The Light Course

GA 320

26 December 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture IV

My dear Friends,

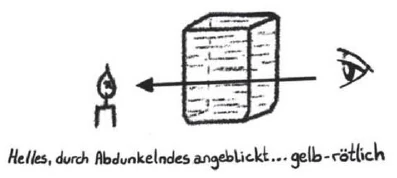

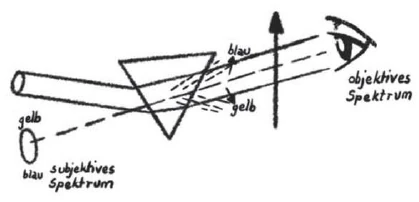

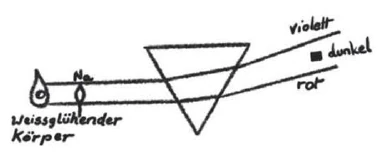

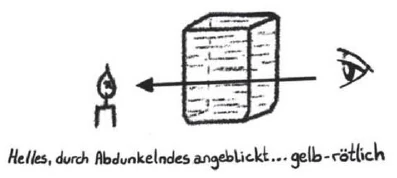

I will begin by placing before you what we may call the “Ur-phenomenon”—primary phenomenon—of the Theory of Colour. By and by, you will find it confirmed and reinforced in the phenomena you can observe through the whole range of so-called optics or Theory of Colour. Of course the phenomena get complicated; the simple Ur-phenomenon is not always easy to recognize at once. But if you take the trouble you will find it everywhere. The simple phenomenon—expressed in Goethe's way, to begin with—is as follows: When I look through darkness at something lighter, the light object will appear modified by the darkness in the direction of the light colours, i.e. in the direction of the red and yellowish tones. If for example I look at anything luminous and, as we should call it, white—at any whitish-shining light through a thick enough plate which is in some way dim or cloudy, then what would seem to me more or less white if I were looking at directly, will appear yellowish or yellow-red (Figure IVa).

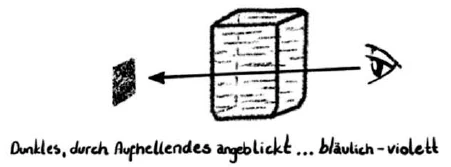

This is the one pole. Conversely, if you have here a simple black surface and look at it directly, you will see it black, but if you interpose a trough of water through which you send a stream of light so that the liquid is illumined, you will be looking at the dark through something light. Blue or violet (bluish-red) tones of colour will appear (Figure IVb). The other pole is thus revealed. This therefore is the Ur-phenomenon: Light through dark—yellow; dark through light—blue.

This simple phenomenon can be seen on every hand if we once accustom ourselves to think more realistically and not so abstractly as in modern science. Please now recall from this point of view the experiment which we have done. We sent a cylinder of light through a prism and so obtained a real scale of colours, from violet to red; we caught it on a screen. I made a drawing of the phenomenon (see Figure IIc and Figure IVc). You will remember; if this is the prism and this the cylinder of light, the light in some way goes through the prism and is diverted upward. Moreover, as we said before, it is not only diverted. It would be simply diverted if a transparent body with parallel faces were interposed. But we are putting a prism into the path of the light—that is, a body with convergent faces. In passing through the prism, the light gets darkened. The moment we send the light through the prism we therefore have to do with two things: first the simple light as it streams on, and then the dimness interposed in the path of the light. Moreover this dimness, as we said, puts itself into the path of the light in such a way that while the light is mainly diverted upward, the dimming that arises, raying upward as it does, shines also in the same direction into which the light itself is diverted. That is to say, darkness rays into the diverted light. Darkness is living, as it were, in the diverted light, and by this means the bluish and violet shades are here produced. But the darkness rays downward too, so, while the cylinder of light is diverted upward, the darkness here rays downward and works contrary to the diverted light but is no match for it. Here therefore we may say: the original bright light, diverted as it is, overwhelms and outdoes the darkness. We get the yellowish or yellow-red colours.

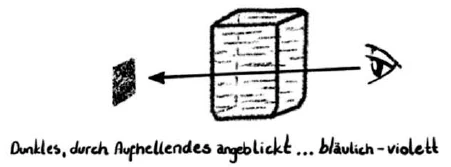

If we now take a sufficiently thin cylinder of light, we can also look in the direction of it through the prism. Instead of looking from outside on to a screen and seeing the picture projected there, we put our eye in the place of this picture, and, looking through the prism, we then see the aperture, through which the cylinder of light is produced, displaced (Figure IVc). Once again therefore adhering strictly to the facts, we have the following phenomenon: Looking along here, I see what would be coming directly towards me if the prism were not there, displaced in a downward direction by the prism. At the same time I see it coloured.

What then do you see in this case? Watch what you see, state it simply and then connect it with the fundamental fact we have just now been ascertaining. Then, what you actually see will emerge in all detail. Only you must hold to what is really seen. For if you are looking thus into the bright cylinder of light—which, once again, is coming now towards you—you see something light, namely the cylinder of light itself, but you are seeing it through dark. (That there is something darkened here, is clearly proved by the fact that blue arises in this region). Through something darkened—through the blue colour, in effect—you look at something light, namely at the cylinder-of-light coming towards you. Through what is dark you look at what is light; here therefore you should be seeing yellow or yellowish-red—in a word, yellow and red,—as in fact you do. Likewise the red colour below is proof that here is a region irradiated with light. For as I said just now, the light here over-whelms the dark. Thus as you look in this direction, however bright the cylinder of light itself may be, you still see it through an irradiation of light, in relation to which it is dark. Below, therefore, you are looking at dark through light and you will see blue or bluish-red. You need but express the primal phenomenon,—it tells you what you actually see. Your eye is here encountered by what you would be seeing in the other instance. Here for example is the blue and you are looking through it; therefore the light appears reddish. At the bottom edge you have a region that is lighted up. However light the cylinder of light may be, you see it through a space that is lit up. Thus you are seeing something darker through an illumined space and so you see it blue. It is the polarity that matters.

For the phenomenon we studied first—that on the screen—you may use the name “objective” colours if you wish to speak in learned terms. This other one—the one you see in looking through the prism—will then be called the “subjective” spectrum. The “subjective” spectrum appears as an inversion of the “objective”.

Concerning all these phenomena there has been much intellectual speculation, my dear Friends, in modern time. The phenomena have not merely been observed and stated purely as phenomena, as we have been endeavouring to do. There has been ever so much speculation about them; indeed, beginning with the famous Newton, Science has gone to the utter-most extremes in speculation. Newton, having first seen and been impressed by this colour-spectrum, began to speculate as to the nature of light. Here is the prism, said Newton; we let the white light in. The colours are already there in the white light; the prism conjures them forth and now they line up in formation. I have then dismembered the white light into its constituents. Newton now imagined that to every colour corresponds a kind of substance, so that seven colours altogether are contained as specific substances in the light. Passing the light through the prism is to Newton like a kind of chemical analysis, whereby the light is separated into seven distinct substances. He even tried to imagine which of the substances emit relatively larger corpuscles—tiny spheres or pellets—and which smaller. According to this conception the Sun sends us its light, we let it into the room through a circular opening and it goes through in a cylinder of light. This light however consists of ever so many corpuscles—tiny little bodies. Striking the surface of the prism they are diverted from their original course. Eventually they bombard the screen. There then these tiny cannon-balls impinge. The smaller ones fly farther up, the larger ones remain farther down. The smallest are the violet, the largest are the red. So then the large are separated from the small.

This idea that there is a substance or that there are a number of substances flying through space was seriously shaken before long by other physicists—Huyghens, Young and others,—until at last the physicists said to themselves: The theory of little corpuscular cannon-balls starting from somewhere, projected through a refracting medium or not as the case may be, arriving at the screen and there producing a picture, or again finding their way into the eye and giving rise in us to the phenomenon of red, etc.,—this will not do after all. They were eventually driven to this conclusion by an experiment of Fresnel's, towards which some preliminary work had however been done before, by the Jesuit Grimaldi among others.

