| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Alois Mager's writing “Theosophy and Christianity”

|

|---|

| Again, Mager's scientific approach does not lead to an understanding of the true facts, but to the assertion of objective untruths about anthroposophy and my relationship to it. |

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Alois Mager's writing “Theosophy and Christianity”

|

|---|

My experience in reading this writing A discussion of 1 with the anthroposophy of Alois Mager could be of profound interest to me. This prompts me to write down here, as a kind of soliloquy, the thoughts that have arisen in me while I was studying Mager's writing “Theosophy and Christianity”. (I must confess that I have only now found the time to read the writing, which was published as early as 1922). There are few people who believe that one can be fair to an opponent. But regardless of the reasons that such people have for their opinion, it seems to me that there are few conditions for me to be unfair to Alois Mager from the outset, even if he appears as my opponent. He belongs to an order that I hold in high esteem and love. Not only do I have many memories of noble, lofty, and far-reaching intellectual achievements that can be attributed to the order in general, without going into the work of the individual members of the order to whom this achievement is owed; but I have also had the good fortune to know and esteem individual members of the order. I have always had a sense for the spirit that prevails in the writings on science by such personalities. While I feel that much of what comes from other contemporary scientific works is foreign to me, there is not a little that comes from this side that touches my soul without any foreignness, even when the content seems to me to be incorrect, one-sided, or prejudiced. And so I was also able to take up with much sympathy what Alois Mager wrote without reference to anthroposophy. This applies to his thoughts on the life of the soul in the presence of God, which are deep in mind and spirit, in particular. I expected Alois Mager to be an opponent. For I know that from the side to which he belongs, either only silence about my anthroposophy can come, or opposition. Anyone who has illusions about this knows little about the world. But what Mager presents had to seem significant to me. And I would like to write down here the thoughts that have come to me about this, like a soliloquy. The essay “Theosophy and Christianity” discusses in four chapters, essentially the Anthroposophy I have described. Mager admits this. On page 31f. we find the words: “I consider it futile to broadly present the goals and teachings of neo-Indian theosophy. We must devote a separate treatise to Steiner's Anthroposophy and its relation to science. There the essentials of Theosophy will be discussed as well. The first chapter, “Theosophy in the Past and Present,” contains a spirited argument that what Mager calls Theosophy was revealed in a great spiritual way in the non-Christian world in Plotinus and Buddha. Mager sees the search of the human soul to come into contact with the divine in a way that naturally follows from the nature of this soul, most vividly realized in the two minds mentioned. For, what appears on Christian ground in this way, Mager does not judge, of course, as coming naturally from the nature of the soul, but as a result of the prevailing divine grace. It seems unnecessary to me to point out here that, especially in earlier times, the state of soul indicated, even if not in the scientific formulation of Plotinus or in the religious depth of Buddha, was much more present in the spiritual life of humanity than Mager assumes when he orients his whole presentation towards the two personalities. But what strikes me most is this: Mager wants to judge the anthroposophy I have presented. He wants to discuss what part of humanity is actually seeking by taking the anthroposophical path of the soul among many others. He wants to develop the content of what is alive in anthroposophy, otherwise what should give meaning to his investigation. Now the whole essence of what I have called anthroposophy is immediately distorted if, in order to explain its content, one refers to earlier descriptions of the spiritual worlds. I have said that I am recording these thoughts as a soliloquy. I do this in order to be able to present unreservedly what only I myself can know with complete certainty from the subjective experience of the matter immediately, but which I must know in just this way. And here I cannot do otherwise than to emphasize again and again that everything essential to my anthroposophy comes from my own spiritual research or insight, that I have borrowed nothing from the historical record in the matter or in the substantiation of the matter. If something I had found myself could be illuminated by being shown in some form or other as already existing elsewhere, then I did so. But I never did it with anything but what had been given in my own view before. Nor did I have any other method while I was referring to the theosophical society's own writings in my own writings. I presented what I had researched and then showed how one or the other appears in those writings. Only the terminology has been borrowed from what already existed, where an existing word made such borrowing desirable in terms of its content. But this has as little to do with the essential content of anthroposophy as the fact that language is used to communicate what has been self-explored has to do with the independence of what is said. One could, of course, also assume that a well-known linguistic expression is borrowed when one uses it in a presentation of something completely new. In the strictest self-knowledge, I have repeatedly asked myself whether this is the case, whether I can speak with my own exact knowledge when I say that what I present as a spiritual view comes from my directly experienced view, and that the historical given plays no role in this. In particular, it was always important to me to be clear about the fact that I did not take any details from what had been handed down historically and insert them into the world of my views. Everything had to be produced within the immediate life of contemplation; nothing could be inserted as a foreign entity. In wanting to bring this into clarity within myself, I have avoided all illusions and sources of illusion with the greatest effort of consciousness. After all, one may rely on a clarity of self-awareness that knows how to distinguish between what is experienced in consciousness in direct connection with the objective being and what emerges from some uncontrollable depths of the soul through something read or otherwise absorbed. I now believe that anyone who really engages with the presentation in my writings should also be able to see through my relationship to spiritual observation as a result. Alois Mager does not do this. For if he had tempted correctly, he would not have presented the content of anthroposophy with reference to Plotinus and Buddha first, but would have shown first how this content arises from the continuation of the development of modern consciousness on the basis of the spirit of science. But what led Mager to write his first chapter leads him in the sequel (page 47) to say: “What strikes us most and most irrefutably about Steiner's Anthroposophy is that it is composed of pieces of thought and knowledge from all peoples and all centuries. Greek mythology, which Steiner became acquainted with at the gymnasium, provides him with the Hyperboreans, Atlanteans, Lemurians, and so forth. He borrowed from the oriental mystery religions, from the Gnostic and Manichaean teachings. The Kant-Laplacean Urn Nebula served as a model for his spiritual primeval world being... This conclusion drawn by Mager about my anthroposophy is a complete objective untruth, in view of the true facts. It is dismaying to see that a fine mind, which wants to apply the means of its objective search for truth correctly in order to arrive at a true-to-life context, misses the truth and presents an illusion as reality. This sense of dismay overshadows all the other feelings I have about Mager's writing, for example that it is antagonistic towards me, that it becomes quite strangely unjust in many places and so widens. My consternation is heightened when I come across another objective untruth. In the second chapter, “Anthroposophy and Science”, Mager gives a commendable account of anthroposophical ideas, considering the brevity of the presentation to which he is obliged. Indeed, he proves himself to be a good judge of certain impressions that are given to spiritual perception as a finer materiality, for example, between the material and the soul. One can see that he has many qualities that enable him to engage with anthroposophy, if it were not for the inhibitions that come from other sides. But now, in this chapter, there is another objective untruth. Mager first tries to put my way of spiritual thinking on the same level as spiritistic or vulgar occult practices. He even uses Staudenmaier's book “Magic as Experimental Science” for this purpose, which a sense of spiritual differences should have protected him from. But now he comes to the following assertion: “The world view that Steiner presents to us, which at first glance appears imposing and seemingly complete, is not the result - as a philosophical world view is - of rational, scientific knowledge, but is gained through spiritual vision, anthroposophical clairvoyance” (page 45). “Steiner has all the knowledge he ever sipped and caught in his life, as he floated and wandered through all fields of knowledge, with an incomparable skill in clairvoyant threads into a bizarre unity.” Mager presents everything as if I had given my ideas about the spiritual world on the basis of an unchecked, unscientifically applied clairvoyance. Is there nothing to be said against such an assertion, considering what can be found in my writings about Goethe, in my “Theory of Knowledge of Goethe's World View”, in “Truth and Science”, in my “Philosophy of Freedom” ? I have presented this as a philosophical primal experience, that one can experience the conceptual in its reality, and that with such an experience one stands in the world in such a way that the human ego and the spiritual content of the world flow together. I have tried to show how this experience is just as real as a sensory experience. And out of this primal experience of spiritual knowledge, the spiritual content of anthroposophy has grown. I endeavored step by step to use 'intellectual, scientific knowledge' with the precision that I acquired in the study of mathematics to control and justify the spiritual view and so on. I only worked in such a way that the spiritual view emerged from 'intellectual, scientific' knowledge. I have strictly rejected all spiritualism and all vulgar occultism. Again, Mager's scientific approach does not lead to an understanding of the true facts, but to the assertion of objective untruths about anthroposophy and my relationship to it. Indeed, one is bound to be dismayed when one sees that an 'investigation' into anthroposophy gradually erodes the very soil in which anthroposophy is to be found. The anthroposophical spiritual researcher sees through the reasons for such mental states, which cannot come to objective facts, from his insights; but Mager is not to be presented here from the point of view of anthroposophy, but merely from the point of view of ordinary consciousness, which he indeed wants to assert in his writing. I ask now: can it still be fruitful to deal with what an opponent presents, when one sees that everything falls to nothing, that he presents to the world about Anthroposophy? Can one discuss assertions that cannot possibly refer to Anthroposophy because they not only paint a distorted image of it, but a complete opposite? (It is no wonder that Mager is unjust to me even in small matters. A clear misprint in one edition of my Theosophy, where the numbering of “mind soul” and “sentience soul” is incorrect – despite the fact that what comes before and after makes it quite clear that this is a misprint — he uses it to make the following comment: “It is characteristic of Steiner's scientific method that he places the intellectual soul before the sentient soul here, which contradicts his usual presentation.” In view of what has been presented, there is no opportunity to enter into a discussion about whether, in Mager's description of Aristotle's psychology in the third chapter, “Soul and Soul Migration”, which Mager even finds quite stimulating, there is the seed for transforming ideas about the soul from what can be observed externally to what is seen spiritually internally; whether, then, the path from Aristotelian intellectualism to anthroposophy does not emerge as a more straightforward one. How satisfying it would be to have such a discussion if Mager had not placed an abyss between what he wants to say and what Anthroposophy has to say. Equally satisfying would be a discussion of repeated lives on earth and karma. But precisely there Mager should see how I repeatedly endeavored in new editions of my “Theosophy” to get to grips with what the spiritual view clearly reveals in this regard, using “intellectual, scientific” knowledge to check it. The chapter “Reincarnation and Karma” in my “Theosophy” is the one that I have reworked most often over time. Yet P. Mager uses a number of sentences from this chapter to create the impression that I gave the “rational-scientific” explanation of this matter in a rather trivial form. Mager also wants to answer the question of why, in this present time, many people are striving for what he calls “theosophy”, and to which he also counts anthroposophy. And he thinks that I speak far too little from the deepest needs of the time; that anthroposophy cannot be what people are looking for. But even to talk about it, one would have to face each other without the abyss. And a discussion about the relationship between Christianity and anthroposophy would be particularly unproductive. So I could only experience P. Mager's writing as something that, by grasping it in the soul's gaze, became more and more distant from me, until I saw: what is said there has basically nothing to do with anthroposophy and me.

