Knowledge as a Source of Healing

GA 198

21 March 1920, Dornach

Lecture II

It behoves me today to link certain aspects of the knowledge gained from earlier studies—with which most of our friends are already acquainted—to what I said yesterday. But once again I want to draw your attention to the essential content of what was then said, namely, that the knowledge, the passive kind of knowledge cultivated today is in reality a comparatively recent production. This indifferent knowledge, shown for instance when medicine is set down as just one science among many, has been developed only in course of the last three or four centuries; whereas in olden times the aim of all knowledge was to heal. Knowledge and the finding of means to heal mankind were, in the sense intended yesterday, one and the same.

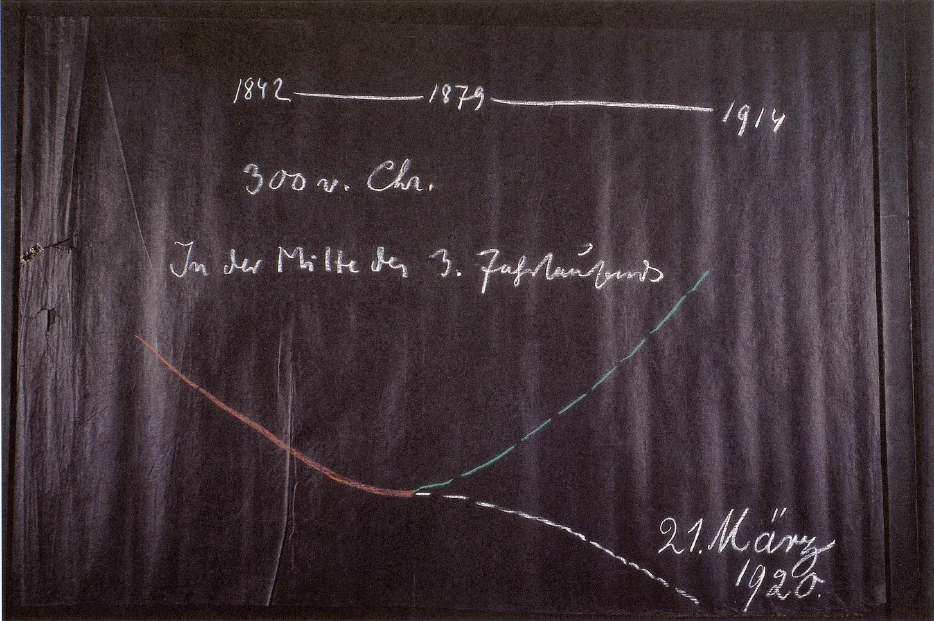

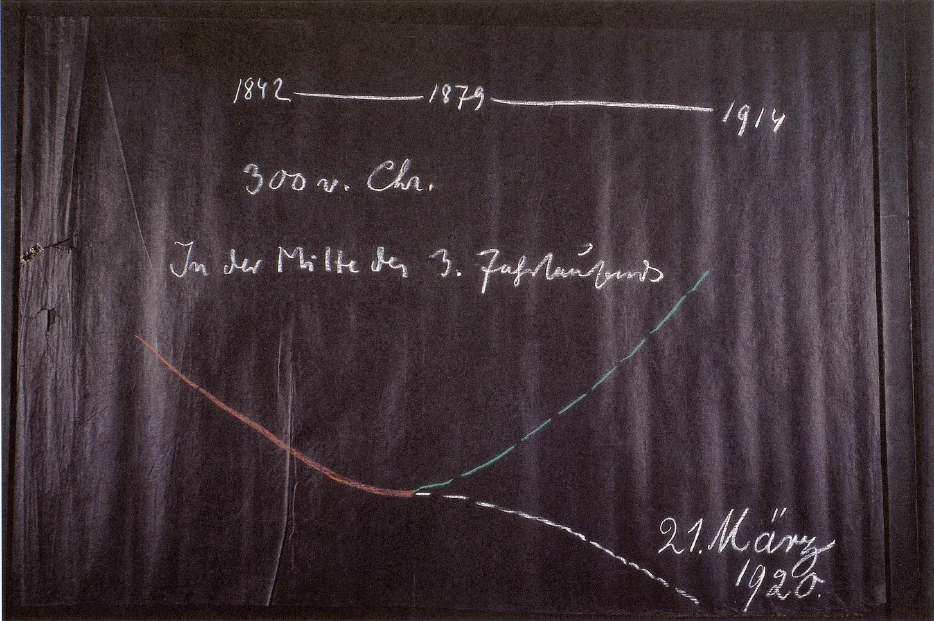

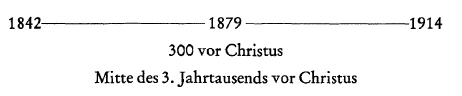

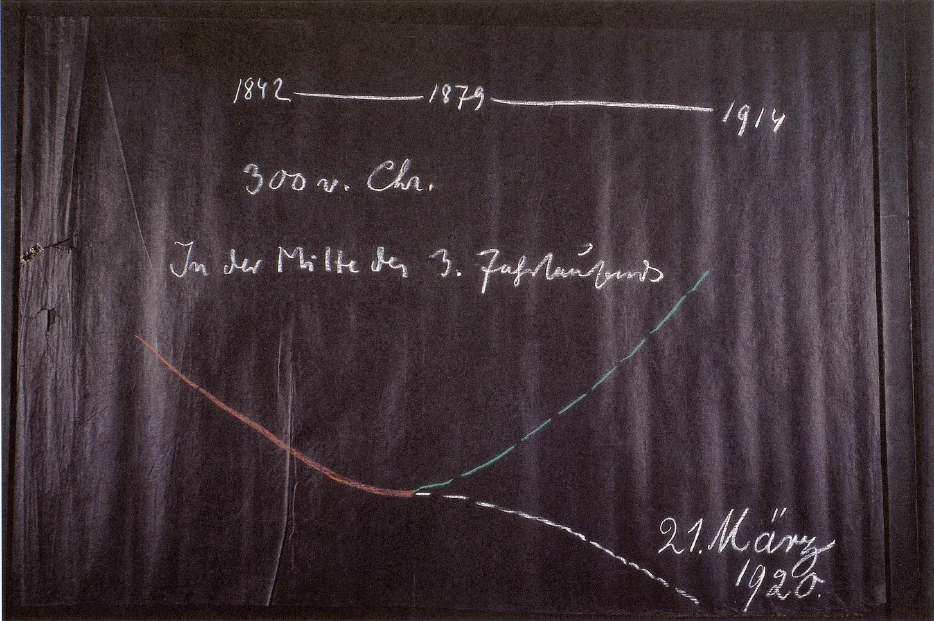

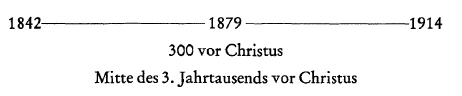

Now from various indications in my lectures you will know that in the last third of the nineteenth century an event of spiritual importance took place; that during the seventies of that century, behind the scenes of world-history, of outer, physical world-history, something of great significance happened. We have some name for it but another name might do just as well—we have called it the victory of the archangelic Being, Michael, over opposing spiritual forces. We will look upon this as an event taking place in the spiritual world and connected with mankind's history. It is in the spiritual world that such events are prepared. This particular one could be said to be in preparation already in 1842. It reached a certain climax in the spiritual world about 1879, and from 1914 on the necessity arose for men on earth to establish a harmonious relation with this spiritual event. What has been happening since 1914 is essentially a struggle on the part of narrow-minded humanity against what, in the opinion of the spiritual powers concerned with the guidance of mankind, should come about. Thus we may say: In the second half of the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth, behind the scenes of human evolution, there was taking place something significant—a challenge to men to submit themselves to the will of those spiritual beings. This would entail a change of direction and the bringing about of a new kind of civilisation, a new conception of social life, of the life of art and all spiritual life on earth. In the course of human evolution there have repeatedly been such events, of which external history takes little account. For external history is indeed a fabrication. Things of this kind have nevertheless definitely happened—one of them taking place 300 years, another in the middle of the third millennium, before the birth of Christ.

Regarding mankind, however, there was a great difference between the experiencing of these two events and that of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Most of you have at least partly experienced the events of the second half of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth, and will know that small notice was taken of how a change should actually come about in the spiritual life.

Hardship will compel mankind to realise the necessity for this. There will be no end to hardship until a sufficient number of human beings have realised this necessity—even in the organising of public affairs. We may indeed ask why no notice has been taken, and whether it was the same in the case of those other experiences, the third millennium and the third century.—But no, it was quite different then. Could people only interpret to history of the Greek soul rightly, even that of the more coarse-grained Romans, they would understand that actually both Greeks and Romans were fully aware that something calling for notice was taking place in the spiritual world. Indeed precisely in the case of the event 300 years before Christ's birth, we can quite well see its gradual preparation, how it then reached a climax and lived itself out. The men of the third, fourth century before Christ's birth were clearly conscious: In the world of spirit something is happening that has an echo in the world of men.—What they thus perceived can today be called the birth of human phantasy—man's faculty of imagination.

You see, human beings, as they are constituted today, consider the way they think: and the way they feel to be the same as thinking and feeling have always been. But that is not so. Indeed in the course of time our sense-perceptions have changed—as I showed yesterday. Naturally, three or four centuries before the birth of Christ creative art was already in existence; it did not arise, however, out of what today is called imagination but out of imagination that was clairvoyant. There who were artists could perceive how the spiritual revealed itself, and they simply copied what was thus revealed. The old atavistic clairvoyance, the old imagination, was inherent in the artist. The phantasy which then arose and was developed till, having come to the climax in the works of Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo, it started to degenerate—this phantasy did not create as if the spiritual appeared in imaginations, but as if something were ordered from within a man, formed from within him. The gift of this phantasy was ascribed by people at that time to strife among the divine beings ruling over them, at whose orders they carried out their earthly deeds.

In the middle of that third millennium, about 2,500 years before Christ's birth, people perceived as something of still greater significance how their whole being was involved in the events which, out of the spiritual world it made an impact on physical events. About that time, still in the third millennium before our era, it would have been deemed very foolish to speak of man's earthly pilgrimage without referring to the spiritual beings around him. This would have seemed nonsense to everyone, for then the earth was thought to be peopled by beings both physical and spiritual.

