The Light Course

GA 320

23 December 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture I

My dear Friends,

After the words which have just been read out, some of which were written over 30 years ago, I would like to say that in the short time at our disposal I shall at most be able to contribute a few side-lights which may help you in forming your outlook upon Nature. I hope that in no very distant future we shall be able to continue. On this occasion, as you must also realize, I was only told that this lecture-course was hoped-for after my arrival here. What I can therefore give during these days will be no more than an episode.

What I am hoping to contribute may well be of use to those of you who are teachers and educators—not to apply directly in your lessons, but as a fundamental trend and tendency in Science, which should permeate your teaching. In view of all the aberrations to which the Science of Nature in our time has been subject, for the teacher and educator it is of great importance to have the right direction of ideas, at any rate in the background.

To the words which our friend Dr. Stein has kindly been recalling, I may add one more. It was in the early nineties. The Frankfurter Freier Hochstift had invited me to speak on Goethe's work in Science. I then said in introduction that I should mainly confine myself to his work in the organic Sciences. For to carry Goethe's world-conception into our physical and chemical ideas, was as yet quite impossible. Through all that lives and works in the Physics and Chemistry of today, our scientists are fated in regard, whatever takes its start from Goethe in this realm, as being almost unintelligible from their point of view. Thus, I opined, we shall have to wait till physicists and chemists will have witnessed—by their own researches—a kind of “reductio ad absurdum” of the existing theoretic structure of their Science. Then and then only will Goethe's outlook come into its own, also in this domain.

I shall attempt in these lectures to establish a certain harmony between what we may call the experimental side of Science and what concerns the outlook, the idea, the fundamental views which we can gain on the results of experiment. Today, by way of introduction,—and, as the saying goes, “theoretically”—I will put forward certain aspects that shall help our understanding. In today's lecture it will be my specific aim to help you understand that contrast between the current, customary science and the kind of scientific outlook which can be derived from Goethe's general world-outlook. We must begin by reflecting, perhaps a little theoretically, upon the premisses of present-day scientific thinking altogether. The scientists who think of Nature in the customary manner of our time, generally have no very clear idea of what constitutes the field of their researches. “Nature” has grown to be a rather vague and undefined conception. Therefore we will not take our start from the prevailing idea of what Nature is, but from the way in which the scientist of modern time will generally work. Admittedly, this way of working is already undergoing transformation, and there are signs which we may read as the first dawning of a new world-outlook. Yet on the whole, what I shall characterize (though in a very brief introductory outline) may still be said to be prevailing.

The scientist today seeks to approach Nature from three vantage-points. In the first place he is at pains to observe Nature in such a way that from her several creatures and phenomena he may form concepts of species, kind and genus. He sub-divides and classifies the beings and phenomena of Nature. You need only recall how in external, sensory experience so many single wolves, single hyenas, single phenomena of warmth, single phenomena of electricity are given to the human being, who thereupon attempts to gather up the single phenomena into kinds and species. So then he speaks of the species “wolf” or “hyena”, likewise he classifies the phenomena into species, thus grouping and comprising what is given, to begin with, in many single experiences. Now we may say, this first important activity is already taken more or less unconsciously for granted. Scientists in our time do not reflect that they should really examine how these “universals”, these general ideas, are related to the single data.

The second thing, done by the man of today in scientific research, is that he tries by experiment, or by conceptual elaboration of the results of experiment, to arrive at what he calls the “causes” of phenomena. Speaking of causes, our scientists will have in mind forces or substances or even more universal entities. They speak for instance of the force of electricity, the force of magnetism, the force of heat or warmth, and so on. They speak of an unknown “ether” or the like, as underlying the phenomena of light and electricity. From the results of experiment they try to arrive at the properties of this ether. Now you are well aware how very controversial is all that can be said about the “ether” of Physics. There is one thing however to which we may draw attention even at this stage. In trying, as they put it, to go back to the causes of phenomena, the scientists are always wanting to find their way from what is known into some unknown realm. They scarcely ever ask if it is really justified thus to proceed from the known to the unknown. They scarcely trouble, for example, to consider if it is justified to say that when we perceive a phenomenon of light or colour, what we subjectively describe as the quality of colour is the effect on us, upon our soul, our nervous apparatus, of an objective process that is taking place in the universal ether—say a wave-movement in the ether. They do not pause to think, whether it is justified thus to distinguish (what is what they really do) between the “subjective” event and the “objective”, the latter being the supposed wave-movement in the ether, or else the interaction thereof with processes in ponderable matter.

Shaken though it now is to some extent, this kind of scientific outlook was predominant in the 19th century, and we still find it on all hands in the whole way the phenomena are spoken of; it still undoubtedly prevails in scientific literature to this day.

Now there is also a third way in which the scientist tries to get at the configuration of Nature. He takes the phenomena to begin with—say, such a simple phenomenon as that a stone, let go, will fall to earth, or if suspended by a string, will pull vertically down towards the earth. Phenomena like this the scientist sums up and so arrives at what he calls a “Law of Nature”. This statement for example would be regarded as a simple “Law of Nature”: “Every celestial body attracts to itself the bodies that are upon it”. We call the force of attraction Gravity or Gravitation and then express how it works in certain “Laws”. Another classical example are the three statements known as “Kepler's Laws”.

It is in these three ways that “scientific research” tries to get near to Nature. Now I will emphasize at the very outset that the Goethean outlook upon Nature strives for the very opposite in all three respects. In the first place, when he began to study natural phenomena, the classification into species and genera, whether of the creatures or of the facts and events of Nature, at once became problematical for Goethe. He did not like to see the many concrete entities and facts of Nature reduced to all these rigid concepts of species, family and genus; what he desired was to observe the gradual transition of one phenomenon into another, or of one form of manifestation of an entity into another. He felt concerned, not with the subdivision and classification into genera, but with the metamorphosis both of phenomena and of the several creatures. Also the quest of so-called “causes” in Nature, which Science has gone on pursuing ever since his time, was not according to Goethe's way of thinking. In this respect it is especially important for us to realize the fundamental difference between natural science and research as pursued today and on the other hand the Goethean approach to Nature.

The Science of our time makes experiments; having thus studied the phenomena, it then tries to form ideas about the so-called causes that are supposed to be there behind them;—behind the subjective phenomenon of light or colour for example, the objective wave-movement in the ether. Not in this style did Goethe apply scientific thinking. In his researches into Nature he does not try to proceed from the so-called “known” to the so-called “unknown”. He always wants to stay within the sphere of what is known, nor in the first place is he concerned to enquire whether the latter is merely subjective, or objective. Goethe does not entertain such concepts as of the “subjective” phenomena of colour and the “objective” wave-movements in outer space. What he beholds spread out in space and going on in time is for him one, a single undivided whole. He does not face it with the question, subjective or objective? His use of scientific thinking and scientific method is not to draw conclusions from the known to the unknown; he will apply all thinking and all available methods to put the phenomena themselves together till in the last resort he gets the kind of phenomena which he calls archetypal,—the Ur-phenomena. These archetypal phenomena—once more, regardless of “subjective or objective”—bring to expression what Goethe feels is fundamental to a true outlook upon Nature and the World. Goethe therefore remains amid the sequence of actual phenomena; he only sifts and simplifies them and then calls “Ur-phenomenon” the simplified and clarified phenomenon, ideally transparent and comprehensive.

Thus Goethe looks upon the whole of scientific method—so to call it—purely and simply as a means of grouping the phenomena. Staying amid the actual phenomena, he wants to group them in such a way that they themselves express their secrets. He nowhere seeks to recur from the so-called “known” to an “unknown” of any kind. Hence too for Goethe in the last resort there are not what may properly be called “Laws of Nature”. He is not looking for such Laws. What he puts down as the quintessence of his researches are simple facts—the fact, for instance, of how light will interact with matter that is in its path. Goethe puts into words how light and matter interact. That is no “law”; it is a pure and simple fact. And upon facts like this he seeks to base his contemplation, his whole outlook upon Nature. What he desires, fundamentally, is a rational description of Nature. Only for him there is a difference between the mere crude description of a phenomenon as it may first present itself, where it is complicated still and untransparent, and the description which emerges when one has sifted it, so that the simple essentials and they alone stand out. This then—the Urphenomenon—is what Goethe takes to be fundamental, in place of the unknown entities or the conceptually defined “Laws” of customary Science.

One fact may throw considerable light on what is seeking to come into our Science by way of Goetheanism, and on what now obtains in Science. It is remarkable: few men have ever had so clear an understanding of the relation of the phenomena of Nature to mathematical thinking as Goethe had. Goethe himself not having been much of a mathematician, this is disputed no doubt. Some people think he had no clear idea of the relation of natural phenomena to those mathematical formulations which have grown ever more beloved in Science, so much so that in our time they are felt to be the one and only firm foundation. Increasingly in modern time, the mathematical way of studying the phenomena of Nature—I do not say directly, the mathematical study of Nature; it would not be right to put it in these words, but the study of natural phenomena in terms of mathematical formulae—has grown to be the determining factor in the way we think even of Nature herself.

Concerning these things we really must reach clarity. You see, dear Friends, along the accustomed way of approach to Nature we have three things to begin with—things that are really exercised by man before he actually reaches Nature. The first is common or garden Arithmetic. In studying Nature nowadays we do a lot of arithmetic—counting and calculating. Arithmetic—we must be clear on this—is something man understands on its own ground, in and by itself. When we are counting it makes no difference what we count. Learning arithmetic, we receive something which, to begin with, has no reference to the outer world. We may count peas as well as electrons. The way we recognize that our methods of counting and calculating are correct is altogether different from the way we contemplate and form conclusions about the outer processes to which our arithmetic is then applied.

