The Light Course

GA 320

24 December 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture II

My dear Friends,

Yesterday I was saying how in our study of Nature we have upon the one hand the purely kinematical, geometrical and arithmetical truths,—truths we are able to gain simply from our own life of thought. We form our thoughts about all that, which in the physical processes around us can be counted, or which is spatial and kinematical in form and movement. This we can spin, as it were, out of our own life of thought. We derive mathematical formulae concerning all that can be counted and computed or that is spatial in form and movement, and it is surely significant that all the truths we thus derive by thought also prove applicable to the processes of Nature. Yet on the other hand it is no less significant that we must have recourse to quite external experiences the moment we go beyond what can be counted and computed or what is purely spatial or kinematical. Indeed we need only go on to the realm of Mass, for it to be so.

In yesterday's lecture we made this clear to ourselves. While in phoronomy we can construct Nature's processes in our own inner life, we now have to leap across into the realm of outer, empirical, purely physical experience. We saw this pretty clearly in yesterday's lecture, and it emerged that modern Physics does not really understand what this leap involves. Till we take steps to understand it, it will however be quite impossible ever to gain valid ideas of what is meant or should be meant by the word “Ether” in Physics. As I said yesterday, present-day Physics (though now a little less sure in this respect) still mostly goes on speaking for example of the phenomena of light and colour rather as follows:—We ourselves are affected, say, by an impression of light or colour—we, that is, as beings of sense and nerve, or even beings of soul. This effect however is subjective. The objective process, going on outside in space and time, is a movement in the ether. Yet if you look it up in the text-books or go among the physicists to ascertain what ideas they have about this “ether” which is supposed to bring about the phenomena of light, you will find contradictory and confused ideas. Indeed, with the resources of Physics as it is today it is not really possible to gain true or clear ideas of what deserves the name of “ether”.

We will now try to set out upon the path that can really lead to a bridging of the gulf between phoronomy and even only mechanics,—inasmuch as mechanics already has to do with forces and with masses. I will write down a certain formula, putting it forward today simply as a well-known theorem. (We can go into it again another time so that those among you who may no longer recall it from your school days can then revise what is necessary for the understanding of it. Now I will simply adduce the essential elements to bring the formula before your minds.)

Let us suppose, first in the sense of pure kinematics, that a point (in such a case we always have to say, a point) is moving in a certain direction. For the moment, we are considering the movement pure and simple, not its causes. The point will be moving more or less quickly or slowly. We say it moves with a greater or lesser “velocity”. Let us call the velocity \(v\). This velocity, once more, may be greater or it may be smaller. So long as we go no farther than to observe that the point moves with such and such velocity, we are in the realm of pure kinematics. But this would not yet lead us to real outer Nature,—not even to what is mechanical in Nature. To approach Nature we must consider how the point comes to be moving. The moving object cannot be the mere thought of a point. Really to move, it must be something in outer space. In short, we must suppose a force to be acting on the point. I will call \(v\) the velocity and \(p\) the force that is acting on the point. Also we will suppose the force not only to be working instantaneously,—pressing upon the point for a single moment which of course would also cause it to move off with a certain velocity if there were no hindrance—but we will presuppose that the force is working continuously, so that the same force acts upon the point throughout its path. Let us call \(s\) the length of the path, all along which the force is acting on the point. Finally we must take account of the fact that the point must be something in space, and this “something” may be bigger or it may be smaller; accordingly, we shall say that the point has a greater or lesser mass. We express the mass, to begin with, by a weight. We can weigh the object which the force is moving and express the mass of it in terms of weight. Let us call the mass, \(m\).

Now if the force \(p\) is acting on the mass \(m\), a certain effect will of course be produced. The effect shows itself, in that the mass moves onward not with uniform speed but more and more quickly. The velocity gets bigger. This too we must take into account; we have an ever growing velocity, and there will be a certain measure of this increase of velocity. A smaller force, acting on the same mass, will also make it move quicker and quicker, but to a lesser extent; a larger force, acting on the same mass, will make it move quicker more quickly. We call the rate of increase of velocity the acceleration; let us denote the acceleration by \(g\). Now what will interest us above all is this:—(I am reminding you of a formula which you most probably know; I only call it to your mind.) Multiply the force which is acting on the given mass by the length of the path, the distance through which it moves; then the resulting product is equal to,—i.e. the same product can also be expressed by multiplying the mass by the square of the eventual velocity and dividing by 2. That is to say:

$$ps=\frac{mv^2}{2}$$Look at the right-hand side of this formula. You see in it the mass. You see from the equation: the bigger the mass, the bigger the force must be. What interests us at the moment is however this:—On the right-hand side of the equation we have mass, i.e. the very thing we can never reach phoronomically. The point is: Are we simply to confess that whatever goes beyond the phoronomical domain must always be beyond our reach, so that we can only get to know it, as it were, by staring at it,—by mere outer observation? Or is there after all perhaps a bridge—the bridge which modern Physics cannot find—between the phoronomical and the mechanical?

Physics today cannot find the transition, and the consequences of this failure are immense. It cannot find it because it has no real human science,—no real physiology. It does not know the human being. You see, when I write \(v^2\), therein I have something altogether contained within what is calculable and what is spatial movement. To that extent, the formula is phoronomical. When I write \(m\) on the other hand, I must first ask: Is there anything in me myself to correspond also to this,—just as my idea of the spatial and calculable corresponds to the \(v\)? What corresponds then to the \(m\)? What am I doing when I write the \(m\)? The physicists are generally quite unconscious of what they do when they write m. This then is what the question amounts to: Can I get a clear intelligible notion of what the \(m\) contains, as by arithmetic, geometry and kinematics I get a clear intelligible notion of what the \(v\) contains? The answer is, you can indeed, but your first step must be to make yourself more consciously aware of this:—Press with your finger against something: you thus acquaint yourself with the simplest form of pressure. Mass, after all, reveals itself through pressure. As I said just now, you realize the mass by weighing it. Mass makes its presence known, to begin with, simply by this: by its ability to exert pressure. You make acquaintance with pressure by pressing upon something with your finger. Now we must ask ourselves: Is there something going on in us when we exert pressure with our finger,—when we, therefore, ourselves experience a pressure—analogous to what goes on in us when we get the clear intelligible notion, say, of a moving body? There is indeed, and to realize what it is, try making the pressure ever more intense. Try it,—or rather, don't! Try to exert pressure on some part of your body and then go on making it ever more intense. What will happen? If you go on long enough you will lose consciousness. You may conclude that the same phenomenon—loss of consciousness—is taking place, so to speak, on a small scale when you exert a pressure that is still bearable. Only in that case you lose, a little of the force of consciousness that you can bear it. Nevertheless, what I have indicated—the loss of consciousness which you experience with a pressure stronger than you can endure—is taking place partially and on a small scale whenever you come into any kind of contact with an effect of pressure—with an effect, therefore, which ultimately issues from some mass.

Follow the thought a little farther and you will no longer be so remote from understanding what is implied when we write down the \(m\). All that is phoronomical unites, as it were, quite neutrally with our consciousness. This is no longer so when we encounter what we have designated \(m\). Our consciousness is dimmed at once. If this only happens to a slight extent we can still bear it; if to a great extent, we can bear it no longer. What underlies it is the same in either case. Writing down \(m\), we are writing down that in Nature which, if it does unite with our consciousness, eliminates it,—that is to say, puts us partially to sleep. You see then, why it cannot be followed phoronomically. All that is phoronomical rests in our consciousness quite neutrally. The moment we go beyond this, we come into regions which are opposed to our consciousness and tend to blot it out. Thus when we write down the formula

$$ps=\frac{mv^2}{2}$$we must admit: Our human experience contains the \(m\) no less than the \(v\), only our normal consciousness is not sufficient here,—does not enable us to seize the \(m\). The \(m\) at once exhausts, sucks out, withdraws from us the force of consciousness. Here then you have the real relationship to man. To understand what is in Nature, you must bring in the states of consciousness. Without recourse to these, you will never get beyond what is phoronomical,—you will not even reach the mechanical domain.

Nevertheless, although we cannot live with consciousness in all that, for instance, which is implied in the letter \(m\), yet with our full human being we do live in it after all. We live in it above all with our Will. And as to how we live in Nature with our Will,—I will now try to illustrate it with an example. Once more I take my start from some-thing you will probably recall from your school-days; I have no doubt you learned it.

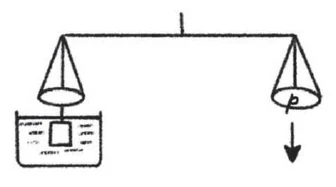

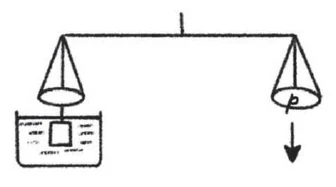

Here is a balance (Figure IIa). I can balance the weight that is on the one side with an object of equal weight, suspended this time, at the other end of the beam. We can thus weigh the object; we ascertain its weight. We now put a vessel there, filled up to here with water, so that the object is submerged in water. Immediately, the beam of the balance goes up on that side. By immersion in water the object has become lighter,—it loses some of its weight. We can test how much lighter it has grown,—how much must be subtracted to restore the balance. We find the object has become lighter to the extent of the weight of water it displaces. If we weigh the same volume of water we get the loss of weight exactly. You know this is called the law of buoyancy and is thus formulated:—Immersed in a liquid, every body becomes as much lighter as is represented by the weight of liquid it displaces. You see therefore that when a body is in a liquid it strives upward,—in some sense it withdraws itself from the downward pressure of weight.

