The Light Course

GA 320

25 December 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture III

My dear Friends,

I am told that the phenomenon with the prism—at the end of yesterday's lecture—has after all proved difficult for some of you to understand. Do not be troubled if this is so; you will understand it better by and by. We shall have to go into the phenomena of light and colour rather more fully. They are the real piece de resistance, even in relation to the rest of Physics, and will therefore provide a good foundation.

You will realize that the main idea of the present course is for me to tell you some of the things which you will not find in the text-books, things not included in the normal lines of the scientific study and only able to be dealt with in the way we do here. In the concluding lectures we shall consider how these reflections can also be made use of in school teaching.

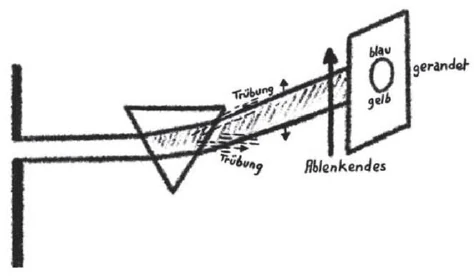

What I was trying to explain is in its essence a special kind of interplay of light and dark—i.e. the unimpaired brightness and on the other hand the dimming or clouding of the light. I was trying to show how through the diverse ways in which light and dark work together—induced especially by the passage of a cylinder of light through a prism—the phenomena of colour, in all their polar relation to one-another, are brought about.

Now in the first place I really must ask you to swallow the bitter pill (I mean, those of you who found things difficult to understand). Your difficulty lies in the fact that you are always hankering after a phoronomical treatment of light and colour. The strange education we are made to undergo instils this mental habit. Thinking of outer Nature, people will restrict themselves to thoughts of a more or less phoronomical character. They will restrict their thoughts to what is arithmetical, spatially formal, and kinematical. Called on to try and think in terms of qualities as you are here, you may well be saying to yourselves: Here we get stuck! You must attribute it to the unnatural direction pursued by Science in modern time. Moreover—I speak especially to Waldorf-School and other teachers—you will yourselves to some extent still have to take the same direction with your pupils. It will not be possible, all at once, to bring the really healthy ideas into a modern school. We must find ways of transition.

For the phenomena of light and colour, let us now begin again, but from the other end. I take my start from a much disputed saying of Goethe's. In the 1780's a number of statements as to the way colours arise in and about the light came to his notice. Among other things, he learned of the prismatic phenomena we were beginning to study yesterday. It was commonly held by physicists, so Goethe learned, that when you let colourless light go through a prism the colourless light is analyzed and split up. For in some such way the phenomena were interpreted. If we let a cylinder of colourless light impinge on the screen, it shows a colourless picture. Putting a prism in the way of the cylinder of light, the physicists went on to say, we get the sequence of colours: red, orange, yellow, green, blue—light blue and dark blue,—violet. Goethe heard of it in this way: the physicists explain it thus, so he was told—The colourless light already contains the seven colours within itself—a rather difficult thing to imagine, no doubt, but that is what they said. And when we make the light go through the prism, the prism really does no more than to fan out and separate what is already there in the light,—the seven colours, into which it is thus analyzed.

Goethe wanted to get to the bottom of it. He began borrowing and collecting instruments,—much as we have been doing in the last few days. He wanted to find out for himself. Buettner, Privy Councillor in Jena, was kind enough to send him some scientific instruments to Weimar. Goethe stacked them away, hoping for a convenient time to begin his investigations. Presently, Councillor Buettner grew impatient and wanted his instruments back. Goethe had not yet begun;—it often happens, one does not get down to a thing right away. Now Goethe had to pack the instruments to send them back again. Meanwhile he took a quick look through the prism, saying to himself as he did so: If then the light is analyzed by the prism, I shall see it so on yonder wall. He really expected to see the light in seven colours. But the only place where he could see any colour at all was at some edge or border-line—a stain on the wall for instance, where the stain, the dark and clouded part, met the lighter surface. Looking at such a place through the prism he saw colours; where there was uniform white he saw nothing of the kind. Goethe was roused. He felt the theory did not make sense. He was no longer minded to send the instruments back, but kept them and went on with his researches. It soon emerged that the phenomenon was not at all as commonly described.

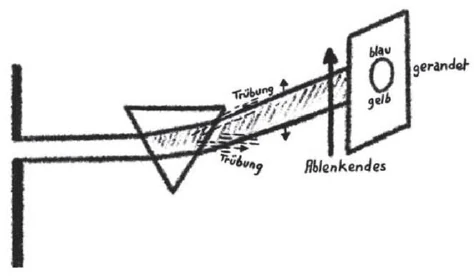

If we let light pass through the space of the room, we get a white circle on the screen. Here we have cut it out very neatly; you see a pretty fair circle. Put a prism in the way of the body of light that is going through there,—the cylinder of light is diverted, (Figure IIc), but what appears in the first place is not the series of seven colours at all, only a reddish colour at the lower edge, passing over into yellow, and at the upper edge a blue passing over into greenish shades. In the middle it stays white.

Goethe now said to himself: It is not that the light is split up or that anything is separated out of the light as such. In point of fact, I am projecting a picture,—simply an image of this circular aperture. The aperture has edges, and where the colours occur the reason is not that they are drawn out of the light, as though the light had been split up into them. It is because this picture which I am projecting—the picture as such—has edges. Here too the fact is that where light adjoins dark, colours appear at the edges. It is none other than that. For there is darkness outside this circular patch of light, while it is relatively light within it.

The colours therefore, to begin with, make their appearance purely and simply as phenomena at the border between light and dark. This is the original, the primary phenomenon. We are no longer seeing the original phenomenon when by reducing the circle in size we get a continuous sequence of colours. The latter phenomenon only arises when we take so small a circle that the colours extend inward from the edges to the middle. They then overlap in the middle and form what we call a continuous spectrum, while with the larger circle the colours formed at the edges stay as they are. This is the primal phenomenon. Colours arise at the borders, where light and dark flow together.

This, my dear Friends, is precisely the point: not to bring in theories to tamper with the facts, but to confine ourselves to a clean straightforward study of the given facts. However, as you have seen, in these phenomena not only colours arise; there is also the lateral displacement of the entire cone of light. To study this displacement further—diagrammatically to begin with—we can also proceed as follows.

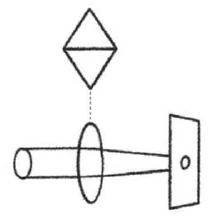

Suppose you put two prisms together so as to make them into a single whole. The lower one is placed like the one I drew yesterday, the upper one the opposite way up (Figure IIIa). If I now made a cylinder of light pass through this double prism, I should of course get something very like what we had yesterday. The light would be diverted—upward in the one case, downward in the other. Hence if I had such a double prism I should get a figure of light still more drawn out than before. But it would prove to be rather indistinct and dark. I should explain this as follows. Catching the picture by a screen placed here, I should get an image of the circle of light as if there were two pushed together, one from either end. But I could now move the screen farther in. Again I should get an image. That is to say, there would be a space—all this is remaining purely within the given facts—a space within which I should always find it possible to get an image. You see then how the double prism treats the light. Moreover I shall always find a red edge outside,—in this case, above and below—and a violet colour in the middle. Where I should otherwise merely get the image extending from red to violet, I now get the outer edges red, with violet in the middle and the other colours in between. By means of such a double prism I should make it possible for such a figure to arise,—and I should get a similar figure if I moved the screen farther away. Within a certain distance either way, such a picture will be able to arise—coloured at the edges, coloured in the middle too, and with transitional colours.

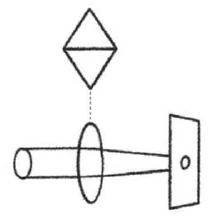

Now we might arrange it so that when moving the screen to and fro there would be a very wide space within which such pictures could be formed. But as you probably divine, the only way of doing this would be to keep on changing the shape of the prism. If for example, taking a prism with a larger angle, I got the picture at a given place, if I then made the angle smaller I should get it elsewhere. Now I can do the whole thing differently by using a prism with curved instead of plane surfaces from the very outset. The phenomenon, difficult to study with the prism, will be much simplified. We therefore have this possibility. We let the cylinder of light go through the space and then put in its way a lens,—which in effect is none other than a double prism with its faces curved. The picture I now get is, to begin with, considerably reduced in size. What then has taken place? The whole cylinder of light has been contracted. Look first at the original cross-section: by interposing the lens I get it narrowed and drawn together. Here then we have a fresh interaction between what is material—the material of the lens, which is a body of glass—and the light that goes through space. The lens so works upon the light as to contract it.

To draw it diagrammatically (Figure IIIa, above), here is a cylinder of light. I let the light go through the lens. If I confronted the light with an ordinary plate of glass or water, the cylinder of light would just go through and a simple picture of it on the screen would be the outcome. Not so if instead of the simple plate, made of glass or water, I have a lens. Following what has actually happened with my drawing, I must say: the picture has grown smaller. The cylinder of light is contracted.

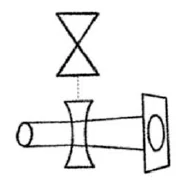

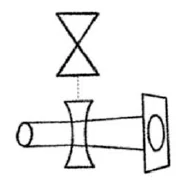

Now there is also another possibility. We could set up a double prism, not as in the former instance but in cross-section as I am now drawing it (Figure IIIb),—the prisms meeting at the angle. I should again get the phenomenon described before, only in this instance the circle would be considerably enlarged. Once again, while moving the screen to and fro within a certain range, I should still get the picture—more or less indistinct. Moreover in this case (Figure IIIb, above and on the right) I should get violet and bluish colours both at the upper and at the lower edge, and red in the middle,—the opposite of what it was before. There would again be the intermediate colours.

