The Origins of Natural Science

GA 326

1 January 1923, Dornach

Lecture VI

[See GA 259 for Rudolf Steiner's introductory words given immediately before this lecture concerning the burning of the first Goetheanum. —rsarchive.org]

In my last lecture, I said that one root of the scientific world conception lay in the fact that John Locke and other thinkers of like mind distinguished between the primary and secondary qualities of things in the surrounding world. Locke called primary everything that pertains to shape, to geometrical and numerical characteristics, to motion and to size. From these he distinguished what he called the secondary qualities, such as color, sound, and warmth. He assigned the primary qualities to the things themselves, assuming that spatial corporeal things actually existed and possessed properties such as form, motion and geometrical qualities; and he further assumed that all secondary qualities such as color, sound, etc. are only effects on the human being. Only the primary qualities are supposed to be in the external things. Something out there has size, form and motion, but is dark, silent and cold. This produces some sort of effect that expresses itself in man's experiences of sound, color and warmth.52In the night from New Year's Eve to New Year's Day 1922/23 the Goetheanum burned down. It was built in ten years, with the help of various artists from many countries. This primarily wooden building, in which each surface and corner was formed artistically (see Steiner, Ways to a New Style in Architecture [London: Anthroposophical Publishing Co. and New York: Anthroposophic Press, 1927]) had been designed in all details by Rudolf Steiner who also managed the construction work through all these years. From the first of January on, the activities had to be transferred into the so-called “Schreinerei,” a building that was used during the construction of the Goetheanum. For the work itself, Rudolf Steiner did not allow any interruption; the afternoon after the fire, the “Three Kings Play” was performed, as was written on the invitations of the ongoing course (see Christmas Plays from Obervfer, trans. A.C. Harwood [London: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1973]). Rudolf Steiner introduced it with a short address, in which he spoke the following words: “great suffering knows how to keep silent about what it is feeling ... The building that was created in ten years through the love and compassion of innumerable friends of the movement was destroyed in one night. But just today the silent suffering experiences what our friends have put in this work. Since we feel that everything we do in our movement is necessary in our present civilization, we will want to continue whatever we can in the given frame, and therefore even in this hour as the flames outside still burn and rise, although such suffering is present, still perform this play which we promised our participants in connection with our course, and which these participants expect. I also will hold the lecture I offered, here in the ‘Schreinerei’ this evening at 8:00 P.M.” (printed in Ansprachen zu den Weihnachtsspielen aus Altem Volkstum [Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1974], GA Bibl. Nr. 274). The beginning of the course's lecture was then devoted to the fire, which is printed in The Younger Generation (Spring Valley, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1984).

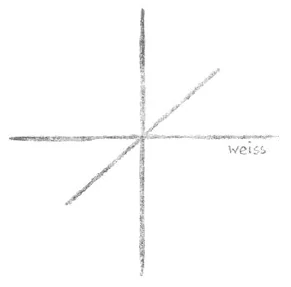

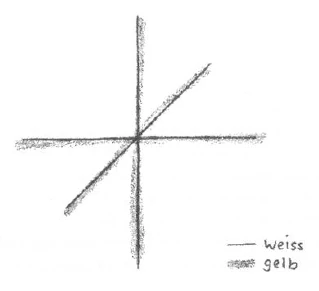

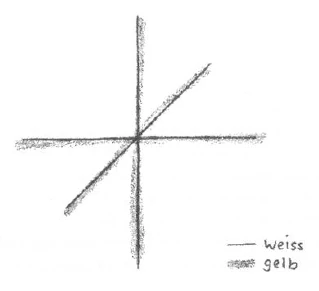

I have also pointed out how, in this scientific age, space became an abstraction in relation to the dimensions. Man was no longer aware that the three dimensions—up-down, right-left, front-back—were concretely experienced within himself. In the scientific age, he no longer took this reality of the three dimensions into consideration. AS far as he was concerned, they arose in total abstraction. He no longer sought the intersecting point of the three dimensions where it is in fact experienced; namely, within man's own being. Instead, he looked for it somewhere in external space, wherever it might be. Thenceforth, this space framework of the three dimensions had an independent existence, but only an abstract thought-out one. This empty thought was no longer experienced as belonging to the external world as well as to man; whereas an earlier age experienced the three spatial dimensions in such a way that man knew he was experiencing them not only in himself but together with the nature of physical corporeality.

The dimensions of space had, as it were, already been abstracted and ejected from man. They had acquired a quite abstract, inanimate character. Man had forgotten that he experiences the dimensions of space in his own being together with the external world; and the same applied to everything concerned with geometry, number, weight, etc. He no longer knew that in order to experience them in their full living reality, he had to look into his own inner being. A man like John Locke transferred the primary qualities—which are of like kind with the three dimensions of space, the latter being a sort of form or shape—into the external world only because the connection of these qualities with man's inner being was no longer known.

The others, the secondary qualities, which were actually experienced qualitatively (as color, tone, warmth, smell or taste,) now were viewed as merely the effects of the things upon man, as inward experiences. But I have pointed out that inside the physical man as well as inside the etheric man these secondary qualities can no longer be found, so that they became free-floating in a certain respect. They were no longer sought in the outer world; they were relocated into man's inner being. It was felt that so long as man did not listen to the world, did not look at it, did not direct his sense of warmth to it, the world was silent. It had primary qualities, vibrations that were formed in a certain way, but no sound; it had processes of some kind in the ether, but no color; it had some sort of processes in ponderable matter (matter that has weight)—but it had no quality of warmth. As to these experienced qualities, the scientific age was really saying that it did not know what to do with them. It did not want to look for them in the world, admitting that it was powerless to do so. They were sought for within man, but only because nobody had any better ideas. To a certain extent science investigates man's inner nature, but it does not (and perhaps cannot) go very far with this, hence it really does not take into consideration that these secondary qualities cannot be found in this inner nature. Therefore it has no pigeonhole for them. Why is this so?

Let us recall that if we really want to focus correctly on something that is related to form, space, geometry or arithmetic, we have to turn our attention to the inward life-filled activity whereby we build up the spatial element within our own organism, as we do with above-below, back-front, left-right. Therefore, we must say that if we want to discover the nature of geometry and space, if we want to get to the essence of Locke's primary qualities of corporeal things, we must look within ourselves. Otherwise, we only attain to abstractions.

In the case of the secondary qualities such as sound, color, warmth, smell and taste, man has to remember that his ego and astral body normally dwell within his physical and etheric bodies but during sleep they can also be outside the physical and etheric bodies. Just as man experiences the primary qualities, such as the three dimensions, not outside but within himself during full wakefulness, so, when he succeeds (whether through instinct or through spiritual-scientific training) in really inwardly experiencing what is to be found outside the physical and etheric bodies from the moment of falling asleep to waking up, he knows that he is really experiencing the true essence of sound, color, smell, taste, and warmth in the external world outside his own body. When, during the waking condition, man is only within himself, he cannot experience anything but picture-images of the true realities of tone, color, warmth, smell and taste. But these images correspond to soul-spirit realities, not physical-etheric ones. In spite of the fact that what we experience as sound seems to be connected with certain forms of air vibrations, just as color is connected with certain processes in the colorless external world, it still has to be recognized that both are pictures, not of anything corporeal, but of the soul-spirit element contained in the external world.