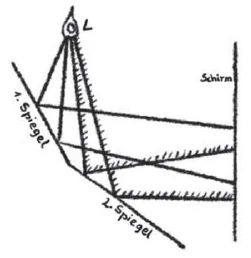

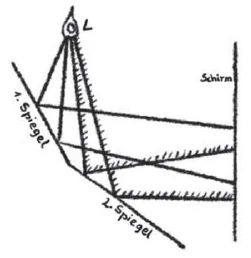

Fresnel's experiment shook the corpuscular theory very considerably. His experiments are indeed most interesting, and we must try to get a clear idea of what is really happening when experiments are set up in the way he did. I beg you now, pay very careful attention to the pure facts; we want to study such a phenomenon quite exactly. Suppose I have two mirrors and a source of light—a flame for instance, shedding its light from here (Figure IVd). If I then put up a screen—say, here—I shall get pictures by means of the one mirror and also pictures by means of the other mirror. Such is the distribution you are to assume; I draw it in cross-section. Here are two looking-glasses—plane mirrors, set at a very small angle to one another,—here is a source of light, I will call it L, and here a screen. The light is reflected and falls on to the screen; so then I can illumine the screen with the reflected light. For if I let the light strike here, with the help of this mirror I can illumine this part of the screen, making it lighter here than in the surrounding region. Now I have here a second mirror, by which the light is reflected a little differently. Part of the cone of light, as reflected from here below (from the second mirror) on to the screen, still falls into the upper part. The inclination of the two mirrors is such that the screen is lighted up both by reflection from the upper mirror and by reflection from the lower. It will then be as though the screen were being illumined from two different places. Now suppose a physicist, witnessing this experiment, were thinking in Newton's way. He would argue: There is the source of light. It bombards the first mirror, hurling its little cannon-balls in this direction. After recoiling from the mirror they reach the screen and light it up. Meanwhile, the others are recoiling from the lower mirror, for many of them go in that direction also. It will be very much lighter on the screen when there are two mirrors than when there is only one. Therefore if I remove the second mirror the screen will surely be less illumined by reflected light than when the two mirrors are there. So would our physicist argue, although admittedly one rather devastating thought might occur to him, for surely while these little bodies are going on their way after reflection, the others are on their downward journey (see the figure). Why then the latter should not hit the former and drive them from their course, is difficult to see. Nay, altogether, in the textbooks you will find the prettiest accounts of what is happening according to the wave-theory, but while these things are calculated very neatly, one cannot but reflect that no one ever figures out, when one wave rushes criss-cross through the other, how can this simply pass unnoticed?

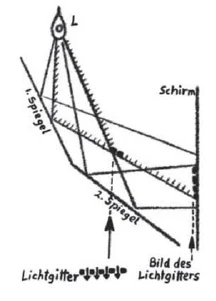

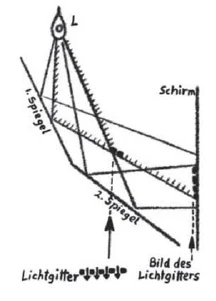

Now let us try to grasp what happens in reality in this experiment. Suppose that this is the one stream of light. It is thrown by reflection across here, but now the other stream of light arrives here and encounters it,—the phenomenon is undeniable. The two disturb each other. The one wants to rush on; the other gets in the way and, in consequence, extinguishes the light coming from the other side. In rushing through it extinguishes the light. Here therefore on the screen we do not get a lighting-up but in reality darkness is reflected across here. So we here get an element of darkness (Figure IVe). But now all this is not at rest,—it is in constant movement. What has here been disturbed, goes on. Here, so to speak, a hole has arisen in the light. The light rushed through; a hole was made, appearing dark. And as an outcome of this “hole”, the next body-of-light will go through all the more easily and alongside the darkness you will have a patch of light so much the lighter. The next thing to happen, one step further on, is that once more a little cylinder of light from above impinges on a light place, again extinguishes the latter, and so evokes another element of darkness. And as the darkness in its turn has thus moved on another step, here once again the light is able to get through more easily. We get the pattern of a lattice, moving on from step to step. Turn by turn, the light from above can get through and extinguishes the other, producing darkness, once again, and this moves on from step to step. Here then we must obtain an alternation of light and dark, because the upper light goes through the lower and in so doing makes a lattice work.

This is what I was asking you most thoroughly to think of; you should be able to follow in your thought, how such a lattice arises. You will have alternating patches of light and dark, inasmuch as light here rushes into light. When one light rushes into another the light is cancelled—turned to darkness. The fact that such a lattice arises is to be explained by the particular arrangement we have made with these two mirrors. The velocity of light—nay, altogether what arises here by way of differences in velocity of light,—is not of great significance. What I am trying to make clear is what here arises within the light itself by means of this apparatus, so that a lattice-work is reflected—light, dark, light, dark, and so on.

Now yonder physicist—Fresnel himself, in fact—argued as follows: If light is a streaming of tiny corpuscular bodies, it goes without saying that the more bodies are being hurled in a particular direction, the lighter it must grow there,—or else one would have to assume that the one corpuscle eats up the other! The simple theory of corpuscular emanation will not explain this phenomenon of alternating light and dark. We have just seen how it is really to be explained. But it did not occur to the physicists to take the pure phenomenon as such, which is what one should do. Instead, and by analogy with certain other phenomena, they set to work to explain it in a materialistic way. Bombarding little balls of matter would no longer do. Therefore they said: Let us assume, not that the light is in itself a stream of fine substances, but that it is a movement in a very fine substantial medium—the “ether”. It is a movement in the ether. And, to begin with, they imagined that light is propagated through the ether in the same way as sound is through air (Euler for instance thought of it thus). If I call forth a sound, the sound is propagated through the air in such a way that if this is the place where the sound is evoked, the air in the immediate neighbourhood is, to begin with, compressed. Compressed air arises here. Now the compressed air presses in its turn on the adjoining air. It expands, momentarily producing in this neighbourhood a layer of attenuated air. Through these successions of compression and expansion, known as waves, we imagine sound to spread. To begin with, they assumed that waves of this kind are also kindled in the ether. However, there were phenomena at variance with this idea; so then they said to themselves: Light is indeed an undulatory movement, but the waves are of a different kind from those of sound. In sound there is compression here, then comes attenuation, and all this moves on. Such waves are “longitudinal”. For light, this notion will not do. In light, the particles of ether must be moving at right angles to the direction in which the light is being propagated. When, therefore, what we call a “ray of light” is rushing through the air—with a velocity, you will recall, of 300,000 kilometres a second—the tiny particles will always be vibrating at right angles to the direction in which the light is rushing. When this vibration gets into our eye, we perceive it.

Apply this to Fresnel's experiment: we get the following idea. The movement of the light is, once again, a vibration at right angles to the direction in which the light is propagated. This ray, going towards the lower one of the two mirrors, is vibrating, say, in this way and impinges here. As I said before, the fact that wave-movements in many directions will be going criss-cross through each other, is disregarded. According to the physicists who think along these lines, they will in no way disturb each other. Here however, at the screen in this experiment, they do; or again, they reinforce each other. In effect, what will happen here? When the train of waves arrives here, it may well be that the one infinitesimal particle with its perpendicular vibrations happens to be vibrating downward at the very moment when the other is vibrating upward. Then they will cancel each other out and darkness will arise at this place. Or if the two are vibrating upward at the same moment, light will arise. Thus they explain, by the vibrations of infinitesimal particles, what we were explaining just now by the light itself. I was saying that we here get alternations of light patches and dark. The so-called wave-theory of light explains them on the assumption that light is a wave-movement in the other [ether?]. If the infinitesimal particles are vibrating so as to reinforce each other, a lighter patch will arise; if contrary to one another, we get a darker patch.

You must realize what a great difference there is between taking the phenomena purely as they are—setting them forth, following them with our understanding, remaining amid the phenomena themselves—and on the other hand adding to them our own inventions. This movement of the ether is after all a pure invention. Having once invented such a notion we can of course make calculations about it, but that affords no proof that it is really there. All that is purely kinematical or phoronomical in these conceptions are merely thought by us, and so is all the arithmetic. You see from this example: our fundamental way of thought requires us so to explain the phenomena that they themselves be the eventual explanation; they must contain their own explanation. Please set great store by this. Mere spun-out theories and theorizings are to be rejected. You can explain what you like by adding things out of the blue, of which man has no knowledge. Of course the waves might conceivably be there, and it might be that the one swings upward when the other downward so that they cancel each other out. But they have all been invented! What is there however without question is this lattice,—this we see fully reflected. It is to the light itself that we must look, if we desire a genuine and not a spurious, explanation.

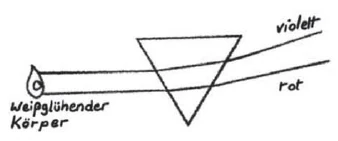

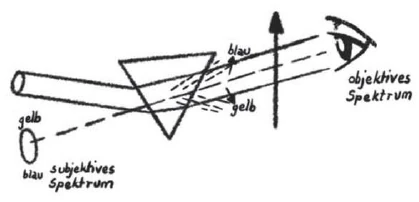

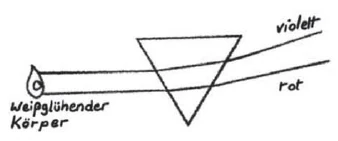

Now I was saying just now: when the one light goes through the other, or enters into any kind of relation to it, it may well have a dimming or even extinguishing effect upon the other, just as the effect of the prism is to dim the light. This is again brought out in the following experiment, which we shall actually be doing, I will now make a drawing of it. We may have what I shewed you yesterday—a spectrum extending from violet to red—engendered directly by the Sun. But we can also generate the spectrum in another way. Instead of letting the Sun shine through an opening in the wall, we make a solid body glow with heat,—incandescent (Figure IVf). When we have by and by got it white-hot, it will also give us such a spectrum. It does not matter if we get the spectrum from the Sun or from an incandescent body.

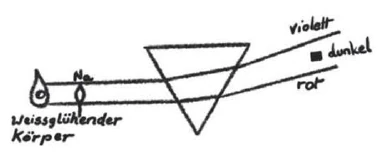

Now we can also generate a spectrum in a somewhat different way (Figure IVg). Suppose this is a prism and this a sodium flame—a flame in which the metal sodium is volatilizing. The sodium is turned to gas; it burns and volatilizes. We make a spectrum of the sodium as it volatilizes. Then a peculiar thing happens. Making a spectrum, not from the Sun or from a glowing solid body but from a glowing gas, we find one place in the spectrum strongly developed. For sodium light it is in the yellow. Here will be red, orange, yellow, you will remember. It is the yellow that is most strongly developed in the spectrum of sodium. The rest of the spectrum is stunted—hardly there at all. All this—from violet to yellow and then again from yellow to red—is stunted. We seem to get a very narrow bright yellow strip, or as is generally said, a yellow line. Mark well, the yellow line also arises inasmuch as it is part of an entire spectrum, only the rest of the spectrum in this case is stunted, atrophied as it were.

