The Light Course

GA 320

2 January 1920, Stuttgart

Lecture IX

My dear Friends,

I am sorry these explanations have had to be so improvised and brief, so that they scarcely go beyond mere aphorisms. It is inevitable. All I can do during these days is to give you a few points of view, with the intention of continuing when I am here again, so that in time these explanations may be rounded off, to give you something more complete. Tomorrow I will give a few concluding aspects, also enabling us to throw some light on the educational use of scientific knowledge. Now to prepare for tomorrow, I must today draw your attention to the development of electrical discoveries, beginning no doubt with things that are well-known to you from your school days. This will enable us, in tomorrow's lecture, to gain a more comprehensive view of Physics as a whole.

You know the elementary phenomena of electricity. A rod of glass, or it may be of resin, is made to develop a certain force by rubbing it with some material. The rod becomes, as we say, electrified; it will attract small bodies such as bits of paper. You know too what emerged from a more detailed observation of these phenomena. The forces proceeding from the glass rod, and from the rod of resin or sealing-wax, prove to be diverse. We can rub either rod, so that it gets electrified and will attract bits of paper. If the electrical permeation, brought about with the use of the glass rod, is of one kind, with the resinous rod it proves to be opposite in kind. Using the qualitative descriptions which these phenomena suggest, one speaks of vitreous and resinous electricities respectively; speaking more generally one calls them “positive” and “negative”. The vitreous is then the positive, the resinous the negative.

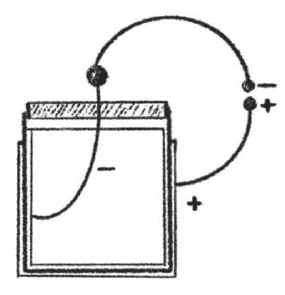

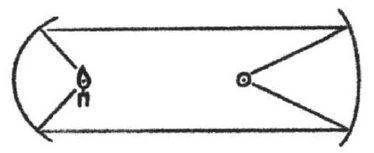

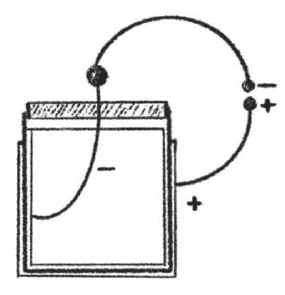

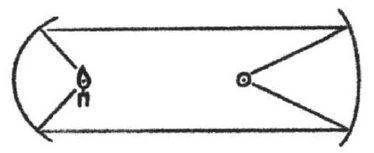

Now the peculiar thing is that positive electricity always induces and brings negative toward itself in some way. You know the phenomenon from the so-called Leyden Jar. This is a vessel with an electrifiable coating on the outside. Then comes an insulating layer (the substance of the vessel). Inside, there is another coating, connected with a metal rod, ending perhaps in a metallic knob (Figure IXa). If you electrify a metal rod and impart the electricity to the one coating, so that this coating will then evince the characteristic phenomena, say, of positive electricity, the other coating thereby becomes electrified negatively. Then, as you know, you can connect the one coating, imbued with positive, and the other, imbued with negative electricity, so as to bring about a connection of the electrical forces, positive and negative, with one another. You have to make connection so that the one electricity can be conducted out here, where it confronts the other. They confront each other with a certain tension, which they seek to balance out. A spark leaps across from the one to the other. We see how the electrical forces, when thus confronting one another, are in a certain tension, striving to resolve it. No doubt you have often witnessed the experiment.

Here is the Leyden Jar,—but we shall also need a two-pronged conductor to discharge it with. I will now charge it. The charge is not yet strong enough. You see the leaves repelling one another just a little. If we charged this sufficiently, the positive electricity would so induce the negative that if we brought them near enough together with a metallic discharger we should cause a spark to fly across the gap. Now you are also aware that this kind of electrification is called frictional electricity, since the force, whatever it may be, is brought about by friction. And—here again, I am presumably still recalling what you already know—it was only at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries that they discovered, in addition to this “frictional electricity”, what is called “contact electricity”, thus opening up to modern Physics a domain which has become notably fruitful in the materialistic evolution of this science.

I need only remind you of the main principles. Galvani observed the leg of a frog which was in touch with metal plates and began twitching. He had discovered something of very great significance. He had found two things at once, truth to tell,—two things that should really be distinguished from one-another and are not yet quite properly distinguished, unhappily for Science, to this day. Galvani had discovered what Volta, a little later, was able to describe simply as “contact electricity”, namely the fact that when diverse metals are in contact, and their contact is also mediated by the proper liquids, an interaction arises—an interaction which can find expression in the form of an electric current from the one metal to the other. We have then the electric current, taking place to all appearances purely within the inorganic realm. But we have something else as well, if once again we turn attention to the discovery made by Galvani. We have what may in some sense be described as “physiological electricity”. It is a force of tension which is really always there between muscle and nerve and which can be awakened when electric currents are passed through them. So that in fact, that which Galvani had observed contained two things. One of them can be reproduced by purely inorganic methods, making electric currents by means of different metals with the help of liquids. The other thing which he observed is there in every organism and appears prominently in the electric fishes and certain other creatures. It is a state of tension between muscle and nerve, which, when it finds release, becomes to all appearances very like flowing electricity and its effects. It was then these discoveries which led upon the one hand to the great triumphs in materialistic science, and on the other hand provided the foundations for the immense and epoch-making technical developments which followed.

Now the fact is, the 19th century was chiefly filled with the idea that we must somehow find a single, abstract, unitary principle at the foundation of all the so-called “forces of Nature”. It was in this direction, as I said before that they interpreted what Julius Robert Mayer, the brilliant Heilbronn doctor had discovered. You will remember how we demonstrated it the other day. By mechanical force we turned a flywheel; this was attached to an apparatus whereby a mass of water was brought into inner mechanical activity. The water thereby became warmer, as we were able to shew. The effect produced—the development of warmth—may truly be attributed to the mechanical work that was done. All this was so developed and interpreted in course of time that they applied it to the most manifold phenomena of Nature,—nor was it difficult to do so within certain limits. One could release chemical forces and see how warmth arose in the process. Again, reversing the experiment which we have just described, warmth could be used in such a way as to evoke mechanical work,—as in the steam-engine and in a multitude of variations.

It was especially this so-called transformation of Nature's forces on which they riveted attention. They were encouraged to do this by what began in Julius Robert Mayer's work and then developed ever further. For it proves possible to calculate, down to the actual figures, how much warmth is needed to produce a given, measurable amount of work; and vice-versa, how much mechanical work is needed to produce a given, measurable amount of warmth or heat. So doing, they imagined—though to begin with surely there is no cause to think of it in this way—that the mechanical work, which we expended for example in making these vanes rotate in the water, has actually been transformed into the warmth. Again, they assumed that when warmth is applied in the steam-engine, this warmth is actually transformed into the mechanical work that emerges. The meditations of physicists during the 19th century kept taking this direction: they were always looking for the kinship between the diverse forces of Nature so-called,—trying to discover kinships which were to prove at last that some abstract, everywhere equal principle is at the bottom of them all, diverse and manifold as they appear. These tendencies were crowned to some extent when near the end of the century Heinrich Hertz, a physicist of some genius, discovered the so-called electric waves—here once again it was waves! It certainly seemed to justify the idea that the electricity that spreads through space is in some way akin to the light that spreads through space,—the latter too being already conceived at that time as a wave-movement in the ether.

That “electricity”—notably in the form of current electricity—cannot be grasped so simply with the help of primitive mechanical ideas, but makes it necessary to give our Physics a somewhat wider and more qualitative aspect,—this might already have been gathered from the existence of induction currents as they are called. Only to indicate it roughly: the flow of an electric current along a wire will cause a current to arise in a neighbouring wire, by the mere proximity of the one wire to the other. Electricity is thus able to take effect across space,—so we may somehow express it. Now Hertz made this very interesting discovery:—he found that the electrical influences or agencies do in fact spread out in space in a way quite akin to the spreading of waves, or to what could be imagined as such. He found for instance that if you generate an electric spark, much in the way we should be doing here, developing the necessary tension, you can produce the following result. Suppose we had a spark jumping across this gap. Then at some other point in space we could put two such “inductors”, as we may call them, opposite and at a suitable distance from one-another, and a spark would jump across here too.

This, after all, is a phenomenon not unlike what you would have if here for instance—Figure IXb—were a source of light and here a mirror. A cylinder of light is reflected, this is then gathered up again by a second mirror, and an image arises here. We may then say, the light spreads out in space and takes effect at a distance. In like manner. Hertz could now say that electricity spreads out and the effect of it is perceptible at a distance. Thus in his own conception and that of other scientists he had achieved pretty fair proof that with electricity something like a wave-movement is spreading out through space,—analogous to the way one generally imagines wave-movements to spread out. Even as light spreads out through space and takes effect at a distance, unfolding as it were, becoming manifest where it encounters other bodies, so too can the electric waves spread out, becoming manifest—taking effect once more—at a distance. You know how wireless telegraphy is based on this.

The favourite idea of 19th century physicists was once again fulfilled to some extent. For sound and light, they were imagining wave-trains, sequences of waves. Also for warmth as it spreads outward into space, they had begun to imagine wave-movements, since the phenomena of warmth are in fact similar in some respects. Now they could think the same of electricity; the waves had only to be imagined long by comparison. It seemed like incontrovertible proof that the way of thinking of 19th century Physics had been right.

