Knowledge as a Source of Healing

GA 198

20 March 1920, Dornach

Lecture I

What holds good for people today as an almost undisputed authority is science; science in the sense in which it is pursued in the educational institutions of the country. We have often spoken of how far the validity of science can go, and it has also been pointed out that people today must free themselves from its authority. I want now to show how it has become a characteristic phenomenon—but only of the last three or four centuries—to regard medicine as one of these sciences which hold sway as authorities. Indeed, everything connected with medicine is just one science among others—a science the effects of which are intended to bring about the healing of the sick. Today it is hardly realised that this relation of medicine to the other sciences, and to the whole field of knowledge, has come about only during the last three or four centuries. For the further back we go in human evolution the more do we find how everything that could be cultivated by man in the way of science, of knowledge, was considered to be more or less of a medical nature—as having to do with healing. And when we look back to those olden times, particularly to the development then of occult science, we see that with the concept of this occult science, of this body of knowledge, there is always bound up the concept of healing. In any healing, spiritual science was always involved. Thus, at that time it could never have been said: Medicine is one science among many!—In those days when pure intellect was not thought to have any place in occult science it was said: In all science, in all knowledge, we must search for what aims at healing the whole human being.—This thought arose in the soul when they spoke.

But now the question necessarily comes up: What was there in those days to be healed? In this age of materialism a man is said to be ill when anything abnormal is noticed in him, either outwardly in his physical functioning or in his behaviour towards the material world. This material concept of illness is indeed, strictly speaking, a product of man's recent evolution, a product of the post-Grecian age. For in the. Greece of that time, where men were more awake and more receptive towards the world than those who came later, there still persisted the concept of illness—and of the tendency to illness—which prevailed in all ages up to the last two or three centuries B.C. Such matters as these have to be somewhat emphasised in order to be understood and perceived in their real significance. In those olden days people were convinced that all human beings permanently carried within them the seeds of illness. That in reality everyone went about the world with the predisposition to illness, was the prevailing conception. All men needed help at least in warding off illness; they needed healing the whole time—such was the opinion. Perhaps those things can be better understood if this notion of them is compared with one we come across a good deal, particularly now in connection with our social affairs and social demands. Many people today consider themselves called upon to make a stir about what is necessary in social, or other matters, for the future betterment of mankind. What conditions would be were their ideas to be carried out, they picture as a paradise on earth indeed, the realisation of certain ideas is even said to mean the dawn of the millennium. Certainly this may be well meant, though it has its roots in poor understanding and still poorer intelligence. But it may have the effect of merely exciting people in the agitator's way. For what could have a more powerful effect of this kind, particularly in a materialistic age, than the promise of a paradise on earth. And if besides they are told it will happen before they die, it is highly probable they will support anyone making the promise. Compared with that, anything like the idea of the “Threefold Commonwealth” appears hard indeed, for it does not speak of a paradise on earth but of a social organism in keeping with life—an organism which can really live. Over against the conception which includes this possible paradise on earth, and is supposed capable of bringing men health by putting their ideals into effect merely through improving conditions on the physical plane—over against this way of thinking lies another.

This other way of thinking, which held good in ancient times and had a quite different shade of feeling, I was trying to describe when I said: All human beings, in so far as they live and work on the physical plane, are to a certain extent hampered by the pre-disposition to sickness, and need constant healing. This conception is founded on what might be expressed thus—that here in the physical world a man is able to deal with the organisations necessary on the physical plane—with his domestic affairs; his rights and so on. But when all this is carried out through his own power alone, when nothing plays a part which has not to do with external institutions, the physical organism of man becomes more and more unhealthy. Ordinary measures are then quite unable to promote a sound social organism but only one that becomes weaker and weaker. For this to be avoided it is necessary for spiritual life to run side-by-side with the measures taken for the physical world. Then this spiritual life has the effect of paralysing the germs of sickness always being produced in men. All knowledge was worthless for mankind—so it was thought—which did not tend to counteract the poison constantly forming in the social organism. The process of cognition is a healing process. It was considered in those olden days that, were knowledge at fault in any particular epoch, the social organism would become sick. Hence, from the first, cognitional power was recognised as a healing force; only in the course of time did the doctor, the teacher, the priest become separate individuals, independent of a leader with knowledge of the Mysteries who was also responsible for the ordering of society as well as being doctor, teacher, priest and so on. All these faculties were originally combined in one man possessing the knowledge which, owing to its particular character, acted as a healing factor for mankind. Later only were they to be differentiated. At that period of human evolution, too, far less attention was paid to individual illness than is the case today. Certainly opinions were formed about individual cases, but they were not told to the patient for fear of hurting his feelings and horrifying him. On the other hand, the measures taken, drawn as far as possible out of the deep sources of knowledge, were considered a social cure.

Such a conception, it is true, could prevail in its fullness only at a time when a man's attitude to himself was quite different from what it is today. We have frequently spoken of how the intellectualism, that now takes such a prominent place in the acquiring of knowledge, is really, in its present form, only three or four hundred years old. This intellectualism, which sees its ideal in the natural laws perceived through abstract concepts, has little to do with the human personality, I have often described what effect this has. Picture anyone studying science today, any branch of science, in one of the usual centres of learning in the civilised world. The student sits there listening to the lecturer only with his head, with his understanding, his intellect; and he watches experiments being made. In all this very little part is taken by his soul, his heart, his being as a whole. It was very different in the old Mysteries when there was no question of remaining aloof. All that worked on the head, on the intellect, at the same time affected the entire man, laying hold of his heart, soul and will, so that his whole being could participate. By thinking in the abstract, by the abstract investigation of nature, our very life has become abstract, so much so that today a man hardly possesses the organ capable of seeing rightly what once was bound up with the whole social life of mankind. We have often spoken here about what in past ages of Judaism was called the “fearful, the inexpressible, name of God”, which eventually found utterance in the word “Jahve.” Why did the name inspire fear? It was because through the very power of the sound, the everyday mood of the one who uttered it, his everyday consciousness, was obliterated and another world arose before him. Because it necessitated the withdrawal of the ordinary consciousness, utterance of the word was dangerous. A man actually felt that when this name vibrated through him he was wafted to another world, where everything was different from the physical world,—This is a mood of soul of which people no longer have, nor can have, any notion. For today, a combination of sounds has no such shattering effect.

All this has to do with the constitution of man's soul and body from which in those times there was more to draw upon than there is now. Today the organic plays the greater part—hunger, thirst, various emotions, desires, the promptings of heart and soul, sympathies and antipathies. All that arises in this way out of man's organisation is, strictly speaking, part of him as an individual—an individual human ego. In the case of the men of old, in addition to hunger, thirst, and the desires of ordinary life, revelations of the divine arose. They felt in what had to do in this way with their own bodily nature and with their own soul, the presence of God. Who worked in them as well as in nature. What arose in these men of olden times made them capable of seeing in surrounding nature not what we see today but the spiritual. Present-day man is not disposed to allow that the very faculty of perception in those earlier days was different from what it is in man today.

One can certainly understand this prejudice, this assumption that the world was always seen in the way we see it today. For those who want proof in such matters, however, even external facts show clearly that the Greeks themselves—so we need not go far back in man's evolution—saw surrounding nature differently from how we do. To spiritual science with its spiritual vision this is perfectly clear, but the knowledge, thus brought to the surface so vividly through spiritual vision, can be arrived at also through physical facts, if we look, for instance, in Greek literature and notice the use of the Greek word chloros. By this they meant green, but curiously enough they used the same word for golden honey and the golden leaves in autumn; it was also applied to the gold of resin. And the Greeks had a word to describe the darkness of hair, which they used as well when speaking of lapis lazuli, that blue stone. No-one can assume the Greeks had blue hair;. So there is ample proof of such things, from which it can be seen that, as a people, the Greeks were simply incapable of distinguishing yellow from green, and that they did not perceive blue as the colour we do but saw everything tinged with the vividness of red or gold. We find all this confirmed by a Roman writer who speaks of how the Greek painters only used four colours—black, white, red, yellow. Judging from our present theory of colour we must say: The Greeks were essentially blind to the colour blue; they did not see the blue in green but only the yellow. The surrounding world had, for them, a much more fiery aspect, for they saw it all with a reddish tinge. The metamorphoses of human evolution thus affect even the way in which a man sees, and as we have said this is capable of external proof. To spiritual vision it is perfectly clear that the whole colour-spectrum of the Greeks was on the red side—that they had little feeling for the blue and violet. For them the violet was much redder than we see it. Were we, according to our present visual conception, to paint the landscape as a Greek saw it, we should have to use quite different colours from those we ordinarily do. They had no knowledge of what we see as nature, and the nature they saw is an unknown world to us. The evolution of mankind progresses indeed by metamorphoses. The point is that the time when intellectualism arose and men became inclined to meditation—the Greeks had little inclination that way—they lived objectively in the world of nature—was the time when a feeling was acquired for the dark colours, the blue, the blue-violet. It was not only the inner nature of the soul that was changed, but also what passed over from the soul into the senses.

