The Light Course

GA 320

3 January 1920, Stuttgart

Lecture X

My dear Friends,

I will now bring these few improvised hours of scientific study to a provisional conclusion. I want to give you a few guiding lines which may help you in developing such thoughts about Nature for yourselves, taking your start from characteristic facts which you can always make visible by experiment. In Science today—and this applies above all to the teacher—it is most important to develop a right way of thinking upon the facts and phenomena presented to us by Nature. You will remember what I was trying to shew yesterday in this connection. I shewed how since the 1890's physical science has so developed that materialism is being lifted right out of its bearings, so to speak, even by Physics itself. This is the point to remember above all in this connection.

The period when Science thought that it had golden proofs of the universality of waves and undulations was followed, as we say, by a new time. It was no longer possible to hold fast to the old wave-theories. The last three decades have in fact been revolutionary. One can imagine nothing more revolutionary in any realm than this most recent period has been in Physics. Impelled by the very facts that have not emerged, Physics has suffered no less a loss than the concept of matter itself in its old form. Out of the old ways of thinking, as we have seen, the phenomena of light had been brought into a very near relation to those of electricity and magnetism. Now the phenomena produced by the passage of electricity through tubes in which the air or gas was highly rarefied, led scientists to see in the raying light itself something like radiating electricity. I do not say that they were right, but this idea arose. It came about in this way:—The electric current until then had always been hidden as it were in wires, and one had little more to go on than Ohm's Law. Now one was able, so to speak, to get a glimpse of the electricity itself, for here it leaves the wire, jumps to the distant pole, and is no longer able as it were to conceal its content in the matter through which it passes.

The phenomena proved complicated. As we say yesterday, manifold types of radiation emerged. The first to be discovered were the so-called cathode rays, issuing from the negative pole of the Hittorf tube and making their way through the partial vacuum. In that they can be deflected by magnetic forces, they prove akin to what we should ordinarily feel to be material. Yet they are also evidently akin to what we see where radiations are at work. This kinship comes out most vividly when we catch the rays (or whatsoever it is that is issuing from the negative electric pole) upon a screen or other object, as we should do with light. Light throws a shadow. So do these radiations. Yet in this very experiment we are again establishing the near relation of these rays to the ordinary element of matter. For you can imagine that a bombardment is taking place from here (as we say yesterday, this is how Crookes thinks of the cathode rays). The “bombs” do not get through the screen which you put in the way; the space behind the screen is protected. This can be shewn by Crookes's experiment, interposing a screen in the way of the cathode rays.

We will here generate the electric current; we pass it through this tube in which the air is rarefied. It has its cathode or negative pole here, its anode or positive pole here. Sending the electricity through the tube, we are now getting the so-called cathode rays. We catch them on a screen shaped like a St. Andrew's cross. We let the cathode rays impinge on it, and on the other side you will see something like a shadow of the St. Andrew's cross, from which you may gather that the cross stops the rays. Observe it clearly, please. Inside the tube is the St. Andrew's cross. The cathode rays go along here; here they are stopped by the cross; the shadow of the cross becomes visible upon the wall of the vessel behind it. I will now bring the shadow which is thus made visible into the field of a magnet. I beg you to observe it now. You will find the shadow influenced by the magnetic field. You see then, just as I might attract a simple bit of iron with a magnet, so too, what here emerges like a kind of shadow behaves like external matter. It behaves materially.

Here then we have a type of rays which Crookes regards as “radiant matter”—as a form of matter neither solid, liquid or gaseous but even more attenuated,—revealing also that electricity itself, the current of electricity, behaves like simple matter. We have, as it were, been trying to look at the current of flowing electricity as such, and what we see seems very like the kind of effects we are accustomed to see in matter.

I will now shew you, what was not possible yesterday, the rays that issue from the other pole and that are called “canal rays”. You can distinguish the rays from the cathode, going in this direction, shimmering in a violet shade of colour, and the canal rays coming to meet them, giving a greenish light. The velocity of the canal rays is much smaller.

Finally I will shew you the kind of rays produced by this apparatus: they are revealed in that the glass becomes fluorescent when we send the current through. This is the kind of rays usually made visible by letting them fall upon a screen of barium platinocyanide. They have the property of making the glass intensely fluorescent. Please observe the glass. You see it shining with a very strong, greenish-yellow, fluorescent light. The rays that shew themselves in this way are the Roentgen rays or X-rays, mentioned yesterday. We observe this kind too, therefore.

Now I was telling you how in the further study of these things it appeared that certain entities, regarded as material substances, emit sheaves of rays—rays of three kinds, to begin with. We distinguished them as \(\alpha\)-, \(\beta\)-, and \(\gamma\)-rays (cf. the Figure IXc). They shew distinct properties. Moreover, yet another thing emerges from these materials, known as radium etc. It is the chemical element itself which as it were gives itself up completely. In sending out its radiation, it is transmuted. It changes into helium, for example; so it becomes something quite different from what it was before. We have to do no longer with stable and enduring matter but with a complete metamorphosis of phenomena.

Taking my start from these facts, I now want to unfold a point of view which may become for you an essential way, not only into these phenomena but into those of Nature generally. The Physics of the 19th century chiefly suffered from the fact that the inner activity, with which man sought to follow up the phenomena of Nature, was not sufficiently mobile in the human being himself. Above all, it was not able really to enter the facts of the outer world. In the realm of light, colours could be seen arising, but man had not enough inner activity to receive the world of colour into his forming of ideas, into his very thinking. Unable any longer to think the colours, scientists replaced the colours, which they could not think, by what they could,—namely by what was purely geometrical and kinematical—calculable waves in an unknown ether. This “ether” however, as you must see, proved a tricky fellow. Whenever you are on the point of catching it, it evades you. It will not answer the roll-call. In these experiments for instance, revealing all these different kinds of rays, the flowing electricity has become manifest to some extent, as a form of phenomenon in the outer world,—but the “ether” refuses to turn up. In fact it was not given to the 19th-century thinking to penetrate into the phenomena. But this is just what Physics will require from now on. We have to enter the phenomena themselves with human thinking. Now to this end certain ways will have to be opened up—most of all for the realm of Physics.

You see, the objective powers of the World, if I may put it so,—those that come to the human being rather than from him—have been obliging human thought to become rather more mobile (albeit, in a certain sense, from the wrong angle). What men regarded as most certain and secure, that they could most rely on, was that they could explain the phenomena so beautifully by means of arithmetic and geometry—by the arrangement of lines, surfaces and bodily forms in space. But the phenomena in these Hittorf tubes are compelling us to go more into the facts. Mere calculations begin to fail us here, if we still try to apply them in the same abstract way as in the old wave-theory.

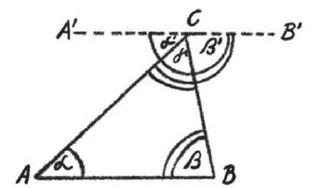

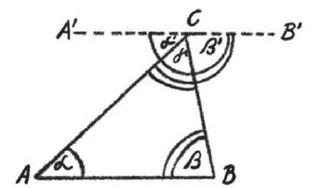

Let me say something of the direction from which it first began, that we were somehow compelled to bring more movement into our geometrical and arithmetical thinking. Geometry, you know, was a very ancient science. The regularities and laws in line and triangle and quadrilateral etc.,—the way of thinking all these forms in pure Geometry—was a thing handed down from ancient time. This way of thinking was now applied to the external phenomena presented by Nature. Meanwhile however, for the thinkers of the 19th century, the Geometry itself began to grow uncertain. It happened in this way. Put yourselves back into your school days: you will remember how you were taught (and our good friends, the Waldorf teachers, will teach it too, needless to say; they cannot but do so),—you were undoubtedly taught that the three angles of a triangle (Figure Xa) together make a straight angle—an angle of 180°. Of course you know this. Now then we have to give our pupils some kind of proof, some demonstration of the fact. We do it by drawing a parallel to the base of the triangle through the vertex. We then say: the angle \(\alpha\), which we have here, shews itself here again as \(\alpha'\). \(\alpha\) and \(\alpha'\) are alternate angles and therefore equal. I can transfer this angle over here, then. Likewise this angle \(\beta\), over here; again it remains the same.

The angle \(\gamma\) stays where it is. If then I have \(\gamma = \gamma\), \(\alpha = \alpha'\) and \(\beta=\beta'\), while \(\alpha'+\beta;' + \gamma'\) taken together give an angle of 180° as they obviously do, \(\alpha + \beta + \gamma\) will do the same. Thus I can prove it so that you actually see it. A clearer or more graphic proof can scarcely be imagined.

However, what we are taking for granted is that this upper line A'B' is truly parallel to the lower line \(AB\),—for this alone enables me to carry out the proof. Now in the whole of Euclid's Geometry there is no way of proving that two lines are really parallel, i.e. that they only meet at an infinite distance, or do not meet at all. They only look parallel so long as I hold fast to a space that is merely conceived in thought. I have no guarantee that it is so in any real space. I need only assume that the two lines meet, in reality, short of an infinite distance; then my whole proof, that the three angles together make 180°, breaks down. For I should then discover: whilst in the space which I myself construct in thought—the space of ordinary Geometry—the three angles of a triangle add up to 180° exactly, it is no longer so when I envisage another and perhaps more real space. The sum of the angles will no longer be 180°, but may be larger. That is to say, besides the ordinary geometry handed down to us from Euclid other geometries are possible, for which the sum of the three angles of a triangle is by no means 180°.