What we can thus observe as an objective phenomenon in Physics, is of great importance in man's own constitution. Our brain, you see, weighs on the average about 1250 grammes. If, when we bear the brain within us, it really weighed as much as this, it would press so heavily upon the arteries that are beneath it that it would not get properly supplied with blood. The heavy pressure would immediately cloud our consciousness. Truth is, the brain by no means weighs with the full 1250 grammes upon the base of the skull. The weight it weighs with is only about 20 grammes. For the brain swims in the cerebral fluid. Just as the outer object in our experiment swims in the water, so does the brain swim in the cerebral fluid; moreover the weight of this fluid which the brain displaces is about 1230 grammes. To that extent the brain is lightened, leaving only about 20 grammes. What does this signify? While, with some justice we may regard the brain as the instrument of our Intelligence and life of soul—at least, a portion of our life of soul—we must not reckon merely with the ponderable brain. This is not there alone; there is also the buoyancy, by virtue of which the brain is really tending upward, contrary to its own weight. This then is what it signifies. With our Intelligence we live not in forces that pull downward but on the contrary, in forces that pull upward. With our Intelligence, we live in a force of buoyancy.

What I have been explaining applies however only to our brain. The remaining portions of our body—from the base of the skull downward, with the exception of the spinal cord—are only to a very slight extent in this condition. Taken as a whole, their tendency is down-ward. Here then we live in the downward pull. In our brain we live in the upward buoyancy, while for the rest we live in the downward pull. Our Will, above all, lives in the downward pull. Our Will has to unite with the downward pressure. Precisely this deprives the rest of our body of consciousness and makes it all the time asleep. This indeed is the essential feature of the phenomenon of Will. As a conscious phenomenon it is blotted out, extinguished, because in fact the Will unites with the downward force of gravity or weight. Our Intelligence on the other hand becomes light and clear inasmuch as we are able to unite with the force of buoyancy,—inasmuch as our brain counteracts the force of gravity. You see then how the diverse ways in which the life of man unites with the material element that underlies it, bring about upon the one hand the submersion of the Will in matter and on the other hand the lightening of Will into Intelligence. Never could Intelligence arise if our soul's life were only bound to downward tending matter. And now please think of this:—We have to consider man, not in the abstract manner of today, but so as to bring the spiritual and the physical together. Only the spiritual must now be conceived in so strong and robust a way as to embrace also the knowledge of the physical. In the human being we then see upon the one hand the lightening into Intelligence, brought about by one kind of connection with the material life—connection namely with the buoyancy which is at work there. Whilst on the other hand, where he has to let his Will be absorbed, sucked-up as it were, by the downward pressure, we see men being put to sleep. For the Will works in the sense of this downward pressure. Only a tiny portion of it, amounting to the 20 grammes' pressure of which we spoke, manages to filter through to the Intelligence. Hence our intelligence is to some extent permeated by Will. In the main however, what is at work in the Intelligence is the very opposite of ponderable matter. We always tend to go up and out beyond our head when we are thinking.

Physical science must be co-ordinated with what lives in man himself. If we stay only in the phoronomical domain, we are amid the beloved abstractions of our time and can build no bridge from thence to the outer reality of Nature. We need a knowledge with a strongly spiritual content,—strong enough to dive down into the phenomena of Nature and to take hold of such things as physical weight and buoyancy for instance, and how they work in man. Man in his inner life, as I was shewing, comes to terms both with the downward pressure and with the upward buoyancy; he therefore lives right into the connection that is really there between the phoronomical and the material domains.

You will admit, we need some deepening of Science to take hold of these things. We cannot do it in the old way. The old way of Science is to invent wave-movements or corpuscular emissions, all in the abstract. By speculation it seeks to find its way across into the realm of matter, and naturally fails to do so. A Science that is spiritual will find the way across by really diving into the realm of matter, which is what we do when we follow the life of soul in Will and Intelligence down into such phenomena as pressure and buoyancy. Here is true Monism: only a spiritual Science can produce it. This is not the Monism of mere words, pursued today with lack of real insight. It is indeed high time, if I may say so, for Physics to get a little grit into its thinking.—so to connect outer phenomena like the one we have been demonstrating with the corresponding physiological phenomena—in this instance, the swimming of the brain. Catch the connection and you know at once: so it must be,—the principle of Archimedes cannot fail to apply to the swimming of the brain in the cerebro-spinal fluid.

Now to proceed: what happens through the facts that with our brain—but for the 20 grammes into which enters the unconscious Will—we live in the sphere of Intelligence? What happens is that inasmuch as we here make the brain our instrument, for our Intelligence we are unburdened of downward-pulling matter. The latter is well-nigh eliminated, to the extent that 1230 grammes' weight is lost. Even to this extent is heavy matter eliminated, and for our brain we are thereby enabled, to a very high degree, to bring our etheric body into play. Unembarrassed by the weight of matter, the etheric body can here do what it wants. In the rest of our body on the other hand, the ether is overwhelmed by the weight of matter. See then this memberment of man. In the part of him which serves Intelligence, you get the ether free, as it were, while for the rest of him you get it bound to the physical matter. Thus in our brain the etheric organisms in some sense overwhelms the physical, while for the rest of our body the forces and functionings of the physical organisation overwhelm those of the etheric.

I drew your attention to the relation you enter into with the outer world whenever you expose yourself to pressure. There is the “putting to sleep”, of which we spoke just now. But there are other relations too, and about one of these—leaping a little ahead—I wish to speak today. I mean the relation to the outer world which comes about when we open our eyes and are in a light-filled space. Manifestly we then come into quite another relation to the outer world than where we impinge on matter and make acquaintance with pressure. When we expose ourselves to light, insofar as the light works purely and simply as light, not only do we lose nothing of our consciousness but on the contrary. No one, willing to go into it at all, can fail to perceive that by exposing himself to the light his consciousness actually becomes more awake—awake to take part in the outer world. Our forces of consciousness in some way unite with what comes to meet us in the light; we shall discuss this in greater detail in due time. Now in and with the light the colours also come to meet us. In fact we cannot say that we see the light as such. With the help of the light we see the colours, but it would not be true to say we see the light itself,—though we shall yet have to speak of how and why it is that we see the so-called white light.

Now the fact is that all that meets us by way of colour really confronts us in two opposite and polar qualities, no less than magnetism does, to take another example—positive magnetism, negative magnetism;—there is no less of a polar quality in the realm of colour. At the one pole is all that which we describe as yellow and the kindred colours—orange and reddish. At the other pole is what we may describe as blue and kindred colours—indigo and violet and even certain lesser shades of green. Why do I emphasise that the world of colour meets us with a polar quality? Because in fact the polarity of colour is among the most significant phenomena of all Nature and should be studied accordingly. To go ahead at once to what Goethe calls the Ur-phenomenon in the sense I was explaining yesterday, this is indeed the Ur-phenomenon of colour. We shall reach it to begin with by looking for colour in and about the light as such. This is to be our first experiment, arranged as well as we are able. I will explain first what it is. The experiment will be as follows:—

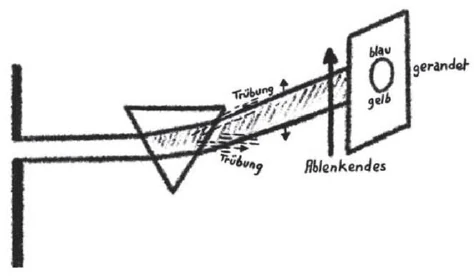

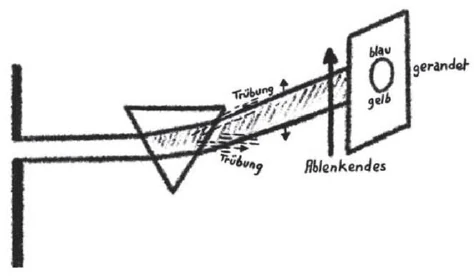

Through a narrow slit—or a small circular opening, we may assume to begin with—in an otherwise opaque wall, we let in light (Figure IIb). We let the light pour in through the slit. Opposite the wall through which the light is pouring in, we put a screen. By virtue of the light that is pouring in, we see an illuminated circular surface on the screen. The experiment is best done by cutting a hole in the shutters, letting the sunlight pour in from outside. We can then put up a screen and catch the resulting picture. We cannot do it in this way; so we are using the lantern to project it. When I remove the shutter, you see a luminous circle on the wall. This, to begin with, is the picture which arises, in that a cylinder of light, passing along here, is caught on the opposite wall. We now put a “prism” into the path of this cylinder of light (Figure IIc).

The light can then no longer simply penetrate to the opposite wall and there produce a luminous circle; it is compelled to deviate from its path. How have we brought this about? The prism is made of two planes of glass, set at an angle to form a wedge. This hollow prism is then filled with water. We let the cylinder of light, produced by the projecting apparatus, pass through the water-prism. If you now look at the wall, you see that the patch of light is no longer down there, where it was before. It is displaced,—it appears elsewhere. Moreover you see a peculiar phenomenon:—at the upper edge of it you see a bluish-greenish light. You see the patch with a bluish edge therefore. Below, you see the edge is reddish-yellow.