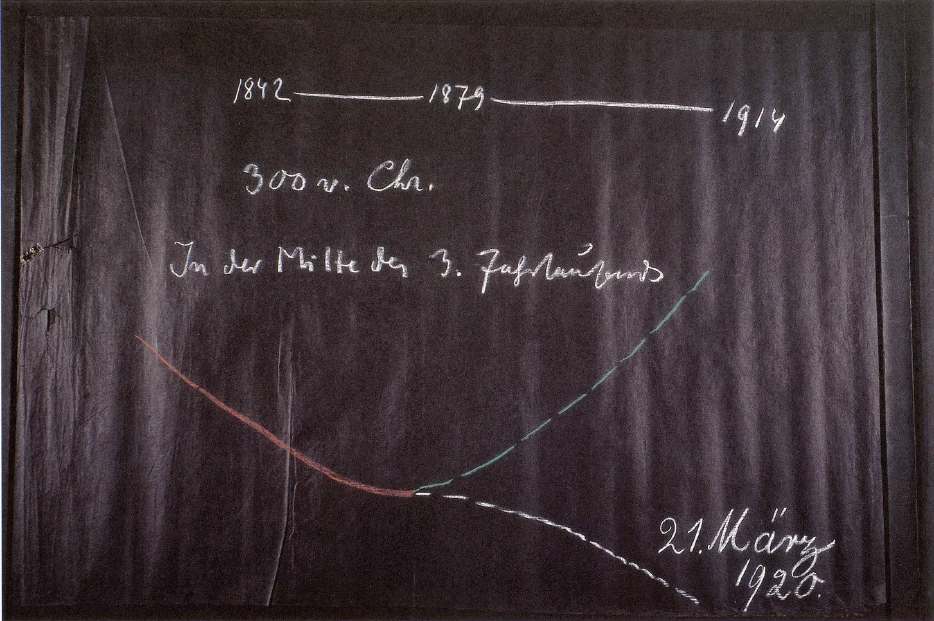

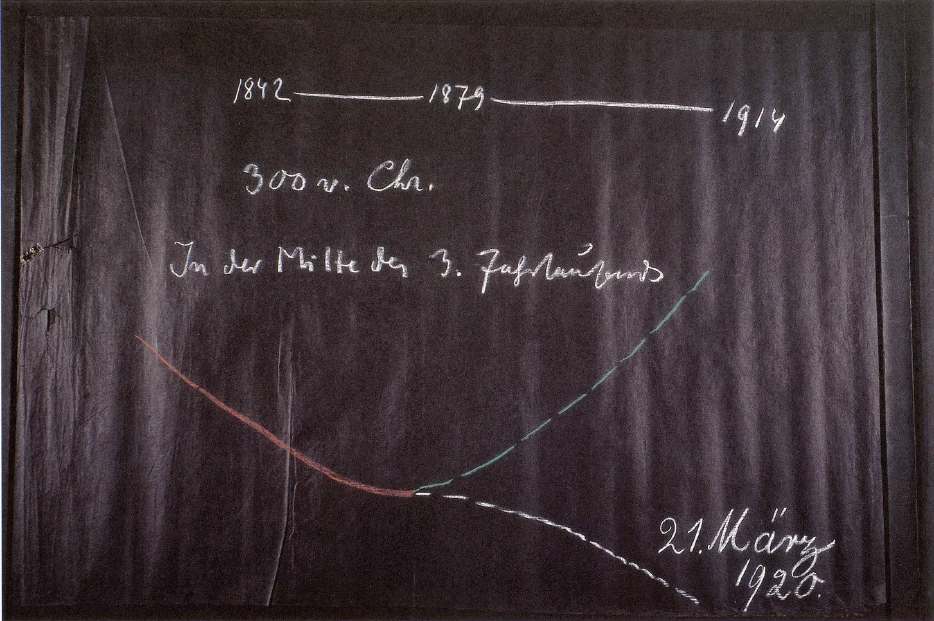

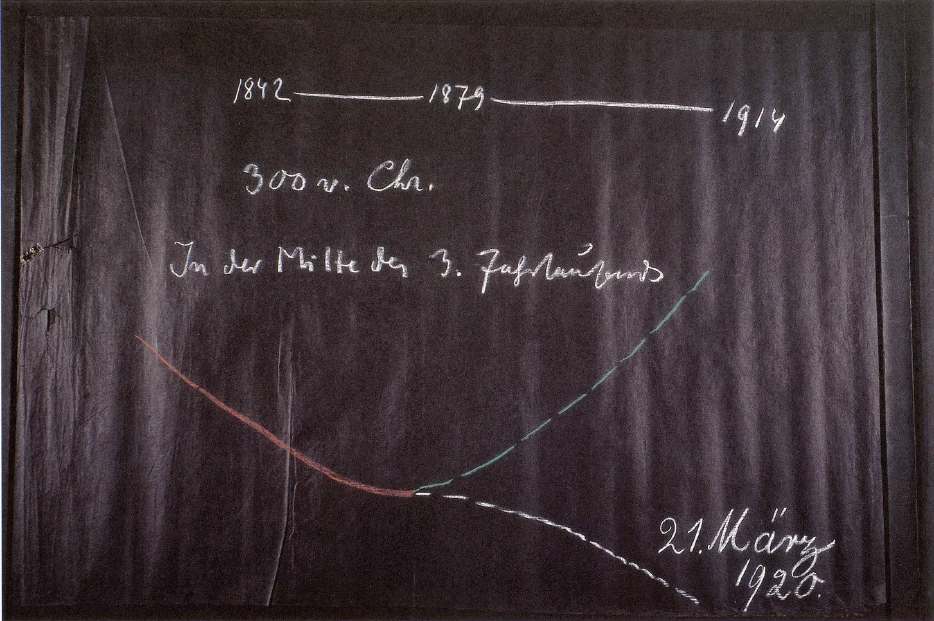

You can therefore say that today, in this fifth postAtlantean period, we are indeed different men in our sense-faculties from the characteristic men of the fourth period, the Greco-Latin people. This is all connected with what has been said before. During the time when spiritual forces still arose from the emotions, from sympathies and antipathies, even from the body in its hunger, thirst, its satiation, these spiritual forces poured into the sense-organs. And these spiritual forces, streaming up from the lower bodily nature to pour themselves into the sense-organs, are those which play the chief part for the eyes in giving life to the various shades of yellow and red, enabling these colours to be perceived. The time has now come when the reverse is the most important task for mankind. The Greeks were still organised in such a way that their beautiful world-conception was mediated through their senses, into which flowed their organic life permeated by spirit. In the course of centuries this spirit-filled organic life has been suppressed by men. Out of our soul, out of our spirit, we must infuse it with fresh life; we must acquire the faculty for making our way into soul and spirit—as spiritual science enables us to do. By acquiring this faculty through spiritual science we shall take the opposite direction. In the case of the Greeks the streams came from the body to pour into the eye (see red in diagram I); the reverse must take place with us; we have so to develop soul and spirit that the streams (see blue in diagram I) from the soul and spirit reach the human organisation; and we must receive these streams in the other senses as well as in the eye. The way for mankind in future must be in the reverse direction to that of the middle of the fourth post-Atlantean culture-epoch. Then the reflective man will once again become a knower of the spirit, but in another form, because of what comes to him from above. We have grown to be sensitive to the blue side of the spectrum.

If I wanted to make a diagram I should have to draw it in the following way: The Greek was susceptible to red, lived in red and was familiar with the red part of the spectrum (see left of diagram II). We, however, must grow more and more accustomed to this part (see right of diagram II). But by doing so, and in that we find blue and blue-violet increasingly attractive, our sense-organs have necessarily to undergo change.