Nineteenth century thinking went a long way in this direction, especially since Lobachevsky, and from this starting-point the question could not but arise: Are then the processes of the real world—the world we see and examine with our senses—ever to be taken hold of in a fully valid way with geometrical ideas derived from a space of our own conceiving? We must admit: the space which we conceive in thought is only thought. Nice as it is to cherish the idea that what takes place outside us partly accords with what we figure-out about it, there is no guarantee that it really is so. There is no guarantee that what is going on in the outer world does really work in such a way that we can fully grasp it with the Euclidean Geometry which we ourselves think out. Might it not be—the facts alone can tell—might it not be that the processes outside are governed by quite another geometry, and it is only we who by our own way of thinking first translate this into Euclidean geometry and all the formulae thereof?

In a word, if we only go by the resources of Natural Science as it is today, we have at first no means whatever of deciding, how our own geometrical or kinematical ideas are related to what appears to us in outer Nature. We calculate Nature's phenomena in the realm of Physics—we calculate and draw them in geometrical figures. Yet, are we only drawing on the surface after all, or are we penetrating to what is real in Nature when we do so? What is there to tell? If people once begin to reflect deeply enough in modern Science—above all in Physics—they will then see that they are getting no further. They will only emerge from the blind alley if they first take the trouble to find out what is the origin of all our phoronomical—arithmetical, geometrical and kinematical—ideas. What is the origin of these, up to and including our ideas of movement purely as movement, but not including the forces? Whence do we get these ideas? We may commonly believe that we get them on the same basis as the ideas we gain when we go into the outer facts of Nature and work upon them with our reason. We see with our eyes and hear with our ears. All that our senses thus perceive,—we work upon it with our intellect in a more primitive way to begin with, without calculating, or drawing it geometrically, or analyzing the forms of movement. We have quite other categories of thought to go on when our intellect is thus at work on the phenomena seen by the senses. But if we now go further and begin applying to what goes on in the outer world the ideas of “scientific” arithmetic and algebra, geometry and kinematics, then we are doing far more—and something radically different. For we have certainly not gained these ideas from the outer world. We are applying ideas which we have spun out of our own inner life. Where then do these ideas come from? That is the cardinal question. Where do they come from? The truth is, these ideas come not from our intelligence—not from the intelligence which we apply when working up the ideas derived from sense-perception. They come in fact from the intelligent part of our Will. We make them with our Will-system—with the volitional part of our soul.

The difference is indeed immense between all the other ideas in which we live as intelligent beings and on the other hand the geometrical, arithmetical and kinematical ideas. The former we derive from our experience with the outer world; these on the other hand—the geometrical, the arithmetical ideas—rise up from the unconscious part of us, from the Will-part which has its outer organ in the metabolism. Our geometrical ideas above all spring from this realm; they come from the unconscious in the human being. And if you now apply these geometrical ideas (I will say “geometrical” henceforth to represent the arithmetical and algebraic too) to the phenomena of light or sound, then in your process of knowledge you are connecting, what arises from within you, with what you are perceiving from without. In doing so you remain utterly unconscious of the origin of the geometry you use. You unite it with the external phenomena, but you are quite unconscious of its source. So doing, you develop theories such as the wave-theory of light, or Newton's corpuscular theory,—it matters not which one it is. You develop theories by uniting what springs from the unconscious part of your being with what presents itself to you in conscious day-waking life. Yet the two things do not directly belong to one-another. They belong as little, my dear Friends, as the idea-forming faculty which you unfold when half-asleep belongs directly to the outer things which in your dreaming, half-asleep condition you perceive. In anthroposophical lectures I have often given instances of how the dream is wont to symbolize. An undergraduate dreams that at the door of the lecture-theatre he gets involved in a quarrel. The quarrel grows in violence; at last they challenge one-another to a duel. He goes on dreaming: the duel is arranged, they go out into the forest, he sees himself firing the shot,—and at the moment he wakes up. A chair has fallen over. This was the impact which projected itself forward into the dream. The idea-forming faculty has indeed somehow linked up with the outer phenomenon, but in a merely symbolizing way,—in no way consistent with the real object. So too, what in your geometrical and phoronomical thinking you fetch up from the subconscious part of your being, when you connect it with the phenomena of light. What you then do has no other value for reality than what finds expression in the dream when symbolizing an objective fact such as the fall and impact of the chair. All this elaboration of the outer world—optical, acoustic and even thermal to some extent (the phenomena of warmth)—by means of geometrical, arithmetical and kinematical thought-forms, is in point of fact a dreaming about Nature. Cool and sober as it may seem, it is a dream—a dreaming while awake. Moreover, until we recognize it for what it is, we shall not know where we are in our Natural Science, so that our Science gives us reality. What people fondly believe to be the most exact of Sciences, is modern mankind's dream of Nature.

But it is different when we go down from the phenomena of light and sound, via the phenomena of warmth, into the realm we are coming into with these rays and radiations, belonging as they do to the science of electricity. For we then come into connection with what in outer Nature is truly equivalent to the Will in Man. The realm of Will in Man is equivalent to this whole realm of action of the cathode rays, canal rays, Roentgen rays. \(\alpha\)-, \(\beta\)- and \(\gamma\)-rays and so on. It is from this very realm—which, once again, is in the human being the realm of Will,—it is from this that there arises what we possess in our mathematics, in our geometry, in our ideas of movement. These therefore are the realms, in Nature and in Man, which we may truly think of as akin to one-another. However, human thinking has in our time not yet gone far enough, really to think its way into these realms. Man of today can dream quite nicely, thinking out wave-theories and the like, but he is not yet able to enter with real mathematical perception into that realm of phenomena which is akin to the realm of human Will, in which geometry and arithmetic originate. For this, our arithmetical, algebraical and geometrical thinking must in themselves become more saturated with reality. It is along these lines that physical science should now seek to go.

Nowadays, if you converse with physicists who were brought up in the golden age of the old wave-theory, you will find many of them feeling a little uncanny about these new phenomena, in regard to which ordinary methods of calculation seem to break down in so many places. In recent times the physicists have had recourse to a new device. Plain-sailing arithmetical and geometrical methods proving inadequate, they now introduce a kind of statistical method. Taking their start more from the outer empirical data, they have developed numerical relations also empirical in kind. They then use the calculus of probabilities. Along these lines it is permissible to say: By all means let us calculate some law of Nature; it will hold good throughout a certain series, but then there comes a point where it no longer works.

There are indeed many things like this in modern Physics,—very significant moments where they lose hold of the thought, yet in the very act of losing it get more into reality. Conceivably for instance, starting from certain rigid ideas about the nature of a gas or air under the influence of warmth and in relation to its surroundings, a scientist of the past might have proved with mathematical certainty that air could not be liquefied. Yet air was liquefied, for at a certain point it emerged that the ideas which did indeed embrace the prevailing laws of a whole series of facts, ceased to hold good at the end of this series. Many examples might be cited. Reality today—especially in Physics—often compels the human being to admit this to himself: “You with your thinking, with your forming of ideas, no longer fully penetrate into reality; you must begin again from another angle.”

We must indeed; and to do this, my dear Friends, we must become aware of the kinship between all that comes from the human Will—whence come geometry and kinematics—and on the other hand what meets us outwardly in this domain that is somehow separated from us and only makes its presence known to us in the phenomena of the other pole. For in effect, all that goes on in these vacuum tubes makes itself known to us in phenomena of light, etc. Whatever is the electricity itself, flowing through there, is imperceptible in the last resort. Hence people say: If only we had a sixth sense—a sense for electricity—we should perceive it too, directly. That is of course wide of the mark. For it is only when you rise to Intuition, which has its ground in the Will, it is only then that you come into that region—even of the outer world—where electricity lives and moves. Moreover when you do so you perceive that in these latter phenomena you are in a way confronted by the very opposite than in the phenomena of sound or tone for instance. In sound or in musical tone, the very way man is placed into this world of sound and tone—as I explained in a former lecture—means that he enters into the sound or tone with his soul and only with his soul. What he then enters into with his body, is no more than what sucks-in the real essence of the sound or tone. I explained this some days ago; you will recall the analogy of the bell-jar from which the air has been pumped out. In sound or tone I am within what is most spiritual, while what the physicist observes (who of course cannot observe the spiritual nor the soul) is but the outer, so-called material concomitant, the movement of the wave. Not so in the phenomena of the realm we are now considering, my dear Friends. For as I enter into these, I have outside me not only the objective, so-called material element, but also what in the case of sound and tone is living in me—in the soul and spirit. The essence of the sound or tone is of course there in the outer world as well, but so am I. With these phenomena on the other hand, what in the case of sound could only be perceived in soul, is there in the same sphere in which—for sound—I should have no more than the material waves. I must now perceive physically, what in the case of sound or tone I can only perceive in the soul.

Thus in respect of the relation of man to the external world the perceptions of sound, and the perceptions of electrical phenomena for instance, are at the very opposite poles. When you perceive a sound you are dividing yourself as it were into a human duality. You swim in the elements of wave and undulation, the real existence of which can of course be demonstrated by quite external methods. Yet as you do so you become aware; herein is something far more than the mere material element. You are obliged to kindle your own inner life—your life of soul—to apprehend the tone itself. With your ordinary body—I draw it diagrammatically (the oval in Figure Xb)—you become aware of the undulations. You draw your ether—and astral body together, so that they occupy only a portion of your space. You then enjoy, what you are to experience of the sound or tone as such, in the thus inwarded and concentrated etheric-astral part of your being. It is quite different when you as human being meet the phenomena of this other domain, my dear Friends. In the first place there is no wave or undulation or anything like that for you to dive into; but you now feel impelled to expand what in the other case you concentrated (Figure Xc). In all directions, you drive your ether—and astral body out beyond your normal surface; you make them bigger, and in so doing you perceive these electrical phenomena.