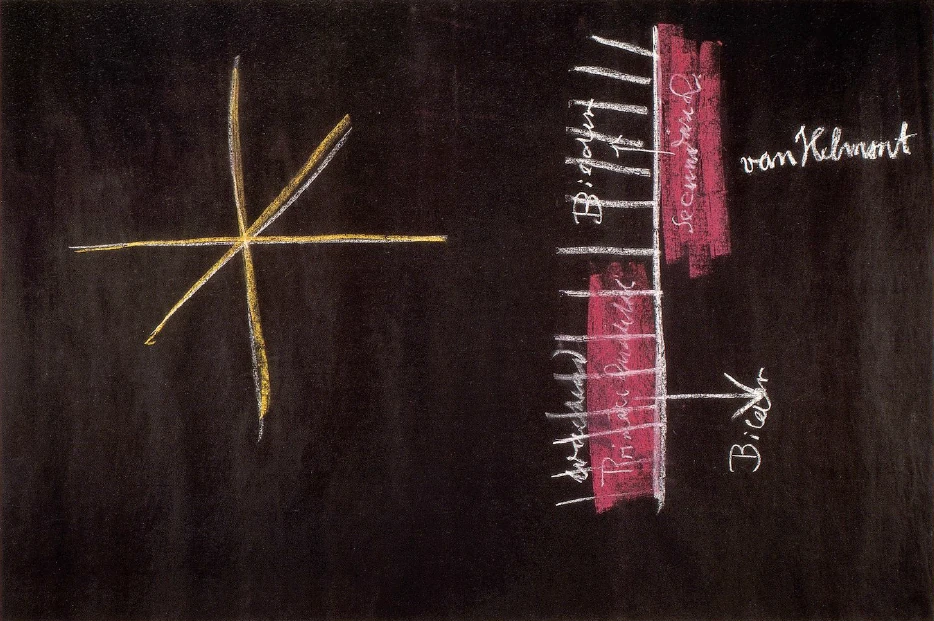

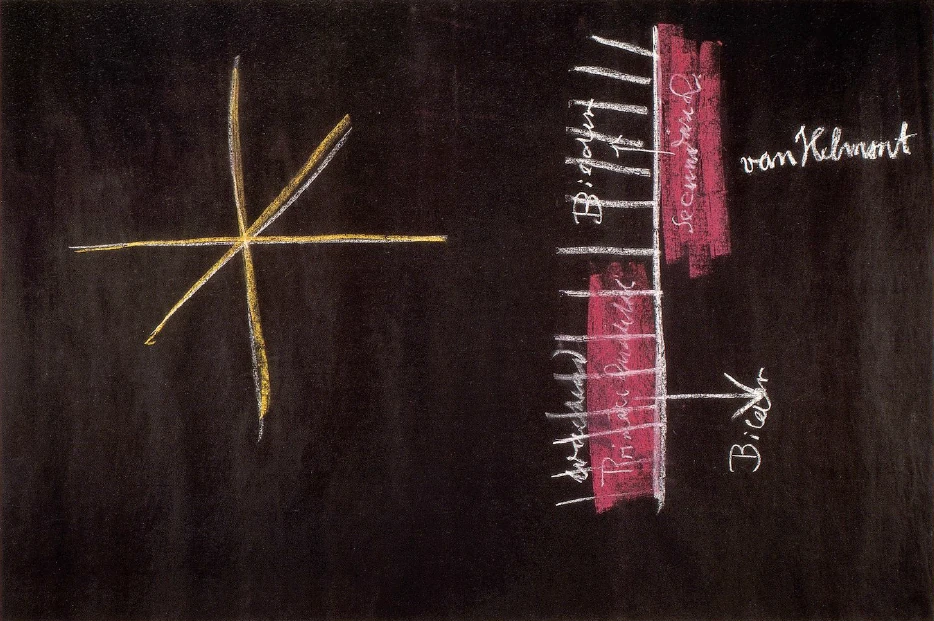

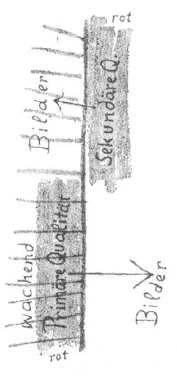

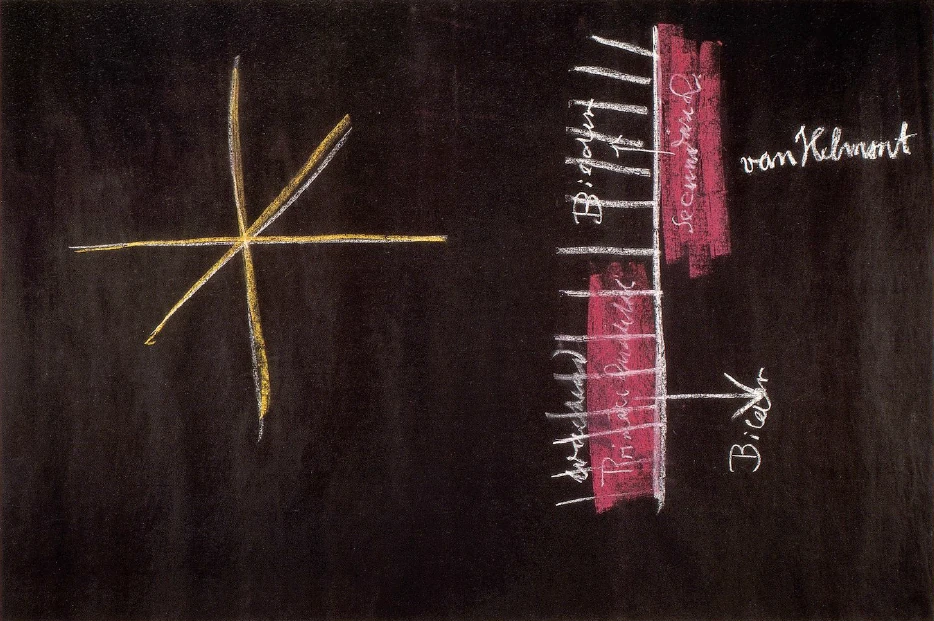

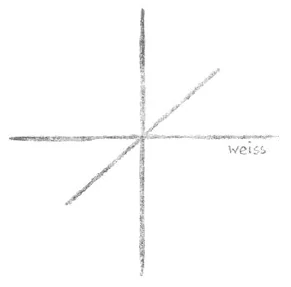

We must be able to tell ourselves: When we experience a sound, a color, a degree of warmth, we experience an image of them. But we experience them as reality, when we are outside our physical body. We can portray the facts in a drawing as follows: Man experiences the primary qualities within himself when fully awake, and projects them as images into the outer world. If he only knows them in the outer world, he has the primary qualities only in images (arrow in sketch). These images are the mathematical geometrical, and arithmetical qualities of things.

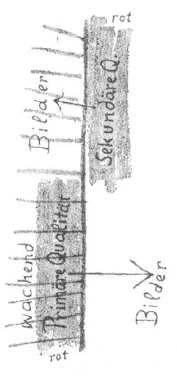

It is different in the case of the secondary qualities. (The horizontal lines stand for the physical and etheric body of man, the red shaded area for the soul-spirit aspect, the ego and astral body.) Man experiences them outside his physical and etheric body,53One can find the basic reality explained in the chapter “Sleep and Death” in An Outline Of Occult Science and in Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment (Spring Valley, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1983). and projects only the images into himself. Because the scientific age no longer saw through this, mathematical forms and numbers became something that man looked for abstractly in the outer world. The secondary qualities became something that man looked for only in himself. But because they are only images in himself, man lost them altogether as realities.

As few isolated thinkers, who still retained traditions of earlier views concerning the outer world, struggled to form conceptions that were truer to reality than those that, in the course of the scientific age, gradually emerged as the official views. Aside from Paracelsus,54Paracelsus, Theophrastus von Hohenheim: Einsiedein, Kanton Schwytz 1493–1541 Salzburg, Md. Ferrara, Professor in Basel. Accomplished physician, scientist, and philosopher. Wrote about chemistry, medical science, biology, astronomy, astrology, alchemy, and theology. The myths about Paracelsus as goldmaker, magician, or charlatan were made up after his death and distorted the picture of his character. Most complete work published by Karl Sudhoff (fourteen volumes). See Riddles of Philosophy. there was, for example, van Helmont,55Helmont, Johann Baptist van: Brussels 1577–1644. Physician and iatrochemist. He managed the differentiation and separation of gases (hydrogen, carbon). He coined the name “gas” for the airy state. who was well aware that man's spiritual element is active when color, tone, and so forth are experienced. During the waking state, however, the spiritual is active only with the aid of the physical body. Hence it produces only an image of what is really contained in sound or color. This leads to a false description of external reality; namely, that purely mathematical-mechanistic form of motion for what is supposed to be experienced as secondary qualities in man's inner being, whereas, in accordance with their reality, their true nature, they can only be experienced outside the body. We should not be told that if we wish to comprehend the true nature of sound, for example, we ought to conduct physical experiments as to what happens in the air that carries us to the sound that we hear. Instead, we should be told that if we want to acquaint ourselves with the true nature of sound, we have to form an idea of how we really experience sound outside our physical and etheric bodies. But these are thoughts that never occurred to the men of the scientific age. They had no inclination to consider the totality of human nature, the true being of man. Therefore they did not find either mathematics or the primary qualities in this unknown human nature; and they did not find the secondary qualities in the external world, because they did not know that man belongs to it also.

I do not say that one has to be clairvoyant in order to gain the right insight into these matters, although a clairvoyant approach would certainly produce more penetrating perceptions in this area. But I do say that a healthy and open mind would lead one to place the primary qualities, everything mathematical-mechanical, into man's inner being, and to place the secondary qualities into the outer world. The thinkers no longer understand human nature. They did not know how man's corporeality is filled with spirit, or how this spirit, when it is awake in a person, must forget itself and devote itself to the body if it is to comprehend mathematics. Nor was it known that this same spirituality must take complete hold of itself and live independently of the body, outside the body, in order to come to the secondary qualities. Concerning all these matters, I say that clairvoyant perception can give greater insight, but it is not indispensable. A healthy and open mind can feel that mathematics belongs inside, while sound, color, etc. are something external.

In my notes on Goethe's scientific works56See Steiner, Goethe the Scientist. Especially see Chapters 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15. in the 1880's, I set forth what healthy feeling can do in this direction. I never mentioned clairvoyant knowledge, but I did show to what extent man can acknowledge the reality of color, tone, etc. without any clairvoyant perception. This has not yet been understood. The scientific age is still too deeply entangled in Locke's manner of thinking. I set it forth again, in philosophic terms, in 1911 at the Philosophic Congress in Bologna.57Lecture of April 8, 1911, at the 9th International Philosophical Congress, “The Psychological Foundations of Anthroposophy,” in Rudolf Steiner, Esoteric Development, Spring Valley, NY: 1982), pp. 25–55. And again it was not understood. I tried to show how man's soul—spirit organization does indeed indwell and permeate the physical and etheric body during the waking state, but still remains inwardly independent. If one senses this inward independence of the soul and spirit, then on also has a feeling for what the soul and spirit have experienced during sleep about the reality of green and yellow, G and C-sharp, warm and cold, sour or sweet. But the scientific age was unwilling to go into a true knowledge of man.

