Historical Necessity and Freewill

GA 179

10 December 1917, Dornach

3. Our Life with the Dead

In an introductory way, I will touch shortly upon a few facts that have already been considered, because we shall need them in the further course of our considerations. I have said that what we may call the threshold between the usual physical world of the senses and the soul-spiritual world lies in man himself, also psychically. It lies in him in such a way that in the usual everyday consciousness with which man is endowed between birth and death, he is really awake only as far as his sense-perceptions, or his perceptive activity, are concerned; he is awake in all that comes to him in the form of ideas—ideas concerning that which he perceives through his senses, or ideas arising out of his own inner being; they make the world intelligible and alive for him. Even a very ordinary self-recollection teaches us (clairvoyant endowment is in no way necessary for this) that when usual human consciousness is fully awake it cannot embrace more than the sphere of the life of ideas and the sphere of sense perceptions. However, we experience in our soul also the world of our feelings and the world of our will. But we have said that we live through this world of our feelings only as we live through a dream; the life of dream enters the ordinary waking consciousness and, inasmuch as we are feeling human beings, we are, in reality, mere dreamers of life. Things occur in the depths of our feeling life, of which our waking consciousness, contained in our ideas and sense perceptions, knows nothing at all. The waking consciousness knows less still concerning the real processes of the life of our will. Man dreams away his feeling life in his usual consciousness, and he sleeps away the life of his will.

Consequently, beneath the life of our thoughts lives a realm in which we ourselves are embedded, and which is only partly known to us; it is only known to us through the waves that break up through the surface.

We have emphasized further, that in this realm, which we dream and sleep away, we live together with human souls that are passing through the existence between death and a new birth. We are only separated from the so-called dead through the fact that we are not in a position to perceive with our ordinary consciousness how the forces of the dead, the life of the dead, the actions of the dead, play into our own life. These forces, these actions of the dead, continually permeate the life of our feeling and the life of our will. Therefore we can live with the dead. And it is indeed important to realize at the present time that the task of Anthroposophy is to develop this consciousness—that we are in touch with the souls of the dead.

The earth will not continue to evolve in the direction of the welfare of humanity unless humanity develops this living feeling of being together with the dead. For the life of the dead plays into the life of the so-called living in many ways.

During the course of these public lectures I have purposely drawn your attention to the historical course of life—what man lives through historically, what he lives through socially, what he lives through in the ethical relationships between people. All this really has the value of a dream, of sleep; the impulses which man develops when he surpasses his personal existence and is active within the community, are impulses of dream and sleep.

People will consider history in quite another way when this has reached their living consciousness; they will no longer consider as history the fable convenue that is usually called history today; but they will realize that historical life can only be understood when that which is dreamed and slept away in usual consciousness, and contains the influences of the deeds, impulses and activities of the so-called dead, is sought in this historical life. The deeds of the dead are interwoven with the impulses of feeling and will of the so-called living. And this is real history.

When the human being has gone through the Gate of Death, he does not cease to be active

within the human community. He continues to be active, although his activity is of another kind. We live under the illusion that our actions are our own, because they flow out of our feelings, out of our impulses of will; in reality they flow out of the deeds of those who have departed, even in the very moment in which we are carrying out our actions.

In the future development of man it will be of great importance to know that when we do something connected with our life in common with other men, we do this together with the dead. But of course, such a consciousness, which is related essentially to the life of the feeling and of the will, must be grasped also by the feeling and by the will. Abstract and dried-out ideas will never be able to grasp this. But ideas that have been taken from the sphere of spiritual science will be able to grasp this. Indeed, people will have to accustom themselves to form quite different conceptions about many things.

You all know that he who is firmly rooted in the comprehension of spiritual-scientific impulses may undertake to remain connected with those who have passed through the Gate of Death. The thoughts of spiritual science, the ideas that we form about the events in the spiritual world, are thoughts that are intelligible to us on earth, but are also intelligible to the souls of the dead. This may result in what we may call “reading to the dead.” When we think of the dead, and in doing so read to them, especially the contents of spiritual science, this is a real intercourse with the dead. For spiritual science speaks a language common to both the souls of the living and of the dead. But what is essential is to approach these things more and more, particularly with the life of feeling, with the illuminated life of feeling.

Man lives, between death and a new birth in an environment which is essentially permeated through and through, not only with living forces, but with living forces full of feeling. This is his lowest sphere. As the insensible mineral kingdom surrounds us during our sense life, so a realm surrounds the dead, which is of such a nature that, when he comes in contact with anything within it, he calls forth pain or joy. Thus, with the dead it is as if we were forced to realize, during life, that as soon as we touch a stone, or the leaf of a tree, we call forth feelings. The departed one can do nothing that does not call forth feelings of joy, feelings of pain, feelings of tension, relaxation, etc., in his surroundings. When we come into contact with the departed human being—this is the case when we read to him—he himself experiences this communion as already mentioned; he becomes aware of this when we read to him; he experiences it in this particular case. In this way the departed one comes in connection with that soul who reads to him, that soul with whom he is in some way related through Karma. The dead is connected with his lowest realm (which we had to bring in connection with the animal kingdom) in such a way that everything he does calls forth joy, pain, etc; he is connected with all that calls forth a relationship with human souls (whether they are human souls living here on the earth, or souls already disembodied and living between death and a new birth) in such a way that his feeling for life is either increased or diminished through what takes place in other souls.

Please realize this clearly. When you read to a so-called living person, you know that he understands what you read to him, in the sense in which we speak of human understanding; but the departed one lives in the contents, the departed one lives in each word that you read to him. He enters into that which passes through your own soul. The departed one lives with you. He lives with you more intensely than was ever possible for him in the life between birth and death. When this companionship with the dead is sought, it is really a very intimate one, and a consciousness endowed with insight intensifies this existence in common with the dead.

If man enters consciously into the realm that we inhabit together with the dead, the intercourse with the dead is such that when you read or speak to the departed one, you hear from him, like a spiritual echo, what you yourself are reading. You see, we must become acquainted with such ideas as these if we wish to gain a real conception of the concrete spiritual world. In the spiritual world things are not the same as here. Here you can hear yourself speak when you are speaking, or you know that you are thinking when you think. If you speak to the dead, or if you enter into a relationship with the dead, your words, or the thoughts you send to him, come to you out of the departed one himself, if you consciously perceive your connection with the dead.

And when you send a message to the dead, you feel as if you were intimately connected with him. If he replies to this message, it seems at first as if you were dimly conscious that the departed one is speaking. You are dimly conscious that the departed one has spoken, and you must now draw out of your own soul what he has spoken. This will make you realize how necessary it is for a real spiritual intercourse to hear from the other one what you yourself think and conceive, to hear out of yourself what the other one says. This is a kind of inversion of the entire relationship between one being and another being. But this inversion takes place when we really enter the spiritual world.

Because the spiritual world is so entirely different from the physical, and because—since about the fifteenth century—people only wish to form conceptions based on the physical world, they displace and obstruct their entrance to the spiritual world. If people would only realize that a world can exist which is, in certain respects—not in all—the direct opposite of what we call the true world; if people would be willing to form ideas which, perhaps, appear most absurd to those who insist upon living only in a materialistic world—then they will transform their souls and attain the possibility of seeing into the spiritual world, which is always around us. It is not that human beings, through their nature, are separated from the spiritual world; but that through habit, through the circumstances of inheritance, they have become entirely unaccustomed, since the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, to forming other ideas than those borrowed from the physical world. This applies even to art. What other scope has modern art than to copy, from the model, what Nature forms outside? Even in art people no longer attach value to what arises freely out of the spiritual life of the soul, and is also something real. But in the free reality that thus arises, people cannot efface what is effective and active in historical events, in the ethical, moral and social life of the community—except that they dream and sleep away this active element. As soon as man goes beyond his own personal concerns, even in the smallest measure—and in every moment of life he goes beyond these—the spiritual world, the world—I must emphasize this again and again—which we share with the dead works through his arm, through his hand, his word, his glance.

As the departed one grows familiar with the realm I have already spoken of, with the lowest one connected with the animal kingdom (just as we become familiar with the mineral, vegetable, animal, and human physical world in the life between birth and death during our gradual growth)—as the departed one continues to develop in the second region, where companionship with all those souls arises, with whom he is karmically connected either directly or indirectly, he evolves to the point of becoming familiar with the kingdom of the Beings who stand above man, if I may use this expression, although it is merely figurative—with the kingdom beginning with the Angeloi and Archangeloi.

Here in the physical world man is, as it were, the crown of creation—many like to emphasize this; he feels himself as the highest of all beings. The minerals are the lowest, then the plants, then the animals, and then man himself He feels that he belongs to the highest kingdom. It is not thus with the dead in the spiritual realm; the dead feels himself connected with the Hierarchies above him, the Hierarchies of the Angeloi, Archangeloi, Archai, etc. As man here in the physical world feels, in a certain sense, that the physical kingdom of man evolves and grows out of the mineral, plant and animal kingdoms, so the departed one feels himself sustained and carried by the Hierarchies above him, in the life between death and a new birth.

