How Can Mankind Find the Christ Again?

GA 187

25 December 1918, Dornach

III. Distribution of Man's Inner Impulses in the Course of His Life

When I made some suggestions last Sunday for a renewal of our Christmas thinking, I spoke of the real, inner human being who comes from the spiritual world and unites with the body that is given to him from the stream of heredity. I described how this human being, when he enters the life he is to experience between birth and death, enters it with a certain sense of equality. I said that someone who observes a child with understanding will notice how he does not yet know of the distinctions that exist in the human social structure, due to all the relationships into which men's karma leads them. I said that if we observe clearly and without prejudice the forces residing in certain capacities and talents, even in genius, we shall be compelled to ascribe these in large measure to the impulses which affect mankind through the hereditary stream; that when such impulses appear clearly in the natural course of that stream, we must call them luciferic. Moreover, in our present epoch these impulses will only be fitted into the social structure properly if we recognize them as luciferic, if we are educated to strip off the luciferic element and, in a certain sense, to offer upon the altar of Christ what nature has bestowed upon us—in order to transform it.

There are two opposite points of view: one is concerned with the differences occurring in mankind through heredity and conditions of birth; the other with the fact that the real kernel of a man's being holds within it at the beginning of his earthly life the essential impulse for equality. This shows that the human being is only observed correctly when he is observed through the course of his whole life, when his development in time is really taken into account. We have pointed out in another connection that the developmental motif changes in the course of life. You will also find reference to this in an article I wrote called “The Ahrimanic and the Luciferic in Human Life,” where it is shown that the luciferic influence plays a certain role in the first half of life, the ahrirnanic in the second half; that both these impulses are active throughout life, but in different ways.

Along with the idea of equality, other ideas have recently been forced into prominence in a tumultuous fashion, in a certain sense precipitating what should have been a tranquil development in the future. They have been set beside the idea of equality, but they should really be worked out slowly in human evolution if they are to contribute to the well-being of humanity and not to disaster. They can only be rightly understood and their significance for life rightly estimated if they are given their proper place in the sequence of a man's life.

Side by side with the idea of equality, the idea of freedom resounds through the modern world. I spoke to you about the idea of freedom some time ago in connection with the new edition of my The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. We are therefore able to appreciate the full importance and range of this impulse in relation to the innermost kernel of man's being. Perhaps some of you know that it has frequently been necessary, from questions here and there, to point to the entirely unique character of the conception of freedom as it i is delineated in my The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. There is a certain fact that I have always found necessary to emphasize in this connection, namely, that the various modern philosophical conceptions of freedom have made the mistake (if you want to call it a mistake) of putting the question thus: Is the human being free or not free? Can we ascribe free will to man? or may we only say that he stands within a kind of absolute natural necessity, and out of this necessity accomplishes his deeds and the resolves of his will? This way of putting the question is incorrect. There is no “either-or.” One cannot say, man is either free or unfree. One has to say, man is in the process of development from unfreedom to freedom. And the way the impulse for freedom is conceived in my The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, shows you that man is becoming ever freer, that he is extricating himself from necessity, that more and more impulses are growing in him that make it possible for him to be a free being within the rest of the world order.

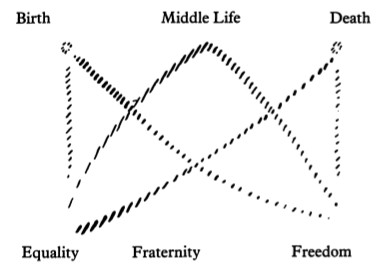

Thus the impulse for equality has its greater intensity at birth—even though not in consciousness, since the latter is not yet developed—and it then decreases. That is to say, the impulse for equality has a descending development. We may make a diagram thus:

At birth we find the height of the impulse for equality, and it moves in a descending curve. With the impulse for freedom the reverse is true. Freedom moves in an ascending curve and has its culmination at death. By that I do not mean to say that man reaches the summit of a freely-acting being when he passes through the gate of death; but relatively, with regard to human life, a man develops the impulse for freedom increasingly up to the moment of death, and he has achieved relatively the greatest possibility of becoming free at the moment he enters the spiritual world through the gate of death. That is to say: while at birth he brings with him out of the spiritual world the sense of equality which then declines during the course of physical life, it is just during his physical lifetime that he develops the impulse toward freedom, and he then enters the spiritual world through the gate of death with the largest measure of this impulse for freedom that he could attain in the course of his physical life.

You see again how one-sidedly the human being is often observed. One fails to take into account the time element in his being. He is spoken of in general terms, in abstracto, because people are not inclined today to consider realities. But man is not a static being; he is an evolving being. The more he develops and the more he makes it possible to develop, so much the more does he fulfill his true task here in the course of physical life. People who are inflexible, who are disinclined to undergo development, accomplish little of their real earthly mission. What you were yesterday you no longer are today, and what you are today you will no longer be tomorrow. These are indeed slight shades of differences; but happy is he in whom they exist at all—for standing still is ahrimanic! There should be shades of difference. No day should pass in a man's life without his receiving at least one thought that alters his nature a little, that enables him to develop instead of merely to exist. Thus we recognize man's true nature—not when we insist in an absolute sense that mankind has the right to freedom and equality in this world—but only when we know that the impulse for equality reaches its culmination at the beginning of life, and the impulse toward freedom at the end. We unravel the complexity of human development in the course of life here on earth only when we take such things into consideration. One cannot simply look abstractly at the whole man and say: he has the right to find freedom, equality, and so forth, within the social structure. These things must be brought to people's attention again through spiritual science, for they have been ignored by the recent developments that move toward abstract ideas and materialism.

The third impulse, fraternity, has its culmination, in a certain sense, in the middle of life. Its curve rises and then falls. (See diagram.) In the middle of life, when the human being is in his least rigid condition—that is, when he is vacillating in the relation of soul to body—then it is that he has the strongest tendency to develop brotherliness. He does not always do so, but at this time he has the predisposition to do so. The strongest prerequisites for the development of fraternity exist in middle life.

Thus these three impulses are distributed over an entire lifetime. In the times we are approaching it will be necessary for our understanding of other men, and also—as a matter of course—for our so-called self-knowledge, that we take such matters into account. We cannot arrive at correct ideas about community life unless we know how these impulses are distributed in the course of life. In a certain sense we Will be unable to live our lives usefully unless we are willing to gain this knowledge; for we will not know exactly what relation a young man bears to an old man, or an older person

to one in middle life, unless we keep in mind the special configuration of these inner impulses.

But now let us connect all this with lectures5Rudolf Steiner, Dornach, 11 Jan. 1918, Ancient Myths, Their Meaning and Connection with Evolution, GA 180 (Vancouver, Steiner Book Centre, 1971). I gave here earlier about the whole human race gradually becoming younger. Perhaps you recall that I explained how the particular dependence of soul development upon the physical organism that a human being has today only during his very earliest years was experienced in ancient times up to old age. (We are speaking now only of post-Atlantean epochs.) I said that in the ancient Indian cultural epoch man was dependent upon his so-called physical development into his fifties, in the way that he is now dependent only in the earliest years. Now in the first years of life man is dependent upon his physical development. We know the kind of break the change of teeth causes, then puberty, and so on. In these early years we see a distinct parallel in the development of soul and of body; then this ceases, vanishes. I pointed out that in older cultural epochs of our post-Atlantean period that was not the case. The possibility of receiving wisdom from nature simply through being a human being—lofty wisdom which was venerated among the ancient Indians, and could still be venerated among the ancient Persians—that possibility existed because the conditions were not the same as they are now. Now a man becomes a finished product in his twenties; he is then no longer dependent upon his physical organism. Starting from his twenties, it gives him nothing more. This was not the case in ancient times. In ancient times the physical organism itself gave wisdom to man's soul into his fifties. It was possible for him in the second half of life, even without special occult training, to extract the forces from his physical organism in an elemental way, and thus attain a certain wisdom and a certain development of will. I pointed to the significance of this for the ancient Indian and Persian epochs, even for the Egypto-Chaldean epoch, when it was possible to say to a boy or girl, or young man or young woman: “When you are old you may expect that something will come into your life, will be bestowed upon you simply by your having become old, because one continues to develop up to the time of death.” Age was looked up to with reverence , because a man said to himself: With old age something will enter my life that I cannot know or cannot will while I am still young. That gave a certain structure to the entire social life which only ceased when during the Greco-Latin epoch this point of time fell back into the middle years of human life. In the ancient Indian civilization man was capable of development up to his fifties. Then during the ancient Persian epoch mankind grew younger: that is, the age of the human race, the capacity for development, fell back to the end of a man's forties. During the Egypto-Chaldean epoch it came between the thirty-fifth and the forty-second year. During the Greco-Latin epoch he was only capable of development up to a point of time between the twenty-eighth and the thirty-fifth year. When the Mystery of Golgotha occurred, he had this capability up to the thirty-third year. This is the wonderful fact we discover in the history of mankind's evolution: that the age of Christ Jesus when he passed through death on Golgotha coincides with the age to which humanity had fallen back at that time.

