The Origins of Natural Science

GA 326

26 December 1922, Dornach

Lecture III

In the last two lectures I tried to indicate the point in time when the scientific outlook and manner of thinking, such as we know it today, arose in the course of time. It was pointed out yesterday that the whole character of this scientific thinking, emerging at the beginning most clearly in Copernicus’ conception of astronomy, depends on the way in which mathematical thinking was gradually related to the reality of the external world. The development of science in modern times has been greatly affected by a change—one might almost say a revolutionary change—in human perception in regard to mathematical thinking itself. We are much inclined nowadays to ascribe permanent and absolute validity to our own manner of thinking.

Nobody notices how much matters have changed. We take a certain position today in regard to mathematics and to the relationship of mathematics to reality. We assume that this is the way it has to be and that this is the correct relationship. There are debates about it from time to time, but within certain limits this is regarded as the true relationship. We forget that in a none too distant past mankind felt differently concerning mathematics. We need only recall what happened soon after the point in time that I characterized as the most important in modern spiritual life, the point when Nicholas Cusanus presented his dissertation to the world. Shortly after this, not only did Copernicus try to explain the movements of the solar system with mathematically oriented thinking of the kind to which we are accustomed today, but philosophers such as Descartes and Spinoza24Spinoza, Benedictus: Amsterdam 1632–1677. The Hague. Philosopher, mathematician, had Humanistic and Talmudistic training. By vocation, optician and politician. His main work Ethics with the characteristic full title Ethica Ordine Geometrica Demonstrata (Ethic Represented by Geometric Method) could only be published by his friends after his death. See Mysticism at the Dawn of the Modern Age and Riddles of Philosophy. began to apply this mathematical thought to the whole physical and spiritual universe.

Even in such a book as his Ethics, the philosopher Spinoza placed great value on presenting his philosophical principles and postulates, if not in mathematical formulae—for actual calculations play no special part—yet in such a manner that the whole form of drawing conclusions, of deducing the later rules from earlier ones, is based on the mathematical pattern. By and by it appeared self-evident to the men of that time that in mathematics they had the right model for the attainment of inward certainty. Hence they felt that if they could express the world in thoughts arranged in the same clear-cut architectural order as in a mathematical or geometrical system, they would thereby achieve something that would have to correspond to reality. If the character of scientific thinking is to be correctly understood, it must be through the special way in which man relates to mathematics and mathematics relates to reality. Mathematics had gradually become what I would term a self-sufficient inward capacity for thinking. What do I mean by that?

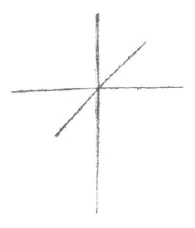

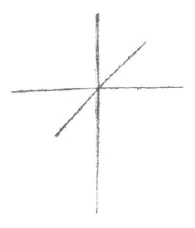

The mathematics existing in the age of Descartes25René Descartes: Lat., Renatus Cartenius, Le Haye (Tourraine) 1598–1650 Stockholm. Mathematician, physicist, philosopher. Educated by the Jesuits in La Fleche, he first became a soldier and was part of some campaigns but turned away from outer life to enter into the loneliness of a striver for knowledge, living first in Paris and then for a long time in Holland. He died in Stockholm, having been called there by Queen Christine. For him, doubt of tradition, but also of all sense perception, was the starting point of his philosophy and he found in self-consciousness the security of all being (“Cogito ergo Sum”). He developed the method of analytical geometry and gave an explanation of the rainbow. Main works: Essays, 1637, in it “Discours de la Methode and Dioptiric,” “Meditationes de Prima Philosophia,” 1641; “Passions de L'Ame,” 1650. See Riddles of Philosophy. and Copernicus can certainly be described more or less in the same terms as apply today. Take a modern mathematician, for example, who teaches geometry, and who uses his analytical formulas and geometrical concepts in order to comprehend some physical process. As a geometrician, this mathematician starts from the concepts of Euclidean geometry, the three-dimensional space (or merely dimensional space, if he thinks of non-Euclidean geometry.)26Non-Euclidian geometry is a prime example of “the self-contained inner ability to think.” C. Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) discovered first that one can think more than only a geometric system. Because nobody understood this, he decided not to publish his results and to withdraw from the fruitless quarrel. Independently of Gauss in 1828 N.I. Lobatschewskij and in 1829 J. Boljai first published their solutions to the same problem. Rudolf Steiner often spoke about the meaning of this achievement, as in Wege und Ziele des geistigen Menschen in the lecture “Der Heutige Stand der Philosophie und Wissenschaft,” (Dornach, Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1973; GA Bibl. Nr. 125). See also: Georg Unger, Physic am Scheidewege (Dornach: 1948), pages 19–28, and Vom Bielden Physikalischer Begriffe, Vol. 3 (Stuttgart: 1967), pages 31–32 and 193–194. In three-dimensional space he distinguishes three mutually perpendicular directions that are otherwise identical. Space, I would say, is a self-sufficient form that is simply placed before one's consciousness in the manner described above without questions being raised such as: Where does this form come from? Or, Where do we get our whole geometrical system?

In view of the increasing superficiality of psychological thinking, it was only natural that man could no longer penetrate to those inner depths of soul where geometrical thought has its base. Man takes his ordinary consciousness for granted and fills this consciousness with mathematics that has been thought-out but not experienced. As an example of what is thought-out but not experienced, let us consider the three perpendicular dimensions of Euclidean space. Man would have never thought of these if he had not experienced a threefold orientation within himself. One orientation that man experiences in himself is from front to back. We need only recall how, from the external modern anatomical and physiological point of view, the intake and excretion of food, as well as other processes in the human organism, take place from front to back. The orientation of these specific processes differs from the one that prevails when, for example, I do something with my right arm and make a corresponding move with my left arm. Here, the processes are oriented left and right. Finally, in regard to the last orientation, man grows into it during earthly life. In the beginning he crawls on all fours and only gradually, stands upright, so that this last orientation flows within him from above downward and up from below.

As matters stand today, these three orientations in man are regarded very superficially. These processes—front to back, right to left or left to right, and above to below—are not inwardly experienced so much as viewed from outside. If it were possible to go back into earlier ages with true psychological insight, one would perceive that these three orientations were inward experiences for the men of that time. Today our thoughts and feelings are still halfway acknowledged as inward experiences, but he man of a bygone age had a real inner experience, for example, of the front-to-back orientation. He had not yet lost awareness of the decrease in intensity of taste sensations from front to back in the oral cavity. The qualitative experience that taste was strong on the tip of the tongue, then grew fainter and fainter as it receded from front to back, until it disappeared entirely, was once a real and concrete experience. The orientation from front to back was felt in such qualitative experiences. Our inner life is no longer as intense as it once was. Therefore, today, we no longer have experiences such as this. Likewise man today no longer has a vivid feeling for the alignment of his axis of vision in order to focus on a given point by shifting the right axis over the left. Nor does he have a full concrete awareness of what happens when, in the orientation of right-left, he relates his right arm and hand to the left arm and hand. Even less does he have a feeling that would enable him to say: The thought illuminates my head and, moving in the direction from above to below, it strikes into my heart. Such a feeling, such an experience, has been lost to man along with the loss of all inwardness of world experience. But it did once exist. Man did once experience the three perpendicular orientation of space within himself. And these three spatial orientations—right-left, front-back, and above-below—are the basis of the three-dimensional framework of space, which is only the abstraction of the immediate inner experience described above.

So what can we say when we look back at the geometry of earlier times? We can put it like this: It was obvious to a man in those ages that merely because of his being human the geometrical elements revealed themselves in his own life. By extending his own above-below, right-left, and front-back orientations, he grasped the world out of his own being.

Try to sense the tremendous difference between this mathematical feeling bound to human experience, and the bare, bleak mathematical space layout of analytical geometry, which establishes a point somewhere in abstract space, draws three coordinating axes at right angles to each other and thus isolates this thought-out space scheme from all living experience. But man has in fact torn this thought-out spatial diagram out of his own inner life. So, if we are to understand the origin of the later mathematical way of thinking that was taken over by science, if we are to correctly comprehend its self-sufficient presentation of structures, we must trace it back to the self-experienced mathematics of a bygone age. Mathematics in former times was something completely different. What was once present in a sort of dream-like experience of three-dimensionality and then became abstracted, exists today completely in the unconscious. As a matter of fact, man even now produced mathematics from his own three-dimensionality. But the way in which he derives this outline of space from his experiences of inward orientation is completely unconscious. None of this rises into consciousness except the finished spatial diagram. The same is true of all completed mathematical structures. They have all been severed from their roots. I chose the example of the space scheme, but I could just as well mention any other mathematical category taken from algebra or arithmetic. They are nothing but schemata drawn from immediate human experience and raised into abstraction.

Going back a few centuries, perhaps to the fourteenth century, and observing how people conceived of things mathematical, we find that in regard to numbers they still had an echo of inward feelings. In an age in which numbers had already become an abstract ads they are today, people would have been unable to find the names for numbers. The words designating numbers are often wonderfully characteristic. Just think of the word “two.” (zwei) It clearly expresses a real process, as when we say entzweien, “to cleave in twain.” Even more, it is related to zweifeln, “to doubt.” It is not mere imitation of an external process when the number two, zwei, is described by the word Entzweien, which indicates the disuniting, the splitting, of something formerly a whole. It is in fact something that is inwardly experienced and only then made into a scheme. It is brought up from within, just as the abstract three-dimensional space-scheme is drawn up from inside the mind.

