The Boundaries of Natural Science

GA 322

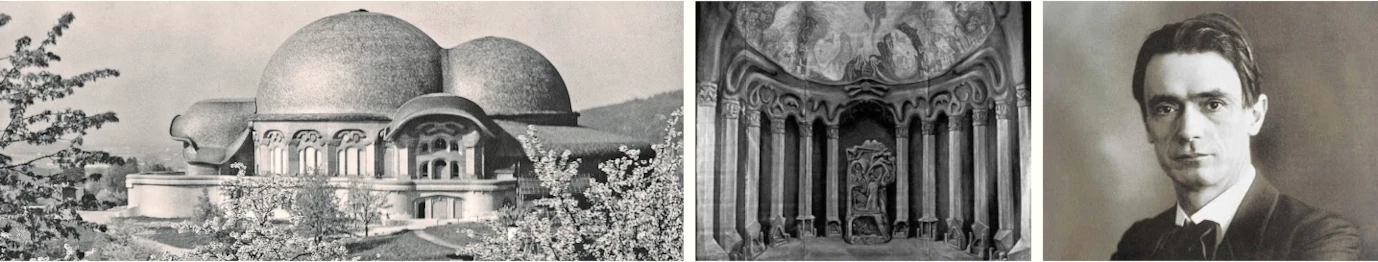

28 September 1920, Dornach

Lecture II

It must be answered, not to meet a human “need to know” but to meet man's universal need to become fully human. And in just what way one can strive for an answer, in what way the ignorabimus can be overcome to fulfil the demands of human evolution—this shall be the theme of our course of lectures as it proceeds.

To those who demand of a cycle of lectures with a title such as ours that nothing be introduced that might interfere with the objective presentation of ideas, I would like, since today I shall have to mention certain personalities, to say the following. The moment one begins to represent the results of human judgment in their relationship to life, to full human existence, it becomes inevitable that one indicate the personalities with whom the judgments originated. Even in a scientific presentation, one must remain within the sphere in which the judgment arises, within the realm of human struggling and striving toward such a judgment. And especially since the question we want above all to answer is: what can be gleaned from modern scientific theories that can become a vital social thinking able to transform thought into impulses for life?—then one must realize that the series of considerations one undertakes is no longer confined to the study and the lecture halls but Stands rather within the living evolution of humanity.

Behind everything with which I commenced yesterday, the modern striving for a mathematical-mechanical world view and the dissolution of that world view, behind that which came to a climax in 1872 in the famous speech by the physiologist, du Bois-Reymond, concerning the limits of natural science, there stands something even more important. It is something that begins to impress itself upon us the moment we want to begin to speak in a living way about the limits of natural science.

A personality of extraordinary philosophical stature still looks over to us with a certain vitality out of the first half of the nineteenth century: Hegel. Only in the last few years has Hegel begun to be mentioned in the lecture halls and in the philosophical literature with somewhat more respect than in the recent past. In the last third of the nineteenth century the academic world attacked Hegel outright, yet one could demonstrate irrefutably that Eduard von Hartmann had been quite right in claiming that during the 1880s only two university lecturers in all of Germany had actually read him. The academics opposed Hegel but not on philosophical grounds, for as a philosopher they hardly knew him. Yet they knew him in a different way, in a way in which we still know him today. Few know Hegel as he is contained, or perhaps better said, as his world view is contained, in the many volumes that sit in the libraries. Those who know Hegel in this original form so peculiar to him are few indeed. Yet in certain modified forms he has become in a sense the most popular philosopher the world has ever known. Anyone who participates in a workers' meeting today or, even better, anyone who had participated in one during the last few decades and had heard what was discussed there; anyone with any sense for the source of the mode of thinking that had entered into these workers' meetings, who really knew the development of modern thought, could see that this mode of thinking had originated with Hegel and flowed through certain channels out into the broadest masses. And whoever investigated the literature and philosophy of Eastern Europe in this regard would find that the Hegelian mode of thinking had permeated to the farthest reaches of Russian cultural life. One thus could say that, anonymously, as it were, Hegel has become within the last few decades perhaps one of the most influential philosophers in human history. On the other hand, however, when one perceives what has come to be recognized by the broadest spectrum of humanity as Hegelianism, one is reminded of the portrait of a rather ugly man that a kind artist painted in such a way as to please the man's family. As one of the younger sons, who had previously paid little attention to the portrait, grew older and really observed it for the first time, he said: “But father, how you have changed!” And when one sees what has become of Hegel one might well say: “Dear philosopher, how you have changed!” To be sure, something extraordinary has happened regarding this Hegelian world view.

Hardly had Hegel himself departed when his school fell apart. And one could see how this Hegelian school appropriated precisely the form of one of our new parliaments. There was a left wing and a right wing, an extreme left and an extreme right, an ultra-radical wing and an ultra-conservative wing. There were men with radical scientific and social views, who felt themselves to be Hegel's true spiritual heirs, and on the other side there were devout, positive theologians who wanted just as much to base their extreme theological conservatism on Hegel. There was a center for Hegelian studies headed by the amiable philosopher, Karl Rosenkranz, and each of these personalities, every one of them, insisted that he was Hegel's true heir.

What is this remarkable phenomenon in the evolution of human knowledge? What happened was that a philosopher once sought to raise humanity into the highest realms of thought. Even if one is opposed to Hegel, it cannot be denied that he dared attempt to call forth the world within the soul in the purest thought-forms. Hegel raised humanity into ethereal heights of thinking, but strangely enough, humanity then fell right back down out of those heights. It drew on the one hand certain materialistic and on the other hand certain positive theological conclusions from Hegel's thought. And even if one considers the Hegelian center headed by the amiable Rosenkranz, even there one cannot find Hegel's philosophy as Hegel himself had conceived it. In Hegel's philosophy one finds a grand attempt to pursue the scientific method right up into the highest heights. Afterward, however, when his followers sought to work through Hegel's thoughts themselves, they found that one could arrive thereby at the most contrary points of view.

Now, one can argue about world views in the study, one can argue within the academies, and one can even argue in the academic literature, so long as worthless gossip and Barren cliques do not result. These offspring of Hegelian philosophy, however, cannot be carried out of the lecture halls and the study into life as social impulses. One can argue conceptually about contrary world views, but within life itself these contrary world views do not fight so peaceably. One must use just such a paradoxical expression in describing such a phenomenon. And thus there stands before us in the first half of the nineteenth century an alarming factor in the evolution of human cognition, something that has proved itself to be socially useless in the highest degree. With this in mind we must then raise the question: how can we find a mode of thinking that can be useful in social life? In two phenomena above all we notice the uselessness of Hegelianism for social life.

One of those who studied Hegel most intensively, who brought Hegel fully to life within himself, was Karl Marx. And what is it that we find in Marx? A remarkable Hegelianism indeed! Hegel up upon the highest peak of the conceptual world—Hegel upon the highest peak of Idealism—and the faithful student, Karl Marx, immediately transforming the whole into its direct opposite, using what he believed to be Hegel's method to carry Hegel's truths to their logical conclusions. And thereby arises historical materialism, which is to be for the masses the one world view that can enter into social life. We thus are confronted in the first half of the nineteenth century with the great Idealist, Hegel, who lived only in the Spirit, only in his ideas, and in the second half of the nineteenth century with his student, Karl Marx, who contemplated and recognized the reality of matter alone, who saw in everything ideal only ideology. If one but takes up into one's feeling this turnabout of conceptions of world and life in the course of the nineteenth century, one feels with all one's soul the need to achieve an understanding of nature that will serve as a basis for judgments that are socially viable.

Now, if we turn on the other hand to consider something that is not so obviously descended from Hegel but can be traced back to Hegel nonetheless, we find still within the first half of the nineteenth century, but carrying over into the second half, the “philosopher of the ego,” Max Stirner. While Karl Marx occupies one of the two poles of human experience mentioned yesterday, the pole of matter upon which he bares all his considerations, Stirner, the philosopher of the ego, proceeds from the opposite pole, that of consciousness. And just as the modern world view, gravitating toward the pole of matter, becomes unable to discover consciousness within that element (as we saw yesterday in the example of du Bois-Reymond), a person who gravitates to the opposite pole of consciousness will not be able to find the material world. And so it is with Max Stirner. For Max Stirner, no material universe with natural laws actually exists. Stirner sees the world as populated solely by human egos, by human consciousnesses that want only to indulge themselves to the full. “I have built my thing on nothing”—that is one of Max Stirner's maxims. And on these grounds Stirner opposes even the notion of Providence. He says for example: certain moralists demand that we should not perform any deed out of egoism, but rather that we should perform it because it is pleasing to God. In acting, we should look to God, to that which pleases Him, that which He commands. Why, thinks Max Stirner, should I, who have built only upon the foundation of ego-consciousness, have to admit that God is after all the greater egoist Who can demand of man and the world that all should be performed as it suits Him? I will not surrender my own egoism for the sake of a greater egoism. I will do what pleases me. What do I care for a God when I have myself?

