| The Mission of Christian Rosenkreutz: Foreword

Translated by Dorothy S. Osmond |

|---|

| In connection with the Congress held by the “Federation of European Sections of the Theosophical Society” in Budapest in the year 1909, Dr. Steiner gave a Lecture-Course entitled: “Theosophy and Occultism of the Rosicrucians.” |

| Stead's spiritualistic circle was influential and the Theosophical Society, with its much purer spiritual foundations, had here a dangerous rival. Dr. Steiner brought light to bear upon all these developments, upon their aims and aberrations, and raised Theosophy to heights far transcending the narrow sphere of the Theosophical Society. |

| The activities of the Star in the East led, finally, to the exclusion of the German section from the Theosophical Society; this, however, had been preceded by the forming of a Union which included people in other countries who opposed this piece of Adyar sectarianism and led to the foundation of the Anthroposophical Society. |

| The Mission of Christian Rosenkreutz: Foreword

Translated by Dorothy S. Osmond |

|---|

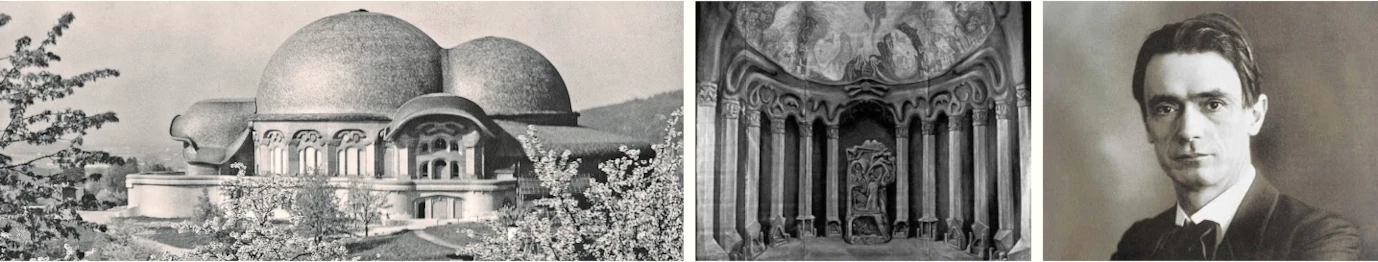

In connection with the Congress held by the “Federation of European Sections of the Theosophical Society” in Budapest in the year 1909, Dr. Steiner gave a Lecture-Course entitled: “Theosophy and Occultism of the Rosicrucians.” The Mystery of Golgotha is there indicated as the great turning-point between the old, now already fading Mystery-wisdom and the wisdom in its new form of revelation wherein account is taken of the faculty of thought possessed by a maturer humanity and of the advance of culture and civilisation. Theosophia, the Divine Wisdom, could not, as in earlier times, flow as inner illumination into the hardened constitution of man. Intellect, the more recent faculty of the soul, was directed to the world of sense and its phenomena. Theosophy was rejected by the scholars with a shrug of the shoulders and the very word brought a supercilious smile from the monists. Dr. Steiner, however, was trying to restore to this word its whole weight and spiritual significance and to show how the roots of all later knowledge lie in Theosophy, how it unites East and West, how in it all the creeds are integral parts of one great harmony. This had also been the fundamental conception of the Founder of the Theosophical Society but she understood nothing of the essence of Christianity and disputed its unique significance. Her tendency to place too much reliance upon spiritualistic communications drew her into the net of an oriental stream only too ready to use this instrument for its own ends—to begin with under the cloak of Neo-Buddhism then represented in the person of Charles Leadbeater, a former priest of the Anglican Church. Annie Besant, a pupil of Charles Bradlaugh, a free-thinker and the most brilliant orator of the day in the field of political and social reform, had also been so deeply influenced by spiritualistic communications that on the advice of William Stead she went to Madame Blavatsky towards the end of the latter's life and became her ardent follower. Stead's spiritualistic circle was influential and the Theosophical Society, with its much purer spiritual foundations, had here a dangerous rival. Dr. Steiner brought light to bear upon all these developments, upon their aims and aberrations, and raised Theosophy to heights far transcending the narrow sphere of the Theosophical Society. Alarmed by this, the Indian inspirers behind the Adyar Society, with their nationalistic aims, took their own measures.—The imminence of a return of Christ was announced and the assertion made that he would incarnate in an Indian boy. A newly founded Order, the “Star in the East,” using the widespread organisation of the Theosophical Society, was expected to achieve the aim that had met with failure in Palestine. Not very long after the Budapest Congress, these developments began to be felt in the sphere of Dr. Steiner's lecturing activities. Disquieted by the beginnings of the propaganda for the Star in the East, Groups begged Dr. Steiner to speak about these matters. This caused alarm to the organisers of the Genoa Congress, who thought that the scientific as well as the esoteric discussions with Dr. Steiner would be too dangerous a ground, and for extremely threadbare reasons the Congress was cancelled at the last moment. Many of those taking part were already on their way—we too. A number of Groups in Switzerland took advantage of this opportunity to ask Dr. Steiner for lectures. They wanted to understand the meaning and significance of the Michael Impulse which denotes the turning-point in the historic evolution of the Mystery-wisdom. The Intelligence ruled over in the spiritual world by the hierarchy of Michael had now come down to humanity. It was for men to receive this Intelligence consciously into their impulses of will and thenceforward to play their part in shaping a future wherein the human “I” will achieve union with the Divine “I.” For this goal of the future men must be prepared, a transformation wrought in their souls; they must “change their hearts and minds.” To bring this about was the task of Rudolf Steiner. The moment had arrived for treading the path which liberates the Spirit from the grip of the material powers. The first healthy step to be taken along this path by the pupil of spiritual knowledge, is study. As the theme chosen for Genoa had been “From Buddha to Christ,” it was natural that the lectures now given in Switzerland should shed the light of Spiritual Science not only upon the earlier connections between the Buddha and Christ Jesus but also upon the lasting connections indicated by the Essene wisdom contained in the Gospels. This is the theme which gives these studies their special character—which could only be brought out by outlining the historical development of the Mystery-wisdom. The ancient revelations of the Mysteries had shed light into many forms of culture, but were now spent; symptoms of decay and increasing sterility of thought were everywhere in evidence. Then, from heights of Spirit, the Michael Impulse came down to the Earth—in order gradually to stir and flame through the hearts of men. The intellect was pervaded by spiritual fire, the lower human “I” lifted nearer to the ideal of times to come: union with the Divine “I.” To awaken understanding of these goals, to establish them firmly on the ground of their spiritual origins and to place them in living pictures before the souls of men—such was the task of Rudolf Steiner. This brought the inevitable counterblow from the opposing powers; into this they knew they must drive their wedge. The development of the human being in freedom, this gift bestowed by Michael, must be checked and the hearts and minds of men incited to resistance. In his Four Mystery Plays, Rudolf Steiner has given us living pictures of this: the human being between Lucifer and Ahriman—now succumbing to their promptings, now overcoming them, but nevertheless bearing them in the soul like a poison that may at any time begin to work. We too shall continue to bear this picture and its substance in our souls. The full content of the lectures, however, has not been preserved, for we possess no good transcriptions. The fact that no really reliable and expert stenographist was available at the time seems like a counterblow from the opposing powers. Besides the abbreviated reports of the Cassel lectures, we have in some cases only fragments, in others, scattered notes strung together. But the essential threads have been preserved and an attempt at compilation has been made. The attempt does not always succeed from the point of view of convincing style, but the impetus for effort in thought and study will be all the stronger. The activities of the Star in the East led, finally, to the exclusion of the German section from the Theosophical Society; this, however, had been preceded by the forming of a Union which included people in other countries who opposed this piece of Adyar sectarianism and led to the foundation of the Anthroposophical Society. For a time, care was necessary to prevent confusion as between the two Societies and so for the Movement associated with him, Rudolf Steiner chose the name Anthroposophy—the Divine Wisdom finding its fulfilment in man. Theosophy and Anthroposophy are one, provided the soul has cast away its dress. And Rudolf Steiner showed us how this can be done. The new Indian Messiah soon cast off the shackles of the renown that had been forced upon him and retired to private life in California. Annie Besant was obliged to renounce her cherished dream and died at a very great age. It is rumoured that the question of the dissolution of the Adyar Society was considered but that this proved impossible owing to the extensive material possessions. Jinarajadasa, my good friend from the days of the founding of the Italian Section, succeeded Annie Besant as President. The branch of the Theosophical Society which had seceded at the time of the Judge conflict and to which Madame Blavatsky's niece belonged, had found in Mrs. Catharine Tingley a leader of energy and initiative, but she too had died. The old conditions have now faded away. Those grotesque edifices of phantasy can no longer be associated with the Anthroposophical, formerly Theosophical, Movement, for they have crumbled to pieces. We can allow the word Theosophy again to come to its own, as did Rudolf Steiner when he was trying to restore to this word its primary and true significance. Besides laying emphasis on the essential character of Spiritual Science in the post-Christian era, the aim of the lectures given in 1911 and 1912 was to explain karma as the flow of destiny and to point to its intimate workings. The lines of development running through the lectures have survived only as pictures of memory; the transcriptions often failed to catch the threads of the logical sequence and the notes or headings jotted down and collected here and there are really no more than indications. But the direction of the spiritual impulses given by Dr. Steiner has been preserved, and justifies, maybe, the attempt at compilation. Through meditative study these impulses will be able to work in us and deepen our souls. |

