The Mysteries of Light, of Space, and of the Earth

GA 194

15 December 1919, Dornach

IV. The Old Mysteries of Light, Space, and Earth

The tasks assigned to the humanity of the present and of the immediate future are great, significant, and peremptory; and it is really necessary to bring forth a strong soul courage in order to do something toward their accomplishment. Anyone who today examines these tasks closely, and tries to get a true insight into the needs of humanity, must often reflect how superficially so-called public affairs are treated. We might say that people today talk politics aimlessly. From a few emotions, from a few entirely egotistic points of view—personal or national—people form their opinions about life, whereas a real desire to gain the factual foundations for a sound judgment would be more in conformity with the seriousness of the present time. In the course of recent months, and even years, I have inquired into the most varied subjects, including the history and the demands of the times, and have given lectures here on such subjects, always with the purpose of furnishing facts which will enable people to form a judgment for themselves—not with the purpose of placing the ready-made judgment before them. The longing to know the realities of life, to know them more and more fundamentally, in order to have a true basis for judgment—that is the important thing today. I must say this especially because the various utterances and written statements which I have made regarding the so-called social question, and regarding the threefold structure of the social organism, are really taken much too lightly, as anyone can clearly see, for the questions asked about these things are concerned far too little with the actual, momentous, basic facts. It is so difficult for people of the present time to arrive at these basic facts, because they are really theoreticians in all realms of life, although they will not acknowledge it. The people who today most fancy themselves to be practical are the most decidedly theoretical, for the reason that they are usually satisfied to form a few concepts about life, and from these to insist upon judging life; whereas it is possible today only by means of a real, universal, and comprehensive penetration into life to form a relevant judgment about what is necessary. One can say that in a certain sense it is at least intellectually frivolous when, without a basis of facts, a man talks politics at random, or indulges in fanciful views about life. It makes one wish for a fundamentally serious attitude of soul toward life.

When in the present time the practical side of our spiritual scientific effort, the Threefold Social Order, is placed before the world as the other side has been, it is a fact that the whole mode of thought and conception employed in the elaboration of this Threefold Social Order is met with prejudices and misgivings. Where do these prejudices and misgivings originate? Well, a man forms concepts about truth (I am still speaking of the social life), concepts about the good, the right, the useful, and so forth, and when he has formed them, he thinks they have absolute value everywhere and always. For example, take a man of western, middle, or eastern Europe with a socialistic bias. He has quite definite socialistically-formulated ideals; but what kind of fundamental concepts underlie these ideals? His fundamental concept is that what satisfies him must satisfy everyone everywhere, and must possess absolute validity for all future time. The man of today has little feeling for the fact that every thought that is to be of value to the social life must be born out of the fundamental character of the time and the place. Therefore he does not easily come to realize how necessary it is for the Threefold Social Order to be introduced with different nuances into our present European culture, with its American appendage. If it is adopted, then the variations suited to the peoples of the different regions will come about of themselves. And besides, when the time comes, on account of the evolution of humanity, that the ideas and thoughts mentioned by me in The Threefold Commonwealth are no longer valid, others must again be found.

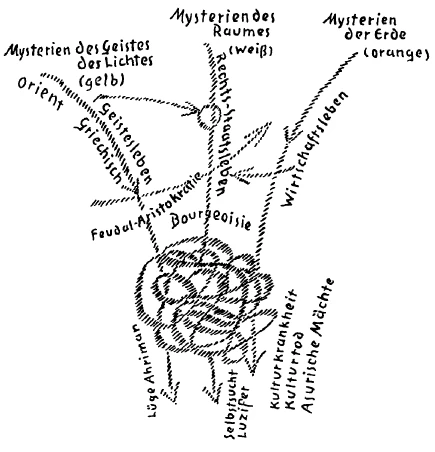

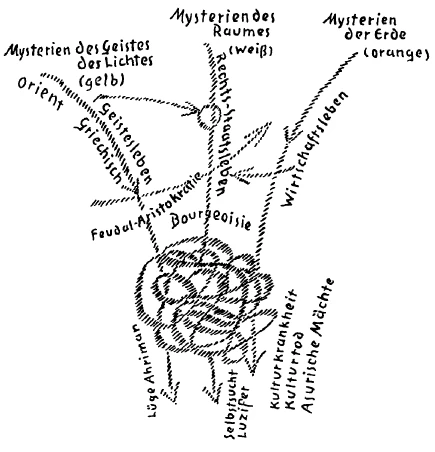

It is not a question of absolute thoughts, but of thoughts for the present and the immediate future of mankind. In order, however, to comprehend in its full scope how necessary is this three-membering of the social organism in an independent spiritual life, an independent rights and political life, and an independent economic life, one must examine without prejudice the way in which the interaction of the spiritual, the political, and the economic has come about in our European-American civilization. This interweaving of the threads—the spiritual threads, those of rights or government, and the economic threads—is by no means an easy matter. Our culture, our civilization, is like a ball of yarn, something wound up, in which are entangled three strands of entirely different origins. Our spiritual life is of essentially different origin from that of our rights or political life, and entirely different again from that of our economic life; and these three strands with different origins are chaotically entangled. I can naturally give only a sketchy idea to-day, because I shall briefly follow these three streams, I might say, to their source.

First, our spiritual life, as it presents itself to one who regards as real the external things, the obvious, is acquired by people through the influence of what still persists of the ancient Greek and Latin cultural life, the Greco-Latin spiritual life, as it has flowed through what later became our high schools and universities. All the rest of our so-called humanistic culture, even down to our elementary schools, is entirely dependent upon that which, as one stream let us say, flowed in first from the Greek element (Diagram 13. orange); for our spiritual life, our European spiritual life, is of Greek origin; it merely passed through the Latin as a sort of way-station. It is true that in modern times something else has mingled with the spiritual life which originated in Greece: namely, that which is derived from what we call technique in the most varied fields, which was not yet accessible to the Greek, the technique of mechanics, the technique of commerce, etc., etc. I might say that the technical colleges, the commercial schools, and so forth, have been annexed to our universities, adding a more modern element to what flows into our souls through our humanistic schools, which reach back to Greece—and by no means flows only into the souls of the so-called educated class; for the socialistic theories which haunt the heads even of the proletariat are only a derivative of that which really had its origin in the Grecian spiritual life; it has simply gone through various metamorphoses. This spiritual life reaches back, however, to a more distant origin, far back in the Orient. What we find in Plato, what we find in Heraclitus, in Pythagoras, in Empedocles, and especially in Anaxagoras, all reaches back to the Orient. What we find in Aeschylus, in Sophocles, in Euripides, in Phidias, reaches back to the Orient. The entire Greek culture goes back to the Orient, but it underwent a significant change on its way to Greece. Yonder in the Orient this spiritual life was decidedly more spiritual than it was in ancient Greece; and in the Orient it issued from what we may call the Mysteries of the Spirit—I may also say the Mysteries of Light (Drawing). The Grecian spiritual life was already filtered and diluted as compared with that from which it had its origin: namely, the spiritual life of the Orient, which depended upon quite special spiritual experiences.

Naturally, we must go back into prehistoric times, for the Mysteries of Light, or the Mysteries of the Spirit, are entirely prehistoric phenomena. If I am to represent to you the character of this spiritual life, the manner of its development, I must do so in the following way: We know, of course, that if we go very far back in human evolution, we find increasingly that human beings of ancient times had an atavistic clairvoyance, a dream-like clairvoyance, through which the mysteries of the universe were revealed to them; and we speak with entire correctness when we say that over the whole civilized Asiatic earth, in the third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh millennium before the Mystery of Golgotha, there dwelt people to whom spiritual truths were revealed through clairvoyance—a clairvoyance that was completely bound to nature, to the blood, and to the bodily organization. This was true of a widely dispersed population; but this atavistic clairvoyance was in a state of decline, and became more and more decadent. This “becoming decadent” of the atavistic clairvoyance is not merely a cultural-historical phenomenon, but is at the same time a phenomenon of the social life of mankind.

Why? Because from various centers of this wide-spread population, but chiefly from a point in Asia, there arose a special kind of human being, so to speak, a human being with special faculties. Besides the atavistic clairvoyance, which still remained to these people in a certain sense—for there still arose out of their inner soul-life a dream-like comprehension of the mysteries of the world—besides this they also had what we call the thinking faculty; and indeed they were the first in the evolution of humanity to have this power. They were the first to have dawning intelligence.

That was a significant social phenomenon when the people of those ancient times, who had only dream-like visions of the mysteries of the world arising within them, saw immigrants enter their territories whom they could still understand, because they also had visions, but who had besides something which they themselves lacked: the power of thought. That was a special kind of human being. The Indians regarded that caste which they designated as Brahman as the descendants of these people who combined the thinking power with atavistic clairvoyance; and when they came down from the higher-lying regions of northern Asia into the southern regions, they were called Aryans. They formed the Aryan population, and their primal characteristic is that they combined the thinking-power with—if I may now use the expression of a later time—with the plebeian faculties of atavistic clairvoyance.

And those mysteries which are called the Mysteries of the Spirit, or particularly, the mysteries of Light, were founded by those people who combined atavistic clairvoyance with the first kindling of intelligence, the inner light of man; and our spiritual culture derives from that which entered humanity at that time as an illuminating spark—it is nothing but a derivative of it.

