The Origins of Natural Science

GA 326

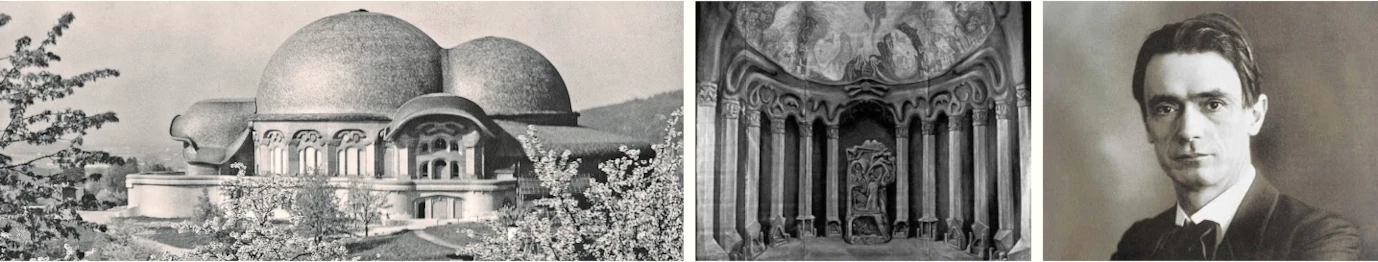

28 December 1923, Dornach

Lecture V

The isolation of man's ideas (especially his mathematical ideas) from his direct experience has proved to be the outstanding feature of the spiritual development leading to modern scientific thinking. Let us place this process once more before our mind's eye.

We were able to look back into ages past, when what man had to acquire as knowledge of the world was experienced in communion with the world. During those epochs, man inwardly did not experience his threefold orientation—up-down, left-right, front-back—in such a manner that he attributed it solely to himself. Instead, he felt himself within the universal whole; hence, his own orientations were to him synonymous with the three dimensions of space. What he pictured of knowledge to himself, he experienced jointly with the world. Therefore, with no uncertainty in his mind, he knew how to apply his concepts, his ideas, to the world. This uncertainty has only arisen along with the more recent civilization. We see it slowly finding its way into the whole of modern thought and we see science developing under this condition of uncertainty. This state of affairs must be clearly recognized.

A few examples can illustrate what we are dealing with . Take a thinker like John Locke, who lived from the seventeenth into the eighteenth century. His writings show what an up-to-date thinker of his age had to say concerning the scientific world perception. John Locke43John Locke: Wrington by Bristol 1632–1704 Oates, Essex. Theologian, philosopher, and physician. Because raised Protestant and Puritan, he was persecuted in England and had to flee to Holland until after the English Revolution of 1689. From 1675–1689 Locke worked with many interruptions at his main work. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, 1690. Originally he had planned a critical presentation of the already recognized teaching of primary and secondary sense characteristics, but then it grew to a perception theory or world view. His Essay was published 4 times in his lifetime. See Riddles of Philosophy, The Philosophy of Freedom, trans. Michael Wilson (Spring Valley, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1964) and “Cardinal Nicolas of Cusa” in Mysticism at the Dawn of the Modern Age. divided everything that man perceives in his physical environment into two aspects. He divided the characteristic features of bodies into primary and secondary qualities. Primary qualities were those that he could only attribute to the objects themselves, such as shape, position, and motion. Secondary qualities in his view were those that did not actually belong to the external corporeal things but were an effect that these objects had upon man. Examples are color, sound, and warmth. Locke stated it thus: “When I hear a sound, outside of me there is vibrating air. In a drawing, I can picture these vibrations in the air that emanate from a sound-aroused body and continue on into my ear. The shape that the waves, as they are called, possess in the vibrating air can be pictured by means of spatial forms. I can visualize their course in time—all this, belonging to the primary qualities, certainly exists in the external world, but it is silent, it is soundless. The quality of sound, a secondary quality, only arises when the vibration of the air strikes my ear, and with it arises that peculiar inner experience that I carry within me as sound. It is the same with color, which is now lumped together with light. There must be something out there in the world that is somehow of a corporeal nature and somehow possesses shape and movement. This exercises an effect on my eye and thus becomes my experience of light or color. It is the same with the other things that present themselves to my senses. The whole corporeal world must be viewed like this; we must distinguish between the primary qualities in it, which are objective, and the secondary qualities, which are subjective and are the effects of the primary qualities upon us.”

Simply put, one could say with Locke that the external world outside of man is form, position, and movement, whereas all that makes up the content of the sense world exists in truth somehow inside us. The actual content of color as a human experience is nowhere in the environment, it lives in me. The actual content of sound is nowhere to be found outside, it lives in me. The same is true of my experience of warmth or cold.

In former ages, when what had become the content of knowledge was experienced jointly with the world, one could not possibly have had this view because, as I have said, a man experienced mathematics by participating in his own bodily orientation and placing this orientation into his own movement. He experienced this, however, in communion with the world. Therefore, his own experience was sufficient reason for assuming the objectivity of position, place, and movement. Also, though in another portion of his inner life, man again had this communion with the world in regard to color, tone, and so forth. Just as the concept of movement was gained through the experience of his own movement, so the concept of color was gained through a corresponding internal experience in the blood, and this experience was then connected with whatever is warmth, color, sound, and so forth in the surrounding world. Certainly, in earlier times, man distinguished position, location, movement, and time-sequence from color, sound, and warmth, but these were distinguished as being different kinds of experiences that were undergone jointly with different kinds of existence in the objective world.

Now, in the scientific age, the determination of place, movement, position, and form ceased to be inward self-experience. Instead, they were regarded as mere hypotheses that were caused by some external reality. When the shape of a cannon is imagined, one can hardly say: This form of the cannon is actually somehow within me. Therefore its identification was directed outward and the imagined form of the cannon was related to something objective. One could not very well admit that a musket-ball was actually flying within one's brain; therefore, the hypothetically thought-out movements were attributed to something objective.

On the other hand, what one saw in the flying musket-ball, the flash by which one perceived it and the sound by which one heart it, were pushed into one's own human nature, since no other place could be found for them. Man no longer knew how he experienced them jointly with the objects; therefore, he associated them with his own being.

It actually took quite some time before those who thought along the lines of the scientific age perceived the impossibility of this arrangement. What had in fact taken place? The secondary qualities, sound, color, and warmth experience, had become, as it were, fair game in the world and, in regard to human knowledge, had to take refuge in man. But before too long, nobody had any idea of how they lived there. The experience, the self-experience, was no longer there. There was no connection with external nature, because it was not experienced anymore. Therefore these experiences were pushed into one's self. So far as knowledge was concerned, they had, as it were, disappeared inside man. Vaguely it was thought that an ether vibration out in space translated itself into form and movement, and this had an effect on the eye, and then worked on the optic nerve, and finally somehow entered the brain. Our thoughts were a means of looking around inside for whatever it was that, as an effect of the primary qualities, supposedly expressed itself in man as secondary qualities. It took a long time, as I said, before a handful of people firmly pointed out the oddity of these ideas. There is something extraordinary in what the Austrian philosopher Richard Wahle44Richard Wahle: 1857–1935, Vienna, Professor of Philosophy. Only valued perceptions, imaginations, and feelings, but rejected all philosophy hitherto written as theories of cognition. The “Ego” is for him “a summary of surface-like, physiologically accompanied pieces of consciousness, which are brought into being by invisible forces.” Some writings: The Whole of Philosophy and Its End, 1894; About the Mechanism of the Spiritual Life, 1906; The Tragic Comedy of Wisdom, 1915; Development of Characters, 1928; Basics of a New Psychiatry, 1931. wrote in his Mechanism of Thinking, though he himself did not realize the full implications of his sentence: “Nihil est in cerebro, quod non est in nervis.” (“There is nothing in the brain that is not in the nerves.” It may not be possible with the means available today to examine the nerves in every conceivable way, but even if we could we would not find sound, color, or warmth experience in them. Therefore, they must not be in the brain either. Actually, one has to admit now that they simply disappear insofar as knowledge is concerned. One examines the relationship of man to the world. Form, position, place, time, etc. are beheld as objective. Sound, warmth, experience and color vanish; they elude one.45See Rudolf Steiner, The Philosophy of Freedom, Chapter 4.

Finally, in the Eighteenth Century, this led Kant46Immanuel Kant: 1724–1804. Lived in Koenigsberg, which he seldom left. Philosopher, scientist, mathematician. Professor in Koenigsberg 1770–1794. Critique of Pure Reason, 1781. Its popular edition Dissertation on Any Future Metaphysics, 1783, his ethic Critique of Practical Reason, 1788, aesthetic and natural theology is handled in Critique of Judgment, 1790. He wrote the first mechanical cosmology 1755. It was taken up and changed by Laplace (1796) and known as the Kant-LaPlace Theory. Rudolf Steiner's exposition on Kant's theory is found in Truth and Knowledge, The Philosophy of Freedom, and An Autobiography, ed. Paul M. Alien, 2nd ed. (Blauvelt, NY: Steinerbooks, Garber Communications, 1980).

