The Light Course

GA 320

29 December 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture VI

My dear Friends,

In our last lecture we were going into certain matters of principle which I will now try to explain more fully. For if we start from the experiences we can gain in the realm of light, it will also help us observe and understand other natural phenomena which we shall presently be studying. I will therefore begin today with these more theoretical reflections and put off the experimental part until tomorrow. We must determine still more exactly the method of our procedure. It is the task of Science to discern and truly to set forth the facts in the phenomena of Nature. Problems of method which this task involves can best be illustrated in the realm of Light.

Men began studying the phenomena of light in rather recent times, historically speaking. Nay, the whole way of thinking about the phenomena of Physics, presented in the schools today, reaches hardly any farther back than the 16th century. The way men thought of such phenomena before the 16th century was radically different. Today at school we get so saturated with the present way of thought that if you have been through this kind of schooling it is extremely difficult for you to find your way back to the pure facts. You must first cultivate the habit of feeling the pure facts as such; please do not take my words in a too trivial meaning. You have to learn to sense the facts, and this takes time and trouble.

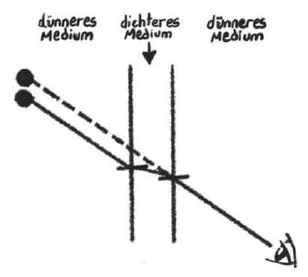

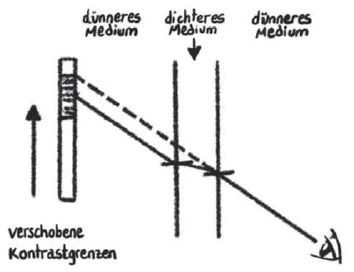

I will now take my start from a particular instance wherein we may compare the way of thought prevailing in the schools today with that which can be gained by following the facts straightforwardly. Suppose this were a plate of glass, seen in cross-section (Figure VIa). Through it you look at a luminous object. As I am drawing it diagrammatically, let me represent the latter simply by a light circle. Cast your mind back to what you learned in your school days. What did they teach you of the phenomenon you see when you observe the luminous object,—with your eye, say, here—looking through the glass? You were no doubt told that rays of light proceed from the luminous object. (We are imagining the eye to be looking in this particular direction,—see the Figure). Rays, you were told, proceed from the shining object. In the direction of the “ray” I am now drawing, the light was said to penetrate from a more tenuous into a denser medium. Simply by looking through the glass and comparing what you see with what you saw before the plate of glass was there, you do indeed perceive the thing displaced. It appears at a different place than without the glass. Now this is said to be due to the light being “refracted”. This is how they are wont to put it:—When the light passes from a more tenuous into a denser medium, to find the direction in which the light will be refracted, you must draw the so-called “normal at the point of incidence”. If the light went on its way without being hindered by a denser medium, it would go on in this direction. But, they now say, the light is “refracted”—in this case, towards the normal, i.e. towards the perpendicular to the glass surface at the point of incidence. Now it goes out again,—out of the glass. (All this is said, you will remember, in tracing how the “ray of light” is seen through the denser medium.) Here then again, at the point of exit from the glass, you will have to erect the normal. If the light went straight on it would go thus: but at this second surface it is again refracted—this time, away from the normal—refracted just enough to make it go on parallel to its original direction. And now the eye, looking as it is from here, is said to produce the final direction of the ray of light and thus to project the luminous object so much the higher up. This then is what we are asked to assume, if we be looking through such a plate of glass. Here, to begin with, the light impinges on the plate, then it is twice refracted—once towards the normal, a second time away from the normal. Then, inasmuch as the eye has the inner faculty to do so (.... or is it to the soul, or to some demon that you ascribe this faculty ....) the light is somehow projected out into space. It is projected moreover to a position different from where it would appear if we were not seeing it through a refracting medium;—so they describe the process.

The following should be observed to begin with, in this connection. Say we are looking at anything at all through the same denser medium, and we now try to discriminate, however delicately, between the darker and lighter portions of what we see. Not only the lighter parts, the darker too will appear shifted upward. The entire complex we are looking at is found to be displaced. Please take this well into account. Here is a darker part bordering on a lighter. The dark is shifted upward, and since one end of it is lighter we see this shifted too. Placing before us any such complex, consisting of a darker and a lighter part, we must admit the lighter part is displaced simply as the upper boundary of the darker. Instead, they speak in such a way as to abstract the one light patch from all the rest that is there. Mostly they speak as though the light patch alone were suffering displacement. Surely this is wrong. For even if I fix my gaze on this one patch of light, it is not true that it alone is shifted upward. The part below it, which I am treating as if it were just nothing when I describe it thus, is shifted upward too. In point of fact, what is displaced in these optical phenomena can never be thus abstractly confined. If therefore I repeat Newton's experiment—I let into the room a cone of light which then gets diverted by the prism—it simply is not true that the cone of light is diverted all alone. Whatever the cone of light is bordering on—above it and below—is diverted too. I really ought never to speak of rays of light or anything of that kind, but only of luminous pictures or spaces-of-light being diverted. In a particular instance I may perhaps want to refer to some isolated light, but even then I still ought not to speak of it in such a way as to build my whole theory of the phenomenon upon it. I still ought to speak in such a way as to refer at the same time to all that borders on the light. Only if we think in this way can we begin to feel what is really going on when the phenomena of colour comes into being before our eyes. Otherwise our very habit of thought begets the impression that in some way the colours spring from the light alone. For from the very outset we have it settled in our mind that the one and only reality we are dealing with is the light. Yet, what we have before us in reality is never simply light as such; it is always something light, bordered on one side or other by darkness. And if the lighter part—the space it occupies—is shifted, the darker part is shifted too. But now, what is this “dark”? You must take the dark seriously,—take it as something real. (The errors that have crept into modern Physics since about the 16th century were only able to creep in because these things were not observed spiritually at the same time. Only the semblance, as appearing to the outer senses, was taken note of; then, to explain this outer semblance, all kinds of theoretical inventions were added to it). You certainly will not deny that when you look at light the light is sometimes more and sometimes less intense. There can be stronger light and less strong. The point is now to understand: How is this light, which may be stronger or weaker related to darkness? The ordinary physicist of today thinks there is stronger light and less strong; he will admit every degree of intensity of light, but he will only admit one darkness—darkness which is simply there when there is no light. There is, as it were, only one way of being black. Yet as untrue as it would be to say that there is only one kind of lightness, just as untrue is it to say that there is only one kind of darkness. It is as one-sided as it would be to declare: “I know four men. One of them owns £25, another £50; he therefore owns more than the other. The third of them is £25 in debt, the fourth is £50 in debt. Yet why should I take note of any difference in their case? It is precisely the same; both are in debt. I will by all means distinguish between more and less property, but not between different degrees of debt. Debt is debt and that is all there is to it.” You see the fallacy at once in this example, for you know very well that the effect of being £25 in debt is less than that of being £50 in debt. But in the case of darkness this is how people think: Of light there are different degrees; darkness is simply darkness. It is this failure to progress to a qualitative way of thinking, which very largely prevents our discovering the bridge between the soul-and-spirit on the one hand, and the bodily realm on the other. When a space is filled with light it is always filled with light of a certain intensity; so likewise, when a space is filled with darkness, it is filled with darkness of a certain intensity. We must proceed from the notion of a merely abstract space to the kind of space that is not abstract but is in some specific way positively filled with light or negatively filled with darkness. Thus we may be confronting a space that is filled with light and we shall call it “qualitatively positive”. Or we may be confronting a space that is filled with darkness and we shall judge it “qualitatively negative” with respect to the realm of light. Moreover both to the one and to the other we shall be able to ascribe a certain degree of intensity, a certain strength. Now we may ask: How does the positive filling of space differ for our perception from the negative? As to the positive, we need only remember what it is like when we awaken from sleep and are surrounded by light,—how we unite our subjective experience with the light that floods and surges all around us. We need only compare this sensation with what we feel when surrounded by darkness, and we shall find—I beg you to take note of this very precisely—we shall find that for pure feeling and sensation there is an essential difference between being given up to a light-filled space and to a darkness-filled space. We must approach these things with the help of some comparison. Truly, we may compare the feeling we have, when given up to a light-filled space, with a kind of in-drawing of the light. It is as though our soul, our inner being, were to be sucking the light in. We feel a kind of enrichment when in a light-filled space. We draw the light into ourselves. How is it then with darkness? We have precisely the opposite feeling. We feel the darkness sucking at us. It sucks us out, we have to give away,—we have to give something of ourselves to the darkness. Thus we may say: the effect of light upon us is to communicate, to give; whilst the effect of darkness is to withdraw, to suck at us and take away. So too must we distinguish between the lighter and the darker colours. The light ones have a quality of coming towards us and imparting something to us; the dark colours on the other hand have a quality of drawing on us, sucking at us, making us give of ourselves. So at long last we are led to say: Something in our outer world communicates itself to us when we are under the influence of light; something is taken from us, we are somehow sucked out, when under the influence of darkness.