This then is what we have to begin with,—this is the “phenomenon”. Let us first hold to the phenomenon, simply describing the fact as it confronts us. In going through the prism, the light is somehow deflected from its path. It now forms a circle away up there, but if we measured it we should find it is not an exact circle. It is drawn out a little above and below, and edged with blue above and yellowish below. If therefore we cause such a cylinder of light to pass through the prismatically formed body of water,—neglecting, as we can in this case, whatever modifications may be due to the plates of glass—phenomena of colour arise at the edges.

Now I will do the experiment again with a far narrower cylinder of light. You see a far smaller patch of light on the screen. Deflecting it again with the help of the prism, once more you see the patch of light displaced,—moved upward. This time however the circle of light is completely filled with colours, The displaced patch of light now appears violet, blue, green, yellow and red, Indeed, if we made a more thorough study of it, we should find in it all the colours of the rainbow in their proper order. We take the fact, purely and simply as we find it; and please—all those of you who learned at school the neatly finished diagrams with rays of light, normals and so on,—please to forget them now. Hold to the simple phenomenon, the pure and simple fact. We see colours arising in and about the light and we can ask ourselves, what is it due to? Look please once more; I will again insert the larger aperture. There is again the cylinder of light passing through space, impinging on the screen and there forming its picture of light (Figure IIb). Again we put the prism in the way. Again the picture of light is displaced and the phenomena of colour appear at the edges (Figure IIc).

Now please observe the following. We will remain purely within the given facts. Kindly observe. If you could look at it more exactly you would see the luminous cylinder of water where the light is going through the prism. This is a matter of simple fact: the cylinder of light goes through the prism of water and there is thus an interpenetration of the light with the water. Pay careful attention please, once more. In that the cylinder of light goes through the water, the light and the water interpenetrate, and this is evidently not without effect for the environment. On the contrary, we must aver (and once again, we add nothing to the facts in saying this):—the cylinder of light somehow has power to make its way through the water-prism to the other side, yet in the process it is deflected by the prism. Were it not for the prism, it would go straight on, but it is now thrown upward and deflected. Here then is something that deflects our cylinder of light. To denote this that is deflecting our cylinder of light by an arrow in the diagram, I shall have to put the arrow thus. So we can say, adhering once again to the facts and not indulging in speculations: By such a prism the cylinder of light is deflected upward, and we can indicate the direction in which it is deflected.

And now, to add to all this, think of the following, which once again is a simple statement of fact. If you let light go through a dim and milky glass or through any cloudy fluid—through dim, cloudy, turbid matter in effect,—the light is weakened, naturally. When you see the light through clear unclouded water, you see it in full brightness; if the water is cloudy, you see it weakened. By dim and cloudy media the light is weakened; you will see this in countless instances. We have to state this, to begin with, simply as a fact. Now in some respect, however little, every material medium is dim. So is this prism here. It always dims the light to some extent. That is to say, with respect to the light that is there within the prism, we are dealing with a light that is somehow dimmed. Here to begin with (pointing to Figure IIc) we have the light as it shines forth; here on the other hand we have the light that has made its way through the material medium. In here however, inside the prism, we have a working-together of matter and light; a dimming of the light arises here. That the dimming of the light has a real effect, you can tell from the simple fact that when you look into light through a dim or cloudy medium you see something more. The dimming has an effect,—this is perceptible. What is it that comes about by the dimming of the light? We have to do not only with the cone of light that is here bent and deflected, but also with this new factor—the dimming of the light, brought about by matter. We can imagine therefore into this space beyond the prism not only the light is shining, but there shines in, there rays into the light the quality of dimness that is in the prism. How then does it ray in? Naturally it spreads out and extends after the light has gone through the prism. What has been dimmed and darkened, rays into what is light and bright. You need only think of it properly and you will admit: the dimness too is shining up into this region. If what is light is deflected upward, then what is dim is deflected upward too. That is to say, the dimming is deflected upward in the same direction as the light is. The light that is deflected upward has a dimming effect, so to speak, sent after it. Up there, the light cannot spread out unimpaired, but into it the darkening, the dimming effect is sent after. Here then we are dealing with the interaction of two things: the brightly shining light, itself deflected, and then the sending into it of the darkening effect that is poured into this shining light. Only the dimming and darkening effect is here deflected in the same direction as the light is. And now you see the outcome. Here in this upward region the bright light is infused and irradiated with dimness, and by this means the dark or bluish colours are produced.

How is it then when you look further down? The dimming and darkening shines downward too, naturally. But you see how it is. Whilst here there is a part of the outraying light where the dimming effect takes the same direction as the light that surges through—so to speak—with its prime force and momentum, here on the other hand the dimming effect that has arisen spreads and shines further, so that there is a space for which the cylinder of light as a whole is still diverted upward, yet at the same time, into the body of light which is thus diverted upward, the dimming and darkening effect rays in. Here is a region where, through the upper parts of the prism, the dimming and darkening goes downward. Here therefore we have a region where the darkening is deflected in the opposite sense,—opposite to the deflection of the light. Up there, the dimming or darkening tends to go into the light; down here, the working of the light is such that the deflection of it works in an opposite direction to the deflection of the dimming, darkening effect. This, then, is the result:—Above, the dimming effect is deflected in the same sense as the light; thus in a way they work together. The dimming and darkening gets into the light like a parasite and mingles with it. Down here on the contrary, the dimming rays back into the light but is overwhelmed and as it were suppressed by the latter. Here therefore, even in the battle between bright and dim—between the lightening and darkening—the light predominates. The consequences of this battle—the consequences of the mutual opposition of the light and dark, and of the dark being irradiated by the light, are in this downward region the red or yellow colours. So therefore we may say: Upward, the darkening runs into the light and there arise the blue shades of colour; downward, the light outdoes and overwhelms the darkness and there arise the yellow shades of colour.

You see, dear Friends: simply through the fact that the prism on the one hand deflects the full bright cone of light and on the other hand also deflects the dimming of it, we have the two kinds of entry of the dimming or darkening into the light,—the two kinds of interplay between them. We have an interplay of dark and light, not getting mixed to give a grey but remaining mutually independent in their activity. Only at the one pole they remain active in such a way that the darkness comes to expression as darkness even within the light, whilst at the other pole the darkening stems itself against the light, it remains there and independent, it is true, but the light overwhelms and outdoes it. So there arise the lighter shades,—all that is yellowish in colour. Thus by adhering to the plain facts and simply taking what is given, purely from what you see you have the possibility of understanding why yellowish colours on the one hand and bluish colours on the other make their appearance. At the same time you see that the material prism plays an essential part in the arising of the colours. For it is through the prism that it happens, namely that on the one hand the dimming is deflected in the same direction as the cone of light, while on the other hand, because the prism lets its darkness ray there too, this that rays on and the light that is deflected cut across each other. For that is how the deflection works down here. Downward, the darkness and the light are interacting in a different way than upward.

Colours therefore arise where dark and light work together. This is what I desired to make clear to you today. Now if you want to consider for yourselves, how you will best understand it, you need only think for instance of how differently your own etheric body is inserted into your muscles and into your eyes. Into a muscle it is so inserted as to blend with the functions of the muscle; not so into the eye. The eye being very isolated, here the etheric body is not inserted into the physical apparatus in the same way, but remains comparatively independent. Consequently, the astral body can come into very intimate union with the portion of the etheric body that is in the eye. Inside the eye our astral body is more independent, and independent in a different way than in the rest of our physical organization. Let this be the part of the physical organization in a muscle, and this the physical organization of the eye. To describe it we must say: our astral body is inserted into both, but in a very different way. Into the muscle it is so inserted that it goes through the same space as the physical bodily part and is by no means independent. In the eye too it is inserted: here however it works independently. The space is filled by both, in both cases, but in the one case the ingredients work independently while in the other they do not. It is but half the truth to say that our astral body is there in our physical body. We must ask how it is in it, for it is in it differently in the eye and in the muscle. In the eye it is relatively independent, and yet it is in it,—no less than in the muscle. You see from this: ingredients can interpenetrate each other and still be independent. So too, you can unite light and dark to get grey; then they are interpenetrating like astral body and muscle. Or on the other hand light and dark can so interpenetrate as to retain their several independence; then they are interpenetrating as do the astral body and the physical organization in the eye. In the one instance, grey arises; in the other, colour. When they interpenetrate like the astral body and the muscle, grey arises; whilst when they interpenetrate like the astral body and the eye, colour arises, since they remain relatively independent in spite of being there in the same space.

Zweiter Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde!

Ich habe Ihnen gestern davon gesprochen, wie auf der einen Seite der Naturbetrachtung steht das bloß Phoronomische, das wir gewinnen können, indem wir einfach die Vorstellungen, die wir uns bilden wollen über alles dasjenige, was an physikalischen Vorgängen durch Zählbares, durch Räumliches und durch die Bewegung verläuft, indem wir uns die Vorstellungen über alles das bilden aus unserem Vorstellungsleben heraus. Dieses Phoronomische, das können wir gewissermaßen aus unserem Vorstellungsleben herausspinnen. Aber so bedeutsam es ist, dass, was wir so auch etwa an mathematischen Formeln gewinnen über alles, was sich auf Zählbares, auf Raum und auf Bewegung bezieht, dass dieses auch passt auf die Naturvorgänge selbst, so bedeutsam ist es auf der anderen Seite, dass wir in dem Augenblick an die äußere Erfahrung herangehen müssen, in dem wir von dem Zählbaren, von dem rein Räumlichen und von der Bewegung zum Beispiel nur [schon] zur Masse vordringen. Das haben wir uns gestern klargemacht, und wir haben vielleicht auch daraus ersehen, dass für die gegenwärtige Physik der Sprung von der inneren Konstruktion des Naturgeschehens durch die Phoronomie in die äußere physische Empirie hineingetan werden muss, ohne dass dieser Sprung eigentlich verstanden werden kann. sehen Sie, ohne dass man wird Schritte dazu machen, diesen Sprung zu verstehen, wird es unmöglich sein, jemals Vorstellungen über das zu gewinnen, was in der Physik der Äther genannt werden soll.

