The Mysteries of Light, of Space, and of the Earth

GA 194

12 December 1919, Dornach

I. The Dualism in the Life of the Present Time

Since our departure has been deferred for a few days more, I shall be able to speak to you here today, tomorrow, and the next day. This affords me special satisfaction, because a number of friends have arrived from England, and in this way I shall be able to address them also before leaving.

These friends will have seen that our Goetheanum Building has progressed during the difficult war years. Up to the present time it could not be completed, it is true, and even now we can hardly predict definitely when it will be finished. But what already exists will show you from what spiritual foundations this building has grown, and how it is connected with the spiritual movement represented here. Hence, on this occasion, when after a long interval I am able to speak again to quite a large number of our English friends, it will be permissible to take our building itself as the starting point of our considerations. Then in the two succeeding days we shall be able to link to what can be said regarding the building a few other things whose presentation at this time may be considered important.

To anyone who observes our building—whose idea at least can now be grasped—the peculiar relation of this building to our spiritual movement will at once occur; and he will get an impression—perhaps just from the building itself, this representation of our spiritual movement—of the purpose of this movement. Suppose that any kind of sectarian movement, no matter how extensive, had felt it necessary to build such a house for its gatherings, what would have happened? Well, according to the needs of this society or association, a more or less large building would have been erected in this or that style of architecture; and perhaps you would have found from some more or less symbolical figures in the interior an indication of what was to take place in it. And perhaps you would have found also a picture here or there indicating what was to be taught or otherwise presented in this building. You will have noticed that nothing of this sort has been done for this Goetheanum. This building has not only been put here externally for the use of the Anthroposophical Movement, or of the Anthroposophical Society, but just as it stands there, in all its details, it is born out of that which our movement purposes to represent before the world, spiritually and otherwise. This movement could not be satisfied to erect a house in just any style of architecture, but as soon as the possibility arose of building such a home of our own, the movement felt impelled to find a style of its own, growing out of the principles of our spiritual science, a style in whose every detail is expressed that which flows through this our movement as spiritual substance. It would have been unthinkable, for example, to have placed here for this movement of ours just any sort of building, in any style of architecture. From this one should at once conclude how remote is the aim of this movement from any kind of sectarian or similar movement, however widespread. It was our task not merely to build a house, but to find a style of architecture which expresses the very same things that are uttered in every word and sentence of our anthroposophically-orientated spiritual science.1Rudolf Steiner, Ways to a New Style in Architecture, and Der Dornacher Bau als Wahrzeichen kunstlerischer Umwandlungs-Impulse (not yet translated).

Indeed, I am convinced that if anyone will sufficiently enter into what can be felt in the forms of this building (observe that I say “can be felt,” not can be speculated about),—he who can feel this will be able to read from his experience of the forms what is otherwise expressed by the word.

This is no externality; it is something which is most inwardly connected with the entire conception of this spiritual movement. This movement purposes to be something different from those spiritual movements, in particular, which have gradually arisen in humanity since the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean cultural period—let us say, since the middle of the 15th century.

And there is an underlying conviction that now, in this present time, it is necessary to introduce into the evolution of humanity something different from anything that has thus far entered into it since the middle of the 15th century. The most characteristic phenomenon in all that has occurred in civilized humanity in the last three or four centuries seems to me to be the following: The external practical life, which of course has become largely mechanized, constitutes today, almost universally, a kingdom in itself,—a kingdom which is claimed as a sort of monopoly by those who imagine themselves to be the practical people of life. Side by side with this external procedure, which has appeared in all realms of the so-called practical life, we have a number of spiritual views, world conceptions, philosophies, or whatever you wish to call them, which in reality have gradually become unrelated to life, but especially so during the last three or four centuries. These views in what they give to man of feelings, sensations, hover above the real activities of life, so to speak. And so crass is the difference between these two currents that we can say: In our day the time has come when they no longer understand each other at all, or perhaps it is better to say, when they find no points of contact for reciprocal influence. Today we maintain our factories, we make our trains run on the tracks, we send our steamboats over the seas, we keep our telegraphs and telephones busy—and we do it all by allowing the mechanism of life to take its course automatically, so to speak, and by letting ourselves become harnessed to this mechanism. And at the same time we preach. We really preach a great deal. The old church denominations preach in the churches, the politicians preach in the parliaments, the various agencies in different fields speak of the claims of the proletariat, of the claims of women. Much, much preaching is done; and the substance of this preaching, in the sense of the present-day human consciousness, is certainly something with distinct purpose. But if we were to ask ourselves where the bridge is between what we preach and what our external life produces in practice, and if we wished to answer honestly and truthfully, we should find that the trend of the present time does not yield a correct answer.

I mention the following phenomenon only because what I wish to call to your attention appears most clearly through this phenomenon: You know, of course, that besides all the rest of the opportunities to preach, there are in our day all kinds of secret societies. Suppose we take from among these societies—let us say—the ordinary Freemasons' Lodges, whether those with the lowest degrees or with the highest. There we find a symbolism, a symbolism of triangle, circle, square, and the like. We even find an expression frequently used in such connections: The Master-Builder of all worlds.

What is all this? Well, if we go back to the 9th, 10th, 11th centuries and look at the civilized world within which these secret societies, these Masonic Lodges, were spread out as the cream of civilization, we find that all the instruments, which today lie as symbols upon the altars of these Masonic Lodges, were employed for house-building and church-building. There were squares, circles, compasses, levels and plummets, and these were employed in external life. In the Masonic Lodges today speeches are delivered concerning these things that have completely lost their connection with practical life; all kinds of beautiful things are said about them, which are without question very beautiful, but which are completely foreign to external life, to life as it is lived. We have come to have ideas, thought-forms, which lack the impulsive force to lay hold upon life. It has gradually become the custom to work from Monday to Saturday and to listen to a sermon on Sunday, but these two things have nothing to do with each other. And when we preach, we often use as symbols for the beautiful, the true, even the virtuous, things which in olden times were intimately connected with the external life, but which now have no relation to it. Indeed we have gone so far as to believe that the more remote from life our sermons are the higher they will rise into the spiritual worlds. The ordinary secular world is considered something inferior. And today we encounter all kinds of demands which rise up from the depths of humanity, but we do not really understand the nature of these demands. For what connection is there between these society sermons, delivered in more or less beautiful rooms, about the goodness of man, about—well, let us say—about loving all men without distinction of race, nationality, etc., even color—what connection is there between these sermons and what occurs externally, what we take part in and further when we clip our coupons and have our dividends paid to us by the banks, which in that way provide for the external life? Indeed, in so doing we use entirely different principles from those of which we speak in our rooms as the principles of good men. For example, we found Theosophical Societies in which we speak emphatically of the brotherhood of all men, but in what we say there is not the slightest impulsive force to control in any way what also occurs through us when we clip our coupons; for when we clip coupons we set in motion a whole series of political-economic events. Our life is completely divided into these two separate streams.

Thus, it may occur—I will give you, not a classroom illustration, but an example from life—it may occur—it even has occurred—that a lady seeks me out and says: “Do you know, somebody came here and demanded a contribution from me, which would then be used to aid people who drink alcohol. As a Theosophist I cannot do that, can I?” That is what the lady said, and I could only reply: “You see, you live from your investments; that being the case, do you know how many breweries are established and maintained with your money?” Concerning what is really involved here the important point is not that on the one hand we preach to the sensuous gratification of our souls, and on the other conduct ourselves according to the inevitable demands of the life-routine that has developed through the last three or four centuries. And few people are particularly inclined to go into this fundamental problem of the present time. Why is this? It is because this dualism between the external life and our so-called spiritual strivings has really invaded life, and it has become very strong in the last three or four centuries. Most people today when speaking of the spirit mean something entirely abstract, foreign to the world, not something which has the power to lay hold of daily life.

The question, the problem, which is indicated here must be attacked at its roots. If we here on this hill had acted in the spirit of these tendencies of the last three or four hundred years, then we would have employed any kind of architect, perhaps a celebrated architect, and have had a beautiful building erected here, which certainly could have been very beautiful in any architectural style. But that was entirely out of the question; for then, when we entered this building, we should have been surrounded by all kinds of beauty of this style or that, and we should have said in it things corresponding to the building—indeed, in about the same way that all the beautiful speeches made today correspond with the external life which people lead. That could not be, because the spiritual science which intends to be anthroposophically orientated had no such purpose. From the beginning its aim was different. It intended to avoid setting up the old false contrast between spirit and matter, whereby spirit is treated in the abstract, and has no possibility of penetrating into the essence and activity of matter. When do we speak legitimately of the spirit? When do we speak truly of the spirit? We speak truly of the spirit, we are justified in speaking of the spirit, only when we mean the spirit as creator of the material. The worst kind of talk about the spirit—even though this talk is often looked upon today as very beautiful—is that which treats the spirit as though it dwelt in Utopia, as if this spirit should not be touched at all by the material. No; when we speak of the spirit, we must mean the spirit that has the power to plunge down directly into the material. And when we speak of spiritual science, this must he conceived not only as merely rising above nature, but as being at the same time valid natural science. When we speak of the spirit, we must mean the spirit with which the human being can so unite himself as to enable this spirit, through man's mediation, to weave itself even into the social life. A spirit of which one speaks only in the drawing room, which one would like to please by goodness and brotherly love, but a spirit that has no intention of immersing itself in our everyday life—such a spirit is not the true spirit, but a human abstraction; and worship of such a spirit is not worship of the real spirit, but is precisely the final emanation of materialism.