Once more I can replace the double prism by a lens,—a lens of this cross-section (Figure IIIb). The other was thick in the middle and thin at the edges; this one is thin in the middle and thick at the edge. Using this lens, I get a picture considerably bigger than the cross-section of the cylinder of light would be without it. I get an enlarged picture, again with colours graded from the edge towards the centre. Following the phenomena in this case I must say: the cylinder of light has been widened,—very considerably thrust apart. Again: the simple fact.

What do we see from these phenomena? Evidently there is an active relation between the material—though it appears transparent in all these lenses and prisms—and what comes to manifestation through the light. We see a kind of interaction between them. Taking our start from what we should get with a lens of this type (thick at the edge and thin in the middle), the entire cylinder of light will have been thrust apart,—will have been widened. We see too how this widening can have come about,—obviously through the fact that the material through which the light has gone is thinner here and thicker here. Here at the edge, the light has to make its way through more matter than in the middle, where it has less matter to go through. And now, what happens to the light? As we said, it is widened out—thrust apart—in the direction of these two arrows. How can it have been thrust apart? It can only be through the fact that it has less matter to go through in the middle and more at the edges. Think of it now. In the middle the light has less matter to go through; it therefore passes through more easily and retains more of its force after having gone through. Here therefore—where it goes through less matter—the force of it is greater than where it goes through more. It is the stronger force in the middle, due to the light's having less matter to go through, which presses the cylinder of light apart. If I may so express myself, you can read it in the facts that this is how it is. I want you to be very clear at this point it is simply a question of true method in our thinking. In our attempts to follow up the phenomena of light by means of lines and diagrams we ought to realize that with every line we draw we ourselves are adding something which has nothing to do with the light as such. The lines I have been drawing are but the limits of the cylinder of light. The cylinder of light is brought about by the aperture. What I draw has nothing to do with the light; I am only reproducing what is brought about by the light's going through the slit. And if I say, “the light moves in this direction”, that again has nothing to do with the light as such; for if I moved the source of light upward, the light that falls on the slit would move in this way and I should have to draw the arrow in this direction. This again would not concern the light as such. People have formed such a habit of drawing lines into the light, and from this habit they have gradually come to talk of “light-rays”. In fact we never have to do with light-rays; here for example, what we have to do with is a cone of light, due to the aperture through which we caused the light to pass. In this instance the cone of light is broadened out, and it is evident: the broadening must somehow be connected with the shorter path the light has to go through in the middle of the lens than at the edge. Due to the shorter path in the middle, the light retains more force; due to the longer path at the edge, more force is taken from it. The stronger light in the middle presses upon the weaker light at the edge and so the cone of light is broadened. You simply read it in the facts.

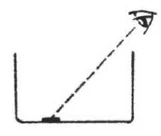

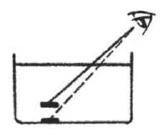

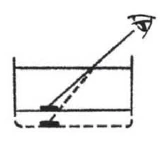

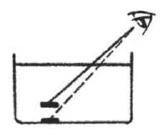

Truth is that where we simply have to do with images or pictures, the physicists speak of all manner of other things,—light-rays and so on. The “light-rays” have become the very basis of materialistic thinking in this domain. To illustrate the point more vividly, we will consider another phenomenon. Suppose I have a vessel here (Figure IIId), filled with liquid—water, for example. On the floor of the vessel there is an object—say, a florin. Here is the eye. I can now make the following experiment. Omitting the water to begin with, I can look down at the object and see it in this direction. What is the fact? An object is lying on the bottom of the vessel (Figure IIIc). I look and see it in a certain direction. Such is the simple fact, but if I now begin explaining: there is a ray of light proceeding from the object to the eye, affecting the eye, and so on,—then, my dear Friends, I am already fancying all kinds of things that are not given.

Now let me fill the vessel with water or some other liquid up to here. A strange thing happens. I draw a line from the eye towards the object in the direction in which I saw it before. Looking in this direction, I might expect to see the same as before, but I do not. A peculiar thing happens. I see the object lifted to some extent. I see it, and with it the whole floor of the vessel lifted upward. We may go into it another time, as to how this effect can be determined, by which I mean measured. I now only refer to the main principle. To what can this effect be due? How shall I answer this question, purely from the facts? Having previously seen the thing in this direction, I expect to find it there again. Yet when I look, I do not see it there but in this other direction. When there was no water in the vessel I could look straight to the bottom, between which and my eye there was only air. Now my sighting line impinges on the water. The water does not let my force of sight go through as easily as the air does; it offers stronger resistance, to which must give way. From the surface of the water onward I must give way to the stronger resistance, and, that I have to do so, comes to expression in that I do not see right down as before but it all looks lifted upward. It is as though it were more difficult for me to see through the water than through the air; the resistance of the water is harder for me to overcome. Hence I must shorten the force and so I myself draw the object upward. In meeting the stronger resistance I draw in the force and shorten it. If I could fill the vessel with a gas thinner than air (Figure IIIe), the object would be correspondingly lowered, since I should then encounter less resistance,—so I should push it downward. Instead of simply noting this fact, the physicists will say: There is a ray of light, sent from the object to the surface of the water. The ray is there refracted. Owing to the transition from a denser medium to a more tenuous, the ray is refracted away from the normal at the point of incidence; so then it reaches the eye in this direction. And now the physicists go on to say a very curious thing. The eye, they say, having received information by this ray of light, produces it on and outward in the same straight line and so projects the object thither. What is the meaning of this? In the conventional Physics they will invent all manner of concepts but fail to reckon with what is evidently there,—with the resistance which the sighting force of the eye encounters in the denser medium it has to penetrate. They want to leave all this out and to ascribe everything to the light alone, just as they say of the prism experiment: Oh, it is not the prism at all; the seven colours are there in the light all the time. The prism only provides the occasion for them to line up like so many soldiers. The seven naughty boys were there in the light already; now they are only made to line up and stand apart. The prism isn't responsible. Yet as we say, the colours are really caused by what arises in the prism. This wedge of dimness is the cause. The colours are not due to the light as such.

Here now you see it again. We must be clear that we ourselves are being active. We, actively, are looking with our eye,—with our line of sight. Finding increased resistance in the water, we are obliged to shorten the line of sight. What say the physicists on the other hand? They speak of rays of light being sent out and refracted and so on. And now the beauty of it, my dear Friends! The light, they say, reaches the eye by a bent and broken path, and then the eye projects the picture outward. So after all they end by attributing this activity to the eye: “The eye projects ...” Only they then present us with a merely phoronomical conception, remote from the given realities. They put a merely fancied activity in place of what is evidently given: the resistance of the denser water to the sighting force of the eye. It is at such points that you see most distinctly how abstract everything is made in our conventional Physics. All things are turned into mere phoronomic systems; what they will not do is to go into the qualities. Thus in the first place they divest the eye of any kind of activity of its own; only from outer objects rays of light are supposed to proceed and thence to reach the eye. Yet in the last resort the eye is said to project outward into space the stimulus which it receives. Surely we ought to begin with the activity of the eye from the very outset. We must be clear that the eye is an active organism.

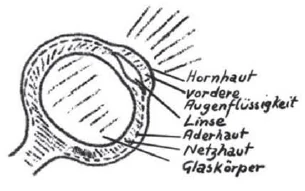

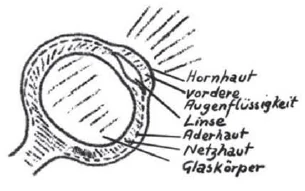

We will today begin our study of the nature of the human eye. Here is a model of it (Figure IIIf). The human eye, as you know, is in form like a kind of sphere, slightly compressed from front to back. Such is the eye-ball, seated in the bony cavity or orbit, and with a number of skins enveloping the inner portion. To draw it in cross-section (Figure IIIf). it will be like this. (When looking at your neighbour's eye you look into the pupil. I am now drawing it from the side and in cross-section.) This then would be a right-hand eye. If we removed the eye from the skull, making an anatomical preparation, the first thing we should encounter would be connective tissue and fatty tissue. Then we should reach the first integument of the eye properly speaking—the so-called sclerotic and the transparent portion of it, the cornea. This outermost integument (I have here drawn it) is sinewy,—of bony or cartilaginous consistency. Towards the front it gets transparent, so that the light can penetrate into the eye. A second layer enveloping the inner space of the eye is then the so-called choroid, containing blood-vessels. Thirdly we get the inner-most layer, the retina so-called, which is continued into the optic nerve as you go farther in into the skull. Herewith we have enumerated the three integuments of the eye, And now behind the cornea, shown here,—embedded in the ciliary muscle—is a kind of lens. The lens is carried by a muscle known as the ciliary muscle. In front is the transparent cornea, between which and the lens is the so-called aqueous humour. Thus when the light gets into the eye it first passes through the transparent cornea, then through the aqueous humour and then through this lens which is inherently movable by means of muscles. From the lens onward the light then reaches what is commonly known as the vitreous body or vitreous humour, filling the entire space of the eye. The light therefore goes through the transparent cornea, through the aqueous humour, the lens itself and the vitreous humour and from thence reaches the retina, which is in fact a ramification of the optic nerve that then goes on into the brain, This, therefore, (Figure IIIf),—envisaging only what is most important to begin with—would be a diagrammatic picture of the essential parts of the eye, embedded as it is in its cavity within the bony skull.

