The Light Course

GA 320

30 December 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture VII

My dear Friends,

We will begin today with an experiment bearing upon our studies of the theory of colour. As I have said before, all I can give you in this Course can only be improvised and aphoristic. Hence too I cannot keep to the conventional categories of the Physics textbooks,—in saying which I do not mean to imply that it would be better if I did. In the last resort I wish to lead you to a certain kind of insight into Science, and you must look on all that I bring forward in the meantime as a kind of preparation. We are not advancing in the usual straight line. We try to gather up the diverse phenomena we need, forming a circle as it were,—then to move forward from the circumference towards the centre.

You have seen that wherever colours arise there is a working-together of light and darkness. What we now have to do is to observe as many phenomena as we can before we try to theorize. We want to form a true conception of what underlies this interplay of light and darkness. Today I will begin by shewing you the phenomenon of coloured shadows, as they are called.

Here are two candles (Figure VIIa),—candles as sources of light—and an upright rod which will throw shadows on this screen. You see two shadows, without perceptible colour. You only need to take a good look at what is here before you, you will be bound to say: the shadow you are seeing on the right is the one thrown by the left-hand source of light. It is produced, in that the light from this source is hidden by the rod. Likewise the shadow on the left arises where the light from the right-hand source is covered. Relatively dark spaces are created,—that is all. Where the shadow is, is simply a dark space. Moreover, looking at the surface of the screen apart from the two bands of shadow, you will agree it is illumined by both sources of light. Now I will colour the one (the left-hand) light. I make the light go through a plate of coloured glass, so that this one of the lights is now coloured—that is, darkened to some extent. As a result, you will see that the shadow of the rod, due to this left-hand source of light—the one which I am darkening to red—this shadow on the right becomes green. It becomes green just as a purely white background does when you look sharply for example at a small red surface for a time, then turn your eye away and look straight at the white. You then see green where you formerly saw red, though there is nothing there. You yourself, as it were, see the green colour on to the white surface. In such a case, you are seeing the green surface as an after-image in time of the red which you were seeing just before, when you exposed your eye to the red surface that was actually there. And so in this case: when I darken the source of light to red, you see the shadow green. What was mere darkness before, you now see green. And now I darken the same source of light to green,—the shadow becomes red. And when I darken it to blue, an orange shadow is produced. If I should darken it to violet, it would give yellow.

And now consider please the following phenomenon; it is most important, therefore I mention it once more. Say in a room you have a red cushion with a white crochet cover, through the rhombic-patterned apertures of which the red of the cushion shines through. You look at the red rhombic pattern and then look away to the white. On the white ground you see the same lattice-work in green. Of course it isn't there, but your own eye is active and makes an after-effect, which, as you focus on the white, generates the green, “subjective” images, as one is wont to call them.

Goethe was familiar with this phenomenon, and also knew that of the coloured shadows. I darken this source of light and get green, said Goethe to himself, and he went on to describe it somewhat as follows: When I darken this source of light, the white screen as a whole shines red. I am not really seeing the white screen; what I see is a reddish-shining colour. In fact I see the screen more or less red. And as an outcome—as with the cushion mentioned just now—I with my own eye generate the contrasting colour. There is no real green here. I only see the green incidentally, because the screen as a whole now has a reddish colour.

However, this idea of Goethe's is mistaken, as you may readily convince yourselves. Take a little tube and look through it, so that you only see the shadow; you will still see it green. You no longer see what is around it, you only see the green which is objectively there at the place you look at. You can convince yourself by this experiment that the green really is objective. It remains green, hence the phenomenon cannot be one of mere contrast but is objective. We cannot now provide for everyone to see it, but as the proverb says, durch zweier Zeugen Mund wird alle Wahrheit kund—two witnesses will always tell the truth. I will produce the phenomenon and you must now look through on to the green strip. It stays green, does it not? So with the other colour: if I engendered red by means of green, it would stay red. Goethe in this instance was mistaken, and as the error is incorporated in his Theory of Colour it must of course be rectified.1After some careful experiments on a later occasion, Dr. Steiner admitted that there is an error here. (See the Translator's Note on this passage.) He also recommended chemical and photographic researches to show the real nature of coloured shadows.

Now to begin with, my dear Friends, along with all the other phenomena which we have studied, I want you to take note of the pure fact we have just demonstrated. In the one case we get a grey, a bit of darkness, a mere shadow. In the other case we permeate the shadow, so to speak, with colour. The light and darkness then work together in a different way. We note that by darkening the light with red the objective phenomenon of the green is called forth. Now side by side with this, I also drew your attention to what appears, as is generally said, “subjectively”. We have then, in the one case, what would be called an “objective” phenomenon, the green that stays there on the screen; though not a permanently fixed colour, it stays as long as we create the requisite conditions. Whilst in the other case we have something, as it were, subjectively conditioned by our eye alone. Goethe calls the green colour that appears to me when I have been exposing my eye for a time to red, the colour or coloured after-image that is evoked or “required” (gefordert),—called forth by reaction.

Now there is one thing we must insist on in this connection. The “subjective, objective” distinction, between the colour that is temporarily fixed here and the colour that seems only to be called forth as an after-image by the eye, has no foundation in any real fact. When I am seeing red through my eyes, as at this moment, you know there is all the physical apparatus we were describing a few days ago; the vitreous body, the lens, the aqueous humour between the lens and the cornea,—a highly differentiated physical apparatus. This physical apparatus, mingling light and darkness as it does in the most varied ways with one another, is in no other relation to the objectively existent ether than all the apparatus we have here set up—the screen, the rod and so on. The only difference is that in the ^one case the whole apparatus is my eye; I see an objective phenomenon through my own eye. It is the same objective phenomenon which I see here, only that this one stays. By dint of looking at the red, my eye will subsequently react with the “required” colour—to use Goethe's term,—the eye, according to its own conditions, being gradually restored to its neutral state. But the real process by means of which I see the green when I see it thus, as we are wont to say, “subjectively”—through the eye alone,—is in no way different from what it is when I fix the colour “objectively” as in this experiment.

Therefore I said in an earlier lecture: You, your subjective being, do not live in such a way that the ether is there vibrating outside of you and the effect of it then finds expression in your experience of colour. No, you yourself are swimming in the ether—you are one with it. It is but an incidental difference, whether you become at one with the ether through this apparatus out here or through a process that goes on in your own eye. There is no real nor essential difference between the green image engendered spatially by the red darkening of the light, and the green afterimage, appearing afterwards only in point of time. Looked at objectively there is no tangible difference, save that the process is spatial in the one case and temporal in the other. That is the one essential difference. A sensible and thoughtful contemplation of these things will lead you no longer to look for the contrast, “subjective and objective” as we generally call it, in the false direction in which modern Science generally tries to see it. You will then see it for what it really is. In the one case we have rigged-up an apparatus to engender colour while our eye stays neutral—neutral as to the way the colours are here produced—and is thus able to enter into and unite with what is here. In the other case the eye itself is the physical apparatus. What difference does it make, whether the necessary apparatus is out there, or in your frontal cavity? We are not outside the things, then first projecting the phenomena we see out into space. We with our being are in the things; moreover we are in them even more fully when we go on from certain kinds of physical phenomena to others. No open-minded person, examining the phenomena of colour in all their aspects, can in the long run fail to admit that we are in them—not, it is true, with our ordinary body, but certainly with our etheric body and thereby also with the astral part of our being.

And now let us descend from Light to Warmth. Warmth too we perceive as a condition of our environment which gains significance for us whenever we are exposed to it. We shall soon see, however, that as between the perception of light and the perception of warmth there is a very significant difference. You can localize the perception of light clearly and accurately in the physical apparatus of the eye, the objective significance of which I have been stressing. But if you ask yourself in all seriousness, “How shall I now compare the relation I am in to light with the relation I am in to warmth?”, you will have to answer, “While my relation to the light is in a way localized—localized by my eye at a particular place in my body,—this is not so for warmth. For warmth the whole of me is, so to speak, the sense-organ. For warmth, the whole of me is what my eye is for the light”. We cannot therefore speak of the perception of warmth in the same localized sense as of the perception of light. Moreover, precisely in realizing this we may also become aware of something more.