Hence we had to erect a building which, in all its details, is conceived, is envisioned, as arising out of that which lives in other ways as well in our anthroposophically-orientated spiritual science. And with this is also connected the fact that in this difficult time a treatment of the social question has arisen from this spiritual science, which does not intend to linger in Utopia, but which from the beginning of its activity intended to be concerned with life; which intended to be the very opposite of every kind of sectarianism; which intended to decipher that which lies in the great demands of the time and to serve these demands.

Certainly in this building much has not succeeded, but today the matter of importance is really not that everything shall be immediately successful, but that in certain things a beginning, a necessary beginning be made; and at least this essential beginning seems to me to have been made with this building. And so, when it shall some day be finished, we shall accomplish what we shall have to accomplish, not within something which would surround us like strange walls; but just as the nutshell belongs to the nut-fruit and is entirely adapted in its form to this nut-fruit, so will each single line, each single form and color of this building be adapted to that which flows through our spiritual movement.

It is necessary that at the present time at least a few people should comprehend what is intended here, for this act of will is the important matter.

I must go back once more to various characteristics which have become evident in the evolution of civilized humanity in the last three or four centuries. We have in this evolution of civilized humanity phenomena which express for us most characteristically the deeper foundations of that which leads ad absurdum in the life of our present humanity; for it is a case of leading ad absurdum. It is a fact that today a large proportion of human souls are actually asleep, are really sleeping. If one is in a place where certain things which today play their role—I might say, as actual counterparts of all civilized life—if one is in a place where these counterparts do not actually appear before one's eyes but still play a part, as they do in numerous regions of the present civilized world, and are significant and symptomatic of that which must spread more and more—then one will find that the souls of the people are outside of, beyond, the most important events of the time; people live along in their everyday lives without keeping clearly in mind what is actually going on in our time, so long as they are not directly touched by these events. It is also true, however, that the real impulses of these events be in the depths of the subconscious or unconscious soul-life of man.

Underlying the dualism I have mentioned there is today another, the dualism which is expressed—I would cite a characteristic example—in Milton's Paradise Lost. But that is only an external symptom of something that permeates all modern thinking, sensibility, feeling, and willing. We have in the modern human consciousness the feeling of a contrast between heaven and hell; others call it spirit and matter. Fundamentally there are only differences of degree between the heaven and hell of the peasant on the land, and the matter and spirit of the so-called enlightened philosopher of our day; the real underlying thought-impulses are exactly the same. The actual contrast is between God and devil, between paradise and hell. People are certain that paradise is good, and it is dreadful that men have left it; paradise is something that is lost; it must be sought again—and the devil is a terrible adversary, who opposes all those powers connected with the concept of paradise. People who have no inkling of the soul-contrasts to be found even in the outermost fringes of our social extremes and social demands cannot possibly imagine what range there is in this dualism between heaven and hell, or between the lost paradise and the earth. For—we must really say very paradoxical things today, if we wish to speak the truth (actually about many things we can scarcely speak the truth today without its often appearing to our contemporaries as madness—but just as in the Pauline sense the wisdom of man may be foolishness before God, so might the wisdom of the men of today, or their madness, also be madness in the opinion of future humanity)—people have gradually dreamed themselves into this contrast between the earth and paradise, and they connect the latter with what is to be striven for as the actual human-divine, not knowing that striving toward this condition of paradise is just as bad for a man, if he intends to have it forthwith, as striving for the opposite would be. For if our concept of the structure of the world resembles that which underlies Milton's Paradise Lost, then we change the name of a power harmful to humanity when it is sought one-sidedly, to that of a divinely good power, and we oppose to it a contrast which is not a true contrast: namely, the devil, that in human nature which resists the good.

The protest against this view is to be expressed in that group which is to be erected in the east part of our building, a group of wood, 9 ½ meters high, in which, or by means of which, instead of the Luciferic contrast between God and the devil, is placed what must form the basis of the human consciousness of the future: the trinity consisting of the Luciferic, of what pertains to the Christ, and of the Ahrimanic.

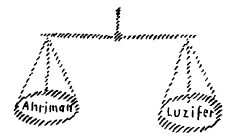

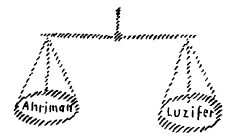

Modern civilization has so little consciousness of the mystery which underlies this, that we may say the following: For certain reasons, about which I shall perhaps speak here again, we have called this building Goetheanum, as resting upon the Goethean views of art and knowledge. But at the same time it must be said just here that in the contrast which Goethe has set up in his Faust between the good powers and Mephistopheles there exists the same error as in Milton's Paradise Lost: namely, on the one side the good powers, on the other the evil power, Mephistopheles. In this Mephistopheles Goethe has thrown together in disordered confusion the Luciferic on the one hand and the Ahrimanic on the other; so that in the Goethean figure, Mephistopheles, for him who sees through the matter, two spiritual individualities are commingled, inorganically mixed up. Man must recognize that his true nature can lie expressed only by the picture of equilibrium,—that on the one side he is tempted to soar beyond his head, as it were, to soar into the fantastic, the ecstatic, the falsely mystical, into all that is fanciful: that is the one power. The other is that which draws man down, as it were, into the materialistic, into the prosaic, the arid, and so on, We understand man only when we perceive him in accordance with his nature, as striving for balance between the Ahrimanic, on one arm of the scales, let us say, and on the other the Luciferic. Man has constantly to strive for the state of balance between these two powers: the one which would like to lead him out beyond himself, and the other tending to drag him down beneath himself. Now modern spiritual civilization has confused the fantastic, the ecstatic quality of the Luciferic with the divine; so that in what is described as paradise, actually the description of the Luciferic is presented, and the frightful error is committed of confusing the Luciferic and the divine—because it is not understood that the thing of importance is to preserve the state of balance between two powers pulling man toward the one side or toward the other.

This fact had first to be brought to light. If man is to strive toward what is called Christian—by which, however, many strange things are often understood today—then he must know clearly that this effort can be made only at the point of balance between the Luciferic and the Ahrimanic; and that especially the last three or four centuries have so largely eliminated the knowledge of the real human being that little is known of equilibrium; the Luciferic has been renamed the divine in Paradise Lost, and a contrast is made between it and the Ahrimanic, which is no longer Ahriman, but which has become the modern devil, or modern matter, or something of the kind. This dualism, which in reality is a dualism between Lucifer and Ahriman, haunts the consciousness of modern humanity as the contrast between God and the devil; and Paradise Lost would really have to be conceived as a description of the lost Luciferic kingdom—it is just renamed.

Thus emphatically must we call attention to the spirit of modern civilization, because it is necessary for humanity to understand clearly how it has come upon a declivitous path (it is a historical necessity, but necessities exist, among other things, to be comprehended), and, as I have said, that it can again begin to ascend only through the most radical corrective. In our time people often take a description of the spiritual world to be a representation of something super-sensible but not existing here on our earth. They would like to escape from the earth environment by means of a spiritual view. They do not know that when man flees into an abstract spiritual kingdom, he does not find the spirit at all, but the Luciferic region. And much that today calls itself Mysticism or Theosophy is a quest for the Luciferic region; for mere knowledge of the spirit cannot form the basis of man's present-day spiritual striving, because it is in keeping with the spiritual endeavor of our time to perceive the relation between the spiritual worlds and the world into which we are born and in which we must live between birth and death.

Especially when we direct our gaze toward spiritual worlds should this question concern us: Why are we born out of the spiritual worlds into this physical world? Well, we are born into this physical world (tomorrow and next day I will develop in greater detail what I shall sketch today)—we are born into this physical world because here on this earth there are things to be learned, things to be experienced, which cannot be experienced in the spiritual worlds; but in order to experience these things we must descend into this physical world, and from this world we must carry up into the spiritual worlds the results of this experience. In order to attain that, however, we must really plunge down into this physical world; our very spirit in its quest for knowledge must dive down into this physical world. For the sake of the spiritual world, we must immerse ourselves in this physical world.

In order to say what I wish to express, let us take—well, suppose we say a normal man of the present time, an average man, who sleeps his requisite number of hours, eats three meals a day, and so on, and who also has spiritual interests, even lofty spiritual interests. Because he has spiritual interests he becomes a member, let us say, of a Theosophical Society, and there does everything possible to learn what takes place in the spiritual worlds. Let us consider such a man, one who has at his fingertips, so to speak, all that is written in the theosophical literature of the day, but who otherwise lives according to the usual customs. Observe this man. What does all the knowledge signify which he acquires with his higher spiritual interests? It signifies something which here upon earth can offer him some inner soul gratification, a sort of real Luciferic orgy, even though it is a sophisticated, a refined soul-orgy. Nothing of this is carried through the gate of death, nothing of it whatever is carried through the gate of death; for among such people—and they are very numerous—there may be some who, in spite of having at their finger-tips what an astral body is, an etheric body, and so on, have no inkling of what takes place when a candle burns; they have no idea what magic acts are performed to run the tramway outside; they travel on it but they know nothing about it. But still more: they do indeed have at their finger-tips what the astral body is, the etheric body, karma, reincarnation,—but they have no notion of what is said today in the gatherings of the proletarians, for example, or what their aims are; it does not interest them. They are interested only in the appearance of the etheric body or astral body—they are not interested in the course pursued by capital since the beginning of the 19th century, when it became the actual ruling power. Knowing about the etheric body, the astral body, is of no use when people are dead! From an actual knowledge of the spiritual world just that must be said. This spiritual knowledge has value only when it becomes the instrument for plunging down into the material life, and for absorbing in the material life what cannot be obtained in the spiritual worlds themselves, but must he carried there.