|

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: What is the Nature of the Opposition to Anthroposophy?

20 Nov 1921, |

|---|

| If anthroposophy wants to explore the supersensible, it does not promote religious feeling, but undermines it. One cannot deny that for many religiously minded people today, these assertions have a great impact. |

| Those who make it do not realize that although many have come to understand that the sensory and the intellectual everywhere point beyond themselves to a supersensory reality, they only accept a type of research that has been brought up through materialism. |

| Anthroposophy now stands in contrast to this. It fully understands the essential character of genuine natural science. It only seeks to show that the latter's turning away from the spiritual arose out of a merely temporal necessity. |

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: What is the Nature of the Opposition to Anthroposophy?

20 Nov 1921, |

|---|

The opponents of anthroposophical thought claim that it robs man of reverence for the unknowable. This assertion is based on the fact that anthroposophy seeks means of knowledge for the spiritual world. That it wants to build a bridge between faith and knowledge. But, it is said, man's position to the spiritual must not be “dragged down” into the realm of knowledge. The essence of faith must be based on the fact that man professes its content out of free devotion, through childlike trust, while scientific knowledge does not demand such trust, but is satisfied with the recognition of what is spread out before the senses and can be grasped by the universally valid intellect. The objects of knowledge cannot, by their own nature, elevate man above himself. If anthroposophy wants to explore the supersensible, it does not promote religious feeling, but undermines it. One cannot deny that for many religiously minded people today, these assertions have a great impact. And yet they are only brought about by the state of mind of the materialistically oriented view. Through the self-confidence with which it presents itself, it has fostered the habit of thinking that claims as a matter of course that only it proceeds from secure presuppositions and arrives at its results by logical demonstration. Without examining this approach more closely, religious natures submit to the assertion that approaches them with great certainty. They become apprehensive for their religious sensibilities; and out of this fear they would like to push the supersensible as far away as possible from the knowable. They feel that the materialistic view ultimately obscures the view of the spiritual; and because only it can be scientific, one must resort to something that man recognizes, although he must renounce all scientific insight with respect to it. Today, anyone who expresses such thoughts is said to be speaking in an outdated way. Real science has, after all, abandoned the materialistic point of view in many of its recognized representatives. And therefore, one should no longer ascribe to them advanced science. But this objection is based on an illusion. Those who make it do not realize that although many have come to understand that the sensory and the intellectual everywhere point beyond themselves to a supersensory reality, they only accept a type of research that has been brought up through materialism. They would like to think beyond the material, but they do not accept thoughts that really break away from the material. The religiously minded cannot be satisfied with what they put forward. Therefore, they prefer to accept the older opinion that science must necessarily be materialistic; the truth about the spirit can therefore only be accessible to a non-scientific faith. An unprejudiced historical reflection on the origin of creeds must shake this opinion. For it shows that all religious beliefs have their origin in something that mankind has once recognized as knowledge. Science has progressed; and those who have not kept pace with progress have retained an older layer of knowledge than their creed. This has thereby become a belief. Every creed was once considered to be science. Now, however, every older science had a body of ideas about the supersensible. The older knowledge, which later became creeds, was not opposed to a “modern” “true” science that was directed only towards the sensual and material. This state of affairs has only arisen in the last three to four centuries in the development of humanity. It reached its zenith in the nineteenth century. Science has banished the spiritual from its realm altogether. Humanity had to come to this point of development. Only through the compulsion to which the human soul must submit by following the strictly necessary course of natural facts with its thinking, could it develop the logical discipline that had to be implanted in it in the course of progress. At this point of development, natural science arose, which knows nothing of the spiritual. It has its justification in the history of human development. What are accepted today as articles of faith are older layers of knowledge with spiritual content. They now stand in opposition to “modern” science. If one wants to accept them, one must give them a basis in truth that has nothing to do with the science that one recognizes as such. Anthroposophy now stands in contrast to this. It fully understands the essential character of genuine natural science. It only seeks to show that the latter's turning away from the spiritual arose out of a merely temporal necessity. It takes the strict method of research of modern science as its starting point, but does not stop at the form that has developed in recent times. Rather, it shows that the human being can develop other powers of knowledge just as consciously as sensory observation and the mind that is bound to it, and thus arrive at a science of the spiritual that comes from the same mindset as natural science. Anthroposophy recognizes how to overcome the prejudice that knowledge hinders man's trusting devotion to the spiritual. It demands that before man approaches the study of the spiritual, he must transcend himself through the development of supersensible powers of knowledge. If he reaches the spiritual in this way, then the religious mood is connected with knowledge. If science were in itself capable of inhibiting this mood, then all creeds should have suffered this result. For they were all once “science”. This brings us to one of the points on which antagonism to anthroposophy is fuelled. It is particularly suited to show how this antagonism arises from an inadequate appreciation of the facts, from an unquestioned acceptance of what is rooted in ingrained habits of thought. Anthroposophy does not want to be accepted uncritically; but anyone who takes it up into their convictions with full awareness knows that it has nothing to fear from close examination. The opponents think that it can only be based on a belief in authority. They often do not realize that their rejection rests solely on just such a belief in authority. |