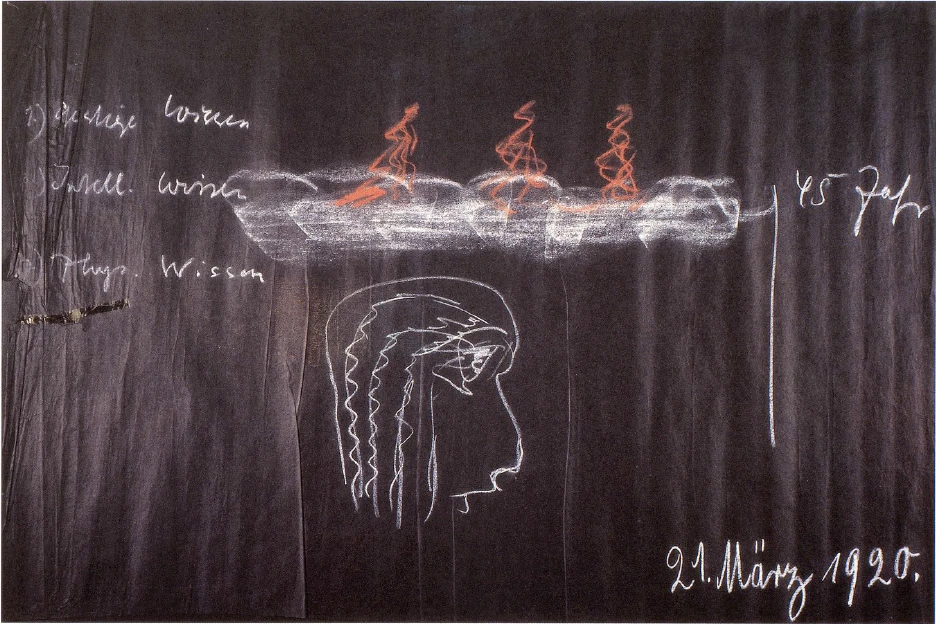

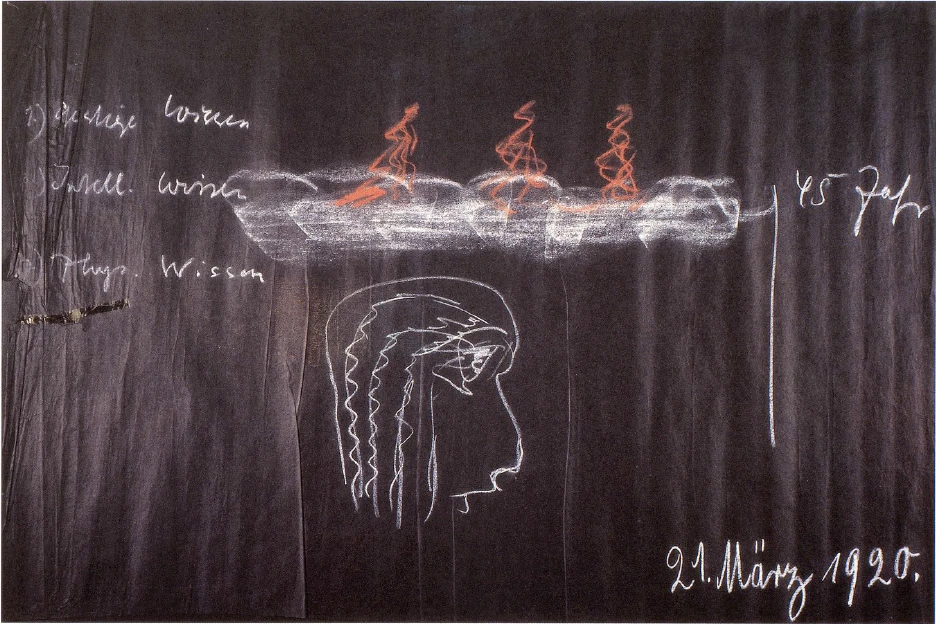

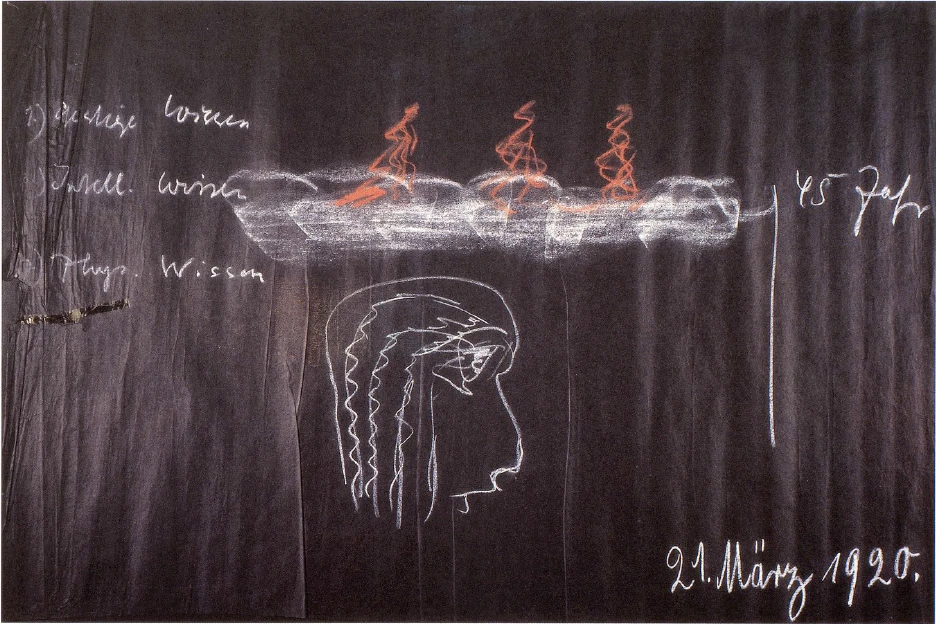

The life of soul that became habitual in the course of the nineteenth century is certainly different from the life of those olden days. Men perceived the ordinary secular events on earth but not the underlying, significantly spiritual strife. How came it that this was not perceived?—It was the result of the special character of our present age, the age which began it the middle of the fifteenth century and is called by us the fifth post-Atlantean epoch. In our present epoch the most outstanding, significant force of which a man can avail himself is intellect, and since the fifteenth century people have attained to great heights as intelligent beings. Today they still take pride in this. It should not be thought, however, that in earlier times there was no kind of intelligence—it was a different kind, it is true, but it arose at the same time as a certain perception. This intelligence was endowed, too, with a spiritual content. We, on the other hand, have an intelligence devoid of spiritual content, a formal intelligence; for in themselves our concepts and ideas are empty—they merely reflect something. Our whole understanding is just a mass of reflected images. It is indeed in the nature of this intelligence, which has been particularly developed since the middle of the fifteenth century, to be simply a reflecting apparatus. What is thus merely reflected does not act within man as a force; it is simply passive. And it is characteristic of this intellect—of which we are so proud—to be passive; we just let it work upon us, give ourselves up to it. Very little force of will is developed in it thus. The most outstanding trait in men now is their hatred of intellect that is active. In face of a situation where thinking is required of them—well, they find that very boring. When it is a question of real thinking there is a general dropping off to sleep—at any rate for the soul. On the other hand, with a film, a cinematograph, when there is no need to think and it is thinking that can go to sleep, when all one has to do is to gaze and passively to give oneself up to what is reeled off, so that thoughts run on of themselves, then there is general satisfaction. It is a passive understanding to which men have grown accustomed, an understanding devoid of force. And what in fact is that? We realise its nature when looking back at the distinction made in human knowledge in the old Mystery schools. There were three categories: first, the knowledge that came from men's physical life, arising out of their common physical experience of the world. Perhaps we could say: First, physical knowledge; secondly, intellectual knowledge, developed by man himself, chiefly in mathematics, knowledge, in effect, in which a man immerses himself—intellectual knowledge; and thirdly, spiritual knowledge, coming from the spiritual and not from the physical. Today, of these three it is intellectual knowledge which is especially cultivated and most in favour. It has become quite an ideal to approach the spiritual life with the passive, unconcerned attitude usually adopted towards mathematics. It is not admitted but all the same true that our present men of learning, for instance our university professors, on leaving the lecture-room like to turn as soon as they can to something quite unconnected with their particular subject. That betrays an abstract relation to knowledge which goes extremely deep.

When I was lecturing in Zurich a few days ago, a workman broke into the discussion. As the Waldorf School and the timetable we have put in place of the usual soul-destroying one had been mentioned, he said: “Your timetable gives too long a stretch for one subject; there should be more change. For when children have gone on with a subject from eight to nine, if they are not to be bored there ought to be something else from nine to ten.” Naturally I could but reply: “It is not the business of the Waldorf School to deal with boredom but to take care that the children's interest is kept alive—and that is the concern of the School pedagogics and didactics.” Thus the idea is very deeply-rooted in people that spiritual life is boring, and easily becomes tiresome as a subject. This is entirely because our intellectual life, consisting as it does merely of pictures, of reflected images, can provide no substance for our spiritual life. And a spiritual life devoid of substance is in a state of isolation—cut off not only from the spiritual world but also from the physical. Actually in the age we live in very little is known either of the physical world or that of the spirit. All that a man knows about is his own imaginings. As a result of intellectuality being just so many reflected images, the man of the nineteenth century was debarred from any knowledge of what was going on spiritually behind the scenes of world-history. He had no share in the experience of that great, momentous change which, behind external world history, came about in the spiritual world during the second half of the nineteenth century. It is through his own endeavours that he has to learn how the physical world should follow the lead of the spiritual world. This lesson is forced upon him, for, if not learnt, increasing hardship will prevail and all present civilisation will go down into barbarism. To avoid this it is necessary for people to be aware inwardly that they must experience something in the same way that, 300 years before Christ's birth, the birth of phantasy was experienced. In our day we have to experience the birth of active intelligence—at that time the active force of imagination arose. At that time it became possible to give imaginative shape to what was created in accordance with external form; now, people must turn to the inward, victorious creation of ideas, through which everyone makes for himself a picture of his own being—setting it before him as a goal. Human beings must acquire self-knowledge in its widest sense, not just by brooding over what they had for dinner, but ,a self-knowledge which sets their whole being in action. That is the kind of self-knowledge demanded for the evolution of those men whose present task is the bringing to birth of an active intelligence.