Now the eye reveals very remarkable features. Examining the contents of this fluid that is between the lens and the cornea through which the light first has to pass, we find it very like any ordinary liquid taken from the outer world. At this place in the human body therefore—in the liquid or aqueous humour of the eye, between the lens and the outer cornea,—a man in his bodily nature is quite of a piece with the outer world. The lens too is to a high degree “objective” and unalive. Not so when we go on to the vitreous body, filling the interior of the eye and bordering on the retina. Of this we can no longer say that it is like any external body or external fluid. In the vitreous humour there is decided vitality,—there is life. Truth is, the farther back we go into the eye, the more life do we find. In the aqueous humour we have a quite external and objective kind of fluid. The lens too is still external. Inside the vitreous body on the other hand we find inherent vitality. This difference, between what is contained in this more outward portion of the eye and what is there in the more contained parts, also reveals itself in another circumstance. Tracing the comparative development of the eye from the lower animals upward, we find that the external fluid or aqueous humour and the lens grow not from within outward but by the forming of new cells from the surrounding and more peripheral cells. I must conceive the forming of the lens rather in this way. The tissue of the lens, also the aqueous humour in the anterior part of the eye, are formed from neighbouring organs, not from within outward; whilst from within the vitreous body grows out to meet them. This is the noteworthy thing. In fact the nature of the outer light is here at work, bringing about that transformation whereby the aqueous humour and the lens originate. To this the living being then reacts from within, thrusting outward a more living, a more vital organ, namely the vitreous body. Notably in the eye, formations whose development is stimulated from without, and others stimulated from within, meet one-another in a very striking way.

This is the first peculiarity of the eye, and there is also another, scarcely less remarkable. The expanse of the retina which you see here is really the expanded optic nerve. Now the peculiar thing is that at the very point of entry of the optic nerve the eye is insensitive; there it is blind. Tomorrow I shall try to show you an experiment confirming this. The optic nerve thence spreads out, and in an area which for the right-hand eye is a little to the right of the point of entry the retina is most sensitive of all. We may begin by saying that it is surely the nerve which senses the light. Yet it is insensitive to light precisely at its point of entry. If it is really the nerve that senses the light we should expect it to do so more intensely at the point of entry, but it does not. Please try to bear this in mind.

That this whole structure and arrangement of the eye is full of wisdom—wisdom, if I may so put it, from the side of Nature—this you may also tell from the following fact. During the day when you look at the objects around you—in so far as you have healthy eyes—they will appear to you more or less sharp and clear, or at least so that their sharpness of outline is fully adequate for orientation. But in the morning when you first awaken you sometimes see the outlines of surrounding objects very indistinctly, as if enveloped with a little halo. The rim of a circle for example will be indistinct and nebular when you have just awakened in the morning. What is it due to? It is due to there being two different kinds of things in our eye, namely the vitreous body and the lens. In origin, as we have seen, they are quite different. The lens is formed more from without, the vitreous body more from within. While the lens is rather unalive, the vitreous body is full of vitality. Now in the moment of awakening they are not yet adapted to one-another. The vitreous body still tries to picture the objects to us in the way it can; the lens in the way it can. We have to wait till they are well adapted to each other. You see again how deeply mobile everything organic is. The whole working of it depends on this. First the activity is differentiated into that of the lens and the vitreous body respectively. From what is thus differentiated the activity is thereupon composed and integrated; so then the one has to adapt itself to the other.

From all these things we shall try gradually to discover how the many-coloured world emerges for us from the relation of the eye to the outer world. Now there is one more experiment I wish to shew today, and from it we may partly take our start tomorrow in studying the relation of the eye to the external world. Here is a disc, mounted on a wheel and painted with the colours which we saw before—those of the rainbow: violet, indigo, blue, green, yellow, orange and red. First look at it and see the seven colours. We will now bring it into rotation. I can turn fairly quickly and you still see the seven colours as such—only rotating. But when I turn quickly enough you can no longer see the colours. You are no doubt seeing a uniform grey. So we must ask: Why do the seven colours appear to us in grey, all of one shade? This we will try to answer tomorrow. Today we will adduce what modern Physics has to say about it,—what is already said in Goethe's time. According to modern Physics, here are the colours of the rainbow: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet. We bring the disc into rotation. The single impression of light has not time enough to make itself felt as such in our eye. Scarcely have I seen the red at a particular place, the quick rotation brings the orange there and then the yellow, and so on. The red itself is there again before I have time to rid myself of the impressions of the other colours. So then I get them all at once. The violet arrives before the impression of the red has vanished. For the eye, the seven colours are thus put together again, which must once more give white.

Such was the scientific doctrine even in Goethe's time, and so he was instructed. Bring a coloured top into quick enough rotation: the seven colours, which in the prism experiment very obediently lined up and stood apart, will re-unite in the eye itself. But Goethe saw no white. All that you ever get is grey, said Goethe. The modern text-books do indeed admit this; they too have ascertained that all you get is grey. However, to make it white after all, they advise you to put a black circle in the middle of the disc, so that the grey may appear white by contrast. A pretty way of doing things! Some people load the dice of “Fortune”, the physicists do so with “Nature”—so they correct her to their liking. You will discover that this is being done with quite a number of the fundamental facts.

I am trying to proceed in such a way as to create a good foundation. Once we have done this, it will enable us to go forward also in the other realms of Physics, and of Science generally.

Dritter Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde!

Es ist mir gesagt worden, dass doch dasjenige, worinnen wir die gestrige Betrachtung gipfeln lassen mussten, die Erscheinung, die durch das Prisma auftritt, dass diese Erscheinung doch Schwierigkeiten dem Verständnisse für viele geboten habe, und ich bitte Sie, darüber sich zu beruhigen. Es wird dieses Verständnis nach und nach kommen. Wir werden uns gerade mit den Licht- und Farbenerscheinungen ein wenig eingehender befassen, damit diese eigentliche piece de resistance - eine solche ist es auch für die übrige Physik -, damit diese uns eine gute Grundlage abgeben könne. Nicht wahr, Sie sehen ein, dass es sich uns zunächst darum handeln muss, dass ich Ihnen gerade einiges von demjenigen sage, was Sie nicht in Büchern finden können und was nicht Gegenstand der gewöhnlichen naturwissenschaftlichen Betrachtungen ist, was wir gewissermaßen nur hier behandeln können. Wir werden dann in den letzten Vorträgen darauf eingehen, wie dasjenige, was wir hier betrachten, auch im Unterricht zu verwerten ist.

Sehen Sie, dasjenige, was ich versuchte gestern auseinanderzusetzen, ist ja im Wesentlichen eine besondere Art des Ineinanderwirkens von Helligkeit und Trübe. Und ich wollte zeigen, dass durch dieses verschiedenartige Zusammenwirken von Helligkeit und Trübe, das besonders auftritt beim Durchgang eines Lichtzylinders durch ein Prisma, dass da die polarisch zueinander sich verhaltenden Farbenerscheinungen entstehen. Zunächst bitte ich Sie, die bittere Pille schon in Empfang zu nehmen, dass die Schwierigkeit des Verständnisses dieser Sache darinnen liegt, dass Sie eigentlich - es geht diejenigen an, die Schwierigkeit des Verständnisses finden - dass Sie eigentlich die Licht- und Farbenlehre phoronomisch gestaltet haben möchten. Die Menschen haben sich nun schon einmal gewöhnt durch unsere sonderbare Erziehung, nur sich solchen Vorstellungen hinzugeben, die mit Bezug auf die äußere Natur mehr oder weniger phoronomisch sind, das heißt sich nur befassen mit dem Zählbaren, mit dem Räumlich-Formalen und mit dem Beweglichen. Nun sollen Sie sich bemühen, in Qualitäten zu denken, und Sie können wirklich in einem gewissen Sinne sagen: Hier stocke ich schon. - Aber schreiben Sie das durchaus zu dem unnatürlichen Gang, den die wissenschaftliche Entwicklung in der neueren Zeit genommen und den sie durchgemacht hat, den Sie sogar werden in gewisser Weise mit Ihren Schülern durchmachen - ich meine jetzt die Lehrer der Waldorfschule” und andere Lehrer. Denn es wird natürlich nicht möglich sein, sogleich gesunde Vorstellungen in die heutige Schule hineinzutragen, sondern wir werden Übergänge schaffen müssen.