Ich habe Ihnen ja schon gestern angedeutet, dass zum Beispiel für die Licht- und Farbenerscheinungen die gegenwärtige Physik, obwohl diese schon in diesen Vorstellungen ins Wanken geraten ist, vielfach noch sagt: Auf uns wird eine Licht- und Farbenwirkung ausgeübt, auf uns als Sinnenwesen, als Nervenwesen oder auch als Seelenwesen. Aber diese Wirkung sei subjektiv. Was draußen im Raum und in der Zeit vor sich geht, das sei objektive Bewegung im Äther. Wenn Sie aber in der heutigen physikalischen Literatur? oder in anderem demjenigen, was man so sagt, im physikalischen Leben, nachsehen über die Vorstellungen, die man sich über diesen Äther gebildet hat, der bewirken soll die Lichterscheinungen, so werden Sie finden, dass diese Vorstellungen einander widersprechend und verworren sind, und man kann auch mit demjenigen, was der heutigen Physik zur Verfügung steht, wirklich sachgemäße Vorstellungen über das, was Äther genannt werden soll, nicht gewinnen.?

Wir wollen einmal versuchen, den Weg anzutreten, der wirklich zur Überbrückung jener Kluft führen kann zwischen Phoronomie und auch nur der Mechanik; denn diese hat es natürlich mit Kräften und mit Massen zu tun. Ich will, obwohl das, was durch diese Formel ausgedrückt wird, uns später noch beschäftigen kann, — sodass auch diejenigen von Ihnen, die sich vielleicht an diese Formel nicht mehr erinnern aus ihrer Schulzeit her, dass die das werden nachholen können, was zum Verständnis gehört - heute will ich sie nur als [Lehrsatz] vorführen. Ich werde die Elemente zusammenstellen, damit Sie sich diese Formel ein wenig vor die Seele rücken können.

Sehen Sie, wenn wir im Sinne jetzt der Phoronomie annehmen, dass ein Punkt - wir müssen da eigentlich immer sagen ein Punkt -, dass ein Punkt sich bewegt, bewegt in dieser Richtung, so bewegt sich solch ein Punkt - wir sehen jetzt nur auf die Bewegung, nicht auf ihre Ursachen - so bewegt sich ein solcher Punkt entweder schneller oder langsamer. Wir können daher sagen: Der Punkt bewegt sich mit gröRerer oder geringerer Geschwindigkeit. Und ich will die Geschwindigkeit v nennen. Diese Geschwindigkeit ist also eine größere oder eine geringere. Solange wir nichts anderes beachten, als dass sich ein solcher Punkt mit einer gewissen Geschwindigkeit bewegt, solange bleiben wir innerhalb der Phoronomie stehen. Aber damit würden wir nicht an die Natur, nicht einmal an die bloß mechanische Natur herankommen können. Wir müssen, wenn wir an die Natur herankommen wollen, darauf Rücksicht nehmen, wodurch der Punkt sich bewegt und dass ein bloß gedachter Punkt sich nicht bewegen kann, dass also der Punkt etwas im äußeren Raum sein muss, wenn er sich bewegen soll. Kurz, wir müssen annehmen, dass eine Kraft wirkt auf diesen Punkt. Das \(v\) will ich die Geschwindigkeit nennen, \(p\) will ich die Kraft nennen, die auf diesen Punkt wirkt. Diese Kraft, wir wollen annehmen, dass sie nun nicht bloß einmal auf diesen Punkt gewissermaßen drückt und ihn in Bewegung bringt, wodurch er ja schließlich fortfliegen würde mit einer Geschwindigkeit, wenn er kein Hindernis fände, sondern wir wollen ausgehen von der Annahme, dass diese Kraft fortwährend wirkt, dass also während dieses ganzen Weges die Kraft auf diesen Punkt wirkt. Und den Weg, während welches diese Kraft auf den Punkt wirkt, will ich s nennen. Das würde also die Wegstrecke sein, während welcher die Kraft auf den Punkt wirkt.

Dann müssen wir außerdem Rücksicht nehmen darauf, dass der Punkt etwas sein muss im Raum, und dieses Etwas, das kann größer oder geringer sein. Je nachdem dieses Etwas größer oder geringer ist, können wir sagen: Der Punkt hat mehr oder weniger Masse. Die Masse drücken wir ja zunächst aus durch das Gewicht. Wir können das, das durch die Kraft bewegt wird, abwiegen und können es durch das Gewicht ausdrücken; \(m\) nenne ich also die Masse. Wenn aber nun auf die Masse \(m\) die Kraft \(p\) wirkt, so muss natürlich eine gewisse Wirkung entstehen. Diese, die äußert sich dadurch, dass die Masse sich nun nicht mit gleichförmiger Geschwindigkeit weiterbewegt, sondern schneller und schneller sich weiterbewegt, dass die Geschwindigkeit immer größer und größer wird. Das heißt, wir müssen darauf Rücksicht nehmen, dass wir es mit einer zunehmenden Geschwindigkeit zu tun haben. Es wird ein gewisses Maß vorhanden sein, nach welchem die Geschwindigkeit zunimmt. Wenn auf dieselbe Masse eine kleinere Kraft wirkt, so wird diese die Bewegung weniger schneller und schneller machen können, und wenn auf dieselbe Masse eine größere Kraft wirkt, so wird sie die Bewegung mehr schneller und schneller machen können. Dieses Maß, in dem die Geschwindigkeit zunimmt, will ich die Beschleunigung nennen und mit \(γ\) bezeichnen.

Was uns aber jetzt vor allen Dingen interessiert, ist das Folgende. Und da will ich Sie eben erinnern an eine Formel, die Sie wahrscheinlich kennen, an die Sie sich nur erinnern sollen. Wenn man das Produkt bildet aus der Kraft, welche auf die Masse wirkt, in die Wegstrecke, so ist dieses Produkt gleich, das heißt es kann auch ausgedrückt werden dadurch, dass man die Masse, multipliziert mit dem Quadrat der Geschwindigkeit [und] durch 2 dividiert, das heißt, es ist \(ps = \frac{mv^2}{2}\). Wenn Sie die von mir aus rechte Seite der Formel in Betracht ziehen, so sehen Sie darinnen eben die Masse. Sie können aus der Gleichung ersehen, dass, je größer die Masse wird, desto größer muss die Kraft sein. Aber, was uns jetzt interessiert, ist das, dass wir auf der rechten Seite der Gleichung die Masse haben, also dasjenige, was wir phoronomisch keineswegs erreichen können. Nun handelt es sich darum: Soll man sich nun einfach gestehen, dass alles dasjenige, was außerhalb des Phoronomischen liegt, immer unerreichbar bleiben müsse, dass wir das gewissermaßen nur vom Anglotzen, vom Anschauen kennenlernen sollen, oder gibt es doch jene Brücke, die die heutige Physik nicht finden kann, zwischen dem Phoronomischen und dem Mechanischen? sehen Sie, die heutige Physik kann den Übergang heute nicht finden - und die Folgen davon sind ungeheuerlich, - aus dem Grunde, weil sie keine wirkliche Menschenkunde, keine wirkliche Physiologie hat, weil man eigentlich den Menschen nicht wirklich kennt. Sehen Sie, schreibe ich \(v^2\) hin, dann habe ich etwas, was rein im Zählbaren und in der Bewegung aufgeht. Insoweit ist. die Formel gewissermaßen eine phoronomische. Schreibe ich das m hin, so muss ich mich fragen: Gibt es irgendetwas in mir selber, was dem entspricht? Ähnlich dem entspricht, wie meine Vorstellung des Zählbaren, des Räumlichen entspricht demjenigen, was ich zum Beispiel mit \(v\) hinschreibe? Was entspricht also dem \(m\)? Was tue ich denn eigentlich? Der Physiker ist sich gewöhnlich nicht bewusst, indem er das \(m\) hinschreibt, was er da tut - was tue ich denn da?

Nun sehen Sie, diese Frage führt darauf zurück: Kann ich überhaupt in ähnlicher Art überschauen, was in dem \(m\) liegt, wie ich phoronomisch überschauen kann, was im \(v\) liegt? Man kann es, wenn man das Folgende sich zum Bewusstsein bringt: Wenn Sie mit dem Finger auf irgendetwas drücken, so machen Sie sich gewissermaßen bekannt mit der einfachsten Form eines Druckes. Die Masse verrät sich ja - ich habe Ihnen gesagt: Man kann sie sich vergegenwärtigen dadurch, dass man sie abwiegt - die Masse kündigt sich durch nichts anderes zunächst an als dadurch, dass sie einen Druck auszuüben vermag. Mit einem solchen Druck kann man sich bekannt machen, indem man mit dem Finger auf etwas drückt. Aber nun muss man sich fragen: Geht in uns etwas Ähnliches vor, wenn wir mit dem Finger auf etwas drücken, also einen Druck erleben, wie wenn wir zum Beispiel einen bewegten Körper überschauen? Ja, es geht schon etwas vor, nur, das was vorgeht, das können Sie sich dadurch klarmachen, dass Sie den Druck immer stärker und stärker machen. Versuchen Sie es einmal - oder versuchen Sie es lieber nicht -, einen Druck auf eine Körperstelle auszuüben und immer mehr und mehr zu verstärken, stärker und stärker zu machen! Was wird geschehen? Nun, wenn Sie ihn genügend stark machen, verlieren Sie die Besinnung, das heißt, Ihr Bewusstsein geht Ihnen verloren. Daraus aber können Sie schließen, dass diese Erscheinung des Bewusstsein-verloren-Gehens gewissermaßen im Kleinen auch stattfindet, wenn Sie den noch erträglichen Druck ausüben. Nur geht ebenso wenig von der Kraft des Bewusstseins verloren, dass Sie es noch aushalten können. Aber das, was ich Ihnen charakterisiert habe als den Bewusstseins-Verlust bei einem so starken Druck, dass man ihn nicht mehr aushalten kann, das ist teilweise im Kleinen auch dann vorhanden, wenn wir irgendwie in Berührung kommen mit einer Druckwirkung, mit einer Wirkung, die von einer Masse ausgeht.

