Earthly Death and Cosmic Life

GA 181

26 March 1918, Berlin

7. Confidence in Life and Rejuvenation of the Soul: a Bridge to the Dead

To study the matter further we must refer to what has already been brought forward.

When the subject under discussion is the relation of souls in human bodies to discarnate souls between death and rebirth, the chief thing is to direct the spiritual vision to the ‘psychic atmosphere’ in which they must meet in order to establish a relationship between them. We found that there must be a certain disposition of soul on the part of the living which, as it were, forms a bridge to the knowledge of the so-called dead. This disposition of soul always betokens the existence of a certain psychic element, and it may be said that when this element exists, when its presence shows the suitable feeling of the living, it is possible for these relations thus to come to pass.

We had to show that this possibility of a blending in the psychic atmosphere is created by the living through two directions of feeling; the first of which may be called the feeling of universal gratitude to all life's experiences. The general relationship of the human soul to its environment falls into an unconscious part and a conscious part. Everyone knows the conscious part; it consists in man's following what meets him in life with sympathy and antipathy and with his general perception. The subconscious part consists in developing, below the threshold of consciousness, a better and more sublime feeling than any we can develop in ordinary consciousness. This feeling can only be described as the knowledge always in the hidden subconscious part of the soul that we must be thankful for every experience of life, even the smallest. Our difficult experiences may for the moment cause us pain, but to a wider view of existence, even painful experiences so present themselves that, not in the surface regions but in the subconscious soul, man can be thankful for them, thankful that life is unceasingly supplied with gifts from the universe. This exists as a real subconscious feeling in the soul. The other direction of feeling is that we must unite our own ego with every being with whom we have anything to do in life. Our actions extend to other beings, some, it may be, even inanimate; but wherever we have done anything, wherever our being has been united with another in action, something remains; and this remainder establishes a permanent relationship between our being and everything with which we have ever been connected. This feeling of kinship is the foundation for a deeper one, a feeling generally unrecognised by the higher soul; a feeling of oneness with the surrounding world.

Those feelings—of gratitude and of union with the environment with which one is karmically united—can come to more and more conscious fruition. To a certain extent a man can awaken in his soul what lives in these feelings and perceptions; and to the degree in which this is done, he qualifies himself to build a bridge to souls living between death and rebirth. Their thoughts can only find the way to us when they are able to penetrate through the realm of the feeling of gratitude which we develop; and we can only find the way to them by fostering in our souls, at least to some extent, a feeling of communion. The fact that we are able to feel gratitude towards the universe enables such a mood to enter our souls. When we wish to enter into relation with the dead in any way, then because we have cultivated this disposition, because we are able to feel it, the way for the dead to reach us is opened; and because we can feel that our being lives in an organic community of which it forms a part, as our finger forms a part of our body, we become ripe to feel the same gratitude to the dead when they are no longer present in the physical body, so that by this means we can reach them with our thoughts. Only when we have acquired something of a disposition of gratitude, a feeling of communion, can we apply them in given cases.

These experiences are not the only ones; subconscious perceptions and moods are of many kinds. All that we develop in the soul opens out the path to the world in which dwell the dead between death and rebirth. Thus there is a very definite feeling existing subconsciously, but which can be gradually brought into the consciousness, a feeling which we may put alongside of the feeling of gratitude; it becomes lost to man in proportion as he degenerates into materialism, although to a certain degree it always exists in the subconsciousness and is never rooted out, even by the strongest materialism. Enrichment, enhancement and an ennobling of life, however, depend on man's raising such things from his subconsciousness to his consciousness. The feeling here referred to can be called universal confidence in the life which flows through and past us;—confidence in life! In a materialistic view of life, this disposition to confidence in life is very difficult to find. It resembles gratitude to life, but is quite another feeling alongside of it; for confidence in life consists in a steadfast disposition of soul, so that life, however it may approach us, has under all circumstances something to give us, so that we can never degenerate to the thought that life could have nothing more to give us. True, we pass through difficult and sorrowful experiences, but in the greater life relations these present themselves as something that most enriches and strengthens us for life. The chief thing is that this enduring disposition existing in the lower soul should be raised to the higher—the feeling: ‘O Life! Thou raisest me and bearest me, thou providest for my progress.’

If such a disposition were fostered in educational systems a tremendous amount would be gained. It is even good to plan our teaching and education so as to show, by individual examples, that life deserves our confidence—just because it is often so hard to understand. When a man considers life from such a standpoint, asking: ‘Art thou worthy of confidence, O Life?’ he finds much that otherwise he would not find in life. Such a mood should not be considered superficially; it should not lead to finding everything in life brilliant and good. On the contrary, in particular cases this very ‘confidence’ in life may lead to a sharp criticism of evil and foolish things. When a man has not confidence in life, this often leads to his avoiding the exercise of criticism towards what is bad and foolish, because he wishes to pass by the things wherein he has no confidence. It is not a matter of having confidence in particular things; that belongs to another sphere. Man has confidence in one thing and not in another, according as the things and beings present themselves; but the point is for him to have confidence in the general life, as a whole, in the common relationships of life, for if he can draw up any of the confidence always present in the subconsciousness, a way is opened for the real observation of the spiritual guidance and wise disposition of life. Anyone who is observant, not in theory but with feeling, says again and again: ‘As the occurrences of life follow one another, they mean something to me when they take me into themselves, they have something to do with me in which I can have confidence.’ This prepares him for the real gradual perception of what spiritually lives and weaves in these things. Anyone who has not this confidence closes himself to this.

Now to apply this to the relations between the living and the dead. When we develop this disposition of confidence, we make it possible for the dead to find his way to us with his thoughts; for thoughts can, as it were, sail on this mood of confidence from him to us. When we have confidence in life, faith in it, we are able to bring the soul into a condition in which the inspirations, which are thoughts sent to us by the dead, can appear;—gratitude towards life, confidence in life as described, belong in a sense together. If we have not this universal confidence in life as a whole, we cannot acquire sufficient confidence in anyone to extend beyond death; it is then simply a ‘memory’ of our confidence. We must realise that if this feeling is to meet with the discarnate dead, no longer incorporated in a physical body, it must be modified, and different from the perceptions and feelings which are extended to friends in the physical body. True, we have confidence in a man in the physical body and this will be useful for the conditions after death; but it is necessary that this confidence should be augmented by the universal, common confidence in life, for the relations of life after death are different. It is not only necessary to ‘remember’ the confidence we had in him in life, but we need to call forth freshly animated confidence in a being who can no longer waken confidence by his physical presence. For this it is necessary that we should ray something into the world, as it were, which has nothing to do with physical things; for the above-described universal confidence in life has nothing to do with physical things.

Just as this confidence places itself side by side with the feeling of gratitude, so something else places itself beside the feeling of oneness which is ever present in the lower soul and can be raised to the higher. That again is something which should receive more consideration than it does. This can be done when the element of which I am about to speak is given consideration in the educational systems of our materialistic age. A great deal depends upon this. If man is to take his right place in the world in the present cycle of time, it is necessary for him to develop a faculty which must be cultivated from knowledge of the spiritual world, not from an undefined instinct;—we might even say he must draw up something from the lower soul which came of itself in earner times of atavistic clairvoyance without any need of cultivation and which, though a few scattered remains still exist, is now gradually disappearing, as is all else derived from olden times. What a man needs in this respect is the possibility through life itself to rejuvenate and refresh again and again his feelings towards what must be encountered in life. We can so squander life that after a certain age we begin to feel more or less ‘tired,’ because we have lost the living share in life and are not able to bring sufficient zest to it for its phenomena to give us joy. Just compare the two extremes: the grasp and acceptance of experience in early youth—and the weary acceptance of life's phenomena in later age. Just consider how many disappointments are connected with this. There is a difference in whether a man is able to make his soul forces take part in a continual resurrection so that each morning is new to his psychic experience, or whether, as it were, the course of his life has wearied him for the appreciation of its phenomena.