| 327. The Agriculture Course (1958): Address to the Agricultural Working Group ('The Ring-Test')

11 Jun 1924, Koberwitz Translated by George Adams |

|---|

| Wegman is an absolute exception; she always saw quite clearly the necessity prevailing in our Society). But a number of them always seemed to believe that the doctor must now apply what proceeds from anthroposophical therapy in the same medical style and manner to which he has hitherto been accustomed. |

| We therefore need the most active members. That is what we need in the Anthroposophical Society as a whole—good, practical people who will not depart from the principle that practical life, after all, calls forth something that cannot be made real from one day to the next. |

| I believe we have truly taken into account the experiences of the Anthroposophical Society. What has now been begun will be a thing of great blessing, and Dornach will not fail to work vigorously with those who wish to be with us as active fellow-workers in this cause. |

| 327. The Agriculture Course (1958): Address to the Agricultural Working Group ('The Ring-Test')

11 Jun 1924, Koberwitz Translated by George Adams |

|---|

My dear friends, Allow me in the first place to express my deep satisfaction that this Experimental Circle has been created as suggested by Count Keyserlingk, and extended to include all those concerned with agriculture who are now present for the first time at such a meeting. In point of time, the foundation has come about as follows. To begin with, Herr Stegemann, in response to several requests, communicated some of the things which he and I had discussed together in recent years concerning the various guiding lines in agriculture, which he himself has tested in one way or another in his very praiseworthy endeavours on his own farm. Thence there arose a discussion between him and our good friend Count Keyserlingk, leading in the first place to a consultation during which the resolution which has to-day been read out was drafted. As a result of this we have come together here to-day. It is deeply satisfying that a number of persons have now found themselves together who will be the bearers, so to speak, of the experiments which will follow the guiding lines (for to begin with they can only be guiding lines) which I have given you in these lectures. These persons will now make experiments in confirmation of these guiding lines, and demonstrate how well they can be used in practice. At such a moment, however, when so good a beginning has been made, we should also be careful to turn to good account the experiences we have had in the past with our attempts in other domains in the Anthroposophical Movement. Above all, we should avoid the mistakes which only became evident during the years when from the central anthroposophical work—if I may so describe it—we went on to other work which lay more at the periphery. I mean when we began to introduce what Anthroposophical Science must and can be for the several domains of life. For the work which this Agricultural Circle has before it, it will not be without interest to hear the kind of experiences we have had in introducing Anthroposophical Science, for example, into the scientific life in general. As a general rule, when it came to this point, those who had hitherto administered the central anthroposophical life with real inner faithfulness and devotion in their own way, and those who stood more at the periphery and wanted to apply it to a particular domain of life, did not as a rule confront one another with full mutual understanding. We experienced it only too well, especially in working with our scientific Research Institutes. There on the one side are the anthroposophists who find their full life in the heart of Anthroposophia itself—in Anthroposophical Science as a world-conception, a content of life which they may even have carried through the world with strong and deep feeling, every moment of their lives. There are the anthroposophists who live Anthroposophia and love it, making it the content of their lives. Generally, though not always, they have the idea that something important has been done when one has gained, here or there, one more adherent, or perhaps several more adherents, for the anthroposophical movement. When they work outwardly at all, their idea seems to be—you will forgive the expression—that people must somehow be able to be won over “by the scruff of the neck.” Imagine, for example, a University professor in some branch of Natural Science. Placed as he is in the very centre of the scientific work on which he is engaged, he ought none the less to be able to be won over there and then—so they imagine. Such anthroposophists, with all their love and good-will, naturally imagine that we should also be able to get hold of the farmer there and then—to get him too “by the scruff of the neck,” so to speak, from one day to another, into the anthroposophical life—to get him in “lock, stock and barrel” with the land and all that is comprised with it, with all the products which his farm sends out into the world. So do the “central anthroposophists” imagine. They are of course in error. And although many of them say that they are faithful followers of mine, often, alas! though it is true enough that they are faithful in their inner feeling, they none the less turn a deaf ear to what I have to say in decisive moments. They do not hear it when I say, for instance, that it is utterly naive to imagine that you can win over to Anthroposophical Science some professor or scientist or scholar from one day to the next and without more ado. Of course you cannot. Such a man would have to break with twenty or thirty years of his past life and work, and to do so, he would have to leave an abyss behind him. These things must be faced as they exist in real life. Anthroposophists often imagine that life consists merely in thought. It does not consist in mere thought. I am obliged to say these things, hoping that they may fall upon the right soil. On the other hand, there are those who out of good and faithful hearts want to unite some special sphere of life with Anthroposophia—some branch of science, for example. They also did not make things quite clear to themselves when they became workers in Spiritual Science. Again and again they set out with the mistaken opinion that we must do these things as they have hitherto been done in Science; that we must proceed precisely in the same way. For instance, there are a number of very good and devoted anthroposophists working with us in Medicine (with regard to what I shall now say, Dr. Wegman is an absolute exception; she always saw quite clearly the necessity prevailing in our Society). But a number of them always seemed to believe that the doctor must now apply what proceeds from anthroposophical therapy in the same medical style and manner to which he has hitherto been accustomed. What do we then experience? Here it is not so much a question of spreading the central teachings of Spiritual Science; here it is more a question of spreading the anthroposophical life into the world. What did we experience? The other people said “Well, we have done that kind of thing before; we are the experts in that line. That is a thing we can thoroughly grasp with our own methods; we can judge of it without any doubt or difficulty. And yet, what these anthroposophists are bringing forward is quite contrary to what we have hitherto found by our methods.” Then they declared that the things we say and do are wrong. We had this experience: If our friends tried to imitate the outer scientists, the latter replied that they could do far better. And in such cases it was undeniable; they can in fact apply their methods better, if only for the reason that in the science of the last few years the methods have been swallowing up the science! The sciences of to-day seem to have nothing left but methods. They no longer set out