Und jetzt brauchen Sie den Gedanken nur weiter zu verfolgen, dann werden Sie nicht mehr ferne davon sein, dasjenige, was mit dem m hingeschrieben wird, zu verstehen. Während alles Phoronomische gewissermaßen neutral mit unserem Bewusstsein vereint wird, sind wir bei dem, was wir mit dem \(m\) bezeichnen, nicht in dieser Lage, sondern da dämpft sich unser Bewusstsein sogleich herab. Kleine Partien der Herabdämpfung des Bewusstseins können wir noch aushalten, große nicht mehr. Aber dasjenige, was zugrunde liegt, ist dasselbe. Indem wir \(m\) hinschreiben, schreiben wir das in der Natur hin, was, wenn es sich mit unserem Bewusstsein vereinigt, dieses Bewusstsein aufhebt, das heißt uns partiell einschläfert. So treten wir mit der Natur in eine Beziehung, aber in eine solche Beziehung, die unser Bewusstsein partiell einschläfert. Sie sehen, warum das nicht phoronomisch verfolgt werden kann. Alles Phoronomische liegt neutral in unserem Bewusstsein. Wenn wir darüber hinausgehen, treten wir in die Partien ein, die unserem Bewusstsein entgegengesetzt liegen und die es aufheben. Also, indem wir die Formel \(ps = \frac{mv^2}{2}\) hinschreiben, müssen wir uns sagen: Unsere Menschenerfahrung enthält ebenso das m wie sie das v enthält, aber unser gewöhnliches Bewusstsein reicht nur nicht aus, um dieses \(m\) zu umfassen. Dieses m saugt uns sogleich die Kraft unseres Bewusstseins aus. Jetzt haben Sie eine reale Beziehung zum Menschen. Eine ganz reale Beziehung zum Menschen. Sie sehen, es müssen Bewusstseinszustände zu Hilfe genommen werden, wenn wir das Naturgemäße verstchen wollen. Ohne diese Zuhilfenahme gelingt es nicht, vom Phoronomischen zum Mechanischen auch nur vorzuschreiten.

Nun aber, wenn wir auch mit unserem Bewusstsein in all dem, was zum Beispiel mit \(m\) bezeichnet werden kann, nicht drinnen leben können, mit unserem ganzen Menschen leben wir doch darinnen. Namentlich leben wir mit unserem Willen darinnen, und wir leben sehr stark mit unserem Willen darinnen. Wie wir in der Natur mit unserem Willen darinnen leben, will ich an einem Beispiel veranschaulichen.

Da muss ich aber ausgehen von etwas, das Sie wieder erinnern müssen aus der Schulzeit. Ich will Ihnen etwas zurückrufen, etwas, was Sie während Ihrer Schulzeit gut kennengelernt haben. Sie wissen, dass, wenn wir hier eine Waage haben, so können wir, wenn wir hier das Waagegewicht darauf geben, einen gleichschweren Gegenstand, den ich eben jetzt nur anhängen will (Zeichnung), um die Waagebalken ins Gleichgewicht zu bringen - wir können diesen Gegenstand abwiegen, wir finden sein Gewicht. In dem Augenblick, wo wir ein Gefäß mit Wasser nehmen, hierherstellen - das bis hierher gefüllt ist (Zeichnung) -, in welches Wasser wir den Gegenstand hineinversenken, in dem Augenblick schnellt der Waagebalken hinauf. Dadurch, dass der Gegenstand ins Wasser getaucht ist, wird er leichter, verliert er von seinem Gewicht. Und wenn wir prüfen, wie viel er leichter geworden ist, wenn wir notieren, wie viel wir abziehen müssen, wenn wir die Waage wieder ins Gleichgewicht bringen, dann finden wir, dass der Gegenstand jetzt um so viel leichter ist, als das Gewicht des Wassers beträgt, das er verdrängt hat. Also, wenn wir diesen Rauminhalt Wasser abwiegen, so gibt uns das den Gewichtsverlust. Sie wissen, man nennt das das Gesetz des Auftriebes und sagt: Jeder Körper wird in einer Flüssigkeit so viel leichter, als das Gewicht der Flüssigkeit beträgt, die er verdrängt. Sie sehen also, wenn ein Körper in einer Flüssigkeit ist, so strebt er nach oben, so entzieht er sich gewisserweise dem Druck nach unten, dem Gewichte. Dasjenige, was man so objektiv physikalisch beobachten kann, das hat in der Konstitution des Menschen eine sehr wichtige Bedeutung.

Sehen Sie, unser Gehirn wiegt durchschnittlich 1250 Gramm. Wenn dieses Gehirn, indem wir es in uns tragen, wirklich 1250 Gramm wiegen würde, dann würde es uns so stark drücken auf die unter ihm befindlichen Blutadern, dass das Gehirn nicht in richtiger Weise mit Blut versorgt werden könnte. Es würde ein starker Druck ausgeübt werden, der das Bewusstsein sogleich umnebeln würde. In Wahrheit drückt das Gehirn gar nicht mit so vollen 1250 Gramm auf die Unterfläche der Schädelhöhle, sondern nur mit etwa 20 Gramm. Das kommt davon her, dass das Gehirn in der Gehirnflüssigkeit schwimmt. So wie der Körper hier im Wasser schwimmt, so schwimmt das Gehirn in der Gehirnflüssigkeit. Und das Gewicht der Gehirnflüssigkeit, die verdrängt wird durch das Gehirn, das beträgt eben ungefähr 1230 Gramm. Um diese wird das Gehirn leichter und hat nur noch 20 Gramm. Das heißt, wenn man nun auch - und das tut man ja mit einem gewissen Recht - das Gehirn als das Werkzeug unserer Intelligenz und unseres Seelenlebens, wenigstens eines Teiles unseres Seelenlebens, betrachtet, so muss man nicht bloß rechnen mit dem wägbaren Gehirn - denn dieses ist nicht alleine da -, sondern dadurch, dass ein Auftrieb da ist, strebt das Gehirn eigentlich nach aufwärts, strebt seiner eigenen Schwere entgegen. Das heißt, wir leben mit unserer Intelligenz nicht in abwärtsziehenden, sondern in aufwärtszichenden Kräften. Wir leben mit unserer Intelligenz. in einem Auftrieb drinnen.

Nun ist das, was ich Ihnen auseinandergesetzt habe, allerdings nur für unser Gehirn so. Die anderen Teile unseres Organismus, also von dem Boden der Schädeldecke nach unten, die sind nur zum kleinsten Teil - nur das Rückenmark - in derselben Lage. Aber im Ganzen streben die anderen Teile des Organismus nach unten. Da leben wir also in dem Zug nach unten. Wir leben im Gehirn im Auftrieb, nach aufwärts, und sonst im Zuge nach unten. Unser Wille lebt durchaus im Zug nach unten. Er muss sich vereinigen mit dem Druck nach unten. Dadurch aber wird ihm das Bewusstsein genommen. Dadurch schläft er fortwährend. Gerade das ist das Wesentliche der Willenserscheinung, dass sie als bewusste ausgelöscht wird, deshalb, weil sich der Wille mit der nach unten gerichteten Schwerkraft vereinigt. Und unsere Intelligenz wird lichtvoll dadurch, dass wir uns vereinigen können mit dem Auftrieb, dass unser Gehirn entgegenarbeitet der Schwerkraft.

Sie sehen, durch die verschiedenartige Vereinigung des menschlichen Lebens mit dem zugrunde liegenden Materiellen wird auf der einen Seite das Untergehen des Willens in der Materie bewirkt und auf der anderen Seite wird die Aufhellung des Willens zur Intelligenz bewirkt. Niemals könnte die Intelligenz entstehen, wenn unser Seelenwesen gebunden wäre an eine bloß nach abwärts strebende Materie.

Nun bedenken Sie, dass wir also eigentlich erleben, richtig erleben, wenn wir nicht in der heutigen Abstraktion den Menschen betrachten, sondern so betrachten, wie er wirklich ist, sodass das Geistige mit dem Physischen zusammenkommt - da muss nur das Geistige so stark gedacht werden, dass es auch die physische Kenntnis umfassen kann -, so haben wir bei ihm auf der einen Seite durch eine besondere Vereinigung mit dem materiellen Leben, nämlich mit dem Auftrieb im materiellen Leben, haben wir die Aufhellung in die Intelligenz und auf der anderen Seite die Einschläferung, wenn wir den Willen gewissermaßen aufsaugen lassen müssen von dem nach unten gerichteten Druck, sodass der Wille im Sinne dieses nach unten gerichteten Druckes wirkt. Er wirkt so. Nur ein kleiner Teil von ihm filtriert sich durch bis zu dem Zwanzig-Gramm-Druck, geht in die Intelligenz hinein - daher ist die Intelligenz etwas vom Willen durchdrungen - geht in die Intelligenz hinein; aber im Wesentlichen haben wir es in der Intelligenz zu tun mit dem, was entgegengesetzt ist der ponderablen Materie. Wir wollen immer über den Kopf hinaus, indem wir denken.