The second of the three to which I have referred is again a thing we do before we come to outer Nature. I mean Geometry,—all that is known by means of pure Geometry. What a cube or an octahedron is, and the relations of their angles,—all these are things which we determine without looking into outer Nature. We spin and weave them out of ourselves. We may make outer drawings on them, but this is only to serve mental convenience, not to say inertia. Whatever we may illustrate by outer drawings, we might equally well imagine purely in the mind. Indeed it is very good for us to imagine more of these things purely in the mind, using the crutches of outer illustration rather less. Thus, what we have to say concerning geometrical form is derived from a realm which, to begin with, is quite away from outer Nature. We know what we have to say about a cube without first having had to read it in a cube of rock-salt. Yet in the latter we must find it. So we ourselves do something quite apart from Nature and then apply it to the latter.

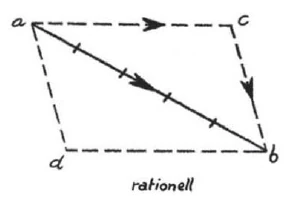

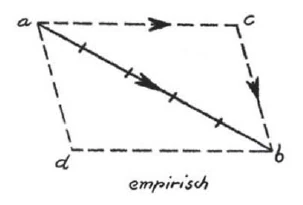

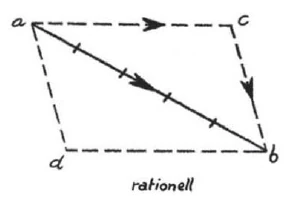

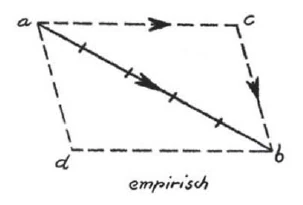

And then there is the third thing which we do, still before reaching outer Nature. I am referring to what we do in “Phoronomy” so-called, or Kinematics, i.e. the science of Movement. Now it is very important for you to be clear on this point,—to realize that Kinematics too is, fundamentally speaking, still remote from what we call the “real” phenomena of Nature. Say I imagine an object to be moving from the point \(a\) to the point \(b\) (Figure 1a). I am not looking at any moving object; I just imagine it. Then I can always imagine this movement from \(a\) to \(b\), indicated by an arrow in the figure, to be compounded of two distinct movements. Think of it thus: the point \(a\) is ultimately to get to \(b\), but we suppose it does not go there at once. It sets out in this other direction and reaches \(c\). If it then subsequently moves from \(c\) to \(b\), it does eventually get to \(b\). Thus I can also imagine the movement from \(a\) to \(b\) so that it does not go along the line \(ab\) but along the line, or the two lines, \(ac\) and \(cb\). The movement \(ab\) is then compounded of the movements \(ac\) and \(cb\), i.e. of two distinct movements. You need not observe any process in outer Nature; you can simply think it—picture it to yourself in thought—how that the movement from \(a\) to \(b\) is composed of the two other movements. That is to say, in place of the one movement the two other movements might be carried out with the same ultimate effect. And when in thinking I picture this. The thought—the mental picture—is spun out of myself. I need have made no outer drawing; I could simply have instructed you in thought to form the mental picture; you could not but have found it valid. Yet if in outer Nature there is really something like the point \(a\)—perhaps a little ball, a grain of shot—which in one instance moves from \(a\) to \(b\) and in another from \(a\) to \(c\) and then from \(c\) to \(b\), what I have pictured to myself in thought will really happen. So then it is in kinematics, in the science of movement also; I think the movements to myself, yet what I think proves applicable to the phenomena of Nature and must indeed hold good among them.

Thus we may truly say: In Arithmetic, in Geometry and in Phoronomy or Kinematics we have the three preliminary steps that go before the actual study of Nature. Spun as they are purely out of ourselves, the concepts which we gain in all these three are none the less valid for what takes place in real Nature.

And now I beg you to remember the so-called Parallelogram of forces, (Figure 1b). This time, the point a will signify a material thing—some little grain of material substance. I exert a force to draw it on from \(a\) to \(b\). Mark the difference between the way I am now speaking and the way I spoke before. Before, I spoke of movement as such; now I am saying that a force draws the little ball from \(a\) to \(b\). Suppose the measure of this force, pulling from \(a\) to \(b\), to be five grammes; you can denote it by a corresponding length in this direction. With a force of five grammes I am pulling the little ball from \(a\) to \(b\). Now I might also do it differently. Namely I might first pull with a certain force from \(a\) to \(c\). Pulling from \(a\) to \(c\) (with a force denoted by this length) I need a different force than when I pulled direct from \(a\) to \(b\). Then I might add a second pull, in the direction of the line from \(c\) to \(b\), and with a force denoted by the length of this line. Having pulled in the first instance from a towards \(b\) with a force of five grammes, I should have to calculate from this figure, how big the pull \(ac\) and also how big the pull \(cd\) would have to be. Then if I pulled simultaneously with forces represented by the lines \(ac\) and \(ad\) of the parallelogram, I should be pulling the object along in such a way that it eventually got to \(b\); thus I can calculate how strongly I must pull towards \(c\) and \(d\) respectively. Yet I cannot calculate this in the same way as I did the displacements in our previous example. What I found previously (as to the movement pure and simple), that I could calculate, purely in thought. Not so when a real pull, a real force is exercised. Here I must somehow measure the force; I must approach Nature herself; I must go on from thought to the world of facts. If once you realize this difference between the Parallelogram of Movements and that of Forces, you have a clear and sharp formulation of the essential difference between all those things that can be determined within the realm of thought, and those that lie beyond the range of thoughts and mental pictures. You can reach movements but not forces with your mental activity. Forces you have to measure in the outer world. The fact that when two pulls come into play—the one from \(a\) to \(c\), the other from \(a\) to \(d\),—the thing is actually pulled from \(a\) to \(b\) according to the Parallelogram of Forces, this you cannot make sure of in any other way than by an outer experiment. There is no proof by dint of thought, as for the Parallelogram of Movements. It must be measured and ascertained externally. Thus in conclusion we may say: while we derive the parallelogram of movements by pure reasoning, the parallelogram of forces must be derived empirically, by dint of outer experience. Distinguishing the parallelogram of movements and that of forces, you have the difference—clear and keen—between Phoronomy and Mechanics, or Kinematics and Mechanics. Mechanics has to do with forces, no mere movements; it is already a Natural Science. Mechanics is concerned with the way forces work in space and time. Arithmetic, Geometry and Kinematics are not yet Natural Sciences in the proper sense. To reach the first of the Natural Sciences, which is Mechanics, we have to go beyond the life of ideas and mental pictures.

Even at this stage our contemporaries fail to think clearly enough. I will explain by an example, how great is the leap from kinematics into mechanics. The kinematical phenomena can still take place entirely within a space of our own thinking; mechanical phenomena on the other hand must first be tried and tested by us in the outer world. Our scientists however do not envisage the distinction clearly. They always tend rather to confuse what can still be seen in purely mathematical ways, and what involves realities of the outer world. What, in effect, must be there, before we can speak of a parallelogram of forces? So long as we are only speaking of the parallelogram of movements, no actual body need be there; we need only have one in our thought. For the parallelogram of forces on the other hand there must be a mass—a mass, that possesses weight among other things. This you must not forget. There must be a mass at the point a, to begin with. Now we may well feel driven to enquire: What then is a mass? What is it really? And we shall have to admit: Here we already get stuck! The moment we take leave of things which we can settle purely in the world of thought so that they then hold good in outer Nature, we get into difficult and uncertain regions. You are of course aware how scientists proceed. Equipped with arithmetic, geometry and kinematics, to which they also add a little dose of mechanics, they try to work out a mechanics of molecules and atoms; for they imagine what is called matter to be thus sub-divided, In terms of this molecular mechanics they then try to conceive the phenomena of Nature, which, in the form in which they first present themselves, they regard as our own subjective experience.

We take hold of a warm object, for example. The scientist will tell us: What you are calling the heat or warmth is the effect on your own nerves. Objectively, there is the movement of molecules and atoms. These you can study, after the laws of mechanics. So then they study the laws of mechanics, of atoms and molecules; indeed, for a long time they imagined that by so doing they would at last contrive to explain all the phenomena of Nature. Today, of course, this hope is rather shaken. But even if we do press forward to the atom with our thinking, even then we shall have to ask—and seek the answer by experiment—How are the forces in the atom? How does the mass reveal itself in its effects,—how does it work? And if you put this question, you must ask again: How will you recognize it? You can only recognize the mass by its effects.

The customary way is to recognize the smallest unit bearer of mechanical force by its effect, in answering this question: If such a particle brings another minute particle—say, a minute particle of matter weighing one gramme—into movement, there must be some force proceeding from the matter in the one, which brings the other into movement. If then the given mass brings the other mass, weighing one gramme, into movement in such a way that the latter goes a centimetre a second faster in each successive second, the former mass will have exerted a certain force. This force we are accustomed to regard as a kind of universal unit. If we are then able to say of some force that it is so many times greater than the force needed to make a gramme go a centimetre a second quicker every second, we know the ratio between the force in question and the chosen universal unit. If we express it as a weight, it is 0.001019 grammes' weight. Indeed, to express what this kind of force involves, we must have recourse to the balance—the weighing-machine. The unit force is equivalent to the downward thrust that comes into play when 0.001019 grammes are being weighed. So then I have to express myself in terms of something very outwardly real if I want to approach what is called “mass” in this Universe. Howsoever I may think it out, I can only express the concept “mass” by introducing what I get to know in quite external ways, namely a weight. In the last resort, it is by a weight that I express the mass, and even if I then go on to atomize it, I still express it by a weight.

