The Social Question as a Problem of Soul Life

GA 190

28 March 1919, Dornach

I. Inner Experience of Language I

There are certain things I have to put before you which apparently have not much to do with what we are at present discussing, with our discussions, that is, of the social question. Tomorrow, however, it will appear that this connection does none the less exist. Last time I concluded by showing why children born in recent times, since 1912–13, say, come from their spiritual life before birth with what one might call a certain reluctance to merge themselves into the cultural inheritance they find on earth as a legacy from their immediate forbears or ancestors of the last century. I told you that among the actual experiences possible in the spiritual world a kind of meeting takes place between the souls of those just dead, who are returning to the spiritual world through the gate of death, and those souls preparing to appear again on the earthly stage. Whatever links with the spiritual world men have had before they die act forcibly when they have passed through the gate of death. This is of special significance in our time. In our time if a faint feeling of the link with the spiritual world still lingers, it is an atavistic one. After passing through the gate of death into the world of spirit, man can therefore receive impulses that they can carry on only if they have consciously concerned themselves with conceptions of the spiritual world. Today there already exists a great difference between those who have died having gained ideas of the spiritual world in one way or another in true thought-forms and those personalities who have lived entirely in the conceptions of our materialistic culture. There is a great difference between these souls in the life after death, and this difference is felt particularly strongly by those souls who are setting about their return into incarnation in an earthly life.

Now you know that in the course of recent times, until well into the twentieth century, the materialistic tendencies, materialistic thinking and feeling, on the earth became more and more intensive. Those rising into the spiritual world, through the gate of death have few impulses which, if I may put it so, awaken in those about to descend to earth pleasurable anticipations of their earthly sojourn.

Its culmination was reached in the second decade of the twentieth century. So those children born in the second decade came to earth with a deep spiritual antipathy to the civilization and learning customary on the earth. This stream of impulses that came to earth with those children helped in large measure to call up the inclination on earth to wipe out this old civilization, to sweep away this culture of capitalistic and technical times. And he who is in a position to penetrate the interrelationship between the physical and super-physical worlds in the right way will not misunderstand when I say that the desire for a spiritual civilization in the hearts and souls of our youngest fellow citizens has contributed essentially to the events on the earth in recent years.

You see, my dear friends, that is—if I may put it thus—the bright side of the sad, the terrible events of recent times. It is a bright side in that it shows that the dreadful things caused by the decadence of the materialistic age have been willed by heaven, sent down as messages in the subconscious of recently-born children. It is an expression of soul which in the most recently born children is something quite different from that in children born in the nineteenth or early twentieth century. It is now essential that mankind should direct finer powers of perception to such things. In these days mankind is proud of being practical: where, however, this practical sense should be most active in observation of actual life, people pass lightly over all these things in their seeing, speaking and thinking. The melancholy expression seen in our youngest children, in their countenances, until their fifth or sixth year is little noticed. Should it be noticed, that in itself would awaken an impulse that must cause a powerful social movement to take place.

But one must acquire the sense for the expression, the physiognomy, of human beings in their earliest years; one must indeed develop such a sense, it is quite essential. Much of the sense for these things can be cultivated (however strange that may sound to many today) by allowing oneself to enter into the aims of Eurhythmy, not just superficially seeking sensation, but with one's whole soul. You will soon see why this is so.

Whoever is in a position, through his occult experiences, to communicate with the dead will readily notice that many thoughts (for it is by means of thoughts that one does communicate with the dead) by which one wishes to have a mutual understanding with the dead are not understood by them. Many thoughts that men have here on earth, customary thoughts, sound to the dead (naturally you must take this in the right way, I am speaking of interchange of thought with the dead) as a foreign incomprehensible language. Probing further into this situation, one finds particularly that verbs, prepositions, and above all interjections, are relatively easily understood by the dead—I repeat relatively easily—but nouns hardly at all. These leave a kind of gap in their grasp of the languages used. The dead never understand if one speaks to them chiefly in nouns. It to noticeable that when a noun is turned into a verb they begin to understand. Speak to the dead, for example, of the germ of something; the word germ in most cases will not be understood. It is as though they had heard nothing. Change the noun into a verb and speak of something germinating and the dead will begin to understand.

Wherein lies the cause? You realise that it lies not in the dead but in ourselves, in those, that is, who speak with the dead. And this is because since the middle of the fifteenth century, at any rate for all mid- and west-European languages—and the more is the farther west one goes—the living feeling for the picture expressed by the noun has been so lost that, when nouns are used, they sound nebulous, echoing only in the mind; indeed few people think of anything actual and real when using nouns. When obliged to turn nouns into verbs they are forced by an inner compulsion to think more concretely. To speak of a germ does not generally mean that a concrete conception of the germ of a plant, say a germinating bean, exists as an image in the mind, especially if the talk is abstract. A picture arises of something vague and nebulous, as it might in the case of some principle. When you say “what germinates” or “that which germinates,” because you have used the verbal form you are at least found to think of something growing, that is, something that moves; which means that you go from the abstract to the concrete. Then because you yourself go from the abstract to the concrete the dead begin to understand you. But, for reasons I have often explained here, because the living connection between those alive on the earth and those who have passed through the gate of death, the discarnate souls, must become increasingly closer, because impulses coming from the dead must work more and more effectively into the earth, then will of necessity take gradually into their language, into their speaking into their thinking something written over from the abstract to the concrete. It must again become an aim of mankind to think imaginatively, pictorially, when they speak.

Now I ask you how many people think concretely when, let us say, they read of legal proceedings, where there were judges who judged, pronounced judgment; to have judged, to pass sentence—that is, to exercise the judicial function.1Translator's note: The argument here is based on the customary use of the german words richten, Richter, das Recht, and rechten, meaning “to judge”, “a judge”, “the right” or “justice”, and “to go to law”, and the root from which they all sprint. Where then is the concrete thinking, or where in the whole world is there any concrete thinking, when the noun. the right or justice is uttered? Just take this very vague abstraction that is in mind when the right, justice, is spoken of, when going to law, the right thing, is expressed in speech. What then is the right really, taken purely from the point of view of language? We have in these days often said that the state should be above all a rights-state—what then is the right considered purely in itself? For most people it remains quite a. shadowy conception, a conception that traffics in the dreariest abstractions. How then is one to arrive at a concrete conception of the right? Let us examine the matter by taking a single case.

You will have heard, my dear friends, certain people called clumsy (literally “left-handed”). What are clumsy people? You see, what we try to do with the left hand when we are not naturally left-handed we usually do awkwardly, not being skilful. at it. When anyone conducts his whole life in the same way as one behaves when doing something with the left hand then he is clumsy. The basis of the description clumsy is the completely concrete conception “he does everything as I myself do when I use my left hand”; no dreary abstraction. but the wholly concrete “he behaves as I do when I use my left hand.” From that arises, apprehended concretely, a contrast in feeling between the left-handed and the right-handed, what is done with the right hand and. what with the left. And what is right-handed (skilful) is contained in the noun “the right”. The right is originally simply what is performed as skillfully for real life as what is done with the right, and not with the left hand.

There you have indeed brought something concrete into the matter. But now picture to yourselves . . . you need only picture it with a clock, but there are numerous other cases in which. one could do something similar as a rule, when you have to regulate a clock, you will not wind with the left hand, but with the right; that is how you regulate a clock. This winding from left to right accomplished with the right hand is the concrete regulating, righting, setting right. One even says “to set right”. There you have the concrete conception of the circular movement from left to right, the putting right. That is to judge, to right. One who has strayed towards the left where he should not be is net right by the judge.

It is by means of such things that one can succeed in linking concrete formative conceptions with the word. You see, such image conceptions were still linked with the words till right into the fifteenth century. But this thinking in imagery has been thrown overboard. We must once more cultivate this making of imaginative conceptions. For the dead understand only what resounds formatively in speech. Everything no longer resounding in imagery—as is generally the case in modern speech—everything that does not produce a picture, which is not formulated in pictures to produce an Imaginative conception in the people concerned is incomprehensible to the dead.

When you consider the matter further you will see that in the transformations into vivid imagery but now is the first to go. Then everything passes into verb form, or at least passes into something that compels one to develop picture conceptions. You see when one cultivates such a style today that picture conceptions underlie it, then as a rule one gets the response that people do not understand this, it is very hard to understand. But he who faces our times honestly will consciously strive to put things in such a form as can be conceived entirely in pictures. In the pamphlet which was published on the social question—where one is forded into abstractions because at present wherever the social question is discussed we get for the most part mere abstractions—in that pamphlet itself I strove as far as possible for a style in which the matter could be presented in picture form. It is especially in the present-day discussions over the social question that the capacity for being abstract is driven to its furthest extent. People have gradually become accustomed to accepting the words as a sort of verbal currency with which they no longer think in any concrete pictures at all. Today, to read a social pamphlet or book you find you must have been for years accustomed to what is meant in order to come to terms with the book at all. The whole meaning of such discussions depends upon the conventional use of words. Who today in speaking of “possessing” deals that the word has a certain connection with “to be possessed”? Yet the genius of speech as I have often remarked is very much more significant than what the single individual can think and speak; it creates innumerable connections that only need to be discovered by the individual for a return into a certain spiritual life. It is just when we tried to find the verb behind every noun and make it a practice not always to speak of light and sound, but to speak of what illumines, of what sounds, and then find ourselves obliged to penetrate more and more into the reality of things in contrast to the non-realities, that then we arrive at a path that can lead to healing.

