| 162. Artistic and Existential Questions in the Light of Spiritual Science: Fourth Lecture

30 May 1915, Dornach |

|---|

| 162. Artistic and Existential Questions in the Light of Spiritual Science: Fourth Lecture

30 May 1915, Dornach |

|---|

If you combine the observations I made here yesterday with the other lectures I gave here a week ago, you will, in a sense, obtain an important key to much of spiritual science. I would just like to outline the main ideas we will need for our further considerations, so that we can orient ourselves. About eight days ago, I pointed out the significance of processes which, from the point of view of the physical world, are called processes of destruction. I pointed out that, from the point of view of the physical world, reality can only be seen in what arises, what emerges, as it were, out of nothing and comes into noticeable existence. So we speak of reality when a plant breaks free from its roots, develops leaf by leaf until it blossoms, and so on. But we do not speak of reality in the same way when we look at the processes of destruction, at the gradual withering, at the gradual fading away, at the final flowing away, one might say, into nothingness. For those who want to understand the world, however, it is absolutely necessary to also look at what is called destruction, at the processes of dissolution, at what ultimately results for the physical world as flowing into nothingness. For consciousness in the physical world can never develop where only sprouting, budding processes take place; consciousness begins only where what has sprouted in the physical world is in turn carried away, destroyed. I have pointed out how the processes that life brings about in us must be destroyed by the soul-spiritual if consciousness is to arise in the physical world. It is indeed the case that when we perceive anything external, our soul-spiritual nature must cause destructive processes in our nervous system, and these destructive processes then convey consciousness. Whenever we become conscious of anything, the processes of consciousness must arise from processes of destruction. And I have pointed out how the most significant process of destruction, the process of death, which is so important for human life, is precisely the creator of consciousness for the time we spend after death. Through this, our soul and spirit experience the complete dissolution and detachment from the physical and etheric bodies, the merging of the physical and etheric bodies into the general physical and etheric world, our spiritual soul draws the power from the process of death to be able to have processes of perception between death and a new birth. The words of Jakob Böhme: “And so death is the root of all life” thus gain their higher meaning for the entire context of world phenomena. Now the question will often have come to your mind: What actually happens during the time that the human soul passes through between death and a new birth? It has often been pointed out that for normal human life this period is long in relation to the time we spend here in the physical body between birth and death. It is short only for those people who live their lives in a worldly manner, who, I would say, come to do only what can truly and genuinely be called criminal. In such cases, there is a short period of time between death and a new birth. But for people who are not solely devoted to selfishness, but spend their lives in a normal way between birth and death, there is usually a relatively long period of time between death and a new birth. But the question must burn in our souls, I would say: What determines the return of a human soul to a new physical embodiment? The answer to this question is intimately connected with everything we can know about the significance of the processes of destruction I have mentioned. Just think that when we enter physical existence with our souls, we are born into very specific circumstances. We are born into a specific age, drawn to specific people. So we are born into very specific circumstances. You must realize quite clearly that our life between birth and death is actually filled with everything into which we are born. What we think, what we feel, what we experience—in short, the entire content of our life depends on the time into which we are born. But now you will also easily understand that what surrounds us when we are born into physical existence depends on previous causes, on what has happened before. Suppose, if I were to draw this schematically, that we are born at a certain point in time and go through life between birth and death. (It was drawn.) If you add what surrounds you, it does not stand there in isolation, but is the effect of what came before. I mean to say: you are brought together with what came before, with people. These people are children of other people, who in turn are children of other people, and so on. If we consider only these physical generational relationships, you will say: When I enter physical existence, I take something from people; during my upbringing, I take a lot from the people around me. But they, in turn, have taken a great deal from their ancestors, from the acquaintances and relatives of their ancestors, and so on. One could say that, going further and further back, people must seek the causes of what they themselves are. If we then allow our thoughts to continue, we can say that we can trace a certain current beyond our birth. This current has, as it were, brought everything that surrounds us in life between birth and death. And if we continue to trace this current upward, we would eventually arrive at a point in time where our previous incarnation took place. So, by tracing time back before our birth, we would have a long period of time in which we lingered in the spiritual world. During this time, many things happened on earth. But what happened brought about the conditions in which we live, into which we are born. And then, finally, we arrive in the spiritual world at the time when we were on earth in a previous incarnation. When we speak of these conditions, we are speaking of average conditions. There are, of course, numerous exceptions, but they all lie, I would say, within the line I indicated earlier for natures that come to earthly incarnation more quickly. What determines that, after a period of time has elapsed, we are born again here? Well, if we look back at our previous incarnations, we see that during our time on earth we were also surrounded by certain conditions, and these conditions had their effects. We were surrounded by people, these people had children, they passed on to their children what their feelings and ideas were, the children in turn passed them on to the next generation, and so on. But if you follow historical life, you will say to yourself: there comes a time in the course of development when you can no longer recognize anything really the same or even similar in the descendants as in their ancestors. Everything is passed on, but the basic character that is present at a certain time appears weakened in the children, even more weakened in the grandchildren, and so on, until a time comes when nothing remains of the basic character of the environment in which one was in the previous incarnation. Thus, the stream of time works to destroy what was once the basic character of the environment. We observe this destruction in the time between death and a new birth. And when the character of the previous age has been wiped out, when nothing of it remains, when that which came to us, as it were, in previous incarnations has been destroyed, then the moment arrives when we enter earthly existence once again. Just as in the second half of our life our life is actually a kind of dismantling of our physical existence, so between death and a new birth there must be a kind of dismantling of earthly conditions, a destruction, a annihilation. And new conditions, a new environment into which we are born, must be there. So we are reborn when everything for which we were previously born has been destroyed and annihilated. Thus, this idea of being destroyed is connected with the successive return of our incarnation on earth. And what our consciousness creates at the moment of death, when we see the body fall away from our spiritual soul, is strengthened at this moment of death, at this viewing of destruction, for viewing the process of annihilation that must take place in earthly conditions between our death and a new birth. Now you will also understand that those who have no interest in what surrounds them on earth, who are basically not interested in any human being or any creature, but are only interested in what is good for themselves and simply steal from one day to the next, are not very strongly connected to the conditions and things on earth. They have no interest in following their slow deterioration, but