One thus becomes entangled and confused within a consciousness out of which one can no longer find the way. Yesterday I remarked how on the one hand we can arrive at clear ideas by awakening in the experience of ideas when we descend into our consciousness. These dreamlike ideas manifest themselves like drives from which we cannot then escape. One would say that Karl Marx achieved clear ideas—if anything his ideas are too clear. That was the secret of his success. Despite their complexity, Marx's ideas are so clear that, if properly garnished, they remain comprehensible to the widest circles. Here clarity has been the means to popularity. And until it realizes that within such a clarity humanity is lost, humanity, as long as it seeks logical consequences, will not let go of these clear ideas.

If one is inclined by temperament to the other extreme, to the pole of consciousness, one passes over onto Stirner's side of the scale. Then one despises this clarity: one feels that, applied to social thinking, this clarity makes man into a cog in a social order modeled on mathematics or mechanics—but into that only, into a mere cog. And if one does not feel oneself cut out for just that, then the will that is active in the depths of human consciousness revolts. Then one comes radically to oppose all clarity. One mocks all clarity, as Stirner did. One says to oneself: what do I care about anything else? What do I care even about nature? I shall project my own ego out of myself and see what happens. We shall see that the appearance of such extremes in the nineteenth century is in the highest degree characteristic of the whole of recent human evolution, for these extremes are the distant thunder that preceded the storm of social chaos we are now experiencing. One must understand this connection if one wants at all to speak about cognition today.

Yesterday we arrived at an indication of what happens when we begin to correlate our consciousness to an external natural world of the senses. Our consciousness awakens to clear concepts but loses itself. It loses itself to the extent that one can only posit empty concepts such as “matter,” concepts that then become enigmatic. Only by thus losing ourselves, however, can we achieve the clear conceptual thinking we need to become fully human. In a certain sense we must first lose ourselves in order to find ourselves again out of ourselves. Yet now the time has come when we should learn something from these phenomena. And what can one learn from these phenomena? One can learn that, although clarity of conceptual thinking and perspicuity of mental representation can be won by man in his interaction with the world of sense, this clarity of conceptual thinking becomes useless the moment we strive scientifically for something more than a mere empiricism. It becomes useless the moment we try to proceed toward the kind of phenomenalism that Goethe the scientist cultivated, the moment we want something more than natural science, namely Goetheanism.

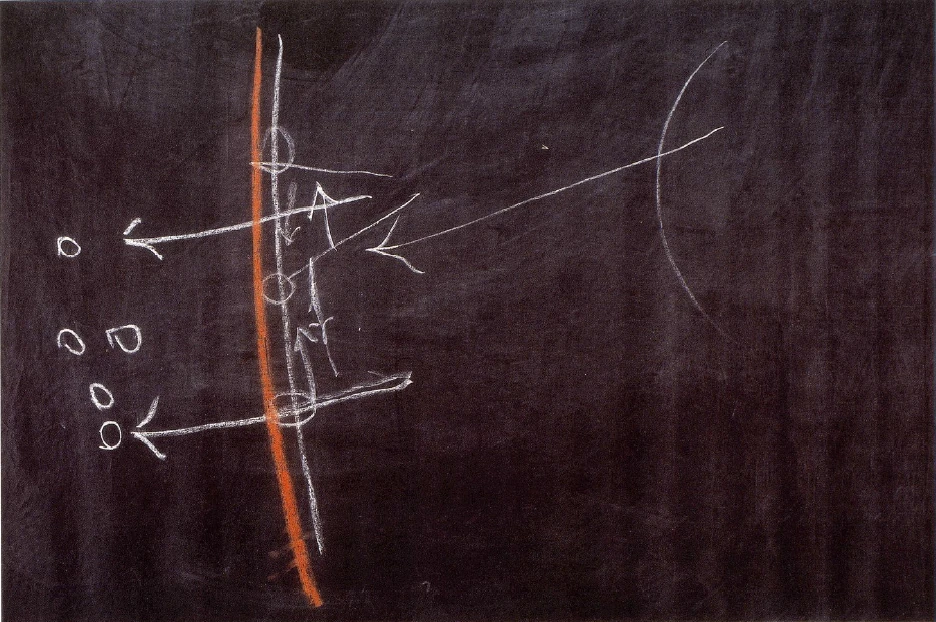

What does this imply? In establishing a correlation between our inner life and the external physical world of the senses we can use the concepts we form in interaction with nature in such a way that we try not to remain within the natural phenomena but to think on beyond them. We are doing this if we do more than simply say: within the spectrum there appears the color yellow next to the color green, and on the other side the blues. We are doing this if we do not simply interrelate the phenomena with the help of our concepts but seek instead, as it were, to pierce the veil of the senses and construct something more behind it with the aid of our concepts. We are doing this if we say: out of the clear concepts I have achieved I shall construct atoms, molecules—all the movements of matter that are supposed to ex-ist behind natural phenomena. Thereby something extraordinary happens. What happens is that when I as a human being confront the world of nature [see illustration], I use my concepts not only to create for myself a conceptual order within the realm of the senses but also to break through the boundary of sense and construct behind it atoms and the like I cannot bring my lucid thinking to a halt within the realm of the senses. I take my lesson from inert matter, which continues to roll on even when the propulsive force has ceased. My knowledge reaches the world of sense, and I remain inert. I have a certain inertia, and I roll with my concepts on beyond the realm of the senses to construct there a world the existence of which I can begin to doubt when I notice that my thinking has only been borne along by inertia.

It is interesting to note that a great proportion of the philosophy that does not remain within phenomena is actually nothing other than just such an inert rolling-on beyond what really exists within the world. One simply cannot come to a halt. One wants to think ever farther and farther beyond and construct atoms and molecules—under certain circumstances other things as well that philosophers have assembled there. No wonder, then, that this web one has woven in a world created by the inertia of thinking must eventually unravel itself again.

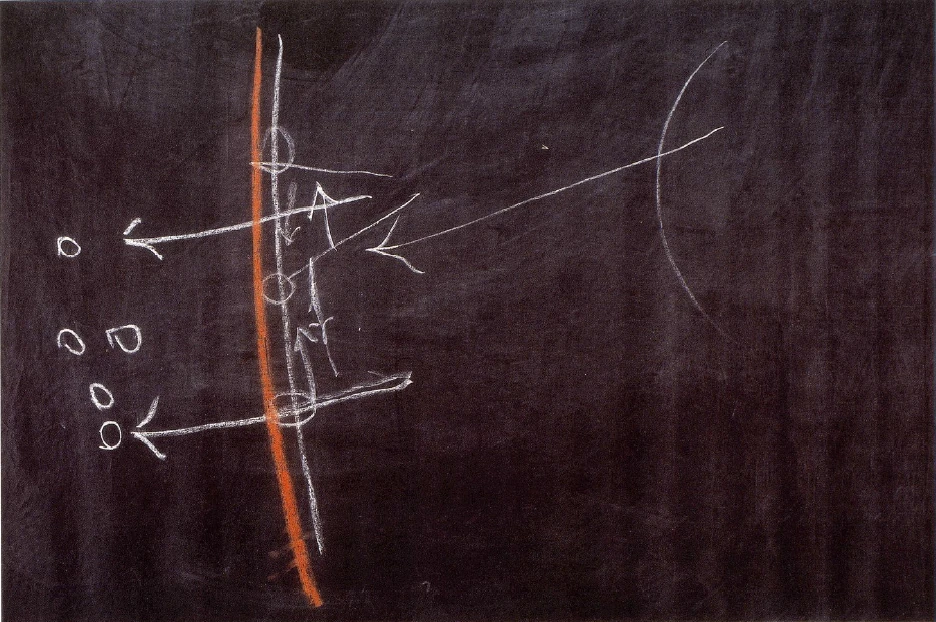

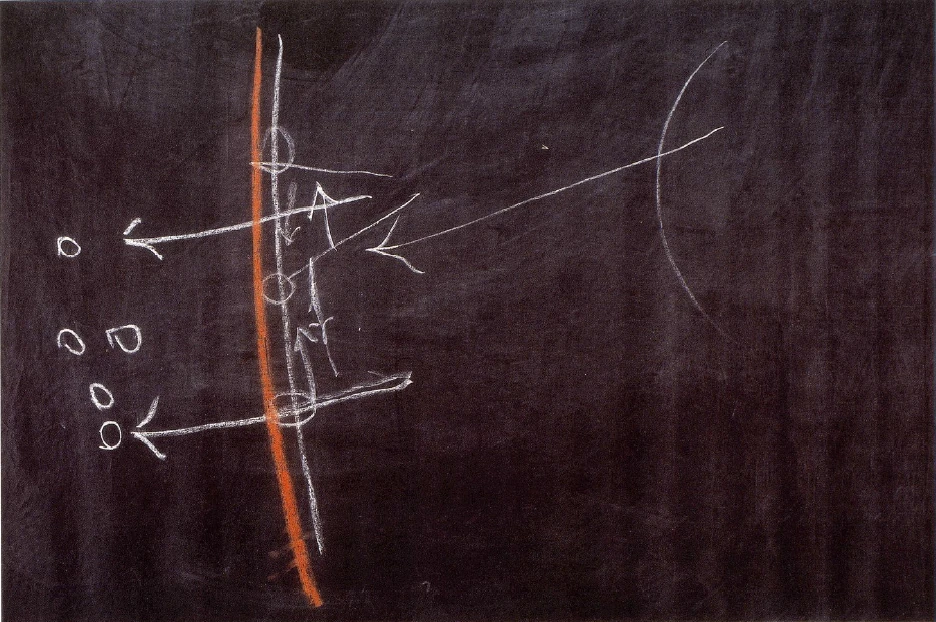

Goethe rebelled against this law of inertia. He did not want to roll onward thus with his thinking but rather to come strictly to a halt at this limit [see illustration: heavy line] and to apply concepts within the realm of the senses. He thus would say to himself: within the spectrum appear to me yellow, blue, red, indigo, violet. If, however, I permeate these appearances of color with my world of concepts while remaining within the phenomena, then the phenomena order themselves of their own accord, and the phenomenon of the spectrum teaches me that when the darker colors or anything dark is placed behind the lighter colors or anything light, there appear the colors which lie toward the blue end of the spectrum. And conversely, if I place light behind dark, there appear the colors which lie toward the red end of the spectrum.

