Anthroposophy and Science

GA 324

17 March 1921, Stuttgart

Lecture II

I pointed out yesterday in my introductory lecture that we can observe a transition from the ordinary knowledge of the world around us to mathematical knowledge, and that this is the beginning of a path of knowledge. This path when continued will lead to an understanding of the spiritual scientific method, as we mean it here, and ultimately to acceptance of it. It will be my special effort in these lectures to characterize the spiritual scientific method in such a way as to completely justify it. To accomplish this task will take the remaining seven lectures.

Today, once again, I would like to consider in greater depth the first stage. I would like to place before you today something which as normal scientific thinking appears here and there in fragments. As these fragments are not always found in the same place and are not seen as a whole, we have the situation that it is not possible to rise in a methodical way from a science that is free of mathematics to one that includes it. We will also have difficultly following in an entirely methodical way the transition from a mathematical penetration of the objective world to a spiritual-scientific penetration into reality. I shall also, as I have already mentioned, try to reach this last phase in a methodical way. We will start today by observing the human being as he experiences himself when he looks at the outer world.

You will know from my lectures, also my book Riddles of the Soul,1See The Case for Anthroposophy, Anthroposophic Press. that one cannot reach a comprehensive observation of man without splitting the entire human organization into three distinctly different members. Naturally we have eventually to deal with the complete human being. This complete man is however a most complicated organism and its members have a certain independence. Finally we will see how what is contained independently in these members combines into a whole.

First we have to look at what I have named in Riddles of the Soul as the nerve-sense man: The member of the human organism that has its primary expression in the head, although from there it extends over the entire organism. Despite this extension we can clearly differentiate this member from the rest of the organism. This physical member is the mediator of our conceptual life. As human beings we make mental pictures and we are able to take the life of these mental pictures to ourselves through our sense organs. From the senses it flows toward our inner organism.

The way we are connected with our life of feeling is similar to the way our mental pictures are related to our nervous system. The present-day psychological approach to these things is quite inexact. Our feeling life is not directly connected to our nerve-sense system, only indirectly. It is directly connected to what we call the rhythmic system in the human organism, consisting mainly of breathing, pulse, and blood circulation. The mistaken idea that the life of feeling, as part of the soul life, is directly connected to our nervous system originates from the fact that what we experience as feeling is always accompanied by mental pictures. The physical expression of this is that the rhythmic system is connected throughout the organism with the nerve-sense system. The fact that our life of feeling is always accompanied by a mental picture of some kind is related organically to the fact that the rhythmic system works back onto the nervous system. This can give the appearance that the life of feeling is directly connected to the nerve-sense system. I have pointed out in Riddles of the Soul that if one studies what occurs in us when we listen to music, one can see the relationship correctly between feeling and the forming of mental pictures.

Besides these two systems, the nerve-sense system which provides the mental image, and the rhythmic System which mediates the life of feeling, we have the metabolic system. Every function of the human organism is contained in these three systems. The metabolic system is the expression of the will, and the real connection between willing and the human organism will become clear only if you study how a metabolic transformative action comes about in us when there is an act of will or even an impulse of will. Every metabolic activity is consciously or unconsciously the physical basis of some act of will or impulse of will. Our capacity for movement is also connected with our will activity and therefore is connected with some kind of metabolic activity. One must be clear about the fact that when we complete a movement in space, this is a primitive activity of the will. To use a saying of Goethe, the “ur-phenomenal” activity of the will can be seen as expressed by the physical transformations that occur in the organism. And, as in the case of feeling, the will activities are indirectly connected with the nerve-sense system through our following our will activities with mental pictures. So we can say, to start with, that our soul life and also our physical life can be divided in three ways organically as well as into three soul aspects.

Let us try today to look at man from a certain point of view so that we may see how these three members of our physical organism and our soul organization relate to one another. We must also go into some detail to achieve our task of showing that spiritual science is a continuation of the familiar scientific way of considering things. First of all, let us consider what I have named the nerve-sense organism. This nerve-sense organism is contained mainly in the head, as I have already mentioned, but from there it extends over the rest of the organism, in a certain way impregnating it. This is not obvious if one looks at just the outer form of a human being, but it does in fact extend inwardly through the whole organism. Take the sense of warmth as an example, which extends over the entire organism. This can be seen as a part of our nerve-sense organization that for the most part is concentrated in the head, in the life of the senses, and yet is extended over the whole organism, making the whole human being into a kind of head in regard to this particular sense of warmth.

For most people it is distasteful nowadays to try to understand this kind of problem. Because we have become so used to an outer way of considering things, the three members of the human organism are considered spatially, as separate from one another. There is a professor of anatomy who takes this view, who has asserted that anthroposophy separates the human organism spatially into head system, chest system, and abdominal system. This is clearly erroneous. It is of course not what we have said; we wish to approach these things precisely, not in dilettante fashion. One must know these things correctly, especially if one also wants to understand how three elements flow into one another and compose the threefold social organism.

To begin with it is empirically evident that it is the head organization that has most to do with cognition, at least mathematical cognition, as it approaches man in the outer world. In relation to this head organizatiion we can now empirically establish that what we can call “dimensionality” confronts us initially as a kind of intimation. You will see best what I mean if we consider the three modes of human activity.

The first of these I would like to call the total act of seeing, observation of the world with our own two eyes. Secondly, I would mention man's arms and hands. Even though they are attached to man's trunk and are therefore in a certain way connected with the metabolic system, they also have an inner relationship to the rhythmic system. Through their attachment near the rhythmic system, they are influenced by the life and functioning of this system. The fact that they are located beside the rhythmic system, which is more hidden, allows them to reveal the nature of what would normally be hidden. Please listen carefully; I repeat: The arms and hands, because of their specific location on the human body and through their life functions, can be seen as belonging to the rhythmic system. The most obvious demonstration of this connection is the way they are used freely in gestures to express feelings. When they are used in this way, they are lifted to a higher function than serving merely the body. In the case of animals, the corresponding members, the legs, are used only to serve the body, but in human beings the arms are freed for a higher function. Through the fact that they are used for gestures in connection with speech, they have the higher function of making the invisible aspects of speech visible.

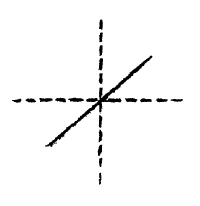

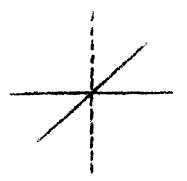

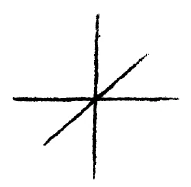

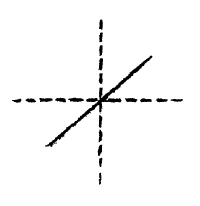

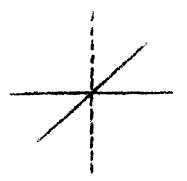

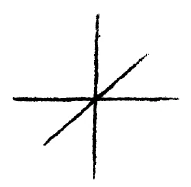

The third mode is the activity of walking, an activity primarily of the limb system. Let us consider the activities of seeing, arm movement, and walking from a scientific point of view. In general, what you see with both eyes presents itself to you in two dimensions and these dimensions are independent of any mental activity. I can represent these two dimensions by these perpendicular coordinates. I will draw these as dotted lines for the purpose of later references I wish to make. With these dotted lines representing two dimensions, I want to express the fact that our mental activity of comprehension is not really involved when we look only at these two dimensions.

The third dimension is in sharp contrast to this. The third dimension of depth does not stand ready-made before our soul independent of any mental activity. It confronts us as something we undergo as an inner operation of the mind when we supplement what we normally see as the surface of things with the depth dimension and thus obtain a three-dimensional body. Roughly speaking, what we actually do in this case is not brought to consciousness. But when we enter into the activity more precisely, we see that one experiences the depth dimension in a different way from width and height dimensions. We can become aware, for instance, how we are able to guess how distant something is from us. In ordinary observation something is added to the mere observation of the eyes when we progress from a surface-picture consciousness to a full-bodied three-dimensional consciousness. So long as we remain within our consciousness, we cannot say how height perception and width perception are achieved. We simply have to accept the height and width dimensions; for the activity of seeing they are simply given. This is not true of the depth dimension. For this reason I will draw it in perspective; I will draw a solid line to represent the difference. In this third dimension of depth, we are able to have the act of perceiving enter our consciousness in a slightly conscious way. Thus we recognize when we examine the act of seeing, that the height and width dimensions are given to us purely in thought; that is, if we penetrate the act of seeing with our thoughts. The depth dimension, however, is based an an activation of consciousness, a kind of half-conscious mental operation. Therefore, what you may already have heard as the physiological and anatomical interpretation of the total act of seeing must be accepted only in reference to the physical components of the act of seeing, to that aspect which does not involve an operation of the mind; only the perception of surface can be attributed to the act of seeing. In contrast, when considering the depth dimension, it is not sufficient to merely consider the activity of the corpora quadrigemina, the organ in the human body upon which the visualizing activity of the eyes depends, the bodily aspect of seeing—here the cerebrum must serve a mediating function, the cerebrum being that part of the brain to which are attributed the anatomical-physiological aspects of the volitional operation of the intellect.

