The Social Question as a Problem of Soul Life

GA 190

29 March 1919, Dornach

II. Inner Experience of Language II

If we now speak a great deal about the social problem that is disturbing our times, it is because the essential thing for us—in addition to what is naturally of particular importance to our contemporaries as such in this problem—is that really the ultimate practical solution of this problem is intimately connected with the fundamentals of Spiritual Science, and therefore those interested in Spiritual Science have a special inducement to regard this question from out of a Spiritual Scientific standpoint. For you see it is urgently necessary that understanding should be aroused in the widest circles for what are the impulses behind the social movement. On the other hand, however, these circles are little prepared to look into the matter fundamentally, to concentrate their gaze on the fundamentals. By degrees a certain comprehension must ray out from those interested in Spiritual Science into the sphere of the social movement, and for this it is necessary to make ourselves acquainted with certain fundamental facts without knowledge of which there can be no real grasp of the social problem. There can be no doubt that the unconscious and subconscious play an enormous part in human social life. What is at work in the social life comes ultimately from what people think and feel, and, according to the impulses of their characters, what they will. But in the age of the development of the consciousness soul this becomes increasingly individual. People become more and more different in their thinking, feeling and willing: this is the task of the epoch of the development of the consciousness soul. Therefore much will spring from subconscious sources in human relationships to flow into the social movement which, begun half a century ago, has today reached a culmination and will spread farther and farther afield making enormous demands of the people. What emerges today are primarily chaotic demands. In place of these, clearer and clearer conceptions and better and better will impulses must appear. It was because these clear conceptions and good impulses of will did not exist that mankind fell into the present catastrophe and this catastrophe will become immeasurably greater. For one cannot say that real goodwill exists extensively in regard to this question. What exists is something like a yielding to what seems to be inevitable. One would willingly give them a morsel now and again, for fear that otherwise their mouths might water. But what must appear in a really deep social understanding? That must live in the hearts of men and must become an essential part of our schooling.

Something of this kind can be attained only when at least a certain number of people on earth, really out of knowledge of human nature, out of knowledge of the relation between physical and the superphysical worlds, cultivate a deeper understanding for these problems than most people can develop by reason of our present superficial culture.

Yesterday you saw how matters stand with what plays its part in the whole man's life as language. Now just think what part, on the other hand, language plays in men's international operation throughout the world. Consider how manifold are the varied feelings and will impulses depending upon languages. Consider again how infinitely much that is not clear in such things prevails among men. Today let us spend a little time on speech. As I mentioned yesterday we had three periods of evolution to come in the post-Atlantean period of human evolution. We live in the fifth, the sixth will follow, to be followed in turn by the seventh. As we saw yesterday, on turning our attention to the development of language, till now we, as earthly men, have developed a certain inclination to abstract, unimaginative thinking. What must be evolved before the end of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch is the imaginative conception, Imagination. It is mankind's special task in this fifth post-Atlantean period to develop the gift of Imagination. I beg of you not to confuse what I am discussing here with those matters set out in the book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds. In that book it is the individual man who is being considered. It is a matter of the esoteric development of the individual man. What I am now considering is the social life of people. The folk genius cultivates imagination. Each one of us must seek his own Imagination for esoteric development: but the folk genius cultivates the Imagination from which must come the common spiritual culture of the future. An imaginative spiritual culture must be developed in the future. Now we have reached, so to speak, the culminating point of abstract spiritual culture, that spiritual culture which everywhere works towards abstraction; from out of that there must be developed a culture with imaginative conceptions. Our culture must be interpenetrated not with thoughts abstractly expressed but with imagery such as we have for example in our group, the Representative of mankind between the luciferic as the one pole and the ahrimanic as the other. And many people will have to tell themselves, more and more people will have to tell themselves, that what really has to do with spiritual life is not to be expressed in abstract thoughts. One should not always be pondering about abstract thoughts, but it is right and living in the right way in the human heart to express oneself through pictures. The life of Imagination in common is what must come.

In the sixth post-Atlantean period a kind of Inspiration of the folk genius should be especially cultivated, out of which should blossom such ideas of rights as will be felt as a kind of gift for the life on earth. The life to be developed in the rights-state is, as I recently pointed out, such a one as is opposed to all life of the Spirit, indeed it is its opposite. When earthly life takes its source healthily and not unhealthily, the principles of rights gradually accepted as such will be felt as gifts from the spiritual world. They will be felt as gifts that come down to the folk genius through Inspiration to rule earthly life, not in a human arbitrary manner, but in the sense of a great spiritual leadership. One could say that it is just through this Inspiration experienced by the folk genius that Ahriman will been enchained. Otherwise an ahrimanic being would be developed over the whole earth.

The last epoch will have to cultivate Intuition. Only under the influence of this Intuition can the whole economic life be developed which men can see as their ideal economic life. But the curious thing is that from now on one cannot so separate things in the more or less abstract way that I have written them up on the board:

V. Imagination

VI. Inspiration

VII. Intuition

You see one can quite well speak of the early Indian epoch, the early Persian, the Egypto-Chaldean, the Graeco-Latin period, an periods existing as such with need limits, in each of which were developed a very distinctive way of life. In the future that will no longer be possible; than the forces at work in civilization will be mingled. Thus the Intuition which will appear in the seventh epoch is already at work in the fifth, Inspiration is active in the fifth, Imagination is not fully acquired in the fifth but will reach its final stages only in the later periods. All these things happen interconnectedly; they are not so strictly separated. So that it is already necessary for men to work towards what should be achieved in the Imaginative life, and in the life of Inspiration and that of Intuition. But externally man must distinguish between the things that are forced into overlapping in time. The life of spirit which has as its prime task for the future to develop the imagination must be cultivated in the emancipated spiritual organisation. The life of Inspiration which will give the folk genius principally the conceptions of rights must be evolved in the separated state. And the Intuitive life, strange as it may appear, must be evolved in the economic life. These spheres must in their externals be kept separate, as has been shown you from various points of view.

You will see deeper into thee different members if you pay attention to what I have been putting forward in regard to language. You see, language is apparently something homogeneous. You regard language as something homogeneous and men feel it to be so. But it is not so. Language is something quite different with respect to the soul-spiritual life of mankind from what it is in respect to social life in the rights state, and again it different in respect to the economic life.

Let us try to characterize what is very difficult to describe. In regard to language think first of poetry. You have often heard the remark how much the man of every sphere of culture when he is a poet (and who is there who is not something of a poet!) is indebted to language. Language is much more creative than is believed. Language contains great and powerful mysteries; the genius of language is something tremendously creative. That is why within the sphere of language the purely humanly creative so seldom emerges: this is noticed only by those who with deep devotion study the evolution of the peoples. In one incarnation men usually remain bound only to a certain epoch, and so have nothing definite to go upon or passing judgment rightly on what I am now meaning. We Germans, for example, nowadays speak now and then with some modifications of meaning; but in so far as we use the uniform educated, we all speak differently from what was customary in the 18th century. Whoever follows attentively the literature of that century until the last third of the century will soon notice that. For the language we use in common as ordinary educated German speech is a result of Goethean creation and of those who are connected with Goethe's creative work: Lessing, Herder, Wieland, Goethe, and to a certain degree Schiller too. A great part of our verbal education did not exist before the time of these spirits! Take the Adelung dictionary, written comparatively recently, and hunt therein for many things which are now current: you will not find them! To a great extent the period which produced Goetheanism was created in language and we lived in what was formed in this way. There you see the individually creative playing into genius of speech as such. In poets one can even speak at that time of creation of the highest order: what follows as epigone is often drawn from the language itself.

So I have often said that when one sees through these things a facile language often strikes one, a dressed-up poetic performance of no distinction. What originally pulses from one's innermost soul is often much more awkward than what is the result of no great poetic gift, but produced by a certain profession of speech, by beautiful verse and the like. It is the same with the other arts. But one must pay attention to such things if one wants to have a concept of how there is a life in the language itself in which we are involved. In penetrating more deeply into this language the possibility will open out for an imaginative feeling and perception. Nowadays there is very much that fights against this learning of the imaginative from speech, because since languages have recently become international, men have with a certain justification acquired many languages, or at least several, up to a certain point. This acquisition of several languages has not yet driven the deeper aspect of the matter to the surface, but actually only the superficial. What the Imagination then brings about—what has to do with perception—has not yet been brought to the surface. Nowadays he who has acquired several languages becomes a slave to the dictionary for a slave to any other handbook that has to do with the languages in question. And so one has to accustom oneself to the horrid unreality that a word in another language that one finds in a dictionary for, say, a word from one's own language is taken to mean exactly the same. In regard to something I shall speak of next, it does certainly mean the same, but it does not do so where inner experience is concerned.

Take the following, for example: in German we say Kopf, in French tête, in Italian testa, and so forth. What does this show? Recall the human head and the head of an animal Kopf for the same reason that we speak of a cabbage as a Kohlkopf; because of its roundness, it's spherical form. So he who as a German calls the head Kopf is: it's so with regard to its form. Tête and testa signify something which testifies, which gives testimony. Thus there are quite different points of view from which one can indicate a member of the human organism. Fuss (foot) is a German word which is connected with Furt (ford), with the Furche (furrow) we make in walking over the ground; that is the point of view from which we as Germans indicate that part of the human organism; pied is the setting down, the indication of something placing itself on the ground: something quite different! The significance of words proceeds from various points of view. And this impulse to describe the same things from different backgrounds is the impress of a subconscious in the character of peoples that is not generally noticed.