Nevertheless, Hertz's experiments proved to be more like a closing chapter of the old. What happens in any sphere of life, can only properly be judged within that sphere. We have been undergoing social revolutions. They seem like great and shattering events in social life since we are looking rather intently in their direction. Look then at what has happened in Physics during the 1890's and the first fifteen years, say, of our century; you must admit that a revolution has here been going on, far greater in its domain than the external revolution in the social realm. It is no more nor less than that in Physics the old concepts are undergoing complete dissolution; only the physicists are still reluctant to admit it. Hertz's discoveries were still the twilight of the old, tending as they did to establish the old wave-theories even more firmly. What afterwards ensued, and was to some extent already on the way in his time, was to be revolutionary.

I refer now to those experiments where an electric current, which you can generate of course and lead to where you want it, is conducted through a glass tube from which the air has to a certain extent been pumped out, evacuated. The electric current, therefore, is made to pass through air of very high dilution. High tension is engendered in the tubes which you here see. In effect, the terminals from which the electricity will discharge into the tube are put far apart—as far as the length of the tube will allow. There is a pointed terminal at either end, one where the positive electricity will discharge (i.e. the positive pole) at the one end, so too the negative at the other. Between these points the electricity discharges; the coloured line which you are seeing is the path taken by the electricity. Thus we may say: What otherwise goes through the wires, appears in the form in which you see it here when it goes through the highly attenuated air. It becomes even more intense when the vacuum is higher. Look how a kind of movement is taking place from the one side and the other,—how the phenomenon gets modified. The electricity which otherwise flows through the wire: along a portion of its path we have been able, as it were, so to treat it that in its interplay with other factors it does at last reveal, to some extent, its inner essence. It shews itself, such as it is; it can no longer hide in the wire! Observe the green light on the glass; that is fluorescent light. I am sorry I cannot go into these phenomena in greater detail, but I should not get where I want to in this course if I did not go through them thus quickly. You see what is there going through the tube,—you see it in a highly dispersed condition in the highly attenuated air inside the tube.

Now the phenomena which thus appeared in tubes containing highly attenuated air or gas, called for more detailed study, in which many scientists engaged,—and among these was Crookes. Further experiments had to be made on the phenomena in these evacuated tubes, to get to know their conditions and reactions. Certain experiments, due among others to Crookes, bore witness to a very interesting fact. Now that they had at last exposed it—if I may so express myself—the inner character of electricity, which here revealed itself, proved to be very different from what they thought of light for instance being propagated in the form of wave-movements through the ether. What here revealed itself was clearly not propagated in that way. Whatever it is that is shooting through these tubes is in fact endowed with remarkable properties, strangely reminiscent of the properties of downright matter. Suppose you have a magnet or electromagnet. (I must again presume your knowledge of these things; I cannot go into them all from the beginning.) You can attract material objects with the magnet. Now the body of light that is going through this tube—this modified form, therefore, of electricity—has the same property. It too can be attracted by the electromagnet. Thus it behaves, in relation to a magnet, just as matter would behave. The magnetic field will modify what is here shooting through the tube.

Experiments of this kind led Crookes and others to the idea that what is there in the tube is not to be described as a wave-movement, propagated after the manner of the old wave-theories. Instead, they now imagined material particles to be shooting through the space inside the tube; these, as material particles, are then attracted by the magnetic force. Crookes therefore called that which is shot across there from pole to pole, (or howsoever we may describe it; something is there, demanding our consideration),—Crookes called it “radiant matter”. As a result of the extreme attenuation, he imagined, the matter that is left inside the tube has reached a state no longer merely gaseous but beyond the gaseous condition. He thinks of it as radiant matter—matter, the several particles of which are raying through space like the minutest specks of dust or spray, the single particles of which, when charged electrically, will shoot through space in this way. These particles themselves are then attracted by the electromagnetic force. Such was his line of thought: the very fact that they can thus be attracted shews that we have before us a last attenuated remnant of real matter, not a mere movement like the old-fashioned ether-movements.

It was the radiations (or what appeared as such) from the negative electric pole, known as the cathode, which lent themselves especially to these experiments. They called them “cathode rays”. Herewith the first breach had, so to speak, been made in the old physical conceptions. The process in these Hittorf tubes (Hittorf had been the first to make them, then came Geissler) was evidently due to something of a material kind—though in a very finely-divided condition—shooting through space. Not that they thereby knew what it was; in any case they did not pretend to know what so-called “matter” is. But the phenomena indicated that this was something somehow identifiable with matter,—of a material nature.

Crookes therefore was convinced that this was a kind of material spray, showering through space. The old wave-theory was shaken. However, fresh experiments now came to light, which in their turn seemed inconsistent with Crookes's theory. Lenard in 1893 succeeded in diverting the so-called rays that issue from this pole and carrying them outward. He inserted a thin wall of aluminium and led the rays out through this. The question arose: can material particles go through a material wall without more ado? So then the question had to be raised all over again:

Is it really material particles showering through space,—or is it something quite different after all? In course of time the physicists began to realize that it was neither the one nor the other: neither of the old conceptions—that of ether-waves, or that of matter—would suffice us here. The Hittorf tubes were enabling them, as it were, to pursue the electricity itself along its hidden paths. They had naturally hoped to find waves, but they found none. So they consoled themselves with the idea that it was matter shooting through space. This too now proved untenable.

At last they came to the conclusion which was in fact emerging from many and varied experiments, only a few characteristic examples of which I have been able to pick out. In effect, they said: It isn't waves, nor is it simply a fine spray of matter. It is flowing electricity itself; electricity as such is on the move. Electricity itself is flowing along here, but in its movement and in relation to other things—say, to a magnet—it shews some properties like those of matter. Shoot a material cannonball through the air and let it pass a magnet,—it will naturally be diverted So too is electricity. This is in favour of its being of a material nature. On the other hand, in going through a plate of aluminium without more ado, it shews that it isn't just matter. Matter would surely make a hole in going through other matter. So then they said: This is a stream of electricity as such. And now this flowing electricity shewed very strange phenomena. A clear direction was indeed laid out for further study, but in pursuing this direction they had the strangest experiences. Presently they found that streams were also going out from the other pole,—coming to meet the cathode rays. The other pole is called the anode; from it they now obtained the rays known as “canal rays”. In such a tube, they now imagined there to be two different kinds of ray, going in opposite directions.

One of the most interesting things was discovered in the 1890's by Roentgen ... From the cathode rays he produced a modified form of rays, now known as Roentgen rays or X-rays. They have the effect of electrifying certain bodies, and also shew characteristic reactions with magnetic and electric forces. Other discoveries followed. You know the Roentgen rays have the property of going through bodies without producing a perceptible disturbance; they go through flesh and bone in different ways and have thus proved of great importance to Anatomy and Physiology.

Now a phenomenon arose, making it necessary to think still further. The cathode rays or their modifications, when they impinge on glass or other bodies, call forth a kind of fluorescence; the materials become luminous under their influence. Evidently, said the scientists, the rays must here be undergoing further modification. So they were dealing already with many different kinds of rays. Those that first issued directly from the negative pole, proved to be modifiable by a number of other factors. They now looked round for bodies that should call forth such modifications in a very high degree—bodies that should especially transform the rays into some other form, e.g. into fluorescent rays. In pursuit of these researches it was presently discovered that there are bodies—uranium salts for example—which do not have to be irradiated at all, but under certain conditions will emit rays in their turn, quite of their own accord. It is their own inherent property to emit such rays. Prominent among these bodies were the kind that contain radium, as it is called.

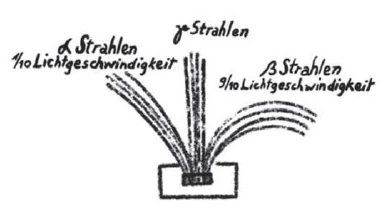

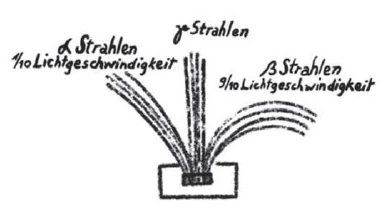

Very strange properties these bodies have. They ray-out certain lines of force—so to describe it—which can be dealt with in a remarkable way. Say that we have a radium-containing body here, in a little vessel made of lead; we can examine the radiation with a magnet. We then find one part of the radiation separating off, being deflected pretty strongly in this direction by the magnet, so that it takes this form (Figure IXc). Another part stays unmoved, going straight on in this direction, while yet another is deflected in the opposite direction. The radiation, then, contains three elements. They no longer had names enough for all the different kinds! They therefore called the rays that will here be deflected towards the right, ß-rays; those that go straight on, γ-rays; and those are deflected in the opposite direction, α-rays.

Bringing a magnet near to the radiating body, studying these deflections and making certain computations, from the deflection one may now deduce the velocity of the radiation. The interesting fact emerges that the ß-rays have a velocity, say about nine-tenths the velocity of light, while the velocity of the α-rays is about one-tenth the velocity of light. We have therefore these explosions of force, if we may so describe them, which can be separated-out and analyzed and then reveal very striking differences of velocity.

