Goetheanism as an Impulse for Man's Transformation

GA 188

3 January 1919, Stuttgart

I. The Difference Between Man and Animal

It has often had to be emphasised here that when the truths of Spiritual Science are put into words it is very easy for them to be misunderstood in some direction. I have spoken to you also of the very varied reasons for this ready misunderstanding of the knowledge and conceptions of Spiritual Science. It must frequently be repeated that naturally it is very easy to find here or there, among those who have had little opportunity for acquiring spiritual depth, that statements concerning Spiritual Science are made on insufficient grounds, and so on. It is also extraordinarily easy when the facts of Spiritual Science are given out to say: “How does so and so know that; where does he get his knowledge?”—when these same people are not even willing to investigate the origin of facts they themselves often advance concerning it and form their judgment entirely in accordance with their own knowledge. It is not difficult to say: “How can he know that? I don't know it” and then to declare in a high and mighty way: “What I do not know no one else knows, others can at best only believe it.” Such a judgement comes about merely because one refuses to go into the sources from which, particularly at the present time, the knowledge Spiritual Science has to be drawn.

Among the misunderstandings arising in this way we may include the belief that Spiritual Science wishes to pronounce sentence, sentence of wholesale extermination, upon all the striving of the age, in so far as this striving proceeds from personalities outside the pale of Spiritual Science. Here too lies mere misunderstanding. Spiritual scientists who seriously and adequately pay heed to present world conditions are very ready to enter into the attitude of mind, the mood of soul, of their contemporaries, and will ask themselves the question: “What is going on in the souls of my seriously minded contemporaries in the direction where we have to look for the improvement of much that both deserves and needs to be improved?” What, however, must above all be borne in mind as a particularly striking fact at present is that just in the case of those who make the most earnest endeavours, there is often a refusal to enter upon concrete knowledge of the spiritual world, recognition of the spiritual world, which can appear to men as a reality and not merely as something to be disclosed through a sum of concepts. Today most men prefer to remain with their experiences altogether in the sense world, and at best they allow that a spiritual world can be disclosed by means of concepts and ideas. They do not want to set out on an investigation where there is any question of penetrating to the spiritual world in actual experience. This aversion to spiritual reality is a characteristic feature of our time; it it is a feature of our time to which attention must be paid particularly by those of us who try to take our stand on the ground of spiritual Science.

By quoting to you from the thoughts of Walther Rathenau, (see Z-269) I have recently shown that the spiritual scientist is indeed able really to appreciate the direction modern thought is taking, within the limits, that is to say, of what is estimable in this thought. But the rejection of the really spiritual that should arise in our time is nevertheless extraordinary. This rejection can be fully experienced when one pays heed to what is being thought. To many people this has appeared as the most shattering feature of the present world situation. For there are men who understand how to estimate all the seriousness of the present time, who have for some time understood how to estimate it. Here too I beg you, my dear friends, not to consider this the superior attitude of a number of anthroposophists; I beg you not to suppose that Anthroposophy as such is claiming to judge the seriousness of the times better than people outside the Anthroposophical Movement. For one could wish that many more inside the Anthroposophical Movement would feel moved by what is so critical in the present state of the world. Within our own ranks today far too many are to be found who in spite of the seriousness of the times have no mind to face up to this seriousness, preferring to be occupied with their own worthy selves instead of being aroused to some interest in the great questions pulsing throughout mankind.

At the outset of our considerations today, I will take an example that may be said to have come my way by chance; if the word is not misunderstood, and there is no need for any misunderstanding. It is an article which, it is true, is out of date today since it was written when the so-called war was still in full swing. Thus the article is not up to date. Also it is not exactly impressive in other ways, for most of the things discussed are treated very one-sidedly. But it comes from a man—and this can be seen from the whole character and way of writing—who is giving his most earnest thought to what should now happen, and what the world has to expect from the events. This article gives a picture of the gradual trend of behaviour on the part of the western powers, the central powers, the eastern powers, during the catastrophe of these last years. Although in a one-sided way, it shows the great dangers from this catastrophe threatening both present and future. The writer has a certain world-outlook. He considers the world not only from the point of view of land frontiers; the world from the point of view of frontiers is also discussed among men today, and if they can satisfy themselves that some particular thing does not happen within their own territory, they make their mind easy. The author of this article has a wider outlook than that of the village pump, he grasps something of world perspective. And in the summing up of his ideas we come to a very remarkable passage. He says; “A fearful destiny beckons to the white races which seems to me an absolute certainty unless a period of the supremacy of great wisdom succeeds that of passion and delusion. For some time we have actually been living in an age very similar to that of the migration of peoples. The tempo has been tremendously increased by the world war. What corresponds to the German races who invaded the civilised lands of olden times from outside, are the rapidly rising lower classes of the people who both in blood and cultural heritage are very different from those who previously held the power. This migration of peoples—it is better to refer to it thus than to call it a war—is good in so far as it necessitates a widening, a widening of the cultural basis and a raising of levels as a whole. But this would be very dangerous were it to come about too rapidly. And this danger will be increased the longer the world war lasts.”

The article is now out of date. The danger has not diminished, but since all his arguments were based on the then existing thirst for war, they are now superannuated. For us here, however, the first part of what I read out must be of special interest—“a fearful destiny beckons to the white races and seems to me an absolute certainty unless a period of the supremacy of great wisdom succeeds that of passion and delusion.” For, as an abstract truth, this is in fact undeniably right. And when anyone expresses the opinion that the only salvation for mankind lies in turning to a supreme science of wisdom and not to any other political or social quackery, we must give recognition to such a fact, such a tendency of thought. At the same time, however, we may not forget that just those men who, it must be admitted, are deeply moved by the earnestness of the times, when it comes to saying: In what do these wise ideas consist that are to succeed the old deluded ideas? It is just such men who immediately fall back on any kind of deluded ideas that have become mere fine words. That is the tragedy, the fearful destiny, of our time, that men indeed became alive to the fact that it is necessary to turn to the spirit, and are then overcome by fear and anxiety when they should turn to it. Then they are at once ready, once more to seize upon the old delusive ideas which have driven mankind to the present fearful destiny. My dear friends, we need only take this example of a widespread tendency in ideas. Were you to ask a law abiding upholder of the Roman Catholic Church whether he was inclined to the belief that the old conceptions have brought us to this time of catastrophe and that they must be got rid of, do you think that he would really be disposed to recognise the necessity for reshaping the ideas that were unable to save men from this dreadful catastrophe? No! He would say that were men to turn again in the right way to Roman Catholicism they would at once became happy. And the reflection would not even enter his head that they have had 1900 years in which to practise their Roman Catholicism and yet have fallen into the catastrophe, that the least we must learn from the catastrophe is the need for a fresh impulse. This is only one example among many. Particularly where this point is concerned it is above all necessary frankly to focus attention on existing conditions.

You see today even for a recognised member of some church or other it is easy to say that Haeckelism or materialism is devil's work and must be rooted out lock, stock and barrel. This is the reverse of what is able to lead men to a sound attitude of soul. Yes, my dear friends, it is very easy to speak thus but when it stops there and no investigation is made into the conditions in question, it is impossible to arrive at any sound solution for the present time, much less for the near future. For if you take any world outlook materialist in feeling and ask yourself: where does it come from historically? If you really wish to get to the root of this, in the end you will be unable to help saying that fundamentally it comes from the way in which Christianity has been preached during these 1900 years by the various Christian churches. Those whose insight goes deeper know that Haeckel's doctrine would have been impossible without the preceding Christianity of the churches. There are people who have remained at the standpoint of the church, as it was, let us say, in the Middle Ages; they continue to uphold the ideas professed by the church in medieaval times. Others have developed these ideas. And among those who have developed them is, for instance, Ernst Haeckel. He is a true child of the conceptions fostered through the centuries by the various churches. This has not arisen outside the church; in the fullest sense it has originated entirely within the teachings of the church itself. Certainly the connections of these things will only be recognised aright if one is endowed by Spiritual Science with a little insight to give one clear vision.

Today, therefore, I want to dwell on one particular point, though some of you may say it is too difficult, but nothing ought to be too difficult for us and we are meant to gain insight.

Now look—if today you read philosophically inspired writings of well-educated learned Catholic men you will find, in all passages where a certain point comes into question, a quite definite outlook developed; and it may be said that you find this outlook developed try the very best of these scholarly Catholics. In passing I should like to point out that I am not at all in the habit of undervaluing the literary training of the Catholic clergy for example. I quite realise (and I have spoken of this in my book Vom Menschenrätsel) the superior schooling shown in the philosophical writings of many Catholic theologians, compared with the writings of those men of philosophical learning who have not made a study of Catholic theology. In this respect one must own that the literature, the theological literature, of protestant learning, of the reformed churches, lags far behind the excellent philosophical training of Catholic theologians. Through their strict schooling these people possess a certain ability to form their concepts really plastically. They have what the famous men of non-Catholic philosophical literature, for instance, have no notion of, that is, a particular faculty of seeing into the nature of a concept, the nature of an idea, and so on. To put it briefly, these people are scholarly. One need not even take one of Haeckel's books, one can take one of Eucken's, to confirm this playing about with concepts, this dreadful treatment of the most important concepts, a treatment merely on the level of a cheap novelette! Or, to give another example, we might take one of Bergson's books that always promote the feeling that he is catching hold of concepts but is unable regally to come to grips with them—like the famous Chinaman who wanting to turn round always catches hold of his pigtail. This absolute confusion in the world of concepts, shown by the people who lack training is never to be found when you come to the philosophical literature of the Catholic Clerics. Thus, for example, in this connection, a book like the three volume History of Idealism by Otto Willmann, a thorough going Catholic who makes his Catholicism evident on every opportunity, takes a much higher place than most of what is written in the realm of philosophy on the non-Catholic side. All this may be quite well recognised while still taking the standpoint that must be taken in Spiritual Science. An inferior spirit may decide differently in this matter, may perhaps be of the opinion that because good schooling is shown, the whole thing is of more value.

