweisen. Aber es liegt einmal in der Natur unseres Zeitalters, daß nach und nach das imaginative Leben sich entwickeln muß. Was ist das Gegenbild des imaginativen Lebens? Das Gegenbild des imaginativen Lebens ist die Erdichtung, die Erdichtung in bezug auf Wirklichkeiten und der damit verknüpfte Leichtsinn im Behaupten dieser oder jener Dinge. Es ist das gleiche, was ich oftmals in diesen Betrachtungen geschildert habe als die Unaufmerksamkeit gegenüber der Wahrheit, gegenüber dem Reellen, dem Wirklichen. Das Schönste, was der Menschheit im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum vorgesetzt ist, das allmähliche Aufsteigen aus dem bloßen einseitigen intellektuellen Leben in das imaginative Leben, das die erste Stufe in die geistige Welt ist, kann abirren in die Unwahrhaftigkeit, in die Erdichtung in bezug auf Wirklichkeiten. Ich sage selbstverständlich nicht: in die «Dichtung» -, denn die ist berechtigt, aber in die «Erdichtung» in bezug auf die Wirklichkeit.

Weiter muß in unserem Zeitalter erstehen — das haben wir auch aus unseren Betrachtungen kennengelernt —, ein besonders gewissenhaftes, seiner Verantwortlichkeit bewußtes Denken. Wenn Sie ins Auge fassen, was in der anthroposophisch orientierten Geisteswissenschaft geboten wird, so werden Sie sich sagen: Man muß, wenn man wirklich verstehen will, was die anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft gibt, scharf gezeichnete Gedanken haben, in denen der Wille lebt, sachgemäß die Wirklichkeit zu verfolgen. Scharfes Denken ist schon notwendig, um unsere Lehre, wenn wir sie so nennen dürfen, aufzunehmen, und vor allen Dingen ein gewisses Ruhen auf dem Gedanken, nicht ein flüchtiges Denken. Wir müssen nun hinarbeiten auf ein solches Denken. Wir müssen uns unablässig bemühen, Gedanken mit scharfen Konturen von uns zu fordern, und uns nicht blind den Sympathien und Antipathien hinzugeben, wenn wir für uns und andere etwas behaupten. Wir müssen nach Begründung, nach Fundierung dessen suchen, was wir behaupten, sonst werden wir niemals in der richtigen Weise in das geisteswissenschaftliche Gebiet eindringen können. Das müssen wir fordern. Und wir erfüllen unsere Aufgabe, wenn wir diese Forderung an uns selbst stellen. Und wenn gefragt wird: Was müssen wir tun in unserer jetzigen schweren Zeit? — so müssen wir uns die Antwort aus dem eben Gesagten heraus formen. Wir müssen uns klar bewußt sein, daß in der Gegenwart jeder Mensch, der will, daß die Evolution der Erde in heilsamer Weise weitergeht, gewissenhaft und ehrlich nach Gedankenobjektivität in der eben geschilderten Weise suchen muß. Das ist eben die Aufgabe der Menschenseele in der gegenwärtigen Zeit. Und weil das so ist, so kann sich auch das korrelative Gift entwickeln: Das vollständige Verlassensein von klaren Gedanken, von Gedanken, die sich mit der Realität verbinden und nichts erdichten, sondern das, was ist, einfach verzeichnen wollen. Das Verlassensein von dieser Sehnsucht nach Objektivität ist im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts immer intensiver und intensiver geworden. Das Abgetrenntsein des Gewissens von dem, was wir jetzt immer als Wahrheit charakterisiert haben, hat im 20. Jahrhundert gegenüber allem Bisherigen einen gewissen Höhepunkt erlangt. Die Wirkung ist dann am schlimmsten, wenn die Leute es so ganz und gar nicht merken; aber gerade das ist ein Charakteristikum unserer Zeit.