There is indeed another occasion in our life, when—as I said once before during these lectures—we are somehow sucked-out as to our consciousness; namely when we fall asleep. Consciousness ceases. It is a very similar phenomenon, like a cessation of consciousness, when from the lighter colours we draw near the darker ones, the blue and violet. And if you will recall what I said a few days ago about the relation of our life of soul to mass,—how we are put to sleep by mass, how it sucks-out our consciousness,—you will feel something very like this in the absorption of our consciousness by darkness. So then you will discern the deep inner kinship between the condition space is in when filled with darkness and on the other hand the filling of space which we call matter, which is expressed in “mass”.

Thus we shall have to seek the transition from the phenomena of light to the phenomena of material existence. We have indeed paved the way, in that we first looked for the fleeting phenomena of light—phosphorescence and fluorescence—and then the firm and fast phenomena of light, the enduring colours. We cannot treat all these things separately; rather let us begin by setting out the whole complex of these facts together.

Now we shall also need to recognize the following, When we are in a light-filled space we do in a way unite with this light-filled space. Something in us swings out into the light-filled space and unites with it. But we need only reflect a little on the facts and we shall recognize an immense difference between the way we thus unite with the light-flooded spaces of our immediate environment and on the other hand the way we become united with the warmth-conditions of our environment,—for with these too, as human beings, we do somehow unite.

We do indeed share very much in the condition of our environment as regards warmth; and as we do so, here once again we feel a kind of polarity prevailing, namely the polarity of warm and cold. Yet we must needs perceive an essential difference between the way we feel ourselves within the warmth-condition of our environment and the way we feel ourselves within the light-condition of our environment. Physics, since the 16th century, has quite lost hold of this difference. The open-mindedness to distinguish how we join with our environment in the experience of light upon the one hand and warmth upon the other has been completely lost; nay, the deliberate tendency has been, somehow to blur and wipe away such differences as these. Suppose however that you face the difference, quite obviously given in point of fact, between the way we experience and share in the conditions of our environment as regards warmth and light respectively. Then in the last resort you will be bound to recognize that the distinction is: we share in the warmth-conditions of our environment with our physical body and in the light-conditions, as we said just now, with our etheric body. This in effect—this proneness to confuse what we become aware of through our ether-body and what we become aware of through our physical body—has been the bane of Physics since the 16th century. In course of time all things have thus been blurred. Our scientists have lost the faculty of stating facts straightforwardly and directly. This has been so especially since Newton's influence came to be dominant, as it still is to a great extent today. There have indeed been individuals who have attempted from time to time to draw attention to the straightforward facts simply as they present themselves. Goethe of course was doing it all through, and Kirchhoff among others tried to do it in more theoretic ways. On the whole however, scientists have lost the faculty of focusing attention purely and simply on the given facts. The fact for instance that material bodies in the neighbourhood of other material bodies will under given conditions fall towards them, has been conceived entirely in Newton's sense, being attributed from the very outset to a force proceeding from the one and affecting the other body—a “force of gravity”. Yet ponder how you will, you will never be able to include among the given facts what is understood by the term “force of gravity”. If a stone falls to the Earth the fact is simply that it draws nearer to the Earth. We see it now at one place, now at another, now at a third and so on. If you then say “The Earth attracts the stone” you in your thoughts are adding something to the given fact; you are no longer purely and simply stating the phenomenon.

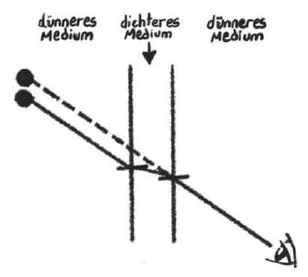

People have grown ever more unaccustomed to state the phenomena purely, yet upon this all depends. For if we do not state the phenomena purely and simply, but proceed at once to thought-out explanations, we can find manifold explanations of one and the same phenomenon. Suppose for example you have two heavenly bodies. You may then say: These two heavenly bodies attract one another,—send some mysterious force out into space and so attract each other (Figure VIb). But you need not say this. You can also say: “Here is the one body, here is the other, and here (Figure VIc) are a lot of other, tiny bodies—particles of ether, it may be—all around and in between the two heavenly bodies. The tiny particles are bombarding the two big ones—bombarding here, there and on all sides;—the ones between, as they fly hither and thither, bombard them too. Now the total area of attack will be bigger outside than in between. In the resultant therefore, there will be less bombardment inside than outside; hence the two bodies will approach each other. They are, in fact, driven towards each other by the difference between the number of impacts they receive in the space between them and outside them.”

There have in fact been people who have explained the force of gravity simply by saying: It is a force acting at a distance and attracts the bodies towards each other. Others have said that that is nonsense; according to them it is unthinkable for any force to act at a distance. They then invite us to assume that space is filled with “ether”, and to assume this bombardment too. The masses then are, so to speak, for ever being sprayed towards each other. To add to these explanations there are no doubt many others. It is a classical example of how they fail to look at the real phenomenon but at once add their thought-out explanations.

Now what is at the bottom of it all? This tendency to add to the phenomena in thought—to add all manner of unknown agencies and fancied energies, presumed to be doing this or that—saves one the need of doing something else. Needless to say, the impacts in the theory of Figure VIc have been gratuitously added, just as the forces acting at a distance have been in the other theory. These adventitious theories, however, relieve one of the need of making one fundamental assumption, from which the people of today seem to be very much averse. For in effect, if these are two independent heavenly bodies and they approach each other, or show that it is in their nature to approach each other, we cannot but look for some underlying reason why they do so; there must be some inner reason. Now it is simpler to add in thought some unknown forces than to admit that there is also another way, namely no longer to think of the heavenly bodies as independent of each other. If for example I put my hand to my forehead, I shall not dream of saying that my forehead “attracts” my hand, but I shall say: It is an inner deed done by the underlying soul-and-spirit. My hand is not independent of my forehead; they are not really separate entities. I shall regard the phenomenon rightly only by recognising myself as a single whole. I should have no reality in mind if I were to say: There is a head, there are two arms and hands, there is a trunk, there are two legs. There would be nothing complete in that; I only have something complete in mind if I describe the whole human body as a single entity,—if I describe the different items so that they belong together. My task is not merely to describe what I see; I have to ponder the reality of what I see. The mere fact that I see a thing does not make it real.

Often I have made the following remark,—for I have had to indicate these things in other lectures too. Take a crystal cube of rock-salt. It is in some respect a totality. (Everything will be so in some respect). The crystal cube can exist by virtue of what it is within the compass of its six faces. But if you look at a rose, cut from the shrub it grew on, this rose is no totality. It cannot, like the cube of rock-salt, exist by virtue of all that is contained within it. The rose can only have existence by being of the rose-bush. The cut rose therefore, though you can see it just as you can see the cube of rock-salt, is a real abstraction; you may not call it a reality by itself.

The implications of this, my dear Friends, are far-reaching. Namely, for every phenomenon, we must examine to what extent it is a reality in itself, or a mere section of some larger whole. If you consider Sun and Moon, or Sun and Earth, each by itself, you may of course invent and add to them a force of gravity, just as you might invent a force of gravity by means of which my forehead would attract my right hand. But in considering Sun and Earth and Moon thus separately, the things you have in mind are not totalities; they are but parts and members of the whole planetary system.

This then is the essential thing; observe to what extent a thing is whole, or but a section of a whole. How many errors arise by considering to be a whole what is in fact only a partial phenomenon within a larger whole! By thus considering only the partial phenomena and then inventing energies to add to these, our scientists have saved themselves the need of contemplating the inherent life of the planetary system. The tendency has been, first to regard as wholes those things in Nature which are only parts, and by mere theories then to construe the effects which arise in fact between them. This therefore, to sum up, is the essential point: For all that meets us in Nature we have to ask: What is the whole to which this thing belongs? Or is it in itself a whole? Even then, in the last resort, we shall find that things are wholes only in certain respects. Even the crystal cube of rock-salt is a totality only in some respect; it too cannot exist save at certain temperatures and under other requisite conditions. Given some other temperature, it could no longer be. Our need is therefore to give up looking at Nature in the fragmentary way which is so prevalent in our time.

Indeed it was only by looking at Nature in this fragmentary way that Science since the 16th century conceived this strange idea of universal, inorganic, lifeless Nature. There is indeed no such thing, just as in this sense there is no such thing as your bony system without your blood. Just as your bony system could only come into being by, as it were, crystallizing out of your living organism as a whole, so too this so-called inorganic Nature cannot exist without the whole of Nature—soul and Spirit-Nature—that underlies it. Lifeless Nature is the bony system, abstracted from Nature as a whole. It is impossible to study it alone, as they began doing ever since the 16th century and as is done in Newtonian Physics to this day.