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Is Anthroposophy Fantasy?

22 Apr 1923, |

|---|

| One or other recognizes that in forming his ideas man experiences something that bears within it an independent, non-material entity; but one does not summon up the energy to live so energetically in this spiritual way of experiencing ideas that one passes from the realization that “ideas are spirit” to an understanding of the real spiritual world, which reveals itself in ideas only as on their surface. One only arrives at the experience: when natural phenomena approach man, he answers them from within with ideas. |

| And because every step of this experience is carried out with the same deliberation as in the field of natural research, measuring and determining weight, anthroposophy can be described as an exact spiritual research. Only those who do not understand the exact nature of their endeavors will lump them together with the nebulous forms of mysticism that so many people are fascinated by today. |

| And the concept of “matter” is only a provisional one, which is justified as long as its spiritual character is not understood. But one must speak of this “justification” after all. For the assumption of matter is justified as long as one faces the world with the senses. |

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Is Anthroposophy Fantasy?

22 Apr 1923, |

|---|

For the development of human spiritual life, there is a self-contained period between the demand, sounding from the Greek striving for knowledge, “know thyself” and the confession, “ignorabimus”, which was derived from the natural scientific view of the world in the last third of the nineteenth century. The ancient Greek sage found the human soul in harmony with life only when knowledge of the world culminated in knowledge of the human being, revealed in self-awareness. The modern thinker who believes that science has pushed him to his confession denies man precisely this culmination of his mental state. When Du Bois-Reymond spoke his “Ignorabimus,” the belief lived in him that all human knowledge could only move between the two poles of matter and consciousness. But these two poles elude human knowledge. We shall be able to recognize the manifestations of matter in so far as they can be expressed in terms of measure, number and weight; but we shall never be able to know what lies behind these manifestations as “matter in space”. Nor shall we be able to recognize how the experience arises in our own soul: “I see red”, “I smell the scent of roses”, and so on, that is, what takes place in our conscious life. For how could one grasp that a mass of moving carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and hydrogen atoms in the brain is not indifferent to how they move, how they have moved, how they will move. We can grasp how the substance in the brain moves, we can define this movement according to mathematical concepts; but we cannot form any idea of how the conscious sensation arises from this movement, like smoke from a flame. Should man go beyond these “limits of his knowledge,” he would have to proceed from knowledge of nature to knowledge of the spirit. And where the talk of the spirit begins, knowledge ends and must give way to faith. That is the ignorabimus (“we shall not know”) confession. It cannot be said that the modern state of mind has gone beyond this confession of ignorance in the recognized quest for knowledge. Certainly, all sorts of attempts have been made to do so; but these are limited to pointing out this or that path to knowledge; however, they do not muster the energy to actually follow these paths with real knowledge in practice. One or other recognizes that in forming his ideas man experiences something that bears within it an independent, non-material entity; but one does not summon up the energy to live so energetically in this spiritual way of experiencing ideas that one passes from the realization that “ideas are spirit” to an understanding of the real spiritual world, which reveals itself in ideas only as on their surface. One only arrives at the experience: when natural phenomena approach man, he answers them from within with ideas. But one does not grasp life in ideas themselves. One looks at how one is stimulated by nature to form ideas; but one does not place oneself in the inner experience that is woven into ideas themselves. Anthroposophy is the first to take this step. And one recognizes it as such because in its experience of ideas, the ideas do not remain ideas but become a spiritual form of perception. Anyone who only sees through the spiritual essence of the ideas must stop at seeing in them spirit-like images of the nature of being, in which he has to content himself with the only incomprehensible content of the spirit. Only he who brings to inner experience the soul activity unconsciously at work in the forming of ideas stands before a spiritual reality through this experience. And this experience can be pursued with a full consciousness, just as it belongs to the mathematician when he pursues his problems. From the habits of thinking that one has acquired from sensory observation and experimentation, one fears today to immediately fall into the nebulous and fantastic if one does not have, when forming ideas, the support of what the senses say, what the measuring methods, what the scales reveal. This does not lead to the conscious activation of the inner soul power that flows through the formation of ideas, and in the experience of which one encounters the spiritual just as much as one encounters the spatially extended through the sense of touch. What is described by anthroposophy as a thought exercise leads to this experience. And because every step of this experience is carried out with the same deliberation as in the field of natural research, measuring and determining weight, anthroposophy can be described as an exact spiritual research. Only those who do not understand the exact nature of their endeavors will lump them together with the nebulous forms of mysticism that so many people are fascinated by today. Some people also claim that precisely because anthroposophy starts from experience, it should not ascribe to itself the character of knowledge. For knowledge is only present where there is a transition from experience to the derivation of the one from the other, to logical processing and so on. Those who say this have failed to notice how all the soul activities through which modern man justifies his scientific approach pass through anthroposophy into experience. In this experience, one does not abandon the scientific approach in order to move on to a fantastic soul activity; rather, one takes the full scientific approach into the experience. In every step of the types of spiritual knowledge described in this weekly from various points of view – imagination, inspiration and genuine intuition – the full fundamental character of science lives on, only in the realm of the spirit rather than in the realm of nature. When Du Bois-Reymond made his confession “We will not know”, he had before his soul how man experiences inwardly: “I see red”, “I smell the scent of roses” and how, beyond this experience, “matter haunts space” and man cannot approach it. He cannot do so along this path either. But when he brings the formation of ideas to conscious experience in the imagination, then he opens the spiritual perception to the spirit, which then reveals itself in inspiration, and the person unites as spirit with the spirit in intuition. In this way, the person finds the spirit. But if he experiences himself in this way, he does not enter through the surface of the rose into the rose through the experience of “seeing red” or “smelling the scent of roses”; but he comes to experience what shines towards him from the rose as red, what streams towards him from the rose as the scent of roses; he finds that he has come to the other side of the red radiance and the scent of roses; matter ceases to “haunt space”; it reveals its spirit, and it is realized that belief in matter is only a preliminary stage to the realization that it is not matter that haunts space either, but spirit that reigns. And the concept of “matter” is only a provisional one, which is justified as long as its spiritual character is not understood. But one must speak of this “justification” after all. For the assumption of matter is justified as long as one faces the world with the senses. Anyone who, in this situation, attempts to assume some spiritual essence behind the sensory perceptions instead of matter is fantasizing about a spiritual world. Only when one penetrates to the spirit in one's inner experience does that which initially 'haunts' one as matter behind the sense impressions transform into a form of the spiritual world, to which one belongs with the eternal part of one's being. This transformation is not dream-like, but vividly and precisely imaginable. |

