Mysteries of the Sun and of the Threefold Man

GA 183

26 August 1918, Dornach

Lecture III

Certain questions will increasingly obtrude themselves upon those who really think, even though in these times of overwhelming materialism these thinkers would prefer to keep them more or leas at a distance. There are many such questions, and today I should like, out of all of them, to pick a few that arise from man, in spite of resisting it, becoming aware of the spiritual world. To such questions belong those, for instance, raised in the course of everyday life; certain men die young, others in old age, others again in middle life. Concerning the fact that on the one hand young children die and on the other hand people grow to old age and then die—concerning this fact questions arise in man to which by the means today called scientific the answer can never be found. Everyone has to own this after inner reflection. Yet in human life these are burning questions; and surely anyone can feel that infinitely much in life must receive enlightenment when we can really get down to these questions: why do some human beings die early, some as children, some as adolescents, some in the middle of the normal period of life? Why do other die old? What significance has this in the whole cosmos?

Men still had ideas, concepts, with which to answer these questions up to that point of time described in these lectures, the time at the beginning of the fourth post-Atlantean period, that is, up to approximately the middle of the eighth pre-Christian century. Men had concepts that came down out of ancient wisdom. In those olden times before the eighth pre-Christian century, ideas were in fact circulating everywhere in the cultural life of the earth giving men, in conformity with the mind of those times, the solution to such questions as are here mentioned. What today we call science cannot connect the right meaning with these questions and has no idea that there is something in them for which men should be seeking a possible answer. All this arises because since the point of time indicated, all conceptions related to spiritual and therefore to immortal man have actually been lost. Only these conceptions remain that are connected with man's transitory nature, man between his birth and his death. I have drawn attention to how in all the old world-conceptions they spoke of the Sun as being threefold; the same sun that is perceived out there by the physical senses as a shining sphere in cosmic space. But behind this sun the wise men of old saw the soul-sun, according to the Greeks Helios, and behind this soul-Sun again, the spiritual-Sun, still identified by Plato, for example, with the Good. Modern men do not see any real sense in speaking of Helios, the soul-Sun, or for that matter of the spiritual-Sun, the Good. But as the physical sun shines upon us here between birth and death, there shines into our ego, if I may say so, during the time we pass between death and a new birth, the spiritual sun identified by Plato with the Good. And during this time between death and a new birth, to speak of a shining sphere in the way it is spoken of in our modern materialistic world-conception has no meaning. Between death and a new birth there is only meaning when we speak of the spiritual-Sun Plato still referred to as the Good. A concept of this kind is just what should show us something. It should lead us to reflect how the matter really stands with regard to the physical representation we form of the world. It is not taken seriously in its full sense, at any rate not so seriously that our outlook on life is actually permeated by it, that in all our physical representations of the world, in what is spread out perceptibly before us, we have to see a kind of illusion, Maya.

It is indeed fundamentally this kind of representation of the Sun that anyone accepts when taking as his authority modern physics, astrophysics, whatever you like to call it. If he were able to travel to the place where the physicist places the sun, on approaching it he would—now let us turn from the conditions of human life and assume that absolute conditions of life could prevail—he would become aware of overpowering heat, this is how he would picture it. And when he had arrived inside the space that the physicist considers to be filled by the sun, he would find in this space red hot gas or something of the kind. This is what the physicist considers to be filled by the sun, he would find in this space red hot gas or something of the kind. This is what the physicist actually pictures—a ball of glowing gas or something like it. But it is not so, my dear friends, that is definitely maya, complete illusion. This representation cannot hold water in face of true physical perception that is possible, let alone what can actually be perceived spiritually. Were it possible to get near the sun, to reach where the sun is, we should find yes, indeed, an getting near, we should find something that would have the same effect as going through floods of light. But when we came right inside, where the physicist supposes the sun to be, we should find first what we could only call empty space. Where the physical sun is supposed to be there is nothing at all, absolutely nothing. I will draw it diagrammatically (blue centre in yellow circle, diagram not available) but in reality nothing is there; there is nothing, there is empty space. But it is a strange kind of empty space: When I say there is nothing there I am not speaking quite accurately—there is less than nothing there. It is not only empty space for there is less than nothing there. And that is something that is an extraordinarily difficult idea for the modern western man to picture. Even today men of the east take this as a matter of course; for them there is absolutely nothing strange or difficult to understand when they are told that less than nothing is there. The man of the west thinks to himself—especially when he is a hard and fast follower of Kant, and there are far more followers of Kant today than those who are consciously so—he thinks to himself that if there is nothing in space then it is just empty space! However this is not the case, there can also be exhausted space. And if indeed you were to look right through this corona of the sun, you would feel the empty space into which you would then enter most uncomfortable—that is to say it would tear you asunder. By that it would show its nature, that it is more—or it is less, however we can best express it, than empty space. You need only seek the help of the simplest mathematical concept and when I say empty space is less than just emptiness you will no longer find my meaning so puzzling. Now let us assume you possess some kind of property. It can also happen that you have given away what you possess and have nothing. But we can have less than nothing, we can have debts. Then we do actually have less than nothing. If we pass from fullness of space to its ever diminishing fullness, we can come to empty space; and we can still go an beyond mere emptiness just as we can go beyond having nothing to having debts. It is a great weakness of the modern world outlook that it does not know this particular kind of—if I may so express it—negative materiality, that it only knows emptiness or fullness and not what is less than emptiness. For because knowledge today, the world outlook today is ignorant of what is less than emptiness, this world outlook is more or less held in the bonds of materialism, strictly confined by materialism—I should like to say, under the ban of materialism. For in man also there is a place that is emptier than empty, not in the whole of him but where there are layers of what is emptier than empty. As a whole, man, physical man, is a being who materially fills a certain space; but there is a certain member of man's nature, of the three I have referred to, that actually has something in it like the sun, emptier than empty. That is—yet, my dear friends, you'll have to put up with it—it is the head. And it is just because man is so organised that his head can become empty and in certain parts more than empty, that this head has the power to make room for the spiritual. Now just picture the matter as it actually is.

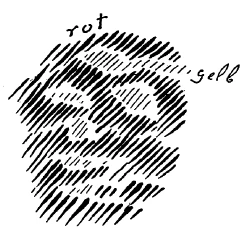

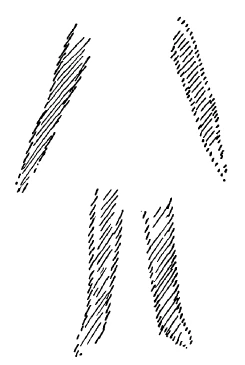

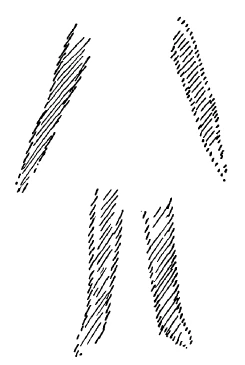

Naturally we have to picture things diagrammatically, but use your imagination and picture that everything materially filling your head I am going to draw in the following way. This is the diagram of your head (see red in diagram 5). but now, if I want to draw it properly, I shall have to leave empty places in this head, these naturally are not very big; but there inside are empty places. And into these empty places can enter what I have recently been calling the young spirit. In these spaces the young spirit with its rays, as it were, is drawn (see yellow in diagram 5).

Now, my dear friends, the materialists say that the brain is the instrument of the soul-life, of the thinking. The reverse is the truth. The holes in the brain, what indeed is more than holes, or one could just say as well less than holes, what therefore is emptier than empty, that is the instrument of the soul-life. And here where the soul-life is not, into which the soul-life is continually pushing, where the space in our skull is filled with brain substance here nothing is thought, here is no soul-experience.

We do not need our physical brain for our life of soul; we need it only to lay hold of our soul-life, physically to lay hold of it. And if the soul-life were not actually alive in the holes of the brain, pushing up everywhere, it would vanish, it would never reach our consciousness. But it lives in the holes of our brain that are emptier than empty.

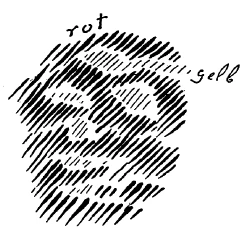

Thus we have gradually to correct our concepts. When we stand in front of a mirror we do not perceive ourselves but only our reflected image. We could forget ourselves ... We see ourselves in the mirror. In the same way man does not experience himself by putting together with his brain what is lying in the holes in that brain. He experiences the way in which his soul-life is everywhere reflected by pushing up against the brain substance. It is reflected everywhere, and man experiences it; what he experiences is actually its reflected image. All that has slipped into the holes, however, because it is then permeated by consciousness in the contrary sense is what makes man conscious when without the resistance of the brain he goes through the gate of death. Now I should like to draw another diagram. Take the following: forgive me if I am rather drastic in portraying the brain and how the holes are left (blue in diagram 6). Here is the brain substance and here the brain leaves its holes and into these holes goes the life of the soul. (yellow)

This soul-life, however, continues, just outside the holes. There come to what naturally is only seen near man but projects indefinitely—man's aura. Now let us think away the brain and imagine we are looking at the soul-life of an ordinary man between birth and death. We should then have to say that seen in this way the condition of the real man between birth and death is such that actually his face is turned to his body thus (see lilac). It is true I shall have to draw this diagram differently. He turns his soul-life to the corporeal. And when we look at the brain the soul-life stretches out like a feeler that creeps into the holes of the brain. What there I made yellow here I make lilac, because that is more appropriate for the view into the living man. Thus, that would be what runs into the brain of the living man.