E.g. in Critique of Pure Reason, “Transcendental Aesthetic, Common Remarks”: “We wanted to say that all our opinions are nothing but the conception of the appearance; that the things we look at are not actually what we take them for, nor is their relation constituted as they appear to us, and that if we would suspend our subject or even our subjective constitution of our senses as a whole, the whole constitution, all relationships of objects in space and time, even time and space itself would disappear. They would only exist in us, not as phenomena in themselves.” to say that even the space and time qualities of things cannot somehow be outside and beyond man. But there had to be some relationship between man and the world. After all, such a relationship cannot be denied if we are to have any idea of how man exists together with the world. Yet, the common experience of man's space and time relationships with the world simply did not exist anymore. Hence arose the Kantian idea: If man is to apply mathematics, for example, to the world, then it is his doing that he himself makes the world into something mathematical. He impresses the whole mathematical system upon the “things in themselves,” which themselves remain utterly unknown.—In the Nineteenth Century science chewed on this problem interminably. The basic nature of man's relation to cognition is simply this: uncertainty has entered into his relationship with the world. He does not know how to recognize in the world what he is experiencing. This uncertainty slowly crept into all of modern thinking. We see it entering bit by bit into the spiritual life of recent times.

It is interesting to place a recent example side by side with Locke's thinking. August Weismann,47August Weismann, Frankfurt A.M. 1834–1914 Freiburg. Biologist, genetic scientist. Theory of polarity between cells (soma) and seed plasma. Determinants as heredity carriers. Writing: Studies on the Descent Theory. a biologist of the Nineteenth Century, conceived the thought: in any living organism, the interplay of the organs (in lower organisms, the interaction of the parts) must be regarded as the essential thing. This leads to comprehension of how the organism lives. But in examining the organism itself, in understanding it through the interrelationship of its parts, we find no equivalent for the fact that the organism must die. If one only observes the organism, so Weismann said, one finds nothing that will explain death. In the living organism, there is absolutely nothing that leads to the idea that the organism must die. For Weismann, the only thing that demonstrates that an organism must die is the existence of a corpse. This means that the concept of death is not gained from the living organism. No feature, no characteristic, found in it indicates that dying is a part of the organism. It is only when the event occurs, when we find a corpse in the place of the living organism, that we know the organism possesses the ability to die.

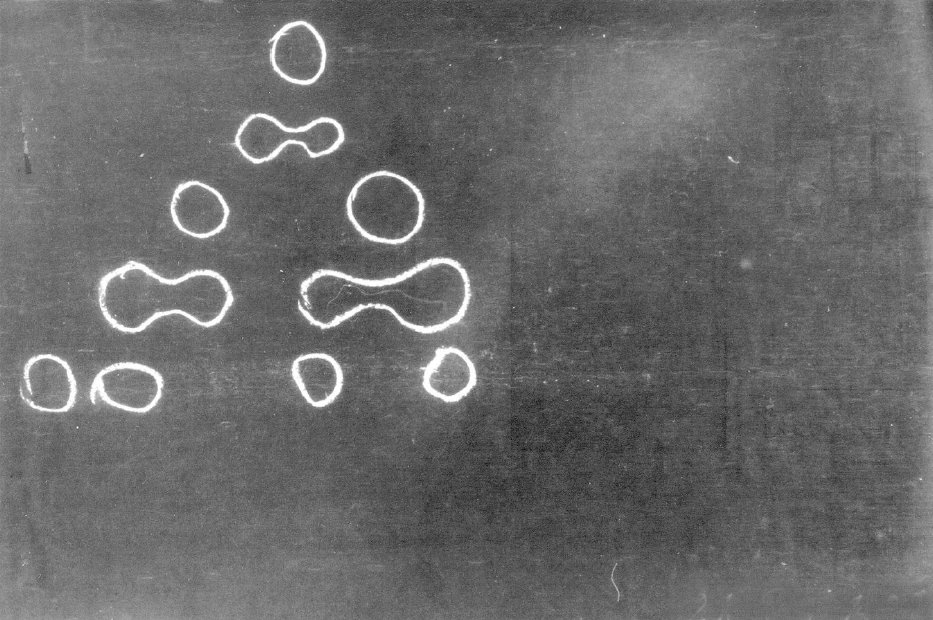

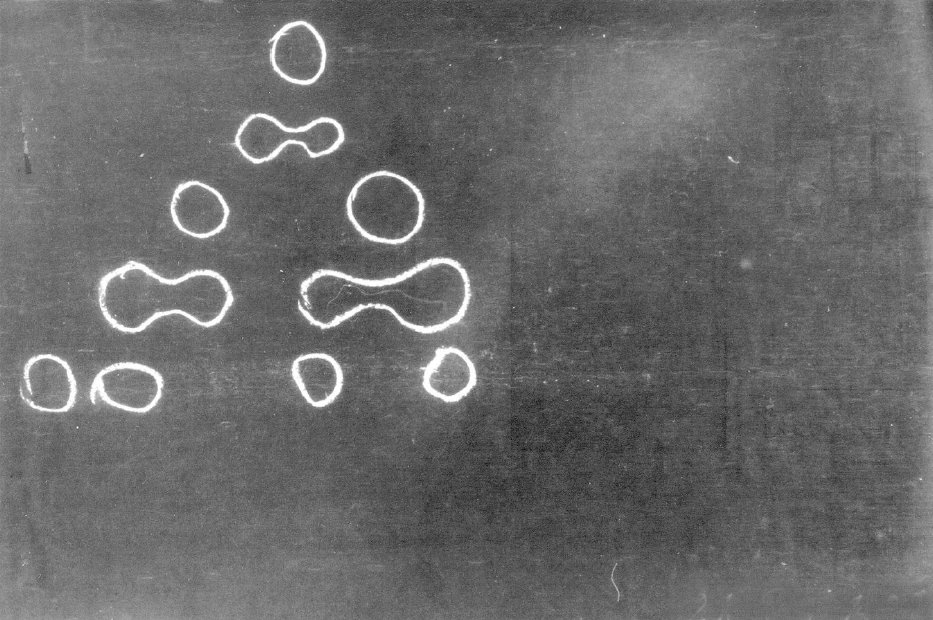

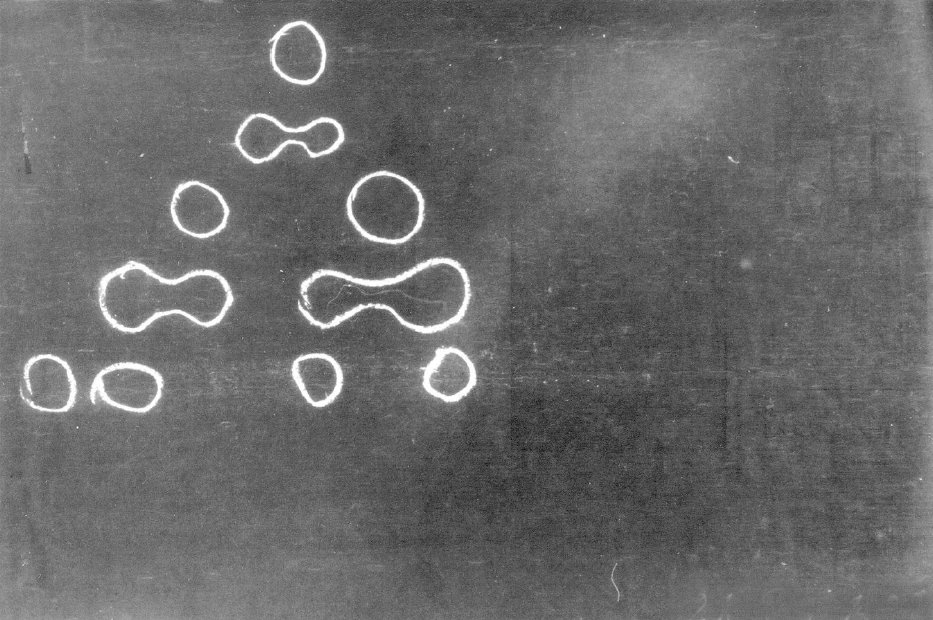

But, says Weismann, there is a class of organisms where corpses are never found. These are the unicellular organisms. They only divide themselves so there are no corpses. The propagation of such beings looks like this:

One divides into two; each of these divides into two again, and so on. There is never a corpse. Weismann therefore concludes that the unicellular beings are immortal. This is the immortality of unicellular beings that was famous in nineteenth-century biology. Why were these organisms considered immortal? Because they never produce any corpses, and because we cannot entertain the concept of death in the organic realm as long as there are no corpses. Where there is no corpse, there is no room for the concept of death. Hence, living beings that produce no corpses are immortal.

This example shows how far man has removed himself in modern times from any connection between the world and his thinking, his inner experiences. His concept of an organism is no longer such that the fact of its death can be perceived from it. This can only be deduced from the existence of something like a corpse. Certainly, if a living organism is only viewed from outside, if one cannot experience what is in it, then indeed one cannot find death in the organism and an external sign is necessary. But this only proves that in his thinking man feels himself separated from the things around him.

From the uncertainty that has entered all thinking concerning the corporeal world, from this divorce between our thoughts and our experience, let us turn back to the time when self-experience still existed. Not only did the inwardly experienced concept exist alongside the externally excogitated concept of a triangle, square, or pentagram, but there were also inwardly experienced concepts of blossoming and fading, of birth and death. This inner experience of birth and death had its gradations. When a child was seen to grow more and more animated, when its face began to express its soul, when one really entered into this growing process of the child, this could be seen as a continuation of the process of birth, albeit a less pronounced and intensive one. There were degrees in the experience of birth. When a man began to show wrinkles and grey hair and grow feeble, this was seen as a first mild degree of dying. Death itself was only the sum total of many less pronounced death experiences, if I may use such a paradox. The concepts of blossoming and decaying, of being born and dying, were inwardly alive.

