The Light Course

GA 320

27 December 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture V

My dear Friends,

Today I will begin by shewing, as well as may be with our limited resources, the experiment of which we spoke last time. You will remember: when an incandescent solid body spreads its light and we let this light go through a prism, we get a “spectrum”, a luminous picture, very like what we should get from the Sun, (compare Figure IVf), towards the end of Lecture IV). Now we can also obtain a luminous picture with the light that spreads from a glowing gas; however this picture only shews one or more single lines of light or little bands of light at different places, according to the substance used, (Figure IVg). The rest of the spectrum is stunted, so to speak. By very careful experiment, it is true, we should perceive that everything luminous gives a complete spectrum—expending all the way from red to violet, to say no more. Suppose for example we make a spectrum with glowing sodium gas: in the midst of a very feeble spectrum there is at one place a far more intense yellow line, making the rest seem even darker by contrast. Sodium is therefore often spoken of as giving only this yellow line.

And now we come to the remarkable fact, which, although not unknown before, was brought to light above all in 1859 by the famous experiment of Kirchhoff and Bunsen. If we arrange things so that the source of light generating the continuous spectrum and the one generating, say, the sodium line, can take effect as it were simultaneously, the sodium line will be found to act like an untransparent body. It gets in the way of the quality of light which would be appearing at this place (i.e. in the yellow) of the spectrum. It blots it out, so that we get a black line here in place of yellow, (Figure IVh). Simply to state the fact, this then is what we have to say: For the yellow of the spectrum, another yellow (the strength of which must be at least equal to the strength of light that is just being developed at this place of the spectrum) acts like an opaque body. As you will presently see, the elements we are compiling will pave the way to an understanding also of this phenomenon. In the first place however we must get hold of the pure facts.

We will now shew you, as well as we are able, that this dark line does really appear in the spectrum when we interpose the glowing sodium. We have not been able to arrange the experiment so as to project the spectrum on to a screen. Instead we will observe the spectrum by looking straight into it with our eyes. For it is possible to see the spectrum in this way too; it then appears displaced downward instead of upward, moreover the colours are reversed. We have already discussed, why it is that the colours appear in this way when we simply look through the prism.

By means of this apparatus, we here generate the cylinder of light; we let it go through here, and, looking into it, we see it thus refracted. (The experiment was shewn to everyone in turn).

To use the short remaining time—we shall now have to consider the relation of colours to what we call “bodies”. As a transition to this problem looking for the relations between the colours and what we commonly call “bodies”—I will however also shew the following experiment. You now see the complete spectrum projected on to the screen. Into the path of the cylinder of light I place a trough in which there is a little iodine dissolved in carbon disulphide. Note how the spectrum is changed. When I put into the path of the cylinder of light the solution of iodine in carbon disulphide, this light is extinguished. You see the spectrum clearly divided into two portions; the middle part is blotted out. You only see the violet on the one side, the reddish-yellow on the other. In that I cause the light to go through this solution—iodine in carbon disulphide—you see the complete spectrum divided into two portions; you only see the two poles on either hand.

It has grown late and I shall now only have time for a for a few matters of principle. Concerning the relation of the colours to the bodies we see around us (all of which are somehow coloured in the last resort), the point will be explained how it comes about that they appear coloured at all. How comes it in effect that the material bodies have this relation to the light? How do they, simply by dint of their material existence so to speak, develop such relation to the light that one body looks red, another blue, and so on. It is no doubt simplest to say: When colourless sunlight—according to the physicists, a gathering of all the colours—falls on a body that looks red, this is due to the body's swallowing all the other colours and only throwing back the red. With like simplicity we can explain why another body appears blue. It swallows the remaining colours and throws back the blue alone. We on the other hand have to eschew these speculative explanations and to approach the fact in question—namely the way we see what we call “coloured bodies”—by means of the pure facts. Fact upon fact in proper sequence will then at last enable us in time to “catch”—as it were, to close in upon—this very complex phenomenon.

The following will lead us on the way. Even in the 17th Century, we may remember, when alchemy was still pursued to some extent, they spoke of so-called “phosphores” or light-bearers. This is what they meant:—A Bologna cobbler, to take one example, was doing some alchemical experiments with a kind of Heavy Spar (Barytes). He made of it what was then called “Bologna stone”. When he exposed this to the light, a strange phenomenon occurred. After exposure the stone went on shining for a time, emitting a certain coloured light. The Bologna stone had acquired a relation to the light, which it expressed by being luminous still after exposure—after the light had been removed. Stones of this kind were then investigated in many ways and were called “phosphores”, If you come across the word “phosphor” or “phosphorus” in the literature of that time, you need not take it to mean what is called “Phosphorus” today; it refers to phosphorescent bodies of this kind—bearers of light, i.e. phos-phores.

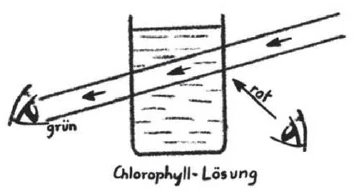

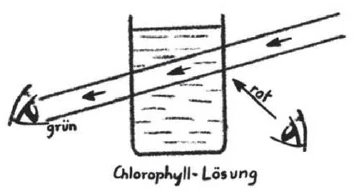

However, even this phenomenon of after-luminescence—phosphor escence—is not the simplest. Another phenomenon is really the simple one. If you take ordinary paraffin oil and look through it towards a light, the oil appears slightly yellow. If on the other hand you place yourself so as to let the light pass through the oil while you look at it from behind, the oil will seem to be shining with a bluish light—only so long, however, as the light impinges on it. The same experiment can be made with a variety of other bodies. It is most interesting if you make a solution of plant green—chlorophyll (Figure Va). Look towards the light through the solution and it appears green. But if you take your stand to some extent behind it—if this (Figure Va) is the solution and this the light going through it, while you look from behind to where the light goes through—the chlorophyll shines back with a red or reddish light, just as the paraffin shone blue.

There are many bodies with this property. They shine in a different way when, so to speak, they of themselves send the light back—when they have somehow come into relation to the light, changing it through their own nature—than when the light goes through them as through a transparent body. Look at the chlorophyll from behind: we see—so to speak—what the light has been doing in the chlorophyll; we see the mutual relation between the light and the chlorophyll. When in this way a body shines with one kind of light while illumined by another kind of light, we call the phenomenon Fluorescence. And, we may say: what in effect is Phosphorescence? It is a Fluorescence that lasts longer. For it is Fluorescence when the chlorophyll, for instance, shines with a reddish light so long as it is exposed to light. When there is Phosphorescence on the other hand, as with the Bologna stone, we can take the light away and the thing still goes on shining for a time. It thus retains the property of shining with a coloured light,—a property the chlorophyll does not retain. So you have two stages. The one is Fluorescence: we make a body coloured so long as we illumine it. The second is Phosphorescence: we cause a body to remain coloured still for a certain time after illumination. And now there is a third stage: the body, as an outcome of whatever it is that the light does with it, appears with a lasting colour. We have this sequence: Fluorescence, Phosphorescence, Colouredness-of-bodies.