It is specially important to consider this in our time, so that it should gain an influence in the systems of education. With respect to such things, we face a significant turning-point in human evolution. Our judgment of earlier epochs is framed under the influence of the modern science of ‘History,’ which is fiction of a strangely distorted kind. It is not even known how it has come about that training and education have been so directed that in later life man does not retain what he should. Under the influence of the present method the most that we produce in later years of life from the faculties exercised during our youthful education is a mere memory. We remember what we learnt, what was said to us, and as a rule we are contented if we do but remember. We do not, however, notice that many mysteries underlie human life, and in this connection one significant mystery. Reference has already been made to it in former lectures from another point of view. Man is a manifold being. We will first observe him as a twofold being. This twofold nature is expressed even in his outer bodily form, which shows us man as a head, and as the remaining part. Let us first divide man in this way. Were we to keep this difference in structure well in mind, we should be able to make very significant discoveries in natural science. If we observe the structure of the head purely physiologically, anatomically, it presents itself as that to which the more material history of evolution, known as the Darwinian theory, may be applied. In respect of his head, man is placed, as it were, in the stream of evolution; but only in respect of his head, not as regards the rest of his organism. In order to understand the descent of man, we must think of the head alone, disregarding the proportion in size, and consider all attached to it. Suppose evolution took such a course that in time to come man developed certain additional organs of still greater significance; this development, this metamorphosis, might go even further. This was actually the case in the past: man was, long ago, actually a head-being only, developing little by little and becoming what he is to-day. What is attached to the head, although physically larger, only grew there later. It is a younger structure. As regards his head, man is descended from the oldest organism, all the rest grew later. The reason why the head is so important to the present man is because it remembers former incarnations. The rest of his organisation is, on the other hand, a preliminary condition for later incarnations. In this respect man is a twofold being. The head is organised quite differently from the rest of the organism. The head is an ossified organ. The fact is that if man had not the rest of his organism, he would certainly be very spiritualised,—but a ‘spiritualised animal’ only. Unless the head were inspired thereto, it would never feel itself as ‘man.’ It points back to the old epochs of Saturn, Sun and Moon, the rest of the organism only to that of the Moon, and indeed to the later part of that period; it only grew on to the head-part and is really in this respect something like a parasite. We may well think of it in this way: the head was once the whole man; below, it had outlets and openings by which it fed. It was a very peculiar being. As it developed, the lower orifices closed to the environment, and therefore were no longer able either to serve for nourishment or to bring the head into connection with the influences streaming in from the environment; and because the head also ossified above, the remaining part of the body then became necessary. This part of the physical organism only came into being at a time when it was no longer possible for the rest of the animal creation to take form. It may be said that this is difficult to imagine. The only reply is that man must take the trouble to realise that the world is not so simple as some would like to believe, some who prefer not to think much in order to understand it. In this respect men experience a number of ideas by which they claim that the world is easy to understand, and they have very remarkable views. There is an abundance of literature by those who hold Kant as a great philosopher. That is due to the fact that they understand no other philosophers, and have to exercise much thought-force to understand Kant. As he was to them the greatest philosopher (in their own opinion men often consider themselves to be the greatest geniuses!) they can understand none of the others. It is only because Kant is so difficult to understand that he is regarded by them as a great philosopher. With this is connected the fact that man is afraid to regard the world as complicated, as requiring the power of thought for its comprehension. These things have been described from various points of view, and when some day my lectures on ‘Occult Physiology’ are published, men will be able to read how it can be proved by embryology, that it is foolish to say that the brain has developed from the spinal cord. The opposite is the case; the brain is a transformed spinal cord of former times, and the present spinal cord is only added to the brain as an appendage. We must learn to understand that what seems the simplest part of man has come into being later than what seems the more complicated; what is more primitive and at a more subordinate stage, has come into being later.

This reference to the twofold nature of man is made here in order to explain the rest, which is the outcome of this duality. The consequence is, that as regards our soul life, which develops under the restrictions of the bodily nature, we ourselves are included in this duality. We have not only the organic development of the head and that of the rest of the organism, but also two different rates, two different velocities in the development of the soul. The development of the head is comparatively rapid, and that of the rest of the organism—we will call it the development of the heart—is about three or four times slower. The condition for the head is that as a rule it closes its development about the 20th year; as regards the head we are old at 20, it is only because we obtain refreshment from the rest of the organism, which develops three or four times as slowly, that we continue our life agreeably. The development of our head is quick, that of the heart, of the rest of the organism, three or four times slower; and in this duality we live our earthly life. In childhood and youth our headorganism can absorb a great deal, therefore we study during that time; but what we then received must be continually renewed and refreshed, must be constantly encompassed by the slower evolutionary progress of the rest of the organs, the progress of the heart.

Now let us reflect that if education, as in our age, only takes into consideration the development of the head, it is because in training and education we only allow any rights to the head, the consequence is that the head is only articulated as a dead organism into the slower progress of the evolution of the rest; it holds this back. The phenomenon that at the present time man grows old early in his soul and inner nature, is chiefly due to the system of training and education. Of course we must not suppose that at the present time we can put the question: How shall we arrange education, so that this shall not happen? This is a very important matter which cannot be answered in a few words, for education would have to be altered in almost every respect, for it would not be a question of memory only, but of something with which man could refresh and revive himself. Let us ask ourselves how many to-day, when they look back to an achievement in childhood, upon all they experienced then, upon what their teachers and relations said, are able to remember more than: ‘You must do this,’ are able to plunge again into what was experienced in youth, looking lovingly back to the hand-clasp, to every single remark, to the sound of the voice, to the permeation with feeling of what was offered them in childhood, experiencing it as a continual fount of rejuvenation? It is connected with the rates of development we experience within us, that man must follow the quicker development of his head, which closes about the 20th year, and that the slower progress of the heart, the evolution of the rest of him, has to be nourished throughout his life. We must not only give the head what is prescribed for it, but also that from which the rest of the organism can again and again draw forth restorative force for the whole of our lives. For this it is necessary that every branch of education should be permeated by a certain artistic element. To-day, when people avoid the artistic element, thinking that to foster the life of fancy—and fancy carries man beyond mere everyday reality—might bring fantasy into education, there is no inclination whatever to pay attention to such mysteries of life. We need only look to certain spheres to see what is here meant—for it does, of course, still exist here and there—and we shall see that something can be realised in this way; but it must be realised by man's again becoming ‘man.’ This is necessary for many reasons; we shall draw attention to one of them.

Those who wish to become teachers to-day are examined as to what they know, but what does this prove? As a rule only that the candidate has for the time of the examination, hammered into his head something which—if he is at all suited for that particular subject—he has been able to gather from many books, day after day acquiring what it is not in the least necessary to acquire in that way. What should be required above all in such examinations is to ascertain whether the candidate has the heart, mind and temperament for gradually establishing a relationship between himself and the children. Examination should not test the candidate's knowledge, but ascertain his power, and whether he is sufficiently a ‘man.’ To make such demands to-day would, I know, simply mean for the present time one of two things. Either it would be said that anyone who demands such tests is quite crazy, such a man does not live in the world of reality; or if reluctant to give such an answer, they would say: ‘Something of the kind does take place, we all want that.’ People suppose that results come about from this training, because they only understand the subject in so far as they bring their consideration to bear upon it.

The foregoing is intended to throw light from a certain side upon something which the lower soul always feels, and which is so difficult to bring up into the higher soul at the present time; something which is desired by the human soul and will be desired more and more as the time goes on;—so that we may see in the right light the fact that the soul needs something wherewith continually to renew the power of its forces, so that we may not grow weary with our progressing life, but are always able to say, full of hope: ‘Each new day will be to us like the first one we consciously experienced.’ For this however we must, in a sense, not need to ‘grow old;’ it is urgently necessary that there should be no occasion to grow old in soul. When we observe how many comparatively young people there are who are dreadfully old and how few regard each day as a new experience given them, as to a lively child, we know what must be achieved and given by a spiritual culture in this domain. Ultimately the feeling here meant is the feeling which acquires the perennial hopefulness of life and enables us to experience the right relation between the living and the so-called dead. Otherwise the facts which should establish our relationship to one of the dead remain too strongly in the memory. A man can remember what he experienced with his dead during life. If, however, when the dead is physically absent we cannot have the feeling that we can always revivify what we experienced with him during life, our feeling and perception are not strong enough to experience this new relationship that the dead is still present as a spiritual being and can work as a spirit. If a man has grown so deadened that he can no longer revive anything of the hopefulness of life, he can no longer feel that a complete transformation has taken place. Formerly he could help himself by meeting his friend in life; now the spirit alone can come to his help. He can meet him, however, if he evolves this feeling of the ever-enduring stimulation of the life-forces, in order to keep the hopefulness of life fresh.

It may seem strange to say so, but a healthy life, especially healthy in the directions which a man might develop here (unless he be in a clouded state of consciousness), never leads to the consideration of life as anything of which he can be tired; for even when he has grown old, a thoroughly sound life leads him to wish to accept each day as something new and fresh. Sound health does not lead a man to say when old: ‘Thank God my life is behind me;’ rather does he say to himself: ‘I should like to go back forty or fifty years and pass through the same circumstances again!’—This is the man who has learnt through wisdom to cheer himself with the thought that what he cannot carry through in this life, he will do more correctly in another. The sound man does not regret anything he has experienced, and if wisdom is needed for this, he does not long to have it in this life, but is able to wait for another. The right confidence in life is built on vigorously maintained life-hopes.

These then, are the feelings which rightly inspire life and at the same time create the bridge between the living here and the dead yonder:—gratitude towards the life which greets us here; confidence in its experiences; an intimate feeling-in-common; the faculty of making hope active in life through ever fresh springing life-forces; these are the inner ethical impulses which, felt in the right way, can supply the highest external social ethics; for ethics, like history, can only be understood in the subconscious realm.

Another question in regard to the relationship of the living to the dead frequently arises: What is the real difference in a relationship between man and man when incarnated in physical bodies, and between them when one is in a physical body and the other not, or when neither is in a physical body? In respect to one point of view I should here like to mention something of importance.