We arrive back at an age of rich spiritual vitality that still existed in the first centuries of Christianity, as can be demonstrated by the fact that mathematics, mathesis, and mysticism were considered to be almost one and the same. Mysticism, mathesis, and mathematics are one, though only in a certain connection. For a mystic of the first Christian centuries, mysticism was something that one experienced more inwardly in the soul. Mathematics was the mysticism that one experienced more outwardly with the body; for example, geometry with the body's orientations to front-and-back, right-and-left, and up-and-down. One could say that actual mysticism was soul mysticism and that mathematics, mathesis, was mysticism of the corporeality. Hence, proper mysticism was inwardly experienced in what is generally understood by this term; whereas mathesis, the other mysticism, as experienced by means of an inner experience of the body, as yet not lost.

As a matter of fact, in regard to mathematics and the mathematical method Descartes and Spinoza still had completely different feelings from what we have today. Immerse yourself in these thinkers, not superficially as in the practice today when one always wants to discover in the thinkers of old the modern concepts that have been drilled into our heads, but unselfishly, putting yourself mentally in their place. You will find that even Spinoza still retained something of a mystical attitude toward the mathematical method.

The philosophy of Spinoza differs from mysticism only in one respect. A mystic like Meister Eckhart or Johannes Tauler27Johannes Tauler: About 1300–1361 Strasbourg. Preacher and pastor, Dominican, mystic, student of Meister Eckhart. Sermons and writings in German by W. Lehmann, 1923; see also Mysticism at the Dawn of the Modern Age, the chapter “Friendship with God.” attempts to experience the cosmic secrets more in the depths of feeling. Equally inwardly, Spinoza constructs the mysteries of the universe along mathematical, methodical lines, not specifically geometrical lines, but lines experienced mentally by mathematical methods. In regard to soul configuration and mood, there is no basic difference between the experience of Meister Eckhart's mystical method and Spinoza's mathematical one. Anyone how makes such a distinction does not really understand how Spinoza experienced his Ethics, for example, in a truly mathematical-mystical way. His philosophy still reflects the time when mathematics, mathesis, and mysticism were felt as one and the same experience in the soul.

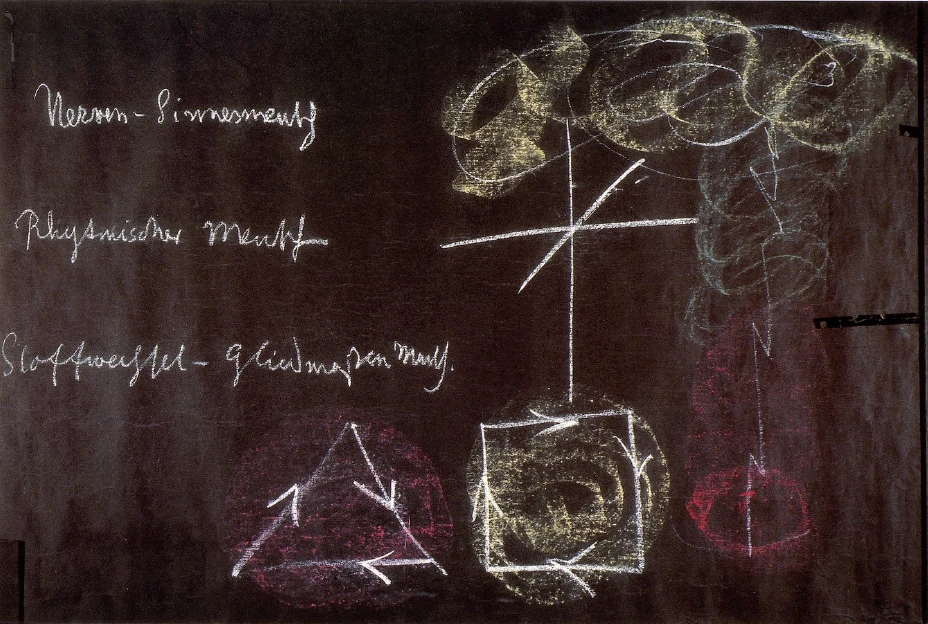

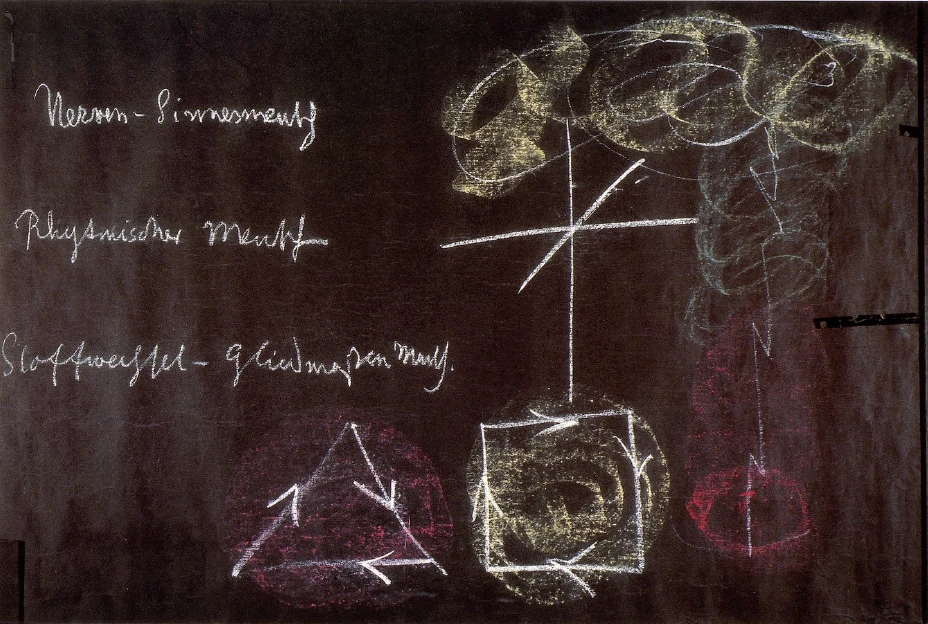

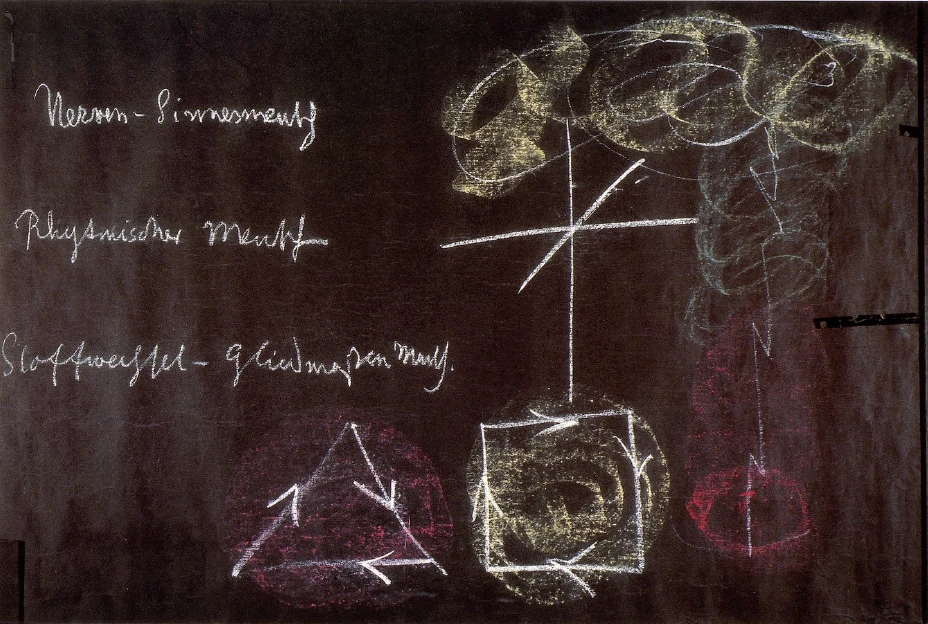

Now, you will perhaps recall how, in my book The Case for Anthroposophy,28Rudolf Steiner, The Case for Anthroposophy (London: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1970). I tried to explain the human organization in a way corresponding to modern thinking. I divided the human organization—meaning the physical one—into the nerve-sense system, the rhythmic system, and the metabolic-limb system. I need not point out to you that I did not divide man into separate members placed side by side in space, although certain academic persons have accused29In a reply to two lectures, which Walter Johannes Stein and Eugen Kolisko gave to defend two articles on “Anthroposophy as Science” in the Goettingen newspaper, Hugo Fuchs, Professor of Anatomy, spoke sarcastically of a human being with head, breast, and belly system. (From a report of the newspaper Die Dreigliederung des Sozialen Organismus, August 1920, No. 5). me of such a caricature. I made it clear that these three systems interpenetrate each other. The nerve-sense system is called the “head system” because it is centered mainly in the head, but it spreads out into the whole body. The breathing and blood rhythms of the chest system naturally extend into the head organization, and so on. The division is functional, not local. An inward grasp of this threefold membering will give you true insight into the human being.

Let us now focus on this division for a certain purpose. To begin with, let us look at the third member of the human organization, that of digestion (metabolism) and the limbs. Concentrating on the most striking aspect of this member, we see that man accomplishes the activities of external life by connecting his limbs with his inner experiences. I have characterized some of these, particularly the inward orientation experience of the three directions of space. In his external movements, in finding his orientation in the world, man's limb system achieves inward orientation in the three directions. In walking, we place ourselves in a certain manner into the experience of above-below. In much that we do with our hands or arms, we bring ourselves into the orientation of right-and-left. To the extent that speech is a movement of the aeriform in man, we even fit ourselves into direction of front-and-back, back-and-front, when we speak. Hence, in moving about in the world, we place our inward orientation into the outer world.