But now consider, you have to do it not just with physical human beings walking about on the physical earth, but with men altogether; you are studying the whole relation to the dead. What is actually characteristic in the matter stands out particularly there. The dead have no sense for this dictionary interpretation of words, but for what is imaginative they have the deepest understanding. But should one form one's thoughts so that one gets the shade of meaning from the spoken sounds, the dead receive at once the imaginative form thus produced. When the German word for the head Kopf is used, the dead have the experience of roundness. When the same word is used in a Latin language he has the experience of what is testified. But this stigmatizing, this mere characterizing, this abstract relating to some single organ or other is not experienced by the dead; what he experiences with the deepest significance passes unnoticed by the man of today with his abstract thoughts. So that in his soul man has a special relation to language. The relation the soul has to whine which is actually far more inward than man's ordinary, everyday relation to language. The soul inwardly feels a difference when one describes a foot by being sent on the ground, or by the fact that a mark, a furrow, is made. The soul feels that; while externally and in the abstract man experiences only the relation of the word to the single organ in question. In its experience of speech the soul is inwardly in much the same condition as when it is disembodied. And what is generally experienced as the only meaning of speech in ordinary life really lies like an outer layer on the surface of speech. A true poet, for example, is just a man who has a fine feeling for the inwardness of language, a finer feeling than others. That man is a real poet who is alive to the imaginative in language, just as an artist is fundamentally not simply one who can paint or sculpt but one who can live in color and form.

These are matters which we must make our own from now on into the future. Without them the further progress of mankind in a favorable way is impossible, for the life of the Spirit would become barren, and mankind would be able to evolve hardly more than an animal existence unless an understanding for such things can be awakened. It is a peculiar fact that when one follows closely how children are born, how they developed in the early years, first babbling, then gradually learned to speak, in the way they learn there mingles into the child's learning to speak a heritage brought down from the experiences that have been going through in the spiritual world before they came down to earth; mingled with it is what the mother, father or nurse contributes to the child's learning to speak. He who can bring a fine observation to bear in this sphere will have surprising experiences from the child who is learning to speak. He will only be able to understand these surprising things when he can make the assumption that a child is actually bringing from the spiritual world some disposition that it mingles with what comes to his speech from outside. In the inward experience of language that human being is living in accordance with what he brings from the spiritual world. But that is the only thing in language that is really spiritual. Actually the one element and language is this inner experience, which we have because we bring with us certain impulses out of the spiritual world.

The other is that language is a mere medium for making oneself understood. Everything that goes on between men as men comes into consideration in it as a means of making themselves understood. We speak with one another so that the one knows what the other wishes to tell him. They are the inwardness of speech is not of account—there a certain convention applies. The point is that we do not think that when someone speaks of a table he means a chair, or when speaking of a chair he means a table. For that men here on the earth merely need a mutual understanding; that deeper, inward feeling for language does not come into it. At the present time this way of understanding language in which language is employed merely as a means of making ourselves mutually understood is actually all that is really experienced. For present day mankind language is not much more than the means by which they understand each other. Today it comes to few to listen to the mysterious inner impulses behind language so as to hear the divine powers as they make themselves known through this very language. There are some personalities today who have noticed that language has an inner life of its own; but among all those who have noticed it this perception arises in a certain whimsical way as, for example, with the poet Hofmannsthal, even the impudent Karl Kraus in Vienna who asserts that it is not feed himself who writes his sentences but that he simply listens to what the language wants to write. He may indeed listen to what the language which is to write, but only as men do who feared what comes from the spiritual world colored by their own emotions, here one-sidedly and falsely—that is shown by his dreadfully impudent writing, as language would never have inspired him. But as we were saying, individuals do already note this communicating by means of speech comes from other worlds and that must be cultivated if one is to find the way to the life of Imagination.

That moment will be of social significance for it is something binding men in a social bond. The common speech, which brings a common imagination, is something that will provide a social deepening. Language as a means of mutual copper hedging could also do that at need—but it is then externalized; as a mere means of communication it depends very much upon convention. Hence the externalizing of the soul's life nowadays, so that language is used really just to gossip with others so that no one knows what the other is thinking. You can indeed say a good deal against this: since so many do not think, some of us know when a statement is made what the other is not thinking! Well now—we understand each other.

Thus in language we have something that particularly points to the life of the Spirit, the life in the spiritual organism: something in language—that is to say, be nearly informative in language which alone comes into consideration today when people take up a dictionary, and because the word means one thing in one language and in another something else, it is simply a question of an external understanding, what lies deeper is not taken into account: whether the one describes something from this impulse, the other from that! There is of course an enormous difference in the soul life, whether by the word Kopf something round, that is the form, is to be understood, as most noun formations in German are plastic imagination, or whether, as in Latin languages, most noun formations originate in the stepping forth of man, how he places himself into the world, not by perception that by placing himself into the world. Great mystery is lie hidden in language.

With regard to the life of economics, we might be deaf and dumb and yet ultimately be able to carry on an economic life. The animals do so. Indeed, in economic life language is so to speak a stranger, a real stranger: we employ speech in the economic life because we happened to be speaking human beings; but we can conduct business in a foreign land, the language of which we do not know, we can buy anything, do everything possible. Men do not need the language at all for the life were language is a complete foreigner. The real inner spiritual element of language is present in the life of the Spirit, the element of language is already externalized in the life of rights—in the economic life everything that language means to man is utterly lost. Yet the economic life, as I have already pointed out, is what, fundamentally, can be the preparation for the life after death. How we conduct ourselves in the economic life, what feelings we unfold in that life, whether we are men who willingly helped another in a brotherly way, or whether we enviously gobble up everything for ourselves, depends upon the fundamental constitution of our soul, is essentially the mute preparation for many impulses which will be developed in the life after death. We bring with us a heritage from the life before birth which, as I described, comes to expression in what a child carried into all that it learns from nurse or mother. We bear with us out of life a mute element which springs up from the brotherliness unfolded in the economic life, and which develops important impulses in the life after death.

It is well that in the economic life language is such a foreign element that even if deaf and dumb we could develop the economic life. For by that means this subconscious soul like is developed that can be carried further when man has gone through the gate of death. Should man gave himself up altogether to what he experiences in his soul, to what can be expressed between man and man, should we, as men, not be able to serve one another without having to speak, we should be able to carry with us little into the world in which we are to live when we have passed through the gate of death.

On the other hand, my dear friends, it is extraordinarily difficult to discuss the pressing demands of the present-day social movement, for these demands are so many economic concerns for mankind. And for language for describing the economic concerns is actually non-existent. Our concepts indeed are not of the least use for discussing the social question. In Europe we should perhaps be able to discuss the social question in quite a different way it in our language we had with the Oriental has in his. There the decadence comes out only in the character of the people; that in their language are spiritual impulses enabling them to show as in gestures what has to be discussed about the social life—whereas we Europeans actually feel that every possible thing should always, as we think, be expressed in plain words. But this is not possible. We have to acquire the feeling that in speaking we are simply producing sound-gestures, hinting at things. Today it is practically only for interjections that man develops a real inwardness in regard to sound-gestures; a little, as I showed yesterday, for verbs; a mere touch of it for adjectives—none for nouns. The latter are completely abstract; and hence are not understood at all by the dead. There are blanks for them when we want to make ourselves understood and express things in language. So it is necessary, in order to make oneself understood by the dead, to transform what one has to say into real gestures, into real pictures, not to try to speak to the dead in words, but always to think better and better in pictures in the way I described yesterday.