We pointed out that humanity is still becoming younger and younger; that is, the age at which it is no longer capable of development continues to decrease. This is significant, for example, when today a man enters public life at the particular age at which humanity now stands—twenty-seven years—without having received anything beside what he took in from the outside up to his twenty-seventh year. I mentioned that in this sense Lloyd-George6David Lloyd-George: 1863–1945. British statesman. Elected to Parliament 1890; Prime Minister during World War I. One of the “Big Four” statesmen at Paris Peace Conference 1919. is the representative man of our time. He entered public life at twenty-seven years. This had far-reaching consequences, which you can of course discover by reading his biography. These facts enable one to understand world conditions from within.

Now what strikes you as the most important fact when you connect what we have just been indicating—the increasing youthfulness of the human race—with the thoughts we have brought before our souls in these last days in relation to Christmas? The state of our development since the Mystery of Golgotha is this, that starting from our thirtieth year we can really gain nothing from our own organism, from what is bestowed upon us by nature. If the Mystery of Golgotha had not taken place, we would be going about here on earth after our 30th year saying to ourselves: Actually we live in the true sense only up to our thirty-second or thirty-third year at most. Up to that time our organism makes it possible for us to live; then we might just as well die. For from the course of nature, from the elemental occurrences of nature, we can gain nothing more for our soul development through the impulses of our organism. If the Mystery of Golgotha had not taken place, the earth would be filled with human beings lamenting thus: Of what use to me is life after my thirty-third year? Up to that time my organism can give me something. After that I might just as well be dead. I really go about here on earth like a living corpse. If the Mystery of Golgotha had not taken place, many people would feel that they are going about on earth like living corpses. But the Mystery of Golgotha, dear friends, has still to be made fruitful. We should not merely receive the Impulse of Golgotha unconsciously, as people now do: we should receive it consciously, in such a manner that through it we may remain youthful up to old age. And it can indeed keep us healthy and youthful if we receive it consciously in the right way. We shall then ' be conscious of its enlivening effect upon our life. This is important!

Thus you see that the Mystery of Golgotha can be regarded as something intensely alive during the course of our earthly life. I said earlier that people are most predisposed to brotherliness in the middle of life—around the thirty-third year, but they do not always develop it. You have the reason for this in what I just said. Those who fail to develop brotherliness, who lack something of brotherliness, simply are too little permeated by the Christ. Since the human being begins to die, in a certain sense, in middle age from the forces of nature, he cannot properly develop the impulse, the instinct, of brotherliness—and still less the impulse toward freedom, which is taken up so little today—unless he brings to life within himself thoughts that come directly from the Christ Impulse. When we turn to the Christ Impulse, it enkindles brotherliness in us directly. To the degree to which a man feels the necessity for brotherliness, he is permeated by Christ.

One is also unable alone to develop the impulse for freedom to full strength during the remainder of one's earthly life. (In future periods of evolution this will be different.) Something entered our earth evolution as human being and flowed forth at the death of Christ Jesus to unite Itself with the earthly evolution of humanity. Therefore Christ is the One who also leads present-day mankind to freedom. We become free in Christ when we are able to grasp the fact that the Christ could really not have become older, could not have lived longer, in a physical body than up to the age of thirty-three years. Suppose hypothetically that He had lived longer: then He would have lived on in a physical body into the years when according to our present earth evolution this body is destined for death. The Christ would have taken up the forces of death. Had he lived to be forty years old, He would have experienced the forces of death in His body. These He would not have wished to experience. He could only have wished to experience those forces that are still the freshening forces for a human being. He was active up to His thirty-third year, to the middle of life; as the Christ He enkindled brotherliness. Then He caused the spirit to flow into human evolution: He gave over to the Holy Spirit what was henceforth to be within the power of man. Through this Holy Spirit, this health-giving Spirit, a human being develops to freedom toward the end of his life. Thus is the Christ Impulse integrated into the concrete life of humanity.

This permeation of man's inner being by the Christ Principle must be incorporated into human knowledge as a new Christmas thought. Mankind must know that we bring equality with us out of the spiritual world. It comes, one might say, from God the Father, and is given to us to bring to earth. Then brotherliness reaches its proper culmination only through the help of the Son. And through the Christ united with the Spirit we can develop the impulse for freedom as we draw near to death.

This activity of the Christ Impulse in the concrete shaping of humanity is something that from now on must be accepted consciously by human souls. This alone will be really health-giving when people's demands for refashioning the social structure become more and more urgent and passionate. In this social structure there live children, youths, middle-aged and old people; and a social structure that embraces them all can only be achieved when it is realized that human beings are not simply abstract Man. The five-year-old child is Man, the twenty-year-old youth, the twenty-year-old young woman, the forty-year-old man—at the present time to undertake an actual observation of human beings, which would result in a consciousness of humanity in the concrete, human beings as they really are. When they are looked at concretely, the abstraction Man-Man-Man has no reality whatsoever. There can only be the fact of a specific human being of a specific age with specific impulses. Knowledge of Man must be acquired, but it can only be acquired by studying the development of the essential living kernel of the human being as he progresses from birth to death. That must come, my dear friends. And probably people will not be inclined to receive such things into their consciousness until they are again able to take a retrospective view of the evolution of mankind.

Yesterday I drew your attention to something that entered human evolution with Christianity. Christianity was born out of the Jewish soul, the Greek spirit, and the Roman body. These were the sheaths, so to speak, of Christianity. But within Christianity is the living Ego, and this can be separately observed when we look back to the birth of Christianity. For the external historian this birth of Christianity has become very chaotic. What is usually written today about the early centuries of Christianity, whether from a Roman Catholic or a Protestant point of view, is very confused wisdom. The essence of much that existed in those first Christian centuries is either entirely forgotten by present theologians or else it has become, may I say, an abomination for them. Just read and observe the strange convulsions of intellectualism—they almost become a kind of intellectual epilepsy—when people have to describe what lived in the first centuries of Christianity as the Gnosis.7Gnosis: esoteric knowledge in Greco-Latin world of the 2nd century A.D. It is considered a sort of devil, this Gnosis, something so demonic that it should absolutely not be admitted into human life. And when such a theologian or other official representative of this or that denomination can accuse anthroposophy of having something in common with gnosticism, he believes he has made the worst possible charge.

Underlying all this is the fact that in the earliest centuries of Christianity gnosticism did indeed penetrate the spiritual life of European humanity—so far as this was of importance for the civilization of that time—and, moreover, much more significantly than is now supposed. There exists on the one hand, not the slightest idea of what this Gnosis actually was; on the other hand, I might say, there is a mysterious fear of it. To most of the present-day official representatives of any religious denomination the Gnosis is something horrible. But it can of course be looked at without sympathy or antipathy, purely objectively. Then it would best be studied from a spiritual scientific standpoint, for external history has little to offer. Western ecclesiastical development took care that all external remains of the Gnosis were properly eradicated, root and branch. There is very little left, as you know—only the Pistis Sophia and the like—and that gives only a vague idea of it. Otherwise the only passages from the Gnosis that are known are those refuted by the Church Fathers. That means really that the Gnosis is only known from the writings of opponents, while anything that might have given some idea of it from an external, historical point of view has been thoroughly rooted out.

An intellectual study of the development of Western theology would make people more critical on this point as well—but such study is rare. It would show them, for instance, that Christian dogma must surely have its foundation in something quite different from caprice or the like. Actually, it is all rooted in the Gnosis. But its living force has been stripped away and abstract thoughts, concepts, the mere hulls are left, so that one no longer recognizes in the doctrines their living origin. Nevertheless, it is really the Gnosis. If you study the Gnosis as far as it can be studied with spiritual scientific methods, you will find a certain light is thrown upon the few things that have been left to history by the opponents of gnosticism. And you will probably realize that this Gnosis points to the very widespread and concrete atavistic-clairvoyant world conception of ancient times. There were considerable remnants of this in the first post-Atlantean epoch, less in the second. In the third epoch the final remnants were worked upon and appeared as gnosticism in a remarkable system of concepts, concepts that are extraordinarily figurative. Anyone who studies gnosticism from this standpoint, who is able to go back, even just historically, to the meager remnants—they are brought to light more abundantly in the pagan Gnosis than in Christian literature—will find that, as a matter of fact, this Gnosis contained wonderful treasures of wisdom relating to a world with which people of our present age refuse to have any connection. So it is not at all surprising that even well-intentioned people can make little of the ancient Gnosis.