Without including the soul and spirit of the human being, it will be quite impossible to gain a true or realistic conception of the phenomena of Physics. Ever-increasingly we shall be obliged to think in this way. The phenomena of sound and tone and light are akin to the conscious element of Thought and Ideation in ourselves, while those of electricity and magnetism are akin to the sub-conscious element of Will. Warmth is between the two. Even as Feeling is intermediate between Thought and Will, so is the outer warmth in Nature intermediate between light and sound on the one hand, electricity and magnetism on the other. Increasingly therefore, this must become the inner structure of our understanding of the phenomena of Nature. It can indeed become so if we follow up all that is latent in Goethe's Theory of Colour. We shall be studying the element of light and tone on the one hand, and of the very opposite of these—electricity and magnetism—on the other. As in the spiritual realm we differentiate between the Luciferic, that is akin to the quality of light, and the Ahrimanic, akin to electricity and magnetism, so also must we understand the structure of the phenomena of Nature. Between the two lies what we meet with in the phenomena of Warmth.

I have thus indicated a kind of pathway for this scientific realm,—a guiding line with which I wished provisionally to sum up the little that could be given in these few improvised hours. It had to be arranged so quickly that we have scarcely got beyond the good intentions we set before us. All I could give were a few hints and indications; I hope we shall soon be able to pursue them further. Yet, little as it is, I think what has been given may be of help to you—and notably to the Waldorf School teachers among you when imparting scientific notions to the children. You will of course not go about it in a fanatical way, for in such matters it is most essential to give the realities a chance to unfold. We must not get our children into difficulties. But this at least we can do: we can refrain from bringing into our teaching too many untenable ideas—ideas derived from the belief that the dream-picture which has been made of Nature represents actual reality. If you yourselves are imbued with the kind of scientific spirit with which these lectures—if we may take them as a fair example—have been pervaded, it will assuredly be of service to you in the whole way you speak with the children about natural phenomena.

Methodically too, you may derive some benefit. I am sorry it was necessary to go through the phenomena at such breakneck speed. Yet even so, you will have seen that there is a way of uniting what we see outwardly in our experiments with a true method of evoking thoughts and ideas, so that the human being does not merely stare at the phenomena but really thinks about them. If you arrange your lessons so as to get the children to think in connection with the experiments—discussing the experiments with them intelligently—you will develop a method, notably in the Science lessons, whereby these lessons will be very fruitful for the children who are entrusted to you.

Thus by the practical example of this course, I think I may have contributed to what was said in the educational lectures at the inception of the Waldorf School. I believe therefore that in arranging these scientific courses we shall also have done something for the good progress of our Waldorf School, which ought really to prosper after the good and very praiseworthy start which it has made. The School was meant as a beginning in a real work for the evolution of our humanity—a work that has its fount in new resources of the Spirit. This is the feeling we must have. So much is crumbling, of all that has developed hitherto in human evolution. Other and new developments must come in place of what is breaking down. This realization in our hearts and minds will give the consciousness we need for the Waldorf School. In Physics especially it becomes evident, how many of the prevailing ideas are in decay. More than one thinks, this is connected with the whole misery of our time. When people think sociologically, you quickly see where their thinking goes astray. Admittedly, here too most people fail to see it, but you can at least take notice of it; you know that sociological ways of thought will find their way into the social order of mankind. On the other hand, people fail to realize how deeply the ideas of Physics penetrate into the life of mankind. They do not know what havoc has in fact been wrought by the conceptions of modern Physics, terrible as these conceptions often are. In public lectures I have often quoted Hermann Grimm. Admittedly, he saw the scientific ideas of his time rather as one who looked upon them from outside. Yet he spoke not untruly when he said, future generations would find it difficult to understand that there was once a world so crazy as to explain the evolution of the Earth and Solar System by the theory of Kant and Laplace. To understand such scientific madness would not be easy for a future age, thought Hermann Grimm. Yet in our modern conceptions of inorganic Nature there are many features like the theory of Kant and Laplace. And you must realize how much is yet to do for the human beings of our time to get free of the ways of Kant and Konigsberg and all their kindred. How much will be to do in this respect, before they can advance to healthy, penetrating ways of thought!

Strange things one witnesses indeed from time to time, shewing how what is wrong on one side joins up with what is wrong on another. What of a thing like this? Some days ago—as one would say, by chance—I was presented with a reprint of a lecture by a German University professor. (He prides himself in this very lecture that there is in him something of Kant and Konigsberg!) It was a lecture in a Baltic University, on the relation of Physics and Technics, held on the 1st of May 1918,—please mark the date! This learned physicist of our time in peroration voices his ideal, saying in effect: The War has clearly shewn that we have not yet made the bond between Militarism and the scientific laboratory work of our Universities nearly close enough. For human progress to go on in the proper way, a far closer link must in future be forged between the military authorities and what is being done at our Universities. Questions of mobilization in future must include all that Science can contribute, to make the mobilization still more effective. At the beginning of the War we suffered greatly because the link was not yet close enough—the link which we must have in future, leading directly from the scientific places of research into the General Staffs of our armies.

Mankind, my dear Friends, must learn anew, and that in many fields. Once human beings make up their minds to learn anew in such a realm as Physics, they will be better prepared to learn anew in other fields as well. Those physicists who go on thinking in the old way, will never be so very far removed from the delightful coalition between the scientific laboratories and the General Staffs. How many things will have to alter! So may the Waldorf School be and remain a place where the new things which mankind needs can spring to life. In the expression of this hope, I will conclude our studies for the moment.

Zehnter Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde!

Ich möchte als einen vorläufigen Schluss dieser paar improvisierten Stunden, die naturwissenschaftliche Betrachtungen enthielten, Ihnen heute einige Richtlinien geben, die Ihnen nützlich sein können, um selbst solche Naturbetrachtungen an der Hand charakteristischer Tatsachen, die man sich durch das Experiment vor Augen führen kann, sich zu bilden. Es handelt sich ja heute im naturwissenschaftlichen Gebiet, namentlich für den Lehrenden, sehr stark darum, dass er sich hineinfinde in eine richtige Vorstellungsart und Betrachtungsweise desjenigen, was die Natur darbietet. Und gestern war ich gerade auch im Hinblick an das eben Gesagte bemüht, Ihnen zu zeigen, wie der Gang der physikalischen Wissenschaft ein solcher ist, nachdem die Neunzigerjahre des vorigen Jahrhunderts herangekommen waren, dass gewissermaßen von der Physik aus der Materialismus aus den Angeln gehoben wird, und auf diesen Gesichtspunkt sollten Sie eigentlich den Hauptwert legen.

Wir haben gesehen, dass auf die Zeit, die glaubte, schon die goldensten Beweise zu haben für die Universalität des Schwingungswesens, eine Zeit gefolgt ist, die unmöglich an der alten Schwingungs- oder Undulations-Hypothese festhalten konnte, eine Zeit, die gewissermaßen in der Physik in den letzten drei Jahrzehnten so revolutionierend gewesen ist, wie nur irgendetwas revolutionierend in seinem Gebiete gedacht werden kann. Denn der Physik ist ja nichts Geringeres verloren gegangen unter dem Zwange der Tatsachen, die sich geboten haben, als der Materiebegriff in der alten Form als solcher.'*

Wir haben gesehen, dass die Lichterscheinungen [zunächst] in nahe Beziehung gebracht worden sind, als [Konsequenz] aus der alten Anschauungsweise heraus, zu den elektromagnetischen Erscheinungen, und dass [dann] zuletzt geführt haben die Erscheinungen des Ganges der Elektrizität durch luftverdünnte oder gasverdünnte Röhren, dass diese Erscheinungen dazu geführt haben, in dem sich ausbreitenden Lichte selbst etwas zu sehen wie sich ausbreitende Elektrizität. Ich sage nicht, dass [man] damit recht hat, aber es ist eben gekommen. Und man hat das dadurch erreicht, dass man gewissermaßen die elektrische Strömung, die man sonst immer wie eingeschlossen hatte in die Drähte, kaum nach einem anderen Gesichtspunkte als nach dem Ohm’schen Gesetze betrachten konnte, dass man die gewissermaßen belauschte bei ihrem Gange, wo sie den Draht verlässt, überspringt auf einen weit entfernten [Pol] und nicht durch die Materie gewissermaßen, durch [die] sie dringt, verbergen kann, was in ihr ist.