This description of the primary and secondary qualities shows quite clearly how man got away from the correct feeling about himself and his connection to the world. The same thing comes out in other connections. Failing to grasp how the mathematical with its three-dimensional character dwells in man, the thinkers likewise could not understand man's spirituality. They would have had to see how man is in a position to comprehend right-left by means of the symmetrical movements of his arms and hands and other symmetrical movements. Through sensing the course taken, for example, by his food, he can experience front-back. He experiences up-down as he coordinates himself in this direction in his earliest years. If we discern this, we see how man inwardly unfolds the activity that produces the three dimensions of space. Let me point out also that the animal does not have the vertical direction in the same way as man does, since its main axis is horizontal, which is what man can experience as front-back. The abstract space framework could no longer produce anything other than mathematical, mechanistic, abstract relationships in inorganic nature. It could not develop an inward awareness of space in the animal or in man.

Thus no correct opinion could be reached in this scientific age concerning the question: How does man relate to the animal, the animal to man? What distinguishes them from one another? It was still dimly felt that there was a difference between the two, hence one looked for the distinguishing features. But nothing could be found in either man or animal that was decisive and consistent. Here is a famous example: It was asserted that man's upper jawbone, in which the upper teeth are located, was in one piece, whereas in the animal, the front teeth were located in a separate one, the inter-maxillary bone, with the actual upper jawbone on either side of them. Man, it was thought, did not possess this inter-maxillary bone. Since one could no longer find the relationship of man to animal by inner soul-spirit means, one looked for it in such external features and said that the animal had an inter-maxillary bone and man did not.

Goethe could not put into words what I have said today concerning primary and secondary qualities. But he had a healthy feeling about all these matters. He knew instinctively that the difference between man and animals must lie in the human form as a whole, not in any single feature. This is why Goethe opposed the idea that the inter-maxillary bone is missing in man. As a young man, he wrote an important article suggesting that there is an inter-maxillary bone in man as well as in the animal. He was able to prove this by showing that in the embryo the inter-maxillary bone is still clearly evident in man although in early childhood this bone fuses with the upper jaw, whereas it remains separate in the animal. Goethe did all this out of a certain instinct, and this instinct led him to say that one must not seek the difference between man and animal in details of this kind; instead, it must be sought for in the whole relation of man's form, soul, and spirit to the world.

By opposing the naturalists who held that man lacks the inter-maxillary bone Goethe brought man close to the animal. But he did this in order to bring out the true difference as regards man's essential nature. Goethe's approach out of instinctive knowledge put him in opposition to the views of orthodox science, and this opposition has remained to this day. This is why Goethe really found no successors in the scientific world. On the contrary, as a consequence of all that had developed since the Fifteenth Century in the scientific field, in the Nineteenth Century the tendency grew stronger to approximate man to the animal. The search for a difference in external details diminished with the increasing effort to equate man as nearly as possible with the animal. This tendency is reflected in what arose later on as the Darwinian idea of evolution. This found followers, while Goethe's conception did not. Some have treated Goethe as a kind of Darwinist, because all they see in him is that, through his work on the inter-maxillary bone,58See Steiner, Goethe the Scientist. he brought man nearer to the animal. But they fail to realize that he did this because he wanted to point out (he himself did not say so in so many words, but it is implicit in his work) that the difference between man and animal cannot be found in these external details.

Since one no longer knew anything about man, one searched for man's traits in the animal. The conclusion was that the animal traits are simply a little more developed in man. As time went by, there was no longer any inkling that even in regard to space man had a completely different position. Basically, all views of evolution that originated during the scientific age were formulated without any true knowledge of man. One did not know what to make of man, so he was simply represented as the culmination of the animal series. It was a though one said: Here are the animals; they build up to a final degree of perfection, a perfect animal; and this perfect animal is man.

My dear friends, I want to draw your attention to how matters have proceeded with a certain inner consistency in the various branches of scientific thinking since its first beginnings in the Fifteenth Century; how we picture our relation to the world on the basis of physics, of physiology, by saying: Out there is a silent and colorless world. It affects us. We fashion the colors and sounds in ourselves as experiences of the effects of the outer world.

At the same time we believe that the three dimensions of space exist outside of us in the external world. We do this, because we have lost the ability to comprehend man as a whole. We do this because our theories of animal and man do not penetrate the true nature of man. Therefore, in spite of its great achievements we can say that science owes its greatness to the fact that it has completely missed the essential nature of man. We were not really aware of the extent to which science was missing this. A few especially enthusiastic materialistic thinkers in the Nineteenth Century asserted that man cannot rightly lay claim to anything like soul and spirit because what appears as soul and spirit is only the effect of something taking place outside us in time and space. Such enthusiasts describe how light works on us; how something etheric (according to their theory) works into us through vibrations along our nerves; how the external air also continues on in breathing, etc. Summing it all up, they said that man is dependent on every rise and fall of temperature, on any malformation of his nervous system, etc. Their conclusion was that man is a creature pitifully dependent on every draft or change of pressure.

Anyone who reads such descriptions with an open mind will notice that, instead of dealing with the true nature of man, they are describing something that turns man into a nervous wreck. The right reply to such descriptions is that a man so dependent on every little draft of air is not a normal person but a neurasthenic. But they spoke of this neurasthenic as if he were typical. They left out his real nature, recognizing only what might make him into a neurasthenic. Through the peculiar character of this kind of thinking about nature, all understanding was gradually lost. This is what Goethe revolted against, though he was unable to express his insights in clearly formulated sentences.

Matters such as these must be seen as part of the great change in scientific thinking since the Fifteenth Century. Then they will throw light on what is essential in this development. I would like to put it like this: Goethe in his youth took a keen interest in what science had produced in its various domains. He studied it, he let it stimulate him, but he never agreed with everything that confronted him, because in all of it he sensed that man was left out of consideration. He had an intense feeling for man as a whole. This is why he revolted in a variety of areas against the scientific views that he saw around him. It is important to see this scientific development since the Fifteenth Century against the background of Goethe's world conception. Proceeding from a strictly historical standpoint, one can clearly perceive how the real being of man is missing in the scientific approach, missing in the physical sciences as well as in the biological.

This is a description of the scientific view, not a criticism. Let us assume that somebody says: “Here I have water. I cannot use it in this state. I separate the oxygen from hydrogen, because I need the hydrogen.” He then proceeds to do so. If I then say what he has done, this is not criticism of his conduct. I have no business to tell him he is doing something wrong and should leave the water alone. Nor is it criticism, when I saw that since the Fifteenth Century science has taken the world of living beings and separated from it the true nature of man, discarding it and retaining what this age required. It then led this dehumanized science to the triumphs that have been achieved.

It is not a criticism if something like this is said; it is only a description. The scientist of modern times needed a dehumanized nature, just as chemist needs deoxygenized hydrogen and therefore has to split water into its two components. The point is to understand that we must not constantly fall into the error of looking to science for an understanding of man.

Sechster Vortrag

Ich habe in einem Teile des letzten Kursvortrages davon gesprochen, wie die naturwissenschaftliche Weltanschauung eine ihrer Wurzeln darinnen hat, daß in jener Zeit, die vergangen ist, seit, ich möchte sagen, dem Geburtsmomente dieser naturwissenschaftlichen Anschauungsweise im 15. Jahrhundert, daß in dieser Zeit John Locke und ähnliche Geister unterschieden haben in dem, was uns sinnesgemäß umgibt, die sogenannten primären Qualitäten der Dinge, der Körperwelt von den sekundären Qualitäten. Primäre Qualitäten nannte Locke zum Beispiel alles dasjenige, was sich auf die Gestalt der Körper, auf deren geometrische Eigentümlichkeit, auf das Zahlenmäßige bezieht, auf die Bewegung bezieht, auf die Größe und so weiter. Davon unterschied er dann alles dasjenige, was er die sekundären Qualitäten nennt, Farbe, Ton, Wärmeempfindung und so weiter. Und während er die primären Qualitäten in die Dinge selbst hineinverlegt, so daß er annimmt, es seien räumliche, körperliche Dinge da, welche Gestalt haben, geometrische Eigentümlichkeiten haben, Bewegungen haben, nimmt er an, daß alles dasjenige, was sekundäre Qualitäten sind, Farbe, Ton usw., nur Wirkungen auf den Menschen seien. Draußen in der Welt seien nur primäre Qualitäten in den Körpern. Irgend etwas, dem Größe, Gestalt, Bewegung zukommt, das aber finster, stumm und kalt ist, irgend etwas übt eine Wirkung aus, und diese Wirkung drückt sich eben aus darinnen, daß der Mensch einen Ton, eine Farbe, eine Wärmequalität usw. erlebt.

Nun wies ich auch in diesen Vorträgen darauf hin, wie in diesem naturwissenschaftlichen Zeitalter das Räumliche schon in bezug auf die Dimensionen ein Abstraktes geworden ist. Der Mensch wußte nichts mehr davon, daß in ihm selbst die drei Dimensionen konkret erlebt wurden als oben-unten, rechts-links, vorne-hinten (siehe Zeichnung S. 86). Er nahm auf diese Konkretheit der drei Dimensionen im naturwissenschaftlichen Zeitalter keine Rücksicht. Für ihn entstanden sie in völliger Abstraktheit. Er suchte den Schnittpunkt der drei Dimensionen nicht mehr da, wo er real erlebt wird, im menschlichen Inneren, er suchte ihn irgendwo — und da kann er dann wo auch immer sein irgendwo im Raume - und konstruierte sich so seine drei Dimensionen. Jetzt hatte dieses Raumschema der drei Dimensionen ein selbständiges, aber nur gedachtes, abstraktes Dasein. Und das Gedachte wurde eben nicht erlebt als sowohl der Außenwelt wie dem Menschen angehörig, während eine frühere Zeit, wie ich sagte, die drei Raumdimensionen so erlebt hat, daß der Mensch wußte, er erlebt sie in sich mit der Natur der physischen Körperlichkeit zusammen.

