The Boundaries of Natural Science

GA 322

29 September 1920, Dornach

Lecture III

We have seen that one arrives at two limits when one seeks either to penetrate more deeply into natural phenomena or, proceeding from the state of normal consciousness, to penetrate more deeply into one's own being in order to uncover the essential nature of consciousness. Yesterday we showed already what happens at the one limit to knowledge. We have seen that man awakes to full consciousness in coming into contact with an external, physical world of sense. Man would remain a more-or-less drowsy being, a being with a sleepy soul, if he could not awake in confronting external nature. And what has happened in the spiritual evolution of humanity, in man's gradual acquisition of knowledge about external nature, is actually nothing other than what happens every morning when we awake out of sleep or dream-consciousness by confronting an external world. This latter is a kind of moment of awakening, and in the course of the evolution of humanity we have to do with a gradual awakening, a kind of long, drawn-out moment of awakening.

Now, we have seen that at this frontier a certain inertia on the part of the soul very easily comes into play, so that when we come up against the extended world of phenomena we do not proceed in the manner of Goethean phenomenology by halting at this frontier and ordering the phenomena according to the representations, concepts, and ideas we have already gained, describing them in a systematic, rational manner, and so forth. Instead, we roll on a bit farther beyond the phenomena with our concepts and ideas and thereby create a world, for example a world of metaphysical atoms, molecules, and so forth. This world, when it is so constituted, is merely a fabrication of the mind, a world into which there enters a creeping doubt, so that we have to unravel again the theoretical web we have spun. And we have seen that it is possible to guard against such a violation of this frontier of our knowledge through phenomenalism, through working purely with the phenomena themselves. We have also had to show that at this point in our striving for knowledge something emerges that commends itself to our use as an immediate necessity: mathematics and that part of mechanics that can be comprehended without any empirical observation, i.e., the entire compass of so-called analytical mechanics.

If we call to mind everything comprehended by mathematics and analytical mechanics, we have before us the system of concepts that allows us to enter into phenomena with the utmost certainty. And yet, as I began to indicate yesterday, one should not deceive oneself, for the whole manner in which we call forth the notions of mathematics and analytical mechanics, this process within our souls, is entirely different from that employed when we experiment with or observe sensory data and then seek to comprehend them, when we try to gather knowledge from sensory experience. In order to arrive at the fullest clarity regarding these matters one must bring all one's mental energy to bear, for in this realm full clarity can be attained only with the greatest mental exertion.

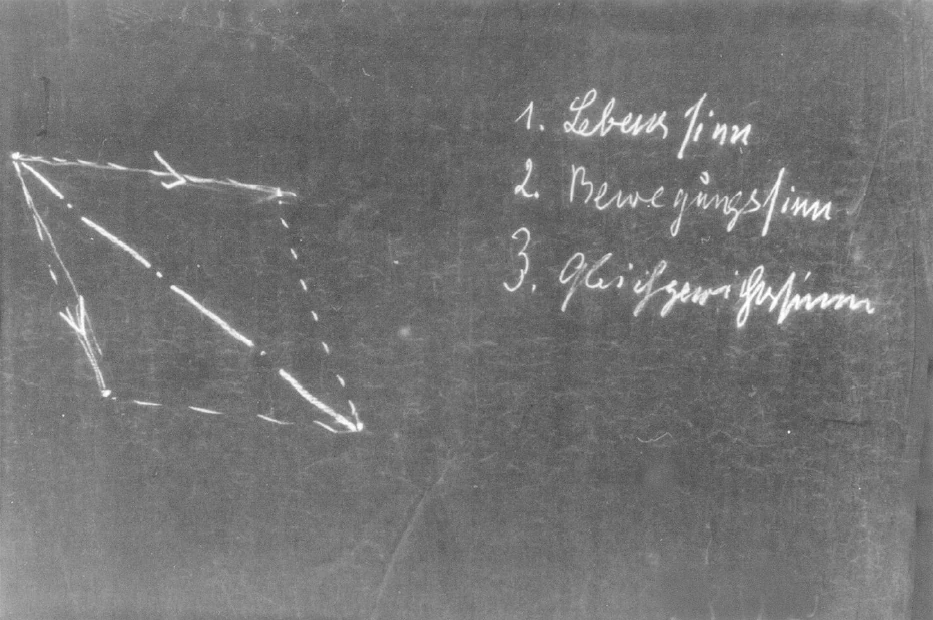

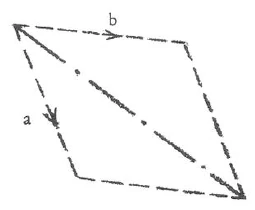

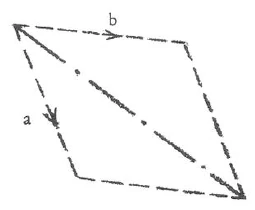

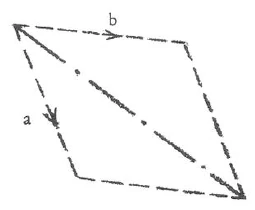

What is the difference between accumulating knowledge from sensory experience in a Baconian manner and the more inward mode of apprehension we find in mathematics and analytical mechanics? One can sharply differentiate the latter from those modes of apprehension that are not inward in this way by formulating clearly the concepts of the parallelogram of motion and the parallelogram of forces. One theorem of analytical mechanics states that two angular vectors proceeding from one point result in a third vector. To say, however, that a vector of a specific force here [see diagram: a] and a vector of a specific force here [b] result in a third force, which can also be determined according to the parallelogram—that is another notion altogether.

The parallelogram of motion lies strictly within the province of analytical mechanics, for it is internally consistent and demands no external proof. In this it is like the Rule of Pythagoras or any other geometrical axiom, but the existence of the parallelogram of forces can be determined only by experience, by experimentation. In this case, we bring something into that which we work through inwardly: the force that can be given only empirically from without. Here we no longer have a pure, analytical mechanics but an “empirical mechanics.” One can thus differentiate sharply between that which is still actually mathematical—as we still conceive mathematics today—and that which leads over into conventional empiricism.

Now one stands before this phenomenon of mathematics as such. We comprehend mathematical truths. We proceed from mathematical phenomena to certain axioms. We weave the fabric of mathematics out of these axioms and then stand before an architectonic whole apprehended by the mind's eye [im inneren Anschauen]. If we are able by means of energetic thinking to differentiate sharply this inner apprehension from anything that can be experienced outwardly, we must see in this fabric of mathematics something that arises through an activity of soul entirely different from that which underlies our experience of the outer objects of sensation. Whether or not we arrive at a satisfactory comprehension of the world depends to a tremendous extent on our being able to make this clear distinction out of inner experience. We thus must ask: where does mathematics originate? Nowadays this question is still not pursued rigorously enough. One does not ask: how is this inner activity of the soul that we need in mathematics, in the wonderful architecture of mathematics—how is this inner activity of the soul different from that whereby we grasp external nature through the senses? One does not pose this question and seek an answer with sufficient rigor, because it is the tragedy of the materialistic world view that, while on the one hand it presses for sensory experience, on the other hand it is driven unawares into an abstract intellectualism, into a realm of abstraction where one is isolated from any true comprehension of the phenomena of the material world.

What kind of capacity is it, then, that we acquire when we engage in mathematics? We want to address ourselves to this question. In order to answer this question we must, I believe, have reached a complete understanding of one thing in particular: we must take fully seriously the concept of becoming as it applies to human life as well. We must begin by acquiring the discipline that modern science can teach us. We must school ourselves in this way and then, taking the strict methodology, the scientific discipline we have learned from modern natural science, transcend it, so that we use the same exacting approach to rise into higher regions, thereby extending this methodology to the investigation of entirely different realms as well. For this reason I believe—and I want this to be expressly stated—that nobody can attain true knowledge of the spirit who has not acquired scientific discipline, who has not learned to investigate and think in the laboratories according to the modern scientific method. Those who pursue spiritual science [Geisteswissenschaft] have less cause to undervalue modern science than anyone. On the contrary, they know how to value it at its full worth. And many people—if I may here insert a personal remark—were extremely upset with me when, before publishing anything pertaining to spiritual science as such, I wrote a great deal about the problems of natural science in a way that appeared necessary to me. So you see it is necessary on the one hand for us to cultivate a scientific habit of mind, so that this can accompany us when we cross the frontiers of natural science. In addition, it is the quality of this scientific method and its results that we must take very seriously indeed.