Nun gehen wir, ich möchte sagen, einmal für die Licht- und Farbenerscheinungen von dem anderen Ende der Sache aus. Eine viel angefochtene Bemerkung Goethes möchte ich heute vorausschicken. Sie können es bei Goethe lesen”, wie er bekannt geworden ist in den Achtzigerjahren des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts mit allerlei Behauptungen über das Auftreten von Farben am Lichte, also über diejenigen Erscheinungen, von denen wir gestern begonnen haben zu sprechen. Es ist ihm gesagt worden, dass die allgemeine Anschauung der Physiker die sci, dass, wenn man farbloses Licht durch ein Prisma gehen lasse, so würde dieses farblose Licht gespalten, zerlegt. Also etwa so wurden die Erscheinungen interpretiert, es wurde gesagt: Wir fangen einen farblosen Lichtzylinder auf, so zeigt er uns zunächst ein farbloses Bild. Wir stellen diesem Lichtzylinder in den Weg das Prisma, so bekommen wir die Aufeinanderfolge der Farben Rot, Orange, Gelb, Grün, Blau - Hellblau, Dunkelblau -, Violett. Nun, das ist etwas, was an Goethe herantrat, und zwar so, dass er erfuhr: Man erklärt sich diese Sache so, dass das farblose Licht eigentlich schon in sich enthält - wie, das ist ja natürlich schwer zu denken, aber das wurde gesagt - in sich enthält diese sieben Farben. Wenn man das Licht durch das Prisma gehen lässt, so tut das Prisma eigentlich nichts anderes als das, was im Licht schon drinnen ist, fächerartig auseinanderlegen, das Licht in die sieben Farben zerlegen.” Nun, Goethe wollte der Sache auf den Grund gehen und lich sich allerlei Instrumente aus, wie wir es versucht haben in diesen Tagen sie auch zusammenzutragen, um selber zu konstatieren, wie die Dinge sind. Er ließ sich diese Instrumente von dem Hofrat Büttner” in Jena nach Weimar hinüberkommen, stapelte sie auf und wollte zu gelegener Zeit versuchen, wie sich die Sache verhält. Der Hofrat Büttner wurde ungeduldig und forderte die Instrumente zurück, als Goethe noch nichts gemacht hatte. Er musste die Instrumente zusammenpacken - bei manchen Dingen passiert uns ja so etwas, dass wir nicht gleich dazu kommen. Er nahm schnell noch das Prisma und sagte: Also, durch das Prisma wird das Licht zerlegt. Ich gucke es mir an an der Wand. - Und nun hat er erwartet, dass das Licht schön siebenfarbig erscheint. Es erschien aber nur da irgendetwas Farbiges, wo irgendein Rand war, wo ein Schmutzfleck war, sodass das Schmutzige, das Trübe, mit dem Hellen zusammenstieß. Da, wenn man durchguckte, sah man Farben. Aber wo gleichmäßiges Weiß war, sah man nichts. Da wurde Goethe stutzig, er wurde irre an dieser ganzen Theorie. Und nun hatte er keinen Sinn mehr für das Zurückschicken der Instrumente. Er behielt sie und verfolgte die Sache weiter. Und da stellte sich heraus, dass die Sache eigentlich gar nicht so ist, wie sie gewöhnlich dargestellt wurde, sondern dass, wenn wir Licht durchlassen durch den Raum des Zimmers, so bekommen wir auf einem Schirm einen weißen Kreis.

Sie sehen hier einen sehr schönen Kreis, wir haben ihn sehr schön geschnitten und haben deshalb einen sehr schönen Kreis bekommen. - Nun, wenn man diesem Lichtkörper, der da durchgeht, in den Weg stellt das Prisma, so wird der Lichtzylinder abgelenkt. Aber es erscheinen zunächst durchaus nicht die sieben aufeinanderfolgenden Farben, sondern nur am unteren Rand tritt das Rötliche auf, das ins Gelbliche übergeht, und am oberen Rand das Bläuliche, das ins Grünliche übergeht. In der Mitte bleibt es weiß.

Was sagte sich nun Goethe? Er sagte sich: Da kommt es also überhaupt nicht darauf an, dass irgendetwas aus dem Licht heraus sich spaltet, sondern ich bilde ja eigentlich ab ein Bild. Dieses Bild ist nur das Abbild des Ausschnittes hier. Der Ausschnitt hat Ränder und die Farben treten nicht deshalb auf, weil sie aus dem Licht herausgeholt werden, gewissermaßen, weil das Licht in sie zerspalten würde, sondern weil ich das Bild entwerfe und das Bild als solches Ränder hat, sodass ich es auch hier mit nichts anderem zu tun habe, als dass dort, wo Helligkeit und Dunkelheit zusammentreten - denn außerhalb dieses Lichtkreises hier ist Dunkelheit in der Umgebung und innen ist es hell -, da an den Rändern treten die Farben auf. Es treten zunächst überhaupt nur die Farben als Randerscheinungen auf, und wir haben, indem wir die Farben als Randerscheinungen zeigen, im Grunde das ursprüngliche Phänomen vor uns. Wir haben gar nicht vor uns das ursprüngliche Phänomen, wenn wir nun den Kreis verkleinern und ein kontinuierliches Farbenbild bekommen. Das kontinuierliche Farbenbild entsteht nur dadurch, dass, während beim großen Kreis die Randfarben eben Randfarben bleiben, setzen sich beim kleinen Kreis vom Rand herein die Farben bis zur Mitte fort, übergreifen sich in der Mitte und bilden, was man ein kontinuierliches Spektrum nennt. Also, die ursprüngliche Erscheinung ist diejenige, dass an den Rändern, wo Helligkeit und Dunkelheit zusammenströmen, Farben auftreten.

Sie sehen, es handelt sich darum, dass wir nicht mit Theorien in die Tatsachen hineinpfuschen, sondern reinlich bleiben bei einem Studium der bloßen Tatsachen, der bloßen Fakta. Nun handelt es sich darum, dass hier ja nicht nur dasjenige auftritt, was wir in den Farben sehen, sondern Sie haben gesehen: Es tritt hier auch auf eine Verschiebung des ganzen Lichtkegels, eine seitliche Ablenkung des ganzen Lichtkegels. Wenn Sie schematisch diese seitliche Ablenkung verfolgen wollen, so könnten Sie es etwa auf die folgende Weise noch verfolgen.

Nehmen Sie an, Sie fügen zwei Prismen [an ihren Basisflächen] zusammen, sodass dann das untere Prisma, das aber ein Ganzes bildet mit dem oberen, so steht wie das, was ich Ihnen gestern aufgezeichnet habe. Das obere Prisma steht entgegengesetzt dem unteren. Würde ich durch dieses Doppel-Prisma einen Lichtzylinder durchgehen lassen, so würde ich natürlich müssen etwas Ähnliches bekommen wie gestern. Ich würde müssen bekommen eine Ablenkung, das eine Mal nach unten, das andere Mal nach oben.“ Ich würde, wenn ich hier ein solches Doppel-Prisma hätte, bekommen eine noch mehr in die Länge gezogene Lichtfigur, aber zu gleicher Zeit würde sich herausstellen, dass diese noch mehr in die Länge gezogene Lichtfigur sehr undeutlich ist, düster ist. Das würde mir dadurch erklärlich werden, dass ich dann, wenn ich hier die Figur mit einem Schirm auffange, so würde ich von diesem Lichtkreis hier ineinandergeschoben bekommen eine Abbildung. Aber ich könnte den Schirm auch hereinrücken. Ich würde wiederum eine Abbildung bekommen. Das heißt, es gäbe hier eine Strecke — das liegt innerhalb der Tatsachen alles —, eine Strecke, auf der ich immer die Möglichkeit, eine Abbildung zu bekommen, antreffen würde. Sie sehen daraus, dass durch das DoppelPrisma mit dem Lichte hantiert wird. Das eine, was ich immer finde, ist, nun, dass ich bekomme immer hier außen einen roten Rand, und zwar jetzt oben und unten, und in der Mitte Violett, sodass ich also jetzt ein solches Bild bekomme: In der Mitte Violett und nach außen einen roten Rand. Während ich sonst bloß bekomme das Bild vom Rot bis zum Violett, bekomme ich jetzt die äußeren Ränder rot und in der Mitte Violett und dazwischen die anderen Farben.

Nun kann man umgehen diese Tatsache, dass hier durch eine gewisse Strecke hindurch Bilder angetroffen werden. Wenn ich den Schirm verschiebe, dann bekomme ich [unterschiedliche] Bilder. Also, ich könnte durch ein solches Doppel-Prisma die Möglichkeit schaffen, dass eine solche Figur entstünde, aber ich würde diese auch bekommen, wenn ich in diese Richtung den Schirm verschieben würde. Ich habe also eine gewisse Strecke, auf der die Möglichkeit der Entstehung eines Bildes vorhanden ist, das an den Rändern farbig ist, aber auch in der Mitte farbig ist und allerlei Übergangsfarben hat.

Nun kann man [vermeiden], dass hier, wenn ich mit dem Schirm auf und ab gehe, so ein ganz weiter Raum [zu durchlaufen] ist, auf dem die Möglichkeit besteht, solche Bilder zu schaffen. Aber Sie ahnen wohl, diese [andere] Möglichkeit [Bilder zu erzeugen] könnte nur geschaffen werden, wenn ich das Prisma immer [geometrisch] ändern würde, wenn ich zum Beispiel, weil bei einem Prisma, dessen Winkel hier größer ist, an einer anderen Stelle das Bild entworfen wird; wenn ich den Winkel kleiner machen würde, würde das Bild an einer anderen Stelle entworfen werden und ich würde diese Strecke kleiner bekommen.

