The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1920–1922

GA 277c

30 October 1921, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

54. Eurythmy Performance

The eurythmy performance took place in its entirety in the domed room of the Goetheanum.

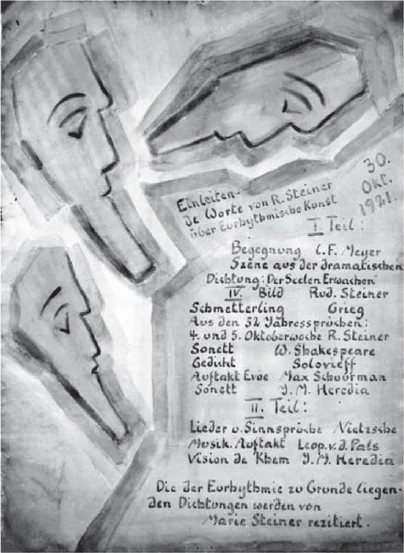

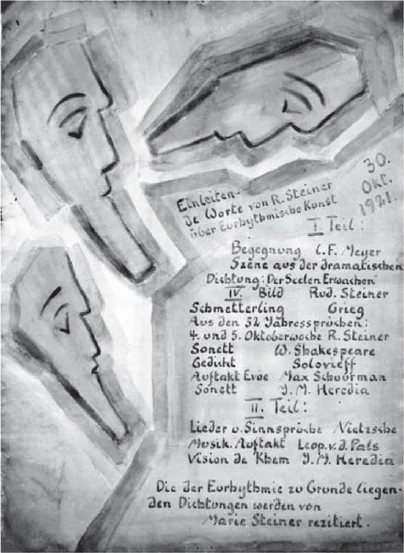

Poster for the Dornach performance, October 30, 1921

My dear audience!

Please allow me, as always before these eurythmic experiments, to introduce our mental image with a few words. I must always emphasize that this is not because I want to explain the mental image as such - and to explain the artistic would itself be an unartistic beginning. The only thing that underlies our eurythmy are special artistic sources that are still more or less unfamiliar today, as well as a formal language that is still unfamiliar today, and I would like to say a few words about these.

I am not talking here about some kind of mimic or pantomimic or even dance art, but about the use of a real language, a language that has come about and, in a certain sense, is being further developed by trying to recognize through - let me use this Goethean expression - sensory-supersensory observation, which movement tendencies - I am not saying movements, but movement tendencies - assert themselves out of the human being when he sings or speaks. When a person sings or speaks, there are always certain underlying tendencies of movement - be it [in] singing or speaking - which already pass over at the moment of emergence, metamorphose into something else, into that which then transforms itself into the air intonation that conveys the tone or the sound.

These tendencies of movement can be studied in two ways: Either by going directly to observing, sensually and supersensibly, what the larynx and the other organs of speech want to perform, so to speak, and what is held in the status nascens, I would say, in the moment of formation; or else one can direct one's attention to something else. One can, as it were, hold up to oneself the person listening, the person listening to singing or speaking. He appears to such an observation as if he actually wants to perform an inner, intimate movement when listening to every sound, every tone. He does not carry it out, but the movement remains restrained, does not become reality. But the understanding of the sound or the comprehension of the tone consists precisely in the inner experience of this arrested movement. If you then take this movement out of the human being and transfer it to the movements that the individual human being can perform through his own organism or the movements that groups of people can perform, you get a visible language.

This visible language must then, of course, first be elevated to an artistic level when it is used, as we are doing here. Just as an ordinary sequence of notes or an arbitrarily uttered sentence that is not formed is not yet artistic, eurythmy as such is only art when it is elevated to the artistic. This enables us to really expand the field of art and to use the whole person or groups of people as an artistic instrument.

Whoever uses today's language, especially the language of civilization, must take into account, ladies and gentlemen, that on the one hand civilized language has already completely adapted itself to the conventional or to the worldly, and on the other hand it adapts itself to the reproduction of thought. On the one side, on the side of the conventional, as well as on the side of the reproduction of thought, language naturally develops towards the inartistic. Thought in itself is an element that kills art. All thought is inartistic. You want to pronounce the sentence as radically as possible.

But also by adapting to the social needs of language, language moves away from the actual artistic. By withdrawing from the experience of the meaning of words to the experience of sound, language can also be returned to the artistic. In fact, the true poet does this all by himself. He already brings an intimate eurythmy into the creation of language. This restrained, intimate eurythmy is simply transformed into externally visible movements, and this gives rise to what appears here as eurythmy.

