The Origins of Natural Science

GA 326

2 January 1923, Dornach

Lecture VII

Continuing with yesterday's considerations concerning the inability of the scientific world conception to grasp the nature of man, we can say that in all domains of science something is missing that is also absent in the mathematical-mechanistic sphere. This sphere has been divorced from man, as if man were absent from the mathematical experience. This line of thought results in a tendency to also separate other processes in the world from man. This in its turn produces an inability to create a real bridge between man and world.

I shall discuss another consequence of this inability later on. Let us focus first of all on the basic reason why science has developed in this way. It was because we lost the power to experience inwardly something that is spoken of in Anthroposophy today and that in former times was perceived by a sort of instinctive clairvoyance. Scientific perception has lost the ability to see into man and grasp how he is composed of different elements.

Let us recall the anthroposophical idea that man is composed of four members—the physical body, the etheric body, the astral body and the I-organization. I need not go into detail about this formation, since you can find it all in my book Theosophy.59Rudolf Steiner, Theosophy (Spring Valley, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1971), pp. 1–39. When we observe the physical body and consider the possibility of inward experiencing one's physical body—we should begin by asking: What do we experience in regard to it? We experience what I have frequently spoken about recently; namely, the right-left, up-down, and front-back directions. We experience motion, the change of place of one's own body. To some extent at least, we also experience weight in various degrees. But weight is experienced in a highly modified form. When these things were still experienced within our various members, we reflected on them a good deal; but in the scientific age, no one gives them any thought. Facts that are of monumental importance for a world comprehension are completely ignored. Take the following fact. Assume that you have to carry a person who weighs as much as you do. Imagine that you carry this person a certain distance. You will consciously experience his weight. Of course, as you walk this distance, you are carrying yourself as well. But you do not experience this in the same way. You carry your own weight through space, but you do not experience this. Awareness of one's own weight is something quite different. In old age, we are apt to say that we feel the weight of our limbs. To some extent this is connected with weight, because old age entails a certain disintegration of the organism. This in turn tears the individual members out of the inward experience and makes them independent—atomizes them, as it were—and in atomization they fall a prey to gravity. But we do not actually feel this at any given moment of our life, so this statement that we feel the weight of our limbs is really only a figure of speech. A more exact science might show that it is not purely figurative, but be that as it may, the experience of our weight does not impinge strongly on our consciousness.

This shows that we have an inherent need to obliterate certain effects that are unquestionably working within us. We obliterate them by means of opposite effects (“opposite” in the sense brought out by the analogy between man and the course of the year in my recent morning lectures.60Rudolf Steiner, Man and the World of Stars: The Spiritual Communion of Mankind (New York: Anthroposophic Press, 1963), pp. 141–172. Nevertheless, whether we are dealing with processes that can be experienced relatively clearly, such as the three dimensions or motion, or with less obvious ones such as those connected with weight, they are all processes that can be experienced in the physical body.

What was thus experienced in former times has since been completely divorced from man. This is most evident in the case of mathematics. The reason it is less obvious in other experiences of the physical body is that the corresponding processes in the body, such as weight or gravity, are completely extinguished for today's form of consciousness. These processes, however, were not always completely obliterated. Under the influence of the mood prevailing under the scientific world conception, people today no longer have any idea of how different man's inner awareness was in the past. True, he did not consciously carry his weight through space in former times. Instead, he had the feeling that along with this weight, there was a counterweight. When he learned something, as was the case with the neophytes in the mysteries, he learned to perceive how, while he always carried his own weight in and with himself, the counter-effect is constantly active in light. It can really be said that man felt that he had to thank the spiritual element indwelling the light for counteracting, within him, the soul-spirit element activity in gravity. In short, we can show in many ways that in older times there was no feeling that anything was completely divorced from man. Within himself, man experienced the processes and events as they occurred in nature. When he observed the fall of a stone, for example, in external nature (an event physically separated from him) he experienced the essence of movement. He experienced this by comparing it with what such a movement would be like in himself. When he saw a falling stone, he experienced something like this: “If I wanted to move in the same way, I would have to acquire a certain speed, and in a falling stone the speed differs from what I observe, for instance, in a slowly crawling creature.” He experienced the speed of the falling stone by applying his experience of movement to the observation of the falling stone. The processes of the external world that we study in physics today were in fact also viewed objectively by the man of former times, but he gained his knowledge with the aid of his own experiences in order to rediscover in the external world the processes going on within himself.

Until the beginning of the Fifteenth Century, all the conceptions of physics were pervaded by something of which one can say that it brought even the physical activities of objects close to the inner life of man. Man experienced them in unison with nature. But with the onset of the Fifteenth Century begins the divorce of the observation of such processes from man. Along with it came the severance of mathematics, a way of thinking which from then on was combined with all science. The inner experience in the physical body was totally lost. What can be termed the inner physics of man was lost. External physics was divorced from man, along with mathematics. The progress thereby achieved consisted in the objectifying of the physical. What is physical can be looked at in two ways. Staying with the example of the falling stone, it can be traced with external vision.  It can also be brought together with the experience of the speed that would have to be achieved if one wanted to run as fast as the stone falls. This produces comprehension that goes through the whole man, not one related only to visual perception.

It can also be brought together with the experience of the speed that would have to be achieved if one wanted to run as fast as the stone falls. This produces comprehension that goes through the whole man, not one related only to visual perception.

To see what happened to the older world view at the dawn of the Fifteenth Century, let us look at a man in whom the transition can be observed particularly well; namely, Galileo.61Galileo Galilei: Pisa 1564–1642 Arcetri by Florence. Discovered isochromism in pendulum, hydrostatic scales, laws of free fall, law of inertia. Numerous astronomical inventions with self-constructed telescope. An Inquisition trial resulted in a banning of the Copernican world system. See Riddles of Philosophy, The Spiritual Guidance of Man, and Laurenz Muellner's speech, “Die Bedeutung Galilei's fuer die Philosophie,” Vienna 1894. (Reprinted in Anthroposophie, 1933/34:29).

His Sermons de Motu Gravium (About the Effects of Gravity) contain the results of his investigations in Pisa. They first only circulated in manuscript copies; first edition: 1854. The final version is in the Discorsi e Dimenstrazioni Mathematiche Intomo a Due Nuove Scieme, published 1638 in Leyden. Also see L. Muellner's speech. Galileo is in a sense the discoverer of the laws governing falling objects. Galileo's main aim was to determine the distance traveled in the first second by a falling body. The older world view placed the visual observation of the falling stone side by side with the inward experience of the speed needed to run at an equal pace. The inner experience was placed alongside that of the falling stone. Galileo also observed the falling stone, but he did not compare it with the inward experience. Instead, he measured the distance traveled by the stone in the first second of its fall. Since the stone falls with increasing speed, Galileo also measured the following segments of its path. He did not align this with any inward experience, but with an externally measured process that had nothing to do with man, a process that was completely divorced from man. Thus, in perception and knowledge, the physical was so completely removed from man that he was not aware that he had the physical inside him as well.

At that time, around the beginning of the Seventeenth Century, a number of thinkers who wanted to be progressive began to revolt against Aristotle,62Such opponents were Bacon, Bruno, Galilei. See Riddles of Philosophy and the speech of L. Muellner, p. 103. who throughout the Middle Ages had been considered the preeminent authority on science. If Aristotle's explanations of the falling stone (misunderstood in most cases today) are looked at soberly, we notice that when something is beheld in the world outside, he always points out how it would be if man himself were to undergo the same process. For him, it is not a matter of determining a given speed by measuring it, but to think of speed in such a way that it can be related to some human experience. Naturally, if you say you must achieve a particular speed, you feel that something alive, something filled with vigor, will be needed for you to do this. You feel a certain inner impetus, and the last thing you would assume is that something is pulling you in the direction you were heading. You would think that you were pushing, not that you were being pulled. This is why the force of attraction, gravity, begins to mean something only in the Seventeenth Century.

Man's idea about nature began to change radically; not just the law of falling bodies, but all the ideas of physics. Another example is the law of inertia, it is generally called. The very name reveals its origin within man. (There is a play on words here. The German term for inertia, Trägheit, really means laziness.) Inertia is something that can be inwardly felt but what has become of the law of inertia in physics under the influence of “Galileoism?” the physicist says: A body, or rather a point, on which no external influence is exercises, which is left to itself, moves through space with uniform velocity. This means that throughout all time-spans it travels the same distance in each second. If no external influence interferes, and the body has achieved a given speed per second, it travels the same distance in each succeeding second.

It is inert. Lacking an external influence, it continues on and on without change. All the physicist does is measure the distance per second, and a body is called inert if the velocity remains constant.

There was a time when one felt differently about this and asked: How is a moving body, traveling a constant distance per second, experienced? It could be experienced by remaining on one and the same condition without ever changing one's behavior. At most, this could only be an ideal for man. He can attain this ideal of inertia only to a very small degree. But if you look at what is called inertia in ordinary life, you see that it is pretty much like doing the same thing every second of your life.

From the Fifteenth Century on, the whole orientation of the human mind was led to such a point that we can fairly say that man forgot his own inward experience. This happens first with the inner experience of the physical organism—man forgets it. What Galileo thought out and applied to matters close to man, such as the law of inertia, was not applied in a wide context. And it was indeed merely thought out, even if Galileo was dealing with things that can be observed in nature.