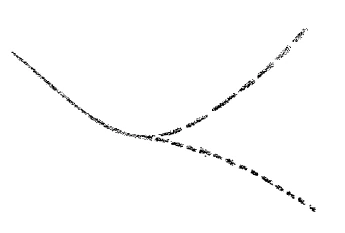

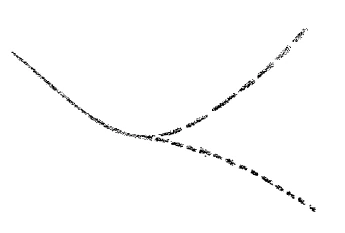

Now, it will happen that human beings in ordinary recollection, in their ordinary memory, will discover something very peculiar. Because people today have become rather insensitive and do not notice what is already in their souls, on looking back over their life they still perceive only memories of their ordinary experiences. But that is not the whole picture; actually a certain change has taken place and more and more people are met with who are having a new experience. When these men look back ten or twenty years they come not only to what they have experienced, but out of that, like an independent entity, there rises something they have not experienced. Psycho-analysis, in its foolishness, examines what thus lies hidden in the soul examines it without realising the nature of our present age. What these foolish psycho-analysts are unable to find, spiritual science must propound, namely, that when we look back—say from our 45th year—and watch our experiences surging past like a stream (see diagram), within them there is not only our past experience; it was so once and even today is all that most of our rather thick-skinned generation perceive. But anyone sensitive to such things will realise that in a backward survey of his life he sees not only the ordinary events but something (red in diagram) he has not experienced, arising from the past experiences of his soul in an almost demoniacal way. And this will increase in intensity. If people do not learn to observe such things they will lose the power to understand them.

Therein lies the danger for future evolution, and deluding oneself is of no avail for it is indeed so. Among the experiences lived through by a man something new will appear, only to be grasped by active intelligence. This is extraordinarily important. Just as in the individual human being something new arises after the change of teeth, then again at puberty, and so on, after a certain period the same kind of metamorphosis occurs in mankind as a whole. This present metamorphosis can be described as follows: If we look back occasionally on our life (and this can also be done in the backward survey over our day) we do not only remember the most obvious experiences, but out of these surge up demonic forms. It almost causes us to say: I have had certain experiences out of which daydreams arise.—This will be quite normal but we have to be alive to it. It will call for much more inward activity on men's part and the overcoming of that passive attitude which promotes despair in face of the great demands of the age. That passivity must be overcome. People's sleepiness, their inability to rouse themselves and to take things with dignity and in earnest, is certainly terrifying. I have already spoken here of how in our day many people cannot even be angry. Anyone incapable of getting angry over what is bad is incapable of enthusiasm over what is good. When, however, active intelligence takes possession of human beings there will be a change. We may indeed say that they are still afraid of the discovery they will then make. For with the coming of active intelligence they will recognise their cherished intellectuality for what it is—recognise the real nature of these arising images. This can be understood only if we remember something I have often mentioned here—that we can feel, we can will, just being alive; but just being alive does not enable us to think. That we cannot do. We are able to think only by bearing permanently within us the principle of death.

This great secret about mankind lies in there being a never-ending stream, as it were, flowing from the senses—let us take the eye as representing them (see diagram). Through what we know as nerve, the senses carry into a man something destructive. It is as if—by way of the nerve-fibres—men were filled through their senses with a crumbling material. When you see, when you hear, even when you are conscious of warmth, there is taking place what is like the crumbling of some material on its way inward from the senses. This crumbling material has to be taken hold of by what streams out from within a man; it must be, as it were, burnt up. Our thinking necessitates a continual struggle against the forces of death in us. Indeed, because he is conscious of his thinking merely in its reflecting capacity, a man does not realise that, strictly speaking, he is alive only in what has nothing to do with his head, his head actually being an organ always in the throes of death. We should be in constant danger of death were merely that to happen which goes on in our head. This permanent dying is checked by the head being united to the rest of the organism, upon which it draws for its vitality. When the human being will have possessed himself of active intelligence as he did of active phantasy in the days of the Greeks and Romans—whereas the imagination of the old atavistic clairvoyance was a passive phantasy—with this active intelligence he will be able to perceive how part of his being is always dying. And this will be important. For just today we have to progress to a state of consciousness enabling us to perceive this permanent dying, so mankind in a past age, even up to the time of the Greeks, perceived what was living in the principle of vitality, in the will and its associated metabolism. What fights against the principle of death, what in a man is continuously disabling that principle of death, is living there. It might be said that in this respect the people of old were superior to those who followed them. They perceived the vitality with their instinctive clairvoyance, perceived the life with which the principle of healing is connected. Indeed, we do not die because our head has the will to die, but, owing to our head being the organ of thinking, we permanently carry within us the germs of sickness. Thus it is necessary for us to pay the price of our thinking by setting counter to the head, with its tendency to disease, the healing forces lying in the rest of our organism. Today it is still little noticed, but forms of disease are becoming to appear—as you know, they change—in which the constant process of death coming from the head will be more easily noticed than many of our present illnesses. Then it will be found that in reality the whole healing process in human beings is to counteract the harmful effects of our intellectual life. Whereas people of old could claim healing to be in their science, their knowledge, in future it will have to be admitted that what we are now making of our intellect, what is becoming of this intellect, of which today we are so proud, should it alone be held valid, will show us in future the gradual fall of mankind into complete decadence. To avert this, science will have to become able to carry within it the forces of healing.—I indicated this yesterday from another point of view; today I do so more from the standpoint of the way in which man is constituted. We must recognise that spiritual science is needed as bearer of a new healing process. For if there be a further development of the intellect of which modern man is so proud, intellect which lives merely in images, then by reason of its predominance all men will become disease-ridden. Measures must be taken to prevent such a thing. I can well imagine some people replying: “But if we discourage this intellectual cleverness, if we do away with intellect”,—and there are indeed those who would like to see the intellect left undeveloped—“then there would be no need to repair the damage it does.”—The true progress of mankind, however, has nothing in common with this Jesuitical principle; rather is it a question of human evolution being such that the healing element developing out of man's soul-forces can have effect on the intellect—otherwise the intellect will take a decadent trend and bring about the downfall of mankind. (See first diagram)

As counter-measure to this, what arises from knowledge of spiritual science, and can permanently hinder the forces of decline in the one-sided intellect, must become effectual.

We come here to a point where once again I have to draw your attention to a very special matter. You will certainly realise that during the nineteenth century, when all I am telling you about today—and have frequently pointed out in the past—was taking place, intellectual materialism was assuming great proportions. Men came to the fore—I need only remind you of Moleschott, Vogt, Gifford—upholding, for instance, the proposition: All thinking consists in a metabolism going on in the brain.—They spoke of phosphorescence pf the brain, and said without phosphorus in the brain there is no thinking. According to this thinking is just a byproduct of a certain digestive process in the brain. And the men saying this cannot be written off as being the stupid ones among their contemporaries. We may think how we like about the theory of these materialists but we can just as well do something else: that is, measure their capacity by that of their contemporaries and ask: Were such people as Moleschott and Gifford the cleverer or those who opposed them out of old religious prejudice and without spiritual science? Was Haeckel the cleverer or his opponents? This question may still be asked today. And when it is not answered in accordance with personal opinion, but with regard to spiritual capacity, naturally it cannot be said that Haeckel's opponents were cleverer than he nor that the opponents of Moleschott and Gifford were cleverer than they. The materialists were very clever people, and what they said was certainly not devoid of significance. How then did all this come about? What was behind it? We must indeed find the answer.

Certainly quite well-intentioned opponents of materialism arose at the time, for example Moriz Carriere whom I have often mentioned. Now he said: If everything man thinks and experiences is merely concocted by the brain, what is propounded by one party is just as much a concoction as what the opposite party says. As far as the truth is concerned there is no difference between a statement of Moleschott or Gifford and what is maintained by the Pope. There is no difference because in both cases they are concoctions of the human brain. There is no way of distinguishing the true from the false. Yet the materialists fight for what appears to them as the truth. They are not justified in doing so but they are astute—capable of a certain quickness of spirit. What then is in question here? You see, these materialists have had to arise in an age when thinking is made up merely of images, lives merely in images. But images are not there without something to act as reflector—which in this case is the brain. Indeed, where ordinary thinking is concerned—the thinking that grew to such heights in the nineteenth century—materialists have right on their side; that is a fact. They are no longer right, however, if they want to maintain that the thinking which transcends that of the intellect is also nothing but images dependent on the body, for that is not so. What transcends the intellect can be acquired only in course of a man's evolution: only by his becoming free of what has to do with the body. The thinking that has come to the fore in the nineteenth century must be explained materialistically. Though composed of images it is entirely dependent on the instrument of the brain, and the remarkable thing is that, for the most part, in face of the life of spirit in the nineteenth century, materialism is actually justified. That life of spirit is bound up with the bodily and material. It is precisely this life of spirit which must be transcended. The human being must rise above it and learn once more to pour spiritual substance into the images. This can be done not only by becoming clairvoyant—as I constantly emphasise there is no necessity for everyone to be so—for spiritual substance can be made to flow into a man's thinking when he reflects upon what another has already investigated spiritually,„ This must not be accepted blindfold; once there, it can be judged. Commonsense will suffice for the understanding of what has, been investigated through spiritual science. The denial of this means that commonsense is not given its due; and anyone who denies it is thinking: Commonsense—civilised people have been developing a great deal of that for a long time. Indeed these civilised people are developing a “very assured” judgment! And if this assured judgment is refuted by the facts they take no notice, refuse to take notice. At the suitable moment such matters—which speak volumes symptomatically—are forgotten.

I will give you just one nice little example. In 1866, at the time of the Prussian victory over Austria, it was said that this was a proof of the superiority of Prussian schools. It gave rise to the saying: “It was the Prussian schoolmasters who won the 1866 victory.” 1First said in 1866 by Oskar Peschel—a professor at Leipzig University. This has been constantly repeated, and it would be interesting to count the times, between 1870 and 1914, that it was said by the qualified and unqualified—mostly the unqualified: “The Prussian victory was won by the schoolmasters.”—I imagine that people today will no longer be so ready to speak anywhere in such a fashion, any more than the truth of this other assertion will be insisted upon in the light of present events. But in this intellectual age, when people are so clever, they are not willing to notice the contradictions to be found in life. Facts play very little part in the intellectual life, but they must do so if the intellect is to be permeated with fresh spiritual content. Then, indeed, it will be manifest that a paralysing process, a decadent process, is appearing in men, which must be overcome by new spiritual knowledge. In the past: men must be said to have sensed, experienced, something of a healing nature in the knowledge surging up from the physical body. In future they will have to learn to see in the development of intellect the cause of disease, and to look to the spirit for healing. The source of healing must indeed be found again in science. This necessity, however, will arise from an opposite direction, when it can be seen how external life, even when proficient in knowledge, makes for sickness in men and must be counteracted by the healing principle.