You see, if we consider the simple phenomenon of warmth that appears when we rub two bodies together, it would be utterly unscientific to say, regarding this isolated phenomenon, that the warmth had been created ex nihilo or simply existed. Rather, we seek the conditions under which this warmth was previously latent and now appears by means of the bodies. We proceed from the one phenomenon to the other and thus take seriously this process of becoming [das Werden]. We must do the same with the concepts that we consider in spiritual science. So we must first of all ask: is that which manifests itself as the ability to perform mathematics present in man throughout his entire existence between birth and death? No, it is not always present. It awakes at a certain point in time. To be sure, we can, while still remaining empirical regarding the outer world, observe with great precision how there gradually arise out of the dark recesses of human consciousness faculties that manifest themselves as the ability to perform mathematics and something like mathematics that we have yet to discuss. If one can observe this emergence in time precisely and soberly, just as scientific research treats the phenomena of the melting or boiling point, one sees that this new faculty emerges at approximately that time of life when the child changes teeth. One must treat such a point in the development of human life with the same attitude with which physics, for example, teaches one to treat the melting or boiling point. One must acquire the ability to carry over into the complicated realm of human life the same strict inner discipline that one can acquire by observing simple physical phenomena according to the methods of modern science. If one does this, one sees that in the course of human development from birth, or rather from conception, up to the change of teeth, the soul faculties enabling one to perform mathematics manifest themselves gradually within the organism but that they are not yet fully present. Now we say that the warmth that manifests itself in a body under certain conditions was latent in that body beforehand, that it was at work within the inner structure of that body. In the same way we must be entirely clear that the capacity to perform mathematics, which becomes most evident at the change of teeth and reveals itself gradually in another sense, was also at work beforehand within the human organization. We thus arrive at an important and valuable insight into the nature of mathematics—mathematics taken, of course, in the very broadest sense. We begin to understand how that which is at our disposal after the change of teeth as a soul faculty worked previously within to organize us. Yes, within the child until approximately its seventh year there works an inner mathematics, an inner mathematics not abstract like our external one but full of active energy, a mathematics which, if I may use Plato's expression, not only can be inwardly envisioned [angeschaut] but is full of active life. Up to this point in time there exists within us something that “mathematicizes” us through and through.

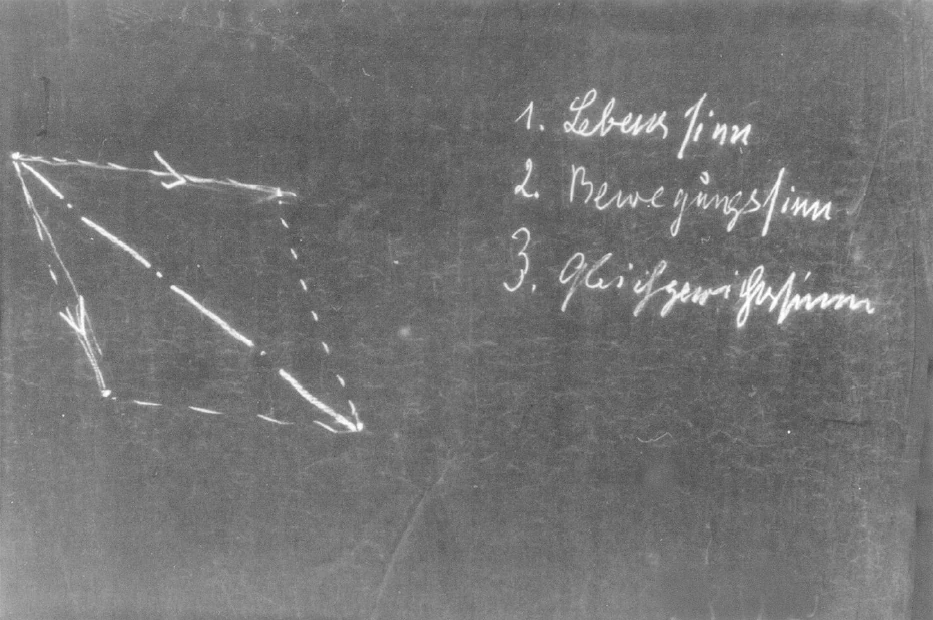

When we ask at first entirely superficially what can be seen by looking empirically at this “latent mathematics” in the body of the young child, we are led to three things resembling inner senses. In the course of these lectures we shall come to see that one can indeed speak of senses within as well. Today I want only to indicate that we are led to something that develops an inward faculty of perception similar to the outward perception developed by the eyes and ears, except that the former remains unconscious within us during these first years. And if we look within, look into our own inner organization not like nebulous mystics but with all our powers of apprehension, we can find within three functions similar to those of the outward senses. We find inner senses that exercise a certain activity, a certain inner mathematics, just in those first several years. One encounters first of all what I would like to call the sense of life. This sense of life manifests itself in later years as a perception of our inner state as a whole. In a certain way we feel either well or unwell. We feel comfortable or uncomfortable: just as we have a faculty for perceiving outwardly with the eyes, so also do we have a faculty for perceiving inwardly. This faculty is directed toward the whole organism and is for that reason dark and dull; yet it is there all the same. We shall have more to say about this later. For the moment I want to anticipate this later discussion only by remarking that this sense of life is—if I may use a tautology—especially active in the vitality of the child up until the change of teeth.

Another inner sense that we must consider when we look within in this way is that which I would like to call the sense of movement. We must form a clear conception of this sense of movement. When we move our limbs, we are aware of this not only by viewing ourselves externally but also by means of an internal perception. Also when we walk: we are conscious that we are walking not only in that we see objects pass and our view of the external world changes but also in that we have an internal perception of the movements of the limbs, of changes within ourselves as we move. Normally we remain unaware of the inner experiences and perception that run parallel to the outer because of the strength of the external impressions, much as a dim light is “extinguished” by a bright one.

And a third inward-looking faculty is the sense of balance. The sense of balance is what enables us to locate ourselves within the world, to avoid falling, to perceive in a certain way how we can bring ourselves into harmony with the forces in our environment. We perceive this process of bringing ourselves into harmony with our environment inwardly. We thus can truly say that we bear within ourselves these three inner senses: the sense of life, the sense of movement, and the sense of balance. They are especially active in childhood up to the change of teeth. Around this time of the change of teeth their activity begins to wane, but observe to take but one example, the sense of balance—observe how at birth the child has as yet nothing enabling it to attain the position of balance it needs in later life. Consider how the child gradually gains control of itself, how it learns at first to crawl on all fours, how it gradually achieves through its sense of balance the ability to stand and to walk, how it finally is able to maintain its own balance.

If one considers the entire process of development from conception to the change of teeth, one sees therein the powerful activity of these three inner senses. And if one can attain a certain insight into what is happening there, one sees that there is at work in the sense of balance and the sense of movement nothing other than a living “mathematicizing” [ein lebendiges Mathematisieren]. In order for it to come to life, the sense of life is there to vitalize it. We thus see a kind of latent realm of mathematics active within man. This activity does not entirely cease at the change of teeth, but it does become at that time considerably less pronounced for the remainder of life. That which is inwardly active in the sense of balance, the sense of movement, and the sense of life becomes free. This latent mathematics becomes free, just as latent heat can become liberated heat. And we see how that which initially was woven through the organism as an element of soul becomes free. We see how this mathematics emerges as abstraction from a condition in which it was originally a concrete force shaping the human organism. And because as human beings we are suspended in the web of existence according to temporal and spatial relationships, we take this mathematics that has become free out into the world and seek to comprehend the external world by means of something that worked within us up until the change of teeth. You see, it is not a denial but rather an extension of natural science that results when one considers rightly what ought to live within spiritual science as attitude and will.

We thus carry what originates within ourselves beyond the frontier of sense perception. We observe man within a process of becoming. We do not simply observe mathematics on the one hand and sensory experience on the other but rather the emergence of mathematics within the developing human being. And now we come to that which truly leads over into spiritual science itself. You see, that which we call forth out of our own inner life, this “mathematicizing,” becomes in the end an abstraction. Yet our experience of it need not remain an abstraction. In our time there is, to be sure, little opportunity for us to experience mathematics in a true light. Yet at a certain point in the development of Western civilization there does come to light something of this sense of a special spirit in mathematics. This comes to light at the point where Novalis, the poet Novalis, who underwent a good mathematical training in his studies, writes about mathematics in his Fragments. He calls mathematics a grand poem, a wonderful, grand poem.

One really must have experienced at some time what it is that leads from an abstract understanding of the geometrical forms to a sense of wonder at the harmony that underlies this inner “mathematicizing.” One really must have had the opportunity to get beyond the cold, sober performance of mathematics, which many people even hate. One must have struggled through as Novalis had in order to stand in awe of the inner harmony and—if I may use an expression you have heard often in a completely different context—the “melody” [Melos] of mathematics.