Ich will Ihnen ein paar Beispiele geben, damit Sie sehen, was ich meine. Ich will wirklich solche Beispiele sine ira — ohne Sympathien und Antipathien - vorbringen. Da ist ein Mann, den ich sehr gut kenne, der das ist, was man einen lieben, netten Menschen nennt. Er steht im öffentlichen Leben, nimmt mit Recht eine sehr ehrenwerte Stellung darin ein und würde sich nicht erlauben, auch nur im Allergeringsten von dem abzuirren, was man Gesinnungstüchtigkeit im öffentlichen Auftreten nennt. Der betreffende Mann hat aber doch vor kurzem einmal das Folgende sehr Charakteristische schreiben können: «Es soll zum Schlusse», das sagt er am Schlusse eines Aufsatzes, «einer, wenn auch nur kurzen Erörterung einer Frage nicht ausgewichen werden...» [Lücke]

Es ist begreiflich, daß in unserer Zeit so etwas gesagt wird, und ich führe es an, weil es von einem wirklich ernsten Menschen von echter Gesinnungstüchtigkeit gesagt worden ist. Aber es ist, wenn man es näher betrachtet, so verlogen, wie nur irgend etwas verlogen sein kann; denn man kann nichts Verlogeneres sagen, als: «Ich werde mitsingen: «Wir treten zum Beten vor Gott den Gerechtem, «Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott> » und so weiter, mit der Stimmung, daß es eben ein Gebet, ein gesungenes Gebet ist, wenn man überhaupt nur diesen Glauben hat, den der Betreffende hier charakterisiert. Es ist geradezu eine Lobrede auf die Verlogenheit. Solche Lobreden auf die Verlogenheit finden Sie heute auf Schritt und Tritt, und sie sind, ich möchte sagen, im guten Glauben gehalten; sie sind das Korrelativgift zu dem, was sich als imaginatives, spirituelles Leben entwickeln muß. Und gerade bei den besten Menschen kann mehr oder weniger im Unbewußten solche Giftwirkung vorhanden sein. Wenn man allerdings weiß, daß so etwas, indem es im sozialen Leben pulsiert, genau so ist, wie wenn man einem menschlichen Organismus einen Tropfen Gift einflößen würde, dann kann man alle diese Dinge in der richtigen Weise beurteilen. Wenn man das aber weiß, dann wird man sich auch verpflichtet fühlen, etwas im Leben zu verwirklichen, was jetzt öfters charakterisiert worden ist: Man wird sich bemühen, ein offenes Auge für die Tatsachen, ein gesundes Beobachten des Lebens zu entwickeln; ohne das kommt man heute nicht aus. Und das Karma, von dem ich gesprochen habe, das sich erfüllt, und das nun nicht das Karma eines einzelnen Volkes, sondern eben der ganzen europäisch-amerikanischen Menschheit des 19. Jahrhunderts ist, das ist schon das Karma dieser Unwahrhaftigkeit, das schleichende Gift der Unwahrhaftigkeit.

Man kann diese Unwahrhaftigkeit ja ganz besonders in Bewegungen besonders erhabener Natur erleben. Ich habe auf meinem Lebensweg da oder dort viel vernommen, was gelogen war; aber ich muß sagen, ich habe nicht gefunden, daß irgendwo anders so grandios gelogen wurde wie da, wo der Grundsatz ausgesprochen ist: Keine Religion ist höher als die Wahrheit. — Ich möchte sagen, mit solcher Intensität wurde doch eigentlich nur da gelogen, wo man zu gleicher Zeit das tiefste Bewußtsein hatte, daß man nur die Wahrheit und nichts anderes als die Wahrheit anstrebe! Gerade da, wo ein Höchstes erstrebt wird, muß am schärfsten achtgegeben werden. Denn dies muß einmal ins Auge gefaßt werden: In früheren Kulturepochen waren andere Möglichkeiten des Abirrens da, in unserer Zeit ist das Abirren in eine Unwahrhaftigkeit, die durch ein Nichtleben mit der Wirklichkeit zustande kommt, die große Gefahr. Ein Nichtleben mit der Wirklichkeit! Bei Menschen, die so gesinnungstüchtig sind wie die Persönlichkeit in dem Beispiel, das ich angeführt habe — der Mensch, der solche Verlogenheit hier geschrieben hat, würde sich eher die Zunge durchschneiden lassen, als bewußt eine Unwahrheit sagen —, wirken die Dinge eben, indem sie in den sozialen Organismus träufeln und soziales Gift werden. Aber natürlich können sie, da sie nun vorhanden sein müssen, auch nach der entgegengesetzten Seite abirren: Sie können auch von dem menschlichen Bewußtsein aufgegriffen werden und zu allerlei Unfug verwendet werden, um nicht ein stärkeres Wort zu gebrauchen.