What was it that Goethe was actually seeking to do? Goethe wanted to find simple phenomena within the complex but above all such phenomena as allowed him to remain within this limit [see illustration], by means of which he did not roll on into a realm that one reaches only through a certain mental inertia. Goethe wanted to adhere to a strict phenomenalism. If we remain within phenomena and if we strive with our thinking to come to a halt there rather than allow ourselves to be carried onward by inertia, the old question arises in a new way. What meaning does the phenomenal world have when I consider it thus? What is the meaning of the mechanics and mathematics, of the number, weight, measure, or temporal relation that I import into this world? What is the meaning of this?

You know, perhaps, that the modern world conception has sought to characterize the phenomena of tone, color, warmth, etc. as only subjective, whereas it characterizes the so-called primary qualities, the qualities of weight, space, and time, as something not subjective but objective and inherent in things. This conception can be traced back principally to the English philosopher, John Locke, and it has to a considerable extent determined the philosophical basis of modern scientific thought. But the real question is: what place within our systematic science of nature as a whole do mathematics, do mechanics—these webs we weave within ourselves, or so it seems at first—what place do these occupy? We shall have to return to this question to consider the specific form it takes in Kantianism. Yet without going into the whole history of this development one can nonetheless emphasize our instinctive conviction that measuring or counting or weighing external objects is essentially different from ascribing to them any other qualities.

It certainly cannot be denied that light, tones, colors, and sensations of taste are related to us differently from that which we could represent as subject to mathematical-mechanical laws. For it really is a remarkable fact,a fact worthy of our consideration: you know that honey tastes sweet, but to a man with jaundice it tastes bitter—so we can say that we stand in a curious relationship to the qualities within this realm—while on the other hand we could hardly maintain that any normal man would see a triangle as a triangle, but a man with jaundice would see it as a square! Certain differentiations thus do exist, and one must be cognizant of them; on the other hand, one must not draw absurd conclusions from them. And to this very day philosophical thinking has failed in the most extraordinary way to come to grips with this most fundamental epistemological question. We thus see how a contemporary philosopher, Koppelmann, overtrumps even Kant by saying, for example—you can read this on page 33 of his Philosophical Inquiries [Weltanschauungsfragen]: everything that relates to space and time we must first construct within by means of the understanding, whereas we are able to assimilate colors and tastes directly. We construct the icosahedron, the dodecahedron, etc.: we are able to construct the standard regular solids only because of the organization of our understanding. No wonder, then, claims Koppelmann, that we find in the world only those regular solids we can construct with our understanding. One thus can find Koppelmann saying almost literally that it is impossible for a geologist to come to a geometer with a crystal bounded by seven equilateral triangles precisely because—so Koppelmann claims—such a crystal would have a form that simply would not fit into our heads. That is out-Kanting Kant. And thus he would say that in the realm of the thing-in-itself crystals could exist that are bounded by seven regular triangles, but they cannot enter our head, and thus we pass them by; they do not exist for us.

Such thinkers forget but one thing: they forget—and it is just this that we want to indicate in the course of these lectures with all the forceful proofs we can muster—that the natural order governing the construction of our head also governs the construction of the regular polyhedrons, and it is for just this reason that our head constructs no other polyhedrons than those that actually confront us in the external world. For that, you see, is one of the basic differences between the so-called subjective qualities of tone, color, warmth, as well as the different qualities of touch, and that which confronts us in the mechanical-mathematical view of the world. That is the basic difference: tone and color leave us outside of ourselves; we must first take them in; we must first perceive them. As human beings we stand outside tone, color, warmth, etc. This is not entirely the case as regards warmth—I shall discuss that tomorrow—but to a certain extent this is true even of warmth. These qualities leave us initially outside ourselves, and we must perceive them. In formal, spatial, and temporal relationships and regarding weight this is not the case. We perceive objects in space but stand ourselves within the same space and the same lawfulness as the objects external to us. We stand within time just as do the external objects. Our physical existence begins and ends at a definite point in time. We stand within space and time in such a way that these things permeate us without our first perceiving them. The other things we must first perceive. Regarding weight, well, ladies and gentlemen, you will readily admit that this has little to do with perception, which is somewhat open to arbitrariness: otherwise many people who attain an undesired corpulence would be able to avoid this by perception alone, merely by having the faculty of perception. No, ladies and gentlemen, regarding weight we are bound up with the world entirely objectively, and the organization by means of which we stand within color, tone, warmth, etc. is powerless against that objectivity.

So now we must above all pose the question: how is it that we arrive at any mathematical-mechanical judgment? How do we arrive at a science of mathematics, at a science of mechanics? How is it, then, that this mathematics, this mechanics, is applicable to the external world of nature, and how is it that there is a difference between the mathematical-mechanical qualities of external objects and those that confront us as the so-called subjective qualities of sensation, tone, color, warmth, etc.?

At the one extreme, then, we are confronted with this fundamental question. Tomorrow we shall discuss another such question. Then we shall have two starting-points from which we can proceed to investigate the nature of science. Thence we shall proceed to the other extreme to investigate the formation of social judgments.

Zweiter Vortrag

Für alle diejenigen, welche von einem Vortragszyklus, der einen Titel trägt wie dieser, verlangen, daß gar nichts eingemischt werde, was gewissermaßen den objektiv-unpersönlichen Gang der Darstellung unterbricht, möchte ich, da ich heute vielfach gerade an Persönlichkeiten werde anzuknüpfen haben, bemerken, daß in dem Augenblicke, wo es sich darum handelt, die Ergebnisse menschlicher Urteilsbildung auch wirklich in ihrer Beziehung zum Leben, zum vollen menschlichen Dasein darzustellen, es unausbleiblich ist, daß man auf gewisse Persönlichkeiten hinweist, von denen eine solche Urteilsbildung ausgegangen ist, daß man sich überhaupt auch in der wissenschaftlichen Darstellung etwas an diejenige Region hält, wo das Urteil entsteht, an die Region des menschlichen Ringens, des menschlichen Strebens nach einem solchen Urteil. Und hier soll ja vor allen Dingen die Frage beantwortet werden: Was kann aus der wissenschaftlichen Urteilsbildung der neueren Zeit herausgeholt werden für das soziale, für das lebendige Denken, das die Ergebnisse des Denkens zu Impulsen des Lebens machen will? — Da muß man schon auch etwas darauf bedacht sein, daß der ganze Gang der Betrachtung, die man anstellt, herausgerissen sei aus der Studierstube und aus den Lehrsälen und gewissermaßen drinnensteht im lebendigen Entwickelungsgange der Menschheit.

Hinter dem, wovon ich gestern ausging als dem modernen Streben nach einer mechanistisch-mathematischen Weltanschauung und dem Auflösen dieser Weltanschauung, hinter dem, was dann so gipfelte in der berühmten Rede von 1872 des Physiologen Du Bois-Reymond über die Grenzen des Naturerkennens, hinter alldem steht aber noch Bedeutsameres; Bedeutsameres, das sich hereindrängt in unsere Beobachtung, wenn wir gerade sprechen wollen im lebendigen Sinne über die Grenzen des Naturerkennens.