The fact that we are dealing with something that emerges from the full human being, while speaking and singing only emerge from a part of the human organization, makes it possible to bring the whole, full experience of a piece of music or poetry to revelation precisely through this eurythmic language. It turns out that - as you will see, eurythmy is accompanied by music on the one hand - that one can sing just as well in eurythmy through a visible sequence of tones as one can sing through audible tones.

And on the other hand, eurythmy is accompanied by poetry. We are then compelled to return from our inartistic age to more artistic ages with regard to the art of recitation and declamation. Our age actually sees the ideal of recitation and declamation more or less in pointing, that is, in treating the prose content of the poetry, not the actual artistic basis. The prose content of the poetry - this prosaic declamation and recitation would not be possible as an accompaniment to eurythmy. It is a question of either going back, let us say in Goethe's poetry, to the imaginative element that always lives in Goethe's poetry, also the imaginative element of language, the phonetic element; or, as is the case with other poets, going back to the musical, dramatic, rhythmic, rhythmic and so on, and allowing this to be clearly communicated through recitation and declamation. And so we can hope that in relation to the latter, a recovery can actually occur by accompanying eurythmy with recitation and declamation.

It is precisely through this that man will be able to experience the sound, at least in the more original languages, the experience of the sound as such, which is particularly noticeable. This has actually been completely lost in the civilized languages. Who today still vividly feels vocalization, which is a co-experience with the world, which is an inner illumination and resounding of that which man experiences in the world? While consonanting is an imitation, a re-experiencing. This wonderful transition from vowel to consonant, from experiencing to reliving, is something that can now be expressed through the special design in this moving language of eurythmy.

Now you can see that eurythmy can also be used on stage [in drama]. We have already seen this by performing scenes from Goethe's “Faust”, namely those that rise up from the usual naturalistic drama to what is the inner experience of the human being, which is synonymous with the human being entering into a relationship with a higher spiritual world. And if one has artistic expression that is not exhausted in straw allegories or abstract symbols, but that comes to real concrete form, just as one otherwise forms external nature or external life by imitation, then one sees that one has the need for the dramatic to rise from the naturalistic to the supersensible - or let us say: the inner-experienced, if you prefer to hear it that way - that we need a stylization that is not accidentally bound to a particular individuality, but that emerges as a matter of course from the whole human being and also from the whole of art, like language or music itself.

Today we will take the liberty of presenting a scene from one of my “Mystery Dramas” as the second number in the first part. In these “Mystery Dramas” I have made the attempt - they are all four connected and it is of course a very short fragment that can be offered today - to form inner experiences, inner connections of man, which he undergoes through his inner development with the supersensible world, without allegory, without symbolism, in that spiritual, spiritual entities in supersensibly conceived figures that come on stage are actually directly spiritually seen in the same way as our external, sensual entities are seen. I may point this out in a few words, because otherwise you might not be able to understand what is actually meant.

Throughout these “mystery dramas” runs the figure of a human being who firstly develops through his own inner being and goes through various stages, but who also develops through the most varied relationships with the natural world, but also in particular with the world of other people. He grows through some of the thoughts and experiences of other people, and the experiences he goes through are attempted to be captured in forms. To those who are able to do so, they also appear in figures that are not merely ordinary symbolic or allegorical figures, but are seen in the same sensual and supersensible way that sensual life as such can be seen through the external senses.

And so Johannes Thomasius appears in this scene, having gone through much. He has arrived at the point where he is now forced into a real, deeper introspection by the surprising things that assail his soul. And so, to a certain extent, his own person confronts him in the form of a double. That which one can feel in oneself as an admonishing second person under certain conditions, but which is basically the basis for true self-knowledge and also for true introspection, confronts Johannes Thomasius. I cannot say that he retouched it (?), because a direct experience is reproduced, because those admonitions, those invitations that this doppelganger speaks can actually be experienced in a directly real way.

And here in this scene we see how Johannes Thomasius has arrived at a stage in his life in which he has, so to speak, lost his own youth. His own youth has become objectively alien to him. As a result, he does not actually have it in his consciousness. But when someone has lost something like a piece of their life, then the whole world is different for them. And so Johannes Thomasius is confronted with his double, his own self, which can be grasped at this moment and which confronts him in all kinds of situations, admonishing, teaching, but also with his own lost youth, which is, so to speak, bound to his own self, which he experiences as another. His own youth dwells with his organic self, which appears in his introspection, like a being that has taken shape.