It was the trend of Newtonian Physics to make as neat as possible an extract of this so-called inorganic Nature, treating it then as something self-contained. This “inorganic Nature” only exists however in the machines which we ourselves piece together from the parts of Nature. And here we come to something radically different. What we are wont to call “inorganic” in Nature herself, is placed in the totality of Nature in quite another way. The only really inorganic things are our machines, and even these are only so insofar as they are pieced together from sundry forces of Nature by ourselves. Only the “put-togetherness” of them is inorganic. Whatever else we may call inorganic only exists by abstraction. From this abstraction however present-day Physics has arisen. This Physics is an outcome of abstraction; it thinks that what it has abstracted is the real thing, and on this assumption sets out to explain whatever comes within its purview

As against this, the only thing we can legitimately do is to form our ideas and concepts in direct connection with what is given to us from the outer world—the details of the sense-world. Now there is one realm of phenomena for which a very convenient fact is indeed given. If you strike a bell and have some light and very mobile device in the immediate neighbourhood, you will be able to demonstrate that the particles of the sounding bell are vibrating. Or with a pipe playing a note, you will be able to show that the air inside it is vibrating. For the phenomena of sound and tone therefore, you have the demonstrable movement of the particles of air or of the bell; so you will ascertain that there is a connection between the vibrations executed by a body or by the air and our perceptions of tone or sound. For this field of phenomena it is quite patent: vibrations are going on around us when we hear sounds. We can say to ourselves that unless the air in our environment is vibrating we shall not hear any sounds. There is a genuine connection—and we shall speak of it again tomorrow—between the sounds and the vibrations of the air.

Now if we want to proceed very abstractly we may argue: “We perceive sound through our organs of hearing. The vibrations of the air beat on our organ of hearing, and when they do so we perceive the sound. Now the eye too is a sense-organ and through it we perceive the colours; so we may say: here something similar must be at work. Some kind of vibration must be beating on the eye. But we soon see it cannot be the air. So then it is the ether.” By a pure play of analogies one is thus led to the idea: When the air beats upon our ear and we have the sensation of a sound, there is an inner connection between the vibrating air and our sensation; so in like manner, when the hypothetical ether with its vibrations beats upon our eye, a sensation of light is produced by means of this vibrating ether. And as to how the ether should be vibrating: this they endeavour to ascertain by means of such phenomena as we have seen in our experiments during these lectures. Thus they think out an universal ether and try to calculate what they suppose must be going on in this ethereal ocean. Their calculations relate to an unknown entity which cannot of course be perceived but can at most be assumed theoretically.

Even the very trifling experiments we have been able to make will have revealed the extreme complication of what is going on in the world of light. Till the more recent developments set in, our physicists assumed that behind—or, should we rather say, within—all thus that lives and finds expression in light and colour there is the vibrating ether, a tenuous elastic substance. And since the laws of impact and recoil of elastic bodies are not so difficult to get to know, they could compute what these vibrating little cobolds must be up to in the ether. They only had to regard them as little elastic bodies,—imagining the ether as an inherently elastic substance. So they could even devise explanations of the phenomena we have been showing,—e.g. the forming of the spectrum. The explanation is that the different kinds of ether-vibrations are dispersed by the prism; these different kinds of vibrations then appear to us as different colours. By calculation one may even explain from the elasticity of the ether the extinction of the sodium line for example, which we perceived in our experiment the day before yesterday.

In more recent times however, other phenomena have been discovered. Thus we can make a spectrum, in which we either create or extinguish the sodium line (i.e., in the latter case, we generate the black sodium line). If then in addition we bring an electro-magnet to bear upon the cylinder of light in a certain way, the electro-magnet affects the phenomenon of light. The sodium line is extinguished in its old place and for example two other lines arise, purely by the effect of the electricity with which magnetic effects are always somehow associated. Here, then, what is described as “electric forces” proves to be not without effect upon those processes which we behold as phenomena of light and behind which one had supposed the mere elastic ether to be working. Such discoveries of the effect of electricity on the phenomena of light now led to the assumption that there must be some kinship between the phenomena of light and those of magnetism and electricity.

Thus in more recent times the old theories were rather shaken. Before these mutual effects had been perceived, one could lean back and rest content. Now one was forced to admit that the two realms must have to do with each other. As a result, very many physicists now include what radiates in the form of light among the electro-magnetic effects. They think it is really electro-magnetic rays passing through space.

Now think a moment what has happened. The scientists had been assuming that they knew what underlies the phenomena of light and colour: namely, undulations in the elastic ether. Now that they learned of the interaction between light and electricity, they feel obliged to regard, what is vibrating there, as electricity raying through space. Mark well what has taken place. First it is light and colour which they desire to explain, and they attribute them to the vibrating ether. Ether-vibrations are moving through space. They think they know what light is in reality,—it is vibrations in the elastic ether. Then comes the moment when they have to say: What we regarded as vibrations of the elastic ether are really vibrations of electro-magnetic force. They know still better now, what light is, than they did before. It is electro-magnetic streams of force. Only they do not know what these are! Such is the pretty round they have been. First a hypothesis is set up: something belonging to the sense-world is explained by an unknown super-sensible, the vibrating ether. Then by and by they are driven to refer this super-sensible once more to something of the sense-world, yet at the same time to confess that they do not know what the latter is. It is a highly interesting journey that has here been made; from the hypothetical search for an unknown to the explanation of this unknown by yet another unknown.

The physicist Kirchhoff was rather shattered and more or less admitted: It will be not at all easy for Physics if these more recent phenomena really oblige us no longer to believe in the undulating ether. And when Helmholtz got to know of the phenomenon, he said: Very well, we shall have to regard light as a kind of electro-magnetic radiation. It only means that we shall now have to explain these radiations themselves as vibrations in the elastic ether. In the last resort we shall get back to these, he said.

The essence of the matter is that a genuine phenomenon of undulation—namely the vibrating of the air when we perceive sounds—was transferred by pure analogy into a realm where in point of fact the whole assumption is hypothetical.

I had to go into these matters of principle today, to give the necessary background. In quick succession we will now go through the most important aspects of those phenomena which we still want to consider. In our remaining hours I propose to discuss the phenomena of sound, and those of warmth, and of electro-magnetics; also whatever explanations may emerge from these for our main theme—the phenomena of optics.

Sechster Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde!

Ich möchte Ihnen doch heute das vorgestern begonnene Prinzipielle weiter auseinandersetzen, weil wir, wenn wir von den am Licht gewonnenen Erfahrungen ausgehen, weiter die Erscheinungen werden beobachten und verstehen können, die sich uns an den anderen Naturerscheinungen, die wir noch betrachten wollen, ergeben können. Ich werde daher heute eine mehr prinzipielle Betrachtung einfügen und das Experimentelle bis morgen verschieben, weil wir eben noch genauer feststellen müssen die Art und Weise, wie wir methodisch unseren Weg verfolgen wollen. Es handelt sich wirklich darum, dass das genau durchgeführt werde, was als Faktisches in den Naturerscheinungen vorliegt. Und um das zu verfolgen, gibt tatsächlich das Licht die meisten Anhaltspunkte.

Nun hat sich ja geschichtlich das ereignet, dass die Menschen angefangen haben, verhältnismäßig spät die Lichterscheinungen zu studieren. Überhaupt, die ganze Art und Weise zu denken physikalisch, wie sie heute in unseren Schulen gegeben ist, reicht kaum hinter das sechzehnte Jahrhundert zurück. Die Art und Weise zu denken über die physikalischen Erscheinungen war vor diesem sechzehnten Jahrhundert eben eine radikal andere. Heute aber wird so stark aufgenommen in der Schule diese Denkweise, dass es wiederum außerordentlich schwierig wird für denjenigen, der durch eine gewisse physikalische Schule gegangen ist, zurückzukehren zu dem rein Tatsächlichen. Man muss sich erst gewöhnen, das rein Tatsächliche - ich möchte sagen und ich bitte, den Ausdruck nicht bloß in seiner Trivialität aufzufassen - das rein Tatsächliche zu fühlen, zu empfinden. Daran muss man sich eigentlich erst gewöhnen. Daher möchte ich ausgehen davon, wie man vergleichen kann die gewohnte schulmäßige Denkweise an einem bestimmten Fall mit demjenigen, was man eigentlich durch ein sachgemäßes Verfolgen des Tatsächlichen gewinnen kann. Ich will von einem einzelnen Fall ausgehen.