When we observe the ego and actual soul life—also called the astral body—by means of spiritual science (the ego, as we have often heard, is the youngest, the baby among the principles of man's organisation, whereas the astral body is somewhat older, though only dating from the Moon evolution) we must say of these two highest principles that they are not as yet so far advanced for man to rely on them alone for power to maintain himself independently of other men. If we were here with one another—each only as ego and astral body—we should be together as though in a sort of primordial jelly. Our entities would merge into each other, we should not be separate and would not know how to distinguish ourselves one from the other. There could be no possibility of knowing whether a hand or leg were one's own or another's (the whole matter would then of course be quite different, we cannot really thus compare the circumstances). We could not even properly recognise our feelings as our own. To perceive ourselves as separated men depends on each one having been drawn out of the general fluid—as we must picture a very early period—like a drop; and in such a way that the individual souls did not flow together again, but each soul-drop was held together as though in a sponge. Something like that really occurred. Only because we as human beings are in etheric and physical bodies are we separated from one another, really separate. In sleep we are only separated by a strong longing for our physical body. This longing which draws us ardently to the physical body, divides us in sleep; otherwise we should drift through one another all night long. It would probably be much against the grain of sentimental minds if they knew how strongly they come into connection with other beings in their neighbourhood. This, however, is not so very bad in comparison with what might be if this ardent longing for the physical body did not exist as long as man is physically incorporated.

We might now ask: What divides our souls from others in the time between death and rebirth? Well: as with our ego and astral body between birth and death we belong to a physical and etheric body, so after death, until rebirth, we are part of quite definite starry structures, in no way the same; each one of us belongs to quite a distinct structure. From out [of] this instinct we speak of ‘man's star.’ This starry structure, taking its physical projection first, is periphically globular, but we can divide it in many ways. The regions overlap each other, but each belongs to another. Expressed spiritually, we might say that each belongs to a different rank of Archangels and Angels. Just as people here are drawn together through their souls, so between death and rebirth, each belongs to a particular starry structure, to a particular rank of Angels and Archangels; their souls all meet together there. The reason this is so, but only apparently (for we must not now go further into the mystery) is because on earth each one has his own physical body. I say ‘apparently’ and you will wonder; but it is surprising when investigated how each has his own starry structure and how these overlap. Let us think of a particular group of Angels and Archangels. In the life between death and rebirth, thousands of Angels and Archangels belong to one soul; imagine only one of all these thousands, taken away and replaced by another, and we have the region of the next soul.

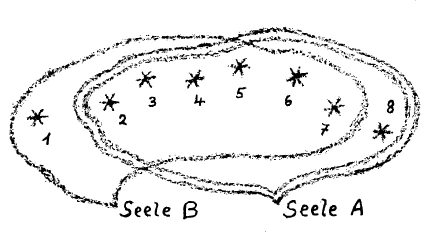

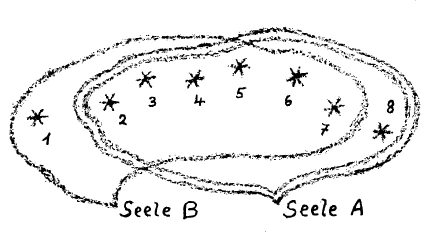

In this diagram two souls have, with one exception, which they have from another realm, the same stars; but no two souls have absolutely similar starry structures. Thus men are individualised between death and rebirth, by having each his special starry structure. From this we see upon what the separation of souls between death and rebirth is based. In the physical world, as we know, this division is effected by the physical body. Man has his physical body as a shell as it were; he observes the world from it, and everything must come to the physical body. All that comes into the soul of man between death and rebirth stands, as regards the relation between his astral body and ego, in a similar way in regard to a starry structure, as here the soul and the ego stand with regard to the physical body. Thus the question as to how this severance comes about is also answered as above.

From these considerations we have seen to-day how we can work upon our souls in forming certain feelings and perceptions, so that the bridge of communication may be formed between the so-called dead and the living. What has just been said can also attract thoughts, perceptive thoughts and thoughtful perceptions, which can in their turn have a share in the creation of this bridge. This takes place by our seeking more and more to form a kind of perception with regard to some particular dead friend which when we have experienced something in the soul, can bring up the impulse to ask ourselves: How would the dead experience what I experience at this moment? By creating the imagination that the dead experienced the event side by side with us and making this really a living feeling, man gauges in a certain respect, either how the dead has intercourse with the living, or the dead with the dead, when we consider the various starry realms given, in relation to our own souls or to each other. We can here surmise what interplays between soul and soul through their assignment to the starry realm. If we concentrate through the presence of the dead upon a directly present interest, if in this way we feel the dead living immediately beside us, then from such things as are discussed to-day we become more and more conscious that the dead really do approach us. The soul will develop a consciousness of this. In this connection we must have confidence in life that these things are so; for if we do not have confidence but are impatient with life, the other truth obtains. What confidence brings is drawn away by impatience; what man might learn through confidence, is made dark by impatience. Nothing is worse, than if by our impatience we conjure up a mist before the soul.

Siebenter Vortrag

Mit ein paar Worten wollen wir zurückkommen, damit der Zusammenhang gewahrt werde, auf das, was vor acht Tagen hier vorgebracht worden ist. Ich sagte: Wenn es sich darum handelt, das Verhältnis der im Leibe verkörperten Menschenseelen zu entkörperten Menschenseelen, die zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt leben, ins Auge zu fassen, so kommt es darauf an, das geistige Auge gewissermaßen auf die «seelische Luft» zu richten, die den Lebenden mit den sogenannten Toten verbinden muß, damit ein Verhältnis zwischen beiden stattfinden könne. Und wir haben zunächst gefunden, daß gewisse Seelenstimmungen, die beim Lebenden vorhanden sein müssen, gewissermaßen die Brücke hinüberschlagen in die Reiche, in denen die sogenannten Toten sind. Seelenstimmungen bedeuten ja immer auch das Vorhandensein eines gewissen seelischen Elementes, und man könnte sagen, eben wenn dieses seelische Element vorhanden ist, wenn es seine Anwesenheit zeigt durch die entsprechenden Gefühle des Lebenden, dann findet die Möglichkeit eines solchen Verhältnisses statt.

Wir mußten dann darauf hinweisen, daß solche Möglichkeit, also gewissermaßen die seelische Luftverbindung, durch zwei Gefühlstichtungen beim Lebenden geschaffen wird. Die eine Gefühlsrichtung ist die, welche man nennen könnte das universelle Dankbarkeitsgefühl gegenüber allen Lebenserfahrungen. Ich sagte: Die Gesamtart, wie sich die Seele des Menschen zur Umgebung überhaupt verhält, zerfällt in einen unterbewußten Teil und in einen bewußten. Den bewußten Teil kennt jeder; er besteht darinnen, daß der Mensch mit Sympathien und Antipathien und mit seinen gewöhnlichen Wahrnehmungen verfolgt, was ihn im Leben trifft. Der unterbewußte Teil aber besteht darinnen, daß wir tatsächlich eben unter der Schwelle des Bewußtseins ein Gefühl entwickeln, das besser, erhabener ist als die Gefühle, die wir im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein entwickeln können, ein Gefühl, das eben nicht anders bezeichnet werden kann als dadurch, daß wir in unserer Unterseele immer wissen, wir haben dankbar zu sein für jede Lebenserfahrung, auch für die kleinste, die an uns herantritt. Daß schwere Lebenserfahrungen an uns herantreten, mag uns gewiß für den Augenblick schmerzlich stimmen; aber für einen größeren Überblick des Daseins nehmen sich auch schmerzliche Lebenserfahrungen so aus, daß man zwar nicht in der Oberseele, aber doch in der Unterseele dankbar dafür sein kann, dankbar dafür, daß vom Universum unser Leben mit fortwährenden Gaben versehen wird. Das ist etwas, was einmal als ein wirklich unterbewußtes Gefühl in der Menschenseele vorhanden ist. Das andere ist, daß wir unser eigenes Ich verbinden mit jedem Wesen, mit dem wir irgendwie im Leben handelnd etwas zu tun gehabt haben. Unsere Handlungen erstrecken sich auf diese oder jene Wesen des Lebens, es können auch sogar unbelebte sein. Aber wo wir etwas getan haben, wo sich unsere Wesenheit mit einer andern Wesenheit handelnd verbunden hat, da bleibt etwas zurück, und dieses Zurückbleibende begründet eine dauernde Verwandtschaft unserer Wesenheit mit alledem, womit wir uns eben jemals verbunden haben. Ich sagte: Dieses Gefühl der Verwandtschaft ist die Grundlage für ein tieferes, der Oberseele gewöhnlich unbekannt bleibendes Gefühl einer Gemeinsamkeit mit der umgebenden Welt, ein Gemeinsamkeitsgefühl.