Then something new enters into one's experience of mathematics. There enters into mathematics, which otherwise remains purely intellectual and, metaphorically speaking, interests only the head, something that engages the entire man. This something manifests itself in such youthful Spirits as Novalis in the feeling: that which you behold as mathematical harmony, that which you weave through all the phenomena of the universe, is actually the same loom that wove you during the first years of growth as a child here an earth. This is to feel concretely man's connection with the cosmos. And when one works one's way through to such an inner experience, which many hold to be mere fantasy because they have not actually attained it themselves, one has some idea what the spiritual scientist [Geistesforscher] experiences when he rises to a more extensive grasp of this “mathematicizing” by undergoing an inner development of which I have yet to speak and which you will find fully depicted in my book, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment.2Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der hoheren Welten?, Berlin, 1909 (Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment. Anthroposophie Press, Spring Valley, N.Y., reprinted 1983). For then the capacity of soul manifesting itself as this inner mathematics passes over into something far more comprehensive. It becomes something that remains just as exact as mathematical thought yet does not proceed solely from the intellect but from the whole man.

On this path of constant inner work—an inner work far more demanding than that performed in the laboratory or observatory or any other scientific institution—one comes to know what it is that underlies mathematics, that underlies this simple faculty of the human soul which can be expanded into something far more comprehensive. In this higher experience of mathematics one comes to know Inspiration. One comes to understand the differences between what lives in us as mathematics and what lives in us as outer-directed empiricism. In this outer-directed empiricism we have sense impressions that give content to our empty concepts. In Inspiration we have something inwardly spiritual, the activity of which manifests itself already in mathematics, if we know how to grasp mathematics properly—something spiritual which in our early years lives and weaves within us. This activity continues. In doing mathematics we experience this in part. We come to realize that the faculty for performing mathematics rests upon Inspiration, and we can come to experience Inspiration itself by evolving into spiritual scientists. Our representations and concepts then receive their content in a way other than through external experience. We can inspire ourselves with the spiritual force that works within us during childhood. For what works within us during our childhood is spirit. The spirit, however, resides in the human body and must be perceived there through the body, within man. It can be viewed in its pure, free form if one acquires through the faculty of Inspiration the capacity not only to think in mathematical concepts but to view that which exists as a real force in that it organizes us through and through up until the seventh year. And that which manifests itself partially in mathematics and reveals itself as a much more expansive realm through Inspiration can be inwardly viewed, if one employs certain spiritual scientific methods about which—as I have said—I plan yet to speak. One thereby gains not merely new results to add to those acquired through the old powers of cognition but rather an entirely new mode of apprehension. One acquires a new “Inspirative” cognition.

The course of human evolution has been such that these powers of Inspirative cognition have receded with the passage of time, after having been present earlier to a very high degree. One must come to understand how Inspiration arises within the inner being of man—that same Inspiration that survives in the West only in the diluted, intellectual experience of mathematics. The experience can be expanded, however, if only one comprehends fully the inner nature of that realm; only then does one begin to understand what lived in that earlier consciousness transmitted to us actually only from the East, from the Vedanta and the other Eastern philosophies that remain so cryptic to the Western mind. For what was it that actually lived within these Eastern philosophies? lt was something that arose through soul faculties of a mathematical nature. It was an Inspiration. It was not merely mathematics but rather something attained within the soul in a way similar to that in which one performs mathematics. Thus I would say that the mathematical atmosphere emanating from the Vedanta and similar ancient world views is something that can be understood from the perspective one attains in rising again to enter the realm of Inspiration. If one can raise to vivid inner life that which works unconsciously in mathematics and the mathematical sciences and can carry it over into another realm, one discovers the same mathematical element that Goethe viewed. Goethe modestly confessed that he did not have proficiency in mathematics in any conventional sense. Goethe has written on his relationship to mathematics in a very interesting series of essays, which you can find in his scientific writings under the heading “Relationship to Mathematics.” Extraordinarily interesting! For despite Goethe's modest confession that he had not acquired a proficiency in the handling of actual mathematical concepts and theories, he does require one thing: he calls for a phenomenalism such as he employed in his own scientific studies. He demands that within the secondary phenomena confronting us in the phenomenal world we seek the archetypal phenomenon [Urphänomen]. But just what kind of activity is this? He demands that we trace external phenomena back to the archetypal phenomenon, in just the same way that the mathematician traces the outward apprehension [äusseres Anschauen] of complex structures back to the axiom. Goethe's archetypal phenomena are empirical axioms, axioms that can be experienced.

Goethe thus demands, in a truly mathematical spirit, that one inwardly permeate phenomena with mathematics. He writes that we must see the archetypal phenomena in such a way that we are able at all times to justify our procedures according to the rigorous requirements of the mathematician. Thus what Goethe seeks is a modified, transformed mathematics, one that suffuses phenomena. He demands this as a scientific activity.

Goethe was able, therefore, to suffuse with light the one pole that otherwise remains so dark if we postulate only the concept of matter. We shall see how Goethe approached this pole; we modern must, however, approach the other, the pole of consciousness. We must investigate in the Same way how soul faculties manifest their activity in the human being, how they proceed from man's inner nature to manifest their activity externally. We shall have to investigate this. It shall become clear that we must complement the method of investigating the external world offered by Goethean phenomenology with a method of comprehending the realm of human consciousness. It must be a mode of comprehension justifiable in the sense in which Goethe's can be justified to the mathematician—a method such as I tried to employ in a modest way in my book, Philosophy of Freedom.3Die Philosophie der Freiheit, Berlin, 1894 (The Philosophy of Freedom, Anthroposophic Press, Spring Valley, N.Y., 1964). Earlier translations of this book (1922, 1938, and 1963) bore the title The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, following a suggestion given by Steiner himself. The English word “freedom” connotes a passive state; the German “Freiheit” (as is clean from the following lecture), an objective basis for moral action achieved through intense inner activity.

At the pole of matter we thus encounter the results yielded by Goethean phenomenology and at the pole of consciousness those attained by pursuing the method that I sought to establish in a modest way in my Philosophy of Freedom.

Tomorrow we will want to pursue this further.

Dritter Vortrag

Wir haben gesehen, daß der Mensch gewissermaßen zu zwei Grenzscheiden kommt, wenn er versucht, von sich aus entweder tiefer in die Naturerscheinungen einzudringen, oder aber wenn er versucht, von dem Gesichtspunkte seines gewöhnlichen Bewußtseins tiefer hinabzudringen in sein eigenes Wesen, um gerade dadurch auch das eigentliche Wesen des Bewußtseins aufzufinden. Wir haben schon gestern darauf hingedeutet, was an der einen Grenze unseres Erkennens geschieht. Wir haben gesehen, daß der Mensch erwacht zum vollen Bewußtsein an seinem Wechselverkehr mit der äußeren physisch-sinnlichen Natur. Der Mensch würde mehr oder weniger ein verschlafenes Wesen sein, ein Wesen mit schläfriger Seele, wenn er nicht an der äußeren Natur erwachen könnte. Und im Grunde genommen geschieht im Laufe der geistigen Entwickelung der Menschheit nichts anderes, als daß sich allmählich vollzieht in dem Erringen von Wissen über die äußere Natur dasjenige, was sich jeden Morgen vollzieht, wenn wir aus dem Schlafe oder aus dem schlafenden Träumen uns an der Außenwelt entzünden zum vollen, wachen Bewußtsein. Im letzteren Falle haben wir es gewissermaßen mit einem Augenblick des Erwachens zu tun. Im Laufe der Menschheitsentwickelung hatten wir es zu tun mit einem allmählichen Erwachen, gewissermaßen mit einem Auseinandergezogensein des Erwachensmomentes.

Nun haben wir gesehen, daß da sehr leicht an dieser Grenze eine Art Trägheitskraft der Seele sich betätigt, daß wir gewissermaßen da, wo wir anstoßen an die ausgebreitete Welt der Phänomene, nicht wie der Phänomenalismus im Goetheschen Sinne das tun will, außen stehenbleiben und die Phänomene nur nach unseren errungenen klaren Vorstellungen, Begriffen und Ideen gewissermaßen zusammenfassen, systematisierend rationell beschreiben und so weiter, sondern daß wir noch eine Weile fortrollen hinter die Phänomene mit unseren Begriffen und Ideen und dadurch zur Statuierung einer Welt kommen, zum Beispiel einer Welt von hinterphysischen Atomen, Molekülen und so weiter, die dann im wesentlichen, wenn sie so errungen wird, eine ausgedachte Welt ist, eine Welt, hinter der sich sogleich der Zweifel einschleicht, so daß wir wiederum auflösen, was wir erst als ein theoretisches Gewebe gesponnen haben. Und wir haben gesehen, daß es möglich ist, im reinen Durcharbeiten der Phänomene selbst, im Phänomenalismus uns zu bewahren vor einem solchen Überschreiten der Grenze unseres Naturerkennens nach dieser Seite hin. Aber wir haben auch darauf aufmerksam machen müssen, daß an dieser Stelle unseres Erkennens auftaucht etwas, was sich dem Gebrauche mit einer unmittelbaren Lebensnotwendigkeit anbietet, das ist die Mathematik und dasjenige, was zum Beispiel in der Mechanik ohne Empirismus begriffen werden kann, also der ganze Umfang der sogenannten analytischen Mechanik.