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Anthroposophy and Idealism

29 Apr 1923, |

|---|

| A better understanding of anthroposophy would be gained than is the case today from some quarters if one were to delve into the nature of the intellectual struggles that took place in the second half of the nineteenth century. |

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Anthroposophy and Idealism

29 Apr 1923, |

|---|

A better understanding of anthroposophy would be gained than is the case today from some quarters if one were to delve into the nature of the intellectual struggles that took place in the second half of the nineteenth century. This was the time when certain thinkers believed that the victory of scientific research over philosophical endeavor, as it had been active in the previous epoch, seemed decisive. They pointed to Hegel, who, in the opinion of these thinkers, had wanted to develop the whole world out of the idea, but who had completely lost the world of reality in his thought constructions; while the sovereign natural science started from this reality and only engaged with ideas to the extent that observation of the sensory world allowed. This way of thinking seemed to be confirmed in every respect by the positive results of natural science. One has only to read books such as Moriz Carriere's “Moral World Order,” published in 1877, and one will become acquainted with a spiritual warrior who wanted to defend the right of idealism against “sovereign natural science.” There were many such spiritual fighters in those days. It may be said that the prevailing school of thought has stepped over them, in the knowledge that their cause is lost. Gradually, no more attention has been paid to them. Through their scientific idealism they wanted to save for humanity the knowledge of the spiritual world. They realized that “sovereign natural science” must endanger this knowledge. They contrasted what could be observed with the world of ideas living in human self-awareness and believed that this was a testimony to the fact that spirit rules in the world. However, they were unable to convince their opponents that the world of ideas speaks of a different reality than the one on which natural science is based. Anthroposophy, looking back at these spiritual warriors, feels differently than the thinkers standing on the ground of “sovereign natural science”. It sees in them personalities who came as far as the door of the spiritual world, but who did not have the strength to open it. Scientific idealism is right; but only as far as someone who sets out to enter a region, but only has the will to reach the border of the region, but not to cross that border. The ideas to which Carriere and his like pointed are like the corpse of a living being, which in its form points to the living, but no longer contains it. The ideas of scientific idealism also point to the life of the spirit, but they do not contain it. Scientific idealism aspired to the ideas; anthroposophy aspires to the spiritual life in the ideas. Behind the thinking power that rises to the ideas, it finds a spiritual formative power that is inherent in the ideas like life in the organism. Behind thinking in the human soul lies imagination. Those who can only experience reality in relation to the sense world must see imagination as just another form of fantasy. In our imagination, we create a world of images to which we do not ascribe any reality in relation to our sensory existence. We shape this world for our own enjoyment, for our inner pleasure. We do not care where we got the gift of creating this world. We let it spring forth from our inner being without reflecting on its origin. In anthroposophy, we can learn something about this origin. What often prevails in man as a frequently exhilarating imagination is the child of the power that works in the child as it grows, which is active in the human being at all when it forms the dead materials into the human form. In man the world has left something of this power of growth, of formative power, something that it does not use up in fashioning the human being. Man takes possession of this remnant of the power that shapes his own being and develops it as imagination. One of the spiritual warriors referred to here also stood at the threshold of this knowledge. Frohschammer, a contemporary of Carrieres, has written a number of books in which he makes imagination the creator of the world, as Hegel made the idea or Schopenhauer the will. But we cannot stop with fantasy any more than we can with ideas. For in fantasy there is a remainder of the power that creates the world and gives form to the human being. We must penetrate behind fantasy with the soul. This happens in imaginative knowledge. This does not merely continue the activity of imagination; it first stops in it, clearly perceiving why, in contrast to the sense world, it can only acknowledge unreality, but then turns around and, moving backwards, reaches the origin of imagination and thinking. She thus enters into spiritual reality, which reveals itself to her through inspiration and intuition (spiritual perception) as she advances. She stands in this spiritual reality as sensory perception stands in physical reality. Imagination can only be confused with fantasy by those who do not feel the jolt of life between the consciousness that depends on the senses and the consciousness that lives in the spirit. But such a person would be like someone who awakens from a dream but does not feel the awakening as a jolt of life, but instead sees both experiences, dreaming and being awake, as equivalent. The abstract thinker fears that imagination will continue to be fantasized; the artistic person feels slightly uncomfortable that the imaginative activity, in which he wants to develop freely, undisturbed by reality, should accept another activity, of which it is a child, but which reigns in the realm of true reality. He imagines that this casts a shadow over the free child of the human soul. But that is not the case. Rather, the experience of spiritual reality only makes the heart beat faster in the realization that the spirit sends an offspring into the world of the senses through art, which only appears unreal in the world of the senses because it has its origin “in another world”. Anthroposophy wants to open the gate where noble spiritual fighters stood in the second half of the nineteenth century, without the strength to unlock this gate. The power of thought showed them the way to the ideas; but this power of thought froze in the ideas; Anthroposophy has the task of melting the frozen power. |

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Anthroposophy and Mysticism

13 May 1923, |

|---|

| Just as 1 Today, mysticism is understood to be the search for inner experiences that satisfy the human being after the longing to know one's own nature and one's relationship to the world has arisen. |

| The anthroposophical researcher must know these things; he must understand the paths and prospects of mysticism. But his path is different. He does not penetrate directly behind the mirror of memory and thus into the bodily organization as the mystic does. |