Eine Gestalt von außerordentlicher philosophischer Größe sieht uns ja heute noch mit einer gewissen Lebendigkeit aus der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts heraus an, es ist Hegel. In Lehrsälen, in der philosophischen Literatur wird ja erst wiederum in den letzten Jahren Hegel mit etwas mehr Achtung genannt als unmittelbar vorher. Im letzten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts bekämpfte man wohl Hegel, namentlich bekämpften ihn Akademiker. Allein man wird wohl ganz wissenschaftlich nachweisen können, daß die in den achtziger Jahren des vorigen Jahrhunderts von Eduard von Hartmann ausgesprochene Behauptung, man könne beweisen, daß überhaupt in Deutschland nur zwei Universitätsdozenten Hegel gelesen haben, richtig ist. Man hat Hegel bekämpft, aber man hat ihn auf philosophischem Boden nicht gekannt. Aber man hat ihn in einer andern Weise gekannt, und in einer gewissen Art kennt man ihn heute noch. Hegel, so wie er beschlossen ist, oder besser gesagt, wie seine Weltanschauung beschlossen ist in der großen Anzahl der Bände, die als Hegels Werke in den Bibliotheken stehen, in dieser ihm ureigenen Gestalt kennen ihn allerdings wenige. Allein in gewissen Verwandlungsformen ist er, man könnte sagen, gerade der populärste Philosoph, den es jemals in der Welt gegeben hat. Wer heute, vielleicht aber noch besser wer vor einigen Jahrzehnten eine Proletarierversammlung mitmachte und hörte, was da diskutiert wurde, wer eine Wahrnehmung dafür hatte, woher die ganze Art der Gedankenbildung in einer solchen Proletarierversammlung kam, der wußte, wenn er wirkliche Erkenntnis der neueren Geistesgeschichte hatte, daß diese Gedankenbildung durchaus von Hegel ausgegangen ist und durch gewisse Kanäle in die breiteste Masse hineingeflossen ist. Und wer Philosophie und Literatur des europäischen Ostens gerade auf diese Frage hin untersuchen würde, der würde finden, daß in das Geistesleben Rußlands in breitestem Umfange die Gedankenformen der Hegelschen Weltanschauung voll eingewoben sind. Und so kann man sagen: Anonym gewissermaßen ist Hegel vielleicht einer der allerwirksamsten Philosophen der Menschheitsgeschichte in den letzten Jahrzehnten der neueren Zeit geworden. — Allein man möchte sagen, wenn man wiederum kennenlernt dasjenige, was da in den breitesten Schichten der neueren Menschheit als Hegeltum lebt, man werde erinnert an jenes Bild, das von einem etwas häßlichen Manne ein wohlwollender Maler gemalt hat, und es so gemalt hat, daß es die Familie gerne sah. Als dann ein jüngerer Sohn herangewachsen war, der vorher das Bild wenig betrachtet hatte, und es sah, da sagte er: Aber Vater, wie hast du dich verändert! - Man möchte sagen, wenn man sieht, was Hegel geworden ist: Aber mein Philosoph, wie hast du dich verändert! — Und es ist ja in der Tat etwas höchst Eigentümliches um diese Hegelsche Weltanschauung.

Kaum war Hegel selber hinweggegangen, so zerfiel seine Schule. Und man konnte sehen, wie diese Hegelsche Schule ganz die Gestalt eines neuen Parlamentes annahm. Es gab da eine Linke, eine Rechte, eine äußerste Rechte, eine äußerste Linke, einen radikalsten, einen konservativsten Flügel. Es gab ganz radikale Menschen mit einer radikalen wissenschaftlichen, mit einer radikalen sozialen Weltanschauung, die sich als die richtigen geistigen Abkömmlinge von Hegel fühlten. Es gab auf der andern Seite vollgläubige positive Theologen, die nun wiederum ihren theologischen Urkonservativismus auf Hegel zurückzuführen wußten. Es gab das Hegel-Zentrum mit dem liebenswürdigen Philosophen Karl Rosenkranz, und alle, alle diese Persönlichkeiten, sie behaupteten jeder für sich, sie hätten die richtige Hegelsche Lehre.

Was liegt denn da eigentlich für ein merkwürdiges weltgeschichtliches Phänomen aus dem Gebiete der Erkenntnisentwickelung vor? Das liegt vor, daß einmal ein Philosoph die Menschheit heraufzuheben versuchte auf die höchste Höhe des Gedankens. Wenn man auch noch so sehr Hegel wird bekämpfen wollen, daß er den Versuch einmal gewagt hat, in reinsten Gedankengebilden die Welt innerlich-seelisch gegenwärtig zu machen, das wird nicht geleugnet werden können. In eine Ätherhöhe des Denkens hob Hegel die Menschheit herauf. Aber kurioserweise, die Menschheit fiel gleich wieder herunter aus dieser ÄAtherhöhe des Denkens. Auf der einen Seite zog sie materialistische Konsequenzen, auf der andern Seite positive theologische Konsequenzen daraus. Und selbst wenn man das Hegelsche Zentrum mit Karl Rosenkranz nimmt, so kann man nicht sagen, daß die Hegelsche Lehre so geblieben ist in dem liebenswürdigen Rosenkranz, wie Hegel sie selber gedacht hat. Da also liegt der Versuch vor, einmal mit dem Wissenschaftsprinzip in höchste Höhen hinaufzusteigen. Aber man konnte sozusagen, indem man nachher Hegels Gedanken in sich selber verarbeitete, die entgegengesetztesten Urteile, die entgegengesetztesten Erkenntnisrichtungen daraus hervorgehen lassen.

Nun, streiten über Weltanschauungen läßt sich in der Studierstube, läßt sich innerhalb der Akademien, läßt sich zur Not auch in der Literatur, wenn nicht gerade an die literarischen Streitigkeiten sich wüste Klatscherei und wüstes Cliquenwesen anschließt. Aber mit dem, was in einer solchen Art aus der Hegelschen Philosophie geworden ist, läßt sich das Urteil nicht loslösen von Studierstuben und Lehrsälen und hinaustragen, so daß es Impuls werde für das soziale Leben. Man kann denkerisch streiten über entgegengesetzte Weltanschauungen, man kann aber nicht gut im äußeren Leben mit entgegengesetzten Lebensanschauungen friedlich sich bekämpfen. Diesen letzten paradoxen Ausdruck müßte man geradezu gebrauchen für ein solches Phänomen. Und so steht, ich möchte sagen, in der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts beängstigend vor uns ein Entwickelungsfaktor des Erkennens, der sich in hohem Grade sozial unbrauchbar erwiesen hat. Und auch demgegenüber müßten wir dann die Frage aufwerfen: Wie kommen wir denn dazu, unser Urteil so zu bilden, daß es brauchbar werde im sozialen Leben? Insbesondere an zwei Erscheinungen können wir diese soziale Unbrauchbarkeit des Hegeltums für das soziale Leben bemerken.

Einer derjenigen, die innerlich am energischsten Hegel studiert haben, die Hegel ganz in sich lebendig gemacht haben, ist Karl Marx. Und was tritt uns in Karl Marx entgegen? Ein merkwürdiges Hegeltum! Hegel auf dem höchsten Gipfel des Ideenbildes droben, auf dem äußersten Gipfel des Idealismus — der treue Schüler Karl Marx das Bild sogleich ins Gegenteil wendend, mit derselben Methode, wie er glaubt, indem er gerade dasjenige, was in Hegel die Wahrheit ist, herauszubilden glaubte, und es wird daraus der historische Materialismus, jener Materialismus, der für breite Massen diejenige Weltanschauung oder Lebensauffassung sein soll, die sich nun wirklich hineintragen lassen soll in das soziale Leben. So begegnet uns in der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts der große Idealist, der nur im Geistigen, in seinen Ideen lebte, Hegel; so begegnet uns in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts sein Schüler Karl Marx, der nur im Materiellen drinnen forschte, der nur im Materiellen drinnen eine Wirklichkeit sehen wollte, der in alledem, was in idealen Höhen lebte, nur Ideologie sah. Man sollte nur einmal durchempfinden diesen Umschlag der Welt- und Lebensauffassungen im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts, und man wird die ganze Stärke desjenigen in sich fühlen, was heute dazu treibt, eine solche Naturerkenntnis zu gewinnen, die, wenn wir sie haben, in uns ein Urteil loslöst, das sozial lebensfähig ist.