Now I must say again and again what an aid to this experiencing in pictures is that part of eurhythmy that we now wish to bring back as visible speech. To perform eurhythmy is to transform what is spoken into the corresponding rhythmical movement, into gesture, and so on. But we must learn to do the opposite as well, to regard as a kind of speech what is set visibly before us. We must learn that what we customarily only looked at as something to say to us: morning says to us something different from what the evening says, and midday speaks differently from the night, and the leaf of a plant glistening with pearly dew says something different from a dry plant leaf. We must again learn the language of all nature. We must learn to penetrate through the abstract perception of nature to a concrete perception of nature. Our Christianity must be widened through a permeation, as I said yesterday, by a healthy paganism. Nature must again become something to us. It is the peculiarity of human evolution in the epoch of the fifth post-Atlantean period up to the present that we have become more and more indifferent towards nature. Certainly men still have a feeling for nature, they like being with nature, they are able to appreciate nature aesthetically, artistically. But they cannot soar to the heights of experiencing the inward life of nature, so that nature speaks to them as one man speaks to another. This is however essential if Intuition is again to play a part in human life. Before the end of the three epochs of which we have been speaking, men must, if they are to evolve healthily, developed a kind of personal relationship to all the details that connect them with nature. Today we can say in the abstract that by eating sugar you strengthen your sense of ego; and by eating less sugar you weaken your sense of ego; that tea dissipates the thoughts, and is the drink of diplomats, the dispenser of superficiality; that coffee is the drink of journalists, setting thoughts logically one after another—which is why journalists haunt coffeehouses, diplomats have tea parties, and so on; all this we can think in the abstract out of the nature of things: but human beings will come to develop in their way a healthy relation to everything that gives them such a relation to the whole of nature as today the animals instinctively possess. The animals know quite well what they eat; originally in their naive condition men also knew it; they have forgotten, unlearned it; and must regain the connection. There are people today—I have often mentioned it—curious people who when at the table have scales of which they weigh out how much meat and so on they should eat, because the dietitians have calculated the amount! In this abstract relations that man develops to the world all sound attitude to the world is lost.we must regain—if you will allow me to put it so—the experiencing of the spirit of sugar, tea, coffee, salt, and all those other things with which we are related through our organism: we must again learn to have these experiences. In this spirit today man experiences in the most abstract way. He feels something when he says “I am a mystic, I am a Theosophist.” What is that? It is a man feeling the divine ego with his own ego, feeling the macrocosm in the microcosm; the divine man within us that can be felt, can be lived . . . and all that that implies. They are of course the greyest, the vaguest, of abstractions. But today it is believed that there is no way out at all from these abstractions. Men nowadays do not look for this concrete experiencing with the whole world. What seems a great thing to men today is the thoughtless chatter of the experience of the God within. They think it very strange when one tells them that they should experience the God in sugar, tea, or coffee, or what not, yet this is really experiencing with the outer world: for the human experience of the external world is gross and materialistic unless something spiritual and the can be foundation of this material existence.

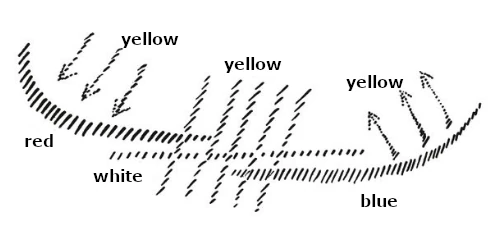

This feeling, for example, that existed in the second post-Atlantean period when everyone in the old Persian civilization felt when he ate anything how much light he took into himself along with it—son was ready to give up its light and in eating food light was also eaten—everyone felt how much light he was taking in: this feeling was an experience in ancient times which must return at a higher stage of consciousness. You see, these ideals naturally appear to be distant; but really they are not so far as people think from what man today holds to be most essential. For on looking into these things one approaches nearer and nearer and more concretely what is common to all mankind. It is just where there is veneration and penetration of nature that there will increasingly arise what sets up even the economic life that seems to us today so material, this dumb economic life, as a member of the divine world order. We shall then realized that the social organism, if it is to be sound must be threefold. It must have the spiritual organization because it is into this, above all, that we carry what we bring with us from the life before birth; it must have the economic organization because in it there must mutely developed what we bear with us through the gate of death, and what will be our impulses after death; and separate from both these, it must have the life of the rights-state because in this sphere above all is imprinted what is valid for this earthly life. Illustrated diagrammatically—here is earthly life, and raying into it, as it were, what we bring with us out of pre-earthly life (yellow arrows); and again we develop in this life what we bear out again (yellow). Here where I have drawn a red line the spiritual is within from the outset, it comes chiefly through language or the like. And here, where I have drawn a blue line, after death the spiritual rays out through the impulses we have absorbed in the economic life (yellow arrows). This in the middle, drawn in brown, is rayed through, as it were, laterally by the spiritual (yellow). The life of rights as such is entirely earthly, but is rayed through laterally. So that Inspiration, which should restrain Ahriman, should be active in the life of rights. We must advance to conceptions of rights, which are really taken from the life of the spirit, and which are really initiation conceptions.

But how can the things of which I have spoken today be straightaway made understandable to wider circles of present-day mankind? They cannot. For what the spiritual-scientific element would need to permeate the whole of the education and culture of the times. Otherwise it would not continue into the future. Therefore the healing of our social life is intimately bound up with the extension of a real understanding for spiritual knowledge. Certainly on the one hand there will gradually arise in people who have the goodwill accept social ideas the urge to receive the spiritual as well. For the most part, however, there are those who struggle against it, who preferred to remain fixed in those things of which I had to say yesterday that they were antipathetic to the children who for some years have been coming out of the spiritual world into life on earth. It is indeed pitiful to see how few people are inclined really to learn from the events;; how very much men today continue to exhibit ideas that they formally had before it became evident that the world that lives in the ideas as driven mankind into the frightful catastrophes of the time. At this juncture mankind should acquire a certain feeling of responsibility and an understanding of these things, and actually also see to the utmost extent these needs of the time. Just think—and this must be said of very many—how people today are fixed fast in egoism and how much cause one might have today to disregard one's own person and turned one's gaze to the great question of mankind. They are so overpoweringly great, these questions of the day, that if one is a sensible person one should scarcely have time to attend to the most limited personal destinies if these individual destinies could not be made fruitful for the great questions for time which already live in the womb of the evolutionary epochs of mankind. One could wish that men would take note of the great discrepancy between the futility of personal destiny today, and they reality that comes to light in the overpowering human problems of the day. One cannot understand the spiritual science in its reality, at least have no understanding of it at the present time, if one has no comprehension and accommodating spirit for these great human problems. Much is now only beginning to unfold: but it is precisely those who attach themselves to a movement for spiritual knowledge who should strive for a specially active understanding of what is being enacted to a wide extent in the social movement of the present day, and what, as can again be seen from today's indications, as wider horizons than is generally thought.

Tomorrow the conclusions that can be drawn from what has been set before you yesterday and today.1See: The Social Question (NSL 101)

Fünfter Vortrag

Wenn wir jetzt viel von der die Zeit bewegenden sozialen Frage sprechen, so ist für uns - außer dem, was natürlich für unsere Zeitgenossen als solche mit von besonderer Wichtigkeit in dieser Frage ist - noch wesentlich, daß die wirklich letzte praktische Lösung, die gegenüber dieser Frage in Betracht kommt, innig zusammenhängt mit geisteswissenschaftlichen Untergründen, und daß daher derjenige, der sich für Geisteswissenschaft interessiert, gerade eine besondere Veranlassung hat, vom geisteswissenschaftlichen Standpunkte aus auf diese Frage hinzusehen. Gewiß ist es heute dringend notwendig, daß in weitesten Kreisen Verständnis erweckt werde für dasjenige, was an Impulsen in der sozialen Bewegung liegt; aber auf der anderen Seite sind diese weitesten Kreise ja wenig vorbereitet, in die Grundlagen der Sache hineinzuschauen, die Sache wirklich aus ihren Fundamenten heraus ins Auge zu fassen. Es muß von den Menschen, die sich für Geisteswissenschaft interessieren, nach und nach auch gerade auf dem Gebiete der sozialen Bewegung ein gewisses Verständnis ausstrahlen, und dazu ist es notwendig, daß wir uns mit gewissen Grundtatsachen bekanntmachen, ohne deren Kenntnis ein wahrhaftiges Verständnis der sozialen Frage gar nicht möglich ist. Denn man täusche sich darüber nicht: Im sozialen Zusammenleben der Menschen spielt das Unbewußte und Unterbewußte eine ungeheuer große Rolle. Dasjenige, was im sozialen Leben wirkt, geht zuletzt doch hervor aus dem, was Menschen denken, was Menschen fühlen und was Menschen aus ihren Charakterimpulsen heraus wollen. Das wird aber im Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseelen-Entwickelung immer individueller und individueller. Die Menschen werden in bezug auf ihr Denken, Fühlen und Wollen immer verschiedener werden müssen: das ist die Aufgabe des Zeitalters der Bewußtseinsseelen-Entwickelung. Daher wird auch aus den unterbewußten Untergründen der Menschen im sozialen Zusammenwirken sehr vieles herausquellen, was hineinspielen wird in die soziale Bewegung, wie sie seit einem halben Jahrhundert begonnen hat, heute auf einem vorläufigen Gipfelpunkt angekommen ist und sich immer weiter und weiter bewegen wird, ungeheuer die Menschen in Anspruch nehmend. Denn, was heute hervortritt, das sind zunächst chaotische Forderungen. An die Stelle dieser chaotischen Forderungen werden immer klarere Vorstellungen und immer bessere und bessere Willensimpulse treten müssen Daß diese klaren Vorstellungen und guten Willensimpulse nicht vorhanden waren, das brachte ja die Menschheit in diese jetzige Katastrophe hinein und wird diese Katastrophe noch in ganz unermeßlicher Art vergrößern. Denn man kann nicht sagen, daß heute schon in weitesten Kreisen ein wirklich guter Wille vorhanden sei mit Bezug auf diese Fragen. Es ist so etwas vorhanden wie ein Nachgeben dem, was einem als das Unvermeidliche erscheint. Man möchte gern da und dort ein Stücklein beigeben, weil man Angst hat, daß das nicht anders gehen könnte, daß einem das Wasser in den Mund rinnen könnte und dergleichen. Aber, was auftreten wird müssen, das ist ein wirkliches inneres soziales Verständnis. Das wird sich hereinleben müssen in die Gemüter der Menschen, und das wird ein Bestandteil sogar unserer Schulerziehung werden müssen.