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Anthroposophy and Mysticism

13 May 1923, |

|---|

Just as 1 Today, mysticism is understood to be the search for inner experiences that satisfy the human being after the longing to know one's own nature and one's relationship to the world has arisen. The not entirely conscious premise here is that man is capable of developing powers of the soul through which he can immerse himself in his own being to the point where he is connected to the roots of world-creating existence. The path taken into the depths of the soul presents itself on closer inspection as a continuation of the path taken in ordinary memory. This reproduces the experiences of the soul in images of what the person has experienced in his or her dealings with the world. The images can be more or less faithful to the experiences, or they can be imaginatively transformed in the most diverse ways. The easiest way to visualize this process, which is naturally very complicated, is to use the comparison with a mirror. The impressions of the external world are received by the human being through the senses and processed by the powers of thought. Within the organism, they encounter processes in which they are not continued, but stopped and, in a given case, reflected like the light images from the mirror wall. However, the reflection occurs in such a way that the human organism has a more or less modifying effect on the impressions received from outside. The mystic now penetrates deeper into his own being with intensified soul forces than is the case with ordinary memory. He pushes, as it were, through the intensified soul forces behind the mirror wall. There he encounters regions of his own organization that are not reached by the process of ordinary memory. The forces of these regions do participate when memory is formed, but they remain unconscious. Their effect only comes to light when the memory image is somewhat different from the direct experience. But what the mystic brings into his consciousness as the causes of these effects is experienced like a memory. It has the pictorial character of a memory. But whereas the latter reproduces experiences that were once present in the person's life on earth but are no longer there at the moment of experiencing them, the mystic experiences images that were never earthly experiences at all. He experiences a world of images in the form of memory thoughts, which is precisely what memory is. When these matters are approached with anthroposophical research, it is found that the processes of one's own body reveal themselves in the mystical images obtained in the manner described. This occurs in a kind of symbolism that is also present in dream images. It can be said that the mystic dreams of the processes of his own bodily organization. It is certainly a great disappointment for some who think differently about mysticism to discover the above. But for those who want to penetrate the mysteries of the world of reality, every kind of knowledge is welcome, including the fact that, when viewed in a certain way from the soul, the bodily processes appear as a web that is like nocturnal dreams. And if we follow this knowledge further, it shows that this fact is a guarantee of how the human body's organization ultimately has its origin in spiritual sources. The anthroposophical researcher must know these things; he must understand the paths and prospects of mysticism. But his path is different. He does not penetrate directly behind the mirror of memory and thus into the bodily organization as the mystic does. He transforms the powers of memory while they are still soul-spiritual, while they are pure thought forces. This happens through the concentration of these powers and their meditative application. He dwells on clear images with highly concentrated soul forces. In doing so, he strengthens these forces within the soul region, while the mystic submerges into the region of the body. The anthroposophical researcher thus arrives at a vision of a finer, more ethereal body of formative forces, which is connected to the physical human body as a higher one. The mystic enters into dreams about the physical body; the anthroposophical researcher arrives at a superphysical reality. This formative forces body no longer lives in spatial forms; it lives in a purely temporal existence. In relation to the spatial physical body, it is a time body. It initially presents the forces at work in the physical body during the earthly existence of the human being in their temporal progression, as in a tableau that can be seen all at once. It differs markedly from a mere comprehensive reminiscence of a person's previous life on earth at a particular moment. Such a memory-image represents more the way the world and people have approached the person remembering; but this characterized life tableau contains the sum and the confused interaction of the impulses coming from within the human being, through which the person has approached the world and other people in sympathy and antipathy. It thus reflects the way in which the person has shaped their life. This life tableau relates to the memory image as the impression in the seal to the imprint in the sealing wax. This life tableau provides the first object of anthroposophical research; from there, further steps can be taken. The arguments presented here show how little sense it makes to lump anthroposophy together with other well-known psychic research methods. In it one has not abstract idealism, but concrete knowledge of the spirit; and so one has not grasped its essential character if one identifies it with this or that form of mysticism, only in order not to engage with its very own nature, but to dismiss it with what one posits as an opinion about such a form or presupposes in the case of many. If this is taken into account, many of the misunderstandings that still circulate around the world today with regard to anthroposophy will disappear.

|

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: The Goetheanum in Dornach and its Work

24 Sep 1922, |

|---|

| It is not intended as a new religion; but religious deepening, which is not hostile to any confession, can be promoted by an understanding of the spiritual world and by the practice of a spirit-filled art. The construction of the Goetheanum already serves this purpose. |

| The educational work is a beginning of this effectiveness. It will depend on the understanding that the Dornach idea finds in wider circles how it will prove effective for the most diverse areas of life. |

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: The Goetheanum in Dornach and its Work