Thus we can grasp this depth dimension when we examine it carefully, using both analytical and synthetic means. The matter of depth perception belongs into the realm of what I would like to call “conscious activation through the human head.”

When we turn our attention from the act of seeing to that activity which may be seen externally through the movement of the arms and hands, we immerse ourselves in an element that is very difficult to grasp consciously. Even so, we can follow what takes place in our life of feeling when we gesture with our arms and hands, which are free for this kind of activity, and we can become aware of the way this action is related to depth perception with our two eyes. What is it really that depth perception mediates to us? It is the exact position of the left and the right eye. It is the convergence of the left axis and right axis of sight. The mental judgment of the distance of some object from us depends upon the distance at which the lines of sight cross each other. Very little of this convergence activity of the eyes lying at the basis of the judgment of depth is outwardly perceptible.

When we turn to the activity of our arms and hands, we find we are able to distinguish more exactly, with little effort of consciousness, what is happening inwardly when we move our arms in the horizontal plane, in the dimension of right-left, in the width dimension. If we look carefully, our judgment in relation to the width dimension is connected with the feeling we have when we consciously move our arms in a horizontal gesture expressing how wide something is. We have a feeling experience of what we call symmetry. This experience takes place particularly in the width dimension, through the feeling that is mediated to us through our left and right arm movements. Through the corresponding movements of our left and right arms we can actually feel our own symmetry. Our grasping in feeling of the width dimension is translated for us chiefly through the medium of symmetry into mental pictures, and we then also evaluate symmetry in our mental life. But we must not overlook the fact that this judging of the symmetry of the width dimension is something secondary: If we only looked at the symmetry without having the accompanying feelings that correspond to the symmetrical aspects of left and right, our experience would be pale, dry and wanting in its full reality. You can understand all that symmetry shows us if you can feel the symmetry. But you can really only feel the symmetry through the delicate process of becoming conscious of the fact that the movements of the left and right arms belong together, and in the same way the movements of the hands belong together. What we experience in feeling thus supports everything we can experience in relation to the width dimension.

But also what we have called the depth dimension in relation to the act of seeing enters our consciousness through something to be found in the activity of our arms. The way the axes of our vision intersect is similar to the way our arms can intersect. When our arms intersect, we have a certain equivalent to the act of seeing. When we cross our arms, first close to us and then farther away, if we follow the points of intersection we can get a sense of depth dimension by trying to experience what is going on in our arms. In these moments we don't experience the width dimension as fully as we do—with no effort on our part—in the act of seeing. But if I would represent symbolically what is expressed in relation to the dimensions by the arms and hands, I would have to sketch the width dimension and the depth dimension as full lines and the height dimension as a dotted line. That is all that I can experience through my arms. The height dimension remains unconscious to us when we make gestures, because we connect our gestures consciously with a surface which is made up of depth and width dimensions.

When does the third dimension show itself in a distinct, conscious way? Actually, it only appears to our consciousness in the act of walking. When we move from one place to another, then the line which is this third, vertical dimension changes continually, and although our consciousness of this third dimension while we walk is almost imperceptible, we must not overlook it. In fact, the half-conscious intellectual awareness we can experience is related to this height dimension.

Therefore, when we examine the act of seeing, which obviously belongs to the head organization, we realize that in the act of seeing there is given ready-made a two-dimensional activity, and in addition we must establish an activity that creates the third dimension—depth. In the action which we have described as representative of the rhythmic system, namely, the free movement of the arms and hands, we can have an inner experience of two spatial dimensions. The third spatial dimension—height—is given to our consciousness in the same way that width and breadth are given for the head organization in the act of seeing. Only in the metabolic-limb system (the connection between these two is only recognized when we study the metabolic activity in the act of walking) is everything open to our consciousness that gives us the full measure of three dimensions.

If you consider the following, you will have something extraordinarily important. The only content of our fully alert consciousness is the life of mental pictures. In contrast to this, our life of feeling does not come into our consciousness with the same clarity. As we shall see later, our feelings by themselves have no greater intensity in our consciousness than our dreams. Dreams are rendered from the clear content of daily life, from the fully alert life of mental pictures; in this way they become distinct mental pictures in our consciousness. In the same way, our feelings in daily life are continually accompanied by the mental pictures representing them during our waking hours. In this way our feelings, which otherwise only possess the intensity of dream life, are brought to the distinct, fully conscious life of mental pictures.

The will-movements remain completely in the subconscious. How do we know anything of the will? Basically, in our everyday consciousness we know nothing of the real nature of the will. This is made clear in the psychology of Theodor Ziehen, for instance, who in his Physiological Psychology speaks only of the life of mental pictures or the representational life of the mind. He says: As psychologists we can only follow the life of mental images, but we find certain mental images to be tinged with feeling. The fact that the life of feeling, as I explained to you just now, is bound up with the rhythmic system and only shines up into the life of mental pictures, this is unknown to Theodor Ziehen. In his view, feelings are only an aspect of the life of mental pictures. This psychologist simply has no insight into the actual organization of the human being, which I have now to describe to you.

Because feelings are bound up with the rhythmic system, they remain in the half-conscious realm of dreaming. And the will activity remains completely unconscious. That's the reason why the average psychologist does not write about it. Just read Theodor Ziehen's strange explanations concerning the activity of the will, and you will see that its real nature is completely missed by such psychologists.

When we observe the result of an act of will, this is only something we are able to look at externally. We do not know what has happened inwardly when a will impulse moves our arm. We only see the arm move; that is, we observe the outer happening afterward. Thus we accompany the manifestations of our will with mental images; they are mediated organically through the metabolic system and the limb system related to it. So it is only in part of the human organism, in the metabolic system—which is the bodily aspect of the soul's will activity—that we experience the reality of all three dimensions of space. In our ordinary process of knowing the reality of the three dimensions cannot be grasped. It cannot be grasped, as we will see, until we are able to look with the same clarity into our will activity as we normally do into our mental activity. It cannot come about in our ordinary way of knowing but only with spiritual-scientific knowledge. It is through the activation of the entire man, of the entire limb-and-metabolic system, that our subconscious experience of the three dimensions comes about. What happens is that what is contained in the metabolic-limb system is lifted into the rhythmic system. There it is experienced in its two-dimensional aspect, not in its total reality. When experienced in two dimensions, the height dimension has already become abstract. Only in the subconscious do we normally experience the height dimension.

You can see how reality becomes an abstraction in the human organization through the human activity itself. In the working of the human organization, the height or vertical dimension already becomes an abstraction, appearing as a mere line, a mere thought in the region of the rhythmic system. Following this up into the nerve-sense system, what occurs? Both height and width become abstraction. We can no longer experience them; they can only be thought by the intellect as we approach the subject afterward. So in the head, the region of our ordinary knowledge, we only have the possibility of expressing the two dimensions abstractly. It is only the depth dimension for which we still have a faint consciousness in the head. So you can see, it is only due to a delicate perception of the depth dimension that we are able to know anything at all in our normal consciousness of the spatial dimensions. Please now consider: With our present constitution, what if depth perception should become equally abstract? Then we would be left with just three abstract lines—and it would never even occur to us to search for the realities represented by those abstract lines.

In this way I have pointed you toward reality. In Kantianism this reality appears in an unreal form. Kantianism speaks of the three dimensions being contained a priori in the human organization, and of the human organization transposing its subjective experience out into space. How is it that Kant came to this one-sided view? He arrived at this because he did not know that what is brought into consciousness in the delicate experience of the depth dimension, and otherwise abstractly, is experienced in its reality in our subconscious. As it is pushed up into consciousness, it is made into an abstraction, with only a small remainder in the case of depth dimension. We experience the reality of the three dimensions through our individual human organization. The reality is present in actuality in the realm of the will, and physiologically in the metabolic-limb system. Initially in this system we are unconscious of reality in our ordinary mind, but we become conscious of it, at first in the thought abstractions of mathematical-geometrical space.

With this subject of the three dimensions I wished to give an example of the ways and means by which spiritual science can penetrate human activity. We don't have to remain on the abstract level—where, for example, Kant regards space and time as a priori—but we can progress to a discovery of the concrete aspects of the reality of the human being. I wanted to use this particular example of the actual meaning of space because it will be useful in the future in leading us to an exact understanding of the mathematical facts from all sides. We will speak further of this tomorrow.