Thus we have placed the phenomena, in a manner of speaking, side by side. What we must try to do is to approach the phenomena rightly with our thinking, our forming of ideas. There is another fundamental idea which you will need to get hold of today, for we shall afterwards want to relate it to all these other things. Please, once again, only think quite exactly of what I shall bring forward. Think as precisely as you can. I will remind you again (as once before in these lectures) of the formula for a velocity, say \(v\). A velocity is expressed, as you know, in dividing \(s\), the distance which the mobile object passes through, by the time \(t\). This therefore is the formula:

$$v=\frac{s}{t}$$Now the opinion prevails that what is actually given in real Nature in such a case is the distance \(s\) the body passes through, and the time \(t\) it takes to do it. We are supposed to be dividing the real distance \(s\) by the real time \(t\), to get the velocity \(v\), which as a rule is not regarded as being quite so real but more as a kind of function, an outcome of the division sum. Thus the prevailing opinion. And yet in Nature it is not so. Of the three magnitudes—velocity, space and time,—velocity is the only one that has reality. What is really there in the world outside us is the velocity; the \(s\) and \(t\) we only get by splitting up the given totality, the \(v\), into two abstract entities. We only arrive at these on the basis of the velocity, which is really there. This then, to some extent, is our procedure. We see a so-called “body” flowing through space with a certain velocity. That it has this velocity, is the one real thing about it. But now we set to work and think. We no longer envisage the quick totality, the quickly moving body; instead, we think in terms of two abstractions. We dismember, what is really one, into two abstractions. Because there is a velocity, there is a distance moved through. This distance we envisage in the first place, and in the second place we envisage the time it takes to do it. From the velocity, the one thing actually there, we by our thinking process have sundered space and time; yet the space in question is not there at all save as an outcome of the velocity, nor for that matter is the time. The space and time, compared to this real thing which we denote as \(v\), are no realities at all, they are abstractions which we ourselves derive from the velocity. We shall not come to terms with outer reality, my dear Friends, till we are thoroughly clear on this point. We in our process of conception have first created this duality of space and time. The real thing we have outside us is the velocity and that alone; as to the “space” and “time”, we ourselves have first created them by virtue of the two abstractions into which—if you like to put it so—the velocity can fall apart for us.

From the velocity, in effect, we can separate ourselves, while from the space and time we cannot; they are within our perceiving,—in our perceiving activity. With space and time we are one. Much is implied in what I am now saying. With space and time we are one. Think of it well. We are not one with the velocity that is there outside us, but we are one with space and time. Nor should we, without more ado, ascribe to external bodies what we ourselves are one with; we should only use it to gain a proper idea of these external bodies. All we should say is that through space and time, with which we ourselves are very intimately united, we learn to know and understand the real velocity. We should not say “The body moves through such and such a distance”; we ought only to say: “The body has a velocity”. Nor should we say, “The body takes so much time to do it,” but once again only this: “The body has a velocity”. By means of space and time we only measure the velocity. The space and time are our own instruments. They are bound to us,—that is the essential thing. Here once again you see the sharp dividing line between what is generally called “subjective”—here, space and time—and the “objective” thing—here, the velocity. It will be good, my dear Friends, if you will bring this home to yourselves very clearly; the truth will then dawn upon you more and more: \(v\) is not merely the quotient of \(s\) and \(t\). Numerically, it is true, \(v\) is expressed by the quotient of \(s\) and \(t\). What I express by this number \(v\) is however a reality in its own right—a reality of which the essence is, to have velocity.

What I have here shewn you with regard to space and time—namely that they are inseparable from us and we ought not in thought to separate ourselves from them—is also true of another thing. But, my dear Friends (if I may say this in passing), people are still too much obsessed with the old Konigsberg habit, by which I mean, the Kantian idea. The “Konigsberg” habit must be got rid of, or else it might be thought that I myself have here been talking “Konigsberg”, as if to say “Space and Time are within us.” But that is not what I am saying. I say that in perceiving the reality outside us the—velocity—we make use of space and time for our perception. In effect, space and time are at once in us and outside us. The point is that we unite with space and time, while we do not unite with the velocity. The latter whizzes past us. This is quite different from the Kantian idea.

Now once again: what I have said of space and time is also true of something else. Even as we are united by space and time with the objective reality, while we first have to look for the velocity, so in like manner, we are in one and the same element with the so-called bodies whenever we behold them by means of light. We ought not to ascribe objectivity to light any more than to space and time. We swim in space and time just as the bodies swim in it with their velocities. So too we swim in the light, just as the bodies swim in the light. Light is an element common to us and the things outside us—the so-called bodies. You may imagine therefore: Say you have gradually filled the dark room with light, the space becomes filled with something—call it \(x\), if you will—something in which you are and in which the things outside you are. It is a common element in which both you, and that which is outside you, swim. But we have still to ask: How do we manage to swim in light? We obviously cannot swim in it with what we ordinarily call our body. We do however swirl in it with our etheric body. You will never understand what light is without going into these realities. We with our etheric body swim in the light (or, if you will, you may say, in the light-ether; the word does not matter in this connection). Once again therefore: With our etheric body we are swimming in the light.

Now in the course of these lectures we have seen how colours arise—and that in many ways—in and about the light itself. In the most manifold ways, colours arise in and about the light; so also they arise, or they subsist, in the so-called bodies. We see the ghostly, spectral colours so to speak,—those that arise and vanish within the light itself. For if I only cast a spectrum here it is indeed like seeing spectres; it hovers, fleeting, in space. Such colours therefore we behold, in and about the light.

In the light, I said just now, we swim with our etheric body. How then do we relate ourselves to the fleeting colours? We are in them with our astral body; it is none other than this. We are united with the colours with our astral body. You have no alternative, my dear Friends but to realise that when and wheresoever you see colours, with your astrality you are united with them. If you would reach any genuine knowledge you have no alternative, but must say to yourselves: The light remains invisible to us; we swim in it. Here it is as with space and time; we ought not to call them objective, for we ourselves are swimming in them. So too we should regard the light as an element common to us and to the things outside us; whilst in the colours we have to recognize something that can only make its appearance inasmuch as we through our astral body come into relation to what the light is doing there.