Much has been preserved in humanity of what was revealed at that time; but we must consider that even the Greeks—just the better educated personalities among them—had seen the ancient gift of atavistic clairvoyance gradually wane and become extinguished, and the thinking-power remained to them. Among the Romans the power of thought alone remained. Among the Greeks there was still a consciousness that this faculty comes from the same source as the ancient atavistic clairvoyance; and therefore Socrates still clearly expressed something which he knew as experience when he spoke of his Daemon as inspiring his truths, which were of course merely dialectic and intellectual.

In art, as well, the Greeks significantly represented the pre-eminence of the intelligent human being, or better, the development of the intelligent human being from the rest of humanity; for the Greeks have in their sculpture (one need only study it closely) three types differing sharply from one another. They have the Aryan type, to which the Apollo head, the Pallas Athene head, the Zeus head, the Hera head belong. Compare the ears of the Apollo with those of a Mercury head, the nose of the Apollo with that of a Mercury head, and you will see what a different type it is. The Greek wanted to show in the Mercury-type that the ancient clairvoyance, which still persisted as superstition and was a lower form of culture, had united with intelligence in the Greek civilization; that this existed at the bottom of Greek culture; and that towering above it was the Aryan whose artistic representation was the Zeus head, the Pallas Athene head, and so forth. And the very lowest races, those with dim remnants of ancient clairvoyance—who also still lived in Greece but were especially to be observed near the borders—are plastically preserved in another type, the Satyr-type, which in turn is quite different from the Mercury-type. Compare the Satyr nose with the Mercury nose, the Satyr ears with the Mercury ears, and so forth. The Greek merged in his art what he bore in his consciousness concerning his development.

What gradually filtered through Greece at that time, by means of the Mysteries of the Spirit or of the Light, and then appeared in modern times, had a certain peculiarity as spirit-culture. It was possessed of such inner impulsive force that it could at the same time, out of itself, establish the rights life of man. Therefore we have on the one hand the revelation of the gods in the Mysteries bringing the spirit to man, and on the other, the implanting of this spirit acquired from the gods into the external social organism, into the theocracies. Everything goes back to the theocracies; and these were able not only to permeate themselves with the legal system, the political system, out of the very nature of the Mysteries, but they were able also to regulate the economic life out of the spirit. The priests of the Mysteries of Light were at the same time the economic administrators of their domains; and they worked according to the rules of the Mysteries. They constructed houses, canals, bridges, looked after the cultivation of the soil, and so forth.

In primitive times civilization grew entirely out of the spiritual life, but it gradually became abstract. From being a spiritual life it became more and more a sum of ideas. Already in the Middle Ages it had become theology, that is, a sum of concepts, instead of the ancient spiritual life, or it had to be confined to the abstract, legalistic form, because there was no longer any relation to the spiritual life. When we look back at the old theocracies we find that the one who ruled received his commission from the gods in the Mysteries. The last derivative is the occidental ruler, but he no longer gives any evidence of having originated from the ruler of the theocracy, with his commission from the gods of the Mysteries. All that remains is crown and coronation robe, the outer insignia, which in later times became more like decorations. If one understands such things it may often be observed that titles go back to the time of the Mysteries; but everything is now externalized.

Scarcely less externalized is that which moves through our secondary schools and universities as spiritual culture, the final echo of the divine message of the Mysteries. The spiritual has flowed into our life, but this has now become utterly abstract, a life of mere ideas. It has become what the socialistically-orientated groups latterly call an ideology, that is, a sum of thoughts that are only thoughts. That is what our spiritual life has really become.

Under its influence the social chaos of our time has developed, because the spiritual life that is so diluted and abstract has lost all impulsive force. We have no choice but to place it again on its own foundation, for only so can it thrive. We must find the way again from the merely rational to the creative spirit, and we shall be able to do so only if we seek to develop out of the spiritual life prescribed by the State the free spiritual life,1The human being is essentially a spiritual being. When he is engaged in art, science, and religion, he is active spiritually; this activity is his spiritual life.—Editor. which will then have the power to awake to life again. For neither a spiritual life controlled by the Church, nor one maintained and protected by the State, nor a spiritual life panting under economic burdens, can be fruitful for humanity, but only an independent spiritual life.

Indeed the time has come for us to find the courage in our souls to proclaim quite frankly before the world that the spiritual life must be placed on its own foundation. Many people are asking: Well, what are we to do? The first thing of importance is to inform people about what is needed: to get as many people as possible to comprehend the necessity, for example, of establishing the spiritual life on its own foundation; to comprehend that what the pedagogy of the 19th century has become can no longer suffice for the welfare of mankind, but that it must be built anew out of a free spiritual life. There is as yet little courage in souls to present this demand in a really radical way; and it can be thus presented only by trying to bring to as many people as possible a comprehension of these conditions. All other social work today is provisional. The most important task is this: to see that it is made possible for more and more people to gain insight into the social requirements, one of which has just been characterized. To provide enlightenment concerning these things through all the means at our disposal—that is now the matter of importance.

We have not yet become productive with regard to the spiritual life, and we must first become productive in this field. Beginnings have been made in this direction, of which I shall speak presently—but we have not yet become productive with regard to the spiritual life; and we must become productive by making the spiritual life independent.

Everything that comes into being on earth leaves remnants behind it. The Mysteries of Light in the present-day oriental culture, the oriental spiritual life, are less diluted than in the Occident, but of course they no longer have anything like the form they had at the time I have described. Yet if we study what the Hindus, the oriental Buddhists, still have today, we shall be much more likely to perceive the echo of that from which our own spiritual life has come; only in Asia it has remained at another stage of existence. We, however, are unproductive; we are highly unproductive. When the tidings of the Mystery of Golgotha spread in the West, whence did the Greek and Latin scholars get the concepts for the understanding of it? They got them from the oriental wisdom. The West did not produce Christianity. It was taken from the Orient. And further: When in English-speaking regions the spiritual culture was felt to be very unfruitful, and people were sighing for its fructification, the Theosophists went to the subjugated Indians to seek the wellsprings for their modern Theosophy. No fruitful source existed among themselves for the means to improve their spiritual life: so they went to the Orient. In addition to this significant fact, you could find many proofs of the unfruitfulness of the spiritual life of the West; and each such proof is at the same time a proof of the necessity for making the spiritual life an independent member in the threefold social organism.

A second strand in the tangled ball is the political or rights current.

There is the crux of the cultural problem, this second current. If we look for it today in the external world, we see it when our honorable judges sit on their benches of justice with the jurors and pass judgment upon crime or offence against the law, or when the magistrates in their offices rule throughout the civilized world—to the despair of those thus ruled. All that we call jurisprudence or government, and all that results as politics from the interaction of jurisprudence and government, constitutes this current (see drawing, white). I call that (orange) the current of the spiritual life, and this (white) the current of rights, or government.

Where does this come from? As a matter of fact this too goes back to the Mystery-culture. It goes back to the Egyptian Mystery-culture, which passed through the southern European regions, then through the prosaic, unimaginative Roman life, where it united with a side branch of the oriental life, and became Roman Catholic Christianity, that is, Roman Catholic ecclesiasticism. Speaking somewhat radically, this Roman Catholic ecclesiasticism is also fundamentally a jurisprudence; for from single dogmas to that great and mighty Judgment, always represented as the Last Judgment throughout the Middle Ages, the utterly different spiritual life of the Orient, which had received the Egyptian impulse from the Mysteries of Space (see drawing), was really transformed into a society of world-magistrates with world-judgments and world-punishments, and sinners, and the good and the evil: it is a jurisprudence. That is the second element existing in our spiritual tangle which we call civilization, and it has been by no means organically combined with the other. That this is the case anyone can learn who goes to a university and hears one after the other, let us say a juridical discourse on political law, and then a theological discourse even on canonical law, if you like, for these are found side by side. Such things have shaped mankind; even in later times, when their origins have been forgotten, they are still shaping human minds. The rights life caused the later spiritual life to become abstract; but externally it influenced human customs, human habits, human systems.

What is the last social offshoot in the decadent oriental spiritual current, whose origin has been forgotten? It is feudal aristocracy. You could no longer recognize that the aristocrat had his origin in the oriental, theocratic spiritual life, for he has stripped off all that; only the social configuration remains (drawing). The journalistic intelligence often has very strange nightmarish visions. One such it had recently when it invented a curious phrase of which it was especially proud: “spiritual aristocracy”—this could be heard now and then. What is that which passed through the Roman Church system, through theocratising jurisprudence, juridical theocracy, became secularized in the civic systems of the Middle Ages, and completely secularized in modern times—what is it in its ultimate derivative? It is the bourgeoisie (drawing). And thus are these spiritual forces in their ultimate derivatives actually jumbled up among men.