These concepts were experienced in communion with the corporeal world. No line was drawn between man's self-experience and the events in nature. Without a coastline, as it were, the inner land of man merged into the ocean of the universe. Owing to this form of experience, man lived himself into the world itself. Therefore, the thinkers of earlier ages, whose ideas no longer receive proper attention from science, had to form quite different ideas concerning something like what Weismann called the “immortality of unicellular beings.” What sort of concept would an ancient thinker have formed had he had a microscope and known something about the division of unicellular organisms? He would have said: First I have the unicellular being; it divides itself into two. Somewhat imprecisely, he might have said: It atomizes itself, it divides itself; for a certain length of time, the two parts are indivisible; then they divide again. As soon as division or atomization begins, death enters in. He would not have derived death from the corpse but from atomization, from the division into parts. His train of thought would have been somewhat as follows: A being that is capable of life, that is in the process of growth, is not atomized; and when the tendency to atomization appears, the being dies. In the case of unicellular beings, he would simply have thought that the two organisms cast off by the first unicellular being were for the moment dead, but would be, so to speak, revived immediately, and so forth. With atomization, with the process of splitting, he would have linked the thought of death. If he had known about unicellular beings and had seen one split into two, he would not have thought that two new ones had come into being. On the contrary, he would have said that out of the living monad, two atoms have originated. Further, he would have said that wherever there is life, wherever one observes life, one is not dealing with atoms. But if they are found in a living being, then a proportionate part of the being is dead. Where atoms are found, there is death, there is something inorganic. This is how matters would have been judged in a former age based on living inner knowledge of the world.

All this is not clearly described in our histories of philosophy, although the discerning reader can have little doubt of it. The reason is that the thought-forms of this older philosophy are totally unlike today's thinking. Therefore anyone writing history nowadays is apt to put his own modern concepts into the minds of earlier thinkers.48Goethe's recital from Faust I, Act 1, Scene 2, “Night,” Gothic Room, Wagner and Faust:

“My friend, the time of past

Is a book with seven seals.

What you call the Spirit of Time

Is fundamentally the Gentleman's own spirit,

In which the times reflect themselves.” But this is impermissible even with a man as recent as Spinoza. In his book on what he justifiably calls ethics, Spinoza follows a mathematical method but it is not mathematics in the modern sense. He expounds his philosophy in a mathematical style, joining idea to idea as a mathematician would. He still retains something of the former qualitative experience of quantitative mathematical concepts. Hence, even in contemplating the qualitative aspect of man's inner life, we can say that his style is mathematical. Today with our current concepts, it would be sheer nonsense to apply a mathematical style to psychology, let alone ethics.

If we want to understand modern thinking, we must continually recall this uncertainty, contrasting it to the certainty that existed in the past but is no longer suited to our modern outlook. In the present phase of scientific thinking, we have come to the point where this uncertainty is not only recognized but theoretical justifications have been offered for it. And example is a lecture given by the French thinker Henri Poincaré49Henry Poincaré: Nancy 1854–1912 Paris. Author of the popular philosophical writings Science and Hypothesis (1902), The Value of Science (1905), Science and Method (1909), and Last Thoughts (1912). The lecture in question was held by Poincaré shortly before his death in a lecture cycle Conferences de Foi et de Vie printed in Le Materialisme Actuel with M.M. Bergson, H. Poincaré, Ch. Gide, Ch. Wagner, Firm Roz, De Witt-Guizotfriedel, Gaston Rion. (Paris: 1918), page 53. in 1912 on current ideas relating to matter. He speaks of the existing controversy or debate concerning the nature of matter; whether it should be thought of as being continuous or discrete; in other words, whether one should conceive of matter as substantial essence that fills space and is nowhere really differentiated in itself, or whether substance, matter, is to be thought of as atomistic, signifying more or less empty space containing within it minute particles that by virtue of their particular interconnections form into atoms, molecules, and so forth.

Aside from what I might call a few decorative embellishments intended to justify scientific uncertainty, Poincaré's lecture comes down to this: Research and science pass through various periods. In one epoch, phenomena appear that cause the thinker to picture matter in a continuous form, making it convenient to conceive of matter this way and to focus on what shows up as continuity in the sense data. In a different period the findings point more toward the concept of matter being diffused into atoms, which are pictured as being fused together again; i.e. matter is not continuous but discrete and atomistic. Poincaré is of the opinion that always, depending on the direction that research findings take, there will be periods when thinking favors either continuity or atomism. He even speaks of an oscillation between the two in the course of scientific development. It will always be like this, he says, because the human mind has a tendency to formulate theories concerning natural phenomena in the most convenient way possible. If continuity prevails for a time, we get tired of it. (These are not Poincaré's exact words, but they are close to what he really intends.) Almost unconsciously, as it were, the human mind then comes upon other scientific findings and begins to think atomistically. It is like breathing where exhalation follows inhalation. Thus there is a constant oscillation between continuity and atomism. This merely results from a need of the human mind and according to Poincaré, says nothing about the things themselves. Whether we adopt continuity or atomism determines nothing about things themselves. It is only our attempt to come to terms with the external corporeal world.

It is hardly surprising that uncertainty should result from an age which no longer finds self-experience in harmony with what goes on in the world but regards it only as something occurring inside man. If you no longer experience a living connection with the world, you cannot experience continuity or atomism. You can only force your preconceived notions of continuity or atomism on the natural phenomena. This gradually leads to the suspicion that we formulate our theories according to our changing needs. Just as we must breath in and out, so we must, supposedly, think first continuistically for a while, then atomistically for a while. If we always thought in the same way, we would not be able to catch a breath of mental air. Thus our fatal uncertainty is confirmed and justified. Theories begin to look like arbitrary whims. We no longer live in any real connection with the world. We merely think of various ways in which we might live with the world, depending on our own subjective needs.

What would the old way of thought have said in such a case? It would have said: In an age when the leading thinkers think continuistically, they are thinking mainly of life. In one in which they think atomistically, they are thinking primarily of death, of inorganic nature, and they view even the organic in inorganic terms.

This is no longer unjustified arbitrariness. This rests on an objective relationship to things. Naturally, I can take turns in dealing with the animate and the inanimate. I can say that the very nature of the animate requires that I conceive of it continuistically, whereas the nature of the inanimate requires that I think of it atomistically. But I cannot say that this is only due to the arbitrary nature of the human mind. On the contrary, it corresponds to an objective relating of oneself to the world. For such perception, the subjective aspect is really disregarded, because one recognizes the animate in nature in continual form and the inanimate in discrete form. And if one really has to oscillate between the two forms of thought, this can be turned in an objective direction by saying that one approach is suited to the living and the other is suited to the dead. But there is no justification for making everything subjective as Poincaré does. Nor is the subjective valid for the way of perception that belonged to earlier times.

The gist of this is that in the phase of scientific thinking immediately preceding our own, there was a turn away from the animate to the inanimate; i.e., from continuity to atomism. This was entirely justified, if rightly understood. But, if we hope to objectively and truly find ourselves in the world, we must find a way out of the dead world of atomism, no matter how impressive it is as a theory. We must get back to our own nature and comprehend ourselves as living beings. Up to now, scientific development has tended in the direction of the inanimate, the atomistic. When, in the first part of the Nineteenth Century, this whole dreadful cell theory of Schleiden50Mathias Jakob Schleiden: Hamburg 1804–1881 Frankfurt A.M. Lawyer, physician, and, mainly, biologist. Developed a cell formation theory in Contributions to Phylogenesis (1838). and Schwann51Theodor Schwann: Neuss 1810–1882 Cologne, biologist. Founded the cell theory with his Microscopic Examinations of the Harmony in Structure and Growth of Animals and Plants (1839). made its appearance, it did not lead to continuity but to atomism. What is more, the scientific world scarcely admitted this, nor has it to this day realized that it should admit it since atomism harmonizes with the whole scientific methodology. We were not aware that by conceiving the organism as divided up into cells, we actually atomized it in our minds, which in fact signifies killing it. The truth of the matter is that any real idea of organisms has been lost to the atomistic approach.

This is what we can learn if we compare Goethe's views on organics with those of Schleiden or the later botanists. In Goethe we find living ideas that he actually experiences. The cell is alive, so the others are really dealing with something organic, but the way they think is just as though the cells were not alive but atoms. Of course, empirical research does not always follow everything to its logical conclusion, and this cannot be done in the case of the organic world. Our comprehension of the organic world is not much aided by the actual observations resulting from the cell theory. The non-atomistic somehow finds its way in, since we have to admit that the cells are alive. But it is typical of many of today's scientific discussions that the issues become confused and there is no real clarity of thought.

Fünfter Vortrag

Es hat sich als das hervorragendste Kennzeichen derjenigen geistigen Entwickelung, aus welcher die naturwissenschaftliche Denkweise der neueren Zeit hervorgegangen ist, herausgestellt die Absonderung der menschlichen Ideen vom unmittelbaren menschlichen Erleben, namentlich, nach den bisherigen Ausführungen, der mathematischen Ideen. Stellen wir uns nur noch einmal vor das Seelenauge, wie das gewesen ist.

Wir haben in ältere Zeiten zurückblicken können, in denen der Mensch gewissermaßen dasjenige, was er erkennend mit der Welt auszumachen hatte, gemeinsam mit ihr erlebte, Zeiten, in denen der Mensch innerlich seine dreifache Orientierung erlebte nach oben-unten, rechts-links, vorne-hinten, in denen er aber diese Orientierung nicht so erlebte, daß er sie sich allein zuschrieb, sondern daß er sich innerhalb des Weltganzen fühlte, so daß zugleich sein Vorne-Hinten die eine, sein Oben-Unten die zweite, sein Rechts-Links die dritte Raumdimension waren. Er erlebte dasjenige, was er in der Erkenntnis sich vorstellte, gemeinsam mit der Welt. Daher war auch keine Unsicherheit in seinem Wesen, wie er seine Begriffe, seine Ideen auf die Welt anwenden solle. Diese Unsicherheit war eben erst mit der neueren Zivilisation heraufgekommen, und wir sehen diese Unsicherheit langsam in das ganze moderne Denken einziehen, und sehen die Naturwissenschaft sich unter dieser Unsicherheit entwickeln. Man muß sich über diesen Tatbestand nur völlig klar sein.

