The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1920–1922

GA 277c

13 November 1921, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

56. Eurythmy Performance

The eurythmy performance took place in its entirety in the carpentry workshop. - Helene Finckh only took partial notes of the speech and did not transcribe it herself.

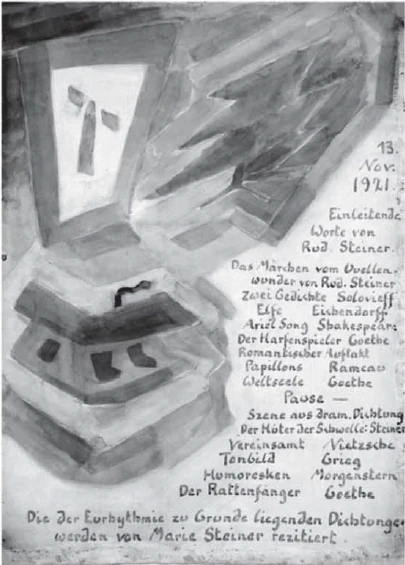

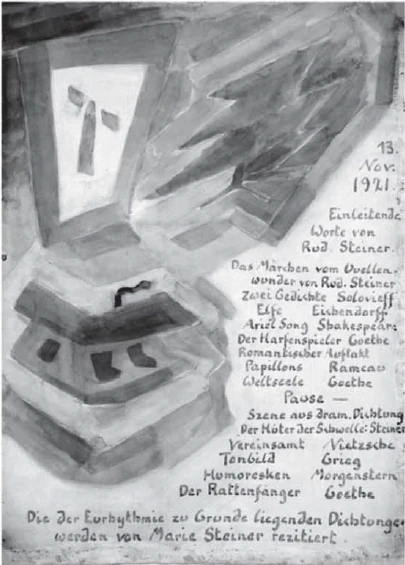

Poster for the performance

My dear audience!

Please allow me to introduce the attempt at our eurythmy performance with a few words, as is usually done before these performances. And not in order to somehow explain the performance - that would be inartistic; the artistic must work through itself in direct observation. But that which forms the basis of our eurythmic attempt as a formal language and as an artistic source is something that is still unfamiliar at present, and therefore a few things can be said about this source and about this artistic formal language.

It is very easy to confuse what we offer in eurythmy with all kinds of mimicry, pantomime or dance-like performances, but this would ignore the essence of this eurythmic artistry. After all, all mimicry and pantomime is based on the fact that the human being begins to express what he can express through the context of sound or tone with gestures or similar movements based on his individual feelings and sensations.

What you will see here on the stage are also movements of the individual human being or also movements of groups of people. So everything that is revealed here in terms of movement is based on a careful study of what, if I may use Goethe's expression, can be seen through the senses as movement tendencies. I am not saying movements, but rather tendencies of movement that underlie the linguistic or musical expression of the human soul. Singing or speaking must therefore be studied carefully, and in order to create eurythmy one must become familiar with those movement intentions of the human organism which then do not emerge, but only emerge, I would like to say, as in the moment of emergence, already disappear as such in the status nascens and transform themselves, metamorphose into the movement of the speech organs and then into the movement of the air, which convey the singing and the sound context of speech to the hearing ear.

Whatever movement intentions are aroused in the human organism are perceived and then transferred to the whole human being. So that the whole person or even groups of people can express themselves through real visible speech or visible singing. This enables us to expand the poetic as well as the musical by revealing our inner movements as they lie in human nature.

You need only pay proper attention to that which is expressed in this way in a truly visible language or a truly visible song, and you will find it: All mimicry and pantomime is such that it leads from the actual content of speech and sound into something more intellectual, which then urges the person himself to give it sensual expression in gesture, mimicry and so on. That which is stimulated in the spectator is then something intellectual and sensual. If, on the other hand, the actual movement tendencies of singing and speaking are transferred to the whole person, then what is revealed appears to be less of the intellectual and sensual and more of the emotional and volitional elements of the human being. And in grasping the eurythmic, we constantly have a stimulus for the feeling, and basically look at the lawfully working will.

This also expresses the considerable distance between mime and pantomime and eurythmy, that one must say: Because there is more of the whole world, of the laws of the world, in man's will than in the imaginative, and this then proceeds inwardly in a purely individual-personal way in man, everything that is shown through eurythmy also appears not as something personal that reveals itself through man, but as something that connects man with the whole world. So that what is revealed by the arbitrary in man and what the world reveals through man himself - which is also expressed in real poetic, musical art - can be brought forth precisely through the art of eurythmy.

