Historical Necessity and Freewill

GA 179

2 December 1917, Dornach

1. On the Functions of the Nervous System and the Threshold of the Spiritual World Meaningless Forms of Thought

In these days I have tried to show you the conditions of human life from an individual aspect, and also from a wider aspect. You will have noticed that even during the public lectures which I held recently, I was anxious to point out the problems of spiritual science needed for an understanding of mankind. For we must abandon certain vicious circles of thought that are now to be found throughout the world, and are, really, one of the causes which led to the catastrophic events of the present.

Above all, people must understand where the boundary line between the so-called physical world and the spiritual really lies. This boundary-line really lies in the very center of man. In order to understand the world, it is very important to know that this boundary-line between the physical world and the spiritual world can be found in man himself. I have often pointed out, from the aspect of spiritual science, the great importance of scientific methods of thinking, both for the present and for the future, and have shown that scientific thought really stands more or less where it has always stood from its beginnings. One might well say that it is qualified to spread darkness over some of the most important truths of life.

Let us be quite clear that the evolution of the times only begins today to introduce scientific thinking gradually into the conceptions of the universe and of life. Today a few monistic societies, and others too, are engaged in introducing scientific conceptions into the consciousness of the general public—often in a shockingly amateurish way. This is only one of the channels through which scientific thinking will flow gradually into the human soul. A far more effective and incisive way is the one of publicity.

Not by chance, but in accordance with an inner reality, the new scientific way of thinking entered the evolution of mankind at the same time as the invention of printing. All new things that mankind has learnt so far through printed books (with the exception of books containing old things that existed already) came from the scientific consciousness. I mean that the new element came from the scientific consciousness. Above all, the way in which thoughts have been captured came from a scientific way of thinking.

Theologians will of course raise this objection: Have we not printed theological wisdom and all kinds of religious things during the last years, decades and centuries? Yes, this is true, but to what has it led us? The way in which human souls have become conversant with spiritual life under the auspices of printing has brought about this result, that the spiritual element has gradually left the sphere of religious consciousness altogether. Under the influence of scientific thought, even Christ-Jesus has become the “simple man of Nazareth” (you know this already) and although he has been characterized in many ways, he has nevertheless been placed on the same level as other great personalities of history—but for the present at least he still stands above the others. The real spiritual element connected with the Mystery of Golgotha gradually disappeared—at least for those who think that they have advanced in the civilization of our times.

I have already explained that the scientific way of thinking was obliged at first to cooperate in producing a certain darkening of the spirit, in support of what the Spirits of Darkness bring into human thinking, ever since 1879. In the scientific sphere this assumes a very subtle aspect. The scientifically trained thinker, or better, the scientific expert who cooperates in the general education of our age and in the formation of a world-conception, cannot help diverting man from casting a glance at the boundary-line between the physical world and the spiritual world, which exists in him. He cannot help this because science is as it is, and he does his very best (excuse this banal expression) to work in this direction by popularizing the scientific methods of thought. A future age will dawn for human thinking (it is terrible that such things are mentioned today – terrible for those who follow a particular line of thought), an age in which certain ideas will be looked upon as comical—ideas now ruling in science, which have not entered the consciousness of the masses, but influence them, because scientists (forgive me) are considered to be authorities.

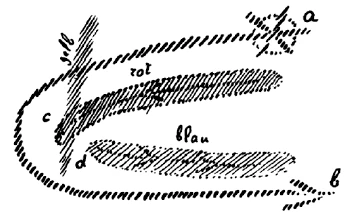

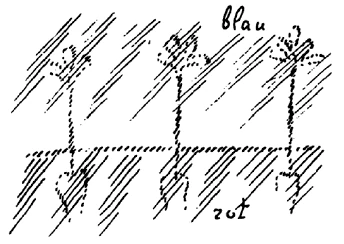

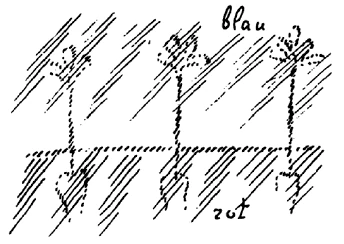

I have often pointed out the following thought—even publicly in my book Riddles of the Soul: It is a current scientific idea that in the nervous system (we will limit ourselves to man, for the moment, although this can also be applied to animals) we can distinguish sensory, or sense-nerves or perceptive nerves, and motor nerves. It can be drawn schematically, by showing, for instance, that any nerve, say a nerve of touch, carries the sensation of touch to the central organ—let us suppose, to the spinal cord. The sensations from the periphery of the body reach the spinal cord. Then, from another point of the spinal cord goes out the so-called motor nerve. From there, the impulse of the will is sent on (see drawing).

In the brain this is shown in a more complicated way, as if the nerves were like telegraphic wires. The sense-impression, the impression on the skin, is led as far as the central organ: from there, an order goes out, as it were, that a movement must be carried out. A fly settles somewhere on the body—this causes a sensation; the sensation is led on to the central organ; there, the order is given to lift the hand as far as the forehead to chase away the fly. From a diagrammatic aspect, this is an idea that is generally accepted. A future age will look on this as something very comical indeed, for it is comical only for him who can detect this. But it is an idea that is accepted by the majority of professional scientists. Open the nearest book on the elements of science dealing with these things and you will find that today we must distinguish between sensory and motor nerves. You will find that they mention particularly the very comical picture of the telegraphic wire—that the sensation is conducted to the central organ and that the order is given out from there for the production of a movement. This picture is still very much diffused in popularized science.

It is far more difficult to see through reality than through the thoughts that set up comparisons with telegraphic wires, reminding us of the most primitive kinds of ideas. Spiritual Science alone enables us to see through reality. An impulse of the will has nothing in common physical matter. Nerves—both sensory and motor nerves—obey a uniform function, and this can be seen no matter whether the nerve-cord is interrupted in the spine or in the brain; in the brain it is merely interrupted in a more complicated way.

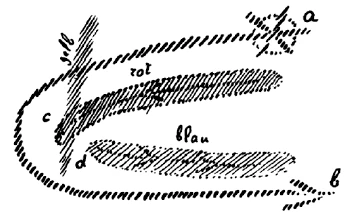

This interruption or break exists not only in order that something from the external world may be conducted through the one half to the central organ and then, in the form of will, from the central organ through the second half to the periphery—this interruption exists for an entirely different reason. Our nervous system is interrupted in this regular way because at the very point of the interruption, reflected in an image in man, there lies the boundary line between physical and spiritual experience; it is the bodily reflection of a complicated spiritual reality. This boundary exists in man in a very remarkable way. Man enters into a relationship with the world immediately around him, and this process is connected with that part of the nerve-cord that goes as far as the interruption. But man must also have a link with his own physical body as a soul-being. This connection with his own physical body is transmitted through the other nerve-cord. When an external impression causes me to move my hand, the impulse to move the hand already lies here (shown in the diagram), already united with the soul, with the sense-impression. And that which is conducted along the whole sensitive nerves, along the so-called motor nerve, from a to b, is not “conducted as a sense-impression as far as c, where an order is given that gives rise to b”– no, the soul-element is already fructified when an impulse of the will takes place at a, and passes through the entire nerve-path indicated in the diagram.

It is quite out of the question that such infantile ideas should correspond to any form of reality—ideas which presuppose that the soul is to be found somewhere between the sensory and the motor nerves, where it receives an impression from the exterior world and transmits an order from there, like a telegraphic operator. This childish idea, which is met with again and again, is very strange when found in conjunction with the demand that science must at all costs avoid being anthropomorphic! Anthropomorphic lines of thought must be avoided, yet people do not realize how anthropomorphic they themselves are, when they say that an impression is received, an order sent out, etc., etc. They talk and talk and have not the slightest idea what mythological beings they conjure into their dreams about the human organism! They would realize it if they would take things seriously.

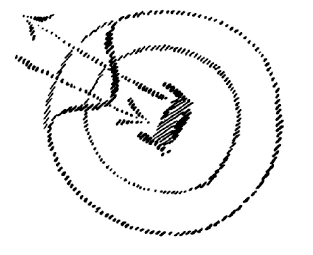

Now the question arises: Why then is the nerve-cord interrupted? It is interrupted because, if this were not so, we should not be included in the whole process. Only because at the point of interruption the impulse springs over the gap, as it were (the same impulse, let us say, an impulse of the will, starts from a), because of this fact, we ourselves are in the world and are at one with this impulse. If the entire process were uninterrupted, with no break at this point, it would be entirely a process of Nature, in which we would not participate.

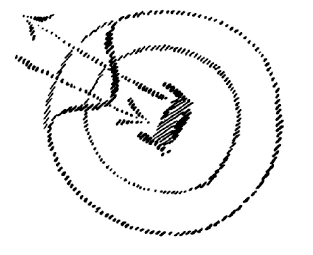

Imagine this process in a so-called reflex movement: A fly settles somewhere on your body, you chase away the fly, and the whole process never enters your consciousness fully. The entire process has its analogy, an entirely justified analogy, in the sphere of physics. Inasmuch as this process demands an explanation by means of physics, the explanation will be only a little more complicated than that of another physical process. Take a rubber ball, for instance: you press it here, and deform it. But the ball fills out again and reassumes its former shape. You press in and the ball presses out again. This is the plain physical process, a reflex movement, except that there is no organ of perception, there is nothing spiritual in the process. But if you interpolate something spiritual at this point by interrupting the process, the rubber ball will feel itself an individual being. However, in this case the rubber ball must have a nervous system, so that it can feel both the world and itself. A nervous system always exists in order that we may feel the world in ourselves: it never exists in order to pass on a sensation along one side of the wire, and a motor impulse along the other side.