on the objective problems; they have been eaten up by their own methods. To-day therefore, you can have scientific researches without any substance to them whatever. And we have had this experience: Scientists who had the most excellent command of their own methods became violently angry when anthroposophists came forward and did nothing else but make use of these methods. What does this prove? In spite of all the pretty things that we could do in this way, in spite of the splendid researches that are being done in the Biological Institute, the one thing that emerged was that the other scientists grew wild with anger when our scientists spoke in their lectures on the basis of the very same methods. They were wild with anger, because they only heard again the things they were accustomed to in their own grooves of thought. But we also had another important experience, namely this: A few of our scientists at last bestirred themselves, and departed to some extent from their old custom of imitating the others. But they only did it half and half. They did it in this way: In the first part of their lectures they would be thoroughly scientific; in the first part of their explanations they would apply all the methods of science, “comme il faut.” Then the audience grew very angry. “Why do they come, clumsily meddling in our affairs? Impertinent fellows, these anthroposophists, meddling in their dilettante way with our science!” Then, in the second part of their lectures, our speakers would pass on to the essential life—no longer elaborated in the old way, but derived as anthroposophical content from realms beyond the Earth. And the same people who had previously been angry became exceedingly attentive, hungry to hear more. Then they began to catch fire! They liked the Spiritual Science well enough, but they could not abide (and what is more, as I myself admitted, rightly not), what had been patched together as a confused “mixtum compositum” of Spiritual Science and Science. We cannot make progress on such lines. I therefore welcome with joy what has now arisen out of Count Keyserlingk's initiative, namely that the professional circle of farmers will now unite on the basis of what we have founded in Dornach—the Natural Science Section. This Section, like all the other things that are now coming before us, is a result of the Christmas Foundation Meeting. From Dornach, in good time, will go out what is intended. There we shall find, out of the heart of Anthroposophia itself, scientific researches and methods of the greatest exactitude. Only, of course, I cannot agree with Count Keyserlingk's remark that the professional farmers' circle should only be an executive organ. From Dornach, you will soon be convinced, guiding lines and indications will go out which will call for everyone at his post to be a fully independent fellow-worker, provided only that he wishes to work with us. Nay more, as will emerge at the end of my lectures (for I shall have to give the first guiding lines for this work at the close of the present lectures) the foundation for the beginning of our work at Dornach will in the first place have to come from you. The guiding lines we shall have to give will be such that we can only begin on the basis of the answers we receive from you. From the beginning, therefore, we shall need most active fellow-workers—no mere executive organs. To mention only one thing, which has been a subject of frequent discussions in these days between Count Keyserlingk and myself—an agricultural estate is always an individuality, in the sense that it is never the same as any other. The climate, the conditions of the soil, provide the very first basis for the individuality of a farm. A farming estate in Silesia is not like one in Thuringia, or in South Germany. They are real individualities. Now, above all in Spiritual Science, vague generalities and abstractions are of no value, least of all when we wish to take a hand in practical life. What is the value of speaking only in vague and general terms of such a practical matter as a farm is? We must always bear in mind the concrete things; then we can understand what has to be applied. Just as the most varied expressions are composed of the twenty-six letters of the alphabet, so you will have to deal with what has been given in these lectures. What you are seeking will first have to be composed from the indications given in these lectures—as words are composed from the letters of the alphabet. If on the basis of our sixty members we wish to speak of practical questions, our task, after all, will be to find the practical indications and foundations of work for those sixty individual farmers. The first thing will be to gather up what we already know. Then our first series of experiments will follow, and we shall work in a really practical way. We therefore need the most active members. That is what we need in the Anthroposophical Society as a whole—good, practical people who will not depart from the principle that practical life, after all, calls forth something that cannot be made real from one day to the next. If those whom I have called the “central anthroposophists” believe that a professor, farmer or doctor—who has been immersed for decades past in a certain milieu and atmosphere—can accept anthroposophical convictions from one day to the next, they are greatly mistaken. The fact will emerge quickly enough in agriculture! The farming anthroposophist no doubt, if he is idealistic enough, can go over entirely to the anthrospophical way of working—say, between his twenty-ninth and his thirtieth year—even with the work on his farm. But will his fields do likewise? Will the whole Organisation of the farm do likewise? Will those who have to mediate between him and the consumer do likewise—and so on and so on? You cannot make them all anthroposophists at once—from your twenty-ninth to your thirtieth year. And when you begin to see that you cannot do so, it is then that you lose heart. That is the point, my dear friends—do not lose heart; know that it is not the momentary success that matters; it is the working on and on with iron perseverance. One man can do more, another less. In the last resort, paradoxical as it may sound, you will be able to do more, the more you restrict yourself in regard to the area of land which you begin to cultivate in our ways. After all, if you go wrong on a small area of land, you will not be spoiling so much as you would on a larger area. Moreover, such improvements as result from our anthroposophical methods will then be able to appear very rapidly, for you will not have much to alter. The inherent efficiency of the methods will be proved more easily than on a large estate. In so practical a sphere as farming these things must come about by mutual agreement if our Circle is to be successful. Indeed, it is very strange—with all good humour and without irony, for one enjoyed it—there has been much talk in these days as to the differences that arose in the first meeting between the Count and Herr Stegemann. Such things bring with them a certain colouring; indeed, I almost thought I should have to consider whether the anthroposophical “Vorstand,” or some one else, should not be asked to be present every evening to bring the warring elements together. By and by however, I came to quite a different conclusion; namely, that what is here making itself felt is the foundation of a rather intimate mutual tolerance among farmers—an intimate “live and let live” among fellow-farmers. They only have a rough exterior. As a matter of fact the farmer, more than many other people, needs Therefore I think I may once again express my deep satisfaction at what has been done by you here. I believe we have truly taken into account the experiences of the Anthroposophical Society. What has now been begun will be a thing of great blessing, and Dornach will not fail to work vigorously with those who wish to be