I have reminded you of all this, in order clearly to describe the point at which we pass, from what can still be determined “a priori”, into the realm of real Nature. We need to be very clear on this point. The truths of arithmetic, geometry and kinematics,—these we undoubtedly determine apart from external Nature. But we must also be clear, to what extent these truths are applicable to that which meets us, in effect, from quite another side—and, to begin with, in mechanics. Not till we get to mechanics, have we the content of what we call “phenomenon of Nature”.

All this was clear to Goethe. Only where we pass on from kinematics to mechanics can we begin to speak at all of natural phenomena. Aware as he was of this, he knew what is the only possible relation of Mathematics to Natural Science, though Mathematics be ever so idolized even for this domain of knowledge.

To bring this home, I will adduce one more example. Even as we may think of the unit element, for the effects of Force in Nature, as a minute atom-like body which would be able to impart an acceleration of a centimetre per second per second to a gramme-weight, so too with every manifestation of Force, we shall be able to say that the force proceeds from one direction and works towards another. Thus we may well grow accustomed—for all the workings of Nature—always to look for the points from which the forces proceed. Precisely this has grown habitual, nay dominant, in Science. Indeed in many instances we really find it so. There are whole fields of phenomena which we can thus refer to the points from which the forces, dominating the phenomena, proceed. We therefore call such forces “centric forces”, inasmuch as they always issue from point-centres. It is indeed right to think of centric forces wherever we can find so many single points from which quite definite forces, dominating a given field of phenomena, proceed. Nor need the forces always come into play. It may well be that the point-centre in question only bears in it the possibility, the potentiality as it were, for such a play of forces to arise, whereas the forces do not actually come into play until the requisite conditions are fulfilled in the surrounding sphere. We shall have instances of this during the next few days. It is as though forces were concentrated at the points in question,—forces however that are not yet in action. Only when we bring about the necessary conditions, will they call forth actual phenomena in their surroundings. Yet we must recognize that in such point or space forces are concentrated, able potentially to work on their environment.

This in effect is what we always look for, when speaking of the World in terms of Physics. All physical research amounts to this: we follow up the centric forces to their centres; we try to find the points from which effects can issue, For this kind of effect in Nature, we are obliged to assume that there are centres, charged as it were with possibilities of action in certain directions. And we have sundry means of measuring these possibilities of action; we can express in stated measures, how strongly such a point or centre has the potentiality of working. Speaking in general terms, we call the measure of a force thus centred and concentrated a “potential” or “potential force”. In studying these effects of Nature we then have to trace the potentials of the centric forces,—so we may formulate it. We look for centres which we then investigate as sources of potential forces.

Such, in effect, is the line taken by that school of Science which is at pains to express everything in mechanical terms. It looks for centric forces and their potentials. In this respect our need will be to take one essential step—out into actual Nature—whereby we shall grow fully conscious of the fact: You cannot possibly understand any phenomenon in which Life plays a part if you restrict yourself to this method, looking only for the potentials of centric forces. Say you were studying the play of forces in an animal or vegetable embryo or germ-cell; with this method you would never find your way. No doubt it seems an ultimate ideal to the Science of today, to understand even organic phenomena in terms of potentials, of centric forces of some kind. It will be the dawn of a new world-conception in this realm when it is recognized that the thing cannot be done in this way, Phenomena in which Life is working can never be understood in terms of centric forces. Why, in effect,—why not? Diagrammatically, let us here imagine that we are setting out to study transient, living phenomena of Nature in terms of Physics. We look for centres,—to study the potential effects that may go out from such centres. Suppose we find the effect. If I now calculate the potentials, say for the three points \(a\), \(b\) and \(c\), I find that \(a\) will work thus and thus on \(A\), \(B\) and \(C\), or \(c\) on \(A'\), \(B'\) and \(C'\); and so on. I should thus get a notion of how the integral effects will be, in a certain sphere, subject to the potentials of such and such centric forces. Yet in this way I could never explain any process involving Life. In effect, the forces that are essential to a living thing have no potential; they are not centric forces. If at a given point \(d\) you tried to trace the physical effects due to the influences of \(a\), \(b\) and \(c\), you would indeed be referring to the effects to centric forces, and you could do so. But if you want to study the effects of Life you can never do this. For these effects, there are no centres such as \(a\) or \(b\) or \(c\). Here you will only take the right direction with your thinking when you speak thus: Say that at \(d\) there is something alive. I look for the forces to which the life is subject. I shall not find them in \(a\), nor in \(b\), nor in \(c\), nor when I go still farther out. I only find them when as it were I go to the very ends of the world—and, what is more, to the entire circumference at once. Taking my start from \(d\), I should have to go to the outermost ends of the Universe and imagine forces to the working inward from the spherical circumference from all sides, forces which in their interplay unite in \(d\). It is the very opposite of the centric forces with their potentials. How to calculate a potential for what works inward from all sides, from the infinitudes of space? In the attempt, I should have to dismember the forces; one total force would have to be divided into ever smaller portions. Then I should get nearer and nearer the edge of the World:—the force would be completely sundered, and so would all my calculation. Here in effect it is not centric forces; it is cosmic, universal forces that are at work. Here, calculation ceases.

Once more, you have the leap—the leap, this time, from that in Nature which is not alive to that which is. In the investigation of Nature we shall only find our way aright if we know what the leap is from Kinematics to Mechanics, and again what the leap is from external, inorganic Nature into those realms that are no longer accessible to calculation,—where every attempted calculation breaks asunder and every potential is dissolved away. This second leap will take us from external inorganic Nature into living Nature, and we must realize that calculation ceases where we want to understand what is alive.

Now in this explanation I have been neatly dividing all that refers to potentials and centric forces and on the other hand all that leads out into the cosmic forces. Yet in the Nature that surrounds us they are not thus apart. You may put the question: Where can I find an object where only centric forces work with their potentials, and on the other hand where is the realm where cosmic forces work, which do not let you calculate potentials? An answer can indeed be given, and it is such as to reveal the very great importance of what is here involved. For we may truly say: All that Man makes by way of machines—all that is pieced together by Man from elements supplied by Nature—herein we find the purely centric forces working, working according to their potentials. What is existing in Nature outside us on the other hand—even in inorganic Nature—can never be referred exclusively to centric forces. In Nature there is no such thing; it never works completely in that way: Save in the things made artificially by Man, the workings of centric forces and cosmic are always flowing together in their effects. In the whole realm of so-called Nature there is nothing in the proper sense un-living. The one exception is what Man makes artificially; man-made machines and mechanical devices.

The truth of this was profoundly clear to Goethe. In him, it was a Nature-given instinct, and his whole outlook upon Nature was built upon this basis. Herein we have the quintessence of the contrast between Goethe and the modern Scientist as represented by Newton. The scientists of modern time have only looked in one direction, always observing external Nature in such a way as to refer all things to centric forces,—as it were to expunge all that in Nature which cannot be defined in terms of centric forces and their potentials. Goethe could not make do with such an outlook. What was called “Nature” under this influence seemed to him a void abstraction. There is reality for him only where centric forces and peripheric or cosmic forces are alike concerned,—where there is interplay between the two. On this polarity, in the last resort, his Theory of Colour is also founded, of which we shall be speaking in more detail in the next few days.

All this, dear Friends, I have been saying to the end that we may understand how the relation is even of Man himself to all his study and contemplation of Nature.—We must be willing to bethink ourselves in this way, the more so as the time has come at last when the impossibility of the existing view of Nature is beginning to be felt—subconsciously, at least. In some respects there is at least a dawning insight that these things must change. People begin to see that the old view will serve no longer. No doubt they are still laughed at when they say so, but the time is not so distant when this derision too will cease. The time is not so very distant when even Physics will be such as to enable one to speak in Goethe's sense. Men will perhaps begin to speak of Colour, for example, more in Goethe's spirit when another rampart has been shaken, which, though reputed impregnable, is none the less beginning to be undermined. I mean the theory of Gravitation. Ideas are now emerging almost every year, shaking the old Newtonian conceptions about Gravitation, and bearing witness how impossible it is to make do with these old conceptions, built as they are on the exclusive mechanism of centric forces.

Today, I think, both teachers who instruct the young, and altogether those who want to play an active, helpful part in the development of culture, must seek a clearer picture of Man's relation to Nature and how it needs to be.

Erster Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde!

Nach den eben verlesenen Worten, von denen einige ja schon über dreißig Jahre alt sind, möchte ich bemerken, dass es natürlich nur zunächst Streiflichter sein können, die ich in dieser kurzen Zeit, die uns zur Verfügung stehen wird, Ihnen werde für die Anschauung des natürlichen Daseins bringen können. Denn erstens werden wir [uns kurzfassen müssen], zumal ja nicht sehr viel Zeit sein wird - ich denke aber, wir werden das diesmal Begonnene in nicht sehr ferner Zukunft weiter hier fortsetzen können —, zweitens aber ist mir ja von der Absicht eines solchen Kurses erst, als ich hier schon angekommen war, Mitteilung gemacht worden. Und daher wird es sich um etwas recht, recht sehr Episodisches in diesen Tagen nur handeln können.