I am pointing this out because the pursuance of this subject leads us into one of the many points where natural science must be corrected before it can supply ideas that correspond approximately to the real facts. The ideas ruling today are instruments of the impulses coming from the Spirits of Darkness. The boundary line between physical and spiritual experience lies in man himself.

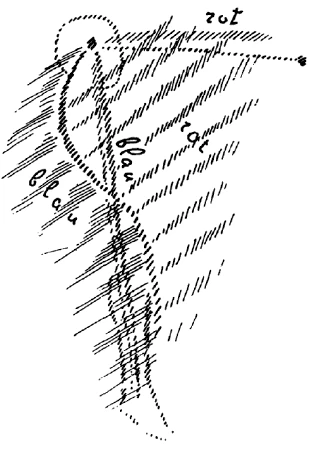

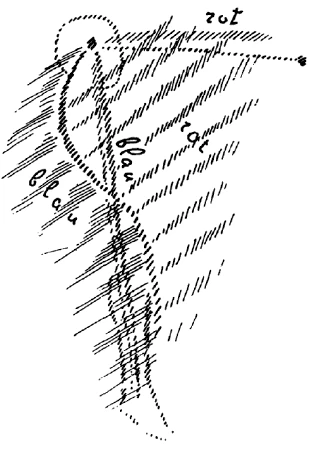

You see, this piece of nerve that I indicated in red really serves to place us into the physical world, so that we may have sensations in the physical world. The other piece of nerve, indicated in blue, really serves to make us feel ourselves as body. There is no essential difference whether we experience a color consciously from outside, through the nerve-cord a c, or whether we experience an organ, or the position of an organ, etc., from inside, through the cord d b; in essence, this is the same. In the one case we experience something physical is in us, i.e., enclosed within our skin. Not only that which is outside, but also what is within us, places us in the process that can be experienced as a will-process. The strength of the perception varies according to the nerve-cords that transmit it—the cord a c, or the cord d b. Indeed, a definite weakening of the intensity takes place. When an idea is linked up with a will-impulse in a, the impulse is passed on from a; when it jumps from c to d, the whole process weakens to such an extent in our consciousness or experience that we experience its continuation—for instance, the lifting of our hand—only with that slight intensity of consciousness which we possess during sleep. When we lift our hand we are again aware of the will, but in the form of a new sensation from another side. Sleep extends continually in an anatomical and physiological sense into our waking life. We are connected with the exterior physical world, but we are completely awake only with that part of our being that goes as far as the interruption of the nerves. What lies in us beyond this interruption in the nerves is wrapped in sleep, even by day. In the present stage of the evolution of the Earth this process is not yet physical; it takes place on a certain spiritual level, although it is connected to a great extent with the lower qualities of human nature. However, I have often expounded the secret that just man's “lower nature” is connected with the higher manifestations of certain spiritual beings. If we note all the places in the human being where the nerves are interrupted, and jot them down in a diagram, we obtain the boundary-line between the experiencing in the physical world and the experience that comes from a higher world. Hence I can use the following diagram: Suppose that I indicate here all the nerve-interruptions—here is the head and here is a leg. Now suppose that a so-called impression goes out from here and that the interruption of the nerve is in this place. “Walking” will be the result, and the real process consists in this—that everything that we experience through the nerve here, is experienced by day in a waking way. But what we experience here as unconscious will is experienced in a sleeping way, even when we are awake. The spiritual world forms and creates directly everything that lies below the point of interruption in the nerves.

You may find these things difficult if you hear them for the first time, but they should make you aware that you cannot enter into the more intimate questions of knowledge without some difficulty.

When it becomes clear to you that everything above the boundary line connects man with the physical world, and everything below the boundary with a spiritual world, of which he possesses only an inferior kind of physical image, you will be able to reach the following conception:—Think of the plant-world; the plants grow out of the earth, but they would not do so unless they received from the universe forces which are intimately connected with the life of the Sun, and which receive everything that the earth generates in the form of forces. All these cosmic forces, everything that pours in from the universe out of the Sun's life, with all that emanates from the earth, belongs to the life of the plants.

This joint action of cosmic and telluric, or earthly, forces is part of the life and existence in the physical world, as we must understand it. The forces working on the plants below this line, from the earth, together with the plant's germinating force (the seed is put into the earth) are of the same kind as those that we must seek here, where the red lines are indicated [original article notes “This diagram cannot be given.”] You must look for the forces that the plant receives from the earth through its roots, above the boundary-line indicated in the diagram. Man takes from the earth in a more delicate way, through his eyes and ears, and above all through his skin, what the plant assimilates from the soil through its roots. Man is an earthly being through his nerves, and through what he receives in the form of telluric or earthly forces in the air he breathes, and in the food that the earth gives him. What the plant receives from the earth (except that the plant sends its roots into the earth), man receives through organs that he unfolds after death, from the earth; but he receives it in a more delicate way, and the plant in a coarser way through its roots.

The plant receives other forces as well; it receives forces that stream in from the Sun's sphere, from the heavenly sphere—the sphere of the cosmic spaces, or the universe. In my diagram, this sphere is indicated in blue; it represents the forces that the plant receives from the universe. They are of the same kind as those indicated in blue, beyond the boundary line. Man draws out of his body what the plant draws out of the universe. From the earth, man receives in a more refined state the forces and substances which the plant assimilates more coarsely from the soil through its roots. From this body, man receives more coarsely the same forces and substances that the plant draws from the universe in a more refined state. These forces do not exist in the universe in the form in which man draws them out of his own body; they existed as such during the old Moon period. Man has preserved them from that period. Through what lies beyond this limit (shown in the blue part of the diagram) man does not receive his perceptions immediately from the present, but from what he brought over as an inheritance from the old Moon period. He has carried the cosmic conditions of a past age into the present. Man has preserved the Moon-conditions in his body.

You can see, therefore, that we are cosmic to a certain extent and are even connected with the universe in such a way that we bear within us an image of what has already been conquered by the universe outside.

This is again an example of what I mentioned last time, that it will not be of much use if we say, from a general, vague and nebulous standpoint, that man must take up again a cosmic way of feeling and cosmic ideas. These things are only of value if we approach them quite concretely, and if we really know how matters stand, how they are connected. This will place the experimental attempts of the present day on a sound basis, on a really sound basis. If we know that everything in the human body lying beyond the nerve-interruptions is connected with the Moon nature, we shall find in the universe and in the life on earth the forces that make us ill or that heal us. We shall find them through these relationships, and when we know how that which lies on this side of the boundary-line is connected with the conditions of the earth (in a finer way than the plant's connection with the soil through its roots), we shall find, in a really conscious way, the connection between illness and health and the qualities of certain plants.

These things are still in the experimental stage. Man's thinking must first be placed on a sound basis, and then there will also be a sound foundation of knowledge for the conceptions and ideas which he develops, in order that his thinking may regulate, permeate, and give a certain structure to the social, ethical, pedagogic and political aspects of life.

In many realms of knowledge, we perceive that just those people, who in their scientific thought are broad-minded, able experts, begin to romance, to talk absolute nonsense, when they transfer their habitual ideas to the sphere of social life. But the sphere of social life is not an entirely independent sphere. The human being, with his physical soul and spiritual nature, takes his place in social life, and it is not possible to separate these things from one another. We must not content ourselves with the fact that men are made scientifically stupid in the social sphere in order that they may only be able to talk nonsense where the social sphere is concerned!

Today it is quite easy to prove that experienced scientists begin to talk nonsense when they cross the boundary between science and spiritual life. Medical men, especially, are very prone to all kinds of absurdities when they enter the spiritual sphere with the ideas that are gained today in the realm of science. We need not search far afield: any example taken from human life will serve, for wherever we look we shall find confusion in this respect.

For instance, here is a pamphlet by a very good doctor, entitled: “The Injurious Effects of the War upon the Nervous System and Mental Life.” In order not to arouse your prejudice, I will not even say what a good doctor he is. This excellent medical man, however, observed the nervous system, concerning which science has not even a glimmer of a correct idea (this can be realized from the few examples I have given today); he observed to what extent the nervous system has been injured by the present war conditions. We need only consider the most primitive examples, in order to show how really sound thinking ceases when scientific conceptions are transferred to that which is connected, to some extent, with the spiritual sphere—I will not even say, the spiritual sphere itself! The discussion of such a subject as “The Injurious Effects of the War upon the Nervous System and Mental Life” implies the necessity of expressing what is supposed to take place in the nerves, as a result of all kinds of things pertaining to the spiritual (mental) life—naturally, that spiritual life which takes its course on the physical plane—through all kinds of ideas which are taken from this spiritual life.

