| 322. The Boundaries of Natural Science: Lecture VI

02 Oct 1920, Dornach Translated by Frederick Amrine, Konrad Oberhuber |

|---|

| 322. The Boundaries of Natural Science: Lecture VI

02 Oct 1920, Dornach Translated by Frederick Amrine, Konrad Oberhuber |

|---|

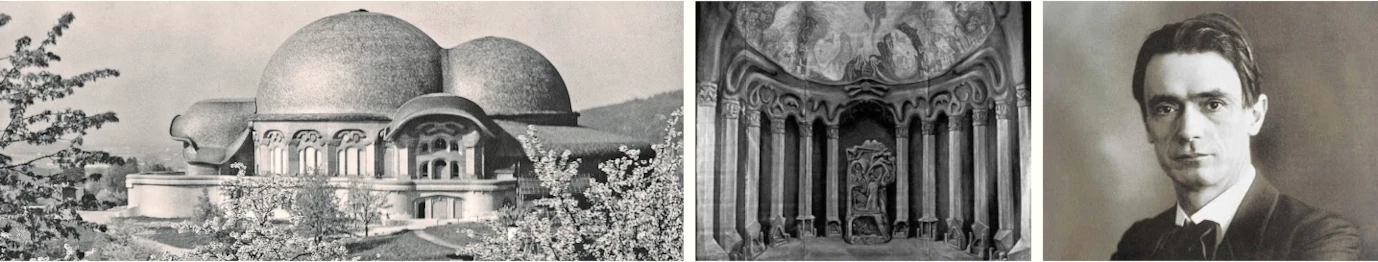

Yesterday I closed with a consideration of what reveals itself at one boundary of scientific thinking as a real and true mode of cognition: I closed with a characterization of Inspiration. I have brought to your attention the way in which man enters through Inspiration a spiritual world: he knows that he is in this world and feels also that he is outside the body. I have shown you how the transition from the experience of a “toneless” musical element to a merger with an individuated element of being occurs. It also became clear in the course of yesterday's considerations of pathological skepticism and hypercriticism that pathological conditions can arise within man if he takes this step out of the body without the accompaniment of the ego, if he does not suffuse the conditions he experiences in Inspiration with full self-consciousness. If one brings the ego into Inspiration, Inspiration represents a healthy, indeed a necessary, step forward in human cognition. Yet in a cultural epoch such as ours, in which man's being is striving to free itself from the physical organism, one cannot allow this condition to come about in an instinctive, unconscious, unhealthy way without the emergence of the pathological conditions we discussed yesterday. For, you see, there exist two poles in human nature. We can either turn to what opens a free, spiritual vision of the highest realities, or, by shunning this, by not summoning sufficient courage to penetrate into these regions with full consciousness but allowing ourselves to be driven by unconscious forces within ourselves, we can call forth illness in the physical organism. And it would be a grave error to believe that one could guard against this illness by electing not to strive into the actual spiritual world. Illness will occur anyway, if the instincts are allowed to drive the astral body, as we call it, out of the organism. Yet especially at the present time, even if we do not investigate the spiritual world ourselves, we are fully protected against the pathological states that I described yesterday—even against those arising only in the soul—by seeking to comprehend rationally the ideas of spiritual science. What is it, however, that we bear into the spiritual world when we take full consciousness with us? You need only follow somewhat man's development from birth to the change of teeth and beyond in Order to realize that, besides the development of speech, thinking, and so forth, an especially important element in this human development is the gradual emergence and transformation of memory. If you then look at the course of human life, you will come to see the tremendous importance of memory for a fully human existence. If, as a result of certain pathological conditions, the continuity of memory is interrupted, so that we cannot recall certain experiences we have had, then a serious illness befalls us, for we feel that the thread of the ego, which otherwise runs through our lives, has been broken. You can consult my book, Theosophy,7 on this: memory is intimately connected with the ego. Thus in pursuing the path I have characterized we must take care not to lose what manifests itself in memory. We must take along with us into the world of Inspiration the power of soul that provides us with memory. Just as in nature everything changes, however—just as the plant, in growing, metamorphoses its green leaves into the red petals of the flower; just as everything in nature is in constant metamorphosis, so it is with everything concerning human existence. If we really bear the faculty of memory out into the world of Inspiration under the full influence of ego-consciousness, it metamorphoses itself. Then one comes to realize that in the moment of one's life in which one investigates the spiritual world in Inspiration, one does not have the normal faculty of memory at one's disposal. One has this faculty of memory at one's disposal in healthy life within the body; outside the body, this faculty is no longer available. This results in something extraordinary—something that, since I present it to your mind's eye for the First time, might seem paradoxical, yet that is fully grounded in reality. Whoever has become a true spiritual scientist, who enters and seeks to experience through Inspiration actual spiritual reality as I have described it in my books, must experience this reality each time anew if he wishes to have it present to consciousness. Thus whenever someone speaks out of Inspiration concerning the spiritual world—not from notes or from mere memory but when he expresses immediately what reveals itself to him in the spiritual world—he must perform the task of spiritual perception each time anew. The faculty of memory has transformed itself. One has retained only the power to call forth the experience again and again. For that reason the spiritual scientist does not have it so easy as one who relies on mere memory. He cannot simply communicate some information out of memory but must call forth anew each time what presents itself to him in Inspiration. In this matter it is essentially the same as it is in normal sense perception of the physical world. If you wish actually to perceive within the physical world of the senses, you cannot turn away from what you wish to perceive and still have the same perception in another place. You must return to the object. In the same way, the spiritual scientist must return to the Same spiritual content of consciousness. And just as in physical perception one must learn to move about in space in order to perceive this or that in turn, the spiritual scientist who has attained Inspiration must learn to move freely within the element of time. He must be able—if you will allow me to use a paradoxical expression—to swim within the element of time. He must learn to travel along with time itself, and when he has learned this, he finds that the faculty of memory has undergone a metamorphosis, that the faculty of memory has transformed itself into something else. What memory performed within the physical world of the senses must be replaced by spiritual perception. This transformed memory, however, gives the spiritual scientist perception of a more encompassing ego. Now the ego is recognized to be more encompassing. When one has transformed memory, which contains the power of the ego between birth and death, the content of the ego cracks the husk that circumscribes but one lifetime. Then the fact of repeated earthly incarnations, alternating with a purely spiritual existence between death and rebirth, emerges as something that can be grasped as a reality. On the other side, the side of consciousness, there emerges something different when one seeks to avoid what an ancient view of the spirit, that of the Vedanta, did not yet know. We in the West feel on the one hand the loftiness of the spiritual view when we steep ourselves in the ancient Oriental wisdom. We feel that in the Vedanta the soul was borne up into spiritual regions in which it could move in a way that the Westerner's normal consciousness can only in mathematical, geometrical, analytic-mechanical thinking. When we descend into the expansive realms that in