Veranschaulichen wir uns das, was da vorliegt, durch einzelne konkrete Beispiele. Nehmen wir einen solchen Denker wie John Locke, der vom 17. ins 18. Jahrhundert herüberlebte, und der ja dasjenige in seinen Schriften darstellte, was ein moderner Denker seiner Zeit über die naturwissenschaftliche Anschauung von der Welt zu sagen hatte. John Locke trennt alles dasjenige, was der Mensch in seiner physischen Umgebung wahrnimmt, in zwei Teile. Er trennt die Merkmale der Körper in sogenannte primäre Merkmale und in sekundäre. Die primären Merkmale sind diejenigen, welche er nicht anders kann als den Dingen selber zuschreiben, Gestaltung, Lage, Bewegung. Die sekundären Merkmale sind diejenigen, von denen er die Anschauung hat, daß sie nicht eigentlich den körperlichen Dingen draußen angehören, sondern nur eine Wirkung darstellen dieser körperlichen Dinge auf den Menschen. Zu diesen Merkmalen der Dinge gehört zum Beispiel die Farbe, der Ton, die Wärme als Wärmewahrnehmbares, Wärmeerlebnis. John Locke sagt: Wenn ich einen Ton höre, so ist außer mir die schwingende Luft. Ich kann diese Bewegungen in der Luft, die vom Ton-erregten Körper kommen und bis an mein Ohr sich fortpflanzen, durch meinetwillen eine Zeichnung darstellen. Die Gestalt, welche, wie man sagt, die Wellen in der schwingenden Luft haben, die kann ich durch räumliche Figuren darstellen, kann sie mir vergegenwärtigen in ihrem Verlauf in der Zeit, also als Bewegung. Dasjenige, was da im Raume vorgeht, was an den Dingen Gestalt, Bewegung, Ortsbestimmung ist, das ist sicher draußen in der Welt. Aber alles dasjenige, was da draußen in der Welt ist, was zu den primären Merkmalen gehört, das ist stumm, das ist tonlos. Die Qualität des Tones, die sekundäre Qualität entsteht erst, wenn die Luftwelle an mein Ohr anschlägt und jenes eigentümliche innere Erlebnis da ist, das ich eben als den Ton in mir trage. So auch ist es mit der Farbe, die nun einfach zusammengeworfen wird mit dem Lichte. Da muß irgend etwas draußen in der Welt sein, was irgendwie körperlich ist, was irgendwie Gestalt, Bewegung hat, und was eine Wirkung durch mein Auge auf mich ausübt und dann zu dem Licht- beziehungsweise Farberlebnis wird. Ebenso ist es bei den anderen Dingen, die uns vorliegen für unsere Sinne. Die ganze körperliche Welt muß so angesehen werden, daß wir an ihr unterscheiden die primären Qualitäten, die objektiv sind, die sekundären Qualitäten, die subjektiv sind, die Wirkungen darstellen der primären Qualitäten auf den Menschen. So also könnte man, wenn man etwas radikal schildert, sagen: Im Sinne des John Locke ist die Welt draußen, außer dem Menschen, Gestalt, Lage, Bewegung, und alles dasjenige, was eigentlich der Inhalt der Sinneswelt ist, das ist in Wahrheit irgendwie im Menschen, das webt eigentlich innerhalb der menschlichen Wesenheit. Der wirkliche Inhalt der Farbe als menschliches Erlebnis ist nirgends da draußen, der webt in mir; der wirkliche Inhalt des Tones ist nirgends da draußen, webt in mir; der wirkliche Inhalt des Wärmeerlebnisses oder Kälteerlebnisses ist nirgends da draußen, webt in mir.

In älteren Zeiten, in denen man mit der Welt gemeinsam dasjenige erlebte, was Erkenntnisinhalt geworden ist, konnte man nicht dieser Anschauung sein, denn man erlebte, wie ich dargestellt habe, durch das Mitmachen der eigenen Körperorientierung und des Hineinstellens dieser Orientierung in die eigene Bewegung, darinnen erlebte man die mathematischen Inhalte. Aber man erlebte das zusammen mit der Welt. Man hatte also auch in seinem Erleben zu gleicher Zeit den Grund, warum man Lage, Ort, Bewegung als objektiv annahm. Aber man hatte, nur für einen anderen Teil des inneren menschlichen Lebens, das Zusammenleben mit der Welt auch für Farbe, Ton und so weiter. Geradeso wie man zu der Vorstellung der Bewegung kam aus dem Erlebnis des eigenen Bewegens als Mensch heraus, so kam man zu der Vorstellung der Farbe, indem man in seiner Blutorganisation ein entsprechendes inneres Erlebnis hatte, und dieses innere Erlebnis zusammenbrachte mit demjenigen, was da draußen in der Welt Wärme, Farbe, Ton und so weiter ist. Man unterschied zwar auch in früherer Zeit Lage, Ort, Bewegung, Zeitenverlauf von Farbe, Ton, Wärmeerlebnis, aber man unterschied sie eben als verschiedene Erlebnisarten, die auch zusammen durchgemacht wurden mit verschiedenen Arten des Seins in der objektiven Welt. Jetzt, im naturwissenschaftlichen Zeitalter, war man dazu gekommen, nicht mehr die Ortsbestimmung, die Bewegung, die Lage, die Gestalt und so weiter als Selbsterlebnis zu haben, sondern nur als etwas Ausgedachtes, das man identifizierte mit demjenigen, was draußen war, draußen ist. Und da es doch nicht ganz gut geht, wenn man sich die Gestalt einer Kanone vorstellt, zu sagen: Diese Gestalt der Kanone ist eigentlich irgendwie in mir -, so identifizierte man da eben nach außen. Man bezog die ausgedachte Gestalt der Kanone auf ein Objektives. Da man schließlich auch nicht gerade zugeben konnte, daß, wenn irgendwo eine Flintenkugel fliegt, die eigentlich im eigenen Gehirn fliege, so identifiizerte man die ausgedachten Bewegungen eben mit dem Objektiven.

Aber dasjenige, was man an der hinfliegenden Flintenkugel sah, das Farbig-Leuchtende, wodurch man es sah, das Tonliche, das man wahrnahm, das schob man in die eigene menschliche Wesenheit hinein, weil man sonst keinen Ort hatte, wo man es unterbringen konnte. Wie man es mit den Dingen zusammen erlebt, das wußte man nicht mehr, also schob man es in die menschliche Wesenheit hinein.

Es hat eigentlich ziemlich lange gebraucht, bis die im Sinne des naturwissenschaftlichen Zeitalters denkenden Menschen auf das Unmögliche dieser Vorstellung gekommen sind. Denn, was war denn eigentlich da geschehen? Die sekundären Qualitäten: Ton, Farbe, Wärmeerlebnis waren ihrerseits in der Welt, ich möchte sagen, einfach vogelfrei geworden, und sie mußten sich für die Erkenntnis in den Menschen hinein flüchten. Wie sie da drinnen wohnen, nun, darüber machte man sich allmählich überhaupt keine Vorstellungen mehr. Das Erlebnis, das Selbsterlebnis war nicht mehr da. Ein Zusammenhang mit der äußeren Natur ergab sich nicht mehr, weil man ihn nicht mehr erlebte. So schob man diese Erlebnisse in sich selber hinein. Und da waren sie für die Erkenntnis sozusagen im Inneren des Menschen eben verschwunden. So halb bewußt - halb klar, halb unklar - stellte man sich vor, daß, sagen wir, draußen im Raume eine Ätherbewegung ist, die man durch Gestalt, Bewegung eben darstellen kann, daß die eine Wirkung ausübe auf das Auge und von da aus auf den Sehnerv. Da geht es irgendwie ins Gehirn hinein. Und im Inneren suchte man nun zunächst in Gedanken dasjenige, was da als eine Wirkung von den primären Qualitäten sich als sekundäre Qualitäten im Menschen selbst ausleben soll. Es hat lange gebraucht, sage ich, bis einzelne Menschen mit einer gewissen Dezidiertheit auf das Sonderbare dieser Vorstellung hinwiesen, und es ist eigentlich etwas außerordentlich Schlagendes, was der österreichische Philosoph Richard Wahle in seinem «Mechanismus des Denkens» hingeschrieben hat, obwohl er durchaus nicht dazu kommt, diesen seinen eigenen Satz voll auszunützen: «Nihil est in cerebro, quod non est in nervis — Nichts ist im Gehirn, was nicht in den Nerven ist.» Nun kann man die Nerven selbstverständlich, auch wenn es heute noch nicht möglich ist mit unseren Mitteln, aber man könnte sie nach allen Richtungen und nach allen Seiten absuchen, man würde in den Nerven den Ton, die Farbe, das Wärmeerlebnis nicht finden. Also sind sie auch nicht im Gehirn. Eigentlich müßte man sich nun gestehen, daß sie einem für die Erkenntnis überhaupt verschwinden. Man untersucht das Verhältnis des Menschen zur Welt. Man behält Gestalt, Lage, Ort, Zeit und so weiter als objektiv; Ton, Wärmeerlebnis, Farbe, sie verschwinden, sie entfallen einem.