The way in which the human being gradually becomes familiar with this kingdom of the Angeloi, Archangeloi, Archai, etc., can be described as follows:—It is like a liberation from Self. Again we must acquire a conception of these things that cannot be won in the physical world of the senses. In this world of the senses, as we grow up from childhood, we gradually become acquainted with things, first with our nearest surroundings, then with what is to be our life experience in a wider sense, etc. We become acquainted with things in such a way that we know—they approach us little by little. This is not the case between death and a new birth. From the moment on, in which we know that we are connected with the Angeloi, we feel as if we had been united with them since eternity, as if we belonged to them, were one with them; yet we are only able to develop our consciousness by reaching the point of separating the idea of the Angeloi from ourselves. Here in the physical world we make our experiences by taking up ideas. In the spiritual world we make our experiences by separating the ideas from ourselves. We know that we carry them within us—and we know that we are entirely filled by them, but we must separate them from ourselves in order to bring them to consciousness. And so we set free the ideas of Angeloi, Archangeloi, Archai.

In the lowest kingdom, man is, as it were, connected with the animalic, which he must strive to conquer, as I have already explained. Then he is connected with the kingdom immediately above this one—the kingdom of the souls with whom he is directly or indirectly linked up through Karma. In this kingdom man experiences his relationship with the Angeloi. His relationship with the kingdom of the Angeloi gives rise, at first, to a great deal of that which creates a right connection with the kingdom of human souls. Hence, in the life between death and a new birth, it is difficult to distinguish between the experiences which man has in common with other human souls and those with the Beings belonging to the kingdom of the Angeloi. There are many links between human beings and the Beings belonging to the kingdom of the Angeloi. Although we can speak of these things merely in comparison, and although we can only allude briefly to them, we may however say:—Just as here, in our physical life, memory leads us back again to some event which we have experienced, so does a Being belonging to the kingdom of the Angeloi lead us to something which we must experience in our life between death and a new birth. Beings belonging to the kingdom of the Angeloi are really the mediators for everything that arises in the life of the so-called dead. And the Angeloi help man in everything that he must do between death and a new birth in connection with the conquest of the animalic (he must raise his animal nature into the spiritual part of his being in order to prepare himself for his next incarnation). If you grasp this in its right meaning you will say:—Because man associates with the Angeloi between death and a new birth, he can form the right kind of relationships in connection with the souls with whom he must come into touch. And because man is in contact with the kingdom of the Angeloi, he can prepare rightly the things that must take place during his next incarnation. The tasks of the Archai, or the Beings belonging to the Spirits of the Time, are common both to the dead and to the living. My explanations will show you that the departed one has more to do with the Angeloi, who regulate his connection to other souls, and with the Archangeloi, who regulate his successive incarnations. But in his association with the Beings of the Hierarchy of the Archai, the dead works together with the so-called living, with those who are incarnated here in the physical body. The dead who is passing through the life between death and a new birth, and the so-called living, in his life between birth and death, are embedded alike in something which the Spirits of the Time weave as an unceasing stream of universal wisdom and universal activity of the will. What the Spirits of the Time thus weave is history, is the ethical-moral life of an age, the social life of an age.

We might say that we can look into the spiritual kingdom and realize:—The so-called dead are there; what they experience in this kingdom—inasmuch as these experiences are their own—is regulated by the Angeloi and Archangeloi; what they experience in common with the so-called living is woven by the Beings who belong to the Hierarchy of the Archai. We cannot fulfill any fruitful work in the social, historical, and ethical-moral life unless we realize this work must come from an element that we share with the dead—the element of the Archai, or Spirits of the Time.

These Spirits of the Time do their work alternately. We have often spoken of this. Through several centuries, one of the Time Spirits weaves the events contained in the stream of historical and social life and in the ethical-moral stream of human events; then another Time Spirit relieves him. The moment in which a Time Spirit relieves another one is most important of all, if we wish to observe what really takes place within the evolution of mankind. We cannot understand this evolution unless we bear in mind the living active influence of the Time Spirits and, in general, of the entire spiritual world. We cannot understand what takes place between man and man unless we consider the kingdom of the Spirit.

Very abstract are man's thoughts concerning that which is social, ethical-moral and historical. He thinks that history, or the stream of events taking place in the course of time, is a continuous current, where one event follows upon the other. He asks:—Why did certain events happen at the beginning of the twentieth century?—Because they were caused by events at the end of the nineteenth century.—Why did certain events happen at the end of the nineteenth century?—Because they were caused by events in the middle of the nineteenth century. And events in the middle of the nineteenth century were caused again by events at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and so on.

This way of considering historical events as the result of immediately preceding events is just the same as if a peasant were to say:—The wheat that I shall harvest this year is the result of the wheat of last year. The seeds remained, and the wheat of last year is again the result of the wheat of the year before last. One thing depends on the other—cause and effect. Except that the peasant does not really follow this rule: he must of course interfere personally in the growth of the wheat. He must first sow the seeds in order that an effect may follow the cause. The effect does not come of itself. From a certain point of view this is one of the most terrible illusions of our materialistic age, for people believe that the effect is the result of the cause; they do not wish to form the simplest thoughts concerning the real truth of these things.

I have already given you an example, by relating to you a sensational event in the life of a human being. It is indeed so, that people prefer to contemplate sensational events rather than consider the other events, which are of exactly the same kind and take place every hour and every moment of our life. I have told you how such an event can occur: A man is accustomed to take his daily walk to a mountainside. He takes this walk every day for a long time. But one day during his walk, on reaching a certain spot, he hears a voice calling out to him:—Why do you go along this path? Is it necessary that you should do this? The voice says more or less these words. On hearing them he becomes thoughtful, steps aside and thinks for a while about the curious thing that has happened to him. Suddenly a piece of rock falls down, which would have killed him had he not stepped aside after hearing the voice. This is a sensational event. But one who considers the world calmly, yet spiritually, will see in this event one of the many which take place every moment of our life. In every moment of our life something else, too, might happen, if this or that would occur.

A very clever man—we know that especially modern people are very clever—would say: Why was this man spared? Because he went away. This is the cause. Very well—but suppose he had not gone away; in this case he would have been killed, and a very clever modern man would argue:--the falling stone is the cause of the man's death. Indeed—seen from outside and in an abstract and formal way—it is true that the falling stone is the cause, and the man's death the effect: but the cause has nothing to do with the effect; it is quite an indifferent matter to the falling stone, where the man was standing. This cause has nothing whatever to do with the effect. Ponder this matter and try to understand what is really contained in all this talk of cause and effect. The so-called cause need not have anything to do with the effect.

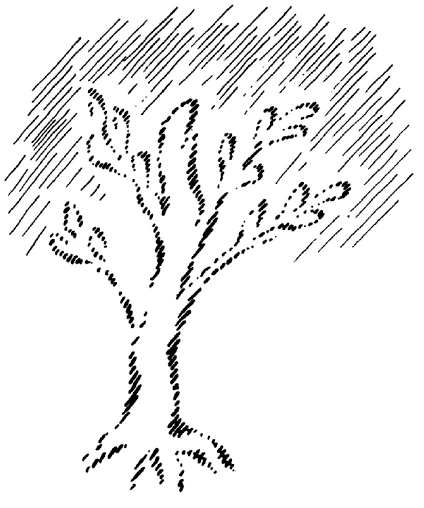

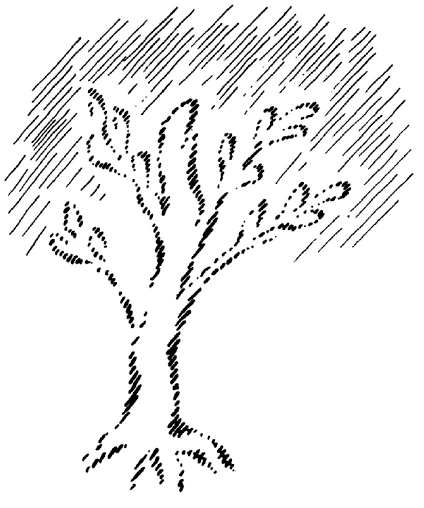

The stone would have taken exactly the same course had the man been standing elsewhere. As far as the stone is concerned, nothing has been changed owing to the fact that the man was warned and went away. I gave you an example that, even in outer quite formal things, the so-called cause need have nothing to do with the so-called effect. The whole way of looking at cause and effect is based entirely on abstraction. It is only possible to speak of cause and effect within certain limits. Take this example, for instance: Here you have a tree with its roots. What takes place in the roots can certainly be considered, in certain respects, as the cause of the growing tree; what takes place in the branches can, to a certain extent, be designated as the cause of the growing leaves. You see, the tree is, to a certain extent, a whole; and a concrete way of looking at life considers totalities and the aspect of the whole; an abstract way of looking at life always links up one thing with another, without considering the complete whole. But for a spiritual way of looking at things it is important to bear in mind the whole. You see, where the outer leaves end, the tree ceases to exist, as well as the inner causes of its growth. Where the leaves end, also the forces of their growth end; but something else begins there. Where these forces end, the spiritual eye can see spiritual beings playing around the tree, spiritual elementary beings. Here begins, if I may say so, a negative tree, which stretches out into infinity, but only apparently so, because after a while it disappears. An elementary existence meets what comes out of the tree; where the tree ceases, it comes into contact with the elementary existence, which grows toward it. It is thus in Nature.