Dadurch aber ist etwas sehr Kompliziertes zum Vorschein gekommen. Wir haben gestern gesehen, wie die verschiedensten Strahlenarten dadurch zum Vorschein gekommen sind. Wir haben gesehen, dass zuerst - ich habe Ihnen ja die Erscheinungen angeführt - wie zuerst bekannt geworden sind die sogenannten Kathodenstrahlen, die von dem negativen Pol der Hittorf’schen Röhren ausgehen und durch den luftverdünnten Raum gehen, wie schon diese Kathodenstrahlen gezeigt haben dadurch, dass sie ablenkbar sind durch magnetische Kräfte, etwas Verwandtes haben mit dem, was man gewöhnlich als Materielles empfindet. Auf der anderen Seite haben sie etwas Verwandtes mit dem, was man durch Strahlungen wahrnimmt. Das zeigt sich ja besonders anschaulich dann, wenn man solche Versuche macht, dass man solche Strahlen, die also in irgendeiner Weise vom [negativen] elektrischen Pol kommen, dass man diese, wie man Licht auffängt, durch einen Schirm oder durch sonst einen Gegenstand auffängt. — Licht wirft Schatten -, solche Strahlungen werfen auch Schatten. Natürlich ist aber gerade dadurch auch die Beziehung hergestellt zu dem gewöhnlichen materiellen Element. Denn wenn Sie sich vorstellen, dass [man] von [der Kathode] hier aus, wie es ja, wie wir gestern gesehen haben, zum Beispiel nach Crookes’ Vorstellungen mit den Kathodenstrahlen geschieht, bombardiert [einen Schirm], so gehen die Bomben nicht durch das Hindernis durch, und dasjenige, was dahinter ist, bleibt ungeschoren. Wir können dieses durch das Crookes’sche Experiment besonders veranschaulichen, indem wir die Kathodenstrahlen auffangen.

Wir werden hier erzeugen den elektrischen Strom, den wir dann leiten durch diese Röhre, die luftverdünnt ist, die hier ihre Kathode, den negativen Pol hat, und hier ihre Anode, den positiven Pol, hat. Wir bekommen also, indem wir durch diese Röhre die Elektrizität treiben, die sogenannten Kathodenstrahlen. Diese fangen wir auf durch ein eingefügtes Andreaskreuz. Wir lassen sie darauf aufprallen, und Sie werden sehen, dass auf der anderen Seite nun etwas sichtbar wird wie der Schatten dieses Andreaskreuzes, was Ihnen bezeugt, dass dieses Andreaskreuz die Strahlen aufhält. Bitte berücksichtigen Sie genau: Das Andreaskreuz ist da drinnen und die Kathodenstrahlen gehen so, werden aufgefangen durch das hier sitzende Kreuz, und es wird der Schatten an der rückwärtigen Wand sichtbar. Ich werde nun diesen Schatten, der hier sichtbar wird, in das magnetische Feld eines Magneten einbeziehen, und ich bitte Sie jetzt, diesen Schatten des Andreaskreuzes zu beobachten. Sie werden [die Lage des Schattens] vom magnetischen Feld beeinflusst finden. Sie sehen? Also Sie sehen, wie ich irgendeinen anderen einfachen, sagen wir, Eisengegenstand mit dem Magneten anziehe, so verhält sich wie äußere Materie dasjenige, was da wie eine Art von Schatten entsteht. Also, es verhält sich auch materiell.

Wir haben also hier auf der einen Seite eine Art von Strahlen, die für Crookes eigentlich sich zurückführen auf strahlende Materie, einen Aggregatzustand, der weder fest, flüssig noch gasförmig ist, sondern der ein feinerer Aggregatzustand ist und der uns aber zeigt, dass diese ganze Elektrizität in ihrer Strömung sich [auf der anderen Seite] so verhält wie einfache Materie. Also, wir haben gewissermaßen den Blick auf die Strömung der fließenden Elektrizität gerichtet, und dasjenige, was wir sehen, enthüllt sich uns so wie dasjenige, was wir als Wirkungen innerhalb der Materie sehen.

Ich will Ihnen nun noch zeigen - weil das gestern nicht möglich war -, wie entstehen diejenigen Strahlen, die vom anderen Pol, [vom positiven Pol], kommen, die ich Ihnen gestern als die Kanalstrahlen charakterisierte. Sie sehen hier unterschieden die [Kathodenstrahlen], die von der Kathode kommen, die nach dieser Richtung gehen, in dem violettlichen Licht schimmern, und die Kanalstrahlen ihnen entgegenkommend mit einer viel geringeren Geschwindigkeit, die das [rötliche] Licht geben.

Nun will ich Ihnen noch zeigen die Strahlenart, die hier durch diese Vorrichtung entsteht und die sich Ihnen besonders dadurch offenbaren wird, dass das Glas Fluoreszenzerscheinungen zeigt, indem wir die elektrische Strömung hindurchleiten. Hier werden wir diejenige Strahlenart bekommen, welche man sonst bekommt, wenn man diese Strahlen durch einen Schirm gehen lässt von Bariumplatinzyanür, und die die Eigenschaft haben, das Glas recht stark fluoreszierend zu machen. Sie sehen das Glas - auf das bitte ich Sie jetzt hauptsächlich Ihre Aufmerksamkeit zu richten - in sehr stark grünlich-gelblich fluoreszierendem Lichte. Die Strahlen, die in solchem sehr stark fluoreszierendem Lichte erscheinen, sind nun eben die schon gestern erwähnten Röntgenstrahlen. Sodass wir auch diese Gattung hier bemerken.

Nun sagte ich Ihnen, dass beim Verfolgen dieser Vorgänge sich herausgestellt hat, wie gewisse, als Stoffe angesehene Entitäten, ganze Bündel von Strahlen, zunächst wenigstens von dreierlei Art, aussenden, die wir gestern unterschieden haben in \(α\)-, \(β\)- und \(γ\)-Strahlen und die deutlich voneinander verschiedene Eigenschaften zeigen. Dass dann diese Substanzen, die man als Radium, Helium und so weiter bezeichnet, aber noch ein Viertes aussenden, das gewissermaßen das Element selbst ist, das sich hingibt und das sich, nachdem es ausgesandt ist, verwandelt hat so, dass, während das Radium ausströmt, es sich verwandelt in Helium, also etwas ganz anderes wird. Wir haben es also nicht zu tun mit festbleibender Materie, sondern mit einer Metamorphose der Erscheinungen.

Nun möchte ich eben gerade in Anknüpfung an diese Dinge einen Gesichtspunkt entwickeln, der gewissermaßen für Sie werden kann der Weg in diese Erscheinungen hinein, überhaupt der Weg in die Naturerscheinungen hinein. Sehen Sie, woran das physikalische Denken des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts hauptsächlich gekrankt hat, das ist, dass die innere Tätigkeit, durch die der Mensch die Naturerscheinungen zu verfolgen suchte, im Menschen nicht beweglich genug war, vor allen Dingen nicht fähig war noch, sich auf die Tatsachen der Außenwelt selbst einzulassen. Man konnte Farben sehen am Lichte entstehen, aber man schwang sich nicht auf zu einem Aufnehmen des Farbigen in sein Vorstellen, in sein Denken, man konnte Farben nicht mehr denken, und man ersetzte die Farben, die man nicht denken konnte, durch das, was man denken konnte, was eben nur phoronomisch ist, durch die errechenbaren Schwingungen eines unbekannten Äthers. Dieser Äther aber, sehen Sie, der ist etwas, was tückisch ist. Denn immer, wenn man ihn aufsuchen will, da stellt er sich nicht. Und alle diese Versuche, die da diese verschiedenen Strahlen zutage gefördert haben, die haben eigentlich gezeigt, dass sich wohl flüssige Elektrizität zeigt, also etwas, was als Erscheinungsform in der Außenwelt liegt, dass sich aber der Äther durchaus nicht stellen will. Nun ist es eben nicht gegeben gewesen dem Denken des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts, in die Erscheinungen selber einzudringen. Das ist aber gerade dasjenige, was vom jetzigen Zeitpunkt ab für die Physik so notwendig sein wird, mit dem menschlichen Vorstellen in die Erscheinungen selbst einzudringen. Dazu aber werden gewisse Wege eröffnet werden müssen gerade für die Betrachtung der physikalischen Erscheinungen.

Sehen Sie, man möchte sagen: Die mehr an den Menschen herankommenden objektiven Mächte, die haben eigentlich das Denken schon gezwungen, etwas beweglicher zu werden, aber man könnte sagen: von einer falschen Ecke aus. sehen Sie, dasjenige, was man als das Sichere betrachtet hat, worauf man sich am allermeisten verlassen hat, das ist ja dasjenige, dass man so schön hat können mit der Rechnung und mit der Geometrie, also mit der Anordnung von Linien, von Flächen und von Körpern im Raume, die Erscheinungen erklären. Dasjenige, wozu einen diese Erscheinungen hier in den Hittorf’schen Röhren zwingen, das ist, dass man mehr an die Tatsachen herantreten muss, dass die Rechnung vielmehr eigentlich doch versagt, wenn man sie in so abstrakter Form anwenden will, wie man das in der früheren Undulations-Lehre getan hat.