One could also compare the two by saying that when mime and pantomime merge into dance, the human being actually completely loses his inner humanity in the forms of dance. The form can therefore also be viewed in this way: In the art of dance, the human being moves, I would like to say - if one expresses it radically - in such a way that the human being is lost, while in eurythmy, in the eurythmic movements, the human being receives his soul. So you could say: In dance the human being loses form, in eurythmy the human being gains form as a soul-spiritual being. This gaining of form is what eurythmy must actually do.

In the eurythmic revelation of a poem, one therefore sees something that is definitely revealed in the poem by the real poetic artist. And in the same way that one can sing audibly through sound, one can also sing visibly through the eurythmic movements, one can also see how the soul is actually constituted, which is expressed in the sound work. So that anyone who takes real pleasure in the artistic must basically see something thoroughly satisfying in such an expansion of the artistic as is revealed in eurythmy.

The fact that eurythmy expresses something deeper in poetry and music is also evident from the fact that recitation and declamation, by acting as companions to eurythmic art, must return to the truly artistic aspect that has been lost in today's inartistic age. Today's age is truly inartistic and can hardly appreciate properly what it means that Schiller, for example, did not always have the literal content of a poem living in his soul, but above all a musical, thematic content. It was this musical, thematic aspect that stirred the waves of his soul. And then, as it were, he first absorbed the literal prose content of the poem into these musical waves of the soul.

And it must be emphasized again and again how Goethe himself rehearsed his jamb dramas like a musician, like a bandmaster with a baton for his actors, in order to express the rhythmic and rhythmic, the musical and thematic, the imaginative and pictorial in the performance over and above the merely prose-like content. These were truly poetic artists.

And the declamatory and recitative must also return to the truly artistic. For one could not accompany eurythmic art with today's recitation, which is only concerned with making the prose content more pointed, so to speak. One can say that one can grasp this in a very special way when the prose content of a poem is particularly pointed in recitation and declamation, apart from all rhythmic and rhythmic, all musical and thematic and all imaginative-formal aspects.

Because the truly poetic is already a restrained eurythmy, one might say an invisible eurythmy, which is only made visible through our eurythmy, declamation and recitation, as we love them today, would not work at all as an accompaniment to eurythmy. We must therefore return to what was regarded as the requirements for recitation and declamation in more artistic eras. This must be felt again today, especially in the echo of eurythmy, so that one can probably also find a revival of the art of recitation and declamation through eurythmy.

This is one side of eurythmy, the artistic side, which is particularly important in a performance of this kind. Eurythmy also has two other sides, two other elements. One is the therapeutic-hygienic element: the movements that are performed in eurythmy are indeed such that they bring about a healthy organization of the human being, and they can therefore also be trained in the same way as they already appear today as the therapeutic-medical side of eurythmy. This is not the same as what occurs artistically, but a metamorphosis, a transformation of the speech movement. But it is also quite possible and is already being practiced today [as eurythmy therapy]. It is justified because every single movement of eurythmy is taken from the healthy human organization and can therefore, when performed in the appropriate way, have a healing effect on the human organization that has become disordered.

You only need to see how a moving human organism challenges the form, the movement, and how the movement in turn reminds us of the form and [how] these inner organic connections between forms of the human organization down to the very core - not only the spatial [come] into consideration here, but also the form of the intensive [interior?] - how this form is connected with all human movements in order to approach the thoroughly healthy aspect of eurythmy.

Just look at a human hand: it can initially be understood as a form, but the form of the human hand would have no meaning if one did not see in it, for example - even when it is at rest - that which can be accomplished in the movement of the fingers or the whole arm. One can really say of everything that man has of form: The form of man is like a movement that has come to rest. And again, if we can look at the movement of the human being in the right way, then it is actually only the form brought out of its rest, so that one sees the human being itself flowing over into the eurythmic in its whole being, that is then what leads over to the hygienic-therapeutic parts.