Ich kann die ganze Sache dadurch zu einer anderen machen, dass ich nun hier nicht ebene Flächen für ein Prisma habe, sondern dass ich von vornherein gekrümmte Flächen nehme. Dadurch wird dasjenige, was beim Prisma noch außerordentlich schwer zu studieren ist, wesentlich vereinfacht. Und wir bekommen dann folgende Möglichkeit: Wir lassen zunächst durchgehen durch den Raum den Lichtzylinder, und jetzt stellen wir die Linse, die also eigentlich nichts anderes ist als ein Doppel-Prisma, aber mit gekrümmten Flächen, die stellen wir in den Weg. Statt des Doppel-Prismas stellen wir die Linse in den Weg. Sie sehen, wenn ich die Linse in den Weg stelle, so bekomme ich das Bild zunächst wesentlich verkleinert. Also, was ist denn da eigentlich geschehen? Der ganze Lichtzylinder ist zusammengezogen. Dieses [auf der linken Seite] ist der ursprüngliche Durchschnitt des Zylinders. Indem ich die Linse in den Weg stelle, bekomme ich den ganzen Lichtzylinder zusammengezogen, verengt. Da haben wir eine neue Wechselwirkung zwischen dem Materiellen, dem Materiellen in der Linse, im Glaskörper, und dem durch den Raum gehenden Licht. Diese Linse wirkt so auf das Licht, dass sie den Lichtzylinder zusammenzieht.

Wir wollen uns die ganze Sache einmal schematisch aufzeichnen: Wenn ich hier einen Lichtzylinder habe, von der Seite gezeichnet, ich lasse sein Licht durch die Linse gehen - wir wollen das heute noch ganz. roh behandeln -, so durch die Linse gehen, während zum Beispiel, wenn ich eine gewöhnliche Glasplatte entgegensetzen würde, würde der Lichtzylinder - oder wenn ich eine Wasserplatte entgegensetzen würde -, so würde der Lichtzylinder einfach durchgehen und es würde sich [auf] dem Schirm eben ein Abbild des Lichtzylinders ergeben. Das ist nicht der Fall, wenn ich nicht eine Glasplatte oder eine Wasserplatte habe, sondern eine Linse. Wenn ich einfach mit den Strichen nachfahre demjenigen, was geschehen ist, so muss ich sagen: Es ist eine Verkleinerung des Bildes, die sich ergeben hat. Also ist der Lichtzylinder zusammengezogen.

Es gibt noch eine andere Möglichkeit. Das ist diese, dass man die Anordnung nachbildet nicht einem solchen Doppel-Prisma, wie ich es dort gezeichnet habe, sondern einem Doppel-Prisma, das so im Durchschnitt gestaltet ist - oder im Querschnitt —, dass mit dieser Kante hier die Prismen aneinanderstoßen. Dann würde ich allerdings dieselbe Beschreibung, die ich gemacht habe, mit einem wesentlich vergrößerten Kreis bekommen. Wiederum würde ich, indem ich mit dem Schirm auf und ab gehe während einer gewissen Strecke, die Möglichkeit haben, das Bild - mehr oder weniger undeutlich - zu bekommen. Ich würde hier in diesem Fall oben Violett, Bläulich haben, unten auch Violett, Blau und in der Mitte würde ich Rot haben. Dort war es umgekehrt. Und dazwischen die Zwischenfarben.”

Ich kann mir wiederum an die Stelle dieses Doppel-Prismas setzen eine Linse mit folgendem Querschnitt:

Während diese Linse [in der vorigen Anordnung] ihrem Querschnitt nach zeigt sich in der Mitte dick und an den Rändern dünn, zeigt sich diese [hier] in der Mitte dünn und an den Rändern dick. In diesem Fall bekomme ich auch durch die Linse hier ein Bild, das wesentlich größer ist, als der gewöhnliche Querschnitt wäre, der von dem Lichtzylinder entstehen würde. Ich bekomme ein vergrößertes Bild, aber auch mit dieser Farbenabstufung an den Rändern und gegen die Mitte zu. Will ich also hier die Erscheinungen verfolgen, so muss ich sagen: Der Lichtzylinder ist auseinandergeweitet worden, er ist im Wesentlichen auseinandergetrieben worden. Das ist das einfache Faktum.

Nun, was sehen wir aus diesen Erscheinungen? Wir sehen aus diesen Erscheinungen, dass eine Beziehung herrscht zwischen dem Materiellen, das uns zunächst als durchsichtiges Materielles entgegentritt in den Linsen oder Prismen, zwischen diesem Materiellen und demjenigen, was durch das Licht zur Erscheinung kommt. Und wir sehen auch in gewissem Sinn eine gewisse Art dieser Wechselwirkung. Denn gehen wir von demjenigen aus, was wir hier durch eine solche Linse gewinnen würden, die an den Rändern dick und in der Mitte dünn ist, was müssen wir uns denn da sagen, wenn wir eine solche Linse vor uns haben? Da müssen wir sagen: Es ist auseinandergetrieben worden der ganze Lichtzylinder, er ist geweitet worden. Und wir sehen auch, wie diese Weitung möglich ist. Diese Weitung kommt ja dadurch zustande, dass das Materielle, durch das das Licht durchgegangen ist, hier [in der Mitte] dünn ist, hier [am Rande] dicker ist. Da muss das Licht durch mehr Materielles dringen als hier in der Mitte, wo es durch weniger Materielles dringt. Was geschieht nun mit dem Lichte? Nun, wir haben ja gesagt, es wird geweitet, es wird auseinandergetrieben. In der Richtung dieser zwei Pfeile wird es auseinandergetrieben. Wodurch kann es nur auseinandergetrieben werden? Nun, lediglich durch den Umstand, dass cs in der Mitte weniger Materie zu passieren hat und an den Rändern mehr. Nun überlegen Sie sich die Sache: In der Mitte hat das Licht weniger Materielles zu passieren, geht also leichter durch, hat also, wenn es durchgegangen ist, noch mehr Kraft. Also, es hat hier mehr Kraft, wo es durch weniger Materielles hindurchgeht, als hier, wo es durch mehr Materielles geht. Diese stärkere Kraft in der Mitte, die hervorgerufen wird dadurch, dass das Licht durch weniger Materielles hindurchgeht, die drückt den Lichtzylinder auseinander. Das ist etwas, was Sie sozusagen an den Fakten unmittelbar ablesen können.

Ich bitte, sich nur ganz klar darüber zu sein, dass es sich hier handelt um eine richtige Behandlung der Methode, um eine richtige Führung des Denkens. Man muss sich klar sein, wenn man das, was durch das Licht erscheint, mit Linien verfolgt, dass man da eigentlich nur etwas hinzuzeichnet, was mit dem Lichte nichts zu tun hat. Wenn ich hier die Linien zeichne, dann zeichne ich bloß die Grenzen des Lichtzylinders. Dieser Lichtzylinder wird durch diese Öffnung bewirkt. Ich zeichne also gar nichts, was mit dem Licht zu tun hat, sondern nur etwas, was hervorgerufen wird dadurch, dass das Licht durch den [kreisförmigen] Spalt durchgeht. Und wenn ich hier sage: In dieser Richtung bewegt sich das Licht, so hat das wiederum mit dem Lichte nichts zu tun; denn würde ich die Lichtquelle hinaufschieben, so würde sich eben das Licht, wenn es durch den Spalt fallen würde, so bewegen, und ich müsste diese Pfeilrichtung so zeichnen. Das alles hätte mit dem Lichte als solchem nichts zu tun. Dieses Zeichnen von Linien in das Licht hinein ist man gewohnt worden zu vollziehen und dadurch ist man allmählich darauf gekommen, von den Lichtstrahlen zu reden. Man hat es nirgends mit den Lichtstrahlen zu tun; man hat es zu tun mit einem Lichtkegel, der hervorgerufen ist durch einen [kreisförmigen] Spalt, durch den man das Licht dringen lässt. Man hat es zu tun mit einer Verbreiterung des Lichtkegels- man muss sagen: Irgendwie muss die Verbreiterung des Lichtkegels zusammenhängen mit dem geringeren Weg hier in der Mitte, den das Licht macht, als hier am Rande. Durch den geringeren Weg hier in der Mitte behält es mehr Kraft, durch den längeren Weg am Rande wird ihm mehr Kraft genommen. Das schwächere Licht am Rande wird gedrückt durch das stärkere Licht in der Mitte, und es wird der Lichtkegel verbreitert. Das ist, was Sie ablesen können.

Nun sehen Sie: Während man es eigentlich nur zu tun hat mit Bildern, redet man in der Physik von allem Möglichen, von den Lichtstrahlen und dergleichen. Diese Lichtstrahlen, die sind nun eigentlich zum Untergrund gerade für das materialistische Denken auf diesem Gebiet geworden.

Wir wollen, um das noch etwas anschaulicher zu machen, was ich eben auseinandergesetzt habe, etwas anderes noch betrachten. Nehmen wir an, wir haben hier eine Wanne, ein kleines Gefäß. Wir haben hier in diesem kleinen Gefäß eine Flüssigkeit, sagen wir zum Beispiel Wasser, und da unten irgendeinen Gegenstand liegen, meinetwegen einen Taler oder dergleichen. Wenn ich hier ein Auge habe, so kann ich folgendes Experiment machen: Ich kann zunächst das Wasser weglassen und kann auf diesen Gegenstand sehen mit dem ‚Auge. So werde ich in dieser Richtung den Gegenstand sehen. Was ist der Tatbestand? Ich habe auf dem Boden eines Gefäßes liegen einen Gegenstand. Ich gucke hin und sehe in einer gewissen Richtung diesen Gegenstand. Das ist der einfache Tatbestand. Wenn ich anfange nun zu zeigen: Von diesem Gegenstand geht ein Lichtstrahl aus, der wird in das Auge geschickt und affiziert das Auge, dann, meine lieben Freunde, fantasiere ich schon alles Mögliche dazu.