Das hat ja schließlich im 18. Jahrhundert dazu geführt, daß Kant gesagt hat, auch die räumlichen und zeitlichen Qualitäten der Dinge können nicht irgendwie draußen sein außer dem Menschen. Da aber doch ein Verhältnis des Menschen zu der Welt da sein sollte — denn dieses Verhältnis kann nicht weggeleugnet werden, wenn man überhaupt sich eine Vorstellung davon machen will, daß man mit der Welt lebt, aber das Zusammenerleben der räumlichen und zeitlichen Verhältnisse des Menschen mit der Welt war eben nicht mehr da -, so entstand denn der Kantsche Gedanke: Wenn der Mensch nun doch zum Beispiel die Mathematik auf die Welt anwenden soll, so muß es ihm zukommen, daß er erst selber die Welt zum Mathematischen macht, daß er das ganze Mathematische hinüberhängt über die «Dinge an sich», die selber völlig unbekannt bleiben. An diesem Problem hat ja auch dann die Naturwissenschaft des 19. Jahrhunderts furchtbar herumgenagt. Wenn man sich den Grundcharakter des eben dargestellten Verhaltens des Menschen im Erkennen vor Augen stellt, so ist es der, daß eine Unsicherheit hineingekommen ist in sein Verhältnis zur Welt. Er weiß nicht, wie er dasjenige, was er erlebt, eigentlich in der Welt sehen soll. Und diese Unsicherheit, sie kam allmählich immer mehr und mehr in dieses ganze moderne Denken hinein. Wir sehen Stück für Stück diese Unsicherheit in das neuere Geistesleben einziehen.

Nun ist es interessant, wenn man sich zu dieser älteren Phase des John Lockeschen Denkens ein Beispiel aus der neueren Zeit hinzustellt. Ein Biologe des 19. Jahrhunderts, Weismann, hat den Gedanken gefaßt, daß man eigentlich, wenn man den Organismus irgendeines Lebewesens biologisch erfaßt, die Wechselwirkung der Organe, oder bei niederen Organismen die Wechselwirkung der Teile als das Wesentliche annehmen muß, daß man dadurch zu einer Erfassung desjenigen kommt, wie der Organismus lebt, daß aber bei der Untersuchung des Organismus selber, bei dem Erkennen des Organismus in der Wechselwirkung seiner Teile sich kein Charakteristikon dafür findet, daß der Organismus auch sterben muß. Wenn man nur auf den Organismus hinschaut, sagte sich Weismann, der in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts gewirkt hat, dann findet man nichts, was das Sterben anschaulich machen kann. Daher, sagte er, gibt es innerhalb des lebendigen Organismus überhaupt nichts, was einen dazu bringen könnte, aus der Wesenheit des Organismus heraus die Idee zu fassen, daß der Organismus sterben müßte. Das einzige, was einem zeigen kann, daß der Organismus sterben muß, ist für Weismann das Vorhandensein der Leiche. Das heißt, man bildet sich den Begriff für das Sterben nicht aus an dem lebendigen Organismus. Man findet kein Merkmal, kein Charakteristikon im lebendigen Organismus, aus dem heraus man erkennen könnte, das Sterbende gehört hinzu zu dem Organismus, sondern man muß erst die Leiche haben. Und wenn dann dieses Ereignis eintritt, daß für einen lebenden Organismus eine Leiche da ist, so ist diese Leiche dasjenige, das einem zeigt: Der Organismus hat auch das Sterbenkönnen für sich.

Nun sagt aber Weismann, es gibt eine Organismenwelt, bei der man niemals Leichen entdecken kann. Das sind die einzelligen Lebewesen. Die teilen sich bloß, da kann man keine Leiche entdecken. Nehmen Sie an: ein einzelliges Lebewesen in seiner Vermehrung. Das Schema stellt sich in folgender Weise dar. Solch ein einzelliges Lebewesen teile sich in zwei, jedes wieder in zwei und so weiter. So geht die Entwickelung vorwärts, niemals ist eine Leiche da. Also, sagt sich Weismann, sind eben die einzelligen Wesen unsterblich. Das ist die berühmte Unsterblichkeit der Einzelligen für die Biologie des 19. Jahrhunderts. Und warum werden sie als unsterblich angesehen? Nun, weil sie eben nirgends eine Leiche zeigen, und weil man den Begriff des Sterbens im Organischen nicht unterbringt, wenn es einem nicht die Leiche zeigt. Wo sich einem also die Leiche nicht zeigt, hat man auch nicht den Begriff des Sterbens unterzubringen. Folglich sind diejenigen Lebewesen, die keine Leiche zeigen, unsterblich.

Sehen Sie, gerade an einem solchen Beispiel zeigt sich, wie weit man in der neueren Zeit von dem Zusammenleben seiner Vorstellungen und überhaupt seiner inneren Erlebnisse mit der Welt sich entfernt hat. Der Begriff des Organismus ist nicht mehr so, daß man ihm noch anmerken kann, er muß auch sterben. Man muß es aus dem äußeren Bestehen des Leichenhaften ersehen, daß der Organismus sterben kann. Gewiß, wenn man einen lebendigen Organismus nur so anschaut, daß man ihn außen hat, wenn man nicht dasjenige, was in ihm ist, miterleben kann, wenn man also nicht sich in ihn hineinleben kann, dann findet man auch nicht das Sterben im Organismus und braucht ein äußeres Merkmal dafür. Das aber bezeugt, daß man sich mit seiner Vorstellung überhaupt von den Dingen getrennt fühlt.

Aber blicken wir jetzt von der Unsicherheit, die in alles Denken über die Körperwelt hineingekommen war durch diese Absonderung der Begriffswelt von dem Selbsterlebnis, blicken wir in jene Zeit zurück, in welcher dieses Selbsterlebnis eben noch da war. Da gab es in der Tat ebenso, wie es nicht nur einen äußerlich gedachten Begriff eines Dreiecks oder Vierecks oder Pentagramms gab, sondern einen innerlich erlebten Begriff, so gab es einen innerlich erlebten Begriff des Entstehens und Vergehens, des Geborenwerdens und Sterbens. Und dieses innere Erlebnis des Geborenwerdens und Sterbens hatte in sich Gradation. Wenn man das Kind von innen nach außen belebter und belebter fand, wenn seine zuerst unbestimmten physiognomischen Züge innere Beseelung annahmen und man sich hineinlebte in dieses Heranleben des ganz kleinen Kindes, so erschien einem das als eine Fortsetzung des Geborenwerdens, gewissermaßen als ein schwächeres, weniger intensives, fortdauerndes Geborenwerden. Man hatte Grade im Erleben des Entstehens. Und wenn der Mensch anfing Runzeln zu kriegen, graue Haare zu kriegen, tatterig zu werden, so hatte man den geringeren Grad des Sterbens, ein weniger intensives Sterben, ein partielles Sterben. Und der Tod war nur die Zusammenfassung von vielen weniger intensiven Sterbeerlebnissen, wenn ich das paradoxe Wort gebrauchen darf. Der Begriff war innerlich belebt, der Begriff des Entstehens sowohl wie der Begriff des Vergehens, der Begriff des Geborenwerdens und der Begriff des Sterbens.

Aber indem man so diesen Begriff erlebte, erlebte man ihn zusammen mit der Körperwelt, so daß man eigentlich keine Grenze zog zwischen dem Selbsterlebnis und dem Naturgeschehen, daß gewissermaßen ohne Ufer das innere menschliche Land überging in das große Meer der Welt. Indem man das so erlebte, lebte man sich auch in die Körperwelt selber hinein. Und da haben diejenigen Persönlichkeiten früherer Zeiten, deren charakteristischste Gedanken und Vorstellungen eigentlich in der äußeren Wissenschaft gar nicht mit Aufmerksamkeit verfolgt werden, daher auch gar nicht richtig verzeichner werden, die haben sich ganz andere Ideen machen müssen über so etwas, wie Weismann hier seine — ich sage das jetzt in Gänsefüßchen — «Unsterblichkeit der Einzelligen» konstruierte. Denn was hätte solch ein älterer Denker, wenn er nun schon durch ein etwa auch damals vorhandenes Mikroskop etwas gewußt hätte von der Teilung der Einzelligen, was hätte er sich für eine Vorstellung gemacht aus dem Zusammenleben mit der Welt? Er hätte gesagt: Ich habe zuerst das einzellige Wesen. Das teilt sich in zwei. Mit einer ungenauen Redeweise würde er vielleicht gesagt haben: Es atomisiert sich, es teilt sich, und für eine gewisse Zeit sind die zwei Teile wiederum als Organismen unteilbar, dann teilen sie sich weiter. Und wenn das Teilen beginnt, wenn das Atomisieren beginnt, dann tritt das Sterben ein. Er würde also nicht aus der Leiche das Sterben entnommen haben, sondern aus dem Atomisieren, aus dem Zerfälltwerden in Teile. Denn er stellte sich etwa vor, daß dasjenige, was lebensfähig ist, im mehr entstehenden Werden ist, daß das unatomisiert ist, und wenn die Tendenz zum Atomisieren auftritt, dann stirbt das Betreffende ab. Bei den Einzellern würde er nur gedacht haben, es sind eben für die zunächst im Momente als tot von einem Einzeller abgestoßenen zwei Wesen die Bedingungen da, daß sie gleich wiederum lebendig gemacht werden, und so fort. Das wäre sein Gedankengang gewesen. Aber mit dem Atomisieren, mit dem Zerklüftetwerden hätte er den Gedanken des Sterbens betont, und in seinem Sinne würde er, wenn der Fall so gewesen wäre, daß man den Einzeller gehabt hätte, der sich zerteilt hätte, und durch die Zerteilung nun nicht zwei neue Einzeller entstanden wären, sondern durch Mangel an Bedingungen des Lebens diese Einzeller sofort übergegangen wären in unorganische Teile, dann würde er gesagt haben: Aus der lebendigen Monade sind zwei Atome entstanden. Und er würde weiter gesagt haben: Überall da, wo man Leben hat, wo man das Leben anschaut, hat man es nicht mit Atomen zu tun. Findet man irgendwo in einem Lebendigen Atome, so ist soviel, als Atome drinnen sind, darinnen tot. Und überall, wo man Atome findet, ist der Tod, ist das Unorganische. So würde aus dem lebendigen inneren Erfahren der Weltempfindung, Weltwahrnehmung, der Weltbegriffe in einer älteren Zeit geurteilt worden sein.