Now I remind you how at the outset of these lectures we endeavoured in a purely spiritual way to understand the formula, v = s/t. We said that the real thing in space is the velocity; it is velocity which justifies us in saying that a thing is real. Here now you see what is exploding as it were, forth from the radiating body, characterized above all by the varying intensity and interplay of the velocities which it contains. Think what it signifies: in the same cylinder of force which is here raying forth, there is one element that wants to move nine times as fast as the other. One shooting force, tending to remain behind, makes itself felt as against the other that tends to go nine times as quickly. Now please pay heed a little to what the anthroposophists alone, we must suppose, have hitherto the right not to regard as sheer madness! Often and often, when speaking of the greatest activities in the Universe which we can comprehend, we had to speak of differences in velocity as the most essential thing. What is it brings about the most important things that play into the life of present time? It is the different velocities with which the normal, the Luciferic and the Ahrimanic spiritual activities work into one-another. It is that differences of velocity are there in the great spiritual streams to which the web and woof of the world is subjected. The scientific pathway which has opened out in the most recent times is compelling even Physics—though, to begin with, unconsciously—to go into differences of velocity in a way very similar to the way Spiritual Science had to do for the great all-embracing agencies of Cosmic Evolution.

Now we have not yet exhausted all that rays forth from this radium-body. The effects shew that there is also a raying-forth of the material itself. But the material thus emanated proves to be radium no longer. It presently reveals itself to be helium for instance—an altogether different substance. Thus we no longer have the conservation,—we have the metamorphosis of matter.

The phenomena to which I have been introducing you, all of them take their course in what may be described as the electrical domain. Moreover, all of them have one property in common. Their relation to ourselves is fundamentally different from that of the phenomena of sound or light for example, or even the phenomena of warmth. In light and sound and warmth we ourselves are swimming, so to speak, as was described in former lectures. The same cannot be said so simply of our relation to the electrical phenomena. We do not perceive electricity as a specific quality in the way we perceive light, for instance. Even when electricity is at last obliged to reveal itself, we perceive it by means of a phenomenon of light. This led to people's saying, what they have kept repeating: “There is no sense-organ for electricity in man.” The light has built for itself in man the eye—a sense-organ with which to see it. So has the sound, the ear. For warmth too, a kind of warmth-organ is built into man. For electricity, they say, there is nothing analogous. We perceive electricity indirectly.

We do, no doubt; but that is all that can be said of it till you go forward to the more penetrating form of Science which we are here at least inaugurating. In effect, when we expose ourselves to light, we swim in the element of light in such a way that we ourselves partake in it with our conscious life, or at least partially so. So do we in the case of warmth and in that of sound or tone. The same cannot be said of electricity. But now I ask you to remember what I have very often explained: as human beings we are in fact dual beings. That is however to put it crudely, for we are really threefold beings: beings of Thought, of Feeling and of Will. Moreover, as I have shewn again and again, it is only in our Thinking that we are really awake, whilst in our feelings we are dreaming and in our processes of will we are asleep—asleep even in the midst of waking life. We do not experience our processes of will directly. Where the essential Will is living, we are fast asleep. And now remember too, what has been pointed out during these lectures. Wherever in the formulae of Physics we write m for mass, we are in fact going beyond mere arithmetic—mere movement, space and time. We are including what is no longer purely geometrical or kinematical, and as I pointed out, this also corresponds to the transition of our consciousness into the state of sleep. We must be fully clear that this is so. Consider then this memberment of the human being; consider it with fully open mind, and you will then admit: Our experience of light, sound and warmth belongs—to a high degree at least, if not entirely—to the field which we comprise and comprehend with our sensory and thinking life. Above all is this true of the phenomena of light. An open-minded study of the human being shews that all these things are akin to our conscious faculties of soul. On the other hand, the moment we go on to the essential qualities of mass and matter, we are approaching what is akin to those forces which develop in us when we are sleeping. And we are going in precisely the same direction when we descend from the realm of light and sound and warmth into the realm of the electrical phenomena.

We have no direct experience of the phenomena of our own Will; all we are able to experience in consciousness is our thoughts about them. Likewise we have no direct experience of the electrical phenomena of Nature. We only experience what they deliver, what they send upward, to speak, into the realms of light and sound and warmth etc. For we are here crossing the same boundary as to the outer world, which we are crossing in ourselves when we descend from our thinking and idea-forming, conscious life into our life of Will. All that is light, and sound, and warmth, is then akin to our conscious life, while all that goes on in the realms of electricity and magnetism is akin—intimately akin—to our unconscious life of Will. Moreover the occurrence of physiological electricity in certain lower animals is but the symptom—becoming manifest somewhere in Nature—of a quite universal phenomenon which remains elsewhere unnoticed. Namely, wherever Will is working through the metabolism, there is working something very similar to the external phenomena of electricity and magnetism.

When in the many complicated ways—which we have only gone through in the barest outline in today's lecture—when in these complicated ways we go down into the realm of electrical phenomena, we are in fact descending into the very same realm into which we must descend whenever we come up against the simple element of mass. What are we doing then when we study electricity and magnetism? We are then studying matter, in all reality. It is into matter itself that you are descending when you study electricity and magnetism. And what an English philosopher has recently been saying is quite true—very true indeed. Formerly, he says, we tried to imagine in all kinds of ways, how electricity is based on matter. Now on the contrary we must assume, what we believe to be matter, to be in fact no more than flowing electricity. We used to think of matter as composed of atoms; now we must think of the electrons, moving through space and having properties like those we formerly attributed to matter.

In fact our scientists have taken the first step—they only do not yet admit it—towards the overcoming of matter. Moreover they have taken the first step towards the recognition of the fact that when in Nature we pass on from the phenomena of light, sound and warmth of those of electricity, we are descending—in the realm of Nature—into phenomena which are related to the former ones as is the Will in us to the life of Thought. This is the gist and conclusion of our studies for today, which I would fain impress upon your minds. After all, my main purpose in these lectures is to tell you what you will not find in the text-books. The text-book knowledge I may none the less bring forward, is only given as a foundation for the other.

Neunter Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde!

Es ist mir ja außerordentlich leid, dass diese Auseinandersetzungen gar so sehr improvisiert sind und aphoristisch bleiben müssen, allein es geht eben nicht anders, als Ihnen in diesen Tagen eine Anzahl von Gesichtspunkten zu geben und dann, wenn ich in einiger Zeit wiederum hier sein werde, die Sache fortzusetzen, sodass Sie dann irgendetwas Abgerundetes mit der Zeit aus diesen Auseinandersetzungen werden bekommen können. Ich muss aber, um Ihnen die paar Gesichtspunkte, die ich Ihnen abschließend morgen entwickeln werde und die wiederum möglich machen, dass wir einige Lichter hinwerfen auf die pädagogische Verwertung der naturwissenschaftlichen Erkenntnisse, ich muss heute Ihren Blick lenken auf die Entwicklung der elektrischen Erscheinungen, der Erscheinungen der Elektrizität, und ich werde anknüpfen an Dinge, die Ihnen eigentlich von der Schulbank her geläufig sind, weil wir eben von da ausgehend dann morgen das Gesamtgebiet der Physik überschauend charakterisieren wollen.

Nicht wahr, die elementaren Dinge der Elektrizitätslehre kennen Sie. Sie wissen, dass es das gibt, was man die Reibungselektrizität nennt, dass man zum Entfalten einer Kraft bringt eine Glasstange, indem man sie mit irgendeinem Reibzeug, wie man es nennt, reibt, oder auch eine Harzstange, dass dadurch die Glasstange oder Harzstange, wie man sagt, elektrisch wird, das heißt kleine Körper, Papierschnitzelchen, anzieht. Sie wissen auch, dass die Beobachtung der Erscheinungen allmählich ergeben hat, dass in ihrer Entfaltung verschieden sind die beiden Kräfte, die ausgehen im einen Fall von der geriebenen Glasstange, im anderen Fall von der geriebenen Harzstange oder der Siegellackstange: Wenn die Stange veranlasst worden ist, Papierschnitzelchen anzuziehen, so wird dasjenige, was von der Glasstange in einer bestimmten Weise, wie man sagt, elektrisch durchtränkt wird, in der entgegengesetzten Weise von der Harzstangen-Elektrizität elektrisch durchtränkt, und man unterscheidet daher, indem man sich mehr an das Qualitative anschließt, Glaselektrizität und Harzelektrizität, oder, indem man das bloß mehr allgemein ausdrückt, positive Elektrizität und negative Elektrizität. Die Glaselektrizität würde die positive, die Harzelektrizität die negative sein.