This man, for instance, brings forward an idea that is supposed to be justified under certain conditions of abnormal life of the nerves, the idea of “over-estimated thoughts.” They are a symptom of diseased nerves. “Over-estimated thoughts”—what does this mean? You see, anyone who brings forward such a conception must make sure that it is really effective in life. What is an over-estimated thought? This doctor says it arises when the feeling, or the sensation, in the thought is emphasized too strongly, when it is a one-sided thought; in fact, he brings forward all kinds of vague ideas. Of course, I cannot give you a precise idea of this, but do not ascribe this lack of a clear definition to spiritual science, for now I am quoting. An over-estimated thought arises, for instance, if one hates a foreign country excessively, owing to the war. A “valued thought” would be real patriotism. But this real patriotism becomes “over-valued” when the nervous system is irritated. One does not only love one's country, but hates the other countries: then the thought has become “over-valued.” The “valued” thought is sound, and from the valued thought one must conclude that the nerves also are sound. But if the thought is over-valued, the nerves are injured. Do we meet reality anywhere, if we characterize, on the one hand a nerve process, and on the other hand a thought which is supposed to have a certain quality? As a thought, it is supposed to be “over-valued”; the nerve process is on one side and the idea “over-valued” on the other. People would do well to think out such things always to the very end, for a thought reveals itself as correct or incorrect, i.e., as real or unreal, only if it is thought to the end. For instance, it would be an over-valued thought if I were to think that I am the King of Spain; undoubtedly this would be an over-valued thought. But it need not be “over-valued” if I really happened to be the King of Spain. In this case my nervous system would be quite sound, although the thought is the same. It has the same content. Hence the thought itself is not over-valued; otherwise we must believe the King of Spain to be afflicted with nerve troubles because he thinks that he is the King of Spain! This is so, is it not? Consequently, this connection is not important, nevertheless there is a great deal of talk about this. There is not only talk: conceptions, definitions, etc., are formed. The results are very strange and not worth more than idle chatter.

You see, now, that this man has formed the idea of over-valued thoughts. The over-valuation of thoughts is a symptom for disturbances in the life of the nerves. Very well. But his sub-consciousness does not feel very much at ease, for sub-consciously he feels that while he is explaining to people all these matters concerning the over-valuation of thoughts, they, too, have all kinds of sub-conscious thoughts, they think there is a flaw in the argument; but this remains, of course, in the sub-consciousness of people, for this person is an “authority”! Hence their impressions must not rise into consciousness , for, with the designation “over-valuation” is expressed not only the vivid and high valuation of the ideas in question, but also their “over-valuation” in connection with the real facts which lie at their foundation. The over-valued thought rules consciousness to such an extent that there is no room beside it for other objective thoughts, which are also justified. The latter are pushed aside and lose their efficacy in consciousness and their influence in bridling and limiting the over-valued thoughts. Thus a one-sided exaggeration arises when judgments are formed, a one-sided tendency in the strivings of the will, and a turning away from all other spheres of thought which are not immediately connected with the center of the over-valued thoughts.

(It is more or less the same thing as arguing that poverty comes from “pauvreté”!)

Certainly, two people may have the same thought substance, but in one case this is Lucifer, in the other case Ahriman, and in a third case it may be in keeping with the normal evolution of humanity. Instead of coining the empty expression “over-valued thoughts,” we must accept the idea of spirituality, such as the luciferic or the ahrimanic spirituality; then we shall know that the important point is to recognize whether a human being wills something out of himself, or whether something else in him wills it. But of course, so-called science still shrinks from such views.

And if we expect real, concrete results from science, things become very amusing! Listen to this:

“First of all, I will define” (he tries to explain himself, because he wishes to show the symptoms of certain nervous disturbances), “first of all, I will define the thoughts that often play the chief role in the nervous disturbances of individuals” (he means also in the modern nationality-mania), “the ideas of despondency, care, fear, lack of courage and of self- confidence.” Very well, these are the things that characterize the nervous system in the life of the nerves that is determined by over-valued thoughts.

Despondency, care, fear, lack of courage and of self-confidence—well, such a lecture is meant to be of help somehow, for this authority does not speak merely to cause vibrations in the air, but because he wishes it to be of use. Hence one would expect this gentleman to tell us how humanity can overcome these handicaps, because he finds, not only in individuals, but also in humanity, lack of courage, care, despondency, lack of self-confidence as symptoms of nervous disturbances; now we should expect him to tell us how to get rid of these things, how to get beyond this lack of courage, care, despondency, lack of self-confidence. One would take this for granted. Indeed he takes it for granted, for he says:

“Thus for a time at least, that discontented, discouraged mood can spread among the great masses of the people, which is to be feared more than anything else. For it leads to the abandonment of strong sound impulses of the will, it loosens the firm, united striving after a goal, and it weakens energy and endurance.”

Now we expect something, and he continues: “Not to be nervous, therefore, means above all courage, confidence, trust in one's own strength, and not swerving from what has been recognized as the right course of action.”

So now we have the conclusion. People are nervous when they are oppressed by care, lack of courage, despondency, lack of self-confidence. How do they get rid of their nervousness? When they are not oppressed by all this! This is quite clear, is it not? When they are not oppressed by all these things!

The worthlessness of thought is carried over into substantiality also in science. Certain authorities have at their disposal all the material, have taken possession of it. It is already confiscated when any attempt is made to work upon it with reason. But when they work upon it themselves, they do so with worthless thoughts. All anatomical, physiological and physical subject matter is consequently lost. Nothing is created, for at the very table where something useful for humanity should be produced, people stand with these worthless thoughts. Certainly nothing can come of the dissection of a corpse, when—forgive the hard expression—an “empty head” dissects. Here already the matter becomes social. Things must be considered from this point of view. And a very promising treatise ends in the manner I have just shown.

I have given you one example. Not be become nervous means above all not to lose courage, confidence and trust. But when today the average reader takes up such a treatise and reads: “The Injurious Effects of the War upon the Nervous System and Mental Life”—and thinks, “here I shall be enlightened, for this is by Professor So-and-so, director of the Medical Hospital in So-and-so.”—well, now he is clear about it, now naturally he is enlightened.

But on page 27, where national hatred is discussed, we read:—“Certainly similar impulses flared up within us, and we found it almost a relief and satisfaction to oppose our greatest enemies with a similar attitude on our side. And yet, only a little quiet consideration is needed to realize that this general national hatred is only the outcome of a diseased, overstimulated attitude of soul, into which the various peoples have fallen through mutually inflaming, inciting and imitating one another.”

How then has the history of national hatred arisen, according to this statement? Here are various peoples: a, b, and c, but neither a, b, nor c is in any way capable of hating, of itself, for the whole history has not arisen thus,—this general national hatred has developed through a diseased, over-stimulated attitude of soul into which the various peoples have fallen through mutually inflaming, inciting and imitating one another. Thus, a cannot bring it about, b also cannot, nor can c; but what each is unable to do, they achieve by mutually provoking one another. Consider how ingenious the thought is. I explain something and have before me a, b, and c. All this is unable to provide an adequate explanation, but does so just the same. I explain something therefore out of nothing at all in the most beautiful manner

People pick up such things and read them without observing that they are simply nonsense.

It is necessary to point out such things for they show how disjointed and worthless the thought is which today assumes authority. Naturally in science, which pertains to what already exists, this does not come to light so strongly and cannot be controlled. But just as people think here in the realm of science, so they also think in social, pedagogical and political life and this has been prepared during the last four centuries. This is the present situation.

So it has come about that gradually out of the disjointed, worthless thought, just such impulses as those which meet us in the present catastrophic events have arisen. Here we must penetrate thoroughly to the roots of the matter. And only when people then come to the surface of things, where the matter becomes actual for the single individual, and may also become so for the social structure of whole peoples, there the matter becomes especially terrible and tragic. It is our task on the one hand to grasp these things, is it not? We must learn to know them within their mutual limits, if we are to understand them. If we wish to understand such an event as the present war, which is so complicated and which unquestionably cannot be grasped in its details from the physical plane, we must—as people say—trace it back to its sources. But everyone believes, when he has traced a matter back to its source, when he has understood it in this manner, that it was a necessity, that it had to happen just as it now is. Today for instance, one does not in the least notice that the one has nothing whatever to do with the other. Because we understand something in its interrelationships, this does not also establish the fact that the event had to take place, that it could not have been omitted. He who tries to make clear to himself, in a more or less intelligent way, why the present war had to come, why it is not something determined by a few people, but something connected with deeper causes in the evolution of humanity—often goes away satisfied and says: Now I understand that nothing else was possible except that this war should come. It is obviously a necessity—in the sense that when we know its causes it develops with absolute necessity out of them, out of these concrete conditions. But this does not mean that we may draw the conclusion that things had to happen just as they have happened. No event arising in world history is necessary in this latter sense. Although in the former sense it is necessary, no event is necessary in this latter sense. Each event might have been different, and each might not have happened at all.

He who speaks of absolute necessity might reflect with the same right: I should like to know when I shall die. Now if I go to a life insurance company, they reckon out—determining the amount of the insurance policies accordingly—how many people out of a certain number have died in a given length of time and how many still live. The insurance money is paid accordingly. I go to a life insurance company for information and it must appear from their calculations whether I shall be dead or not in 1922.

This is naturally complete nonsense. But it is exactly the same nonsense when we try to derive the necessity of one event from another, from the realization of the cause that must lead to it. Here I touch upon a theme which indeed is not easy, for the reason that just in this sphere the most disjointed ideas are prevalent, because very little will to become clear about things exists in this realm today.

If we really wish to be clear on this point, we must recognize that when something takes place, it does so under the influence of certain conditions. In the sequence of circumstances we always come to a certain point where there are beginnings—real beginnings. If today we see a sapling that is still small, later on it will become larger; the largeness of the tree develops of necessity from its smallness. After a short time we may say: It is a necessity that this tree has developed thus. I could see how it developed according to necessity when it was still very small, perhaps while it was unfolding its very first germinating forces out of the earth. If I am a botanist I can see that in time a large tree must of necessity arise. But if the seed had not fallen into the earth at this particular spot—perhaps someone planted it there, but if he had not done so—then here would be a point where necessity would not have been introduced. For necessity must begin here. We have before us a mighty oak, let us say—it is not here in reality—we look at it and admire it; it was once naturally a sapling and has grown from this sapling, according to necessity. But now imagine that a good-for-nothing boy (or girl!) had come along while it was still very small and pulled it up. Because it is pulled up, the whole necessity does not result. In a negative sense also the necessity may be done away with. Starting points, where necessities begin, these reveal themselves to the thought that conforms to reality. This is the essential point.