What are we really perceiving when we come into relation to the warmth-condition of our surroundings? We must admit, we have a very distinct perception of the fact that we are swimming in the warmth-element of our environment. And yet, what is it of us that is swimming? Please answer for yourselves the question: What is it that is swimming when you are swimming in the warmth of your environment? Take then the following experiment. Fill a bucket with water just warm enough for you to feel it lukewarm. Put both your hands in—not for long, only to test it. Then put your left hand in water as hot as you can bear and your right hand in water as cold as you can bear. Then put both hands quickly back again into the lukewarm water. You will find the lukewarm water seeming very warm to your right hand and very cold to your left. Your left hand, having become hot, perceives as cold what your right hand, having become cold, perceives as warmth. Before, you felt the same lukewarmness on either side. What is it then? It is your own warmth that is swimming there. Your own warmth makes you feel the difference between itself and your environment. What is it therefore, once again,—what is it of you that is swimming in the warmth-element of your environment? It is your own state-of-warmth, brought about by your own organic process. Far from this being an unconscious thing, your consciousness indwells it. Inside your skin you are living in this warmth, and according to the state of this your own warmth you converse—communicate and come to terms—with the element of warmth in your environment, wherein your own bodily warmth is swimming. It is your warmth-organism which really swims in the warmth of your environment.—If you think these things through, you will come nearer the real processes of Nature—far nearer than by what is given you in modern Physics, abstracted as it is from all reality.

Now let us go still farther down. We experience our own state-of-warmth by swimming with it in our environment-of-warmth. When we are warmer than our environment we feel the latter as if it were drawing, sucking at us; when we are colder we feel as though it were imparting something to us. But this grows different again when we consider how we are living in yet another element. Once more then: we have the faculty of living in what really underlies the light; we swim in the element of light. Then, in the way we have been explaining, we swim in the element of warmth. But we are also able to swim in the element of air, which of course we always have within us. We human beings, after all, are to a very small extent solid bodies. More than 90% of us is just a column of water, and—what matters most in this connection—the water in us is a kind of intermediary between the airy and the solid state. Now we can also experience ourselves quite consciously in the airy element, just as we can in the element of warmth. Our consciousness descends effectively into the airy element. Even as it enters into the element of light and into the element of warmth, so too it enters into the element of air. Here again, it can “converse”, it can communicate and come to terms with what is taking place in our environment of air. It is precisely this “conversation” which finds expression in the phenomena of sound or tone. You see from this: we must distinguish between different levels in our consciousness. One level of our consciousness is the one we live with in the element of light, inasmuch as we ourselves partake in this element. Quite another level of our consciousness is the one we live with in the element of warmth, inasmuch as we ourselves, once more, are partaking in it. And yet another level of our consciousness is the one we live with in the element of air, inasmuch as we ourselves partake also in this. Our consciousness is indeed able to dive down into the gaseous or airy element. Then are we living in the airy element of our environment and are thus able to perceive the phenomena of sound and of musical tone. Even as we ourselves with our own consciousness have to partake in the phenomena of light so that we swim in the light-phenomena of our environment; and as we have to partake in the element of warmth so that we swim also in this; so too must we partake in the element of air. We must ourselves have something of the airy element within us in a differentiated form so that we may be able to perceive—when, say, a pipe, a drum or a violin is resounding—the differentiated airy element outside us. In this respect, my dear Friends, our bodily nature is indeed of the greatest interest even to outward appearance. There is our breathing process: we breathe-in the air and breathe it out again. When we breathe-out the air we push our diaphragm upward. This involves a relief of tension, a relaxation, for the whole of our organic system beneath the diaphragm. In that we raise the diaphragm as we breathe-out and thus relieve the organic system beneath the diaphragm, the cerebrospinal fluid in which the brain is swimming is driven downward. Here now the cerebrospinal fluid is none other than a somewhat condensed modification, so to speak, of the air, for it is really the out-breathed air which brings about the process. When I breathe-in again, the cerebrospinal fluid is driven upward. I, through my breathing, am forever living in this rhythmic, downward-and-upward, upward-and-downward undulation of the cerebrospinal fluid, which is quite clearly an image of my whole breathing process. In that my bodily organism partakes in these oscillations of the breathing process, there is an inner differentiation, enabling me to perceive and experience the airy element in consciousness. Indeed by virtue of this process, of which admittedly I have been giving only a rather crude description, I am forever living in a rhythm-of-life which both in origin and in its further course consists in an inner differentiation of the air.

In that you breathe and bring about—not of course so crudely but in a manifold and differentiated way—this upward and downward oscillation of the rhythmic forces, there is produced within you what may itself be described as an organism of vibrations, highly complicated, forever coming into being and passing away again. It is this inner organism of vibrations which in our ear we bring to bear upon what sounds towards us from without when, for example, the string of a musical instrument gives out a note. We make the one impinge upon the other. And just as when you plunge your hand into the lukewarm water you perceive the state-of-warmth of your own hand by the difference between the warmth of your hand and the warmth of the water, so too do you perceive the tone or sound by the impact and interaction of your own inner, wondrously constructed musical instrument with the sound or tone that comes to manifestation in the air outside you. The ear is in a way the bridge, by which your own inner “lyre of Apollo” finds its relation, in ever-balancing and compensating interplay, with the differentiated airy movement that comes to you from without. Such, in reality is hearing. The real process of hearing—hearing of the differentiated sound or tone—is, as you see, very far removed from the abstraction commonly presented. Something, they say, is going on in the space outside, this then affects my ear, and the effect upon my ear is perceived in some way as an effect on my subjective being. For the “subjective being” is at long last referred to—described in some kind of demonology—or rather, not described at all. We shall not get any further if we do not try to think out clearly, what is the underlying notion in this customary presentation. You simply cannot think these notions through to their conclusion, for what this school of Physics never does is to go simply into the given facts.

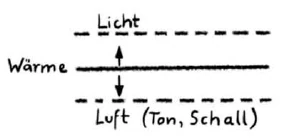

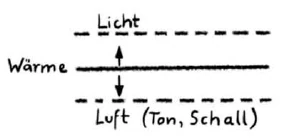

Thus in effect we have three stages in man's relation to the outer world—I will describe them as the stage of Light, the stage of Warmth, and that of Tone or Sound. There is however a remarkable fact in this connection. Look open-mindedly at your relation to the element of light—your swimming in the element of light—and you will have to admit: It is only with your etheric body that you can live in what is there going on in the outer world. Not so when you are living in the element of warmth. You really live in the warmth-element of your environment with your whole bodily nature. Having thus contemplated how you live in light and warmth, look farther down—think how you live in the element of tone and sound—and you will recognize: Here you yourself are functioning as an airy body. You, as a living organism of air, live in the manifoldly formed and differentiated outer air. It is no longer the ether; it is external physical matter, namely air. Our living in the warmth-element is then a very significant border-line. Our life in the element of warmth is for our consciousness a kind of midway level—a niveau. You recognize it very clearly in the simple fact that for pure feeling and sensation you are scarcely able to distinguish outer warmth from inner warmth. Your life in the light-element however lies above this level:—

For light, you ascend as it were into a higher, into an etheric sphere, therein to live with your consciousness. On the other hand you go beneath this level, beneath this niveau, when in perceiving tone or sound you as a man-of-air converse and come to terms with the surrounding air. While upon this niveau itself (in the perceiving of warmth) you come to terms with the outer world in a comparatively simple way.

Now bring together what I have just been shewing with what I told you before out of Anatomy and Physiology. Then you will have to conceive the eye as the physical apparatus, to begin with. Indeed the farther outward you go, the more physical do you find the eye to be; the farther in you go, the more is it permeated with vitality. We therefore have in us a localized organ—the eye—with which to lift ourselves above a certain level or niveau. Upon this actual niveau we live as it were on equal terms with our environment; with our own warmth we meet the warmth of our environment and perceive the difference, whatever it may be. Here we have no such specialized organ as the eye; the whole of us, we ourselves in some way, become the sense-organ. And we dive down beneath this level or niveau when functioning as airy man,—when we converse and come to terms with the differentiated outer air. Here once again the “conversation” becomes localized—localized namely in this “lyre of Apollo”, in this rhythmic play of our whole organism, of which the rhythmic play of our spinal fluid is but the image and the outcome. Here then again we have something localized—only beneath the niveau this time, whilst in the eye it is above this midway level.

The Psychology of our time is, as you see, in an even sorrier position than the Physiology and Physics, and we can scarcely blame our physicists if they speak so unrealistically of what is there in the outer world, since they get so little help from the psychologists. The latter, truth to tell, have been only too well disciplined by the Churches, which have claimed all the knowledge of the soul and Spirit for their own domain. Very obediently the psychologists restrict their study to the external apparatus, calling this external apparatus “Man”. They speak no doubt of soul and mind, or even Spirit, but in mere words, mere sounding phrases, until Psychology becomes at last a mere collection of words. For in their books they never tell us what we are to understand by soul and mind and Spirit,—how we should conceive them. So then the physicists come to imagine that the light is there at work quite outside us; this light affects the human eye. The eye somehow responds; at any rate it receives an impression. This then becomes subjective inner experience. Now comes the veriest tangle of confused ideas. The physicists allege it to be much the same as to the other sense-organs. They follow what they learn from the psychologists. In text-books of Psychology you will generally find a chapter on the Science of the Senses, as though such a thing as “sense” or “sense-organ” in general existed. But if you put it to the test: study the eye,—it is completely different from the ear. The one indeed lies above and the other beneath the “niveau” which we explained just now. In their whole form and structure, eye and ear prove to be totally diverse organs. This surely is significant and should be borne in mind. Today now we will go thus far; please think it over in the meantime. Taking our start from this, we will tomorrow speak of the science of sound and tone, whence you will then be able to go on into the other realms of Physics.

