The Mysteries of Light, of Space, and of the Earth

GA 194

13 December 1919, Dornach

II. The Development of Architecture

I spoke to you yesterday of the relations of anthroposophical spiritual science to the forms of our building, and I wished particularly to point out that these relations are not external ones, but that the spirit which rules in our spiritual science has flowed, so to speak, into these forms. Special importance must be attached to the fact that it is possible to maintain that an actual understanding of these forms through feeling indicates, in a certain sense, a deciphering of the inner meaning existing in our Movement. Today I should like to take up a few things concerning the building, in order then to present today and tomorrow some important anthroposophical matters.

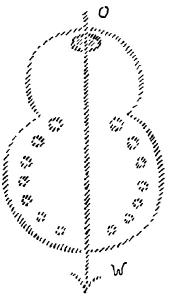

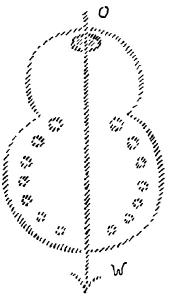

You will see when you contemplate the building that its ground-plan consists of two intersecting circles, one smaller than the other; so that I may sketch it roughly thus:

The whole building has an east-west orientation; and you will note that this east-west line is the only axis of symmetry; that is, everything is constructed symmetrically upon this axis.

For the rest, we do not have a mere mechanical repetition of forms, such as we find elsewhere in architecture, perchance with identical capitals, or the like, but we have an evolution of forums, as I explained in detail yesterday, with the later ones emerging from the preceding.1Compare: Der Dornacher Bau als Wahrzeichen kunstlerischer Umwandlungs-Impulse (not yet translated).

You will find seven columns on the left and seven on the right, defining the outer circular passage; and I mentioned yesterday that these seven columns have capitals and pedestals, with corresponding architraves above, which develop their forms in continuous evolution.

When you feel this ground-plan—and you must comprehend it through feeling—you will have, simply in these two intersecting circles, some-thing which points to the evolution of humanity. I said yesterday that a very significant, incisive change in the evolution of humanity occurred about the middle of the 15th century. What is exteriorly and academically called “history” is only a fable convenue, for it records external facts in such a way as to make it appear that the human being was essentially the same in the 8th or 9th century as, let us say, in the 18th or 19th. There are, however, modern historians—for example, Lamprecht—who have discovered that this is nonsense, that as a matter of fact man's soul-constitution and soul-mood were entirely different before and after the point of time indicated. We are at present in the midst of an evolution which we can only understand when we realize that we are developing toward the future with special soul forces, and that those soul forces which had been developed before the 15th century are now still, we might say, haunting the souls of men, becoming fainter and fainter; but that they belong to what is perishing, to what is condemned to fall out of human evolution. We must develop a consciousness concerning this important change in the evolution of humanity if we are to be qualified at all to have anything to say about the concerns of humanity in the present and the immediate future.

Such things find expression particularly when people wish to refer significantly to what they feel, what they sense. We need only to remind ourselves of one fact in the development of architecture which has already been mentioned here, but to which I wish to refer again today, in order to show by an example how the evolution of humanity strides forward.

Just observe the forms of a Greek temple! How can they be understood? Only by realizing clearly that the whole architectural idea of this Greek temple takes its orientation from the fact that it was the dwelling place of a god or a goddess, whose statue was placed within it. All the forms of the Greek temple would be absurdities if it were not conceived as the shelter, the abode, of the god or goddess who was intended to dwell in it.

If we proceed from the forms of the Greek temple to the next forms of construction which are significant, we come to the Gothic cathedral. Anyone who has the feeling upon entering a Gothic cathedral that in this cathedral he has before him something completed, something finished, does not understand the forms of Gothic architecture; just as anyone fails to understand the forms of the Greek temple who can regard it as if it contained no statue of a god. A Greek temple with-out the image of a god—we need only to imagine that it is there, but it must be imagined in order to understand the form—a Greek temple without the statue of a god is an impossibility to the understanding which comes through feeling. A Gothic cathedral which is empty is also an impossibility for the person who really has some feeling for such things. The Gothic cathedral is complete only when the congregation is in it, when it is filled with people—really, only when it is filled with people and the word is spoken to them, so that the spirit of the word rules over the congregation or in their hearts. Then the Gothic cathedral is complete. But the congregation belongs to it; otherwise the forms are unintelligible.

What kind of an evolution really confronts us in the evolution from the Greek temple to the Gothic cathedral—for the other forms are actually intermediate ones, whatever mistaken historical interpretation may say about it—what kind of an evolution confronts us there? If we look at the Greek civilization, this flower of the fourth post-Atlantean period, we must say that in the Greek consciousness there still lived something of the tarrying of divine-spiritual powers among men; only that the people felt impelled to erect dwelling places for their gods whom they could represent to themselves only in images. The Greek temple was the abode of the god or the goddess, of whose presence among them the people were conscious. Without this consciousness of the presence of divine-spiritual powers the phenomenon of the Greek temple in the Greek civilization is unthinkable.

If we go on now from the summit of the Greek civilization to its close, toward the end of the fourth post-Atlantean period, that is, toward the 8th, 9th, or 10th Christian century, we come to the forms of Gothic architecture, which requires the congregation to complete it. Everything corresponds to the feeling life of the humanity of that time. Human beings were then naturally different in their soul-disposition from those living when Greek thought was at its height. There was no longer a consciousness of the immediate presence of divine-spiritual powers; they were thought of as being far removed to the beyond. The earthly kingdom was often accused of having deserted the divine-spiritual powers. The material world was looked upon as something to be avoided, from which the eyes were to be averted and to be turned instead toward the spiritual powers. The individual sought by joining with the others in the congregation—going in quest, as it were, of the group-spirit of humanity—the rule of the spiritual, which in this way acquired a certain abstract quality: hence the Gothic forms also produce an abstract-mathematical impression, as contrasted with those of Greek architecture, which appear more dynamic, and which have something of the comfortable inclusion of the god or goddess. In the Gothic forms every-thing is aspiring, everything points to the fact that what the soul thirsts for must be sought in remote spiritual regions. For the Greek his god and his goddess were present; he heard their whispers, as it were, with the ear of the soul. In the time of the Gothic architecture the longing soul could only have an inkling of the presence of the divine in upward-pointing forms.

Thus in its soul-mood humanity had become filled with longing, so to speak; it built upon longing, upon seeking, believing that it was possible to be more successful in this seeking through union with the congregation; but it was always convinced that what is recognized as the divine-spiritual is not directly active among men, but conceals itself in mysterious depths. Now if one wished to express what was thus yearningly striven for and sought, it could only be done by linking it in one way or another with something mysterious. The contemporary expression of this whole soul-mood of the people was the temple or, we could also say, the cathedral, which in its proper typical form is the Gothic cathedral. But again, if that which man yearned for as the highest of all mysteries was observed with spiritual vision, then at the very moment when one was about to rise from the earthly to the super-earthly, it would be necessary to pass over from the mere Gothic to something else, which—we might say—did not unite the physical congregation, but caused to tend toward one central point, toward a mysterious central point, the whole spirit of humanity striving together—or the souls and spirits of humanity striving together.

If you imagine, let us say, the totality of human souls as streaming together from all directions, you have in a certain way united on the earth the humanity of the whole earth, as in a great cathedral, which was not however thought of as Gothic, although it should have the same significance as the Gothic cathedral. In the Middle Ages such things were connected with the Biblical narrative—and if you imagine that the seventy-two disciples (it is not necessary to think of physical history, but of the spirituality which in those times actually did permeate the physical view of the world)—if you imagine, as was believed in accordance with the spirit of the time, that the seventy-two disciples of Christ spread out in all directions and implanted in souls the spirit which was to flow together in the Mystery of Christ: then in all that streamed back again from those in whose souls the disciples had implanted the Christ Spirit, in the rays which come from all directions from all those souls, you have that which the man of the early Middle Ages conceived in the most comprehensive and universal way as striving toward the Mystery.

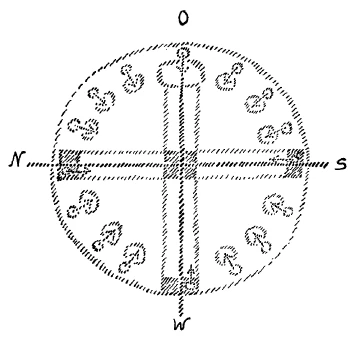

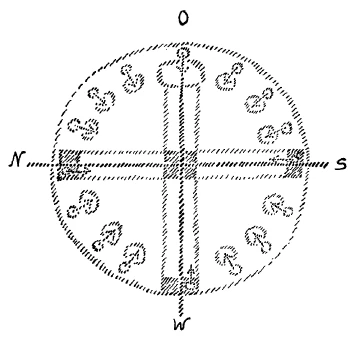

It is not necessary perhaps to draw all seventy-two pillars, but I merely indicate them (see drawing), and you are to imagine that there were seventy-two. From these seventy-two pillars, then, would come the rays which tend from all humanity toward the Mystery of Christ. En-close the whole with some kind of wall—it would not be Gothic, but I have already told you why one did not stop sharply with the Gothic—enclose it with a wall whose ground-plan is a circle; and if you imagine here the seventy-two pillars, you would have the cathedral which encloses all humanity, so to speak. And if you also imagine it as having an east-west orientation, then naturally you must sense in it an entirely different ground-plan from that of our building, which is constructed from two segments of circles—the feeling toward this ground-plan must be entirely different, and I tried to describe this feeling roughly for you: it would then be supposed that the principal lines of orientation of a building erected according to this ground-plan would have the form of a cross, and that the main aisles would be arranged according to this cross-form (see drawing.)