So etwas kann aber nur erreicht werden, wenn wirklich aus der Erkenntnis der Menschennatur, aus der Erkenntnis der Beziehungen zwischen sinnlicher und übersinnlicher Welt wenigstens eine Anzahl von Menschen auf der Erde ein tieferes Verständnis entwickeln für diese Fragen, als es die meisten Menschen heute wegen der oberflächlichen Zeitbildung entwickeln können.

Sie haben gestern gesehen, wie es eigentlich mit dem steht, was als Sprache im ganzen Menschenleben eine Rolle spielt. Nun bedenken Sie, welche Rolle anderseits wiederum die Sprachen spielen im internationalen Zusammenleben der Menschen über die Erde hin. Bedenken Sie, wie unendlich viel Empfindungen und Willensimpulse der mannigfaltigsten Art abhängen von den Sprachen. Und bedenken Sie wiederum, wie unendlich viele Unklarheiten gerade mit Bezug auf solche Dinge unter den Menschen der Gegenwart herrschen. Bleiben wir heute noch einmal ein wenig bei der Sprache stehen. Wir haben — ich erwähnte es gestern - vor uns drei Entwickelungszeiträume der nachatlantischen Menschheitsentwickelung. Wir leben im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum; auf den wird der sechste folgen und auf diesen der siebente; wir haben bis jetzt - und, wie Sie gestern gesehen haben, sogar unter Einstellung der Sprachenentwickelung - als Erdenmenschheit eigentlich einen gewissen Hang zu abstraktem Denken, zu unbildlichem Denken entwickelt. Dasjenige, was sich aber entwickeln muß, bevor dieser fünfte nachatlantische Zeitraum zu Ende geht, das ist bildliches Vorstellen, Imagination. Und es ist die spezielle Aufgabe dieses fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums, in der Erdenmenschheit die Gabe der Imagination zu entwickeln. Verwechseln Sie bitte dieses, was ich jetzt auseinandersetze, nicht mit den Dingen, die in dem Buche stehen «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?». In diesem Buche ist vom einzelnen individuellen Menschen die Rede. Das ist Gegenstand der esoterischen Entwickelung des einzelnen Menschen. Dasjenige, wovon ich jetzt spreche, ist soziales Völkerleben. Der Volksgenius entwickelt die Imagination. Seine eigene Imagination zu seiner esoterischen Entwickelung, die muß jeder für sich suchen; aber der Volksgenius entwickelt die Imagination, aus der heraus folgen muß die gemeinsame Geisteskultur der Zukunft. Eine imaginative Geisteskultur muß sich in der Zukunft entwickeln. Heute haben wir gewissermaßen den Kulminationspunkt der abstrakten Geisteskultur, der Geisteskultur, welche überall auf Abstraktion hinarbeitet; aus dem heraus muß sich eine Geisteskultur entwickeln mit bildhaften Vorstellungen. Durchdrungen muß gewissermaßen unsere Kultur werden von demjenigen, was man nicht wird in abstrakten Gedanken aussprechen wollen, sondern in solchen Bildern, wie zum Beispiel unsere «Gruppe» eines ist: mit dem Menschheitsrepräsentanten in der Mitte, mit dem Luziferischen als einem Pol, mit dem Ahrimanischen als anderem Pol. Und viele Menschen, immer mehr Menschen werden sich sagen müssen: Dasjenige, was eigentlich das Geistesleben angeht, ist nicht auszudrücken in abstrakten Gedanken. Man soll nicht immer um die abstrakten Gedanken fragen, sondern es ist richtig und sich recht einlebend in das menschliche Gemüt, eben sich auszudrücken durch Bilder. Das bildhafte Gemeinsamkeitsleben, das ist dasjenige, was auftreten muß.

Im sechsten nachatlantischen Zeitraum soll sich insbesondere eine Art Inspiration der Volksgenien entwickeln. Und aus dieser Inspiration heraus sollen sich entwickeln Rechtsvorstellungen, welche empfunden werden wie eine Art Gabe für das irdische Leben. Das Leben, das im Rechtsstaat entwickelt wird, ist ja, wie ich Ihnen neulich schon auseinandergesetzt habe, ein solches, das entgegengesetzt ist allem Geistesleben. Das Staatsleben ist der Gegensatz zu allem Geistesleben. Wenn das Erdenleben heilsam verlaufen soll, nicht unheilsam, so muß dasjenige, was als Rechtsprinzipien sich nach und nach geltend machen wird, so empfunden werden wie Gaben aus der geistigen Welt, die durch Inspiration herunterkommen an den Volksgenius, um das irdische Leben zu regeln, so daß es nicht von menschlicher Willkür bloß, sondern im Sinne einer großen geistigen Führerschaft geregelt ist. Man könnte auch sagen: Gerade durch diese Inspiration, die der Volksgenius erfahren muß, wird Ahriman gefesselt werden. Sonst würde sich ein ahrimanisches Wesen über die ganze Erde hin entwickeln.

Und der letzte Zeitraum würde vorzugsweise die Intuition zu entwickeln haben. Erst unter dem Einfluß dieser Intuition kann sich das ganze Wirtschaftsleben entwickeln, wie man es eigentlich als Wirtschaftsleben wie ein Ideal auffassen könnte. Aber das ist das Eigentümliche, daß von jetzt ab man nicht die Dinge so trennen kann, wie ich es eben auch mehr oder weniger abstrakt auf die Tafel geschrieben habe: V.: Imagination — VI.: Inspiration — VII.: Intuition.

Man kann ganz gut sprechen vom urindischen Zeitraum, urpersischen Zeitraum, ägyptisch-chaldäischen Zeitraum, griechisch-lateinischen Zeitraum, als für sich bestehende Zeiträume, die nach hinten und vorne abgegrenzt sind; in jedem entwickelt sich eine ganz bestimmte Art des Menschenlebens. Das kann man zukünftig nicht mehr, da vermischen sich die Kulturimpulse. So daß, was als intuitives Leben im siebenten Zeitraum auftritt, in den fünften Zeitraum schon hereinwirkt, auch Inspiration in den fünften hereinwirkt, während die Imagination, die im fünften nicht voll erreicht wird, in den späteren Zeiträumen nachgetragen werden kann. Das geht alles durcheinander, wir sind nicht so streng voneinander abgegrenzt. Die Menschheit hat jetzt schon nötig, hinzuarbeiten auf dasjenige, was im imaginativen, im inspirierten Leben, im intuitiven Leben erreicht werden soll. Aber was zeitlich sich gewissermaßen durcheinanderschiebt, das muß eben gerade äußerlich vom Menschen auseinandergehalten werden. Das Geistesleben, das vorzugsweise gegen die Zukunft hin die Imagination zu entwickeln haben wird, dieses Geistesleben, das muß in der emanzipierten geistigen Organisation sich entwickeln. Das inspirierte Leben, das für den Volksgenius vorzugsweise die Rechtsvorstellungen geben wird, das muß sich im abgesonderten Staate entwickeln. Und das intuitive Leben, so sonderbar das erscheint, das muß sich im Wirtschaftsleben entwickeln. Es müssen diese Gebiete äußerlich auseinandergehalten werden, was ja von vielen Gesichtspunkten aus vor Ihnen schon vorgetragen worden ist.

Nun werden Sie wiederum ein Stück tiefer in diese Gliederung eindringen, wenn Sie gerade dasjenige, was ich so auseinandergehalten habe, mit Bezug auf die Sprache ins Auge fassen. Sehen Sie, die Sprache ist scheinbar etwas ganz Einheitliches. Sie halten die Sprache für etwas Einheitliches, und die Menschen empfinden die Sprache wie etwas ganz Einheitliches. Das ist sie aber nicht. Die Sprache ist etwas ganz anderes mit Bezug auf das eigentliche geistig-seelische Leben des Menschen, wieder etwas ganz anderes mit Bezug auf das soziale Zusammenleben im Rechtsstaate, und wiederum etwas ganz anderes ist die Sprache mit Bezug auf das Wirtschaftsleben.