In this polished Catholic philosophical literature one point will always confront you, a point that has an extraordinary way of hoodwinking the modern thinker. It is the point that always comes into evidence when there is question of the difference between man and animal. I think you will agree that the ordinary readers of Haeckel, the ordinary upholders of Haeckel, always proceed to minimise the difference between man and animal as much as possible, to arouse as much belief as they can that men as a whole is only to a certain extent a more highly developed animal. This is not done by the Catholic men of learning but they always bring forward something that appears to them as a radical difference between animal and man. They raise the point that the animal gets no further than the ordinary conception it acquires of an object by first smelling it, of another object by smelling that or inspecting it, and so on; that the animal always stops at mere detailed, unindividual ideas, whereas man has the capacity for forming deduced abstract concepts and of summing things up. This is indeed a fundamental difference, for when the matter is grasped in this way man is really definitely distinguished from the animals. The animal noticing only details cannot develop what is spiritual; abstract concepts must live in the spiritual. For this reason one has to recognise that in man there lives a soul specially adapted for forming abstract concepts; whereas the animal with its particular kind of inner life has no power of forming these abstract concepts.

Whoever an this point keeps in mind the corresponding Catholic statements will say to himself: Here is something tremendously significant, that through good philosophical training on this decisive, fundamentally decisive, point, the distinction can be shown between man and animal. Modern men do not in the least appreciate the significance of such a matter. When, for instance, the uproar was set going for which Drews was responsible, namely, the discussion whether Jesus ever lived, when at that time a great gathering took place in Berlin about the problem “Did Jesus ever Live?” the Catholic theologian Wasmann1Erich Wasmann, born 1859 in Meran, became a Jesuit and late a priest. He investigated the life of Ants and among other works wrote The Souls of Men and Animism 1904. also spoke. Naturally he could only say things that the others considered very reactionary. But in spite of the fact that speeches were made at the time by the shining lights of protestant theology in Berlin strictly speaking in those speeches only two utterances, and what supported them, seemed to me really on a better level, not on a present-day level but on a rather higher level. One was an exposition launched by—now I do not wish to say anything derogatory, I am actually praising the man—a learned idler of the first water. (I don't think I can praise him more than by calling him a learned idler of the first water.) Through his intellectuality and the special information he possessed on the most varied subjects, through his great knowledge, the man might have been able to do a great deal. But when I had something to do with him—eighteen, nineteen years ago for fifteen years he had been writing a Revision of Logics and I think he must have been writing it ever since, for in the meantime I have never come across this Revision of Logic. At that time he said something that is quite correct—at the present time men actually become quite frightening when they begin to think—that is they were quite frightening then. One need listen to only two or three propositions, either in a scientific or non-scientific talk, and immediately the most terrible lack of logic can be observed. What (said he) men must observe so that they do not arrive at the most horrible delusive conceptions usual nowadays, can be written on a quarto sheet (so he thought); it is only necessary to take note of this quarto sheet. I am sure I do not know if he will present this quarto sheet as his Revision of Logic! As I said, this Revision of Logic had then gone on for fifteen years since when eighteen, nineteen years have passed; I do not know how for it has got by now. But I want to give him a word of praise by calling him a witty, intelligent do-nothing, because I mean by this that were he not a witty do-nothing ha could do tremendously much. At that time he said something very fine: The Catholic Church one day had to hear that the comets which consist of nucleus and tail are heavenly bodies like the others and move in accordance with laws like other heavenly bodies. As in face of existing facts it could no longer be denied that comets are also heavenly bodies, the Catholic Church decided to allow that the laws of celestial space should also be applied to comets; but they first gave way only where the nucleus was concerned and not the tail. Now in this he was wanting to express merely symbolically that as a rule the Catholic Church is prone only to yield to absolute necessity just as it was not until 1827 that it allowed its adherents to recognise the Copernican world-outlook. But when the Church had to give way to what was most necessary it did at least hold back the tail in the matter! This is an observation which I found highly descriptive of the situation.

The other observation, however, was made by the investigator of ants, the Catholic Wasmann, who not only does excellent work with ants but is a well-trained philosopher as well. He said: “Really gentleman you can not understand me in the least for none of you knows in reality how to think in terms of philosophy. No one who thinks philosophically talks as you do!” And in point of fact he was quite right. There is no doubt that he hit the nail on the heed. Now there is a neat little publication by Wasmann concerning the difference between man and animal which puts forward in clear outlines what I have just now indicated, that is, man's faculty to think really in abstract concepts, a faculty which the animal certainly is not supposed to possess. This is something extraordinarily deceptive, my dear friends, for in a certain way it is convincing for anyone who has schooled his thinking to the point of being able to grasp the whole bearing of such an assertion.

But now let us look at the matter from the point of view of Spiritual Science, there the whole affair will meet you in its true meaning. For you see when we start from Spiritual Science, from the conceptions and experiences in connection with it which can be acquired in the spiritual world, we see, on the one side that without the considerations of Spiritual Science we may arrive at the delusive statement or which I have just spoken, and that it must actually hold good for anyone who will not become a spiritual scientist just because he has had a good training in philosophy. This is seen on the one hand. On the other hand one sees the following—sees it simply by observing things in the world—that when with the hypotheses of Spiritual Science man and animal are compared, it becomes apparent that man confronts the objects in the world in a series of single observations afterwards forming abstract concepts by all manner of thought processes in which he reunites what he has seen as separate entities. It may also be admitted that the animal does not possess this kind of abstraction, it does not practise this activity of abstraction. The curious thing is, however, that the abstract concept is not lacking in the animal, that, in its soul the animal is actually living in the most abstract concepts which we men only form with much difficulty, and that the animal does not see things separately as we do. Where we excel is just in our freer use of the senses and in a quite definite kind of co-operation between senses and inner emotions and will-impulses. We have that advantage over the animal. The sureness of instinct possessed by animals rests on the very fact that the animal from the start lives with those abstract concepts that we have first to form. We differ from animals in the emancipation of our senses and in their freer use where the outer world is concerned, also in being able to pour will into our senses which the animal is unable to do. What we men do not have but must first acquire, namely, the abstract concept, is just what the animal does have, strange as it may seem. It is true every animal has only a limited sphere but in this sphere it has this kind of concept, however odd this appears. Man's attention is directed to one dog, two, three dogs, and he then forms the abstract concept “dog”. The animal in this sphere has the same abstract concept “dog” that me have, it has the quite exact concept without needing to form it. We have first to form it which the animal has no need to do. The animal, however, has no capacity for distinguishing with precision one dog from another or for giving it any precise individuality through sense-perception.

Thus you see, my dear friends, if we do not acquire the faculty for going into the real facts through Spiritual Science, we deceive ourselves in a certain respect concerning what is most essential. We believe because men must develop the capacity to form abstract concepts that through such concepts we are to be differentiated from animals who do not possess this capacity. But the animal has no need of the capacity, since it has abstract concepts to start with. The animal has an entirely different kind of sense-perception from that of man. It is just the outer sense-perception that is quite different.