Even the adjective is much better than the noun. I'm speaking much more concretely when I say “he who is diligent” than when I say “The diligent”. But “the diligent” is indeed much more concrete than what I call up the dreadful specter (for the dead really feel it a dreadful specter), the dreadful specter “diligence”. When you speak of “the how”, “the what”—Goethe once claimed the apt phrase “I ponder the What, I should rather ponder the How” (Das was bedenke, mehr bedenke Wie)—it is for the dead a speech full of life because they themselves need to feel concretely when you use such words as what and how as now. Today when you talk about a principle—“I take a certain standpoint on principle”—you have for the dead called up to specters, first the “principle”, were generally no one now thinks of a principal at something concrete, secondly “standpoint”. Consider this ghost of a “standpoint”. It has generated greatly already in our language and in all West European languages,, so that in speaking of it for the most part, everything significant is left out. Sometimes the compositor even corrects one! When in the manuscript I write “when one sees something from out of a certain standpoint” then the compositor generally cross out the “out”, and one has to insert it again in one's revision; for people have become accustomed to utter the nonsense “When one sees something from a standpoint”. To speak in concrete terms one has to say “to see something from out of a standpoint”, and thereby say something concrete but when one speaks of seeing a thing from a standpoint—for one speaking concretely the only possible conception is that one sees something from a point on which he stands; a little piece of a point! Now, a little piece of a point is surely a bit difficult to think of.

You see, such things are extraordinarily important and significant, for they give an intimation of the relation between the sense world and the world of the spirit. These things give a conception about this relation between the sensible and the supersensible much more than what it is today often so impressively given in abstract words. And as for the methods—my dear friends, just look through the literature of spiritual science which I have tried to put into writing, and test the method there—it is a test which apparently few have carried out; the method always is to explain one thing by another, so that the matters are mutually clarified. And a real understanding of the spirit can be arrived at in no other way than by one thing referring to another. Take for example the one word spirit! Anyone who wants to avoid the materialistic thinks that he must for ever be speaking of spirit, spirit, spirit. Take the word Geist in the German language. In Latin it has a still more concrete character: Spiritus, which is something which for most people does not clearly indicate what they understand by our word geist, and on further consideration it all becomes very abstract because you cannot conceive a Spiritus, can you? That is the fundamental concrete conception. But “Spirit Self” (Geistselbst), “spirit” (Geist), what is that? What is its actual concrete significance? Do not most people imagine the spirit—as I have often complained—as something materially very tenuous, absolutely thin, like a thin mist, and if they want to speak of spirit, they speak of vibrations. At theosophical gatherings, at least at their teas, I have so often heard people speak of “such good vibrations”! I do not know what they mean by these vibrations, in any case they were conjuring a very material process into the room. These worth Geist, Gischt, Geischt, Geschti, and so on, a sort of vapour issuing from some opening: this would be the concrete conception. In our time, however, the fifth post-Atlantean age of civilization, one cannot arrive in this way at a concrete idea of Geist, spirit: it is impossible. For you either remain in some shadowy abstraction that you connect with the word “spirit” (Geist) or you are obliged to think of Spiritus, spirits of wine: in thinking of an inspired (begeistert) man you then arrive at a very curious picture. Or else you are obliged to think of something welling up, spurting out of a crevice, a vent hole, and thus arrive at a concrete conception.

Now in the method as carried out here in the anthroposophical prosecution of spiritual Science the attempt is made, by means of many-sided conditions of the conceptions in question, gradually to lead over into the concrete. Just think, if from one side only it is mentioned that the human being is divided into physical body, etheric body, astral body, sentient soul, intellectual soul, consciousness soul, spirit self . . . and here “spirit” comes in—spirit-self, life spirit, spirit man. It can only take effect with full consciousness, for most people who hear the matter can come to no concrete conception of it at all. But then it soon follows that the people will be told—“Look at the course of human life: from birth to the seventh year, to the change of teeth, the physical body comes principally into activity, then till the fourteenth year the etheric body, then the sentient-body, then from the twenty-first to the twenty-eighth year the sentient soul, then in the thirties the intellectual soul,” and so on. With that people are told: “Observe the concrete man from the outside developing through the course of his life and the differences that appear. If at the beginning of his twenties you look at a man with his special characteristics, these characteristics will be symptoms for what you pictured when the expression “sentient soul” is employed. If you look at a child with his characteristic of doing everything that his elders do, of doing everything through his physical body, then in the way the child behaves you will get an idea of what one understands by “physical body.” And if you look at an old man with his gray hair and wrinkled countenance, with the flesh noticeably withering and observe him in his movements, the way he acts, you no longer see as in the child, how whatever is in him is acting chiefly through the sheaths, instead you see in the old man, indeed, what is beginning to free itself from the physical body. Observing the old man, you will gradually get an idea of the spirit from his gestures, his way of behavior. Comparing an old man with a child and comparing the gestures of the old with those imitated by the young, there is awakened in your soul a feeling of the difference between spirit and matter. Think how in that way the pictorial power in imaginative ideas is helped, my dear friends. It is an indication that one should. think concretely of the course of human life, and then gain an experience of filling your onetime abstract words with concrete content.

Again we try in every way possible to show how, for example, mankind itself has become younger and younger—how we are now twenty-seven years old, that is—we have in our civilization arrived as mankind at our twenty-seventh. year. When you compare what you can know of early civilisation-periods with what you hope of later periods that will again support imaginative thinking. Through forming conceptions by way of comparing and relating them you progress from the abstract to the concrete, and strive to prevent the abstract from having any longer a value in itself, but to lead over to the concrete, to discover the genius of speech.

In this the school must come to the help of what is a great task of civilization. In the school this creation of concrete ideas should be made a practice so that in speaking one begins to feel oneself into the speech, to feel oneself in the world in speaking. Take as an example that I have written something on the black-board. Someone says “I do not understand it”. . . Think of the confused abstractions you sometimes have in mind when you say “I do not understand”. They would become concrete if you would picture to yourself that you want to grasp it, take it in, comprehend it. But you do not grasp it, you remain aloof—you do not get into touch with the matter. But you must think with your very hands. Try with the most important words. What will you be doing? You will in fact be doing eurhythmy in spirit! When indeed you speak concretely you do eurhythmy in spirit. You cannot do anything else than eurhythmy in spirit. He who is actively alive in sea things finds most men of today—if you will allow me to say so—sluggards, men who go round with their hands in their pockets and then want to talk without any feeling. For, spiritually considered, abstract thinking is putting the feet together and the hands in the pockets, and withdrawing everything as far into oneself as possible. This is how the man of today speaks. To leave out the concrete from one's thinking is just to be slovenly. But most men are that today. People must become more mobile inwardly, that is, they must feel with the world. Even those who do this often do so unconsciously. One knows people who place their finger on their nose when considering anything. They are quite unconscious of the fact that this is an actual concrete eurhythmic expression of the strong feeling of self when deciding on something. People today do not even consider why they have a left and a right hand, or two eyes. And in learned books the most foolish things—which explain nothing—are said of the seeing with two eyes. If we did not possess two hands so that we can grip one with the other we would not be able to have any clear idea of our own self, our “I”. It is only because we can grasp the one hand with the other, the like with like, that the conception “I” is attainable in the right way. And just as we can cross the left hand with the right, as we experience ourselves, and are astonished at this experience, at experiencing ourselves, we also cross the axis of sight in our eyes, although this crossing is not so visible as that of the hands. And we have two eyes which we can cross for the same reason as we have two arms and two heads.

If we wish to keep in sight the deeper essentials of human development from the present into the future we must bear in mind the necessity of taking up into our speech what the speech of today lacks. Because of its lack man is shut off from the whole world in which he is between death and a new birth. Hence we are exhorted, when we would establish a connection with a dead person, not simply to speak with him in verbal conceptions, for that achieves little, but to think of some concrete situation—you have stood near him in some particular way, have heard his voice, have shared an experience—to think quite concretely of the situation and everything that happened in relation to it that makes a connection with the dead. Today man uses language in a sense which shuts him off completely from the world of the dead; the genius of speech has died to a greet extent, and must be reanimated. Much that is customary today in the use of language should be dropped. A very great deal depends upon this, my dear friends. For it is only by actually trying to listen to the genius of speech lying behind the concrete words that we shell come back to imaginative conception (which I have already mentioned here as essential for future evolution). Then we shall gradually free ourselves altogether from distorted abstractions.