Daß das nicht so deutlich in unseren Darstellungen des Geisteslebens früherer Zeiten steht — für denjenigen, der richtig lesen kann, ist jedoch daran eigentlich nicht zu zweifeln —, daß es aber nicht so steht, namentlich nicht so steht in den modernen Darstellungen etwa der früheren Naturphilosophie oder der früheren Philosophie, davon ist der Grund nur, daß die Denkformen dieser älteren Philosophie, dieser Naturphilosophie dem heutigen Denken schon so unähnlich sind, daß ein jeder, der zum Beispiel Geschichte schreibt, eben «der Herren eignen Geist» in die früheren Köpfe hineinphantasiert. Aber so kann man nicht einmal über den Spinoza schreiben, denn Spinoza stellt dar in seinem Buch, das er mit Recht eine Ethik nennt, stellt dar nach mathematischer Methode, nicht indem er Mathematik im heutigen Sinne treibt, sondern indem er die mathematische Art, Idee an Idee zu reihen, für seine Philosophie anwendet. Damit gibt er aber den Beweis, daß in ihm noch etwas ist von dem früheren qualitativen Erleben der quantitativen mathematischen Begriffe. So daß man auch bei Ausdehnung der Betrachtung auf das Qualitative des Innenerlebens des Menschen vom Mathematischen sprechen kann. Heute mit unseren Begriffen das Mathematische auf das Psychologische anwenden zu wollen oder gar auf das Ethische, wäre natürlich der reinste Unsinn.

Sie sehen also, wollen wir einen wichtigen Punkt erfassen in dem modernen Denken, so müssen wir auf diese Unsicherheit gegenüber einer früher allerdings vorhandenen größeren Sicherheit hinweisen, wenn sie auch für unsere heutige Anschauungsweise nicht mehr geeignet ist. Aber diese Unsicherheit, sie hat ja endlich dazu geführt, daß in der gegenwärtigen Phase naturwissenschaftlichen Denkens sogar, ich möchte sagen, schon theoretische Rechtfertigungen dieser Unsicherheiten aufgetreten sind. In dieser Beziehung ist außerordentlich interessant ein Vortrag, den der französische Denker und Forscher Henri Poincare über die neueren Gedanken über die Materie gehalten hat. Da spricht er davon, wie Streit herrscht oder Diskussion darüber, ob man sich das Materielle mehr kontinuierlich denken soll, oder ob man es mehr diskret denken soll, ob man es so sich denken soll, daß gewissermaßen durch den Raum ausfüllende substantielle Wesenhaftigkeit geht, die nirgends wirklich in sich getrennt ist, oder ob man das Substantielle, das Materielle atomistisch denken soll, das heißt mehr oder weniger den leeren Raum und darinnen kleinste Teilchen, die durch ihre besondere Aneinanderlagerung Atome, Moleküle und so weiter bilden. Und wenn man von einigen, ich möchte sagen, dekorativen Ausmalungen dieser Rechtfertigung der Unsicherheit absieht, so enthält der Vortrag Poincarés eigentlich dieses, daß er sagt: Die Forschung, die Wissenschaft geht eben durch verschiedene Zeitalter hindurch. In dem einen Zeitalter liegen Erscheinungen vor, welche den Denker veranlassen, die Materie kontinuierlich zu denken. Es ist bequem, gerade gegenüber den Erscheinungen dieses Zeitalters, die Materie kontinuierlich zu denken und bei dem stehenzubleiben, was nun auch in Kontinuität sich zeigt bei dem äußeren Zusammenhang des Sinnlich-Gegebenen. In einem anderen Zeitalter treten mehr Forschungsresultate auf, denen gegenüber es bequem ist, die Materie zu zerklüften in Atome, diese sich wieder aneinanderlagern zu lassen, also nicht ein Kontinuierliches sich vorzustellen, sondern ein.Diskretes, ein Atomistisches. Und nun meint Poincar&, es würde eben immer so sein, daß je nachdem die Forschungsresultate nach der einen oder nach der anderen Richtung hin tendieren, es Zeitalter geben werde, die kontinuistisch denken, und Zeitalter, die atomistisch denken. Er redet sogar von einer Oszillation im Laufe der wissenschaftlichen Entwickelung zwischen Kontinuismus und Atomismus. Und so wird es immer sein, denn, sagt er, der menschliche Geist hat eben das Bedürfnis, in der ihm bequemsten Weise über die Erscheinungen sich Theorien zu bilden. Wenn er sich eine Zeitlang eine kontinuistische Theorie gebildet hat, dann — nun, das sind nicht seine Worte, aber man kann das, was er eigentlich meint, mit diesen Worten charakterisieren — wird er das müde. Andere Forschungsresultate ergeben sich ihm, man möchte sagen, auf unbewußte Art, und er beginnt atomistisch zu denken, ebenso wie man, nachdem man eingeatmet hat, auch wieder ausatmet. Und so soll Oszillation fortwährend sein, soll wechseln Kontinuismus-Atomismus, Kontinuismus-Atomismus und so weiter. Das gehe bloß aus einem Bedürfnis des menschlichen Geistes selber hervor, und eigentlich würden wir gar nichts über die Dinge aussagen. Es entscheide gar nichts über die Dinge, ob wir kontinuistisch denken oder atomistisch denken, sondern das sei bloß der Versuch des menschlichen Geistes, mit der körperlichen Welt draußen zurechtzukommen.

Es ist kein Wunder, daß das Zeitalter, das eben die Selbsterlebnisse nicht mehr im Zusammenhang findet mit dem Weltgeschehen, sondern diese nur als etwas im Inneren des Menschen selber Vorhandenes ansieht, daß es eben in Unsicherheit kommt. Erlebt man sein Zusammensein mit der Welt nicht mehr, so kann man auch nicht Kontinuismus und Atomismus erleben, sondern eben nur den vorher ausgedachten Kontinuismus oder den vorher ausgedachten Atomismus über die Erscheinungen hinüberstülpen. So daß man eigentlich auf diese Art allmählich zu der Vorstellung kommen würde, der Mensch bilde sich seine Theorien eben nach seinen wechselnden Bedürfnissen. So wie er einatmen und dann ausatmen muß, so müsse er eine Zeitlang kontinuistisch denken und dann eine Zeitlang atomistisch denken. Und eigentlich könne er geistig nicht Luft schnappen, wenn er immer kontinuistisch denke; er müsse wiederum atomistisch denken, damit er geistige Luft kriege. Es ist also dadurch lediglich die Unsicherheit konstatiert und gerechtfertigt, die sogar umgedeutet wird halb und halb in eine Willkür. Man lebt überhaupt nicht mehr mit der Welt zusammen, sondern sagt, daß man so oder so mit ihr zusammenleben könne, je nachdem eben das eigene subjektive Bedürfnis ist.

Aber was würde eine ältere Denkweise, eben diejenige, die ich öfter schon angeführt habe, in einem solchen Falle gesagt haben? Sie würde gesagt haben: Nun ja, in einem Zeitalter, in dem die tonangebenden Denker kontinuistisch denken, da denken sie vorzugsweise an das Leben. In demjenigen Zeitalter, in dem die tonangebenden Denker atomistisch denken, da denken sie vorzugsweise an das Tote, an die unorganische Natur und konstruieren auch in das Organische das Unorganische hinein.

Sehen Sie, das ist nicht mehr ungerechtfertigte Willkür, sondern das beruht auf einem objektiven Verhältnis zu den Dingen. Natürlich kann ich mich einmal mit einem Lebendigen, ein anderes Mal mit einem Toten beschäftigen, kann sagen: Aus dem inneren Wesen des Lebendigen folgt, daß ich es kontinuistisch denken muß, und ich muß sagen aus dem inneren Wesen des Toten: Ich muß es atomistisch denken. Aber ich kann nicht sagen, das entspricht bloß einer Willkür des menschlichen Geistes. Es entspricht einem objektiven In-Beziehung-Setzen zur Welt, nicht einem bloßen subjektiven Bedürfnis des menschlichen Geistes. Das Subjektive bleibt dabei eigentlich für die Erkenntnis ganz unberücksichtigt. Denn man erkennt das Lebendige in der Natur auf kontinuistische Art, man erkennt das Tote in der Natur auf atomistische Art. Und wenn einer wirklich nötig hat, oszillatorisch abzuwechseln eben zwischen dem atomistischen Denken und dem kontinuistischen Denken, dann muß das eben auch ins Objektive gewendet werden, dann muß man eben sagen: Da mußt du einmal an das Lebendige, das andere Mal an das Tote denken. Aber es hat keine Berechtigung, daß das durch eine solche Anschauungsart, wie etwa die Poincares, ins Subjektive hineingepfercht wird, und daß etwa für eine Anschauungsweise, wie ich sie jetzt für ältere Phasen der Menschheitsentwickelung auseinandergesetzt habe, das Subjektive in derselben Weise Geltung hätte.