Es waren also gewissermaßen schon die Raumdimensionen von dem Menschen abgesondert und nach außen geworfen worden und hatten dadurch einen völlig abstrakten, unlebendigen Charakter angenommen. Der Mensch wußte nicht mehr, daß er die Raumdimensionen — und solches kann ja auch gesagt werden von allem anderen, das geometrisch ist, das zahlenmäßig ist, das gewichtmäßig ist usw. -, daß er alles das in seinem Inneren erlebt mit der Außenwelt zusammen, daß er aber eigentlich, um es in seiner Konkretheit, in seiner vollen, lebendigen Wirklichkeit zu erleben, in sein Inneres blicken müsse, um es da gerechtfertigt zu finden. Und eigentlich ist es so, daß eine Persönlichkeit wie John Locke nur deshalb die primären Qualitäten, die von der Art sind wie die drei Raumdimensionen — denn die drei Raumdimensionen sind eine Art Gestaltung -—, in die Außenwelt verlegte, weil nicht mehr gewußt wurde der Zusammenhang dieser Qualitäten mit dem menschlichen Inneren.

Die anderen, die sekundären Qualitäten, die als Sinnesinhalt eigentlich qualitativ erlebt werden, wie Farbe, Ton, Wärmequalität, Geruch, Geschmack, die wurden nunmehr nur als die Wirkungen der Dinge auf den Menschen, als innere Erlebnisse angesehen. Aber ich habe ja darauf hingewiesen, wie im Inneren des physischen Menschen, auch im Inneren des ätherischen Menschen, ja diese sekundären Qualitäten nicht mehr gefunden werden können, wie sie daher in gewisser Beziehung auch für dieses Innere des Menschen vogelfrei geworden sind. Man suchte sie nicht mehr in der Außenwelt, man verlegte sie in das menschliche Innere. Man sagte: Wenn der Mensch nicht zuhört der Welt, wenn der Mensch nicht hinschaut auf die Welt, wenn der Mensch nicht seinen Wärmesinn der Welt offenbart, dann ist die Welt stumm und so weiter. Sie hat primäre Qualitäten, bestimmt gestaltete Luftwellen, aber sie hat keinen Ton; sie hat irgendwie Vorgänge im Äther, aber sie hat keine Farbe; sie hat irgendwelche Vorgänge in der ponderablen Materie, in der Materie, die ein Gewicht hat, aber sie hat nicht dasjenige, was Wärmequalität ist usw. Eigentlich war damit in diesem naturwissenschaftlichen Zeitalter für diese erlebten Sinnesqualitäten nichts anderes gesagt, als: Man weiß sie eigentlich nicht unterzubringen. In der Welt wollte man sie nicht suchen. Man gestand sich, daß man keine Macht habe, sie in der Welt zu finden. Im Inneren suchte man sie zwar, aber nur, weil man gedankenlos war oder ist. Gedankenlos war oder ist man in dem Sinne, daß man ja keine Rücksicht darauf nimmt, daß, wenn man nun dieses Innere des Menschen, soweit man es nun gelten läßt, wirklich durchforscht, das heißt, wenn man es durchforscht, soweit dies natürlich möglich ist — aber das geschieht ja nur als ein Ideal, so daß man eigentlich nicht von der Tatsache eines vollendeten Durchforschens reden kann -, wenn man also dieses Innere durchforscht, so findet man nirgends diese sekundären Qualitäten. Man weiß sie daher eigentlich in der Welt nicht unterzubringen. Woher kommt dieses?

Nun, erinnern wir uns noch einmal: Will man in rechter Weise irgend etwas anschauen, das sich auf Gestaltliches, Räumliches, Geometrisches oder auch Arithmetisches bezieht, will man solches wirklich richtig anschauen, so muß man die innere Tätigkeit ins Auge fassen, diese lebensvolle Tätigkeit, wodurch der Mensch in seinem eigenen Organismus das Räumliche sich konstruiert, wie im Oben und Unten, Vorne und Hinten, Rechts und Links. Man muß also in diesem Falle sagen: Willst du finden das Wesen des Geometrisch-Räumlichen - man könnte aber auch ganz sinngemäß sagen: Willst du finden das Wesen der Lockeschen primären Qualitäten der körperlichen Dinge -, so mußt du in dich selber hineinschauen, sonst kommst du nur auf Abstraktionen. Nun ist es mit den sekundären Qualitäten, Ton, Farbe, Wärmequalität, Gerüchen, Geschmack so, daß der Mensch davon etwas wissen muß — es kann ja dieses Wissen sehr instinktiv nur sein, aber etwas wissen muß er davon -, daß er mit seinem geistig-seelischen Wesen ja nicht bloß in seinem physischen und ätherischen Leib lebt, sondern daß er auch außerhalb dieser Leiber sein kann mit seinem Ich und seinem astralischen Leibe, nämlich im Schlafzustande. Aber ebenso wie der Mensch bei einem vollen, intensiv empfundenen Wachzustande nicht außer sich, sondern in sich die primären Qualitäten erlebt, wie im speziellen Fall die drei Dimensionen, so weiß der Mensch, wenn es ihm entweder durch Instinkte oder durch eine instinktive Selbsterkenntnis oder auch durch geisteswissenschaftliche Schulung gelingt, das auch wirklich innerlich zu erleben, was außerhalb vom physischen Leib und Ätherleib vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen ist, dann weiß er auch, daß er das wahre Wesen von Ton, Farbe, Geruch, Geschmack, Wärmequalität wirklich dann in der Außenwelt erlebt außerhalb seines Leibes. Wenn der Mensch im Wachzustande bloß in seinem Inneren ist, so kann er nichts anderes erleben als die Bilder der wahren Realitäten von Ton, Farbe, Wärmequalität, Geruch, Geschmack. Aber diese Bilder entsprechen geistig-seelischen Realitäten, nicht physisch-ätherischen Realitäten. Trotzdem dasjenige, was wir als Ton erleben, so stark zusammenzuhängen scheint — es tut es ja auch, aber in einer ganz anderen Hinsicht — mit bestimmt gestalteten Luftwellen, wie Farbe zusammenhängt mit gewissen Vorgängen in der farblosen Außenwelt, so muß eben dennoch anerkannt werden, daß Ton, Farbe und so weiter Bilder sind, nicht vom Körperlichen, sondern vom Geistigen, GeistigSeelischen, das in der Außenwelt ist.

Wir müssen also uns sagen können: Wenn wir einen Ton, eine Farbe, eine Wärmequalität erleben, dann erleben wir sie im Bilde. Aber wir erleben sie real, wenn wir außerhalb unseres Leibes sind. Und so können wir etwa schematisch den Tatbestand in der folgenden Weise darstellen (siehe Zeichnung): Die primären Qualitäten erlebt der Mensch wachend, voll wachend, in sich, und schaut sie in die Außenwelt hinein in Bildern; wenn er sie nur in der Außenwelt weiß, so hat er diese primären Qualitäten nur in Bildern (Pfeil). Diese Bilder sind das Mathematische, das Geometrische, das Arithmetische an den Dingen.

Mit den sekundären Qualitäten ist es anders. Die erlebt der Mensch wenn ich den physischen und Ätherleib des Menschen mit diesen waagerechten Strichen bezeichne und das Geistig-Seelische, das Ich und das Astralische, mit dem Roten -, die erlebt der Mensch außerhalb seines physischen und Ätherleibes und er projiziert in sich herein nur die Bilder. Weil das nicht mehr durchschaut wurde im naturwissenschaftlichen Zeitalter, wurden gewissermaßen die mathematischen Formen, die Zahlen auch, zu etwas, das der Mensch nur in der Außenwelt abstrakt suchte. Die sekundären Qualitäten, sie wurden etwas, das der Mensch nur in sich suchte. Aber weil sie da bloße Bilder sind, verlor er sie eben für die Wirklichkeit vollständig.

Es war ja so, daß einzelne Persönlichkeiten, die noch Traditionen aus älteren Anschauungen über die Außenwelt hatten, damit rangen, sich Vorstellungen zu machen, welche wirklichkeitsgemäßer waren als diejenigen, welche, ich möchte sagen, als die offiziellen im Laufe des naturwissenschaftlichen Zeitalters allmählich heraufkamen. So zum Beispiel, außer Paracelsus, auch van Helmont, der sich durchaus bewußt war, daß, wenn Farbe, Ton usw. erlebt werden, das Geistige des Menschen in Tätigkeit ist. Aber weil dieses Geistige im Wachzustande nur mit Hilfe des physischen Leibes sich betätigt, erzeugt es in sich bloß ein Bild von dem, was als Wesen in Ton, Farbe und so weiter enthalten ist, und so kommt man dann zu einer unzutreffenden Beschreibung der äußeren Wirklichkeit, nämlich zu der reinen mathematisch-mechanischen Bewegungsform, Bewegungsgestaltung für dasjenige, was als sekundäre Qualitäten im Menscheninneren erlebt werden soll. Während es in Wahrheit seiner Realität, seiner Wirklichkeit gemäß allein außerhalb des Menschenleibes erlebt werden kann. Man muß zu dem Menschen nicht sagen: Wenn du das wahre Wesen zum Beispiel des Tones erkennen willst, so mußt du physikalische Experimente machen über dasjenige, was sich, wenn du einen Ton hörst, innerlich in der Luft sich abspielt, die den Ton zu dir bringt, sondern dann mußt du dem Menschen sagen: Wenn du das wahre Wesen des Tones kennenlernen willst, so mußt du dir eine Vorstellung davon bilden, wie du eigentlich den Ton außer deinem physischen und ätherischen Leibe erlebst. Das sind aber Gedanken, welche von den Menschen des naturwissenschaftlichen Zeitalters eben nicht gedacht wurden, weil diese Menschen eben nicht auf die vollständige Menschennatur eingehen wollten, weil sie keine Neigung entwickelten, die wahre Wesenheit des Menschen kennenzulernen. Und so fanden sie eben in der ihnen unbekannten Menschennatur nicht die Mathematik oder auch die primären Qualitäten; und so fanden sie in der Außenwelt — weil sie nicht wußten, daß der Mensch ja der Außenwelt auch angehört — nicht die sekundären Qualitäten.