The plant ceases to exist when it grows out of the soil, and the causes of its growth cease when the plant ceases. But an elementary existence from the universe grows toward the plant.

In the lecture on human life from the aspect of spiritual science, I have mentioned some of these things. The plants grow out of the soil from below. A spiritual element grows toward the plant from above. It is thus with all beings. What you observe in Nature is contained in all existence. Above all, there is a stream of social, ethical-moral and historical life. Events do not consist in a continuous stream, but a Time Spirit reigns for a while; another one replaces him; a third one replaces him; a fourth one replaces him; and so on. When a Time Spirit replaces another one, there is a difference also in the stream of continuous events. When such a new period begins, it is not possible to say that its events are the immediate effect of preceding events. They are not the effect of the preceding ones, in the sense in which we imagine this.

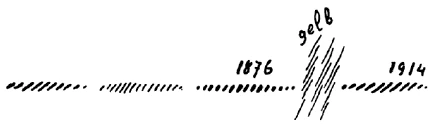

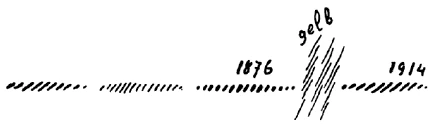

There is indeed an order of law in the successive course of events, but what we generally call necessity is an illusion, if we look upon it as it is often looked upon today. In the course of continuous events, we have something similar to what we find when we look at the tree—where the tree ceases, the elementary tree begins; but in Nature, a being belonging to the visible kingdom of the senses touches a being that remains invisible to the senses, a super-sensible being; the world of the senses and the super-sensible world touch. There is something similar also in the course of Time. Just as the physical tree ceases and an elementary tree begins, so also in the course of Time, something ceases and something new begins. There are epochs in which old events and old impulses cease, as it were, and are replaced by new ones. At such points of time, people like to keep to Lucifer and Ahriman, who help them to maintain what is really dead. It is possible to keep alive in human consciousness impulses and forces that are, in reality, dead. This is not possible in Nature. If someone cultivates exactly the same kind of ideas in 1914 that were justified in 1876, he can do so of course. He can do this because, in the continuous stream of human events, which is seized by Ahriman and Lucifer, the old can be maintained even if it is already dead. It is the same as if someone were to make a tree grow on and on without ceasing, after it had reached its natural limits. In the course of history we generally find that people cannot face a new epoch rightly; in other words, that they cannot place themselves at the service of the new Time Spirit.

In our age this is particularly important. During the last weeks we have spoken of the spiritual events of 1879. This was the end of an epoch. Something died and ceased to exist, just as the tree ceases. From 1879 onward it became necessary (this is of course still necessary today and will be so for a long time) that people should open themselves to the ideas and impulses coming from the spiritual world. Otherwise the old impulses become Ahrimanic or Luciferic.

These remarks contain something very important. The last third of the nineteenth century was an important time in the evolution of humanity. It was necessary, and it is still necessary, that people should become accessible to the influence of inspired ideas. People must open themselves to these. But looked upon from outside (we shall not only look upon this from outside, but study the deeper inner meaning), looked upon from outside, things have a very hopeless aspect. Impulses did come from the spiritual world. They came streaming in and worked in order that men might be led beyond this point, beyond the year 1879, and in order that they might open themselves to inspired ideas. They were impulses that could give men thoughts enabling them to become conscious, even at the end of the nineteenth century, that whenever we fulfill actions of a historical, social or ethical-moral value within the life of the community, we fulfill them together with our dead, and with the Archangeloi, Angeloi, and Archai. These impulses were there; they were there, but went past many people without leaving a trace. I have said that today I will first consider these things from an outer aspect, and it is good if you realize how apparently everything went past without leaving a trace. In the second half of the nineteenth century important things and important impulses already existed, and there were people who proclaimed and wrote significant thoughts. If we look at these thoughts today they may seem abstract. This is indeed so. But they are not abstract thoughts and they should not remain as they were then. (I repeat once more that this is looked upon from outside, tomorrow we shall consider these things from an inner aspect.) This was the case more or less in all spheres of modern civilized life. For instance—who studies the life of this country, Switzerland, in such a way as to say: In the fifties of the nineteenth century a man lived here in Switzerland, a man with great ideas, that were indeed of a philosophical kind. But had they been accepted by two or three, had they been popularized, would they not have had a very fruitful, spiritualizing influence on the entire history of Switzerland? Who considers, for instance, that in the middle of the nineteenth century a high spirit lived in Otto Heinrich Jäger? He is one of the greatest men of Switzerland. But who knows his name now, and who names him? Who is aware of the fact that although his thoughts had an abstract appearance they were only apparently abstract. They might have become concrete, they might have blossomed and borne fruit, because something very great was in this man, who taught at the Zurich University and wrote books on great thoughts, thoughts that should enter the life of the present. He wrote on the idea of human liberty and its connection with the entire spiritual world. Otto Heinrich Jager wrote, here in Switzerland, a kind of “Philosophy of Spiritual Activity,” from another point of view than my own The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, which arose in the nineties.

Innumerable examples like this one could be given. The most fruitful ideas germinated and greened, but what is recounted today as the spiritual history of the nineteenth century leading into the twentieth century is the least significant part of all that really took place, and the most important part, that influenced it most of all, has not been considered at all.

This is how matter stand, from an exterior aspect, to begin with. Perhaps they will look more hopeful when we shall look at them from an inner standpoint.

Dritter Vortrag

Ich will kurz einige Tatsachen, die angeführt worden sind, noch einmal einleitungsweise berühren, weil wir sie für den Fortgang unserer Betrachtungen brauchen werden. Ich habe gesagt, daß im Menschen selber, auch seelisch, dasjenige liegt, was wir die Schwelle der gewöhnlichen sinnlich-physischen Welt und der seelisch-geistigen Welt nennen können. Und zwar so, daß wir im gewöhnlichen Wachbewußtsein, mit dem der Mensch ausgerüstet ist zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode, eigentlich nur in bezug auf die sinnlichen Wahrnehmungen völlig wachen, in bezug also auf die Wahrnehmung alles desjenigen, was durch unsere Sinne an uns herankommt, ferner in bezug auf alles das, was wir an Vorstellungen entwickeln, seien es Vorstellungen, die wir uns machen über das sinnlich Wahrgenommeng, seien es Vorstellungen, die aus unserem Innern auftauchen zum Begreifen, zum Beleben der Welt. Schon eine ganz gewöhnliche Selbstbesinnung lehrt uns — keineswegs ist dazu hellseherische Begabung notwendig -, daß das gewöhnliche Menschheitsbewußtsein völlig wachend nicht mehr umfassen kann als das Gebiet des Vorstellungslebens und das Gebiet der Sinneswahrnehmungen. In unserer Seele selbst erleben wir außerdem unsere Gefühlswelt und unsere Willenswelt. Aber wir haben gesagt, daß wir unsere Gefühlswelt nur so durchleben, wie wir etwa einen Traum durchleben, daß das Traumleben sich in das gewöhnliche Wachbewußtsein herein erstreckt, und wir eigentlich, indem wir fühlende Menschen sind, Träumer des Lebens sind. Denn auf dem Grunde des Gefühlslebens gehen Dinge vor, von denen das Wachbewußtsein im Vorstellen und im Sinneswahrnehmen nichts weiß. Noch weniger weiß das wache Bewußtsein etwas von den wirklichen Vorgängen des Willenslebens. Das Gefühlsleben verträumt der Mensch im gewöhnlichen Wachbewußtsein, das Willensleben verschläft er. So daß also unter unserem Vorstellungsleben ein Reich lebt, in das wir selber eingebettet sind, und das uns nur zum Teil bekannt ist, uns nur bekannt ist durch die Wogen, die heraufschlagen über seine Oberfläche.

Ferner haben wir betont, daß in diesem Reich, das also der Mensch verträumt, verschläft, mit uns gemeinschaftlich leben die Menschenseelen in dem Dasein zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Wir sind also von den sogenannten Toten nur dadurch getrennt, daß wir nicht in der Lage sind, mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein wahrzunehmen, wie die Kräfte der Toten, das Leben der Toten, die Handlungen der Toten in unser eigenes Leben hereinspielen. Denn diese Kräfte, diese Handlungen der Toten durchdringen unser Gefühlsleben und unser Willensleben fortwährend. Wir leben also mit den Toten. Und es ist schon von Bedeutung, sich klarzumachen in dieser unserer Gegenwart, wie Geisteswissenschaft die Aufgabe hat, dieses Bewußtsein des Zusammengehörens mit den Totenseelen zu entwikkeln.

Der Rest der Erdenentwickelung wird nicht verfließen können, wenn er zum Heile der Menschheit verfließen soll, ohne daß die Menschheit dieses lebendige Gefühl von dem Zusammensein mit den Toten entwickelt. Denn das Leben der Toten spielt auf mannigfaltigen Umwegen herein in das Leben der sogenannten Lebendigen.