If after this I want to draw, let us say, physical man, I could best indicate that by perhaps here drawing in for you the boundary set to the faculty of memory. You would go outside there and there you would have the outer boundary, the boundary of cognition, of which I have also spoken to you. For that you will just have to remember diagram 5 and diagram 3 drawn yesterday).

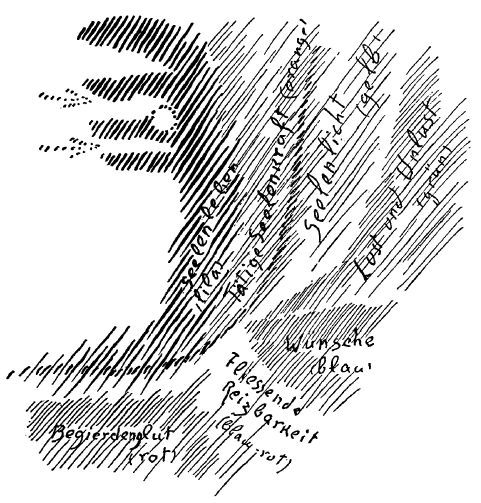

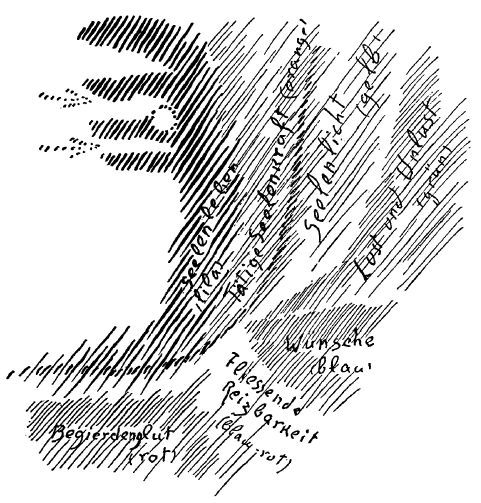

But now this is the reality—when man is looked at spiritually from without, his soul-life stretches into him thus... so I will draw the single elongation only where the brain is concerned (diagram 7). But this soul-life in itself is also differentiated. So to follow up this soul-life further I should have to draw... another region here (red under the lilac), here another region blue); thus all this would belong to what constitutes man's aura. Then another region (green). You see how this part I am now drawing lies beyond the boundary of man's cognition. Then the region (yellow)—in reality all this belongs to man—and this region (orange.)

When man is asleep this moves more or less out of the body, as it was drawn yesterday (diagram 2), but when man is awake it is more or lass within the body. So that actually, perceived with the soul, the aura is in the immediate vicinity of the body. And if the physical man is described this is done by saying that this physical man consists of lungs, heart, liver, gall and so on; This is done in physical anatomy, this is done in physiology. But you can do the same when describing the man of soul and spirit who in this way actually stretches out into the holes in man, in what is more than empty in man. You can describe this in the same way—only then you must mention of what this soul-and spirit man consists. just as in physical man the organs are differentiated, here the different currents must be separated. It can be said: in here where it is red, physical man would stand thus in profile, the face turned in this direction, for example, the eyes here (diagram 7), and here would be the region of burning desire (red). That would be part of the man of soul-and-spirit who has taken his substance from the region known in my book Theosophy as the region of burning desire. Thus something taken from burning desire and introduced into man gives this part of him.

If I am describing this in detail what I have here colored lilac I should have to call soul-life. As you know, a certain part of the soul-sphere, of the soul-land, has been given the name soul-life. This substance of it would have this violet color,this lilac, and forms in man a part of his soul-spiritual being.

And if we continue in this way the orange here would have to be called active soul-force. So that you have to remember that your soul-life is what during your life between birth and death enters you with most intensity by way of your senses. And behind, checking itself, not so well able to enter, held up by the soul-life, there is the active soul-force.

Still further behind there is what is called soul-light (yellow in diagram 8). To a certain extent attached to this soul-light, pressing itself through, there would be what is taken from the region of liking and disliking which I should have to give to the green area. Wishes, we should ascribe to the sphere of what is approximately blue. And now pushing up here, the real blue, that is approaching blue red, this would be the region of mobile susceptibility. These are auric currents that I here call burning desire, mobile susceptibility, and wishes. As you know, these auric currents, these auric streams, constitute the world of soul, they also constitute the man of soul and spirit who may be said to be built out

of the ingredients of this soul world.

Then when death comes the physical body falls away, and man withdraws what has projected into the holes in the body. He takes it away and by so doing (we can now think away physical man) he comes into a certain relation with the soul-world and then with the spirit-land as you will find it described in Theosophy. He has this relationship by having in him its ingredients, but during physical life these are bound up with the physical body and then they become free. Becoming free, however, as a whole it is gradually changed. During physical life—if I leave out the differentiations and draw the soul-life thus—the feelers (lilac in diagram 8) reach out into our holes; after death these feelers are drawn back. By their being drawn back, however, the soul-life itself becomes hollowed out and the life of the spirit coming from the other side rises into the life of soul (yellow).

In the same degree as man ceases to dive into the physical, the soul-spiritual lights up and, from the other side, penetrates his aura with light. And just as man is able to acquires a consciousness through the reflection caused by the continual pushing of the soul-spiritual against the physical body, he now acquires a consciousness by drawing himself back against the light. This light is that of the Sun, the original light that is the Good. Thus, whereas during his physical life as man of soul and spirit he pushes against what is related to the Sun, namely, against the more than empty holes in the brain, after death when he withdraws himself he pushes against the other Sun, the Good-Sun, the original sun.

You see, my dear friends, how the possibility of receiving concepts of life between death and a new birth is bound up with the basic ideas of primeval mysteries. For we are placed into this whole cosmic life in true way I have been picturing during these last few days. It is true, however, that we have to go more deeply into the framework of actual human evolution throughout earthly time to come to correct concepts of these matters. I think you will agree it might be possible that someone through a special stroke of luck—if one might so call it—were able to see clairvoyantly, the whole of what I have been describing. This stroke of luck, however, could only bring him to the point of seeing ever changing images. It is something like this—a man through some kind of miracle—but nowadays it would not happen through a miracle—or let us say through clairvoyant vision, super-sensible vision, a man might see something of the nature of what I have been trying to picture, namely man's life of soul and spirit. You will find it obvious that this should look rather different from what a short time ago I was describing as the normal aura, if you understand what I was describing only a few days ago as the aura revealed when the whole man is seen, that is, physical man with his encircling aura. But now I have taken out the man of soul und spirit, so that this man of soul and spirit has been abstracted from the physical man.

From this you recognise that in one case the colors have to be arranged in one way, in another case in another way; you recognise also that for super-sensible consciousness things look very different. Try simply to see man's aura—as it is while man is in the physical body—then look at this aura. Turn your attention that is, from the man of soul and spirit, and try to see the man why stretches out his organs into physical man. But when you see the man during the time between death and a new birth, then you also see how the whole changes. Above all, the region that is red here (Diagram 7) goes away, goes here, and the yellow goes below, the whole gradually gets into disorder. These things can be perceived but the percept has something confusing about it. Therefore it will not be easily possible for modern man to bring meaning and significance into this confusion if he does not turn to other expedients.

Now we have shown that man's head points to the past whereas the extremities man points to the future. This is entirely a polaric contrast, both the head and the extremities of man (remember what was said yesterday) are actually one and the same, only the head is a very old formation, it is overformed. That is why it has the holes; so far the extremities man has not these holes; on the surface he is still full of matter. To have these holes is a sign of over development. Development in a backward sense can be seen in the head and much hangs on that. Much depends too on man being able to understand that extremities man is a recent metamorphosis—the head an old metamorphosis. And because extremities man is a recent metamorphosis he has not so far developed the capacity to think in physical life but his consciousness remains unconscious; he does not open up to the man of soul and spirit such holes as are in the brain.

You see it is infinitely important for spiritual culture, and will in future become more and more so, for us to perceive that these two things that outwardly, physically, are as totally different from one another as the head man and extremities man, are according to soul and spirit, one and the same, and only differ because they are at different stages of development in time. Many mysteries lie in this particular fact that two equal physical things at different stages of their development in time, can be really one and the same that, though outwardly physically different, this is only due to the conditions of their change, of their metamorphosis.

Goethe with his theory of metamorphosis began in an elementary way to form concepts by which all this can be understood. Whereas otherwise since ancient times there has been a deadlock in the formation of concepts, with Goethe the faculty of forming concepts once more arose. And these concepts are those of living metamorphoses. Goethe, it is true, always began with the most simple. He said: when we look at a plant we have its green leaf; but the green leaf changes into the flower petal, into the colorsome petal of the flower. Both are the same, only one is the metamorphosis of the other. And as the green leaf of the plant and the red petal of the rose are different metamorphoses, the same thing at a different stage, man's head and his extremities organism too are simply metamorphoses of one another. When we take Goethe's thought on the metamorphosis of the plant we have something primitive, simple; but this thought can blossom into something of the greatest and can serve to describe man's passing from one incarnation to the next. We see the plant with its green leaf and its blossom, and say: this blossom, this red blossom of the rose is the metamorphosis of the green leaf of the plant. We see a man standing before us and say: that head you are carrying is the metamorphosis of arms, hands, legs, feet of your previous incarnation, and what you now have as arms, hands, legs and feet will be changed into your head of the next incarnation.