Wollen wir einmal versuchen, ein wenig das zu charakterisieren, was zu charakterisieren sehr schwierig ist. Denken Sie bei der Sprache zunächst einmal an die Dichtung. Sie haben von mir schon öfter erwähnt gefunden, wieviel der Mensch eines jeden Kulturgebietes, wenn er Dichter ist - und wer ist nicht ein bißchen Dichter -, eigentlich der Sprache verdankt. Viel mehr als man glaubt, schafft eigentlich die Sprache. Die Sprache enthält große, gewaltige Geheimnisse; der Sprachgenius ist etwas ungeheuer Schöpferisches. Daher ist es so selten, daß innerhalb des Sprachlichen das eigene Menschlich-Schöpferische auftritt. Das bemerkt nur der, der mit einer gewissen innerlichen Hingabe die Entwickelung der Völker betrachtet. Die Menschen stehen ja gewöhnlich in einer Inkarnation eben auch nur in einem Zeitalter drinnen. Daher haben sie keinen rechten Anhaltspunkt, um so etwas, was ich jetzt meine, ordentlich zu beurteilen. Wir Deutschen zum Beispiel, wir sprechen heute da und dort etwas nuanciert; aber insofern wir die einheitliche, gebildete deutsche Umgangssprache sprechen, sprechen wir alle anders, als etwa gesprochen worden ist im 18. Jahrhundert. Wer aufmerksam die Literatur verfolgt bis ins letzte Drittel des 18. Jahrhunderts herein, der wird das schon merken. Denn die Sprache, die wir heute sprechen als gemeinsame, gebildete deutsche Umgangssprache, die ist ein Geschöpf des Goetheschen Schaffens und derjenigen Menschen, die mit diesem Goetheschen Schaffen zusammenhängen: Lessing, Herder, Wieland sogar, und ein wenig auch Schiller. Eine ganze große Summe von Wortbildungen waren ja vor diesen Geistern nicht vorhanden! Nehmen Sie sich das Adelungsche Wörterbuch und versuchen Sie einmal, manche Dinge, die heute gang und gäbe sind, nun im Adelungschen Wörterbuch, das verhältnismäßig spät geschrieben ist, aufzufinden: Sie werden sie nicht finden! In hohem Maße war dieses Zeitalter, das den Goetheanismus hervorgebracht hat, sprachschöpferisch, und wir leben in dem, was auf diese Art geschaffen worden ist. Da sehen Sie hineinspielen das Individual-Schöpferische in das, was der Sprachgenius als solcher ist. Da kann man auch bei Dichtern von Schöpferischem erster Natur sprechen; was dann nachkommt als Epigonen, das schöpft wieder vielfach bloß aus der Sprache heraus.

Daher habe ich Ihnen öfter gesagt: Wenn man diese Dinge durchschaut, imponiert einem oftmals eine glatte Sprache, eine so recht geschniegelte dichterische Leistung gar nicht besonders. Das Originelle, was wirklich aus dem Innersten der Seele heraus pulsiert, das ist manchmal viel, viel ungeschickter als dasjenige, was aus gar keiner groRen Dichterkraft, aber mit einer gewissen Vollendung der Sprache, mit schönen Versen und dergleichen gemacht wird. Es ist ja auch in den anderen Künsten so. Solche Dinge müssen ins Auge gefaßt werden, wenn man einen Begriff bekommen will, wie im Sprachlichen selbst ein Leben ist, in das wir eingeschaltet sind. Und in der Vertiefung in diese Sprache wird sich ergeben die Möglichkeit eines imaginativen Fühlens und Empfindens. Es ist gewiß heute sehr vieles, was widerstrebt diesem Lernen des Imaginativen von der Sprache, weil die Menschen mit einem gewissen Recht, da die Sprachen in der letzten Zeit international geworden sind, gewöhnlich viele Sprachen bis zu einem gewissen Grade sich aneignen, oder wenigstens mehrere Sprachen. Diese Aneignung mehrerer Sprachen hat zunächst noch nicht das Tiefere der Sache an die Oberfläche getrieben, sondern eigentlich nur das Oberflächliche der Sache. Das Empfindungsgemäße, das die Imagination vermittelt, das ist noch nicht an die Oberfläche getrieben worden. Es muß heute derjenige, der sich mehrere Sprachen aneignet, doch Sklave der Wörterbücher werden, oder zum Sklaven der sonstigen Handbücher der betreffenden Sprachen. Dadurch lernt man, sich die ungeheuerliche Unwahrheit anzueignen, daß ein Wort, das man für ein Wort der eigenen Sprache im Wörterbuch einer anderen Sprache angeführt findet, dasselbe bedeute wie in der eigenen Sprache. Gewiß, in bezug auf dasjenige, was ich nachher anführen werde, bedeutet es dasselbe, aber es bedeutet nicht dasselbe mit Bezug auf das innerliche Erleben.

Nehmen Sie zum Beispiel folgendes: Im Deutschen sagen wir «Kopf», im Französischen «tete», italienisch «testa» und so fort. Worauf weist das hin? «Kopf» sagen wir zum menschlichen Kopf, zum tierischen Kopf aus demselben Grunde, aus dem wir zum Kohlkopf «Kopf» sagen: weil das Ding rund ist, weil das Ding kugelig ist. Derjenige also, der deutsch den Kopf bezeichnet, der setzt ab, stilisiert mit Bezug auf die Form. T£te, testa, das ist abgestellt mit Bezug auf Zeugnisablegung, etwas bezeugen, testieren. Da ist ein ganz anderer Gesichtspunkt eingenommen, um dieses selbe Glied des menschlichen Organismus zu bezeichnen. «Fuß» sagen wir im Deutschen: das hängt zusammen mit Furt, mit dem Eindruck der Furche, die wir machen, wenn wir über den Boden hinschleifen; das ist der Gesichtspunkt, unter dem wir als Deutsche dieses Organ des menschlichen Organismus bezeichnen; «pied» — das Aufstellen, das Bezeichnen des Sich-auf-denBoden-Aufstellens: etwas ganz anderes! Die Valeurs der Worte gehen aus verschiedenen Gesichtspunkten hervor. Und es prägt sich in diesem Impetus, dieselben Dinge aus ganz bestimmten Untergründen heraus zu bezeichnen, ein Unterbewußtsein im Volkscharakter aus, das man gewöhnlich gar nicht berücksichtigt.

Nun denken Sie sich aber, Sie haben es nicht bloß mit auf der physischen Erde herumwandelnden physischen Menschen, sondern überhaupt mit Menschen zu tun; Sie studieren das ganze Verhältnis an den Toten. Da tritt eigentlich das Charakteristische der Sache erst ganz besonders hervor. Der Tote hat für dieses lexikographische Sprechen von einem Wort zum anderen eigentlich gar keinen Sinn, und er hat gerade für das Imaginative an der Sache den allertiefsten Sinn. Bildet man nun den Gedanken so, daß er die Gedankennuance bekommt von den sprachlichen Lauten, so hat der Tote zunächst die imaginative Form, die er bekommt. Er empfindet, wenn ihm das Wort für den «Kopf» deutsch gesagt wird, er empfindet die Rundung. Wenn ihm dasselbe Wort in einer romanischen Sprache gesagt wird, empfindet er das Bezeugende. Aber dieses Systematisieren, dieses Abstellen bloß, dieses abstrakte Beziehen auf irgendein einzelnes Organ, das erlebt der Tote nicht mit; er erlebt gerade dasjenige in der allerbedeutsamsten Weise, was der Mensch in der heutigen Abstraktheit gar nicht merkt. So daß der Mensch als Seele ein ganz besonderes Verhältnis zur Sprache hat. Es ist eigentlich das, was die Seele als Verhältnis zur Sprache hat, viel innerlicher als das allgemeine, gewöhnliche, alltägliche Verhältnis des Menschen zur Sprache. Innerlich fühlt schon die Seele diesen Unterschied, ob man den Fuß bezeichnet dadurch, daß man sich darauf stellt, oder dadurch, daß man eine Furt, eine Furche macht. Die Seele fühlt das; äußerlich abstrakt empfindet der Mensch nur die Beziehung des Wortes zu dem betreffenden einzelnen Organ. Die Seele ist innerlich in ihrem Sprachempfinden sehr ähnlich der Art, wie sie ist, wenn sie entkörpert ist. Und dasjenige, was man im gewöhnlichen Leben vielfach eigentlich als das einzige der Sprache empfindet, das legt sich nur wie eine äußere Schicht über die Sprache hinüber. Und ein wahrer Dichter zum Beispiel ist eigentlich nur derjenige, der für dieses Innerliche der Sprache ein feines Gefühl hat, ein feineres Gefühl als die anderen. Wer wirklich das Imaginative der Sprache miterlebt, der ist eigentlich erst ein Dichter, wie im Grunde genommen ein Künstler nicht derjenige ist, der malen oder bildhauern kann, sondern derjenige, der in Farben oder in Formen leben kann.

Solche Dinge müssen sich die Menschen aneignen von der Gegenwart ab in die Zukunft hinein. Ohne diese Dinge ist ein weiteres Fortleben der Menschheit in gedeihlicher Weise nicht möglich, weil das menschliche Geistesleben abdorren würde und die Menschen nur noch ein animalisches Leben entwickeln könnten, wenn Verständnis für solche Dinge nicht Platz greifen würde. Und das ist das Eigentümliche: Wenn man verfolgt, wie Kinder geboren werden, ihre ersten Kinderjahre entwickeln, erst lallen, dann allmählich sprechen lernen, da ist in dieser Art, wie sie sprechen lernen, etwas darinnen, was hineinmischt in das Sprechenlernen der Kinder eine Erbschaft, die sie herunterbringen aus den Erfahrungen, die sie noch in der geistigen Welt durchgemacht haben, bevor sie heruntergeboren worden sind; da vermischt sich etwas davon mit dem, was Mutter oder Amme oder Vater oder sonst irgend jemand dann im Sprechenlernen dem Kinde beibringt. Wer auf diesem Gebiete feiner beobachten kann, der wird ungeheure Überraschungen erleben, die ihm die Kinder darbieten, die sprechen lernen. Und er wird diese Überraschungen nur verstehen können, wenn er die Voraussetzung machen kann: das Kind bringt sich wirklich aus der geistigen Welt etwas von Anlagen mit, etwas, das es hineinmischt in dasjenige, was ihm von außen zum Sprechen kommt. In dem innerlichen Empfinden der Sprache lebt der Mensch etwas nach, was er sich mitbringt aus der geistigen Welt. Das aber ist das einzige, was wirklich an der Sprache das Geistige ist. Das ist eigentlich das eine Element der Sprache, dieses innerliche Erleben, das wir deshalb haben können, weil wir uns gewisse Impulse aus der geistigen Welt mitbringen.