In this connection a most profound change in human conceptions is needed. For men have informed themselves about all kinds of scientific concepts that have become popular today. Wither they have learnt them in some school through direct tuition or they have received the information from any doubtful source: what I am referring to is those newspaper articles that circulate scientific conceptions throughout the world. Men are under the domination of these scientific conceptions. Where what I have been referring to is concerned, men are absolutely dominated by what I might call an instinctive bias towards the belief that animals really see their environment in the same way as men do. When a man takes his dog for a walk he instinctively believes that the dog is seeing the world in the same way as he does himself, that the dog is seeing the grass, the wheat, the stone in the same colours as he does. He also thinks—if he can think at all—that he can deal in abstractions and therefore has abstract concepts which, however, the dog doesn't have; and so on. Yet it is not so. This dog running beside us is living just as much in abstract concepts as we are. In fact he is living in them with greater intensity. And he has no need to acquire them, for from the start he is living in them to a high degree. It is not the same however, with external perception; which gives him quite a different picture. You need only be attentive to certain things that can be observed in life. These are certainly not always taken sufficiently in earnest. I could give you quite a number of examples to show you in this direction how men from pure instinct think upside down. For instance I was once going down a street in Zurich, I think it was, after a lecture held at the evening meeting of one of our Groups. A coachman was waiting there whose horse refused to answer to the rein and showed signs of shying. The coachman said it was afraid of its own shadow. He of course saw the horse's shadow thrown on the wall by his lamps and supposed that the horse saw the shadow just as he did. Naturally he had no inkling of what was going on in—can I say—the horse's soul, nor what was going on in his own soul. He sees the horse's shadow but the horse has a vivid sense of being in that bit of space in the etheric body where the shadow is formed. This is a quite different process of inner perception—a very different process. You see, you have here the collision between the old way of thinking back to the most elementary, the most instinctive perception of naive men, and what must come into men through the new Spiritual Science. It is true you will first seriously have to take stock of what lies at the root of this. For with regard to such things the crass materialism of a Vogt or Moleschott, a Clifford or Spencer, and so on, differs far less from the handed down creeds of individual religions than does the new way at thought underlying Spiritual Science. Today certain materialists actually think that there is not much difference between man and animal. They may same time have also heard it ring out (even if the bells were not ringing together) that man can form abstract concepts which nevertheless are different from the usual conceptions of the senses. But they say to themselves: Abstract concepts! Perhaps those are nothing very important, nothing very essential; fundamentally men do not differ from animals. Modern materialism as a whole is actually the creation of Church creeds. This must be faced in all seriousness and it will then be seen that it is a question of a fresh kind of conception for the soul of man if we are not to prefer going back to the old conceptions with the idea that all will then soon go well!

But can we say that men are able simply to forbear from turning to the real life of the spirit and at the same time go on? No those are quite right who says “a fearful destiny is beckoning to the white man which seems to me absolutely certain unless a period of the supreme rule of wisdom succeeds that of passion and illusion.” People should recognise, however, that the greater part of the scientific conceptions throughout the world today fall under the category of illusion. This should be thoroughly understood. In their stream of development men have come to the point which we have often described by saying that, since the fifteenth century, mankind has been in the epoch of the consciousness soul. And this development of the consciousness soul takes place in the way I have often described. Let us look at very important characteristic in the development of the consciousness soul.

Last time indeed I pointed out to you that everything perceived by the spiritual investigator, that is to say, everything lying in mankind's development which is raised by him into consciousness, even when not recognised, goes on in man's subconscious. Men go through certain experiences while developing towards the future. They go through these experiences unconsciously When the do not draw them up, bring them into consciousness, as they are meant to do in this epoch of the development of the consciousness soul. But it is just in this epoch that much that would rise in man's subconscious is thrust back again.

Among other things there comes to man in an ever greater degree a certain part of that experience which may be called “the meeting with the Guardian of the Threshold”. Undoubtedly, my dear friends, if men with to enter the spiritual world in full consciousness, to develop Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition, they must enter the sphere of the supersensible world with fuller experiences, with quite different experiences. It might be said they must pass the Guardian of the Threshold with greater thoroughness than the whole mass of mankind are obliged to do in the course of this epoch of the consciousness-soul. Up to a certain degree, however, by the end of the development of the consciousness-soul man must in some measure have passed the Guardian of the Threshold. He can let this happen the easy way by passing in a state of unconsciousness. But Spiritual Science is there to prevent this happening. It has to draw attention to what is now taking place in the evolution of mankind. Whoever holds people back from Spiritual Science is doing no less than forcing them not consciously but unconsciously to approach the Guardian of the Threshold who appears on mankind's horizon in this particular epoch.

To put it differently. From about 1413, for the 2160 years that the epoch of the consciousness soul lasts, mankind in one incarnation or another will have to pass the Guardian of the Threshold and, if only partly, go through what can be experienced in connection with the Guardian. Man can be forced by materially minded men to pass by unconsciously or he can in freedom make the resolve to listen to Spiritual Science and thus experience something in passing the Guardian of the Threshold, either through his own vision or through sound human understanding. And in thus going by the Guardian of the Threshold something will be experienced that enables men to form correct, pertinent conceptions about the concrete supersensible world—above all conceptions enabling them to direct this conceiving, this thinking, in a certain free, unprejudiced direction conducive to reality.

To make thinking in accordance with reality so that it can actually enter into the impulses lying in events and does not live merely in abstractions like modern science, which has knowledge only of external processes—I have often described this as the greatest achievement of Spiritual Science. To know certain things about the spiritual world is becoming a necessity for men. And through this they must be able to judge their position in the world from the point of view of a spiritual horizon, whereas their judgment now has only a physical horizon. You are already judging something in a new and right way when, for instance, you bring the thoughts to fruition in you that animals do not lack abstract ideas but actually live in those that are very abstract, and again, that man is differentiated from the animal by the development of his senses which are freed from the narrow connection with life in the body. It is only through this that one arrives at suitable conceptions concerning the difference between man and animal. This is outwardly expressed by the organisation of the senses in animals standing in a very pronounced relation to the whole life and organisation of the body. The bodily organisation in the animal extends very considerably into the senses.

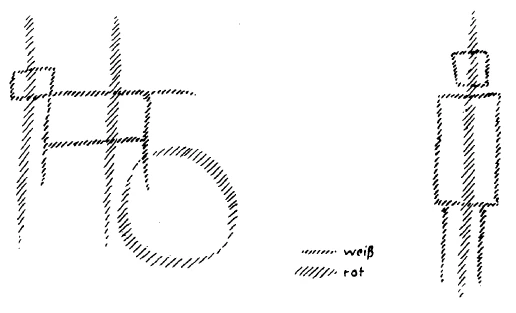

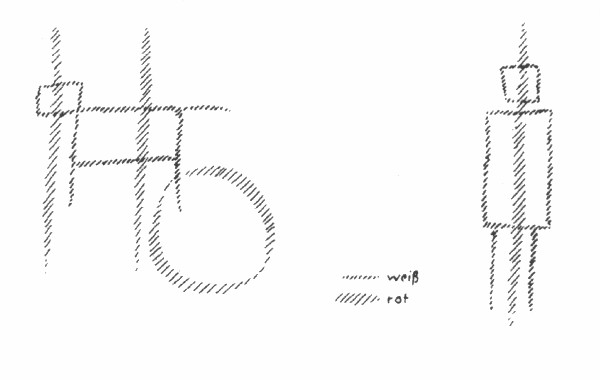

Let us consider the eye. It is quite well known to natural scientists that the eyes of lower animals have in them organs filled with blood (take as example, the habellifom and ensiform processes) which in a living way establish a relation between the inner eye and the entire organisation: whereas the human eye has no such organisation, being much more independent. This growth of independence in the senses, this emancipation of the senses from the organisation as a whole, is something that only arises in the human being. For this reason, however, the whole world of the senses is much more in connection with the will in man than in the animal. I once expressed this morphologically in a different way drawing your attention to the same fact from a different point of view, as follows. If we take the threefold organism, the organs of the extremities, breast, head, and if I draw it as a diagram, in the animal this is the head organism, this the breast organism and this the organism of the extremities (see diagram). The head is immediately above the earth, the earth is under the head organism in all animals, approximately of course, according to the nature of the being. The spine is above the earth's axis or the radius of the earth.

In man his head stands on his own breast organism and extremities organism. In man the breast organism is under the head organism, as in the primal the earth is under the head organism; man stands with his heed on his own earth. In the animal there is a separation between the will-organism that is, the extremities organism, the rear extremities, and the head. In man the will, the will-organism, is inserted directly into the head and the whole into the radius of the earth. For this reason the senses are, as it were, flooded by the will and this is characteristic of man; thus he is in reality distinct from the animal because his senses are flooded by the will. It is not the will but a deeper element that flows through the senses in the case of the animal; thus there is a more intimate connection between the organisation of the senses and the organism as a whole. Man lives far more in the outer world, animals live far more in their own private world. Man in his use of the tools of his senses liven much more in the external world.

Now consider, my dear friends! We are at present living in the age of the consciousness soul; and what does this mean? It means, as I have shown you several times, that we are pressing towards a time when consciousness will become a mere reflection, when only reflected images will be present in consciousness; for the age of the consciousness soul is also the age of intellectuality. (see Lecture IV) And in this intellectual age man actually first arrives at developing his faculty for abstraction to an absolute art. In this age of intellectualism and materialism the most abstract concepts are formed.

Now we may think of two people; one a well trained philosopher, as well trained as Catholic theologians are. Holding his particular views this man ought to say what he will not sir recognising the dilemma in which we find ourselves because centuries of Christianity have brought about materialism; this he finds unpleasant. He must, however, actually Bays man in the age of the consciousness soul can best form abstract concepts, and in this way has raised himself as far as possible above the animal.