Ich sage nicht, daß man hellsichtig sein müsse, um in diesen Dingen die richtige Einsicht zu bekommen, sondern ich muß betonen, daß zwar die hellsichtige Weltenerklärung tiefere intensive Erkenntnisse gerade auch auf diesem Gebiete geben kann, daß aber eine gesunde Selbstschau durchaus dahin führt, das Mathematische, die primären Qualitäten, das Mathematisch-Mechanische auch in das Innere des Menschen zu verlegen, die sekundären Qualitäten auch in die Außenwelt des Menschen zu verlegen. Man kannte die Menschennatur nicht mehr. Man wußte nicht in Wirklichkeit, wie die Körperlichkeit des Menschen erfüllt ist von der Geistigkeit, wie die Geistigkeit, indem sie wachend im Menschen ist, sich vergessen muß, sich ganz hingeben muß dem Körper, damit sie das Mathematische begreift. Und man wußte auch nicht das andere, daß die Geistigkeit sich ganz in sich zusammenfassen muß und unabhängig vom Körper, das heißt außerhalb des Körpers, leben muß, um zu den sekundären Qualitäten zu kommen. Über alle diese Dinge, sage ich, kann die hellseherische Anschauung intensivere Einsichten geben, aber sie ist nicht nötig. Eine Selbstschau, eine wirkliche, gesunde Selbstschau kann fühlen, in richtigem Gefühl erkennen, daß Mathematik auch etwas innerlich Menschliches ist, Ton, Farbe usw. auch etwas Äußerliches sind.

Ich habe das, was einfach ein gesundes Empfinden, das aber zu wirklichen Erkenntnissen führt, nach dieser Richtung haben kann, in den achtziger Jahren in meinen Einleitungen zu «Goethes Naturwissenschaftlichen Schriften» dargestellt. Da ist auf keine hellseherische Erkenntnis Rücksicht genommen, aber es ist gezeigt, inwieweit der Mensch ohne hellseherische Erkenntnis zur Anerkennung der Realität von Farbe, Ton usw. kommen kann. Dies hat man noch nicht verstanden. Das naturwissenschaftliche Zeitalter ist in der Lockeschen Denkungsweise noch zu sehr befangen. Dies konnte man nicht verstehen, konnte es auch nicht verstehen, als ich es, ich möchte sagen, philosophisch geschürzt, 1911 deutlich ausführte am Philosophischen Kongreß in Bologna. Da versuchte ich zu zeigen, wie das GeistigSeelische des Menschen beim Wachzustande zwar im physischen und Ätherleib ist, aber seiner Qualität nach, gewissermaßen indem es den physischen und Ätherleib erfüllt, doch innerlich selbständig bleibt. Fühlt man diese innerliche Selbständigkeit des Geistig-Seelischen des Menschen, dann hat man auch eine Nachempfindung von dem, was das Geistig-Seelische im Schlafen von den Realitäten des Grünen und Gelben, des G und Cis, des Warmen und Kalten, des Sauren und Süßen usw. erlebt hat. Aber eben auf eine wirkliche Menschenerkenntnis wollte zunächst das naturwissenschaftliche Zeitalter nicht eingehen.

Wir sehen an dieser Charakteristik des Verhältnisses des Menschen zur Welt nach den primären und sekundären Qualitäten ganz deutlich, wie der Mensch abkommt davon, über sich und sein Verhältnis zur Welt eine richtige Empfindung zu haben. Aber dasselbe steckte auch in anderen Vorstellungen, die man über den Menschen gewann, darinnen. Weil man keine Anschauung gewinnen konnte davon, wie das Mathematische in seinen drei Dimensionen im Inneren des Menschen lebt, konnte man auch nicht das Wesentliche des Menschen in bezug auf seine Geistigkeit durchschauen. Denn dieses Wesentliche hätte darinnen bestanden, daß man sich gesagt hätte: Der Mensch ist in der Lage, das Rechts-Links durch die symmetrische Bewegung seiner Arme und Hände, durch die anderen symmetrisch durch ihn vollbrachten Bewegungen zu erfassen. Er ist, indem er zum Beispiel den Gang seiner Nahrungsmittel fühlt, in der Lage, zu erleben das Vorne und Hinten. Er erlebt das Oben und Unten, weil er sich ja während seines Lebens erst in dieses Oben und Unten hineinordnet. Durchschaut man dieses, dann sieht man ja, wie der Mensch innerlich die Tätigkeit entfaltet, die in der Erzeugung der drei Raumdimensionen liegt, und man wird, wenn man vom Menschen spricht in seinem Verhältnisse zur Tierwelt, auf das Charakteristische hinweisen, daß ja das Tier nicht in derselben Weise wie der Mensch zum Beispiel das Oben und Unten hat, weil es seine wesentliche Körperachse in der Horizontalen hat, also in demjenigen, was der Mensch als vorne und hinten empfinden kann. Das abstrakte Raumschema genügte nicht mehr, um etwas anderes als mathematisch-mechanisch-abstrakte Verhältnisse in der unorganischen Natur zu ergründen. Es genügte zum Beispiel nicht, um über das innere Erleben des Raumes, auf der einen Seite beim Tier, auf der anderen Seite beim Menschen, eine Anschauung zu entwickeln.

Und so konnte zunächst in diesem naturwissenschaftlichen Zeitalter keine richtige Meinung entstehen über die Frage: Wie verhält sich eigentlich der Mensch zum Tier, das Tier zum Menschen? Wodurch unterscheiden sie sich? Da man aber doch noch fühlte in einer gewissen Weise: Es ist ein Unterschied zwischen dem Menschen und dem Tiere — so suchte man ihn in allerlei Merkmalen, die nicht durchgreifend charakteristisch sein können, weder für den Menschen noch für die Tiere. Und davon ist ein sehr bedeutsames Beispiel das, daß man mit Bezug auf die obere Kinnlade des Menschen, in der die Oberzähne sitzen, gesagt hat: Dieser Kinnladenknochen ist beim Menschen ein einziger; beim Tiere ist er so, daß die vorderen Schneidezähne in einem abgesonderten Zwischenkiefer drinnen sitzen, und erst zu beiden Seiten dieses Zwischenkiefers ist der eigentliche Oberkiefer. Der Mensch habe diesen Zwischenkiefer nicht. Nachdem man also keine Fähigkeit mehr hatte, durch innerlich Geistig-Seelisches das Verhältnis des Tieres zum Menschen zu finden, sah man es in etwas so Äußerlichem, daß man sagte: Das Tier hat den Zwischenkiefer, der Mensch hat ihn nicht.

Goethe war derjenige, der zwar solche Erkenntnisse wie diese, die ich heute ausgesprochen habe über primäre und sekundäre Qualitäten, nicht in Worte fassen konnte, auch keine äußerlichen Gedanken mit völliger Klarheit sich darüber erringen konnte, aber Goethe hatte ein gesundes Gefühl von all diesen Dingen. Vor allen Dingen wußte Goethe instinktiv, man muß in der ganzen Bildung des Menschen seinen Unterschied von den Tieren finden und nicht in etwas Einzelnem. Deshalb wurde Goethe zum Bekämpfer der Idee von dem fehlenden Zwischenkieferknochen am Menschen. Und er schrieb als junger Mann seine bedeutungsvolle Abhandlung, die dem Menschen wie dem Tiere einen Zwischenkiefer in der oberen Kinnlade zuschreibt. Und es gelang ihm, den vollgültigen Tatsachenbeweis für diese Behauptung zu finden, indem er eben zeigte, wie noch im embryonalen Zustande beim Menschen der Zwischenkiefer durchaus zu sehen ist, wie er aber, indem der Mensch sich entwickelt, also schon beim kleinen Kinde, mit dem Oberkiefer verwächst, während er bei dem Tier getrennt bleibt. Goethe hat das alles aus einem gewissen richtigen Erkenntnisinstinkte heraus behandelt, und aus diesem Erkenntnisinstinkte heraus ist er zunächst dazu gekommen, zu sagen: Man darf nicht in solchen Einzelheiten den Unterschied des Menschen von den Tieren finden wollen, man muß ihn in dem ganzen Verhältnis seiner Gestaltung, seines Seelischen, seines Geistigen zur Welt suchen. Deshalb bedeutet die Bekämpfung der Naturforscher, die dem Menschen den Zwischenkiefer absprechen, die Bekämpfung dieser Naturforscher durch Goethe auf der einen Seite, daß er in bezug auf die Äußerlichkeiten den Menschen nahe herangebracht hat an die Tiere, um ihn andererseits gerade in bezug auf sein eigentliches Wesen in seinem wahren Unterschiede hinstellen zu können. Diese Anschauungsweise, die Goethe aus einem Erkenntnisinstinkt heraus der Form derjenigen Naturwissenschaft entgegengesetzt hat, die diese bis zu ihm angenommen hatte, die sie auch heute noch hat, diese Anschauungsweise Goethes fand ja eigentlich keine Nachfolge innerhalb der naturwissenschaftlichen Kreise. Dagegen trat gerade im 19. Jahrhundert immer mehr als Konsequenz alles desjenigen, was sich auf naturwissenschaftlichem Felde herausgebildet hatte seit dem 15. Jahrhundert, die Tendenz auf, den Menschen dem Tier anzunähern, nicht um seinen Unterschied von ihm in Äußerlichkeiten zu suchen, sondern um sein Wesen ganz nahe an die Tiere heranzutragen. Und diese Tendenz, sie ist dann enthalten in dem, was als darwinistischer Entwickelungsgedanke und so weiter auftrat. Das hat Nachfolge gefunden. Goethes Anschauung hat keine Nachfolge gefunden. Ja, manche haben Goethe sogar als eine Art Darwinisten behandelt, weil sie an Goethe nur gerade das sehen, daß er durch so etwas, wie es der Zwischenkiefer ist, den Menschen dem Tiere nahegebracht hat. Aber sie sehen nicht, daß er dies getan hat, um gewissermaßen darauf hinzuweisen — er hat nicht selber mit ausdrücklichen Worten darauf hingewiesen, aber es liegt in seiner Weltanschauung -, daß in etwas ganz anderem als in diesen Äußerlichkeiten der Unterschied des Menschen von den Tieren gefunden werden müßte.