Zweiter Vortrag

Ich habe schon gestern in dem einleitenden Vortrage darauf hingewiesen, wie bei der Betrachtung des Überganges menschlicher Erkenntnis von dem gewöhnlichen Erkennen der Außenwelt zum mathematischen Erkennen sich die erste Etappe jenes Weges ergibt, der dann weiter verfolgt dazu führt, auch die geisteswissenschaftliche Methode, wie sie hier gemeint ist, zu durchschauen und anzuerkennen. Es wird ja gerade in diesen Vorträgen mein Bestreben sein, die geisteswissenschaftliche Methode zu charakterisieren und zu rechtfertigen. Das kann im Grunde genommen erst als Ergebnis desjenigen zutage treten, was ich in diesen sieben Vorträgen auseinanderzusetzen habe.

Heute möchte ich noch einmal etwas genauer eingehen auf die erste Etappe. Ich möchte vor Sie eine Betrachtung hinstellen, wie sie heute noch in dem wissenschaftlichen Denken vielleicht da oder dort in Fragmenten wohl zutage tritt, wie sie aber zusammenfassend nicht vorhanden ist, und weil sie zusammenfassend nicht vorhanden ist, so liegt auch das vor, daß man dann nicht in der Lage ist, sich methodisch zu erheben von der Umwandlung noch mathematikfreier Wissenschaft zu mathematischer Wissenschaft, von dieser Umwandlung dann zu der anderen, die wir als ganz sachgemäß aus ihr hervorgehend erkennen werden, vom mathematischen Durchdringen der Objektivität zu einem geisteswissenschaftlichen Durchdringen des wirklichen Seins. Ich werde, wie schon angedeutet, ganz stufenweise und methodisch versuchen, diese letzte Etappe durch unsere Betrachtung zu erreichen.

Dazu werden wir heute ausgehen von einer Betrachtung des Menschen, so wie er sich selber erlebt im Anschauen, im Beobachten der äußeren Welt. Es wird Ihnen aus Vorträgen, die hier gehalten worden sind, oder wenigstens aus Seminarreferaten, dann aber aus der Lektüre meines Buches «Von Seelenrätseln» bekannt sein, daß man zu einer vollständigen und zureichenden Betrachtung des Menschen doch nur dadurch kommt, daß man einsieht, wie die gesamtmenschliche Organisation sich für ihn in drei deutlich voneinander unterschiedene Glieder spaltet. Wir haben es gewiß zu tun mit dem einheitlichen Menschen. Aber dieser einheitliche Mensch wirkt gerade als der komplizierteste Organismus, der uns zunächst bekannt ist, dadurch, daß er gegliedert ist, ich möchte sagen, in drei Teilorganisationen, die eine gewisse Selbständigkeit in sich haben, die aber dann gerade dadurch, daß sie alles das, was in ihnen liegt, durch diese Selbständigkeit ausbilden und dann wiederum zu einem Ganzen zusammenwirkend gestalten, die konkrete Einheitlichkeit der menschlichen Organisation zustande bringen. Wir haben es da zu tun zunächst mit dem, was ich in meinem Buche «Von Seelenrätseln» genannt habe den Nerven-Sinnesmenschen, dasjenige Glied der menschlichen Organisation, das ja zunächst im menschlichen Haupte seinen am meisten adäquaten Ausdruck hat, das aber von da aus sich wiederum erstreckt über die ganze menschliche Organisation. Allein man darf deswegen, weil solch ein Glied der menschlichen Organisation doch wiederum die Gesamtorganisation durchdringt, nicht übersehen, daß solch ein selbständiges Glied vorhanden ist. Wir können einmal ganz genau unterscheiden von der übrigen menschlichen Organisation — und wir werden auch darüber des weiteren noch zu sprechen haben - den Nerven-Sinnesmenschen, alles dasjenige, was der Vermittler ist unseres Vorstellungslebens. Wir sind vorstellende Menschen dadurch, daß wir imstande sind, dasjenige, was vorstellendes Leben ist, uns selber zu vermitteln durch dasjenige Organ, das man zusammenfassen kann als die Sinne und das von den Sinnen nach der inneren Organisation sich hinziehende Nervensystem.

Nicht in demselben Sinne wie durch das Vorstellungsleben hängen wir mit diesem Nervensystem zusammen durch unser Gefühlsleben. Nur die ungenaue psychologische Betrachtungsweise der neuesten Zeit läßt das übersehen. Das Gefühlsleben ist nicht unmittelbar geknüpft an das Nerven-Sinnessystem, sondern nur mittelbar. Das Gefühlsleben ist unmittelbar geknüpft an alles dasjenige, was wir in der menschlichen Organisation nennen können das rhythmische System, das sich am meisten auslebt in Atmung, in Pulsschlag und in der Blutzirkulation. Die Täuschung, daß unser Gefühlsleben als ein Teil unseres Seelenlebens auch unmittelbar zusammenhänge mit dem Nerven-Sinnessystem, kommt daher, daß wir ja alles dasjenige, was sich in uns als Menschen gefühlsmäßig abspielt, fortwährend mit Vorstellungen begleiten. Und so wie unser Gefühlsleben seelisch fortwährend von Vorstellungen begleitet ist, so ist auch organisch unser rhythmisches System, das sich ja über den ganzen Organismus erstreckt, in Verbindung mit unserem Nerven-Sinnessystem. Es ist eine ähnliche Beziehung zwischen dem rhythmischen System und dem Nerven-Sinnessystem im Körper, wie in der Seele die Beziehung ist zwischen dem Gefühlsleben und dem Vorstellungsleben. Dadurch allein aber drückt sich nun mittelbar unser Gefühlsleben auch durch das Nerven-Sinnessystem aus, daß eben erst in unserem Organismus vermittelt wird das Erleben des Fühlens, das zu seinem Werkzeug im Organismus das rhythmische System hat, daß dieses nun zurückwirkt auf das Nerven-Sinnessystem und dadurch der Schein entsteht, als ob auch unmittelbar das Gefühlsleben mit dem Nerven-Sinnessystem zusammenhinge. Ich habe in meinem Buche «Von Seelenrätseln» besonders darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß man zum Beispiel beim Studieren desjenigen, was im Menschen beim musikalischen Auffassen vorgeht, gerade auf eine leichte Art darauf kommen kann, wie dieses eben charakterisierte Verhältnis im Menschen besteht.

Außer diesen beiden Systemen, dem Nerven-Sinnessystem, das das Vorstellungsleben, dem rhythmischen System, das das Gefühlsleben vermittelt, haben wir dann das Stoffwechselsystem. Und in den drei Systemen, Nerven-Sinnessystem, rhythmisches System, Stoffwechselsystem, haben wir restlos in bezug auf alles Funktionelle den menschlichen Organismus gegeben. Unmittelbar enspricht das Stoffwechselsystem dem Seelenleben des Wollens, und ein wirkliches Studium des Zusammenhangs zwischen Wollen und menschlichem Organismus wird erst zustande kommen, wenn man die Sache so verfolgen wird, daß man untersuchen wird, wie der Stoffwechselumsatz ist, wenn ein Willensakt oder auch nur ein Willensimpuls sich vollzieht. Jeder Stoffwechselumsatz ist eigentlich bewußt oder unbewußt die physische Grundlage einer Willenstatsache oder eines Willensimpulses. Es hängen zugleich mit dem Stoffwechsel zusammen unsere Bewegungen, und wegen dieser Tatsache, daß mit unserem Stoffwechsel unsere Bewegungen zusammenhängen, hängt auch unsere Beweglichkeit seelisch wiederum mit der Willensbetätigung zusammen. Man muß sich klar sein darüber, daß, indem wir eine Bewegung im Raume ausführen, dieses, ich möchte sagen, die primitivste Willensbetätigung ist. Aber — um dieses Goethesche Wort zu gebrauchen - bei einer urphänomenalen Willensbetätigung ist eben jener Stoffwechselumsatz, der einer Bewegung in uns zugrunde liegt, als solcher physischer Ausdruck für das Seelische einer Willensbetätigung. Und nur dadurch, daß wir wiederum vorstellungsgemäß unsere Willensbetätigungen verfolgen, hängen diese Willensbetätigungen nun auch mittelbar zusammen mit dem NervenSinnessystem. So können wir, ich will das zunächst vorbereitend sagen, das seelische Leben und auch das physische Leben des Menschen in einer Art von Gliederung in drei selbständige organische und seelische Glieder betrachten.