We know how, by placing the sun in the center instead of the earth, and by letting the planets move in circles around the sun, and by calculating the position of a given planetary body in the heavens, Copernicus produced a new cosmic system in a physical sense. This was the picture that Copernicus drew of our planetary, our solar system. And it was a picture that certainly can be drawn. Yet, this picture did not make a radical turn toward the mathematical attitude that completely divorces the external world from man. Anyone reading Copernicus's text gets the impression that Copernicus still felt the following. In the complicated lines, by means of which the earlier astronomy tried to grasp the solar system, it not only summed up the optical locations of the planets; it also had a feeling for what would be experienced if one stood amid these movements of the planets. In former ages people had a very clear idea of the epicycles the planets were thought to describe. In all this there was still a certain amount of human feeling. Just as you can understand the position of, let us say, an arm when you are painting a picture of a person because you can feel what it is like to be in such a position, so there was something alive in tracing the movement described by a planet around its fixed star. Indeed, even in Kepler's63Johannes Kepler: Weil der Stadt (Wuerttemberg) 1571–1630 Regensburg. Mathematician, physicist, astronomer, discoverer of the astronomical telescope. Astronomer and mathematician to three emperors. Persecuted as a Protestant. Totally exhausted through his life misery, he died prematurely at the “Reichstag” at Regensburg, where he hoped to secure his subsistence. To calculate his three laws of the motion of the planets he used the observation data of Tycho Brahe, whose follower he was at the court of Prague. On the other hand, the Copernican planetary system was the starting point for the finding of the three laws of the planets. Kepler was the first who tried to interpret the motion of the planetary orbit and moved the center of force to the sun. See The Spiritual Guidance of Man and, about the three planetary laws Das Verhaeltnis der Verschiedenen Naturwissenschaftlichen Gebiete zur Astronomie (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1981), GA Bibl. Nr. 323. case—perhaps especially in his case—there is still something of a human element in his calculating the orbits described by the planets.

Now Newton applies Galileo's abstracted principle to the heavenly bodies, adopting something like the Copernican view and conceiving things somewhat as follows: A central body, let us say a sun, attracts a planet in such a way that this force of attraction decreases in proportion to the square of the distance. It becomes smaller and smaller in proportion to the square, but increases in proportion to the mass of the bodies. If the attracting body has a greater mass, the force of attraction is porportionately greater.

If the distance is greater, the force of attraction decreases, but always in such a way that if the distance is twice as great, the attraction is four times less; if it is three times as great, nine times less, and so forth. Pure measuring is instilled into the picture, which, again, is conceived as completely abstracted from man. This was not yet so with Copernicus and Kepler but with Newton, a so-called “objective” something is excogitated and there is no longer any experience, it is all mere excogitation. Lines are drawn in the direction in which one looks and forces are, as it were, imagined into them, since what one sees is not force; the force has to be dreamed up. Naturally, one says “thought up” as long as one believes in the whole business; but when one no longer has faith in it, one says, “dreamed up.”

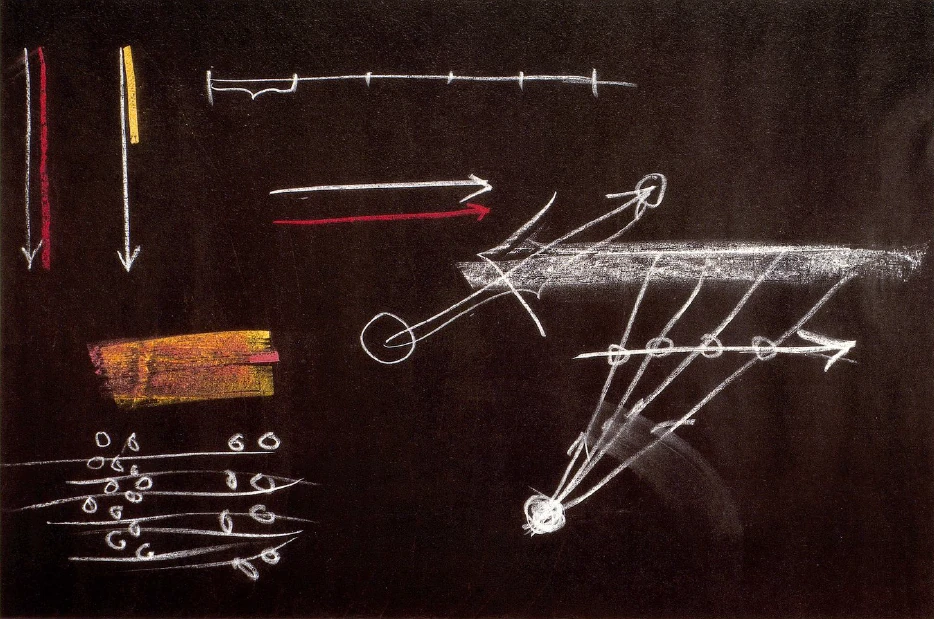

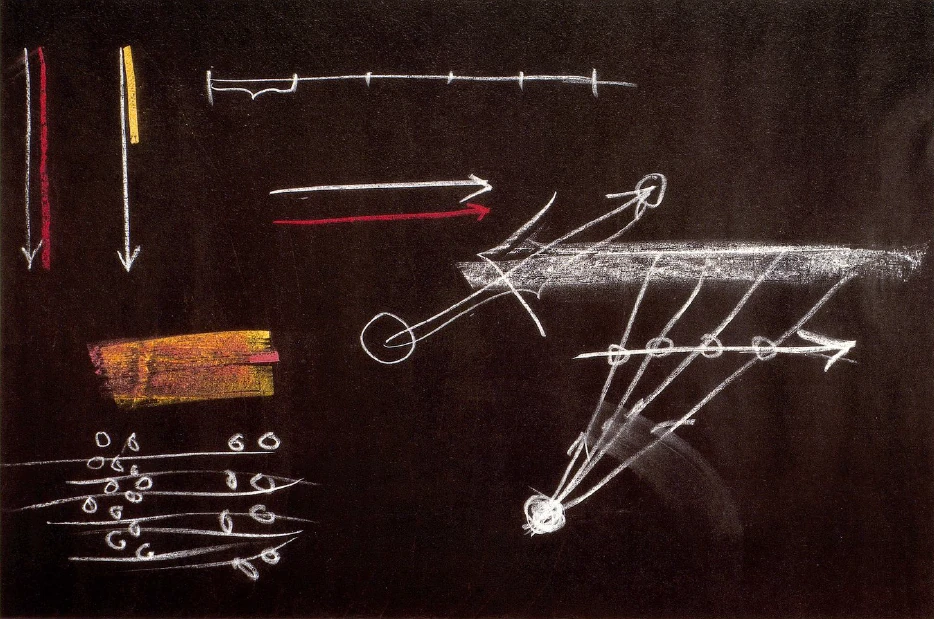

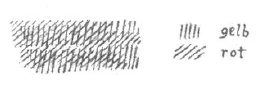

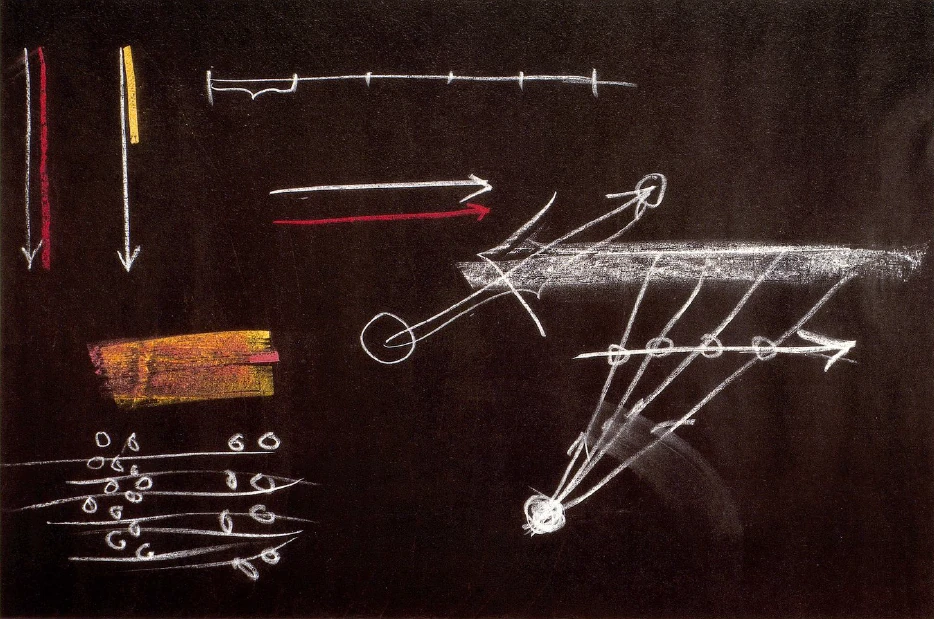

Thus we can say that through Newton the whole abstracted physical mode of conception becomes generalized so far that is applied to the whole universe. In short, the aim is to completely forget all experience within man's physical body; to objectify what was formerly pictured as closely related to the experience of the physical body; to view it in outer space independent of the physical corporeality, although this space had first been torn out of the body experience; and to find ways to speak of space without even thinking about the human being. Through separation from the physical body, through separation of nature's phenomena from man's experience in the physical body, modern physics arises. It comes into existence along with this separation of certain processes of nature from self-experience within the physical human body (yellow in sketch). Self experience is forgotten (red in Fig. 1)

By permeating all external phenomena with abstract mathematics, this kind of physics could not longer understand man. What had been separated from man could not be reconnected. In short, there emerges a total inability to bring science back to man.