with us as active fellow-workers in this cause. We can only be glad, that what is now being done in Koberwitz has been thus introduced. And if Count Keyserlingk so frequently refers to the burden I took upon myself in coming here, I for my part would answer—though not in order to call up any more discussion:– What trouble have I had? I had only to travel here, and am here under the best and most beautiful conditions. All the unpleasant talks are undertaken by others; I only have to speak every day, though I confess I stood before these lectures with a certain awe—for they enter into a new domain. My trouble after all, was not so great. But when I see all the trouble to which Count Keyserlingk and his whole household have been put—when I see those who have come here—then I must say, for so it seems to me, that all the countless things that had to be done by those who have helped to enable us to be together here, tower above what I have had to do, who have simply sat down in the middle of it all when all was ready. In this, then, I cannot agree with the Count. Whatever appreciation or gratitude you feel for the fact that this Agricultural Course has been achieved, I must ask you to direct your gratitude to him, remembering above all that if he had not thought and pondered with such iron strength, and sent his representative to Dornach, never relinquishing his purpose—then, considering the many things that have to be done from Dornach, it is scarcely likely that this Course in the farthest Eastern corner of the country could have been given. Hence I do not at all agree that your feelings of gratitude should be expended on me, for they belong in the fullest sense to Count Keyserlingk and to his House. That is what I wished to interpolate in the discussion. For the Moment, there is not much more to be said—only this. We in Dornach shall need, from everyone who wishes to work with us in the Circle, a description of what he has beneath his soil, and what he has above it, and how the two are working together. If our indications are to be of use to you, we must know exactly what the things are like, to which these indications refer. You from your practical work will know far better than we can know in Dornach, what is the nature of your soil, what kind of woodland there is and how much, and so on; what has been grown on the farm in the last few years, and what the yield has been. We must know all these things, which, after all, every farmer must know for himself if he wants to run his farm in an intelligent way—with “peasant wit.” These are the first indications we shall need: what is there on your farm, and what your experiences have been. That is quickly told. As to how these things are to be put together, that will emerge during the further course of the conference. Fresh points of view will be given which may help some of you to grasp the real connections between what the soil yields and what the soil itself is, with all that surrounds it. With these words I think I have adequately characterised the form which Count Keyserlingk wished the members of the Circle to fill in. As to the kind and friendly words which the Count has once again spoken to us all, with his fine-feeling distinction between “farmers” and “scientists,” as though all the farmers were in the Circle and all the scientists at Dornach—this also cannot and must not remain so. We shall have to grow far more together; in Dornach itself, as much as possible of the peasant-farmer must prevail, in spite of our being “scientific.” Moreover, the science that shall come from Dornach must be such as will seem good and evident to the most conservative, “thick-headed” farmer. I hope it was only a kind of friendliness when Count Keyserlingk said that he did not understand me—a special kind of friendliness. For I am sure we shall soon grow together like twins—Dornach and the Circle. In the end he called me a “Grossbauer,” that is, a yeoman farmer—thereby already showing that he too has a feeling that we can grow together. All the same, I cannot be addressed as such merely on the strength of the little initial attempt I made in stirring the manure—a tack to which I had to give myself just before I came here. (Indeed it had to be continued, for I could not go on stirring long enough. You have to stir for a long time; I could only begin to stir, then someone else had to continue). These are small matters, but it was not out of this that I originally came. I grew up entirely out of the peasant folk, and in my spirit I have always remained there—I indicated this in my autobiography. Though it was not on a large farming estate such as you have here; in a smaller domain I myself planted potatoes, and though I did not breed horses, at any rate I helped to breed pigs. And in the farmyard of our immediate neighbourhood I lent a hand with the cattle. These things were absolutely near my life for a long time; I took part in them most actively. Thus I am at any rate lovingly devoted to farming, for I grew up in the midst of it myself, and there is far more of that in me than the little bit of “stirring the manure“” just now. Perhaps I may also declare myself not quite in agreement with another matter at this point. As I look back on my own life, I must say that the most valuable farmer is not the large farmer, but the small peasant farmer who himself as a little boy worked on the farm. And if this is to be realised on a larger scale—translated into scientific terms—then it will truly have to grow “out of the skull of a peasant,” as they say in Lower Austria. In my life this will serve me far more than anything I have subsequently undertaken. Therefore, I beg you to regard me as the small peasant farmer who has conceived a real love for farming; one who remembers his small peasant farm and who thereby, perhaps, can understand what lives in the peasantry, in the farmers and yeomen of our agricultural life. They will be well understood at Dornach; of that you may rest assured. For I have always had the opinion (this was not meant ironically, though it seems to have been misunderstood) I have always had the opinion that their alleged stupidity or foolishness is “wisdom before God,” that is to say, before the Spirit. I have always considered what the peasants and farmers thought about their things far wiser than what the scientists were thinking. I have invariably found it wiser, and I do so to-day. Far rather would I listen to what is said of his own experiences in a chance conversation, by one who works directly on the soil, than to all the Ahrimanic statistics that issue from our learned science. I have always been glad when I could listen to such things, for I have always found them extremely wise, while, as to science—in its practical effects and conduct I have found it very stupid. This is what we at Dornach are striving for, and this will make our science wise—will make it wise precisely through the so-called “peasant stupidity.” We shall take pains at Dornach to carry a little of this peasant stupidity into our science. Then this stupidity will become—“wisdom before God.” Let us then work together in this way; it will be a genuinely conservative, yet at the same time a most radical and progressive beginning. And it will always be a beautiful memory to me if this Course becomes the starting point for carrying some of the real and genuine “peasant wit” into the methods of science. I must not say that these methods have become stupid, for that would not be courteous, but they have certainly become dead. Dr. Wachsmuth has also set aside this deadened science, and has called for a living science which must first be fertilised by true “peasant wisdom.” Let us then grow together thus like good Siamese Twins—Dornach and the Circle. It is said of twins that they have a common feeling and a common thinking. Let us then have this common feeling and thinking; then we shall go forward in the best way in our domain. |

