| 36. A Lecture on Pedagogy

17 Dec 1922, |

|---|

| The artist would like his work to be grasped by feeling, not by the understanding. For then the warmth with which he has experienced it is communicated to the beholder. But this warmth is repelled by an intellectual explanation. |

| One would like to fashion one's methods of training and instruction so that not only the child's cold understanding may be aroused and developed, but warmth of heart may be engendered too. The anthroposophical view of the world is in full agreement with this. |

| Yet the forces concerned have not been lost; they continue to work; they have merely been transformed. They have undergone a metamorphosis. (There are still other forces in the child's organism which undergo metamorphosis in a similar way.) |

| 36. A Lecture on Pedagogy

17 Dec 1922, |

|---|

The present is the age of intellectualism. The intellect is that faculty of soul in the exercise of which man's inner being participates least. One speaks with some justification of the cold intellectual nature; we need only reflect how the intellect acts upon artistic perception or practice. It dispels or impedes. And artists dread that their creations may be conceptually or symbolically explained by the intelligence. In the clarity of the intellect the warmth of soul which, in the act of creation, gave life to their works, is extinguished. The artist would like his work to be grasped by feeling, not by the understanding. For then the warmth with which he has experienced it is communicated to the beholder. But this warmth is repelled by an intellectual explanation. In social life intellectualism separates men from one another. They can only work rightly within the community when they are able to impart to their deeds—which always involve the weal or woe of their fellow beings—something of their soul. One man should experience not only another's activity but something of his soul. In a deed, however, which springs from intellectualism, a man withholds his soul nature. He does not let it flow over to his neighbour. It has long been said that in the teaching and training of children intellectualism operates in a crippling way. In saying this one has in mind, in the first place, only the child's intelligence, not the teacher's. One would like to fashion one's methods of training and instruction so that not only the child's cold understanding may be aroused and developed, but warmth of heart may be engendered too. The anthroposophical view of the world is in full agreement with this. It accepts fully the excellent educational maxims which have grown from this demand. But it realises clearly that warmth can only be imparted from soul to soul. On this account it holds that, above all, pedagogy itself must become ensouled, and thereby the teachers' whole activity. In recent times intellectualism has permeated strongly into methods of instruction and training. It has achieved this indirectly, by way of modern science. Parents let science dictate what is good for the child's body, soul and spirit. And teachers, during their training, receive from science the spirit of their educational methods. But science has achieved its triumphs precisely through intellectualism. It wants to keep its thoughts free of anything from man's own soul life, letting them receive everything from sense observation and experiment. Such a science could build up the excellent knowledge of nature of our time, but it cannot found a true pedagogy. A true pedagogy must be based upon a knowledge that embraces man with respect to body, soul and spirit. Intellectualism only grasps man with respect to his body, for to observation and experiment the bodily alone is revealed. Before a true pedagogy can be founded, a true knowledge of man is necessary. This Anthroposophy seeks to attain. One cannot come to a knowledge of man by first forming an idea of his bodily nature with the help of a science founded merely on what can be grasped by the senses, and then asking whether this bodily nature is ensouled, and whether a spiritual element is active within it. In dealing with a child such an attitude is harmful. For in him, far more than in the adult, body, soul and spirit form a unity. One cannot care first for the health of the child from the point of view of a merely natural science, and then want to give to the healthy organism what one regards as proper from the point of view of soul and spirit. In all that one does to the child and with the child one benefits or injures his bodily life. In man's earthly life soul and spirit express themselves through the body. A bodily process is a revelation of soul and spirit. Material science is of necessity concerned with the body as a physical organism; it does not come to a comprehension of the whole man. Many feel this while regarding pedagogy, but fail to see what is needed to-day. They do not say: pedagogy cannot thrive on material science; let us therefore found our pedagogic methods out of pedagogic instincts and not out of material science. But half-consciously they are of this opinion. We may admit this in theory, but in practice it leads to nothing, for modern humanity has lost the spontaneity of the life of instinct. To try to-day to build up an instinctive pedagogy on instincts which are no longer present in man in their original force, would remain a groping in the dark. We come to see this through anthroposophical knowledge. We learn to know that the intellectualistic trend in science owes its existence to a necessary phase in the evolution of mankind. In recent times man passed out of the period of instinctive life. The intellect became of predominant significance. Man needed it in order to advance on his evolutionary path in the right way. It leads him to that degree of consciousness which he must attain in a certain epoch, just as the individual must acquire particular capabilities at a particular period of his life. But the instincts are crippled under the influence of the intellect, and one cannot try to return to the instinctive life without working against man's evolution. We must accept the significance of that full consciousness which has been attained through intellectualism, and—in full consciousness—give to man what instinctive life can no longer give him. We need for this a knowledge of soul and spirit which is just as much founded on reality as is material, intellectualistic science. Anthroposophy strives for just this, yet it is this that many people shrink from accepting. They learn to know the way modern science tries to understand man. They feel he cannot be known in this way, but they will not accept that it is possible to cultivate a new mode of cognition and—in clarity of consciousness equal to that in which one penetrates the bodily nature—attain to a knowledge of soul and spirit. So they want to return to the instincts again in order to understand the child and train him. But he must go forwards; and there is no other way than to extend anthropology by acquiring Anthroposophy, and sense knowledge by acquiring spiritual knowledge. We have to learn all over again. Men are terrified at the complete change of thought required for this. From unconscious fear they attack Anthroposophy as fantastic, yet it only wants to proceed in the spiritual domain as soberly and as carefully as material science in the physical. Let us consider the child. About the seventh year of life he develops his second teeth. This is not merely the work of the period of time immediately preceding. It is a process that begins with embryonic development and only concludes with the second teeth. These forces, which produce the second teeth at a certain stage of development, were always active in the child's organism. They do not reveal themselves in this way in subsequent periods of life. Further teeth formations do not occur. Yet the forces concerned have not been lost; they continue to work; they have merely been transformed. They have undergone a metamorphosis. (There are still other forces in the child's organism which undergo metamorphosis in a similar way.) If we study in this way the development of the child's organism we discover that these forces are active before the change of teeth. They are absorbed in the processes of nourishment and growth. They live in undivided unity with the body, freeing themselves from it about the seventh year. They live on as soul forces; we find them active in the older child in feeling and thinking. Anthroposophy shows that an etheric organism permeates the physical organism of man. Up to the seventh year the whole of this etheric organism is active in the physical. But now a portion of the etheric organism becomes free from direct activity in the physical. It acquires a certain independence, becoming thereby an independent vehicle of the soul life, relatively free from the physical organism. In earth life, however, soul experience can only develop with the help of this etheric organism. Hence the soul is quite embedded in the body before the seventh year. To be active during this period, it must express itself through the body. The child can only come into relationship with the outer world when this relationship takes the form of a stimulus which runs its course within the body. This can only be the case when the child imitates. Before the change of teeth the child is a purely imitative being in the widest sense. His training must consist in this: that those around him perform before him what he is to imitate. The child's educator should experience within himself what it is to have the whole etheric organism within the physical. This gives him knowledge of the child. With abstract principles alone one can do nothing. Educational practice requires an anthroposophical art of education to work out in detail how the human being reveals himself as a child. Just as the etheric organism is embedded in the physical until the change of teeth, so, from the change of teeth until puberty, there is embedded in the physical and etheric a soul organism, called the astral organism by Anthroposophy. As a result of this the child develops a life that no longer expends itself in imitation. But he cannot yet govern his relation to others in accordance with fully conscious thoughts regulated by intellectual judgment. This first becomes possible when, at puberty, a part of the soul organism frees itself from the corresponding part of the etheric organism. From his seventh to his fourteenth or fifteenth year the child's life is not mainly determined by his relation to those around him in so far as this results from his power of judgment. It is the relation which comes through authority that is important now. This means that, during these years, the child must look up to someone whose authority he can accept as a matter of course. His whole education must now be fashioned with reference to this. One cannot build upon the child's power of intellectual judgment, but one should perceive clearly that the child wants to accept what is put before him as true, good and beautiful, because the teacher, whom he takes for his model, regards it as true, good and beautiful. Moreover the teacher must work in such a way that he not merely puts before the child the True, the Good and the Beautiful, but—in a sense—is these. What the teacher is passes over into the child, not what he teaches. All that is taught should be put before the child as a concrete ideal. Teaching itself must be a work of art, not a matter of theory. |