the Orient were accessible to normal consciousness, however, we find something that we Westerners, because of our more advanced state of evolution, can no longer bear: we find an extensive symbolism, an allegorization of the natural world. It is this symbolism, this allegorization, this thinking about external nature in images, that makes us clearly aware that we are being led away from reality, away from a true investigation of nature. This has become part of certain religious confessions. Certain religious confessions are at a loss how to proceed with this act of symbolization, of mythologization, which has become decadent. For us in the West, that which the Oriental, living in an illusory world, applied directly in this way to external nature, that with which he believed himself capable of arriving at insights concerning the natural world—for us at present this has value only as an exercise preliminary to further spiritual research. We must acquire the soul faculty that the Oriental employed in symbolism and anthropomorphism. We must exercise this faculty inwardly and remain fully conscious thereby: we lapse into superstitions, into rhapsodic enthusiasm for nature, if we employ this faculty to any end but the cultivation of our soul. Later I shall have occasion to speak here about the particulars of this—which, by the way, you can find in my book, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment. By taking this faculty that the Oriental turned outward and employing it inwardly, as an activity of inner schooling [Kraft des Übens], by first developing a pictorial representation in such a way within, one actually begins to arrive at new insights on the other side, on the side of consciousness. One gradually achieves a transformation of abstract, merely notional thinking into pictorial thinking. Then there arises what I can only call an experiential thinking [erlebendes Denken]. One experiences pictorial thinking. Why does one experience this? One experiences nothing other than what is active within the physical body during the first years of childhood, as I have described it to you. One experiences not the human organism that has taken static form in space but rather what lives and weaves within man. One experiences it in pictures. One gradually struggles through to a viewing of the life of the soul in its actuality. On the other side the content of consciousness gradually emerges within cognition: pictorial representation, a life within Imagination. And without entering into this life of Imaginations, modern psychology shall not progress. In this way, and in this way only, by entering into Imagination, there will arise again a psychology that is more than word-games, a psychology that actually looks into the soul of man. Just as the time has come in which, as a result of general cultural relationships, man is gradually excarnating from the physical body and striving for Inspiration, as we have seen in the example of Nietzsche, the time has come in which man, if he desires self-knowledge, should feel himself led toward Imagination. Man must descend deeper into himself than was necessary in the course of previous cultural history. If evolution is not to lapse into barbarism, humanity must attain a true image of itself [Selbstschau], and humanity can accomplish this only by accepting the knowledge offered by Imagination. That man is striving to descend deeper into his inner self than has been the case in evolution heretofore is shown, again, in the phenomena of pathological diseases of a particularly modern form. These have been described very recently by those who are able to study them from the point of view of medicine or psychiatry. It is shown above all in the emergence of agoraphobia, claustrophobia, and astraphobia—illnesses of a sort that arise especially frequently in our time. Even if they usually are observed only as pathological conditions requiring psychiatric treatment, the more acute observer can see something else altogether. He sees agoraphobia, astraphobia, and so forth already emerging from the soul-nature of humanity, just as he saw Inspiration arising pathologically in Friedrich Nietzsche. Above all, he can observe states of soul that often appear outwardly normal from which emerges agoraphobia—morbid dread of open spaces. He sees emerging something that appears as astraphobia, a state in which one fails to come to terms with an inner sensation. This inner feeling can grow to the extent that the Organs of digestion are attacked, and digestion is disturbed. He comes to know what might be called fear of isolation, agoraphobias,8 in which one cannot remain atone but only where there is company assembled all around and so forth. Such things emerge. These things show that humanity is presently striving for Imagination and that an illness that must otherwise become an illness of the entire culture can be counteracted only by developing Imagination. Agoraphobia—this is an illness that manifests itself in many people in a frightening way. These people grow up, and from a certain point in their lives onward remarkable conditions manifest themselves. If such a person steps out of the house into a square devoid of people he is stricken with a fear that is entirely incomprehensible to him. He is afraid of something; he does not dare go a step further into the empty square, and if he does, it can happen that he falls down on his knees or perhaps even topples over in a faint. The moment that even a child comes, the sufferer grasps its arm or merely reaches out to touch the child: in this moment he feels himself inwardly strengthened again, and the agoraphobia subsides. One case that has been described in the medical literature is particularly interesting. A young man who felt himself strong enough even to become an officer is overcome by agoraphobia while on maneuvers as he is sent out to map some terrain. His fingers tremble; he is unable to draw. Wherever there is emptiness around him, or what he perceives as emptiness, he is beset with fears that he immediately senses to be pathological. He is in the vicinity of a mill. In order to be able to perform his duty at all, he must keep a small child at his side, and its mere presence is enough for him to be able to resume drawing. We ask ourselves: what is the cause of such phenomena? Why is it that there are, for example, people who, when they have somehow forgotten to leave open the door to their bedrooms at night—something that has perhaps long since become a habit with them—wake in the night dripping sweat and can do nothing but leap up to open the door, for they cannot stand to be in an enclosed space. There are such people. Some suffer to such an extent that they must have all the doors and windows open. If their house is on a square, they must leave open the door leading out, so that they know they are free and can get out into the open at any time. This claustrophobia is something that one sees emerging—even if it often does not emerge in so radical a form—if one is able to observe human states of soul more closely. And then there are people who feel, even to a physical degree, something inexplicable happening within them. What is it? It is an approaching thunderstorm or some other atmospheric condition. There are otherwise intelligent people who must draw the curtains whenever there is lightning or thunder. Then they must sit in a dark room, for only in this way can they protect themselves from what they experience