| 262. Correspondence with Marie Steiner 1901–1925: 115a. Letter from Marie von Sivers to Mieta Waller

02 Feb 1914, |

|---|

| Steiner's social work and respect for humanity, even if the immediate initiative for this particular act came from the warm hearts of two artists, Miss Stinde and Countess Kalckreuth, who were leading the anthroposophical work in Munich, and was then carried out by Miss v. Sivers and Miss M. Waller in Berlin. These art rooms were intended for the general public, as hospitable places that should offer not only warmth and comfort, but also beauty, aesthetics and intellectual stimulation. |

| The large art room on Motzstraße with its adjoining rooms was converted into a day nursery, where Miss Samweber, who had fled from Bolshevik Russia, developed a devoted activity, supported by the ladies of the Anthroposophical Society, who looked after the children and provided them with care and food, all based on donations. |

| 262. Correspondence with Marie Steiner 1901–1925: 115a. Letter from Marie von Sivers to Mieta Waller

02 Feb 1914, |

|---|

115aMarie von Sivers to Mieta Waller in Berlin 2/II Dear Mouse, Your eurythmy picture is very beautiful, it captures the rhythm of the subject perfectly, and we could vividly imagine ourselves in your dance movements. I would be delighted if I could find time to be taught by you. Now I have to be an inspiratrice, as Dr. Steiner calls it, that is, a silent figure beside him when he is creating. I can't take my writing with me to all these remote places – I didn't have time to do any editing this time, so I have to be content with the role of the silent inspiratrice. It was nice to sit alone for a few hours, but mostly it is a buzzing in the workshop that makes your head buzz, and a steam heating glow that is quite unbearable. I spend the other hours of inspiration in the model itself; it's like being in a cellar. Dr. Hamerling is hard at work under one of the domes. Waves of life condensed into wax pass from one mold to the other; under the other dome I sit quite uncomfortably with Hamerling's hymns and inspire until I become stiff. Today I freed myself from some of that and wrote a few letters. Yesterday we sat under the domes until midnight. Otherwise we have terribly boring bureau meetings every evening; today was no exception. Outside, there is wonderful sunshine and dazzling white snow all day long. I think the weather is lovely; Dr. insists that the climate here is very exhausting and makes working difficult. That may be. You just want to be lazy and process the air; the ascent is always difficult here, but very pretty in the snow. You just need the right footwear. Tell1 Olga v. Sivers, sister of Marie v. Sivers. that she absolutely must bring us valenki the next time she comes from St. Petersburg; these are the best for wading in the snow, keeping your feet dry and preventing slipping. I will get two pairs, one high to wear directly on my stockings, and another to wear on my boots. We will be very happy with these when we go hiking. Dr. must also have some. I will be very happy when you go to Hanover; I cannot do my work here and need a few days to myself. Dr. will arrive on Friday morning. 3/II I have just asked him to look in the timetable. We travel together to Kassel, where we arrive at 9:37 a.m. (Friday). The doctor continues his journey at 9:46 and arrives in Hannover at 12:23. There are two morning trains leaving Berlin for you, one at 7:44 a.m. arriving in Hannover at 11:25 a.m.; the other at 7:53 a.m. arriving in Hannover at 12:17 p.m. So if you are late with one, you can still make the other. It is better for you to go to bed early and get up early than to spend a night alone in a hotel. You may have corresponded with Miss Müller 2, as you intended, about the hotel, but now Dr. would have to be sent by telegram to get the name of the hotel, or you would have to be at the train station in Hannover to intercept him, otherwise he would probably go to his old hotel, which I only believe is called Reichspost, but I don't know for sure. In the art room 3 On Sunday, I thought of the poems by Morgenstern that were recited in Leipzig 4 to speak. Here I don't have the possibility to speak anything aloud and therefore can't take anything new. I am still waiting for a message about the hotel; perhaps Frl. Müller can order lunch in advance. After lunch, you must ensure that Dr. Steiner has absolute peace and quiet until his public lecture. Much love and best regards to everyone, Marie.

|

| 332b. Current Social and Economic Issues: Resignation of Rudolf Steiner as Chairman of the Supervisory Board of “Kommender Tag AG” at the Third Annual General Meeting

22 Jun 1923, |

|---|

| It concerns the fact that the affairs of the Anthroposophical Movement have recently taken on such a form that In the future, it will be impossible for me to take on other activities of this kind, such as the position of chairman of the supervisory board of “Kommenden Tages”, in addition to my work for the Anthroposophical Movement in the narrower sense. The esteemed attendees – and they are, of course, the more numerous – who are members of the Anthroposophical Society, know that the circumstances of the Anthroposophical Movement have changed a great deal, especially in recent years. On the one hand, it is absolutely clear that a spiritual movement such as anthroposophy – and I do not want to say specifically anthroposophical, but a spiritual movement such as anthroposophy – lies at the lies at the very bottom of the innermost needs of an ever-greater number of people, and that therefore the Anthroposophical Movement, which has existed for more than 20 years now as a partial movement, so to speak, in this great stream, that the Anthroposophical Movement makes, one might say, more demands on those who have already been destined by fate to care for it and it has been clear for some time that, in addition to everything that is incumbent upon me for the anthroposophical movement, it is no longer possible to engage fruitfully in other activities without the tasks that I already have for the anthroposophical movement being disturbed or compromised. |

| 332b. Current Social and Economic Issues: Resignation of Rudolf Steiner as Chairman of the Supervisory Board of “Kommender Tag AG” at the Third Annual General Meeting