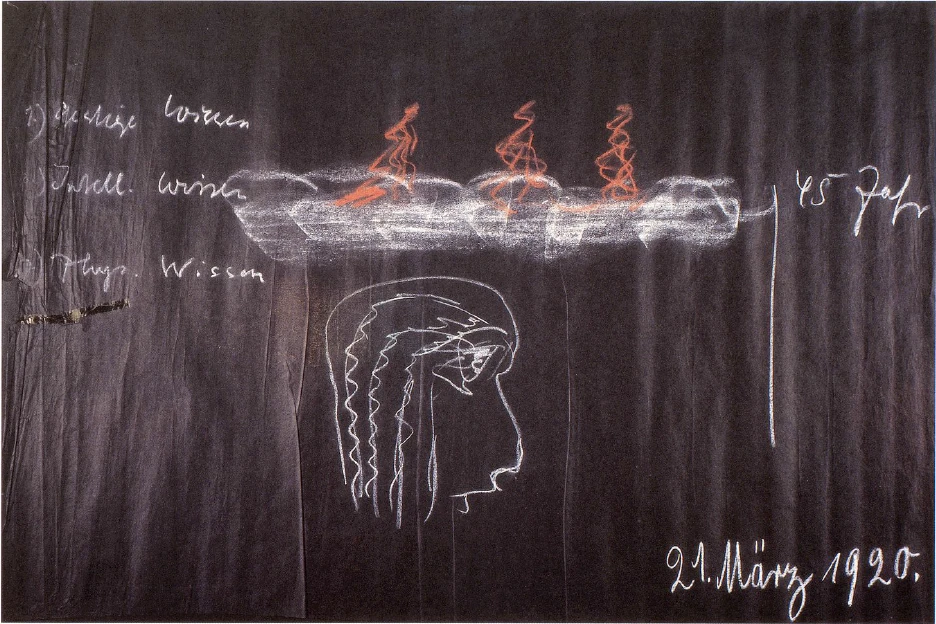

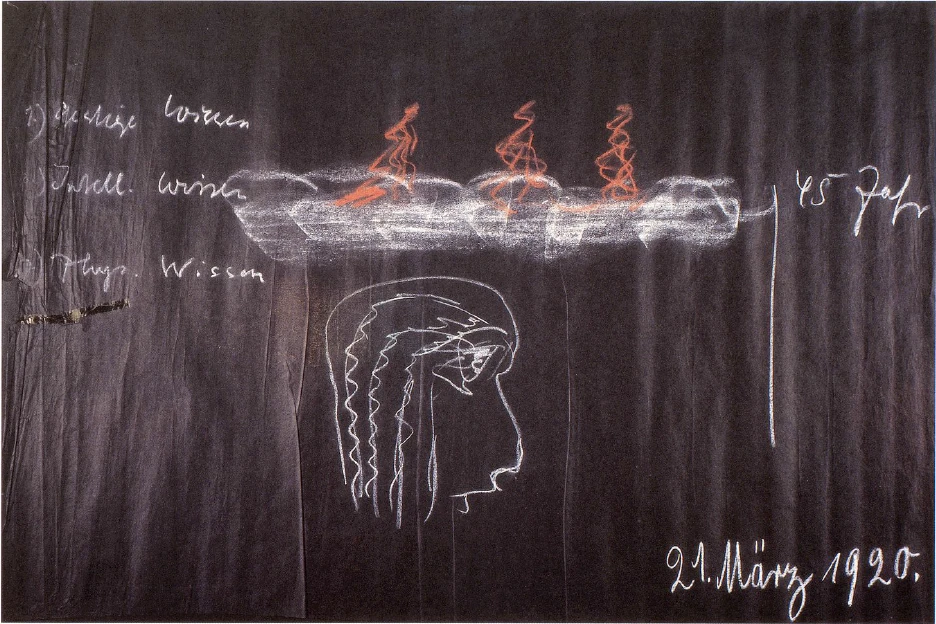

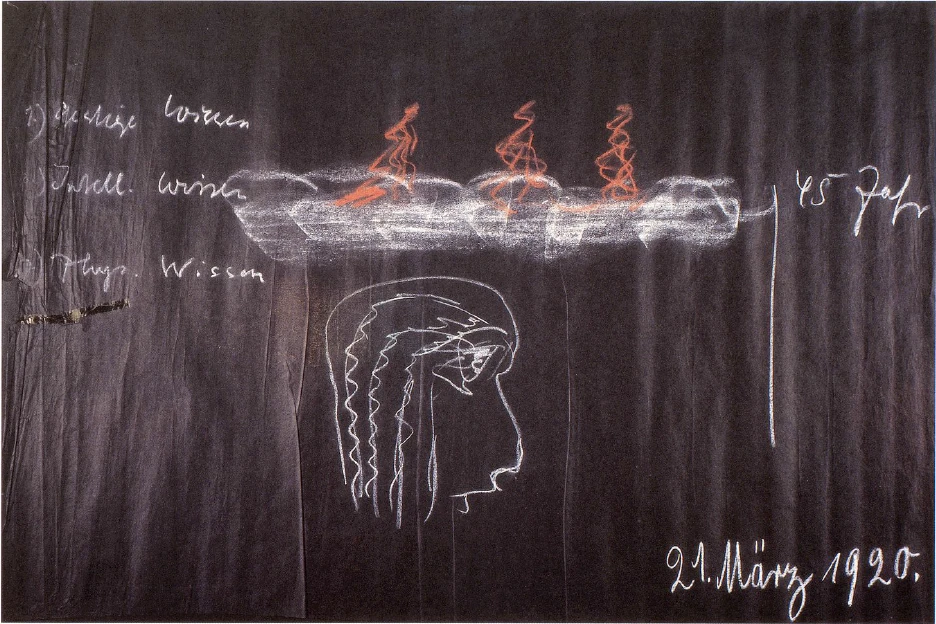

The sense-organs must become quite different in their finer structure from how they were. What then gradually pours into the sense-organs in a natural way, develops through the eye, for example. Imagination; through the ear. Inspiration; through the sense of warmth, Intuition. Thus there must be developed: through the eye: Imagination, through the ear: Inspiration, through the warmth-sense: Intuition.

In the course of human evolution the finer structure of man's organisation goes through a metamorphosis, becomes different.

People today must be awake to such things, for they are standing at a momentous cross-roads; it is indeed a time when it has to be decided whether they can take the way enabling them to receive impressions from above. Pure intellectualism does not suffice; we must permeate intellectualism with spirit and soul. Then what develops within us as spirit and soul will work into the human organisation. But what if we do not develop it? When any organ is destined for a purpose for which it is not used, it perishes—is killed. There you have in the human organism itself what a past age, out of the assumptions of the time, accepted for the evolution of mankind. Just consider your eyes—into those eyes must be poured what should stream from above as spiritual life into the people of the future. Should this not come about, the eyes are doomed to suffer. Through their very nature they must deteriorate; and it is the same in the case of the ears, the same with the sense of warmth. What kind of knowledge then must we look for? A knowledge that will heal our organism of its tendency to sickness. We have to find our way back to perceiving that all knowledge—in so far as it is connected with man should be of a healing nature. We must return to the concept that we have to seek knowledge for this healing virtue, that medicine is not just one science among others, but that in the process of human evolution all knowledge must be a healing factor. This is because human beings all the time need that what arises in them on the physical plane should be healed. The man who promises an earthly paradise is not speaking rightly; he alone tells the truth who makes it clear: When everything has been done to establish good earthly conditions, a man has still to seek his connection with the spiritual world. For even the best conditions on earth need perpetual healing—healing that penetrates right into the human organism, as this, too, is always prone to sickness. In so many words: There must be a spiritual life in men with power to form healing forces out of itself.

Among the many grounds, which, out of the anthroposophical world-conception, have contributed to giving life to the idea of the “threefold” are those you may gather from what I have been saying today. For this idea of the “threefold” is such that, look where you will in man's present evolution—provided you can observe in the right way—the need for this membering into three is manifest to those who have a faculty for seeking the truth. Those with a little logic who, hearing about this “threefold” idea cannot immediately grasp it, or perhaps find it at variance with some other idea, should wait till they learn more about it. Then they will see that there is not just one proof nor one source alone for proving the necessity for the “threefold”, but that these are numberless. For wherever you look you find instances bearing independent witness to what I might describe as the present necessity for spreading this idea of the “threefold” in our social organism. And one of the most important spheres of all lies in the knowledge and understanding of the being of man himself. But where do we find science—so proud of its abstraction—turning its attention to the concrete?—The Greeks were still distinctly conscious that when they gave rein to their feelings the divine revealed itself to them. And we must acquire the faculty for bringing down spiritual forces of the soul from the spiritual heights; they must reveal nature to us, show us what nature is. In other words we must grow to realise that we cannot learn to know nature by perceiving it outwardly, but only with sense-organs strengthened by what comes from above—with an eye made keen by Imagination, an ear sharpened through Inspiration, and a sense of warmth through Intuition—that is to say, through selfless experience of the things and processes surrounding us.