Der Mensch kann diese beiden Gefühle, das Gefühl der Dankbarkeit und das Gefühl der Gemeinsamkeit mit der Umgebung, mit der er irgendwie karmisch verbunden war, immer mehr und mehr bewußt ausleben. Er kann gewissermaßen das, was in diesen Gefühlen und Empfindungen lebt, heraufheben in die Seele; und in dem Maße, als er gerade diese beiden Empfindungen heraufhebt in die Seele, macht er sich geeignet, die Brücke zu schlagen zu den Seelen, die ihr Leben zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt verbringen. Denn die Gedanken dieser Seelen können zu uns nur den Weg finden, wenn sie durch den Bereich des von uns entwickelten Dankbarkeitsgefühls wirklich durchdringen können; und wir können einzig und allein dadurch den Weg zu ihnen finden, daß unsere Seele wenigstens einigermaßen sich gewöhnt hat, wirkliche Gemeinschaft zu pflegen. Daß wir imstande sind, dem Universum gegenüber Dankbarkeit zu empfinden, läßt auch zuweilen eine solche Dankbarkeitsstimmung in unsere Seele fallen, wenn wir mit den Toten in irgendeine Verbindung treten wollen, daß wir geübt haben eine solche Dankbarkeitsstimmung, daß wir in der Lage sind, sie fühlen zu können, das bahnt den Gedanken des Toten den Weg zu uns. Und daß wir empfinden können: Es lebt unser Wesen in einer organischen Gemeinschaft, von der es ein Teil ist, wie unser Finger von unserem Körper, das macht uns reif dazu, auch gegenüber den Toten, wenn sie nicht mehr im physischen Leibe anwesend sind, eine solche Dankbarkeit zu empfinden, damit wir mit unseren Gedanken zu ihnen herüberkommen. Wenn man sich auf einem Gebiete so etwas angeeignet hat wie Dankbarkeitsstimmung, die Gemeinsamkeitsempfindung, dann hat man erst die Möglichkeit, sie im gegebenen Falle auch anzuwenden.

Nun sind diese Empfindungen nicht die einzigen, sondern solcher unterbewußter Empfindungen und unterbewußter Seelenstimmungen sind noch mannigfaltige vorhanden. Alles was wir in unseren Seelen ausbilden, bahnt mehr den Weg in die Welt, wo die Toten zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt sind. So stellt sich eine ganz bestimmte Empfindung, die unterbewußt immer vorhanden ist, aber ins Bewußtsein allmählich heraufgebracht werden kann, der Dankbarkeit an die Seite, eine Empfindung, die dem Menschen um so mehr abhanden kommt, je mehr er ins Materialistische umschlägt. Aber im Unterbewußten ist sie bis zu einem gewissen Grade immer vorhanden und ist eigentlich selbst durch den stärksten Materialismus nicht auszurotten. Aber eine Bereicherung, eine Erhöhung, eine Veredelung des Lebens hängt davon ab, daß man solche Dinge auch heraufholt aus dem Unter.bewußten ins Bewußte. Die Empfindung, die ich meine, ist das, was man bezeichnen könnte mit dem allgemeinen Vertrauen in das durch uns hindurchflutende und an uns vorbeiflutende Leben, Vertrauen zum Leben! Innerhalb einer materialistischen Lebensauffassung ist die Stimmung des Vertrauens zum Leben außerordentlich schwer zu finden. Sie ist sogar ähnlich der Dankbarkeit gegenüber dem Leben, aber doch wieder eine andere Empfindung, die sich dieser Dankbarkeit an die Seite stellt. Denn Vertrauen zum Leben besteht darin, daß eine unerschütterliche Stimmung in der Seele vorhanden ist, daß das Leben, wie es auch an uns herantreten mag, unter allen Umständen uns etwas zu geben hat, daß wir niemals auch nur auf den Gedanken verfallen können, daß das Leben uns durch dieses oder jenes, was es uns entgegenbringt, nichts zu geben hätte. Gewiß, wir machen schwere Lebenserfahrungen, leidvolle Lebenserfahrungen durch, aber in einem größeren Lebenszusammenhange stellen sich gerade leidvolle und schwere Lebenserfahrungen als die heraus, die uns am meisten das Leben bereichern, uns am meisten für das Leben stärken. Es handelt sich darum, diese fortdauernde Stimmung, die in der Unterseele wieder vorhanden ist, ein wenig in die Oberseele heraufzuheben, diese Stimmung: Du, Leben, du hebst und trägst mich, du sorgst dafür, daß ich vorwärtskomme.

Wenn im Erziehungssystem für die Pflege einer solchen Stimmung etwas getan würde, so wäre außerordentlich viel gewonnen. Erziehung ‚und Unterricht daraufhin anzulegen, geradezu an einzelnen Beispielen zu zeigen, wie das Leben gerade dadurch, daß es oftmals schwer zu durchdringen ist, Vertrauen verdiente, es würde ganz besonders viel bedeuten, wenn diese Stimmung in das Erziehungs- und Untetrichtssystem überginge. Denn indem man geradezu das Leben unter einem solchen Gesichtspunkte betrachtet: Verdienst du Vertrauen, o Leben? - stellt sich heraus, daß man vieles findet, was man sonst nicht im Leben findet. Man betrachte eine solche Stimmung nur ja nicht oberflächlich. Es darf eine solche Sache nicht dazu führen, nun alles glänzend und gut im Leben zu finden. Im Gegenteil, es kann in den einzelnen Fällen gerade dieses Vertrauen-haben-zum-Leben zu einer scharfen Kritik von schlimmen, törichten Dingen führen. Und gerade wenn man kein Vertrauen hat zum Leben, führt das oftmals dazu, daß man vermeidet, Kritik zu üben an Schlechtem und Törichtem, weil man vorübergehen will an dem, wozu man kein Vertrauen hat. Es handelt sich ja nicht darum, daß man zu dem einzelnen Dinge Vertrauen habe, das gehört in ein anderes Gebiet. Man hat zu dem einen Ding Vertrauen, zu einem andern nicht, je nachdem sich die Dinge und Wesenheiten darbieten. Aber zu dem Gesamtleben, zu dem Gesamtzusammenhalt des Lebens Vertrauen haben, darum handelt es sich. Denn, kann man etwas von dem im Unterbewußtsein immer vorhandenen Vertrauen zum Leben heraufholen, so bahnt es den Weg, um das Geistige, die weisheitsvolle Fügung und Führung im Leben auch wirklich zu beobachten. Wer sich, nicht theoretisch, sondern empfindend immer wieder und wieder sagt: So wie die Erscheinungen des Lebens aufeinanderfolgen, so bedeuten sie für mich etwas, indem sie mich in sich aufnehmen und etwas mit mir zu tun haben, wozu ich Vertrauen haben kann -, der. bereitet sich gerade damit vor, um das, was geistig lebt und webt in den Dingen, wirklich auch nach und nach wahrzunehmen. Wer dieses Vertrauen nicht hat, der verschließt sich vor dem, was geistig in den Dingen lebt und webt.

Nun die Anwendung auf das Verhältnis der Lebenden zu den Toten. Indem man diese Stimmung des Vertrauens entwickelt, macht man es wiederum dem Toten möglich, mit seinen Gedanken den Weg zu uns zu finden; denn auf dieser Vertrauensstimmung können die Gedanken gewissermaßen von ihm zu uns segeln. Wenn wir im allgemeinen Vertrauen zum Leben, Glauben an das Leben haben, werden wir die Seele in eine solche Verfassung bringen können, daß in ihr jene Eingebungen erscheinen können, welche die von den Toten gesandten Gedanken sind. Dankbarkeit gegenüber dem Leben, Vertrauen zum Leben in der geschilderten Form gehören in einer gewissen Weise zusammen. Wir können, wenn wir nicht dieses allgemeine Weltvertrauen haben, zu einem Menschen nicht ein solch starkes Vertrauen gewinnen, das über den Tod hinausreicht, sonst ist es Erinnerung an das Vertrauen. Sie müssen sich schon vorstellen, daß die Gefühle, wenn sie den nicht mehr im physischen Leibe verkörperten Toten treffen sollen, in einer andern Weise abgewandelt sein müssen als die Empfindungen, die Gefühle, die zu dem Menschen gehen, der im physischen Leibe da ist. Gewiß, wir können zu einem Menschen im physischen Leibe Vertrauen haben, dieses Vertrauen wird auch etwas für den Zustand nach dem Tode nützen. Aber es ist notwendig, daß dieses Vertrauen durch das universelle, durch das allgemeine Vertrauen verstärkt werde, weil ja der Tote nach dem Tode in andern Verhältnissen lebt, weil wir nicht bloß nötig haben, uns an das Vertrauen zu erinnern, das wir schon im Leben zu ihm gehabt haben, sondern weil wir auch nötig haben, immer neubelebtes Vertrauen an eine Wesenheit, die nicht mehr durch ihre physische Anwesenheit Vertrauen erweckt, hervorzurufen. Dazu ist notwendig, daß wir gewissermaßen etwas in die Welt hinausstrahlen, was nichts zu tun hat mit den physischen Dingen. Und mit physischen Dingen nichts zu tun hat das geschilderte universelle Vertrauen zum Leben.