Das andere ist, daß die Sprache ein bloßes Verständigungsmittel ist. Als Verständigungsmittel kommt sie für alles dasjenige in Betracht, was die Menschen als Gleiche untereinander angeht. Wir reden miteinander, damit der eine von dem anderen weiß, was ihm der mitteilen will. Da kommt das innere Gefüge der Sprache nicht so sehr in Betracht, da kommt eine gewisse Konvention in Betracht. Da kommt in Betracht, daß wir nicht glauben, wenn einer «Tisch» sagt, er meine einen Stuhl, und wenn einer «Stuhl» sagt, er meine einen Tisch. Darüber brauchen sich die Menschen sozusagen hier auf der Erde nur miteinander zu verständigen; da spielt dasjenige nicht hinein, was innerliches Erleben der Sprache ist. Für die heutige Gegenwart ist diese Art des Sprachverstehens, wo die Sprache bloß als ein Verständigungsmittel genommen wird, eigentlich das einzige, was wirklich erlebt wird. Für die Menschen heute ist ja die Sprache nicht viel mehr als das Mittel, sich untereinander zu verständigen. Lauschen den geheimnisvollen inneren Impulsen der Sprache, um aus ihnen herauszuhören das göttliche Walten, wie es sich gerade durch die Sprache kundgibt, das ist heute wenigen Menschen eigen. Es gibt einige Persönlichkeiten der Gegenwart, die bemerkt haben, daß die Sprache selber ein innerliches Leben hat; aber bei allen, von denen dies bemerkt worden ist, tritt dieses Apergu eigentlich mit einer gewissen Koketterie auf, wie zum Beispiel bei dem Dichter Hofmannsthal oder selbst bei dem frechen Karl Kraus in Wien, der immer behauptet, daß er gar nicht selber seine Sätze schreibe, sondern daß er nur hinhöre auf das, was die Sprache schreiben will. Daß er dasjenige, was die Sprache schreiben will, zwar anhört, aber dann gerade so, wie wenn man aus der geistigen Welt heraus nach seinen eigenen Emotionen hört, schief und falsch, das bezeugt ja, daß er so furchtbar frech schreibt, wie die Sprache niemals ihn inspirieren würde. — Aber, wie gesagt, einzelne Menschen bemerken heute schon dieses Mitteilen der Sprache, das dann aus anderen Welten heraus kommt, und das gepflegt werden muß, wenn die Menschen den Weg finden sollen zu dem imaginativen Leben.

Das wird ein wichtiges soziales Moment sein, denn es ist eben etwas, was die Menschen sozial bindet. Die gemeinsame Sprache, die eine gemeinsame Imagination bringt, das ist etwas, was eine soziale Tiefe abgeben wird. Das kann die Sprache als Verständigungsmittel zur Not auch noch, aber sie ist dann veräußerlicht; sie beruht darin, worinnen sie bloß Verständigungsmittel ist, sehr auf Konvention. Daher auch die Veräußerlichung des Seelenlebens heute, daß die Menschen im Grunde die Sprache nur haben, um anderen vorzuplappern, damit der eine weiß, was der andere denkt. Ja, Sie können gegen diesen Satz einwenden: da ja so viele nicht denken, so wissen manche, wenn eine Mitteilung gemacht wird, was der andere nicht denkt! Nun aber - wir verstehen uns doch.

So haben wir in der Sprache etwas, was insbesondere hinweist auf das Geistesleben, auf das Leben in dem geistigen Organismus. Etwas anderes in der Sprache ist das bloß Verständigende, was einzig und allein im Grunde genommen heute in Betracht kommt, wenn die Leute ein Wörterbuch nehmen. Dieses weist auf das Rechtsleben. Und weil in der einen Sprache das Wort so heißt, in der anderen Sprache so, da kommt es bloß auf das äußerliche Verständnis an, da wird gar nicht der Unterklang in Betracht gezogen: ob der eine aus dem Impuls, der andere aus jenem Impuls heraus etwas bezeichnet! Da ist natürlich ein Riesenunterschied im Seelenleben, wenn man bei «Kopf» das Gerundete, also die Form zu verstehen hat, wie überhaupt die meisten substantivischen Bildungen im Deutschen plastische Imaginationen sind, oder ob, wie in den romanischen Sprachen, die meisten substantivischen Bildungen hergenommen sind vom Auftreten des Menschen, von dem Sich-in-die-Welt-Stellen, nicht vom Anschauen, sondern von dem Sich-Hinstellen in die Welt. Da verbergen sich große Geheimnisse in den Sprachen.

Mit Bezug auf das Wirtschaftsleben, da können wir alle taubstumm sein und doch ein Wirtschaftsleben führen. Die Tiere führen es ja auch. Im Wirtschaftsleben ist die Sprache gewissermaßen ein Fremdling, ein richtiger Fremdling. Wir gebrauchen die Sprache im Wirtschaftsleben, weil wir nun schon einmal sprechende Menschen sind; aber man kann wirtschaften in einem fremden Lande, dessen Sprache man gar nicht kennt; man kann alles einkaufen, alles mögliche tun. Überhaupt - die Menschen brauchen die Sprache nicht gerade um des Wirtschaftslebens willen: da ist die Sprache ein vollständiger Fremdling. Das eigentliche geistige innere Element der Sprache ist im Geistesleben vorhanden; veräußerlicht schon wird das innere sprachliche Element im Rechtsleben, und völlig verloren geht alles, was die Sprache eigentlich für den Menschen bedeutet, im Wirtschaftsleben. Aber dafür ist auch das Wirtschaftsleben, wie ich Ihnen ausgeführt habe, dasjenige, welches auf seinem Grund und Boden entwickeln kann gerade die Vorbereitung für das Leben nach dem Tode. Wie wir uns im Wirtschaftsleben verhalten, welche Gefühle wir im Wirtschaftsleben entwickeln, ob wir Menschen sind, die gern einem anderen wirtschaftlich brüderlich beistehen, oder ob wir Neidhammel sind und alles nur selber verfressen wollen: das hängt schon zusammen mit der Grundkonstitution unserer Seele, und das ist im wesentlichen die stumme Vorbereitung für viele Impulse, die sich im nachtodlichen Leben zu entwickeln haben. Wir bringen uns eine Erbschaft herein aus dem vorgeburtlichen Leben, die sich, wie ich es geschildert habe, ausspricht in dem, was das Kind hineinträgt in das, was es lernt von der Amme oder der Mutter. Wir tragen aus dem Leben heraus ein stummes Element, das gerade aus der im Wirtschaftsleben sich entfaltenden Brüderlichkeit aufkeimt und das wichtige Impulse entwickelt im nachtodlichen Leben.

Es ist gut, daß wir im Wirtschaftsleben die Sprache als einen solchen Fremdling haben, daß wir das Wirtschaftsleben auch entwickeln könnten, wenn wir taubstumm wären. Denn dadurch gerade entwickelt sich dieses unterbewußte Seelenleben, das dann eine Fortsetzung erfahren kann, wenn der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen ist. Würde der Mensch ganz aufgehen in dem, was er seelisch erlebt, in dem, was ausgesprochen werden kann zwischen Mensch und Mensch, würden wir nicht als Menschen einander dienen können in nicht ausgesprochener Weise, dann würden wir wenig hineintragen können in die Welt, die wir zu durchleben haben, nachdem wir die Pforte des Todes durchschritten haben.

Aber auf der anderen Seite ist es außerordentlich schwierig, gerade die heutigen drängenden Forderungen der sozialen Bewegung zu besprechen, denn die heutigen drängenden Forderungen der sozialen Bewegung sind vielfach Wirtschaftssorgen der Menschheit. Und die Sprache ist eigentlich gar nicht da, um Wirtschaftssorgen zu besprechen. Unsere Begriffe taugen eigentlich am allerwenigsten für die Besprechung der sozialen Frage. Wir würden die soziale Frage vielleicht in Europa auf eine ganz andere Weise besprechen können, wenn wir alles dasjenige in der Sprache hätten, was die Orientalen in ihrer Sprache haben. Es ist dort nur der Volkscharakter in der Dekadenz; aber in der Sprache sind geistige Impulse da, die dann die Möglichkeit bieten, wie durch Gebärden hinzuweisen auf dasjenige, was gerade mit Bezug auf das soziale Leben zu besprechen ist, während wir Europäer eigentlich das Gefühl haben, es solle alles stets, wie wir glauben, in deutlichen Worten zum Ausdrucke kommen. Das kann es aber gar nicht. Wir müssen uns das Gefühl aneignen, daß, indem wir sprechen, wir eigentlich nichts anderes machen als Lautgesten hervorbringen, auf die Dinge hindeuten. Denn eine richtige Innerlichkeit mit Bezug auf die Lautgeste entwickelt ja der Mensch heute fast nur noch für die Interjektion; ein wenig, wie ich gestern auseinandergesetzt habe, für die Zeitwörter, für die Verben; einen Anflug noch für die Eigenschaftswörter, gar keinen für die Substantiva. Die sind etwas völlig Abstraktes; daher verstehen die Toten diese Substantiva gar nicht. Es bleiben für sie Lücken, wenn wir uns mit ihnen verständigen und in der Sprache die Dinge zum Ausdruck bringen wollen. Daher hat man nötig, sich dem Toten verständlich zu machen dadurch, daß man innerlich das, was man sagen will, in wirkliche Gesten verwandelt, in wirkliche Bilder verwandelt, nicht versucht in Worten zu denken dem Toten gegenüber, sondern immer besser und besser versucht in Bildern zu denken, nach der Art, wie ich das gestern angeführt habe.