Today we have a physical science which is taught in its most diversified branches in our universities. Experiments are made, research is carried on, and so forth, and physical science comes into being. With this modern science we develop our technical arts; we even heal people with it today—we do everything imaginable. Side by side with this physical science there are the religions denominations. But I ask you, have you ever taken cognizance of the content of the usual Sunday sermons in which, for example, the Kingdom of Christ is spoken of, and so on? What relation is there between modern science and what is said in these sermons? For the most part, none whatever; the two things go on separate paths. The people one group believe themselves capable of speaking about God and the Holy Spirit and all kinds of things—in abstract forms. Even though they claim to feel these things, still they present abstract views about them. The others speak of a nature devoid of spirit; and no bridge is being built between them, Then we have in modern times even all kinds of theosophical views, mystical views. Well, these mystical views tell of everything imaginable which is remote from life, but they say nothing of human life, because they have not the force to dive down into human life. I should just like to ask whether a Creator of Worlds would be spoken of in the right sense if one thought of him as a very interesting and lovely spirit, to be sure, but as being quite incapable of creating worlds? The spiritual powers that are frequently talked about today never could have been world-creators; for the thoughts we develop about them are not even capable of entering into our knowledge of nature or our knowledge of man's social life.

Perhaps I may without being immodest illustrate what I mean with an example. In one of my recent books, Riddles of the Soul, I have brought to your attention—and I have often mentioned it in oral lectures—what nonsense is taught in the present-day physiology,—that is, one of our physical sciences: the nonsense that there are two kinds of nerves in man, the motor nerves, which underlie the will, and the sensory nerves, which underlie perceptions and sensations. Since telegraphy has become known we have this illustration from it: from the eye the nerve goes to the central organ, then from the central organ it goes out to one of the members; we see something make a movement, as a limb—there goes the telegraph wire from this organ, the eye, to the central organ; that causes activity in the motor nerve, then the movement is carried out. We permit science to teach this nonsense. We must permit it to be taught, because in our abstract spiritual view we speak of every sort of thing, but do not develop such thoughts as are able positively to gear into the machinery of nature. We have not the strength in our spiritual views to develop a knowledge about nature itself. The fact is, there is no difference between motor nerves and sensory nerves, but what we call voluntary nerves are also sensory nerves. The only reason for their existence is that we may be aware of our own members when movements are to be executed. The hackneyed illustration of tubes proves exactly the opposite of what is intended to be proved. I will not go into it further because you have not the requisite knowledge of physiology. I should very much like some time to discuss these things in a group of people versed in physiology and biology; but here I wish only to call your attention to the fact that we have on the one hand a science of the physical world, and on the other a discoursing and preaching about spiritual worlds which does not penetrate any of the real worlds of nature that lie before us. But we need a knowledge of the spirit strong enough to become at the same time a physical science. We shall attain that only when we take account of the intention which I wished to bring to your notice today. If we had intended to found a sectarian movement which, like others, has merely some kind of dogmatic opinion about the divine and the spiritual, and which needs a building, we should have erected any kind of a building, or had it erected. Since we did not wish that, but wished rather to indicate, even in this external action, that we intend to plunge down into life, we had to erect this building entirely out of the will of spiritual science itself. [Cf. Rudolf Steiner, Der Baugedanke des Goetheanum (with 104 illustrations), Not the yet translated.] And in the details of this building it will some day be seen that actually important principles—which today are placed in a very false light under the influence of the two dualisms mentioned—can be established on their sound foundation.

I should like to call your attention today to just one more thing. Observe the seven successive columns which stand on each side of our main building. There you have capitals above, pedestals below. They are not alike, but each is developed from the one preceding it; so that you get a perception of the second capital when you immerse yourself deeply in the first and its forms, when you cause the idea of metamorphosis to become alive, as something organic, and really have such a living thought that it is not abstract, but follows the laws of growth. Then you can see the second capital develop out of the first, the third out of the second, the fourth out of the third, and so on to the seventh. Thus the effort has been made to develop in living metamorphosis one capital, one part of an architrave, and so on, from another, to imitate that creative activity that exists as spiritual creative activity in nature itself, when nature causes one form to come forth from another. I have the feeling that not a single capital could be other than it now is.

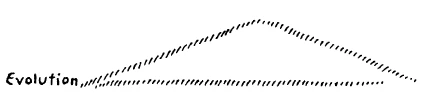

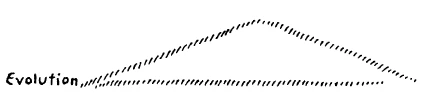

But here something very strange has resulted. When people speak today of evolution, they often say: development, development, evolution, first the imperfect, then the more nearly perfect, the more differentiated, and so on; and the more nearly perfect things always become at the same time more complicated. This I could not bear out when I let the seven capitals originate one from another according to metamorphosis, for when I came to the fourth capital, and had then to develop the next, the fifth, which should be more nearly perfect than the fourth, this fourth revealed itself to me as the most complicated. That is to say, when I did not merely pursue abstract things in thought, like a Haeckel or a Darwin, but when I had to make the forms so that each one came forth from the preceding—just as in nature itself one form after another emerges from the vital forces—then I was compelled to make the fifth form more elaborate in its surfaces, it is true, than the fourth, but the entire form became simpler, not more complicated. And the sixth became simpler yet, and the seventh still more so. Thus I realized that evolution is not a progression to ever greater and greater differentiation, but that evolution is first an ascent to a higher point, and after having reached this point is then a descent to more and more simple forms.

That resulted entirely from the work itself; and I could see that this principle of evolution manifested in artistic work is the same as the principle of evolution in nature. For if you consider the human eye, it is certainly more nearly perfect than the eyes of some animals; but the eyes of some animals are more complicated than the human eye. They have, for example, enclosed within them certain blood-filled organs—the metasternum, the fan—which do not exist in human beings; they have dissolved, as it were. The human eye is simplified in comparison with the forms of some animal eyes. If we study the development of the eye, we find that it is at first primitive, simple, then it becomes more and more complicated; but then it is again simplified, and the most nearly perfect is not the most complicated, but is, rather, a simpler form than the one to be found midway.

And it was essential to do likewise when developing artistically something which an inner necessity enjoined. The aim here was not research, but union with the vital forces themselves. And here in this building we strove to fashion the forms in such a way that in this fashioning dwell the same forces which underlie nature as the spirit of nature. A spirit is sought which is actually creative, a spirit which lives in what is produced in the world, and does not merely preach. That is the essential thing. That is also the reason why many a member here had to be severely rebuked for wanting our building fitted out with all sorts of symbols and the like. There is not a single symbol in the building, but all are forms which imitate the creative activity of the spirit in nature itself.

Thus there has been the beginning of an act of will which must find its continuation; and it is desirable that this very phase of the matter be understood—that it be understood how the springs of human intention, of human creativeness, which are necessary for modern humanity in all realms, are really to be sought. We live today in the midst of demands; but they are all individual demands springing from the various spheres of life; and we need also coordination. This cannot come from something which merely hovers in the environment of external visible existence; for something super-perceptible underlies all that is visible, and in our time this must be comprehended. I would say that close attention should be given to the things that are happening today, and the idea that the old is collapsing will by no means be found so absurd—but then there must be something to take its place! To be reconciled to this thought there is nevertheless needed a certain courage, which is not acquired in external life, but must be achieved in the innermost self.

I would not define this courage, but would characterize it. The sleeping souls of our time will certainly be overjoyed if someone appears somewhere who can paint as Raphael or Leonardo did. That is comprehensible. But today we must have the courage to say that only he has a right to admire Raphael and Leonardo who knows that in our day one cannot and must not create as Raphael and Leonardo did. Finally, to make this clear, we can say something very philistine: that only he has a right today to appreciate the spiritual range of the Pythagorean theorem who does not believe that this theorem is to be discovered today for the first time. Everything has its time, and things must be comprehended by means of the concrete time in which they occur.

As a matter of fact, more is needed today than many people are willing to bring forth, even when they join some kind of spiritual movement. We need today the knowledge that we have to face a renewal of the life of human evolution. It is cheap to say that our age is a time of transition. Any age is a time of transition; only it is important to know what is in transition. So I would not voice the triviality that one age is a time of transition, but I want to say something else: It is continually being said that nature and life make no leaps. A man considers himself very wise when he says: “Successive development; leaps never!” Well, nature is continually making leaps: it fashions step by step the green leaf, it transforms this to the calyx-leaf, which is of another kind, to the colored petal, to the stamen, and to the pistil. Nature makes frequent leaps when it fashions a single creation—the larger life makes constant revolutions. We see how in human life entirely new conditions appear with the change of teeth, how entirely new conditions appear with puberty; and if man's present capacity for observation were not so crude a third epoch in human life could be perceived about the twentieth year, and so on, and so on.