Now, however, will come an objection that evidently sits heavily on your souls. You will say: good gracious but I leave my legs and feet behind, my arms and hands too; I do not take them into my next incarnation ... how then should my head be made out of them? It is true, this objection can be made. But once again you are coming here up against Maya. It is not true that you actually leave behind your legs, feet, hands, arms. It is indeed untrue. You say that because you still cling to Maya, the great illusion.

What indeed with the ordinary consciousness you refer to as your arms, hands, legs and feet, are not your arms, hands, legs and feet at all, but what as blood and other juices fills out the real arms, hands, feet and legs. This again is a difficult idea but it is true. Suppose that here you have arms, hands, feet and legs, but that what is here is spiritual, spiritual forces. Now please to think that your arms, hands, legs and feet are forces—super-sensible forces. Had you these alone you would not see them with your eyes; they are filled out, these forces, with juices, with the blood, and you see what as mineral substance, fluid or partly solid—the smallest part solid—fills out what is invisible (hatching in diagram 9). What you leave in the grave or what is burnt is only what might be called the mineral enclosure. Your arms and hands, legs and feet are not visible, they are forces and you take them with you, you take the forms with you. You say: I have hands and feet. Anyone who sees into the spiritual world does not say: I have hands and feet, he says; there are spirits of form, Elohim, they think cosmic thoughts, and their thoughts are my arms and hands, my legs and feet; and their thoughts are filled out with blood and other fluids. But neither are blood and the other fluids what they appear physically; these again are the ideas of spirits of wisdom, and what the physicist calls matter is only outer semblance. The physicist ought to say when he comes to matter: here I come to the thoughts of the spirits of wisdom, the Kyriotetes. And where you see arms, hands, feet, legs, you cannot touch them but should say: here the spirits of form are building into these shapes their cosmic thoughts.

In short, my dear friends, strange as it sounds, there are no such things as your bodies, but where your body is in space there intermingled with one another live the cosmic thoughts of the higher hierarchies. And were you able to see correctly and not in accordance with Maya, you would say: into here there project the cosmic thoughts of the Exusiai, the spirits of form, the Elohim. These cosmic thoughts make themselves visible to me by being filled out with the cosmic thoughts of the spirits of wisdom. That gives us arms and hands, legs and feet. Nothing, absolutely nothing, as it appears in Maya is there before the spiritual vision, out there stand the cosmic thoughts. And these cosmic thoughts crowd together, are condensed, pushed into one another; for this reason they appear to us as these shadow figures of ours that go around, which we believe to have reality. Thus, as far as the physical man is concerned, he does not exist at all.

With certain justification we can say that in the hour of death the spirits of form separate their cosmic thoughts from those of the spirits of wisdom. The spirits of form take their thoughts up into the air, the spirits of wisdom sink their material thoughts into the earth. This brings it about that in the corpse an aftershadow of the thoughts of the spirits of wisdom still exists when the spirits of form have taken back their thoughts into the air. That is physical death—that is its reality.

In short, when we begin to think about the reality we come to the dissolution of what is commonly called the physical world. For this physical world derives its existence from the spirits of the higher hierarchies pushing in their intermingled thoughts, and I beg you to imagine that finely distributed quantities of water are introduced in some way which form a thick mist. That is why your body appears as a kind of shadow-form, because the thoughts of the spirits of form penetrate those of the spirits of wisdom, the formative thoughts enter the thoughts of substance. In face of this conception the whole world dissolve into the spiritual. We must, however, have the possibility of imagining the world to be really spiritual, of knowing that it is only apparent that my arms and hands, my feet and legs are given over to the earth. That is what it seems; in reality the metamorphosis of my arms and legs, hands and feet begins there and comes to completion in the life between death and a new birth, when my arms and legs, hands and feet become the head of my next incarnation.

I have been here telling you many things that perhaps at least in their form may have struck you as something strange. But what is all this ultimately of which we have been speaking but an ascending from man as he appears, to man as he really is, ascending from what lives externally in Maya to the successive ranks of the hierarchies.

It is only when we do this, my dear friends, that we are able to speak in a form that is ripe today of how man is permitted to know a so-called higher self. When we simply rant about a higher self, when we simply say: I feel a higher self within me . . . then this higher self is a mere empty abstraction with no content; for the ordinary self is in the hands of Maya, is itself Maya. The higher self has only one meaning when we speak of it in connection with the world of the higher hierarchies. To talk of the higher self without paying heed to the world that consists of the spirits of form and the angels, archangels and so on, to speak of the higher self without reference to this world, means that we are speaking of empty abstractions, and at the same time signifies that we are not talking of what lives in man between death and a new birth. For as here we live with animals, plants and minerals, between death and a new birth we live with the kingdoms of the higher hierarchies of whom we have so often spoken. Only when we gradually come nearer to these ideas and concepts (in a week, perhaps, we shall be speaking of them) shall we approach what can answer the question: why do many human beings die as mere children, many in old age, others in middle age?

Now, my dear friends, what I have just given you in outline are concrete concepts of what is real in the world. Truly they are not abstract concepts I have been describing, they are concrete concepts of world reality. These concrete concepts were given, for a more atavistic perception, it is true, in the ancient mysteries. Since the eighth pre-Christian century they have been lost to human perception, but through a deepening of our comprehension of the Christ-Being they must be found again. And this can only be realised on the path of spiritual science.

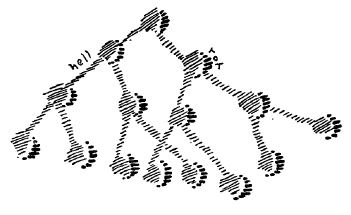

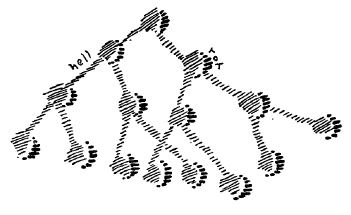

Let us make ourselves from a certain point of view another kind of picture of human evolution. We will here keep before us exceedingly important concepts. Now it can be said that when we go back in the evolution of man we discover—and I have often described this—that in ancient days men had more of the group-soul, and that the individual souls were membered into what was group-soul. You can read about this in various cycles:1For example: Universe, Earth and Man, and Egyptian Myths and Mysteries. we can then diagrammatically represent human evolution and say: in olden days there were group-souls and each of these split up (it would appear thus to soul perception but different for the perception of the spirit). But each of these souls clothed itself with a body that here in this figure I indicate with red strokes. (Diagram 10).

Up to the time of the Pythagorean school this drawing, or something like it, was always made and it was said: look at your body, so far as that is concerned men are separated, each having his own body (that is why the red strokes are isolated). Where the souls are concerned however, mankind is a unity, since we go back—it is true a long way back—to the group-soul. There we have a unity. If you think away the red, the while will form a unified figure (see diagram.)

There is sense in speaking of this figure only if we have first spoken of the spiritual as has been done here today; for then we know everything that is working together in these souls, how the higher hierarchies are working together on these souls. There is no sense in speaking of this figure if our gaze is not fixed on the hierarchies. It was thus that they spoke up to the time of the Pythagorean School; and it was from the Pythagorean School that Apollonius learned what I spoke about yesterday and about which I shall be talking further in these next weeks. But then after the eighth pre-Christian century, when the Pythagorean Schools were in their decadence, the possibility of thus speaking was lost. And gradually the concepts that are concrete, that have reality by being related to the higher hierarchies—these concepts have become confused and hazy to people. Thus there has come to them in the place of Angels, Archangels, Archai, Spirits of Form, Spirits of Movement, Spirits of Wisdom, Thrones, instead of all this concrete weaving of the spirit, they arrived at a concept that now played a certain part in the perception of the Greeks—the concept of the pneuma. Everything became hazily confused: Pneuma, universal spirit, this indistinct concept still so loved today by the Pantheists ... spirit, spirit, spirit ... I have often spoken of how the Pantheists place spirit everywhere; that goes back to Greek life. Again this figure is portrayed ... but you can now see how what was once concrete, the fullness of the Godhead, now became an abstract concept—Pneuma. The white is Pneuma, the red physical matter (see diagram 10) if we are considering the evolution of man. The Greeks, however, at least still preserved some perception of this Pneuma, for they always saw something of the aura. Thus, for them, what you can picture in these white branches was always of an auric nature, something really perceptible. There is the great significance of the transition from that constituted Greece to all that was Roman—that the Greeks still in their perception experienced Pneuma as something actual and spiritual, but that the Romans did so no longer. Everything now becomes quite abstract with the Romans, completely abstract; concepts and nothing more. The Romans are the people of abstract concepts.