22 Jun 1923, |

|---|

I myself will have something to say regarding this point, ladies and gentlemen. It concerns the fact that the affairs of the Anthroposophical Movement have recently taken on such a form that In the future, it will be impossible for me to take on other activities of this kind, such as the position of chairman of the supervisory board of “Kommenden Tages”, in addition to my work for the Anthroposophical Movement in the narrower sense. The esteemed attendees – and they are, of course, the more numerous – who are members of the Anthroposophical Society, know that the circumstances of the Anthroposophical Movement have changed a great deal, especially in recent years. On the one hand, it is absolutely clear that a spiritual movement such as anthroposophy – and I do not want to say specifically anthroposophical, but a spiritual movement such as anthroposophy – lies at the lies at the very bottom of the innermost needs of an ever-greater number of people, and that therefore the Anthroposophical Movement, which has existed for more than 20 years now as a partial movement, so to speak, in this great stream, that the Anthroposophical Movement makes, one might say, more demands on those who have already been destined by fate to care for it and it has been clear for some time that, in addition to everything that is incumbent upon me for the anthroposophical movement, it is no longer possible to engage fruitfully in other activities without the tasks that I already have for the anthroposophical movement being disturbed or compromised. The latter must not happen under any circumstances, on the one hand because of the increasing demands on the Anthroposophical Movement and because of the ever-widening interest, which demands an expansion of my work precisely in this regard, in this direction. On the other hand, this Anthroposophical Movement, through countless things that can only be described as misleading, has to reckon with an opposition today that, well, I would say, if it is to be countered in the right way, will cause work and, above all, worry and the like. So, taking all these things into account, I had no choice, esteemed attendees, but to recently decide to resign from my position as chairman of the supervisory board of “The Coming Day” and from the supervisory board in general, which I hereby do in a very official manner. The situation is such that, in practical terms, I have recently had to limit my work for the “Coming Day” to that which - precisely because of the other demands - will have to remain so in the coming period. If I am to do the work for the “Day to Come” that is to flow into its various institutions, and if I am to do the work for the Waldorf School, in which the “Day to Come” is also extremely interested in a certain respect, if I am to do this work , which will have to be provided in a positive and substantial way in the form of my advice to 'Der Kommende Tag', then I will have to admit to myself that I will withdraw all the more from the activity, which will be able to take place in the future without me and perhaps better without me than with me. The supervisory board and the board of directors of “Tomorrow” are, after all, an absolutely sure guarantee for all those who, as shareholders and otherwise, have an interest in “Tomorrow” , that this Coming Day will continue to work in this direction even after my resignation, in the fruitful way it has set itself, and in the way it is in the interest of the shareholders and the world in general. I must say that the situation of the “Kommende Tag” is such that today I can only ask those shareholders whose trust in the “Kommende Tag” is perhaps somewhat connected with the fact that I took over the position of chairman of the supervisory board years ago, I can only urgently ask those whose trust is connected with this fact not to lose an ounce of that trust, but on the contrary to continue to place it in a greatly increased measure in the excellent management of “The Coming Day”. I would like to say that it was clear to me from the very beginning, when I took over the position of Chairman of the Supervisory Board three years ago, that this could only be for a relatively short time. For the situation that now exists was entirely foreseeable, and although it was of course clear to me at the time that a large part of my work for the Anthroposophical Movement would be affected, ... I did it anyway. Isn't it true that “Der Kommende Tag” came about because a number of personalities who had emerged from the Anthroposophical Movement wanted to support an undertaking that was designed to be socially sustainable in the future. The “Kommende Tag” was to be founded as a kind of model example of what should be done by combining enterprises, in particular combining personalities who are interested in social issues in economic life. Through this union, the “Kommende Tag” was to be established as a kind of model example. The personalities who founded it turned to me for advice at the time. We hammered out the preliminary details, the intentions and the principles together, and in the early days we tried to steer the “Coming Day” in the direction in which it should be steered. The actual initiative did not come from me. From the very beginning, I was, so to speak, in the role of an advisor. At the time, I found it quite natural that friends approached me and wanted me to take over the position of Chairman of the Supervisory Board, and for me to be on the Supervisory Board at all. But what made it desirable for the first period of time, even if it was entirely decisive for the decisions at the time, cannot be decisive for continued membership of the Supervisory Board. And all this together with the fact that I am quite certain of the excellent management - I can tell you that I would not resign if “Der Kommende Tag” did not stand on absolutely secure feet and was in a future-proof situation - since that is the case is the case, because you can have full confidence in the “Day to Come”, even if I withdraw, perhaps even more so, as I have already mentioned, then, my dear attendees, you will not withdraw your confidence in the “Day to Come”. So you will understand that the reasons for my resignation are decisive, and I ask you to accept this resignation in the sense in which it has just been characterized. Above all, it is my duty at this moment to express my heartfelt thanks to the other members of the supervisory board for their dedicated work, for the extraordinarily difficult work that had to be done in the early years, for the work that, I would say, suffered from ever-increasing opposition and caused serious concern. I would also like to thank these members of the supervisory board in a special way for the warm way in which this collaboration has taken place; both those members of the supervisory board who are the originators of the original ideas of “The Day to Come” and those who, as members of the works council, have joined the supervisory board in accordance with the law. Those who have worked on the organization and further implementation of the ideas and affairs of “The Day to Come” over the last three years know just how much dedicated work is needed to accomplish things in an appropriate and proper manner. But I believe that more and more people will feel how grateful we are to the members of the supervisory board for their dedication, and it will therefore be understandable that I express my heartfelt thanks to the supervisory board and wish that its work in the near and distant future will be rewarded with the most beautiful fruits. Secondly, I would like to express my warmest thanks to the board of directors, above all to the prudent, dedicated and extremely objective director of the board, Mr. Emil Leinhas, and to the other members of the board as a whole for their dedicated work. It has not exactly become easier for social and economic enterprises to carry out their management activities in recent times. It requires not only an extremely exhausting amount of work, but above all, constant thoughtfulness and constant prudence, which it is neither necessary nor even possible to describe in detail here. But if you have seen all this, if you have had to go through all this, so to speak, if you have had to see from day to day how things have actually been worked on, especially by the management of our board in recent times and since the beginning, it will also be understood that, out of a very special inner satisfaction and heartfelt feeling, I would also like to express my warmest thanks to the members of the board, above all to the director, Mr. Emil Leinhas, when I leave. In doing so, I would also like to express my heartfelt thanks to all those who, from the inner circle of the Anthroposophical Movement and from further afield, have turned their interest and attention to the endeavors of “Der Kommende Tag” and have simply given “Der Kommende Tag” the opportunity to survive through their sympathy and participation within the circle of shareholders. I would like to express my most sincere thanks to all of you on my resignation! I now ask you to take note of my resignation from the position of Chairman of the Supervisory Board and from the Supervisory Board in general. This brings us to the fourth item on the agenda. Since I have now resigned and no longer bear responsibility, I ask the Deputy Chairman of the Supervisory Board, Dr. Unger, to take over the chairmanship of this Annual General Meeting. |

| 251. The History of the Anthroposophical Society 1913–1922: The Reason for the Opposition of Max Seiling

08 May 1917, Berlin |

|---|

| Isn't it truly wonderful – I have mentioned this often and I don't want to bore you today, but I must mention it at some point – isn't it truly wonderful that those who fight the hardest against that which wants to live in our Anthroposophical Society are often those who have emerged from this society themselves. We have witnessed the grotesque spectacle of what is alive in our Society being fought against, and the arguments used for this fight are taken from my writings! |

| Think – as I said, I don't want to bore you with this, but such things must be mentioned briefly – think: a short time ago, and following on from that, a series of other articles appeared that I have not read, by a man who was in our society for years, who went through everything in our society – in which the man in question wants to prove all kinds of contradictions in my works. |

| And such truths underlie very many things which certainly harm society at first, but with society they harm the matter. And when we consider how many Ahrimanic powers are waiting to place obstacles and hindrances in the way of our movement, then we will want to pay a little attention to what, despite having become bad enough, today still looks, I might say, like the beginning of a countermovement. |

| 251. The History of the Anthroposophical Society 1913–1922: The Reason for the Opposition of Max Seiling