This is the way the man of the Middle Ages conceived his ideal cathedral. If east is here and west here (see drawing), then we should have north and south here. And then in the north, south, and west there would be three doors, and here in the east would be a sort of lateral high altar, and a kind of altar at each pillar; but-here, where the beams of the cross intersect, would have to stand the temple of the temple, the cathedral of the cathedral—a sort of epitome of the whole, a representation in miniature of the whole. We should say in modern speech, which has become abstract: here would stand a little tabernacle, but in the form of the whole.

What I have drawn for you here you should imagine in a style of architecture which only approximates the real Gothic, which still includes all sorts of Romanesque forms, but which has throughout the orientation I have indicated. In this I have drawn for you at the same time the sketch of the Grail-temple, as conceived by the man of the Middle Ages, that Grail-temple which was, so to speak, the ideal of construction toward the end of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch,—a cathedral in which the longings of all humanity orientated to Christ flowed together—just as in the single cathedral the longings of the members of the congregation flowed together; and just as in the Greek temple the people felt them-selves united even when they were not in it—for the Greek temple demands only that the god or goddess be in it, not the people—in other words, as the Greek people of a certain territory felt that they were united through their temple with their god or goddess. If we wish to speak in accordance with the facts, we can say: When the Greek de-scribed his relation to the temple, he did it in somewhat the following way: When he said in speaking of any person—say Pericles—“Pericles dwells in this house,” this was not intended to mean that the man him-self who uttered it had a relation of ownership or any other relation to the house; but he simply realized the fact of his union with Pericles when he said: “Pericles dwells in this house.” With exactly the same shade of feeling the Greek would also have expressed his relation to what was to be deciphered in the style of architecture, thus: “Athene dwells in this house,”—it is the abode of the goddess—or, “Apollo dwells in this house!”

The congregation of the Middle Ages could not say that with regard to their cathedral, because it was not the house in which the divine-spiritual being dwelt; it was the house which expressed in every single form the gathering-place where the people attuned their souls to the mysteriously divine. Therefore, in what I might call the prototype-temple, at the end of the fourth post-Atlantean period, there stood in the center the temple of the temple, the cathedral of the cathedral; and of the whole one might say: “If anyone enters here, he will be able herein to lift himself to the mysteries of the universe.” It was necessary to enter the cathedral. Of the Greek temple it was only necessary to say: “That is the house of Apollo; that is the house of Pallas.” And at the central point in that prototype-temple, where the beams of the cross intersect—at the central point the Holy Grail was enshrined, there it was preserved.

You see we must in this way follow the soul-attitude characterizing each historical epoch, otherwise we cannot come to know what really happened. And most of all, we cannot without such observation learn what soul-forces are beginning to bud again in our time.

The Greek temple, then, enclosed the god or goddess, and the people knew that the gods were present among men. But the man of the Middle Ages did not feel that; he felt that in a sense the earthly world was deserted by God, forsaken by the Divine. He felt the longing to find the way back to the gods, or to God.

Indeed we are today only at the starting point, for only a few centuries have elapsed since the great change in the middle of the 15th century. Most people scarcely notice what is unfolding, but something is unfolding; human souls are becoming different; and that must also be different which must now flow anew into the forms in which the consciousness of the time is embodied. These things cannot, of course, be grasped by speculating about them with the reason, with the intellect; they can only be sensed, felt, viewed artistically. Anyone who wishes to put them into abstract concepts does not really understand them; but they can be indicated descriptively in the most various ways. So it must be said that the Greek felt the god or the goddess as his contemporary, as his fellow-citizen. The man of the Middle Ages had the cathedral which served, not as the dwelling-place for the god, but which was intended to be in a sense the entrance-door to the way which leads to the divine. The people gathered together in the cathedral and their yearning arose, as it were, out of the group-soul of humanity. That is the characteristic quality, that this entire humanity of the Middle Ages had something which can be understood only in the light of the group-soul. Up to the middle of the 15th century the individual human being was not of such importance as he has become since that time. Since then the most essential characteristic in the human being is the striving to be an individuality, the striving to concentrate individual forces of personality, to find a central point within himself.

Neither can that be understood which is arising in the exceedingly varied social demands of our time unless the dominion of the individual spirit in each single human being is discerned, the desire of each individual to stand upon the foundation of his own being.

Because of this there is something that becomes especially important for man at this time; it began about the middle of the 15th century and will not come to a close until about the third millennium—something of very special importance for this time set in then. You see it is quite indefinite to say that each man strives for his particular individuality. The group-spirit, even when it comprises only small groups, is much more comprehensible than is that to which each single human being aspires out of the well-spring of his own individuality. For this reason it is particularly important for the people of modern times to understand what may be called seeking balance between opposite poles.

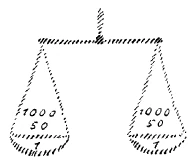

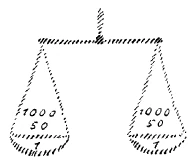

The one wishes to soar beyond the head, as it were. All that causes a man to be a dreamer, a visionary, a deluded person, all that fills him with indefinite mystical impulses toward some indefinite infinity—even if he is pantheist or theist or whatever else, and there are many of the kind today—that is the one pole. The other is that of prosiness, aridity—expressed trivially, but not with unreality as concerns the spirit of the present time, certainly not—the pole of philistinism, of narrow-mindedness, the pole which draws us down to earth into materialism. These two poles of force are in man, and between them stands the essential being of man, seeking equilibrium. In how many ways can equilibrium be sought? You can represent that to yourselves by the illustration of the scales (see drawing). In how many ways can one seek balance between two poles pulling in opposite directions?

If here on one side of the scales there are 50 grams or 50 kilograms, and also here on the other side, they balance, do they not? But if here on one side there is one kilogram and one kilogram on the other, they still balance; and if there are a thousand here and a thousand here, they balance! You can seek equilibrium in innumerable ways. That corresponds to the infinite number of ways of being an individual human being. Hence for people of the present it is very essential to comprehend that their nature consists in the struggle for balance between two opposite poles. And the indefiniteness of the effort for balance is that very indefiniteness of which I spoke before. Therefore the man of the present time will succeed in his seeking only if he unites this seeking with the struggle for balance.

Just as it was important for the Greek to feel: In the commonwealth to which I belong Pallas rules, Apollo rules; that is the abode of Pallas, that, of Apollo; just as it was important for the people of the Middle Ages to know: There is a place of assembly which enshrines something—be it relics of a saint, or even the Holy Grail—there is a place of assembly, in which, when the people gather, the soul-yearnings can flow toward indefinite mysterious things,—so is it important for modern man to develop a feeling for what he is as an individual human being; that as an individual human being he is a seeker for equilibrium, between two opposite, two polaric forces. From the point of view of the soul it may be expressed thus: On one side that force holds sway through which man wishes to soar beyond his head, as it were, the ecstatic, the fantastic, that which would develop rapture and takes no account of the real conditions of existence. As from the point of view of the soul we can characterize one extreme in this way, and the other by saying that it pulls toward the earth, toward the insipid, the barren, the aridly intellectual, and so on, and so on, we can also say, speaking physiologically, that the one pole is everything that heats the blood, and if heated too much it becomes feverish. Expressed physiologically, the one pole is everything connected with the forces of the blood; the other pole all that is connected with the ossifying, the petrifying of man, which if it goes to the physiological extreme would lead to sclerosis in most varied forms. And man must also maintain his balance physiologically between sclerosis and fever as the terminal poles. Life consists fundamentally in seeking the balance between the insipid, the arid, the philistine, and the ecstatically fantastic. We are healthy in soul when we find this balance. We are healthy in body when we can live in balance between fever and sclerosis, ossification. That can be done in an endless number of ways, and in it the individuality can express itself.

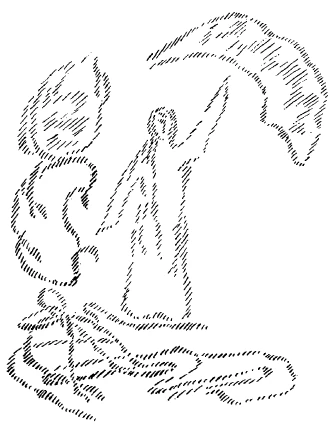

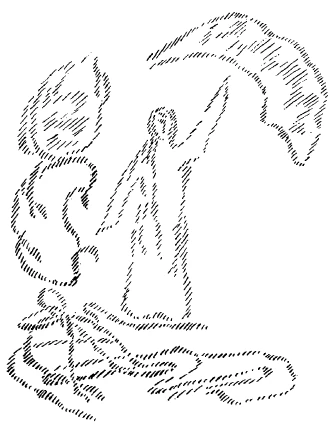

It is in this sense that modern man must come to understand, through his feeling, the ancient Apollo-saying: “Know thou thyself.” But “Know thou thyself” not in some abstract way; “Know thou thyself in the struggle for balance.” Therefore we have to set up at the east end of the building what is intended to cause the human being to feel this struggle for balance. That is to be represented in the plastic wood group mentioned yesterday, with the Christ-Form as the central figure—the Christ-Form which we have tried to fashion in such a way that one may imagine: It was really thus that the Christ went about in Palestine at the beginning of our era in the man Jesus of Nazareth. The conventional pictures of the bearded Christ are actually only creations of the fifth or sixth century, and they are really not in any way true portraits, if I may use the expression. That has been attempted here: to produce a true portrait of Christ, Who is to be at the same time the Representative of the seeking human being, the human being striving for balance.