A third element is the pedagogical-didactic area. In the Waldorf School in Stuttgart, founded by Emil Molt and directed by me, eurythmy was introduced as a compulsory subject for all classes - from the classes with the six to seven-year-old children right up to the last class - alongside physical gymnastics as a kind of spiritual gymnastics. And it can be said that experience already shows how the children perceive this art of movement, this inspired, spiritual gymnastics, as a matter of course. Just as the child in its early years finds its way into human language as a matter of course through its human nature, so the older child, if the matter is properly cultivated, finds its way into the visible language of eurythmy as a matter of course. For the child instinctively feels very soon: here it has something that not only sets its body in motion like gymnastics based on physiological movement, but the child has something that sets the whole person in motion - body, soul and spirit. And the child perceives this as something inwardly satisfying, without realizing it, it feels it instinctively.

But there are many other things to consider. I can only mention that gymnastics can certainly benefit the human organism. One day we will think more impartially [about gymnastics] than we do today, where these things are often overestimated out of materialistic judgments. Eurythmically inspired, spiritualized gymnastics does not neglect the body, but it does take the soul and spirit into consideration. And therefore one can say that while ordinary gymnastics is only concerned with the development of the body, eurythmy, for example, if it is practiced in the right way with children, is particularly concerned with the growing child, with the initiative of the will. Anyone who considers the whole misery of the present time will admit: This is something that the present and the following generation will need very, very much, [this will initiative].

Apart from these last two aspects, we are only dealing with the artistic elements of eurythmy in our performance today. And one may well say, although every time we perform such artistic performances, I must ask the audience for their indulgence, as I do today, one may well say: because we ourselves are the strictest critics, we know how much imperfection is contained in this beginning. But one can also have the conviction, if one considers the innermost nerve, the essence of eurythmic art: It is not finished, it is capable of development.

From month to month, we ourselves have endeavored to bring ever different and ever newer sides of eurythmy to the surface. And those of our audience who have seen earlier mental images will also be able to observe how we have tried to make progress, especially in the introductions and endings of the poems that are not accompanied by music or poetic language, where the mood of the poem is introduced or fades away. But in all this we are still at the beginning. The art of eurythmy is by no means finished, and one guarantee of this is that it does not make use of an external tool, but of the human being himself. In its lawful inner organization, the things can be developed that enter into movement from form, that want to pass over, if one is able to look at it in the right way.

And because it makes use of the human being himself, this eurythmic art need not be finished. Goethe says, characterizing the artistic in its relationship to man in a deeply meaningful way: "When man has reached the summit [of nature], he sees himself again as a whole nature, which in itself has to produce another summit. To this end, he increases himself by imbuing himself with all perfections and virtues, by calling upon choice, order, harmony and meaning, and] finally [elevates himself] in this way to the production of the work of art." - Goethe means that man, by elevating himself to the production of the work of art, creates a higher nature out of nature itself through his powers. But this must be particularly the case when man makes himself an instrument, when he does not merely take order, harmony, measure and meaning from the outside world, as in the external, musical instruments, or even from his arbitrariness - as in mimic and pantomimic revelation - but when he takes order, measure, harmony and meaning from the secrets of human organization itself. Man is [now] a small world and contains in his own organization all the secrets that are otherwise poured out over the rest of the world. Therefore, that which makes use of man as an instrument must also artistically reveal the secrets of the world.

One may therefore hope that this eurythmic art, which today is perhaps only an attempt at a beginning, will continue to develop and will one day be able to stand alongside the older, legitimate arts as a fully justified younger art

56. Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Die Eurythmie-Aufführung fand gesamthaft in der Schreinerei statt. — Die Ansprache wurde von Helene Finckh teilweise nur lückenhaft mitgeschrieben und nicht von ihr selbst übertragen. Plakat für die Aufführung

Meine verehrten Anwesenden!

Gestatten Sie, dass ich den Versuch unserer eurythmischen Aufführung mit einigen Worten einleite, wie das sonst vor diesen Aufführungen geschieht. Und zwar nicht aus dem Grunde, um die Aufführung irgendwie zu erklären - das wäre unkünstlerisch; das Künstlerische muss in unmittelbarer Anschauung durch sich selbst wirken. Aber dasjenige, was als Formensprache und als künstlerische Quelle unserem eurythmischen Versuch zugrunde liegt, ist ein gegenwärtig noch Ungewohntes, und daher darf gerade über diese Quelle und über diese künstlerische Formensprache einiges gesagt werden.