Matters such as these afford us insight into the course of human evolution—in so far as this is a reality. Today history does not give us a real picture of human evolution but merely worthless abstractions. Man today is deficient in a sense of reality, having indeed very little of it. During the nineteenth century, people in mid-Europe became very proficient at giving out what of a spiritual nature was already there. One of the most arresting examples of this is the case of Herman Grimm who, as a writer about the works of Goethe—such as Tasso or Iphigenie ranks very high. He was, however, quite unable to portray Goethe the man. Although he wrote a biography of him, in it Goethe seems a mere shadow. Spiritual force was not there in the nineteenth century; people were living in images.; and images have no power to enforce the reality which is so necessary for the future. We must understand not only what human beings create, but above all the human being himself, and through him nature, in a more all-embracing sense than hitherto. I believe it to be possible for such things to work in all seriousness upon the human heart and soul. It is likely to be some time before a sufficient number of people allow themselves to be fired by the knowledge that, if not permeated by the spirit, mankind will be overcome by disease. At least those should accept this knowledge who have come nearer to an understanding of anthroposophy.

There is one thing which must be recognised—that many who have accepted anthroposophy have come to our Movement out of what I might call subtle egoistic tendencies, wishing to have something for the comfort of their souls. They want the satisfaction of gaining certain knowledge about the spiritual world. But that will not do. This is not a matter of basking in the personal satisfaction of participating in the spiritual. What people need is actively to intervene in the affairs of the material world from out of the spirit—through the spirit to gain mastery over the material world. There will be no end to all the misery that has come upon mankind till people understand this and, understanding, allow it to influence their will.

One would so gladly see—at least among anthroposophists—this kind of insight, this kind of will, taking effect. Certainly it may be asked: What can a mere handful of human beings do against the blindness of the whole world?—But that is not right. To speak in that way has absolutely no justification. For in saying this there is no thought that what concerns us here is first to strengthen the will-power—then we can await what will come. Let everyone from his own sphere in life do what lies in him; he may then await what is done by others. But at least let him do it—do it above all so that as many people as possible in the world may be moved by the urgent need for spiritual renewal.

Only if we are watchful, and take a firm stand where anthroposophy has placed us, can we ourselves make any progress or set our will to work on what is necessary to ensure the progress of all mankind.

Zweiter Vortrag

Es wird mir heute obliegen, einiges von den Erkenntnissen, die früheren Betrachtungen zugrunde lagen, die einer größeren Anzahl unserer Freunde bereits bekannt sind, von da und dort her zusammenzuschließen mit dem, was ich gestern gesagt habe. Ich will nur noch einmal darauf aufmerksam machen, daß der wesentliche Inhalt des gestern Gesagten der war, daß ein solches gewissermaßen neutrales Erkennen, wie wir es gegenwärtig pflegen, im Grunde ein Geschöpf ist der neueren Zeit, daß sich ein solches gleichgültiges Erkennen, welches die Medizin als eine Wissenschaft neben die anderen hinstellt, eben erst im Lauf der letzten drei bis vier Jahrhunderte herausgebildet hat, während alles Erkennen in alten Zeiten abgezielt hat auf das Heilen; und Erkennen und Auffinden von Mitteln zur Heilung der Menschheit war ein und dasselbe in dem Sinne, wie ich das gestern angedeutet habe. Nun wissen Sie aus verschiedenen Andeutungen, die da oder dort in Vorträgen gemacht worden sind, daß in das letzte Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts ein wichtiges geistiges Ereignis hineinfällt, daß in den siebziger Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts gewissermaßen hinter den Kulissen der Weltgeschichte, der äußeren physischen Weltgeschichte Bedeutendes geschehen ist. Um für dieses Ereignis einen Namen zu haben — man könnte ja ebensogut einen anderen Namen dafür haben -, haben wir es genannt den Sieg jenes Erzengelwesens, das wir bezeichnen als den Erzengel Michael, über entgegengesetzte geistige Kräfte. Dieses Ergebnis, wir wollen es zunächst einmal als einen Vorgang der geistigen Welt betrachten, mit der unsere Menschengeschichte zusammenhängt. Solche Ereignisse spielen sich so ab, daß sie sich zunächst in der geistigen Welt vorbereiten. Von dem Ereignis, das ich jetzt meine, könnte man etwa sagen, es habe sich vorbereitet seit dem Jahre 1842. Es ist dann in der geistigen Welt zu einer gewissen Entscheidung gekommen etwa 1879, und es liegt die Notwendigkeit vor, daß die Menschen auf der Erde im Einklange mit diesem geistigen Ereignis sich verhalten seit dem Jahre 1914. Dasjenige, was seit dem Jahre 1914 geschehen ist, das ist im wesentlichen ein Anstürmen der menschlichen Borniertheit gegen dasjenige, was eigentlich geschehen sollte nach der Meinung derjenigen geistigen Mächte, welchen die Führung der Menschheit obliegt. So daß wir also sagen können: In der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, in der ersten Zeit des 20. Jahrhunderts ging hinter den Kulissen unserer Menschheitsentwickelung sehr Bedeutsames vor, was ja ist eine Aufforderung an die Menschheit, sich so zu verhalten, wie es diese geistigen Wesen wollen: einen Umschwung herbeizuführen, etwas zu tun, was eine neue Art von Zivilisation in die Menschheit bringt, eine neue Art der Auffassung des sozialen Lebens, des künstlerischen Lebens, des geistigen Lebens auf der Erde überhaupt. Solche Ereignisse waren in der Menschheitsentwickelung wiederholt da. Die äußere Geschichte verzeichnet solche Ereignisse wenig, weil die äußere Geschichte eben doch eine Fable convenue ist, aber diese Ereignisse waren eben wiederholt da. Dasjenige Ereignis, welches sich vergleichen läßt mit dem erwähnten, liegt etwa dreihundert Jahre vor Christi Geburt, ein weiteres zurückliegendes liegt etwa in der Mitte des 3. Jahrtausends vor Christi Geburt:

Nun besteht aber in bezug auf die Menschheit ein ganz wesentlicher Unterschied zwischen dem Erleben dieser zwei Ereignisse und dem Erleben desjenigen Ereignisses, das sich abgespielt hat im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert; denn die meisten von Ihnen haben ja wenigstens teilweise noch miterlebt die Ereignisse von der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, von dem Beginne des 20. Jahrhunderts, und die meisten von Ihnen werden auch wissen, wie wenig die Menschheit als solche Notiz genommen hat davon, daß ein Umschwung im geistigen Leben wirklich stattfinden sollte.

Die Menschheit wird durch die Not dazu gezwungen werden, von dieser Notwendigkeit Notiz zu nehmen. Und nicht eher wird die Not aufhören, bis eine genügend große Anzahl von Menschen auch mit Bezug auf die Gestaltung der öffentlichen Angelegenheiten Notiz genommen haben wird von dieser Notwendigkeit. Wir können die Frage aufwerfen: Warum haben die Menschen keine Notiz genommen? Und war das auch gegenüber den beiden anderen Erlebnissen, demjenigen des 3. Jahrtausends, demjenigen etwa im 3. Jahrhundert ebenso? — Nein, bei diesen Ereignissen war es eben durchaus nicht so. Würde man richtig lesen können dasjenige, was die Seelengeschichte des griechischen, sogar des ja ein wenig grobkörnig veranlagten römischen Volkes ist, man würde vernehmen, daß in der Tat innerhalb des griechischen Volkes, innerhalb des römischen Volkes durchaus ein Bewußtsein vorhanden war: In der geistigen Welt geschieht etwas, auf das man Rücksicht nehmen muß. — Ja, gerade bei dem Ereignis, das um das Jahr 300 vor Christi Geburt liegt, können wir sehr gut sehen, wie es sich langsam vorbereitet, wie es auf einen gewissen Höhepunkt kommt und wie es sich dann auslebt. Die Menschen dieses 3., 4. Jahrhunderts vor Christi Geburt hatten ein deutliches Bewußtsein davon: Es geschieht etwas in der Geisteswelt, das spielt herein in die Welt der Menschen. — Und dasjenige, was sie da sahen, wir können es heute bezeichnen: das war die eigentliche Geburt der menschlichen Phantasie.

Sie wissen ja, die Menschen von heute sind schon einmal so, sie denken: So wie man heute denkt, wie man heute fühlt, so hat man immer gedacht, so hat man immer gefühlt. — Aber es ist nicht so, sondern sogar die Sinneswahrnehmungen haben sich im Laufe der Zeit geändert, wie ich Ihnen gestern gezeigt habe. Es war natürlich auch schon künstlerisches Schaffen vor dem 3. oder 4. Jahrhundert vor Christi Geburt da; aber dieses künstlerische Schaffen ging nicht aus dem hervor, was wir heute Phantasie nennen. Dieses künstlerische Schaffen ging aus einer wirklichen hellseherischen Imagination hervor. Diejenigen, die Künstler waren, konnten schauen, wie sich ihnen das Geistige enthüllte, und sie kopierten einfach das Geistige, das sich ihnen enthüllte. Das alte atavistische Hellsehen, die alte Imagination war dasjenige, was der Künstler zugrunde liegend hatte. Jene Phantasie, die damals erst aufkam und die dann sich weiter ausbildete bis zu den Schöpfungen eines Leonardo oder Raffael oder Michelangelo, um dann wieder talab zu gehen, diese Phantasie nimmt dazumal ihren Ursprung, diese Phantasie, die nicht so schafft, als ob ein Geistiges erscheint, imaginiert wird, sondern als ob man nur aus sich selbst heraus etwas anordnete, als ob man nur aus sich selbst heraus etwas gestaltete. Und daß sie mit der Phantasie begabt wurden, das schrieben die Menschen dieser Zeit zu einem Kampfe von göttlichen Wesen, die über ihnen walteten, in deren Auftrag sie auf der Erde handelten.

Noch viel, viel bedeutsamer vernahmen die Menschen in der Mitte des 3. Jahrtausends, etwa im Jahre 2500 vor Christi Geburt, wie ihr ganzes Sein eingespannt war in Ereignisse, die aus der geistigen Welt hereinragten in die physischen Ereignisse. Um diese Zeit, noch in der Mitte des 3. Jahrtausends vor unserer Zeitrechnung, hätte kein Mensch es sinnvoll gefunden, zu sagen: Hier wandeln die Menschen auf der Erde herum - und nicht zu sagen: Geistige Wesen sind da. - Das würde jedem Menschen ein Unsinn geschienen haben, denn man dachte sich die Erde bevölkert von dem, was physisch und geistig zugleich war.