You will see then in this group two figures (see drawing No. VII): here the falling Lucifer, here the upward-striving Lucifer; here below, connected with Lucifer, as it were, an Ahrimanic form, and here a second Ahrimanic form. The Representative of Humanity is placed between the Ahrimanic form—the philistine, the insipid, the aridly materialistic—and the Lucifer-form—the ecstatic, the fantastic; between the Ahriman-figure—all that leads to petrifaction, to sclerosis—and the Lucifer-figure—the representation of all that leads man feverishly out beyond the limit of what his health can endure.

After we have placed in the center, as it were, the Gothic cathedral, which encloses no image, but either the relics of saints or even the Holy Grail—that is, something no longer directly connected with beings living on earth—then we come back again, I might say, to the idea of the building as enclosing something, but now enclosing the being of man in his struggle for balance.

If destiny permits it, and this building can some day be completed, he who sits within it will have directly before him, while he is looking upon the Being who gives meaning to the earth evolution, something which suggests to him to say: the Christ-Being. But this is to be felt in an artistic way. It must not be merely reasoned about speculatively as being the Christ, but it must be felt. The whole is artistically conceived, and what comes to artistic expression in the forms is the most important part. But it is nevertheless intended to suggest to the human being through feeling—I might say to the exclusion of the intellect, which is to be merely the ladder to feeling—that he is to look toward the east of the building and be able to say: “That art thou.” But now, not an abstract definition of man, for balance can be effected in innumerable ways. Not an image of a god is enclosed, for it is true for Christians also that they are to make no image of a God—not an image of a god is enclosed, but that is enclosed which has developed of the qualities of the human group-soul into the individual force-entity of each separate human being. And the working and weaving of the individual impulse is taken into account in these forms.—

If you do not reason about what I have now said (that of course, is the favorite method today), but if you penetrate it with the feeling, and realize that nothing is symbolized or thought out with the intellect, but that first of all the effort has at least been made to let it flow out in artistic forms: then you have the basic principle which is intended to be expressed in this Goetheanum Building; but you have also the nature of the connection between that which purposes to be anthroposophically-orientated spiritual science and the inner spirit of human evolution. In our time one cannot reach this anthroposophical spiritual science except by way of the great modern demands of humanity's present and immediate future. We must really learn to speak in a different way about that which is actually bearing mankind toward the future.

There are now many kinds of secret societies which take pride in them-selves, but which are really nothing more nor less than mere custodians of that which is still being projected into the present out of the time before the great turning point in the 15th century,—a fact which frequently comes to expression even quite externally. We have also repeatedly been able to experience that such aspiration has penetrated our ranks. How very often, when some one wishes to express the special merit of a so-called occult movement is reference made to its age. We had among us at one time, for example, a man who wished to play himself up a little bit as a Rosicrucian; and when he said something, which was generally his most personal, trivial opinion, he almost never failed to add: “as the old Rosicrucians used to say;” and he never omitted the “old.” If one looks about among many of the secret societies of the present time, it will be seen everywhere that the value of the things advocated consists in being able to point to their venerable age. Some go back to Rosicrucianism—in their own way of course—others naturally go back much farther still, especially to Egypt; and if anybody today can retail Egyptian temple wisdom, a large proportion of humanity will be taken in at the mere announcement.

Most of our friends know that we have continually emphasized that this anthroposophically-orientated spiritual movement has nothing to do with this straining after the ancient. Its endeavor concerns that which is now being revealed directly from the spiritual world to this physical world. Therefore about many things it must speak differently from some secret societies,—which are to be taken seriously, but which are nevertheless building upon antiquated foundations, and are at present still playing a prominent role in human events. When you hear such people talking (indeed, sometimes in this day their own inclinations make them speak), people who are initiated into certain mysteries of present day secret societies, you will notice that they speak chiefly of three things. First, of that which the real seeker for the spiritual world experiences, and which he cannot possibly avoid when he first crosses the threshold of that world, namely, the meeting with powers which are the actual enemies of mankind, the real essential opponents of the physical human being living here on earth as he is intended by the Divine Powers to live. That is to say, these people know that what is concealed from the ordinary human consciousness is permeated by those powers which may be called with some justice the essential causes of illness and death, but with whom also is interwoven all that is connected with human birth. And you can hear from the people who know something of these things that one ought to be silent about them, because what lies beyond the normal consciousness cannot be revealed to profane humanity. (In speaking thus they really mean the immature souls who have not made them-selves strong enough for it—and indeed that includes a large proportion of humanity.)

The second experience is, that at the moment in which man learns to recognize the truth (it can be recognized only when one has knowledge of super-sensible mysteries) he learns to recognize also to what extent everything that can be affirmed merely through sense observation of the environing world is illusion, deception,—indeed, the more exact the external research, the greater the illusion. This loss of the solid ground from under his feet which the man of our time especially needs, so that he can say, “That is a fact, for I have seen it”—this loss takes place with the crossing of the threshold.

The third is, that at the moment we begin to do the work of a human being—whenever human deeds are accomplished, whether working with tools or cultivating the ground, but especially when we perform human deeds which we weave into the web of the social organism—when we work in this way we do something which not only concerns us as men, but which is related to the whole universe. Of course man believes to-day that when he builds a locomotive, or makes a telephone or a lightning conductor or a table, or when he cures the sick, or even fails to cure, or does anything at all,—he believes that such things play a role only with-in human evolution on earth. No; it is a deep truth which I have indicated in my mystery-drama, The Portal of Initiation, that when some-thing occurs here, there are resultant events in the whole universe (call to mind the scene between Strader and Capesius). The people who today know something of these things begin with these three experiences, which are, however, preserved in these societies in the form they had be-fore the middle of the 15th century—and in this form they are often greatly misunderstood. Such people begin with these things, referring first to the mysteries of illness, health, birth, and death; second, to the mystery of the great illusion in the sense world; third, to the mystery of the universal significance of human work; and they speak in a certain way. What is said about all these things, and especially about these most important things, must be different from the past. I should like to give you an idea how differently such things were spoken of in the past, how what was said flowed out into the general consciousness, how it permeated the ordinary natural science, the ordinary social thinking, and so on; and how they must be spoken of in the future, whenever the truth is really spoken; how what then comes from the secret sources of the striving for knowledge must flow out into the external knowledge of nature, into the external social view, and so forth.

Of this mighty metamorphosis—which should be understood today, because men must awake fully from the group consciousness to the individual consciousness—of this great metamorphosis, this historic metamorphosis, I should like to speak to you further.

Zehnter Vortrag

Gestern habe ich Ihnen gesprochen von den Beziehungen anthroposophisch orientierter Geisteswissenschaft zu den Formen unseres Baues. Ich wollte besonders darauf hinweisen, daß die Beziehungen dieses Baues zu unserer Geisteswissenschaft nicht äußerliche sind, sondern daß gewissermaßen der Geist, der waltet in unserer Geisteswissenschaft, eingeflossen ist in diese Formen. Und ein besonderer Wert muß darauf gelegt werden, daß gewissermaßen behauptet werden kann, daß ein wirkliches, empfindungsgemäßes Verstehen dieser Formen ein Ablesen des inneren Sinnes bedeutet, der in unserer Bewegung vorhanden ist, Ich möchte heute noch auf einiges auf den Bau Bezügliches eingehen, um dann daran anknüpfend einige wichtige Dinge aus der Anthroposophie Ihnen heute oder morgen vorzubringen.

Sie werden sehen, wenn Sie sich den Bau betrachten, daß sein Grundriß zwei ineinandergreifende Kreise sind, ein kleinerer und ein größerer, so daß ich etwa schematisch den Grundriß so zeichnen könnte (es wird der Grundriß gezeichnet).

Der ganze Bau ist von Osten nach Westen orientiert. (Es wird die Ost-West-Linie gezogen.) Nun werden Sie gesehen haben, daß diese Ost-West-Linie die einzige Symmetrie-Achse ist, daß also alles symmetrisch auf diese Achse hin orientiert ist.

Im übrigen haben wir es nicht zu tun mit einem bloßen mechanischen Wiederholen der Formen, wie man es sonst in der Baukunst findet, etwa mit gleichen Kapitälen oder dergleichen, sondern wir haben es zu tun, wie ich schon gestern ausführte, mit einer Evolution der Formen, mit einem Hervorgehen späterer Formen aus früheren Formen.

Sie finden, abschließend den äußeren Umgang, sieben Säulen zur Linken und sieben zur Rechten. (Die Säulen werden angedeutet.) Und ich habe schon gestern erwähnt, daß diese sieben Säulen Kapitäle und Sockel haben und über sich die entsprechenden Architrave, die in fortlaufender Evolution ihre Formen entwickeln.