Well-intentioned people? I mean, for instance, people like Professor Jeremias of Leipzig, who would indeed be willing to study these things. But he can form no mental picture of what these ancient concepts refer to—when, for example, mention is made of a spiritual being Jaldabaoth, who is supposed with a sort of arrogance to have declared himself ruler of the world, then to have been reprimanded by his mother, and so on. Even from what has been historically preserved, such mighty images radiate to us as the following: Jaldabaoth said, “I am God the Father; there is no one above me.” And his mother answered, “Do not lie! Above thee is the Father of all, the first Man, and the Son of Man.” Then—it is further related—Jaldabaoth called his six co-workers and they said, “Let us make man in our image.” Such imaginations, quite self-explanatory, were numerous and extensive in what existed as the Gnosis. In the Old Testament we find only remnants of this pictorial wisdom preserved by Jewish tradition. It lived especially in the Orient, whence its rays reached the West; and only in the third or fourth century did these begin to fade in the West. But then there were still some after-effects among the Waldenses and Cathars8Waldenses and Cathars: heretical Christian sects in western Europe, 12th and 13th centuries. They joined the Reformation movement during the 16th century. that finally died out.

People of our time can hardly imagine the condition of the souls living in civilized Europe during the first Christian centuries, in whom there lived not merely mental pictures like those of present-day Roman Catholics, but in a supreme degree vivid, unmistakable echoes of this mighty world-picture of the Gnosis. What we see when we look back at those souls is vastly different from what we find in books that have been written about these centuries by ecclesiastical and secular theologians and other scholars. In the books there is nothing of all that lived in those great and powerful imaginative pictures describing a world of which, as I have said, people of our time have no conception. That is why a man possessing present-day scholarship can do nothing with such concepts—for instance, with Jaldabaoth, his mother, the six co-workers, and so on. He does not know what to do with them. They are words, word-husks; what they refer to, he does not know. Still less does he know how the people of that earlier age ever came to form such concepts. A modern person can only say, “Well, of course, the ancient Orientals had lively imaginations; they developed all that fantasy.” We ourselves must marvel that such a person has not the slightest idea how little imagination a primitive human being has, what a minor role it plays, for instance, among peasants. In this respect the mythologists have done wonders! They have invented the stories of simple people transforming the drifting clouds, the wind driving the clouds, and so on, into all sorts of beings. They have no idea how the earlier humanity to whom they attribute all this were really constituted in their souls, that they were as far removed as could possibly be from such poetic fashioning. The fantasy really exists in the circles of the mythologists, the scholars who think out such things. That is the real fantasy!

What people suppose to have been the origin of mythology is pure error. They do not know today to what its words and concepts refer. Certain, may I say, clear hints concerning their interpretation are therefore no longer given any serious attention. Plato pointed very precisely to the fact that a human being living here in a physical body has remembrance of something experienced in the spiritual world before this physical life. But present-day philosophers can make nothing of this Platonic memory-knowledge; for them it is something that Plato too had imagined. In reality, Plato still knew with certainty that the Greek soul was predisposed to unfold in itself what it had experienced in the spiritual world before birth, though it still possessed only the last residue of this ability. Anyone who between birth and death perceives only by means of his physical body and who works over his perceptions with a present-day intellect, cannot grant any rational meaning to observations that have not even been made in a physical body but were made between death and a new birth. Before birth human beings were in a world in which they could speak of Jaldabaoth who rose up in pride, whose mother admonished him, who summoned the six co-workers. That is a reality for the human being between death and a new birth, just as plants, animals, minerals, and other human beings are realities for him here in this world, about which he speaks when he is confined in a physical body. The Gnosis contained what was brought into this physical world at birth; and it was possible to a certain extent up to the Egypto-Chaldean epoch, that is, up to the eighth century before the Christian era, for human beings to bring very much with them from the time they had spent between death and a new birth. What was brought in those epochs from the spiritual world and clothed in concepts, in ideas, is the Gnosis. It continued to exist in the Greco-Latin epoch, but it was no longer directly perceived; it was a heritage existing now as ideas. Its origin was known only to select spirits such as Plato, in a lesser degree to Aristotle also. Socrates knew of it too, and indeed paid for this knowledge with his death.

Now what were the conditions in this Greco-Latin age in the fourth post-Atlantean epoch? Only meager recollections of time before birth could now be brought over into life, but something was brought over, and in this Greek period it was still distinct. People today are inordinately proud of their power of thinking, but actually they can grasp very little with it. The thinking power that the Greeks developed was of a different nature. When the Greeks entered earthly life through birth, the images of their experiences before birth were lost; but the thinking force that they had used before birth to give an intelligent meaning to the images still remained. Greek thinking differed completely from our so-called normal thinking, for the Greek thinking was the result of pondering over imaginations that had been experienced before birth. Of the imaginations themselves little was recalled; the essential thing that remained was the discernment that had helped a person before birth to find his way in the world about which imaginations had been formed. The waning of this thinking power was the important factor in the development of the fourth post-Atlantean period, which continued, as you know, into the fifteenth century of the Christian era.

Now in this fifth epoch the power to think must again be developed, out of our earthly culture. Slowly, haltingly, we must develop it out of the scientific world view. Today we are at the beginning of it. During the fourth post-Atlantean period, that is, from 747 B.C. to 1413 A.D.—the Event of Golgotha lies between—there was a continual decrease of thinking power. Only in the fifteenth century did it begin slowly to rise again; by the third millennium it will once more have reached a considerable height. Of our present-day power of thought mankind need not be especially proud; it has declined. The thinking power, still highly developed, that was the heritage of the Greeks shaped the thoughts with which the gnostic pictures were set in order and mastered. Although the pictures were no longer as clear as they had been for the Egyptians or the Babylonians, for example, the thinking power was still there. But it gradually faded. That is the extraordinary way things worked together in the earliest Christian centuries.

The Mystery of Golgotha breaks upon the world. Christianity is born. The waning thinking power, still very active in the Orient but also reaching over into Greece, tried to understand this event. The Romans had little understanding of it. This thinking power tried to understand the Event of Golgotha from the standpoint of the thinking used before birth, the thinking of the spiritual world. And now something significant occurred: this gnostic thinking came face to face with the Mystery of Golgotha. Now let us consider the gnostic teachings about the Mystery of Golgotha, which are such an abomination to present-day, especially Christian, theologians. Much is to be found in them from the ancient atavistic teachings, or from teachings that are permeated by the ancient thought-force; and many significant and impressive things are said in them about the Christ that today are termed heretical, shockingly heretical. Gradually this power of gnostic thought declined. We still see it in Manes9Manes: 216–274 A.D. See Rudolf Steiner, Nurnberg, 25 June 1908, Apocalypse of St. John, GA 104 (London, Rudolf Steiner Press, 1977). in the third century, and we still see it as it passes over to the Cathars—downright heretics from the Catholic point of view: a great, forceful, grandiose interpretation of the Mystery of Golgotha. This ebbed away, strangely enough, in the early centuries, and people were little inclined to apply any effort toward an understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha. These two things, you see, were engaged in a struggle: the gnostic teaching, wishing to comprehend the Mystery of Golgotha through powerful spiritual thinking; and the other teaching, that reckoned with what was to come, when thought would no longer have power, when it would lack the penetration needed to understand the Mystery of Golgotha, when it would be abstract and unfruitful. The Mystery of Golgotha, a cosmic mystery, was reduced to hardly more than a few sentences at the beginning of the Gospel of St. John, telling of the Logos, of His entrance into the world and His destiny in the world, using as few concepts as possible; for what had to be taken into account was the decreasing thinking power.

Thus the gnostic interpretation of Christianity gradually died out, and a different conception of it arose, using as few concepts as possible. But of course the one passed over into the other: concepts like the dogma of the Trinity were taken over from gnostic ideas and reduced to abstractions, mere husks of concepts.The really vital fact is this, that an inspired gnostic interpretation of the Mystery of Golgotha was engaged in a struggle with the other explanation, which worked with as few concepts as possible, estimating what humanity would be like by the fifteenth century with the ancient, hereditary, acute thinking power declining more and more. It was also reckoning that this would eventually have to be acquired again, in elementary fashion, through the scientific observation of nature. You can study it step by step. You can even perceive it as an inner soul-struggle if you observe St. Augustine,10Augustine: 354–430 A.D. See Rudolf Steiner, Dornach, 22 May 1920, The Redemption of Thinking, GA 74 (Spring Valley, Anthroposophic Press, 1983). who in his youth became acquainted with gnostic Manichaeism, but could not digest that and so turned away to so-called “simplicity,” forming primitive concepts. These became more and more primitive. Even so, in Augustine there appeared the first dawning light of what had again to be acquired: knowledge starting from man, from the concrete human being. In ancient gnostic times one had tried to reach the human being by starting from the world. Now, henceforth, the start must be made from man: knowledge of the world must be acquired from knowledge of the human being. This must be the direction we take in the future. I explained this here some time ago and tried to point to the first dawning light in humanity. One finds it, for instance, in the Confessions of St. Augustine—but it was still thoroughly chaotic. The essential fact is that humanity became more and more incapable of taking in what streamed to it from the spiritual world, what had existed among the ancients as imaginative wisdom and then was active in the Gnosis, what had evoked the power of acute thinking that still existed among the Greeks. Thus the Greek wisdom, even though reduced to abstract concepts, still provided the ideas that allowed some understanding of the spiritual world. This then ceased; nothing of the spiritual world could any longer be understood through those dying ideas.