Nun fülle ich bis hierher das Gefäß mit Wasser oder irgendeiner Flüssigkeit an. Nun stellt sich etwas ganz Besonderes heraus. Ich ziehe dieselbe Richtung, in der ich früher den Gegenstand habe, vom Auge zum Gegenstand hin, ich gucke, gucke nach der Richtung, in der ich früher geguckt habe.” Ich könnte erwarten, dasselbe zu sehen, tue es aber nicht, sondern etwas höchst Merkwürdiges tritt ein: Ich sche den Gegenstand etwas gehoben. Ich sche ihn so, dass er mit dem ganzen Boden in die Höhe gehoben wird. Wie man das feststellen, ich meine messen kann, darüber können wir ja noch sprechen. Ich will jetzt nur das Prinzipielle sagen. Worauf kann denn das nur beruhen, wenn ich mir die Frage beantworte nach dem reinen Tatbestand? Nun, ich erwarte: Wenn ich früher so gesehen habe, den Gegenstand wiederum in der Richtung zu finden. Ich richte das Auge darauf hin, aber ich sche ihn nicht in der Richtung, ich sche ihn in der anderen Richtung. Ja, früher, als noch kein Wasser in dem Trog war, da konnte ich bis zu dem Boden direkt hinunterschauen, und zwischen meinem Auge und dem Boden war nur die Luft. Jetzt stößt meine Visierlinie hier das Wasser. Das lässt meine Sehkraft nicht so einfach durch wie die Luft, sondern stellt ihr stärkeren Widerstand entgegen, und ich muss vor dem stärkeren Widerstand zurückweichen. Von hier ab muss ich vor dem stärkeren Widerstand zurückweichen. Dieses Zurückweichen drückt sich dadurch aus, dass ich nicht bis unten sehe, sondern dass das Ganze gehoben erscheint. Ich sche gewissermaßen schwerer durch das Wasser als durch die Luft, überwinde den Widerstand des Wassers schwerer als den Widerstand der Luft. Daher muss ich die Kraft verkürzen, ziehe also selbst den Gegenstand herauf. Ich verkürze die Kraft dadurch, dass ich den stärkeren Widerstand finde. Würde ich in der Lage sein, den Boden des Gefäßes [für das sehen] zu senken und [dementsprechend] hier ein Gas hineinzufüllen, das dünner wäre als die Luft, dann würde der Gegenstand sich hier senken, weil ich jetzt weniger Widerstand fände. Ich würde daher den Gegenstand hinunterschieben.

Nam, Der Physiker konstatiert nicht diesen Tatbestand, sondern er sagt: Nun ja, da wird ein Lichtstrahl geworfen bis zu der Oberfläche des Wassers. Dieser Lichtstrahl wird hier gebrochen, und weil ein Übergang stattfindet zwischen einem dichteren Medium und einem dünneren, wird der Lichtstrahl vom Einfallslot gebrochen, kommt hier in das Auge. Und jetzt sagt er etwas höchst Kurioses: Aber das Auge, das, nachdem es die Nachricht bekommen hat durch den Lichtstrahl, das verlängert jetzt den Weg nach außen und projiziert den Gegenstand an diese Stelle hin.

Das heißt: Man findet alle möglichen Begriffe, aber man rechnet nicht mit dem, was da ist, mit dem Widerstand, den die Visierkraft des Auges selber findet in dem Dichteren, in das sie eindringen muss. Man möchte gewissermaßen alles weglassen und dem Licht alles selbst zuschieben, so wie man hier beim Prisma sagt: Oh, das Prisma macht gar nichts, sondern die sieben Farben sind schon im Lichte drinnen. Das Prisma gibt nur die Veranlassung, dass sie sich hübsch nebeneinander hinstellen wie Soldaten, die sieben Farben; aber da drinnen sind schon diese sieben unartigen Buben zusammen, die gezwungen werden, auseinanderzutreten. Das Prisma macht gar nichts davon.

Wir haben gesehen: Gerade dasjenige, was im Prisma entsteht, dieser getrübte Keil ist es, der die Farben verursacht. Die Farben selber haben gar nichts mit dem Lichte selber zu tun. Und Sie sehen hier wiederum, während wir hier [beim mit Wasser gefüllten Gefäß] uns klar sein müssen, dass wir eine aktive Tätigkeit ausüben, mit dem Auge hin visieren und einen stärkeren Widerstand im Wasser finden, dadurch gezwungen sind, die Visierlinie abzukürzen durch den stärkeren Widerstand. [Da] sagt der Physiker: Da werden Lichtstrahlen geworfen, die werden gebrochen und so weiter. Und dann das Allerschönste, gerade an dieser Stelle, meine lieben Freunde! Sehen Sie, der Physiker sagt, der heutige Physiker: Da wird also zunächst das Licht ins Auge auf gebrochenem Wege gelangen, dann projiziert das Auge das Bild nach außen. - Was heißt das? Zum Schlusse sagt er doch: Das Auge projiziert. Er setzt nur eine phoronomische Vorstellung, eine von allen Realitäten verlassene Vorstellung, eine reine Fantasietätigkeit anstelle dessen, was sich unmittelbar darbietet: der Widerstand des dichteren Wassers gegen die Visierkraft des Auges.

Gerade an solchen Punkten merken Sie am allerdeutlichsten, wie alles gerade in unserer Physik verabstrahiert ist, wie alles zur Phoronomie gemacht werden soll, wie man nicht will in die Qualitäten hineingehen. Auf der einen Seite also entkleidet man das Auge jedweder Aktivität - von den Gegenständen gehen die Lichtstrahlen aus, gelangen in das Auge -, auf der anderen Seite aber wieder projiziert das Auge dasjenige, was es als Reiz bekommt, nach außen. Dasjenige aber, was nötig ist, ist, dass man von vornherein von der Aktivität des Auges ausgeht, dass man sich klar ist: Das Auge ist ein tätiger Organismus.

Nun sehen Sie, hier haben wir ein Modell des Auges, und wir werden heute beginnen, uns zunächst auch ein wenig zu befassen mit dem Wesen des menschlichen Auges. Das Auge, das menschliche Auge, ist ja eine Art Kugel, nur von vorne nach hinten etwas zusammengedrückt, eine Kugel, die hier in der Knochenhöhle drinnen sitzt so, dass eine Reihe von Häuten zunächst das Innere dieses Auges umgibt. Wenn ich den Durchschnitt zeichnen will, so müsste ich da so zeichnen - ich zeichne Ihnen das Auge jetzt so auf. sehen Sie, wenn Sie das Auge so anschauen wie das Ihres Nachbarn, so sehen Sie in die Pupille; ich zeichne aber das Auge so von der Seite. Es ist übrigens gleich. Ich will den Durchschnitt zeichnen. Das, was ich jetzt zeichne, wäre das rechte Auge und es müsste da eben so gehalten werden. Das Äußerste, was man zunächst findet, wenn man das Auge etwa aus dem Schädel herauspräparieren würde, das wäre Bindegewebe, Fett. Dann aber kommt man zu der eigentlichen ersten Umhüllung des Auges, der sogenannten Sklerotika, Hornhaut. Sehnig, knochig, knorpelig ist die äußerste Umhüllung. Ich habe sie hier gezeichnet. Sie wird nach vorne durchsichtig. Sie sehen hier, sie wird nach vorne durchsichtig, sodass das Licht von hier aus in das Auge eindringen kann. Eine zweite Schichte, die den Innenraum hier auskleidet, ist die sogenannte Aderhaut. Sie enthält die Blutgefäße. Wir würden sie etwa hier haben. Und als Drittes würden wir bekommen die innerste Schichte, die sogenannte Netzhaut, die sich dann nach dem Schädel zu in dem Sehnerv fortsetzt. Hier also würde der Sehnerv nach innen gehen, würde bilden die Netzhaut. Und damit haben wir die drei Umhüllungen des Auges aufgezählt.

Nun aber, hinter dieser Hornhaut, eingebettet hier in den Ziliarmuskel, ist eine Art Linse. Sie wird hier durch einen Muskel, den man den Ziliarmuskel nennt, getragen. Nach vorne ist hier die durchsichtige Hornhaut, und zwischen der Linse und ihr ist dasjenige, was man die wässerige Flüssigkeit nennt, sodass, wenn das Licht in das Auge eindringt, es erst die durchsichtige Hornhaut passiert, die wässerige Flüssigkeit passiert, dann durch diese Linse geht, die in sich beweglich ist durch Muskeln. Dann aber gelangt das Licht weiter von dieser Linse aus in dasjenige, was nun ausfüllt den ganzen Augenraum und was man gewöhnlich den Glaskörper nennt. Sodass das Licht also geht durch die durchsichtige Hornhaut, die Flüssigkeit, die Linse selbst, den Glaskörper und von da dann an die Netzhaut, die eine Verzweigung ist des Sehnervs, der dann in das Gehirn geht. Das sind zunächst schematisch - wir wollen zunächst das Prinzipielle uns vor Augen stellen —, schematisch diejenigen Dinge, die uns veranschaulichen können, was dieses Auge, das da in eine Höhle der Schädelknochen eingebettet ist, für Teile hat.