Wenn Sie diesen Grundriß empfinden, dann werden Sie einfach in diesen zwei ineinandergreifenden Kreisen — aber Sie müssen es empfindungsgemäß erfassen — etwas haben, was hinweist auf die Entwickelung der Menschheit. Ich habe schon gestern gesagt, daß ungefähr in der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts ein ganz bedeutungsvoller Einschnitt in der Entwickelung der Menschheit zu verzeichnen ist. Dasjenige, was man schulmäßig und äußerlich «Geschichte» nennt, das ist ja nur eine Fable convenue, denn die verzeichnet äußere Tatsachen so, daß dabei der Schein hervorgerufen wird, als wenn es mit dem Menschen im wesentlichen schon im 8., 9. Jahrhunderte so gestanden hätte, wie es etwa im 18. oder 19. Jahrhundert gestanden hat. Es sind ja sogar schon neuere Geschichtsschreiber darauf gekommen, zum Beispiel Lamprecht, daß dies ein Unsinn ist, daß in der Tat die Seelenverfassung und Seelenstimmung der Menschen eine ganz andere war vor und nach dem angedeuteten Zeitpunkte. Und wir in der Gegenwart stehen in einer Entwickelung drinnen, die wir nur verstehen können, wenn wir uns bewußt werden, daß wir mit eigenartigen Seelenkräften uns der Zukunft entgegen entwickeln, und daß diejenigen Seelenkräfte, die ihre Entwickelung durchgemacht haben bis in diejenige des 15. Jahrhunderts, zwar jetzt noch, man könnte sagen, in den Menschenseelen spuken - sie klingen ab -, daß sie aber zu dem gehören, was untergeht, zu dem, was verurteilt ist dazu, aus der Menschheitsevolution herauszufallen. Über diesen wichtigen Umschwung in der Menschheitsentwickelung muß man ein Bewußtsein entwickeln, wenn man überhaupt fähig werden soll, über die Angelegenheiten der Menschheit in der Gegenwart und in der nächsten Zukunft mitzureden.

Solche Dinge drücken sich besonders da aus, wo die Menschen bedeutungsvoll hinweisen wollen auf dasjenige, was sie fühlen, was sie empfinden. Wir brauchen uns ja nur an eines in der Entwickelung der Baukunst zu erinnern, was wir hier ja schon angeführt haben, auf das ich aber heute erneut wiederum hinweisen will, um an einem Beispiele zu zeigen, wie die Entwickelung der Menschheit fortschreitet.

Betrachten Sie einmal die Formen eines griechischen Tempels. Wie kann man die Formen eines griechischen Tempels verstehen? Man kann sie nur verstehen, wenn man sich klar darüber ist, daß der ganze Baugedanke dieses griechischen Tempels daraufhin orientiert ist, den Tempel zum Wohnhaus des Gottes oder der Göttin zu machen, die man als Standbild darinnen hatte. Alle Formen des griechischen Tempels wären ein Unding, wenn man ihn nicht so auffaßte, daß er die Umhüllung, das Wohnhaus des Gottes oder der Göttin ist, die drinnenstehen sollten.

Schreiten wir vor von den Formen des griechischen Tempels zu den nächsten, wiederum signifikanten Formen des Bauens, so kommen wir zu dem gotischen Dom. Wer in einen gotischen Dom hineingeht und das Gefühl hat, er habe mit diesem gotischen Dom etwas Abgeschlossenes, Fertiges vor sich, der versteht die Formen des gotischen Baues nicht, ebensowenig wie derjenige die Formen des griechischen Tempels versteht, der ihn auch so betrachten kann, daß kein Götterbild drinnensteht. Ein griechischer Tempel ohne Götterbild — wir brauchen es uns ja nur drinnen zu denken, aber es muß eben, um die Form zu verstehen, drinnen gedacht werden -, ein griechischer Tempel ohne Götterbild ist eine Unmöglichkeit für das empfindende Verständnis. Ein gotischer Dom, der leer ist, ist auch eine Unmöglichkeit für den Menschen, der wirklich so etwas empfindet. Der gotische Dom ist erst fertig, wenn die Gemeinde drinnen ist, wenn er mit Menschen angefüllt ist, und eigentlich nur dann, wenn er mit Menschen angefüllt ist und zu den Menschen gesprochen wird, so daß der Geist des Wortes über der Gemeinde oder in den Herzen der Gemeinde waltet. Dann ist der gotische Dom fertig. Aber die Gemeinde gehört dazu, sonst sind die Formen nicht verständlich.

Was haben wir denn da eigentlich für eine Evolution vor uns von dem griechischen Tempel bis zum gotischen Dom? Das andere sind im Grunde genommen Zwischenformen, was auch darüber irrtümliche Geschichtsauslegung sagen möge. Was haben wir denn da für eine Evolution vor uns? Wenn wir auf die griechische Kultur hinblicken, diese Blüte der vierten nachatlantischen Periode, so müssen wir sagen: Im griechischen Bewußtsein lebte noch etwas von dem Verweilen göttlich-geistiger Gewalten unter den Menschen, nur daß die Menschen dazu verhalten waren, ihren Göttern, die sie sich selbst nur in den Bildern vergegenwärtigen konnten, Wohnhäuser zu bauen. Der griechische Tempel war das Wohnhaus des Gottes oder der Göttin, von denen man das Bewußtsein hatte: sie gehen herum unter den Menschen. Ohne dieses Bewußtsein der Gegenwart göttlich-geistiger Mächte ist die Hineinstellung des griechischen Tempels in die griechische Kultur gar nicht zu denken.

Schreiten wir nun vorwärts von der Blüte der griechischen Kultur zu dem Auslauf dieser Kultur gegen das Ende der vierten nachatlantischen Periode, also gegen die Zeiten des 8., 9., 10. nachchristlichen Jahrhunderts, so kommen wir hinein in die Formen der gotischen Baukunst, die da fordert die Gemeinde. Alles entspricht dem Empfindungsleben der Menschen der damaligen Zeit. Die Menschen waren in ihrer Seelenstimmung natürlich anders in dieser Zeit, als in der Hochblüte des griechischen Denkens. Das Bewußtsein von der unmittelbaren Gegenwart göttlich-geistiger Mächte war nicht vorhanden, die göttlich-geistigen Mächte waren fern in ein Jenseits versetzt. Das irdische Reich war vielfach angeklagt als ein solches des Abfallens von den göttlich-geistigen Mächten. Das Materielle sah man an als etwas, das zu meiden ist, von dem der Blick abzuwenden ist, der dagegen hinzuwenden ist zu den geistigen Mächten. Und der eine Mensch suchte im Anschluß an den anderen in der Gemeinde — gewissermaßen aufsuchend den Gruppengeist der Menschheit — das Walten des Geistigen, das damit auch den Charakter eines gewissen Abstrakten gewonnen hatte. Daher machen die Formen der Gotik auch einen abstrakt-mathematischen Eindruck gegenüber den mehr dynamisch wirkenden Formen der griechischen Baukunst, die etwas haben vom wohnlichen Umfassen des Gottes oder der Göttin. In den gotischen Formen ist alles aufstrebend, es ist alles darauf hinweisend, daß in geistigen Fernen gesucht werden muß dasjenige, wonach die Seele dürstet. Dem Griechen war sein Gott und seine Göttin da. Er hörte gewissermaßen mit seinem Seelenohr deren Raunen, Die sehnsüchtige Seele nur konnte in Formen, die nach oben zuliefen, das Göttliche ahnen in der Zeit der Gotik.

So war die Menschheit gewissermaßen mit Bezug auf ihre Seelenstimmung sehnsüchtig geworden, baute auf Sehnsuchten, baute auf das Suchen, glaubte in diesem Suchen glücklicher sein zu können durch den Zusammenschluß in der Gemeinde, aber war immer überzeugt, daß dasjenige, was als das Göttlich-Geistige anzuerkennen ist, nicht etwas ist, was unmittelbar unter den Menschen waltet, sondern was in geheimnisvollen Untergründen sich verbirgt. Wenn man nun dasjenige, was man da sehnsüchtig erstrebte, sehnsüchtig suchte, ausdrücken wollte, konnte man es nur so ausdrücken, daß man irgendwie es anknüpfte an ein Geheimnisvolles. Der Zeitausdruck für diese ganze Seelenstimmung der Menschen ist der Tempel oder der Dom, könnten wir auch sagen, der in seiner eigentlichen, typischen Form der gotische Dom ist. Aber wenn man wiederum dasjenige, was man als das allerhöchst Geheimnisvolle ersehnte, in das geistige Blickfeld rückte, so mußte man gerade in der Zeit, in der man vom Irdischen ins Überirdische sich erheben wollte, von der bloßen Gotik zu etwas anderem übergehen, das, man möchte sagen, nun nicht die physische Gemeinde vereinte, sondern den ganzen zusammenstrebenden Geist der Menschheit oder die zusammenstrebenden Seelengeister der Menschheit nach einem Mittelpunkt, nach einem geheimnisvollen Mittelpunkt hinstreben ließ.