Man kann sehr leicht dasjenige, was wir in der Eurythmie bieten, verwechseln mit allerlei mimischen, pantomimischen oder tanzartigen Darbietungen, aber gerade dadurch würde das Wesentliche dieses Eurythmisch-Künstlerischen eben nicht beachtet werden. Alles Mimische, Pantomimische beruht ja doch darauf, dass der Mensch dasjenige, was er durch den Laut- oder durch den Tonzusammenhang äußern kann, dass er das aus seinen individuellen Gefühlen und Empfindungen heraus mit Gebärden oder dergleichen Bewegungen beginnt.

Auch dasjenige, was Sie hier auf der Bühne sehen werden, sind Bewegungen des einzelnen Menschen oder auch Bewegungen von Menschengruppen. Also alles dasjenige, was hier bewegungsmäßig sich offenbart, das beruht auf einem sorgfältigen Studium desjenigen, was man, wenn ich mich des Ausdrucks Goethes bedienen darf, sinnlich-übersinnlich schauen kann als Bewegungstendenzen. Ich sage nicht Bewegungen, sondern Bewegungs-Tendenzen sind es, die dem sprachlichen oder dem musikalischen Ausdruck der Menschenseele zugrunde liegen. Das Singen oder Sprechen muss also sorgfältig studiert werden, und man muss diejenigen Bewegungsabsichten des menschlichen Organismus kennenlernen, um Eurythmie zu schaffen, welche dann nicht herauskommen, sondern wie im Moment des Entstehens nur herauskommen, möchte ich sagen, im status nascens schon verschwinden als solche und sich umwandeln, metamorphorphosieren in die Bewegung der Sprechorgane und dann in die Bewegung der Luft, die den Gesang und den Lautzusammenhang der Sprache für das hörende Ohr vermitteln.

Dasjenige nun, was im menschlichen Organismus an Bewegungsabsichten erregt wird, das wird aufgefasst und wird dann auf den ganzen Menschen übertragen. Sodass der ganze Mensch oder auch Menschengruppen durch eine wirkliche sichtbare Sprache oder auch sichtbaren Gesang sich ausdrücken können. Dadurch ist man imstande, das Dichterische sowohl wie das Musikalische dadurch zu erweitern, dass man seine inneren Bewegungen, wie sie in der Menschennatur liegen, offenbart.

Man braucht dasjenige, was auf diese Weise in einer wirklich sichtbaren Sprache oder einem wirklich sichtbaren Gesang zum Ausdrucke kommt, nur gehörig zu beachten, so wird man finden: Alles Mimische, Pantomimische ist so, dass es von dem eigentlichen Sprach- und Toninhalt herüberleitet in etwas mehr Gedankliches, das dann dazu drängt, durch den Menschen selbst sinnlichen Ausdruck in der Gebärde, in der Mimik und so weiter zu bekommen. Es ist dasjenige, was angeregt wird bei dem Zuschauer, dann etwas Gedanklich-Sinnliches. Dagegen, wenn auf den ganzen Menschen die eigentlichen Bewegungstendenzen des Singens und Sprechens übertragen werden, dann erscheint dasjenige, was sich offenbart, durchaus weniger nach dem Gedanklichen und nach dem Sinnlichen hinübergedrängt, sondern mehr nach dem Gefühlsmäßigen und nach den Willenselementen des Menschen. Und wir haben im Erfassen des Eurythmischen fortwährend dadurch eine Anregung für das Gefühl, und schauen an, im Grunde genommen, den gesetzmäßig wirkenden Willen.

Auch darin äußert sich die beträchtliche Distanz zwischen Mimisch-Pantomimischem und Eurythmie, dass man sagen muss: Weil im Willen des Menschen überhaupt mehr von der gesamten Welt, von den Weltgesetzmäßigkeiten liegt als im Vorstellungmäßigen, und das dann innerlich bloß individuell-persönlich im Menschen abläuft, erscheint auch alles dasjenige, was durch die Eurythmie gezeigt wird, nicht als etwas Persönliches, das sich durch den Menschen offenbart, sondern als etwas, was den Menschen mit der ganzen Welt verbindet. Sodass man dasjenige, was eben dasjenige von dem Willkürlichen im Menschen und was die Welt durch den Menschen selber offenbaren lässt — was ja in der wirklichen dichterischen, musikalischen Kunst durchaus auch zum Ausdrucke kommt -, sodass das gerade durch die eurythmische Kunst hervorgebracht werden kann.