Nun ist das Eigentümliche, dass positive Elektrizität negative Elektrizität immer in gewisser Weise herbeizieht. Sie können diese Erscheinung aus der sogenannten Leidener Flasche ersehen, also in jenem Gefäß, das außen mit einem elektrisierbaren Belag versehen ist, das hier [innerhalb dieses Belags] dann isoliert ist, das dann [ganz] im Innern mit einem anderen [elektrisierbaren] Belag versehen ist, der sich fortsetzt in eine Metallstange mit einem Metallkopf. Wenn man nun eine [Glasstange] elektrisch gemacht hat und diese Elektrizität mitteilt - was man kann - dem äußeren Belag, so wird der äußere Belag positiv elektrisch, erzeugt die Erscheinungen der positiven Elektrizität. Dadurch aber wird der innere Belag negativ elektrisch. Und wir können, wie Sie wissen, dann, indem wir verbinden den Belag, der mit positiver Elektrizität angefüllt ist, und den Belag,

der mit negativer Elektrizität angefüllt ist, wir können es zu einer Verbindung der positiv elektrischen und negativ elektrischen Kraft bringen, wenn wir sie in eine solche Lage versetzen, dass die eine Elektrizität sich bis hierher fortsetzen kann und sich gegenübersteht der anderen. Sie stehen sich mit einer gewissen Spannung gegenüber und fordern ihren Ausgleich. Es springt der Funke von dem einen auf das andere über. Wir sehen also, dass Elektrizitätskräfte, die sich so gegenüberstehen, eine gewisse Spannung haben und zum Ausgleich streben. Der Versuch wird vor Ihnen oftmals gemacht worden sein.

Sie sehen hier die Leidener Flasche. Aber wir brauchen noch eine [Entladungs-]Gabel. Ich will einmal hier laden. Es ist noch zu schwach. Ein bisschen stoßen sich die Plättchen [des Elektroskops] ab. Es würde also, wenn wir hier genügend laden würden, die positive Elektrizität die negative hervorrufen, und wir würden, wenn wir beide einander gegenüberstehend hätten, durch eine Entladungsgabel den Funken zum Überspringen bringen. Sie wissen aber auch, dass diese Art, elektrisch zu werden, eben mit dem Ausdruck Reibungselektrizität bezeichnet wird, weil man es zu tun hat eben mit der durch Reibung hervorgegangenen, irgendwie gearteten Kraft - so möchte ich vorläufig sagen.

Nun wurde, wie ich Ihnen auch nur zu wiederholen brauche, eigentlich erst um die Wende des achtzehnten und neunzehnten Jahrhunderts zu dieser Reibungselektrizität hinzugefunden, entdeckt dasjenige, was man Berührungselektrizität nennt. Und damit wurde für die moderne Physik ein Gebiet eröffnet, das sich gerade außerordentlich fruchtbar erwiesen hat für die materialistische Ausgestaltung der Physik. Ich brauche Sie auch da nur an das Prinzip zu erinnern. Galvani beobachtete einen Froschschenkel, der in Verbindung war mit Metallplatten und der in Zuckungen geriet, und hatte damit eigentlich, man möchte sagen, etwas außerordentlich Bedeutsames gefunden, - zwei Dinge zugleich gefunden, die nur voneinander abgetrennt werden mussten und die heute noch nicht ganz sachgemäß voneinander abgetrennt sind zum Unheil der naturwissenschaftlichen Betrachtungen. Galvani hatte dasjenige gefunden, was wenig später Volta'® eben als die eigentliche Berührungselektrizität'' bezeichnen konnte. Er hatte die Tatsache gefunden, dass, wenn zwei verschiedene Metalle sich berühren, so, dass ihre Berührung vermittelt wird durch entsprechende Flüssigkeiten, so entsteht eine Wechselwirkung, die in Form einer elektrischen Strömung von dem einen Metall zu dem andern sich äußern kann.

Damit haben wir die elektrische Strömung, die verläuft rein auf dem Gebiete des unorganischen Lebens scheinbar, wir haben aber, indem wir hinblicken auf dasjenige, was Galvani eigentlich bloßlegte, auch noch das, was man gewissermaßen als physiologische Elektrizität bezeichnen kann, einen Kraftspannungszustand, der eigentlich immer besteht zwischen Muskel und Nerv und der geweckt werden kann, wenn elektrische Ströme durch Muskel und Nerv hindurchgeführt werden. Sodass in der Tat dasjenige, was Galvani damals gesehen hat, zweierlei enthielt: Dasjenige, das man einfach auf unorganischem Gebiet nachbilden kann, indem man Metalle durch Vermittlung von Flüssigkeiten zur Ausbildung der elektrischen Ströme bringt. Dann auch hat er beobachtet dasjenige, was in jedem Organismus ist, bei gewissen elektrischen Fischen und anderen Tieren besonders hervortritt als Spannungszustand zwischen Muskel und Nerv, der sich auf den äußeren Anblick ähnlich ausnimmt in seinem Ausgleich wie strömende Elektrizität und ihre Wirkungen. Damit war aber alles dasjenige gefunden, was dann zu gewaltigen wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnisfortschritten auf materialistischem Gebiet einerseits geführt hat, was auf der anderen Seite so gewaltige, epochemachende Grundlagen für die Technik ergeben hat.

Nun handelt es sich darum, dass ja das neunzehnte Jahrhundert hauptsächlich angefüllt war von der Anschauung, man müsse etwas herausfinden, was als ein abstrakt Einheitliches allen Naturkräften — wie man sie nennt — zugrunde liegt. In dieser Richtung hatte man ja auch dasjenige, wovon ich Ihnen schon gesprochen habe, ausgedeutet, was in den vierziger Jahren des vorigen Jahrhunderts Julius Robert Mayer, der bekannte geniale Heilbronner Arzt, zutage gefördert hat. Wir haben vorgeführt, was von ihm zutage gefördert worden ist: Wir haben mechanische Kraft entwickelt, indem wir ein Schwungrad in Drehung gebracht haben, das Wasser in innere mechanische Tätigkeit versetzt haben. Dadurch aber ist das Wasser wärmer geworden. Die Erwärmung konnten wir nachweisen, und man kann sagen, dass diese Entwicklung der Wärme eine Wirkung ist der mechanischen Leistung, der mechanischen Arbeit, die da war.

Diese Dinge hat man so ausgedeutet, dass man sie auf die verschiedensten Naturerscheinungen angewendet hat, was man ja auch in gewissen Grenzen leicht konnte. Man konnte die Entfaltung von chemischen Kräften bewirken, konnte sehen, wie auch aus der Entfaltung von chemischen Kräften Wärme sich bildet, man konnte umgekehrt Wärme gebrauchen, wie es ja in der Dampfmaschine geschieht im umfassendsten Sinne, um mechanische Arbeit hervorzurufen. Man hat den Blick insbesondere gerichtet auf diese sogenannte Umwandlung der Naturkräfte, und man war dazu veranlasst durch dasjenige, was man immer weiter ausgebildet hat, was bei Julius Robert Mayer seinen Anfang genommen hat, dass man zahlenmäßig berechnen kann, wie viel Wärme notwendig ist, um eine bestimmte, messbare Arbeit hervorzubringen, und umgekehrt, wie viel mechanische Arbeit notwendig ist, um ein bestimmtes, messbares Wärmequantum hervorzubringen. Man stellte sich vor, obwohl nicht Veranlassung dazu vorhanden ist, dass sich einfach verwandle Arbeit, die man verrichtet hat, indem man die Schaufelscheiben im Wasser in Drehung versetzt hat, dass sich diese mechanische Arbeit in Wärme umgewandelt habe. Man nahm an, dass sich, wenn wir Wärme anwenden in der Dampfmaschine, diese Wärme umwandelt in dasjenige, was dann als mechanische Leistung auftritt. Diese Richtung des Denkens nahm das physikalische Nachsinnen im neunzehnten Jahrhundert an, und daher war es bestrebt, Verwandtschaft zu finden zwischen den verschiedenen sogenannten Naturkräften, Verwandtschaften, die zeigen sollten, dass wirklich irgendetwas abstrakt Gleiches in all diesen verschiedenen Naturkräften eigentlich steckt.

Eine gewisse Krönung hat dieses Bestreben gefunden, als am Ende des neunzehnten oder gegen das Ende des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts mit einer gewissen Genialität der Physiker Hertz'% die sogenannten elektrischen Wellen gefunden hat - also auch hier Wellen! -, welche eine gewisse Berechtigung gaben, dasjenige, was als Elektrizität sich ausbreitet, in Verwandtschaft zu denken mit demjenigen, was als Licht sich ausbreitet, das man ja auch als eine wellenförmige Bewegung des Äthers sich dachte. Dass dasjenige, was man als Elektrizität anzusprechen hatte, namentlich in der Form der strömenden Elektrizität [in Drähten], nicht so einfach mit den primitiven mechanischen Grundbegriffen zu erfassen ist, sondern eigentlich notwendig macht, ein wenig schon den Ausblick der Physik auf das Qualitative zu erweitern: Das hätte schon zeigen können das Vorhandensein dessen, was man Induktionsströme nennt, wo dadurch, dass - ich will das hier nur roh andeuten - ein elektrischer Strom im Draht sich bewegt, ein in der Nähe befindlicher Strom entsteht einfach dadurch, dass der eine Draht in der Nachbarschaft des anderen ist. Es geschehen also Wirkungen der Elektrizität durch den Raum - so könnte man etwa sagen.