Ebenso wie sich das Vertrauen neben die Dankbarkeit hinstellt, so stellt sich auch neben das Gemeinschaftsgefühl etwas hin, was immer in der Unterseele vorhanden ist, aber auch wieder in die Oberseele heraufgeholt werden kann. Das ist wieder etwas, was man auch mehr berücksichtigen sollte, als man es tut. Und das kann man, wenn dieses Element, von dem ich jetzt sprechen will, in unserer materialistischen Zeit im Unterrichts- und Erziehungssystem berücksichtigt würde. Davon hängt ungemein viel ab. Soll der Mensch im gegenwärtigen Zeitenzyklus in der richtigen Weise sich in die Welt hineinstellen, dann hat er notwendig, etwas auszubilden, ich könnte auch sagen, etwas aus der Unterseele heraufzuholen, was in den früheren Zeiten des atavistischen Hellsehens von selbst kam, was nicht gepflegt zu werden brauchte, wovon spärliche Reste noch vorhanden sind, die aber nach und nach verschwinden, wie alles aus den alten Zeiten Stammende verschwindet, was aber heute gepflegt werden muß, und zwar gepflegt werden muß aus der Erkenntnis der geistigen Welt heraus, nicht aus unbestimmten Instinkten. Was der Mensch in dieser Beziehung braucht, ist die Möglichkeit, seine Gefühle für das, was ihn im Leben trifft, immer wieder und wieder zu verjüngen, zu erfrischen an dem Leben selber. Wir können das Leben so verbringen, daß wir von einem gewissen Lebensalter an mehr oder weniger uns müde fühlen, weil wir die lebendige Teilnahme am Leben verlieren, weil wir nicht mehr genug für das Leben aufbringen können, damit uns seine Erscheinungen Freude machen. Man vergleiche nur miteinander, wenn man äußere Extreme verbindet: das Ergreifen und Entgegennehmen der Erlebnisse in früher Jugend und das müde Entgegennehmen der Lebenserscheinungen im späten Alter. Denken Sie, wie viele Enttäuschungen mit solchen Dingen zusammenhängen. Es ist ein Unterschied, ob der Mensch imstande ist, seine Seelenkraft gewissermaßen einer fortwährenden Auferstehung teilhaftig werden zu lassen, daß ihr jeder Morgen neu ist für das seelische Erleben, oder ob er gewissermaßen im Laufe des Lebens für die Erscheinungen ermüdet. |

Dies zu berücksichtigen, ist in unserer Zeit außerordentlich wichtig, weil es bedeutsam’ ist, daß es auch auf das Erziehungssystem Einfluß gewinne. Wir gehen nämlich gerade mit Bezug auf solche Dinge einer bedeutungsvollen Wendung in der Menschheitsentwickelung entgegen. Die Beurteilung früherer Menschheitsepochen geschieht unter dem Einfluß unsefer Geschichte, die ja eine Fable convenue ist, wirklich in außerordentlich schiefer Weise. Man weiß nicht, wie die letzten Jahrhunderte die Menschen dazu gebracht haben, immer mehr und mehr Erziehung und namentlich Unterricht so einzurichten, daß der Mensch in seinem späteren Leben nicht dasjenige von der Erziehung und dem Unterricht hat, was er eigentlich von ihnen haben sollte. Das Äußerste, was wir unter dem Einfluß der heutigen Verhältnisse im späteren Lebensalter für das aufbringen, was wir während der Jugend in der Erziehung aufgewendet haben, ist eine Erinnerung. Wir erinnern uns an das, was wir gelernt haben, was uns gesagt worden ist, und man ist in der Regel auch zufrieden, wenn man sich daran erinnert. Dabei aber berücksichtigt man ganz und gar nicht, daß das menschliche Leben zwar vielen Geheimnissen, aber mit Bezug auf diese Dinge einem bedeutsamen Geheimnisse unterliegt. In einer früheren Betrachtung habe ich hier von diesem Geheimnis schon von einem andern Gesichtspunkte aus eine Andeutung gemacht.

Der Mensch ist ein vielfältiges Wesen. Wir betrachten ihn zunächst, insofern er ein zwiespältiges Wesen ist. Die Zwiespältigkeit — sagte ich in einer früheren Betrachtung — drückt sich schon in der äußeren Leibesform aus. Diese zeigt uns den Menschen als Haupt und als den übrigen Menschen. Wir wollen zunächst den Menschen trennen in das Haupt und den übrigen Menschen. Würde man nur einmal diesen Unterschied im ganzen Bau des Menschen ins Auge fassen, so würde man schon naturwissenschaftlich ganz bedeutende Entdeckungen machen können. Wenn man nämlich den Bau des Hauptes rein physiologisch, anatomisch betrachtet, so stellt sich gerade das Haupt als das heraus, worauf sich die mehr materialistisch gedachte Abstammungslehre, was man heute Darwinische Theorie nennt, anwenden läßt. In bezug auf seinen Kopf ist der Mensch gewissermaßen in diese Entwickelungsströmung hineingestellt, aber nur in bezug auf seinen Kopf, nicht in bezug auf seinen übrigen Organismus. Sie müssen sich, um diese Abstammung des Menschen zu begreifen, die Sache so vorstellen, daß Sie sich, ganz abgesehen vom Größenverhältnis, das menschliche Haupt vorstellen und das andere darangewachsen. Denken Sie sich einmal, die Entwickelung ginge so vor sich, daß der Mensch sich in die Zukunft entwickelte und irgendwelche Organe noch besondere Anhangorgäane bekämen. Die Entwickelung, die Umgestaltung könnte ja weitergehen. So war es aber in der Vergangenheit: Der Mensch war vor Zeiten bloß eigentlich als Haupteswesen vorhanden, und dieses Haupt hat sich immer weiter- und weitergebildet, und ist zu dem geworden, was es heute ist. Und was an dem Haupte dranhängt, wenn dies auch physisch größer ist, ist erst später dazugewachsen. Das ist eine jüngere Bildung. In bezug auf sein Haupt stammt der Mensch ab von den ältesten Organismen, und das andere außer dem Haupt ist erst später dazugewachsen. Dadurch kommt es auch, daß das Haupt beim heutigen Menschen immer so wichtig ist, weil es an die vorherige Inkarnation erinnert. Der übrige Organismus — darauf habe ich auch schon aufmerksam gemacht - ist dagegen die Vorbedingung für die spätere Inkarnation. Der Mensch ist in dieser Beziehung ein ganz zwiespältiges Wesen. Das Haupt ist ganz anders veranlagt als der übrige Organismus. Das Haupt ist ein verknöchertes Organ. Es ist so, daß der Mensch, wenn er den übrigen Organismus nicht hätte, zwar sehr vergeistigt, aber ein vergeistigtes Tier wäre, Das Haupt kann niemals, wenn es nicht dazu inspiriert wird, sich als Mensch fühlen. Es weist zurück auf die alte Saturn-, Sonnen- und Mondenzeit. Der übrige Organismus weist nur bis in die Mondenzeit, und zwar in die spätere Mondenzeit zurück; er ist an den Hauptesteil darangewachsen und ist in dieser Beziehung wirklich etwas wie ein Parasit des Hauptes. Sie können es sich gut vorstellen: Das Haupt war einmal der ganze Mensch, es hatte nach unten hin Ausfluß- und Auslauforgane, durch die es sich ernährte. Es war ein ganz eigentümliches Wesen. Aber indem es sich weiterentwickelte, indem sich die Öffnungen nach unten so entwickelten, daß sie sich nicht mehr in die Umgebung hinein öffneten und dadurch nicht mehr für die Ernährung dienen konnten und das Haupt mit den von der Umgebung einstrahlenden Einflüssen in Verbindung bringen konnten, und so das Haupt nach oben zu auch verknöcherte, war der übrige Ansatz nötig geworden. Dieser übrige Organismus ist erst damit nötig geworden. Dieser Teil der physischen Organisation ist erst zu einer Zeit entstanden, als für die übrige Tierheit keine Möglichkeit mehr war, zu entstehen. Sie werden sagen: So etwas, wie ich es jetzt dargestellt habe, ist schwer zu denken. Darauf kann ich aber immer wieder nur entgegnen: Man muß sich eben Mühe geben, so etwas zu denken; denn die Welt ist nicht so einfach, wie es die Leute gerne haben möchten, damit sie nicht viel über die Welt denken brauchen, um sie zu begreifen. In dieser Beziehung erlebt man das Mannigfaltigste, was die Leute für Ansprüche stellen, damit die Welt ja möglichst leicht zu begreifen sei. Darin haben die Menschen ganz merkwürdige Ansichten. Es gibt eine reiche Kant-Literatur von allen den Leuten, die Kant nach allen Richtungen für einen ungeheuren Philosophen halten. Das rührt aber nur davon her, daß die Leute keine andern Philosophen verstehen und schon so viel Gedankenkraft aufwenden müssen, um Kant zu verstehen. Und da er doch immer ein großer Philosoph ist - sich selber hält man ja oft für das Allergenialste —, so begreifen sie die andern erst recht nicht. Und nur weil sie Kant schon so schwer begreifen, ist er für sie ein großer Philosoph. Damit hängt es auch zusammen, daß man sich scheut, die Welt als kompliziert gelten zu lassen, und Kraft aufwenden muß, um sie zu verstehen. Wir haben von diesen Dingen schon von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten aus gesprochen. Und wenn einmal meine Vorträge über «Okkulte Physiologie» erscheinen werden, wird man auch im einzelnen lesen können, wie man auch embryologisch nachweisen kann, daß es ein Unsinn ist zu sagen: Das Gehirn ist aus dem Rückenmark entwickelt. Umgekehrt ist es der Fall: Das Gehirn ist ein umgewandeltes Rückenmark von einstmals, und das heutige Rückenmark hat sich an das heutige Gehirn als ein Anhängsel erst angegliedert. Man muß nur begreifen lernen, daß das, was beim Menschen das Einfachere ist, später entstanden ist als das, was als das Kompliziertere erscheint; was primitiver ist, steht auf einer untergeordneteren Stufe, ist später entstanden.