But we do not reach these starting points when we observe merely the outer course of events. We reach them only when we can at least feel the spiritual foundations. For just as you have here a bunch of roses, and when you form a concept of it, if you are an abstract person, an idea will result which is a copy of the reality (for the bunch of roses is real and the idea of it is a copy of reality)—so for the occultist the bunch of roses is not a reality at all when he conceives it, because the bunch of roses does not exist; the roses can only exist when with their roots they are connected with the earth. The real concept does not result when we form an image of something that is from the outset external, but only when we have formed out of the reality this fully experienced concept. But this fully experienced concept yields itself only to spiritual-scientific contemplation—even in the case of outer sense reality.

A valid concept of a world-historical event is only reached when we can view this event according to the methods of spiritual science. Here we find that it may indeed be traced in regard to its necessity; we find its ramifications, its roots within reality. But something is accomplished only by actually tracing the roots, not by the general statement of an abstract necessity.

Had, for instance, certain events during the eighties of the nineteenth century been different, the events in 1914 would also have been different. But this is just the important point, not to proceed as the historian does, who says: What now takes place is the effect of preceding events, these are in turn the effect of preceding events, which are the effect of still other events, etc. We come thus not only to the beginning of the world, but still farther, into cornplete nothingness. One such idea rolls along behind the other. This, however, is not the important point, but we must follow the matter concretely to where it first took root. Just as the root of a plant begins somewhere, so also do events. Seeds are sown in the course of time. If the seeds are not sown, then the events do not arise. I have touched upon a theme here that I naturally cannot exhaust today. We will have more to say later on this subject that I will describe essentially thus: “In spite of all considerations of necessity, there is not a single event which is absolutely necessary.”

It is really essential that men of the present day should, in their whole attitude of mind, emerge from this frightful dogmatism that permeates modern science, and that matters should be [taken] seriously.

I will give you a good example. At Zurich and Basle I endeavored to explain what nonsense it is to consider a sequence of historical events in such a way that one event must necessarily arise from another. This is the same as if I said: Here is a light that illumines first an object a, then an object b, then an object c. I do not notice the light itself, but merely the fact that first a, then b, then c in turn becomes illumined. I should be mistaken if, on seeing a and then b illumined, I were to say that b is lighted from a, and when I see that c is illumined, I were then to say: c is lighted from b. This would be quite incorrect, for the illumination of b and c have nothing to do with a; they all receive light from a common source. I gave this example in my lectures in order to explain historical events.

Now suppose that somebody found this idea quite a nice one. This is possible, is it not, that an idea which has sprung up on anthroposophical soil should be found quite good? Indeed, here and there even our opponents have taken such ideas to use for themselves. Many indeed have become opponents because such things had to be censured. Thus it is quite possible that an analogy brought forward from an anthroposophical quarter should not be absolutely foolish. Suppose some person took it and used it in a connection differing from that in which I had used it. Suppose that he used it dogmatically, not symptomatically as I did. Suppose that he used it from quite a different attitude of mind, and that I heard a lecture in which he said: “The sequence of cause and effect is quite wrongly explained by saying that effect b is the result of cause a, effect c of cause b, for this would be the same as saying: ‘When three objects, a, b, and c, are illumined, then b is illumined by a, c by b’.”

Suppose I am listening to all this, and that the explanation is not given in the same connection in which I spoke at Basle and Zurich, then I should perhaps object to the lecturer's conclusions, arising from his connection. I should perhaps say: “Supposing that a, b and c are luminescent substances—there are such substances; when exposed to light they become luminous and can give light even when the source of light is removed—suppose that a, being luminescent, actually illumines b, and that b, being luminescent, illumines c, then b would in truth be lighted by a, and c by b. In this way the whole analogy can become very brittle, when it is used by someone who, in the course of his lecture, has not explained that concepts for the realities in the spiritual life are like photographs, which differ when taken from different points of view. If this is not said at the outset, if the lecturer does not lead up to ideas that conform to reality, so that these ideas are always ideas from a certain point of view, then what has been said quite rightly from a certain perspective may become nonsense when used in an absolute sense.

The difference lies in this: Does the speaker start from reality or ideas? If from the latter, he will always be one-sided. If he takes as his starting point reality—since he can only bring forward ideas and nothing else, and every idea is one-sided—he may and must produce one-sided ideas, for that is quite obvious. You will now understand that a complete, a fundamental alteration of the soul-life is essential. For this reason it is easy for people to criticize many ideas of which I am the author. I do not know if anyone has hit upon this particular criticism. I have myself already made all the criticisms that are necessary.

Men must now realize in what way the idea is related to the reality. Only then shall we be able to penetrate into reality. Otherwise we shall always quarrel about ideas. Today the whole world is fighting about ideas in the social sphere, even when this fight has been transformed into external deeds. The fight about ideas changes very frequently into external deeds. These things lead into the intimacies of the spiritual life. Those who would understand existence must reflect on such things.

I have called your attention to these matters today in a more theoretical way. Next time I will speak of contemporary history from this standpoint and will show how far certain events have been necessary, and how far they were quite unnecessary, how quite different events might have happened, and how the catastrophes under which we all suffer need not have happened at all. We shall speak of these important questions in the next lecture.

Erster Vortrag

Wir werden heute fortfahren, einiges hinzuzutragen zu den Betrachtungen, die wir angestellt haben. Es war mir in dieser Zeit viel darum zu tun, begreiflich zu machen, von welchen Bedingungen das menschliche Leben abhängt im einzelnen und in dem großen Zusammenhange. Sie haben gesehen, wie auch in den öffentlichen Vorträgen, die ich in dieser Zeit halten durfte, es mir darauf ankam, gerade jetzt auf diejenigen Probleme der Geisteswissenschaft hinzuweisen, welche für das Begreifen der Menschheit notwendig sind, um aus gewissen Vorstellungskreisen herauszukommen, in die sich die Menschheit gewissermaßen über den ganzen Erdkreis hin eingesponnen hat und die letzten Endes doch mit zu den Veranlassungen der jetzigen katastrophalen Ereignisse gehören.

Vor allen Dingen wird es sich darum handeln, daß die Menschen einsehen lernen müssen, wo die Grenze zwischen der sogenannten physischen und der geistigen Welt liegt. Diese Grenze liegt eigentlich mitten im Menschen drinnen. Gerade dieser Satz ist wichtig für das Verständnis der Welt: daß wir die Grenze zwischen der physischen und geistigen Welt in dem Menschen selber drinnen sehen. Die naturwissenschaftliche Denkungsweise, deren große Bedeutung für die Gegenwart und die Zukunft ich vom Gesichtspunkt der Geisteswissenschaft oftmals hervorgehoben habe, ist aber jetzt, wo sie noch mehr oder weniger immer an ihrem Ausgangspunkte steht, eigentlich dazu geeignet, über gewisse wichtige Lebenswahrheiten, man könnte schon sagen, zunächst sogar Finsternis zu verbreiten.

Machen wir uns nur klar, daß sich die Zeitentwickelung eigentlich heute erst dazu anschickt, das naturwissenschaftliche Denken allmählich in die Welt- und Lebensanschauungen ganz einzuführen. Heute beschäftigen sich — in einer oftmals haarsträubend dilettantischen Weise — gewisse Monisten- oder andere Vereine damit, naturwissenschaftliche Weltanschauung dem Allgemeinbewußtsein zuzuführen. Allein dies ist ja nur der eine Weg, durch den allmählich dieses naturwissenschaftliche Denken in die Menschenseele fließt. Der viel wirksamere, einschneidendere Weg ist der durch die Publizistik.

Nicht umsonst, sondern durchaus innerlich zusammengehörig fallen in die Menschheitsentwickelung der Einschnitt der neueren naturwissenschaftlichen Denkungsweise und die Erfindung der Buchdruckerkunst zusammen. Denn dasjenige, was bisher durch den Druck als Ursprüngliches in die Menschheit eingegangen ist, selbstverständlich abgesehen von dem, was man von früher schon Dagewesenem gedruckt hat, ist im wesentlichen aus naturwissenschaftlichem Bewußtsein hervorgegangen. Ich meine, das Neue ist aus naturwissenschaftlichem Bewußtsein hervorgegangen, und vor allen Dingen die Art und Weise, in die man die Gedanken eingefangen hat, ist aus naturwissenschaftlicher Denkweise hervorgegangen.

Nun werden natürlich Theologen gegenüber einem solchen Ausspruch sagen: Ja, haben wir denn nicht auch unsere theologische Weisheit und alle möglichen frommen Dinge in den letzten Jahren und Jahrzehnten und Jahrhunderten gedruckt? — Ja, das ist allerdings wahr, aber wozu hat es geführt? Diese Art und Weise, wie unter der Flagge des Druckes das geistige Leben sich eingelebt hat in die Seelen der Menschen, hat dazu geführt, daß nach und nach ganz geschwunden ist auch aus dem Gebiete des religiösen Bewußtseins das spirituelle Element. Und selbst aus dem Christus Jesus, das wissen Sie ja, hat man unter dem Einfluß der naturwissenschaftlichen Denkweise den «schlichten Mann aus Nazareth» gemacht, den man zwar versucht in der verschiedensten Weise zu charakterisieren, der aber doch eigentlich schon dabei angelangt ist, mit den andern großen Persönlichkeiten der Welt in eine Linie gestellt zu werden, wenn auch vorläufig noch auf einem besonderen Gipfel. Das eigentlich Geistige, das mit dem Mysterium von Golgatha verknüpft ist, das ist nach und nach dahingeschwunden, wenigstens für diejenigen, die da glauben, mit der Zeitenbildung vorwärtsgeschritten zu sein.