they return very soon to repair what they have done, in order to truly live with the conditions they must live with, so that they may learn to understand their gradual destruction. Those who have never lived with earthly conditions do not understand their destruction, their dissolution. Therefore, those who have lived very intensively in the basic character of any age, who have immersed themselves completely in the basic character of any age, have above all the tendency, unless something else intervenes, to bring about the destruction of that into which they were born and to reappear when something completely new has emerged. Of course, I would say that there are exceptions at the top. And these exceptions are particularly important for us to consider. Let us assume that one lives in a movement such as the spiritual scientific movement today, at a time when it is not in tune with everything around it, when it is something completely foreign to its surroundings. This spiritual scientific movement is not what we were born into, but rather what we have to work on, what we want to see enter into the spiritual cultural development of the earth. It is then a matter above all of living with the conditions that are opposed to spiritual science, and of reappearing on Earth when the Earth has changed to such an extent that spiritual scientific conditions can truly take hold of cultural life. So here we have the exception upwards. There are exceptions downwards and upwards. Certainly, the most serious co-workers of spiritual science today are preparing to reappear in an earthly existence as soon as possible, while at the same time working during the course of this earthly existence to bring about the disappearance of the conditions into which they were born. So you see, if you take up the last thought, that you are in a sense helping the spiritual beings to guide the world by devoting yourselves to what lies in the intentions of the spiritual beings. When we consider the circumstances of our time today, we must say that, on the one hand, we have something that is eminently heading toward decadence and decline. Those who have a heart and soul for spiritual science have been placed in this age, as it were, to see how ripe it is for decline. Here on earth, they are introduced to that which can only be known on earth, but they carry this knowledge up into the spiritual worlds, where they now see the decline of the age and will return when a new age is to be brought about, which lies precisely in the innermost impulses of spiritual scientific striving. In this way, the plans of the spiritual leaders, the spiritual guides of Earth's evolution, are promoted by what such people, who are concerned with something that is not, so to speak, part of the culture of the times, take into themselves. You may be familiar with the accusations frequently made by people today against those who profess spiritual science, that they are concerned with something that often appears outwardly fruitless, that does not outwardly intervene in the circumstances of the time. Yes, there is indeed a need for people in their earthly existence to concern themselves with things that are important for further development, but not immediately for the present time. If one objects to this, one should only consider the following. Imagine that these were successive years: 1915, 1914, 1913, 1912. [IMAGE OMITTED FROM PREVIEW] We could then continue. Suppose these were consecutive years and these were the grain crops (center) of the consecutive years. And what I am drawing here would always be the mouths (right) that consume these grains. Now someone might come along and say: Only the arrow pointing from the grains of corn into the mouths (→) has any meaning, because that is what sustains the people of the successive years. And he might say: Anyone who thinks realistically looks only at these arrows pointing from the grains of corn to the mouths. But the grains of corn care little about this arrow. They do not care about it at all, but only have the tendency to develop into the next year's grain. Only the grain kernels care about this arrow (→); they don't care at all that they will be eaten, they don't care about that at all. That is a side effect, something that happens incidentally. Every grain kernel has, if I may say so, the will, the impulse, to pass into the next year in order to become a grain kernel again. And it is good for the mouths that the grains of corn follow this arrow direction (→), because if all the grains of corn followed this arrow direction (→), then the mouth here would have nothing to eat next year! If all the grains of corn from 1913 had followed this arrow (→), then the mouths of 1914 would have nothing to eat. If someone wanted to apply materialistic thinking consistently, they would examine the grains of corn to determine their chemical composition so that they would produce the best possible food products. But that would not be a good observation, because this tendency does not lie in the grains of corn at all, but rather in the grains of corn lies the tendency to ensure further development and to evolve into next year's grain of corn. So it is with the world process. Those who truly follow the world process are those who ensure that evolution continues, and those who become materialists follow the mouths that only see this arrow here (→). But those who ensure that the world continues need not be deterred in their efforts to prepare for the times to come, any more than the grains of corn are deterred from preparing for the next year, even if the mouths here demand arrows pointing in a completely different direction. At the end of “The Riddles of Philosophy,” I pointed to this way of thinking, pointing out that what is called materialistic knowledge can be compared to eating a grain of corn, that what really happens in the world can be compared to what what happens to a grain of corn through reproduction until the following year. Therefore, what is called scientific knowledge is just as insignificant for the inner nature of things as eating is for the growth of grain, which has no inner significance. And today's science, which is concerned only with the way in which what can be known from things can be brought into the human mind, does exactly the same as the man who uses the grain for food, for what the grains of corn are when eaten has nothing to do with the inner nature of the grain. into the human mind, does exactly the same as the man who uses the grain for food, because what the grains of corn are when eaten has nothing to do with the inner nature of the grains of corn, just as external knowledge has nothing to do with what develops inside things. In this way, I tried to throw a thought into the philosophical hustle and bustle, and it will be interesting to see whether it will be understood, or whether even such a very plausible thought will again and again be met with the foolish reply: Yes, Kant has already proven that knowledge cannot approach things. He only proved it with regard to knowledge that can be compared to the consumption of grains of corn, and not with regard to knowledge that arises with the progressive development that is in things. But we must already familiarize ourselves with the fact that we must repeat again and again, in all possible forms—but not in hasty forms, not in agitational forms, not in fanatical forms—what is the principle and essence of spiritual science to our age and to the age that is coming, until it is drummed into people's heads. For it is precisely characteristic of our age that Ahriman has made people's skulls very hard and dense, and that they can only be softened again very slowly. So no one, I would say, needs to shrink back from the necessity of emphasizing again and again, in all possible forms, what is the essence and impulse of spiritual science. But now let us look at another demand that was made here yesterday in connection with various prerequisites, namely the demand that in our time there must be a growing reverence for truth, a reverence for knowledge, not for authoritative knowledge, but for knowledge that is acquired. The attitude must grow that one should not judge out of nothing, but out of the knowledge one has acquired about the processes of the world. Now, when we are born into a particular age, we are dependent on our environment, completely dependent on what is in our environment. But this is connected, as we have seen, with the whole stream of development, with the whole upward striving, so that we are born into circumstances that are dependent on previous circumstances. Just consider how we are placed there. Certainly, we are placed there through our karma, but we are nevertheless placed in what surrounds us as something very specific, as something that has a certain character. And now consider how this makes us dependent in our judgment. We