Wir wollen nun heute einmal versuchen, wie mit Bezug auf den beobachtenden Menschen von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkt aus sich diese drei Glieder der menschlichen physischen und seelischen Organisation verhalten. Da möchte ich vor allen Dingen dasjenige betrachtend vor Sie hinstellen, was die Anschauung der Dimensionalität des Raumes ist. Wir müssen schon auf diese, ich möchte sagen, exakteren, minuziöseren Dinge eingehen, weil ja gerade diese Vorträge dazu dienen wollen, geisteswissenschaftliche Betrachtung als Fortsetzung der gewöhnlichen wissenschaftlichen Betrachtung exakt zu zeigen. Wir betrachten da zunächst dasjenige, was ich Nerven-Sinnesorganismus genannt habe. Dieser Nerven-Sinnesorganismus ist ja hauptsächlich, wie ich schon gesagt habe, in der Hauptesorganisation, in der Kopforganisation des Menschen enthalten, und von der Kopforganisation, die in der Hauptsache den Nerven-Sinnesmenschen enthält, dehnt sich dann das Nerven-Sinnesleben über den übrigen menschlichen Organismus aus, diesen gewissermaßen imprägnierend. Man könnte sagen, für eine nun nicht äußerlich genommene Betrachtung des Menschen setzt sich der Kopf durch den ganzen Menschen fort. Wenn wir zum Beispiel innerhalb der Sinnesorganisation die Wärmeperzeption über den ganzen Organismus ausgedehnt haben, so bedeutet das nichts anderes, als daß diejenige Organisationsart, die hauptsächlich im Kopfe für den wichtigsten Teil des Sinnenlebens gelegen ist, für dieses Spezielle der Wärmeempfindung sich nun über den ganzen menschlichen Organismus ausdehnt, so daß in gewisser Beziehung mit Bezug auf die Wärmeperzeption der ganze Mensch Kopf ist.

Sehen Sie, diese Auseinandersetzung werden einem heutzutage außerordentlich übelgenommen. Denn man hat sich so sehr an äußerliche Betrachtungsweisen gewöhnt, daß man meint, man müsse, wenn von drei Gliedern des menschlichen Organismus geredet wird, diese so ganz räumlich gesondert nebeneinanderstellen können, und ein Professor der Anatomie, der nach solcher räumlichen Sonderung strebte, hat dann den Geschmack gehabt, zu sagen, es würde geteilt durch Anthroposophie der Mensch in ein Kopfsystem, in ein Brustsystem und in ein Bauchsystem. Nun ja, mit solchen Dingen kann man unsachlich Anthroposophie treffen. Aber darum handelt es sich ja gewiß nicht, sondern es handelt sich darum, sachgemäß auf diese Dinge wirklich einzugehen und wissen zu lernen, daß in der Wirklichkeit die Dinge nicht so räumlich gesondert sind, wie man es sich heute vielfach dilettantisch vorstellt, sondern daß sie ineinandergreifen, ineinanderfließen — was ja insbesondere auch beachtet werden muß, wenn man richtig verstehen will das Ineinanderwirken der drei Glieder des dreigliedrigen sozialen Organismus.

Nun, die Kopforganisation ist ja ganz gewiß diejenige Organisation, die, zunächst ergibt das der rein empirische Tatbestand, am meisten mit dem Erkennen, wenigstens mit dem mathematischen Erkennen, das zunächst in der äußeren Welt an den Menschen herantritt, zu tun hat. Bei dieser Kopforganisation können wir nun rein empirisch konstatieren, daß dasjenige, was wir Dimensionalität nennen können, uns, ich möchte sagen, zunächst nur in einem Anflug entgegentritt. Wir werden das, um was es sich hier handelt, am besten einsehen, wenn wir drei Betätigungsweisen des Menschen ins Auge fassen; die erste diejenige, die ich nennen möchte den totalen Sehakt, das Sehen, das Beobachten der Welt mit den Augen. Aber, wie Sie gleich sehen werden, es handelt sich um den totalen Sehakt, nämlich um das Beobachten der äußeren Objekte mit unseren zwei Augen. Zweitens haben die Arme und Hände des Menschen, obzwar sie am Rumpfe befestigt sind, und obzwar sie in einer gewissen Beziehung durchaus zum Gliedmaßensystem gehören, doch auch wiederum eine innige Beziehung zum rhythmischen System. Sie sind durch ihr besonderes Ansetzen in der Nähe des rhythmischen Systems gewissermaßen durch das Leben, durch das Funktionelle am Menschen umgestaltet. Sie sind angepaßt als Gliedmaßen demjenigen Leben, das wir das rhythmische Leben nennen können, und weil sie nach außen gelegen sind, die Arme und die Hände, so können wir uns an ihnen manches verdeutlichen, was wir uns zunächst an den inneren Gliedern des rhythmischen Systems nicht so leicht dürften verdeutlichen können. Also wohlgemerkt, es handelt sich darum, daß wir in Armen und Händen wohl Gliedmaßen haben, daß aber diese Gliedmaßen wegen ihrer besonderen Stellung am menschlichen Organismus, ich möchte sagen, durch das Leben, durch das Funtionelle angepaßt sind dem Rhythmischen. Sie können dieses Rhythmische in den Armen, in den Händen verfolgen, wenn Sie sich sagen, wie stark dasjenige, was wir im Gefühl haben, also in demjenigen, was mit dem rhythmischen System zusammenhängt, in der Gebärde, in der freien Beweglichkeit der Arme und der Hände zum Ausdruck kommt. Es sind eben im Menschenleben diese Gliedmaßen ganz und gar, möchte ich sagen, um eine Stufe des Erlebens heraufgehoben. . Sie sind veranlagt als Gliedmaßen, sind aber durchaus nicht so wie beim Tiere in den Dienst gestellt, in dem eben die Gliedmaßen stehen, sondern sind befreit von dem Dienst des Gliedmaßenlebens und werden, ich möchte sagen, wie in einer unsichtbaren Sprache zu einem Ausdruck des menschlichen Gefühlslebens, sind also angepaßt dem rhythmischen System. Als dritte Funktion möchte ich dann vor Sie hinstellen dasjenige, was wir als das Gehen betrachten können, also eine im eminentesten Sinne durch das Gliedmaßensystem des Menschen vor sich gehende Betätigung.

Sehen, Armbewegung und Gehen, wir wollen sie einmal nun wirklich wissenschaftlich vor die Seele führen. Das Sehen mit den zwei Augen: Wenn man es betrachtet in seiner TIotalität, so kommt man darauf, daß zunächst, völlig von aller Verstandestätigkeit unabhängig, das Gesehene sich uns darstellt in zwei Dimensionen. Ich kann, wenn ich das Gesehene Ihnen darstellen will seiner Dimensionalität nach, einfach die zwei Dimensionen hier auf die Tafel zeichnen (siehe Zeichnung) als zwei aufeinander senkrecht stehende Koordinaten. Ich möchte es so zeichnen, daß das mit späteren Ableitungen stimmt, indem ich die beiden Linien nur punktiere. Ich möchte in dieser Tatsache, daß ich die beiden Linien nur punktiere, zum Ausdruck bringen, daß eigentlich in unser Verstandesbewußtsein dieses Zweidimensionale gar nicht aufgenommen wird, wenn wir sehen.