But history itself is also an organism, and such leaps take place in it; only they are not observed. People of today have no conception what a significant leap occurred at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, or more properly, in the middle of the 15th century. And what was introduced at that time is pressing toward fulfilment in the middle of our century. And it is truly no weaving of idle fancies but exact truth when we say that the events which so agitate humanity, and which recently have reached such a culmination, disclose themselves as a trend toward something in preparation, which is about to break violently into human evolution in the middle of this century. Anyone must understand these things who does not wish, out of some kind of arbitrariness, to set up ideals for human evolution, but who wills to find, among the creating—forces of the world, spiritual science, which can then enter into life.

Neunter Vortrag

Da sich unsere Abreise noch um einige Tage verzögert hat, bin ich heute, morgen und übermorgen in der Lage, hier zu Ihnen zu sprechen. Es gereicht mir das zur besonderen Befriedigung, da eine Anzahl Freunde aus England hier angekommen sind, zu denen ich auf diese Weise auch noch vor der Abreise einiges werde sprechen können.

Diese Freunde werden gesehen haben, daß unser Bau des Goetheanum in den schweren Jahren fortgeschritten ist. Er konnte ja allerdings bis zum heutigen Tage nicht vollendet werden, und wir können auch kaum heute irgendeinen Zeitpunkt seiner Vollendung mit Bestimmtheit voraussagen. Aber dasjenige, was heute schon vorhanden ist, wird Ihnen zeigen, aus welchen geistigen Grundlagen heraus dieser Bau erwachsen ist und wie er zusammenhängt mit der geistigen Bewegung, die hier vertreten wird. Daher wird es gerade bei dieser Gelegenheit, wo ich nach langer Zeit auch wiederum zu unseren englischen Freunden in größerer Zahl sprechen kann, gestattet sein, heute den Ausgangspunkt der Betrachtungen gerade von unserem Bau selbst zu nehmen. Wir werden dann in den beiden folgenden Tagen an dasjenige, was im Zusammenhang mit dem Bau gesagt werden kann, einiges andere anschließen können, von dem behauptet werden darf, daß es vielleicht gerade in der Gegenwart wichtig ist ausgesprochen zu werden.

Wer unseren Bau, der ja heute wenigstens seiner Idee nach schon zu überschauen ist, betrachtet, dem wird der eigentümliche Zusammenhang dieses Baues mit unserer geistigen Bewegung auffallen, und er wird einen Eindruck bekommen, vielleicht gerade aus diesem Bau, dieser Repräsentanz unserer Geistesbewegung, welcher Art diese Bewegung sein will. Denken Sie, wenn irgendeine, wenn auch noch so ausgebreitete sektiererische Bewegung in die Notwendigkeit sich versetzt gefühlt hätte, für ihre Versammlungen ein solches Haus zu bauen, was würde geschehen sein? Nun, es würde, entsprechend den Bedürfnissen dieser Gesellschaft oder Vereinigung, ein mehr oder weniger großer Bau aufgeführt worden sein in diesem oder jenem Baustile, und Sie hätten vielleicht innerhalb dieses Baues durch das eine oder durch das andere mehr oder weniger sinnbildliche Zeichen einen Hinweis gefunden auf dasjenige, was in diesem Bau gemacht werden soll. Sie hätten vielleicht auch da oder dort ein Bild gefunden, das hingewiesen hätte auf das, was in diesem Bau beabsichtigt wird gelehrt oder sonst vorgebracht zu werden. Das alles, werden Sie bemerkt haben, hat sich so für diesen Bau des Goetheanum nicht vollzogen. Dieser Bau ist nicht nur in äußerlicher Weise zum Gebrauche der anthroposophischen Bewegung oder der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft hingestellt worden, sondern so wie er dasteht, in allen seinen Einzelheiten, ist er herausgeboren aus dem, was in geistiger Beziehung und auch sonst unsere Bewegung vor der Welt vorstellen will. Diese Bewegung konnte sich nicht damit begnügen, ein Haus aufzurichten in diesem oder jenem Baustile, diese Bewegung fühlte sich in dem Augenblicke, in dem die Rede sein konnte von dem Bau eines solchen eigenen Hauses, gedrungen, einen eigenen Stil aus den Grundlagen unserer Geisteswissenschaft heraus zu finden, einen Stil, durch den in allen Einzelheiten ausgedrückt ist dasjenige, was als geistige Substanz durch diese unsere Bewegung fließt. Hier zum Beispiel wäre undenkbar gewesen, ein beliebiges Haus in einem beliebigen Baustil gerade für diese unsere Bewegung etwa herstellen zu lassen. Daraus sollte man von vornherein schließen, wie weit abstehend dasjenige ist, was mit dieser Bewegung gedacht ist, von irgendwelcher, sei es auch noch so stark verbreiteten sektiererischen oder ähnlichen Bewegung. Wir hatten nötig, nicht bloß ein Haus zu bauen, sondern einen Baustil zu finden, der genau dasselbe ausspricht, was durch jedes Wort, durch jeden Satz unserer anthroposophisch orientierten Geisteswissenschaft ausgesprochen wird.

Ja, ich habe die Überzeugung, daß wenn man hinlänglich eingehen wird auf das, was in den Formen dieses Baues wirklich empfunden werden kann — beachten Sie, ich sage: empfunden werden kann, nicht spintisiert werden kann -, daß der, welcher dies empfinden kann, aus den empfundenen Formen dieses Baues wird ablesen können dasjenige, was sonst ausgesprochen wird durch das Wort.

Dies ist keine Äußerlichkeit, dies ist etwas, was innerlichst zusammenhängt mit der ganzen Art, wie diese geistige Bewegung gedacht ist. Diese geistige Bewegung will etwas anderes sein, als namentlich jene geistigen Bewegungen, welche in der Menschheit nach und nach heraufgekommen sind seit dem Beginne der fünften nachatlantischen Kulturperiode, sagen wir, seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts. Und die Überzeugung liegt zugrunde, daß es heute, daß es dieser Gegenwart notwendig ist, etwas anderes in die Evolution der Menschheit hineinzustellen, als sich bisher seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts in diese Menschheitsevolution hineingestellt hat. Das Charakteristischste für alles dasjenige, was sich in der zivilisierten Menschheit in den letzten drei bis vier Jahrhunderten vollzogen hat, scheint mir das Folgende zu sein: Die äußere Lebenspraxis im weitesten Umkreise, die sich ja im starken Maße mechanisiert hat, bildet heute ein Reich für sich. Sie bildet ein Reich für sich, welches gewissermaßen wie ein Monopol in Anspruch nehmen diejenigen, die sich einbilden Lebenspraktiker zu sein. Neben dieser äußeren Lebensprazis, die sich auf allen Gebieten des sogenannten praktischen Lebens ausgestaltet hat, haben wir eine Summe von geistigen Anschauungen, Weltanschauungen, Philosophien oder wie man es nennen will, die im Grunde genommen nach und nach, aber insbesondere im Laufe der letzten drei bis vier Jahrhunderte, lebensfremd geworden sind, die gewissermaßen in dem, was sie dem Menschen geben an Gefühlen, an Empfindungen, über der eigentlichen Lebenspraxis schweben. Und so kraß ist die Differenz zwischen diesen beiden Strömungen, daß man sagen kann: Mit unserer Gegenwart ist die Zeit angebrochen, in der sich diese zwei Strömungen durchaus nicht mehr verstehen, oder vielleicht besser gesagt, in denen sie keine Anknüpfungspunkte finden, um gegenseitig aufeinander zu wirken. Wir versorgen heute unsere Fabriken, wir bringen unsere Eisenbahnen zum Fahren über dieSchienen und wir schicken unsere Dampfschiffe über dieMeere, wir lassen unsere Telegraphen und Telephone spielen, wir tun das alles, indem wir gewissermaßen die Lebensmechanik automatisch ablaufen lassen und uns selber hineinspannen lassen in diese Lebensmechanik. Und wir predigen daneben. Man predigt eigentlich viel. Die alten Kirchenbekenntnisse predigen in den Kirchen, die Politiker predigen in den Parlamenten, die verschiedenen Bestrebungen auf den verschiedenen Gebieten reden von den Forderungen des Proletariats, von den Forderungen der Frauen. Viel, viel wird gepredigt, und der Inhalt dieses Predigens, er ist ja im Sinne des heutigen Menschheitsbewußtseins etwas gewiß klar Gewolltes. Aber wenn wir uns fragen würden: Wo ist die Brücke zwischen dem, was wir predigen und dem, was unser äußerliches Leben in seiner Praxis zimmert, so würden wir, wenn wir ehrlich und wahrheitsgemäß antworten wollten, eine richtige Antwort nicht finden aus der gegenwärtigen Zeitbewegung heraus.