My dear friends, in our days you find in science the same diagram! You can come upon it today in materialistic books on science. You will find the same diagram, exactly the same, as you would have found in the old Mysteries, in the Pythagorean Schools, where everything was still related to the hierarchies. You have it with the Greeks where everything is related to the Pneuma; again today you find it drawn, and we shall see what it has now become. Today the scientist says as he makes this same drawing on the blackboard for his students: in the propagation of the human race the substance of the parents' germ cells passes over to the children; but part of this substance remains so that it can again pass over to the children and and again there remains some of this to pass over anew to the children. And another part of the germ cell substance develops so that it can form the cells of the physical body. You have exactly the same diagram, only the modern scientist sees in the white (see diagram) the continuity of the substance of the germ cell. He says; if we go back to our old human ancestors and take this germ cell substance of both male and female, and then go to present day man and take his, it is still the same stream, the substance is continuous. There always remains in this germ substance something eternal—so the scientist imagines—and only half of the germ plasma goes over into the new body. The scientist has still the same figure but no longer has the pneuma; the white is now for him the material germ substance—nothing is left of soul and spirit, it is just material substance. You can read this today in scientific books, and it is taken as a great and significant discovery. That is the materialising of a higher spiritual perception that has passed through the process of abstraction; in the midst stands the abstract concept. And it is really amusing that a modern scientist has written a book (for those whose thinking is sound, it is amusing) in which he says right out: what the Greeks still represented as Pneuma is today the continuity of the germ substance. Yes, it is foolish, but today it counts for great wisdom.

From this you can, however, see one thing, it is not the drawing that does it! And you will therefore understand why to a certain extent I have always been against drawing diagrams so long as we were still trying to run our Anthroposophy within the Theosophical Society. One had only to enter any theosophical branch and the walls as a rule would be plastered with all manner of diagrams; there were drawings of every possible thing with words attached; there ware whole genealogical trees and every possible kind of sketch. However, my dear friends, these drawings are not important. What matters is that we should really be able to have living conceptions; for the same drawing can represent the soul-spiritual in the flowing of hierarchies, the purely material in the continuous germ-plasm. These things are seen very hazily by modern man. Therefore it is so important to be clear that the Greeks still knew something of the real self in man, of the real spiritual and that it was the Romans who made the transition to the abstract concept. You can see all this in what is external. When the Greek talked about his Gods, he did so in a way that made it quite evident that he was still picturing concrete figures behind these Gods. For the Romans the Gods, in reality, ware only names, only expressions, abstractions and they became abstractions more and more. For Greek a certain idea was ever present that in the man before him the hierarchies were living, that in each man the hierarchies were living a different life. Thus the hierarchies were living differently in every man. The Greek knew the reality of man, and when he said, that is Alcibiades, that is Socrates, or that is Plato, he still had the concept that there in Alcibiades, Socrates or Plato ware rising up, within each in a different way, the cosmic thoughts of the hierarchies. And because the cosmic thoughts arose differently these figures appeared different.

All this was entirely lacking in the Roman. For this reason he formed for himself a system of concepts that reached its climax when from the time of Augustus on and actually from an earlier date, the Roman Caesar was held to be God. The Godhead gradually became an abstraction and the Roman Caesar was himself a God because the concept of God had become completely abstract. This applies to the rest of their concepts; and it was particularly the case with the concepts that lived deeply in the Roman nature as concepts of rights, moral concepts. Thus, in place of all that in olden days was a living reality, there arose a number of abstractions. And all these abstractions lasted on as a heritage throughout the middle ages and descended to modern times, remaining as heritage down to the nineteenth century—abstract concepts carried into every sphere.

In the nineteenth century there came something startling. Man himself was entirely lost sight of among all these abstract concepts! The Greeks still had a presentiment of the real man who descends here after being formed and fashioned out of the cosmos; in the time of the Roman empire all knowledge of him was lost. The nineteenth century was needed to rediscover him through all the connections I have been showing you and will go on showing you even more exactly. The discovery of man took place now from the opposite pole. Greece wanted to see man as descending from the hierarchies, divine man; in place of this the Romans set up a series of abstract concepts; the nineteenth century—the eighteenth century too but particularly the nineteenth—was needed to rediscover man from the other side, from his animal side. And he could not be grasped with abstract concepts; this was the great shock. This was the great shock and the deep cleft that arose; what is this actually that stands there on two legs and fidgets with its hands, and eats and drinks all manner of things; what is it? The Greeks still knew, then a change took place when concepts became abstract. Now it comes as something startling to men of the nineteenth century; it stands there and there are no concepts with which to grasp it. It is taken for simply a higher form of animal. On the one hand, in science it produces Darwinism, on the other hand, in the spiritual it brings about socialism which would place man into society as a mere animal. Here is man standing transfixed before himself—what is this thing? And he is powerless to answer the question.

That is the situation today; that is the situation that will produce not only concepts that are right or wrong according as men will them, but is called upon to create facts either catastrophic or beneficial. And the situation is—the shock men have when seeing themselves. We must find the elements once more for te understanding of spiritual man. These elements will not be found unless we turn to the theory of metamorphosis. There lies the essential point. Goethe's concepts of metamorphosis are alone able to grasp the ever changing phenomena which offer themselves to the perception of the reality.

Now one might say that spiritual evolution has always moved in this direction. Even at the time when the Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz in the seventeenth century was being published in so wonderful a way—other writings too—the endeavour was already there to provide for the arising of a social structure for man compatible with his true nature. (In Das Reich I have referred to this in a series of articles concerning The Chemical Wedding). In this way the Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz by the so-called Valentin Andreae arose. On the other hand, however, there also arose the book he called Reformation des Ganzer Menschengeschlectes (Reformation of the whole Human Race), where he gives a great political survey of how social conditions ought to be. Then, it was the thirty years war that swept the thing away! Today, there is the possibility that the ordering of the world either sweep things away once more ... or carry them right into human evolution. With this we are touching an the great fundamental questions of the day, with which men should be occupying themselves instead of with all the secondary matters that engross them. If only men concerned themselves about basic questions they would find means and ways of bringing fruitful concepts into modern reality—then we could get away from abstract concepts.

It is not very easy to distinguish reality from illusion. For that, we must have the will to go right into life with all seriousness and all good will, and not be bound down by programmes and prejudices. I could tell many tales about this but now I will refer to one fact only. In the beginning of the nineties of the last century a number of people foregathered in various towns of Europe and brought about something of an American nature, namely, the Movement for Ethical Culture. At that time it was the intellectuals who were connected with founding these societies for Ethical Culture. These people produced very beautiful things, and if today you read the articles written at that time by the promoters of Societies for Ethical Culture ... if you have a taste for butter, you will probably even today be enchanted by all the beautiful, wonderfully beautiful ideals, in which these people indulged. And indeed it was no pleasant task to go against this reveling in butter: However, I wrote an article at the time in one of the first numbers of Die Zunkunft (The Future), against all this oiliness in “ethical culture,” and denounced it in awful words. Naturally it was a shameful deed—how should it not have been when these people had set out to make the whole world ethical, moral—how should it not have been disgraceful to turn upon anything so good: At that time I was living in Weimar but on paying a visit to Berlin I had a conversation with Herman Grimm who said:

“What is the matter with ‘ethical culture'? Go and see the people themselves. You will find that here in Berlin those who hold meetings about ethics are really thoroughly nice kind people—one could not have any objection to them. They can even be congenial and very pleasant.” This was not to be denied and at the moment Herman Grimm had just as much right on his side as I had. Outwardly and momentarily, one of us was as right as the other, one could be proved right just as well as the other. And I am not for maintaining that from the point of view of pure logic my grounds for opposing these ethical philosophers were any more sound than those brought forward by them—I wouldn't be sure. But, my dear friends, from all this highfalutin idealism the present catastrophe has arisen! And only those people were right, and have been justified by events, who said at the time; with all your talking and luxuriating in buttery ideals, by means of which you would bring universal peace and universal morals to man, you have produced nothing but what I then called social carcinoma that had to end in this catastrophic present. Time has shown who was working with concrete concepts, who with merely those that are abstract. When they are simply abstract in character, there is no distinguishing who is right and who is wrong. The only thing that decides is whether a concept finds its right setting in the course of actual events. A professor teaching science in a university can naturally prove everything he says to be right in a most beautiful and logical way. And all this goes into the holes in the head (and this today I naturally may be allowed to say with the very best intention). But you see it is not a question of bringing forward apparently good logical grounds; for when these thoughts sink into a head such as Lenin's they become Bolshevism. What matters is what a thought is in reality, not what can be thought about it or felt about it in an abstract way, but what force goes to the forming of it in its reality. And if we test the world-conception that is chiefly talked of today—for the others, specified yesterday, were more in picture form—when one brings socialism to the test, it is not a question today of sitting oneself down to cram (as we say for ‘study') Karl Marx, or Lassalle, or Bernstein, to study their books, to study these authors. No! It is a question of having a feeling, a living experience for what will become of human progress if a number of men—the sort of men who stand at a machine—have these thoughts. That is what matters, and not to have thoughts about the social structure in the near future that are learnt in the customary course of modern diplomatic schooling, Now is the time when it is important to weigh thoughts so as to be able to answer the question: what are the times wanting for the coming decades? Today the time has already come when it is not allowed to sit in comfort in the various magisterial seats and to go on cherishing what is old. The time has come when men must bear the shock of seeing themselves, and when the thought must rise up in those responsible anywhere for anything: How is this question to be solved out of the spiritual life?