Nehmen Sie einmal an, Sie hätten hier den Querschnitt irgendeiner Glasplatte. Durch diese Glasplatte würden Sie beobachten hier irgendein Leuchtendes. Ich will die Sache schematisch zeichnen, will statt dieses Leuchtenden einfach, sagen wir, hier einen leuchtenden Kreis hierher zeichnen. Nun werden Sie, wenn Sie sich wiederum zurückdenken auf die Schulbank, sich dabei erinnern, was Sie für die Beobachtung von diesem Punkte durch das Auge für diese Erscheinung eigentlich gelernt haben. Da ist Ihnen gesagt worden, von diesem Leuchtenden gingen Strahlen, sagen wir, aus. Wir wollen auf eine bestimmte Schrichtung des Auges reflektieren. Es gingen von diesem Leuchtenden Strahlen aus, das heißt in der Richtung dieses Strahls dringt das Licht, wie man sagt, aus einem dünneren Medium in ein dichteres Medium ein. Man kann wahrnehmen, wenn man einfach durchschaut und dann vergleicht dasjenige, was sich nach dem DurchSchauen durch die Platte ergibt, mit demjenigen, was da ist, zunächst, dass das Leuchtende verschoben ist, an einer anderen Stelle erscheint, als es erscheint, ohne dass man cs durch eine Platte sieht. Nun sagt man, das rühre davon her, dass das Licht gebrochen werde. Man sagt: Indem das Licht aus einem dünneren in ein dichteres Medium eintritt, müsse man, um die Richtung zu bekommen, in der das Licht gebrochen wird, müsse man ein sogenanntes Einfallslot zeichnen, und dann, wenn das Licht seinen Weg sonst, ohne dass es gehindert würde durch ein solches dichteres Mittel, fortsetzen würde, so würde es ja in dieser [gestrichelten] Richtung gehen; aber das Licht wird [beim Eintritt in das dichtere Medium] gebrochen, wie man sagt, und zwar in diesem Falle gebrochen zum Einfallslote, zu dieser Senkrechten, die man im Einfallspunkt errichtet. Und wenn es wiederum austritt, das Licht, wenn man also verfolgt, wie man den Lichtstrahl durch das dichtere Medium durch sieht, müsste man wiederum sagen: Hier ist wiederum ein Einfallslot zu errichten, hier würde der Strahl, wenn er seinen Weg fortsetzen würde, so gehen; er wird aber jetzt wiederum gebrochen, und zwar in diesem Falle vom Einfallslote und so stark, dass seine Richtung jetzt parallel ist zur früheren. Wenn das Auge nun so schaut, so verlängert es sich die letzte Richtung und versetzt das Leuchtende eine Strecke höher hinauf, sodass man also, wenn man so durchschaut, annehmen muss: Hier fällt das Licht ein, wird zweimal gebrochen, das cine Mal zum Einfallslot, das andere Mal vom Einfallslot, und es wird dadurch, dass das Auge die innere Fähigkeit hat - oder die Seele oder irgendein Dämon, wie man sagen will -, es wird hinausversetzt das Licht in den Raum, und zwar an eine andere Stelle des Raumes, als es erscheinen würde, wenn man es nicht durch ein brechendes Medium, wie man sagt, sehen würde.

Nun handelt es sich aber darum, Folgendes festzuhalten. sehen Sie, wenn man das Folgende versucht, wenn man versucht, ein wenig Unterschied zu machen zwischen einer etwas, ich will sagen, helleren Stelle und einer etwas dunkleren Stelle‘ und dieses anschaut durch dasselbe dichtere Mittel, so wird man nicht etwa bloß dieses Hellere nach oben verschoben finden, sondern man wird auch das etwas Dunklere nach oben verschoben finden. Man wird den ganzen Komplex, den man sieht hier, verschoben finden. Ich bitte Sie, das wohl zu beachten. Wir sehen hier verschoben ein Dunkleres, das von einem Helleren begrenzt wird, wir sehen das Dunklere nach oben geschoben, und weil es ein helleres Ende hat, so sehen wir das auch mit nach oben geschoben. sehen Sie, wenn man solch einen Komplex hinstellt, ein Dunkleres und ein Helleres, dann muss man sagen: Es wird eigentlich das Hellere nur als die obere Grenze verschoben. Wenn man abstrahiert einen hellen Fleck, dann spricht man aber oftmals so, als ob nur dieser helle Fleck verschoben würde. Das aber ist ein Unding. Aber auch, wenn ich hier auf diesen hellen Fleck hinschaue, so ist es nicht wahr, dass bloß er verschoben wird, sondern in Wirklichkeit wird dasjenige, was ich da unten das Nichts nenne, auch hinaufverschoben.

Dasjenige, was verschoben wird, ist niemals irgendetwas, was ich so abstrakt abgrenzen kann. Wenn ich also das Experiment mache, das Newton gemacht hat, wenn ich einlasse einen Lichtkegel, dieser abgelenkt wird durch das Prisma, so ist es nicht wahr, dass bloß der Lichtkegel verschoben wird, sondern es wird auch dasjenige, von dem von oben her und nach unten hin der Lichtkegel die Grenze ist, das wird mitverschoben. Ich sollte niemals sprechen von irgendwelchen Lichtstrahlen oder dergleichen, sondern von verschobenen Lichtbildern oder Lichträumen. Und will ich irgendwo von einem isolierten Licht sprechen, so kann ich davon gar nicht so sprechen, dass ich irgendetwas in der Theorie auf dieses isolierte Licht beziehe, sondern ich muss so sprechen, dass ich mein Gesprochenes zugleich auf das, was angrenzt, beziehe.

Nur wenn man so denkt, kann man wirklich fühlen, was da eigentlich vorgeht, wenn man der Entstehung der Farbenerscheinungen gegenübersteht. Man bekommt sonst eben einfach durch seine Denkweise den Eindruck, als ob aus dem Lichte heraus irgendwie die Farben entstünden. Man hat sich vorher den Gedanken zurechtgelegt, dass man es nur mit dem Licht zu tun habe. In Wirklichkeit hat man es nicht mit dem Licht zu tun, sondern mit irgendetwas Hellem, an das an der einen oder andern Seite Dunkelheit angrenzt. Und ebenso wie dieses Helle als Raumlicht verschoben wird, ebenso wird das Dunkle verschoben. Aber was ist denn dieses Dunkle, was ist es eigentlich? sehen Sie, dieses Dunkle muss eben auch durchaus real erfasst werden. Und alles das, was da seit etwa dem sechzehnten Jahrhundert in die neuere Physik eingezogen ist, das konnte nur deshalb einziehen, weil man niemals die Dinge zugleich geistig beobachtet hat, weil man immer die Dinge nur nach dem äußeren Sinnenschein beobachtet hat und dann hinzuerfunden hat zur Erklärung dieses Sinnenscheins allerlei Theorien.

Sie werden keineswegs in Abrede stellen können, dass, wenn Sie auf Licht schauen, das eine Mal das Licht stärker, das andere Mal schwächer ist. Stärkeres und schwächeres Licht gibt es. Nun handelt es sich darum, zu verstehen, wie dieses Licht, das stärker und schwächer sein kann, sich nun eigentlich zu der Dunkelheit verhält. Der gewöhnliche Physiker denkt heute, es gibt stärkeres und schwächeres Licht, alle möglichen Lichtgrade der Stärke nach, aber eine einzige Dunkelheit, die eben einfach dann da ist, wenn das Licht nicht da ist. Also ist Schwarz auf einerlei Weise. So wenig es nur einerlei Helligkeit gibt, ebenso wenig gibt cs nur einerlei Dunkelheit, und davon zu reden, dass es nur einerlei Dunkelheit gibt, ist so einseitig, wie wenn man sagen würde: Ich kenne vier Menschen. Der eine davon hat ein Vermögen von fünfhundert Mark, der andere ein Vermögen von tausend Mark. Der eine hat also ein größeres Vermögen als der andere. Der dritte aber hat fünfhundert Mark Schulden und der vierte tausend Mark Schulden. Aber was soll ich mich da weiter bekümmern um diesen Unterschied? Das ist schließlich dasselbe. Beide haben eben Schulden. Ich will unterscheiden zwischen den Graden des Vermögens, aber ich will nicht erst unterscheiden zwischen den Graden der Schulden, sondern Schulden sind Schulden. In diesem Falle fällt einem ja die Sache auf, weil ja die Wirkung von fünfhundert Mark Schulden eine geringere ist als die Wirkung von tausend Mark Schulden. Bei der Dunkelheit verhält man sich aber so: Licht hat verschiedene Helligkeitsgrade, Dunkelheit ist Dunkelheit. Das ist es, dass man nicht vorrückt zu einem qualitativen Denken, was uns so sehr hindert, die Brücke zwischen dem Seelisch-Geistigen [auf der einen Seite] und dem Körperlichen auf der anderen Seite zu finden. Wenn ein Raum von Licht erfüllt ist, so ist er eben mit Licht von einer bestimmten Stärke erfüllt, wenn ein Raum mit Dunkelheit erfüllt ist, so ist er mit Dunkelheit von einer bestimmten Stärke erfüllt, und man muss fortschreiten von dem bloß abstrakten Raum zu demjenigen Raum, der nicht abstrakt ist, sondern in irgendeiner Weise positiv erfüllt ist durch Licht, negativ erfüllt ist durch Dunkelheit. Man kann also gegenüberstehen dem lichterfüllten Raum und kann ihn nennen: Er ist qualitativ positiv. Man kann gegenüberstehen dem dunkelheiterfüllten Raum und kann ihn qualitativ negativ mit Bezug auf die Lichtverhältnisse finden. Beides aber kann mit einem bestimmten Intensitätsgrade, mit einer bestimmten Stärke angesprochen werden.