Und eben nicht umsonst ist im Verlauf der öffentlichen Vorträge aufmerksam darauf gemacht worden, wie das geschichtliche Leben, wie das, was der Mensch historisch durchlebt, sozial durchlebt, wie das, was er in bezug auf die ethischen Vorgänge unter den Menschen durchlebt, eigentlich den Wert eines Traumes, eines Schlafes hat; daß die Impulse, welche der Mensch entwickelt, wenn er aus seiner Persönlichkeit herausgeht, wenn er also in der menschlichen Gemeinschaft wirkt, Traumes-, Schlafesimpulse sind.

Die Menschen werden Geschichte ganz anders ansehen, wenn ihnen dies zum lebendigen Bewußtsein gekommen ist. Sie werden als Geschichte nicht mehr jene Fable convenue ansehen, welche man heute allgemein Geschichte nennt, sondern sie werden einsehen, daß geschichtliches Leben nur verstanden werden kann, wenn in diesem geschichtlichen Leben dasjenige gesucht wird, was für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein verträumt, verschlafen wird, in das aber hineinspielen zunächst, wie wir gesehen haben, die Impulse, die Taten, die Handlungen der sogenannten Toten. Es verweben sich die Handlungen der Toten mit dem Fühlen, mit den Willensimpulsen der sogenannten Lebendigen. Und das ist eigentlich Geschichte.

Der Mensch hört nicht auf, tätig zu sein innerhalb der menschlichen Gemeinschaft, wenn er durch des Todes Pforte gegangen ist. Er fährt fort, tätig zu sein, wenn auch in einer andern Weise, als er hier im physischen Leib tätig sein muß. Aber vieles von dem, wovon der Mensch wegen seiner Illusionen glaubt, daß er es tue, weil es aus seinen Gefühlen, aus seinen Willensimpulsen fließt, fließt in Wahrheit bis in unsere eigenen Tage, wo wir die entsprechenden Handlungen vollziehen, aus den Handlungen derer, die hinübergegangen sind.

Zu wissen, daß der Mensch in dem Augenblicke, wo es sich um sein Leben in menschlicher Gemeinschaft handelt, auch in Gemeinschaft mit den Toten handelt, das wird ein Bedeutsames sein in der Entwickelung der Menschen in der Zukunft. Nur muß selbstverständlich ein solches Bewußtsein, das sich im wesentlichen auf das Gefühls-, auf das Willensleben bezieht, auch vom Fühlen und Willen erfaßt werden. Die abstrakten, die trockenen Vorstellungen werden das niemals erfassen können, aber Vorstellungen, die genommen sind aus dem Umfange der Geisteswissenschaft, die werden das erfassen können. Über vieles allerdings werden sich die Menschen gewöhnen müssen, ganz andere Begriffe zu bilden.

Sie wissen ja alle, daß derjenige, der fest drinnensteht im Erfassen der geisteswissenschaftlichen Impulse, versuchen kann, mit denjenigen in Verbindung zu bleiben, die hingegangen sind durch die Pforte des Todes. Und an den Gedanken der Geisteswissenschaft, an den Ideen, die wir uns bilden über die Vorgänge in den geistigen Welten, haben wir solche Gedanken, die uns Erdenmenschen verständlich sind, die aber auch den toten Seelen verständlich sind. Und daraus ergibt sich dasjenige, was wir nennen: Vorlesen den Toten. Wenn wir gerade über Materien der Geisteswissenschaft im Gedanken an die Toten vorlesen, dann ist das ein wirkliches Gemeinschaftsleben mit den Toten. Denn die Geisteswissenschaft spricht eine Sprache, die den lebenden und den toten Seelen gemeinschaftlich ist. Aber es handelt sich darum, immer mehr und mehr gerade mit dem Gefühlsleben, mit dem durchleuchteten Gefühlsleben an diese Dinge heranzukommen.

Denn bedenken Sie einiges von dem, was ich gestern gesagt habe. Der Mensch lebt zwischen Tod und einer neuen Geburt in einer Umgebung, die im wesentlichen ganz durchsetzt ist nicht nur von Lebendigkeit, sondern von fühlender Lebendigkeit. Das ist schon sein unterstes Reich, habe ich gesagt. Wie für uns das fühllose Mineralreich dasjenige ist, was uns während unseres Sinnenlebens umgibt, ist um den Toten ein so geartetes Reich, daß, wenn er nur irgend etwas darin berührt, er Schmerz oder Freude hervorruft. So ist es bei den Toten, wie wenn wir im Leben wissen müßten, sobald wir irgendeinen Stein berühren, ein Baumblatt berühren, so rufen wir Gefühle hervor. Nichts kann der Tote tun, ohne daß er in seiner Umgebung Gefühle der Freude, Gefühle des Schmerzes, Gefühle der Spannung, Gefühle der Entspannung und so weiter hervorbringt. Indem wir mit dem Toten in einer Verbindung stehen, wie sie durch das Vorlesen gegeben ist, tritt dann für den Toten selbst jene Gemeinschaft auf, von der wir auch schon gesprochen haben, aber eben für diesen besonderen Fall des Vorlesens. Dadurch tritt der Tote in Verbindung mit der Seele, die ihm hier vorliest, mit der Seele, die ihm irgendwie karmisch besonders verbunden ist. Und so wie der Tote in seinem untersten Reiche, das wir mit dem Tierreich in Verbindung bringen mußten, in einem solchen Verhältnisse steht, daß alles, was er tut, Freude, Leid und so weiter hervorbringt, so steht er mit alledem, was Zusammenhang mit Menschenseelen hervorruft — seien es Menschenseelen, die hier auf der Erde leben, seien es Menschenseelen, die schon entkörpert sind und zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt leben -, in einer solchen Verbindung, daß er durch dasjenige, was in andern Seelen vorgeht, entweder ein gehobenes oder ein abgelähmtes Lebensgefühl erhält.

Machen Sie sich das einmal klar. Wenn Sie hier einem sogenannten Lebenden vorlesen, so wissen Sie, der versteht in dem Sinne, wie man vom menschlichen Verständnisse spricht, dasjenige, was Sie ihm vorlesen. Der Tote lebt darinnen, der Tote lebt in jedem Wort, das Sie ihm vorlesen, der Tote dringt ein in dasjenige, was durch Ihr eigenes Gemüt zieht. Der Tote lebt mit Ihnen, er lebt intensiver mit Ihnen, als er jemals in dem Leben zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode hat leben können. Das kann sich Ihnen steigern zum Verständnisse der Gemeinschaft mit dem Toten. Und diese Gemeinschaft mit dem Toten ist eigentlich, wenn sie gesucht wird, eine recht innige, und es steigert sich dieses Zusammensein mit dem Toten durch schauendes Bewußtsein.

Tritt der Mensch wirklich bewußt in jenes Reich, das wir mit den Toten gemeinschaftlich bewohnen, dann ist der Verkehr mit den Toten so: Wenn Sie dem Toten zum Beispiel vorlesen oder vorsprechen, so hören Sie von ihm wie von einem Geisterecho das, was Sie selber vorlesen. Mit solchen Begriffen muß man sich bekanntmachen, wenn man eine wirkliche Vorstellung von der konkreten geistigen Welt gewinnen will. Die Dinge sind in der geistigen Welt anders als hier. Hier hören Sie sich sprechen, oder wissen sich denkend, wenn Sie sprechen, oder wenn Sie denken. Sprechen Sie zu Toten, oder gehen Sie mit dem Toten denkend eine Verbindung ein, so tönt Ihnen, wenn die Verbindung bewußt ist im Schauen, aus dem Toten selbst dasjenige heraus, was Sie zu ihm sprechen, oder was Sie denkend, vorstellend an ihn richten.

Und weiter, wenn Sie dem Toten eine Mitteilung machen, dann haben Sie das Gefühl des innigen Verbundenseins. Und antwortet er Ihnen auf diese Mitteilung, dann ist das so, daß Sie zunächst das unbestimmte Bewußtsein haben: der Tote spricht. Sie haben das unbestimmte Bewußtsein: der Tote hat gesprochen, und Sie müssen nun aus der eigenen Seele hervorholen, was er gesprochen hat. Sie erkennen daraus, wie notwendig es zu einem wirklichen Geistverkehr ist, von dem andern zu hören dasjenige, was man selber denkt und vorstellt, aus sich selbst zu hören dasjenige, was der andere spricht. Dies ist eine Art von Umkehrung des ganzen Verhältnisses von Wesen zu Wesen. Aber diese Umkehrung findet statt, wenn wirklich eingetreten wird in die geistige Welt.