24 Sep 1922, |

|---|

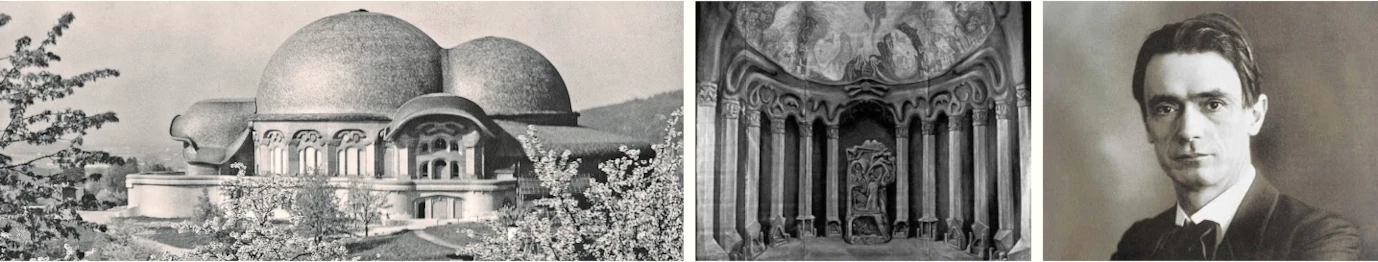

The Goetheanum NoteNum in the Swiss town of Dornach, near Basel, is intended to be a place of higher learning for the cultivation of a science and art rooted in the spirit. All sectarian aspirations are to be excluded here. It is not intended as a new religion; but religious deepening, which is not hostile to any confession, can be promoted by an understanding of the spiritual world and by the practice of a spirit-filled art. The construction of the Goetheanum already serves this purpose. It is not a building constructed in a historically handed-down art form. Here one beholds a new style, which may be found to be still imperfect in its kind, perhaps even still burdened with artistic errors; but it has emerged from the striving of the present day, which is directed towards a new style just as the human spirit once longed for Greek or Gothic or Baroque forms. Today there are many people in all parts of the civilized world who are convinced of the necessity of such a renewal of style. These convictions should find a center at the Goetheanum. The architecture, painting and sculpture of this building are all inspired by this idea. The dynamics and symmetry of ancient architecture were to be brought out of the mathematical-mechanical sphere and into that of an organic-living building concept. The plastic form was to be fertilized from the world of exact observation, and the color harmony was to be transformed into a revelation of the spiritual through the experience of such observation. What was striven for in this way may account for the still imperfect character of the Goetheanum building today, but it can also become the starting point for a comprehensive will in this direction in the future. This building provides the setting for scientific, artistic, educational and social work. The science cultivated here aims at a true spiritual knowledge. It does not stand in opposition to the recognized sciences of the present day; it allows them to express their insights where their legitimate methods must speak. But it comes to the conclusion that there are true spiritual scientific methods alongside the natural scientific ones. These do not consist of external experimental work, but in a development of the powers of the human soul that are hidden from ordinary consciousness. But this method does not lead to nebulous mysticism, but to abilities that work just as precisely as mathematical-geometric ones. That is why one can speak of an exact supersensible seeing. The mathematical ability works exactly; it develops in an elementary way in the human soul; this seeing works just as exactly; it must be attained by the human being through self-education. For anthropology, this vision progresses scientifically from the knowledge of the transitory human nature to the immortal essence of the human being; for cosmology, the same occurs for the spiritual laws of world evolution. A comprehensive literature of the anthroposophical movement provides information about the details of the development of exact supersensible vision. There one finds the paths from anthropology to anthroposophy, from cosmology to cosmosophy. Of the arts, only eurythmy and some declamatory and dramatic arts can be cultivated alongside music. Eurythmy, which is already being cultivated at the Goetheanum and in many other places, is not to be confused with the mimic or dance-like arts. It is based on drawing movements from the depths of the human being. These movements are drawn from human nature in the same way that nature draws language. Eurythmy is a visible language and can be artistically shaped in the same way as audible language by the poet. It then accompanies declamation, recitation and music. Poetry and music thus receive a revelation that they do not yet have through sound and tone alone. Efforts are also being made to cultivate other arts at the Goetheanum. In particular, mystery plays are to be performed soon. The Goetheanum also has an educational impact on young people. In Dornach itself, only children who are beyond compulsory school age can be given individual lessons. However, there is the prospect that a complete primary school can soon be established in Basel. We have such a school in Stuttgart through the Waldorf School. This was founded in 1919 by Emil Molt with about 150 children. Today it has around 700 pupils. There are about 35 teachers. Children are accepted there from the age of six, and the teaching and education is intended to continue until they are accepted into university. So far, eleven classes have been set up. The intention is to add another class each year. If conditions permit, a kind of kindergarten will be added later. The education and teaching are based on the complete knowledge of the human being that can be provided by a true spiritual science. This pedagogy does not contradict the principles of proven educators of the most recent times. It is in full agreement with them. But it works with the knowledge that a true science of the spirit can provide. No one dogmatic direction, not even anthroposophy, should be given undue emphasis; instead, spiritual knowledge should flow into the pedagogical methodology; everything that the teacher can know through spiritual knowledge should become an art of teaching and educating. In each school year, exactly what the human nature of the child requires is cultivated. Spirit, soul and body develop in complete harmony. For example, in the early school years, it is necessary to steer pedagogical methods away from the abstract and intellectual and towards an artistic approach to teaching reading and writing. In this way, the children's capacity for concentration is far better utilized than in the conventional teaching methods. In the Waldorf school there are children from all classes of the population; they receive a general human education and instruction. How the spiritual science of the Goetheanum would like to influence social life can be seen in my book “The Core Points of the Social Question in the Necessities of Life Today and in the Future”. The educational work is a beginning of this effectiveness. It will depend on the understanding that the Dornach idea finds in wider circles how it will prove effective for the most diverse areas of life. The willingness of many individuals to make sacrifices has been needed to bring about what can be found in Dornach so far. But the sacrifices that these personalities have made in abundance seem to be coming to an end in the near future; and the work in Dornach should be able to continue. To do this, it is urgently necessary that the beautiful interest that the Dornach idea has so far found in a not inconsiderable circle should extend to very wide circles, and that it should be recognized by them as a necessity of the time. This will only be possible if the Goetheanum in Dornach becomes a center where the spiritual, artistic and educational work characterized here can be carried out continuously in such a way that people will gather there from time to time to learn about the Goetheanum idea in theory and in practice. Then it will be independently cultivated by them in other places and, from its imperfect beginning, can be brought to ever more perfect stages in the civilized world. Such centralization and dissemination will be necessary if the activity of the personalities working in Dornach and Stuttgart, who are now called to the most diverse places to speak about the Goetheanum idea, is not to be too fragmented.

|

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Anthroposophy, Education, School

25 Dec 1921, |

|---|

| Anthroposophy strives for an understanding of the world and humanity that it can apply in a fruitful way to the art of teaching and educating. |

| One cannot understand the phenomena of childhood without also seeing in them the characteristics of the adult human being. |

| You cannot do anything with such beautiful principles as long as you do not carry in your own soul an understanding of the whole course of human life. And anthroposophical knowledge of the human being strives for such an understanding. |

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Anthroposophy, Education, School