Wenn Sie sich etwa vorstellen die Gesamtheit der menschlichen Seelen wie von allen irdischen Himmelsrichtungen her zusammenströmend, so haben Sie gewissermaßen die Menschheit der ganzen Erde auf dieser Erde vereint als in einem großen Dome, den man nun nicht gotisch dachte, obwohl er denselben Sinn haben sollte wie der gotische Dom. Solche Dinge wurden im Mittelalter angeknüpft an das Biblische. Und wenn man sich etwa vorstellt, daß die zweiundsiebzig Jünger — man braucht ja nicht an physische Geschichte zu denken, sondern an das Geistige, das in diesen Zeiten durchaus die physische Anschauung der Welt durchwebte -, wenn Sie sich also vorstellen, wie nach dem Geiste der Zeit gedacht war, daß die zweiundsiebzig Jünger Christi sich nach allen Himmelsrichtungen verbreiteten und in die Seelen den Geist pflanzten, der zusammenströmen sollte in dem Mysterium Christi: so haben Sie in all dem, was wiederum von jenen zurückströmte, in deren Seelen die Jünger den Christus-Geist hineingetragen haben, in den Strahlen, die von all diesen Seelen aus allen Himmelsrichtungen kommen, dasjenige, was in umfassendster, in universellster Weise der frühmittelalterliche Mensch dachte als das zum Geheimnis Hinstrebende. Ich brauche vielleicht nicht alle zweiundsiebzig zu zeichnen, aber ich kann es andeuten (es wird gezeichnet). Ich deute das nur an, denken Sie sich aber, es wären das zweiundsiebzig Pfeiler. Von diesen zweiundsiebzig Pfeilern würden also die Strahlen kommen, welche aus der Gesamtmenschheit nach dem Geheimnisse Christi hinstreben. Umschließen Sie das Ganze mit einer irgendwie gearteten Wandung - gotisch würde es dann nicht sein, aber ich sagte ja auch schon, warum man nicht bei dem Gotischen streng stehen blieb -, deren Grundriß ein Kreis ist, und denken Sie sich hier die zweiundsiebzig Pfeiler, so würden Sie den Dom haben, der gewissermaßen die ganze Menschheit umfaßt. Denken Sie sich auch den von Osten nach Westen orientiert, so haben Sie darinnen natürlich einen ganz anderen Grundriß zu empfinden als bei unserem Bau, der aus den zwei Kreisstücken zusammengesetzt ist. Die Empfindung diesem Grundriß gegenüber muß eine ganz andere sein, und ich versuchte, skizzenhaft Ihnen diese Empfindung zu beschreiben. Es würde dann zu denken sein, daß die Hauptorientierungslinien eines solchen Baues, der nach diesem Grundriß aufgebaut ist, Kreuzesform haben, und man würde sich etwa zu denken haben, daß Hauptgänge nach dieser Kreuzesform angeordnet wären.

So dachte sich allerdings der mittelalterliche Mensch seinen IdealDom. Wir würden (es wird weitergezeichnet), wenn das hier Osten, das hier Westen ist, dann hier Norden und Süden haben und dann würden im Norden, Süden und Westen drei Tore sein, hier im Osten würde eine Art Hauptaltar sein, und bei jedem Pfeiler würde eine Art Seitenaltar sein. Da aber, wo die Kreuzesbalken sich durchschneiden, da würde stehen müssen der Tempel des Tempels, der Dom des Domes: da würde gewissermaßen die Zusammenfassung des Ganzen sein, im Kleinen eine Wiederholung desjenigen, was das Ganze ist. Wir würden etwa in der modernen, abstrakt gewordenen Sprache sagen: Hier würde stehen ein Sakramentshäuschen, aber in der Form des Ganzen.

Denken Sie sich dies, was ich Ihnen hier aufgezeichnet habe, in einem Stil, in einem Baustil, der erst angenähert ist an die eigentliche Gotik, der noch allerlei romanische Formen in sich schließt, aber der durchaus die Orientierung hat, die ich Ihnen hier angedeutet habe, dann habe ich Ihnen damit die Skizze des Graltempels aufgezeichnet, wie sich ihn der mittelalterliche Mensch vorstellte, jenes Graltempels, der gewissermaßen das Ideal des Bauens war in der Zeit, die sich dem Ausgang der vierten nachatlantischen Epoche näherte: Ein Dom, in dem zusammenströmten die Sehnsuchten der ganzen nach Christus hin orientierten Menschheit, so wie in dem einzelnen Dom zusammenströmten die Sehnsuchten der Glieder der Gemeinde, und so, wie sich verbunden fühlten im griechischen Tempel die Menschen, auch wenn sie nicht drinnen waren — denn der griechische Tempel fordert nur, daß der Gott oder die Göttin drinnen ist, nicht die anderen Menschen -, so also wie sich verbunden fühlten die griechischen Menschen eines Territoriums durch ihren Tempel mit ihrem Gott oder ihrer Göttin. Will man sachgemäß sprechen, so kann man sagen: Indem der Grieche von seinem Verhältnis zu dem 'Tempel redete, schilderte er die Sache etwa in folgender Weise. So wie er von irgendeinem Menschen der Erde, meinetwegen dem Perikles, sagte: Der Perikles wohnt in diesem Hause - so drückt dieser Satz: Der Perikles wohnt in diesem Hause - nicht aus, daß der Mensch selber, der das ausspricht, irgendeine Eigentums- oder sonstige Beziehung zu dem Hause hat, aber er empfindet doch die Art, wie er verbunden ist mit dem Perikles, indem er sagt: Der Perikles wohnt in diesem Hause! — Genau mit derselben Empfindungsnuance würde der Grieche sein Verhältnis auch ausgesprochen haben zu dem, was im Baustil zu lesen war, damit ausdrückend: die Athene wohnt in diesem Hause, das ist das Wohnhaus der Göttin, oder: der Apollo wohnt in diesem Hause!

Das konnte die mittelalterliche Gemeinde, die den Dom hatte, nicht sagen. Denn das war nicht das Haus, in welchem die göttlich-geistige Wesenheit wohnte, das war das Haus, das ausdrückte in jeder einzelnen Form den Versammlungsort, in dem man die Seele hinstimmte zu dem Geheimnisvoll-Göttlichen. Daher war in dem, ich möchte sagen, «Urtempel» vom Ausgange der vierten nachatlantischen Zeit, in der Mitte der Tempel des Tempels, der Dom des Domes. Und von dem Ganzen konnte man sagen: Geht man hier hinein, dann kann man darinnen sich erheben zu den Geheimnissen des Weltenalls! — In den Dom mußte man hineingehen. Von dem griechischen Tempel brauchte man bloß zu sagen: Das ist das Haus des Apollo, das ist das Haus der Pallas. - Und der Mittelpunkt jenes Urtempels, wo sich die Balken des Kreuzes schneiden, der Mittelpunkt, der barg den Heiligen Gral, der war da aufbewahrt.

Sehen Sie, in dieser Art muß man die Stimmung verfolgen, durch welche die einzelnen geschichtlichen Perioden charakterisiert sind, sonst lernt man dasjenige, was eigentlich geschehen ist, nicht kennen. Und man kann vor allen Dingen ohne eine solche Betrachtung nicht kennenlernen, welche seelischen Kräfte sich wiederum in unserer Gegenwart ansetzen.

Also, der griechische Tempel umschloß den Gott oder die Göttin, von denen man wußte: Sie sind unter den Menschen anwesend. Aber das fühlte der mittelalterliche Mensch nicht, der fühlte gewissermaßen die irdische Welt Gott-verlassen, göttlich verlassen. Er fühlte die Sehnsucht, den Weg zu finden zu den Göttern oder zu dem Gotte.

Wir stehen ja heute allerdings erst am Ausgangspunkt, denn es sind ja nur ein paar Jahrhunderte seit dem großen Umschwung in der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts verflossen. Die meisten Menschen sehen kaum dasjenige, was da aufgeht, aber es geht etwas auf, es wird anders mit den Seelen der Menschen. Und dasjenige, was nun wiederum in die Formen hineinfließen muß, in denen man das Zeitbewußtsein verkörpert, das muß auch wieder anders sein. Diese Dinge lassen sich allerdings nicht mit dem Verstande, mit dem Intellekt ausspintisieren, diese Dinge lassen sich nur empfinden, fühlen, künstlerisch anschauen. Und derjenige, der sie auf abstrakte Begriffe bringen will, der versteht sie eigentlich nicht. Aber man kann doch in der verschiedensten Weise charakterisierend auf diese Dinge hinweisen. Und so muß gesagt werden: Der Grieche fühlte gewissermaßen den Gott oder die Göttin wie seine Zeitgenossen, wie seine Mitbewohner. Der mittelalterliche Mensch hatte den Dom, der dem Gotte nicht als Wohnhaus diente, der aber gewissermaßen die Einlaßpforte sein sollte zu dem Wege, der zu dem Göttlichen führt. Die Menschen versammelten sich in dem Dom und suchten gewissermaßen aus der Gruppenseele der Menschheit heraus. Das ist das Charakteristische, daß diese ganze mittelalterliche Menschheit etwas hatte, das nur zu verstehen ist aus dem Gruppenseelenhaften heraus. Der einzelne, individuelle Mensch kam bis in die Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts nicht so in Betracht wie seit jener Zeit. Seit jener Zeit ist dasjenige, was das Wesentlichste im Menschen ist, das Streben, Individualität zu sein, das Streben, individuelle Persönlichkeitskräfte zusammenzufassen, gewissermaßen einen Mittelpunkt in sich selber zu finden.

Man versteht auch nicht dasjenige, was in den verschiedensten sozialen Forderungen unserer Zeit aufsteigt, wenn man nicht dieses Walten des Individualgeistes in jedem einzelnen Menschen kennt, dieses Stehenwollen eines jeden einzelnen Menschen auf der Grundlage seines Wesens.