There is however one more thing I want to demonstrate today. It is among the great achievements of modern Physics; it is in truth a very great achievement. You know that if you merely rub a surface with your finger—exerting pressure, using some force as you do so,—the surface will get warm. By this exertion you have generated warmth. So too by calling forth out-and-out mechanical processes in the objective world external to yourself, you can engender warmth. Now as a basis for tomorrow's lecture, we have rigged up this apparatus. If you were now to look and read the thermometer inside, you would find it a little over 16° C. The vessel contains water. Immersed in the body of water is a kind of drum or flywheel which we now bring into quick rotation, thus doing mechanical work, whirling the portions of the water all about, stirring it thoroughly. After a time we shall look at the thermometer again and you will see that it has risen. By dint of purely mechanical work the water will have gained in warmth. That is to say, warmth is produced by mechanical work. It was especially Julius Robert Mayer who drew attention to this fact, which was then worked out more arithmetically. Mayer himself derived from it the so-called “mechanical equivalent of warmth” (or of heat). Had they gone on in the same spirit in which he began, they would have said no more than that a certain number, a certain figure expresses the relation which can be measured when warmth is produced by dint of mechanical work or vice-versa. But they exploited the discovery in metaphysical fashion. Namely they argued: If then there is this constant ratio between the mechanical work expended and the warmth produced, the warmth or heat is simply the work transformed. Transformed, if you please!—where in reality all that they had before them was the numerical expression of the relation between the two.

Siebenter Vortrag

Meine Lieben Freunde!

Wir wollen heute beginnen mit einem Versuch, der noch knüpfen soll an unsere Betrachtungen über die Farbenlehre. Es ist ja, wie gesagt, durchaus nur möglich, dass ich Ihnen Improvisiertes, gewissermaßen Aphoristisches in diesen Vorträgen vorbringe. Daher muss ich auch die gewöhnlichen Kategorien, die Sie in den Physikbüchern finden, vermeiden. Ich will nicht sagen, dass es deshalb besser wäre, wenn ich diese Kategorien einhalten könnte, allein ich möchte Sie ja zuletzt zu einer bestimmten naturwissenschaftlichen Einsicht führen, und alles dasjenige, was ich vorher vorbringe, betrachten Sie als eine Art Vorbereitung, die nicht so gemacht wird, dass man, wie es sonst üblich ist, in gerader Linie fortschreitet, sondern dass man die Erscheinungen zusammensucht, die man braucht, gewissermaßen einen Kreis schafft und dann nach dem Mittelpunkt vordringt.

Sie haben gesehen, dass wir es zu tun haben, wenn Farben entstehen, mit einem Zusammenwirken von Licht und Finsternis. Nun handelt es sich darum, dass man möglichst viele wirkliche Erscheinungen beobachtet, bevor man sich eine Anschauung bildet über das, was in dieser Wechselwirkung von Licht und Finsternis eigentlich zugrunde liegt. Und da möchte ich Ihnen heute zunächst dieses Phänomen der sogenannten farbigen Schatten vorführen.

Ich werde von zwei Lichtquellen aus, die diese Kerzchen hier darstellen, durch diesen Stab Ihnen Schatten auf dem Schirm erzeugen, der Ihnen gegenübersteht. Sie sehen zwei Schatten, welche eine deutliche Farbe nicht haben. Sie brauchen nur dasjenige, was hier ist, ordentlich anzuschauen, so werden Sie sich sagen müssen: Der Schatten, den Sie hier rechts sehen, ist natürlich der Schatten, der von dieser Lichtquelle [links] ausgeht und der dadurch entsteht, dass das Licht von dieser Quelle ausgeht und durch den Stab verdeckt wird. Und der Schatten [links] ist derjenige, der entsteht, indem das Licht unserer rechten Lichtquelle verdeckt wird. Wir haben es also hier im Grunde genommen nur zu tun mit der Erzeugung gewisser dunkler Räume. Das, was im Schatten liegt, ist eben dunkler Raum. Nun können Sie noch sehen: Wenn Sie die Fläche des Schirmes außerhalb der beiden Schattenbänder sich ansehen, so werden Sie sich sagen: Sie [wird] beleuchtet von den zwei Lichtquellen. Sodass wir es also da zu tun haben mit Licht.

Ich will nun das eine [linke] der Lichter färben, das heißt, ich will es gehen lassen durch eine farbige Glasplatte, sodass das eine der Lichter gefärbt wird. Wir wissen, was da geschieht: Es wird das eine der Lichter abgedunkelt. So! Aber jetzt sehen Sie, dass durch dieses Abdunkeln der Schatten [rechts], welcher durch den Stab bewirkt wird von meiner linken Lichtquelle aus, deren Licht ich gerade abdunkle und rötlich mache, dass dieser [rechte] Schatten grün wird. Er wird so grün, wie grün wird - wenn Sie zum Beispiel scharf an eine kleine rote Fläche hinschauen, dann von dieser roten Fläche das Auge abwenden und dann einfach in gerader Richtung nach einer weißen Fläche lenken -, so sehen Sie [wie grün wird] dasjenige, was Sie früher rot gesehen haben, ohne dass etwas da ist, sondern gleichsam [tritt] die grüne Farbe [von] selber auf die Fläche hin. Wie Sie da [beim Nachbild] sehen die grüne Fläche als ein zeitliches Nachbild der roten Fläche, die Sie früher wirklich gesehen haben, indem Sie das Auge dem Rot exponiert haben, - so sehen Sie hier [beim farbigen Schatten], indem ich die [linke] Lichtquelle rot abdunkle, ihren [rechten] Schatten [grün]. Also, was früher [vor der Einfügung der farbigen Glasplatte] bloße Dunkelheit war, sehen Sie jetzt grün. Wenn ich dieselbe Lichtquelle grün abdunkeln werde, beobachten Sie dann, was dann entsteht! Sie sehen, der Schatten entsteht dann rot. Wenn ich dieselbe Lichtquelle blau abdunkle, so sehen Sie, der Schatten entsteht dann gelblich [-orange]; würde ich die Lichtquelle violett abdunkeln, so gäbe es Orange [-Gelb].

Nun bitte ich Sie, Folgendes zu berücksichtigen - gerade dieses Phänomen ist von einer großen Bedeutung. Wenn Sie - ich erwähne das deshalb noch einmal - wenn Sie zum Beispiel irgendwo liegen haben, sagen wir, ein Kissen, ein Kissen, das einen weißen Überzug hat, der über einen roten Überzug gezogen ist und der so gehäkelt ist, dass er da [ausgelassen] so rote Rhomben hat, und Sie sehen nach diesen roten Rhomben zuerst hin und von da weg auf das Weiße [einer Fläche], so sehen Sie dieselbe Gitterung auf dem Weißen grün. Sie ist natürlich nicht dort, aber Ihr Auge übt eine Nachwirkung [aus], und diese erzeugt, indem Sie visieren nach dem Weiß, die grünen — wie man sagt — subjektiven Bilder.

Nun, Goethe wusste diese letztere Ihnen erwähnte Erscheinung und er kannte auch dieses Phänomen der farbigen Schatten. Er sagte sich: Ich dunkle diese [eine] Lichtquelle [durch einen roten Farbfilter] ab, bekomme Grün, und nun beschreibt er das in der folgenden Weise. Er sagt: Wenn ich hier die Lichtquelle abdunkle, so wird der ganze weiße Schirm mit einem roten Schein bedeckt und ich sche dann eigentlich nicht den weißen Schirm, sondern einen roten Schein, ich sehe den Schirm rötlich. Dadurch erzeuge ich, wie bei dem Kissen, mit meinem Auge die Kontrastfarbe Grün, sodass also hier kein wirkliches Grün wäre, sondern es wird nur nebenbei gesehen, weil der Schirm rötlich gefärbt ist. Aber diese Goethe’sche Anschauung ist falsch. Sie können sich leicht überzeugen, dass sie falsch ist, denn wenn Sie eine kleine Röhre nehmen und durchblicken, sodass Sie bloß, nach der Abdunklung [durch einen roten Farbfilter], diesen grünen Streifen ansehen, so sehen Sie ihn auch grün. Sie sehen dann nicht dasjenige, was in der Umgebung ist, sondern Sie sehen nur das objektiv an dieser Stelle vorhandene Grün. Sie können sich dadurch überzeugen, dass das Grün objektiv ist, dass hier abgedunkelt wird und dass Sie dann das Grün ansehen. Es bleibt grün, kann also nicht eine Kontrasterscheinung sein, sondern ist eine objektive Erscheinung. Wir können das jetzt nicht so machen, dass es alle sehen einzeln: Aber durch zweier Zeugen Mund wird alle Wahrheit kund.*' Ich werde die Erscheinung hervorrufen und Sie müssen so durchsehen, dass Sie auf das grüne Band hinsehen. Das bleibt grün, nicht wahr? Und ebenso würde die andere Farbe, wenn ich durch Grün Rot erzeugen würde, die andere Farbe Rot bleiben. In diesem Falle hat Goethe in seine Farbenlehre den Irrtum, dem er sich hingegeben hart, aufgenommen, und der muss natürlich durchaus korrigiert werden.