Nun, sehen wir nach einer andern Seite hin, nach etwas, was zwar nicht so sehr betont hat, daß es aus Hegel stammt, was aber nichtsdestoweniger historisch ganz gut auf Hegel zurückgeführt werden kann, so finden wir den Ich-Philosophen noch aus der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, aber herüberragend in die zweite Hälfte, wir finden Max Stirner. Während Karl Marx den einen Pol des menschlichen Anschauens, auf den wir gestern hingewiesen haben, die Materie zur Grundlage seiner Betrachtung macht, geht Stirner, der Ich-Philosoph Max Stirner, aus von dem andern Pole, von dem Bewußtseinspol. Und gerade deshalb, weil die neuere Weltanschauung, indem sie nach dem materiellen Pol hinzielt, das Bewußtsein nicht aus ihm heraus finden kann, wie wir gestern an dem Beispiel Du Bois-Reymonds gesehen haben, so wird auf der andern Seite die Folge sein, daß eine Persönlichkeit, die sich nun ganz nur auf das Bewußtsein stellt, die materielle Welt nicht finden kann. Und so ist es bei Max Stirner. Für Max Stirner gibt es im Grunde genommen kein materielles Weltall mit Naturgesetzen. Für Max Stirner gibt es nur eine Welt, die einzig und allein bevölkert ist von menschlichen Ichen, von menschlichen Bewußtseinen, die ganz und gar nur sich ausleben wollen. «Ich hab’ mein Sach’ auf nichts gestellt», das ist so eine der Losungen Max Stirners. Und von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus lehnt sich Max Stirner selbst gegen eine göttliche Weltenführung auf. Er sagt zum Beispiel: Da fordern gewisse Ethiker, gewisse Sittenlehrer, wir sollen nicht aus Selbstsucht irgendeine Tat begehen, sondern wir sollen sie begehen, weil sie Gott gefällt; wir sollen auf Gott hinschauen, indem wir eine Tat begehen, auf das, was ihm gefällt, was er anordnet, was ihm sympathisch ist. Warum sollte ich das —- meint Max Stirner -, der ich meine Sache lediglich auf die Spitze des Ich-Bewußtseins stellen will, warum sollte ich zugeben, daß Gott nun der große Egoist sei, der verlangen kann von der Welt, der Menschheit, daß alles so gemacht werde, wie es ihm gefällt! Ich will nicht um des großen Egoismus willen meinen persönlichen Egoismus aufgeben. Ich will die Dinge tun, die mir gefallen. Was geht mich ein Gott an, wenn ich nur mich habe.

Das ist das Sich-Verwickeln, Sich-Verwirren in das Bewußtsein, das dann nicht mehr aus sich herauskann. Ich habe gestern darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie wir auf der einen Seite zu klaren Ideen kommen können, indem wir erwachen an dem äußeren physisch-sinnlichen Dasein, wie wir aber, wenn wir wiederum dann hinuntersteigen in unser Bewußtsein, zu traumhaften Ideen kommen, die sich wie triebartig in die Welt hineinstellen und aus denen wir nicht wieder herauskommen. Zu klaren Ideen, man möchte sagen, zu überklaren Ideen ist schon Karl Marx gekommen. Und das war das Geheimnis seines Erfolges. Die Ideen von Marx sind so klar, daß, trotzdem sie kompliziert sind, sie eben für die weitesten Kreise, wenn sie recht zugerichtet werden, verständlich sind. Da hat die Klarheit zur Popularität verholfen. Und solange nicht bemerkt wird, daß eben innerhalb einer solchen Klarheit die Menschheit verloren ist, so lange wird man sich, wenn man konsequent sein will, eben an diese Klarheit halten.

Neigt man aber seiner ganzen Anlage nach zu dem andern Pol, zu dem Bewußtseinspol, ja dann, dann geht man mehr nach der Stirnerschen Seite hinüber. Dann verachtet man diese Klarheit, dann fühlt man, daß, sozial angewendet, diese Klarheit den Menschen zwar zu einem klaren Rade in der mathematisch-mechanisch gedachten sozialen Ordnung macht, aber eben zu einem Rad. Ist man dann nicht dazu veranlagt, dann revoltiert der Wille, dann revoltiert dieser Wille, der auf dem untersten Grunde des menschlichen Bewußtseins tätig ist. Und dann lehnt man sich auf gegen alle Klarheit. Dann spottet man, wie Stirner gespottet hat, aller Klarheit. Dann sagt man: Was geht mich irgend etwas anderes an, was geht mich selbst die Natur an, ich stelle mein Ich aus mir heraus und sehe, was daraus wird. - Wir werden noch sehen, wie es im höchsten Grade charakteristisch ist für die ganze neuere Menschheitsentwickelung, daß solche Extreme, solche scharf ausgesprochenen Extreme gerade im 19. Jahrhundert aufgetreten sind, denn sie sind das Wetterleuchten desjenigen, was wir jetzt als soziales Chaos erleben, als Gewitter. Diesen Zusammenhang, den muß man verstehen, wenn man heute überhaupt über Erkenntnis reden will.

Wir sind gestern dazu gekommen, hinzuweisen auf der einen Seite auf das, was der Mensch vollzieht, indem er sich in Wechselbeziehung versetzt mit der natürlich-sinnlichen Außenwelt. Sein Bewußtsein erwacht zu klaren Begriffen, aber es verliert sich selbst, es verliert sich so selbst, daß der Mensch nur inhaltlich leere Begriffe, wie den Begriff der Materie hinpfahlen kann, Begriffe, vor denen er dann so steht, daß sie ihm zum Rätsel werden. Aber wir kommen eben nicht anders, als indem wir uns so selbst verlieren, zu solchen klaren Begriffen, die wir brauchen zur Entwickelung unseres vollen Menschentums. Wir müssen uns eben in einer gewissen Weise zunächst verlieren, damit wir uns wieder finden können durch uns selbst. Aber heute ist die Zeit gekommen, wo man an diesen Phänomenen etwas lernen soll. Und was kann man an diesen Phänomenen lernen? Man kann dasjenige lernen, daß zwar die ganze Klarheit der Begriffe, die ganze Durchsichtigkeit des Vorstellungslebens an dem Verkehr mit der äußeren sinnlich-natürlichen Welt für den Menschen gewonnen werden kann, daß aber in dem Augenblicke diese Klarheit der Begriffe unbrauchbar wird, wenn wir mehr erhalten wollen in der Naturwissenschaft als einen bloßen Phänomenalismus, nämlich jenen Phänomenalismus, den Goethe als Naturforscher pflegen wollte, wenn wir mehr wollen als Naturwissenschaft, nämlich den Goetheanismus.

Was heißt das? Nun, wenn wir an den Wechselverkehr zwischen unserem Inneren und der Außenwelt, der sinnlich-physischen Außenwelt herankommen, dann können wir unsere Begriffe, die wir uns heranbilden an der Natur, noch gebrauchen, um nicht in der erscheinenden Natur stehenzubleiben, sondern noch hinter diese erscheinende Natur dahinter zu denken. Das tun wir, wenn wir nicht bloß sagen, im Spektrum erscheint neben der gelben Farbe die grüne Farbe und auf der andern Seite beginnt das Bläuliche, wenn wir nicht bloß die Phänomene, die Erscheinungen aneinandergliedern mit Hilfe des Mittels unserer Begriffe, sondern wenn wir diesen Sinnesteppich gleichsam mit unseren Begriffen durchstechen wollen und hinter ihm durch unsere Begriffe noch etwas konstruieren wollen. Das tun wir, wenn wir sagen: Ich bilde mir aus den klar gewonnenen Begriffen heraus Atome, Moleküle, dasjenige, was hinter den Erscheinungen der Natur sein soll, Bewegungen innerhalb der Materie. Da geschieht nämlich etwas Merkwürdiges. Da geschieht das, daß wenn ich hier als Mensch bin (siehe Zeichnung), den Sinneserscheinungen gegenüberstehe, ich meine Begriffe nicht allein dazu gebrauche, um für mich eine Erkenntnisordnung in dieser Sinneswelt zu begründen, sondern ich durchstoße die Grenze der Sinneswelt und konstruiere dahinter Atome und dergleichen. Ich kann gewissermaßen nicht stillstehen mit meinen klaren Begriffen bei der Sinneswelt. Ich bin gewissermaßen ein Schüler der trägen Materie, die immer noch fortrollt, wenn sie an einem Orte angekommen ist, auch wenn die Kraft des Fortrollens schon nachgelassen hat. Meine Erkenntnis kommt bis an die Sinneswelt heran, und ich bin träge, ich habe ein gewisses Beharrungsvermögen, ich rolle mit meinen Begriffen hinter die Sinneswelt noch hinunter und konstruiere mir da eine Welt, an der ich dann wiederum zweifle, wenn ich merke, daß ich nur meiner Trägheit gefolgt bin mit meinem ganzen Denken.

Es ist interessant, daß ein großer Teil der Philosophie, die sich ja nicht im Sinnlichen bewegt, im Grunde genommen auch nichts anderes ist als ein solches Fortrollen in der Trägheit hinter dasjenige, was eigentlich in der Welt wirklich vorliegt. Man kann nicht stillestehen. Man will noch hinten weiter, weiter, weiter denken und konstruiert Atome und Moleküle, konstruiert unter Umständen auch manches andere, was die Philosophen dahinter konstruiert haben. Kein Wunder, daß man dieses Selbstgespinst, das man aus Beharrungsvermögen in der Welt aufgerichtet hat, dann wiederum auflösen muß.

Gegen dieses Trägheitsgesetz lehnte sich Goethe auf. Er wollte ein solches Fortrollen des Denkens nicht, er wollte stehenbleiben, streng stehenbleiben an dieser Grenze (siehe Zeichnung: dicker Strich), und er wollte innerhalb der Sinneswelt die Begriffe anwenden. So daß er sich sagte: Im Spektrum erscheint mir Gelb, im Spektrum erscheint mir Blau, Rot, Indigo, Violett. Wenn ich aber diese verschiedenen Farbenerscheinungen mit meiner Begriffswelt durchdringe und innerhalb der Phänomene bleibe, so stellen sich mir die Phänomene, die Erscheinungen selbst zusammen, und ich bekomme aus der Tatsache des Spektrums heraus: Wenn sich dunklere Farben oder überhaupt Dunkelheit hinter hellere Farben oder überhaupt hinter die Helligkeit stellen, so bekomme ich dasjenige, was gegen das Blau des Spektrums zu liegt. Umgekehrt: Wenn ich das Helle hinter das Dunkle stelle, bekomme ich, was gegen das Rot des Spektrums zu liegt.