Auch so könnte man etwa die beiden vergleichen, dass man sagt: Wenn das Mimisch-Pantomimische in das Tänzerische übergeht, so verliert der Mensch in den Formen des Tanzes eigentlich das innerlich Menschliche vollkommen. Man kann daher auch die Form durchaus so betrachten: In der Tanzkunst bewegt der Mensch sich, ich möchte sagen - wenn man das radikal ausdrückt - so, dass der Mensch sich abhandenkommt, während in der Eurythmie, in den eurythmischen Bewegungen der Mensch gerade sein Seelisches erhält. Man möchte sagen also: Im Tanz verliert der Mensch die Form, in der Eurythmie gewinnt gerade der Mensch als seelisch-geistiges Wesen Form. Dieses Formgewinnen, das ist dasjenige, wodurch eigentlich das Eurythmische wirken muss.

Man sieht daher in der eurythmischen Offenbarung eines Gedichtes etwas, was durchaus durch den wirklichen dichterischen Künstler in das Gedicht hineingeheimnisst ist. Und ebenso kann man ja auch zu einem Musikalischen, wie man tonlich hörbar singen kann, kann man auch durch die eurythmischen Bewegungen sichtbar singen -, ebenso kann man ja da sehen, wie eigentlich das Seelische beschaffen ist, was im Tonwerke zum Ausdrucke kommt. Sodass derjenige, der eine wirkliche Freude an dem Künstlerischen hat, in einer solchen Erweiterung des Künstlerischen, wie es in der Eurythmie zutage tritt, im Grunde auch etwas durchaus Befriedigendes sehen wird müssen.

Dass sich ein Tieferes in Dichtung und in dem Musikalischen durch die Eurythmie zum Ausdrucke bringt, das geht ja auch daraus hervor, dass Rezitation und Deklamation, indem sie als Begleiter der eurythmischen Kunst auftreten, zu ihrem, im heutigen unkünstlerischen Zeitalter abhanden gekommenen wirklich Künstlerischen zurückkehren müssen. Das heutige Zeitalter ist ja wirklich unkünstlerisch und kann kaum in richtiger Weise schätzen, was es heißt, dass zum Beispiel Schiller immer zunächst nicht einen wortwörtlichen Inhalt eines Gedichtes in seiner Seele leben hatte, sondern vor allem ein Musikalisches, Thematisches. Dieses Musikalische, Thematische war es, was die Wogen seiner Seele bewegte. Und dann fing er gewissermaßen in diese musikalischen Scelenwogen erst den wortwörtlichen Prosainhalt des Gedichtes auf.

Und man muss immer wieder betonen, wie Goethe selbst seine Jambendramen wie ein Musiker, wie ein Kapellmeister mit Taktstock seinen Schauspielern einstudierte, um über das bloß Prosahafte des Inhaltes das Rhythmisch-Taktmäßige, das Musikalisch-Thematische, das Imaginativ-Bildhafte auch in der Darstellung zum Ausdrucke zu bringen. Das waren eben wirklich dichterische Künstler.

Und zu einem wirklich Künstlerischen muss auch das Deklamatorische und Rezitatorische kommen, wiederum zurückkehren. Denn man könnte eurythmische Kunst nicht begleiten mit der heutigen Rezitation, die nur darauf sieht, dass der Prosainhalt gewissermaßen pointiert wird. Man kann sagen, man kann das ganz besonders begreifen, wenn abgesehen von allem Rhythmisch-Taktmäßigen, von allem Musikalisch-Thematischen und allem Imaginativ-Formhaften der Prosagehalt eines Gedichtes besonders pointiert wird im Rezitieren und Deklamieren.

Das würde - weil ja das wirklich Dichterische schon eine verhaltene Eurythmie ist, eine, man möchte sagen unsichtbare Eurythmie, die durch unsere Eurythmie eben nur in das Sichtbare herübergenommen wird -, das Deklamieren und Rezitieren, wie man sie heute liebt, würde gar nicht gehen als Begleitung zur Eurythmie. Daher muss zu dem, was in künstlerischeren Zeitepochen als Erfordernisse für Rezitation und Deklamation angesehen worden war, zurückgekehrt werden. Das muss heute wiederum empfunden werden, gerade im Anklange an die Eurythmie, sodass man wohl auch eine Belebung von Rezitations- und Deklamationskunst wird durch die Eurythmie finden können.