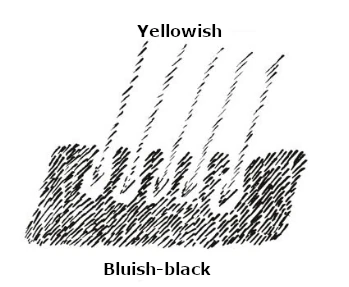

Something else is involved in this. A man feels an enormous satisfaction today in thinking in abstractions, free from the reality that the senses bring him. But he simply comes thereby into gaps in his conceptions; at least they are gaps for the dead. Today when people repeat spirit, spirit, spirit, the words are just so many blanks for nothing concrete is called forth. Most present-day thoughts are abstractions. The farther east one goes, say Europeans the more pictorial speech becomes. And that is just the reason why speech is more nearly related to spiritual things the farther east one goes; because it is more in the form of pictures. Speaking in abstractions should not lead away at all from the concrete sense-conception, but should simply illuminate it. Just think how many of you, my dear friends, thought concretely of the sentence I have just spoken: the sense-conception that have reality should be illumined by the abstractions? You may imagine the concrete sense-conception as a darkness which is illumined by the abstraction. So when we utter the sentence “into our concrete conceptions abstractions enter to illumine them” we think of rays of light falling into a dark room which is blue-black except where the yellow rays stream in. So when I state “into our concrete sense-conceptions the abstractions send their light” I have in mind a dark room into which fall bright rays of light. For how many people is it the case today that they really have such a picture in mind? They say aloud the word illumine without having any of the actual concrete conception in what you would call a spiritual sense. But the important thing is that when we pass over into abstraction, we do not only have a different picture of the concrete, of the physical, that we experience the change in conception. We can make this experience our own on watching eurhythmy; for then through another, less over-worked, medium, through the medium of gesture, what lies within the words comes to expression. And men can find their way back to imagery in ideas.

Few men are conscious that a hand outstretched is an actual “I”, for they do not know that in uttering “I” and connecting it with a concrete conception that they are extending a part of their etheric body. But gradually they realise that they are extending something of their etheric body in uttering “I” by watching the same movement in eurhythmy. It is no arbitrary matter that is introduced here, but actually something connected very strongly, very powerfully with the development of our civilization.

It is important to grasp this. Our period now is the fifth post-Atlantean, that is one, then we have the sixth and seventh ahead of us leading to a great break in human development. During this fifth post-Atlantean period speech must again recover its concrete character, and conceptions become pictures again. Only in this way can we fulfil the task of this fifth post-Atlantean period. Now speech will return less and lees to picture-conceptions the more the state gains control of the spiritual life. The more schools, and spiritual activities have come under state control in the last centuries the more abstract has all life become. Only the spiritual life based on itself will be able to call up this necessary symbolization of man's spiritual being which must be evoked. In the course of the fifth post-Atlantean period things will appear which will act most disturbingly on the spiritual strivings. During this period everyone will only rightly experience himself who can imagine himself in the following situation: “You are in the world, you must be conscious that on the one side you are constantly approaching luciferic beings, and on the other ahrimanic.” This living feeling of standing an man within this trinity must impress itself more and more on mankind in this fifth post-Atlantean period, thereby overcoming the great dangers of the period. The most varied human characters will appear in this fifth post-Atlantean period: idealists will be present, and materialists. But the danger for the idealists will always be that of entering luciferic regions in their conceptions, of becoming fanatics, visionaries, passionate enthusiasts, Lenins, Trotskys, without ground, real actual ground, under their feet, with their wills they can easily become ahrimanic, despotic, tyrannical. What real difference is there between a Czar and a Lenin? In their idea materialists easily become luciferic, prosaic, pedantic, dry, bourgeois; and in their wills become luciferic: greedy, animal, nervous, sensitive, hysterical. I will write this up on the boards:

Idealists: Ideas can easily become luciferic: fanatical, visionary, passionately enthusiastic. Wills can easily become ahrimanic: despotic, tyrannical.

Materialists: Ideas can easily become ahrimanic, prosaic, pedantic, bourgeois. Wills can easily become luciferic: animal, greedy, nervous, hysterical,

You see, idealists and materialists are exposed to similar dangers from different sides in this fifth post-Atlantean period—the idealists to both the luciferic and the ahrimanic: only from the side of ideas to the luciferic, from the side of will to the ahrimanic while materialists are exposed to the ahrimanic more, in their ideas., and to the luciferic more in their wills, The various characters that arise will have this in very different degrees. That is where the difficulty of bringing mankind forward will lie: for all that will be a source of error. Whether he be idealist or materialist, man will never be able to progress aright unless he has the good will to penetrate into material reality in full understanding, and on the other hand also letting the spirit enlighten him in the right way, that is, when he is not one-sided. One should not become one-sided where the most concrete outlooks on life are concerned, in particular not there.

Whoever likes only children faces the danger that very strong ahrimanic influences affect him; whoever prefers the old is in danger of being affected by the strongest luciferic influences, Many-sided interests will be essential for men if they wish to help civilization to evolve fruitfully towards the future. That is the foremost task of this fifth post-Atlantean period.

But these three consecutive periods will encroach upon each other considerably. What comes two expression in the sixth, and even what the seventh expresses, must already be unfolding in the fifth. There will not be so much differentiation in the future as there has been in the past. In the sixth period it will above all be necessary for men to cause the ahrimanic to be fettered, that is to come to terms with reality. How does one come to term with reality? For this it is essential in the first place that the life of rights that has separated from the cultural and economic spheres, that this life of rights in which men must live together democratically must now become as conscious in a higher way as it was unconscious in the Egypto-Chaldaic period. In everything that goes on between man and man, men must learn to experience significant processes on a higher level. Such ideas must become as living as they are presented in my last mystery play, in the Egyptian scene, where Capesius says that what takes place there in little has significance for the whole of world events. When men once more realise that no one can lie without a mighty uproar being made in the spiritual world, then things will be fulfilled as they must be in the sixth post-Atlantean period. And when we arrive once more at the possibility of a wise paganism alongside Christianity then what must come to pass in the seventh period, but is even now particularly essential, will be realised. Humanity has lost its relationship to nature. The gestures of nature no longer speak to man. How many can have any clear idea today when one says: in summer the earth is asleep, in winter awake? It seems a mere abstraction. But it is no abstraction. Such a relation to the whole of nature must be gained so that man can feel once more his identity with all nature.

These are matters that are essential for the inner life of the soul. Of how it is connected with all that we call social impulse we shall speak further tomorrow.

Vierter Vortrag

Zunächst werde ich einiges vorzubringen haben, das scheinbar weniger mit den Auseinandersetzungen, die wir jetzt hier pflegen, zusammenhängt: mit den Auseinandersetzungen nämlich über die soziale Frage. Aber es wird sich morgen schon herausstellen, wie dieser Zusammenhang doch vorhanden ist. Ich habe das letzte Mal damit geschlossen, daß ich Ihnen gezeigt habe, aus welchen Gründen Kinder, die in den letzten Jahren, so seit 1912/1913 geboren werden, mitbringen aus ihrem geistigen Leben vor der Geburt, man könnte sagen, eine gewisse ‚Abneigung, in dasjenige sich hineinzuleben, was sie durch die unmittelbaren oder mittelbaren Vorfahren der letzten Jahrhunderte hier auf der Erde vorfinden wie ein Kulturerbgut. Ich habe Ihnen gesagt, daß unter den konkreten Erfahrungen, die man über die geistige Welt machen kann, die ist, daß eine Art Begegnung stattfindet in der geistigen Welt zwischen den Seelen derer, welche jüngst verstorben sind, die also durch die Pforte des Todes hinauf in die geistige Welt zurückkehren, und jenen Seelen, die sich eben anschicken, den irdischen Schauplatz wiederum zubetreten. Welche Zusammenhänge die Menschen gehabt haben mit der geistigen Welt, bevor sie gestorben sind, das wirkt sehr stark nach, wenn die Menschen durch die Todespforte gegangen sind. Das hat insbesondere eine große Bedeutung für unsere Zeit. In unserer Zeit sind nur wenige atavistische Gefühle im Menschen noch vorhanden, die ihn zusammenhängen lassen mit der geistigen Welt. Daher bekommt er Impulse, die er dann hinauftragen kann, nachdem er durch die Todespforte eingetreten ist in diese geistige Welt, nur dann, wenn er sich bewußt in Vorstellungen mit der geistigen Welt befaßt. Es ist schon einmal heute ein größerer Unterschied zwischen solchen Verstorbenen, die von irgendwoher Ideen bekommen haben über die geistige Welt, Ideen, die in wirklicher Gedankenform sind, und solchen Persönlichkeiten, die lediglich in den Vorstellungen unserer materialistischen Kultur gelebt haben. Es ist ein großer Unterschied zwischen diesen Seelen im nachtodlichen Leben, und namentlich empfinden stark diesen Unterschied die Seelen, welche sich eben anschicken, wiederum auf die Erde herunter zur Verkörperung zu kommen.

Nun wissen Sie ja, daß im Lauf der letzten Zeit, bis in das 20. Jahrhundert herein, die materialistischen Neigungen, das materialistische Denken und Empfinden auf der Erde immer intensiver und intensiver geworden sind. Die Menschen, die also durch die Todespforte in die geistige Welt hinaufkommen, haben wenig Impulse, die gewissermaßen, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, sympathische Erwartungen erwekken für ihren Erdenaufenthalt bei denen, die nun heruntersteigen wollen auf die Erde.