Assume now that in this space \(ABCD\) you have in some way brought about a phenomenon of colour—say, a spectrum. I mean now, a phenomenon that takes its course purely within the light. You must refer it to an astral relation to the light. But you may also have the phenomenon of colour in the form of a coloured surface. This therefore—from \(A\) to \(C,\) say—may be appearing to you as a coloured body, a red body for example. We say, then, \(AC\) is red. You look towards the surface of the body, and, to begin with, you will imagine rather crudely. Beneath the surface it is red, through and through. This time, you see, the case is different. Here too you have an astral relation; but from the astral relation you enter into with the colour in this instance you are separated by the bodily surface. Be sure you understand this rightly! In the one instance you see colours in the light—spectral colours. There you have astral relations of a direct kind; nothing is interposed between you and the colours. When on the other hand you see the colours of bodily objects, something is interposed between you and your astral body, and through this something you none the less entertain astral relations to what we call “bodily colours”. Please take these things to heart and think them through. For they are basic concepts—very important ones—which we shall need to elaborate. Only on these lines shall we achieve the necessary fundamental concepts for a truer Physics.

One more thing I would say in conclusion. What I am trying to present in these lectures is not what you can get from the first text-book you may purchase. Nor is it what you can get by reading Goethe's Theory of Colour. It is intended to be, what you will find in neither of the two, and what will help you make the spiritual link between them. We are not credulous believers in the Physics of today, nor need we be of Goethe. It was in 1832 that Goethe died. What we are seeking is not a Goetheanism of the year 1832 but one of 1919,—further evolved and developed. What I have said just now for instance—this of the astral relation—please think it through as thoroughly as you are able.

Fünfter Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde!

Es soll heute damit begonnen werden, dass, so gut es geht bei unseren beschränkten Mitteln, der Versuch Ihnen gezeigt wird, von dem wir gestern gesprochen haben. Sie wissen wohl noch: Ich habe gesagt, dass, wenn ein glühender fester Körper sein Licht verbreitet und wir dieses Licht durch ein Prisma senden, so bekommen wir einähnliches Spektrum, ein ähnliches Lichtbild, wie von der Sonne. Wir bekommen aber auch [ein Spektrum], wenn wir ein glühendes Gas ein sich verbreitendes Licht erzeugen lassen; aber wir bekommen in diesem Falle ein Lichtbild, das nur an einer Stelle - oder für verschiedene Stoffe auch an mehreren Stellen - eigentliche Lichtlinien oder kleine Lichtbänder zeigt. Das übrige Spektrum ist dann verkümmert.

Man würde, wenn man Anstalten machte, genaue Versuche anzustellen, schon wahrnehmen, dass eigentlich für alles Leuchtende ein vollständiges Spektrum vorhanden ist, also ein Spektrum, das da reichte vom Roten ins Violette meinetwillen hinein. Wenn wir zum Beispiel durch das glühende Natriumgas ein Spektrum erzeugen, so bekommen wir eben ein sehr, sehr schwaches Spektrum und an einer Stelle desselben eine [stärkere] gelbe Linie, die auch noch durch ihre Kontrastwirkung alles andere abdämpft. Daher sagt man: Das Natrium liefert überhaupt nur diese gelbe Linie.

Nun ist das Eigentümliche, dass - im Wesentlichen ist ja diese Tatsache, obwohl sie früher schon mannigfaltig bekannt war, erneuert worden durch den Kirchhoff-Bunsen’schen Versuch im Jahre 1859 -, es ist das Eigentümliche, wenn man gewissermaßen gleichzeitig wirken lässt jene Lichtquelle, die das kontinuierliche Spektrum erzeugt, und jene Lichtquelle, von der so etwas wie die Natriumlinie kommt, dass dann einfach diese Natriumlinie wirkt wie ein undurchsichtiger Körper, sich gerade der Farbenqualität entgegenstellt, die an der Stelle sein würde - also hier dem Gelb -, es auslöscht, sodass man statt des Gelb dort eine schwarze Linie hat. Also, was man, wenn man innerhalb der Fakten stehen bleibt, sagen kann, ist, dass für das Gelb im Spektrum ein anderes Gelb, das mindestens in seiner Stärke gleich sein muss der Stärke, die an dieser Stelle gerade entwickelt wird, dass dieses wie ein undurchsichtiger Körper wirkt. Sie werden sehen, es werden sich schon aus den Elementen, die wir zusammenstellen, Unterlagen für ein Verstehen finden. Wir müssen uns zunächst nur an das Faktische halten.

Nun, wir werden, so gut das geht, Ihnen zeigen, dass wirklich diese schwarze Linie im Spektrum ist, wenn wir das glühende Natrium einschalten. Nur können wir den Versuch nicht so machen, dass wir das Spektrum auffangen, sondern wir machen es so, dass wir das Spektrum betrachten, indem wir es durch das Auge anschauen. Man kann auch dadurch das Spektrum sehen, nur liegt es, statt dass es nach oben verschoben ist, umgekehrt nach unten verschoben, und die Farben sind umgekehrt. Wir haben ja davon gesprochen, warum diese Farben so erscheinen, wenn ich einfach durch das Prisma durchschaue. Wir erzeugen den Lichtzylinder aus diesem Apparat heraus, lassen ihn hier durch und schauen hier [den gebrochenen Lichtzylinder] an, sehen also zu gleicher Zeit, indem wir ihn anschauen, die schwarze Natriumlinie. Ich hoffe, es wird sich Ihnen zeigen; aber Sie [müssen] in vollkommenster militärischer Ordnung — was ja auch jetzt in Deutschland nicht zu schwierig sein soll - herankommen und hineinschauen. (Das Experiment wird jedem Einzelnen vorgeführt.)

Nun, meine lieben Freunde, wir wollen die kurze Zeit, die uns bleibt, noch benützen. Wir werden jetzt müssen übergehen zur Betrachtung des Verhältnisses der Farben zu den sogenannten Körpern. Nicht wahr, um zu dem Problem übergehen zu können, die Beziehungen zu suchen der Farben zu den sogenannten Körpern, möchte ich Ihnen noch Folgendes zeigen. Sie sehen jetzt aufgefangen auf dem Schirm das vollständige Spektrum. Ich werde jetzt dem Lichtzylinder in den Weg stellen einen kleinen Trog, der in sich hat Schwefelkohlenstoff, in dem etwas Jod aufgelöst ist, und ich bitte Sie, die Veränderung des Spektrums dadurch zu betrachten - nun, nicht wahr, ich wollte nur haben, dass es an den Rändern [des Spektrums] etwas durchlässt; jedenfalls dasjenige, was Sie sehen, das ist, dass Sie hier ein deutliches Spektrum sehen, und, wenn ich in den Weg des Lichtzylinders die Auflösung von Jod in Schwefelkohlenstoff stelle, so löscht dieses vollständig aus das Licht. Jetzt sehen Sie klar das Spektrum in seine zwei Teile auseinandergelegt dadurch, dass der mittlere Teil ausgelöscht ist. Also, Sie sehen nur das Violett auf der einen Seite und das Rot-Gelbliche auf der anderen Seite. So sehen Sie das vollständige Spektrum dadurch, dass ich das Licht durch die Lösung von Jod in Schwefelkohlenstoff gehen lasse, in zwei Teile auseinandergelegt, und Sie sehen nur die beiden Pole.