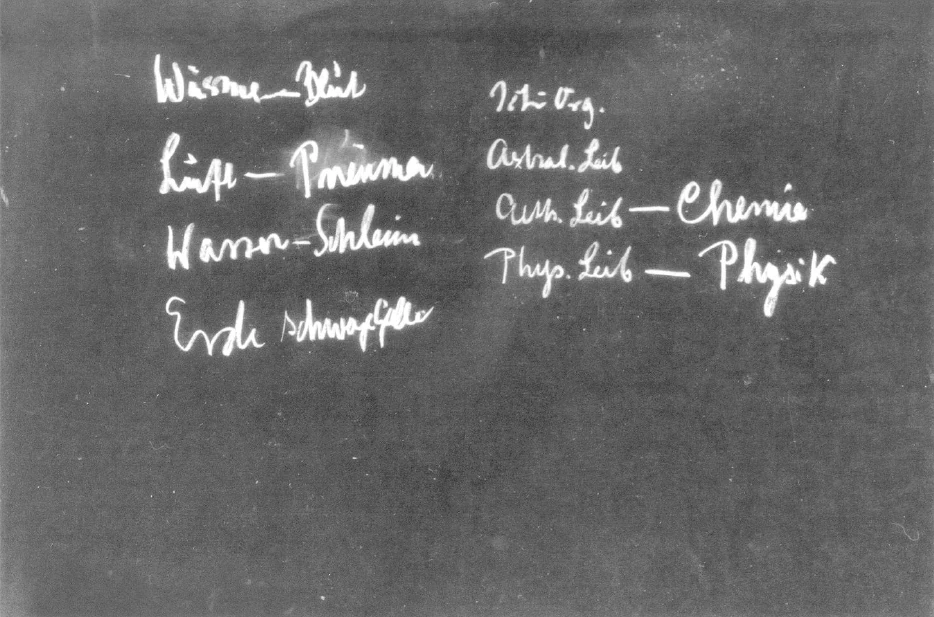

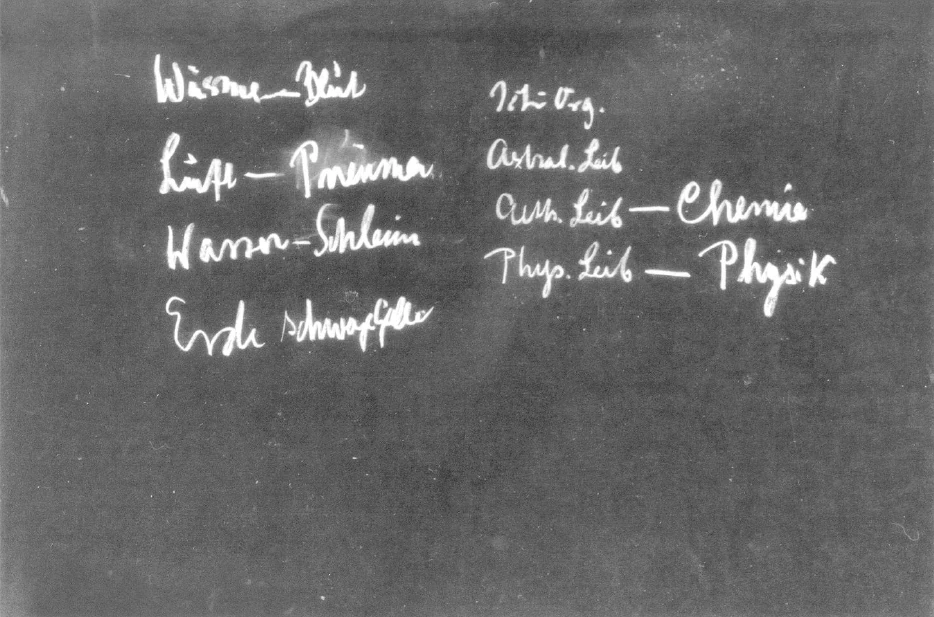

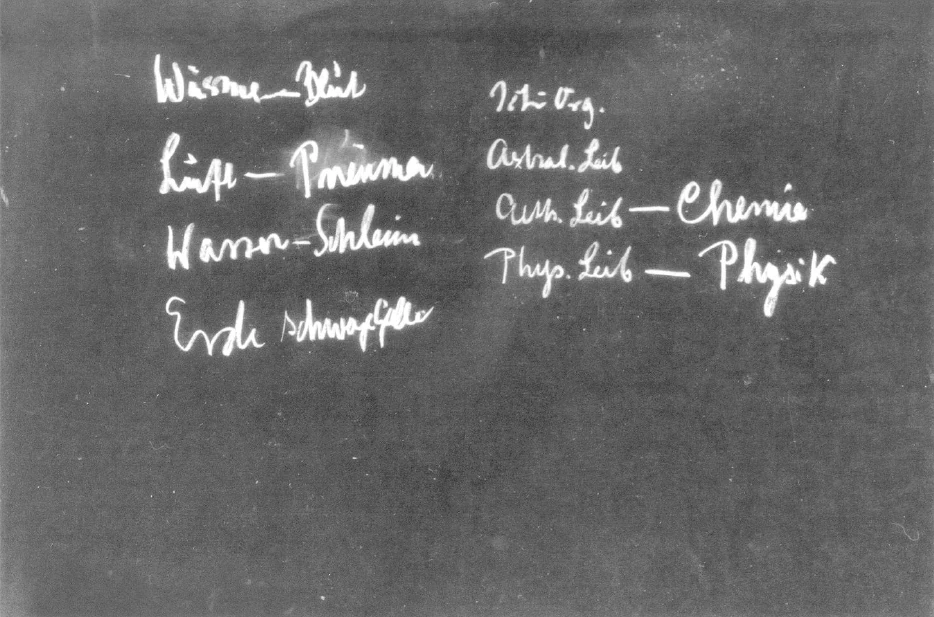

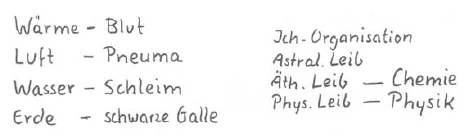

In physical respects you do not notice this quite so much; but you do notice it if you ask: What about man's self-experience in the etheric body, in this subtle organism? Man experiences quite a bit in it. But this was separated from man even earlier and more radically. This abstraction, however, was not as successful as in physics. Let us go back to a scientist of the first Christian centuries, the physician Galen.64Galen: Pergamon, Asia Minor 129 A.D.–199 Rome. Physician and philosopher. Studies in Pergamon and travel for study to Corinth, Smyrna, and Alexandria. Personal physician of Emperor Marcus Aurelius. His one hundred and fifty medical texts with fifteen commentaries were the basis for future medicine and pharmacology. One hundred twenty-five texts concerning philosophy, mathematics, and jurisprudence. Looking at what lived in external nature and following the traditions of his time, Galen distinguished four elements—earth, water, air and fire (we would say warmth.) We see these if we look at nature. But, looking inward and focusing on the self-experience of the etheric body,65Rudolf Steiner, A Road to Self Knowledge: The Threshold of the Spiritual World (London: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1975), pp. 19–27,100–106. one asks: How do I experience these elements, the solid, the watery, the airy and the fiery in myself? Then, in those times the answer was: I experience them with my etheric body. One experienced it as inwardly felt movements of the fluids; the earth as “black gall,” the watery as “phlegm,” the airy as “pneuma” (what is taken in through the breathing process,) and warmth as “blood.” In the fluids, in what circulates in the human organism, the same thing was experienced as what was observed externally. Just as the movement of the falling stone was accompanied by an experience in the physical body, so the elements were experienced in inward processes. The metabolic process, where (so it was thought) gall, phlegm, and blood work into each other, was felt as the inner experience of one's own body, but a form of inward experience to which corresponded the external processes occurring between air, water, fire and earth.

| Warmth | -Blood | -Ego Organization | |

| Air | -Pneuma | -Astral Body | |

| Water | -Phlegm | -Etheric Body | -Chemistry |

| Earth | -Black Gall | -Physical body | -Physics |

Here, however, we did not succeed in completely forgetting all inner life and still satisfying external observation. In the case of a falling body, one could measure something; for example, the distance traveled in the first second. One arrived at a “law of inertia” by thinking of moving points that do not alter their condition of movement but maintain their speed. By attempting to eject from the inward experience something that the ancients strongly felt to be a specific inner experience; namely, the four elements, one was able to forget the inner content but one could not find in the external world any measuring system. Therefore the attempt to objectify what related to these matters, as was done in physics, remained basically unsuccessful to this day. Chemistry could have become a science that would rank alongside physics, if it had been possible to take as much of the etheric body into the external world as was accomplished in the physical body. In chemistry, however, unlike physics, we speak to this day of something rather undefined and vague, when referring to its laws.66This is confirmed in chemical textbooks. They speak of chemistry as “a primarily empirical science.” In its laws one cannot come to mathematically definite values but to approximate numbers, whose limits are defined in tabular form. Therefore authors of chemical subject books need to add limiting explanations, such as “usually is valid,” or “generally one can say.” Chemical laws are mostly derived from physical laws, as for instance in the main theses of thermodynamics. It is thought unscientific to think otherwise than mechanically. Literature: H. Remy, Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie, 7th ed., 2 vols. (Leipzig: 1954), Volume I, pages 14–23, 37, 50, 71–73. What was done with physics in regard to the physical body was in fact the aim of chemistry in regard to the etheric body. Chemistry states that if substances combine chemically, and in doing so can completely alter their properties, something is naturally happening.

But if one wants to go beyond this conception, which is certainly the simplest and most convenient, one really does not know much about this process. Water consists of hydrogen and oxygen; the two must be conceived as mixed together in the water somehow but no inwardly experiencable concept can be formed of this. It is commonly explained in a very external way: hydrogen consists of atoms (or molecules if you will) and so does oxygen. These intermingle, collide, and cling to one another, and so forth. This means that, although the inner experience was forgotten, one did not find oneself in the same position as in physics, where one could measure (and increasingly physics became a matter of measuring, counting and weighing.) Instead, one could only hypothesize the inner process. In a certain respect, it has remained this way in chemistry to this day, because what is pictured as the inner nature of chemical processes is basically only something read into them by thought.

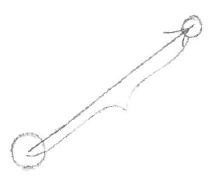

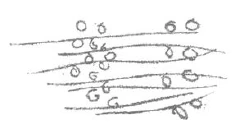

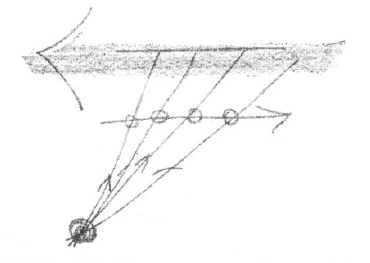

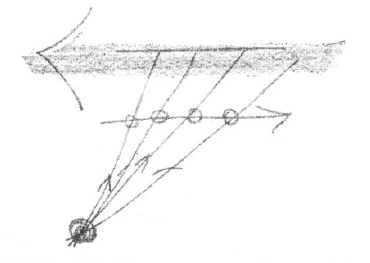

Chemistry will attain the level of physics only when with full insight into these matters, we can again relate chemistry with man, though not, of course, with the direct experience possessed by the old instinctive clairvoyance. We will only succeed in this when we gain enough insight into physics to be able to consolidate our isolated fragments of knowledge into a world conception and bring our thoughts concerning the individual phenomena into connection with man. What happens on one side, when we forget all inner experience and concentrate on measuring externals (thus remaining stuck in the so-called “objective”) takes its revenge on the other side. It is easy enough to say that inertia is expressed by the movement of a point that travels the same distance in each succeeding second. But there is no such point. This uniform movement occurs nowhere in the domain of human observation. A moving object is always part of some relationship, and its velocity is hampered here or there. In short, what could be described as inert mass,67See Georg Unger, Vom Bilden Physicalischer Begriffe, Volume 1, pages 41–49 and 57. or could be reduced to the law of inertia, does not exist. If we speak of movement and cannot return to the living inner accompanying experience of it, if we cannot relate the velocity of a falling body to the way we ourselves would experience this movement, then we must indeed say that we are entirely outside the movement and must orient ourselves by the external world. If I observe a moving body (see Fig. 7) and if these are its successive positions, I must somehow perceive that this body moves. If behind it there is a stationary wall, I follow the direction of movements and tell myself that the body moves on in that direction. But what is necessary in addition is that from my own position (dark circle) I guide this observation, in other words, become aware of an inward experience. If I completely leave out the human being and orient myself only out there, then, regardless of whether the object moves or remains stationary, while the wall moves, the result will be the same. I shall no longer be able to distinguish whether the body moves in one or the wall behind it in the opposite direction. I can basically make all the calculations under either one or the other assumption.