Nur deshalb erwähne ich die folgende Erscheinung, weil dies am anschaulichsten durch diese Erscheinung zutage tritt: Sie wissen ja, es gibt für die heutige Menschheit außer allen übrigen Gelegenheiten zu predigen allerlei Geheimgesellschaften. Nehmen wir von diesen Geheimgesellschaften, sagen wir, die gewöhnlichen Freimaurerlogen, auch diejenigen mit ihren allertiefsten Graden oder höchsten Graden, da finden wir eine Symbolik: Dreieck, Kreis, Winkelmaß und ähnliches. Wir finden sogar ein in solchen Zusammenhängen häufig gebrauchtes Wort: Der Baumeister aller Welten.

Was ist das alles? Ja, wenn wir zurückgehen ins 9., 10., 11. Jahrhundert und uns die zivilisierte Welt ansehen, innerhalb welcher diese Geheimgesellschaften, diese Freimaurerlogen wie eine Cr&me in der Zivilisation sich ausbreiteten, da finden wir, daß all die Instrumente, die heute als Symbol auf dem Altare dieser Freimaurerlogen liegen, verwendet worden sind zum Hausbau und zum Kirchenbau. Man hat Winkelmaße, man hat Kreise, das heißt Zirkel gehabt, hat Wasserwaagen gehabt, Lote, man hat sie verwendet in der äußeren Lebenspraxis. In den Freimaurerlogen hält man, in Anknüpfung an die Dinge, die ihren Zusammenhang mit der Lebenspraxis vollständig verloren haben, Reden und sagt allerlei schöne Sachen darüber, die ja gewiß sehr schön sind, die aber dem äußeren Leben, der äußeren Lebenspraxis vollständig fremd sind. Wir sind zu Ideen gekommen, zu Gedankengebilden gekommen, denen die Stoßkraft fehlt, um ins Leben einzugreifen. Wir sind allmählich dahin gekommen, daß unsere Menschen vom Montag bis Samstag arbeiten und sonntags sich die Predigt anhören. Diese zwei Dinge haben nichts miteinander zu tun. Und wir brauchen oftmals, indem wir predigen, die Dinge, die in älteren Zeiten mit der äußeren Lebenspraxis in innigem Zusammenhang gestanden haben, als Symbole für das Schöne, für das Wahre, sogar für das Tugendhafte. Aber die Dinge sind lebensfremd. Ja, wir sind soweit gekommen zu glauben, daß, je lebensfremder unsere Predigten sind, sie sich desto mehr in die geistigen Welten erheben. Die gewöhnliche profane Welt, die ist etwas Minderwertiges. Und heute sieht man hin auf allerlei Forderungen, die aus den Tiefen der Menschheit aufsteigen, aber man versteht diese Forderungen in ihrem Wesen eigentlich nicht. Denn was ist wohl oftmals für ein Zusammenhang zwischen jenen Gesellschaftspredigten, die in mehr oder weniger schönen Zimmern gesprochen werden darüber, wie der Mensch gut ist, darüber, wie man, nun, sagen wir, alle Menschen liebt ohne Unterschied von Rasse, Nation und so weiter, Farbe sogar, was ist denn für ein Zusammenhang zwischen diesen Predigten und dem, was äußerlich geschieht und was wir mit dadurch fördern, was wir mit dadurch treiben, daß wir unsere Coupons abschneiden und uns auszahlen lassen unsere Renten aus den Banken, die damit die äußere Lebenspraxis versorgen, mit wahrhaftig ganz anderen Prinzipien also als diejenigen sind, von denen wir als den Prinzipien der guten Menschen sprechen in unseren Stuben. Wir begründen zum Beispiel theosophische Gesellschaften, in denen wir für alle Menschen gerade von Brüderlichkeit reden, aber wir haben in dem, was wir reden, nicht die geringste Stoßkraft, um dasjenige irgendwie zu beherrschen, was auch durch uns geschieht, wenn wir unsere Coupons abschneiden. Denn indem wir die Coupons abschneiden, setzen wir eine ganze Summe von volkswirtschaftlichen Dingen in Bewegung. Unser Leben zerfällt ganz und gar in diese zwei voneinander getrennten Strömungen.

So kann es vorkommen - ich erzähle nicht ein Schulbeispiel, sondern ein Beispiel aus dem Leben -, es kann vorkommen, ist sogar vorgekommen, daß eine Dame mich aufsuchte und sagte: Ja, da kommt jemand und fordert von mir einen Beitrag, der aber dann verwendet wird dazu, Leute zu unterstützen, die Alkohol trinken. Das kann ich doch als’Theosophin nicht tun! — So sagte die Dame. Ich konnte nur antworten: Sehen Sie, Sie sind Rentiere, wissen Sie denn, wieviel Brauereien mit Ihrem Vermögen gegründet und unterhalten werden? — Es handelt sich für dasjenige, auf was es ankommt, nicht darum, daß wir auf der einen Seite predigen zur wollüstigen Befriedigung unserer Seele, und auf der anderen Seite uns ins Leben hineinstellen so wie es die Lebensroutine, die durch die letzten drei bis vier Jahrhunderte heraufgekommen ist, einmal fordert. Wenige Menschen sind heute überhaupt geneigt, auf dieses Grundproblem der Gegenwart einzugehen. Woher kommt dieses? Es kommt daher, daß wirklich dieser Dualismus ins Leben getreten ist — und am stärksten geworden ist in den letzten drei bis vier Jahrhunderten — zwischen dem äußeren Leben und zwischen unseren sogenannten geistigen Bestrebungen. Die meisten Menschen reden, wenn sie heute vom Geiste reden, von etwas ganz Abstraktem, Weltenfremdem, nicht von etwas, das in das alltägliche Leben einzugreifen vermag.

Die Frage, das Problem, auf das damit hingedeutet wird, das muß an seiner Wurzel angepackt werden. Wäre hier auf diesem Hügel im Sinne dieser Bestrebungen der letzten drei bis vier Jahrhunderte gehandelt worden, dann hätte man sich vielleicht an einen beliebigen Architekten gewendet, einen berühmten Architekten und hätte einen schönen Bau hier aufführen lassen, der ja gewiß hätte sehr schön sein können aus irgendeinem Baustil heraus. Darum konnte es sich nie handeln. Denn wir wären dann hineingegangen in diesen Bau, wir wären umgeben gewesen von allem möglichen Schönen aus diesem oder jenem Stil, und wir hätten drinnen Dinge gesprochen, die zu diesem Bau gepaßt hätten, ungefähr so, wie eben all die schönen Reden, die heute gehalten werden, passen zu der äußeren Lebenspraxis, welche die Menschen pflegen. Das konnte nicht so sein, denn so war nicht die Geisteswissenschaft gemeint, die sich anthroposophisch orientieren will. Diese war vom Anfang an anders gemeint. Die war so gemeint, daß nicht aufgerichtet wurde der alte falsche Gegensatz zwischen Geist und Materie, wobei dann vom Geiste in abstracto gehandelt wird und dieser Geist keine Möglichkeit hat, in das Wesen und Weben der Materie unterzutauchen. Wann spricht man berechtigt vom Geiste, wann spricht man in Wahrheit vom Geiste? Nur dann spricht man in Wahrheit vom Geiste, spricht man berechtigt vom Geiste, wenn man den Geist als Schöpfer meint desjenigen, was materiell ist. Es ist schlimmste Rede vom Geiste, wenn auch diese schlimmste Rede vom Geiste oftmals heute als die schönste angesehen wird, wenn man von dem Geiste als im Wolkenkuckucksheim spricht, in einer solchen Weise spricht, daß dieser Geist gar nicht berührt werden sollte von dem Materiellen. Nein, von dem Geiste muß man so sprechen, daß man den Geist meint, der die Kraft hat unmittelbar unterzutauchen in das Materielle. Und wenn man von der Geisteswissenschaft spricht, so darf diese nicht nur so gedacht werden, daß sie sich bloß erhebt über die Natur, sondern daß sie zu gleicher Zeit vollwertige Naturwissenschaft ist. Wenn man vom Geiste spricht, so muß der Geist gemeint sein, mit dem sich der Mensch verbinden kann so, daß dieser Geist auch in das soziale Leben durch die Vermittlung des Menschen hinein sich verweben kann. Ein Geist, von dem man bloß im Salon spricht als dem, welchem man durch das Gutsein und durch die Bruderliebe wohlgefallen will, und der sich wohl hütet unterzutauchen in das unmittelbare Leben, ein solcher Geist ist nicht der wahre Geist. Ein solcher Geist ist eine menschliche Abstraktion, und die Erhebung zu ihm ist nicht die Erhebung zum wirklichen Geist, sondern sie ist gerade der letzte Ausfluß des Materialismus.