Das hatte seine Kulmination im zweiten Jahrzehnt des 20. Jahrhunderts erreicht. Und so kamen diejenigen Kinder, die im zweiten Jahrzehnt des 20. Jahrhunderts geboren waren, mit einer starken geistigen Antipathie gegen dasjenige, was hergebrachte Kultur, hergebrachte Bildung war, auf der Erde an. Dieser Strom von Impulsen, der da mit diesen jüngstgeborenen Kindern auf die Erde hereinkam, der hat mächtig dazu beigetragen, auf der Erde die Neigung hervorzurufen, diese alte Kultur, diese Kultur der kapitalistischen und technischen Zeit wegzuwischen, wegzufegen. Und wer in der rechten Weise in der Lage ist, einzugehen auf den Zusammenhang zwischen der physischen und der überphysischen Welt, der wird nicht mißverstehen, wenn gesagt wird, daß, was in den Herzen und Seelen unserer jüngsten irdischen Mitbürger lebt an Begierde nach einer spirituellen Kultur, wesentlich mitgewirkt hat an demjenigen, was in den letzten Jahren auf der Erde sich ereignet hat. Sehen Sie, meine lieben Freunde, das ist gewissermaßen, wenn ich sagen darf, die Lichtseite der traurigen, der fürchterlichen Ereignisse der letzten Jahre. Es ist deshalb eineLichtseite, weil es zeigt, daß das Furchtbare, das angerichtet worden ist, wenn man sich so ausdrücken darf, wegen der Versumpftheit des materialistischen Zeitalters, vom Himmel gewollt worden ist und als Botschaft heruntergeschickt worden ist durch das Unterbewußte der jüngstgeborenen Kinder. Das ist der Seelenausdruck, der ein ganz anderer ist bei den allerjüngsten Kindern, als bei denjenigen, die etwa im 19. oder im Anfange des 20. Jahrhunderts geboren worden sind. Und es wird schon notwendig sein, daß sich die Menschheit auf solche feineren Beobachtungen einrichtet. Heute ist die Menschheit stolz auf ihren praktischen Sinn. Aber wo sich dieser praktische Sinn betätigen sollte im wirklichen Lebensbeobachten, da wird über alles hinweggesehen, da wird über alleshinweggeredet und hinweggedacht. Den melancholischen Ausdruck, der sich auf zahlreichen jüngsten Kindern, Kinderantlitzen zeigt seit fünf bis sechs Jahren, den bemerken heute die Menschen wenig. Würden sie ihn bemerken, so würden sie daraus den Impuls schöpfen - schon daraus -, daß eine mächtige soziale Bewegung Platz greifen muß.

Aber man muß eben sich aneignen den Sinn für den Blick, für die Physiognomie, die der Mensch trägt in den allerjüngsten Jahren seines Erdendaseins; dazu ist allerdings notwendig, daß die Menschen diesen Sinn ausbilden. Nun kann viel von diesem Sinne ausgebildet werden, so grotesk es heute für manchen sich noch ausnehmen mag, wenn das gesagt wird, wenn man sich ein wenig - aber nun nicht bloß, indem man auf Sensation ausgeht, sondern indem man mit der Seele dabei ist — einläßt auf dasjenige, was eigentlich die Eurythmie will. Sie werden gleich sehen aus welchem Grunde.

Wer heute in der Lage ist, durch seine okkulte Erfahrung mit den Toten zu verkehren, der bemerkt sehr bald - man verkehrt mit den Toten ja durch Gedanken -, daß sehr viele Gedanken, durch die man sich selber mit den Toten verständigen will, von diesen Toten nicht verstanden werden. Viele von den Gedanken der Menschen hier auf Erden, von den Gedanken, an die sich die Menschen gewöhnt haben, klingen für die Toten — Sie müssen das natürlich entsprechend nehmen, ich rede von Gedankenverkehr mit den Toten -, wie eine unverständliche, eine fremde Sprache. Und wenn man näher auf dieses ganze Verhältnis eingeht, so findet man namentlich, daß Verben, Zeitwörter, auch Präpositionen und vor allen Dingen Interjektionen von den Toten verhältnismäßig leicht verstanden werden, Substantiva, Hauptwörter hingegen fast gar nicht. Die bilden sozusagen im Sprachverstehen der Toten eine gewisse Lücke. Da versteht der Tote nimmer, wenn man viel in Hauptwörtern mit ihm sprechen will. Und man merkt, wenn man versucht, das Hauptwort in ein Verbum umzusetzen, daß er dann anfängt zu verstehen. Wenn Sie zum Beispiel zu einem Toten sagen: Der Keim für irgend etwas -, so bleibt ihm das Wort «der Keim» in den meisten Fällen unverständlich, ja, es ist, als ob er überhaupt nichts hörte. Wenn Sie sagen, etwas keimt, wenn Sie also «der Keim» verwandeln in das Verbum: etwas keimt -, dann fängt er an zu verstehen.

Woran liegt das? Sie kommen darauf, daß das durchaus nicht an dem Toten liegt, sondern das liegt an einem selbst. Das liegt an dem Menschen, der mit dem Toten spricht, und zwar aus dem Grunde, weil die heutigen Menschen seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts, wenigstens für alle mittel- und westeuropäischen Sprachen - es ist um so mehr der Fall, je weiter man nach Westen kommt -, verloren haben für die Substantiva das lebendige Bildgefühl, was das Substantive ausdrückt: es ist so irgend etwas Nebuloses, was nur eigentlich im Verständnis anklingt, wenn der Mensch heute ein Substantivum sagt; die wenigsten Menschen denken überhaupt noch etwas Wirkliches, wenn sie in einem Substantivum sprechen. Wenn sie dann das Substantivum in ein Verbum verwandeln müssen, dann sind sie innerlich gezwungen, ein bißchen konkreter zu denken. Wenn einer sagt «der Keim», so werden Sie in den meisten Fällen, insbesondere wenn er in abstrakten Reden redet, nicht finden, daß er sich konkret irgendeinen Pflanzenkeim, etwa eine keimende Bohne, irgendwie noch im Bilde vorstellt; er stellt sich etwas ganz Nebuloses im Bilde vor, so irgend etwas im Prinzip. Wenn Sie sagen «was keimt», oder «dasjenige, welches keimt», so sind Sie wenigstens gezwungen, dadurch daß Sie die Verbalform haben, an das Herauskommen zu denken, also doch an irgend etwas, das sich bewegt. Das heißt: Sie gehen aus dem Abstrakten ins Konkrete hinein. Dadurch, daß Sie selbst aus dem Abstrakten ins Konkrete hineingehen, beginnt der Tote Sie zu verstehen. Aber die Menschen werden genötigt werden, weil aus Gründen, die ich hier oftmals angeführt habe, die lebendigen Zusammenhänge zwischen den hier auf der Erde lebenden und den durch die Pforte des Todes gegangenen, unverkörperten Seelen immer enger und enger werden müssen, weil die Impulse der Toten immer mehr und mehr hereinwirken müssen auf die Erde, allmählich in ihre Sprache, in ihr Sprechen und damit in ihr Denken etwas aufzunehmen, welches vom Abstrakten ins Konkrete herüberführt. Das muß geradezu ein Bestreben der Menschen werden, wiederum bildhaft, imaginativ zu denken, wenn gesprochen wird.

Nun frage ich Sie: Wie viele Menschen denken zum Beispiel konkret, wenn sie, sagen wir, lesen von einer Gerichtsverhandlung, wo Richter waren, die gerichtet haben, Urteile gesprochen haben, also die richterliche Tätigkeit ausübten? Wo in aller Welt wird konkret gedacht, wenn irgend jemand das Hauptwort ausspricht, das Substantivum «das Recht»? Stellen Sie sich nur einmal diese schattenhafteste Abstraktheit vor, die in den Köpfen vorhanden ist, wenn vom Recht gesprochen wird, wenn «rechten», «das Richtige» in der Sprache zum Ausdruck kommt? Was ist denn eigentlich, rein sprachlich genommen, das Recht? Wir haben jetzt viel gesprochen davon, daß der Staat vor allem ein Rechtsstaat sein soll. Was ist denn rein so für sich genommen das Recht? Es bleibt für die meisten eine ganz schattenhafte Vorstellung, eine Vorstellung, die in Abstraktionen wüstester Art spielt. Wie können Sie denn zu einer konkreten Vorstellung vom Recht kommen? Wollen wir da einmal im einzelnen Fall die Sache durchgehen.

Sie haben schon gehört, daß man gewisse Menschen linkisch nennt. Was sind linkische Menschen? Sehen Sie, was wir mit der linken Hand auszuführen versuchen, wenn wir nicht gerade Linkshänder sind, das tun wir gewöhnlich ungeschickt, da sind wir nicht anstellig dazu. Wenn jemand sich in seinem ganzen Leben so verhält, wie man sich selber verhält, wenn man etwas mit der linken Hand tut, so ist er linkisch. Es liegt der Bezeichnung «linkisch» die ganz konkrete Vorstellung zugrunde: Der macht alles so, wie ich es mache, wenn ich etwas mit der linken Hand tue; nicht irgendeine wüste Abstraktheit, sondern das ganz Konkrete: Der verhält sich so, wie ich mich in den Fällen verhalte, wo ich etwas mit der linken Hand mache. Daraus entsteht, konkret aufgefaßt, ein Gefühlsgegensatz zwischen dem Linkischen und dem Rechtsischen, demjenigen, was man mit der rechten Hand macht und dem, was man mit der linken Hand macht. Und das, was rechtsisch ist, das wird im Substantivum «das Recht». Das Recht ist einfach ursprünglich dasjenige, was so geschickt für die Wirklichkeit gemacht wird, wie das, was man mit der rechten und nicht mit der linken Hand macht.