But the spiritual scientist may also come along and sort what is characteristic of man in this age of the development of the consciousness soul is his particularly strong faculty for being able to form abstract concepts. Where does this take him? It actually takes him back into the animal kingdom. And this explains a very great deal. It also explains to you how the fact of man being prone to get as near animals as he can, arises just because he there meets the abstraction of the concept. Moreover it makes clear to you something else that arises frequently today in the carrying on and conduct of life. Science will become increasingly abstract and man in his social life will increasingly wish to live like beasts of the field, simply attending to his most ordinary needs, hunger and so forth. The spiritual scientist shows up the inner connection between the faculty for abstraction and the animal nature. At all events man roes through the experience of this inner connection in the age of the consciousness soul. If he is hindered in the way already described, he goes through the experience unconsciously. Innumerable human beings go through What the depths of their soul tells them: you are becoming more and more like an animal and just by going forward you will become ever more so. Man will have this fright on his path of progress. It is this too that causes men to keep so willingly to the old conservative concepts.

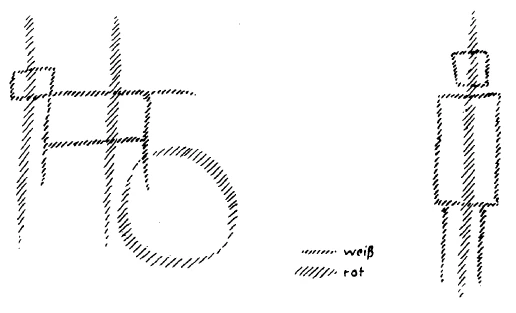

Should this be? And should this unconscious appearance of animal nature hold man back from going forward when he comes to the Guardian of the Threshold? No, this should not happen—but something else has to take place. By going beck during his apparent progress, this backsliding of of man's must so happen that it is not simply a matter of going forward and then back (as it certainly would be were man to develop only a faculty for abstraction), for then man would come back to the earlier stages of his development, he would return altogether to the animal. No, there must be a going backward, but like this (see diagram); an advance must take place, a going upward that must lead into the spiritual.

What we lose by entering into abstractions we must deprive of power by filling our abstract reflected images with the spiritual, by taking up the spiritual into our abstractions. By that we go forward. Man, in front of the Guardian of the Threshold is consciously or unconsciously faced with the formidable decision either through abstract concepts to become more animal than the animal and, to quote Goethe's Faust ‘rub his nose in any filth’; or, on the other hand, the moment he enters abstraction to pour into his abstract concepts what streams out of the spiritual world in the way we have described during these last days. (see Z-269) Then man will begin to estimate rightly his place in the world, for then he understands how he is caught up in evolution. Then he knows why in a Certain point of this evolution—just through abstractions, the danger threatens him of sinking back to the animal. When man in primitive culture epochs stood at the animal stage He was distinguished from the animal not by his abstract concepts but by his senses. The animal had better abstract concepts. It is only now that man can develop abstract concepts at need, animals have much better ones. Once I gave another example of this when I said: How long ago in evolution is it since man tried to make paper? The wasp has been able to do it in building its nest, for millions of years! And just look at what comes to light through animals in the way of active, effective understanding, in wisdom, intellectuality and the faculty for abstraction, even though it appears one-sidedly in the various animals! Men foolishly call this instinct; but when you look into the matter, my dear friends, you will know that there are very few men indeed today who with all their faculty for abstraction come so far with this faculty that they get beyond the one sidedness of the present animal types.

Thus man is placed before this important decision, either to return to the animal condition, in a very great measure to be “more animal than any animal” to use Mephistopheles' expression from Faust—Ahriman Mephistopheles would like to attain this in man—or he must accept the spiritual. (See Lecture V.)

A certain intensity of conception is indeed necessary if man wishes to know what is indicated for him in the progress of time, in the necessities brought about by time. Here man must go deep into world-evolution. And he must not shrink from preparing himself through the concepts of Spiritual Science for the more difficult concepts, the concepts bearing reality. For it is natural, when for the first time anyone hears the kind of things I have been saying today, for him to say: This is pure madness!—That is quite easy to understand. But, my dear friends, we can also imagine that some one may regard very much of whet has been done for years by the clever as pure madness, and accordingly hold the great majority to be mad. But then he would be able to understand why this great majority should take him—an exception—for a madman. For in a company of madmen it is not themselves they hold to be mad but the clever people.

By reason of this, man learns however to make his whole perception of the world fruitful. He learns to make fruitful just what in reality has always distinguished him from the animal. Strictly speaking man is thoroughly unobservant about his own faculties, and he will become so increasingly if he develops only intellectuality in the age of the consciousness soul. If we go back to earlier ages we frequently find among talented men that they still had a certain sense also for their surroundings. If we take the conceptions that these men of old formed about certain animals, for example, these are often full of good sense. The conceptions in modern books on Zoology from the standpoint of abstractions are often quite honest and worthy of recognition, but full of sense, my dear friends, they certainly are not. I should like to ask you, in the first place, whether among the conceptions given out today in schools there are really any capable of leading you into the actual life of the animals? Moreover do not men today notice the timid gaze with which whole herds, whole groups of animals look out into the world—the timid, intimidated gaze? O, we shall learn to see it again when through our faculty of abstraction we have been driven to the Guardian of the Threshold, and are able once more to have sympathy with the animal—not the sympathy often produced artificially but a sympathy corresponding to to an elementary inner experience. It can be said that a peculiar intimidation, as it were, a timid outlook upon the world, is widespread among all the higher animals, all the warm-blooded animals. I was walking once with a university man and at a certain place on our way we saw deer, stags, scampering away from anything and everything. This man said to me: “Something must be the reason for this; formerly men must have tormented animals, shooting them and so on, so that the animal souls have become accustomed to fear men.” But there are other things besides men that animals fear.

Thus people look for the reason why certain animals are afraid. There is no need to look for the reason, my dear friends. Fear is, of course, a quite general universal characteristic of animals. When animals are not afraid it is just because they have been trained and given different habits in some particular way. Fear is innate in the animal because the animal has in a high degree the faculty for abstraction, for abstract concepts, and lives in them. For you must realise that the world you acquire after long study, when you have learned to live in the abstract—this is the world in which the animal lives. And the world here in which man lives in his senses is for the animals, in spite of animals possessing senses, for them far more unknown than for man—and man himself has fear of the unknown. This is thoroughly in accordance with deep truth, The animal gases into the world with timidity; this has definite import. Recently I have spoken of it in an article on “The Ahrimanic and Luciferic in the Life of Man” in the recent number of the publication “Das Reich”: men are afraid in face of spiritual life; how is it that they become so afraid? It comes about by their having at the present time to meet the Guardian of the Threshold in the subconscious. There they come to the decision of which I have spoken; there they approach the animal. The animal is afraid, the animals are going through the region of fear. The connection is thus. And the condition of fear will increase more and more if men do not take serious pains really to learn about, really to take to themselves, the world they have to meet—the spiritual world.

There are only quite a few men in these days into whom something of former atavistic conceptions of world reality have penetrated through the general illusive conceptions. When the animal is observed in its whole connection with the development of nature, when its organisation is looked at in relation to the ordering of nature, what exactly is the animal? You see when the old Moon evolution was in existence, in regard to outer organisation there was still no differentiation between the higher animals and man of today. The differentiation is a product of earth evolution only. Man has gone through the normal evolution of the earth, but the animal has not; the animal dried up, as it were, during the Moon evolution. Its organisation does not fit in with earth evolution, whoever has seen into this—in modern times a few people, Hegel among them, have instinctively seen into this—whoever has done so can answer the question: what exactly is the animal in the form of its organisation? Nature becomes sick and the sickness of nature is the animal, especially the higher animal. In the animal organisation there holds sway the sickness of nature, the sickness of the whole earth. This development of disease in the earth, this unhealthy falling back into the old Moon evolution, is the higher animal nature, not so much the lower animals but those that are higher. But this also is something that, in the decisive moment of passing the Guardian of the Threshold, man meets unconsciously unless he wills to do so consciously.

And if you compare what I have just been saying with the different ways in which the American West, the European centre, and the East meet the Guardian of the Threshold of which I spoke in lectures some time ago, (see R. XLVII) if you compare these you will see how it is possible to get one's bearings where what is happening to mankind on earth is concerned, if only one will go right into these things. Then it will be grasped that in admitting these conceptions man would really arrive finally at thinking differently about himself and his relation to his fellows. Today all serious people should at some time consider the question that can arise in such a sentence as the one referred to: “It seems to me a certainty that a fearful destiny beckons to the white races unless a period of the supreme dominion of wisdom succeeds that of passion and delusive conceptions.” Where these wise conceptions are to be found, how they are to be obtained—these questions Spiritual Science is quite ready to answer (see R. 40)—And Spiritual Science, my deer friends, would like to give the answer to the most important questions of the day. And when anyone comes who feels as deeply as this man what is necessary for the times, he may be told: If you wish no longer to be afraid that a fearful destiny is beckoning to white men, then begin to observe the world and its phenomena in the way of Spiritual Science!