Das ist die eine, die künstlerische Seite der Eurythmie, die ja namentlich bei einer solchen Aufführung zutage treten will. Diese Eurythmie hat noch zwei andere Seiten, zwei andere Elemente. Das eine ist das therapeutisch-hygienische Element: Diejenigen Bewegungen, die ausgeführt werden in der Eurythmie, sind ja durchaus so, dass sie eine gesundende Organisation des Menschen hervorbringen, und sie können daher auch so ausgebildet werden, wie sie als therapeutisch-medizinische Seite der Eurythmie ja heute schon auftreten. Das ist nicht dasselbe wie dasjenige, was künstlerisch auftritt, sondern eine Metamorphosierung, eine Umbildung der Sprachbewegung. Aber sie ist durchaus auch möglich, wird [als Heileurythmie] heute schon gepflegt. Sie ist deshalb berechtigt, weil jede einzelne Bewegung des Eurythmischen eben durchaus aus der gesunden menschlichen Organisation hervorgeholt ist und deshalb, ausgeführt in der entsprechenden Weise, eine gesundmachende Wirkung auf die menschliche Organisation, die in Unordnung geraten ist, hervorbringen [kann].

Man braucht nur zu sehen, wie ein bewegter menschlicher Organismus die Form, die Bewegung herausfordert und wie wiederum die Bewegung an die Form durchaus erinnert und [wie] diese inneren organischen Zusammenhänge zwischen Formen der menschlichen Organisation bis ins Innerste hinein - nicht nur die räumlichen [kommen] dabei in Betracht, sondern auch die Form des Intensiven [Inneren?] -, wie diese Form mit allen menschlichen Bewegungen zusammenhängt, um das durchaus Gesunde der Eurythmie anzugehen.

Man sehe sich einmal eine menschliche Hand an: Sie kann zunächst als Form aufgefasst werden, aber die Form der menschlichen Hand hat keinem Sinn, wenn man bei ihr nicht sehen würde zum Beispiel - auch wenn sie ruhend ist — dasjenige, was an Bewegung der Finger oder des ganzen Armes vollzogen werden kann. Man kann wirklich von allem, was der Mensch von Form an sich trägt, sagen: Die Form des Menschen ist wie eine zur Ruhe gekommene Bewegung. Und wiederum, wenn wir die Bewegung des Menschen in richtiger Weise anschauen können, so ist sie eigentlich nur die Form aus ihrer Ruhe herausgebracht, sodass man den Menschen selber in das Eurythmische überfließen sieht in seiner ganzen Wesenheit, Das ist dann dasjenige, was dann zu hygienisch-therapeutischen Teilen hinüberführt.

Und ein drittes Element ist das pädagogisch-didaktische Gebiet. In der von Emil Molt gegründeten und von mir geleiteten Waldorfschule in Stuttgart wurde für alle Klassen - von den Klassen, die die sechs- bis siebenjährigen Kinder haben, bis zur letzten Klasse hinauf - die Eurythmie neben dem physischen Turnen als eine Art geistig-seelischen Turnens als ein obligatorischer Lehrgegenstand eingeführt. Und man kann sagen: Schon jetzt zeigt die Erfahrung, wie die Kinder als ein Selbstverständliches diese Bewegungskunst, dieses beseelte, durchgeistigte Turnen empfinden. Wie das Kind in den frühen Jahren sich einfach durch die menschliche Wesenheit selbstverständlich in die menschliche Sprache hineinfindet, so findet sich das ältere Kind, wenn die Sache richtig gepflegt wird, wie durch Selbstverständlichkeit in die sichtbare Sprache der Eurythmie hinein. Denn das Kind fühlt instinktiv sehr bald: Hier hat es etwas, was nicht nur seinen Leib in Bewegung bringt wie das auf physiologischer Bewegung basierende Turnen, sondern es hat das Kind etwas, was den vollen Menschen in Bewegung versetzt - nach Leib, Seele und Geist. Und das empfindet das Kind als ein eben innerlich Befriedigendes, ohne dass cs sich dies klarmacht, empfindet es dies durchaus instinktiv.

Aber vieles andere kommt noch in Betracht. Ich kann wohl als Einzelnes nur erwähnen, dass das Turnen den menschlichen Organismus ganz gewiss befördern kann. Man wird zwar einmal unbefangener denken [über das Turnen], als man heute denkt, wo man aus materialistischen Urteilen heraus diese Dinge vielfach überschätzt. Das eurythmisch beseelte, durchgeistigte Turnen vernachlässigt nicht den Leib, aber es nimmt eben durchaus auch Rücksicht auf Seele und Geist. Und daher kann man sagen: Während es das gewöhnliche Turnen nur mit der Förderung des Leibes zu tun hat, hat man es zum Beispiel in der Eurythmie, wenn sie in der richtigen Weise bei den Kindern gepflegt wird, namentlich mit dem heranwachsenden Kinde, mit der Willensinitiative zu tun. Derjenige, der die ganze Misere der heutigen Zeit in Betracht zieht, der wird zugeben: Das ist etwas, was die jetzige und die folgende Generation sehr, sehr brauchen wird, [diese Willensinitiative].