do not always see this clearly, but it is really so. So that we must say to ourselves, even if it is connected with our karma: What would it be like if we had not been born at a certain time in a certain place, but fifty years earlier in another place? Then we would have acquired the form and inner direction of our judgments from the different circumstances of our environment, just as we have acquired them from the place where we were born, wouldn't we? So that, on closer self-observation, we really come to the conclusion that we are born into a certain milieu, into a certain environment, that we are dependent on this milieu in our judgments and in our feelings, that this milieu reappears, as it were, when we judge. Now think how different it would be, I mean, if Luther had been born in the 10th century and in a completely different place! So even with a personality who has an enormously strong influence on their environment, we can see how they incorporate into their own judgments what is characteristic of the age, whereby the personality actually reflects the impulses of the age. And this is true of every human being, except that those in whom it is most evident are the least aware of it. Those who are most likely to reflect only the impulses of the environment into which they were born are usually the ones who talk most about their freedom, their independent judgment, their lack of prejudice, and so on. When, on the other hand, we see people who are not as thoroughly dependent on their environment as most people are, we see that it is precisely such people who are most aware of what makes them dependent on their environment. And one of those who never got rid of the idea of dependence on their environment is the one we have just seen pass before our eyes, Goethe. He knew in the most eminent sense that he would not be who he was if he had not been born in Frankfurt am Main in 1749, and so on. He knew that, in a sense, his age spoke through him. This enlivened and moved his behavior in an extraordinary way. He knew that his judgment had been shaped by certain inclinations and circumstances he had observed in his father's house. His judgment had been shaped by his student days in Leipzig. His judgment had been shaped by his move to Strasbourg. This made him want to escape from his circumstances and enter into completely different ones, so that in the 1880s, one might say, he suddenly disappeared into the night and only told his friends about his disappearance when he was already far away, after it was impossible to bring him back under the circumstances at that time. He wanted to get out so that something else could speak through him. And if you take many of Goethe's statements from his formative years, you will notice this feeling, this sense of dependence on his environment everywhere. Yes, but what should Goethe have strived for then, when he became fully aware that one is actually completely dependent on one's environment, when he connected his feelings and perceptions of this dependence with the thoughts we have expressed today? He would have had to say: Yes, what my environment is, is dependent on the whole current of history, right back to my ancestors. I will always remain dependent. I would have to transport myself back in my thoughts, in my soul experience, to a time when today's conditions did not yet exist, when conditions were completely different. Then, if I could put myself in those conditions, I would come to an independent judgment, not only judging how my time judges my time, but how I judge when I lift myself completely out of my time. Of course, it cannot be a matter of such a person, who feels this to be necessary, transporting himself into his own former incarnation. But essentially he must transport himself to a time connected with a former incarnation, when he lived in completely different circumstances. And when he now transports himself back to this incarnation, he will not be dependent as he was before, because the circumstances have become completely different; the former circumstances have been destroyed, have come to an end. It is, of course, something else when I now transport myself back to a time whose entire environment, whose entire milieu has disappeared. What do you actually have then? Well, you have to say: before, you live your life there, you enjoy life; you are interwoven with life. You can no longer be interwoven with the life that has been destroyed, with the life of an earlier time; you can only live through this life spiritually and soulfully. Then one could say: “We have life in its colorful reflection.” Yes, what would have to happen if such a person, who felt this, wanted to portray this emergence from the circumstances of the present and the arrival at an objective judgment from a standpoint that is no longer possible today? He would have to portray this in such a way that he is transported back to completely different circumstances. Whether this is exactly the previous incarnation or not is irrelevant; what matters are circumstances that were completely different on earth. And he would have to strive to fill his soul with the impulses that existed at that time. He would have to put himself into a kind of phantasmagoria, identify with this phantasmagoria, and live in it, live in a kind of phantasmagoria that represents an earlier time. But this is what Goethe strives for when he continues his “Faust” in the second part. Think about it: he first places Faust in the circumstances of the present, where he lets him experience everything that can be experienced in the present. But deep down he feels that this cannot lead to any true judgment, because I am always influenced by what is around me; I have to get out, I have to go back to a time whose circumstances have been completely changed in our time and therefore cannot influence my judgment. That is why Goethe lets Faust travel all the way back to classical Greek times and lets him enter and experience the classical Walpurgis Night. What he can experience in the present in the deepest sense, he has depicted in the Nordic Walpurgis Night. Now he must go back to the classical Walpurgis Night, because from the classical Walpurgis Night to the Nordic Walpurgis Night, all conditions have changed. What was essential to the classical Walpurgis Night has disappeared, and new conditions have arisen, symbolized by the Nordic Walpurgis Night. There you have the justification for Faust's return to the Greek era. The entire second part of Faust is the realization of what can be called: “In the colorful reflection we have life.” First, there is still a passage through the conditions of the present, but these are conditions that are already preparing for destruction. We see what is developing at the imperial court, where the devil takes the place of the fool, and so on. We see the creation of the homunculus, how the escape from the present is sought, and how, in the third act, Faust now enters the classical era. Goethe had already written the beginning at the turn of the 18th century; the other scenes were added in 1825, but the Helena scene had already been written in 1800, and Goethe calls it a “classical phantasmagoria” to indicate through the words that he means a return to conditions that are not the physical, real conditions of the present. That is what is significant about Goethe's Faust poem: that it is, I would say, a work of striving, a work of struggle. I have emphasized clearly enough in recent times that it would be nonsense to regard Goethe's Faust poem as a finished work of art. I have done enough to show that there can be no question of a finished work of art. But as a work of striving, as a work of struggle, this Faust poem is so significant. Only then can one understand what Goethe achieved intuitively, when one allows oneself to be illuminated by what our spiritual science can shed on such a composition, and sees how Faust looks into the classical era, into the milieu of Greek culture, where conditions were completely different in the fourth post-Atlantean era than in our fifth post-Atlantean era. One really gains the highest respect for this struggle when one sees how Goethe began working on Faust in his early youth, how he gave himself over to everything that was accessible to him at the time, without really understanding it very well. Really, when approaching Faust, one must apply this point of view of spiritual science, because the judgments that the outer world sometimes makes are too foolish in relation to Faust. How could the spiritual scientist fail to notice that time and again people who consider themselves particularly clever come up and point out how magnificently Faust expresses his creed, and say: Yes, in contrast to everything that so many people say about some kind of confession of faith, one should remember more and more the conversation between Faust and Gretchen:

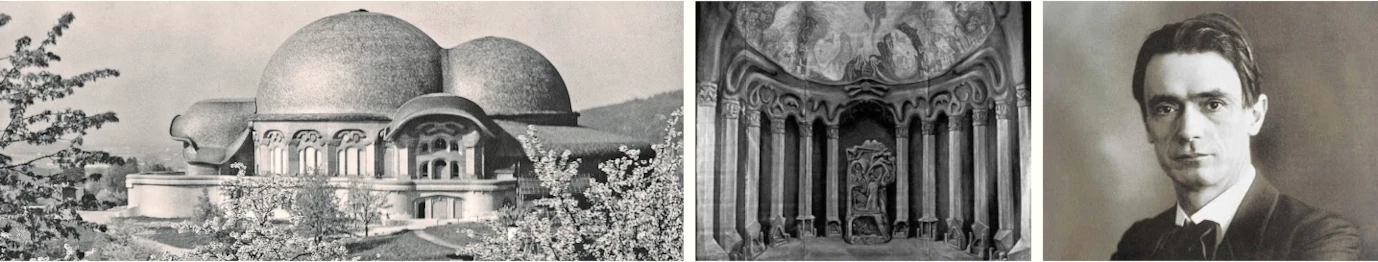

Well, you know what Faust is discussing with Gretchen, and what is always cited when someone thinks they need to emphasize what should not be seen as religious profundity and what should be seen as religious sentiment. But they fail to consider that in this case Faust was forming his religious confession for the sixteen-year-old Gretchen, and that all the clever professors are actually demanding that people never go beyond Gretchen's point of view in their religious beliefs. The moment one presents Faust's confession to Gretchen as something particularly sublime, one demands that humanity never rise above Gretchen's point of view. This is actually convenient and easy to achieve. One can also very easily boast that it is all feeling and so on, but one fails to notice that it is Gretchen's point of view. Goethe, for his part, strove quite differently to make his Faust the bearer of a continuous struggle, as I have now indicated again with reference to this placing oneself in a completely earlier age in order to obtain the truth. Perhaps at the same time or slightly earlier, when Goethe wrote this “classical-romantic phantasmagoria,” this transposition of Faust into Greek antiquity, he wanted to clarify once again how his Faust should actually unfold, what he wanted to portray in Faust. And so Goethe wrote down a plan. It was based on his Faust at that time: a foundation, a number of scenes from the first part, and probably also the Helena scene. Goethe wrote down: “Ideal striving for influence and empathy with the whole of nature.” So, as the century drew to a close, Goethe took up “the old Tragelaphen, the barbaric composition” again, as he said, at Schiller's suggestion. This is how he rightly described his Faust at the end of the century, for it had been written scene after scene. Now he said to himself: What have I actually done here? And he placed before his mind's eye this striving Faust, emerging from scholarship and drawing closer to nature. Then he wrote down: I wanted to present: 1. “Ideal striving to influence and empathize with the whole of nature. This is how he sketched the manifestation of the earth spirit. Now I have shown you how, after the manifestation of the earth spirit, Wagner, who appears, should actually be only a means for Faust's self-knowledge, should be only what is in Faust himself, a part of Faust. What is struggling within Faust? What is Faust doing now, with something struggling within him? He realizes: Until now, you have only lived in your surroundings, in what the outer world has offered you. He can see this best in the part of himself that is Wagner, who is completely content. Faust is in the process of achieving something in order to free himself from what he was born into, but Wagner wants to remain entirely what he is, wants to remain in what he is outwardly. What is it that lives out outwardly in the world from generation to generation, from epoch to epoch? It is the form into which human striving is imprinted. The spirits of form work outside on that into which we are to enter. But if man does not want to die in form, if he really wants to progress, he must always strive beyond this form. “Struggle between form and formlessness,” Goethe also writes. 3. “Struggle between form and formlessness.”But now Faust looks at the form: the Faust in Wagner there inside. He wants to be free of this form. This is a striving for the content of this form, a new content that can spring from within. When we decided to erect a building here for the spiritual sciences, we could have looked at all possible forms, studied all possible styles, and then built a new building from them, as many architects of the 19th century did, and as we find everywhere outside. In that case, we would have created nothing new from the form that has come about in the development of the world: Wagnerian nature. But we preferred to take the “formless content,” we sought from what is initially formless, what is only content, to take the living experience of spiritual science and pour it into new forms. Faust does this by rejecting Wagner:

“Preference for formless content,” Goethe also writes. And this is the scene he wrote when Faust rejects Wagner: 4. “Preference for formless content over empty form.” But form becomes empty over time. If, after a hundred years, someone were to build exactly the same building as we have built today, it would again be an empty form. That is what we must take into account. That is why Goethe writes: 5. “Content brings form with it.” That is what I want us to experience, and that is what we want with our building: content brings form with it. And: “Form,” writes Goethe, “is never without content.” Certainly it is never without content, but the Wagnerians do not see the content in it, so they accept only the empty form. The form is as justified as it can possibly be. But it is precisely in this that progress consists, that the old form is overcome by the new content. 6. “Form is never without content.”1. Ideal striving for influence and empathy with the whole of nature. And now a sentence that Goethe wrote down to give his “Faust” the impetus, so to speak, a highly characteristic sentence. For the “Wagners” who think about it: Yes, form, content, how can I concoct that, how can I bring that together? - You can easily imagine a person in the present day who wants to be an artist and says to himself: Well, yes, the humanities, that's all very well. But it's none of my business what these muddle-headed people come up with as the humanities. But they want to build a house that, I believe, incorporates Greek, Renaissance, and Gothic styles; and there I see what they are thinking in the house they are building, how the content corresponds to the form. One could imagine that this would happen. It has to come if people think about eliminating contradictions, when the world is made up of contradictions and it is important to be able to place contradictions side by side. Goethe writes: 7. “These contradictions, instead of being united, must be made more disparate.” That is, he wants to portray them in his “Faust” in such a way that they stand out as strongly as possible: “These contradictions, instead of being united, must be made more disparate.” And to do this, he once again juxtaposes two characters, one who lives entirely in form and is content when he clings to form, greedily digging for treasures of knowledge and happy when he finds earthworms. In our time, we could say: greedy for the secret of becoming human, and happy when he discovers, for example, that human beings originated from an animal species similar to our hedgehogs and rabbits. Edinger, one of the most important physiologists of our time, recently gave a lecture on the origin of human beings from a primitive form similar to our hedgehogs and rabbits. It is not true that the human world descended from apes, semi-apes, and so on; science has already moved beyond that. We must go further back, to where the animal species first branched off. There were once ancestors that resembled hedgehogs and rabbits, and on the other side we have humans as their descendants. Isn't it true that because humans are most similar to rabbits and hedgehogs in certain aspects of their brain structure, they must have descended from something similar? These animal species have survived, while the others have naturally all died out. So, dig greedily for treasures and be happy when you find rabbits and hedgehogs. That is one kind of striving, striving merely in form. Goethe wanted to portray this in Wagner, and he knows well that it is an intelligent striving; people are not stupid, they are intelligent. Goethe calls it “bright, cold, scientific striving.” “Wagner,” he adds. 8. “Bright, cold, scientific striving: Wagner.” The other, the disparate, is what one wants to work out from within with every fiber of one's soul, after not finding it in form. Goethe calls it “dull, warm, scientific striving”; he contrasts it with the other and adds: “student.” Now that Wagner has confronted Faust, the student also confronts him. Faust remembers how he used to be a student, what he absorbed, such as philosophy, law, medicine, and unfortunately also theology, how he said when he was still a student: “All this makes me feel so stupid, as if a mill wheel were turning in my head.” But that is all in the past. He can no longer put himself back in that position. But it all had an effect on him. So: 9. “Dull, warm, scientific striving: student.” And so it goes on. From then on, we actually see Faust becoming a student and then once again immersing himself in everything that enables one to take in the present. Goethe now calls the rest of the first part, insofar as it was already finished and still needed to be completed, the following: 10. “The enjoyment of life as seen from outside; in dullness and passion, first part.” This is how precisely Goethe understands what he has created. Now he wants to say: How should it continue? How should Faust really emerge from this enjoyment of life by the person into an objective worldview? He must come to the form, but he must now grasp the form with his whole being. And we have seen how far he must go back, to a place where conditions are completely different. There the form then confronts him as a reflection of life. The form confronts him in such a way that he now takes it up by becoming one with the truth that was valid at that time, and casts off everything that had to happen at that time. In other words, he tries to put himself into the time insofar as it was not permeated by Lucifer. He tries to go back to the divine standpoint of ancient Greece. And when one lives into the external world in such a way that one enters into it with one's whole being, but takes nothing from the circumstances into which one has grown, then one arrives at what Goethe calls beauty in the highest sense. That is why he says: “enjoyment of deeds.” No longer enjoyment of the person, enjoyment of life. Enjoyment of action, going out, gradually removing oneself from oneself. Settling into the world is enjoyment of action outwardly and enjoyment with consciousness. 11. “Enjoyment of action outwardly and enjoyment with consciousness; second part. Beauty.” What Goethe was unable to achieve in his struggle because his time was not yet the time of spiritual science, he nevertheless sketched out at the turn of the 18th to the 19th century. For Goethe wrote some very significant words at the end of this sketch, which was a recapitulation of what he had done in the first part. He had already planned to write a kind of third part to his “Faust”; but only the two parts were completed, and they do not express everything Goethe wanted to say. For that he would have needed spiritual science. What Goethe wanted to portray there is the experience of the whole of creation outside, when one has emerged from one's personal life. This entire experience of creation outside, in objectivity in the world outside, so that creation is experienced from within by carrying the truly inner outwards, is sketched out by Goethe, I would say, stammeringly with the words: “Enjoyment of creation from within” – that is, not from his point of view, in that he has stepped out of himself. 12. “Enjoyment of creation from within.” With this “enjoyment of creation from within,” Faust would now have entered not only the classical world, but also the world of the spiritual. Then there is something else at the end, a very strange sentence that refers to the scene Goethe wanted to create, did not create, but wanted to create, which he would have created if he had already lived in our time, but which was foreshadowed to him. He wrote: | 13. “Epilogue in chaos on the way to hell.” I have heard very intelligent people discuss the meaning of this last sentence: “Epilogue in chaos on the way to hell.” People have said: So Goethe really had the idea in 1800 that Faust would go to hell and deliver an epilogue in chaos before entering hell? So it was only much, much later that he decided not to let Faust go to hell! I have heard many, many very learned discussions about this, many, many discussions! It means that in 1800 Goethe was not yet free from the idea of letting Faust go to hell after all. But they did not think that it was not Faust who delivered the epilogue, but of course Mephistopheles, after Faust had escaped to heaven! Delivering the epilogue — we would say today — Lucifer and Ahriman on their way to hell; on their way to hell, they would discuss what they had experienced with the striving Faust. I wanted to draw your attention once again to this recapitulation and to Goethe's exposition because it shows us in the most eminent sense how Goethe, with all that he was able to gain in his time, strove toward the path that leads straight upward into the realm of spiritual science. One can only view “Faust” in its true sense if one asks oneself: Why has “Faust” remained, at its core, an imperfect work of literature, even though it is the greatest work of literature in the world and Faust is the representative of humanity in that he strives to break out of his milieu and is even carried back to an earlier age? Why, then, has this Faust remained an unsatisfactory work of literature? Because it merely represents the striving for what spiritual science is to incorporate into the development of human culture. It is good to focus on this fact and to consider that at the turn of the 18th to the 19th century, a work of literature emerged in which the figure at the center of this work, Faust, was to be lifted out of all the restrictive barriers that must surround human beings as they go through repeated earthly lives. The significance of Faust is that, however intensely he was born out of his folk culture, he nevertheless grew beyond it and into the universal human condition. Faust has none of the narrow barriers of folklore, but strives upward toward the universal human nature, so that we find him not only as the Faust of modern times, but also, in the second part, as a Faust who stands as a Greek among Greeks. It is an enormous setback in our time that, in the course of the 19th century, people began once again to place the greatest emphasis on the barriers to human development and even to see in the “national idea” something that could somehow still be a bearer of culture for our era. Humanity could wonderfully climb up to an understanding of what spiritual science should be, if one wanted to understand something like what is hidden in Faust. It was not for nothing that Goethe wrote to Zelter, when he was writing the second part of Faust, that he had hidden much in Faust that would only gradually come to light. Herman Grimm, of whom I have often spoken to you, pointed out that Goethe will only be fully understood in a thousand years. I must say that I believe this too. When people have delved even deeper than they have in our time, they will understand more and more of what lies in Goethe. Above all, however, they will understand what he strove for, what he struggled for, what he was unable to express. For if you were to ask Goethe whether what he put into the second part of Faust was also expressed in his Faust, he would say: No! But we can be convinced that if we were to ask him today: Are we, with spiritual science, on the path that you once strove for, as it was possible at that time? he would say: What spiritual science is, is moving along my paths. And so, since Goethe allowed his Faust to go back to Greek times in order to show him as someone who understood the present, it is permissible to say: Reverence for truth, reverence for knowledge that is wrested from the knowledge of the milieu, from the limitations of the environment, that is what we must acquire. And it is truly like a warning from current events, which are showing us how humanity is heading toward the opposite extreme, toward judging things as superficially as possible, and would prefer to go back only as far as the events of 1914 in order to explain all the terrible things we are experiencing today. But those who want to understand the present must judge it from a higher vantage point than the present itself. This is what I have wanted to place in your souls as a feeling during these days, a feeling that I have wanted to show you how it follows from a truly inner, living understanding of spiritual science, and how it has been sought by the greatest minds of the past, such as Goethe. By not merely accepting what comes before our souls in these reflections as something theoretical, but by processing it in our souls, by letting it live in the meditations of our souls, it only then becomes living spiritual science. May we hold fast to this, to much, indeed to everything that passes through our souls as spiritual science! |