Erster Vortrag

Wie oft mußten wir eigentlich hier betonen, daß die geisteswissenschaftlichen Wahrheiten, wenn sie ausgesprochen werden, nach der einen oder andern Richtung hin leicht mißzuverstehen sind. Und ich habe Ihnen ja auch von den verschiedensten Gründen gesprochen, aus denen es sicher leicht ist, diese geisteswissenschaftlichen Anschauungen und Erkenntnisse zu mißkennen, mißzuverstehen. Es ist immer wieder und wiederum zu sagen, daß es natürlich ungemein leicht ist, wenn man wenig Gelegenheit gehabt hat, sich in Spirituelles zu vertiefen, da oder dort zu finden, daß die Dinge, die geisteswissenschaftlich zutage treten, nicht voll begründet sind oder dergleichen. Es ist auch ungemein leicht zu sagen: Woher weiß denn der oder jener, welcher geisteswissenschaftlich etwas mitteilt, woher weiß er das? - wenn man nicht darauf eingehen will, das zu durchschauen, was er selbst oftmals darüber vorgebracht hat, von woher er diese Dinge weiß, und man lediglich das Urteil sich bildet nach dem, was man selber weiß. Das ist ja nicht schwer zu sagen: Woher kann der das wissen? Ich weiß es doch nicht! — und dann souverän zu erklären: Dasjenige, was ich nicht weiß, das weiß auch kein anderer, da kann ein anderer höchstens doch nur noch glauben! — Aber ein solches Urteil kommt nur dadurch zustande, daß man sich eben gar nicht darauf einläßt, auf die Quellen einzugehen, aus denen insbesondere in der heutigen Zeit geisteswissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse geschöpft werden müssen.

Zu den auf diese Art zustande gekommenen Mißverständnissen kann nun auch gehören, daß man glaubt, die Geisteswissenschaft wolle in Bausch und Bogen ein Verdammungs-, ein Vernichtungsurteil aussprechen über das ganze Streben der Zeit, insofern dieses Streben von Persönlichkeiten ausgeht, die außerhalb der Geisteswissenschaft stehen. Aber auch da liegt nur ein Mißverständnis vor. Gerade der Geisteswissenschafter, der ernst und würdig den heutigen Weltzustand ins Auge faßt, wird wohl eingehen auf die Gemütslage, auf die Seelenstimmung der Zeitgenossen und wird sich die Frage vorlegen: Was geht in den Seelen der ernsten Zeitgenossen der Gegenwart vor, in der Richtung, in der eine Besserung manches Verbesserungswürdigen oder Verbesserungsnotwendigen eben gesucht werden muß? — Was aber hier vor allen Dingen als eine besonders in der Gegenwart außerordentlich markante Tatsache ins Auge gefaßt werden muß, das ist, daß gerade abgelehnt wird, manchmal von den strebendsten Zeitgenossen abgelehnt wird das konkrete Eingehen auf das Wissen von der geistigen Welt, auf die Erkenntnis von der geistigen Welt, die als eine Wirklichkeit vor den Menschen treten kann und nicht bloß als etwas, was man durch eine Summe von Begriffen erschließt. Die meisten Menschen möchten eben heute mit ihren Erfahrungen nur in der Sinneswelt stehenbleiben und eine geistige Welt höchstens zugeben als durch Begriffe, durch Ideen erschließbar. Sie möchten sich nicht anschließen an eine Forschung, welche von Mitteln spricht, in die geistige Welt erlebnisgemäß wirklich einzudringen. Dieses Ablehnen der wirklichen Geistigkeit, das ist allerdings ein charakteristischer Zug unserer Zeit; das ist ein Zug unserer Zeit, den insbesondere wir, die wir versuchen, uns auf den Boden der Geisteswissenschaft zu stellen, berücksichtigen müssen. Sonst bleiben wir doch außerhalb dieser Geisteswissenschaft stehen, uns nur auf sie einlassend als wie auf etwas, was neben andern Dingen, die in der Gegenwart zutage treten, doch auch berücksichtigt werden sollte.

Ich habe vor kurzem hier, dadurch, daß ich Ihnen die Gedanken Walther Rathenaus vorführte, gezeigt, daß der Geisteswissenschafter schon in der Lage ist, innerhalb der Grenzen, in welcher gegenwärtige Gedankenrichtungen zu würdigen sind, diese Gedankenrichtungen auch wirklich zu würdigen. Aber auffällig ist eben doch diese Zurückweisung des wirklichen geistigen Einschlages, der in unserer Zeit kommen soll. Dieses Ablehnen kann man ja auf Schritt und Tritt erfahren, wenn man aufmerksam ist auf das, was die Leute heute denken. Gewiß, es ist vor viele Menschen in der Gegenwart das Erschütternde der gegenwärtigen Weltenlage getreten; es gibt Menschen, die den ganzen Ernst der gegenwärtigen Zeit zu würdigen verstehen und auch schon seit einiger Zeit zu würdigen verstanden haben. Auch da bitte ich Sie, sich durchaus nicht der Hochnäsigkeit mancher Anthroposophen zu befleißigen und zu meinen, daß Anthroposophie als solche schon eine Anweisung gibt, besser den Ernst der Zeit zu würdigen, als ihn Leute würdigen, die außerhalb der anthroposophischen Bewegung stehen. Denn man möchte auch, daß innerhalb dieser anthroposophischen Bewegung gar mancher mehr in seinem Gemüte berührt würde von dem Entscheidenden in unserer gegenwärtigen Weltenlage. Man findet nur allzuhäufig gerade innerhalb unserer Reihen Menschen, die heute, trotz des Ernstes der Zeit, nicht auf diesen Ernst hinblicken mögen und lieber sich mit ihrer eigenen werten Persönlichkeit beschäftigen, statt einiges Interesse für die großen Fragen in sich zu erregen, die durch die Menschheit pulsieren.

Ich will bei der heutigen Betrachtung von einem Beispiel ausgehen, das mir, man kann sagen zufällig - wenn man das Wort nicht mißversteht, und wir brauchen es nicht mißzuverstehen - in die Hände gekommen ist; ein Aufsatz, der allerdings insofern heute veraltet ist, als er geschrieben wurde, während der sogenannte Krieg noch in vollem Gange war. Also der Aufsatz ist heute veraltet. Er ist auch sonst nicht gerade eindringlich, da er die meisten Dinge, die er bespricht, sehr einseitig behandelt. Allein er rührt doch her von einem Menschen das sieht man nach der ganzen Haltung, nach der ganzen Schreibweise -, der sich die ernstesten Gedanken darüber macht, was nun eigentlich geschehen soll, was die Welt von den Ereignissen zu erwarten hat. Er stellt dar, dieser Aufsatz, wie sich die Westmächte, die Mittelmächte, die Ostmächte allmählich verhalten haben innerhalb der Katastrophe der letzten Jahre. Er stellt die großen Gefahren, wenn auch einseitig, aber doch immerhin dar, die aus dieser Katastrophe heraus heute lauern und in die Zukunft hineinlauern werden. Der Verfasser hat einen gewissen Weltblick. Er betrachtet die Welt nicht nur vom Gesichtspunkt der Landesgrenzen; auch das soll ja unter den heutigen Menschen noch vorkommen, daß sie die Welt nur vom Gesichtspunkt ihrer Landesgrenzen betrachten, und wenn sie sich dann beruhigen können, daß innerhalb ihres Landes das oder jenes noch nicht stattfindet, dann sind sie unbesorgt. Der Verfasser dieses Aufsatzes sieht immerhin nicht nur den Umkreis des Kitchturmes, sondern er sieht doch etwas von der Weltperspektive. Und seine Gedanken zusammenfassend, kommt er zu einem sehr merkwürdigen Satze. Er sagt: «Daß ein furchtbares Schicksal der weißen Menschheit winkt; dies scheint mir unter allen Umständen gewiß, es sei denn, daß eine Periode supremer Weisheitsherrschaft sehr bald die der Leidenschaft und Wahnvorstellungen ablöst. Wir leben in der Tat seit lange schon in der Periode, die mit der Völkerwanderungszeit viel Ähnlichkeit hat. Das Tempo wird durch den Weltkrieg ungeheuer beschleunigt. Was den damals von außen in altes Kulturland einwandernden Germanenstämmen entspricht, sind die beträchtlichen, aufsteigenden unteren Volksschichten, die sowohl dem Blut wie dem Kulturerbe nach von den bisher herrschenden sehr verschieden sind. Daß diese Völkerwanderung» - es ist in der Tat viel besser, von einer Völkerwanderung als von einem Kriege zu sprechen - «überhaupt stattfindet, ist gut insofern, als sie Verbreitung bedingt, eine Verbreitung der Kulturbasis und eine Hebung vom Gesamtniveau. Sehr gefährlich aber ist es, wenn sie zu schnell verläuft. Und diese Gefahr wird vergrößert, je länger der Weltkrieg dauert.»