Dagegen liegt es anders mit der dritten Dimension. Die dritte Dimension, wir können sie nennen die Tiefendimension, also die Tiefe von unseren Augen aus gesehen, diejenige Dimension, die in der Richtung von rückwärts nach vorne liegt, steht nicht in gleichem Sinne fertig vor unserer Seele, ganz unabhängig etwa von unserem Verstand. Sie steht vor uns als dasjenige, was wir als innere Verstandesoperation vollziehen, wenn wir die sonst flächenhaft gesehenen Dinge zum Körperhaften ergänzen durch die Tiefendimension. Was wir da ausführen, entzieht sich in einer gröberen Weise allerdings unserer bewußten Tätigkeit. Allein, wenn man in feinerer Art auf die bewußte Tätigkeit eingeht, so wird man durchaus darauf kommen, daß man diese Tiefendimension in einer anderen Weise erlebt als die beiden anderen, die ich nennen will die Höhen- und die Breitendimension. Man kann schon gewahr werden, wie man in einer gewissen Weise abschätzt in bezug auf diese Tiefendimension, wie weit irgend etwas von uns entfernt ist. Es kommt zu der gewöhnlichen Anschauung, zu der Augenanschauung etwas hinzu, wenn wir die Flächendimensionalität ergänzen im Bewußtsein zur körperhaften Dimensionalität, so daß wir sagen können: Solange wir innerhalb unseres Bewußtseins stehenbleiben, können wir nicht sagen, wie dasjenige zustande kommt, was Höhendimension ist und Breitendimension. Wir müssen Höhendimension und Breitendimension einfach hinnehmen. Sie sind in der Sehanschauung einfach gegeben. Nicht so die Tiefendimension, also die dritte Dimension. Ich zeichne sie deshalb hier perspektivisch als Vollinie ein, womit ich andeuten will, daß diese Vollinie als Tiefendimension schon auf einer ins Bewußtsein wenigstens leise hereinspielenden Betätigung, auf einer bewußten, sagen wir, halbbewußten Betätigung beruht, so daß wir sagen können: Wenn wir den Sehakt ins Auge fassen, so sind uns zunächst rein gedanklich, nämlich erst wenn wir den Sehakt gedanklich durchdringen, die Höhen- und die Breitendimensionen gegeben. Die Tiefendimension beruht schon auf einer Betätigung des Bewußtseins, auf einer Betätigung der halbbewußten Verstandesoperation. Daher muß auch, wie Sie ja vielleicht schon gehört haben, die anatomisch-physiologische Ausdeutung des totalen Sehaktes so verfahren, daß sie dem Sehen eigentlich nur zuschreibt — also demjenigen, was Sehen ist noch ohne Verstandestätigkeit — das Zustandekommen der gesehenen Flächenausdehnung. Dagegen muß sie zuschreiben schon der Großhirntätigkeit, also nicht mehr der Vierhügeltätigkeit, diesem Organ im menschlichen Körper, von welchem die veranschaulichende Augenbetätigung abhängt, das körperliche Verhalten beim Sehen, sondern es muß bezüglich der Tiefendimension dem Großhirn, dem Vermittler auch der willensmäßigen Verstandesoperationen, das Anatomisch-Physiologische zugeschrieben werden. Wir können schon in einer gewissen Weise, wenn auch, ich möchte sagen, leise vom Bewußtsein erfaßt, die Tiefendimension synthetisch und analytisch behandeln. Sie gehört in den Bereich desjenigen, was ich nennen möchte die bewußte Betätigung durch das menschliche Haupt.

Wenn wir nun vom Sehakt übergehen zu demjenigen Akt, der entsteht durch die Betätigung in der Arme- und Händebewegung, dann handelt es sich darum, daß wir eintauchen in ein allerdings noch schwer mit dem Bewußtsein zu ergreifendes Element. Aber wir können schon immerhin auf dasjenige, was sich vollzieht, indem wir verfolgen unser Gefühlsleben jetzt in freier Betätigung unserer Arme und Hände und der Gebärden, wir können schon ebenso hier auf dasjenige, was eigentlich der Mensch tut, aufmerksam werden, wie wir aufmerksam werden auf die Betätigung in bezug auf die Tiefendimension durch die zwei menschlichen Augen. Was ist es denn eigentlich, was uns diese Tiefendimension vermittelt? Es ist die Einstellung des linken und des rechten Auges. Es ist die Übereinanderkreuzung der linken und der rechten Augenachse. Ob diese Übereinanderkreuzung in größerer oder geringerer Entfernung von uns selber sich vollzieht, davon hängt die hauptverstandesmäßige Beurteilung der Tiefendimension ab. Es ist wenig äußerlich anschaulich diejenige Betätigung, die der Beurteilung dieser Tiefendimension eigentlich zugrunde liegt.

Wenn wir nun davon übergehen auf die Betätigung der menschlichen Arme und Hände, dann finden wir, daß wir allerdings in deutlicher Weise schon unterscheiden können auch nur bei einer einigermaßen stattfindenden Anstrengung unseres Bewußtseins, daß wir allerdings, indem wir die Arme in horizontalem Kreise bewegen, deutlich unterscheiden können, wie sich diese Armbewegung bewußt abspielt in der Dimension des Rechts-Links, also in der Dimension, die ich als die Breitendimension bezeichnen möchte. Wer das menschliche Leben genauer zu analysieren imstande ist, der wird wissen, daß alles dasjenige, was der Mensch beurteilt in bezug auf diese Breitendimension, ja in der Tat zusammenhängt mit demjenigen Fühlen, das wir haben, indem wir uns wissen als ein Mensch, der die volle Breitendimension durchmißt mit einem linken und mit einem rechten Arme. Wir haben ein gefühlsmäßiges Erleben desjenigen, was wir Symmetrie nennen, welches Erleben vorzugsweise ja in der Breitendimension sich abspielt. Wir haben ein solches Erleben vor allen Dingen durch das Gefühl, das wir vermittelt bekommen durch unseren linken und rechten Arm. Allerdings übersetzt sich nun dieses Fühlen unserer eigenen Symmetrie vorzugsweise durch die entsprechenden Bewegungen des linken und rechten Armes, die wir fühlen, so daß wir das Symmetriesein in diesem zusammengehörigen Bewegen des linken und rechten Armes fühlen. Es übersetzt sich uns das gefühlsmäßige Erfassen der Breitendimension vorzugsweise durch die Symmetrie in ein Vorstellungsleben, und wir beurteilen dann die Symmetrie auch im Vorstellungsleben. Allein Sie werden nicht übersehen können, daß dieses Beurteilen der Symmetrien der Breitendimension im Grunde genommen etwas Sekundäres ist, und derjenige, der nur anschauen könnte das Symmetrische und nicht ein Gefühl haben würde beim Symmetrischen, beim Entsprechen des symmetrischen Links dem symmetrischen Rechts, der würde die Symmetrie doch blaß und trocken und nüchtern und verstandesmäßig bloß erleben. Derjenige lebt richtig in allem drinnen, was uns Symmetrie sagen kann, der symmetrisch auch erfühlen kann. Aber erfühlen können wir das Symmetrische als Menschen nur dadurch, daß wir uns in einer leisen Weise immer bewußt werden der Zusammengehörigkeit der Bewegungen des linken und des rechten Armes, beziehungsweise der linken und der rechten Hand. Auf das, was wir da gefühlsmäßig erleben, stützt sich eigentlich alles dasjenige, was wir mit Bezug auf die Breitendimension erleben können.

Aber auch dasjenige, was wir vorher in bezug auf den Sehakt die Tiefendimension genannt haben, wird uns in einer gewissen Weise doch bewußt durch etwas, was ja auch mit unseren Armen zustande kommt. Wie wir die Sehlinien, die Visierlinien kreuzen, so kreuzen wir ja auch die Arme, und es ist, ich möchte sagen, die gröbere Übersetzung des Sehaktes, wenn wir die Arme irgendwo kreuzen. Wir können gerade durch das Aufeinanderfolgen der Punkte, die wir bekommen, wenn wir die Arme kreuzen, uns hineinleben in dasjenige, was Tiefendimension ist, so daß wir, wenn wir vollständig erleben dasjenige, was wir in unserer Armorganisation haben, nun durchaus nicht fertig vor uns haben die zweite Dimension, die Breitendimension, wie wir sie beim Sehakt fertig vor uns haben, sondern wenn wir symbolisch ausdrücken wollen dasjenige, was nun in bezug auf die Dimensionalität beim Arme- und Händeorganismus entsteht, so müßte ich so zeichnen: die Breitendimension, die Tiefendimension (voll ausgezogene Linien). Und nur die Höhendimension, die ist fertig für dasjenige, was ich erlebe durch meine Armorganisation (punktierte Linie). Wir lassen, indem wir unsere Gebärden ausführen, indem wir gewissermaßen mit unseren Gebärden bewußt durchsetzen diejenige Fläche, welche sich zusammensetzt aus der Tiefen- und aus der Breitendimension, vollständig im Unbewußten liegen die Höhendimension, die dritte Dimension. Wann tritt diese dritte Dimension eigentlich erst in das deutliche Bewußtsein? Sie tritt in das deutliche Bewußtsein erst beim Gehakt. Wenn wir uns vom Ort bewegen, da wird die Linie, welche in dieser dritten Dimension, in der Höhendimension liegt, fortwährend eine andere, und wenn auch wiederum das Verstandesbewußtsein von dieser dritten Dimension beim Gehen ein außerordentlich leises ist, so können wir doch nicht übersehen, daß es in der Tat halbbewußt innerhalb der Verstandesoperation liegt, diese dritte Dimension in Erwägung zu ziehen. Gewiß, im groben äußeren Bewußtsein rechnen wir nicht mit der Veränderung dieser Linie in der Höhendimension. Aber indem wir überhaupt gehen und das Gehen als einen Willensakt entwickeln, verändern wir fortwährend diese Linie in der Höhendimension, und wir müssen uns sagen: Es ist ebenso leise bewußt dasjenige, was in dieser dritten Dimension vorgeht, für das Gehen, wie leise bewußt ist für den Sehakt dasjenige, was in der Tiefendimension vorgeht. Wenn wir also die Dimensionalität jetzt zeichnen wollen für dasjenige, was mit Hilfe des eigentlichen Gliedmaßenorgans geschieht, das nicht an irgend etwas anderes als an die Gliedmaßenbetätigung angepaßt ist, wenn wir die Dimensionalität studieren am Gehakt, der an die Beine und Füße gebunden ist, dann werden wir sagen können: da drinnen, bei diesem Gehakt, fühlen wir verstandesgemäß eine Betätigung innerhalb aller drei Dimensionen, so daß ich den Gehakt dann zu zeichnen habe mit drei Vollinien.