in the atmospheric conditions. This is astraphobia, or morbid fear of thunderstorms. What is the cause of these states that we observe already very clearly in the souls of human beings today, especially in those who for a long time surrender themselves devoutly to a certain dogmatism? In these people one observes precisely these states of soul, even if they have not manifested themselves yet physically. These states are just beginning to appear. Their emergence works to upset a balanced, calm approach to life. They also emerge in such a way that they call forth all kinds of pathological conditions that are ascribed to every sort of thing, because the physical symptoms of claustrophobia, agoraphobia, or astraphobia are not yet manifest, while they must actually be ascribed to the particular configuration of soul arising within man. What is the cause of such conditions? They are the result of our need not only to experience the life of the soul discarnately but also to bring this experience of the discarnate soul down into the physical body. We must allow it to immerse itself consciously. Just as that which I have described to you in the course of these lectures gradually extricates itself from the body between birth and the change of teeth, so also that which is experienced externally, which we could call experience of the astral, immerses itself again in the physical organism between the change of teeth and puberty. And what takes place in puberty is nothing other than this immersion between approximately the seventh and fourteenth years. The independent soul-spirit that man has developed must immerse itself in the body again, and what then emerges as physical love, as sexual desire, is nothing other than the result of this immersion I have described to you. One must come to understand this immersion clearly. Whoever wishes to gain a true understanding of the basis of consciousness must be able to effect this in a fully conscious, healthy way, using such methods as I shall describe here later. That is to say, he must learn to immerse himself in the physical body. Then he attains an initial experience of what manifests itself as an Imaginative representation of the inner realm. Here a faculty of formal representation framed for an external, three-dimensional world of plastic forms is insufficient. To perform this inner activity one needs a mobile faculty of formal representation: one must be able to overcome gradually everything spatial in Imagination and to immerse oneself in the representation of something intensive, something that radiates activity. In short, one must immerse oneself in such a way that in descending one can still clearly differentiate between oneself and one's body. Whatever inheres in the subject cannot be known. If one can keep what one experiences outside from immersing unconsciously in the physical body, one descends into the physical body and experiences in descending the essence of this body up to the level of consciousness in Imagination, in pictures. Whoever fails to keep these pictures separate, however, and allows them to slip into the physical body, confronting the physical body not as an object but as something subjective, brings the sensation of space down into the physical body with him The astral thereby coalesces with the physical to a greater degree than should be allowed. The experience of the external world coalesces with man's inner life, and because he makes subjective what should have remained objective, he can no longer experience space normally. Fear of empty space, fear of lonely places, fear of the astrality diffused through space, of Storms, perhaps even of the moon and Stars, rise up within one. One lives too deeply within oneself. Thus it is necessary that all exercises leading to the life of Imagination protect one against descending too deeply into the body. One must immerse oneself in the body in such a way that the ego remains outside. One may not take the ego out into the world of Imagination in the way that one must carry the ego out into the world of Inspiration. Although one worked toward Imagination through a process of symbolization, through pictorial representation, in Imagination itself all pictures created by mere fantasy disappear. Now objective pictures emerge instead. Only that which actually lives within the human form ceases to confront one as an object. One loses the outward human form and there emerges a diversity of living forms from the human etheric. One now sees not the unified human form but the profusion of animal forms that interpenetrate and merge to create the human form. One comes to know in an inward way what lives within the realms of plants and minerals. One learns this through introspection. One learns what can never be learned through atomism and molecularism: one learns what actually lives within the realms of plants and minerals. And how is it that we avoid bringing the ego down into the physical body when we strive for Imagination? Only by developing the power of love more nobly than in normal life, where love is led by the powers of the bodily senses. Only by acquiring the selfless power of love, freedom from egotism not only regarding the realm of humanity but also regarding the realm of nature. Only by allowing all that leads to Imagination to be borne by love, by merging this power of love with every object of cognition that we seek in this manner. Again we have divergent tendencies: the healthy tendency to extend the power of love into Imagination or the pathological tendency to expose ourselves to fear of what is outside. We experience what lies outside with our ego and then, without restraining our ego, bear it down into the body, giving rise to agoraphobia, claustrophobia, and astraphobia. Yet we enjoy the prospect of an extremely high mode of cognition if we can develop in a healthy way what threatens humanity in its pathological form and would lead it into barbarism. In this way one attains a true knowledge of man. One surpasses all that anatomy, physiology, and biology can teach; one attains a true knowledge of man by actually seeing through the physical body. Oh, man comes to know himself in a way so different from that which nebulous mystics believe, who think that some abstract divinity reveals itself to them when they delve down within. Oh no, something rich and concrete reveals itself; something that provides insight into the human organism, into the nature of the lungs, the liver, and so forth. Only this can be the basis of a true anatomy, a true physiology; only this can serve as the basis for a true understanding of man and also for a true medical science. One has developed two faculties within human nature. On the side of matter is the faculty of Inspiration, developed by gradually discovering within matter a spiritual realm that expands out into the tableau Mr. Arenson has depicted for you here. The other faculty is developed by discovering within oneself the realms that I described as the basis of a true knowledge of man, of a true medical science, when I spoke here earlier this year before almost forty medical doctors. These two faculties, however, those of Inspiration and Imagination, can join together. The one can coalesce with the other, but it must happen in full consciousness and by comprehending the cosmos in love. Then there arises a third faculty, a confluence of Imagination and Inspiration in true, spiritual Intuition. Then we rise up to that which allows us to recognize