| 36. Language and the Spirit of Language

23 Jul 1922, |

|---|

| It is not a Spirit that has been put there first by man's consciousness, but a Spirit that works in the subconsciousness and that man finds already there before him in the language as he learns it. And by this road man can really come to understand how their own spirit is a creation of the Spirit of language, of the ‘Speech-Spirit.’ On this road, the necessary conditions for getting to the Speech-Spirit are all there. |

| In face of the tendency towards the separation of peoples into languages it is one of the most urgent tasks of the times to create a counter-tide towards understanding each other. There is much talk about ‘Humanism’ in these days, and of cultivating the genuine human principle common to all men. |

| In the conventional and scientific language of the day, the overtone in the soul must of necessity be abstract, but the undertone should not be abstract too. In primitive stages of civilisation men had a visual sense of language. |

| 36. Language and the Spirit of Language

23 Jul 1922, |

|---|

People talk of the ‘spirit of a language,’ but it could hardly be said that there are many at the present day for whom the conception, so expressed, presents any very clear picture to the mind's eye. What they mean when they use these words, are general characteristic peculiarities in the formation of words and sounds, in the turn of sentences and the handling of imagery. Whatever ‘spirituality’ there may be exists in their minds alone and never goes beyond abstractions. As for anything worthy of the name of ‘Spirit’—they never get so far as that. There are, however, two ways we can take to find the ‘Spirit’ of language to-day in all its living force. One of these ways is discovered by the soul which pushes on beyond mere conceptual thinking to that seeing which reveals the life and being of things. This kind of sight is an inner experience, an inward realisation of a spiritual actuality which must not be confounded with any vague, mystic sensation of a general ‘something.’ It is an actuality that contains nothing sensibly perceptible, but is no less ‘substantial’ in the spiritual sense. In this kind of sight the seer travels far away from anything that can be expressed in language. What he sees cannot directly find its way to the lips. He clutches at words and has at once the feeling that the substance of his vision is changed. And—if he is bent on telling others about it—now begins his battle with the language. There is no possible form of speech that he does not press into his service to make a picture of what he has seen. Chimes and reminiscences of sounds, turns and twists of phrasing—he leaves nothing unexplored within the realms of the sayable. It is a hard inner struggle. And finally he has to say to himself: ‘This language is obstinate and has a will of its own. It says every conceivable thing in its own fashion. You will have to “give in” to it and humour it if you want it to accept your observations and receive them into itself.’ When we come to mould in speech what we have seen in spirit, then we find that we are dealing, not with a mass of soft wax that allows itself to be modeled into any form, but that we have to do with a living Spirit—the Spirit of language, the ‘Speech-Spirit.’ And, if it is honestly fought out in this manner, the battle may end excellently, indeed quite delightfully. For there comes a moment when we feel: ‘The Spirit of the language has laid hold of what I saw, has taken it up!’ The very words and turns of phrase in themselves take on something of a spiritual nature. They cease to be mere signs of what they usually ‘signify’ and slip into the very form of the thing seen. And then begins something like living intercourse with the Spirit of the language. The language takes on a personal quality. We feel that we can, as it were, discuss things with it, come to terms with it, as we should with another human being. That is one way by which we may begin to feel the Spirit of language as a living being. We come to the second way, as a rule, by going through the first. But this is not necessary and we can quite well take it independently. We are well on this second path when we realise the original, concrete significance of words and idioms that have come in the present day to have a merely abstract character, and feel them in all their first, fresh, visual meaning. We speak to-day, for instance, of an ‘inborn conviction,’ and say also that a conviction is ‘born in upon’ us. When we say in the present day, ‘I have an inborn conviction,’ we feel that the soul is already in the position of having laboured through to the inner verification of a thing. We have already learnt to feel ourselves detached from and ‘outside’ words. But if we feel our way back into the word again, there rises up, as a similar process on different planes, the bringing-to-birth in the body and the bringing-to-birth in the soul. We have visibly before us what actually goes on in the soul when a conviction is ‘born in’ upon it. Take another instance. We say of a person who is affable and obliging, that he is ready to ‘fall in’ with others. Such expressions open up a wealth of inner life. A person who is prone to falling loses his balance, takes leave of his consciousness. And one who is ready to ‘fall in’ with others lets himself go for the time being, sinks his own consciousness in that of the other. He goes through inwardly, something not altogether remote from what is meant by ‘falling down in a faint.’ If we have a healthy sense for such things, if we feel them in a genuine, matter-of-fact way and are not merely playing a clever game with words or trying to find ingenious arguments for debatable theories, then we are driven finally to admit to ourselves that in the formation of language there does dwell Intelligence, Reason, Spirit. It is not a Spirit that has been put there first by man's consciousness, but a Spirit that works in the subconsciousness and that man finds already there before him in the language as he learns it. And by this road man can really come to understand how their own spirit is a creation of the Spirit of language, of the ‘Speech-Spirit.’ On this road, the necessary conditions for getting to the Speech-Spirit are all there. The results of modern research contain everything requisite. And a great deal indeed has already been done. What is needed now is the conscious construction of a psychological science of language. It is, however, not so much our concern here to point out whatever may be needed in this direction, as to indicate things that have a practical bearing on life. Anyone who considers such facts as the above and looks at them all round, must come to recognise that deeply hidden in language there is something that leads out and beyond it to something higher, something that is over language—to the Spirit itself. And this Spirit is not such that in the manifold languages it too can be manifold. It lives within them all as a single unity. This spiritual unity amongst the languages is lost when they shed their first native, elemental vitality and are seized by the spirit of abstraction. Then comes the time when a man in speaking no longer has within him the Spirit, but only the verbal clothing of the Spirit. It is quite a different matter for a man's soul whether, in using such expressions as the above, he feels within him the picture of what actually takes place between two people when one, let us say, ‘falls in’ with the other—or whether he only attaches to the phrase a conventional, abstract notion of the relation between them. The more directly abstract men's sense of language becomes, the more their souls become cut off from one another. Whatever is abstract is peculiar to the individual. He elaborates it for himself and lives in it as in something identified with his own private ego. This element of abstractedness, it is true, is only perfectly to be achieved in the world of concepts; but to some degree a very near approach to it has been made in words and phrases as actually sensed and used, especially in the languages of civilised nations. But in the age in which we are now living, in face of all that tends towards the disseverance of men and peoples, every bond that links them together must be consciously fostered. For even between men who speak different tongues, that which divides them falls away when each sees and feels the visible reality imaged in his own form of speech. To awaken the slumbering ‘Speech-Spirit’ in each language should be an important element in all social education. Anyone who turns his mind to such matters must find how much the prosecution of any movement—of what people to-day call social movements—depends on watching the living process of men's souls, not on mere thinking and studying over external institutions and schemes. In face of the tendency towards the separation of peoples into languages it is one of the most urgent tasks of the times to create a counter-tide towards understanding each other. There is much talk about ‘Humanism’ in these days, and of cultivating the genuine human principle common to all men. But, for any such tendency to become quite genuine, it needs to be applied seriously to the different concrete provinces of life. Think what it means for anyone who once has felt words and phrases invested with an absolutely distinct and visible reality. How much fuller and keener is the sense a man then has of his own human nature than when language is merely felt in its abstraction! We need not think, of course, when a person sees a picture and says, ‘How delicious!’ that, whilst looking at the picture, he must at the same time have a vision of his joints being loosened until he is in a state of such complete ‘delectation’ that he begins to feel as if his being were dissolved! Still, anyone who has once vividly felt the corresponding picture in his soul, will—when he speaks such words—have a quite different inner experience from one who has never known them as anything but an abstraction. In the conventional and scientific language of the day, the overtone in the soul must of necessity be abstract, but the undertone should not be abstract too. In primitive stages of civilisation men had a visual sense of language. In its more advanced stages this visual sense of language must be provided by education in order that it may not be wholly lost. |