Ich möchte auf der einen Seite etwas geben, was für den Pädagogen brauchbar sein kann, weniger vielleicht brauchbar sein kann nach der Richtung hin, dass er es unmittelbar so, wie ich es geben werde hier, inhaltlich im Unterricht verwerten wird können, als vielmehr nach der Richtung hin, dass es das Lehren durchdringen könne als eine gewisse wissenschaftliche Grundrichtung. Auf der anderen Seite wird ja immer für den Pädagogen es von ganz besonderer Bedeutung sein, neben den mancherlei Abirrungen, welche gerade das Naturwissen in der neueren Zeit erfahren hat, wenigstens im Hintergrunde das Richtige zu haben, und auch von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus möchte ich Ihnen einzelne Anhaltspunkte geben.

Ich möchte zu den Worten, an die freundschaftlicherweise von Dr. Stein eben erinnert worden ist, ein anderes hinzufügen, das ich im Beginne der Neunzigerjahre aussprechen musste, als ich vom Frankfurter Freien Hochstift aufgefordert wurde, einen Vortrag über Goethes Naturwissenschaft zu halten. Ich sagte dazumal in der Einleitung, dass ich mich darauf beschränken müsse - in den Neunzigerjahren des vorigen Jahrhunderts war es gewesen -, mehr über die Beziehungen Goethes zur organischen Naturwissenschaft zu sprechen. Denn dasjenige, was Goethe’sche Weltanschauung ist, heute schon hineinzutragen etwa in die physikalische und chemische Anschauung, das ist schier eine Unmöglichkeit, weil einfach die Physiker und Chemiker heute dazu verurteilt sind, durch alles das, was in Physik und Chemie lebt, das von Goethe Ausgehende geradezu als eine Art Unsinn anzusehen, als etwas, wobei sie sich nichts vorstellen können. Und ich meinte damals, man müsse abwarten, bis Physik und Chemie durch ihre eigene Forschung gewissermaßen geführt werde einzusehen, wie der Grundbau ihres wissenschaftlichen Strebens sich selber ad absurdum führt. Dann werde die Zeit gekommen sein, wo auch auf dem Gebiet der Physik und Chemie Goethe’sche Ansichten Platz greifen können.

Nun werde ich mich bemühen, einen Einklang zu schaffen zwischen dem, was man etwa experimentelle Naturwissenschaft nennen kann, und dem, was die Anschauung betrifft, die man über die Ergebnisse des Experiments gewinnen kann. Heute möchte ich einleitungsweise und - wie man oft sagt - theoretisch einiges zur Verständigung vorbringen. Ich möchte heute geradezu darauf abzielen, hinzuarbeiten auf ein wirkliches Verstehen des Gegensatzes zwischen landläufiger, gebräuchlicher Naturwissenschaft und demjenigen, was man als naturwissenschaftliche Anschauung aus Goethes allgemeiner Weltanschauung gewinnen kann. Wir werden dazu allerdings ein wenig auf die Voraussetzungen des naturwissenschaftlichen Denkens heute eben, wie man oftmals sagt, theoretisch eingehen müssen. Wer heute im landläufigen Sinne über die Natur denkt, der macht sich gewöhnlich nicht eine klare Vorstellung darüber, was eigentlich sein Forschungsfeld ist. Natur ist, ich möchte sagen, zu einem ziemlich unbestimmten Begriff geworden. Wir wollen daher nicht ausgehen etwa von der Anschauung, die man heute hat über das Wesen dessen, was Natur ist, sondern vielmehr davon, wie in der Naturwissenschaft gewöhnlich gearbeitet wird. Diese Arbeitsweise, wie ich sie charakterisieren werde, ist ja in der Tat etwas in Umwandlung begriffen, und es gibt manches, was man deuten kann wie die Morgenröte einer neuen Weltanschauung. Aber im Ganzen herrscht doch dasjenige, was ich Ihnen heute ganz einleitungsweise charakterisieren möchte.

Der Forscher sucht heute von drei Ausgangspunkten aus der Natur beizukommen. Das Erste ist, dass er versucht, die Natur so zu beobachten, dass er von den Naturwesen und Naturerscheinungen aus zu Art- und Gattungsbegriffen kommt. Er versucht zu gliedern die Naturerscheinungen und Wesenheiten. Sie brauchen sich nur daran zu erinnern, wie dem Menschen in der äußeren, sinnlichen Erfahrung gegeben sind, ich will sagen, einzelne Wölfe, einzelne Hyänen, einzelne Wärmeerscheinungen, einzelne Elektrizitätserscheinungen und wie er dann versucht, solche einzelnen Erscheinungen zusammenzufassen und in Arten und Gattungen zu vereinigen; wie er spricht von der Art Wolf, der Art Hyäne und so weiter, wie er auch bei den Naturerscheinungen spricht von gewissen Arten, wie er also das zusammenfasst, was im Einzelnen gegeben ist. Man möchte sagen: Diese wichtige erste Tätigkeit, die ausgeübt wird im Naturforschen, sie wird schon etwas unter der Hand ausgeübt. Man wird sich nicht bewusst, dass man eigentlich nachforschen müsste, wie sich dieses Allgemeine, zu dem man kommt, wenn man einteilt und gliedert, wie sich das zu der Einzelheit verhält.

Das Zweite, was heute getan wird, wenn man sich auf dem Felde der Naturforschung betätigt, ist, dass man versucht, entweder durch das vorbereitende Experiment oder durch dasjenige, was sich daran anschließt durch die begriffliche Verarbeitung der Ergebnisse desselben, dass man versucht, zu dem zu kommen, was man die Ursachen der Erscheinungen nennt. Wenn man von denselben spricht, so hat man ja oftmals im Sinne Kräfte, Stoffe - man spricht von der Kraft der Elektrizität, der Kraft des Magnetismus, der Kraft der Wärme und so weiter - man hat auch im Sinne Umfassenderes oftmals. Man spricht davon, dass hinter den Lichterscheinungen oder auch hinter den Elektrizitätserscheinungen so etwas ist wie der unbekannte Äther. Man versucht, aus den Ergebnissen der Experimente auf die Eigenschaften dieses Äthers zu kommen. Sie wissen, alles dasjenige, was über diesen Äther ausgesagt wird, ist außerordentlich strittig. Aber auf eines darf wohl dabei gleich aufmerksam gemacht werden: Man versucht, indem man so, wie man sagt, zu den Ursachen der Erscheinungen aufsteigen will, vom Bekannten in eine Art Unbekanntes hinein den Weg, und man fragt nicht viel darüber nach, welche Berechtigung eigentlich vorliegt, von dem Bekannten in das Unbekannte hineinzukommen. Man gibt sich nur wenig zum Beispiel Rechenschaft darüber, welches Recht eigentlich vorliegt, davon zu sprechen, dass, wenn wir irgendeine Licht- oder Farbenerscheinung wahrnehmen, so ist das, was wir subjektiv als Farbenqualität bezeichnen, die Wirkung auf uns, auf unser Seelisches, auf unseren Nervenapparat, [ist] die Wirkung eines objektiven Vorgangs, der sich im Weltenäther als Wellenbewegung abspielt. Sodass wir eigentlich unterscheiden müssten den subjektiven und den objektiven Vorgang, der in einer Wellenbewegung des Äthers oder in [einer] Wechselwirkung desselben und den Vorgängen in der ponderablen Materie besteht, dass wir eigentlich dieses Zweifache hätten.

Diese Anschauungsweise, die jetzt ja ein wenig ins Wanken gekommen ist, die war diejenige, die das neunzehnte Jahrhundert beherrscht hat und die eigentlich in der Art und Weise, wie man über die Erscheinungen spricht, heute noch überall zu finden ist, die noch unsere wissenschaftliche Literatur durchdringt, die durchdringt die Art und Weise, wie über die Dinge gesprochen wird.

Dann aber ist noch ein Drittes, wodurch sich der sogenannte Naturforscher zu nähern sucht der Konfiguration der Natur. Das ist, dass er die Erscheinungen ins Auge fasst. Nehmen wir eine einfache Erscheinung, diejenige, dass jeder Stein, wenn wir ihn loslassen, zur Erde fällt oder, wenn wir ihn an eine Schnur anbinden und hängen lassen, er in senkrechter Richtung zur Erde zieht. Solche Erscheinungen fasst man zusammen und kommt von diesen Erscheinungen zu demjenigen, was man Naturgesetz nennt. So betrachtet man es als ein einfaches Naturgesetz, wenn man sagt: Jeder Weltenkörper zieht die auf ihm befindlichen Körper an. Man nennt die Kraft, die da wirkt, die Gravitation oder Schwerkraft, und man spricht solch eine Kraft in bestimmten Gesetzen aus. Ein Musterbeispiel für solche Gesetze sind zum Beispiel die drei Kepler’schen Gesetze.

Nun, auf diese drei Arten versucht sich die sogenannte Naturforschung der Natur zu nähern. Nun möchte ich gleich dem entgegenstellen, wie Goethe’sche Naturanschauung eigentlich von allen dreien das Gegenteil anstrebt. Erstens war für Goethe, als er anfing, sich mit den Naturerscheinungen zu befassen, die Gliederung in Arten und Gattungen sowohl der Naturwesen wie der Naturtatsachen sogleich etwas höchst Problematisches. Er wollte nicht gelten lassen die Hinaufführung der einzelnen konkreten Wesen und konkreten Tatsachen auf gewisse starre Art- und Gattungsbegriffe, wollte vielmehr verfolgen den allmählichen Übergang der einen Erscheinung in die andere, wollte verfolgen den Übergang der einen Gestaltung eines Wesens in die andere Gestaltung eines Wesens. Das, worum es ihm zu tun war, war nicht artliche und gattungsmäßige Gliederung, sondern es war Metamorphose, sowohl der Naturerscheinungen wie auch der einzelnen Wesenheiten in der Natur.