Let us look at the true process, rather than the merely illusionary one, in a specific mathematical case. It is an illusionary process, taking place purely in abstract schemes of thought, when I find somewhere in the universe a process in space, and I approach it as an analytical mathematician in such a way that I draw or imagine the three coordinate axes of the usual spatial system and arrange this external process into Descartes’ purely artificial space scheme.

This is what occurs above, in the realm of thought schemes, through the nerve-sense system. One would not achieve a relationship to such a process in space if it were not for what one does with one's limbs, with one's whole body, if it were not for inserting oneself into the whole world in accordance with the inward orientation of above-below, right-left, and front-back. When I walk forward, I know that on one hand I place myself in the vertical direction in order to remain upright. I am also aware that in walking I adjust my direction to the back-to-front orientation, and when I swim and use my arms, I orient myself in right and left. I do not understand all this if I apply Descartes’ space scheme, the abstract scheme of the coordinate axes. What gives me the impression of reality in dealing with matters of space is found only when I say to myself: Up in the head, in the nerve system, an illusory image arises of something that occurs deep down in the subconscious. Here, where man cannot reach with his ordinary consciousness, something takes place between his limb system and the universe. The whole of mathematics, of geometry, is brought up out of our limb system of movement. We would not have geometry if we did not place ourselves into the world according to inward orientation. In truth, we geometrize when we lift what occurs in the subconscious into the illusory of the thought scheme. This is the reason why it appears so abstractly independent to us. But his is something that this only come about in recent times. In the age in which mathesis, mathematics, was still felt to be something close to mysticism, the mathematical relationship to all things was also viewed as something human.

Where is the human factor if I imagine an abstract point somewhere in space crossed by three perpendicular directions and then apply this scheme to a process perceived in actual space? It is completely divorced from man, something quite inhuman. This non-human element, which has appeared in recent times in mathematical thinking, was once human. But when was it human?

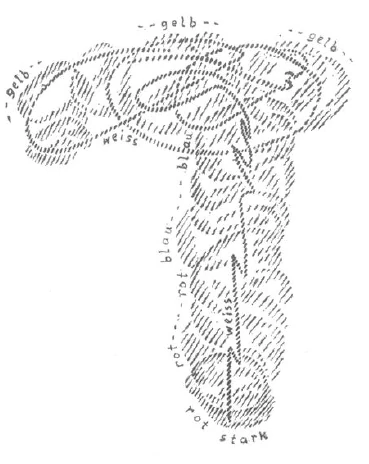

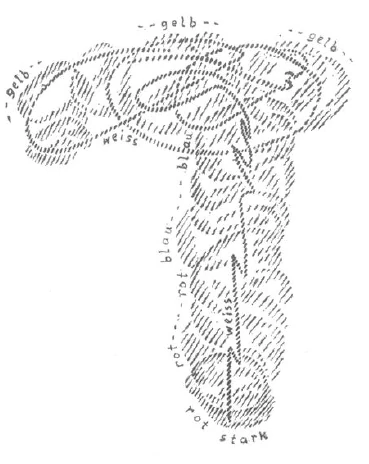

The actual date has already been indicated, but the inner aspect is still to be described. When was it human? It was human when man did not only experience in his movements and his inward orientation in space that he stepped forward from behind and moved in such a way that he was aware of his vertical as well as the horizontal direction, but when he also felt the blood's inward activity in all such moving about, in all such inner geometry. There is always blood activity when I move forward. Think of the blood activity present when, as an infant, I lifted myself up from the horizontal to an upright position! Behind man's movements, behind his experience of the world by virtue of movements, (which can also be, and at one time was, an inward experience) there stands the experience of the blood. Every movement, small or large, that I experience as I perform it contains its corresponding blood experience. Today blood is to us the red fluid that seeps out when we prick our skin. We can also convince ourselves intellectually of its existence. But in the age when mathematics, mathesis, was still connected with mysticism, when in a dreamy way the experience of movement was inwardly connected with that of blood, man was inwardly aware of the blood. It was one thing to follow the flow of blood through the lungs and quite another to follow it through the head. Man followed the flow of the blood in lifting his knee or his foot, and he inwardly felt and experienced himself through and through in his blood. The blood has one tinge when I raise my foot, another when I place it firmly on the ground. When I lounge around and doze lazily, the blood's nuance differs from the one it has when I let thoughts shoot through my head. The whole person can take on a different form when, in addition to the experience of movement, he has that of the blood. Try to picture vividly what I mean. Imagine that you are walking slowly, one step at a time; you begin to walk faster; you start to run, to turn yourself, to dance around. Suppose that you were doing all this, not with today's abstract consciousness, but with inward awareness: You would have a different blood experience at each stage, with the slow walking, then the increase in speed, the running, the turning, the dancing. A different nuance would be noted in each case. If you tried to draw this inner experience of movement, you would perhaps have to sketch it like this (white line.) But for each position in which you found yourself during this experience of movement, you would draw a corresponding inward blood experience (red, blue, yellow—see Figure 2)

Of the first experience, that of movement, you would say that you have it in common with external space, because you are constantly changing your position. The second experience, which I have marked by means of the different colors, is a time experience, a sequence of inner intense experiences.

In fact, if you run in a triangle, you can have one inner experience of the blood. You will have a different one if you run in a square.

What is outwardly quantitative and geometric, is inwardly intensely qualitative in the experience of the blood.

It is surprising, very surprising, to discover that ancient mathematics spoke quite differently about the triangle and the square. Modern nebulous mystics describe great mysteries, but there is no great mystery here. It is only what a person would have experienced inwardly in the blood when he walked the outline of a triangle or a square, not to mention the blood experience corresponding to the pentagram. In the blood the whole of geometry becomes qualitative inward experience. We arrive back at a time when one could truly say, as Mephistopheles does in Goethe's Faust, “Blood is a very special fluid.”30From Goethe's Faust, Part I, the scene in the Student Room with Faust and Mephisto. See Rudolf Steiner, The Occult Significance of the Blood (London: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1967). This is because, inwardly experienced, the blood absorbs all geometrical forms and makes of them intense inner experiences. Thereby man learns to know himself as well. He learns to know what it means to experience a triangle, a square, a pentagram; he becomes acquainted with the projection of geometry on the blood and its experiences. This was once mysticism. Not only was mathematics, mathesis, closely related to mysticism, it was in fact the external side of movement, of the limbs, while the inward side was the blood experience. For the mystic of bygone times all of mathematics transformed itself out of a sum of spatial formations into what is experienced in the blood, into an intensely mystical rhythmic inner experience.

We can say that once upon a time man possessed a knowledge that he experienced, that he was an integral part of; and that at the point in time that I have mentioned, he lost this oneness of self with the world, this participation in the cosmic mysteries. He tore mathematics loose from his inner being. No longer did he have the experience of movement; instead, he mathematically constructed the relationships of movement outside. He no longer had the blood experience; the blood and its rhythm became something quite foreign to him. Imagine what this implies: Man tears mathematics free from his body and it becomes something abstract. He loses his understanding of the blood experience. Mathematics no longer goes inward. Picture this as a soul mood that arose at a specific time. Earlier, the soul had a different mood than later. Formerly, it sought the connection between blood experience and experience of movement; later, it completely separated them. It no longer related the mathematical and geometrical experience to its own movement. It lost the blood experience. Think of this as real history, as something that occurs in the changing moods of evolution. Verily, a man who lived in the earlier age, when mathesis was still mysticism, put his whole soul into the universe. He measured the cosmos against himself. He lived in astronomy.

Modern man inserts his system of coordinates into the universe and keeps himself out of it. Earlier, man sensed a blood experience with each geometrical figure. Modern man feels no blood experience; he loses the relationship to his own heart, where the blood experiences are centered. Is it imaginable that in the seventh or eighth century, when the soul still felt movement as a mathematical experience and blood as a mystical experience, anybody would have founded a Copernican astronomy with a system of coordinates simply inserted into the universe and totally divorced from man? No, this became possible only when a specific soul constitution arose in evolution. And after that something else became possible as well. The inward blood awareness was lost. Now the time had come to discover the movements of the blood externally through physiology and anatomy. Hence you have this change in evolution: On one hand Copernican astronomy, on the other the discovery of the circulation of the blood by Harvey,31William Harvey, 1578–1658, physiologist, Professor of Anatomy, London, discoverer of the main bloodstream: De Motu Cordis et Sanguinis (1628). a contemporary of Bacon and Hobbes. A world view gained by abstract mathematics cannot produce anything like the ancient Ptolemaic theory, which was essentially bound up with man and the living mathematics he experienced within himself. Now, one experiences an abstract system of coordinates starting with an arbitrary zero point. No longer do we have the inward blood experience; instead, we discover the physical circulation of the blood with the heart in the center.

The birth of science thus placed itself into the whole context of evolution in both its conscious and unconscious processes. Only in this way, out of the truly human element, can one understand what actually happened, what had to happen in recent times for science—so self-evident today—to come into being in the first place. Only thus could it even occur to anybody to conduct such investigations as led, for example, to Harvey's discovery of the circulation of the blood. We shall continue with this tomorrow.