Out of the will to heal has science developed. Into the will to heal must science return. What we look upon as science today, showing such veneration for its authority, is only an intermediate state: which state, however, is leading in the social sphere to the most terrible conflict. We shall continue on this theme tomorrow.

Erster Vortrag

Was heute den Menschen als eine fast unumstrittene Autorität gilt, das ist Wissenschaft, Wissenschaft eben in demjenigen Sinne, in dem diese Wissenschaft heute auf unseren staatlich abgestempelten Lehranstalten getrieben wird. Wir haben öfters über die Geltungsmöglichkeiten dieser Wissenschaft gesprochen, haben auch hingewiesen darauf, wie gerade von dieser Autorität die Menschheit der Gegenwart loskommen müsse. Heute will ich darauf hinweisen, daß es ja eine charakteristische Erscheinung geworden ist — auch erst seit den letzten drei bis vier Jahrhunderten -, als eine von diesen Wissenschaften, die Geltung haben, die Autorität haben, die Medizin zu betrachten. Alles, was mit der Medizin zusammenhängt, ist eben eine Wissenschaft unter den anderen, eine Wissenschaft, welche in ihrem weiteren Verfolge führen soll zum Heilen, zum Heilen des kranken Menschen. Man denkt kaum heute daran, daß dieses Verhältnis von Medizin zu anderen Wissenschaften und zu der Gesamtheit der Wissenschaften sich auch erst in den letzten drei bis vier Jahrhunderten herausgebildet hat. Denn je weiter wir in der Menschheitsentwickelung zurückgehen, desto mehr sehen wir, wie alles, was der Mensch an Wissenschaft, an Erkenntnis ausbilden konnte, mehr oder weniger als medizinisch angesehen wurde, als etwas angesehen wurde, was mit Heilen etwas zu tun hat. Und wenn wir zurückgehen insbesondere in die Entwickelung der okkulten Wissenschaften in älteren Zeiten, so ist mit dem Begriff der okkulten Wissenschaften, der Geheimwissenschaften, der Begriff des Heilens immer verbunden gewesen. Immer hatten mit irgendeiner Art des Heilens die geistigen Wissenschaften etwas zu tun. So daß man damals in älteren Zeiten nicht sagen konnte: Medizin ist eine Wissenschaft unter vielen -, sondern daß man sagte in diesen älteren Zeiten, in denen höchstens das rein Intellektuelle nicht zu dem Okkulten gerechnet worden ist: In aller Wissenschaft, in aller Erkenntnis muß etwas gesucht werden, das zuletzt abzweckt auf ein Heilen des ganzen Menschen. — Man sprach also in dem Sinne, daß man sich diesen Gedanken vor die Seele rückte.

Nun muß man aber fragen: Was sollte denn da geheilt werden, was war denn da zu heilen? — Heute, in der Zeit des Materialismus, spricht man von Krankheit, wenn am Menschen durch äußere materielle Vorgänge oder durch sein Verhalten in der sinnlichen Welt irgend etwas Abnormes zu bemerken ist. Auch dieser, man möchte sagen materialistische Begriff von Krankheit, auch er ist im Grunde genommen erst ein Produkt der neueren Entwickelung der Menschheit, ein Produkt der nachgriechischen Zeit. Denn in jenem Griechenland, in dem eine aufgewecktere, für die Welt empfänglichere Menschheit wohnte, als die spätere Menschheit es ist, war im Grunde genommen noch jener Begriff von Krankheit, und namentlich Krankheitsmöglichkeit, vorhanden, der allen Zeiten eigen war, die weiter zurückliegen als etwa zwei, drei vorchristliche Jahrhunderte. Man muß solche Dinge, damit sie verstanden werden, damit man nicht ihre eigentliche Bedeutung doch überhöre, man muß solche Dinge etwas radikal sagen. Die Grundanschauung in älteren Zeiten war, daß eigentlich die ganze Menschheit fortwährend die Anlage zum ständigen Kranksein mit sich herumträgt. Alle Menschen sind im Grunde genommen fortwährend mit Krankheitsanlagen in der Welt herumgehend — das ist im Grunde die Anschauung gewesen. Alle Menschen sind wenigstens der vorbeugenden Heilung bedürftig; man muß fortwährend heilen an der Menschheit, das war die Meinung. Vielleicht wird man am besten verständlich in diesen Sachen, wenn man diese Meinung vergleicht mit einer, die uns insbesondere heute aus unseren sozialen Verhältnissen und sozialen Forderungen häufig entgegentritt. Wir sehen heute auftreten viele Menschen, welche sich berufen fühlen, agitatorisch zu sprechen von dem, was der Menschheit, sagen wir, in sozialer Beziehung oder in anderer Beziehung notwendig ist, damit sie einer besseren Zukunft entgegengehe. Diese Menschen schildern ungefähr dasjenige, was erreicht werden würde, wenn ihre Ideen zur Geltung kommen, als eine Art Paradies auf Erden. Man sagt wohl auch, das Tausendjährige Reich müsse nun endlich anbrechen, wenn die Ideen gewisser Menschen sich Geltung verschaffen könnten. Gewiß, es ist eine Meinung, die vielleicht das Gute will, aber aus schlechtem Verstande und aus noch schlechterer Vernunft kommt, aber es ist eine Meinung, die agitatorisch wirken kann. Und was sollte agitatorischer wirken, als wenn man den Menschen, namentlich einer materialistischen Zeit, das Paradies auf Erden verspricht! Wenn man es ihnen noch gar verspricht für die Zeit, bevor sie selber sterben, so hat man sie mit einer großen Wahrscheinlichkeit zu Anhängern.

Demgegenüber wird ja schwer aufkommen, wenn so etwas auftritt wie die Idee von der «Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus», die nicht von dem Paradies auf Erden spricht, sondern von dem, was lebensfähig als sozialer Organismus ist, was leben kann. Gegenüber dieser Anschauung, die es ja involviert, daß ein solches Paradies auf Erden möglich sei, daß eine allgemeine, ideal wirkende Gesundung der Menschen durch bloße Einrichtungen auf dem physischen Plane sich herstellen lassen könne, gegenüber dieser Meinung steht mit einer ganz anderen Empfindungsfärbung da jene Meinung in alten Zeiten, die ich versuchte, Ihnen zu charakterisieren, indem ich sagte, diese Meinung ging dahin: Alle Menschen, insofern sie hier auf dem physischen Plane leben und wirken, sind bis zu einem gewissen Grade mit Krankheitsanlagen behaftet und bedürfen fortwährend der Heilung. - Denn diese Anschauung fußte auf dem Folgenden. Sie sagte: Hier in der physischen Welt kann der Mensch dasjenige tun, was zu Einrichtungen auf diesem physischen Plane führt. Der Mensch kann dasjenige tun, was seine Wirtschaft besorgt, was sein Recht besorgt und so weiter. — Aber wenn alles das, was so besorgt wird, nur durch seine eigene Kraft fortläuft, wenn nichts hineinwirkt als dasjenige, was sich auf die äußeren Institutionen des physischen Planes bezieht, dann wird der soziale Organismus der Menschheit immer kränker und kränker. Man kann nämlich gar nicht durch äußere Maßnahmen einen gesunden sozialen Organismus hervorrufen, sondern nur einen solchen, der immer kränker und kränker wird. Damit er das nicht werde, hat man nötig, parallel gehen zu lassen den Maßnahmen, die für die physische Welt getroffen werden, geistiges Leben. Und dieses geistige Leben wirkt so, daß es gewissermaßen die Krankheitskeime, die sich fortwährend in dem Menschen erzeugen, paralysiert. Jede Erkenntnis, so dachte man, die nicht darauf hinausläuft, das sich fortwährend bildende Gift der sozialen Ordnung zu resorbieren, jede solche Erkenntnis ist ein Unding in der Menschheit. Erkenntnisprozeß ist Heilungsprozeß. Und würde, so dachte man in alten Zeiten, die Erkenntnis für irgendeine Epoche ganz aussetzen, dann würde der soziale Organismus in Krankheit verfallen. Daher bezeichnete man erkennende Kraft von vornherein als heilende Kraft; und erst im Laufe der Zeit haben sich abgesondert von dem Mysterienerkenner — der zu gleicher Zeit Führer der sozialen Ordnung, Arzt und Priester war — der Arzt, der Lehrer, der Priester und so weiter. Das hat sich alles erst aus dem herausdifferenziert, was gemeinsam in dem Menschen lebte, der jene Erkenntnis in sich besaß, die zu gleicher Zeit durch ihre Eigenart die Medizin der Menschheit war. Man hat sich auch in älteren Zeiten der Menschheitsentwickelung viel, viel weniger mit einzelnen Krankheiten befaßt als heute. Man hatte über diese einzelnen Erkrankungen seine besonderen Ansichten, die man dem heutigen Menschen gar nicht einmal sagen darf, denn sie verletzen sein Gefühl, sie kommen ihm grausam vor. Aber dafür war dasjenige, was man trieb, was man versuchte zu schöpfen aus tiefen Erkenntnisquellen, gedacht als soziale Medizin.