| 36. An Observer of World Crises

26 Feb 1922, Translated by Henry B. Monges |

|---|

| Civilization has been cleft from the beginning by a gaping abyss. There are periods of history which conceal it under all sorts of underbrush. There are human generations which either walk along its edges carefree or try to deny its existence by closing their eyes; and there are other generations which, when compelled to gaze into its depths, wish to turn away, shuddering, yet are unable to do so. |

| The war is now over; it has ruined every single nation on the European continent and to the last degree disorganized the whole. The peoples of Europe, unable under present conditions even to live, to say nothing of healing the wounds of war, are individually and collectively confronted with a choice either of finding and following with determination new ways, or of perishing completely.” |

| The new parasites of economic disorganization, the complaining opulent of yesterday, the petit-bourgeois sinking to the level of the proletarian, the credulous worker laboring under the delusion that he can establish a new world-order, all seem embraced by the same catastrophe, all seem to be blind men digging their own graves.” |

| 36. An Observer of World Crises

26 Feb 1922, Translated by Henry B. Monges |

|---|

In his book The Three Crises; an Inquiry into the Present Political World Situation, J. J. Ruedorffer offers an exposition of world events which could only be the work of a man whose experience has enabled him to develop an opinion in conformity with facts. From the author's description, it is on every page apparent that he has for long years lived deeply with his ideas in the events taking place around him. He remarks in his Introduction: “This Inquiry was written in May 1920 as a supplement to an enlarged, new edition of my Basic Trends in World Politics. But in accordance with the wishes of my publisher it is now issued as a separate book.” We may read this book as the confession of a man who asks world history what it has to say concerning the present state of the world. Without any political party prejudices, he seeks a reply to this question. But his opening words express only despair: “Without comprehension my contemporaries stand confronting world events. What is happening, from what causes, and to what end? This best of all worlds was, to be sure, intelligent up to the present, and has now fallen into a state of insanity. Revolution follows revolution, and peoples rage against themselves. No! the world was neither intelligent until recently, nor has it now suddenly fallen prey to insanity. Civilization has been cleft from the beginning by a gaping abyss. There are periods of history which conceal it under all sorts of underbrush. There are human generations which either walk along its edges carefree or try to deny its existence by closing their eyes; and there are other generations which, when compelled to gaze into its depths, wish to turn away, shuddering, yet are unable to do so. From an age of the first kind we have entered an age of the second.” Three present-day crises are described by the author. Evidence of the first he sees in the position into which nations—especially the European—have been forced, and in which they find it impossible to arrange their mutual relationships without clashes. A second crisis is evident to him in the fact that the governments of the various states have gradually lost their power to the contending political parties, so that what happens does not depend upon the governments, but upon the mechanism in the play of party-influence. A third crisis is apparent in the sum total of the social strivings which press up to the surface from the subconscious depths of the masses, who have no insight into the results of their own efforts, indeed, who, in their very desire to bring about an improvement in the present conditions of life, themselves destroy the possibility of a general social community of human beings. At the conclusion of each one of the three chapters dealing with these three crises stands a confession of despair, summarizing the content of the author's research. The first chapter concludes thus: “The untenable condition of Europe before the war has now become, through war and peace, a hundredfold more untenable. At that time a grand but thoughtless state of prosperity—in danger of being wrecked one fine day because of the instability of the European balance of power—was threatened with being swallowed by a world war. It was to the common interest of the European peoples to avoid this world war. Lack of insight into their common interest, lack of cool political leadership—independent of demagogues, and able to survey the common danger—finally permitted it to break out. The war is now over; it has ruined every single nation on the European continent and to the last degree disorganized the whole. The peoples of Europe, unable under present conditions even to live, to say nothing of healing the wounds of war, are individually and collectively confronted with a choice either of finding and following with determination new ways, or of perishing completely.” Of the second crisis he says the following: “This sickness of the political organism deprives the reasonable of leadership and permits the handing over of political decisions to manifold. irrelevant, subordinate, and private interests. It limits the freedom of movement, disperses the political will, and, besides this, is followed in most cases by a dangerous governmental instability. The period of unruly nationalism before the war, the, war itself, the condition of Europe after the war, have all placed enormous demands on the reasoning ability of the states, on their calmness, and on their freedom of movement. The fact that, with the increase of their tasks, the nations' ability to master them did not also increase but decreased, has completed the catastrophe. If democracy is to endure, it must be honest and courageous enough to state the facts, although by so doing it appears to testify against itself; Europe stands face to face with ruin!” In the third chapter we find the following: “It is a profound tragedy how every attempt at a better handling of affairs, every word of reform, is caught in the meshes of this catastrophe and over and over ensnared, so that it finally falls to the ground without effect; how the European bourgeoisie, either thoughtlessly clinging to a false notion of the age—continued progress of mankind—or just plodding along the customary road, lamenting their lot, do not see and do not want to see that they are nourished by the stored up energy of previous years, and scarcely capable of recognizing the infirmities of the present world-order, to say nothing of bringing forth out of themselves a new one; how, on the other hand, the proletariat, becoming in nearly all countries ever more radical, convinced of the un- tenability of the present state of affairs, and believing themselves the bringers of salvation by sponsoring a new world order, are in reality, only the unconscious instruments of destruction and ruin, including even their own. The new parasites of economic disorganization, the complaining opulent of yesterday, the petit-bourgeois sinking to the level of the proletarian, the credulous worker laboring under the delusion that he can establish a new world-order, all seem embraced by the same catastrophe, all seem to be blind men digging their own graves.” We would not turn aside from this confession so distressed, did the writer's style and attitude betray the literary observer, rather than the practical man who wants to write factually because he feels himself standing in the midst of events. After one has read the three chapters speaking of the downfall of civilization, the anxious soul asks: how does the author of such an exposition think about the question: What ought to happen? In answer we read: “Only a change of the world's mind, a change of will in the participating Great Powers, can create a Supreme European Council based on reason.” There is no indication how this “change of mind,” this “change of will,” is to be accomplished. Even after such a stirring insight into the impossibility of continuing with the old ideas, there is no evidence of the courage required to seek the conditions upon which recovery depends. If we seek these conditions, we come to what has often been expressed in this magazine [The Goetheanum]: The social organization of mankind has at all times received its nourishment from the spiritual content of the human evolutionary stream. Ideas which should sustain the social organization, as well as the economic life, must stem from the union of men's souls with an actual spirit-world. Otherwise these thoughts are merely intellectual. But the sense for such a union with the spirit-world is lacking in just such a personality as the author of the Three Crises. He is able to think about what his senses perceive, and about what his intellect can combine from those perceptions. Beyond this—only a blank. For after this negative confession another confession should come forth; namely: old ideas were created out of living spirit, and have, indeed, fulfilled their mission; we cannot continue to be nourished by the “stored up” ideas of earlier periods. New ideas must be born; to accomplish which, a union with the spirit-world is a necessity. But to such a continuance of the confession belongs the courage not only to speak of “change of mind” and “change of will,” but to acknowledge that mankind's turning away from a vivid experience of the spirit has led to the impossibility of recognizing in full consciousness the reasons for the catastrophe that threatens, although these are seen. Mr. Ruedorffer sees clearly enough; but he does not understand what he sees. Only the sustaining power of ideas born of the spirit, ideas which permit warmth to flow into human souls, which permit the human being to look upward from earth-bound daily labor to his world mission, to his relationship with the universe, only the sustaining power of such ideas will guide his hand to fruitful work and enable him to establish a human brotherhood. Today the world disdains those who speak thus of the spirit. Civilization, however, will recover its health only at the cessation of this disdain. We may speak of a “three-membering” of the physical human organism: the nerve-sense organism, the rhythmic organism, and the metabolic-limb organism. We must acknowledge that the two other organisms decay when the metabolic organism no longer brings real substances to the whole. In the social organism a reversed condition prevails. This organism is composed of the economic, the politico-rights, and the spiritual organisms. The other two decay when the spiritual organism does not receive real ideas, born of spiritual experience, and impart them to the other two. Just as the human body needs real substance to sustain it, so does the human social organism need real spirit. There are still people of the present day who confess something like fear of the spirit. These people are inclined to scent superstition, sentimental enthusiasm, lack of scientific method, when someone speaks of the spiritual world, not just in superficial phrases, but in a manner that indicates its real content—an accepted procedure when speaking of nature and history. Only when this secret fear is overcome can we know what really is contained in present world events. If the conquest is not achieved, we stop short at mere seeing. The book in review speaks only of this sort of seeing. |