Sechster Vortrag

Gewisse Fragen werden dem denkenden Menschen sich doch immer wieder und wiederum aufdrängen, wenn er auch in Zeiten, in denen die materialistische Kultur überwiegt, diesen Fragen mehr oder weniger aus dem Wege gehen möchte. Es sind viele Fragen. Ich möchte heute ein paar aus der großen Reihe der Fragen herausheben, die davon kommen, daß der Mensch doch, selbst wenn er sich sträubt, eine geistige Welt anzuerkennen, den Eindruck dieser geistigen Welt verspürt. Zu solchen Fragen gehört zum Beispiel diese, die ja, man möchte sagen, das Leben alltäglich aufwirft: Gewisse Menschen sterben jung, andere sterben ganz alt, andere dazwischen. Gegenüber dieser Tatsache, daß auf der einen Seite ganz junge Kinder sterben, auf der andern Seite Leute ganz alt werden und dann sterben, erheben sich für den Menschen Fragen, welche mit den Mitteln, die man heute wissenschaftliche Mittel nennt, niemals — bei klarer Besinnung wird das jeder zugeben müssen — werden zu beantworten sein. Und doch sind sie für das Menschenleben brennende Fragen, und jeder kann eigentlich empfinden, daß sich für das Leben Unendliches aufklären müßte dadurch, daß man diesen Fragen nahetreten könnte: Warum sterben Menschen zuweilen früher, im Kindesalter, im Jugendalter, in der Mitte der gewöhnlichen Lebenszeit? Warum sterben andere alt? Was hat das für eine Bedeutung im gesamten Weltenall?

Sich solche Fragen zu beantworten, dazu hatten die Menschen bis zu jenem Zeitpunkte, den ich Ihnen in diesen Betrachtungen schon angegeben habe, bis zu dem Zeitpunkt der beginnenden vierten nachatlantischen Zeit, so ungefähr bis in die Mitte des 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhunderts, noch Vorstellungen, Begriffe. Aus alter Weisheit herüberbekommen hatten sie Begriffe. Es gab auch in jenen alten Zeiten, die dem 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert vorangingen, über die damalige Erdenkultur verbreitet überall Vorstellungen, welche nach dem Sinn der damaligen Zeit den Menschen Aufschluß gaben über solche Fragen wie die eben angedeuteten. Dasjenige, was wir heute Wissenschaft nennen, kann nicht einmal einen rechten Sinn verbinden mit solchen Fragen, kommt gar nicht darauf, daß etwas mit diesen Fragen gegeben ist, wozu man irgendeine Antwort suchen sollte. Das alles rührt davon her, daß in der Zeit, die seit dem eben angedeuteten Zeitpunkte verflossen ist, eigentlich alle Vorstellungen verlorengegangen sind, die sich auf den geistigen und damit auf den ewigen Menschen beziehen. Es sind nur diejenigen Vorstellungen geblieben, die sich auf den vergänglichen Menschen und den zwischen Geburt und Tod eingeschlossenen Menschen beziehen.

Ich habe darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß in allen alten Weltanschauungen von einer dreifachen Sonne gesprochen wurde, von jener Sonne, die man mit den physischen Sinnen wahrnimmt als eine leuchtende Kugel im Weltenraume draußen. Hinter dieser Sonne aber sahen die alten Weisen die seelische Sonne - im griechischen Sinne gesprochen, den Helios — und erst hinter dieser seelischen Sonne die geistige Sonne, die zum Beispiel noch Plato identifizierte mit dem Guten. Es hat für den heutigen Menschen eigentlich keinen rechten Sinn, von dem Helios, der seelischen Sonne, oder gar von der geistigen Sonne, von dem Guten, zu sprechen. Aber so wie uns hier zwischen Geburt und Tod die physische Sonne leuchtet, so scheint, wenn ich sagen darf, in unser Ich hinein in der Zeit, die wir verbringen zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, die geistige Sonne, die eben noch von Plato identifiziert wird mit dem Guten. Für die Zeit zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt von dieser leuchtenden Kugel zu sprechen, von der unsere heutige materialistische Weltanschauung spricht, hat keinen Sinn; zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt hat nur Sinn zu sprechen von der geistigen Sonne, von dem, was Plato noch als das Gute bezeichnet. Aber gerade ein solcher Begriff sollte uns auf etwas hinweisen. Er sollte uns darauf hinweisen, nachzudenken, wie es sich eigentlich verhält mit dem, was wir uns als physische Vorstellung von der Welt bilden. Daß wir in dem, was wir uns als physische Vorstellungen von der Welt bilden, in dem, was sinnenfällig vor uns ausgebreitet ist, zu sehen haben eine Art von Täuschung, eine Art von Maja, das wird doch nicht im vollen Sinne des Wortes ernst genommen, wenigstens nicht so ernst, daß die Anschauung des Lebens wirklich mit diesen Dingen durchdrungen würde.

So eine Art Vorstellung von der Sonne hat im Grunde derjenige, der die heutige Physik, Astrophysik meinetwillen, autoritativ nimmt: Wenn er da hinauflahren könnte, wohin die Physiker die Sonne versetzen, so würde er, indem er sich der Sonne nähert — nun, sehen wir jetzt von menschlichen Lebensbedingungen ab, setzen wir voraus, daß die Lebensbedingungen absolut sein könnten -, gewaltige Hitze verspüren, so stellt er es sich vor, und er würde da, wenn er innerhalb des Raumes ankommt, den sich der Physiker von der Sonne ausgefüllt denkt, innerhalb dieses Raumes glühendes Gas oder dergleichen finden. So stellt sich der Physiker ja das eigentlich vor: einen glühenden Gasball oder so etwas. Aber so ist es nicht, das ist eine richtige Maja, eine richtige Täuschung. Und diese Vorstellung hält vor den wahren physikalischen Anschauungen, die man gewinnen kann, auch nicht stand, geschweige denn vor der wirklichen übersinnlichen Anschauung. Wenn man sich nämlich wirklich der Sonne nähern könnte und dahin kommen würde, wo die Sonne ist — ja, indem man sich nähert, da findet man schon so etwas, wie wenn man durch flutendes Licht durchgehen müßte (es wird gezeichnet: gelber Kreis, innen blauer Kern); aber wenn man da hineinkommt, wo die Physiker die physische Sonne vermuten, findet man zunächst das, was man ansprechen könnte als leeren Raum. Da ist überhaupt nichts; es ist gar nichts da, wo man die physische Sonne vermutet. Ich zeichne es schematisch (blau), weil eigentlich nichts dort ist. Da ist nichts, da ist leerer Raum. Aber ein sonderbarer leerer Raum ist das! Wenn ich sage: Es ist nichts da -, so rede ich eigentlich nicht ganz richtig; es ist weniger als nichts da. Es ist nicht nur ein leerer Raum da, sondern es ist weniger als nichts da. Und das ist es, was als eine Vorstellung für abendländische Menschen heute außerordentlich schwer zu bilden ist. Der Morgenländer hat diese Vorstellung auch heute noch ohne weiteres; für den ist es gar nichts Wunderbares oder Schwerverständliches, wenn man ihm davon spricht, daß da weniger als nichts ist. Der Abendländer denkt sich, und er denkt sich das insbesondere, wenn er ein waschechter Kantianer ist, denn viel mehr Leute, als man heute denkt, sind Kantianer, sind unbewußte Kantianer: Wenn nichts im Raum ist, so ist es eben leeret Raum! — Aber das ist nicht der Fall; es kann auch ausgeschöpfter Raum sein. Wenn Sie nämlich da durch diese Sonnenkorona durchsehen würden, so würden Sie diesen leeren Raum, in den Sie da eintreten würden, höchst unbehaglich empfinden: er zerreißt Sie nämlich. Und darin zeigt er seine Wesenheit, daß er mehr ist - oder weniger ist, wie ich besser sagen kann - als ein leerer Raum. Sie brauchen ja nur die einfachsten mathematischen Begriffe zu Hilfe zu nehmen, so wird Ihnen nicht ganz unklar bleiben können, was ich da meine: leerer Raum ist weniger noch als bloß leer. Nehmen wir an, Sie besitzen irgend etwas an Vermögen. Aber es kann auch vorkommen, daß Sie alles, was Sie besitzen, ausgegeben haben, daß Sie nichts haben. Aber man kann weniger als nichts haben: man kann Schulden haben, dann hat man wirklich weniger als nichts. Man kann, wenn man von der Raumerfüllung zu immer dünnerer und dünnerer Raumerfüllung übergeht, bis zum leeren Raum kommen; man kann aber dann hinter die bloße Leerheit noch hinübergehen, wie man von dem Nichts zu den Schulden gehen kann.

Das ist der größte Fehler der heutigen Weltanschauung, daß sie diese eigentümliche Art von negativer Stofflichkeit -— wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf — nicht kennt, daß sie nur die Leerheit kennt und die Erfüllung, und nicht dasjenige, was weniger ist als die Leerheit. Denn dadurch, daß das heutige Wissen, die heutige Weltanschauung das, was weniger ist als die Leerheit, nicht kennt, dadurch wird diese heutige Weltanschauung mehr oder weniger im Materialismus festgehalten, richtig im Materialismus festgehalten, ich möchte sagen: gebannt in den Materialismus. Denn es gibt auch im Menschen, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, einen Ort, welcher leerer ist als leer; nicht in seiner Gänze, aber welcher eingelagert hat Teile, die leerer sind als leer. Im ganzen ist ja der Mensch - ich meine der physische Mensch ein Wesen, welches einen Raum materiell ausfüllt; aber ein gewisses Glied der menschlichen Natur, von den dreien, die ich angeführt habe, hat tatsächlich etwas in sich, was sonnenähnlich ist, leerer ist als leer. Das ist - ja, Sie müssen es schon hinnehmen - der Kopf. Und gerade darauf, daß der Mensch so organisiert ist, daß sein Kopf sich immer entleeren kann und in gewissen Gliedern leerer sein kann als leer, dadurch hat dieser Kopf die Möglichkeit, das Geistige sich einzulagern. Stellen Sie sich einmal die Sache vor, wie sie eigentlich ist. Natürlich muß man die Dinge sich schematisch vorstellen; aber denken Sie sich, alles dasjenige, was materiell Ihren Kopf ausfüllt, würde ich schematisch durch das Folgende zeichnen. Das wäre schematisch Ihr Kopf (siehe Zeichnung, rot). Nun aber muß ich, wenn ich ihn vollständig zeichnen will, in diesem Kopf leere Stellen lassen. Das ist natürlich jetzt nicht so groß, aber drinnen sind leere Stellen. In diese leeren Stellen kann dasjenige hinein, was ich Ihnen den jungen Geist genannt habe in diesen Tagen. In die leeren Stellen hinein muß der junge Geist, gewissermaßen in seinen Strahlen, gezeichnet werden (gelb).