25 Dec 1921, |

|---|

Anthroposophy strives for an understanding of the world and humanity that it can apply in a fruitful way to the art of teaching and educating. Its knowledge of human nature is not compiled from random observations made about human beings. It goes to the very foundations of the human being. She sees the human being in general in each individual human individuality. But she does not turn into abstract theory that dissolves the human being into general forces in her desire to understand him. Her thoughts about the human being are experiences of the human being. Her insights enliven the feelings for the human being. They reveal the secrets not only of the human being in general, but also of each particular human nature before the soul's gaze. Anthroposophy unites theoretical world observation with direct, vital insight. It does not need to artificially apply general laws to the individual phenomena of life; it remains in the fullness of life from the very beginning, in that it sees the universal itself as life. In this way, it is also a practical understanding of the human being. It knows how to help when it perceives this or that quality in the growing human being. It can form an idea of where such a quality comes from and where it points. And it strives for such an understanding of the human being that the knowledge also provides the skill to treat such a quality. In the knowledge of the human being, the insight into the human nature is conveyed. One need only fully develop the views that anthroposophy comes to about the human being, and they will naturally become the art of education and teaching. An abstract knowledge of the human being leads away from the love of humanity that must be the fundamental force of all education and teaching. An anthroposophical view of the human being must increase love of humanity with every advance in knowledge of the human being. If we wish to study the living organism, we must direct our attention to the relation of each individual part to the life of the whole, and also to the way in which the whole is effectively manifested in each part. We cannot understand the brain unless we have a clear insight into the workings of the heart. But it is the same in the life of man as it unfolds in time. One cannot understand the phenomena of childhood without also seeing in them the characteristics of the adult human being. The life of man is a whole; it is an organism in time. The child learns to look up to the adult with reverence. It learns veneration for human beings. This reverence, this veneration for human beings, is imprinted on the being; but it also changes in the course of life. For life is transformation. Reverence for human beings, veneration for human beings, which take root in the human soul during childhood - they appear in later life as the strength in the human being that can effectively comfort another human being, that can give him strong advice. No man of forty-five will have the warmth of comfort and counsel in his words who has not been brought as a child to look at other people with shy reverence, to honor them in the right way. And so it is with everything in human life. It is the same with the physical and the soul-spiritual. One understands the physical only if one grasps it in each of its members as a revelation of the spiritual. And one gains insight into the spiritual only if one is able to observe its revelations in the physical correctly. Childhood cannot reveal its essence through that which it only allows to be observed in itself. Human life is a whole. And only a comprehensive knowledge of the human being leads to an understanding of the child's life. In the abstract, this is easily admitted. But anthroposophy wants to develop this view into a concrete knowledge and art of life. It must develop into an art of education and teaching that feels responsible for the whole of human life by being entrusted with the growing human being. It sounds very nice to say: develop the child's individual abilities, get everything you do in your education and teaching out of these abilities. You cannot do anything with such beautiful principles as long as you do not carry in your own soul an understanding of the whole course of human life. And anthroposophical knowledge of the human being strives for such an understanding. When this is stated, one often hears the retort: you don't need anthroposophy for that. Surely all that is already contained in the principles of modern education. It is there, to be sure, in their abstract principles. But the point is that a real knowledge of the human being in body, soul and spirit leads to the transformation of abstract demands into real, life-filled art. And for this practical implementation, knowledge of the human being is necessary, which, although based on the good foundations of modern scientific knowledge, advances from these to a spiritual understanding of the human being. Anyone who approaches the human being with the ideas that the study of nature gives them may well come to the view that one develops this or that human disposition; but this view remains an abstract demand as long as one does not see the disposition as a partial revelation in the whole human being, in body, soul and spirit. One would like to say: the world view that is recognized today makes demands on education and teaching; but it lacks the possibility of fulfilling these demands through a practical knowledge of life: anthroposophy wants to provide this practical knowledge of life. Anyone who sees this will not find in anthroposophy an opponent of modern views and developmental forces in any area, but can hope for it to fulfill what lies abstractly in these views and forces. Humanity will have to admit that much of what it currently considers practical must be relegated to the realm of life illusions; and much of what it considers idealistic and impractical must be seen as the real thing. Such a change of perspective will be particularly necessary in the field of education and teaching. The great questions of human life lead to the children's and schoolroom. |

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Pedagogy and Art

01 Apr 1923, |

|---|

| It allows one to be happy in earnest and full of character in joy. Nature is only understood through the intellect; it is only experienced through artistic perception. The child who is taught to understand matures into 'ability' when understanding is practised in a lively way; but the child who is introduced to art matures into 'creativity'. |

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Pedagogy and Art

01 Apr 1923, |

|---|

The art of pedagogy 1 can only be based on genuine knowledge of human nature. And this cannot be complete if it is limited to mere observation. One does not get to know the human being through passive knowledge. At least to a certain extent, what one knows about the human being must be experienced as sensed by the creative part of one's own being; one must sense it in one's own will as a knowing activity. A passive knowledge of the human being can only lead to a lame educational and teaching practice. For the transition from such knowledge to practice must consist of external instructions for activity. Even if one gives oneself these instructions, they remain external. Knowledge of the human being as the basis of pedagogy must begin to live by being absorbed. One must immediately experience every thought about the human being as one's own nature, just as one experiences proper breathing and proper blood circulation as one's own health. When faced with the task of educating and teaching a child, knowledge of the human being must flow naturally into action. And love must live in this naturalness. There is no such thing as passive knowledge of the human being, and then the external consideration: because this or that is so and so in the child, therefore you must do this or that. There is only direct experience, which is what it recognizes in its own existence. And then the educational treatment of the child becomes an activity that arises in love and takes on its necessary character because it is experienced through the child. A knowledge of the human being that is woven into life takes up the child's essence like the eye takes up color. Knowledge of nature can remain theory; for the healthy feeling person, knowledge of the human being as theory is like having to experience oneself as a skeleton. There is no sense in speaking of a difference between theory and practice in the knowledge of the human being. For a knowledge of the human being that cannot become active in life practice is a sum of ideas that hover shadow-like in the mind but do not reach people. A life practice that is not illuminated by knowledge of the human being gropes uncertainly in the dark. If the teacher has the right attitude, then he has the prerequisite for developing his humanity in front of his pupils in a way that is full of life and invigorating, and for encouraging the emerging human being to reveal himself. And the right educational attitude is the essential thing in all pedagogical work. This attitude draws attention to the child's expressions of life, which appear as germinal states of the developing human being. The human being must be active in his work without losing himself in a mechanism of work. The child's nature demands that preparation for work be based on the revelation of the human being. The child wants to be active because activity is part of human nature. The harsh world demands that adults produce finished work. In the child, the developing human being demands activity, which, if guided correctly, develops the seed of work. Those who, with genuine insight into the human being, can eavesdrop on the child's being on the way from play to life's work will overhear the nature of teaching and learning at this intermediate stage. For in childhood, play is the serious revelation of the inner urge to activity, in which the human being has his true existence. It is a careless way of putting it to say that children should “learn by playing”. A teacher who organized his work accordingly would only educate people for whom life is more or less a game. But the ideal of educational and teaching practice is to awaken in the child a sense of learning with the same seriousness with which it plays, as long as playing is the only emotional content of life. An educational and teaching practice that sees this through will give art the right place and its cultivation the right extent. Life is often a strict teacher for the educator as well. It makes its demands on the training of the mind. Therefore, one will do too much rather than too little in relation to this training. It is the moral that truly makes man human. An immoral person does not reveal the full human being within himself. Therefore, it would be a sin against human nature not to cultivate the moral development of the child to the fullest extent. Art is the fruit of man's free nature. One must love art if one is to recognize its necessity for the full human being. Life does not compel love. But it thrives only in love. It wants to be in the unconstrained element. Schiller was the only one who sensed this; and this perception led him to write his “Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man”. Schiller sees the most important element of all educational art in the penetration of man with the aesthetic state of mind. Man should permeate the cognitive drive with cognitive love in such a way that he behaves like the creative artist or the aesthetically receptive person in his activity. And he should experience duty as the expression of his innermost human nature, as he feels in aesthetic experience. (On this occasion, reference may be made to the excellent presentation of Schiller's intentions in Heinrich Deinhardt's writing “Beiträge zur Würdigung Schillers”, which was recently published by Kommenden Tag Verlag in Stuttgart). It is a pity that Schiller's “Aesthetic Letters” have had such a limited effect on pedagogy. A stronger impact would have had a significant effect on the place of art in educational and teaching practice. Art, both visual and poetic-musical, is required by children's nature. And there is an engagement with art that is appropriate even for children when they reach school age. As an educator, one should not talk too much about this or that art being 'useful' for the development of this or that human ability. Art is there for art's sake, after all. But as an educator, one should love art so much that one does not want to deprive the developing human being of the experience of it. And then you will see what the experience of art does for the developing human being – the child. It is only through art that the mind comes to true life. The sense of duty matures when the urge to be active artistically conquers matter in freedom. The artistic sense of the educator and teacher brings soul into the school. It allows one to be happy in earnest and full of character in joy. Nature is only understood through the intellect; it is only experienced through artistic perception. The child who is taught to understand matures into 'ability' when understanding is practised in a lively way; but the child who is introduced to art matures into 'creativity'. In 'ability', the human being expresses himself; in 'creativity', he grows with his ability. The child who models or paints, however clumsily, awakens the soul in himself through his activity. The child who is introduced to the musical and poetic senses the sense of being moved by an ideal soul. He receives a second one to his humanity. All this will not be achieved if art is taught only on the side, if it is not organically integrated into the other forms of education and instruction. All instruction and education should be a unified whole. Knowledge, life training, and practice in practical skills should lead to the need for art; artistic experience should foster a desire for learning, observing, and acquiring skills.