Wir erleben also — wenn Sie rückblicken auf dasjenige, was ich gesagt habe, werden Sie ein deutliches Bewußtsein davon bekommen im Sehakt, der in ganz ausgesprochenem Maße angehört der Hauptes- oder Kopforganisation, eine fertige Zweidimensionalität und eine Betätigung zur Herstellung der dritten Dimension, der Tiefe. Wir erleben in demjenigen, was wir als den Ausdruck gebrauchten für das rhythmische System, in der Arme- und Händebewegung, die Dimensionalität so, daß wir in unserem eigenen Akt zwei Dimensionen voll erleben und die dritte Dimension noch ebenso fertig im Bewußtsein dasteht wie sonst die zwei zur Fläche sich bildenden Dimensionen für die Kopforganisation im Sehakt. Erst im eigentlichen Gliedmaßenorganismus, der also zum dritten System, zum Stoffwechselsystem des Menschen gehört — den erkennen wir nur, wenn wir die das Gehen begleitenden Stoffumsetzungen studieren -, in diesem dritten System enthüllt sich uns alles dasjenige, was den Raum durchmißt nach seinen drei Dimensionen.

Nun brauchen Sie nur noch die folgende Erwägung anzustellen, so werden Sie auf außerordentlich Wichtiges kommen. Alles dasjenige, was in unserem Vorstellungsleben enthalten ist, ist im Grunde genommen der einzige Inhalt unseres vollen wachenden Bewußtseins. Dasjenige aber, was in unserem Gefühlsleben enthalten ist, kommt nicht mit derselben Deutlichkeit, mit derselben lichten Klarheit in unser Bewußtsein herein. Wir werden im weiteren Verlauf dieser Betrachtungen noch sehen, wie die eigentlichen Gefühle keine stärkere Intensität im Bewußtsein haben als die Träume und genauso wie die Träume dann vom Tagesleben, vom voll erwachten Vorstellungsleben reproduziert werden, dadurch deutliche Vorstellungen werden, also ins klare Bewußtsein hereintreten, so werden fortwährend auch beim wachen Tagesleben die Gefühle begleitet von den sie ausdrückenden Vorstellungen. Dadurch werden unsere Gefühle, die sonst nur mit der Intensität des Traumlebens auftreten, in das deutliche, helle Bewußtsein eben des Vorstellungslebens hereingezogen.

Vollständig im Unterbewußtsein bleiben ja die eigentlichen Willensbewegungen ihrer Wesenheit nach. Wodurch wissen wir eigentlich etwas vom Willen? Im Grunde genommen wissen wir von dem Willen selbst seiner Wesenhaftigkeit nach im gewöhnlichen Erkennen ja nichts, und das findet sich, ich möchte sagen, auch dokumentiert, ausgesprochen in einer solchen Psychologie wie der von Theodor Ziehen, der ja im Grunde genommen in seiner «Physiologischen Psychologie» nur vom Vorstellungsleben spricht. Die Tatsache, die er aber nicht kennt, die ich Ihnen eben jetzt vorgeführt habe, daß das Gefühlsleben eigentlich an den rhythmischen Organismus gebunden ist und nur aufstrahlt in das Vorstellungsleben, die bringt Theodor Ziehen abstrakt so zum Ausdruck, daß er sagt: Eigentlich können wir als Psychologen nur das Vorstellungsleben verfolgen und finden gewisse Vorstellungen gefühlsbetont. — Also gewissermaßen wären die Gefühle nur Eigenschaften des Vorstellungslebens. Das alles beruht eben darauf, daß von einem solchen Psychologen die eigentliche menschliche Organisation nicht durchschaut wird, die sich eben durchaus so verhält, wie ich jetzt zum Ausdruck gebracht habe. Die Gefühle bleiben, weil sie an den rhythmischen Organismus gebunden sind, im halbbewußten Zustand des Traumes, und völlig im Unbewußten bleibt das eigentliche Wesen der Willensakte. Daher werden sie von den gewöhnlichen Psychologen überhaupt nicht mehr beschrieben. Lesen Sie die sonderbaren Ausführungen gerade Theodor Ziehens über die Willensbetätigung, so werden Sie sehen, daß dem Beobachtungsvermögen dieser Psychologen die innere Betätigung des Willens- wir werden darauf zu sprechen kommen, wie sie ist- durchaus aus der Hand fällt. In der äußeren Beobachtung haben wir eben nichts anderes gegeben als das, was wir anschauen können, das Ergebnis eines Willensaktes. Wir wissen nicht das Innere, was sich vollzogen hat, wenn ein Willensimpuls unseren Arm bewegt. Wir sehen nur den Arm sich bewegen, also die äußere Tatsache beobachten wir hinterher. Wir begleiten dadurch die Offenbarungen unseres Willens mit Vorstellungen und dadurch betrachten wir sie, die sonst durchaus nur organisch durch das Stoffwechselsystem und das mit dem in Verbindung stehende Gliedmaßensystem vermittelt sind, auch als zusammenhängend mit dem Vorstellungswesen.

Aber erst in diesem Gliede des menschlichen Organismus, in dem Stoffwechselsystem, das also körperlich entspricht dem Seelischen des Willensaktes, enthüllt sich uns die Dreidimensionalität, die daher innig zusammenhängt mit einem menschlichen System, dessen Betätigung sich im wesentlichen unbewußt abspielt. Diese Dreidimensionalität kann uns ihrer Wirklichkeit nach also eigentlich nicht für die gewöhnliche Erkenntnis vorliegen. Sie kann erst enthüllt werden, wie wir sehen werden, wenn wir ebenso mit lichter Klarheit hinschauen in unser Willensleben wie sonst in unser Vorstellungsleben. Das kann mit dem gewöhnlichen Erkennen nicht geschehen, sondern, wie wir sehen werden, erst mit dem geisteswissenschaftlichen Erkennen. Darauf aber, auf der Gesamtbetätigung des Menschen, auf alldem, was in seinem Gliedmaßen- und Stoffwechselsystem lebt, ruht die Dreidimensionalität als Erleben im Unterbewußtsein. Und was geschieht? Aus dem Unterbewußtsein wird sie heraufgehoben zunächst von der Willens-Gliedmaßensphäre in die rhythmische Sphäre. Da wird sie dann nur noch erlebt als Zweidimensionaliität, und die dritte Dimension, die noch im Willenswirken unmittelbar erlebt wird in ihrer Realität, diese dritte Dimension, die Höhendimension, ist bereits abstrakt geworden.

Sie sehen hier in der menschlichen Organisation das Abstraktwerden der Realität durch die Betätigung des Menschen selbst. Sie erleben im Unterbewußtsein diese Höhendimension. Durch die menschliche Organisation wird diese Höhendimension schon abstrakt zur bloßen gezogenen Linie, zum bloßen Gedanken in der rhythmischen Organisation. Und in der Nerven-Sinnesorganisation, was tritt da ein? Die beiden Dimensionen werden abstrakt. Sie werden nicht mehr erlebt. Sie können nur noch gedacht werden mit dem hinterher an die Sache herankommenden Verstand, so daß wir in dem Organ unserer eigentlichen gewöhnlichen Erkenntnis, in dem Kopfe, nur die Möglichkeit haben, die zwei Dimensionen abstrakt verstandesmäßig zum Ausdruck zu bringen. Nur von der dritten, der Tiefendimension, haben wir, ich möchte sagen, ein leises Bewußtsein auch noch in unserem Haupte. Sie sehen also, dadurch, daß wir dieses leise Bewußtsein von der Tiefendimension in unserem Haupte haben, sind wir in der Lage, überhaupt noch etwas zu wissen im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein von der Realität der Dimensionen. Würde durch unsere Organisation diese Tiefendimension, die wir eigentlich nur am Sehakt ordentlich studieren können, ebenso abstrakt, dann würden wir überhaupt nur drei abstrakte Linien haben. Wir würden gar nicht darauf kommen, Realitäten für diese drei abstrakten Linien zu suchen.