Ich will zunächst, meine lieben Freunde, nichts anderes, als dass Sie sich unter den mancherlei Erscheinungen auch bewahren das rein Faktische, das wir jetzt vorgeführt haben, dass also ein Grau, das heißt ein Dunkles, das sonst als bloßer Schatten entsteht, dann, wenn wir den Schatten selbst mit Farbe gewissermaßen durchtränken, dass dann in anderer Weise Helligkeit und Dunkelheit zusammenwirken, als wenn ich den Schatten nicht durchtränkte mit einer Farbe. Und wir merken uns, dass hier durch die Abdunkelung des Lichtes mit dem Rot, dass dadurch die objektive Erscheinung des Grün hervorgerufen wird. Nun habe ich Sie hingewiesen auf dasjenige, was da [im Nachbild] subjektiv erscheint - wie man sagt, subjektiv. Wir haben [beim farbigen Schatten] eine, wie man sagt, objektive Erscheinung, das Grün, das auf dem Schirm gewissermaßen bleibt, wenn es auch nicht fixiert ist, so lange, als wir die Bedingungen dazu hergestellt haben, und hier [beim Nachbild] etwas, was gewissermaßen subjektiv, von unserem Auge allein abhängig ist. Goethe nennt die grüne Farbe, die dann erscheint, wenn ich eine Zeit lang das Auge der Farbe exponiert habe, die geforderte Farbe, das geforderte Nachbild, das durch die Gegenwirkung selbst hervorgerufen wird.

Nun, hier ist eines streng festzuhalten. Die Unterscheidung des Subjektiven und des Objektiven, zwischen der hier [beim farbigen Schatten] vorübergehend fixierten Farbe und der durch das Auge scheinbar bloß als Nachbild geforderten Farbe, diese Unterscheidung hat in keinem objektiven Tatbestand irgendeine Rechtfertigung. Ich habe es [beim Nachbilde] zu tun, indem ich durch mein Auge hier das Rot sehe, einfach mit all den Ihnen beschriebenen physikalischen Apparaten, Glaskörper, Linse, die Flüssigkeit zwischen der Linse und der Hornhaut. Ich habe es mit einem sehr differenzierten physikalischen Apparat zu tun. Dieser physikalische Apparat, der in der mannigfaltigsten Weise Helligkeit und Dunkelheit durcheinandermischt, der steht zu dem objektiv vorhandenen Äther in gar keiner anderen Beziehung als die Apparate, die ich hier aufgestellt habe, der Schirm, die Stange und so weiter. Das eine Mal, [beim Nachbild,] ist bloß die ganze Vorrichtung, die ganze Maschinerie mein Auge, und ich sehe ein objektives Phänomen durch mein Auge, genau dasselbe objektive Phänomen, das ich hier [beim farbigen Schatten] sehe, nur dass hier das Phänomen bleibt. Wenn ich aber mein Auge mir herrichte durch das Sehen so, dass es nachher in der sogenannten geforderten Farbe wirkt, so stellt sich das Auge in seinen Bedingungen wieder her im neutralen Zustand. Aber dasjenige, wodurch ich Grün sehe, ist durchaus kein anderer Vorgang, wenn ich [beim Nachbild] sogenannt subjektiv durch das Auge sehe, als wenn ich hier [beim farbigen Schatten] objektiv die Farbe fixiere.

Deshalb sagte ich: Sie leben nicht so mit Ihrer Subjektivität, dass der Äther draußen Schwingungen macht und die Wirkung derselben als Farbe zum Ausdruck kommt, sondern Sie schwimmen im Äther, sind eins mit ihm, und es ist nur ein anderer Vorgang, ob Sie eins werden mit dem Äther hier durch die Apparate oder durch etwas, was sich in Ihrem Auge selber vollzieht. Es ist [kein] wirklicher, wesenhafter Unterschied zwischen dem räumlich erzeugten grünen Bild durch die rote Verdunkelung und dem grünen Nachbild, das eben nur zeitlich erscheint; es ist ein - objektiv besehen - greifbarer Unterschied nicht, nur der, dass das eine Mal der Vorgang räumlich, das andere Mal der Vorgang zeitlich ist. Das ist der einzige wesenhafte Unterschied.

Die sinngemäße Verfolgung solcher Dinge führt Sie dahin, jenes Entgegenstellen des sogenannten Subjektiven und des Objektiven nicht in der falschen Richtung zu sehen, in der es fortwährend von der neueren Naturwissenschaft gesehen wird, sondern die Sache so zu sehen, wie sie ist, nämlich dass wir das eine Mal eine Vorrichtung haben, durch die wir Farben erzeugen, unser Auge neutral bleibt, das heißt sich neutral macht gegen das Farbenentstehen, also dasjenige, was da ist, mit sich vereinigen kann. Das andere Mal wirkt es selbst als physikalischer Apparat. Ob aber dieser physikalische Apparat hier (außen) ist oder in Ihrer Stirnhöhle drinnen ist, ist einerlei. Wir sind nicht außer den Dingen und projizieren erst die Erscheinungen in den Raum, wir sind durchaus mit unserer Wesenheit in den Dingen und sind umso mehr in den Dingen, als wir aufsteigen von gewissen physikalischen Erscheinungen zu anderen physikalischen Erscheinungen. Kein Unbefangener, der die Farbenerscheinungen durchforscht, kann anders, als sich sagen: Mit unserem gewöhnlichen körperlichen Wesen stecken wir nicht drinnen, sondern mit unserem ätherischen und dadurch mit unserem astralischen Wesen.

Wenn wir vom Lichte heruntersteigen zur Wärme, die wir auch wahrnehmen als etwas, was ein Zustand unserer Umgebung ist, der für uns eine Bedeutung gewinnt, wenn wir ihm exponiert sind, so werden wir bald sehen: Es ist eine bedeutsame Modifikation zwischen dem Wahrnehmen des Lichtes und dem Wahrnehmen der Wärme. Für die Lichtwahrnehmung können Sie genau lokalisieren diese Wahrnehmung in dem physikalischen Apparat des Auges, dessen objektive Bedeutung ich eben charakterisiert habe. Für die Wärme, was müssen Sie sich denn da sagen? Wenn Sie wirklich sich fragen: Wie kann ich vergleichen die Beziehung, in der ich zum Lichte stehe, mit der Beziehung, in der ich zur Wärme stehe? Ja, so müssen Sie sich auf diese Frage antworten: Zum Lichte stehe ich so, dass mein Verhältnis lokalisiert ist gewissermaßen durch mein Auge an einen bestimmten Körperort. Das ist aber bei der Wärme nicht so. Für sie bin ich gewissermaßen ganz Sinnesorgan. Ich bin für sie ganz dasselbe, was für das Licht das Auge ist. Sodass wir also sagen können: Von der Wahrnehmung der Wärme können wir nicht im selben lokalisierten Sinne sprechen wie von der Wahrnehmung des Lichtes. Aber gerade, indem wir die Aufmerksamkeit auf so etwas richten, können wir noch auf etwas anderes kommen.