I lose the ability to understand a movement inwardly if I do not partake of it with my own experience. This applies, if I may say so, to many other aspects of physics. Having excluded the participating experience, I am prevented from building any kind of bridge to the objective process. If I myself am running, I certainly cannot claim that it is a matter of indifference whether I run or the ground beneath me moves in the opposite direction. But if I am watching another person moving over a given area, it makes no difference for merely external observation whether he is running or the ground beneath him is moving in the opposite direction. Our present age has actually reached the point, where we experience, if I may put it this way, the world spirit's revenge for our making everything physical abstract.

Newton was still quite certain that he could assume absolute movements, but now we can see numerous scientists trying to establish the fact that movement, the knowledge of movement, has been lost along with the inner experience of it. Such is the essence of the Theory of Relativity,68See Footnote 40. which is trying to pull the ground from under Newtonism. This theory of relativity is a natural historical result. It cannot help but exist today. We will not progress beyond it if we remain with those ideas that have been completely separated from the human element. If we want to understand rest or motion, we must partake in the experience. If we do not do this, then even rest and motion are only relative to one another.

Siebenter Vortrag

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, meine lieben Freunde, es sind von vielen Seiten von unseren Freunden und den Freunden unserer Sache Kundgebungen ihrer Anteilnahme und ihrer Verbundenheit mit unserem Schmerze über den Verlust des Goetheanums eingelaufen. Ich werde mir dann erlauben, morgen oder übermorgen über die einzelnen Kundgebungen Ihnen Bericht zu erstatten.

Nun möchte ich heute in Fortsetzung der gestern gepflogenen Auseinandersetzungen über, man könnte sagen, das Unvermögen der naturwissenschaftlichen Weltanschauung, die seit dem 15. Jahrhunderte heraufgekommen ist, den Menschen in seinem Wesen erkennend zu erfassen, sagen: Es fehlt eben auf allen Gebieten dieser Weltanschauung an dem, woran es schon im Mathematisch-Mechanischen fehlt. Man hat das Mathematisch-Mechanische abgesondert vom Menschen. Man betrachtet es so, als ob beim Erleben des Mathematischen der Mensch nicht mehr dabei wäre. Dieser Gang der menschlichen Vorstellungen für das Mathematische, er hat zur Folge auf der einen Seite, daß das Bestreben entsteht, auch anderes im Weltengebiete vor sich gehendes Geschehen vom Menschen abzusondern und es in keine Verbindung mehr zu bringen mit der menschlichen Wesenheit. Dadurch entsteht auf der anderen Seite das Unvermögen, erkennend eine wirkliche Brücke zu schaffen zwischen dem Menschen und der Welt.

Über eine andere Folge dieses Unvermögens werde ich dann noch später sprechen. Betrachten wir aber zunächst einmal, ich möchte sagen, die Grundursache, warum die naturwissenschaftliche Entwickelung diesen Gang genommen hat. Sie hat die Möglichkeit verloren, dasjenige innerlich zu erleben, wovon heute in der Anthroposophie gesprochen wird, und was in älteren Zeiten der Menschheitsentwickelung Gegenstand einer instinktiven Anschauung oder, wenn das Wort nicht mißverstanden wird, eines instinktiven Hellsehens war. Das Hineinschauen in den Menschen und ihn aus verschiedenen Elementen zusammengesetzt finden, das ist der naturwissenschaftlichen Anschauung verlorengegangen.

Erinnern wir uns doch, wie wir gliedern den Menschen, um seinem Wesen nahezukommen, innerhalb unserer anthroposophischen Anschauung. Wir reden von dem physischen Leib des Menschen, von dem ätherischen Leib, von dem astralischen Leib und von der Ich-Organisation des Menschen. Wollen wir uns das einmal heute zum Verständnis der Entwickelung naturwissenschaftlicher Weltanschauung recht vor Augen halten: Physischer Leib, ätherischer Leib, astralischer Leib, Ich-Organisation. Ich brauche diese Gliederung des Menschen heute nicht des Näheren auseinanderzusetzen, da ja jeder zum Beispiel in meinem Buche «’Theosophie» das Nötige darüber finden kann. Aber wir wollen uns nun doch einmal an dieser Gliederung des Menschen orientieren. Wir wollen uns zunächst fragen, wenn wir auf den physischen Leib des Menschen hinschauen und ins Auge fassen die Möglichkeit der inneren Orientierung, also die Möglichkeit, seinen physischen Leib innerlich zu erleben, was erlebt man denn dann an diesem physischen Leibe? Man erlebt eben gerade an dem physischen Leib dasjenige, wovon ich ja jetzt öfter gesprochen habe, das Rechts-Links, das Oben-Unten, das Vorne-Hinten. Man erlebt an dem physischen Leib die Anschauung der Bewegung als Ortsveränderung dieses eigenen physischen Leibes. Man erlebt an diesem physischen Leib aber auch, wenigstens bis zu einem gewissen Grade, variiert, zum Beispiel das Gewicht. Aber man erlebt das Gewicht eben in einer durchaus modifizierten Art. Als diese Dinge noch erlebt wurden in den verschiedenen Gliedern der Menschheitsorganisation, da dachte man eben über Dinge nach, über die nachzudenken man im naturwissenschaftlichen Zeitalter keine Neigung mehr hatte. Tatsachen, die für das Weltverständnis von fundamentaler Bedeutung sind, ließ man völlig unbeachtet. Nehmen Sie einmal die folgende Tatsache: Nehmen Sie an, daß Sie etwa einen Menschen tragen würden, der, wenn Sie ihn auf die Waage setzen, gleich schwer ist mit Ihnen. Nehmen Sie an, Sie tragen diesen Menschen. Sie gehen mit diesem Menschen irgendeine Strecke, indem Sie ihn tragen. Sie werden ein Erlebnis von seinem Gewichte haben. Indem Sie selber durch die gleiche Raumstrecke gehen, tragen Sie auch sich selber. Aber das erleben Sie nicht in derselben Weise. Es ist tatsächlich so, daß Sie ja Ihr Gewicht durch den Raum tragen, aber es nicht erleben. Ins Erleben wird das eigene Gewicht ganz anders hereingenommen. Wenn man alt wird, so fühlt man in einem gewissen Sinne seine Glieder so, daß man sagt, man fühle ihre Schwere. Das hängt auch in einem gewissen Sinne mit der Schwere, mit dem Gewichte zusammen, weil Altwerden eben ein gewisses Zerfallen des Organismus bedeutet, wodurch seine einzelnen Teile mehr herausgerissen werden aus dem inneren Erleben, selbständig werden, ich möchte sagen, atomisiert werden, und in der Atomisierung der Schwere verfallen. Aber wir könnten das natürlich in keinem Momente unseres Lebens bis zur Tatsächlichkeit bringen. Vielleicht werden wir sogar sagen, wir können ja den Ausdruck, daß wir die Schwere unserer Glieder fühlen, nur vergleichsweise brauchen. Eine genauere Wissenschaft zeigt allerdings, daß es nicht bloß vergleichsweise ist, sondern daß es etwas Bedeutsames an sich hat. Aber jedenfalls, das Erleben unseres eigenen Gewichtes zeigt sich eigentlich für unser Bewußtsein als eine Art Auslöschen unseres eigenen Gewichtes.

Nun, da haben wir also die im Menschenwesen liegende Notwendigkeit, Wirkungen, die zweifellos innerhalb dieser Menschenwesenheit sind, im Menschen auszulöschen, auszulöschen durch entgegengesetzte Wirkungen, derart entgegengesetzt, wie ich das für die Totalität des Menschen auseinandergesetzt habe, als ich die Analogie zwischen dem Menschen und dem Jahreslauf in den anderen Vorträgen, in den anthroposophischen Vorträgen, zur Darstellung brachte. Aber wir haben immerhin, ob wir nun die mehr deutlich erlebbaren Vorgänge, wie die drei Raumdimensionen, die Bewegung, oder die weniger deutlichen Vorgänge des Gewichtes erleben, wir haben Vorgänge, die erlebt werden können in dem physischen Leibe des Menschen.