Nun, von der Ecke, von der zuerst etwas wie ein Zwang zum Beweglichmachen des arithmetischen und des geometrischen Denkens gekommen ist, möchte ich Ihnen zuerst sprechen. Nicht wahr, die Geometrie war etwas sehr Altes. Wie man sich aus der Geometrie heraus Gesetzmäßigkeiten an Linien, Dreiecken, Vierecken und so weiter vorstellt, das ist etwas Althergekommenes und das hat man angewendet auf dasjenige, was sich einem als äußere Erscheinungen in der Natur bietet. Nun ist aber gerade vor dem Denken des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts diese Geometrie etwas ins Wanken gekommen, und das ist auf die folgende Weise geschehen: Nicht wahr, versetzen Sie sich wiederum gut auf die Schulbank, so wissen Sie, überall wird Ihnen gelehrt - und unsere lieben Waldorfschullehrer lehren es selbstverständlich auch, müssen es ja lehren -, wenn man ein Dreieck hat und die drei Winkel nimmt, so sind diese drei Winkel zusammen ein gestreckter oder 180°. Das ist Ihnen bekannt. Nun fühlt man sich natürlich gedrängt - und muss sich gedrängt fühlen -, auch den Schülern eine Art Beweis zu geben dafür, dass diese drei Winkel zusammen 180° sind. Man macht ja das dadurch, dass man hier [durch die Spitze \(C\)] eine Parallele zieht zu der Grundlinie des Dreiecks, dass man sagt: Derselbe Winkel, der hier als \(α\) ist, zeigt sich hier als \(α’\). \(α\) und \(α’\) sind Wechselwinkel. Sie sind gleich. Ich kann also einfach diesen Winkel hier herüberlegen. Ebenso kann ich diesen Winkel \(β\) hier herüberlegen und habe hier das gleiche. Nun, der Winkel \(γ\) bleibt ja liegen, und wenn \(γ = γ\) und \(α’ = α\) und \(β’ = β\) ist und \(α’ + β’ + γ\) zusammen einen gestreckten Winkel geben, so müssen auch \(α + β + γ\) einen gestreckten Winkel zusammen bilden. Ich kann also das klar anschaulich beweisen.

Etwas Klareres und Anschaulicheres kann es, möchte man sagen, gar nicht geben. Nun aber, die Voraussetzung, die man da macht, indem man dies beweist, ist die, dass diese obere Linie \(A’-B’\) parallel ist zu \(A-B\). Denn nur dadurch bin ich in der Lage, den Beweis zu führen. Nun gibt es aber in der ganzen Euklid’schen Geometrie kein Mittel zu beweisen, dass zwei Linien parallel sind, das heißt sich in unendlicher Entfernung erst schneiden, das heißt gar nicht schneiden. Das sieht so aus, als ob sie parallel wären, nur solange ich beim gedachten Raum bleibe. Nichts verbürgt mir, dass das auch bei einem wirklichen Raum so der Fall ist. Und wenn ich daher nur das eine annehme, dass diese beiden Geraden sich nicht in unendlicher Entfernung erst schneiden, sondern sich real früher schneiden, dann geht mein ganzer Beweis für die 180° der Dreieckswinkel kaputt, dann würde ich herausbekommen - dass zwar nicht in dem Raum, den ich mir selber in Gedanken konstruiere und mit dem sich die gewöhnliche Geometrie befasst, dass zwar in diesem Raum die Dreieckswinkel 180° als Winkelsumme haben -, dass aber, sobald ich einen vielleicht anderen, wirklichen Raum ins Auge fasse, dass die Winkelsumme des Dreiecks gar nicht mehr 180°, sondern vielleicht größer ist. Das heißt, es sind außer der gewöhnlichen, von Euklid herstammenden Geometrie noch andere Geometrien möglich, für welche die Summe der Dreieckswinkel durchaus nicht 180° ist.

Mit Auseinandersetzungen nach dieser Richtung hat sich das Denken des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts, namentlich seit Lobatschewski, viel beschäftigt, und daran schließend musste doch die Frage entstehen: Sind denn nun eigentlich die Vorgänge der Wirklichkeit, die wir da verfolgen mit unseren Sinnen, wirklich auch zu fassen, vollgültig zu fassen mit denjenigen Vorstellungen, die wir als geometrische Vorstellungen in dem von uns gedachten Raum gewinnen? Der von uns gedachte Raum ist zweifellos gedacht. Wir können zwar als eine schöne Vorstellung hegen, dass dasjenige, was da draußen außer uns geschieht, teilweise zusammentrifft mit demjenigen, was wir darüber aushecken, aber es garantiert uns nichts dafür, dass dasjenige, was draußen geschieht, so wirke, dass wir es restlos begreifen durch die von uns ausgedachte Euklid’sche Geometrie. Es könnte sehr leicht sein — darüber könnten uns aber nur die Tatsachen selber belehren -, dass die Dinge draußen nach einer ganz anderen Geometrie vorgehen und wir sie erst bei unserer Auffassung übersetzen in die Euklid’sche Geometrie und ihre Formeln.

Das heißt, wir haben zunächst, wenn wir uns bloß einlassen auf dasjenige, was der Wissenschaft der Natur heute zur Verfügung steht, gar keine Möglichkeit, irgendetwas zunächst darüber zu entscheiden, wie sich verhalten unsere geometrischen, überhaupt die phoronomischen Vorstellungen zu demjenigen, was uns draußen in der Natur erscheint. Wir rechnen, zeichnen die Naturerscheinungen, insofern sie physikalisch sind. Aber ob wir da nur irgendetwas äußerlich nur an der Oberfläche zeichnen oder in irgendetwas von der Natur eindringen, darüber ist zunächst ja nichts auszumachen. Und wenn man einmal anfangen wird, gründlichst zu denken in der namentlich physikalischen Naturwissenschaft, dann, meine lieben Freunde, dann wird man in eine furchtbare Sackgasse hineinkommen, dann wird man sehen, wie man nicht weiterkommt. Und man wird nur weiterkommen, wenn man sich zuerst belehren wird über den Ursprung unserer phoronomischen Vorstellungen, unserer Vorstellungen über das Zählen, über das Geometrische und auch unserer Vorstellungen über die bloße Bewegung, nicht über die Kräfte.

Woher kommen denn alle diese phoronomischen Vorstellungen? No, man kann so gewöhnlich den Glauben haben, sie kommen aus demselben Grunde heraus, aus dem die Vorstellungen kommen, die wir auch gewinnen, wenn wir uns auf die äußeren Tatsachen der Natur einlassen und diese verstandesmäßig bearbeiten. Wir sehen durch unsere Augen, hören durch unsere Ohren, wir verarbeiten das durch die Sinne Wahrgenommene mit dem Verstande zunächst primitiv, ohne dass wir es zählen, ohne dass wir es zeichnen, ohne dass wir auf die Bewegung schauen. Wir richten uns nach ganz anderen Begriffskategorien. Da ist unser Verstand an der Hand der Sinneserscheinungen tätig. Aber wenn wir nun anfangen, sogenannt wissenschaftliche Geometrie-, Arithmetik- oder Algebra- [oder] Bewegungs-Vorstellungen anzuwenden auf dasjenige, was da äußerlich vorgeht, dann tun wir doch etwas anderes noch, dann wenden wir Vorstellungen an, die wir ganz sicher nicht aus der Außenwelt gewonnen haben, sondern die wir aus unserem Inneren herausgesponnen haben.

Woher kommen denn diese Vorstellungen eigentlich? — das ist die Kardinalfrage. Woher kommen denn diese Vorstellungen? Diese Vorstellungen, sehen Sie, die kommen nämlich gar nicht aus unserer Intelligenz, die wir anwenden, wenn wir die Sinnesvorstellungen verarbeiten, sondern diese Vorstellungen kommen eigentlich aus dem intelligenten Teil unseres Willens, die machen wir mit unserer Willensstruktur, mit dem Willensteil unserer Seele. Es ist ein gewaltiger Unterschied zwischen allen anderen Vorstellungen unserer Intelligenz und den geometrischen und arithmetischen und BewegungsVorstellungen. Die anderen Vorstellungen gewinnen wir an den Erfahrungen der Außenwelt; diese Vorstellungen, die geometrischen, die arithmetischen Vorstellungen, die steigen auf aus dem unbewussten Teile von uns, aus dem Willensteile, der sein äußeres Organ im Stoffwechsel hat. Daraus steigen zum Beispiel im eminentesten Sinne die geometrischen Vorstellungen auf. Diese kommen aus dem Unbewussten im Menschen. Und wenn Sie anwenden diese geometrischen Vorstellungen - ich werde sie jetzt gebrauchen auch für die arithmetischen und algebraischen Vorstellungen -, wenn Sie sie gebrauchen für Lichterscheinungen oder Schall- oder Tonerscheinungen, dann verbinden Sie in Ihrem Erkenntnisprozess dasjenige, was Ihnen von innen aufsteigt, mit demjenigen, was Sie äußerlich wahrnehmen.

Ja, unbewusst bleibt Ihnen dabei der ganze Ursprung der aufgewendeten Geometrie. Sie vereinigen diese aufgewendete Geometrie mit den äußeren Erscheinungen. Unbewusst bleibt Ihnen der ganze Ursprung. Und Sie bilden aus solchen Theorien wie die Undulations-Theorie - es ist ja ganz gleichgültig, ob man diese oder die [Emissions-]Theorie Newtons ausbildet -, Sie bilden aus Theorien, indem Sie vereinigen, was aus Ihrem unbewussten Teil aufsteigt, mit demjenigen, was sich Ihnen als bewusstes Tagesleben darstellt. [In den] Schallerscheinungen und so weiter durchdringen [Sie] das eine mit dem anderen. Diese beiden Dinge gehören zunächst nicht zusammen. Sie gehören so wenig zusammen, meine lieben Freunde, wie Ihr vorstellendes Vermögen mit den äußeren Dingen zusammengehört, die Sie wahrnehmen in einer Art von Halbschlaf.