Was nehmen wir denn eigentlich wahr, wenn wir in ein Verhältnis treten zu dem Wärmezustand unserer Umgebung? Ja, da nehmen wir eigentlich dieses Schwimmen in dem Wärmeelement unserer Umgebung sehr deutlich wahr. Nur: Was schwimmt denn? Bitte, beantworten Sie sich diese Frage, was da eigentlich schwimmt, wenn Sie in der Wärme Ihrer Umgebung schwimmen. Nehmen Sie folgendes Experiment. Sie versuchen, einen Trog zu füllen mit einer mäßig warmen Flüssigkeit, mit mäßig warmem Wasser, mit einem Wasser, das Sie als lauwarm empfinden, wenn Sie beide Hände hineinstecken - nicht lange hineinstecken, Sie probieren das nur. Dann machen Sie Folgendes: Sie stecken zuerst die linke Hand in möglichst warmes Wasser, wie Sie es gerade noch ertragen können, dann die rechte Hand in möglichst kaltes Wasser, wie Sie es auch gerade noch ertragen können, und dann stecken Sie rasch die linke und die rechte Hand in das lauwarme Wasser. Sie werden sehen, dass der rechten Hand das lauwarme Wasser sehr warm vorkommt und der linken sehr kalt. Die heiß gewordene Hand von links fühlt dasselbe als Kälte, was die kalt gewordene Hand von rechts als Wärme fühlt. Vorher fühlten Sie eine gleichmäßige Lauigkeit. Was ist denn das eigentlich? Ihre eigene Wärme, die schwimmt [in der Wärme der Umgebung], und ihre eigene Wärme verursacht, dass Sie die Differenz zwischen ihr und der Umgebung fühlen. Dasjenige, was von Ihnen schwimmt in dem Wärmeelement Ihrer Umgebung, was ist es denn? Es ist Ihr eigener Wärmezustand, der durch Ihren organischen Prozess herbeigeführt wird, der ist nicht etwas Unbewusstes, in dem lebt Ihr Bewusstsein. Sie leben innerhalb Ihrer Haut in der Wärme, und je nachdem [wie] diese ist, setzen Sie sich auseinander mit dem Wärmeelement Ihrer Umgebung. In diesem schwimmt Ihre eigene Körperwärme. Ihr Wärmeorganismus schwimmt in der Umgebung.

Denken Sie sich solche Dinge durch, dann geraten Sie ganz anders in die Nähe der wirklichen Naturvorgänge als durch dasjenige, was Ihnen die heute ganz verabstrahierte und aus aller Realität herausgezogene Physik bieten kann.

Nun gehen wir aber noch weiter hinunter. Wir haben gesehen, wenn wir erleben unseren eigenen Wärmezustand, dann können wir sagen, dass wir ihn dadurch erleben, dass wir mit ihm schwimmen in unserer Wärmeumgebung, also entweder, dass wir wärmer sind als unsere Umgebung und es empfinden als uns aussaugend - wenn die Umgebung kalt ist -, oder wenn wir kälter sind, es empfinden, als ob uns die Umgebung etwas gibt. [Da] wird es nun ganz anders, wenn wir in einem anderen Element leben.

Sehen Sie, wir können also in dem leben, was dem Licht zugrunde liegt. Wir schwimmen im Lichtelement. Wir haben jetzt durchgeführt, wie wir im Wärmeelement schwimmen. Wir können aber auch im Luftelement schwimmen, das wir eigentlich fortwährend in uns haben. Wir sind ja in sehr geringem Maße ein fester Körper, wir sind eigentlich nur zu ein paar Prozent ein fester Körper als Mensch, wir sind eigentlich über neunzig Prozent eine Wassersäule, und Wasser ist eigentlich, insbesondere in uns, nur ein Mittelzustand zwischen dem luftförmigen und dem festen Zustande. Wir können uns durchaus in dem luftartigen Element selber erleben, so wie wir uns im wärmcartigen Element erleben, das heißt, unser Bewusstsein steigt effektiv hinunter in das luftartige Element. Wie es in das Lichtelement steigt und in das Wärmeelement, so steigt es in das Luftelement. Indem es aber in das Luftelement steigt, kann es sich wiederum auseinandersetzen mit demjenigen, was in der Luftumgebung geschieht, und diese Auseinandersetzung ist dasjenige, was in der Erscheinung des Schalls, des Tones zum Vorschein kommt.

Sie sehen, wir müssen gewisse Schichten unseres Bewusstseins unterscheiden. Wir leben mit einer ganz anderen Schichte unseres Bewusstseins mit dem Lichtelement, indem wir selber teilnehmen an ihm, wir leben mit einer anderen Schichte unseres Bewusstseins im Wärmeelement, indem wir selber teilnehmen an ihm, und wir leben in einer anderen Schichte unseres Bewusstseins im Luftelement, indem wir selber teilnehmen an ihm. Wir leben, indem unser Bewusstsein imstande ist, hinunterzutauchen in das gasige, luftförmige Element, wir leben in dem luftförmigen Element unserer Umgebung und können uns dadurch fähig machen, Schallerscheinungen wahrzunehmen, Töne wahrzunehmen. Gerade so, wie wir selbst mit unserem Bewusstsein teilnehmen müssen an den Lichterscheinungen, damit wir in den Lichterscheinungen unserer Umgebung schwimmen können, wie wir teilnehmen müssen am Wärmeelement, damit wir in ihm schwimmen können, so müssen wir auch teilnehmen an dem Luftigen, wir müssen selber in uns differenziert etwas Luftiges haben, damit wir das äußere, meinetwegen durch eine Pfeife, eine Trommel, eine Violine differenzierte Luftige wahrnehmen können.

In dieser Beziehung, meine lieben Freunde, ist unser Organismus etwas außerordentlich interessant sich Darbietendes. Wir atmen die Luft aus - unser Atmungsprozess besteht ja darinnen, dass wir Luft ausatmen und Luft wieder einatmen. Indem wir Luft ausatmen, treiben wir unser Zwerchfell in die Höhe. Das ist aber mit einer Entlastung unseres ganzen organischen Systems unter dem Zwerchfell in einer Verbindung. Dadurch wird gewissermaßen, weil wir das Zwerchfell nach oben bringen beim Ausatmen und unser organisches System unter dem Zwerchfell entlastet wird, dadurch wird das Gehirnwasser, in dem das Gehirn schwimmt, nach abwärts getrieben, dieses Gehirnwasser, das aber nichts anderes ist als eine etwas verdichtete Modifikation, möchte ich sagen, der Luft; denn in Wahrheit ist es die ausgeatmete Luft, die das bewirkt. Wenn ich wieder einatme, wird das Gehirnwasser nach aufwärts getrieben [in der] Höhle des Rückenmarkes - es ist ein Sack - wird wiederum hinaufgetrieben, und ich lebe fortwährend, indem ich atme, in diesem von oben nach unten und von unten nach oben sich vollziehenden [Schwingen] des Gehirnwassers, das ein deutliches Abbild meines ganzen Atmungsprozesses ist. Lebe ich mit meinem Bewusstsein dadurch, dass teilnimmt mein Organismus an diesen Oszillationen des Atmungsprozesses, dann ist das eine innerliche Differenzierung im Erleben eines Luftwahrnehmens, und ich stehe eigentlich fortwährend durch diesen Vorgang, den ich nur etwas grob geschildert habe, fortwährend in einem Lebensrhythmus darinnen, der in seiner Entstehung und in seinem Verlauf in Differenzierung der Luft besteht.

Dasjenige, meine lieben Freunde, was da innerlich entsteht, indem Sie-natürlich nicht so grob, sondern in mannigfaltiger Weise differenziert, sodass dieses Auf- und Abschwingen der rhythmischen Kräfte, die ich gekennzeichnet habe, selber etwas ist wie ein komplizierter, fortwährend entstehender und vergehender Schwingungsorganismus -, diesen innerlichen Schwingungsorganismus [erleben]: Den bringen wir in unserem Ohre zum Zusammenstoßen mit demjenigen, was von außen zum Beispiel, sagen wir, wenn eine Saite angeschlagen wird, an uns tönt. Und gerade so, wie Sie den Wärmezustand Ihrer eigenen Hand, wenn Sie sie ins lauwarme Wasser hineinheben, wahrnehmen durch die Differenz zwischen der Wärme Ihrer Hand und der Wärme des Wassers, so nehmen Sie wahr den entsprechenden Ton oder Schall durch das Gegeneinanderwirken Ihres inneren, so wunderbar gebauten Musikinstrumentes mit demjenigen, was äußerlich in der Luft als Töne, als Schall, zum Vorschein kommt. Das Ohr ist gewissermaßen nur die Brücke, durch die Ihre innere Leier des Apollo sich ausgleicht in einem Verhältnis mit demjenigen, was von außen an differenzierter Luftbewegung an Sie herantritt.

Sie sehen, der wirkliche Vorgang - wenn ich ihn real schildere -, der wirkliche Vorgang beim Hören, nämlich beim Hören des differenzierten Schalles, des Tones, der ist von jener Abstraktion weit verschieden, von der man sagt: Draußen, da wirkt etwas, das affiziert mein Ohr. Die Affektion des Ohres wird als eine Wirkung auf mein subjektives Wesen wahrgenommen, das man wiederum - ja, mit welcher [Terminologie] auch - beschreibt oder eigentlich nicht beschreibt. Ja, man kommt nicht weiter, wenn man klar ausdenken will, was da eigentlich immer als Idee zugrunde gelegt wird. Man kann gewisse Dinge, die gewöhnlich angeschlagen werden, nicht zu Ende denken, weil diese Physik weit entfernt ist, einfach auf die Tatsachen einzugehen.