Aber auch in dem Sinn, wie das noch die ganze Nach-Goethe’sche Naturforschung getan hat, auf sogenannte Naturursachen zu gehen, auch das war nicht eigentlich nach Goethes Vorstellungsart, und gerade in diesem Punkt ist es von großer Wichtigkeit, sich bekannt zu machen mit dem prinzipiellen Unterschied, der besteht zwischen der Art der gegenwärtigen Naturforschung und der Art, wie Goethe an die Natur herantritt.

Die gegenwärtige Naturforschung macht Experimente. Sie verfolgt also die Erscheinungen, dann versucht sie, diese begrifflich zu verarbeiten und sucht sich Vorstellungen zu bilden über dasjenige, was hinter den Erscheinungen als die sogenannten Ursachen steht, zum Beispiel hinter der subjektiven Licht- und Farbenerscheinung die objektive Wellenbewegung im Äther.

Goethe verwendet das ganze naturwissenschaftliche Denken nicht in diesem Stil. Er geht gar nicht in seiner Naturforschung von dem sogenannten Bekannten in das sogenannte Unbekannte hinein, sondern er will immer in dem Bekannten stehen bleiben, ohne dass er sich zunächst darum bekümmert, ob das Bekannte bloß subjektiv ist, also eine Wirkung auf unsere Sinne oder auf unsere Nerven oder auf unsere Seele, oder ob es objektiv ist. Solche Begriffe, wie die der subjektiven Farbenerscheinungen und der objektiven Wellenbewegungen draußen im Raums, solche bildet sich Goethe gar nicht, sondern ihm ist dasjenige, was er ausgebreitet im Raum, was er vorgehend in der Zeit sieht, ein durchaus Einheitliches, bei dem er sich nicht nach Subjektivität und Objektivität fragt. Er verwendet gar nicht jenes Denken und jene Methoden, die in der Naturwissenschaft angewendet werden, dazu, um von dem Bekannten auf das Unbekannte zu schließen, sondern er verwendet alles Denken, alle Methoden dazu, die Phänomene, die Erscheinungen selbst so zusammenzustellen, dass man durch diese Zusammenstellung der Phänomene, der Erscheinungen, zuletzt solche Erscheinungen bekommt, die er Urphänomene nennt, die nun wiederum, ohne dass man Rücksicht nimmt auf subjektiv und objektiv, das aussprechen, was er zur Grundlage seiner Welt- und Naturbetrachtung machen will. Also, Goethe bleibt stehen innerhalb der Reihe der Erscheinungen, vereinfacht sie nur und betrachtet dann dasjenige, was sich als einfache Erscheinungen überschauen lässt, als das Urphänomen.

Goethe betrachtet also das Ganze, was man nennen kann naturwissenschaftliche Methode, nur als Werkzeug, um innerhalb der Erscheinungssphäre selbst so die Erscheinungen zu gruppieren, dass sie selbst ihre Geheimnisse aussprechen. Nirgends versucht Goethe von einem sogenannten Bekannten auf irgendein Unbekanntes zu rekurrieren. Daher gibt es für Goethe auch nicht das, was man Naturgesetz nennen kann.

Ein Naturgesetz sehen Sie, wenn ich sage: Bei den Umläufen um die Sonne machen die Planeten gewisse Bewegungen, bei denen diese und diese Bahnen beschrieben werden. Für Goethe handelte es sich nicht darum, zu solchen Gesetzen zu kommen, sondern dasjenige, was er ausspricht als die Grundlage seines Forschens, sind Tatsachen, zum Beispiel die Tatsache, wie zusammenwirken Licht und in den Weg des Lichts gestellte Materie. Wie die zusammenwirken, das spricht er in Worten aus, das ist kein Gesetz, sondern eine Tatsache. Und solche Tatsachen sucht er seiner Naturbetrachtung zugrunde zu legen. Er will nicht von dem Bekannten zu dem Unbekannten aufsteigen, er will auch nicht Gesetze haben, er will im Grunde genommen eine Art rationeller Naturbeschreibung haben. Nur dass ein Unterschied für ihn besteht zwischen der Beschreibung des Phänomens, das unmittelbar ist, das kompliziert ist, und dem anderen, das man herausgeschält hat, das nur noch die einfachsten Elemente aufweist, das dann ebenso von Goethe der Naturbetrachtung zugrunde gelegt wird wie sonst das Unbekannte oder auch der rein begrifflich festgesetzte, gesetzmäßige Zusammenhang.

Nun liegt noch etwas vor, was geradezu Licht verbreiten kann über dasjenige, was herein will in unsere Naturbetrachtung im Goetheanismus, und über dasjenige, was da ist. Es liegt vor die merkwürdige Tatsache, dass kaum irgendjemand so klare Anschauungen hatte über die Beziehungen der Naturerscheinungen zu der mathematischen Betrachtung wie Goethe. Das wird ja immer gewöhnlich bestritten. Einfach, weil Goethe selbst kein ausgepichter Mathematiker war, wird bestritten, dass er eine klare Anschauung hatte [von den Beziehungen] der Naturerscheinungen zu den mathematischen Formulierungen, die immer beliebter und beliebter geworden sind und die eigentlich im Grunde genommen das einfach Sichere in der Naturbetrachtung heute sind. Nun handelt es sich darum, dass in neuerer Zeit immer mehr und mehr diese mathematische Betrachtungsweise der Naturerscheinungen - also, es wäre falsch, zu sagen: die mathematische Naturbetrachtung -, diese Betrachtung der Naturerscheinungen durch mathematische Formulierungen, dass diese gerade auch maßgebend geworden ist für die Art, wie man sich die Natur selbst vorstellt.

Nun muss man über diese Dinge zur Klarheit kommen. Sehen Sie, da haben wir, ich möchte sagen, auf dem gebräuchlichen Wege zur Natur hin eigentlich zunächst dreierlei. Dieses Dreierlei, das ist vom Menschen angewendet, bevor er eigentlich zur Natur kommt. Das Erste ist die gewöhnliche Arithmetik. Wir rechnen außerordentlich viel in der Naturbetrachtung heute, wir rechnen und zählen. Nun muss man sich klar darüber sein, dass die Arithmetik etwas ist, was der Mensch durchaus durch sich selbst begreift. Es ist ganz gleichgültig, was wir zählen, wenn wir zählen. Indem wir Arithmetik in uns aufnehmen, nehmen wir erwas in uns auf, das zunächst gar keinen Bezug zur Außenwelt hat. Daher können wir ebenso gut Erbsen wie Elektronen zählen. Die Art und Weise, wie wir einsehen, dass unsere Zähl- und Rechnungsmethoden richtig sind, die ist etwas ganz anderes als das, was sich uns ergibt in dem Vorgang, auf den wir die Arithmetik anwenden.

Das Zweite ist noch immer etwas, was wir ausüben, bevor wir eigentlich an die Natur herankommen. Es ist das, was Gegenstand der Geometrie ist. Was ein Würfel, was ein Oktaeder ist, wie ihre Winkel sind, das machen wir aus, ohne dass wir unsere Beobachtung über die Natur ausdehnen, das ist etwas, was wir aus uns herausspinnen. Dass wir die Dinge zeichnen, ist nur etwas, was unserer Trägheit dient. Wir könnten ebenso gut alles dasjenige, was wir durch Zeichnung veranschaulichen, uns bloß vorstellen, und es ist sogar nützlich, wenn wir uns manches bloß vorstellen und weniger die Leiter der Veranschaulichung benützen. Daraus ergibt sich, dass dasjenige, was wir auszusagen haben über die geometrische Form, aus einem Gebiet genommen ist, das zunächst fern der äußeren Natur steht. Was wir auszusagen haben über einen Würfel, das wissen wir, ohne dass wir es ablesen vom Steinsalzwürfel. Aber es muss sich an diesem auch finden. Wir machen etwas also fern der Natur und wenden es dann auf die Natur an.

Ein Drittes, mit dem wir noch immer nicht an die Natur herandringen, ist das, was wir treiben in der sogenannten Phoronomie, in der Bewegungslehre. Nun ist es doch von einer gewissen Wichtigkeit, dass Sie sich klarmachen, wie auch diese Phoronomie etwas ist, was im Grunde genommen noch ferne steht der sogenannten wirklichen Naturerscheinung, Sehen Sie, wenn ich mir vorstelle - ich sehe nicht auf einen bewegten Gegenstand hin, sondern ich stelle mir vor -, dass ein Gegenstand sich bewegt von - sagen wir - von Punkt \(a\) nach Punkt \(b\). Ich sage sogar, es bewege sich der Punkt \(a\) nach Punkt \(b\) hin. Das stelle ich mir vor. Nun kann ich mir jederzeit vorstellen, dass diese Bewegung von \(a\) nach \(b\), die ich durch den Pfeil angedeutet habe, aus zwei Bewegungen zusammengesetzt ist. Nämlich, denken Sie sich einmal: Der Punkt \(a\) würde nach \(b\) kommen sollen, aber er würde nicht gleich die Richtung nach \(b\) einschlagen, sondern er würde sich zunächst in dieser Richtung bewegen bis \(c\). Wenn er sich dann hinterher von \(c\) nach \(b\) bewegt, so kommt er auch bei \(b\) an. Ich kann also die Bewegung von \(a\) nach \(b\) mir auch so vorstellen, dass sie nicht auf der Linie \(a-b\) verläuft, sondern auf der Linie oder auf den zwei Linien \(a-c-b\). Das heißt, ich kann mir vorstellen, dass die Bewegung \(a-b\) zusammengesetzt ist aus der Bewegung \(a-c\) und \(c-b\), also aus zwei anderen Bewegungen. Sie brauchen gar nicht einen Naturvorgang zu verfolgen, sondern Sie können sich vorstellen, dass die Bewegung \(a-b\) aus den beiden anderen Bewegungen zusammengesetzt ist, das heißt, dass statt der einen Bewegung die beiden anderen Bewegungen mit demselben Effekt ausgeführt werden könnten. Wenn ich mir das vorstelle, so ist dieses Vorgestellte rein aus mir herausgesponnen. Denn statt dass ich das gezeichnet habe, hätte ich Ihnen Anleitung geben können zum Vorstellen der Sache, und das müsste eine für Sie gültige Vorstellung sein.