| 179. Historical Necessity and Freewill: Lecture VII

17 Dec 1917, Dornach Translator Unknown |

|---|

| 179. Historical Necessity and Freewill: Lecture VII

17 Dec 1917, Dornach Translator Unknown |

|---|

In the lectures given during this week there lies much which can lead us to understand the nature of man in its connection with the historical evolution of humanity in such a way as to enable us to gradually form a conception of necessity and free will. Such questions can be less easily decided by means of definitions and combinations of words than by bringing together the relevant truths from the spiritual world. In our age humanity must accustom itself more and more to acquire a different form of understanding for reality from the one so prevalent today, which, after all, holds to very secondary and nebulous concepts bound up with the definitions of words. If we consider what certain persons who think themselves especially clever write and say, we have the feeling that they speak in concepts and ideas which are only apparently clear; in reality however, they are as lacking in clarity as if someone were to speak of a certain object which is made, for example, out of a gourd, so that the gourd is transformed into a flask and used as such. We can then speak about this object as if we were speaking of a gourd, for it is a gourd in reality; but we can also speak of it as if it were a flask, for it is used as a flask. Indeed, the things of which we speak are first determined by the connections we are dealing with; as soon as we no longer rely upon words when we are speaking, but upon a certain perception, then everyone will know whether we mean a flask or a gourd. But then we may not confine ourselves to a description or a definition of the object. For as long as we confine ourselves to a description or definition of this object it can just as well be a gourd as a flask. In a similar way, that which is spoken of today by many philologists—persons who consider themselves very clever—may be the human soul, but it may also be the human body—it may be gourd or it may be flask. I include in this remark a great deal of what is taken seriously at the present time (partly to the detriment of humanity). For this reason it is necessary that a striving should proceed from anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, for which clear, precise thinking is above all a necessity, a striving to perceive the world not in the way in which it is customary today (not by confusing the gourd and the flask) but to see everywhere what is real, be it outer physical reality, or spiritual reality. We cannot in any case arrive at a real concept of what comes into consideration for the human being when we hold only to definitions and the like; we can do so only when we bear in mind the relationships of life in their reality. And just where such important concepts as freedom (free will) and necessity in social and moral life are concerned, we attain clarity only when we place side by side such spiritual facts as those brought out in these lectures, and always strive to balance one against the other in order to reach a judgment as to reality. Bear in mind that over and over again—even in public lectures and also here—I have brought out with a certain intensity, from the most varied points of view, the fact that we can only rightly grasp what we call concepts when we bring them into relation with our bodily organism, in such a way that the basis of concepts in the body is not seen in something growing and flourishing, but just the opposite—something dying, something in partial decay in the body. I have expressed this in public lectures by saying that the human being really dies continually in his nervous system. The nerve-process is such that it must limit itself to the nervous system. For if it were to spread itself over the rest of the organism, if in the rest of the organism the same thing were to go on that goes on in the nerves, this would signify the death of man at every moment. We may say that concepts arise where the organism destroys itself. We die continuously in our nervous system. For this reason spiritual science is placed under the necessity of pursuing other processes besides the ascending processes which natural science of today considers authentic. These ascending processes are the processes of growth; they reach their summit within the unconscious. Only when the organism begins to develop the processes of decline does the activity of the soul appear which we designate as conceptual or indeed as perceptive activity of the senses. This process of destruction, this slow process of death, must exist if anything at all is to be conceived. I have shown that the free actions of human beings rest upon just this fact, that the human being is in a position to seek the impulses for his actions out of pure thoughts. These pure thoughts have [the] most influence upon the processes of disintegration in the human organism. What happens in reality when man enacts a free deed? Let us realize what happens in the case of an ordinary person when he performs an act out of moral fantasy—you know now what I mean by this—out of moral fantasy, this means out of a thinking which is not ruled by sense-impulses, sense-desires and passions—what really takes place here in man? The following takes place: He gives himself up to pure thoughts; these form his impulses. They cannot impel him through what they are; the impulses must come from man himself. Thoughts are mere mirror-pictures, they belong to Maya. Mirror-pictures cannot compel. Man must compel himself under the influence of clear concepts. Upon what do clear concepts work? They work most strongly upon the process of disintegration in the human organism; they bring this about. So we may say that on the one side the process of disintegration arises out of the organism, and on the other, the pure deed-thought (Tat-Gedanke) comes to meet this disintegrating process out of the spiritual world. I mean by this the thought that lies at the basis of deed. Free actions arise by uniting these two through the interaction of the process of disintegration and willed thinking. I have said that the process of disintegration is not caused by pure thinking; it is there in any case, in fact it is always there. If man does not oppose these processes of disintegration with something coming out of pure thinking, then the disintegrating process is not transformed into an up-building process, then a part that is slowly dying remains within the human being. If you think this through, you will see that the possibility exists that just through the failure to perform free actions man fails to arrest a death process within him. Herein lies one of the subtlest thoughts which man must accept. He who understands this thought can no longer have any doubt in life about the existence of human freedom. An action that is performed in freedom does not occur through something that is caused within the organism but occurs where the cause ceases, in other words, out of a process of disintegration. There must be something in the organism where the causes cease; only then can the pure thought, as motive of the action, set in. But such disintegrating processes are always there, they only remain unused to a certain extent when man does not perform free deeds. But this also shows the characteristics of an age that will have nothing to do with an understanding of the idea of freedom in its widest extent. The age running from the second half of the 19th century to the present has set itself the particular task of dimming down more and more the idea of freedom in all spheres of life, as far as knowledge is concerned, and of excluding it entirely from practical life. People did not wish to understand freedom, they would not have freedom. Philosophers have made every effort to prove that everything arises out of human nature through a certain necessity. Certainly, a necessity underlies man's nature; but this necessity ceases as disintegrating processes begin, as the sequence of causes comes to an end. When freedom has set in at the point where the necessity in the organism ceases, one cannot say that man's actions arise out of an inner necessity, for they arise only when this necessity ceases. The whole mistake consists in the fact that people have been unwilling to understand not only the up-building forces in the organism, but also the disintegrating processes. However, in order to understand what really underlies man's nature it will be necessary to develop a greater capacity to do this than in our age. Yesterday we saw how necessary it is to be able to look with the eye of the soul upon what we call the human Ego. But just in our times human beings are not very gifted in comprehending this reality of the Ego. I will give an illustration. I have often referred to the remarkable scientific achievement of Theodor Ziehen “Die physiologische Psychologie”—“Physiological Psychology.” On page 205 the Ego is also spoken of; but Ziehen is never in a position even to indicate the real Ego, he merely speaks of the Ego-concept. We know that this is only a mirror-picture of the real Ego. But it is particularly interesting to hear how a distinguished thinker of today—but one who believes that he can exhaust everything with natural scientific ideas—speaks about the Ego. Ziehen says:

And now Ziehen attempts to say something about the thought-content of the Ego-concept. Let us now see what the distinguished scholar has to say concerning what we must really think when we think about our Ego.