Solch eine Anschauung konnte allerdings nur vorhanden sein mit ihrer ganzen Kraft in einer Zeit, in der der Mensch anders zu sich selbst stand als heute. Wir haben es ja öfters besprochen, daß der Intellektualismus, der heute insbesondere auch im Erkennen herrscht, im Grunde genommen auch nur, so wie er heute herrscht, in dieser Form zwei, drei, vier Jahrhunderte alt ist. Dieser Intellektualismus, der sein Ideal in durch abstrakte Gedanken wahrzunehmenden Naturgesetzen sieht, der greift nicht ein in die menschliche Persönlichkeit. Ich habe es Ihnen öfters charakterisiert, wie dieses Nichteingreifen sich darstellt. Stellen Sie sich einmal den heutigen Studenten irgendeiner Wissenschaft vor, irgendeines Wissenschaftsgebietes an einer unserer gebräuchlichen Lehranstalten über die ganze zivilisierte Welt hin. Es ist so, daß man sagen muß: Dieser Student sitzt da, er hört nur mit seinem Kopf, mit seinem Verstande, mit seinem Intellekt dasjenige an, was ihm vorgebracht wird, sieht dasjenige an, was ihm vorexperimentiert wird; aber in einem sehr geringen Grade ist sein Gemüt, sein Herz, sein ganzer Mensch beteiligt bei dem, was da vorgebracht wird. Das war bei der alten Mysterienweisheit nicht so. Da konnte man nicht in dieser Weise gleichgültig bleiben. Da war alles, was auf den Kopf wirkte, was auf den Intellekt wirkte, zu gleicher Zeit den ganzen Menschen ergreifend, das war Gemüt und Willen erfassend, das war so, daß man eben als ganzer Mensch dabei sein konnte. Durch das abstrakte Denken, durch das abstrakte Naturforschen ist auch unser Leben abstrakt geworden, so abstrakt geworden, daß der Mensch heute kaum ein Organ hat, dasjenige noch im rechten Lichte zu sehen, was verbunden war mit dem ganzen sozialen Leben einer alten Menschheit. Wir haben öfters auch hier schon gesprochen von dem, was man im hebräischen Altertum den unaussprechlichen Namen des Gottes genannt hat, der dann in der Folge aussprechbar wurde, in der Lautfolge J-A-H-V-E. Warum war dieser Name unaussprechlich? Weil, wer ihn in jenen alten Zeiten aussprach, durch die Gewalt der Laute die alltägliche Gesinnung, das alltägliche Bewußtsein abgedämpft erhielt. Eine andere Welt stand vor ihm auf, und gefährlich war es, den Namen auszusprechen, weil die gewöhnliche Besinnung schwinden mußte. Es war tatsächlich so, daß der Mensch fühlte: Wenn dieser Name vibriert durch seine Leiblichkeit, dann ist er als Mensch in eine andere Welt entrückt, in eine Welt, in der andere Dinge vorgehen als in dieser physischen Welt. — Das ist eine Seelenverfassung des Menschen, von der der heutige Mensch keine Ahnung mehr hat, von der er nichts wissen kann. Denn eine Lautzusammenstellung hat heute nicht jene erschütternde Wirkung, die sie einstmals hatte.

Mit alldem hängt es zusammen, daß auch aufsteigen konnte aus jener anderen Seelen- und Leibesverfassung des alten Menschen mehr, als heute aus der Seelen- und Leibesverfassung des Menschen aufsteigen kann. Heute steigt aus dieser Seelen- und Leibesverfassung zunächst das Organische auf. Hunger, Durst, andere Emotionen steigen auf, diese oder jene Begehrungen, diese oder jene Gemütsbewegungen, diese oder jene Sympathien und Antipathien steigen auf. All das, was so aufsteigt aus der Organisation des Menschen, es bezieht sich im Grunde genommen auf den einzelnen Menschen, auf das einzelne menschliche Ego. Aber bei den alten Menschen kam herauf mit Hunger und Durst, mit den Begehrungen, die sich aufs gewöhnliche Leben beziehen, Offenbarung eines Göttlichen. Der alte Mensch fühlte in dem, was er gewissermaßen aus seiner eigenen Leiblichkeit und aus seiner eigenen Seelischkeit heraus verwendete, den Gott mit, der wie in der Natur so auch in ihm wirkte. Das, was aufstieg, das ließ in diesen alten Menschen die Fähigkeit erstehen, in der ganzen umgebenden Natur nicht nur das zu sehen, was wir heute sehen, sondern zu sehen Geistiges. Davon macht sich der heutige Mensch überhaupt nicht gern eine Vorstellung, daß selbst das Auffassungsvermögen beim früheren Menschen anders war als beim heutigen Menschen.

Dieses Vorurteil ist ja allerdings ein recht begreifliches, das darin besteht, daß man annimmt, so, wie wir heute die Welt sehen, habe man sie immer gesehen. Aber selbst äußerliche Tatsachen beweisen für den, der nur solche Beweise haben will, mit aller nur nötigen Klarheit, daß selbst schon die Griechen — wir brauchen also nicht weit zurückzugehen in der Entwickelung der Menschheit — die den Menschen umgebende Natur anders gesehen haben als wir. Geisteswissenschaft kommt durch das geistige Schauen mit voller Klarheit darauf; aber auf das, was in dieser Beziehung Geistesschau mit voller Klarheit an die Oberfläche bringt, kann man auch schon durch die äußere Erkenntnis der physischen Tatsachen kommen, wenn man in der griechischen Literatur Umschau hält und die eigentümliche Tatsache bemerkt, daß die Griechen ein Wort hatten für Grün: chlorós. Aber kurioserweise bezeichneten sie mit demselben Worte, das sie für das, was wir Grün nennen, anwendeten, den gelben Honig und die gelben Blätter im Herbst; die gelben Harze bezeichneten sie so. Die Griechen hatten ein Wort, welches sie gebrauchten, wenn sie dunkle Haare benennen wollten; mit demselben Wort bezeichneten sie den Stein Lapislazulii, den blauen Stein. Niemand wird annehmen können, daß die Griechen blaue Haare hatten. Solche Dinge kann man wirklich bis zu einem hohen Grade von Beweiskraft bringen, und man sieht daraus, daß die Griechen einfach als Volk Gelb von Grün nicht unterschieden haben, Blau als Farbe nicht so bemerkt haben wie wir, daß sie alles lebendig nach dem Rötlichen, nach dem Gelblichen hin gesehen haben. Das alles wird noch bekräftigt dadurch, daß uns die römischen Schriftsteller erzählen, die griechischen Maler hätten mit nur vier Farben gemalt, mit Schwarz und Weiß, mit Rot und Gelb

Wenn wir nach unseren heutigen Erfahrungen der Farbenlehre urteilen, so müssen wir sagen: Eine wesentliche Eigenschaft der Griechen war, daß sie blaublind waren, daß sie auch die blaue Nuance in dem Grün nicht gesehen haben, sondern nur die gelbe Nuance. Die ganze Umgebung war für die Griechen viel feuriger, weil sie alles nach dem Rötlichen hin gesehen haben. Bis in diese Art, zu sehen, geht dasjenige, was Entwickelungsmetamorphosen in der Menschheit sind. Wie gesagt, man kann das äußerlich zeigen. Die Geistesschau zeigt es mit aller Deutlichkeit, daß der Grieche sein ganzes Farbenspektrum nach der Rotseite hin verschoben hatte und nicht empfand nach der blauen und violetten Seite hin. Das Violett sah er viel röter, als wir es sehen, als es der heutige Mensch sieht. Würden wir nach unserer heutigen Augenvorstellung die Landschaft malen, die der Grieche gesehen hat, so müßten wir sie eben mit ganz anderen Farben malen, als wir heute gewöhnt sind. Und das, was wir als Natur sehen, kannte der Grieche nicht, und dasjenige, was der Grieche als Natur sah, kennen wir nicht. Die Entwickelung der Menschheit schreitet eben metamorphosisch vorwärts, und das Wesentliche ist, daß die Zeit, in der der Intellektualismus heraufgestiegen ist, in der der Mensch nachdenklich wurde - der Grieche war nicht nachdenklich, der Grieche lebte gegenständlich in der natürlichen Welt —, die gleiche Zeit ist, in der sich umsetzte die Empfindung für die dunkle Farbe, für das Blaue, für das Blau-Violette. Nicht verändert sich bloß das Innere der Seelen, sondern es verändert sich auch dasjenige, was von der Seele in die Sinne hineinlebt.