Hier sehen Sie, wie in der Tat sich zusammenschließen muss das physische Erkennen mit demjenigen, was im Menschen lebt. Bleiben wir innerhalb des Phoronomischen stehen, dann haben wir es zu tun mit den heute so beliebten Abstraktionen, und wir können keine Brücke bauen zwischen diesen beliebten Abstraktionen und demjenigen, was die äußere Naturwirklichkeit ist. Wir brauchen eine Erkenntnis mit so stark geistigem Inhalt, dass dieser geistige Inhalt wirklich untertauchen kann in die Naturerscheinungen und dass er zum Beispiel so etwas begreifen kann, wie das physikalische Gewicht und der Auftrieb im Menschen selber wirken.

Nun habe ich Ihnen gezeigt, wie der Mensch sich innerlich auseinandersetzt mit dem Druck nach unten und dem Auftrieb, wie er sich also hineinlebt in den Zusammenhang zwischen Phoronomischem und Materiellem. Aber Sie sehen, man braucht dazu eine neue wissenschaftliche Vertiefung. Mit der alten wissenschaftlichen Gesinnung ist das nicht zu machen. Diese erfindet Wellenbewegungen oder Emissionen -, die sind aber auch nur rein abstrakt. Die sucht den Weg hinüber in die Materie geradezu durch Spekulation, kann ihn natürlich dadurch nicht finden. Eine wirklich geistige Wissenschaft, die sucht den Weg hinüber in die Materie, indem sie versucht, wirklich unterzutauchen in die Materie, indem also das Seelenleben nach Wille und Intelligenz verfolgt wird bis in die Druck- und Auftriebserscheinungen hinein. Da haben Sie wirklichen Monismus. Der kann nur entstehen von der geistigen Wissenschaft aus. Nicht jener Wortmonismus, der vom Nichtwissen heute so stark getrieben wird. Aber es ist eben notwendig, dass gerade die Physik - no”, wenn ich mich des Ausdrucks bedienen darf - ein wenig Grütze in den Kopf bekommt, dass sie solche Erscheinungen [berücksichtigt], die da sind, indem man das auf der anderen Seite mit der physiologischen Erscheinung des Schwimmens des Gehirns in Zusammenhang bringt. Sobald man den Zusammenhang hat, weiß man: So muss es sein, denn es kann das archimedische Prinzip nicht aufhören Geltung zu haben für das im Gehirnwasser schwimmende Gehirn.

Nun aber, was geschieht denn dadurch, dass wir mit Ausnahme der 20 Gramm, in die der unbewusste Wille hineinspielt, durch unser Gehirn eigentlich leben in der Sphäre des Intelligenten? Dadurch sind wir, insofern wir uns des Gehirns als Werkzeug bedienen, für unsere Intelligenz entlastet von dem nach unten ziehenden Materiellen. Das schaltet in so hohem Grad aus, dass ein Gewicht von 1230 Gramm verloren geht. In so hohem Grad schaltet sich die Materie aus. Dadurch, dass sie sich in so hohem Grad [ausschaltet], sind wir in der Lage, wirksam sein zu lassen in besonderem Maße für unser Gehirn unseren Ätherleib. Der kann tun, was er will, weil er nicht beirrt wird durch die Schwere der Materie. Im übrigen Organismus wird der Äther überwältigt von der Schwere der Materie. Da haben Sie eine Gliederung des Menschen, dass Sie für alles, was der Intelligenz dient, gewissermaßen den Äther frei bekommen; für alles andere haben Sie den Äther an die physische Materie gebunden. Sodass für unser Gehirn der Ätherorganismus übertönt den physischen Organismus, und für den übrigen Leib die Einrichtung und die Kräfte unseres physischen Organismus übertönen die des Ätherorganismus.

Nun, ich habe Sie vorher aufmerksam gemacht auf jene Beziehung, in die Sie zur Außenwelt treten, wenn Sie sich einem Druck aussetzen. Da ist eine Einschläferung vorhanden. Es gibt aber auch noch andere Beziehungen, und eine will ich heute vorwegnehmen, das ist die Beziehung zur Außenwelt, die eintritt, wenn wir die Augen aufmachen und in einem lichterfüllten Raum sind. Da findet offenbar eine ganz andere Beziehung zur Außenwelt statt, als wenn wir auf die Materie aufstoßen und mit dem Druck Bekanntschaft machen. Wenn wir uns dem Licht exponieren, ja, da geht nicht nur nichts vom Bewusstsein verloren, sondern, sofern das Licht nur als Licht wirkt, kann jeder, der da will, empfinden, dass sein Bewusstsein Anteil nimmt gegenüber der Außenwelt dadurch, dass er sich dem Licht exponiert, geradezu mehr aufwacht. Die Kräfte des Bewusstseins vereinigen sich in einer gewissen Weise - wir werden das noch genauer besprechen? -, vereinigen sich gewissermaßen mit demjenigen, was uns im Licht entgegentritt. Aber im Licht und am Licht treten uns ja auch Farben entgegen. Das Licht ist eigentlich etwas, von dem wir gar nicht sagen können, dass wir es sehen können. Mithilfe des Lichtes sehen wir die Farben, aber wir können nicht eigentlich sagen, dass wir das Licht sehen. Warum wir das sogenannte weiße Licht? sehen, davon werden wir noch sprechen.

Nun handelt es sich darum, dass alles dasjenige, was uns als Farbe entgegentritt, uns eigentlich ebenso polarisch entgegentritt, wie uns entgegentritt polarisch, sagen wir, der Magnetismus: positiver Magnetismus, negativer Magnetismus. So tritt uns auch dasjenige, was uns als Farbe entgegentritt, das tritt uns entgegen polarisch. Auf der einen Seite des Poles ist alles das, was wir etwa Gelb und, mit dem Gelb verwandt, Orange und Rötlich bezeichnen können. Auf der anderen Seite des Poles ist Blau und alles das, was wir verwandt mit dem Blau, Indigo und selbst noch mindere Schichten von Grün, Violett bezeichnen können, Warum sage ich, dass uns das Farbige polarisch entgegentritt? Sehen Sie, die Polarität des Farbigen, die muss wie, ich möchte sagen, eine der signifikantesten Erscheinungen in der ganzen Natur nur richtig studiert werden. Wenn Sie gleich schreiten wollen zu demjenigen, was in dem Sinn, wie ich Ihnen das gestern auseinandergesetzt habe, Goethe das Urphänomen nennt, so kann man zu diesem Urphänomen des Farbigen zunächst dadurch kommen, dass man das Farbige am Licht überhaupt aufsucht.

Nun wollen wir heute als ein erstes Experiment das Farbige am Licht, so gut es geht, aufsuchen. Ich werde zunächst das Experiment Ihnen erklären. Das können wir in der folgenden Weise: Sehen Sie, man kann durch einen schmalen Spalt, der - zunächst nehmen wir ihn kreisförmig an - in eine sonst undurchsichtige Wand eingeschnitten ist, Licht einlassen. Dieses Licht lassen wir also durch diesen Spalt hereinfluten. Wenn wir dieses Licht hereinfluten lassen und gegenüber der Wand, durch die das Licht hereinflutet, einen Schirm stellen, so erscheint eine beleuchtete Kreisfläche durch das hereinflutende Licht. Am besten macht man das Experiment, indem man in [den Fensterladen] ein Loch schneidet und das Licht hereinfluten lässt.

Man kann da einen Schirm aufstellen und das Bild auffangen, das so entsteht. Wir können das hier nicht machen, aber dafür mithilfe dieses Projektions-Apparates, indem wir den Verschluss wegnehmen. Da bekommen wir, wie Sie sehen, eine leuchtende Kreisfläche. Diese leuchtende Kreisfläche ist also zunächst nichts anderes als das Bild, das entsteht dadurch, dass hier ein Lichtzylinder, der sich hierher fortpflanzt, von der gegenüberliegenden Wand aufgefangen wird.

Nun kann man in den Weg dieses Lichtzylinders, der da hereinfällt, ein sogenanntes Prisma schieben. Dann ist das Licht gezwungen, nicht einfach nach der gegenüberliegenden Wand hinzudringen und dort den Kreis zu bewirken, sondern dann ist das Licht gezwungen, von seinem Weg abzukommen. Wir bewirken das dadurch, dass wir ein Prisma, welches dadurch gestaltet ist, dass wir hier ebene Glasscheiben haben, die keilförmig angeordnet sind, ein Hohlprisma geformt haben; ausgefüllt [wird] dieses Hohlprisma mit Wasser. Wir lassen den Lichtzylinder, der hier entstanden ist, durch dieses Wasserprisma hindurch. So sehen Sie, wenn Sie jetzt hinschauen auf die Wand, dass nicht an der Stelle, wo früher da unten diese Scheibe war, sie ist, sondern Sie sehen, dass sie gehoben ist, dass sie an einer anderen Stelle erscheint. Sie sehen aber außerdem noch etwas Merkwürdiges. Sie sehen oben den Rand in einem bläulich-grünlichen Licht, mit einem bläulich-grünlichen Rand, bläulichen Rand. Sie sehen unten den Rand rötlich-gelb. Da haben wir zunächst dasjenige, was wir cin Phänomen nennen, eine Erscheinung. Halten wir an dieser Erscheinung zunächst fest. Wir müssen sie also so zeichnen - also Zeichnen wir den Tatbestand auf: Also, es kommt das Licht von seinem Weg irgendwie ab, indem es durch das Prisma geht. Es bildet da oben einen Kreis. Würden wir ihn abmessen, so würden wir finden, dass es kein genauer Kreis war, sondern nach oben und unten ein wenig in die Länge gezogen ist und oben bläulich und unten gelblich gerandet. Sie sehen also, wenn wir einen solchen Lichtzylinder durch das prismatisch geformte Wasser gehen lassen - wir können absehen von den Veränderungen, die die Glasplatten hervorrufen -, so treten an den Rändern Farbenerscheinungen auf.