Dasjenige, was da einst in früheren Zeiten erlebt wurde, das wurde seither völlig abgesondert vom Menschen. Das wurde gewissermaßen aus ihm herausgestellt. Bei der Mathematik ist es uns ja ganz anschaulich geworden. Bei anderen Erlebnissen des physischen Leibes wird es eben aus dem Grunde weniger anschaulich, weil im Leibe die entsprechenden Vorgänge, so wie das Gewicht, wie die Schwere, eben für das Bewußtsein, wie es heute ist, wie es sich entwickelt hat, ganz ausgelöscht werden. Aber sie waren eben nicht immer ganz ausgelöscht. Man hat heute, beeinflußt durch dasjenige, was der naturwissenschaftlichen Vorstellung als Menschenseelenstimmung zugrunde liegt, eben keine Idee mehr davon, wie das innere Erleben des Menschen doch anders war. Gewiß, sein eigenes Gewicht trug der Mensch nicht in früheren Zeiten bewußt durch den Raum. Aber er hatte dafür das Gefühl, daß dieses Gewicht zwar vorhanden ist, aber auch ein Gegengewicht vorhanden ist. Und wenn er etwas lernte, wie es zum Beispiel bei den Schülern der Mysterien der Fall war, dann lernte er erkennen, wie er zwar seine eigene Schwere in sich und immer mit sich trägt, wie aber in dem Lichte auch die Gegenwirkung fortwährend tätig ist. So daß der Mensch in gewisser Beziehung — es kann das schon so ausgedrückt werden — fühlte, er müsse jener Geistigkeit, die im Lichte ist, dankbar sein, daß sie in ihm entgegenwirkt derjenigen Geistigkeit und Seelenhaftigkeit, die in der Schwere wirkt. Kurz, man könnte überall nachweisen, eine Anschauung von etwas, das von dem Menschen wie ganz abgetrennt wäre, gab es eigentlich in älteren Zeiten nicht. Der Mensch erlebte die Vorgänge in sich gemeinsam mit demjenigen, was solche Vorgänge in der Natur sind. Der Mensch erlebte zum Beispiel, wenn er in der Natur, der Tatsächlichkeit nach abgesondert von sich, den Fall eines Steines sah, das Wesen der Bewegung. Dies erlebte er an dem Vergleich, was in ihm selber eine solche Bewegung sein würde. Wenn er also einen fallenden Stein sah, so erlebte er etwa dieses: Wenn ich in derselben Weise mich bewegen wollte, dann müßte ich mir eine gewisse Geschwindigkeit geben, und diese Geschwindigkeit, die ist beim fallenden Steine anders, als wenn ich zum Beispiel eine ganz langsame, kriechende Wesenheit vor mir sehe. Es erlebte der Mensch die Geschwindigkeit des fallenden Steines dadurch, daß er sein Bewegungserlebnis anwandte auf die Anschauung des fallenden Steines. So wurden tatsächlich diejenigen Vorgänge der Außenwelt, die wir heute zur Physik zählen, von jenen älteren Menschen allerdings auch objektiv angesehen, aber ihr Erkennen wurde durchaus so betrieben, daß man das eigene Erleben zu diesem Erkennen zu Hilfe nahm, um das, was in einem vorgeht, wieder zu schauen in demjenigen, was draußen in der Welt vorgeht. Und so liegt eigentlich in der ganzen physikalischen Anschauungsweise bis zum Beginn des 15. Jahrhunderts etwas, wovon man sagen kann: Diese physikalische Anschauungsweise brachte die Objekte der Natur selbst in ihrem physischen Geschehen dem inneren Erleben des Menschen nahe. Der Mensch erlebte auch da mit der Natur. Aber mit dem 15. Jahrhundert beginnt die Absonderung der Anschauung solcher Vorgänge vom Menschen. Und mit ihr die Absonderung des Mathematischen, eine Denkweise, die sich ja dann mit der ganzen Naturwissenschaft verbindet. Jetzt erst war eigentlich völlig verloren das Innenerleben im physischen Leibe. Jetzt war völlig verloren dasjenige, was innere Physik des Menschen ist. Die äußere Physik wurde ebenso vom Menschen abgesondert wie dieMathematik selbst. Der Fortschritt, der dadurch geschehen ist, besteht in der, ich möchte sagen, Verobjektivierung des Physikalischen. Sehen Sie, man kann in zweifacher Weise ein eminent Physikalisches anschauen. Bleiben wir bei dem fallenden Stein. Man kann diesen fallenden Stein verfolgen (Zeichnung, Pfeil) mit der äußeren Anschauung und man kann ihn zusammenbringen mit dem Erlebnis jener Geschwindigkeit, in die man sich versetzen müßte, wenn man selber so rasch laufen wollte, wie der Stein fällt. So ergibt sich ein Verständnis durch den ganzen Menschen, nicht bloß ein Verständnis, das nur zusammenhängt mit der Gesichtswahrnehmung.

Betrachten wir jetzt dasjenige, was aus einer solchen älteren Anschauung mit dem Beginne des 15. Jahrhunderts wird. Gehen wir von diesem Ausgangspunkte zu jener Persönlichkeit, an der man ganz besonders diesen Übergang, den ich auf diese Weise charakterisiert habe, sehen kann, gehen wir zu Galilei. Galilei ist ja gewissermaßen der Entdecker der Fallgesetze, wie man sie nennt. Und das wichtigste Objektive an diesem Fallgesetze Galileis ist, daß er bestimmt hat, einen wie großen Weg ein fallender Körper in der ersten Sekunde zurücklegt. So daß also eine ältere Anschauung neben das Sehen des fallenden Steines das innere Erlebnis hingestellt hat von der Geschwindigkeit, in die man sich versetzen muß, wenn man es dem fallenden Steine gleich tun will. Neben den fallenden Stein setzte man das innere Erlebnis (Zeichnung, rot). Galilei betrachtet auch den fallenden Stein. Aber er setzt hinzu nicht das innere Erlebnis, sondern er mißt die Länge des Weges im äußerlich gewordenen Raume, die der Stein, wenn er anfängt zu fallen, bis zum Ende der ersten Sekunde durchmißt. Da der Stein mit beschleunigter Geschwindigkeit fällt, so mißt er dann auch die nächsten Wegstrecken. Also er stellt daneben kein inneres Erlebnis, sondern etwas, was man äußerlich abmißt, ein Vorgang, der gar nichts zu tun hat mit dem Menschen, er wird vollständig von dem Menschen getrennt. Das Physikalische wird in der Anschauung, in der Erkenntnis so aus dem Menschen herausgeworfen, daß man sich gar kein Bewußtsein mehr davon verschafft, daß man es eigentlich auch innerlich hat.

Es entsteht ja auch in dieser Zeit vom Beginne des 17. Jahrhunderts eine Gegnerschaft gegen Aristoteles, der durch das ganze Mittelalter hindurch als die große Autorität der Wissenschaft angesehen worden war — der sie ja aber auch aufgehalten hat, diese Wissenschaft —, es entsteht eine Gegnerschaft gegen Aristoteles bei all denjenigen Geistern, die vorwärts wollen. Wenn man die heute vielfach mißverstandenen Erklärungen des Aristoteles über so etwas wie den fallenden Stein sachgemäß ins Auge faßt, so laufen sie eben auf das hinaus, daß er überall angibt, wenn man draußen in der Welt etwas sieht, wie das wäre, wenn man es selbst durchmachen würde. Für ihn handelt es sich also nicht darum, die Geschwindigkeit festzusetzen durch Abmessen, sondern die Geschwindigkeit so vorzustellen, daß der Vorgang mit einem Erlebnis des Menschen in Beziehung gebracht wird. Natürlich, wenn der Mensch sich sagt, er muß sich in diese Geschwindigkeit versetzen, dann fühlt er gewissermaßen hinter dem Sich-Versetzen in diese Geschwindigkeit auch etwas Lebendiges, in sich Kraftvolles, wodurch er sich in diese Geschwindigkeit versetzt. Er fühlt in einer gewissen Beziehung den eigenen inneren Anstoß, und es liegt ihm natürlich ganz ferne, zu denken, da zieht ihn etwas hin in die Richtung, in die er geht. Er denkt viel eher darüber nach, wie er stößt, als daß er denkt, es zieht ihn etwas. Daher wird Anziehungskraft, Gravitation, eigentlich erst in diesem Zeitalter des 17. Jahrhunderts etwas, was für die menschliche Anschauung eine Bedeutung hat. In radikaler Weise ändern sich die Vorstellungen, die der Mensch sich über die Natur macht. Und so wie ich es beim Fallgesetz gezeigt habe, so ist es für alle physikalischen Vorstellungen. Eine von diesen Vorstellungen ist zum Beispiel diese, die man heute in der Physik das Trägheitsgesetz nennt. Beharrungsvermögen sagt man auch. Aber Trägheitsgesetz ist ja etwas sehr allgemein so Benanntes. Es verrät noch dieses Trägheitsgesetz seinen Ursprung vom Menschen. Ich brauche Ihnen nicht zu schildern, was Trägheit beim Menschen bedeutet, denn davon hat ja wohl jeder eine Erfahrung. Es ist jedenfalls etwas, was innerlich erlebt werden kann. Was ist das Trägheitsgesetz unter dem Einflusse des Galileismus in der Physik geworden? In der Physik ist es das geworden, daß man sagt: Ein Körper — oder ein Punkt, muß man eigentlich sagen —, ein Punkt, auf den kein äußerer Einfluß ausgeübt wird, der sich selbst überlassen ist, bewegt sich im Raume mit gleichförmiger Geschwindigkeit, das heißt, er legt durch alle Zeiträume hindurch in jeder Sekunde dieselbe Raumstrecke zurück. So daß, wenn kein äußerer Einfluß da ist und der Körper einmal in der Geschwindigkeit ist, daß er sich in der Sekunde so weit bewegt, so bewegt er sich auch in jeder folgenden Sekunde ebensoweit (siehe Zeichnung). Er ist träge. Er hat kein Bestreben, wenn kein äußerer Einfluß ausgeübt wird auf ihn, sich zu ändern in dieser Beziehung. Er läuft immer so fort, daß er in jeder Sekunde dieselbe Wegstrecke zurücklegt. Es wird nur noch gemessen, gemessen die Wegstrecke in einer Sekunde. Ja, man nennt dann einen Körper träge, wenn er so sich zeigt, daß er in jeder Sekunde dieselbe Wegstrecke zurücklegt.

Einstmals hat man das anders empfunden. Einstmals hat man gesagt: Wie erlebt man einen solchen bewegten Körper, der in jeder Sekunde dieselbe Wegstrecke zurücklegt? Man erlebt ihn so, daß man in dem Zustand, in dem man einmal ist, beharrt, daß man gar niemals eingreift in sein eigenes Verhalten. Man kann das als Mensch natürlich höchstens als ein Ideal betrachten. Der Mensch erreicht dieses Ideal der Trägheit nur in sehr geringem Maße. Aber man wird merken, wenn man das hat, was man Trägheit im gewöhnlichen Leben nennt, man wird merken, daß das immerhin eine Annäherung an dieses ist, immerfort in jeder Sekunde des Lebens dasselbe zu machen.