Now the distinguished scholar emphatically points out that we must also think of our name and of our title if we are to grasp or to encompass our Ego in the form of concept.

Thus “this simple Ego” is only a “theoretical fiction” that means a mere fantasy-concept, which constructs itself when we put together our name, title, or let us assume our rank and other such things also, which make us important! By means of such points we can see the whole weakness of the present way of thinking. And this weakness must be held in mind the more firmly because of the fact that what proves itself to be a decided weakness for the knowledge of the life of the soul is a strength for the knowledge of outer natural scientific facts. What is inadequate for a knowledge of the life of the soul, just this is adequate for penetrating the obvious facts in their immediate outer necessity. We must not deceive ourselves in regard to the fact that it is one of the characteristics of our times, that people who may be great in one field are exponents of the greatest nonsense in another. Only when we hold this fact clearly in mind—which is so well adapted to throw sand in the eyes of humanity—can we in any way follow with active thought what is required in order to raise again that power which man needs in order to acquire concepts that can penetrate fruitfully and healingly into life. For only those concepts can take firm hold of life as it is today, which are drawn out of the depths of true reality—where we are not afraid to enter deeply into true reality. But it is just this that many people shun today. At present people are very often inclined to reform the spiritual reality, without first having perceived the true reality out of which they should draw their impulses. Who today does not go about reforming everything in the world—or at least, believing he can reform it? What do people not draw up from the soul out of sheer nothingness! But at a time such as this only those things can be fruitful which are drawn up from the depths of spiritual reality itself. For this the Will must be active. The vanity that wishes to take up every possible idea of reform on the basis of emptiness of soul is just as harmful for the development of our present time as materialism itself. At the conclusion of a previous lecture I called your attention to how the true Ego of man, the Ego which indeed belongs to the will-nature and which for this reason is immersed in sleep for the ordinary consciousness, must be fructified through the fact that already through public instruction man is led to a concrete grasp of the great interests of the times, by realizing what (Gap in the text) struction man is led to a concrete grasp of the great interests of the times, by realizing what spiritual forces and activities enter into our events and have an influence upon them. This cannot be accomplished with generalized, nebulous speeches about the spirit, but with knowledge of the concrete spiritual events, as we have described them in these lectures, where we have indicated, according to dates, how here and there certain of these powers and forces from the spiritual world have intervened here in the physical. This brought about what I was able to describe to you as the joint work of the so-called dead and of the so-called living in the whole development of humanity. For the reality of our life of feeling and of will is in the realm where the dead also are. We can say that the reality of our Ego and of our astral body is in the same realm where the dead can also be found. The same thing is meant in both cases. This, however, indicates a common realm in which we are embedded, in which the dead and the living work together upon the tapestry which we may call the social, moral, and historical life of man in its totality; the periods of existence which are lived through between death and a new birth also belong to this realm. We have indicated in these lectures how between death and a new birth the so-called departed one has the animal kingdom as his lowest kingdom, just as the mineral kingdom is our lowest kingdom. We have also pointed out in a certain way, how the departed one has to work within the being of the animal kingdom, and has to build up out of the laws of the animalic the organization that again forms the basis for his next incarnation. We have shown how as second kingdom the departed one experiences all those connections which have their karmic foundation here in the physical world and which, correspondingly transformed, continue within the spiritual world. A second kingdom thus arises for the departed one, which is woven together of all the karmic connections that he has established at any time in an earthly incarnation. Through this, however, everything that the human being has developed between death and a new birth gradually spreads itself out, one might say, quite concretely over the whole of humanity. The third kingdom through which the human being then passes can be conceived as the kingdom of the Angels. In a certain sense we have already pointed out the role of the Angels during the life between death and a new birth. They carry as it were the thoughts from one human soul to another and back again; they are the messengers of the common life of thought. Fundamentally speaking, the Angels are those Beings among the higher Hierarchies of whom the departed one has the clearest living experience—he has a clear living experience of the relationships with animals and human beings, established through his karma; but among the Beings of the higher Hierarchies he has the clearest conception of those belonging to the Hierarchy of the Angels, who are really the bearers of thoughts, indeed of the soul-content from one being to another, and who also help the dead to transform the animal world. When we speak of the concerns of the dead as personal concerns, we might say that the Beings of the Hierarchy of the Angels must strive above all to look after the personal concerns of the dead. The more universal affairs of the dead that are not personal are looked after more by the Beings of the Kingdom of the Archangeloi and Archai. If you recall the lectures in which I have spoken about the life between death and a new birth, you will remember that part of the life of the so-called dead consists in spreading out his being over the world and in drawing it together again within himself I have already described and substantiated this more deeply. The life of the dead takes its course in such a way that a kind of alternation takes place between day and night, but so that active life arises from within the departed. He knows that this active life which thus arises is only the reappearance of what he has experienced in that other state which alternates with this one, when his being is spread out over the world and is united with the outer world. Thus when we come into contact with one who is dead we meet alternating conditions, a condition, for instance, where his being is spread out over the world, where he grows, as it were, with his own being into the real existence of his surroundings, into the events of his surroundings. The time when he knows least of all is when his own being that is in a kind of sleeping state grows into the spiritual world around him. When this again rises up within him it constitutes a kind of waking state and he is aware of everything, for his life takes its course within Time and not in space. Just as with our waking day-consciousness we have outside in space that which we take up in our consciousness, and then again withdraw from it in sleep—so from a certain moment onward the departed one takes over into the next period of time the experiences which he has passed through in a former one; these then fill his consciousness. It is a life entirely within Time. And we must become familiar with this. Through this rhythmic life within Time, the departed enters into a very definite relationship with the Beings of the hierarchy of the Archangeloi and of the Archai. He has not as clear a conception of these Archangeloi and Archai Beings as of the Angels, of man, and of the animal; above all he always has this conception that these Beings, the Archai and Archangeloi, work together with him in this awaking and falling asleep, awaking and falling asleep, in this rhythm which takes place within the course of time. The departed one, when he is able to do so, must always bring to consciousness what he experienced unknowingly in the preceding period of time; then he always has the consciousness that a Being of the Hierarchy of the Archai has awakened him; he is always conscious that he works together with the Archai and Archangeloi in all that concerns this rhythmic life. Let us firmly grasp the fact that just as in a waking state we realize that we perceive the outer world of which we know nothing during sleep, just as we realize that this outer world sinks into darkness when we fall asleep, so in the soul of the so-called dead lives this consciousness—Archai, Archangeloi, these are the Beings with whom I am united in a common work in order that I may pass through this life of falling asleep and awaking, falling asleep and awaking, and so forth. We might say that the departed one associates with