From diverse bodies we can make spectra of this kind appearing not as a proper spectrum but in the form of bright, luminous lines. From this you see that vice-versa, if we do not know what is in a flame and we make a spectrum of it, we can conclude, if we get this yellow spectrum for example, that there is sodium in the flame. So we can recognize which of the metals is there.

But the remarkable thing comes about when we combine the two experiments. We generate this cylinder of light and the spectrum of it, while at the same time we interpose the sodium flame, so that the glowing sodium somehow unites with the cylinder of light (Figure IVh). What happens then is very like what I was shewing you in Fresnel's experiment. In the resulting spectrum you might expect the yellow to appear extra strong, since it is there to begin with and now the yellow of the sodium flame is added to it. But this is not what happens. On the contrary, the yellow of the sodium flame extinguishes the other

yellow and you get a dark place here. Precisely where you would expect a lighter part you get a darker. Why is it so? It simply depends on the intensity of force that is brought to bear. If the sodium light arising here were selfless enough to let the kindred yellow light arising here it would have to extinguish itself in so doing. This it does not do; it puts itself in the way at the very place where the yellow should be coming through. It is simply there, and though it is yellow itself, the effect of it is not to intensify but to extinguish. As a real active force, it puts itself in the way, even as an indifferent obstacle might do; it gets in the way. This yellow part of the spectrum is extinguished and a black strip is brought about instead. From this again you see, we need only bear in mind what is actually there. The flowing light itself gives us the explanation.

These are the things which I would have you note. A physicist explaining things in Newton's way would naturally argue: If I here have a piece of white—say, a luminous strip—and I look at it through the prism, it appears to me in such a way that I get a spectrum: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, dark blue, violet (Figure IVi). Goethe said: Well, at a pinch, that might do. If Nature really is like that—if she has made the light composite—we might well assume that with the help of the prism this light gets analyzed into its several parts. Good and well; but now the very same people who say the light consists of these seven colours—so that the seven colours are parts or constituents of the light—these same people allege that darkness is just nothing,—is the mere absence of light. Yet if I leave a strip black in the midst of white—if I have simple white paper with a black strip in the middle and look at this through a prism,—then too I find I get a rainbow, only the colours are now in a different order (Figure IVk),—mauve in the middle, and on the one side merging into greenish-blue. I get a band of colours in a different order. On the analysis-theory I ought now to say: then the black too is analyzable and I should thus be admitting that darkness is more than the mere absence of light. The darkness too would have to be analyzable and would consist of seven colours. This, that he saw the black band too in seven colours, only in a different order,—this was what put Goethe off. And this again shews us how needful it is simply to take the phenomena as we find them.

Vierter Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde!

Wir sind leider mit dem Zusammenstellen des Experimentier-Materials noch nicht weit genug gediehen. Daher werden wir manche Dinge, die wir heute machen wollten, erst morgen machen, und ich werde müssen den Vortrag heute mehr so einrichten, dass ich einiges, was uns nützlich sein wird in den nächsten Tagen, Ihnen noch zur Darstellung bringe, gewissermaßen mit einer kleinen Änderung meiner Absichten.

Ich möchte zunächst einfach vor Sie hinstellen dasjenige, was man nennen könnte das Urphänomen der Farbenlehre. Es wird sich darum handeln, dass Sie nach und nach dieses Urphänomen der Farbenlehre bewahrheitet, bekräftigt finden an den Erscheinungen, die Sie im ganzen Umfang der sogenannten Optik oder Farbenlehre beobachten können. Natürlich komplizieren sich die Erscheinungen, und das einfache Phänomen tritt nicht überall gleich so bequem in die äußere Offenbarung. Aber wenn man sich die Mühe gibt, finder man es überall. Dieses einfache Phänomen, zunächst in Goethe’scher Art ausgesprochen, ist das: Sicht man ein Helleres durch Dunkelheit, dann wird das Helle durch die Dunkelheit in dem Sinn der hellen [Farbe erscheinen], in dem Sinn des Gelblichen oder Rötlichen, mit anderen Worten: Sehe ich zum Beispiel irgendein leuchtendes, sogenanntes weißlich scheinendes Licht durch eine genügend dicke Platte, die irgendwie abgetrübt ist, so erscheint mir dasjenige, was ich sonst, indem ich es direkt anschaue, weißlich sehe, das erscheint mir gelblich, gelb-rötlich. Hell durch Dunkelheit erscheint gelb oder gelblich-rötlich. Das ist der eine Pol: Hell durch Dunkel erscheint gelb oder gelb-rötlich.

Umgekehrt, wenn Sie hier, ich will sagen, einfach eine schwarze Fläche haben, Sie schauen sie direkt an, dann sehen Sie eben die schwarze Fläche. Nehmen Sie aber an, ich habe hier einen Wassertrog, durch diesen Wassertrog jage ich Helligkeit durch, sodass er aufgehellt ist. Also, ich habe hier eine erhellte Flüssigkeit. Dann sehe ich das Dunkle dunkel durch Hell, durch Erhelltes. Da erscheint Blau oder Violett, das heißt Blaurot, das heißt der andere Pol der Farbe.

Das ist das Urphänomen: Hell durch Dunkel - Gelb; Dunkel durch Hell - Blau. Sehen Sie, dieses einfache Phänomen kann eben überall gesehen werden, wenn man sich nur gewöhnt, real zu denken, nicht abstrakt zu denken, wie eben die heutige Wissenschaft denkt.

Nun erinnern Sie sich von diesem Gesichtspunkt aus an den Versuch, den wir schon gemacht haben, wo wir haben einen Lichtzylinder durchgehen lassen durch ein Prisma und haben bekommen, indem der Lichtzylinder durch das Prisma durchging, eine wirkliche Farbenskala, die wir aufgefangen haben, vom Violett bis zum Rot. Dieses Phänomen, ich habe es Ihnen ja schon aufgezeichnet. Wir konnten sagen: Wenn wir hier das Prisma haben, wir haben hier den Lichtzylinder, dann geht das Licht in irgendeiner Weise durch das Prisma hindurch, wird nach oben abgelenkt. Und wir haben gesagt: Hier findet nicht nur eine Ablenkung statt. Eine [bloße] Ablenkung würde stattfinden, wenn ein Gegenstand, ein durchsichtiger Gegenstand dem Lichte in den Weg gestellt würde, der parallele Flächen hat. Aber es wird [hier] das Prisma, das zusammengehende Flächen hat, dem Lichte in den Weg gestellt. Dadurch bekommen wir im Durchgang durch das Prisma eine Verdunkelung des Lichtes. Wir haben also in dem Augenblicke, wo wir das Licht durch das Prisma hindurchjagen, es zu tun mit zweierlei, erstens mit dem einfachen, fortströmenden hellen Licht, dann aber mit dem dem Licht in den Weg gestellten Trüben. Aber dieses Trübe, das sich dem Licht in den Weg stellt, das, haben wir gesagt, stellt sich so dem Lichte in den Weg, dass, während das Licht in der Hauptsache nach oben abgelenkt wird, wird dasjenige, was als Trübung entsteht, indem es nach oben strahlt, mit seinen Strahlen in der Richtung der Ablenkung sein. Das heißt, es strahlt Dunkelheit in das abgelenkte Licht hinein. Dunkelheit lebt gewissermaßen im abgelenkten Licht. Dadurch entsteht hier [oben] das Bläuliche, Violette. Aber die Dunkelheit strahlt auch nach unten. Da strahlt sie, während der Lichtzylinder so [nach oben] abgelenkt wird, nach unten, und sie wirkt entgegengesetzt dem abgelenkten Licht, kommt gegen dieses nicht auf und wir können sagen: Da übertönt das abgelenkte helle Licht die Dunkelheit, und wir bekommen [unten] die gelblichen oder gelblich-rötlichen Farben.

Nehmen wir einen genügend dünnen Lichtzylinder, so können wir, wenn wir in der Richtung dieses Lichtzylinders [zum Prisma hin] schauen - mit unseren Augen können wir ja durch das Prisma hindurchsehen -, statt dass wir von außen auf einem Schirm anschauen das Bild, das entworfen wird, wir können unser Auge an die Stelle dieses Bildes stellen. Dann sehen wir, wenn wir durch das Prisma hindurchsehen, dasjenige, was hier ein Ausschnitt ist, durch den uns der Lichtzylinder entsteht, das sehen wir verschoben. Wir haben also hier wiederum, wenn wir innerhalb der Fakten stehen bleiben, das Phänomen vor uns: Wenn ich hier hinschaue, so sehe ich dasjenige, was mir sonst direkt [geradeaus] zukommen würde, sehe ich durch das Prisma nach unten verschoben. Aber ich sehe es außerdem farbig. Sie sehen es überall farbig.