There is therefore already an attempt to shape something of that which leads the human being into a spiritual world. That is why in this scene, apart from Johannes Thomasius himself - who of course has to be portrayed in a naturalistic way, who is not allowed to eurythmize - figures appear that can actually be characterized if one can make an organic stylization, as is possible through eurythmy - not an arbitrary stylization, but an organic stylization arising from the thing itself, from the essential nature of the thing itself - then the guardian of the threshold appears, that which is called the guardian of the threshold, that which those who venture to speak of the spiritual world perceive as standing before the ordinary consciousness, not letting it into the spiritual world.

The human being cannot, if he [does not] have the maturity through the necessary preparation, look directly into the spiritual world; that would be harmful for him. That is why it is said that there is something like a guardian before the spiritual world, again such a figure that is neither allegorical nor symbolic, that is a real experience, but which cannot be represented in the external, naturalistic sense. Then there is a figure that I always call the Ahrimanic figure in anthroposophical spiritual science, Ahriman. It is the figure that lives in every human being. If man had no heart, but only intellect, if he had no devotion, no love for the world, but only criticism - there is something of this in every human being - then he would wander through the world as such an Ahrimanic being. And that is why we see these two alien figures - the guardian who is supposed to lead people to something that seems positive or rather natural, [how that] can be experienced quite soulfully, what this guardian leads people to, [and] how that is mocked by the ahrimanic figure who distorts and caricatures everything.

And through the experiences that this Johannes Thomasius undergoes in this way, he then only becomes mature enough to get to know personalities with whom he has been in a relationship for a long time; [he becomes mature enough] to see Mary and his teacher, the Benedictus, in a new form. They appear very briefly at the end of the scene. And one should have the feeling that everything that passes through the soul of Johannes Thomasius like a light from the spiritual world makes him ready to see personalities such as Benedictus and Mary, whom he has accompanied through a large part of his life, only then in their true essence, in a new form.

It is only in these things that one notices how one needs this stylization, which is drawn from the whole of human organization, which has nothing accidental about it, but which grows out of the human being like language and song.

And that is one side of eurythmy, the artistic side. There are two other sides that I would like to mention briefly: the first is what I call the hygienic element, the hygienic-therapeutic element. All the movements that are performed in eurythmy are taken from the healthy human organization. Not the movements that you will see here - they are indeed oriented towards the artistic - but other movements that can be extracted, transformations, metamorphoses of these movements, which, when performed, also have healing effects in this area. We are in the process of developing this further - we are already developing eurythmy therapy.

A third element is the pedagogical and didactic element. Emil Molt founded the Waldorf School in Stuttgart, which I directed, where eurythmy was introduced as a compulsory subject alongside gymnastics. Eurythmy is a spiritual gymnastics, whereas ordinary gymnastics is basically based only on physiology, on what one can study if one only looks at the human body. Without in any way treating the physical in a detrimental way, it must be said that what occurs in eurythmy as an animated gymnastics, if the matter is developed pedagogically and didactically, brings the child into movement, naturally brings the whole human being into movement in body, soul and spirit. Without neglecting the physical, the child is led through all school classes in such a way that it can express itself in physical movements of body, soul and spirit. Even though the Waldorf School has only been in existence for a little over two years, we can see how the children, if it is done in the right way, experience eurythmy as something natural [and] just as they learn to speak at an earlier age, so they will experience these eurythmic movements as something natural. But in particular, the initiative of the will, which is usually ignored in ordinary gymnastics, will increase, which will be very much needed by both the present and especially the next generation. The initiative of the will will be better developed through eurythmy if people are prepared for it now, at a young age, through eurythmy, this spiritualized and spiritualized gymnastics.

At the end - as always, this time too - I would like to apologize for the fact that we are still at the beginning of our eurythmy art. We are aware of this, we are our own harshest critics; nevertheless, we strive to advance eurythmy from month to month and are also convinced that eurythmy offers such opportunities for development that a perspective can open up for us for a significant artistic development - precisely through this eurythmy.