Nun habe ich allerdings viel Zeit verloren, und ich werde Ihnen nur noch einiges Prinzipielle sagen können. Nicht wahr, die Hauptfrage bezüglich des Verhältnisses der Farben zu den Körpern, die wir um uns herum sehen - und alle Körper sind in gewisser Weise farbig -, die Hauptsache muss sein, zu erklären, wie es kommt, dass uns die Körper ringsherum farbig erscheinen, also ein gewisses Verhältnis zum Licht ihrerseits haben, gewissermaßen durch ihr materielles Sein ein Verhältnis zum Licht entwickeln. Der eine Körper erscheint rot, der andere blau und so weiter. Man kommt ja natürlich am einfachsten dadurch zurecht, dass man sagt: Wenn farbloses Sonnenlicht — worunter der Physiker eine Versammlung aller Farben versteht auf einen Körper fällt, der da rot erscheint, so rühre das davon her, dass dieser Körper alle anderen Farben, außer Rot, verschlucke und nur dieses Rot zurückwerfe. Man hat es auch einfach zu erklären, wie ein Körper blau ist. Der verschluckt eben alle anderen Farben und wirft nur das Blau zurück. Nun handelt es sich darum, überhaupt ein solches spekulatives Prinzip des Erklärens auszuschließen und sich dem offenbar etwas komplizierten Faktum des Sehens der sogenannten farbigen Körper durch ein Faktum zu nähern, Faktum an Faktum zu reihen, um so einzufangen dasjenige, was sich als das komplizierteste Phänomen darstellt.

Nun führt uns auf den Weg das Folgende. Wir erinnern uns, dass schon im siebzehnten Jahrhundert, als die Leute noch viel Alchemie getrieben haben, von den sogenannten Phosphoren gesprochen worden ist, von den Lichtträgern. Unter Phosphoren hat man dazumal das Folgende verstanden. Da hat - nehmen wir ein Beispiel ein Schuster in Bologna alchemistisch experimentiert mit einer Art Schwerspat, mit dem sogenannten Bologneser Stein. Er hat ihn dem Lichte ausgesetzt, und es stellte sich ihm die merkwürdige Erscheinung her: Wenn er diesen Stein dem Licht exponierte, dass dann der Stein hinterher eine Zeit lang in einer gewissen Farbe leuchtete. Also, der Bologneser Stein hat zum Licht ein Verhältnis gewonnen, und dieses Verhältnis hat dieser Bologneser Stein in der Weise zum Ausdruck gebracht, dass er, nachdem er dem Lichte exponiert war, nachdem auch das Licht hinweggeschafft war, nachleuchtete. Deshalb nannte man solche Steine, die man verschiedentlich untersucht hat nach dieser Richtung, Phosphore. Wenn Ihnen also in der Literatur dieser Zeit der Ausdruck Phosphor begegnet, so müssen Sie nicht dasjenige darunter verstehen, was heute darunter verstanden wird, sondern solche phosphoreszierende Körper, Lichtträger, Phosphore. Nun ist aber diese Erscheinung des Nachleuchtens, des Phosphoreszierens, eigentlich auch schon nicht mehr das ganz Einfache, sondern das Einfache ist eine andere Erscheinung.

Wenn Sie gewöhnliches Petroleum nehmen und Sie sehen durch das Petroleum durch nach einem Leuchtenden, so sehen Sie das Petroleum schwach gelb. Wenn Sie sich aber so stellen, dass Sie das Licht durch das Petroleum durchgehen lassen und es von hinten anschauen, so erscheint Ihnen das Petroleum bläulich leuchtend - so lange aber nur, als das Licht darauffällt. Diesen Versuch kann man mit verschiedenen anderen Körpern machen. Besonders interessant wird er, wenn man Chlorophyll, Pflanzengrün, auflöst. Wenn man durch eine solche Lösung ins Licht schaut, so erscheint sie grün, wenn man sich aber gewissermaßen hinten her aufstellt, sodass man hier die Lösung hat und hier das durchgehende Licht, und man sieht nun von hinten die Stelle an, wo hier das Licht durchgeht, dann leuchtet das Chlorophyll zurück rötlich, rot, so wie das Petroleum blau leuchtet. Es gibt nun die verschiedensten Körper, welche in dieser Weise zeigen, dass sie in einer anderen Weise leuchtend werden, wenn sie das Licht gewissermaßen zurücksenden von sich aus, also mit dem Licht ein Verhältnis eingegangen haben, das durch ihre eigene Natur verändert worden ist, als wenn das Licht durch sie hindurchgeht wie durch einen durchsichtigen Körper. Wenn wir das Chlorophyll von hinten [vor einem dunklen Hintergrund] anschauen, so sehen wir gewissermaßen dasjenige, was das Licht im Chlorophyll angestellt hat, das Verhältnis zwischen dem Licht und dem Chlorophyll. Diese Erscheinung des Leuchtens des Körpers mit einem Licht, während er von jenem Licht beschienen ist, das nennt man nun Fluoreszenz. Und wir können sagen: Die Phosphoreszenz, was ist sie nur? Sie ist nur eine Fluoreszenz, die andauert. Die Fluoreszenz besteht darinnen, dass zum Beispiel das Chlorophyll so lange rötlich erscheint, als das Licht darauf wirkt; bei der Phosphoreszenz ist es so, dass wir das Licht wegnehmen können und zum Beispiel der Schwerspat noch ein wenig nachleuchtet. Also, er bewahrt sich diese Eigenschaft des farbigen Leuchtens, während sich bei dem Chlorophyll die Eigenschaft des farbigen Leuchtens nicht bewahrt. Jetzt haben Sie zwei Stufen: Die eine ist die Fluoreszenz — wir machen einen Körper farbig, solange wir ihn beleuchten -, die zweite Stufe ist die Phosphoreszenz — wir machen einen Körper farbig eine gewisse Zeit hinterher noch. Und jetzt ist eine dritte Stufe: Der Körper erscheint dauernd farbig durch irgendetwas, was das Licht mit ihm vornimmt — Fluoreszenz, Phosphoreszenz, Körperfarbigsein!