the external material world to be a spiritual world, the inner realm of the soul and spirit with its material foundations as a continuous whole; we rise up to that which grants us knowledge of the expansion of human existence beyond earthly life, as I have described it to you here in other lectures. One comes thus on the one side to know the realms of plants, animals, and minerals in their inmost essences, in their spiritual content, through Inspiration. By coming to know the human organs through Imagination one creates the basis for a true organology, and by uniting in Intuition what one has learned about plants, animals, and minerals with what Imagination reveals concerning the human organs, one attains a true therapy, a science of medication that knows in a real sense how to apply the external to the internal. The true doctor must understand medications cosmologically; he must understand the human organs anthropologically, or actually anthroposophically. He must come to grasp the external world through Inspiration, the inner world through Imagination, and he must achieve a therapy based upon real Intuition. You see what a prospect opens before us if we are able to comprehend spiritual science in its true form. To be sure, this spiritual science still has to shed many externals and much that still adheres to it in the minds of those who believe they can nurture it with fantasies and dilettantism of every sort. Spiritual science must develop a method of research as rigorous as mathematics and analytical mechanics. On the other hand, spiritual science must rid itself of all superstitions. Spiritual science must truly be able to call forth in light-filled clarity the love that otherwise overcomes man if he can call it forth out of instinct. Then spiritual science will be a seed that will grow and send its forces out into all the sciences and thus into human life. For this reason, let me bring to a dose what I have had to say to you in these lectures with one more brief consideration. Beforehand I would like to say that there is, of course, still much that can be read between the lines of my descriptions. Some of this I shall make legible in two lectures this evening and tomorrow: they will elaborate what I could only intimate in the short time available to us for this course. Only what is gained by attaining Imagination on the one hand and Inspiration on the other, and then uniting Imagination and Inspiration in Intuition, gives man the inner freedom and strength enabling him to conceive ideas that can then be effected in social life. And only those who experience contemporary life with a sleeping soul can fall to see everything that is brewing in the most frightful way, threatening a horrific future. What is the spiritual cause of this? The spiritual cause of this is something one can perceive by studying attentively recent human evolution as it manifests itself in extremely prominent individuals. How human beings strove in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to arrive at clear concepts, to arrive at truly inward, clear impulses for three concepts that are of the very greatest importance for social life: the concept of capital, the concept of labor, and the concept of commodities! Just look at the relevant literature from the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries to see how human beings strove to understand what capital actually means within the social process, to see how that which human beings strove to understand in concepts has passed over into frightful struggles in the external world. Just look how intimately the particular feeling emerging within humanity in the present age corresponds to what they are able to feel and think concerning the function, the meaning of labor within the social organism. Then look at the hopelessly inadequate definition of “commodity”! Human beings strove to bring three practical concepts into clear focus. In the course of life in the civilized world today one Sees everywhere a lack of clarity regarding the triad, capital, labor, commodities. And one cannot rise up to answer the question: what function does capital have within the social organism? One is able to answer this question only when, out of a true spiritual science, by means of Imagination and Inspiration united in Intuition, one understands that a proper impulse for the functioning of capital can be found within the spiritual life as an independently subsisting part of the social organism. Only true Imagination can bring real comprehension of this part of the social organism. And one will come to realize something else as well. One will realize that one can come to understand labor's functioning within the social organism when one no longer understands what is produced by human labor in terms of the product, so that one no longer conceives commodities in the Marxist manner as congealed labor or even congealed time. Rather, one will realize that the results of human labor can be understood by arriving at a representation, at a free experience of that which can proceed from man. The concept of labor will become clear only to those who know what is revealed to man through Inspiration. And the concept of “commodity” is the most complicated imaginable. For no single man is able to comprehend what commodities are in their actual existence in life. Anyone who wishes to define commodities has not the slightest inkling what knowledge is. “Commodity” cannot be defined, for one can define in this sense or formulate conceptually only what concerns but one individual, what one man alone can comprehend with his soul. Commodities, however, always exist in the interaction between a number of human beings and a number of individuals of a certain type. Commodities exist in the interaction between producers, consumers, and those who mediate between them. The impoverished concepts of barter and purchase, products of a discipline that fails to recognize the limits of natural science, shall never prove adequate to an understanding of commodities. Commodities, the products of human labor, exist in the relationship between several individuals, and if a solitary man undertakes to understand commodities “as such,” he is on the wrong track. Commodities must be understood as a function of the socially contracted majority of human beings, of association. Commodities must be understood in terms of association; they must exist in association. Only when associations are formed that process what originates with the producers, businessmen, and consumers will there arise—not out of the individual but through association, through the worker associations—the social concept, the concept of “commodity,” that human beings must share before there can exist a healthy economic life. If human beings would only take the trouble to ascend to that which the spiritual scientist can convey from the realm of higher cognition, they would find concepts giving rise to the social forms we must develop if we wish to reverse the course of a civilization on the decline. It is thus no mere theoretical interest, no mere scientific need, that underlies all we shall strive for here. It is rather the most urgent need that the work and the research we do here make human beings mature enough that they can go forth from this place to all the corners of the earth, taking with them such ideas and social impulses as really can buoy up an age so rapidly sinking and reverse the course of a world so clearly in decline.