Ich will nun das Experiment noch einmal machen mit einem Lichtzylinder, der viel schmäler ist. Sie sehen nun eine viel kleinere Scheibe da unten. - Wenn wir das Experiment das nächste Mal machen, werden wir es besser schneiden, dann wird es auch weißer sein. - Nun lenken wir diese kleine Scheibe durch das Prisma ab, so sehen Sie hier oben, also wiederum nach oben verschoben, sehen Sie den Lichtfleck, den Lichtkreis; aber Sie sehen jetzt ziemlich diesen Lichtkreis ganz von Farben durchzogen. Sie sehen, wenn ich das, was Sie hier jetzt haben, zeichnen will, Sie sehen, dass da oben jetzt das Verschobene so ist, dass es violett, blau, grün, gelb, rot erscheint. Ja, wenn wir genau das alles verfolgen könnten, es würde in den vollkommenen Regenbogenfarben angeordnet sein. Bitte, wir nehmen rein das Faktum, und ich bitte jetzt alle diejenigen von Ihnen, welche in der Schule gelernt haben all die schönen Zeichnungen von Lichtstrahlen, von Einfallsloten und so weiter, zu vergessen und sich an die reine Erscheinung zu halten, an das reine Faktum zu halten. Wir sehen am Lichte Farben entstehen und wir können uns fragen: Woran liegt es denn, dass am Licht solche Farben entstehen?

Nun sehen Sie, wenn ich noch einmal den großen Kreis einschalte, so haben wir also den durch den Raum gehenden Lichtzylinder, der dort auftrifft auf den Schirm und dort ein Lichtbild formiert. Wenn wir einschalten in den Weg dieses Lichtzylinders wiederum das Prisma, dann bekommen wir die Verschiebung dieses Lichtbildes und außerdem an den Rändern die farbigen Erscheinungen.

Nun aber bitte ich Sie, das Folgende zu beobachten. Wir bleiben rein innerhalb der Fakten stehen. Ich bitte Sie, zu beobachten: Wenn Sie so ein bisschen herumschauen würden, so würden Sie, indem das Licht durchgeht durch das Glasprisma, würden Sie sehen genau da drinnen den leuchtenden Wasserzylinder. Der Lichtzylinder geht - das ist rein faktisch - durch das Wasserprisma durch und es findet also statt eine Ineinanderfügung des Lichtes mit dem Wasser. Bitte, darauf jetzt wohl zu achten. Indem der Lichtzylinder durch das Wasserprisma hindurchgeht, findet statt eine Ineinanderfügung des Lichtes mit dem Wasser. Dieses, was sich da ineinanderfügt von Licht und Wasser, das ist nun keineswegs unwirksam für die [weitere] Umgebung, sondern wir müssen sagen: Da geht der Lichtzylinder, der hat - wie gesagt, wir bleiben innerhalb der Fakten stehen - der hat irgendwie die Kraft, auf die andere Seite des Prismas durch das Prisma durchzudringen. Aber er wird durch das Prisma abgelenkt. Er würde so [geradeaus] gehen; aber er wird hinaufgehoben, wird abgelenkt, dieser Lichtzylinder, sodass wir konstatieren müssen: Hier ist etwas vorhanden, was uns den Lichtzylinder ablenkt. Wenn ich das andeuten will durch einen Pfeil, das, was uns den Lichtzylinder ablenkt, so müsste ich dies durch diesen Pfeil tun. Nun können wir sagen — wie gesagt, rein innerhalb der Fakten stehen bleiben, nicht spekulieren - nun können wir sagen: Durch ein solches Prisma wird der Lichtzylinder abgelenkt nach oben und wir können die Ablenkungsrichtung angeben.

Nun bitte ich Sie, zu alledem das Folgende hinzuzudenken, was wiederum nur Fakten entspricht. Wenn Sie durch ein trübes Milchglas oder nur durch eine irgendwie getrübte Flüssigkeit, also durch eine getrübte Materie, Licht dringen lassen, so wird dieses Licht abgeschwächt selbstverständlich. Sie sehen, indem Sie durch ungetrübtes Wasser das Licht sehen, es in seiner Helligkeit. Bei getrübtem Wasser sehen Sie es abgeschwächt. Das können Sie in unzähligen Fällen beobachten, dass durch getrübte Medien, durch getrübte Mittel, das Licht abgeschwächt wird. Das ist etwas, was man zunächst als Faktum auszusprechen hat. In irgendeiner Beziehung, wenn auch noch so wenig, ist aber jedes materielle Mittel, also auch das, was hier als Prisma steht, ein getrübtes Mittel. Es trübt immer das Licht ab, das heißt, mit Bezug auf das Licht, das da innerhalb des Prismas ist, haben wir es zu tun mit einem abgetrübten Licht. Da [links] haben wir es zu tun mit scheinendem Licht. Da [rechts] haben wir es zu tun mit dem Licht, das sich den Durchgang verschafft hat durch das Mittel. Hier aber, innerhalb des Prismas, haben wir es zu tun mit einem Zusammenwirken von Materie mit dem Licht, mit dem Entstehen einer Trübung. Dass aber eine Trübung wirkt, das können Sie einfach dadurch entnehmen, [dass,] wenn Sie eben durch ein getrübtes Mittel Licht ansehen, Sie noch etwas sehen. Also eine Trübung wirkt - es ist das wahrnehmbar.

Was entsteht durch die Trübung? Wir haben es also nicht bloß zu tun mit dem fortschreitenden und abbiegenden Lichtkegel, sondern außerdem noch mit dem, was sich da hineinstellt als eine Trübung des Lichtes, bewirkt durch die Materie. Wir können uns also vorstellen: Hier in diesem Raum nach dem Prisma, da scheint nicht nur herein das Licht, sondern da scheint herein, da strahlt in das Licht hinein, was da als Trübung im Prisma lebt. Das strahlt da hinein. Und wie strahlt das da hinein? Ja, sehen Sie, das breitet sich natürlich da aus, nachdem das Licht durch das Prisma gegangen ist. Das Getrübte strahlt in das Helle hinein. Und Sie brauchen sich die Sache nur richtig zu überlegen, so können Sie sich sagen: Da scheint das Trübe hinauf, und wenn das Helle abgelenkt wird, wird auch das Trübe nach oben abgelenkt. Das heißt, die Trübung, die wird abgelenkt nach oben, hier in derselben Richtung, in der die Helligkeit abgelenkt wird. Es wird gewissermaßen der Helligkeit, die nach oben abgelenkt wird, noch eine Trübung nachgeschickt. Die Helligkeit kann also da nach oben nicht ohne Weiteres sich ausbreiten. In sie hinein wird die Trübung nachgeschickt. Und wir haben es zu tun mit zwei Zusammenwirkenden, mit der abgelenkten Helligkeit und mit dem Hineinschicken der Trübung in diese Helligkeit, nur dass die Ablenkung der Trübung in derselben Richtung geschieht wie die der Helligkeit. Den Erfolg sehen Sie: Dadurch, dass nach oben hin in die Helligkeit der Schein der Trübung hineinstrahlt, entstehen die dunklen Farben, die bläulichen Farben.

Und nach unten, wie ist es denn da? Nach unten scheint natürlich auch die Trübung. Aber Sie sehen ja, während hier [oben] eine Partie ist des ausstrahlenden Lichts, wo die Trübung nach derselben Richtung [nach oben] geht wie das mit Wucht durchgehende Licht, haben wir hier [unten] eine Ausbreitung desjenigen, was als Trübung entsteht, sodass es hin scheint und es einen Raum gibt, für den im allgemeinen der Lichtzylinder nach oben abgelenkt wird. Aber in diesen nach oben abgelenkten Lichtkörper strahlt [hier unten] ein die Trübung. Und hier [unten] haben wir eine Partie, wo durch die [schmaleren] Partien des Prismas die Trübung nach unten geht. Dadurch haben wir hier eine Partie, wo die Trübung im entgegengesetzten Sinn abgelenkt wird, als die Ablenkung ist der Helligkeit.