And now still a third stream unites itself with the other two. If you would observe it today in the external world, where does this third current appear in an especially characteristic way? Well, there actually was in Central Europe a method of demonstrating to certain people where these final remnants of something originally different were to be found. It happened when the man of Central Europe sent his son to an office in London or New York to learn the methods of the economic system. In the methods of the economic life, whose roots are to be found in the popular customs of the Anglo-American world, the final consequence is to be seen of that which has been developed as outgrowths from what I might call the Mysteries of the Earth, of which, for example, the Druid Mysteries are only a special variety. In the times of the primitive European people the Mysteries of the Earth still contained a peculiar kind of wisdom-filled life. That European population, which was quite barbaric, which knew nothing regarding the revelations of oriental wisdom, or of the Mysteries of Space, or of what later became Roman Catholicism—that population which advanced to meet the spreading Christianity possessed a strange kind of life-steeped-in-wisdom, peculiar to it, which was entirely physical wisdom. Of this one can at best study only the most external usages, which are recorded in the history of this current: namely, the festivals of those people from whom have come the customs and habits of England and America. The festivals were here brought into entirely different relations from those in Egypt, where the harvest was connected with the stars. Here the harvest as such was the festive occasion; and the highest solemn festivals of the year were connected with other things than was the case in Egypt: namely, with things that belong entirely to the economic life. We have here without doubt something which goes back to the economic life.

If we wish to comprehend the whole spirit of this matter, we must say to ourselves: Over from Asia and up from the South men transplanted a spiritual life and a rights life which they had received from above and brought down to earth. Then, in the third current, an economic life sprang up which had to develop of itself and work its way up, which really was originally so completely economic in its legal customs and in its spiritual adaptations that, for example, one of the yearly festivals consisted in the celebration of the fructification of the herds as a special festival in honor of the gods; and there were similar festivals all derived from the economic aspect of life. If we go through the regions of northern Russia, middle Russia, Sweden, Norway, or into those regions which until a short time ago were parts of Germany, or to France, at least northern France, and to what is now Great Britain—if we go through these regions, we find dispersed everywhere a population which, before the spread of Christianity in ancient times, undoubtedly had a pronounced economic life. And what ancient customs can still be found, such as festivals of legal practices and festivals in honor of the gods, are an echo of this ancient economic culture.

This economic culture met what came from the other side. At first it did not succeed in developing an independent rights life and spiritual life. The primitive legal customs were discarded because Roman law flowed in, and the primitive spiritual customs were cast aside because the Greek spiritual life had entered. And so this economic life becomes sterile at first, and only gradually works its way out of this sterility; it can succeed in this, however, only by overcoming the chaotic condition created by the introduction of the spiritual life and rights life from outside. Consider the present Anglo-American spiritual life. In this you have two things very sharply differentiated from one another. First, you have everywhere in the Anglo-American spiritual life, more than anywhere else on earth, the so-called secret societies, which have considerable influence, much more than people know. They are undoubtedly the keepers—and are proud to be the keepers—of the ancient spiritual life, of the Egyptian or oriental spiritual life, which is completely diluted and evaporated into mere symbols,—symbols no longer understood but having a certain great power among those in authority. That, however, is ancient spiritual life, not spiritual life grown in its own soil. Side by side with this there is a spiritual life which does grow entirely in economic soil, but hitherto it has produced only very small blossoms, and these in abundance.

Anyone who studies such things and is able to understand them knows very well that Locke, Hume, Mill, Spencer, Darwin, and others, are nothing but these little blossoms springing from the economic life. You can get quite exactly the thoughts of a Mill or a Spencer from the economic life. Social democracy has elevated this to a theory, and considers the spiritual life as a derivative of the economic life. That is what we encounter first: everything is brought forth from the so-called practical—actually from life's routine, not from its real practice. So that going along side by side are such things as Darwinism, Spencerism, Millism, Humeism—and the diluted Mystery teachings, which are perpetuated in the various sectarian developments, such as the Theosophical Society, the Quakers, and so forth. The economic life has the will to rise, but has not yet made much progress, having produced thus far only these small blossoms. The spiritual life and the rights life are exotic plants and—I beg you to note this well—they are more and more exotic the farther we go toward the West in the European civilization.

There has always been in Central Europe something—I might say like a resistance, a struggling against the Greek spiritual life on the one hand and against the Roman Catholic rights life on the other. An opposition has always been there. An illustration of it is the Central European philosophy, of which really nothing is known in England. Actually, Hegel cannot be translated into the English language; it is impossible. Hence, nothing is known of him in England, where German philosophy is called Germanism, by which is meant something an intelligent person cannot be bothered with. In just this German philosophy, however—with the exception of one incident, namely, when Kant was completely ruined by Hume, and there divas brought into German philosophy that abominable Kant-Hume element, which has really caused such devastation in the heads of Central European humanity—with the exception of this incident, we have later, after all, the second blossoming of this struggle in Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel; and we already have the search for a free spiritual life in Goethe, who would have nothing to do with the final echo of the Roman Catholic jurisprudence in what is called the law of nature. Just feel the legal element in the shabby robes and the strange caps which the judges still have from ancient times, and feel it likewise in the science of nature, the law of nature—the legal element is still there! The expression “law of nature” has no sense in connection, for example, with the Goethean science of nature, which deals only with the primordial phenomenon, the primordial fact.

There for the first time is radical protest made; but naturally it remained only a beginning. That was the first advance toward the free spiritual life: the Goethean science of nature; and in Central Europe there already exists the first impulse even toward the independent rights life, or political life. Read such a work as that of Wilhelm van Humboldt, who was even Prussian minister of public instruction—read The Sphere and Duties of Government,2Translated by Joseph Coulthard, London, 1845. and you will see the first beginning toward the construction of an independent rights life, or political life, of the independence of the true political realm. It is true it has never gone beyond beginnings, and these are found as far back as the first half of the 19th century, even at the end of the 18th century. It must be borne in mind, however, that there are nevertheless in Central Europe important impulses in this very direction, impulses which can be carried on, which must not be left unconsidered, and which may flow into the impulse of the Threefold Social Organism.

In his first book Nietzsche wrote that passage that I have quoted in my book on Nietzsche3“Extirpation des deutschen Geistes zu Gunsten des deutschen Reiches,” Extirpation of the German Spirit in favor of the German Empire—quoted in Friedrich Nietzsche, ein Kampfer gegen seine Zeit (not translated). in the very first pages, a premonition of something tragic in the German spiritual life. Nietzsche tried at that time in the foreword to his work, The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, to characterize the events of 1870–71, the founding of the German Empire. Since then this strangulation of the German spirit has been thoroughly accomplished; and when in the last five or six years three-fourths of the world fell upon this former Germany (I do not wish to speak about the causes or the guilty, but only to sketch the configuration, the world situation), it was really then already the corpse of the German spiritual life. But when anyone speaks as I did yesterday, characterizing the facts without prejudice, no one should infer that there is not still in this German spiritual life much that must come forth, that must be considered, that intends to be considered, in spite of the future gypsy-like condition. For what was the real cause of the ruin of the German people? This question must also be answered without prejudice. They were ruined because they too wanted to share in materialism, and they have no talent for materialism. The others have good talents for it. The Germans have in general that quality which Herman Grimm characterized excellently when he said: The Germans as a rule retreat when it would be beneficial for them to go boldly forward, and they storm ahead with terrific energy when it would be better for them to hold back. That is a very good description of an inner quality of character of this German people; for the Germans have had propulsive force throughout the centuries, but not the ability to sustain this force. Goethe was able to present the primordial phenomenon, but he could not reach the beginnings of spiritual science. He could develop a spirituality, as, for example, in his Faust, or in his Wilhelm Meister, which could have revolutionized the world if the right means had been found; but the outer personality of this gifted man achieved nothing more than that in Weimar he put on fat and had a double chin, became a stout privy counselor, who was also uncommonly industrious as minister, but still was obliged at times to wink at certain things, especially in political life.

The world ought to understand that such phenomena as Goethe and Humboldt represent everywhere beginnings, and that it would really be a loss to the world and not a profit, to fail to take into account what lives in the German evolution in an unfinished state, but to which must come forth. For after all, the Germans do not have the predisposition which the others have in such remarkable degree the farther we go toward the West: namely, to rise on all occasions to ultimate abstractions. What the Germans have in their spiritual life is called “abstractions” only by those who are unable to experience it; and because they themselves have squeezed out the life, they believe others lack it too. The Germans have not the talent for pressing on to ultimate abstractions. This was shown in their political life, in their most unfortunate political life! If the Germans had had from the beginning the great talent for monarchy which the French have preserved so brilliantly to this day, they would never have become the victims of “Wilhelmism”; they would neither have countenanced this strange caricature of a monarch, nor have needed him. It is true that the French call themselves republicans, but they have among them a secret monarch who firmly holds together the structure of the state, who keeps a terribly tight rein on the people's minds; for in reality the spirit of Louis XIV is everywhere present. Naturally, only a decadent form remains, but it is there. There is no doubt that a secret monarch is there among the French people; for it is really shown in every one of their cultural manifestations. And the talent for abstraction demonstrated in Woodrow Wilson is the ultimate talent for abstraction in the political field. Those fourteen points of the world's schoolmaster, which in every word bear the stamp of the impractical and unachievable, could only originate in a mind wholly formed for the abstract, with no discernment whatever for true realities.

There are two things which the cultural history of civilization will doubtless find it difficult to understand. One I have often characterized in the words of Herman Grimm—the Kant-Laplace theory, in which many people still believe. Herman Grimm said so finely in his Goethe: People will some day have difficulty in comprehending that malady now called science, which makes its appearance in the Kant-Laplace theory, according to which all that we have around us today arose through agglomeration, out of a universal world-mist; and this is supposed to continue until the whole thing falls back again into the sun. A putrid bone around which a hungry dog circles is a more appetizing morsel than these fanciful ideas, this fantastic concept of world-evolution. So thinks Herman Grimm. Naturally, there will some day be great difficulty in explaining this Kant-Laplace theory from the standpoint of the scientific insanity of the 19th and 20th centuries!