the Archangeloi and Archai just as in waking consciousness we associate with the plant and mineral world of our physical surroundings. Man cannot however look back upon this interplay of forces in which he is interwoven between death and a new birth. Why not? We may indeed say, why not, but just this looking back is something which man must learn; yet it is difficult for him to learn this owing to the materialistic mentality of today. I would like to show you in a diagram why man does not look back upon this. [IMAGE OMITTED FROM PREVIEW] Let us suppose that you are facing the world with all your organs of perception and understanding. This will give you a conceptual and perceptive content of a varied kind. I will designate the consciousness of a single moment by drawing different rings or small circles. These indicate what exists in the consciousness during the space of a moment. You know that a memory-process takes place when you look back over events—but in a different manner than modern psychologists imagine this. The time into which you can look back, to which your memory extends, is indicated by this line; it really indicates the space which here reaches a blind alley. This would be the point in your third, fourth or fifth year that is as far back as you can remember in life. Thus all the thoughts which arise when you look back upon your past experiences lie within this space of time. Let us suppose that you think of something in your thirtieth year for instance, and while you are thinking of this you remember something that you experienced ten years ago. If you picture very vividly what is actually taking place in the soul you will be able to form the following thought. You will say, if I look back to the point of time in my childhood which is as far back as I can remember, this constitutes a “sack” in the soul, which has its limits; its blunt end is the point which lies as far back in my childhood as I am able to remember. This is a sort of “sack” in the soul; it is the space of time which we can grasp in memory. Imagine such a “soul-sack” into which you can look while you are looking back in memory; these are the extreme limits of the sack which correspond in reality to the limit between the etheric body and the physical. This boundary must exist, otherwise ... well, to picture it roughly, the events that call forth memory would then always fall through at this point. You would be able to remember nothing, the soul would be a sack without a bottom, everything would fall through it. Thus, a boundary must be there. An actual “soul-sack” must be there. But at the same time this “soul-sack” prevents you from perceiving what you have lived through outside it. You yourself are non-transparent in the life of your soul because you have memories; you are non-transparent because you have the faculty of memory. You see therefore—that which causes us to have a proper consciousness for the physical plane is at the same time the cause of our being unable to look with our ordinary consciousness into the region that lies behind memory. For it does really lie behind memory. But we can make the effort to gradually transform our memories to some extent. However we must do this carefully. We can begin by trying to keep before us in meditation with more and more accuracy something which we can remember, until we feel that it is not merely something which we take hold of in memory, but something which really remains there. One who develops an intensive, active life of the spirit will gradually have the feeling that memory is not something that comes and goes, comes and goes—but that memory contains something permanent. Indeed, work in this direction can only lead to the conviction that what rises within memory is of a lasting nature and really remains present as Akashic Record, for it does not disappear. What we remember remains in the world, it is there in reality. But we do not progress any further with this method; for merely to remember accurately our personal experiences, and the knowledge that memory remains—this method is in a higher sense too egotistical to lead farther than just to this conviction. On the contrary, if you were to develop beyond a certain point just this capacity of looking upon the permanency of your own experiences, you would obstruct all the more your outlook into the free world of spirit. Instead of the sack of memories, your own life stands there all the more compactly and prevents you from looking through. Another method may be used in contrast to this; through it, the impressions in the Akashic Record become remarkably transparent, if I may use this expression. When we are once able to look through the stationary memories, we look with a sure eye into the spiritual world with which we are connected between death and a new birth. But to attain this we must not use merely the stationary memories of our own life; these become more and more compact, and we can see through them less and less. They must become transparent. And they become transparent if we make an ever stronger attempt to remember not so much what we have experienced from our own point of view, but more what has come to us from outside. Instead of remembering for instance what we have learned, we should remember the teacher, his manner of speech, what effect he had upon us and what he did with us. We should try to remember how the book arose out of which we learned this or that. We should remember above all what has worked upon us from the outer world. A beautiful and really wonderful beginning, indeed an introduction to such a memory, is Goethe's Wahrheit and Dichtung (his autobiography) where he shows how Time has formed him, how various forces have worked upon him. Because Goethe was able to achieve this in his life, and looked back on his life not from the standpoint of his own experiences, but from the standpoint of others and of the events of the times that worked upon him, he was able to have such deep insight into the spiritual world. But this is at the same time the way that enables us to come into deeper touch with the time which has taken its course between our last death and our present birth. Thus you see that today I am referring you, from another point of view, to the same thing to which I have already referred—to extend our interests beyond the personal, to turn our interests and attention not upon ourselves, but upon that that has formed us, that out of which we have arisen. It is an ideal to be able to look back upon time, upon a remote antiquity, and to investigate all the forces that have formed these “fine fellows”—the human beings. Indeed, when we describe it thus, this offers few difficulties; it is no simple task, but it bears rich fruit because it requires great selflessness. It is just this method that awakens the forces which enable us to enter with our Ego the sphere which the dead have in common with the living. To know ourselves, is less important than to know our time; the task of public instruction in a not too distant future will be to know our time in its concrete reality, not as it now stands in history books ... but time such as it has evolved out of spiritual impulses. Thus we are also led to extend out interest to a characteristic of our age and its rise from the universal world process. Why did Goethe strive so intense to know Greek art, to understand his age, through and through, to weigh it against earlier ages? Why did he make his Faust go back as far as the Greek age, as far as the age of Helen of Troy, and seek Chiron and the Sphinxes? Because he wished to know his own age and how it had worked upon him, as he could know it only by measuring it against an earlier age. But Goethe does not let his Faust sit still and decipher old state-records, but he leads him back along paths of the soul to the impulses by which he himself has been formed. Within him lies much of that which leads the human being on the one hand to a meeting with the dead, and on the other hand with the Spirits of Time, with the Archangels (this is now evident through the connection of the dead with the Archangels). Through the fact that man comes together with the dead, he also comes in touch with the Archangels and with the Spirits of Time. Just the impulses that Goethe indicated in his Faust contain that through which the human being extends his interest to the Time Spirit, and that which is preeminently necessary for our times. It is indeed necessary for our times to look in a different way for instance upon Faust. Most of those who study Faust hardly find the real problems contained in it. A few are able to formulate these problems, but the answers are most curious. Take for example the passage where Goethe really indicates to us that we should reflect. Do people always reflect at this point? Yet Goethe spares no effort to make it clearly understood that people should reflect upon certain things. For instance you know that Erichtho speaks about the site of the Classical Walpurgis-night; she withdraws and the air-traveler Homunculus appears with Faust and Mephistopheles. You will recall the first speeches of Homunculus, Mephistopheles and Faust. After Faust has touched the ground and called out. “Where is she?”—Homunculus says:—

Homunculus says:—