Was sehen Sie da eigentlich hier? Wenn Sie sich vergegenwärtigen, was Sie hier sehen, und rein aussprechen, was Sie sehen im Zusammenhang mit demjenigen, was wir eben festgestellt haben, dann ergibt sich Ihnen dasjenige, was Sie wirklich sehen, auch für die Einzelheit, unmittelbar. Sie müssen sich nur an das Gesehene halten. Nicht wahr, wenn Sie so hinschauen auf den Lichtzylinder — weil er Ihnen entgegenkommt, der helle Lichtzylinder -, also ein Helles sehen Sie, aber Sie sehen das Helle - no, nicht wahr, ein deutlicher Beweis, dass Sie hier oben ein Abgedunkeltes haben, ist, dass die blaue Farbe entsteht - also, Sie sehen durch das Abgedunkelte, durch die blaue Farbe, ein Helles, durch ein Dunkles ein Helles. Also müssen Sie hier Gelb oder Gelb-rötlich sehen, also Gelb und Rot. Und unten ist Ihnen die rote Farbe ebenso ein Beweis, dass Sie ein Aufgehelltes haben. - Ich habe Ihnen ja gesagt, das Hell übertönt die Dunkelheit. Also sehen Sie, indem Sie hinschauen: Wie hell auch sein mag der Lichtzylinder, Sie sehen ihn noch durch ein Aufgehelltes. Also, er ist dunkel gegenüber dem Aufgehellten. Sie sehen also ein Dunkles durch ein Erhelltes, und Sie müssen es unten blau sehen oder blaurot.

Sie brauchen bloß das Phänomen auszusprechen, dann haben Sie auch dasjenige, was Sie sehen können. Das, was sich dem Auge darbietet, ist, was Sie sonst sehen, das ist das, das Blau, durch das Sie hindurchschauen. Also erscheint das Hell rötlich. Am unteren Rand haben Sie die Erhelltheit. Wie hell auch der Lichtzylinder sein mag, Sie sehen ihn durch ein Erhelltes. Also sehen Sie ein Dunkleres durch ein Erhelltes und Sie sehen es rot. Darauf kommt es an, es kommt auf das Polarische an.

Das Erstere kann man, wenn man gelehrt sein will, die objektiven Farben nennen, das am Schirm. Das andere, was man sieht, wenn man durch das Prisma schaut, kann man nennen das subjektive Spektrum. Das subjektive Spektrum erscheint in Umkehrung des objektiven Spektrums. Wenn wir so sprechen, dann haben wir ganz gelehrt gesprochen.

Nun, über diese Erscheinungen, meine lieben Freunde, ist ja sehr viel, namentlich im Laufe der neueren Zeit, gegrübelt worden. Nicht nur, dass man hat so, wie wir es jetzt versucht haben, die Erscheinungen angesehen und sie reinlich ausgesprochen, sondern man hat über die Dinge gegrübelt, und das äußerste Grübeln ist ja schon angegangen, als der berühmte Newton über das Licht deshalb nachgedacht hat, weil ihm zuerst dieses Farbenspektrum sich dargeboten hat. Newton hat sich allerdings [mit seinen objektiven Versuchen mit dem schmalen Spalt] die sogenannte Erklärung - eine solche ist es immer nur - verhältnismäßig leicht gemacht. Er hat gesagt: Nun, wenn wir eben das Prisma haben, so lassen wir weißes Licht hinein. Da drinnen sind schon die Farben enthalten, das Prisma lockt sie hervor, und dann marschieren sie der Reihe nach auf. Ich habe einfach das weiße Licht zerlegt. Nun hat sich Newton vorgestellt: Jeder Farbenart entspricht ein bestimmter Stoff, sodass also in dem Gesamten stofflich sieben Farben enthalten sind. Gewissermaßen ist für ihn dieses Durchlassen des Lichtes durch das Prisma eine Art chemischer Zerlegung des Lichtes in sieben einzelne Stoffe. Er hat sich sogar Vorstellungen gemacht, welche Stoffe größere Korpuskeln, Kügelchen, aussenden und welche Stoffe kleinere. Nun also liegt in diesem Sinne die Sache so, dass die Sonne uns Licht sendet; wir lassen das Licht ein durch den kreisförmigen Spalt, da [beim Prisma] fällt es auf als ein Lichtzylinder. Aber dieses Licht besteht in lauter kleinen Korpuskeln, kleinen Körperchen, die hier aufstoßen, dann werden sie von ihrer Richtung abgelenkt, und dann bombardieren sie den Schirm und da fallen die kleinen Kanonenkügelchen auf. Die kleinen fliegen nach oben, die großen nach unten, die kleinen sind die violetten, die großen sind die roten, nicht wahr? Und so sondern sich die großen von den kleinen ab.

Diese Anschauung, dass da ein Stoff oder verschiedene Stoffe durch die Welt fliegen, die wurde sehr bald erschüttert von anderen Physikern, Huygens und Young und anderen, und es ist endlich dazu gekommen, dass man sich gesagt hat: So geht es doch nicht, dass da diese kleinen Kügelchen von irgendwo ausgehen und einfach durch das Medium getrieben werden oder auch nicht durch ein Medium getrieben werden und entweder auf einem Schirm ankommen, ein Bild erzeugen, oder in das Auge gelangen, um bei uns die Erscheinung des Rot und so weiter hervorzurufen. Damit geht es doch nicht. Und ich möchte sagen: Zuletzt wurden die Menschen dazu getrieben, sich zu beweisen, dass cs so nicht gehe, durch einen Versuch, der ja allerdings auch schon vorbereitet war, sogar bei dem Jesuiten Grimaldi, auch durch andere. Es wurde diese ganze Anschauung wesentlich erschüttert durch dasjenige, was durch Fresnel*? als Versuch angestellt worden ist.

Diese Fresnel’schen Versuche sind außerordentlich interessant. Aber man muss sich einmal klar werden, was da eigentlich geschieht in der Anordnung, die Fresnel seinen Versuchen gegeben hat. Aber ich bitte Sie, jetzt wirklich auf die Tatsachen recht sehr achtzugeben, denn es handelt sich darum, dass wir wirklich ganz genau ein Phänomen studieren. - Sehen Sie, nehmen Sie an, ich hätte zwei Spiegel und habe hier eine Lichtquelle, das heißt, mit einer Flamme leuchte ich von da aus, sodass ich, wenn ich hier einen Schirm aufstelle, Bilder bekomme durch diesen [ersten] Spiegel und Bilder bekomme von dem anderen [zweiten] Spiegel. Nehmen Sie also an - ich werde das zeichnen im Durchschnitt - zwei sehr wenig gegeneinander geneigte Spiegel. Hier habe ich eine Lichtquelle-ich will sie Z nennen - [und] einen Schirm, so spiegelt sich mir das Licht, indem es hier [auf den ersten Spiegel] auffällt, sodass ich in der Lage sein kann, hier durch das reflektierte Licht den Schirm zu beleuchten. Ich werde - wenn ich das Licht hier [auf den ersten Spiegel] auffallen lasse, so kann ich durch den Spiegel den Schirm hier beleuchten, sodass er hier in der Mitte heller ist als in der Umgebung. Nun habe ich aber hier einen zweiten Spiegel, durch den wird das Licht etwas anders reflektiert, und es wird gewissermaßen noch ein Teil desjenigen, was von hier unten [gespiegelt wird], von meinem Lichtkegel, nach dem [unteren oder zweiten] Spiegel [zum Schirm] hin dirigiert wird - das fällt noch hinein in das Obere [des durch den ersten Spiegel Gespiegelte], sodass durch die Neigung wird gewissermaßen, was der obere Spiegel spiegelt, wird als Helligkeit auf den Schirm geworfen; was vom unteren Spiegel gespiegelt wird, wird auch als Helligkeit darauf geworfen. Man kann sagen, dass cs für diesen Schirm so ist, wie wenn er von zwei Orten aus erhellt würde.

Nehmen Sie nun an, es habe einen Physiker gegeben, der das sieht. Dieser Physiker, der das sieht, dächte newtonisch. Dann wird er sich sagen: Da ist die Lichtquelle, die bombardiert zuerst den ersten Spiegel, der schmeißt ihre Kügelchen hierher. Diese prallen [vom ersten Spiegel] ab, kommen auf den Schirm und erhellen ihn. Aber auch von dem unteren Spiegel prallen die Kügelchen ab. Da kommen viele Kügelchen an. Es muss viel heller sein, wenn die zwei Spiegel da sind, als wenn nur der eine Spiegel da ist. Richte ich die Sache so ein, dass ich den zweiten Spiegel wegmache, so müsste [der Schirm] durch das hergeworfene Licht weniger erhellt sein, als wenn ich die zwei Spiegel habe.

Allerdings, ein Gedanke, sehen Sie, könnte diesem Physiker kommen, der richtig fatal wäre. Denn diese Korpuskeln, diese Körperchen, die müssen diesen Weg [vom zweiten Spiegel nach oben] machen, da kommen die anderen [vom ersten Spiegel] herunter. Warum just nun diejenigen, die da herunterkommen, gar nicht auf diese [von unten, vom zweiten Spiegel kommenden Körperchen] stoßen und sie wegschleudern, das ist außerordentlich schwer einzusehen. - Überhaupt, Sie können in unseren Physikbüchern sehr schöne Erzählungen über die Wellentheorie finden. Aber während die Dinge sehr schön berechnet werden, muss man immer den Gedanken haben, dass man niemals berechnet, wenn so eine Welle durch die andere durchsaust - das geht immer so ganz unbemerkt ab. Wollen wir einmal in Wirklichkeit auffassen, was hier eben eigentlich geschieht.