The second thing will be the explanation of the unbelievable fact that there ever could be a large number of people to take seriously the humbug of the fourteen points of Woodrow Wilson—in an age that is socially so serious.

If we study the things that stand side by side in the world we find in what a peculiar way the economic life, the political rights life, and the spiritual life are entangled. If we do not wish to perish because of the extreme degeneration which has come into the spiritual life and the rights life, we must turn to the Threefold Social Order, which from independent roots will build an economic life now struggling to emerge, but unable to do so unless a rights life and a spiritual life, developed in freedom, come to meet it. These things have their deep roots in the whole of humanity's evolution and in human social life; and these roots must be sought. People must now be made to realize that way down at the bottom, on the ground I might say, crawls the economic life, managed by Anglo-American habits of thought; and that it will be able to climb up only when it works in harmony with the whole world, with that for which others also are qualified, for which others also are gifted. Otherwise the gaining of world dominion will become a fatality for it.

If the world continues in the course it has been taking under the influence of the degenerating spiritual life derived from the Orient, then this spiritual life, although at one end it was the most sublime truth, will at the other rush into the most fearful lies. Nietzsche was impelled to describe how even the Greeks had to guard themselves from the lies of life through their art. And in reality art is the divine child which keeps men from being swallowed up in lies. If this first branch of civilization is pursued only one-sidedly, then this stream empties into lies. In the last five or six years more lies have been told among civilized humanity than in any other period of world history; in public life the truth has scarcely been spoken at all; hardly a word that has passed through the world was true. While this stream empties into lies (see drawing), the middle stream empties into self-seeking; and an economic life like the Anglo-American, which should end in world-dominion—if the effort is not made to bring about its permeation by the independent spiritual life and the independent political life, it will flow into the third of the abysses of human life, into the third of these three. The first abyss is lies, the degeneration of humanity through Ahriman; the second is self-seeking, the degeneration of humanity through Lucifer; the third is, in the physical realm, illness and death; in the cultural realm, the illness and death of culture.

The Anglo-American world may gain world dominion; but without the Threefold Social Order it will, through this dominion, pour out cultural death and cultural illness over the whole earth; for these are just as much a gift of the Asuras as lies are a gift of Ahriman, and self-seeking, of Lucifer. So the third, a worthy companion of the other two, is a gift of the Azuric powers!

We must get the enthusiasm from these things which will fire us now really to seek ways of enlightening as many people as possible. Today the mission of those with insight is the enlightenment of humanity. We must do as much as possible to oppose to that foolishness which fancies itself to be wisdom, and which thinks it has made such marvellous progress—to oppose to that foolishness what we can gain from the practical aspect of anthroposophically-orientated spiritual science.

My dear friends, if I have been able to arouse in you in some measure the feeling that these things must be taken with profound seriousness, then I have attained a part of what I should very much like to have attained through these words.

When we meet again in a week or two, we shall speak further of similar things. Today I wished only to call forth in you a feeling that at the present time the really most important work is to enlighten people in the widest circles.

Zwolfter Vortrag

Die Aufgaben, welche der Menschheit in der Gegenwart und in der nächsten Zukunft gestellt sind, sind einschneidende, bedeutsame, große. Und es handelt sich darum, daß in der Tat ein starker seelischer Mut aufgebracht werden muß, um etwas zur Bewältigung dieser Aufgaben zu tun. Wer heute diese Aufgaben sich besieht und einen wirklichen Einblick sich zu verschaffen sucht in dasjenige, was der Menschheit not tut, der muß oftmals denken an die oberflächliche Leichtigkeit, mit der heute die öffentlichen, die sogenannten öffentlichen Angelegenheiten genommen werden. Man möchte sagen, die Menschen politisieren heute ins Blaue hinein. Aus ein paar Emotionen heraus, aus ein paar ganz egoistischen oder volksegoistischen Gesichtspunkten heraus bilden sich die Menschen ihre Anschauung über das Leben, während es dem Ernste der Gegenwart angemessen wäre, eine gewisse Sehnsucht danach zu haben, die tatsächlichen Untergründe für ein gesundes Urteil wirklich zu gewinnen. Ich habe im Laufe der letzten Monate und auch Jahre hier über die verschiedensten Gegenstände, auch der Zeitgeschichte und der Zeitforderungen Vorträge gehalten und Betrachtungen angestellt, immer zu dem Ziel, Tatsachen zu liefern, welche den Menschen in den Stand setzen können, sich ein Urteil zu bilden, nicht um das Urteil vor Sie fertig hinzustellen. Die Sehnsucht, die Tatsachen des Lebens kennenzulernen, gründlicher und immer gründlicher kennenzulernen, um eine wirkliche Unterlage für ein Urteil zu haben, darauf kommt es heute an. Ich muß dieses insbesondere deshalb sagen, weil die verschiedenen Äußerungen, die verschiedenen schriftstellerischen Darlegungen, die ich getan habe mit Bezug auf die sogenannte soziale Frage und mit Bezug auf die Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus, wirklich, wie man deutlich sehen kann, viel zu leicht genommen werden, weil diesen Dingen gegenüber viel zu wenig die Fragen gestellt werden nach den schwerwiegenden tatsächlichen Grundlagen. Die Menschen der Gegenwart kommen so schwer zu diesen tatsächlichen Grundlagen, weil sie, trotzdem sie das nicht wahr haben wollen, eigentlich auf allen Gebieten des Lebens Theoretiker sind. Diejenigen, die sich heute am meisten einbilden, Praktiker zu sein, die sind die stärksten Theoretiker, aus dem Grund, weil sie sich gemeiniglich damit begnügen, ein paar Vorstellungen, wenige Vorstellungen über das Leben sich zu bilden und von diesen wenigen Vorstellungen über das Leben dieses Leben beurteilen wollen, während es heute nur einem wirklichen, universellen und umfassenden Eingehen auf das Leben möglich ist, ein sachgemäßes Urteil über dasjenige zu gewinnen, was notwendig ist. Man kann sagen, in gewissem Sinne ist es heute eine wenigstens intellektuelle Frivolität, wenn man ohne sachgemäße Grundlagen ins Blaue hinein politisiert oder lebensanschaulich phantasiert. Den Lebensernst möchte man auf dem Grunde der Seelen heute wünschen.

Wenn gewissermaßen wie die andere Seite, auch die praktische Seite unseres geisteswissenschaftlichen Strebens in der neuesten Zeit vor die Welt hingestellt ist, die Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus, so ist es so, daß schon der ganzen Art des Denkens und Vorstellens, die da waltet in der Ausarbeitung dieses dreigliedrigen sozialen Organismus, heute Vorurteile und namentlich Vorempfindungen entgegengebracht werden. Diese Vorurteile, namentlich Vorempfindungen, woher stammen sie? Ja, der Mensch bildet sich heute Vorstellungen über dasjenige, was die Wahrheit ist - ich rede jetzt immer vom sozialen Leben -, er bildet sich Vorstellungen von dem, was das Gute, was das Rechte ist, was das Nützliche ist und so weiter. Und wenn er sich dann gewisse Vorstellungen gebildet hat, dann ist er der Meinung, diese Vorstellungen haben nun ganz absolute Geltung für überall und für immer. Zum Beispiel, nehmen wir einen sozialistisch orientierten Menschen West- oder Mittel- oder Osteuropas. Er hat ganz bestimmte sozialistisch formulierte Ideale. Aber was hat er diesen sozialistisch formulierten Idealen gegenüber gewissermaßen für Untergrund vorstellungen? Er hat die Untergrundvorstellung: dasjenige, wovon er sich vorstellen muß, daß es ihn befriedigt, das müsse nun alle Menschen über die ganze Erde hin befriedigen, und das müsse gelten ohne Ende für das gesamte zukünftige Erdendasein. Daß alles dasjenige, was als Gedanke für das soziale Leben gelten soll, herausgeboren sein muß aus dem Grundcharakter der Zeit und des Ortes, dafür hat man heute wenig Empfindung. Daher kommt man auch nicht leicht darauf, wie notwendig es ist, daß, mit verschiedenen Nuancen, unserer heutigen europäischen Kultur mit ihrem amerikanischen Anhange die Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus eingefügt werde. Wird sie eingefügt, so wird schon von selbst die Nuancierung in bezug auf den Raum, das heißt auf die verschiedenen Gebiete der Erdenvölker eintreten. Und außerdem: Nach derjenigen Zeit, nach welcher, der Menschheitsevolution wegen, die heute in den «Kernpunkten der sozialen Frage» von mir erwähnten Ideen und Gedanken nicht mehr gelten können, müssen eben andere wieder gefunden werden.