A man of the present day can easily feel that the Greek ideas are in fact applicable to something entirely different from that to which they were applied. This is a peculiarity of Hellenism. The Greeks still had the ideas but no longer the imaginations. Especially in Aristotle this is very striking. It is very singular. You know there are whole libraries about Aristotle, and everything concerning him is interpreted differently. People even dispute whether he accepted reincarnation or pre-existence. This has all come about because his words can be interpreted in various ways. It is because he worked with a system of concepts applicable to a supersensible world but he no longer had any perception of that world. Plato had much more understanding of it; therefore his system of concepts could be worked out better in that sense. Aristotle was already involved in abstract concepts and could no longer see that to which his thought-forms referred. It is a peculiar fact that in the early centuries there was a struggle between a conception of the Mystery of Golgotha that illuminated it with the light of the supersensible world, and the fanaticism that then developed to refute this. Not everyone saw through these things, but some did. Those who did see through them did not face them honestly. A primitive interpretation of the Mystery of Golgotha, an interpretation that was rabid about using only a few concepts, led to fanaticism.

Thus we see that supersensible thinking was eliminated more and more from the Christian world conception, from every world conception. It faded away and ceased. We can follow from century to century how the Mystery of Golgotha appeared to people as something tremendously significant that had entered earth evolution, and yet how the possibility of their comprehending it with any system of concepts vanished—or of comprehending the world cosmically at all. Look at that work from the ninth century, De Divisione Naturae by Scotus Erigena.11Scotus Erigena: 810–877 A.D. See Rudolf Steiner, Riddles of Philosophy, GA 18 (Spring Valley, Anthroposophic Press, 1973). It still contains pictures of a world evolution, even though the pictures are abstract. Scotus Erigena indicates very beautifully four stages of a world evolution, but throughout with inadequate concepts. We can see that he is unable to spread out his net of concepts and make intelligible, plausible, what he wishes to gather together. Everywhere, one might say, the threads of his concepts break. It is very interesting that this becomes more noticeable from century to century, so that finally the lowest point in the spinning of concept-threads was reached in the fifteenth century. Then an ascent began again, but it did not get beyond the most elementary stage. It is interesting that on the one hand people cherished the Mystery of Golgotha and turned to it with their hearts, but declared that they could not understand it. Gradually there was a general feeling that it could not be understood. On the other hand the study of nature began at the very time when concepts vanished. Observation of nature entered the life of that time, but there were no concepts for actually grasping the phenomena that were being observed.

It is characteristic of this period, at the turn of the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean epoch, halfway through the Middle Ages, that there were insufficient concepts both for the budding observation of nature and for the revelations of saving truths. Think how it was with Scholasticism in this respect: it had religious revelations, but no concepts out of the culture of the time that would enable it to work over these religious revelations. It had to employ Aristotelianism; this had to be revived. The Scholastics went back to Hellenism, to Aristotle, to find concepts with which to penetrate the religious revelations; and they elaborated these with the Greek intellect because the culture of their own time had no intellect of its own—if I may use such a paradox. So the very people who worked the most honestly, the Scholastics, did not use the intellect of their time, because there was none, none that belonged to their culture. It was characteristic of the period from the tenth to the fifteenth century that the most honest of the Scholastics made use of the ancient Aristotelian concepts to explain natural phenomena; they also employed them to formulate religious revelations. Only thereafter did there rise again, as from hoary depths of spirit, an independent mode of thinking—not very far developed, even to this day—the thinking of Copernicus and Galileo. This must be further developed in order to rise once more to supersensible regions.

Thus we are able to look into the soul, into the ego, so to speak, of Christianity, which had merely clothed itself with the Jewish soul, the Greek spirit, and the Roman body. This ego of Christianity had to take into account the dying-out of supersensible understanding, and therefore had to permit the comprehensive gnostic wisdom to shrink, as it were—one may even say, to shrink to the few words at the beginning of the Gospel of John. For the evolution of Christianity consists essentially of the victory of the words of St. John's Gospel over the content of the Gnosis. Then, of course, everything passed over into fanaticism, and gnosticism was exterminated, root and branch.

All these things are linked to the birth of Christianity. We must take them into consideration if we want to receive a real impulse for the consciousness of humanity that must be developed anew, and an impulse for the new Christmas thought. We must come again to a kind of knowledge that relates to the supersensible. To that end we must understand the supersensible force working into the being of man, so that we may be able to extend it to the cosmos. We must acquire anthroposophy, knowledge of the human being, which will be able to engender cosmic feeling again. That is the way. In ancient times man could survey the world, because he entered his body at birth with memories of the time before birth. This world, which is a likeness of the spiritual world, was an answer to questions he brought with him into this life. Now the human being confronts this world bringing nothing with him, and he must work with primitive concepts like those, for instance, of contemporary science. But he must work his way up again; he must now start from the human being and rise to the cosmos. Knowledge of the cosmos must be born in the human being. This too belongs to a conception of Christmas that must be developed in the present epoch, in order that it may be fruitful in the future.

Dritter Vortrag

Als ich am letzten Sonntag einige Andeutungen machte über die Erneuerung des Weihnachtsgedankens, da sprach ich davon, wie der Mensch - ich meinte den wirklichen inneren Menschen, der sich, herauskommend aus der geistigen Welt, verbindet mit dem, was ihm übergeben wird aus der Vererbungsströmung heraus -, wie dieser Mensch beim Eintritt in das Dasein, das er verlebt zwischen der Geburt und dem Tod, hereinkommt mit einem gewissen Impulse der Gleichheit. Ich sagte, man könne, verständig beobachtend, dieses Geltendmachen des Gleichheitsimpulses beim Kinde bemerken: das Kind kennt noch nicht die Differenzierungen, die innerhalb der Menschheit in der sozialen Struktur auftreten durch die Verhältnisse, in die das Karma den Menschen einführt. Ich sagte dann: Klar und unbefangen besehen, stellten sich gewisse Fähigkeiten, Begabungen, selbst das Genie so dar, daß wir die Kräfte, die in diesen Fähigkeiten, Begabungen, selbst im Genie leben, vielfach zuzuschreiben haben den Impulsen, die in der Vererbungslinie, Vererbungsströmung auf den Menschen wirken und daß man solche Impulse zunächst, wie sie rein im Naturlauf der Vererbungsströmung auftreten, als luziferische Impulse anzusprechen habe, daß in unserer gegenwärtigen Zeitepoche diese Impulse nur dann von dem Menschen in der rechten Weise in die soziale Struktur hereingestellt werden, wenn er sie ansieht als luziferische Impulse und wenn er dazu erzogen wird, das Luziferische abzustreifen, gewissermaßen darzubringen am Altar des Christus dasjenige, was die Natur ihm übermittelt hat, es umzuwandeln, zu metamorphosieren.

Zwei Gesichtspunkte halten wir also auseinander. Den einen Gesichtspunkt: was zu tun ist mit den durch die Blutsverhältnisse, durch die Geburtsverhältnisse auftretenden Differenzierungen der Menschheit. Und den andern: daß der eigentliche Wesenskern des Menschen beim Anfang des irdischen Lebens wesentlich den Impuls der Gleichheit in sich trägt. Damit ist hingewiesen darauf, daß der Mensch nur richtig betrachtet wird, wenn er in seinem ganzen Lebenslauf betrachtet wird, wenn die zeitliche Entwickelung zwischen Geburt und Tod wirklich ins Auge gefaßt wird. Wir haben gerade hier in einer andern Beziehung hingewiesen darauf, wie Entwickelungsmotive sich verändern im Laufe des Lebens zwischen Geburt und Tod. Und in anderer Weise finden Sie hingewiesen auf diese Entwickelungsmotive in meinem Aufsatz, den ich in der letzten Nummer des «Reiches» geschrieben habe über das Ahrimanische und Luziferische im menschlichen Leben. Da ist darauf hingewiesen, wie das Luziferische in der ersten Lebenshälfte eine gewisse Rolle spielt, das Ahrimanische in der zweiten Lebenshälfte, wie diese Impulse des Ahriman und Luzifer durch das ganze Leben hindurch wirken, aber in verschiedener Art.

Neben der Idee der Gleichheit haben sich in der neueren Zeit andere Ideen, wie ich dazumal am Sonntag sagte, in tumultuarischer Weise vorgedrängt, gewissermaßen vorausnehmend die ruhige Entwickelung der Zukunft, zunächst in der Idee vorausnehmend dasjenige, was langsam in der Menschheitsentwickelung sich ausleben muß, wenn es zum Heile und nicht zum Unheil gereichen soll. Es haben sich andere Ideen neben die Idee der Gleichheit hingestellt; aber auch diese andern Ideen kann man hinsichtlich ihrer Bedeutung für das Leben nur dann richtig verstehen und würdigen, wenn man sie in den Zeitenlauf des menschlichen physischen Daseins richtig hineinstellt.