Gegenüber der Art des Seelenlebens in jenen alten Zeiten ist diejenige allerdings etwas anderes, die im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts Platz gegriffen hat, denn die Menschen nahmen wahr, wie auf der Erde die profanen, die gewöhnlichen Ereignisse sich abspielten. Daß aber da ein bedeutender Geisteskampf dahintersteht, das nahmen die Menschen nicht wahr. Woher kommt das, daß sie das nicht wahrnahmen? Das kommt gerade von der Eigentümlichkeit dieses unseres Zeitalters, das, wie Sie wissen, um die Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts begonnen hat, und in dem wir noch drinnenstehen, das wir als den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum bezeichnen. In diesem Zeitalter, also in dem, in dem wir drinnenstehen, da ist die hervorragendste, die bedeutsamste Kraft, deren sich der Mensch bedienen kann, der Intellekt. Die Menschen sind seit dem 15. Jahrhundert besonders groß geworden als intelligente Wesen. Sie sind heute noch stolz darauf, die Menschen, daß sie so intelligente Wesen sind. Man soll nur ja nicht glauben, daß nicht auch eine andere Form von Intelligenz in früheren Zeiten vorhanden war, nur wurde diese Intelligenz zugleich mit einem gewissen Schauen geboren. Es wurde diese Intelligenz mit einem gewissen geistigen Inhalte zugleich in dem Menschen geschaffen. Wir haben eine Intelligenz, die eigentlich keinen wirklichen geistigen Inhalt hat, die eigentlich bloß formell ist, denn unsere Begriffe und Ideen haben eigentlich in sich selbst nichts, sie sind nur Spiegelbilder von etwas. Unser ganzer Verstand ist eine Summe von bloßen Spiegelbildern von etwas. Das ist ja das Wesen jener Intelligenz, die sich seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts ganz besonders entwickelt hat, daß der Verstand nur ein Spiegelungsapparat ist. Aber solches, wie es sich da spiegelt, das hat im Grunde genommen im Menschen keine Kraft. Das ist im Grunde genommen passiv. Das ist ja das eigentümliche desjenigen Verstandes, auf den die gegenwärtige Menschheit so stolz ist, daß dieser Verstand passiv ist. Wir lassen ihn auf uns wirken, wir geben uns ihm hin. Wir entwickeln wenig Willenskraft in diesem Verstande. Das ist heute das hervorragendste Kennzeichen der Menschen, daß sie eigentlich den tätigen Verstand hassen. Wenn sie irgendwo sein sollen, wo ihnen zugemutet wird, mit dem, was vorgebracht wird, mitzudenken, so ist das langweilig, sehr langweilig. Da beginnt das allgemeine Einschlafen sehr bald, wenigstens das seelische Einschlafen: sobald gedacht werden soll. Dagegen wenn es ein Kinematograph ist, wenn man nicht zu denken braucht, sondern wenn das Denken eher eingeschläfert wird, wenn man bloß zu sehen braucht und nur sich passiv hinzugeben dem, was sich abspielt, und wenn die Gedanken so wie selbständige Räder ablaufen, da fühlt sich der Mensch heute befriedigt. Es ist der passive Verstand, an den sich die Menschen gewöhnt haben. Dieser passive Verstand hat keine Kraft, denn dieser passive Verstand, was ist er denn eigentlich? Man lernt sein Wesen kennen, wenn man sich erinnert, wie die Arten des menschlichen Wissens noch eingeteilt waren in alten Mysterienschulen. Da hat man drei Arten des Wissens unterschieden: Erstens jenes Wissen, das da kommt aus dem physischen Leben des Menschen, das gewissermaßen aufsteigt aus dem physischen Miterleben der Welt, man könnte sagen: das physische Wissen; zweitens das intellektuelle Wissen, jenes Wissen, das man selber bildet, hauptsächlich in der Mathematik, jenes Wissen, in dem man drinnenlebt, das intellektuelle Wissen; drittens das geistige Wissen, dasjenige Wissen, das nicht aus dem Physischen, sondern aus dem Geistigen kommt. Von diesen drei Arten des Wissens ist in unserem Zeitalter besonders gepflegt und besonders beliebt das intellektuelle Wissen. Es ist förmlich ein Ideal geworden, dem geistigen Leben so gegenüberzustehen, wie man gewohnt worden ist, der Mathematik gegenüberzustehen, dem geistigen Leben mit einer gewissen Neutralität, mit einer gewissen Gleichgültigkeit gegenüberzustehen. Es ist eigentlich unerhört, aber wahr, daß in unserer Zeit auch die Träger des Wissens, zum Beispiel Hochschulprofessoren, wenn sie die Türen hinter sich zugemacht haben und draußen sind, daß sie dann so schnell wie möglich etwas anderes treiben wollen, was nicht mit ihrem Wissen zusammenhängt. Es ist ein abstraktes Hingeben an das Wissen, und das, das geht eigentlich recht tief.

Als ich vor ein paar Tagen in Zürich öffentlich vortrug, da griff in die Diskussion ein Proletarier ein. Da ich etwas erwähnt hatte von der Waldorfschule und von dem Ersatz des den Geist wirklich tötenden Stundenplanes, da meinte er: Ein solcher Stundenplan würde aber zu lang bei einem Gegenstande stehenbleiben, man müßte schon Abwechslung haben; wenn den Kindern ein Gegenstand von acht bis neun zu langweilig geworden ist, dann muß von neun bis zehn ein anderer Gegenstand kommen, sonst wird es den Kindern zu langweilig! — Ich konnte natürlich nur erwidern: Das ist nicht die Aufgabe der Waldorfschule, auf die Langweiligkeit zu rechnen, sondern dafür zu sorgen, daß es den Kindern nicht langweilig wird, daß die Kinder wirklich dabei sind bei der Sache; das ist gerade die Aufgabe jener Pädagogik und Didaktik, die in der Waldorfschule gepflegt werden soll. — Es ist also so sehr den Leuten in Fleisch und Blut übergegangen, daß eigentlich das geistige Leben langweilig ist, und daß man vom geistigen Leben loskommen muß, ja nicht im Fach aufgehen muß. Das kommt aber lediglich davon her, daß unser ganzes intellektuelles Leben eigentlich nur aus Bildern besteht, aus Spiegelbildern, daß wir nicht Substanz in diesem geistigen Leben haben.

Ein solches, nicht von Substanz erfülltes Geistesleben, das ist eigentlich abgeschlossen, sowohl abgeschlossen von der physischen Welt, wie abgeschlossen von der geistigen Welt. Eigentlich weiß unsere Zeit weder von der physischen Welt noch von der geistigen viel. Sie weiß eigentlich nur von dem, was sie sich selber ausdenkt. Wegen dieses Charakters unserer Intellektualität als einer Summe von Spiegelbildern war der Mensch des 19. Jahrhunderts ausgeschlossen davon, etwas zu wissen von dem, was geistig hinter den Kulissen der Weltgeschichte vorging. Er erlebte jenen großen, bedeutsamen Umschwung nicht mit, der sich im Geistigen hinter der äußeren Weltgeschichte vollzog in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, und er muß erst durch eigene Anstrengungen lernen, daß die physische Welt folgen müsse der geistigen Welt. Er wird es lernen müssen, denn wenn er es nicht lernt, wird die Not immer größer und größer werden und die Zivilisation wird über die ganze gegenwärtige zivilisierte Welt hin in Barbarei übergehen. Um das zu vermeiden, ist eben notwendig, daß der Mensch gewahr werde innerlich, daß er ebenso etwas erleben müsse, wie erlebt worden ist um das Jahr 300 vor Christi Geburt die Geburt der Phantasie. So muß in unserer Zeit erlebt werden die Geburt des tätigen Verstandes: damals die tätige Einbildungskraft, jetzt die Geburt des tätigen Verstandes. Dazumal entstand die Möglichkeit, durch Nachschaffung von äußeren Formen phantasievoll zu gestalten. Jetzt muß die Menschen ergreifen ein inneres kraftvolles Schaffen von Ideen, durch die sich jeder selber ein Bild seines eigenen Wesens macht und sich dieses vorsetzt als dasjenige, dem er nachstrebt. Selbsterkenntnis im weitesten Umfange des Wortes muß die Menschen ergreifen; aber nicht eine Selbsterkenntnis, in der man nur brütet über dasjenige, was man gestern gegessen hat, sondern eine Selbsterkenntnis, die es bringt bis zu einem Betätigen des eigenen Wesens. Und diese Selbsterkenntnis wird von der Entwickelung des Menschen, der eben zur Geburt des tätigen Verstandes aufsteigen muß, klar gefordert.