Daher mußten wir einen Bau aufrichten, der in allen seinen Einzelheiten herausgedacht ist, herausgeschaut ist aus demjenigen, was sonst auch in unserer anthroposophisch orientierten Geisteswissenschaft lebt. Und damit hängt es auch zusammen, daß in dieser schweren Zeit hervorgegangen ist eine Behandlung der sozialen Frage aus dieser Geisteswissenschaft, die nicht im Wolkenkuckucksheim weilen will, sondern die Lebenssache sein wollte vom Anfange ihres Wirkens an, die gerade das Entgegengesetzte sein wollte von jeder Art von Sektiererei, die ablesen wollte dasjenige, was in den großen Forderungen der Zeit liegt, und die dienen wollte diesen Forderungen der Zeit. Gewiß, an diesem Bau ist vieles nicht gelungen. Aber es handelt sich heute wahrhaftig auch nicht darum, daß alles gleich gelinge, sondern es handelt sich darum, daß in gewissen Dingen ein Anfang, ein notwendiger Anfang gemacht werde. Und dieser notwendige Anfang scheint mir wenigstens mit diesem Bau gemacht worden zu sein. So werden wir, wenn dieser Bau einstmals fertig sein wird, nicht in irgend etwas, was uns als fremdartige Wände umgibt, dasjenige vollziehen, was wir zu vollziehen haben werden, sondern so wie die Nußschale zur Nußfrucht gehört und in ihrer Form ganz angepaßt ist dieser Nußfrucht, so wird angepaßt sein jede einzelne Linie, jede einzelne Form und Farbe dieses Baues demjenigen, was durch unsere geistige Bewegung fließt.

Es wäre schon notwendig, daß in der Gegenwart wenigstens von einer Anzahl von Menschen dieses Wollen eingesehen werde, denn auf dieses Wollen kommt es an.

Ich muß noch einmal zurückkommen auf manches Charakteristische, das in den letzten drei bis vier Jahrhunderten in der Evolution der zivilisierten Menschheit zutage getreten ist. Wir haben in dieser Evolution der zivilisierten Menschheit Erscheinungen, die uns so recht charakteristisch ausdrücken die tieferen Grundlagen desjenigen, was sich in der Gegenwart im Leben der Menschen ad absurdum führt; denn ein Adabsurdum-Führen ist es. Es ist zwar so, daß heute ein großer Teil der Menschenseelen eigentlich schläft, wirklich schläft. Ist man irgendwo, wo gewisse Dinge, die heute, ich möchte sagen, als wirkliche Widerbilder, Gegenbilder alles zivilisierten Lebens sich abspielen, ist man irgendwo, wo diese Gegenbilder einem nicht direkt vor Augen treten, aber doch in zahlreichen Gegenden der heutigen zivilisierten Welt sich abspielen und bedeutungsvoll, symptomatisch sind für dasjenige, was immer weiter und weiter um sich greifen muß, dann findet man: Ja, die Menschen sind mit ihren Seelen draußen, außerhalb der wichtigsten Zeitereignisse. Die Menschen leben in den Alltag hinein, ohne sich klar vor Augen zu halten, was eigentlich in der Gegenwart vorgeht, solang sie nur nicht unmittelbar berührt werden von diesen Vorgängen. Aber allerdings, es liegen auch die eigentlichen Impulse dieser Vorgänge in den Tiefen des unterbewußten oder unbewußten Seelenlebens der Menschen.

Zugrunde liegend dem Dualismus, den ich angeführt habe, ist ja heute ein anderer: der Dualismus, der sich zum Beispiel ausspricht — ich meine ein charakteristisches Beispiel anzuführen — durch Miltons «Verlorenes Paradies». Aber es ist das nur ein äußeres Symptom für etwas, was durch das ganze moderne Denken, Empfinden, Fühlen und Wollen geht. Wir haben im neueren Menschheitsbewußtsein das Gefühl eines Gegensatzes zwischen dem Himmel und der Hölle, andere nennen es Geist und Materie. Es sind nur im Grunde genommen Gradunterschiede zwischen dem Himmel und der Hölle des Bauern draußen auf dem Lande und zwischen Materie und Geist des sogenannten aufgeklärten Philosophen unserer Tage. Die eigentlichen Denkimpulse, die zugrunde liegen, sind genau die gleichen. Der eigentliche Gegensatz ist der zwischen Gott und Teufel, zwischen dem Paradies und der Hölle. Sicher ist es den Menschen: Das Paradies ist gut, und es ist schrecklich, daß die Menschen aus dem Paradiese herausgekommen sind; das Paradies ist etwas Verlorenes, es muß wieder gesucht werden, und der Teufel ist ein schrecklicher Widersacher, der entgegensteht all denjenigen Mächten, die man verbindet mit dem Begriff des Paradieses. Menschen, die keine Ahnung davon haben, wie Seelengegensätze walten bis in die äußersten Ranken unserer sozialen Gegensätze und sozialen Forderungen hinein, die können sich gar nicht vorstellen, welche Tragweite in diesem Dualismus liegt zwischen Himmel und Hölle oder zwischen dem verlorenen Paradiese und der Erde. Man muß heute schon recht Paradoxes sagen, wenn man die Wahrheit sagen will, man kann eigentlich kaum heute über manche Dinge die Wahrheit sagen, ohne daß diese Wahrheit wie ein Wahnsinn oftmals unseren Zeitgenossen erscheint. Aber so wie im paulinischen Sinne die Weisheit der Menschen eine Torheit vor Gott sein kann, so könnte die Weisheit der Menschen von heute, oder der Wahnsinn der Menschen von heute, auch Wahnsinn sein für die Anschauung der Menschen der Zukunft. Die Menschen haben sich allmählich in einen solchen Gegensatz zwischen der Erde und dem Paradiese hineingeträumt, sie bringen das Paradiesische zusammen mit dem, was als das eigentlich Menschlich-Göttliche anzustreben ist, und wissen nicht, daß das Anstreben dieses Paradiesischen ebenso schlimm für den Menschen ist, wenn er es ohne weiteres will, als das Anstreben des Gegensatzes wäre. Denn wenn man die Struktur der Welt so vorstellt, wie sie als Vorstellung zugrunde liegt dem «Verlorenen Paradies» von Milton, dann tauft man um eine der Menschheit abträgliche Macht, wenn sie einseitig angestrebt wird, in die göttlich-gute Macht und stellt ihr einen Gegensatz gegenüber, der kein wahrer Gegensatz ist: den Gegensatz des Teufels, den Gegensatz desjenigen, was in der menschlichen Natur an dem Guten Widerstrebendem liegt.

Der Protest gegen diese Anschauung soll liegen in jener Gruppe, die im Osten unseres Baues innen aufgestellt werden soll, eine neuneinhalb Tafel 14

Meter hohe Holzgruppe, in der an die Stelle, oder durch die an die Stelle des luziferischen Gegensatzes zwischen Gott und dem Teufel dasjenige gesetzt wird, was dem Menschheitsbewußtsein der Zukunft zugrunde liegen muß: die Trinität zwischen dem Luziferischen, dem ChristusGemäßen und dem Ahrimanischen.

Von dem Geheimnis, das da zugrunde liegt, hat die neuere Zivilisation so wenig ein Bewußtsein, daß man das Folgende sagen kann. Wir haben aus gewissen Gründen, über die ich vielleicht auch noch hier wiederum sprechen werde, diesen Bau «Goetheanum» genannt, als bauend auf Goethescher Kunst- und Erkenntnisgesinnung. Aber zu gleicher Zeit muß gerade hier gesagt werden: In dem Gegensatze, den Goethe in seinem «Faust» aufgerichtet hat zwischen den guten Mächten und dem Mephistopheles, liegt derselbe Irrtum wie in Miltons «Verlorenem Paradies»: auf der einen Seite die guten Mächte, auf der anderen Seite die schlechte Macht Mephistopheles. In diesem Mephistopheles hat Goethe bunt durcheinandergeworfen das Luziferische auf der einen Seite, das Ahrimanische auf der anderen Seite, so daß in der Goetheschen Mephistopheles-Figur für den, der die Sache durchschaut, zwei geistige Individualitäten durcheinandergemischt sind, unorganisch durcheinandergemischt sind. Erkennen muß der Mensch, wie sein wahres Wesen nur ausgedrückt werden kann durch das Bild des Gleichgewichtes: Wie der Mensch auf der einen Seite versucht ist, gewissermaßen über seinen Kopf hinauszuwollen, hinauszuwollen in das Phantastisch-Schwärmerische hinein, hinauszuwollen in das falsch Mystische hinein, hinauszuwollen in all dasjenige, was phantastisch ist. Das ist die eine Macht. Die andere Macht ist diese, die den Menschen gewissermaßen herunterzieht in das Materialistische, in das Nüchterne, Trockene und so weiter. Nur dann verstehen wir den Menschen, wenn wir ihn auffassen seinem Wesen nach als strebend nach dem Gleichgewichte zwischen, sagen wir, auf dem einen Waagebalken dem Ahrimanischen, auf dem anderen Waagebalken dem Luziferischen. (Siehe Zeichnung, S. 165.)

Der Mensch hat fortwährend die Gleichgewichtslage zwischen diesen beiden Mächten anzustreben, zwischen demjenigen, das ihn hinausführen möchte über sich selbst, und demjenigen, das ihn herabziehen möchte unter sich selbst. Nun hat die neuere Geisteszivilisation verwechselt das Phantastisch-Schwärmerische des Luziferischen mit dem Göttlichen. So daß in dem, was als Paradies geschildert wird, in der Tat die Schilderung des Luziferischen vorliegt, und daß man die furchtbare Verwechselung begeht zwischen dem Luziferischen und dem Göttlichen, weil man nicht weiß, daß es darauf ankommt, die Gleichgewichtslage zwischen zwei den Menschen nach der einen oder nach der anderen Seite hin zerrenden Mächten zu halten.