Ich habe diese Einfügung von der Zwiespältigkeit des Menschen nur deshalb gemacht, damit Sie das andere begreifen, was die Folge ist dieser Zwiespältigkeit. Und die Folge ist, daß wir mit unserem seelischen Leben, das sich ja unter den Bedingungen der Leiblichkeit entwickelt, auch in dieser Zwiespältigkeit drinnenstehen. Wir haben nicht nur organisch die Kopfentwickelung und die Entwickelung des übrigen Organismus, sondern wir haben auch zwei verschiedene Tempi, zwei verschiedene Geschwindigkeiten in unserer seelischen Entwickelung. Unsere Kopfentwickelung geht nämlich verhältnismäßig schnell, und die Entwickelung, die den übrigen Organismus zur Ausbildung bringt - ich will sie die Herzensentwickelung nennen -, geht verhältnismäßig langsamer, geht etwa drei- bis viermal langsamer. Was den Kopf zur Bedingung hat, ist mit seiner Entwickelung in der Regel mit den Zwanzigerjahren des Menschen schon abgeschlossen; mit Bezug auf den Kopf sind wir alle mit zwanzig Jahren schon Greise. Und nur weil fortwährend die Erfrischung von dem übrigen Organismus kommt, der sich aber drei- bis viermal langsamer entwickelt, leben wir in einer annehmbaren Weise weiter. Unsere Kopfentwickelung geht schnell; unsere Herzensentwickelung, die aber die Entwickelung des übrigen Organismus ist, geht drei- bis viermal langsamer. Und in diesem Zwiespalt stehen wir mit unserem Erleben drinnen. Unsere Kopfentwickelung kann gerade in unserer Kindheit und Jugendzeit eine ganze Menge aufnehmen. Daher lernen wir in der Kindheit und Jugendzeit. Was aber da aufgenommen wird, muß fortwährend erneuert, erfrischt werden, muß fortwährend eingefaßt werden von dem langsameren Gang der übrigen Organentwickelung, von der Herzensentwickelung.

Nun denken Sie sich, wenn die Erziehung so ist wie jetzt in unserem Zeitalter, wo Erziehung und Unterricht nur auf die Kopfausbildung Rücksicht nehmen, so ist, weil wir in Unterricht und Erziehung gewissermaßen nur den Kopf zu seinem Rechte kommen lassen, die Folge davon die, daß der Kopf wie ein toter Organismus in den langsameren Gang der übrigen Entwickelung sich eingliedert, daß er diese zurückhält, und daß die Menschen seelisch früh alt werden. Diese Erscheinung, daß die Menschen im heutigen Zeitalter innerlich seelisch früh alt werden, hängt im wesentlichen mit dem Erziehungs- und Unterrichtssystem zusammen. Natürlich dürfen Sie nicht denken, daß man jetzt die Frage stellen kann: Wie soll man den Unterricht einrichten, damit er nicht so ist? — Das ist eine sehr bedeutsame Sache, die man nicht mit zwei Worten beantworten kann. Denn fast alles vom Unterricht muß anders eingerichtet werden, damit er nicht nur etwas ist für das Gedächtnis, woran man sich erinnert, sondern etwas, durch das man sich erfrischt, sich erneuert. Man frage sich, wie viele Menschen heute, wenn sie zu einer Kindheitsverrichtung zurückblicken, auf alles, was sie da erlebt haben, was ihnen die Lehrer und die Tanten gesagt haben, so zurückzudenken vermögen, daß sie nicht nur sich erinnern: Das sollst du so und so machen -, sondern daß sie immer wieder von neuem hinuntertauchen in das, was sie in der Jugend durchgemacht haben, liebevoll hinblicken zu jedem Handgriff, zu jeder einzelnen Bemerkung, zu dem Stimmklang, zu der Gefühlsdurchdringung dessen, was ihnen in der Kindheit dargeboten wurde, und es so empfinden, daß es stets ein immer uns erneuernder Verjüngungsquell ist. Das hängt zusammen mit den Tempi, welche wir in uns erleben: daß der Mensch seiner schnelleren Kopfentwickelung folgen muß, die in den Zwanzigerjahren abgeschlossen ist, und dem langsameren Gange der Herzensentwickelung, der Entwickelung des übrigen Menschen, der für das ganze Leben gespeist werden soll. Wir dürfen dem Kopf nicht nur das geben, was nur für den Kopf bestimmt ist, sondern wir müssen ihm auch das geben, woraus der übrige Organismus immer wieder und wieder durch das ganze Leben erfrischende Kräfte ziehen kann. Dazu ist zum Beispiel notwendig, daß alle einzelnen Zweige des Unterrichtes von einem gewissen künstlerischen Element durchzogen sein müssen. Heute, wo man das künstlerische Element flieht, weil man glaubt, daß durch eine gewisse Pflege des Phantasielebens — und die Phantasie ist ja etwas, was den Menschen über die bloße alltägliche Wirklichkeit hinüberbringt — die Phantastik in den Unterricht hineingebracht werden könnte, ist ganz und gar keine Neigung vorhanden, ein solches Geheimnis des Lebens zu berücksichtigen. Man braucht nur auf einzelnen Gebieten etwas zu sehen von dem, was ich jetzt meine - es ist ja natürlich da oder dort noch vorhanden -, dann wird man sehen, daß so etwas schon geleistet werden kann, aber es kann besonders dadurch geleistet werden, daß die Menschen namentlich wieder Menschen werden. Dazu ist Mannigfaltiges notwendig. Auf eines möchte ich in dieser Beziehung aufmerksam machen.

Man prüft heute diejenigen, die Lehrer werden wollen, darauf hin, ob sie dieses und jenes kennen. Was aber stellt man dadurch fest? In der Regel doch nur das, daB der Betreffende einmal in der Zeit, für die er gerade die Prüfung abzulegen hat, in seinem Kopf etwas hineingehamstert hat, was er, wenn er einigermaßen geschickt ist, für jede einzelne Unterrichtsstunde sich aus so und so vielen Büchern zusammenlesen könnte, was man sich Tag für Tag für den Unterricht aneignen könnte, was gar nicht notwendig ist, sich in dieser Weise anzueignen, wie es gegenwärtig betrieben wird. Was aber vor allen Dingen bei einem solchen Examen notwendig wäre, das ist, daß man erfahren sollte, ob der Betreffende Herz und Sinn hat, ob er das Blut dafür hat, allmählich ein Verhältnis von sich zu den Kindern zu begründen. Nicht das Wissen sollte man durch das Examen prüfen, sondern erkennen sollte man, wie stark und wie viel der Betreffende Mensch ist. — Ich weiß: Solche Forderungen an die heutige Zeit stellen, heißt für die Gegenwart nur zweierlei. Entweder sagt man: Wer so etwas fordert, ist ja ganz verrückt, ein solcher Mensch lebt nicht in der wirklichen Welt! - Oder, wenn man eine solche Antwort nicht geben will, sagt man: So etwas geschieht ja immerfort, das wollen wir doch alle. - Die Menschen glauben nämlich, daß durch das, was geschieht, schon die Dinge erfüllt werden, weil sie nur das von den Dingen verstehen, was sie selbst hineinbringen.

Ich habe dieses ausgeführt, selbstverständlich um erstens von einer gewissen Seite her ein Licht auf das Leben zu werfen, dann aber auch, um gerade dies, was die Unterseele des Menschen immer fühlt, was so schwer gerade in der heutigen Zeit in die Oberseele heraufzubringen ist, wonach aber die Seele des Menschen verlangt und in der Zukunft immer mehr und mehr verlangen wird, um dies ins rechte Licht zu stellen, daß wir etwas in der Seele brauchen von der Macht, die Kräfte dieser Seele immerfort so zu erneuern, daß wir nicht mit dem fortschreitenden Leben müde werden, sondern immer hoffnungsvoll dastehen und sagen: Jeder neue Tag wird uns ebenso sein wie der erste, den wir bewußt erlebt haben. -— Dazu müssen wir aber in einer gewissen Weise nicht alt zu werden brauchen; das ist dringend notwendig, daß wir nicht alt zu werden brauchen. Wenn man heute sieht, wie verhältnismäßig junge Menschen, Männer und Frauen, eigentlich seelisch schon so furchtbar alt sind, so sehr wenig darauf aus sind, jeden Tag aufs neue das Leben als etwas zu empfinden, was ihnen gegeben wird wie dem frischen Kinde, dann weiß man, was auf diesem Gebiete durch eine geistige Zeitkultur eben geleistet werden muß, gegeben werden muß. Und letzten Endes ist es eben doch so, daß das Gefühl, welches ich hier meine, dies Gefühl der nie, nie, nie schwächer werdenden Lebenshoffnung doch geeignet macht, das rechte Verhältnis zwischen den Lebenden und den sogenannten Toten zu empfinden. Sonst bleibt die Sache, die das Verhältnis zu einem Toten begründen soll, zu stark in der Erinnerung stecken. Man kann sich erinnern, was man mit dem Toten während des Lebens erlebt hat. Wenn man aber nicht die Möglichkeit hat, nachdem der Tote physisch fort ist, ein solches Gefühl zu haben, daß man immer neu erlebt, was man während des Lebens mit ihm durchgemacht hat, so kann man nicht so stark fühlen, nicht so stark empfinden, wie es notwendig ist unter diesem neuen Verhältnis zu empfinden: Der Tote ist ja nur noch als Geistwesen da und soll als Geist wirken. — Hat man sich so abgestumpft, daß man nichts mehr erfrischen kann an Lebenshoffnungen, so kann man nicht mehr fühlen, daß eine vollständige Umwandlung stattgefunden hat. Vorher konnte man sich dadurch helfen, daß einem der Mensch im Leben entgegentrat; jetzt aber steht einem nur der Geist zu Hilfe. Man kommt ihm aber entgegen, wenn man dieses Gefühl entwickelt der immerwährenden Erneuerung der Lebenskräfte, um die Lebenshoffnungen frisch zu erhalten.