Damit habe ich Sie auf die Realität, auf die Wirklichkeit gewiesen für dasjenige, was im Kantianismus in einer unwirklichkeitsgemäßen Weise zutage tritt. Da wird gesagt, der Raum sei mit seinen drei Dimensionen a priori in der menschlichen Organisation enthalten, und die menschliche Organisation versetze eigentlich ihre subjektiven Erlebnisse in den Raum hinein. Warum kam Kant zu dieser Einseitigkeit? Er kam dazu, weil er nicht wußte, daß dasjenige, was wir nur in der leisen Andeutung der Tiefendimension durch die Nerven-Sinnesorganisation, aber sonst abstrakt erleben, im Unterbewußten in der Realität erlebt wird, dann heraufgetrieben wird in das Bewußtsein und dadurch zur Abstraktion gebracht wird bis zu diesem kleinen Rest in der Tiefendimension. Die Dreidimensionalität erleben wir durch unsere eigene menschliche Organisation. Sie ist in ihrer Realität vorhanden in dem Willenssystem und physiologisch-physisch in dem Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßensystem. Sie ist zunächst unbewußt für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein und wird diesem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nur bewußt in der Abstraktheit des mathematisch-geometrischen Raumes.

Ich wollte Ihnen damit ein Beispiel zunächst geben von der Art und Weise, wie Geisteswissenschaft auf die menschliche Betätigung eingehen kann, wie sie eben nicht bei Abstraktionen stehen bleibt wie das Apriori im Kantischen Sinn von Raum und Zeit, sondern wie sie wirklich konkret eingeht auf die Wirklichkeit des Menschen und dadurch darauf kommt, wie sich die Dinge eigentlich im Menschen verhalten. Ich wollte Ihnen gerade dieses Beispiel geben, weil uns dieses Beispiel der eigentlichen Bedeutung des Raumes, wie ich noch weiter ausführen werde, nun hineinführt in eine genauere Erkenntnis des Wesens des Mathematischen nach allen Seiten hin.

Davon dann morgen weiter.

Second Lecture

Yesterday, in my introductory lecture, I pointed out how, when considering the transition of human knowledge from the ordinary perception of the external world to mathematical knowledge, the first stage of a path emerges which, when pursued further, leads to an understanding and recognition of the spiritual scientific method as it is meant here. It will be my aim in these lectures to characterize and justify the spiritual scientific method. This can only become apparent as the result of what I have to discuss in these seven lectures.

Today I would like to go into the first stage in more detail. I would like to present to you a view that may still be found here and there in fragments in scientific thinking today, but which does not exist in summary form, and because it does not exist in summary form, it is also the case that we are then unable to methodically rise above the transformation from science that is still free of mathematics to mathematical science, and from this transformation to the other, which we will recognize as emerging quite appropriately from it, from the mathematical penetration of objectivity to a spiritual-scientific penetration of real being. As already indicated, I will attempt to reach this final stage step by step and methodically through our consideration.

To this end, we will start today with a consideration of the human being as he experiences himself in looking at and observing the external world. You will know from lectures that have been given here, or at least from seminar papers, but also from reading my book “Von Seelenrätseln” (On the Riddles of the Soul), that a complete and adequate consideration of the human being can only be achieved by understanding how the entire human organization is divided into three clearly distinct parts. We are certainly dealing with a unified human being. But this unified human being appears to be the most complex organism known to us, precisely because it is divided, I would say, into three sub-organizations, which have a certain independence within themselves, but which, precisely because they develop everything that lies within them through this independence and then interact to form a whole, bring about the concrete unity of the human organization. We are dealing here first of all with what I have called in my book “Von Seelenrätseln” (On the Riddles of the Soul) the nerve-sense human being, that part of the human organization which has its most adequate expression in the human head, but which from there extends over the entire human organization. However, because such a member of the human organization permeates the entire organization, we must not overlook the fact that such an independent member exists. We can distinguish quite precisely from the rest of the human organization — and we will have more to say about this later — the nerve-sense human being, everything that is the mediator of our life of imagination. We are thinking human beings in that we are able to convey to ourselves what thinking life is through the organ that can be summarized as the senses and the nervous system extending from the senses according to the inner organization.

We are not connected to this nervous system through our feeling life in the same sense as through our thinking life. Only the imprecise psychological approach of recent times allows this to be overlooked. The emotional life is not directly linked to the nervous-sensory system, but only indirectly. The emotional life is directly linked to everything that we can call the rhythmic system in the human organization, which is most evident in breathing, the pulse, and blood circulation. The deception that our emotional life, as part of our soul life, is also directly connected with the nerve-sensory system comes from the fact that we constantly accompany everything that takes place emotionally within us as human beings with mental images. And just as our emotional life is constantly accompanied by mental images, so too is our rhythmic system, which extends throughout the entire organism, organically connected to our nervous and sensory system. There is a similar relationship between the rhythmic system and the nervous and sensory system in the body as there is between the emotional life and the life of ideas in the soul. But it is only through this that our emotional life is indirectly expressed through the nervous-sensory system, because it is only in our organism that the experience of feeling, which has the rhythmic system as its tool in the organism, is mediated, so that this now reacts back on the nervous-sensory system and thereby creates the appearance as if the emotional life were also directly connected with the nervous-sensory system. In my book Von Seelenrätseln (On the Riddles of the Soul), I drew particular attention to the fact that, for example, when studying what goes on in a person when they perceive music, it is easy to see how this relationship, which I have just characterized, exists in human beings.

In addition to these two systems, the nervous-sensory system, which mediates the life of the imagination, and the rhythmic system, which mediates the life of feeling, we then have the metabolic system. And in these three systems, the nervous-sensory system, the rhythmic system, and the metabolic system, we have the human organism completely in terms of all its functions. The metabolic system corresponds directly to the soul life of the will, and a real study of the connection between the will and the human organism will only come about when one pursues the matter in such a way that one investigates how the metabolic turnover is when an act of will or even just an impulse of will takes place. Every metabolic process is actually, consciously or unconsciously, the physical basis of an act of will or an impulse of will. At the same time, our movements are connected with metabolism, and because our movements are connected with our metabolism, our mental mobility is in turn connected with the activity of the will. It must be clear that when we perform a movement in space, this is, I would say, the most primitive act of will. But — to use Goethe's words — in a primal phenomenal act of will, it is precisely this metabolic process underlying a movement within us that is the physical expression of the soul in an act of will. And it is only because we in turn follow our acts of will in our imagination that these acts of will are now also indirectly connected with the nervous-sensory system. So we can, I want to say this first by way of preparation, consider the soul life and also the physical life of the human being in a kind of division into three independent organic and soul members.

Today, we will try to examine how these three parts of the human physical and spiritual organization relate to each other from a certain point of view with reference to the observing human being. First of all, I would like to present to you what is the perception of the dimensionality of space. We must go into these, I would say, more precise, more minute details, because these lectures are intended precisely to show spiritual scientific observation as a continuation of ordinary scientific observation. We will first consider what I have called the nerve-sense organism. This nerve-sense organism is, as I have already said, mainly contained in the head organization of the human being, and from the head organization, which mainly contains the nerve-sense human being, the nerve-sense life then extends over the rest of the human organism, impregnating it, so to speak. One could say that, when viewing the human being from an external perspective, the head continues throughout the entire human being. If, for example, we have extended the perception of warmth throughout the entire organism within the sensory organization, this means nothing other than that the type of organization that is mainly located in the head for the most important part of sensory life now extends throughout the entire human organism for this special aspect of the perception of warmth, so that in a certain sense, with regard to the perception of warmth, the whole human being is head.

You see, this kind of discussion is taken extremely badly nowadays. For people have become so accustomed to external points of view that they think that when we speak of three parts of the human organism, we must be able to place them spatially separate from one another, and an anatomy professor who sought such spatial separation then had the taste to say that anthroposophy divides the human being into a head system, a chest system, and a belly system. Well, yes, one can attack anthroposophy in an unobjective way with such things. But that is certainly not the point. The point is to approach these things in a proper way and learn to know that in reality things are not spatially separated as many people today imagine in a dilettantish way, but that they interlock, flow into one another — which must be taken into account if one wants to understand correctly the interaction of the three members of the threefold social organism.

Now, the head organization is certainly the organization which, at first glance, based on purely empirical facts, has the most to do with cognition, at least with mathematical cognition, which initially approaches humans in the external world. In this head organization, we can now state purely empirically that what we can call dimensionality initially presents itself to us, I would say, only in a hint. We can best understand what this is all about if we consider three modes of human activity; the first is what I would call the total act of seeing, seeing, observing the world with our eyes. But, as you will soon see, this is the total act of seeing, namely observing external objects with our two eyes. Secondly, although the arms and hands of human beings are attached to the trunk and, in a certain sense, belong to the limb system, they also have an intimate relationship with the rhythmic system. Due to their special position close to the rhythmic system, they are, in a sense, transformed by life, by the functional aspects of human beings. As limbs, they are adapted to the life we can call rhythmic life, and because they are located on the outside, the arms and hands, we can use them to clarify many things that we would not be able to clarify so easily with the inner limbs of the rhythmic system. So, mind you, it is a matter of the fact that we have limbs in our arms and hands, but that these limbs, because of their special position in the human organism, are adapted to the rhythmic life, I would say, through life itself, through their function. You can trace this rhythmic quality in the arms and hands when you consider how strongly what we feel, that is, what is connected with the rhythmic system, is expressed in the gestures and free movement of the arms and hands. In human life, these limbs are, I would say, raised to a higher level of experience. They are designed as limbs, but they are not used in the same way as in animals, where the limbs are used for movement. Instead, they are freed from the function of limb life and become, I would say, an expression of human emotional life in an invisible language, and are therefore adapted to the rhythmic system. As a third function, I would then like to present to you what we can consider to be walking, that is, an activity that takes place in the most eminent sense through the human limb system.