Da haben Sie schon etwas Konkretheit in die Sache hineingebracht. Jetzt aber stellen Sie sich einmal vor — Sie brauchen sich es ja nur an der Uhr vorzustellen, aber es gibt zahlreiche andere Fälle, wo man Ähnliches tun könnte -, Sie werden in der Regel nicht, wenn Sie eine Uhr zu richten haben, mit der linken Hand drehen, sondern mit der rechten Hand: da richten Sie die Uhr. Dieses Drehen von links nach rechts, das man mit der rechten Hand macht, das ist das konkrete Richten, Rechten. Man sagt sogar «zurechtrichten». Da haben Sie die konkrete Vorstellung des von links nach rechts im Kreisegehens, des Zurechtsetzens. Das ist richten. Einer der nach links abgeirrt ist, wohin er nicht sollte, den setzt der Richter zurecht.

Durch solche Dinge kommen Sie darauf, konkrete bildhafte Vorstellungen mit dem Worte noch zu verbinden. Sehen Sie, solche bildhafte Vorstellungen waren mit den Worten bis ins 15. Jahrhundert bei allen Menschen noch verknüpft. Dieses bildhafte Vorstellen ist erst abgeworfen worden. Dazu muß man sich wiederum zurückbändigen, zu diesem bildhaften Vorstellen. Denn der Tote versteht nur dasjenige, was noch bildhaft in der Sprache drinnen klingt. Alles das, was - wie es beim heutigen Sprechen zumeist der Fall ist-nicht mehr bildhaft klingt, was nicht mehr bildhaft formuliert ist, so daß bei dem Betreffenden eine bildhafte Vorstellung sitzt, das ist für die Toten unverständlich.

Wenn Sie die Sache weiter überlegen, dann werden Sie sehen, daß bei allem Umsetzen ins Bildhafte eigentlich das Substantivische zuerst verlorengeht. Das geht alles ins Verbale, ins Zeitwortgemäße über, oder wenigstens geht es in etwas so über, daß man genötigt ist, bildhafte Vorstellungen zu entwickeln. Wenn man heute einen solchen Stil entwickelt, daß überall bildhafte Vorstellungen zugrunde liegen, dann bekommt man in der Regel zur Antwort: Die Leute verstehen das nicht, das ist schwer verständlich. Aber wer es ehrlich meint mit unserer Zeit, der strebt bewußt einen solchen Stil an, der vorgestellt werden kann durch und durch in Bildern. Ich habe jetzt in der Broschüre, die über soziale Fragen erscheint — selbst da, wo man so sehr gedrängt ist zu Abstraktionen, weil die Gegenwart, da wo über die soziale Frage diskutiert wird, fast nur noch Abstraktionen zutage fördert -, selbst da habe ich angestrebt, möglichst so zu stilisieren, daß die Dinge in Bilder umgesetzt werden können. Gerade bei den heutigen Redereien über die soziale Frage ist das Abstraktionsvermögen zum Alleräußersten getrieben. Und die Menschen haben sich allmählich angewöhnt, die Worte gewissermaßen wie Redemünzen hinzunehmen, bei denen sie ganz und gar nicht mehr an irgend etwas konkret Bildliches denken. Lesen Sie heute eine soziale Broschüre oder ein soziales Buch: da können Sie nur zurechtkommen, wenn Sie sich jahrelang hineingewöhnt haben in dasjenige, was gemeint ist, denn nur auf dem konventionellen Gebrauch der Worte beruht eigentlich der ganze Sinn solcher Reden. Wer fühlt heute, wenn er von «Besitzenden» spricht, daß dieses Wort einen gewissen Zusammenhang hat mit besessen sein! Und dennoch, der Sprachgenius, der, wie ich oftmals bemerkt habe, viel, viel bedeutender ist als dasjenige, was das einzelne menschliche Individuum denken und sprechen kann, der hat unzählige Beziehungen geschaffen, welche von dem Individuum nur entdeckt zu werden brauchen, um wiederum hineinzukommen in ein gewisses geistiges Leben. Und gerade wenn wir uns bestreben, hinter jedem Substantivum sein Verbum zu suchen, und geradezu übungsgemäß nicht immer vom Licht und vom Schall sprechen, sondern von dem sprechen, was leuchtet, und von dem, was schallt, und dann uns genötigt finden, immer mehr und mehr auf Wesenhaftiges einzugehen gegenüber dem Nichtwesenhaften, dann kommen wir auf eine Bahn, die in dieser Beziehung heilsam sein kann.

Viel besser als das Substantivum ist schon das Adjektivum. Viel konkreter ist es, wenn ich sage: Wer fleißig ist —, als wenn ich einfach sage: Der Fleißige. - Aber «der Fleißige» ist schon wiederum viel konkreter, als wenn ich gar das furchtbare Gespenst - der Tote empfindet es nämlich als ein furchtbares Gespenst - «der Fleiß» zitiere. Wenn Sie sagen: das Wie, das Was - Goethe prägt einmal den schönen Satz: Das Was bedenke, mehr bedenke Wie -, dann ist das für den Toten deshalb eine lebendige Sprache, weil Sie selbst genötigt sind, indem Sie substantivisch solche Worte gebrauchen wie Was und Wie, konkret zu fühlen. Wenn Sie heute sagen: Ich stehe aus Prinzip auf einem gewissen Standpunkte —, dann haben Sie für den Toten zwei Gespenster zitiert, erst das «Prinzip», denn kaum ein Mensch denkt sich heute bei Prinzip etwas Konkretes, zweitens: «Standpunkt.» Dieses Gespenst «StandPunkt» ist ja in unserer Sprache und in allen westeuropäischen Sprachen schon so korrumpiert, daß man, wenn einer spricht, meistens schon das Allerwichtigste wegläßt. Sogar die Setzer korrigieren einen manchmal! Wenn ich in einem Manuskript schreibe: Wenn man von einem Standpunkte aus etwas sieht -, dann korrigiert der Setzer das «aus» zumeist heraus, und man muß es in der Korrektur wieder einsetzen; denn die Leute haben sich gewöhnt, den Unsinn zu sagen: Wenn man von einem Standpunkte etwas sieht. - Man kann, wenn man konkret spricht, nur sagen: Wenn man von einem Standpunkte aus etwas sieht dadurch wird eine Konkretheit hineingelegt. Aber wenn man von einem Standpunkte etwas sieht — da ist höchstens für den, der konkret spricht, die Vorstellung möglich, sich vorzustellen, daß man von dem Punkt etwas sieht, worauf der steht: ein Stückchen von dem Punkt. Na, ein Stückchen von dem Punkt ist schon an sich schwer vorzustellen, nicht wahr?

Sehen Sie, diese Dinge sind außerordentlich wichtig und bedeutsam, denn sie weisen auf die Intimitäten der Beziehungen zwischen der sinnlichen und der geistigen Welt hin. Diese Dinge geben viel mehr eine Vorstellung über die Beziehungen des Sinnlichen und des Übersinnlichen, als das meiste, was in abstrakten Worten heute darüber geprägt wird. Gehen Sie einmal diejenige geisteswissenschaftliche Literatur durch, die ich versucht habe zu schreiben, und prüfen Sie sie auf ihre Methode hin. Das ist eine Prüfung, die wahrscheinlich bis heute die wenigsten Menschen vollzogen haben, denn immer ist die Methode eingeschlagen, daß eigentlich das eine durch das andere erklärt wird, daß immer die Dinge aufeinander hinweisen. Und ein wirkliches Geistesverständnis kann man auf gar keine andere Weise hervorrufen, als daß ein Ding immer auf anderes hinweist. Nehmen Sie nur einmal das Wort «Geist»! Geist, Geist, Geist — glaubt heute jeder immer sprechen zu müssen, der über den Materialismus hinweg sein will. Nehmen wir «Geist» in der deutschen Sprache. In der lateinischen trägt es ja einen noch mehr konkreten Charakter: Spiritus — aber, nicht wahr, das ist etwas, was die meisten Menschen nicht sehr stark zum Geiste hinführen wird, nach dem, was man unter «Geist» versteht, und wenn Sie dann nachdenken darüber, so wird die Sache sehr abstrakt, weil Sie sich doch nicht vorstellen können einen «Spiritus», nicht wahr? Das ist aber die konkrete Vorstellung, die zugrunde liegt. Aber, was ist «Geist»? Die meisten Menschen stellen sich ja, wenn sie sich den Geist vorstellen - ich habe das oft getadelt - eine sehr, sehr dünne Materie nur vor, so einen recht dünnen Nebel, und wenn sie irgendwo vom Geiste sprechen wollen, reden sie von «Vibrationen». Ich habe früher oft gehört, nicht gerade in theosophischen Versammlungen, aber bei theosophischen Tees, daß die Leute gesagt haben: Da sind so gute Vibrationen! — Ich weiß nicht, wie sie das meinten, aber jedenfalls ist ja auch das ein sehr materieller Vorgang, den man hineinphantasiert in den Raum. Das Wort «Geist», «Gischt», «Geischt», «Geschti» ist ja so etwas wie Dampf, der heraus-gischt aus irgendeiner Öffnung; das würde die konkrete Vorstellung sein. Aber in unserer heutigen Zeit, in dem fünften nachatlantischen Kulturzeitalter, kann man auf diese Weise gar nicht zu irgendeiner konkreten Vorstellung über den Geist kommen; das ist ja rein unmöglich. Denn, nicht wahr, entweder bleiben Sie bei irgendeiner schattenhaften Abstraktion stehen, die Sie mit dem Worte «Geist» verbinden, oder Sie sind genötigt, an Spiritus, an Weingeist zu denken; bei einem «begeisterten Menschen» werden Sie dann zu einer kuriosen Vorstellung kommen. Oder aber Sie denken an Gischt, Geischt, an etwas, was aus irgendeinem Spalt, in dem sich ein Ventil öffnet, heraus-gischt. Da würden Sie zu dem Konkreten kommen.