| 36. The Scientific Method of Anthroposophy

19 Feb 1922, Translated by Lisa D. Monges |

|---|

| There were many, however, who could not concede that science as such can speak of anything but the material conditions of the spiritual and psychic. Under this trend of thought, psychology slipped into the habit of merely describing the processes in the nervous system. |

| There was the sustaining hope that gradually clear concepts of these complicated formations might be evolved The thinkers of today who again hold that underlying, file there is something special, which employs the physical and chemical for the purpose of higher activity, find themselves dis appointed in this hope. New hope is linked to what is undertaken in regard to the problem. The unprejudiced observer, however, must oppose this with the same reasoning which in the 19th Century led to discarding the prevalent conception of a “life-force.” |

| 36. The Scientific Method of Anthroposophy

19 Feb 1922, Translated by Lisa D. Monges |

|---|

For decades it has been the conviction of many people that scientific materialism must be superseded. When opinions are expressed on this subject, they usually refer to the mode of thought current in the 19th Century, which was considered inseparable from a true scientific attitude. To this mode of thought any mention of spirit and soul as beings who may be observed independent of their material conditions was unscientific. Only when the human being was observing material processes did he feel himself standing on solid scientific ground. The development of spirit and soul was seen in connection with material processes; and, by pointing to these material processes which take place during spiritual and psychic phenomena, people believed they did the only thing scientifically possible. There have always been thoughtful people who did not believe it possible to gain knowledge of the spirit and soul by means of the mode of thought characterized above. There were many, however, who could not concede that science as such can speak of anything but the material conditions of the spiritual and psychic. Under this trend of thought, psychology slipped into the habit of merely describing the processes in the nervous system. Thus, what can be observed by means of the senses was made the basis for gaining knowledge concerning the soul. Today there are many who hold that by this method of consideration the soul is lost to human perception. It is felt that in observing the life of the nerves we are confronted with the merely material, and that the latter cannot give answers to questions which spirit and soul must ask about themselves. There are today scientific thinkers, worthy of being taken seriously, who as a result of such feelings forsake the materialistic point of view and come to the conviction that the spiritual must be thought of as effective within the material. In the middle of the 19th Century it was the common belief that, by overcoming the old conception of “life-force,” great scientific progress had been made. According to this conception, a special force is active within the life processes, capable of drawing into its sphere physical and chemical agencies in such a way that life is called forth. This conception was rejected. The physical and chemical were thought to be so constituted as to be able—in their complicated formations—to reveal themselves as life. There was the sustaining hope that gradually clear concepts of these complicated formations might be evolved The thinkers of today who again hold that underlying, file there is something special, which employs the physical and chemical for the purpose of higher activity, find themselves dis appointed in this hope. New hope is linked to what is undertaken in regard to the problem. The unprejudiced observer, however, must oppose this with the same reasoning which in the 19th Century led to discarding the prevalent conception of a “life-force.” The reasoning ran thus: The kind of thinking which permits the clear survey of relationships in the physical and chemical spheres loses itself, when it speaks of “life-force,” in the unclear and nebulous. It was recognized that the approach which leads to physical and chemical relationships cannot lead to the “mystical” life-force. What was thus recognized was thoroughly justified. And when those entertaining new hopes in the sense indicated will have gained full clarity in the matter, they will have arrived at the same conclusions which in the 19th Century led to a rejection of “life-force.” A healthy development is possible in this connection only it we recognize that the mode of thought fully justified in the realm of the physical and chemical must be transformed when we advance to a consideration of the regions of life, soul, and spirit. The human being must first transform his thinking, it he would acquire the right to speak about these regions scientifically. Anthroposophy rests upon this basis. It does not, therefore, feel compelled to destroy the scientific edifice of physics and chemistry in order to build with the same thought-methods something different. It holds that this edifice of science has been established on secure foundations, but that within it must not seek life, soul, and spirit. If this be true, say those passing superficial judgment, then Anthroposophy places itself outside of science and may claim for itself, at best, certainty of belief. Anyone who talks that way is not turning vigorously from a consideration of nature back to a consideration of the human being. At the present time, our manner of observing the physical and chemical is based upon a particular constitution of the human soul. And scientific certainty is not the result of something revealed by nature, but of an inner experience of observation. What is experienced by the soul while observing nature gives certainty. Anthroposophical knowledge advances from this to other soul experiences which may be ours if thinking, trained in physical and chemical science, has transformed itself and acquired the faculty of imaginative, inspirative, and intuitive perception. And the latter experiences of the soul permit a similar certainty to gleam forth. Those who deny the certainty of these other forms of knowledge fail to tell us why they admit the certainty of physics and chemistry. From habit they give themselves up to the latter and reject what has not become a fixed habit. Anthroposophy asks: Why do we accept as certain the knowledge of physics and chemistry? It sees the reason in a particular mode of soul experience. It acquires this mode as a guiding line for knowledge. And it does not deviate from it even when, through transformed thinking, it tries to gain truths concerning life, soul, and spirit. For this reason, Anthroposophy is fully able to acknowledge the mode of thought which in physics and chemistry has led to the most significant results in the modern age. It is even obliged to credit materialism with the development of that mode of human perception which leads to sound judgment in the sphere of the non-living. But it is likewise obliged to consider it impossible for this mode of perception to establish anything but physics and chemistry. But whoever takes pains to make clear to himself how such a mode of perception comes into being can see that, with the same inner certainty, other modes are possible: those for the regions of life, soul, and spirit. The person who does not treat science as something external to which he accustoms himself, but experiences it in inner clarity, cannot stop short at the physical and chemical realm; for to him the metamorphosis of sensuous and intellectual knowledge into the forms of imagination, inspiration, and intuition is nothing bill an advancement of the child's form to that of the adult The same forces are active in the adult as in the child. The same scientific method is employed in the knowledge of life, soul, and spirit as in physics and chemistry. |