Aber jetzt, wenn man sich fragt: Ja, wie unterscheidet sich denn für unser Wahrnehmungsvermögen dieses positive Erfülltsein des Raumes von dem negativen Erfülltsein des Raumes? - Dieses positive Erfülltsein des Raumes, wir brauchen uns nur zu erinnern, wie es ist, wenn wir aufwachen, von Licht umgeben sind, unser subjektives Erleben vereinigen mit demjenigen, was uns als Licht umflutet, wir brauchen diese Empfindung nur zu vergleichen mit demjenigen, was wir empfinden, wenn wir von Dunkelheit umgeben sind, und wir werden finden - ich bitte jetzt, das sehr genau ins Auge beziehungsweise in den Verstand zu fassen -, wir werden uns klar werden müssen, dass rein für die Empfindung ein Unterschied besteht in dem Hingegebensein an den lichterfüllten Raum und in dem Hingegebensein an den dunkelheiterfüllten Raum. Nun kann man sich diesen Dingen überhaupt nur durch Vergleiche nähern.

Sehen Sie, man kann vergleichen jene Empfindung, die man hat, wenn man sich mit dem lichterfüllten Raum zusammenfindet, man kann das vergleichen mit einer Art Einsaugen des Lichtes durch unser seelisches Wesen. Wir empfinden ja eine Bereicherung, wenn wir im lichterfüllten Raum sind. Es ist ein Einsaugen des Lichtes. Wie ist es denn mit der Dunkelheit? Da ist genau die entgegengesetzte Empfindung. Die Dunkelheit saugt an uns, die saugt uns aus, der müssen wir uns hingeben, an die müssen wir etwas abgeben. Sodass wir sagen können: Die Wirkung des Lichtes auf uns ist eine mitteilende, die Wirkung der Dunkelheit auf uns ist eigentlich eine saugende. Und so müssen wir auch unterscheiden zwischen den hellen und dunklen Farben. Die helleren Farben haben etwas auf uns Losgehendes, das sich uns mitteilt; die dunkleren Farben haben etwas, das an uns saugt, dem wir uns hingeben müssen. Damit aber kommen wir dazu, uns zu sagen: Irgendetwas aus der Außenwelt teilt sich uns mit, indem Licht auf uns wirkt; irgendetwas wird uns weggenommen, wir werden ausgesaugt, indem Dunkelheit auf uns wirkt.

Wir werden - ich habe Sie schon in den Vorträgen auf das aufmerksam gemacht - wir werden in einer gewissen Beziehung auch sonst mit Bezug auf unser Bewusstsein ausgesaugt, wenn wir einschlafen. Da hört unser Bewusstsein auf. Es ist eine ganz ähnliche Erscheinung des Aufhörens unseres Bewusstseins, wenn wir uns von den immer helleren Farben nach den dunkleren Farben, nach dem Blau und Violett, nähern. Und wenn Sie sich erinnern an das, was ich Ihnen gesagt habe in diesen Tagen über die Beziehung unseres Seelischen zur Masse, wenn Sie sich erinnern an dieses Hineinschlafen in die Masse, an dieses Aufgesogenwerden des Bewusstseins durch die Masse, dann werden Sie ein Ähnliches empfinden durch das Aufgesogensein des Bewusstseins durch die Dunkelheit, und Sie werden die innere Verwandtschaft herausfinden zwischen dem Dunkelsein des Raumes und jener anderen Erfülltheit des Raumes, die man Materie nennt und die sich als Masse äußert, das heißt, wir werden den Weg zu suchen haben von den Lichterscheinungen hinüber einfach zu den Erscheinungen des materiellen Daseins, und wir haben uns schon den Weg dadurch gebahnt, dass wir zuerst gleichsam die flüchtigen Lichterscheinungen der Phosphoreszenz und Fluoreszenz aufgesucht haben und dann feste Lichterscheinungen. In den festen Lichterscheinungen haben wir bleibende Farben. Wir können diese Dinge nicht einzeln betrachten, wir wollen zunächst einmal den ganzen Komplex der Dinge vor uns hinstellen.

Nun handelt es sich darum, noch Folgendes einzusehen. Sehen Sie, wenn man im lichterfüllten Raum ist, so vereinigt man sich in gewisser Weise mit diesem lichterfüllten Raum. Man kann sagen: Etwas in uns schwimmt hinaus in diesen lichterfüllten Raum und vereinigt sich mit ihm. Aber man braucht nur ein klein wenig auf das [wirklich] Tatbeständliche zu reflektieren, dann wird man einen großen Unterschied finden zwischen diesem Vereinigtsein mit der unmittelbaren lichtflutenden Umgebung und jenem Vereintsein, das man als Mensch auch hat, nämlich mit dem Verereintsein mit dem Wärmezustand der Umgebung. Wir nehmen an diesem Wärmezustand der Umgebung teil, wir nehmen an ihm teil, indem wir auch etwas wie eine Polarität dieses Wärmezustandes empfinden, das Warme und das Kalte. Aber wir können doch nicht anders, als einen Unterschied wahrnehmen zwischen dem Sichfühlen in dem Wärmezustand der Umgebung und dem Sichfühlen in dem Lichtzustand der Umgebung. Dieser Unterschied ist nicht nur der neueren Physik seit dem sechzehnten Jahrhundert vollständig verloren gegangen, man kann sagen, nicht nur die Unbefangenheit im Unterscheiden des Lichtmiterlebens und des Wärmemiterlebens ist verloren gegangen, sondern man hat darauf hingearbeitet, solche Unterschiede in irgendeiner Art zu verwischen. Wer diesen Unterschied wirklich ins Auge fasst, der im Tatsächlichen ganz einfach gegeben ist, zwischen dem Miterleben des Wärmezustandes und dem Miterleben des Lichtzustandes der Umgebung, der kann zuletzt gar nicht anders als unterscheiden, dass wir an dem Wärmezustand mit unserem physischen Leibe beteiligt sind und an dem Lichtzustand eben mit unserem Ätherleibe beteiligt sind.

Das Durcheinanderwerfen desjenigen, was wir gewahr werden durch unseren Ätherleib, und desjenigen, was wir gewahr werden durch unseren physischen Leib, das ist zu einem ganz besonderen Übel geworden für die neuere physikalische Betrachtung seit dem sechzehnten Jahrhundert, und dadurch hat sich nach und nach alles verwischt. Denn sehen Sie, man hat verlernt, namentlich seit die Physik allmählich gekommen ist unter den Newton’schen Einfluss, der eigentlich heute noch immer wirksam ist, man hat verlernt, Tatbestände unmittelbar auszusprechen. Einzelne Menschen haben ja wiederum versucht, auf das Unmittelbare der Tatbestände hinzuweisen, Goethe im Großen, und Menschen, wie zum Beispiel Kirchhoff, in einer mehr theoretischen Weise. Aber im Ganzen hat man eigentlich verlernt, die Aufmerksamkeit rein auf die Tatbestände zu richten. Und so hat man zum Beispiel im Sinne von Newton den Tatbestand aufgefasst, dass materielle Körper, die sich in der Nähe von anderen materiellen Körpern befinden, auf diese anderen materiellen Körper hinfallen unter entsprechenden Voraussetzungen. Man hat dieses zugeschrieben einer Kraft, die von dem einen Körper ausgeht und auf den anderen ausgeübt wird, der Schwerkraft. Sie können sich aber überlegen, so viel Sie wollen, und Sie werden niemals dasjenige, was man unter dem Worte Schwerkraft versteht, unter die Tatbestände rechnen können. Wenn ein Stein zur Erde fällt, so ist der Tatbestand lediglich der, dass er sich der Erde nähert. Sie sehen ihn an einem Orte, sehen ihn an einem zweiten Orte, an einem dritten Orte und so weiter. Wenn Sie sagen: Die Erde zieht den Stein an, so denken Sie zum Tatbestand etwas hinzu, Sie sprechen die Erscheinung, das Phänomen nicht mehr rein aus. Dies hat man sich immer mehr und mehr abgewöhnt, die Erscheinung rein auszusprechen; aber es kommt darauf an, die Erscheinung rein auszusprechen. Denn, sehen Sie, spricht man die Erscheinungen nicht rein aus, sondern geht man über zu erdachten Erklärungen, dann kann man die verschiedensten erdachten Erklärungen finden, die oftmals das Gleiche erklären.

Nehmen Sie also an, Sie haben zwei - meinetwillen - Weltenkörper, so können Sie sagen: Diese beiden Weltenkörper ziehen sich gegenseitig an; sie senden da so etwas Unbekanntes wie eine Kraft in den Raum hinaus und ziehen sich gegenseitig an. Sie brauchen aber nicht zu sagen: Diese Körper ziehen sich gegenseitig an, sondern Sie müssen sich sagen: Hier ist der eine Körper, hier ist der andere Körper, hier sind viele andere kleine Körperchen, meinetwillen sogar Ätherteilchen, hierzwischen auch; diese Ätherteilchen sind in Bewegung, bombardieren die beiden Weltenkörper, das bombardiert so hin, das so her, und was dazwischen ist, fliegt hin und her und bombardiert auch.

Nun ist die Angriffsfläche hier [da draußen] eine größere als die da [zwischen] drinnen. Daher wird da drinnen weniger bombardiert, außen wird mehr bombardiert. Die Folge davon ist, dass sich die Weltenkörper einander nähern, sie werden gegeneinandergestoßen durch den Unterschied, der besteht zwischen der Anzahl der Stöße, die zwischen drinnen ausgeführt werden, und der Anzahl der Stöße, die außen ausgeführt werden.