Sie haben tatsächlich drei Stufen vor sich der Beziehungen des Menschen zur Außenwelt, ich möchte sagen: die Lichtstufe, die Wärmestufe, die Ton- oder Schallstufe. Aber sehen Sie, da liegt etwas sehr Eigentümliches noch vor. Wenn Sie unbefangen Ihr Verhältnis, das heißt Ihr Schwimmen im Lichtelement betrachten, dann müssen Sie sich sagen: Sie können selbst nur als Ätherorganismus in demjenigen, was da draußen in der Welt vor sich geht, leben. Indem Sie im Wärmeelement leben, leben Sie mit Ihrem ganzen Organismus im Wärmeelement Ihrer Umgebung darinnen. Jetzt lenken Sie den Blick von diesem Drinnenleben herunter bis zum Drinnenleben im Ton- und Schallelement, dann leben Sie eigentlich, indem Sie selbst werden zum Luftorganismus, leben Sie in der differenziert gestalteten äußeren Luft darinnen. Das heißt, nicht mehr im Äther, sondern eigentlich schon in der äußeren physikalischen Materie, in der Luft leben Sie da drinnen.

Daher ist das Leben im Wärmeelement eine ganz bedeutsame Grenze. Gewissermaßen bedeutet das Wärmeelement, das Leben in ihm, für Ihr Bewusstsein ein Niveau. Dieses Niveau können Sie auch sehr deutlich dadurch wahrnehmen, dass Sie ja schließlich äußere und innere Wärme in der reinen Empfindung kaum unterscheiden können. Aber das Leben im Lichtelement liegt über diesem Niveau. Sie steigen gewissermaßen in eine höhere ätherische Sphäre hinauf, um mit Ihrem Bewusstsein drinnen zu leben. Und Sie dringen unter jenes Niveau, wo Sie mit der Außenwelt in verhältnismäßig einfacher Weise sich ausgleichen, hinunter, indem Sie als Luftmensch sich mit der Luft auseinandersetzen in den Ton- oder Schallwahrnehmungen.

Das Auge kann man nicht anders als eine Art von physikalischem Apparat auffassen. Wenn Sie alles das zusammenhalten, was ich jetzt gezeigt habe, mit demjenigen, was ich über die Anatomie und Physiologie gesagt habe, so können Sie nicht anders, als das Auge als physikalischen Apparat auffassen. Je weiter nach außen Sie gehen, desto physischer finden Sie das Auge, je mehr nach innen, desto mehr von Vitalität durchzogen. Wir haben also ein in uns lokalisiertes Organ, um uns über ein gewisses Niveau zu erheben. Wir leben dann auf einem gewissen Niveau auf gleich und gleich mit der Umgebung, indem wir mit unserer Wärme ihr entgegentreten und die Differenz irgendwo wahrnehmen. Da haben wir kein so spezialisiertes Organ als das Auge, da werden wir selbst ganz in gewisser Weise zum Sinnesorgan. Jetzt tauchen wir unter dieses Niveau hinunter. Wo wir Luftmensch werden, wo wir uns auseinandersetzen mit der differenzierten äußeren Luft, da lokalisiert sich wiederum diese Auseinandersetzung - das lokalisiert sich zwischen dem, was in uns vorgeht, dieser Leier des Apollo, dieser Rhythmisierung unseres Organismus, die nur nachgebildet ist in der Rhythmisierung des Rückenmarkwassers, [und der differenziert gestalteten äußeren Luft]. Was da vorgeht, ist durch eine Brücke verbunden. Da ist also wiederum solch eine Lokalisation, aber jetzt unter dem Niveau, wie wir im Auge eine solche Lokalisation über dem Niveau haben.

Sehen Sie, unsere Psychologie, die ist eigentlich in einer noch schlimmeren Lage als unsere Physiologie und unsere Physik, und man kann es eigentlich den Physikern nicht sehr krummnehmen, dass sie sich so unrealistisch ausdrücken über das, was in der Außenwelt ist, weil sie gar nicht unterstützt werden von den Psychologen. Die Psychologen sind dressiert worden von den Kirchen, die in Anspruch genommen haben alles Wissen über Seele und Geist. Daher hat diese Dressur, die die Psychologen angenommen haben, sie dazu geführt, eigentlich nur den äußeren Apparat als den Menschen zu betrachten und die Seele und den Geist nur noch in Wortklängen, in Phrasen, zu haben. Unsere Psychologie ist eigentlich nur eine Sammlung von Worten. Denn was sich die Menschen eigentlich vorstellen sollen bei Seele und Geist, darüber gibt es eigentlich nichts, und so kommt es, dass es den Physikern vorkommt, wenn draußen Licht wirkt, so affiziert es das Auge, das Auge übt eine Gegenwirkung aus oder aber es empfängt einen Eindruck, und das ist ein inneres, subjektives Erleben. Da beginnen dann ganze Knäuel von Unklarheiten. Und in ganz ähnlicher Weise, sagen es die Physiker nach, ist es bei den anderen Sinnesorganen. Wenn Sie heute eine Psychologie durchlesen, so finden Sie darinnen eine Sinneslehre. Vom Sinn wird gesprochen, vom allgemeinen Sinn, als ob es so etwas gäbe. Man versuche nur zu studieren das Auge. Es ist etwas ganz anderes als das Ohr. Ich habe Ihnen das gekennzeichnet, das Liegen unter und über dem Niveau. Auge und Ohr sind ganz verschiedenartig innerlich gebildete Organe, und das ist cs, worauf in bedeutsamer Weise Rücksicht genommen werden muss.

Bleiben wir hier einmal stehen, überlegen Sie sich das, und morgen wollen wir von diesem Punkte aus über die Schallehre, die Tonlehre sprechen, damit Sie von dort aus wiederum die anderen physikalischen Gebiete erobern können.

Ich möchte Ihnen heute nur noch eines vorführen. Das ist das, was man in gewisser Beziehung das Glanzstück der modernen Physik nennen kann, was in gewisser Beziehung auch ein Glanzstück ist. Sehen Sie, wenn Sie einfach mit dem Finger über eine Fläche streichen, also einen Druck ausüben durch Ihre eigene Anstrengung, so wird die Fläche warm. Sie erzeugen dadurch, dass Sie einen Druck ausgeübt haben, Wärme. Man kann nun umgekehrt - nicht umgekehrt, sondern in derselben Linie - dadurch, dass man objektive mechanische Vorgänge hervorruft, die ausgesprochen mechanische Vorgänge sind, wiederum Wärme erzeugen, und wir haben als eine weitere Grundlage für dasjenige, was wir dann morgen weiter betrachten wollen, diesen Apparat improvisiert. Wenn Sie jetzt sehen würden, wie hoch das Thermometer steht in diesem Apparat, so bekommen Sie heraus am Thermometerstand 16 Grad und etwas. Nun werden wir in diesem Gefäße - darinnen, da haben wir Wasser und in diesem Wasserkörper darinnen haben wir ein Schwungrad, eine Trommel, die wir in rasche Drehung versetzen, sodass diese eine mechanische Arbeit leistet, im Wasser die Teile ordentlich durcheinanderwirft, das Wasser aufschaufelt, - und wir werden nach einiger Zeit das Thermometer wieder anschauen. So können Sie nach einiger Zeit das Thermometer anschauen und sie werden sehen, dass es gestiegen ist, dass also durch bloß mechanische Arbeit das Wasser an Wärme zugenommen hat, das heißt, es wird durch mechanische Arbeit Wärme produziert. Das hat man dann verarbeitet, zuerst in rechnungsmäßiger Weise, nachdem besonders Julius Mayer darauf aufmerksam gemacht hatte. Julius Mayer hat cs selbst verarbeitet zu dem sogenannten mechanischen Wärme-Äquivalent. Hätte man es in seinem Sinne ausgebaut, so hätte man damit nichts anderes gesagt, als dass eine bestimmte Zahl der Ausdruck ist für das, was man an der Wärme messen kann durch mechanische Arbeit und umgekehrt. Das aber ist dann in einer übersinnlichen, metaphysischen Weise ausgewertet worden, indem man gesagt hat: Also, wenn ein konstantes Verhältnis besteht zwischen der geleisteten Arbeit und der Wärme, so ist dies einfach umgewandelte Arbeit - umgewandelte! -, während man [es eigentlich] mit nichts anderem zunächst zu tun hatte als mit dem zahlenmäßigen Ausdruck des Zusammenhangs zwischen der mechanischen Arbeit und der Wärme.

Seventh Lecture

My dear friends!