|

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Pedagogy and Morality

08 Apr 1923, |

|---|

| The child lives completely absorbed in its surroundings until the period around the seventh year, when it undergoes the change of teeth. One could say that the child is completely absorbed in its surroundings. Just as the eye lives in colors, so the child lives entirely in the expressions of life in its surroundings. |

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Pedagogy and Morality

08 Apr 1923, |

|---|

The tasks of the educator and teacher 1 culminate in what he can achieve for the moral conduct of the youth entrusted to him. He faces great difficulties in this task within the elementary school education. One of these difficulties is that moral education must permeate everything he does for his students; a separate moral education can achieve much less than the orientation of all other education and all other teaching towards the moral. But this is entirely a matter of pedagogical tact. Because roughly formulated “moral applications” in all possible cases, even if they are still so forceful at the moment they are applied, do not achieve what is intended in the further course. - Another difficulty is that the child who enters elementary school has already formed the basic moral attitudes of life. The child lives completely absorbed in its surroundings until the period around the seventh year, when it undergoes the change of teeth. One could say that the child is completely absorbed in its surroundings. Just as the eye lives in colors, so the child lives entirely in the expressions of life in its surroundings. Every gesture, every movement of the father and mother is experienced in a corresponding way in the child's entire inner organism. The brain of the human being is formed during this period. And during this period of life everything that gives the organism its inner character emanates from the brain. And the brain reproduces in the finest way what takes place through the environment as a revelation of life. The child's learning to speak is based entirely on this. But it is not only the external aspects of the behavior of the environment that resonate in the child's being and imprint the character on its inner being, but also the spiritual and moral content of these external aspects. A father who reveals himself to his child through expressions of anger will cause the child to develop a tendency to express anger in gestures, even in the finest organic tissue structures. A timid and hesitant mother implants organic structures and movement tendencies in the child that cause the child to have a tool in its body that the soul then wants to use in a timid and hesitant way. During the phase of life when the teeth change, the child has an organism that reacts spiritually and morally on the soul in a very specific way. It is in this state, with an organism oriented towards the moral, that the child is received by the teacher and educator of the elementary school. If he does not see through this fact, he is exposed to the danger of imparting moral impulses to the child, which are unconsciously rejected by the child because it has the inhibitions of the nature of its own body to accept them. The essential thing, however, is that when the child enters primary school, he has the basic tendencies acquired by imitating his environment, but that these can be transformed with the right treatment. A child who has grown up in an environment of violent temper has received its organic formation from it. This must not be left unnoticed. It must be taken into account. But it can be transformed. If one takes it into account, one can shape it in the second phase of childhood, from the change of teeth to sexual maturity, in such a way that it provides the soul with the basis for quick-wittedness, presence of mind, and courage in those situations in life where such qualities are necessary. A child's organization, which is the result of a fearful, timid environment, can also provide the basis for the development of a noble sense of modesty and chastity. Genuine knowledge of the human being is therefore the basic requirement for moral education. Those who educate and teach must, however, bear in mind what the child's nature requires for its development in general between the change of teeth and sexual maturity. (These requirements can be found in the pedagogical course I have outlined and described in this weekly journal and which Albert Steffen has now published in book form). The transformation of basic moral principles and the further development of those that must be regarded as right can only be achieved by appealing to the emotional life, to moral sympathies and antipathies. And it is not abstract maxims and ideas that appeal to the emotional life, but images. In teaching, one has ample opportunity to present images of human existence and behavior, and even of non-human existence and behavior, to the child's mind, by which moral sympathies and antipathies can be aroused. Emotional judgment of the moral should be formed in the period between the change of teeth and sexual maturity. Just as the child, until the change of teeth, is devoted to imitating the immediate expressions of life in the environment, so in the period from the change of teeth to sexual maturity, it is devoted to the authority of what the teacher and educator say. A person cannot awaken to the proper use of moral freedom in later life if he has not been able to develop devotedly to the self-evident authority of his educators in the second phase of life. If this applies to all education and teaching, it applies to the moral in particular. The child looks at the revered educator and feels what is good and what is evil. He is the representative of the world order. The developing human being must first learn about the world through adult humans.The significance of the educational impulse contained in such learning can be seen when one seeks the right relationship to the child after the first third of the second phase of life, roughly between the ninth and tenth birthdays, in true human insight. A most important point in life is reached there. One notices that the child, half unconsciously, is going through something essential in a more or less dark feeling. The ability to approach the child in the right way is of incalculable value for his or her entire later life. If we wish to express consciously what the child experiences in its dream-like feelings, we must say: the question arises in the soul: where does the teacher get the strength that I, believing in him with reverence, receive? As a teacher, one must prove before the unconscious depths of the child's soul that one has the authority that comes from being firmly grounded in the world order. With true knowledge of human nature, one will find that at this point in time some children need few words, spoken correctly, while others need many. But something decisive must happen then. And only the being of the child itself can teach what has to happen. And for the moral strength, moral security, moral attitude of the child, unspeakably important things can be achieved by the educator at this point in life. If moral judgment has been properly developed with sexual maturity, it can be incorporated into free will in the next stage of life. The young person leaving elementary school will carry with them the feeling, from the psychological after-effects of their school days, that the moral impulses in social interaction with fellow human beings unfold from the inner strength of their human nature. And after sexual maturity, the will will emerge as morally strong if it has previously been cultivated in the rightly nurtured moral judgment of feeling.

|

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Introductory Words to a Eurythmy Performance

23 Sep 1923, |

|---|

| Eurythmy is not intended for an indirect understanding of the intellect, but for direct perception. The eurythmist must learn the visible language form by form, just as a human being must learn to speak. |

| 36. Collected Essays from “Das Goetheanum” 1921–1925: Introductory Words to a Eurythmy Performance

23 Sep 1923, |

|---|