Ich sagte, die naturwissenschaftliche Denkweise hat zunächst geradezu mitwirken müssen zu einer gewissen Verfinsterung, zu einer Unterstützung desjenigen, was nun seit 1879 durch die Geister der Finsternis in das menschliche Denken hineingebracht werden soll. Und auf naturwissenschaftlichem Gebiete zeigt sich die Sache in einer recht raffinierten Art, raffiniert deshalb, weil der naturwissenschaftlich nicht nur Durchgebildete, sondern der naturwissenschaftlich fachmännisch Gebildete, wenn er heute mitarbeitet an der allgemeinen Bildung der Zeit, an der Gestaltung der Weltanschauung, gar nicht anders kann, so wie heute die Wissenschaft einmal ist — lassen Sie mich das triviale Wort anwenden -, als «aus bestem Wissen und Gewissen heraus» so zu wirken, daß durch die Popularisierung der naturwissenschaftlichen Denkweise der Mensch geradezu abgebracht wird davon, den Blick hinwerfen zu können auf die Grenze, die in ihm selber ist zwischen der physischen Welt und der geistigen Welt. Es wird eine Zukunft des Menschendenkens anbrechen, es ist fürchterlich, daß dies heute gesagt werden muß, fürchterlich für die nach einer gewissen Richtung heute Gebildeten, da werden gewisse Vorstellungen, die heute in der Wissenschaft herrschen — und die zwar nicht im populären Bewußtsein sehr vorhanden sind, aber auf das populäre Bewußtsein dadurch wirken, daß man heute die Wissenschafter als, verzeihen Sie, Autoritäten ansieht -, gewisse Vorstellungen der Gegenwart werden vor einem künftigen Zeitbewußtsein geradezu komisch anmuten müssen.

Auf eine Vorstellung habe ich öfters hingewiesen, öffentlich nun auch in meinem Buch «Von Seelenrätseln»: Es ist eine gangbare naturwissenschaftliche Vorstellung heute, daß man im Nervensystem - bleiben wir zunächst beim Menschen, aber in ähnlicher Weise, nur in ähnlicher Weise ist das auch beim Tiere gültig -, daß man im Nervensystem unterscheidet zwischen den sogenannten sensiblen, sensitiven Nerven — Sinnesnerven, Wahrnehmungsnerven - und motorischen Nerven. Schematisch kann das nur so dargestellt werden, daß zum Beispiel irgendein Nerv, sagen wir ein Tastnerv, die Tastempfindung hineinträgt bis zum Zentralorgan, sagen wir bis zum Rückenmark; da mündet dasjenige, was da aus der Peripherie des Leibes geleitet wird, in einem Horn des Rükkenmarks. Und dann geht von einem andern Horn, Vorderhorn, der sogenannte motorische Nerv aus, da wird wiederum weitergeleitet der Willensimpuls (siehe Zeichnung S. 12).

Beim Gehirn ist das nur komplizierter dargestellt, so etwa, wie wenn die Nerven eine Art Telegraphendrähte wären. Der Sinneseindruck, der Hauteindruck wird bis zum Zentralorgan geleitet, dort wird gewissermaßen der Befehl erteilt, daß eine Bewegung ausgeführt werden soll. Eine Fliege setzt sich irgendwo auf einen Körperteil, das macht einen Eindruck, das wird geleitet bis zum Zentralorgan; dort wird der Befehl gegeben, die Hand bis zu der Stelle zu erheben und die Fliege wird weggejagt. Es ist eine, schematisch angedeutet, sehr gangbare Vorstellung. Künftigen Zeiten wird diese Vorstellung außerordentlich komisch erscheinen, denn sie ist ja nur komisch für denjenigen, der die Tatsachen durchschaut. Aber es ist eine Vorstellung, von der heute ein großer Teil der fachmännischen und fachmännischesten Wissenschaft beherrscht ist. Sie können das nächstbeste Elementarbuch, das Sie über solche Dinge unterrichtet, aufschlagen, und Sie werden finden, man habe zu unterscheiden zwischen Sinneswahrnehmungsnerven und motorischen Nerven. Und man wird besonders das urkomische Bild von den Telegraphenleitungen — wie der Eindruck bis zum Zentralorgan geleitet und dort der Befehl gegeben wird, daß die Bewegung entstehe gerade in populären Werken heute noch immer sehr verbreitet finden können.

Die Wirklichkeit ist allerdings schwieriger zu durchschauen, als die an die primitivsten Vorstellungen erinnernden Vergleichsvorstellungen von den Telegraphendrähten. Die Wirklichkeit kann nur durchschaut werden, wenn sie eben mit Geisteswissenschaft durchschaut wird. Daß ein Willensimpuls erfolgt, hat mit einem solchen Vorgange, den man in kindischer Weise so ausdrückt, als ob da irgendwo in einem materiellen Zentralorgan ein Befehl erteilt würde, wirklich gar nichts zu tun. Die Nerven sind nur da, um einer einheitlichen Funktion zu dienen, sowohl diejenigen Nerven, die man heute sensitive Nerven nennt, wie auch diejenigen, die man motorische Nerven nennt. Und ob nun im Rückenmark oder im Gehirn der Nervenstrang durchbrochen ist, beides weist auf dasselbe hin; im Gehirn ist er nur in komplizierterer Weise durchbrochen.

Diese Durchbrechung ist nicht deshalb da, damit durch die eine Hälfte, wenn ich so sagen darf, von der Außenwelt etwas zum Zentralorgan geleitet wird und dann vom Zentralorgan durch die andere Hälfte, nachdem sie in einen Willen umgewandelt worden ist, weitergeleitet würde. Diese Unterbrechung ist aus einem ganz andern Grunde da. Daß wir unser Nervensystem so gebaut haben, daß es in dieser Regelmäßigkeit durchbrochen ist, hat seinen Grund darin: An der Stelle, wo unsere Nerven durchbrochen sind, da liegt im Abbilde im Menschen allerdings nur im körperlichen Abbilde einer komplizierten geistigen Wirklichkeit — die Grenze zwischen physischem und geistigem Erfahren, physischem und geistigem Erleben. Sie ist allerdings im Menschen auf eine merkwürdige Weise enthalten. Sie ist so enthalten, daß der Mensch mit der ihm zunächstliegenden physischen Welt in eine solche Beziehung tritt, daß mit dieser Beziehung der Teil des Nervenstranges, der bis zu jener Unterbrechung geht, etwas zu tun hat. Aber der Mensch muß auch als seelisches Wesen eine Beziehung haben zu seinem eigenen physischen Leib. Diese Beziehung, die er zu seinem eigenen physischen Leib hat, ist durch den andern Teil vermittelt. Wenn ich eine Hand bewege, dadurch veranlaßt, daß ein äußerer Sinneseindruck auf mich gemacht worden ist, dann liegt der Impuls, daß diese Hand bewegt wird, vereinigt von der Seele mit dem Sinneseindruck, schematisch dargestellt, schon bereits hier (siehe Zeichnung, a). Und dasjenige, was geleitet wird, wird auf den ganzen sensitiven Nerven und den sogenannten motorischen Nerven entlang geleitet von a bis zu b. Das ist nicht so, daß der Sinneseindruck erst bis zu c geht und dann von da aus ein Befehl geht, damit b dazu veranlaßt werde - nein, wenn ein Willensimpuls stattfindet, lebt das Seelische schon völlig bei a und geht durch den ganzen unterbrochenen Nervenweg durch.

Es ist keine Rede davon, daß solche kindische Vorstellung, als ob die Seele da irgendwo säße zwischen den sensitiven und motorischen Nerven und wie ein Telegraphist die Eindrücke der Außenwelt empfangen und dann den Befehl aussenden würde, es ist keine Rede davon, daß diese kindische Vorstellung irgendeiner auch wie immer gearteten Wirklichkeit entsprechen würde. Diese kindische Vorstellung, die wir immer hören, nimmt sich recht sonderbar komisch aus neben der Forderung, man solle ja in der Naturwissenschaft nicht anthropomorphistisch sein! Da fordern nun die Leute, man solle ja nicht anthropomorphistisch sein und merken nicht, wie anthropomorphistisch sie sind, wenn sie Worte gebrauchen wie: Ein Eindruck wird empfangen, ein Befehl wird ausgegeben und so weiter. - Sie reden darauf los, ohne auch nur eine Ahnung davon zu haben, was sie alles für mythologische Wesen — wenn sie die Worte ernst nehmen würden — hineinträumen in den menschlichen Organismus.

Nun entsteht aber die Frage: Warum ist der Nervenstrang unterbrochen? — Er ist unterbrochen aus dem Grunde, weil wir, wenn er nicht unterbrochen wäre, nicht eingeschaltet wären in den ganzen Vorgang. Nur dadurch, daß gewissermaßen der Impuls hier an der Unterbrechungsstelle überspringt - der gleiche Impuls, wenn es ein Willensimpuls ist, geht schon von a aus -, dadurch sind wir selbst drinnen in der Welt, dadurch sind wir bei diesem Impuls dabei. Würde er einheitlich sein, würde hier nicht eine Unterbrechung sein, so wäre das ganze ein Naturvorgang, ohne daß wir dabei wären.