08 May 1917, Berlin |

|---|

Our time is not very inclined to build that bridge that must be built to the realm where the dead and the high spirits are; and our time, in many respects, my dear friends, one can even say it has a hatred, a truly hateful attitude towards the spiritual world. And it is incumbent on the spiritual scientist who wants to be a Christian, it is incumbent on the spiritual scientist to familiarize himself with the hostile forces of our spiritual scientific development, to pay a little attention to them, because the matter has really deep reasons. It has its reasons where the reasons are for all the forces that counteract true human progress today. Isn't it truly wonderful – I have mentioned this often and I don't want to bore you today, but I must mention it at some point – isn't it truly wonderful that those who fight the hardest against that which wants to live in our Anthroposophical Society are often those who have emerged from this society themselves. We have witnessed the grotesque spectacle of what is alive in our Society being fought against, and the arguments used for this fight are taken from my writings! Everywhere else, people at least get their reasons from outside; here with us we experience the strange phenomenon that what is built on throwing filth at me — the expression is not exaggerated — is constantly being substantiated with quotations from my own writings. It is a phenomenon whose deeper reasons will have to be investigated, because they are connected with one another in many ways, my dear friends. There is a continuous line, a continuous current, from the quiet gossip that sometimes runs rampant in our society to the Ahrimanic attacks, but one must only grasp things by their right name; this is more necessary today, my dear friends, than at any other time. Think – as I said, I don't want to bore you with this, but such things must be mentioned briefly – think: a short time ago, and following on from that, a series of other articles appeared that I have not read, by a man who was in our society for years, who went through everything in our society – in which the man in question wants to prove all kinds of contradictions in my works. The person in question knows very well what the situation is with these so-called contradictions; he is of course very well aware of all the nonsense he is asserting. But you can assert anything in the world if you want, especially if you find a community that believes in good faith; you can also refute such things. But what are the causes? The same man who writes this very pompous article once published a small work with our publishing house, and after some time he again requested to publish another work with our publishing house. However, because he had used various things from my writings without authorization in this writing in an improper way, we could not exactly – since he said that the things in my writings are imperfect and he wanted to perfect them – we could not exactly publish this writing, and so we had to reject it. Today, if we had not rejected the writing, the man would still have been a good follower, despite always grumbling and grumbling. He does not tell the world that he now hates just because we could not publish the writing. But he now finds a whole edifice of all sorts of contradictions. Such reasons, my dear friends, which are the real reasons, which are the most pernicious, selfish reasons, you will usually find behind the most shameful attacks. Now, in addition to these disgraceful attacks, there is usually another phenomenon. There is a kind of person among us who does not turn their goodwill to those who are right, but to those who spread gossip, who do all kinds of wrong things, and who find that those who defend themselves against these things are terribly wrong. It is a very common phenomenon. Indeed, this phenomenon goes a step further, as things intensify. Some time ago, we were really quite badly insulted in our circle; although we were actually quite, quite reserved in our defense — we were not interested in this defense, because one has more important, more positive things to do — not the slightest thing was done from our side, but everything from the other side. But still – Dr. Steiner received a letter saying that she should do everything she can to help the people who throw things at us in this way, to meet them halfway and to help them in turn, to encourage them to live together with us in harmony. If the writers of such letters (and it is very often women who write them) then find that they are not obeyed to a T, they think: What despicable theosophists! They want to be called theosophists, and yet when they are insulted they cannot even find it in themselves to ask people for forgiveness! Yes, you see, when I tell this to my dear friends, it seems grotesque; but that is really how these things are in the broadest sense. Because this attitude: to apply the most tremendous love and goodwill to sin, this attitude is an extraordinarily popular one, and one must stand in amazement before it again and again. These things are symptomatic of significance. And they are significant for the simple reason that the worst enemies of our cause will actually come from among those who take the weapons with which they wage a war of this kind from our own cause. And if these things are not properly appreciated, then nothing will come of it but that, as it happens so very often now, a spiritual movement that wants to do its best for the spiritual progress of humanity will, for some time, be made impossible. I have often interwoven precisely this remark into my lectures; but this remark is not taken very seriously. And above all, one very often finds: That one harmonious mood should not be interrupted by such things. But my dear friends, it is not I who am interrupting you, and I would certainly prefer it not to be necessary to interrupt the harmonious mood. But it is extremely important for the sake of the matter at hand that we consider this in the context of the great impulses that are to pass through our movement. For today's superficial humanity, it naturally means an enormous amount when opponents grow out of the circle of anthroposophists themselves. It is of course easier for outsiders to forge their credentials. For these things, one must be willing to develop an unprejudiced, absolutely unprejudiced judgment, and not develop unkindness – forgive the grotesque, paradoxical word – unkindness towards a person who, purely because because he has had a book rejected, trumpets all kinds of things out into the world, one must not be unkind to this person by keeping quiet about it, because that is the truth, and the truth must be told. And such truths underlie very many things which certainly harm society at first, but with society they harm the matter. And when we consider how many Ahrimanic powers are waiting to place obstacles and hindrances in the way of our movement, then we will want to pay a little attention to what, despite having become bad enough, today still looks, I might say, like the beginning of a countermovement. It is the beginning. And this, in particular, is connected with the hatred and antipathy towards the rise of a spiritual movement. My dear friends, when it comes to certain phenomena, it is not true to keep repeating that these people are convinced of what they are saying. It is not true. If you trace this conviction back to its roots, they turn out as I have just explained in this specific case. My dear friends! It is necessary to say these things because anyone who really looks into the spiritual life of the present and what is needed for it says to himself: It takes such an effort to overcome the obstacles that come from outside that there is truly no time to keep in mind what comes from within in the way I have indicated. But it will have to be considered. Yes, my dear friends, the ways are not quite easy. If someone writes something in a magazine, no matter how well it is refuted, not much comes of it. And some of these things that have been written are so long since they could easily be condemned with a court action. But do you think that our movement would be served if we had to take part in 25 court cases? That is probably how many there would be. Then it would be easy to get a conviction. In order to work with all our intensity on the impulses of our spiritual movement, it is necessary for those who want to be loyal to our movement to, above all, overcome the prejudices mentioned, which culminates in our not always turning our benevolence to the side that does something wrong; that those people are found to be the best members who go against us ourselves. Usually the people who act on this impulse are unaware of it, but I say it so that they will pay attention. The trivial gossip usually starts, then it ends somewhere, where someone can write, in a long, lying newspaper article, which is often only the last link in an avalanche that comes crashing down. The seed may be that someone could not keep his tongue, or out of his very ordinary selfishness found that someone should have done something that the person concerned had to refrain from doing for good reasons, and so on, and so on. What matters most is that we rise above such prejudices and look at things in their truth, getting used to looking at things in their truth. Then we will also find ways and means to represent and carry things through in their truth, so to speak. Please excuse me for linking this smaller reflection to the larger reflection after our time had already expired, but given the intensity and the outrageousness with which there is now a furor in private and journalistic life against what we do, it is necessary that at least the thing in which the reasons are to be found be pointed out. |

| 274. Introductions for Traditional Christmas Plays: Introduction

25 Dec 1923, Dornach |

|---|

| Translated by Steiner Online Library Show German during the founding meetings of the General Anthroposophical Society. Yesterday I took the liberty of saying a few words about the historical origin of the plays that we are performing for you here during this Christmas Conference. |