Neben der Idee der Gleichheit tönt gewissermaßen durch die moderne Welt die Idee der Freiheit. Ich habe über die Idee der Freiheit vor einiger Zeit zu Ihnen in Anlehnung an die Neuauflage meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» gesprochen. Wir sind also in der Lage, die ganze Wichtigkeit und Tragweite dieser Idee der Freiheit im Zusammenhang mit dem innersten Wesenskern des Menschen zu würdigen. Vielleicht wissen aber auch einige von Ihnen, daß öfters durch Fragen da und dort notwendig geworden ist, auf das ganz Besondere der Freiheitsauffassung hinzuweisen, wie sie in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» herrscht. Ich habe immer nötig gehabt, einen Gesichtspunkt mit Bezug auf die Freiheitsidee besonders hervorzuheben, nämlich den, daß die ganze neuere Zeit, die verschiedenen philosophischen Anschauungen über die Freiheit eigentlich den Fehler gemacht haben — wenn man es Fehler nennen will -, die Frage so zu stellen: Ist der Mensch frei oder unfrei? Kann man dem Menschen freien Willen zuschreiben oder darf man ihm nur zuschreiben, daß er in einer wie absoluten Naturnotwendigkeit drinnensteht und auch aus dieser Notwendigkeit heraus seine Handlungen, seine Willensentschlüsse vollführt? — Die Fragestellung ist unrichtig. Es gibt kein solches Entweder-Oder. Man kann nicht sagen, der Mensch ist entweder frei oder unfrei, sondern er ist begriffen in der Entwickelung von der Unfreiheit zur Freiheit. Und die Art und Weise, wie Sie aufgefaßt finden den Freiheitsimpuls in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit», zeigt Ihnen, daß der Mensch immer freier und freier wird, daß er sich herauswindet aus der Notwendigkeit und immer mehr und mehr in ihm die Impulse wachsen, die ihm möglich machen, ein freies Wesen innerhalb der sonstigen Weltenordnung zu sein.

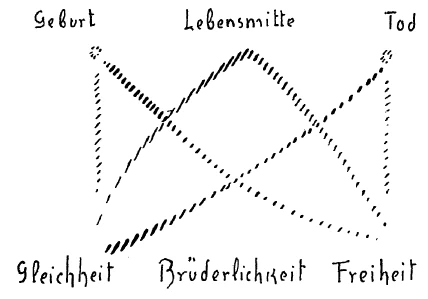

So hat denn der Impuls der Gleichheit seine Kulmination beim Geborenwerden — wenn auch nicht im Bewußtsein, da das noch nicht so entwickelt da schon leben kann -, dann fällt er ab. Der Impuls der Gleichheit hat also eine absteigende Entwickelung. Schematisch können wir das so zeichnen:

Bei der Geburt ist eine Kulmination der Gleichheitsidee da, und die Gleichheit bewegt sich in einer absteigenden Kurve. Umgekehrt ist es nun bei der Freiheitsidee. Die Freiheit bewegt sich in einer aufsteigenden Kurve und hat ihre Kulmination im Tode. Ich will damit nicht sagen, daß der Mensch, indem er durch die Pforte des Todes geht, den höchsten Gipfel eines freitätigen Wesens erreicht. Aber relativ, mit Bezug auf das Menschenleben entwickelt der Mensch den Impuls der Freiheit gegen den Moment des Todes hin immer mehr und mehr, und relativ hat er sich am meisten die Möglichkeit, ein freies Wesen zu sein, in dem Augenblick erworben, wo er durch des Todes Pforte in die geistige Welt eintritt. Während er also, indem er durch die Geburt in das physische Dasein eintritt, aus der geistigen Welt herausträgt die Gleichheit, die dann absteigt in der Entwickelung des physischen Lebenslaufes, entwickelt er gerade im physischen Lebenslaufe den Freiheitsimpuls und steigt mit dem ihm im physischen Lebenslauf erreichbaren Höchstmaß des Freiheitsimpulses durch die Pforte des Todes in die geistige Welt hinein.

Sie sehen daraus wiederum, wie einseitig oftmals das Menschenwesen betrachtet wird. Man bezieht nicht die Zeit in dieses Menschenwesen ein. Man redet vom Menschen im allgemeinen, in abstracto, weil man heute nicht geneigt ist, auf Wirklichkeiten einzugehen. Aber der Mensch ist nicht ein stehenbleibendes Wesen, er ist ein Wesen im Werden. Und je mehr er wird, je mehr er sich selbst in die Möglichkeit versetzt, zu werden, desto mehr erfüllt er gewissermaßen hier im physischen Lebenslaufe schon seine wirkliche Aufgabe. Diejenigen Menschen, die starr bleiben, die abgeneigt sind, eine Entwickelung durchzumachen, entwickeln wenig von dem, was eigentlich ihre irdische Mission ist. Was Sie gestern waren, sind Sie heute nicht mehr, und was Sie heute sind, werden Sie morgen nicht mehr sein. Es sind das allerdings kleine Nuancen. Wohl dem, bei dem es überhaupt Nuancen sind, denn das Stehenbleiben ist ahrimanisch. Nuancen sollten da sein. Es sollte wenigstens gewissermaßen im Leben des Menschen kein Tag vor sich gehen, ohne daß er wenigstens einen Gedanken in sich aufnimmt, der ein wenig sein Wesen ändert; der ein wenig ihn in die Möglichkeit versetzt, ein werdendes Wesen, nicht bloß ein seiendes Wesen zu sein. Und so kann man den Menschen wirklich nur betrachten seiner eigentlichen Natur nach, wenn man nun nicht sagt im absoluten Sinn: Der Mensch hat in der Welt die Prätention auf Freiheit, Gleichheit -, sondern wenn man weiß, wie der Impuls der Gleichheit seine Kulmination erlangt im Lebensbeginn, wie der Impuls der Freiheit seine Kulmination erlangt am Lebensende. Man schaut erst dann in dieses Komplizierte des menschlichen Werdens auch im Lebenslauf hier auf der Erde hinein, wenn man solche Dinge in Betracht zieht, wenn man nicht abstrakt einfach hinsieht auf den ganzen Menschen und sagt: Er hat Anspruch, verwirklicht zu sehen in der sozialen Struktur Freiheit, Gleichheit und so weiter. — Das sind die Dinge, die durch Geisteswissenschaft wiederum dem menschlichen Gemüt nahekommen müssen, die außer acht gelassen worden sind von der nach Abstraktion und dadurch nach Materialismus hinstrebenden neueren Entwickelung.

Nun der dritte der Impulse: die Brüderlichkeit. Ihr ist eigen, daß sie die Kulmination in einem gewissen Sinne in der Mitte des Lebens hat. Ihre Kurve steigt an (siehe Zeichnung Seite 44) und fällt wiederum. Man kann allerdings dafür die Sache nur so aussprechen, daß man sagt: In der Mitte des Lebens, wenn der Mensch in seinem labilsten, das heißt schwankenden Zustand ist mit Bezug auf das Verhältnis des Seelischen zum Leiblichen, da hat der Mensch die stärkste Veranlagung, die Brüderlichkeit zu entwickeln. Er entwickelt sie nicht immer, aber er hat Veranlagung dazu. Es sind sozusagen für die Entwickelung der Brüderlichkeit die stärksten Vorbedingungen gegeben in der Lebensmitte.

So verteilen sich diese drei Impulse über das ganze menschliche Leben hin. In der Zeit, der wir entgegenleben, wird es notwendig für das Verständnis des Menschen und dann selbstverständlich auch für die sogenannte Selbsterkenntnis des Menschen, daß so etwas berücksichtigt werde. Man wird nicht zu richtigen Ideen über das Zusammenleben der Menschen kommen können, wenn man nicht wissen wird, wie sich die Impulse auf den Lebenslauf des Menschen verteilen. Man wird gewissermaßen nicht konkret leben können, wenn man diese Erkenntnis sich nicht wird erwerben wollen; denn man wird nicht wissen, wie konkret ein junger Mensch zu einem alten, ein älterer zu einem in mittleren Lebensjahren stehenden Menschen steht, wenn man nicht die besondere Konfiguration dieser inneren Impulse des menschlichen Wesens ins Auge faßt.