Nun wird in der Methode, die hier in dem anthroposophischen Betrieb der Geisteswissenschaft eingeführt ist, versucht, durch die gegenseitigen Bedingungen der Vorstellungen, auf die angespielt ist, diese ins Konkrete allmählich überzuführen. Denken Sie doch, daß nur auf der einen Seite davon gesprochen wird, der Mensch zerfalle in physischen Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib, Empfindungsseele, Verstandesseele, Bewußtseinsseele; und dann tritt «Geist» auf: Geistselbst, Lebensgeist, Geistesmensch. Es wird mit vollem Bewußtsein nur angeschlagen, da davon überhaupt die meisten, welche die Sache anhören, noch keine konkreten Vorstellungen bekommen können. Dann aber folgt sehr bald darauf, daß den Leuten gesagt wird: Betrachtet den Lebenslauf eines Menschen: von der Geburt bis zum siebenten Jahre, bis zum Zahnwechsel, ist vorzugsweise der physische Leib in Tätigkeit, dann bis zum vierzehnten Jahre der ätherische Leib, dann der Empfindungsleib, dann vom einundzwanzigsten bis zum achtundzwanzigsten Jahre die Empfindungsseele, dann in den Dreißigerjahren die Verstandes- oder Gemütsseele und so weiter. Damit wird der Mensch darauf hingewiesen: Beobachte äußerlich an dem konkreten Menschen, der sich durch seinen Lebenslauf hin entwickelt, welche Verschiedenheiten auftreten. Siehst du einen Menschen mit seinen besonderen Eigentümlichkeiten an, der im Anfang der Zwanzigerjahre ist, so seien dir diese Eigentümlichkeiten Symptome für dasjenige, was du vorzustellen hast, wenn der Ausdruck «Empfindungsseele» gebraucht wird. Siehst du ein Kind mit seiner Eigentümlichkeit, alles das zu tun, was der Große tut, durch die Hülle des Leibes zu leben, dann bekommst du in der Art, wie das Kind sich gebärdet, eine Vorstellung davon, was man eigentlich unter «physischem Leib» versteht. Und siehst du einen alten Menschen mit grauen Haaren und runzeligem Gesicht, wo die Materie bemerklich welkt, und du beobachtest ihn in seinen Bewegungen, in der Art und Weise, wie er sich darlebt, dann siehst du nicht mehr wie beim Kinde, wie sich da etwas, das ja in ihm ist, vorzüglich durch die Hülle darlebt, sondern du siehst in dem Greise wirksam dasjenige, was sich schon beginnt loszulösen vom physischen Leib. Beobachte den Greis: du wirst an seinen Gebärden, an der Art seines Verhaltens allmählich aufsteigen zu einer Vorstellung vom Geiste. Wenn du den Greis vergleichst mit dem Kinde und die Gebärde des Greises vergleichst mit den kindlichen Imitationsgebärden, dann erweckt sich in deiner Seele ein Gefühl des Unterschieds zwischen Geist und Materie. - Denken Sie, wie da der Bildlichkeit, dem imaginativen Vorstellen geholfen wird. Da wird der Mensch darauf hingewiesen: Stelle dir konkret den Lebenslauf eines Menschen vor und empfinde an diesem Lebenslauf etwas, dann füllen sich deine sonstigen abstrakten Worte mit konkreten Inhalten an.

Und wiederum wird versucht, auf alle mögliche Weise zu zeigen, wie die Menschheit als solche immer jünger und jünger geworden ist, wie wir jetzt siebenundzwanzig Jahre alt sind, das heißt, wie unsere Kultur darin besteht, daß wir siebenundzwanzig Jahre alt sind als Menschheit. Wenn Sie das vergleichen mit dem, was Sie wissen können von früheren Kulturperioden, was Sie erhoffen können von späteren Kulturperioden, so unterstützt Ihnen das wiederum das bildliche Vorstellen. Vergleichsweise, beziehungsweise Vorstellungen bilden, das ist etwas, wodurch Sie vorschreiten vom Abstrakten zum Konkreten und dahin gelangen, die Abstraktionen allmählich überhaupt nicht mehr als Abstraktionen gelten zu lassen, sondern ins Konkrete überzuführen, den Sprachgenius zu belauschen.

Da müßte nun wirklich heute die Schule zu Hilfe kommen demjenigen, was eine große Kulturaufgabe ist. Übungen müßten in der Schule angestellt werden in diesem Konkretmachen der Vorstellungen, damit der Mensch anfange, wenn er etwas spricht, sich in dem Sprechen drinnen zu fühlen, im Sprechen in der Welt sich zu fühlen. Nehmen Sie zum Beispiel an, ich habe etwas auf die Tafel geschrieben. Irgend jemand sagt einem: Das begreife ich nicht. - Denken Sie an die schattenhaften Abstraktionen, die Sie manchmal in Ihrem Gemüte haben, wenn Sie sagen: Das begreife ich nicht. - Konkret würden die nämlich werden, wenn Sie sich vorstellen wollten, Sie wollten das begreifen, hin-greifen, doch Sie begreifen es nicht, Sie bleiben zurück, Sie kommen nicht an die Sache. - Aber da müßten Sie mit Ihren Händen das vorstellen. Versuchen Sie das gerade bei den wichtigsten Worten, was werden Sie dann tun? Sie werden eigentlich im Geiste Eurythmie treiben! Wenn Sie nämlich konkret sprechen, so treiben Sie im Geiste Eurythmie. Sie können gar nicht anders, als im Geiste Eurythmie treiben. Und derjenige, der in solchen Dingen lebendig drinnensteht, der empfindet die meisten heutigen Menschen — verzeihen Sie — als schreckliche Faulpelze, als Menschen, die eigentlich immer herumgehen mit den Händen in den Hosentaschen und sich nicht bewegen wollen und dann reden. Denn abstrakt vorstellen, das ist, geistig empfunden, die Hacken und auch die Fußspitzen zusammenmachen, die Hände in die Hosentaschen tun und alles so einzwängen in sich, wie man nur kann! So redet der heutige Mensch. Die Konkretheit fortlassen aus den Vorstellungen: das heißt nämlich «latsch» sein! Aber so sind die meisten heutigen Menschen. Die Menschen müssen innerlich wieder beweglich werden, das heißt, sie müssen sich mitfühlen mit der Welt. Selbst diejenigen, die das tun, die tun es manchmal nur unbewußt. Man kennt Menschen, wenn sie über etwas nachdenken, so machen sie es mit dem Finger an der Nase. Daß dies aber eine ganz konkrete eurythmische Vorstellung ist für das Sich-stark-fühlen-Wollen, um etwas zu entscheiden, dessen werden sich die Menschen gar nicht bewußt. Die Menschen denken ja heute nicht einmal darüber nach, warum sie eine rechte und eine linke Hand haben, oder warum sie zwei Augen haben. Und in den gelehrten Büchern stehen namentlich über das Sehen mit den zwei Augen die allertollsten Dinge, die eigentlich gar nichts erklären. Hätten wir nämlich nicht zwei Hände, so daß wir die linke mit unserer rechten angreifen könnten, so könnten wir nie eine ordentliche Ich-Vorstellung haben. Nur daß wir Gleiches mit Gleichem von rechts nach links angreifen, dadurch wird die Ich-Vorstellung allmählich in der rechten Weise möglich. Und geradeso wie wir mit der rechten Hand die linke zur Kreuzung bringen können, wie wir uns selber empfinden und erstaunt sind über unser Empfinden, über das, daß wir uns empfinden, so kreuzen wir auch die Augenachsen. Die sind nur nicht so sichtbar gekreuzt wie die beiden Hände. Und damit wir kreuzen können, haben wir zwei Augen, aus demselben Grund, warum wir zwei Hände respektive Arme haben.