Vielleicht erinnern sich manche von Ihnen, wie merkwürdig es berührt hat, als ich in München vor Jahren zum ersten Mal auf diese Verhältnisse, sogar in einem öffentlichen Vortrage, radikal hingewiesen habe. Ich sagte damals: Im Verlaufe der menschlichen Evolution entwickeln sich auf dem physischen Plane die Impulse des Guten und des Bösen. Wodurch entwickeln sich diese Impulse? Dadurch, daß gewisse Kräfte, die eigentlich in die höhere geistige Welt gehören, hier unten in der physischen Welt mißbraucht werden. Würden die Diebe ihre Diebsinstinkte, die Mörder ihre Mordinstinkte, die Lügner ihre Lügeninstinkte, statt sie auf dem physischen Plane auszuleben, dazu verwenden, höhere Kräfte zu entwickeln, so würden sie sehr bedeutende höhere Kräfte ausbilden. Der Fehler besteht nur darin, daß sie die Kräfte, die sie entwickeln, nicht auf dem richtigen Plane entwickeln. Das Böse, sagte ich, ist ein von einem andern Plane herunterversetztes Gutes. Dadurch wird der Mensch, der ein Dieb oder ein Mörder oder ein Lügner ist, selbstverständlich nicht besser: Aber begreifen muß man die Dinge, sonst kommt man nicht dahinter und verfällt unbewußt diesen Gefahren.

Es ist kein Wunder, daß es in unserer Zeit viele Menschen gibt, die einfach nicht fassen, daß es jetzt Aufgabe zu werden beginnt, sich mit spirituellen Angelegenheiten zu befassen. Daher tun sie es auch nicht, sondern sie überlassen sich den materialistischen Instinkten. Aber sie entwickeln in sich die Gifte, die durch Spirituelles aufgelöst werden sollten. Was ist die Folge? Die Gifte entwickeln sich und werden in Menschen, die das Spirituelle abweisen, zu Kräften, welche sie zu richtigen Lügnern machen, ob bewußt oder unbewußt ist mehr eine Gradfrage. Die gleichen Kräfte könnten aber angewendet werden, um sehr schön die spirituelle Wissenschaft zu begreifen.

Bedenken Sie, was wir da im Grunde für eine gewichtige Erkenntnis vor uns haben, und wie wir durch ein Erfassen einer so gewichtigen Erkenntnis einen Hauptnerv im Karma unserer Zeit begreifen können, wenn wir nur dazunehmen, was ich gestern sagte: Eine Einzelheit läßt sich nicht aus der Gesamtmenschheit herausreißen. Die Menschheit ist ein Ganzes. — Gerade als das Gegenbild des spirituellen Strebens muß in unserer Zeit ein scharfes Übel vorhanden sein. Und dieses Übel wirklich in seiner Wesenheit zu erkennen, damit man es auch dann erkennt, wenn es einem im Leben entgegentritt und man es in der richtigen Weise bekämpfen kann, das gehört schon zu den Aufgaben des Menschen unserer Zeit.