Goethe says so beautifully: "When man has reached the summit of nature, he sees himself again as a whole nature, which has to produce another summit in itself. To this end he raises himself by imbuing himself with all perfections and virtues, calling upon choice, harmony, order and meaning and finally rising to the production of the work of art. - If external instruments are not used, but man himself, who basically still carries the laws of the universe within him in a mysterious way, if man makes himself an instrument, if order, measure, harmony and meaning are brought out of his own organization, then something must arise through this microcosm as an artistic instrument which, if it is further developed, will undoubtedly be able to stand alongside the older, fully entitled arts as a fully entitled younger art.

54. Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Die Eurythmie-Aufführung fand gesamthaft im Kuppelraum des Goetheanum statt.

Plakat für die Aufführung Dornach, 30. Oktober 1921

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Gestatten Sie, dass ich wie immer vor diesen eurythmischen Versuchen, unsere Vorstellung mit ein paar Worten einleite. Ich muss immer betonen, dass das nicht aus dem Grunde geschieht, weil ich etwa die Vorstellung als solche erklären möchte - und Künstlerisches zu erklären wäre ja selbst ein unkünstlerisches Beginnen. Allein dasjenige, was unserer Eurythmie zugrunde liegt, sind besondere, heute noch mehr oder weniger ungewohnte künstlerische Quellen und ebenso eine heute noch ungewohnte Formensprache, und über diese möchte ich ein paar Worte sagen.

Es handelt sich hier nicht um irgendwelche mimische oder pantomimische oder gar Tanzkunst, sondern es handelt sich um die Verwendung einer wirklichen Sprache, einer Sprache, die dadurch zustande gekommen ist und in gewissem Sinne auch weiter ausgebildet wird, dass durch - lassen Sie mich diesen Goethe’schen Ausdruck gebrauchen - sinnlich-übersinnliches Schauen versucht wird, zu erkennen, welche Bewegungstendenzen - ich sage nicht, Bewegungen, sondern Bewegungstendenzen - aus dem Menschen heraus sich geltend machen, wenn er singt oder spricht. Wenn der Mensch singt oder spricht, so liegen immer gewisse Bewegungstendenzen zugrunde - sei es [beim] Singen oder Sprechen -, die im Moment des Entstehens schon übergehen, sich metamorphosieren in anderes, in dasjenige, was dann sich umwandelt in die Lufttingierung, die den Ton oder den Laut vermittelt.

Diese Bewegungstendenzen, man kann sie in zweifacher Weise studieren: Entweder, indem man direkt darauf losgeht, sinnlich-übersinnlich zu beobachten, was gewissermaßen der Kehlkopf und die anderen Sprachorgane ausführen wollen und was im status nascens, möchte ich sagen, im Entstehungsmomente festgehalten wird; oder aber, man kann seine Aufmerksamkeit auf anderes lenken. Man kann gewissermaßen sich vorhalten den zuhörenden Menschen, der also dem Singen oder Sprechen zuhörende Mensch. Der erscheint einer solchen Beobachtung so, als ob er eigentlich bei diesem Anhören jedes Lautes, jedes Tones, eine innerliche, intime Bewegung ausführen möchte. Er führt sie nicht aus, sondern die Bewegung bleibt verhalten, kommt nicht zur Realität. Aber das Verstehen des Lautes oder das Auffassen des Tones besteht eben in dem innerlichen Erleben dieser aufgehaltenen Bewegung. Wenn man dann diese Bewegung herausholt aus dem Menschen und sie überträgt auf dasjenige, was der einzelne Mensch durch seinen eigenen Organismus an Bewegungen ausführen kann oder was Menschengruppen an Bewegungen ausführen können, so bekommt man eben eine sichtbare Sprache.

Diese sichtbare Sprache muss dann natürlich erst, wenn sie verwendet wird, wie wir es hier tun, in das Künstlerische heraufgehoben werden. So, wie ja auch eine gewöhnliche Tonfolge oder ein beliebig ausgesprochener Satz, die nicht gestaltet sind, noch nichts Künstlerisches sind, so ist Eurythmie als solche erst Kunst dann, wenn sie ins Künstlerische heraufgehoben wird. Dadurch ist man in der Lage, das Kunstgebiet wirklich zu erweitern und zu verwenden den ganzen Menschen oder auch Menschengruppen wie ein künstlerisches Instrument.