Sehen Sie, gewiss, das Licht fällt hier herunter, wird hierher [zum Schirm] herübergeworfen, fällt auch auf den zweiten Spiegel, wird hierher geworfen. Das Licht ist also auf dem Weg zum Spiegel, wird hier herübergeworfen — das ist immer der Weg des Lichts. Was geschieht nun aber eigentlich? Nun, nehmen wir an, wir hätten hier so einen Lichtgang. Jetzt wird er hier herübergeworfen. Jetzt kommt aber hier der andere Lichtgang, der trifft auf. Das ist ein Phänomen, das nicht zu leugnen ist. Wir haben hier den Lichtgang; aber da kommt der andere, der trifft da auf. Die beiden stören sich gegenseitig. Der will da durchsausen, der andere stellt sich in den Weg. Die Folge davon ist: Wenn er da durchsausen will, dass er das von da kommende Licht zunächst auslöscht; er löscht es aus. Indem er durchsaust, löscht er das Licht aus. Dadurch aber bekommen wir überhaupt hier [beim Schirm] nicht eine Helligkeit, sondern es spiegelt sich hier in Wahrheit die Dunkelheit herüber, sodass wir also hier [beim Schirm] eine Dunkelheit kriegen. Nun ist aber die ganze Geschichte nicht in Ruhe, sondern das ist in fortwährender Bewegung. Dieses, was hier gestört worden ist, das geht weiter. Da ist also gleichsam ein Loch im Licht entstanden. Nicht wahr, es ist ja das Licht durchgesaust, es ist ein Loch entstanden. Dieses erscheint dunkel. Aber dadurch wird der nächste Lichtkörper umso leichter durchgehen und Sie werden neben der Dunkelheit einen umso helleren Fleck haben. Das Nächste wiederum, was geschieht, ist das, dass, indem das hier weiterschreitet, wiederum ein solcher kleiner Lichtzylinder von oben aufstößt auf eine Helligkeit, sie wiederum auslöscht, wiederum eine Dunkelheit hervorruft. Dadurch, dass diese weiterschreitet, kann das Licht wiederum leichter durch. Wir haben es zu tun mit einem solchen fortschreitenden Gitter, wo das Licht, das von oben kommt, immer durch kann und, indem es auslöscht, wiederum Dunkelheit bringt, die aber fortschreitet. Wir müssen also hier abwechselnd Helligkeit und Dunkelheit bekommen dadurch, dass das obere Licht durch das untere durchgeht und so ein Gitter macht.

Das ist, was ich Sie gebeten habe, genau zu denken. Denn Sie müssen verfolgen, wie ein Gitter entsteht. Sie haben Helligkeiten und Dunkelheiten dadurch abwechselnd, dass Licht ins Licht hineinsaust. Wenn Licht in Licht hineinsaust, so wird das Licht eben aufgehoben, wird das Licht in Dunkelheit verwandelt. Die Entstehung eines solchen Lichtgitters müssen wir also dadurch erklären, dass wir die Anordnung getroffen haben durch diese Spiegel. Sie werden das Phänomen immer so bekommen, wenn Sie hier eine Lichtquelle haben, deren Lichtgeschwindigkeit gar nicht in Betracht kommt. Im Hinblick auf die Geschwindigkeit des Lichtes, überhaupt dasjenige, was an Verschiedenheiten der Lichtgeschwindigkeit hier auftritt, hat keine große Bedeutung. Was ich zeigen möchte, ist hier dasjenige: Was innerhalb des Lichtes selbst auftritt mithilfe des Apparates, ist hier [dasjenige], dass sich das Gitter abspiegelt: hell, dunkel, hell, dunkel.

Aber jener Physiker- es war Fresnel selber -, der sagte sich: Wenn das Licht die Ausströmung von Körperchen ist, so ist es selbstverständlich, dass, wenn mehr Körperchen hingeschleudert werden, dann muss es heller werden, sonst müsste ein Körperchen das andere aufzehren. Also nach der bloßen Ausstrahlungstheorie kann nicht erklärt werden, dass Helligkeit und Dunkelheit miteinander abwechseln. Wie es zu erklären ist, wir haben es eben gesehen. Aber nun sehen Sie, das Phänomen so zu nehmen, wie es eigentlich sein muss, das fiel nun gerade wiederum den Physikern nicht ein, sondern im Zusammenhang mit gewissen anderen Erscheinungen versuchten sie eine Erklärung im Sinne des Materialismus. Mit den hinbombardierenden Stoffkügelchen ging es nicht mehr. Deshalb sagte man: Nehmen wir an, das Licht ist nicht ein Hinströmen von feinen Stoffen, sondern nur eine Bewegung in einem feinen Stoff, in dem Äther, Bewegung im Äther. Und zuerst stellte man sich vor - zum Beispiel tat das Euler -, das Licht pflanze sich in diesem Äther etwa so fort wie der Schall in der Luft. Wenn ich einen Schall errege, so pflanzt sich der ja durch die Luft fort, aber so, dass zunächst, wenn hier der Schall erregt wird, die Luft in der Umgebung zusammengedrückt wird. Dadurch entsteht verdichtete Luft. Die verdichtete Luft, die hier entsteht, die drückt wiederum auf die Umgebung. Sie dehnt sich aus. Dadurch aber ruft sie sporadisch gerade in der Nähe eine verdünnte Luftschicht hervor. Durch solche Verdickungen und Verdünnungen, die man Wellen nennt, stellt man sich vor, dass der Schall sich ausbreitet. Und so nahm man an, dass solche Wellen auch im Äther erregt werden. Aber mit gewissen Erscheinungen stimmte die Sache nicht, und so sagte man sich: Eine Wellenbewegung ist das Licht wohl, aber es schwingt nicht so, wie es beim Schall ist. Beim Schall ist es so, dass hier eine Verdichtung ist, dann kommt eine Verdünnung, und das schreitet so fort. Das sind Längswellen. Also, es folgt die Verdünnung auf die Verdichtung, und ein Körper, der bewegt sich darinnen in der Richtung der Fortpflanzung so hin und zurück. Das konnte man sich beim Lichte nicht so vorstellen. Da ist es so, dass, wenn sich das Licht so fortpflanzt, dann bewegen sich die Ätherteilchen senkrecht zur Richtung der Fortpflanzung; sodass wir also, wenn dasjenige, was man einen Lichtstrahl nennt, da durch die Luft saust - es saust ja so ein Lichtstrahl mit 300000 Kilometer Geschwindigkeit -, wenn man da die Richtung hat, in der das Licht dahinsaust, dann schwingen da die kleinen Teilchen immer senkrecht darauf. Wenn dann dieses Schwingen in unser Auge kommt, dann nehmen wir das wahr.

Wenn man das auf den Fresnel’schen Versuch anwendet, sehen Sie hier, dann, wenn sich das Licht so fortpflanzt, dann schwingt es jetzt da weiter, so, schwingt es so weiter, sodass eigentlich die Bewegung des Lichtes ein senkrechtes Schwingen ist auf die Richtung, in der sich das Licht fortpflanzt. Ja, dieser Strahl hier, der auf den unteren Spiegel geht, würde also so schwingen, setzt sich so fort, stößt hier auf. Nun, wie gesagt, dieses Durcheinandergehen der Wellenzüge, über das sieht man da hinweg. Die stören sich da nicht im Sinne dieser so denkenden Physiker. Aber hier [beim Schirm] stören sie sich sogleich, oder aber sie unterstützen sich. Denn was soll nun hier geschehen? Ja, nicht wahr, hier [beim Schirm] kann es nun so sein, dass, wenn dieser Wellenzug hier ankommt, das [eine] kleinste Teilchen hier, das senkrecht schwingt, just hinunterschwingt, wenn das [andere] da just hinaufschwingt. Dann heben sie sich auf, dann müsste Dunkelheit entstehen. Wenn aber hier [beim Schirm] das [eine Teilchen gerade] aufschwingt, und das andere hier so [ebenfalls auf-] schwingt, und [wenn] das [eine] Teilchen hier gerade hinunterschwingt, wenn das andere hinunterschwingt, oder hinaufschwingt, wenn das andere hinaufschwingt, dann müsste die Helligkeit entstehen, sodass man also hier aus den Schwingungen der kleinsten Teilchen dasselbe erklärt, was wir aus dem Lichte selber erklärt haben. Ich habe gesagt, dass man hier abwechselnd helle und dunkle Stellen hat, aber die moderne sogenannte [Undulations-]Theorie erklärt sie dadurch, dass das Licht eine Schwingung des Äthers ist, dass hier, wenn die kleinsten Teilchen so schwingen, dass sie einander unterstützen, dann entsteht ein hellerer Fleck, wenn sie im entgegengesetzten Sinne schwingen, dann entsteht ein dunklerer Fleck.