Dadurch aber wird für den Menschen etwas ganz besonders wichtig in dieser Zeit, die mit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts begonnen hat und gegen das vierte Jahrtausend zu erst enden wird. Damit tritt etwas ein, was für diese Zeit von ganz besonderer Wichtigkeit ist. Denn sehen Sie, es ist etwas Unbestimmtes ausgedrückt, wenn man sagen muß: Jeder Mensch strebt nach seiner besonderen Individualität. Der Gruppengeist, selbst wenn er nur kleinere Gruppen umfaßt, ist etwas viel Faßbareres als dasjenige, was jeder einzelne Mensch aus dem Urquell seiner Individualität heraus erstrebt. Daher kommt es, daß ganz besonders wichtig wird für diesen Menschen der neueren Zeit das zu verstehen, was man nennen kann: Gleichgewicht suchen zwischen den entgegengesetzten Polen.

Das eine will gewissermaßen über den Kopf hinaus. Alles, was den Menschen dazu bringt, Schwärmer, Phantast, Wahnmensch zu sein, was ihn erfüllt mit unbestimmten mystischen Regungen nach irgendeinem unbestimmten Unendlichen, ja, was ihn selbst erfüllt, wenn er Pantheist oder Theist oder irgend so etwas ist, was man ja heute so häufig ist, das ist der eine Pol. Der andere Pol ist der der Nüchternheit, der Trockenheit, trivial gesprochen, aber nicht unwirklich gesprochen gegenüber dem Geiste der Gegenwart, wahrhaftig nicht unwirklich gesprochen: der Pol der Philistrosität, der Pol des Spießbürgertums, der Pol, der uns hinunterzieht zur Erde in den Materialismus hinein. Diese zwei Kräftepole sind im Menschen, und zwischen denen darinnen steht das Menschenwesen, hat es das Gleichgewicht zu suchen. Auf wie viele Arten kann man denn das Gleichgewicht suchen? Sie können sich das wiederum durch das Bild der Waage vorstellen (es wird gezeichnet). Auf wie viele Arten kann man denn das Gleichgewicht suchen zwischen zwei nach entgegengesetzten Richtungen ziehenden Polen?

Nicht wahr, wenn hier auf der einen Waagschale fünfzig Gramm oder fünfzig Kilogramm sind, und hier auch, so ist Gleichgewicht. Aber wenn hier auf der einen Waagschale ein Kilogramm ist, und hier auf der anderen Waagschale auch ein Kilogramm, so ist auch Gleichgewicht, und wenn hier tausend und hier tausend sind, so ist auch Gleichgewicht.

Auf unendlich viele Arten können Sie das Gleichgewicht suchen. Das entspricht den unendlich vielen Arten, individueller Mensch zu sein. Daher ist für den gegenwärtigen Menschen so wesentlich, einzusehen, daß sein Wesen in dem Streben nach Gleichgewicht zwischen den entgegengesetzten Polen besteht. Und das Unbestimmte des Suchens nach Gleichgewicht ist eben jenes Unbestimmte, von dem ich Ihnen vorhin gesprochen habe.

Daher kommt der Mensch der Gegenwart mit seinem Suchen nur zurecht, wenn er sich mit diesem Suchen anlehnt an das Streben nach dem Gleichgewichte.

So wichtig, wie es für den Griechen war, zu fühlen, in dem Gemeinwesen, dem ich angehöre, waltet die Pallas, waltet der Apollo, das ist das Haus der Pallas, das ist das Haus des Apollo, so wichtig es für den mittelalterlichen Menschen war, zu wissen: es gibt einen Versammlungsort, der birgt etwas — seien es die Reliquien eines Heiligen, sei es der Heilige Gral selber —, es gibt einen Versammlungsort, in dem, wenn man sich da versammelt, die Seelensehnsuchten nach dem unbestimmten Geheimnisvollen strömen können, so wichtig ist es für den modernen Menschen, ein Empfinden dafür zu entwickeln, was er ist als individueller Mensch: daß er als individueller Mensch ein Sucher des Gleichgewichtes ist zwischen zwei entgegengesetzten, zwei polarischen Kräften. Man kann seelisch das so ausdrücken, daß man sagt: Auf der einen Seite waltet das, wodurch der Mensch gewissermaßen über seinen Kopf hinaus will, das Schwärmerische, das Phantastische, dasjenige, was Lust entwickeln will, die nicht sich kümmert um die realen Bedingungen des Daseins. So wie man das eine Extrem seelisch so bezeichnen kann, so das andere Extrem so, daß es hinüberzieht nach der Erde, nach dem Nüchternen, Trockenen, trocken Intellektuellen und so weiter. Physiologisch ausgedrückt kann man auch so sagen: Der eine Pol ist alles dasjenige, wo das Blut hinkocht, und kocht es zu stark, so wird es fieberhaft. Physiologisch ausgedrückt ist der eine Pol alles dasjenige, was mit den Kräften des Blutes zusammenhängt, der andere Pol alles dasjenige, was zusammenhängt mit dem Knochigwerden, dem Petrifizieren des Menschen, was, wenn es ins physiologische Extrem geht, zur Sklerose in den verschiedensten Formen führen würde. Und zwischen der Sklerose und dem Fieber als den radikalen Endpolen muß auch physiologisch der Mensch sein Gleichgewicht bewahren. Das Leben besteht im Grunde genommen in dem Gleichgewichtsuchen zwischen dem Nüchternen, Trockenen, Philiströsen und dem SchwärmerischPhantastischen. Seelisch gesund sind wir, wenn wir das Gleichgewicht finden zwischen dem Schwärmerisch-Phantastischen und dem TrockenPhiliströsen. Körperlich gesund sind wir, wenn wir im Gleichgewichte leben können zwischen dem Fieber und der Sklerose, der Verknöcherung. Und das kann auf unendlich viele Weise geschehen, darinnen kann die Individualität leben.

Das ist dasjenige, worin der Mensch gerade in der modernen Zeit erfühlen muß den alten Apollo-Spruch «Erkenne dich selbst». Aber «Erkenne dich selbst» nicht in irgendeiner Abstraktion: «Erkenne dich selbst in dem Streben nach Gleichgewicht.» Deshalb haben wir im Osten des Baues aufzustellen dasjenige, was den Menschen empfinden lassen kann dieses Streben nach Gleichgewicht. Und das soll in der gestern erwähnten plastischen Holzgruppe zur Darstellung kommen, die als Mittelpunktsfigur hat die Christus-Gestalt, die Christus-Gestalt, die versucht worden ist so zu gestalten, daß man sich vorstellen kann: $o hat wirklich der Christus in dem Menschen Jesus von Nazareth gewandelt im Beginne unserer Zeitrechnung in Palästina. Die konventionellen Bilder des bärtigen Christus, sie sind ja eigentlich erst Schöpfungen des 5., 6. Jahrhunderts, und sie sind wahrhaftig nicht irgendwie, wenn ich den Ausdruck gebrauchen darf, porträtgetreu. Das ist versucht worden: einen porträtgetreuen Christus zu schaffen, der der Repräsentant zugleich sein soll des suchenden, des nach Gleichgewicht strebenden Menschen. (Es wird gezeichnet.)

Sie werden dann an dieser Gruppe zwei Figuren sehen: Hier den stürzenden Luzifer, hier den hinaufstrebenden Luzifer. Hier unten, gewissermaßen verbunden mit Luzifer, eine ahrimanische Gestalt, und hier eine zweite ahrimanische Gestalt. Hineingestellt der Menschheitsrepräsentant zwischen der ahrimanischen Gestalt: dem Philiströsen, dem Nüchtern-Trocken-Materialistischen; und der Luzifer-Gestalt: dem Schwärmerischen, Phantastischen. Der Ahriman-Gestalt: alldem, was den Menschen führt zur Petrifizierung, zur Sklerose; der LuziferGestalt: Repräsentanz alles dessen, was den Menschen fiebrig über das Maß derjenigen Gesundheit hinausführt, das er ertragen kann.

Und so kommt man, nachdem gewissermaßen in die Mitte hineingestellt ist der gotische Dom, der kein solches Bildnis umschließt, sondern entweder die Reliquien der Heiligen oder auch den Heiligen Gral — also irgend etwas, was nicht mehr mit unmittelbar hier Wandelnden zusammenhängt —, so kommt man, ich möchte sagen, wiederum zurück zu dem, daß der Bau etwas Umschließendes wird, aber jetzt umschließt die Menschenwesenheit in ihrem Streben nach Gleichgewicht.

Wenn das Schicksal es will-und einmal dieser Bau vollendet werden kann, wird gewissermaßen der, welcher darinnen sitzt, unmittelbar vor sich haben das, was ihm nahelegt, indem er hinsieht auf die Wesenheit, die der Erdenevolution Sinn gibt, auszusprechen: Die Christus-Wesenheit. Aber die Sache soll künstlerisch empfunden werden. Es darf das nicht spintisierend etwa nur als der Christus intellektuell gedacht werden, sondern es muß empfunden werden. Das Ganze ist künstlerisch gedacht, und was künstlerisch in den Formen zum Ausdruck kommt, das ist das Wichtigste. Dennoch aber soll es gerade rein empfindungsgemäß, ich möchte sagen, mit Ausschluß des Intellektuellen, das nur die Leiter zur Empfindung sein soll, dem Menschen nahelegen, nach dem Osten hinzuschauen und sagen zu können: «Das bist Du», aber jetzt nicht eine abstrakte Definition des Menschen, denn das Gleichgewicht kann auf unendlich viele Arten hergestellt werden. Nicht ein Götterbild ist umschlossen — denn es gilt ja auch für die Christen, daß sie sich von dem Gotte kein Bild machen sollen -, nicht ein Götterbild ist umschlossen, aber dasjenige ist umschlossen, was aus dem Gruppenseelenhaften des Menschen sich herausgebildet hat zu der Individual-Kraftwesenheit jedes einzelnen Menschen. Und dem Wirken und Weben des Individual-Impulses ist Rechnung getragen in diesen Formen.