Diese Tatsache mußte zunächst aufgedeckt werden. Wenn der Mensch streben soll nach demjenigen, was man das Christliche nennt, worunter aber heute sonderbare Dinge oftmals verstanden werden, dann muß er sich klar sein, daß dies nur ein Streben sein kann in der Gleichgewichtslage zwischen dem Luziferischen und dem Ahrimanischen, und daß namentlich die drei bis vier letzten Jahrhunderte so sehr ausgeschaltet haben die Erkenntnis des wirklichen Menschenwesens, daß man von dem Gleichgewichte wenig weiß und das Luziferische umgetauft hat in das Göttliche in dem «Verlorenen Paradies», und einen Gegensatz gemacht hat aus dem Ahrimanischen, der kein Ahriman mehr ist, aber der zum modernen Teufel oder zur modernen Materie oder zu irgend etwas dergleichen geworden ist. Dieser Dualismus, der in Wirklichkeit ein Dualismus ist zwischen Luzifer und Ahriman, dieser Dualismus spukt im Bewußtsein der modernen Menschheit als der Gegensatz zwischen Gott und dem Teufel. Und das «Verlorene Paradies» müßte eigentlich aufgefaßt sein als eine Schilderung des verlorenen luziferischen Reiches, es ist nur umgetauft.

So stark muß man heute in den Geist der neueren Zivilisation hineinweisen, weil es nötig ist, daß die Menschheit sich klar werde darüber, wie sie auf eine abschüssige Bahn - es ist eine historische Notwendigkeit, aber Notwendigkeiten sind doch auch dazu da, daß man sie begreift —, wie sie auf eine abschüssige Bahn gekommen ist und, wie gesagt, nur durch die radikalste Kur wiederum aufwärts kommen kann. Oftmals versteht man heute unter der Schilderung der geistigen Welt eine Darstellung dessen, was übersinnlich ist, was aber nicht lebt hier auf unserer Erde. Man möchte mit einer geistigen Anschauung flüchten von dem, was uns hier auf unserer Erde umgibt. Man weiß nicht, daß man — indem man also flieht in ein abstraktes geistiges Reich — gerade nicht den Geist, sondern die luziferische Region findet. Und manches, was sich heute Mystik nennt, was sich heute Theosophie nennt, ist ein Aufsuchen der luziferischen Region. Denn das bloße Wissen von einem Geiste, das kann dem heutigen Geistesstreben der Menschen nicht zugrunde liegen, weil es angemessen ist diesem heutigen, diesem gegenwärtigen Geistesstreben, zu erkennen den Zusammenhang zwischen den geistigen Welten und der Welt, in die wir hineingeboren werden, um zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode in ihr zu leben.

Diese Frage sollte uns vor allen Dingen dann gerade berühren, wenn wir den Blick nach geistigen Welten richten: Warum werden wir aus den geistigen Welten heraus in diese physische Welt hineingeboren? — Nun, wir werden in diese physische Welt hineingeboren — und ich werde morgen und übermorgen dasjenige, was ich heute skizziere, genauer ausführen —, weil es hier auf dieser Erde Dinge zu erfahren, Dinge zu erleben gibt, die in den geistigen Welten nicht erlebt werden können, sondern um diese zu erleben, muß man heruntersteigen in diese physische Welt, und man muß aus dieser physischen Welt die Ergebnisse dieses Erlebens hinauftragen in die geistigen Welten. Man muß, um das zu erreichen, aber auch in diese physische Welt untertauchen, muß gerade mit seinem Geist erkenntnismäßig in diese physische Welt untertauchen. Um der geistigen Welt willen muß man in diese physische Welt untertauchen.

Nehmen wir einmal, um es radikal zu sagen, was ich aussprechen will, einen normalen Menschen der Gegenwart, der sich redlich ernährt, seine gehörige Anzahl von Stunden schläft, frühstückt, zu Mittag und zu Abend ißt und so weiter, und der auch geistige Interessen hat, sogar hohe geistige Interessen, der Mitglied, sagen wir, einer theosophischen Gesellschaft wird, weil er geistige Interessen hat, da alles mögliche treibt, um zu wissen, was in den geistigen Welten vorgeht. Nehmen wir einen solchen Menschen, der sozusagen im kleinen Finger alles dasjenige hat, was in dieser oder jener theosophischen Literatur der Gegenwart notifiziert wird, der aber sonst nach den gewöhnlichen Usancen des Lebens lebt. Nehmen wir ihn, diesen Menschen! Was bedeutet all sein Wissen, das er sich aneignet mit seinen höheren geistigen Interessen? Es bedeutet etwas, was hier auf dieser Erde ihm einige innerliche seelische Wollust bereiten kann, so einen richtigen luziferischen Genuß, wenn es auch ein raffinierter, verfeinerter Seelengenuß ist. Es wird nichts davon durch des Todes Pforte getragen, gar nichts davon wird durch des Todes Pforte getragen. Denn es kann unter solchen Menschen — und sie sind sehr häufig — solche geben, die, trotzdem sie im kleinen Finger haben, was ein Astralleib, ein Ätherleib und so weiter ist, keine Ahnung davon haben, was vorgeht, wenn eine Kerze brennt. Sie haben keine Ahnung davon, welche Zauberkunststücke aufgeführt werden, damit draußen die Tramway fährt. Sie fahren zwar damit, aber sie wissen nichts davon. Aber noch mehr: sie haben zwar im kleinen Finger, was Astralleib, Ätherleib ist, Karma, Reinkarnation, aber sie haben keine Ahnung davon, was gesprochen wird, angestrebt wird zum Beispiel heute in den Versammlungen proletarischer Menschen. Es interessiert sie nicht. Es interessiert sie nur, wie der Ätherleib ausschaut, wie der Astralleib ausschaut, es interessiert sie nicht, welche Wege das Kapital macht, indem es seit dem Beginne des 19. Jahrhunderts die eigentlich herrschende Macht geworden ist. Das Wissen vom Ätherleib, Astralleib, das nützt nichts, wenn die Menschen gestorben sind. Gerade das muß man aus einer wirklichen Erkenntnis der geistigen Welt heraus sagen. Es hat erst dann einen Wert, wenn dieses geistige Erkennen das Instrument wird, um unterzutauchen in das materielle Leben und da im materiellen Leben dasjenige aufzunehmen, was in den geistigen Welten selber nicht aufgenommen werden kann, was aber hineingetragen werden muß.

Wir haben heute eine Naturwissenschaft, die wird an unseren Universitäten auf den verschiedensten Gebieten gelehrt. Es wird experimentiert, es wird geforscht und so weiter. Da kommt die Naturwissenschaft zustande. Mit dieser Naturwissenschaft speisen wir unsere Technik, mit dieser Naturwissenschaft heilen wir heute auch schon die Menschen, tun alles mögliche. Daneben gibt es kirchliche Bekenntnisse. Aber ich frage Sie, haben Sie schon Kenntnis genommen von dem Inhalte so gewöhnlicher Sonntagnachmittagspredigten, wo zum Beispiele gesprochen wird von dem Reich Christi und so weiter? Welche Beziehung ist zwischen der Naturwissenschaft und dem, was da gesprochen wird? Zumeist gar keine. Beide Dinge gehen nebeneinander her. Die einen glauben, sie haben die rechte Kraft, um über Gott und den Heiligen Geist und alles mögliche zu reden. Wenn sie auch sagen, sie empfänden die Dinge, sie reden doch in abstrakten Formen, in abstrakten Anschauungen darüber. Die anderen reden von einer geistlosen Natur. Keine Brücke wird geschlagen! Dann haben wir in der neueren Zeit selbst allerlei theosophische Anschauungen bekommen, mystische Anschauungen bekommen. Ja, diese mystischen Anschauungen, sie reden über alles mögliche Lebensferne, aber sie reden nicht vom Menschenleben, weil sie nicht die Kraft haben, unterzutauchen in das Menschenleben. Ich möchte einmal fragen, ob denn im rechten Sinne von einem Weltenschöpfer geredet wäre, wenn man ihn so ausdächte, daß er ja ein sehr interessanter schöner Geist wäre, aber niemals hätte zur Weltschöpfung kommen können? Die geistigen Mächte, von denen heute oftmals geredet wird, die hätten niemals zur Weltschöpfung kommen können, denn die Gedanken, die wir über diese entwickeln, die sind nicht einmal imstande einzugreifen in dasjenige, was unser Wissen über die Natur oder unser Wissen über das soziale Leben der Menschen ist.

Ich darf vielleicht, ohne unbescheiden zu werden, an einem Beispiel erläutern, was ich meine. In einem meiner letzten Bücher - «Von Seelenrätseln» — habe ich darauf aufmerksam gemacht, und ich habe es ja öfter in mündlichen Vorträgen ausgesprochen, welcher Unsinn gelehrt wird in der heutigen Physiologie, also auch einer Naturwissenschaft: der Unsinn, daß es zweierlei Nerven im Menschen gibt, motorische Nerven, die dem Willen zugrunde liegen, und sensitive Nerven, die den Wahrnehmungen, den Empfindungen zugrunde liegen. Nun, seit es Telegraphie gibt, hat man ja das Bild von der Telegraphie. Also: vom Auge geht der Nerv zum Zentralorgan, dann vom Zentralorgan aus geht er wiederum zu irgendeinem Gliede. Wir sehen irgend etwas sich da bewegen als ein Glied, da geht der Telegraphendraht von diesem Organ, vom Auge, zum Zentralorgan, das setzt den Bewegungsnerv in Tätigkeit, dann wird die Bewegung ausgeführt.