Sie müssen jetzt nur ins Auge fassen, welcher Unterschied besteht zwischen der reinen Auffassung des Phänomens, dem Stehenbleiben innerhalb der Phänomene, dem Verfolgen der Phänomene und dem Hinstellen der Phänomene und [dem] Hinzuerfinden zu den Phänomenen [von] etwas, was man eben nur hinzuerfunden hat. Denn diese ganze Bewegung des Äthers ist ja nur hinzuerfunden. Man kann natürlich so etwas, was man erfunden hat, berechnen. Aber das, dass man darüber rechnen kann, ist ja kein Beweis dafür, dass die Sache auch da ist. Denn das bloß Phoronomische ist eben ein bloß Gedachtes, und das Rechnerische ist auch bloß ein Gedachtes. Sie sehen daraus, dass wir darauf angewiesen sind, nach unserer Grunddenkweise die Phänomene so zu erklären, dass sie sich uns selber als Erklärung ergeben, dass sie die Erklärung in sich selber enthalten darauf bitte ich den größten Wert zu legen -, dass hinausgeworfen werden muss, was bloße Spintisiererei ist. Alles kann man erklären, wenn man hinzufügt etwas, wovon kein Mensch etwas weiß. Diese Wellen zum Beispiel könnten natürlich da sein, und es könnte sein, wenn eine herunterschwingt und die andere hinaufschwingt, dass sie sich dann aufheben - aber man hat sie erfunden. Aber was unbedingt da ist, ist dieses Gitter hier, und dieses Gitter sehen wir sich hier treulich spiegeln. Man muss schon auf das Licht schauen, wenn man zu dem kommen will, was unverfälschte Erklärung ist.

Weipglühender Körper Nun habe ich Ihnen gesagt: Wenn das eine Licht durch das andere durchgeht, mit ihm überhaupt in irgendeine Beziehung tritt, dann wirkt unter Umständen das eine Licht trübend auf das andere Licht, auslöschend auf das andere Licht, wie das Prisma selber trübend wirkt. Das stellt sich ganz besonders dadurch heraus, dass man - wir werden den Versuch wirklich machen -, dass man den folgenden Versuch macht. Sehen Sie, ich will das, um was es sich dabei handelt, aufzeichnen: Nehmen wir an, wir haben dasjenige, was ich Ihnen gestern zeigte, wir haben wirklich ein solches Spektrum, und zwar direkt durch die Sonne erzeugt; wir haben ein solches Spektrum bekommen vom Violett bis zum Rot. Wir könnten ein solches Spektrum auch erzeugen, indem wir nicht die Sonne durch einen solchen [kreisförmigen] Spalt durchscheinen ließen, sondern dadurch, dass wir an diese Stelle hier einen festen Körper herbrächten, den wir glühend machten. Dann würden wir auch allmählich, wenn er bis zur Weißglut kommt, die Möglichkeit haben, ein solches Spektrum zu haben. Es ist gleichgültig, ob ein Sonnenspektrum [vorliegt] oder ob das Spektrum von einem weiß glühenden Körper kommt.

Nun können wir aber auch noch auf eine etwas modifizierte Art ein Spektrum erzeugen. Nehmen wir an, wir haben hier ein Prisma und wir haben hier eine Natriumflamme, das heißt ein sich verflüchtigendes Metall: Natrium. Gas wird Natrium da. Das Gas brennt, verflüchtigt sich, und wir erzeugen ein Spektrum von diesem sich verflüchtigenden Natrium. So tritt etwas sehr Eigentümliches auf. Wenn wir das Spektrum erzeugen nicht von der Sonne oder nicht von einem festen glühenden Körper, sondern von einem glühenden Gas, dann ist eine einzige Stelle im Spektrum sehr stark ausgebildet, und zwar bekommt Natriumlicht besonders das Gelb. Wir haben hier, nicht wahr, Rot, Orange, Gelb. Der gelbe Teil, der ist beim Natrium besonders stark ausgebildet. Das übrige Spektrum ist beim Natriummetall verkümmert, fast gar nicht vorhanden. Also, alles vom Violett bis zum Gelb herein und vom Gelben bis zum Rot ist verkümmert. Wir bekommen daher scheinbar einen ganz schmalen gelben Streifen, man sagt eine gelbe Linie. Die entsteht dadurch, dass sie der Teil eines ganzen Spektrums ist. Das andere des Spektrums ist nur verkümmert. So kann man von den verschiedensten Körpern solche Spektren finden, die eigentlich keine Spektren sind, sondern nur leuchtende Linien. Daraus ersehen Sie, dass man umgekehrt, wenn man nicht weiß, was da eigentlich in einer Flamme drinnen ist, und man ein solches Spektrum erzeugt, dass dann, wenn man ein gelbes Spektrum kriegt, in der Flamme Natrium sein muss. Man kann erkennen, mit welchem Metall man es zu tun hat.

Das Eigentümliche aber, was entsteht, wenn man nun diese zwei Versuche kombiniert, sodass man erzeugt diesen Lichtzylinder hier, und das Spektrum erzeugt hier, zu gleicher Zeit die Natriumflamme hineintut, sodass das glühende Natrium sich vereinigt mit dem Lichtzylinder - was da geschieht, ist etwas ganz Ähnliches, als was ich Ihnen vorhin beim Fresnel’schen Versuch gezeigt habe. Man könnte erwarten, dass hier besonders stark das Gelb auftreten würde, weil das Gelb schon drinnen ist; dann kommt noch das Gelb vom Natrium dazu. Aber das ist nicht der Fall, sondern das Gelbe vom Natrium löscht das andere Gelb aus, und es entsteht hier eine dunkle Stelle. Also, wo man erwarten würde, dass Helleres entsteht, [entsteht] eine dunkle Stelle! Warum denn? Das hängt lediglich ab von der Kraft, die entwickelt wird. Nehmen Sie an, es wäre das Natriumlicht, das da entsteht, so selbstlos, dass es das verwandte gelbe Licht einfach durch sich hindurchließe, dann müsste es sich ganz auslöschen. Das tut es aber nicht, sondern stellt sich in den Weg gerade an der Stelle, wo das Gelb herüberkommen sollte, stellt sich in den Weg. Es ist da, und trotzdem es gelb ist, wirkt es nicht etwa verstärkend, sondern wirkt auslöschend, trotzdem es gelb ist, weil es sich einfach als eine Kraft in den Weg stellt, gleichgültig, ob das, was sich da in den Weg stellt, etwas anderes ist oder nicht. Das ist einerlei. Der gelbe Teil des Spektrums wird ausgelöscht. Es entsteht dort eine schwarze Stelle.

Sie sehen daraus, dass man bloß wiederum das zu bedenken braucht, was da ist. Da stellt sich einem aus dem flutenden Licht selbst heraus die Erklärung dar. Das sind eben die Dinge, auf die ich Sie hinweisen möchte. sehen Sie, der Physiker, der im Sinne Newtons erklärt, der müsste natürlich sagen: Wenn ich hier ein Weißes habe, also einen leuchtenden Streifen, und ich gucke mit dem Prisma durch nach diesem leuchtenden Streifen, so erscheint er mir so, dass ich ein Spektrum bekomme: Rot, Orange, Gelb, Grün, Blau, Dunkelblau, Violett.

Nun, sehen Sie, Goethe sagte: Ja, zur Not geht’s ja noch. Wenn die Natur wirklich so ist, dass sie das Licht zusammengesetzt gemacht hat, so könnte man ja annehmen, dass dieses Licht durch das Prisma wirklich in seine Teile zerlegt wird. Schön, aber dabei behaupten ja dieselben Menschen, die das sagen, dass das Licht aus diesen sieben Farben als seinen Teilen besteht, zu gleicher Zeit, dass die Dunkelheit gar nichts ist, nur die Abwesenheit des Lichtes ist. Ja, aber wenn ich hier einen schwarzen Streifen lasse zwischen Weiß - ganz weißes Papier habe und hier einen schwarzen Streifen -, und ich gucke durch das Prisma durch, so bekomme ich auch einen Regenbogen, nur sind seine Farben anders angeordnet. Da ist er in der Mitte Violett [-Purpur] und geht nach der einen Seite ins [Bläuliche und nach der anderen Seite ins Gelblich-] Grünliche. Da bekomme ich ein anders angeordnetes Band. Aber ich müsste sagen, im Sinne der Zerlegungstheorie: Das Schwarze ist auch zerlegbar. Also, ich müsste zugeben, dass die Dunkelheit nicht bloß die [Abwesenheit] des Lichtes ist. Die Dunkelheit müsste auch zerlegbar sein. Sie müsste aber auch aus sieben Farben bestehen. Das ist es, was Goethe irre gemacht hat, dass er auch den schwarzen Streifen siebenfarbig sah, nur in anderer Anordnung. Das ist also dasjenige, was wiederum nötigt, einfach die Phänomene so zu nehmen, wie sie sind.

Nun, wir werden sehen, dass wir morgen wiederum um halb zwölf Uhr in der Lage sind, Ihnen das, was ich Ihnen heute leider nur theoretisch auseinandersetzen konnte, vorzuführen.

Fourth Lecture

My dear friends!

Unfortunately, we have not yet made sufficient progress in gathering the materials for the experiments. Therefore, we will have to postpone some of the things we wanted to do today until tomorrow, and I will have to organize today's lecture in such a way that I can still present some of the things that will be useful to us in the coming days, with a slight change to my original plans.