Wenn wir ins Auge fassen alles dasjenige, was Mathematik umfaßt, was analytische Mechanik umfaßt, dann kommen wir zu den sichersten Begriffssystemen, mit denen wir in die Phänomene hineinarbeiten können. Allein, man kann sich doch nicht verhehlen - ich habe gestern schon darauf hingewiesen -, daß die ganze Art und Weise, wie wir uns mathematische Vorstellungen ausbilden und wie wir auch ausbilden Vorstellungen der analytischen Mechanik, daß diese innere Seelenarbeit eine durchaus andere ist als diejenige, die wir vollziehen, wenn wir aus der Erfahrung heraus, aus der Sinneserfahrung heraus experimentieren oder beobachten und die Tatsachen der Experimente oder die Ergebnisse der Beobachtungen zusammenfassen, eben das äußere Erfahrungswissen sammeln. Man sollte sich, damit man in diesen Dingen zur völligen Klarheit kommt, stark besinnen, denn einen andern Weg zur Klarheit gibt es auf diesem Felde nicht als den des starken Besinnens.

Welcher Unterschied ist zwischen dem Sammeln eines Erfahrungswissens etwa im Baconschen Sinne und zwischen der innerlich die Dinge ergreifenden Art, wie es in der Mathematik und in der analytischen Mechanik der Fall ist? Man kann für die letztere geradezu eine scharfe Grenze ziehen gegenüber dem, was nicht auf solch innere Weise erfaßt ist, wenn man sich einfach den Begriff des Bewegungsparallelogramms und dann den Begriff des Kräfteparallelogramms klar bildet. Daß sich aus zwei voneinander unter einem Winkel abweichenden Bewegungen eine resultierende Bewegung ergibt, das ist ein Satz der analytischen Mechanik. Daß sich, wenn hier (a) eine Kraft wirkt von einer bestimmten angebbaren Stärke und hier (b) eine Kraft wirkt von einer bestimmten angebbaren Stärke, sich eine resultierende Kraft ergibt, die auch nach diesem Parallelogramm feststellbar ist, das sind zwei voneinander ganz verschiedene Vorstellungsinhalte. Das Bewegungsparallelogramm gehört im strengen Sinne der analytischen Mechanik an, denn es läßt sich innerlich beweisen wie irgendein Satz der Mathematik, wie zum Beispiel der pythagoreische Lehrsatz oder irgendein anderer. Daß es das Kräfteparallelogramm gibt, kann nur ein Ergebnis der Erfahrung, des Experimentes sein. Da bringen wir in dasjenige, was wir innerlich verarbeiten, etwas hinein, die Kraft, die uns nur äußerlich durch Erfahrung, durch Empirie gegeben sein kann. Da also haben wir es schon zu tun mit der Erfahrungsmechanik, nicht mehr mit der rein analytischen Mechanik. Sie sehen, da kann man streng die Grenze ziehen zwischen dem, was im eigentlichen Sinn noch mathematisch ist, so wie man Mathematik heute noch aufzufassen hat, und dem, was in die gewöhnliche Sinnesempirie hinüberführt.

Nun steht man vor dieser Tatsache der Mathematik als solcher. Wir fassen die mathematischen Wahrheiten auf. Wir bringen die mathematischen Erscheinungen auf gewisse Axiome zurück. Wir bauen uns dann das ganze Gewebe der Mathematik aus diesen Axiomen auf, und wir stehen gewissermaßen vor einer im Anschauen, aber inneren Anschauen ergriffenen Architektonik. Und wir müssen, wenn wir imstande sind, durch starke Besinnung eine scharfe Grenze zu ziehen gegenüber allem äußerlich Erfahrbaren, in diesem mathematischen Gewebe etwas sehen, was durch eine ganz andere Seelentätigkeit zustande kommt, als diejenige ist, durch welche wir äußerlich sinnlich erfahren und auffassen. Daß wir, ich möchte sagen, wiederum durch eine innerliche Erfahrung diesen Unterschied genau machen können, davon hängt im Grunde genommen ungeheuer viel für ein befriedigendes Weltbegreifen ab. Wir müssen also fragen: Woher kommt uns die Mathematik? Und diese Frage, die wird eben gegenwärtig noch immer nicht scharf genug gestellt. Man frägt nicht: Wie ist verschieden diese innere Seelentätigkeit, die wir in der Mathematik, im Aufbau der Mathematik, in dieser wunderbaren Architektonik brauchen, wie ist verschieden diese Seelenfähigkeit von derjenigen Seelenfähigkeit, durch die wir durch äußere Sinne die physisch-sinnliche Natur auffassen? Und man stellt und beantwortet diese Frage nicht in genügendem Maße heute, weil es die Tragik der materialistischen Weltanschauung ist, daß sie, während sie auf der einen Seite zur sinnlich-physischen Erfahrung hindrängt, auf der andern Seite wiederum hingetrieben wird, ohne daß sie es weiß, in einen abstrakten Intellektualismus, in ein abstraktes Wesen, durch das man gerade entfernt wird von einem wirklichen Ergreifen der Tatsachen der materiellen Welt.

Was ist es denn, was wir als eine Fähigkeit ausbilden, indem wir mathematisieren? Diese Frage wollen wir einmal stellen. Es muß, wenn man diese Frage beantworten will, eines, glaube ich, ganz in uns als Verständnis aufgegangen sein. Das ist auf der einen Seite: Wir müssen es auch im Menschenleben mit dem Begriff des Werdens ernst nehmen, das heißt, wir müssen ausgehen von dem, was gerade im hohen Grade disziplinierend ist an der modernen Naturwissenschaft, wir müssen uns an dem erziehen und müssen gewissermaßen das, was wir an strenger Methode, an wissenschaftlicher Disziplin uns anerzogen haben in der Naturwissenschaft der neueren Zeit, wir müssen das über diese Naturwissenschaft selber hinauszutreiben wissen, so daß wir in höhere Gebiete aufsteigen mit derselben Gesinnung, die wir in der Naturwissenschaft haben, aber mit Ausdehnung der Methoden auf ganz andere Gebiete. Ich glaube deshalb auch nicht und sage das ganz unumwunden, daß zu einem wirklichen geisteswissenschaftlichen Erkennen derjenige kommen kann, der nicht im strengen Sinne des Wortes eine naturwissenschaftliche Disziplin sich erworben hat, der nicht forschen und denken gelernt hat in den Laboratorien und durch die Methode der neueren Naturwissenschaft. Am allerwenigsten hat Geisteswissenschaft Veranlassung, diese neuere Naturwissenschaft zu unterschätzen. Im Gegenteil, sie weiß sie völlig zu schätzen. Und mir selber - wenn ich diese persönliche Bemerkung machen darf - nehmen es ja viele Leute reichlich übel, daß ich, bevor ich eigentlich Geisteswissenschaftliches veröffentlicht habe, zunächst manches geschrieben habe gerade über naturwissenschaftliche Probleme in derjenigen Beleuchtung, die mir notwendig zu sein schien. Also es handelt sich darum, daß wir uns auf der einen Seite diese naturwissenschaftliche Gesinnung aneignen, damit sie fortwirkt, wenn wir über die Grenzen des Naturerkennens hinauskommen. Und zweitens müssen wir uns sogar die Qualität dieses Naturerkennens beziehungsweise der Ergebnisse dieses Naturerkennens recht sehr ernst werden lassen.