Von diesen beiden letzteren Seiten abgesehen, haben wir es heute nur zu tun in unserer Aufführung mit den künstlerischen Elementen der Eurythmie. Und man darf wohl sagen, obwohl jedes Mal, wenn wir solche künstlerischen Aufführungen vollziehen, ich so wie auch heute bitten muss die verehrten Zuschauer um Nachsicht, man darf doch wohl sagen: Weil wir selbst strengste Kritiker sind, wissen wir, wie viel Unvollkommenes in diesem Anfange enthalten ist. Aber man kann auch, wenn man gerade den innersten Nerv, das Wesen der eurythmischen Kunst ins Auge fasst, die Überzeugung haben: Sie ist nicht fertig, sie ist entwicklungsfähig.

Wir haben uns ja selbst von Monat zu Monat doch bemüht, immer andere und immer neuere Seiten des Eurythmischen an die Oberfläche zu bringen. Und diejenigen verchrten Zuschauer, die frühere Vorstellungen gesehen haben, werden auch be[ob]Jachten können, wie wir versucht haben, Fortschritte insbesondere in den nicht von Musik oder der dichterischen Sprache begleiteten Einleitungen und Ausklängen der Dichtungen, wo die Stimmung der Dichtung eingeleitet wird oder ausklingt, da haben wir in der letzten Zeit einiges einfügen können, was die eurythmische Kunst wiederum erweitert. Aber bei all dem stehen wir heute bei einem Anfange. Sie ist aber durchaus nicht fertig, diese Eurythmiekunst, und eine Garantie dafür bietet wohl das, dass sie sich nicht eines äußeren Werkzeuges bedient, sondern des Menschen selbst. In seiner gesetzmäßigen inneren Organisation lassen sich die Dinge herausentwickeln, die aus der Form heraus in die Bewegung eintreten, übergehen wollen, wenn man es in der richtigen Weise anzuschauen vermag.

Und weil sie sich des Menschen selbst bedient, deshalb muss diese eurythmische Kunst nicht fertig sein. Goethe sagt, indem er das Künstlerische damit in seinem Verhältnis zum Menschen tief bedeutsam charakterisiert: «Wenn der Mensch auf den Gipfel [der Natur gestellt ist, so sieht er sich wieder als eine ganze Natur an, die in sich abermals einen Gipfel hervorzubringen hat. Dazu steigert er sich, indem er sich mit allen Vollkommenheiten und Tugenden durchdringt, Wahl, Ordnung, Harmonie und Bedeutung aufruft, und sich] endlich auf diese Art zur Produktion des Kunstwerkes [erhebt].» - Goethe meint, dass der Mensch, indem er sich zur Produktion des Kunstwerks erhebt, eine höhere Natur aus der Natur selber heraus schafft durch seine Kräfte. Das muss aber dann ganz besonders der Fall sein, wenn der Mensch sich selbst zum Instrument macht, Ordnung, Harmonie, Maß, Bedeutung nicht bloß aus der Außenwelt nimmt, wie in den äußerlichen, musikalischen Instrumenten, oder auch nicht aus seiner Willkür - wie in der mimischen und pantomimischen Offenbarung —, sondern wenn er Ordnung, Maß, Harmonie und Bedeutung aus den Geheimnissen der menschlichen Organisation selber holt. Der Mensch ist [nun] einmal eine kleine Welt und enthält in seiner eigenen Organisation alle die Geheimnisse, die sonst über die übrige Welt ausgegossen sind. Daher muss dasjenige auch die Weltengeheimnisse künstlerisch enthüllen, was sich des Menschen als eines Instrumentes bedient.

Man darf daher hoffen, dass diese eurythmische Kunst, die heute vielleicht erst der Versuch eines Anfanges ist, sich weiter entwickeln werde und einstmals als eine voll berechtigte jüngere Kunst neben den älteren berechtigten Künsten wird stehen können