Es wurde die ganze Vorstellungsorientierung des Menschen vom 15. Jahrhundert ab in eine Richtung gelenkt, die damit bezeichnet ist: Der Mensch vergißt sein inneres Erleben. Zunächst haben wir es hier mit dem inneren Erleben des physischen Organismus zu tun. Der Mensch vergißt es. Und dasjenige, was Galilei für solche dem Menschen naheliegende Dinge, wie das Fallgesetz, das Trägheitsgesetz, ersonnen hat — denn es ist ja ein Ersinnen, ein Ersinnen, das allerdings sich beschäftigt mit dem, was in der Natur beobachtet werden kann -, dasjenige, was Galilei auf Naheliegendes angewendet hat, es wurde nun auch in einem weiteren Umfange angewendet.

Wir wissen, wie Kopernikus ein neues Weltsystem im physischen Sinne heraufgebracht hat dadurch, daß er die Sonne in den Mittelpunkt rückte, nicht mehr die Erde, daß er die Planeten in Kreisen um diese Sonne sich herumbewegen ließ, und darnach dann beurteilte den Ort irgendeines planetarischen Körpers am Himmel. Das war ein Bild, das Kopernikus entworfen hat von unserem Planetensystem, Sonnensystem, ein Bild, das man ja auch aufzeichnen kann. Ja, dieses Bild strebte noch nicht ganz radikal nach jener mathematischen Gesinnung hin, welche die Außenwelt ganz absondert vom Menschen. Wer die Schriften des Kopernikus liest, der bekommt durchaus die Anschauung, daß Kopernikus noch fühlt, die ältere Astronomie, die hat in den komplizierten Linien, durch welche sie das Sonnensystem zum Beispiel hat begreifen wollen, nicht nur die aufeinanderfolgenden, sagen wir, optischen Orte der Planeten zusammengefaßt, sondern diese ältere Astronomie, die hat auch eine Empfindung gehabt von dem, was erlebt werden würde, wenn der Mensch drinnen stecken würde in diesen Bewegungen des Planetensystems. Man möchte sagen: In älteren Zeiten hatten die Leute eine sehr deutliche Vorstellung von den Epizyklen und so weiter, von denen man sich dachte, daß gewisse Sterne sie beschreiben. Da war aber überall noch, ich möchte sagen, wenigstens ein Schatten von menschlichem Empfinden darinnen. So wie man, sagen wir, wenn jemand einen Menschen malt mit einer bestimmten Armstellung, wie man diese Armstellung begreift, weil man selbst erleben kann, wie es einem ist, wenn man diese Armstellung macht, so war noch etwas Lebendiges im Nacherleben eines solchen Herumgehens eines Planeten um seinen Fixstern. Ja, selbst bei Kepler - bei diesem sogar besonders stark — ist noch etwas durchaus Menschliches in den Berechnungen der Planetenbahnen.

Das abgesonderte Galileische Prinzip, das wendet nun Newton an auf die Himmelskörper, indem er so etwas wie das kopernikanische System hinnimmt in der Anschauung, indem er solche Vorstellungen konstruiert wie etwa diese: Ein Zentralkörper, also eine Sonne, sagen wir, zieht einen Planeten so an, daß die Kraft dieser Anziehung abnimmt mit dem Quadrat der Entfernung, immer kleiner und kleiner wird, aber im Quadrat kleiner, und zunimmt mit der Masse der Körper. Also wenn der anziehende Körper größere Masse hat, ist die Anziehungskraft größer. Wenn die Entfernung größer wird, wird die Anziehungskraft immer kleiner, aber so, daß sie, wenn die Entfernung zweimal so groß ist, viermal kleiner wird, wenn sie dreimal so groß ist, neunmal kleiner wird und so weiter. Wiederum wird jetzt in das Bild ein reines Messen verlegt, das wiederum ganz abgesondert gedacht wird vom Menschen. Bei Kopernikus und Kepler ist es noch nicht so; bei Newton wird ein sogenanntes objektives Etwas konstruiert, wobei gar nichts mehr von einem Erleben bemerkt wird, sondern wo nur konstruiert wird. Es werden Linien konstruiert in der Richtung, in der man sieht, und da gewissermaßen Kräfte hineingeträumt — denn das, was man sieht, ist ja keine Kraft, die Kraft muß dazu geträumt werden. Man sagt natürlich: dazu gedacht, so lange man an die Sache glaubt, und wenn man nicht mehr daran glaubt, so sagt man: hinzugeträumt. So daß man sagen kann: Durch Newton wird die abgesonderte physikalische Anschauungsweise nun so weit generalisiert, daß sie auf den ganzen Weltenraum angewendet wird. Kurz, es ist das Bestreben vorhanden, ganz und gar zu vergessen das Erleben innerhalb des physischen Leibes des Menschen, und dasjenige, was man früher eng verbunden gedacht hat mit dem Erleben des physischen Leibes, das verobjektiviert zu sehen, unabhängig von diesem physischen Leibe im Raume draußen, den man selbst erst aus dem physischen Leib herausgerissen hat, und Mittel und Wege zu finden, um davon zu reden, ohne überhaupt auch nur an den Menschen zu denken. So daß man sagen kann: Durch die Absonderung vom physischen Leibe, durch die Absonderung des in der Natur Angeschauten vom Erlebnis im physischen Leibe des Menschen entsteht die neuere Physik, die eigentlich erst da ist mit dieser Absonderung gewisser Naturvorgänge vom Selbsterleben im menschlichen physischen Leibe (Zeichnung, gelb).

Nun hatte man auf der einen Seite vergessen das Selbsterleben im physischen Leibe (vgl. Zeichnung 5.103, rot). Aber indem man nun alles da draußen mit dem abgesonderten Mathematisieren, mit der abgesonderten physikalischen Anschauungsweise durchtränkte (gelb), konnte man nicht wieder zurück mit dieser Physik in den Menschen herein. Was man erst abgesondert hatte, das konnte man nicht wieder auf den Menschen anwenden. Kurz, es entsteht die andere Seite der Sache, das Unvermögen, wiederum zum Menschen zurückzukommen mit dem Wissenschaftlichen.

Nun, beim Physikalischen bemerkt man das nicht so; aber man bemerkt es sehr stark, wenn man sich jetzt frägt: Wie ist es mit dem Selbsterleben des Menschen im ätherischen Leibe, in diesem feineren Organismus? Da erlebt ja der Mensch auch allerlei. Aber dieses Erleben, das ist noch früher und mit einem stärkeren Radikalismus vom Menschen abgesondert worden. Nur war man da nicht so glücklich beim Absondern, wie man es in der Physik war. Denn gehen wir einmal zurück auf einen naturwissenschaftlichen Menschen der ersten christlichen Jahrhunderte, auf den Arzt Galen, da finden wir, daß Galen, indem er ins Auge faßt, was in der äußeren Natur lebt, im Sinne seines Zeitalters die vier Elemente unterscheidet: Erde, Wasser, Luft und Feuer — wir würden sagen: Wärme. Das nimmt man wahr, wenn man den Blick nach außen richtet. Richtet man aber den Blick nach innen, richtet man den Blick auf das Selbsterleben des ätherischen Leibes und frägt man sich: Wie erlebt man diese Elemente, das feste Erdige, das Wässerige, das Luftförmige, das Wärmende, Feurige in sich? — da sagte man sich eben damals: Man erlebt es mit dem ätherischen Leibe. Dann erlebt man es als innerlich erfühlte Säftebewegung, und zwar die Erde als «schwarze Galle», das Wasser als «Schleim», die Luft eben als «Pneuma», als dasjenige, was durch den Atmungsprozeß aufgenommen wird, die Wärme als «Blut». Man erlebt also in den Säften, in demjenigen, was überhaupt im menschlichen Organismus zirkuliert, innerlich dasselbe, was man äußerlich anschaut. So wie man die Bewegung des fallenden Steines im physischen Leibe miterlebt, so erlebt man die Elemente mit in den innerlichen Vorgängen; wie im Stoffwechselprozeß, wie man sich dachte, Galle, Schleim und Blut durcheinanderwirken, das empfand man als das innere Erlebnis des eigenen Leibes, aber als diejenige Form des inneren Erlebnisses, der die äußeren Vorgänge entsprechen, diejenigen Vorgänge, die sich zwischen Luft, Wasser, Feuer, Erde abspielen.

Nun gelang es einem hier nicht so entschieden und radikal, das innere Leben zu vergessen und noch genügend mitzubringen für die äußere Anschauung. Beim Fall konnte man messen, etwa den Fallraum in der ersten Sekunde. Ein Trägheitsgesetz bekam man, indem man sich dachte, daß es eben bewegte Punkte geben kann, die ihren Bewegungszustand nicht ändern, sondern ihre Geschwindigkeit beibehalten. Aber indem man das, was so spezifisch eigentümlich als Innenerlebnis in älteren Zeiten empfunden wurde, aus diesem Innenerlebnis hinauswerfen wollte, die Elemente, konnte man zwar das Innere vergessen, aber man brachte in die Außenwelt nicht so etwas Ähnliches mit, wie es das Messen usw. war oder ist. So gelang es einem nicht, in derselben Weise das hierauf Bezügliche zu objektivieren wie das Physikalische. Und so ist es im Grunde bis heute noch geblieben. Und daher ist bis heute die Chemie, die dadurch hätte entstehen können, daß man in derselben Weise so viel hätte heraustragen können aus sich in die Außenwelt für den ätherischen Leib, wie es für den physischen gelungen ist, die dadurch hätte etwas werden können, was sich der Physik an die Seite stellen ließe, diese Chemie ist so etwas nicht geworden, sondern heute noch immer so, daß sie, wenn sie von ihren Gesetzen sprechen will, von etwas ziemlich Unbestimmtem und Vagem spricht. Denn in der Tat will die Chemie dasselbe in bezug auf den ätherischen Leib, was man mit der Physik gemacht hat in bezug auf den physischen Leib. Die Chemie sagt zwar: Wenn sich Körper chemisch verbinden, wobei sie ja ihre Eigenschaften vollständig ändern können bis auf den Aggregatzustand, dann geschieht natürlich etwas. Aber wenn man nicht bloß zu der Vorstellung greifen will, die ja die einfachste und bequemste ist, so weiß man nicht viel über dieses Geschehen. Wasser besteht aus Wasserstoff und Sauerstoff — ja, die beiden muß man sich im Wasser irgendwie ineinander denken (Zeichnung, gelb und rot); aber wie das ineinander gedacht werden soll, darüber wird keine innerlich erlebbare Vorstellung gebildet. Man erklärt es dann durch etwas Außerliches, aber recht äußerlich: Der Wasserstoff bestehe aus Atomen oder Molekülen meinetwillen, der Sauerstoff auch. Die fahren durcheinander, prallen aufeinander und bleiben aneinander haften und so weiter. Das heißt, man war, indem man das innere Erlebnis vergaß, nun nicht in derselben Lage wie bei der Physik, wo man messen konnte — denn immer mehr kam es der Physik auf das Messen, Zählen und Wägen an -, sondern man war genötigt, sich den inneren Vorgang rein auszudenken. Und so ist es in einer gewissen Beziehung mit der Chemie bis heute geblieben. Denn dasjenige, was für das Innere solcher chemischen Vorgänge heute noch vorgestellt wird, das ist im Grunde genommen etwas zu den Vorgängen Hinzugedachtes.