Es hat Menschen gegeben, die die Schwerkraft so erklärt haben, dass sic gesagt haben: Da ist eine Fernkraft, die die Körper anzieht —, und es hat Menschen gegeben, die gesagt haben: Das ist ein Unsinn. Es ist das ganz undenkbar, die Wirkung der Kraft in die Ferne anzunehmen. Also, nehmen wir an den Raum durch den Äther erfüllt, und nehmen wir dieses Bombardieren dazu, dann werden die Massen gegeneinandergesprudelt. Neben diesen Erklärungen gibt es noch alle möglichen Erklärungen. Es ist das nur ein Musterbeispiel, wie nicht gesehen wird heute auf das wirkliche Phänomen, sondern wie hinzugedacht werden allerlei Erklärungen. Was liegt aber dem eigentlich zugrunde? Ja, sehen Sie, dieses Hinzudenken von allerlei unbekannten Agenzien, illusorischen Energien, die allerlei tun, das erspart einem etwas. Selbstverständlich ist es ebenso hinzugedacht, was man hier als Stöße hinzutheoretisiert, wie dasjenige, was man als Fernkräfte hinzutheoretisiert. Aber es überhebt einem dieses Hinzudenken einer Annahme, die heute den Menschen furchtbar unangenehm ist. Denn sehen Sie, es ist immer so, dass man fragen muss, wenn da zwei unabhängige Weltenkörper voneinander sind, die sich nähern - die zeigen, dass es zu ihrer Wesenheit gehört, sich zu nähern - ja, dann muss etwas zugrunde liegen, was das Nähern bewirkt. Es muss irgendeine Begründung für das Nähern da sein.

Nun ist das Einfachere, man denkt Kräfte hinzu, als dass man sich sagt, es gibt noch einen anderen Weg, nämlich den Weg, die Weltenkörper nicht unabhängig voneinander zu denken. Wenn ich zum Beispiel die Hand an meine Stirne lege, so wird es mir nicht einfallen zu sagen: Meine Stirne zieht die Hand an, sondern ich werde sagen: Das ist ein innerer Akt, der ausgeübt wird durch dasjenige, was seelisch-geistig zugrunde liegt. Es ist eben meine Hand von meiner Stirne nicht unabhängig, das sind nicht eigentlich zwei Dinge, die Hand und die Stirne. Ich komme nur dazu, die Sache richtig zu betrachten, wenn ich mich als Ganzes betrachte. Ich betrachte nicht eigentlich eine Realität, wenn ich gehen würde und sagen würde: Da ist ein Kopf, da sind zwei Arme mit den Händen daran, da ist ein Rumpf, da sind zwei Beine. Nein, das ist keine vollständige Betrachtung, sondern eine vollständige Betrachtung ist es, wenn ich dem Dr. Steiner seinen einheitlichen Organismus schildere, wenn ich die Dinge so schildere, dass sie zusammengchören, das heißt, ich habe die Aufgabe, nicht bloß dasjenige, was ich sehe, zu schildern, sondern ich habe die Aufgabe, nachzudenken über die Realität desjenigen, was ich sehe. Dadurch, dass ich etwas sehe, ist es eben noch kein Reales.

Ich habe, weil ich solche Dinge oftmals auch in anderen Vorträgen andeutete, das Folgende wiederholt gesagt: Nehmen Sie einen Steinsalzwürfel. Dieser ist in gewisser Beziehung ein Ganzes - alles ist in gewisser Beziehung ein Ganzes. Er kann durch den Komplex desjenigen, was er ist innerhalb seiner sechs Flächen, kann er bestehen. Wenn Sie aber eine Rose anschauen, die Sie abgeschnitten haben, so ist diese Rose kein Ganzes; denn die kann nicht in derselben Weise durch den Komplex dessen, was in ihr ist, bestehen wie der Steinsalzwürfel, sondern die Rose kann nur bestehen dadurch, dass sie am Rosenstock ist. Daher ist die abgeschnittene Rose, obzwar Sie sie ebenso gut wahrnehmen wie den Steinsalzwürfel, eine reale Abstraktion, sie ist etwas, das für sich gar nicht als Realität angesprochen werden darf. Daraus folgt etwas außerordentlich Erhebliches, meine lieben Freunde; daraus folgt, dass wir jeder Erscheinung gegenüber nachforschen müssen, inwiefern sie eine Realität ist oder inwiefern sie nur etwas Herausgeschnittenes ist aus einem Ganzen. Wenn Sie die Sonne und den Mond oder die Sonne und die Erde für sich betrachten, so können Sie natürlich ebenso gut eine Schwerkraft hinzuerfinden, eine Gravitation, wie Sie eine Gravitation erfinden, dass meine Stirne die rechte Hand anzieht. Aber Sie betrachten Dinge, die kein Ganzes sind, sondern die Glieder des ganzen planetarischen Systems sind, wenn Sie die Sonne und die Erde und den Mond betrachten.

Das, sehen Sie, ist das Wichtigste, dass man beobachtet, inwiefern etwas ein Ganzes ist oder aus einem Ganzen herausgeschnitten ist. Unzähliges, was eigentlich ganz irrtümlich ist, entsteht dadurch, dass man dasjenige, was nur eine Teilerscheinung ist in einem andern, als ein Ganzes betrachtet. Aber sehen Sie, man hat sich durch dieses Betrachten der Teilerscheinungen und durch das Hinzuerfinden der Energien erspart, das Leben des Planetensystems zu betrachten. Das heißt, man hat darnach gestrebt, dasjenige in der Natur, was Teil ist, wie ein Ganzes zu betrachten und dann alles dasjenige, was als Wirkungen entsteht, einfach durch Theorien entstehen zu lassen.

Ich will dasjenige, was hier eigentlich vorliegt, Ihnen zusammenfassen mit dem Folgenden. sehen Sie, es kommt darauf an, dass wir uns bei allem, was uns in der Natur entgegentritt, fragen: Zu welchem Ganzen gehört es, oder ist es selbst ein Ganzes? - Und wir werden zuletzt nur in einer gewissen Beziehung Ganzheiten finden, denn auch ein Steinsalzwürfel ist nur in einer gewissen Beziehung eine Ganzheit, auch er kann nicht bestehen, ohne dass ein bestimmter Temperaturgrad da ist oder andere Verhältnisse da sind. Bei einem anderen Temperaturgrad würde er nicht bestehen können. Wir haben eigentlich überall die Notwendigkeit, nicht so zerstückelt die Natur zu betrachten, wie das gemeiniglich geschieht.

Nun, sehen Sie, nur dadurch, dass man die Natur so zerstückelt betrachtet, ist man in die Lage gekommen seit dem sechzehnten Jahrhundert, jenes sonderbare Gebilde hinzustellen, das man universelle, unorganische, leblose Natur nennt. Diese unorganische, leblose Natur gibt es nämlich gar nicht, so wenig es Ihr Knochensystem ohne Ihr, sagen wir, Blutsystem gibt. Wie das Knochensystem sich nur herauskristallisiert aus Ihrem übrigen Organismus, so gibt es nicht die sogenannte unorganische Natur ohne die zugrunde liegende ganze Natur, ohne die seelische und geistige Natur. Diese leblose Natur ist das herausgegliederte Knochensystem der ganzen Natur, und es ist unmöglich, die unorganische Natur für sich selbst zu betrachten, wie man begonnen hat seit dem sechzehnten Jahrhundert, sie für sich selbst zu betrachten in der Newton’schen Physik. Aber diese Newton’sche Physik, sie ist darauf ausgegangen, so rein herauszuschälen diese sogenannte unorganische Natur. Diese ist nur vorhanden als unorganische Natur, wenn wir selbst Maschinen machen, wenn wir selbst aus den Teilen der Natur etwas zusammensetzen. Aber das ist radikal verschieden von dem, wie das sogenannte Unorganische in der Natur selbst drinnen steht. Es gibt ein einziges wirklich Unorganisches, das sind unsere Maschinen, und zwar nur insofern wir sie durch Kombination der Naturkräfte zusammenstellen. Eigentlich nur das Zusammengestellte daran ist das Unorganische. Ein anderes Unorganisches gibt es nur als Abstraktion. Aber aus dieser Abstraktion ist die moderne Physik entstanden. Sie ist nichts weiter als Abstraktion, die dasjenige, was sie abstrahiert hat, für eine Realität hält, und die dann alles, was sich ihr darbietet, nach ihrer theoretischen Annahme erklären will.