Today we will begin with an experiment that will tie in with our considerations on color theory. As I have already said, it is entirely possible that what I present to you in these lectures will be improvised, aphoristic, so to speak. For this reason, I must avoid the usual categories found in physics textbooks. I do not mean to say that it would be better if I could adhere to these categories, but I would ultimately like to lead you to a certain scientific insight, and you should regard everything I have said so far as a kind of preparation, which is not done in the usual way, proceeding in a straight line, but rather by gathering together the phenomena that are needed, creating a circle, so to speak, and then advancing toward the center.

You have seen that when colors arise, we are dealing with an interaction between light and darkness. Now it is a matter of observing as many real phenomena as possible before forming an opinion about what actually underlies this interaction between light and darkness. And today I would like to begin by demonstrating this phenomenon of so-called colored shadows.

Using two light sources, represented by these candles here, I will cast shadows on the screen opposite you through this rod. You will see two shadows that do not have a distinct color. You only need to look closely at what is here, and you will say to yourself: The shadow you see here on the right is, of course, the shadow cast by this light source [on the left], which is created when the light from this source is blocked by the stick. And the shadow [on the left] is the one created when the light from our right light source is blocked. So basically, we are only dealing with the creation of certain dark spaces. What lies in the shadow is simply dark space. Now you can see that if you look at the surface of the screen outside the two shadow bands, you will say to yourself: it is illuminated by the two light sources. So we are dealing with light here.

I now want to color one [left] of the lights, that is, I want to let it pass through a colored glass plate so that one of the lights is colored. We know what happens: one of the lights is darkened. There! But now you see that this darkening causes the shadow [on the right], which is cast by the rod from my left light source, whose light I am currently darkening and turning reddish, to turn green. It turns green, just as green as it gets—for example, if you look intently at a small red area, then turn your eyes away from this red area and simply look straight ahead at a white area—you will see [how green] what you previously saw as red becomes, without anything being there, but rather the green color [appears] on the surface as if by itself. Just as you see the green area [in the afterimage] as a temporary afterimage of the red area that you actually saw earlier by exposing your eyes to the red, so here [in the colored shadow], when I darken the [left] light source red, you see its [right] shadow [green]. So what was previously [before the colored glass plate was inserted] mere darkness, you now see as green. If I darken the same light source to green, observe what happens! You see, the shadow then appears red. If I darken the same light source blue, you will see that the shadow then appears yellowish [orange]; if I darken the light source violet, there would be orange [yellow].

Now I ask you to consider the following—this phenomenon is of great importance. If you—I mention this again—if you have something lying somewhere, say a pillow with a white cover that has a red cover pulled over it and is crocheted so that it has red diamonds [omitted], and you look first at these red diamonds and then away from them to the white [surface], you see the same grid pattern on the white in green. Of course, it is not there, but your eye exerts an aftereffect, and this, by focusing on the white, produces the green—as one might say—subjective images.

Now, Goethe was aware of this latter phenomenon you mentioned, and he also knew about the phenomenon of colored shadows. He said to himself: I darken this [one] light source [with a red color filter], get green, and now he describes this in the following way. He says: When I darken the light source here, the entire white screen is covered with a red glow and I then actually do not see the white screen, but a red glow; I see the screen reddish. In this way, as with the cushion, I create the contrasting color green with my eye, so that there is no real green here, but it is only seen incidentally because the screen is reddish in color. But this Goethean view is incorrect. You can easily convince yourself that it is incorrect, because if you take a small tube and look through it so that you only see this green stripe after darkening [with a red color filter], you will also see it green. You do not see what is in the surroundings, but only the green that is objectively present at this point. You can convince yourself that the green is objective, that it is darkened here and that you then see the green. It remains green, so it cannot be a contrast phenomenon, but is an objective phenomenon. We cannot do this now so that everyone can see it individually: But through the mouths of two witnesses, all truth shall be made known.* I will produce the phenomenon and you must look through it so that you see the green band. It remains green, doesn't it? And likewise, if I were to produce red through green, the other color would remain red. In this case, Goethe has incorporated into his theory of colors the error to which he had devoted himself so ardently, and this must of course be corrected.

First of all, my dear friends, I want nothing more than for you to preserve among the various phenomena the pure fact that we have now demonstrated, namely that a gray, that is, a dark color, which otherwise arises as a mere shadow, then, when we saturate the shadow itself with color, so to speak, that brightness and darkness interact in a different way than if I did not saturate the shadow with a color. And we note that here, by darkening the light with red, the objective appearance of green is produced. Now I have pointed out to you what appears subjectively [in the afterimage]—as one says, subjectively. With colored shadows, we have what we call an objective appearance, the green that remains on the screen, so to speak, even if it is not fixed, as long as we have created the conditions for it, and here [with the afterimage] we have something that is, so to speak, subjective, dependent solely on our eye. Goethe calls the green color that appears when I have exposed my eye to the color for a while the required color, the required afterimage, which is caused by the counteraction itself.

Now, one thing must be strictly noted here. The distinction between the subjective and the objective, between the color temporarily fixed here [in the colored shadow] and the color apparently demanded by the eye merely as an afterimage, this distinction has no justification whatsoever in any objective fact. I am dealing with it [in the afterimage] by seeing the red here through my eye, simply with all the physical apparatus I have described to you, the glass body, the lens, the fluid between the lens and the cornea. I am dealing with a very sophisticated physical apparatus. This physical apparatus, which mixes light and darkness in the most varied ways, has no other relationship to the objectively existing ether than the apparatus I have set up here, the screen, the rod, and so on. In one case [with the afterimage], it is merely the entire apparatus, the entire machinery, that is my eye, and I see an objective phenomenon through my eye, exactly the same objective phenomenon that I see here [with the colored shadow], only that here the phenomenon remains. But when I adjust my eye by seeing in such a way that it subsequently appears in the so-called required color, the eye returns to its neutral state. But that through which I see green is by no means a different process when I see [in the afterimage] subjectively through the eye than when I objectively fix the color here [in the colored shadow].

That is why I said: You do not live with your subjectivity in such a way that the ether outside causes vibrations and the effect of these vibrations is expressed as color, but rather you float in the ether, are one with it, and it is only a different process whether you become one with the ether here through the apparatus or through something that takes place in your eye itself. There is [no] real, essential difference between the spatially produced green image through the red darkening and the green afterimage, which only appears temporarily; objectively speaking, there is no tangible difference, only that in one case the process is spatial and in the other temporal. That is the only essential difference.

The logical pursuit of such things leads you to see the opposition between the so-called subjective and the objective not in the wrong direction, as it is continually seen by modern science, but to see things as they are, namely that in one case we have a device through which we produce colors, our eye remaining neutral, that is, it makes itself neutral to the emergence of colors, so that it can unite with what is there. At other times, it acts as a physical apparatus. But whether this physical apparatus is here (outside) or inside your forehead cavity is irrelevant. We are not outside of things and project appearances into space; we are thoroughly present with our essence in things and are all the more in things as we ascend from certain physical appearances to other physical appearances. No unbiased person who investigates color phenomena can help but say: We are not inside with our ordinary physical being, but with our etheric and thus with our astral being.

When we descend from light to heat, which we also perceive as something that is a state of our environment that gains meaning for us when we are exposed to it, we soon see that there is a significant difference between the perception of light and the perception of heat. For the perception of light, you can precisely locate this perception in the physical apparatus of the eye, whose objective significance I have just characterized. For warmth, what must you say to yourself? If you really ask yourself: How can I compare the relationship I have to light with the relationship I have to warmth? Yes, you must answer this question as follows: I relate to light in such a way that my relationship is localized, so to speak, by my eye at a specific location on my body. But this is not the case with heat. For heat, I am, so to speak, the entire sensory organ. I am to heat what the eye is to light. So we can say that we cannot speak of the perception of heat in the same localized sense as we speak of the perception of light. But it is precisely by focusing our attention on something like this that we can arrive at something else.

What do we actually perceive when we enter into a relationship with the thermal state of our environment? Yes, we actually perceive very clearly this floating in the thermal element of our environment.

But what is floating? Please answer this question: what is actually floating when you are floating in the warmth of your environment? Try the following experiment. Try to fill a trough with a moderately warm liquid, with moderately warm water, with water that you perceive as lukewarm when you put both hands in it – don't put them in for long, just try it. Then do the following: first put your left hand in water that is as warm as you can bear, then put your right hand in water that is as cold as you can bear, and then quickly put both hands in the lukewarm water. You will see that the lukewarm water feels very warm to your right hand and very cold to your left hand. The hand on the left, which has become hot, feels the same as the cold felt by the hand on the right, which has become cold. Before, you felt an even lukewarmness. What is that actually? It is your own warmth floating [in the warmth of the environment], and your own warmth causes you to feel the difference between it and the environment. What is it that floats in the heat element of your environment? It is your own state of heat, brought about by your organic processes; it is not something unconscious; it is where your consciousness lives. You live within your skin in the heat, and depending on what this is like, you interact with the heat element of your environment. Your own body heat floats in this. Your heat organism floats in the environment.