|

| 322. The Boundaries of Natural Science: Lecture VII

02 Oct 1920, Dornach Translated by Frederick Amrine, Konrad Oberhuber |

|---|

| 322. The Boundaries of Natural Science: Lecture VII

02 Oct 1920, Dornach Translated by Frederick Amrine, Konrad Oberhuber |

|---|

It is to be hoped that my discussions of the boundaries of natural science have been able to furnish at least some indications of the difference between what spiritual science calls knowledge of the higher worlds and the mode of knowledge proceeding from everyday consciousness or ordinary science. In everyday life and in ordinary science our powers of cognition are those we have acquired through the conventional education that carries us up to a certain stage in life and whatever this education has enabled us to make of inherited and universally human qualities. The mode of cognition that anthroposophically oriented spiritual science terms knowledge of the higher worlds has its basis in a further self-cultivation, a further self-development; one must become aware that in the later stages of life one can advance through self-education to a higher consciousness, just as a child can advance to the stage of ordinary consciousness. The things we sought in vain at the two boundaries of natural science, the boundaries of matter and of ordinary consciousness, reveal themselves only when one attains this higher consciousness. In ancient times the Eastern sages spoke of such an enhanced consciousness that renders accessible to man a level of reality higher than that of everyday life; they strove to achieve a higher development, similar to the one we have described, by means of an inner self-cultivation that corresponded to their racial characteristics and evolutionary stage. The meaning of what radiates forth from the ancient Eastern wisdom-literature becomes fully apparent only when one realizes what such a higher level of development reveals to man. If one were to characterize the path of development these sages followed, one would have to describe it as a path of Inspiration. For in that epoch humanity had a kind of natural propensity to Inspiration, and in order to understand these paths into the higher realms of cognition, it will be useful if First we can gain clarity concerning the path of development followed by these ancient Eastern sages. I want to make it clear from the start, however, that this path can no longer be that of our Western civilization, for humanity is in a process of constant evolution, ever moving forward. And whoever desires—as many have—to return to the instructions given in the ancient Eastern wisdom-literature in order to enter upon the paths of higher development actually desires to turn back the tide of human evolution or shows that he has no real understanding of human progress. In ordinary consciousness we reside within our thought life, our life of feeling, and our life of will, and we initially substantiate what surges within the soul as thought, feeling, and will in the act of cognition. And it is in the interaction with percepts of the external world, with physical-sensory perceptions, that our consciousness First fully awakens. It is necessary to realize that the Eastern sages, the so-called initiates of the East, cultivated perception, thinking, feeling, and willing in a way different from their cultivation in everyday life. We can attain an understanding of this path of development leading into the higher worlds when we consider the following. In certain ages of life we develop what we call the soul-spirit toward a greater freedom, a greater independence. We have been able to show how the soul-spirit, which functions in the earliest years of childhood to organize the physical body, emancipates itself, becomes free in a sense with the change of teeth. We have shown how man then lives freely with his ego in this soul-spirit, which now places itself at his disposal, while formerly it occupied itself—if I may express myself thus—with the organization of the physical body. As we enter into ever-greater participation in everyday life, however, there arises something that initially prevents this emancipated soul-spirit from growing into the spiritual world in normal consciousness. As human beings, we must traverse the path that leads us into the external world with the requisite faculties during our life between birth and death. We must acquire such faculties as allow us to orient ourselves within the external, physical-sensory world. We must also develop such faculties as allow us to become useful members of the social community we form with other human beings. What arises is threefold. These three things bring us into a proper relationship with other human beings in our environment and govern our interaction with them. These are: language, the ability to understand the thoughts of our fellow men, and the acquisition of an understanding, or even a kind of perception, of another's ego. At first glance these three things—perception of language, perception of thoughts, and perception of the ego—appear simple, but for one who seeks knowledge earnestly and conscientiously these things are not so simple at all. Normally we speak of five senses only, to which recent physiological research adds a few inner senses. Within conventional science it is thus impossible to find a complete, systematic account of the senses. I will want to speak to you an this subject at some later time. Today I want only to say that it is an illusion to believe that linguistic comprehension is implicit in the sense of hearing, of that which contemporary physiology dreams to be the organization of the sense of hearing. just as we have a sense of hearing, so also do we have a sense of language. By this I do not mean the sense that guides us in speaking—for this is also called a sense—but that which enables us to comprehend the perception of speech-sounds, just as the auditory senses enable us to perceive tones as such. And when we have a comprehensive physiology, it will be known that this sense of speech is analogous to the other and can rightfully be called a sense in and of itself. It is only that this sense extends over a larger part of the human constitution than the other, more localized senses. Yet it is a sense that nevertheless can be sharply delineated. And we have, in fact, a further sense that extends throughout virtually all of our body—the sense that perceives the thoughts of others. For what we perceive as word is not yet thought. We require other organs, a sensory organization different from that which perceives only words as such, if we want to understand within the word the thought that another wishes to communicate. In addition, we are equipped with an analogous sense extending throughout our entire bodily organization, which we can call the sense for the perception of another person's ego. In this regard even philosophy has reverted to childishness in recent times, for one can often hear it argued: we encounter another man; we know that a human has such and such a form. Since the being that we encounter is formed in the way we know ourselves to be formed, and sine we know ourselves to be ego-bearers, we conclude through a kind of unconscious inference: aha, he bears an ego within as well. This directly contradicts the psychological reality. Every acute observer knows that it is not an inference by analogy but rather a direct perception that brings us awareness of another's ego. I think that a friend or associate of Husserl's school in Göttingen, Max Scheler, is the only philosopher actually to hit upon this direct perception of the ego. Thus we must differentiate three higher senses, so to speak, above and beyond the ordinary human senses: the sense that perceives language, the sense that perceives thoughts, and the sense that perceives another's ego. These senses arise within the course of human development to the same extent that the soul-spirit gradually emancipates itself between birth and the change of teeth in the way I have described. These three senses lead initially to interaction with the rest of humanity. In a certain way we are introduced into social life among other human beings by the possession of these three senses. The path one thus follows via these three senses, however, was followed in a different way by the ancients—especially the Indian sages—in order to attain higher knowledge. In striving for this goal of higher knowledge, the soul was not moved toward the words in such a way that one sought to arrive at an understanding of what the other was saying. The powers of the soul were not directed toward the thoughts of another person in such a way as to perceive them, nor toward the ego of another in such a way as to perceive it sympathetically. Such matters were left to everyday life. When the sage returned from his striving for higher