So haben wir gewissermaßen die Erscheinungen nebeneinandergestellt. Es handelt sich jetzt nur darum, dass wir uns in sachgemäßer Weise den Erscheinungen mit unseren Vorstellungen nähern. Dazu ist es nötig, dass Sie heute noch eine gewisse Vorstellung aufnehmen, die wir dann in der nächsten Stunde mit alledem zusammen verarbeiten werden.

Sehen Sie -, aber ich bitte Sie jetzt wiederum durchaus nur an das zu denken, was ich Ihnen vorbringe, und möglichst exakt und genau zu denken - ich erinnere Sie - wir haben sie ja schon erwähnt - an die Formel [für] \(v\), die Geschwindigkeit. Irgendeine Geschwindigkeit, was immer geschwind ist, sie wird ausgedrückt, wie Sie wissen, indem \(s\), die Strecke, die das Bewegliche durchläuft, dividiert durch die Zeit [\(t\)], sodass die Formel heißt: \(v=\frac{s}{t}\). Nun besteht die Meinung, dass man hat irgendwo in der Natur eine durchlaufene Raumstrecke \(s\), eine Zeit, während welcher die Raumstrecke durchlaufen worden ist, und dann dividiert man die reale Raumstrecke \(s\) durch die reale Zeit und bekommt die Geschwindigkeit, die man eigentlich als etwas nicht gerade sehr Reales, sondern mehr als eine Funktion [von Raum und Zeit] betrachtet, als etwas, das man als Rechnungsresultat herausbekommt.

So ist es in der Natur nicht. Von diesen drei Größen: Geschwindigkeit, Raum und Zeit, ist die Geschwindigkeit das einzige wirklich Reale, das einzige Wirkliche. Dasjenige, was außer uns ist, ist die Geschwindigkeit; das andere, \(s\) und \(t\), das bekommen wir nur dadurch, dass wir gewissermaßen dividierend spalten das einheitliche \(v\) in zwei abstrakte Dinge, die wir auf Grundlage vorhandener Geschwindigkeit bilden. Wir verfahren gewissermaßen so: Wir sehen einen sogenannten Körper mit einer gewissen Geschwindigkeit durch den Raum fliegen. Dass er diese Geschwindigkeit hat, ist das einzig Wirkliche. Aber wir denken jetzt, statt dass wir diese Totalität des Geschwinden, des geschwinde fliegenden Körpers, ins Auge fassen, wir denken in zwei Abstraktionen; wir zerteilen uns das, was eine Einheit ist, in zwei Abstraktionen. Dadurch, dass eine Geschwindigkeit da ist, ist ein gewisser Weg da. Den betrachten wir zuerst. Dann betrachten wir extra als Zweites die Zeit, während welcher dieser Weg durchmessen wird, und haben aus der Geschwindigkeit, die einzig und allein da ist, herausgeschält durch unseren Auffassungsprozess Raum und Zeit. Aber dieser Raum ist gar nicht anders da, als dass ihn die Geschwindigkeit macht, und die Zeit auch nicht anders. Raum und Zeit, bezogen auf dieses Reale, dem wir das v zuschreiben, sind keine Realitäten, sind Abstrakta, die wir eben von der Geschwindigkeit aus bilden. Und wir kommen nur zurecht, meine lieben Freunde, mit der äußeren Realität, wenn wir uns klar sind darüber, dass wir in unserem Auffassungsprozess diese Zweiheit, Raum und Zeit, erst geschaffen haben, dass wir außer uns als Reales nur die Geschwindigkeit haben, dass wir Raum und Zeit erst geschaffen haben meinetwillen durch die zwei Abstraktionen, in die uns die Geschwindigkeit auseinanderfallen kann.

Von der Geschwindigkeit können wir uns trennen, von Raum und Zeit können wir uns nicht trennen, die sind in unserem Wahrnehmen, in unserer wahrnehmenden Tätigkeit drinnen, wir sind eins mit Raum und Zeit! Was ich jetzt sage, ist von großer Tragweite: Wir sind eins mit Raum und Zeit! Bedenken Sie das! Wir sind nicht eins mit der Geschwindigkeit draußen, aber mit Raum und Zeit. Ja, dasjenige, womit wir eins sind, das sollten wir nicht so ohne Weiteres den äußeren Körpern zuschreiben, sondern wir sollten es nur benützen, um in einer entsprechenden Weise zur Vorstellung der äußeren Körper zu kommen. Wir sollten sagen: Durch Raum und Zeit, mit denen wir innig verbunden sind, lernen wir erkennen die Geschwindigkeit, aber wir sollten nicht sagen: Der Körper läuft eine Strecke durch, sondern nur: Der Körper hat eine Geschwindigkeit. Wir sollten auch nicht sagen: Der Körper braucht eine Zeit, sondern nur: Der Körper hat eine Geschwindigkeit. Wir messen durch Raum und Zeit die Geschwindigkeit. Raum und Zeit sind unsere Instrumente und sie sind an uns gebunden, und das ist. das Wichtige. Hier sehen Sie einmal wiederum scharf abgegrenzt das sogenannte Subjektive mit Raum und Zeit und das Objektive, was die Geschwindigkeit ist. Es wird sehr gut sein, meine lieben Freunde, wenn Sie sich gerade dieses recht, recht klarmachen, denn dann wird Ihnen eines aufleuchten innerlich, es wird Ihnen klar werden, dass v nicht bloß der Quotient aus s und t ist, sondern dass allerdings der Zahl nach das v ausgedrückt wird durch den Quotienten von \(s\) und \(t\), aber was ich da durch die Zahl ausdrücke, ist innerlich durch sich ein Reales, dessen Wesen besteht darinnen, eine Geschwindigkeit zu haben. Was ich Ihnen hier für Raum und Zeit gezeigt habe, dass sie gar nicht trennbar sind von uns, dass wir uns nicht abtrennen dürfen von ihnen, das gilt nun auch von etwas anderem.