Wer eine heutige, insbesondere Zivilisationssprache nimmt, der muss ja berücksichtigen, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, dass auf der einen Seite gerade die zivilisierte Sprache sich schon völlig angepasst hat an das Konventionelle oder an das Weltgemäße, auf der anderen Seite sich anpasst der Wiedergabe der Gedanken. Sowohl nach der einen Seite, nach der Seite des Konventionellen, wie nach der Seite der Wiedergabe der Gedanken entwickelt sich natürlich die Sprache nach dem Unkünstlerischen hin. Der Gedanke an sich ist ja ein kunsttötendes Element. Alles Gedankliche ist unkünstlerisch. Man möchte den Satz so radikal wie möglich aussprechen.

Aber auch durch Anpassung an die sozialen Bedürfnisse der Sprache rückt die Sprache aus dem eigentlichen Künstlerischen heraus. Durch das Zurückziehen auf das nun nicht Wortbedeutungserlebnis, sondern auf das Ton- oder Lauterlebnis kann man die Sprache auch wiederum zurückführen auf das Künstlerische. Das tut eigentlich im Grunde genommen der wahre Dichter ganz von selbst. Er bringt schon eine intime Eurythmie in die Gestaltung des Sprachlichen hinein. Diese verhaltene, intime Eurythmie, die wird eben einfach in äußerlich sichtbare Bewegungen verwandelt, und dadurch entsteht dasjenige, was hier als Eurythmie auftritt.

Dass man es da zu tun hat mit etwas, was aus dem vollen Menschen hervorgeht, während das Sprechen und Singen doch nur aus einem Teil der menschlichen Organisation hervorgehen, das macht eben möglich, dass man auch das ganze, volle Erlebnis eines Tonstückes oder einer Dichtung zur Offenbarung gerade durch diese eurythmische Sprache bringen kann. Es zeigt sich, dass - Sie werden ja sehen, wie das Eurythmische auf der einen Seite vom Musikalischen begleitet ist -, dass man ebenso gut in der Eurythmie durch sichtbare Tonfolge singen kann, wie man eben durch hörbare Töne singen kann.

Und auf der anderen Seite wird das Eurythmische begleitet von der Dichtung. Da ist man dann genötigt, aus unserem unkünstlerischen Zeitalter zurückzukehren in Bezug auf Rezitations- und Deklamationskunst wiederum zu künstlerischeren Zeitaltern. Unser Zeitalter sieht eigentlich doch mehr oder weniger das Ideal des Rezitierens und Deklamierens in dem Pointieren, das heißt in dem Behandeln des Prosagehaltes der Dichtung, nicht der eigentlichen künstlerischen Unterlage. Der Prosagehalt der Dichtung - dieses prosaische Deklamieren und Rezitieren wäre als Begleitung der Eurythmie gar nicht möglich. Da handelt es sich darum, dass man entweder zurückgeht, sagen wir bei der Goethe’schen Dichtung zurückgeht auf das imaginative Element, das immer gerade in den Goethe’schen Dichtungen lebt, auch das Imaginative sonst der Sprache, das Lautende; oder aber, wie es bei anderen Dichtern der Fall ist, zurückgeht auf das Musikalische, Dramatische, auf das Rhythmische, Taktmäßige und so weiter, und das deutlich durchvernehmen lässt durch das Rezitieren und Deklamieren. Und so darf man hoffen, dass in Bezug auf das Letztere wiederum eine Gesundung eintreten kann tatsächlich, indem wir Ihnen hier rezitatorisch und deklamatorisch die Eurythmie begleiten.

Es wird ja auch gerade dadurch der Mensch versetzt werden können in ein Erleben des Lautes, jedenfalls in den ursprünglicheren Sprachen ganz besonders bemerkbaren Erleben des Lautes als solchem. Das ist ja eigentlich ganz verloren gegangen in den zivilisierten Sprachen. Wer fühlt heute noch lebendig das Vokalisieren, das ein Miterleben mit der Welt ist, das ein innerliches Aufleuchten und Auftönen desjenigen ist, was der Mensch an der Welt erlebt? Während das Konsonantieren ein Nachahmen, ein Nacherleben ist. Dieser wunderbare Übergang vom Vokal zum Konsonanten, vom Miterleben zum Nacherleben, das ist etwas, was nun durch die besondere Gestaltung in dieser bewegten Sprache der Eurythmie zum Ausdrucke kommen kann.