Stellen Sie sich denselben Vorgang, den Sie bei einer sogenannten Reflexbewegung haben, vor: Eine Fliege setzt sich Ihnen irgendwo hin, der ganze Vorgang kommt Ihnen gar nicht voll zum Bewußtsein, aber Sie wehren die Fliege ab. Dieser ganze Vorgang hat sein Analogon, sein ganz gerechtfertigtes Analogon auf physikalischem Gebiete. Insofern dieser Vorgang physikalische Erklärung herausfordert, muß diese Erklärung nur etwas komplizierter sein als ein anderer physikalischer Vorgang. Nehmen Sie an, Sie haben hier einen Kautschukball, Sie stoßen hinein, Sie deformieren den Kautschukball: das geht wieder heraus, richtet sich wieder her. Sie stoßen nochmals hinein; er stößt wieder heraus. Das ist der einfache physikalische Vorgang: eine Reflexbewegung. Nur ist kein Wahrnehmungsorgan eingeschaltet, nichts Geistiges ist eingeschaltet. Schalten Sie hier etwas Geistiges ein (innerer Kreis) und unterbrechen Sie hier (Zentrum), dann fühlt sich die Kautschukkugel als ein Eigenwesen. Die Kautschukkugel müßte dann allerdings, um sowohl die Welt wie sich zu empfinden, ein Nervensystem einschalten. Aber das Nervensystem ist immer da, um die Welt in sich zu empfinden, niemals irgendwie da, um auf der einen Seite des Drahtes eine Sensation zu leiten und auf der andern Seite des Drahtes einen motorischen Impuls zu leiten.

Ich deute dieses an aus dem Grunde, weil dies, wenn es weiter verfolgt wird, auf einen der zahlreichen Punkte hinführt, wo Naturwissenschaft korrigiert werden muß, wenn sie zu Vorstellungen führen soll, die einigermaßen der Wirklichkeit gewachsen sind. Die Vorstellungen, die heute herrschen, sind eben weiter nichts als solche Vorstellungen, die den Impulsen der Geister der Finsternis dienen. Im Menschen selber ist die Grenze zwischen dem physischen Erleben und dem geistigen Erleben.

Dieses Stück des Nervs, das ich rot gezeichnet habe (Abb. S.12), dient im wesentlichen dazu, um uns hineinzustellen in die physische Welt, um uns Empfindung zu vermitteln innerhalb der physischen Welt. Das andere Stück des Nervs, das ich blau bezeichnet habe, dient im wesentlichen dazu, um uns selbst uns empfinden zu lassen als Leib. Und es ist kein wesentlicher Unterschied, ob wir eine Farbe außen bewußt erleben durch den Strang a-c, oder ob wir innerlich ein Organ oder eine Organlage oder dergleichen erleben durch den Strang d-b; das ist im wesentlichen dasselbe. Das eine Mal erleben wir ein Physisches, das nicht in uns zu sein scheint, das andere Mal erleben wir ein Physisches, das in uns ist, das heißt innerhalb unserer Haut. Dadurch aber sind wir eingeschaltet, daß wir bei einem Willensvorgang alles das erleben können, was nicht nur außen ist, sondern auch was innerlich an uns ist. Aber die Stärke der Wahrnehmung ist verschieden vermittelt durch den Strang a-c und durch den Strang d-b. Dasjenige, was eintritt, ist allerdings eine wesentliche Abschwächung der Intensität. Wenn wir eine Vorstellung mit einem Willensimpuls zusammen formen in a, so wird dieser Impuls von a aus weitergeleitet. Indem er von c auf d überspringt, schwächt sich das Ganze so ab für unser Bewußtsein, für unser bewußtes Erleben, daß wir das weitere, was wir nun in uns erleben, die Hebung der Hand und so weiter, nur mit der geringen Intensität des Bewußtseins erleben, die wir sonst auch im Schlafe haben. Wir sehen das Wollen erst wiederum, wenn die Hand sich bewegt, wenn wir wieder von einer andern Seite her eine Sensation haben.

Der Schlaf dehnt sich in der Tat anatomisch, physiologisch in das wache Leben fortwährend hinein. Wir stehen mit der äußeren physischen Welt in Verbindung und wachen eigentlich immer nur mit demjenigen Teil unseres Wesens, welcher bis zu der Unterbrechung der Nerven geht. Was jenseits der Unterbrechung der Nerven in uns selber liegt, das verschlafen wir auch am Tage. Das ist aber ein Vorgang, der noch nicht physisch ist in der jetzigen Phase der Erdenentwickelung, sondern noch in einer gewissen geistigen Höhe vor sich geht, wenn das auch vielfach zu tun hat mit den niederen Eigenschaften der Menschennatur. Aber ich habe hier schon öfter von dem Geheimnis gesprochen, daß, was im Menschen niedere Natur ist, gerade zusammenhängt mit den höheren Äußerungen gewisser geistiger Wesenheiten.

Würde man im Menschen alle diejenigen Stellen sammeln, wo Nervenunterbrechungen sind, und würde man das aufzeichnen, dann würde man zeichnungsgemäß die Grenze bekommen zwischen dem Erleben in der physischen Welt und dem Erleben aus einer höheren Welt heraus. Daher kann ich auch folgendes Schema gebrauchen. Nehmen Sie einmal an - ich zeichne hier alle Nervenunterbrechungen schematisch auf —, nehmen Sie an, da wäre der Kopf und da wäre ein Bein. Nun nehmen wir an, von hier aus ginge ein sogenannter Eindruck, und hier wäre die Nervenunterbrechungsstelle «Gehen» erfolgt. Was real ist, ist dann dieses: hier ist alles dasjenige, was der Mensch durch den Nerv erlebt, wachend bei Tag erlebt; hier ist das, was der Mensch erlebt als einen unterbewußten Willen, auch im Wachen schlafend erlebt. Und alles dasjenige, was nun unter der Nervenunterbrechungsstelle liegt, wird von der geistigen Welt heraus direkt gebildet, geschaffen.

Die Vorstellungen werden Ihnen, wenn Sie sie das erste Mal hören, vielleicht etwas schwierig sein. Allein sie sollen in Ihnen auch die Vorstellung hervorrufen, daß man ohne gewisse Schwierigkeiten in die intimeren Dinge der Erkenntnis des Menschen doch nicht hineinkommen kann.

Wenn Sie das so ansehen, daß hier (rot) alles dasjenige ist, was den Menschen mit der physischen Welt verbindet, unter dieser Grenze alles dasjenige, was den Menschen mit einer geistigen Welt verbindet, die nur heute ein untergeordnetes physisches Abbild hat in ihm — wenn Sie dies ins Auge fassen, dann können Sie eine andere Vorstellung damit verbinden. Diese andere Vorstellung, die Sie damit verbinden sollen, ist die folgende: Denken Sie sich einmal die Pflanzenwelt. Die Pflanzen wachsen aus der Erde heraus; aber sie würden nicht aus der Erde herauswachsen, wenn sie nicht aus dem Kosmos herein Kräfte empfingen, Kräfte, die mit dem Sonnenleben innig zusammenhängen, welche alles das in Empfang nehmen, was von der Erde heraus gekraftet wird. Lesen Sie, um das besser zu verstehen, noch einmal die Abhandlung über «Das menschliche Leben vom Gesichtspunkte der Geisteswissenschaft». Zum Leben der Pflanzenwelt gehört dieses ganze Kosmische, das von dem Kosmos herein vom Sonnenleben kommt, zusammen mit dem, was von der Erde herauf kommt.

Dieses Zusammenwirken aber des Kosmischen mit demjenigen, was tellurisch, was irdisch ist, das gehört überhaupt zum Leben, zum Dasein innerhalb der physischen Welt, so wie wir sie aufzufassen haben. Und dieselben Kräfte, die unter diesem Strich (siehe Zeichnung) aus der Erde heraus auf die Pflanze wirken, zusammen mit der Samenkraft der Pflanze - der Same wird ja auch in die Erde hineingetan -, diese selbe Masse von Kräften derselben Art, die müssen Sie hier suchen, hier, wo die roten Striche sind. Diesseits der Grenze, die ich schematisch angedeutet habe, müssen Sie meinetwillen die Kräfte suchen, die Sie sonst durch die Wurzeln von der Erde kommend für die Pflanzen suchen.

Der Mensch nimmt durch seine Augen, durch seine Ohren, namentlich durch seine Haut, von der Erde in verfeinerter Art dasjenige auf, was die Pflanze durch ihre Wurzeln aus dem Boden der Erde aufsaugt. Die Pflanze ist ein Erdenwesen durch ihre Wurzeln. Der Mensch ist ein Erdenwesen durch seine Nerven und durch dasjenige, was er als das Irdische, das Tellurische aufnimmt durch seine Lungen, durch seine Nahrung, die er von der Erde hereinbekommt. Alles das, was für die Pflanze von der Erde kommt - nur daß die Pflanze die Wurzeln in die Erde hineinversenkt -, nimmt der Mensch auf durch seine Organe, nur daß er das in verfeinerter Weise aufnimmt, die Pflanze gröber durch die Wurzeln.