So können Sie sich sagen: Schon mit Bezug auf die Fähigkeiten unserer Sinne sind wir heute, in der fünften nachatlantischen Zeit, andere Menschen als sogar noch die Menschen, die charakteristische Menschen der vierten nachatlantischen Periode, der griechisch-lateinischen waren. Das alles hängt mit dem vorigen zusammen. In der Zeit, in der noch aus den Emotionen, aus den Sympathien und Antipathien, selbst aus dem Körperlichen, wie Hunger und Durst und Sättigung, aufstiegen spirituelle Kräfte, da ergossen sich diese spirituellen Kräfte bis in die Sinnesorgane hinein, Und die gewissermaßen aus dem Unterleiblichen heraufströmenden, sich in die Sinnesorgane hineinergießenden Kräfte, sie sind für den Sinn des Auges diejenigen, die vorzugsweise die gelben und die roten Farbennuancen beleben, die Fähigkeit beleben, diese Farbennuance wahrzunehmen. Wir sind heute in das Zeitalter eingetreten, wo das Umgekehrte zu einer wichtigen Aufgabe der Menschheit wird. Die Griechen waren noch so organisiert, daß ihre schöne Weltanschauung dadurch durch ihre Sinne vermittelt wurde, daß in diese Sinne sich hineinergoß ihr durchgeistigtes organisches Leben. Wir haben unterdrückt als Menschheit durch Jahrhunderte dieses durchgeistigte organische Leben. Wir müssen es von der Seele aus, vom Geiste aus wieder beleben. Wir müssen uns die Fähigkeit aneignen, ins SeelischGeistige einzudringen, wie das Geisteswissenschaft vermitteln will. Und indem wir uns die Fähigkeit aneignen, ins Geistig-Seelische hineinzudringen, wie das Geisteswissenschaft vermitteln will, werden wir den umgekehrten Weg machen. Bei den Griechen war es so, daß von dem Leiblichen aus gewissermaßen die Strömungen gingen und sich ergossen bis ins Auge hinein (siehe Zeichnung, rot); bei uns muß das Umgekehrte stattfinden. Wir müssen das Geistig-Seelische ausbilden (siehe Zeichnung, blau), die Strömung muß sich von diesem GeistigSeelischen nach der Organisation des Menschen erstrecken, und wir müssen vom Geistig-Seelischen die Strömungen in das Auge und in die anderen Sinne hineinbekommen. Der umgekehrte Weg muß derjenige der Zukunftsmenschheit werden gegenüber dem, der bis in die Mitte der vierten nachatlantischen Kultur der Weg der Menschheit war. Dann wird aus dem nachdenklichen Menschen wiederum der geisterkennende, der in einer anderen Form geist-erkennende Mensch, der von oben angelegt wird. Wir sind hineingewachsen in die Empfänglichkeit für den blauen Teil des Spektrums.

Wenn ich das schematisch aufzeichnen wollte, so müßte ich so zeichnen: Der Grieche war vorzugsweise empfänglich in dem Rot, er lebte in dem Rot. Der Grieche lebte sich in diesen Teil des Spektrums hinein (siehe Zeichnung, links); wir müssen uns in diesen Teil (siehe Zeichnung, rechts) des Spektrums immer mehr und mehr hineinleben. Aber indem wir uns in diesen Teil des Spektrums hineinleben, indem wir in einer gewissen Weise immer mehr und mehr lieb gewinnen die blaue und blau-violette Farbe, müssen sich ja unsere Sinnesorgane völlig ummetamorphosieren, umwandeln.

Die Sinnesorgane müssen in ihrer feineren Struktur etwas ganz anderes werden, als sie waren. Was sich da hineinergießt in die Sinnesorgane, das ist dasjenige, was allmählich auf naturgemäßem Wege durch das Auge zum Beispiel die Imagination ausbildet, durch das Ohr die Inspiration, durch den Wärmesinn die Intuition. Es müssen also ausgebildet werden: durch das Auge: Imagination, durch das Ohr: Inspiration, durch den Wärmesinn: die Intuition.

Die feinere Struktur im Gange der menschlichen Entwickelung, die feinere Struktur des menschlichen Organismus im Gange der menschlichen Entwickelung macht eine Metamorphose durch, wird eine andere.

Auf solche Dinge muß der Mensch der Gegenwart hinsehen, denn er steht drinnen in einem wichtigen Übergangszeitpunkt; er steht drinnen in der Zeit, in der sich entscheiden muß, ob er wohl kann den Übergang finden, gewissermaßen die Eindrücke von oben zu empfangen. Wir dürfen nicht beim bloßen Intellektualismus bleiben, wir müssen den Intellektualismus vergeistigen und verseelischen. Dann wird aber dasjenige, was als Geistiges und Seelisches sich in uns ausbildet, bis in die menschliche Organisation hinein wirken. Und wenn wir es nicht ausbilden? Wenn irgendein Organ zu etwas bestimmt ist und man gebraucht es nicht dazu, stirbt es ab, ertötet sich. Da haben Sie in der menschlichen Organisation selber, was eine alte Zeit aus anderen Erkenntnisvoraussetzungen heraus für die Entwickelung der ganzen Menschheit angenommen hat. Sehen Sie auf Ihre Augen hin: in diese Augen hinein muß sich ergießen dasjenige, was von oben herunter als spirituelles Leben in die Zukunftsmenschheit einströmen soll. Strömt es nicht ein, dann sind diese Augen dazu verurteilt, krank zu werden. Durch ihre eigene Natur müssen die Augen der Menschen krank werden, ebenso die Ohren, ebenso der Wärmesinn.

Was müssen wir denn suchen für eine Erkenntnis? Eine diese Krankheitsanlagen unseres eigenen Organismus heilende Erkenntnis. Wir müssen wiederum den Weg zurück finden zu der Auffassung, daß alle Erkenntnis, insofern sie an den Menschen heran will, einen medizinischen Charakter habe. Wir müssen wiederum den Begriff bekommen können, daß wir Erkenntnis um des Heilens willen zu suchen haben, daß Medizin nicht nur ist auch eine Erkenntnis unter anderen Erkenntnissen, und daß alle Erkenntnis im Entwickelungsprozeß der Menschheit ein Heilfaktor sein muß, weil die Menschheit es nötig hat, dasjenige, was in ihr auf dem physischen Plane entsteht, fortwährend geheilt zu bekommen. Nicht derjenige redet der Menschheit das Richtige vor, der ihr ein irdisches Paradies verspricht, sondern derjenige allein redet die Wahrheit, der den Menschen klarmacht: Auch wenn wir alles tun, um brauchbare irdische Zustände herzustellen, so muß der Mensch seinen Zusammenhang mit der geistigen Welt suchen! — Denn selbst die besten irdischen Zustände müssen fortwährend geheilt werden, geheilt werden bis in den menschlichen Organismus hinein. Auch dieser ist fortwährend mit Krankheitsanlagen durchsetzt. Das heißt, es muß ein Geistesleben in der Menschheit da sein, welches die Kraft hat, heilende Mächte aus sich heraus zu bilden.