Nun sieht man, dass man auch bühnenmäßig [im Drama Eurythmie einsetzen kann]. Wir haben das schon gesehen, indem wir Szenen aus dem Goethe’schen «Faust» aufgeführt haben, und zwar solche, welche sich aus der gewöhnlichen naturalistischen Dramatik erheben zu dem, was innerliches Erleben des Menschen ist, was ja gleichbedeutend damit ist, dass der Mensch mit einer höheren geistigen Welt in Beziehung tritt. Und wenn man da Künstlerisches hat, das nicht in strohernen Allegorien oder in abstrakten Symbolen sich erschöpft, sondern das zu wirklicher konkreter Gestaltung kommt, wie man sonst eben nachahmend die äußere Natur oder das äußere Leben gestaltet, dann sieht man aber, dass man nötig hat dadurch, dass das Dramatische sich aus dem Naturalistischen erhebt zum Übersinnlichen - oder sagen wir: das Innerlich-Erlebte, wenn man das lieber hört -, dass man da nötig hat ein Stilisieren, das nicht zufällig nur an eine besondere Einzelheit gebunden ist, sondern wie mit einer Selbstverständlichkeit aus dem ganzen Menschen und auch der ganzen Kunst hervorgeht wie die Sprache oder die Musik selber.

Wir werden uns heute erlauben, gleich im ersten Teil als zweite Nummer eine Szene vorzuführen aus einem meiner «Mysteriendramen». In diesen «Mysteriendramen» habe ich den Versuch gemacht - sie sind durchaus alle vier zusammenhängend und es ist natürlich heute ein ganz kurzes Fragment, das geboten werden kann -, innere Erlebnisse, innere Zusammenhänge des Menschen, die er durch seine innere Entwicklung durchmacht mit der übersinnlichen Welt, diese zu gestalten ohne Allegorie, ohne Symbolisches, indem Geistiges, geistige Wesenheiten in übersinnlich gedachten Gestalten, die auf die Bühne kommen, tatsächlich eben unmittelbar so geistig angeschaut sind, wie unsere äußerlichen, sinnlichen Wesenheiten angeschaut sind. Ich darf mit ein paar Worten hinweisen darauf, weil Ihnen ja sonst vielleicht nicht verständlich sein könnte, was eigentlich gemeint ist.

Durch diese ganzen «Mysteriendramen» geht hindurch die Gestalt eines Menschen, der sich entwickelt erstens durch sein eigenes Inneres und durch verschiedene Stufen hindurchgeht, der sich aber auch entwickelt durch die mannigfaltigsten Beziehungen zu der natürlichen Welt, aber auch namentlich zu der Welt anderer Menschen. An manchen Gedanken und Erlebnissen anderer Menschen wächst er, und die Erlebnisse, die er da durchmacht, die sind versucht, in Gestalten festzuhalten. Sie erscheinen demjenigen, der das vermag, durchaus auch in Gestalten, die eben nicht bloß gewöhnliche symbolische oder allegorische Gestalten sind, sondern geradeso geschaut werden sinnlich-übersinnlich, wie das sinnliche Leben als solches geschaut werden kann durch die äußeren Sinne.

Und so tritt in dieser Szene Johannes Thomasius auf, nachdem er vieles durchgemacht hat. Er ist an dem Punkte angekommen, wo er durch das Überraschende, das seine Seele bestürmt, nun in die Notwendigkeit versetzt ist zu einer richtigen, tieferen Selbstschau. Und so tritt ihm gewissermaßen sein eigener Mensch in Form eines Doppelgängers entgegen. Dasjenige, was man als mahnender zweiter Mensch in sich empfinden kann unter gewissen Voraussetzungen, was aber doch im Grunde genommen die Unterlage ist für wahre Selbsterkenntnis und auch für wahre Selbstschau, das tritt dem Johannes Thomasius entgegen. Ich kann nicht sagen, dass er sie retouchiert (?), weil ein unmittelbares Erlebnis wiedergegeben ist, weil tatsächlich jene Mahnungen, jene Aufforderung, die dieser Doppelgänger spricht, tatsächlich unmittelbar real erlebt werden können.