Let us now consider seeing, arm movement, and walking in a truly scientific manner. Seeing with the two eyes: when we consider it in its totality, we come to the conclusion that, initially, completely independent of all intellectual activity, what we see presents itself to us in two dimensions. If I want to represent what I see to you in terms of its dimensionality, I can simply draw the two dimensions here on the board (see drawing) as two perpendicular coordinates. I would like to draw it in such a way that it is consistent with later derivations by only marking the two lines with dots. By only marking the two lines with dots, I would like to express the fact that this two-dimensionality is not actually perceived by our intellectual consciousness when we see.

The situation is different with the third dimension. The third dimension, which we can call the depth dimension, i.e., the depth as seen from our eyes, the dimension that lies in the direction from back to front, does not stand before our soul in the same sense, completely independent of our mind. It stands before us as that which we carry out as an inner mental operation when we supplement the things we otherwise see as flat with the depth dimension to make them physical. What we do here, however, eludes our conscious activity in a rather crude way. But if we look at conscious activity in a more subtle way, we will definitely come to the conclusion that we experience this depth dimension in a different way than the other two, which I will call the height and width dimensions. We can already become aware of how, in a certain way, we estimate how far something is from us in relation to this depth dimension. Something is added to the usual perception, to the perception of the eyes, when we supplement the dimensionality of the surface in our consciousness with physical dimensionality, so that we can say: As long as we remain within our consciousness, we cannot say how the dimensions of height and width come about. We simply have to accept the dimensions of height and width. They are simply given in visual perception. This is not the case with the dimension of depth, i.e., the third dimension. I therefore draw it here in perspective as a solid line, by which I mean to indicate that this solid line as depth dimension is already based on an activity that plays at least faintly into consciousness, on a conscious, let us say, semi-conscious activity, so that we can say: When we contemplate the act of seeing, the height and width dimensions are initially given to us purely in thought, that is, only when we penetrate the act of seeing with our thoughts. The depth dimension is already based on an activity of consciousness, on an activity of the semi-conscious operation of the intellect. Therefore, as you may already have heard, the anatomical-physiological interpretation of the total act of seeing must proceed in such a way that it actually attributes to seeing — that is, to what seeing is without intellectual activity — the coming into being of the seen surface extension. On the other hand, it must attribute to the activity of the cerebrum, and thus no longer to the activity of the four hills, that organ in the human body on which the illustrative activity of the eyes depends, the physical behavior during seeing. With regard to the depth dimension, the anatomical-physiological must be attributed to the cerebrum, which is also the mediator of volitional mental operations. We can already, in a certain way, albeit, I would say, only faintly perceived by consciousness, treat the depth dimension synthetically and analytically. It belongs to the realm of what I would like to call the conscious activity of the human head.

If we now move from the act of seeing to the act that arises from the activity of the arms and hands, we are entering a realm that is still difficult to grasp with the conscious mind. But we can already gain some insight into what is happening by following our emotional life as it freely manifests itself in the activity of our arms and hands and in our gestures. We can already become aware of what human beings actually do here, just as we become aware of the activity in relation to the depth dimension through the two human eyes. What is it that actually conveys this depth dimension to us? It is the position of the left and right eyes. It is the crossing of the left and right eye axes. Whether this crossing takes place at a greater or lesser distance from ourselves determines the main intellectual assessment of the depth dimension. The activity that actually underlies the assessment of this depth dimension is not very visible externally.

If we now move on to the activity of the human arms and hands, we find that we can already distinguish clearly, even with only a moderate effort of our consciousness, that when we move our arms in a horizontal circle, we can clearly distinguish how this arm movement consciously takes place in the right-left dimension, that is, in the dimension that I would like to call the width dimension. Anyone who is able to analyze human life more closely will know that everything that humans judge in relation to this width dimension is in fact connected with the feeling we have when we know ourselves to be human beings who measure the full width dimension with a left and a right arm. We have an emotional experience of what we call symmetry, an experience that takes place primarily in the breadth dimension. We have this experience above all through the feeling we get from our left and right arms. However, this feeling of our own symmetry is translated primarily through the corresponding movements of the left and right arms that we feel, so that we feel the symmetry in this coordinated movement of the left and right arms. The emotional perception of the width dimension is primarily translated into our imagination through symmetry, and we then also judge symmetry in our imagination. However, you will not be able to overlook the fact that this assessment of the symmetries of the width dimension is basically something secondary, and that someone who could only look at the symmetrical and had no feeling for the symmetrical, for the correspondence of the symmetrical left to the symmetrical right, would experience symmetry as pale, dry, sober, and purely intellectual. Those who can also feel symmetry live fully in everything that symmetry can tell us. But as human beings, we can only feel symmetry by quietly becoming aware of the unity of the movements of the left and right arms, or the left and right hands. Everything we experience in relation to the horizontal dimension is actually based on what we experience emotionally.

But even what we previously referred to as the depth dimension in relation to the act of seeing becomes conscious to us in a certain way through something that also happens with our arms. Just as we cross the lines of sight, the lines of vision, we also cross our arms, and I would say that crossing our arms somewhere is a cruder translation of the act of seeing. It is precisely through the succession of points that we obtain when we cross our arms that we can empathize with what depth is, so that when we fully experience what we have in our arm organization, we are by no means finished with the second dimension, the breadth dimension, as we have it finished before us in the act of seeing. But if we want to express symbolically what now arises in relation to dimensionality in the arm and hand organism, I would have to draw it like this: the breadth dimension, the depth dimension (fully drawn lines). And only the height dimension is complete for what I experience through my arm organization (dotted line). By performing our gestures, by consciously imposing with our gestures, as it were, the surface that is composed of the depth and width dimensions, we leave the height dimension, the third dimension, completely in the unconscious. When does this third dimension actually enter into clear consciousness? It enters into clear consciousness only when we walk. When we move from one place to another, the line that lies in this third dimension, in the height dimension, is constantly changing, and even if the conscious awareness of this third dimension is extremely faint when we walk, we cannot overlook the fact that it is indeed semi-conscious within the operation of the mind to take this third dimension into consideration. Certainly, in our gross outer consciousness we do not reckon with the change of this line in the dimension of height. But by walking at all and developing walking as an act of will, we are constantly changing this line in the height dimension, and we must say to ourselves: What is happening in this third dimension is just as faintly conscious for walking as what is happening in the depth dimension is faintly conscious for the act of seeing. So if we now want to draw the dimensionality of what happens with the help of the actual limb organ, which is not adapted to anything other than limb activity, if we study the dimensionality of the walking act, which is bound to the legs and feet, then we will be able to say: inside, in this walking act, we feel intellectually an activity within all three dimensions, so that I then have to draw the walking act with three solid lines.

So we experience — if you look back at what I have said, you will become clearly aware of this in the act of seeing, which belongs to a very large extent to the head or brain organization, a finished two-dimensionality and an activity to produce the third dimension, depth. We experience in what we used as an expression for the rhythmic system, in the movement of the arms and hands, the dimensionality in such a way that in our own act we fully experience two dimensions and the third dimension stands just as complete in our consciousness as the two dimensions that form the surface for the head organization in the act of seeing. Only in the actual limb organism, which thus belongs to the third system, the human metabolic system—which we can only recognize when we study the metabolic processes accompanying walking—in this third system is everything that measures space in its three dimensions revealed to us.

Now you only need to consider the following, and you will arrive at something extremely important. Everything contained in our imagination is, in essence, the sole content of our full waking consciousness. However, what is contained in our emotional life does not enter our consciousness with the same clarity, with the same luminous clarity. In the further course of these considerations, we will see how the actual feelings have no greater intensity in consciousness than dreams, and just as dreams are then reproduced by daily life, by fully awakened imaginative life, thereby becoming clear mental images, i.e., entering into clear consciousness, so too are feelings in waking daily life continually accompanied by the mental images that express them. In this way, our feelings, which otherwise only occur with the intensity of dream life, are drawn into the clear, bright consciousness of the life of imagination.