Wenn Sie das, was ich jetzt gesagt habe, nicht mit dem Verstande denken -— das ist ja heute eine beliebte Art —, sondern wenn Sie es mit dem Gefühl durchdringen und sich denken, daß nichts symbolisiert ist oder verstandesmäßig ausgedacht ist, sondern vor allem wenigstens versucht worden ist, es ausströmen zu lassen in künstlerischen Formen, dann haben Sie das Grundprinzip, das sich in diesem Bau des Goetheanum ausdrücken soll. Dann haben Sie aber auch die Art und Weise, wie zusammenhängt mit dem inneren Geist der Menschheitsevolution das, was sein will anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft. In dieser Zeit kommt man dieser anthroposophisch orientierten Geisteswissenschaft nicht nahe, wenn man den Weg nicht sucht aus den großen Forderungen heraus der neueren Zeit der menschlichen Gegenwart und der nächsten menschlichen Zukunft. Wir müssen wirklich anders reden lernen über dasjenige, was eigentlich die Menschen der Zukunft entgegenträgt.

Es gibt jetzt mancherlei auf sich stolze Geheimgesellschaften, die aber im Grunde genommen mehr oder weniger nichts anderes sind als doch nur Träger dessen, was noch hereinragt aus der Zeit vor der großen Wende im 15. Jahrhundert. Das drückt sich ja oftmals auch sehr äußerlich aus. Auch wir haben es ja oftmals erfahren können, daß in unsere Reihen hereinragt solches Streben. Wie oft und oft wird, wenn man das besonders Wertvolle eines sogenannten okkulten Strebens ausdrücken will, darauf hingewiesen, wie alt die Sache ist. Wir hatten zum Beispiel einmal einen Mann unter uns, der wollte so ein bißchen sich aufspielen als einen Rosenkreuzer. Und der hat überhaupt, wenn er etwas gesagt hat, was zumeist nichts anderes war als seine höchst eigene, triviale Privatmeinung, nie versäumt zu sagen: wie die «alten» Rosenkreuzer gesagt haben. Aber das «alte» hat er nie ausgelassen. Und wenn man nachschaut bei mancherlei der gegenwärtigen Geheimgesellschaften, überall sieht man den Wert der Dinge, die man vertritt, darinnen, daß man auf das höchste Alter hinweisen kann. Manche gehen zurück auf das Rosenkreuzertum - in ihrer Art selbstverständlich -—, manche natürlich noch viel weiter, besonders ins alte Ägypten, und wenn irgend jemand ägyptische Tempelweisheit heute verschleißen kann, dann fällt schon ein großer Teil der Menschheit auf die bloße Ankündigung hin herein.

Die meisten unserer Freunde wissen, daß wir stets betont haben: mit diesem Streben nach dem Alten hat diese anthroposophisch orientierte Geistesbewegung nichts zu tun. Sie strebt nach dem, was jetzt unmittelbar aus der geistigen Welt heraus sich für diese physische Welt offenbart. Daher muß sie über vieles anders reden, als auch ernst zu nehmende, aber doch auf das Antiquierte bauende Geheimgesellschaften, die gegenwärtig noch in dem Geschehen der Menschheit eine große Rolle spielen. Wenn Sie solche Leute reden hören - es wird ihnen ja aus dem eigenen Willen heraus heute manchmal der Mund geöffnet -, die eingeweiht sind in gewisse Geheimnisse der gegenwärtigen Geheimgesellschaften, so werden Sie hören, wie sie hauptsächlich von drei Dingen reden. Erstens von jenem Erlebnis, das der wirkliche Sucher nach der geistigen Welt hat, wenn er die Schwelle zur geistigen Welt überschreitet, das darinnen besteht, daß man nicht umhin kann, sobald man die Schwelle zur geistigen Welt überschreitet, zuammenzukommen mit Mächten, welche die wirklichen Feinde der Menschheit sind, welche die wahren, realen, wesenhaften Gegner des hier auf der Erde lebenden physischen Menschen sind, so wie dieser physische Mensch von den göttlichen Mächten intendiert wird. Das heißt: Es wissen diese Leute, daß dasjenige, was sich vor dem gewöhnlichen Menschenbewußtsein verhüllt, durchwoben ist von denjenigen Mächten, die mit einem gewissen Rechte genannt werden dürfen die wesenhaften Ursachen von Krankheit und Tod, mit denen aber auch verwoben ist all dasjenige, was mit der menschlichen Geburt zusammenhängt. Und Sie können dann hören von jenen Menschen, die von solchen Dingen etwas wissen, daß über diese Dinge geschwiegen werden müsse — ich sag es im Konjunktiv —, weil man der profanen Menschheit — so sagt man, man meint eigentlich die unreifen Seelen, die sich nicht stark genug gemacht haben dazu, und allerdings gehört ja dazu ein großer Teil der Menschheit — nicht offenbaren könne, was da jenseits des normalen Bewußtseins ist.

Das zweite Erlebnis ist, daß der Mensch in dem Augenblicke, wo er die Wahrheit erkennen lernt — die Wahrheit kann man erst erkennen lernen, wenn man die Geheimnisse des Übersinnlichen kennen lernt -, auch erkennen lernt, inwiefern alles dasjenige, was man durch bloße sinnliche Beobachtung der Umwelt aussagen kann, Illusion, Täuschung ist; wenn das noch so exakt erforscht ist, ja, dann erst recht Täuschung ist. Dieses Verlieren des Bodens unter den Füßen, den insbesondere der heutige Mensch braucht, das Verlieren des festen Bodens, so daß er sagen kann: Das ist eine Tatsache, denn ich habe es gesehen — das hört auf nach dem Überschreiten der Schwelle.

Das dritte ist, daß in dem Augenblicke, wo wir beginnen Menschenwerk zu verrichten - sei es, indem wir mit Werkzeugen arbeiten oder den Boden bearbeiten, überhaupt Menschenwerk verrichten, namentlich aber dann, wenn wir Menschenwerk verrichten, indem wir es in das Gewebe des sozialen Organismus einweben -—, daß wir dann etwas machen, was nicht bloß uns als Menschen angeht, sondern etwas machen, was dem ganzen Universum angehört. Der Mensch glaubt heute selbstverständlich, wenn er eine Lokomotive konstruiert, oder wenn er ein Telephon macht oder einen Blitzableiter oder einen Tisch, oder wenn er einen Kranken heilt oder auch nicht heilt, ihn krank bleiben läßt, oder irgend etwas anderes tut, das seien Dinge, die sich nur abspielen innerhalb der Menschheitsentwickelung auf der Erde. Nein, dasjenige, was ich angedeutet habe in meinem Mysteriendrama «Die Pforte der Einweihung», daß sich im ganzen Weltenall Ereignisse abspielen, wenn hier etwas geschieht — erinnern Sie sich an die Szene zwischen Strader und Capesius —, das ist eine tiefe Wahrheit.

An diese drei Erlebnisse knüpfen die Menschen an, die heute etwas wissen von den Dingen, welche aber in diesen Gesellschaften in der Form von vor der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts aufbewahrt werden und oftmals höchst mißverstanden aufbewahrt werden. An diese Dinge knüpfen die Menschen an, indem sie hinweisen: erstens auf das Geheimnis von Krankheit, Gesundheit, Geburt und Tod, zweitens auf das Geheimnis der großen Illusion im Sinnlichen, drittens auf das Geheimnis der universellen Bedeutung des Menschenwerkes. Und sie sprechen in einer gewissen Weise davon. Über alle diese Dinge - und gerade über diese wichtigsten Dinge- muß in der Zukunft anders gesprochen werden als in der Vergangenheit. Und eine Vorstellung davon möchte ich Ihnen geben, wie anders in der Vergangenheit über solche Dinge gesprochen worden ist, was dann herausgeflossen ist in das allgemeine Bewußtsein, durchdrungen hat das gewöhnliche Naturwissen, das gewöhnliche soziale Denken und so weiter, und wie in der Zukunft gesprochen werden muß da, wo man wirklich von der Wahrheit spricht, wie dann herausfließen muß dasjenige, was aus den geheimen Quellen des Erkenntnisstrebens kommt, in die äußere Naturerkenntnis, in die äußere soziale Anschauung und so weiter.

Von dieser gewaltigen Metamorphose — die man aber heute verstehen soll, weil die Menschen aus dem Gruppenbewußtsein heraus völlig erwachen müssen zum individuellen Bewußtsein —, von dieser großen Metamorphose, von dieser historischen Metamorphose möchte ich Ihnen noch sprechen.