Und hier in dieser Szene tritt uns entgegen, wie Johannes Thomasius angekommen ist auf einer Lebensstufe, in der er gewissermaßen seine eigene Jugend verloren hat. Diese eigene Jugend, sie ist ihm objektiv fremd geworden. Dadurch hat er sie eben eigentlich nicht in seinem Bewusstsein. Aber wenn jemand etwas wie ein Stück seines Lebens verloren hat, dann ist ja die ganze Welt für ihn anders. Und so steht Johannes Thomasius seinem in diesem Moment erfassbaren Doppelgänger, seinem eigenen Selbst gegenüber, das mahnend, lehrend, in allen möglichen Situationen ihm entgegentritt, aber auch seiner eigenen verlorenen Jugend gegenüber, das gebunden ist gewissermaßen an sein eigenes Selbst, das er wie ein anderes erlebt. Es wohnt bei seinem organischen Selbst, das in der Selbstschau auftritt, die eigene Jugend wie Gestalt gewordenes Wesen.

Es ist also schon durchaus etwas von dem ja versucht zu gestalten, was den Menschen durchaus hineinführt in eine geistige Welt. Deshalb tritt in dieser Szene außer dem Johannes Thomasius selbst - der ja natürlich naturalistisch dargestellt werden muss, der nicht eurythmisieren darf -, außer ihm treten Gestalten auf, die man durchaus eigentlich charakterisieren kann, wenn man eine organische Stilisierung vornehmen kann, wie es eben durch die Eurythmie möglich ist — nicht eine willkürliche Stilisierung, sondern eine organische, aus der Sache selbst, aus der Wesenhaftigkeit der Sache selbst sich ergebende Stilisierung -, es tritt dann auf der Hüter der Schwelle, dasjenige, was man den Hüter der Schwelle nennt, dasjenige, was der, der von der geistigen Welt zu sprechen sich erkühnt, empfindet als vor dem gewöhnlichen Bewusstsein stehend, es nicht hineinlassend in die geistige Welt.

Der Mensch kann ja nicht, wenn er [nicht] durch die nötige Vorbereitung die Reife hat, unmittelbar hineinschauen in die geistige Welt; das wäre für ihn schädlich. Daher sagt man: Es stche vor der geistigen Welt etwas wie ein Hüter, wiederum solch eine Gestalt, die weder allegorisch noch symbolisch ist, die ein wirkliches Erlebnis ist, die aber doch eben nicht im äußeren, naturalistischen Sinne dargestellt werden kann. Dann tritt noch auf eine Gestalt, die ich immer in der anthroposophischen Geisteswissenschaft die ahrimanische Gestalt nenne, Ahriman. Es ist diejenige Gestalt, die in jedem Menschen lebt. Wenn der Mensch kein Herz, sondern nur Verstand hätte, wenn er keine Hingabe, keine Liebe für die Welt hätte, sondern nur Kritik — etwas ist ja von dem in jedem Menschen -, dann würde er als solches ahrimanisches Wesen durch die Welt wandern. Und daher sehen wir diese beiden einander fremden Gestalten - der Hüter, der die Menschen hinführen soll zu etwas, was positiv oder besser natürlich anmutet, [wie das] durchaus seelenhaft erlebt werden kann, wozu dieser Hüter den Menschen führt, [und] wie das verspottet wird durch die ahrimanische Gestalt, die alles verzerrt, karikiert.

Und durch die Erlebnisse, die dieser Johannes Thomasius in dieser Art durchmacht, wird er dann erst reif, Persönlichkeiten kennen zu lernen, zu denen er seit lange in einem Verhältnisse steht; [er wird reif,] Maria und seinen Lehrer, den Benedictus, in einer neuen Gestalt zu sehen. Die treten dann ganz kurz am Ende der Szene auf. Und man soll die Empfindung haben, dass das alles, was wie ein Aufleuchten der geistigen Welt da durch die Seele des Johannes Thomasius zieht, dass das ihn reif macht, Persönlichkeiten wie Benedictus und Maria, die er durch einen großen Teil seines Lebens hindurch begleitet hat, dann erst in ihrer wahren Wesenheit, in neuer Gestalt zu schauen.

An diesen Dingen bemerkt man erst, wie man diese Stilisierung braucht, die aus dem Ganzen der menschlichen Organisation hervorgeholt ist, die nichts Zufälliges hat, sondern die aus dem Menschen herauswächst wie die Sprache und der Gesang.