Eine der Physik gewachsene Chemie wird man erst haben, wenn man mit voller Einsicht des heute Dargestellten daran gehen wird — wenn man auch nicht mehr das unmittelbare Erlebnis des Menschen hat wie ein früheres instinktives Hellsehen -, dennoch die Chemie wiederum mit dem Menschen zusammenzubringen. Das wird natürlich nicht früher gelingen, als bis man eine Einsicht darinnen hat, daß man eigentlich auch in bezug auf das Physikalische - wenigstens zur Vervollständigung der einzelnen Kenntnis zur Weltanschauung - die Gedanken über die einzelnen Erscheinungen mit dem Menschen wird zusammenbringen müssen. Denn was einem auf der einen Seite dadurch geschieht, daß man das innere Erleben vergißt und an das Äußere dann herangeht und äußerlich messen will - im Äußeren, im sogenannten Objektiven stehenbleiben will -, das rächt sich auf der anderen Seite. Denn man kann leicht sagen: Trägheit drückt sich aus in der Bewegung eines Punktes, der in jeder Zeitsekunde denselben Weg zurücklegt. Aber solch einen Punkt gibt es nicht. Diese gleichförmige Bewegung kommt nirgends vor da, wo man beobachtet mit den menschlichen Mitteln. Sie kommt nirgends vor, denn ein Bewegliches ist immer in irgendeinem Zusammenhang, wird da oder dort beeinträchtigt in seiner Geschwindigkeit. Kurz, das, was man als träge Masse schildern könnte, oder was man auf das Trägheitsgesetz bringen könnte, das gibt es nicht. Aber wenn man von Bewegung spricht und nicht zurückgehen kann auf das innere Miterleben der Bewegung, also auf das Zusammenerleben mit der Natur, auf das Erfassen, sagen wir, der Fallgeschwindigkeit durch die Art, wie man selbst erleben würde in dieser Geschwindigkeit, dann muß man eben sagen, ja, da bin ich ganz heraußen aus der Bewegung. Ich muß mich an der Außenwelt orientieren. Wenn ich also hier einen Körper sich bewegen sehe (siehe Zeichnung), und wenn das seine aufeinanderfolgenden Orte sind, so muß ich irgendwie wahrnehmen, daß sich dieser Körper bewegt. Wenn hier hinten eine Wand ist, so sehe ich in dieser Richtung, sehe dann in dieser Richtung, sehe in dieser Richtung usw. Wenn ich mir die hintere Wand ruhig denke, dann sage ich: Der Körper bewegt sich in dieser Richtung fort. - Aber es würde dazu noch notwendig sein, daß ich von hier aus (dunkler Kreis) die Anschauung leite, also ein inneres Erlebnis noch gewahr werde.

Orientiere ich mich nur da draußen, lasse ich den Menschen ganz weg, sondere ich ihn völlig ab, dann kommt dasselbe heraus, ob hier ein Gegenstand sich weiter bewegt, oder ob er ruht und die Wand sich so bewegt (siehe Zeichnung). Ich kann schlechterdings nicht mehr unterscheiden, ob der Körper nach der einen Richtung sich bewegt oder die dahinterliegende Wand nach der entgegengesetzten Richtung. Und berechnen kann ich im Grunde genommen alles unter der einen und unter der anderen Voraussetzung.

Also ich verliere die Möglichkeit, innerlich die Bewegung überhaupt zu erfassen, wenn ich sie nicht miterlebe. Und das gilt auch für andere physikalische Ingredienzien, wenn ich so sagen darf. Indem man das Miterleben herausgeworfen hat, ist man verhindert, irgend noch eine Brücke hinüber zu schlagen zum objektiven Geschehen. Wenn ich selbst laufe, so wird es mir nicht gelingen, zu sagen, es sei gleichgültig, ob ich laufe oder ob der Boden sich in der entgegengesetzten Richtung bewege; aber wenn ich selbst einen anderen Menschen in Äußerlichkeit betrachte, der sich über einen Boden bewegt, so ist es für diese bloß äußerliche Anschauung ganz gleichgültig, ob der Mensch dahinläuft, oder ob der Boden unter ihm nach der anderen Richtung geht. Und die Gegenwart hat es tatsächlich dahin gebracht, daß sie, ich möchte sagen, die Rache des Weltengeistes für dieses Absondern des Physikalischen erlebt.

Während Newton noch ganz sicher war, er könne absolute Bewegungen annehmen, sehen wir heute zahlreiche Leute sich bemühen, zu konstatieren, wie die Bewegung, die Erkenntnis der Bewegung zugleich mit dem inneren Erleben verlorengegangen ist. Das ist ja das Wesen der Relativitätstheorie, die den Newtonismus heute aus den Angeln heben will. Diese Relativitätstheorie ergibt sich auf eine ganz historische Weise. Sie muß da sein heute, denn man kommt über sie nicht hinaus, wenn man eben nur innerhalb derjenigen Vorstellungen bleibt, die vom Menschen ganz abgesondert wurden. Denn will man Ruhe oder Bewegung erkennen, dann muß man sie miterleben. Erlebt man sie nicht mit, dann sind selbst Ruhe und Bewegung zueinander nur relativ.

Nun, wir werden morgen um acht Uhr hier über diese Dinge weiter sprechen.

Seventh Lecture

My dear friends, many of our friends and friends of our cause have sent expressions of sympathy and solidarity with our grief over the loss of the Goetheanum. I will take the liberty of reporting on the individual expressions tomorrow or the day after tomorrow.

Now, continuing yesterday's discussion about what one might call the inability of the scientific worldview that has emerged since the 15th century to grasp the essence of human beings, I would like to say that what is lacking in all areas of this worldview is precisely what is lacking in mathematics and mechanics. Mathematics and mechanics have been separated from man. They are regarded as if man were no longer present when experiencing mathematics. This course of human mental images for mathematics has the consequence, on the one hand, that the endeavor arises to separate other events taking place in the world from man and to bring them into no connection with the human being. This results, on the other hand, in an inability to cognitively build a real bridge between human beings and the world.

I will speak later about another consequence of this inability. But first, let us consider, I would say, the fundamental reason why scientific development has taken this course. It has lost the ability to experience inwardly what is spoken of today in anthroposophy and what in earlier times of human development was the object of instinctive perception or, if the word is not misunderstood, of instinctive clairvoyance. Looking into the human being and finding him composed of various elements has been lost to the scientific view.

Let us remember how we divide the human being in order to approach its essence within our anthroposophical view. We speak of the physical body of the human being, the etheric body, the astral body, and the ego organization of the human being. Let us keep this in mind today in order to understand the development of the scientific worldview: physical body, etheric body, astral body, ego organization. I do not need to go into detail about this division of the human being today, since everyone can find the necessary information in my book Theosophy, for example. But let us now orient ourselves to this division of the human being. Let us first ask ourselves, when we look at the physical body of the human being and consider the possibility of inner orientation, that is, the possibility of experiencing one's physical body inwardly, what does one experience in this physical body? It is precisely in the physical body that one experiences what I have spoken about frequently, namely right and left, up and down, front and back. In the physical body, one experiences the perception of movement as a change in the location of one's own physical body. However, one also experiences variations in the physical body, at least to a certain extent, such as weight. But one experiences weight in a thoroughly modified way. When these things were still experienced in the various members of the human organization, people thought about things that they no longer had any inclination to think about in the scientific age. Facts that are of fundamental importance for understanding the world were completely ignored. Take the following fact: Suppose you were carrying a person who, when you put them on the scales, weighs the same as you. Suppose you are carrying this person. You walk some distance with this person, carrying him. You will experience his weight. As you walk the same distance yourself, you are also carrying yourself. But you do not experience this in the same way. It is true that you are carrying your weight through space, but you do not experience it. Your own weight is experienced in a completely different way. When you get old, you feel your limbs in a certain way that makes you say you feel their heaviness. In a sense, this is also related to heaviness, to weight, because growing old means a certain decay of the organism, whereby its individual parts are torn more out of the inner experience, become independent, I would say atomized, and decay in the atomization of heaviness. But of course we could never bring this to actuality at any moment of our lives. Perhaps we will even say that we can only use the expression that we feel the heaviness of our limbs in a comparative sense. A more precise science shows, however, that it is not merely comparative, but that it has something significant in itself. But in any case, the experience of our own weight actually appears to our consciousness as a kind of extinction of our own weight.

Now, then, we have the necessity inherent in human beings to extinguish effects that are undoubtedly present within this human being, to extinguish them through opposite effects, so opposite that I have explained this for the totality of the human being when I presented the analogy between the human being and the course of the year in the other lectures, in the anthroposophical lectures. But whether we experience the more clearly perceptible processes, such as the three dimensions of space and movement, or the less clearly perceptible processes of weight, we have processes that can be experienced in the physical body of the human being.