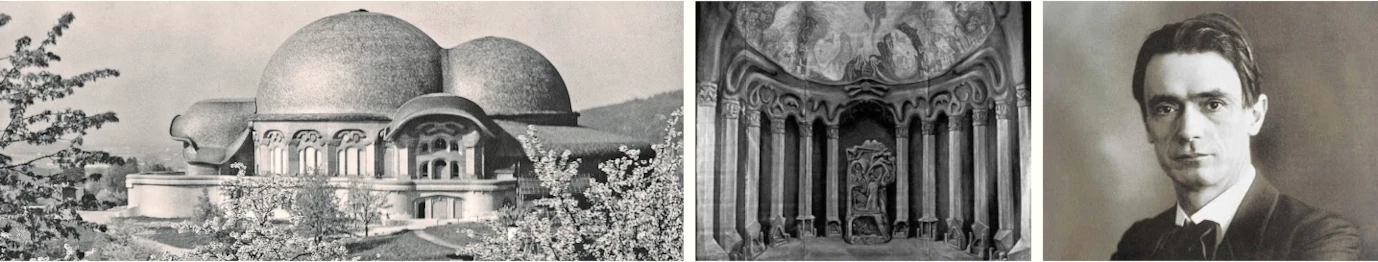

| 36. Second Goetheanum

|

|---|

| Rudolf Steiner, asking him to give us the thought which underlies the building. To rebuild the Goetheanum in conformity with the underlying thought of its purpose is no easy task. |

| This working centre can only be built by one who experiences every detail of its form from a spiritual, artistic outlook; the same outlook through which he experiences with understanding every word that is spoken out of Anthroposophy. By reason of the softness of wood it was possible to build a Hall in that material in such a way that one could strive to imitate the creating of organic forms in Nature. |

| Wide steps will lead from the ground to the terrace and thus to the Portal. Under the terrace there will be the cloak rooms. The designer of the building is convinced that the shape of the hills upon one of which the Goetheanum will stand, will be in keeping with the structure of this concrete building. |

| 36. Second Goetheanum

|

|---|

The rebuilding of the Goetheanum has been the subject of much discussion in the Press and has aroused interest in the widest circles. We are now in a position to publish a picture of what the future building will be like and have also approached Dr. Rudolf Steiner, asking him to give us the thought which underlies the building. To rebuild the Goetheanum in conformity with the underlying thought of its purpose is no easy task. An entire change of outlook was necessary because the old building was constructed principally of wood and the new one is to be entirely of concrete. It has to be borne in mind that there must be no contradiction between the form of the building which is to be devoted to the cultivation of Anthroposophy and the nature of Anthroposophy itself. Its creation must come from the spiritual sources from whence flows spiritual knowledge for the intellect but from whence flows also art forms and style for the imagination that has sensibility. It strives for the primval origins of knowledge but also for artistic form in style and proportions. It would be absurd for anyone to build the working centre for Anthroposophy who, with any kind of artistic perception, looked upon the nature of Anthroposophy from a merely external standpoint. This working centre can only be built by one who experiences every detail of its form from a spiritual, artistic outlook; the same outlook through which he experiences with understanding every word that is spoken out of Anthroposophy. By reason of the softness of wood it was possible to build a Hall in that material in such a way that one could strive to imitate the creating of organic forms in Nature. The organic character of the whole building made it necessary that even the smallest part in the structure could not be different; just as in Nature, no detail—say for instance the lobe of the human ear—could possibly be constructed otherwise. Starting from the artistic realization of this organic creating of Nature, one is led to an 'organic' style of Architectural construction in contradistinction to one relying solely on what is static or dynamic—a style in which even what is of Nature is raised to what is of Spirit through creative fancy. Thus, for instance, in the lobby of the old Goetheanum which visitors entered before attaining the great auditorium, it was possible to make a structure where the forms in the wood clearly denoted: 'the auditorium is ready for those outside to enter.' But the peculiarities of special forms were quite over-ruled by each part being incorporated and made one with the whole building. The same thing could be observed in the outward form of the building. Here was revealed through art all that was constructed and embraced for the object of Anthroposophical work. This way of building from constructive thoughts cannot be carried out in concrete as in wood. For this reason it has taken nearly a whole year to construct the new model. When building in wood one works forms and spaces into the wood; by carving out surfaces, shapes arise. The opposite is the case with concrete, a material from which shapes arise through raising surfaces within the limits of the necessary space. This applies also to the building of forms which tend outwards. Surfaces, lines, angles and so on, must be placed so that what is formed within presses out into the outward forms and thus expresses itself. Besides all this it was necessary to construct the second Goetheanum more economically with regard to space than the first which was in reality but one single Hall and was built so that it made a frame for both lectures and performances. Now however we must have two stories, a lower one for work and lectures, with a stage for auditions; and an upper one, the auditorium and stage which can also be used for lectures. This inner arrangement had to follow the architectural lines and surfaces which tend outwards. This can be seen in the shape of the roof which this time will not be a cupola. Anyone with a feeling for form will realize how it has been attempted to solve the difficulty of making the roof on one hand artistic and in conformity with the rake of the auditorium and on the other hand to enclose the stage with its tore rooms. Perhaps a way will be found through unprejudiced, artist's consideration to carry out the architecture in accord with the necessities of its outline and connect all with the forms of the west front which we have already ventured to give. The building will stand upon a terrace. Thus it will be possible to walk round the building on a level raised above the ground. Wide steps will lead from the ground to the terrace and thus to the Portal. Under the terrace there will be the cloak rooms. The designer of the building is convinced that the shape of the hills upon one of which the Goetheanum will stand, will be in keeping with the structure of this concrete building. When he made the wooden building he was not yet at home with these nature forms as he is now when he can look back over a decade during which time he has learnt to know and to love them. He can create the building out of their own spirit, and in a way quite different to that which was possible eleven years ago. [IMAGE REMOVED FROM PREVIEW] |

| 36. West-East Aphorisms

01 Jan 1922, |

|---|

| If the Eastern man finds today in his reality of spirit the power to give the strength of existence to Maja, and if the Western man discovers life in his reality of Nature, so that he shall see the Spirit at work in his ideology, then will understanding come about between East and West. In hoary antiquity the humanity of the Orient experienced in knowledge a lofty spirituality. |

| In the human word mounting upward we behold with understanding the cosmic Word whose descent our consciousness once experienced.” The man of the East has no understanding for “proof”. |

| If the man of the West releases from his proof the life of truth, the man of the East will understand him. if, at the end of the Western man's struggle for proof, the Eastern man discovers his unproven dreams of truth in a true awaking, the man of the West will then have to greet him as a fellow-worker who can accomplish what he himself cannot accomplish in work for the progress of humanity. |