Nun war es Hertz gelungen, auf das ganz Interessante zu kommen, dass in der Tat die Ausbreitung der elektrischen Agenzien etwas Verwandtes hat mit allem, was sich wellenförmig ausbreitet oder so gedacht werden kann. So hatte Hertz gefunden, dass, wenn man etwa einen elektrischen Funken erzeugt auf dieselbe Weise, wie er hier [mit der Leidener Flasche] erzeugt wird, wenn man hier also den elektrischen Funken erzeugt, das heißt die Spannung zur Entwicklung bringt, so würde man können das Folgende erreichen: Nehmen Sie an, hier hätten wir diesen überspringenden Funken. Wir würden immer die Möglichkeit haben, an einem entsprechenden Ort, irgendwo anders, zwei solche - man könnte sie kleine Induktoren nennen — einander gegenüberzustellen. Sie müssen nur [an] einem bestimmten [anderen] Orte sich gegenübergestellt werden. Und es würde in einiger entsprechender Entfernung entstehen können ein Überspringen auch hier, was ja keine andere Erscheinung wäre als eine solche, die ähnlich ist derjenigen, wo meinetwillen hier eine Lichtquelle ist, hier ein Spiegel ist, der [Lichtkegel] reflektiert wird, durch einen anderen Spiegel hier gesammelt wird und hier das Bild dann erscheint. Man kann sprechen von einer Ausbreitung des Lichtes und von einer Wirkung, die in der Entfernung sich vollzieht. So konnte auch Hertz sprechen von einer Ausbreitung der Elektrizität, deren Wirkung in entsprechender Entfernung wahrnehmbar ist, und hatte damit nach seiner und anderer Auffassung das zustande gebracht, was ein Beweis wäre dafür, dass wirklich durch die Elektrizität sich etwas verbreitet, was einer wellenförmigen Bewegung entspricht, so, wie man sich überhaupt wellenförmige Bewegungen in ihrer Ausbreitung denkt.

Wie also das Licht durch den Raum sich verbreitet und zur Wirkung gelangt in Entfernungen, wenn es auf andere Körper auftrifft und gewissermaßen da entfaltet werden kann, so können auch die elektrischen Wellen sich ausbreiten und in der Entfernung wieder entfalten. Das liegt dann zugrunde der sogenannten [drahtlosen] Telegrafie, wie Sie wissen, und man hat es also mit einer gewissen Erfüllung der Lieblingsidee der Physiker des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts zu tun, dass man, was man beim Schall sich vorstellt als Wellenzüge und beim Licht sich vorstellt als Wellenzüge, was man begonnen hat, weil die Wärmeerscheinungen ähnliche Erscheinungen aufweisen, bei der sich verbreitenden Wärme als Wellenbewegung sich vorzustellen, das konnte man auch bei der Elektrizität, bei der man sich nur recht lange Wellen vorzustellen hat. Das konnte man sich auch bei der Elektrizität vorstellen. Es war gewissermaßen damit etwas geliefert, was wie unwiderleglich bewies, dass die Denkweise der Physik im neunzehnten Jahrhundert voll begründet ist.

Und dennoch, es ist mit den Hertz’schen Versuchen etwas gegeben, was darauf hinweist, dass mit ihnen eigentlich ein Abschluss des Alten sich vollzogen hat. sehen Sie, alles dasjenige, was sich in gewissen Gebieten vollzieht, das kann ja doch eigentlich nur innerhalb dieser gewissen Gebiete auch entsprechend beurteilt werden. Wenn wir jetzt Revolutionen erlebt haben, so erscheinen uns diese als gewaltige Erschütterungen des sozialen Lebens, weil wir eben auf ihre Gebiete besonders hinschauen. Derjenige, der auf das hinschaut, was mit den Neunzigerjahren des vorigen Jahrhunderts und mit den anderthalb Jahrzehnten dieses Jahrhunderts geschehen ist auf dem Gebiet der Physik, der muss sagen, dass sich da eigentlich eine Revolution vollzogen hat, die in ihrem Gebiete viel stärker ist als auf ihrem die äußere Revolution. Denn man braucht nicht mehr und nicht weniger zu sagen, als dass man auf physikalischem Gebiet in einer vollständigen Auflösung der alten physikalischen Begriffe im Grunde genommen darinnen steckt und dass sich die Physiker nur noch wehren, diese Auflösung wirklich zuzugeben.

Während dasjenige, was Hertz zutage gefördert hat, durchaus die Abendröte des Alten noch ist, weil es eigentlich dazu geführt hat, die alte Wellentheorie zu erhärten, ist dasjenige, was später gekommen ist, was auch schon zu Hertzens Zeit vorhanden war, gewissermaßen schon vorbereitend da war, das ist von revolutionierender Bedeutung für die Physik geworden." Und das besteht darinnen, dass man den elektrischen Strom, der erzeugt und weitergeleitet werden kann, nun leitet durch Röhren, in denen die Luft ausgepumpt ist bis zu einem gewissen Grade, sodass man also den elektrischen Strom leitet durch eine Luft, die außerordentlich stark verdünnt ist. Sie sehen hier [in der Gasentladungsröhre] den Spannungszustand einfach dadurch hervorgerufen, dass die Enden, an denen sich die Elektrizität entladen kann, so weit auseinandergeschoben sind, wie hier die Röhrenlänge ist, sodass dasjenige, was man eine Spitze nennen kann, durch die sich die positive Elektrizität entlädt, der positive Pol, auf der einen Seite ist und der negative Pol auf der anderen Seite ist. Zwischen diesen beiden Spitzen entlädt sich die Elektrizität, und die farbige Linie, die Sie hier sehen, ist der Weg, den die Elektrizität nimmt. Sodass man sagen kann: Dasjenige, was sonst durch die Drähte geht, das nimmt, indem es sich durch die verdünnte Luft fortpflanzt, diese Form an, die Sie hier sehen. Das ist also bei stärker verdünnter Luft noch stärker. Sie sehen schon hier, dass gewissermaRen eine Art Bewegung stattfindet von der einen und anderen Seite her, wie sich die Erscheinung wesentlich modifiziert.

So haben wir also die Möglichkeit, dasjenige, was durch den Draht als Elektrizität strömt, auf einem Teil seines Weges gewissermaßen so zu behandeln, dass es zeigt in Wechselwirkung mit anderem etwas von seiner inneren Wesenheit. Es zeigt sich, wie es ist, indem es sich nicht durch den Draht verbergen kann. Beobachten Sie das grüne Licht an dem Glas! Das ist fluoreszierendes Licht.

Es tut mir leid, dass ich die Sachen nicht genauer besprechen kann, aber ich würde nicht erreichen, was ich erreichen möchte, wenn ich nicht so skizzenhaft spräche.

Sie sehen, was da durchgeht, in einem sehr zerstobenen Zustand, in der stark verdünnten Luft der Röhre. Nun, die Erscheinungen, die sich so in luft- oder gasverdünnten Röhren zeigten, die brauchen nur studiert zu werden - die mannigfachsten Persönlichkeiten haben sich an diesem Studium beteiligt, unter anderen hat sich daran beteiligt Crookes. Und es handelt sich darum, zu verfolgen, wie sich die Erscheinungen in der Röhre eigentlich verhalten, und dass man versucht, mit den Erscheinungen, die sich in der Röhre ergeben, Versuche zu machen. Nun, gewisse Versuche, die zum Beispiel auch Crookes gemacht hat, die bezeugten, dass dasjenige, was da, ich möchte sagen, als innerer Charakter der Elektrizität sich zeigt, wo wir sie bloßgelegt haben, das wies darauf hin, dass man es nicht zu tun haben kann mit irgendetwas, was sich so fortpflanzt, wie man sich’s vorstellen wollte, dass sich das Licht durch Wellenbewegungen des Äthers fortpflanzt. Denn dasjenige, was da hinschießt durch die Röhre, das hat merkwürdige Eigenschaften, Eigenschaften, die stark erinnern an die Eigenschaften desjenigen, was einfach Materielles ist. Wenn Sie einen [Permanent-]Magneten haben oder einen Elektro-Magneten - ich muss da appellieren an dasjenige, was Sie schon wissen, es kann heute nicht alles besprochen werden -, so können Sie Materielles anziehen durch den Magneten. Dieselbe Eigenschaft, angezogen werden zu können durch den Magneten, die hat auch dieser Lichtkörper, der da durchgeht, diese modifizierte Elektrizität. Sie verhält sich ganz so zu einem Magneten, wie sich Materie zum Magneten verhält. Das magnetische Feld modifiziert dasjenige, was da durchschießt.

Solche und ähnliche Versuche haben Crookes und andere Personen dazu geführt, sich vorzustellen, dass da drinnen nicht das ist, was man im alten Sinne eine fortschreitende Wellenbewegung nennen kann, sondern dass da drinnen materielle Teilchen sind, die durch den Raum schießen und die als materielle Teilchen angezogen werden von der magnetischen Kraft. Crookes nannte daher dasjenige, was da hinüberschießt, was da wenigstens irgendwie in Betracht kommen müsse, strahlende Materie, und er stellte sich vor, dass durch die Verdünnung nach und nach die Materie, die da drinnen ist in der Röhre, in einen solchen Zustand gekommen ist, dass sie nicht nur ein Gas ist, sondern etwas ist, was schon über den Gaszustand hinausgeht, was eben strahlende Materie ist, Materie, deren einzelne Teile durch den Raum strahlen, die also gewissermaßen fein zerteilter Staub ist, dessen Körnchen durch die elektrische Ladung selbst die Eigenschaft haben, durch den Raum zu schießen. Diese Teilchen selbst, die würden nun angezogen von der elektromagnetischen Kraft. Dass sie angezogen würden, das beweise eben, dass wir es zu tun haben mit den letzten Resten von wirklichem Materiellem, nicht bloß mit einer Bewegung nach der Art der im alten Sinn gedachten Ätherbewegung.