Ich möchte hier eine Bemerkung machen, die Ihnen vielleicht sonderbar erscheint. Ein gesundes Leben, das besonders nach den Richtungen hin gesund ist, die jetzt hier entwickelt wurden, führt, wenn es nicht zu einer Bewußtseinstrübung kommt, niemals dazu, das Leben als etwas zu betrachten, dessen man überdrüssig ist; sondern das ganz gesund verbrachte Leben führt dazu, wenn man älter geworden ist, jeden Tag dieses Leben immer von neuem, von frischem anfangen zu wollen. Nicht das ist das Gesunde, daß man, wenn man alt geworden ist, denkt: Gott sei Dank, daß man das Leben hinter sich hat! -, sondern daß man sich sagen kann: Ich möchte gleich wieder, wo ich jetzt vierzig oder fünfzig Jahre alt bin, zurückgehen und die Sache noch einmal durchmachen! - Und das ist das Gesunde, daß man sich durch Weisheit darüber trösten lernt, daß man es nicht in diesem Leben ausführen kann, sondern in einer korrigierten Weise in einem andern Leben. Das ist das Gesunde: gar nichts vermissen zu wollen von alledem, was man durchgemacht hat, und, wenn Weisheit dazu nötig ist, es nicht in diesem Leben haben zu wollen, sondern auf ein folgendes warten zu können. Das ist das Vertrauen, das auf richtiges Vertrauen zum Leben und auf die rege erhaltenen Lebenshoffnungen gebaut ist. |

So haben wir die Gefühle, die das Leben in der richtigen Weise durchseelen und die zugleich die Brücke schaffen zwischen den Lebenden hier und den Lebenden dort: Dankbarkeit gegenüber dem Leben, das an uns herantritt, Vertrauen zu den Erfahrungen dieses Lebens, intimes Gemeinsamkeitsgefühl, die Fähigkeit, die Lebenshoffnungen durch immer neu erstehende frische Lebenskräfte rege zu machen. Dies sind innere, ethische Impulse, die, in der richtigen Weise erfühlt, auch die allerbeste äußere soziale Ethik abgeben können, weil das Ethische, gerade wie das Historische, nur erfaßt werden kann, wenn es im Unterbewußten erfaßt wird, wie ich es selbst im öffentlichen Vortrage gezeigt habe.

Ein anderes, das ich noch hervorheben möchte für das Verhältnis der Lebenden zu den Toten, ist eine Frage, die immer wieder und wieder auftreten kann, die Frage: Worin besteht eigentlich der Unterschied in dem Verhältnis zwischen Mensch und Mensch, insofern Mensch und Mensch im physischen Leibe verkörpert sind, und zwischen Mensch und Mensch, insofern der eine im physischen Leibe, der andere nicht, oder beide nicht im physischen Leibe verkörpert sind? - Im Hinblick auf einen Gesichtspunkt möchte ich da etwas Besonderes angeben.

Wenn wir geisteswissenschaftlich den Menschen betrachten in bezug auf sein Ich und in bezug auf sein eigentliches Seelenleben, das man auch den astralischen Leib nennen kann - in bezug auf das Ich habe ich oft gesagt, daß es das jüngste, das Baby unter den Gliedern der Menschenorganisation ist, während der astralische Leib etwas älter ist, aber nur seit der alten Mondenentwickelung -, so muß man in bezug auf diese beiden höchsten Glieder der menschlichen Wesenheit sagen: Sie sind noch nicht so weit entwickelt, daß der Mensch die Macht hätte, wenn er sich nur auf sie stützte, sich selbständig zu erhalten gegenüber den andern Menschen. Wenn wir hier beieinander wären jeder nur als Ich und Astralleib, nicht auch in unseren Ätherleibern und physischen Leibern lebend, so wären wir alle wie in einer Art Urbrei beieinander.-Es würden unsere Wesen durcheinander verschwimmen; wir wären nicht voneinander getrennt, wir wüßten auch nicht uns voneinander zu unterscheiden. Es könnte gar keine Rede davon sein, daß jemand wüßte — die Sachen lägen ja dann ganz anders, und man kann die Verhältnisse nicht so ohne weiteres miteinander vergleichen -, was seine Hand oder sein Bein wäre, oder was die Hand und das Bein des andern wäre. Aber nicht einmal seine Gefühle könnte man ordentlich als die seinigen erkennen. Daß wir als Menschen uns getrennt empfinden, rührt davon her, daß ein jeder aus der gesamten flüssigen Masse, die wir uns für einen bestimmten früheren Zeitraum vorzustellen haben, in Tropfenform herausgerissen ist. Damit aber die einzelnen Seelen nicht wieder zusammenrinnen, müssen wir uns denken, daß jeder Seelentropfen wie in ein Stück Schwamm hineingegangen ist, und dadurch werden sie auseinandergehalten. Dergleichen ist wirklich geschehen. Nur dadurch, daß wir als Menschen in physischen Leibern und Ätherleibern stecken, sind wir voneinander gesondert, richtig gesondert. Im Schlafe sind wir nur dadurch voneinander gesondert, daß wir dann die starke Begierde nach unserem physischen Leib haben. Diese Begierde, die ganz und gar nach unserem physischen Leib brünstig hinschlägt, trennt uns im Schlafe, sonst würden wir in der Nacht ganz durcheinanderschwimmen, und es würde wahrscheinlich empfindsamen Gemütern sehr wider den Strich gehen, wenn sie wüßten, wie stark sie schon in Zusammenhang kommen mit dem Wesen der Wesenheiten ihrer Umgebung. Aber das ist nicht besonders arg im Vergleich zu dem, was sein würde, wenn dieses brünstige Begierdenverhältnis zum physischen Leib nicht bestünde, solange der Mensch leiblich verkörpert ist.

Nun können wir die Frage aufwerfen: Was sondert unsere Seelen voneinander in der Zeit zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt? So wie wir mit unserem Ich und unserem astralischen Leib zwischen Geburt und Tod einem physischen Leibe und Ätherleibe angehören, so gehören wir nach dem Tode, also zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt, mit unserem Ich und astralischen Leib einem ganz bestimmten Sternengebiete an, keiner demselben, jeder einem ganz bestimmten Sternengebiete. Aus diesem Instinkt heraus spricht man von dem «Stern des Menschen». Sie werden begreifen: Das Sternengebiet - wenn Sie zunächst seine physische Projektion nehmen - ist peripherisch kugelig, und das können Sie in der mannigfaltigsten Weise verteilen. Die Gebiete überdecken sich, jeder aber gehört einem andern an. Man kann auch sagen, wenn man es seelisch ausdrücken will: Jeder gehört einer andern Reihe von Archangeloi und Angeloi an. So wie sich die Menschen hier durch ihre Seelen zusammenfinden, so gehört zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt jeder einem besonderen Sternengebiete, einer besonderen Reihe von Angeloi und Archangeloi an, und sie finden sich dann hier mit ihren Seelen zusammen. Nur ist es so, aber auch nur scheinbar — doch auf dieses Mysterium will ich jetzt nicht weiter eingehen -, daß auf der Erde jeder seinen eigenen physischen Leib hat. Ich sage: scheinbar -, und Sie werden sich verwundern; aber es ist völlig erforscht, wie auch jeder sein eigenes Sternengebilde hat, aber wie diese sich überdecken. Denken Sie sich eine bestimmte Gruppe von Angeloi und Archangeloi. Zu einer Seele gehören Tausende von Archangeloi und Angeloi im Leben zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt. Denken Sie sich von diesen Tausenden nur einen weg, so kann dieser eine gewissermaßen ausgetauscht werden: dann ist dies das Gebiet der nächsten Seele. In dieser Zeichnung haben zwei Seelen mit Ausnahme bin des einen Sternes, den sie aus einem andern Gebiete haben, das gleiche, aber absolut gleich haben nicht zwei Seelen ihr Sternengebiet. Dadurch sind die Menschen zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt individualisiert, daß jeder sein besonderes Sternengebiet hat. Daraus kann man ersehen, worauf zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt die Trennung von Seele zu Seele beruht. Hier in der physischen Welt wirkt die Trennung so, wie wir sie kennen durch den physischen Leib: Der Mensch hat gewissermaßen seinen physischen Leib als Hülle, er betrachtet von ihm aus die Welt, und alles muß an diesen physischen Leib herankommen. Alles was in die Seele des Menschen zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt kommt, steht in bezug auf das Verhältnis zwischen seinem astralischen Leib und seinem Ich in einer ähnlichen Weise in Zusammenhang mit einem Sternengebiet, wie hier die Seele und das Ich.mit dem physischen Leib in Verbindung stehen. Die Frage also: Wodurch tritt die Sonderung ein? — beantwortet sich auf die Weise, wie ich es eben angegeben habe.