| 36. West-East Aphorisms

01 Jan 1922, |

|---|

We lose the human being from our field of vision if we do not fix the eye of the soul upon his entire nature in all its life-manifestations. We should not speak of man's knowledge, but of the complete man manifesting himself in the act of cognition. In cognition, man uses as an instrument his sense-nerve nature. For feeling, he is served by the rhythm living in the breath and the circulation of the blood. When he wills metabolism becomes the physical basis of his existence. But rhythm courses into the physical occurrence within the sense-nerve nature; and metabolism is the material bearer of the life of thought, even in the most abstract thinking, feeling lives and the waves of will pulsate. The ancient Oriental entered into his dream-like thinking more from the rhythmic life of feeling than does the man of the present age. The Oriental experienced for this reason more of the rhythmic weaving in his life of thought, while the Westerner experiences more of the logical indications. In ascending to super-sensible vision, the Oriental Yogi interwove conscious breath with conscious thinking, in this way, he laid hold in his breath upon the continuing rhythm of cosmic occurrence. As he breathed, he experienced the world as Self. Upon the rhythmic waves of conscious breath, thought moved through the entire being of man. He experienced how the Divine-Spiritual causes the spirit-filled breath to stream continuously into man, and how man thus becomes a living soul. The man of the present age must seek his super-sensible knowledge in a different way. He cannot unite his thinking with the breath. Through meditation, he must lift his thinking out of the life of logic to vision. In vision, however, thought weaves in a spirit element or music and picture. It is released from the breath and woven together with the spiritual in the world. The Self is now experienced, not in connection with the breath in the single human being, but in the environing world of spirit. The Eastern man once experienced the world in himself, and in his spiritual life today he has the echo of this. The Western man stands at the beginning of his experience, and is on the way to find himself in the world. If the Western man should wish to become a Yogi, he would have to become a refined egoist, for Nature has already given him the feeling of the Self. which the Oriental had only in a dream-like way. If the Yogi had sought for himself in the world as the Western man must do, he would have led his dream-like thinking into unconscious sleep, and would have been psychically drowned. The Eastern man had the spiritual experience as religion, art, and science in complete unity. He made sacrifices to his spiritual-divine Beings. As a gift of grace, there flowed to him from them that which lifted him to the state of a true human being. This was religion. But in the sacrificial ceremony and the sacrificial place there was manifest to him also beauty, through which the Divine-Spiritual lived in art. And out of the beautiful manifestations of the Spirit there flowed science. Toward the West streamed the waves of wisdom that were the beautiful light of the spirit and inspired piety in the artistically inspired man. There religion developed its own being, and only beauty still continued united with wisdom. Heracleitos and Anaxagoras were men wise in the world who thought artistically; Aeschylos and Sophocles were artists who moulded the wisdom of the world. Later wisdom was given over to thinking; it became knowledge. Art was transferred to its own world. Religion, the source of all, became the heritage of the East; art became the monument of the time when the middle region of the earth held sway; knowledge became the independent mistress of its own field in man's soul. Thus did the spiritual life of the West come to existence. A complete human being like Goethe discovered the world of spirit immersed In knowledge. But he longed to see the truth of knowledge in the beauty of art. This drove him to the south. Whoever follows him in the spirit may find a religiously Intimate knowledge striving in beauty toward artistic revelation. If the Western man beholds in his cold knowledge the spiritual-divine streaming forth below him and glancing with beauty, and if the Eastern man senses in his religion of wisdom, warm with feeling and speaking of the beauty of the cosmos, the knowledge that makes man free, transforming itself in man into the power of will, then will the Eastern man in his feeling intuition no longer accuse the thinking Western man of being soulless, and the thinking Western man will no longer condemn the intuitively feeling Eastern man as an alien to the world. Religion can be deepened by knowledge filled with the life of art. Art can be made alive through knowledge born out of religion. Knowledge can be illuminated by religion upheld by art. The Eastern man spoke of the sense-world as an appearance in which there lived a lesser manifestation of what he experienced as spirit in utter reality within his own soul. The Western man speaks of the world of ideas as an appearance where there lives in shadowy form what he experiences as Nature in utter reality through his senses. What was the Maja of the senses to the Eastern man is self-sufficing reality to the Western man. What is the ideology constructed by the mind to the Western man was self-creating reality to the Eastern man. If the Eastern man finds today in his reality of spirit the power to give the strength of existence to Maja, and if the Western man discovers life in his reality of Nature, so that he shall see the Spirit at work in his ideology, then will understanding come about between East and West. In hoary antiquity the humanity of the Orient experienced in knowledge a lofty spirituality. This spirituality, laid hold upon in thought, pulsated through the feeling; it streamed out into the will. The thought was not yet the percept which reproduces objects. It was real being which bore into the inner nature of man the life of the spiritual world. The man of the East lives today in the echoes of this lofty spirituality. The eye of his cognition was once not directed toward Nature. He looked through Nature at the spirit. When the adaptation to Nature began, man did not at once see Nature; he saw the spirit by the way of Nature; he saw ghosts. The last residues of a lofty spirituality became, on the way from East to West, the superstitious belief in ghosts. To the Western man, a knowledge of Nature was given as Copernicus and Galileo arose for him. He had to look into his own inner nature in order to seek for the spirit. There the spirit was still concealed from him, and he beheld only appetites and instincts. But these are material ghosts, taking their place before the eyes of the soul because this is not yet inwardly adapted to the spirit. When the adaptation to the spirit begins, the inner ghosts will vanish, and man will took upon the spirit through his own inner nature, as the ancient man of the East looked upon the spirit through Nature. Through the world of the inner ghosts the West will reach the spirit. The Western ghost superstition is the beginning of the knowledge of spirit. What the East bequeathed to the West as a superstitious belief in ghosts is the end of the knowledge of spirit. Men should find their way past the ghosts into the spirit—and thus will a bridge be built between East and West. The man of the East feels “I” and sees “World”; the I is the moon which reflects the world. The man of the West thinks the “World” and radiates into the world of his own thought “I”. The I is a sun which irradiates the world of pictures. If the Eastern man comes to feel the rays of the sun in the shimmer of his moon of wisdom, and the Western man experiences the shimmer of moon-wisdom in the rays of his sun of will, then shall the will of the West release the will of the East. The ancient Oriental felt himself to be in a social order willed by the Spirit. The commandments of the spiritual Power, brought to his consciousness by his Leader, gave him the conception as to how he should integrate himself with this order. These leaders derived such conceptions out of their vision in the super-sensible world. Those who were led felt that in such conceptions lay the main directions transmitted to them for their spiritual, political and economic life. Views regarding man's relationship to the spiritual, the relationship between man and man, the handling of the economic affairs were derived for them from the same sources, commandments willed by the spirit. The spiritual life, the social-political order, the handling of the economic affairs were experienced as a unity. The farther culture progressed toward the West, the more relationship of rights between man and man and the handling of economic affairs were separated from the spiritual life in human consciousness. The spiritual life became more independent. The other members of the social order still continued to constitute a unity. But, with the further penetration of the West, they also became separated. 3y the side of the element of rights and the state, which for a time controlled everything economic, there took form an independent economic thinking. The Western man is still living amidst the processes of this last separation. At the same time, there arises for him the task to mould into a higher unity the separated members of the social life—the life of the spirit, the control of rights and of the state, the handling of economic affairs, if he achieves this, the man of the East will look upon this creation with understanding, for he will again discover what he once lost, the unity of human experience. Among the partial currents whose interaction and reciprocal conflict compose human history, there is included the conquest or labor by man's consciousness. In the ancient Orient, man labored in accordance with an order imposed upon him by the will of the Spirit, in this reeling, he was either a master or a worker. With the migration of the life of culture toward the West, there came into human consciousness the relationship between man and man. into this was woven the labor which one performs for others. Into the concepts of rights there penetrated the concept of the value of work. A great part of Roman history represents this growing together of the concepts of rights and of work. With the further penetration of culture into the West, economic life took on more and more complicated forms, It drew labor into itself when the structure of rights which this had hitherto taken on was not yet adequate for the demands of the new forms. Disharmony arose between the conceptions of work and of rights. The re-establishment of harmony between the two is the great social problem of the West. How labor can discover its form within the entity of rights, and not be torn out of this entity in the handling of economic affairs, constitutes—the content or the problem, if the West begins to advance toward this solution, through insight and in social peace, the East will meet this with understanding. But, if this problem generates in the West a stand in thinking which manifests itself in social turmoil, the East will not be able to acquire confidence in the further evolution of humanity through the West. The unity between the spiritual life, human rights, and the handling of economic affairs, in accordance with an order willed by the Spirit, can survive only so long as the tilling of the soil is predominant in economics, while trade and industry are subordinate to agricultural economics. It is for this reason that the social thinking of the ancient Orient, willed by the Spirit, bears with reference to the handling of economic affairs a character adapted to agricultural economics. With the course of civilization toward the West, trade first becomes an independent element in economics. It demands the determination of rights. It must be possible to carry on business with everyone. With reference to this, there are only abstract standards of rights. As civilization advanced still farther toward the West, production in industry becomes an independent element in the handling of economic affairs. It is possible to produce useful goods only when the producer and those persons with whom he must work in this production live in a relationship which corresponds with human capacities and needs. The unfolding of the industrial element demands out of :he economic life associative unions so moulded that men know their needs to be satisfied in these so far as the natural conditions make this possible, To discover the fight associative life is the task of the West. If it proves to be capable of this task, the East will say: “Our life once flowed into brotherhood. In the course of time, this disappeared; the advance of humanity took it away from us. The West causes it to blossom again out of the associative economic life. It restores the vanished confidence in true humanness.” When the ancient man composed a poem, he felt that spiritual Power spoke through him. In Greece the poet let the Muse speak through him to his fellowmen. This consciousness was a heritage of the ancient Orient. With the passage of the spiritual life toward the West, poetry became more and more the manifestation of man himself. In the ancient Orient, the spiritual Powers sang through man to men. The cosmic word resounded from the gods down to man. in the West, it has become the human word. It must find the way upward to the spiritual Powers. Man must learn to create poetry in such a way that the Spirit may listen to him. The West must mould a language suited to the Spirit. Then will the East say: “The divine Word, which once streamed for us from heaven to earth, finds its way back from the hearts of men into the spiritual world. In the human word mounting upward we behold with understanding the cosmic Word whose descent our consciousness once experienced.” The man of the East has no understanding for “proof”. He experiences in vision the content of his truths, and knows them in this way. And what man knows he does not prove. The man of the West demands everywhere “proofs”. Everywhere he strives to reach the content of his truths out of the external reflection by means of thought, and interprets them in this way. But what is interpreted must be “proven”. If the man of the West releases from his proof the life of truth, the man of the East will understand him. if, at the end of the Western man's struggle for proof, the Eastern man discovers his unproven dreams of truth in a true awaking, the man of the West will then have to greet him as a fellow-worker who can accomplish what he himself cannot accomplish in work for the progress of humanity. |