I would first like to present to you what could be called the fundamental phenomenon of color theory. You will gradually find this fundamental phenomenon of color theory to be true and confirmed in the phenomena that you can observe throughout the entire scope of what is known as optics or color theory. Of course, the phenomena become more complicated, and the simple phenomenon does not always reveal itself so conveniently in the external world. But if you take the trouble to look for it, you will find it everywhere. This simple phenomenon, initially expressed in Goethe's manner, is this: if you see something brighter through darkness, then the brightness appears through the darkness in the sense of the bright [color], in the sense of yellowish or reddish, in other words: For example, if I see some kind of luminous, so-called whitish light through a sufficiently thick plate that is somehow tinted, then what I would otherwise see as whitish when looking at it directly appears yellowish, yellow-reddish to me. Light through darkness appears yellow or yellowish-reddish. That is one pole: light through darkness appears yellow or yellowish-red.

Conversely, if you have, say, a black surface here and you look at it directly, you see the black surface. But suppose I have a trough of water here and I shine light through it so that it is illuminated. So, I have an illuminated liquid here. Then I see the dark as dark through the light, through the illuminated. Blue or violet appears, that is, blue-red, which is the other pole of the color.

This is the primordial phenomenon: light through dark—yellow; dark through light—blue. You see, this simple phenomenon can be seen everywhere, if you just get used to thinking realistically, not abstractly, as science does today.

Now, from this point of view, remember the experiment we already did, where we passed a light cylinder through a prism and, as the light cylinder passed through the prism, we obtained a real color scale, which we captured, from violet to red. I have already recorded this phenomenon for you. We could say: if we have the prism here and the light cylinder here, then the light passes through the prism in some way and is deflected upwards. And we said: Not only is there a deflection taking place here. A [mere] deflection would take place if an object, a transparent object with parallel surfaces, were placed in the path of the light. But [here] the prism, which has converging surfaces, is placed in the path of the light. This causes the light to darken as it passes through the prism. So at the moment when we send the light through the prism, we are dealing with two things: first, with the simple, flowing bright light, and then with the dim light that is placed in the path of the light. But this dim light that is placed in the path of the light, we have said, places itself in the path of the light in such a way that while the light is mainly deflected upward, that which arises as dimness, by shining upward, will be with its rays in the direction of the deflection. That is, it radiates darkness into the deflected light. Darkness lives, so to speak, in the deflected light. This produces the bluish, violet color here [above]. But the darkness also radiates downward. As the light cylinder is deflected [upwards], it radiates downwards and acts in opposition to the deflected light, does not come into contact with it, and we can say that the deflected bright light drowns out the darkness, and we get [below] the yellowish or yellowish-reddish colors.

If we take a sufficiently thin light cylinder, then when we look in the direction of this light cylinder [towards the prism] – we can see through the prism with our eyes – instead of looking at the image projected onto a screen from the outside, we can place our eye at the point where this image is projected. Then, when we look through the prism, we see what is here a section through which the light cylinder appears to us; we see it shifted. So here again, if we stick to the facts, we have the phenomenon before us: when I look here, I see what would otherwise come directly [straight ahead] toward me, I see it shifted downward through the prism. But I also see it in color. You see it in color everywhere.

What do you actually see here? If you think about what you see here and say out loud what you see in connection with what we have just established, then what you really see becomes immediately clear to you, even in detail. You just have to stick to what you see. Isn't that right, when you look at the light cylinder like that—because it is coming toward you, the bright light cylinder—you see something bright, but you see the light—no, isn't it true that clear proof that you have something darkened up here is that the blue color appears—so you see something light through the darkened area, through the blue color, something light through something dark. So here you must see yellow or reddish-yellow, that is, yellow and red. And below, the red color is also proof that you have something lightened. I told you, the light overpowers the darkness. So you see, when you look at it: no matter how bright the light cylinder may be, you still see it through something lightened. So it is dark compared to the lightened area. So you see something dark through something lightened, and you must see it blue or blue-red at the bottom.

You only need to describe the phenomenon, and then you will also have what you can see. What presents itself to the eye is what you would otherwise see, that is, the blue that you see through. So the light appears reddish. At the bottom edge, you have the lightness. No matter how bright the light cylinder may be, you see it through something that is lightened. So you see something darker through something that is lightened, and you see it red. That is what matters; it depends on the polarity.

The former, if one wants to be scholarly, can be called the objective colors, those on the screen.

The other thing you see when you look through the prism can be called the subjective spectrum. The subjective spectrum appears as a reversal of the objective spectrum. When we speak in this way, we have spoken very learnedly. Well, my dear friends, these phenomena have been pondered over a great deal, especially in recent times.

Not only have people looked at the phenomena as we have now attempted to do and described them clearly, but they have also pondered over them, and the most extreme pondering began when the famous Newton thought about light because he was first presented with this color spectrum. Newton, however, made the so-called explanation – for that is all it is – relatively easy for himself [with his objective experiments with the narrow slit]. He said: Well, if we have the prism, let us allow white light to pass through it. The colors are already contained within it; the prism draws them out, and then they march out in succession. I simply broke down the white light. Newton imagined that each type of color corresponds to a specific substance, so that the whole contains seven colors. In a sense, for him, the passing of light through the prism is a kind of chemical decomposition of light into seven individual substances. He even imagined which substances emit larger corpuscles, or globules, and which substances emit smaller ones. So in this sense, the sun sends us light; we let the light in through the circular slit, where [at the prism] it falls as a cylinder of light. But this light consists of tiny corpuscles, tiny bodies that collide here, then they are deflected from their direction, and then they bombard the screen and the little cannonballs fall down. The small ones fly upwards, the large ones downwards, the small ones are the violet ones, the large ones are the red ones, aren't they? And so the large ones separate from the small ones.

This view that there is a substance or different substances flying through the world was very soon shaken by other physicists, Huygens and Young and others, and it finally came to the conclusion that: It cannot be that these little balls originate somewhere and are simply driven through the medium, or not driven through a medium, and either arrive on a screen, produce an image, or enter the eye to cause us to perceive red and so on. That cannot be the case. And I would like to say: Ultimately, people were driven to prove to themselves that it couldn't be like that, through an experiment that had already been prepared, even by the Jesuit Grimaldi, and by others. This whole view was fundamentally shaken by what Fresnel*? attempted as an experiment.

These Fresnel experiments are extremely interesting. But we must first understand what is actually happening in the arrangement that Fresnel used for his experiments. I ask you to pay close attention to the facts, because we are studying a phenomenon in great detail. - Suppose I have two mirrors and a light source here, that is, I am shining a flame from there so that when I set up a screen here, I get images through this [first] mirror and images from the other [second] mirror. So suppose—I'll draw this on average—two mirrors that are very slightly inclined toward each other. Here I have a light source—I'll call it Z—[and] a screen, so that the light is reflected back to me by striking here [on the first mirror], so that I can illuminate the screen here through the reflected light. When I let the light fall here [on the first mirror], I can illuminate the screen here through the mirror so that it is brighter here in the middle than in the surrounding area. But now I have a second mirror here, through which the light is reflected slightly differently, and part of what is reflected from down here [by my cone of light] is directed toward the [lower or second] mirror, which is still in the upper part [of the image reflected by the first mirror], so that the angle causes what the upper mirror reflects to be reflected back into the upper part. mirror [towards the screen] – this falls into the upper part [of what is reflected by the first mirror], so that, due to the angle, what the upper mirror reflects is projected onto the screen as brightness; what is reflected by the lower mirror is also projected onto it as brightness. One could say that cs is like this screen being illuminated from two places.

Now suppose there was a physicist who saw this. This physicist, seeing this, would think in Newtonian terms. He would say to himself: There is the light source, which first bombards the first mirror, which throws its particles here. These bounce off [the first mirror], hit the screen and illuminate it. But the little balls also bounce off the lower mirror. Many little balls arrive there. It must be much brighter when the two mirrors are there than when only one mirror is there. If I arrange things so that I remove the second mirror, then [the screen] should be less illuminated by the light thrown onto it than when I have the two mirrors.

However, a thought could occur to this physicist that would be really fatal. Because these corpuscles, these tiny bodies, have to travel this path [from the second mirror upwards], while the others come down [from the first mirror]. Why it is that those coming down do not collide with those coming up [from below, from the second mirror] and throw them away is extremely difficult to understand. In general, you can find very nice explanations of wave theory in our physics books. But while things are calculated very nicely, you always have to bear in mind that you can never calculate when one wave rushes through another—it always happens completely unnoticed. Let's try to understand what is actually happening here in reality.