Nun haben Sie aus diesen Betrachtungen heute ersehen, wie wir auf unsere Seele in der Ausbildung gewisser Gefühle und Empfindungen wirken können, damit die Verbindungsbrücke geschlagen wird zwischen den sogenannten Toten und den Lebenden. Auch das letzte, was ich gesagt habe, ist geeignet, um in uns Gedanken, ich darf sagen, empfindende Gedanken oder gedankliche Empfindungen heranzuziehen, die sich wiederum an der Schöpfung dieser Brücke beteiligen können. Das geschieht dadurch, daß wir versuchen, mit Bezug auf einen bestimmten Toten immer mehr und mehr jene Empfindungsart auszubilden, die, wenn man etwas erlebt, in der Seele heraufkommen läßt den Impuls, sich zu fragen: Wie würde der Tote dieses jetzt, was du in diesem Augenblick erlebst, miterleben? Dazu die Imagination schaffen, als ob der Tote neben uns das Erlebnis mitmacht; und das recht lebendig machen, dann ahmt man in einer gewissen Beziehung die Art und Weise nach, wie entweder der Tote mit dem Lebenden oder der Tote mit Toten verkehrt, indem Sie das, was Ihnen verschiedene Sternengebiete geben, auf das Verhältnis Ihrer Seele beziehen oder aufeinander beziehen. Man ahmt schon hier das nach, was von Seele zu Seele spielt durch die Zugeteiltheit zu den Sternengebieten. Wenn man sich gewissermaßen konzentriert durch die Anwesenheit des Toten auf ein unmittelbar gegenwärtiges Interesse, wenn man auf diese Weise den Toten unmittelbar lebendig neben sich empfindet, dann wird aus solchen Dingen, die ich heute erörtert habe, auch immer mehr und mehr das Bewußtsein erwachsen, daß der Tote wirklich an uns herankommt. Die Seele wird sich auch ein Bewußtsein davon entwickeln. In dieser Beziehung muß man eben auch Vertrauen haben zum Dasein, daß die Dinge werden. Denn, wenn man nicht Vertrauen, sondern Ungeduld zum Leben hat, dann gilt die andere Wahrheit: Was das Vertrauen bringt, vertreibt die Ungeduld; was man durch das Vertrauen erkennen würde, verfinstert sich durch die Ungeduld. Nichts ist schlimmer, als wenn man sich durch die Ungeduld einen Nebel vor die Seele zaubert.

Seventh Lecture

Let us return briefly to what was presented here eight days ago, so that the context remains clear. I said: When it comes to understanding the relationship between human souls embodied in the body and disembodied human souls living between death and rebirth, it is important to focus the spiritual eye, as it were, on the “soul air” that must connect the living with the so-called dead in order for a relationship between the two to exist. And we found at first that certain soul moods, which must exist in the living, form a bridge, as it were, to the realms where the so-called dead are. Moods of the soul always imply the presence of a certain spiritual element, and one could say that when this spiritual element is present, when it shows its presence through the corresponding feelings of the living, then the possibility of such a relationship arises.

We then had to point out that such a possibility, i.e., a kind of spiritual air connection, is created by two emotional tendencies in the living. One emotional tendency is what one might call a universal feeling of gratitude toward all life experiences. I said: The overall way in which the human soul relates to its environment can be divided into a subconscious part and a conscious part. Everyone is familiar with the conscious part; it consists in the fact that human beings pursue what affects them in life with sympathies and antipathies and with their ordinary perceptions. The subconscious part, however, consists in the fact that we actually develop a feeling just below the threshold of consciousness that is better, more sublime than the feelings we can develop in ordinary consciousness, a feeling that cannot be described other than by saying that in our lower soul we always know that we have to be grateful for every experience in life, even the smallest, that comes our way. That difficult life experiences come our way may certainly make us feel painful for the moment; but from a broader perspective of existence, even painful life experiences can be seen in such a way that, although not in the upper soul, we can still be grateful in the lower soul, grateful that the universe provides our life with continuous gifts. This is something that exists as a truly subconscious feeling in the human soul. The other thing is that we connect our own ego with every being with whom we have had some kind of interaction in life. Our actions extend to this or that being in life, and they can even be inanimate beings. But where we have done something, where our being has been connected with another being through action, something remains behind, and this remnant establishes a lasting relationship between our being and everything with which we have ever been connected. I said: This feeling of kinship is the basis for a deeper feeling of commonality with the surrounding world, which usually remains unknown to the higher soul, a feeling of togetherness.

Human beings can live out these two feelings, the feeling of gratitude and the feeling of togetherness with the environment with which they were somehow karmically connected, more and more consciously. They can, in a sense, lift up into their souls what lives in these feelings and sensations; and to the extent that they lift up these two sensations into their souls, they make themselves capable of building a bridge to the souls that spend their lives between death and new birth. For the thoughts of these souls can only find their way to us if they can truly penetrate the realm of the feeling of gratitude we have developed; and we can find the way to them only if our soul has at least to some extent become accustomed to cultivating real communion. The fact that we are capable of feeling gratitude toward the universe sometimes allows such a feeling of gratitude to fall into our soul when we want to enter into some kind of connection with the dead, that we have practiced such a feeling of gratitude that we are able to feel it, paves the way for the thoughts of the dead to reach us. And the fact that we can feel that our being lives in an organic community of which it is a part, just as our finger is a part of our body, makes us ready to feel such gratitude toward the dead, even when they are no longer present in their physical bodies, so that we can reach out to them with our thoughts. Once you have acquired something like a feeling of gratitude, a sense of community, in one area, you then have the opportunity to apply it in other areas.

Now, these feelings are not the only ones; there are many other subconscious feelings and subconscious moods. Everything we develop in our souls paves the way to the world where the dead are between death and rebirth. Thus, a very specific feeling, which is always present in the subconscious but can gradually be brought to consciousness, joins gratitude, a feeling that people lose the more they turn to materialism. But in the subconscious it is always present to a certain degree and cannot actually be eradicated even by the strongest materialism. But an enrichment, an elevation, a refinement of life depends on bringing such things up from the subconscious into the conscious. The feeling I mean is what could be described as a general trust in the life that flows through us and around us, trust in life! Within a materialistic view of life, this feeling of trust in life is extremely difficult to find. It is similar to gratitude towards life, but it is a different feeling that accompanies this gratitude. For trust in life consists in the presence of an unshakeable mood in the soul, that life, however it may approach us, has something to give us under all circumstances, that we can never even entertain the thought that life has nothing to give us through this or that which it brings us. Certainly, we go through difficult experiences in life, painful experiences, but in the greater context of life, it is precisely these painful and difficult experiences that enrich our lives the most and strengthen us the most for life. It is a matter of raising this persistent mood, which is present in the lower soul, a little into the higher soul, this mood: You, life, you lift me up and carry me, you ensure that I move forward.

If something were done in the education system to cultivate such a mood, an extraordinary amount would be gained. To design education and teaching to show, using specific examples, how life, precisely because it is often difficult to understand, deserves trust, would mean a great deal if this mood were to carry over into the education and teaching system. For by looking at life from this perspective: Do you deserve trust, O life? — it turns out that one finds many things that one would not otherwise find in life. One should not view such a mood superficially. It must not lead to finding everything in life shiny and good. On the contrary, in individual cases, it is precisely this trust in life that can lead to sharp criticism of bad and foolish things. And it is precisely when one has no trust in life that one often avoids criticizing what is bad and foolish, because one wants to pass over what one has no trust in. It is not a matter of having trust in individual things; that belongs to another realm. One has trust in one thing and not in another, depending on how things and beings present themselves. But it is a matter of having confidence in life as a whole, in the overall cohesion of life. For if one can draw upon the confidence in life that is always present in the subconscious, it paves the way for truly observing the spiritual, the wise providence and guidance in life. Those who say to themselves again and again, not theoretically but intuitively: “The way the phenomena of life follow one another, they mean something to me because they take me in and have something to do with me, something I can trust in”—those people are preparing themselves to gradually perceive what lives and weaves spiritually in things. Those who do not have this trust close themselves off from what lives and weaves spiritually in things.