Fassen Sie aber das, was wir jetzt auseinandergesetzt haben, zusammen mit Betrachtungen, die wir früher hier angestellt haben über das allmähliche Jüngerwerden des ganzen Menschengeschlechtes. Erinnern Sie sich, wie ich auseinandergesetzt habe, daß die eigentümliche Abhängigkeit, welche der Mensch vom Körperlichen mit Bezug auf die seelische Entwickelung heute nur in seinen allerjüngsten Lebensjahren hat, gefühlt wurde, erlebt wurde in alten Zeiten — wir sprechen jetzt nur von nachatlantischen Zeiten - bis ins hohe Alter hinauf. Bis in die Fünfzigerjahre hinauf war der Mensch, sagte ich, in der urindischen Kultur so abhängig von seiner physischen, sogenannten physischen Entwickelung, wie er es heute nur in den jüngsten Jahren ist. Der Mensch ist in den ersten Lebensjahren abhängig von seiner physischen Entwickelung. Wir wissen, was für einen Einschnitt in der physischen Entwickelung der Zahnwechsel bildet, dann wiederum die Geschlechtsreife und so weiter. In den ersten Entwickelungsjahren sehen wir einen deutlichen Parallelismus zwischen seelischer und körperlicher Entwickelung. Das hört dann auf, das schwindet dann. Und ich habe darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie das in älteren Kulturepochen der nachatlantischen Zeit nicht der Fall war. Jene Möglichkeit, zu naturgegebener Weisheit zu kommen einfach dadurch, daß man Mensch war, zu jener hohen Weisheit zu kommen, die man verehrte bei den alten Indern, die man noch verehren konnte bei den alten Persern und so weiter, jene Möglichkeit war dadurch gegeben, daß die Sache nicht so war wie jetzt, wo der Mensch in den Zwanzigerjahren ein fertiges Wesen wird, wo er nicht mehr abhängig bleibt von seiner physischen Organisation. Die physische Organisation gibt ihm dann nichts mehr. Das war nicht der Fall in alten Zeiten, sagte ich. Da gab die physische Organisation selbst die Weisheit den Menschen in die Seelen herein bis in die Fünfzigerjahre hinauf. Da war man in der zweiten Lebenshälfte auch ohne besondere okkulte Entwickelung in die Möglichkeit versetzt, auf elementare Art aus der körperlichen Entwickelung die Kräfte herauszusaugen, um zu einer gewissen Weisheit und Willensentwickelung zu kommen. Ich habe Sie aufmerksam gemacht, was das bedeutete für die alten indischen oder für die persischen Zeiten, selbst noch für die ägyptisch-chaldäischen Zeiten, wo dann, wenn man jung war, ein Knabe oder Mädchen oder Jüngling oder Jungfrau war, man hingewiesen werden konnte darauf: Wenn du alt wirst, hast du zu erwarten, daß einfach durch das Altwerden hereinbricht in dein Menschenleben dasjenige, was dir beschert ist dadurch, daß du eben eine Entwickelung durchmachst bis zum Tode hin. - Auch das war gegeben, daß man mit Ehrfurcht zum Alter hinaufsah, weil man sich sagte: Es wirkt mit dem Alter etwas herein in das Leben, was man noch nicht wissen kann, nicht wollen kann, wenn man noch ein junger Mensch ist. - Das gab dem ganzen sozialen Leben eine gewisse Struktur, die eigentlich erst aufhörte, als das während der griechisch-lateinischen Zeit zurückging bis in die mittleren Lebensjahre des Menschen. Bis in die Fünfzigerjahre war in der urindischen Kultur der Mensch entwickelungsfähig. Dann verjüngte sich der Mensch, also ging das Alter des Menschengeschlechtes, das heißt, diese Entwikkelungsfähigkeit zurück bis zum Ende der Vierzigerjahre während der urpersischen Zeit, und nur noch zwischen dem fünfunddreißigsten bis zweiundvierzigsten Jahre wirkte sie während der ägyptisch-chaldäischen Zeit. Während der griechisch-lateinischen Zeit war der Mensch nur entwickelungsfähig zwischen dem achtundzwanzigsten und fünfunddreißigsten Jahre. In der Zeit, als das Mysterium von Golgatha geschah, war der Mensch entwickelungsfähig eben bis zum dreiunddreißigsten Jahre. Das ist das Wunderbare, das man in der Entwickelungsgeschichte der Menschheit entdeckt: daß das Alter des durch den Tod auf Golgatha gehenden Christus Jesus zusammenfällt mit jenem Alter, bis zu dem die Menschheit dazumal zurückgegangen war. Und dann haben wir noch darauf hingewiesen, wie die Menschheit immer jünger und jünger wird, das heißt, bis zu einer immer geringeren Anzahl von Jahren entwickelungsfähig bleibt, wie es etwas Besonderes bedeutet, wenn der Mensch heute gerade im charakteristischen Jahre, in dem die Menschheit heute steht — im siebenundzwanzigsten Jahre sagte ich Ihnen -, eintritt in das öffentliche Leben und nichts anderes mitbekommen hat als dasjenige, was von außen bis zum siebenundzwanzigsten Jahre aufgenommen wurde. Ich führte an, wie ZL/oyd George gerade in dieser Beziehung der repräsentative Mensch unserer Zeit ist, weil er mit siebenundzwanzig Jahren in das öffentliche Leben eingetreten ist. Ungeheuer vieles folgt daraus. Sie können das in der Biographie von Lloyd George nachlesen. Diese Dinge machen aber möglich, die Verhältnisse der Welt von innen heraus zu durchschauen.

Nun, was ist Ihnen aber die Hauptsache, wenn Sie diesen Gesichtspunkt, den wir da für das Immer-Jüngerwerden des Menschengeschlechtes ins Auge gefaßt haben, verbinden mit den Gesichtspunkten, die wir gerade in diesen Tagen im Zusammenhang mit dem Weihnachtsgedanken uns vor die Seele geführt haben? Das ist das Charakteristische für unsere Gegenwartsentwickelung nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha, daß wir eigentlich durch das, was dem Menschen von Natur zugeteilt ist, aus unserem Organismus heraus nichts gewinnen können von den Dreißigerjahren an. Würde nicht das Mysterium von Golgatha eingetreten sein, wir würden gewissermaßen von unseren Dreißigerjahren an hier auf der Erde herumgehen und würden uns dann sagen: Eigentlich leben wir ja nur richtig bis so zum zweiunddreißigsten, dreiunddreißigsten Jahre höchstens. Da gibt uns unser Organismus die Möglichkeit des Lebens. Dann könnten wir ebensogut sterben. Denn durch den Naturlauf, durch die elementarischen Naturereignisse können wir nichts mehr durch die Impulse unseres Organismus für unsere seelische Entwickelung gewinnen. — Das würden wir sagen müssen, wenn das Mysterium von Golgatha nicht eingetreten wäre. Voll müßte die Erde sein, wenn dieses Mysterium von Golgatha nicht eingetreten wäre, von den Klagen der Menschen, die dahingingen, daß die Menschen sagten: Was habe ich eigentlich von meinem Leben vom dreiunddreißigsten Lebensjahre an! Bis dahin ist es möglich, daß mir mein Organismus etwas gibt. Von da ab könnte ich ebensogut tot sein, ich gehe eigentlich als ein lebendiger Leichnam hier auf der Erde herum. — Das würden viele Menschen empfinden, daß sie wie ein lebendiger Leichnam auf der Erde herumgehen würden, wenn dieses Mysterium von Golgatha nicht eingetreten wäre. Aber dieses Mysterium von Golgatha soll eben auch noch fruchtbar gemacht werden. Wir sollen nicht bloß unbewußt, wie es für die Menschen der Fall ist, in uns den Impuls von Golgatha aufnehmen, sondern wir sollen ihn bewußt aufnehmen. Wir sollen bewußt ihn so aufnehmen, daß wir gewissermaßen durch den Impuls von Golgatha jugendfrisch bleiben bis in das Alter hinein. Und er kann uns gesund und jugendfrisch erhalten, wenn wir ihn in der richtigen Weise bewußt aufnehmen. Und wir werden uns dann auch dieses Erfrischenden des Mysteriums von Golgatha für unser Leben bewußt werden. Und das ist wichtig, meine lieben Freunde!