| 274. Introductions for Traditional Christmas Plays: Introduction

25 Dec 1923, Dornach |

|---|

Translated by Steiner Online Library during the founding meetings of the General Anthroposophical Society. Yesterday I took the liberty of saying a few words about the historical origin of the plays that we are performing for you here during this Christmas Conference. Today I would just like to add something about the way these plays were performed in the Hungarian German colonies at the time when Karl Julius Schröer found them there in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The plays were the handwritten property of the most respected families in the village, so to speak. And they were performed from the village in which they were available, in neighboring villages within a radius of two to three hours. When the grape harvest was over in the fall, around the middle or end of October, the village's farming dignitaries would meet and discuss – not every year, but when fate would have it, I would say. The school teacher, who was also the notary, was not present; he kept to the intelligentsia, and the intelligentsia disdained these plays. But the farmers, after a few years when the plays were not performed for some reason, then said: Well, it wouldn't hurt our young boys if they had something better to do at Christmas time! And then they discussed whether there were any real men around who could be used to play. A list was put together. But then, when the men were asked if they wanted to play, and if they were chosen to play, they were subject to a number of strict conditions. It says a lot for these areas that the boys – think about it, the whole time from October to Christmas and Epiphany – were not allowed to get drunk, were not allowed to go to the Dirndl and what we certainly cannot do here, had to obey absolutely the one who rehearsed the matter with them. Now, if we were to demand something like that, the other players would be very annoyed with us! So these exercises were carried out with extraordinary diligence for weeks, during which the plays were rehearsed. But there was something else we could not do. Whoever forgot something or did something badly had to pay a half-kreuzer fine. Well, we can't do that either, we can't impose penalties for forgetting! And so these exercises were carried out in the strictest way until the first Sunday of Advent. Because on Advent Sunday they already started playing the 'Paradeis' play, which you saw yesterday. At Christmas there was the 'Christ-Birth' play and around January 6th there was the play that will be shown here in the next few days. The arrangement of the play – I already mentioned some of it yesterday – was that the boys gathered and dressed up at the teacher's house, and from there they went to the inn where the performance took place. But the devil had already been sent away earlier. You saw him yesterday too. He was equipped with a cow horn and did something that we, on the other hand, cannot imitate, because he blew into each window. Perhaps the people in our village would also enjoy this, but we don't want to try it for the time being. Then he also jumped onto each cart and caused trouble. Then he joined the whole gang, as it was called. It was performed as follows: in the middle of the inn hall was the stage, and on the walls were benches for the audience. Karl Julius Schröer, my old friend and teacher, described the staging to me in great detail; after all, he wrote these plays down based on the way he heard them from the farmers themselves, and then corrected them according to the manuscript. Nevertheless, mistakes were made. And I must say that it is only over the years that I have come across some of the original text of these plays. For example, we could never get along with the first two lines that God speaks in the Paradeis play over the years. Schröer says: “Adam, take the living breath that you receive with the day.” It doesn't rhyme, nor does it make sense. It doesn't rhyme, nor does it make sense. It was only this year that it became clear to me that it is absolutely true:

with the date. That is absolutely traditional, that is, on this day. That is absolutely what was written there. I therefore found it really painful when, a few years ago, these plays were reprinted with tremendous sloppiness and carelessness. I have often been asked to reissue these plays; I did not want to do so without first editing these plays. But such prints were made with great carelessness, and so line after line of such nonsense can be seen everywhere in the prints that are now in circulation. Of course, we have different means at our disposal here. We are not playing in an inn and cannot develop the same level of simplicity as was possible there, but nevertheless: in terms of the basic character, we would like to present these plays as they were originally performed among the peasants until the mid-19th century. You will get to know plays in which you can really see the basic customs of the people of yore. In these greetings, as they are presented before this Christmas Play, for example, there is something that beautifully established contact between the players and the audience of that time. Everyone actually felt that they belonged to the event, which at that time was precisely due to these greetings, which are actually something wonderful. Therefore, I have investigated whether there was not also such a greeting before the Paradeis play, and you could really, without the historical document being available, purely from the spirit of tradition, have such a greeting performed for the Paradeis play last year. You will also see that in these plays, the most inner piety truly does prevail, sincere, honest piety, always together with a certain earthiness. And that is precisely something that is found in the fundamental character of Christian piety at that time. It was thoroughly honest, without sentimentality. The farmer could not become sentimental, he could not make a long face; he also had to laugh, even with the most pious. And that comes across to us in such a beautiful way in these plays. Some expressions will be noticed as unknown in the language, for example, some people will not know what “Kletzen gefressen” means. These are dried pears and plums that are eaten as such, especially in these areas at Christmas time. The pears were dried, then cut into slices; the plums were dried, and that is what the Kletzen were made of. But these dried fruits were especially baked into the bread, and in the bread these small pieces of the Kletzen were enjoyed with particular appetite. At Christmas, the Kletzen bread was something very special in these parts. That is why you heard in the Paradeis-Spiel:

than if they had eaten the apple in paradise! It is precisely in such things, which are so rooted in folklore, that one can see how genuinely these plays have been preserved. Now, we would like to present to you what has been preserved from ancient folklore as a piece of medieval history that extends into the present. Perhaps I may also draw your attention to our poster, which is more appropriate to the Shepherds Play than to the Three Kings Play, but it has already been used by us today. We wanted to capture in pictures the mood of what these Christmas plays can still be in the present day. On the occasion of the Christmas Conference 1923/24, both the Paradise Play and the Christmas Play were performed on 24 and 25 December at 4:30 a.m. and 6 a.m. due to the large crowds. Both speeches correspond almost word for word, so only the first introduction is printed here. |

| The Temple Legend: enote

Translated by John M. Wood |

|---|

| (It was reformed in 1924 as the Free High School for Spiritual Science.) Constructed on the basis of anthroposophical knowledge in the form of ideas, a teaching was to have been imparted about the higher stages of knowledge through imagination, inspiration and intuition, as later elaborated still further by Rudolf Steiner in his published writings (cf. |

| At the same time members were to be given a real understanding that as members of the School they should regard themselves as responsible participants in anthroposophical affairs and in the dissemination of anthroposophical knowledge. The main contents of the instructions of the first section are already published in the book, Guidance in Esoteric Training, Rudolf Steiner Press 1972. |

| As Rudolf Steiner still taught within the Theosophical Society when these lectures were given, he made use of the customary terminology of that time. For historical reasons we have forborne substituting the expression ‘theosophy’ for ‘anthroposophy’, as was usually done at the specific request of Rudolf Steiner after the German Section of the Theosophical Society had re-formed under the title Anthroposophical Society. |

| The Temple Legend: enote

Translated by John M. Wood |

|

|---|---|

|

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Twenty-First Meeting

22 Nov 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch |

|---|

| But, you must do this carefully. A Mr. G., a member of the Anthroposophical Society who wants to find some pictures, is mentioned. Dr. Steiner: I am a little fearful of that. |

| A teacher asks if paintings from an anthroposophical painter should be hung. Dr. Steiner: It depends upon how they are done. It is important that the children have pictures that will make a lasting impression upon them. |

| You need to consider what is in Stuttgart as a whole. The Anthroposophical Society and the Waldorf School are together the spiritual part of the threefold organism. The Union for Threefolding should be the political part, and the Waldorf teachers should help it with their advice. |

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Twenty-First Meeting

22 Nov 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch |

|---|