Indem wir über diese Dinge sprechen, bringen wir die großen Gesichtspunkte, die mit dem Karma unserer Zeit zusammenhängen, unmittelbar in Verhältnis zu dem, was in unserer Zeit lebt und im weitesten Umkreise viel, viel Schlimmes bewirkt. An der Oberfläche sehen wir, wie in mächtigen Wogen, die viel mehr verschlingen als man denkt, die Lüge heute durch die Welt pulst. Die Lüge hat ja ein ungeheuer starkes Leben. Aber an solchen Betrachtungen, wie wir sie heute angestellt haben, sehen Sie, wie die Lüge nur das korrelative Gegenbild ist des seinsollenden aber nicht vorhandenen spirituellen Strebens. Ich möchte sagen, die göttlich-geistige Weisheit der Welt hat den Menschen die Möglichkeit gegeben, spirituell zu streben. Wir haben das Gift in uns, das wir auflösen können; aber wir müssen es auch auflösen, sonst bleibt es in uns wie eine Art Partialleichnam.

Lassen Sie mich für solche Dinge Beispiele aus dem Tagesleben geben, wobei wir ja gleichzeitig das Ziel verfolgen können, gewisse Dinge, die uns heute auf Schritt und Tritt entgegenkommen, die mit dem Leben, mit allem Übel und Leiden der Gegenwart zusammenhängen, besser zu verstehen. Denn nach und nach zu einem Verständnis der schmerzlichen Ereignisse der Gegenwart zu kommen, das ist ja auch dasjenige, was wir in diesen Betrachtungen, soweit sie uns nun gegönnt sind, anstreben. Solche Dinge sage ich wirklich nur, um gewissermaßen im Formellen die Art und Weise, wie die Impulse wirken, zu charakterisieren, nicht um einen Menschen zu charakterisieren, sondern um Tatsachen zu charakterisieren an Beispielen.

Da treibt sich hier in der Schweiz ein Mensch herum, der vor vielen Jahren in Berlin Advokat war, ein Winkeldichter, der durch allerlei Dinge, die er angerichtet hat, veranlaßt worden ist, es im Auslande zu versuchen. Seit Jahren treibt er sich im Auslande herum, und jetzt, da der Krieg ausgebrochen ist, schrieb er das in der ganzen Peripherie Aufsehen machende Buch «J’accuse». Man kann sagen, daß diese ganze « J accuse»- Angelegenheit zu den allertraurigsten Begleiterscheinungen unserer Zeit gehört, weil sie ein so charakteristisches Symptom ist. «J accuse» ist ein dickes Buch, und gewisse Leute, die es wissen können, behaupten, um nur ein Beispiel anzuführen, daß es keine norwegische Hütte gibt, in der dieses Buch nicht zu finden wäre. Es gehört also zu den allerverbreitetsten Büchern. Im Frühling las ich in Berlin einen Artikel über dieses Buch, von jemandem geschrieben, der etwas gilt. Dieser sagt, «J’accuse» wäre ihm empfohlen worden von einem Menschen, den er außerordentlich schätzt. Aus der Art der Darstellung kann man entnehmen, wer dieser von ihm geschätzte Mensch ist: es ist jemand, der in Holland als ein großes Licht gilt, der aber nicht einmal imstande war, das ganze Hintertreppenartige des « J’accuse»-Buches — wenn man nur auf das Formale sieht — zu beurteilen. Man kann eben heute als ein großer Mann gelten und in solchen Dingen durchaus urteilslos sein.

Nun hat sich jetzt eben wieder dieser bekannt-unbekannte Verfasser von «J’accuse» in der Zeitung «Humanite» mit folgender Gedankenform vernehmen lassen — wie gesagt, kommt es mir nicht auf das Persönliche, sondern darauf an, zu charakterisieren, was in unserer Zeit alles möglich ist: