The Origins of Natural Science

GA 326

3 January 1923, Dornach

Lecture VIII

I have tried to show how various domains of scientific thought originated in modern times. Now I will try to throw light from a certain standpoint on what was actually happening in the development of these scientific concepts. Then we shall better understand what these concepts signify in the whole evolutionary process of mankind. We must clearly understand that the phenomena of external culture are inwardly permeated by a kind of pulse beat that originates from deeper insights. Such insights need not always be ones that are commonly taught, but still they are at the bottom of the development. Now, I would only like to say that we can better understand what we are dealing with in this direction if we include in our considerations what in certain epochs was practiced as initiation science, a science of the deeper foundations of life and history.

We know that the farther we go back in history,69Steiner, The Boundaries of Natural Science, pp. 59–87. Chapters 5 and 6, as well as 7 and 8. the more we discover an instinctive spiritual knowledge, an instinctive clairvoyant perception of what goes on behind the scenes. Moreover, we know that it is possible in our time to attain to a deeper knowledge, because since the last third of the Nineteenth Century, after the high tide of materialistic concepts and feelings, simply through the relationship of the spiritual world to the physical, the possibility arose to draw spiritual knowledge once again directly from the super-sensible world. Since the last third of the Nineteenth Century, it has been possible to deepen human knowledge to the point where it can behold the foundations of what takes place in the external processes of nature.

So we can say that an ancient instinctive initiation science made way for an exoteric civilization in which little was felt of any direct spirit knowledge, but now it is fully conscious rather than instinctive.

We stand at the beginning of this development of a new spirit knowledge. It will unfold further in the future. If we have a certain insight into what man regarded as knowledge during the age of the old instinctive science of initiation, we can discover that until the beginning of the Fourteenth Century, opinions prevailed in the civilized world that cannot be directly compared with any of our modern conceptions about nature. They were ideas of quite a different kind. Still less can they be compared with what today's science calls psychology. There too, we would have to say that it is of quite a different kind. The soul and spirit of man as well as the physical realm of nature were grasped in concepts and ideas that today are understood only by men who specifically study initiation science. The whole manner of thinking and feeling was quite different in former times.

If we examine the ancient initiation science, we find that, in spite of the fragmentary ways in which it has been handed down, it had profound insights, deep conceptions, concerning man and his relation to the world.

People today do not greatly esteem a work like De Divisione Naturae (Concerning the Division of Nature) by John Scotus Erigena70Johannes Scotus Erigena: also Eriugena, Ireland 810–877 France. Pre-Scholastic philosopher, theologian with extensive comprehension of language. Came from Britain to France. Led the Emperor's Academy in Paris 845–877. Finished his translation of Dionysius the Areopagite in 858. His main work was De Divisione Naturae (Division of Nature), 867. He taught out of a Platonic comprehension. He stood up for the introduction of the hierarchical order in the worldly administration of the church. See also Mysticism at the Dawn of the Modern Age. in the Ninth Century. They do not bother with it because such a work is not regarded as an historical document since it comes from a time when men thought differently from the way they think today, so differently that we can no longer understand such a book. When ordinary philosophers describe such topics in their historical writings, one is offered mere empty words. Scholars no longer enter into the fundamental spirit of a work such as that of John Scotus Erigena on the division of nature, where even the term nature signifies something other than in modern science. If, with the insight of spiritual science, we do enter into the spirit of such a text, we must come to the following rather odd conclusion: This Scotus Erigena developed ideas that give the impression of extraordinary penetration into the essence of the world, but he presented these ideas in an inadequate and ineffective form. At the risk of speaking disrespectfully of a work that is after all very valuable, one has to say that Erigena himself no longer fully understood what he was writing about. One can see that in his description. Even for him, though not to the same extent as with modern historians of philosophy, the words that he had gleaned from tradition were more or less words only, and he could no longer enter into their deeper meaning. Reading his works, we find ourselves increasingly obliged to go farther back in history. Erigena's writings lead us directly back to those of the so-called pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite.71The copy in Greek originated in the fifteenth century. Dionysius was a member of the Areopag in Athens and a student of the Apostle Paul (Acts 17:34). The setting up of the 3 times 3 hierarchies by Dionysius was adapted as dogma by the Catholic church. His writings in Latin translation were taken up enthusiastically, and were still taken as authentic in the seventeenth century. See Riddles of Philosophy, The Redemption of Thinking, Die Ursprungsimpulse der Geisteswissenschaft (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1974), GA Bibl. Nr. 96, and Otto Willmann, Geschichte des Idealismus, Volume II, paragraph 59. I will now leave aside the historical problem of when Dionysius lived, and so forth. But again from Dionysius the Areopagite one is led still farther back. To continue the search one must be equipped with spiritual science. But finally, going back to the second and third millennia before Christ, one comes upon very deep insights that have been lost to mankind. Only as a faint echo are they present in writings such as those of Erigena.

Even if we go no further back than the Scholastics, we can find, hidden under their pedantic style, profound ideas concerning the way in which man apprehends the outer world, and how there lives the super-sensible on one side and on the other side the sense perceptible, and so on. If we take the stream of tradition founded on Aristotle who, in his logical but pedantic way, had in turn gathered together the ancient knowledge that had been handed down to him, we find the same thing—deep insights that were well understood in ancient times and survived feebly into the Middle Ages, being repeated in the successive epochs, and were always less and less understood. That is the characteristic process. At last in the Thirteenth or Fourteenth Century, the understanding disappears almost entirely, and a new spirit emerges, the spirit of Copernicus and Galileo, which I have described in the previous lectures.

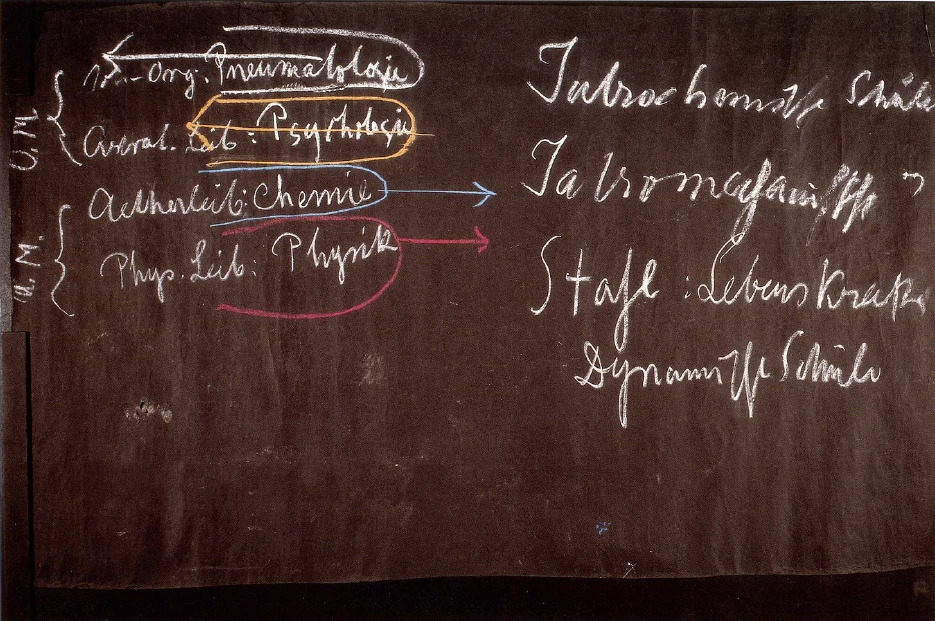

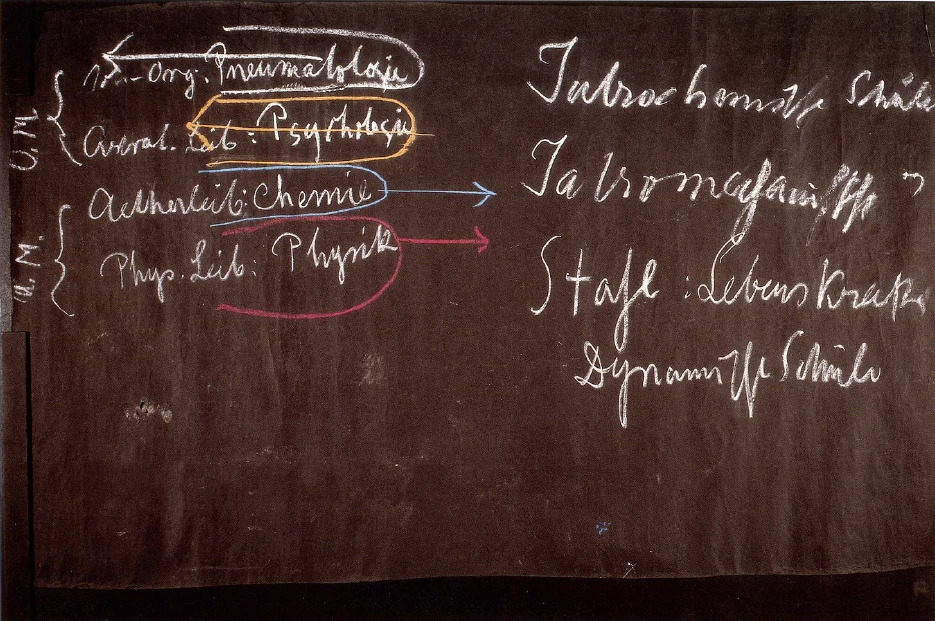

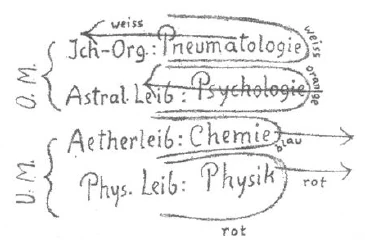

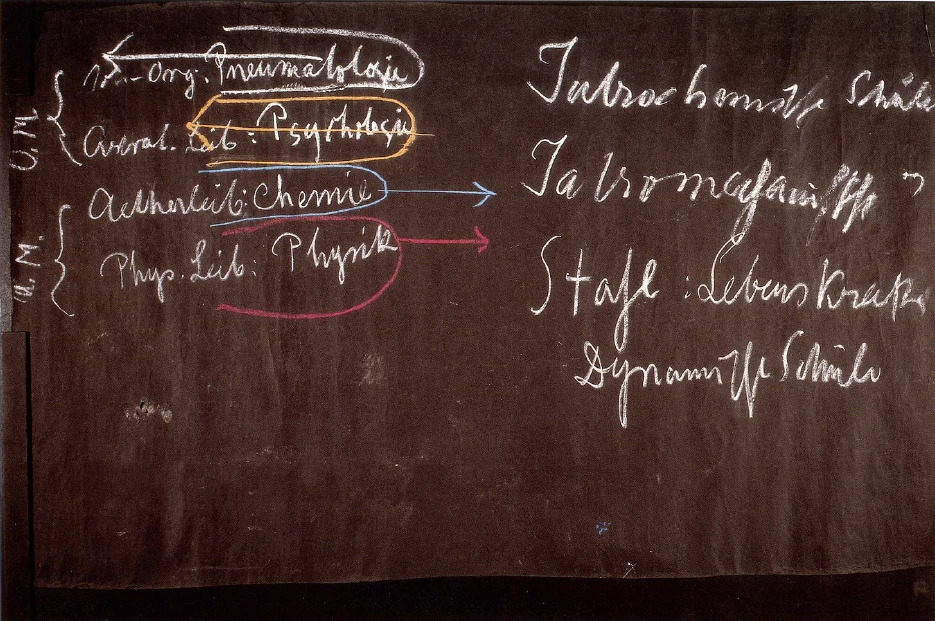

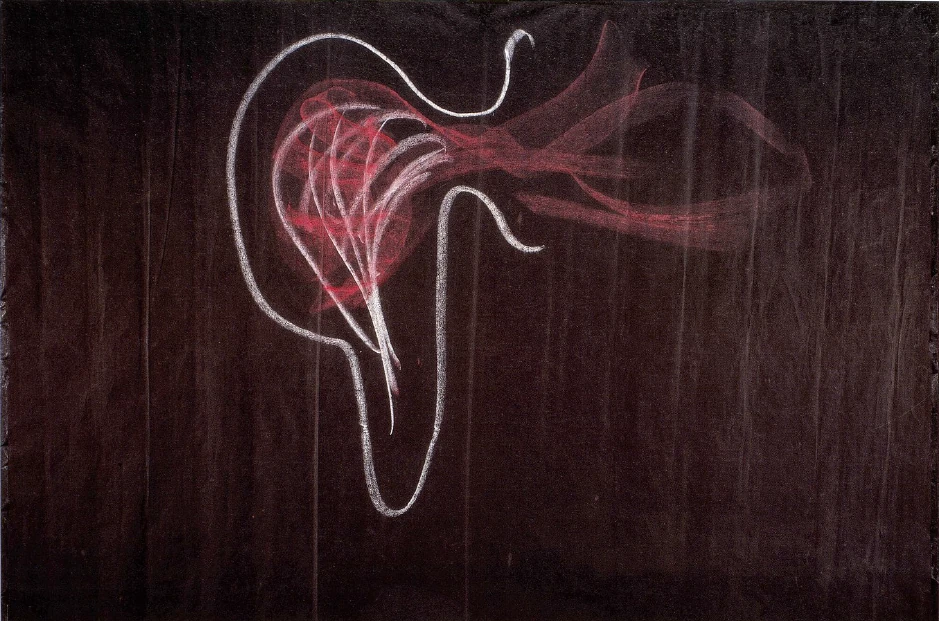

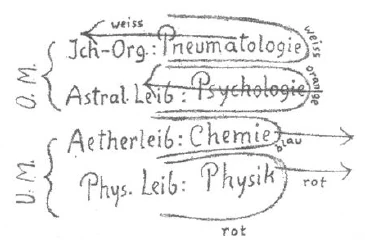

In all studies, such as those I have just outlines, it is found that this ancient knowledge is handed down through the ages until the Fourteenth Century, though less and less understood. This ancient knowledge amounted essentially to an inner experience of what goes on in man himself. The explanations of the last few lectures should make this comprehensible: It is the experiencing of the mathematical-mechanical element in human movement, the experiencing of a certain chemical principle, as we would say today, in the circulation of man's bodily fluids, which are permeated by the etheric body. Hence, we can even look at the table that I put on the blackboard yesterday from an historical standpoint. If we look at the being of man with our initiation science today, we have the physical body, the etheric body, the astral body (the inner life of the soul,) and the ego organization. As I pointed out yesterday, there existed (arising out of the ancient initiation science) an inner experience of the physical body, an inward experience of movement, an inner experience of the dimensionality of space, as well as experiences of other physical and mechanical processes. We can call this inner experience the experiencing of physics in man. But this experience of physics in man is at the same time the cognition of the very laws of physics and mechanics. There was a physics of man directed toward the physical body. It would not have occurred to anyone in those times to search for physics other than through the experience in man. Now, in the age of Galileo and Copernicus, together with the mathematics that was thenceforth applied in physics, what was inwardly experienced is cast out of man and grasped abstractly. It can be said that physics sunders itself from man, whereas formerly it was contained in man himself.

Something similar was experienced with the fluid processes, the bodily fluids of the human organism. These too were inwardly experienced. Yesterday I referred to the Galen who, in the first Christian centuries, described the following fluids in man: black gall, blood, phlegm, and the ordinary means of the intermingling of these fluids by the way they influence each other. Galen did not arrive at these statements by anything resembling today's physiological methods. They were based mainly on inward experiences. For Galen too these were largely a tradition, but what he thus took from tradition we once experienced inwardly in the fluid part of the human organism, which in turn was permeated by the etheric body.

For this reason, in the beginning of my Riddles of Philosophy,72See Steiner, Riddles of Philosophy. I did not describe the Greek philosophers in the customary way. Read any ordinary history of philosophy and you will find this subject presented more or less as follows: Thales73Thales of Milet: About 650–560 B.C. pondered on the origin of our sense world and sought for it in water. Heraclitus looked for it in fire. Others looked for it in air. Still others in solid matter, for example in something like atoms. It is amazing that this can be recounted without questions being raised. People today do not notice that it basically defies explanation why Thales happened to designate water while Heraclitus74Heraclitus of Ephesus: About 550–480 B.C. chose fire as the source of all things. Read my book Riddles of Philosophy, and you will see that the viewpoint of Thales, expressed in the sentence “All things have originated from water,” is based on an inner experience. He inwardly felt the activity of what in his day was termed the watery element. He sensed that the basis of the external process in nature was related to this inner activity; thus he described the external out of inner experiences. It was the same with Heraclitus who, as we would say today, was of a different temperament. Thales, as a phlegmatic, was sensitive to the inward “water” or “phlegm.” Therefore he described the world from the phlegmatic's viewpoint: everything has come from water. Heraclitus, as a choleric, experienced the inner “fire.” He described the world the way he experienced it. Besides them, there were other thinkers, who are no longer mentioned by external tradition, who knew still more concerning these matters. Their knowledge was handed down and still existed as tradition in the first Christian centuries; hence Galen could speak of the four components of man's inner fluidic system.

What was then known concerning the inner fluids, namely, how these four fluids—yellow gall, black gall, blood, and phlegm—influence and mix with one another really amounts to an inner human chemistry, though it is of course considered childish today. No other form of chemistry existed in those days. The external phenomena that today belong to the field of chemistry were then evaluated according to these inward experiences. We can therefore speak of an inner chemistry based on experiences of the fluid man who is permeated by the ether body. Chemistry was tied to man in former ages. Later it emerged, as did mathematics and physics, and became external chemistry (see Figure 1.) Try to imagine how the physics and chemistry of ancient times were felt by men. They were experienced as something that was, as it were, a part of themselves, not as something that is mere description of an external nature and its processes. The main point was: it was experienced physics, experienced chemistry.

In those ages when men felt external nature in their physical and etheric bodies, the contents of the astral body and the ego organization were also experienced differently than in later times.

Today was have a psychology, but it is only an inventory of abstractions, though no one admits this. You will find in it thinking, feeling, willing, as well as memory, imagination, and so forth, but treated as mere abstractions. This gradually arose from what was still considered as one's own soul contents. One had cast out chemistry and physics; thinking, feeling and willing were retained. But what was left eventually became so diluted that it turned into no more than an inventory of lifeless empty abstractions, and it can be readily proved that this is so. Take, for example, the people who still spoke of thinking or willing as late as the Fifteenth or Sixteenth Century.75See also the personalities spoken of in Mysticism at the Dawn of the Modern Age. If you study the older texts on these subjects you will see that people expressed themselves concerning these matters in a concrete way. You have the feeling, when such a person speaks about thinking, that he speaks as if this thinking were actually a series of inner processes within him, as if the thoughts were colliding with each other or supporting each other. This is still an experiencing of thoughts. It is not yet as abstract a matter as it became later on. During and towards the end of the Nineteenth Century, it was an easy thing for the philosophers to deny all reality to these abstractions. They saw thoughts as inner mirror pictures, as was done in an especially brilliant way by Richard Wahle, who declared that the ego, thinking, feeling, and willing were only illusions. Instead of abstractions, the inner soul contents become illusions.

In the age when man felt that his walking was a process that took place simultaneously in him and the world, and when he still sensed the circulating fluids within him, he knew, for instance, that when he moved about in the heat of the sun (when external influences were present) that the blood and phlegm circulated differently in him than was the case in winter. Such a man experienced the blood and phlegm circulation within himself, but he experienced it together with the sunshine or the lack thereof. And just as he experienced physical and chemical aspects in union with the outside world, so he also experienced thinking, feeling, and willing together with the world. He did not think they were occurring only within himself as was done in later ages when they gradually evaporated into complete abstractions. Instead he experienced what occurred in him in thinking, feeling, and willing, or in the circulation of the fluids as part of the realm of the astral, the soul being of man, which in that age was the subject of a psychology.

Psychology now became tightly tied to man. With the dawn of the scientific age, man drove physics and chemistry out into the external world; psychology, on the other hand, he drove into himself. This process can be traced in Francis Bacon and John Locke. All that is experienced of the external world, such as tone, color, and warmth, is pressed into man's interior.

This process is even more pronounced in regard to the ego organization. This gradually became a very meager experience. The way man looked into himself, the ego became by degrees something like a mere point. For that reason it became easy to philosophers to dispute its very existence. Not ego consciousness, but the experience of the ego was for men of former ages something rich in content and fully real. This ego experience expressed itself in something that was a loftier science than psychology, a science that can be called pneumatology. In later times this was also pressed into the interior and thinned out into our present quite diluted ego feeling.

When man had the inward experience of his physical body, he had the experience of physics; simultaneously, he experienced what corresponds in outer nature to the processes in his physical body. It is similar in the case of the etheric body. Not only the etheric, was experienced inwardly, but also the physical fluid system, which is controlled by the etheric. Now, what is inwardly experienced when man perceives the psychological, the processes of his astral body? The “air man”—if I may put it this way—is inwardly experienced. We are not only solid organic formations, not only fluids or water formations, we are always gaseous-airy as well. We breathe in the air and breathe it out again. We experienced the substance of psychology in intimate union with the inner assimilation of air. This is why psychology was more concrete. When the living experience of air (which can also be outwardly traced) was cast out of the thought contents, these thought contents became increasingly abstract, became mere thought. Just think how an old Indian philosopher strove in his exercises to become conscious of the fact that in the breathing process something akin to the thought process was taking place. He regulated his breathing process in order to progress his thinking. He knew that thinking, feeling and willing are not as flimsy as we today make them out to be. He knew that through breathing they were related to both outer and inner nature, hence with air. As we can say that man expelled the physical and chemical aspects from his organization, we can also say that he sucked in the psychological aspect, but in doing so he rejected the external element, the air-breath experience. He withdrew his own being from the physical and chemical elements and merely observed the outer world with physics and chemistry; whereas he squeezed external nature (air) out of the psychological. Likewise, he squeezed the warmth element out of the pneumatological realm, thus reducing it to the rarity of the ego.

If I call the physical and etheric bodies, the “lower man,” and call the astral body and ego-organization the “upper man,” I can say that in the transition from an older epoch to the scientific age, man lost the inner physical and chemical experience, and came to grasp external nature only with his concepts of physics and chemistry. In psychology and pneumatology, on the other hand, man developed conceptions from which he eliminated outer nature and came to experience only so much of nature as remained in his concepts. In psychology, this was enough so that he at least still had words for what went on in his soul. As to the ego, however, this was so little that pneumatology (partially because theological dogmatism had prepared this development) completely faded out. It shrank down to the mere dot of the ego.

All this took the place of what had been experienced as a unity, when men of old said: We have four elements, earth, water, air and fire. Earth we experience in ourselves when we experience the physical body. Water we experience in ourselves when we experience the etheric body as the agent that moves, mixes, and separates the fluids. Air is experienced when the astral body is experienced in thinking, feeling, and willing, because these three are experienced as surging with the inner breathing process. Finally, warmth, or fire as it was then called, was experienced in the sensation of the ego.

So we may say that the modern scientific view developed by way of a transformation of man's whole relation to himself. If you follow historical evolution with these insights, you will find what I told you earlier—that in each new epoch we see new descriptions of the old traditions, but these are always less and less understood. The worlds of men like Paracelsus, van Helmont, or Jacob Boehme,76Jacob Boehme: Altseidenberg, Goerlitz 1575–1624 Goerlitz. Mystic. His profession was shoemaker. First writing Aurora, 1612. Further writings from 1619 onwards, despite the prohibition. See Riddles of Philosophy. bear witness to such ancient traditions.

One who has insight into these matters gets the impression that in Jacob Boehme's case a very simple man is speaking out of sources that would lead too far today to discuss. He is difficult to comprehend because of his clumsiness. But Jacob Boehme shows profound insight in his awkward descriptions, insights that have been handed down through the generations. What was the situation of a person like Jacob Boehme? Giordano Bruno, his contemporary, stood among the most advanced men of his time, whereas we see in Jacob Boehme's case that he obviously read all kinds of books that are naturally forgotten today. These were full of rubbish. But Boehme was able to find a meaning in them. Awkwardly and with great difficulty Boehme presents the primeval wisdom that he had gleaned from his still more awkward and inadequate sources. His inward enlightenment enabled him to return to an earlier stage.

If we now look at the Fifteenth, Sixteenth, and especially the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries, and if we leave aside isolated people like Paracelsus and Boehme (who appear like monuments to a bygone age,) and if we look at the exoteric stream of human development in the light of initiation science, we gain the impression that nobody knows anything at all anymore about the deeper foundations of things. Physics and chemistry have been eliminated from man, and alchemy has become the subject of derision. Of course, people were justified in scoffing at it, because what still remained of the ancient traditions in medieval alchemy could well be made fun of. All that is left is psychology, which has become confined to man's inner being, and a very meager pneumatology. People have broken with everything that was formerly known of human nature., On one hand, they experience what has been separated from man; and on the other, what has been chaotically relegated into his interior. And in all our search for knowledge, we see what I have just described.

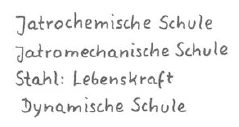

In the Seventeenth Century, a theory arose that remains quite unintelligible if considered by itself, although if it is viewed in the context of history it becomes comprehensible. The theory was that those processes in the human body that have to do with the intake of food, are based on a kind of fermentation. The foods man eats are permeated with saliva and then with digestive fluids such as those in the pancreas, and thus various degrees of fermentation processes, as they were called, are achieved. If one looks at these ideas from today's viewpoint (which naturally will also be outgrown in the future) one can only make fun of them. But if we enter into these ideas and examine them closely, we discover the source of these apparently foolish ideas. The ancient traditions, which in a man like Galen were based on inward experiences and were thus well justified, were now on the verge of extinction. At the same time, what was to become external objective chemistry was only in its beginnings. Men had lost the inner knowledge, and the external had not yet developed. Therefore, they found themselves able to speak about digestion only in quite feeble neo-chemical terms, such as the vague idea of fermentation. Such men were the late followers of Galen's teachings. They still felt that in order to comprehend man, one must start from the movements of man's fluids, his fluid nature. But at the same time, they were beginning to view chemical aspects only by means of the external processes. Therefore they seized the idea of fermentation, which could be observed externally, and applied it to man. Man had become an empty bag because he no longer experienced anything within himself. What had grown to be external science was poured into this bag. In the Seventeenth Century, of course, there was not much science to pour. People had the vague idea about fermentation and similar processes, and these were rashly applied to man. Thus arose the so-called iatrochemical school77Iatrochemistry: Name from the Greek “Iatro,” physician. Work with homeopathic remedies in continuation of Paracelsus' (1493–1541) method of healing, in the beginning with retention of his opinion about sulfur, mercury, and salt. The Iatrochemical School was established during Paracelsus' last years of life. It degenerated in the middle of the seventeenth century. In its place stepped Robert Boyle's chemistry (1627–1691), for which iatrochemistry had done good preparation. J.B. van Helmont (1577–1644) was one of the main contributors to Iatrochemical literature. of medicine.

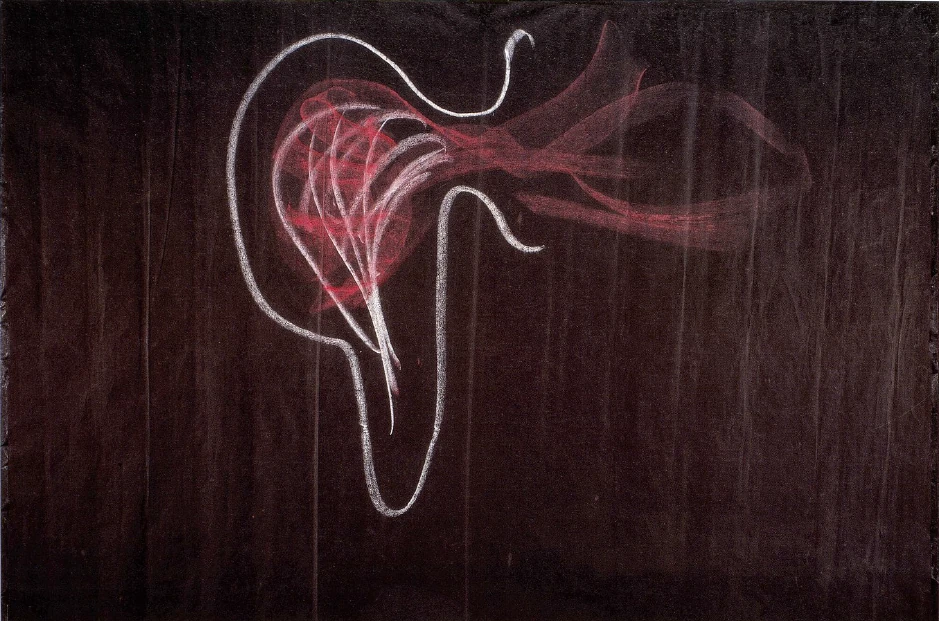

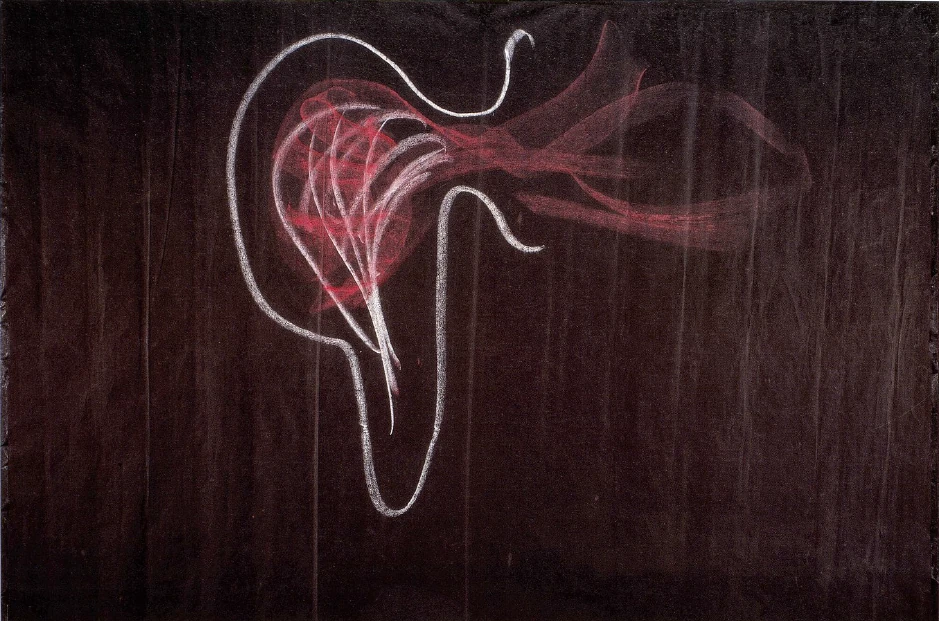

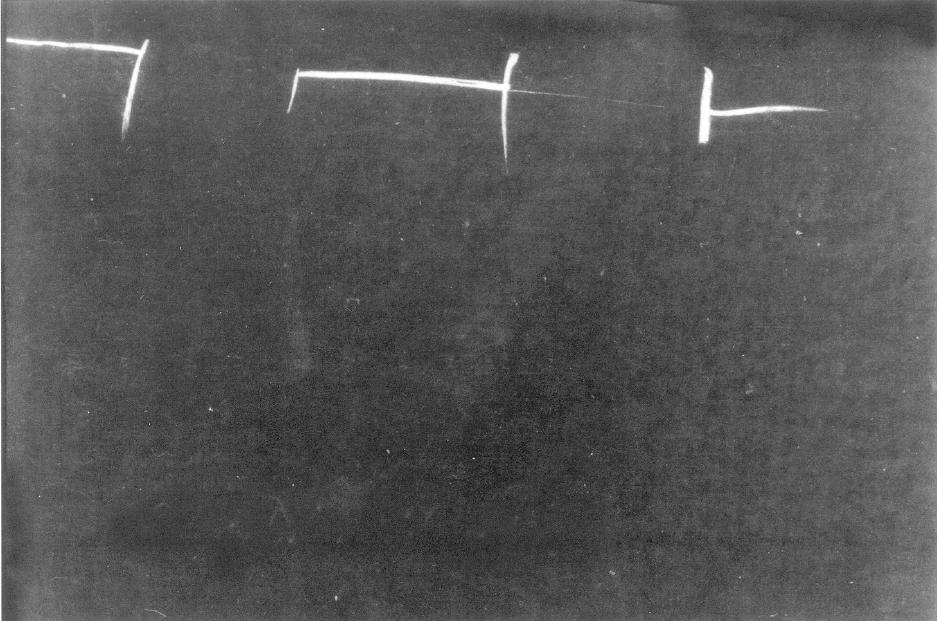

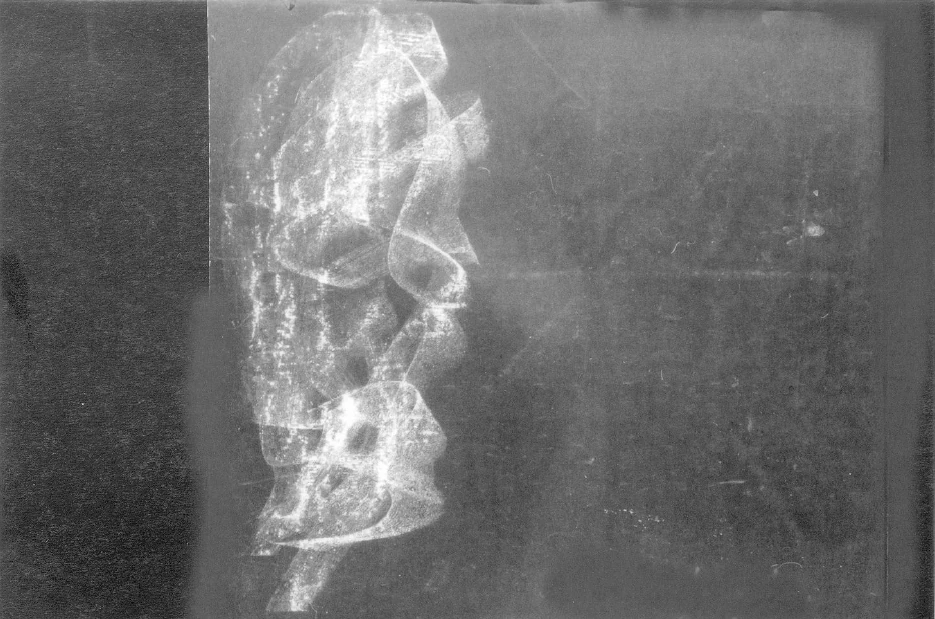

In considering these iatrochemists, we must realize that they still had some inkling of the ancient doctrine of fluids, which was based on inner experience. Others, who were more or less contemporaries of the iatrochemists, no longer had any such inkling, so they began to view man the way he appears to us today when we open an anatomy book. In such books we find descriptions of the bones, the stomach, the liver, etc. and we are apt to get the impression that this is all there is to know about man and that he consists of more or less solid organs with sharply defined contours. Of course, from a certain aspect, they do exist. But the solid aspect—the earth element, to use the ancient terminology—comprises at most one tenth of man's organization. It is more accurate to say that man is a column of fluids. The mistake is not in what is actually said, but in the whole method of presentation. It is gradually forgotten that man is a column of fluids in which the clearly contoured organs swim. Laymen see the pictures and have the impression that this is all they need to understand the body. But this is misleading. It is only one tenth of man. The remainder ought to be described by drawing a continuous stream of fluids (see Figure 2) interacting in the most manifold ways in the stomach, liver and so forth. Quite erroneous conceptions arise as to how man's organism actually functions, because only the sharply outlined organs are observed. This is why in the Nineteenth Century, people were astonished to see that if one drinks a glass of water, it appears to completely penetrate the body and be assimilated by his organs. But when a second or third glass of water is consumed, it no longer gives the impression that it is digested in the same manner. These matters were noticed but could no longer be explained, because a completely false view was held concerning the fluid organization of man. Here etheric body is the driving agent that mixes or separates the fluids, and brings about the processes of organic chemistry in man.

In the Seventeenth Century, people really began to totally ignore this “fluid man” and to focus only on the solidly contoured parts. In this realm of clearly outlined parts, everything takes place in a mechanical way. One part pushes another; the other moves; things get pumped; it all works like suction or pressure pumps. The body is viewed from a mechanical standpoint, as existing only through the interplay of solidly contoured organs. Out of the iatrochemical theory or alongside it, there arose iatromechanics and even iatromathematics.78Iatromechanics and Iatromathematics. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the proponents of these teachings were nearly all university professors, while iatrochemistry was represented by a union of practicing physicians. But that was true only in the Romantic countries and England. In Italy the main universities were Padua, Pisa, and Rome. There the teachings were rejected on philosophic grounds, because they were based on experience. Germany, where both branches worked hand in hand, was an exception and in a special position.

Naturally, people began to think that the heart is really a pump that mechanically pumps the blood through the body, because they no longer knew that our inner fluids have their own life and therefore move on their own. They never dreamed that the heart is only a sense organ that checks on the circulation of the fluids in its own way. The whole matter was inverted. One no longer saw the movement and inner vitality of the fluids, or the etheric body active therein. The heart became a mechanical apparatus and has remained so to this day for the majority of physiologists and medical men.

The iatrochemists still had some faint knowledge concerning the etheric body. There was full awareness of it in what Galen described. In van Helmont or Paracelsus there was still an inkling of the etheric body, more than survived in the official iatrochemists who conducted the schools of that time. In the iatromechanists no trace whatsoever remained of this ether body; all conception of it had vanished into tin air. Man was seen only as a physical body, and that only to the extent that he consists of solid parts. These were now dealt with by means of physics, which had in the meantime also been cast out of the human being. Physics was now applied externally to man, whom one no longer understood. Man had been turned into an empty bag, and physics had been established in an abstract manner. Now this same physics was reapplied to man. Thus one no longer had the living being of man, only an empty bag stuffed with theories.

It is still this way today. What modern physiology or anatomy tells us of man is not man at all, it is physics that was cast out of man and is now changed around to be fitted back into man. The more intimately we study this development, the better we see destiny at work. The iatrochemists had a shadowy consciousness of the etheric body, the iatromechanists had none. Then came a man by the name of Stahl79Georg Ernst Stahl: Ansbach 1650–1734, Berlin. Physician and chemist, Professor of Medicine. Exponent of Animism and Vitalism and the hypothesis of the “life forces” in his major work Theoria Medico Vera, 1707. who, considering his time, was an unusually clever man. He had studied iatrochemistry, but the concepts of the “inner fermentation processes” seemed inadequate to him because they only transplanted externalized chemistry back into the human bag. With the iatromechanists he was still more dissatisfied because they only placed external mechanical physics back into the empty bag. No knowledge, no tradition existed concerning the etheric body as the driving force of the moving fluids. It was not possible to gain information about it. So what did Stahl do? He invented something, because there was nothing left in tradition. He told himself: the physical and chemical processes that go on in the human body cannot be based on the physics and chemistry that are discovered in the external world. But he had nothing else to put into man Therefore he invented what he called the “life force,” the “vital force,” With it he founded the dynamic school. Stahl was gifted with a certain instinct. He felt the lack of something that he needed; so he invented this “vital force.” The Nineteenth Century had great difficulty in getting rid of this concept. It was really only an invention, but it was very hard to rid science of this “life force.”

Great efforts were made to find something that would fit into this empty bag that was man. This is why men came to think of the world of machines. They knew how a machine moves and responds. So the machine was stuffed into the empty bag in the form of L'homme machine by La Mettrie.80Offray de la Mettrie: Malo 1709–1751 Berlin. Physician and writer. Main work is L'Homme Machine, published in Leyden 1748. Man is a machine. The materialism, or rather the mechanics, of the Eighteenth Century, such as we see in Holbach's Systeme de la nature,81Baron Dietrich von Hollenbach: Heidesheim, Rheinpfalz 1723–1789 Paris. His main work Systeme de la Nature ou des Lois du Monde Physique et du Monde Moral appeared 1770 under the pseudonym Mira-baud. He only recognized mobile, material atoms, even in regard to thinking, and he based morals on self love. which Goethe so detested in his youth, reflects the total inability to grasp the being of man with the ideas that prevailed at that time in outer nature. The whole Nineteenth Century suffered from the inability to take hold of man himself.

But there was a strong desire somehow or other to work out a conception of man. This led to the idea of picturing him s a more highly evolved animal. Of course, the animal was not really understood either, since physics, chemistry, and psychology, all in the old sense, are needed for this purpose even if pneumatology is unnecessary. But nobody realized that all this is also required in order to understand the animal. One had to start somewhere, so in the Eighteenth Century man was compared to the machine and in the Nineteenth Century he was traced back to the beast. All this is quite understandable from the historical standpoint. It makes good sense considering the whole course of human evolution. It was, after all, this ignorance concerning the being of man that produced our modern opinions about man. The development towards freedom, for example, would never have occurred had the ancient experience of physics, chemistry, psychology, and pneumatology survived. Man had to lose himself as an elemental being in order to find himself as a free being. He could only do this by withdrawing from himself for a while and paying no attention to himself any longer. Instead, he occupied himself with the external world, and if he wanted theories concerning his own nature, he applied to himself what was well suited for a comprehension of the outer world. During this interim, when man took the time to develop something like the feeling of freedom, he worked out the concepts of science; these concepts that are, in a manner of speaking, so robust that they can grasp outer nature. Unfortunately, however, they are too coarse for the being of man, since people do not go to the trouble of refining these ideas to the point where they ca also grasp the nature of man. Thus modern science arose, which is well applicable to nature and has achieved great triumphs. But it is useless when it comes to the essential being of man.

You can see that I am not criticizing science. I am only describing it. Man attains his consciousness of freedom only because he is no longer burdened with the insights that he carried within himself and that weighed him down. The experience of freedom came about when man constructed a science that in its robustness was only suited to outer nature. Since it does not offer the whole picture and is not applicable to man's being, this science can naturally be criticized in turn. It is most useful in physics; in chemistry, weak points begin to show up; and psychology becomes completely abstract. Nevertheless, mankind had to pass through an age that took its course in this way in order to attain to an individually modulated moral conception of the world and to the consciousness of freedom. We cannot understand the origin of science if we look at it only from one side. It must be regarded as a phenomenon parallel to the consciousness of freedom that is arising during the same period, along with all the moral and religious implications connected with this awareness.

This is why people like Hobbes82Thomas Hobbes: Malmesbury 1588–1679 Hardwicke. English natural philosopher and humanist. Opera Philosophica, 1688. All phenomena in nature and humanity, even the psychological ones, are result of mobility of bodies. The social processes are traced back to mechanical processes. The leading force in this process is the egoism of the single human being. The state which is “crushing everything underfoot,” he called “Leviathan” and said: “The natural social condition is the war of all against all.” and Bacon, who were establishing the ideas of science, found it impossible to connect man to the spirit and soul of the universe. In Hobbes' case, the result was that, on the one hand, he cultivated the germinal scientific concepts in the most radical way, while, on the other hand, he cast all spiritual elements out of social life and decreed “the war of all against all.” He recognized no binding principle that might flow into social life from a super-sensible source, and therefore he was able, though in a somewhat caricatured form, to discuss the consciousness of freedom in a theoretical way for the first time.

The evolution of mankind does not proceed in a straight line. We must study the various streams that run side by side. Only then can we understand the significance of man's historical development.

Achter Vortrag

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, liebe Freunde, in fortdauernder Weise kommen Kundgebungen an des Verbundenseins und des Schmerzteilens. Ich werde mir erlauben, morgen oder übermorgen die betreffenden Kundgebungen hier mitzuteilen.

Ich habe versucht zu zeigen, wie einzelne Gebiete des naturwissenschaftlichen Denkens in der neueren Zeit entstehen. Ich möchte eine Ausführung einschalten, welche bestimmt sein soll, ein wenig zu beleuchten dasjenige, was sich da vollzogen hat in dieser Bildung naturwissenschaftlicher Anschauungen, weil man besser verstehen kann, um was es sich da eigentlich im Gesamtfortgange der Menschheitsentfaltung handelt, wenn man von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus auf die Dinge Licht wirft. Man muß sich ja durchaus klar darüber sein, daß dasjenige, was in der äußeren Kultur und Zivilisation der Menschheit auftritt, innerlich, ich möchte sagen, wie von einer Art von Pulsschlag durchströmt ist, durchzuckt ist, einem Pulsschlag, der von tieferen Einsichten herrührt, die nicht gerade immer als solche Einsichten wirken müssen, die gelehrt werden, sondern die auf eine andere Weise tatsächlich der Entwickelung zugrunde liegen, auf eine Weise, die ich nun auch in den nächsten Tagen noch andeuten werde. Jetzt möchte ich nur sagen, daß man besser versteht, um was es sich nach dieser Richtung handelt, wenn man dasjenige zu Hilfe nimmt, was in bestimmten Zeiten Initiationswissenschaft war, Wissenschaft von den tieferen Grundlagen des Lebens und des Weltgeschehens.

Wir wissen, je weiter wir in der Menschheitsentwickelung zurückgehen, desto mehr treffen wir auf ein instinktives geisteswissenschaftliches Erkennen, auf instinktives hellsichtiges Anschauen desjenigen, was gewissermaßen hinter den Kulissen des Daseins vorgeht. Und wir wissen ferner, daß es in der Gegenwart möglich ist, zu einem tieferen Wissen zu kommen, weil, wenn ich mich populär ausdrücken will, seit dem letzten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts nach der Entwickelung der Hochflut materialistischer Anschauungen und materialistischer Empfindungen, die im 19. Jahrhundert eingetreten sind, sich einfach durch das Verhältnis der geistigen Welt zur physischen Welt die Möglichkeit ergeben hat, daß geistige Erkenntnisse unmittelbar wiederum aus der übersinnlichen Welt herausgeholt werden. Es ist möglich seit dem letzten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts, die menschliche Erkenntnis so zu vertiefen, daß es dazu kommt, geistig in seinen Grundlagen dasjenige anzuschauen, was sich im äußeren Naturgeschehen abspielt.

So daß man etwa sagen kann: Eine ältere, instinktive Initiationswissenschaft macht einer exoterischen Menschheitszivilisation Platz, einer Zivilisation, in der von einem unmittelbaren Geistwissen wenig zu spüren ist in der Welt. Und dann kommt wiederum eine neue Morgenröte von Geistwissen, jetzt vollbewußtem, nicht mehr instinktivem Geisteswissen.

Wir stehen im Anfange dieser Entwickelung eines neuen Geisteswissens. Es wird das aber in die Zukunft hinein sich weiter entfalten. Wenn man nun Einblicke hat in dasjenige, was der Mensch als seine Erkenntnis ansah während der Zeit der alten, instinktiven Initiationswissenschaft, dann ergibt sich einem auf dem Hintergrunde dieser Einsichten, daß bis zum Beginne des 14. Jahrhunderts in der zivilisierten Welt Ansichten vorhanden waren, die nicht unmittelbar zu vergleichen sind mit unseren heutigen Naturerkenntnissen, weil sie von ganz anderer Art waren, die andrerseits noch weniger zu vergleichen sind mit demjenigen, was etwa die heutige Wissenschaft Seelenkunde oder Psychologie nennt. Auch da muß man sagen, daß sie anderer Art war. Man hat sowohl das Geistig-Seelische des Menschen wie auch das Physisch-Natürliche in einer gewissen Weise in Vorstellungen gefaßt, die heute gar nicht mehr von den Menschen, die nicht ausdrücklich sich mit Initiationswissenschaft befassen, verstanden werden. Es war eine ganz andere Art, zu denken, zu empfinden.

Wenn wir nun mit dem, was alte Initiationswissenschaft war, diese auch durch die Geschichte teilweise wenigstens bekannten Einsichten des früheren Zeitalters vergleichen, so finden wir, trotz der mangelhaften Überlieferung, daß vorhanden waren tiefe Einsichten, tiefe Vorstellungen über den Menschen, über das Verhältnis des Menschen zur Welt und so weiter. Man läßt sich heute nicht gern darauf ein, etwa so etwas zu würdigen, wie das Werk über die Einteilung der Natur von Johannes Scotus Erigena im 9. Jahrhundert. Man läßt sich nicht darauf ein, weil man solch ein Werk nicht als ein historisches Denkmal nimmt aus einer Zeit, in der eben ganz anders gedacht wurde als heute, in der so gedacht wurde, wie man es gar nicht mehr versteht, wenn man solch ein Werk heute liest. Und wenn gewöhnliche Philosophen in ihrer Geschichtsschreibung solche Dinge darstellen, so hat man es eigentlich nur mit Worten zu tun. Ein Eingehen auf den eigentlichen Geist eines solchen Werkes, wie das von Johannes Scotus Erigena über die Einteilung der Natur, wobei Natur etwas ganz anderes bedeutet als das Wort Natur in der späteren Naturwissenschaft, ein Eingehen auf diesen Geist ist eigentlich nicht mehr da. Kann man bei geisteswissenschaftlicher Vertiefung doch darauf eingehen, so muß man sich merkwürdigerweise folgendes sagen: Dieser Scotus Erigena hat Ideen entwickelt, die auf einen den Eindruck machen, daß sie außerordentlich tief hineingehen in das Wesen der Welt, aber er hat diese Ideen ganz zweifellos in einer nicht zulänglichen, nicht eindringlichen Form in seinem Werke dargestellt. Wenn man sich nicht der Gefahr aussetzen würde, gegenüber einem immerhin überragenden Werke der Menschheitsentwickelung respektlos zu sprechen, so würde man im Grunde eigentlich sagen müssen, daß schon Johannes Scotus Erigena selbst nicht mehr völlig gewußt hat, was er schreibt. Man sieht das seiner Darstellung an. Für ihn selber waren, wenn auch nicht in dem Grade, wie es für die heutigen Geschichtsschreiber der Philosophie der Fall ist, doch schon die Worte, die er aus der Tradition entnommen hat, mehr oder weniger nur Worte, deren tiefen Inhalt er selber nicht mehr einsah. Man ist eigentlich immer mehr genötigt, wenn man diese Dinge liest, in der Geschichte zurückzugehen. Und von Scotus Erigena wird man ja, das ist leicht ersichtlich aus seinen Schriften, unmittelbar geführt auf die Schriften des sogenannten Pseudo-Dionysius des Areopagiten. Ich will jetzt auf dieses Entwickelungsproblem nicht eingehen, wann der gelebt hat und so weiter. Und von diesem Dionysius dem Areopagiten wird man wiederum weiter zurückgeführt. Da muß man dann schon wirklich ausgerüstet mit Geisteswissenschaft weiterforschen, und man kommt endlich etwa, wenn man in das 2., 3. Jahrtausend vorchristlicher Zeit zurückgeht, zu tiefen Einsichten, die eben der Menschheit verlorengegangen sind, die eben nur in einem schwachen Nachklange vorhanden sind in solchen Schriften wie denen von Johannes Scotus Erigena.

Aber auch noch wenn wir uns richtig vertiefen können in die Werke selbst der Scholastiker, dann werden wir finden, daß hinter der unglaublich pedantisch-schulmäßig zugerichteten Darstellung tiefe Ideen liegen über die Art, wie der Mensch die äußere Welt, die ihm entgegentritt, auffaßt; wie in diesem Auffassen auf der einen Seite lebt das Übersinnliche, auf der anderen Seite lebt das Sinnliche und so weiter. Und wenn man die fortlaufende Tradition nimmt, die sich auf Aristoteles wiederum begründet, der in einer logisch-pedantischen Weise ein altes Wissen, das ihm überliefert war, selbst wieder zusammengefaßt hat, so stößt man auf dasselbe: Tiefe Einsichten, die einmal in alten Zeiten gut verstanden worden sind, die ins Mittelalter hineinreichen, die wiederholt werden in den aufeinanderfolgenden Zeitepochen und die immer weniger verstanden werden. Das ist das Charakteristische dann. Und im 13., 14. Jahrhundert verschwindet dann das Verständnis fast vollständig, und es tritt ein ganz neuer Geist auf, eben der kopernikanisch-galileische Geist, den ich Ihnen ja in den letzten Vorträgen seinem Wesen nach zu charakterisieren versuchte.

Überall, wo man solche Nachforschungen, deren Geist ich eben jetzt angedeutet habe, anstellt, findet man, daß dieses alte Wissen, das so von Epoche zu Epoche, immer weniger verstanden, fortgepflanzt wird bis ins 14. Jahrhundert herein, daß dieses alte Wissen im wesentlichen bestand in einem innerlichen Erleben desjenigen, was im Menschen selbst vor sich geht, also in dem Erleben — es wird das sehr verständlich sein nach den Auseinandersetzungen der letzten Tage — des MathematischMechanischen beim menschlichen Sich-Bewegen, in dem Erleben eines gewissen Chemischen, wie wir heute sagen würden, bei der inneren Säftebewegung des Menschen, die vom ätherischen Leib durchzogen ist. So daß wir wirklich das Schema, das ich Ihnen gestern auf die Tafel geschrieben habe (siehe $. 109), auch gewissermaßen geschichtlich betrachten können. Wir können es nämlich so betrachten: Sehen wir heute wiederum mit unserer Initiationswissenschaft das Wesen des Menschen an, so haben wir den physischen Leib, den ätherischen Leib oder Bildekräfteleib, den astralischen Leib - das innerlich Seelische — und die Ich-Organisation. Ich habe nun schon gestern gesagt, es bestand eben, als aus der alten Initiationswissenschaft hervorgehend, ein innerliches Erleben des physischen Leibes, ein innerliches Erleben desjenigen, was Bewegung ist, ein innerliches Erleben der Dimensionalität des Raumes, Erleben aber auch von anderen physisch-mechanischen Vorgängen, und wir können dieses innerliche Erleben das Erleben des Physikalischen im Menschen nennen. Zugleich ist dieses Erleben des Physikalischen im Menschen eben das Erkennen von physikalisch-mechanischen Gesetzen: eine Physik des menschlichen Wesens nach dem physischen Leibe hin gab es. Niemandem wäre es eingefallen damals, Physik anders zu suchen als durch das Erleben im Menschen. Im galilei-kopernikanischen Zeitalter wird nun mit der Mathematik zugleich, die ja dann auf die Physik angewendet wird, dasjenige, was so innerlich erlebt wird, herausgeworfen aus dem Menschen und nur noch abstrakt erfaßt. So daß wir also sagen können: Die Physik rückt aus dem Menschen heraus, während sie vorher im Menschen selbst beschlossen war.

Einen ganz ähnlichen Prozeß erlebte man mit dem, was innerlich im Menschen erfahren wurde als Säftevorgänge, Vorgänge der wässerigen, der flüssigen Bestandteile des menschlichen Organismus. Ich wies gestern auf Galen in den ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten hin, der den Menschen innerlich so beschrieb, daß er sagte: Im Menschen lebt «schwarze Galle», die in den Säfteströmen zirkuliert, «Blut», «Schleim» und die gewöhnliche Galle, die «weiße» oder «gelbe Galle». Durch das Ineinanderströmen, durch das sich gegenseitige Beeinflussen dieser Säfteströmungen entwickelt sich das menschliche Wesen in der physischen Welt. Aber dasjenige, was da Galen behauptete, das hatte er nicht durch Methoden, die unseren heutigen physiologischen Methoden ähnlich sind, sondern das beruhte im wesentlichen noch auf innerem Erleben. Galen hatte es zwar auch schon traditionell. Aber was er traditionell hatte, was er einfach der Überlieferung entnahm, das erlebte man einstmals innerlich im flüssigen Teile des menschlichen Organismus, der vom ätherischen oder Bildekräfteleib durchzogen ist.

Aus dieser Tatsache heraus schilderte ich auch im Beginne meiner «Rätsel der Philosophie» die griechischen Philosophen nicht so, wie man sie gewöhnlich schildert. Wenn Sie in den gewöhnlichen Geschichten der Philosophie nachlesen, so finden Sie ja überall die Sache so verzeichnet: Thales dachte nach über den Ursprung desjenigen, was in der Sinneswelt ist, und er suchte den Ursprung, den Ausgangspunkt für alles im Wasser. Heraklit suchte den Ausgangspunkt im Feuer, andere in der Luft, andere im Festen, zum Beispiel in einer Art von Atomen und so weiter. Daß so etwas gesagt werden kann, ohne daß man sich Rechenschaft darüber gibt, daß es im Grunde unerklärlich ist, warum der Thales gerade das Wasser, der Heraklit das Feuer als den Ursprung der Dinge erklärte, das fällt ja heute den Menschen nicht weiter auf. Sie brauchen nur nachzulesen in meinem Buche «Die Rätsel der Philosophie» und Sie werden sehen, wie einfach die Ansicht des Thales, die sich ausdrückte in dem Satze: Alles ist aus dem Wasser entsprungen —, auf einem inneren Erlebnis beruhte. Er fühlte die Tätigkeit dessen, was man dazumal eben das Wässerige nannte, und mit dieser innerlichen Tätigkeit fühlte er verwandt dasjenige, was dem äußeren Naturvorgang zugrunde liegt, und er schilderte also aus inneren Erlebnissen heraus das Äußere. Ebenso Heraklit, der, möchte ich sagen, von anderem Temperament war. Thales war, wie wir heute sagen würden, eben Phlegmatiker, der in dem innerlichen «Wasser» oder «Schleim» lebte. Er schilderte also die Welt als ein Phlegmatiker: Alles ist aus dem Wasser entsprungen. — Heraklit war der Choleriker, der das innerliche «Feuer» erlebte. Er schilderte die Welt so, wie er sie erlebte. Und daneben gab es, nicht mehr verzeichnet heute in der äußeren Überlieferung, noch eindringlichere Geister. Die wußten noch mehr über die Dinge. Dasjenige, was sie wußten, ging dann weiter und war als Überlieferung vorhanden in den ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten, so daß Galen eben von seinen vier Bestandteilen des inneren Säftewesens des Menschen sprechen konnte.

Das, was man da wußte über das innere Säftewesen, wie diese vier Gattungen von Säften: gelbe Galle, schwarze Galle, Blut und Schleim ineinandergehen, sich mischen — was man heute für eine Kinderei ansieht, nun, das ist ja begreiflich -, das ist eigentlich dasjenige, was innere menschliche Chemie ist. Eine andere Chemie gab es eben damals nicht. Denn dasjenige, was man äußerlich als Erscheinungen ansah, die heute in das Gebiet der Chemie gehören, das beurteilte man nach diesen inneren Erlebnissen, so daß wir von einer inneren Chemie reden können, die auf Erlebnissen des vom Ätherleib durchzogenen Säftemenschen, wenn ich mich des Ausdrucks bedienen darf, beruht. Und so haben wir in der älteren Zeit diese Chemie an den Menschen gebunden. Sie tritt später heraus, ebenso wie die Mathematik und wie die Physik, und wird äußerliche Chemie (siehe Schema). Denken Sie nur einmal, wie diese Physik und diese Chemie der älteren Zeiten von den Menschen empfunden worden sind! Sie sind empfunden worden als etwas, was gewissermaßen ein Stück von ihnen selbst war, nicht als etwas, was bloß Beschreibung einer äußeren Natur mit ihren Vorgängen ist. Das war das Wesentliche. Es war erlebte Physik, erlebte Chemie. In einer solchen Zeit, in der man die äußere Natur in seinem physischen, in seinem Ätherleib fühlte, erlebte man auch dasjenige, was im astralischen Leibe ist und was in der Ich-Organisation ist, anders als später. Wir haben heute eine Psychologie. Aber diese Psychologie, sie ist - man sollte sich es gestehen, aber man tut es nicht -, sie ist tatsächlich ein Inventar von lauter Abstraktionen. Denken, Fühlen, Wollen finden Sie da drinnen wie auch Gedächtnis, Phantasie und so weiter eigentlich nur als Abstraktionen angeführt. Das entstand allmählich aus dem, was man da nun als seinen eigenen Seeleninhalt noch gelten ließ. Die Chemie und die Physik hatte man herausgeworfen, Denken, Fühlen und Wollen, das warf man nicht heraus, das behielt man, aber es verdünnte sich allmählich so, daß es eigentlich nur noch ein Inventar wurde von den wesenlosesten Abstraktionen. Das läßt sich auf die leichteste Weise beweisen, daß das wesenlose Abstraktionen wurden. Denn, nehmen wir zum Beispiel die Leute, die etwa im 15., 16. Jahrhundert noch vom Denken, Wollen sprachen. So wie sie sprachen — bitte, nehmen Sie ältere Schriften über diese Dinge -, hat das alles noch den Charakter des Konkreteren. Man hat das Gefühl, wenn so ein Mensch über das Denken redet, dann redet er noch so, als ob dieses Denken wirklich noch eine Summe von inneren Vorgängen in ihm wäre, als ob die Gedanken sich stoßen würden, sich tragen würden. Es ist auch noch ein Erleben von Gedanken. Die Sache ist noch nicht so abstrakt, wie sie später geworden ist. Später ist sie so etwas geworden, daß dann, als das 19. Jahrhundert gekommen ist und das Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts, es den Philosophen leicht geworden war, diesen Abstraktionen überhaupt alle Realität abzusprechen und nur noch davon zu sprechen, daß es innere Spiegelbilder seien und so weiter, was ja in besonders geistreicher Weise eben der öfter angeführte Richard Wahle gemacht hat, der nun das Ich, das Denken, Fühlen und Wollen nur noch für Illusionen erklärt. Aus Abstraktionen werden sie dann Illusionen, die inneren Seeleninhalte.

Eben in derjenigen Zeit, in der der Mensch sein Gehen als einen Vorgang gefühlt hat, der sich mit ihm und der Welt zugleich abspielt, in der er seine Säftebewegung gespürt hat, so daß er wußte, wenn er sich, sagen wir, im heißen Sonnenscheine bewegt, also äußere Wirkungen da sind, so bewegen sich Blut und Schleim in ihm anders, als im kalten Winter. Er erlebte die Blut-Schleimbewegungen in sich, aber er erlebte sie zusammen mit dem Sonnenschein oder mit der Abwesenheit des Sonnenscheins. So wie er ja das Physische und Chemische mit der Welt zusammen erlebte, so erlebte er auch Denken, Fühlen, Wollen mit der Welt zusammen. Er versetzte sie nicht bloß in sein Inneres in der Art wie spätere Zeiten, wo sie allmählich zu vollständigen Abstraktionen verdufteten, sondern in dem Erfahren dessen, was da vor sich geht im Menschen, und jetzt nicht in dem, was Säftebewegung ist, oder was physische Bewegungen, physische Kräfteentfaltungen sind, sondern in dem, was der astralischen Wesenheit des Menschen, dem Seelischen angehört, in diesem Erleben war das enthalten, was für die damalige Zeit Gegenstand einer Psychologie war (siehe Schema $.120).

Die wurde nun ganz an den Menschen gebunden. Mit dem heraufkommenden naturwissenschaftlichen Zeitalter stieß also der Mensch die Physik hinaus in die Welt, die Chemie hinaus in die Welt; die Psychologie stieß er in sich selber hinein. Man kann diesen Prozeß bei Baco von Verulam, bei John Locke namentlich verfolgen. Alles dasjenige, was erfahren wird als Seeleninhalt an der Außenwelt: Ton, Farbe, Wärmequalität, wird hineingestoßen in den Menschen.

Noch mehr spielt sich dieser Prozeß ab in bezug auf die Ich-Organisation. Die Ich-Organisation wurde allmählich wirklich ein recht dünnes Erlebnis. So, wie man da in sich hineinschaut, ist das Ich allmählich etwas Punktartiges geworden. Daher es wiederum für die Philosophen sehr leicht geworden ist, es wegzudisputieren. Nicht das Ich-Bewußtsein, aber das Erlebnis des Ich war für ältere Zeiten ein Inhaltserfülltes, Vollwirkliches. Und das Erleben des Ich drückte sich aus in dem, was nun eine Wissenschaft war, höher als die Psychologie, eine Wissenschaft, die man Pneumatologie nennen kann. Auch diese nahm der Mensch in späteren Zeiten in sich herein und verdünnte sie zu seiner wirklich recht dünnen Ich-Empfindung (siehe Schema S.120).

Wenn der Mensch das Innenerlebnis seines physischen Leibes hatte, hatte er das Physikerlebnis, er hatte zu gleicher Zeit dasjenige, was in der äußeren Natur als gleichartig mit den Vorgängen in seinem physischen Leibe vor sich geht. Und so ähnlich ist es mit dem Ätherleib. Bei diesem wurde nun nicht nur das Ätherische, sondern auch die physische Säftewelt, aber beherrscht von dem Ätherischen, innerlich erlebt. Was wird denn erlebt innerlich, indem der Mensch das Psychologische wahrnimmt, indem er die Vorgänge seines astralischen Leibes erlebt? Da wird innerlich erlebt dasjenige, was, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, der Luftmensch ist. Wir sind ja nicht nur feste organische Gebilde, säftehaltige organische Gebilde, also wässerige Gebilde, sondern wir sind ja fortwährend auch innerlich gasig-luftig. Wir atmen die Luft ein, atmen sie wieder aus. In innigem Vereine mit der innerlichen Luftverarbeitung erlebte der Mensch den Inhalt der Psychologie. Daher war sie konkreter. Als man das Lufterlebnis herausgeworfen hatte, dasjenige, was man auch äußerlich verfolgen kann, herausgeworfen hatte aus dem Denkinhalte, da wurde der Denkinhalt eben immer mehr abstrakt, bloßer Gedanke. Denken Sie, wie der indische Philosoph in seinen Übungen gestrebt hat, sich so recht bewußt zu werden, daß im Atmen, im Atmungsprozeß etwas Verwandtes mit dem Denkprozeß vor sich ging. Er machte einen geregelten Atmungsprozef, um in seinem Denken vorwärtszukommen. Er wußte, Denken, Fühlen, Wollen ist etwas, was nicht solch luftiges Zeug ist, wie wir es heute anschauen, sondern was immerhin mit der äußeren Natur und namentlich mit der inneren Natur nach dem Atmen hin zusammenhing, was also zusammenhing mit der Luft. Kann man also sagen: Das Physikalische, das Chemische warf der Mensch aus seiner Organisation heraus, so kann man auch sagen: Das Psychologische sog er ein, aber er warf das äußere Element, nämlich das Luft-Atemerlebnis heraus. Aus dem Physischen und Chemischen warf er sich selber heraus und beobachtete nur mehr als Physik und Chemie die äußere Welt; aus dem Psychologischen warf er die äußere Welt, die Luft heraus, und ebenso warf er aus dem Pneumatologischen das Wärmehafte heraus. Dadurch wurde es zu der Dünnheit des Ichs gemacht.

Also wenn ich dies, physischen Leib und Ätherleib, den unteren Menschen nenne (siehe Schema S.120), astralischen Leib und Ich-Organisation den oberen Menschen nenne, so kann ich sagen: Die geschichtliche Entwickelung beim Übergange von einem älteren Zeitalter zu dem naturwissenschaftlichen zeigt, daß der Mensch das Physische, das Chemische aus sich herauswarf und in seine physischen und chemischen Begriffe nur mehr die äußere Natur aufnahm. In der Psychologie und Pneumatologie entwickelte der Mensch Vorstellungen, aus denen er die äußere Natur herauswarf und nur noch das erlebte, was noch davon im Inneren in seinen Vorstellungen übrig blieb. In der Psychologie blieb ihm so viel übrig, daß er wenigstens noch Worte hatte für Seeleninhalte. Für das Ich blieb ihm so wenig übrig, daß die Pneumatologie, teilweise vorbereitet allerdings durch die Dogmatik, aber auch sonst vollständig verschwand. Es schrumpfte alles zu dem Punkte des Ich zusammen.

Das trat an Stelle desjenigen, was einst rein einheitlich erlebt worden ist, wenn man sagte: Man hat vier Elemente, Erde, Wasser, Luft, Feuer; die Erde erlebt man in sich selber, wenn man den physischen Leib erlebt; das Wasser erlebt man in sich selber, wenn man den Ätherleib erlebt als Säftebeweger und Säftemischer und Entmischer; die Luft erlebt man, wenn man den astralischen Leib erlebt in Denken, Fühlen und Wollen, denn das Denken, Fühlen und Wollen erlebte man als wogend auf dem innerlichen Atmungsvorgang; und die Wärme oder das Feuer, wie man es damals nannte, erlebte man in der IchEmpfindung.

So können wir also sagen: In einer Umwandelung des ganzen Verhältnisses des Menschen zu sich selber entwickelte sich die naturwissenschaftliche Anschauung der neueren Zeit. Und wenn man mit diesen Einsichten eben die geschichtliche Entwickelung verfolgt, so findet man erstens das, was ich Ihnen früher gesagt habe, und in jeder neuen Epoche neue Darstellungen der alten Überlieferungen, aber immer weniger verstanden. Und merkwürdige Zeugnisse solcher alten Überlieferungen sind dann die Anschauungen etwa eines Paracelsus, van Helmonts, Jakob Böhmes.

Bei Jakob Böhme hat derjenige, der sich Einsichten in solche Dinge verschaffen kann, unmittelbar die Erfahrung, daß da ein außerordentlich einfacher Mensch spricht, der aus Quellen seine Erkenntnis hat, die heute zu besprechen ja nicht möglich sind, die zu weit führen würden, daß aber eigentlich in einer Weise, die wirklich deshalb schwer verständlich ist, weil sie sehr ungeschickt ist, Jakob Böhme in dieser ungeschickten Darstellung tiefe alte Einsichten aufnimmt, die sich einfach volksmäßig fortgepflanzt haben. In welcher Lage war denn so jemand wie Jakob Böhme? Während Giordano Bruno, der demselben Zeitalter angehört, in der für ihn neuesten Phase der Entwickelung der Menschheit so drinnensteht, wie ich das in einem früheren Vortrage dieses Kurses dargestellt habe, sehen wir bei Jakob Böhme, daß er ganz offenbar zur Hand bekommt allerlei Werke, die heute natürlich verschollen sind. Durch eine innere Anlage geht ihm auf an Werken, die buntestes Zeug in der äußeren Darstellung repräsentieren, daß das auf einen Ursinn zurückgeht. Und er stellt wiederum, ich möchte sagen, unter ungeheuren inneren Hemmnissen, wodurch die Sache eben ungeschickt wird, diese Urweisheit, die er von noch ungeschickteren, unzulänglichen Überlieferungen übernommen hatte, dar. Er konnte aber zurückgehen zu einer früheren Stufe infolge seiner inneren Erleuchtung.

Und geht man nun in das 15., 16. Jahrhundert, und namentlich ins 17. und 18. Jahrhundert, und sieht man über solche einzelnen Erscheinungen wie Paracelsus und Jakob Böhme, die eigentlich nur da sind wie Denkmäler einer alten Zeit, hinweg und nimmt das, was im fortlaufenden exoterischen Strom der Menschheitsentwickelung vorhanden ist, so bekommt man, indem man den Maßstab der Initiationswissenschaft anlegt und die Sache mit ihrem Lichte beleuchtet, den Eindruck: Da weiß keiner mehr irgendwie von den tieferen Grundlagen des Weltenwesens. Da ist schon das eingetreten, daß Physik herausgeworfen ist aus dem Menschen, daß Chemismus herausgeworfen ist aus dem Menschen, da tritt schon der Spott auf über Alchimie. Man hatte ja natürlich recht mit diesem Spott, denn dasjenige, was noch erhalten war von den alten Traditionen als mittelalterliche Alchimie, darüber konnte man spotten. Man hatte die ins Innere des Menschen genommene Psychologie und eine sehr dünne Pneumatologie. Also man hatte gebrochen mit demjenigen, was man früher vom Menschen gewußt hat, und man erlebte auf der einen Seite das vom Menschen Getrennte, auf der anderen Seite das in den Menschen chaotisch Hineingeworfene. Und man möchte sagen, überall zeigte sich in dem, was man nun als Menschenerkenntnis anstrebte, diese eben charakterisierte Tatsache.

Da tritt zum Beispiel im 17. Jahrhunderte eine Anschauung auf, die, wenn man sie als einzelne Anschauung ins Auge faßt, eigentlich ziemlich unverständlich bleibt, die aber, in die Historie hineingestellt, ganz verständlich wird, da taucht die Ansicht auf, daß die ganze Summe der Vorgänge, die ein Mensch in seinem Inneren als Ernährungsvorgänge hat, auf einer Art von Gärung beruhen. Dasjenige, was der Mensch als Nahrungsmittel aufnimmt, das speichelt er ein, durchdringt es mit Säften, zum Beispiel der Pankreas, und da vollziehen sich verschiedene Grade von Gärungsprozessen, wie man es etwa nannte. Wenn man vom heutigen Anschauen aus, das ja natürlich auch wieder nur ein Vorübergehendes ist, diese Dinge betrachtet, so kann man ja natürlich darüber höhnen. Aber dann strebt man nicht nach Einsicht, sondern höchstens nach einer professoralen Darstellung. Wenn man aber darauf eingeht, so sieht man, woher solche allerdings merkwürdigen Ansichten über den Menschen kommen. Ganz im Verglimmen sind die alten Traditionen, die noch bei Galen und noch früher auf inneren Erlebnissen beruhten und einen guten Sinn hatten. Und dasjenige, was jetzt äußerlich als abgestoßene Chemie da sein sollte, das ist nur in den allerersten Elementen da. Das Innere hat man nicht mehr; das Äußere hat sich noch nicht entwickelt. Und so ist man in der Lage, nur in außerordentlich schwachen neuchemischen Vorstellungen, wie etwa einer unbestimmt gedachten Gärung, von den innerlichen Ernährungsvorgängen sprechen zu können. Und es waren die Nachzügler der Galenlehre, welche zwar noch etwas fühlten, daß man ausgehen muß, wenn man den Menschen verstehen will, von seiner Säftebewegung, also von dem Flüssigen in ihm, welche aber zu gleicher Zeit schon anfingen, das Chemische nur an den äußeren Vorgängen zu betrachten, und welche also die äußerlich betrachteten Gärungsvorgänge nun auf den Menschen anwendeten. Der Mensch war ein leerer Sack geworden, weil er nichts mehr in sich erlebte. In diesen leeren Sack füllte man dasjenige jetzt hinein, was äußere Wissenschaft geworden war. Nun, damals im 17. Jahrhundert war es noch wenig. Da hatte man unbestimmte Vorstellungen über Gärungen und ähnliche Prozesse. Die schob man jetzt in den Menschen hinein. Das war im 17. Jahrhundert die sogenannte Jatrochemische Schule.

Wenn man die Jatrochemiker in Betracht zieht, so sagt man sich, die haben noch in ihren Vorstellungen so etwas wie kleine Schatten der alten Säftelehre, die auf innerem Erleben beruhte. Andere aber, die mehr oder weniger Zeitgenossen dieser Jatrochemiker waren, die hatten auch solche schattenhaften Vorstellungen gar nicht mehr, und die fingen nun an, den Menschen so zu betrachten, wie er sich etwa ausnimmt, wenn wir heute ein Anatomiebuch aufschlagen. Wenn wir heute ein Anatomiebuch aufschlagen, da wird der Mensch so dargestellt: Meinetwillen wird ein Knochensystem dargestellt, der Magen, das Herz, die Leber dargestellt, und unwillkürlich bekommt dann derjenige, der das verfolgt, den Eindruck, als ob das der ganze Mensch wäre und der aus mehr oder weniger festen Organen mit scharfen Konturen bestünde. Diese sind ja auch da in gewisser Beziehung. Aber das Feste — das Erdige, im alten Sinne gesprochen - ist ja höchstens ein Zehntel vom Menschen. Im übrigen ist der Mensch eine Flüssigkeitssäule. Natürlich nicht in der Mitteilung, aber in der betrachtenden Methode wurde das allmählich ganz vergessen, daß der Mensch eine Flüssigkeitssäule ist, und daß in dieser Flüssigkeitssäule drinnen sich bilden diese Organe mit den festen Konturen, die darinnen nur schwimmen, die man heute eben einfach aufzeichnet und dadurch insbesondere bei Laien die Vorstellung hervorruft, als ob man damit den Menschen verstanden hätte. Wenn Sie die heutigen Bilder des anatomischen Atlasses anschauen, da haben Sie das entwickelt, aber es gibt ein falsches Bild. Es ist nur ein Zehntel vom Menschen. Den anderen Menschen müßte man darstellen, indem man hineinzeichnet in diese Gebilde, in Magen, Leber usw., einen fortwährenden Säftestrom in der mannigfaltigsten Weise, ein Ineinanderwirken von Säften, eine Wechselwirkung von Säften (siehe Zeichnung S.128). Wie das eigentlich ist, darüber hat man ganz falsche Vorstellungen bekommen, weil man gewissermaßen nur mehr die festbegrenzten Organe des Menschen betrachtete. Und so kam es zum Beispiel, daß im 19. Jahrhundert die Leute außerordentlich frappiert waren, daß, wenn der Mensch das erste Glas Wasser trinkt - ich will jetzt von Wasser sprechen -, daß das den Eindruck macht, es geht ganz durch durch den Menschen und wird von seinen Organen überall verarbeitet in der Weise, wie es aufgefaßt wird. Wenn er aber das zweite, wenn er das dritte Glas Wasser trinkt, so macht das gar nicht den Eindruck, als ob das in derselben Weise verarbeitet würde. Diese Dinge hat man dann bemerkt, aber man kann sie nicht mehr erklären, weil man eine ganz falsche Anschauung, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, vom Flüssigkeitsmenschen gewonnen hat, in dem der Ätherleib die treibende Wesenheit gewesen ist, die die Flüssigkeiten mischt und entmischt, die organische Chemie im Menschen bewirkt.

Nun, im 17. Jahrhundert hat man wirklich angefangen, diesen Flüssigkeitsmenschen nach und nach ganz zu ignorieren und nur die fest begrenzten Teile ins Auge zu fassen. Dadurch kam allmählich das heraus, daß man den Menschen ansah wie einen Zusammenhang von festen Teilen. Da, innerhalb dieser Welt von fest begrenzten Teilen, spielt sich alles in mechanischer Ordnung ab. Da stößt eins das andere; das bewegt sich; da werden Dinge gepumpt, da wirken die Dinge in der Art von Saugpumpen oder Druckpumpen. Mechanisch also betrachtet man den Menschenleib wie einen nur durch den Zusammenhang von fest begrenzten Organen existierenden Leib. Und allmählich wurde aus der jatrochemischen Ansicht, eigentlich gleichzeitig schon mit ihr, die jatromechanische oder gar jatromathematische Anschauung. Da florierte natürlich ganz besonders stark eine solche Anschauung, daß das Herz eigentlich eine Pumpe sei, die das Blut durch den Körper pumpt - nicht wahr, so richtig mechanisch -, weil man nicht mehr wußte, daß die innerlichen Säfte des Menschen innerliches Leben haben, daß also die Säfte sich selbst bewegen, daß das Herz nur ein Sinnesorgan ist, um diese Säftebewegung in seiner Art wahrzunehmen. So kehrte man die ganze Sache um, sah nicht mehr hin auf die Säftebewegung, auf die innere Lebendigkeit der Säftebewegung, auf den Ätherleib, der da drinnen wirkt, und das Herz wurde ein mechanischer Apparat, ist es im Grunde genommen heute noch für die meisten sogenannten Physiologen und Mediziner.

Also die Jatrochemiker haben noch einen Schatten vom Wissen über den Ätherleib. In demjenigen, was Galen vortrug, war durchaus ein volles Bewußtsein des Ätherleibes vorhanden. In demjenigen, was van Helmont zum Beispiel vortrug oder Paracelsus, ist ein schattenhaftes Bewußtsein vorhanden von dem Ätherleib, ein noch schattenhafteres bei den offiziellen Jatrochemikern, die die Schule versorgten. Gar kein Bewußtsein mehr von diesem Ätherleib war vorhanden bei den Jatromechanikern. Da war alle Vorstellung vom ÄÄtherleib verduftet, und man stellte den Menschen nur als physischen Leib vor, da aber nur nach seinen festen Bestandteilen, die man aber jetzt behandelte mit der Physik, die man nun auch schon herausgeworfen hatte aus dem Menschen, die man also äußerlich anwendete auf den nicht mehr verstandenen Menschen. Man hatte zuerst den Menschen zu einem leeren Sack gemacht — ich möchte das Beispiel noch einmal gebrauchen -, hatte draußen die Physik in abstrakter Weise begründet und nun diese Physik zurück in den Menschen geworfen. So daß man nicht die lebendige Wesenheit des Menschen hatte, sondern einen leeren Sack, ausgefüllt mit Theorien.

So ist es heute noch. Denn dasjenige, was uns heute etwa die Physiologie oder die Anatomie vom Menschen erzählt, das ist ja nicht der Mensch, es ist die aus dem Menschen herausgeworfene Physik, die nun umgeändert ist, indem man sie wiederum in den Menschen hineingestopft hat. Gerade wenn man so recht innerlich die Entwickelung betrachtet, so sieht man, wie das Schicksal da ging. Die Jatrochemiker hatten noch ein Schattenbewußtsein vom Ätherleib, die Jatromechaniker gar nichts mehr davon. Da kam einer, Stahl. Er war eigentlich, wenn man sein Zeitalter berücksichtigt, ein außerordentlich gescheiter Mensch. Er hatte offenbar bei den Jatrochemikern sich umgesehen. Diese innerlichen Gärungsprozesse, die erschienen ihm unzulänglich, weil sie ja auch nur die schon nach außen geworfene Chemie wiederum in den Menschensack zurückversetzen. Die Jatromechaniker erst recht, denn die versetzen ja nur die äußere mechanische Physik in den Menschensack zurück. Aber vom Ätherleib als der treibenden Kraft der Säftebewegung war nichts mehr da, keine Tradition. Es gab keine Möglichkeit, sich darüber zu informieren. Was tat Stahl im 17., 18. Jahrhundert? Er erfand sich etwas, weil in der Tradition nichts mehr da war - er erfand sich etwas. Er sagte sich: Das, was im Menschen vor sich geht an physikalischen, an chemischen Vorgängen, das kann doch wirklich nicht auf diese Physik und Chemie gebaut sein, die man da nun für die Außenwelt findet. Aber er hatte nichts anderes, um es in den Menschen hereinzubringen. So erfand er sich dasjenige, was er «Lebenskraft» nannte. Dadurch begründete er die dynamische Schule. Es war also eine nachträgliche Erfindung für etwas, was man verloren hatte. Stahl war eigentlich tatsächlich noch von einem gewissen Instinkt beseelt. Ihm fehlte etwas. Weil er es nicht hatte, so erfand er es wenigstens: Lebenskraft. Das 19. Jahrhundert hatte wieder alle Mühe, diese Lebenskraft loszukriegen. Sie war ja auch in Wirklichkeit nichts weiter als eine Erfindung, und man hat also wieder sich alle Mühe gegeben, diese Lebenskraft loszukriegen.

Es ist also tatsächlich so, daß man ringt, in diesen leeren Sack «Mensch» wiederum etwas hineinzubringen, was irgendwie hineinpaßt. So kam man darauf, wiederum auf der anderen Seite sich zu sagen: Das Maschinelle haben wir. Wie eine Maschine sich bewegt und reagiert, das weiß man. Und so steckte man in den leeren Menschensack die Maschine hinein: «L’homme machine» von de La Mettrie. Der Mensch ist eine Maschine. Der Materialismus oder eigentlich Mechanismus des 18. Jahrhunderts wie etwa im «Systeme de la nature» von Holbach, das Goethe in seiner Jugend so furchtbar gehaßt hat, er ist die Ohnmacht, an das Wesen des Menschen heranzukommen mit demjenigen, was in der äußeren Natur in der damaligen Zeit schon und später so wirksam geworden ist. Und noch das 19. Jahrhundert nagte an diesem Unvermögen: An den Menschen konnte man nicht herankommen.

Nun aber wollte man doch mit irgend etwas den Menschen vorstellen. Also verfiel man darauf, ihn als höher entwickeltes Tier vorzustellen. Das Tier verstand man zwar auch nicht, denn mit Ausnahme der Pneumatologie brauchte man für das Verständnis des Tieres nun auch im alten Sinne Physik, Chemie, Psychologie. Aber daß man für das Tier so etwas auch braucht, wenn man es verstehen will, das merkte man zunächst nicht. Man ging halt von etwas aus, nicht wahr. Und so führte man den Menschen früher, im 18. Jahrhundert, auf die Maschine, im 19. Jahrhundert auf das Tier zurück. Das alles ist historisch gut zu begreifen. Im ganzen Fortgang der Menschheitsent. wickelung hat das seinen guten Sinn, denn unter dem Einflusse dieser Unkenntnis vom Menschenwesen entstanden die neuzeitlichen Empfindungen über den Menschen. Wären die alten Ansichten geblieben von der innerlichen Physik, von der innerlichen Chemie, der vom Menschen außerhalb seiner selbst erlebten Psychologie und Pneumatologie, so wäre zum Beispiel die Freiheitsentwickelung niemals in der Menschheitsentwickelung erwacht. Der Mensch mußte sich als elementares Wesen verlieren, um sich als freies Wesen zu finden. Das konnte er nur, wenn er gewissermaßen eine Weile zurücktrat von sich, sich nicht mehr beachtete, sich mit dem Äußeren befaßte und, wenn er Theorien über sich wollte, das in sich hereinnahm, was nun zum Verständnis der äußeren Welt sehr gut paßte. In dieser Zwischenzeit, in der der Mensch sich mit sich Zeit ließ, um so etwas wie Freiheitsempfindung zu entwickeln, in dieser Zwischenzeit entwickelte der Mensch die naturwissenschaftlichen Vorstellungen, jene Vorstellungen, die, ich möchte sagen, so robust sind, daß sie die äußere Natur begreifen können, aber zu grob sind für das Wesen des Menschen, weil er sich nicht die Mühe machte, sie so zu verfeinern, daß sie auch den Menschen mitbegreifen. Es entstanden die naturwissenschaftlichen Begriffe, die auf die Natur gut anwendbar sind, ihre großen Triumphe feiern, die aber unbrauchbar sind, um das Wesen des Menschen in sich aufzunehmen.

Hieraus sehen Sie auch, daß ich wirklich nicht eine Kritik liefere über das Naturwissenschaftliche, sondern daß ich nur Charakteristik liefern will. Gerade dadurch erlangt ja der Mensch sein ganzes Freiheitsbewußtsein, daß er nicht mehr belastet war mit alledem, wovon er eigentlich belastet sein mußte, als er so eigentlich die ganze Sache noch in sich trug. Dieses Freiheitserlebnis für den Menschen kam, als der Mensch sich eine Wissenschaft zimmerte, die in ihrer Robustheit nur für die äußere Natur paßte, und da sie ja doch nun eben nicht eine Totalität ist, natürlich auch wiederum Kritik erfahren kann, nicht anwendbar ist auf den Menschen, anwendbar ist eigentlich nur am bequemsten als Physik, in der Chemie fängt es schon an zu hapern, die Psychologie wird eigentlich ein vollständiges Abstraktum. Aber die Menschen mußten durch ein Zeitalter, das in dieser Weise verläuft, hindurchgehen, um eben nach einer ganz anderen Seite, nach der Seite des Freiheitsbewußtseins, zu einer individuell nuancierten Moralauffassung von der Welt zu kommen. Man kann die Entstehung der Naturwissenschaft im neueren Zeitalter nicht verstehen, wenn man sie nur einseitig betrachtet, wenn man sie nicht so betrachtet, daß sie eine Parallelerscheinung ist des nun in demselben Zeitalter heraufkommenden Freiheitsbewußtseins des Menschen und alles dessen, was moralisch und religiös mit diesem Freiheitsbewußtsein zusammenhängt.

Daher sehen wir, wie solche Leute, die wie Hobbes oder Bacon die Ideen der Naturwissenschaft begründen, wie denen die Möglichkeit entfällt — lesen Sie sich das nach bei Hobbes -, den Menschen anzugliedern an dasjenige, was Geist und Seele im Weltenall ist. Und es kommt bei Hobbes das heraus, daß er auf der einen Seite schon, ich möchte sagen, in radikalster Weise die naturwissenschaftlichen Vorstellungen im Keime bildet, daß er auf der anderen Seite aus dem menschlichen sozialen Leben auch alles Geistige herauswirft, den Krieg aller gegen alle statuiert, also nichts Bindendes anerkennt, das von irgendeinem Übersinnlichen kommt im sozialen Leben, daher er in einer etwas karikierten Form eigentlich zum ersten Mal theoretisch das Freiheitsbewußtsein bespricht.

Ja, geradlinig ist eben durchaus die Entwickelung der Menschheit nicht. Man muß die nebeneinander hergehenden Strömungen betrachten, dann erst kommt man dazu, den Sinn der geschichtlichen Entwickelung des Menschen zu begreifen.

Eighth Lecture

Distinguished audience, dear friends, expressions of solidarity and shared grief continue to arrive. I will take the liberty of sharing the relevant expressions here tomorrow or the day after tomorrow.

I have attempted to show how individual areas of scientific thought have emerged in recent times. I would like to insert an explanation that is intended to shed some light on what has taken place in the formation of scientific views, because it is easier to understand what is actually happening in the overall process of human development when one looks at things from a certain point of view. One must be quite clear that what appears in the outer culture and civilization of humanity is, inwardly, I would say, is permeated, is shot through by a kind of pulse, a pulse that comes from deeper insights that do not always have to appear as insights that are taught, but which actually underlie development in a different way, in a way that I will also indicate in the next few days. Now I would just like to say that one understands better what this direction is about if one takes as an aid what was at certain times the science of initiation, the science of the deeper foundations of life and world events.