Nun sehen Sie, in Wirklichkeit kann man aber eigentlich nicht anders, als sich seine Begriffe, seine Ideen bilden an demjenigen, was man äußerlich an der Sinneswelt gegeben hat. Nun hat man für ein Erscheinungsgebiet, ich möchte sagen, eine äußerst bequeme Tatsache gegeben: Wenn man eine Glocke anschlägt und etwa irgendeine leichte, bewegliche Vorrichtung in die Nähe der Glocke bringt, so kann man daran anschaulich machen, dass diese Glocke, welche tönt, auch in ihren Teilen schwingt. Wenn man einen Glockenton oder ein Pfeifenrohr nimmt, so kann man anschaulich machen, dass die Luft im Rohre schwingt, und man wird aus der Bewegung der Luft- oder Glockenteilchen einen Zusammenhang konstatieren können für die Tonerscheinungen, die Schallerscheinungen, zwischen den Schwingungen, die ein Körper macht oder die Luft, und den Wahrnehmungen des Tones. Für dieses Erscheinungsfeld liegt gewissermaßen offen zutage, dass wir es zu tun haben in der Umgebung mit Schwingungen, wenn wir Töne hören. Wir können uns sagen: Ohne dass die Luft in unserer Umgebung schwingt, werden wir nicht Töne hören. Es besteht also ein Zusammenhang - über ihn werden wir morgen noch sprechen - zwischen den Luftschwingungen und den Tönen.

Nun sehen Sie, wenn man nun so ganz abstrakt vorgeht, so kann man sagen: Man nimmt den Ton durch die Gehörorgane wahr. An das Gehörorgan stoßen die Luftschwingungen auf. Wenn sie aufstoßen, so nimmt man den Ton wahr. Und nun kann man, da das Auge doch auch ein Sinnesorgan ist, durch das Auge die Farben wahrnehmen und sagen: Da muss etwas Ähnliches vorliegen, also muss da auch irgendetwas von einer Schwingung anschlagen an das Auge. Aber die Luft kann es nicht sein, das stellt sich sehr bald heraus. So ist es der Äther. Also, man bildet, ich möchte sagen, durch ein reines Analogiespiel die Vorstellung aus: Wenn die Luft an unser Ohr anschlägt und wir einen Ton empfinden, so besteht ein Zusammenhang zwischen der schwingenden Luft und der Tonempfindung. Wenn der hypothetische Äther mit seinen Schwingungen an unser Auge anstößt, so vermittelt sich in ähnlicher Weise eine Lichtempfindung durch diesen schwingenden Äther. Wie er schwingt, dieser Äther, darauf sucht man zu kommen durch Erscheinungen, wie wir sie experimentell in diesen Vorträgen kennengelernt haben. Das heißt, man denkt sich eine Ätherwelt und rechnet aus, wie es in diesem Äthermeer zugehen soll. Man rechnet etwas aus, was sich auf irgendeine Entität bezieht, die man selbstverständlich nicht wahrnehmen kann, die man nur theoretisch annehmen kann.

Nun ist, wie Sie schon aus den Kleinigkeiten gesehen haben, die wir experimentell durchgemacht haben, nun ist dasjenige, was innerhalb der Lichtwelt vorgeht, etwas außerordentlich Kompliziertes, und bis in gewisse Zeiten der neueren physikalischen Entwicklung hat man angenommen, hinter all dem, oder eigentlich in all dem, müsste man sagen, was sich da als Lichtwelt, als Farbenwelt auslebt, ist ein schwingender Äther, ein feiner elastischer Stoff. Da man die Gesetze, wonach elastische Körper aufeinander aufprallen und sich abstoßen, leicht kennen kann, so kann man berechnen, was da diese kleinen schwingenden Kobolde im Äther tun, indem man sie einfach als elastische kleine Körper betrachtete, indem man den Äther gewissermaßen als etwas in sich Elastisches sich vorstellte. Man kann da kommen bis zu Erklärungen jener Erscheinungen, die wir uns vorgeführt haben, wo wir ein Spektrum bilden. Es werden einfach verschiedene Arten von Ätherschwingungen auseinandergelöst, die dann in den verschiedenen Farben uns erscheinen. Man kann auch durch ein gewisses Rechnen dahin kommen, jenes Auslöschen, das wir uns vorgestern vorgeführt haben, zum Beispiel der Natriumlinie, sich aus der Elastizität des Äthers heraus begreiflich zu machen. Nun aber sind in der neueren Zeit zu diesen Erscheinungen andere hinzugetreten. Man kann ein Lichtspektrum entwerfen, die Natriumlinie darinnen auslöschen oder erzeugen - wie Sie wollen -, die schwarze Linie erzeugen, und man kann dann außerdem, dass man dann diesen ganzen Komplex erzeugt hat, man kann auch noch in den Lichtzylinder in einer bestimmten Weise den Elektromagneten hineinwirken lassen, und siehe da, es geschieht eine Wirkung von dem Elektromagneten auf die Lichterscheinung. Die Natriumlinie wird an ihrer Stelle ausgelöscht und zwei andere zum Beispiel entstehen, rein durch die Wirkung der Elektrizität, die immer etwas mit magnetischen Wirkungen verknüpft ist. Also, es entsteht eine Wirkung desjenigen, was wir als elektrische Kräfte beschrieben bekommen, auf jene Vorgänge, die man als Lichterscheinungen sieht und hinter denen man sich den bloßen [mechanisch aufgefassten] elastischen Äther denkt. Dass man da die Wirkung der Elektrizität auf diese Lichterscheinung wahrgenommen hart, das führte nun dazu, eine Verwandtschaft anzunehmen zwischen den Licht- und den magnetisch-elektrischen Erscheinungen. So ist in der neueren Zeit ein wenig Erschütterung gekommen. Früher konnte man sich aufs Faulbett legen, weil man diese Wechselwirkung noch nicht wahrgenommen hatte. Jetzt aber musste man sich sagen: Es muss das eine mit dem anderen etwas zu tun haben. - Das hat dazu geführt, dass eine große Anzahl von Physikern gegenwärtig in diesem, was sich da als Licht ausbreitet, auch eine elektromagnetische Wirkung sehen, dass es eigentlich elektromagnetische Strahlen sind, was da durch den Raum geht.

Nun denken Sie sich, was da passiert ist. Da ist Folgendes passiert: Man hat früher angenommen, man weiß, was hinter den Licht- und Farbenerscheinungen ist: Schwingungen, Undulationen im [mechanisch aufgefassten] elastischen Äther. Jetzt ist es [dahin] gekommen dadurch, dass man die Wechselwirkungen zwischen Licht und Elektrizität kennengelernt hat, dass man das, was da eigentlich schwingt, als Elektrizität ansehen muss, als fortstrahlende Elektrizität — bitte fassen Sie die Sache ganz genau!

Das Licht, die Farben will man erklären. Diese führt man zurück auf schwingenden Äther. Da geht etwas durch den Raum. Jetzt glaubte man, man hätte gewusst, was das Licht eigentlich ist - Schwingungen des elastischen Äthers. Jetzt kam man in die Notwendigkeit zu sagen: Was aber die Schwingungen des elastischen Äthers sind, sind elektrisch-magnetische Strömungen. Nun weiß man sogar genauer als früher, was das Licht ist. Es sind elektrisch-magnetische Strömungen; nur weiß man nicht, was diese elektrisch-magnetischen Strömungen sind. Man hat also den schönen Weg gemacht, eine Hypothese anzunehmen, das Sinnliche durch das unbekannte Übersinnliche des undulierenden Äthers zu erklären. Man ist nach und nach gezwungen worden, dieses Übersinnliche wiederum auf ein Sinnliches zurückzuführen, aber sich zu gleicher Zeit zu gestehen, dass man nicht weiß, was das nun ist. Es ist in der Tat ein höchst interessanter Weg, der da beschritten worden ist von einem hypothetischen Suchen eines Unbekannten zu dem Erklären dieses Unbekannten durch ein anderes Unbekanntes. Der Physiker Kirchhoff hat sich eigentlich entsetzt gesagt: Wenn diese neueren Erscheinungen notwendig machen, dass man an den Äther mit seinen Schwingungen nicht mehr glauben kann, dann ist das kein Vorteil für die Physik, und Helmholtz zum Beispiel, als er diese Erscheinungen kennenlernte, der sagte: Gut, man kommt natürlich nicht darüber hinweg, das Licht als eine Art elektrisch-magnetischer Strahlung zu betrachten und dann muss man halt diese wieder zurückführen auf die Schwingungen des elastischen Äthers. Zuletzt wird es doch so kommen. — Das Wesentliche ist, dass man eine ehrliche Undulationserscheinung, das Schwingen der Luft, wenn wir Töne wahrnehmen, rein analogisch übertragen hat in ein Gebiet hinein, in dem die ganze Annahme eben durchaus eine hypothetische ist.

Ich musste Ihnen diese prinzipielle Auseinandersetzung geben, damit wir nun rasch hintereinander durchlaufen können das Wichtigste, was uns die Erscheinungen darbieten, die wir dann betrachten wollen. Ich habe vor, in den Stunden, die noch bleiben, nachdem wir uns diese Untergrundlage jetzt gebildet haben, mit Ihnen zu besprechen die Schallerscheinungen, die Wärmeerscheinungen und die elektromagnetischen Erscheinungen und dasjenige, was diese [Erscheinungen an] Erklärungen wiederum zurückwerfen auf die optischen Erscheinungen.

Sixth Lecture

My dear friends!