Aber die Pflanze nimmt noch andereKräfte auf. Die Pflanze nimmt die Kräfte auf, welche ihr aus dem Sonnenreiche, aus dem himmlischen Reiche - räumlich-himmlischen Reiche -, aus dem Kosmos zukommen. Dieses Gebiet habe ich blau schraffiert: das sind die Kräfte, welche die Pflanze aus dem Kosmos aufnimmt. Diese Kräfte sind von derselben Art, wie die blau schraffierten Kräfte jenseits der Grenze, die ich angegeben habe. Der Mensch zieht aus seinem Leibe heraus das, was die Pflanze aus dem Kosmos hereinzieht. Von der Erde zieht der Mensch verfeinert diejenigen Kräfte und Substanzen, welche die Pflanze durch ihre Wurzeln vergröbert aus dem Boden zieht. Aus seinem Leibe heraus zieht der Mensch dieselben Kräfte und Substanzen vergröbert, welche die Pflanze verfeinert aus dem Kosmos zieht. Denn so, wie er sie heute aus dem eigenen Leibe herauszieht, so sind sie nicht als Kräfte unmittelbar gegenwärtig im Kosmos vorhanden, sondern sie sind so vorhanden gewesen während der alten Mondenzeit. Von dieser hat sie der Mensch bewahrt. Der Mensch nimmt durch das, was jenseits dieser Grenze im hier gezeichneten blauen Teile enthalten ist, nicht unmittelbar aus der Gegenwart wahr, sondern aus dem, was er durch die Erbschaft der alten Mondenzeit bewahrt hat. Er hat das Kosmische einer alten Zeit in die Gegenwart hereingetragen. In seinem Leib hat der Mensch die Mondenverhältnisse aufbewahrt. Und so sehen Sie, daß wir in einer gewissen Weise kosmisch sind; sogar so mit dem Kosmos zusammenhängen, daß wir in uns tragen ein Abbild desjenigen, was der Kosmos draußen schon überwunden hat.

Wiederum ein Beispiel für das, was ich das letzte Mal hier angeschlagen habe: daß nichts dienlich sein wird, wenn man nur so vom allgemeinen, verschwommenen, nebelnden Standpunkte aus davon redet, daß der Mensch wiederum ein kosmisches Empfinden oder kosmische Vorstellungen in sich aufnehmen müsse. Diese Dinge haben nur Wert, wenn sie völlig konkret an den Menschen herantreten, wenn wirklich gewußt wird, wie die Dinge liegen, wie sich die Dinge verhalten. Dadurch wird dasjenige, was heute nur ein Probieren ist, eben auf eine gesunde, wirkliche gesunde Grundlage gestellt. Und wenn man weiß, wie alles das, was jenseits der Nervenunterbrechungen im Innern des menschlichen Leibes liegt, mit dem mondartigen Wesen zusammenhängt, dann wird man herausfinden können aus den Verwandtschaften heraus, welche krankmachenden oder heilenden Kräfte im Kosmos und im Erdenleben zu finden sind. Und wenn man wissen wird, in welcher Weise das, was diesseits der Grenze liegt, so zusammenhängt mit den Erdenverhältnissen, nur im verfeinerten Sinne, wie die Pflanze durch ihre Wurzeln mit den Bodenverhältnissen zusammenhängt, dann wird man die Beziehung zwischen Krankheit und Gesundheit und zwischen dem Wesen gewisser Pflanzen wirklich in bewußter Art auffinden können.

Heute sind die Dinge ein Probieren. Auf gesunde Grundlage muß zuerst das menschliche Erkennen gestellt werden, und dann wird auf gesunde Grundlage auch gestellt werden können, was der Mensch an Begriffen und Vorstellungen entwickelt, um das soziale, das sittliche, das pädagogische, das politische Leben irgendwie mit seinen eigenen Vorstellungen zu regeln, durchdringen zu können, ihm eine Struktur verleihen zu können.

Wir machen auf vielen Gebieten die Wahrnehmung, daß gerade diejenigen, die naturwissenschaftlich groß, fachmännisch gediegen denken, ganz gräßlich zu fabulieren, zu schwätzen anfangen, wenn sie ihre gewohnten Vorstellungen übertragen auf das Gebiet des sozialen Lebens. Aber dieses Gebiet des sozialen Lebens ist ja nicht ein ganz selbständiges Gebiet. Der Mensch steht darinnen mit seiner physischen, seelischen, geistigen Natur, und man kann die Dinge nicht voneinander trennen. Und es darf nicht bei der Tatsache bleiben, daß die Menschheit auf dem sozialen Gebiet naturwissenschaftlich dumm gemacht wird, damit sie auf dem sozialen Gebiet nur zu schwätzen vermag.

Man kann heute ohne Schwierigkeit leicht nachweisen, wie gediegene Naturforscher ins Schwätzen hineinkommen, wenn sie die Grenze zwischen Naturwissenschaft und dem geistigen Leben überschreiten. Besonders Mediziner sind auf diesem Gebiet außerordentlich produktiv im Hervorbringen von allerlei Geschwätz, wenn es sich darum handelt, mit den Vorstellungen, die auf naturwissenschaftlichem Gebiete heute gewonnen werden, ins geistige Gebiet herüberzugehen. Man braucht nur irgend etwas herauszugreifen. Greift nur hinein ins volle Menschenleben - wo ihr es nur anfaßt, ist es in dieser Beziehung heute konfus.

Da habe ich zum Beispiel eine Broschüre: «Die Schädigungen der Nerven und des geistigen Lebens durch den Krieg», von einem ausgezeichneten Mediziner. Ich will gar nicht, um Ihr Vorurteil nicht zu erregen, sagen von einem wie ausgezeichneten Mediziner. Aber dieser ausgezeichnete Mediziner, er betrachtete nun dieses Nervensystem, über das die Naturwissenschaft ja eigentlich nicht einmal einen Schimmer von einer richtigen Vorstellung hat - nach den paar Andeutungen, die ich heute gegeben habe, können Sie das sehen -, er betrachtete nun dieses Nervensystem, wie es malträtiert wird durch die gegenwärtigen Kriegsverhältnisse. Ja, man braucht nur an das Allerprimitivste zu denken und man kann darauf hinweisen, wie das wirklich vernünftige Denken aufhört, wenn herübergeleitet werden die naturwissenschaftlichen Vorstellungen auf das, was mit dem geistigen Gebiete, ich will nur sagen, etwas zu tun hat, gar nicht einmal noch das geistige Gebiet selber ist. Nicht wahr, wenn man so etwas bespricht wie «Die Schädigungen der Nerven und des geistigen Lebens durch den Krieg», dann hat man die Notwendigkeit vor sich, dasjenige, was angeblich in den Nerven vor sich gehen soll, auszudrücken durch allerlei vom geistigen Leben Entnommenem - natürlich von dem geistigen Leben, das hier auf dem physischen Plane verläuft -, durch allerlei Vorstellungen, die diesem geistigen Leben entnommen sind.

Nun gibt zum Beispiel dieser Herr hier die Vorstellung - die unter gewissen Verhältnissen des abnormen Nervenlebens berechtigt sein soll -, die Vorstellung von «überwertigen Ideen». Überwertige Ideen sind ein Symptom für kranke Nerven. Überwertige Ideen - was ist eine überwertige Idee? Wenn man einen solchen Begriff aufstellt, dann muß man sich klar sein, daß ein solcher Begriff lebenswirklich sein muß. Aber was ist eine überwertige Idee? Eine überwertige Idee ist für jenen Mann etwas, das entsteht, wenn die Empfindungs- und Gefühlsbetonung der Idee zu stark ist, wenn sie einseitig ist. Allerlei so vage Vorstellungen bringt er eben heran. Ich kann Ihnen natürlich keine bestimmte Vorstellung davon geben. Schreiben Sie, wenn ich das nicht bestimmt definiere, es nicht der Geisteswissenschaft zu, denn ich muß ja referieren. Eine überwertige Idee entsteht zum Beispiel, wenn man, durch den Krieg veranlaßt, eine fremde Nation zu viel haßt. Eine «wertige Idee» ist die richtige Vaterlandsliebe. Aber diese richtige Vaterlandsliebe wird, wenn das Nervensystem irritiert ist, überwertig. Man liebt nicht nur sein Vaterland, sondern man haßt die andern Völker: jetzt ist dieIdee überwertig geworden. Die wertige Idee ist gesund, und man muß aus der wertigen Idee schließen, daß auch die Nerven gesund sind. Wenn aber die Idee überwertig ist, so sind auch die Nerven geschädigt.

Trifft man irgendwo die Wirklichkeit, wenn man auf der einen Seite so einen Nervenvorgang charakterisiert, auf der andern Seite eine Idee, die nun eine gewisse Eigenschaft haben soll? Sie soll überwertig als Idee sein. Auf der einen Seite ist der Nervenvorgang, auf der andern Seite ist Ideeüberwertiges. Die Leute würden gut tun, solche Dinge immer zu Ende zu denken, denn ein Gedanke zeigt sich nur dann in seiner Richtigkeit oder Unrichtigkeit beziehungsweise in seiner Wirklichkeitsgemäßheit oder Wirklichkeitsungemäßheit, wenn man ihn zu Ende denkt. Eine überwertige Idee wäre es, wenn ich mir vorstellen würde, ich wäre der König von Spanien. Nicht wahr, ganz zweifellos wäre das eine überwertige Idee. Aber jene Idee brauchte durchaus nicht überwertig zu sein, wenn ich es wirklich wäre. Dann wäre mein Nervensystem ganz gesund und ich hätte dieselbe Idee. Die Idee hat denselben Inhalt. Die Idee als solche ist also doch wohl nicht überwertig, denn sonst müßte man den König von Spanien als krank ansehen in seinem Nervensystem, weil er denkt, er wäre der König von Spanien, nicht wahr? Also auf diesen Zusammenhang kommt es überhaupt gar nicht an. Dennoch wird herumgeschwätzt über diese Dinge. Und man redet nicht nur herum, sondern man bildet auch Begriffe, Definitionen aus und so weiter, und man kommt dann zu Merkwürdigem, was nicht mehr ist als Geschwätz.