Diesen Unsinn läßt man die Naturwissenschaft lehren. Man muß sie ihn lehren lassen, denn man redet in einer abstrakten geistigen Anschauung von allem möglichen, nur entwickelt man nicht solche Gedanken, die positiv eingreifen können in das Naturgetriebe. Man hat nicht die Stärke in dem, was die geistigen Anschauungen sind, um ein Wissen über die Natur selbst zu entwickeln. Es gibt nämlich nicht einen Unterschied zwischen motorischen und sensitiven Nerven, sondern dasjenige, was man Willensnerven nennt, sind auch sensitive Nerven, sie sind nur dazu da, um unsere eigenen Glieder dann wahrzunehmen, wenn Bewegungen ausgeführt werden sollen. Das Schulbeispiel der Tabes, das beweist gerade das Gegenteil dessen, was bewiesen werden soll. Ich will nicht weiter darauf eingehen, weil unter Ihnen nicht entsprechende physiologische Vorkenntnisse sind. Ich würde allerdings über diese Dinge im Kreise von physiologisch, biologisch vorgebildeten Leuten einmal sehr gerne darüber reden. Hier will ich aber nur darauf aufmerksam machen, daß wir auf der einen Seite eine Naturwissenschaft haben, auf der anderen Seite ein Reden und Predigen von geistigen Welten, das nicht eindringt in irgendwelche realen Welten, die uns in der Natur vorliegen. Das aber brauchen wir. Wir brauchen eine Erkenntnis des Geistes, die so stark ist, daß sie zu gleicher Zeit Naturwissenschaft werden kann. Die werden wir nur erlangen, wenn wir das Wollen berücksichtigen, auf das ich Sie heute hier aufmerksam machen wollte. Hätten wir eine sektiererische Bewegung begründen wollen, die nur auch irgendeine Dogmatik über das Göttliche und Geistige hat und die einen Bau braucht, so hätten wir irgendeinen Bau aufgeführt, respektive aufführen lassen. Da wir das nicht wollten, sondern da wir schon in dieser äußeren Handlung andeuten wollten, daß wir untertauchen wollen in das Leben, mußten wir uns auch diesen Bau ganz aus dem Wollen der Geisteswissenschaft heraus selber bauen. Und an den Einzelheiten..dieses Baues wird man einmal sehen, daß tatsächlich wichtige Prinzipien, die heute unter dem Einflusse der erwähnten zwei Dualismen in das falscheste Licht gerückt werden, auf ihre gesunde Grundlage gestellt werden können. Ich möchte Sie nur auf eines heute noch aufmerksam machen.

Sehen Sie sich einmal die aufeinanderfolgenden sieben Säulen an, die auf jeder Seite unseres Hauptbaues stehen (es wird gezeichnet): Da haben Sie darüber Kapitäle, darunter Sockel. Die sind nicht gleich, sondern jeder folgende entwickelt sich aus dem vorhergehenden. So daß Sie eine Anschauung bekommen des zweiten Kapitäls, wenn Sie sich lebensvoll in das erste und seine Formen hineinversetzen, lebendig werden lassen den Gedanken der Metamorphose als Organisches, und jetzt wirklich einen so lebendigen Gedanken haben, daß dieser Gedanke nicht abstrakt ist, sondern daß er dem Wachsen folgt. Dann können Sie das zweite Kapitäl aus dem ersten entwickelt sehen, das dritte aus dem zweiten, das vierte aus dem dritten und so weiter bis zum siebenten. So ist versucht worden, in lebendiger Metamorphose ein Kapitäl, ein Architravstück und so weiter aus dem anderen heraus zu entwickeln, nachzubilden dasjenige Schaffen, das als geistiges Schaffen in der Natur selber lebt, indem die Natur eine Gestalt aus der anderen hervorgehen läßt. Ich habe das Gefühl, daß kein Kapitäl anders sein könnte als es nun ist.

Aber dabei hat sich etwas sehr Merkwürdiges herausgestellt. Wenn heute die Leute von Evolution reden, da sagen sie oftmals: Entwickelung, Entwickelung, Evolution, erst das Unvollkommene, dann das etwas weiter Vollkommene, das mehr Differenzierte und so fort, und immer werden die vollkommeneren Dinge auch die komplizierteren. Das konnte ich nicht durchführen, als ich die sieben Kapitäle auseinander entstehen ließ nach der Metamorphose, sondern als ich zum vierten Kapitäl kam, ergab sich mir, daß ich dieses vierte, da ich nun das nächste, das fünfte, das vollkommener sein sollte, als das vierte, auszubilden hatte als das komplizierteste. Das heißt, als ich nicht wie Haeckel oder Darwin nur in Gedanken die abstrakten Dinge verfolgte, sondern als ich die Formen so machen mußte, wie die Form hervorgeht aus dem Vorhergehenden - so wie in der Natur selbst eine Form nach der anderen aus den Vitalkräften hervorgeht -, da war ich genötigt, zwar die fünfte Form in ihren Flächen kunstvoller zu machen als die vierte, aber nicht komplizierter, sondern einfacher wurde die ganze Form. Und die sechste wurde wieder einfacher und die siebente wieder einfacher. Und so stellte sich mir heraus, daß Evolution nicht ein Fortschreiten zu immer Differenzierterem und Differenzierterem ist (es wird die Gerade an die Tafel gezeichnet), sondern daß Evolution ein Ansteigen ist zu einem höheren Punkte, dann aber wiederum ein Fallen in Einfacheres und Einfacheres.

Das ergab sich einfach aus dem Arbeiten selbst. Und ich konnte sehen, wie dieses im künstlerischen Arbeiten sich ergebende Prinzip der Evolution dasselbe ist, wie das Prinzip der Evolution in der Natur.

Denn betrachten Sie das menschliche Auge, so ist es ja sicher vollkommener als die Augen mancher Tiere. Aber die Augen mancher Tiere sind komplizierter als das Menschenauge. Sie haben zum Beispiel innen eingeschlossen gewisse bluterfüllte Organe, den Schwertfortsatz, den Fächer, die beim Menschen nicht da sind, gewissermaßen aufgelöst sind. Das menschliche Auge ist wieder vereinfacht gegenüber den Formen mancher Tieraugen. Verfolgen wir die Entwickelung des Auges, so finden wir: es ist zuerst primitiv, einfach, dann wird es immer komplizierter und komplizierter, dann aber vereinfacht es sich wiederum, und das Vollkommenste ist nicht das Komplizierteste, sondern wiederum ein Einfacheres als das in der Mitte Stehende.

Und man war dazu genötigt, es selbst so zu machen, indem man künstlerisch das ausbildete, was eine innere Notwendigkeit auszubilden hieß. Nicht wurde hier angestrebt über etwas zu forschen, sondern die Verbindung mit den Vitalkräften selbst wurde angestrebt. Und in unserem Bau hier wurde angestrebt die Formen so zu gestalten, daß in diesem Gestalten dieselben Kräfte drinnen liegen, die als der Geist der Natur dieser Natur zugrunde liegen. Ein Geist wird gesucht, der nun tatsächlich schöpferisch ist, der in den Produktionen der Welt drinnen lebt, der nicht bloß predigt. Das ist das Wesentliche. Das ist auch der Grund, warum es manches absetzte hier gegenüber denen, die auch unseren Bau ausgestalten wollten mit allen möglichen Symbolen und dergleichen. Es ist kein einziges Symbol im Bau, sondern alles sind die Formen, die dem Schaffen vom Geist in der Natur selbst nachgebildet sind.

Damit aber ist der Anfang eines Wollens gegeben, das seine Fortsetzung finden muß. Und zu wünschen wäre es, daß gerade dieser Gesichtspunkt der Sache verstanden würde, daß verstanden würde, wie in der Tat gesucht werden sollen Urquellen menschlichen Intendierens, menschlichen Schaffens, die auf allen Gebieten notwendig sind für die neuere Menschheit. Wir leben ja heute mitten in Forderungen. Aber es sind alles einzelne Forderungen, aus den verschiedenen Lebenskreisen heraus sprießen diese Forderungen auf. Wir brauchen aber auch eine Zusammenfassung. Sie kann nicht von irgend etwas kommen, was nur im Umkreise des äußeren sichtbaren Daseins schwebt, denn allem Sichtbaren liegt das Übersichtbare zugrunde, und dieses muß man heute erfassen. Ich möchte sagen: Man sollte gar sehr hinhören auf die Dinge, die heute geschehen, und man wird finden, daß es gar kein so absurder Gedanke ist, daß das Alte zusammenfällt. Dann muß aber etwas da sein, das an die Stelle treten kann. Doch um mit diesem Gedanken sich zu befreunden, braucht man einen gewissen Mut, der nicht im äußeren Leben erworben wird, sondern der innerlichst erworben werden muß.