What was once experienced in earlier times has since been completely separated from the human being. It has been taken out of him, so to speak. In mathematics, this has become very clear to us. In other experiences of the physical body, it becomes less clear for the simple reason that the corresponding processes, such as weight and heaviness, are completely eliminated from consciousness as it is today, as it has developed. But they were not always completely eliminated. Today, influenced by what underlies the scientific mental image of the human soul, we no longer have any idea how different the inner experience of human beings used to be. Certainly, in earlier times, human beings did not consciously carry their own weight through space. But they had the feeling that this weight was present, but that there was also a counterweight. And when they learned something, as was the case with the students of the mysteries, for example, they learned to recognize how they carry their own heaviness within themselves and always with themselves, but how the counteracting force is also constantly at work in the light. So that human beings felt, in a certain sense — it can be expressed in this way — that they had to be grateful to the spirituality that is in the light for counteracting the spirituality and soulfulness that is at work in heaviness. In short, one could prove everywhere that a view of something that was completely separate from human beings did not actually exist in earlier times. Human beings experienced the processes within themselves together with what such processes are in nature. For example, when they saw a stone falling in nature, which was actually separate from themselves, they experienced the essence of movement. They experienced this by comparing it with what such a movement would be within themselves. So when they saw a falling stone, they experienced something like this: if they wanted to move in the same way, they would have to give themselves a certain speed, and this speed is different for a falling stone than if they saw, for example, a very slow, crawling creature in front of them. Man experienced the speed of the falling stone by applying his experience of movement to the observation of the falling stone. Thus, those processes of the external world that we today consider to be physics were indeed viewed objectively by those older people, but their recognition was carried out in such a way that they used their own experience to help them recognize what was going on inside themselves in what was going on outside in the world. And so, in the entire physical way of looking at things up until the beginning of the 15th century, there is something about which one can say: This physical way of looking at things brought the objects of nature themselves, in their physical events, closer to the inner experience of human beings. Human beings also experienced nature there. But with the 15th century, the separation of the perception of such processes from human beings began. And with it came the separation of mathematics, a way of thinking that then became associated with the whole of natural science. Only now was the inner experience in the physical body completely lost. Now what is the inner physics of human beings was completely lost. External physics was separated from human beings just as mathematics itself was. The progress that has been made as a result consists, I would say, in the objectification of the physical. You see, there are two ways of looking at something that is eminently physical. Let us stay with the falling stone. One can follow this falling stone (drawing, arrow) with external perception, and one can bring it together with the experience of the speed one would have to move at if one wanted to run as fast as the stone is falling. This results in an understanding through the whole human being, not just an understanding that is only connected with visual perception.

Let us now consider what became of this older view at the beginning of the 15th century. Let us start from this point and move on to the personality in whom this transition, which I have characterized in this way, can be seen most clearly: Galileo. Galileo is, in a sense, the discoverer of the laws of falling bodies, as they are called. And the most important objective aspect of Galileo's laws of falling bodies is that he determined how far a falling body travels in the first second. Thus, an older view placed alongside the observation of the falling stone the inner experience of the speed one must move at if one wants to do the same as the falling stone. The inner experience was placed alongside the falling stone (drawing, red). Galileo also observes the falling stone. But he does not add the inner experience; instead, he measures the length of the path in the external space that the stone travels from the moment it begins to fall until the end of the first second. Since the stone falls at an accelerated speed, he then also measures the next distances. So he does not place an inner experience alongside it, but something that is measured externally, a process that has nothing to do with human beings; it is completely separated from human beings. In perception and cognition, the physical is thrown out of human beings to such an extent that one is no longer even aware that one actually has it internally.

At the beginning of the 17th century, opposition arose against Aristotle, who had been regarded throughout the Middle Ages as the great authority on science — but who had also held science back — opposition arose against Aristotle among all those minds that wanted to move forward. If one properly considers Aristotle's explanations of such things as falling stones, which are widely misunderstood today, they boil down to the fact that he states everywhere that when one sees something out in the world, it is as if one were experiencing it oneself. For him, it is not a matter of determining speed by measurement, but of imagining speed in such a way that the process is related to human experience. Of course, when a person says to himself that he must move at this speed, he feels, behind the act of moving at this speed, something alive, something powerful within himself, which causes him to move at this speed. He feels his own inner impulse in a certain relationship, and it is naturally quite foreign to him to think that something is pulling him in the direction he is going. He thinks much more about how he is pushing than about being pulled. That is why gravitational force, gravity, only became something that had meaning for human perception in the 17th century. The mental images that humans have of nature change radically. And as I have shown in the case of the law of falling bodies, this is true for all physical concepts. One of these concepts, for example, is what we now call the law of inertia in physics. It is also referred to as the principle of conservation of momentum. But the law of inertia is a very general term. It still betrays its human origin. I don't need to describe to you what inertia means in humans, because everyone has experience of it. In any case, it is something that can be experienced internally. What has the law of inertia become under the influence of Galileism in physics? In physics, it has become the principle that a body — or rather, a point — a point on which no external influence is exerted, which is left to itself, moves in space at a constant speed, that is, it covers the same distance in every second throughout all periods of time. So that if there is no external influence and the body is once at a speed such that it moves that distance in one second, it also moves the same distance in every subsequent second (see drawing). It is inert. It has no desire to change in this respect unless an external influence is exerted on it. It always continues to move so that it covers the same distance every second. Only the distance covered in one second is measured. Yes, a body is called inert when it behaves in such a way that it covers the same distance every second.

Once upon a time, people felt differently. Once upon a time, people said: How do you experience such a moving body that covers the same distance every second? You experience it in such a way that you remain in the state you are in, that you never intervene in your own behavior. As a human being, of course, you can only regard this as an ideal. Human beings achieve this ideal of inertia only to a very limited extent. But you will notice that when you have what is called inertia in everyday life, you will notice that this is at least an approximation of it, of doing the same thing every second of your life.

From the 15th century onwards, the entire orientation of human imagination was steered in a direction that can be described as follows: human beings forget their inner experience. First of all, we are dealing here with the inner experience of the physical organism. Human beings forget it. And what Galileo conceived for things that are close to human experience, such as the law of falling bodies and the law of inertia — for it is indeed a conception, a conception that is, however, concerned with what can be observed in nature — what Galileo applied to things that are close to human experience was now also applied in a wider context.

We know how Copernicus brought about a new world system in the physical sense by placing the sun at the center, no longer the earth, by having the planets move in circles around this sun, and then judging the location of any planetary body in the sky. This was an image that Copernicus designed of our planetary system, the solar system, an image that can also be drawn. Yes, this image did not yet strive radically toward that mathematical mindset which separates the external world completely from human beings. Anyone who reads Copernicus' writings gets the impression that Copernicus still felt that the older astronomy, with the complicated lines through which it sought to understand the solar system, for example, did not merely summarize the successive, let us say, optical locations of the planets, but that this older astronomy also had a sense of what would be experienced if a human being were stuck inside these movements of the planetary system. One might say that in earlier times, people had a very clear mental image of the epicycles and so on, which were thought to describe certain stars. But there was still, I would say, at least a shadow of human feeling in it. Just as, say, when someone paints a person with a certain arm position, you understand that arm position because you can experience for yourself what it is like to make that arm position, so there was still something alive in the reliving of such a planet moving around its fixed star. Yes, even with Kepler—with him especially so—there is still something thoroughly human in the calculations of planetary orbits.

Newton applies the isolated Galilean principle to the heavenly bodies by accepting something like the Copernican system in his view, by constructing mental images such as the following: A central body, say a sun, attracts a planet in such a way that the force of this attraction decreases with the square of the distance, becoming smaller and smaller, but smaller in the square, and increases with the mass of the bodies. So if the attracting body has a larger mass, the force of attraction is greater. As the distance increases, the force of attraction becomes smaller and smaller, but in such a way that when the distance is twice as great, it becomes four times smaller, when it is three times as great, it becomes nine times smaller, and so on. Once again, pure measurement is transferred into the picture, which in turn is thought of as completely separate from human beings. This is not yet the case with Copernicus and Kepler; with Newton, a so-called objective something is constructed, whereby nothing at all is noticed of experience, but only construction takes place. Lines are constructed in the direction in which one sees, and forces are, as it were, dreamed into them — for what one sees is not a force; the force must be dreamed into it. Of course, one says: thought into it, as long as one believes in it, and when one no longer believes in it, one says: dreamed into it. So that one can say: through Newton, the separate physical way of looking at things is now so generalized that it is applied to the entire universe. In short, there is an endeavor to forget completely the experience within the physical body of the human being, and to see as objectified that which was previously thought to be closely connected with the experience of the physical body, independent of this physical body in space outside, which one has first torn out of the physical body, and to find ways and means of talking about it without even thinking about the human being at all. So that one can say: Through the separation from the physical body, through the separation of what is seen in nature from the experience in the physical body of the human being, the newer physics arises, which actually only exists with this separation of certain natural processes from self-experience in the human physical body (drawing, yellow).

Now, on the one hand, people had forgotten self-experience in the physical body (cf. drawing 5.103, red). But by saturating everything out there with separate mathematization, with a separate physical view (yellow), it was no longer possible to return to the human being with this physics. What had first been separated could not be applied to the human being again. In short, the other side of the coin emerges: the inability to return to the human being with science.

Now, one does not notice this so much in physics, but one notices it very strongly when one asks oneself: What about the self-experience of the human being in the etheric body, in this finer organism? There, too, the human being experiences all kinds of things. But this experience has been separated from the human being even earlier and with greater radicalism. Only, they were not as successful in separating them as they were in physics. For if we go back to a natural scientist of the early Christian centuries, to the physician Galen, we find that Galen, looking at what lives in external nature, distinguishes, in the spirit of his age, the four elements: earth, water, air, and fire — we would say: heat. This is what we perceive when we look outward. But if we turn our gaze inward, if we focus on the self-experience of the etheric body and ask ourselves: How do we experience these elements, the solid earthiness, the wateriness, the airiness, the warmth, the fieriness within ourselves? — then people at that time said: We experience it with the etheric body. Then one experiences it as an inwardly felt movement of juices, namely the earth as “black bile,” the water as “phlegm,” the air as “pneuma,” that which is taken in through the breathing process, and the warmth as “blood.” Thus, in the juices, in that which circulates in the human organism, one experiences inwardly the same thing that one sees outwardly. Just as one experiences the movement of a falling stone in the physical body, so one experiences the elements in the inner processes; just as in the metabolic process, one imagined bile, mucus, and blood interacting with one another, one felt this as the inner experience of one's own body, but as the form of inner experience corresponding to the external processes, those processes taking place between air, water, fire, and earth.