Nun liegt die Sache so, daß in der Tat, da sich die Sache auf eine innerliche Weise zeigt, daß in der zunächst hinter uns liegenden Phase naturwissenschaftlichen Denkens eine Hinwegwendung geschehen ist vom Lebendigen zum Toten, daher auch vom Kontinuismus zum Atomismus, der ja in bezug auf das Unorganische, in bezug auf das Tote, wenn er richtig verstanden wird, selbstverständlich gerechtfertigt ist. Aber wenn der Mensch sich einmal wiederum objektiv und wahrhaft selbst in der Welt wird finden wollen, dann muß er den Weg suchen, wie er von der großartig entwickelten, atomistisch gedachten, aber doch toten Welt zu seinem eigenen Wesen zurückkommen und sich schon als Organismus lebendig erfassen kann. Denn bisher gipfelte die Entwickelung darin, die Richtung zum Toten, das heißt zum Atomistischen zu nehmen. Und als diese ganz furchtbare Zellentheorie Schleidens und Schwanns in der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts auftrat, da wurde sie nicht der Weg zum Kontinuismus, sondern sie wurde der Weg zum Atomismus, und zwar, ohne daß man es wirklich zugab und ohne daß es einem bis heute einfiel, daß man es eigentlich zugeben müßte, weil es dem ganzen methodischen Gang der Anschauung entspricht. Und ohne daß man gewahr wurde, daß so, wie man den Organismus sich zerklüftet dachte in Zellen, man ihn eigentlich in Gedanken atomisierte, das heißt eigentlich tötete, ist wirklich die Sache so, daß für die atomistische Betrachtungsweise der Begriff des Organismus überhaupt verlorengegangen ist.

Das ist ja das Bedeutsame in dem Bilde, das man bekommt, wenn man gegenüberstellt die Goethesche Organik etwa der eines Schleiden oder der späteren Botaniker, daß man bei Goethe überall lebendige, erlebte Ideen hat, während nun auf der anderen Seite, trotzdem die Zelle ein Lebendiges ist, und man also eigentlich in Wirklichkeit auf ein Lebendiges hingewiesen wird, die Art, wie man denkt, doch so ist, als wenn die Zellen gar nicht lebten, sondern Atome wären. Natürlich geht da die empirische Forschung ja nicht immer mit dem Rationalen der Sache mit, weil man ja das auch nicht kann gegenüber dem Lebendigen. Auf der anderen Seite wird aber auch das Erfassen des Organischen nicht angepaßt demjenigen, was die wirkliche Beobachtung auch über die Zellenlehre gibt. Es nistet sich das Unatomistische nur ein, weil man, wenn man die wirkliche Zelle studiert, eben nicht anders kann, als sie als ein Lebendiges zu charakterisieren. Aber das ist ja gerade das Charakteristische für viele heutige Darstellungen, daß man die Dinge durcheinanderwirft und die Klarheit nicht eigentlich liebt.

Darüber dann werde ich in der nächsten Kursstunde, die also am Montag sein wird, weiter sprechen.

Fifth Lecture

The separation of human ideas from immediate human experience, particularly, according to the previous explanations, mathematical ideas, has emerged as the most outstanding characteristic of the spiritual development from which the scientific way of thinking of modern times has emerged. Let us just imagine once again how this was.

We have been able to look back to earlier times when human beings, in a sense, experienced together with the world what they had to make out with their senses. times when human beings experienced their threefold orientation inwardly, upward-downward, right-left, forward-backward, but did not experience this orientation in such a way that they attributed it to themselves alone, but rather felt themselves to be within the whole world, so that at the same time their forward-backward was the first, their upward-downward the second, and their right-left the third spatial dimension. He experienced what he imagined in his cognition together with the world. Therefore, there was no uncertainty in his being as to how he should apply his concepts and ideas to the world. This uncertainty had only just emerged with the newer civilization, and we see this uncertainty slowly creeping into all modern thinking and see natural science developing under this uncertainty. One must be completely clear about this fact.

Let us illustrate what we have here with a few concrete examples. Let us take a thinker such as John Locke, who lived from the 17th to the 18th century and who, in his writings, expressed what a modern thinker of his time had to say about the scientific view of the world. John Locke divides everything that humans perceive in their physical environment into two parts. He separates the characteristics of bodies into so-called primary characteristics and secondary characteristics. The primary characteristics are those that he cannot help but attribute to the things themselves, such as form, position, and movement. The secondary characteristics are those that he believes do not actually belong to physical things outside, but only represent the effect of these physical things on humans. These characteristics of things include, for example, color, sound, and warmth as a perceptible sensation of heat. John Locke says: When I hear a sound, the vibrating air is outside of me. I can represent these movements in the air, which come from the sound-excited body and propagate to my ear, as a drawing for my own sake. The shape that the waves in the vibrating air are said to have, I can represent through spatial figures, I can visualize them in their progression in time, that is, as movement. What is happening in space, what is shape, movement, and location in things, is certainly out there in the world. But everything that is out there in the world, everything that belongs to the primary characteristics, is mute, is toneless. The quality of the sound, the secondary quality, only arises when the air wave strikes my ear and that peculiar inner experience is there, which I carry within me as sound. The same is true of color, which is simply thrown together with light. There must be something out there in the world that is somehow physical, that has some kind of form or movement, and that has an effect on me through my eyes and then becomes the experience of light or color. The same is true of other things that are present to our senses. The entire physical world must be viewed in such a way that we distinguish between its primary qualities, which are objective, and its secondary qualities, which are subjective and represent the effects of the primary qualities on humans. So, to describe it radically, one could say: in the sense of John Locke, the world outside, apart from human beings, is form, position, movement, and everything that actually constitutes the content of the sensory world is in reality somehow within human beings, it actually weaves within the human essence. The real content of color as a human experience is nowhere out there; it weaves within me; the real content of sound is nowhere out there; it weaves within me; the real content of the experience of heat or cold is nowhere out there; it weaves within me.

In earlier times, when people experienced together with the world what has become the content of knowledge, they could not hold this view, because, as I have described, they experienced the mathematical content through the participation of their own bodily orientation and the placement of this orientation in their own movement. But one experienced this together with the world. So in one's experience, one also had at the same time the reason why one accepted position, location, and movement as objective. But one had, only for another part of inner human life, coexistence with the world also for color, sound, and so on. Just as one arrived at the mental image of movement from the experience of one's own movement as a human being, one arrived at the mental image of color by having a corresponding inner experience in one's blood organization and bringing this inner experience together with what is out there in the world as warmth, color, sound, and so on. In earlier times, a distinction was also made between the position, location, movement, and passage of time of color, sound, and the experience of warmth, but these were distinguished as different types of experience that were also undergone together with different types of being in the objective world. Now, in the age of natural science, people had come to no longer experience location, movement, position, shape, and so on as self-experience, but only as something imagined, which they identified with what was outside, what is outside. And since it does not work very well to imagine the shape of a cannon and say: This shape of the cannon is actually somehow inside me, one simply identified it with the outside world. One related the imagined shape of the cannon to something objective. Since one could not admit that when a bullet flies somewhere, it actually flies inside one's own brain, one identified the imagined movements with the objective world.

But what one saw in the flying shotgun bullet, the colorful glow through which one saw it, the sound one perceived, one pushed into one's own human essence, because one had no other place to put it. One no longer knew how one experienced it together with things, so one pushed it into the human essence.

It actually took quite a long time before people thinking in terms of the scientific age realized the impossibility of this mental image. For what had actually happened? The secondary qualities: sound, color, the experience of warmth were, so to speak, simply outlawed in the world, and they had to take refuge in human beings in order to be recognized. How they lived there, well, gradually people lost all mental images of that. The experience, the self-experience, was no longer there. There was no longer any connection with external nature because it was no longer experienced. So these experiences were pushed into the self. And there they were, so to speak, inside the human being, where they disappeared from consciousness. Half consciously, half clearly, half unclearly, one imagined that, say, there was an ether movement outside in space that could be represented by form and movement, that this exerted an effect on the eye and from there on the optic nerve. Somehow it went into the brain. And inside, one first sought in one's thoughts that which, as an effect of the primary qualities, was to be lived out as secondary qualities in the human being himself. It took a long time, I would say, before individual people pointed out with any degree of decisiveness the strangeness of this mental image, and it is actually something extremely striking that the Austrian philosopher Richard Wahle wrote in his Mechanismus des Denkens (Mechanism of Thought), although he does not fully exploit his own statement: “Nihil est in cerebro, quod non est in nervis — Nothing is in the brain that is not in the nerves.” Now, of course, even if it is not yet possible with our means, one could search the nerves themselves in all directions and on all sides, but one would not find sound, color, or the experience of heat in the nerves. So they are not in the brain either. Actually, one would now have to admit that they disappear completely from our perception. One investigates the relationship between humans and the world. One retains form, position, location, time, and so on as objective; sound, the sensation of heat, color disappear, they are lost to us.