Es wird so kommen, daß die Menschen in der gewöhnlichen Erinnerung, in dem gewöhnlichen Gedächtnis etwas sehr Eigentümliches finden werden. Heute geht es gerade noch an, weil man etwas grobkörnig geworden ist und die Dinge nicht bemerkt, die eigentlich schon in der Seele des Menschen vorhanden sind. Heute geht es gerade noch an, daß, wenn man zurückdenkt in seinem eigenen Leben, daß dann aus diesem eigenen Leben, in das man zurückblickt, nur die Erinnerungen an die gewöhnlichen Erlebnisse kommen. Aber das ist nicht mehr rein so, das ist eigentlich nicht mehr ganz so, sondern es kommen immer wiederum und wiederum Menschen unter uns vor, die schon etwas anderes erleben, die, wenn sie zurückdenken, was sie vor zehn, zwanzig Jahren erlebt haben, so kommt ihnen nicht nur dasjenige herauf, was sie erlebt haben, sondern es kommt ihnen herauf etwas, was sie nicht erlebt haben, was aber aus dem Erlebten wie eine selbständige Wesenheit aufsteigt. Und die psychoanalytische Torheit, die prüft in den Seelen das Zurückliegende ohne eine Erkenntnis des Wesens der Gegenwart. Dasjenige, was die törichte Psychoanalyse nicht finden kann, das muß Geisteswissenschaft vor die Menschen hinstellen, daß in der Tat, wenn wir von irgendeinem Lebensalter —- sagen wir von unserem 45. Jahre — zurückschauen und alle die Wogen der Erlebnisse wie so eine Strömung erblicken (siehe Zeichnung), so sind darinnen nicht nur diese Erlebnisse, die wir durchlebt haben; das war gewissermaßen einmal so, und eine große Anzahl etwas «dickschleimiger» Menschen, die erleben auch heute noch nichts anderes. Derjenige, der sensitiv ist für solche Sachen, der erlebt, daß bei einer Rückschau auf das Leben nicht nur diese gewöhnlichen Erlebnisse vorhanden sind, sondern er erlebt etwas, was da herausragt (rot), was er nicht erlebt hat, sondern das wie dämonisch aus den vergangenen Seelenerlebnissen herauskommt. Und das wird immer stärker und stärker werden. Wenn die Menschen nicht lernen, auf so etwas aufmerksam zu sein, dann werden sie darüber den Verstand verlieren. Das ist die Gefahr der menschlichen Entwickelung in die Zukunft hinein. Und über so etwas darf man sich nicht Illusionen machen, denn das ist so. In den Erlebnissen, die der Mensch durchmacht, wird sich ein Neues zeigen, das nur mit diesem tätigen Verstande zu ergreifen ist. Das ist etwas außerordentlich Bedeutsames! Wie in dem Lebensalter des einzelnen Menschen Neues auftritt nach dem Zahnwechsel, nach der Geschlechtsreife und so weiter, so tritt in der ganzen Menschheit nach einem bestimmten Zeitalter eine solche Metamorphose ein, und die Metamorphose unseres Zeitalters kann man in dieser Weise charakterisieren, daß, wenn man sich zurückerinnert auf sein Leben manchmal — man kann es schon bei der Rückerinnerung, die man über einen Tag macht, bemerken -, man nicht nur sich erinnert an dasjenige, was man im grobklotzigen Sinne erlebt hat, sondern daß herausquellen aus diesen Erlebnissen dämonische Gestaltungen. So ist es ungefähr, wie wenn man sich sagen müßte: Ja, wir haben das und das erlebt; aber nachträglich träume ich jetzt aus diesen Erlebnissen heraus Tagträume, die nachher aus diesen Erlebnissen herauskommen.

Das wird zum Normalen gehören, man muß auf das aufmerksam sein. Das aber wird von den Menschen fordern, daß der Mensch innerlich viel aktiver werde, daß er jenes Passive überwinde, das die gegen_ wärtige Menschheit hat und das den Menschen zur Verzweiflung treibt gegenüber den großen Anforderungen der Zeit. Dieses Passive muß von der Menschheit überwunden werden. Was heute an Schläfrigkeit in der Menschheit waltet, dieses Sich-nicht-aufraffen-Können, die Dinge ernst und würdig zu nehmen, das ist ja allerdings etwas Furchtbares. In unserer Zeit haben viele Menschen gar nicht die Fähigkeit, über irgend etwas entrüstet zu sein. Wer aber nicht entrüstet sein kann über das Schlechte, kann nicht über das Gute begeistert sein. Wenn aber dieser tätige Verstand Besitz ergreift von den Menschen, dann wird damit etwas anderes verbunden sein. Und man kann sagen: Heute fürchtet sich noch die Menschheit vor jener Erfahrung, die sie da machen wird. - Denn, sehen Sie, man wird den Verstand dadurch kennenlernen, daß er tätig sein wird, man wird die gepriesene Intellektualität kennenlernen, und es wird sich herausstellen, was sie eigentlich ist, diese Intellektualität, was es ist, dieses Entstehen von Bildern. Man begreift es nur, wenn man etwas ins Auge faßt, was ich hier auch schon öfters auseinandergesetzt habe: Wir können fühlen, wir können wollen, indem wir leben, aber wir könnten nicht, wenn wir nur lebten, auch denken. Das könnten wir nicht. Wir können denken nur aus dem Grunde, weil wir fortwährend das Todesprinzip in uns tragen. Das ist dieses große Geheimnis der Menschen, daß gewissermaßen von den Sinnen aus — wenn ich das Auge nehme als den Repräsentanten der Sinne (siehe Zeichnung) — fortwährend strömt durch dasjenige, was man als Nerv auffaßt, Zerstörendes in den Menschen hinein. Es ist, wie wenn der Mensch von den Sinnen aus durch die Nervenstränge mit einem sich zerbröckelnden Materiellen ausgefüllt würde. Wenn Sie sehen, wenn Sie hören, oder auch, wenn Sie nur Warmes fühlen, es ist wie ein von den Sinnen nach innen sich zerbröckelndes Materielles. Dieses sich zerbröckelnde Materielle, das muß erfaßt werden von demjenigen, was aus dem Inneren des Menschen ausströmt. Es muß gewissermaßen verbrannt werden. Wir müssen fortwährend, indem wir denken, gegen den in uns waltenden Tod kämpfen. Der Mensch weiß .heute eben nicht, weil er sich nur bewußt ist seines Denkens als Spiegelbilder, daß er im Grunde genommen nur lebt mit dem, was nicht Kopf ist, daß der Kopf eigentlich nur ein fortwährend absterbendes Organ ist. Wir wären fortwährend der Gefahr des Sterbens ausgesetzt, wenn nur das geschehen würde, was in unserem Kopfe ist. Dieses fortwährende Sterben wird nur verhindert dadurch, daß der Kopf mit dem anderen Organismus verbunden ist und die Vitalität des anderen Organismus das Sterben verhindert. Wenn der Mensch sich aneignen wird diesen tätigen Verstand — so wie sich angeeignet hat die Menschheit in der Griechen-, in der Römerzeit die tätige Phantasie, während die Imagination des alten atavistischen Hellsehens eine passive Phantasie war -, dann wird er in sich selber wahrnehmen das fortwährende Absterben eines Teiles seines Wesens. Das wird wichtig sein. Denn so, wie wir hineinwachsen müssen in einen Bewußtseinszustand, durch den wir das fortwährende Absterben eines Teiles unseres Wesens wahrnehmen, so hat eine alte Menschheit, die aber noch bis in die Griechenzeit hineinragte, wahrgenommen dasjenige, was im Vitalitätsprinzip des Menschen lebt, was im Willen lebt und in dem mit dem Willen zusammenhängenden Stoffwechsel lebt. Da lebt dasjenige, was das Absterbeprinzip bekämpft, was fortwährend des Menschen Absterbeprinzip lähmt.

Man könnte sagen: In dieser Beziehung waren die Alten besser daran, als diejenigen sein werden, die da nachkommen in unserem Zeitalter. Die Alten haben wahrgenommen, indem sie ein instinktives Hellsehen gehabt haben, die Vitalität, das Leben. Mit dieser Vitalität, mit diesem Leben ist eben im Zusammenhange das Heilungsprinzip. Wir sterben zwar nicht dadurch, daß unser Kopf sterben will, aber wir tragen fortwährend Krankheitskeime in uns durch unseren Kopf dadurch, daß er das Organ unseres Denkens ist, und haben fortwährend nötig, den Tribut abzutragen an unser Denken, der darin besteht, daß wir dem krankmachenden Kopf entgegensetzen die Heilungskräfte des übrigen Organismus. Heute wird es noch wenig bemerkt, allein es werden auftreten Krankheitsformen — Sie wissen ja, daß sie sich ändern -, bei denen man den Ausgang aus dem menschlichen Haupte besser bemerken wird, als man das für viele Krankheiten der Gegenwart bemerkt. Dann wird man einsehen, daß im Grunde genommen der ganze gesunde Prozeß des Menschen, der in ihm verläuft, ein Heilungsvorgang ist gegen die Schädigung unseres Intellektlebens. Während die Alten also von ihrer Wissenschaft, von ihrer Erkenntnis sagen konnten, daß in ihr etwas Heilendes ist, wird man in der Zukunft sagen müssen: Das, was wir aus unserem Verstande machen, das, was aus dem wird, worauf wir heute so stolz sind, das wird uns in der Zukunft zeigen, daß, wenn es allein waltet, die Menschen nach und nach in die Dekadenz, in die völlige Dekadenz verfallen würden, daß dagegen geltend gemacht werden muß ein Wissen, das wiederum entgegenstellen kann

heilende Kräfte. Ich habe das gestern von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte aus angedeutet, heute mehr aus der Konstitution des Menschen heraus. Wir müssen einsehen, daß wir Geisteswissenschaft brauchen als den Träger eines neuen Heilungsprozesses. Denn wenn jener in bloßen Bildern lebende Intellekt, auf den heute die Menschheit so stolz ist, sich in dieser Richtung nur weiter ausbildet, dann würde durch das Walten dieses Intellektes die ganze Menschheit einen Krankheitsprozeß durchmachen. Diesem Krankheitsprozeß muß entgegengearbeitet werden. Ich könnte mir zwar denken, daß es auch Menschen geben könnte, die nunmehr sagen: Also verhindern wir einmal das Gescheitwerden durch den Verstand, schaffen wir den Intellekt ab — es gibt ja auch solche Menschen, die dafür sorgen möchten, daß der Intellekt sich nicht entwickelt -, dann braucht man seine Schäden nicht zu heilen. - Aber mit diesem jesuitischen Prinzip kann der wahre Fortschritt der Menschen nichts gemein haben, sondern es handelt sich darum, daß schon einmal die Entwickelung der Menschen so sein müßte, daß dasjenige, was aus des Menschen Seelenkräften sich entwickelte, das Heilsame, daß das herauf sich entwickelte bis zum Intellekt; sonst wird es sich abwärts entwickeln und den Menschen in den Niedergang hineinbringen. Dagegen muß sich geltend machen dasjenige, was aus geisteswissenschaftlicher Erkenntnis kommt und was fortwährend entgegenwirken kann den Niedergangskräften, die gerade aus dem einseitigen Intellekte kommen.