Was wollte Goethe eigentlich? Goethe wollte aus den komplizierten Phänomenen einfache heraussuchen, aber durchaus solche, mit denen er innerhalb dieser Grenze (siehe Zeichnung) stehenblieb, durch die er nicht hineinrollte in ein Gebiet, in das man nur durch träges Fortrollen, durch ein gewisses geistiges Beharrungsvermögen hineinkommt. So wollte Goethe innerhalb des Phänomenalismus stehenbleiben. Wenn man so innerhalb des Phänomenalismus stehenbleibt, und wenn man sein ganzes Denken daraufhin einrichtet, so stehenzubleiben, nicht dem Beharrungsvermögen, das ich charakterisiert habe, zu folgen, dann tritt in einer neuen Weise die alte Frage auf: Welche Bedeutung hat nun in dieser Welt, die ich so phänomenal betrachte, dasjenige, was ich aus Mechanik und Mathematik hineinbringe, was ich hineinbringe an Zahl, an Maß, an Gewicht oder an Zeitverhältnissen? Was hat denn das für eine Bedeutung?

Sie wissen ja vielleicht, daß eine neuere Auffassung dahin ging, dasjenige, was zunächst in den Phänomenen des Tones, der Farbe, der Wärme und so weiter lebt, das gewissermaßen nur subjektiv anzuschauen, dagegen die sogenannten primären Qualitäten der Dinge, das Räumliche, das Zeitliche, das Gewicht, als etwas nicht Subjektives, sondern Objektives, den Dingen Inhärierendes anzuschauen. Diese Anschauung, sie geht im wesentlichen auf den englischen Philosophen Locke zurück, und sie beherrscht bis zu einem hohen Grade auch die philosophischen Grundlagen des modernen naturwissenschaftlichen Denkens. Aber im Grunde genommen ist die Frage: Welche Stellung nimmt in unserem ganzen Wissenschaftssystem der äußeren Natur gegenüber die Mathematik, nimmt die Mechanik, die wir ja eigentlich aus uns selber herausspinnen - so sieht sich die Sache wenigstens zunächst an -, welche Stellung nehmen sie ein? Wir werden noch auf diese Frage zurückkommen müssen, indem wir die besondere Gestaltung, die diese Frage durch den Kantianismus angenommen hat, werden ins Auge fassen müssen. Aber ohne daß wir auf Historisches unmittelbar dabei eingehen, können wir doch betonen, daß wir ja instinktiv überzeugt davon sind, wenn wir die Dinge messen oder zählen, oder wenn wir ihr Gewicht bestimmen, daß wir dann etwas wesentlich anderes von der Außenwelt statuieren, als wenn wir die andern Qualitäten der Außenwelt den Dingen zuschreiben.

Es läßt sich ja doch nicht leugnen, daß Licht, Farben, Töne, Geschmacksempfindungen in einer andern Beziehung zu uns stehen als dasjenige, was wir in der Außenwelt so darstellen können, daß es den mathematisch-mechanischen Gesetzen unterliegt. Denn es ist doch immerhin eine bemerkenswerte Tatsache, die schon ins Auge gefaßt werden muß, daß — Sie wissen, Honig schmeckt süß, aber wenn einer gelbsüchtig ist, schmeckt er für ihn bitter —, so daß wir also sagen können, wir stehen schon in einer merkwürdigen Weise gegenüber diesen Qualitäten der Welt in dieser Welt darinnen, während wir nicht gut sagen können, daß irgendwie ein normaler Mensch ein Dreieck für ein Dreieck ansieht und ein Gelbsüchtiger es etwa für ein Viereck ansehen würde! Also Unterscheidungen sind schon da, und an diesen Unterscheidungen muß gelernt werden, aber es müssen nicht absurde Folgerungen daraus gezogen werden. Und in einer merkwürdig ungeklärten Weise steht bis zum heutigen Tage philosophisches Denken diesen Fundamentaltatsachen aller Erkenntnisentwickelung gegenüber. Da gewahren wir zum Beispiel, wie ein neuerer Philosoph, der Professor Koppelmann, in seinen «Weltanschauungsfragen» den Kant noch überkantet, indem er zum Beispiel sagt — Sie können das auf Seite 33 von Koppelmanns «Weltanschauungsfragen» lesen —: Alles dasjenige, was sich auf den Raum und die Zeit bezieht, wir müssen es innerlich erst mit dem Verstand konstruieren, während wir Farben und Geschmäcke unmittelbar in uns aufnehmen. Wir konstruieren das Tetraeder, das Oktaeder, das Dodekaeder und so weiter, wir können nur vermöge unserer Verstandeseinrichtung die gewöhnlichen regulären Körper konstruieren. Was Wunder — meint Koppelmann -, daß uns in der Welt nur diejenigen regulären Körper entgegentreten können, die wir durch unseren Verstand konstruieren können. — Und so finden Sie fast wörtlich bei Koppelmann den Satz: Es ist ausgeschlossen, daß einmal ein Geologe kommt und einen Kristall dem Geometer gibt, welcher von sieben gleichseitigen Dreiecken begrenzt ist, einfach aus dem Grunde — meint Koppelmann -, weil ein solcher Kristall eine Gestalt hätte, die in unseren Kopf nicht hineinginge. — Das ist «überkanten» des Kantianismus. Und da würde man sagen können, in der Welt des Dinges an sich könnten also unter Umständen allerdings solche Kristalle eventuell existieren, die von sieben regulären Dreiecken begrenzt wären, aber in unseren Kopf gehen sie nicht herein, daher gehen wir an ihnen vorbei, sie sind für uns nicht da.

Solche Denker vergessen nur das eine, sie vergessen — und das ist es, worauf wir scharf mit aller Beweiskraft im Verlaufe dieser Vorträge hinweisen wollen -, sie vergessen, daß unser Kopf aus denselben Gesetzmäßigkeiten des äußeren Daseins heraus konstruiert ist, aus denen wir die regulären Polyeder und so weiter konstruieren, und daß unser Kopf daher aus dieser seiner Konstruktion heraus keine andern Polyeder konstruiert als diejenigen, die draußen auch vorkommen. Denn, sehen Sie, das ist einer der Grundunterschiede zwischen den sogenannten subjektiven Qualitäten Ton, Farbe, Wärme, auch den verschiedenen Qualitäten des Tastsinnes und so weiter, und demjenigen, was uns in dem mechanisch-mathematischen Weltbilde entgegentritt. Das ist der Grundunterschied: Ton, Farbe, sie lassen uns selbst außer uns; wir müssen sie erst aufnehmen, wir müssen sie erst wahrnehmen. Wir stehen als Menschen außer Ton, Farbe, Wärme und so weiter. Mit der Wärme ist es nicht ganz so, das werde ich morgen zu besprechen haben, aber in einem gewissen Grade ist es auch mit der Wärme so. Sie lassen uns zunächst außer uns, und wir müssen sie wahrnehmen. Das ist bei Gestalt-, bei Raumverhältnissen, bei Zeitverhältnissen, bei Gewichtsverhältnissen nicht der Fall. Wir nehmen die Dinge räumlich wahr, aber wir sind selbst in demselben Raume und in die gleiche Gesetzmäßigkeit hineingestellt, in der die Dinge außer uns stehen. Wir stehen in der Zeit drinnen wie die äußeren Dinge. Wir beginnen unser physisches Leben in einem gewissen Zeitpunkte, enden es in einem Zeitpunkte. In Raum und Zeit stehen wir so drinnen, daß diese Dinge gleichsam durch uns hindurchgehen, ohne daß wir sie erst wahrnehmen. Die andern Dinge müssen wir erst wahrnehmen. Bezüglich des Gewichtes, nun ja, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, da werden Sie auch zugeben, daß das mit der Wahrnehmung, die ja ein wenig der Willkür unterliegt, nicht viel zu tun hat, denn sonst würde mancher, der durch seine Beleibtheit zu einem ihm unerwünschten Gewichte kommt, dieses vermeiden durch die bloße Erkenntnis, durch das bloße Wahrnehmungsvermögen. Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, auch in unseren Gewichtsverhältnissen werden wir schon ganz objektiv von der Welt aufgenommen, ohne daß wir durch dieselbe Organisation etwas dagegen machen können, durch die wir uns verbinden mit Farbe, Ton, Wärme und so weiter.