Sehen Sie, wenn wir die ganz einfache Erscheinung nehmen, daß wir einen Körper mit einem andern reiben und Wärme zum Vorschein kommt, so sagen wir in der Naturwissenschaft gegenüber einem solchen vorliegenden Teilphänomen nicht: Diese Wärme ist aus dem Nichts heraus entstanden, oder diese Wärme ist einfach da -, sondern wir suchen nach den Bedingungen, unter denen diese Wärme latent gewesen ist vorher und dann durch die Körper gewissermaßen zum Vorschein gekommen ist. Wir gehen da von einer Erscheinung zur andern über und nehmen das Werden ernst. So müssen wir es auch machen, wenn wir einen Begriff in die Geisteswissenschaft hineinbringen wollen. Und so müssen wir uns zunächst fragen: Ist denn dasjenige, was Mathematisieren ist, im Menschen immer da, insofern er sein Dasein durchlebt zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode? - Nein, es ist nicht immer da. Das Mathematisieren erwacht erst. Und zwar können wir - und dabei bleiben wir auch noch innerhalb der Empirie gegenüber der äußeren Welt stehen — ganz genau beobachten, wie allmählich diejenigen Seelenfähigkeiten gewissermaßen aus dem dunklen Untergrunde des menschlichen Bewußtseins heraus erwachen, die sich dann gerade im Mathematisieren und in Ähnlichem, was wie das Mathematisieren ist, von dem wir gleich nachher sprechen wollen, äußern. Dieser Zeitpunkt, wenn man ihn nur genau und ordentlich ins Auge zu fassen vermag, wenn man ihn nur so behandelt, wie die Naturforschung zum Beispiel die Erscheinung des Schmelzpunktes oder des Siedepunktes behandelt, dieser Zeitpunkt liegt etwa in derjenigen Lebensepoche, in der das Kind die Zähne wechselt, in der aus den Milchzähnen die zweiten Zähne werden. Man muß nur solch einen Lebensentwickelungspunkt aus derselben Gesinnung heraus ins Auge fassen, wie man zum Beispiel in der Physik gelernt hat, den Schmelzpunkt oder den Siedepunkt zu behandeln. Man muß sich die Fähigkeit erwerben, ins Komplizierte des Menschenlebens hinein diese strenge innere Disziplin zu tragen, die man sich aus den einfachen physikalischen Phänomenen, indem man sie im Sinne der neueren Wissenschaft beobachtet, erwerben kann. Und wenn man das tut, dann sieht man, daß in der menschlichen Entwickelung von der Geburt an, oder sagen wir besser von der Empfängnis an, bis zu diesem Punkte des Zahnwechsels sich zwar allmählich aus der Organisation herausarbeiten die Seelenfähigkeiten, die dann mathematisieren, aber sie sind eben noch nicht da. Und so wie wir sagen, daß die Wärme, die latent ist in einem Körper und in einem bestimmten Zustande zum Vorschein kommt, früher in dem Körper, in der inneren Struktur des Körpers gearbeitet hat, so müssen wir uns klar sein darüber, daß dasjenige, was als Fähigkeit des Mathematisierens in der Zeit des Zahnwechsels besonders stark, allmählich aber in gewissem anderem Sinne zum Vorscheine kommt, daß das früher in der Organisation des Menschen drinnen gearbeitet hat. Und so bekommen wir einen merkwürdigen, bedeutsamen Begriff über dieses Mathematisieren, im weitesten Sinne natürlich. Wir bekommen den Begriff, daß dasjenige, was wir als Seelenfähigkeit nach dem Zahnwechsel als Menschen anwenden, daß das vorher in uns organisierend wirkt. Ja, in dem Kinde bis zum siebenten Jahre ungefähr ist eine innere Mathematik, eine innere Mathematik, die nun nicht so abstrakt ist wie unsere äußere, sondern die kraftdurchsetzt ist, die, wenn ich diesen Ausdruck Platos gebrauchen darf, nicht nur angeschaut werden kann, sondern die lebensvoll tätig ist. Es existiert in uns etwas bis zu diesem Zeitpunkte, das mathematisiert, das uns innerlich durchmathematisiert.

Wenn wir zunächst, ich möchte sagen, ganz oberflächlich fragen nach dem, was uns da empirisch zutage tritt, wenn wir gewissermaßen auf die latente Mathematik sehen in dem jugendlichen Kindeskörper, dann werden wir geführt auf drei Dinge, die nach innen zu sinnesähnlich sind. Wir werden noch im Laufe der Vorträge sehen, daß wir wirklich da auch von Sinnen sprechen können. Heute will ich nur dieses andeuten, daß wir auf etwas kommen, was nach innen zu ein solches Wahrnehmungsvermögen entwickelt, das uns nur in den ersten Jahren unbewußt bleibt, wie die Augen, die Ohren nach außen ein Wahrnehmungsleben entwickeln. Und wir können, wenn wir da in unser Inneres, aber in das Innere der Organisation sehen, nicht nach dem Muster der nebulosierenden Mystiker, sondern mit voller Macht und Erkenntnis hinschauen auf dieses menschliche Innere, dann können wir drei sinnesähnliche Funktionen, möchte ich sagen, finden, durch die eine Tätigkeit ausgeübt wird, in gewissem Sinne mathematisierend, gerade in den ersten Lebensjahren. Das ist erstens dasjenige, was ich den Lebenssinn nennen möchte. Dieser Lebenssinn, er äußert sich im späteren Leben als eine Gesamtempfindung unseres Inneren. Wir fühlen uns in einer gewissen Weise wohl oder nicht wohl. Wir fühlen uns behaglich oder unbehaglich, geradeso wie wir ein Wahrnehmungsvermögen durch die Augen nach außen haben, so haben wir ein Wahrnehmungsvermögen nach innen. Nur ist dieses Wahrnehmungsvermögen gewissermaßen auf den ganzen Organismus gerichtet, ist dadurch dumpf und dunkel, aber es ist da. Wir werden darüber noch einiges zu sprechen haben. Jetzt will ich nur Späteres vorausnehmend sagen, daß dieser Lebenssinn - wenn ich die Tautologie gebrauchen darf - in der Vitalität des Kindes ganz besonders tätig ist bis zum Zahnwechsel hin.

Und ein Zweites, auf das wir Rücksicht nehmen müssen, wenn wir so ins Innere des Menschen hineinschauen, das ist dasjenige, was ich den Bewegungssinn nennen möchte. Wir müssen uns von diesem Bewegungssinn eine klare Vorstellung bilden. Wenn wir unsere Glieder bewegen, so wissen wir davon nicht nur dadurch, daß wir uns etwa äußerlich anschauen, sondern wir haben ein innerliches Wahrnehmen von der Bewegung der Glieder. Auch wenn wir gehen, so haben wir nicht nur ein Bewußtsein von unserem Gehen dadurch, daß wir an den Gegenständen vorübergehen und sich uns der Anblick der Außenwelt verändert, sondern wir haben eine innerliche Wahrnehmung von der Bewegung der Glieder, von Veränderungen in uns, indem wir uns bewegen. Wir achten nur gewöhnlich nicht darauf, weil wir durch die Stärke der Eindrücke der Außenwelt dasjenige, was da innerlich parallel geht an innerem Erleben, an innerem Wahrnehmen, nicht beachten, so wie ein kleines Licht in seiner Stärke durch ein großes Licht ausgelöscht wird.

Und ein Drittes, nach innen Gehendes, ist der Gleichgewichtssinn.

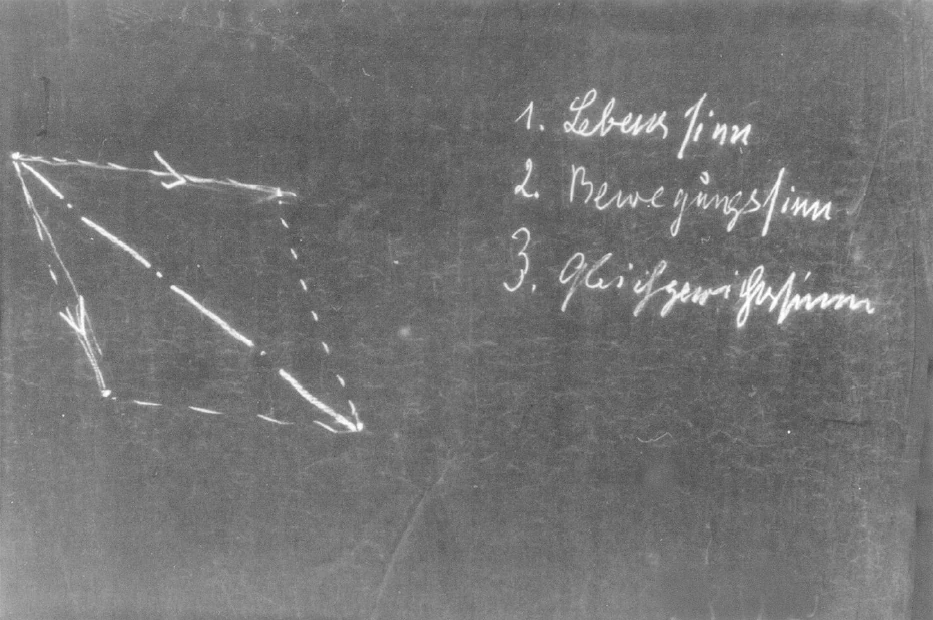

1. Lebenssinn

2. Bewegungssinn

3. Gleichgewichtssinn

Dieser Gleichgewichtssinn, er ist in uns dasjenige, wodurch wir uns in einer gewissen Weise in die Welt hineinstellen, nicht umfallen, in einer gewissen Weise wahrnehmen, wie wir uns in Harmonie bringen mit den Kräften unserer Umgebung. Und dieses In-Harmonie-Bringen mit den Kräften unserer Umgebung nehmen wir innerlich wahr. So daß wir wirklich sagen können, wir tragen in uns diese drei inneren Sinne: Lebenssinn, Bewegungssinn, Gleichgewichtssinn. Sie sind in ganz besonderem Maße in dem kindlichen Alter tätig bis zum Zahnwechsel hin. Es verglimmt ihre Tätigkeit gegen den Zahnwechsel hin. Aber beobachten Sie — nur um ein Beispiel herauszugreifen — den Gleichgewichtssinn, beobachten Sie, wie das Kind, indem es sein Leben beginnt, noch gar nichts hat, was ein Ergreifen der Gleichgewichtslage, die es braucht für das Leben, darbieten würde. Bedenken Sie, wie das Kind sich allmählich erfängt, wie es zuerst auf allen vieren kriechen lernt, wie es erst allmählich durch den Gleichgewichtssinn dahin kommt, zu stehen, zu gehen, wie es dahin kommt, sich selber im Gleichgewichte zu erfassen.