Ich habe Ihnen öfter Beispiele genannt in anthroposophischen Vorträgen", wie der menschliche Traum symbolisiert: Ein Mensch träumt, dass er mit einem anderen Menschen als Student steht an der Türe eines Hörsaales, beide geraten in Streit, der Streit wird stark, sie fordern sich - alles wird geträumt -, es wird geträumt, wie sie hinausgehen in den Wald, es wird das Duell arrangiert. Der Betreffende träumt noch, wie er losschießt. In dem Moment wacht er auf und - der Stuhl ist umgefallen. Das war der Stoß, der sich nach vorne fortsetzt in den Traum. Die vorstellende Kraft hat sich in einer nur symbolisierenden Weise, nicht in der dem Objekt adäquaten Erscheinung, verbunden mit demjenigen, was äußere Erscheinung ist.

In einer ähnlichen Weise verbindet sich dasjenige, was Sie in dem Phoronomischen heraufholen aus dem unterbewussten Teil Ihres Wesens, mit den Lichterscheinungen. Sie zeichnen Lichtstrahlen geometrisch. Dasjenige, was Sie da vollziehen, hat keinen anderen Realitätswert als dasjenige, was sich im Traum ausdrückt, wenn Sie solche objektiven Fakten wie den Stoß des Stuhles symbolisierend vorstellen. Dieses ganze Bearbeiten der optischen, akustischen und zum Teil der Wärme-Außenwelt durch geometrische und arithmetische und Bewegungs-Vorstellungen, das ist in Wahrheit, wenn auch ein sehr nüchternes, so doch ein waches Träumen über die Natur. Und bevor man nicht erkennt, wie das ein waches Träumen ist, wird man nicht mit der Naturwissenschaft so zurechtkommen, dass diese Naturwissenschaft einem Realitäten liefert. Dasjenige, worinnen man glaubt, ganz exakte Wissenschaft zu haben, das ist der Natur-Traum der modernen Menschheit.

Wenn Sie aber nun hinuntersteigen von den Lichterscheinungen, von den Schallerscheinungen über die Wärmeerscheinungen in das Gebiet, das man betritt mit diesen Strahlungserscheinungen, die eben ein besonderes Kapitel der Elektrizitätslehre sind, dann verbindet man sich mit demjenigen, was äußerlich in der Natur gleichwertig ist mit dem menschlichen Willen. Aus demselben Gebiet im Menschen, das als Willensgebiet gleichwertig ist dem Wirkensgebiet der Kathoden-, Kanal-, Röntgenstrahlen, der a-, ß-, y-Strahlen und so weiter, aus diesem selben Gebiet, das beim Menschen das Willensgebiet ist, hebt sich heraus dasjenige, was wir in unserer Mathematik, in unserer Geometrie, in unseren Bewegungs-Vorstellungen haben. Da kommen wir erst in verwandte Gebiete hinein."

Nun ist aber das heutige menschliche Denken auf diesen Gebieten nicht so weit, bis hinein in diese Gebiete noch wirklich zu denken. "Träumen kann der heutige Mensch, indem er Undulationstheorien ausdenkt, aber mathematisch ergreifen das Gebiet der Erscheinungen, insofern das verwandt ist mit dem menschlichen Willensgebiet, aus dem auch urständet die Geometrie, die Arithmetik, das bringt der Mensch heute noch nicht zustande. Dazu muss das arithmetische, das algebraische, das geometrische Vorstellen, die müssen selbst noch wirklichkeitsdurchtränkter werden, und auf diesen Weg muss sich gerade die physikalische Wissenschaft begeben.

Wenn Sie sich heute mit Physikern unterhalten, die ihre Bildung noch in der Zeit erlangt haben, in der die Undulations-Theorie blühte, so finden sich viele von ihnen recht unbehaglich diesen neueren Erscheinungen gegenüber, weil die rechnerischen Vorstellungen dabei an allen möglichen Ecken und Enden ein bisschen flöten gehen. Und man hat ja in den letzten Zeiten sich schon anders geholfen, indem man, weil das ganz gesetzmäßige Arithmetisieren, Geometrisieren nicht mehr ging, hat man eingeführt eine Art statistischer Methode, die einem gestattet, mehr in Anknüpfung an die äußeren empirischen Tatsachen auch empirische Zahlenverbindungen zu knüpfen und da mit der Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung zu operieren, wobei einem erlaubt ist zu sagen: Man rechnet eben eine Gesetzmäßigkeit aus, die eine gewisse Reihe hindurch dauert; dann kommt man an einen Punkt, wo die Geschichte nicht mehr so geht.

Solche Dinge zeigen oftmals gerade in dem Entwicklungsgang der neueren Physik, wie man zwar den Gedanken verliert, aber gerade dadurch, dass man den Gedanken verliert, in die Wirklichkeit hineinkommt. So zum Beispiel wäre es leicht denkbar gewesen, dass, unter gewissen starren Vorstellungen über die Natur eines erwärmten Gases oder erwärmter Luft und dem Verhalten dieser erwärmten Luft gegenüber der Umgebung unter gewissen Bedingungen, jemand mit einer ebensolchen mathematischen Sicherheit bewiesen hätte, dass die Luft niemals hätte verflüssigt werden können. Sie ist doch verflüssigt worden, weil man an einer gewissen Stelle sich gezeigt hat, dass gewisse Vorstellungen, die Gesetzmäßigkeiten einer Reihe überbrücken, am Ende dieser Reihe nicht mehr gelten. Solche Beispiele könnten viele angeführt werden.

Solche Beispiele zeigen, wie die Wirklichkeit heute gerade auf physikalischem Gebiet vielfach zwingt den Menschen, sich zu gestehen: Mit deinem Denken, mit deinem Vorstellen tauchst du nicht mehr voll in die Wirklichkeit unter. Du musst die ganze Sache an einem anderen Ende beginnen. - Und eben, um an diesem anderen Ende zu beginnen, ist es so notwendig, meine lieben Freunde, dass man die Verwandtschaft fühle zwischen all dem, was aus dem menschlichen Willen kommt - und daher kommt die Phoronomie -, und demjenigen, was einem äußerlich so entgegentritt, dass es getrennt ist von einem, und einem nur durch die Erscheinungen des anderen Pols sich ankündigt: Alles das, was durch die [Entladungs-] Röhren da geht, kündigt sich an mit Licht und so weiter. Aber das, was als Elektrizität fließt, das ist durch sich selbst nicht wahrnehmbar. Daher sagen die Leute: Wenn man einen sechsten Sinn hätte für die Elektrizität, würde man sie auch direkt wahrnehmen. - Es ist natürlich ein Unsinn, denn nur dann, wenn man aufsteigt zur Intuition, die im Willen ihre Grundlage hat, dann kommt man in die Region auch für die Außenwelt hinein, in welcher die Elektrizität lebt und webt. Aber man bemerkt damit zugleich, dass man in diesen Erscheinungen, die man hier in dem zuletzt betrachteten Gebiet [der Elektrizitätserscheinungen] hat, gewissermaßen das Umgekehrte vor sich hat wie beim Schall oder beim Ton.

Beim Schall oder beim Ton liegt das Eigentümliche vor, durch das bloße Hineingestelltsein des Menschen in die Schall- oder Tonwelt, wie ich es charakterisiert habe, es liegt das Eigentümliche vor, dass der Mensch sich nur mit der Seele in den Schall oder Ton als solchen hineinlebt und dass dasjenige, wo hinein er sich lebt durch den Leib, bloß dasjenige ist, was im Sinn einer solchen Betrachtung, wie ich sie in diesen Tagen gegeben habe, ansaugt das wirkliche Wesen des Schalles oder Tones - Sie erinnern sich des Vergleiches mit dem ausgepumpten Rezipienten -, ansaugt! Da bin ich drinnen, beim [Erleben von] Schall, beim Ton, in dem Geistigsten. Und dasjenige, was der Physiker beobachtet, der natürlich nicht das Geistige, nicht das Seelische beobachten kann, das ist die äußere sogenannte materielle Parallel-Erscheinung der Bewegung, der Welle [in der physischen Außenwelt].

Komme ich zu den Erscheinungen des letztbetrachteten Gebietes [der Elektrizität], dann, meine lieben Freunde, habe ich außer mir nicht nur die objektive - sogenannte - Materialität, sondern ich habe außer mir dasselbe [Seelisch-Geistige], was sonst in mir in Schall und Ton lebt, im Seelischen, Geistigen als Schall und Ton lebt. Es ist im Wesentlichen auch im Äußeren vorhanden, aber ich bin mit diesem Äußeren verbunden. Hier [bei der Elektrizität] habe ich in derselben, ich möchte sagen, in derselben Sphäre [der Außenwelt], in der ich nur die Wellen, die materiellen Wellen des Tones habe, da habe ich dasjenige [Seelisch-Geistige], was sonst beim Tone eben nur seelisch wahrgenommen werden kann. Da [in der Außenwelt] muss ich dasselbe physisch wahrnehmen, was ich beim [Erleben vom] Tone nur seelisch wahrnehmen kann.