Aber dieses Auge zeigt außerordentlich große Merkwürdigkeiten. Zunächst, wenn wir studieren die Flüssigkeit, die da ist zwischen dieser Linse und der Hornhaut, durch die das Licht durchgehen muss, so ist diese Flüssigkeit ihrem Gehalte nach fast eine richtige Flüssigkeit, fast eine äußere Flüssigkeit. An der Stelle, wo der Mensch seine Augenflüssigkeit hat, zwischen der Linse und der äußeren Hornhaut, ist der Mensch seiner Leiblichkeit nach ganz so, gewissermaßen, wie ein Stück Außenwelt. Es ist fast so, dass diese Flüssigkeit, die da ist in der äußersten Peripherie des Auges, kaum sich unterscheidet von einer Flüssigkeit, die ich mir hier auf die Hand schütten würde. Und das, was hier die Linse ist, diese Linse, das ist auch noch etwas sehr, sehr Objektives, sehr, sehr Unlebendiges. Gehe ich dagegen an den Glaskörper über, der das Innere des Auges ausfüllt und an die Nervenhaut grenzt, so kann ich diesen Glaskörper keineswegs so betrachten, dass ich sage: Das ist auch etwas, was fast wie eine äußere Flüssigkeit oder ein äußerer Körper ist. Da drinnen ist schon Vitalität, da drinnen ist Leben, sodass, je weiter wir zurückgehen im Auge, desto mehr dringen wir heran an das Leben. Hier haben wir eine Flüssigkeit, die fast ganz objektiv äußerlich ist, die Linse ist auch noch äußerlich; aber beim Glaskörper stehen wir schon innerhalb eines Gebildes, das in sich Vitalität hat.

Dieser Unterschied zwischen all dem, was da draußen ist, und dem, was da drinnen ist, der zeigt sich auch noch in etwas anderem. Auch das könnte man schon heute naturwissenschaftlich studieren. Wenn man nämlich die Bildung des Auges komparativ von der niederen Tierreihe aus verfolgt, so findet man, dass dasjenige, was äußerer Flüssigkeitskörper ist und Linse, dass das nicht von innen herauswächst, sondern dass sich das ansetzt, indem sich [an] die umliegenden Zellen Zellen ansetzen. Also, ich müsste mir die Bildung der Linse so vorstellen, dass das Linsengewebe, und dass auch die vordere Augenflüssigkeit entsteht aus den benachbarten Organen und nicht von innen heraus, während beim Inneren das so ist, dass der Glaskörper [dem Äußeren] entgegenwächst. sehen Sie, da haben wir das Merkwürdige: Hier wirkt die Natur des äußeren Lichtes und bewirkt jene Umwandlung, die Flüssigkeit und Linse hervorbringt. Auf das reagiert das Wesen von innen und schiebt ihm ein Lebendigeres, ein Vitaleres entgegen, den Glaskörper. Gerade im Auge treffen sich die Bildungen, die von außen angeregt werden, und diejenigen, die von innen aus angeregt werden, in einer ganz merkwürdigen Weise. Das ist die nächste Eigentümlichkeit des Auges.

Es gibt noch eine andere. Es gibt die Eigentümlichkeit des Auges, die darinnen besteht, dass diese sich ausbreitende Netzhaut eigentlich der sich ausbreitende Sehnerv ist. Nun besteht gerade just die Eigentümlichkeit - ich werde morgen versuchen ein Experiment zu zeigen, das diese bekräftigt -, die Eigentümlichkeit, dass hier, wo der Sehnerv eintritt, das Auge unempfindlich ist. Da ist es blind. Es breitet sich dann der Sehnerv aus, und an einer Stelle, die also hier für das rechte Auge etwas rechts liegt von der Eintrittsstelle, ist die Netzhaut am empfindlichsten. Man kann nun sagen: Der Nerv ist dasjenige, was das Licht empfindet. Aber er empfindet das Licht just nicht da, wo er eintritt. Man sollte glauben, wenn der Nerv wirklich das wäre, was das Licht empfindet, dann müsste er am stärksten es empfinden da, wo er eintritt. Das tut er aber nicht. Das bitte ich im Auge zunächst zu behalten.

Nun, dass diese Einrichtung des Auges eine außerordentlich, ich möchte sagen, von Weisheit der Natur erfüllte ist, das können Sie etwa aus dem Folgenden entnehmen: Wenn Sie so des Tags über die Gegenstände um sich herum beschauen, ja, dann finden Sie, dass die Gegenstände Ihnen, soweit Ihre Augen gesund sind, erscheinen mehr oder weniger scharf, aber so, dass die Schärfe, die Deutlichkeit für Ihre Orientierung genügt. Wenn Sie aber des Morgens aufwachen, da sehen Sie manchmal sehr undeutlich die Ränder der Gegenstände, da sehen Sie diese so wie mit einem kleinen Nebel umgeben. Wenn das ein Kreis ist, sehen Sie da etwas herum wie etwas Undeutliches, wenn Sie des Morgens gerade aufgewacht sind. Worauf beruht denn das? Das beruht darauf, dass wir dreierlei in unserem Auge haben, zunächst den Glaskörper - wir wollen sogar nur auf zweierlei Rücksicht nehmen -, den Glaskörper und die Linse. Sie haben, wie wir gesehen haben, ganz verschiedenen Ursprung. Die Linse ist mehr von außen gebildet, der Glaskörper mehr von innen, die Linse ist mehr unlebendig, der Glaskörper von Vitalität durchzogen. In dem Augenblick, wo wir aufwachen, sind beide einander noch nicht angepasst. Der Glaskörper will uns noch die Gegenstände so abbilden, wie er es kann, und die Linse so, wie sie es kann. Und wir müssen erst warten, bis sie sich gegenseitig eingestellt haben. Daraus ersehen Sie, wie innerlich beweglich das Organische ist und wie die Wirkung des Organischen darauf beruht, dass zunächst differenziert wird in Linse und Glaskörper die Tätigkeit und dann die Tätigkeit wiederum aus dem Differenzierten zusammengesetzt wird. Da muss sich dann das eine an das andere anpassen.

Wir wollen aus allen diesen Dingen versuchen, nach und nach darauf zu kommen, wie sich aus dem Wechselverhältnis des Auges und der Außenwelt die farbenbunte Welt ergibt. Zu diesem Zweck, um dann morgen daran anknüpfen zu können Betrachtungen über diese Beziehung des Auges zur Außenwelt, wollen wir uns noch folgendes Experiment vor Augen führen.

Sehen Sie, ich habe hier eine Scheibe so bestrichen, dass ich sie bestrichen habe mit den Farben, die uns vorhin als Regenbogenfarben Violett, Indigo, Blau, Grün, Gelb, Orange, Rot vor Augen getreten sind. Wenn Sie dieses Rad hier anschauen, so sehen Sie diese sieben Farben - ich habe es so gut gemacht, als es eben geht mit diesen Farben. Nun werden wir zuerst die Scheibe drehen. Sie sehen noch immer, nur eben in Bewegung, die sieben Farben und ich kann ziemlich stark drehen und Sie sehen in Bewegung die sieben Farben. Nun werde ich aber recht schnell die Scheibe zur Rotierung bringen. Sie sehen, wenn die Sache stark genug rotiert, so sehen Sie nicht mehr die Farben, sondern Sie sehen, ich glaube, ein einfarbiges Grau. Nicht wahr? Oder haben Sie etwas anderes gesehen? («Lila», «Rötlich».) Ja, das ist nur aus dem Grunde, weil das Rot etwas zu stark ist gegenüber den anderen Farben. Ich habe zwar versucht, die Stärke durch den Raum auszugleichen,“ aber Sie würden, wenn die Anordnung ganz richtig wäre, eigentlich ein einfarbiges Grau sehen. Wir müssen uns dann fragen: Warum erscheinen uns diese sieben Farben in einfarbigem Grau? Diese Frage wollen wir morgen beantworten. Heute wollen wir nur noch hinstellen, was die moderne Physik sagt. Sie sagt - hat auch schon zu Goethes Zeiten gesagt: Da habe ich die Regenbogenfarben Rot, Orange, Gelb, Grün, Blau, Indigo, Violett. Jetzt bringe ich die Scheibe in Rotierung. Dadurch kommt der Lichteindruck nicht zur Geltung im Auge, sondern wenn ich hier das Rot eben gesehen habe, dann ist durch die rasche Rotierung schon das Orange da, und wenn ich das Orange gesehen habe, schon das Gelb und so weiter. Und dann, während ich noch die übrigen Farben habe, ist schon wieder das Rot da. Dadurch habe ich alle Farben zu gleicher Zeit. Es ist der Eindruck vom Rot noch nicht vorüber, wenn das Violett kommt. Dadurch setzt man für das Auge die sieben Farben zusammen und das muss wiederum Weiß geben.

Dieses war auch die Lehre zu Zeiten Goethes. Goethe hat das als Lehre empfangen: Wenn man den Farbenkreisel macht, ihn rasch rotieren lässt, dann werden die sieben Farben, die so artig gewesen sind, auseinanderzutreten aus dem Lichtzylinder, die werden sich wieder vereinigen im Auge selbst. Aber Goethe hat niemals ein Weiß gesehen, sondern er hat gesagt: Es kommt niemals etwas anderes zustande als ein Grau." Allerdings, die neueren Physikbücher finden auch, dass nur ein Grau zustande kommt. Aber damit die Geschichte doch weiß wird, so raten sie, man soll in der Mitte einen schwarzen Kontrastkreis machen, dann wird das Grau im Kontrast weiß erscheinen. Also, Sie sehen, in einer netten Weise wird das gemacht. Manche Leute machen es mit «fortune», die Physiker machen es mit «nature». So wird die Natur korrigiert. Das findet überhaupt bei einer Anzahl der fundamentalsten Tatsachen statt, dass die Natur korrigiert wird.