Aber wenn in der Natur wirklich so etwas wie ein Punkt \(a\) da ist, ein kleines Schrotkorn etwa, und sich einmal von \(a\) nach \(b\) bewegt und ein anderes Mal von \(a\) nach \(c\) und von \(c\) nach \(b\) bewegt, so geschieht das wirklich, was ich mir vorgestellt habe. Das heißt, in der Bewegungslehre ist es so, dass ich mir die Bewegungen vorstelle, aber dass dieses Vorgestellte anwendbar ist auf die Naturerscheinungen, sich bewähren muss an den Naturerscheinungen.

So also können wir sagen: In Arithmetik, in Geometrie, in Phoronomie haben wir die drei Vorstufen der Naturbetrachtung. Die Begriffe, die wir dabei gewinnen, spinnen wir ganz aus uns selbst heraus; aber sie sind maßgebend für dasjenige, was in der Natur geschieht.

Ja, nun bitte ich Sie, einen kleinen Erinnerungsspaziergang zu machen in Ihr mehr oder weniger lang zurückliegendes Physikstudium und sich zu erinnern, dass einmal darin Ihnen so etwas entgegengetreten ist wie das sogenannte Kräfte-Parallelogramm, das heißt dasjenige, wenn auf einen Punkt \(a\) eine Kraft wirkt, so kann diese Kraft den Punkt \(a\) ziehen nach dem Punkt \(b\). Also unter dem Punkt \(a\) verstehe ich irgendetwas Materielles, sagen wir wiederum ein kleines Körnchen. Das ziehe ich durch eine Kraft von \(a\) nach \(b\). Bitte den Unterschied zu beachten zwischen dem, wie ich jetzt spreche und wie ich vorhin gesprochen habe. Ich habe vorhin von der Bewegung gesprochen, jetzt spreche ich davon, dass eine Kraft das \(a\) nach \(b\) zieht. Wenn Sie das Maß der Kraft, das von \(a\) nach \(b\) zieht, sagen wir mit fünf Gramm, ausdrücken durch Strecken: ein Gramm, zwei Gramm, drei Gramm, vier Gramm, fünf Gramm, so können Sie sagen: Ich ziehe mit der Kraft von fünf Gramm das \(a\) nach \(b\).

Ich könnte den ganzen Vorgang auch anders gestalten, könnte mit einer gewissen Kraft das \(a\) zuerst nach c ziehen. Um das \(a\) nach \(c\) zu ziehen, brauche ich eine andere Kraft, als um es von \(a\) direkt nach \(b\) zu ziehen. Wenn ich es aber von \(a\) nach \(c\) ziehe, also statt dass ich so [nach \(b\)] ziehe, ziehe ich so [nach \(c\)] - dann kann ich noch einen zweiten Zug [ausführen]. Ich kann ziehen in derselben Richtung, die hier durch die Verbindungslinie von \(c\) nach \(b\) angegeben ist, und ich muss dann ziehen mit einer Kraft, welche entspricht dieser Linie. Wenn ich also hier [bei \(a\)] mit einer Kraft von fünf Gramm ziehe, so müsste ich aus dieser Figur ausrechnen, wie groß der Zug \(a-c\) sein muss und wie groß der Zug von \(c-b\) sein muss. Und wenn ich zu gleicher Zeit ziehe von \(a\) nach \(c\) und \(a\) nach \(d\), so ziehe ich das \(a\) so fort, dass es zuletzt nach \(b\) kommt, und ich kann berechnen, wie stark ich nach \(c\) und wie stark ich nach \(d\) ziehen muss.

Das kann ich nicht so ausrechnen, wie ich die Bewegung ausrechnen kann im obigen Beispiel. Was ich hier oben für die Bewegung finde, das kann ich in der Vorstellung ausrechnen. Sobald ein wirklicher Zug, das heißt eine wirkliche Kraft ausgeübt wird, muss ich diese Kraft irgendwie messen. Da muss ich an die Natur selbst herangehen, da muss ich schreiten von der Vorstellung in die Tatsachenwelt hinein. Und je klarer Sie sich machen diesen Unterschied zwischen dem Bewegungs-Parallelogramm - ein Parallelogramm wird es ja auch, wenn Sie sich dieses [ erste Figur, \(d\) ] ergänzen -, zwischen dem Bewegungs-Parallelogramm und dem Kräfte-Parallelogramm, dann haben sie klar und scharf ausgedrückt den Unterschied zwischen all dem, was sich innerhalb der Vorstellung festsetzen lässt, und dem, was da liegt, wo die Vorstellungen aufhören.

Sie können zu Bewegungen in der Vorstellung kommen, aber nicht zu Kräften. Die müssen Sie in der Außenwelt messen. Und Sie können überhaupt nur konstatieren, dass das \(a\) nach \(b\) gezogen wird nach den Gesetzen des Kräfte-Parallelogramms, wenn zwei Züge ausgeübt werden, von a nach \(c\) und von \(a\) nach \(d\), wenn Sie es äußerlich experimentell feststellen. Es gibt gar keinen Vorstellungsbeweis wie oben. Das muss äußerlich gemessen werden.

Daher kann man sagen: Das Bewegungs-Parallelogramm wird gewonnen aus der bloßen Vernunft heraus. Das Kräfte-Parallelogramm muss gewonnen werden auf empirische Weise durch äußere Erfahrungen. Und indem Sie unterscheiden Bewegungs-Parallelogramm von Kräfte-Parallelogramm, haben Sie haarscharf vor sich den Unterschied zwischen Phoronomie und Mechanik. Die Mechanik, die es schon zu tun hat mit Kräften, nicht mehr bloß mit Bewegungen, ist bereits eine Naturwissenschaft. Eine eigentliche Naturwissenschaft ist Arithmetik, ist Geometrie, ist Phoronomie noch nicht. Nur die Mechanik hat es mit der Wirkung von Kräften im Raum und in der Zeit zu tun. Aber man muss über das Vorstellungsleben hinausgehen, wenn man zu dieser ersten Naturwissenschaft, zu der Mechanik, vorschreiten will.

Nun, schon hier in diesem Punkt denken eigentlich unsere Zeitgenossen nicht klar genug. Denn, sehen Sie, ich will Ihnen an einem Beispiel anschaulich machen, wie eigentlich der gewaltige Sprung ist von der Phoronomie in die Mechanik hinein. Die phoronomischen Erscheinungen können verlaufen ganz innerhalb des Vorstellungsraumes; aber zunächst werden die mechanischen Erscheinungen nur von uns geprüft werden können an der Außenwelt. Aber man macht sich das so wenig klar, dass man eigentlich immer etwas konfundiert dasjenige, was man noch mathematisch einsehen kann, mit demjenigen, worinnen schon die Entitäten der Außenwelt spielen. Denn, was muss da sein, wenn wir vom Kräfte-Parallelogramm reden? Solange wir vom Bewegungs-Parallelogramm reden, braucht nichts da zu sein als ein gedachter Körper. Aber dort beim Kräfte-Parallelogramm muss schon da sein eine Masse, eine Masse, die zum Beispiel Gewicht hat. Ja, darüber muss man sich klar sein: In a muss eine Masse sein. Jetzt fühlt man sich wohl auch gedrungen zu fragen: Was ist das eigentlich, eine Masse?

Ja, da wird man gewissermaßen sagen müssen: Hier stocke ich schon. Denn es stellt sich gewissermaßen heraus, dass, wo man verlässt dasjenige, was in der Vorstellungswelt so festgesetzt werden kann, dass es für die Natur gilt, dass [wenn] man da hineinkommt, dass man auf ziemlich unsicherem Gebiete steht. Sie wissen ja, dass man sich, um gewissermaßen mit Arithmetik, mit Geometrie und Phoronomie und mit dem, was man dann ein bisschen hereinholt von der Mechanik, [auszukommen,] sich mit dem ausrüstet, dass man versucht, in dem man das, was man Materie nennt, sich zerteilt denkt in Moleküle und Atome, dass man versucht, durch die Mechanik der Moleküle, der Atome sich vorzustellen die Naturerscheinungen, die man zunächst als subjektive Erfahrungen betrachtet.

Wir greifen irgendeinen warmen Körper an. Der Naturforscher erzählt uns: Das, was du da Wärme nennst, ist Wirkung auf deine Wärmenerven. Objektiv vorhanden ist die Bewegung der Moleküle, der Atome. Die kannst du studieren nach den Gesetzen der Mechanik. Und so studiert man die Gesetze der Mechanik, [die Mechanik der] Atome und Moleküle, und man hat ja lange Zeit geglaubt, durch das Studium der Mechanik [der] Atome und so weiter überhaupt alle Naturerscheinungen erklären zu können. Heute ist das ja schon im Wanken. Aber auch dann muss man, selbst wenn man bis zum Atom gedanklich vorgeht, durch allerlei Experimente dazu kommen, sich zu fragen: Ja, wie tritt denn da die Kraft auf? Wie wirkt die Masse? Wenn man bis zum Atom vordringt, so muss man fragen um die Masse des Atoms, und wenn man nach dieser fragt, muss man [auch] fragen: Wie erkennt man sic? Man kann gewissermaßen die Masse auch nur an ihrer Wirkung erkennen.