Ja, die Materialisten sagen: Das Gehirn ist das Werkzeug des Seelenlebens, des Denkens. - Das Umgekehrte ist wahr: Die Löcher im Gehirn, ja sogar dasjenige, was mehr ist als Löcher, oder ich könnte auch sagen, weniger ist als Löcher, was leerer ist als leer, das ist das Werkzeug des Seelenlebens. Und da, wo das Seelenleben nicht ist, wo das Seelenleben fortwährend aufstößt, wo der Raum unseres Schädels mit Gehirnmasse ausgefüllt ist, da wird nichts gedacht, da wird nichts seelisch erlebt. Wir brauchen unser physisches Gehirn nicht zum Seelenleben, sondern wir brauchen es nur, damit wir das Seelenleben einfangen, physisch einfangen. Wenn da nicht das Seelenleben, das in den Löchern des Gehirnes eigentlich lebt, überall aufstoßen würde, so

vol würde es verfliegen; es käme uns nicht zum Bewußtsein. Aber es lebt in den Löchern des Gehirns, die leerer sind als leer.

So müssen wir uns die Begriffe allmählich korrigieren. Wir nehmen, wenn wir vor dem Spiegel stehen, nicht uns wahr, sondern unser Spiegelbild. Uns können wir vergessen. Wir sehen uns im Spiegel drinnen. So erlebt der Mensch auch nicht sich, indem er durch sein Gehirn dasjenige zusammenhält, was in den Löchern des Gehirnes liegt; er erlebt, wie sich überall sein Seelenleben spiegelt, indem es an die Gehirnmasse anstößt. Es spiegelt sich überall; das erlebt der Mensch. Er erlebt eigentlich sein Spiegelbild. Das aber, was da in die Löcher hereingeschlüpft ist, das ist dasjenige, was dann, wenn der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes geht, ohne die Widerlage des Gehirnes seiner selbst bewußt wird, weil es dann in entgegengesetzter Weise mit Bewußtsein durchsetzt wird.

Nun will ich ein anderes Schema aufzeichnen. Nehmen Sie das Folgende. Bitte, ich will jetzt das Gehirn recht drastisch zeichnen, wie das Löcher läßt (blau). Da sei die Gehirnmasse, da lasse es die Löcher, und dahinein in diese Löcher geht das Seelenleben (gelb). Dieses Seelenleben, das setzt sich aber vor den Löchern fort. Da kommen wir in die ja natürlich nur in der Nähe des Menschen sichtbare, aber ins Unbestimmte auslaufende Menschenaura hinein.

Denken wir uns jetzt das Gehirn weg, und denken wir uns, wir sehen beim gewöhnlichen Menschen zwischen Geburt und Tod das Seelenleben an, dann würden wir sagen müssen: Der wahre Mensch, in dieser Weise gesehen, der ist in seinem Zustande zwischen Geburt und Tod so, daß er eigentlich - da muß ich allerdings das jetzt anders schematisch zeichnen - sein Antlitz seinem Körper so zuwendet (siehe Zeichnung Seite 105, lila); sein Seelenleben wendet er dem Körperlichen zu. Und wenn wir auf das Gehirn sehen, so streckt dieses Seelenleben hier Fühlhörner vor, die in die Löcher des Gehirns hineingehen. Was ich dort (siehe Zeichnung Seite 102) gelb gezeichnet habe, zeichne ich hier lila, weil das besser dem Anblick im lebenden Menschen entspricht. Das wäre das, was sich ins Gehirn erstreckt beim lebenden Menschen.

Wollte ich jetzt danach etwa den physischen Menschen zeichnen, so würde ich das am besten dadurch andeuten können, daß ich Ihnen etwa hier die Grenze, die mit dem Erinnerungsvermögen gegeben ist, hereinzeichne. Sie würde da nach außen gehen, und da würde die äußere Grenze, die Grenze des Erkennens sein, von der ich Ihnen ja auch gesprochen habe. Da brauchen Sie sich ja nur an die letzthin und gestern gemachte Zeichnung zu erinnern.

Jetzt aber ist es wirklich so, daß, wenn man von außen den Menschen geistig anschaut, sich das Seelenleben so in den Menschen hinein erstreckt. Ich will also das einzelne Hineinerstrecken nur in bezug auf das Gehirn zeichnen. Aber dieses Seelenleben ist in sich auch differenziert: so würde ich, wenn ich dieses Seelenleben weiter verfolgen würde, hier eine andere Region zeichnen müssen (rot unter dem Lila), hier eine andere Region (blau); das würde also alles zu der den Menschen konstituierenden Aura gehören. Dann eine andere Region (grün): Sie sehen, dieser Teil, den ich da jetzt schematisch zeichne, liegt jenseits der Grenze des menschlichen Erkennens. Dann diese Region (gelb) - im Grunde genommen gehört das alles zum Menschen - und diese Region (orange).

Das bewegt sich, wenn der Mensch einschläft, mehr oder weniger aus dem Körper heraus, so wie das gestern gezeichnet worden ist (Zeichnung Seite 77); wenn der Mensch wachend ist, mehr oder weniger in den Körper hinein, so daß eigentlich die Aura nur in der unmittelbarsten Umgebung des Körpers seelisch wahrzunehmen ist. Wenn man den physischen Menschen beschreibt, dann tut man es so, daß man sagt: Dieser physische Mensch besteht aus Lunge, Herz, Leber, Galle und so weiter. Das sagt der physische Anatom, der Physiologe und so weiter. Geradeso können Sie aber den geistig-seelischen Menschen beschreiben, der in dieser Weise sich eigentlich in die Löcher des Menschen hereinerstreckt, in das, was mehr ist als Leere, in den Menschen hineinerstreckt. Sie können das ebenso beschreiben. Da müssen Sie dann nur angeben, aus was dieser geistig-seelische Mensch besteht. Und ebenso wie man beim physischen Menschen Organe unterscheidet, so kann man hier Strömungen unterscheiden. Man kann sagen: Hier, wo ich das Rot gezeichnet habe, würde der physische Mensch so im Profil drinnenstehen, hierher das Gesicht gerichtet haben, hier etwa die Augen (siehe Zeichnung); hier würde sein die Region der Begierdenglut (rot). Das würde ein Bestandteil des seelisch-geistigen Menschen sein, der seiner Substanz nach entnommen ist der Region, die Sie aus der «Theosophie» kennen als die Region der Begierdenglut. Also Begierdenglut, gewissermaßen etwas von ihr entnommen, in den Menschen hineinversetzt, gibt diese Partie des Menschen. Das, was ich hier lila gezeichnet habe, das würde ich bezeichnen müssen, wenn ich die Einzelheiten beschriebe, mit Seelenleben. Sie wissen, eine bestimmte Partie des Seelengebietes, des Seelenlandes, ist mit «Seelenleben» bezeichnet. Die Substanz daraus würde dieses Violette, dieses Lila sein, was im Menschen einen Teil des GeistigSeelischen bildet.

Das, was ich hier als orange bezeichnet habe, würden wir zu nennen haben, wenn wir diese Benennung beibehielten, tätige Seelenkraft. So daß Sie sich vorzustellen hätten: Dasjenige, was am intensivsten durch Ihre Sinne in Sie hineingeht beim Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod, das ist das Seelenleben; und dahinter, sich auch hinstopfend, aber nicht so hineinkönnend, aufgehalten werdend durch das Seelenleben: tätige Seelenkraft. Und noch mehr dahinter dasjenige, was man nennen kann: Seelenlicht. Ich habe es hier gelb bezeichnet. Ziemlich anschließend an dieses Seelenlicht, sich so durchdrückend, würde dann das sein, was der Region von Lust und Unlust entnommen ist. Das würde ich hier etwa dem grünen Gebiete zuzuschreiben haben (siehe Zeichnung). Dann würde dem schon bläulich werdenden Gebiete zuzuschreiben sein: Wünsche. Und anstoßend nun hier an das Blaue, schon wiederum mehr in das Blaurote hineingehend, das würde die Region fließender Reizbarkeit sein. Das, was ich hier nenne Begierdenglut, fließende Reizbarkeit, Wünsche, das sind aurische Strömungen. Diese aurischen Strömungen konstituieren, wie Sie wissen, die Seelenwelt; sie konstituieren aber auch den seelisch-geistigen Menschen, der etwa so aufgebaut ist aus den Ingredienzien dieser Seelenwelt.