You see, of course, the light falls down here, is thrown over here [to the screen], also falls on the second mirror, is thrown over here. So the light is on its way to the mirror, is thrown over here—that is always the path of light. But what is actually happening? Well, let's assume we have a light path here. Now it is thrown over here. But now the other light path comes along and hits it. This is a phenomenon that cannot be denied. We have the light beam here, but then the other one comes and hits it. The two interfere with each other. One wants to rush through, the other stands in its way. The result is that when it wants to rush through, it first extinguishes the light coming from there; it extinguishes it. By rushing through, it extinguishes the light. As a result, however, we do not get any brightness here [on the screen], but in reality the darkness is reflected here, so that we get darkness here [on the screen]. Now, however, the whole story is not static, but in constant motion. What has been disturbed here continues. So, as it were, a hole has been created in the light. Isn't that right? The light has been blown through, and a hole has been created. This appears dark. But this makes it easier for the next light body to pass through, and you will have an even brighter spot next to the darkness. The next thing that happens is that as this continues, another small cylinder of light from above hits a bright spot, extinguishes it, and causes darkness again. As this continues, the light can pass through more easily. We are dealing with a kind of progressive grid where the light coming from above can always pass through and, as it extinguishes, brings darkness, which however progresses. So here we must alternately obtain brightness and darkness by the upper light passing through the lower light and thus forming a grid.

That is what I asked you to think about carefully. Because you have to follow how a grid is created. You have alternating brightness and darkness because light rushes into light. When light rushes into light, the light is canceled out and turned into darkness. We must therefore explain the formation of such a grid of light by the arrangement we have made with these mirrors. You will always get this phenomenon if you have a light source here whose speed of light is not taken into account. With regard to the speed of light, the differences in the speed of light that occur here are of no great significance. What I want to show here is this: what occurs within the light itself with the aid of the apparatus is that the grid is reflected: light, dark, light, dark.

But that physicist—it was Fresnel himself—said to himself: If light is the emanation of tiny particles, then it is obvious that if more particles are thrown out, it must become brighter, otherwise one particle would have to consume the other. So, according to the mere theory of radiation, it cannot be explained that brightness and darkness alternate with each other. We have just seen how this can be explained. But now you see, taking the phenomenon as it actually is did not occur to the physicists, but in connection with certain other phenomena they tried to find an explanation in terms of materialism. The bombardment of tiny particles of matter no longer worked. Therefore, they said: Let us assume that light is not a flow of fine substances, but only a movement in a fine substance, in the ether, movement in the ether. And at first, people imagined – Euler did, for example – that light propagated in this ether in much the same way as sound propagates in the air. When I make a sound, it propagates through the air, but in such a way that when the sound is first produced here, the air in the surrounding area is compressed. This creates compressed air. The compressed air that is created here in turn presses on the surrounding area. It expands. However, this causes it to sporadically create a layer of rarefied air in the immediate vicinity. It is imagined that sound propagates through such compressions and rarefactions, which are called waves. And so it was assumed that such waves are also excited in the ether. But certain phenomena did not fit in with this theory, and so it was said: Light is indeed a wave motion, but it does not oscillate in the same way as sound. With sound, there is a compression, then a rarefaction, and this continues. These are longitudinal waves. So, rarefaction follows compression, and a body moves back and forth within it in the direction of propagation. This was difficult to imagine with light. When light propagates in this way, the ether particles move perpendicular to the direction of propagation; so that when what we call a ray of light rushes through the air—a ray of light rushes at a speed of 300,000 kilometers—if you have the direction in which the light is rushing, then the small particles always oscillate perpendicular to it. When this oscillation reaches our eye, we perceive it.

If you apply this to Fresnel's experiment, you can see here that when the light propagates like this, it continues to oscillate, so that the movement of the light is actually a perpendicular oscillation to the direction in which the light propagates. Yes, this beam here, which goes to the lower mirror, would therefore oscillate like this, continue like this, and hit here. Now, as I said, you can see past this confusion of wave trains. They do not interfere with each other in the sense of physicists who think this way. But here [at the screen] they interfere with each other immediately, or they support each other. Because what is supposed to happen here? Yes, isn't it true that here [at the screen] it could be that when this wave train arrives here, the smallest particle here, which oscillates vertically, oscillates downwards just when the other one there oscillates upwards. Then they cancel each other out, and darkness would ensue. But if here [at the screen] the [one particle] vibrates upward, and the other here vibrates upward as well, and [if] the [one] particle here vibrates downwards, when the other vibrates downwards, or vibrates upwards, when the other vibrates upwards, then brightness should arise, so that here, from the vibrations of the smallest particles, we can explain the same thing that we have explained from light itself. I have said that here we have alternating light and dark spots, but the modern so-called [undulation] theory explains them by saying that light is a vibration of the ether, that here, when the smallest particles vibrate in such a way that they support each other, a brighter spot arises, and when they vibrate in the opposite direction, a darker spot arises.

Now you just have to consider the difference between the pure perception of the phenomenon, remaining within the phenomena, following the phenomena, and positing the phenomena and adding to the phenomena something that has simply been added. For this whole movement of the ether is only added. Of course, one can calculate something that one has invented. But the fact that one can calculate it is no proof that the thing is there. For the purely kinematic is merely a thought, and the calculative is also merely a thought. You can see from this that we are dependent on explaining phenomena in accordance with our basic way of thinking in such a way that they present themselves to us as an explanation, that they contain the explanation within themselves—I ask you to attach the greatest importance to this—that what is mere speculation must be discarded. Everything can be explained if you add something that no one knows anything about. These waves, for example, could of course be there, and it could be that when one swings down and the other swings up, they cancel each other out — but this has been invented. But what is definitely there is this grid here, and we see this grid faithfully reflected here. You have to look at the light if you want to arrive at an unadulterated explanation.

Incandescent body Now I have told you: When one light passes through another, when it enters into any kind of relationship with it, then under certain circumstances one light has a clouding effect on the other light, extinguishing the other light, just as the prism itself has a clouding effect. This becomes particularly apparent when one carries out the following experiment – we will actually do this. Look, I want to record what this is all about: Let us assume that we have what I showed you yesterday, that we really have such a spectrum, produced directly by the sun; we have obtained such a spectrum from violet to red. We could also produce such a spectrum not by allowing the sun to shine through such a [circular] slit, but by placing a solid body here that we made incandescent. Then, gradually, when it becomes white-hot, we would also have the possibility of obtaining such a spectrum. It does not matter whether a solar spectrum [is present] or whether the spectrum comes from a white-hot body.

Now we can also produce a spectrum in a slightly modified way. Let's assume we have a prism here and a sodium flame, i.e., a volatile metal: sodium. Gas becomes sodium. The gas burns, evaporates, and we generate a spectrum from this evaporating sodium. This produces something very peculiar. If we generate the spectrum not from the sun or from a solid glowing body, but from a glowing gas, then a single point in the spectrum is very strongly developed, and sodium light takes on a particularly yellow color. Here we have red, orange, and yellow. The yellow part is particularly strong in sodium. The rest of the spectrum is reduced in sodium metal, almost non-existent. So everything from violet to yellow and from yellow to red is reduced. This gives us what appears to be a very narrow yellow stripe, or a yellow line. This is because it is part of the entire spectrum. The rest of the spectrum is simply diminished. In this way, you can find spectra from a wide variety of substances that are not actually spectra, but only glowing lines. From this you can see that, conversely, if you don't know what is actually in a flame and you produce such a spectrum, then if you get a yellow spectrum, there must be sodium in the flame. You can tell which metal you are dealing with.

But the peculiar thing that happens when you combine these two experiments, so that you create this light cylinder here and the spectrum here, and at the same time put the sodium flame in it, so that the glowing sodium combines with the light cylinder—what happens is very similar to what I showed you earlier in Fresnel's experiment. One might expect the yellow to appear particularly strongly here, because the yellow is already inside; then the yellow from the sodium is added. But that is not the case; instead, the yellow from the sodium extinguishes the other yellow, and a dark spot appears here. So where one would expect something brighter to appear, a dark spot appears! Why is that? It depends solely on the force that is developed. Suppose the sodium light that is produced is so selfless that it simply allows the related yellow light to pass through it, then it would have to extinguish itself completely. But it doesn't do that; instead, it gets in the way at the very point where the yellow should come through, it gets in the way. It is there, and even though it is yellow, it does not have a reinforcing effect, but rather an extinguishing effect, even though it is yellow, because it simply stands in the way as a force, regardless of whether what stands in its way is something else or not. It does not matter. The yellow part of the spectrum is extinguished. A black spot appears there.

You can see from this that you only need to consider what is there. The explanation presents itself from the flooding light itself. These are the things I would like to point out to you. You see, a physicist who explains things in Newton's terms would naturally have to say: If I have something white here, i.e., a bright strip, and I look through the prism at this bright strip, it appears to me as a spectrum: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, dark blue, violet.

Well, you see, Goethe said: Yes, that's acceptable, if necessary. If nature really is such that it has composed light in this way, then one could assume that this light is really broken down into its parts by the prism. Fine, but the same people who say this also claim that light consists of these seven colors as its parts, and at the same time that darkness is nothing at all, only the absence of light. Yes, but if I leave a black stripe here between white—I have completely white paper and a black stripe here—and I look through the prism, I also get a rainbow, only its colors are arranged differently. There it is violet [purple] in the middle and goes to one side into [bluish and to the other side into yellowish-] greenish. I get a differently arranged band. But I would have to say, in the sense of the decomposition theory: The black is also decomposable. So, I would have to admit that darkness is not merely the [absence] of light. Darkness must also be decomposable. But it must also consist of seven colors. That is what confused Goethe, that he also saw the black stripe as seven colors, only in a different arrangement. So that is what again makes it necessary to simply take the phenomena as they are.

Well, we will see tomorrow at half past eleven whether we are able to demonstrate to you what I have unfortunately only been able to explain to you in theory today.