Sie sehen, ich suche so vorzugehen, dass die Basis geschaffen wird. Wir werden gerade, wenn wir eine richtige Basis schaffen, für alle anderen Gebiete die Möglichkeit bekommen, vorwärtszukommen.

Third Lecture

My dear friends!

I have been told that the culmination of yesterday's contemplation, the phenomenon that occurs through the prism, presented difficulties for many in terms of understanding, and I ask you to remain calm about this. This understanding will come gradually. We will deal with the phenomena of light and color in a little more detail so that this actual pièce de résistance—which it is also for the rest of physics—can provide us with a good foundation. You see, you understand that we must first deal with telling you some things that you cannot find in books and that are not the subject of ordinary scientific considerations, things that we can only deal with here, so to speak. In the last lectures, we will then go into how what we are considering here can also be used in teaching.

You see, what I tried to explain yesterday is essentially a special kind of interaction between light and darkness. And I wanted to show that this different interaction between light and darkness, which occurs particularly when a light cylinder passes through a prism, gives rise to color phenomena that are polar to each other. First of all, I ask you to accept the bitter pill that the difficulty in understanding this matter lies in the fact that you actually—this concerns those who find it difficult to understand—want the theory of light and color to be structured kinematically. Through our peculiar education, people have become accustomed to indulging only in mental images that are more or less kinematic in relation to external nature, that is, to concern themselves only with what is countable, with spatial form and with movement. Now you must make an effort to think in terms of qualities, and you can truly say in a certain sense: Here I am already stuck. But attribute that entirely to the unnatural course that scientific development has taken in recent times and that you are even going through in a certain way with your students—I am referring now to the teachers at the Waldorf School and other teachers. For it will not, of course, be possible to introduce healthy ideas into today's schools immediately; we will have to create transitions.

Now let us start, I would say, from the other end of the matter, with the phenomena of light and color. I would like to begin today with a much-contested remark by Goethe. You can read it in Goethe, as it became known in the 1880s, with all kinds of assertions about the appearance of colors in light, that is, about the phenomena we began to talk about yesterday. He was told that the general view of physicists was that when colorless light is passed through a prism, this colorless light is split, broken down. This is roughly how the phenomena were interpreted. It was said: We capture a colorless cylinder of light, and it initially shows us a colorless image. We place the prism in the path of this light cylinder, and we get the sequence of colors red, orange, yellow, green, blue—light blue, dark blue—violet. Now, this is something that struck Goethe, and he learned that This phenomenon is explained by saying that colorless light actually already contains within itself—how, that is of course difficult to imagine, but that is what was said—it contains within itself these seven colors. When light is passed through the prism, the prism actually does nothing other than what is already inside the light, spreading it out like a fan, breaking the light down into the seven colors." Well, Goethe wanted to get to the bottom of the matter and borrowed all kinds of instruments, as we have tried to gather them together in these days, in order to ascertain for himself how things really were. He had these instruments sent over to Weimar from Jena by the court councillor Büttner, stacked them up and wanted to try them out at the appropriate time to see how they worked. Court councillor Büttner grew impatient and demanded the instruments back when Goethe had not yet done anything. He had to pack up the instruments – sometimes things like that happen to us, we don't get round to them straight away. He quickly took the prism and said: “So, the prism breaks up the light. I'll look at it on the wall.” And now he expected the light to appear in seven beautiful colors. But all that appeared was something colored where there was a rim, where there was a speck of dirt, so that the dirty, the cloudy, collided with the light. There, when you looked through it, you saw colors. But where there was uniform white, you saw nothing. Goethe was puzzled; he was confused by this whole theory. And now he no longer saw any point in sending the instruments back. He kept them and pursued the matter further. And it turned out that things were not actually as they were usually presented, but that when we let light pass through the space of the room, we get a white circle on a screen.

Here you can see a very nice circle. We cut it very carefully and therefore got a very nice circle. - Now, if you place the prism in the path of this light passing through, the light cylinder is deflected. But at first, the seven consecutive colors do not appear at all, only the reddish color appears at the lower edge, which turns into yellow, and at the upper edge the bluish color, which turns into green. In the middle it remains white.

What did Goethe say to himself? He said: So it doesn't matter at all that something splits out of the light, because I am actually reproducing an image. This image is only a reproduction of the section here. The section has edges, and the colors do not appear because they are extracted from the light, as it were, because the light would split them up, but because I design the image and the image as such has edges, so that I have nothing else to do here than to draw the colors where light and darkness meet — because outside this circle of light here, there is darkness in the surroundings and inside it is light — the colors appear at the edges. At first, only the colors appear as edge phenomena, and by showing the colors as edge phenomena, we basically have the original phenomenon before us. We do not have the original phenomenon in front of us at all when we now reduce the circle and obtain a continuous color image. The continuous color image arises only because, while in the large circle the edge colors remain edge colors, in the small circle the colors continue from the edge to the center, overlap in the center, and form what is called a continuous spectrum. So, the original phenomenon is that colors appear at the edges where light and dark converge.

You see, it is important that we do not interfere with the facts with theories, but remain strictly focused on studying the bare facts, the bare facts. Now, it is not only what we see in the colors that occurs here, but as you have seen, there is also a shift of the entire cone of light, a lateral deflection of the entire cone of light. If you want to trace this lateral deflection schematically, you could do so in the following way.

Suppose you join two prisms [at their base surfaces] so that the lower prism, which forms a whole with the upper one, stands as I drew for you yesterday. The upper prism is opposite the lower one. If I were to pass a light cylinder through this double prism, I would naturally have to get something similar to yesterday. I would have to get a deflection, once downwards and once upwards." If I had such a double prism here, I would get an even more elongated light figure, but at the same time it would turn out that this even more elongated light figure is very indistinct, gloomy. This would be explained by the fact that if I were to catch the figure here with a screen, I would get an image pushed together from this circle of light here. But I could also move the screen in. I would again get an image. That means there would be a distance here—this is all within the realm of possibility—a distance at which I would always have the possibility of getting an image. You can see from this that the double prism manipulates the light. The one thing I always find is that I always get a red edge here on the outside, now at the top and bottom, and violet in the middle, so that I now get an image like this: violet in the middle and a red edge on the outside. Whereas normally I only get the image from red to violet, now I get the outer edges red and violet in the middle with the other colors in between.

Now, you can get around the fact that images are encountered over a certain distance here. When I move the screen, I get [different] images. So, I could use a double prism to create the possibility of such a figure, but I would also get it if I moved the screen in this direction. So I have a certain distance over which it is possible for an image to appear that is colored at the edges, but also colored in the middle and has all kinds of transition colors.

Now, when I move the screen up and down, I can [avoid] having such a wide space [to traverse] where it is possible to create such images. But you can probably guess that this [other] possibility [of creating images] could only be created if I always changed the prism [geometrically], for example, because with a prism whose angle is larger here, the image is projected at a different point; if I made the angle smaller, the image would be projected at a different point and I would get this distance smaller.

I can change the whole thing by not having flat surfaces for a prism here, but by using curved surfaces from the outset. This greatly simplifies what is extremely difficult to study with a prism. And then we have the following option: First, we let the light cylinder pass through the space, and now we place the lens, which is actually nothing more than a double prism but with curved surfaces, in the path. Instead of the double prism, we place the lens in the path. You see, when I place the lens in the path, the image is initially greatly reduced in size. So what has actually happened here? The entire light cylinder has been contracted. This [on the left] is the original cross-section of the cylinder. By placing the lens in the path, I contract the entire light cylinder, narrowing it. We now have a new interaction between the material, the material in the lens, in the glass body, and the light passing through the room. This lens acts on the light in such a way that it contracts the light cylinder.

Let's sketch the whole thing schematically: If I have a light cylinder here, drawn from the side, I let its light pass through the lens – we want to keep it white today. treat it roughly—pass through the lens, while, for example, if I were to place an ordinary glass plate opposite it, the light cylinder—or if I were to place a water plate opposite it—would simply pass through and an image of the light cylinder would appear on the screen. This is not the case if I do not have a glass plate or a water plate, but a lens. If I simply trace what has happened with lines, I have to say: what has resulted is a reduction in the size of the image. So the light cylinder has been contracted.

There is another possibility. This is that one reproduces the arrangement not with a double prism as I have drawn it there, but with a double prism that is designed in such a way—or in cross-section—that the prisms meet at this edge here. Then, however, I would obtain the same description that I have given with a considerably enlarged circle. Again, by moving the screen up and down over a certain distance, I would be able to obtain the image, albeit more or less indistinctly. In this case, I would have violet and bluish at the top, violet and blue at the bottom, and red in the middle. There, it was the other way around. And in between, the intermediate colors.

I can again place myself at the position of this double prism with a lens with the following cross-section:

While this lens [in the previous arrangement] appears thick in the middle and thin at the edges, this one [here] appears thin in the middle and thick at the edges. In this case, I also get an image through the lens here that is much larger than the usual cross-section that would be created by the light cylinder. I get an enlarged image, but also with this color gradation at the edges and towards the center. So if I want to follow the phenomena here, I have to say: The light cylinder has been expanded, it has essentially been driven apart. That is the simple fact.