cognition, from his sojourn in spiritual worlds to everyday life, he employed these three senses in the ordinary manner. When he wanted to exercise the method of higher cognition, however, he needed these senses in a different way. He did not allow the soul's forces to penetrate through the word while perceiving speech, in order to comprehend the other through his language; rather, he stopped short at the word itself. Nothing was sought behind the word; rather, the streaming life of the soul was sent out only as far as the word. He thereby achieved an intensified perception of the word, renouncing all attempts to understand anything more by means of it. He permeated the word with his entire life of soul, using the word or succession of words in such a way that he could enter completely into the inner life of the word. He formulated certain aphorisms, simple, dense aphorisms, and then strove to live within the sounds, the tones of the words. And he followed with his entire soul life the sound of the word that he vocalized. This practice then led to a cultivation of living within aphorisms, within the so-called “mantras.” It is characteristic of mantric art, this living within aphorisms, that one does not comprehend the content of the words but rather experiences the aphorisms as something musical. One unites one's own soul forces with the aphorisms, so that one remains within the aphorisms and so that one strengthens through continual repetition and vocalization one's own power of soul living within the aphorisms. This art was gradually brought to a high state of development and transformed the soul faculty that we use to understand others through language into another. Through vocalization and repetition of the mantras there arose within the soul a power that led not to other human beings but into the spiritual world. And if, through these mantras, the soul has been schooled in such a way and to such an extent that one feels inwardly the weaving and streaming of this power of soul, which otherwise remains unconscious because all one's attention is directed toward understanding another through the word; if one has come so far as to feel such a power to be an actual force in the soul in the same way that muscular tension is experienced when one wishes to do something with one's arm, one has made oneself sufficiently mature to grasp what lies within the higher power of thought. In everyday life a man seeks to find his way to another via thought. With this power, however, he grasps the thought in an entirely different way. He grasps the weaving of thought in external reality, penetrates into the life of external reality, and lives into the higher realm that I have described to you as Inspiration. Following this path, then, we approach not the ego of the other person but the egos of individual spiritual beings who surround us, just as we are surrounded by the entities of the sense world. What I depict here was self-evident to the ancient Eastern sage. In this way he wandered with his soul, as it were, upward toward the perception of a realm of spirit. He attained in the highest degree what can be called Inspiration, and his constitution was suited to this. He had no need to fear, as the Westerner might, that his ego might somehow become lost in this wandering out of the body. In later times, when, owing to the evolutionary advances made by humanity, a man might very easily pass out of his body into the outer world without his ego, precautionary measures were taken. Care was taken to ensure that whoever was to undergo this schooling leading to higher knowledge did not pass unaccompanied into the spiritual world and fall prey to the pathological skepticism of which I have spoken in these lectures. In the ancient East the racial constitution was such that this was nothing to fear. As humanity evolved further, however, this became a legitimate concern. Hence the precautionary measure strictly applied within the Eastern schools of wisdom: the neophyte was placed under an authority, but not any outward authority—fundamentally speaking, what we understand by “authority” First appeared in Western civilization. There was cultivated within the neophytes, through a process of natural adaptation to prevailing conditions, a dependence on a leader or guru. The neophyte simply perceived what the leader demonstrated, how the leader stood firmly within the spiritual world without falling prey to pathological skepticism or even inclining toward it. This perception fortified him to such an extent on his own entry into Inspiration that pathological skepticism could never assail him. Even when the soul-spirit is consciously withdrawn from the physical body, however, something else enters into consideration: one must re-establish the connection with the physical body in a more conscious manner. I said this morning that the pathological state must be avoided in which one descends only egotistically, and not lovingly, into the physical body, for this is to lay hold of the physical body in the wrong way. I described the natural process of laying hold of the physical body between the seventh and fourteenth years, which is through the love-instinct being impressed upon it. Yet even this natural process can take a pathological turn: in such cases there arise the harmful afflictions I described this morning as pathological states. Of course, this could have happened to the pupils of the ancient Eastern sages as well: when they were out of the body they might not have been able to bind the soul-spirit to the physical body again in the appropriate manner. One further precautionary measure thus was employed, one to which psychiatrists—some at any rate—have had recourse when seeking cures for patients suffering from agoraphobia or the like. They employed ablutions, cold baths. Expedients of an entirely physical nature have to be employed in such cases. And when you hear on the one hand that in the mysteries of the East—that is, the schools of initiation, the schools that led to Inspiration—the precautionary measure was taken of ensuring dependence on the guru, you hear on the other hand of the employment of all kinds of devices, of ablutions with cold water and the like. When human nature is understood in the way made possible by spiritual science, customs that otherwise remain rather enigmatic in these ancient mysteries become intelligible. One was protected against developing a false sense of spatiality resulting from an insufficient connection between the soul-spirit and the physical body. This could drive one into agoraphobia and the like or to seek social intercourse with one's fellow men in an inappropriate way. This represents a danger, but one which can and should—indeed must—be avoided in any training that leads to higher cognition. It is a danger, because in following the path I have described leading to Inspiration one bypasses in a certain sense the path via language and thought to the ego of one's fellow man. If one then quits the physical body in a pathological manner—even if one is not attempting to attain higher cognition but is lifted out of the body by a pathological condition—one can become unable to interact socially with one's fellow men in the right way. Then precisely that which arises in the usual, intended manner through properly regulated spiritual study can develop pathologically. Such a person establishes a connection between his soul-spirit and his physical body: by delving too deeply into it he experiences his body so egotistically that he learns to hate interaction with his fellow men and becomes antisocial. One can often see the results of such a pathological condition manifest themselves in the world in quite a frightening manner. I once met a man who was a remarkable example of such a type: he came from a family that inclined by nature toward a freeing of the soul-spirit from the physical body and also contained certain personalities—I came to know one of them extremely well—who sought a path into the spiritual worlds. One rather degenerate individual, however, developed this tendency in an abnormal, pathological way and finally arrived at the point where he would allow nothing whatever from the external world to contact his own body. Naturally he had to eat, but—we are speaking here among adults—he washed himself with his own urine, because he feared any water that came from the outside world. But then again I would rather not describe all the things he would do in order to isolate his body totally from the external world and shun all society. He did these things because his soul-spirit was too deeply incarnated, too closely bound to the physical body. It is entirely in keeping with the spirit of Goetheanism to bring together that which leads to the highest goal attainable by earthly man and that which leads to pathological depths. One