Der Aufsatz ist heute veraltet. Die Gefahr ist nicht weniger groß geworden, aber da er alle Argumente aus dem noch vorhandenen Kriegswüten ableitet, so sind seine Argumente veraltet. Uns aber muß hier insbesondere der erste Satz interessieren, den ich vorgelesen habe: «Daß ein furchtbares Schicksal der weißen Menschheit winkt, scheint mir unter allen Umständen gewiß, es sei denn, daß eine Periode supremer Weisheitsherrschaft sehr bald die der Leidenschaft und Wahnvorstellungen ablöst.» - Denn das ist in der Tat als abstrakte Wahrheit unbedingt richtig. Und wenn jemand es einmal ausspricht, daß die einzige Rettung der Menschheit in dem Sich-Hinwenden zu einer supremen Weisheitsherrschaft liegt, und nicht zu irgendwelchen andern politischen oder sozialen Quacksalbereien, dann müssen wir eine solche Tatsache, eine solche Gedankenrichtung anerkennen. Aber wir dürfen dabei eben durchaus nicht vergessen, daß gerade solche Menschen, von denen wir zugeben müssen, daß sie in allen Tiefen ihres Wesens ergriffen sind von dem Ernst der Zeitlage, daß gerade solche Menschen, wenn es sich nun darum handelt, zu sagen, worin denn die Weisheitsvorstellungen bestehen, die die alten Wahnvorstellungen ablösen sollen, daß sie dann doch gleich wieder zurückfallen auf irgendwelche, zu schönen Worten gewordene alte Wahnvorstellungen. Denn das ist gerade die Tragik, das ist das furchtbare Schicksal unserer Zeit, daß die Menschen zwar aufmerksam darauf werden: Es ist notwendig, zum Geiste sich hinzuwenden -, daß sie aber immer Furcht und Angst überkommt, wenn sie sich zum Geiste hinwenden sollen; daß sie dann gleich wieder bereit sind, nach den alten Wahnvorstellungen zu greifen, die die Menschheit hineingetrieben haben in das gegenwärtige furchtbare Schicksal. Wir brauchen ja nur das Beispiel einer sehr verbreiteten Vorstellungsrichtung zu nehmen.

Glauben Sie, wenn Sie einen richtiggehenden, sagen wir trivial, Vertreter des römisch-katholischen Kirchenbekenntnisses fragen, ob er geneigt sein würde zu glauben, daß die alten Vorstellungen in die katastrophale Zeit hineingeführt haben, daß sie von neuen abgelöst werden müssen, glauben Sie, daß er wirklich geneigt sein würde, an die Notwendigkeit einer Erneuerung derjenigen Vorstellungen zu glauben, welche die Menschheit nicht retten haben können vor dieser furchtbaren Katastrophe? Nein, er würde sagen: Wenn die Menschen nur wiederum richtig römisch-katholisch werden, dann werden sie schon glücklich werden. - Und er wird gar nicht auf den Einfall kommen, sich zu sagen, daß sie doch tausendneunhundert Jahre hindurch Zeit gehabt haben, römisch-katholisch zu sein und dennoch in die Katastrophe hineingekommen sind; daß also zum mindesten die Katastrophe lehren muß, daß man neue Impulse braucht. Das ist nur ein Beispiel für viele. Es ist überhaupt notwendig, gerade mit Bezug auf diesen Punkt rückhaltlos die Zusammenhänge, die da bestehen, vor Augen zu führen.

Es ist heute leicht, selbst für einen als echt geltenden Anhänger dieser oder jener Kirche, zu sagen: Der Haeckelismus oder der Materialismus, das ist eine Teufelssache, das muß mit Stumpf und Stiel ausgerottet werden. — Das ist das Gegenteil von dem, was die Menschen: in eine heilsame Seelenverfassung hineinführen kann. Ja, man kann wohl so sprechen, aber wenn man bei dieser Aussage bleibt und nicht die Zusammenhänge untersucht, die dabei in Betracht kommen, dann wird man unmöglich zu etwas kommen können, was der Gegenwart und noch weniger der nächsten Zukunft heilsam sein kann. Denn wenn Sie irgendeine materialistisch gefärbte Weltanschauungsempfindung aufnehmen und sich fragen: Woher kommt sie historisch? — dann werden Sie, wenn Sie wirklich Einsicht gewinnen wollen, gar nicht umhin können, sich zuletzt doch zu sagen: sie kommt ja im Grunde gerade aus der Art, das Christentum zu vertreten, wie dieses Christentum tausendneunhundert Jahre lang von den verschiedenen Konfessionen vertreten worden ist. Der Tiefersehende weiß, daß Haeckelismus ohne das vorangehende Christentum der Kirche gar nicht möglich gewesen wäre. Es gibt Leute, die sind auf dem Standpunkt der Kirche zurückgeblieben, sagen wir, wie sie im Mittelalter war; die vertreten heute noch immer die Gedanken, die die Kirche im Mittelalter gehabt hat. Andere haben diese Gedanken weitergebildet. Und diejenigen, die sie weitergebildet haben, unter denen ist zum Beispiel Ernst FHaeckel. Er ist ein gerader Abkömmling der durch die verschiedenen Kirchen jahrhundertelang gepflogenen Vorstellungen. Das ist nicht außerhalb der Kirche entstanden, das ist im tieferen Sinne durchaus innerhalb der Kirchenlehren entstandene Wahrheit. Allerdings, richtig die Zusammenhänge erkennen wird man erst dann, wenn man sich ein wenig befruchtet mit geisteswissenschaftlichen Einsichten, um diese Dinge ins Auge zu fassen.

Ich will Ihnen daher heute - obwohl vielleicht einzelne von Ihnen sagen werden, die Sache ist zu schwer, aber es darf uns nichts zu schwer sein, man soll Einsicht gewinnen -, ich möchte Ihnen heute “ zunächst einmal einen Punkt besonders auseinandersetzen.

Wenn Sie heute philosophisch angehauchte Schriften gut geschulter, zum Beispiel katholischer Gelehrter lesen, da werden Sie überall mit Bezug auf einen gewissen Punkt eine ganz bestimmte Anschauung ausgebildet finden. Und man kann sagen: Sie finden diese Anschauung ausgebildet bei den allerbesten dieser katholisch geschulten Gelehrten. — Ich möchte dabei gleich bemerken, daß ich durchaus nicht geneigt bin, die formale Schulung des katholischen Klerus zum Beispiel zu unterschätzen. Ich kenne sehr gut - ich habe das auch ausgesprochen in meinem Buch «Vom Menschenrätsel» — die bessere Schulung, die gerade manche katholischen Theologen haben, wenn sie philosophisch schreiben, gegenüber den Schreibereien der nicht durch die katholische Theologie gegangenen philosophischen Gelehrten zum Beispiel. In dieser Beziehung, muß man sagen, ist die gelehrte Literatur, die theologische Literatur der protestantischen, der reformierten Geistlichen weit zurück hinter der guten philosophischen Schulung der katholischen Theologen. Diese Leute haben durch ihre strenge Schulung eine gewisse Fähigkeit, ihre Begriffe wirklich plastisch auszubilden; sie haben — was zum Beispiel Menschen, die heute berühmt sind in der nichtkatholischen philosophischen Literatur, nicht einmal als Ahnung haben - eine gewisse Fähigkeit, einzusehen, was ein Begriff ist, was eine Idee ist und dergleichen, kurz, diese Leute haben eine gewisse Schulung. Man braucht nicht einmal ein Buch von Haeckel zu nehmen, man kann ein Buch von Eucken nehmen, um diese Begriffspurzelei festzustellen, diese schreckliche, bloß feuilletonistische Herumrederei über die wichtigsten Begriffe, oder man kann zum Beispiel ein Buch von Bergson nehmen, wo man immer das Gefühl hat: der fängt die Begriffe ab, ohne mit ihnen hantieren zu können, wie der bekannte Chinese, der sich umdrehen will und immer seinen Zopf abfängt. Dieses absolute Taumeln in der Begriffswelt, das bei diesen ungeschulten Leuten der Fall ist, das werden Sie nicht finden, wenn Sie sich einlassen auf die vom katholischen Klerus ausgehende philosophische Literatur, so daß in dieser Beziehung zum Beispiel ein Buch wie die dreibändige «Geschichte des Idealismus» von Otto Willmann, einem waschechten Katholiken, der auf jeder Seite seinen Katholizismus zur Schau trägt, weit höher steht als das meiste, was von nichtkatholischer Seite gerade heute auf philosophischem Gebiete geschrieben wird. Das alles kann man durchaus wissen und dennoch den Standpunkt einnehmen, den man eben als Geisteswissenschafter einnehmen muß. Inferiorität des Geistes mag auf diesem Gebiete anders entscheiden, mag zum Beispiel der Meinung sein: weil da gute Schulung ist, so ist sie überhaupt mehr wert. Nun, das mag sein; aber man kann durchaus sich auch der Objektivität befleißen, wenn man genötigt ist, einen bestimmten Gesichtspunkt im Leben einzunehmen.