Meine lieben Freunde, es ist jetzt noch viel Königsbergerei in den Menschen, ich meine: Kantianismus. Diese Königsbergerei muss noch ganz heraus. Denn es könnte jemand glauben, ich hätte jetzt selber so gesprochen im Sinn der Königsbergerei. Da würde es heißen: Raum und Zeit sind in uns. Aber ich sage nicht: Raum und Zeit sind in uns, sondern: Indem wir das Objektive, die Geschwindigkeit, wahrnehmen, gebrauchen wir zur Wahrnehmung Raum und Zeit. Raum und Zeit sind gleichzeitig in uns und außer uns, aber wir verbinden uns mit Raum und Zeit, während wir uns mit der Geschwindigkeit nicht verbinden. Die saust an uns vorbei. Also, das ist etwas wesentlich anderes als das Kantisch-Königsbergische.

Nun gilt das eben auch noch von etwas anderem, was ich von Raum und Zeit gesagt habe. Wir sind ebenso, wie wir durch Raum und Zeit mit der Objektivität verbunden sind, aber diese Geschwindigkeit erst suchen müssen, so sind wir in einem Element mit den sogenannten Körpern drinnen, indem wir sie durch das Licht sehen. Wir dürfen ebenso wenig von einer Objektivität des Lichtes reden, wie wir reden dürfen von einer Objektivität von Raum und Zeit. Wir schwimmen in Raum und Zeit ebenso, wie mit einer gewissen Geschwindigkeit Körper darinnen schwimmen. Wir schwimmen im Licht, wie die Körper im Licht schwimmen. Das Licht ist ein gemeinsames Element zwischen uns und demjenigen, was außer uns ist als sogenannte Körper. Ja, Sie können sich also vorstellen: Wenn Sie das Dunkle allmählich erhellt haben durch Licht, so erfüllt sich der Raum mit irgendetwas — wir wollen es meinetwillen x nennen -, etwas, in dem Sie drinnen sind, in dem auch dasjenige, was außer Ihnen ist, drinnen ist. Ein gemeinsames Element, in dem Sie und die Elemente schwimmen. Wir haben uns nun zu fragen: Wie machen wir denn das eigentlich, dass wir da in dem Lichte schwimmen? Mit unserem sogenannten Körper können wir nicht darinnen schwimmen, aber wir schwimmen in der Tat mit unserem Ätherleibe drinnen. Es kommt kein Begreifen des Lichtes zustande, wenn man nicht auf die Wirklichkeiten übergeht. Wir schwimmen mit unserem Ätherleibe im Lichte drinnen — meinetwegen sagen Sie: im Lichtäther; darauf kommt es nicht an. Also, wir schwimmen mit dem Ätherleibe im Lichte drinnen.

Nun haben wir im Laufe der Zeit gesehen, wie in der verschiedensten Weise am Lichte Farben entstehen. In der verschiedensten Weise entstehen am Lichte Farben und wiederum entstehen in den sogenannten Körpern Farben oder bestehen in ihnen Farben. Wir sehen gewissermaßen die gespenstigen Farben, die entstehen und vergehen im Licht. Wenn ich nur ein Spektrum herwerfe, ist es wie Gespenster, es huscht gewissermaßen im Raume. Wir sehen am Lichte solche Farben. Ja, meine lieben Freunde, wie ist es denn da? Im Lichte schwimmen wir drinnen mit unserem Ätherleibe. Wie verhalten wir uns zu den Farben, die da hinhuschen? Da ist es nicht anders, als dass wir da drinnen sind mit unserem Astralleibe, da sind wir mit den Farben verbunden mit unserem Astralleibe. Meine lieben Freunde, es bleibt Ihnen nichts übrig, als sich klar zu sein darüber: Wo Sie auch Farben sehen, sind Sie mit Ihrer Astralität mit den Farben verbunden. Da bleibt Ihnen nichts anderes übrig, um zu einer realen Erkenntnis zu kommen, als sich zu sagen: Während das Licht eigentlich unsichtbar bleibt, wir schwimmen drinnen. So wie Raum und Zeit von uns auch nicht Objektivitäten genannt werden sollen, weil wir mit den Dingen schwimmen, so sollten wir das Licht auch als gemeinsames Element betrachten, die Farben aber nur als etwas, was nur dadurch hervortreten kann, dass wir zu dem, was das Licht da macht, durch unseren Astralleib in Beziehung treten.

Jetzt aber nehmen Sie an, Sie haben irgendwie in diesem Raume hier \(A-B-C-D\) irgendeine Farbenerscheinung, irgendein Spektrum, oder so etwas, zustande gebracht, aber eine Erscheinung, die nur im Lichte verläuft. Da müssen Sie rekurrieren auf eine astrale Beziehung zu dem Licht. Aber Sie können auch zum Beispiel dieses hier als Oberfläche gefärbt haben, sodass gewissermaßen Ihnen das \(A-C\) als Körper, sagen wir, rot erscheint. Wir sagen: \(A-C\) ist rot. Da sehen Sie zur Körperoberfläche hin und stellen sich zunächst hin grob vor: Unter der Körperoberfläche, da sei das durch und durch rot. Sehen Sie, das ist etwas anderes. Da haben Sie auch eine astrale Beziehung, aber Sie sind von dieser astralen Beziehung, die Sie eingehen zur Farbe, durch die Körperoberfläche getrennt. Fassen Sie das wohl auf! Sie sehen Farben im Lichte, Spektralfarben, Sie haben astrale Beziehungen direkter Natur, es stellt sich nichts zwischen Sie und diese Farben. Sie sehen die Körperfarben, es stellt sich etwas zwischen sie und Ihren Astralleib und durch dieses Etwas hindurch gehen Sie doch astrale Beziehungen zu den Körperfarben ein. Diese Dinge bitte ich Sie genau in Ihr Gemüt aufzunehmen und durchzudenken; denn das sind wichtige Grundbegriffe, die wir verarbeiten werden. Und dadurch allein werden wir für eine wirkliche Physik Grundbegriffe bekommen.

Ich möchte nur noch zum Schlusse erwähnen: Sehen Sie, ich versuche Ihnen hier nicht vorzutragen dasjenige, was Sie sich leicht verschaffen können, wenn Sie sich das nächstbeste Lehrbuch kaufen. Ich will auch nicht versuchen, Ihnen das vorzutragen, was Sie lesen können, wenn Sie Goethes Farbenlehre lesen, sondern dasjenige, was Sie in beiden nicht finden können, wodurch Sie aber beide in entsprechender Weise sich geistig zuführen können. Wir brauchen durchaus, wenn wir auch nicht Physikergläubige sind, auch nicht wiederum Goethegläubige zu werden; denn Goethe ist 1832 gestorben, und wir bekennen uns nicht zu einem Goetheanismus vom Jahre 1832, sondern zu einem vom Jahre 1919, also zu einem fortgebildeten Goctheanismus. Dasjenige, was ich Ihnen also heute gesagt habe von der astralen Beziehung, das bitte ich besonders durchzudenken.