Und das ist die eine, die künstlerische Seite der Eurythmie. Es gibt noch zwei andere Seiten, die ich nur kurz erwähnen will: Es ist das erstens dasjenige, was ich bezeichne als das hygienische Element, das hygienisch-therapeutische Element. Alle Bewegungen, die ausgeführt werden im Eurythmischen, sind ja herausgeholt aus der gesunden menschlichen Organisation. Nicht die Bewegungen, die Sie hier sehen werden - die sind ja durchaus auf das Künstlerische hin orientiert -, aber andere Bewegungen sind es, die man herausholen kann, Umgestaltungen, Metamorphosen dieser Bewegungen, die, wenn sie ausgeführt werden, eben durchaus heilende Wirkungen auch auf diesem Gebiete darstellen. Wir sind daran, die Sache weiter auszubauen - es gibt jetzt schon den Ausbau einer Heileurythmie.

Ein drittes Element ist das pädagogisch-didaktische Element. Emil Molt in Stuttgart gründete die von mir geleitete Waldorfschule, in der neben dem Turnen die Eurythmie als ein obligatorischer Unterrichtsgegenstand eingeführt worden ist. Es ist die Eurythmie ein seelisches, ein geistiges Turnen; während das gewöhnliche Turnen im Grunde genommen doch nur auf Physiologie aufgebaut ist, auf dasjenige, was man studieren kann, wenn man auf den Leib des Menschen nur sieht. Ohne das Leibliche irgendwie in abträglicher Weise zu behandeln, ist doch zu sagen, dass dasjenige, was da in der Eurythmie auftritt als ein beseeltes Turnen, wenn die Sache pädagogisch-didaktisch ausgebildet wird, das Kind in eine Bewegung bringt, in Selbstverständlichkeit in Bewegung bringt den ganzen Menschen nach Leib, Seele und Geist. Ohne dass also das Leibliche vernachlässigt wird, wird das Kind durch alle Schulklassen hindurchgeführt so, dass es sich aussprechen kann in körperlichen Bewegungen nach Leib, Seele und Geist. Man sieht auch, trotzdem die Waldorfschule erst etwas über zwei Jahre besteht, wie die Kinder, wenn es in richtiger Weise gemacht wird, die Eurythmie als etwas Selbstverständliches erleben [und] so, wie sie in einem früheren Lebensalter das Sprechen lernen, so diese eurythmischen Bewegungen als etwas Selbstverständliches erleben werden. Aber namentlich wird die Initiative des Willens, die ja beim gewöhnlichen Turnen meistens unberücksichtigt bleibt, die Initiative des Willens größer, die sowohl die jetzige wie besonders auch die nächste Generation gar sehr brauchen werden. Die Initiative des Willens wird durch die Eurythmie besser ausgebildet werden, wenn die Menschen jetzt schon, in jugendlichem Alter, durch die Eurythmie, dieses durchseelte und durchgeistigte Turnen, dazu vorbereitet werden.

Ich darf zum Schlusse - wie sonst immer, so auch diesmal - um Entschuldigung bitten, weil wir noch im Anfange mit unserer eurythmischen Kunst stehen. Wir sind uns dessen bewusst, sind selbst unsere strengsten Kritiker; trotzdem bemühen wir uns von Monat zu Monat die Eurythmie weiter zu bringen und haben auch die Überzeugung, dass in der Eurythmie solche Entwicklungsmöglichkeiten sind, dass eine Perspektive sich uns auftun kann für eine bedeutsame Kunstentwicklung — gerade durch diese Eurythmie.

Goethe sagt so schön: Wenn der Mensch auf den Gipfel der Natur gestellt ist, so sieht er sich wieder als eine ganze Natur an, die in sich abermals einen Gipfel hervorzubringen hat. Dazu steigert er sich, indem er sich mit allen Vollkommenheiten und Tugenden durchdringt, Wahl, Harmonie, Ordnung und Bedeutung aufruft und sich endlich bis zur Produktion des Kunstwerkes erhebt. - Wenn nun nicht äußerliche Instrumente benützt werden, sondern der Mensch selbst, der ja im Grunde noch die Gesetzmäßigkeiten des Alls in sich trägt in geheimnisvoller Weise, wenn der Mensch selbst sich zum Instrument macht, wenn Ordnung, Maß, Harmonie und Bedeutung aus der eigenen Organisation hervorgeholt wird, dann muss durch diesen Mikrokosmos als eines künstlerischen Instrumentes etwas entstehen, was einmal ganz zweifellos, wenn es weiter entwickelt wird, sich als eine vollberechtigte jüngere Kunst neben die älteren, vollberechtigten Künste wird hinstellen können.