Nun muß ich immer wieder sagen: Unterstützen kann uns in diesem Bilderempfinden dasjenige, was wir jetzt wiederum als eine sichtbare Sprache bringen wollen — das eurythmische Element. Das Eurythmisieren ist ein Umsetzen des Sprachlichen in den entsprechenden Bewegungsrhythmus, in die Geste und so weiter. Aber wir müssen umgekehrt auch wiederum lernen, dasjenige, was uns sichtbarlich entgegentritt, wie eine Art von Sprache zu empfinden. Wir müssen lernen, wie uns etwas sagt dasjenige, was gewöhnlich von uns nur angeschaut wird: der Morgen sagt uns etwas anderes als der Abend, und der Mittag sagt uns etwas anderes als die Nacht; ein mit Tauperlen besetztes Pflanzenblatt sagt uns etwas anderes als ein trockenes Pflanzenblatt. Das Sprechen der ganzen Natur müssen wir wieder verstehen lernen. Wir müssen lernen, durchzudringen durch das abstrakte Anschauen der Natur zu einem konkreten Anschauen der Natur. Unser Christentum muß erweitert werden durch ein Sich-Durchdringen, wie ich schon gestern gesagt habe, mit einem gesunden Heidentum. Die Natur muß uns wiederum etwas werden. Das ist das Eigentümliche der Menschheitsentwickelung in der bisherigen Epoche des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums, daß wir der Natur gegenüber immer gleichgültiger und gleichgültiger geworden sind. Gewiß, die Menschen haben noch Naturgefühl, sie sind gern in der Natur, sie wissen auch künstlerisch, ästhetisch die Natur zu empfinden. Aber sie können sich nicht dazu aufschwingen, das Innerlich-Lebendige der Natur wirklich so zu erleben, daß die Natur zu ihnen spricht, wie ein Mensch zu dem anderen Menschen spricht. Das aber ist notwendig, wenn wirklich wieder Intuition in das Menschenleben eintreten soll.

Bevor alle diese drei Zeiträume, von denen wir da sprechen, abgelaufen sind, muß die Menschheit, wenn sie sich gesund entwickeln soll, zu allen Einzelheiten, durch die sie mit der Natur zusammenhängt, eine Art persönlichen Verhältnisses entwickeln. Dasjenige, was wir heute abstrakt sagen können: Wenn du Zucker issest, so verstärkst du deine Egoität; wenn du weniger Zucker issest, schwächst du deine Egoität; Tee ist dasjenige, was die Gedanken auseinandertreibt, das Diplomatengetränk, das Mittel, oberflächlich zu werden; Kaffee ist das Journalistengetränk, das in abstrakter Logik einen Gedanken an den anderen setzt, daher Journalisten so gern ins Kaffeehaus gehen, Diplomaten zu Tees und so weiter -, das können wir heute aus der Natur der Dinge heraus abstrakt entwickeln, aber die Menschen werden erst später dazu kommen, ein gesundes Verhältnis zu entwickeln zu allem, was ihnen so ein Verhältnis zur ganzen Natur gibt, wie die Tiere es instinktiv heute haben. Die Tiere wissen ganz genau, was sie fressen; die Menschen haben das ursprünglich in naiven Verhältnissen auch gewußt, was sie essen, aber sie haben es vergessen, haben es verlernt, sie müssen wiederum dieses Verhältnis gewinnen. Heute gibt es - ich erwähnte das schon öfters - merkwürdige Menschen, die haben, indem sie bei ihrem Tische sitzen, eine Waage, da wägen sie ab, wieviel Fleisch und andere Dinge sie essen sollen - weil das ausgerechnet ist, nicht wahr, von den Nahrungsmittelchemikern!

Unter diesem abstrakten Verhältnis, das der Mensch zur Welt entwickelt, geht alles gesunde Sich-Inbeziehungsetzen zur Welt verloren. Wir müssen wiederum — verzeihen Sie, wenn ich das so ausspreche den Geist des Zuckers, den Geist des Tees, den Geist des Kaffees, des Salzes, den Geist aller anderen Dinge erleben, mit denen wir in Beziehung stehen einfach durch unseren Organismus; wir müssen das wiederum erfahren lernen, erleben lernen. Heute empfindet der Mensch auf dem Gebiete in allerabstraktester Form. Er fühlt sich was, wenn er sagt: Ich bin ein Mystiker, ich bin ein Theosoph. — Was ist das? Ein Mensch, der innerlich mit seinem Ich das göttliche Ich fühlt, der den Makrokosmos im Mikrokosmos fühlt; der göttliche Mensch in unserem Inneren, der wird fühlbar, der lebt - na, und wie das alles heißt. Das sind natürlich die allergrauesten, die allernebelhaftesten Abstraktionen. Aber die Menschen haben heute den Glauben, daß man über diese Abstraktionen überhaupt nicht hinauskommen könne. Das konkrete Miterleben mit der ganzen Welt, das suchen heute die Menschen nicht. Das gedankenlose Hinschwätzen von dem Erleben von Gott in seinem Inneren, das erscheint den Menschen heute etwas Großes. Wenn man ihnen sagt, sie sollen den Gott des Zuckers oder des Kaffees oder des Tees erleben - ich weiß nicht, sie denken darüber sehr sonderbar, die Menschen, und doch ist dieses das wirkliche Miterleben mit der Außenwelt: weil das menschliche Erleben der Außenwelt grob und materiell ist, wenn nicht gerade den materiellen Erlebnissen ein Geistiges zugrunde liegen kann.

In der zweiten nachatlantischen Periode war es zum Beispiel noch so, daß jeder, der innerhalb der urpersischen Kultur etwas aß, auch fühlte, wieviel Licht er damit in sich aufnimmt. Die Sonne bereitet zu, gibt ihr Licht ab; wenn man ißt, ißt man das Licht mit; es fühlte ein jeder, wieviel Licht er in sich bekommt. Das ist in alten Zeiten erlebt worden, das muß auf einer höheren Stufe des Bewußtseins wiederkehren. Sehen Sie, das sind natürlich alles weitausschauende Ideale, aber sie sind eigentlich nicht so ferne, als man glaubt, dem, was die Menschen heute am notwendigsten haben. Denn gerade wenn man auf diese Dinge hinschaut, dann wird man sich immer mehr und mehr konkret und real dem nähern, was den Menschen gemeinsam ist. Das haben wir nun sehr nötig, uns dem zu nähern, was den Menschen gemeinsam ist. Und gerade auf dem Gebiete der Naturverehrung, auf dem Gebiete des Naturdurchschauens wird immer mehr und mehr dasjenige herauskommen, was auch das Wirtschaftsleben, das uns heute so materiell erscheint, dieses stumme Wirtschaftsleben gewissermaßen als ein Glied der göttlichen Weltordnung hinstellt. Und dann werden wir verstehen: Der soziale Organismus muß, wenn er gesund ist, dreifach gegliedert sein. Er muß die geistige Organisation haben, weil wir in diese vorzugsweise dasjenige hineintragen, was wir aus dem vorgeburtlichen Leben uns mitbringen; er muß die wirtschaftliche Organisation haben, weil sich in dieser stumm entwickeln muß dasjenige, was wir durch die Todespforte tragen und was Impulse nach dem Tode werden; und er muß abgesondert von diesen beiden anderen das Leben des Rechtsstaates haben, weil auf diesem Gebiete sich vorzugsweise dasjenige ausprägt, was für dieses irdische Leben gilt. Schematisch ausgedrückt:

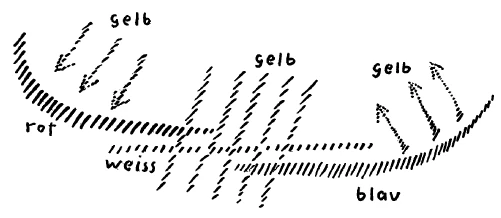

Wenn dieses das irdische Leben ist (siehe Zeichnung), so kommt in dieses irdische Leben herein, es gewissermaßen überstrahlend, dasjenige, was wir uns aus dem vorgeburtlichen Leben mitbringen (gelbe Pfeile, links); und wiederum entwickeln wir in diesem Leben dasjenige, was wir hinaustragen (gelb, rechts). In dem, was ich hier als rote Linie bezeichnet habe, ist von vornherein dasjenige drinnen, was geistig ist; es kommt vorzugsweise durch die Sprachen oder durch ähnliches hinein. In dem, was ich hier blau gezeichnet habe, strahlt nach dem Tode durch die Impulse, die wir aufgesogen haben im Wirtschaftsleben, das Geistige aus (gelbe Pfeile). Dieses Mittlere, das ich weiß gezeichnet habe, wird von dem Geistigen gewissermaßen seitwärts durchstrahlt (gelb). Das Rechtsleben ist als solches ganz irdisch, aber es wird gewissermaßen seitwärts durchstrahlt, so daß die Inspiration, die den Ahriman bändigen soll, im Rechtsleben sich ausleben soll. Wir müssen zu Rechtsvorstellungen vordringen, die wirklich dem Geistesleben entnommen sind, die eigentlich Initiationsvorstellungen sind.