Wenn dann der Tod eintritt, dann ist das so, daß der physische Leib abfällt und der Mensch das fortnimmt, was sich durch seine Löcher in ihn hineinerstreckt hat. Er nimmt es nun fort. Dadurch, daß er es fortnimmt — wir können uns diesen physischen Menschen wegdenken -, kommt nun der Mensch in eine gewisse Verwandtschaft mit der Seelenwelt, und dann auch mit dem Geisterland, wie Sie es ja in der «Theosophie» dargestellt finden. Er hat eine gewisse Verwandtschaft dadurch, daß er diese Ingredienzen in sich hat. Aber während des physischen Lebens sind sie gebunden an den physischen Leib; dann werden sie frei. Dadurch aber, daß sie frei werden, verwandelt sich nach und nach das Ganze. Während es so war, daß sich - wenn ich jetzt die Differenzierungen weglasse und das Seelenleben so zeichne während des physischen Lebens die Fühler (dunkel schraffiert) in unsere Löcher hineinerstrecken, nehmen sich nach dem Tode diese Fühler zurück. Dadurch aber, daß sich die Fühler zurücknehmen, höhlt sich das Seelenleben selbst aus, und im Seelenleben drinnen geht das geistige Leben auf; von der andern Seite geht das geistige Leben auf (hell schraffiert).

In dem selben Maße, in welchem der Mensch aufhört unterzutauchen in den physischen Leib, hellt sich auf sein Geistig-Seelisches, diese seine Aura von der andern Seite durchleuchtend. Und wie derMensch ein Bewußtsein erlangen kann dadurch, daß beim Hineinstoßen des Seelisch-Geistigen in den physischen Körper dieses immer anstößt und dadurch sich immer spiegelt, so bekommt der Mensch jetzt dadurch ein Bewußtsein, daß er sich zurückzieht gegen das Licht. Aber dies ist jenes Licht der Sonne, welches das erste Licht ist: das Gute. Während der Mensch also während seines physischen Lebens als geistig-seelisches Wesen gegen das Sonnenverwandte, nämlich gegen die überleeren Löcher im Gehirn stößt, stößt er, sich zurückziehend nach dem Tode, nach der andern Sonne, nach der guten Sonne, nach der ersten Sonne.

Sie sehen, wie zusammenhängt mit den Grundvorstellungen der uralten Mysterien die Möglichkeit, Begriffe zu erhalten von dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Denn so stecken wir drinnen in diesem ganzen kosmischen Leben, wie ich es Ihnen jetzt in diesen Tagen dargestellt habe. Aber allerdings muß man, um richtige Begriffe von diesen Dingen zu bekommen, tiefer in das eigentliche Gefüge der menschlichen Evolution durch die Erdenzeit hindurch eingehen. Nicht wahr, es wäre ja möglich, daß jemand durch besonderen Glücksfall, wie man das so nennen könnte, hellsichtig das Ganze, was ich jetzt dargestellt habe, schaute. Aber der Glücksfall könnte nicht weiter gehen, als daß er sich verwandelnde Gebilde schaut. Etwa so: Nehmen wir an, ein Mensch würde durch irgendein Wunder - es geschieht schon nicht durch ein Wunder -, durch irgend etwas hellsichtig, übersinnlich schauend, so würde er schon, so ähnlich, wie ich es hier versucht habe aufzuzeichnen, das geistig-seelische Leben des Menschen sehen. Daß dies etwas anders ausschaut, als was ich vor einiger Zeit als Normalaura aufgezeichnet habe, das werden Sie begreiflich finden, wenn Sie verstehen, daß ich vor einigen Tagen das aufgezeichnet habe (siehe Seite 31), was sich als Aura ergibt, wenn man den ganzen Menschen sieht, also den physischen Menschen und die Aura ringsherum; jetzt habe ich aber herausgeholt den geistigseelischen Menschen, so daß der geistig-seelische Mensch von dem physischen Menschen abstrahiert wird.

Daran sehen Sie schon, daß man einmal so, das andere Mal anders die Farben setzen muß; daran sehen Sie auch, daß für das übersinnliche Bewußtsein die Dinge sehr verschieden ausschauen. Nehmen Sie sich vor, die Aura des Menschen einfach so zu sehen, wie sie ist, indem der Mensch den physischen Leib hat, dann sehen Sie diese Aura - also wenn Sie sich vornehmen, abgesehen vom geistig-seelischen Menschen jetzt den Menschen zu sehen, der nur seine Organe vorstreckt in den physischen Menschen hinein. Aber wenn Sie nun den Menschen in der Zeit zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt sehen, da sehen Sie wiederum, wie sich das Ganze verwandelt. Da geht also vor allen Dingen diese Region, die ich hier rot gezeichnet habe, weg von hier, geht hier herauf, das Gelbe geht hier herunter, das Ganze kommt nach und nach durcheinander. Man kann solche Dinge anschauen, aber das Anschauen hat etwas Verwirrendes. Und daher werden sich auch für den neueren Menschen nicht leicht Möglichkeiten finden, Sinn und Bedeutung in. dieses Verwirrende hineinzubringen, wenn er nicht zu andern Hilfsmitteln seine Zuflucht nimmt.

Wir haben hingewiesen darauf, daß das Haupt des Menschen, der Kopf, auf die Vergangenheit weist, der Extremitätenmensch auf die Zukunft weist. Es ist ein vollständiger Gegensatz, polarisch; beides, das Haupt des Menschen und der Extremitätenmensch - erinnern Sie sich nur an dasjenige, was ich gestern auseinandergesetzt habe -, beide sind eigentlich ein und dasselbe; nur daß das Haupt eben eine sehr alte Bildung ist, eine Überbildung. Daher hat es auch die Löcher. Der Extremitätenmensch hat diese Löcher noch nicht; der ist eben noch ganz von Materie ausgefüllt. Löcher kriegen, das ist ein Zeichen von Überentwickelung. Rückgängige Entwickelung im Haupte sehen können, darauf kommt viel an. Und viel kommt darauf an, daß man verstehen kann: der Extremitätenmensch ist eine junge Metamorphose, das Haupt ist eine alte Metamorphose. Und weil der Extremitätenmensch eine junge Metamorphose ist, kann er noch nicht hier im physischen Leben denken, sondern es bleibt sein Bewußtsein unbewußt. Er öffnet nicht dem geistig-seelischen Menschen solche Löcher wie das Gehirn.

Das ist von unendlicher Wichtigkeit und wird in Zukunft immer wichtiger und wichtiger werden für die Geisteskultur: einzusehen so etwas, daß zwei Dinge, die äußerlich physisch ganz voneinander verschieden sind wie der Kopfmensch und der Extremitätenmensch, geistig-seelisch ein und dasselbe sind, nur der Zeit nach auf verschiedenen Entwickelungsstufen. Viele Geheimnisse liegen gerade in dieser Tatsache, daß zwei physisch verschiedene Dinge dadurch, daß sie auf zeitlich verschiedenen Entwickelungsstufen stehen, eigentlich ein und dasselbe sein können. Sie sind äußerlich physisch etwas ganz Verschiedenes, aber Verwandlungszustände, also Metamorphosen eines und desselben.

In elementarer Weise hat den Anfang mit Begriffen, durch die man so etwas erfassen kann, eben Goethe gemacht mit seiner Metamorphosenlehre. Während sonst eigentlich in der Ausbildung der Begriffe ein Stillstand ist seit alten Zeiten, setzt bei Goethe wiederum die Fähigkeit ein, Begriffe zu bilden. Und diese Begriffe sind die lebendigen Metamorphosenbegriffe. Goethe hat allerdings angefangen mit dem Einfachsten. Er hat gesagt: Wenn wir eine Pflanze anschauen, so haben wir das grüne Pflanzenblatt, aber das verwandelt sich dann in das farbige Blumenblatt. Beides ist ein und dasselbe, es sind nur Metamorphosen voneinander. -— So wie das grüne Pflanzenblatt und das rote Rosenblatt verschiedene Metamorphosen sind, ein und dasselbe auf verschiedenen Stufen, so sind das Haupt des Menschen und der Extremitätenorganismus einfach Metamorphosen voneinander. Wenn wir den Goetheschen Metamorphosengedanken für die Pflanze nehmen, haben wir etwas Primitives, Einfaches; aber es kann dieser Gedanke fruchtbar gemacht werden für ein Höchstes: für das Beschreiben des Überganges des Menschen von einer Inkarnation in die andere. Wir sehen eine Pflanze mit grünem Blatt und mit der Blüte und sagen: Die Blüte, die rote Rosenblüte ist umgewandelt aus dem grünen Pflanzenblatt. Wir sehen einen Menschen vor uns stehen und sagen: Das Haupt, das du trägst, das sind deine umgewandelten Arme, Hände, Beine, Füße aus der vorhergehenden Inkarnation; und das, was du jetzt an dir, wie Arme, Hände, Beine, Füße trägst, das wird sich umwandeln für die nächste Inkarnation in deinen Kopf.