Nun, man hat sich gewöhnt, das Kleinste, was man anspricht als Träger mechanischer Kraft, so an der Wirkung zu erkennen, dass man sich die Frage beantwortet hat: Wenn ein solcher kleinster Teil einen anderen kleinen Teil, sagen wir einen kleinen Teil einer Materie von dem Gewicht eines Gramms, in Bewegung versetzt, so muss da eine Kraft ausgehen von dieser Materie, die die andere in Bewegung versetzt. Wenn diese Masse die andere Masse, welche ein Gramm schwer ist, so in Bewegung versetzt, dass diese andere Masse in einer Sekunde einen Zentimeter weit fliegt, so hat die erste Masse eine Kraft angewendet. Also, wenn eine Kraft angewendet wird so, dass ein Gramm in einer Sekunde einen Zentimeter weit fliegt, so hat die erste Masse eine Kraft angewendet, diese hat man sich gewöhnt als eine Art von Welteneinheit zu betrachten. Und wenn man sagen kann: Irgendeine Kraft ist sovielmal größer als diese Kraft, welche man anwenden muss, um ein Gramm in einer Sekunde einen Zentimeter weit zu bringen, so weiß man, wie sich diese Kraftanwendung zu einer gewissen Welteneinheit verhält. Diese Welteneinheit ist, wenn man sie ausdrücken würde durch ein Gewicht, ist [so] groß [wie] 0,001019 Gramm. Also würde man sagen können: Solch ein atomistischer Körper, über dessen Kraftanwendung wir nicht weiter zurückgehen in der Natur, der ist imstande, irgendeinem Körper von einem Gramm Größe einen solchen Schubs zu geben, dass dieser in einer Sekunde einen Zentimeter weit fliegt.

Aber ausdrücken, was in dieser Kraft steckt, wie kann man es nur? Ja, wenn man auf die Waage geht: Diese Kraft kommt gleich dem Druck, der sich ausdrückt durch 0,001019 Gramm beim Wägen. Also, durch etwas sehr Äußerliches, Reales muss ich mich ausdrücken, wo ich an das heranwill, was in der Welt Masse genannt wird. Ich kann dasjenige, was ich da ersinne als Masse, dadurch ausdrücken, dass ich etwas, was ich auf äußerlichen Wegen kennenlerne, ein Gewicht, ins Feld führe. Ich drücke die Masse nur aus durch ein Gewicht. Selbst wenn ich in das Atomisieren der Masse gehe, drücke ich mich durch ein Gewicht aus.

Damit möchte ich Ihnen eben scharf den Punkt bezeichnen, wo wir gewissermaßen aus dem a priori Festzustellenden in das Naturgemäße hineinkommen. Und ich möchte Sie darauf aufmerksam machen, wie notwendig es ist, sich klarzumachen, inwieweit anwendbar ist dasjenige, was wir außer aller Natur feststellen in Arithmetik, Geometrie, Phoronomie, inwieweit das maßgebend sein kann für das, was uns eigentlich von ganz anderer Seite entgegentritt, was uns zum ersten Mal entgegentritt in der Mechanik und was eigentlich erst der Inhalt dessen sein kann, was wir als Naturerscheinung bezeichnen.

Sehen Sie, Goethe war sich darüber klar, dass man von Naturerscheinungen überhaupt erst sprechen kann in dem Augenblick, wo wir von der Phoronomie in die Mechanik eintreten. Und weil er dieses wusste, daher war es ihm so klar, welche Beziehung einzig und allein die für die Naturwissenschaft auch so vergötterte Mathematik für diese Naturwissenschaft haben kann.

An einem Beispiele möchte ich Ihnen dies noch klarmachen: So wie wir sagen können, das einfachste Element in der Naturkraftwirkung, das wäre irgendein atomistischer Körper, der imstande ist, ein Gramm in einer Sekunde einen Zentimeter weit zu schleudern, so wie wir das sagen können, so können wir schließlich bei allen Kraftwirkungen davon sprechen, dass von irgendeiner Seite her die Kraft ausgeht und nach irgendeiner Seite hin wirkt. Daher können wir uns gewöhnen - und diese Gewöhnung ist ja auch in der Naturwissenschaft gang und gäbe - für die Naturwirkungen gewissermaßen überall die Punkte aufzusuchen, von denen die Kräfte ausgehen. Wir werden an zahlreichen Fällen sehen, dass wir gewissermaßen Erscheinungsfelder haben werden, und von diesen gehen wir zurück auf die Punkte, von denen die Kräfte ausgehen, die die Erscheinungen beherrschen. Daher spricht man für solche Kräfte, für die man die Punkte sucht, von denen sie ausgehen, damit sie die Erscheinungsfelder beherrschen: Man spricht von Zentralkräften, weil sie immer von Zentren ausgehen. Wir könnten auch sagen: Von Zentralkräften sind wir berechtigt zu reden, wenn wir an einen Punkt gehen, von dem aus ganz bestimmte Kräfte gehen, die ein Erscheinungsfeld beherrschen. Dann aber muss nicht immer dieses Kräftespiel wirklich stattfinden, sondern es kann so sein, dass in dem Zentralpunkt gewissermaßen nur die Möglichkeit vorhanden ist, dass dieses Kräftespiel stattfindet und dass erst dadurch, dass gewisse Bedingungen eintreten in der umliegenden Sphäre, diese Kräfte zur Tätigkeit kommen.

Wir werden sehen im Laufe dieser Tage, wie gewissermaßen in den Punkten Kräfte konzentriert sind, die noch nicht spielen. Erst wenn wir gewisse Bedingungen erfüllen, dann rufen sie in ihrer Umgebung Erscheinungen hervor. Aber wir müssen doch einsehen, dass in diesem Punkt oder in diesem Raum Kräfte konzentriert sind, die auf ihre Umgebung wirken können. Das ist es eigentlich, was wir immer aufsuchen, wenn wir von der Welt physikalisch reden. Alles physikalische Forschen besteht darin, dass wir die Zentralkräfte nach ihren Zentren hin verfolgen, dass wir versuchen, zu den Punkten vorzudringen, von welchen Wirkungen ausgehen können. Daher müssen wir annehmen, dass es für solche Naturwirkungen Zentren gibt, die gewissermaßen nach gewissen Richtungen hin mit Wirkungsmöglichkeiten geladen sind. Diese Wirkungsmöglichkeiten können wir allerdings durch allerlei Vorgänge messen und wir können auch in Maßen ausdrücken, wie stark solch ein Punkt wirken kann. Wir nennen da im Allgemeinen, wenn in einem solchen Punkt Kräfte konzentriert sind, die wirken können, wenn wir gewisse Bedingungen erfüllen, wir nennen das Maß solcher Kräfte, die da konzentriert sind, das Potential, das Kräfte-Potential. Daher können wir auch sagen: Wir gehen darauf aus, wenn wir Naturwirkungen studieren, Zentralkräfte nach ihren Potentialen hin zu verfolgen. Wir gehen nach gewissen Mittelpunkten hin, um diese Mittelpunkte als Ausgangspunkte von Potentialkräften zu studieren.

Sehen Sie, das ist im Grunde genommen der Gang, den diejenige naturwissenschaftliche Richtung macht, die alles in Mechanik verwandeln möchte. Sie sucht die Zentralkräfte, beziehungsweise die Potentiale der Zentralkräfte.

Hier handelt es sich darum, nun, wie durch einen wichtigen Schritt in der Natur selbst sich klar zum Bewusstsein zu bringen: Sie können unmöglich eine Erscheinung, in die das Leben hineinspielt, verstehen, wenn Sie nur nach dieser Methode vorgehen, wenn Sie nur suchen die Potentiale für Zentralkräfte. Wenn Sie nach dieser Methode studieren wollten, sagen wir, das Kräftespiel in einem tierischen Keim oder in einem pflanzlichen Keim, Sie würden nie zurechtkommen. Es ist ja ein Ideal der heutigen Naturwissenschaft, auch die organischen Erscheinungen durch Potentiale zu studieren, durch irgendwie geartete Zentralkräfte. Das wird die Morgenröte einer neuen Weltanschauung auf diesem Gebiete sein, dass man darauf kommen wird: Durch das Verfolgen solcher Zentralkräfte geht es nicht, kann man Erscheinungen, in die das Leben spielt, nicht studieren. Denn warum nicht? Ja, stellen wir uns einmal schematisch vor, wir gingen darauf aus, [physikalisch] Naturvorgänge zu studieren. Wir gehen zu Zentren, studieren die Wirkungsmöglichkeiten, die von solchen Zentren ausgehen können. Da finden wir die Wirkung. Also, wenn ich die drei Punkte \(a\), \(b\), \(c\) in ihren Potentialen ausrechne, so finde ich, dass \(a\) auf \(α\), \(β\), \(γ\) wirken kann, ebenso c wirken kann auf \(α'\), \(β'\), \(γ'\) und so weiter. Ich bekäme dann eine Anschauung darüber, wie die Wirkung einer gewissen Sphäre sich abspielt unter dem Einfluss von Potentialen von gewissen Zentralkräften.