Denn nun hat der gute Herr diesen Begriff von überwertigen Ideen ausgebildet. Die Überwertigkeit der Idee ist nun das Symptom für das unrichtige Nervenleben. Na, schön! Aber seinem Unterbewußten ist nicht recht wohl dabei, weil er unterbewußt doch fühlt: während er die ganze Sache von der Überwertigkeit der Ideen den Leuten vorträgt, haben die wiederum allerlei unterbewußte Ideen von dem, daß die Sache doch nicht recht stimmt. Bei den Zuhörern bleibt die Sache heute selbstverständlich unterbewußt, denn der Herr ist eine Autorität — verzeihen Sie! -, da dürfen die Eindrücke nicht ins Bewußtsein dringen. «Denn mit der Bezeichnung der «Überwertigkeit soll nicht nur die an sich lebhafte hohe Bewertung der betreffenden Vorstellungen, sondern eben auch ihre «Überwertung» im Verhältnis zur realen Bedeutung der ihnen wirklich zugrunde liegenden Tatsächlichkeiten ausgedrückt werden. Die überwertige Idee beherrscht dasBewußtsein so sehr, daß neben ihr nicht genügend Platz für andere, objektiv ebenfalls berechtigte Ideen vorhanden ist. Darum werden letztere verdrängt, verlieren ihre Wirksamkeit im Bewußtsein und ihren Einfluß auf die Beschränkung und Zügelung der überwertigen Vorstellungen. So entsteht die einseitige Übertreibung in der Urteilsbildung, die einseitige Richtung der Willensbestrebungen, die Abkehr von allen andern Gedankenkreisen, die mit dem Zentrum der überwertigen Ideen nicht unmittelbar zusammenhängen.» So wie wenn man sagt: Die Armut kommt von der Pauvret€ so ungefähr ist es!

«Daher erscheint dem ruhig urteilenden Beobachter das nervös erregte Bewußtsein stets als etwas Unvernünftiges, als etwas geistig Haltloses, und es entspricht daher durchaus der Tatsächlichkeit, wenn der ruhige Zuschauer den nervös erregten Menschen mit den Worten: ‹So nimm doch Vernunft an, so sei doch vernünftig!›, wieder auf die rechte Bahn des Denkens und Urteilens zu bringen versucht.»

Nun also hat er von der Überwertigkeit der Ideen gesprochen, von ihrem Zusammenhang mit dem Nervensystem. Aber nun wird ihm etwas schwül im Unterbewußtsein, denn die Geschichte ist ja nur ein Gerede, und es paßt schlecht. Na, da setzt er denn die Rede fort: «Wir dürfen aber die «überwertige Idee» nicht ohne weiteres jeder überhaupt gefühlsbetonten und ungewöhnlich lebhaften Vorstellungsweise gleichstellen. Auch alles Edle und Hohe, was den Menschengeist bewegt und ihn zu großen Taten befähigt, was Hingabe und Begeisterung für eine große Tat und für die Anspannung aller Kräfte zur Erreichung eines großen Zieles erweckt, auch dies entspringt nur aus großen Ideen, die den Geist beherrschen und ihm die Kraft und Ausdauer des Willens geben, ohne die ein zielbewußtes Handeln nicht möglich ist.»

Überwertige Ideen, sie zerstören das Nervensystem, sind wenigstens ein Symptom dafür; aber alles Hohe und Edle ist eigentlich ebenso. Es gibt keinen rechten Unterschied. Aber er muß wenigstens erwähnen, daß die Geschichte eigentlich ebenso ist.

«Überall in der Geschichte des Einzelnen und in der Geschichte der Völker sehen wir die großen Taten vollbracht unter dem Einfluß einer großen leitenden Idee, die ihren 'Träger unaufhaltsam und auf der gleichen Bahn und in derselben Richtung festhielt und vorwärts trieb, ihn erst befähigte zu jener unermüdlichen Ausdauer, die trotz Hindernissen und Widerständen das einmal erkannte und erstrebte Ziel erreichen konnte. Was wäre aus Galilei, aus Richard Wagner, aus Bismarck und aus vielen andern großen Männern geworden ohne die Schwungkraft einer großen leitenden Idee, die den Geist jahre- und jahrzehntelang trotz aller Kämpfe und Widerstände in eine bestimmte Richtung des Wollens vorwärts trieb!» - die also «überwertig» war, die ganz ausgesprochen «überwertig» war!

Da wird manchmal solch ein Anflug von Ehrlichkeit vollzogen. Es gibt eine naturwissenschaftliche Richtung, die alle Genies zugleich für etwas verrückt erklärt, weil ja auf diesem Boden so ein richtiger Unterschied zwischen der Genialität und der Verrücktheit ohnedies nicht herauszufinden ist. Und ich habe Ihnen gesagt, daß es heute auch schon Werke gibt, die den Christus Jesus als einen pathologisch Kranken hinstellen, so daß eigentlich das ganze Christentum der Ausfluß der Tatsache ist, daß einmal einer in Palästina, der den Namen Jesus geführt hat, nicht recht gescheit war. Das ist heute Gegenstand von verschiedenen ernst gemeinten, als wissenschaftlich angesehenen Persönlichkeiten.

Die Leerheit solchen Denkens, die tritt manchmal in krasser Art zutage, so wenn der betreffende Herr dann gleich fortfährt: «Aber darin liegt die Tragik des Menschengeistes, daß die Vorstellungen, welche mit größter Stärke das Bewußtsein erfüllen, nicht immer die richtigen sind» — sehr tief ist hier die Tragik des Menschengeistes erklärt, außerordentlich tief! - «und sich nicht immer einfügen in den geordneten Zusammenhang der äußeren Welt.»

Nun haben wir es! Wie weit ist es von solchen Vorstellungen zu der Erkenntnis, die nur erreicht werden kann auf Grundlage von solchen Betrachtungen, wie wir sie hier anstellen. Gewiß, es kann in zwei Menschen dieselbe Vorstellungsmasse anwesend sein, nur ist sie das eine Mal, sagen wir luziferisch, das andere Mal ahrimanisch, das dritte Mal ist sie im Sinne der normalen Menschheitsentwickelung. Statt das inhaltsleere Wort «überwertige Ideen» zu bilden, muß der Begriff einer Geistigkeit eingeführt werden, wie die luziferische oder ahrimanische Geistigkeit, so daß man weiß: darauf kommt es an, daß man erkennt, ob der Mensch selbst will, oder ob ein anderes in ihm will. Aber davor schreckt natürlich solche angebliche Wissenschaft heute noch zurück.

Sehr nett werden dann die Dinge, wenn man erwarten will, daß nun wirklich etwas Substantielles vorgebracht wird: «Da nenne ich zunächst» - er will zunächst das angeben, wodurch sich gewisse nervöse Störungen beim Menschen ankündigen —, «da nenne ich zunächst dieselben Vorstellungen, welche auch bei der Nervosität des Einzelnen oft die größte Rolle spielen:» - er meint, beim heutigen Völkerwahn eben auch - «die Vorstellungen der Verzagtheit, der Sorge, des Kleinmuts, der Mutlosigkeit, des mangelnden Selbstvertrauens.»

Das sind also diejenigen Dinge, welche das gestörte Nervensystem charakterisieren beim nervösen Leben, das unter überwertigen Ideen steht. Verzagtheit, Sorge, Kleinmut, Mutlosigkeit, mangelndes Selbstvertrauen. Nicht wahr, solch ein Vortrag ist doch Mittel dazu, daß er irgendwie nützlich sein könnte. Denn um bloß die Luftwellen zu erregen, wird wahrscheinlich die betreffende Autorität nicht sprechen, sondern um irgendwie nützlich zu sein. Man sollte also erwarten, daß der betreffende Herr nun sagt, wie die Menschheit darüber hinauskommt, da er wie beim einzelnen Menschen, so auch in der Menschheit findet, daß heute Mutlosigkeit, Verzagtheit, Sorge, mangelndes Selbstvertrauen Symptome sind für die Nervenstörung. Man sollte glauben, daß er nun sagt, wie diese Geschichten zu beheben sind, wie man über diese Mutlosigkeit, Sorge, Verzagtheit, mangelndes Selbstvertrauen hinauskommt. Man sollte das voraussetzen. Er setzt es eigentlich auch voraus. Er sagt daher: «Und so kann, wenigstens zeitweise, in großen Volksschichten jene mutlose unzufriedene Stimmung einreißen, die wir mehr zu fürchten haben als alles andere. Denn sie führt zum Nachlassen kräftiger Willensregungen, zur Lockerung der festen einheitlichen Zielstrebigkeit, zur Schwächung der Energie und Ausdauer.»

Nun erwartet man also etwas, nicht wahr? Da sagt er: «Nicht nervös werden heißt daher in erster Linie Mut, Zuversicht und Vertrauen auf die eigene Kraft und das als richtig erkannte Handeln nicht verlieren.»