Aber jetzt kommt ein Einwand, der Ihnen offenbar in der Seele schwer sitzt. Jetzt werden Sie sagen: Ja, um Gottes willen, aber ich lasse doch meine Beine und meine Füße zurück, und meine Arme und meine Hände auch; die nehme ich doch nicht mit in die nächste Inkarnation! Wie soll denn da mein Kopf daraus werden? - Nicht wahr, das kann man einwenden. Wiederum stehen Ste eben hier vor einer Maja. Es ist nämlich nicht wahr, daß Sie wirklich Ihre Beine und Ihre Füße, Ihre Hände und Ihre Arme zurücklassen. Das ist nämlich nicht wahr; das sagen Sie deshalb, weil Sie an der Maja, an der großen Täuschung hängenbleiben. Was Sie nämlich mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein Ihre Arme und Hände, Ihre Beine und Füße nennen, das sind nicht Ihre Arme und Hände und Ihre Beine und Füße, sondern das ist dasjenige, was als Blut und andere Säfte Ihre Arme und Hände und Ihre Beine und Füße ausfüllt. Es ist hier wieder eine schwierige Vorstellung, aber es ist so. - Nehmen Sie an, hier haben Sie Arme und Hände, Beine und Füße; aber das, was hier ist, ist geistig, das sind geistige Kräfte. Bitte, stellen Sie sich vor:

Ihre Arme und Hände, Ihre Beine und Füße seien Kräfte, übersinnliche Kräfte. Würden Sie nur sie haben, Sie würden sie nicht mit den Augen sehen. Sie sind angefüllt, diese Kräfte sind angefüllt mit den Säften, mit dem Blute, und das, was als mineralische Masse, flüssig oder zum Teil fest, zum geringsten Teile fest, Unsichtbares ausfüllt, das sehen Sie (schraffiert). Was Sie im Grabe lassen, was verbrannt wird, das sind nur, ich möchte sagen, die mineralischen Einschlüsse. Ihre Arme und Hände, Ihre Beine und Füße sind nicht sichtbare Füße und so weiter, sie sind Kräfte, und diese nehmen Sie mit. Die Formen nehmen Sie mit. Sie sagen: Ich habe Hände und Füße. - Derjenige, der in die geistigen Welten hineinsieht, der sagt nicht: Ich habe Hände und Füße -, sondern er sagt: Es gibt Geister der Form, Elohim, die denken kosmisch, und deren Gedanken sind meine Arme und Hände und Beine und Füße; und deren Gedanken sind mit Blut und andern Säften ausgefüllt. - Aber Blut und andere Säfte sind auch wiederum nicht das, als was sie im Physischen erscheinen; diese Stofle sind wiederum die Vorstellungen der Geister der Weisheit, und dasjenige, was der Physiker Stoff nennt, das ist nur der äußere Schein. Wo der Physiker den Stoff hinsetzt, müßte er sagen: Da stoße ich auf einen Gedanken der Geister der Weisheit, der Kyriotetes. Und wo Sie Arme und Hände, Beine und Füße sehen, da können Sie nicht einmal darauf stoßen, da müssen Sie sagen: Hier bilden die kosmischen Gedanken der Geister der Form meine Formen. — Kurz, so sonderbar das klingt: Ihren Körper gibt es ja gar nicht, sondern da, wo im Raume Ihr Körper ist, da leben durcheinander die kosmischen Gedanken der höheren Hierarchien. Und würden Sie nicht der Maja gemäß, sondern richtig sehen, so würden Sie sagen: Hier erstrecken sich herein die kosmischen Gedanken der Exusiai, der Geister der Form, der Elohim. Diese kosmischen Gedanken machen sich mir sichtbar, indem sie ausgefüllt sind mit den kosmischen Gedanken der Geister der Weisheit. Das gibt Arme und Hände, Beine und Füße. Gar nicht steht das da, als was es in der Maja erscheint, vor dem geistigen Blicke, sondern da stehen die kosmischen Gedanken, und diese kosmischen Gedanken ballen sich zusammen, kondensieren sich, schieben sich ineinander, und daher erscheinen sie uns als diese Schattenfigur, als die wir herumgehen, von der wir glauben, daß sie wirklich ist. Also den physischen Menschen, den gibt es gar nicht.

Wir können mit einem gewissen Recht sagen: In der Stunde des Todes scheiden die Geister der Form ihre kosmischen Gedanken von den kosmischen Gedanken der Geister der Weisheit. Die Geister der Form nehmen ihre Gedanken in die Luft hinauf, die Geister der Weisheit senken ihre stofflichen Gedanken in die Erde hinein. Dadurch ist im Leichnam so ein Nachschatten von den Gedanken der Geister der Weisheit noch vorhanden, wenn die Geister der Form ihre Gedanken zurückgenommen haben in die Luft. Das ist der physische Tod; das ist er in Wahrheit.

Kurz, wenn wir anfangen, über Wirklichkeiten zu denken, so kommen wir zu einer Auflösung desjenigen, was gewöhnlich die physische Welt genannt wird. Denn diese physische Welt besteht dadurch, daß die Geister der höheren Hierarchien ihre Gedanken ineinanderschieben, und deshalb - bitte stellen Sie sich vor: fein verteilte Wasserpartien gehen irgendwo hinein und bilden einen dichten Nebel - erscheint Ihr Leib auch so als ein Schattengebilde, weil die Gedanken der Geister der Form hineindringen in die Gedanken der Geister der Weisheit, die Formgedanken in die Stoffgedanken hineingehen. Die ganze Welt löst sich vor dieser Anschauung in Geistiges auf. Aber man muß die Möglichkeit haben, die Welt wirklich geistig vorzustellen, zu wissen: Das ist nur etwas ganz Scheinbares, daß meine Arme und Hände, meine Füße und Beine der Erde übergeben werden. In Wirklichkeit beginnt da die Metamorphose meiner Arme und Beine, Hände und Füße und vollendet sich in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, und meine Arme und Beine, Hände und Füße werden mein Kopf in der nächsten Inkarnation.

Ich habe Ihnen mancherlei jetzt gesprochen, was Sie wenigstens in der Form vielleicht etwas sonderbar berührt hat. Aber was ist denn das schließlich, was wir da besprochen haben, anderes, als daß wir vom scheinbaren Menschen aufsteigen zum wahren Menschen, von dem, was äußerlich in der Maja lebt, aufsteigen zu der Stufenfolge der Hierarchien? Nur wenn man das tut, kann man in einer reifen Form heute davon sprechen, daß der Mensch in sich wissen darf ein sogenanntes höheres Selbst. Wenn man bloß deklamiert von dem höheren Selbst, wenn man bloß sagt: Ich fühle in mir ein höheres Selbst - da ist dieses höhere Selbst ein reines leeres Abstraktum, da hat es keinen Inhalt; denn das gewöhnliche Selbst gehört der Maja an, ist also selbst Maja. Das höhere Selbst hat nur einen Sinn, wenn man von ihm spricht gegenüber der Welt der höheren Hierarchien. Vom höheren Selbst zu sprechen, ohne auf die Welt Rücksicht zu nehmen, die da besteht aus den Geistern der Form und den Engeln, Erzengeln und so weiter, vom höheren Selbst zu sprechen, ohne auf diese Welt Rücksicht zu nehmen, bedeutet: man spricht von leeren Abstraktionen, bedeutet zugleich: man spricht nicht von demjenigen, was da lebt im Menschen zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Denn so wie wir hier mit Tieren, Pflanzen und Mineralien leben, so leben wir zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt mit den Reichen der höheren Hierarchien, von denen wir oftmals gesprochen haben. Nur wenn man sich nach und nach diesen Vorstellungen und Begriffen nähert, dann — wir werden davon erst vielleicht in acht Tagen sprechen -, dann kommt man zu einer Annäherung an so etwas, was Antwort geben kann auf die Frage: Warum sterben manche Menschen als junge Kinder, warum manche im höchsten Alter, andere dazwischen ?

Was ich Ihnen jetzt skizzenhaft dargestellt habe, sind konkrete Begriffe für die Wirklichkeiten der Welt. Es sind ja wahrhaftig nicht abstrakte Begriffe, die ich Ihnen dargestellt habe, es sind konkrete Begriffe für die Wirklichkeiten der Welt. Diese konkreten Begriffe, sie gab es, allerdings für ein mehr atavistisches Anschauen, in den alten Mysterien. Sie sind für das menschliche Anschauen verlorengegangen von dem 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert an; sie müssen durch eine Vertiefung in der Auffassung des Christus-Wesens wiederum gewonnen werden. Das kann nur auf geisteswissenschaftlichem Wege geschehen.

Verschaffen wir uns von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus noch einmal eine Art Vorstellung von der Menschheitsevolution. Wir wollen jetzt sehr, sehr wichtige Begriffe ins Auge fassen. Da kann man sagen: Wenn man zurückgeht in der Menschheitsentwickelung, da kommt man - ich habe ja das öfter dargestellt — darauf, daß in alten Zeiten die Menschen mehr Gruppenseelen hatten und sich dann erst die individuellen Seelen hineingliederten in das Gruppenseelentum. Sie können das in verschiedenen Zyklen lesen. Dann könnte man schematisch die Entwickelung der Menschheit so darstellen, daß man sagt: In alten Zeiten gab es Gruppenseelen; jede dieser Gruppenseelen spaltete sich wiederum —- das würde für eine bloße seelische Anschauung sein, für eine geistige wäre es etwas anders -, aber jede solche Seele umkleidet sich mit einem Leibe, den ich hier in der Form mit einem roten Strich andeute (siehe Zeichnung Seite 114).