Und so müssen wir vor allen Dingen heute die Frage vor uns hinstellen: Wie kommt das mathematisch-mechanische Urteil überhaupt an uns heran? Wie kommen wir zu einer Mathematik, zu einer Mechanik, und wie kommt es, daß diese Mathematik und diese Mechanik anwendbar ist auf die äußere Natur, und wie kommt es, daß ein Unterschied ist zwischen den mathematisch-mechanischen Qualitäten der Dinge der Außenwelt und zwischen dem, was uns als die sogenannten Sinnesqualitäten sogenannter subjektiver Natur entgegentritt, Ton, Farbe, Wärmequalitäten und so weiter?

Nun, diese Kardinalfrage, sie steht an dem einen Ende. Eine andere werden wir morgen noch entdecken. Dann werden wir die zwei Ausgangspunkte des Wissenschaftlichen haben. Wir werden uns dann weiterbewegen und an dem andern Ende die Bildung des sozialen Urteils finden.

Second Lecture

For all those who expect a lecture series with a title such as this to be free of anything that might interrupt the objective, impersonal flow of the presentation, I would like to point out that, since I will be referring to many individuals today, it is inevitable that I will have to refer to certain personalities in order to presenting the results of human judgment in their relationship to life, to the fullness of human existence, it is inevitable that one must refer to certain personalities from whom such judgment originated, that one must, even in scientific presentation, remain somewhat within the realm where judgment arises, the realm of human struggle, of human striving for such judgment. And here, above all, the question must be answered: What can be gained from the scientific judgment of modern times for social, for living thinking, which wants to turn the results of thinking into impulses for life? — One must also be mindful that the entire course of consideration must be torn out of the study and the lecture halls and, in a sense, placed within the living process of human development.

Behind what I started with yesterday as the modern striving for a mechanistic-mathematical worldview and the dissolution of this worldview, behind what then culminated in the famous speech of 1872 by the physiologist Du Bois-Reymond on the limits of natural knowledge, behind all this stands something even more significant; something more significant that intrudes into our observation when we want to speak in a living sense about the limits of knowledge of nature. A figure of extraordinary philosophical greatness still looks down on us today with a certain vitality from the first half of the 19th century: Hegel. In lecture halls and in philosophical literature, Hegel has only been mentioned with a little more respect in recent years than immediately before. In the last third of the 19th century, Hegel was fought against, especially by academics. However, it can be scientifically proven that the claim made by Eduard von Hartmann in the 1880s that only two university lecturers in Germany had read Hegel is correct. Hegel was fought against, but he was not known on philosophical grounds. However, he was known in another way, and in a certain sense he is still known today. Hegel, as he is defined, or rather, as his worldview is defined in the large number of volumes that stand in libraries as Hegel's works, is indeed known to few in his true form. But in certain transformed forms, he is, one might say, precisely the most popular philosopher who has ever lived. Who today, perhaps even better, who attended a proletarian assembly a few decades ago and heard what was being discussed, who had a sense of where the whole way of thinking in such a proletarian assembly came from, knew, if they had a real understanding of recent intellectual history, that this way of thinking originated entirely with Hegel and flowed through certain channels into the broadest masses. And anyone who would examine the philosophy and literature of Eastern Europe with this question in mind would find that the thought forms of Hegel's worldview are fully woven into the intellectual life of Russia in the broadest sense. And so one can say: Anonymous, in a sense, Hegel has perhaps become one of the most influential philosophers in human history in the last decades of modern times. But one might say that when one becomes acquainted with what lives as Hegelianism in the broadest strata of modern humanity, one is reminded of a picture painted by a benevolent artist of a rather ugly man, painted in such a way that the family liked it. When a younger son, who had previously paid little attention to the picture, grew up and saw it, he said: But father, how you have changed! One is tempted to say, when one sees what Hegel has become: But my philosopher, how you have changed! And there is indeed something highly peculiar about this Hegelian worldview.No sooner had Hegel himself passed away than his school fell apart. And one could see how this Hegelian school took on the form of a new parliament. There was a left wing, a right wing, an extreme right wing, an extreme left wing, a most radical wing, and a most conservative wing. There were very radical people with a radical scientific and radical social worldview who felt themselves to be the true intellectual descendants of Hegel. On the other side, there were devout positive theologians who, in turn, traced their theological ultra-conservatism back to Hegel. There was the Hegel Center with the amiable philosopher Karl Rosenkranz, and all, all of these personalities claimed for themselves that they had the correct Hegelian doctrine.

What is this strange phenomenon in world history in the field of the development of knowledge? It is that a philosopher once attempted to raise humanity to the highest heights of thought. No matter how much one may wish to attack Hegel for having dared to attempt to make the world inwardly and spiritually present in the purest forms of thought, this cannot be denied. Hegel raised humanity to an ethereal height of thought. But curiously, humanity immediately fell back down from this etherial height of thought. On the one hand, it drew materialistic conclusions from this, and on the other hand, positive theological conclusions. And even if one takes Karl Rosenkranz as the center of Hegel's thought, one cannot say that Hegel's teaching remained in the amiable Rosenkranz as Hegel himself had conceived it. So there we have the attempt to ascend to the highest heights with the principle of science. But by subsequently processing Hegel's thoughts within oneself, one could, so to speak, arrive at the most contradictory judgments and the most contradictory directions of knowledge.

Now, one can argue about worldviews in the study, one can argue within the academies, one can even argue in literature if necessary, provided that literary disputes are not accompanied by vicious gossip and clique formation. But with what has become of Hegel's philosophy in this way, it is impossible to detach the judgment from the study and the lecture hall and carry it out into the world so that it becomes an impulse for social life. One can argue intellectually about opposing worldviews, but one cannot fight peacefully in external life with opposing views of life. This last paradoxical expression is precisely what one would have to use for such a phenomenon. And so, I would say, in the first half of the 19th century, we are faced with a frightening factor in the development of knowledge that has proved to be highly socially useless. And in response to this, we must then ask the question: How do we come to form our judgment in such a way that it becomes useful in social life? We can see this social uselessness of Hegelianism for social life in two phenomena in particular.

One of those who studied Hegel most energetically, who brought Hegel to life within himself, was Karl Marx. And what do we encounter in Karl Marx? A strange Hegelianism! Hegel at the highest peak of the realm of ideas, at the extreme summit of idealism—his faithful disciple Karl Marx immediately turning the picture upside down, using the same method he believes in, by trying to develop precisely what he believes to be the truth in Hegel, and turning it into historical materialism, that materialism which is supposed to be the worldview or conception of life for the broad masses, which is now really supposed to be carried over into social life. Thus, in the first half of the 19th century, we encounter the great idealist Hegel, who lived only in the spiritual realm, in his ideas; and in the second half of the 19th century, we encounter his disciple Karl Marx, who researched only in the material realm, who wanted to see reality only in the material realm, who saw only ideology in everything that lived in ideal heights. One need only feel this reversal of worldviews and attitudes toward life in the course of the 19th century to sense the full force of what is driving us today to gain such an understanding of nature that, once we have it, it will release in us a judgment that is socially viable.

Now, let us look at another side, at something that, although not so strongly emphasized as coming from Hegel, can nevertheless be traced back to Hegel quite well historically. We find the ego philosopher still in the first half of the 19th century, but towering over the second half, we find Max Stirner. While Karl Marx makes matter the basis of his consideration, which is one pole of human perception that we pointed out yesterday, Stirner, the ego philosopher Max Stirner, starts from the other pole, the pole of consciousness. And precisely because the newer worldview, in aiming at the material pole, cannot find consciousness out of it, as we saw yesterday in the example of Du Bois-Reymond, the consequence will be, on the other hand, that a personality that now places itself entirely on consciousness cannot find the material world. And so it is with Max Stirner. For Max Stirner, there is basically no material universe with natural laws. For Max Stirner, there is only one world, populated solely by human egos, by human consciousnesses that want nothing more than to live themselves out. “I have staked nothing on anything” is one of Max Stirner's slogans. And from this point of view, Max Stirner himself rebels against divine world governance. He says, for example: Certain ethicists, certain moralists, demand that we should not commit any act out of selfishness, but that we should commit it because it pleases God; we should look to God when we commit an act, to what pleases him, what he commands, what is sympathetic to him. Why should I—says Max Stirner—who wants to place my cause solely on the tip of my ego consciousness, why should I admit that God is now the great egoist who can demand of the world, of humanity, that everything be done as he pleases! I do not want to give up my personal egoism for the sake of great egoism. I want to do the things that please me. What does God have to do with me when I have only myself?

This is the entanglement, the confusion in consciousness, which then can no longer escape from itself. Yesterday I pointed out how, on the one hand, we can arrive at clear ideas by awakening to external physical and sensory existence, but how, when we descend again into our consciousness, we arrive at dreamlike ideas that impose themselves on the world like impulses and from which we cannot escape. Karl Marx already arrived at clear ideas, one might say overly clear ideas. And that was the secret of his success. Marx's ideas are so clear that, despite their complexity, they are understandable to the widest circles when properly presented. Clarity has helped them to become popular. And as long as it is not noticed that humanity is lost within such clarity, then, if one wants to be consistent, one will adhere to this clarity.