Diese Versuche konnte man insbesondere machen mit demjenigen, was ausstrahlt, was sich als Ausstrahlendes ergab von dem negativ elektrischen Pol, von der sogenannten Kathode, und man studierte da diese Ausstrahlungen von der Kathode und nannte sie Kathodenstrahlen. Damit also war, ich möchte sagen, die erste Bresche in die alte physikalische Auffassung geschlagen. Man hatte in den Hittorf’schen Röhren - Hittrorf war der Erste, der, dann kam Geißler, solche Röhren konstruiert hat - einen Vorgang, der bewies, dass man es eigentlich mit einem durch den Raum gehenden Materiellen, durch den Raum schießenden Materiellen, wenn auch in sehr fein verteiltem Zustande, zu tun hat. Was in dem steckt, was man die Materie nannte, war ja damit nicht ausgemacht, aber es war jedenfalls auf etwas hingedeutet, was man mit dem Materiellen identifizieren musste.

Crookes war es also klar, dass er es da mit durch den Raum hindurchstäubendem Materiellem zu tun hatte. Diese Anschauung erschütterte die alte Wellenlehre. Auf der anderen Seite aber kamen dann wiederum andere Versuche, welche nun die Crookes’sche Anschauung nicht rechtfertigten. So gelang es Lenard 1893"%, diese sogenannten [Kathoden- oder Elektronen-]Strahlen, die von diesem [negativen] Pol ausgehen, von ihrem Weg abzubringen - man kann sie ja abbringen -, und er konnte sie nach außen leiten, er konnte eine Aluminiumwand einschalten und durch sie die Strahlen leiten.'"? Da entstand zunächst die Frage: Kann das so einfach sein, dass materielle Teilchen da so ohne Weiteres durch eine materielle Wand durchgehen? - Man musste also wieder die Frage aufwerfen: Sind das also materielle Teilchen, die da durch den Raum stieben? Ist es doch nicht etwas anderes, was durch den Raum stiebt?

Nun, sehen Sie, das führte allmählich dazu, einzusehen, dass man weder mit dem alten Schwingungsbegriff noch mit dem alten Materiebegriff auf diesem Gebiet weiterkommt. Man war gewissermaßen in der Lage, durch die Hittorf’schen Röhren, der Elektrizität auf ihren Schleichwegen nachzugehen. Man hatte Hoffnungen, Wellenbewegungen zu finden; man konnte sie nicht finden. Man hatte sich nun damit getröstet: Also ist es durch den Raum schießende Materie. Auch das ging wiederum nicht recht, und so sagte man sich zum Schlusse, was nun tatsächlich durch die verschiedensten Versuche, von denen ich nur einzelne charakteristische Ihnen hier anführen konnte, man sagte sich: Es sind nicht Schwingungen vorhanden, es ist auch nicht eine solche zerstäubte Materie vorhanden, sondern es ist bewegte, strömende Elektrizität vorhanden. Die Elektrizität selbst strömt, aber sie zeigt, indem sie strömt, gewisse Eigenschaften, durch die sie sich verhält zu anderem, sagen wir zum Magneten, wie Materie. Natürlich, wenn Sie eine [Metall-]Kugel durch den Raum schießen lassen und Sie lassen sie am Magneten vorbeigehen, so wird sie von ihrem Wege abgelenkt. So macht es auch die Elektrizität. Das spricht dafür, dass sie etwas Materielles ist. Aber da sie ohne Weiteres durch eine Aluminiumplatte durchgeht wiederum, erweist sie sich doch wiederum nicht als Materie. Materie macht ja zum Beispiel ein Loch, wenn sie durch andere Materie durchgeht. Also sagte man: strömende Elektriz.

Diese strömende Elektrizität, sie zeigte nun die allermerkwürdigsten Dinge, und ich möchte sagen: An der Richtung, die sich ergab für die Betrachtung, konnte man die merkwürdigsten Entdeckungen machen. So konnte man nach und nach verfolgen, wie ebenso Ströme ausgehen von dem anderen Pol, die sich begegnen mit den Kathodenstrahlen. Man nennt das [andere] Ende die Anode und bekam die Strahlen, die Kanalstrahlen genannt wurden. Sodass man in einer solchen Röhre zwei sich begegnende Strahlen zu haben glaubte.

Etwas besonders Interessantes ergab sich in den Neunzigerjahren des vorigen Jahrhunderts, als Röntgen die Kathodenstrahlen leitete - auffing, könnte man sagen - auf eine Art Schirm, den er in den Weg der Kathodenstrahlen stellte. Als Röntgen auffing diese Strahlen durch den Schirm, der aus der Materie besteht, die aus gewissen chemischen theoretischen Untergründen heraus Bariumplatinzyanür genannt wird, also, wenn man die Kathodenstrahlen auffangen lässt durch einen Schirm von Bariumplatinzyanür, so bekommt man eine Modifikation durch diese Strahlen. Die Strahlen gehen modifiziert weiter, und man bekommt Strahlen, die auf gewisse Körper elektrisierend wirken, die sich auch zeigen in Wechselwirkung mit gewissen magnetischen und elektrischen Kräften. Man bekommt dasjenige, was man gewohnt worden ist, die Röntgenstrahlen oder X-Strahlen zu nennen. Daran haben sich wieder andere Entdeckungen geschlossen. Sie wissen, dass diese Röntgenstrahlen die Eigenschaft haben, dass sie durch die Körper gehen können, ohne dass sie wahrnehmbare Störungen hervorrufen, dass sie durch das Fleisch, durch die Knochen gehen in verschiedener Art, sodass sie große Bedeutung gewonnen haben für die Physiologie und Anatomie.

Nun trat eine Erscheinung auf, die nötig macht, sich weitere Gedanken zu machen. Es trat die Erscheinung [auf], dass, wenn diese Kathodenstrahlen oder ihre Modifikationen Glaskörper oder andere Körper treffen, eine gewisse Art von Fluoreszenz hervorgerufen

wird, das heißt, dass diese Materien leuchtend werden dadurch. Da sagte man sich, da müssen diese Strahlen wiederum weiter modifiziert worden sein. Man hat es da also mit einer ganzen Menge von Strahlenarten zu tun. Die Strahlen, die da direkt kamen von dem negativen Pol, die erwiesen sich als modifizierbar durch allerlei anderes. Man hat versucht nun, Körper zu finden, von denen man geglaubt hat, dass sie diese Modifikation sehr stark hervorrufen können, dass sie also sehr stark diese hingeworfenen Strahlen in etwas anderes verwandeln, zum Beispiel in Fluoreszenzstrahlen. Und auf diese Weise ist man darauf gekommen, dass man Körper haben kann wie zum Beispiel Uransalze, die gar nicht nötig haben, erst bestrahlt zu werden unter allen Umständen, sondern die unter gewissen Verhältnissen selbst diese Strahlen wiederum aussenden, die also die innere Eigenschaft haben, solche Strahlen auszusenden. Und unter diesen Körpern waren ja insbesondere die Körper, die man die radiumhaltigen nennt. Da haben gewisse Körper höchst merkwürdige Eigenschaften. Sie strahlen, sagen wir, zunächst gewisse Kraftlinien aus, die in merkwürdiger Weise behandelt werden können.

Wenn wir solch eine Ausstrahlung haben von einem radiumhaltigen Körper - [der Körper ist] hier in einem Bleitröglein drinnen und wir haben hier [bei der Öffnung] die Ausstrahlung -, so können wir untersuchen diese Ausstrahlung mit dem Magneten. Dann finden wir, dass sich etwas absondert von dieser Ausstrahlung, die wir durch den Magneten stark hier [nach rechts] herüberleiten können, das dann diese Form annimmt. Etwas anderes bleibt starr und pflanzt sich in dieser Richtung [geradlinig nach oben] fort; etwas anderes wird in entgegengesetztem Sinn [nach links] abgelenkt, das heißt, es steckt hier ein Dreifaches darinnen. Zuletzt hatte man schon gar nicht mehr genug Namen, um das zu bezeichnen. Deshalb nannte man dasjenige, was nach rechts abgelenkt werden kann, \(γ\)-Strahlen, die in gerader Linie folgenden die y-Strahlen und die nach entgegengesetzter Richtung abgelenkt werden, nannte man die \(γ\)-Strahlen. Wenn man gewisse Rechnungen anstellt, dann kann man dadurch, dass man einen Magneten demjenigen, was da strahlt, seitlich herankommen lässt, dadurch kann man die Ablenkung studieren und damit die Geschwindigkeit. Und da stellte sich das Interessante heraus, dass die \(γ\)-Strahlen etwa sich bewegen mit \(\frac{9}{10}\) Lichtgeschwindigkeit, die a-Strahlen mit etwa \(\frac{1}{10}\) Lichtgeschwindigkeit. Wir haben also da gewissermaßen Kraft-Explosionen, die wir getrennt haben, analysiert haben, und die uns zeigen, wie sie auffallende Verschiedenheiten in der Geschwindigkeit haben.