Dritter Vortrag

Es ist von mir versucht worden, in den beiden letzten Betrachtungen den Zeitpunkt anzudeuten, in dem innerhalb der neueren Menschheitsentwickelung naturwissenschaftliche Anschauung und naturwissenschaftliches Denken, wie wir es heute verstehen, entstanden ist, und ich konnte gestern darauf hinweisen, daß der ganze Charakter dieses naturwissenschaftlichen Denkens, wie er zuerst am deutlichsten hervortritt in der Auffassung der Astronomie durch Kopernikus, daß dieser ganze Charakter des naturwissenschaftlichen Denkens abhängig ist von der Art, wie man allmählich im Laufe der Menschheitsentwickelung die Mathematik, das mathematische Denken in ein Verhältnis brachte zur äußeren Weltwirklichkeit. In der Tat hängt außerordentlich viel für die wissenschaftliche Entwickelung der neueren Zeit davon ab, daß auch in bezug auf das mathematische Denken selber ein Umschwung — man möchte fast sagen: eine Revolution — der menschlichen Anschauung eingetreten ist. In der Gegenwart ist man ja so sehr geneigt, die Art und Weise, wie man selber denkt in dieser Gegenwart, gewissermaßen als etwas absolut Geltendes hinzustellen, und gar nicht das Augenmerk darauf zu richten, wie sich die Dinge verändert haben. Man hat heute eine gewisse Stellung zur Mathematik und wiederum eine gewisse Anschauung über das Verhältnis des Mathematischen zu dem Weltwirklichen. Und man denkt, das sei eben einmal das Gegebene, das richtige Verhältnis. Gewiß, man diskutiert darüber, aber innerhalb gewisser Grenzen betrachtet man das als das richtige Verhältnis und denkt nicht daran, in welch einer uns eigentlich gar nicht so besonders ferne liegenden Vergangenheit über die Mathematik selber von der Menschheit anders empfunden worden ist. Man brauchte sich nur einmal mit einer genügenden Schärfe daran zu erinnern, wie auch nicht lange nach jenem Zeitpunkt, den ich als den bedeutungsvollsten des neueren Geisteslebens bezeichnet habe, bald nach diesem Zeitpunkt, in dem der Kusaner seine bedeutungsvollen Auseinandersetzungen der Welt gegeben hat, wie bald nach diesem Zeitpunkte nicht nur Kopernikus mit einem mathematisch orientierten Denken die Bewegungen des Sonnensystems erklären wollte, mit einem schon so mathematisch orientierten Denken, wie wir es auch heute gewöhnt sind, sondern wie auch Philosophen - Cartesius, Spinoza — geradezu ihr Ideal darinnen gesehen haben, die Art und Weise, wie man in der Mathematik denkt, auf das umfassendste Darstellen des ganzen physischen und geistigen Weltengebäudes anzuwenden.

Spinoza, der Philosoph, legte einen besonderen Wert darauf, seine philosophischen Grundsätze und Forderungen selbst in einem solchen Buche, wie in seiner «Ethik» so darzustellen, daß, wenn auch nicht mathematische Formeln, wenn auch nicht Rechnungen in diesem Buche eine besondere Rolle spielen, eben doch die Art des Schließens, die Art, spätere Gesetze aus früheren herzuleiten, nach dem Muster des Mathematischen geschehe. Das war nach und nach den Zeitgenossen wie etwas Selbstverständliches erschienen, daß man in der Mathematik ein Musterbild für die Erlangung innerer Gewißheit in sich selber trage, und daß, wenn es gelinge, den Weltenverlauf durch Gedanken so auszudrücken, daß diese Gedanken in der haarscharfen Architektonik aneinandergegliedert sind, wie die Gedanken des mathematischen, des geometrischen Systems, daß man dadurch eben etwas erreiche, was der Wirklichkeit entsprechen müsse. Aber die besondere Art, wie man sich zur Mathematik und zum Verhältnis der Mathematik zur Wirklichkeit stellt, die muß, wenn man den Charakter naturwissenschaftlichen Denkens richtig erfassen will, durchaus verstanden werden. Die Mathematik war in jener Zeit allmählich das geworden, was man im Verhältnis zu etwas Früherem, das ich gleich nachher charakterisieren werde, nennen könnte: ein sich selbst genugsames inneres Denkvermögen. Was meine ich damit?

Man kann schon sagen, daß man die Mathematik für die Zeit des Descartes, des Cartesius, für die Zeit des Kopernikus so charakterisieren kann, wie man das annähernd auch noch heute kann. Nehmen wir zum Beispiel einmal den heutigen Mathematiker, der Geometrie darstellt, der innerhalb der geometrischen Vorstellungswelt ja auch seine analytischen Formeln sucht, um diese oder jene physikalischen Vorgänge zu begreifen. Dieser Mathematiker geht als Geometer, zunächst in der Auffassung der euklidischen Geometrie, von dem dreidimensionalen Raume aus oder überhaupt von dem dimensionalen Raum, wenn man etwa auch auf die nichteuklidische Geometrie Rücksicht nehmen wollte, und er unterscheidet im dreidimensionalen Raum drei aufeinander senkrecht stehende, aber im übrigen gleichartige Richtungen. Es ist der Raum, ich möchte sagen, ein sich selbst genügendes Gebilde, das einfach so, wie ich es jetzt beschrieben habe, vor das Bewußtsein hingestellt wird, ohne daß viel gefragt wird: Woher kommt dieses Gebilde, woher kommt überhaupt das ganze geometrische Vorstellen? — Bei der Äußerlichkeit, welche in der neueren Zeit das psychologische Denken allmählich angenommen hat, war es auch natürlich, daß der Mensch nicht in jene Seelentiefen, überhaupt nicht in jene inneren Tiefen hinuntersteigen konnte, aus denen die Grundlagen zum Beispiel des geometrischen Denkens heraufkommen. Der Mensch nimmt einfach sein gewöhnliches Bewußtsein hin und erfüllt dieses gewöhnliche Bewußtsein mit der erdachten, aber nicht erlebten Mathematik. Nehmen wir es im speziellen Fall mit den erdachten, nicht erlebten, drei aufeinander senkrecht stehenden Dimensionen des euklidischen Raumes. Aber niemals wäre der Mensch zu jenem Erdenken der drei aufeinander senkrecht stehenden Dimensionen des euklidischen Raumes gekommen, wenn er nicht in sich erlebte eine dreifache Orientierung.

Die eine Orientierung, die der Mensch in sich erlebt, ist von vorne nach rückwärts. Wir brauchen nur daran zu denken, wie sich in der äußerlichen heutigen anatomisch-physiologischen Betrachtungsweise für den Menschen - ich spreche dabei nur vom Menschen, nicht von den Tieren, das ist in diesem Zusammenhange nicht notwendig -, wie sich für den Menschen, sagen wir zum Beispiel die Nahrungsaufnahme, das Absondern und auch sonstige Vorgänge des Organismus in der Richtung von vorn nach hinten abspielen, und wie diese Orientierung ganz bestimmter Vorgänge im Inneren des Menschen verschieden ist von dem, wenn ich zum Beispiel irgend etwas ausführe mit meinem rechten Arm, und dazu symmetrisch etwas ausführe mit meinem linken Arm. Da sind die Vorgänge orientiert nach rechts und links. Und endlich brauchen wir uns nur zu erinnern, wie mit Bezug auf eine andere Orientierung der Mensch eigentlich erst während seines Erdendaseins in diese hineinwächst: Er kriecht im Anfange und richtet sich allmählich erst so auf, daß eine Orientierung in ihm selber von oben nach unten oder von unten nach oben fließt.

So wie die Dinge heute stehen, nimmt man diese drei Orientierungen des Menschen recht äußerlich hin, indem man ja nicht innerlich erlebt, sondern von außen anschaut, was Vorgänge im menschlichen Organismus sind, die sich im wesentlichen von vorn nach hinten, oder solche, die sich von rechts nach links oder von links nach rechts, oder solche, die sich von oben nach unten abspielen. Könnte man seelenbetrachtend in frühere Zeitalter zurückgehen mit einer wirklichen Psychologie, so würde man eben wissen, daß für eine ältere Menschenempfindung, ein älteres Menschenerleben diese drei Orientierungen innere Erlebnisse waren. So wie wir heute als innere Erlebnisse, ich möchte sagen, halbwegs noch anerkennen das Gedanken-Haben, Gefühle-Haben, so hatte der Mensch einer früheren Zeit ein richtiges inneres Erlebnis zum Beispiel von dem Von-vorn-nach-Hinten. Für ihn war noch nicht verlorengegangen, sagen wir, die Ablähmung des vorne in der Mundhöhle sich intensiv entwickelnden Geschmacks gegen hinten zu. Das Qualitative, das darinnen lag, daß man den Geschmack intensiv vorne auf der Zunge fühlte, und dann ihn immer schwächer und schwächer empfand, indem er sich zurückzog in der Orientierung von vorne nach hinten und endlich sich ganz verlor, dieses Erleben war einmal für das innere menschliche Erleben etwas ganz Reales, Konkretes. Man verfolgte mit solchen Qualitätserlebnissen die Orientierung von vorne nach hinten. Der Mensch ist eben nicht mehr so innerlich, wie er einmal war. Daher hat er solche Erlebnisse, wie ich sie eben charakterisiert habe, heute nicht mehr. Ebensowenig hat der Mensch heute eine lebendige Empfindung von der Einstellung der Augenachse, um irgendeinen Punkt durch das Übergreifen der rechten Augenachse über die linke zu fixieren. Ebensowenig hat der Mensch heute eine voll konkrete Empfindung von dem, was ihm wird als Mensch, wenn er in der Orientierung rechts-links zuordnet, sagen wir, den rechten Arm und die rechte Hand dem linken Arm und der linken Hand. Und erst recht eine solche Empfindung wie die, daß man sich sagen kann: Im Haupte durchleuchtet mich der Gedanke, er schlägt ein, indem er sich in der Orientierung von oben nach unten bewegt in mein Herz -, eine solche Empfindung, ein solches Erlebnis ist eben mit der Innerlichkeit des Welterlebens für den Menschen verlorengegangen. Aber ein solches Erleben war da. Der Mensch hat zunächst in sich die drei aufeinander senkrecht stehenden Raumorientierungen erlebt. Und diese drei Raumorientierungen, sein Rechts-Links, sein Vorne-Hinten, sein Oben-Unten, die sind die Grundlage des dreidimensionalen Raumschemas. Das dreidimensionale Raumschema ist erst eine Abstraktion dieses Ihnen eben charakterisierten unmittelbaren Erlebens. Wie können wir also sprechen, etwa wenn wir auf ältere Zeiten hinschauen zu der Geometrie, zu diesem Teil der Mathematik? Wir können so sprechen, daß wir sagen, der Mensch früherer Zeiten war sich klar darüber, daß er sich sagen konnte: Durch meine Menschlichkeit offenbart sich mir in meinem eigenen Leben das Mathematische, das Geometrische, und indem ich verlängere mein Oben-Unten, mein RechtsLinks, mein Vorne-Hinten, umfasse ich von mir aus die Welt.

Man muß nur einmal empfinden, was für ein gewaltiger Unterschied besteht zwischen dieser an das menschliche Erleben gebundene mathematischen Empfindung und dem kahlen, öden mathematischen Raumschema der analytischen Geometrie, die irgendwohin in einen abstrakten Raum einen Punkt stellt, drei aufeinander senkrechte Koordinatenachsen zieht und das erdachte Raumschema von allem Erleben abgesondert hat. Aber dieses erdachte Raumschema hat sich der Mensch erst aus seinem eigenen Innenleben herausgerissen. So daß man tatsächlich die Entstehung der späteren mathematischen Anschauungsweise, die dann die Naturwissenschaft ergriffen hat, wenn man sie richtig verstehen will in ihrem selbstgenugsamen Hinstellen ihrer Gebilde, daß man sie ableiten muß aus der erlebten Mathematik einer früheren Zeit. Die Mathematik einer früheren Zeit war eben etwas ganz anderes. Und dasjenige, was einmal vorhanden war in einem, ich möchte sagen, traumhaften Erleben der inneren Dreidimensionalität und was sich dann verabstrahiert hat, das ist heute völlig im Unbewußten vorhanden. In der Tat ist es auch heute beim Menschen noch so, daß er sich die Mathematik aus seiner eigenen inneren Dreidimensionalität herausholt. Aber dieses Herausholen des Raumschemas aus demjenigen, was der Mensch an innerer Orientierung erlebt, geschieht auf völlig unbewußte Weise. Davon kommt nichts ins Bewußtsein herauf. Ins Bewußtsein kommt herauf zum Beispiel das fertige Raumschema, wie überhaupt alle fertigen, von ihrer Wurzel abgelösten mathematischen Gebilde. Ich habe das Beispiel des Raumschemas gewählt. Ich könnte ebensogut irgendeine andere mathematische Kategorie anführen, auch noch mathematische Kategorien aus der Algebra, aus der Analysis, aus der Arithmetik. Sie sind nichts anderes, als aus unmittelbarem menschlichem Erleben ins Abstrakte heraufgeholte Schemata.

Sehen Sie, wenn man weiter zurückgeht auf die Art und Weise, wie die Menschen über das Mathematische gedacht haben, zurückgeht um etwa ein paar Jahrhunderte vor dem 15., 16. oder 17. Jahrhundert, dann findet man, daß die Menschen wenigstens noch einen Nachklang von Empfindung hatten bei den Zahlen. Sie hätten ja auch nicht in der Zeit, in der die Zahlen schon jenes Abstrakte geworden waren, das sie heute sind, sie hätten ja auch nicht Namen für die Zahlen finden können. Die Namen für die Zahlen sind oftmals so außerordentlich charakteristisch. Denken Sie doch nur an das Wort «Zwei», das deutlich noch einen konkreten Vorgang ausdrückt: entzweien, ja das sogar zusammenhängt mit zweifeln. Aber es ist nicht die Nachbildung eines Äußeren, wenn die Zahl Zwei bezeichnet wird durch das Entzweien, sondern es ist tatsächlich ein im Inneren Erlebtes, das zum Schema gemacht wird, ein aus dem Inneren Heraufgeholtes, geradeso wie das Abstrakte dreidimensionale Raumschema aus dem Inneren herausgeholt ist.

Und da kommen wir zurück zu einer Zeit, die in ihrer vollen geistigen Lebendigkeit zum Beispiel vorhanden war noch in den ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten, und deren geistige Eigentümlichkeit schon daraus ersehen werden kann, daß Mathematik, Mathesis mit Mystik fast als eins angesehen wurde. Mystik, Mathesis, Mathematik sind eines, wenn auch nur in gewisser Beziehung. Für einen Mystiker in den ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten ist die eigentliche Mystik dasjenige, was man mehr seelisch innerlich erlebt, die Mathematik ist jene Mystik, die man mehr äußerlich mit dem Körper erlebt, zum Beispiel die Geometrie mit den Orientierungen des Körpers nach vorne-hinten, rechtslinks, oben-unten. Man möchte sagen, die eigentliche Mystik ist eben seelische Mystik, und die Mathematik, Mathesis, ist körperliche Mystik. Man erlebt innerlich die eigentliche Mystik eben in dem, was man sehr häufig Mystik nennt, und man erlebt die Mathesis, die andere Mystik, indem man ein Innenerlebnis des Körperlichen hat, indem man dieses Innenerlebnis noch nicht verloren hat.

Tatsächlich ist auch der Charakter, wie Cartesius und Spinoza von der Mathematik noch fühlen oder auch von der mathematischen Methode noch fühlen, ganz anders geartet. Man vertiefe sich nur einmal, aber nicht so äußerlich, wie man das heute tut, wo man immer die jetzigen, uns in den Kopf eingehämmerten Begriffe auch bei den alten Denkern finden will, sondern selbstlos aus sich herausgehend, in diese Denker, und man wird finden, daß selbst noch Spinoza etwas von mystischem Empfinden hat, indem er sich der mathematischen Methode hingibt. Schließlich unterscheidet sich die Philosophie des Spinoza von der Mystik eigentlich gar nicht anders als dadurch, daß ein Mystiker von der Art eines Meisters Eckhart oder des Johannes Tauler eben mehr auf dem Gefühlsgrunde seine Weltengeheimnisse zu erleben versucht, während sie ein Spinoza, aber ebenso innerlich, in mathematisch-methodischen Linien, die eben nicht gerade geometrische Linien sind, aber nach mathematischer Methode innerlich erlebt werden, sich konstruiert. In bezug auf die Seelenverfassung und Seelenstimmung im Erleben der mystischen Methode des Meisters Eckhart und der mathematischen Methode des Spinoza ist eigentlich kein Unterschied. Und derjenige, der einen Unterschied macht, der versteht eben eigentlich gar nicht, wie Spinoza richtig mathematisch-mystisch seine «Ethik» zum Beispiel erlebt hat. Da ist noch ein Nachklang bei diesem Philosophen aus derjenigen Zeit, in der Mathematik, Mathesis und Mystik als einerlei Erlebnisse der Seele empfunden worden sind.

Nun werden Sie vielleicht, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden und lieben Freunde, sich erinnern, wie ich in meinem Buche über «Seelenrätsel» den Versuch gemacht habe, die menschliche Organisation wiederum in einer dem modernen Denken gemäßen Weise zu finden. Ich muß auf die Stelle dieses Buches «Von Seelenrätseln» verweisen. Dort habe ich die menschliche Organisation, unter der ich zunächst die physische Organisation verstehe, gegliedert in das Nerven-Sinnessystem, in das rhythmische System und in das Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßensystem. Ich brauche hier nicht besonders darauf hinzuweisen, daß damit nicht etwa, wie das von universitärer Seite aus karikiert worden ist, eine solche Gliederung des Menschen gemeint ist, wo die einzelnen Glieder nebeneinandergestellt werden im Raume. Es wird Ihnen ja aus der Darstellung, die ich in meinem Buche «Von Seelenrätseln» gegeben habe, klar sein, daß diese Glieder ineinandergreifen, daß das NervenSinnessystem, wenn man es Kopfsystem nennt, eben durchaus nur der Hauptsache nach im Haupte, im Kopfe lokalisiert ist, daß es aber eben im ganzen Menschen sich ausbreitet, daß diese drei Systeme ineinandergehen, daß natürlich auch der Atmungs- und Blutrhythmus von dem mittleren Menschen, von dem Brustmenschen herauf sich erstreckt in die Kopfesorganisation und so weiter. Die Gliederung ist also eine funktionelle, sie ist nicht eine lokale. Aber man lernt den Menschen doch durchschauen, wenn man ein inneres Verständnis für diese Gliederung hat.

Nun wollen wir uns einmal diese Gliederung heute zu einem bestimmten Ziele vor Augen stellen. Fassen wir zunächst einmal das dritte Glied der menschlichen Organisation, den Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenmenschen ins Auge. Wir können ja zunächst unser Augenmerk auf dasjenige richten, was uns in diesem Gliede der Menschenwesenheit besonders ins Auge fällt. Wir können das Augenmerk darauf richten, daß der Mensch sein äußeres Leben, insofern er ein Sinneswesen ist, dadurch vollbringt im Erdendasein, daß er dasjenige, was in seinen Gliedmaßen lebt, anschließt an die inneren Erlebnisse, von denen ich einzelne charakterisiert habe, namentlich das innere Orientierungserlebnis nach den drei Raumrichtungen. Das Gliedmaßensystem des Menschen fügt sich gewissermaßen in seinen äußeren Bewegungen, in seiner Einorientierung in die Welt in dasjenige ein, was innere Orientierung in den drei genannten Richtungen ist. Wir fügen uns in einer gewissen Weise in das Erlebnis des Oben und Unten im Gehen ein. Wir fügen uns bei manchem, was wir mit unseren Händen ausführen oder mit unseren Armen, in die Orientierungsrichtung rechts-links ein. Ja wir fügen uns mit unserem Sprechen sogar, insofern das Sprechen eine Bewegung des Luftartigen im Menschen ist, der Richtung vornehinten, hinten-vorne ein. Indem wir uns in der Welt bewegen, stellen wir unsere innere Orientierung in die äußere Welt hinein.

Sehen wir jetzt einmal den wahren Vorgang gegenüber dem bloß Illusionären in einem bestimmten mathematischen Falle an. Es ist etwas Illusionäres, etwas rein im Gedankenschema Verlaufendes, wenn ich irgendwo im Weltenall einen Raumvorgang finde, und ich gehe dann als analytischer Mathematiker an diesen Raumvorgang so heran, daß ich mir die drei Koordinaten des gewöhnlichen Koordinatenachsen-Systems aufzeichne oder auch denke, und nun irgendeinen äußeren Vorgang, der dem Raum angehört, in dieses rein konstruierte Raumschema des Descartes, des Cartesius einordne. Das ist ja nur dasjenige, was sich, ich möchte sagen, da oben durch das NervenSinnessystem des Menschen in dem Gebiete des Gedankenschematischen abspielt. Zu einem Verhältnis des Menschen zu einem solchen Vorgang im Raume würde man nicht kommen, wenn nicht zugrunde läge das, was man mit seinen Gliedmaßen tut, mit seinem ganzen Menschen übrigens auch tut, daß man nach der inneren Orientierung des Oben-Unten, Rechts-Links, Vorne-Hinten sich hineinstellt in die ganze Welt. Ich weiß, wenn ich nach vorwärts gehe, daß ich mich auf der einen Seite in das Oben und Unten einstelle, um aufrecht bleiben zu können. Ich weiß aber auch, daß ich mich in das Hinten und Vorne mit meiner Gangrichtung hineinstelle, und wenn ich etwa schwimme und die Arme benütze, orientiere ich mich mit dem Rechts-Links hinein in die Welt. Ich habe gar nicht dasjenige, was der Sache zugrunde liegt, wenn ich das Cartesiussche Raumschema nehme, das abstrakte Koordinatenachsen-System nehme. Ich habe dasjenige, was überhaupt dem Menschen den Eindruck der Wirklichkeit gibt, wenn er mit den Raumdingen verkehrt, erst dann, wenn ich mir sage, da oben im KopfNervensystem spielt sich eigentlich das illusionäre Bild ab von etwas, was tief im Unterbewußtsein, nämlich da sich abspielt, wo der Mensch eben nicht mit seinem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein hinkommt, was sich abspielt zwischen seinem Gliedmaßensystem und der Welt. Und die ganze Mathematik, die Geometrie, ist heraufgeholt aus unserem Bewegungssystem. Wir hätten keine Geometrie, wenn wir nicht nach innerlicher Orientierung uns in die Welt hineinstellten. In Wahrheit geometrisieren wir, indem wir dasjenige, was sich im Unbewußten abspielt, in das Illusionäre des Gedankenschemas heraufheben. Dadurch erscheint es uns als etwas so abstrakt Selbständiges. Das ist aber eben erst dasjenige, was in der neueren Zeit eingetreten ist. In der Zeit, in der die Mathesis, die Mathematik der Mystik noch nahe empfunden wurde, da wurde einem auch das mathematische Verhalten zu den Dingen noch etwas Menschliches. Was ist denn schließlich Menschliches darinnen enthalten, wenn ich einen Nullpunkt, den ich irgendwo in den Raum auch nur gedacht hineinstelle, durchkreuzen lasse von drei aufeinander senkrechten Richtungen, und dieses Raumschema zusammenfallen lasse mit einem Vorgang, den ich im wirklichen Raume wahrnehme? Es ist ja ganz abgesondert vom Menschen, es ist ja etwas ganz Unmenschliches. Dieses Unmenschliche, das eben in der neueren Zeit aufgetreten ist im mathematischen Gedankenbau, dieses Unmenschliche war einmal ein Menschliches. Aber wann war es ein Menschliches?

Nun, die äußere Zeit habe ich Ihnen ja eigentlich angegeben, aber das Innere davon ist noch zu charakterisieren. Wann war es ein Menschliches? Damals war es ein Menschliches, als der Mensch hinter seinen Bewegungen, hinter seinem Einordnen, seiner inneren Orientierung in den Raum nicht nur innerlich noch erlebte: Du gehst von hinten nach vorne und bewegst dich so, daß du dein Gleichgewicht erlebst von oben und unten, und du bildest vielleicht ein anderes Gleichgewicht mit dem Rechts-Links -, sondern als der Mensch auch noch fühlte, daß ja in jedem solchen Gehen, in jeder solcher Geometrie innerlich das Blut tätig ist. Es ist ja immer eine Bluttätigkeit dabei, wenn ich nach vorne gehe. Und was war für eine Bluttätigkeit vorhanden, als ich als Kind mich aufrichtete aus der horizontalen Lage in die vertikale Lage! Hinter den Bewegungen des Menschen, hinter dem Erleben der Welt durch das Bewegen, das ja auch ein innerliches Erlebnis sein kann und es einmal war, hinter dem steht das Blutserlebnis. Denn in der kleinsten und in der größten Bewegung, die ich erlebe, indem ich sie selber ausführe, liegt ja das Blutserlebnis, das damit verknüpft ist. Nur sehen wir heute eben das Blut als dasjenige an, was sich uns darbietet, wenn wir in die Haut stechen und da der rote Saft herausfließt, oder wenn wir uns in ähnlicher Weise äußerlich von dem Dasein des Blutes überzeugen. Aber die Zeit, wo die Mathematik, die Mathesis noch angeschlossen war an die Mystik, wo das Bewegungserlebnis innerlich, wenn auch traumhaft, in Verbindung war mit dem Blutserlebnis, diese Zeit erlebte das Blut innerlich. Das heißt, der Mensch wurde etwas anderes, wenn er verfolgte, wie durch seine Lungenadern das Blut durchrollt, als wenn durch seine Kopfadern das Blut durchrollt. Und er verfolgte das Durchrollen des Blutes beim Aufheben des Knies, beim Aufheben des Fußes, und er durchfühlte sich, durchlebte sich innerlich in seinem Blut. Das Blut hat eine andere Schattierung, wenn ich den Fuß hoch aufhebe, als wenn ich ihn auf den Boden gesetzt habe. Das Blut hat eine andere Schattierung, wenn ich blöde dasitze und faul schlafe, als wenn ich Gedanken durch den Kopf schießen lasse. So kann der ganze Mensch innerlich Gestalt werden, in verschiedenen Nuancierungen Gestalt werden, wenn er das Blutserlebnis hinter dem Bewegungserlebnis hat. Stellen Sie sich lebendig das vor, was ich hier meine. Denken Sie sich, Sie gehen langsam, Schritt vor Schritt; Sie fangen an schneller zu gehen; Sie fangen an zu laufen; Sie fangen an sich zu drehen, in allerlei Weise zu tanzen, und denken Sie, Sie würden nicht mit dem heutigen abstrahierenden Bewußtsein, sondern mit innerlichem Erleben zuerst die ganz langsame Art haben, sich in den Raum hineinzustellen in allen drei Orientierungen; Sie würden das Schnellerwerden haben, Sie würden das Laufen haben, das Drehen, das Tanzen, aber Sie würden dabei immer haben das entsprechende Blutserlebnis. Zuerst jene innere Schattierung, die Sie natürlich nur immer empfindend erleben können, beim Langsamgehen. Beim Laufen, beim Drehen, beim Tanzen wäre es jeweils anders, so daß Sie, wenn Sie recht vom Inneren heraus Ihr Bewegungserlebnis hinzeichnen wollten, vielleicht folgendes hinzeichnen müßten (Zeichnung, weiße Linie). Aber jetzt würden Sie hinzeichnen für jede Lage, in der Sie während dieses Bewegungserlebens waren, ein innerliches Blutserlebnis (rot, blau, gelb).

Das erste Erlebnis, das Bewegungserlebnis, von dem würden Sie sagen, Sie erleben es gemeinsam mit dem äußeren Raume, denn Sie gehen fortwährend aus Ihrem Orte heraus. Das zweite Erlebnis, das ich durch Farben gekennzeichnet habe, ist ein Zeiterlebnis, ist eine Aufeinanderfolge von inneren intensiven Erlebnissen.

Sie können in der Tat auch, wenn Sie nun die Kunst ausführen, im Dreieck zu laufen, ein innerliches Erlebnis haben als Blutserlebnis:

Wenn Sie im Viereck laufen, können Sie ein anderes Blutserlebnis haben. Dasjenige, was äußerlich quantitativ, was äußerlich geometrisch ist, ist innerlich im Blutserlebnis intensiv qualitativ:

Das ist das Überraschende, das ungeheuer Überraschende, wenn man darauf kommt, daß eine ältere Mathematik ganz anders redet vom Dreieck und Viereck. Wenn darinnen gesehen wird allerlei Geheimnisvolles, so ist das nicht ein Geheimnisvolles, wie es die heutigen nebulosen Mystiker beschreiben, sondern es ist dasjenige, was einer etwa beim Dreieck erlebt hätte innerlich im Blute, wenn er das Dreieck abgelaufen wäre, was einer innerlich erlebt hätte im Blute, wenn er das Viereck abgelaufen wäre. Und gar jenes Blutserlebnis, das für das Pentagramm gilt! Sie sehen, im Blute wird die ganze Geometrie qualitativ inneres Erlebnis. Wir kommen in die Zeit zurück, die wahrhaftig sagen durfte: Blut ist ein ganz besonderer Saft. Denn wird er innerlich erlebt, dieser Saft, so saugt er alle geometrischen Gebilde auf, macht sie zu intensiven inneren Erlebnissen. Aber der Mensch lernt sich ja dadurch auch selber kennen. Er lernt kennen, was es heißt, ein Dreieck erleben, was es heißt, ein Viereck erleben, was es heißt, ein Pentagramm erleben, und er lernt die Projektion der Geometrie auf das Blut und seine Erlebnisse kennen. Das war einmal Mystik. Die Mathematik, die Mathesis, stand nicht nur nahe der Mystik, sondern sie war überhaupt die Bewegungsaußenseite, die Gliedmaßenseite für das Innenerlebnis, für das Blutserlebnis. Die ganze Mathematik verwandelte sich aus einer Summe von Raumesgebilden für den Mystiker einstiger Zeiten in dasjenige, was im Blute erlebt wird, in rhythmisches Innenerlebnis, aber intensives mystisches, rhythmisches Innenerlebnis.

Man kann sagen: Der Mensch hatte einmal eine Erkenntnis, die er erlebte, bei der war er ganz dabei, und er verlor gerade in dem Zeitpunkte, den ich Ihnen charakterisiert habe, dieses Dabeisein seiner eigenen Wesenheit mit der Welt, dieses Dabeisein bei den Weltgeheimnissen. Er riß sich die Mathematik aus seinem Inneren heraus. Er hatte nicht mehr das Bewegungserlebnis, konstruierte sich aber mathematisch die Zusammenhänge der Bewegungen draußen. Er hatte nicht mehr das Blutserlebnis. Dadurch wurde ihm überhaupt das Blut in seinem Rhythmus etwas ganz Fremdes, er wurde sich selber fremd dabei in seinem Blutserlebnis. Denken Sie sich, der Mensch reißt die Mathematik von seinem Körper los, sie wird ein Abstraktes. Er verliert das Verständnis für das Blutserlebnis. Die Mathematik geht nicht mehr nach dem Inneren. Und denken Sie sich das einmal als eine Stimmung der Seele, die einmal auftrat. Denken Sie sich, daß die Seele früher anders gestimmt war, als sie später gestimmt wurde, daß sie früher so gestimmt war, daß sie eben den Zusammenhang zwischen Blutserlebnis und Bewegungserlebnis suchte, und nachher von diesem das eine ganz abgesondert hatte, das mathematische und geometrische Erlebnis ganz abgesondert hatte, nicht mehr auf die eigene Bewegung bezog, das Blutserlebnis verlor. Denken Sie sich das wirklich als Historie, als ein in den Stimmungen der Menschheitsentwickelung Auftretendes. Ja, ein Mensch, der früher gelebt hat, als Mathesis noch Mystik war, der setzte seinen ganzen Menschen in die Welt hinein, der mußte mit seinem eigenen Bewegungswesen den Kosmos abmessen. Er als Mensch maß den Kosmos ab. Er lebte in der Astronomie darinnen. Der neuere Mensch stellt ein Koordinatenachsen-System in den Kosmos hinein und nimmt sich selbst heraus. Der ältere Mensch empfand bei jeder geometrischen Figur ein Blutserlebnis. Der neuere Mensch empfindet kein Blutserlebnis, verliert den Zusammenhang zu seinem eigenen Herzen, in dem die Blutserlebnisse zentriert sind. Kann sich irgend jemand denken, daß etwa im 7., 8. Jahrhundert des Mittelalters, als die Stimmung mit dem Bewegungserlebnis als mathematischem Erlebnis und mit dem Blutserlebnis als mystischem Erlebnis noch vorhanden war, daß da jemand eine Kopernikanische Astronomie begründet hätte, mit einem Koordinatenachsen-System einfach hineingestellt in die Welt, abgesondert von dem Menschen? Nein, das wurde erst möglich, als in der Menschheitsentwickelung diese besondere Seelenverfassung auftrat. Und bald darnach wurde etwas anderes möglich. Das innere Blutserlebnis ist verlorengegangen. Die Zeit war reif, nun die Blutbewegungen am physischen Menschenkörper äußerlich physiologisch-anatomisch zu ergründen. Und Sie haben so jenen Umschwung in der Menschheitsentwickelung, auf der einen Seite die Kopernikanische Astronomie und auf der anderen Seite die Entdeckung des Blutkreislaufes durch Harvey, den Zeitgenossen des Bacon, des Hobbes, denn jenes In-die-Welt-Schauen mit abstrakter Mathematik kann nicht mehr die alte Ptolemäische Theorie ergeben. Die ist im wesentlichen an den Menschen und seine erlebte Mathematik gebunden. Jetzt erlebt man das Abgesonderte, mit einem beliebigen Nullpunkt auftretende Koordinatenachsen-System. Jetzt hat man nicht mehr innerlich das Blutserlebnis, jetzt entdeckt man physisch die Blutzirkulation mit dem Herzen in der Mitte.

So stellte sich die Geburt der Naturwissenschaft in die ganze Menschheitsentwickelung hinein, in ihre bewußten und unterbewußten Prozesse, und nur so versteht man aus dem wirklichen Menschlichen heraus, was sich eigentlich zugetragen hat und was da sein mußte in der neueren Zeit, damit die uns heute so selbstverständliche Naturwissenschaft überhaupt hat entstehen können, damit jemandem erst einfallen konnte, solche Untersuchungen zu machen, wie sie etwa zu der Harveyschen Entdeckung des Blutkreislaufes führten. Dies, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, werde ich dann morgen fortsetzen.

Third Lecture

In the last two lectures, I attempted to indicate the point in time within the recent development of humanity when scientific observation and scientific thinking, as we understand them today, came into being, and yesterday I was able to point out that the entire character of this scientific thinking, as it first emerged most clearly in Copernicus' view of astronomy, that this entire character of scientific thinking depends on the way in which, in the course of human development, mathematics and mathematical thinking were gradually brought into relation with the external reality of the world. In fact, an extraordinary amount depends on the scientific development of modern times on the fact that a reversal — one might almost say a revolution — of human perception has also taken place with regard to mathematical thinking itself. At present, we are so inclined to regard the way we think in the present as something absolutely valid, and not to pay any attention to how things have changed. Today, we have a certain attitude toward mathematics and, in turn, a certain view of the relationship between mathematics and the real world. And we think that this is simply the given, the correct relationship. Certainly, we discuss it, but within certain limits we consider it to be the correct relationship and do not think about how, in a past that is actually not so distant, humanity perceived mathematics itself differently. One need only remember with sufficient clarity how, not long after that moment which I have described as the most significant in recent intellectual life, not long after that moment when the Cusanus presented his significant arguments to the world, not long after that moment, not only did Copernicus attempt to explain the movements of the solar system with mathematically oriented thinking, with a way of thinking that was already as mathematically oriented as we are accustomed to today, but philosophers—Cartesius, Spinoza—also saw in it their ideal, the way of thinking in mathematics, to be applied to the most comprehensive representation of the entire physical and spiritual structure of the world.

Spinoza, the philosopher, placed particular emphasis on presenting his philosophical principles and demands in a book such as his “Ethics” in such a way that, even if mathematical formulas and calculations do not play a special role in this book, the manner of reasoning, the manner of deriving later laws from earlier ones, follows the pattern of mathematics. Gradually, it seemed natural to his contemporaries that mathematics provided a model for attaining inner certainty within oneself, and that if one succeeded in expressing the course of the world through thoughts in such a way that these thoughts were linked together in a precise architectural structure, like the thoughts of the mathematical, geometric system, one would thereby achieve something that must correspond to reality. But the particular way in which one relates to mathematics and to the relationship between mathematics and reality must be thoroughly understood if one wants to grasp the character of scientific thinking. At that time, mathematics had gradually become what one might call, in relation to something earlier, which I will characterize in a moment, a self-sufficient inner faculty of thought. What do I mean by that?

It can be said that mathematics in the time of Descartes, Cartesius, and Copernicus can be characterized in much the same way as it can still be characterized today. Take, for example, today's mathematician who studies geometry and who, within the geometric world of ideas, seeks analytical formulas to understand this or that physical process. This mathematician, as a geometer, starts from the three-dimensional space of Euclidean geometry, or even from dimensional space in general, if one also wants to take non-Euclidean geometry into account, and distinguishes three directions in three-dimensional space that are perpendicular to each other but otherwise identical. Space is, I would say, a self-sufficient construct that is simply presented to our consciousness as I have just described it, without us asking many questions: Where does this construct come from, where does the whole geometric concept come from? — With the external nature that psychological thinking has gradually assumed in recent times, it was also natural that humans could not descend into those depths of the soul, into those inner depths from which the foundations of geometric thinking, for example, arise. Man simply accepts his ordinary consciousness and fills this ordinary consciousness with mathematics that is conceived but not experienced. Let us take the specific case of the conceived, not experienced, three perpendicular dimensions of Euclidean space. But humans would never have come up with the idea of the three perpendicular dimensions of Euclidean space if they had not experienced a threefold orientation within themselves.

The first orientation that humans experience within themselves is from front to back.

We need only think of how, in today's external anatomical and physiological view of human beings — I am speaking only of human beings, not of animals, which is not necessary in this context — how, for human beings, let us say, for example, the intake of food, the secretion and other processes of the organism take place in the direction from front to back, and how this orientation of very specific processes within the human being differs from when, for example, I perform an action with my right arm and then perform a symmetrical action with my left arm. In this case, the processes are oriented to the right and left. And finally, we need only remember how, with regard to a different orientation, the human being actually grows into this during his earthly existence: he crawls at the beginning and gradually straightens up so that an orientation flows within him from top to bottom or from bottom to top.As things stand today, these three orientations of the human being are accepted quite superficially, because we do not experience them internally, but look from the outside at what processes in the human organism are essentially from front to back, or those that are from right to left or from left to right, or those that are from top to bottom. If we could go back to earlier times with a real psychology of the soul, we would know that for an older human perception, an older human experience, these three orientations were inner experiences. Just as we today still recognize, to some extent, thinking and feeling as inner experiences, people in earlier times had a real inner experience, for example, of the front-to-back orientation. They had not yet lost, so to speak, the paralysis of the taste that developed intensively in the front of the mouth toward the back. The qualitative aspect of feeling the taste intensely at the front of the tongue and then feeling it become weaker and weaker as it receded from the front to the back and finally disappeared completely was once something very real and concrete for the inner human experience. With such qualitative experiences, people followed the orientation from front to back. Human beings are simply no longer as inwardly focused as they once were. That is why they no longer have experiences such as those I have just described. Nor do people today have a vivid sense of the position of their eye axis in order to fix their gaze on a point by crossing the right eye axis over the left. Nor do people today have a fully concrete sense of what it means to be human when they assign right and left in their orientation, say, the right arm and the right hand to the left arm and the left hand. And even less so do they have a sense that allows them to say: The thought shines through my head, it strikes me as it moves from top to bottom into my heart—such a feeling, such an experience has been lost to humans with the inner nature of their experience of the world. But such an experience did exist. Humans initially experienced the three perpendicular spatial orientations within themselves. And these three spatial orientations, his right-left, his front-back, his up-down, are the basis of the three-dimensional spatial scheme. The three-dimensional spatial scheme is only an abstraction of this immediate experience that I have just characterized for you. So how can we speak, for example, when we look back to earlier times, to geometry, to this part of mathematics? We can speak in such a way that we say that people in earlier times were clear that they could say to themselves: Through my humanity, the mathematical and geometric reveal themselves to me in my own life, and by extending my up-down, my right-left, my front-back, I encompass the world from my own perspective.

One only has to feel what an enormous difference there is between this mathematical perception bound to human experience and the bare, desolate mathematical spatial scheme of analytical geometry, which places a point somewhere in an abstract space, draws three perpendicular coordinate axes, and has separated the imagined spatial scheme from all experience. But this imagined spatial scheme was first torn out of man's own inner life. So that, if one wants to understand it correctly, one must derive the later mathematical way of thinking, which then took hold of natural science, with its self-sufficient positing of its constructs, from the experienced mathematics of an earlier time. The mathematics of an earlier time was something completely different. And what once existed in what I would call a dreamlike experience of inner three-dimensionality, and what then became abstract, is now completely present in the unconscious. In fact, even today, humans still extract mathematics from their own inner three-dimensionality. But this extraction of the spatial scheme from what humans experience in their inner orientation happens in a completely unconscious way. Nothing of this comes up into consciousness. What comes up into consciousness is, for example, the finished spatial scheme, as indeed all finished mathematical structures detached from their roots. I have chosen the example of the spatial scheme. I could just as easily have cited any other mathematical category, including mathematical categories from algebra, analysis, or arithmetic. They are nothing more than schemata abstracted from immediate human experience.

You see, if you go back further in time to the way people thought about mathematics, back to a few centuries before the 15th, 16th or 17th century, you will find that people still had at least a vestige of feeling for numbers. After all, at a time when numbers had not yet become the abstract entities they are today, they could not have found names for them. The names for numbers are often extremely characteristic. Just think of the word “two,” which clearly expresses a concrete process: to divide into two, which is even related to the word “doubt.” But it is not a reproduction of something external when the number two is described as splitting in two; it is actually an inner experience that has been turned into a pattern, something brought up from within, just as the abstract three-dimensional spatial pattern is brought out from within.

And this brings us back to a time when, for example, the first Christian centuries were still full of spiritual vitality, and whose spiritual uniqueness can already be seen in the fact that mathematics, mathesis, was regarded as almost one with mysticism. Mysticism, mathesis, and mathematics are one, albeit only in a certain sense. For a mystic in the early Christian centuries, true mysticism is what is experienced more inwardly, in the soul, while mathematics is the mysticism that is experienced more outwardly, with the body, for example, geometry with the orientation of the body forward-backward, right-left, up-down. One might say that true mysticism is spiritual mysticism, and mathematics, mathesis, is physical mysticism. One experiences true mysticism internally in what is very often called mysticism, and one experiences mathesis, the other mysticism, by having an internal experience of the physical, by not having lost this internal experience.

In fact, the character of how Cartesius and Spinoza still feel about mathematics or even about the mathematical method is of a completely different nature. Just delve into it once, but not in the superficial way we do today, where we always want to find the current concepts that have been hammered into our heads in the works of the ancient thinkers, but rather selflessly, going out from ourselves into these thinkers, and you will find that even Spinoza has something of a mystical sensibility in his devotion to the mathematical method. Ultimately, Spinoza's philosophy differs from mysticism only in that a mystic of the type of Meister Eckhart or Johannes Tauler tries to experience the secrets of the world more on the basis of feeling, while Spinoza, just as inwardly, constructs himself in mathematical-methodical lines that are not exactly geometric lines, but are experienced inwardly according to mathematical method. There is actually no difference between the state of mind and mood in the experience of Meister Eckhart's mystical method and Spinoza's mathematical method. And those who make a difference do not really understand how Spinoza correctly experienced his “Ethics,” for example, in a mathematical-mystical way. There is still an echo in this philosopher from a time when mathematics, mathesis, and mysticism were perceived as one and the same experience of the soul.

Now, my dear friends and distinguished audience, you may remember how, in my book on “The Riddle of the Soul,” I attempted to find the human organization in a way that is in keeping with modern thinking. I must refer you to the passage in this book, “On the Riddle of the Soul.” There I divided the human organization, by which I mean primarily the physical organization, into the nervous-sensory system, the rhythmic system, and the metabolic-limb system. I need not point out here that this does not mean, as has been caricatured by university scholars, a division of the human being in which the individual members are placed side by side in space. It will be clear to you from the description I gave in my book “Von Seelenrätseln” (On the Riddles of the Soul) that these parts are interrelated, that the nervous-sensory system, if you call it the head system, is only located in the head in the main, in the head, but that it spreads throughout the whole human being, that these three systems intertwine, that naturally the respiratory and blood rhythms also extend from the middle human being, from the chest, up into the head organization, and so on. The division is therefore functional, not local. But one learns to understand the human being when one has an inner understanding of this division.

Now let us consider this division today with a specific goal in mind. Let us first consider the third member of the human organization, the metabolic-limb human being. We can begin by focusing our attention on what particularly strikes us in this member of the human being. We can focus on the fact that human beings, insofar as they are sensory beings, accomplish their outer life in their earthly existence by connecting what lives in their limbs with the inner experiences I have characterized, namely the inner experience of orientation in the three spatial directions. The limb system of the human being is, in a sense, integrated into his outer movements, into his orientation in the world, into what is inner orientation in the three directions mentioned above. We integrate ourselves in a certain way into the experience of up and down when we walk. In many things we do with our hands or arms, we fit ourselves into the right-left orientation. Yes, we even fit ourselves into the front-back orientation with our speech, insofar as speech is a movement of the airy element in the human being. By moving in the world, we place our inner orientation into the outer world.

Let us now consider the true process as opposed to the merely illusory in a specific mathematical case. It is something illusory, something that exists purely in the mind, when I find a spatial process somewhere in the universe, and then, as an analytical mathematician, I approach this spatial process in such a way that I record or even think of the three coordinates of the usual coordinate axis system, and then classify any external process belonging to space in this purely constructed spatial scheme of Descartes, of Cartesius. That is only what takes place, I would say, up there through the human nervous-sensory system in the realm of thought patterns. One would not arrive at a relationship between the human being and such a process in space if it were not for what one does with one's limbs, and indeed with one's whole being, namely, that one positions oneself in the whole world according to the inner orientation of up-down, right-left, front-back. When I walk forward, I know that I am aligning myself with up and down in order to remain upright. But I also know that I am aligning myself with back and front in the direction I am walking, and when I swim and use my arms, I orient myself with right and left in relation to the world. I don't have what underlies this when I take the Cartesian coordinate system, the abstract coordinate axis system. I have what gives humans the impression of reality when they interact with spatial objects only when I tell myself that up there in the nervous system of the head, an illusory image is actually playing out of something that is deep in the subconscious, namely where humans cannot reach with their ordinary consciousness, what is happening between their limb system and the world. And all of mathematics, geometry, is brought up from our movement system. We would have no geometry if we did not orient ourselves inwardly when we entered the world. In truth, we geometrize by elevating what is happening in the unconscious into the illusory realm of thought patterns. This makes it appear to us as something abstract and independent. But this is precisely what has happened in recent times. In the days when mathesis, the mathematics of mysticism, was still felt to be close at hand, mathematical behavior toward things was still something human. What is human about placing a zero point, which I have only imagined somewhere in space, and crossing it with three perpendicular lines, and then allowing this spatial scheme to coincide with a process that I perceive in real space? It is completely separate from humans; it is something completely inhuman. This inhumanity, which has emerged in recent times in mathematical thought, was once human. But when was it human?