Wenn Sie nun diesen ganzen Umfang desjenigen, was vorgeht zwischen der Empfängnis und dem Zahnwechsel, erfassen, so sehen Sie darinnen ein starkes Arbeiten dieser drei inneren Sinne. Und wenn Sie dann durchschauen dasjenige, was da geschieht, dann merken Sie, daß im Gleichgewichtssinn und im Bewegungssinn sich nichts anderes abspielt, als ein lebendiges Mathematisieren. Und damit es lebendig ist, deswegen ist eben der Lebenssinn dabei, der es durchlebendigt. So sehen wir innerlich gewissermaßen latent eine ganze Mathematik an dem Menschen tätig sein, die dann nicht etwa ganz abstirbt mit dem Zahnwechsel, aber die wesentlich weniger deutlich wird für das spätere Leben. Das, was da innerlich im Menschen tätig ist durch Gleichgewichtssinn, durch Bewegungssinn, durch Lebenssinn, das wird frei. Die latente Mathematik wird eine freie, wie die latente Wärme eine freie Wärme werden kann. Und wir sehen dann, wie dasjenige, was als Seelisches zunächst den Organismus durchwoben hat, durchseelt hat, wie das als Seelenleben frei wird, wie die Mathematik aufsteigt als Abstraktion aus dem Zustande, in dem sie zuerst konkret im menschlichen Organismus gearbeitet hat. Und wir gehen dann von dieser Mathematik, weil wir ja den räumlichen und den Zeitverhältnissen nach als Mensch ganz eingespannt sind in das Gesamtdasein, wir gehen dann, nachdem wir freigemacht haben diese Mathematik, mit ihr an die Außenwelt heran und erfassen die Außenwelt mit demjenigen, was bis zum Zahnwechsel in uns gearbeitet hat. Sie sehen, es ist nicht ein Verleugnen der Naturwissenschaft, es ist nur ein Weiterführen der Naturwissenschaft, was da zustande kommt, wenn man recht betrachtet dasjenige, was in Geisteswissenschaft als Gesinnung und als Wille leben soll.

Und nun tragen wir also über die Grenze der sinnlichen Wahrnehmung hinaus dasjenige, was aus uns selber kommt. Werdend betrachten wir den Menschen. Wir betrachten nicht einfach Mathematik auf der einen Seite, sinnliche Erfahrung auf der andern Seite, sondern wir betrachten das Entstehen der Mathematik in dem werdenden Menschen. Und jetzt komme ich allerdings zu dem, was dann im eigentlichen Sinne ins Geisteswissenschaftliche hineinführt. Sehen Sie, wir müssen sagen, es wird zuletzt eine Abstraktion, was wir da aus dem Inneren herausarbeiten, dieses Mathematisierende. Allein es braucht nicht eine Abstraktion für unser Erleben zu bleiben. In unserer Zeit ist allerdings wenig Gelegenheit dazu vorhanden, das Erleben des Mathematischen in einem rechten, wahren Lichte zu sehen. Aber an einer bedeutsamen Stelle unserer abendländischen Zivilisation tritt doch zutage etwas von diesem Spüren eines besonderen Geistes in der Mathematik. Das ist da, wo Novalis, der Dichter Novalis, der ja während seiner akademischen Bildung eine gute mathematische Schulung sich angeeignet hatte, wo er — Sie können es nachlesen in seinen Fragmenten — über Mathematik redet. Er nennt die Mathematik ein großes Gedicht, ein wunderbares, großes Gedicht.

Man muß einmal nachempfunden haben, was einen von dem abstrakten Erfassen der geometrischen Formen treiben kann zu dem bewundernden Empfinden der inneren Harmonie, die in diesem Mathematisieren liegt. Man muß die Möglichkeit gehabt haben, von jener kalten, nüchternen Tätigkeit, die viele sogar an der Mathematik hassen, sich hindurchgerungen zu haben, ich möchte sagen in Novalisscher Weise, zu dem Bewundern der inneren Harmonie und - wenn ich den Ausdruck gebrauchen darf, den Sie ja jetzt hier öfter aus einem ganz andern Gebiete heraus gehört haben — des Melos der Mathematik.

Da mischt sich in das mathematische Erleben etwas Neues hinein. Da mischt sich in das mathematische Erleben, das sonst rein intellektualistisch ist, bildlich gesprochen bloß unseren Kopf interessiert, da mischt sich etwas hinein, was nun den ganzen Menschen in Anspruch nimmt und was im Grunde genommen bei solch jugendlich gebliebenen Geistern wie Novalis nichts anderes ist als ein Fühlen der Tatsache: Was du da als mathematische Harmonien erschaust, womit du die Phänomene des Weltenalls durchwebst, das ist ja im Grunde genommen nichts anderes, als was dich gewoben hat während der ersten Zeit deiner kindlichen Entwickelung hier auf der Erde. - Das heißt konkret fühlen den Zusammenhang des Menschen mit dem Kosmos. Und wenn man sich so durcharbeitet durch ein inneres Erleben, das manche für ein bloßes Phantasiegebilde halten, weil sie es eben nicht in Wirklichkeit durchgemacht haben, wenn man sich so durchringt durch ein solches Erleben, dann bekommt man einen Begriff von dem, was der Geistesforscher erlebt, wenn er sich durch jene innere Entwikkelung, von der ich auch noch Andeutungen geben werde, die Sie im Ganzen geschildert finden in meinem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?», wenn er sich durch eine solche innere Empfindung erhebt zu einer weiteren inneren Erfassung dieses Mathematisierens. Denn dann geht die Seelenfähigkeit, die sich in diesem Mathematisieren äußert, in eine viel umfassendere über. Dann wird sie etwas, was so exakt bleibt wie das mathematische Denken, was aber nun nicht mehr aus der Intellektualität oder aus dem intellektuellen Anschauen allein heraus kommt, sondern was aus dem ganzen Menschen heraus kommt. Dann lernt man auf diesem Wege, aber immer innerlich arbeitend, an einer härteren inneren Arbeit, als diejenige ist, die im Laboratorium oder auf der Sternwarte oder in einer andern wissenschaftlichen Stätte verrichtet wird, dann lernt man dasjenige erkennen, was der Mathematik, diesem einfachen menschlichen Seelengewebe zugrunde liegt, was aber erweitert werden kann und etwas viel Umfassenderes werden kann. Man lernt an der Mathematik erkennen, was Inspiration ist. Man lernt erkennen, worauf der Unterschied beruht zwischen dem, wie Mathematik in uns lebt, und wie die äußere Empirie in uns lebt. Bei der äußeren Empirie haben wir die Sinneseindrücke, die uns die leeren Begriffe mit Inhalt erfüllen. Bei der Inspiration haben wir ein inneres Geistiges, das schon die Mathematik durchzieht, wenn wir diese Mathematik nur richtig erfassen, das lebt, das uns während unserer kindlichen Jahre als Geistiges organisierend durchlebt und durchwebt. Es bleibt das im Menschen. Aber wir erfahren es dadurch, daß wir mathematisieren, auf einem Teilgebiete. Wir lernen auffassen, daß die Art, wie wir uns der Mathematik bemächtigen, auf einer Inspiration beruht, und wir können dann in geistesforscherischer Entwickelung diese Inspiration selbst erleben. Wir bekommen Inhalt auf eine andere Weise als durch äußere Erfahrung in unsere Vorstellungen, in unsere Begriffe hinein. Wir können uns inspirieren mit demjenigen aus der geistigen Welt, das in uns arbeitet während unserer kindlichen Jahre. Das, was da in uns arbeitet während unserer kindlichen Jahre, ist Geist. Aber es steckt im menschlichen Leibe, und es muß durch den menschlichen Leib am Menschen angeschaut werden. Es kann in seiner reinen, freien Gestalt angeschaut werden, wenn man sich durch das inspirierende Vermögen nicht nur erwirbt zu denken in mathematischen Begriffen, sondern anzuschauen dasjenige, was da lebt als ein Reales, indem es uns durchorganisiert bis zu unserem siebenten Jahre. Und es kann — wie gesagt, ich werde von den geisteswissenschaftlichen Methoden noch sprechen - das angeschaut werden, was auf einem Teilgebiete in der Mathematik lebt, was an einem viel weiteren Gebiete uns sich offenbart durch Inspiration. Man erwirbt sich dann nicht nur neue Ergebnisse zu den alten Erkenntniskräften, wenn man zu dieser Inspiration aufrückt, sondern man erwirbt sich dabei die Möglichkeit, neu anzuschauen. Man erwirbt sich neue inspirierende Erkenntnisse. Die Menschheitsentwickelung ist so, daß diese inspirierenden Erkenntniskräfte im Laufe der Zeit etwas zurückgetreten sind, nachdem sie innerhalb der menschlichen Entwickelung schon in einem sehr hohen Maße einmal vorhanden gewesen sind. Wenn man nämlich erkennen gelernt hat, wie entsteht im inneren Menschenwesen dasjenige, was Inspiration ist, was uns Abendländern in einem gewissen Sinne, nur bis zum Intellektualismus verdünnt, in der Mathematik geblieben ist, was aber erweitert werden kann, wenn man dieses vollständig innerlich durchschaut, dann erst versteht man, was gelebt hat in jener Weltanschauung, deren Reste uns eigentlich nur aus dem Oriente herüberkommen, deren Reste für den Abendländer so schwer verständlich sind, was gelebt hat in der Vedantaphilosophie und in den andern Philosophien des Orients. Denn, was war denn eigentlich dasjenige, das in diesen Philosophien des Orients gelebt hat? Es war etwas, was durch Seelenfähigkeiten mathematischer Art zustande gekommen ist. Es war eine Inspiration. Es war nur nicht Mathematik, sondern es war etwas, was nach dem Muster des Mathematisierens innerlich seelisch errungen worden ist. Deshalb möchte ich sagen: Die mathematische Atmosphäre, die ausfließt aus dem, was die Gedanken der Vedantaphilosophie und ähnlicher philosophischer Weltanschauungs-Vorstellungen des alten Orients sind, die man aber eben, um das zu erkennen, erfassen muß von dem Gesichtspunkte aus, den man sich erwirbt, wenn man selber wiederum in die Inspiration einmündet, wenn man dasjenige, was unbewußt im Mathematisieren und in der mathematisierenden Naturwissenschaft getrieben wird, in sich lebendig macht und es auf ein weiteres Gebiet bringen kann, diese mathematische Atmosphäre schwebteGoetbe vor. — Goethe hat bescheiden gestanden, daß er im gewöhnlichen Sinne eine mathematische Kultur nicht habe. Goethe hat seine Beziehung zur Mathematik in sehr interessanten Abhandlungen, die Sie in seinen naturwissenschaftlichen Schriften lesen können in der Aufsatzreihe «Verhältnis zur Mathematik», behandelt. Außerordentlich interessant! Denn trotzdem Goethe bescheiden gesteht, daß er ein eigentliches mathematisches, geschicktes Handhaben der mathematischen Begriffe und Anschauungen nicht hat, sich nicht erworben habe, so verlangt er doch eines, er verlangt einen Phänomenalismus, wie er ihn geübt hat in seinen naturwissenschaftlichen Betrachtungen. Er verlangt zurückzugehen von den sekundären Erscheinungen, die uns zunächst in der Außenwelt entgegentreten, zu dem Urphänomen. Aber was für ein Zurückgehen verlangt er? Er verlangt ein solches Zurückgehen zu den Urphänomenen, wie es der Mathematiker übt, wenn er von den komplizierteren Gebilden des äußeren Anschauens zu dem Axiom zurückgeht. Die Urphänomene sollen die empirischen Axiome, die erfahrbaren Axiome sein.