Es handelt sich nicht um absolute Gedanken, sondern es handelt sich um Gedanken für die Gegenwart und für die nächste Menschheitszukunft. Aber um das in seiner vollen Tragweite einzusehen, wie notwendig diese Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus in ein selbständiges Geistesleben, in ein selbständiges Rechts- und Staatsleben, in ein selbständiges Wirtschaftsleben ist, muß man einmal einen unbefangenen Blick werfen auf die Art, wie in unserer europäisch-amerikanischen Zivilisation zustandegekommen ist das Ineinanderwirken von Geist, Staat und Wirtschaft. Dieses Ineinanderwirken der Fäden, des Geistesfadens, des Rechts- oder Staatsfadens und des Wirtschaftsfadens ist keineswegs etwas Leichtes. Unsere Kultur, unsere Zivilisation ist ein Knäuel, was aufgewickelt etwas ist, worinnen drei Fäden verwickelt sind, die ganz verschiedenen Ursprungs sind. Unser Geistesleben ist wesentlich anderen Ursprunges als unser Rechts- oder Staatsleben und wiederum ganz anderen Ursprunges als unser Wirtschaftsleben. Und diese drei Strömungen mit verschiedenem Ursprunge, sie sind chaotisch miteinander verwickelt. Ich kann heute natürlich nur skizzenhaft darstellen, weil ich in der Kürze - ich möchte sagen bis zum Urquell diese drei Strömungen verfolgen werde.

Unser Geistesleben, wie es sich zunächst darbietet für den, der die Dinge äußerlich wirklich nimmt, sinnenfällig wirklich nimmt, es wird dadurch von den Menschen angeeignet, daß die Menschen auf sich wirken lassen jene Fortsetzung des alten griechischen und lateinischen Kulturlebens, des griechisch-lateinischen Geisteslebens, wie es zunächst geflossen ist durch das, was dann später unsere Gymnasien geworden sind, durch das, was unsere Universitäten geworden sind. Denn unsere übrige sogenannte humanistische Bildung bis in die Volksschule herunter ist ja ganz abhängig von dem, was als eine Strömung, sagen wir, hereinfließt (es wird gezeichnet, gelb, siehe Seite 229) zunächst vom griechischen Elemente. Denn das, was wir als Geistesleben haben, als unser europäisches Geistesleben, ist zunächst doch griechischen Ursprungs, durch das Lateinische nur hindurchgegangen. Das Lateinische ist eine Durchgangsstation. Allerdings hat sich in der neuesten Zeit mit diesem von Griechenland her stammenden Geistesleben anderes vermischt, welches aus dem stammt, was wir die Technik der verschiedensten Gebiete nennen, die dem Griechen noch nicht zugänglich war: die Technik des mechanischen Wesens, die Technik des kaufmännischen Wesens und so weiter. Ich könnte sagen: Zu unseren Universitäten sind die technischen Hochschulen, die kommerziellen Hochschulen und so weiter getreten, die ein neuzeitlicheres Element hinzubringen zu dem, was durch unsere humanistischen, auf das Griechentum zurückgehenden Schulen in unsere Seelen hineinfließt; nicht etwa bloß in die Seelen irgendeiner sogenannten gebildeten Klasse hineinfließt, denn dasjenige, was heute sozialistische "Theorien sind, was in den Köpfen auch der Proletarier spukt, es ist nur eine Ableitung desjenigen, was vom griechischen Geistesleben eigentlich herstammt. Es ist nur durch verschiedene Metamorphosen durchgegangen. Dieses Geistesleben geht aber seinem weiteren Ursprunge nach durchaus zurück bis in den Orient hinein. Und dasjenige, was wir finden bei Plato, was wir finden bei Heraklit, bei Pythagoras, bei Empedokles, namentlich bei Anaxagoras, das alles geht zurück nach dem Orient. Dasjenige, was wir bei Äschylos, bei Sophokles, bei Euripides finden, es geht zurück nach dem Orient, was wir bei Phidias finden, es geht zurück nach dem Orient. Die griechische Kultur geht durchaus zurück nach dem Orient. Sie hat eine bedeutende Wandlung durchgemacht auf dem Wege vom Orient nach Griechenland. Im Orient drüben war diese Geisteskultur wesentlich spiritueller, als sie im alten Griechenland war, und sie war im Oriente ein Ausfluß desjenigen, was man nennen kann: die Mysterien des Geistes, ich kann auch sagen die Mysterien des Lichtes (es wird wieder gezeichnet, siehe Seite 229). Schon ein filtriertes, ein verdünntes Geistesleben war das griechische gegenüber jenem Geistesleben, von dem es seinen Ursprung genommen hat, dem orientalischen Geistesleben. Dieses beruhte auf ganz besonderen geistigen Erfahrungen. Wenn ich Ihnen diese geistigen Erfahrungen beschreiben soll, so müßte ich sie Ihnen in der folgenden Weise charakterisieren.

Natürlich müssen wir in vorhistorische Zeiten zurückgehen, denn die Mysterien des Lichtes oder die Mysterien des Geistes sind durchaus vorhistorische Erscheinungen. Wenn ich Ihnen darstellen soll den Charakter dieses Geisteslebens, wie es sich gebildet hat, so muß ich das Folgende sagen. Wir wissen ja, wenn wir sehr weit zurückgehen in der Menschheitsevolution, so finden wir immer mehr und mehr, daß die Menschen der alten Zeiten ein atavistisches Hellsehen, ein träumerisches Hellsehen hatten, durch das sich ihnen die Geheimnisse des Weltenalls enthüllten. Und wir sprechen durchaus richtig, wenn wir sagen, daß über die ganze, im dritten, vierten, fünften, sechsten, siebenten Jahrtausend vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha zivilisierte asiatische Erde Menschen wohnten, denen sich für ihr durchaus naturgebundenes, an das Blut, an die leibliche Organisation gebundenes Hellsehen geistige Wahrheiten offenbarten. Das war gewissermaßen die im weiten Umkreis verbreitete Bevölkerung. Aber dieses atavistische Hellsehen, es war in absteigender Entwickelung, es kam immer mehr und mehr in die Dekadenz. Und dieses In-die-Dekadenz-Kommen des atavistischen Hellsehens ist nicht bloß eine kulturhistorische Erscheinung, es ist zugleich eine Erscheinung des sozialen Lebens der Menschheit.

Warum? Weil aus dieser weiten Masse der Erdenbevölkerung von verschiedenen Zentren her, hauptsächlich aber von einem Zentrum in Asien, gewissermaßen aufstand eine besondere Art von Menschen, eine Art von Menschen mit besonderen Fähigkeiten. Diese Menschen hatten außer dem atavistischen Hellsehen, das ihnen in einer gewissen Beziehung noch geblieben war - es stieg noch aus ihrem inneren Seelenleben traumhaftes Erfassen der Geheimnisse der Welt auf —, außer diesem traumhaften Erfassen der Welt hatten sie aber noch dasjenige — und zwar als erste Menschen der Menschheitsentwickelung —, was wir die Denkkraft nennen. Sie hatten zuerst die aufdämmernde Intelligenz.

Das war eine bedeutsame soziale Erscheinung, daß jene alten Menschen, die nichts hatten als die traumhaft aufsteigenden Schauungen über die Geheimnisse der Welt, Einwanderer in ihre Territorien kommen sahen, die sie noch verstehen konnten, weil die auch Schauungen hatten, die aber etwas schon hatten, was sie selbst nicht hatten: die Denkkraft. Das war eine besondere Menschensorte. Die Inder sahen diejenige Kaste, die sie als die Brahmanen-Kaste bezeichneten, als die Nachkommen dieser Menschen an, die mit dem atavistischen Hellsehen die Denkkraft verbanden. Und als sie in die südlichen Gegenden von den höhergelegenen nördlichen Gegenden Asiens hinunterstiegen, da machte sich für sie geltend der Name Arier. Das ist die arische Bevölkerung. Ihr Urkennzeichen ist dieses, daß sie - wenn ich mich jetzt des späteren Ausdrucks bedienen darf — mit den plebejischen Fähigkeiten des atavistischen Hellsehens die Denkkraft verbanden.

Und diejenigen Mysterien, die man die Mysterien des Geistes oder namentlich die Mysterien des Lichtes nennt, wurden begründet von solchen Menschen, die das atavistische Hellsehen mit dem ersten Aufflammen der Intelligenz, dem inneren Lichte des Menschen verbanden. Und eine Dependenz desjenigen, was dazumal als ein erleuchtender Funke in die Menschheit kam, ist unsere Geistesbildung, aber eben durchaus eine Dependenz.

Es hat sich in der Menschheit manches erhalten von dem, was da geoffenbart worden war. Aber man muß bedenken, daß schon die Griechen, gerade die gebildeteren Persönlichkeiten unter den Griechen, die alte atavistische Hellsehergabe hatten verglimmen, verlöschen sehen, und daß ihnen geblieben war die Denkkraft. Bei den Römern ist nur die Denkkraft geblieben. Bei den Griechen war noch das Bewußtsein vorhanden, daß auch die Denkkraft aus denselben Quellen heraufkommt, aus denen das alte atavistische Hellsehen kam. Daher sprach Sokrates noch durchaus etwas aus, was er als Erlebnis kannte, wenn er von seinem Dämon sprach, der ihm seine ja allerdings nur dialektischen, intelligenten Wahrheiten eingab.