Niemals werde ich auf diesem Wege die Möglichkeit finden, etwas zu erklären, in das Lebendiges hineinspielt. Denn warum? Weil die Kräfte, die nun für das Lebendige in Betracht kommen, kein Potential haben und keine Zentralkräfte sind, sodass, wenn Sie hier versuchen würden, in \(d\) physikalische Wirkungen zu suchen unter dem Einfluss von \(a\), \(b\), \(c\), so würden Sie auf Zentralkräfte zurückgehen können; wenn Sie [ in \(d\) ] Lebenswirkungen studieren wollen, können Sie niemals so sagen. Warum? Weil es keine Zentren \(a\), \(b\), \(c\) gibt für die Lebenswirkungen, sondern Sie kommen nur mit der Vorstellung zurecht, wenn Sie sagen: Nun, ich habe in d Lebendiges, nun suche ich die Kräfte, die auf das Leben wirken. In \(a\), \(b\), \(c\) kann ich sie nicht finden, wenn ich noch weiter gehe auch nicht, sondern gewissermaßen nur, wenn ich an der Welten Ende gehe, und zwar an den ganzen Umkreis der Welten Ende. Das heißt, ich müsste hier von d ausgehend bis ans Weltenende gehen und mir vorstellen, dass von der Kugelsphäre herein überall Kräfte wirkten, die so zusammenspielten, dass sie in d zusammenkommen.

Es ist also das volle Gegenteil von Zentralkräften, die ein Potential haben. Wie sollte ich ein Potential ausrechnen für dasjenige, was da von der Unendlichkeit des Raumes von allen Seiten hereinspielt! Da würde es so zu rechnen [sein]: Ich würde die Kräfte zu zerteilen haben, eine Gesamtkraft würde ich in immer kleinere Partien zerteilen müssen und dann käme ich immer mehr an den Rand der Welt und dann würde die Kraft zersplittern. Jede Rechnung würde auch zersplittern, weil hier nicht Zentralkräfte, sondern Universalkräfte ohne Potential wirken. Hier hört das Rechnen auf. sehen Sie, das ist der Sprung wiederum von dem unlebendigen Natürlichen in das lebendige Natürliche hinein.

Nun kommt man mit einer wirklichen Naturbetrachtung nur zurecht, wenn man auf der einen Seite weiß, wie der Sprung von der Phoronomie in die Mechanik ist und wie wiederum der Sprung ist von der äußeren Natur in dasjenige, was nicht mehr durch Rechnung erreicht werden kann, weil jede Rechnung zersplittert, weil jedes Potential sich auflöst. Man kommt durch diesen zweiten Sprung von der äußeren unorganischen Natur in die lebendige Natur hinein. Aber man muss sich klar sein darüber, wie alles Rechnen aufhört, um das zu begreifen, was das Lebendige ist.

Nun habe ich Ihnen hier hübsch auseinandergeschält alles, was auf Potential- und Zentralkräfte zurückführt und was auf Universalkräfte hinführt. Aber draußen in der Natur ist das nicht so auseinandergeschält. Sie können die Frage aufwerfen: Wo ist etwas vorhanden, wo nur Zentralkräfte wirken nach Potentialen, und wo ist das andere vorhanden, wo Universalkräfte wirken, die nicht nach Potentialen sich berechnen lassen? Man kann eine Antwort darauf geben, aber diese beweist sogleich, auf welche wichtigen Gesichtspunkte man dabei rekurrieren muss. Man kann sagen: Alles das, was der Mensch an Maschinen herstellt, was aus den Elementen der Natur heraus kombiniert ist, dabei findet man rein abstrakt Zentralkräfte nach ihrem Potential. Was aber, auch Unlebendiges, in der Natur draußen ist, lässt sich trotzdem nicht restlos nach Zentralkräften beobachten. Das gibt es nicht, das geht nicht auf. Sondern es handelt sich darum, dass überall, wo man es zu tun hat mit nicht künstlich vom Menschen Hergestelltem, dass da ein Zusammenfluss stattfindet zwischen Zentralkraftwirkungen und Universalkraftwirkungen. Man findet im ganzen Reich der sogenannten Natur nichts, was im wahren Sinn des Wortes unlebendig ist, außer dem, was der Mensch künstlich herstellt, sein Maschinelles, sein Mechanisches.

Und das war, ich möchte sagen, in einem tiefen Naturinstinkt für Goethe etwas, was ihm durchaus klar-unklar war, weil es bei ihm Naturinstinkt war, worauf er aber seine ganze Naturanschauung baute. Und der Gegensatz zwischen Goethe und dem Naturforscher, wie er repräsentiert wird durch Newton, besteht eigentlich darinnen, dass die Naturforscher [nur] das betrachtet haben in der neueren Zeit: die äußere Natur durchaus im Sinn der Zurückführung auf Zentralkräfte zu beobachten, aus ihr gewissermaßen alles das hinauszuwälzen, was sich nicht durch Zentralkräfte und Potentiale feststellen lässt. Goethe wollte solch eine Betrachtung nicht gelten lassen, weil für ihn dasjenige, was man unter dem Einfluss dieser Betrachtung Natur nennt, nur eine wesenlose Abstraktion ist. Für ihn ist ein wirkliches Reale nur das, in das hineinspielen sowohl Zentralkräfte wie peripherische [Kräfte] als Universalkräfte. Und auf diesen Gegensatz ist im Grunde genommen auch seine ganze Farbenlehre aufgebaut. Nun, davon wird ja in den nächsten Tagen im Einzelnen zu sprechen sein.

Sehen Sie, ich musste insbesondere durch Berücksichtigung dessen, was ich mir vorgesehen habe heute, diese Einleitung zu Ihnen sprechen als eine Verständigung darüber, wie eigentlich das Verhältnis des Menschen zu der Naturbetrachtung ist. Man muss in unserer Zeit umso mehr einmal sich einer solchen Betrachtung hinwenden, wie wir sie heute gepflogen haben, aus dem Grunde, weil eigentlich heute wirklich die Zeit herangekommen ist, wo schimmert, möchte ich sagen, unterbewusst das Unmögliche der heutigen Naturanschauung [und] mancherlei von der Einsicht, dass es anders werden muss. Man lacht heute noch vielfach darüber, wenn Leute darauf kommen, dass es mit der alten Anschauung nicht geht. Aber es wird eine Zeit kommen, die gar nicht ferne liegt, wo dieses Lachen den Menschen vergehen wird, die Zeit, wo man auch physikalisch im Sinne Goethes wird sprechen können. Man wird vielleicht über die Farben im Sinne Goethes sprechen, wenn eine andere Burg erstürmt sein wird, die als noch viel fester gilt und die eigentlich heute auch schon ins Wanken gekommen ist. Das ist die Burg der Gravitationslehre. Gerade auf diesem Gebiete tauchen heute fast jedes Jahr Anschauungen auf, die an den Newton’schen Vorstellungen von der Gravitation rütteln, die davon sprechen, wie unmöglich es eigentlich ist, mit diesen Newton’schen Vorstellungen von der Gravitation zurechtzukommen, die ja rein darauf beruhen, dass der bloße Mechanismus der Zentralkräfte einzig und allein figurieren soll.

Ich glaube, dass gerade heute der Lehrer der Jugend sowohl wie derjenige, der überhaupt in die Kulturentwicklung eingreifen will, sich schon ein klares Bild davon machen muss, wie der Mensch zur Natur stehen muss.

First Lecture

My dear friends!

Following the words just read, some of which are already over thirty years old, I would like to note that, of course, I can only offer you a glimpse of the natural existence in the short time available to us. Firstly, we will have to be brief, especially as there will not be much time – but I think we will be able to continue what we have begun here in the not too distant future. Secondly, I was only informed of the intention to hold such a course after I had already arrived here. And so these few days can only be a very, very brief introduction.

On the one hand, I would like to provide something that may be useful for educators, perhaps less useful in the sense that they will be able to use it directly in their teaching in the way I am presenting it here, but rather in the sense that that it can permeate teaching as a certain basic scientific orientation. On the other hand, it will always be of particular importance for educators, alongside the various aberrations that natural science has experienced in recent times, to have at least the right background knowledge, and it is also from this point of view that I would like to give you some points of reference.

I would like to add something to the words that Dr. Stein has just kindly recalled, something I had to say at the beginning of the 1990s when I was asked by the Frankfurt Freies Hochstift to give a lecture on Goethe's natural science. I said at the time in my introduction that I would have to limit myself—this was in the 1990s—to talking more about Goethe's relationship to organic natural science. For it is simply impossible to incorporate Goethe's worldview into the physical and chemical view of the world today, because physicists and chemists today are condemned by everything that lives in physics and chemistry to regard everything that emanates from Goethe as a kind of nonsense, as something they cannot imagine. And I thought at the time that we would have to wait until physics and chemistry were guided, as it were, by their own research to see how the fundamental structure of their scientific endeavors leads them to absurdity. Then the time will come when Goethe's views will also be able to take hold in the fields of physics and chemistry.

Now I will endeavor to create harmony between what can be called experimental natural science and the view that can be gained from the results of experiments. Today, by way of introduction and—as is often said—theoretically, I would like to offer a few points for understanding. Today, I would like to aim directly at working toward a real understanding of the contrast between conventional, commonly accepted natural science and what can be gained as a scientific view from Goethe's general worldview. To do this, however, we will have to go into the prerequisites of scientific thinking today, as it is often called, in a somewhat theoretical way. Anyone who thinks about nature in the conventional sense today does not usually have a clear mental image of what his field of research actually is. Nature, I would say, has become a rather vague concept. We therefore do not want to start from the view that people have today about the nature of what nature is, but rather from how natural science is usually practiced. This way of working, as I will characterize it, is indeed undergoing a transformation, and there are many things that can be interpreted as the dawn of a new worldview. But on the whole, what I would like to characterize for you today as a preliminary introduction still prevails.