Und so verlangt Goethe, gerade mit echt mathematischem Geiste, ein inneres Hineintragen der Mathematik in die Phänomene. Und er spricht das aus, indem er sagt: Wir suchen die Urphänomene, indem wir uns bewußt sind, daß wir sie so suchen müssen, daß wir im strengsten Sinne dem Mathematiker nach seiner Gesinnung dafür Rechenschaft ablegen können. — Was Goethe also sucht, das ist ein modifiziertes, ein metamorphosiertes Mathematisieren, ein Hineintragen des Mathematisierens in die Phänomene. Dies verlangt er als eine naturwissenschaftliche Tätigkeit.

Damit hat Goethe einiges Licht gebracht in den einen Pol, der sich sonst so finster ausnimmt, wenn wir den bloßen Materiebegriff statuieren. Wir werden sehen, wie Goethe an diesen einen Pol gekommen ist, wie wir Moderne aber versuchen müssen, an den andern Pol, an den Bewußtseinspol zu kommen. Wir werden auf der andern Seite nun ebenso suchen müssen, wie Seelenfähigkeiten sich tätig erweisen in der menschlichen Wesenheit, wie sie aus der Natur des Menschen herauswachsen und sich äußerlich betätigen. Wir werden das suchen müssen. Wir werden dann sehen, daß gegenübergestellt werden müßte dem, was Goethesche Phänomenologie ist als Erfassung der Außenwelt, ein ebensolches Erfassen der menschlichen Bewußtseinswelt, ein Erfassen, das nun im strengsten Sinne eine solche Rechenschaft ablegen will wie Goethe der Mathematik gegenüber, ein Erfassen, wie ich es in bescheidener Weise versucht habe in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit».

So stehen am Materienpole diejenigen Ergebnisse, die aus dem Goetheanismus stammen, am Bewußtseinspole diejenigen Ergebnisse, die gefunden werden können auf dem methodischen Wege, auf dem ich versuchte, in bescheidener Weise meine «Philosophie der Freiheit» aufzubauen.

Davon wollen wir dann morgen weiter sprechen.

Third Lecture

We have seen that human beings come to two boundaries, so to speak, when they try either to penetrate more deeply into natural phenomena on their own initiative, or when they try to descend more deeply into their own being from the standpoint of their ordinary consciousness in order to discover the true nature of consciousness. Yesterday we already pointed out what happens at one boundary of our knowledge. We saw that human beings awaken to full consciousness through their interaction with the external physical-sensory nature. Human beings would be more or less sleepy beings, beings with sleepy souls, if they could not awaken to external nature. And basically, nothing else happens in the course of the spiritual development of humanity than that, in the acquisition of knowledge about external nature, what happens every morning when we awaken from sleep or from dreaming and become fully conscious of the external world, gradually takes place. In the latter case, we are dealing, as it were, with a moment of awakening. In the course of human evolution, we have been dealing with a gradual awakening, with a kind of spreading out of the moment of awakening.Now we have seen that a kind of inertia of the soul very easily comes into play at this boundary, that where we encounter the spread-out world of phenomena, we do not, as phenomenalism in Goethe's sense wants us to do, remain outside and summarize the phenomena only according to our acquired clear mental images, concepts and ideas, describe them in a systematic and rational way, and so on, but that we roll on for a while behind the phenomena with our concepts and ideas and thereby arrive at the establishment of a world, for example, a world of behind-physical atoms, molecules, and so on, which, when achieved in this way, is essentially an imagined world, a world behind which doubt immediately creeps in, so that we again dissolve what we have first spun as a theoretical web. And we have seen that it is possible, by working through the phenomena themselves, in phenomenalism, to preserve ourselves from such a transgression of the limits of our knowledge of nature in this direction. But we have also had to point out that at this point in our knowledge something emerges that lends itself to use with an immediate necessity for life, namely mathematics and that which can be understood in mechanics without empiricism, i.e., the entire scope of so-called analytical mechanics.

If we consider everything that mathematics encompasses, everything that analytical mechanics encompasses, then we arrive at the most reliable systems of concepts with which we can work our way into phenomena. However, one cannot deny – as I pointed out yesterday that the whole way in which we form mathematical mental images and how we also form mental images of analytical mechanics, that this inner mental work is completely different from that which we perform when we experiment or observe from experience, from sensory experience, and summarize the facts of the experiments or the results of the observations, that is, when we gather external empirical knowledge. In order to achieve complete clarity in these matters, one must reflect deeply, for there is no other way to clarity in this field than that of deep reflection.

What is the difference between gathering empirical knowledge in the Baconian sense and the way in which things are grasped inwardly, as is the case in mathematics and analytical mechanics? For the latter, one can draw a sharp line between what is not grasped in this inner way and what is, if one simply forms a clear concept of the parallelogram of motion and then the parallelogram of forces. That two motions deviating from each other at an angle result in a resulting motion is a theorem of analytical mechanics. That when (a) a force of a certain specified strength acts here and (b) a force of a certain specified strength acts here, a resulting force arises which can also be determined according to this parallelogram, are two completely different concepts. The parallelogram of motion belongs strictly to analytical mechanics, because it can be proven internally like any mathematical theorem, such as the Pythagorean theorem or any other. The existence of the parallelogram of forces can only be a result of experience, of experimentation. We bring into what we process internally something that can only be given to us externally through experience, through empiricism. So here we are already dealing with empirical mechanics, no longer with purely analytical mechanics. You see, a strict line can be drawn between what is still mathematical in the true sense, as mathematics is still understood today, and what leads over into ordinary sensory empiricism.