Weil die geistige Welt so durchaus anders ist als die physische Welt und die Menschen seit dem 15. Jahrhundert ungefähr sich nur Vorstellungen bilden wollen, die im Sinne der physischen Welt geartet sind, so verlegen sich, verbauen sich die Menschen den Zugang zur geistigen Welt. Wenn die Menschen sich einmal herbeilassen werden, wenigstens die Möglichkeit vor sich hinzustellen, daß es eine Welt geben kann, die in gewissem Sinne, nicht in allem, entgegengesetzt ist derjenigen, die der Mensch hier die wahre Welt nennt, wenn sich die Menschen einmal werden Vorstellungen bilden wollen, die vielleicht demjenigen als die allerverrücktesten erscheinen, der nur in materialistischer Welt leben will, dann erst werden die Menschen ihre Seelen so umformen, daß sie die Möglichkeit erhalten, wirklich hineinzuschauen in diese geistige Welt, die ja fortwährend um uns herum ist. Es ist nicht so, daß die Menschen unbedingt durch ihre Natur getrennt wären von der geistigen Welt, sondern es ist deshalb so, weil die Menschen durch Gewöhnung, durch Vererbungsverhältnisse, seit dem 14. und 15. Jahrhundert sich ganz abgewöhnt haben, andere Vorstellungen zu bilden als diejenigen, die hier der physischen Welt entlehnt sind. Ist es ja sogar so für die Kunst geworden! Was will denn die heutige Kunst noch anderes bilden als das, was nach dem Modell gebildet ist, was sich draußen in der Natur auch bildet. Selbst in der Kunst wollen die Menschen nicht mehr gelten lassen das, was auch als ein Reales frei aufsteigt aus dem Geistesleben der Seele. Aber die Menschen können nicht das tilgen, was in den geschichtlichen Ereignissen, im ethisch-moralischen Zusammenleben, im sozialen Zusammenleben selbst als frei Aufsteigendes wirksam und tätig ist, wenn sie es auch verträumen, verschlafen. Sobald der Mensch auch nur im geringsten über das hinausgeht, was seine ureigensten, persönlichsten Angelegenheiten sind - und er geht ja in jedem Augenblicke des Lebens darüber hinaus -, so wirkt durch seinen Arm, durch seine Hand, durch sein Wort, durch seinen Blick die geistige Welt, jene Welt, die wir — das muß ich immer wieder betonen mit den Toten gemeinschaftlich haben.

Der Tote lebt sich nun in das Reich ein, von dem ich schon gesprochen habe, so wie wir uns, indem wir von Kindheit auf wachsen, in dem Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod einleben in die mineralische, die pflanzliche, die tierische, die menschliche physische Welt. Indem er sich so einlebt in das unterste Gebiet, das mit dem Tierreich etwas zu tun hat, in das zweite Gebiet, worin sich die Gemeinschaft ausbildet mit all den Seelen, mit denen der Tote in einer unmittelbaren oder mittelbaren karmischen Verbindung steht, so entwickelt sich der Tote zugleich dazu, sich in das Reich derjenigen Wesen einzuleben, die nun — wenn ich den Ausdruck gebrauchen darf, obwohl er nur etwas uneigentlich gemeint sein kann — über dem Menschen stehen: in das Reich der Angeloi, Archangeloi, Archai zunächst.

Hier in der physischen Welt steht der Mensch da - viele betonen das so gern - als die Krone der physischen Schöpfung. Er fühlt sich hier als das höchste der Wesen. Die mineralischen Wesen sind die untersten, dann die pflanzlichen Wesen, dann die tierischen Wesen, dann er, der Mensch. Er fühlt sich als dem höchsten Reiche angehörig. So ist es nicht mit den Toten im geistigen Reiche; denn der Tote fühlt sich als sich anschließend an die Hierarchien, die über ihm stehen: die Hierarchien der Angeloi, Archangeloi, Archai und so weiter. So wie der Mensch sich hier in der physischen Welt gewissermaßen hervorgehend, hervorwachsend fühlt aus dem mineralischen, dem pflanzlichen und tierischen Reiche, dem physischen Menschenreich, so fühlt der Tote sich gehalten, getragen von den über ihm stehenden Hierarchien in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt.

Die Art, wie sich der Mensch allmählich in diese Reiche einlebt, in die Reiche der Angeloi, Archangeloi, Archai und so weiter, kann man so bezeichnen, daß man sagt: Man fühlt es wie ein Loslösen von sich. — Wiederum müssen wir uns eine Vorstellung aneignen von diesen Dingen, die man in der physisch-sinnlichen Welt gar nicht gewinnen kann. In der physisch-sinnlichen Welt lernen wir, wenn wir von Kindheit auf wachsen, allmählich die Dinge kennen: zuerst unsere nächste Umgebung, dann dasjenige, was im weiteren Umkreise unsere Lebenserfahrung werden soll und so weiter. Wir lernen die Dinge so kennen, daß wir wissen, sie treten nach und nach an uns heran. Das ist nicht der Fall zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Da fühlen wir von dem Momente an, wo wir wissen, jetzt stehen wir in Beziehung zu den Angeloi, da fühlen wir, wie wenn wir mit ihnen schon von Ewigkeit her verbunden gewesen wären, wie wenn wir zu ihnen gehörten, eines mit ihnen wären, aber wie wenn das Bewußtsein sich nur dadurch entwickeln kann, daß wir gewissermaßen es dahin bringen, die Vorstellung von den Angeloi von uns loszulösen. Hier in der physischen Welt machen wir unsere Erfahrungen dadurch, daß wir die Vorstellungen aufnehmen. In der geistigen Welt machen wir unsere Erfahrungen dadurch, daß wir die Vorstellungen gewissermaßen aus uns heraus loslösen. Wir wissen, wir tragen sie in uns; und wir wissen, wir sind ganz und gar von ihnen erfüllt. Aber wir müssen sie, damit wir sie zum Bewußtsein bringen können, von uns loslösen. Und so lösen wir los die Vorstellungen der Angeloi, der Archangeloi, der Archai.

Gleichsam durch das unterste Reich ist der Mensch mit dem Wesen des Tierischen verbunden, das er in dem Sinne, wie ich es schon auseinandergesetzt habe, zu bemeistern hat. Dann bildet sich das darüberstehende Reich zu den Seelen, mit denen der Mensch karmisch, mittelbar oder unmittelbar, verbunden ist. Dann erfährt er seine Beziehungen zum Reiche der Angeloi. Durch die Beziehungen zum Reiche der Angeloi tritt vieles von dem erst ein, was die rechten Beziehungen gibt zu dem Reich der Menschenseelen. So daß man eigentlich schwer für das Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt trennen kann das, was der Mensch zu tun hat mit den andern Menschenseelen, und dasjenige, was er zu tun hat mit den Wesen aus dem Reiche der Angeloi. Menschen und Wesen aus dem Reiche der Angeloi, sie haben ja viel miteinander zu tun. Man kann sagen - obwohl man natürlich über diese Dinge nur vergleichsweise sprechen kann, obwohl alles Sprechen nur Andeutungen geben kann, ist es doch richtig -, so wie uns hier im physischen Leben die Erinnerung wieder hinträgt zu irgendeinem Ereignisse, das wir durchgemacht haben, so trägt in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt ein Wesen aus dem Reich der Angeloi uns hin zu irgend etwas, zu dem wir getragen werden sollen, das wir erleben sollen. Die Wesen aus dem Reich der Angeloi sind eigentlich die Vermittler für alles dasjenige, was sich ausbildet im Leben des sogenannten Toten.

Und für alles das, was der Mensch zu tun hat zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt mit Bezug auf die Bemeisterung des Tierischen — er hat ja seine eigene tierische Natur einzupflanzen seinem Geistwesen, damit er sich vorbereitet zu der nächsten Inkarnation -, helfen die Archangeloi. Dann, wenn Sie dies in rechtem Sinne erfassen, werden Sie sich sagen: Dadurch, daß der Mensch zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt teilhaftig wird des Verkehrs mit den Angeloi, kommt er in die Lage, seine rechten Beziehungen, seine rechten Verhältnisse anzuknüpfen zu den Seelen, mit denen er eben Verhältnisse anknüpfen soll. Dadurch, daß der Mensch in Beziehung tritt zu dem Reich der Archangeloi, wird der Mensch in die Lage versetzt, in der richtigen Weise sich vorzubereiten für das, was ablaufen soll für die nächste Erdeninkarnation.

Die Archai, jene Wesen, welche wir auch die Wesen des Zeitgeistes genannt haben, sind aber jene Wesen, welche gemeinschaftlich tätig sind in ihren Aufgaben für die Toten und für die Lebendigen. Aus meinen Andeutungen können Sie entnehmen, daß im wesentlichen der Tote mit den Angeloi so zu tun hat, daß diese sein Verhältnis zu andern Seelen regeln; daß die Archangeloi sein Verhältnis zu seinen fortlaufenden Inkarnationen regeln. Was der Tote zu tun hat mit jenen Wesen, die der Hierarchie der Archai angehören, das hat er - auf dem gemeinschaftlichen Boden mit den sogenannten Lebendigen — mit denen zu tun, die hier im physischen Leibe inkarniert sind. Der Tote in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt und der sogenannte Lebende hier zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode, sie sind in gleicher Weise eingebettet in etwas, was wie eine fortströmende Weltenweisheit und Weltenwillenstätigkeit gewoben wird von den Zeitgeistern. Was wiederum gewoben wird von den Zeitgeistern, ist Geschichte, ist ethisch-moralisches Leben eines Zeitalters, ist soziales Leben eines Zeitalters.