Weil man nichts mehr vom Menschen wußte, suchte man seine eigenen wesentlichen Merkmale bei dem Tiere und sagte sich: Da sind die tierischen Merkmale, die sind nur etwas höher entwickelt beim Menschen. Daß der Mensch schon rein räumlich eine ganz andere Lage zur Welt in der Anschauung erhalten müsse, davon hatte man immer weniger und weniger eine Ahnung. Und im Grunde genommen sind alle Anschauungen über die Entwickelung des Lebendigen im naturwissenschaftlichen Zeitalter eben so entstanden, daß sie Systeme bildeten mit Ausschluß einer wirklichen Erkenntnis des Menschen. Man wußte mit der Wesenheit des Menschen nichts anzufangen. Daher stellte man ihn nur wie den Schlußpunkt der Tierreihe dar. Man sagte gewissermaßen: Da sind die Tiere; dann bringen es die Tiere noch zu einem letzten Grade der Vollkommenheit, zu einem vollkommensten Tier, und dieses vollkommenste Tier, das ist eben der Mensch.

Ich wollte, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden und lieben Freunde, Sie mit diesen Auseinandersetzungen darauf aufmerksam machen, wie sogar mit einer gewissen innerlichen Konsequenz in den verschiedenen Gebieten des naturwissenschaftlichen Denkens seit der ersten Phase dieses Denkens, vom 15. Jahrhundert an bis heute, vorgegangen worden ist, wie der Mensch sich auf dem Gebiete der Physik, der Physiologie sein Verhältnis zur Welt ausmalt, indem er sagt: Da draußen ist eine stumme, eine farblose Welt. Die wirkt auf dich. Du bildest die Farbe aus, du bildest die Töne aus in dir als Erlebnis der Wirkungen der Außenwelt. - Wie der Mensch sich dieses sagte auf der einen Seite und auf der anderen sich auch sagte: Es gibt in der Außenwelt ohne dich die drei Raumdimensionen —, wie sich der Mensch das sagte, weil er die Fähigkeit verloren hatte, auf das Vollkommene des Menschen einzugehen, so bildete er sich auch in seinen Anschauungen über die tierische und menschliche Gestaltung solche Vorstellungen aus, welche nicht eingingen auf das wirkliche Wesen des Menschen. Und so kann man eigentlich, trotz dieser großen, gewaltigen Fortschritte, die von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus mit Recht als menschliche Fortschritte allerersten Ranges geschildert werden, man kann sagen: Die naturwissenschaftliche Weltanschauung ist gerade dadurch groß geworden, daß sie vom Menschen und seinem Wesen völlig abgesehen hat. Allerdings bekam man eigentlich keine rechte Ahnung davon, wie sehr man von dem wirklichen Menschen absieht, indem man ihn naturwissenschaftlich betrachtete. Man kann zum Beispiel bei besonders enthusiastischen materialistischen Denkern des 19. Jahrhunderts geschildert finden, wie der Mensch gar nichts besonders Seelisch-Geistiges für sich in Anspruch nehmen dürfe, denn dasjenige, was als Seelisch-Geistiges erscheint, das sei ja nur die Wirkung desjenigen, was äußerlich räumlich-zeitlich sich vollzieht. Und da beschrieben solche enthusiastischen Naturdenker, wie das Licht auf den Menschen wirkt, also das Ätherische nach ihrer Anschauungsweise, wie das sich in seinen Nerven nach innen vibrierend fortsetzt, wie aber auch in der Atmung sich die äußere Luft in ihm fortsetzt usw. Und dann sagten sie etwa zusammenfassend: Oh, der Mensch ist ja von jeder 'Temperaturerhöhung, von jeder Temperaturerniedrigung abhängig. Der Mensch ist abhängig von alledem, was zum Beispiel auftritt als Deformation seines Nervensystems. Man spitzte etwa eine solche Auseinandersetzung zu, indem man sagte: Der Mensch ist ein Geschöpf, abhängig von jedem Zug oder Druck der Luft und dergleichen.

Derjenige, der unbefangen solche Beschreibungen nimmt, der kann merken, daß da nicht das eigentliche Wesen des Menschen beschrieben ist, sondern das beschrieben ist, wodurch dieses Menschenwesen ein Neurastheniker wird. Denn zum Beispiel kann man durchaus, wenn man die Betrachtungen, welche materialistische Denker des 19. Jahrhunderts vom Menschen gaben, sagen: Ja, das wären nicht Menschen, das wären spezifische Neurastheniker, wenn der Mensch so von jedem Luftzug abhängig wäre, wie da diese materialistischen Denker ihn schildern. Von diesem Neurastheniker sprach man als vom Menschen, ließ dasjenige, was das eigentliche Wesen ist, aus, und wußte nur noch dasjenige, wodurch dieses wahre Wesen, das unbekannt blieb, ein Neurastheniker wird. Überall fällt nach und nach durch den besonderen Charakter, den das Denken über die Natur angenommen hat, aus diesem Denken das wahre Wesen des Menschen heraus. Man verliert für die Anschauung das wahre Wesen des Menschen. Das ist dasjenige, wogegen eigentlich Goethe revoltiert hat, trotzdem er nicht imstande war, durch klar formulierte Sätze dasjenige auszusprechen, was er seinen Anschauungen nach als richtig erkannt hatte.

Man muß solches, was ich Ihnen jetzt vorgeführt habe, verfolgen in dem inneren Umschwung der Entwickelung des naturwissenschaftlichen Denkens seit dem 15. Jahrhundert, und man wird finden, daß man gerade dadurch das, worauf es ankommt in dieser Entwickelung, im richtigen Lichte ansieht. Ich möchte sagen: Goethe interessierte sich in seiner Jugend intensiv für dasjenige, was die Naturwissenschaft auf ihren verschiedenen Gebieten hervorgebracht hatte. Er studierte es, ließ sich von der Naturwissenschaft anregen, war aber nicht mit allem einverstanden, was da an ihn herantrat, weil er in allem fühlte, daß der Mensch aus diesen Anschauungen herausgeworfen war. Goethe aber fühlte intensiv den vollen Menschen. Daher revoltierte er auf den mannigfaltigsten Gebieten gegen die naturwissenschaftliche Anschauung, die er um sich herum sah. Und es kommt schon darauf an, daß man diese naturwissenschaftliche Entwickelung seit dem 15. Jahrhundert auch dadurch begreift, daß man sie auf dem Hintergrunde des Goetheschen Weltanschauungssystems anschaut. Da kommt man am besten darauf, wenn man rein historisch vorgehen will, wie dieser Betrachtung das eigentliche Wesen des Menschen fehlt, fehlt schon in den physikalischen Wissenschaften, fehlt auch in den biologischen Wissenschaften.

Das soll keine Kritik sein der naturwissenschaftlichen Weltanschauung, sondern nur eine Charakteristik. Denn nehmen wir einmal an, daß jemand sagt: Hier habe ich Wasser. Das kann ich so nicht brauchen. Ich sondere den Sauerstoff vom Wasserstoff ab, weil ich den Wasserstoff brauche. — Er sondert den Sauerstoff vom Wasserstoff ab. Wenn ich das Ergebnis dann feststelle, so ist das keine Kritik seines Verhaltens. Ich habe ihm nicht zu sagen: Du machst etwas Unrichtiges, denn du mußt das Wasser sein lassen. - Das Wasser ist kein Wasserstoff. Ebensowenig ist es eine Kritik, wenn ich sage: Die naturwissenschaftliche Entwickelung seit dem 15. Jahrhundert nahm die Welt der Lebewesen und sonderte, wie der Chemiker vom Wasser den Sauerstoff absondert, den Menschen in seinem eigentlichen Wesen ab, warf ihn weg und behielt das zurück, was die damalige Zeit brauchte, so wie der andere den Wasserstoff braucht, und führte die menschlose Naturwissenschaft zu den Triumphen, zu denen sie eben führte. — Es handelt sich nicht um eine Kritik, wenn man so etwas ausspricht, sondern um eine Charakteristik. Der neuere Naturforscher brauchte gewissermaßen die Natur menschlos, so wie irgendein Chemiker brauchen kann den Wasserstoff sauerstofflos und daher nötig hat zu teilen das Wasser in Wasserstoff und Sauerstoff. Aber man muß verstehen, um was es sich handelt, so daß man nicht immerfort wieder in den Fehler verfällt, doch irgendwo durch die Naturwissenschaften das Wesen des Menschen suchen zu wollen. Das wäre geradeso unmöglich, wie wenn man in dem Wasserstoff, den einem jemand daherbringt, auch den Sauerstoff suchen würde, den er aus dem Wasser ausgeschieden hat.