Tenth Lecture

Yesterday I spoke to you about the relationship between anthroposophically oriented spiritual science and the forms of our buildings. I wanted to point out in particular that the relationship between these buildings and our spiritual science is not an external one, but that the spirit that reigns in our spiritual science has, in a sense, flowed into these forms. And special value must be placed on the fact that it can be said that a real, intuitive understanding of these forms means reading the inner meaning that is present in our movement. Today I would like to go into a few more details about the building, and then, building on that, I will present some important things from anthroposophy to you today or tomorrow.

If you look at the building, you will see that its floor plan consists of two interlocking circles, one smaller and one larger, so that I could draw the floor plan schematically as follows (the floor plan is drawn).

The entire building is oriented from east to west. (The east-west line is drawn.) Now you will have seen that this east-west line is the only axis of symmetry, so that everything is symmetrically oriented towards this axis.

Incidentally, we are not dealing here with a mere mechanical repetition of forms, as is otherwise found in architecture, for example with identical capitals or the like, but rather, as I explained yesterday, with an evolution of forms, with later forms emerging from earlier ones.

Finally, you will find the outer enclosure, seven columns on the left and seven on the right. (The columns are indicated.) And I already mentioned yesterday that these seven columns have capitals and bases and above them the corresponding architraves, which develop their forms in a continuous evolution.

If you feel this outline, then you will simply have something in these two interlocking circles — but you must grasp it intuitively — that points to the development of humanity. I already said yesterday that around the middle of the 15th century, a very significant turning point in the development of humanity can be observed. What is called “history” in schools and outwardly is only a fable convenue, because it records external facts in such a way as to give the impression that human beings were essentially the same in the 8th or 9th centuries as they were in the 18th or 19th centuries. Even more recent historians, such as Lamprecht, have come to realize that this is nonsense, that in fact the mental and emotional constitution of human beings was completely different before and after the period indicated. And we in the present are in the midst of a development that we can only understand if we become aware that we are developing toward the future with unique soul forces, and that those soul forces that have undergone their development up to that of the 15th century are still, one might say, haunting the souls of human beings — they are fading away — but that they belong to what is passing away, to what is doomed to fall out of human evolution. We must develop an awareness of this important turning point in human evolution if we are to become capable of having a say in the affairs of humanity in the present and in the near future.

Such things are particularly evident where people want to point meaningfully to what they feel, what they sense. We need only recall one thing in the development of architecture, which we have already mentioned here, but which I would like to point out again today in order to show, by means of an example, how the development of humanity is progressing.

Consider the forms of a Greek temple. How can one understand the forms of a Greek temple? One can only understand them if one is clear that the entire architectural concept of this Greek temple is oriented toward making the temple the dwelling place of the god or goddess whose statue was placed inside. All the forms of the Greek temple would be absurd if one did not understand it as the enclosure, the dwelling place of the god or goddess who was to stand inside.

If we move on from the forms of the Greek temple to the next significant forms of building, we come to the Gothic cathedral. Anyone who enters a Gothic cathedral and feels that they are faced with something complete and finished does not understand the forms of Gothic architecture, just as someone who can view a Greek temple without imagining any images of gods inside it does not understand the forms of Greek architecture. A Greek temple without an image of a god—we only need to imagine it inside, but in order to understand the form, it must be imagined inside—a Greek temple without an image of a god is impossible for the sensitive understanding. A Gothic cathedral that is empty is also impossible for people who truly feel this way. The Gothic cathedral is only complete when the congregation is inside, when it is filled with people, and actually only then when it is filled with people and spoken to, so that the spirit of the word reigns over the congregation or in the hearts of the congregation. Then the Gothic cathedral is complete. But the congregation belongs to it, otherwise the forms are not understandable.

What kind of evolution do we actually have before us from the Greek temple to the Gothic cathedral? The others are basically intermediate forms, whatever erroneous interpretations of history may say about them. What kind of evolution do we have before us? When we look at Greek culture, this flowering of the fourth post-Atlantean period, we must say: in the Greek consciousness there was still something of the lingering divine-spiritual forces among human beings, only that human beings were inclined to build dwellings for their gods, whom they could only imagine in pictures. The Greek temple was the dwelling place of the god or goddess whom they were conscious of walking among the people. Without this consciousness of the presence of divine spiritual powers, the Greek temple would be inconceivable in Greek culture.

Let us now move forward from the flowering of Greek culture to the decline of this culture towards the end of the fourth post-Atlantean period, that is, towards the times of the 8th, 9th, and 10th centuries AD, and we come to the forms of Gothic architecture, which the community demands. Everything corresponds to the emotional life of the people of that time. The mood of the people was naturally different in this period than it was during the heyday of Greek thought. There was no awareness of the immediate presence of divine spiritual powers; the divine spiritual powers were far removed in an afterlife. The earthly realm was often accused of having fallen away from the divine spiritual powers. The material was seen as something to be avoided, something from which one must turn away and instead turn toward spiritual powers. And one person after another in the community sought—in a sense, seeking the group spirit of humanity—the rule of the spiritual, which had thus also acquired a certain abstract character. This is why Gothic forms also make an abstract, mathematical impression compared to the more dynamic forms of Greek architecture, which have something of the cozy embrace of a god or goddess. In Gothic forms, everything is aspiring, everything points to the fact that what the soul thirsts for must be sought in spiritual realms. The Greek had his god and goddess there. He heard their whispers with the ear of his soul, so to speak. Only the longing soul could sense the divine in forms that pointed upward during the Gothic period.

Thus, in terms of their soul mood, humanity had become longing, built on longings, built on searching, believed that in this searching they could be happier through union in the community, but was always convinced that what is to be recognized as the divine-spiritual is not something that reigns directly among human beings, but rather something hidden in mysterious depths. If one wanted to express what one was longingly striving for, what one was longingly searching for, one could only do so by somehow linking it to something mysterious. The expression of this whole mood of the human soul is the temple or the cathedral, which we could also say is, in its true, typical form, the Gothic cathedral. But when one brought into the spiritual field of vision that which one longed for as the highest mystery, one had to, precisely at a time when one wanted to rise from the earthly to the super-earthly, move on from mere Gothic to something else, something that, one might say, did not unite the physical community, but rather allowed the whole striving spirit of humanity, or the striving soul spirits of humanity, to strive toward a center, toward a mysterious center.

If you imagine, for example, the totality of human souls flowing together from all earthly directions, you have, in a sense, united the whole of humanity on this earth as in a great dome, which was not conceived as Gothic, although it was intended to have the same meaning as the Gothic cathedral. In the Middle Ages, such things were linked to the Bible. And if you imagine, for example, that the seventy-two disciples—you need not think of physical history, but of the spiritual, which in those times thoroughly permeated the physical view of the world— if you imagine, then, how people thought according to the spirit of the time, that the seventy-two disciples of Christ spread out in all directions and planted in souls the spirit that was to flow together in the mystery of Christ: then you have, in all that flowed back from those into whose souls the disciples carried the Christ spirit, in the rays coming from all these souls from all directions, that which the early medieval human being thought in the most comprehensive, most universal way as striving toward the mystery. Perhaps I don't need to draw all seventy-two, but I can indicate them (it is drawn). I am only indicating them, but imagine that there are seventy-two pillars. From these seventy-two pillars would come the rays that strive toward the mystery of Christ from the whole of humanity. Enclose the whole thing with some kind of wall—it wouldn't be Gothic, but I already explained why we didn't stick strictly to the Gothic style—whose ground plan is a circle, and imagine the seventy-two pillars here, and you would have the cathedral, which in a sense encompasses all of humanity. Imagine it oriented from east to west, and you will naturally perceive a completely different ground plan than in our building, which is composed of two circular sections. The sensation of this floor plan must be completely different, and I have tried to sketch this sensation for you. One would then think that the main lines of orientation of such a building, which is constructed according to this floor plan, are cross-shaped, and one would have to imagine that the main aisles are arranged according to this cross shape.

This is indeed how medieval people imagined their ideal cathedral. We would (continuing the drawing) have north and south here, if this is east and this is west, and then there would be three gates in the north, south, and west, and here in the east there would be a kind of main altar, and at each pillar there would be a kind of side altar. But where the cross beams intersect, there would have to stand the temple of the temple, the cathedral of the cathedral: there would be, so to speak, the summary of the whole, a repetition in miniature of what the whole is. In modern, abstract language, we would say: here would stand a tabernacle, but in the form of the whole.

Imagine what I have described here in a style, an architectural style, which is only approximately Gothic, which still contains all kinds of Romanesque forms, but which is definitely oriented in the direction I have indicated here, and then I have sketched for you the Temple of the Grail as medieval man imagined it, that Grail Temple which was, in a sense, the ideal of building in the time approaching the end of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch: a cathedral in which the longings of all humanity oriented toward Christ flowed together, just as in the individual cathedral the longings of the members of the community flowed together, and just as people felt connected in the Greek temple, even if they were not inside it—for the Greek temple only requires that the god or goddess be inside, not other people—so too did the Greek people of a territory feel connected through their temple with their god or goddess. To speak accurately, one can say: When the Greek spoke of his relationship to the temple, he described it in the following way. Just as he said of any person on earth, Pericles, for example: Pericles lives in this house—so this sentence expresses: Pericles lives in this house—not because the person saying it has any ownership or other relationship to the house, but because they feel connected to Pericles when they say, “Pericles lives in this house!” The Greek would have expressed his relationship to what could be read in the architectural style with exactly the same nuance, saying: Athena lives in this house, this is the dwelling place of the goddess, or: Apollo lives in this house!