Man möchte sagen, hinaufblicken können wir in das Reich des Geistes und uns sagen: Da sind die sogenannten Toten; was sie in ihrem Reiche erleben, das wird geregelt, insoferne dieses Erlebte ihre eigenen Angelegenheiten sind, durch die Angeloi und Archangeloi; was sie gemeinschaftlich mit den sogenannten Lebendigen erleben, das wird gewoben von den Wesen, die zu der Hierarchie der Archai gehören. Und so können wir gar nicht fruchtbar im sozialen, im geschichtlichen, im ethisch-moralischen Leben wirken, ohne daß wir uns bewußt sind: dieses Wirken muß heraus erwachsen aus dem mit den Toten gemeinschaftlichen Elemente, muß heraus erwachsen aus dem Elemente der Archai, der Zeitgeister.

Diese Zeitgeister aber lösen sich ab in bezug auf ihre Aufgabe. Darüber haben wir ja wiederholt gesprochen. Ein solcher Zeitgeist webt an dem Geschicke des fortgehenden geschichtlichen Stromes und sozialen Stromes, des moralisch-ethischen Stromes im Menschengeschehen gewisse Jahrhunderte hindurch, dann wird er durch einen andern Zeitgeist abgelöst. Die Zeitpunkte, in denen ein Zeitgeist den andern ablöst, sind die allerwichtigsten für die Beobachtung desjenigen, was eigentlich innerhalb der Menschheitsentwickelung vor sich geht. Denn man kann die Menschheitsentwickelung nicht verstehen, wenn man nicht das lebendige Hereinwirken der Zeitgeister und damit überhaupt der ganzen geistigen Welt ins Seelenauge faßt; man kann nicht verstehen, was eigentlich zwischen den Menschen geschieht, wenn man nicht das Reich des Geistes in Erwägung zieht.

Abstrakt, höchst abstrakt denkt der Mensch über das, was sozial, was ethisch-moralisch, was historisch abläuft. So wie wenn die Geschichte ein fortlaufender Strom wäre, wo immer eins aufs andere folgt, so stellt sich der Mensch den Zeitenstrom des Geschehens vor. Er frägt: Warum sind die Ereignisse im Beginne des 20. Jahrhunderts so, wie sie eben sind? — Weil sie verursacht sind von den Ereignissen am Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts. Warum sind die Ereignisse am Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts so geworden? — Weil sie verursacht sind von denen in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts. Und die Ereignisse in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts sind wiederum verursacht durch die Ereignisse im Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts und so fort.

Es ist diese Betrachtungsweise, die immer die geschichtlichen Ereignisse als Folgen der unmittelbaren früheren betrachtet, ungefähr ebenso gescheit, als wenn der Bauer sagen würde: Der Weizen, den ich dieses Jahr haben werde, ist die Folge des Weizens vom vorigen Jahre, die Samen sind geblieben; der vom vorigen Jahre ist wiederum die Folge des Weizens vom vorvorigen Jahre. — Eins schließt sich an das andere, Wirkung immer an die Ursache. Es tut es nur nicht, wenn nicht nachgeholfen wird! Denn der Bauer muß selbstverständlich persönlich eingreifen: er muß die Saat erst aussäen, damit Wirkung wird aus der Ursache. Von selbst wird nicht Wirkung aus der Ursache. Das ist von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus sogar die schrecklichste Illusion des materialistischen Zeitalters, daß die Menschen glauben: Wirkung entsteht aus der Ursache, und daß die Menschen sich nicht die einfachsten Gedanken bilden wollen über die Wahrheit dieser Verhältnisse.

Ich habe Ihnen schon ein Ereignis als Beispiel angeführt, das ein sensationelles Ereignis im Menschengeschehen ist. Aber es ist schon einmal so, daß die Menschen auf solche sensationellen Ereignisse leichter hinschauen als auf die andern Ereignisse, die von genau derselben Art sind, aber sich stündlich, ja augenblicklich innerhalb unseres Lebens immer vollziehen. Ich habe Sie aufmerksam gemacht darauf, wie so ein Ereignis verfließt: Ein Mann ist gewöhnt, einen Spaziergang zu machen an einem Berghang; er machte ihn durch lange Zeit hindurch täglich. Aber eines Tages, als er ausgeht und an eine bestimmte Stelle des Weges kommt, hört er,wie wenn eineStimme ihm zutönen würde, so ungefähr: Warum gehst du denn eigentlich diesen Weg? Hast du es denn nötig, dies zu tun? - so ähnlich. Er wird bedenklich, als er diese Stimme hört; er tritt zur Seite, besinnt sich einen Augenblick über das Sonderbare, das sich zugetragen hat - ein Felsblock stürzt herab, der ihn ganz sicher zerschmettert hätte, wenn er nicht durch die Stimme auf die Seite getreten wäre. Es ist ein sensationelles Ereignis. Aber für denjenigen, der die Welt nüchtern und doch geistig betrachtet, ist es nichts anderes als ein solches Ereignis, wie es sich in jedem Augenblick unseres Lebens vollzieht. Denn in jedem Augenblick unseres Lebens könnte auch etwas anderes geschehen, wenn dies oder jenes eintreten würde.

Der sehr gescheite Mensch - wir wissen, daß insbesondere die Menschen der Gegenwart sehr gescheit sind -, er sagt: Ja, warum ist jener Mensch nicht erschlagen worden? — Weil er weggegangen ist! Das ist die Ursache. - Na schön; aber nehmen wir an, er wäre nicht weggegangen, er wäre erschlagen worden, dann würde der sehr gescheite Mensch der Gegenwart sagen: Der herabfallende Stein ist die Ursache, daß der Mensch erschlagen worden ist.

Rein formell, äußerlich abstrakt ist es schon richtig: der herabfallende Stein ist die Ursache, und der Tod des Menschen ist die Wirkung. Aber daß die Ursache mit der Wirkung nicht das geringste zu tun hat - denn für den herabfallenden Stein gilt genau dasselbe, ob der Mensch dort steht oder nicht dort steht -, bedenkt er nicht. Diese Ursache hat mit jener Wirkung nicht das geringste zu tun. Bedenken Sie das nur einmal ordentlich und versuchen Sie sich dann klarzumachen, was es mit aller Ursache-und-Wirkung-Rederei eigentlich für eine Bedeutung hat. Die sogenannte Ursache braucht nicht das geringste mit ihrer Wirkung zu tun zu haben. Für den Stein würde sich genau derselbe Vorgang abspielen, wenn der Mann nicht dort stehen würde, und er spielt sich auch ab: es ist für den Stein, als der Mann gewarnt wurde und weggegangen ist, nichts anderes geschehen.

Ich führte Ihnen dies als ein Beispiel dafür an, daß selbst in solchen äußeren, rein formellen Dingen die sogenannte Ursache mit der sogenannten Wirkung nichts zu tun zu haben braucht. Diese ganze Betrachtung von Ursache und Wirkung kommt nur aus der Abstraktion heraus. Von Ursache und Wirkung zu sprechen ist nur angängig innerhalb gewisser Grenzen. Nehmen Sie einmal an: Sie hätten hier einen Baum, der habe hier seine Wurzeln. Nun, was in den Wurzeln vorgeht, das ist in einer gewissen Beziehung sicherlich als Ursache zu bezeichnen für dasjenige, was da wächst; was in den Zweigen vorgeht, ist mit einem gewissen Rechte wiederum als Ursache dessen zu bezeichnen, was in den Blättern vorgeht. Der Baum ist in einer gewissen Beziehung ein Ganzes; und die konkrete Lebensbetrachtung geht auf Totalitäten, geht aufs Ganze; die abstrakte Lebensbetrachtung, die schließt immer eins an das andere an, ohne sich zu fragen: wo ist ein abgeschlossenes Ganzes? Für die geistige Lebensbetrachtung ist dies aber von Bedeutung, daß man sich einer Ganzheit bewußt wird. Denn sehen Sie, da wo die äußersten Blätter sind, da hört der Baum auf mit dem, was innerliche Ursachen sind für das, was da geschieht. Wo die Blätter aufhören, da hören auch die verursachenden Kräfte auf. Wo aber die verursachenden Kräfte aufhören, da greift anderes ein. Hier, wo die verursachenden Kräfte aufhören, sehen Sie, wenn Sie geistig schauen, den Baum umspielt von geistiger Wesenhaftigkeit, von geistigen Elementarwesen, da beginnt, wenn ich so sagen darf, ein negativer Baum, der sich ins Unendliche hinausdehnt — nur scheinbar ins Unendliche, denn er verliert sich nach einiger Zeit. Dem Hinauswachsen des Baumes begegnet ein elementarisches Dasein, und da, wo der Baum aufhört, berührt er sich mit elementarisch ihm entgegenwachsendem Dasein (Siehe Zeichnung S. 66). So ist es in der Natur. Die Pflanze, indem sie aus dem Boden herausschießt, hört auf. Die Ursachen hören da auf, wo die Pflanze aufhört. Aber entgegen wächst der Pflanze aus dem Weltenall herein ein elementarisches Dasein.