So müssen diese Dinge betrachtet werden gerade dann, wenn man in richtiger Weise über sie diese historischen Anschauungen gewinnen will. Morgen werde ich weiter fortfahren in der Schilderung der Geburt und Entwickelung der Naturwissenschaft in der neueren Zeit.

Sixth Lecture

In part of the last lecture, I spoke about how the scientific worldview has its roots in the fact that in the time that has passed since I would say, the birth of this scientific worldview in the 15th century, John Locke and similar minds distinguished between what surrounds us in a sensory way, the so-called primary qualities of things, the physical world, and the secondary qualities. Locke called primary qualities, for example, everything that relates to the shape of bodies, to their geometric properties, to numbers, to movement, to size, and so on. He then distinguished from this everything he called secondary qualities, such as color, sound, heat, and so on. And while he locates the primary qualities in things themselves, so that he assumes that there are spatial, physical things that have shape, geometric properties, and movements, he assumes that everything that is a secondary quality, such as color, sound, etc., is only an effect on humans. Outside in the world, there are only primary qualities in bodies. Something that has size, shape, and movement, but is dark, silent, and cold, exerts an effect, and this effect is expressed in the fact that humans experience a sound, a color, a quality of warmth, and so on.

Now, in these lectures, I also pointed out how, in this scientific age, space has become abstract in relation to dimensions. People no longer knew that the three dimensions were concretely experienced within themselves as up-down, right-left, front-back (see drawing on p. 86). In the scientific age, they took no account of the concreteness of the three dimensions. For them, they arose in complete abstraction. They no longer sought the intersection of the three dimensions where it is actually experienced, in the human interior, but somewhere else — and there it can then be anywhere in space — and thus constructed their three dimensions. Now this spatial scheme of the three dimensions had an independent, but only imagined, abstract existence. And what was imagined was not experienced as belonging to both the external world and to human beings, whereas in an earlier time, as I said, the three dimensions of space were experienced in such a way that human beings knew that they experienced them within themselves together with the nature of physical corporeality.

Thus, the spatial dimensions had already been separated from human beings and thrown outwards, thereby taking on a completely abstract, lifeless character. Human beings no longer knew that they experienced the spatial dimensions — and the same can be said of everything else that is geometric, numerical, weighty, etc. — that he experiences everything within himself together with the external world, but that in order to experience it in its concreteness, in its full, living reality, he must look within himself to find it justified. And in fact, it is only because the connection between these qualities and the human inner world was no longer known that a personality such as John Locke transferred the primary qualities, which are of the same nature as the three spatial dimensions — for the three spatial dimensions are a kind of configuration — to the external world.

The other, secondary qualities, which are actually experienced qualitatively as sensory content, such as color, sound, warmth, smell, and taste, were now regarded only as the effects of things on human beings, as inner experiences. But I have pointed out how, within the physical human being, and also within the etheric human being, these secondary qualities can no longer be found, how they have therefore, in a certain sense, become outlawed for this inner part of the human being. They were no longer sought in the external world; they were transferred to the human interior. It was said: if human beings do not listen to the world, if they do not look at the world, if they do not reveal their sense of warmth to the world, then the world is silent, and so on. It has primary qualities, specifically formed air waves, but it has no sound; it has processes of some kind in the ether, but it has no color; it has some processes in ponderable matter, in matter that has weight, but it does not have what constitutes warmth, etc. In this scientific age, this meant nothing more than that we did not know where to place these sensory qualities. We did not want to look for them in the world. We admitted that we had no power to find them in the world. They were sought within, but only because people were or are thoughtless. They were or are thoughtless in the sense that they do not take into account that if one really searches this inner being of the human being, as far as one allows it, that is, if one searches it through as far as this is naturally possible — but this only happens as an ideal, so that one cannot really speak of the fact of a complete search — if one searches this inner self, one finds these secondary qualities nowhere. One therefore does not really know where to place them in the world. Where does this come from?.

Well, let us remember once again: if one wants to look at something in the right way, something that relates to form, space, geometry or even arithmetic, if one wants to look at it really correctly, one must consider the inner activity, this life-filled activity through which human beings construct space in their own organism, as in up and down, front and back, right and left. In this case, we must therefore say: if you want to find the essence of the geometric-spatial — but you could also say, quite meaningfully: if you want to find the essence of Locke's primary qualities of physical things — then you must look within yourself, otherwise you will only arrive at abstractions. Now, with secondary qualities, sound, color, warmth, smells, and taste, that human beings must know something about them—this knowledge may be very instinctive, but they must know something about them—because their spiritual-soul nature does not live solely in their physical and etheric bodies, but can also exist outside these bodies with their ego and astral body, namely in the state of sleep. But just as human beings, in a full, intensely felt waking state, do not experience the primary qualities outside themselves but within themselves, as in the special case of the three dimensions, so too, when human beings succeed, either through instinct or through instinctive self-knowledge or through spiritual scientific training, in actually experiencing inwardly what is outside the physical body and etheric body from the moment of falling asleep until the moment of waking up, then they also know that they are then truly experiencing the true essence of sound, color, smell, taste, and warmth in the external world outside their bodies. When human beings are awake and only within themselves, they can experience nothing other than the images of the true realities of sound, color, warmth, smell, and taste. But these images correspond to spiritual-soul realities, not physical-etheric realities. Nevertheless, although what we experience as sound seems to be so closely connected — and indeed it is — but in a completely different way — with certain air waves, just as color is connected with certain processes in the colorless external world, we must nevertheless recognize that sound, color, and so on are images, not of the physical, but of the spiritual, the spiritual-soul, which is in the external world.

We must therefore be able to say to ourselves: when we experience a sound, a color, a quality of warmth, we experience them in images. But we experience them in reality when we are outside our bodies. And so we can schematically represent the facts in the following way (see drawing): Human beings experience primary qualities while awake, fully awake, within themselves, and see them in the external world in images; if they only know them in the external world, they only have these primary qualities in images (arrow). These images are the mathematical, geometric, and arithmetic aspects of things.

It is different with the secondary qualities. Man experiences these when I designate the physical and etheric bodies of man with these horizontal lines and the spiritual-soul, the I and the astral, with the red lines – man experiences these outside his physical and etheric bodies and projects only the images into himself. Because this was no longer understood in the age of natural science, mathematical forms, including numbers, became something that people sought only in the external world in an abstract way. The secondary qualities became something that people sought only within themselves. But because they are mere images, they were completely lost to reality.

It was the case that individual personalities who still had traditions from older views of the external world struggled to form mental images that were more realistic than those which, I would say, gradually emerged as the official ones during the scientific age. For example, apart from Paracelsus, there was also van Helmont, who was well aware that when color, sound, etc. are experienced, the spiritual aspect of human beings is active. But because this spiritual element in the waking state can only act with the help of the physical body, it produces within itself merely an image of what is contained as essence in sound, color, and so on, and thus one arrives at an inaccurate description of external reality, namely, the purely mathematical-mechanical form of movement, the movement pattern for what is to be experienced as secondary qualities within the human being. Whereas in truth, according to its reality, it can only be experienced outside the human body. One must not say to a person: If you want to recognize the true essence of sound, for example, you must conduct physical experiments on what happens internally in the air that brings the sound to you when you hear it. Instead, one must say to the person: If you want to know the true nature of sound, you must form a mental image of how you actually experience sound outside your physical and etheric body. But these are thoughts that were not thought by the people of the scientific age, because these people did not want to go into the complete nature of the human being, because they did not develop any inclination to know the true nature of the human being. And so they did not find mathematics or even the primary qualities in human nature, which was unknown to them; and so they did not find the secondary qualities in the outer world — because they did not know that human beings also belong to the outer world.

I am not saying that one must be clairvoyant in order to gain the right insight into these things, but I must emphasize that, although clairvoyant explanations of the world can provide deeper and more intense insights, especially in this area, healthy self-observation leads to the conclusion that the mathematical, the primary qualities, the mathematical-mechanical, into the inner life of human beings, and the secondary qualities into the outer world of human beings. People no longer understood human nature. They did not really know how the physical nature of human beings is filled with spirituality, how spirituality, in being awake within human beings, must forget itself, must give itself completely to the body in order to understand the mathematical. And one did not know the other thing either, that spirituality must gather itself together completely and live independently of the body, that is, outside the body, in order to attain the secondary qualities. I say that clairvoyant perception can give more intense insights into all these things, but it is not necessary. Self-observation, real, healthy self-observation, can feel, recognize with true feeling, that mathematics is also something inner and human, and that tone, color, etc. are also something external.