Die Griechen haben auch künstlerisch bedeutsam hingestellt das Herausragen des Intelligenzmenschen, besser gesagt, das Herauswachsen des Intelligenzmenschen aus der anderen Menschheit: Denn die Griechen haben in ihrer Plastik — man studiere sie nur genau - drei stark voneinander verschiedene Typen. Sie haben den arischen Typus, den der Apollo-Kopf hat, der Pallas-Athene-Kopf, der Zeus-Kopf, der Hera-Kopf. Vergleichen Sie die Ohren des Apollo mit den Ohren eines Merkur-Kopfes, die Nase des Apollo mit der Nase eines MerkurKopfes, da werden Sie sehen, welch anderer Typus das ist. Der Grieche wollte hinweisen, wie im Merkur-Typus zusammengeflossen ist im Griechentum mit der Intelligenz dasjenige, was altes, vergangenes Hellsehen war, das noch als Aberglaube fortlebte, das niedere Bildung war, wie dieses auf dem Grunde der Kultur da war, und wie hinausragte der Arier, dessen künstlerische Repräsentanz der Zeus-Kopf, Pallas-AtheneKopf und so weiter war. Und die ganz unten stehenden, mit den trüben Überresten des alten Hellsehertums vorhandenen Rassen, die auch noch in Griechenland lebten, aber namentlich an der Peripherie von Griechenland von den Griechen wahrgenommen wurden, sind wiederum in einem anderen Typus plastisch erhalten: in dem Satyr-Typus, der wieder ganz anders ist als der Merkur-Typus. Vergleichen Sie die SatyrNase mit der Merkur-Nase, die Satyr-Ohren mit den Merkur-Ohren und so weiter. Der Grieche hat in seiner Kunst zusammenfließen lassen dasjenige, was er in seinem Bewußtsein über sein Werden trug.

Das, was dadurch die Mysterien des Geistes oder des Lichtes in allmählicher Filtrierung durch Griechenland dann auf die Neuzeit heraufkam, das hatte aber eine gewisse Eigentümlichkeit als Geisteskultur. Es war als Geisteskultur mit solcher inneren Stoßkraft versehen, daß es aus sich heraus zu gleicher Zeit das Rechtsleben der Menschen begründen konnte. Daher auf der einen Seite die Offenbarung der Götter in den Mysterien, die dem Menschen den Geist bringen, und die Einpflanzung dieses von den Göttern erworbenen Geistes in den äußeren sozialen Organismus, in die Theokratien. Alles geht zurück auf die Theokratien. Und diese Theokratien waren nicht nur imstande, aus dem Mysterienwesen selbst heraus sich mit dem Rechte zu durchdringen, mit dem politischen Wesen zu durchdringen, sondern auch das Wirtschaftsleben zu regeln aus dem Geiste heraus. Die Mysterienpriester der Mysterien des Lichtes waren zu gleicher Zeit die ökonomischen, die wirtschaftlichen Verwalter ihrer Gebiete. Sie wirtschafteten nach den Regeln der Mysterien. Sie bauten die Häuser, sie bauten die Kanäle, sie bauten die Brücken, sie sorgten auch für das Bebauen des Bodens und so weiter.

Das war in der Urzeit eine Kultur durchaus aus dem Geistesleben heraus. Aber diese Kultur verabstrahierte. Aus geistigem Leben wurde sie immer mehr und mehr eine Summe von Ideen. Im Mittelalter ist sie schon Theologie, das heißt, eine Summe von Begriffen, statt des alten geistigen Lebens, oder sie ist angewiesen darauf, weil man mit dem geistigen Leben nicht mehr zusammenhing, abstrakt gehalten zu werden, kurial gehalten zu werden. Denn wenn wir nach den alten Theokratien zurückblicken, da finden wir, daß derjenige, der da herrscht, von den Göttern in den Mysterien dazu seinen Auftrag erhalten hat. Die letzte Dependenz ist der abendländische Herrscher. Man sieht ihm gar nicht mehr an, daß er die letzte Dependenz des aus den Mysterien von den Göttern mit seinem Auftrage hervorgegangenen Beherrschers der Theokratie ist. Alles, was geblieben ist, ist Krone und Krönungsmantel. Das sind die äußeren Insignien, die nun später mehr Orden wurden. Den Titeln merkt man manchmal noch an, wenn man solche Dinge versteht, wie sie zurückgehen auf die Mysterienzeit. Aber alles ist veräußerlicht.

Kaum weniger veräußerlicht ist dasjenige, was durch unsere Gymnasien und Universitäten wallt als Geisteskultur, als letzter Nachklang der göttlichen Botschaften der Mysterien. Es ist das Geistesleben in unser Leben eingeflossen, aber es ist ganz abstrakt geworden, es ist bloßes Vorstellungsleben geworden. Es ist das geworden, wovon endlich die sozialistisch orientierten Kreise sagen: es ist eine Ideologie geworden, das heißt, eine Summe von Gedanken, die nur Gedanken sind. Zu dem ist wirklich unser Geistesleben geworden.

Unter diesem Geistesleben hat sich dasjenige heranentwickelt, was das heutige soziale Chaos ist, weil das Geistesleben, das so filtriert ist, das so verabstrahiert ist, alle Stoßkraft verloren hat. Und wir sind darauf angewiesen, das Geistesleben wiederum auf seine eigenen Grundlagen zu stellen, denn nur so kann es gedeihen. Wir müssen wiederum von dem bloß gedachten Geist zu dem schaffenden Geist den Weg finden. Das können wir nur, wenn wir aus dem staatlichen Geistesleben heraus das freie Geistesleben zu entwickeln suchen, das dann auch die Kraft haben wird, wiederum zum Leben eben zu erwachen. Denn weder ein von der Kirche gegängeltes, noch ein vom Staate bewahrtes und beschütztes Geistesleben, noch ein unter der Last des Wirtschaftens keuchendes Geistesleben kann für die Menschheit fruchtbar sein, sondern nur das auf sich selbst gestellte Geistesleben.

Ja, heute ist es an der Zeit, daß wir den Mut in unseren Seelen aufbringen, frank und frei vor der Welt zu vertreten, daß das Geistesleben auf seinen eigenen Boden gestellt werden müsse. Viele Menschen fragen heute: Was sollen wir denn tun? Das Nächste, worauf es ankommt, das ist, daß wir die Menschen aufklären über das, was notwendig ist. Daß wir möglichst viele Menschen gewinnen, die einsehen, wie notwendig es ist, zum Beispiel das Geistesleben auf seinen eigenen Boden zu stellen, daß wir möglichst viele Menschen gewinnen, die es einsehen, daß dasjenige, was Pädagogik des 19. Jahrhunderts für Volks-, Mittel- und Hochschulen geworden ist, nicht weiter der Menschheit zum Heil gereichen kann, sondern daß neu gebaut werden müsse aus einem freien Geistesleben heraus. Es ist noch wenig der Mut in den Seelen vorhanden, wirklich in radikaler Weise diese Forderung zu stellen. Und man kann sie ja nur stellen, wenn man dahin arbeiter, daß möglichst viele Menschen die Einsicht in diese Verhältnisse gewinnen. Alle andere soziale Arbeit ist heute provisorisch. Das ist dasjenige, was das Wichtigste ist: zu sehen, zu arbeiten, daß immer mehr und mehr Menschen die Einsicht in die sozialen Notwendigkeiten, von denen die eben charakterisierte eine ist, gewinnen können. Aufklärung über diese Dinge verschaffen mit allen Mitteln, die uns zur Verfügung stehen, das ist es, worauf es heute ankommt.

Wir sind noch nicht produktiv geworden in bezug auf das Geistesleben, und wir werden erst produktiv werden in bezug auf das Geistesleben. Ansätze dazu sind vorhanden, ich werde gleich davon sprechen, aber wir sind noch nicht produktiv geworden in bezug auf das Geistesleben. Wir müssen produktiv werden durch die Verselbständigung des Geisteslebens.

Alles was auf der Erde entsteht, läßt Reste zurück. Die Mysterien des Lichtes sind in der heutigen orientalischen Kultur, im orientalischen Geistesleben weniger filtriert als im Abendlande, aber doch durchaus nicht mehr in der Gestalt, in der sie damals waren in der Zeit, die ich geschildert habe. Doch kann man, wenn man das studiert, was die Hindus heute noch haben, was die orientalischen Buddhisten haben, viel eher den Nachklang desjenigen vernehmen, wovon wir selber unser Geistesleben haben, nur ist es auf einer anderen Altersstufe in Asien stehengeblieben. Aber wir sind unproduktiv, wir sind in hohem Grade unproduktiv. Als sich im Abendlande dieKunde von dem Mysterium von Golgatha verbreitet hat — woher nahmen die griechischen, die lateinischen Gelehrten die Begriffe, um das Mysterium von Golgatha zu begreifen? Sie nahmen sie aus der orientalischen Weisheit. Das Abendland hat das Christentum nicht hervorgebracht, es ist aus dem Orient entnommen.

Und ein anderes: Als man die geistige Kultur in englisch sprechenden Gegenden recht unfruchtbar fühlte und nach einer Befruchtung des Geisteslebens seufzte, da gingen die Theosophen zu den unterworfenen Indern und suchten dort ihre Quelle für ihre neuzeitliche Theosophie. Für dasjenige, was man suchte, um das spirituelle Leben zu verbessern, war keine fruchtbare Quelle im eigenen Leben da: man ging nach dem Orient. Und neben diesem Signifikanten könnten Sie viele Beweise für die Unfruchtbarkeit des Geisteslebens im Abendlande finden. Und jeder Beweis für die Unfruchtbarkeit des Geisteslebens im Abendlande ist zu gleicher Zeit ein Beweis für die Notwendigkeit der Verselbständigung des Geisteslebens im dreigliedrigen sozialen Organismus.