Ich habe das gerade in dem Vortrage, der über «Das menschliche Leben vom Gesichtspunkte der Geisteswissenschaft» handelt, in einigem angedeutet. Die Pflanzen wachsen aus dem Boden von unten hinauf, Geistiges wächst von oben herunter den Pflanzen entgegen. So ist es mit allen Wesen. Was Sie hier für die Natur sehen, das ist aber in allem Dasein vorhanden. Vor allen Dingen ist ein Strom des sozialen, des erhisch-moralischen, des geschichtlichen Werdens vorhanden. Nicht solch ein fortlaufender Strom ist das Geschehene, sondern ein Zeitgeist regiert während einer gewissen Zeit, ein anderer löst ihn ab, ein dritter löst ihn ab, ein vierter löst ihn ab und so weiter. Und an den Stellen, wo ein Zeitgeist den andern ablöst, da ist auch im Strom des fortlaufenden Geschehens ein Unterschied, ein solcher Einschnitt, daß man nicht sagen kann, das, was da folgt, ist unmittelbar die Wirkung des Vorhergehenden. Es ist nicht die Wirkung des Vorhergehenden in dem Sinne, wie man sich das vorstellt.

Gesetzmäßigkeit ist schon vorhanden in dem, was aufeinanderfolgend auftritt. Aber das, was man gewöhnlich «Notwendigkeit» nennt, das ist eine Illusion, wenn man es so auffaßt, wie es heute vielfach aufgefaßt wird. Im Strom des fortlaufenden Geschehens ist es ganz ähnlich, wie an einer solchen Stelle, wo der Baum aufhört und der elementare Baum beginnt; nur daß in der Natur hier ein Wesen des sichtbaren, des sinnlich-sichtbaren Reiches angrenzt an ein Wesen, das sinnlich-unsichtbar ist, das übersinnlich ist. Hier grenzt Sinnliches an Übersinnliches - hier im Zeitenstrom grenzt Gleichartiges aneinander; aber ebenso wie hier der sichtbare Baum aufhört und der Elementarbaum beginnt, so hört auch hier etwas auf und ein anderes beginnt.

So gibt es Zeitepochen, in denen die alten Geschehnisse, die alten Impulse, gewissermaßen aufhören und neue eingreifen müssen. Die Menschen halten sich in solchen Zeitpunkten oftmals gern an Luzifer und Ahriman und behalten das noch fort, was in Wirklichkeit eigentlich schon abgestorben ist. Im Bewußtsein kann man das noch fortbehalten, was in Wirklichkeit schon abgestorben ist. In der Natur kann man das nicht. Wenn jemand im Jahre 1914 Ideen genau derselben Art kultivieren will, wie sie berechtigt waren im Jahre 1876, so kann er das. Er kann es aus dem Grunde, weil man im fortlaufenden Strom des Menschengeschehens, in dem man sich an Ahriman und Luzifer klammert, das Alte bewahren kann, wenn es auch in Wirklichkeit schon tot ist. Aber es ist dasselbe, wie wenn einer wollte den Baum fortwachsen machen, so daß er nicht aufhört, wenn er seine natürlichen Grenzen erreicht hat. In der Geschichte geschieht es in der Regel, daß die Menschen nicht die Möglichkeit finden, einer neuen Epoche sich in der entsprechenden Weise richtig entgegenzusetzen, das heißt, sich in den Dienst des neuen Zeitgeistes zu stellen.

Und gerade für unsere Zeit ist dies von einer ganz besonderen, durchdringenden Wichtigkeit. Wir haben in diesen ganzen Wochen von dem gesprochen, was geistig Wichtiges vorgegangen ist 1879 (siehe Zeichnung, gelb). Da ging ein Zeitalter zu Ende, da starb etwas ab, da hörte etwas auf, so wie hier der Baum aufhört. Von da ab war es nötig - und ist bis heute nötig geblieben selbstverständlich, und wird noch lange nötig sein —, daß die Menschen zugänglich werden für Ideen, für Impulse, die aus der geistigen Welt selbst heraus sind. Sonst verwandelt sich das Alte in Ahrimanisches, Luziferisches.

Mit dieser Andeutung ist außerordentlich Wichtiges gesagt. Denn in diesem letzten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts war eine wichtige Zeit in der Menschheitsentwickelung. Notwendig war es und notwendig bleibt es, daß die Menschen den Sinn sich eröffnen für das Eingreifen inspirierter Ideen; dafür müssen die Menschen empfänglich werden. Allerdings, äußerlich betrachtet - wir werden aber die Sache nicht bloß äußerlich betrachten, sondern wir werden auf die tiefere, innerliche Betrachtung eingehen -, äußerlich betrachtet sieht es zunächst so aus,‘ als wenn eigentlich die Dinge recht trostlos lägen. Aus den geistigen Welten kamen schon die Impulse, die hereinströmten, hereinwirkten, um die Menschen über diesen Zeitpunkt des Jahres 1879 hinwegzuführen so, daß sie für inspirierte Ideen empfänglich geworden wären. Es waren schon die Impulse da, um den Menschen Gedanken zu geben, daß sie schon am Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts hätten das Bewußtsein haben können: Wenn wir geschichtlich, wenn wir sozial, wenn wir ethisch-moralisch im Gemeinschaftsleben handeln, dann handeln unsere Toten, handeln die Angeloi, handeln die Archangeloi, handeln die Archai unter uns. - Das war da. Die Impulse waren da, sie gingen nur an vielen Menschen zunächst spurlos vorüber.

Ich sage, ich betrachte das heute zunächst äußerlich, und es ist gut, wenn man sich einmal klarmacht, wie scheinbar spurlos alles vorbeigegangen ist. Wichtige Dinge, wichtige Impulse hat es schon gegeben in dieser zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, indem Menschen schon da waren, die bedeutungsvolle Gedanken gehabt, bedeutungsvolle Gedanken dargelegt haben. Wenn Sie diese heute ansehen werden, so sehen diese Gedanken selbst wie abstrakte Gedanken aus, gewiß, aber sie sind keine abstrakten Gedanken. Auch sollten sie nicht so bleiben, wie sie dazumal waren. Ich wiederhole es noch einmal, äußerlich ist das jetzt betrachtet, morgen werden wir es innerlich betrachten.

In allen Gebieten der heutigen Bildungswelt fast war das so. Wer betrachtet denn zum Beispiel, um ein Nächstes zu berühren, hier in diesem Lande, der Schweiz, dieses Leben so, daß er sich sagen würde: Hier in der Schweiz hat im 19. Jahrhundert in den fünfziger Jahren ein Mensch gewirkt, der bedeutungsvolle Gedanken hegte, die dazumal allerdings philosophische Gedanken waren, die aber von zwei oder drei andern hätten aufgenommen, popularisiert zu werden gebraucht, und die in der fruchtbarsten Weise hätten eingreifen und die ganze Geschichte der Schweiz durchgeistigen können! - Wer denkt zum Beispiel, daß ein Geist ersten Ranges in Otto Heinrich Jäger geschaffen hat in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts, einer der größten, die hier in der Schweiz geschaffen haben? Wo ist sein Name, wo wird er genannt? Wo ist das Bewußtsein dafür vorhanden, daß, obzwar die Gedanken abstrakt zutage getreten sind, scheinbar abstrakt, sie doch hätten konkret werden und blühen und Früchte tragen können, weil ein Größtes durch diesen Kopf gegangen ist, der an der Universität in Zürich gelehrt hat, der Bücher geschrieben hat über die wichtigsten Ideen - die hineingeweht werden müßten in das Leben der Gegenwart -, über die Idee der menschlichen Freiheit und ihres Zusammenhanges mit der ganzen geistigen Welt. Von ‘einem andern Gesichtspunkte, als dann meine Freiheitsphilosophie in den neunziger Jahren entstanden ist, hat Otto Heinrich Jäger hier in der Schweiz eine Art Freiheitsphilosophie geschaffen.

Und so wie dieses eine Beispiel könnte man überall unzählige anführen. Es sprießten und sproßten die fruchtbarsten Ideen. Aber das, was man heute erzählt als Geistesgeschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts und bis in das 20. Jahrhundert herein, ist das Allerunbedeutendste von dem, was sich wirklich zugetragen hat. Und das Allerbedeutendste, das Eindrücklichste, ist nicht berücksichtigt worden. So sehen die Dinge, zunächst äußerlich betrachtet, aus. Die innerlichen Betrachtungen werden vielleicht trostreicher aussehen.

Third Lecture

I would like to briefly touch upon some facts that have been mentioned, as we will need them for the continuation of our considerations. I have said that within the human being himself, including in his soul, lies what we can call the threshold between the ordinary sensory-physical world and the soul-spiritual world. This is so in the sense that in the ordinary waking consciousness with which human beings are endowed between birth and death, we are actually only fully awake in relation to sensory perceptions, that is, in relation to the perception of everything that comes to us through our senses, and furthermore in relation to everything we develop in our imagination, whether these are ideas we form about what we perceive with our senses or ideas that arise from within us to comprehend and enliven the world. Even ordinary self-reflection teaches us — without any need for clairvoyant abilities — that ordinary human consciousness, when fully awake, cannot encompass anything more than the realm of the life of ideas and the realm of sensory perceptions. In our soul itself, we also experience our world of feelings and our world of will. But we have said that we only live through our world of feelings as we live through a dream, that dream life extends into ordinary waking consciousness, and that, as feeling human beings, we are actually dreamers of life. For at the bottom of emotional life there are things going on of which waking consciousness knows nothing in imagination and sensory perception. Even less does waking consciousness know anything about the real processes of the life of the will. Human beings dream away their emotional life in ordinary waking consciousness and sleep through their will life. Thus, beneath our life of imagination there is a realm in which we ourselves are embedded and which is only partially known to us, known to us only through the waves that break upon its surface.