Ein Punkt wird Ihnen in dieser gut geschulten katholischen philosophischen Literatur immer entgegentreten, ein Punkt, der auch ungemein viel Blendendes für den heutigen Denker hat; das ist der, der immer in Betracht kommt, wenn die Leute zu sprechen kommen auf den Unterschied des Menschen vom Tiere. Nicht wahr, die gewöhnlichen Haeckel-Leser und Haeckel-Bekenner, die werden ja immer darauf ausgehen, den Unterschied des Menschen vom Tier möglichst zu verwischen, möglichst den Glauben zu erwecken, daß der Mensch im ganzen nur ein gewissermaßen höher ausgebildetes Tier ist. Das tun die katholischen Gelehrten nicht, sondern sie heben immer etwas hervor, was ihnen als radikaler Unterschied erscheint zwischen dem Menschen und dem Tiere. Sie heben hervor, daß das Tier bei der gewöhnlichen Anschauung bleibt, die es gewinnt von dem Gegenstand, den es jetzt beriecht, von dem nächsten Gegenstand, den es dann beriecht oder beschaut und so weiter; daß das Tier gewissermaßen immer nur in einzelnen individuellen Vorstellungen bleibt, während der Mensch die Fähigkeit hat, abgezogene, abstrakte Begriffe sich zu bilden, die Dinge zusammenzufassen. Das ist in der Tat ein radikaler Unterschied, weil der Mensch, wenn man die Sache so auffaßt, dadurch sich wirklich radikal vom Tier unterscheidet. Das Tier, das nur die Einzelheiten ins Auge faßt, kann nicht in sich die Geistigkeit ausbilden, weil ja die abstrakten Begriffe in der Geistigkeit leben müssen. Und dadurch muß man dazu kommen, anzuerkennen, daß im Menschen diese besondere Seele lebt, die eben die abstrakten Begriffe bildet, während das Tier mit seiner besonderen Art des Innenlebens diese abstrakten Begriffe nicht bilden kann.

Wer auf diesen Punkt hin die entsprechenden katholischen Auseinandersetzungen ins Auge faßt, der sagt sich: Das ist etwas ungeheuer Bedeutsames, daß durch gute philosophische Schulung auf diesen entscheidenden, radikal entscheidenden Punkt in dem Unterschied zwischen Mensch und Tier richtig hingewiesen werden kann. Die Menschen würdigen in der Gegenwart gar nicht die Tragweite einer solchen Sache. Als zum Beispiel der Rummel dazumal losgegangen war, den Drews veranstaltet hat, diese Auseinandersetzung, ob Jesus gelebt hat oder nicht, als damals in Berlin eine große Versammlung abgehalten worden ist, wo alle möglichen und unmöglichen Leute geredet haben über das Problem: Hat Jesus gelebt? — da hat auch der katholische Theologe Wasmann darüber gesprochen, und er konnte natürlich nur Dinge sagen, die die andern als sehr rückständig betrachtet haben. Aber trotzdem dazumal eigentlich die Koryphäen, namentlich der Berliner protestantischen Theologie, geredet haben, so sind mir im Grunde genommen in den damaligen Reden doch als wirklich auf einem etwas besseren Niveau - nicht auf dem Gegenwartsniveau, aber einem etwas besseren Niveau - zwei Aussprüche beziehungsweise die Unterlagen dieser Aussprüche erschienen. Das eine war eine Ausführung, die ein — ich will damit gar nichts Schlimmes sagen, sondern eigentlich den Mann loben — gelehrter Bummler allerersten Ranges dazumal losgelassen hat. Ich glaube ihn nicht besser loben zu können, als indem ich ihn einen gelehrten Bummler allerersten Ranges nenne. Der Mann hätte nämlich durch seinen Scharfsinn und durch seine eigenartigen Kenntnisse auf den verschiedensten Gebieten, durch ein großes Wissen viel leisten können. Schon damals, als ich mit ihm verkehrte — das ist achtzehn, neunzehn Jahre her -, hatte er schon seit fünfzehn Jahren, glaube ich, an einer Revision der Logik geschrieben, und ich glaube, er muß auch seither noch daran schreiben, denn diese Revision der Logik ist mir mittlerweile nicht zu Gesicht gekommen. Er hat dazumal schon gesagt, was ganz richtig ist: die Menschen seien eigentlich ganz fürchterlich in der Gegenwart, sie seien nämlich dann ganz fürchterlich, wenn sie zu denken anfangen, denn man brauche nur zwei, drei Sätze, sei es in einem wissenschaftlichen oder in einem unwissenschaftlichen Gespräch heute zu hören, um zu beobachten, wie gleich die furchtbarste Unlogik einsetzt. Das, meinte er, was die Menschen beobachten müßten, damit sie nicht in die grauslichsten Wahnvorstellungen kommen, die heute gang und gäbe sind, das ließe sich auf eine Quartseite aufschreiben, man brauche nur diese Quartseite wirklich zu berücksichtigen. Ich weiß ja nicht, ob er diese Quattseite als Revision der Logik zustande bringen will; wie gesagt, dazumal waren es schon fünfzehn Jahre, seither sind noch achtzehn, neunzehn Jahre verflossen, ich weiß nicht, wie weit er jetzt ist mit dieser Revision der Logik. Aber ich will ihn also loben, indem ich ihn einen geistreichen, geistvollen Bummelanten nenne, weil ich damit andeuten will, daß er, wenn er nicht ein geistreicher Bummelant wäre, furchtbar viel leisten könnte. Der hat dazumal etwas sehr Schönes gesagt, er hat nämlich gesagt: Ja, die katholische Kirche mußte eines Tages hören, daß die Kometen, die ja aus Kern und Schwanz bestehen, Himmelskörper wie die andern sind und nach Gesetzen sich bewegen, wie die andern Himmelskörper auch. Als nun gar nicht mehr geleugnet werden konnte, nach den Dingen, die da einmal vorlagen, daß die Kometen auch solche Himmelskörper seien wie die andern, da entschloß sich die katholische Kirche zuzugeben, daß man auf die Kometen auch die übrigen Himmelsbahngesetze anwende; aber sie gab es zunächst nur mit Bezug auf den Kern, noch nicht mit Bezug auf den Schwanz zu. - Nun, er wollte damit symbolisch nur ausdrükken, daß die katholische Kirche in der Regel nur geneigt ist, das Notwendigste zuzugeben, wie sie ja 1827 erst die kopernikanische Weltanschauung für ihre Bekenner erlaubt hat; daß sie aber selbst dann, wenn sie das Notwendigste zugeben muß, wenigstens noch den Schwanz von der Sache zurückbehält! Das ist eine Bemerkung, von der ich fand, daß sie eigentlich ganz gut die Situation charakterisierte.

Die andere Bemerkung aber, die war getan eben gerade von dem katholischen Ameisenforscher Wasmann - er ist ein ausgezeichneter Ameisenforscher, aber er ist auch ein gut geschulter Philosoph -, der da sagte: Eigentlich, meine Herren, können Sie mich ja gar nicht verstehen, denn in Wirklichkeit wissen Sie alle nicht, wie man philosophisch denkt; derjenige, der philosophisch denkt, der redet eben nicht so wie Sie! - Und in der Tat, er hatte damit recht, es ist ganz zweifellos, daß er damit den Nagel auf den Kopf traf. Nun gibt es gerade eine kleine, nette Schrift von Wasmann über den Unterschied zwischen Mensch und Tier, welche scharf hervorhebt, was ich jetzt eben angedeutet habe: diese Fähigkeit der Menschen, wirklich in abstrakten Begriffen zu denken, die das Tier eben nicht haben soll. Das ist etwas, was außerordentlich blendend ist, weil es ja nach einer gewissen Richtung hin überzeugend ist für den, der sich nur in seinem Denken so weit geschult hat, daß er die ganze Tragkraft einer solchen Behauptung ins Auge fassen kann.

Aber nun sehen wir die Sache einmal geisteswissenschaftlich an, da wird Ihnen erst die ganze Geschichte in ihrer Bedeutung vor Augen treten. Wenn wir geisteswissenschaftlich ausgehen von den Anschauungen, von den Erfahrungen, die man darüber gewinnen kann in der spirituellen Welt, dann begreift man auf der einen Seite, daß ohne die geisteswissenschaftlichen Betrachtungen diese blendende Behauptung zustande kommen kann, von der ich eben gesprochen habe, daß sie auch eigentlich für jeden, der nicht Geisteswissenschafter werden will, gelten muß, gerade wenn er gut philosophisch geschult ist; das sieht man auf der einen Seite ein. Auf der andern Seite sieht man aber folgendes, man sieht es einfach, indem man die Dinge in der Welt betrachtet: Wenn man mit geisteswissenschaftlichen Voraussetzungen den Menschen mit dem Tiere vergleicht, dann zeigt sich, daß der Mensch zwar den Dingen der Welt gegenübertritt in einzelnen Beobachtungen und sich dann abstrakte Begriffe bildet durch allerlei Denkoperationen, in denen er zusammenfaßt, was er vereinzelt sieht. Man kann auch zugeben, daß das Tier diese Abstraktion nicht hat, daß das Tier diese Tätigkeit der Abstraktion nicht ausübt. Aber das Kuriose ist, daß die abstrakten Begriffe dem Tiere nicht fehlen, daß das Tier mit seiner Seele gerade in den allerabstraktesten Begriffen lebt, die wir Menschen uns mühevoll bilden, und daß das Tier die einzelne Anschauung nicht so hat wie wir. Was wir voraushaben, ist gerade, daß wir einen viel freieren Gebrauch der Sinne, eine ganz bestimmte Art von Zusammenwirken von Sinnen und inneren Emotionen und Willensimpulsen haben. Das haben wir vor dem Tier voraus. Aber die Sicherheit des Instinktes, welche die Tiere haben, die beruht gerade darauf, daß das Tier von vornherein mit solchen abstrakten Begriffen lebt, die wir uns erst bilden müssen. Worin wir uns von dem Tier u nterscheiden, das ist, daß sich unsere Sinne emanzipieren und freier werden im Gebrauch nach der Außenwelt zu, und daß wir auch in unsere Sinne den Willen hineingießen können, den das Tier nicht hineingießen kann. Aber das, was wir Menschen nicht haben, sondern uns erst erwerben müssen, die abstrakten Begriffe, die hat gerade das Tier, so sonderbar es einem erscheinen mag. Gewiß, es hat jedes Tier nur ein bestimmtes Gebiet, aber auf diesem Gebiete hat das Tier solche abstrakten Begriffe, so sonderbar es einem erscheinen mag. Der Mensch ist darauf angewiesen, einen, zwei, drei Hunde zu sehen; er bildet sich daraus den abstrakten Begriff «Hund». Das Tier hat auf diesem Gebiete, und zwar ganz genau, denselben abstrakten Begriff «Hund», den wir haben, es braucht sich ihn nicht zu bilden. Wir müssen uns ihn erst bilden, das Tier braucht das nicht. Aber das Tier hat nicht die Fähigkeit, den einen Hund von dem andern genau zu unterscheiden, genau zu individualisieren durch die Sinneswahrnehmungen.