| 37. Writings on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society 1902–1925: Kürschner's Pocket Dictionary of Conversation

13 Dec 1884, |

|---|

| The small size was not achieved at the expense of content, but by using easy-to-understand abbreviations to maximize the space available. The small book was produced at relatively great expense. |

| 37. Writings on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society 1902–1925: Kürschner's Pocket Dictionary of Conversation

13 Dec 1884, |

|---|

Berlin and Stuttgart, W. Spemann publishing house To compile the most necessary information from all branches of knowledge on 840 pages, as has actually been done here, was only possible thanks to Professor Kürschner's remarkable prudence and skill in literary matters. The book is intended to meet a twofold need: firstly, to enable those for whom the small editions of Meyer and Brockhaus are still too expensive to purchase an encyclopedia, and secondly – and this is arguably more important – to serve the needs of the moment. The act of looking up information, which is often time-consuming and laborious in the larger works of this genre, can be done here in the shortest possible time, so that the book will be useful in many cases even for those who own a larger encyclopedia. The small size was not achieved at the expense of content, but by using easy-to-understand abbreviations to maximize the space available. The small book was produced at relatively great expense. In addition to Kürschner, it had eighteen contributors. The greatest care was taken to ensure that the articles were complete. It should be emphasized that, in addition to the articles usually included in an encyclopedia, it also contains information about courts, life, fire and pension insurance companies, military districts, legations, consulates and more. Brought about with great sacrifice and true diligence, the book should soon enjoy a corresponding distribution. Rudolf Steiner. |

| 37. Writings on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society 1902–1925: Austria-Hungary: The Death of the Crown Prince and the Reaction

10 Mar 1889, |

|---|

| Deutsche Post, vol. 3, no. 10 (our own report) Vienna, March 2. The tenth budget debate under the Taaffe ministry is just beginning. What will it bring us? Severe accusations against the government from the benches of the left, complaints from those of the right emphasizing that they support this government because nothing better is available from the majority. |

| How long will it take before the Germans here become truly politically mature? The number of those who understand that it is the German idea, first and foremost, that every German must serve, and that it is nothing short of sacrilegious to make completely insignificant, subordinate issues into the figureheads of parties, is dwindling. |

| 37. Writings on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society 1902–1925: Austria-Hungary: The Death of the Crown Prince and the Reaction