Furthermore, we have emphasized that in this realm, which human beings dream away and sleep through, the human souls live together with us in the existence between death and a new birth. We are therefore separated from the so-called dead only by the fact that we are not able to perceive with our ordinary consciousness how the forces of the dead, the life of the dead, the actions of the dead play into our own lives. For these forces, these actions of the dead, continually permeate our emotional life and our will. We therefore live with the dead. And it is important to realize in our present time how spiritual science has the task of developing this consciousness of belonging together with the souls of the dead.

The rest of the earth's development cannot flow, if it is to flow for the good of humanity, without humanity developing this living feeling of being together with the dead. For the life of the dead plays into the life of the so-called living in many different ways.

And it is not for nothing that attention has been drawn in the course of public lectures to how historical life, what human beings experience historically, socially, what they experience in relation to ethical processes among human beings, actually has the value of a dream, of sleep; that the impulses which man develops when he steps out of his personality, when he acts in the human community, are dream impulses, sleep impulses.

People will view history quite differently when they have become vividly aware of this. They will no longer regard history as the fable convenue that is generally called history today, but will realize that historical life can only be understood if one seeks in this historical life that which is dreamt away, slept away by ordinary consciousness, but into which, as we have seen, the impulses, deeds, and actions of the so-called dead initially play. The actions of the dead are interwoven with the feelings and impulses of the so-called living. And that is actually history.

Human beings do not cease to be active within the human community when they pass through the gates of death. They continue to be active, albeit in a different way than they must be active here in the physical body. But much of what human beings believe they do because of their illusions, because it flows from their feelings and impulses of will, actually flows down to our own day, when we carry out the corresponding actions, from the actions of those who have passed away.

To know that at the moment when it is a matter of one's life in human community, one is also acting in community with the dead, will be something significant in the development of human beings in the future. Of course, such a consciousness, which essentially relates to the life of feeling and will, must also be grasped by feeling and will. Abstract, dry ideas will never be able to grasp this, but ideas taken from the realm of spiritual science will be able to grasp it. However, people will have to get used to forming completely different concepts about many things.

You all know that those who are firmly grounded in the understanding of spiritual science impulses can try to remain in contact with those who have passed through the gate of death. And we have thoughts about spiritual science, about the ideas we form about the processes in the spiritual worlds, which are understandable to us as earthly human beings, but which are also understandable to the dead souls. And this gives rise to what we call reading aloud to the dead. When we read aloud about spiritual science in our thoughts for the dead, this is a real community life with the dead. For spiritual science speaks a language that is common to living and dead souls. But it is a matter of approaching these things more and more with the life of feeling, with a life of feeling that has been illuminated.Consider some of what I said yesterday. Between death and a new birth, human beings live in an environment that is essentially permeated not only by liveliness, but by feeling liveliness. I said that this is already their lowest realm. Just as the insentient mineral realm is what surrounds us during our sensory life, so the dead are surrounded by a realm of such a nature that if they touch anything in it, they cause pain or pleasure. It is the same with the dead as if we had to know in life that as soon as we touch a stone or a leaf on a tree, we evoke feelings. The dead can do nothing without evoking feelings of joy, pain, tension, relaxation, and so on in their surroundings. By being connected to the dead through reading aloud, the dead themselves experience the community we have already spoken of, but in this particular case of reading aloud. This brings the dead person into contact with the soul who is reading to them, with the soul that is somehow particularly connected to them through karma. And just as the dead person in their lowest realm, which we had to associate with the animal kingdom, is in such a relationship that everything they do evokes joy, suffering, and so on, so he stands in such a relationship with everything that has to do with human souls — whether they are human souls living here on earth or human souls that have already left the body and are living between death and a new birth — that through what is going on in other souls, he either receives an uplifted or a depressed feeling of life.

Think about this for a moment. When you read aloud to someone who is alive, you know that they understand what you are reading in the sense of human understanding. The dead live within you; the dead live in every word you read aloud; the dead penetrate what passes through your own mind. The dead live with you, they live more intensely with you than they could ever have lived in the life between birth and death. This can increase your understanding of the community with the dead. And this community with the dead is actually, when sought, a very intimate one, and this togetherness with the dead is increased through conscious observation.

If a person consciously enters that realm which we inhabit together with the dead, then communication with the dead is as follows: for example, when you read aloud or recite something to the dead, you hear what you are reading as if it were an echo from a spirit. One must become familiar with such concepts if one wants to gain a real understanding of the concrete spiritual world. Things are different in the spiritual world than they are here. Here you hear yourself speaking, or you know that you are thinking when you speak or when you think. If you speak to the dead, or if you enter into a connection with the dead through your thoughts, then, when the connection is conscious in your vision, what you say to them, or what you think or imagine about them, sounds to you as if it were coming from the dead themselves.

Furthermore, when you communicate something to the dead, you have a feeling of intimate connection. And if they respond to your communication, you first have the vague awareness that the dead are speaking. You have the vague awareness that the dead have spoken, and you must now draw from your own soul what they have said. From this you recognize how necessary it is for real spiritual communication to hear from the other person what you yourself think and imagine, and to hear from yourself what the other person says. This is a kind of reversal of the whole relationship between beings. But this reversal takes place when one truly enters the spiritual world.

Because the spiritual world is so completely different from the physical world, and because since the 15th century people have wanted to form ideas that are only of a physical nature, they have blocked and obstructed their access to the spiritual world. Once people deign to at least consider the possibility that there may be a world which, in a certain sense, not in everything, is opposed to the one that man here calls the true world, when people are willing to form ideas that may seem completely crazy to those who want to live only in a materialistic world, only then will people transform their souls in such a way that they will have the opportunity to really look into this spiritual world that is constantly around us. It is not that human beings are necessarily separated from the spiritual world by their nature, but rather that, through habit and heredity, since the 14th and 15th centuries, they have completely lost the ability to form ideas other than those borrowed from the physical world. This has even become the case in art! What else does contemporary art want to create other than what is modeled on what is formed outside in nature? Even in art, people no longer want to accept what arises freely as real from the spiritual life of the soul. But people cannot erase what is effective and active as something freely emerging in historical events, in ethical and moral coexistence, in social coexistence itself, even if they dream it away or sleep through it. As soon as a person goes even slightly beyond what are his most intimate, personal affairs — and he does so at every moment of his life — the spiritual world, that world which we — I must emphasize this again and again — have in common with the dead, works through his arm, through his hand, through his word, through his gaze.

The dead person now lives into the realm of which I have already spoken, just as we, growing up from childhood, live into the mineral, plant, animal, and human physical worlds between birth and death. As he lives into the lowest realm, which has something to do with the animal kingdom, into the second realm, in which the community is formed with all the souls with whom the dead person has a direct or indirect karmic connection, the dead person simultaneously develops into settling into the realm of those beings who now — if I may use the expression, although it can only be meant somewhat improperly — stand above human beings: into the realm of the angeloi, archangeloi, archai, for the time being.

Here in the physical world, human beings stand — as many like to emphasize — as the crown of physical creation. Here they feel themselves to be the highest of all beings. Mineral beings are the lowest, then plant beings, then animal beings, then humans. Humans feel that they belong to the highest realm. This is not the case with the dead in the spiritual realm, for the dead feel that they belong to the hierarchies above them: the hierarchies of the angeloi, archangeloi, archai, and so on. Just as human beings here in the physical world feel themselves emerging, growing out of the mineral, plant, and animal kingdoms, the physical human kingdom, so the dead feel themselves held, carried by the hierarchies above them in the life between death and a new birth.

The way in which human beings gradually settle into these realms, into the realms of the angeloi, archangeloi, archai, and so on, can be described as follows: one feels it as a detachment from oneself. Again, we must acquire a conception of these things that cannot be gained in the physical-sensory world. In the physical-sensory world, as we grow up from childhood, we gradually learn about things: first our immediate surroundings, then what is to become our life experience in the wider world, and so on. We learn about things in such a way that we know they come to us gradually. This is not the case between death and a new birth. From the moment we know that we are now in relationship with the Angeloi, we feel as if we have been connected with them for eternity, as if we belong to them, as if we are one with them, but as if consciousness can only develop by us, as it were, detaching the idea of the Angeloi from ourselves. Here in the physical world, we gain experience by taking in ideas. In the spiritual world, we gain experience by detaching ideas from ourselves, as it were. We know that we carry them within us, and we know that we are completely filled with them. But in order to bring them into consciousness, we must detach them from ourselves. And so we detach the ideas of the Angeloi, the Archangeloi, the Archai.