Fifth Lecture

My dear friends!

Today we will begin, as best we can with our limited means, to demonstrate the experiment we spoke about yesterday. You will recall that I said that when a glowing solid body emits light and we pass this light through a prism, we obtain a spectrum, a light image, similar to that of the sun. However, we also obtain [a spectrum] when we allow a glowing gas to produce a spreading light; but in this case we obtain a light image that shows actual lines of light or small bands of light at only one point—or, for different substances, at several points. The rest of the spectrum is then reduced.

If one were to undertake precise experiments, one would perceive that there is actually a complete spectrum for everything that glows, i.e., a spectrum that extends from red to violet, for my sake. If, for example, we produce a spectrum using glowing sodium gas, we obtain a very, very weak spectrum with a [stronger] yellow line at one point, which also dampens everything else due to its contrasting effect. This is why we say that sodium only produces this yellow line.

Now, the peculiar thing is that – although this fact was already widely known in the past, it was renewed by the Kirchhoff-Bunsen experiment in 1859 – it is peculiar that when the light source that produces the continuous spectrum and the light source from which something like the sodium line comes are allowed to act simultaneously, so to speak, this sodium line simply acts like an opaque body, opposing the color quality that would be at that point—in this case, yellow—and extinguishing it, so that instead of yellow, there is a black line. So, if we stick to the facts, what we can say is that for the yellow in the spectrum, another yellow, which must be at least equal in intensity to the intensity that is currently developing at this point, acts like an opaque body. You will see that the elements we are putting together will provide a basis for understanding. For now, we just have to stick to the facts.

Well, we will show you as best we can that this black line really is in the spectrum when we switch on the glowing sodium. However, we cannot do the experiment in such a way that we capture the spectrum; instead, we will look at the spectrum by viewing it through the eye. You can also see the spectrum this way, only instead of being shifted upward, it is shifted downward, and the colors are reversed. We have already discussed why these colors appear this way when I simply look through the prism. We produce the light cylinder from this apparatus, let it pass through here, and look here [at the refracted light cylinder], so that we see the black sodium line at the same time as we look at it. I hope you will see it, but you [must] approach it in perfect military order—which should not be too difficult in Germany at present—and look inside. (The experiment is demonstrated to each individual.)

Well, my dear friends, let us make use of the short time we have left. We must now move on to consider the relationship between colors and so-called bodies. In order to move on to the problem of seeking the relationships between colors and so-called bodies, I would like to show you the following. You now see the complete spectrum captured on the screen. I will now place a small trough containing carbon disulfide with a little iodine dissolved in it in front of the light cylinder, and I ask you to observe the change in the spectrum as a result—well, I just wanted it to let something through at the edges [of the spectrum]; anyway, what you see is that you have a clear spectrum here, and when I place the iodine solution in carbon disulfide in the path of the light cylinder, it completely extinguishes the light. Now you can clearly see the spectrum split into two parts because the middle part is extinguished. So you only see the violet on one side and the red-yellow on the other. This is how you see the complete spectrum by letting the light pass through the solution of iodine in carbon disulfide, split into two parts, and you only see the two poles.

Now, however, I have lost a lot of time, and I will only be able to tell you a few basic principles. The main question regarding the relationship between colors and the bodies we see around us—and all bodies are colored in a certain way—must be to explain how it is that the bodies around us appear colored to us, i.e., how they have a certain relationship to light, how they develop a relationship to light through their material existence, so to speak. One body appears red, another blue, and so on. The simplest way to deal with this is, of course, to say that when colorless sunlight—which physicists understand to be a collection of all colors—falls on a body that appears red, this is because that body absorbs all colors except red and reflects only the red. It is also easy to explain how a body is blue. It absorbs all other colors and reflects only blue. Now it is a matter of ruling out such a speculative principle of explanation altogether and approaching the apparently somewhat complicated fact of seeing so-called colored bodies through a fact, stringing fact upon fact in order to capture what presents itself as the most complicated phenomenon.

Now the following leads us on our way. We remember that as early as the seventeenth century, when people were still very much into alchemy, there was talk of so-called phosphors, or light carriers. At that time, phosphors were understood as follows. Let us take an example: a cobbler in Bologna was experimenting with alchemy using a type of barite, the so-called Bolognese stone. He exposed it to light and observed a strange phenomenon: when he exposed this stone to light, it glowed in a certain color for a while afterwards. So, the Bolognese stone had acquired a relationship with light, and this relationship was expressed by the Bolognese stone in such a way that, after it had been exposed to light and the light had been removed, it continued to glow. That is why stones that were investigated in various ways in this direction were called phosphors. So if you come across the term phosphorus in the literature of that time, you should not understand it as what we understand today, but rather as phosphorescent bodies, light carriers, phosphors. However, this phenomenon of afterglow, of phosphorescence, is actually not that simple, but rather a different phenomenon.

If you take ordinary petroleum and look through it at something luminous, you will see the petroleum as a faint yellow. But if you position yourself so that the light passes through the petroleum and you look at it from behind, the petroleum appears bluish and luminous—but only as long as the light falls on it. This experiment can be done with various other substances. It becomes particularly interesting when chlorophyll, the green pigment in plants, is dissolved. If you look through such a solution into the light, it appears green, but if you stand behind it so that you have the solution here and the light passing through here, and you now look from behind at the point where the light passes through here, the chlorophyll glows reddish, red, just as the petroleum glows blue. There are now all kinds of bodies that show in this way that they glow in a different way when they reflect the light back from themselves, so to speak, that is, when they have entered into a relationship with the light that has been changed by their own nature, as if the light passes through them like through a transparent body. When we look at chlorophyll from behind [against a dark background], we see, as it were, what the light has done to the chlorophyll, the relationship between the light and the chlorophyll. This phenomenon of the body glowing with a light while it is illuminated by that light is called fluorescence. And we can say: What is phosphorescence? It is simply fluorescence that lasts. Fluorescence consists in the fact that, for example, chlorophyll appears reddish as long as light acts on it; with phosphorescence, we can remove the light and, for example, the barite continues to glow a little. So it retains this property of colored luminescence, whereas chlorophyll does not retain the property of colored luminescence. Now you have two stages: one is fluorescence—we make a body colored as long as we illuminate it—the second stage is phosphorescence—we make a body colored for a certain time afterwards. And now there is a third stage: the body appears permanently colored by something that the light does to it — fluorescence, phosphorescence, body color!

So we have, in a sense, juxtaposed the phenomena. Now it is just a matter of approaching the phenomena in an appropriate way with our mental images. To do this, it is necessary that you take in a certain mental image today, which we will then work on together with everything else in the next lesson.