Eine zweite Strömung in dem Knäuelwickel ist die Staats- oder Rechtsströmung. Da ist der Knüppel in unserer Kultur, die zweite Strömung. Wenn sie der Mensch heute äußerlich anschaut, wenn er sich äußerlich mit ihr bekannt macht, da sieht er sie, wenn unsere ehrwürdigen Richter auf ihren Richterstühlen mit den Geschworenen sitzen und über die Verbrechen oder Vergehen richten, oder wenn die Verwaltungsbeamten in ihrer Bürokratie walten über unsere zivilisierte Welt hin, zum Verzweifeln derjenigen, die so verwaltet werden. Alles dasjenige, was wir Jurisprudenz, was wir Staat nennen, und alles, was in Verbindung von Jurisprudenz und Staat als Politik entsteht, das ist diese Strömung (siehe Zeichnung S. 229, weiß). Es ist — wie ich das (orange) die Strömung des Geisteslebens nennen kann, so ist dieses die Strömung des Rechtes, des Staates (weiß).

Woher kommt dies? Allerdings geht das auch auf Mysterienkultur zurück. Es geht zurück auf ägyptische Mysterienkultur, die durch die südlichen europäischen Gegenden gegangen ist, und die dann durchgegangen ist durch das nüchterne, phantasielose Wesen der Römer, sich verbunden hat im phantasielosen Wesen der Römer mit einem Seitenast des orientalischen Wesens und da das katholische Christentum beziehungsweise das katholische Kirchentum geworden ist (siehe Zeichnung). Dieses katholische Kirchentum, das ist im Grunde genommen, wenn auch etwas radikal gesprochen, auch eine Jurisprudenz. Denn von einzelnen Dogmen bis zu jenem gewaltigen, großen Gerichte, das immer als « Jüngstes Gericht» dargestellt wurde durch das ganze Mittelalter, wurde das ganz andersartige Geistesleben des Orients, da es den ägyptischen Einschlag hatte aus den Mysterien des Raumes, im Grunde genommen verwandelt in eine Gesellschaft von Weltenrichtern mit Weltenurteilen und Weltenbestrafungen und Sündern und Guten und Bösen: Es ist eine Jurisprudenz. Und das ist das zweite Element, das in unserem Geistesknäuel in der Verwirrung, die wir Zivilisation nennen, drinnen lebt und sich keineswegs organisch mit dem anderen verbunden hat. Daß es sich nicht verbunden hat, das kann jeder erfahren, der einmal an die Universität geht und meinetwillen nacheinander hört eine juristische Rede über Staatsrecht und nachher hört eine theologische Rede, meinetwillen über kanonisches Recht sogar. Das liegt nebeneinander. Aber diese Dinge sind menschengestaltend gewesen. Selbst in späteren Zeiten, wo man ihre Ursprünge vergessen hat, gestalten sie die Menschengemüter noch. Verabstrahierend wirkte das Rechtsleben auf das spätere Geistesleben, aber im äußeren Leben war es in den Menschensitten, Menschengewohnheiten, Menscheneinrichtungen schaffend. Und das, was in der dekadenten Geistesströmung des Orients der letzte soziale Ausläufer war, was ist es denn, wovon man nicht mehr den Ursprung erkennt? Das ist die Feudal-Aristokratie (siehe Zeichnung). Dem Adeligen könnten Sie nicht mehr ansehen, daß er seinen Ursprung hat aus dem orientalisch theokratischen Geistesleben, denn er hat alles abgestreift, es ist nur noch die soziale Konfiguration geblieben. Die Journalisten-Intelligenz, die bekommt manchmal so merkwürdige Alpdruckerscheinungen! Sie bekam solche Alpdruckerscheinung in der neueren Zeit und erfand ein kurioses Wort, auf das sie besonders stolz wurde: «Geistes-Aristokratie». Das konnte man ab und zu hören. Dasjenige, was durch die römische Kirchenverfassung durchgehend, durch die theokratisierende Jurisprudenz, die jurisprudenzende Theokratie hindurchgehend, sich dann verweltlicht im mittelalterlichen Städtewesen, sich völlig verweltlicht in der neueren Zeit, was ist das in der äußersten Dependenz? Das ist die Bourgeoisie (siehe Zeichnung). Und so sind getreulich unter den Menschen durcheinandergewürfelt diese geistigen Kräfte in ihren äußersten Dependenzen.

Eine dritte Strömung verbindet sich schon auch noch damit. Wenn Sie sie heute von außen beobachten (Zeichnung, orange), wo zeigt sich diese dritte Strömung äußerlich sinnenfällig besonders charakteristisch? Ja, es gab für Mitteleuropa geradezu eine Methode, gewissen Leuten zu demonstrieren, wo sich diese äußersten Dependenzen eines auch ursprünglich anderen entfalteten. Das geschah, wenn der mitteleuropäische Mensch seinen Sohn ins Kontor nach London oder nach New York schickte, damit er dort die Usancen des Wirtschaftens lerne. In den Usancen des Wirtschaftslebens, deren Ursprung in Volksgewohnheiten der anglo-amerikanischen Welt liegen, da ist die letzte Konsequenz desjenigen zu sehen, was sich entwickelt hat in Dependenzen aus dem, was ich nennen möchte, die Mysterien der Erde, von denen zum Beispiel die Druiden-Mysterien nur eine besondere Abart waren. Die Mysterien der Erde enthielten in Urzeiten europäischer Bevölkerung noch eine eigentümliche Art des Weisheitslebens. Jener europäischen Bevölkerung, die nichts wußte, ganz barbarisch war gegenüber den Offenbarungen der orientalischen Weisheit, gegenüber den Mysterien des Raumes, gegenüber dem, was dann zum Katholizismus wurde, jener Bevölkerung, die entgegenkam dem sich ausbreitenden Christentum, ihr war eigen eine eigentümliche Art des Weisheitslebens, das ganz und gar physische Weisheit war. Man kann historisch davon höchstens noch die alleräußersten Gebräuche studieren, die in der Geschichte dieser Strömung aufgezeichnet sind: wie zusammenhingen die Festlichkeiten derjenigen Menschen, aus denen die Usancen, die Gewohnheiten Englands und Amerikas geworden sind. DieFestlichkeiten wurden hier in ganz andere Beziehungen gebracht als in Ägypten, wo die Ernte mit den Sternen zusammenhing. Hier war die festliche Gelegenheit die Ernte als solche, und mit anderen Dingen als dort, mit Dingen, die durchaus dem Wirtschaftsleben angehören, hingen die höchsten Festlichkeiten des Jahres zusammen. Wir haben hier durchaus etwas, was auf das Wirtschaftsleben zurückgeht. Und wollen wir den ganzen Geist dieser Sache erfassen, dann müssen wir uns sagen: Von Asien herüber und vom Süden herauf verpflanzen Menschen ein Geistes- und Rechtsleben, das sie von oben her empfangen haben und herunterführen zur Erde. Da, in der dritten Strömung, sprießt ein Wirtschaftsleben auf, das sich hinaufentwickeln muß, das sich hinaufranken muß, das ursprünglich eigentlich in seinen Rechtsusancen, in seinen geistigen Einrichtungen ganz und gar nur Wirtschaftsleben ist, so weit Wirtschaftsleben, daß zum Beispiel eines der besonderen Jahresfeste darinnen bestand, daß man die Befruchtung der Herden als besonderes Fest zu Ehren der Götter feierte. Und ähnliche Feste gab es: alles aus dem Wirtschaftsleben herausgedacht. Und wenn wir in die Gegenden Nordrußlands, Mittelrußlands, Schwedens, Norwegens gehen, oder in diejenigen Gegenden, die bis vor kurzer Zeit die Gegenden Deutschlands waren, nach Frankreich, wenigstens Nordfrankreich, und nach dem heutigen Großbritannien, wenn wir diese Gegenden durchgehen, überall finden wir ausgebreitet eine Bevölkerung, die durchaus vor der Ausbreitung des Christentums in alten Zeiten eine deutlich ausgesprochene Wirtschaftskultur hatten. Und das, was noch als die alten Sitten, als Rechtssittenfest, Götterfestes-Sitte gefunden werden kann, ist Nachklang dieser alten Wirtschaftskultur. (Die Zeichnung an der Tafel ist nun vollständig.)