Aber solche Dinge, von denen ich Ihnen heute gesprochen habe, wie sollen sie weiteren Kreisen der Gegenwartsmenschen so ohne weiteres schon verständlich sein? Das können sie ja nicht! Dazu wird schon notwendig sein, daß das geisteswissenschaftliche Element unsere gesamte Zeitbildung und Zeitkultur durchdringt. Ohne das geht es in die Zukunft hinein nicht. Deshalb hängt die Gesundung unseres sozialen Lebens innig zusammen mit der Ausbreitung eines wirklichen Verständnisses für Geist-Erkenntnis. Freilich wird auf der anderen Seite bei denjenigen Menschen, die einen guten Willen haben zur Aufnahme sozialer Vorstellungen, nach und nach der Drang entstehen, auch Geistiges in sich aufzunehmen. Am meisten sträuben werden sich diejenigen gegen das Geistige, welche starr stehenbleiben wollen bei jenen Dingen, von denen ich gerade gestern sagen mußte, daß sie antipathisch sind den Kindern, die seit einer Anzahl von Jahren aus der geistigen Welt in diese irdische Welt heruntersteigen. Da ist es allerdings manchmal jammervoll, wenn man so sieht, wie wenig die Menschen geneigt sind, von den Ereignissen wirklich zu lernen, wie sehr die Menschen heute noch immer die Vorstellungen zeigen, die sie früher gehabt haben, bevor sich geoffenbart hat, daß die Welt, welche in diesen Vorstellungen lebt, eben die Menschheit in diese furchtbare Zeitkatastrophe hineingetrieben hat. Da sollte sich der Menschheit bemächtigen ein gewisses Gefühl der Verantwortlichkeit, und ein Verständnis dafür, nun wirklich einmal in weiterem Umfange diese Zeitbedürfnisse auch zu sehen! Denken Sie nur, wie man heute — mit Bezug auf sehr viele Menschen muß das gesagt werden - sehr egoistisch in sich selbst steckt, und wieviel Ursache man heute hätte, eigentlich so ziemlich von der eigenen Person ganz abzusehen und auf die großen Fragen der Menschheit hinzuschauen! Sie sind ja so überwältigend groß, diese Menschheitsfragen heute, daß man kaum, wenn man ein vernünftiger Mensch ist, Zeit finden sollte, die engsten persönlichen Schicksale ins Auge zu fassen, wenn diese engsten persönlichen Schicksale nicht fruchtbar gemacht werden können für die großen Zeitfragen, die heute eben im Schoße der Entwickelungsepoche der Menschheit liegen. Man möchte, daß die Menschen die starke Diskrepanz bemerken zwischen dem Wesenlosen, das heute persönliches Schicksal ist, und dem Wesentlichen, das in den großen, heute überwältigenden Menschheitsfragen zutage tritt. Und man kann in Wirklichkeit Geisteswissenschaft nicht verstehen, wenigstens in der gegenwärtigen Zeit nicht verstehen, wenn man nicht für diese großen Menschheitsfragen Verständnis und Entgegenkommen hat. Manches beginnt sich jetzt doch zu entwickeln; aber gerade von denjenigen, die sich in einem gewissen Sinne bekennen zur Geist-Erkenntnis-Bewegung, von denen sollte ein besonders energisches Verständnis erstrebt werden dessen, was sich in weitem Umfange in der sozialen Bewegung der Gegenwart abspielt und was, wie Sie auch wiederum aus diesen heutigen Andeutungen ersehen können, weitere Horizonte hat, als man gewöhnlich denkt.

Auf den gestern und heute gemachten Voraussetzungen wollen wir dann morgen einen Abschluß aufbauen.

Fifth Lecture

When we speak now of the social question that is moving our times, it is essential for us—apart from what is of particular importance to our contemporaries in this question—that the truly ultimate practical solution that can be considered for this question is intimately connected with spiritual scientific foundations, and that therefore those who are interested in spiritual science have a special reason to look at this question from the standpoint of spiritual science. Certainly, it is urgently necessary today to awaken understanding in the widest circles for the impulses that lie behind the social movement; but on the other hand, these widest circles are ill-prepared to look into the foundations of the matter, to really grasp the matter from its foundations. People who are interested in the humanities must gradually develop a certain understanding, especially in the field of social movements, and to this end it is necessary that we familiarize ourselves with certain basic facts, without knowledge of which a true understanding of the social question is impossible. For let us not deceive ourselves: in the social life of human beings, the unconscious and the subconscious play an enormously important role. What ultimately has an effect in social life comes out of what people think, what people feel, and what people want out of their character impulses. However, in the age of consciousness soul evolution, this is becoming more and more individual. People will have to become more and more different in their thinking, feeling, and willing: that is the task of the age of consciousness soul evolution. Therefore, much will spring forth from the subconscious depths of human beings in social interaction, which will play into the social movement that began half a century ago, has now reached a provisional peak, and will continue to move further and further, placing enormous demands on human beings. For what is emerging today are initially chaotic demands. These chaotic demands will have to be replaced by increasingly clear ideas and increasingly better impulses of will. The fact that these clear ideas and impulses of good will were not present is what brought humanity into its present catastrophe and will increase this catastrophe in an immeasurable way. For one cannot say that there is already a really good will in the widest circles with regard to these questions. There is something like a surrender to what appears to be inevitable. People would like to give in a little here and there because they are afraid that there is no other way, that their mouths might water, and so on. But what must emerge is a genuine inner social understanding. This will have to become ingrained in people's minds, and it will even have to become part of our school education.

But something like this can only be achieved if, based on an understanding of human nature and the relationship between the sensory and supersensible worlds, at least a number of people on earth develop a deeper understanding of these questions than most people today are able to develop due to the superficial nature of modern education.

Yesterday you saw how things actually stand with regard to the role that language plays in the whole of human life. Now consider, on the other hand, what role languages play in the international coexistence of people across the Earth. Consider how infinitely many feelings and impulses of the will of the most diverse kinds depend on languages. And consider again how infinitely many ambiguities prevail among people today, especially with regard to such things. Let us dwell a little longer on language today. As I mentioned yesterday, we have before us three periods of development in the post-Atlantean evolution of humanity. We are living in the fifth post-Atlantean period, which will be followed by the sixth and then the seventh. Up to now, even with the cessation of language development, we as the human race on Earth have actually developed a certain tendency toward abstract thinking, toward thinking without images. But what must develop before this fifth post-Atlantean period comes to an end is pictorial imagination. And it is the special task of this fifth post-Atlantean period to develop the gift of imagination in the human race on Earth. Please do not confuse what I am now explaining with the things that are written in the book How to Know Higher Worlds. That book speaks of the individual human being. That is the subject of the esoteric development of the individual human being. What I am speaking of now is social life among peoples. The genius of a people develops imagination. Each individual must seek his own imagination for his esoteric development, but the genius of a people develops the imagination from which the common spiritual culture of the future must arise. An imaginative spiritual culture must develop in the future. Today we have, so to speak, the culmination point of abstract spiritual culture, the spiritual culture that works toward abstraction everywhere; out of this must develop a spiritual culture with pictorial ideas. Our culture must, so to speak, be permeated by that which cannot be expressed in abstract thoughts, but rather in images such as our “group” is: with the representative of humanity in the middle, with the Luciferic as one pole, with the Ahrimanic as the other pole. And many people, more and more people, will have to say to themselves: What actually concerns the life of the spirit cannot be expressed in abstract thoughts. One should not always ask about abstract thoughts, but it is right and fitting for the human mind to express itself through images. The pictorial life of community is what must emerge.

In the sixth post-Atlantean period, a kind of inspiration of the folk genius is to develop. And out of this inspiration, legal concepts are to develop which are felt as a kind of gift for earthly life. Life as it develops in a constitutional state is, as I explained to you recently, opposed to all spiritual life. State life is the opposite of all spiritual life. If earthly life is to be beneficial, not harmful, then what gradually asserts itself as legal principles must be perceived as gifts from the spiritual world, which descend through inspiration to the genius of the people in order to regulate earthly life so that it is not governed solely by human arbitrariness, but in the sense of a great spiritual leadership. One could also say that it is precisely through this inspiration, which the genius of the people must experience, that Ahriman will be bound. Otherwise, an Ahrimanic being would develop throughout the whole earth.

And the last period would preferably have to develop intuition. Only under the influence of this intuition can the whole economic life develop as one could actually conceive of economic life as an ideal. But the peculiar thing is that from now on, one cannot separate things as I have just written on the board in a more or less abstract way: V.: Imagination — VI.: Inspiration — VII.: Intuition.