needs only slight acquaintance with Goethe's theory of metamorphosis to realize this. Goethe seeks to understand how the individual organs, for example of the plant, develop out of each other, and in order to understand their metamorphosis he is particularly interested in observing the conditions that arise through the abnormal development of a leaf, a blossom, or the stamen. Goethe realizes that precisely by contemplating the pathological the essence of the healthy can be revealed to the perceptive observer. And one can follow the right path into the spiritual world only when one knows wherein the essence of human nature actually lies and in what diverse ways this complicated inner being can come to expression. We see from something else as well that even in the later period the men of the East were predisposed by nature to come to a halt at the word. They did not penetrate the word with the forces of the soul but lived within the word. We see this, for example, in the teachings of the Buddha. One need only read these teachings with their many repetitions. I have known Westerners who treasured editions of the Buddha's teachings in which the numerous repetitions had been eliminated and the words of a sentence left to occur only once. Such people believed that through such a condensed version, in which everything occurs only once, they would gain a true understanding of what the Buddha had actually intended. From this it is clear that Western civilization has gradually lost all understanding of Eastern man. If we simply take the Buddha's teachings word for word; if we take the content of these teachings, the content that we, as human beings of the West, chiefly value, then we do not assimilate the essence of these teachings: that is possible only when we are carried along with the repetitions, when we live in the flow of the words, when we experience the strengthening of the soul's forces that is induced by the repetitions. Unless we acquire a faculty for experiencing something from the constant repetitions and the rhythmical recurrence of certain passages, we do not get to the heart of Buddhism's actual significance. It is in this way that one must gain knowledge of the inner nature of Eastern culture. Without this acquaintance with the inner nature of Eastern culture one can never arrive at a real understanding of our Western religious creeds, for in the final analysis these Western religious creeds stem from Eastern wisdom. The Christ event is a different matter. For that is an actual event. It stands as a fact within the evolution of the earth. Yet the ways and means of understanding what came to pass through the Mystery of Golgotha were drawn during the first Christian centuries entirely from Eastern wisdom. It was through this wisdom that the fundamental event of Christianity was originally understood. Everything progresses, however. What had once been present in Eastern primeval wisdom—attained through Inspiration—spread from the East to Greece and is still recognizable as art. For Greek art was, to be sure, bound up with experiences different from those usually connected with art today. In Greek art one could still experience what Goethe strove to regain when he spoke of the deepest urge within him: he to whom nature begins to unveil her manifest secrets longs for her worthiest interpreter—art. For the Greeks, art was a way to slip into the secrets of world existence, a manifestation not merely of human fantasy but of what arises in the interaction between this faculty and the revelations of the spiritual world revealed through Inspiration. That which still flowed through Greek art, however, became more and more diluted, until finally it became the content of the Western religious creeds. We thus must conceive the source of the primeval wisdom as fully substantial spiritual life that becomes impoverished as evolution proceeds and provides the content of religious creeds when it finally reaches the Western world. Human beings who are constitutionally suited for a later epoch therefore can find in this diluted form of spiritual life only something to be viewed with skepticism. And in the final analysis it is nothing other than the reaction of the Western temperament [Gemüt] to the now decadent Eastern wisdom that gradually produces atheistic skepticism in the West. This skepticism is bound to become more and more widespread unless it is countered with a different stream of spiritual life. Just as little as a creature that has reached a certain stage of development—let us say has undergone a certain aging process—can be made young again in every respect, so little can a form of spiritual life be made young again when it has reached old age. The religious creeds of the West, which are descendants of the primeval wisdom of the East, can yield nothing that would fully satisfy Western humanity again when it advances beyond the knowledge provided during the past three or four centuries by science and observation of nature. An ever-more profound skepticism is bound to arise, and anyone who has insight into the processes of world evolution can say with assurance that a trend of development from East to West must necessarily lead to an increasingly pronounced skepticism when it is taken up by souls who are becoming more and more deeply imbued with the fruits of Western civilization. Skepticism is merely the march of the spiritual life from East to West, and it must be countered with a different spiritual stream flowing henceforth from West to East. We ourselves are living at the crossing-point of these spiritual streams, and in the further course of these considerations we will want to see how this is so. But first it must be emphasized that the Western temperament is constitutionally predisposed to follow a path of development leading to the higher worlds different from that of the Eastern temperament. Just as the Eastern temperament strives initially for Inspiration and possesses the racial qualities suitable for this, the Western temperament, because of its peculiar qualities (they are at present not so much racial qualities as qualities of soul) strives for Imagination. It is no longer the experience of the musical element in mantric aphorisms to which we as Westerners should aspire but something else. As Westerners we should strive in such a way that we do not pursue with particular vigour the path that opens out when the soul-spirit emerges from the physical body but rather the path that presents itself later, when the soul-spirit must again unite with the physical organism by consciously grasping the physical body. We see the natural manifestation of this in the emergence of the bodily instinct: whereas Eastern man sought his wisdom more by sublimating the forces at work between birth and the seventh year, Western man is better fitted to develop the forces at work between the time of the change of teeth and puberty, in that there is lifted up into the soul-spirit that which is natural for this epoch of humanity. We come to this when, just as in emerging from the body we carry the ego with us into the realm of Inspiration, we now leave the ego outside when we delve again into the body. We leave it outside, but not in idleness, not forgetting or surrendering it, not suppressing it into unconsciousness, but rather conjoining it with pure thinking, with clear, keen thinking, so that finally one has this inner experience: my ego is totally suffused with all the clear thinking of which I have become capable. One can experience just this delving down into the body in a very clear and distinct manner. And at this point you will perhaps allow me to relate a personal experience, because it will help you to understand what I really mean. I have spoken to you about the conception underlying my book, Philosophy of Freedom. This book is actually a modest attempt to win through to pure thinking, the pure thinking in which the ego can live and maintain a firm footing. Then, when pure thinking has been grasped in this way, one can strive for something else. This thinking, left in the power of an ego that now feels itself to be liberated within free spirituality [frei und unabhängig in freier Geistigkeit], can then be excluded from the process of perception. Whereas in ordinary life one sees color, let us say, and at the same time imbues the color with conceptual activity, one can now extract the concepts from the entire process of elaborating percepts and draw the percept itself directly into ones bodily constitution. Goethe undertook to do this and has already taken the First steps in this direction. Read the last chapter of his Theory of Colors, entitled “The Sensory-Moral Effect of Color”: in every color-effect he experiences something that unites itself profoundly not only with the faculty of perception but with the whole man. He experiences