Wir können sagen: Wir haben hier [unten] die Trübung, die hineinwill in die Helligkeit; aber im unteren Teil ist die Helligkeit so, dass sie entgegengesetzt wirkt in ihrer Ablenkung, der Ablenkung der Trübung. Die Folge davon ist, dass, während oben die Ablenkung der Trübung im selben Sinn erfolgt wie die der Helligkeit und sie also gewissermaßen zusammenwirken, die Trübung sich also sozusagen wie ein Parasit hineinmischt [und die Oberhand gewinnt]; hier unten [dagegen] strahlt zurück die Trübung in die Helligkeit hinein, wird aber von der Helligkeit überwältigt, gewissermaßen unterdrückt, sodass hier die Helligkeit vorherrscht - auch [vorherrscht] in dem Kampf zwischen der Helligkeit und der Trübung, und die Folgen dieses Kampfes zwischen Helligkeit und Trübung, die Folgen dieses Gegeneinander-sich-Stellens und des Durchschienenwerdens der "Trübung von der Helligkeit, das sind nach unten die roten oder gelben Farben. Sodass man sagen [kann], meine lieben Freunde: Nach oben läuft Trübung in Helligkeit ein, [übertönt sie] und es entstehen blaue Nuancen; nach unten übertönt eine Helligkeit die hineinlaufende "Trübe oder Dunkelheit, und es entstehen die gelb[-rot]en Nuancen.

Sie sehen also hier, meine lieben Freunde, dass wir es einfach dadurch, dass das Prisma ablenkt, auf der einen Seite ablenkt den vollen hellen Lichtkegel, auf der anderen Seite ablenkt die Trübung, haben wir es nach zwei Seiten hin mit einem verschiedenen Hineinspielen der Dunkelheit, der Trübung, in das Helle zu tun. Wir haben ein Zusammenspiel von Dunkelheit und Helligkeit, die nicht zu einem Grau sich miteinander vermischen, sondern selbstständig wirksam bleiben, nur nach dem einen Pol hin so wirksam bleiben, dass die Dunkelheit gewissermaßen nach der Helligkeit, also so wirken kann, dass sie innerhalb der Helligkeit zur Geltung kommt, aber eben als Dunkelheit. Auf der anderen Seite stemmt sich die Trübung entgegen der Helligkeit, bleibt vorhanden als selbstständig, aber wird übertönt von der Helligkeit. Da entstehen die hellen Farben, das Gelbliche.

So haben Sie, indem Sie rein innerhalb der Fakten bleiben, dadurch, dass Sie das nehmen, was da ist, dadurch haben Sie rein aus der Anschauung heraus die Möglichkeit zu verstehen, warum auf der einen Seite die gelblich[-rötlich]en Farben, auf der anderen die bläulichen erscheinen, und Sie sehen zu gleicher Zeit daraus, dass das materielle Prisma einen ganz wesentlichen Anteil hat an dieser Entstehung der Farben, indem es ja durch das Prisma geschieht, dass nach der einen Seite hin in demselben Sinn die Trübung abgelenkt wird wie der Lichtkegel, aber auch, weil das Prisma eben ausstrahlen lässt nach der anderen Seite hin seine Dunkelheit. Auch dahin, wo schon abgelenkt ist, kreuzen sich das Fortstrahlende und das Abgelenkte. Dadurch entsteht die Ablenkung [der Trübung] nach unten, und es wirken nach unten anders zusammen die Dunkelheit und die Helligkeit als nach oben. Farben entstehen also da, wo zusammenwirken Dunkelheit und Helligkeit.

Das ist dasjenige, was ich Ihnen heute besonders klarmachen wollte. Sie müssen, wenn Sie sich nun überlegen wollen, ich möchte sagen, aus welcher Ecke heraus das am besten zu begreifen ist, da müssen Sie nur zum Beispiel daran denken, dass zum Beispiel Ihr Ätherleib anders eingeschaltet [ist] im Muskel als im Auge: Im Muskel so, dass er sich mit den Funktionen des Muskels verbindet, im Auge ist er so eingeschaltet, dass gewissermaßen, weil das Auge sehr isoliert ist, der Ätherleib nicht eingeschaltet ist in den physischen Apparat, [sondern] verhältnismäßig selbstständig ist. Dadurch kann mit dem Ätherleibteil im Auge der Astralleib eine innige Verbindung eingehen. Unser astralischer Leib ist innerhalb des Auges ganz anders selbstständig als innerhalb unserer anderen physischen Organisation.

Nehmen Sie an, das [da] wäre ein Teil der physischen Organisation, in einem Muskel, das [hier] wäre physische Organisation des Auges [es wird gezeichnet; vgl. Zeichnung des Auges am Ende des dritten Vortrags]. Wenn wir beschreiben, so müssen wir sagen: Unser Astralleib ist eingeschaltet sowohl da [im Muskel] wie da [im Auge]; aber es ist ein beträchtlicher Unterschied. Da [im Muskel] ist er so eingeschaltet, dass er durch denselben Raum geht wie der physische Körper, aber nicht selbstständig. Hier ist er auch eingeschaltet, im Auge; aber da wirkt er selbstständig. Den Raum füllen beide in gleicher Weise aus; aber das eine Mal [im Auge] wirken die Ingredienzien selbstständig, das andere Mal [im Muskel] wirken sie nicht selbstständig. Daher ist das nur halb gesagt, wenn man sagt: Unser Astralleib ist im physischen Leibe drinnen. Wir müssen fragen, wie er drinnen ist. Denn er ist anders drinnen im Auge und anders im Muskel. Im Auge ist er relativ selbstständig, trotzdem er drinnen ist wie im Muskel.

Daraus sehen Sie, dass Ingredienzien einander durchdringen können und dennoch selbstständig sein können. So können Sie Helligkeit und Dunkelheit zum Grau vereinigen, dann sind sie einander so durchdringend wie Astralleib und Muskel. Oder aber sie können sich so durchdringen, dass sie selbstständig bleiben, dann durchdringen sie sich so wie unser Astralleib und die physische Organisation im Auge. Das eine Mal entsteht Grau, das andere Mal entsteht Farbe. Wenn sie sich so durchdringen wie Astralleib und Muskeln, so entsteht Grau, und wenn sie sich so durchdringen wie unser Astralleib und unser Auge, so entsteht Farbe, weil sie relativ selbstständig bleiben, trotzdem sie im selben Raume sind.

Second Lecture

My dear friends!

Yesterday I spoke to you about how, on the one hand, there is the purely kinematic aspect of observing nature, which we can gain by simply forming mental images of everything that occurs in physical processes through quantifiable, spatial, and movement-related phenomena, by forming these images from our imagination. This kinematic aspect can be spun out, as it were, from our life of imagination. But as significant as it is that what we gain in this way, for example in mathematical formulas about everything that relates to the quantifiable, to space and to movement, also fits the natural processes themselves, it is equally important that we turn to external experience at the moment when we move from the countable, the purely spatial, and movement to, for example, mass. We made this clear yesterday, and we may also have seen from this that, for contemporary physics, the leap from the internal construction of natural events through kinematics into external physical empiricism must be made without this leap actually being understood. You see, without taking steps to understand this leap, it will be impossible to ever gain mental images of what in physics is to be called ether.

I already indicated to you yesterday that, for example, with regard to the phenomena of light and color, contemporary physics, although it has already begun to waver in these mental images, still says in many cases: A light and color effect is exerted upon us, upon us as sensory beings, as nervous beings, or even as soul beings. But this effect is subjective. What goes on outside in space and time is said to be objective movement in the ether. But if you look in today's physics literature... or in other sources of what is commonly said in the world of physics, about the ideas that have been formed about this ether that is supposed to cause the phenomena of light, you will find that these ideas are contradictory and confused, and even with what is available to modern physics, it is impossible to gain a truly accurate mental image of what is to be called ether.

Let us try to embark on a path that can truly bridge the gap between kinematics and even mechanics, for mechanics naturally deals with forces and masses. Although what is expressed by this formula may occupy us later—so that even those of you who may not remember this formula from your school days will be able to catch up on what is necessary for understanding—today I will only present it as a [theorem]. I will put the elements together so that you can get a feel for this formula.

Now, if we assume, in accordance with kinematics, that a point—we must always say a point—is moving in this direction, then such a point moves—we are now only looking at the movement, not its causes—such a point moves either faster or slower. We can therefore say: The point moves with greater or lesser speed. And I will call this speed \(v\). This speed is therefore greater or lesser. As long as we consider nothing else than that such a point moves with a certain speed, we remain within the realm of kinematics. But this would not bring us any closer to nature, not even to mere mechanical nature. If we want to approach nature, we must take into account what causes the point to move and that a purely imagined point cannot move, that the point must therefore be something in external space if it is to move. In short, we must assume that a force is acting on this point. I will call \(v\) the speed and \(p\) the force acting on this point. Let us assume that this force does not merely press on this point once, so to speak, and set it in motion, whereby it would eventually fly away at a certain speed if it did not encounter any obstacles. Instead, let us assume that this force acts continuously, so that the force acts on this point throughout its entire path. I will call the path along which this force acts on the point s. This would therefore be the distance over which the force acts on the point.

Then we must also take into account that the point must be something in space, and this something can be larger or smaller. Depending on whether this something is larger or smaller, we can say: The point has more or less mass. We initially express mass by means of weight. We can weigh what is moved by the force and express it in terms of weight; I will call this \(m\) the mass. But if a force \(p\) acts on the mass \(m\), then of course a certain effect must occur. This effect manifests itself in the fact that the mass does not continue to move at a constant speed, but moves faster and faster, so that the speed becomes greater and greater. This means that we must take into account that we are dealing with an increasing speed. There will be a certain measure by which the velocity increases. If a smaller force acts on the same mass, it will be able to make the movement less and less faster, and if a larger force acts on the same mass, it will be able to make the movement faster and faster. I will call this measure by which the velocity increases acceleration and denote it by \(γ\).