Sie sehen also, dieses Mysterium von Golgatha kann als etwas sehr, sehr Lebendiges innerhalb unseres irdischen Lebenslaufes aufgefaßt werden. Ich sagte vorhin, die Menschen sind am meisten veranlagt in der Lebensmitte, so um das dreiunddreißigste Jahr herum, für die Brüderlichkeit. Aber sie bilden nicht immer diese Brüderlichkeit aus. Hier haben Sie den Grund in dem, was ich eben gesagt habe. Diejenigen, die die Brüderlichkeit nicht ausbilden, bei denen es etwas mangelt an der Brüderlichkeit, die sind eben zu wenig dutchchristet. Weil der Mensch gewissermaßen in der Lebensmitte erstirbt durch die Kräfte des Naturlaufes, kann er sowohl den Impuls, den Instinkt der Brüderlichkeit wie namentlich den Impuls der Freiheit, den die Menschen heute so wenig aufnehmen, nicht ordentlich entwickeln, wenn er nicht lebendig macht in sich Gedanken, die unmittelbar von dem Christus-Impuls herkommen. Daher ist der Christus-Impuls unmittelbar, indem wir zu ihm uns hinwenden, die Anfeuerung zur Brüderlichkeit. In dem Maße, in dem man empfindet die Notwendigkeit der Brüderlichkeit, durchchristet man sich. Aber der Mensch würde allein während des Restes der Erdenzeit — in künftigen Entwickelungen wird es anders sein — nicht dahin kommen, die ganze Stärke des Freiheitsimpulses zu entwickeln. Da tritt dasjenige in unsere Erdenentwickelung als Menschen ein, was beim Tode des Christus Jesus ausgeflossen ist und sich mit der Erdenentwickelung der Menschheit vereinigt hat. Daher ist Christus im wesentlichen auch der Führer der heutigen Menschheit zur Freiheit. Wir werden in Christo frei, wenn wir den Christus-Impuls so verstehen, daß wir ganz darauf einzugehen wissen, daß der Christus eigentlich nicht älter werden konnte im physischen Leib, oder nicht länger leben konnte im physischen Leibe als bis zum dreiunddreißigsten Jahre hin. Nehmen wit hypothetisch an, er hätte länger gelebt, so würde er in einem physischen Menschenleibe in die Zeit hineingelebt haben, wo dieser physische Leib eigentlich nach der gegenwärtigen Erdenentwickelung zum Ersterben bestimmt ist. Da würde er die Ersterbekräfte gerade als der Christus aufgenommen haben. Wäre er vierzig Jahre alt geworden, so hätte er im Leibe erlebt die Ersterbekräfte. Die konnte er nicht erleben wollen. Er konnte nur dasjenige erleben wollen, was noch die erfrischenden Kräfte des Menschen sind. Bis dahin wirkt er, bis zum dreiunddreißigsten Jahre, bis zur Lebensmitte, regt als der Christus die Brüderlichkeit an, übergibt dann dasjenige, was in des Menschen Kraft liegen soll, indem er ausfließen läßt in die Entwickelung der Menschen den Geist, dem Heiligen Geiste. Durch diesen Heiligen Geist, diesen gesundenden Geist entwickelt sich der Mensch gegen sein Lebensende hin zur Freiheit. So gliedert sich der ChristusImpuls ein in dieses konkrete menschliche Leben.

Solch eine innerliche Durchdringung des Menschenwesens mit dem Christus-Prinzip, das ist es, was als ein neuer Weihnachtsgedanke aufgenommen werden muß vom Menschenwissen. Wissen muß man, wie der Mensch mit der Gleichheit aus der geistigen Welt herauskommt. Das ist etwas, was ihm mitgegeben wird, was gewissermaßen aus dem Vatergott ist. Dann kann aber die Kulmination der Brüderlichkeit in der richtigen Weise nur durch des Sohnes Hilfe und durch den mit dem Geist vereinigten Christus die Entwickelung zum Freiheitsimpuls gegen den Tod hin in die Menschheitsentwickelung eintreten.

Dieses Mitwirken des Christus-Impulses in der konkreten Menschheitsausgestaltung, das ist dasjenige, was von jetzt ab in das Bewußtsein der Seelen aufgenommen werden muß. Das allein wird richtig heilsam sein, wenn die Forderungen der Menschen immer drängender und brennender werden in bezug darauf, wie man gestalten soll die soziale Struktur. Aber in dieser sozialen Struktur leben Kinder, junge, mittlere und alte Leute, und eine soziale Struktur, die alle umfaßt, wird man nur finden können, wenn man weiß, daß Mensch nicht einfach gleich Mensch ist. Das fünfjährige Kind ist Mensch, der zwanzigjährige Jüngling, die zwanzigjährige Jungfrau ist Mensch, der vierzigjährige Mensch ist Mensch, alles ist Mensch. Aber dieses chaotische Durcheinanderwerfen, das bringt es nicht zu einer solchen Erkenntnis des Menschen, wie sie notwendig ist, um die Forderungen der Zukunft, der Gegenwart auch, zu erfüllen. Das chaotische Durcheinanderwerfen bringt es höchstens dazu, daß man meint: Mensch ist Mensch, also muß er mit zwanzig Jahren ungefähr ins Parlament gewählt werden. — Diese Dinge sind zerstörend für die wirkliche soziale Struktur. Sie beruhen darauf, daß der Mensch in der Gegenwart nicht eintreten will in die Menschenbeobachtung und das daraus hervorgehende Menschheitsbewußtsein, welches den Menschen konkret so nimmt, wie er ist. Aber konkret genommen ist die Abstraktion Mensch, Mensch, Mensch, gar nicht vorhanden, sondern es ist immer ein konkreter Mensch eines bestimmten Lebensalters mit bestimmten Impulsen. Menschenerkenntnis muß erworben werden; aber sie muß erworben werden, wenn man die Entwickelung desjenigen, was als Wesenskern im Menschen von der Geburt bis zum Tode lebt, ins Auge faßt. Das ist etwas, was auftreten muß! Und man wird wahrscheinlich nur geneigt sein, solche Dinge aufzunehmen in das Menschheitsbewußtsein, wenn man wiederum in der Lage ist, Rückblicke auf die Menschheitsentwickelung zu machen.

Gestern habe ich Sie hingewiesen auf etwas, was in die Menschheitsentwickelung eingetreten ist mit dem Christentum, indem das Christentum gewissermaßen herausgeboren ist aus der jüdischen Seele, aus dem griechischen Geist, aus dem römischen Leib. Das sind gewissermaßen die Hüllen des Christentums geworden. Aber im Christentum ist das lebendige Ich darinnen, und das kann wiederum abgesondert betrachtet werden, indem man zurückblickt auf diese Geburt des Christentums. Für die äußere Geschichtsschreibung ist diese Geburt des Christentums ziemlich chaotisch geworden. Dasjenige, was heute gewöhnlich - sei es von katholischer, sei es von protestantischer Seite — geschrieben wird über die ersten Jahrhunderte des Christentums, ist eine ziemlich chaotische Weisheit. Manches, was gelebt hat in den ersten Jahrhunderten des Christentums, ist überhaupt gerade für die Theologen der Gegenwart seiner eigentlichen Wesenheit nach entweder ganz vergessen oder zu einem Horror, könnte man sagen, geworden. Denn lesen Sie nur nach, in welche sonderbaren Konvulsionen des Intellektuellen, Konvulsionen, daß die Leute fast schon, möchte ich sagen, bis zu einer Art intellektueller Epilepsie kommen, wenn sie charakterisieren sollen dasjenige, was in den ersten Jahrhunderten des Christentums als Gnosis gelebt hat. Das ist schon so eine Art Teufel, so etwas Dämonisches, etwas, das man nur ja nicht ordentlich hereinlassen soll in das menschliche Leben, diese Gnosis! Und wenn nun gar solch ein Theologe oder sonstiger offizieller Vertreter dieses oder jenes Bekenntnisses die Anthroposophie anschuldigen kann, daß sie etwas gemein hätte mit der Gnosis, dann glaubt er schon, das Allerschlimmste gesagt zu haben.

Nun, alldem liegt aber zugrunde, daß in den ersten Jahrhunderten der Entwickelung des Christentums diese Gnosis in der Tat viel bedeutsamer in das geistige Leben der europäischen Menschheit eingriff, soweit sie dazumal für die Zivilisation in Betracht kam, als man heute glaubt. Man hat auf der einen Seite gar keine Vorstellung davon, was diese Gnosis eigentlich war, und hat auf der andern Seite, ich möchte sagen, eine geheimnisvolle Furcht. Es ist diese Gnosis für die meisten gegenwärtigen offiziellen Vertreter dieses oder jenes Religionsbekenntnisses etwas Horribles. Man kann sie aber nun wirklich betrachten ohne besondere Sympathie und Antipathie, rein als etwas Tatsächliches. Dann muß man die Sache wohl geisteswissenschaftlich studieren, weil die äußere Geschichte nicht viel bietet. Die kirchliche Entwickelung des Abendlandes hat dafür gesorgt, daß eigentlich alle historischen Denkmäler dieser Gnosis mit Stumpf und Stiel ziemlich ausgerottet wurden. Es ist nur weniges, wie Sie wissen, und was nur ein unklares Bild von der Gnosis wiedergibt, wie die «Pistis Sophia» und dergleichen, übriggeblieben. Sonst weiß man aus der Gnosis nur die Sätze, die von den Kirchenvätern widerlegt werden. Also im Grunde genommen kennt man die Gnosis nur aus der Schriftstellerei der Gegner; während das, was äußerlich historisch eine Vorstellung von ihr geben könnte, ziemlich mit Stumpf und Stiel ausgerottet worden ist.