If you think things through like this, you will come much closer to the real natural processes than through what physics, which today is completely abstract and removed from all reality, can offer you.

But let us go even further. We have seen that when we experience our own state of warmth, we can say that we experience it by floating with it in our warm environment, either because we are warmer than our environment and feel it sucking us in—when the environment is cold—or because we are colder and feel as if the environment is giving us something. [Da] It becomes completely different when we live in a different element.

You see, we can live in what underlies light. We swim in the light element. We have now demonstrated how we swim in the heat element. But we can also swim in the air element, which we actually have within us all the time.

We are only a very small part of a solid body; as humans, we are actually only a few percent solid. We are actually over ninety percent water, and water is actually, especially within us, only an intermediate state between the gaseous and solid states. We can definitely experience ourselves in the air element, just as we experience ourselves in the heat element, which means that our consciousness effectively descends into the air element. Just as it rises into the light element and into the heat element, so it rises into the air element. But as it rises into the air element, it can again engage with what is happening in the air environment, and this engagement is what appears in the form of sound, of tone.You see, we have to distinguish between certain layers of our consciousness. We live with a completely different layer of our consciousness with the light element, by participating in it ourselves; we live with another layer of our consciousness in the heat element, by participating in it ourselves; and we live in another layer of our consciousness in the air element, by participating in it ourselves. We live because our consciousness is able to dive down into the gaseous, air-like element; we live in the air-like element of our environment and are thus able to perceive sound phenomena, to perceive tones. Just as we ourselves must participate with our consciousness in the light phenomena in order to be able to swim in the light phenomena of our environment, just as we must participate in the heat element in order to be able to swim in it, so too must we participate in the airy element. we must have something airy within ourselves in a differentiated form so that we can perceive the external air, differentiated, for example, by a pipe, a drum, or a violin.

In this respect, my dear friends, our organism is something extraordinarily interesting to observe. We breathe out the air – our breathing process consists of breathing out air and breathing it in again. When we breathe out, we push our diaphragm upwards. This is connected with a relief of our entire organic system below the diaphragm. In a sense, because we raise the diaphragm when we exhale and our organic system below the diaphragm is relieved, the cerebral fluid in which the brain floats is driven downward. This cerebral fluid is nothing more than a slightly condensed modification, I would say, of the air; for in truth it is the exhaled air that causes this. When I breathe in again, the cerebral fluid is driven upward [in the] cavity of the spinal cord—it is a sac—and is driven upward again, and I live continuously by breathing, in this [oscillation] of the cerebral fluid from top to bottom and from bottom to top, which is a clear reflection of my entire breathing process. If I live with my consciousness participating in these oscillations of the breathing process, then this is an internal differentiation in the experience of perceiving air, and I actually stand continuously, through this process, which I have only described in a somewhat crude manner, in a life rhythm that consists in the differentiation of air in its origin and in its course.

That, my dear friends, which arises internally, not so crudely, of course, but differentiated in manifold ways, so that this rising and falling of the rhythmic forces I have described is itself something like a complex, constantly arising and passing organism of vibration—this internal organism of vibration [experience]: We bring it into our ears to collide with what sounds to us from outside, for example, when a string is struck. And just as you perceive the warmth of your own hand when you lift it into lukewarm water through the difference between the warmth of your hand and the warmth of the water, so you perceive the corresponding tone or sound through the interaction of your inner, wonderfully constructed musical instrument with what appears externally in the air as tones, as sound. The ear is, in a sense, only the bridge through which your inner lyre of Apollo balances itself in relation to what approaches you from outside as differentiated air movement.

You see, the real process—when I describe it realistically—the real process of hearing, namely hearing differentiated sound, tone, is very different from the abstraction that we refer to when we say: Something outside is affecting my ear. The effect on the ear is perceived as an effect on my subjective being, which in turn is described, or rather not described, using whatever terminology one chooses. Yes, one gets nowhere if one wants to think clearly about what is actually always taken as the underlying idea. Certain things that are usually brought up cannot be thought through to their conclusion because this physics is far removed from simply dealing with the facts.

You actually have three stages ahead of you in terms of human relationships with the outside world: I would say the light stage, the heat stage, and the sound stage. But you see, there is something very peculiar ahead. If you look impartially at your relationship, that is, your swimming in the element of light, then you must say to yourself: you yourself can only live as an etheric organism in what is going on out there in the world. By living in the element of warmth, you live with your whole organism in the warmth element of your environment within. Now direct your gaze down from this inner life to the inner life in the sound and noise element, then you actually live by becoming an air organism yourself, you live in the differentiated outer air within. That means you no longer live in the ether, but actually already in the outer physical matter, in the air within.

Therefore, life in the heat element is a very significant boundary. In a sense, the heat element, life in it, represents a level for your consciousness. You can perceive this level very clearly because you can hardly distinguish between external and internal heat in pure sensation. But life in the light element lies above this level. You ascend, as it were, into a higher etheric sphere in order to live there with your consciousness. And you descend below the level where you balance yourself with the outside world in a relatively simple way, by engaging with the air as an air being in your perceptions of sound or noise.

The eye can only be understood as a kind of physical apparatus. If you hold together everything I have just shown you with what I have said about anatomy and physiology, you cannot help but understand the eye as a physical apparatus. The further outwards you go, the more physical you find the eye; the further inwards, the more it is permeated with vitality. So we have an organ located within us that enables us to rise above a certain level. We then live on a certain level, on an equal footing with our environment, by confronting it with our warmth and perceiving the difference somewhere. We do not have an organ as specialized as the eye; in a sense, we ourselves become the sensory organ. Now let us dive below this level. Where we become air beings, where we deal with the differentiated external air, this confrontation is localized again—it is localized between what is going on inside us, this lyre of Apollo, this rhythmization of our organism, which is only reproduced in the rhythmization of the spinal fluid, [and the differentiated external air]. What is happening there is connected by a bridge. So there is again such a localization, but now below the level where we have such a localization above the level in the eye.

You see, our psychology is actually in an even worse state than our physiology and our physics, and one cannot really blame physicists for expressing themselves so unrealistically about what is in the external world, because they are not supported by psychologists at all. Psychologists have been trained by the churches, which have claimed all knowledge about the soul and spirit. This training, which psychologists have accepted, has led them to view only the external apparatus as the human being and to have the soul and spirit only in words and phrases. Our psychology is actually just a collection of words. Because there is actually nothing that people should imagine when they think of the soul and spirit, and so it seems to physicists that when light acts on the outside, it affects the eye, the eye exerts a counteraction or receives an impression, and that is an inner, subjective experience. This is where a whole tangle of ambiguities begins. And in a very similar way, physicists say, it is with the other sense organs. If you read a psychology book today, you will find a theory of the senses. There is talk of the sense, of the general sense, as if there were such a thing. Just try to study the eye. It is something completely different from the ear. I have pointed this out to you, the lying below and above the level. The eye and the ear are completely different organs in their internal structure, and this is something that must be taken into account in a significant way.

Let us pause here for a moment, think about this, and tomorrow we will take up the subject of acoustics, the study of sound, so that you can then go on to conquer the other areas of physics.

I would like to show you just one more thing today. This is what can be called, in a certain sense, the highlight of modern physics, which is also a highlight in a certain sense. You see, if you simply run your finger over a surface, that is, exert pressure through your own effort, the surface becomes warm. By exerting pressure, you generate heat. Conversely—not conversely, but along the same lines—by causing objective mechanical processes that are distinctly mechanical processes, we can in turn generate heat, and we have improvised this apparatus as a further basis for what we want to consider further tomorrow. If you were to look at the thermometer in this apparatus now, you would see that it reads 16 degrees and a little more. Now we will put water into this vessel, and inside this body of water we have a flywheel, a drum, which we set in rapid rotation so that it performs mechanical work, mixing the parts in the water thoroughly, scooping up the water, and after a while we will look at the thermometer again. After a while, you can look at the thermometer and you will see that it has risen, that is, that the water has increased in heat through mechanical work alone, which means that heat is produced by mechanical work. This was then processed, first in a mathematical way, after Julius Mayer had drawn attention to it. Julius Mayer himself processed it into the so-called mechanical heat equivalent. If it had been developed in his sense, it would have meant nothing more than that a certain number is the expression of what can be measured in terms of heat through mechanical work and vice versa. However, this was then interpreted in a supernatural, metaphysical way by saying: So, if there is a constant relationship between the work performed and the heat, then this is simply converted work—converted!—while [in reality] it was initially nothing more than the numerical expression of the relationship between mechanical work and heat.