I described what can simply be a healthy feeling, but one that leads to real insights in this direction, in the 1980s in my introductions to Goethe's Scientific Writings. No clairvoyant knowledge was taken into account, but it was shown to what extent human beings can come to recognize the reality of color, sound, etc. without clairvoyant knowledge. This has not yet been understood. The scientific age is still too much caught up in Lockean thinking. This could not be understood, nor could it be understood when I explained it, I would say philosophically, in 1911 at the Philosophical Congress in Bologna. There I tried to show how the spiritual-soul life of the human being, although it is in the physical and etheric body when awake, nevertheless remains internally independent in terms of its quality, in a sense by filling the physical and etheric body. If one feels this inner independence of the spiritual-soul aspect of the human being, then one also has a sense of what the spiritual-soul aspect experiences in sleep from the realities of green and yellow, G and C sharp, warm and cold, sour and sweet, etc. But the scientific age did not want to go into real knowledge of human beings at first.

We see very clearly in this characterization of the relationship of human beings to the world according to primary and secondary qualities how human beings lose the ability to have a correct perception of themselves and their relationship to the world. But the same thing was also contained in other mental images that were gained about human beings. Because it was impossible to gain any insight into how mathematics lives in its three dimensions within human beings, it was also impossible to see through to the essence of human beings in relation to their spirituality. For this essence would have consisted in saying to oneself: Human beings are able to grasp right and left through the symmetrical movement of their arms and hands and through the other symmetrical movements they perform. For example, by feeling the passage of their food, they are able to experience front and back. They experience up and down because, during their lives, they first place themselves in this up and down. If you see this, you can see how humans internally develop the activity that lies in the creation of the three spatial dimensions, and when you talk about humans in relation to the animal world, you will point out the characteristic feature that animals do not have up and down in the same way as humans, for example, because their essential body axis is horizontal, that is, in what humans perceive as front and back. The abstract spatial scheme was no longer sufficient to explore anything other than mathematical-mechanical-abstract relationships in inorganic nature. For example, it was not sufficient to develop a view of the inner experience of space, on the one hand in animals and on the other in humans.

And so, in this scientific age, no correct opinion could initially be formed on the question: How does man actually relate to animals, and animals to man? How do they differ? However, people still felt in a certain way: There is a difference between humans and animals — so people sought it in all kinds of characteristics that cannot be thoroughly characteristic of either humans or animals. A very significant example of this is that, with reference to the upper jaw of humans, in which the upper teeth are located, it has been said: This jawbone is a single bone in humans; in animals, it is such that the front incisors are located in a separate intermaxillary bone, and only on both sides of this intermaxillary bone is the actual upper jaw. Humans do not have this intermaxillary bone. So, once it was no longer possible to find the relationship between animals and humans through inner spiritual and mental qualities, it was seen in something so external that it was said: Animals have the intermaxillary bone, humans do not.

Goethe was someone who, although he could not put into words insights such as those I have expressed today about primary and secondary qualities, nor could he form any external thoughts about them with complete clarity, nevertheless had a healthy feeling for all these things. Above all, Goethe knew instinctively that the difference between humans and animals must be found in the whole of human education and not in something individual. That is why Goethe became an opponent of the idea that humans lack a premaxillary bone. As a young man, he wrote his significant treatise, which attributes a premaxillary bone in the upper jaw to both humans and animals. And he succeeded in finding complete factual proof for this assertion by showing how, even in the embryonic state of humans, the intermaxillary bone is clearly visible, but how, as humans develop, i.e., already in small children, it grows together with the upper jaw, while in animals it remains separate. Goethe dealt with all this out of a certain instinctive knowledge, and out of this instinctive knowledge he initially came to say: One must not seek the difference between humans and animals in such details; one must seek it in the whole relationship of their form, their soul, their spirit to the world. Therefore, Goethe's opposition to natural scientists who deny that humans have an intermediate jaw means, on the one hand, that he brought humans closer to animals in terms of their external appearance in order to be able to show their true differences in terms of their actual nature. This view, which Goethe opposed out of an instinct for knowledge to the form of natural science that had been accepted until his time and which still prevails today, did not really find any followers within scientific circles. In contrast, the 19th century saw the emergence of a tendency, as a consequence of everything that had developed in the field of natural science since the 15th century, to bring humans closer to animals, not in order to seek their differences in external characteristics, but to bring their essence closer to that of animals. And this tendency is then contained in what emerged as the Darwinian theory of evolution and so on. This has found followers. Goethe's view has found no followers. Indeed, some have even treated Goethe as a kind of Darwinist because they see in Goethe only that he brought man closer to animals through something like the intermaxillary bone. But they do not see that he did this in order to point out, as it were — he did not point it out explicitly, but it lies in his worldview — that the difference between humans and animals must be found in something quite different from these external features.

Because people knew nothing more about human beings, they sought their essential characteristics in animals and said to themselves: There are the animal characteristics, they are only somewhat more highly developed in human beings. People had less and less of an idea that human beings, purely in terms of space, must have a completely different relationship to the world in their perception. And basically, all views on the development of living beings in the scientific age arose in such a way that they formed systems that excluded any real knowledge of man. People did not know what to make of the essence of man. Therefore, they simply placed him at the end of the animal chain. They said, in a manner of speaking: There are the animals; then the animals reach a final degree of perfection, a most perfect animal, and this most perfect animal is man.

I wanted, my dear friends and distinguished audience, to draw your attention to these debates and show you how, with a certain inner consistency, the various branches of scientific thinking have proceeded since the first phase of this thinking, from the 15th century to the present day, and how man imagines his relationship to the world in the fields of physics and physiology by saying: Out there is a silent, colorless world. It acts upon you. You form colors, you form sounds within yourself as experiences of the effects of the external world. How man said this to himself on the one hand, and on the other hand also said: There are three spatial dimensions in the external world without you — how man said this to himself because he had lost the ability to respond to the perfection of man, he also formed mental images in his views of animal and human form that did not correspond to the real nature of man. And so, despite these great, tremendous advances, which from a certain point of view can rightly be described as human advances of the highest order, one can say: The scientific worldview has become great precisely because it has completely disregarded man and his nature. However, one did not really have any idea of how much one disregarded the real human being by viewing him scientifically. For example, particularly enthusiastic materialistic thinkers of the 19th century described how human beings could not claim anything particularly spiritual for themselves, because what appears to be spiritual is merely the effect of what takes place externally in space and time. And such enthusiastic natural philosophers described how light affects humans, that is, according to their view, how the etheric continues to vibrate inwardly in their nerves, but also how the external air continues in them through breathing, etc. And then they said, for example, in summary: Oh, humans are dependent on every increase in temperature, on every decrease in temperature. Man is dependent on everything that occurs, for example, as a deformation of his nervous system. Such a discussion was exaggerated by saying: Man is a creature dependent on every movement or pressure of the air and the like.

Anyone who takes such descriptions at face value can see that they do not describe the true nature of human beings, but rather what makes them neurasthenic. For example, if we consider the views of 19th-century materialist thinkers on human beings, we can say: Yes, those would not be human beings, they would be specific neurasthenics, if human beings were as dependent on every breath of air as these materialistic thinkers describe them. They spoke of this neurasthenic as a human being, leaving out what is the actual essence, and knowing only that which makes this true essence, which remained unknown, a neurasthenic. Everywhere, little by little, the true nature of man is falling out of this thinking because of the special character that thinking about nature has taken on. We are losing sight of the true nature of man. This is what Goethe actually rebelled against, even though he was unable to express in clearly formulated sentences what he had recognized as true according to his own views.

One must trace what I have just presented to you in the inner upheaval of the development of scientific thinking since the 15th century, and one will find that this is precisely what is important in this development. I would say that in his youth Goethe was intensely interested in what natural science had produced in its various fields. He studied it, allowed himself to be inspired by natural science, but did not agree with everything that came his way, because he felt in everything that human beings were excluded from these views. Goethe, however, felt intensely the whole human being. That is why he rebelled in the most diverse fields against the scientific view he saw around him. And it is important to understand this scientific development since the 15th century by viewing it against the background of Goethe's worldview. The best way to arrive at this conclusion, if one wants to proceed purely historically, is to note that this view lacks the actual essence of the human being, which is already missing in the physical sciences and also in the biological sciences.

This is not meant to be a criticism of the scientific worldview, but merely a characteristic description. For let us suppose that someone says: Here I have water. I cannot use it like this. I separate the oxygen from the hydrogen because I need the hydrogen. — He separates the oxygen from the hydrogen. When I then observe the result, this is not a criticism of his behavior. I do not have to say to him: You are doing something wrong because you must leave the water alone. — Water is not hydrogen. Nor is it a criticism when I say: Scientific development since the 15th century took the world of living beings and, just as chemists separate oxygen from water, separated human beings from their true nature, threw them away, and kept what was needed at the time, just as others need hydrogen, and led inhuman science to the triumphs to which it led. — It is not a criticism to say such a thing, but rather a characterization. The modern natural scientist needed nature to be inhuman, in a sense, just as a chemist may need hydrogen to be oxygen-free and therefore needs to separate water into hydrogen and oxygen. But one must understand what is at stake, so that one does not constantly fall back into the error of seeking the essence of man somewhere in the natural sciences. That would be just as impossible as seeking the oxygen that someone has extracted from water in the hydrogen that they bring you.

These things must be viewed in this way if one wants to gain a correct understanding of these historical views. Tomorrow I will continue with the description of the birth and development of natural science in modern times.