Wenn wir uns nicht die Fähigkeit erwerben, durch Geisteswissenschaft auf den wahren Tatbestand der Wirklichkeit einzugehen, so täuschen wir uns in einer gewissen Beziehung über das Allerwesentlichste. Wir glauben, weil wir Menschen die Fähigkeit entwickeln müssen, abstrakte Begriffe zu bilden, so unterscheiden wir uns durch die abstrakten Begriffe vom Tiere, das diese Fähigkeit nicht besitzt. Aber das Tier braucht diese Fähigkeit gar nicht, weil es die abstrakten Begriffe von vornherein hat. Das Tier hat eine ganz andere Art von Sinnesanschauung als wir Menschen. Gerade die äußere Sinnesanschauung ist ganz verschieden.

In dieser Beziehung ist sogar eine sehr tief eingreifende Umwandlung in den menschlichen Vorstellungen notwendig. Denn über allerlei naturwissenschaftliche Begriffe, die heute schon populär geworden sind, haben sich ja die Menschen unterrichtet. Entweder haben sie sie in einer gewissen Schule, durch direkten Unterricht lernen können, oder sie haben sich unterrichtet durch jenes Abwaschwasser — ich wollte sagen durch jene Zeitungslektüre -, womit heute die naturwissenschaftlichen Vorstellungen in alle Welt hinausströmen. Aber die Menschen sind beherrscht von diesen naturwissenschaftlichen Vorstellungen. Mit Bezug auf das, was ich Ihnen eben angedeutet habe, da sind die Menschen ganz tief beherrscht von einem, fast könnte man sagen, instinktiven Hang zu glauben, daß das Tier wirklich in der Umgebung dasselbe sieht wie der Mensch. Wenn er mit seinem Hunde spazieren geht, so hat er den instinktiven Glauben, daß der Hund die Welt so sieht, wie er sie sieht, daß er ebenso das Gras farbig, den Weizen gefärbt, die Steine gefärbt sieht, wie er selber. Und dann hat er, wenn er einigermaßen denken kann, auch noch den Glauben: er selber kann abstrahieren und hat daher abstrakte Begriffe, sein Hund aber abstrahiert nicht und so weiter. Und dennoch ist es nicht so. Dieser Hund, der neben uns geht, lebt geradeso in den abstrakten Begriffen wie wir. Ja, er lebt sogar intensiver darinnen als wir. Er braucht sie auch gar nicht zu erwerben, sondern er lebt vom Anfange an intensiv darinnen. Aber die äußere Anschauung hat er nicht so, die gibt ihm ein ganz anderes Bild. Sie brauchen nur aufmerksam zu sein auf gewisse Beobachtungen, die man im Leben machen kann. Allerdings, man nimmt die Dinge nicht immer ernst genug. Ich könnte Ihnen eine ganze Anzahl von Beispielen anführen, aus denen Ihnen hervorgehen würde, wie der Mensch rein instinktiv in dieser Richtung verkehrt denkt. Zum Beispiel ging ich einmal, es war in Zürich, glaube ich, von einem Vortrag, der an einem Zweigabend gehalten worden war, auf die Straße. Da wartete ein Kutscher, und das Pferd wollte nicht recht gehen, machte Miene, ein bißchen zu scheuen. Da sagte der Kutscher: Das fürchtet sich vor seinem Schatten. - Er sah natürlich den Schatten des Pferdes, den die Laterne auf die Wand warf, und deshalb setzte er voraus, daß das Pferd ganz genau ebenso diesen Schatten sehe wie er. Er hatte natürlich keine Ahnung davon, was, wenn ich sagen darf, in der Seele des Pferdes und was in seiner Seele vorgeht. Er sieht den Schatten des Pferdes, aber das Pferd hat ein lebendiges Gefühl vom Sein in jenem Raumteil des Ätherleibes, wo sich der Schatten bildet. Das ist ein ganz anderer Vorgang, in bezug auf die innere Anschauung ein ganz anderer Vorgang.

Da haben Sie das Aufeinanderprallen der bisherigen Denkweise bis in die elementarsten, instinktivsten Anschauungen naiver Menschen hinein mit dem, was geisteswissenschaftlich neu in die Menschen hineinkommen muß. Sie werden allerdings erst mit allem Ernste würdigen müssen, was hier eigentlich zugrunde liegt. Denn mit Bezug auf solche Dinge unterscheidet sich der ärgste Materialismus eines Vog/ oder Moleschoft oder Clifford oder Spencer und so weiter viel weniger von dem hergebrachten Bekenntnisbegriffe der einzelnen Konfessionen, als sich dasjenige unterscheidet, was als eine neue Denkweise der Geisteswissenschaft zugrunde liegend von diesen Bekenntnissen sich unterscheiden muß. Denn eigentlich denken gewisse Materialisten doch heute: Der Mensch unterscheidet sich nicht sehr vom Tiere. Sie haben auch einmal etwas davon läuten gehört, wenn auch nicht die Glocken zusammenschlagen vernommen, daß der Mensch sich abstrakte Begriffe machen kann, die doch etwas anderes sind als die gewöhnlichen bloß sinnlichen Vorstellungen; aber sie sagen sich: Abstrakte Begriffe, das ist vielleicht doch nicht so etwas Wichtiges, so etwas Wesentliches, also im Grunde genommen unterscheidet sich der Mensch nicht von dem Tiere. — Der gesamte Materialismus der Gegenwart ist eigentlich eine Schöpfung der Kirchenbekenntnisse. Das muß man nur wirklich ganz ernsthaftig ins Auge fassen, dann wird man sehen, daß eine Erneuerung der Vorstellungsart der Menschenseelen hier in Betracht kommt, wenn man nicht dabei stehenbleiben will: Nun wiederum zurück zu den alten Vorstellungen, dann wird es schon gut gehen!

Man kann aber nicht etwa sagen, daß die Menschen es einfach unterlassen könnten, sich nun zu wirklichem Geistesleben hinzuwenden, und es auch so weitergehen könnte! Nein, diejenigen haben schon recht, die da sagen, «...daß ein furchtbares Schicksal der weiBen Menschheit winkt, scheint mir unter allen Umständen gewiß, es sei denn, daß eine Periode supremer Weisheitsherrschaft sehr bald die der Leidenschaft und Wahnvorstellungen ablöst». Nur sollten solche Leute auch einsehen, daß zu den Wahnvotrstellungen der größte Teil der wissenschaftlichen Vorstellungen über die Welt heute gehört. Das sollte eben durchaus eingesehen werden. Die Menschheit ist in ihrer Entwickelungsströmung an dem Punkt angekommen, den wir oftmals dadurch charakterisieren, daß wir sagen: Seit dem 15. Jahrhundert ist die Menschheit im Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele. Und diese Entwickelung der Bewußtseinsseele findet so statt, wie ich es eben öfter charakterisiert habe. Sehen wir einmal auf ein sehr wichtiges Charakteristikon mit Bezug auf die Entwickelung der Bewußtseinsseele hin.

Ich habe Ihnen schon das letzte Mal angedeutet: Alles was der Geistesforscher erkennt, das heißt ins Bewußtsein heraufhebt gerade von solchen Dingen, die in der Entwickelung der Menschheit liegen, das geht, auch wenn es nicht erkannt wird, bei den Menschen im Unterbewußtsein vor sich. Die Menschheit geht einmal, indem sie nach der Zukunft hin sich entwickelt, durch gewisse Erfahrungen hindurch. Sie geht unbewußt durch diese Erfahrungen hindurch, wenn sie es nicht vorzieht, sie ins Bewußtsein heraufzubringen, was eben im Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseelenentwickelung geschehen sollte. Aber gerade in diesem Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseelenentwikkelung wird heute noch manches, was an den Menschen im Unterbewußtsein herantritt, zurückgestoßen.