An ganz entgegengesetzten Polen im Verhältnis des Menschen zur Außenwelt stehen die Tonwahrnehmungen und zum Beispiel die Wahrnehmungen der elektrischen Erscheinungen. Nehmen Sie Ton wahr, dann zerlegen Sie sich gewissermaßen selbst in eine menschliche Zweiheit. Sie schwimmen in dem ja auch äußerlich nachweisbaren Wellen-, Undulations-Element. Sie gewahren: Da drinnen ist noch etwas anderes als das bloß Materielle. Sie sind genötigt, innerlich sich regsam zu machen, um den Ton aufzufassen. Mit Ihrem Leibe, mit Ihrem gewöhnlichen Leibe, den ich hier [links] schematisch hinzeichne, gewahren Sie die Undulation, die Schwingungen. Sie ziehen zusammen in sich Ihren Äther- und Astralleib, der nur einen Teil Ihres Raumes dann ausfüllt, und erleben das, was Sie erleben sollen in dem Tone, in dem innerlich konzentrierten Ätherischen und Astralischen Ihres Wesens.

Treten Sie gegenüber als Mensch den Erscheinungen des letzten Gebietes [der Elektrizität], dann, meine lieben Freunde, haben Sie zunächst [im sinnlichen Wahrnehmen] überhaupt nichts von irgendeiner Schwingung und dergleichen. Aber Sie fühlen sich veranlasst, dasjenige, was Sie früher konzentriert haben, zu expandieren. Sie treiben überall Ihren Ätherleib und Astralleib über Ihre Oberfläche heraus, machen sie größer, und nehmen dadurch [übersinnlich] wahr diese elektrischen Erscheinungen.

Ohne dass man zum Geistig-Seelischen des Menschen fortschreitet, wird man nicht in der Lage sein, eine wahrheitsgemäße und wirklichkeitsgemäße Stellung zu den physikalischen Erscheinungen zu gewinnen. Man wird müssen sich vorstellen immer mehr und mehr: Schall-, Tonerscheinungen, Lichterscheinungen, die sind verwandt unserem bewussten Vorstellungselemente; Elektrizitäts- und magnetische Erscheinungen, sie sind verwandt unserem unterbewussten Willenselemente, und Wärme liegt dazwischen. Wie das Gefühl zwischen Vorstellung und Willen, so liegt die äußere Wärme der Natur zwischen Licht und Schall auf der einen Seite und zwischen Elektrizität und Magnetismus auf der anderen Seite. Die Struktur der Betrachtung der Naturerscheinungen muss daher immer mehr und mehr werden - und sie kann es werden, wenn man [methodisch] der Goethe’schen Farbenlehre nachgeht -, muss immer mehr und mehr werden eine Betrachtung des Licht-Ton-Elementes auf der einen Seite und des völlig entgegengesetzten Elektrizitäts-MagnetismusElementes auf der anderen Seite. Wie wir im Geistigen unterscheiden zwischen Luziferisch-Lichtischem und Ahrimanisch-Elektrizi tätsartigem, Ahrimanisch-Magnetismusartigem, so müssen wir auch die Struktur der Naturerscheinungen betrachten. Und gleichgültig zwischen beiden liegt dasjenige, was uns in den Erscheinungen der Wärme entgegentritt.

Damit habe ich Ihnen für dieses Gebiet eine Art Richtweg angegeben, Richtungslinien, in die ich vorläufig zusammenfassen wollte dasjenige, was Ihnen in diesen paar improvisierten Stunden hat von mir vorgetragen werden können. Es ist ja selbstverständlich, dass mit der Raschheit, mit der das Ganze inszeniert werden musste, das Ganze in den Absichten stecken geblieben ist, dass Ihnen nur einige Anregungen gegeben werden konnten, von denen ich hoffe, dass sie sich in recht baldiger Zeit hier ausbauen werden lassen. Ich glaube aber auch, dass Ihnen das hier Gegebene helfen kann, insbesondere den Lehrern an der Waldorfschule helfen kann, indem Sie werden da, wo Sie werden den Kindern naturwissenschaftliche Vorstellungen beibringen, darauf sehen, dass Sie zwar nicht unmittelbar, ich möchte sagen in fanatischer Weise, die Kinder so unterrichten, dass dann schon diese Kinder hinausgehen in die Welt und sagen: Alle Universitätsprofessoren sind Esel.

Denn in diesen Dingen kommt es nicht so sehr auf Tatsachen an, sondern darauf, dass sich Wirklichkeiten in entsprechender Weise entwickeln können. Es handelt sich also darum, dass wir nicht unsere Kinder beirren. Aber wir können ja das erreichen, dass wir wenigstens nicht zu viele unmögliche Vorstellungen in den Unterricht einmischen, Vorstellungen, die nur entnommen sind dem Glauben, dass das Traumbild, das über die Natur gemacht wird, eine äußere reale Wirklichkeit habe. So wird, wenn Sie sich selbst mit einer gewissen wissenschaftlichen Gesinnung durchdringen, welche durchdringt, ich möchte sagen als Exempel, dasjenige, was ich Ihnen in diesen Stunden vorgetragen habe, so wird Ihnen das [für] die Art und Weise, wie Sie mit den Kindern über die Naturerscheinungen reden, durch diese Art und Weise, dienen können. Aber auch in methodischer Weise glaube ich, dass Sie manches haben können. Obwohl ich gerne weniger im Galopp durch diese Erscheinungen hindurchgegangen wäre, als es nötig war, so werden Sie doch gesehen haben, dass man in einer gewissen Weise verbinden kann das äußerlich Anschauliche im Experiment mit demjenigen, wodurch man Vorstellungen über die Dinge hervorruft, sodass der Mensch die Dinge nicht bloß anglotzt, sondern nachdenkt, und wenn Sie Ihren Unterricht so einrichten, dass Sie die Kinder an dem Experiment denken lassen, mit ihnen das Experiment vernünftig besprechen, dann werden Sie gerade im naturwissenschaftlichen Unterricht eine Methode entwickeln, welche diese Naturwissenschaft fruchtbar machen wird für die Ihnen anvertrauten Kinder. Damit glaube ich gerade durch ein Exempel etwas hinzugefügt zu haben noch an dasjenige, was ich im pädagogischen Kurs" bei Beginn des Unterrichtes an der Waldorfschule gesagt habe.

Und jetzt muss ich noch eine nebensächliche Bemerkung machen. Nicht wahr, die Zeit, in der ich diesmal hier sein konnte, war bemessen, und ich hatte sie gedacht auszufüllen mit Verschiedenem. Seit wir den pädagogischen Kurs haben abhalten können, war meine Zeit so ausgefüllt immer, dass es bis jetzt noch nicht dazu gekommen ist - wie auch zu manch anderem nicht -, die nachgeschriebenen Vorträge des pädagogischen Kurses für Sie zur Vervielfältigung zu bringen." Das muss natürlich in der allernächsten Zeit geschehen. Aber ich habe gedacht, es werde sich während meiner hiesigen Anwesenheit die Sache fertig machen lassen. Dann hätten Sie aber diese [naturwissenschaftlichen] Kurse nicht gehabt. Es bleibt also nichts anderes übrig - ich glaube, Sie werden höchstens noch vierzehn Tage zu warten haben -, als die Sache zurückzustellen. Ich werde aber dann sorgen, dass Sie diesen pädagogischen Kurs in seinen Nachschriften überliefert erhalten, sofern Sie Lehrer hier an der Waldorfschule sind.

So ist natürlich auch manches andere nicht möglich gewesen. Aber ich glaube, auf der anderen Seite, dadurch, dass wir diese Kurse haben einrichten können, haben wir dennoch auch etwas getan, was wiederum beitragen kann zu dem Gedeihen unserer Waldorfschule, welche sich wirklich entwickeln sollte -und nach dem guten, so sehr anerkennenswerten Anlauf kann sie ja das -, welche ein Anfang sein sollte von einem aus Neuem heraus schöpfenden Wirken für unsere Menschheitsentwicklung. Wenn wir uns durchdringen mit diesem Bewusstsein: Es ist eben so vieles Brüchige in demjenigen, was sich bisher heraufentwickelt hat in der Menschheitsentwicklung, und es muss anderes Neugebildetes an dessen Stelle treten, dann werden wir gerade für diese Waldorfschule das richtige Bewusstsein haben.

Gerade an der Physik zeigt es sich, dass eine ganze Anzahl von Vorstellungen wirklich außerordentlich brüchig sind, und dieses hängt zusammen doch mehr, als man denkt, mit dem ganzen Elend unserer Zeit. Nicht wahr, wenn die Menschen soziologisch denken, so merkt man gleich, wo sie schief denken - das heißt, die meisten merken es auch nicht. Aber man kann es bemerken, weil man ja weiß, dass soziologische Vorstellungen gehen in die soziale Ordnung der Menschen hinein. Aber wie gründlich die physikalischen Anschauungen in das ganze Leben der Menschheit hineingehen, davon bildet man sich doch nicht eine genügende Vorstellung, und so weiß man nicht, was die manchmal so schrecklichen Vorstellungen der neueren Physik eigentlich für Unheil in Wahrheit angerichtet haben. Ich habe ja öfter zitiert, auch in öffentlichen Vorträgen, wie Herman Grimm, der nur, ich möchte sagen, seinerseits von außen die naturwissenschaftlichen Vorstellungen angesehen hat, es mit einem gewissen Recht ausgesprochen hat, wie zukünftige Generationen schwer werden cs sich begreiflich machen können, dass es einmal so eine wahnsinnige Welt gegeben hat, die sich die Entwicklung der Erde und des ganzen Sonnensystems aus der Kant-Laplace’schen Theorie heraus erklärt hat. Diesen wissenschaftlichen Wahnsinn zu begreifen, wird später einmal nicht leicht sein.