10 Mar 1889, |

|---|

Deutsche Post, vol. 3, no. 10 (our own report) Vienna, March 2. The tenth budget debate under the Taaffe ministry is just beginning. What will it bring us? Severe accusations against the government from the benches of the left, complaints from those of the right emphasizing that they support this government because nothing better is available from the majority. This ministry has no fundamental support anywhere. Then the budget will be approved by a large majority and Taaffe will continue to 'rule'. He is a telling example of how the inability of a person often has something in common with genius, namely that it is often irreplaceable. Indeed, Taaffe can do something that would be difficult for a truly talented man in Austria: he can stay in his post. But these last words are not to be interpreted as if we wanted to make any concessions to the inactivity into which the German opposition is increasingly falling. The political inactivity of the Germans in Austria is simply dismal, and the role they play must, if it continues, be a miserable one. How long will it take before the Germans here become truly politically mature? The number of those who understand that it is the German idea, first and foremost, that every German must serve, and that it is nothing short of sacrilegious to make completely insignificant, subordinate issues into the figureheads of parties, is dwindling. Such a course of action would lead us completely into political quagmire and is doubly dangerous now, when a harrowing event in our royal house has significantly changed the political situation. In the late Crown Prince, we had a prince who was truly friendly to education and a fighter for truth and light in the best sense of the word. We saw from his various public addresses how powerfully he felt about unadulterated truth free from authority, and how unfeigned this feeling was can be seen from the recently published letters to his former teacher of natural sciences, Dr. Jos. Krist. One had the conviction that the Crown Prince was a powerful bulwark against any reaction. When he exposed the spiritualist fraud Bastian some time ago, he did so, as he himself said, with the specific intention of doing something against superstition in the higher circles. The hope of education was with this prince. Now he is gone, and already the fateful influences of the reactionary powers are revealing themselves before our eyes. The confessors are at the top. We are exposed to the danger of a terrible regression. It is no longer considered taboo to openly state that there is a serious flaw in the liberal education of the crown prince, and high-ranking church leaders boast that they raised their warning voice in time and in a decisive manner against the irreligious influence of modern researchers on the mind of the Austrian heir to the throne. It was distressing to go out on the streets of Vienna in the days when the sad news from Mayerling came. Everywhere one saw signs of the deepest sympathy for the unfortunate prince. People who had never known each other addressed each other in the streets to communicate their shock. But leaving aside all these outbursts of emotion, and the loyalty and attachment of the Austrian peoples to their imperial house, and looking at the matter objectively, the death of Crown Prince Rudolf is the most serious blow that could have hit progress in Austria. We looked to the future with joy when we saw the chivalrous prince among scholars and researchers in the pursuit of science. This prospect has now died with him. Now we are once again completely dependent on ourselves. Crown Prince Rudolf was thoroughly pro-education, but he was also no supporter of Taaffe's system of government. We must now fight our fight against reaction without such a powerful protector. This event should, however, serve as further proof to the Germans that unity alone can lead them out of the doubt in which they find themselves. Steiner |

| 37. Writings on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society 1902–1925: Regarding the Establishment of a German Branch of the Theosophical Society

Berlin |

|---|

| He also instructed me by a special letter (dated July 22) to take the initiative in founding this section. It is understandable that I myself, at this moment of foundation, feel compelled to address a few words to the brothers in the branches. This is all the more understandable as I have every reason to say how aware I am that the prospect of the post of Secretary General has given me a very special trust. |

| 37. Writings on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society 1902–1925: Regarding the Establishment of a German Branch of the Theosophical Society

Berlin |

|---|

To the branch: Most honored Sir! By the deed of foundation of July 22, 1902, President H.S. Olcott has approved the founding of a German section of the “Theosophical Society”. He also instructed me by a special letter (dated July 22) to take the initiative in founding this section. It is understandable that I myself, at this moment of foundation, feel compelled to address a few words to the brothers in the branches. This is all the more understandable as I have every reason to say how aware I am that the prospect of the post of Secretary General has given me a very special trust. I am also aware of the great responsibility that this office places on me. I had to do some serious soul-searching when I was asked to take up the post. Above all, I had to ask myself whether I was allowed to accept such an office, given my short affiliation with the Theosophical Society. My reasons cannot be misunderstood by the Theosophists to whom I speak. The time when I joined the “Theosophical Society” was for me the end point of many years of inner development. I joined no earlier than when I knew that the spiritual forces I had to serve were present in the “Theosophical Society”. And from that moment on, it was completely clear to me that I should belong to the Theosophical Society. I did not need to say that if the members of the German branches of the “Theosophical Society” consider me worthy, I not only may, but must follow their call. To the Theosophists I say that my personality is no more decisive for my decision in this direction than it will ever be in the future in the conduct of my office. I want to “serve” in the sense that one of our best German Theosophists will express in a forthcoming writing. For those who have only recently joined the “Theosophical Society”, especially for those who are still doubtful in themselves whether it is the right thing to join our Society, which H. $. Olcott founded in association with H. P. Blavatsky, and at the head of which the former still stands; or whether it is not better, or just as good, to join another so-called “Theosophical Society”; for them I remark the following. The proof that we as the German section of the “Theosophical Society” will achieve what every true Theosophist wants to achieve - more or less consciously - can only be provided by our future work. In this respect, joining us is certainly a matter of trust for many at present. I myself know that there are forces within the “Theosophical Society” to achieve what we are striving for. I have known this since I joined, and my presence at the last annual meeting (July 1902) in London, where I was able to approach the leading personalities, was a new affirmation for me. Whether we will achieve what we are called to do within the German-speaking population will depend on the trust that will be placed in us, and no less on how our work is received. We ourselves will serve no one other than the spiritual powers that guide us. What we have to give in our “service” cannot be revealed by the day, but only by time. Just one more word. If the German section of the “Theosophical Society” is to accomplish what it is called upon to do in view of the present spiritual conditions and the “signs of the times” in German-speaking regions, then it needs a Theosophical monthly. It will be my task to establish such a publication. I can only give the assurance here that I see the necessity of such a journal, and ask you all to accept this journal as the organ of the German section of the “Theosophical Society”. With the highest esteem and fraternal greetings |

| 37. Writings on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society 1902–1925: 1902 Annual Report for the German Section of the Theosophical Society

25 Dec 1902, Berlin |

|---|

| A review, which is to be edited by Dr. Rudolf Steiner under the name of Luzifer, is to appear either on the Ist January or the 1st April. The books printed in the course of last year were: «The Mystic in the awakening of spiritual life in the new times,» Dr. |

| 37. Writings on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society 1902–1925: 1902 Annual Report for the German Section of the Theosophical Society

25 Dec 1902, Berlin |

|---|

Translated by Marie Steiner for the twenty-seventh Anniversary and Convention of the Theosophical Society To the President-Founder, TS: received with much pleasure the Charter of 22nd July, 1902, and made all necessary preparations for the formation of the German Section of the TS. At the general meeting of the 19th and 20th of October this Section was formally constituted, and the Executive Committee chosen. The ten lodges forming our section are: Berlin, Charlottenburg, Düsseldorf, Hamburg, Stuttgart, Hannover, Lugano (Switzerland), Munich, Cassel and Leipzig. The names of the Executive Committee are: Dr. Rudolf Steiner, General Secretary (ex-officio), and the Mesdames and Messrs. Henriette von Holten, Julius Engel, Bernard Hubo, Richard Bresch, Dr. HübbeSchleiden, Günther Wagner, Ludwig Deinhard, Bruno Berg, Adolf Kolbe, Gustav Rüdiger, Adolf Oppel, Marie von Sivers and Dr. Noll. The President of the Leipzig Lodge is issuing the Vâhan. A review, which is to be edited by Dr. Rudolf Steiner under the name of Luzifer, is to appear either on the Ist January or the 1st April. The books printed in the course of last year were: «The Mystic in the awakening of spiritual life in the new times,» Dr. Rudolf Steiner; «Christianity as a mystical fact,» Dr. Rudolf Steiner; «Goethe’s Faust: a picture of his Esoteric Philosophy,» Dr. Rudolf Steiner; «Occult Psychology,» by Ludwig Deinhard; «Is Death an End?» by B. Hubo, and translations of «Thought Power» and «Evolution of Life and Form,» by Mrs. Besant, and «Fragments of a Faith Forgotten,» by G.R.S. Mead. Our task for the coming year will be the recruiting of members and an increased activity by writings and lectures in the service of Theosophy, as well as an attempt to introduce Theosophy into the various branches of German spiritual life. The German Section began its activity with the visit of Mrs. Besant, who gave on 20th October a lecture to the members of the T.S., and on the 21st, another to a large public gathering, upon «Theosophy, its meaning and objects.» The Rules of the German Section were discussed in the General Meeting and adopted. The head-quarters of the German Section is in Berlin. Accept my assurance that I shall work in the service of the Theosophical Society in every way to the utmost of my strength. Rudolf Steiner, |