Unter den mancherlei Gründen, die dazu geführt haben, aus anthroposophisch orientierter Weltanschauung die Idee der «Dreigliederung» zu gebären, sind auch diejenigen, die Sie entnehmen können aus meinen heutigen Auseinandersetzungen, denn diese Idee der Dreigliederung ist eine solche, daß man hinschauen kann in diese Ecke, in jene Ecke, in eine dritte und vierte Ecke der Menschheitsentwickelung — wenn man nur richtig beobachten kann, so ergibt sich für die heutigen, wirklich das Wahre wollenden menschlichen Fähigkeiten die Notwendigkeit dieser Dreigliederung. Diejenigen, die da glauben, mit ihrem bißchen Logik, wenn sie einmal von dieser Dreigliederung hören, irgend etwas nicht gleich verstehen zu können oder es mit irgend etwas in Widerspruch zu finden, die sollten warten, bis sie sich genauer mit der Sache bekanntmachen. Dann werden sie sehen, daß es nicht einen Beweis oder eine Beweisströmung für die Notwendigkeit der Dreigliederung gibt, sondern unzählige. Denn wohin man schaut, überall gibt es Beobachtungen, die unabhängig von den anderen dasjenige beweisen, was ich nennen könnte: notwendiges Auftreten der Idee von der «Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus» in unserer heutigen Gegenwart. Und eine der allerwichtigsten Ecken ist doch die Erkenntnis, die Erfassung der Menschenwesenheit selber. Aber wo ist denn die heutige Wissenschaft, die so stolz auf ihre Abstraktion ist, geneigt, auf das wirklich Konkrete einzugehen? Noch der Grieche hatte ein deutliches Bewußtsein davon: Wenn er aufsteigen läßt seine Emotionen, so offenbart sich ihm ein Göttliches. -— Wir müssen erlangen die Fähigkeit, herabzuholen aus geistigen Höhen die geistigen Seelenkräfte, und sie müssen uns eine Natur offenbaren, sie müssen uns zeigen, wie die Natur ist. Das heißt, wir müssen uns klarwerden können, daß wir durch äußeres Anschauen die Natur nicht erkennen können, sondern nur mit denjenigen Sinnesorganen, die geschärft sind durch dasjenige, was sich von oben ergibt, mit einem Auge, das geschärft ist durch die Imagination, mit einem Ohr, das geschärft ist durch die Inspiration, mit einem Wärmesinn, der geschärft ist durch die Intuition, durch das selbstlose Erleben der Dinge und Vorgänge, die in unserer Umgebung sind.

Aus dem Willen zum Heilen ist Wissenschaft geworden. In den Willen zum Heilen muß Wissenschaft wiederum einmünden. Was wir heute als Wissenschaft ansehen und so hoch als Autorität verehren, das ist nur ein Zwischenzustand, der aber eigentlich gerade auf sozialem Gebiet zu den fürchterlichsten Disharmonien führt. Von alledem wollen wir dann morgen weiter sprechen.

First Lecture

What is regarded today as an almost unquestioned authority is science, science in the sense in which it is pursued today in our state-approved educational institutions. We have often spoken about the validity of this science and have also pointed out how humanity today must free itself from this authority. Today I would like to point out that it has become a characteristic phenomenon—only in the last three or four centuries—to regard medicine as one of these sciences that have validity and authority. Everything related to medicine is simply one science among others, a science which, in its further pursuit, is supposed to lead to healing, to the healing of sick people. Today, we hardly think about the fact that this relationship between medicine and other sciences, and to the totality of the sciences, has only developed in the last three or four centuries. For the further back we go in human evolution, the more we see how everything that human beings were able to develop in terms of science and knowledge was more or less regarded as medical, as something that had to do with healing. And if we go back in particular to the development of the occult sciences in earlier times, the concept of the occult sciences, the secret sciences, has always been associated with the concept of healing. The spiritual sciences have always had something to do with some kind of healing. So that in earlier times it was not possible to say: Medicine is one science among many — but rather, in those earlier times, when at most the purely intellectual was not considered part of the occult, it was said: In all science, in all knowledge, something must be sought that ultimately aims at healing the whole human being. — People spoke in this sense, placing this idea before their souls.

But now we must ask: What was to be healed, what was there to heal? — Today, in the age of materialism, we speak of illness when something abnormal is noticed in a person through external material processes or through their behavior in the sensory world. This materialistic concept of illness is also, one might say, fundamentally a product of the more recent development of humanity, a product of the post-Greek era. For in Greece, where a more alert humanity lived, more receptive to the world than later humanity, there still existed, in essence, the concept of illness, and especially the possibility of illness, which was characteristic of all times further back than, say, two or three centuries before Christ. In order to understand such things, and so as not to overlook their true meaning, one must express them somewhat radically. The basic view in earlier times was that all of humanity actually carries within itself the predisposition to be constantly ill. All people are, in essence, constantly walking around in the world with predispositions to illness — that was basically the view. All people are at least in need of preventive healing; one must continually heal humanity, that was the opinion. Perhaps these matters can best be understood by comparing this opinion with one that we frequently encounter today, particularly in our social circumstances and social demands. Today we see many people who feel called upon to speak agitatorily about what is necessary for humanity, say, in social relations or in other relations, in order for it to move toward a better future. These people describe what would be achieved if their ideas were put into practice as a kind of paradise on earth. It is also said that the thousand-year kingdom must finally dawn when the ideas of certain people prevail. Certainly, it is an opinion that perhaps wants good, but it comes from bad understanding and even worse reasoning, yet it is an opinion that can have an agitational effect. And what could be more inflammatory than promising people, especially in a materialistic age, paradise on earth! If you promise them this before they die, you are very likely to win them over as followers.

In contrast, it will be difficult for something like the idea of the “threefold social organism” to gain ground, which does not speak of paradise on earth, but of what is viable as a social organism, what can live. Opposed to this view, which implies that such a paradise on earth is possible, that a general, ideal healing of human beings can be brought about by mere institutions on the physical plane, stands the view of ancient times, which I tried to characterize by saying that this view was as follows: All human beings, insofar as they live and work here on the physical plane, are to a certain degree afflicted with disease and are in constant need of healing. For this view was based on the following. It said: Here in the physical world, human beings can do what leads to institutions on this physical plane. Human beings can do what is necessary for their economy, what is necessary for their rights, and so on. But if everything that is done in this way proceeds solely through their own power, if nothing influences it except what relates to the external institutions of the physical plane, then the social organism of humanity will become sicker and sicker. For it is impossible to bring about a healthy social organism through external measures; one can only bring about one that becomes sicker and sicker. To prevent this from happening, it is necessary to allow spiritual life to run parallel to the measures taken for the physical world. And this spiritual life works in such a way that it paralyzes, so to speak, the germs of disease that are constantly being produced in human beings. It was thought that any knowledge that did not lead to the absorption of the poison that was constantly forming in the social order was an absurdity in humanity. The process of knowledge is a process of healing. And in ancient times, it was thought that if knowledge were to cease completely for any period of time, the social organism would fall into disease. Therefore, the power of knowledge was regarded from the outset as a healing power; and only in the course of time did the doctor, the teacher, the priest, and so on, separate themselves from the mystery knower, who was at the same time the leader of the social order, the doctor, and the priest. All this differentiated itself from what lived collectively in the human being who possessed that knowledge, which at the same time, through its peculiar nature, was the medicine of humanity. In earlier times of human development, people were much less concerned with individual diseases than they are today. They had their own particular views on these individual diseases, which cannot even be told to people today because they would hurt their feelings and seem cruel to them. But what they did, what they tried to create from deep sources of knowledge, was intended as social medicine.

Such a view could only exist with its full force at a time when people had a different relationship to themselves than they do today. We have often discussed that intellectualism, which prevails today, especially in cognition, is basically only two, three, four centuries old in its present form. This intellectualism, which sees its ideal in natural laws perceived through abstract thoughts, does not intervene in the human personality. I have often characterized for you how this non-intervention manifests itself. Imagine a student today studying any science, any field of science, at one of our common educational institutions throughout the civilized world. One must say that this student sits there and listens only with his head, with his mind, with his intellect to what is presented to him, looks at what is pre-experimented for him; but his mind, his heart, his whole being is involved to a very small degree in what is being presented. This was not the case with the ancient mystery wisdom. There, one could not remain indifferent in this way. Everything that affected the head, that affected the intellect, simultaneously affected the whole human being, grasping the mind and the will, so that one could be present as a whole human being. Through abstract thinking, through abstract natural science, our life has also become abstract, so abstract that people today hardly have any organ left to see in the right light what was connected with the whole social life of an ancient humanity. We have often spoken here of what in Hebrew antiquity was called the unpronounceable name of God, which later became pronounceable in the sound sequence J-A-H-V-E. Why was this name unpronounceable? Because whoever uttered it in those ancient times had their everyday mindset, their everyday consciousness, dampened by the power of the sounds. Another world arose before them, and it was dangerous to utter the name because ordinary consciousness had to disappear. It was indeed the case that people felt that when this name vibrated through their physical bodies, they were transported as human beings into another world, a world in which things happened differently than in this physical world. This is a state of mind that people today no longer have any idea about, that they cannot know anything about. For a combination of sounds does not have the same stirring effect today that it once had.