This ultimately led Kant to say in the 18th century that even the spatial and temporal qualities of things cannot somehow exist outside of humans. But since there should be a relationship between humans and the world—for this relationship cannot be denied if one wants to have any mental image of living with the world—but the coexistence of the spatial and temporal relationships of humans with the world was no longer there, Kant's idea arose: If humans are to apply mathematics to the world, for example, then it must be up to them to first make the world mathematical, to suspend all mathematics over the “things in themselves,” which remain completely unknown. The natural sciences of the 19th century also grappled terribly with this problem. If we consider the fundamental character of the human behavior in cognition just described, we see that uncertainty has entered into man's relationship to the world. He does not know how he is actually to see what he experiences in the world. And this uncertainty gradually entered more and more into all modern thinking. We see this uncertainty creeping into the newer intellectual life bit by bit.

Now it is interesting to compare this older phase of John Locke's thinking with an example from more recent times. A 19th-century biologist, Weismann, conceived the idea that when one biologically studies the organism of any living being, one must assume the interaction of the organs, or in lower organisms the interaction of the parts, as the essential factor, that one thereby arrives at an understanding of how the organism lives, but that in the investigation of the organism itself, in the recognition of the organism in the interaction of its parts, no characteristic feature can be found that indicates that the organism must also die. If one looks only at the organism, said Weismann, who was active in the second half of the 19th century, one finds nothing that can illustrate dying. Therefore, he said, there is nothing within the living organism that could lead one to conceive, from the essence of the organism, that the organism must die. For Weismann, the only thing that can show us that the organism must die is the presence of the corpse. This means that we do not form the concept of dying from the living organism. We find no feature, no characteristic in the living organism from which we could recognize that dying belongs to the organism; rather, we must first have the corpse. And when this event occurs, when there is a corpse of a living organism, this corpse is what shows us that the organism also has the capacity to die.

But now Weismann says that there is a world of organisms in which corpses can never be found. These are single-celled organisms. They simply divide, so no corpse can be found. Take, for example, a single-celled organism in the process of reproduction. The pattern is as follows. Such a single-celled organism divides into two, each of which divides again into two, and so on. Development continues in this way, and there is never a corpse. So, Weismann concludes, single-celled organisms are immortal. This is the famous immortality of single-celled organisms in 19th-century biology. And why are they considered immortal? Well, because they show no signs of death, and because the concept of death cannot be applied to organic beings if there is no corpse. Where there is no corpse, there is no concept of death. Consequently, living beings that show no signs of death are immortal.

You see, this example shows just how far we have strayed in modern times from the coexistence of our mental images and inner experiences with the world. The concept of the organism is no longer such that we can still see that it must also die. We must see from the external existence of the corpse that the organism can die. Certainly, if one looks at a living organism only from the outside, if one cannot experience what is inside it, if one cannot live into it, then one does not find death in the organism and needs an external sign for it. But this testifies that one feels completely separated from things in one's mental image.

But let us now look away from the uncertainty that had entered into all thinking about the physical world through this separation of the world of concepts from self-experience, and look back to the time when this self-experience was still there. Just as there was not only an externally conceived concept of a triangle, a square, or a pentagram, but also an internally experienced concept, so there was an internally experienced concept of coming into being and passing away, of being born and dying. And this inner experience of being born and dying had gradations within itself. When one found the child more and more animated from the inside out, when its initially indeterminate physiognomic features took on inner animation and one lived oneself into this coming to life of the very small child, this appeared as a continuation of being born, in a sense as a weaker, less intense, continuing being born. There were degrees in the experience of coming into being. And when a person began to get wrinkles, gray hair, and become frail, one had the lesser degree of dying, a less intense dying, a partial dying. And death was only the summation of many less intense experiences of dying, if I may use the paradoxical word. The concept was internally animated, the concept of coming into being as well as the concept of passing away, the concept of being born and the concept of dying.

But by experiencing this concept in this way, one experienced it together with the physical world, so that one did not actually draw a line between self-experience and natural events, so that, in a sense, the inner human realm flowed without boundaries into the great sea of the world. By experiencing this, one also lived oneself into the physical world. And so the personalities of earlier times, whose most characteristic thoughts and ideas are not really followed with any attention in external science and therefore do not appear correctly in the records, had to form completely different ideas about something like what Weismann constructed here—I say this now in quotation marks—“the immortality of single-celled organisms.” For what would such an older thinker, if he had known something about the division of single-celled organisms through a microscope that may have existed at the time, have made of his mental image of coexistence with the world? He would have said: First I have the single-celled organism. It divides into two. Using imprecise language, he might have said: It atomizes, it divides, and for a certain time the two parts are again indivisible as organisms, then they divide further. And when the division begins, when the atomization begins, then death occurs. He would not have deduced death from the corpse, but from atomization, from disintegration into parts. For he imagined that what is viable is in the process of becoming, that it is unatomized, and when the tendency to atomize arises, then the thing in question dies. In the case of single-celled organisms, he would have thought that the conditions were present for two beings, which were initially rejected by a single-celled organism as dead, to be brought back to life immediately, and so on. That would have been his line of thought. But with atomization, with fragmentation, he would have emphasized the idea of dying, and in his view, if the case had been that one had a single-celled organism that had divided itself and that the division had not resulted in two new single-celled organisms, but rather that these single-celled organisms had immediately turned into inorganic parts due to a lack of conditions for life, then he would have said: Two atoms have emerged from the living monad. And he would have gone on to say: Wherever there is life, wherever one looks at life, one is not dealing with atoms. If one finds atoms anywhere in a living being, then whatever atoms are inside are dead. And wherever one finds atoms, there is death, there is the inorganic. This is how the living inner experience of world perception, world awareness, and world concepts would have been judged in an earlier time.

That this is not so clear in our descriptions of the spiritual life of earlier times — for those who can read correctly, there is actually no doubt about it — but that it is not so, especially not in modern descriptions of, for example, earlier natural philosophy or earlier philosophy, is only because the forms of thinking of this older philosophy, this natural philosophy, are so dissimilar to today's thinking that anyone who writes history, for example, simply imagines “the spirit of the masters” into the minds of earlier people. But one cannot even write about Spinoza in this way, for Spinoza presents in his book, which he rightly calls Ethics, presents according to mathematical method, not by practicing mathematics in the modern sense, but by applying to his philosophy the mathematical method of linking idea to idea. In doing so, however, he proves that there is still something in him of the earlier qualitative experience of quantitative mathematical concepts. So that even when extending the consideration to the qualitative aspect of human inner experience, one can still speak of the mathematical. Today, to want to apply the mathematical to the psychological or even to the ethical using our concepts would, of course, be pure nonsense.

So you see, if we want to grasp an important point in modern thinking, we must point to this uncertainty in contrast to a greater certainty that existed in the past, even if it is no longer suitable for our present way of thinking. But this uncertainty has ultimately led to the emergence of theoretical justifications for these uncertainties in the current phase of scientific thinking. In this regard, a lecture given by the French thinker and researcher Henri Poincaré on the latest ideas about matter is extremely interesting. He talks about how there is controversy or discussion about whether one should think of matter as more continuous or more discrete, whether one should think of it as a substantial essence that fills space, so to speak, and is nowhere really separate in itself, or whether one should think of the substantial, the material, atomistically, that is, more or less empty space containing tiny particles which, through their particular arrangement, form atoms, molecules, and so on. And if we disregard some, I would say, decorative embellishments of this justification of uncertainty, Poincaré's lecture actually contains the following: Research, science, passes through different ages. In one age, there are phenomena that cause the thinker to conceive of matter as continuous. It is convenient, precisely in relation to the phenomena of this age, to conceive of matter as continuous and to remain with what now also appears in continuity in the external connection of the sensually given. In another age, more research results appear, in relation to which it is convenient to divide matter into atoms, to allow these to be joined together again, thus not to imagine something continuous, but something discrete, something atomistic. And now Poincaré believes that it will always be the case that, depending on whether research results tend in one direction or the other, there will be ages that think in a continuous manner and ages that think in an atomistic manner. He even speaks of an oscillation between continuism and atomism in the course of scientific development. And so it will always be, because, he says, the human mind has a need to form theories about phenomena in the way that is most comfortable for it. Once it has formed a continuous theory for a while, then—well, these are not his words, but one can characterize what he actually means with these words—it grows tired of it. Other research results arise, one might say, unconsciously, and he begins to think atomistically, just as one exhales after inhaling. And so oscillation is supposed to be continuous, continuity and atomism are supposed to alternate, continuity and atomism and so on. This arises solely from a need of the human mind itself, and we would actually say nothing at all about things. Whether we think continuistically or atomistically does not determine anything about things, but is merely an attempt by the human mind to cope with the physical world outside.

It is no wonder that the age that no longer finds self-experience in connection with world events, but regards it only as something existing within human beings themselves, is entering a period of uncertainty. If one no longer experiences one's togetherness with the world, one cannot experience continuism and atomism, but only impose the previously conceived continuism or atomism on the phenomena. In this way, one would gradually arrive at the mental image that human beings form their theories according to their changing needs. Just as one must breathe in and then breathe out, one must think continuistically for a time and then atomistically for a time. And actually, one cannot mentally catch one's breath if one always thinks continuistically; one must think atomistically again in order to get mental air. This merely establishes and justifies uncertainty, which is even reinterpreted half and half as arbitrariness. One no longer lives with the world at all, but says that one can live with it in one way or another, depending on one's own subjective needs.

But what would an older way of thinking, the one I have already mentioned several times, have said in such a case? It would have said: Well, in an age when the leading thinkers think in terms of continuity, they prefer to think about life. In an age when the leading thinkers think atomistically, they prefer to think about death, about inorganic nature, and they also construct the inorganic into the organic.