Today, I would like to continue discussing the principles I began the day before yesterday, because if we start from the experiences gained in the light, we will be able to continue observing and understanding the phenomena that may arise in the other natural phenomena we still want to consider. I will therefore insert a more fundamental consideration today and postpone the experimental part until tomorrow, because we need to determine more precisely how we want to proceed methodically. It is really a matter of carrying out precisely what is factually present in natural phenomena. And light actually provides the most clues for pursuing this.

Historically, people began to study light phenomena relatively late. In fact, the whole way of thinking about physics as taught in our schools today hardly goes back beyond the sixteenth century. Before the sixteenth century, the way of thinking about physical phenomena was radically different. Today, however, this way of thinking is so strongly absorbed in school that it becomes extremely difficult for those who have gone through a certain type of physics education to return to the purely factual. One must first become accustomed to feeling, to sensing, the purely factual—and I ask you not to take this expression in its trivial sense. You really have to get used to it. Therefore, I would like to start by comparing the usual school-based way of thinking in a specific case with what you can actually gain by properly pursuing the facts. I will start with a single case.

Suppose you have a cross-section of a glass plate here. Through this glass plate, you would observe something luminous here. I will draw a diagram of this and, instead of the light source, simply draw a glowing circle here. Now, if you think back to your school days, you will remember what you learned about observing this phenomenon through your eyes. You were told that rays emanated from this light source. Let us reflect on a specific direction of the eye. Rays emanated from this luminous object, which means that in the direction of this ray, light penetrates, as one says, from a thinner medium into a denser medium. If you simply look through it and then compare what you see after looking through the plate with what is there, you can see that the luminous object has shifted and appears in a different place than it does when you look at it without the plate. Now, it is said that this is because the light is refracted. It is said that when light enters a denser medium from a thinner one, in order to determine the direction in which the light is refracted, one must draw a so-called ray of incidence, and then, if the light were to continue its path without being impeded by such a denser medium, it would go in this [dashed] direction; but the light is refracted [upon entering the denser medium], as they say, and in this case refracted to the incident ray, to this perpendicular line that is drawn at the point of incidence. And when it emerges again, the light, if one follows the ray of light as it passes through the denser medium, one would have to say again: Here again, a perpendicular must be erected; here, if the ray were to continue on its path, it would go in this direction; but now it is refracted again, in this case by the perpendicular, and so strongly that its direction is now parallel to the previous one. When the eye looks in this way, it extends the last direction and shifts the luminous object a distance higher, so that when one looks through it in this way, one must assume: Here the light enters, is refracted twice, once by the incident ray and once by the incident ray, and because the eye has the inner ability—or the soul or some demon, as one might say— it is displaced into space, to a different point in space than it would appear if one did not see it through a refracting medium, as they say.

Now, however, it is important to note the following. You see, if you try the following, if you try to make a slight difference between a somewhat, let's say, brighter spot and a somewhat darker spot, and look at this through the same denser medium, you will not only find the brighter spot shifted upwards, but you will also find the somewhat darker spot shifted upwards. You will find that the entire complex that you see here has been shifted. Please note this carefully. Here we see a darker area that is bordered by a lighter area, and we see that the darker area has been shifted upward, and because it has a lighter end, we also see that it has been shifted upward. You see, when you place such a complex, a darker and a lighter one, then you have to say: Actually, only the lighter one is shifted as the upper boundary. However, when you abstract a light spot, you often speak as if only this light spot were shifted. But that is absurd. But even if I look at this light spot here, it is not true that only it is being shifted; in reality, what I call nothingness down there is also being shifted upward.

What is being shifted is never something that I can define so abstractly. So if I do the experiment that Newton did, if I let in a cone of light that is deflected by the prism, it is not true that only the cone of light is shifted, but also that which is bounded by the cone of light from above and below is shifted along with it. I should never speak of any light rays or the like, but rather of displaced light images or light spaces. And if I want to speak of isolated light somewhere, I cannot speak of it in such a way that I refer anything in theory to this isolated light, but I must speak in such a way that I refer what I say to what is adjacent to it at the same time.

Only if you think this way can you really feel what is actually happening when you are confronted with the emergence of color phenomena. Otherwise, your way of thinking simply gives you the impression that the colors somehow arise from the light. You have previously decided that you are only dealing with light. In reality, you are not dealing with light, but with something bright that is bordered on one side or the other by darkness. And just as this brightness is shifted as spatial light, so too is the darkness shifted. But what is this darkness, what is it actually? You see, this darkness must also be grasped as something entirely real. And everything that has entered modern physics since around the sixteenth century could only do so because people never observed things mentally at the same time, because they always observed things only according to their external appearance and then invented all kinds of theories to explain this appearance.

You cannot deny that when you look at light, sometimes it is stronger and sometimes weaker. There is stronger and weaker light. Now it is a matter of understanding how this light, which can be stronger and weaker, actually relates to darkness. The ordinary physicist today thinks there is stronger and weaker light, all possible degrees of light according to its intensity, but only one darkness, which is simply there when there is no light. So black is the same in every way. Just as there is not only one brightness, there is not only one darkness, and to say that there is only one darkness is as one-sided as saying: I know four people. One of them has a fortune of five hundred dollars, the other has a fortune of a thousand dollars. So one has a greater fortune than the other. But the third has five hundred dollars in debt and the fourth has a thousand dollars in debt. But why should I bother about this difference? It's the same thing, after all. Both of them have debts. I want to distinguish between the degrees of wealth, but I don't want to distinguish between the degrees of debt; debt is debt. In this case, the difference is obvious because the effect of five hundred marks of debt is less than the effect of a thousand marks of debt. But with darkness, we behave differently: light has different degrees of brightness, but darkness is darkness. It is this failure to advance to qualitative thinking that so greatly hinders us from finding the bridge between the spiritual [on the one hand] and the physical [on the other]. When a room is filled with light, it is filled with light of a certain intensity; when a room is filled with darkness, it is filled with darkness of a certain intensity, and one must progress from the merely abstract room to the room that is not abstract but is in some way positively filled with light or negatively filled with darkness. One can therefore stand opposite the light-filled space and call it qualitatively positive. One can stand opposite the dark space and find it qualitatively negative in relation to the lighting conditions. However, both can be addressed with a certain degree of intensity, with a certain strength.

But now, if one asks oneself: Yes, how does this positive filling of space differ from the negative filling of space in our perception? - This positive filling of space, we need only remember what it is like when we wake up, surrounded by light, uniting our subjective experience with what floods us as light, we only need to compare this sensation with what we feel when we are surrounded by darkness, and we will find — I ask you now to focus very closely on this with your eyes or your mind — we will have to realize that, purely in terms of sensation, there is a difference between being immersed in a light-filled room and being immersed in a dark room. Now, one can only approach these things through comparison.

You see, you can compare the sensation you have when you find yourself in a light-filled room with a kind of sucking in of light by our soul. We feel enriched when we are in a light-filled room. It is a sucking in of light. What about darkness? There is exactly the opposite sensation. Darkness sucks us in, it sucks us out, we have to surrender to it, we have to give something to it. So we can say that the effect of light on us is communicative, while the effect of darkness on us is actually sucking. And so we must also distinguish between light and dark colors. The lighter colors have something that moves us, that communicates with us; the darker colors have something that sucks us in, to which we must surrender ourselves. This leads us to say: something from the outside world communicates with us through the effect of light; something is taken away from us, we are sucked out by the effect of darkness.

We are – as I have already pointed out in my lectures – we are also sucked out in a certain way in relation to our consciousness when we fall asleep. That is when our consciousness ceases. It is a very similar phenomenon to the cessation of our consciousness when we approach the darker colors, the blue and violet, from the increasingly lighter colors. And if you remember what I have told you in recent days about the relationship between our soul and the mass, if you remember this falling asleep into the mass, this absorption of consciousness by the mass, then you will feel something similar through the absorption of consciousness by the darkness, and you will discover the inner relationship between the darkness of the room and that other fullness of the room which is called matter and which manifests itself as mass, that is to say, we will have to seek a way from the phenomena of light to the phenomena of material existence, and we have already paved the way by first seeking out the fleeting light phenomena of phosphorescence and fluorescence, and then solid light phenomena. In solid light phenomena, we have permanent colors. We cannot consider these things individually; we must first of all place the whole complex of things before us.

Now it is a matter of realizing the following. You see, when you are in a light-filled room, you unite in a certain way with this light-filled room. One could say that something within us floats out into this light-filled space and unites with it. But if we reflect just a little on what is really happening, we will find a great difference between this union with the immediate light-flooded environment and the union that we as human beings also have, namely with the warmth of the environment. We participate in this state of warmth in our surroundings; we participate in it by also perceiving something like a polarity in this state of warmth, the warm and the cold. But we cannot help perceiving a difference between feeling ourselves in the state of warmth in our surroundings and feeling ourselves in the state of light in our surroundings. This difference has not only been completely lost in modern physics since the sixteenth century; one could say that not only has the impartiality in distinguishing between the experience of light and the experience of heat been lost, but that efforts have been made to blur such differences in some way. Anyone who really considers this difference, which is actually quite simple, between experiencing the state of warmth and experiencing the state of light in the environment, cannot ultimately help but distinguish that we are involved in the state of warmth with our physical body and in the state of light with our etheric body.