Diese Wirtschaftskultur begegnet sich mit dem, was von der anderen Seite kommt. Zunächst hat es diese Wirtschaftskultur nicht dazu gebracht, ein selbständiges Rechts- und Geistesleben zu entwickeln. Die ursprünglichen Rechtsusancen sind abgeworfen worden, weil das römische Recht eingeflossen ist, die ursprünglichen Geistesusancen sind abgeworfen worden, weil das griechische Geistesleben eingeflossen ist. Zunächst wird dieses Wirtschaftsleben steril, und arbeitet nach und nach sich wiederum heraus, kann sich aber nur herausarbeiten, wenn es die Chaotisierung mit dem von fremd her angenommenen Geistesleben und Rechtsleben überwindet. Nehmen Sie das heutige anglo-amerikanische Geistesleben. In diesem englisch-amerikanischen Geistesleben haben Sie zwei sehr stark voneinander unterschiedene Dinge. Erstens haben Sie überall mehr als sonstwo auf der Erde im anglo-amerikanischen Geistesleben die sogenannten Geheimgesellschaften, die ziemlich starken Einfluß haben, viel mehr als die Leute wissen. Sie sind durchaus die Bewahrer alten Geisteslebens, und sie sind stolz darauf, die Bewahrer ägyptischen oder orientalischen Geisteslebens zu sein, das ganz und gar filtriert, bis ins Symbol verflüchtigt ist; bis ins Symbol, das man nicht mehr versteht, verflüchtigt ist, aber bei den Oberen eine gewisse große Macht hat. Das ist aber altes Geistesleben, nicht auf eigenem Boden erwachsenes Geistesleben. Daneben ist ein Geistesleben da, das auf dem Wirtschaftsboden durchaus wächst, aber so kleine Blümchen erst treibt, ganz als kleineBlümchen wuchert am Wirtschaftsboden.

Wer solche Dinge studiert und verstehen kann, der weiß gut, daß Locke, Hume, Mill, Spencer, Darwin und andere durchaus diese Blümchen sind aus dem Wirtschaftsleben heraus. Man kann ganz genau die Gedanken eines Mill, die Gedanken eines Spencer aus dem Wirtschaftsleben heraus gewinnen. Die Sozialdemokratie hat das dann zur Theorie erhoben und betrachtet das Geistesleben als eine Dependenz des Wirtschaftslebens. Das ist da zunächst vorhanden, alles herausgeholt aus dem sogenannten Praktischen, eigentlich aus der Lebensroutine heraus, nicht aus der wirklichen Lebenspraxis. So daß da nebeneinandergehen solche Dinge wie der Darwinismus, Spencerismus, Millismus, Humeismus und die filtrierten Mysterienlehren, die dann ihre Fortsetzungen finden in den verschiedenen sektiererischen Evolutionen, die Theosophische Gesellschaft, die Quäker und so weiter. Das Wirtschaftsleben, das herauf will, hat erst die kleinen Blümchen getrieben, ist noch gar nicht weit. Dasjenige, was Geistesleben ist, dasjenige, was Rechtsleben ist: fremde Pflanzen! Und am allermeisten fremde Pflanzen — das bitte ich wohl zu beachten -, fremde Pflanzen um so mehr, je mehr wir in der europäischen Zivilisation nach dem Westen gehen.

Denn in Mitteleuropa, da hat es immer etwas gegeben, was, ich möchte sagen, wie ein Sich-Wehren war, ein Ankämpfen war gegen das griechische Geistesleben auf der einen Seite und das römisch-katholische Rechtsleben auf der anderen Seite. Ein Sich-Aufbäumen hat es da immer gegeben. Ein Beispiel für dieses Aufbäumen ist die mitteleuropäische Philosophie. In England weiß man in Wirklichkeit eigentlich nichts von dieser mitteleuropäischen Philosophie. Man kann in Wirklichkeit den Hegel nicht übersetzen in die englische Sprache, es ist nicht möglich. Man weiß nichts von ihm. Deutsche Philosophie nennt man ja in England Germanismus und meint damit etwas, womit sich ein vernünftiger Mensch nicht befassen kann. Aber gerade in dieser deutschen Philosophie, mit Ausnahme einer Episode -— wo nämlich Kant durch Hume gründlich’ verdorben worden ist, und dieses scheußlicheKantischHumesche Element in die deutsche Philosophie hineingebracht worden ist, das wirklich in den Köpfen der mitteleuropäischen Menschheit so heilloses Unheil angerichtet hat —, mit Ausnahme dieser Episode haben wir immerhin nachher die Nachblüte dieses Aufbäumens gerade in Fichte, Schelling, Hegel. Und wir haben das Suchen nach einem freien Geistesleben schon in Goethe, der nichts mehr wissen will von dem letzten Nachklang der römisch-katholischen Jurisprudenz in dem, was man Naturgesetz nennt. Fühlen Sie ebenso, wie in dem schäbig gewordenen Talar und in den sonderbaren Mützen, die noch die Richter aus der alten Zeit haben — heute machen sie Petitionen, daß sie das ablegen können -, fühlen Sie ebenso in der Naturwissenschaft, in dem Naturgesetze, «Gesetz», das Juristische noch drinnen! Denn der ganze Ausdruck «Naturgesetz» hat zum Beispiel der Goetheschen Naturwissenschaft gegenüber, die nur mit dem Urphänomen, die nur mit der Urtatsache arbeitet, keinen Sinn. Da ist zum ersten Mal radikal angekämpft — aber natürlich ist das alles in dem Beginn geblieben -, das war der erste Vorstoß nach dem freien Geistesleben: die Goethesche Naturwissenschaft. Und in diesem Mitteleuropa gibt es sogar schon den ersten Anstoß zu dem selbständigen Rechts- oder Staatsleben. Lesen Sie solch eine Schrift wie die Wilhelms von Humboldt. Der Mann ist sogar preußischer Unterrichtsminister gewesen. Lesen Sie die Schrift von Wilhelm von Humboldt. Sie hat früher - ich weiß nicht, wie viel sie jetzt kostet - in der Reclamschen Universal-Bibliothek bloß zwanzig Pfennige gekostet. Lesen Sie diese Schrift: «Ideen zu einem Versuch, die Grenzen der Wirksamkeit des Staates zu bestimmen», dann werden Sie sehen den ersten Ansatz, das selbständige Rechts- oder Staatsleben, die Selbständigkeit des eigentlichen politischen Gebietes zu konstruieren. Allerdings ist es eben niemals weiter als zu Ansätzen gekommen. Diese Ansätze liegen zurück bis in die erste Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, sogar bis in das Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts. Aber man muß nur bedenken, daß immerhin doch in diesem Mitteleuropa gerade nach dieser Richtung hin wichtige Impulse da sind, Impulse, an die angeknüpft werden kann, die nicht unberücksichtigt gelassen werden sollen, die einmünden können in den Impuls vom dreigliedrigen sozialen Organismus.

Nietzsche hat in eines seiner ersten Bücher dasjenige Wort geschrieben, das ich wieder zitiert habe in meinem Nietzsche-Buch gleich auf den ersten Seiten, und mit dem geahnt wird etwas wie die Tragik des deutschen Geisteslebens. Nietzsche versuchte dazumal in seiner Schrift «David Strauß, der Bekenner und Schriftsteller» die Ereignisse von 1870/71, die Begründung des Deutschen Reiches zu charakterisieren mit dem Wort: «Exstirpation des deutschen Geistes zu Gunsten des deutschen Reiches». Seither ist dieser Kehlkopfschnitt des deutschen Geistes gründlich durchgeführt worden. Und als in den letzten fünf bis sechs Jahren drei Viertel der Welt über dieses ehemalige Deutschland sich hermachten - ich will nicht über die Ursachen und über die Schuldigen sprechen, sondern eben nur die Konfiguration, die Weltlage angeben -, da war es im Grunde genommen schon der Leichnam des deutschen Geisteslebens. Aber wenn man so spricht, wie ich gestern gesprochen habe, unbefangen die Tatsachen charakterisierend, so sollte man nicht heraushören, daß nicht vieles noch drinnenliegt in diesem deutschen Geistesleben, was trotz der zukünftigen Zigeunerhaftigkeit herauskommen muß, was beachtet werden muß, was beachtet sein will. Denn woran sind im Grunde genommen die Deutschen zugrunde gegangen? Man muß sich auch diese Frage unbefangen einmal beantworten. Die Deutschen sind daran zugrunde gegangen, daß sie es auch mitmachen wollten mit dem Materialismus, und weil sie kein Talent haben zum Materialismus. Die anderen haben gute Talente für den Materialismus. Die Deutschen haben überhaupt jene Eigentümlichkeit, die einmal Herman Grimm ausgezeichnet charakterisiert hat, indem er sagte: Die Deutschen weichen in der Regel dann zurück, wenn es ihnen heilsam wäre, kühn vorzuschreiten, und sie stürmen furchtbar stark vor, wenn es ihnen heilsam wäre, sich zurückzuhalten. — Es ist das ein sehr gutes Wort für eine innere Charaktereigenschaft gerade des deutschen Volkes. Denn die Deutschen haben Stoßkraft durch die Jahrhunderte gehabt, aber nicht die Fähigkeit, die Stoßkraft durchzuhalten. Goethe konnte das Urphänomen hinstellen, aber es nicht bis zu den Anfängen der Geisteswissenschaft bringen. Er konnte eine Geistigkeit entwickeln, wie zum Beispiel in seinem «Faust» oder in seinem «Wilhelm Meister», welche die Welt hätte revolutionieren können, wenn die rechten Wege gefunden worden wären. Dagegen brachte es die äußere Persönlichkeit dieses genialen Menschen nur so weit, daß er in Weimar Fett ansetzte und ein Doppelkinn hatte, ein dicker Geheimrat wurde, der ungemein fleißig war auch als Minister, aber der doch genötigt war, fünfte grad sein zu lassen, wie man sagt, gerade im politischen Leben.