Now we are faced with this fact of mathematics as such. We grasp mathematical truths. We reduce mathematical phenomena to certain axioms. We then construct the entire fabric of mathematics from these axioms, and we stand, as it were, before an architecture that is visible to the eye but grasped through inner contemplation. And if we are able, through intense reflection, to draw a sharp line between everything that can be experienced externally, we must see something in this mathematical fabric that comes about through a completely different activity of the soul than that through which we experience and comprehend externally with our senses. The fact that we can, I would say, make this distinction precisely through an inner experience is, in essence, of tremendous importance for a satisfactory understanding of the world. We must therefore ask: Where does mathematics come from? And this question is still not being asked sharply enough at present. We do not ask: How is this inner activity of the soul, which we need in mathematics, in the structure of mathematics, in this wonderful architecture, different from the activity of the soul through which we perceive physical and sensory nature through our external senses? And we do not ask and answer this question sufficiently today because it is the tragedy of the materialistic worldview that, while on the one hand it pushes us toward sensory-physical experience, on the other hand, it is driven, without knowing it, into abstract intellectualism, into an abstract being, through which one is removed from a real grasp of the facts of the material world.

What is it that we develop as a capacity by mathematising? Let us ask this question. If we want to answer this question, I believe that one thing must be clear to us. On the one hand, we must take seriously the concept of becoming in human life, which means that we must start from what is highly disciplining in modern natural science. we must educate ourselves in this and, in a sense, take what we have learned through strict methods and scientific discipline in modern natural science and push it beyond natural science itself, so that we ascend to higher realms with the same attitude we have in natural science, but with the methods extended to completely different areas. I therefore do not believe, and I say this quite frankly, that anyone who has not acquired a scientific discipline in the strict sense of the word, who has not learned to research and think in laboratories and through the methods of modern natural science, can arrive at a true spiritual scientific understanding. The humanities have the least reason to underestimate these newer natural sciences. On the contrary, they appreciate them fully. And I myself — if I may make this personal remark — am often criticized by many people for having written, before I actually published anything in the humanities, a number of articles on scientific problems, viewed from the perspective that seemed necessary to me. So, on the one hand, we need to adopt this scientific attitude so that it continues to have an effect when we go beyond the limits of natural knowledge. And secondly, we must take the quality of this natural knowledge, or rather the results of this natural knowledge, very seriously.

You see, if we take the very simple phenomenon of rubbing one body against another and heat appears, we do not say in natural science, in response to such a partial phenomenon, that this heat has arisen out of nothing, or that this heat is simply there—but rather we look for the conditions under which this heat was latent beforehand and then, as it were, came to the fore through the bodies. We move from one phenomenon to another and take becoming seriously. We must do the same when we want to introduce a concept into spiritual science. And so we must first ask ourselves: Is that which is mathematizing always present in human beings, insofar as they live their lives between birth and death? No, it is not always there. Mathematization only awakens. And we can observe very precisely — while remaining within the realm of empirical observation of the external world — how those soul abilities gradually awaken, as it were, from the dark depths of human consciousness, which then express themselves in mathematization and in similar things that are like mathematization, which we will discuss in a moment. This moment, if one can only grasp it precisely and properly, if one treats it in the same way that natural science treats, for example, the phenomenon of the melting point or the boiling point, this moment lies approximately in that period of life when the child changes teeth, when the milk teeth are replaced by the second teeth. One must view such a point in the development of life from the same perspective as one has learned to treat the melting point or boiling point in physics, for example. One must acquire the ability to apply this strict inner discipline to the complexity of human life, which can be acquired from simple physical phenomena by observing them in the spirit of modern science. And when we do that, we see that in human development from birth, or rather from conception, up to this point of tooth replacement, the soul abilities that then mathematize gradually emerge from the organization, but they are not yet there. And just as we say that the heat that is latent in a body and in a certain state comes to the fore, has previously been at work in the body, in the inner structure of the body, so we must be clear that what emerges as the ability to do mathematics, which is particularly strong at the time of the change of teeth but gradually emerges in a certain other sense, has previously been at work within the human organization. And so we gain a remarkable, significant concept of this mathematizing, in the broadest sense, of course. We gain the concept that what we apply as a soul ability after the change of teeth as human beings has previously been working within us in an organizing way. Yes, in children up to about the age of seven there is an inner mathematics, an inner mathematics that is not as abstract as our outer mathematics, but is imbued with power, which, if I may use Plato's expression, cannot only be observed, but is actively alive. Until this point in time, there is something within us that mathematizes, that mathematizes us internally.

If we first ask, I would say, very superficially, about what appears empirically, if we look, so to speak, at the latent mathematics in the body of a young child, then we are led to three things that are inwardly similar to the senses. We will see in the course of these lectures that we can really speak of senses here. Today I just want to hint at this, that we are coming to something that develops inwardly into a faculty of perception that remains unconscious to us only in the first years, just as the eyes and ears develop a life of perception outwardly. And when we look into our inner being, but into the inner being of our organization, not according to the pattern of nebulous mystics, but with full power and insight into this human inner being, then we can find, I would say, three sense-like functions through which an activity is carried out, in a certain sense mathematically, especially in the first years of life. The first is what I would like to call the meaning of life. This meaning of life manifests itself in later life as an overall feeling within us. We feel comfortable or uncomfortable in a certain way. We feel at ease or uneasy, just as we have a faculty of perception through our eyes toward the outside world, so we have a faculty of perception toward the inside. However, this perception is directed toward the entire organism, so to speak, and is therefore dull and dark, but it is there. We will have more to say about this later. For now, I would just like to say, anticipating what will come later, that this meaning of life—if I may use the tautology—is particularly active in the vitality of the child until the change of teeth.

And a second thing we must take into account when we look into the inner life of human beings is what I would like to call the sense of movement. We must form a clear mental image of this sense of movement. When we move our limbs, we are not only aware of this by looking at ourselves externally, but we also have an inner perception of the movement of our limbs. Even when we walk, we are not only aware of our walking because we pass objects and the view of the outside world changes, but we also have an inner perception of the movement of our limbs, of changes within us as we move. We usually do not pay attention to this because the strength of the impressions of the external world prevents us from noticing what is happening internally in parallel with our inner experience and inner perception, just as a small light is extinguished by a large light.

And a third, inward-going sense is the sense of balance.

1. Sense of life

2. Sense of movement

3. Sense of balance

This sense of balance is what enables us to stand in the world in a certain way, not to fall over, to perceive in a certain way how we bring ourselves into harmony with the forces around us. And we perceive this bringing into harmony with the forces around us internally. So we can truly say that we carry these three inner senses within us: the sense of life, the sense of movement, and the sense of balance. They are particularly active in childhood until the teeth are replaced. Their activity diminishes towards the time when the teeth are replaced. But observe — just to pick out one example — the sense of balance. Observe how, at the beginning of its life, the child has nothing that would enable it to grasp the position of balance that it needs for life. Consider how the child gradually learns to crawl on all fours, how it gradually learns to stand and walk through its sense of balance, how it learns to keep itself in balance.

If you now grasp the whole scope of what takes place between conception and the change of teeth, you will see within it the powerful workings of these three inner senses. And when you then see through what is happening there, you will realize that nothing else is taking place in the sense of balance and the sense of movement than a living mathematization. And in order for it to be alive, the sense of life is involved, which animates it. Thus, we see, as it were, a whole mathematics working latently within the human being, which does not die off completely with the change of teeth, but becomes much less apparent in later life. What is at work within the human being through the sense of balance, through the sense of movement, through the sense of life, becomes free. The latent mathematics becomes free, just as latent heat can become free heat. And we then see how that which initially interwove the organism as soul life, how it became soul life, how it becomes free as soul life, how mathematics rises as an abstraction from the state in which it first worked concretely in the human organism. And then we proceed from this mathematics, because as human beings we are completely bound by spatial and temporal conditions to the whole of existence. After we have freed this mathematics, we approach the outer world with it and grasp the outer world with what has been working within us since we were children. You see, it is not a denial of natural science, it is only a continuation of natural science that comes about when one correctly considers what should live in spiritual science as attitude and will.

And now we carry that which comes from ourselves beyond the limits of sensory perception. We consider the human being as becoming. We do not simply consider mathematics on the one hand and sensory experience on the other, but we consider the emergence of mathematics in the developing human being. And now I come to what actually leads us into spiritual science. You see, we must say that what we work out from within, this mathematizing, ultimately becomes an abstraction. But it does not need to remain an abstraction for our experience. In our time, however, there is little opportunity to see the experience of mathematics in a true light. But at a significant point in our Western civilization, something of this sense of a special spirit in mathematics does come to light. This is where Novalis, the poet Novalis, who had acquired a good mathematical education during his academic training, talks about mathematics—you can read about it in his fragments. He calls mathematics a great poem, a wonderful, great poem.