Ich erinnere Sie an dieser Stelle, dass wir rein geistig im Beginne dieser Betrachtungen die Formel zu erfassen versuchten: \(v=\frac{s}{t}\) und haben gesagt, dass das Reale im Raum die Geschwindigkeit ist, dass auf die Geschwindigkeit das ankommt, was einen berechtigt, hier von Wirklichem zu sprechen. Hier sehen Sie, wie dasjenige, was da, ich möchte sagen, herausexplodiert, sich hauptsächlich dadurch charakterisiert, dass man es zu tun hat mit verschieden stark aufeinander wirkenden Geschwindigkeiten. Denken Sie sich nur einmal, was das bedeutet, dass in demselben Kraftzylinder, der hier herausstrahlt, etwas drinnen ist, was sich neunmal so schnell bewegen will als das andere, dass also eine schießende Kraft, die zurückbleiben will gegen die andere, die neunmal so schnell gehen will, sich geltend macht.

Nun bitte ich, ein wenig auf dasjenige zu sehen, wovon nur Anthroposophen das Recht haben, es heute noch nicht als Verrücktheit anzusehen. Ich bitte, sich daran zu erinnern, wie oft und oft wir sprechen mussten, dass in den größten uns überschaubaren Aktionen der Welt Geschwindigkeitsunterschiede das Wesentliche sind. Wodurch spielen denn in unsere Gegenwart wichtigste Erscheinungen herein? Dadurch, dass mit verschiedener Geschwindigkeit die normalen, die luziferischen, die ahrimanischen Wirkungen ineinander spielen, dass Geschwindigkeitsdifferenzen in den geistigen Strömungen, denen das Weltgefüge unterworfen ist, vorhanden sind. Der Weg, der sich der Physik eröffnet hat in der letzten Zeit, zwingt sie, auf Geschwindigkeitsdifferenzen in einem ganz ähnlichen Sinn, vorläufig ganz unbewusst, einzugehen, wie sie die Geisteswissenschaft geltend machen muss für die umfassendsten Agenzien der Welt.

Es ist aber damit noch nicht erschöpft alles dasjenige, was da aus diesem Radiumkörper herausstrahlt, sondern es strahlt noch etwas anderes heraus, was wiederum in seinen Wirkungen nachgewiesen werden kann und was sich in diesen Wirkungen zeigt als etwas, das ausstrahlt wie eine Ausstrahlung der Radiummaterie, was sich aber nach und nach nicht mehr als Radium zeigt, sondern zum Beispiel als Helium, was ein ganz anderer Körper ist. Dieses Radium sendet also nicht nur dasjenige, was da in ihm ist, als Agenzien aus, sondern dieses Radium gibt sich selber hin und wird dabei etwas anderes. Mit der Konstanz der Materie hat das nicht mehr viel zu tun, sondern mit einer Metamorphose der Materie.

Nun habe ich Ihnen heute Erscheinungen vorgeführt, welche alle verlaufen in einem Gebiet, das man nennen könnte das elektrische Gebiet. Diese Erscheinungen, sie haben alle ein Gemeinsames, nämlich das Gemeinsame, dass sie sich zu uns selber ganz anders verhalten wie zum Beispiel die Schall-, die Licht- und selbst die Wärmeerscheinungen. In Licht, Schall und Wärme schwimmen wir gewissermaßen so darinnen, wie wir das in den vorhergehenden Betrachtungen beschrieben haben. Das können wir von den elektrischen Erscheinungen nicht so ohne Weiteres sagen. Denn Elektrizität nehmen wir nicht als so etwas Spezifisches wahr wie das Licht. Wir nehmen selbst dann, wenn die Elektrizität gezwungen wird, sich uns zu enthüllen, sie durch eine Lichterscheinung wahr. Das hat ja längst dazu geführt, dass man immer sagt: Elektrizität hat keinen Sinn im Menschen. Das Licht hat im Menschen das Auge als Sinn, der Schall das Ohr, für die Wärme ist eine Art von Wärmesinn konstruiert; für die Elektrizität ist so etwas Ähnliches, sagt man, nicht vorhanden. Man nimmt sie mittelbar wahr. Aber über diese Charakteristik des mittelbaren Wahrnehmens kann man eben nicht hinausgehen, wenn man nicht vorrückt zu einer solchen naturwissenschaftlichen Betrachtung, wie wir sie hier wenigstens inauguriert haben. Wenn wir uns dem Lichte exponieren, so tun wir es so, dass wir in dem Lichtelemente darinnen schwimmen und wir selber an ihm teilnehmen, [wenigstens] teilweise, mit unserem Bewusstsein teilnehmen; ebenso bei der Wärme, ebenso beim Schall, beim Ton. Das können wir nicht sagen bei der Elektrizität.

Aber nun bitte ich Sie, sich zu erinnern daran, wie ich Ihnen immer vorgeführt habe, wie wir Menschen eigentlich sind - wir Menschen sind ja, grob gesprochen, Doppelwesen, eigentlich in Wirklichkeit dreigliedrige Wesen: Denkwesen, Fühlwesen, Willenswesen -, und ich konnte Ihnen immer zeigen, dass wir eigentlich nur in unserem Denken wachen, dass wir in unseren Gefühlen träumen, in unseren Willensvorgängen, auch wenn wir wachend sind, schlafen. Die Willensvorgänge erleben wir nicht unmittelbar, wir verschlafen dasjenige, was im wesentlichen Wille ist, und in diesen Betrachtungen habe ich Sie darauf hingewiesen, wie, wenn wir in den physikalischen Formeln, wo wir das m gleich Masse hinschreiben, wie wir, da wir da hinausgehen von dem bloßen Zählbaren, von der Bewegung und von der Zeit, vom Raum, zu etwas übergehen, was nicht bloß phoronomisch ist, so müssen wir uns klar sein, dass dem entspricht ein Übergehen unseres Bewusstseins in einen Schlafzustand. Wenn Sie unbefangen betrachten diese Gliederung der menschlichen Wesenheit, so können Sie sich sagen: Das Erleben von Licht, Schall, Wärme fällt bis zu einem gewissen Grade, bis zu einem gewissen hohen Grade in das Feld, das wir mit unserem Sinnesvorstellungsleben umfassen, besonders stark die Lichterscheinungen - sodass das sich zeigt einfach dadurch, dass wir unbefangen den Menschen studieren, sodass das alles sich zeigt als verwandt mit unseren bewussten Seelenkräften. Indem wir zum eigentlich Massenhaften, zum Materiellen vorschreiten, nähern wir uns demjenigen, was verwandt ist mit den Kräften, die sich in uns entwickeln, wenn wir schlafen.

Genau denselben Weg machen wir, meine lieben Freunde, wenn wir aus dem Gebiet des Lichtes, des Schalles, der Wärme hinuntersteigen in das Gebiet der elektrischen Erscheinungen. Wir erleben unsere Willenserscheinungen nicht direkt, sondern dasjenige, was wir von ihnen vorstellen können; wir erleben die elektrischen Erscheinungen der Natur nicht direkt, sondern dasjenige, was sie heraufliefern in das Gebiet des Lichtes, des Schalles, der Wärme und so weiter. Wir betreten nämlich für die Außenwelt, ich möchte sagen, denselben Orkus, indem wir schlafen, den wir betreten in uns selbst, wenn wir aus unserem vorstellenden, bewussten Leben hinuntersteigen in unser Willensleben. Während verwandt ist alles dasjenige, was Licht, Schall, Wärme ist, mit unserem bewussten Leben, ist innig verwandt alles dasjenige, was auf dem Gebiet der Elektrizität und des Magnetismus sich abspielt, mit unserem unbewussten Willensleben. Und das Auftreten der physiologischen Elektrizität bei gewissen niederen Tieren, das ist nur ein Symptom, ein sich an einer bestimmten Stelle der Natur äußerndes Symptom für eine sonst nicht bemerkbare, aber allgemeine Erscheinung: Überall, wo Wille durch den Stoffwechsel wirkt, wirkt ein den äußeren elektrischen und magnetischen Erscheinungen Ähnliches. Und man steigt eigentlich, indem man auf den komplizierten Wegen, die wir heute nur roh skizzieren konnten, in dem man hinuntersteigt auf diesen Wegen in das Gebiet der elektrischen Erscheinungen, steigt man in dasselbe Gebiet hinunter, in das man hinuntersteigen muss, wenn man überhaupt nur zur Masse kommt.