yellow and scarlet as “attacking” colors, penetrating him, as it were, through and through, filling him with warmth, while he regards blue and violet as colors that draw one out of oneself, as cold colors. The whole man experiences something in the act of sense perception. Sense perception, together with its content, passes down into the organism, and the ego with its pure thought content remains, so to speak, hovering above. We exclude thinking inasmuch as we take into and fill ourselves with the whole content of the perception, instead of weakening it with concepts, as we usually do. We train ourselves specially to achieve this by systematically pursuing what came to be practiced in a decadent form by the men of the East. Instead of grasping the content of the perception in pure, strictly logical thought, we grasp it symbolically, in pictures, allowing it to stream into us as a result of a kind of detour around thinking. We steep ourselves in the richness of the colors, the richness of the tone, by learning to experience the images inwardly, not in terms of thought but as pictures, as symbols. Because we do not suffuse our inner life with the thought content, as the psychology of association would have it, but with the content of perception indicated through symbols and pictures, the living inner forces of the etheric and astral bodies stream toward us from within, and we come to know the depths of consciousness and of the soul. It is in this way that genuine knowledge of the inner nature of man is acquired, and not by means of the blathering mysticism that nebulous minds often claim to be a way to the God within. This mysticism leads to nothing but abstraction and cannot satisfy anyone who wishes to become a man in the full sense of the ward. If one desires to do real research concerning human physiology, thinking must be excluded and the picture-forming activity sent inward, so that the physical organism reacts by creating Imaginations. This is a path that is only just beginning in the development of Western culture, but it is the path that must be trodden if the influence that streams over from the East, and would lead to decadence if it atone were to prevail, is to be confronted with something capable of opposing it, so that our civilization may take a path of ascent and not of decline. Generally speaking, however, it can be said that human language itself is not yet sufficiently developed to be able to give full expression to the experiences that one undergoes in the inner recesses of the soul. And it is at this point that I would like to relate a personal experience to you. Many years ago, in a different context, I made an attempt to give expression to what might be called a science of the human senses. In spoken lectures I succeeded to some extent in putting this science of the twelve senses into words, because in speaking it is more possible to turn language this way and that and ensure understanding by means of repetitions, so that the deficiencies of our language, which is not yet capable of expressing these super-sensible things, is not so strongly felt. Strangely enough, however, when I wanted many years ago to write down what I had given as actual anthroposophy in order to put it into a form suitable for a book, the outer experiences an being interiorized became so sensitive that language simply failed to provide the words, and I believe that the beginning of the text—several sheets of print—lay for some five or six years at the printer's. It was because I wanted to write the whole book in the style in which it began that I could not continue writing, for the simple reason that at the stage of development I had then reached, language refused to furnish the means for what I wished to achieve. Afterward I became overloaded with work, and I still have not been able to finish the book. Anyone who is less conscientious about what he communicates to his fellow men out of the spiritual world might perhaps smile at the idea of being held up in this way by a temporarily insurmountable difficulty. But whoever really experiences and can permeate with a full sense of responsibility what occurs when one attempts to describe the path that Western humanity must follow to attain Imagination knows that to find the right words entails a great deal of effort. As a meditative schooling it is relatively easy to describe, and this has been done in my book, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment. If one's aim, however, is to achieve definite results such as that of describing the essential nature of man's senses—a part, therefore, of the inner makeup and constitution of humanity—it is then that one encounters the difficulty of grasping Imaginations and presenting them in sharp contours by means of words. Nevertheless, this is the path that Western humanity must follow. And just as the man of the East was able to experience through his mantras the entry into the spiritual nature of the external world, so must the Westerner, leaving aside the entire psychology of association, learn to enter into his own being by attaining the realm of Imagination. Only by penetrating into the realm of Imagination will he acquire the true knowledge of humanity that is necessary in order for humanity to progress. And because we in the West must live much more consciously than the men of the East, we cannot simply say: whether or not humanity will gradually attain this realm of Imagination is something that can be left to the future. No—this world of Imagination, because we have passed into the stage of conscious human evolution, must be striven for consciously; there can be no halting at certain stages. For what happens if one halts at a certain stage? Then one does not meet the ever-increasing spread of skepticism from East to West with the right countermeasures but with measures that result from the soul-spirit uniting too radically, too deeply and unconsciously, with the physical body, so that too strong a connection is formed between the soul-spirit and the physical body. Yes, it is indeed possible for a human being not only to think materialistically but to be a materialist, because the soul-spirit is too strongly linked with the physical body. In such a man the ego does not live freely in the concepts of pure thinking he has attained. If one descends into the body with pictorial perception, one delves with the ego and the concepts into the body. And if one then spreads this around and suffuses it throughout humanity, it gives rise to a spiritual phenomenon well known to us—dogmatism of all kinds. Dogmatism is nothing other than the translation into the realm of the soul-spirit of a condition that at a lower stage manifests itself pathologically as agoraphobia and the like, and that—because these things are related—also shows itself in something else, which is a metamorphosis of fear, in superstition of every variety. An unconscious urge toward Imagination is held back through powerful agencies, and this gives rise to dogmatism of all types. These types of dogmatism must gradually be replaced by what is achieved when the world of ideas is kept within the sphere of the ego; when progress is made toward Imagination, the true nature of man is experienced inwardly, and this Western path into the spiritual world is followed in a different way. It is this other path through Imagination that must establish the stream of spiritual science, the process of spiritual evolution that muss make its way from West to East if humanity is to progress. It is supremely important at the present time, however, for humanity to recognize what the true path of Imagination should be, what path must be taken by Western spiritual science if it is to be a match for the Inspiration and its fruits that were attained by ancient Eastern wisdom in a form suited to the racial characteristics of those peoples. Only if we are able to confront the now decadent Inspiration of the East with Imaginations which, sustained by the spirit and saturated with reality, have arisen along the path leading to a higher spiritual culture; only if we can call this culture into existence as a stream of spiritual life flowing from West to East, are we bringing to fulfillment what is actually living deep within the impulses for which humanity is striving. It is these impulses that are now exploding in social cataclysms because they cannot find other expression. In tomorrow's lecture we will speak further of the path of Imagination and of how the way to the higher worlds is envisaged by anthroposophical spiritual science. |

| 322. The Boundaries of Natural Science: Lecture VIII

03 Oct 1920, Dornach Translated by Frederick Amrine, Konrad Oberhuber |

|---|

| 322. The Boundaries of Natural Science: Lecture VIII

03 Oct 1920, Dornach Translated by Frederick Amrine, Konrad Oberhuber |

|---|