Nun würde aber ein verständiges Betrachten der theologischen Entwickelung des Abendlandes — nur findet ein solches verständiges Betrachten in der Regel nicht statt — die Menschen auch auf diesem Punkte nachdenklicher machen. Man würde zum Beispiel, wenn man verständig die Entwickelung der christlichen Dogmatik betrachtete, darauf kommen, daß diese christliche Dogmatik doch noch in etwas anderem wurzeln müsse als in irgendeiner bloßen Willkür oder dergleichen. Im Grunde wurzeln diese Dogmen alle in der Gnosis. Nur ist das Lebendige der Gnosis abgestreift worden und die abstrakten Gedanken und Begriffshülsen sind geblieben, so daß man in den Dogmen diesen lebendigen Ursprung nicht mehr erkennt. Dieser lebendige Ursprung liegt aber eigentlich in der Gnosis. Wenn Sie die Gnosis, soweit sie geisteswissenschaftlich studiert werden kann, wirklich verfolgen, dann wirft das einem auch ein gewisses Licht auf die wenigen Dinge, die historisch übriggelassen worden sind von den Gegnern der Gnosis. Und dann sagen Sie sich wahrscheinlich: Diese Gnosis weist hin auf die ganz ausgebreitete, sehr konkrete atavistische Hellseherweltanschauung der alten Zeiten, die in ihren Resten noch ziemlich vorhanden war in der Zeit des ersten nachatlantischen Kulturzeitraumes, im zweiten schon weniger; dann, als im dritten die letzten Reste des alten Hellsehertums über die Welt verloren worden sind, sind sie eben in der Gnosis in einem wunderbaren Begriffssystem, das aber ganz außerordentlich bildlich ist, zutage getreten. Wer von diesem Punkte aus die Gnosis ansieht, wer in der Lage ist, auch nur historisch zurückzugehen zu den spärlichen Resten, die dann in der heidnischen Gnosis reichlicher als in der christlichen Literatur zutage gefördert werden können, der findet, daß in dieser Gnosis tatsächlich wunderbare Weisheitsschätze schon da waren, eine Weisheit, die sich auf eine Welt bezog, von der die Menschen gegenwärtig überhaupt nichts wissen wollen. So daß es gar nicht zu verwundern ist, daß selbst gutmeinende Menschen mit der alten Gnosis nicht viel anzufangen wissen, etwa solche Menschen wie der Professor Jeremias in Leipzig, der ja willig wäre, auf die Dinge einzugehen; aber er kann keine Vorstellung erwerben, auf was sich eigentlich diese alten Begriffe beziehen, auf was es sich bezieht, wenn da gesprochen wird von einem geistigen Wesen Jaldabaoth, das in einem gewissen Hochmut sich aufgeworfen hätte zum Herrn der Welt, dann von seiner Mutter zurechtgewiesen worden wäre und so weiter. Solche mächtigen Bilder strahlen herein selbst aus dem historisch Aufbewahrten, solche mächtige Bilder wie dieses, wo wirklich Jaldabaoth sagt: Ich bin Vatergott, über mir ist niemand. — Und die Mutter erwidert: Lüge nicht, über dir ist der Vater von allem, der erste Mensch und des Menschen Sohn. — Da rief — so wird weiter erzählt — Jaldabaoth seine sechs Mitarbeiter, und sie sprachen: Laßt uns den Menschen machen nach unserem Bilde.

Da haben Sie einen merkwürdigen Dialog zwischen Jaldabaoth und seiner Mutter, und dann das Heranrufen der sechs andern Mitarbeiter, die zu dem Entschluß kommen: Laßt uns den Menschen machen nach unserem Bilde. — Aber solche Bilder, solche Imaginationen, die eigentlich ganz anschaulich sind, sie waren zahlreich und umfangreich vorhanden in dem, was als Gnosis herrschte. Man hat im Alten Testament eigentlich nur Reste: diejenigen Reste, die die jüdische Überlieferung behalten hat, von einer umfangreichen Bilderweisheit, die in der alten Gnosis enthalten war, vorzugsweise im Oriente lebte, deren Strahlen aber herüberwirkten ins Abendland, und die eigentlich erst im 3., 4. Jahrhundert für das Abendland mehr oder weniger verglommen sind, dann noch nachgewirkt haben bei den Waldensern und Katharern, aber doch verglommen sind.

Wie es ausgeschaut hat in den ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten in den Seelen der Menschen, in denen nicht etwa bloß die Vorstellungen lebten, die heute bei den Katholiken leben, sondern in denen durchaus Nachklänge dieser mächtigen Bilderwelt der Gnosis lebendig waren, davon machen sich die heutigen Menschen nicht viele Begriffe. Es sieht ungeheuer anders aus, wenn man zurückschaut in das, was in den Seelen der ersten Jahrhunderte innerhalb der europäischen zivilisierten Länder lebte, ungeheuer anders, als wenn man in die Bücher hineinsieht, welche die kirchlichen und weltlichen Theologen und sonstigen Gelehrten über diese ersten Jahrhunderte schrieben. Denn für diese Bücher fällt all das fort, was lebendig war in solchen mächtigen, gewaltigen Bildern, die sich, wie gesagt, auf eine Welt bezogen, von der sich die heutigen Menschen keine Vorstellung machen. Daher weiß ein im Sinne der heutigen Bildung ausgebildeter Mensch nichts anzufangen mit diesen Begriffen, die da zu ihm herüberkommen. Den Jaldabaoth, dessen Mutter, die sechs Mitarbeiter, andere Dinge, die auftreten: er weiß sie auf nichts anzuwenden. Sie sind Worte, sind Worthülsen; er weiß nicht, worauf sie sich beziehen. Und noch weniger weiß er, wie die Menschen einmal dazu gekommen sind, solche Vorstellungen sich zu bilden. Daher kann der moderne Mensch nicht anders als sich sagen: Nun, die alten Orientalen haben eine starke Phantasie gehabt, die haben das alles phantastisch ausgebildet! Man ist immer nur sehr verwundert darüber, daß diese Herren gar keine Ahnung davon haben, wie eigentlich der elementarisch lebende Mensch wenig Phantasie hat, wie diese Phantasie zum Beispiel bei den Bauern eine ungeheuer geringe Rolle spielt. In dieser Beziehung haben auch die Mythenforscher Ungeheures geleistet. Sie haben nämlich ausgedacht, wie die einfachen Leute die ziehenden Wolken, die vom Winde getriebenen Wolken phantastisch zu allen möglichen Wesen umgestaltet haben und so weiter. Die Leute haben keine Ahnung davon, wie eigentlich die Menschen, denen sie das zuschreiben, in ihrer Seele beschaffen sind, daß diese so weit wie nur irgend möglich entfernt sind, in solcher Weise poetisch das auszugestalten. Die Phantasie herrscht nur in den Kreisen der Mythologen, der Gelehrten, die so etwas ausdenken. Das ist wirkliche Phantasie.

Das, was die Leute sich so ausgedacht haben als den Ursprung der Mythologie und so weiter, ist eben bloßer Irrtum. Und es wissen die Menschen heute nicht, auf was eigentlich sich die Worte, die Begriffe beziehen, von denen da gesprochen wurde. Gewisse, ich möchte sagen, deutliche Hinweise, wie die Dinge gemeint sind, können daher auch gar nicht mehr richtig berücksichtigt werden. P/ato hat die Leute noch sehr genau darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß der Mensch, indem er hier im physischen Leibe lebt, sich an etwas erinnert, was er vor diesem physischen Leben in der geistigen Welt erlebt hat. Aber mit diesem platonischen Gedächtniswissen wissen die heutigen Philosophen nichts anzufangen. Das sei auch so etwas, was Plato phantasiert habe — während Plato eben noch wußte, daß die griechische Seele schon so veranlagt war, aber nur die letzten Reste dieser Veranlagung noch hatte, etwas in sich zu entwickeln, was vor der Geburt in der geistigen Welt erlebt war. Wer zwischen Geburt und Tod nur wahrnimmt im physischen Leibe und die Wahrnehmung mit dem heutigen Verstande verarbeitet, der kann keinen vernünftigen Sinn verbinden mit den Betrachtungen, die gar nicht gefaßt worden sind im physischen Leibe zwischen Geburt und Tod, sondern die gefaßt worden sind zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, die da durchlebt worden sind, bevor man geboren wurde. Da waren die Menschen in einer Welt, in der sie reden konnten von Jaldabaoth, der sich in Hochmut auflehnt, den seine Mutter ermahnt, der die sechs Mitarbeiter herbeiholt. Das ist für den Menschen zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt eine solche Wahrheit, wie hier für den in den Leib eingebannten Menschen Pflanzen, Tiere, Mineralien und andere Menschen die Welt sind, von der er redet. Und die Gnosis enthielt dasjenige, was bei der Geburt mitgebracht wurde in die physische Welt herein. Und bis zu einem gewissen Grade war es den Menschen möglich bis zum ägyptisch-chaldäischen Zeitraum hin, also bis in das 8. Jahrhundert der vorchristlichen Zeitrechnung, vieles mitzubringen aus der Zeit, die zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt durchlebt wurde. Was da mitgebracht wurde und in Begriffe, in Ideen gekleidet wurde, das ist Gnosis. Das lebte dann fort im griechisch-lateinischen Zeitraum, wo es nicht mehr unmittelbar wahrgenommen wurde, wo es als ein Erbgut in Ideen noch vorhanden war, wo nur auserlesene Geister den Ursprung wußten, wie Plato, in einem geringen Grade auch Aristoteles. Sokrates wußte auch davon, Sokrates büßte in Wirklichkeit gerade dieses Wissen mit dem Tode. Da muß man den Ursprung der Gnosis suchen.