Hier ist es, wo ich Sie auf etwas aufmerksam machen muß, auf etwas ganz Bestimmtes. Sie werden ja wissen, daß in demselben 19. Jahrhundert, in dem all das sich abgespielt hat, wovon ich Ihnen heute erzähle, worauf ich Sie öfters aufmerksam gemacht habe, daß da der Verstandesmaterialismus groß geworden ist. Menschen sind aufgetreten — ich brauche nur zu erinnern an Moleschott, Vogt, Clifford und so weiter -, die etwa den Satz vertreten haben: Alles Denken besteht nur in einem Stoffwechsel des Gehirns. - Von einem Phosphoreszieren des Gehirns hat man gesprochen, indem man sagte: Ohne Phosphor im Gehirn, kein Denken. — Also das Denken ist nur etwas, was ein Nebenprozeß ist einer gewissen Gehirnverdauung. Man kann nicht sagen, daß die Menschen, die das aufgebracht haben, zu den dümmsten ihres Zeitalters gehört haben. Denn — man mag über diesen Satz der theoretischen Materialisten denken, wie man will — man kann ja auch etwas anderes tun, man kann den Maßstab der Kapazität anlegen an die Menschen dieses Zeitalters und kann fragen: Waren nun solche Leute, wie Moleschott oder Clifford oder ähnliche, gescheiter, oder diejenigen, die aus irgendwelchen alten Bekenntnisvorurteilen es damals bekämpft haben, es bekämpft haben ohne Geisteswissenschaft? War Haeckel gescheiter, oder waren seine Gegner gescheiter? — Diese Frage kann heute noch immer aufgeworfen werden. Und wenn man nicht sein Urteil einrichtet nach seiner Meinung, sondern nach der Beobachtung der geistigen Kapazität, so kann man natürlich nicht sagen, daß die Gegner von Haeckel gescheiter waren als Haeckel, oder die Gegner von Moleschott und Clifford gescheiter waren als Moleschott und Clifford. Die Materialisten waren sehr gescheite Menschen, und dasjenige, was sie ausgesagt haben, war ganz gewiß nicht ohne Bedeutung. Woher kommt es denn? Was steckt eigentlich dahinter? Darauf muß man kommen, sich die Frage zu beantworten, was da eigentlich dahintersteckt. Gewiß, es traten dann auch ganz wohlmeinende Gegner der Materialisten auf, so zum Beispiel Moriz Carriere, von dem ich Ihnen auch schon gesprochen habe. Er sagte: Wenn das alles, was der Mensch denkt und in der Seele erlebt, nur vom Gehirn ausgekocht wird, so ist ja alles dasjenige, was von der einen Seite vorgebracht wird, ebenso ausgekocht wie dasjenige, was von der anderen Seite vorgebracht wird. Also ist eigentlich kein Wahrheitsunterschied zwischen dem, was Moleschott und Clifford behaupten, und dem, was der Papst behauptet. — Es ist kein Unterschied, denn beides wird ausgekocht von dem menschlichen Gehirn. Man kann nicht unterscheiden zwischen wahr und falsch. Dennoch kämpfen die Materialisten für die Wahrheit, die sie allerdings in ihrem Sinne auslegen. Aber sie haben kein Recht, für die Wahrheit zu kämpfen; doch sie sind scharfsinnig, sie haben eine gewisse geistige Kapazität. Was liegt denn da eigentlich vor?

Da liegt das vor, daß diese Materialisten auftreten mußten in einem Zeitalter, in dem das Denken nur in Bildern abgefaßt, in Bildern lebt, und Bilder sind nicht da, ohne daß ein Spiegelapparat abläuft, und der Spiegelapparat ist das Gehirn. Für das gewöhnliche Denken, für das Denken, das im 19. Jahrhundert groß geworden ist, haben nämlich die Materialisten recht. Das ist die Tatsache. Nicht recht hätte der Materialismus nur dann, wenn er behaupten würde, alles Denken, das über den Intellekt hinausgeht, das sei auch bloß Bild, es sei abhängig von der Leiblichkeit; denn das ist nicht der Fall. Dieses, was über den Intellekt hinausgeht, kann nur durch eine menschliche Entwickelung erreicht werden, nur dadurch, daß man sich unabhängig macht von der Leiblichkeit. Aber dasjenige Denken, das sich gerade im 19. Jahrhundert geltend gemacht hat, das muß materialistisch gedeutet werden. Das ist ganz abhängig, wenn es auch eben Bilder sind, von dem Werkzeug des menschlichen Gehirnes, und das Merkwürdige ist, daß man mit dem Materialismus gerade am meisten Recht hat gegenüber dem Geistesleben dieses 19. Jahrhunderts. Dieses Geistesleben des 19. Jahrhunderts ist tatsächlich an die leibliche Materie gebunden. Aber gerade über dieses Geistesleben muß hinausgekommen werden. Über dieses Geistesleben muß der Mensch sich erheben. Er muß wiederum hineingießen lernen in die Bilder geistige Substanz. Das kann man nicht nur dadurch, daß man hellseherisch wird, denn das brauchen — das muß ich immer wieder sagen - nicht alle zu werden; sondern geistige Substanz läßt man schon in sein Denken einfließen, wenn man nur dasjenige, was geistig erforscht ist, nachdenkt; nicht urteilslos! Man kann es beurteilen, wenn es einmal da ist; der gesunde Menschenverstand reicht völlig aus, um zu begreifen, was von der Geisteswissenschaft erforscht ist. Wenn man das leugnet, so nimmt man nur keine Rücksicht auf den gesunden Menschenverstand; wenn man das leugnet, so denkt man: Der gesunde Menschenverstand, der ist dasjenige, was nun seit langer Zeit schon in der zivilisierten Menschheit großgezogen wird. — Ja, diese zivilisierte Menschheit, die entwickelt ja «sehr sichere» Urteile! Und wenn dann diese Urteile durch die Tatsachen widerlegt werden, dann merkt sie das gar nicht, will es nicht merken. Solche Dinge, die symptomatisch weithin sprechen, die werden im rechten Augenblicke vergessen.

Ich will Ihnen nur ein kleines niedliches Beispielchen sagen: Es war 1866, da sagte man, dasjenige, was dazumal geschehen war — der Sieg Preußens über Österreich -, der sei ein Beweis für die Vorzüglichkeit der preußischen Schulen, und das Sprichwort kam auf: 1866 hat der preußische Schulmeister gesiegt. -— Das hat man immer wieder und wiederum wiederholt. Und es würde interessant sein, zusammenzuziehen, wie oft von 1870 ab bis 1914 von allen möglichen berufenen, aber namentlich unberufenen Leuten der Satz wiederholt worden ist: Die preußischen Siege hat der preußische Schulmeister errungen. — Ich glaube, man wird jetzt nicht irgendwie ein ähnlich geartetes Sprichwort an die Stelle setzen, und die Wahrheit des anderen will sich jetzt nicht mehr so recht behaupten lassen gegenüber den Ereignissen, die nunmehr eingetreten sind. Aber im Zeitalter des Intellektes, wo man ganz gescheit ist, da merkt man nicht gerne die Widersprüche, die sich im Leben zeigen. Die Tatsachen spielen ja in ein intellektuelles Leben wenig herein; aber diese Tatsachen, sie werden mässen hereinspielen, wenn das rein Intellektuelle wiederum durchtränkt wird mit geistigem Inhalt. Dann aber wird sich eben zeigen, wie in die Menschheit hereinkommt gerade ein Ablähmungs-, ein Dekadenzprozeß und wie der durch eine neue geistige Erkenntnis überwunden werden muß. Man kann sagen: Die Alten haben gespürt, empfunden in ihrer Erkenntnis, die aus dem physischen Leibe aufkochte, das Heilende. In Zukunft wird die Menschheit sich gewöhnen müssen, in der Ausbildung des Intellektes das Kränkende, das Krankmachende zu erkennen, um die Notwendigkeit zu empfinden, aus dem Geiste herauszuholen das Heilende. Wieder muß werden die Wissenschaft ein Quell des Heilens. Aber aus einer entgegengesetzten Ecke wird die Nötigung kommen, aus der Ecke, die zeigt, daß das äußere Leben, gerade wenn es in der Erkenntnis vorschreitet, ein die Menschheit krankmachendes ist, dem eben das Heilprinzip entgegengestellt werden muß.

Mit solchen Dingen greifen wir ein in den Entwickelungsgang der Menschheit, insoweit er eine Wirklichkeit ist. Die heutige Geschichte schildert ja nicht die Wirklichkeit der menschlichen Entwickelung, sondern wertlose Abstraktionen. Das ist dasjenige, was dem heutigen Menschen so mangelt, der Wirklichkeitssinn. Ihn hat der heutige Mensch wenig. In Mitteleuropa ist man groß geworden im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts in der Darstellung desjenigen, was als Geistiges schon da war. Eine der wunderbarsten Darstellungen dessen, was schon da war, finden wir bei Herman Grimm. Herman Grimm hat gerade seine Höhe erreicht, wenn er über Goethes «Tasso», über Goethes «Iphigenie» geschrieben hat. Er konnte aber nicht Goethe selbst schildern. Es gibt ja auch eine Goethe-Biographie von ihm, aber da steht Goethe da wie ein Schatten. Die geistige Kraft war nicht da im 19. Jahrhundert. Man lebte in Bildern, und Bilder können die Wirklichkeit nicht bezwingen. In der Zukunft muß diese Wirklichkeit bezwungen werden. Wir müssen nicht nur begreifen menschliche Schöpfungen, wir müssen begreifen den Menschen selbst vor allen Dingen und durch den Menschen dann wiederum in einem umfassenderen Sinne die Natur mehr, als wir sie begreifen bisher. Solche Dinge, glaube ich, könnten mit dem nötigen Ernst anschlagen an das menschliche Gemüt. Es wird wahrscheinlich noch manche Zeit verfließen, bevor eine genügende Anzahl von Menschen sich findet, die sich durchdringen lassen von dem Feuer, das schon ausgehen kann von einer solchen Erkenntnis, die ja zeigt: Die Menschheit muß krank werden, wenn sie nicht will sich durchgeistigen! — Aber wenigstens diejenigen, die etwas nähergetreten sind dem anthroposophischen Erkennen, die sollten sich durchdringen lassen von dieser Erkenntnis.

Eines wird Platz greifen müssen; vielfach sind diejenigen, die Anthroposophen geworden sind, gekommen an diese anthroposophische Bewegung aus, ich möchte sagen, feineren egoistischen Tendenzen heraus: sie wollten etwas haben für ihr seelisches Wohlbefinden, sie wollten befriedigt sein, etwas erfahren über die geistige Welt nach irgendeiner Richtung hin. Damit wird es nicht getan sein. Dasjenige, um was es sich handelt, ist nicht, daß wir uns persönlich auf ein Ruhekissen legen können, weil wir befriedigt sind über unseren Anteil an der geistigen Welt. Dasjenige, was die Menschheit braucht, ist ein tätiges Eingreifen vom Geiste aus in die materielle Welt, ein Bezwingen der materiellen Welt vom Geiste aus. Und ehe man das nicht durchschaut und sich dann weiter von diesem Durchschauen in seinem Wollen führen läßt, eher kann aus der Not, die jetzt über die Menschheit gekommen ist, nicht hinausgelangt werden.