Now, I ask you again to think only about what I am presenting to you and to think as precisely and accurately as possible. I remind you that we have already mentioned the formula for \(v\), the velocity. Any speed, whatever it may be, is expressed, as you know, by \(s\), the distance traveled by the moving object, divided by the time [\(t\)], so that the formula is: \(v=\frac{s}{t}\). Now, there is the opinion that somewhere in nature there is a distance \(s\) that has been traveled, a time during which the distance has been traveled, and then you divide the real distance \(s\) by the real time and get the speed, which is actually considered not something very real, but more of a function [of space and time], something that you get as a result of a calculation.

That is not how it is in nature. Of these three quantities: speed, space, and time, speed is the only thing that is truly real, the only thing that is real. What is outside of us is speed; the other two, \(s\) and \(t\), we only obtain by dividing the uniform \(v\) into two abstract things, which we form on the basis of existing speed. We proceed as follows: we see a so-called body flying through space at a certain speed. The fact that it has this speed is the only thing that is real. But instead of contemplating this totality of speed, of the rapidly flying body, we think in two abstractions; we divide what is a unity into two abstractions. Because there is a speed, there is a certain path. We consider this first. Then we consider separately, as a second thing, the time during which this path is traversed, and from the speed, which is the only thing that exists, we extract space and time through our process of perception. But this space is not there in any other way than that it is made by speed, and time is no different. Space and time, in relation to this reality to which we attribute v, are not realities, they are abstractions that we form from speed. And we can only cope with external reality, my dear friends, if we are clear that we have created this duality, space and time, in our process of perception, that we have nothing real outside ourselves except speed, that we have created space and time for our own sake through the two abstractions into which speed can break us down.

We can separate ourselves from speed, but we cannot separate ourselves from space and time; they are within our perception, within our perceptive activity; we are one with space and time! What I am saying now is of great significance: we are one with space and time! Consider this! We are not one with the speed outside, but with space and time. Yes, we should not readily attribute to external bodies that with which we are one, but we should only use it to arrive at a corresponding mental image of external bodies. We should say: Through space and time, with which we are intimately connected, we learn to recognize speed, but we should not say: The body runs a distance, but only: The body has a speed. Nor should we say: The body needs time, but only: The body has a speed. We measure speed through space and time. Space and time are our instruments and they are bound to us, and that is what is important. Here you can see once again a sharp distinction between the so-called subjective with space and time and the objective, which is speed. It will be very good, my dear friends, if you make this very clear to yourselves, because then something will dawn on you internally, you will realize that v is not merely the quotient of \(s\) and \(t\), but that, although \(v\) is expressed numerically by the quotient of \(s\) and \(t\), what I express by the number is, internally, a reality whose essence consists in having a speed. What I have shown you here about space and time, that they are inseparable from us, that we must not separate ourselves from them, now also applies to something else.

My dear friends, there is still a lot of Königsbergerei in people, I mean Kantianism. This Königsbergerei must be completely eliminated. For someone might believe that I myself have now spoken in the spirit of Königsbergism. That would mean: space and time are within us. But I do not say: space and time are within us, but rather: in perceiving the objective, speed, we use space and time for perception. Space and time are simultaneously within us and outside us, but we connect ourselves with space and time, while we do not connect ourselves with speed. It rushes past us. So, this is something fundamentally different from Kant's Königsberg argument.

Now, this also applies to something else I said about space and time. Just as we are connected to objectivity through space and time, but first have to seek out this speed, we are also in an element with the so-called bodies by seeing them through light. We cannot speak of an objectivity of light any more than we can speak of an objectivity of space and time. We swim in space and time just as bodies swim in them at a certain speed. We swim in light just as bodies swim in light. Light is a common element between us and what is outside us as so-called bodies. Yes, you can imagine it like this: When you gradually illuminate the darkness with light, the space is filled with something—let us call it x for the sake of argument—something in which you are inside, in which everything outside you is also inside. A common element in which you and the elements float. We must now ask ourselves: How do we actually do this, float in the light? We cannot swim in it with our so-called body, but we do indeed swim in it with our etheric body. There can be no understanding of light unless we move on to realities. We swim with our etheric body in the light — call it light ether if you like; it does not matter. So we swim with our etheric body in the light.

Now, over time, we have seen how colors arise in the light in various ways. Colors arise in the light in various ways, and in turn colors arise in the so-called bodies or exist in them. We see, as it were, the ghostly colors that arise and disappear in the light. When I throw a spectrum around, it is like ghosts, flitting about in the room, as it were. We see such colors in the light. Yes, my dear friends, how is it there? We float inside the light with our etheric bodies. How do we relate to the colors that flit about there? It is no different than if we were there with our astral body; there we are connected to the colors with our astral body. My dear friends, you have no choice but to be clear about this: wherever you see colors, you are connected to them with your astrality. You have no choice but to come to a real realization by saying to yourself: While the light itself remains invisible, we are swimming inside it. Just as space and time should not be called objectivities because we are swimming with things, so we should regard light as a common element, but colors only as something that can emerge through our astral body's relationship with what the light is doing.

Now suppose you have somehow brought about some kind of color phenomenon, some kind of spectrum, or something like that in this space \(A-B-C-D\), but a phenomenon that only occurs in the light. You must then refer to an astral relationship to the light. But you could also, for example, have colored this here as a surface, so that \(A-C\) appears to you as a body, let's say red. We say: \(A-C\) is red. You look at the surface of the body and initially imagine roughly that beneath the surface of the body, it is red throughout. You see, that is something else. You also have an astral relationship, but you are separated from this astral relationship that you enter into with the color by the surface of the body. Understand that! You see colors in the light, spectral colors, you have astral relationships of a direct nature, there is nothing between you and these colors. You see the colors of the body, something stands between you and your astral body, and through this something you enter into astral relationships with the colors of the body. I ask you to take these things into your mind and think them through carefully, for these are important basic concepts that we will be working with. And through this alone will we obtain basic concepts for a real physics.

I would just like to mention one last thing: You see, I am not trying to tell you something that you can easily find out by buying the nearest textbook. Nor am I trying to tell you what you can read in Goethe's Theory of Colors, but rather what you cannot find in either of them, which will enable you to bring both together in your mind in an appropriate way. Even if we are not believers in physics, we certainly do not need to become believers in Goethe; for Goethe died in 1832, and we do not profess a Goetheanism of 1832, but one of 1919, that is, a Goetheanism that has been further developed. What I have told you today about the astral relationship, I ask you to think through carefully.