But if one's whole disposition tends toward the other pole, toward the pole of consciousness, then one leans more toward Stirner's side. Then one despises this clarity, then one feels that, when applied socially, this clarity does indeed make man a clear cog in the mathematically and mechanically conceived social order, but only a cog. If one is not predisposed to this, then the will revolts, then this will, which is active at the lowest level of human consciousness, revolts. And then one rebels against all clarity. Then one mocks, as Stirner mocked, all clarity. Then one says: What does anything else matter to me, what does nature itself matter to me, I put my ego outside myself and see what becomes of it. We will see how it is highly characteristic of the whole of recent human development that such extremes, such sharply pronounced extremes, have arisen precisely in the 19th century, for they are the lightning flashes of what we are now experiencing as social chaos, as a storm. This connection must be understood if one wants to talk about knowledge at all today.

Yesterday we came to point out, on the one hand, what human beings accomplish by placing themselves in a relationship of interaction with the natural-sensory external world. His consciousness awakens to clear concepts, but it loses itself, it loses itself so much that man can only come up with concepts that are empty of content, such as the concept of matter, concepts that then stand before him as riddles. But we have no choice but to lose ourselves in this way in order to arrive at the clear concepts we need for the development of our full humanity. We must first lose ourselves in a certain way so that we can find ourselves again through ourselves. But today the time has come when we must learn something from these phenomena. And what can we learn from these phenomena? We can learn that, although the whole clarity of concepts, the whole transparency of the life of ideas, can be gained for human beings through contact with the external, sensory, natural world, this clarity of concepts becomes useless the moment we want to obtain more from natural science than mere phenomenalism, namely that phenomenalism which Goethe wanted to cultivate as a natural scientist, when we want more than natural science, namely Goetheanism.What does that mean? Well, when we approach the interaction between our inner world and the outer world, the sensory-physical outer world, we can still use the concepts we form from nature in order not to remain stuck in apparent nature, but to think beyond this apparent nature. We do this when we do not merely say that the color green appears next to the color yellow in the spectrum and that the color blue begins on the other side, when we do not merely link phenomena, appearances, with the help of our concepts, but when we want to pierce this sensory tapestry, as it were, with our concepts and construct something behind it with our concepts. We do this when we say: I form atoms, molecules, that which is supposed to be behind the phenomena of nature, movements within matter, out of clearly gained concepts. Something strange happens here. What happens is that when I am here as a human being (see drawing), facing sensory phenomena, I do not use my concepts solely to establish an order of knowledge for myself in this sensory world, but I pierce the boundary of the sensory world and construct atoms and the like behind it. In a sense, I cannot stand still with my clear concepts in the sensory world. I am, in a sense, a student of inert matter, which continues to roll along even when it has arrived at a place, even if the force of rolling has already subsided. My knowledge reaches as far as the sensory world, and I am sluggish, I have a certain perseverance, I roll with my concepts beyond the sensory world and construct a world there, which I then doubt again when I realize that I have only followed my sluggishness with all my thinking.

It is interesting that a large part of philosophy, which does not move in the realm of the senses, is basically nothing more than such a rolling forward in inertia beyond what actually exists in the world. One cannot stand still. One wants to think further and further behind, and constructs atoms and molecules, and under certain circumstances also constructs many other things that philosophers have constructed behind them. No wonder that one must then dissolve this self-spun web that one has erected in the world out of perseverance.

Goethe rebelled against this law of inertia. He did not want such a rolling forward of thought; he wanted to stand still, to stand strictly at this boundary (see drawing: thick line), and he wanted to apply concepts within the sensory world. So he said to himself: Yellow appears to me in the spectrum, blue, red, indigo, violet appear to me in the spectrum. But when I penetrate these different color phenomena with my conceptual world and remain within the phenomena, the phenomena, the appearances themselves, come together, and I derive from the fact of the spectrum: When darker colors or darkness in general are placed behind lighter colors or behind light in general, I get what lies opposite the blue of the spectrum. Conversely, when I place light behind dark, I obtain what lies opposite the red of the spectrum.

What did Goethe actually want? Goethe wanted to select simple phenomena from among the complicated ones, but only those with which he remained within this boundary (see drawing), through which he did not roll into an area that can only be entered by sluggish rolling, by a certain mental perseverance. In this way, Goethe wanted to remain within phenomenalism. If one remains within phenomenalism in this way, and if one organizes one's entire thinking in such a way as to remain there, not to follow the perseverance that I have characterized, then the old question arises in a new way: What significance does that which I bring in from mechanics and mathematics, that which I bring in in terms of numbers, measurements, weights, or time relations, have in this world that I view so phenomenally? What significance does it have?

You may know that a more recent view has been to regard what initially exists in the phenomena of sound, color, heat, and so on as something that is, in a sense, only subjective, while the so-called primary qualities of things, such as spatiality, temporality, and weight, are regarded as something not subjective but objective, inherent in things. This view essentially goes back to the English philosopher Locke, and it also dominates to a high degree the philosophical foundations of modern scientific thinking. But basically, the question is: What position do mathematics and mechanics, which we actually spin out of ourselves—at least that is how it appears at first glance—occupy in our entire scientific system in relation to external nature? We will have to return to this question later, when we consider the particular form that this question has taken in Kantianism. But without going into historical details, we can emphasize that we are instinctively convinced that when we measure or count things, or when we determine their weight, we are making a fundamentally different statement about the external world than when we attribute other qualities of the external world to things.

It cannot be denied that light, colors, sounds, and taste sensations stand in a different relationship to us than that which we can represent in the external world in such a way that it is subject to mathematical and mechanical laws. For it is, after all, a remarkable fact that must be taken into account: you know that honey tastes sweet, but if someone is jaundiced, it tastes bitter to them, so that we can say we already stand in a strange way in relation to these qualities of the world in this world, while we cannot say that a normal person sees a triangle as a triangle and a person with jaundice sees it as a square! So distinctions already exist, and we must learn from these distinctions, but we must not draw absurd conclusions from them. And in a strangely unexplained way, philosophical thinking still stands today in relation to these fundamental facts of all cognitive development. We see, for example, how a recent philosopher, Professor Koppelmann, goes even further than Kant in his Weltanschauungsfragen (Questions of Worldview), saying, for example—you can read this on page 33 of Koppelmann's Weltanschauungsfragen—that Everything that relates to space and time must first be constructed internally with the mind, whereas colors and tastes are perceived directly within us. We construct the tetrahedron, the octahedron, the dodecahedron, and so on; we can only construct the usual regular bodies by means of our intellectual faculties. What wonder, says Koppelmann, that we encounter in the world only those regular bodies that we can construct with our minds. — And so you find almost verbatim in Koppelmann the sentence: It is impossible that a geologist might one day give a geometer a crystal bounded by seven equilateral triangles, simply because, says Koppelmann, such a crystal would have a shape that would not fit into our heads. — That is “over-Kantianism.” And one could say that in the world of things in themselves, such crystals bounded by seven regular triangles could possibly exist under certain circumstances, but they cannot fit into our minds, so we ignore them; they do not exist for us.

Such thinkers forget only one thing, they forget — and this is what we want to point out sharply with all the power of evidence in the course of these lectures — they forget that our minds are constructed according to the same laws of external existence from which we construct regular polyhedra and so on, and that our minds therefore, by virtue of their construction, cannot construct any polyhedra other than those that also exist outside. For, you see, this is one of the fundamental differences between the so-called subjective qualities of sound, color, warmth, and also the various qualities of the sense of touch and so on, and that which confronts us in the mechanical-mathematical world picture. That is the fundamental difference: sound and color leave us outside ourselves; we must first take them in, we must first perceive them. As human beings, we stand outside sound, color, warmth, and so on. It is not quite the same with warmth, which I will discuss tomorrow, but to a certain extent it is also true of warmth. They first take us outside ourselves, and we have to perceive them. This is not the case with form, spatial relationships, temporal relationships, or weight relationships. We perceive things spatially, but we ourselves are placed in the same space and subject to the same laws as the things outside us. We exist in time just like external things. We begin our physical life at a certain point in time and end it at another point in time. We exist in space and time in such a way that these things pass through us, as it were, without us first perceiving them. We must first perceive other things. With regard to weight, well, my dear friends, you will admit that this has little to do with perception, which is somewhat arbitrary, for otherwise many people who have become overweight through their own fault would avoid this by mere knowledge, by mere perception. Ladies and gentlemen, even in our weight ratios, we are perceived quite objectively by the world, without being able to do anything about it through the same organization that connects us with color, sound, warmth, and so on.

And so, above all, we must ask ourselves today: How does mathematical-mechanical judgment come to us in the first place? How do we arrive at mathematics, at mechanics, and how is it that these mathematics and mechanics are applicable to external nature, and how is it that there is a difference between the mathematical-mechanical qualities of things in the external world and between what we encounter as the so-called sensory qualities of so-called subjective nature, sound, color, warmth qualities, and so on?

Well, this cardinal question stands at one end. We will discover another tomorrow. Then we will have the two starting points of science. We will then move on and find the formation of social judgment at the other end.