All this is connected with the fact that more could rise from the soul and body of the ancient human being than can rise from the soul and body of the human being today. Today, the organic rises first from this state of soul and body. Hunger, thirst, other emotions arise, this or that desire, this or that mood, this or that sympathy or antipathy arises. Everything that arises in this way from the organization of the human being basically relates to the individual human being, to the individual human ego. But in ancient times, along with hunger and thirst, along with desires related to ordinary life, there arose a revelation of the divine. Ancient humans felt in what they used, as it were, out of their own physicality and soul life, the God who was at work in them as in nature. What arose gave these ancient people the ability to see in the whole of nature around them not only what we see today, but also spiritual things. People today do not like to imagine that even the powers of perception were different in ancient times than they are today.

This prejudice is, of course, quite understandable, consisting in the assumption that the world has always been seen as we see it today. But even external facts prove with all necessary clarity to those who want such proof that even the Greeks — we need not go far back in the development of humanity — saw the nature surrounding human beings differently than we do. Spiritual science arrives at this conclusion with complete clarity through spiritual observation; but what spiritual observation brings to the surface with complete clarity in this regard can also be arrived at through external knowledge of physical facts, if one looks around in Greek literature and notices the peculiar fact that the Greeks had a word for green: chlorós. But curiously, they used the same word that they applied to what we call green to describe yellow honey and the yellow leaves in autumn; they also used it to describe yellow resins. The Greeks had a word that they used when they wanted to name dark hair; they used the same word to describe lapis lazuli, the blue stone. No one can assume that the Greeks had blue hair. Such things can really be proven to a high degree of certainty, and we can see from this that the Greeks as a people simply did not distinguish yellow from green, did not perceive blue as a color as we do, and saw everything as having a reddish or yellowish hue. All this is confirmed by the fact that Roman writers tell us that Greek painters painted with only four colors: black and white, red and yellow.

Judging by our present-day experience of color theory, we must say that an essential characteristic of the Greeks was that they were blue-blind, that they did not see the blue nuance in green, but only the yellow nuance. The whole environment was much more fiery for the Greeks because they saw everything in reddish tones. This way of seeing reflects the metamorphoses of human development. As I said, this can be demonstrated externally. Spiritual vision shows very clearly that the Greeks had shifted their entire color spectrum toward the red side and did not perceive the blue and violet sides. They saw violet much redder than we see it, than modern humans see it. If we were to paint the landscape that the Greeks saw according to our present-day visual perception, we would have to paint it in colors quite different from those we are accustomed to today. And what we see as nature, the Greeks did not know, and what the Greeks saw as nature, we do not know. The development of humanity proceeds metamorphically, and the essential thing is that the time in which intellectualism arose, in which man became thoughtful — the Greeks were not thoughtful — the Greeks lived objectively in the natural world —, is the same time in which the perception of dark colors, of blue, of blue-violet, was transformed. It is not only the inner life of the soul that changes, but also that which lives from the soul into the senses.

So you can say that, even with regard to the abilities of our senses, we today, in the fifth post-Atlantean era, are different people than even the people who were characteristic of the fourth post-Atlantean era, the Greco-Latin era. All of this is connected with what came before. In the period when spiritual forces still arose from emotions, from sympathies and antipathies, even from physical needs such as hunger, thirst, and satiety, these spiritual forces poured into the sense organs. And the forces that flowed up from the lower abdomen, so to speak, into the sense organs, are those that primarily enliven the yellow and red color nuances for the sense of sight, enlivening the ability to perceive these color nuances. Today, we have entered an age in which the opposite is becoming an important task for humanity. The Greeks were still organized in such a way that their beautiful worldview was conveyed through their senses, because their spiritualized organic life poured into these senses. As humanity, we have suppressed this spiritualized organic life for centuries. We must revive it from the soul, from the spirit. We must acquire the ability to penetrate into the soul-spiritual, as spiritual science seeks to teach us. And by acquiring the ability to penetrate into the soul-spiritual, as spiritual science seeks to teach us, we will take the opposite path. With the Greeks, the currents flowed out from the physical body, so to speak, and poured into the eye (see drawing, red); with us, the opposite must take place. We must develop the spiritual-soul life (see drawing, blue), the current must extend from this spiritual-soul life to the organization of the human being, and we must bring the currents from the spiritual-soul life into the eye and into the other senses. The reverse path must become the path of future humanity, as opposed to the path that was the path of humanity until the middle of the fourth post-Atlantean culture. Then the thoughtful human being will once again become the spirit-knowing human being, the spirit-knowing human being in a different form, who is created from above. We have grown into receptivity for the blue part of the spectrum.

If I wanted to draw this schematically, I would have to draw it like this: The Greek was primarily receptive to red; he lived in red. The Greek lived himself into this part of the spectrum (see drawing, left); we must live ourselves more and more into this part (see drawing, right) of the spectrum. But as we live our way into this part of the spectrum, as we in a certain way grow more and more fond of the blue and blue-violet colors, our sense organs must undergo a complete metamorphosis, a transformation.

The sense organs must become something completely different in their finer structure than they were before. What pours into the sense organs is what gradually develops in a natural way through the eye, for example, the imagination, through the ear, inspiration, and through the sense of warmth, intuition. So the following must be developed: through the eye, imagination; through the ear, inspiration; through the sense of warmth, intuition.

The finer structure in the course of human development, the finer structure of the human organism in the course of human development undergoes a metamorphosis and becomes something else.

Contemporary human beings must look to such things, for they are in the midst of an important transition; they are in a time when it must be decided whether they can indeed make the transition, so to speak, to receive impressions from above. We must not remain with mere intellectualism; we must spiritualize and enlarge the soul of intellectualism. Then what develops in us as spiritual and soul-life will work its way into the human organization. And if we do not develop it? If any organ is destined for a purpose and is not used for that purpose, it dies, it kills itself. There you have in the human organism itself what ancient times, based on different premises of knowledge, assumed to be necessary for the development of the whole of humanity. Look at your eyes: into these eyes must pour that which is to flow down from above as spiritual life into the future humanity. If it does not flow in, then these eyes are doomed to become diseased. By their very nature, human eyes must become diseased, as must the ears and the sense of warmth.

What kind of knowledge must we seek? Knowledge that heals these predispositions to disease in our own organism. We must find our way back to the view that all knowledge, insofar as it is intended for human beings, has a medical character. We must once again be able to grasp the concept that we must seek knowledge for the sake of healing, that medicine is not just one form of knowledge among others, and that all knowledge must be a healing factor in the development process of humanity, because humanity needs to continually heal what arises within it on the physical plane. It is not those who promise humanity an earthly paradise who speak the truth, but only those who make it clear to people that even if we do everything we can to create useful earthly conditions, human beings must seek their connection with the spiritual world! For even the best earthly conditions must be continually healed, healed down into the human organism. This too is constantly riddled with the seeds of disease. This means that there must be a spiritual life within humanity that has the power to generate healing forces from within itself.

Among the various reasons that led to the idea of the “threefold social order” being born out of an anthroposophically oriented worldview are also those that you can glean from my remarks today, for this idea of the threefold social order is such that one can look into this corner, into that corner, into a third and fourth corner of human development — if one can observe correctly, then the necessity of this threefold social order becomes apparent to the human faculties of today that truly desire the truth. Those who believe, with their little bit of logic, that once they hear about this threefold division, they cannot immediately understand something or find it contradictory to something else, should wait until they have familiarized themselves more closely with the matter. Then they will see that there is not one proof or a stream of proofs for the necessity of the threefold division, but countless ones. For wherever one looks, there are observations that independently of one another prove what I might call the necessary emergence of the idea of the “threefold social organism” in our present time. And one of the most important aspects is the recognition and understanding of human nature itself. But where is today's science, so proud of its abstraction, inclined to engage with what is truly concrete? Even the Greeks were clearly aware of this: when they let their emotions rise, something divine was revealed to them. We must acquire the ability to bring down the spiritual soul forces from spiritual heights, and they must reveal nature to us, they must show us what nature is like. This means that we must be able to realize that we cannot know nature through external observation, but only with those sense organs that have been sharpened by what comes from above, with an eye sharpened by imagination, with an ear sharpened by inspiration, with a sense of warmth sharpened by intuition, through the selfless experience of the things and processes that are in our environment.

The will to heal has become science. Science must in turn flow back into the will to heal. What we regard today as science and revere as such a high authority is only an intermediate state, which, however, leads to the most terrible disharmony, especially in the social sphere. We will talk more about all this tomorrow.