Was tut man, wenn man Elektrizität und Magnetismus studiert? Man studiert die Materie konkret. Steigen Sie zur Materie hinunter, indem Sie Elektrizität und Magnetismus studieren! Und es ist wahr, recht wahr, was ein englischer Philosoph gesagt hat: Früher hat man in verschiedenster Weise geglaubt, dass der Elektrizität Materie zugrunde liegt. Jetzt muss man annehmen, dass dasjenige, was man als Materie glaubt, eigentlich nichts anderes ist als flüssige Elektrizität. Früher hat man die Materie atomisiert. Jetzt denkt man: Die Elektronen, die bewegen sich durch den Raum und haben ähnliche Eigenschaften wie früher die Materie. Man hat den ersten Schritt gemacht - nur gibt man ihn noch nicht zu - zur Überwindung der Materie und den ersten Schritt dazu, anzuerkennen, dass man hinuntersteigt im Reich der Natur, indem man von den Licht-, Schall-, Wärmeerscheinungen zu den elektrischen Erscheinungen [übergeht], dass man hinuntersteigt zu demjenigen, was sich zu diesen [Licht-, Schall- und Wärme-]Erscheinungen verhält wie unser Wille zu unserem Vorstellungsleben. Das möchte ich Ihnen auf die Seele legen als ein Fazit der heutigen Betrachtung. Ich will Ihnen ja hauptsächlich das sagen, was Sie in den Büchern nicht vorfinden. Was davon doch vorgeführt wird, möchte ich nur sagen als etwas, was das andere begründet.

Ninth Lecture

My dear friends!

I am extremely sorry that these discussions are so improvised and must remain aphoristic, but there is no other way than to give you a number of points of view at this time and then, when I am here again in a while, to continue the discussion so that you can eventually gain a more rounded view from these discussions. However, in order to present to you the few points of view that I will develop tomorrow in conclusion, and which will in turn enable us to shed some light on the pedagogical application of scientific findings, I must today direct your attention to the development of electrical phenomena, the phenomena of electricity, and I will pick up on things that are actually familiar to you from school, because tomorrow we want to characterize the entire field of physics from that starting point.

You are familiar with the elementary concepts of electricity. You know that there is such a thing as friction electricity, that a glass rod can be made to generate a force by rubbing it with some kind of friction material, or a resin rod, and that this causes the glass rod or resin rod to become electrically charged, i.e., it attracts small objects such as pieces of paper. You also know that observation of these phenomena has gradually revealed that the two forces that emanate in one case from the rubbed glass rod and in the other case from the rubbed resin rod or sealing wax rod are different in their development: When the rod has been caused to attract small pieces of paper, that which is, as it were, electrically saturated by the glass rod in a certain way is electrically saturated in the opposite way by the electricity of the resin rod, and therefore, following more closely the qualitative aspect, a distinction is made between glass electricity and resin electricity, or, to express it more generally, positive electricity and negative electricity. Glass electricity would be positive, resin electricity negative.

Now, the peculiar thing is that positive electricity always attracts negative electricity in a certain way. You can see this phenomenon in the so-called Leiden bottle, i.e., in that vessel which is provided with an electrifyable coating on the outside, which is then insulated here [inside this coating], and which is then [completely] provided with another [electrifiable] coating, which continues into a metal rod with a metal head. If you now electrify a [glass rod] and transfer this electricity—which is possible—to the outer coating, the outer coating becomes positively electrified and produces the phenomena of positive electricity. This, however, makes the inner coating negatively electrified. And then, as you know, by connecting the coating filled with positive electricity and the coating filled with negative electricity, we can bring about a connection between the positive and negative electrical forces if we place them in such a position that one electricity can continue to here and face the other.

They face each other with a certain tension and demand to be balanced. The spark jumps from one to the other. We see, therefore, that electrical forces that are thus opposed to each other have a certain tension and demand to be balanced. They face each other with a certain tension and demand to be balanced. The spark jumps from one to the other. We can see, then, that electrical forces facing each other in this way have a certain tension and strive for balance. This experiment will have been performed many times before you.

Here you see the Leyden jar. But we still need a [discharge] fork. I will charge it here. It is still too weak. The plates [of the electroscope] repel each other slightly. So, if we charged it sufficiently, the positive electricity would cause the negative electricity, and if we had both opposite each other, we would cause the spark to jump by using a discharge fork. But you also know that this type of electrification is referred to as frictional electricity, because it involves a force of some kind that is produced by friction – that is how I would describe it for now.

Now, as I need only repeat, it was not until the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that this friction electricity was discovered, along with what is called contact electricity. This opened up a field for modern physics that has proved extremely fruitful for the materialistic development of physics. I need only remind you of the principle here. Galvani observed a frog's leg that was connected to metal plates and began to twitch, and in doing so he had actually discovered something extremely significant – two things at once, which only needed to be separated from each other and which, to the detriment of scientific observation, have not yet been completely separated. Galvani had discovered what Volta was able to describe a little later as “actual contact electricity.” He had discovered the fact that when two different metals touch each other in such a way that their contact is mediated by appropriate liquids, an interaction occurs which can manifest itself in the form of an electric current flowing from one metal to the other.

This gives us the electric current that appears to flow purely in the realm of inorganic life, but by looking at what Galvani actually revealed, we also have what can be described as physiological electricity, a state of tension that actually always exists between muscles and nerves and can be awakened when electrical currents are passed through muscles and nerves. So what Galvani saw at that time actually contained two things: that which can be easily reproduced in the inorganic realm by causing metals to form electric currents through the mediation of liquids. He also observed what is present in every organism, particularly in certain electric fish and other animals, as a state of tension between muscle and nerve, which appears similar in its balance to flowing electricity and its effects. This discovery led to tremendous scientific advances in the materialistic field on the one hand, and on the other hand, it laid the tremendous, epoch-making foundations for technology.

Now, the thing is that the nineteenth century was mainly filled with the view that something had to be discovered that lay at the basis of all natural forces—as they are called—as an abstract unity. This was also the interpretation given to what I have already told you about, which was brought to light in the 1840s by Julius Robert Mayer, the well-known genius physician from Heilbronn. We have demonstrated what he brought to light: we developed mechanical power by setting a flywheel in rotation, which set the water in internal mechanical motion. But this caused the water to become warmer. We were able to prove the warming, and it can be said that this development of heat is an effect of the mechanical power, the mechanical work that was there.

These things were interpreted in such a way that they were applied to a wide variety of natural phenomena, which was easy to do within certain limits. It was possible to bring about the unfolding of chemical forces, to see how heat is formed from the unfolding of chemical forces, and, conversely, to use heat, as happens in the steam engine in the most comprehensive sense, to produce mechanical work. Particular attention was paid to this so-called transformation of natural forces, and this was prompted by what had been developed further and further, beginning with Julius Robert Mayer, namely that it is possible to calculate numerically how much heat is necessary to produce a certain measurable amount of work and, conversely, how much mechanical work is necessary to produce a certain measurable amount of heat. It was imagined, although there was no reason for it, that the work done by turning the paddle wheels in the water was simply transformed, that this mechanical work was converted into heat. It was assumed that when we apply heat in the steam engine, this heat is converted into what then appears as mechanical power. This line of thinking was adopted by physical speculation in the nineteenth century, and therefore it sought to find affinities between the various so-called forces of nature, affinities that would show that there really is something abstractly the same in all these different forces of nature.

This endeavor found a certain culmination at the end of the nineteenth century or toward the end of the nineteenth century when, with a certain genius, the physicist Hertz discovered the so-called electric waves—waves here as well! These gave a certain justification for thinking of what spreads as electricity as related to what spreads as light, which was also thought of as a wave-like movement of the ether. The fact that what was referred to as electricity, particularly in the form of flowing electricity [in wires], cannot be grasped so easily with primitive mechanical concepts, but actually makes it necessary to broaden the outlook of physics a little towards the qualitative: This could already have been demonstrated by the existence of what are called induction currents, where, because—I will only hint at this here—an electric current moves in a wire, a current arises in the vicinity simply because one wire is in the neighborhood of the other. Effects of electricity therefore occur through space—one could say.

Hertz had now succeeded in arriving at the very interesting conclusion that the propagation of electrical agents does indeed have something in common with everything that propagates in waves or can be thought of in this way. Hertz had discovered that if you generate an electric spark in the same way as it is generated here [with the Leyden jar], i.e., if you generate the electric spark here, that is, if you bring the voltage to development, you could achieve the following: Suppose we had this spark jumping here. We would always have the possibility of placing two such—one might call them small inductors—opposite each other at a corresponding location somewhere else. They only need to be placed opposite each other at a specific [other] location. And at a certain distance, a spark could also jump here, which would be no different from a phenomenon similar to the one where, for the sake of argument, there is a light source here, a mirror here that reflects the [cone of light], which is collected by another mirror here, and the image then appears here. One can speak of a propagation of light and of an effect that takes place at a distance. Hertz was thus able to speak of a propagation of electricity, the effect of which is perceptible at a corresponding distance, and had thereby, in his opinion and that of others, established what would be proof that something really does propagate through electricity, corresponding to a wave-like motion, just as one generally conceives of wave-like motions in their propagation.

Just as light propagates through space and has an effect at distances when it strikes other bodies and can, so to speak, unfold there, so too can electric waves propagate and unfold again at a distance. This is the basis of what is known as [wireless] telegraphy, as you know, and so we are dealing with a certain fulfillment of the favorite idea of nineteenth-century physicists, that what we imagine as waves in sound and light, which we began to imagine because heat phenomena exhibit similar phenomena, can also be imagined as wave movements in propagating heat. could also be imagined in the case of electricity, where one only has to imagine very long waves. This could also be imagined in the case of electricity. In a sense, this provided something that irrefutably proved that the way of thinking in physics in the nineteenth century was fully justified.