Das ist, was man sich vor Augen führen muß, wenn man die intimeren Notwendigkeiten der menschlichen Entwickelung von der Gegenwart in die Zukunft ins Auge fassen will: diese Notwendigkeit, in die Sprache dasjenige aufzunehmen, was der Sprache heute fehlt. Und weil es fehlt, schließt sich der Mensch ab von der ganzen Welt, in der er ist zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Deshalb wird immer ermahnt, wenn man eine Verbindung herstellen will mit einem Toten, nicht einfach mit ihm in Wortvorstellungen zu sprechen, denn das führt nicht zu viel, sondern irgendeine konkrete Situation zu denken: So hast du neben ihm gestanden, seine Stimme hast du gehört, das hat dich in der Empfindung mit ihm zusammengeführt -, ganz konkret sich die Situation und alles, was dabei vorgekommen ist, zu denken, das verbindet mit dem Toten. Denn die Menschen brauchen heute die Sprache in einem Sinn, durch den sie geradezu von der Welt der Toten abgeschlossen werden; der Sprachgenius ist zum größten Teil eben gestorben und muß wiederum verlebendigt werden. Da muß wahrscheinlich vieles fallen, was die Leute heute gewöhnt sind, als Sprachfügungen und dergleichen zu haben! Das ist es, worauf vieles, vieles ankommt, meine lieben Freunde. Denn nur dadurch werden wir — was ich schon einmal hier erwähnte als notwendig für die zukünftige Entwickelung - in das imaginative Vorstellen wieder hineinkommen, indem wir wirklich versuchen, dem Sprachgenius abzulauschen, was den Worten Konkretes zugrunde liegt. Da werden wir überhaupt die vertrackte Abstraktion allmählich losbekommen.

Und etwas anderes wird eintreten. Heute fühlt der Mensch eine ungeheure Befriedigung, wenn er in Abstraktionen denken kann, wenn er loskommt von der Wirklichkeit, die für ihn die sinnliche Wirklichkeit ist. Aber er kommt eigentlich dadurch nur in lauter Vorstellungslöcher hinein, wenigstens für den Toten sind sie Vorstellungslöcher. Und wenn heute die Leute von Geist, Geist, Geist sprechen, so sind das ebenso viele Vorstellungslöcher, denn die Menschen stellen sich nichts Konkretes vor. Die meisten Gedanken sind heute Abstraktionen. Je weiter man nach dem Osten geht - sagen die Europäer -, um so bildhafter wird die Sprache. Das ist es gerade, warum die Sprache geistverwandter ist, je weiter man nach Osten kommt: Weil sie bildhafter ist. In Abstraktionen sprechen sollte nämlich gar nicht wegführen vom sinnlich-konkreten Vorstellen, sondern es sollte das sinnlich-konkrete Vorstellen nur durchleuchten. Aber denken Sie nur einmal: Haben viele oder werden viele von Ihnen an das Konkrete desjenigen Satzes gedacht haben, den ich jetzt ausgesprochen habe: Die sinnlich-wirklichen Vorstellungen sollen durch die Abstraktionen durchleuchtet werden? — Sie müssen sich also die sinnlich-konkreten Vorstellungen dunkel vorstellen, eine Finsternis; in die wird durch die Abstraktion hineingeleuchter. Also indem wir den Satz aussprechen: In unsere konkreten Vorstellungen wird durch die Abstraktion hineingeleuchtet -, denken wir uns Lichtstrahlen in einen dunklen Raum hineinfallend, der womöglich blauschwarz ist, während das Hineinfallende gelblich hineinstrahlt. Indem ich den Satz ausspreche: In unsere konkreten sinnlichen Vorstellungen leuchten die Abstraktionen hinein —, habe ich einen dunklen Raum im Geiste, in den helle Lichtstrahlen hineinfallen (siehe Zeichnung). Bei wie vielen Menschen ist das heute der Fall, daß wirklich in ihrem Gemüte solch ein Bild lebt? Sie sprechen das Wort «durchleuchten» aus, ohne daß sie die konkrete Vorstellung in dem, was sie geistigen Sinn nennen, irgendwie noch haben. Aber darauf kommt es an, daß wir nicht nur das Konkrete, das Sinnliche anders vorstellen, wenn wir zur Abstraktion übergehen, sondern daß wir eine Empfindung haben von diesem Andersvorstellen! Diese Empfindung können wir-uns aneignen, wenn wir gerade das Boryilimische anschauen; denn da komm durch ein:anderes Mittel, das weniger abgebraucht ist, durch das Mittel der Gebärde dasjenige, was in den Worten liegt, zum Ausdruck. Und die Menschen können sich wieder zurückfinden zu dem bildlichen Vorstellen.

Es ist wenigen Menschen bewußt, daß eine Handstreckung ein wirkliches I ist, weil sie nicht wissen, wenn sie I aussprechen und dieses I mit einer konkreten Vorstellung verknüpft ist, daß sie etwas strecken in ihrem Ätherleib. Aber Sie kommen allmählich darauf, daß Sie etwas strecken in Ihrem ätherischen Leib, wenn Sie I aussprechen, wenn Sie eben dieselbe Bewegung in der Eurythmie beobachten. Das ist also keine willkürliche Sache, die jetzt hereingetragen wird, sondern es ist tatsächlich eine Sache, die mit unserer Kulturentwickelung außerordentlich stark zusammenhängt.

Sehen Sie, es ist wichtig, dies zu begreifen. Wir haben jetzt den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum; dann haben wir noch vor uns den sechsten und siebenten bis zu einem großen Einschnitt in der Menschheitsentwickelung. Während dieses fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums müssen die Sprachen wiederum zurückkehren zur Konkretisierung, zum bildhaften Vorstellen. Nur auf diese Weise können wir die Aufgabe dieses fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums wirklich erfüllen. Nun werden die Sprachen um so weniger zurückkehren zum bildhaften Vorstellen, je mehr der Staat das geistige Leben unterjochen wird. Je mehr Schulen und Geistesbetriebe verstaatlicht worden sind in den letzten Jahrhunderten, desto abstrakter ist das ganze Leben geworden. Erst das auf sich selbst gebaute Geistesleben wird diese notwendige Verbildlichung des geistigen Wesens des Menschen herbeiführen können, die herbeigefürt werden muß. Innerhalb dieser Bestrebung werden Dinge auftreten im Laufe des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums, die sehr störend eingreifen werden in die spirituellen Bestrebungen. Während dieses fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums wird jeder Mensch sich nur richtig empfinden, der sich denken kann in der Situation: Du bist stehend in der Welt, du mußt dir bewußt sein, daß du auf der einen Seite immerfort nahekommst luziferischer Wesenheit, auf der anderen Seite nahekommst ahrimanischer Wesenheit (es wird gezeichnet). Dieses lebendige Gefühl, in diese Trinität hineingestellt zu sein als Mensch, das muß die Menschen während des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums immer mehr und mehr durchdringen; dadurch kommen sie über die großen Gefahren dieses fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums hinaus. Die mannigfaltigsten Menschencharaktere werden auftreten während dieses fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums: Da werden Idealisten sein, da werden Materialisten sein. Aber die Idealisten, die werden immerfort vor der Gefahr stehen, daß sie mit ihren Vorstellungen in luziferische Regionen hineinkommen, daß sie Schwärmer, Phantasten, Schwarmgeister, Lenine, Trotzkijs werden, ohne wirklichen Boden unter den Füßen; mit ihrem Willen können sie leicht ahrimanisch werden, despotisch, tyrannisch. Was ist eigentlich für ein Unterschied zwischen einem Zaren und einem Lenin? — Die Materialisten werden in ihren Vorstellungen leicht ahrimanisch werden, nüchtern, philiströs, trocken, bürgerlich; in ihrem Willen können die Materialisten luziferisch werden; animalisch, begierlich, nervös, sensitiv, hysterisch. Ich will das auf die Tafel schreiben:

Idealisten:

Vorstellungen können leicht luziferisch werden;

Schwärmer, Phantasten, Schwarmgeister.

Wille kann leicht ahrimanisch werden; despotisch, tyrannisch.