Man möchte so gerne, daß wenigstens in den Kreisen der Anthroposophen eine solche Einsicht und auch ein solcher Wille Platz greift. Gewiß, man kann sagen: Was können wir paar Leute tun gegen die Verblendung der ganzen Welt! — Das ist nicht richtig. Ein solcher Ausspruch ist ganz und gar nicht richtig. Denn indem man dieses sagt, denkt man gar nicht daran, daß es sich eben darum handelt, diesen Willen erst fähig zu machen und dann abzuwarten, was kommt. Tue ein jeder an seiner Stelle dasjenige, was er kann, und er mag abwarten, was die anderen tun; aber tue er es auch wirklich, tue er es vor allen Dingen so, daß eine möglichst große Anzahl von Menschen in der Welt zusammenleben, die zunächst durchdrungen sind von der Notwendigkeit einer geistigen Erneuerung, dann wird etwas anderes schon nachkommen. Heute sind viele Kräfte am Werke, diese geistige Erneuerung zu verhindern. Nur wenn wir wachsam sind, wenn wir feststehen auf dem Boden, auf den Geisteswissenschaft uns stellt, können wir vorwärtskommen und dasjenige wollen, was schon einmal heute notwendig ist für das Vorwärtskommen der Menschheit.

Second Lecture

Today it will be my task to bring together some of the insights that formed the basis of earlier considerations, which are already known to a large number of our friends, with what I said yesterday. I would just like to point out once again that the essential content of what I said yesterday was that such a kind of neutral knowledge as we currently practice is basically a creature of modern times, that such an indifferent knowledge, which medicine places alongside other sciences, has only developed in the last three or four centuries, whereas in ancient times all knowledge was aimed at healing; and recognizing and discovering means of healing humanity were one and the same in the sense I indicated yesterday. Now you know from various hints made here and there in lectures that an important spiritual event took place in the last third of the 19th century, that in the 1870s, behind the scenes of world history, of external physical world history, something significant happened. In order to have a name for this event — one could just as well have given it another name — we have called it the victory of that archangelic being whom we call Archangel Michael over opposing spiritual forces. Let us first regard this result as a process in the spiritual world with which our human history is connected. Such events unfold in such a way that they are first prepared in the spiritual world. One could say that the event I am referring to now has been in preparation since 1842. A certain decision was then made in the spiritual world around 1879, and it is necessary that human beings on earth behave in accordance with this spiritual event since 1914. What has happened since 1914 is essentially an onslaught of human narrow-mindedness against what should actually have happened according to the opinion of those spiritual powers responsible for guiding humanity. So we can say that in the second half of the 19th century and in the early 20th century, something very significant was happening behind the scenes of human development, which is a call to humanity to behave as these spiritual beings want us to: to bring about a change, to do something that would bring a new kind of civilization to humanity, a new way of understanding social life, artistic life, spiritual life on earth in general. Such events have occurred repeatedly in human development. Outer history records few such events, because outer history is, after all, a fable convenue, but these events have occurred repeatedly. The event that can be compared to the one mentioned above took place about three hundred years before the birth of Christ, and another one took place around the middle of the third millennium before Christ:

Now, however, there is a very significant difference between humanity's experience of these two events and its experience of the event that took place in the 19th and 20th centuries; for most of you have at least partially witnessed the events of the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, and most of you will also know how little humanity as such took notice of the fact that a turning point in spiritual life was really about to take place.

Humanity will be forced by necessity to take note of this necessity. And the necessity will not cease until a sufficiently large number of people have taken note of it, also with regard to the shaping of public affairs. We can ask the question: Why did people not take notice? And was this also the case with the other two experiences, that of the third millennium and that of the third century? No, this was not at all the case with these events. If one could correctly read the spiritual history of the Greek people, and even of the somewhat coarse-grained Roman people, one would hear that there was indeed a consciousness within the Greek people and within the Roman people that something was happening in the spiritual world that had to be taken into account. Yes, especially in the event that took place around 300 BC, we can see very clearly how it slowly prepared itself, how it reached a certain climax, and how it then played itself out. The people of the 3rd and 4th centuries BC were clearly aware of this: something was happening in the spiritual world that was affecting the world of human beings. And what they saw there, we can describe today as the actual birth of the human imagination.

You know, people today are like that: they think that the way we think and feel today is the way people have always thought and felt. But that is not the case. Even sensory perceptions have changed over time, as I showed you yesterday. Of course, there was artistic creation before the third or fourth century BC, but this artistic creation did not arise from what we today call imagination. This artistic creation arose from a real clairvoyant imagination. Those who were artists could see how the spiritual revealed itself to them, and they simply copied the spiritual that revealed itself to them. The ancient atavistic clairvoyance, the ancient imagination, was what lay at the foundation of the artist. That imagination, which first arose at that time and then developed further until it reached the creations of Leonardo, Raphael, or Michelangelo, only to decline again, that imagination has its origin in those days, that imagination which does not create as if something spiritual appears, is imagined, but as if one merely arranges something out of oneself, as if one merely shapes something out of oneself. And that they were endowed with imagination, that they could imagine, was not a gift from God, but a gift from the spiritual world. as if something spiritual appears, is imagined, but as if one arranges something solely from within oneself, as if one creates something solely from within oneself. And the fact that they were gifted with imagination, the people of that time attributed to a struggle between divine beings who ruled over them and on whose behalf they acted on earth.

Even more significantly, in the middle of the third millennium, around 2500 BC, people perceived how their entire existence was caught up in events that protruded from the spiritual world into physical events. Around this time, still in the middle of the third millennium BC, no one would have found it meaningful to say, “Here, people walk around on Earth,” without adding, “Spiritual beings are there.” That would have seemed nonsense to everyone, because people thought the Earth was populated by beings that were both physical and spiritual.

However, the nature of the soul life in those ancient times is somewhat different from that which took hold in the course of the 19th century, for people perceived how profane, ordinary events took place on earth. But they did not perceive that there was a significant spiritual struggle behind them. Why did they not perceive this? This comes precisely from the peculiarity of our age, which, as you know, began in the middle of the 15th century and in which we still live, which we call the fifth post-Atlantean period. In this age, that is, in the age in which we live, the most outstanding, the most significant power that human beings can use is the intellect. Since the 15th century, human beings have become particularly great as intelligent beings. People today are still proud of being such intelligent beings. One should not believe that another form of intelligence did not exist in earlier times, but this intelligence was born together with a certain way of seeing. This intelligence was created in human beings together with a certain spiritual content. We have an intelligence that has no real spiritual content, that is merely formal, because our concepts and ideas have nothing in themselves; they are only reflections of something else. Our entire mind is a sum of mere reflections of something else. That is the essence of the intelligence that has developed particularly since the middle of the 15th century, that the mind is only a mirroring apparatus. But what is reflected there has, in essence, no power in human beings. It is essentially passive. That is the peculiarity of the mind of which contemporary humanity is so proud, that this mind is passive. We allow it to work on us, we surrender ourselves to it. We develop little willpower in this intellect. The most outstanding characteristic of people today is that they actually hate the active intellect. If they are expected to be somewhere where they are expected to think along with what is being presented, they find it boring, very boring. Very soon, everyone begins to fall asleep, at least spiritually, as soon as they are expected to think. On the other hand, when it is a movie, when one does not need to think, but rather when thinking is lulled to sleep, when one merely needs to see and passively surrender to what is happening, and when thoughts run like independent wheels, then people today feel satisfied. It is the passive mind to which people have become accustomed. This passive mind has no power, for what is this passive mind? We come to know its nature when we remember how the types of human knowledge were classified in the ancient mystery schools. There, three types of knowledge were distinguished: first, the knowledge that comes from the physical life of the human being, which rises, as it were, from the physical experience of the world; one could say: physical knowledge; secondly, intellectual knowledge, the knowledge that one forms oneself, mainly in mathematics, the knowledge in which one lives, intellectual knowledge; thirdly, spiritual knowledge, the knowledge that does not come from the physical, but from the spiritual. Of these three types of knowledge, intellectual knowledge is particularly cultivated and popular in our age. It has become a veritable ideal to approach spiritual life in the same way that we have become accustomed to approaching mathematics, with a certain neutrality, with a certain indifference. It is actually unheard of, but true, that in our time even the bearers of knowledge, for example university professors, when they have closed the doors behind them and are outside, want to do something else as quickly as possible that has nothing to do with their knowledge. It is an abstract devotion to knowledge, and that actually goes quite deep.

When I gave a public lecture in Zurich a few days ago, a proletarian intervened in the discussion. I had mentioned something about Waldorf schools and replacing the timetable, which really kills the spirit, and he said: But such a timetable would spend too much time on one subject; you need variety; if the children find one subject boring from eight to nine, then there has to be another subject from nine to ten, otherwise the children will get bored! “Of course, I could only reply: 'It is not the task of the Waldorf school to anticipate boredom, but to ensure that the children do not get bored, that the children are really engaged in what they are doing; that is precisely the task of the pedagogy and didactics that should be cultivated in the Waldorf school. — So it has become so ingrained in people that intellectual life is actually boring and that one must break away from intellectual life, that one must not become absorbed in a subject. But this comes solely from the fact that our entire intellectual life actually consists only of images, of mirror images, that we have no substance in this intellectual life.

Such a spiritual life, devoid of substance, is actually closed off, both from the physical world and from the spiritual world. In fact, our age knows little about either the physical world or the spiritual world. It knows only what it thinks up for itself. Because of this character of our intellectuality as a sum of mirror images, the people of the 19th century were excluded from knowing anything about what was going on spiritually behind the scenes of world history. They did not experience the great, significant upheaval that took place in the spiritual realm behind the outer world history in the second half of the 19th century, and they must first learn through their own efforts that the physical world must follow the spiritual world. They will have to learn this, because if they do not, hardship will become greater and greater, and civilization will descend into barbarism throughout the entire civilized world. To avoid this, it is necessary for human beings to become aware within themselves that they must experience something similar to what was experienced around the year 300 BC, when imagination was born. In our time, the birth of the active intellect must be experienced: then it was the active power of imagination, now it is the birth of the active intellect. At that time, the possibility arose to create imaginatively by reproducing external forms. Now, human beings must grasp an inner, powerful creation of ideas through which each person forms a picture of their own being and sets this as the goal they strive for. Self-knowledge in the broadest sense of the word must seize people; but not a self-knowledge in which one merely broods over what one ate yesterday, but a self-knowledge that leads to the activity of one's own being. And this self-knowledge is clearly demanded by the development of human beings, who must rise to the birth of the active intellect.