So aber wie diese Kant-Laplace’sche Theorie gibt es vieles, was heute in unseren Vorstellungen über die unorganische Natur ist. ‚Aber sehen Sie, wie werden sich die Menschen noch freimachen müssen von Kantisch-Königsbergischem und Ähnlichem, wenn sie zu durchgreifenden gesunden Vorstellungen werden vorrücken wollen! Man erfährt da ganz sonderbare Dinge, an denen man sehen kann, wie sich das Verkehrte auf der einen Seite zusammenkettet mit dem Verkehrten auf der anderen Seite. Es ist doch etwas wie zum an die Wand Hinaufkriechen, was man in der folgenden Weise erfahren kann. Ich habe in diesen Tagen — wie man sagt, zufällig - vorgelegt bekommen den abgedruckten Vortrag, den ein deutscher Universitätsprofessor, der sich sogar in diesem Vortrag kundgibt als etwas Kantisch-Königsbergisches, wie der an einer Universität des Baltenlandes über die Beziehungen von Physik und Technik gesprochen hat. Der Vortrag ist am 1. Mai 1918 gehalten. Ich bitte das Datum zu beachten: am 1. Mai 1918. Der Mann, der gelehrter Physiker der Gegenwart ist, spricht sein Ideal am Schlusse dieses Vortrages aus und sagt ungefähr: Der Verlauf dieses Krieges hat klar gezeigt, dass wir viel zu wenig schon den Bund haben herstellen können zwischen der wissenschaftlichen Laboratoriumsarbeit der Hochschulen und dem Militarismus. In der Zukunft muss, damit die Menschheit in entsprechender Weise sich fortentwickeln können, ein viel näheres Band geknüpft werden zwischen den militärischen Stellen und zwischen demjenigen, was an den Universitäten vorgeht, denn es muss in die Mobilisierungsfragen der Zukunft schon einbezogen werden alles dasjenige, was von der Wissenschaft heraus die Mobilisierung zu etwas besonders Kräftigem wird machen können. Wir litten im Beginne dieses Krieges gar sehr darunter, dass dieses innige Band noch nicht geschlungen war, das daher führen soll in der Zukunft von den wissenschaftlichen Versuchsanstalten in die Generalstäbe hinein.

Meine lieben Freunde, es muss die Menschheit umlernen, und sie wird umlernen müssen auf vielen Gebieten. Kann sie sich entschlieRen, auf einem solchen Gebiet, wie die Physik es ist, umzulernen, so wird sie am leichtesten auch dann bereit sein, auf anderen Gebieten umzulernen. Die Physiker aber, die so im alten Sinne denken, die werden immer nicht gar weit entfernt sein von der netten Koalition zwischen der wissenschaftlichen Versuchsanstalt und den Generalstäben.

Es muss vieles anders werden. Möge die Waldorfschule immer eine Stätte sein, wo das erkeimt, was eben anders sein soll! Mit diesem Wunsche möchte ich zunächst diese Betrachtungen schließen.

Tenth Lecture

My dear friends!

As a preliminary conclusion to these few improvised hours devoted to scientific observations, I would like to give you some guidelines that may be useful to you in forming your own observations of nature based on characteristic facts that can be demonstrated through experimentation. Today, in the field of natural science, it is very important, especially for teachers, to find the right way of thinking about and observing what nature presents to us. Yesterday, with this in mind, I endeavored to show you how the course of physical science has been since the 1890s, when materialism was, so to speak, uprooted from physics, and it is this point of view that you should actually place the main emphasis on.

We have seen that the period which believed it already had the most golden proofs of the universality of vibration was followed by a period which could not possibly hold on to the old vibration or undulation hypothesis, a time that has been as revolutionary in physics in the last three decades as anything can be considered revolutionary in its field. For physics has lost nothing less than the concept of matter in its old form as such under the pressure of the facts that have presented themselves.We have seen that light phenomena [initially] were closely related, as [consequence] of the old way of looking at things, with electromagnetic phenomena, and that [then] finally the phenomena of the passage of electricity through air-diluted or gas-diluted tubes led to these phenomena being seen as something like propagating electricity in the propagating light itself. I am not saying that this is correct, but it is what happened. And this was achieved by considering the electric current, which had always been regarded as enclosed in the wires, from a different point of view than that of Ohm's law, by observing it, as it were, as it left the wire and jumped to a distant [pole] and not through the matter through which it passes, concealing what is inside it.

But this has brought something very complicated to light. Yesterday we saw how the most diverse types of rays have come to light as a result. We saw that first—I have already described the phenomena to you—the so-called cathode rays, which emanate from the negative pole of Hittorf's tubes and pass through the rarefied air, have been shown to have something in common with what we usually perceive as material, as evidenced by the fact that they can be deflected by magnetic forces. On the other hand, they have something in common with what we perceive through radiation. This becomes particularly clear when we conduct experiments in which we capture these rays, which originate in some way from the [negative] electric pole, in the same way that we capture light, using a screen or some other object. Light casts shadows, and such rays also cast shadows. Of course, this also establishes the relationship to the ordinary material element. For if you imagine that [one] from [the cathode] here, as we saw yesterday, for example, according to Crookes' ideas with the cathode rays, bombards [a screen], the bombs do not pass through the obstacle, and what is behind it remains unscathed. We can illustrate this particularly well with Crookes' experiment by capturing the cathode rays.

Here we will generate an electric current, which we will then conduct through this tube, which is evacuated of air and has its cathode, the negative pole, here and its anode, the positive pole, here. So, by driving electricity through this tube, we obtain what are known as cathode rays. We collect these using a cross inserted into the tube. We allow them to strike the cross, and you will see that something becomes visible on the other side, like the shadow of this cross, which proves to you that this cross is stopping the rays. Please note carefully: the St. Andrew's cross is inside and the cathode rays travel like this, are caught by the cross sitting here, and the shadow becomes visible on the rear wall. I will now place this shadow that is visible here in the magnetic field of a magnet, and I ask you to observe the shadow of the St. Andrew's cross. You will find that [the position of the shadow] is influenced by the magnetic field. You see? So you see how I attract some other simple, let's say, iron object with the magnet, and what appears there as a kind of shadow behaves like external matter. So it also behaves materially.

So here we have, on the one hand, a kind of radiation which Crookes actually traces back to radiant matter, a state of aggregation that is neither solid, liquid nor gaseous, but a finer state of aggregation which shows us, however, that all this electricity behaves [on the other side] like simple matter in its flow. So, we have, in a sense, directed our gaze toward the flow of flowing electricity, and what we see reveals itself to us as what we see as effects within matter.

I would now like to show you – because it was not possible yesterday – how the rays that come from the other pole, [the positive pole], which I characterized yesterday as channel rays, are formed. Here you can see the [cathode rays] coming from the cathode, shining in this direction in a violet light, and the channel rays coming towards them at a much slower speed, giving off a [reddish] light.

Now I would like to show you the type of rays that are produced here by this device and which will be particularly evident to you in that the glass exhibits fluorescence when we pass an electric current through it. Here we will obtain the type of rays that are otherwise obtained when these rays are passed through a screen of barium platinocyanide, which have the property of making the glass fluoresce quite strongly. You see the glass—on which I now ask you to focus your attention—in a very strong greenish-yellowish fluorescent light. The rays that appear in such very strong fluorescent light are precisely the X-rays mentioned yesterday. So we can also observe this type here.

Now, I told you that in pursuing these processes, it has become apparent that certain entities, regarded as substances, emit whole bundles of rays, initially of at least three kinds, which we distinguished yesterday as \(α\)-, \(β\)-, and \(γ\)-rays and which exhibit clearly different properties. That these substances, which are called radium, helium, and so on, emit a fourth substance, which is, in a sense, the element itself, which gives itself away and, after being emitted, is transformed in such a way that while the radium flows out, it is transformed into helium, thus becoming something completely different. So we are not dealing with fixed matter, but with a metamorphosis of phenomena.

Now, following on from these things, I would like to develop a point of view that can, in a sense, become for you the path into these phenomena, indeed the path into natural phenomena in general. You see, the main flaw in nineteenth-century physical thinking was that the inner activity through which human beings sought to follow natural phenomena was not flexible enough within human beings and, above all, was not yet capable of engaging with the facts of the external world itself. One could see colors arise in the light, but one did not swing oneself up to take in the colorful in one's mental image, in one's thinking; one could no longer think colors, and one replaced the colors that one could not think with what one could think, which is only kinematic, with the calculable vibrations of an unknown ether. But this ether, you see, is something that is treacherous. For whenever one seeks it, it does not present itself. And all these attempts that have brought these various rays to light have actually shown that liquid electricity does indeed manifest itself, that is, something that exists as a phenomenon in the external world, but that the ether does not want to present itself at all. Now, it was not possible for nineteenth-century thinking to penetrate into the phenomena themselves. But this is precisely what will be so necessary for physics from now on, to penetrate into the phenomena themselves with human imagination. To do this, however, certain paths will have to be opened up, especially for the observation of physical phenomena.

You see, one might say: the objective forces that are closer to human beings have actually forced thinking to become more flexible, but one could say: from the wrong angle. You see, what has been regarded as certain, what we have relied on most, is precisely that we have been able to explain phenomena so beautifully with calculations and geometry, that is, with the arrangement of lines, surfaces, and bodies in space. What these phenomena here in Hittorf's tubes force us to do is to approach the facts more closely, to recognize that arithmetic actually fails when you try to apply it in such an abstract form as was done in the earlier theory of undulations.