Materialisten: Sie sehen: Idealisten und Materialisten, sie sind, nur von verschiedenen Seiten her, im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum den gleichen Gefahren ausgesetzt, die Idealisten von seiten der Vorstellungen dem Luziferischen, von seiten des Willens dem Ahrimanischen; die Materialisten von seiten der Vorstellungen dem Ahrimanischen und von seiten des Willens dem Luziferischen. Die verschiedenen Charaktere, die auftreten, werden das in den verschiedensten Abstufungen haben. Da wird die Schwierigkeit liegen, die Menschheit wirklich vorwärtszubringen, denn all das werden zugleich Quellen des Abirrens der Menschheit sein. Denn niemals wird der Mensch einseitig als Idealist oder als Materialist richtig vorwärtskommen können, sondern nur dann, wenn er den guten Willen hat, ebenso in die materielle Wirklichkeit verständnisvoll einzudringen, wie auch auf der anderen Seite sich vom Geiste in der richtigen Weise erleuchten zu lassen. Aber einseitig soll man nicht werden selbst mit Bezug auf die allerkonkretesten Anschauungen des Lebens, da erst recht nicht. Wer nur Kinder gerne hat, der steht vor der Gefahr, daß sehr starke ahrimanische Einflüsse auf ihn wirken; wer nur Alte gerne hat, steht vor der Gefahr, daß sehr starke luziferische Einflüsse auf ihn wirken. Vielseitigkeit der Interessen, das ist dasjenige, was den Menschen notwendig wird, wenn sie Beihilfe leisten wollen zu einem fruchtbaren Entwickeln der Kultur nach der Zukunft hin. Das wird vorzugsweise die Aufgabe des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums sein. Aber diese drei Zeiträume, die noch folgen müssen, werden sehr ineinander übergreifen. Das, was für den sechsten zum Ausdruck kommt, muß auch schon mitentwickelt werden in dem fünften, und auch das, was in dem siebenten zum Ausdruck kommt; es kann nicht alles so geschieden werden in der Zukunft, wie es in der Vergangenheit geschieden war. Und für den sechsten Zeitraum, da wird vor allen Dingen notwendig sein, daß die Menschen es dahin bringen, das Ahrimanische zu fesseln, das heißt, mit der Wirklichkeit so recht fertig zu werden. Wie werden sie mit der Wirklichkeit fertig? Dazu ist notwendig vor allen Dingen, daß das Rechtsleben, das ausgesondert hat das geistige Leben und das Wirtschaftsleben, daß dieses Rechtsleben, also dasjenige, was von Mensch zu Mensch demokratisch leben muß, jetzt so bewußt werden muß, wie es während der ägyptisch-chaldäischen Kulturperiode unbewußt war. Es muß der Mensch lernen, bei alledem, was vorgeht in der Welt zwischen Mensch und Mensch, bedeutsame Vorgänge höher zu empfinden. Lebendig werden solche Vorstellungen werden müssen, wie sie angeschlagen waren in meinem letzten Mysteriendrama in jener ägyptischen Szene, wo von Capesius ausgesprochen wird, wie dasjenige, was da im engen Raume vorgeht, eine Bedeutung hat für das ganze Weltgeschehen. Wenn die Menschen wissen werden wiederum, daß man niemanden anlügen kann, ohne daß in der geistigen Welt mächtige Dinge toben, dann wird so etwas erfüllt werden, wie es immer mehr erfüllt werden muß in dem sechsten nachatlantischen Zeitraum. - Und wenn wir wiederum kommen zu der Möglichkeit eines weisheitsvollen Heidentums neben dem Christentum, dann wird etwas von dem verwirklicht, was für den siebenten nachatlantischen Zeitraum, aber auch schon für jetzt ganz besonders notwendig ist. Die Menschen haben verloren das Verhältnis zur Natur. Die Natur spricht nicht mehr in Gebärden zu den Menschen. Wie viele Menschen können sich heute noch etwas davon vorstellen, wenn man sagt: Im Sommer schläft die Erde, im Winter wacht die Erde? - Das ist für sie eine Abstraktion. Es ist keine Abstraktion! Zur ganzen Natur muß wiederum ein solches Verhältnis gewonnen werden, daß der Mensch sich eigentlich als etwas Gleiches fühlt mit der ganzen Natur. Das sind Dinge, die für das intimere Seelenleben wesentlich sind. Wie sie zusammenhängen mit dem, was wir soziale Impulse nennen können, davon wollen wir dann morgen weiter sprechen.

Vorstellungen können leicht ahrimanisch werden;

nüchtern, philiströs, trocken, bürgerlich.

Wille kann leicht luziferisch werden;

Fourth Lecture

First, I will have a few things to say that may seem less relevant to the discussions we are having here, namely the discussions about the social question. But tomorrow it will become clear how these things are connected. Last time, I concluded by showing you the reasons why children born in recent years, since 1912/1913, bring with them from their spiritual life before birth, one might say, a certain 'aversion to living into what they find here on earth as a cultural heritage from their immediate or indirect ancestors of the last centuries. I told you that among the concrete experiences that can be had of the spiritual world is that a kind of encounter takes place in the spiritual world between the souls of those who have recently died, who thus return through the gate of death to the spiritual world, and those souls who are just preparing to reenter the earthly scene. The connections that people had with the spiritual world before they died have a very strong effect after they have passed through the gate of death. This is particularly significant for our time. In our time, only a few atavistic feelings remain in human beings that connect them to the spiritual world. Therefore, they receive impulses that they can carry upward after they have entered the spiritual world through the gate of death only if they consciously engage with the spiritual world in their imagination. There is already a great difference today between those who have died and who have received ideas about the spiritual world from somewhere, ideas that are in real thought form, and those personalities who have lived solely in the ideas of our materialistic culture. There is a great difference between these souls in the afterlife, and this difference is felt particularly strongly by those souls who are preparing to come back down to earth to be incarnated.

Now you know that in recent times, up until the 20th century, materialistic tendencies, materialistic thinking and feeling have become more and more intense on Earth. The people who thus ascend through the gate of death into the spiritual world have little impulse, so to speak, to awaken sympathetic expectations for their stay on earth in those who now want to descend to earth.

This reached its culmination in the second decade of the 20th century. And so the children born in the second decade of the 20th century came to earth with a strong spiritual antipathy toward what was traditional culture and education. This stream of impulses that came into the world with these newly born children contributed powerfully to the tendency on earth to wipe away, to sweep away, this old culture, this culture of the capitalist and technological age. And anyone who is able to understand the connection between the physical and the superphysical world in the right way will not misunderstand when it is said that what lives in the hearts and souls of our youngest fellow citizens in their longing for a spiritual culture has played a significant part in what has happened on earth in recent years. You see, my dear friends, this is, in a sense, if I may say so, the bright side of the sad, terrible events of recent years. It is a bright side because it shows that the terrible things that have been done, if I may put it that way, because of the stagnation of the materialistic age, were willed by Heaven and sent down as a message through the subconscious of the most recently born children. This is the expression of the soul, which is completely different in the youngest children than in those born in the 19th or early 20th centuries. And it will be necessary for humanity to attune itself to such subtle observations. Today, humanity is proud of its practical sense. But where this practical sense should be applied in the observation of real life, everything is overlooked, talked away, and thought away. The melancholic expression that has been evident in many young children, in children's faces, for the past five or six years is hardly noticed by people today. If they did notice it, they would draw from it the impulse—from that alone—that a powerful social movement must take hold.

But one must acquire the sense of observation, of the physiognomy that human beings carry in the earliest years of their earthly existence; for this, it is necessary that people develop this sense. Now, much of this sense can be developed, however grotesque it may seem to some today when it is said, if one allows oneself — not merely by seeking sensation, but by being present with one's soul — to engage a little with what eurythmy actually aims at. You will soon see why.

Anyone who is able to communicate with the dead through occult experience will very soon notice — for one communicates with the dead through thoughts — that many of the thoughts one uses to communicate with the dead are not understood by them. Many of the thoughts of people here on earth, the thoughts that people have become accustomed to, sound to the dead — you must take this in the appropriate sense, I am talking about communication with the dead — like an incomprehensible, foreign language. And if you look more closely at this whole relationship, you will find that verbs, time words, prepositions, and above all interjections are relatively easy for the dead to understand, whereas nouns, on the other hand, are almost impossible for them to understand. They form, so to speak, a certain gap in the language comprehension of the dead. The dead can never understand you if you try to speak to them using many nouns. And you notice that when you try to convert the noun into a verb, they begin to understand. For example, if you say to a dead person, “The seed for something,” the word “seed” will remain incomprehensible to them in most cases; it is as if they heard nothing at all. If you say something germinates, if you convert “the germ” into the verb: something germinates, then he begins to understand.

Why is that? You come to the conclusion that it is not at all the fault of the dead person, but rather your own. It is because of the person who is talking to the dead, and that is because since the middle of the 15th century, at least in all the languages of Central and Western Europe — and the further west you go, the more this is the case — people have lost the living image that nouns express: it is something nebulous that only really resonates in our understanding when we say a noun today; very few people still think of anything real when they speak in nouns. When they then have to turn the noun into a verb, they are inwardly compelled to think a little more concretely. When someone says “the germ,” in most cases, especially if they are speaking abstractly, you will not find that they are still imagining any concrete plant germ, such as a germinating bean, in their mind; they imagine something completely nebulous, something in principle. When you say “what germinates” or “that which germinates,” you are at least forced, by the verbal form, to think of something coming out, that is, of something that moves. This means that you move from the abstract to the concrete. By moving from the abstract to the concrete, the dead begin to understand you. But people will be compelled to do so because, for reasons I have often mentioned here, the living connections between those living here on earth and the disembodied souls who have passed through the gate of death must become ever closer and closer, because the impulses of the dead must increasingly influence the earth, gradually to take into their language, into their speech, and thus into their thinking something that leads from the abstract to the concrete. It must become an aspiration of human beings to think pictorially and imaginatively when they speak.

Now I ask you: How many people think concretely, for example, when they read about a court hearing where judges were passing judgment, pronouncing verdicts, in other words, exercising judicial authority? Where in the world is concrete thinking taking place when someone utters the noun “the law”? Just imagine the shadowy abstraction that exists in people's minds when they talk about the law, when “right,” “the right thing” is expressed in language. What is law, purely in linguistic terms? We have talked a lot about the state being, above all, a constitutional state. But what is law in and of itself? For most people, it remains a very vague concept, a concept that plays out in the wildest abstractions. How can you arrive at a concrete concept of law? Let's go through this in detail using a specific example.